User login

Mortality 12 times higher in children with congenital Zika

About 80% of people infected with Zika virus show no symptoms, and that’s particularly problematic during pregnancy. The infection can cause birth defects and is the origin of numerous cases of microcephaly and other neurologic impairments.

The large amount of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Brazilian cities, in addition to social and political problems, facilitated the spread of Zika to the point that the country recorded its highest number of congenital Zika syndrome notifications from 2015 to 2018. Since then, researchers have investigated the extent of the problem.

One of the most compelling findings about the dramatic legacy of Zika in Brazil was published Feb. 24 in The New England Journal of Medicine: After tracking 11,481,215 children born alive in Brazil up to 36 months of age between the years 2015 and 2018, the researchers found that the mortality rate was about 12 times higher among children with congenital Zika syndrome in comparison to children without the syndrome. The study is the first to follow children with congenital Zika syndrome for 3 years and to report mortality in this group.

“This difference persisted throughout the first 3 years of life,” Enny S. Paixão, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Fiocruz-Bahia’s Instituto Gonçalo Moniz, in Brazil, said in an interview.

At the end of the study period, the mortality rate was 52.6 deaths (95% confidence interval, 47.6-58.0) per 1,000 person-years among children with congenital Zika syndrome and 5.6 deaths (95% CI, 5.6-5.7) per 1,000 person-years among those without the syndrome. The mortality rate ratio among children with congenital Zika syndrome, compared with those without it, was 11.3 (95% CI, 10.2-12.4). Data analysis also showed that the 3,308 children with the syndrome were born to mothers who were younger and had fewer years of study when compared to the mothers of their 11,477,907 counterparts without the syndrome.

“If the children survived the first month of life, they had a greater chance of surviving during childhood, because the mortality rates drop,” said Dr. Paixão. “In children with congenital Zika syndrome, this rate also drops, but slowly. The more we stratified by period – neonatal, post neonatal, and the period from the first to the third year of life – the more we saw the relative risk increase. After the first year of life, children with the syndrome were almost 22 times more likely to die compared to children without it. It was hard to believe the data.” Dr. Paixão added that the mortality observed in this study is comparable with the findings of previous studies.

In addition to the large sample size – more than 11 million children – another unique aspect of the work was the comparison with healthy live births. “Previous studies didn’t have this comparison group,” Dr. said Paixão.

Perhaps the major challenge of the study, Dr. Paixão explained, was the fragmentation of the data. “In Brazil we have high-quality data systems, but they are not interconnected. We have a database with all live births, another with mortality records, and another with all children with congenital Zika syndrome. The first big challenge was putting all this information together.”

The solution found by the researchers was to use data linkage – bringing information about the same person from different data banks to create a richer dataset. Basically, they linked the data from the live births registry with the deaths that occurred in the studied age group plus around 18,000 children with congenital Zika syndrome. This was done, said Dr. Paixão, by choosing some identifying variables (such as mother’s name, address, and age) and using an algorithm that evaluates the probability that the “N” in one database is the same person in another database.

“This is expensive, complex, [and] involves super-powerful computers and a lot of researchers,” she said.

The impressive mortality data for children with congenital Zika syndrome obtained by the group of researchers made it inevitable to think about how the country should address this terrible legacy.

“The first and most important recommendation is that the country needs to invest in primary care, so that women don’t get Zika during pregnancy and children aren’t at risk of getting the syndrome,” said Dr. Paixão.

As for the affected population, she highlighted the need to deepen the understanding of the syndrome’s natural history to improve survival and quality of life of affected children and their families. One possibility that was recently discussed by the group of researchers is to carry out a study on the causes of hospitalization of children with the syndrome to develop appropriate protocols and procedures that reduce admissions and death in this population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 80% of people infected with Zika virus show no symptoms, and that’s particularly problematic during pregnancy. The infection can cause birth defects and is the origin of numerous cases of microcephaly and other neurologic impairments.

The large amount of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Brazilian cities, in addition to social and political problems, facilitated the spread of Zika to the point that the country recorded its highest number of congenital Zika syndrome notifications from 2015 to 2018. Since then, researchers have investigated the extent of the problem.

One of the most compelling findings about the dramatic legacy of Zika in Brazil was published Feb. 24 in The New England Journal of Medicine: After tracking 11,481,215 children born alive in Brazil up to 36 months of age between the years 2015 and 2018, the researchers found that the mortality rate was about 12 times higher among children with congenital Zika syndrome in comparison to children without the syndrome. The study is the first to follow children with congenital Zika syndrome for 3 years and to report mortality in this group.

“This difference persisted throughout the first 3 years of life,” Enny S. Paixão, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Fiocruz-Bahia’s Instituto Gonçalo Moniz, in Brazil, said in an interview.

At the end of the study period, the mortality rate was 52.6 deaths (95% confidence interval, 47.6-58.0) per 1,000 person-years among children with congenital Zika syndrome and 5.6 deaths (95% CI, 5.6-5.7) per 1,000 person-years among those without the syndrome. The mortality rate ratio among children with congenital Zika syndrome, compared with those without it, was 11.3 (95% CI, 10.2-12.4). Data analysis also showed that the 3,308 children with the syndrome were born to mothers who were younger and had fewer years of study when compared to the mothers of their 11,477,907 counterparts without the syndrome.

“If the children survived the first month of life, they had a greater chance of surviving during childhood, because the mortality rates drop,” said Dr. Paixão. “In children with congenital Zika syndrome, this rate also drops, but slowly. The more we stratified by period – neonatal, post neonatal, and the period from the first to the third year of life – the more we saw the relative risk increase. After the first year of life, children with the syndrome were almost 22 times more likely to die compared to children without it. It was hard to believe the data.” Dr. Paixão added that the mortality observed in this study is comparable with the findings of previous studies.

In addition to the large sample size – more than 11 million children – another unique aspect of the work was the comparison with healthy live births. “Previous studies didn’t have this comparison group,” Dr. said Paixão.

Perhaps the major challenge of the study, Dr. Paixão explained, was the fragmentation of the data. “In Brazil we have high-quality data systems, but they are not interconnected. We have a database with all live births, another with mortality records, and another with all children with congenital Zika syndrome. The first big challenge was putting all this information together.”

The solution found by the researchers was to use data linkage – bringing information about the same person from different data banks to create a richer dataset. Basically, they linked the data from the live births registry with the deaths that occurred in the studied age group plus around 18,000 children with congenital Zika syndrome. This was done, said Dr. Paixão, by choosing some identifying variables (such as mother’s name, address, and age) and using an algorithm that evaluates the probability that the “N” in one database is the same person in another database.

“This is expensive, complex, [and] involves super-powerful computers and a lot of researchers,” she said.

The impressive mortality data for children with congenital Zika syndrome obtained by the group of researchers made it inevitable to think about how the country should address this terrible legacy.

“The first and most important recommendation is that the country needs to invest in primary care, so that women don’t get Zika during pregnancy and children aren’t at risk of getting the syndrome,” said Dr. Paixão.

As for the affected population, she highlighted the need to deepen the understanding of the syndrome’s natural history to improve survival and quality of life of affected children and their families. One possibility that was recently discussed by the group of researchers is to carry out a study on the causes of hospitalization of children with the syndrome to develop appropriate protocols and procedures that reduce admissions and death in this population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 80% of people infected with Zika virus show no symptoms, and that’s particularly problematic during pregnancy. The infection can cause birth defects and is the origin of numerous cases of microcephaly and other neurologic impairments.

The large amount of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Brazilian cities, in addition to social and political problems, facilitated the spread of Zika to the point that the country recorded its highest number of congenital Zika syndrome notifications from 2015 to 2018. Since then, researchers have investigated the extent of the problem.

