User login

Delta variant could drive herd immunity threshold over 80%

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Shorter antibiotic course okay for UTIs in men with no fever

A week of antibiotics appears just as effective as 2 weeks in treating afebrile men with urinary tract infections (UTIs), researchers say.

Shortening the course of treatment could spare patients side effects from the medications and reduce the risk that bacteria will develop resistance to the drugs, said Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of infectious diseases at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

“You’d like to be on these drugs for as short [an] amount of time as gets the job done,” he told this news organization. The study was published online July 28 in JAMA.

Researchers have recently found that shorter courses of antimicrobials are effective in the treatment of other types of infection and for UTIs in women. However, UTIs in men are thought to be more complicated because the male urethra is longer.

To see whether reducing length of treatment could be effective in men as well, Dr. Drekonja and colleagues compared 7-day and 14-day regimens in men treated at U.S. Veterans Affairs medical centers in Minnesota and Texas.

They recruited 272 men who had symptoms of UTI and were willing to participate. All the men received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or ciprofloxacin for 7 days. Half the men were randomly assigned to continue this treatment for an additional 7 days; the other half received placebo pills for an additional 7 days.

The average age of the men was 69 years. Urine samples were cultured from 87.9% of the men. In 60.7% of these samples, the researchers found more than 100,000 CFU/mL; in 16.3%, they found lower colony counts; and in 23.0%, they found no growth of bacteria. The most common organism they isolated was Escherchia coli.

Results for the two groups were similar. Symptoms resolved 14 days after completion of the course of treatment in 90.4% of those who received 14 days of antibiotics, versus 91.9% of those who received 7 days of antibiotics plus 7 days of placebo pills. At 1.5%, the difference between the two arms was within the predetermined boundary for noninferiority.

The percentage of those who experienced recurrence of symptoms within 28 days of stopping medication was also similar between the two groups. Among those who received 7 days of antibiotics, 10.3% experienced recurrence of symptoms, compared to 16.9% of those assigned to 14 days of antibiotics.

There was no significant difference in the resolution of UTI symptoms between the two groups by type of antibiotic, pretreatment bacteriuria count, or study site.

Adverse events were also similar in the two groups, occurring in 20.6% of the men who received 7 days of antibiotics, versus 24.3% of the men who received 14 days of treatment. In both groups, 8.8% of patients had diarrhea, which was the most common adverse event.

Clinicians should not worry that antibiotic resistance is more likely to develop or that symptoms will recur when patients don’t finish a prescribed course of treatment, Dr. Drekonja said. “That is an old piece of guidance that has persisted for such a long time,” he said. “And it makes all of us in the infectious disease field cringe.”

Rather, the current thinking is that the more antibiotics patients take, the more resistance bacteria will develop, he said.

The success of the 7-day regimen raises the question of whether an even shorter course would work equally well. It’s not clear how short a course of antibiotics will do the trick. Research in certain populations, such as patients with spinal cord injuries, has suggested that recurrences are more frequent with 3 days of antibiotics than with 14, “so there could be a floor that you do need to go beyond,” Dr. Drekonja said.

“We’re not really sure how much people need,” agreed Daniel Morgan, MD, a professor of epidemiology and public health and medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, which is why this study is important. “It really defined that 1 week is better than 2 weeks,” he said in an interview.

Another way that clinicians can reduce the use of antibiotics by men with UTIs is to consider alternative diagnoses and to culture urine samples when UTI seems like the most likely cause of their symptoms, said Dr. Morgan, who co-authored an accompanying editorial.

He pointed out that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued a black box warning on fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, because they increase the risk for tendinitis and tendon rupture. Nitrofurantoin and amoxicillin-clavulanate are better alternatives for UTIs, he said.

Even some men with fevers and UTIs may need no more than 7 days of antibiotics, said Dr. Morgan. Dr. Drekonja said he generally prescribes at least 10 days antibiotics for these men.

The study was funded by the VA Merit Review Program. Dr. Drekonja and Dr. Morgan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A week of antibiotics appears just as effective as 2 weeks in treating afebrile men with urinary tract infections (UTIs), researchers say.

Shortening the course of treatment could spare patients side effects from the medications and reduce the risk that bacteria will develop resistance to the drugs, said Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of infectious diseases at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

“You’d like to be on these drugs for as short [an] amount of time as gets the job done,” he told this news organization. The study was published online July 28 in JAMA.

Researchers have recently found that shorter courses of antimicrobials are effective in the treatment of other types of infection and for UTIs in women. However, UTIs in men are thought to be more complicated because the male urethra is longer.

To see whether reducing length of treatment could be effective in men as well, Dr. Drekonja and colleagues compared 7-day and 14-day regimens in men treated at U.S. Veterans Affairs medical centers in Minnesota and Texas.

They recruited 272 men who had symptoms of UTI and were willing to participate. All the men received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or ciprofloxacin for 7 days. Half the men were randomly assigned to continue this treatment for an additional 7 days; the other half received placebo pills for an additional 7 days.

The average age of the men was 69 years. Urine samples were cultured from 87.9% of the men. In 60.7% of these samples, the researchers found more than 100,000 CFU/mL; in 16.3%, they found lower colony counts; and in 23.0%, they found no growth of bacteria. The most common organism they isolated was Escherchia coli.

Results for the two groups were similar. Symptoms resolved 14 days after completion of the course of treatment in 90.4% of those who received 14 days of antibiotics, versus 91.9% of those who received 7 days of antibiotics plus 7 days of placebo pills. At 1.5%, the difference between the two arms was within the predetermined boundary for noninferiority.

The percentage of those who experienced recurrence of symptoms within 28 days of stopping medication was also similar between the two groups. Among those who received 7 days of antibiotics, 10.3% experienced recurrence of symptoms, compared to 16.9% of those assigned to 14 days of antibiotics.

There was no significant difference in the resolution of UTI symptoms between the two groups by type of antibiotic, pretreatment bacteriuria count, or study site.

Adverse events were also similar in the two groups, occurring in 20.6% of the men who received 7 days of antibiotics, versus 24.3% of the men who received 14 days of treatment. In both groups, 8.8% of patients had diarrhea, which was the most common adverse event.

Clinicians should not worry that antibiotic resistance is more likely to develop or that symptoms will recur when patients don’t finish a prescribed course of treatment, Dr. Drekonja said. “That is an old piece of guidance that has persisted for such a long time,” he said. “And it makes all of us in the infectious disease field cringe.”

