User login

Azithromycin doesn’t prevent recurrent wheezing after acute infant RSV

Azithromycin administered for severe early-life respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis did not prevent recurrent wheezing in affected children over the next 2-4 years, a randomized, single-center study found.

Antibiotics are frequently given to patients with RSV bronchiolitis, although this practice is not supported by American Academy of Pediatrics clinical guidelines. Many doctors will prescribe them anyway if they see redness in the ears or other signs of infection, lead author Avraham Beigelman, MD, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis, said in an interview.

The double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, presented at the 2022 meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology in Phoenix, was simultaneously published online Feb. 27, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine–Evidence.

Since azithromycin has shown anti-inflammatory benefit in chronic lung diseases and is a mainstay of care in cystic fibrosis and had shown previous effects in RSV patients, this trial examined its potential for preventing future recurrent wheezing in infants hospitalized with RSV who are at risk for developing asthma later. About half of children admitted to the hospital for RSV will develop asthma by age 7, Dr. Beigelman said.

“We were very surprised that azithromycin didn’t help in this trial given our previous findings,” Dr. Beigelman said.

And while those given azithromycin versus those given a placebo showed no significant decrease in recurrent wheezing, there was a slight suggestion that treatment with antibiotics of any kind may increase the risk of later wheezing in infants hospitalized with the virus.

“The study was not designed to tease at the effects of different antibiotics or combinations of antibiotics, so we have to be very cautious about this trend,” Dr. Beigelman said. “There may be short-term effects and long-term effects. Certain antibiotics may affect the infant microbiome in other parts of the body, such as the gut, [in] a way that may predispose to asthma. But all these associations suggest that early-life antibiotics for viral infections are not good for you.”

He pointed to the longstanding question among clinicians whether it is the antibiotic that’s increasing the risk of the harm or the condition for which the antibiotic is prescribed. These exploratory data, however, suggest that antibiotics for RSV may be causing harm.

In pursuit of that hypothesis, his group has collected airway microbiome samples from these infants and plan to investigate whether bacteria colonizing the airway may interact with the antibiotics to increase wheezing. The researchers will analyze stool samples from the babies to see whether the gut microbiome may also play a role in wheezing and the subsequent risk of developing childhood asthma.

Study details

The trial prospectively enrolled 200 otherwise healthy babies aged 1-18 months who were hospitalized at St. Louis Children’s Hospital for acute RSV bronchiolitis. Although RSV is a very common pediatric virus, only bout 3% of babies will require hospitalization in order to receive oxygen, Dr. Beigelman said.

Babies were randomly assigned to receive placebo or oral azithromycin at 10 mg/kg daily for 7 days, followed by 5 mg/kg daily for 7 days. Randomization was stratified by recent open-label antibiotic use. The primary outcome was recurrent wheeze, defined as a third episode of post-RSV wheeze over the following 2-4 years.

The biologic activity of azithromycin was clear since nasal-wash interleukin at day 14 after randomization was lower in azithromycin-treated infants. But despite evidence of activity, the risk of post-RSV recurrent wheeze was similar in both arms: 47% in the azithromycin group versus 36% in the placebo group, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-2.29; P = .11).

Nor did azithromycin lower the risk of recurrent wheeze in babies already receiving other antibiotics at the time of enrollment (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.43-2.07). As for antibiotic-naive participants receiving azithromycin, there was a slight signal of potential increased risk of developing recurrent wheezing (HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.03-3.1).

The bottom line? The findings support current clinical guidelines recommending against the use of antibiotics for RSV. “At the very least, azithromycin and antibiotics in general have no benefit in preventing recurrent wheeze, and there is a possibility they may be harmful,” Dr. Beigelman said.

This trial is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Beigelman reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Sanofi. Two study coauthors disclosed various ties to industry.

Azithromycin administered for severe early-life respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis did not prevent recurrent wheezing in affected children over the next 2-4 years, a randomized, single-center study found.

Antibiotics are frequently given to patients with RSV bronchiolitis, although this practice is not supported by American Academy of Pediatrics clinical guidelines. Many doctors will prescribe them anyway if they see redness in the ears or other signs of infection, lead author Avraham Beigelman, MD, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis, said in an interview.

The double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, presented at the 2022 meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology in Phoenix, was simultaneously published online Feb. 27, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine–Evidence.

Since azithromycin has shown anti-inflammatory benefit in chronic lung diseases and is a mainstay of care in cystic fibrosis and had shown previous effects in RSV patients, this trial examined its potential for preventing future recurrent wheezing in infants hospitalized with RSV who are at risk for developing asthma later. About half of children admitted to the hospital for RSV will develop asthma by age 7, Dr. Beigelman said.

“We were very surprised that azithromycin didn’t help in this trial given our previous findings,” Dr. Beigelman said.

And while those given azithromycin versus those given a placebo showed no significant decrease in recurrent wheezing, there was a slight suggestion that treatment with antibiotics of any kind may increase the risk of later wheezing in infants hospitalized with the virus.

“The study was not designed to tease at the effects of different antibiotics or combinations of antibiotics, so we have to be very cautious about this trend,” Dr. Beigelman said. “There may be short-term effects and long-term effects. Certain antibiotics may affect the infant microbiome in other parts of the body, such as the gut, [in] a way that may predispose to asthma. But all these associations suggest that early-life antibiotics for viral infections are not good for you.”

He pointed to the longstanding question among clinicians whether it is the antibiotic that’s increasing the risk of the harm or the condition for which the antibiotic is prescribed. These exploratory data, however, suggest that antibiotics for RSV may be causing harm.

In pursuit of that hypothesis, his group has collected airway microbiome samples from these infants and plan to investigate whether bacteria colonizing the airway may interact with the antibiotics to increase wheezing. The researchers will analyze stool samples from the babies to see whether the gut microbiome may also play a role in wheezing and the subsequent risk of developing childhood asthma.

Study details

The trial prospectively enrolled 200 otherwise healthy babies aged 1-18 months who were hospitalized at St. Louis Children’s Hospital for acute RSV bronchiolitis. Although RSV is a very common pediatric virus, only bout 3% of babies will require hospitalization in order to receive oxygen, Dr. Beigelman said.

Babies were randomly assigned to receive placebo or oral azithromycin at 10 mg/kg daily for 7 days, followed by 5 mg/kg daily for 7 days. Randomization was stratified by recent open-label antibiotic use. The primary outcome was recurrent wheeze, defined as a third episode of post-RSV wheeze over the following 2-4 years.

The biologic activity of azithromycin was clear since nasal-wash interleukin at day 14 after randomization was lower in azithromycin-treated infants. But despite evidence of activity, the risk of post-RSV recurrent wheeze was similar in both arms: 47% in the azithromycin group versus 36% in the placebo group, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-2.29; P = .11).

Nor did azithromycin lower the risk of recurrent wheeze in babies already receiving other antibiotics at the time of enrollment (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.43-2.07). As for antibiotic-naive participants receiving azithromycin, there was a slight signal of potential increased risk of developing recurrent wheezing (HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.03-3.1).

The bottom line? The findings support current clinical guidelines recommending against the use of antibiotics for RSV. “At the very least, azithromycin and antibiotics in general have no benefit in preventing recurrent wheeze, and there is a possibility they may be harmful,” Dr. Beigelman said.

This trial is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Beigelman reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Sanofi. Two study coauthors disclosed various ties to industry.

Azithromycin administered for severe early-life respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis did not prevent recurrent wheezing in affected children over the next 2-4 years, a randomized, single-center study found.

Antibiotics are frequently given to patients with RSV bronchiolitis, although this practice is not supported by American Academy of Pediatrics clinical guidelines. Many doctors will prescribe them anyway if they see redness in the ears or other signs of infection, lead author Avraham Beigelman, MD, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis, said in an interview.

The double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, presented at the 2022 meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology in Phoenix, was simultaneously published online Feb. 27, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine–Evidence.