One of the most compelling findings about the dramatic legacy of Zika in Brazil was published Feb. 24 in The New England Journal of Medicine: After tracking 11,481,215 children born alive in Brazil up to 36 months of age between the years 2015 and 2018, the researchers found that the mortality rate was about 12 times higher among children with congenital Zika syndrome in comparison to children without the syndrome. The study is the first to follow children with congenital Zika syndrome for 3 years and to report mortality in this group.

“This difference persisted throughout the first 3 years of life,” Enny S. Paixão, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and Fiocruz-Bahia’s Instituto Gonçalo Moniz, in Brazil, said in an interview.

At the end of the study period, the mortality rate was 52.6 deaths (95% confidence interval, 47.6-58.0) per 1,000 person-years among children with congenital Zika syndrome and 5.6 deaths (95% CI, 5.6-5.7) per 1,000 person-years among those without the syndrome. The mortality rate ratio among children with congenital Zika syndrome, compared with those without it, was 11.3 (95% CI, 10.2-12.4). Data analysis also showed that the 3,308 children with the syndrome were born to mothers who were younger and had fewer years of study when compared to the mothers of their 11,477,907 counterparts without the syndrome.

“If the children survived the first month of life, they had a greater chance of surviving during childhood, because the mortality rates drop,” said Dr. Paixão. “In children with congenital Zika syndrome, this rate also drops, but slowly. The more we stratified by period – neonatal, post neonatal, and the period from the first to the third year of life – the more we saw the relative risk increase. After the first year of life, children with the syndrome were almost 22 times more likely to die compared to children without it. It was hard to believe the data.” Dr. Paixão added that the mortality observed in this study is comparable with the findings of previous studies.

In addition to the large sample size – more than 11 million children – another unique aspect of the work was the comparison with healthy live births. “Previous studies didn’t have this comparison group,” Dr. said Paixão.

Perhaps the major challenge of the study, Dr. Paixão explained, was the fragmentation of the data. “In Brazil we have high-quality data systems, but they are not interconnected. We have a database with all live births, another with mortality records, and another with all children with congenital Zika syndrome. The first big challenge was putting all this information together.”

The solution found by the researchers was to use data linkage – bringing information about the same person from different data banks to create a richer dataset. Basically, they linked the data from the live births registry with the deaths that occurred in the studied age group plus around 18,000 children with congenital Zika syndrome. This was done, said Dr. Paixão, by choosing some identifying variables (such as mother’s name, address, and age) and using an algorithm that evaluates the probability that the “N” in one database is the same person in another database.

“This is expensive, complex, [and] involves super-powerful computers and a lot of researchers,” she said.

The impressive mortality data for children with congenital Zika syndrome obtained by the group of researchers made it inevitable to think about how the country should address this terrible legacy.

“The first and most important recommendation is that the country needs to invest in primary care, so that women don’t get Zika during pregnancy and children aren’t at risk of getting the syndrome,” said Dr. Paixão.

As for the affected population, she highlighted the need to deepen the understanding of the syndrome’s natural history to improve survival and quality of life of affected children and their families. One possibility that was recently discussed by the group of researchers is to carry out a study on the causes of hospitalization of children with the syndrome to develop appropriate protocols and procedures that reduce admissions and death in this population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘In the presence of kindness’: humanitarian Paul Farmer dies

Renowned infectious disease specialist, humanitarian, and healthcare champion for many of the world’s most vulnerable patient populations, Paul Edward Farmer, MD, died suddenly in his sleep from an acute cardiac event on Feb. 21 in Rwanda, where he had been teaching. He was 62.

Dr. Farmer cofounded the Boston-based global nonprofit Partners In Health and spent decades providing healthcare to impoverished communities worldwide, fighting on the frontline to protect underserved communities against deadly pandemics.

Dr. Farmer was the Kolokotrones University Professor and chair of the department of global health and social medicine in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He served as chief of the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston.

“Paul dedicated his life to improving human health and advocating for health equity and social justice on a global scale,” said HMS dean George Q. Daley in a letter to the HMS community. “I am particularly shaken by his passing because he was not only a consummate colleague and a beloved mentor, but a close friend. To me, Paul represented the heart and soul of Harvard Medical School.”

He was also chancellor and cofounder of the University of Global Health Equity in Kigali, Rwanda. Before his death, he spent several weeks teaching at the university.

“Paul Farmer’s loss is devastating, but his vision for the world will live on through Partners In Health,” said Partners In Health CEO Sheila Davis in a statement. “Paul taught all those around him the power of accompaniment, love for one another, and solidarity. Our deepest sympathies are with his family.”

Dr. Farmer was born in North Adams, Mass., and grew up in Florida with his parents and five siblings. He attended Duke University on a Benjamin N. Duke Scholarship and received his medical degree in 1988, followed by his PhD in 1990 from Harvard University.

His humanitarian work began when he was a college student volunteering in Haiti in 1983 working with dispossessed farmers. In 1987, he cofounded Partners In Health with the goal of helping patients in poverty-stricken corners of the world.

Under Dr. Farmer’s leadership, the nonprofit tackled major public health crises: Haiti’s devastating 2010 earthquake, drug-resistant tuberculosis in Peru and other countries, and an Ebola outbreak that tore through West Africa.

Dr. Farmer documented his 2014-2015 experience treating Africa’s Ebola patients in a book called “Fevers, Feuds, and Diamonds: Ebola and the Ravages of History.”

He wrote that by the time he arrived, “western Sierra Leone was ground zero of the epidemic, and Upper West Africa was just about the worst place in the world to be critically ill or injured.”

One of his greatest qualities was his ability to connect with patients – to treat them “not like ones who suffered, but like a pal you’d joke with,” said Pardis Sabeti, MD, PhD, a Harvard University geneticist who also spent time in Africa and famously sequenced samples of the Ebola virus’ genome.

Dr. Sabeti and Dr. Farmer bonded over their love for Sierra Leone, and their grief over losing a close colleague to Ebola, Sheik Humarr Khan, who was one of the area’s leading infectious disease experts.

Dr. Sabeti first met Dr. Farmer years earlier as a first-year Harvard medical student when she enrolled in one of his courses. She said students introduced themselves, one by one, each veering into heartfelt testimonies about what Dr. Farmer’s work had meant to them.

Dr. Farmer and Dr. Sabeti were just texting on Feb. 19, and the two were “goofing around in our usual way, and scheming about how to make the world better, as we always did.”

Dr. Farmer was funny, mischievous, and above all, exactly what you would expect upon meeting him, Dr. Sabeti said.

“It’s cliché, but the energetic kick you get from just being in his presence, it’s almost otherworldly,” she said. “It’s not even otherworldly in the sense of: ‘I just came across – greatness.’ It’s more: ‘I just came across kindness.’ ”

Dr. Farmer’s work has been widely distributed in publications including Bulletin of the World Health Organization, The Lancet, the New England Journal of Medicine, Clinical Infectious Diseases, and Social Science & Medicine.

He was awarded the 2020 Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, the Margaret Mead Award from the American Anthropological Association, the American Medical Association’s Outstanding International Physician (Nathan Davis) Award, and, with his Partners In Health colleagues, the Hilton Humanitarian Prize.

He is survived by his wife, Didi Bertrand Farmer, and their three children.

A verison of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Renowned infectious disease specialist, humanitarian, and healthcare champion for many of the world’s most vulnerable patient populations, Paul Edward Farmer, MD, died suddenly in his sleep from an acute cardiac event on Feb. 21 in Rwanda, where he had been teaching. He was 62.

Dr. Farmer cofounded the Boston-based global nonprofit Partners In Health and spent decades providing healthcare to impoverished communities worldwide, fighting on the frontline to protect underserved communities against deadly pandemics.

Dr. Farmer was the Kolokotrones University Professor and chair of the department of global health and social medicine in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He served as chief of the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston.

