User login

Virtual Respiratory Urgent Clinics for COVID-19 Symptoms

Virtual care (VC) has emerged as an effective mode of health care delivery especially in settings where significant barriers to traditional in-person visits exist; a large systematic review supports feasibility of telemedicine in primary care and suggests that telemedicine is at least as effective as traditional care.1 Nevertheless, broad adoption of VC into practice has lagged, impeded by government and private insurance reimbursement requirements as well as the persistent belief that care can best be delivered in person.2-4 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, states that enacted parity legislation that required private insurance companies to provide reimbursement coverage for telehealth services saw a significant increase in the number of outpatient telehealth visits (about ≥ 30% odds compared with nonparity states).3

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person medical appointments were converted to VC visits to reduce increased exposure risks to patients and health care workers.5 Prior government and private sector policies were suspended, and payment restrictions lifted, enabling adoption of VC modalities to rapidly accommodate the emergent need and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for virtual care.6-11

The CDC guidelines on managing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need to provide care in the safest way for patients and health care personnel and emphasized the importance of optimizing telehealth services. The federal government facilitated telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic via temporary measures under the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration. This included Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act flexibility to use everyday technology for VC visits, regulatory changes to deliver services to Medicare and Medicaid patients, permission of telehealth services across state lines, and prescribing of controlled substances via telehealth without an in-person medical evaluation.7

In response, health care providers (HCPs) and health care organizations created or expanded on existing telehealth infrastructure, developing virtual urgent care centers and telephone-based programs to evaluate patients remotely via screening questions that triaged them to a correct level of response, with possible subsequent virtual physician evaluation if indicated.12,13

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) also shifted to a VC model in response to COVID-19 guided by a unique perspective from a well-developed prior VC experience.14-16 As a federally funded system, the VHA depends on workload documentation for budgeting. Since 2015, the VHA has provided workload credit and incentivized HCPs (via pay for performance) for the use of VC, including telephone visits, video visits, and secure messaging. These incentives resulted in higher rates of telehealth utilization before the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the private sector (with 4.2% and 0.7% of visits within the VHA being telephone and video visits, respectively, compared with telehealth utilization rates of 1.0% for Medicare recipients and 1.1% in an all-payer database).16

Historically, VHA care has successfully transitioned from in-person care models to exclusively virtual modalities to prevent suspension of medical services during natural disasters. Studies performed during these periods, specifically during the 2017 hurricane season (during which multiple VHA hospitals were closed or had limited in-person service available), supported telehealth as an efficient health care delivery method, and even recommended expanding telehealth services within non-VHA environments to accommodate needs of the general public during crises and postdisaster health care delivery.17

Armed with both a well-established telehealth infrastructure and prior knowledge gained from successful systemwide implementation of virtual care during times of disaster, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) primary care quickly transitioned to a VC model in response to COVID-19.16 Early in the pandemic, a rapid transition to virtual care (RTVC) model was developed, including implementation of virtual respiratory urgent clinics (VRUCs), defined as virtual respiratory symptom triage clinics, staffed by primary care providers (PCPs) aimed at minimizing patient and health care worker exposure risk.

Methods

VACHS consists of 8 primary care sites, including a major tertiary care center, a smaller medical center with full ambulatory services, and 6 community-based outpatient clinics with only primary care and mental health. There are 80 individual PCPs delivering care to 58,058 veterans. VRUCs were established during the COVID-19 pandemic to cover patients across the entire health care system, using a rotational schedule of VA PCPs.

COVID-19 Urgent Clinics Program

Within the first few weeks of the pandemic, VACHS primary care established VRUCS to provide expeditious virtual assessment of respiratory or flu-like symptoms. Using the established telehealth system, the intervention aimed to provide emergent screening, testing, and care to those with potential COVID-19 infections. The model also was designed to minimize exposures to the health care workforce and patients.

Retrospective analysis was performed using information obtained from the electronic health record (EHR) database to describe the characteristics of patients who received care through the VRUCs, such as demographics, era of military service, COVID-19 testing rates and results, as well as subsequent emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions. A secondary aim included collection of additional qualitative data via a random sample chart review.

Virtual clinics were established January 22, 2020, and data were analyzed over the next 3 months. Data were retrieved and analyzed from the EHR, and codes were used to categorize the VRUCs.

Results

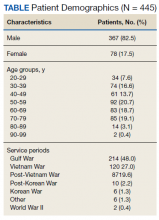

A total of 445 unique patients used these clinics during this period. Unique patients were defined as individual patients (some may have used a clinic more than once but were counted only once). Of this group, 82% were male, and 48% served in the Gulf War era (1990 to present). A total of 51% of patients received a COVID-19 test (clinics began before wide testing availability), and 10% tested positive. Of all patients using the clinics, approximately 5% were admitted to the hospital, and 18% had at least 1 subsequent ED visit (Table).

A secondary aim included review of a random sample of 99 patient charts to gain additional information regarding whether the patient was given appropriate isolation precautions, was in a high-exposure occupation (eg, could expose a large number of people), and whether there was appropriate documentation of goals of care, health care proxy or referral to social work to discuss advance directives. In addition, we calculated the average length of time between patients’ initial contact with the health care system call center and the return call by the PCP (wait time).Of charts reviewed, the majority (71%) had documentation of appropriate isolation precautions. Although 25% of patients had documentation of a high-risk profession with potential to expose many people, more than half of the patients had no documentation of occupation. Most patients (86%) had no updated documentation regarding goals of care, health care proxy, or advance directives in their urgent care VC visit. The average time between the patient initiating contact with the health care system call center and a return call to the patient from a PCP was 104 minutes (excluding calls received after 3:30

Discussion

This analysis adds to the growing literature on use of VC during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we describe the population of patients who used VRUCs within a large health care system in a RTVC. This analysis was limited by lack of available testing during the initial phase of the pandemic, which contributed to the lower than expected rates of testing and test positivity in patients managed via VRUCs. In addition, chart review data are limited as the data includes only what was documented during the visit and not the entire discussion during the encounter.

Several important outcomes from this analysis can be applied to interventions in the future, which may have large public health implications: Several hundred patients who reported respiratory symptoms were expeditiously evaluated by a PCP using VC. The average wait time to full clinical assessment was about 1.5 hours. This short duration between contact and evaluation permitted early education about isolation precautions, which may have minimized spread. In addition, this innovation kept patients out of the medical center, eliminating chains of transmission to other vulnerable patients and health care workers.

Our retrospective chart review also revealed that more than half the patients were not queried about their occupation, but of those that were asked, a significant number were in high-risk professions potentially exposing large numbers of people. This would be an important aspect to add to future templated notes to minimize work-related exposures. Also, we identified that few HCPs discussed goals of care with patients. Given the nature of COVID-19 and potential for rapid decompensation especially in vulnerable patients, this also would be important to include in the future.

Conclusions

VC urgent care clinics to address possible COVID-19 symptoms facilitated expeditious PCP assessment while keeping potentially contagious patients outside of high-risk health care environments. Streamlining and optimizing clinical VC assessments will be imperative to future management of COVID-19 and potentially to other future infectious pandemics. This includes development of templated notes incorporating counseling regarding appropriate isolation, questions about high-contact occupations, and goals of care discussions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Robert F. Walsh, MHA.

1. Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using telehealth to expand access to essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated June 10, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html

3. Harvey JB, Valenta S, Simpson K, Lyles M, McElligott J. Utilization of outpatient telehealth services in parity and nonparity states 2010-2015. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(2):132-136. doi:10.1089/tmj.2017.0265

4. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1601705

5. Rockwell KL, Gilroy AS. Incorporating telemedicine as part of COVID-19 outbreak response systems. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(4):147-148. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.42784

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare facility guidance. Updated April 17, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care.html

7. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Policy changes during COVID-19. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/policy-changes-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

8. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriation Act of 2020. 134 Stat. 146. Published February 2, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-2021-02-02/html/CREC-2021-02-02-pt1-PgS226.htm

9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Updated January 20, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Coverage and payment related to COVID-19 Medicare. 2020. Published March 23, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/03052020-medicare-covid-19-fact-sheet.pdf

11. American Telemedicine Association. ATA commends 2020 Congress for giving HHS authority to waive restrictions on telehealth for Medicare beneficiaries in response to the COVID-19 outbreak [press release]. Published March 5, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.americantelemed.org/press-releases/ata-commends-congress-for-waiving-restrictions-on-telehealth-for-medicare-beneficiaries-in-response-to-the-covid-19-outbreak

12. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679-1681. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2003539

13. Khairat S, Meng C, Xu Y, Edson B, Gianforcaro R. Interpreting COVID-19 and Virtual Care Trends: Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18811. Published 2020 Apr 15. doi:10.2196/18811

14. Ferguson JM, Jacobs J, Yefimova M, Greene L, Heyworth L, Zulman DM. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans Health Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(3):453-462. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocaa284

15. Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced in-person and increased telehealth outpatient visits during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(1):129-131. doi:10.7326/M20-3026

16. Spelman JF, Brienza R, Walsh RF, et al. A model for rapid transition to virtual care, VA Connecticut primary care response to COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3073-3076. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06041-4

17. Der-Martirosian C, Chu K, Dobalian A. Use of telehealth to improve access to care at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs during the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 13]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;1-5. doi:10.1017/dmp.2020.88

Virtual care (VC) has emerged as an effective mode of health care delivery especially in settings where significant barriers to traditional in-person visits exist; a large systematic review supports feasibility of telemedicine in primary care and suggests that telemedicine is at least as effective as traditional care.1 Nevertheless, broad adoption of VC into practice has lagged, impeded by government and private insurance reimbursement requirements as well as the persistent belief that care can best be delivered in person.2-4 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, states that enacted parity legislation that required private insurance companies to provide reimbursement coverage for telehealth services saw a significant increase in the number of outpatient telehealth visits (about ≥ 30% odds compared with nonparity states).3

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person medical appointments were converted to VC visits to reduce increased exposure risks to patients and health care workers.5 Prior government and private sector policies were suspended, and payment restrictions lifted, enabling adoption of VC modalities to rapidly accommodate the emergent need and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for virtual care.6-11

The CDC guidelines on managing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need to provide care in the safest way for patients and health care personnel and emphasized the importance of optimizing telehealth services. The federal government facilitated telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic via temporary measures under the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration. This included Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act flexibility to use everyday technology for VC visits, regulatory changes to deliver services to Medicare and Medicaid patients, permission of telehealth services across state lines, and prescribing of controlled substances via telehealth without an in-person medical evaluation.7

In response, health care providers (HCPs) and health care organizations created or expanded on existing telehealth infrastructure, developing virtual urgent care centers and telephone-based programs to evaluate patients remotely via screening questions that triaged them to a correct level of response, with possible subsequent virtual physician evaluation if indicated.12,13

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) also shifted to a VC model in response to COVID-19 guided by a unique perspective from a well-developed prior VC experience.14-16 As a federally funded system, the VHA depends on workload documentation for budgeting. Since 2015, the VHA has provided workload credit and incentivized HCPs (via pay for performance) for the use of VC, including telephone visits, video visits, and secure messaging. These incentives resulted in higher rates of telehealth utilization before the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the private sector (with 4.2% and 0.7% of visits within the VHA being telephone and video visits, respectively, compared with telehealth utilization rates of 1.0% for Medicare recipients and 1.1% in an all-payer database).16

Historically, VHA care has successfully transitioned from in-person care models to exclusively virtual modalities to prevent suspension of medical services during natural disasters. Studies performed during these periods, specifically during the 2017 hurricane season (during which multiple VHA hospitals were closed or had limited in-person service available), supported telehealth as an efficient health care delivery method, and even recommended expanding telehealth services within non-VHA environments to accommodate needs of the general public during crises and postdisaster health care delivery.17

Armed with both a well-established telehealth infrastructure and prior knowledge gained from successful systemwide implementation of virtual care during times of disaster, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) primary care quickly transitioned to a VC model in response to COVID-19.16 Early in the pandemic, a rapid transition to virtual care (RTVC) model was developed, including implementation of virtual respiratory urgent clinics (VRUCs), defined as virtual respiratory symptom triage clinics, staffed by primary care providers (PCPs) aimed at minimizing patient and health care worker exposure risk.

Methods

VACHS consists of 8 primary care sites, including a major tertiary care center, a smaller medical center with full ambulatory services, and 6 community-based outpatient clinics with only primary care and mental health. There are 80 individual PCPs delivering care to 58,058 veterans. VRUCs were established during the COVID-19 pandemic to cover patients across the entire health care system, using a rotational schedule of VA PCPs.

COVID-19 Urgent Clinics Program

Within the first few weeks of the pandemic, VACHS primary care established VRUCS to provide expeditious virtual assessment of respiratory or flu-like symptoms. Using the established telehealth system, the intervention aimed to provide emergent screening, testing, and care to those with potential COVID-19 infections. The model also was designed to minimize exposures to the health care workforce and patients.

Retrospective analysis was performed using information obtained from the electronic health record (EHR) database to describe the characteristics of patients who received care through the VRUCs, such as demographics, era of military service, COVID-19 testing rates and results, as well as subsequent emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions. A secondary aim included collection of additional qualitative data via a random sample chart review.

Virtual clinics were established January 22, 2020, and data were analyzed over the next 3 months. Data were retrieved and analyzed from the EHR, and codes were used to categorize the VRUCs.

Results

A total of 445 unique patients used these clinics during this period. Unique patients were defined as individual patients (some may have used a clinic more than once but were counted only once). Of this group, 82% were male, and 48% served in the Gulf War era (1990 to present). A total of 51% of patients received a COVID-19 test (clinics began before wide testing availability), and 10% tested positive. Of all patients using the clinics, approximately 5% were admitted to the hospital, and 18% had at least 1 subsequent ED visit (Table).