Rather, the current thinking is that the more antibiotics patients take, the more resistance bacteria will develop, he said.

The success of the 7-day regimen raises the question of whether an even shorter course would work equally well. It’s not clear how short a course of antibiotics will do the trick. Research in certain populations, such as patients with spinal cord injuries, has suggested that recurrences are more frequent with 3 days of antibiotics than with 14, “so there could be a floor that you do need to go beyond,” Dr. Drekonja said.

“We’re not really sure how much people need,” agreed Daniel Morgan, MD, a professor of epidemiology and public health and medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, which is why this study is important. “It really defined that 1 week is better than 2 weeks,” he said in an interview.

Another way that clinicians can reduce the use of antibiotics by men with UTIs is to consider alternative diagnoses and to culture urine samples when UTI seems like the most likely cause of their symptoms, said Dr. Morgan, who co-authored an accompanying editorial.

He pointed out that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued a black box warning on fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, because they increase the risk for tendinitis and tendon rupture. Nitrofurantoin and amoxicillin-clavulanate are better alternatives for UTIs, he said.

Even some men with fevers and UTIs may need no more than 7 days of antibiotics, said Dr. Morgan. Dr. Drekonja said he generally prescribes at least 10 days antibiotics for these men.

The study was funded by the VA Merit Review Program. Dr. Drekonja and Dr. Morgan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A week of antibiotics appears just as effective as 2 weeks in treating afebrile men with urinary tract infections (UTIs), researchers say.

Shortening the course of treatment could spare patients side effects from the medications and reduce the risk that bacteria will develop resistance to the drugs, said Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of infectious diseases at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center.

“You’d like to be on these drugs for as short [an] amount of time as gets the job done,” he told this news organization. The study was published online July 28 in JAMA.

Researchers have recently found that shorter courses of antimicrobials are effective in the treatment of other types of infection and for UTIs in women. However, UTIs in men are thought to be more complicated because the male urethra is longer.

To see whether reducing length of treatment could be effective in men as well, Dr. Drekonja and colleagues compared 7-day and 14-day regimens in men treated at U.S. Veterans Affairs medical centers in Minnesota and Texas.

They recruited 272 men who had symptoms of UTI and were willing to participate. All the men received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or ciprofloxacin for 7 days. Half the men were randomly assigned to continue this treatment for an additional 7 days; the other half received placebo pills for an additional 7 days.

The average age of the men was 69 years. Urine samples were cultured from 87.9% of the men. In 60.7% of these samples, the researchers found more than 100,000 CFU/mL; in 16.3%, they found lower colony counts; and in 23.0%, they found no growth of bacteria. The most common organism they isolated was Escherchia coli.

Results for the two groups were similar. Symptoms resolved 14 days after completion of the course of treatment in 90.4% of those who received 14 days of antibiotics, versus 91.9% of those who received 7 days of antibiotics plus 7 days of placebo pills. At 1.5%, the difference between the two arms was within the predetermined boundary for noninferiority.

The percentage of those who experienced recurrence of symptoms within 28 days of stopping medication was also similar between the two groups. Among those who received 7 days of antibiotics, 10.3% experienced recurrence of symptoms, compared to 16.9% of those assigned to 14 days of antibiotics.

There was no significant difference in the resolution of UTI symptoms between the two groups by type of antibiotic, pretreatment bacteriuria count, or study site.

Adverse events were also similar in the two groups, occurring in 20.6% of the men who received 7 days of antibiotics, versus 24.3% of the men who received 14 days of treatment. In both groups, 8.8% of patients had diarrhea, which was the most common adverse event.

Clinicians should not worry that antibiotic resistance is more likely to develop or that symptoms will recur when patients don’t finish a prescribed course of treatment, Dr. Drekonja said. “That is an old piece of guidance that has persisted for such a long time,” he said. “And it makes all of us in the infectious disease field cringe.”

Rather, the current thinking is that the more antibiotics patients take, the more resistance bacteria will develop, he said.

The success of the 7-day regimen raises the question of whether an even shorter course would work equally well. It’s not clear how short a course of antibiotics will do the trick. Research in certain populations, such as patients with spinal cord injuries, has suggested that recurrences are more frequent with 3 days of antibiotics than with 14, “so there could be a floor that you do need to go beyond,” Dr. Drekonja said.

“We’re not really sure how much people need,” agreed Daniel Morgan, MD, a professor of epidemiology and public health and medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, which is why this study is important. “It really defined that 1 week is better than 2 weeks,” he said in an interview.

Another way that clinicians can reduce the use of antibiotics by men with UTIs is to consider alternative diagnoses and to culture urine samples when UTI seems like the most likely cause of their symptoms, said Dr. Morgan, who co-authored an accompanying editorial.

He pointed out that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued a black box warning on fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, because they increase the risk for tendinitis and tendon rupture. Nitrofurantoin and amoxicillin-clavulanate are better alternatives for UTIs, he said.

Even some men with fevers and UTIs may need no more than 7 days of antibiotics, said Dr. Morgan. Dr. Drekonja said he generally prescribes at least 10 days antibiotics for these men.

The study was funded by the VA Merit Review Program. Dr. Drekonja and Dr. Morgan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