“Paul dedicated his life to improving human health and advocating for health equity and social justice on a global scale,” said HMS dean George Q. Daley in a letter to the HMS community. “I am particularly shaken by his passing because he was not only a consummate colleague and a beloved mentor, but a close friend. To me, Paul represented the heart and soul of Harvard Medical School.”

He was also chancellor and cofounder of the University of Global Health Equity in Kigali, Rwanda. Before his death, he spent several weeks teaching at the university.

“Paul Farmer’s loss is devastating, but his vision for the world will live on through Partners In Health,” said Partners In Health CEO Sheila Davis in a statement. “Paul taught all those around him the power of accompaniment, love for one another, and solidarity. Our deepest sympathies are with his family.”

Dr. Farmer was born in North Adams, Mass., and grew up in Florida with his parents and five siblings. He attended Duke University on a Benjamin N. Duke Scholarship and received his medical degree in 1988, followed by his PhD in 1990 from Harvard University.

His humanitarian work began when he was a college student volunteering in Haiti in 1983 working with dispossessed farmers. In 1987, he cofounded Partners In Health with the goal of helping patients in poverty-stricken corners of the world.

Under Dr. Farmer’s leadership, the nonprofit tackled major public health crises: Haiti’s devastating 2010 earthquake, drug-resistant tuberculosis in Peru and other countries, and an Ebola outbreak that tore through West Africa.

Dr. Farmer documented his 2014-2015 experience treating Africa’s Ebola patients in a book called “Fevers, Feuds, and Diamonds: Ebola and the Ravages of History.”

He wrote that by the time he arrived, “western Sierra Leone was ground zero of the epidemic, and Upper West Africa was just about the worst place in the world to be critically ill or injured.”

One of his greatest qualities was his ability to connect with patients – to treat them “not like ones who suffered, but like a pal you’d joke with,” said Pardis Sabeti, MD, PhD, a Harvard University geneticist who also spent time in Africa and famously sequenced samples of the Ebola virus’ genome.

Dr. Sabeti and Dr. Farmer bonded over their love for Sierra Leone, and their grief over losing a close colleague to Ebola, Sheik Humarr Khan, who was one of the area’s leading infectious disease experts.

Dr. Sabeti first met Dr. Farmer years earlier as a first-year Harvard medical student when she enrolled in one of his courses. She said students introduced themselves, one by one, each veering into heartfelt testimonies about what Dr. Farmer’s work had meant to them.

Dr. Farmer and Dr. Sabeti were just texting on Feb. 19, and the two were “goofing around in our usual way, and scheming about how to make the world better, as we always did.”

Dr. Farmer was funny, mischievous, and above all, exactly what you would expect upon meeting him, Dr. Sabeti said.

“It’s cliché, but the energetic kick you get from just being in his presence, it’s almost otherworldly,” she said. “It’s not even otherworldly in the sense of: ‘I just came across – greatness.’ It’s more: ‘I just came across kindness.’ ”

Dr. Farmer’s work has been widely distributed in publications including Bulletin of the World Health Organization, The Lancet, the New England Journal of Medicine, Clinical Infectious Diseases, and Social Science & Medicine.

He was awarded the 2020 Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, the Margaret Mead Award from the American Anthropological Association, the American Medical Association’s Outstanding International Physician (Nathan Davis) Award, and, with his Partners In Health colleagues, the Hilton Humanitarian Prize.

He is survived by his wife, Didi Bertrand Farmer, and their three children.

A verison of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Renowned infectious disease specialist, humanitarian, and healthcare champion for many of the world’s most vulnerable patient populations, Paul Edward Farmer, MD, died suddenly in his sleep from an acute cardiac event on Feb. 21 in Rwanda, where he had been teaching. He was 62.

Dr. Farmer cofounded the Boston-based global nonprofit Partners In Health and spent decades providing healthcare to impoverished communities worldwide, fighting on the frontline to protect underserved communities against deadly pandemics.

Dr. Farmer was the Kolokotrones University Professor and chair of the department of global health and social medicine in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He served as chief of the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston.

“Paul dedicated his life to improving human health and advocating for health equity and social justice on a global scale,” said HMS dean George Q. Daley in a letter to the HMS community. “I am particularly shaken by his passing because he was not only a consummate colleague and a beloved mentor, but a close friend. To me, Paul represented the heart and soul of Harvard Medical School.”

He was also chancellor and cofounder of the University of Global Health Equity in Kigali, Rwanda. Before his death, he spent several weeks teaching at the university.

“Paul Farmer’s loss is devastating, but his vision for the world will live on through Partners In Health,” said Partners In Health CEO Sheila Davis in a statement. “Paul taught all those around him the power of accompaniment, love for one another, and solidarity. Our deepest sympathies are with his family.”

Dr. Farmer was born in North Adams, Mass., and grew up in Florida with his parents and five siblings. He attended Duke University on a Benjamin N. Duke Scholarship and received his medical degree in 1988, followed by his PhD in 1990 from Harvard University.

His humanitarian work began when he was a college student volunteering in Haiti in 1983 working with dispossessed farmers. In 1987, he cofounded Partners In Health with the goal of helping patients in poverty-stricken corners of the world.

Under Dr. Farmer’s leadership, the nonprofit tackled major public health crises: Haiti’s devastating 2010 earthquake, drug-resistant tuberculosis in Peru and other countries, and an Ebola outbreak that tore through West Africa.

Dr. Farmer documented his 2014-2015 experience treating Africa’s Ebola patients in a book called “Fevers, Feuds, and Diamonds: Ebola and the Ravages of History.”

He wrote that by the time he arrived, “western Sierra Leone was ground zero of the epidemic, and Upper West Africa was just about the worst place in the world to be critically ill or injured.”

One of his greatest qualities was his ability to connect with patients – to treat them “not like ones who suffered, but like a pal you’d joke with,” said Pardis Sabeti, MD, PhD, a Harvard University geneticist who also spent time in Africa and famously sequenced samples of the Ebola virus’ genome.

Dr. Sabeti and Dr. Farmer bonded over their love for Sierra Leone, and their grief over losing a close colleague to Ebola, Sheik Humarr Khan, who was one of the area’s leading infectious disease experts.

Dr. Sabeti first met Dr. Farmer years earlier as a first-year Harvard medical student when she enrolled in one of his courses. She said students introduced themselves, one by one, each veering into heartfelt testimonies about what Dr. Farmer’s work had meant to them.

Dr. Farmer and Dr. Sabeti were just texting on Feb. 19, and the two were “goofing around in our usual way, and scheming about how to make the world better, as we always did.”

Dr. Farmer was funny, mischievous, and above all, exactly what you would expect upon meeting him, Dr. Sabeti said.

“It’s cliché, but the energetic kick you get from just being in his presence, it’s almost otherworldly,” she said. “It’s not even otherworldly in the sense of: ‘I just came across – greatness.’ It’s more: ‘I just came across kindness.’ ”

Dr. Farmer’s work has been widely distributed in publications including Bulletin of the World Health Organization, The Lancet, the New England Journal of Medicine, Clinical Infectious Diseases, and Social Science & Medicine.

He was awarded the 2020 Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, the Margaret Mead Award from the American Anthropological Association, the American Medical Association’s Outstanding International Physician (Nathan Davis) Award, and, with his Partners In Health colleagues, the Hilton Humanitarian Prize.

He is survived by his wife, Didi Bertrand Farmer, and their three children.

