User login

Large study affirms what we already know: Masks work to prevent COVID-19

It also shows that surgical masks are more effective than cloth face coverings.

The study, which was published ahead of peer review, demonstrates the power of careful investigation and offers a host of lessons about mask wearing that will be important worldwide. One key finding of the study, for example, is that wearing a mask doesn’t lead people to abandon social distancing, something public health officials had feared might happen if masks gave people a false sense of security.

“What we really were able to achieve is to demonstrate that masks are effective against COVID-19, even under a rigorous and systematic evaluation that was done in the throes of the pandemic,” said Ashley Styczynski, MD, who was an infectious disease fellow at Stanford (Calif.) University when she collaborated on the study with other colleagues at Stanford, Yale, and Innovations for Poverty Action, a large research and policy nonprofit organization that currently works in 22 countries.

“And so, I think people who have been holding out on wearing masks because [they] felt like there wasn’t enough evidence for it, we’re hoping this will really help bridge that gap for them,” she said.

It included more than 600 unions – or local governmental districts in Bangladesh – and roughly 340,000 people.

Half of the districts were given cloth or surgical face masks along with continual reminders to wear them properly; the other half were tracked with no intervention. Blood tests of people who developed symptoms during the study verified their infections.

Compared to villages that didn’t mask, those in which masks of any type were worn had about 9% fewer symptomatic cases of COVID-19. The finding was statistically significant and was unlikely to have occurred by chance alone.

“Somebody could read this study and say, ‘OK, you reduced COVID-19 by 9%. Big deal.’ And what I would respond to that would be that, if anything, we think that that is a substantial underestimate,” Dr. Styczynski said.

One reason they think they underestimated the effectiveness of masks is that they tested only people who were having symptoms, so people who had only very mild or asymptomatic infections were missed.

Another reason is that, among people who had symptoms, only one-third agreed to undergo a blood test. The effect may have been bigger had participation been universal.

Local transmission may have played a role, too. Rates of COVID-19 in Bangladesh were relatively low during the study. Most infections were caused by the B.1.1.7, or Alpha, variant.

Since then, Delta has taken over. Delta is thought to be more transmissible, and some studies have suggested that people infected with Delta shed more viral particles. Masks may be more effective when more virus is circulating.

The investigators also found important differences by age and by the type of mask. Villages in which surgical masks were worn had 11% fewer COVID-19 cases than villages in which masks were not worn. In villages in which cloth masks were worn, on the other hand, infections were reduced by only 5%.

The cloth masks were substantial. Each had three layers – two layers of fabric with an outer layer of polypropylene. On testing, the filtration efficiency of the cloth masks was only about 37%, compared with 95% for the three-layer surgical masks, which were also made of polypropylene.

Masks were most effective for older individuals. People aged 50-60 years who wore surgical masks were 23% less likely to test positive for COVID, compared with their peers who didn’t wear masks. For people older than 60, the reduction in risk was greater – 35%.

Rigorous research

The study took place over a period of 8 weeks in each district. The interventions were rolled out in waves, with the first starting in November 2020 and the last in January 2021.

Investigators gave each household free cloth or surgical face masks and showed families a video about proper mask wearing with promotional messages from the prime minister, a head imam, and a national cricket star. They also handed out free masks.

Previous studies have shown that people aren’t always truthful about wearing masks in public. In Kenya, for example, 88% of people answering a phone survey said that they wore masks regularly, but researchers determined that only 10% of them actually did so.

Investigators in the Bangladesh study didn’t just ask people if they’d worn masks, they stationed themselves in public markets, mosques, tea stalls, and on roads that were the main entrances to the villages and took notes.

They also tested various ways to educate people and to remind them to wear masks. They found that four factors were effective at promoting the wearing of masks, and they gave them an acronym – NORM.

- N for no-cost masks.

- O for offering information through the video and local leaders.

- R for regular reminders to people by investigators who stand in public markets and offer masks or encourage anyone who wasn’t wearing one or wasn’t wearing it correctly.

- M for modeling, in which local leaders, such as imams, wear masks and remind their followers to wear them.

These four measures tripled the wearing of masks in the intervention communities, from a baseline level of 13% to 42%. People continued to wear their masks properly for about 2 weeks after the study ended, indicating that they’d gotten used to wearing them.

Dr. Styczynski said that nothing else – not text message reminders, or signs posted in public places, or local incentives – moved the needle on mask wearing.

Saved lives and money

The study found that the strategy was cost effective, too. Giving masks to a large population and getting people to use them costs about $10,000 per life saved from COVID, on par with the cost of deploying mosquito nets to save people from malaria, Dr. Styczynski said.

“I think that what we’ve been able to show is that this is a really important tool to be used globally, especially as countries have delays in getting access to vaccines and rolling them out,” she said.

Dr. Styczynski said masks will continue to be important even in countries such as the United States, where vaccines aren’t stopping transmission 100% and there are still large portions of the population who are unvaccinated, such as children.

“If we want to reduce COVID-19 here, it’s really important that we consider the ongoing utility of masks, in addition to vaccines, and not really thinking of them as one or the other,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from GiveWell.org. The funder had no role in the study design, interpretation, or the decision to publish.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It also shows that surgical masks are more effective than cloth face coverings.

The study, which was published ahead of peer review, demonstrates the power of careful investigation and offers a host of lessons about mask wearing that will be important worldwide. One key finding of the study, for example, is that wearing a mask doesn’t lead people to abandon social distancing, something public health officials had feared might happen if masks gave people a false sense of security.

“What we really were able to achieve is to demonstrate that masks are effective against COVID-19, even under a rigorous and systematic evaluation that was done in the throes of the pandemic,” said Ashley Styczynski, MD, who was an infectious disease fellow at Stanford (Calif.) University when she collaborated on the study with other colleagues at Stanford, Yale, and Innovations for Poverty Action, a large research and policy nonprofit organization that currently works in 22 countries.

“And so, I think people who have been holding out on wearing masks because [they] felt like there wasn’t enough evidence for it, we’re hoping this will really help bridge that gap for them,” she said.

It included more than 600 unions – or local governmental districts in Bangladesh – and roughly 340,000 people.

Half of the districts were given cloth or surgical face masks along with continual reminders to wear them properly; the other half were tracked with no intervention. Blood tests of people who developed symptoms during the study verified their infections.

Compared to villages that didn’t mask, those in which masks of any type were worn had about 9% fewer symptomatic cases of COVID-19. The finding was statistically significant and was unlikely to have occurred by chance alone.

“Somebody could read this study and say, ‘OK, you reduced COVID-19 by 9%. Big deal.’ And what I would respond to that would be that, if anything, we think that that is a substantial underestimate,” Dr. Styczynski said.

One reason they think they underestimated the effectiveness of masks is that they tested only people who were having symptoms, so people who had only very mild or asymptomatic infections were missed.

Another reason is that, among people who had symptoms, only one-third agreed to undergo a blood test. The effect may have been bigger had participation been universal.

Local transmission may have played a role, too. Rates of COVID-19 in Bangladesh were relatively low during the study. Most infections were caused by the B.1.1.7, or Alpha, variant.

Since then, Delta has taken over. Delta is thought to be more transmissible, and some studies have suggested that people infected with Delta shed more viral particles. Masks may be more effective when more virus is circulating.

The investigators also found important differences by age and by the type of mask. Villages in which surgical masks were worn had 11% fewer COVID-19 cases than villages in which masks were not worn. In villages in which cloth masks were worn, on the other hand, infections were reduced by only 5%.