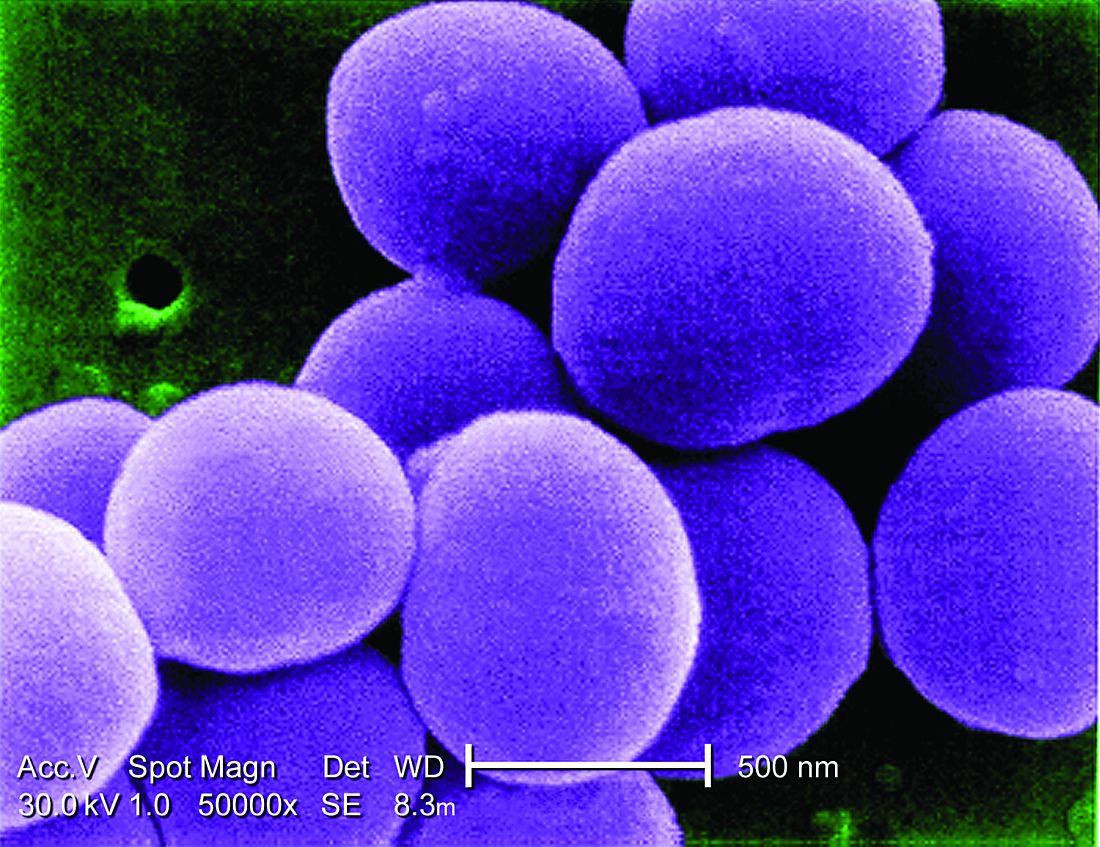

Untreatable, drug-resistant fungus found in Texas and Washington, D.C.

The CDC has reported two clusters of Candida auris infections resistant to all antifungal medications in long-term care facilities in 2021. Because these panresistant infections occurred without any exposure to antifungal drugs, the cases are even more worrisome. These clusters are the first time such nosocomial transmission has been detected.

In the District of Columbia, three panresistant isolates were discovered through screening for skin colonization with resistant organisms at a long-term acute care facility (LTAC) that cares for patients who are seriously ill, often on mechanical ventilation.

In Texas, the resistant organisms were found both by screening and in specimens from ill patients at an LTAC and a short-term acute care hospital that share patients. Two were panresistant, and five others were resistant to fluconazole and echinocandins.

These clusters occurred simultaneously and independently of each other; there were no links between the two institutions.

Colonization of skin with C. auris can lead to invasive infections in 5%-10% of affected patients. Routine skin surveillance cultures are not commonly done for Candida, although perirectal cultures for vancomycin-resistant enterococci and nasal swabs for MRSA have been done for years. Some areas, like Los Angeles, have recommended screening for C. auris in high-risk patients – defined as those who were on a ventilator or had a tracheostomy admitted from an LTAC or skilled nursing facility in Los Angeles County, New York, New Jersey, or Illinois.

In the past, about 85% of C. auris isolates in the United States have been resistant to azoles (for example, fluconazole), 33% to amphotericin B, and 1% to echinocandins. Because of generally strong susceptibility, an echinocandin such as micafungin or caspofungin has been the drug of choice for an invasive Candida infection.

C. auris is particularly difficult to deal with for several reasons. First, it can continue to live in the environment, on both dry or moist surfaces, for up to 2 weeks. Outbreaks have occurred both from hand (person-to-person) transmission or via inanimate surfaces that have become contaminated. Equally troublesome is that people become colonized with the yeast indefinitely.

Meghan Lyman, MD, of the fungal diseases branch of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said in an interview that facilities might be slow in recognizing the problem and in identifying the organism. “We encounter problems in noninvasive specimens, especially urine,” Dr. Lyman added.

“Sometimes ... they consider Candida [to represent] colonization so they will often not speciate it.” She emphasized the need for facilities that care for ventilated patients to consider screening. “Higher priority ... are places in areas where there’s a lot of C. auris transmission or in nearby areas that are likely to get introductions.” Even those that do speciate may have difficulty identifying C. auris.

Further, Dr. Lyman stressed “the importance of antifungal susceptibility testing and testing for resistance. Because that’s also something that’s not widely available at all hospitals and clinical labs ... you can send it to the [CDC’s] antimicrobial resistance lab network” for testing.

COVID-19 has brought particular challenges. Rodney E. Rohde, PhD, MS, professor and chair, clinical lab science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, said in an interview that he is worried about all the steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics patients receive.

They’re “being given medical interventions, whether it’s ventilators or [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or IVs or central lines or catheters for UTIs and you’re creating highways, right for something that may be right there,” said Dr. Rohde, who was not involved in the CDC study. “It’s a perfect storm, not just for C. auris, but I worry about bacterial resistance agents, too, like MRSA and so forth, having kind of a spike in those types of infections with COVID. So, it’s kind of a doubly dangerous time, I think.”

Multiresistant bacteria are a major health problem, causing illnesses in 2.8 million people annually in the United States, and causing about 35,000 deaths.

Dr. Rohde raised another, rarely mentioned concern. “We’re in crisis mode. People are leaving our field more than they ever had before. The medical laboratory is being decimated because people have burned out after these past 14 months. And so I worry just about competent medical laboratory professionals that are on board to deal with these types of other crises that are popping up within hospitals and long-term care facilities. It kind of keeps me awake.”

Dr. Rohde and Dr. Lyman shared their concern that COVID caused a decrease in screening for other infections and drug-resistant organisms. Bare-bones staffing and shortages of personal protective equipment have likely fueled the spread of these infections as well.

In an outbreak of C. auris in a Florida hospital’s COVID unit in 2020, 35 of 67 patients became colonized, and 6 became ill. The epidemiologists investigating thought that contaminated gowns or gloves, computers, and other equipment were likely sources of transmission.

Low pay, especially in nursing homes, is another problem Dr. Rohde mentioned. It’s an additional problem in both acute and long-term care that “some of the lowest-paid people are the environmental services people, and so the turnover is crazy.” Yet, we rely on them to keep everyone safe. He added that, in addition to pay, he “tries to give them the appreciation and the recognition that they really deserve.”