A verison of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: The Omicron surge has become a retreat

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

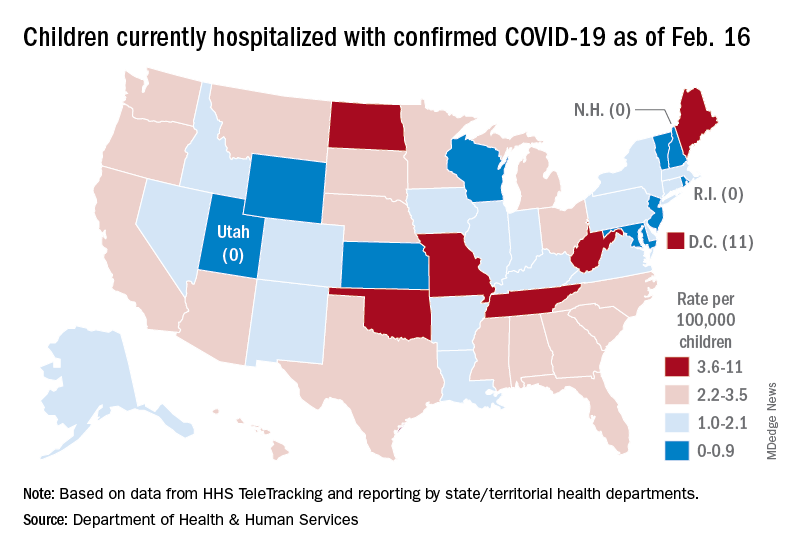

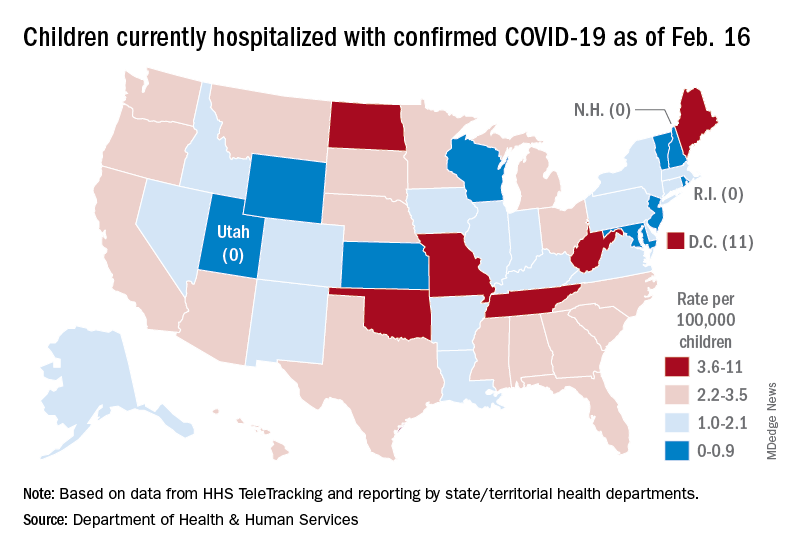

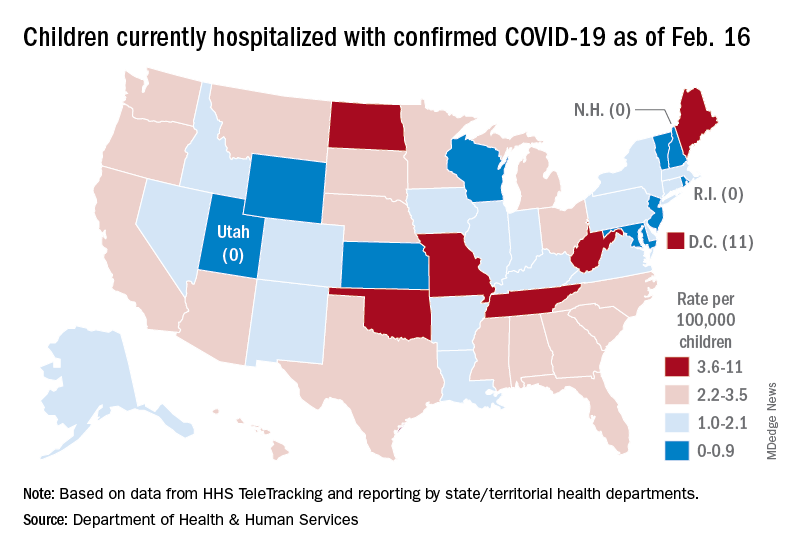

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

New ivermectin, HCQ scripts highest in GOP-dominated counties

New prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and ivermectin increased in 2020, driven particularly by rates in counties with the highest proportion of Republican votes in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that U.S. prescribing of hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin during the COVID-19 pandemic may have been influenced by political affiliation,” wrote Michael L. Barnett, MD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The researchers used data from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse to analyze commercial and Medicare Advantage medical claims from January 2019 through December 2020 for more than 18.5 million adults living in counties with at least 50 enrollees.

Using U.S. Census data and 2020 presidential election results, the researchers classified counties according to their proportion of Republican voters and then examined whether those proportions were associated with that county’s rates of new prescriptions for HCQ, ivermectin, methotrexate sodium, and albendazole. Methotrexate is prescribed for similar conditions and indications as HCQ, and albendazole is prescribed for similar reasons as ivermectin, although neither of the comparison drugs has been considered for COVID-19 treatment.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for HCQ as a COVID-19 treatment on March 28, 2020, but the agency revoked the EUA 3 months later on June 15. Ivermectin never received an EUA for COVID treatment, but an in vitro study published April 3, 2020 claimed it had an antiviral effect.

The National Institutes of Health recommended against using ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment on Aug. 1, 2020, but a few months later, on Nov. 13, a flawed clinical trial – later retracted – claimed ivermectin was 90% effective in treating COVID-19. Despite the lack of evidence for ivermectin’s efficacy, a Senate committee meeting on Dec. 8, 2020, included testimony from a physician who promoted its use.

In comparing ivermectin and HCQ prescription rates with counties’ political composition, the researchers adjusted their findings to account for differences in the counties’ racial composition and COVID-19 incidence as well as enrollees’ age, sex, insurance type, income, comorbidity burden, and home in a rural or urban area.

The results showed an average of 20 new HCQ prescriptions per 100,000 enrollees in 2019, but 2020 saw a sharp increase and drop in new HCQ prescriptions in March-April 2020, independent of counties’ breakdown of political affiliation.

“However, after June 2020, coinciding with the revocation of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s emergency use authorization for hydroxychloroquine, prescribing volume was significantly higher in the highest vs. lowest Republican vote share counties,” the authors report. The gradual increase from June through December 2020 averaged to 42 new prescriptions per 100,000, a 146% increase over 2019 rates that was driven largely by the 25% of counties with the highest proportion of Republican voters.

Similarly, rates of new ivermectin prescriptions in December 2020 were more than nine times higher in counties with the highest Republican vote share, compared with new prescriptions throughout 2019. The researchers found no differences in new prescriptions for methotrexate or albendazole in 2020 based on counties’ proportion of Republican votes.

Since the study is an ecological, observational one, it cannot show causation or shed light on what role patients, physicians, or other factors might have played in prescribing patterns. Nevertheless, the authors noted the potentially negative implications of their findings.

“Because political affiliation should not be a factor in clinical treatment decisions, our findings raise concerns for public trust in a nonpartisan health care system,” the authors write.

Coauthor Ateev Mehrotra, MD, MPH, reported personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, and coauthor Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, reported personal fees from Bioverativ, Merck, Janssen, Edwards Lifesciences, Novartis, Amgen, Eisai, Otsuka, Vertex, Celgene, Sanofi-Aventis, Precision Health Economics (now PRECISIONheor), Analysis Group, and Doubleday and hosting the podcast Freakonomics, M.D. The other coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. No external funding source was noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and ivermectin increased in 2020, driven particularly by rates in counties with the highest proportion of Republican votes in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that U.S. prescribing of hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin during the COVID-19 pandemic may have been influenced by political affiliation,” wrote Michael L. Barnett, MD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The researchers used data from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse to analyze commercial and Medicare Advantage medical claims from January 2019 through December 2020 for more than 18.5 million adults living in counties with at least 50 enrollees.