The cloth masks were substantial. Each had three layers – two layers of fabric with an outer layer of polypropylene. On testing, the filtration efficiency of the cloth masks was only about 37%, compared with 95% for the three-layer surgical masks, which were also made of polypropylene.

Masks were most effective for older individuals. People aged 50-60 years who wore surgical masks were 23% less likely to test positive for COVID, compared with their peers who didn’t wear masks. For people older than 60, the reduction in risk was greater – 35%.

Rigorous research

The study took place over a period of 8 weeks in each district. The interventions were rolled out in waves, with the first starting in November 2020 and the last in January 2021.

Investigators gave each household free cloth or surgical face masks and showed families a video about proper mask wearing with promotional messages from the prime minister, a head imam, and a national cricket star. They also handed out free masks.

Previous studies have shown that people aren’t always truthful about wearing masks in public. In Kenya, for example, 88% of people answering a phone survey said that they wore masks regularly, but researchers determined that only 10% of them actually did so.

Investigators in the Bangladesh study didn’t just ask people if they’d worn masks, they stationed themselves in public markets, mosques, tea stalls, and on roads that were the main entrances to the villages and took notes.

They also tested various ways to educate people and to remind them to wear masks. They found that four factors were effective at promoting the wearing of masks, and they gave them an acronym – NORM.

- N for no-cost masks.

- O for offering information through the video and local leaders.

- R for regular reminders to people by investigators who stand in public markets and offer masks or encourage anyone who wasn’t wearing one or wasn’t wearing it correctly.

- M for modeling, in which local leaders, such as imams, wear masks and remind their followers to wear them.

These four measures tripled the wearing of masks in the intervention communities, from a baseline level of 13% to 42%. People continued to wear their masks properly for about 2 weeks after the study ended, indicating that they’d gotten used to wearing them.

Dr. Styczynski said that nothing else – not text message reminders, or signs posted in public places, or local incentives – moved the needle on mask wearing.

Saved lives and money

The study found that the strategy was cost effective, too. Giving masks to a large population and getting people to use them costs about $10,000 per life saved from COVID, on par with the cost of deploying mosquito nets to save people from malaria, Dr. Styczynski said.

“I think that what we’ve been able to show is that this is a really important tool to be used globally, especially as countries have delays in getting access to vaccines and rolling them out,” she said.

Dr. Styczynski said masks will continue to be important even in countries such as the United States, where vaccines aren’t stopping transmission 100% and there are still large portions of the population who are unvaccinated, such as children.

“If we want to reduce COVID-19 here, it’s really important that we consider the ongoing utility of masks, in addition to vaccines, and not really thinking of them as one or the other,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from GiveWell.org. The funder had no role in the study design, interpretation, or the decision to publish.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It also shows that surgical masks are more effective than cloth face coverings.

The study, which was published ahead of peer review, demonstrates the power of careful investigation and offers a host of lessons about mask wearing that will be important worldwide. One key finding of the study, for example, is that wearing a mask doesn’t lead people to abandon social distancing, something public health officials had feared might happen if masks gave people a false sense of security.

“What we really were able to achieve is to demonstrate that masks are effective against COVID-19, even under a rigorous and systematic evaluation that was done in the throes of the pandemic,” said Ashley Styczynski, MD, who was an infectious disease fellow at Stanford (Calif.) University when she collaborated on the study with other colleagues at Stanford, Yale, and Innovations for Poverty Action, a large research and policy nonprofit organization that currently works in 22 countries.

“And so, I think people who have been holding out on wearing masks because [they] felt like there wasn’t enough evidence for it, we’re hoping this will really help bridge that gap for them,” she said.

It included more than 600 unions – or local governmental districts in Bangladesh – and roughly 340,000 people.

Half of the districts were given cloth or surgical face masks along with continual reminders to wear them properly; the other half were tracked with no intervention. Blood tests of people who developed symptoms during the study verified their infections.

Compared to villages that didn’t mask, those in which masks of any type were worn had about 9% fewer symptomatic cases of COVID-19. The finding was statistically significant and was unlikely to have occurred by chance alone.

“Somebody could read this study and say, ‘OK, you reduced COVID-19 by 9%. Big deal.’ And what I would respond to that would be that, if anything, we think that that is a substantial underestimate,” Dr. Styczynski said.

One reason they think they underestimated the effectiveness of masks is that they tested only people who were having symptoms, so people who had only very mild or asymptomatic infections were missed.

Another reason is that, among people who had symptoms, only one-third agreed to undergo a blood test. The effect may have been bigger had participation been universal.

Local transmission may have played a role, too. Rates of COVID-19 in Bangladesh were relatively low during the study. Most infections were caused by the B.1.1.7, or Alpha, variant.

Since then, Delta has taken over. Delta is thought to be more transmissible, and some studies have suggested that people infected with Delta shed more viral particles. Masks may be more effective when more virus is circulating.

The investigators also found important differences by age and by the type of mask. Villages in which surgical masks were worn had 11% fewer COVID-19 cases than villages in which masks were not worn. In villages in which cloth masks were worn, on the other hand, infections were reduced by only 5%.

The cloth masks were substantial. Each had three layers – two layers of fabric with an outer layer of polypropylene. On testing, the filtration efficiency of the cloth masks was only about 37%, compared with 95% for the three-layer surgical masks, which were also made of polypropylene.

Masks were most effective for older individuals. People aged 50-60 years who wore surgical masks were 23% less likely to test positive for COVID, compared with their peers who didn’t wear masks. For people older than 60, the reduction in risk was greater – 35%.

Rigorous research

The study took place over a period of 8 weeks in each district. The interventions were rolled out in waves, with the first starting in November 2020 and the last in January 2021.

Investigators gave each household free cloth or surgical face masks and showed families a video about proper mask wearing with promotional messages from the prime minister, a head imam, and a national cricket star. They also handed out free masks.

Previous studies have shown that people aren’t always truthful about wearing masks in public. In Kenya, for example, 88% of people answering a phone survey said that they wore masks regularly, but researchers determined that only 10% of them actually did so.

Investigators in the Bangladesh study didn’t just ask people if they’d worn masks, they stationed themselves in public markets, mosques, tea stalls, and on roads that were the main entrances to the villages and took notes.

They also tested various ways to educate people and to remind them to wear masks. They found that four factors were effective at promoting the wearing of masks, and they gave them an acronym – NORM.

- N for no-cost masks.

- O for offering information through the video and local leaders.

- R for regular reminders to people by investigators who stand in public markets and offer masks or encourage anyone who wasn’t wearing one or wasn’t wearing it correctly.

- M for modeling, in which local leaders, such as imams, wear masks and remind their followers to wear them.

These four measures tripled the wearing of masks in the intervention communities, from a baseline level of 13% to 42%. People continued to wear their masks properly for about 2 weeks after the study ended, indicating that they’d gotten used to wearing them.

Dr. Styczynski said that nothing else – not text message reminders, or signs posted in public places, or local incentives – moved the needle on mask wearing.

Saved lives and money

The study found that the strategy was cost effective, too. Giving masks to a large population and getting people to use them costs about $10,000 per life saved from COVID, on par with the cost of deploying mosquito nets to save people from malaria, Dr. Styczynski said.

“I think that what we’ve been able to show is that this is a really important tool to be used globally, especially as countries have delays in getting access to vaccines and rolling them out,” she said.

Dr. Styczynski said masks will continue to be important even in countries such as the United States, where vaccines aren’t stopping transmission 100% and there are still large portions of the population who are unvaccinated, such as children.

