User login

Children and COVID: Weekly cases at lowest level since August

New cases of COVID-19 in children continued their descent toward normalcy, falling below 100,000 in a week for the first time since early August 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and 94% since the Omicron-fueled peak of 1.15 million during the week of Jan. 14-20, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The total number of child cases is 12.7 million since the pandemic began, with children representing 19% of all cases.

New admissions also stayed on a downward path, as the rate dropped to 0.24 per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years on March 5, a decline of nearly 81% since hitting 1.25 per 100,000 on Jan. 15. The latest 7-day average for daily admissions, 178 per day from Feb. 27 to March 5, was 29% lower than the previous week and almost 81% lower than the peak of 914 per day for Jan. 10-16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The story is the same for emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID-19, which are reported as a percentage of all ED visits. On March 4, the 7-day average for children aged 0-11 years was 0.8%, compared with a high of 13.9% in mid-January, while 12- to 15-year-olds had dropped from 12.4% to 0.5% and 16- to 17-year-olds went from 12.6% down to 0.5%, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Florida’s surgeon general says no to the vaccine

Vaccination, in the meantime, is struggling to maintain a foothold against the current of declining cases. Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo said that “the Florida Department of Health is going to be the first state to officially recommend against the COVID-19 vaccines for healthy children,” NBC News reported March 7. With such a move, “Florida would become the first state to break from the CDC on vaccines for children,” CNN said in its report.

Vaccinations among children aged 5-11 years, which hit 1.6 million in 1 week shortly after emergency use was authorized in early November, declined quickly shorty thereafter and only rose slightly during the Omicron surge. Since mid-January, the number of children receiving an initial dose has declined for seven consecutive weeks and is now lower than ever, based on CDC data compiled by the AAP.

Just over one-third of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, while 26.4% are fully vaccinated. Among children aged 12-17, just over two-thirds (67.8%) have received at least one dose, 57.8% have completed the vaccine regimen, and 21.9% have gotten a booster, the CDC reported.

As of March 2, “about 8.4 million children 12-17 have yet to receive their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose,” the AAP said. About 64,000 children aged 12-17 had received their first dose in the previous week, the group noted, which was the second-lowest weekly total since the vaccine was approved for children aged 12-15 in May of 2021.

New cases of COVID-19 in children continued their descent toward normalcy, falling below 100,000 in a week for the first time since early August 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and 94% since the Omicron-fueled peak of 1.15 million during the week of Jan. 14-20, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The total number of child cases is 12.7 million since the pandemic began, with children representing 19% of all cases.

New admissions also stayed on a downward path, as the rate dropped to 0.24 per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years on March 5, a decline of nearly 81% since hitting 1.25 per 100,000 on Jan. 15. The latest 7-day average for daily admissions, 178 per day from Feb. 27 to March 5, was 29% lower than the previous week and almost 81% lower than the peak of 914 per day for Jan. 10-16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The story is the same for emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID-19, which are reported as a percentage of all ED visits. On March 4, the 7-day average for children aged 0-11 years was 0.8%, compared with a high of 13.9% in mid-January, while 12- to 15-year-olds had dropped from 12.4% to 0.5% and 16- to 17-year-olds went from 12.6% down to 0.5%, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Florida’s surgeon general says no to the vaccine

Vaccination, in the meantime, is struggling to maintain a foothold against the current of declining cases. Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo said that “the Florida Department of Health is going to be the first state to officially recommend against the COVID-19 vaccines for healthy children,” NBC News reported March 7. With such a move, “Florida would become the first state to break from the CDC on vaccines for children,” CNN said in its report.

Vaccinations among children aged 5-11 years, which hit 1.6 million in 1 week shortly after emergency use was authorized in early November, declined quickly shorty thereafter and only rose slightly during the Omicron surge. Since mid-January, the number of children receiving an initial dose has declined for seven consecutive weeks and is now lower than ever, based on CDC data compiled by the AAP.

Just over one-third of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, while 26.4% are fully vaccinated. Among children aged 12-17, just over two-thirds (67.8%) have received at least one dose, 57.8% have completed the vaccine regimen, and 21.9% have gotten a booster, the CDC reported.

As of March 2, “about 8.4 million children 12-17 have yet to receive their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose,” the AAP said. About 64,000 children aged 12-17 had received their first dose in the previous week, the group noted, which was the second-lowest weekly total since the vaccine was approved for children aged 12-15 in May of 2021.

New cases of COVID-19 in children continued their descent toward normalcy, falling below 100,000 in a week for the first time since early August 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and 94% since the Omicron-fueled peak of 1.15 million during the week of Jan. 14-20, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The total number of child cases is 12.7 million since the pandemic began, with children representing 19% of all cases.

New admissions also stayed on a downward path, as the rate dropped to 0.24 per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years on March 5, a decline of nearly 81% since hitting 1.25 per 100,000 on Jan. 15. The latest 7-day average for daily admissions, 178 per day from Feb. 27 to March 5, was 29% lower than the previous week and almost 81% lower than the peak of 914 per day for Jan. 10-16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The story is the same for emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID-19, which are reported as a percentage of all ED visits. On March 4, the 7-day average for children aged 0-11 years was 0.8%, compared with a high of 13.9% in mid-January, while 12- to 15-year-olds had dropped from 12.4% to 0.5% and 16- to 17-year-olds went from 12.6% down to 0.5%, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Florida’s surgeon general says no to the vaccine

Vaccination, in the meantime, is struggling to maintain a foothold against the current of declining cases. Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo said that “the Florida Department of Health is going to be the first state to officially recommend against the COVID-19 vaccines for healthy children,” NBC News reported March 7. With such a move, “Florida would become the first state to break from the CDC on vaccines for children,” CNN said in its report.

Vaccinations among children aged 5-11 years, which hit 1.6 million in 1 week shortly after emergency use was authorized in early November, declined quickly shorty thereafter and only rose slightly during the Omicron surge. Since mid-January, the number of children receiving an initial dose has declined for seven consecutive weeks and is now lower than ever, based on CDC data compiled by the AAP.

Just over one-third of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, while 26.4% are fully vaccinated. Among children aged 12-17, just over two-thirds (67.8%) have received at least one dose, 57.8% have completed the vaccine regimen, and 21.9% have gotten a booster, the CDC reported.

As of March 2, “about 8.4 million children 12-17 have yet to receive their initial COVID-19 vaccine dose,” the AAP said. About 64,000 children aged 12-17 had received their first dose in the previous week, the group noted, which was the second-lowest weekly total since the vaccine was approved for children aged 12-15 in May of 2021.

FDA committee recommends 2022-2023 influenza vaccine strains

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee has chosen the influenza vaccine strains for the 2022-2023 season in the northern hemisphere, which begins in the fall of 2022.

On March 3, the committee unanimously voted to endorse the World Health Organization’s recommendations as to which influenza strains to include for coverage by vaccines for the upcoming flu season. Two of the four recommended strains are different from last season.

The committee also heard updates on flu activity this season. So far, data from the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) network, which consists of seven study sites, have not shown that the vaccine is protective against influenza A. “We can say that it is not highly effective,” Brendan Flannery, PhD, who leads the U.S. Flu VE network for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview. He was not involved with the advisory committee meeting. Flu activity this season has been low, he explained, so there are fewer cases his team can use to estimate vaccine efficacy. “If there’s some benefit, it’s hard for us to show that now,” he said.

Vaccine strains

The panel voted to include a A/Darwin/9/2021-like strain for the H3N2 component of the vaccine; this is changed from A/Cambodia/e0826360/2020. For the influenza B Victoria lineage component, the committee voted to include a B/Austria/1359417/2021-like virus, a swap from this year’s B/Washington/02/2019-like virus. These changes apply to the egg-based, cell-culture, and recombinant vaccines. Both new strains were included in WHO’s 2022 influenza vaccine strain recommendations for the southern hemisphere.

For the influenza A H1N1 component, the group also agreed to include a A/Victoria/2570/2019 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus for the egg-based vaccine and the A/Wisconsin/588/2019 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus for cell culture or recombinant vaccines. These strains were included for the 2021-2022 season. The panel also voted for the inclusion of a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagata lineage) as the second influenza B strain for the quadrivalent egg-based, cell culture, or recombinant vaccines, which is unchanged from this flu season.

‘Sporadic’ flu activity

While there was an uptick in influenza activity this year compared to the 2020-2021 season, hospitalization rates are lower than in the four seasons preceding the pandemic (from 2016-2017 to 2019-2020). As of Feb. 26, the cumulative hospitalization rate for this flu season was 5.2 hospitalizations per 100,000 individuals. There have been eight pediatric deaths due to influenza so far this season, compared to one pediatric death reported to the CDC during the 2020-2021 flu season.

About 4.1% of specimens tested at clinical laboratories were positive for flu. Since Oct. 30, 2.7% of specimens have been positive for influenza this season. Nearly all viruses detected (97.7%) have been influenza A.

Lisa Grohskopf, MD, MPH, a medical officer in the influenza division at the CDC who presented the data at the meeting, described flu activity this season as “sporadic” and noted that activity is increasing in some areas of the country. According to CDC’s weekly influenza surveillance report, most states had minimal influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, although Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, and Utah had slightly higher ILI activity as of Feb. 26. Champaign-Urbana, Illinois; St. Cloud, Minnesota; and Brownwood, Texas, had the highest levels of flu activity in the country.

Low vaccine effectiveness

As of Jan. 22, results from the U.S. Flu VE network do not show statistically significant evidence that the flu vaccine is effective. Currently, the vaccine is estimated to be 8% effective against preventing influenza A infection (95% confidence interval, –31% to 36%) and 14% effective against preventing A/H3N2 infection (95% CI, –28% to 43%) for people aged 6 months and older.

The network did not have enough data to provide age-specific VE estimates or estimates of effectiveness against influenza B. This could be due to low flu activity relative to prepandemic years, Dr. Flannery said. Of the 2,758 individuals enrolled in the VE flu network this season, just 147 (5%) tested positive for the flu this season. This is the lowest positivity rate observed in the Flu VE network participants with respiratory illness over the past 10 flu seasons, Dr. Grohskopf noted. In comparison, estimates from the 2019 to 2020 season included 4,112 individuals, and 1,060 tested positive for flu.

“We are really at the bare minimum of what we can use for a flu vaccine effectiveness estimate,” Dr. Flannery said about the more recent data. The network was not able to produce any estimates about flu vaccine effectiveness for the 2020-2021 season because of historically low flu activity.

The Department of Defense also presented vaccine efficacy estimates for the 2021–2022 season. The vaccine has been 36% effective (95% CI, 28%-44%) against all strains of the virus, 33% effective against influenza A (95% CI, 24%-41%), 32% effective against A/H3N2 (95% CI, 3%-53%), and 59% effective against influenza B (95% CI, 42%-71%). These results are from a young, healthy adult population, Lieutenant Commander Courtney Gustin, DrPH, MSN, told the panel, and they may not be reflective of efficacy rates across all age groups.

Though these findings suggest there is low to no measurable benefit against influenza A, Dr. Flannery said the CDC still recommends getting the flu vaccine, as it can be protective against other circulating flu strains. “We have been able to demonstrate protection against other H3 [viruses], B viruses, and H1 viruses in the past,” he said. And as these results only show protection against mild disease, “there is still possibility that there’s benefit against more severe disease,” he added. Studies measuring effectiveness against more severe outcomes are not yet available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee has chosen the influenza vaccine strains for the 2022-2023 season in the northern hemisphere, which begins in the fall of 2022.

On March 3, the committee unanimously voted to endorse the World Health Organization’s recommendations as to which influenza strains to include for coverage by vaccines for the upcoming flu season. Two of the four recommended strains are different from last season.

The committee also heard updates on flu activity this season. So far, data from the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) network, which consists of seven study sites, have not shown that the vaccine is protective against influenza A. “We can say that it is not highly effective,” Brendan Flannery, PhD, who leads the U.S. Flu VE network for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview. He was not involved with the advisory committee meeting. Flu activity this season has been low, he explained, so there are fewer cases his team can use to estimate vaccine efficacy. “If there’s some benefit, it’s hard for us to show that now,” he said.

Vaccine strains

The panel voted to include a A/Darwin/9/2021-like strain for the H3N2 component of the vaccine; this is changed from A/Cambodia/e0826360/2020. For the influenza B Victoria lineage component, the committee voted to include a B/Austria/1359417/2021-like virus, a swap from this year’s B/Washington/02/2019-like virus. These changes apply to the egg-based, cell-culture, and recombinant vaccines. Both new strains were included in WHO’s 2022 influenza vaccine strain recommendations for the southern hemisphere.

For the influenza A H1N1 component, the group also agreed to include a A/Victoria/2570/2019 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus for the egg-based vaccine and the A/Wisconsin/588/2019 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus for cell culture or recombinant vaccines. These strains were included for the 2021-2022 season. The panel also voted for the inclusion of a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagata lineage) as the second influenza B strain for the quadrivalent egg-based, cell culture, or recombinant vaccines, which is unchanged from this flu season.