A secondary aim included review of a random sample of 99 patient charts to gain additional information regarding whether the patient was given appropriate isolation precautions, was in a high-exposure occupation (eg, could expose a large number of people), and whether there was appropriate documentation of goals of care, health care proxy or referral to social work to discuss advance directives. In addition, we calculated the average length of time between patients’ initial contact with the health care system call center and the return call by the PCP (wait time).Of charts reviewed, the majority (71%) had documentation of appropriate isolation precautions. Although 25% of patients had documentation of a high-risk profession with potential to expose many people, more than half of the patients had no documentation of occupation. Most patients (86%) had no updated documentation regarding goals of care, health care proxy, or advance directives in their urgent care VC visit. The average time between the patient initiating contact with the health care system call center and a return call to the patient from a PCP was 104 minutes (excluding calls received after 3:30

Discussion

This analysis adds to the growing literature on use of VC during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we describe the population of patients who used VRUCs within a large health care system in a RTVC. This analysis was limited by lack of available testing during the initial phase of the pandemic, which contributed to the lower than expected rates of testing and test positivity in patients managed via VRUCs. In addition, chart review data are limited as the data includes only what was documented during the visit and not the entire discussion during the encounter.

Several important outcomes from this analysis can be applied to interventions in the future, which may have large public health implications: Several hundred patients who reported respiratory symptoms were expeditiously evaluated by a PCP using VC. The average wait time to full clinical assessment was about 1.5 hours. This short duration between contact and evaluation permitted early education about isolation precautions, which may have minimized spread. In addition, this innovation kept patients out of the medical center, eliminating chains of transmission to other vulnerable patients and health care workers.

Our retrospective chart review also revealed that more than half the patients were not queried about their occupation, but of those that were asked, a significant number were in high-risk professions potentially exposing large numbers of people. This would be an important aspect to add to future templated notes to minimize work-related exposures. Also, we identified that few HCPs discussed goals of care with patients. Given the nature of COVID-19 and potential for rapid decompensation especially in vulnerable patients, this also would be important to include in the future.

Conclusions

VC urgent care clinics to address possible COVID-19 symptoms facilitated expeditious PCP assessment while keeping potentially contagious patients outside of high-risk health care environments. Streamlining and optimizing clinical VC assessments will be imperative to future management of COVID-19 and potentially to other future infectious pandemics. This includes development of templated notes incorporating counseling regarding appropriate isolation, questions about high-contact occupations, and goals of care discussions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Robert F. Walsh, MHA.

Virtual care (VC) has emerged as an effective mode of health care delivery especially in settings where significant barriers to traditional in-person visits exist; a large systematic review supports feasibility of telemedicine in primary care and suggests that telemedicine is at least as effective as traditional care.1 Nevertheless, broad adoption of VC into practice has lagged, impeded by government and private insurance reimbursement requirements as well as the persistent belief that care can best be delivered in person.2-4 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, states that enacted parity legislation that required private insurance companies to provide reimbursement coverage for telehealth services saw a significant increase in the number of outpatient telehealth visits (about ≥ 30% odds compared with nonparity states).3

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person medical appointments were converted to VC visits to reduce increased exposure risks to patients and health care workers.5 Prior government and private sector policies were suspended, and payment restrictions lifted, enabling adoption of VC modalities to rapidly accommodate the emergent need and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for virtual care.6-11

The CDC guidelines on managing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need to provide care in the safest way for patients and health care personnel and emphasized the importance of optimizing telehealth services. The federal government facilitated telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic via temporary measures under the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration. This included Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act flexibility to use everyday technology for VC visits, regulatory changes to deliver services to Medicare and Medicaid patients, permission of telehealth services across state lines, and prescribing of controlled substances via telehealth without an in-person medical evaluation.7

In response, health care providers (HCPs) and health care organizations created or expanded on existing telehealth infrastructure, developing virtual urgent care centers and telephone-based programs to evaluate patients remotely via screening questions that triaged them to a correct level of response, with possible subsequent virtual physician evaluation if indicated.12,13

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) also shifted to a VC model in response to COVID-19 guided by a unique perspective from a well-developed prior VC experience.14-16 As a federally funded system, the VHA depends on workload documentation for budgeting. Since 2015, the VHA has provided workload credit and incentivized HCPs (via pay for performance) for the use of VC, including telephone visits, video visits, and secure messaging. These incentives resulted in higher rates of telehealth utilization before the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the private sector (with 4.2% and 0.7% of visits within the VHA being telephone and video visits, respectively, compared with telehealth utilization rates of 1.0% for Medicare recipients and 1.1% in an all-payer database).16

Historically, VHA care has successfully transitioned from in-person care models to exclusively virtual modalities to prevent suspension of medical services during natural disasters. Studies performed during these periods, specifically during the 2017 hurricane season (during which multiple VHA hospitals were closed or had limited in-person service available), supported telehealth as an efficient health care delivery method, and even recommended expanding telehealth services within non-VHA environments to accommodate needs of the general public during crises and postdisaster health care delivery.17

Armed with both a well-established telehealth infrastructure and prior knowledge gained from successful systemwide implementation of virtual care during times of disaster, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) primary care quickly transitioned to a VC model in response to COVID-19.16 Early in the pandemic, a rapid transition to virtual care (RTVC) model was developed, including implementation of virtual respiratory urgent clinics (VRUCs), defined as virtual respiratory symptom triage clinics, staffed by primary care providers (PCPs) aimed at minimizing patient and health care worker exposure risk.

Methods

VACHS consists of 8 primary care sites, including a major tertiary care center, a smaller medical center with full ambulatory services, and 6 community-based outpatient clinics with only primary care and mental health. There are 80 individual PCPs delivering care to 58,058 veterans. VRUCs were established during the COVID-19 pandemic to cover patients across the entire health care system, using a rotational schedule of VA PCPs.

COVID-19 Urgent Clinics Program

Within the first few weeks of the pandemic, VACHS primary care established VRUCS to provide expeditious virtual assessment of respiratory or flu-like symptoms. Using the established telehealth system, the intervention aimed to provide emergent screening, testing, and care to those with potential COVID-19 infections. The model also was designed to minimize exposures to the health care workforce and patients.

Retrospective analysis was performed using information obtained from the electronic health record (EHR) database to describe the characteristics of patients who received care through the VRUCs, such as demographics, era of military service, COVID-19 testing rates and results, as well as subsequent emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions. A secondary aim included collection of additional qualitative data via a random sample chart review.

Virtual clinics were established January 22, 2020, and data were analyzed over the next 3 months. Data were retrieved and analyzed from the EHR, and codes were used to categorize the VRUCs.

Results

A total of 445 unique patients used these clinics during this period. Unique patients were defined as individual patients (some may have used a clinic more than once but were counted only once). Of this group, 82% were male, and 48% served in the Gulf War era (1990 to present). A total of 51% of patients received a COVID-19 test (clinics began before wide testing availability), and 10% tested positive. Of all patients using the clinics, approximately 5% were admitted to the hospital, and 18% had at least 1 subsequent ED visit (Table).