Using U.S. Census data and 2020 presidential election results, the researchers classified counties according to their proportion of Republican voters and then examined whether those proportions were associated with that county’s rates of new prescriptions for HCQ, ivermectin, methotrexate sodium, and albendazole. Methotrexate is prescribed for similar conditions and indications as HCQ, and albendazole is prescribed for similar reasons as ivermectin, although neither of the comparison drugs has been considered for COVID-19 treatment.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for HCQ as a COVID-19 treatment on March 28, 2020, but the agency revoked the EUA 3 months later on June 15. Ivermectin never received an EUA for COVID treatment, but an in vitro study published April 3, 2020 claimed it had an antiviral effect.

The National Institutes of Health recommended against using ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment on Aug. 1, 2020, but a few months later, on Nov. 13, a flawed clinical trial – later retracted – claimed ivermectin was 90% effective in treating COVID-19. Despite the lack of evidence for ivermectin’s efficacy, a Senate committee meeting on Dec. 8, 2020, included testimony from a physician who promoted its use.

In comparing ivermectin and HCQ prescription rates with counties’ political composition, the researchers adjusted their findings to account for differences in the counties’ racial composition and COVID-19 incidence as well as enrollees’ age, sex, insurance type, income, comorbidity burden, and home in a rural or urban area.

The results showed an average of 20 new HCQ prescriptions per 100,000 enrollees in 2019, but 2020 saw a sharp increase and drop in new HCQ prescriptions in March-April 2020, independent of counties’ breakdown of political affiliation.

“However, after June 2020, coinciding with the revocation of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s emergency use authorization for hydroxychloroquine, prescribing volume was significantly higher in the highest vs. lowest Republican vote share counties,” the authors report. The gradual increase from June through December 2020 averaged to 42 new prescriptions per 100,000, a 146% increase over 2019 rates that was driven largely by the 25% of counties with the highest proportion of Republican voters.

Similarly, rates of new ivermectin prescriptions in December 2020 were more than nine times higher in counties with the highest Republican vote share, compared with new prescriptions throughout 2019. The researchers found no differences in new prescriptions for methotrexate or albendazole in 2020 based on counties’ proportion of Republican votes.

Since the study is an ecological, observational one, it cannot show causation or shed light on what role patients, physicians, or other factors might have played in prescribing patterns. Nevertheless, the authors noted the potentially negative implications of their findings.

“Because political affiliation should not be a factor in clinical treatment decisions, our findings raise concerns for public trust in a nonpartisan health care system,” the authors write.

Coauthor Ateev Mehrotra, MD, MPH, reported personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, and coauthor Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, reported personal fees from Bioverativ, Merck, Janssen, Edwards Lifesciences, Novartis, Amgen, Eisai, Otsuka, Vertex, Celgene, Sanofi-Aventis, Precision Health Economics (now PRECISIONheor), Analysis Group, and Doubleday and hosting the podcast Freakonomics, M.D. The other coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. No external funding source was noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and ivermectin increased in 2020, driven particularly by rates in counties with the highest proportion of Republican votes in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that U.S. prescribing of hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin during the COVID-19 pandemic may have been influenced by political affiliation,” wrote Michael L. Barnett, MD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston and colleagues.

The researchers used data from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse to analyze commercial and Medicare Advantage medical claims from January 2019 through December 2020 for more than 18.5 million adults living in counties with at least 50 enrollees.

Using U.S. Census data and 2020 presidential election results, the researchers classified counties according to their proportion of Republican voters and then examined whether those proportions were associated with that county’s rates of new prescriptions for HCQ, ivermectin, methotrexate sodium, and albendazole. Methotrexate is prescribed for similar conditions and indications as HCQ, and albendazole is prescribed for similar reasons as ivermectin, although neither of the comparison drugs has been considered for COVID-19 treatment.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for HCQ as a COVID-19 treatment on March 28, 2020, but the agency revoked the EUA 3 months later on June 15. Ivermectin never received an EUA for COVID treatment, but an in vitro study published April 3, 2020 claimed it had an antiviral effect.

The National Institutes of Health recommended against using ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment on Aug. 1, 2020, but a few months later, on Nov. 13, a flawed clinical trial – later retracted – claimed ivermectin was 90% effective in treating COVID-19. Despite the lack of evidence for ivermectin’s efficacy, a Senate committee meeting on Dec. 8, 2020, included testimony from a physician who promoted its use.

In comparing ivermectin and HCQ prescription rates with counties’ political composition, the researchers adjusted their findings to account for differences in the counties’ racial composition and COVID-19 incidence as well as enrollees’ age, sex, insurance type, income, comorbidity burden, and home in a rural or urban area.

The results showed an average of 20 new HCQ prescriptions per 100,000 enrollees in 2019, but 2020 saw a sharp increase and drop in new HCQ prescriptions in March-April 2020, independent of counties’ breakdown of political affiliation.

“However, after June 2020, coinciding with the revocation of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s emergency use authorization for hydroxychloroquine, prescribing volume was significantly higher in the highest vs. lowest Republican vote share counties,” the authors report. The gradual increase from June through December 2020 averaged to 42 new prescriptions per 100,000, a 146% increase over 2019 rates that was driven largely by the 25% of counties with the highest proportion of Republican voters.

Similarly, rates of new ivermectin prescriptions in December 2020 were more than nine times higher in counties with the highest Republican vote share, compared with new prescriptions throughout 2019. The researchers found no differences in new prescriptions for methotrexate or albendazole in 2020 based on counties’ proportion of Republican votes.

Since the study is an ecological, observational one, it cannot show causation or shed light on what role patients, physicians, or other factors might have played in prescribing patterns. Nevertheless, the authors noted the potentially negative implications of their findings.

“Because political affiliation should not be a factor in clinical treatment decisions, our findings raise concerns for public trust in a nonpartisan health care system,” the authors write.

Coauthor Ateev Mehrotra, MD, MPH, reported personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, and coauthor Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, reported personal fees from Bioverativ, Merck, Janssen, Edwards Lifesciences, Novartis, Amgen, Eisai, Otsuka, Vertex, Celgene, Sanofi-Aventis, Precision Health Economics (now PRECISIONheor), Analysis Group, and Doubleday and hosting the podcast Freakonomics, M.D. The other coauthors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. No external funding source was noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Treatment for BV, trichomoniasis approved for adolescents

The antimicrobial agent, marketed as Solosec, was first approved in 2017 as a treatment for BV in adult women. In 2021, it was approved for the treatment of trichomoniasis in adult men and women.

Lupin Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures the drug, announced the expanded approval for adolescents in a news release.

The medication is meant to be taken as a single dose. It comes in a packet that should be sprinkled onto applesauce, yogurt, or pudding and consumed without chewing or crunching.

The treatment option may help “address gaps in care related to adherence,” said Tom Merriam, an executive director with Lupin.

Bacterial vaginosis is a common vaginal infection. Trichomoniasis is the most common nonviral, curable STI in the United States. Sexual partners of patients with trichomoniasis can be treated at the same time.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is one of the possible side effects of secnidazole treatment, the drug’s label notes.

The antimicrobial agent, marketed as Solosec, was first approved in 2017 as a treatment for BV in adult women. In 2021, it was approved for the treatment of trichomoniasis in adult men and women.

Lupin Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures the drug, announced the expanded approval for adolescents in a news release.

The medication is meant to be taken as a single dose. It comes in a packet that should be sprinkled onto applesauce, yogurt, or pudding and consumed without chewing or crunching.

The treatment option may help “address gaps in care related to adherence,” said Tom Merriam, an executive director with Lupin.