‘Sporadic’ flu activity

While there was an uptick in influenza activity this year compared to the 2020-2021 season, hospitalization rates are lower than in the four seasons preceding the pandemic (from 2016-2017 to 2019-2020). As of Feb. 26, the cumulative hospitalization rate for this flu season was 5.2 hospitalizations per 100,000 individuals. There have been eight pediatric deaths due to influenza so far this season, compared to one pediatric death reported to the CDC during the 2020-2021 flu season.

About 4.1% of specimens tested at clinical laboratories were positive for flu. Since Oct. 30, 2.7% of specimens have been positive for influenza this season. Nearly all viruses detected (97.7%) have been influenza A.

Lisa Grohskopf, MD, MPH, a medical officer in the influenza division at the CDC who presented the data at the meeting, described flu activity this season as “sporadic” and noted that activity is increasing in some areas of the country. According to CDC’s weekly influenza surveillance report, most states had minimal influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, although Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, and Utah had slightly higher ILI activity as of Feb. 26. Champaign-Urbana, Illinois; St. Cloud, Minnesota; and Brownwood, Texas, had the highest levels of flu activity in the country.

Low vaccine effectiveness

As of Jan. 22, results from the U.S. Flu VE network do not show statistically significant evidence that the flu vaccine is effective. Currently, the vaccine is estimated to be 8% effective against preventing influenza A infection (95% confidence interval, –31% to 36%) and 14% effective against preventing A/H3N2 infection (95% CI, –28% to 43%) for people aged 6 months and older.

The network did not have enough data to provide age-specific VE estimates or estimates of effectiveness against influenza B. This could be due to low flu activity relative to prepandemic years, Dr. Flannery said. Of the 2,758 individuals enrolled in the VE flu network this season, just 147 (5%) tested positive for the flu this season. This is the lowest positivity rate observed in the Flu VE network participants with respiratory illness over the past 10 flu seasons, Dr. Grohskopf noted. In comparison, estimates from the 2019 to 2020 season included 4,112 individuals, and 1,060 tested positive for flu.

“We are really at the bare minimum of what we can use for a flu vaccine effectiveness estimate,” Dr. Flannery said about the more recent data. The network was not able to produce any estimates about flu vaccine effectiveness for the 2020-2021 season because of historically low flu activity.

The Department of Defense also presented vaccine efficacy estimates for the 2021–2022 season. The vaccine has been 36% effective (95% CI, 28%-44%) against all strains of the virus, 33% effective against influenza A (95% CI, 24%-41%), 32% effective against A/H3N2 (95% CI, 3%-53%), and 59% effective against influenza B (95% CI, 42%-71%). These results are from a young, healthy adult population, Lieutenant Commander Courtney Gustin, DrPH, MSN, told the panel, and they may not be reflective of efficacy rates across all age groups.

Though these findings suggest there is low to no measurable benefit against influenza A, Dr. Flannery said the CDC still recommends getting the flu vaccine, as it can be protective against other circulating flu strains. “We have been able to demonstrate protection against other H3 [viruses], B viruses, and H1 viruses in the past,” he said. And as these results only show protection against mild disease, “there is still possibility that there’s benefit against more severe disease,” he added. Studies measuring effectiveness against more severe outcomes are not yet available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee has chosen the influenza vaccine strains for the 2022-2023 season in the northern hemisphere, which begins in the fall of 2022.

On March 3, the committee unanimously voted to endorse the World Health Organization’s recommendations as to which influenza strains to include for coverage by vaccines for the upcoming flu season. Two of the four recommended strains are different from last season.

The committee also heard updates on flu activity this season. So far, data from the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) network, which consists of seven study sites, have not shown that the vaccine is protective against influenza A. “We can say that it is not highly effective,” Brendan Flannery, PhD, who leads the U.S. Flu VE network for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview. He was not involved with the advisory committee meeting. Flu activity this season has been low, he explained, so there are fewer cases his team can use to estimate vaccine efficacy. “If there’s some benefit, it’s hard for us to show that now,” he said.

Vaccine strains

The panel voted to include a A/Darwin/9/2021-like strain for the H3N2 component of the vaccine; this is changed from A/Cambodia/e0826360/2020. For the influenza B Victoria lineage component, the committee voted to include a B/Austria/1359417/2021-like virus, a swap from this year’s B/Washington/02/2019-like virus. These changes apply to the egg-based, cell-culture, and recombinant vaccines. Both new strains were included in WHO’s 2022 influenza vaccine strain recommendations for the southern hemisphere.

For the influenza A H1N1 component, the group also agreed to include a A/Victoria/2570/2019 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus for the egg-based vaccine and the A/Wisconsin/588/2019 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus for cell culture or recombinant vaccines. These strains were included for the 2021-2022 season. The panel also voted for the inclusion of a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagata lineage) as the second influenza B strain for the quadrivalent egg-based, cell culture, or recombinant vaccines, which is unchanged from this flu season.

‘Sporadic’ flu activity

While there was an uptick in influenza activity this year compared to the 2020-2021 season, hospitalization rates are lower than in the four seasons preceding the pandemic (from 2016-2017 to 2019-2020). As of Feb. 26, the cumulative hospitalization rate for this flu season was 5.2 hospitalizations per 100,000 individuals. There have been eight pediatric deaths due to influenza so far this season, compared to one pediatric death reported to the CDC during the 2020-2021 flu season.

About 4.1% of specimens tested at clinical laboratories were positive for flu. Since Oct. 30, 2.7% of specimens have been positive for influenza this season. Nearly all viruses detected (97.7%) have been influenza A.

Lisa Grohskopf, MD, MPH, a medical officer in the influenza division at the CDC who presented the data at the meeting, described flu activity this season as “sporadic” and noted that activity is increasing in some areas of the country. According to CDC’s weekly influenza surveillance report, most states had minimal influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, although Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, and Utah had slightly higher ILI activity as of Feb. 26. Champaign-Urbana, Illinois; St. Cloud, Minnesota; and Brownwood, Texas, had the highest levels of flu activity in the country.

Low vaccine effectiveness

As of Jan. 22, results from the U.S. Flu VE network do not show statistically significant evidence that the flu vaccine is effective. Currently, the vaccine is estimated to be 8% effective against preventing influenza A infection (95% confidence interval, –31% to 36%) and 14% effective against preventing A/H3N2 infection (95% CI, –28% to 43%) for people aged 6 months and older.

The network did not have enough data to provide age-specific VE estimates or estimates of effectiveness against influenza B. This could be due to low flu activity relative to prepandemic years, Dr. Flannery said. Of the 2,758 individuals enrolled in the VE flu network this season, just 147 (5%) tested positive for the flu this season. This is the lowest positivity rate observed in the Flu VE network participants with respiratory illness over the past 10 flu seasons, Dr. Grohskopf noted. In comparison, estimates from the 2019 to 2020 season included 4,112 individuals, and 1,060 tested positive for flu.

“We are really at the bare minimum of what we can use for a flu vaccine effectiveness estimate,” Dr. Flannery said about the more recent data. The network was not able to produce any estimates about flu vaccine effectiveness for the 2020-2021 season because of historically low flu activity.

The Department of Defense also presented vaccine efficacy estimates for the 2021–2022 season. The vaccine has been 36% effective (95% CI, 28%-44%) against all strains of the virus, 33% effective against influenza A (95% CI, 24%-41%), 32% effective against A/H3N2 (95% CI, 3%-53%), and 59% effective against influenza B (95% CI, 42%-71%). These results are from a young, healthy adult population, Lieutenant Commander Courtney Gustin, DrPH, MSN, told the panel, and they may not be reflective of efficacy rates across all age groups.

Though these findings suggest there is low to no measurable benefit against influenza A, Dr. Flannery said the CDC still recommends getting the flu vaccine, as it can be protective against other circulating flu strains. “We have been able to demonstrate protection against other H3 [viruses], B viruses, and H1 viruses in the past,” he said. And as these results only show protection against mild disease, “there is still possibility that there’s benefit against more severe disease,” he added. Studies measuring effectiveness against more severe outcomes are not yet available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaccine update: The latest recommendations from ACIP

In a typical year, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has three 1.5- to 2-day meetings to make recommendations for the use of new and existing vaccines in the US population. However, 2021 was not a typical year. Last year, ACIP held 17 meetings for a total of 127 hours. Most of these were related to vaccines to prevent COVID-19. There are now 3 COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use in the United States: the 2-dose mRNA-based Pfizer-BioNTech/Comirnaty and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines and the single-dose adenovirus, vector-based Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 vaccine.