“If we want to reduce COVID-19 here, it’s really important that we consider the ongoing utility of masks, in addition to vaccines, and not really thinking of them as one or the other,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from GiveWell.org. The funder had no role in the study design, interpretation, or the decision to publish.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health care–associated infections spiked in 2020 in U.S. hospitals

Several health care-associated infections in U.S. hospitals spiked in 2020 compared to the previous year, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis published Sept. 2 in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. Soaring hospitalization rates, sicker patients who required more frequent and intense care, and staffing and supply shortages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are thought to have contributed to this increase.

This is the first increase in health care–associated infections since 2015.

These findings “are a reflection of the enormous stress that COVID has placed on our health care system,” Arjun Srinivasan, MD (Capt, USPHS), the associate director of the CDC’s Health care-Associated Infection Prevention Programs, Atlanta, told this news organization. He was not an author of the article, but he supervised the research. “We don’t want anyone to read this report and think that it represents a failure of the individual provider or a failure of health care providers in this country in their care of COVID patients,” he said. He noted that health care professionals have provided “tremendously good care to patients under extremely difficult circumstances.”

“People don’t fail – systems fail – and that’s what happened here,” he said. “Our systems that we need to have in place to prevent health care–associated infection simply were not as strong as they needed to be to survive this challenge.”

In the study, researchers used data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, the CDC’s tracking system for health care–associated infections. The team compared national standard infection ratios – calculated by dividing the number of reported infections by the number of predicted infections – between 2019 and 2020 for six routinely tracked events:

- Central line–associated bloodstream infections.

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

- Ventilator-associated events (VAEs).

- Infections associated with colon surgery and abdominal hysterectomy.

- Clostridioides difficile infections.

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections.

Infections were estimated using regression models created with baseline data from 2015.

“The new report highlights the need for health care facilities to strengthen their infection prevention programs and support them with adequate resources so that they can handle emerging threats to public health, while at the same time ensuring that gains made in combating HAIs [health care–associated infections] are not lost,” said the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology in a statement.

The analysis revealed significant national increases in central line–associated bloodstream infections, CAUTIs, VAEs, and MRSA infections in 2020 compared to 2019. Among all infection types, the greatest increase was in central-line infections, which were 46% to 47% higher in the third quarter and fourth quarter (Q4) of 2020 relative to the same periods the previous year. VAEs rose by 45%, MRSA infections increased by 34%, and CAUTIs increased by 19% in Q4 of 2020 compared to 2019.

The influx of sicker patients in hospitals throughout 2020 led to more frequent and longer use of medical devices such as catheters and ventilators. The use of these devices increases risk for infection, David P. Calfee, MD, chief medical epidemiologist at the New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, said in an interview. He is an editor of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology and was not involved with the study. Shortages in personal protective equipment and crowded intensive care units could also have affected how care was delivered, he said. These factors could have led to “reductions in the ability to provide some of the types of care that are needed to optimally reduce the risk of infection.”

There was either no change or decreases in infections associated with colon surgery or abdominal hysterectomy, likely because there were fewer elective surgeries performed, said Dr. Srinivasan. C. difficile–associated infections also decreased throughout 2020 compared to the previous year. Common practices to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in hospitals, such as environmental cleaning, use of personal protective equipment, and patient isolation, likely helped to curb the spread of C. difficile. Although these mitigating procedures do help protect against MRSA infection, many other factors, notably, the use of medical devices such as ventilators and catheters, can increase the risk for MRSA infection, Dr. Srinivasan added.

Although more research is needed to identify the reasons for these spikes in infection, the findings help quantify the scope of these increases across the United States, Dr. Calfee said. The data allow hospitals and health care professionals to “look back at what we did and then think forward in terms of what we can do different in the future,” he added, “so that these stresses to the system have less of an impact on how we are able to provide care.”

Dr. Srinivasan and Dr. Calfee report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several health care-associated infections in U.S. hospitals spiked in 2020 compared to the previous year, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis published Sept. 2 in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. Soaring hospitalization rates, sicker patients who required more frequent and intense care, and staffing and supply shortages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are thought to have contributed to this increase.

This is the first increase in health care–associated infections since 2015.

These findings “are a reflection of the enormous stress that COVID has placed on our health care system,” Arjun Srinivasan, MD (Capt, USPHS), the associate director of the CDC’s Health care-Associated Infection Prevention Programs, Atlanta, told this news organization. He was not an author of the article, but he supervised the research. “We don’t want anyone to read this report and think that it represents a failure of the individual provider or a failure of health care providers in this country in their care of COVID patients,” he said. He noted that health care professionals have provided “tremendously good care to patients under extremely difficult circumstances.”

“People don’t fail – systems fail – and that’s what happened here,” he said. “Our systems that we need to have in place to prevent health care–associated infection simply were not as strong as they needed to be to survive this challenge.”

In the study, researchers used data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, the CDC’s tracking system for health care–associated infections. The team compared national standard infection ratios – calculated by dividing the number of reported infections by the number of predicted infections – between 2019 and 2020 for six routinely tracked events:

- Central line–associated bloodstream infections.

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

- Ventilator-associated events (VAEs).

- Infections associated with colon surgery and abdominal hysterectomy.

- Clostridioides difficile infections.

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections.

Infections were estimated using regression models created with baseline data from 2015.

“The new report highlights the need for health care facilities to strengthen their infection prevention programs and support them with adequate resources so that they can handle emerging threats to public health, while at the same time ensuring that gains made in combating HAIs [health care–associated infections] are not lost,” said the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology in a statement.

The analysis revealed significant national increases in central line–associated bloodstream infections, CAUTIs, VAEs, and MRSA infections in 2020 compared to 2019. Among all infection types, the greatest increase was in central-line infections, which were 46% to 47% higher in the third quarter and fourth quarter (Q4) of 2020 relative to the same periods the previous year. VAEs rose by 45%, MRSA infections increased by 34%, and CAUTIs increased by 19% in Q4 of 2020 compared to 2019.

The influx of sicker patients in hospitals throughout 2020 led to more frequent and longer use of medical devices such as catheters and ventilators. The use of these devices increases risk for infection, David P. Calfee, MD, chief medical epidemiologist at the New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, said in an interview. He is an editor of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology and was not involved with the study. Shortages in personal protective equipment and crowded intensive care units could also have affected how care was delivered, he said. These factors could have led to “reductions in the ability to provide some of the types of care that are needed to optimally reduce the risk of infection.”

There was either no change or decreases in infections associated with colon surgery or abdominal hysterectomy, likely because there were fewer elective surgeries performed, said Dr. Srinivasan. C. difficile–associated infections also decreased throughout 2020 compared to the previous year. Common practices to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in hospitals, such as environmental cleaning, use of personal protective equipment, and patient isolation, likely helped to curb the spread of C. difficile. Although these mitigating procedures do help protect against MRSA infection, many other factors, notably, the use of medical devices such as ventilators and catheters, can increase the risk for MRSA infection, Dr. Srinivasan added.

Although more research is needed to identify the reasons for these spikes in infection, the findings help quantify the scope of these increases across the United States, Dr. Calfee said. The data allow hospitals and health care professionals to “look back at what we did and then think forward in terms of what we can do different in the future,” he added, “so that these stresses to the system have less of an impact on how we are able to provide care.”

Dr. Srinivasan and Dr. Calfee report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several health care-associated infections in U.S. hospitals spiked in 2020 compared to the previous year, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis published Sept. 2 in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. Soaring hospitalization rates, sicker patients who required more frequent and intense care, and staffing and supply shortages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are thought to have contributed to this increase.

