User login

Being overweight ups risk of severe COVID-19 in hospital

In a global meta-analysis of more than 7,000 patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19, individuals with overweight or obesity were more likely to need respiratory support but were not more likely to die in the hospital, compared to individuals of normal weight.

Compared to patients without diabetes, those with diabetes had higher odds of needing invasive respiratory support (with intubation) but not for needing noninvasive respiratory support or of dying in the hospital.

“Surprisingly,” among patients with diabetes, being overweight or having obesity did not further increase the odds of any of these outcomes, the researchers wrote. The finding needs to be confirmed in larger studies, they said, because the sample sizes in these subanalyses were small and the confidence intervals were large.

The study by Danielle K. Longmore, PhD, of Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI), Melbourne, and colleagues from the International BMI-COVID consortium, was published online April 15 in Diabetes Care.

This new research “adds to the known data on the associations between obesity and severe COVID-19 disease and extends these findings” to patients who are overweight and/or have diabetes, Dr. Longmore, a pediatric endocrinologist with a clinical and research interest in childhood and youth obesity, said in an interview.

Immunologist Siroon Bekkering, PhD, of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, explained that never before have so much data of different types regarding obesity been combined in one large study. Dr. Bekkering is a coauthor of the article and was a principal investigator.

“Several national and international observations already showed the important role of overweight and obesity in a more severe COVID-19 course. This study adds to those observations by combining data from several countries with the possibility to look at the risk factors separately,” she said in a statement from her institution.

“Regardless of other risk factors (such as heart disease or diabetes), we now see that too high a BMI [body mass index] can actually lead to a more severe course in [coronavirus] infection,” she said.

Study implications: Data show that overweight, obesity add to risk

These latest findings highlight the urgent need to develop public health policies to address socioeconomic and psychological drivers of obesity, Dr. Longmore said.

“Although taking steps to address obesity in the short term is unlikely to have an immediate impact in the COVID-19 pandemic, it will likely reduce the disease burden in future viral pandemics and reduce risks of complications like heart disease and stroke,” she observed in a statement issued by MCRI.

Coauthor Kirsty R. Short, PhD, a research fellow at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, noted that “obesity is associated with numerous poor health outcomes, including increased risk of cardiometabolic and respiratory disease and more severe viral disease including influenza, dengue, and SARS-CoV-1.

“Given the large scale of this study,” she said, “we have conclusively shown that being overweight or obese are independent risk factors for worse outcomes in adults hospitalized with COVID-19.”

“At the moment, the World Health Organization has not had enough high-quality data to include being overweight or obese as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease,” added another author, David P. Burgner, PhD, a pediatric infectious diseases clinician scientist from MCRI.

“Our study should help inform decisions about which higher-risk groups should be vaccinated as a priority,” he observed.

Does being overweight up risk of worse COVID-19 outcomes?

About 13% of the world’s population are overweight, and 40% have obesity. There are wide between-country variations in these data, and about 90% of patients with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese, the researchers noted.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reported that the prevalence of obesity in 2016-2017 was 5.7% to 8.9% in Asia, 9.8% to 16.8% in Europe, 26.5% in South Africa, and 40.0% in the United States, they added.

Obesity is common and has emerged as an important risk factor for severe COVID-19. However, most previous studies of COVID-19 and elevated BMI were conducted in single centers and did not focus on patients with overweight.

To investigate, the researchers identified 7,244 patients (two-thirds were overweight or obese) who were hospitalized with COVID-19 in 69 hospitals (18 sites) in 11 countries from Jan. 17, 2020, to June 2, 2020.

Most patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the Netherlands (2,260), followed by New York City (1,682), Switzerland (920), St. Louis (805), Norway, Italy, China, South Africa, Indonesia, Denmark, Los Angeles, Austria, and Singapore.

Just over half (60%) of the individuals were male, and 52% were older than 65.

Overall, 34.8% were overweight, and 30.8% had obesity, but the average weight varied considerably between countries and sites.

Increased need for respiratory support, same mortality risk

Compared with patients with normal weight, patients who were overweight had a 44% increased risk of needing supplemental oxygen/noninvasive ventilation, and those with obesity had a 75% increased risk of this, after adjustment for age (< 65, ≥ 65), sex, hypertension, diabetes, or preexisting cardiovascular disease or respiratory conditions.

Patients who were overweight had a 22% increased risk of needing invasive (mechanical) ventilation, and those with obesity had a 73% increased risk of this, after multivariable adjustment.

Being overweight or having obesity was not associated with a significantly increased risk of dying in the hospital, however.

“In other viral respiratory infections, such as influenza, there is a similar pattern of increased requirement for ventilatory support but lower in-hospital mortality among individuals with obesity, when compared to those with normal range BMI,” Dr. Longmore noted. She said that larger studies are needed to further explore this finding regarding COVID-19.

Compared to patients without diabetes, those with diabetes had a 21% increased risk of requiring invasive ventilation, but they did not have an increased risk of needing noninvasive ventilation or of dying in the hospital.

As in previous studies, individuals who had cardiovascular and preexisting respiratory diseases were not at greater risk of needing oxygen or mechanical ventilation but were at increased risk for in-hospital death. Men had a greater risk of needing invasive mechanical ventilation, and individuals who were older than 65 had an increased risk of requiring oxygen or of dying in the hospital.

A living meta-analysis, call for more collaborators

“We consider this a ‘living meta-analysis’ and invite other centers to join us,” Dr. Longmore said. “We hope to update the analyses as more data are contributed.”

No specific project funded the study. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a global meta-analysis of more than 7,000 patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19, individuals with overweight or obesity were more likely to need respiratory support but were not more likely to die in the hospital, compared to individuals of normal weight.

Compared to patients without diabetes, those with diabetes had higher odds of needing invasive respiratory support (with intubation) but not for needing noninvasive respiratory support or of dying in the hospital.

“Surprisingly,” among patients with diabetes, being overweight or having obesity did not further increase the odds of any of these outcomes, the researchers wrote. The finding needs to be confirmed in larger studies, they said, because the sample sizes in these subanalyses were small and the confidence intervals were large.

The study by Danielle K. Longmore, PhD, of Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI), Melbourne, and colleagues from the International BMI-COVID consortium, was published online April 15 in Diabetes Care.

This new research “adds to the known data on the associations between obesity and severe COVID-19 disease and extends these findings” to patients who are overweight and/or have diabetes, Dr. Longmore, a pediatric endocrinologist with a clinical and research interest in childhood and youth obesity, said in an interview.

Immunologist Siroon Bekkering, PhD, of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, explained that never before have so much data of different types regarding obesity been combined in one large study. Dr. Bekkering is a coauthor of the article and was a principal investigator.

“Several national and international observations already showed the important role of overweight and obesity in a more severe COVID-19 course. This study adds to those observations by combining data from several countries with the possibility to look at the risk factors separately,” she said in a statement from her institution.

“Regardless of other risk factors (such as heart disease or diabetes), we now see that too high a BMI [body mass index] can actually lead to a more severe course in [coronavirus] infection,” she said.

Study implications: Data show that overweight, obesity add to risk

These latest findings highlight the urgent need to develop public health policies to address socioeconomic and psychological drivers of obesity, Dr. Longmore said.

“Although taking steps to address obesity in the short term is unlikely to have an immediate impact in the COVID-19 pandemic, it will likely reduce the disease burden in future viral pandemics and reduce risks of complications like heart disease and stroke,” she observed in a statement issued by MCRI.

Coauthor Kirsty R. Short, PhD, a research fellow at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, noted that “obesity is associated with numerous poor health outcomes, including increased risk of cardiometabolic and respiratory disease and more severe viral disease including influenza, dengue, and SARS-CoV-1.

“Given the large scale of this study,” she said, “we have conclusively shown that being overweight or obese are independent risk factors for worse outcomes in adults hospitalized with COVID-19.”

“At the moment, the World Health Organization has not had enough high-quality data to include being overweight or obese as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease,” added another author, David P. Burgner, PhD, a pediatric infectious diseases clinician scientist from MCRI.

“Our study should help inform decisions about which higher-risk groups should be vaccinated as a priority,” he observed.

Does being overweight up risk of worse COVID-19 outcomes?

About 13% of the world’s population are overweight, and 40% have obesity. There are wide between-country variations in these data, and about 90% of patients with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese, the researchers noted.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reported that the prevalence of obesity in 2016-2017 was 5.7% to 8.9% in Asia, 9.8% to 16.8% in Europe, 26.5% in South Africa, and 40.0% in the United States, they added.

Obesity is common and has emerged as an important risk factor for severe COVID-19. However, most previous studies of COVID-19 and elevated BMI were conducted in single centers and did not focus on patients with overweight.

To investigate, the researchers identified 7,244 patients (two-thirds were overweight or obese) who were hospitalized with COVID-19 in 69 hospitals (18 sites) in 11 countries from Jan. 17, 2020, to June 2, 2020.

Most patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the Netherlands (2,260), followed by New York City (1,682), Switzerland (920), St. Louis (805), Norway, Italy, China, South Africa, Indonesia, Denmark, Los Angeles, Austria, and Singapore.

Just over half (60%) of the individuals were male, and 52% were older than 65.

Overall, 34.8% were overweight, and 30.8% had obesity, but the average weight varied considerably between countries and sites.

Increased need for respiratory support, same mortality risk

Compared with patients with normal weight, patients who were overweight had a 44% increased risk of needing supplemental oxygen/noninvasive ventilation, and those with obesity had a 75% increased risk of this, after adjustment for age (< 65, ≥ 65), sex, hypertension, diabetes, or preexisting cardiovascular disease or respiratory conditions.

Patients who were overweight had a 22% increased risk of needing invasive (mechanical) ventilation, and those with obesity had a 73% increased risk of this, after multivariable adjustment.

Being overweight or having obesity was not associated with a significantly increased risk of dying in the hospital, however.

“In other viral respiratory infections, such as influenza, there is a similar pattern of increased requirement for ventilatory support but lower in-hospital mortality among individuals with obesity, when compared to those with normal range BMI,” Dr. Longmore noted. She said that larger studies are needed to further explore this finding regarding COVID-19.

Compared to patients without diabetes, those with diabetes had a 21% increased risk of requiring invasive ventilation, but they did not have an increased risk of needing noninvasive ventilation or of dying in the hospital.