Bacterial vaginosis is a common vaginal infection. Trichomoniasis is the most common nonviral, curable STI in the United States. Sexual partners of patients with trichomoniasis can be treated at the same time.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is one of the possible side effects of secnidazole treatment, the drug’s label notes.

The antimicrobial agent, marketed as Solosec, was first approved in 2017 as a treatment for BV in adult women. In 2021, it was approved for the treatment of trichomoniasis in adult men and women.

Lupin Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures the drug, announced the expanded approval for adolescents in a news release.

The medication is meant to be taken as a single dose. It comes in a packet that should be sprinkled onto applesauce, yogurt, or pudding and consumed without chewing or crunching.

The treatment option may help “address gaps in care related to adherence,” said Tom Merriam, an executive director with Lupin.

Bacterial vaginosis is a common vaginal infection. Trichomoniasis is the most common nonviral, curable STI in the United States. Sexual partners of patients with trichomoniasis can be treated at the same time.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is one of the possible side effects of secnidazole treatment, the drug’s label notes.

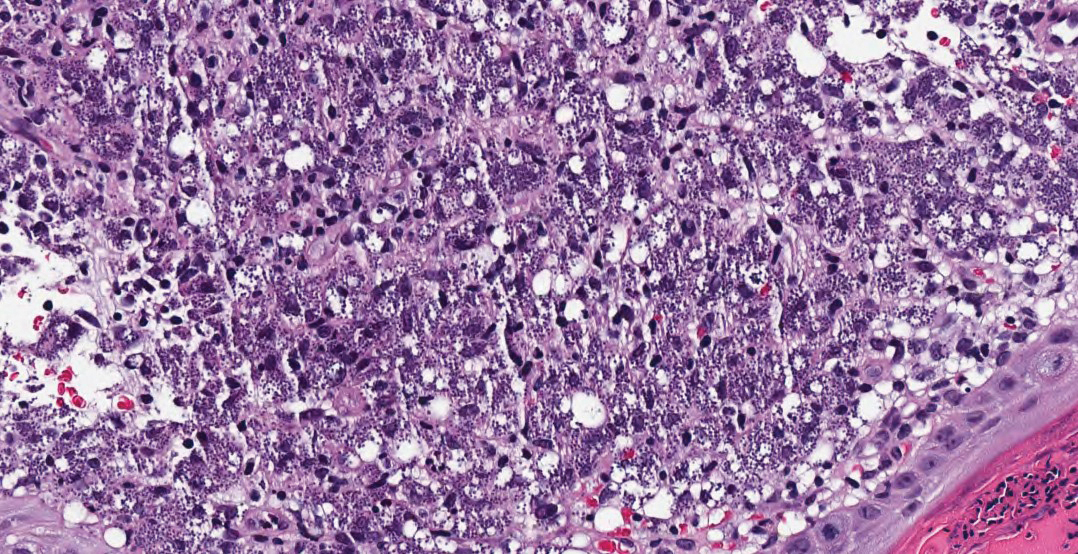

Full results of anal cancer study point to barriers to care

Reports based on a press release in October 2021 suggested it, but now the full data tell the story:

“We now show, for the first time, that treatment of anal HSIL is effective in reducing the incidence of anal cancer,” said Joel Palefsky, MD, lead investigator of the Anal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) study and founder/director of the Anal Neoplasia Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco. “These data should be included in an overall assessment for inclusion of screening for and treating HSIL as standard of care in people living with HIV.”

Dr. Palefsky presented the full results in a special session at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, which drew excitement, gratitude, and relief from both researchers and clinicians, who flocked to the session.

But it’s not just people with HIV who will benefit from this research. Dr. Palefsky suggested that the findings should also be considered as guides for other people at high-risk for anal cancer, such as people who are immunocompromised for other reasons, including those with lupus, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, or cisgender women who have had vulvar or cervical cancer or precancer.

“If we can show efficacy in the most challenging group of all, which are people living with HIV, we think the results can be as good, if not even better, in the other groups at high risk of anal cancer,” Dr. Palefsky said.

But to serve anyone – whether living with HIV or not – infrastructure, algorithms, and workforce training are going be needed to meet the currently unserved people through use of high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) and other screening technology, he said.

Dr. Palefsy and colleagues screened 10,723 people living with HIV being served at 15 clinics nationwide. More than half, 52.2%, had anal HSIL – 53.3% of the cisgender men living with HIV in the trial, 45.8% of the cis women living with HIV, and a full 62.5% of transgender participants.

Those 4,446 participants were split evenly between the treatment arm and the control arm. Those in the treatment arm received treatment for HSIL on their first study visit via one of five options: hyfrecation, office-based electrocautery ablation, infrared coagulation, topical 5-fluorouracil cream, or topical imiquimod. Then, every 6 months after that, they came in for HRA, blood tests, anal Pap smears, and biopsies to check for any lingering or new HSIL. If clinicians found such cells, they received treatment again. If biopsies still showed HSIL and clinician and participant were worried about cancer, they could come in as frequently as every 3 months and receive treatment each time.

The active-monitoring control group still received an anal Pap smear, blood tests, biopsy, and HRA every 6 months – a level of care that is currently not mandated anywhere for people living with HIV, Dr. Palefsky said in an interview. They were also able to come in for more frequent monitoring (every 3 months) if clinicians were worried about cancer.

“Those in both arms would have been getting more attention than if they had not participated in the study,” he said.

In addition, during screening, researchers found that cancer was already present in 17 other people, who skipped the study to go right to treatment.

Participants reflected the demographics of the HIV epidemic in the United States. They were older (median age, 51 years), mostly gay (78%), and cisgender male (80%). Close to half, 42%, were Black, and 16% were Latinx. In addition, cisgender women made up 16% of the participants and transgender people, and nonbinary individuals accounted for more than 3% of the participants. In addition, one in three smoked.

The vast majority of participants had well-controlled HIV and healthy immune systems, though half in each arm had a history of AIDS, defined as lowest-ever CD4 immune cell counts below 200. Today, more than 80% of participants had undetectable viral loads, defined as a viral load less than 50 copies/mL, and another 7% had HIV viral loads below 200. In total, 9.3% in the treatment arm and 10.9% in the control arm had HIV viral loads higher than that. At time of enrollment, CD4 counts were above 600 in each group, indicating healthy immune systems.

Although all participants were there because they had anal HSIL, more than 1 in 10 – 13% – had abnormal cells so extensive that they covered more than half of the anal canal or the perianal region.

Once everyone was enrolled, researchers began monitoring and treatment, looking specifically for 31 cases of cancer – a number the team had determined that they’d need in order to draw any conclusions. Dr. Palefsky didn’t have to wait long. They were still trying to enroll the last 1,000 participants to have the power necessary to reach that number when the cancer diagnoses came in.

Dr. Palefsky told this news organization that the reason for that is unclear. It could be that some of those cases would have resolved on their own, and so the swiftness with which they reached the required number of cancer cases belies their seriousness. It could also be that the particular people who enrolled in this trial were engaging in behaviors that put them at even higher risk for anal cancer than the population of people living with HIV in the United States.

Or it could be that symptom-based screening is missing a lot of cancers that currently go untreated.

“So perhaps we will be seeing an increase in anal cancer reported in the future compared to the currently reported rates,” he said. “We don’t really know.”

Regardless of the reason for the speed to cases of cancer, the results were definitive: Nine participants were diagnosed with invasive anal cancer in the treatment arm, while 21 were diagnosed with invasive anal cancer in the control arm. That’s a 57% reduction in cancer occurrence between the arms. Or, to put it another way, the rate of anal cancer among people in the treatment arm was 173 per 100,000 people-years. In the active monitoring arm, it was 402 per 100,000 person-years. For context, the overall rate of anal cancer among people living with HIV is 50 per 100,000 person-years. The rate in the general U.S. population is 8 per 100,000 people-years.