This is the first increase in health care–associated infections since 2015.

These findings “are a reflection of the enormous stress that COVID has placed on our health care system,” Arjun Srinivasan, MD (Capt, USPHS), the associate director of the CDC’s Health care-Associated Infection Prevention Programs, Atlanta, told this news organization. He was not an author of the article, but he supervised the research. “We don’t want anyone to read this report and think that it represents a failure of the individual provider or a failure of health care providers in this country in their care of COVID patients,” he said. He noted that health care professionals have provided “tremendously good care to patients under extremely difficult circumstances.”

“People don’t fail – systems fail – and that’s what happened here,” he said. “Our systems that we need to have in place to prevent health care–associated infection simply were not as strong as they needed to be to survive this challenge.”

In the study, researchers used data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, the CDC’s tracking system for health care–associated infections. The team compared national standard infection ratios – calculated by dividing the number of reported infections by the number of predicted infections – between 2019 and 2020 for six routinely tracked events:

- Central line–associated bloodstream infections.

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

- Ventilator-associated events (VAEs).

- Infections associated with colon surgery and abdominal hysterectomy.

- Clostridioides difficile infections.

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections.

Infections were estimated using regression models created with baseline data from 2015.

“The new report highlights the need for health care facilities to strengthen their infection prevention programs and support them with adequate resources so that they can handle emerging threats to public health, while at the same time ensuring that gains made in combating HAIs [health care–associated infections] are not lost,” said the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology in a statement.

The analysis revealed significant national increases in central line–associated bloodstream infections, CAUTIs, VAEs, and MRSA infections in 2020 compared to 2019. Among all infection types, the greatest increase was in central-line infections, which were 46% to 47% higher in the third quarter and fourth quarter (Q4) of 2020 relative to the same periods the previous year. VAEs rose by 45%, MRSA infections increased by 34%, and CAUTIs increased by 19% in Q4 of 2020 compared to 2019.

The influx of sicker patients in hospitals throughout 2020 led to more frequent and longer use of medical devices such as catheters and ventilators. The use of these devices increases risk for infection, David P. Calfee, MD, chief medical epidemiologist at the New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, said in an interview. He is an editor of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology and was not involved with the study. Shortages in personal protective equipment and crowded intensive care units could also have affected how care was delivered, he said. These factors could have led to “reductions in the ability to provide some of the types of care that are needed to optimally reduce the risk of infection.”

There was either no change or decreases in infections associated with colon surgery or abdominal hysterectomy, likely because there were fewer elective surgeries performed, said Dr. Srinivasan. C. difficile–associated infections also decreased throughout 2020 compared to the previous year. Common practices to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in hospitals, such as environmental cleaning, use of personal protective equipment, and patient isolation, likely helped to curb the spread of C. difficile. Although these mitigating procedures do help protect against MRSA infection, many other factors, notably, the use of medical devices such as ventilators and catheters, can increase the risk for MRSA infection, Dr. Srinivasan added.

Although more research is needed to identify the reasons for these spikes in infection, the findings help quantify the scope of these increases across the United States, Dr. Calfee said. The data allow hospitals and health care professionals to “look back at what we did and then think forward in terms of what we can do different in the future,” he added, “so that these stresses to the system have less of an impact on how we are able to provide care.”

Dr. Srinivasan and Dr. Calfee report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NIH on HIV vaccine failure: ‘Get your HIV-negative, at-risk patients on PrEP tomorrow’

Last year, Katherine Gill, MBChB, an HIV prevention researcher in Cape Town, South Africa, realized how jaded she’d become to vaccine research when the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine came back as 95% effective. In her career conducting HIV clinical trials, she had never seen anything like it. Even HIV prevention methods she had studied that had worked, such as the dapivirine ring, had an overall efficacy of 30%.

The COVID-19 success story started to soften her views toward another vaccine trial she was helping to conduct, a trial in HIV that used the same platform as Johnson & Johnson’s successful COVID-19 vaccine.

“When the COVID vaccine was cracked so quickly and seemingly quite easily, I did start to think, ‘Well, maybe … maybe this will work for HIV,’ “ she said in an interview.

That turned out to be false hope. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that the trial Dr. Gill was helping to conduct, HVTN 705, was stopping early because it hadn’t generated enough of an immune response in participants to justify continuing. It was the second HIV vaccine to fail in the last year. It’s also the latest in what has been a litany of disappointments in the attempt to boost the human immune system to fight HIV without the need for ongoing HIV treatment.

In HVTN 705, known as the Imbokodo study (imbokodo is a Zulu word that’s part of a saying about women being strong as rocks), researchers used the platform made up of a common cold virus, adenovirus 26, to deliver a computer-generated mosaic of HIV antigens to participants’ immune systems. That mosaic of antigens is meant to goose the immune system into recognizing HIV if it were exposed to it.

When HIV enters the body, it infiltrates immune cells and replicates within them. To the rest of the immune system, those cells still register as just typical T-cells. The rest of the immune system can’t see that the virus is spreading through the very cells meant to protect the body from illness. That, plus the armor of sugary glycoproteins encasing the virus, has made HIV nearly impervious to vaccination.

Then, those so-called “prime” shots were followed by a second shot that targets glycoprotein 140, on the most common HIV subtype (or clade) in Africa, clade C. In the Imbokodo trial, a total of 2,637 women from five sub-Saharan African countries received shots at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. Then researchers followed the women from month 7 to 2 years after their third dose, testing their blood to see if their immune systems had generated the immune response the vaccine was meant to induce – and whether such immune response was associated with lower rates of HIV.

When researchers looked at the first 2 years of data, they learned that the vaccine was safe. And they found a total of 114 new cases of HIV – 51 among women who received the vaccine and 63 among those who received a placebo. That’s a 25.2% efficacy rate – but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The results are frustrating, said Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the AIDS division at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). NIAID is one of the funders of the study.

“This [trial] is a little more confounding, in that there is this low level of statistically insignificant difference between vaccine and placebo that starts somewhere around month 9 and then just kind of indolently is maintained over the next 15 months,” he said in an interview. “That’s kind of frustrating. Does it mean there’s a signal or is this just chance? Because that’s what statistics tell us, not to believe your last data point.”

What this means for the future direction of vaccine research is unclear. A sister study to Imbokodo, called Mosaico, recently finished enrolling participants. Mosaico uses the same adenovirus 26 platform, but it’s loaded with different antigens and targets a different glycoprotein for a different HIV subtype. If that trial shows success, it could mean that the platform is right, but the targets in the Imbokodo vaccine were wrong.

Dr. Dieffenbach said that before NIAID decides what to do with Mosaico they’ve asked researchers to analyze the data on the people who did respond, to see if those people have some specific variant of HIV or some other biomarker that could be used to form the next iteration of an HIV vaccine candidate. Only after that will they make a decision about Mosaico.

But he added that it does make him wonder if vaccine approaches that rely on nonneutralizing antibodies like this one have a ceiling of effectiveness that’s just too low to alter the course of the epidemic.

“I think we’ve discovered that there’s not a floor to [these nonneutralizing approaches], but there probably is a ceiling,” he said. “I don’t know if we’re going to get better than” a 25%-29% efficacy rate with those approaches.

The Imbokodo findings reminded Mitchell Warren, executive director of the global HIV prevention nonprofit, AVAC, of the data released in January from the Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) trial. That trial pitted the broadly neutralizing antibody (bNAb) VCR01 against HIV – and mostly, it lost.