A secondary aim included review of a random sample of 99 patient charts to gain additional information regarding whether the patient was given appropriate isolation precautions, was in a high-exposure occupation (eg, could expose a large number of people), and whether there was appropriate documentation of goals of care, health care proxy or referral to social work to discuss advance directives. In addition, we calculated the average length of time between patients’ initial contact with the health care system call center and the return call by the PCP (wait time).Of charts reviewed, the majority (71%) had documentation of appropriate isolation precautions. Although 25% of patients had documentation of a high-risk profession with potential to expose many people, more than half of the patients had no documentation of occupation. Most patients (86%) had no updated documentation regarding goals of care, health care proxy, or advance directives in their urgent care VC visit. The average time between the patient initiating contact with the health care system call center and a return call to the patient from a PCP was 104 minutes (excluding calls received after 3:30

Discussion

This analysis adds to the growing literature on use of VC during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we describe the population of patients who used VRUCs within a large health care system in a RTVC. This analysis was limited by lack of available testing during the initial phase of the pandemic, which contributed to the lower than expected rates of testing and test positivity in patients managed via VRUCs. In addition, chart review data are limited as the data includes only what was documented during the visit and not the entire discussion during the encounter.

Several important outcomes from this analysis can be applied to interventions in the future, which may have large public health implications: Several hundred patients who reported respiratory symptoms were expeditiously evaluated by a PCP using VC. The average wait time to full clinical assessment was about 1.5 hours. This short duration between contact and evaluation permitted early education about isolation precautions, which may have minimized spread. In addition, this innovation kept patients out of the medical center, eliminating chains of transmission to other vulnerable patients and health care workers.

Our retrospective chart review also revealed that more than half the patients were not queried about their occupation, but of those that were asked, a significant number were in high-risk professions potentially exposing large numbers of people. This would be an important aspect to add to future templated notes to minimize work-related exposures. Also, we identified that few HCPs discussed goals of care with patients. Given the nature of COVID-19 and potential for rapid decompensation especially in vulnerable patients, this also would be important to include in the future.

Conclusions

VC urgent care clinics to address possible COVID-19 symptoms facilitated expeditious PCP assessment while keeping potentially contagious patients outside of high-risk health care environments. Streamlining and optimizing clinical VC assessments will be imperative to future management of COVID-19 and potentially to other future infectious pandemics. This includes development of templated notes incorporating counseling regarding appropriate isolation, questions about high-contact occupations, and goals of care discussions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Robert F. Walsh, MHA.

1. Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using telehealth to expand access to essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated June 10, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html

3. Harvey JB, Valenta S, Simpson K, Lyles M, McElligott J. Utilization of outpatient telehealth services in parity and nonparity states 2010-2015. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(2):132-136. doi:10.1089/tmj.2017.0265

4. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1601705

5. Rockwell KL, Gilroy AS. Incorporating telemedicine as part of COVID-19 outbreak response systems. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(4):147-148. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.42784

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare facility guidance. Updated April 17, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care.html

7. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Policy changes during COVID-19. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/policy-changes-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

8. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriation Act of 2020. 134 Stat. 146. Published February 2, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-2021-02-02/html/CREC-2021-02-02-pt1-PgS226.htm

9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Updated January 20, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Coverage and payment related to COVID-19 Medicare. 2020. Published March 23, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/03052020-medicare-covid-19-fact-sheet.pdf

11. American Telemedicine Association. ATA commends 2020 Congress for giving HHS authority to waive restrictions on telehealth for Medicare beneficiaries in response to the COVID-19 outbreak [press release]. Published March 5, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.americantelemed.org/press-releases/ata-commends-congress-for-waiving-restrictions-on-telehealth-for-medicare-beneficiaries-in-response-to-the-covid-19-outbreak

12. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679-1681. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2003539

13. Khairat S, Meng C, Xu Y, Edson B, Gianforcaro R. Interpreting COVID-19 and Virtual Care Trends: Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18811. Published 2020 Apr 15. doi:10.2196/18811

14. Ferguson JM, Jacobs J, Yefimova M, Greene L, Heyworth L, Zulman DM. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans Health Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(3):453-462. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocaa284

15. Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced in-person and increased telehealth outpatient visits during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(1):129-131. doi:10.7326/M20-3026

16. Spelman JF, Brienza R, Walsh RF, et al. A model for rapid transition to virtual care, VA Connecticut primary care response to COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3073-3076. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06041-4

17. Der-Martirosian C, Chu K, Dobalian A. Use of telehealth to improve access to care at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs during the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 13]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;1-5. doi:10.1017/dmp.2020.88

1. Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using telehealth to expand access to essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated June 10, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html

3. Harvey JB, Valenta S, Simpson K, Lyles M, McElligott J. Utilization of outpatient telehealth services in parity and nonparity states 2010-2015. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(2):132-136. doi:10.1089/tmj.2017.0265

4. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1601705

5. Rockwell KL, Gilroy AS. Incorporating telemedicine as part of COVID-19 outbreak response systems. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(4):147-148. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.42784

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare facility guidance. Updated April 17, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care.html

7. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Policy changes during COVID-19. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/policy-changes-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

8. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriation Act of 2020. 134 Stat. 146. Published February 2, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-2021-02-02/html/CREC-2021-02-02-pt1-PgS226.htm

9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Updated January 20, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Coverage and payment related to COVID-19 Medicare. 2020. Published March 23, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/03052020-medicare-covid-19-fact-sheet.pdf

11. American Telemedicine Association. ATA commends 2020 Congress for giving HHS authority to waive restrictions on telehealth for Medicare beneficiaries in response to the COVID-19 outbreak [press release]. Published March 5, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.americantelemed.org/press-releases/ata-commends-congress-for-waiving-restrictions-on-telehealth-for-medicare-beneficiaries-in-response-to-the-covid-19-outbreak

12. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679-1681. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2003539

13. Khairat S, Meng C, Xu Y, Edson B, Gianforcaro R. Interpreting COVID-19 and Virtual Care Trends: Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18811. Published 2020 Apr 15. doi:10.2196/18811

14. Ferguson JM, Jacobs J, Yefimova M, Greene L, Heyworth L, Zulman DM. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans Health Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(3):453-462. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocaa284

15. Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced in-person and increased telehealth outpatient visits during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(1):129-131. doi:10.7326/M20-3026

16. Spelman JF, Brienza R, Walsh RF, et al. A model for rapid transition to virtual care, VA Connecticut primary care response to COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3073-3076. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06041-4

17. Der-Martirosian C, Chu K, Dobalian A. Use of telehealth to improve access to care at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs during the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 13]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;1-5. doi:10.1017/dmp.2020.88

The Delta Factor

Several weeks ago, I received a call from my brother who, though not a health care professional, wanted me to know he thought the public was being too critical of scientists and physicians who “are giving us the best advice they can about COVID. People think they should have all the answers. But this virus is complicated, and they don’t always know what is going to happen next.” What makes his charitable read of the public health situation remarkable is that he is a COVID-19 survivor of one of the first reported cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome, which several expert neurologists believe is the result of COVID-19. Like so many other COVID-19 long-haul patients, he is left with lingering symptoms and residual deficits.1

I use this personal story as the overture to this piece on why I am changing my opinion regarding a COVID-19 mandate for federal practitioners. In June I raised ethical concerns about compelling vaccination especially for service members of color based on a current and historical climate of mistrust and discrimination in health care that compulsory vaccination could exacerbate.2 Instead, I followed the lead of Secretary of Defense J. Lloyd Austin III and advocated continued education and encouragement for vaccine-hesitant troops.3 So in 2 months what has so radically changed to lead Secretary Austin and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Secretary Denis R. McDonough to mandate vaccination for their workforce?4,5