Since azithromycin has shown anti-inflammatory benefit in chronic lung diseases and is a mainstay of care in cystic fibrosis and had shown previous effects in RSV patients, this trial examined its potential for preventing future recurrent wheezing in infants hospitalized with RSV who are at risk for developing asthma later. About half of children admitted to the hospital for RSV will develop asthma by age 7, Dr. Beigelman said.

“We were very surprised that azithromycin didn’t help in this trial given our previous findings,” Dr. Beigelman said.

And while those given azithromycin versus those given a placebo showed no significant decrease in recurrent wheezing, there was a slight suggestion that treatment with antibiotics of any kind may increase the risk of later wheezing in infants hospitalized with the virus.

“The study was not designed to tease at the effects of different antibiotics or combinations of antibiotics, so we have to be very cautious about this trend,” Dr. Beigelman said. “There may be short-term effects and long-term effects. Certain antibiotics may affect the infant microbiome in other parts of the body, such as the gut, [in] a way that may predispose to asthma. But all these associations suggest that early-life antibiotics for viral infections are not good for you.”

He pointed to the longstanding question among clinicians whether it is the antibiotic that’s increasing the risk of the harm or the condition for which the antibiotic is prescribed. These exploratory data, however, suggest that antibiotics for RSV may be causing harm.

In pursuit of that hypothesis, his group has collected airway microbiome samples from these infants and plan to investigate whether bacteria colonizing the airway may interact with the antibiotics to increase wheezing. The researchers will analyze stool samples from the babies to see whether the gut microbiome may also play a role in wheezing and the subsequent risk of developing childhood asthma.

Study details

The trial prospectively enrolled 200 otherwise healthy babies aged 1-18 months who were hospitalized at St. Louis Children’s Hospital for acute RSV bronchiolitis. Although RSV is a very common pediatric virus, only bout 3% of babies will require hospitalization in order to receive oxygen, Dr. Beigelman said.

Babies were randomly assigned to receive placebo or oral azithromycin at 10 mg/kg daily for 7 days, followed by 5 mg/kg daily for 7 days. Randomization was stratified by recent open-label antibiotic use. The primary outcome was recurrent wheeze, defined as a third episode of post-RSV wheeze over the following 2-4 years.

The biologic activity of azithromycin was clear since nasal-wash interleukin at day 14 after randomization was lower in azithromycin-treated infants. But despite evidence of activity, the risk of post-RSV recurrent wheeze was similar in both arms: 47% in the azithromycin group versus 36% in the placebo group, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-2.29; P = .11).

Nor did azithromycin lower the risk of recurrent wheeze in babies already receiving other antibiotics at the time of enrollment (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.43-2.07). As for antibiotic-naive participants receiving azithromycin, there was a slight signal of potential increased risk of developing recurrent wheezing (HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.03-3.1).

The bottom line? The findings support current clinical guidelines recommending against the use of antibiotics for RSV. “At the very least, azithromycin and antibiotics in general have no benefit in preventing recurrent wheeze, and there is a possibility they may be harmful,” Dr. Beigelman said.

This trial is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Beigelman reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Sanofi. Two study coauthors disclosed various ties to industry.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE–EVIDENCE

Some physicians still lack access to COVID-19 vaccines

It would be overused and trite to say that the pandemic has drastically altered all of our lives and will cause lasting impact on how we function in society and medicine for years to come. While it seems that the current trend of the latest Omicron variant is on the downslope, the path to get to this point has been fraught with challenges that have struck at the very core of our society. As a primary care physician on the front lines seeing COVID patients, I have had to deal with not only the disease but the politics around it. I practice in Florida, and I still cannot give COVID vaccines in my office.

I am a firm believer in the ability for physicians to be able to give all the necessary adult vaccines and provide them for their patients. The COVID vaccine exacerbated a majorly flawed system that further increased the health care disparities in the country. The current vaccine system for the majority of adult vaccines involves the physician’s being able to directly purchase supplies from the vaccine manufacturer, administer them to the patients, and be reimbursed.

Third parties can purchase vaccines at lower rates than those for physicians

The Affordable Care Act mandates that all vaccines approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must be covered. This allows for better access to care as physicians will be able to purchase, store, and deliver vaccines to their patients. The fallacy in this system is that third parties get involved and rebates or incentives are given to these groups to purchase vaccines at a rate lower than those for physicians.

In addition, many organizations can get access to vaccines before physicians and at a lower cost. That system was flawed to begin with and created a deterrent for access to care and physician involvement in the vaccination process. This was worsened by different states being given the ability to decide how vaccines would be distributed for COVID.

Many pharmacies were able to give out COVID vaccines while many physician offices still have not received access to any of the vaccines. One of the major safety issues with this is that no physicians were involved in the administration of the vaccine, and it is unclear what training was given to the individuals injecting that vaccine. Finally, different places were interpreting the recommendations from ACIP on their own and not necessarily following the appropriate guidelines. All of these factors have further widened the health care disparity gap and made it difficult to provide the COVID vaccines in doctors’ offices.

Recommended next steps, solutions to problem

The question is what to do about this. The most important thing is to get the vaccines in arms so they can save lives. In addition, doctors need to be able to get the vaccines in their offices.

Many patients trust their physicians to advise them on what to do regarding health care. The majority of patients want to know if they should get the vaccine and ask for counseling. Physicians answering patients’ questions about vaccines is an important step in overcoming vaccine hesitancy.

Also, doctors need to be informed and supportive of the vaccine process.

The next step is the governmental aspect with those in power making sure that vaccines are accessible to all. Even if the vaccine cannot be given in the office, doctors should still be recommending that patients receive them. Plus, doctors should take every opportunity to ask about what vaccines their patients have received and encourage their patients to get vaccinated.

The COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective and have been monitored for safety more than any other vaccine. There are multiple systems in place to look for any signals that could indicate an issue was caused by a COVID-19 vaccine. These vaccines can be administered with other vaccines, and there is a great opportunity for physicians to encourage patients to receive these life-saving vaccines.

While it may seem that the COVID-19 case counts are on the downslope, the importance of continuing to vaccinate is predicated on the very real concern that the disease is still circulating and the unvaccinated are still at risk for severe infection.

Dr. Goldman is immediate past governor of the Florida chapter of the American College of Physicians, a regent for the American College of Physicians, vice-president of the Florida Medical Association, and president of the Florida Medical Association Political Action Committee. You can reach Dr. Goldman at [email protected].

It would be overused and trite to say that the pandemic has drastically altered all of our lives and will cause lasting impact on how we function in society and medicine for years to come. While it seems that the current trend of the latest Omicron variant is on the downslope, the path to get to this point has been fraught with challenges that have struck at the very core of our society. As a primary care physician on the front lines seeing COVID patients, I have had to deal with not only the disease but the politics around it. I practice in Florida, and I still cannot give COVID vaccines in my office.

I am a firm believer in the ability for physicians to be able to give all the necessary adult vaccines and provide them for their patients. The COVID vaccine exacerbated a majorly flawed system that further increased the health care disparities in the country. The current vaccine system for the majority of adult vaccines involves the physician’s being able to directly purchase supplies from the vaccine manufacturer, administer them to the patients, and be reimbursed.

Third parties can purchase vaccines at lower rates than those for physicians

The Affordable Care Act mandates that all vaccines approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must be covered. This allows for better access to care as physicians will be able to purchase, store, and deliver vaccines to their patients. The fallacy in this system is that third parties get involved and rebates or incentives are given to these groups to purchase vaccines at a rate lower than those for physicians.

In addition, many organizations can get access to vaccines before physicians and at a lower cost. That system was flawed to begin with and created a deterrent for access to care and physician involvement in the vaccination process. This was worsened by different states being given the ability to decide how vaccines would be distributed for COVID.

Many pharmacies were able to give out COVID vaccines while many physician offices still have not received access to any of the vaccines. One of the major safety issues with this is that no physicians were involved in the administration of the vaccine, and it is unclear what training was given to the individuals injecting that vaccine. Finally, different places were interpreting the recommendations from ACIP on their own and not necessarily following the appropriate guidelines. All of these factors have further widened the health care disparity gap and made it difficult to provide the COVID vaccines in doctors’ offices.