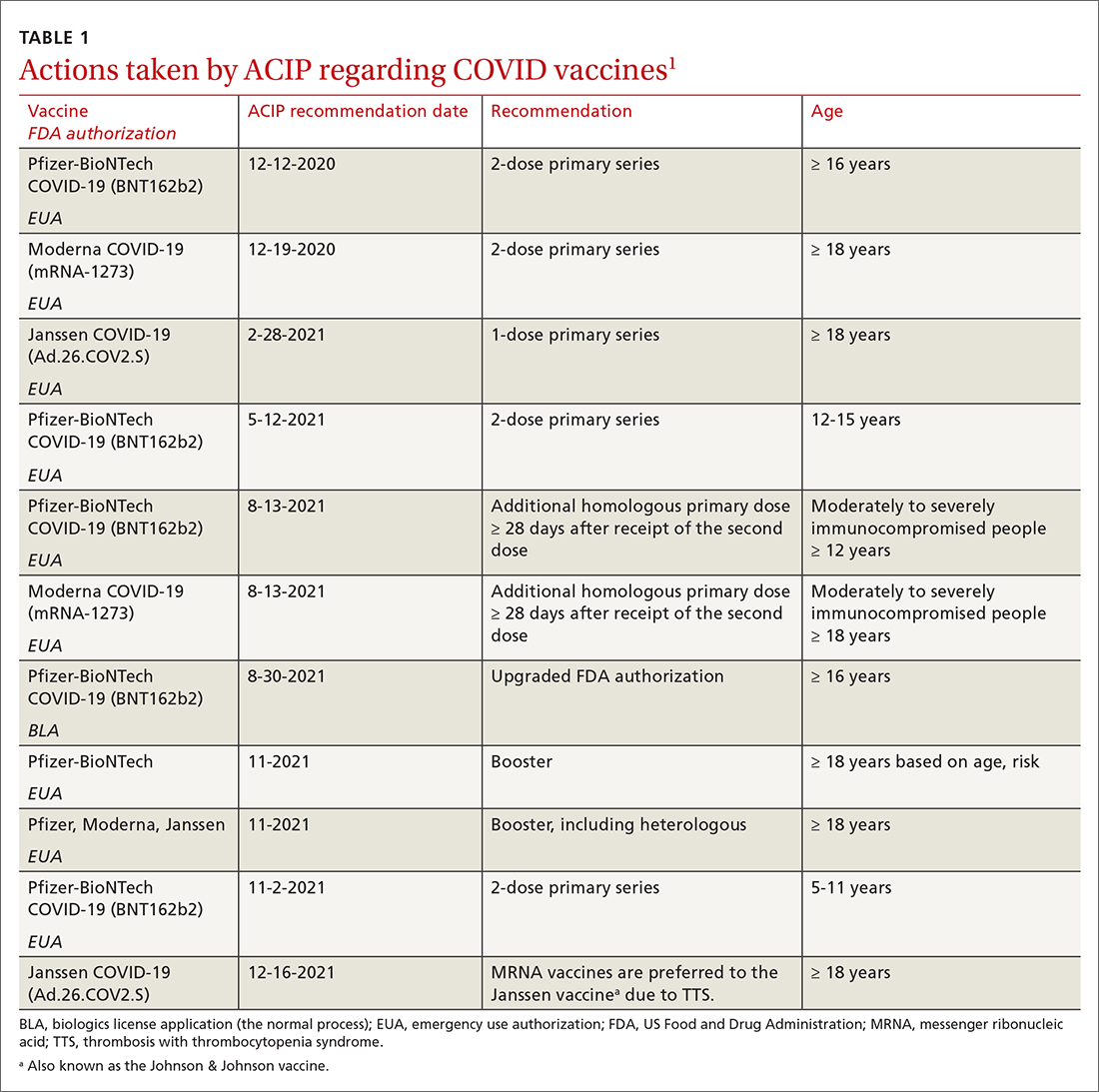

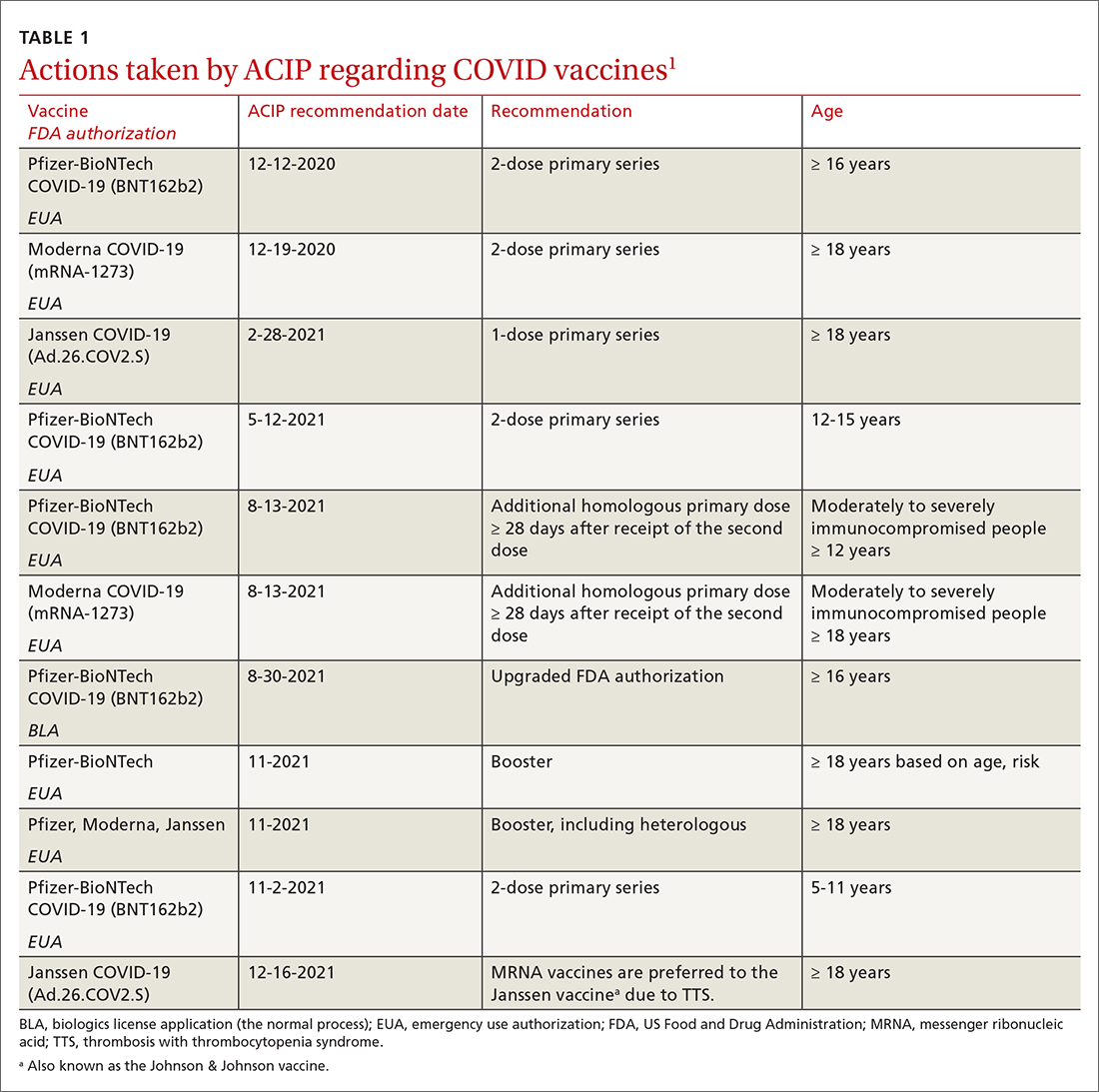

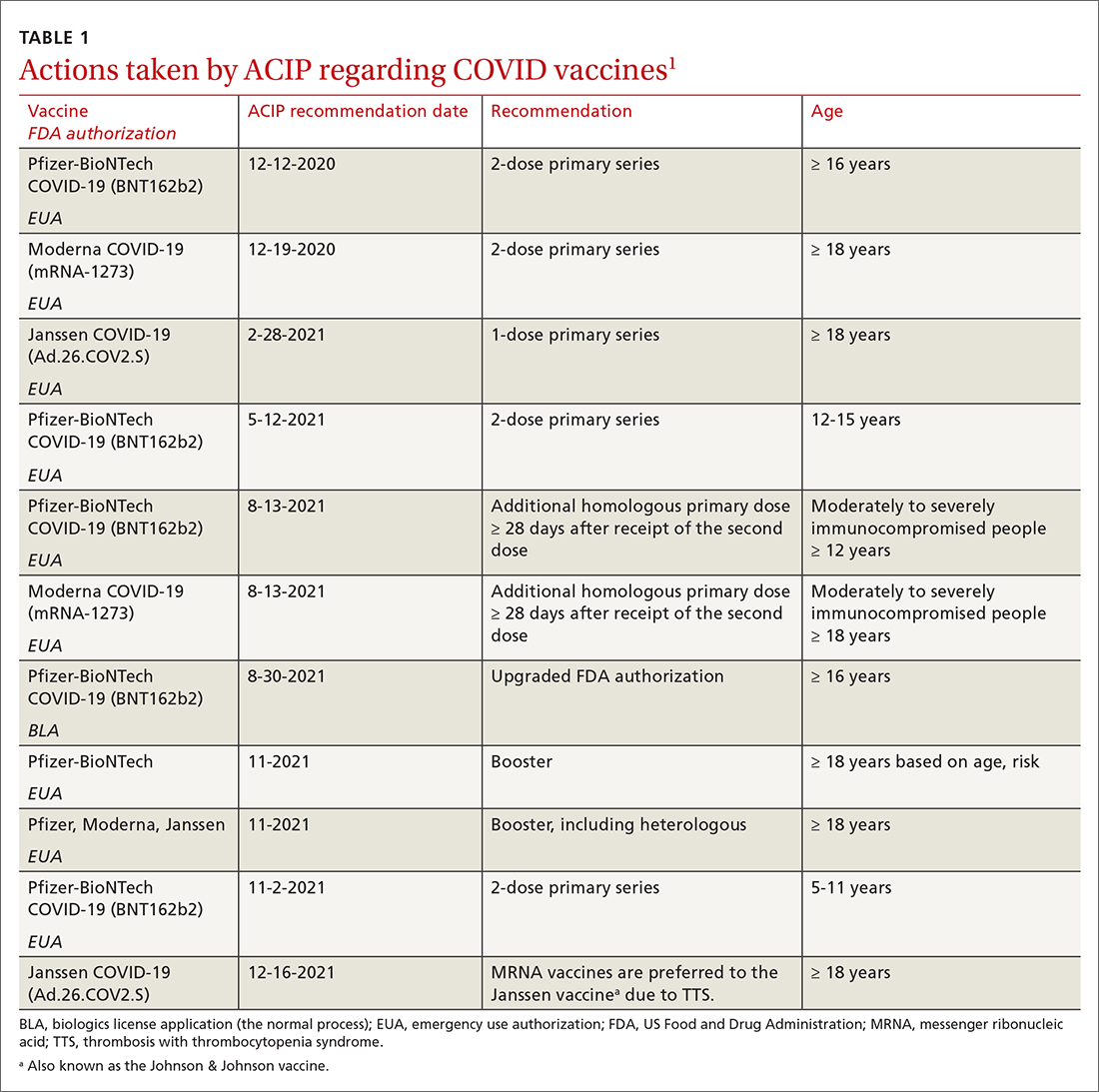

TABLE 11 includes the actions taken by the ACIP from late 2020 through 2021 related to COVID-19 vaccines. All of these recommendations except 1 occurred after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the product using an emergency use authorization (EUA). The exception is the recommendation for use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) for those ages 16 years and older, which was approved under the normal process 8 months after widespread use under an EUA.

Hepatitis B vaccine now for all nonimmune adults up through 59 years

Since the introduction of hepatitis B (HepB) vaccines in 1980, the incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections in the United States has been reduced dramatically; there were an estimated 287,000 cases in 19852 and 19,200 in 2014.3 However, the incidence among adults has not declined in recent years and among someage groups has actually increased. Among those ages 40 to 49 years, the rate went from 1.9 per 100,000 in 20114 to 2.7 per 100,000 population in 2019.5 In those ages 50 to 59, there was an increase from 1.1 to 1.6 per 100,000 population over the same period of time.4,5