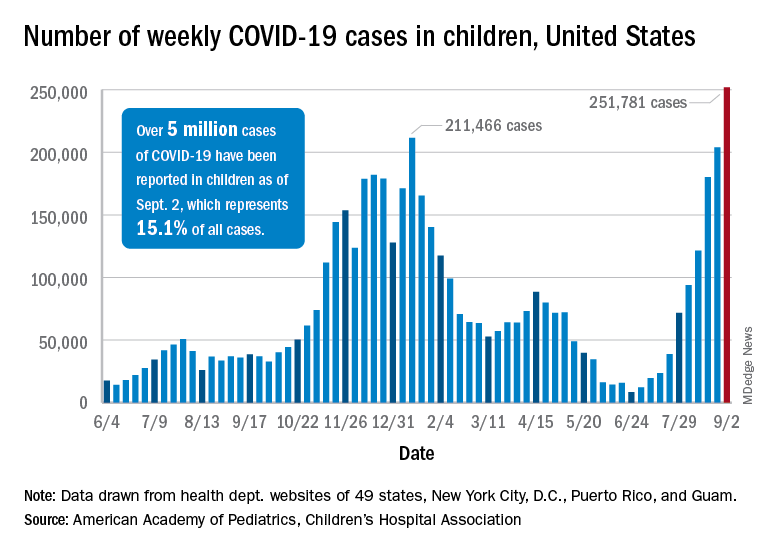

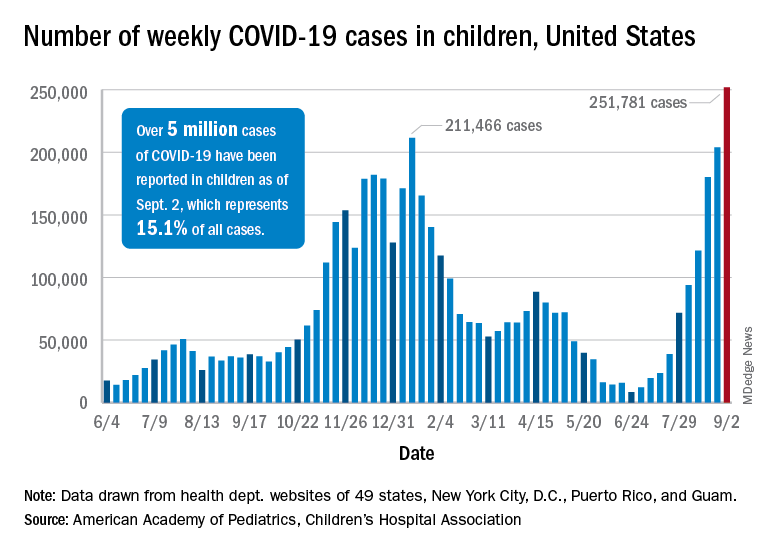

I am calling the change the Delta Factor. This is not to be confused with the spy-thrillers that ironically involved rescuing a scientist! The Delta Factor is a catch-all phrase to cover the protean public health impacts of the devastating COVID-19 Delta variant now ravaging the country. Depending on the area of the country as of mid-August, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 80% to > 90% of new cases were the Delta variant.6 An increasing number of these cases sadly are in children.7

According to the CDC, the Delta variant is more than twice as contagious as index or subsequent strains: making it about as contagious as chicken pox. The unvaccinated are the most susceptible to Delta and may develop more serious illness and risk of death than with other strains. Those who are fully vaccinated can still contract the virus although usually with milder cases. More worrisome is that individuals with these breakthrough infections have the same viral load as those without vaccinations, rendering them vectors of transmission, although for a shorter time than unvaccinated persons.8

The VA first mandated vaccination among its health care employees in July and then expanded it to all staff in August.9 The US Department of Defense (DoD) mandatory vaccination was announced prior to US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) full approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.10 Secretary Austin asked President Biden to grant a waiver to permit mandatory vaccination even without full FDA approval, and Biden has indicated his support, but the full approval expedited the time line for implementation.11

Both agencies directly referenced Delta as a primary reason for their vaccination mandates. The VA argued that the mandate was necessary to protect the safety of veterans, while the DoD noted that vaccination was essential to ensure the health of the fighting force. In his initial announcement, Secretary McDonough explicitly mentioned the Delta variant as a primary reason for his decision. noting “it’s the best way to keep veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”4 Similarly, Secretary Austin declared, “We will also be keeping a close eye on infection rates, which are on the rise now due to the Delta variant and the impact these rates might have on our readiness.”5

VA and DoD leadership emphasized the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine and urged employees to voluntarily obtain the vaccine or obtain a religious or medical exemption. Those without such an exemption must adhere to masking, testing, and other restrictions.5 As anticipated in the earlier editorial, there has been opposition to the mandate from the workforce of the 2 agencies and their political supporters some of whom view vaccine mandates as violations of personal liberty and bodily integrity and for whom rampant disinformation has amplified entrenched distrust of the government.12

The decision to shift from voluntary to mandatory vaccination of federal employees responsible for the health care of veterans and the defense of citizens, which may seem

Finally and most important, for a vaccine or other public health intervention to be ethically mandated it must have a high probability of attaining a serious purpose: here preventing the harms of sickness and death especially in the most vulnerable. In July, the White House COVID-19 Response Team reported that “preliminary data from several states over the last few months suggest that 99.5% of deaths from COVID-19 in the United States were in unvaccinated people” and were preventable.15 Ethically, even as mandates are implemented across the federal workforce, efforts to educate, encourage, and empower vaccination especially among disenfranchised cohorts must continue. But as a recently leaked CDC internal document acknowledged about the Delta Factor, “the war has changed” and so has my opinion about mandating vaccination among those upon whose service depends the life and security of us all.16

1. CBS Good Morning. Christopher Cross on his near-fatal COVID illness. Published October 18, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/christopher-cross-on-his-near-fatal-covid-illness

2. Geppert CM. Mistrust and mandates: COVID-19 vaccination in the military. Fed Pract. 2021;38(6):254-255. doi:10.12788/fp.0143

3. Garmone J, US Department of Defense. Secretary of defense addresses vaccine hesitancy in the military. Published February 25, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/2516511/secretary-of-defense-addresses-vaccine-hesitancy-in-military

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA mandates COVID-19 vaccines among its medical employees including VHA facilities staff [press release]. Published July 26, 2021. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5696

5. US Department of Defense, Secretary of Defense. Memorandum for all Department of Defense employees. Published August 9, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Aug/09/2002826254/-1/-1/0/MESSAGE-TO-THE-FORCE-MEMO-VACCINE.PDF

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID data tracker. Variant proportions. Updated August 17, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions

7. American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: state data level report. Updated August 23, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state|-level-data-report

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Delta variant: what we know about the science. Update August 19, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/delta-variant.html

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA expands mandate for COVID-19 vaccines among VHA employees [press release]. Published August 12, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5703

10. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published August 23, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

11. Garamone J, US Department of Defense. Biden to approve Austin’s request to make COVID-19 vaccine mandatory for service members. Published August 9, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/2724982/biden-to-approve-austins-request-to-make-covid-19-vaccine-mandatory-for-service