There are a few specific measures that can be taken to protect patients. Dr. Lyman concluded. “The best way is identifying cases and really ensuring good infection control to prevent the spread.” It’s back to basics – limiting broad-spectrum antibiotics and invasive medical devices, and especially good handwashing and thorough cleaning.

Dr. Lyman and Dr. Rohde have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The CDC has reported two clusters of Candida auris infections resistant to all antifungal medications in long-term care facilities in 2021. Because these panresistant infections occurred without any exposure to antifungal drugs, the cases are even more worrisome. These clusters are the first time such nosocomial transmission has been detected.

In the District of Columbia, three panresistant isolates were discovered through screening for skin colonization with resistant organisms at a long-term acute care facility (LTAC) that cares for patients who are seriously ill, often on mechanical ventilation.

In Texas, the resistant organisms were found both by screening and in specimens from ill patients at an LTAC and a short-term acute care hospital that share patients. Two were panresistant, and five others were resistant to fluconazole and echinocandins.

These clusters occurred simultaneously and independently of each other; there were no links between the two institutions.

Colonization of skin with C. auris can lead to invasive infections in 5%-10% of affected patients. Routine skin surveillance cultures are not commonly done for Candida, although perirectal cultures for vancomycin-resistant enterococci and nasal swabs for MRSA have been done for years. Some areas, like Los Angeles, have recommended screening for C. auris in high-risk patients – defined as those who were on a ventilator or had a tracheostomy admitted from an LTAC or skilled nursing facility in Los Angeles County, New York, New Jersey, or Illinois.

In the past, about 85% of C. auris isolates in the United States have been resistant to azoles (for example, fluconazole), 33% to amphotericin B, and 1% to echinocandins. Because of generally strong susceptibility, an echinocandin such as micafungin or caspofungin has been the drug of choice for an invasive Candida infection.

C. auris is particularly difficult to deal with for several reasons. First, it can continue to live in the environment, on both dry or moist surfaces, for up to 2 weeks. Outbreaks have occurred both from hand (person-to-person) transmission or via inanimate surfaces that have become contaminated. Equally troublesome is that people become colonized with the yeast indefinitely.

Meghan Lyman, MD, of the fungal diseases branch of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said in an interview that facilities might be slow in recognizing the problem and in identifying the organism. “We encounter problems in noninvasive specimens, especially urine,” Dr. Lyman added.

“Sometimes ... they consider Candida [to represent] colonization so they will often not speciate it.” She emphasized the need for facilities that care for ventilated patients to consider screening. “Higher priority ... are places in areas where there’s a lot of C. auris transmission or in nearby areas that are likely to get introductions.” Even those that do speciate may have difficulty identifying C. auris.

Further, Dr. Lyman stressed “the importance of antifungal susceptibility testing and testing for resistance. Because that’s also something that’s not widely available at all hospitals and clinical labs ... you can send it to the [CDC’s] antimicrobial resistance lab network” for testing.

COVID-19 has brought particular challenges. Rodney E. Rohde, PhD, MS, professor and chair, clinical lab science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, said in an interview that he is worried about all the steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics patients receive.

They’re “being given medical interventions, whether it’s ventilators or [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or IVs or central lines or catheters for UTIs and you’re creating highways, right for something that may be right there,” said Dr. Rohde, who was not involved in the CDC study. “It’s a perfect storm, not just for C. auris, but I worry about bacterial resistance agents, too, like MRSA and so forth, having kind of a spike in those types of infections with COVID. So, it’s kind of a doubly dangerous time, I think.”

Multiresistant bacteria are a major health problem, causing illnesses in 2.8 million people annually in the United States, and causing about 35,000 deaths.

Dr. Rohde raised another, rarely mentioned concern. “We’re in crisis mode. People are leaving our field more than they ever had before. The medical laboratory is being decimated because people have burned out after these past 14 months. And so I worry just about competent medical laboratory professionals that are on board to deal with these types of other crises that are popping up within hospitals and long-term care facilities. It kind of keeps me awake.”

Dr. Rohde and Dr. Lyman shared their concern that COVID caused a decrease in screening for other infections and drug-resistant organisms. Bare-bones staffing and shortages of personal protective equipment have likely fueled the spread of these infections as well.

In an outbreak of C. auris in a Florida hospital’s COVID unit in 2020, 35 of 67 patients became colonized, and 6 became ill. The epidemiologists investigating thought that contaminated gowns or gloves, computers, and other equipment were likely sources of transmission.

Low pay, especially in nursing homes, is another problem Dr. Rohde mentioned. It’s an additional problem in both acute and long-term care that “some of the lowest-paid people are the environmental services people, and so the turnover is crazy.” Yet, we rely on them to keep everyone safe. He added that, in addition to pay, he “tries to give them the appreciation and the recognition that they really deserve.”

There are a few specific measures that can be taken to protect patients. Dr. Lyman concluded. “The best way is identifying cases and really ensuring good infection control to prevent the spread.” It’s back to basics – limiting broad-spectrum antibiotics and invasive medical devices, and especially good handwashing and thorough cleaning.

Dr. Lyman and Dr. Rohde have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The CDC has reported two clusters of Candida auris infections resistant to all antifungal medications in long-term care facilities in 2021. Because these panresistant infections occurred without any exposure to antifungal drugs, the cases are even more worrisome. These clusters are the first time such nosocomial transmission has been detected.

In the District of Columbia, three panresistant isolates were discovered through screening for skin colonization with resistant organisms at a long-term acute care facility (LTAC) that cares for patients who are seriously ill, often on mechanical ventilation.

In Texas, the resistant organisms were found both by screening and in specimens from ill patients at an LTAC and a short-term acute care hospital that share patients. Two were panresistant, and five others were resistant to fluconazole and echinocandins.

These clusters occurred simultaneously and independently of each other; there were no links between the two institutions.

Colonization of skin with C. auris can lead to invasive infections in 5%-10% of affected patients. Routine skin surveillance cultures are not commonly done for Candida, although perirectal cultures for vancomycin-resistant enterococci and nasal swabs for MRSA have been done for years. Some areas, like Los Angeles, have recommended screening for C. auris in high-risk patients – defined as those who were on a ventilator or had a tracheostomy admitted from an LTAC or skilled nursing facility in Los Angeles County, New York, New Jersey, or Illinois.