As in previous studies, individuals who had cardiovascular and preexisting respiratory diseases were not at greater risk of needing oxygen or mechanical ventilation but were at increased risk for in-hospital death. Men had a greater risk of needing invasive mechanical ventilation, and individuals who were older than 65 had an increased risk of requiring oxygen or of dying in the hospital.

A living meta-analysis, call for more collaborators

“We consider this a ‘living meta-analysis’ and invite other centers to join us,” Dr. Longmore said. “We hope to update the analyses as more data are contributed.”

No specific project funded the study. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a global meta-analysis of more than 7,000 patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19, individuals with overweight or obesity were more likely to need respiratory support but were not more likely to die in the hospital, compared to individuals of normal weight.

Compared to patients without diabetes, those with diabetes had higher odds of needing invasive respiratory support (with intubation) but not for needing noninvasive respiratory support or of dying in the hospital.

“Surprisingly,” among patients with diabetes, being overweight or having obesity did not further increase the odds of any of these outcomes, the researchers wrote. The finding needs to be confirmed in larger studies, they said, because the sample sizes in these subanalyses were small and the confidence intervals were large.

The study by Danielle K. Longmore, PhD, of Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI), Melbourne, and colleagues from the International BMI-COVID consortium, was published online April 15 in Diabetes Care.

This new research “adds to the known data on the associations between obesity and severe COVID-19 disease and extends these findings” to patients who are overweight and/or have diabetes, Dr. Longmore, a pediatric endocrinologist with a clinical and research interest in childhood and youth obesity, said in an interview.

Immunologist Siroon Bekkering, PhD, of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, explained that never before have so much data of different types regarding obesity been combined in one large study. Dr. Bekkering is a coauthor of the article and was a principal investigator.

“Several national and international observations already showed the important role of overweight and obesity in a more severe COVID-19 course. This study adds to those observations by combining data from several countries with the possibility to look at the risk factors separately,” she said in a statement from her institution.

“Regardless of other risk factors (such as heart disease or diabetes), we now see that too high a BMI [body mass index] can actually lead to a more severe course in [coronavirus] infection,” she said.

Study implications: Data show that overweight, obesity add to risk

These latest findings highlight the urgent need to develop public health policies to address socioeconomic and psychological drivers of obesity, Dr. Longmore said.

“Although taking steps to address obesity in the short term is unlikely to have an immediate impact in the COVID-19 pandemic, it will likely reduce the disease burden in future viral pandemics and reduce risks of complications like heart disease and stroke,” she observed in a statement issued by MCRI.

Coauthor Kirsty R. Short, PhD, a research fellow at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, noted that “obesity is associated with numerous poor health outcomes, including increased risk of cardiometabolic and respiratory disease and more severe viral disease including influenza, dengue, and SARS-CoV-1.

“Given the large scale of this study,” she said, “we have conclusively shown that being overweight or obese are independent risk factors for worse outcomes in adults hospitalized with COVID-19.”

“At the moment, the World Health Organization has not had enough high-quality data to include being overweight or obese as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease,” added another author, David P. Burgner, PhD, a pediatric infectious diseases clinician scientist from MCRI.

“Our study should help inform decisions about which higher-risk groups should be vaccinated as a priority,” he observed.

Does being overweight up risk of worse COVID-19 outcomes?

About 13% of the world’s population are overweight, and 40% have obesity. There are wide between-country variations in these data, and about 90% of patients with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese, the researchers noted.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reported that the prevalence of obesity in 2016-2017 was 5.7% to 8.9% in Asia, 9.8% to 16.8% in Europe, 26.5% in South Africa, and 40.0% in the United States, they added.

Obesity is common and has emerged as an important risk factor for severe COVID-19. However, most previous studies of COVID-19 and elevated BMI were conducted in single centers and did not focus on patients with overweight.

To investigate, the researchers identified 7,244 patients (two-thirds were overweight or obese) who were hospitalized with COVID-19 in 69 hospitals (18 sites) in 11 countries from Jan. 17, 2020, to June 2, 2020.

Most patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the Netherlands (2,260), followed by New York City (1,682), Switzerland (920), St. Louis (805), Norway, Italy, China, South Africa, Indonesia, Denmark, Los Angeles, Austria, and Singapore.

Just over half (60%) of the individuals were male, and 52% were older than 65.

Overall, 34.8% were overweight, and 30.8% had obesity, but the average weight varied considerably between countries and sites.

Increased need for respiratory support, same mortality risk

Compared with patients with normal weight, patients who were overweight had a 44% increased risk of needing supplemental oxygen/noninvasive ventilation, and those with obesity had a 75% increased risk of this, after adjustment for age (< 65, ≥ 65), sex, hypertension, diabetes, or preexisting cardiovascular disease or respiratory conditions.

Patients who were overweight had a 22% increased risk of needing invasive (mechanical) ventilation, and those with obesity had a 73% increased risk of this, after multivariable adjustment.

Being overweight or having obesity was not associated with a significantly increased risk of dying in the hospital, however.

“In other viral respiratory infections, such as influenza, there is a similar pattern of increased requirement for ventilatory support but lower in-hospital mortality among individuals with obesity, when compared to those with normal range BMI,” Dr. Longmore noted. She said that larger studies are needed to further explore this finding regarding COVID-19.

Compared to patients without diabetes, those with diabetes had a 21% increased risk of requiring invasive ventilation, but they did not have an increased risk of needing noninvasive ventilation or of dying in the hospital.

As in previous studies, individuals who had cardiovascular and preexisting respiratory diseases were not at greater risk of needing oxygen or mechanical ventilation but were at increased risk for in-hospital death. Men had a greater risk of needing invasive mechanical ventilation, and individuals who were older than 65 had an increased risk of requiring oxygen or of dying in the hospital.

A living meta-analysis, call for more collaborators

“We consider this a ‘living meta-analysis’ and invite other centers to join us,” Dr. Longmore said. “We hope to update the analyses as more data are contributed.”

No specific project funded the study. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

IV drug users: The new face of candidemia

Background: Intravenous drug use is an increasingly common risk factor for candidemia as the opioid crisis worsens. This study quantifies this change and characterizes the changing epidemiology of candidemia.

Study design: A cross-sectional study.

Setting: Health departments in nine states.

Synopsis: IV drug users typically have a very distinctive phenotype among all patients with candidemia: They are younger (35 vs. 63 years), are more likely to be homeless, are not black, are smokers; they have hepatitis C, have no malignancies, have polymicrobial bacteremia, and have acquired the infection outside of the hospital. They are much less likely to die of the infection (8.6% vs 27.5%), compared with the non-IV drug users. In four states, the proportion of candidemia associated with IV drug use more than doubled, from 7% to 15% during 2014-2017, representing a possible shift in the epidemiology of candidemia.

The study did not quantify or address complications that many hospitalists see, such as endocarditis, endophthalmitis, and osteomyelitis. The study looked at only nine states, so results may not be generalizable. Nevertheless, the robust analysis suggests an alarming, increasing trend.

Bottom line: As the opioid crisis worsens, hospitalists should consider candidemia in hospitalized IV drug users and should evaluate patients with candidemia for IV drug use.

Citation: Zhang AY et al. The changing epidemiology of candidemia in the United States: Injection drug use as an increasingly common risk factor – Active surveillance in selected sites, United States, 2014-2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Nov 2. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1061.

Dr. Raghavan is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Background: Intravenous drug use is an increasingly common risk factor for candidemia as the opioid crisis worsens. This study quantifies this change and characterizes the changing epidemiology of candidemia.

Study design: A cross-sectional study.

Setting: Health departments in nine states.

Synopsis: IV drug users typically have a very distinctive phenotype among all patients with candidemia: They are younger (35 vs. 63 years), are more likely to be homeless, are not black, are smokers; they have hepatitis C, have no malignancies, have polymicrobial bacteremia, and have acquired the infection outside of the hospital. They are much less likely to die of the infection (8.6% vs 27.5%), compared with the non-IV drug users. In four states, the proportion of candidemia associated with IV drug use more than doubled, from 7% to 15% during 2014-2017, representing a possible shift in the epidemiology of candidemia.

The study did not quantify or address complications that many hospitalists see, such as endocarditis, endophthalmitis, and osteomyelitis. The study looked at only nine states, so results may not be generalizable. Nevertheless, the robust analysis suggests an alarming, increasing trend.

Bottom line: As the opioid crisis worsens, hospitalists should consider candidemia in hospitalized IV drug users and should evaluate patients with candidemia for IV drug use.

Citation: Zhang AY et al. The changing epidemiology of candidemia in the United States: Injection drug use as an increasingly common risk factor – Active surveillance in selected sites, United States, 2014-2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Nov 2. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1061.

Dr. Raghavan is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Background: Intravenous drug use is an increasingly common risk factor for candidemia as the opioid crisis worsens. This study quantifies this change and characterizes the changing epidemiology of candidemia.

Study design: A cross-sectional study.

Setting: Health departments in nine states.

Synopsis: IV drug users typically have a very distinctive phenotype among all patients with candidemia: They are younger (35 vs. 63 years), are more likely to be homeless, are not black, are smokers; they have hepatitis C, have no malignancies, have polymicrobial bacteremia, and have acquired the infection outside of the hospital. They are much less likely to die of the infection (8.6% vs 27.5%), compared with the non-IV drug users. In four states, the proportion of candidemia associated with IV drug use more than doubled, from 7% to 15% during 2014-2017, representing a possible shift in the epidemiology of candidemia.

The study did not quantify or address complications that many hospitalists see, such as endocarditis, endophthalmitis, and osteomyelitis. The study looked at only nine states, so results may not be generalizable. Nevertheless, the robust analysis suggests an alarming, increasing trend.

Bottom line: As the opioid crisis worsens, hospitalists should consider candidemia in hospitalized IV drug users and should evaluate patients with candidemia for IV drug use.

Citation: Zhang AY et al. The changing epidemiology of candidemia in the United States: Injection drug use as an increasingly common risk factor – Active surveillance in selected sites, United States, 2014-2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Nov 2. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1061.