12. Watson J. Potential military vaccine mandate brings distrust, support. Associated Press. August 5, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-business-health-coronavirus-pandemic-6a0f94e11f5af1e0de740d44d7931d65

13. Giubilini A. Vaccination ethics. Br Med Bull. 2021;137(1):4-12. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldaa036

14. Steinhauer J. Military and V.A. struggle with vaccination rates in their ranks. The New York Times. July 1, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/01/us/politics/military-va-vaccines.html

15. The White House. Press briefing by White House COVID-19 Response Team and public health officials. Published July 8, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/press-briefings/2021/07/08/press-briefing-by-white-house-covid-19-response-team-and-public-health-officials-44

16. Adutaleb Y, Johnson CY, Achenbach J. ‘The war has changed’: Internal CDC document urges new messaging, warns delta infections likely more severe. The Washington Post. July 29, 2021. Accessed August 21, 2021 https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/07/29/cdc-mask-guidance

Several weeks ago, I received a call from my brother who, though not a health care professional, wanted me to know he thought the public was being too critical of scientists and physicians who “are giving us the best advice they can about COVID. People think they should have all the answers. But this virus is complicated, and they don’t always know what is going to happen next.” What makes his charitable read of the public health situation remarkable is that he is a COVID-19 survivor of one of the first reported cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome, which several expert neurologists believe is the result of COVID-19. Like so many other COVID-19 long-haul patients, he is left with lingering symptoms and residual deficits.1

I use this personal story as the overture to this piece on why I am changing my opinion regarding a COVID-19 mandate for federal practitioners. In June I raised ethical concerns about compelling vaccination especially for service members of color based on a current and historical climate of mistrust and discrimination in health care that compulsory vaccination could exacerbate.2 Instead, I followed the lead of Secretary of Defense J. Lloyd Austin III and advocated continued education and encouragement for vaccine-hesitant troops.3 So in 2 months what has so radically changed to lead Secretary Austin and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Secretary Denis R. McDonough to mandate vaccination for their workforce?4,5

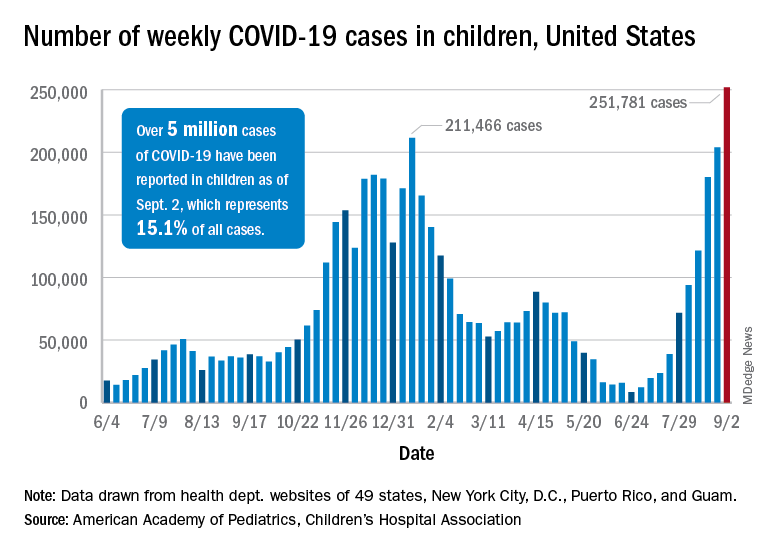

I am calling the change the Delta Factor. This is not to be confused with the spy-thrillers that ironically involved rescuing a scientist! The Delta Factor is a catch-all phrase to cover the protean public health impacts of the devastating COVID-19 Delta variant now ravaging the country. Depending on the area of the country as of mid-August, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 80% to > 90% of new cases were the Delta variant.6 An increasing number of these cases sadly are in children.7

According to the CDC, the Delta variant is more than twice as contagious as index or subsequent strains: making it about as contagious as chicken pox. The unvaccinated are the most susceptible to Delta and may develop more serious illness and risk of death than with other strains. Those who are fully vaccinated can still contract the virus although usually with milder cases. More worrisome is that individuals with these breakthrough infections have the same viral load as those without vaccinations, rendering them vectors of transmission, although for a shorter time than unvaccinated persons.8

The VA first mandated vaccination among its health care employees in July and then expanded it to all staff in August.9 The US Department of Defense (DoD) mandatory vaccination was announced prior to US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) full approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.10 Secretary Austin asked President Biden to grant a waiver to permit mandatory vaccination even without full FDA approval, and Biden has indicated his support, but the full approval expedited the time line for implementation.11

Both agencies directly referenced Delta as a primary reason for their vaccination mandates. The VA argued that the mandate was necessary to protect the safety of veterans, while the DoD noted that vaccination was essential to ensure the health of the fighting force. In his initial announcement, Secretary McDonough explicitly mentioned the Delta variant as a primary reason for his decision. noting “it’s the best way to keep veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”4 Similarly, Secretary Austin declared, “We will also be keeping a close eye on infection rates, which are on the rise now due to the Delta variant and the impact these rates might have on our readiness.”5

VA and DoD leadership emphasized the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine and urged employees to voluntarily obtain the vaccine or obtain a religious or medical exemption. Those without such an exemption must adhere to masking, testing, and other restrictions.5 As anticipated in the earlier editorial, there has been opposition to the mandate from the workforce of the 2 agencies and their political supporters some of whom view vaccine mandates as violations of personal liberty and bodily integrity and for whom rampant disinformation has amplified entrenched distrust of the government.12

The decision to shift from voluntary to mandatory vaccination of federal employees responsible for the health care of veterans and the defense of citizens, which may seem

Finally and most important, for a vaccine or other public health intervention to be ethically mandated it must have a high probability of attaining a serious purpose: here preventing the harms of sickness and death especially in the most vulnerable. In July, the White House COVID-19 Response Team reported that “preliminary data from several states over the last few months suggest that 99.5% of deaths from COVID-19 in the United States were in unvaccinated people” and were preventable.15 Ethically, even as mandates are implemented across the federal workforce, efforts to educate, encourage, and empower vaccination especially among disenfranchised cohorts must continue. But as a recently leaked CDC internal document acknowledged about the Delta Factor, “the war has changed” and so has my opinion about mandating vaccination among those upon whose service depends the life and security of us all.16

Several weeks ago, I received a call from my brother who, though not a health care professional, wanted me to know he thought the public was being too critical of scientists and physicians who “are giving us the best advice they can about COVID. People think they should have all the answers. But this virus is complicated, and they don’t always know what is going to happen next.” What makes his charitable read of the public health situation remarkable is that he is a COVID-19 survivor of one of the first reported cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome, which several expert neurologists believe is the result of COVID-19. Like so many other COVID-19 long-haul patients, he is left with lingering symptoms and residual deficits.1

I use this personal story as the overture to this piece on why I am changing my opinion regarding a COVID-19 mandate for federal practitioners. In June I raised ethical concerns about compelling vaccination especially for service members of color based on a current and historical climate of mistrust and discrimination in health care that compulsory vaccination could exacerbate.2 Instead, I followed the lead of Secretary of Defense J. Lloyd Austin III and advocated continued education and encouragement for vaccine-hesitant troops.3 So in 2 months what has so radically changed to lead Secretary Austin and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Secretary Denis R. McDonough to mandate vaccination for their workforce?4,5