VCR01 worked only on HIV variants that 30% of participants had. But in those 30%, it was 75% effective at preventing HIV. Now you have Imbokodo, with its potential 25% activity against HIV, something that may have been a fluke. This, to Mr. Warren, requires a rethinking of the whole HIV vaccine enterprise while “doubling, tripling, quadrupling down” on the HIV prevention methods we know work, such as preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Dr. Dieffenbach agreed. To clinicians, Dr. Dieffenbach said the message of this HIV vaccine trial is flush with urgency: “Get your HIV-negative, at-risk people on PrEP tomorrow.”

There are now two pills approved for HIV prevention, both of which have been found to be up to 99% effective when taken consistently. A third option, injectable cabotegravir (Vocabria), has been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration for approval. The federal Ready, Set, PrEP program makes the pill available for free for those who qualify, and recently the Biden administration reaffirmed that, under the Affordable Care Act, insurance companies should cover all costs associated with PrEP, including lab work and exam visits.

But for the 157 women who participated in the trial at Dr. Gill’s site in Masiphumelele, on the southwestern tip of South Africa, the trial was personal, said Jason Naidoo, community liaison officer at the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation, which conducted a portion of the study. These were women whose parents, siblings, or children were living with HIV or had died from AIDS-defining illnesses, he said. Their lives were chaotic, traveling at a moment’s notice to hometowns on the Eastern Cape, an 11-hour car ride away – longer by bus – for traditional prayers, funerals, and other important events.

Mr. Naidoo remembers arranging buses for the women to return for scheduled clinic visits, leaving the Eastern Cape in the afternoon and arriving in Masiphumelele in the early morning hours, just to keep the clinic appointment. Then, they’d turn around and return east.

They did this for 3 years, he said.

“The fact that these participants have stuck to this and been dedicated amidst all of the chaos talks about their commitment to actually having a vaccine for HIV,” he said. “They know their own risk profile as young Black women in South Africa, and they understand the need for an intervention for the future generations.

“So you can understand the emotion and the sense of sadness, the disappointment – the incredible [dis]belief that this [the failure of the vaccine] could have happened, because the expectations are so, so high.”

For Dr. Gill, who is lead investigator for Imbokodo in Masiphumelele, the weariness toward vaccines is back. Another trial is underway for an HIV vaccine with a platform that was successful in COVID-19 – using messenger RNA (mRNA), like the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines did.

“I think we need to be careful,” she said, “thinking that the mRNA vaccines are going to crack it.”

Dr. Dieffenbach, Dr. Gill, and Mr. Naidoo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The study was funded by Janssen, a Johnson & Johnson company, with NIAID and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last year, Katherine Gill, MBChB, an HIV prevention researcher in Cape Town, South Africa, realized how jaded she’d become to vaccine research when the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine came back as 95% effective. In her career conducting HIV clinical trials, she had never seen anything like it. Even HIV prevention methods she had studied that had worked, such as the dapivirine ring, had an overall efficacy of 30%.

The COVID-19 success story started to soften her views toward another vaccine trial she was helping to conduct, a trial in HIV that used the same platform as Johnson & Johnson’s successful COVID-19 vaccine.

“When the COVID vaccine was cracked so quickly and seemingly quite easily, I did start to think, ‘Well, maybe … maybe this will work for HIV,’ “ she said in an interview.

That turned out to be false hope. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that the trial Dr. Gill was helping to conduct, HVTN 705, was stopping early because it hadn’t generated enough of an immune response in participants to justify continuing. It was the second HIV vaccine to fail in the last year. It’s also the latest in what has been a litany of disappointments in the attempt to boost the human immune system to fight HIV without the need for ongoing HIV treatment.

In HVTN 705, known as the Imbokodo study (imbokodo is a Zulu word that’s part of a saying about women being strong as rocks), researchers used the platform made up of a common cold virus, adenovirus 26, to deliver a computer-generated mosaic of HIV antigens to participants’ immune systems. That mosaic of antigens is meant to goose the immune system into recognizing HIV if it were exposed to it.

When HIV enters the body, it infiltrates immune cells and replicates within them. To the rest of the immune system, those cells still register as just typical T-cells. The rest of the immune system can’t see that the virus is spreading through the very cells meant to protect the body from illness. That, plus the armor of sugary glycoproteins encasing the virus, has made HIV nearly impervious to vaccination.

Then, those so-called “prime” shots were followed by a second shot that targets glycoprotein 140, on the most common HIV subtype (or clade) in Africa, clade C. In the Imbokodo trial, a total of 2,637 women from five sub-Saharan African countries received shots at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. Then researchers followed the women from month 7 to 2 years after their third dose, testing their blood to see if their immune systems had generated the immune response the vaccine was meant to induce – and whether such immune response was associated with lower rates of HIV.

When researchers looked at the first 2 years of data, they learned that the vaccine was safe. And they found a total of 114 new cases of HIV – 51 among women who received the vaccine and 63 among those who received a placebo. That’s a 25.2% efficacy rate – but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The results are frustrating, said Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the AIDS division at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). NIAID is one of the funders of the study.

“This [trial] is a little more confounding, in that there is this low level of statistically insignificant difference between vaccine and placebo that starts somewhere around month 9 and then just kind of indolently is maintained over the next 15 months,” he said in an interview. “That’s kind of frustrating. Does it mean there’s a signal or is this just chance? Because that’s what statistics tell us, not to believe your last data point.”

What this means for the future direction of vaccine research is unclear. A sister study to Imbokodo, called Mosaico, recently finished enrolling participants. Mosaico uses the same adenovirus 26 platform, but it’s loaded with different antigens and targets a different glycoprotein for a different HIV subtype. If that trial shows success, it could mean that the platform is right, but the targets in the Imbokodo vaccine were wrong.

Dr. Dieffenbach said that before NIAID decides what to do with Mosaico they’ve asked researchers to analyze the data on the people who did respond, to see if those people have some specific variant of HIV or some other biomarker that could be used to form the next iteration of an HIV vaccine candidate. Only after that will they make a decision about Mosaico.

But he added that it does make him wonder if vaccine approaches that rely on nonneutralizing antibodies like this one have a ceiling of effectiveness that’s just too low to alter the course of the epidemic.

“I think we’ve discovered that there’s not a floor to [these nonneutralizing approaches], but there probably is a ceiling,” he said. “I don’t know if we’re going to get better than” a 25%-29% efficacy rate with those approaches.

The Imbokodo findings reminded Mitchell Warren, executive director of the global HIV prevention nonprofit, AVAC, of the data released in January from the Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) trial. That trial pitted the broadly neutralizing antibody (bNAb) VCR01 against HIV – and mostly, it lost.

VCR01 worked only on HIV variants that 30% of participants had. But in those 30%, it was 75% effective at preventing HIV. Now you have Imbokodo, with its potential 25% activity against HIV, something that may have been a fluke. This, to Mr. Warren, requires a rethinking of the whole HIV vaccine enterprise while “doubling, tripling, quadrupling down” on the HIV prevention methods we know work, such as preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Dr. Dieffenbach agreed. To clinicians, Dr. Dieffenbach said the message of this HIV vaccine trial is flush with urgency: “Get your HIV-negative, at-risk people on PrEP tomorrow.”

There are now two pills approved for HIV prevention, both of which have been found to be up to 99% effective when taken consistently. A third option, injectable cabotegravir (Vocabria), has been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration for approval. The federal Ready, Set, PrEP program makes the pill available for free for those who qualify, and recently the Biden administration reaffirmed that, under the Affordable Care Act, insurance companies should cover all costs associated with PrEP, including lab work and exam visits.