Dr. Raghavan is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Head to Toe: Recommendations for Physician Head and Shoe Coverings to Limit COVID-19 Transmission

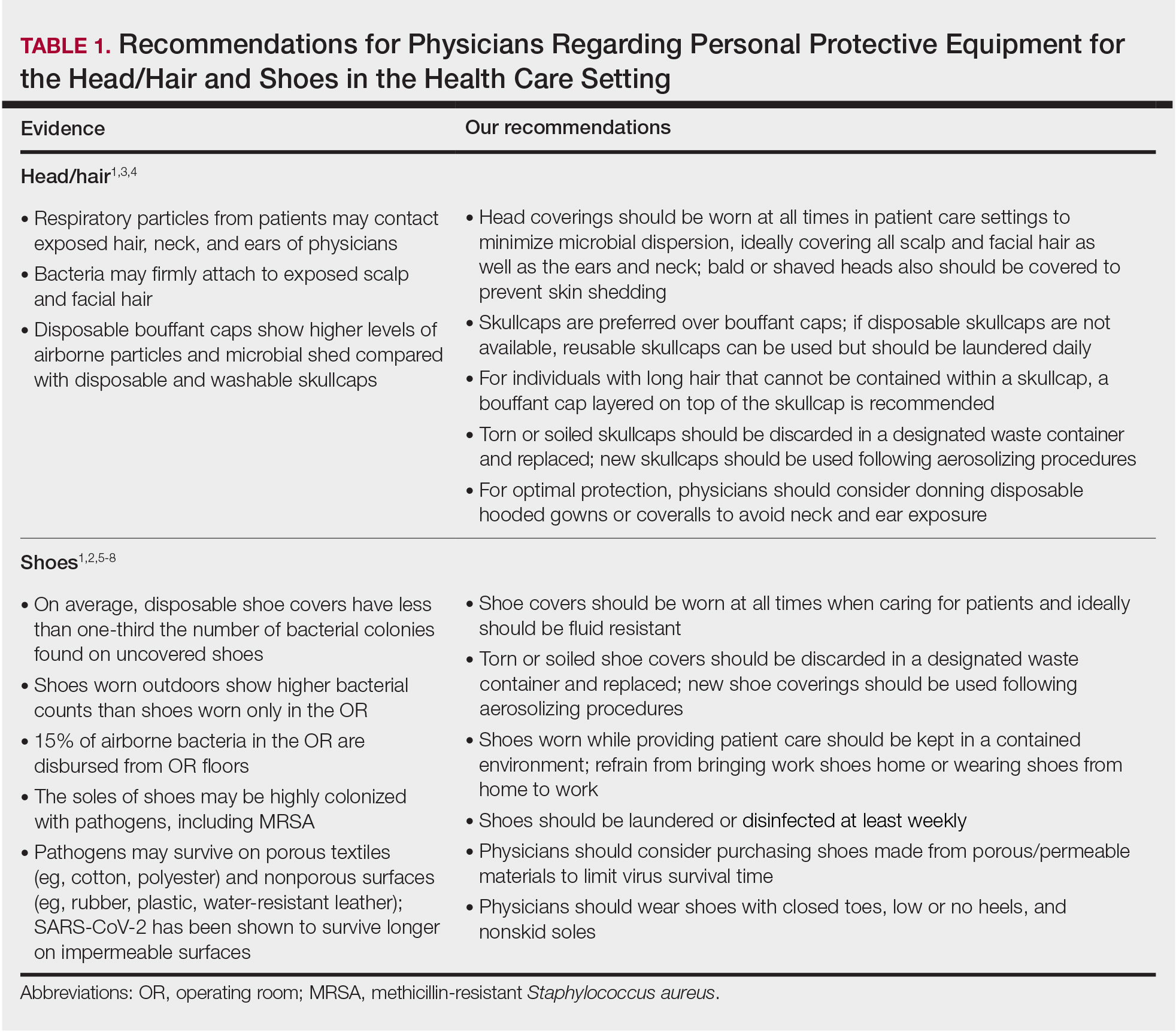

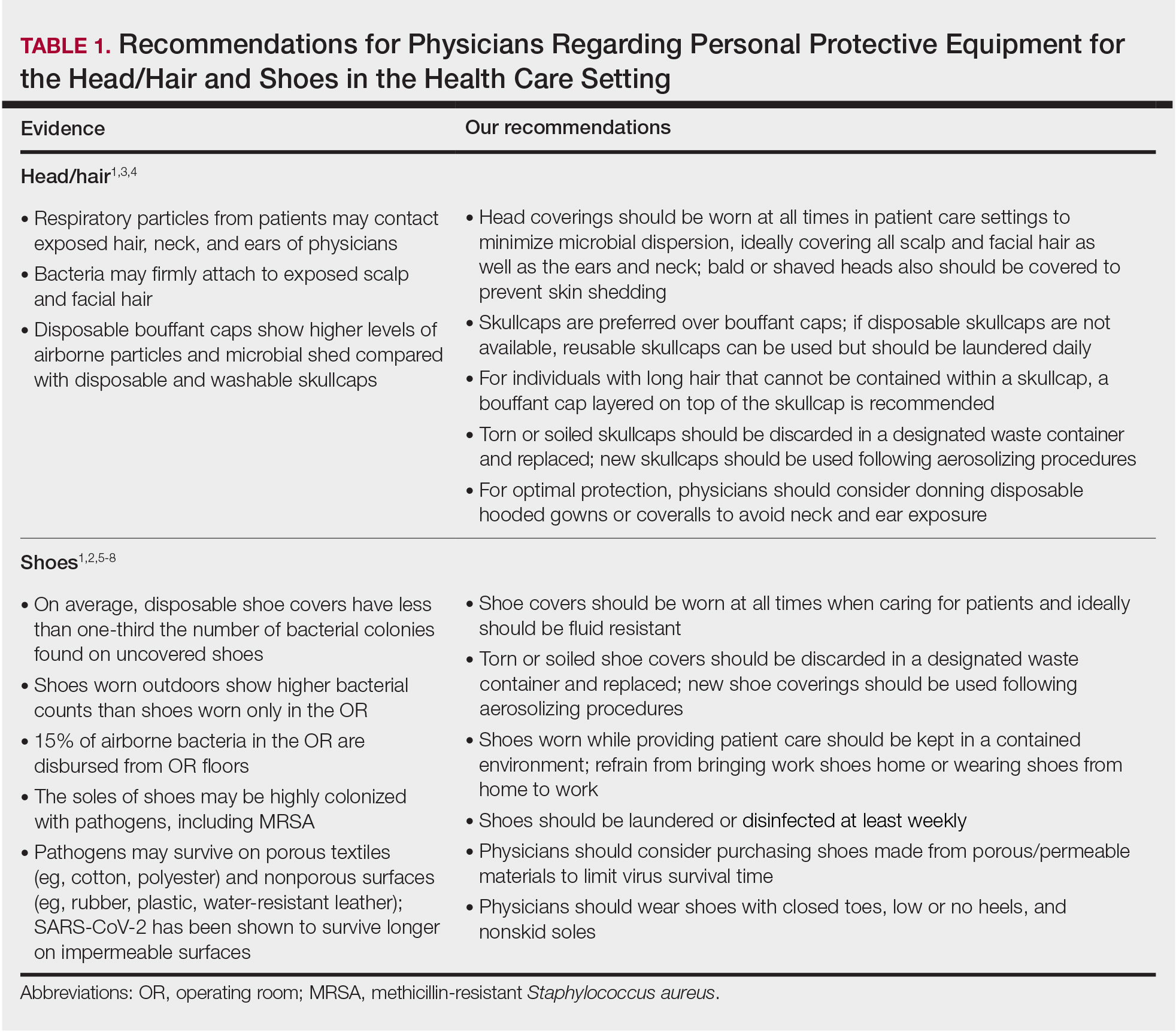

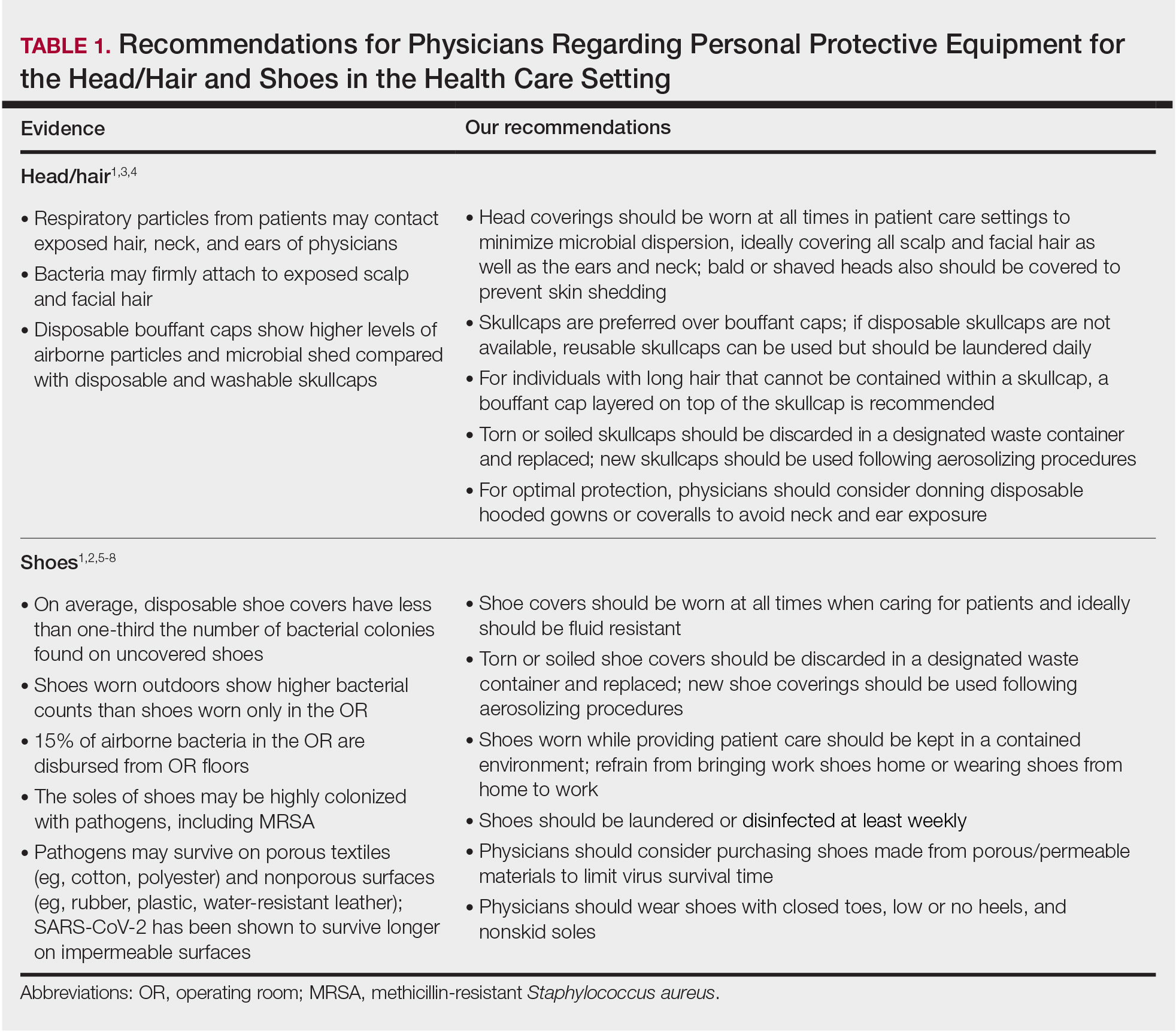

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is an important component in limiting transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines for appropriate PPE use, but recommendations for head and shoe coverings are lacking. In this article, we analyze the literature on pathogen transmission via hair and shoes and make evidence-based recommendations for PPE selection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pathogens on Shoes and Hair