I am calling the change the Delta Factor. This is not to be confused with the spy-thrillers that ironically involved rescuing a scientist! The Delta Factor is a catch-all phrase to cover the protean public health impacts of the devastating COVID-19 Delta variant now ravaging the country. Depending on the area of the country as of mid-August, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 80% to > 90% of new cases were the Delta variant.6 An increasing number of these cases sadly are in children.7

According to the CDC, the Delta variant is more than twice as contagious as index or subsequent strains: making it about as contagious as chicken pox. The unvaccinated are the most susceptible to Delta and may develop more serious illness and risk of death than with other strains. Those who are fully vaccinated can still contract the virus although usually with milder cases. More worrisome is that individuals with these breakthrough infections have the same viral load as those without vaccinations, rendering them vectors of transmission, although for a shorter time than unvaccinated persons.8

The VA first mandated vaccination among its health care employees in July and then expanded it to all staff in August.9 The US Department of Defense (DoD) mandatory vaccination was announced prior to US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) full approval of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.10 Secretary Austin asked President Biden to grant a waiver to permit mandatory vaccination even without full FDA approval, and Biden has indicated his support, but the full approval expedited the time line for implementation.11

Both agencies directly referenced Delta as a primary reason for their vaccination mandates. The VA argued that the mandate was necessary to protect the safety of veterans, while the DoD noted that vaccination was essential to ensure the health of the fighting force. In his initial announcement, Secretary McDonough explicitly mentioned the Delta variant as a primary reason for his decision. noting “it’s the best way to keep veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”4 Similarly, Secretary Austin declared, “We will also be keeping a close eye on infection rates, which are on the rise now due to the Delta variant and the impact these rates might have on our readiness.”5

VA and DoD leadership emphasized the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine and urged employees to voluntarily obtain the vaccine or obtain a religious or medical exemption. Those without such an exemption must adhere to masking, testing, and other restrictions.5 As anticipated in the earlier editorial, there has been opposition to the mandate from the workforce of the 2 agencies and their political supporters some of whom view vaccine mandates as violations of personal liberty and bodily integrity and for whom rampant disinformation has amplified entrenched distrust of the government.12

The decision to shift from voluntary to mandatory vaccination of federal employees responsible for the health care of veterans and the defense of citizens, which may seem

Finally and most important, for a vaccine or other public health intervention to be ethically mandated it must have a high probability of attaining a serious purpose: here preventing the harms of sickness and death especially in the most vulnerable. In July, the White House COVID-19 Response Team reported that “preliminary data from several states over the last few months suggest that 99.5% of deaths from COVID-19 in the United States were in unvaccinated people” and were preventable.15 Ethically, even as mandates are implemented across the federal workforce, efforts to educate, encourage, and empower vaccination especially among disenfranchised cohorts must continue. But as a recently leaked CDC internal document acknowledged about the Delta Factor, “the war has changed” and so has my opinion about mandating vaccination among those upon whose service depends the life and security of us all.16

1. CBS Good Morning. Christopher Cross on his near-fatal COVID illness. Published October 18, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/christopher-cross-on-his-near-fatal-covid-illness

2. Geppert CM. Mistrust and mandates: COVID-19 vaccination in the military. Fed Pract. 2021;38(6):254-255. doi:10.12788/fp.0143

3. Garmone J, US Department of Defense. Secretary of defense addresses vaccine hesitancy in the military. Published February 25, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/2516511/secretary-of-defense-addresses-vaccine-hesitancy-in-military

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA mandates COVID-19 vaccines among its medical employees including VHA facilities staff [press release]. Published July 26, 2021. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5696

5. US Department of Defense, Secretary of Defense. Memorandum for all Department of Defense employees. Published August 9, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Aug/09/2002826254/-1/-1/0/MESSAGE-TO-THE-FORCE-MEMO-VACCINE.PDF

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID data tracker. Variant proportions. Updated August 17, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions

7. American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: state data level report. Updated August 23, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state|-level-data-report

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Delta variant: what we know about the science. Update August 19, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/delta-variant.html

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA expands mandate for COVID-19 vaccines among VHA employees [press release]. Published August 12, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5703

10. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published August 23, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

11. Garamone J, US Department of Defense. Biden to approve Austin’s request to make COVID-19 vaccine mandatory for service members. Published August 9, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/2724982/biden-to-approve-austins-request-to-make-covid-19-vaccine-mandatory-for-service

12. Watson J. Potential military vaccine mandate brings distrust, support. Associated Press. August 5, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-business-health-coronavirus-pandemic-6a0f94e11f5af1e0de740d44d7931d65

13. Giubilini A. Vaccination ethics. Br Med Bull. 2021;137(1):4-12. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldaa036

14. Steinhauer J. Military and V.A. struggle with vaccination rates in their ranks. The New York Times. July 1, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/01/us/politics/military-va-vaccines.html

15. The White House. Press briefing by White House COVID-19 Response Team and public health officials. Published July 8, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/press-briefings/2021/07/08/press-briefing-by-white-house-covid-19-response-team-and-public-health-officials-44

16. Adutaleb Y, Johnson CY, Achenbach J. ‘The war has changed’: Internal CDC document urges new messaging, warns delta infections likely more severe. The Washington Post. July 29, 2021. Accessed August 21, 2021 https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/07/29/cdc-mask-guidance

1. CBS Good Morning. Christopher Cross on his near-fatal COVID illness. Published October 18, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/christopher-cross-on-his-near-fatal-covid-illness

2. Geppert CM. Mistrust and mandates: COVID-19 vaccination in the military. Fed Pract. 2021;38(6):254-255. doi:10.12788/fp.0143

3. Garmone J, US Department of Defense. Secretary of defense addresses vaccine hesitancy in the military. Published February 25, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/2516511/secretary-of-defense-addresses-vaccine-hesitancy-in-military

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA mandates COVID-19 vaccines among its medical employees including VHA facilities staff [press release]. Published July 26, 2021. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5696

5. US Department of Defense, Secretary of Defense. Memorandum for all Department of Defense employees. Published August 9, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Aug/09/2002826254/-1/-1/0/MESSAGE-TO-THE-FORCE-MEMO-VACCINE.PDF

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID data tracker. Variant proportions. Updated August 17, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions

7. American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: state data level report. Updated August 23, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state|-level-data-report

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Delta variant: what we know about the science. Update August 19, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/delta-variant.html

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA expands mandate for COVID-19 vaccines among VHA employees [press release]. Published August 12, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5703

10. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published August 23, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

11. Garamone J, US Department of Defense. Biden to approve Austin’s request to make COVID-19 vaccine mandatory for service members. Published August 9, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/2724982/biden-to-approve-austins-request-to-make-covid-19-vaccine-mandatory-for-service

12. Watson J. Potential military vaccine mandate brings distrust, support. Associated Press. August 5, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-business-health-coronavirus-pandemic-6a0f94e11f5af1e0de740d44d7931d65

13. Giubilini A. Vaccination ethics. Br Med Bull. 2021;137(1):4-12. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldaa036