But for the 157 women who participated in the trial at Dr. Gill’s site in Masiphumelele, on the southwestern tip of South Africa, the trial was personal, said Jason Naidoo, community liaison officer at the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation, which conducted a portion of the study. These were women whose parents, siblings, or children were living with HIV or had died from AIDS-defining illnesses, he said. Their lives were chaotic, traveling at a moment’s notice to hometowns on the Eastern Cape, an 11-hour car ride away – longer by bus – for traditional prayers, funerals, and other important events.

Mr. Naidoo remembers arranging buses for the women to return for scheduled clinic visits, leaving the Eastern Cape in the afternoon and arriving in Masiphumelele in the early morning hours, just to keep the clinic appointment. Then, they’d turn around and return east.

They did this for 3 years, he said.

“The fact that these participants have stuck to this and been dedicated amidst all of the chaos talks about their commitment to actually having a vaccine for HIV,” he said. “They know their own risk profile as young Black women in South Africa, and they understand the need for an intervention for the future generations.

“So you can understand the emotion and the sense of sadness, the disappointment – the incredible [dis]belief that this [the failure of the vaccine] could have happened, because the expectations are so, so high.”

For Dr. Gill, who is lead investigator for Imbokodo in Masiphumelele, the weariness toward vaccines is back. Another trial is underway for an HIV vaccine with a platform that was successful in COVID-19 – using messenger RNA (mRNA), like the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines did.

“I think we need to be careful,” she said, “thinking that the mRNA vaccines are going to crack it.”

Dr. Dieffenbach, Dr. Gill, and Mr. Naidoo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The study was funded by Janssen, a Johnson & Johnson company, with NIAID and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last year, Katherine Gill, MBChB, an HIV prevention researcher in Cape Town, South Africa, realized how jaded she’d become to vaccine research when the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine came back as 95% effective. In her career conducting HIV clinical trials, she had never seen anything like it. Even HIV prevention methods she had studied that had worked, such as the dapivirine ring, had an overall efficacy of 30%.

The COVID-19 success story started to soften her views toward another vaccine trial she was helping to conduct, a trial in HIV that used the same platform as Johnson & Johnson’s successful COVID-19 vaccine.

“When the COVID vaccine was cracked so quickly and seemingly quite easily, I did start to think, ‘Well, maybe … maybe this will work for HIV,’ “ she said in an interview.

That turned out to be false hope. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that the trial Dr. Gill was helping to conduct, HVTN 705, was stopping early because it hadn’t generated enough of an immune response in participants to justify continuing. It was the second HIV vaccine to fail in the last year. It’s also the latest in what has been a litany of disappointments in the attempt to boost the human immune system to fight HIV without the need for ongoing HIV treatment.

In HVTN 705, known as the Imbokodo study (imbokodo is a Zulu word that’s part of a saying about women being strong as rocks), researchers used the platform made up of a common cold virus, adenovirus 26, to deliver a computer-generated mosaic of HIV antigens to participants’ immune systems. That mosaic of antigens is meant to goose the immune system into recognizing HIV if it were exposed to it.

When HIV enters the body, it infiltrates immune cells and replicates within them. To the rest of the immune system, those cells still register as just typical T-cells. The rest of the immune system can’t see that the virus is spreading through the very cells meant to protect the body from illness. That, plus the armor of sugary glycoproteins encasing the virus, has made HIV nearly impervious to vaccination.

Then, those so-called “prime” shots were followed by a second shot that targets glycoprotein 140, on the most common HIV subtype (or clade) in Africa, clade C. In the Imbokodo trial, a total of 2,637 women from five sub-Saharan African countries received shots at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. Then researchers followed the women from month 7 to 2 years after their third dose, testing their blood to see if their immune systems had generated the immune response the vaccine was meant to induce – and whether such immune response was associated with lower rates of HIV.

When researchers looked at the first 2 years of data, they learned that the vaccine was safe. And they found a total of 114 new cases of HIV – 51 among women who received the vaccine and 63 among those who received a placebo. That’s a 25.2% efficacy rate – but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The results are frustrating, said Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the AIDS division at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). NIAID is one of the funders of the study.

“This [trial] is a little more confounding, in that there is this low level of statistically insignificant difference between vaccine and placebo that starts somewhere around month 9 and then just kind of indolently is maintained over the next 15 months,” he said in an interview. “That’s kind of frustrating. Does it mean there’s a signal or is this just chance? Because that’s what statistics tell us, not to believe your last data point.”

What this means for the future direction of vaccine research is unclear. A sister study to Imbokodo, called Mosaico, recently finished enrolling participants. Mosaico uses the same adenovirus 26 platform, but it’s loaded with different antigens and targets a different glycoprotein for a different HIV subtype. If that trial shows success, it could mean that the platform is right, but the targets in the Imbokodo vaccine were wrong.

Dr. Dieffenbach said that before NIAID decides what to do with Mosaico they’ve asked researchers to analyze the data on the people who did respond, to see if those people have some specific variant of HIV or some other biomarker that could be used to form the next iteration of an HIV vaccine candidate. Only after that will they make a decision about Mosaico.

But he added that it does make him wonder if vaccine approaches that rely on nonneutralizing antibodies like this one have a ceiling of effectiveness that’s just too low to alter the course of the epidemic.

“I think we’ve discovered that there’s not a floor to [these nonneutralizing approaches], but there probably is a ceiling,” he said. “I don’t know if we’re going to get better than” a 25%-29% efficacy rate with those approaches.

The Imbokodo findings reminded Mitchell Warren, executive director of the global HIV prevention nonprofit, AVAC, of the data released in January from the Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) trial. That trial pitted the broadly neutralizing antibody (bNAb) VCR01 against HIV – and mostly, it lost.

VCR01 worked only on HIV variants that 30% of participants had. But in those 30%, it was 75% effective at preventing HIV. Now you have Imbokodo, with its potential 25% activity against HIV, something that may have been a fluke. This, to Mr. Warren, requires a rethinking of the whole HIV vaccine enterprise while “doubling, tripling, quadrupling down” on the HIV prevention methods we know work, such as preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Dr. Dieffenbach agreed. To clinicians, Dr. Dieffenbach said the message of this HIV vaccine trial is flush with urgency: “Get your HIV-negative, at-risk people on PrEP tomorrow.”

There are now two pills approved for HIV prevention, both of which have been found to be up to 99% effective when taken consistently. A third option, injectable cabotegravir (Vocabria), has been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration for approval. The federal Ready, Set, PrEP program makes the pill available for free for those who qualify, and recently the Biden administration reaffirmed that, under the Affordable Care Act, insurance companies should cover all costs associated with PrEP, including lab work and exam visits.

But for the 157 women who participated in the trial at Dr. Gill’s site in Masiphumelele, on the southwestern tip of South Africa, the trial was personal, said Jason Naidoo, community liaison officer at the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation, which conducted a portion of the study. These were women whose parents, siblings, or children were living with HIV or had died from AIDS-defining illnesses, he said. Their lives were chaotic, traveling at a moment’s notice to hometowns on the Eastern Cape, an 11-hour car ride away – longer by bus – for traditional prayers, funerals, and other important events.

Mr. Naidoo remembers arranging buses for the women to return for scheduled clinic visits, leaving the Eastern Cape in the afternoon and arriving in Masiphumelele in the early morning hours, just to keep the clinic appointment. Then, they’d turn around and return east.