Hair and shoes may act as vehicles for pathogen transmission. In a study that simulated contamination of uncovered skin in health care workers after intubating manikins in respiratory distress, 8 (100%) had fluorescent markers on the hair, 6 (75%) on the neck, and 4 (50%) on the shoes.1 In another study of postsurgical operating room (OR) surfaces (517 cultures), uncovered shoe tops and reusable hair coverings had 10-times more bacterial colony–forming units compared to other surfaces. On average, disposable shoe covers/head coverings had less than one-third bacterial colony–forming units compared with uncovered shoes/reusable hair coverings.2

Hair characteristics and coverings may affect pathogen transmission. Exposed hair may collect bacteria, as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis attach to both scalp and facial hair. In one case, β-hemolytic streptococci cultured from the scalp of a perioperative nurse was linked to postsurgical infections in 20 patients.3 Hair coverings include bouffant caps and skullcaps. The bouffant cap is similar to a shower cap; it is relatively loose and secured around the head with elastic. The skullcap, or scrub cap, is tighter but leaves the neck nape and sideburns exposed. In a study comparing disposable bouffant caps, disposable skullcaps, and home-laundered cloth skullcaps worn by 2 teams of 5 surgeons, the disposable bouffant caps had the highest permeability, penetration, and microbial shed of airborne particles.4

Physicians’ shoes may act as fomites for transmission of pathogens to patients. In a study of 41 physicians and nurses in an acute care hospital, shoe soles were positive for at least one pathogen in 12 (29.3%) participants; methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was most common. Additionally, 98% (49/50) of shoes worn outdoors showed positive bacterial cultures compared to 56% (28/50) of shoes reserved for the OR only.5 In a study examining ventilation effects on airborne pathogens in the OR, 15% of OR airborne bacteria originated from OR floors, and higher bacterial counts correlated with a higher number of steps in the OR.2 In another study designed to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 distribution on hospital floors, 70% (7/10) of quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays performed on floor samples from intensive care units were positive. In addition, 100% (3/3) of swabs taken from hospital pharmacy floors with no COVID-19 patients were positive for SARS-CoV-2, meaning contaminated shoes likely served as vectors.6 Middle East respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza viruses may survive on porous and nonporous materials for hours to days.7Enterococcus, Candida, and Aspergillus may survive on textiles for up to 90 days.3

Recommendations for Hair and Shoe Coverings

We recommend that physicians utilize disposable skullcaps to cover the hair and consider a hooded gown or coverall for neck/ear coverage. We also recommend that physicians designate shoes that remain in the workplace and can be easily washed or disinfected at least weekly; physicians may choose to wash or disinfect shoes more often if they frequently are performing procedures that generate aerosols. Additionally, physicians should always wear shoe coverings when caring for patients (Table 1).