14. Steinhauer J. Military and V.A. struggle with vaccination rates in their ranks. The New York Times. July 1, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/01/us/politics/military-va-vaccines.html

15. The White House. Press briefing by White House COVID-19 Response Team and public health officials. Published July 8, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/press-briefings/2021/07/08/press-briefing-by-white-house-covid-19-response-team-and-public-health-officials-44

16. Adutaleb Y, Johnson CY, Achenbach J. ‘The war has changed’: Internal CDC document urges new messaging, warns delta infections likely more severe. The Washington Post. July 29, 2021. Accessed August 21, 2021 https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/07/29/cdc-mask-guidance

Right Ventricle Dilation Detected on Point-of-Care Ultrasound Is a Predictor of Poor Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is increasingly being used by critical care physicians to augment the physical examination and guide clinical decision making, and several protocols have been established to standardize the POCUS evaluation.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, POCUS has been a valuable tool as standard imaging techniques were used judiciously to minimize exposure of personnel and use of personal protective equipment (PPE).2

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) New York Harbor Healthcare System (VANYHHS) intensive care unit (ICU) on initial clinical examination included POCUS, which was helpful to examine deep vein thromboses, cardiac function, and the presence and extent of pneumonia. An international expert consensus on the use of POCUS for COVID-19 published in December 2020 called for further studies defining the role of lung and cardiac ultrasound in risk stratification, outcomes, and clinical management.3

The objective of this study was to review POCUS findings and correlate them with severity of illness and 30-day outcomes in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Methods

The study was submitted to and reviewed by the VANYHHS Research and Development committee and study approval and informed consent waiver was granted. The study was a retrospective chart review of patients admitted to the VANYHHS ICU between March and April 2020, a tertiary health care center designated as a COVID-19 hospital.

Patients admitted to the ICU aged > 18 years with a diagnosis of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, diagnosis of COVID-19, and documentation of POCUS findings in the chart were included in the study. A patient was considered to have a COVID-19 diagnosis following a positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction test documented in the electronic health record (EHR). Acute respiratory failure was defined as hypoxemia < 94% and the need for either supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula > 2 L/min, high flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation, or mechanical ventilation.

To minimize personnel exposure, initial patient evaluations and POCUS examinations were performed by the most senior personnel (ie, fellowship trained, board-certified pulmonary critical care attending physicians or pulmonary and critical care fellowship trainees). Three members of the team had certification in advanced critical care echocardiography by the National Board of Echocardiography and oversaw POCUS imaging. POCUS examinations were performed with a GE Heathcare Venue POCUS or handheld unit. After use, ultrasound probes and ultrasound units were disinfected with wipes designated by the manufacturer and US Environmental Protection Agency for use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The POCUS protocol used by members of the team was as follows: POCUS lung—at least 2 anterior fields and 1 posterior/lateral field looking at the costophrenic angle on each hemithorax with a phased array or curvilinear probe. A linear probe was used to look for subpleural changes per physician discretion.4,5 Lung ultrasound findings in anterior lung fields were documented as A lines, B lines (as defined by the bedside lung ultrasound in emergency [BLUE] protocol)anterior pleural abnormalities or consolidations.4,5 The costophrenic point findings were documented as presence of consolidation or pleural effusion.

The POCUS cardiac examination consisted of parasternal long and short axis views, apical 4 chamber view, subcostal and inferior vena cava (IVC) view. Left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction was visually estimated as reduced or normal. Right ventricular (RV) dilation was considered present if RV size approached or exceeded LV size in the apical 4 chamber view. RV dysfunction was considered present if in addition there was flattening of interventricular septum, RV free wall hypokinesis or reduced tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE).6 IVC was documented as collapsible or plethoric by size and respirophasic variability (2 cm and 50%). Other POCUS examinations including venous compression were done at the discretion of the treating physician.7 POCUS was also used for the placement of central and arterial lines and to guide fluid management.8

The VA EHR and Venue image local archives were reviewed for patient demographics, laboratory findings, imaging studies and outcomes. All ICU attending physician and fellow notes were reviewed for POCUS lung, cardiac and vascular findings. The chart was also reviewed for management changes as a result of POCUS findings. Patients who had at minimum a POCUS lung or cardiac examination documented in the EHR were included in the study. For patients with serial POCUS the most severe findings were included.

Patients were divided into 2 groups based on 30-day outcome: discharge home vs mortality for comparison. POCUS findings were also compared by need for mechanical ventilation. Patients still hospitalized or transferred to other facilities were excluded from the analysis. A Student t test was used for comparison between the groups for continuous normally distributed variables. Linear and stepwise regression models were used to evaluate univariate and multivariate associations of baseline characteristics, biomarker, and ultrasound findings with patient outcomes. Analyses were performed using R 4.0.2 statistical software.

Results

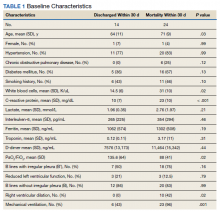

Eighty-two patients were admitted to the VANYHHS ICU in March and April 2020, including 12 nonveterans. Sixty-four had COVID-19 and acute respiratory failure. POCUS findings were documented in 43 (67%) patients. Thirty-nine patients had documented lung examinations, and 25 patients had documented cardiac examinations. Patients were divided into 2 groups by 30-day outcome (discharge home vs mortality) for statistical analysis. Five patients who were either still hospitalized or had been transferred to another facility were excluded.

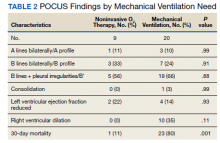

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the study stratified by 30-day outcomes are shown in Table 1. The study group was predominantly male (95%). Patients with poor 30-day outcomes were older, had higher white blood cell counts, more severe hypoxemia, higher rates of mechanical ventilation and RV dilation (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). RV dilation was an independent predictor of mortality (odds ratio [OR], 12.0; P = .048).

Serial POCUS documented development or progression of RV dilation and dysfunction from the time of ICU admission in 4 of the patients. The presence of B lines with irregular pleura was predictive of a lower arterial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2/FiO2) by a value of 71 compared with those without B lines with irregular pleura (P = .005, adjusted R2 = 0.238). All patients with RV dilation had bilateral B lines with pleural irregularities on lung ultrasound. Vascular POCUS detected 4 deep vein thromboses (DVT).7 An arterial thrombus was also detected on focused examination. There was a higher mortality in patients who required mechanical ventilation; however, there was no difference in POCUS characteristics between the groups (Table 2).

Two severely hypoxemic patients received systemic tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) after findings of massive RV dilation with signs of volume and pressure overload and clinical suspicion of pulmonary embolism (PE). One of these patients also had a popliteal DVT. Both patients were too unstable to transport for additional imaging or therapies. Therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated on 4 patients with positive DVT examinations. In a fifth case an arterial thrombectomy and anticoagulation was required after diminished pulses led to the finding of an occlusive brachial artery thrombus on vascular POCUS.

Discussion

POCUS identified both lung and cardiac features that were associated with worse outcomes. While lung ultrasound abnormalities were very prevalent and associated with worse PaO2 to FiO2 ratios, the presence of RV dilation was associated most clearly with mortality and poor 30-day outcomes in the critical care setting.