In the past, about 85% of C. auris isolates in the United States have been resistant to azoles (for example, fluconazole), 33% to amphotericin B, and 1% to echinocandins. Because of generally strong susceptibility, an echinocandin such as micafungin or caspofungin has been the drug of choice for an invasive Candida infection.

C. auris is particularly difficult to deal with for several reasons. First, it can continue to live in the environment, on both dry or moist surfaces, for up to 2 weeks. Outbreaks have occurred both from hand (person-to-person) transmission or via inanimate surfaces that have become contaminated. Equally troublesome is that people become colonized with the yeast indefinitely.

Meghan Lyman, MD, of the fungal diseases branch of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said in an interview that facilities might be slow in recognizing the problem and in identifying the organism. “We encounter problems in noninvasive specimens, especially urine,” Dr. Lyman added.

“Sometimes ... they consider Candida [to represent] colonization so they will often not speciate it.” She emphasized the need for facilities that care for ventilated patients to consider screening. “Higher priority ... are places in areas where there’s a lot of C. auris transmission or in nearby areas that are likely to get introductions.” Even those that do speciate may have difficulty identifying C. auris.

Further, Dr. Lyman stressed “the importance of antifungal susceptibility testing and testing for resistance. Because that’s also something that’s not widely available at all hospitals and clinical labs ... you can send it to the [CDC’s] antimicrobial resistance lab network” for testing.

COVID-19 has brought particular challenges. Rodney E. Rohde, PhD, MS, professor and chair, clinical lab science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, said in an interview that he is worried about all the steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics patients receive.

They’re “being given medical interventions, whether it’s ventilators or [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or IVs or central lines or catheters for UTIs and you’re creating highways, right for something that may be right there,” said Dr. Rohde, who was not involved in the CDC study. “It’s a perfect storm, not just for C. auris, but I worry about bacterial resistance agents, too, like MRSA and so forth, having kind of a spike in those types of infections with COVID. So, it’s kind of a doubly dangerous time, I think.”

Multiresistant bacteria are a major health problem, causing illnesses in 2.8 million people annually in the United States, and causing about 35,000 deaths.

Dr. Rohde raised another, rarely mentioned concern. “We’re in crisis mode. People are leaving our field more than they ever had before. The medical laboratory is being decimated because people have burned out after these past 14 months. And so I worry just about competent medical laboratory professionals that are on board to deal with these types of other crises that are popping up within hospitals and long-term care facilities. It kind of keeps me awake.”

Dr. Rohde and Dr. Lyman shared their concern that COVID caused a decrease in screening for other infections and drug-resistant organisms. Bare-bones staffing and shortages of personal protective equipment have likely fueled the spread of these infections as well.

In an outbreak of C. auris in a Florida hospital’s COVID unit in 2020, 35 of 67 patients became colonized, and 6 became ill. The epidemiologists investigating thought that contaminated gowns or gloves, computers, and other equipment were likely sources of transmission.

Low pay, especially in nursing homes, is another problem Dr. Rohde mentioned. It’s an additional problem in both acute and long-term care that “some of the lowest-paid people are the environmental services people, and so the turnover is crazy.” Yet, we rely on them to keep everyone safe. He added that, in addition to pay, he “tries to give them the appreciation and the recognition that they really deserve.”

There are a few specific measures that can be taken to protect patients. Dr. Lyman concluded. “The best way is identifying cases and really ensuring good infection control to prevent the spread.” It’s back to basics – limiting broad-spectrum antibiotics and invasive medical devices, and especially good handwashing and thorough cleaning.

Dr. Lyman and Dr. Rohde have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Increases in new COVID cases among children far outpace vaccinations

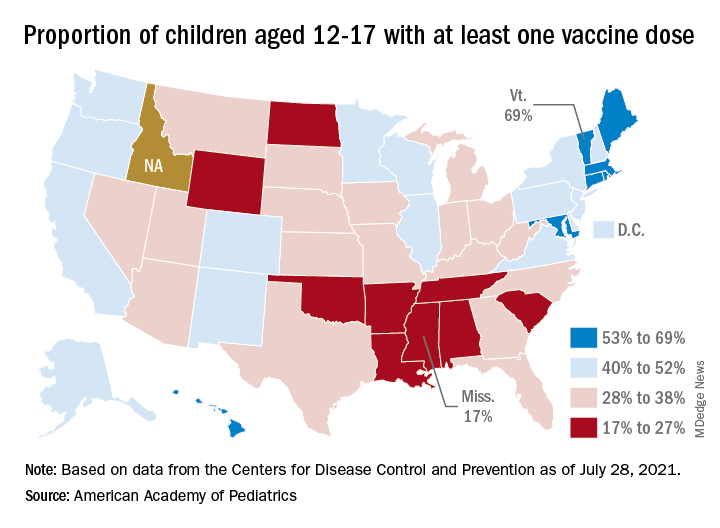

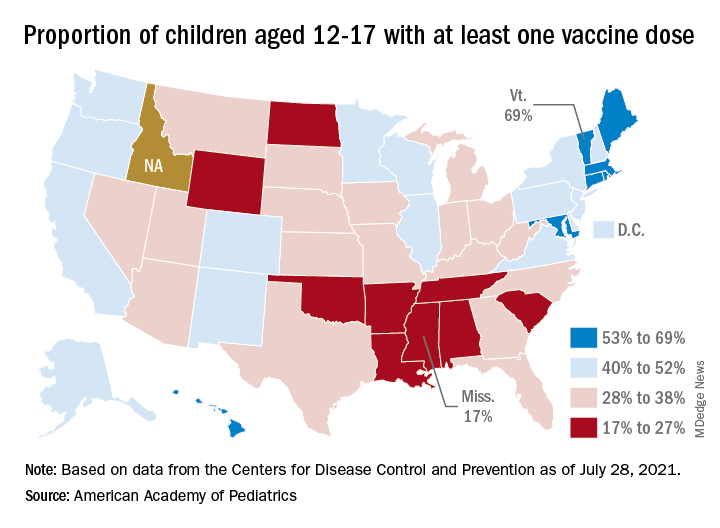

New COVID-19 cases in children soared by almost 86% over the course of just 1 week, while the number of 12- to 17-year-old children who have received at least one dose of vaccine rose by 5.4%, according to two separate sources.