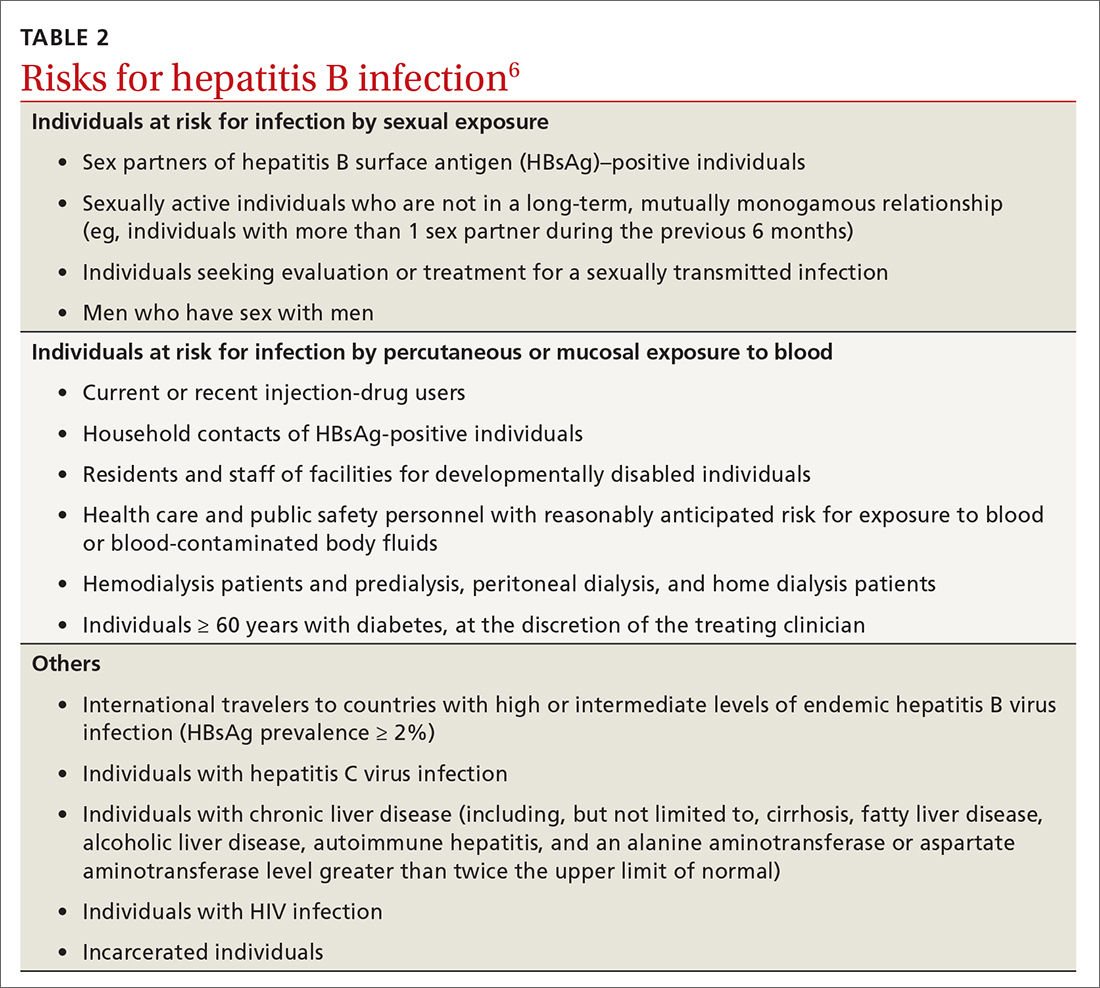

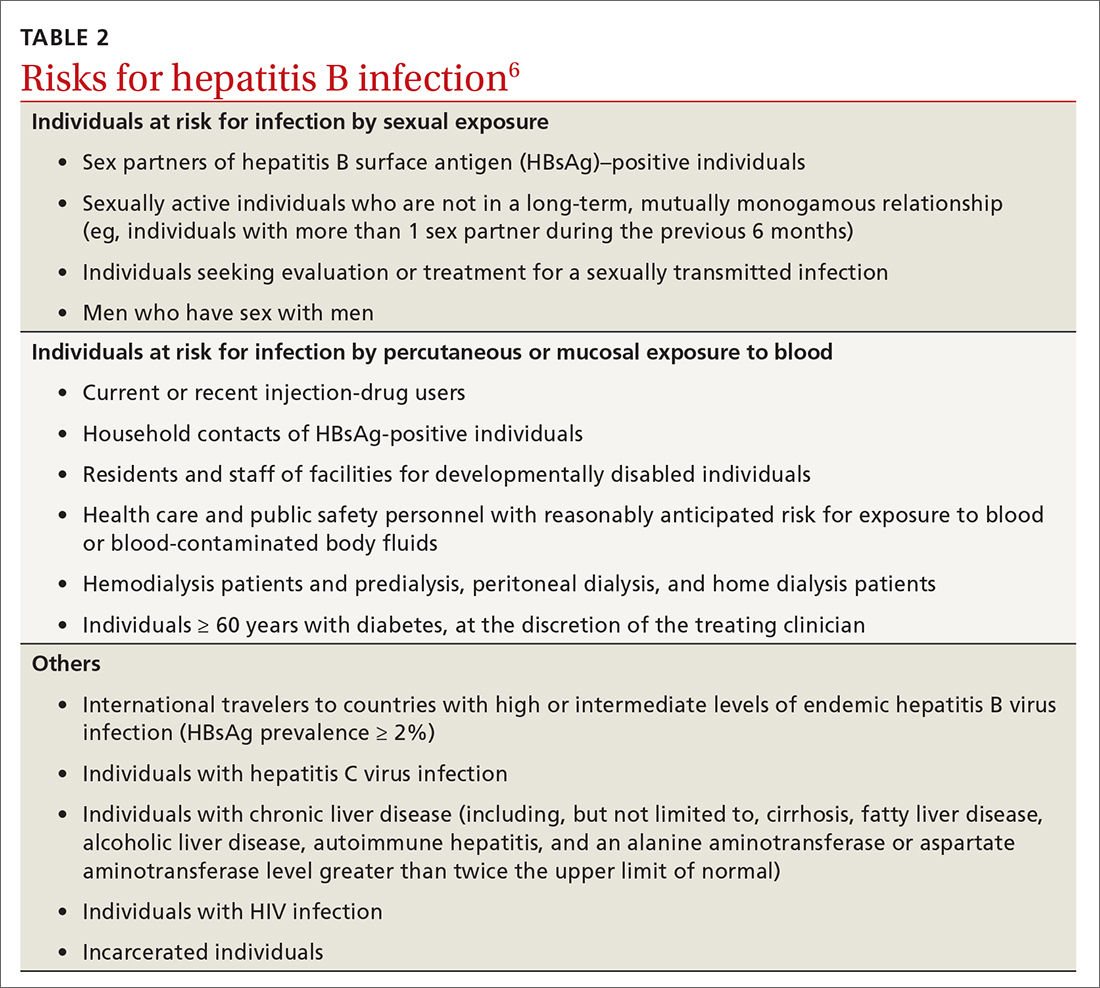

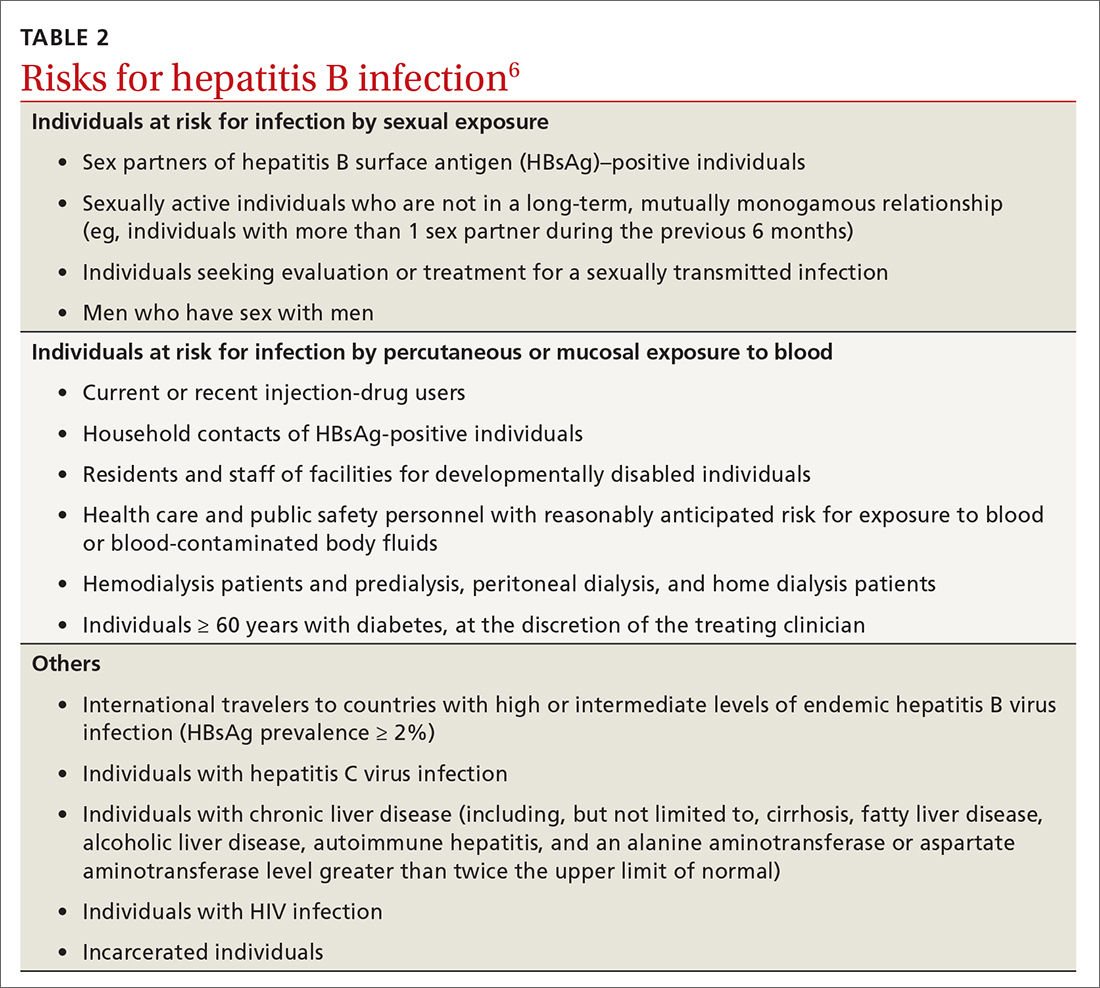

Recommendations for using HepB vaccine in adults have been based on risk that involves individual behavior, occupation, and medical conditions (TABLE 26). The presence of these risk factors is often unknown to medical professionals, who rarely ask about or document them. And patients can be reluctant to disclose them for fear of being stigmatized. The consequence has been a low rate of vaccination in at-risk adults.

At its November 2021 meeting, ACIP accepted the advice of the Hepatitis Work Group to move to a universal adult recommendation through age 59.7 ACIP believed that the incidence of acute infection in those ages 60 and older was too low to merit a universal recommendation. The new recommendation states that

Multiple HepB vaccine products are available for adults. Two are recombinant-based and require 3 doses: Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck). One is recombinant based and requires only 2 doses: Heplisav-B (Dynavax Technologies). A new product recently approved by the FDA, PREHEVBRIO (VBI Vaccines), is another recombinant 3-dose option that the ACIP will consider early in 2022. HepB and HepA vaccines can also be co-administered with Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline).

Pneumococcal vaccines: New PCV vaccines alter prescribing choices

The ACIP recommendations for pneumococcal vaccines in adults have been very confusing, involving 2 vaccines: PCV13 (Prevnar13, Pfizer) and PPSV23 (Pneumovax23, Merck). Both PCV13 and PPSV23 given in series were recommended for immunocompromised patients, but only PPSV23 was recommended for those with chronic medical conditions. For those 65 and older, PPSV23 was recommended for all individuals (including those with no chronic or immunocompromising condition), and PCV13 was recommended for those with immunocompromising conditions. Other adults in this older age group could receive PCV13 based on individual risk and shared clinical decision making.8

Continue to: This past year...