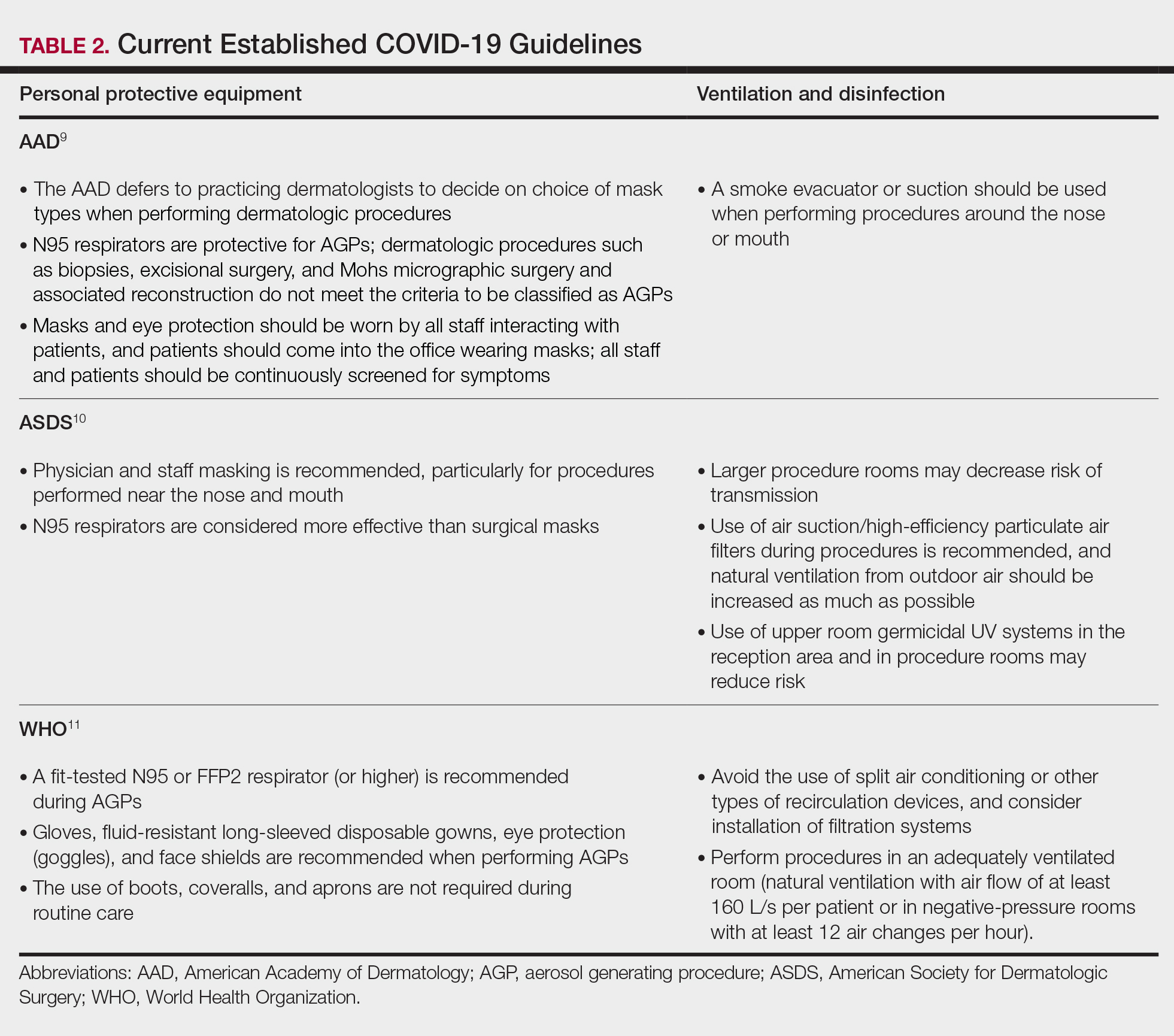

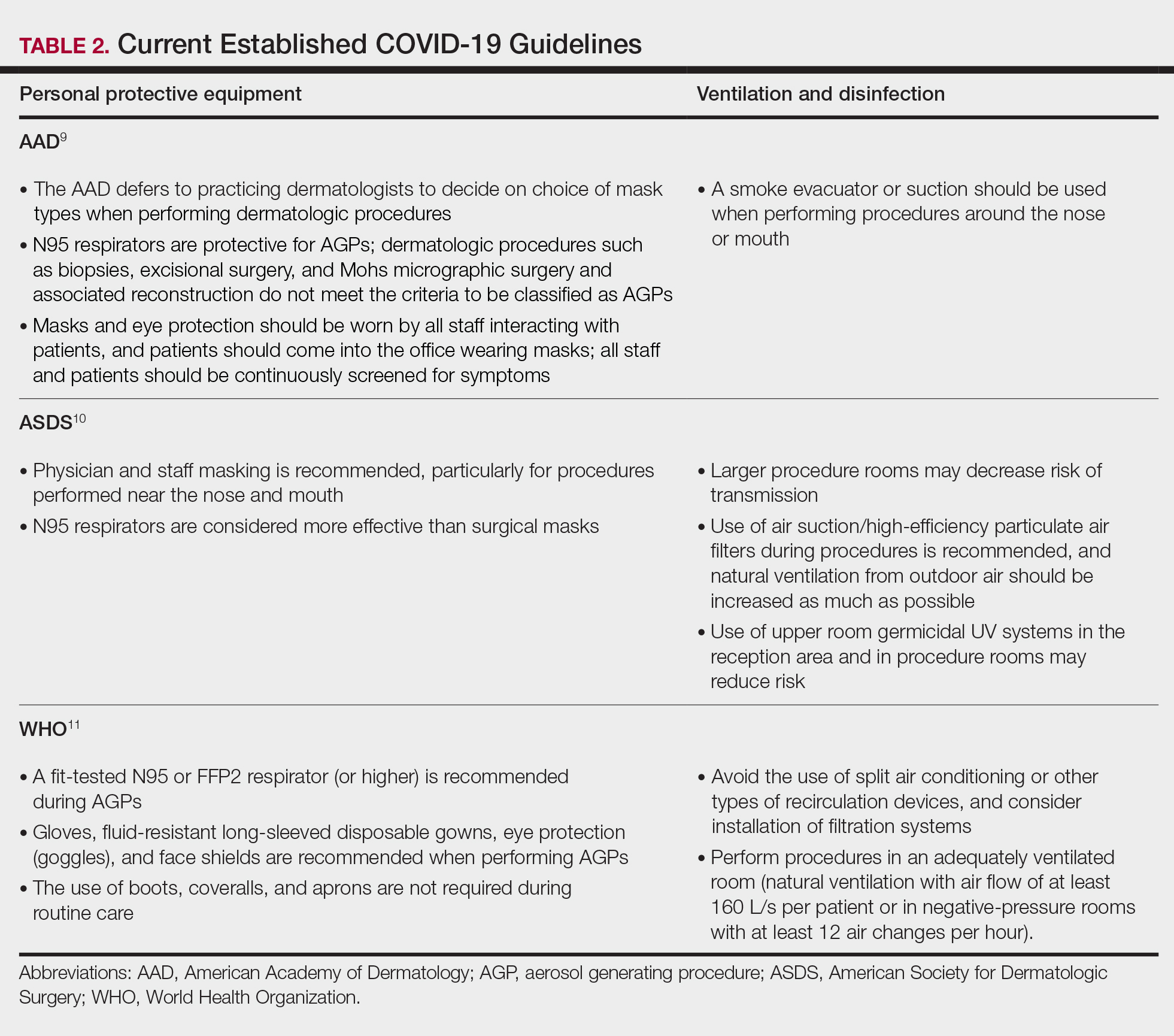

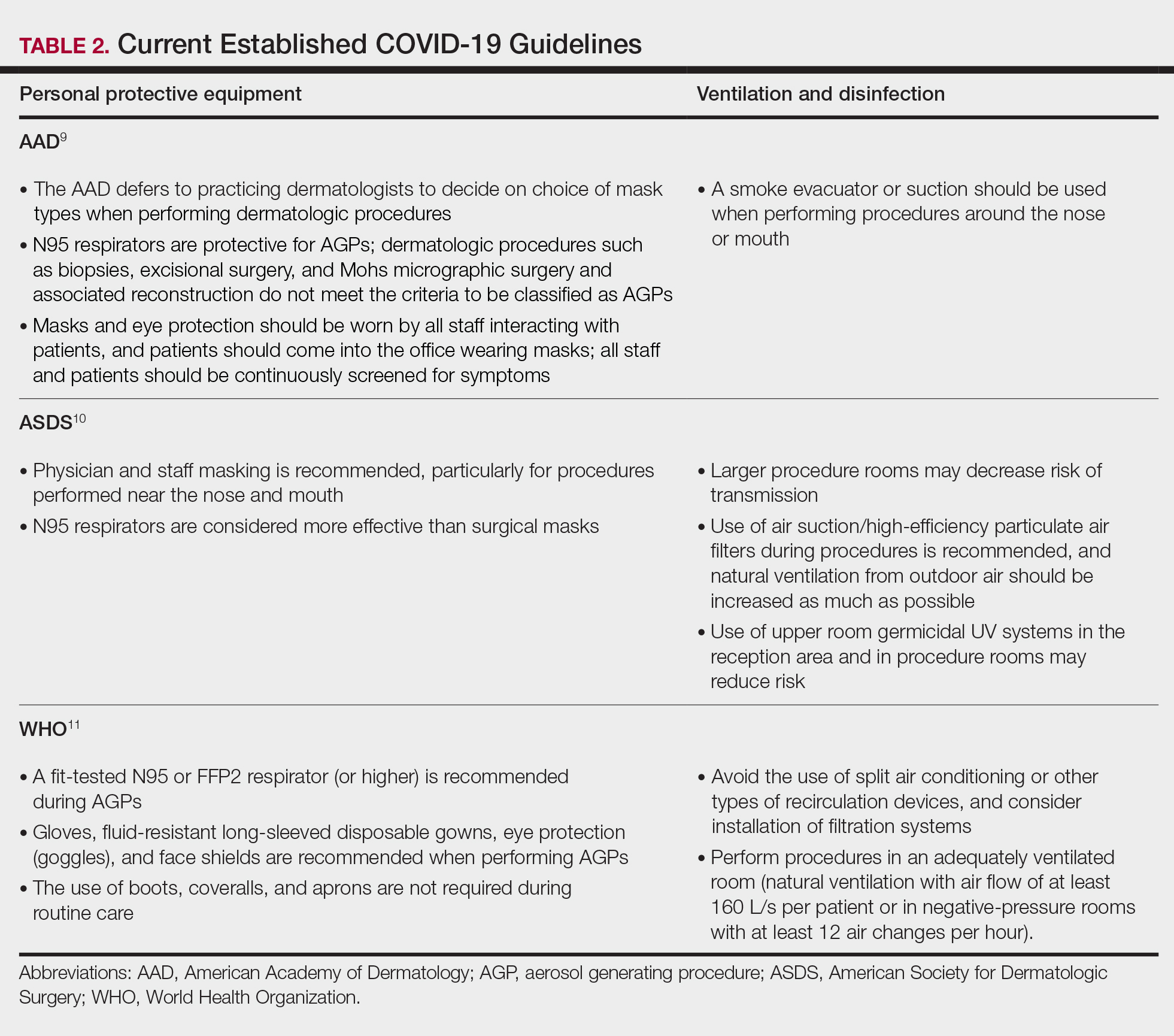

Our hair and shoe covering recommendations may serve to protect dermatologists when caring for patients. These protocols may be particularly important for dermatologists performing high-risk procedures, including facial surgery, intraoral/intranasal procedures, and treatment with ablative lasers and facial injectables, especially when the patient is unmasked. These recommendations may limit viral transmission to dermatologists and also protect individuals living in their households. Additional established guidelines by the American Academy of Dermatology, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and World Health Organization are listed in Table 2.8-10

Current PPE recommendations that do not include hair and shoe coverings may be inadequate for limiting SARS-CoV-2 exposure between and among physicians and patients. Adherence to head covering and shoe recommendations may aid in reducing unwanted SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the health care setting, even as the pandemic continues.

- Feldman O, Meir M, Shavit D, et al. Exposure to a surrogate measure of contamination from simulated patients by emergency department personnel wearing personal protective equipment. JAMA. 2020;323:2091-2093. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6633

- Alexander JW, Van Sweringen H, Vanoss K, et al. Surveillance of bacterial colonization in operating rooms. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14:345-351. doi:10.1089/sur.2012.134

- Blanchard J. Clinical issues—August 2010. AORN Journal. 2010;92:228-232. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.06.001

- Markel TA, Gormley T, Greeley D, et al. Hats off: a study of different operating room headgear assessed by environmental quality indicators. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:573-581. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.014

- Kanwar A, Thakur M, Wazzan M, et al. Clothing and shoes of personnel as potential vectors for transfer of health care-associated pathogens to the community. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:577-579. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2019.01.028

- Guo ZD, Wang ZY, Zhang SF, et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1583-1591. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200885

- Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, et al. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:235-250. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html#ref10

- American Academy of Dermatology. Clinical guidance for COVID-19. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/clinical-guidance

- Narla S, Alam M, Ozog DM, et al. American Society of Dermatologic Surgery Association (ASDSA) and American Society for Laser Medicine & Surgery (ASLMS) guidance for cosmetic dermatology practices during COVID-19. Updated January 11, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.asds.net/Portals/0/PDF/asdsa/asdsa-aslms-cosmetic-reopening-guidance.pdf

- World Health Organization. Country & technical guidance—coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance-publications

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is an important component in limiting transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines for appropriate PPE use, but recommendations for head and shoe coverings are lacking. In this article, we analyze the literature on pathogen transmission via hair and shoes and make evidence-based recommendations for PPE selection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pathogens on Shoes and Hair

Hair and shoes may act as vehicles for pathogen transmission. In a study that simulated contamination of uncovered skin in health care workers after intubating manikins in respiratory distress, 8 (100%) had fluorescent markers on the hair, 6 (75%) on the neck, and 4 (50%) on the shoes.1 In another study of postsurgical operating room (OR) surfaces (517 cultures), uncovered shoe tops and reusable hair coverings had 10-times more bacterial colony–forming units compared to other surfaces. On average, disposable shoe covers/head coverings had less than one-third bacterial colony–forming units compared with uncovered shoes/reusable hair coverings.2

Hair characteristics and coverings may affect pathogen transmission. Exposed hair may collect bacteria, as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis attach to both scalp and facial hair. In one case, β-hemolytic streptococci cultured from the scalp of a perioperative nurse was linked to postsurgical infections in 20 patients.3 Hair coverings include bouffant caps and skullcaps. The bouffant cap is similar to a shower cap; it is relatively loose and secured around the head with elastic. The skullcap, or scrub cap, is tighter but leaves the neck nape and sideburns exposed. In a study comparing disposable bouffant caps, disposable skullcaps, and home-laundered cloth skullcaps worn by 2 teams of 5 surgeons, the disposable bouffant caps had the highest permeability, penetration, and microbial shed of airborne particles.4

Physicians’ shoes may act as fomites for transmission of pathogens to patients. In a study of 41 physicians and nurses in an acute care hospital, shoe soles were positive for at least one pathogen in 12 (29.3%) participants; methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was most common. Additionally, 98% (49/50) of shoes worn outdoors showed positive bacterial cultures compared to 56% (28/50) of shoes reserved for the OR only.5 In a study examining ventilation effects on airborne pathogens in the OR, 15% of OR airborne bacteria originated from OR floors, and higher bacterial counts correlated with a higher number of steps in the OR.2 In another study designed to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 distribution on hospital floors, 70% (7/10) of quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays performed on floor samples from intensive care units were positive. In addition, 100% (3/3) of swabs taken from hospital pharmacy floors with no COVID-19 patients were positive for SARS-CoV-2, meaning contaminated shoes likely served as vectors.6 Middle East respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza viruses may survive on porous and nonporous materials for hours to days.7Enterococcus, Candida, and Aspergillus may survive on textiles for up to 90 days.3

Recommendations for Hair and Shoe Coverings

We recommend that physicians utilize disposable skullcaps to cover the hair and consider a hooded gown or coverall for neck/ear coverage. We also recommend that physicians designate shoes that remain in the workplace and can be easily washed or disinfected at least weekly; physicians may choose to wash or disinfect shoes more often if they frequently are performing procedures that generate aerosols. Additionally, physicians should always wear shoe coverings when caring for patients (Table 1).