Meanwhile, the increase over the past 2 weeks – from 23,551 new cases for July 16-22 to almost 72,000 – works out to almost 205%, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children represented 19.0% of the cases reported during the week of July 23-29, and they have made up 14.3% of all cases since the pandemic began, with the total number of cases in children now approaching 4.2 million, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. About 22% of the U.S. population is under the age of 18 years.

As of Aug. 2, just over 9.8 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine, which was up by about 500,000, or 5.4%, from a week earlier, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Children aged 16-17 have reached a notable milestone on the journey that started with vaccine approval in December: 50.2% have gotten at least one dose and 40.3% are fully vaccinated. Among children aged 12-15 years, the proportion with at least one dose of vaccine is up to 39.5%, compared with 37.1% the previous week, while 29.0% are fully vaccinated (27.8% the week before), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The national rates for child vaccination, however, tend to hide the disparities between states. There is a gap between Mississippi (lowest), where just 17% of children aged 12-17 years have gotten at least one dose, and Vermont (highest), which is up to 69%. Vermont also has the highest rate of vaccine completion (60%), while Alabama and Mississippi have the lowest (10%), according to a solo report from the AAP.

New COVID-19 cases in children soared by almost 86% over the course of just 1 week, while the number of 12- to 17-year-old children who have received at least one dose of vaccine rose by 5.4%, according to two separate sources.

Meanwhile, the increase over the past 2 weeks – from 23,551 new cases for July 16-22 to almost 72,000 – works out to almost 205%, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children represented 19.0% of the cases reported during the week of July 23-29, and they have made up 14.3% of all cases since the pandemic began, with the total number of cases in children now approaching 4.2 million, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. About 22% of the U.S. population is under the age of 18 years.

As of Aug. 2, just over 9.8 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine, which was up by about 500,000, or 5.4%, from a week earlier, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Children aged 16-17 have reached a notable milestone on the journey that started with vaccine approval in December: 50.2% have gotten at least one dose and 40.3% are fully vaccinated. Among children aged 12-15 years, the proportion with at least one dose of vaccine is up to 39.5%, compared with 37.1% the previous week, while 29.0% are fully vaccinated (27.8% the week before), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The national rates for child vaccination, however, tend to hide the disparities between states. There is a gap between Mississippi (lowest), where just 17% of children aged 12-17 years have gotten at least one dose, and Vermont (highest), which is up to 69%. Vermont also has the highest rate of vaccine completion (60%), while Alabama and Mississippi have the lowest (10%), according to a solo report from the AAP.

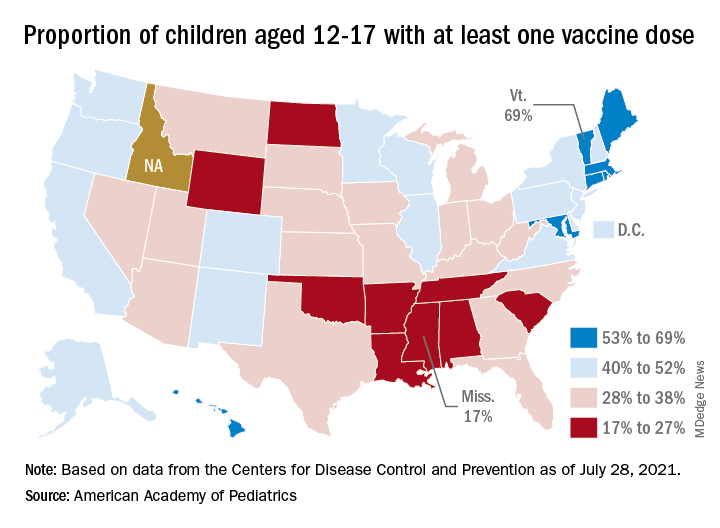

New COVID-19 cases in children soared by almost 86% over the course of just 1 week, while the number of 12- to 17-year-old children who have received at least one dose of vaccine rose by 5.4%, according to two separate sources.

Meanwhile, the increase over the past 2 weeks – from 23,551 new cases for July 16-22 to almost 72,000 – works out to almost 205%, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children represented 19.0% of the cases reported during the week of July 23-29, and they have made up 14.3% of all cases since the pandemic began, with the total number of cases in children now approaching 4.2 million, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. About 22% of the U.S. population is under the age of 18 years.

As of Aug. 2, just over 9.8 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine, which was up by about 500,000, or 5.4%, from a week earlier, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Children aged 16-17 have reached a notable milestone on the journey that started with vaccine approval in December: 50.2% have gotten at least one dose and 40.3% are fully vaccinated. Among children aged 12-15 years, the proportion with at least one dose of vaccine is up to 39.5%, compared with 37.1% the previous week, while 29.0% are fully vaccinated (27.8% the week before), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The national rates for child vaccination, however, tend to hide the disparities between states. There is a gap between Mississippi (lowest), where just 17% of children aged 12-17 years have gotten at least one dose, and Vermont (highest), which is up to 69%. Vermont also has the highest rate of vaccine completion (60%), while Alabama and Mississippi have the lowest (10%), according to a solo report from the AAP.

Doctors’ offices may be hot spot for transmission of respiratory infections

Prior research has examined the issue of hospital-acquired infections. A 2014 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that 4% of hospitalized patients acquired a health care–associated infection during their stay. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that, on any given day, one in 31 hospital patients has at least one health care–associated infection. However, researchers for the new study, published in Health Affairs, said evidence about the risk of acquiring respiratory viral infections in medical office settings is limited.

“Hospital-acquired infections has been a problem for a while,” study author Hannah Neprash, PhD, of the department of health policy and management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, said in an interview. “However, there’s never been a similar study of whether a similar phenomenon happens in physician offices. This is especially relevant now when we’re dealing with respiratory infections.”

Methods and results

For the new study, Dr. Neprash and her colleagues analyzed deidentified billing and scheduling data from 2016-2017 for 105,462,600 outpatient visits that occurred at 6,709 office-based primary care practices. They used the World Health Organization case definition for influenzalike illness “to capture cases in which the physician may suspect this illness even if a specific diagnosis code was not present.” Their control conditions included exposure to urinary tract infections and back pain.

Doctor visits were considered unexposed if they were scheduled to start at least 90 minutes before the first influenzalike illness visit of the day. They were considered exposed if they were scheduled to start at the same time or after the first influenzalike illness visit of the day at that practice.