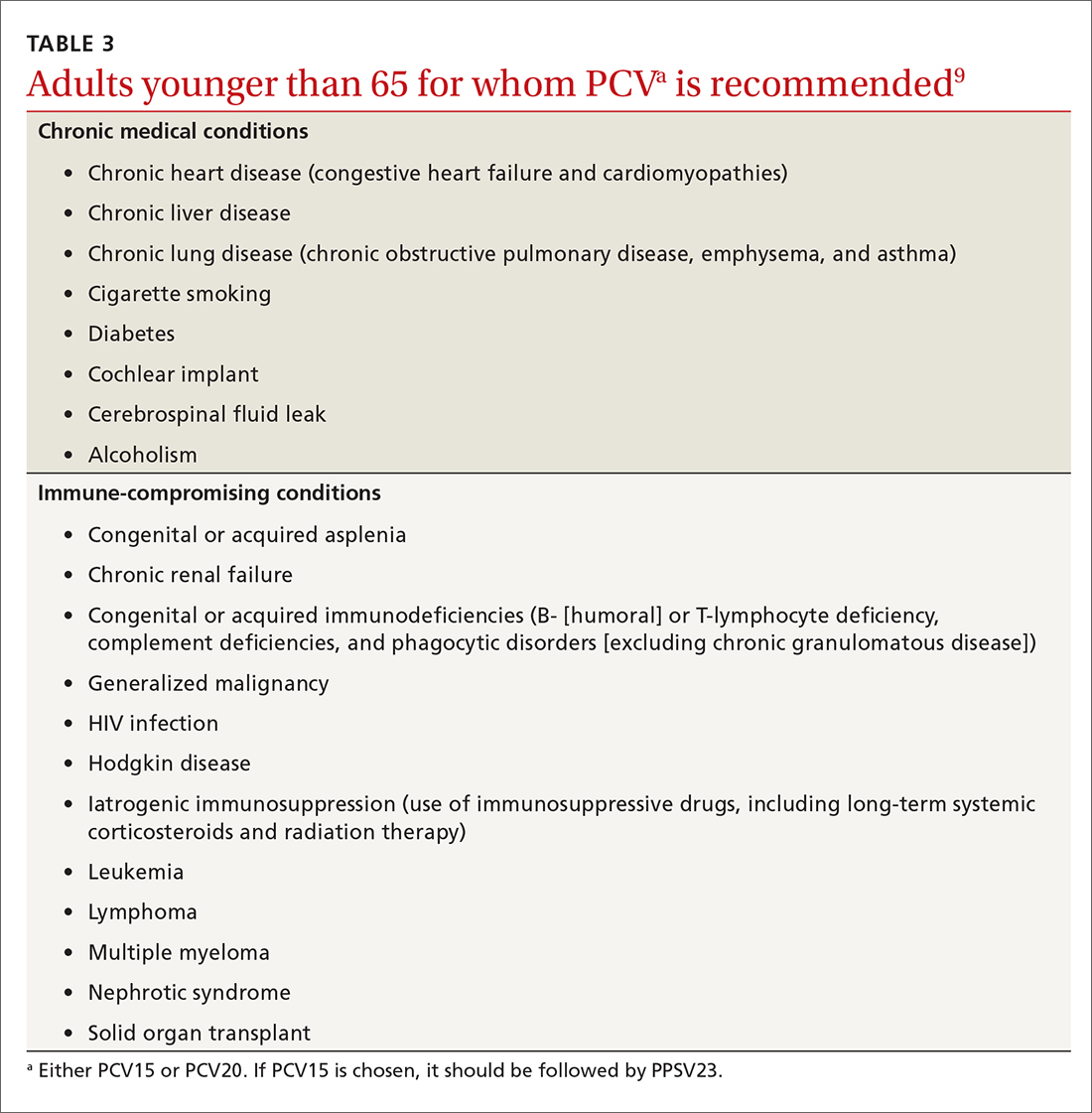

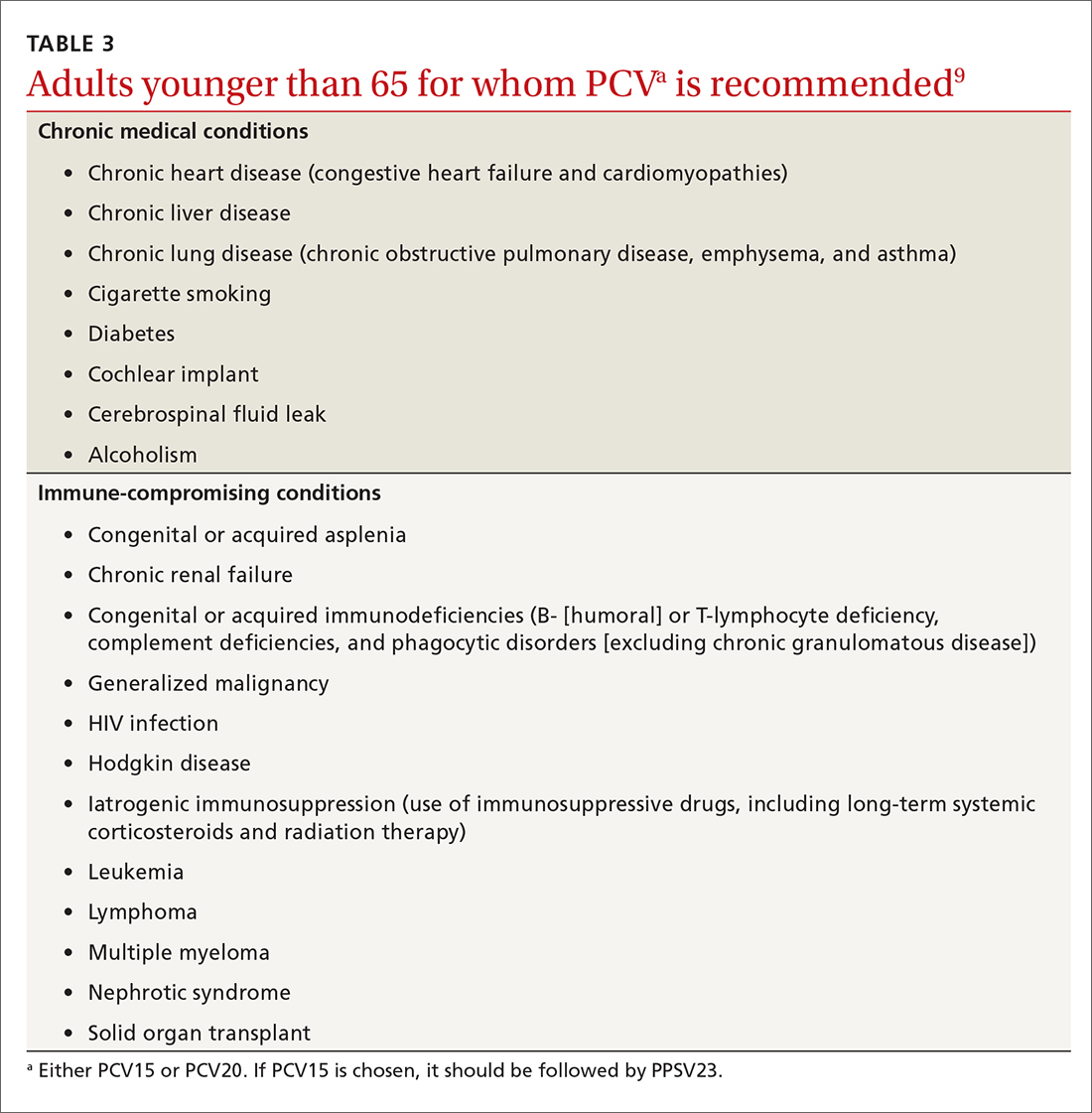

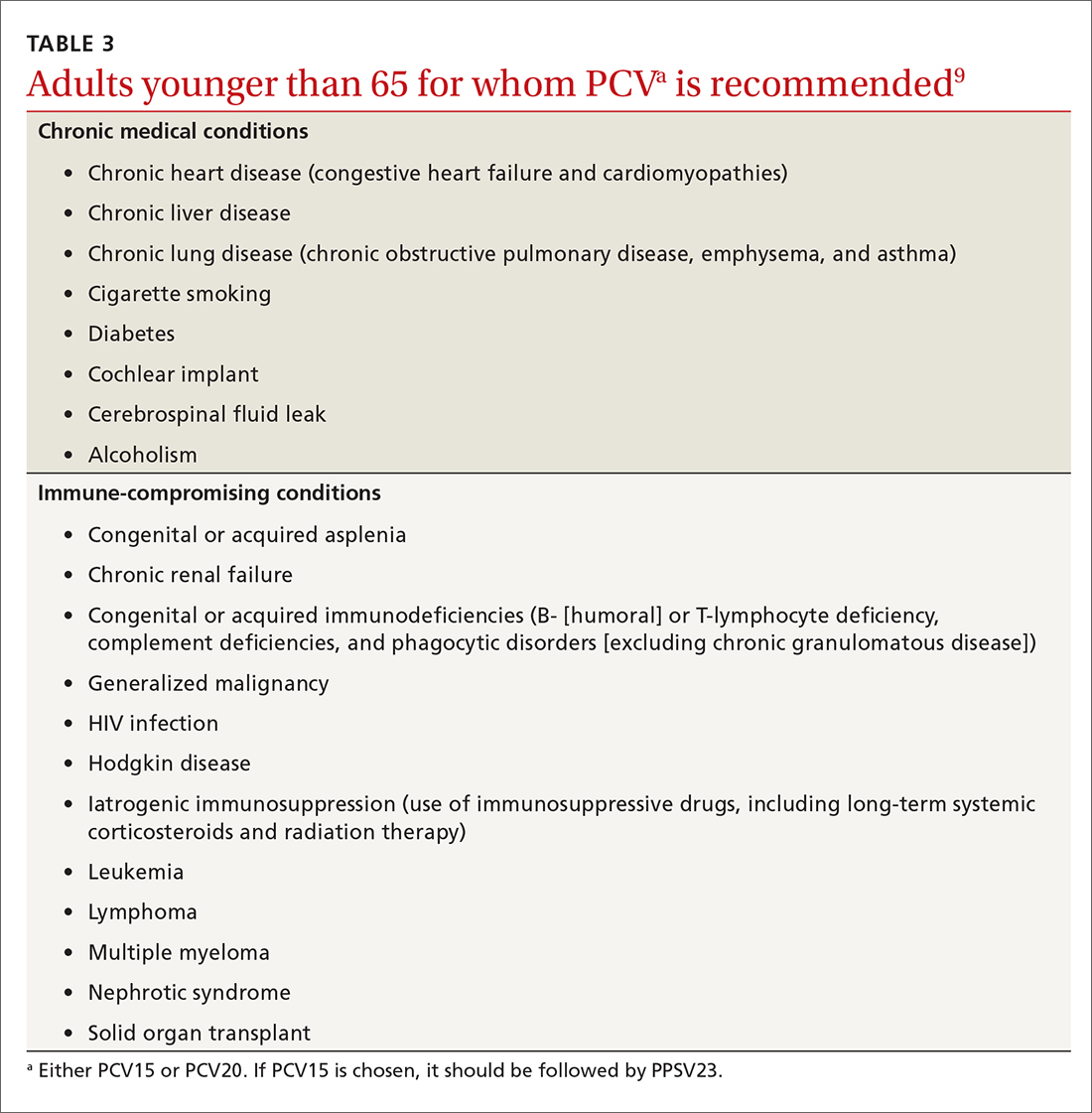

This past year, 2 new PCV vaccines were approved by the FDA: PCV15 (Vaxneuvance, Merck) and PCV20 (Prevnar20, Pfizer). While considering these new vaccines, the ACIP re-assessed its entire approval of pneumococcal vaccines. First, they retained the cutoff for universal pneumococcal vaccination at 65 years. For those younger than 65, they combined chronic medical conditions and immunocompromising conditions into a single at-risk group (TABLE 39). They then issued the same recommendation for older adults and those younger than 65 with risks: to receive a PCV vaccine, either PCV15 or PCV20. If they receive PCV15, it should be followed by PPSV23. PPSV23 is not recommended for those who receive PCV20. Therefore,

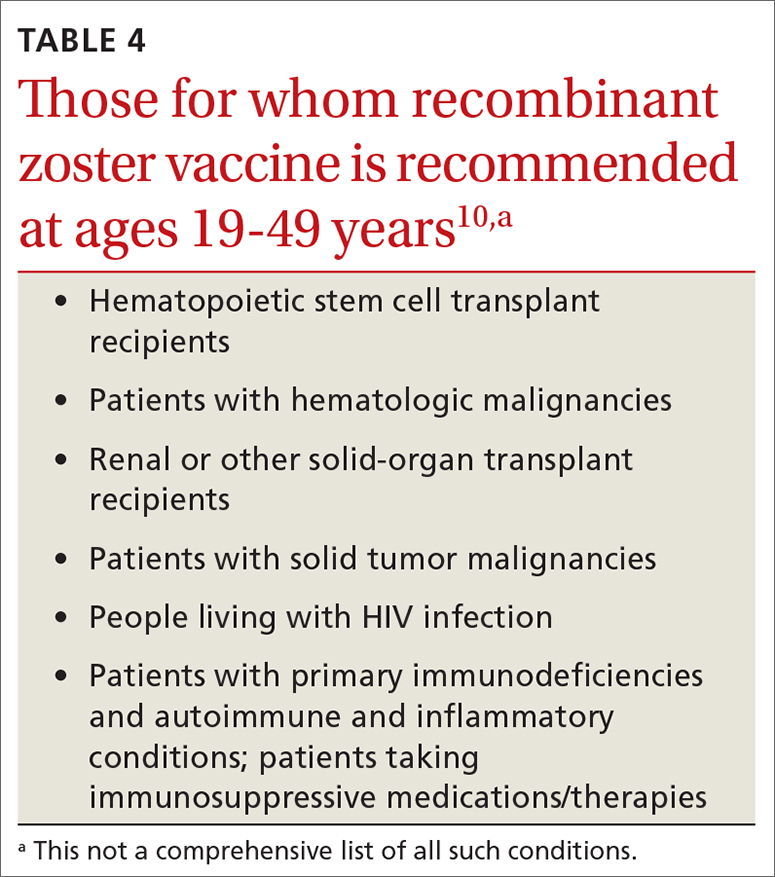

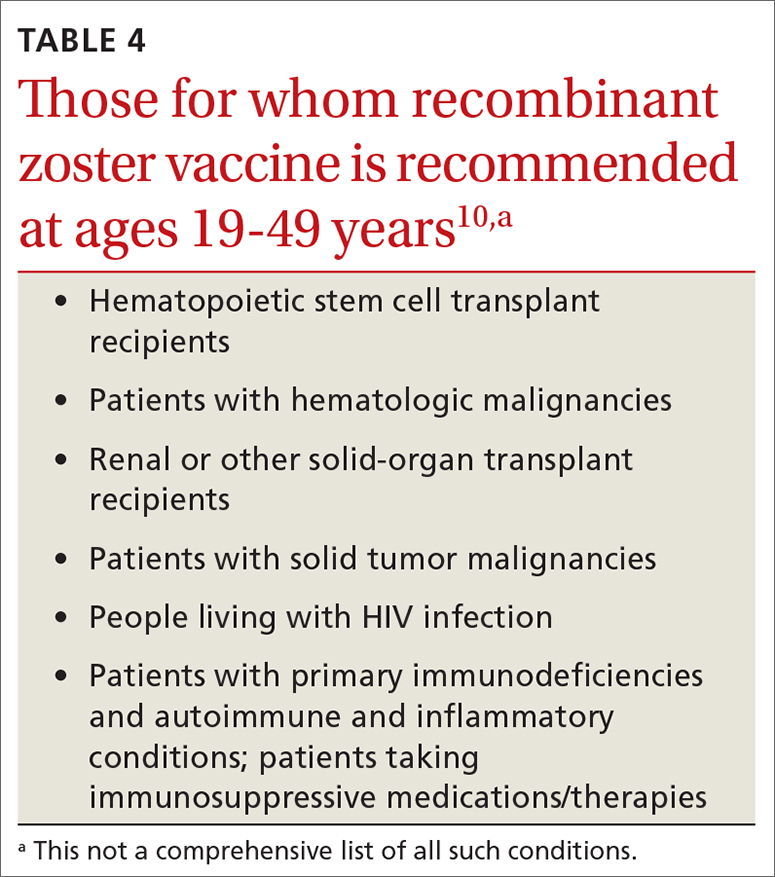

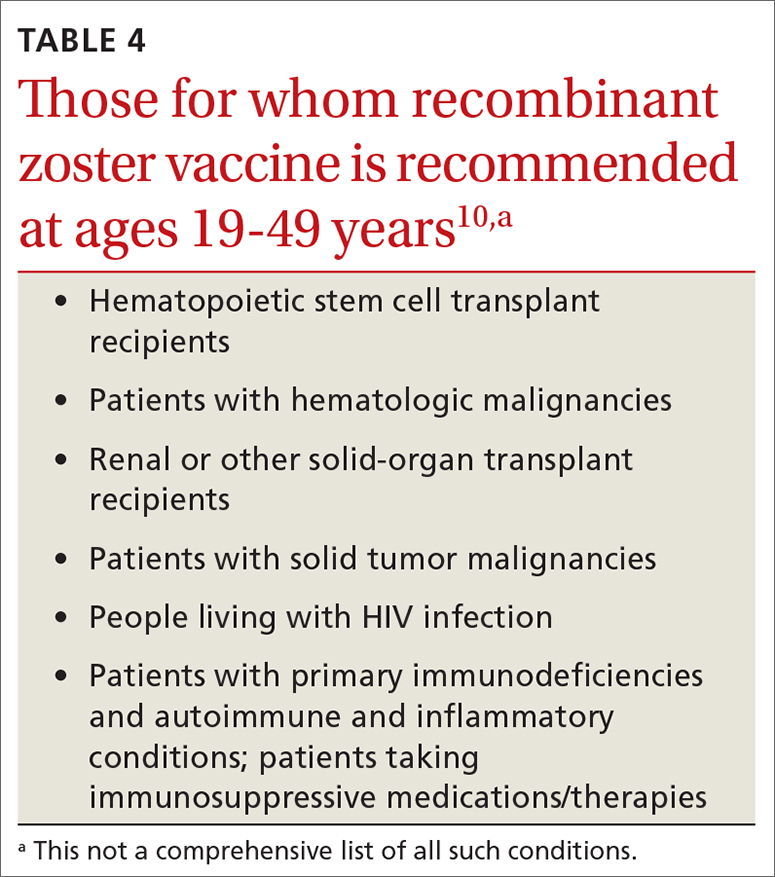

Recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV) has been licensed and recommended in the United States since 2017 in a 2-dose schedule for adults ages 50 years and older. In the summer of 2021, the FDA expanded the indication for use of RZV to include individuals 18 to 49 years of age who are or will be immunodeficient or immunosuppressed due to known disease or therapy. In October, the ACIP agreed and recommended 2 RZV doses for those 19 years and older in these risk groups (TABLE 410).