Recommended next steps, solutions to problem

The question is what to do about this. The most important thing is to get the vaccines in arms so they can save lives. In addition, doctors need to be able to get the vaccines in their offices.

Many patients trust their physicians to advise them on what to do regarding health care. The majority of patients want to know if they should get the vaccine and ask for counseling. Physicians answering patients’ questions about vaccines is an important step in overcoming vaccine hesitancy.

Also, doctors need to be informed and supportive of the vaccine process.

The next step is the governmental aspect with those in power making sure that vaccines are accessible to all. Even if the vaccine cannot be given in the office, doctors should still be recommending that patients receive them. Plus, doctors should take every opportunity to ask about what vaccines their patients have received and encourage their patients to get vaccinated.

The COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective and have been monitored for safety more than any other vaccine. There are multiple systems in place to look for any signals that could indicate an issue was caused by a COVID-19 vaccine. These vaccines can be administered with other vaccines, and there is a great opportunity for physicians to encourage patients to receive these life-saving vaccines.

While it may seem that the COVID-19 case counts are on the downslope, the importance of continuing to vaccinate is predicated on the very real concern that the disease is still circulating and the unvaccinated are still at risk for severe infection.

Dr. Goldman is immediate past governor of the Florida chapter of the American College of Physicians, a regent for the American College of Physicians, vice-president of the Florida Medical Association, and president of the Florida Medical Association Political Action Committee. You can reach Dr. Goldman at [email protected].

It would be overused and trite to say that the pandemic has drastically altered all of our lives and will cause lasting impact on how we function in society and medicine for years to come. While it seems that the current trend of the latest Omicron variant is on the downslope, the path to get to this point has been fraught with challenges that have struck at the very core of our society. As a primary care physician on the front lines seeing COVID patients, I have had to deal with not only the disease but the politics around it. I practice in Florida, and I still cannot give COVID vaccines in my office.

I am a firm believer in the ability for physicians to be able to give all the necessary adult vaccines and provide them for their patients. The COVID vaccine exacerbated a majorly flawed system that further increased the health care disparities in the country. The current vaccine system for the majority of adult vaccines involves the physician’s being able to directly purchase supplies from the vaccine manufacturer, administer them to the patients, and be reimbursed.

Third parties can purchase vaccines at lower rates than those for physicians

The Affordable Care Act mandates that all vaccines approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must be covered. This allows for better access to care as physicians will be able to purchase, store, and deliver vaccines to their patients. The fallacy in this system is that third parties get involved and rebates or incentives are given to these groups to purchase vaccines at a rate lower than those for physicians.

In addition, many organizations can get access to vaccines before physicians and at a lower cost. That system was flawed to begin with and created a deterrent for access to care and physician involvement in the vaccination process. This was worsened by different states being given the ability to decide how vaccines would be distributed for COVID.

Many pharmacies were able to give out COVID vaccines while many physician offices still have not received access to any of the vaccines. One of the major safety issues with this is that no physicians were involved in the administration of the vaccine, and it is unclear what training was given to the individuals injecting that vaccine. Finally, different places were interpreting the recommendations from ACIP on their own and not necessarily following the appropriate guidelines. All of these factors have further widened the health care disparity gap and made it difficult to provide the COVID vaccines in doctors’ offices.

Recommended next steps, solutions to problem

The question is what to do about this. The most important thing is to get the vaccines in arms so they can save lives. In addition, doctors need to be able to get the vaccines in their offices.

Many patients trust their physicians to advise them on what to do regarding health care. The majority of patients want to know if they should get the vaccine and ask for counseling. Physicians answering patients’ questions about vaccines is an important step in overcoming vaccine hesitancy.

Also, doctors need to be informed and supportive of the vaccine process.

The next step is the governmental aspect with those in power making sure that vaccines are accessible to all. Even if the vaccine cannot be given in the office, doctors should still be recommending that patients receive them. Plus, doctors should take every opportunity to ask about what vaccines their patients have received and encourage their patients to get vaccinated.

The COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective and have been monitored for safety more than any other vaccine. There are multiple systems in place to look for any signals that could indicate an issue was caused by a COVID-19 vaccine. These vaccines can be administered with other vaccines, and there is a great opportunity for physicians to encourage patients to receive these life-saving vaccines.

While it may seem that the COVID-19 case counts are on the downslope, the importance of continuing to vaccinate is predicated on the very real concern that the disease is still circulating and the unvaccinated are still at risk for severe infection.

Dr. Goldman is immediate past governor of the Florida chapter of the American College of Physicians, a regent for the American College of Physicians, vice-president of the Florida Medical Association, and president of the Florida Medical Association Political Action Committee. You can reach Dr. Goldman at [email protected].

GI involvement may signal risk for MIS-C after COVID

While evaluating an adolescent who had endured a several-day history of vomiting and diarrhea, I mentioned the likelihood of a viral causation, including SARS-CoV-2 infection. His well-informed mother responded, “He has no respiratory symptoms. Does COVID cause GI disease?”

Indeed, not only is the gastrointestinal tract a potential portal of entry of the virus but it may well be the site of mediation of both local and remote injury and thus a harbinger of more severe clinical phenotypes.

As we learn more about the clinical spectrum of COVID, it is becoming increasingly clear that certain features of GI tract involvement may allow us to establish a timeline of the clinical course and perhaps predict the outcome.

The GI tract’s involvement isn’t surprising

The ways in which the GI tract serves as a target organ of SARS-CoV-2 have been postulated in the literature. In part, this is related to the presence of abundant receptors for SARS-CoV-2 cell binding and internalization. The virus uses angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors to enter various cells. These receptors are highly expressed on not only lung cells but also enterocytes. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 receptors allows GI involvement, leading to microscopic mucosal inflammation, increased permeability, and altered intestinal absorption.

The clinical GI manifestations of this include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, which may be the earliest, or sole, symptoms of COVID-19, often noted before the onset of fever or respiratory symptoms. In fact, John Ong, MBBS, and colleagues, in a discussion about patients with primary GI SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptoms, use the term “GI-COVID.”

Clinical course of GI manifestations

After SARS-CoV-2 exposure, adults most commonly present with respiratory symptoms, with GI symptoms reported in 10%-15% of cases. However, the overall incidence of GI involvement during SARS-CoV-2 infection varies according to age, with children more likely than adults to manifest intestinal symptoms.

There are also differences in incidence reported when comparing hospitalized with nonhospitalized individuals. In early reports from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, 11%-43% of hospitalized adult patients manifested GI symptoms. Of note, the presence of GI symptoms was associated with more severe disease and thus predictive of outcomes in those admitted to hospitals.

In a multicenter study that assessed pediatric inpatients with COVID-19, GI manifestations were present in 57% of patients and were the first manifestation in 14%. Adjusted by confounding factors, those with GI symptoms had a higher risk for pediatric intensive care unit admission. Patients admitted to the PICU also had higher serum C-reactive protein and aspartate aminotransferase values.

Emerging data on MIS-C

In previously healthy children and adolescents, the severe, life-threatening complication of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) may present 2-6 weeks after acute infection with SARS-CoV-2. MIS-C appears to be an immune activation syndrome and is presumed to be the delayed immunologic sequelae of mild/asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. This response manifests as hyperinflammation in conjunction with a peak in antibody production a few weeks later.

One report of 186 children with MIS-C in the United States noted that the involved organ system included the GI tract in 92%, followed by cardiovascular in 80%, hematologic in 76%, mucocutaneous in 74%, and respiratory in 70%. Affected children were hospitalized for a median of 7 days, with 80% requiring intensive care, 20% receiving mechanical ventilation, and 48% receiving vasoactive support; 2% died. In a similar study of patients hospitalized in New York, 88% had GI symptoms (abdominal pain, vomiting, and/or diarrhea). A retrospective chart review of patients with MIS-C found that the majority had GI symptoms with any portion of the GI tract potentially involved, but ileal and colonic inflammation predominated.