Our hair and shoe covering recommendations may serve to protect dermatologists when caring for patients. These protocols may be particularly important for dermatologists performing high-risk procedures, including facial surgery, intraoral/intranasal procedures, and treatment with ablative lasers and facial injectables, especially when the patient is unmasked. These recommendations may limit viral transmission to dermatologists and also protect individuals living in their households. Additional established guidelines by the American Academy of Dermatology, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and World Health Organization are listed in Table 2.8-10

Current PPE recommendations that do not include hair and shoe coverings may be inadequate for limiting SARS-CoV-2 exposure between and among physicians and patients. Adherence to head covering and shoe recommendations may aid in reducing unwanted SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the health care setting, even as the pandemic continues.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is an important component in limiting transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidelines for appropriate PPE use, but recommendations for head and shoe coverings are lacking. In this article, we analyze the literature on pathogen transmission via hair and shoes and make evidence-based recommendations for PPE selection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pathogens on Shoes and Hair

Hair and shoes may act as vehicles for pathogen transmission. In a study that simulated contamination of uncovered skin in health care workers after intubating manikins in respiratory distress, 8 (100%) had fluorescent markers on the hair, 6 (75%) on the neck, and 4 (50%) on the shoes.1 In another study of postsurgical operating room (OR) surfaces (517 cultures), uncovered shoe tops and reusable hair coverings had 10-times more bacterial colony–forming units compared to other surfaces. On average, disposable shoe covers/head coverings had less than one-third bacterial colony–forming units compared with uncovered shoes/reusable hair coverings.2

Hair characteristics and coverings may affect pathogen transmission. Exposed hair may collect bacteria, as Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis attach to both scalp and facial hair. In one case, β-hemolytic streptococci cultured from the scalp of a perioperative nurse was linked to postsurgical infections in 20 patients.3 Hair coverings include bouffant caps and skullcaps. The bouffant cap is similar to a shower cap; it is relatively loose and secured around the head with elastic. The skullcap, or scrub cap, is tighter but leaves the neck nape and sideburns exposed. In a study comparing disposable bouffant caps, disposable skullcaps, and home-laundered cloth skullcaps worn by 2 teams of 5 surgeons, the disposable bouffant caps had the highest permeability, penetration, and microbial shed of airborne particles.4

Physicians’ shoes may act as fomites for transmission of pathogens to patients. In a study of 41 physicians and nurses in an acute care hospital, shoe soles were positive for at least one pathogen in 12 (29.3%) participants; methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was most common. Additionally, 98% (49/50) of shoes worn outdoors showed positive bacterial cultures compared to 56% (28/50) of shoes reserved for the OR only.5 In a study examining ventilation effects on airborne pathogens in the OR, 15% of OR airborne bacteria originated from OR floors, and higher bacterial counts correlated with a higher number of steps in the OR.2 In another study designed to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 distribution on hospital floors, 70% (7/10) of quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays performed on floor samples from intensive care units were positive. In addition, 100% (3/3) of swabs taken from hospital pharmacy floors with no COVID-19 patients were positive for SARS-CoV-2, meaning contaminated shoes likely served as vectors.6 Middle East respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza viruses may survive on porous and nonporous materials for hours to days.7Enterococcus, Candida, and Aspergillus may survive on textiles for up to 90 days.3

Recommendations for Hair and Shoe Coverings

We recommend that physicians utilize disposable skullcaps to cover the hair and consider a hooded gown or coverall for neck/ear coverage. We also recommend that physicians designate shoes that remain in the workplace and can be easily washed or disinfected at least weekly; physicians may choose to wash or disinfect shoes more often if they frequently are performing procedures that generate aerosols. Additionally, physicians should always wear shoe coverings when caring for patients (Table 1).

Our hair and shoe covering recommendations may serve to protect dermatologists when caring for patients. These protocols may be particularly important for dermatologists performing high-risk procedures, including facial surgery, intraoral/intranasal procedures, and treatment with ablative lasers and facial injectables, especially when the patient is unmasked. These recommendations may limit viral transmission to dermatologists and also protect individuals living in their households. Additional established guidelines by the American Academy of Dermatology, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, and World Health Organization are listed in Table 2.8-10

Current PPE recommendations that do not include hair and shoe coverings may be inadequate for limiting SARS-CoV-2 exposure between and among physicians and patients. Adherence to head covering and shoe recommendations may aid in reducing unwanted SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the health care setting, even as the pandemic continues.

- Feldman O, Meir M, Shavit D, et al. Exposure to a surrogate measure of contamination from simulated patients by emergency department personnel wearing personal protective equipment. JAMA. 2020;323:2091-2093. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6633

- Alexander JW, Van Sweringen H, Vanoss K, et al. Surveillance of bacterial colonization in operating rooms. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14:345-351. doi:10.1089/sur.2012.134

- Blanchard J. Clinical issues—August 2010. AORN Journal. 2010;92:228-232. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.06.001

- Markel TA, Gormley T, Greeley D, et al. Hats off: a study of different operating room headgear assessed by environmental quality indicators. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:573-581. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.014

- Kanwar A, Thakur M, Wazzan M, et al. Clothing and shoes of personnel as potential vectors for transfer of health care-associated pathogens to the community. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:577-579. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2019.01.028

- Guo ZD, Wang ZY, Zhang SF, et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1583-1591. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200885

- Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, et al. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:235-250. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html#ref10

- American Academy of Dermatology. Clinical guidance for COVID-19. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/clinical-guidance

- Narla S, Alam M, Ozog DM, et al. American Society of Dermatologic Surgery Association (ASDSA) and American Society for Laser Medicine & Surgery (ASLMS) guidance for cosmetic dermatology practices during COVID-19. Updated January 11, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.asds.net/Portals/0/PDF/asdsa/asdsa-aslms-cosmetic-reopening-guidance.pdf

- World Health Organization. Country & technical guidance—coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance-publications

- Feldman O, Meir M, Shavit D, et al. Exposure to a surrogate measure of contamination from simulated patients by emergency department personnel wearing personal protective equipment. JAMA. 2020;323:2091-2093. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6633

- Alexander JW, Van Sweringen H, Vanoss K, et al. Surveillance of bacterial colonization in operating rooms. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013;14:345-351. doi:10.1089/sur.2012.134

- Blanchard J. Clinical issues—August 2010. AORN Journal. 2010;92:228-232. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2010.06.001

- Markel TA, Gormley T, Greeley D, et al. Hats off: a study of different operating room headgear assessed by environmental quality indicators. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:573-581. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.014

- Kanwar A, Thakur M, Wazzan M, et al. Clothing and shoes of personnel as potential vectors for transfer of health care-associated pathogens to the community. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:577-579. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2019.01.028

- Guo ZD, Wang ZY, Zhang SF, et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1583-1591. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200885

- Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, et al. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:235-250. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Surface (Fomite) Transmission for Indoor Community Environments. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/surface-transmission.html#ref10

- American Academy of Dermatology. Clinical guidance for COVID-19. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/clinical-guidance

- Narla S, Alam M, Ozog DM, et al. American Society of Dermatologic Surgery Association (ASDSA) and American Society for Laser Medicine & Surgery (ASLMS) guidance for cosmetic dermatology practices during COVID-19. Updated January 11, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.asds.net/Portals/0/PDF/asdsa/asdsa-aslms-cosmetic-reopening-guidance.pdf

- World Health Organization. Country & technical guidance—coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Accessed March 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance-publications

Practice Points

- Consistent use of personal protective equipment, including masks, face shields, goggles, and gloves, may limit transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

- Hair and shoes also may transmit SARS-CoV-2, but recommendations for hair and shoe coverings to prevent SARS-CoV-2 are lacking.

Line of therapy matters for assessing biologic’s serious infection risk in RA

The order in which tocilizumab (Actemra) is used in the sequence of treatments for rheumatoid arthritis could be muddying the waters when it comes to evaluating patients’ risk for serious infection.

According to new data emerging from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register – Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA), the line of therapy is a confounding factor when examining the risk for serious infection with not only tocilizumab but also other biologic agents.

The good news for patients, however, is that there doesn’t appear to be any overall greater risk for serious infection with one biologic over another when the line of therapy is taken into account.

“We don’t have any strong signal that there is an increased risk of serious infections with tocilizumab, compared to TNF inhibitors,” rheumatologist Kim Lauper, MD, of Geneva University Hospitals, said in an interview after presenting the data at the annual conference of the British Society for Rheumatology.

This is in contrast to studies where an increased risk of infections with tocilizumab has been seen when compared to TNF inhibitors. However, those studies did not account for the line of therapy, explained Dr. Lauper, who is also a clinical research fellow in the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England), where the BSRBR-RA is managed.

“Tocilizumab is a treatment that we often give to patients after several other treatments, so they’re really different patients,” Dr. Lauper observed. Indeed, in the “real-world” setting, patients taking tocilizumab tend to be older, have longer disease duration, and have worse functional status than do those who might receive other biologics.

To look at the effect of line of therapy on the serious infection risk associated with commonly used biologic drugs, Dr. Lauper and associates examined data on more than 33,000 treatment courses, representing more than 62,500 patient-years.

Using etanercept as the comparator – because it represents the largest group of patients in the BSRBR-RA – the serious infection risk for tocilizumab, rituximab, adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, and abatacept were calculated as an overall rate, and for their use as first-, second-, third-, fourth-, or fifth-line therapy.

The researchers adjusted their analysis for some clear baseline differences between the treatment groups, including age, prior treatment, disease duration, and comorbidities. Seropositivity, smoking status, general health status, and disease activity scores were also adjusted for in the analysis.

Crude hazard ratios (HRs), compared with etanercept, before and after adjusting for these already-known confounding factors were 1.0 and 1.2 for tocilizumab, 1.1 and 1.1 for adalimumab, 1.4 and 1.3 for infliximab, 0.6 and 0.8 for certolizumab pegol, 0.9 and 1.0 for rituximab, and 0.9 and 1.2 for abatacept.

Stratifying by line of therapy, however, changed the results: HRs were no longer significantly different, compared with etanercept, for tocilizumab, adalimumab, and infliximab for most lines of therapy.

Indeed, while the risk for serious infection occurring with tocilizumab was 20% higher overall, compared with etanercept, that risk was actually lower if tocilizumab had been used as first- or fifth-line therapy (HRs for both, 0.9) but higher if it had been used as a third- or fourth-line therapy (HR of 1.4 for both).

“We often use tocilizumab as a second-line, third-line, or even fourth-line therapy, and if we don’t adjust for anything, we can have the impression that there are more infections with tocilizumab. But then, when we adjust for confounding factors and the line of therapy, we don’t have this anymore,” Dr. Lauper said.