This recommendation was based on the elevated risk of herpes zoster documented in those with immune-suppressing conditions and therapies. In the conditions studied, the incidence in these younger adults exceeded that for older adults, for whom the vaccine is recommended.10 There are many immune conditions and immune-suppressing medications. The ACIP Zoster Work Group did not have efficacy and safety information on the use of RZV in each one of them, even though their recommendation includes them all. Many of these patients are under the care of specialists whose specialty societies had been recommending zoster vaccine for their patients, off label, prior to the FDA authorization.

Rabies vaccine is now available in 2-dose schedule

People who should receive rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with rabies vaccine include laboratory personnel who work with rabies virus, biologists who work with bats, animal care professionals, wildlife biologists, veterinarians, and travelers who may be at risk of encountering rabid dogs. The recommendation has been for 3 doses of rabies vaccine at 0, 7, and 21-28 days. The ACIP voted at its June 2021 meeting to adopt a 2-dose PrEP schedule of 0 and 7 days.11 This will be especially helpful to travelers who want to complete the recommended doses prior to departure. Those who have sustained risk over time can elect to have a third dose after 21 days and before 3 years, or elect to have titers checked. More detailed clinical advice will be published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 2022.

Dengue vaccine: New rec for those 9-16 years

In 2019, the FDA approved the first dengue vaccine for use in the United States for children 9 to 16 years old who had laboratory-confirmed previous dengue virus infection and who were living in an area where dengue is endemic. The CYD-TDV dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia) is a live-attenuated tetravalent vaccine built on a yellow fever vaccine backbone. Its effectiveness is 82% for prevention of symptomatic dengue, 79% for prevention of dengue-associated hospitalizations, and 84% against severe dengue.12

Continue to: Dengue viruses...

Dengue viruses (DENV) are transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. There are 4 serotypes of dengue, and all 4 appear to be circulating in most endemic countries. Clinical disease varies from a mild febrile illness to severe disease. The most common clinical presentation includes sudden onset of fever, headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia and arthralgia, abdominal pain, and nausea.

Severe disease includes plasma leakage, shock, respiratory distress, severe bleeding, and organ failure. While severe dengue can occur with a primary infection, a second infection with a different DENV increases the risk of severe dengue. A small increased risk of severe dengue occurs when dengue infection occurs after vaccination in those with no evidence of previous dengue infection. It is felt that the vaccine serves as a primary infection that increases the risk of severe dengue with subsequent infections. This is the reason that the vaccine is recommended only for those with a documented previous dengue infection.

At its June 2021 meeting, the ACIP recommended 3-doses of Dengvaxia, administered at 0, 6, and 12 months, for individuals 9 to 16 years of age who have laboratory confirmation of previous dengue infection and live in endemic areas.12 These areas include the territories and affiliated states of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, US Virgin Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau. Puerto Rico accounts for 85% of the population of these areas and 95% of reported dengue cases.12The reason for the delay between FDA approval and the ACIP recommendation was the need to wait for a readily available, accurate laboratory test to confirm previous dengue infection, which is now available. There are other dengue vaccines in development including 2 live-attenuated, tetravalent vaccine candidates in Phase 3 trials.

1. ACIP. COVID-19 vaccine recommendations. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/covid-19.html

2. CDC. Division of viral hepatitis. Disease burden from viral hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. Accessed February 8 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/PDFs/disease_burden.pdf

3. CDC. Surveillance for viral hepatitis – United States, 2014. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2014surveillance/commentary.htm#:~:text=HEPATITIS%20B-,Acute%20Hepatitis%20B,B%20cases%20occurred%20in%202014

4. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance: United States, 2011. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2011surveillance/pdfs/2011HepSurveillanceRpt.pdf

5. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance report, 2019. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/HepB.htm

6. Schillie S, Harris A, Link-Gelles R, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of a hepatitis B vaccine with a novel adjuvant. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:455-458.

7. CDC. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Meeting recommendations, November 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html

8. Matanock A, Lee G, Gierke R, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1069-1075.

9. Kobayashi M. Considerations for use of PCV15 and PCV20 in U.S. adults. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-02/24-25/05-Pneumococcal-Kobayashi.pdf

10. Anderson TC, Masters NB, Guo A, et al. Use of recombinant zoster vaccine in immunocompromised adults aged ≥19 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:80-84.

11. CDC. ACIP recommendations. June 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

12. Paz-Bailey G. Dengue vaccine. Evidence to recommendation framework. Presented to the ACIP June 24, 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-06/03-Dengue-Paz-Bailey-508.pdf

In a typical year, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has three 1.5- to 2-day meetings to make recommendations for the use of new and existing vaccines in the US population. However, 2021 was not a typical year. Last year, ACIP held 17 meetings for a total of 127 hours. Most of these were related to vaccines to prevent COVID-19. There are now 3 COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use in the United States: the 2-dose mRNA-based Pfizer-BioNTech/Comirnaty and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines and the single-dose adenovirus, vector-based Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 vaccine.

TABLE 11 includes the actions taken by the ACIP from late 2020 through 2021 related to COVID-19 vaccines. All of these recommendations except 1 occurred after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the product using an emergency use authorization (EUA). The exception is the recommendation for use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) for those ages 16 years and older, which was approved under the normal process 8 months after widespread use under an EUA.

Hepatitis B vaccine now for all nonimmune adults up through 59 years

Since the introduction of hepatitis B (HepB) vaccines in 1980, the incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections in the United States has been reduced dramatically; there were an estimated 287,000 cases in 19852 and 19,200 in 2014.3 However, the incidence among adults has not declined in recent years and among someage groups has actually increased. Among those ages 40 to 49 years, the rate went from 1.9 per 100,000 in 20114 to 2.7 per 100,000 population in 2019.5 In those ages 50 to 59, there was an increase from 1.1 to 1.6 per 100,000 population over the same period of time.4,5

Recommendations for using HepB vaccine in adults have been based on risk that involves individual behavior, occupation, and medical conditions (TABLE 26). The presence of these risk factors is often unknown to medical professionals, who rarely ask about or document them. And patients can be reluctant to disclose them for fear of being stigmatized. The consequence has been a low rate of vaccination in at-risk adults.

At its November 2021 meeting, ACIP accepted the advice of the Hepatitis Work Group to move to a universal adult recommendation through age 59.7 ACIP believed that the incidence of acute infection in those ages 60 and older was too low to merit a universal recommendation. The new recommendation states that

Multiple HepB vaccine products are available for adults. Two are recombinant-based and require 3 doses: Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck). One is recombinant based and requires only 2 doses: Heplisav-B (Dynavax Technologies). A new product recently approved by the FDA, PREHEVBRIO (VBI Vaccines), is another recombinant 3-dose option that the ACIP will consider early in 2022. HepB and HepA vaccines can also be co-administered with Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline).

Pneumococcal vaccines: New PCV vaccines alter prescribing choices

The ACIP recommendations for pneumococcal vaccines in adults have been very confusing, involving 2 vaccines: PCV13 (Prevnar13, Pfizer) and PPSV23 (Pneumovax23, Merck). Both PCV13 and PPSV23 given in series were recommended for immunocompromised patients, but only PPSV23 was recommended for those with chronic medical conditions. For those 65 and older, PPSV23 was recommended for all individuals (including those with no chronic or immunocompromising condition), and PCV13 was recommended for those with immunocompromising conditions. Other adults in this older age group could receive PCV13 based on individual risk and shared clinical decision making.8

Continue to: This past year...

This past year, 2 new PCV vaccines were approved by the FDA: PCV15 (Vaxneuvance, Merck) and PCV20 (Prevnar20, Pfizer). While considering these new vaccines, the ACIP re-assessed its entire approval of pneumococcal vaccines. First, they retained the cutoff for universal pneumococcal vaccination at 65 years. For those younger than 65, they combined chronic medical conditions and immunocompromising conditions into a single at-risk group (TABLE 39). They then issued the same recommendation for older adults and those younger than 65 with risks: to receive a PCV vaccine, either PCV15 or PCV20. If they receive PCV15, it should be followed by PPSV23. PPSV23 is not recommended for those who receive PCV20. Therefore,

Recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV) has been licensed and recommended in the United States since 2017 in a 2-dose schedule for adults ages 50 years and older. In the summer of 2021, the FDA expanded the indication for use of RZV to include individuals 18 to 49 years of age who are or will be immunodeficient or immunosuppressed due to known disease or therapy. In October, the ACIP agreed and recommended 2 RZV doses for those 19 years and older in these risk groups (TABLE 410).

This recommendation was based on the elevated risk of herpes zoster documented in those with immune-suppressing conditions and therapies. In the conditions studied, the incidence in these younger adults exceeded that for older adults, for whom the vaccine is recommended.10 There are many immune conditions and immune-suppressing medications. The ACIP Zoster Work Group did not have efficacy and safety information on the use of RZV in each one of them, even though their recommendation includes them all. Many of these patients are under the care of specialists whose specialty societies had been recommending zoster vaccine for their patients, off label, prior to the FDA authorization.

Rabies vaccine is now available in 2-dose schedule

People who should receive rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with rabies vaccine include laboratory personnel who work with rabies virus, biologists who work with bats, animal care professionals, wildlife biologists, veterinarians, and travelers who may be at risk of encountering rabid dogs. The recommendation has been for 3 doses of rabies vaccine at 0, 7, and 21-28 days. The ACIP voted at its June 2021 meeting to adopt a 2-dose PrEP schedule of 0 and 7 days.11 This will be especially helpful to travelers who want to complete the recommended doses prior to departure. Those who have sustained risk over time can elect to have a third dose after 21 days and before 3 years, or elect to have titers checked. More detailed clinical advice will be published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 2022.

Dengue vaccine: New rec for those 9-16 years

In 2019, the FDA approved the first dengue vaccine for use in the United States for children 9 to 16 years old who had laboratory-confirmed previous dengue virus infection and who were living in an area where dengue is endemic. The CYD-TDV dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia) is a live-attenuated tetravalent vaccine built on a yellow fever vaccine backbone. Its effectiveness is 82% for prevention of symptomatic dengue, 79% for prevention of dengue-associated hospitalizations, and 84% against severe dengue.12

Continue to: Dengue viruses...

Dengue viruses (DENV) are transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. There are 4 serotypes of dengue, and all 4 appear to be circulating in most endemic countries. Clinical disease varies from a mild febrile illness to severe disease. The most common clinical presentation includes sudden onset of fever, headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia and arthralgia, abdominal pain, and nausea.

Severe disease includes plasma leakage, shock, respiratory distress, severe bleeding, and organ failure. While severe dengue can occur with a primary infection, a second infection with a different DENV increases the risk of severe dengue. A small increased risk of severe dengue occurs when dengue infection occurs after vaccination in those with no evidence of previous dengue infection. It is felt that the vaccine serves as a primary infection that increases the risk of severe dengue with subsequent infections. This is the reason that the vaccine is recommended only for those with a documented previous dengue infection.

At its June 2021 meeting, the ACIP recommended 3-doses of Dengvaxia, administered at 0, 6, and 12 months, for individuals 9 to 16 years of age who have laboratory confirmation of previous dengue infection and live in endemic areas.12 These areas include the territories and affiliated states of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, US Virgin Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau. Puerto Rico accounts for 85% of the population of these areas and 95% of reported dengue cases.12The reason for the delay between FDA approval and the ACIP recommendation was the need to wait for a readily available, accurate laboratory test to confirm previous dengue infection, which is now available. There are other dengue vaccines in development including 2 live-attenuated, tetravalent vaccine candidates in Phase 3 trials.

In a typical year, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has three 1.5- to 2-day meetings to make recommendations for the use of new and existing vaccines in the US population. However, 2021 was not a typical year. Last year, ACIP held 17 meetings for a total of 127 hours. Most of these were related to vaccines to prevent COVID-19. There are now 3 COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use in the United States: the 2-dose mRNA-based Pfizer-BioNTech/Comirnaty and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines and the single-dose adenovirus, vector-based Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 vaccine.

TABLE 11 includes the actions taken by the ACIP from late 2020 through 2021 related to COVID-19 vaccines. All of these recommendations except 1 occurred after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the product using an emergency use authorization (EUA). The exception is the recommendation for use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) for those ages 16 years and older, which was approved under the normal process 8 months after widespread use under an EUA.

Hepatitis B vaccine now for all nonimmune adults up through 59 years

Since the introduction of hepatitis B (HepB) vaccines in 1980, the incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections in the United States has been reduced dramatically; there were an estimated 287,000 cases in 19852 and 19,200 in 2014.3 However, the incidence among adults has not declined in recent years and among someage groups has actually increased. Among those ages 40 to 49 years, the rate went from 1.9 per 100,000 in 20114 to 2.7 per 100,000 population in 2019.5 In those ages 50 to 59, there was an increase from 1.1 to 1.6 per 100,000 population over the same period of time.4,5

Recommendations for using HepB vaccine in adults have been based on risk that involves individual behavior, occupation, and medical conditions (TABLE 26). The presence of these risk factors is often unknown to medical professionals, who rarely ask about or document them. And patients can be reluctant to disclose them for fear of being stigmatized. The consequence has been a low rate of vaccination in at-risk adults.