Researchers quantified whether exposed patients were more likely to return with a similar illness in the next 2 weeks, compared with nonexposed patients seen earlier in the day

They found that 2.7 patients per 1,000 returned within 2 weeks with an influenzalike illness.

Patients were more likely to return with influenzalike illness if their visit occurred after an influenzalike illness visit versus before, the researchers said.

The authors of the paper said their new research highlights the importance of infection control in health care settings, including outpatient offices.

Where did the exposure occur?

Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., said he was not surprised by the findings, but noted that it’s hard to say if the exposure to influenzalike illnesses happened in the office or in the community.

“If you start to see individuals with influenza in your office it’s because [there’s influenza] in the community,” Dr. Hijano explained. “So that means that you will have more patients coming in with influenza.”

To reduce the transmission of infections, Dr. Neprash suggested that doctors’ offices follow the CDC guidelines for indoor conduct, which include masking, washing hands, and “taking appropriate infection control measures.”

So potentially masking within offices is a way to minimize transmission between whatever people are there to be seen when it’s contagious, Dr. Neprash said.

“Telehealth really took off in 2020 and it’s unclear what the state of telehealth will be going forward. [These findings] suggest that there’s a patient safety argument for continuing to enable primary care physicians to provide visits either by phone or by video,” he added.

Dr. Hijano thinks it would be helpful for doctors to separate patients with respiratory illnesses from those without respiratory illnesses.

Driver of transmissions

Dr. Neprash suggested that another driver of these transmissions could be doctors not washing their hands, which is a “notorious issue,” and Dr. Hijano agreed with that statement.

“We did know that the hands of physicians and nurses and care providers are the main driver of infections in the health care setting,” Dr. Hijano explained. “I mean, washing your hands properly between encounters is the single best way that any given health care provider can prevent the spread of infections.”

“We have a unique opportunity with COVID-19 to change how these clinics are operating now,” Dr. Hijano said. “Many clinics are actually asking patients to call ahead of time if you have symptoms of a respiratory illness that could be contagious, and those who are not are still mandating the use of mask and physical distance in the waiting areas and limiting the amount of number of patients in any given hour. So I think that those are really big practices that would kind of make an impact in respiratory illness in terms of decreasing transmission in clinics.”

The authors, who had no conflicts of interest said their hope is that their study will help inform policy for reopening outpatient care settings. Dr. Hijano, who was not involved in the study also had no conflicts.

Prior research has examined the issue of hospital-acquired infections. A 2014 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that 4% of hospitalized patients acquired a health care–associated infection during their stay. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that, on any given day, one in 31 hospital patients has at least one health care–associated infection. However, researchers for the new study, published in Health Affairs, said evidence about the risk of acquiring respiratory viral infections in medical office settings is limited.

“Hospital-acquired infections has been a problem for a while,” study author Hannah Neprash, PhD, of the department of health policy and management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, said in an interview. “However, there’s never been a similar study of whether a similar phenomenon happens in physician offices. This is especially relevant now when we’re dealing with respiratory infections.”

Methods and results

For the new study, Dr. Neprash and her colleagues analyzed deidentified billing and scheduling data from 2016-2017 for 105,462,600 outpatient visits that occurred at 6,709 office-based primary care practices. They used the World Health Organization case definition for influenzalike illness “to capture cases in which the physician may suspect this illness even if a specific diagnosis code was not present.” Their control conditions included exposure to urinary tract infections and back pain.

Doctor visits were considered unexposed if they were scheduled to start at least 90 minutes before the first influenzalike illness visit of the day. They were considered exposed if they were scheduled to start at the same time or after the first influenzalike illness visit of the day at that practice.

Researchers quantified whether exposed patients were more likely to return with a similar illness in the next 2 weeks, compared with nonexposed patients seen earlier in the day

They found that 2.7 patients per 1,000 returned within 2 weeks with an influenzalike illness.

Patients were more likely to return with influenzalike illness if their visit occurred after an influenzalike illness visit versus before, the researchers said.

The authors of the paper said their new research highlights the importance of infection control in health care settings, including outpatient offices.

Where did the exposure occur?

Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., said he was not surprised by the findings, but noted that it’s hard to say if the exposure to influenzalike illnesses happened in the office or in the community.

“If you start to see individuals with influenza in your office it’s because [there’s influenza] in the community,” Dr. Hijano explained. “So that means that you will have more patients coming in with influenza.”

To reduce the transmission of infections, Dr. Neprash suggested that doctors’ offices follow the CDC guidelines for indoor conduct, which include masking, washing hands, and “taking appropriate infection control measures.”

So potentially masking within offices is a way to minimize transmission between whatever people are there to be seen when it’s contagious, Dr. Neprash said.

“Telehealth really took off in 2020 and it’s unclear what the state of telehealth will be going forward. [These findings] suggest that there’s a patient safety argument for continuing to enable primary care physicians to provide visits either by phone or by video,” he added.

Dr. Hijano thinks it would be helpful for doctors to separate patients with respiratory illnesses from those without respiratory illnesses.

Driver of transmissions

Dr. Neprash suggested that another driver of these transmissions could be doctors not washing their hands, which is a “notorious issue,” and Dr. Hijano agreed with that statement.

“We did know that the hands of physicians and nurses and care providers are the main driver of infections in the health care setting,” Dr. Hijano explained. “I mean, washing your hands properly between encounters is the single best way that any given health care provider can prevent the spread of infections.”

“We have a unique opportunity with COVID-19 to change how these clinics are operating now,” Dr. Hijano said. “Many clinics are actually asking patients to call ahead of time if you have symptoms of a respiratory illness that could be contagious, and those who are not are still mandating the use of mask and physical distance in the waiting areas and limiting the amount of number of patients in any given hour. So I think that those are really big practices that would kind of make an impact in respiratory illness in terms of decreasing transmission in clinics.”

The authors, who had no conflicts of interest said their hope is that their study will help inform policy for reopening outpatient care settings. Dr. Hijano, who was not involved in the study also had no conflicts.

Prior research has examined the issue of hospital-acquired infections. A 2014 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that 4% of hospitalized patients acquired a health care–associated infection during their stay. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that, on any given day, one in 31 hospital patients has at least one health care–associated infection. However, researchers for the new study, published in Health Affairs, said evidence about the risk of acquiring respiratory viral infections in medical office settings is limited.