They did this for 3 years, he said.

“The fact that these participants have stuck to this and been dedicated amidst all of the chaos talks about their commitment to actually having a vaccine for HIV,” he said. “They know their own risk profile as young Black women in South Africa, and they understand the need for an intervention for the future generations.

“So you can understand the emotion and the sense of sadness, the disappointment – the incredible [dis]belief that this [the failure of the vaccine] could have happened, because the expectations are so, so high.”

For Dr. Gill, who is lead investigator for Imbokodo in Masiphumelele, the weariness toward vaccines is back. Another trial is underway for an HIV vaccine with a platform that was successful in COVID-19 – using messenger RNA (mRNA), like the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines did.

“I think we need to be careful,” she said, “thinking that the mRNA vaccines are going to crack it.”

Dr. Dieffenbach, Dr. Gill, and Mr. Naidoo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The study was funded by Janssen, a Johnson & Johnson company, with NIAID and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antiviral Therapy Improves Hepatocellular Cancer Survival

Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the most common type of hepatic cancers, accounting for 65% of all hepatic cancers.1 Among all cancers, HCC is one of the fastest growing causes of death in the United States, and the rate of new HCC cases are on the rise over several decades.2 There are many risk factors leading to HCC, including alcohol use, obesity, and smoking. Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) poses a significant risk.1

The pathogenesis of HCV-induced carcinogenesis is mediated by a unique host-induced immunologic response. Viral replication induces production of inflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interferon (IFN), and oxidative stress on hepatocytes, resulting in cell injury, death, and regeneration. Repetitive cycles of cellular death and regeneration induce fibrosis, which may lead to cirrhosis.3 Hence, early treatment of HCV infection and achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) may lead to decreased incidence and mortality associated with HCC.

Treatment of HCV infection has become more effective with the development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) leading to SVR in > 90% of patients compared with 40 to 50% with IFN-based treatment.4,5 DAAs have been proved safe and highly effective in eradicating HCV infection even in patients with advanced liver disease with decompensated cirrhosis.6 Although achieving SVR indicates a complete cure from chronic HCV infection, several studies have shown subsequent risk of developing HCC persists even after successful HCV treatment.7-9 Some studies show that using DAAs to achieve SVR in patients with HCV infection leads to a decreased relative risk of HCC development compared with patients who do not receive treatment.10-12 But data on HCC risk following DAA-induced SVR vs IFN-induced SVR are somewhat conflicting.

Much of the information regarding the association between SVR and HCC has been gleaned from large data banks without accounting for individual patient characteristics that can be obtained through full chart review. Due to small sample sizes in many chart review studies, the impact that SVR from DAA therapy has on the progression and severity of HCC is not entirely clear. The aim of our study is to evaluate the effect of HCV treatment and SVR status on overall survival (OS) in patients with HCC. Second, we aim to compare survival benefits, if any exist, among the 2 major HCV treatment modalities (IFN vs DAA).

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of patients at Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Tennessee to determine whether treatment for HCV infection in general, and achieving SVR in particular, makes a difference in progression, recurrence, or OS among patients with HCV infection who develop HCC. We identified 111 patients with a diagnosis of both HCV and new or recurrent HCC lesions from November 2008 to March 2019 (Table 1). We divided these patients based on their HCV treatment status, SVR status, and treatment types (IFN vs DAA).

The inclusion criteria were patients aged > 18 years treated at the Memphis VAMC who have HCV infection and developed HCC. Exclusion criteria were patients who developed HCC from other causes such as alcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatitis B virus infection, hemochromatosis, patients without HCV infection, and patients who were not established at the Memphis VAMC. This protocol was approved by the Memphis VAMC Institutional Review Board.

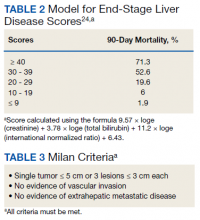

HCC diagnosis was determined using International Classification of Diseases codes (9th revision: 155 and 155.2; 10th revision: CD 22 and 22.9). We also used records of multidisciplinary gastrointestinal malignancy tumor conferences to identify patient who had been diagnosed and treated for HCV infection. We identified patients who were treated with DAA vs IFN as well as patients who had achieved SVR (classified as having negative HCV RNA tests at the end of DAA treatment). We were unable to evaluate Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging since this required documented performance status that was not available in many patient records. We selected cases consistent with both treatment for HCV infection and subsequent development of HCC. Patient data included age; OS time; HIV status HCV genotype; time and status of progression to HCC; type and duration of treatment; and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use. Disease status was measured using the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (Table 2), Milan criteria (Table 3), and Child-Pugh score (Table 4).

Statistical Analysis

OS was measured from the date of HCC diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined from the date of HCC treatment initiation to the date of first HCC recurrence. We compared survival data for the SVR and non-SVR subgroups, the HCV treatment vs non-HCV treatment subgroups, and the IFN therapy vs DAA therapy subgroups, using the Kaplan-Meier method. The differences between subgroups were assessed using a log-rank test. Multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to identify factors that had significant impact on OS. Those factors included age; race; alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use; SVR status; HCV treatment status; IFN-based regimen vs DAA; MELD, and Child-Pugh scores. The results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CI. Calculations were made using Statistical Analysis SAS and IBM SPSS software.

Results

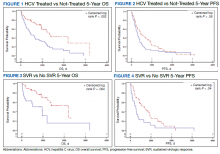

The study included 111 patients. The mean age was 65.7 years; all were male and half of were Black patients. The gender imbalance was due to the predominantly male patient population at Memphis VAMC. Among 111 patients with HCV infection and HCC, 68 patients were treated for HCV infection and had significantly improved OS and PFS compared with the nontreatment group. The median 5-year OS was 44.6 months (95% CI, 966-3202) in the treated HCV infection group compared with 15.1 months in the untreated HCV infection group with a Wilcoxon P = .0005 (Figure 1). Similarly, patients treated for HCV infection had a significantly better 5-year PFS of 15.3 months (95% CI, 294-726) compared with the nontreatment group 9.5 months (95% CI, 205-405) with a Wilcoxon P = .04 (Figure 2).

Among 68 patients treated for HCV infection, 51 achieved SVR, and 34 achieved SVR after the diagnosis of HCC. Patients who achieved SVR had an improved 5-year OS when compared with patients who did not achieve SVR (median 65.8 months [95% CI, 1222-NA] vs 15.7 months [95% CI, 242-853], Wilcoxon P < .001) (Figure 3). Similarly, patients with SVR had improved 5-year PFS when compared with the non-SVR group (median 20.5 months [95% CI, 431-914] vs 8.9 months [95% CI, 191-340], Wilcoxon P = .007 (Figure 4). Achievement of SVR after HCC diagnosis suggests a significantly improved OS (HR 0.37) compared with achievement prior to HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.23-1.82, P = .41)

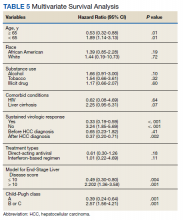

Multivariate Cox regression was used to determine factors with significant survival impact. Advanced age at diagnosis (aged ≥ 65 years) (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.320-0.880; P = .01), SVR status (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.190-0.587; P < .001), achieving SVR after HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.20-0.71; P = .002), low MELD score (< 10) (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.30-0.80; P = .004) and low Child-Pugh score (class A) (HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.24-0.64; P = .001) have a significant positive impact on OS. Survival was not significantly influenced by race, tobacco, drug use, HIV or cirrhosis status, or HCV treatment type. In addition, higher Child-Pugh class (B or C), higher MELD score (> 10), and younger age at diagnosis (< 65 years) have a negative impact on survival outcome (Table 5).

Discussion

The survival benefit of HCV eradication and achieving SVR status has been well established in patients with HCC.13 In a retrospective cohort study of 250 patients with HCV infection who had received curative treatment for HCC, multivariate analysis demonstrated that achieving SVR is an independent predictor of OS.14 The 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 97% and 94% for the SVR group, and 91% and 60% for the non‐SVR group, respectively (P < .001). Similarly, according to Sou and colleagues, of 122 patients with HCV-related HCC, patients with SVR had longer OS than patients with no SVR (P = .04).15 One of the hypotheses that could explain the survival benefit in patients who achieved SVR is the effect of achieving SVR in reducing persistent liver inflammation and associated liver mortality, and therefore lowering risks of complication in patients with HCC.16 In our study, multivariate analysis shows that achieving SVR is associated with significant improved OS (HR, 0.33). In contrast, patients with HCC who have not achieved SVR are associated with worse survival (HR, 3.24). This finding supports early treatment of HCV to obtain SVR in HCV-related patients with HCC, even after development of HCC.

Among 68 patients treated for HCV infection, 45 patients were treated after HCC diagnosis, and 34 patients achieved SVR after HCC diagnosis. The average time between HCV infection treatment after HCC diagnosis was 6 months. Our data suggested that achievement of SVR after HCC diagnosis suggests an improved OS (HR, 0.37) compared with achievement prior to HCC diagnosis (HR, 0.65; 95% CI,0.23-1.82; P = .41). This lack of statistical significance is likely due to small sample size of patients achieving SVR prior to HCC diagnosis. Our results are consistent with the findings regarding the efficacy and timing of DAA treatment in patients with active HCC. According to Singal and colleagues, achieving SVR after DAA therapy may result in improved liver function and facilitate additional HCC-directed therapy, which potentially improves survival.17-19

Nagaoki and colleagues found that there was no significant difference in OS in patients with HCC between the DAA and IFN groups. According to the study, the 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 96% and 96% for DAA patients and 93% and 73% for IFN patients, respectively (P = .16).14 This finding is consistent with the results of our study. HCV treatment type (IFN vs DAA) was not found to be associated with either OS or PFS time, regardless of time period.

A higher MELD score (> 10) and a higher Child-Pugh class (B or C) score are associated with worse survival outcome regardless of SVR status. While patients with a low MELD score (≤ 10) have a better survival rate (HR 0.49), a higher MELD score has a significantly higher HR and therefore worse survival outcomes (HR, 2.20). Similarly, patients with Child-Pugh A (HR, 0.39) have a better survival outcome compared with those patients with Child-Pugh class B or C (HR, 2.57). This finding is consistent with results of multiple studies indicating that advanced liver disease, as measured by a high MELD score and Child-Pugh class score, can be used to predict the survival outcome in patients with HCV-related HCC.20-22

Unlike other studies that look at a single prognostic variable, our study evaluated prognostic impacts of multiple variables (age, SVR status, the order of SVR in relation to HCC development, HCV treatment type, MELD score and Child-Pugh class) in patients with HCC. The study included patients treated for HCV after development of HCC along with other multiple variables leading to OS benefit. It is one of the only studies in the United States that compared 5-year OS and PFS among patients with HCC treated for HCV and achieved SVR. The studies by Nagaoki and colleagues and Sou and colleagues were conducted in Japan, and some of their subset analyses were univariate. Among our study population of veterans, 50% were African American patients, suggesting that they may have similar OS benefit when compared to White patients with HCC and HCV treatment.

Limitations

Our findings were limited in that our study population is too small to conduct further subset analysis that would allow statistical significance of those subsets, such as the suggested benefit of SVR in patients who presented with HCC after antiviral therapy. Another limitation is the all-male population, likely a result of the older veteran population at the Memphis VAMC. The mean age at diagnosis was 65 years, which is slightly higher than the general population. Compared to the SEER database, HCC is most frequently diagnosed among people aged 55 to 64 years.23 The age difference was likely due to our aging veteran population.

Further studies are needed to determine the significance of SVR on HCC recurrence and treatment. Immunotherapy is now first-line treatment for patients with local advanced HCC. All the immunotherapy studies excluded patients with active HCV infection. Hence, we need more data on HCV treatment timing among patients scheduled to start treatment with immunotherapy.

Conclusions

In a population of older veterans, treatment of HCV infection leads to OS benefit among patients with HCC. In addition, patients with HCV infection who achieve SVR have an OS benefit over patients unable to achieve SVR. The type of treatment, DAA vs IFN-based regimen, did not show significant survival benefit.

1. Ghouri YA, Mian I, Rowe JH. Review of hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, etiology, and carcinogenesis. J Carcinog. 2017;16:1. Published 2017 May 29. doi:10.4103/jcar.JCar_9_16

2. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492

3. Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):674-687. doi:10.1038/nrc1934

4. Falade-Nwulia O, Suarez-Cuervo C, Nelson DR, Fried MW, Segal JB, Sulkowski MS. Oral direct-acting agent therapy for hepatitis c virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):637-648. doi:10.7326/M16-2575

5. Kouris G, Hydery T, Greenwood BC, et al. Effectiveness of Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir and predictors of treatment failure in members with hepatitis C genotype 1 infection: a retrospective cohort study in a medicaid population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(7):591-597. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.7.591

6. Jacobson IM, Lawitz E, Kwo PY, et al. Safety and efficacy of elbasvir/grazoprevir in patients with hepatitis c virus infection and compensated cirrhosis: an integrated analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1372-1382.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.050

7. Nahon P, Layese R, Bourcier V, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma after direct antiviral therapy for HCV in patients with cirrhosis included in surveillance programs. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1436-1450.e6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.01510.

8. Innes H, Barclay ST, Hayes PC, et al. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C and sustained viral response: role of the treatment regimen. J Hepatol. 2018;68(4):646-654. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.033

9. Romano A, Angeli P, Piovesan S, et al. Newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced hepatitis C treated with DAAs: a prospective population study. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):345-352. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.009

10. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, Chayanupatkul M, Cao Y, El-Serag HB. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(4):996-1005.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.0122

11. Singh S, Nautiyal A, Loke YK. Oral direct-acting antivirals and the incidence or recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2018;9(4):262-270. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2018-101017

12. Kuftinec G, Loehfelm T, Corwin M, et al. De novo hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence in hepatitis C cirrhotics treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Hepat Oncol. 2018;5(1):HEP06. Published 2018 Jul 25. doi:10.2217/hep-2018-00033

13. Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 Pt 1):329-337. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005

14. Nagaoki Y, Imamura M, Nishida Y, et al. The impact of interferon-free direct-acting antivirals on clinical outcome after curative treatment for hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison with interferon-based therapy. J Med Virol. 2019;91(4):650-658. doi:10.1002/jmv.25352

15. Sou FM, Wu CK, Chang KC, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of HCC occurrence after antiviral therapy for HCV patients between sustained and non-sustained responders. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(1 Pt 3):504-513. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2018.10.017

16. Roche B, Coilly A, Duclos-Vallee JC, Samuel D. The impact of treatment of hepatitis C with DAAs on the occurrence of HCC. Liver Int. 2018;38(suppl 1):139-145. doi:10.1111/liv.13659

17. Singal AG, Lim JK, Kanwal F. AGA clinical practice update on interaction between oral direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C infection and hepatocellular carcinoma: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(8):2149-2157. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.046