Elizabeth Whittaker, MD, and colleagues described the clinical characteristics of children in eight hospitals in England who met criteria for MIS-C that were temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. At presentation, all of the patients manifested fever and nonspecific GI symptoms, including vomiting (45%), abdominal pain (53%), and diarrhea (52%). During hospitalization, 50% developed shock with evidence of myocardial dysfunction.

Ermias D. Belay, MD, and colleagues described the clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with MIS-C that were reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of 1,733 patients identified, GI symptoms were reported in 53%-67%. Over half developed hypotension or shock and were admitted for intensive care. Younger children more frequently presented with abdominal pain in contrast with adolescents, who more frequently manifest respiratory symptoms.

In a multicenter retrospective study of Italian children with COVID-19 that was conducted from the onset of the pandemic to early 2021, GI symptoms were noted in 38%. These manifestations were mild and self-limiting, comparable to other viral intestinal infections. However, a subset of children (9.5%) had severe GI manifestations of MIS-C, defined as a medical and/or radiologic diagnosis of acute abdomen, appendicitis, intussusception, pancreatitis, abdominal fluid collection, or diffuse adenomesenteritis requiring surgical consultation. Overall, 42% of this group underwent surgery. The authors noted that the clinical presentation of abdominal pain, lymphopenia, and increased C-reactive protein and ferritin levels were associated with a 9- to 30-fold increased probability of these severe sequelae. In addition, the severity of the GI manifestations was correlated with age (5-10 years: overall response, 8.33; >10 years: OR, 6.37). Again, the presence of GI symptoms was a harbinger of hospitalization and PICU admission.

Given that GI symptoms are a common presentation of MIS-C, its diagnosis may be delayed as clinicians first consider other GI/viral infections, inflammatory bowel disease, or Kawasaki disease. Prompt identification of GI involvement and awareness of the potential outcomes may guide the management and improve the outcome.

These studies provide a clear picture of the differential presenting features of COVID-19 and MIS-C. Although there may be other environmental/genetic factors that govern the incidence, impact, and manifestations, COVID’s status as an ongoing pandemic gives these observations worldwide relevance. This is evident in a recent report documenting pronounced GI symptoms in African children with COVID-19.

It should be noted, however, that the published data cited here reflect the impact of the initial variants of SARS-CoV-2. The GI binding, effects, and aftermath of infection with the Delta and Omicron variants is not yet known.

Cause and effect, or simply coincidental?

Some insight into MIS-C pathogenesis was provided by Lael M. Yonker, MD, and colleagues in their analysis of biospecimens from 100 children: 19 with MIS-C, 26 with acute COVID-19, and 55 controls. They demonstrated that in children with MIS-C the prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the GI tract led to the release of zonulin, a biomarker of intestinal permeability, with subsequent trafficking of SARS-CoV-2 antigens into the bloodstream, leading to hyperinflammation. They were then able to decrease plasma SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen levels and inflammatory markers, with resulting clinical improvement after administration of larazotide, a zonulin antagonist.

These observations regarding the potential mechanism and triggers of MIS-C may offer biomarkers for early detection and/or strategies for prevention and treatment of MIS-C.

Bottom line

The GI tract is the target of an immune-mediated inflammatory response that is triggered by SARS-CoV-2, with MIS-C being the major manifestation of the resultant high degree of inflammation. These observations will allow an increased awareness of nonrespiratory symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection by clinicians working in emergency departments and primary care settings.

Clues that may enhance the ability of pediatric clinicians to recognize the potential for severe GI involvement include the occurrence of abdominal pain, leukopenia, and elevated inflammatory markers. Their presence should raise suspicion of MIS-C and lead to early evaluation.

Of note, COVID-19 mRNA vaccination is associated with a lower incidence of MIS-C in adolescents. This underscores the importance of COVID vaccination for all eligible children. Yet, we clearly have our work cut out for us. Of 107 children with MIS-C who were hospitalized in France, 31% were adolescents eligible for vaccination; however, none had been fully vaccinated. At the end of 2021, CDC data noted that less than 1% of vaccine-eligible children (12-17 years) were fully vaccinated.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is now authorized for receipt by children aged 5-11 years, the age group that is at highest risk for MIS-C. However, despite the approval of vaccines for these younger children, there is limited access in some parts of the United States at a time of rising incidence.

We look forward to broad availability of pediatric vaccination strategies. In addition, with the intense focus on safe and effective therapeutics for SARS-CoV-2 infection, we hope to soon have strategies to prevent and/or treat the life-threatening manifestations and long-term consequences of MIS-C. For example, the recently reported central role of the gut microbiota in immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection offer the possibility that “microbiota modulation” may both reduce GI injury and enhance vaccine efficacy.

Dr. Balistreri has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

William F. Balistreri, MD, is the Dorothy M.M. Kersten Professor of Pediatrics; director emeritus, Pediatric Liver Care Center; medical director emeritus, liver transplantation; and professor, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, department of pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. He has served as director of the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Cincinnati Children’s for 25 years and frequently covers gastroenterology, liver, and nutrition-related topics for this news organization. Dr Balistreri is currently editor-in-chief of the Journal of Pediatrics, having previously served as editor-in-chief of several journals and textbooks. He also became the first pediatrician to act as president of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. In his spare time, he coaches youth lacrosse.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While evaluating an adolescent who had endured a several-day history of vomiting and diarrhea, I mentioned the likelihood of a viral causation, including SARS-CoV-2 infection. His well-informed mother responded, “He has no respiratory symptoms. Does COVID cause GI disease?”

Indeed, not only is the gastrointestinal tract a potential portal of entry of the virus but it may well be the site of mediation of both local and remote injury and thus a harbinger of more severe clinical phenotypes.

As we learn more about the clinical spectrum of COVID, it is becoming increasingly clear that certain features of GI tract involvement may allow us to establish a timeline of the clinical course and perhaps predict the outcome.

The GI tract’s involvement isn’t surprising

The ways in which the GI tract serves as a target organ of SARS-CoV-2 have been postulated in the literature. In part, this is related to the presence of abundant receptors for SARS-CoV-2 cell binding and internalization. The virus uses angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors to enter various cells. These receptors are highly expressed on not only lung cells but also enterocytes. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 receptors allows GI involvement, leading to microscopic mucosal inflammation, increased permeability, and altered intestinal absorption.

The clinical GI manifestations of this include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, which may be the earliest, or sole, symptoms of COVID-19, often noted before the onset of fever or respiratory symptoms. In fact, John Ong, MBBS, and colleagues, in a discussion about patients with primary GI SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptoms, use the term “GI-COVID.”

Clinical course of GI manifestations

After SARS-CoV-2 exposure, adults most commonly present with respiratory symptoms, with GI symptoms reported in 10%-15% of cases. However, the overall incidence of GI involvement during SARS-CoV-2 infection varies according to age, with children more likely than adults to manifest intestinal symptoms.

There are also differences in incidence reported when comparing hospitalized with nonhospitalized individuals. In early reports from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, 11%-43% of hospitalized adult patients manifested GI symptoms. Of note, the presence of GI symptoms was associated with more severe disease and thus predictive of outcomes in those admitted to hospitals.

In a multicenter study that assessed pediatric inpatients with COVID-19, GI manifestations were present in 57% of patients and were the first manifestation in 14%. Adjusted by confounding factors, those with GI symptoms had a higher risk for pediatric intensive care unit admission. Patients admitted to the PICU also had higher serum C-reactive protein and aspartate aminotransferase values.

Emerging data on MIS-C

In previously healthy children and adolescents, the severe, life-threatening complication of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) may present 2-6 weeks after acute infection with SARS-CoV-2. MIS-C appears to be an immune activation syndrome and is presumed to be the delayed immunologic sequelae of mild/asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. This response manifests as hyperinflammation in conjunction with a peak in antibody production a few weeks later.

One report of 186 children with MIS-C in the United States noted that the involved organ system included the GI tract in 92%, followed by cardiovascular in 80%, hematologic in 76%, mucocutaneous in 74%, and respiratory in 70%. Affected children were hospitalized for a median of 7 days, with 80% requiring intensive care, 20% receiving mechanical ventilation, and 48% receiving vasoactive support; 2% died. In a similar study of patients hospitalized in New York, 88% had GI symptoms (abdominal pain, vomiting, and/or diarrhea). A retrospective chart review of patients with MIS-C found that the majority had GI symptoms with any portion of the GI tract potentially involved, but ileal and colonic inflammation predominated.

Elizabeth Whittaker, MD, and colleagues described the clinical characteristics of children in eight hospitals in England who met criteria for MIS-C that were temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. At presentation, all of the patients manifested fever and nonspecific GI symptoms, including vomiting (45%), abdominal pain (53%), and diarrhea (52%). During hospitalization, 50% developed shock with evidence of myocardial dysfunction.

Ermias D. Belay, MD, and colleagues described the clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with MIS-C that were reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of 1,733 patients identified, GI symptoms were reported in 53%-67%. Over half developed hypotension or shock and were admitted for intensive care. Younger children more frequently presented with abdominal pain in contrast with adolescents, who more frequently manifest respiratory symptoms.

In a multicenter retrospective study of Italian children with COVID-19 that was conducted from the onset of the pandemic to early 2021, GI symptoms were noted in 38%. These manifestations were mild and self-limiting, comparable to other viral intestinal infections. However, a subset of children (9.5%) had severe GI manifestations of MIS-C, defined as a medical and/or radiologic diagnosis of acute abdomen, appendicitis, intussusception, pancreatitis, abdominal fluid collection, or diffuse adenomesenteritis requiring surgical consultation. Overall, 42% of this group underwent surgery. The authors noted that the clinical presentation of abdominal pain, lymphopenia, and increased C-reactive protein and ferritin levels were associated with a 9- to 30-fold increased probability of these severe sequelae. In addition, the severity of the GI manifestations was correlated with age (5-10 years: overall response, 8.33; >10 years: OR, 6.37). Again, the presence of GI symptoms was a harbinger of hospitalization and PICU admission.

Given that GI symptoms are a common presentation of MIS-C, its diagnosis may be delayed as clinicians first consider other GI/viral infections, inflammatory bowel disease, or Kawasaki disease. Prompt identification of GI involvement and awareness of the potential outcomes may guide the management and improve the outcome.

These studies provide a clear picture of the differential presenting features of COVID-19 and MIS-C. Although there may be other environmental/genetic factors that govern the incidence, impact, and manifestations, COVID’s status as an ongoing pandemic gives these observations worldwide relevance. This is evident in a recent report documenting pronounced GI symptoms in African children with COVID-19.

It should be noted, however, that the published data cited here reflect the impact of the initial variants of SARS-CoV-2. The GI binding, effects, and aftermath of infection with the Delta and Omicron variants is not yet known.

Cause and effect, or simply coincidental?

Some insight into MIS-C pathogenesis was provided by Lael M. Yonker, MD, and colleagues in their analysis of biospecimens from 100 children: 19 with MIS-C, 26 with acute COVID-19, and 55 controls. They demonstrated that in children with MIS-C the prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the GI tract led to the release of zonulin, a biomarker of intestinal permeability, with subsequent trafficking of SARS-CoV-2 antigens into the bloodstream, leading to hyperinflammation. They were then able to decrease plasma SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen levels and inflammatory markers, with resulting clinical improvement after administration of larazotide, a zonulin antagonist.

These observations regarding the potential mechanism and triggers of MIS-C may offer biomarkers for early detection and/or strategies for prevention and treatment of MIS-C.

Bottom line

The GI tract is the target of an immune-mediated inflammatory response that is triggered by SARS-CoV-2, with MIS-C being the major manifestation of the resultant high degree of inflammation. These observations will allow an increased awareness of nonrespiratory symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection by clinicians working in emergency departments and primary care settings.

Clues that may enhance the ability of pediatric clinicians to recognize the potential for severe GI involvement include the occurrence of abdominal pain, leukopenia, and elevated inflammatory markers. Their presence should raise suspicion of MIS-C and lead to early evaluation.

Of note, COVID-19 mRNA vaccination is associated with a lower incidence of MIS-C in adolescents. This underscores the importance of COVID vaccination for all eligible children. Yet, we clearly have our work cut out for us. Of 107 children with MIS-C who were hospitalized in France, 31% were adolescents eligible for vaccination; however, none had been fully vaccinated. At the end of 2021, CDC data noted that less than 1% of vaccine-eligible children (12-17 years) were fully vaccinated.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is now authorized for receipt by children aged 5-11 years, the age group that is at highest risk for MIS-C. However, despite the approval of vaccines for these younger children, there is limited access in some parts of the United States at a time of rising incidence.

We look forward to broad availability of pediatric vaccination strategies. In addition, with the intense focus on safe and effective therapeutics for SARS-CoV-2 infection, we hope to soon have strategies to prevent and/or treat the life-threatening manifestations and long-term consequences of MIS-C. For example, the recently reported central role of the gut microbiota in immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection offer the possibility that “microbiota modulation” may both reduce GI injury and enhance vaccine efficacy.

Dr. Balistreri has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

William F. Balistreri, MD, is the Dorothy M.M. Kersten Professor of Pediatrics; director emeritus, Pediatric Liver Care Center; medical director emeritus, liver transplantation; and professor, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, department of pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. He has served as director of the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Cincinnati Children’s for 25 years and frequently covers gastroenterology, liver, and nutrition-related topics for this news organization. Dr Balistreri is currently editor-in-chief of the Journal of Pediatrics, having previously served as editor-in-chief of several journals and textbooks. He also became the first pediatrician to act as president of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. In his spare time, he coaches youth lacrosse.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While evaluating an adolescent who had endured a several-day history of vomiting and diarrhea, I mentioned the likelihood of a viral causation, including SARS-CoV-2 infection. His well-informed mother responded, “He has no respiratory symptoms. Does COVID cause GI disease?”

Indeed, not only is the gastrointestinal tract a potential portal of entry of the virus but it may well be the site of mediation of both local and remote injury and thus a harbinger of more severe clinical phenotypes.

As we learn more about the clinical spectrum of COVID, it is becoming increasingly clear that certain features of GI tract involvement may allow us to establish a timeline of the clinical course and perhaps predict the outcome.

The GI tract’s involvement isn’t surprising

The ways in which the GI tract serves as a target organ of SARS-CoV-2 have been postulated in the literature. In part, this is related to the presence of abundant receptors for SARS-CoV-2 cell binding and internalization. The virus uses angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors to enter various cells. These receptors are highly expressed on not only lung cells but also enterocytes. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 receptors allows GI involvement, leading to microscopic mucosal inflammation, increased permeability, and altered intestinal absorption.

The clinical GI manifestations of this include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, which may be the earliest, or sole, symptoms of COVID-19, often noted before the onset of fever or respiratory symptoms. In fact, John Ong, MBBS, and colleagues, in a discussion about patients with primary GI SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptoms, use the term “GI-COVID.”

Clinical course of GI manifestations

After SARS-CoV-2 exposure, adults most commonly present with respiratory symptoms, with GI symptoms reported in 10%-15% of cases. However, the overall incidence of GI involvement during SARS-CoV-2 infection varies according to age, with children more likely than adults to manifest intestinal symptoms.

There are also differences in incidence reported when comparing hospitalized with nonhospitalized individuals. In early reports from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, 11%-43% of hospitalized adult patients manifested GI symptoms. Of note, the presence of GI symptoms was associated with more severe disease and thus predictive of outcomes in those admitted to hospitals.

In a multicenter study that assessed pediatric inpatients with COVID-19, GI manifestations were present in 57% of patients and were the first manifestation in 14%. Adjusted by confounding factors, those with GI symptoms had a higher risk for pediatric intensive care unit admission. Patients admitted to the PICU also had higher serum C-reactive protein and aspartate aminotransferase values.

Emerging data on MIS-C

In previously healthy children and adolescents, the severe, life-threatening complication of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) may present 2-6 weeks after acute infection with SARS-CoV-2. MIS-C appears to be an immune activation syndrome and is presumed to be the delayed immunologic sequelae of mild/asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. This response manifests as hyperinflammation in conjunction with a peak in antibody production a few weeks later.

One report of 186 children with MIS-C in the United States noted that the involved organ system included the GI tract in 92%, followed by cardiovascular in 80%, hematologic in 76%, mucocutaneous in 74%, and respiratory in 70%. Affected children were hospitalized for a median of 7 days, with 80% requiring intensive care, 20% receiving mechanical ventilation, and 48% receiving vasoactive support; 2% died. In a similar study of patients hospitalized in New York, 88% had GI symptoms (abdominal pain, vomiting, and/or diarrhea). A retrospective chart review of patients with MIS-C found that the majority had GI symptoms with any portion of the GI tract potentially involved, but ileal and colonic inflammation predominated.

Elizabeth Whittaker, MD, and colleagues described the clinical characteristics of children in eight hospitals in England who met criteria for MIS-C that were temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. At presentation, all of the patients manifested fever and nonspecific GI symptoms, including vomiting (45%), abdominal pain (53%), and diarrhea (52%). During hospitalization, 50% developed shock with evidence of myocardial dysfunction.

Ermias D. Belay, MD, and colleagues described the clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with MIS-C that were reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of 1,733 patients identified, GI symptoms were reported in 53%-67%. Over half developed hypotension or shock and were admitted for intensive care. Younger children more frequently presented with abdominal pain in contrast with adolescents, who more frequently manifest respiratory symptoms.

In a multicenter retrospective study of Italian children with COVID-19 that was conducted from the onset of the pandemic to early 2021, GI symptoms were noted in 38%. These manifestations were mild and self-limiting, comparable to other viral intestinal infections. However, a subset of children (9.5%) had severe GI manifestations of MIS-C, defined as a medical and/or radiologic diagnosis of acute abdomen, appendicitis, intussusception, pancreatitis, abdominal fluid collection, or diffuse adenomesenteritis requiring surgical consultation. Overall, 42% of this group underwent surgery. The authors noted that the clinical presentation of abdominal pain, lymphopenia, and increased C-reactive protein and ferritin levels were associated with a 9- to 30-fold increased probability of these severe sequelae. In addition, the severity of the GI manifestations was correlated with age (5-10 years: overall response, 8.33; >10 years: OR, 6.37). Again, the presence of GI symptoms was a harbinger of hospitalization and PICU admission.

Given that GI symptoms are a common presentation of MIS-C, its diagnosis may be delayed as clinicians first consider other GI/viral infections, inflammatory bowel disease, or Kawasaki disease. Prompt identification of GI involvement and awareness of the potential outcomes may guide the management and improve the outcome.

These studies provide a clear picture of the differential presenting features of COVID-19 and MIS-C. Although there may be other environmental/genetic factors that govern the incidence, impact, and manifestations, COVID’s status as an ongoing pandemic gives these observations worldwide relevance. This is evident in a recent report documenting pronounced GI symptoms in African children with COVID-19.

It should be noted, however, that the published data cited here reflect the impact of the initial variants of SARS-CoV-2. The GI binding, effects, and aftermath of infection with the Delta and Omicron variants is not yet known.

Cause and effect, or simply coincidental?

Some insight into MIS-C pathogenesis was provided by Lael M. Yonker, MD, and colleagues in their analysis of biospecimens from 100 children: 19 with MIS-C, 26 with acute COVID-19, and 55 controls. They demonstrated that in children with MIS-C the prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the GI tract led to the release of zonulin, a biomarker of intestinal permeability, with subsequent trafficking of SARS-CoV-2 antigens into the bloodstream, leading to hyperinflammation. They were then able to decrease plasma SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen levels and inflammatory markers, with resulting clinical improvement after administration of larazotide, a zonulin antagonist.

These observations regarding the potential mechanism and triggers of MIS-C may offer biomarkers for early detection and/or strategies for prevention and treatment of MIS-C.

Bottom line

The GI tract is the target of an immune-mediated inflammatory response that is triggered by SARS-CoV-2, with MIS-C being the major manifestation of the resultant high degree of inflammation. These observations will allow an increased awareness of nonrespiratory symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection by clinicians working in emergency departments and primary care settings.

Clues that may enhance the ability of pediatric clinicians to recognize the potential for severe GI involvement include the occurrence of abdominal pain, leukopenia, and elevated inflammatory markers. Their presence should raise suspicion of MIS-C and lead to early evaluation.

Of note, COVID-19 mRNA vaccination is associated with a lower incidence of MIS-C in adolescents. This underscores the importance of COVID vaccination for all eligible children. Yet, we clearly have our work cut out for us. Of 107 children with MIS-C who were hospitalized in France, 31% were adolescents eligible for vaccination; however, none had been fully vaccinated. At the end of 2021, CDC data noted that less than 1% of vaccine-eligible children (12-17 years) were fully vaccinated.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is now authorized for receipt by children aged 5-11 years, the age group that is at highest risk for MIS-C. However, despite the approval of vaccines for these younger children, there is limited access in some parts of the United States at a time of rising incidence.

We look forward to broad availability of pediatric vaccination strategies. In addition, with the intense focus on safe and effective therapeutics for SARS-CoV-2 infection, we hope to soon have strategies to prevent and/or treat the life-threatening manifestations and long-term consequences of MIS-C. For example, the recently reported central role of the gut microbiota in immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection offer the possibility that “microbiota modulation” may both reduce GI injury and enhance vaccine efficacy.

Dr. Balistreri has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

William F. Balistreri, MD, is the Dorothy M.M. Kersten Professor of Pediatrics; director emeritus, Pediatric Liver Care Center; medical director emeritus, liver transplantation; and professor, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, department of pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. He has served as director of the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Cincinnati Children’s for 25 years and frequently covers gastroenterology, liver, and nutrition-related topics for this news organization. Dr Balistreri is currently editor-in-chief of the Journal of Pediatrics, having previously served as editor-in-chief of several journals and textbooks. He also became the first pediatrician to act as president of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. In his spare time, he coaches youth lacrosse.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

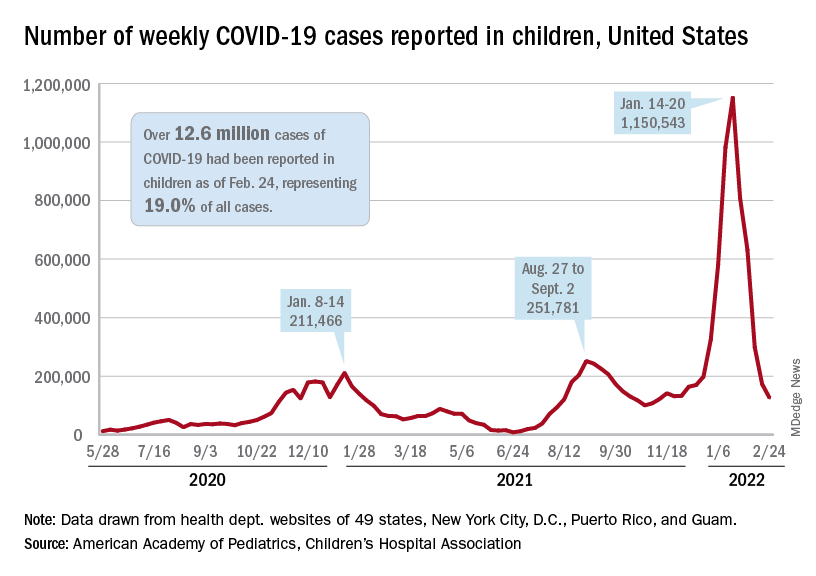

Children and COVID: New cases down to pre-Omicron level

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children dropped for the fifth consecutive week, but the rate of decline slowed considerably, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The national count of new cases has now fallen for five straight weeks since peaking Jan. 14-20, and this week’s figure is the lowest since the pre-Omicron days of mid-November, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Over 12.6 million pediatric cases have been reported by those jurisdictions since the start of the pandemic, representing 19.0% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The highest cumulative rate among the states, 27.5%, can be found in Vermont, followed by New Hampshire (26.7%) and Alaska (26.6%). Alabama’s 12.1% is lower than any other jurisdiction, but the state stopped reporting during the summer of 2021, just as the Delta surge was beginning. The next two lowest states, Florida (12.8%) and Utah (13.9%), both define children as those aged 0-14 years, so the state with the lowest rate and no qualifiers is Idaho at 14.3%, the AAP/CHA data show.

The downward trend in new cases is reflected in other national measures. The daily rate of new hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years was 0.32 per 100,000 population on Feb. 26, which is a drop of 75% since admissions peaked at 1.25 per 100,000 on Jan. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent 7-day average (Feb. 20-26) for child admissions with confirmed COVID-19 was 237 per day, compared with 914 per day during the peak week of Jan. 10-16. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits by age group, are down even more. The 7-day average was 1.2% on Feb. 25 for children aged 0-11 years, compared with a peak of 13.9% in mid-January, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. The current rates for older children are even lower.

The decline of the Omicron surge over the last few weeks is allowing states to end mask mandates in schools around the country. The governors of California, Oregon, and Washington just announced that their states will be lifting their mask requirements on March 11, and New York State will end its mandate on March 2, while New York City is scheduled to go mask-free as of March 7, according to District Administration.

Those types of government moves, however, do not seem to be entirely supported by the public. In a survey conducted Feb. 9-21 by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 43% of the 1,502 respondents said that all students and staff should be required to wear masks in schools, while 40% said that there should be no mask requirements at all.

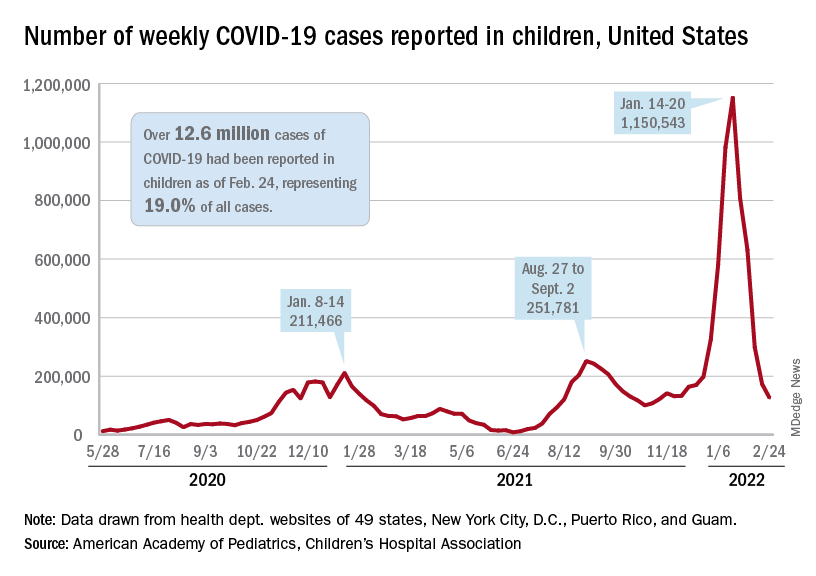

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children dropped for the fifth consecutive week, but the rate of decline slowed considerably, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The national count of new cases has now fallen for five straight weeks since peaking Jan. 14-20, and this week’s figure is the lowest since the pre-Omicron days of mid-November, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Over 12.6 million pediatric cases have been reported by those jurisdictions since the start of the pandemic, representing 19.0% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The highest cumulative rate among the states, 27.5%, can be found in Vermont, followed by New Hampshire (26.7%) and Alaska (26.6%). Alabama’s 12.1% is lower than any other jurisdiction, but the state stopped reporting during the summer of 2021, just as the Delta surge was beginning. The next two lowest states, Florida (12.8%) and Utah (13.9%), both define children as those aged 0-14 years, so the state with the lowest rate and no qualifiers is Idaho at 14.3%, the AAP/CHA data show.

The downward trend in new cases is reflected in other national measures. The daily rate of new hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years was 0.32 per 100,000 population on Feb. 26, which is a drop of 75% since admissions peaked at 1.25 per 100,000 on Jan. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent 7-day average (Feb. 20-26) for child admissions with confirmed COVID-19 was 237 per day, compared with 914 per day during the peak week of Jan. 10-16. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits by age group, are down even more. The 7-day average was 1.2% on Feb. 25 for children aged 0-11 years, compared with a peak of 13.9% in mid-January, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. The current rates for older children are even lower.

The decline of the Omicron surge over the last few weeks is allowing states to end mask mandates in schools around the country. The governors of California, Oregon, and Washington just announced that their states will be lifting their mask requirements on March 11, and New York State will end its mandate on March 2, while New York City is scheduled to go mask-free as of March 7, according to District Administration.

Those types of government moves, however, do not seem to be entirely supported by the public. In a survey conducted Feb. 9-21 by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 43% of the 1,502 respondents said that all students and staff should be required to wear masks in schools, while 40% said that there should be no mask requirements at all.

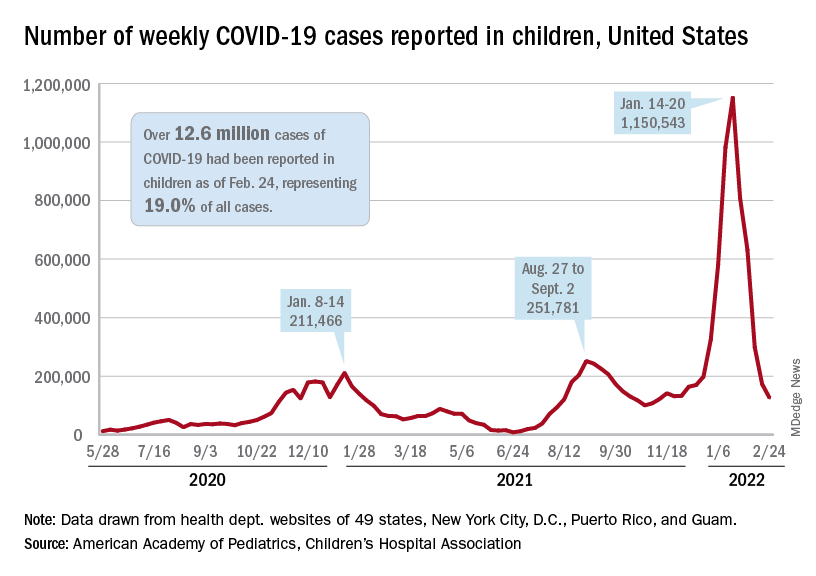

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children dropped for the fifth consecutive week, but the rate of decline slowed considerably, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The national count of new cases has now fallen for five straight weeks since peaking Jan. 14-20, and this week’s figure is the lowest since the pre-Omicron days of mid-November, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Over 12.6 million pediatric cases have been reported by those jurisdictions since the start of the pandemic, representing 19.0% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The highest cumulative rate among the states, 27.5%, can be found in Vermont, followed by New Hampshire (26.7%) and Alaska (26.6%). Alabama’s 12.1% is lower than any other jurisdiction, but the state stopped reporting during the summer of 2021, just as the Delta surge was beginning. The next two lowest states, Florida (12.8%) and Utah (13.9%), both define children as those aged 0-14 years, so the state with the lowest rate and no qualifiers is Idaho at 14.3%, the AAP/CHA data show.

The downward trend in new cases is reflected in other national measures. The daily rate of new hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years was 0.32 per 100,000 population on Feb. 26, which is a drop of 75% since admissions peaked at 1.25 per 100,000 on Jan. 15, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent 7-day average (Feb. 20-26) for child admissions with confirmed COVID-19 was 237 per day, compared with 914 per day during the peak week of Jan. 10-16. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits by age group, are down even more. The 7-day average was 1.2% on Feb. 25 for children aged 0-11 years, compared with a peak of 13.9% in mid-January, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. The current rates for older children are even lower.

The decline of the Omicron surge over the last few weeks is allowing states to end mask mandates in schools around the country. The governors of California, Oregon, and Washington just announced that their states will be lifting their mask requirements on March 11, and New York State will end its mandate on March 2, while New York City is scheduled to go mask-free as of March 7, according to District Administration.

Those types of government moves, however, do not seem to be entirely supported by the public. In a survey conducted Feb. 9-21 by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 43% of the 1,502 respondents said that all students and staff should be required to wear masks in schools, while 40% said that there should be no mask requirements at all.

Nasal microbiota show promise as polyp predictor

A study of the nasal microbiome helped researchers predict recurrent polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis patients with more than 90% accuracy, based on data from 85 individuals.

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) has a significant impact on patient quality of life, but the underlying mechanism of the disease has not been well studied, and treatment options remain limited, wrote Yan Zhao, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and study coauthors.

Previous research has shown that nasal microbiome composition differs in patients with and without asthma, and some studies suggest that changes in microbiota could contribute to CRSwNP, the authors wrote. The researchers wondered if features of the nasal microbiome can predict the recurrence of nasal polyps after endoscopic sinus surgery and serve as a potential treatment target.

In a study in Allergy, the researchers examined nasal swab samples from 85 adults with CRSwNP who underwent endoscopic sinus surgery between August 2014 and March 2016 at a single center in China. The researchers performed bacterial analysis and gene sequencing on all samples.

The patients ranged in age from 18-73 years, with a mean age of 46 years, and included 64 men and 21 women. The primary outcome was recurrence of polyps. Of the total, 39 individuals had recurrence, and 46 did not.

When the researchers compared microbiota from swab samples of recurrent and nonrecurrent patients, they found differences in composition based on bacterial genus abundance. “Campylobacter, Bdellovibrio, and Aggregatibacter, among others, were more abundant in swabs from CRSwNP recurrence samples, whereas Actinobacillus, Gemella, and Moraxella were more abundant in non-recurrence samples,” they wrote.

The researchers then tested their theory that distinct nasal microbiota could be a predictive marker of risk for future nasal polyp recurrence. They used a training set of 48 samples and constructed models from nasal microbiota alone, clinical features alone, and both together.

The regression model identified Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, Moryella, Aggregatibacter, Butyrivibrio, Shewanella, Pseudoxanthomonas, Friedmanniella, Limnobacter, and Curvibacter as the most important taxa that distinguished recurrence from nonrecurrence in the specimens. When the model was validated, the area under the curve was 0.914, yielding a predictor of nasal polyp recurrence with 91.4% accuracy.

“It is highly likely that proteins, nucleic acids, and other small molecules produced by nasal microbiota are associated with the progression of CRSwNP,” the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Further, the nasal microbiota could maintain a stable community environment through the secretion of various chemical compounds and/or inflammatory factors, thus playing a central role in the development of CRSwNP.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the analysis of nasal flora only at the genus level in the screening phase, the use only of bioinformatic analysis for recurrence prediction, and the inclusion only of subjects from a single center, the researchers noted. Future studies should combine predictors to increase accuracy and include deeper sequencing, they said. However, the results support data from previous studies and suggest a strategy to meet the need for predictors of recurrence in CRSwNP, they concluded.

“There is a critical need to understand the role of the upper airway microbiome in different phenotypes of CRS,” said Emily K. Cope, PhD, assistant director at the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, in an interview. “This was one of the first studies to evaluate the predictive power of the microbiome in recurrence of a common CRS phenotype – CRS with nasal polyps,” she said. “Importantly, the researchers were able to predict recurrence of polyps prior to the disease manifestation,” she noted.

“Given the nascent state of current upper airway microbiome research, I was surprised that they were able to predict polyp recurrence prior to disease manifestation,” Dr. Cope said. “This is exciting, and I can imagine a future where we use microbiome data to understand risk for disease.”

What is the take-home message for clinicians? Although the immediate clinical implications are limited, Dr. Cope expressed enthusiasm for additional research. “At this point, there’s not a lot we can do without validation studies, but this study is promising. I hope we can understand the mechanism that an altered microbiome might drive (or be a result of) polyposis,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the program for the Changjiang scholars and innovative research team, the Beijing Bai-Qian-Wan talent project, the Public Welfare Development and Reform Pilot Project, the National Science and Technology Major Project, and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences. The researchers and Dr. Cope disclosed no financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of the nasal microbiome helped researchers predict recurrent polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis patients with more than 90% accuracy, based on data from 85 individuals.

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) has a significant impact on patient quality of life, but the underlying mechanism of the disease has not been well studied, and treatment options remain limited, wrote Yan Zhao, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and study coauthors.

Previous research has shown that nasal microbiome composition differs in patients with and without asthma, and some studies suggest that changes in microbiota could contribute to CRSwNP, the authors wrote. The researchers wondered if features of the nasal microbiome can predict the recurrence of nasal polyps after endoscopic sinus surgery and serve as a potential treatment target.

In a study in Allergy, the researchers examined nasal swab samples from 85 adults with CRSwNP who underwent endoscopic sinus surgery between August 2014 and March 2016 at a single center in China. The researchers performed bacterial analysis and gene sequencing on all samples.

The patients ranged in age from 18-73 years, with a mean age of 46 years, and included 64 men and 21 women. The primary outcome was recurrence of polyps. Of the total, 39 individuals had recurrence, and 46 did not.

When the researchers compared microbiota from swab samples of recurrent and nonrecurrent patients, they found differences in composition based on bacterial genus abundance. “Campylobacter, Bdellovibrio, and Aggregatibacter, among others, were more abundant in swabs from CRSwNP recurrence samples, whereas Actinobacillus, Gemella, and Moraxella were more abundant in non-recurrence samples,” they wrote.

The researchers then tested their theory that distinct nasal microbiota could be a predictive marker of risk for future nasal polyp recurrence. They used a training set of 48 samples and constructed models from nasal microbiota alone, clinical features alone, and both together.

The regression model identified Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, Moryella, Aggregatibacter, Butyrivibrio, Shewanella, Pseudoxanthomonas, Friedmanniella, Limnobacter, and Curvibacter as the most important taxa that distinguished recurrence from nonrecurrence in the specimens. When the model was validated, the area under the curve was 0.914, yielding a predictor of nasal polyp recurrence with 91.4% accuracy.

“It is highly likely that proteins, nucleic acids, and other small molecules produced by nasal microbiota are associated with the progression of CRSwNP,” the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Further, the nasal microbiota could maintain a stable community environment through the secretion of various chemical compounds and/or inflammatory factors, thus playing a central role in the development of CRSwNP.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the analysis of nasal flora only at the genus level in the screening phase, the use only of bioinformatic analysis for recurrence prediction, and the inclusion only of subjects from a single center, the researchers noted. Future studies should combine predictors to increase accuracy and include deeper sequencing, they said. However, the results support data from previous studies and suggest a strategy to meet the need for predictors of recurrence in CRSwNP, they concluded.

“There is a critical need to understand the role of the upper airway microbiome in different phenotypes of CRS,” said Emily K. Cope, PhD, assistant director at the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, in an interview. “This was one of the first studies to evaluate the predictive power of the microbiome in recurrence of a common CRS phenotype – CRS with nasal polyps,” she said. “Importantly, the researchers were able to predict recurrence of polyps prior to the disease manifestation,” she noted.

“Given the nascent state of current upper airway microbiome research, I was surprised that they were able to predict polyp recurrence prior to disease manifestation,” Dr. Cope said. “This is exciting, and I can imagine a future where we use microbiome data to understand risk for disease.”

What is the take-home message for clinicians? Although the immediate clinical implications are limited, Dr. Cope expressed enthusiasm for additional research. “At this point, there’s not a lot we can do without validation studies, but this study is promising. I hope we can understand the mechanism that an altered microbiome might drive (or be a result of) polyposis,” she said.