The experimental treatment was such a definitive success that the investigators stopped the trial and shifted all participants in the control arm to treatment.

‘We have to build’

Before Dr. Palefsky was even done presenting the data, clinicians, people living with HIV, and experts at the session were already brainstorming as to how to get these results into practice.

“These data are what we have long needed to fuel some action on this important problem, including medical cost reimbursement through insurance and increasing the number of persons trained and capable in anal cancer screening,” John Brooks, MD, head of the epidemiology research team at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of HIV/AIDS prevention, wrote in the virtual chat.

Jeff Taylor, a member of the ANCHOR advisory board and a person living with HIV who participated in one of the first azidothymidine trials in the late 1980s, responded quickly.

“What kind of advocacy from researchers, HIV clinicians and [people living with HIV] is needed to get this on treatment guidelines, HRA providers trained and certified, and payors to cover this so [people living with HIV] actually have access to lifesaving screening and [treatment]?” Mr. Taylor asked.

It’s a serious challenge. David Malebranche, MD, an Atlanta-based internal medicine physician who specializes in sexual health and HIV, commented in an interview. When he saw the initial press release last year on the ANCHOR findings, his first reaction was: “Thank god. We finally have some data to show what we’ve been trying to get people to do” all along.

But then he wondered, who is going to perform these tests? It’s a fair question. Currently, the wait for an HRA is 6-12 months in many parts of the country. And Dr. Malebranche can’t imagine this being added to his already full plate as a primary care provider.

“If you tell a primary care provider now that they have to do a rectal Pap smear, that’s going to be a problem while you’re also asking them to screen each patient for depression, anxiety, domestic abuse, intimate partner violence, all the healthcare maintenance and all the other screening tests – and then you deal with not only the urgent complaint but then all the complex medical issues on top of that – in a 15-minute or 10-minute visit,” he said.

Now that we have these data, he said, “we have to build.”

Dr. Palefsky agreed. Very few centers have enough people skilled at performing HRAs to meet the current demand, and it’s not realistic to expect clinicians to perform an HRA every 6 months like the study team did. There need to be algorithms put in place to help practitioners figure out who among their patients living with HIV could benefit from this increased screening, as well as biomarkers to identify HSIL progression and regression without the use of HRA, Dr. Palefsky told attendees. And more clinicians need to be recruited and trained to read HRAs, which can be difficult for the untrained eye to decipher.

Dr. Malebranche added another, more fundamental thing that needs to be built. Dr. Malebranche has worked in HIV clinics where the majority of his patients qualify for insurance under the Ryan White Program and get their medications through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program. While Ryan White programs can provide critical wraparound care, Dr. Malebranche has had to refer out for something like an HRA or cancer treatment. But the people who only access care through such programs may not have coverage with the clinics that perform HRA or that treat cancer. And that’s if they can even find someone to see them.

“If I live in a state like Georgia, which doesn’t have Medicaid expansion and we have people who are uninsured, where do you send them?” Dr. Malebranche asked. “This isn’t theoretical. I ran into this problem when I was working at the AIDS Healthcare Foundation last year. ... This is a call for infrastructure.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Brooks reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Palefsky has received consultant fees from Merck, Vir Biotechnology, Virion Therapeutics, and Antiva Bioscience, as well as speaker fees from Merck. Dr. Malebranche has received consulting and advising fees from ViiV Healthcare.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Reports based on a press release in October 2021 suggested it, but now the full data tell the story:

“We now show, for the first time, that treatment of anal HSIL is effective in reducing the incidence of anal cancer,” said Joel Palefsky, MD, lead investigator of the Anal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) study and founder/director of the Anal Neoplasia Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco. “These data should be included in an overall assessment for inclusion of screening for and treating HSIL as standard of care in people living with HIV.”

Dr. Palefsky presented the full results in a special session at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, which drew excitement, gratitude, and relief from both researchers and clinicians, who flocked to the session.

But it’s not just people with HIV who will benefit from this research. Dr. Palefsky suggested that the findings should also be considered as guides for other people at high-risk for anal cancer, such as people who are immunocompromised for other reasons, including those with lupus, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, or cisgender women who have had vulvar or cervical cancer or precancer.

“If we can show efficacy in the most challenging group of all, which are people living with HIV, we think the results can be as good, if not even better, in the other groups at high risk of anal cancer,” Dr. Palefsky said.

But to serve anyone – whether living with HIV or not – infrastructure, algorithms, and workforce training are going be needed to meet the currently unserved people through use of high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) and other screening technology, he said.

Dr. Palefsy and colleagues screened 10,723 people living with HIV being served at 15 clinics nationwide. More than half, 52.2%, had anal HSIL – 53.3% of the cisgender men living with HIV in the trial, 45.8% of the cis women living with HIV, and a full 62.5% of transgender participants.

Those 4,446 participants were split evenly between the treatment arm and the control arm. Those in the treatment arm received treatment for HSIL on their first study visit via one of five options: hyfrecation, office-based electrocautery ablation, infrared coagulation, topical 5-fluorouracil cream, or topical imiquimod. Then, every 6 months after that, they came in for HRA, blood tests, anal Pap smears, and biopsies to check for any lingering or new HSIL. If clinicians found such cells, they received treatment again. If biopsies still showed HSIL and clinician and participant were worried about cancer, they could come in as frequently as every 3 months and receive treatment each time.

The active-monitoring control group still received an anal Pap smear, blood tests, biopsy, and HRA every 6 months – a level of care that is currently not mandated anywhere for people living with HIV, Dr. Palefsky said in an interview. They were also able to come in for more frequent monitoring (every 3 months) if clinicians were worried about cancer.

“Those in both arms would have been getting more attention than if they had not participated in the study,” he said.

In addition, during screening, researchers found that cancer was already present in 17 other people, who skipped the study to go right to treatment.

Participants reflected the demographics of the HIV epidemic in the United States. They were older (median age, 51 years), mostly gay (78%), and cisgender male (80%). Close to half, 42%, were Black, and 16% were Latinx. In addition, cisgender women made up 16% of the participants and transgender people, and nonbinary individuals accounted for more than 3% of the participants. In addition, one in three smoked.

The vast majority of participants had well-controlled HIV and healthy immune systems, though half in each arm had a history of AIDS, defined as lowest-ever CD4 immune cell counts below 200. Today, more than 80% of participants had undetectable viral loads, defined as a viral load less than 50 copies/mL, and another 7% had HIV viral loads below 200. In total, 9.3% in the treatment arm and 10.9% in the control arm had HIV viral loads higher than that. At time of enrollment, CD4 counts were above 600 in each group, indicating healthy immune systems.

Although all participants were there because they had anal HSIL, more than 1 in 10 – 13% – had abnormal cells so extensive that they covered more than half of the anal canal or the perianal region.

Once everyone was enrolled, researchers began monitoring and treatment, looking specifically for 31 cases of cancer – a number the team had determined that they’d need in order to draw any conclusions. Dr. Palefsky didn’t have to wait long. They were still trying to enroll the last 1,000 participants to have the power necessary to reach that number when the cancer diagnoses came in.

Dr. Palefsky told this news organization that the reason for that is unclear. It could be that some of those cases would have resolved on their own, and so the swiftness with which they reached the required number of cancer cases belies their seriousness. It could also be that the particular people who enrolled in this trial were engaging in behaviors that put them at even higher risk for anal cancer than the population of people living with HIV in the United States.

Or it could be that symptom-based screening is missing a lot of cancers that currently go untreated.

“So perhaps we will be seeing an increase in anal cancer reported in the future compared to the currently reported rates,” he said. “We don’t really know.”

Regardless of the reason for the speed to cases of cancer, the results were definitive: Nine participants were diagnosed with invasive anal cancer in the treatment arm, while 21 were diagnosed with invasive anal cancer in the control arm. That’s a 57% reduction in cancer occurrence between the arms. Or, to put it another way, the rate of anal cancer among people in the treatment arm was 173 per 100,000 people-years. In the active monitoring arm, it was 402 per 100,000 person-years. For context, the overall rate of anal cancer among people living with HIV is 50 per 100,000 person-years. The rate in the general U.S. population is 8 per 100,000 people-years.

The experimental treatment was such a definitive success that the investigators stopped the trial and shifted all participants in the control arm to treatment.

‘We have to build’

Before Dr. Palefsky was even done presenting the data, clinicians, people living with HIV, and experts at the session were already brainstorming as to how to get these results into practice.

“These data are what we have long needed to fuel some action on this important problem, including medical cost reimbursement through insurance and increasing the number of persons trained and capable in anal cancer screening,” John Brooks, MD, head of the epidemiology research team at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of HIV/AIDS prevention, wrote in the virtual chat.

Jeff Taylor, a member of the ANCHOR advisory board and a person living with HIV who participated in one of the first azidothymidine trials in the late 1980s, responded quickly.

“What kind of advocacy from researchers, HIV clinicians and [people living with HIV] is needed to get this on treatment guidelines, HRA providers trained and certified, and payors to cover this so [people living with HIV] actually have access to lifesaving screening and [treatment]?” Mr. Taylor asked.

It’s a serious challenge. David Malebranche, MD, an Atlanta-based internal medicine physician who specializes in sexual health and HIV, commented in an interview. When he saw the initial press release last year on the ANCHOR findings, his first reaction was: “Thank god. We finally have some data to show what we’ve been trying to get people to do” all along.

But then he wondered, who is going to perform these tests? It’s a fair question. Currently, the wait for an HRA is 6-12 months in many parts of the country. And Dr. Malebranche can’t imagine this being added to his already full plate as a primary care provider.

“If you tell a primary care provider now that they have to do a rectal Pap smear, that’s going to be a problem while you’re also asking them to screen each patient for depression, anxiety, domestic abuse, intimate partner violence, all the healthcare maintenance and all the other screening tests – and then you deal with not only the urgent complaint but then all the complex medical issues on top of that – in a 15-minute or 10-minute visit,” he said.

Now that we have these data, he said, “we have to build.”

Dr. Palefsky agreed. Very few centers have enough people skilled at performing HRAs to meet the current demand, and it’s not realistic to expect clinicians to perform an HRA every 6 months like the study team did. There need to be algorithms put in place to help practitioners figure out who among their patients living with HIV could benefit from this increased screening, as well as biomarkers to identify HSIL progression and regression without the use of HRA, Dr. Palefsky told attendees. And more clinicians need to be recruited and trained to read HRAs, which can be difficult for the untrained eye to decipher.

Dr. Malebranche added another, more fundamental thing that needs to be built. Dr. Malebranche has worked in HIV clinics where the majority of his patients qualify for insurance under the Ryan White Program and get their medications through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program. While Ryan White programs can provide critical wraparound care, Dr. Malebranche has had to refer out for something like an HRA or cancer treatment. But the people who only access care through such programs may not have coverage with the clinics that perform HRA or that treat cancer. And that’s if they can even find someone to see them.

“If I live in a state like Georgia, which doesn’t have Medicaid expansion and we have people who are uninsured, where do you send them?” Dr. Malebranche asked. “This isn’t theoretical. I ran into this problem when I was working at the AIDS Healthcare Foundation last year. ... This is a call for infrastructure.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Brooks reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Palefsky has received consultant fees from Merck, Vir Biotechnology, Virion Therapeutics, and Antiva Bioscience, as well as speaker fees from Merck. Dr. Malebranche has received consulting and advising fees from ViiV Healthcare.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Reports based on a press release in October 2021 suggested it, but now the full data tell the story:

“We now show, for the first time, that treatment of anal HSIL is effective in reducing the incidence of anal cancer,” said Joel Palefsky, MD, lead investigator of the Anal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) study and founder/director of the Anal Neoplasia Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco. “These data should be included in an overall assessment for inclusion of screening for and treating HSIL as standard of care in people living with HIV.”

Dr. Palefsky presented the full results in a special session at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, which drew excitement, gratitude, and relief from both researchers and clinicians, who flocked to the session.

But it’s not just people with HIV who will benefit from this research. Dr. Palefsky suggested that the findings should also be considered as guides for other people at high-risk for anal cancer, such as people who are immunocompromised for other reasons, including those with lupus, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, or cisgender women who have had vulvar or cervical cancer or precancer.

“If we can show efficacy in the most challenging group of all, which are people living with HIV, we think the results can be as good, if not even better, in the other groups at high risk of anal cancer,” Dr. Palefsky said.

But to serve anyone – whether living with HIV or not – infrastructure, algorithms, and workforce training are going be needed to meet the currently unserved people through use of high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) and other screening technology, he said.

Dr. Palefsy and colleagues screened 10,723 people living with HIV being served at 15 clinics nationwide. More than half, 52.2%, had anal HSIL – 53.3% of the cisgender men living with HIV in the trial, 45.8% of the cis women living with HIV, and a full 62.5% of transgender participants.

Those 4,446 participants were split evenly between the treatment arm and the control arm. Those in the treatment arm received treatment for HSIL on their first study visit via one of five options: hyfrecation, office-based electrocautery ablation, infrared coagulation, topical 5-fluorouracil cream, or topical imiquimod. Then, every 6 months after that, they came in for HRA, blood tests, anal Pap smears, and biopsies to check for any lingering or new HSIL. If clinicians found such cells, they received treatment again. If biopsies still showed HSIL and clinician and participant were worried about cancer, they could come in as frequently as every 3 months and receive treatment each time.

The active-monitoring control group still received an anal Pap smear, blood tests, biopsy, and HRA every 6 months – a level of care that is currently not mandated anywhere for people living with HIV, Dr. Palefsky said in an interview. They were also able to come in for more frequent monitoring (every 3 months) if clinicians were worried about cancer.

“Those in both arms would have been getting more attention than if they had not participated in the study,” he said.

In addition, during screening, researchers found that cancer was already present in 17 other people, who skipped the study to go right to treatment.

Participants reflected the demographics of the HIV epidemic in the United States. They were older (median age, 51 years), mostly gay (78%), and cisgender male (80%). Close to half, 42%, were Black, and 16% were Latinx. In addition, cisgender women made up 16% of the participants and transgender people, and nonbinary individuals accounted for more than 3% of the participants. In addition, one in three smoked.

The vast majority of participants had well-controlled HIV and healthy immune systems, though half in each arm had a history of AIDS, defined as lowest-ever CD4 immune cell counts below 200. Today, more than 80% of participants had undetectable viral loads, defined as a viral load less than 50 copies/mL, and another 7% had HIV viral loads below 200. In total, 9.3% in the treatment arm and 10.9% in the control arm had HIV viral loads higher than that. At time of enrollment, CD4 counts were above 600 in each group, indicating healthy immune systems.

Although all participants were there because they had anal HSIL, more than 1 in 10 – 13% – had abnormal cells so extensive that they covered more than half of the anal canal or the perianal region.

Once everyone was enrolled, researchers began monitoring and treatment, looking specifically for 31 cases of cancer – a number the team had determined that they’d need in order to draw any conclusions. Dr. Palefsky didn’t have to wait long. They were still trying to enroll the last 1,000 participants to have the power necessary to reach that number when the cancer diagnoses came in.

Dr. Palefsky told this news organization that the reason for that is unclear. It could be that some of those cases would have resolved on their own, and so the swiftness with which they reached the required number of cancer cases belies their seriousness. It could also be that the particular people who enrolled in this trial were engaging in behaviors that put them at even higher risk for anal cancer than the population of people living with HIV in the United States.