At its November 2021 meeting, ACIP accepted the advice of the Hepatitis Work Group to move to a universal adult recommendation through age 59.7 ACIP believed that the incidence of acute infection in those ages 60 and older was too low to merit a universal recommendation. The new recommendation states that

Multiple HepB vaccine products are available for adults. Two are recombinant-based and require 3 doses: Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck). One is recombinant based and requires only 2 doses: Heplisav-B (Dynavax Technologies). A new product recently approved by the FDA, PREHEVBRIO (VBI Vaccines), is another recombinant 3-dose option that the ACIP will consider early in 2022. HepB and HepA vaccines can also be co-administered with Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline).

Pneumococcal vaccines: New PCV vaccines alter prescribing choices

The ACIP recommendations for pneumococcal vaccines in adults have been very confusing, involving 2 vaccines: PCV13 (Prevnar13, Pfizer) and PPSV23 (Pneumovax23, Merck). Both PCV13 and PPSV23 given in series were recommended for immunocompromised patients, but only PPSV23 was recommended for those with chronic medical conditions. For those 65 and older, PPSV23 was recommended for all individuals (including those with no chronic or immunocompromising condition), and PCV13 was recommended for those with immunocompromising conditions. Other adults in this older age group could receive PCV13 based on individual risk and shared clinical decision making.8

Continue to: This past year...

This past year, 2 new PCV vaccines were approved by the FDA: PCV15 (Vaxneuvance, Merck) and PCV20 (Prevnar20, Pfizer). While considering these new vaccines, the ACIP re-assessed its entire approval of pneumococcal vaccines. First, they retained the cutoff for universal pneumococcal vaccination at 65 years. For those younger than 65, they combined chronic medical conditions and immunocompromising conditions into a single at-risk group (TABLE 39). They then issued the same recommendation for older adults and those younger than 65 with risks: to receive a PCV vaccine, either PCV15 or PCV20. If they receive PCV15, it should be followed by PPSV23. PPSV23 is not recommended for those who receive PCV20. Therefore,

Recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV) has been licensed and recommended in the United States since 2017 in a 2-dose schedule for adults ages 50 years and older. In the summer of 2021, the FDA expanded the indication for use of RZV to include individuals 18 to 49 years of age who are or will be immunodeficient or immunosuppressed due to known disease or therapy. In October, the ACIP agreed and recommended 2 RZV doses for those 19 years and older in these risk groups (TABLE 410).

This recommendation was based on the elevated risk of herpes zoster documented in those with immune-suppressing conditions and therapies. In the conditions studied, the incidence in these younger adults exceeded that for older adults, for whom the vaccine is recommended.10 There are many immune conditions and immune-suppressing medications. The ACIP Zoster Work Group did not have efficacy and safety information on the use of RZV in each one of them, even though their recommendation includes them all. Many of these patients are under the care of specialists whose specialty societies had been recommending zoster vaccine for their patients, off label, prior to the FDA authorization.

Rabies vaccine is now available in 2-dose schedule

People who should receive rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with rabies vaccine include laboratory personnel who work with rabies virus, biologists who work with bats, animal care professionals, wildlife biologists, veterinarians, and travelers who may be at risk of encountering rabid dogs. The recommendation has been for 3 doses of rabies vaccine at 0, 7, and 21-28 days. The ACIP voted at its June 2021 meeting to adopt a 2-dose PrEP schedule of 0 and 7 days.11 This will be especially helpful to travelers who want to complete the recommended doses prior to departure. Those who have sustained risk over time can elect to have a third dose after 21 days and before 3 years, or elect to have titers checked. More detailed clinical advice will be published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 2022.

Dengue vaccine: New rec for those 9-16 years

In 2019, the FDA approved the first dengue vaccine for use in the United States for children 9 to 16 years old who had laboratory-confirmed previous dengue virus infection and who were living in an area where dengue is endemic. The CYD-TDV dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia) is a live-attenuated tetravalent vaccine built on a yellow fever vaccine backbone. Its effectiveness is 82% for prevention of symptomatic dengue, 79% for prevention of dengue-associated hospitalizations, and 84% against severe dengue.12

Continue to: Dengue viruses...

Dengue viruses (DENV) are transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. There are 4 serotypes of dengue, and all 4 appear to be circulating in most endemic countries. Clinical disease varies from a mild febrile illness to severe disease. The most common clinical presentation includes sudden onset of fever, headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia and arthralgia, abdominal pain, and nausea.

Severe disease includes plasma leakage, shock, respiratory distress, severe bleeding, and organ failure. While severe dengue can occur with a primary infection, a second infection with a different DENV increases the risk of severe dengue. A small increased risk of severe dengue occurs when dengue infection occurs after vaccination in those with no evidence of previous dengue infection. It is felt that the vaccine serves as a primary infection that increases the risk of severe dengue with subsequent infections. This is the reason that the vaccine is recommended only for those with a documented previous dengue infection.

At its June 2021 meeting, the ACIP recommended 3-doses of Dengvaxia, administered at 0, 6, and 12 months, for individuals 9 to 16 years of age who have laboratory confirmation of previous dengue infection and live in endemic areas.12 These areas include the territories and affiliated states of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, US Virgin Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau. Puerto Rico accounts for 85% of the population of these areas and 95% of reported dengue cases.12The reason for the delay between FDA approval and the ACIP recommendation was the need to wait for a readily available, accurate laboratory test to confirm previous dengue infection, which is now available. There are other dengue vaccines in development including 2 live-attenuated, tetravalent vaccine candidates in Phase 3 trials.

1. ACIP. COVID-19 vaccine recommendations. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/covid-19.html

2. CDC. Division of viral hepatitis. Disease burden from viral hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. Accessed February 8 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/PDFs/disease_burden.pdf

3. CDC. Surveillance for viral hepatitis – United States, 2014. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2014surveillance/commentary.htm#:~:text=HEPATITIS%20B-,Acute%20Hepatitis%20B,B%20cases%20occurred%20in%202014

4. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance: United States, 2011. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2011surveillance/pdfs/2011HepSurveillanceRpt.pdf

5. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance report, 2019. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/HepB.htm

6. Schillie S, Harris A, Link-Gelles R, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of a hepatitis B vaccine with a novel adjuvant. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:455-458.

7. CDC. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Meeting recommendations, November 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html

8. Matanock A, Lee G, Gierke R, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1069-1075.

9. Kobayashi M. Considerations for use of PCV15 and PCV20 in U.S. adults. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-02/24-25/05-Pneumococcal-Kobayashi.pdf

10. Anderson TC, Masters NB, Guo A, et al. Use of recombinant zoster vaccine in immunocompromised adults aged ≥19 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:80-84.

11. CDC. ACIP recommendations. June 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

12. Paz-Bailey G. Dengue vaccine. Evidence to recommendation framework. Presented to the ACIP June 24, 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-06/03-Dengue-Paz-Bailey-508.pdf

1. ACIP. COVID-19 vaccine recommendations. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/covid-19.html

2. CDC. Division of viral hepatitis. Disease burden from viral hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. Accessed February 8 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/PDFs/disease_burden.pdf

3. CDC. Surveillance for viral hepatitis – United States, 2014. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2014surveillance/commentary.htm#:~:text=HEPATITIS%20B-,Acute%20Hepatitis%20B,B%20cases%20occurred%20in%202014

4. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance: United States, 2011. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2011surveillance/pdfs/2011HepSurveillanceRpt.pdf

5. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance report, 2019. Hepatitis B. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/HepB.htm

6. Schillie S, Harris A, Link-Gelles R, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of a hepatitis B vaccine with a novel adjuvant. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:455-458.

7. CDC. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Meeting recommendations, November 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html

8. Matanock A, Lee G, Gierke R, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1069-1075.

9. Kobayashi M. Considerations for use of PCV15 and PCV20 in U.S. adults. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-02/24-25/05-Pneumococcal-Kobayashi.pdf

10. Anderson TC, Masters NB, Guo A, et al. Use of recombinant zoster vaccine in immunocompromised adults aged ≥19 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:80-84.

11. CDC. ACIP recommendations. June 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

12. Paz-Bailey G. Dengue vaccine. Evidence to recommendation framework. Presented to the ACIP June 24, 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-06/03-Dengue-Paz-Bailey-508.pdf

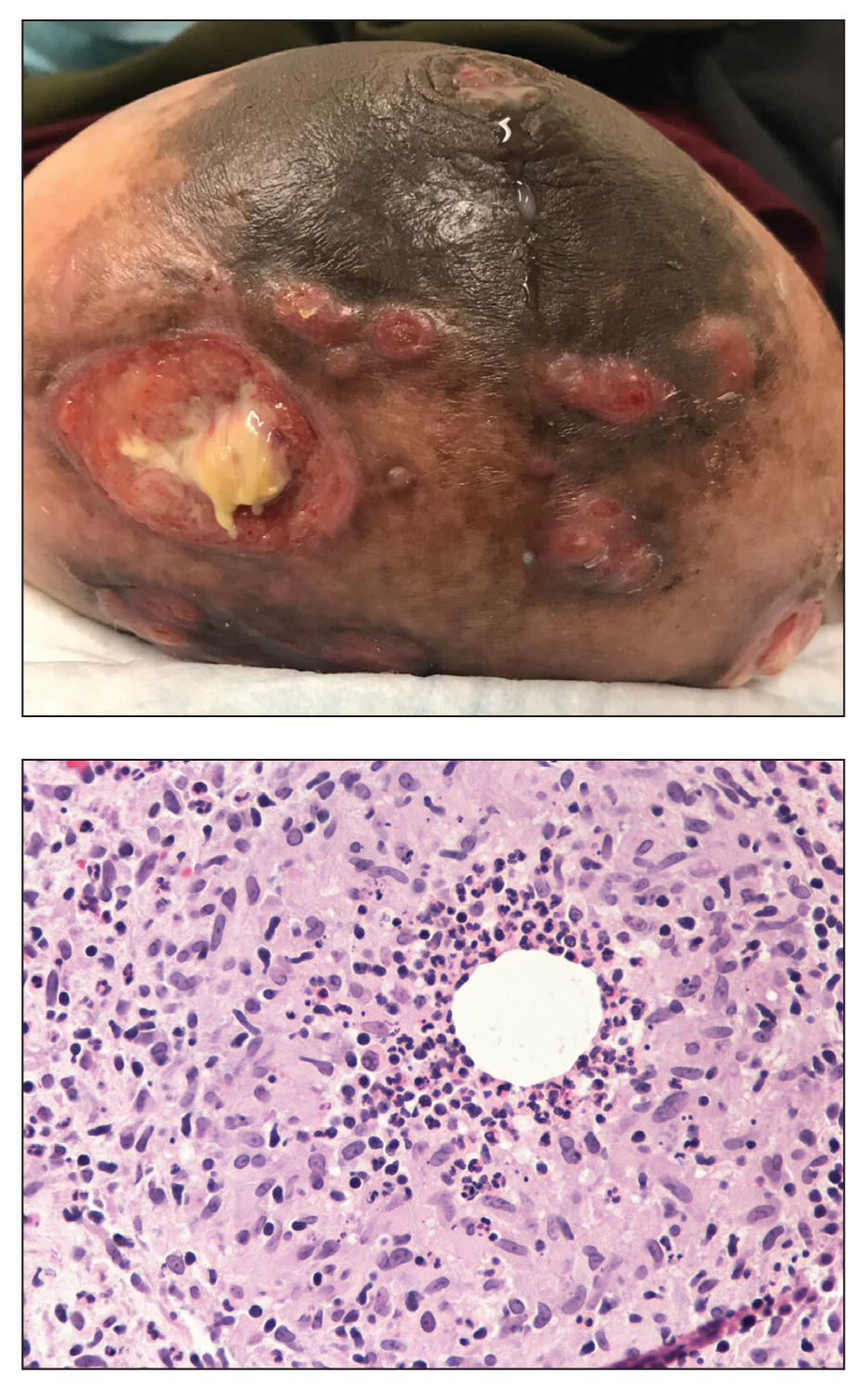

Painful Ulcerating Lesions on the Breast

The Diagnosis: Cystic Neutrophilic Granulomatous Mastitis

The histopathologic findings in our patient were characteristic of cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis (CNGM), a rare granulomatous mastitis associated with Corynebacterium and suppurative lipogranulomas. Although not seen in our patient, the lipid vacuoles may contain gram-positive bacilli.1 The surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate contains Langerhans giant cells, lymphocytes, and neutrophils. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis is seen in parous women of reproductive age. Physical examination demonstrates a palpable painful mass on the breast. Wound cultures frequently are negative, likely due to difficulty culturing Corynebacterium and prophylactic antibiotic treatment. Given the association with Corynebacterium species, early diagnosis of CNGM is essential in offering patients the most appropriate treatment. Prolonged antibiotic therapy specifically directed to corynebacteria is required, sometimes even beyond resolution of clinical symptoms. The diagnosis of CNGM often is missed or delayed due to its rarity and many potential mimickers. Clinically, CNGM may be virtually impossible to discern from invasive carcinoma.1

Our patient was treated with vancomycin and cefepime with incision and drainage as an inpatient. Upon discharge, she was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg daily tapered by 10 mg every 5 days over 1 month and doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She was then transitioned to topical hydrocortisone and bacitracin; she reported decreased swelling and pain. No new lesions formed after the initiation of therapy; however, most lesions remained open. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis remains a challenging entity to treat, with a variable response rate reported in the literature for antibiotics such as doxycycline and systemic and topical steroids as well as immunosuppressants including methotrexate.2,3

Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis can be distinguished from hidradenitis suppurativa clinically because ulcerating lesions can involve the superior portions of the breast in CNGM, whereas hidradenitis suppurativa typically is restricted to the lower intertriginous parts of the breast. Other mimics of CNGM can be distinguished with biopsy. Histology of pyoderma gangrenosum lacks prominent granuloma formation. Although sarcoidosis and mycobacterial infection show prominent granulomas, neither show the characteristic lipogranulomas seen in CNGM. Additionally, the granulomas of sarcoidosis are much larger and deeper than CNGM. Mycobacterial granulomas also typically reveal bacilli with acid-fast bacilli staining or via wound culture.