“Hospital-acquired infections has been a problem for a while,” study author Hannah Neprash, PhD, of the department of health policy and management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, said in an interview. “However, there’s never been a similar study of whether a similar phenomenon happens in physician offices. This is especially relevant now when we’re dealing with respiratory infections.”

Methods and results

For the new study, Dr. Neprash and her colleagues analyzed deidentified billing and scheduling data from 2016-2017 for 105,462,600 outpatient visits that occurred at 6,709 office-based primary care practices. They used the World Health Organization case definition for influenzalike illness “to capture cases in which the physician may suspect this illness even if a specific diagnosis code was not present.” Their control conditions included exposure to urinary tract infections and back pain.

Doctor visits were considered unexposed if they were scheduled to start at least 90 minutes before the first influenzalike illness visit of the day. They were considered exposed if they were scheduled to start at the same time or after the first influenzalike illness visit of the day at that practice.

Researchers quantified whether exposed patients were more likely to return with a similar illness in the next 2 weeks, compared with nonexposed patients seen earlier in the day

They found that 2.7 patients per 1,000 returned within 2 weeks with an influenzalike illness.

Patients were more likely to return with influenzalike illness if their visit occurred after an influenzalike illness visit versus before, the researchers said.

The authors of the paper said their new research highlights the importance of infection control in health care settings, including outpatient offices.

Where did the exposure occur?

Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., said he was not surprised by the findings, but noted that it’s hard to say if the exposure to influenzalike illnesses happened in the office or in the community.

“If you start to see individuals with influenza in your office it’s because [there’s influenza] in the community,” Dr. Hijano explained. “So that means that you will have more patients coming in with influenza.”

To reduce the transmission of infections, Dr. Neprash suggested that doctors’ offices follow the CDC guidelines for indoor conduct, which include masking, washing hands, and “taking appropriate infection control measures.”

So potentially masking within offices is a way to minimize transmission between whatever people are there to be seen when it’s contagious, Dr. Neprash said.

“Telehealth really took off in 2020 and it’s unclear what the state of telehealth will be going forward. [These findings] suggest that there’s a patient safety argument for continuing to enable primary care physicians to provide visits either by phone or by video,” he added.

Dr. Hijano thinks it would be helpful for doctors to separate patients with respiratory illnesses from those without respiratory illnesses.

Driver of transmissions

Dr. Neprash suggested that another driver of these transmissions could be doctors not washing their hands, which is a “notorious issue,” and Dr. Hijano agreed with that statement.

“We did know that the hands of physicians and nurses and care providers are the main driver of infections in the health care setting,” Dr. Hijano explained. “I mean, washing your hands properly between encounters is the single best way that any given health care provider can prevent the spread of infections.”

“We have a unique opportunity with COVID-19 to change how these clinics are operating now,” Dr. Hijano said. “Many clinics are actually asking patients to call ahead of time if you have symptoms of a respiratory illness that could be contagious, and those who are not are still mandating the use of mask and physical distance in the waiting areas and limiting the amount of number of patients in any given hour. So I think that those are really big practices that would kind of make an impact in respiratory illness in terms of decreasing transmission in clinics.”

The authors, who had no conflicts of interest said their hope is that their study will help inform policy for reopening outpatient care settings. Dr. Hijano, who was not involved in the study also had no conflicts.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Early transition to oral beta-lactams for low-risk S. aureus bacteremia may be acceptable

Background: There is consensus that LR-SAB can be safely treated with 14 days of antibiotic therapy, but the use of and/or proportion of duration of oral antibiotics is not clear. There is evidence that oral therapy has fewer treatment complications, compared with IV treatments. Objective of this study was to assess the safety of early oral switch (EOS) prior to 14 days for LR-SAB.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Single institution tertiary care hospital in Wellington, New Zealand.

Synopsis: Study population included adults with health care–associated SAB deemed low risk (no positive blood cultures >72 hours after initial positive culture, no evidence of deep infection as determined by an infectious disease consultant, no nonremovable prosthetics). The primary outcome was occurrence of SAB-related complication (recurrence of SAB, deep-seated infection, readmission, attributable mortality) within 90 days.

Of the initial 469 episodes of SAB, 100 met inclusion, and 84 of those patients had EOS. Line infection was the source in a majority of patients (79% and 88% in EOS and IV, respectively). Only 5% of patients had MRSA. Overall, 86% of EOS patients were treated with an oral beta-lactam, within the EOS group, median duration of IV and oral antibiotics was 5 and 10 days, respectively. SAB recurrence within 90 days occurred in three (4%) and one (6%) patients in EOS vs. IV groups, respectively (P = .64). No deaths within 90 days were deemed attributable to SAB. Limitations include small size, single center, and observational, retrospective framework.

Bottom line: The study suggests that EOS with oral beta-lactams in selected patients with LR-SAB may be adequate; however, the study is too small to provide robust high-level evidence. Instead, the authors hope the data will lead to larger, more powerful prospective studies to examine if a simpler, cheaper, and in some ways safer treatment course is possible.

Citation: Bupha-Intr O et al. Efficacy of early oral switch with beta-lactams for low-risk Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Feb 3;AAC.02345-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02345-19.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: There is consensus that LR-SAB can be safely treated with 14 days of antibiotic therapy, but the use of and/or proportion of duration of oral antibiotics is not clear. There is evidence that oral therapy has fewer treatment complications, compared with IV treatments. Objective of this study was to assess the safety of early oral switch (EOS) prior to 14 days for LR-SAB.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Single institution tertiary care hospital in Wellington, New Zealand.

Synopsis: Study population included adults with health care–associated SAB deemed low risk (no positive blood cultures >72 hours after initial positive culture, no evidence of deep infection as determined by an infectious disease consultant, no nonremovable prosthetics). The primary outcome was occurrence of SAB-related complication (recurrence of SAB, deep-seated infection, readmission, attributable mortality) within 90 days.

Of the initial 469 episodes of SAB, 100 met inclusion, and 84 of those patients had EOS. Line infection was the source in a majority of patients (79% and 88% in EOS and IV, respectively). Only 5% of patients had MRSA. Overall, 86% of EOS patients were treated with an oral beta-lactam, within the EOS group, median duration of IV and oral antibiotics was 5 and 10 days, respectively. SAB recurrence within 90 days occurred in three (4%) and one (6%) patients in EOS vs. IV groups, respectively (P = .64). No deaths within 90 days were deemed attributable to SAB. Limitations include small size, single center, and observational, retrospective framework.