“Line of therapy in itself is not a risk for serious infections,” she said in qualifying the conclusions that could be drawn from the study. “It may be a marker of the disease or some patient characteristic that is associated with a higher risk of infections.” Nevertheless, it should be taken into account when evaluating serious outcomes and possibly other safety and effectiveness outcomes.

“I understand concentrating on the hospitalized infections because the data are so much more robust,” observed consultant rheumatologist Jon Packham, BM, DM, of Haywood Hospital in Stoke-on-Trent, England, who chaired the session. He queried if there were any data on milder or just antibiotic-treated infections. At present, there aren’t those data to look at, Dr. Lauper responded, as this is something that’s difficult for registers to capture because doctors often do not log them in the databases.

There are also too few data on Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors currently in the BSRBR-RA at present to be able to look at their rate of serious infection by line of therapy, Dr. Lauper noted. Because JAK inhibitors act on cytokines different from those affected by biologics for RA, there may be a difference there, but more data are needed on the JAK inhibitors before that question can be analyzed.

Dr. Lauper did not state having any disclosures. The BSRBR-RA is funded by the BSR via restricted income grants from several U.K. pharmaceutical companies, which has included or currently includes AbbVie, Celltrion, Hospira, Pfizer, UCB, Roche, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, and Merck.

The order in which tocilizumab (Actemra) is used in the sequence of treatments for rheumatoid arthritis could be muddying the waters when it comes to evaluating patients’ risk for serious infection.

According to new data emerging from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register – Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA), the line of therapy is a confounding factor when examining the risk for serious infection with not only tocilizumab but also other biologic agents.

The good news for patients, however, is that there doesn’t appear to be any overall greater risk for serious infection with one biologic over another when the line of therapy is taken into account.

“We don’t have any strong signal that there is an increased risk of serious infections with tocilizumab, compared to TNF inhibitors,” rheumatologist Kim Lauper, MD, of Geneva University Hospitals, said in an interview after presenting the data at the annual conference of the British Society for Rheumatology.

This is in contrast to studies where an increased risk of infections with tocilizumab has been seen when compared to TNF inhibitors. However, those studies did not account for the line of therapy, explained Dr. Lauper, who is also a clinical research fellow in the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England), where the BSRBR-RA is managed.

“Tocilizumab is a treatment that we often give to patients after several other treatments, so they’re really different patients,” Dr. Lauper observed. Indeed, in the “real-world” setting, patients taking tocilizumab tend to be older, have longer disease duration, and have worse functional status than do those who might receive other biologics.

To look at the effect of line of therapy on the serious infection risk associated with commonly used biologic drugs, Dr. Lauper and associates examined data on more than 33,000 treatment courses, representing more than 62,500 patient-years.

Using etanercept as the comparator – because it represents the largest group of patients in the BSRBR-RA – the serious infection risk for tocilizumab, rituximab, adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, and abatacept were calculated as an overall rate, and for their use as first-, second-, third-, fourth-, or fifth-line therapy.

The researchers adjusted their analysis for some clear baseline differences between the treatment groups, including age, prior treatment, disease duration, and comorbidities. Seropositivity, smoking status, general health status, and disease activity scores were also adjusted for in the analysis.

Crude hazard ratios (HRs), compared with etanercept, before and after adjusting for these already-known confounding factors were 1.0 and 1.2 for tocilizumab, 1.1 and 1.1 for adalimumab, 1.4 and 1.3 for infliximab, 0.6 and 0.8 for certolizumab pegol, 0.9 and 1.0 for rituximab, and 0.9 and 1.2 for abatacept.

Stratifying by line of therapy, however, changed the results: HRs were no longer significantly different, compared with etanercept, for tocilizumab, adalimumab, and infliximab for most lines of therapy.

Indeed, while the risk for serious infection occurring with tocilizumab was 20% higher overall, compared with etanercept, that risk was actually lower if tocilizumab had been used as first- or fifth-line therapy (HRs for both, 0.9) but higher if it had been used as a third- or fourth-line therapy (HR of 1.4 for both).

“We often use tocilizumab as a second-line, third-line, or even fourth-line therapy, and if we don’t adjust for anything, we can have the impression that there are more infections with tocilizumab. But then, when we adjust for confounding factors and the line of therapy, we don’t have this anymore,” Dr. Lauper said.

“Line of therapy in itself is not a risk for serious infections,” she said in qualifying the conclusions that could be drawn from the study. “It may be a marker of the disease or some patient characteristic that is associated with a higher risk of infections.” Nevertheless, it should be taken into account when evaluating serious outcomes and possibly other safety and effectiveness outcomes.

“I understand concentrating on the hospitalized infections because the data are so much more robust,” observed consultant rheumatologist Jon Packham, BM, DM, of Haywood Hospital in Stoke-on-Trent, England, who chaired the session. He queried if there were any data on milder or just antibiotic-treated infections. At present, there aren’t those data to look at, Dr. Lauper responded, as this is something that’s difficult for registers to capture because doctors often do not log them in the databases.

There are also too few data on Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors currently in the BSRBR-RA at present to be able to look at their rate of serious infection by line of therapy, Dr. Lauper noted. Because JAK inhibitors act on cytokines different from those affected by biologics for RA, there may be a difference there, but more data are needed on the JAK inhibitors before that question can be analyzed.

Dr. Lauper did not state having any disclosures. The BSRBR-RA is funded by the BSR via restricted income grants from several U.K. pharmaceutical companies, which has included or currently includes AbbVie, Celltrion, Hospira, Pfizer, UCB, Roche, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, and Merck.

The order in which tocilizumab (Actemra) is used in the sequence of treatments for rheumatoid arthritis could be muddying the waters when it comes to evaluating patients’ risk for serious infection.

According to new data emerging from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register – Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA), the line of therapy is a confounding factor when examining the risk for serious infection with not only tocilizumab but also other biologic agents.

The good news for patients, however, is that there doesn’t appear to be any overall greater risk for serious infection with one biologic over another when the line of therapy is taken into account.

“We don’t have any strong signal that there is an increased risk of serious infections with tocilizumab, compared to TNF inhibitors,” rheumatologist Kim Lauper, MD, of Geneva University Hospitals, said in an interview after presenting the data at the annual conference of the British Society for Rheumatology.

This is in contrast to studies where an increased risk of infections with tocilizumab has been seen when compared to TNF inhibitors. However, those studies did not account for the line of therapy, explained Dr. Lauper, who is also a clinical research fellow in the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England), where the BSRBR-RA is managed.

“Tocilizumab is a treatment that we often give to patients after several other treatments, so they’re really different patients,” Dr. Lauper observed. Indeed, in the “real-world” setting, patients taking tocilizumab tend to be older, have longer disease duration, and have worse functional status than do those who might receive other biologics.

To look at the effect of line of therapy on the serious infection risk associated with commonly used biologic drugs, Dr. Lauper and associates examined data on more than 33,000 treatment courses, representing more than 62,500 patient-years.

Using etanercept as the comparator – because it represents the largest group of patients in the BSRBR-RA – the serious infection risk for tocilizumab, rituximab, adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, and abatacept were calculated as an overall rate, and for their use as first-, second-, third-, fourth-, or fifth-line therapy.

The researchers adjusted their analysis for some clear baseline differences between the treatment groups, including age, prior treatment, disease duration, and comorbidities. Seropositivity, smoking status, general health status, and disease activity scores were also adjusted for in the analysis.

Crude hazard ratios (HRs), compared with etanercept, before and after adjusting for these already-known confounding factors were 1.0 and 1.2 for tocilizumab, 1.1 and 1.1 for adalimumab, 1.4 and 1.3 for infliximab, 0.6 and 0.8 for certolizumab pegol, 0.9 and 1.0 for rituximab, and 0.9 and 1.2 for abatacept.

Stratifying by line of therapy, however, changed the results: HRs were no longer significantly different, compared with etanercept, for tocilizumab, adalimumab, and infliximab for most lines of therapy.

Indeed, while the risk for serious infection occurring with tocilizumab was 20% higher overall, compared with etanercept, that risk was actually lower if tocilizumab had been used as first- or fifth-line therapy (HRs for both, 0.9) but higher if it had been used as a third- or fourth-line therapy (HR of 1.4 for both).

“We often use tocilizumab as a second-line, third-line, or even fourth-line therapy, and if we don’t adjust for anything, we can have the impression that there are more infections with tocilizumab. But then, when we adjust for confounding factors and the line of therapy, we don’t have this anymore,” Dr. Lauper said.

“Line of therapy in itself is not a risk for serious infections,” she said in qualifying the conclusions that could be drawn from the study. “It may be a marker of the disease or some patient characteristic that is associated with a higher risk of infections.” Nevertheless, it should be taken into account when evaluating serious outcomes and possibly other safety and effectiveness outcomes.

“I understand concentrating on the hospitalized infections because the data are so much more robust,” observed consultant rheumatologist Jon Packham, BM, DM, of Haywood Hospital in Stoke-on-Trent, England, who chaired the session. He queried if there were any data on milder or just antibiotic-treated infections. At present, there aren’t those data to look at, Dr. Lauper responded, as this is something that’s difficult for registers to capture because doctors often do not log them in the databases.

There are also too few data on Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors currently in the BSRBR-RA at present to be able to look at their rate of serious infection by line of therapy, Dr. Lauper noted. Because JAK inhibitors act on cytokines different from those affected by biologics for RA, there may be a difference there, but more data are needed on the JAK inhibitors before that question can be analyzed.

Dr. Lauper did not state having any disclosures. The BSRBR-RA is funded by the BSR via restricted income grants from several U.K. pharmaceutical companies, which has included or currently includes AbbVie, Celltrion, Hospira, Pfizer, UCB, Roche, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, and Merck.

FROM BSR 2021

Pediatric bronchiolitis: Less is more

A common cause of infant morbidity and hospitalization in developed countries, infant viral bronchiolitis, has long been bedeviled by treatment uncertainty beyond supportive care.

Rationales for most pharmacologic treatments continue to be debated, and clinical practice guidelines generally advise respiratory and hydration support, discouraging the use of chest radiography, albuterol, glucocorticoids, antibiotics, and epinephrine.

Despite evidence that the latter interventions are ineffective, they are still too often applied, according to two recent studies, one in Pediatrics, the other in JAMA Pediatrics.

“The pull of the therapeutic vacuum surrounding this disease has been noted in the pages of this journal for at least 50 years, with Wright and Beem writing in 1965 that ‘energies should not be frittered away by the annoyance of unnecessary or futile medications and procedures’ for the child with bronchiolitis,” said emergency physicians Matthew J. Lipshaw, MD, MS, of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and Todd A. Florin, MD, MSCE, of Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

These remarks came in their editorial in Pediatrics wryly titled: “Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There” and published online to accompany a recent study of three network meta-analyses.

Led by Sarah A. Elliott, PhD, of the Alberta Research Centre for Health Evidence at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, this analysis amalgamated 150 randomized, controlled trials comparing a placebo or active comparator with any bronchodilator, glucocorticoid steroid, hypertonic saline solution, antibiotic, helium-oxygen therapy, or high-flow oxygen therapy. It then looked at the following outcomes in children aged 2 years and younger: hospital admission rate on day 1, hospital admission rate within 7 days, and total hospital length of stay.

Few treatments seemed more effective than nebulized placebo (0.9% saline) for short-term outcomes, the authors found. While nebulized epinephrine and nebulized hypertonic saline plus salbutamol appeared to reduce admission rates during the index ED presentation, and hypertonic saline, alone or in combination with epinephrine, seemed to reduce hospital stays, such treatment had no effect on admissions within 7 days of initial presentation. Furthermore, most benefits disappeared in higher-quality studies.

Concluding, albeit with weak evidence and low confidence, that some benefit might accrue with hypertonic saline with salbutamol to reduce admission rates on initial presentation to the ED, the authors called for well-designed studies on treatments in inpatients and outpatients.

According to Dr. Lipshaw, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics, the lack of benefit observed in superior studies limits the applicability of Dr. Elliott and colleagues’ results to immediate clinical practice. “These findings could be used, however, to target future high-quality studies toward the medications that they found might be useful,” he said in an interview.

For the present, other recent research augurs well for strategically reducing unnecessary care. In a paper published online in JAMA Pediatrics, Libby Haskell, MN, of the ED at Starship Children’s Hospital in Auckland, New Zealand, and associates reported on a cluster-randomized, controlled trial of targeted interventions.

Conducted in 2017 at 26 hospitals and with 3,727 babies in New Zealand and Australia, the study addressed drivers of non–evidence-based approaches with behavior-modifying approaches such as on-site clinical leads, stakeholder meetings, a train-the-trainer workshop, education, and audit and feedback.

The authors reported a 14.1% difference in rates of compliance during the first 24 hours of hospitalization favoring the intervention group for all five bronchiolitis guideline recommendations. The greatest change was seen in albuterol and chest radiography use, with other improvements in ED visits, inpatient consultations, and throughout hospitalization.

“These results provide clinicians and hospitals with clear implementation strategies to address unnecessary treatment of infants with bronchiolitis,” Dr. Haskell’s group wrote. Dr. Lipshaw agreed that multifaceted deimplementation packages including clinician and family education, audit and feedback, and clinical decision support have been successful. “Haskell et al. demonstrated that it is possible to successfully deimplement non–evidence-based practices for bronchiolitis with targeted inventions,” he said. “It would be wonderful to see their success replicated in the U.S.”

Why the slow adoption of guidelines?

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued bronchiolitis guidelines for babies to 23 months in 2014 and updated them in 2018. Why, then, has care in some centers been seemingly all over the map and counter to guidelines? “Both parents and clinicians are acting in what they believe to be the best interests of the child, and in the absence of high-value interventions, can feel the need to do something, even if that something is not supported by evidence,” Dr. Lipshaw said.

Furthermore, with children in obvious distress, breathing fast and with difficulty, and sometimes unable to eat or drink, “we feel like we should have some way to make them feel better quicker. Unfortunately, none of the medications we have tried seem to be useful for most children, and we are left with supportive care measures such as suctioning their noses, giving them oxygen if their oxygen is low, and giving them fluids if they are dehydrated.”

Other physicians agree that taking a less-is-more approach can be challenging and even counterintuitive. “To families, seeing their child’s doctor ‘doing less’ can be frustrating,” admitted Diana S. Lee, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Beyond that, altering practice behavior will need more than guidelines, Dr. Lee said in an interview. “Haskell et al. showed targeted behavior-change interventions improved compliance with bronchiolitis guidelines, but such change requires motivation and resources, and the sustainability of this effect over time remains to be seen.”

At Dr. Lipshaw’s institution, treatment depends on the attending physician, “but we have an emergency department care algorithm, which does not recommend any inhaled medications or steroids in accordance with the 2014 AAP guidelines,” he said.

Similarly at Mount Sinai, practitioners strive to follow the AAP guidelines, although their implementation has not been immediate, Dr. Lee said. “This is a situation where we must make the effort to choose not to do more, given current evidence.”

But Michelle Dunn, MD, an attending physician in the division of general pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said the American practice norm already tends more to the observance than the breach of the guidelines, noting that since 2014 quality improvement efforts have been made throughout the country. “At our institution, we have effectively reduced the use of albuterol in patients with bronchiolitis and we use evidence-based therapy as much as possible, which in the case of bronchiolitis generally involves supportive management alone,” she said in an interview.

Still, Dr. Dunn added, many patients receive unnecessary diagnostic testing and ineffective therapies, with some providers facing psychological barriers to doing less. “However, with more and more evidence to support this, hopefully, physicians will become more comfortable with this.”

To that end, Dr. Lipshaw’s editorial urges physicians to “curb the rampant use of therapies repeatedly revealed to be ineffective,” citing team engagement, clear practice guidelines, and information technology as key factors in deimplementation. In the meantime, his mantra remains: “Don’t just do something, stand there.”

The study by Dr. Elliot and colleagues was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Knowledge Synthesis grant program. One coauthor is supported by a University of Ottawa Tier I Research Chair in Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Another is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis and Translation and the Stollery Science Laboratory. Dr. Lipshaw and Dr. Florin disclosed no financial relationships relevant to their commentary. Dr. Haskell and colleagues were supported, variously, by the National Health and Medical Research Council of New Zealand, the Center of Research Excellence for Pediatric Emergency Medicine, the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program, Cure Kids New Zealand, the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, and the Starship Foundation. Dr. Lee and Dr. Dunn had no competing interests to disclose with regard to their comments.

A common cause of infant morbidity and hospitalization in developed countries, infant viral bronchiolitis, has long been bedeviled by treatment uncertainty beyond supportive care.

Rationales for most pharmacologic treatments continue to be debated, and clinical practice guidelines generally advise respiratory and hydration support, discouraging the use of chest radiography, albuterol, glucocorticoids, antibiotics, and epinephrine.

Despite evidence that the latter interventions are ineffective, they are still too often applied, according to two recent studies, one in Pediatrics, the other in JAMA Pediatrics.

“The pull of the therapeutic vacuum surrounding this disease has been noted in the pages of this journal for at least 50 years, with Wright and Beem writing in 1965 that ‘energies should not be frittered away by the annoyance of unnecessary or futile medications and procedures’ for the child with bronchiolitis,” said emergency physicians Matthew J. Lipshaw, MD, MS, of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and Todd A. Florin, MD, MSCE, of Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

These remarks came in their editorial in Pediatrics wryly titled: “Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There” and published online to accompany a recent study of three network meta-analyses.

Led by Sarah A. Elliott, PhD, of the Alberta Research Centre for Health Evidence at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, this analysis amalgamated 150 randomized, controlled trials comparing a placebo or active comparator with any bronchodilator, glucocorticoid steroid, hypertonic saline solution, antibiotic, helium-oxygen therapy, or high-flow oxygen therapy. It then looked at the following outcomes in children aged 2 years and younger: hospital admission rate on day 1, hospital admission rate within 7 days, and total hospital length of stay.

Few treatments seemed more effective than nebulized placebo (0.9% saline) for short-term outcomes, the authors found. While nebulized epinephrine and nebulized hypertonic saline plus salbutamol appeared to reduce admission rates during the index ED presentation, and hypertonic saline, alone or in combination with epinephrine, seemed to reduce hospital stays, such treatment had no effect on admissions within 7 days of initial presentation. Furthermore, most benefits disappeared in higher-quality studies.

Concluding, albeit with weak evidence and low confidence, that some benefit might accrue with hypertonic saline with salbutamol to reduce admission rates on initial presentation to the ED, the authors called for well-designed studies on treatments in inpatients and outpatients.

According to Dr. Lipshaw, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics, the lack of benefit observed in superior studies limits the applicability of Dr. Elliott and colleagues’ results to immediate clinical practice. “These findings could be used, however, to target future high-quality studies toward the medications that they found might be useful,” he said in an interview.

For the present, other recent research augurs well for strategically reducing unnecessary care. In a paper published online in JAMA Pediatrics, Libby Haskell, MN, of the ED at Starship Children’s Hospital in Auckland, New Zealand, and associates reported on a cluster-randomized, controlled trial of targeted interventions.

Conducted in 2017 at 26 hospitals and with 3,727 babies in New Zealand and Australia, the study addressed drivers of non–evidence-based approaches with behavior-modifying approaches such as on-site clinical leads, stakeholder meetings, a train-the-trainer workshop, education, and audit and feedback.

The authors reported a 14.1% difference in rates of compliance during the first 24 hours of hospitalization favoring the intervention group for all five bronchiolitis guideline recommendations. The greatest change was seen in albuterol and chest radiography use, with other improvements in ED visits, inpatient consultations, and throughout hospitalization.

“These results provide clinicians and hospitals with clear implementation strategies to address unnecessary treatment of infants with bronchiolitis,” Dr. Haskell’s group wrote. Dr. Lipshaw agreed that multifaceted deimplementation packages including clinician and family education, audit and feedback, and clinical decision support have been successful. “Haskell et al. demonstrated that it is possible to successfully deimplement non–evidence-based practices for bronchiolitis with targeted inventions,” he said. “It would be wonderful to see their success replicated in the U.S.”

Why the slow adoption of guidelines?

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued bronchiolitis guidelines for babies to 23 months in 2014 and updated them in 2018. Why, then, has care in some centers been seemingly all over the map and counter to guidelines? “Both parents and clinicians are acting in what they believe to be the best interests of the child, and in the absence of high-value interventions, can feel the need to do something, even if that something is not supported by evidence,” Dr. Lipshaw said.