- Wu JM, Turashvili G. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis: an update. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:445-453. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2019-206180

- Steuer AB, Stern MJ, Cobos G, et al. Clinical characteristics and medical management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:460-464. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4516

- Dobinson HC, Anderson TP, Chambers ST, et al. Antimicrobial treatment options for granulomatous mastitis caused by Corynebacterium species [published online July 1, 2015]. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2895-2899. doi:10.1128/JCM.00760-15

The Diagnosis: Cystic Neutrophilic Granulomatous Mastitis

The histopathologic findings in our patient were characteristic of cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis (CNGM), a rare granulomatous mastitis associated with Corynebacterium and suppurative lipogranulomas. Although not seen in our patient, the lipid vacuoles may contain gram-positive bacilli.1 The surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate contains Langerhans giant cells, lymphocytes, and neutrophils. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis is seen in parous women of reproductive age. Physical examination demonstrates a palpable painful mass on the breast. Wound cultures frequently are negative, likely due to difficulty culturing Corynebacterium and prophylactic antibiotic treatment. Given the association with Corynebacterium species, early diagnosis of CNGM is essential in offering patients the most appropriate treatment. Prolonged antibiotic therapy specifically directed to corynebacteria is required, sometimes even beyond resolution of clinical symptoms. The diagnosis of CNGM often is missed or delayed due to its rarity and many potential mimickers. Clinically, CNGM may be virtually impossible to discern from invasive carcinoma.1

Our patient was treated with vancomycin and cefepime with incision and drainage as an inpatient. Upon discharge, she was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg daily tapered by 10 mg every 5 days over 1 month and doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She was then transitioned to topical hydrocortisone and bacitracin; she reported decreased swelling and pain. No new lesions formed after the initiation of therapy; however, most lesions remained open. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis remains a challenging entity to treat, with a variable response rate reported in the literature for antibiotics such as doxycycline and systemic and topical steroids as well as immunosuppressants including methotrexate.2,3

Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis can be distinguished from hidradenitis suppurativa clinically because ulcerating lesions can involve the superior portions of the breast in CNGM, whereas hidradenitis suppurativa typically is restricted to the lower intertriginous parts of the breast. Other mimics of CNGM can be distinguished with biopsy. Histology of pyoderma gangrenosum lacks prominent granuloma formation. Although sarcoidosis and mycobacterial infection show prominent granulomas, neither show the characteristic lipogranulomas seen in CNGM. Additionally, the granulomas of sarcoidosis are much larger and deeper than CNGM. Mycobacterial granulomas also typically reveal bacilli with acid-fast bacilli staining or via wound culture.

The Diagnosis: Cystic Neutrophilic Granulomatous Mastitis

The histopathologic findings in our patient were characteristic of cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis (CNGM), a rare granulomatous mastitis associated with Corynebacterium and suppurative lipogranulomas. Although not seen in our patient, the lipid vacuoles may contain gram-positive bacilli.1 The surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate contains Langerhans giant cells, lymphocytes, and neutrophils. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis is seen in parous women of reproductive age. Physical examination demonstrates a palpable painful mass on the breast. Wound cultures frequently are negative, likely due to difficulty culturing Corynebacterium and prophylactic antibiotic treatment. Given the association with Corynebacterium species, early diagnosis of CNGM is essential in offering patients the most appropriate treatment. Prolonged antibiotic therapy specifically directed to corynebacteria is required, sometimes even beyond resolution of clinical symptoms. The diagnosis of CNGM often is missed or delayed due to its rarity and many potential mimickers. Clinically, CNGM may be virtually impossible to discern from invasive carcinoma.1

Our patient was treated with vancomycin and cefepime with incision and drainage as an inpatient. Upon discharge, she was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg daily tapered by 10 mg every 5 days over 1 month and doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She was then transitioned to topical hydrocortisone and bacitracin; she reported decreased swelling and pain. No new lesions formed after the initiation of therapy; however, most lesions remained open. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis remains a challenging entity to treat, with a variable response rate reported in the literature for antibiotics such as doxycycline and systemic and topical steroids as well as immunosuppressants including methotrexate.2,3

Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis can be distinguished from hidradenitis suppurativa clinically because ulcerating lesions can involve the superior portions of the breast in CNGM, whereas hidradenitis suppurativa typically is restricted to the lower intertriginous parts of the breast. Other mimics of CNGM can be distinguished with biopsy. Histology of pyoderma gangrenosum lacks prominent granuloma formation. Although sarcoidosis and mycobacterial infection show prominent granulomas, neither show the characteristic lipogranulomas seen in CNGM. Additionally, the granulomas of sarcoidosis are much larger and deeper than CNGM. Mycobacterial granulomas also typically reveal bacilli with acid-fast bacilli staining or via wound culture.

- Wu JM, Turashvili G. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis: an update. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:445-453. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2019-206180

- Steuer AB, Stern MJ, Cobos G, et al. Clinical characteristics and medical management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:460-464. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4516

- Dobinson HC, Anderson TP, Chambers ST, et al. Antimicrobial treatment options for granulomatous mastitis caused by Corynebacterium species [published online July 1, 2015]. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2895-2899. doi:10.1128/JCM.00760-15

- Wu JM, Turashvili G. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis: an update. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:445-453. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2019-206180

- Steuer AB, Stern MJ, Cobos G, et al. Clinical characteristics and medical management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:460-464. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4516

- Dobinson HC, Anderson TP, Chambers ST, et al. Antimicrobial treatment options for granulomatous mastitis caused by Corynebacterium species [published online July 1, 2015]. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2895-2899. doi:10.1128/JCM.00760-15

A 36-year-old puerperal woman presented with painful, unilateral, ulcerating breast lesions (top) of 3 months’ duration that developed during pregnancy and drained pus with blood. No improvement was seen with antibiotics or incision and drainage. Biopsy of a lesion showed stellate granulomas with cystic spaces and suppurative lipogranulomas where central lipid vacuoles were rimmed by neutrophils and an outer cuff of epithelioid histiocytes (bottom). Acid-fast bacilli, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, Gram, and Steiner staining did not reveal any microorganisms. Additionally, wound cultures were negative.

Veterans Potentially Exposed to HIV, HCV at Georgia Hospital

Testing is ongoing after more than 4,600 veterans who had received care at the Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Dublin, Georgia, were alerted that they may have been exposed to HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. The exposure was due to improperly sterilized equipment. At least some of the patients have tested positive, but the facility has not indicated the number, the diseases, or whether the infections were the result of the exposure.

A mid-January internal review at the hospital found that not all steps were being followed in the procedures for sterilizing equipment between patients. Patients who had dentistry, endoscopy, urology, podiatry, optometry, or surgical procedures in 2021 may have been exposed to blood-borne pathogens.

In response, the VA sent teams from other hospitals to help, including a team from the Augusta Veterans Affairs Medical Center to reprocess all equipment and staff from VA facilities in Atlanta, South Carolina, and Alabama to provide personnel training. All staff at Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center have since been retrained on all current guidelines.

The hospital says it’s still testing exposed veterans. Hospital spokesperson James Huckfeldt told a Macon-based newspaper, The Telegraph, that veterans with positive test results will undergo additional testing to determine whether the transmission is new or preexisting. “The findings from the additional testing will be used to accurately diagnose any impacted veterans and ensure that they receive appropriate medical treatment,” he said.

Manuel M. Davila, director of the hospital, sent letters to the patients at risk, alerting them to the exposure. “We sincerely apologize and accept responsibility for this mistake and are taking steps to prevent it from happening in the future,” Davilla wrote. “This event is unacceptable to us as well, and we want to work with you to correct the situation and ensure your safety and well-being. Because your safety is important to us and because we want to honor your trust in us, we want you to know that when concerns are raised over our processes or procedures, we take immediate steps to stop everything and make sure things are.”

Davilla reassured the veterans that “we are confident that the risk of infectious disease is very low.”

The Carl Vinson Medical Center has set up a communication center to answer questions for veterans: (478) 274-5400.

Testing is ongoing after more than 4,600 veterans who had received care at the Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Dublin, Georgia, were alerted that they may have been exposed to HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. The exposure was due to improperly sterilized equipment. At least some of the patients have tested positive, but the facility has not indicated the number, the diseases, or whether the infections were the result of the exposure.

A mid-January internal review at the hospital found that not all steps were being followed in the procedures for sterilizing equipment between patients. Patients who had dentistry, endoscopy, urology, podiatry, optometry, or surgical procedures in 2021 may have been exposed to blood-borne pathogens.

In response, the VA sent teams from other hospitals to help, including a team from the Augusta Veterans Affairs Medical Center to reprocess all equipment and staff from VA facilities in Atlanta, South Carolina, and Alabama to provide personnel training. All staff at Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center have since been retrained on all current guidelines.

The hospital says it’s still testing exposed veterans. Hospital spokesperson James Huckfeldt told a Macon-based newspaper, The Telegraph, that veterans with positive test results will undergo additional testing to determine whether the transmission is new or preexisting. “The findings from the additional testing will be used to accurately diagnose any impacted veterans and ensure that they receive appropriate medical treatment,” he said.

Manuel M. Davila, director of the hospital, sent letters to the patients at risk, alerting them to the exposure. “We sincerely apologize and accept responsibility for this mistake and are taking steps to prevent it from happening in the future,” Davilla wrote. “This event is unacceptable to us as well, and we want to work with you to correct the situation and ensure your safety and well-being. Because your safety is important to us and because we want to honor your trust in us, we want you to know that when concerns are raised over our processes or procedures, we take immediate steps to stop everything and make sure things are.”

Davilla reassured the veterans that “we are confident that the risk of infectious disease is very low.”

The Carl Vinson Medical Center has set up a communication center to answer questions for veterans: (478) 274-5400.

Testing is ongoing after more than 4,600 veterans who had received care at the Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Dublin, Georgia, were alerted that they may have been exposed to HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. The exposure was due to improperly sterilized equipment. At least some of the patients have tested positive, but the facility has not indicated the number, the diseases, or whether the infections were the result of the exposure.

A mid-January internal review at the hospital found that not all steps were being followed in the procedures for sterilizing equipment between patients. Patients who had dentistry, endoscopy, urology, podiatry, optometry, or surgical procedures in 2021 may have been exposed to blood-borne pathogens.

In response, the VA sent teams from other hospitals to help, including a team from the Augusta Veterans Affairs Medical Center to reprocess all equipment and staff from VA facilities in Atlanta, South Carolina, and Alabama to provide personnel training. All staff at Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center have since been retrained on all current guidelines.

The hospital says it’s still testing exposed veterans. Hospital spokesperson James Huckfeldt told a Macon-based newspaper, The Telegraph, that veterans with positive test results will undergo additional testing to determine whether the transmission is new or preexisting. “The findings from the additional testing will be used to accurately diagnose any impacted veterans and ensure that they receive appropriate medical treatment,” he said.

Manuel M. Davila, director of the hospital, sent letters to the patients at risk, alerting them to the exposure. “We sincerely apologize and accept responsibility for this mistake and are taking steps to prevent it from happening in the future,” Davilla wrote. “This event is unacceptable to us as well, and we want to work with you to correct the situation and ensure your safety and well-being. Because your safety is important to us and because we want to honor your trust in us, we want you to know that when concerns are raised over our processes or procedures, we take immediate steps to stop everything and make sure things are.”

Davilla reassured the veterans that “we are confident that the risk of infectious disease is very low.”

The Carl Vinson Medical Center has set up a communication center to answer questions for veterans: (478) 274-5400.

Reactivation of a BCG Vaccination Scar Following the First Dose of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine