User login

Children and COVID: CDC gives perspective on hospitalizations

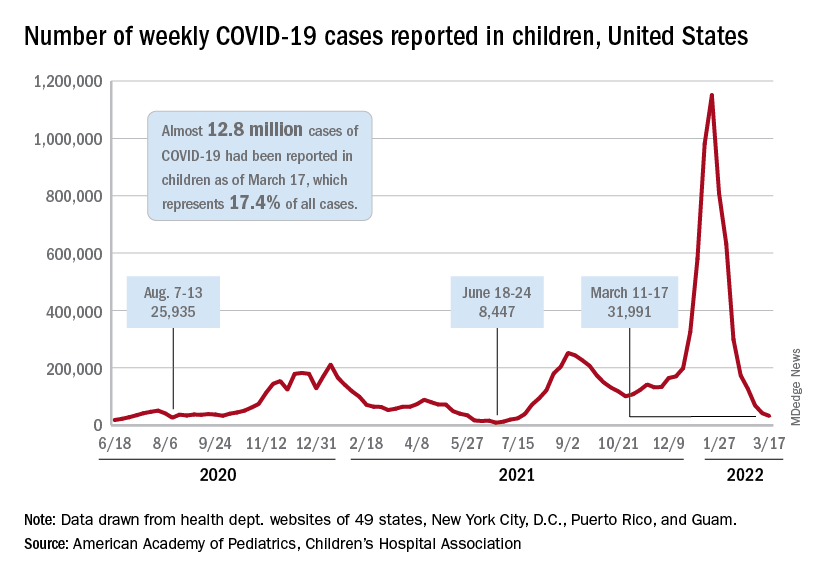

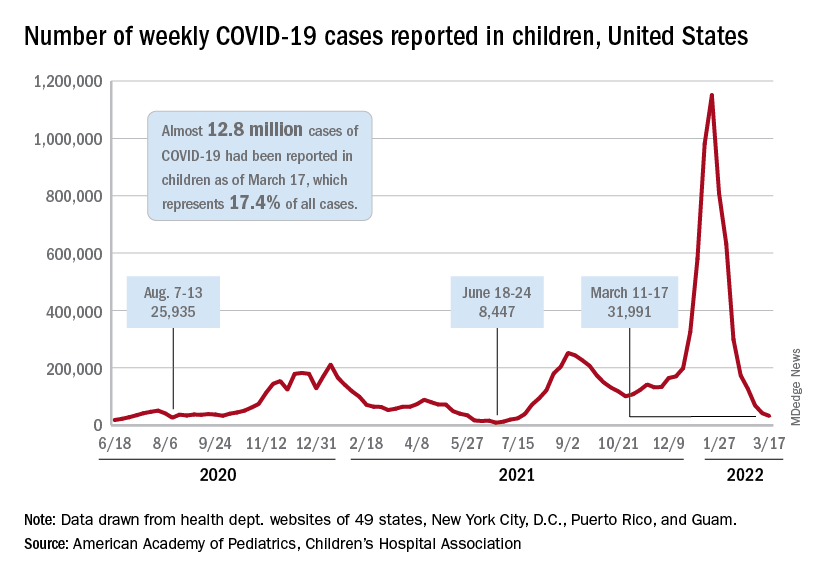

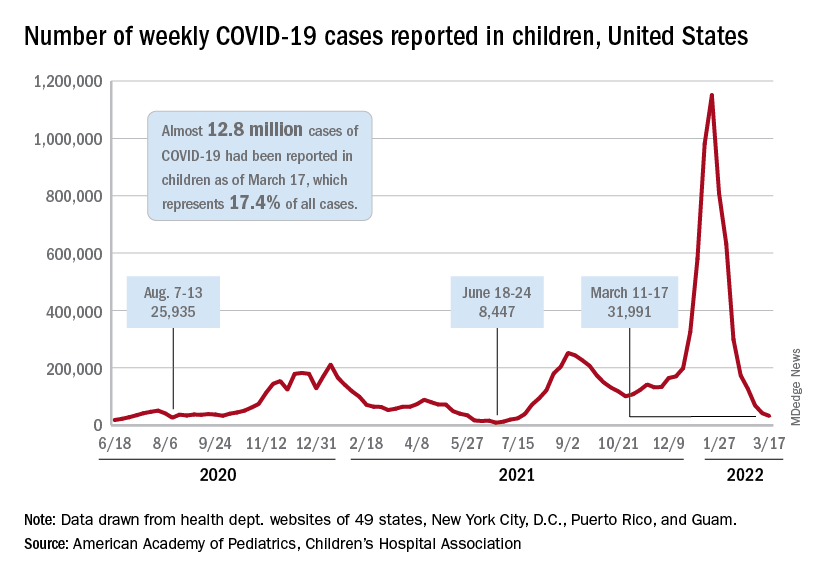

New COVID-19 cases in children fell by 23% as the latest weekly count dropped to its lowest level since July of 2021, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when the early stages of the Delta surge led to 23,551 cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The two organizations put the total number of cases at nearly 12.8 million from the start of the pandemic to March 17, with children representing 19.0% of cases among all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases at almost 12.0 million as of March 21, or 17.5% of the nationwide total.

COVID-related hospitalizations also continue to fall, and two new studies from the CDC put children’s experiences during the Omicron surge and the larger pandemic into perspective.

One study showed that hospitalization rates for children aged 4 years and younger during the Omicron surge were five times higher than at the peak of the Delta surge, with the highest rates occurring in infants under 6 months of age. That report was based on the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET), which covers 99 counties across 14 states (MMWR. 2022 March 18;71[11]:429-36).

The second study compared child hospitalizations during 1 year of the COVID pandemic (Oct. 1, 2020, to Sept. 30, 2021) with three influenza seasons (2017-2018 through 2019-2020). The pre-Omicron hospitalization rate for those under age 18 years, 48.2 per 100,000 children, was higher than any of the three flu seasons: 33.5 per 100,000 in 2017-2018, 33.8 in 2018-2019, and 41.7 for 2019-2020, the investigators said in a medRxiv preprint.

Most of the increased COVID burden fell on adolescents aged 12-17, they said. The COVID hospitalization rate for that age group was 59.9 per 100,000, versus 12.2-14.1 for influenza, while children aged 5-11 had a COVID-related rate of 25.0 and flu-related rates of 24.3-31.7, and those aged 0-4 had rates of 66.8 for COVID and 70.9-91.5 for the flu, Miranda J. Delahoy of the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team and associates reported.

New COVID-19 cases in children fell by 23% as the latest weekly count dropped to its lowest level since July of 2021, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when the early stages of the Delta surge led to 23,551 cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The two organizations put the total number of cases at nearly 12.8 million from the start of the pandemic to March 17, with children representing 19.0% of cases among all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases at almost 12.0 million as of March 21, or 17.5% of the nationwide total.

COVID-related hospitalizations also continue to fall, and two new studies from the CDC put children’s experiences during the Omicron surge and the larger pandemic into perspective.

One study showed that hospitalization rates for children aged 4 years and younger during the Omicron surge were five times higher than at the peak of the Delta surge, with the highest rates occurring in infants under 6 months of age. That report was based on the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET), which covers 99 counties across 14 states (MMWR. 2022 March 18;71[11]:429-36).

The second study compared child hospitalizations during 1 year of the COVID pandemic (Oct. 1, 2020, to Sept. 30, 2021) with three influenza seasons (2017-2018 through 2019-2020). The pre-Omicron hospitalization rate for those under age 18 years, 48.2 per 100,000 children, was higher than any of the three flu seasons: 33.5 per 100,000 in 2017-2018, 33.8 in 2018-2019, and 41.7 for 2019-2020, the investigators said in a medRxiv preprint.

Most of the increased COVID burden fell on adolescents aged 12-17, they said. The COVID hospitalization rate for that age group was 59.9 per 100,000, versus 12.2-14.1 for influenza, while children aged 5-11 had a COVID-related rate of 25.0 and flu-related rates of 24.3-31.7, and those aged 0-4 had rates of 66.8 for COVID and 70.9-91.5 for the flu, Miranda J. Delahoy of the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team and associates reported.

New COVID-19 cases in children fell by 23% as the latest weekly count dropped to its lowest level since July of 2021, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when the early stages of the Delta surge led to 23,551 cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The two organizations put the total number of cases at nearly 12.8 million from the start of the pandemic to March 17, with children representing 19.0% of cases among all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases at almost 12.0 million as of March 21, or 17.5% of the nationwide total.

COVID-related hospitalizations also continue to fall, and two new studies from the CDC put children’s experiences during the Omicron surge and the larger pandemic into perspective.

One study showed that hospitalization rates for children aged 4 years and younger during the Omicron surge were five times higher than at the peak of the Delta surge, with the highest rates occurring in infants under 6 months of age. That report was based on the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET), which covers 99 counties across 14 states (MMWR. 2022 March 18;71[11]:429-36).

The second study compared child hospitalizations during 1 year of the COVID pandemic (Oct. 1, 2020, to Sept. 30, 2021) with three influenza seasons (2017-2018 through 2019-2020). The pre-Omicron hospitalization rate for those under age 18 years, 48.2 per 100,000 children, was higher than any of the three flu seasons: 33.5 per 100,000 in 2017-2018, 33.8 in 2018-2019, and 41.7 for 2019-2020, the investigators said in a medRxiv preprint.

Most of the increased COVID burden fell on adolescents aged 12-17, they said. The COVID hospitalization rate for that age group was 59.9 per 100,000, versus 12.2-14.1 for influenza, while children aged 5-11 had a COVID-related rate of 25.0 and flu-related rates of 24.3-31.7, and those aged 0-4 had rates of 66.8 for COVID and 70.9-91.5 for the flu, Miranda J. Delahoy of the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team and associates reported.

WHO issues new TB guidelines for children and adolescents

The World Health Organization now recommends shortened treatment for children with mild tuberculosis, as well as two oral TB treatments (bedaquiline and delamanid) for use in children of all ages. The updated guidelines for TB management in children and adolescents were announced March 21 ahead of World Tuberculosis Day on March 24.

The agency also called for increased investment in global TB programs, noting that in 2020, TB deaths increased for the first time in over a decade. “We cannot falter in our commitment to reach and save every man, woman, child, family, and community impacted by this deadly disease,” said Tereza Kasaeva, MD, PhD, director of the WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme during a press conference.

TB is the 13th-leading cause of death and the second top infectious killer after COVID-19, with more than 4,100 people dying from TB every day. WHO estimates that 1.1 million children fall ill with TB each year.

Calls for investment

The increase in TB deaths from 1.4 million in 2019 to 1.5 million in 2020 was coupled with a decrease in funding. From 2019-2020, global spending for TB diagnostic, treatment, and prevention services fell from $5.8 billion to $5.3 billion. This is less than half of the $13 billion target funding amount for 2022, Dr. Kasaeva said.

Efforts to expand access to TB care have fallen short mainly because of this lack of funding, especially for children. In 2020, about 63% of children under 15 years of age with TB either did not receive or were not reported to have access to TB diagnosis and treatment services, which rose to 72% in children under age 5. Almost two-thirds of children under age 5 also did not receive TB preventive treatment in 2022, according to WHO statistics.

The socioeconomic ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as ongoing conflict in Eastern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East have “further exacerbated the situation,” Dr. Kasaeva said. “This conveys the urgent need to dramatically increase investments to ramp up the fight against TB and achieve commitments to end TB made by global leaders.”

Dr. Kasaeva laid out WHO’s main points for global investment in TB care:

- Increase domestic and international funding to close gaps in TB research and program implementation. For countries with smaller economies, increased international investment will be necessary in the short or medium term to help regain progress.

- Double funding for TB research, including vaccines.

- Invest in sustaining TB programs and services during the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing crises so care is not disrupted.

New guidelines

Dr. Kasaeva also noted that adoption of WHO’s new guidelines for children and adolescents should be fast-tracked to improve access to and quality of care. The updates include:

- Rapid molecular tests called Xpert Ultra should be used as the initial test for TB in children and adolescents.

- Diagnostic testing can now include noninvasive specimens, like stool samples.

- Children with mild TB can be treated with a , rather than 6 months. This shortened regimen will allow children to return to school faster and save money for families and the health care system, said Kerri Viney, MD, PhD, a team lead for the WHO Tuberculosis Programme, with a focus on vulnerable populations, including children. She presented the new guidelines during the WHO press conference.

- The recommended treatment regimen for TB meningitis has also been shortened from 12 to 6 months.

Two oral medications for drug-resistant TB (bedaquiline and delamanid) are now recommended for use in children of all ages. “There is no longer a need for painful injections that can have serious side effects, including deafness,” Dr. Viney said.

Health systems should develop new models of decentralized and integrated TB care to bring TB care closer to where children live.

The guidelines are available on the WHO website.

“The WHO guidelines issued today are a game changer for children and adolescents with TB,” Dr. Kasaeva said. The next step is assisting countries in implementing these updates so that children and adolescents globally have access to high quality TB care,” Dr. Viney added. “We have the policy recommendations. We have the implementation guidance, we have child-friendly formulations of TB medicines,” she said. “Let us not wait any longer. Let us invest to end TB in children and adolescents.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The World Health Organization now recommends shortened treatment for children with mild tuberculosis, as well as two oral TB treatments (bedaquiline and delamanid) for use in children of all ages. The updated guidelines for TB management in children and adolescents were announced March 21 ahead of World Tuberculosis Day on March 24.

The agency also called for increased investment in global TB programs, noting that in 2020, TB deaths increased for the first time in over a decade. “We cannot falter in our commitment to reach and save every man, woman, child, family, and community impacted by this deadly disease,” said Tereza Kasaeva, MD, PhD, director of the WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme during a press conference.

TB is the 13th-leading cause of death and the second top infectious killer after COVID-19, with more than 4,100 people dying from TB every day. WHO estimates that 1.1 million children fall ill with TB each year.

Calls for investment

The increase in TB deaths from 1.4 million in 2019 to 1.5 million in 2020 was coupled with a decrease in funding. From 2019-2020, global spending for TB diagnostic, treatment, and prevention services fell from $5.8 billion to $5.3 billion. This is less than half of the $13 billion target funding amount for 2022, Dr. Kasaeva said.

Efforts to expand access to TB care have fallen short mainly because of this lack of funding, especially for children. In 2020, about 63% of children under 15 years of age with TB either did not receive or were not reported to have access to TB diagnosis and treatment services, which rose to 72% in children under age 5. Almost two-thirds of children under age 5 also did not receive TB preventive treatment in 2022, according to WHO statistics.

The socioeconomic ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as ongoing conflict in Eastern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East have “further exacerbated the situation,” Dr. Kasaeva said. “This conveys the urgent need to dramatically increase investments to ramp up the fight against TB and achieve commitments to end TB made by global leaders.”

Dr. Kasaeva laid out WHO’s main points for global investment in TB care:

- Increase domestic and international funding to close gaps in TB research and program implementation. For countries with smaller economies, increased international investment will be necessary in the short or medium term to help regain progress.

- Double funding for TB research, including vaccines.

- Invest in sustaining TB programs and services during the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing crises so care is not disrupted.

New guidelines

Dr. Kasaeva also noted that adoption of WHO’s new guidelines for children and adolescents should be fast-tracked to improve access to and quality of care. The updates include:

- Rapid molecular tests called Xpert Ultra should be used as the initial test for TB in children and adolescents.

- Diagnostic testing can now include noninvasive specimens, like stool samples.

- Children with mild TB can be treated with a , rather than 6 months. This shortened regimen will allow children to return to school faster and save money for families and the health care system, said Kerri Viney, MD, PhD, a team lead for the WHO Tuberculosis Programme, with a focus on vulnerable populations, including children. She presented the new guidelines during the WHO press conference.

- The recommended treatment regimen for TB meningitis has also been shortened from 12 to 6 months.

Two oral medications for drug-resistant TB (bedaquiline and delamanid) are now recommended for use in children of all ages. “There is no longer a need for painful injections that can have serious side effects, including deafness,” Dr. Viney said.

Health systems should develop new models of decentralized and integrated TB care to bring TB care closer to where children live.

The guidelines are available on the WHO website.

“The WHO guidelines issued today are a game changer for children and adolescents with TB,” Dr. Kasaeva said. The next step is assisting countries in implementing these updates so that children and adolescents globally have access to high quality TB care,” Dr. Viney added. “We have the policy recommendations. We have the implementation guidance, we have child-friendly formulations of TB medicines,” she said. “Let us not wait any longer. Let us invest to end TB in children and adolescents.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The World Health Organization now recommends shortened treatment for children with mild tuberculosis, as well as two oral TB treatments (bedaquiline and delamanid) for use in children of all ages. The updated guidelines for TB management in children and adolescents were announced March 21 ahead of World Tuberculosis Day on March 24.

The agency also called for increased investment in global TB programs, noting that in 2020, TB deaths increased for the first time in over a decade. “We cannot falter in our commitment to reach and save every man, woman, child, family, and community impacted by this deadly disease,” said Tereza Kasaeva, MD, PhD, director of the WHO Global Tuberculosis Programme during a press conference.

TB is the 13th-leading cause of death and the second top infectious killer after COVID-19, with more than 4,100 people dying from TB every day. WHO estimates that 1.1 million children fall ill with TB each year.

Calls for investment

The increase in TB deaths from 1.4 million in 2019 to 1.5 million in 2020 was coupled with a decrease in funding. From 2019-2020, global spending for TB diagnostic, treatment, and prevention services fell from $5.8 billion to $5.3 billion. This is less than half of the $13 billion target funding amount for 2022, Dr. Kasaeva said.

Efforts to expand access to TB care have fallen short mainly because of this lack of funding, especially for children. In 2020, about 63% of children under 15 years of age with TB either did not receive or were not reported to have access to TB diagnosis and treatment services, which rose to 72% in children under age 5. Almost two-thirds of children under age 5 also did not receive TB preventive treatment in 2022, according to WHO statistics.

The socioeconomic ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as ongoing conflict in Eastern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East have “further exacerbated the situation,” Dr. Kasaeva said. “This conveys the urgent need to dramatically increase investments to ramp up the fight against TB and achieve commitments to end TB made by global leaders.”

Dr. Kasaeva laid out WHO’s main points for global investment in TB care:

- Increase domestic and international funding to close gaps in TB research and program implementation. For countries with smaller economies, increased international investment will be necessary in the short or medium term to help regain progress.

- Double funding for TB research, including vaccines.

- Invest in sustaining TB programs and services during the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing crises so care is not disrupted.

New guidelines

Dr. Kasaeva also noted that adoption of WHO’s new guidelines for children and adolescents should be fast-tracked to improve access to and quality of care. The updates include:

- Rapid molecular tests called Xpert Ultra should be used as the initial test for TB in children and adolescents.

- Diagnostic testing can now include noninvasive specimens, like stool samples.

- Children with mild TB can be treated with a , rather than 6 months. This shortened regimen will allow children to return to school faster and save money for families and the health care system, said Kerri Viney, MD, PhD, a team lead for the WHO Tuberculosis Programme, with a focus on vulnerable populations, including children. She presented the new guidelines during the WHO press conference.

- The recommended treatment regimen for TB meningitis has also been shortened from 12 to 6 months.

Two oral medications for drug-resistant TB (bedaquiline and delamanid) are now recommended for use in children of all ages. “There is no longer a need for painful injections that can have serious side effects, including deafness,” Dr. Viney said.

Health systems should develop new models of decentralized and integrated TB care to bring TB care closer to where children live.

The guidelines are available on the WHO website.

“The WHO guidelines issued today are a game changer for children and adolescents with TB,” Dr. Kasaeva said. The next step is assisting countries in implementing these updates so that children and adolescents globally have access to high quality TB care,” Dr. Viney added. “We have the policy recommendations. We have the implementation guidance, we have child-friendly formulations of TB medicines,” she said. “Let us not wait any longer. Let us invest to end TB in children and adolescents.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antiretroviral therapy associated with less risk of preterm birth

Over the past decade, data have suggested that antiretroviral therapy (ART) may be associated with an increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, namely, preterm birth (PTB). But a combination of methodologic challenges, demographic gaps, and spotty clinical data has left the question unresolved, especially for pregnant women with HIV who reside in developed countries.

“Given that a lot of the emerging data has come out of resource-limited settings where patient and clinical characteristics are different from developed world settings like the United States, we felt that this was an important question to address,” Kartik Venkatesh, MD, PhD, a high-risk obstetrician and perinatal epidemiologist at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, told this news organization.

In a prospective cohort study of U.S. women with or at risk for HIV, Dr. Venkatesh and his colleagues found that ART exposure (including highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART]) was associated with as much as an 80% decline in the likelihood of PTB (defined as birth less than 34 weeks). The study was published in HIV Medicine.

24 years of data analyzed

Dr. Venkatesh and his team analyzed self-reported birth data of women with singleton live-born pregnancies enrolled in the ongoing, multicenter, prospective observational Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) from Oct. 1, 1995, to March 31, 2019.

“We first looked at women with HIV versus without HIV, [who were] matched on many clinical and sociodemographic characteristics and at similarly high risk of some of these obstetrical outcomes like PTB,” explained Dr. Venkatesh. “We then looked at the relative impact of antiretroviral therapy amongst women living with HIV compared to no antiretroviral therapy.”

ART regimens were classified as none, monotherapy, dual therapy, or HAART. (HAART was defined as more than three antiretrovirals, including at least one protease inhibitor [PI], nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, integrase inhibitor, or entry inhibitor.) In this cohort, for 63.5% of women receiving ART, therapy was initiated before pregnancy (mean duration of HAART, 6 years), and most were virally suppressed.

Among the 4,944 women assessed in the WIHS trial, 74% (3,646) had HIV. In total, 383 women had 488 singleton deliveries, including 218 women with HIV (272 deliveries) and 165 without HIV (216 deliveries). Sociodemographics in both cohorts were well matched. For most participants, the mean age was 40-41 years at delivery, most were non-Hispanic Black persons, and the mean pregnancy body mass index was greater than or equal to 29 kg/m2. Of the women with HIV, 33% had chronic hypertension; of those without HIV, 42.1% had chronic hypertension; 4.7% and 5.0%, respectively, had pregestational diabetes.

The findings showed that PTB risk less than 34 weeks was similar between women with (10%) and without (8%) HIV (adjusted risk ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-2.31). Among deliveries to women with HIV who were receiving ART, PTB risk less than 34 weeks was lower with HAART (7%), compared with not receiving ART (26%) (aRR, 0.19), as well as with monotherapy or dual therapy (3% vs. no ART) (aRR, 0.12). Notably, 67% of deliveries to women receiving HAART included a PI-containing regimen, but these women were not significantly more likely to have a PTB less than 34 weeks, compared with women taking non-PI HAART regimens (aRR, 2.61; 95% CI, 0.65-10.59). Results were similar for secondary outcomes (PTB less than 28 weeks, less than 37 weeks).

Filling in the gaps toward the safest regimen

“This study spans 25 years, so it covers a lot of the history of HIV in pregnancy and is reassuring around using ART in pregnancy,” Shahin Lockman, MD, told this news organization. Dr. Lockman is an associate professor of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a co-PI of the Botswana Clinical Trials Unit at the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership. She was not involved in the study. “One of the worst things for a mother and for pregnancy outcomes, for the fetus and baby’s health and development, is uncontrolled maternal HIV,’’ she said.

Dr. Lockman also noted potential confounders that drive poor birth outcomes in Southern African women, compared with U.S. women, making comparisons between this and other observational studies difficult. Still, she said that the question is not whether women should be receiving treatment but whether or not there are differences between antiretroviral regimens.

“One of the areas that we did not go deeper into was the subtype of antiretroviral therapy, given the relatively small study numbers [did not] allow us to do a robust analysis,” Dr. Venkatesh said.

Rather, he emphasized that the findings might lend more weight to speculation that immunologic characteristics associated with HIV status and immunotherapy – such as low CD4 cell counts prior to delivery, or duration of HIV infection – may be important drivers of adverse birth outcomes among women with HIV taking ART.

And at least in this cohort, many of these characteristics were similar between the treatment groups.

Both researchers agree that the findings – while reassuring – highlight the importance of collecting robust obstetric and safety data as part of prospective databases of individuals living with HIV, not only in resource-limited settings but also among the domestic U.S. population.

“We’ve learned a lot over the last 10 years,” Dr. Lockman said. “Some regimens (like lopinavir/ritonavir or nevirapine) are associated with significantly worse birth outcomes, whereas efavirenz doesn’t seem to be, or less so, and dolutegravir seems to be associated with even better outcomes. So, I think that where we are moving is to regimens that are the safest.”

Moving forward, Dr. Venkatesh explained, not only should researchers focus on exploring which antiretrovirals are safest in this context but also if the use of preexposure prophylaxis during conception periods affects birth outcomes.

Dr. Venkatesh and Dr. Lockman report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the past decade, data have suggested that antiretroviral therapy (ART) may be associated with an increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, namely, preterm birth (PTB). But a combination of methodologic challenges, demographic gaps, and spotty clinical data has left the question unresolved, especially for pregnant women with HIV who reside in developed countries.

“Given that a lot of the emerging data has come out of resource-limited settings where patient and clinical characteristics are different from developed world settings like the United States, we felt that this was an important question to address,” Kartik Venkatesh, MD, PhD, a high-risk obstetrician and perinatal epidemiologist at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, told this news organization.

In a prospective cohort study of U.S. women with or at risk for HIV, Dr. Venkatesh and his colleagues found that ART exposure (including highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART]) was associated with as much as an 80% decline in the likelihood of PTB (defined as birth less than 34 weeks). The study was published in HIV Medicine.

24 years of data analyzed

Dr. Venkatesh and his team analyzed self-reported birth data of women with singleton live-born pregnancies enrolled in the ongoing, multicenter, prospective observational Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) from Oct. 1, 1995, to March 31, 2019.

“We first looked at women with HIV versus without HIV, [who were] matched on many clinical and sociodemographic characteristics and at similarly high risk of some of these obstetrical outcomes like PTB,” explained Dr. Venkatesh. “We then looked at the relative impact of antiretroviral therapy amongst women living with HIV compared to no antiretroviral therapy.”

ART regimens were classified as none, monotherapy, dual therapy, or HAART. (HAART was defined as more than three antiretrovirals, including at least one protease inhibitor [PI], nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, integrase inhibitor, or entry inhibitor.) In this cohort, for 63.5% of women receiving ART, therapy was initiated before pregnancy (mean duration of HAART, 6 years), and most were virally suppressed.

Among the 4,944 women assessed in the WIHS trial, 74% (3,646) had HIV. In total, 383 women had 488 singleton deliveries, including 218 women with HIV (272 deliveries) and 165 without HIV (216 deliveries). Sociodemographics in both cohorts were well matched. For most participants, the mean age was 40-41 years at delivery, most were non-Hispanic Black persons, and the mean pregnancy body mass index was greater than or equal to 29 kg/m2. Of the women with HIV, 33% had chronic hypertension; of those without HIV, 42.1% had chronic hypertension; 4.7% and 5.0%, respectively, had pregestational diabetes.

The findings showed that PTB risk less than 34 weeks was similar between women with (10%) and without (8%) HIV (adjusted risk ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-2.31). Among deliveries to women with HIV who were receiving ART, PTB risk less than 34 weeks was lower with HAART (7%), compared with not receiving ART (26%) (aRR, 0.19), as well as with monotherapy or dual therapy (3% vs. no ART) (aRR, 0.12). Notably, 67% of deliveries to women receiving HAART included a PI-containing regimen, but these women were not significantly more likely to have a PTB less than 34 weeks, compared with women taking non-PI HAART regimens (aRR, 2.61; 95% CI, 0.65-10.59). Results were similar for secondary outcomes (PTB less than 28 weeks, less than 37 weeks).

Filling in the gaps toward the safest regimen

“This study spans 25 years, so it covers a lot of the history of HIV in pregnancy and is reassuring around using ART in pregnancy,” Shahin Lockman, MD, told this news organization. Dr. Lockman is an associate professor of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a co-PI of the Botswana Clinical Trials Unit at the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership. She was not involved in the study. “One of the worst things for a mother and for pregnancy outcomes, for the fetus and baby’s health and development, is uncontrolled maternal HIV,’’ she said.

Dr. Lockman also noted potential confounders that drive poor birth outcomes in Southern African women, compared with U.S. women, making comparisons between this and other observational studies difficult. Still, she said that the question is not whether women should be receiving treatment but whether or not there are differences between antiretroviral regimens.

“One of the areas that we did not go deeper into was the subtype of antiretroviral therapy, given the relatively small study numbers [did not] allow us to do a robust analysis,” Dr. Venkatesh said.

Rather, he emphasized that the findings might lend more weight to speculation that immunologic characteristics associated with HIV status and immunotherapy – such as low CD4 cell counts prior to delivery, or duration of HIV infection – may be important drivers of adverse birth outcomes among women with HIV taking ART.

And at least in this cohort, many of these characteristics were similar between the treatment groups.

Both researchers agree that the findings – while reassuring – highlight the importance of collecting robust obstetric and safety data as part of prospective databases of individuals living with HIV, not only in resource-limited settings but also among the domestic U.S. population.

“We’ve learned a lot over the last 10 years,” Dr. Lockman said. “Some regimens (like lopinavir/ritonavir or nevirapine) are associated with significantly worse birth outcomes, whereas efavirenz doesn’t seem to be, or less so, and dolutegravir seems to be associated with even better outcomes. So, I think that where we are moving is to regimens that are the safest.”

Moving forward, Dr. Venkatesh explained, not only should researchers focus on exploring which antiretrovirals are safest in this context but also if the use of preexposure prophylaxis during conception periods affects birth outcomes.

Dr. Venkatesh and Dr. Lockman report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the past decade, data have suggested that antiretroviral therapy (ART) may be associated with an increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, namely, preterm birth (PTB). But a combination of methodologic challenges, demographic gaps, and spotty clinical data has left the question unresolved, especially for pregnant women with HIV who reside in developed countries.

“Given that a lot of the emerging data has come out of resource-limited settings where patient and clinical characteristics are different from developed world settings like the United States, we felt that this was an important question to address,” Kartik Venkatesh, MD, PhD, a high-risk obstetrician and perinatal epidemiologist at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, told this news organization.

In a prospective cohort study of U.S. women with or at risk for HIV, Dr. Venkatesh and his colleagues found that ART exposure (including highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART]) was associated with as much as an 80% decline in the likelihood of PTB (defined as birth less than 34 weeks). The study was published in HIV Medicine.

24 years of data analyzed

Dr. Venkatesh and his team analyzed self-reported birth data of women with singleton live-born pregnancies enrolled in the ongoing, multicenter, prospective observational Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) from Oct. 1, 1995, to March 31, 2019.

“We first looked at women with HIV versus without HIV, [who were] matched on many clinical and sociodemographic characteristics and at similarly high risk of some of these obstetrical outcomes like PTB,” explained Dr. Venkatesh. “We then looked at the relative impact of antiretroviral therapy amongst women living with HIV compared to no antiretroviral therapy.”

ART regimens were classified as none, monotherapy, dual therapy, or HAART. (HAART was defined as more than three antiretrovirals, including at least one protease inhibitor [PI], nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, integrase inhibitor, or entry inhibitor.) In this cohort, for 63.5% of women receiving ART, therapy was initiated before pregnancy (mean duration of HAART, 6 years), and most were virally suppressed.

Among the 4,944 women assessed in the WIHS trial, 74% (3,646) had HIV. In total, 383 women had 488 singleton deliveries, including 218 women with HIV (272 deliveries) and 165 without HIV (216 deliveries). Sociodemographics in both cohorts were well matched. For most participants, the mean age was 40-41 years at delivery, most were non-Hispanic Black persons, and the mean pregnancy body mass index was greater than or equal to 29 kg/m2. Of the women with HIV, 33% had chronic hypertension; of those without HIV, 42.1% had chronic hypertension; 4.7% and 5.0%, respectively, had pregestational diabetes.

The findings showed that PTB risk less than 34 weeks was similar between women with (10%) and without (8%) HIV (adjusted risk ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-2.31). Among deliveries to women with HIV who were receiving ART, PTB risk less than 34 weeks was lower with HAART (7%), compared with not receiving ART (26%) (aRR, 0.19), as well as with monotherapy or dual therapy (3% vs. no ART) (aRR, 0.12). Notably, 67% of deliveries to women receiving HAART included a PI-containing regimen, but these women were not significantly more likely to have a PTB less than 34 weeks, compared with women taking non-PI HAART regimens (aRR, 2.61; 95% CI, 0.65-10.59). Results were similar for secondary outcomes (PTB less than 28 weeks, less than 37 weeks).

Filling in the gaps toward the safest regimen

“This study spans 25 years, so it covers a lot of the history of HIV in pregnancy and is reassuring around using ART in pregnancy,” Shahin Lockman, MD, told this news organization. Dr. Lockman is an associate professor of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a co-PI of the Botswana Clinical Trials Unit at the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership. She was not involved in the study. “One of the worst things for a mother and for pregnancy outcomes, for the fetus and baby’s health and development, is uncontrolled maternal HIV,’’ she said.

Dr. Lockman also noted potential confounders that drive poor birth outcomes in Southern African women, compared with U.S. women, making comparisons between this and other observational studies difficult. Still, she said that the question is not whether women should be receiving treatment but whether or not there are differences between antiretroviral regimens.

“One of the areas that we did not go deeper into was the subtype of antiretroviral therapy, given the relatively small study numbers [did not] allow us to do a robust analysis,” Dr. Venkatesh said.

Rather, he emphasized that the findings might lend more weight to speculation that immunologic characteristics associated with HIV status and immunotherapy – such as low CD4 cell counts prior to delivery, or duration of HIV infection – may be important drivers of adverse birth outcomes among women with HIV taking ART.

And at least in this cohort, many of these characteristics were similar between the treatment groups.

Both researchers agree that the findings – while reassuring – highlight the importance of collecting robust obstetric and safety data as part of prospective databases of individuals living with HIV, not only in resource-limited settings but also among the domestic U.S. population.

“We’ve learned a lot over the last 10 years,” Dr. Lockman said. “Some regimens (like lopinavir/ritonavir or nevirapine) are associated with significantly worse birth outcomes, whereas efavirenz doesn’t seem to be, or less so, and dolutegravir seems to be associated with even better outcomes. So, I think that where we are moving is to regimens that are the safest.”

Moving forward, Dr. Venkatesh explained, not only should researchers focus on exploring which antiretrovirals are safest in this context but also if the use of preexposure prophylaxis during conception periods affects birth outcomes.

Dr. Venkatesh and Dr. Lockman report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

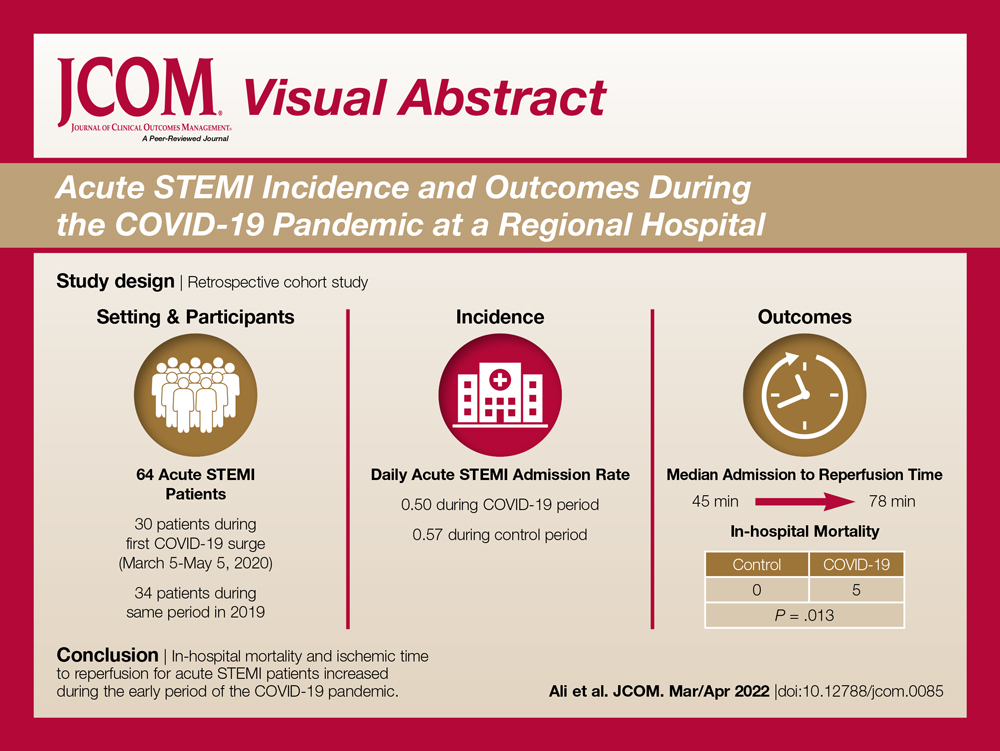

Acute STEMI During the COVID-19 Pandemic at a Regional Hospital: Incidence, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes

From the Department of Medicine, Medical College of Georgia at the Augusta University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership, Athens, GA (Syed H. Ali, Syed Hyder, and Dr. Murrow), and the Department of Cardiology, Piedmont Heart Institute, Piedmont Athens Regional, Athens, GA (Dr. Murrow and Mrs. Davis).

Abstract

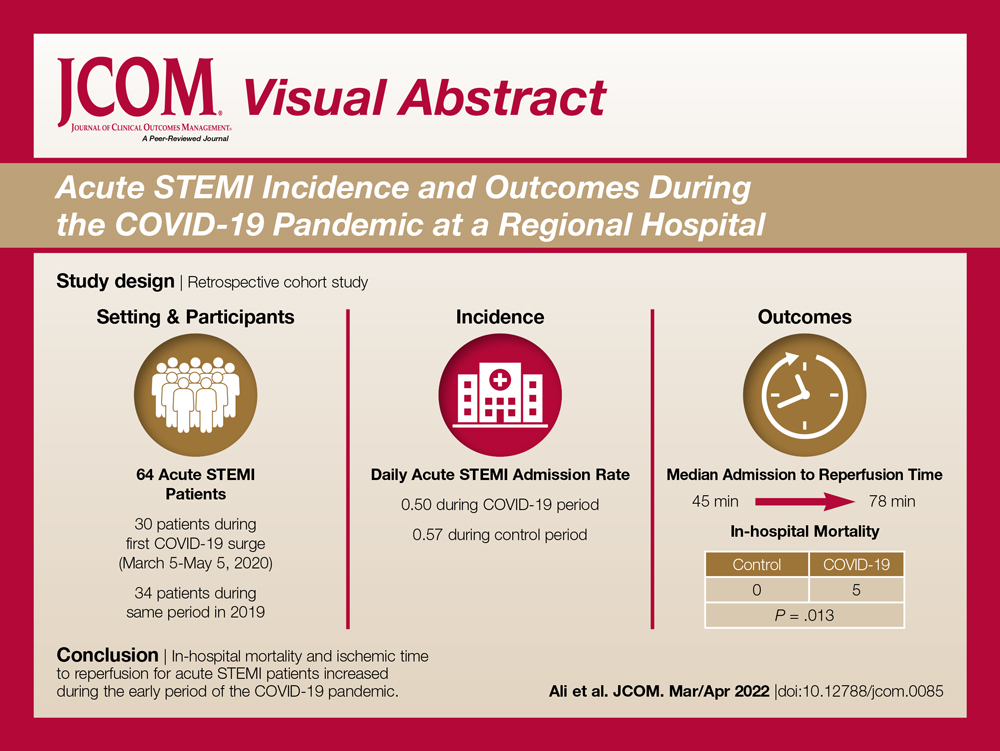

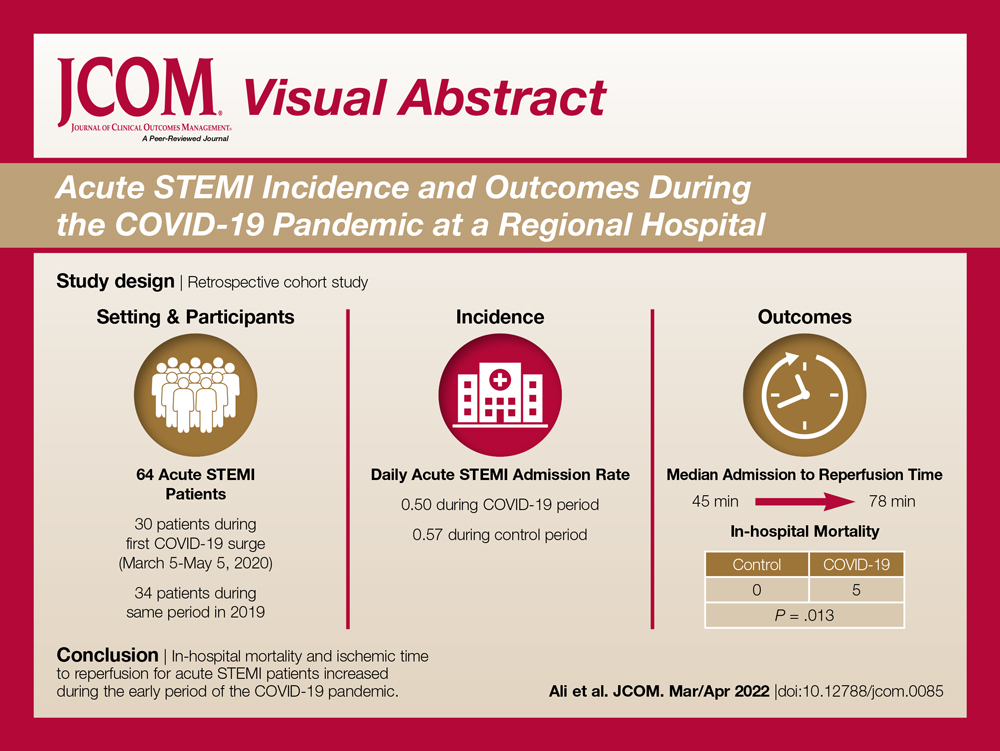

Objectives: The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) during the early COVID-19 pandemic at Piedmont Athens Regional (PAR), a 330-bed tertiary referral center in Northeast Georgia.

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted at PAR to evaluate patients with acute STEMI admitted over an 8-week period during the initial COVID-19 outbreak. This study group was compared to patients admitted during the corresponding period in 2019. The primary endpoint of this study was defined as a composite of sustained ventricular arrhythmia, congestive heart failure (CHF) with pulmonary congestion, and/or in-hospital mortality.

Results: This study cohort was composed of 64 patients with acute STEMI; 30 patients (46.9%) were hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with STEMI in both the COVID-19 and control groups had similar comorbidities, Killip classification score, and clinical presentations. The median (interquartile range) time from symptom onset to reperfusion (total ischemic time) increased from 99.5 minutes (84.8-132) in 2019 to 149 minutes (96.3-231.8; P = .032) in 2020. Hospitalization during the COVID-19 period was associated with an increased risk for combined in-hospital outcome (odds ratio, 3.96; P = .046).

Conclusion: Patients with STEMI admitted during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak experienced longer total ischemic time and increased risk for combined in-hospital outcomes compared to patients admitted during the corresponding period in 2019.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, hospitalization, outcomes.

The emergence of the SARS-Cov-2 virus in December 2019 caused a worldwide shift in resource allocation and the restructuring of health care systems within the span of a few months. With the rapid spread of infection, the World Health Organization officially declared a pandemic in March 2020. The pandemic led to the deferral and cancellation of in-person patient visits, routine diagnostic studies, and nonessential surgeries and procedures. This response occurred secondary to a joint effort to reduce transmission via stay-at-home mandates and appropriate social distancing.1

Alongside the reduction in elective procedures and health care visits, significant reductions in hospitalization rates due to decreases in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and catheterization laboratory utilization have been reported in many studies from around the world.2-7 Comprehensive data demonstrating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on acute STEMI patient characteristics, clinical presentation, and in-hospital outcomes are lacking. Although patients with previously diagnosed cardiovascular disease are more likely to encounter worse outcomes in the setting of COVID-19, there may also be an indirect impact of the pandemic on high-risk patients, including those without the infection.8 Several theories have been hypothesized to explain this phenomenon. One theory postulates that the fear of contracting the virus during hospitalization is great enough to prevent patients from seeking care.2 Another theory suggests that the increased utilization of telemedicine prevents exacerbation of chronic conditions and the need for hospitalization.9 Contrary to this trend, previous studies have shown an increased incidence of acute STEMI following stressful events such as natural disasters.10

The aim of this study was to describe trends pertaining to clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute STEMI during the early COVID-19 pandemic at Piedmont Athens Regional (PAR), a 330-bed tertiary referral center in Northeast Georgia.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at PAR to evaluate patients with STEMI admitted to the cardiovascular intensive care unit over an 8-week period (March 5 to May 5, 2020) during the COVID-19 outbreak. COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020, in the United States. The institutional review board at PAR approved the study; the need for individual consent was waived under the condition that participant data would undergo de-identification and be strictly safeguarded.

Data Collection

Because there are seasonal variations in cardiovascular admissions, patient data from a control period (March 9 to May 9, 2019) were obtained to compare with data from the 2020 period. The number of patients with the diagnosis of acute STEMI during the COVID-19 period was recorded. Demographic data, clinical characteristics, and primary angiographic findings were gathered for all patients. Time from symptom onset to hospital admission and time from hospital admission to reperfusion (defined as door-to-balloon time) were documented for each patient. Killip classification was used to assess patients’ clinical status on admission. Length of stay was determined as days from hospital admission to discharge or death (if occurring during the same hospitalization).

Adverse in-hospital complications were also recorded. These were selected based on inclusion of the following categories of acute STEMI complications: ischemic, mechanical, arrhythmic, embolic, and inflammatory. The following complications occurred in our patient cohort: sustained ventricular arrhythmia, congestive heart failure (CHF) defined as congestion requiring intravenous diuretics, re-infarction, mechanical complications (free-wall rupture, ventricular septal defect, or mitral regurgitation), second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, atrial fibrillation, stroke, mechanical ventilation, major bleeding, pericarditis, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, and in-hospital mortality. The primary outcome of this study was defined as a composite of sustained ventricular arrhythmia, CHF with congestion requiring intravenous diuretics, and/or in-hospital mortality. Ventricular arrythmia and CHF were included in the composite outcome because they are defined as the 2 most common causes of sudden cardiac death following acute STEMI.11,12

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables and categorical variables were compared using the paired t-test. A 2-sided P value <.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Mean admission rates for acute STEMI hospitalizations were determined by dividing the number of admissions by the number of days in each time period. The daily rate of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 individuals was obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 database. All data analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 64 patients, of whom 30 (46.9%) were hospitalized between March 5 and May 5, 2020, and 34 (53.1%) who were admitted during the analogous time period in 2019. This reflected a 6% decrease in STEMI admissions at PAR in the COVID-19 cohort.

Acute STEMI Hospitalization Rates and COVID-19 Incidence

The mean daily acute STEMI admission rate was 0.50 during the study period compared to 0.57 during the control period. During the study period in 2020 in the state of Georgia, the daily rate of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases ranged from 0.194 per 100,000 on March 5 to 8.778 per 100,000 on May 5. Results of COVID-19 testing were available for 9 STEMI patients, and of these 0 tests were positive.

Baseline Characteristics

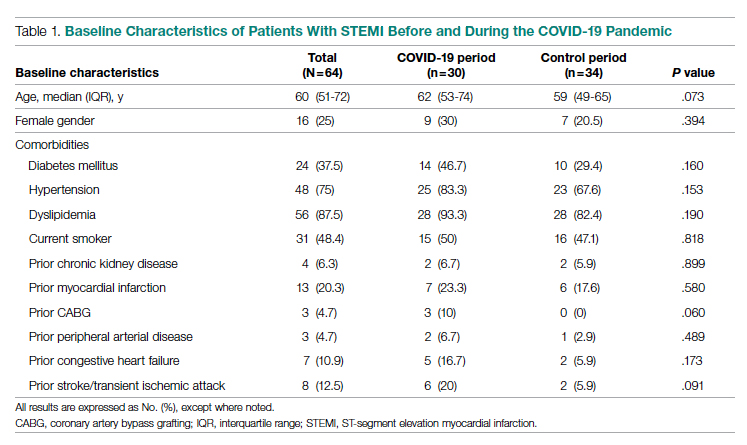

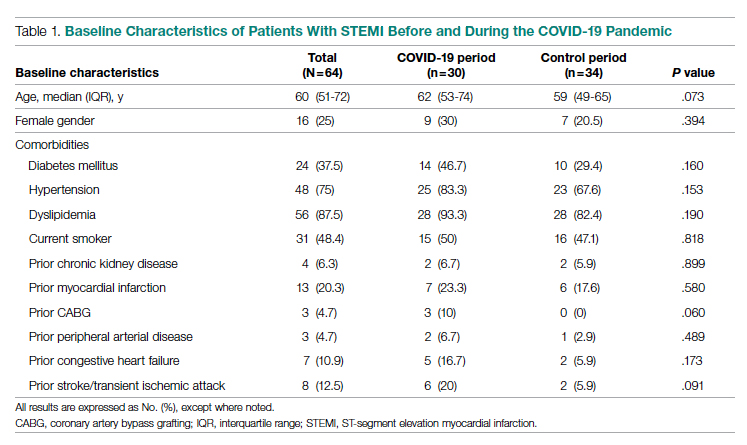

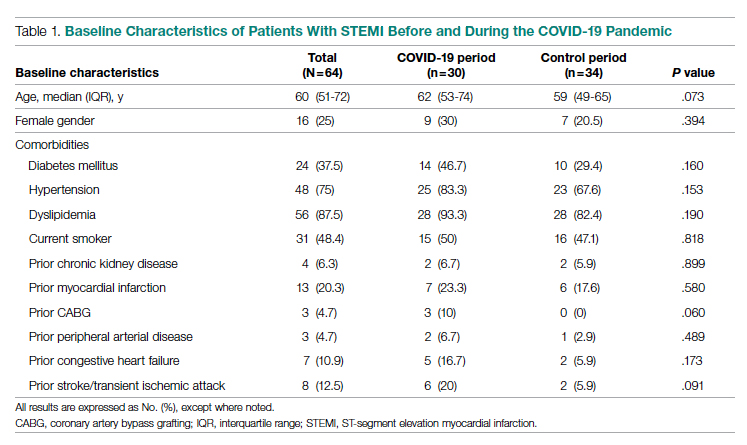

Baseline characteristics of the acute STEMI cohorts are presented in Table 1. Approximately 75% were male; median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was 60 (51-72) years. There were no significant differences in age and gender between the study periods. Three-quarters of patients had a history of hypertension, and 87.5% had a history of dyslipidemia. There was no significant difference in baseline comorbidity profiles between the 2 study periods; therefore, our sample populations shared similar characteristics.

Clinical Presentation

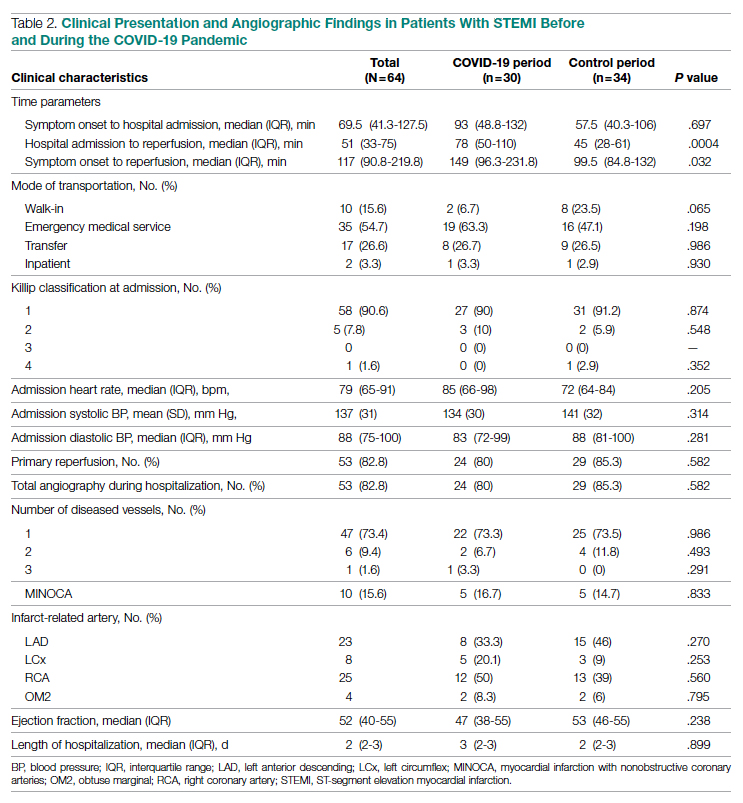

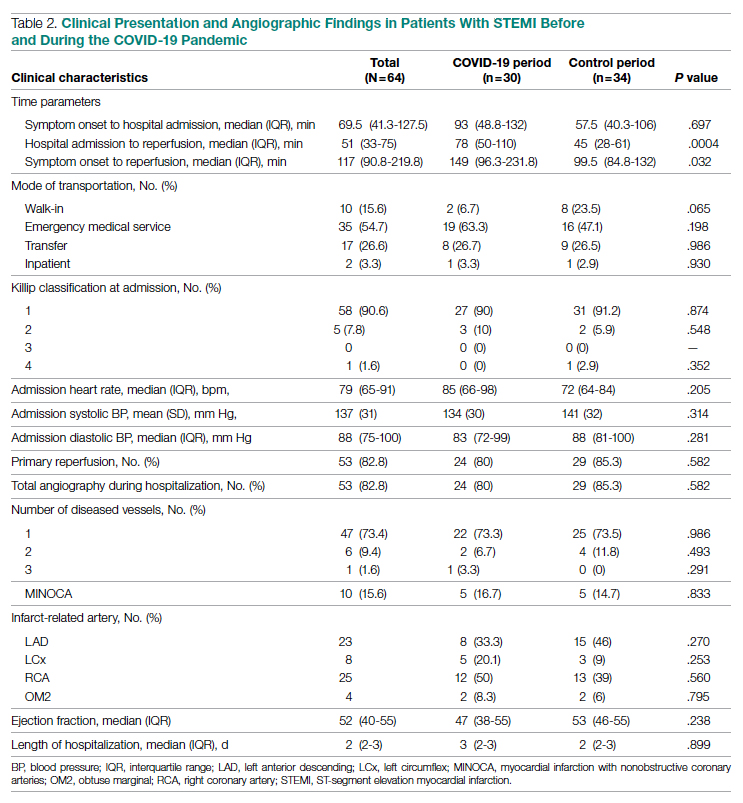

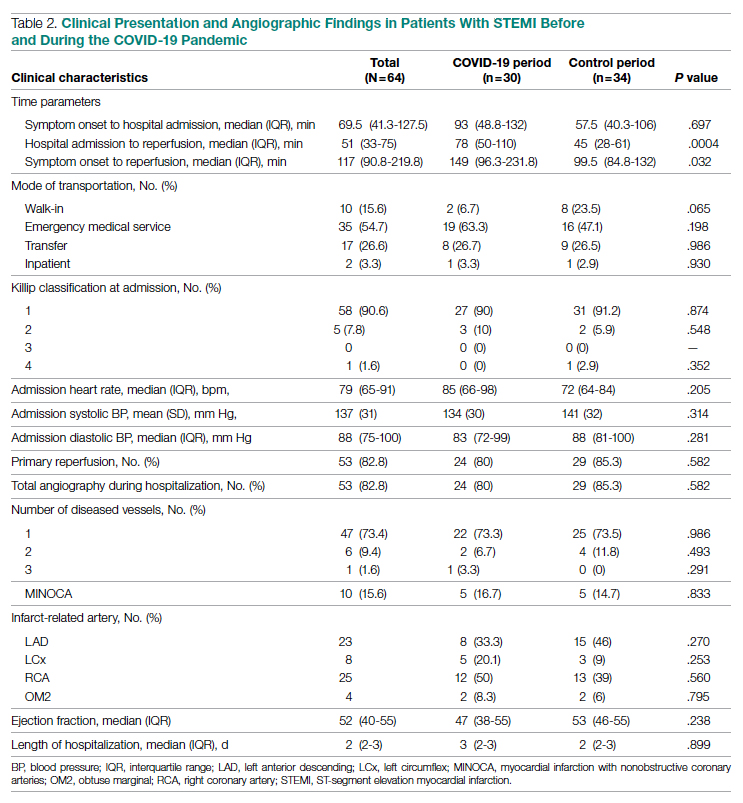

Significant differences were observed regarding the time intervals of STEMI patients in the COVID-19 period and the control period (Table 2). Median time from symptom onset to hospital admission (patient delay) was extended from 57.5 minutes (IQR, 40.3-106) in 2019 to 93 minutes (IQR, 48.8-132) in 2020; however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .697). Median time from hospital admission to reperfusion (system delay) was prolonged from 45 minutes (IQR, 28-61) in 2019 to 78 minutes (IQR, 50-110) in 2020 (P < .001). Overall time from symptom onset to reperfusion (total ischemic time) increased from 99.5 minutes (IQR, 84.8-132) in 2019 to 149 minutes (IQR, 96.3-231.8) in 2020 (P = .032).

Regarding mode of transportation, 23.5% of patients in 2019 were walk-in admissions to the emergency department. During the COVID-19 period, walk-in admissions decreased to 6.7% (P = .065). There were no significant differences between emergency medical service, transfer, or in-patient admissions for STEMI cases between the 2 study periods.

Killip classification scores were calculated for all patients on admission; 90.6% of patients were classified as Killip Class 1. There was no significant difference between hemodynamic presentations during the COVID-19 period compared to the control period.

Angiographic Data

Overall, 53 (82.8%) patients admitted with acute STEMI underwent coronary angiography during their hospital stay. The proportion of patients who underwent primary reperfusion was greater in the control period than in the COVID-19 period (85.3% vs 80%; P = .582). Angiographic characteristics and findings were similar between the 2 study groups (Table 2).

In-Hospital Outcomes

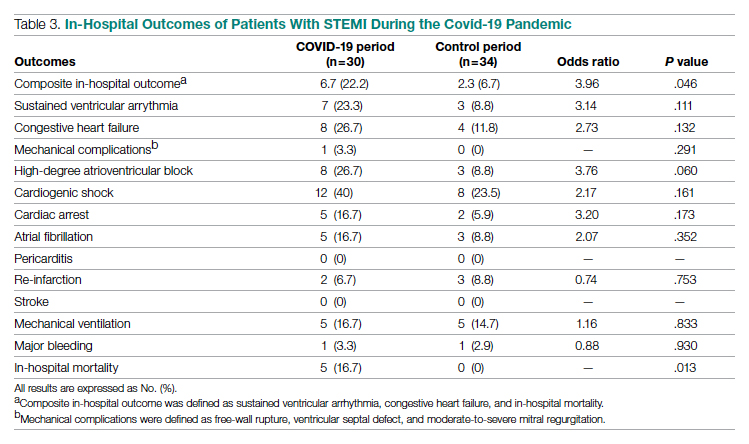

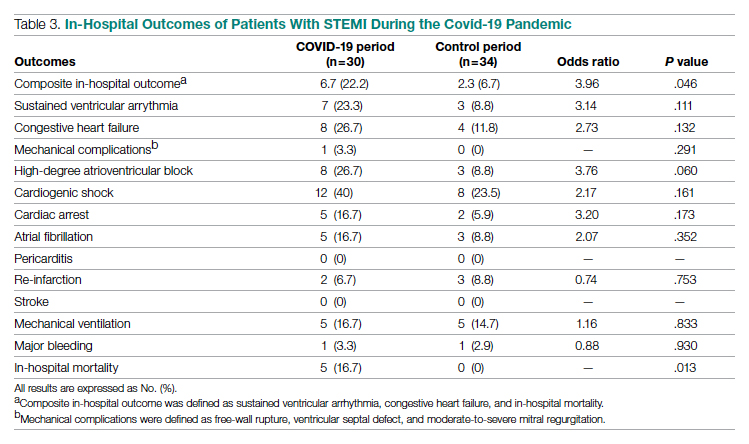

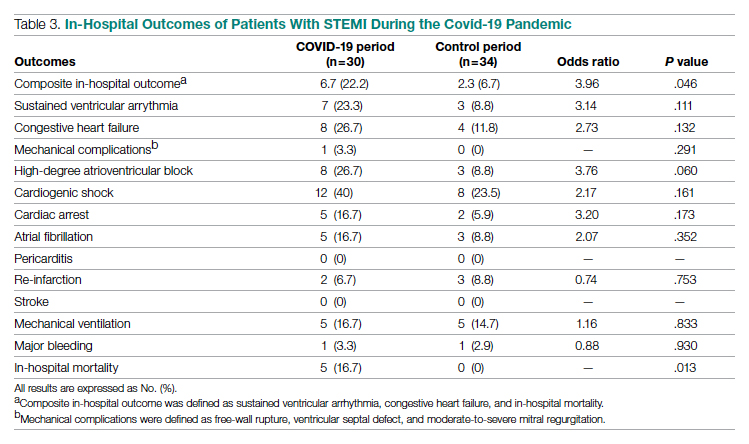

In-hospital outcome data were available for all patients. As shown in Table 3, hospitalization during the COVID-19 period was independently associated with an increased risk for combined in-hospital outcome (odds ratio, 3.96; P = .046). The rate of in-hospital mortality was greater in the COVID-19 period (P = .013). We found no significant difference when comparing secondary outcomes from admissions during the COVID-19 period and the control period in 2019. For the 5 patients who died during the study period, the primary diagnosis at death was acute STEMI complicated by CHF (3 patients) or cardiogenic shock (2 patients).

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study at PAR looks at the impact of COVID-19 on hospitalizations for acute STEMI during the initial peak of the pandemic. The key findings of this study show a significant increase in ischemic time parameters (symptom onset to reperfusion, hospital admission to reperfusion), in-hospital mortality, and combined in-hospital outcomes.

There was a 49.5-minute increase in total ischemic time noted in this study (P = .032). Though there was a numerical increase in time of symptom onset to hospital admission by 23.5 minutes, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .697). However, this study observed a statistically significant 33-minute increase in ischemic time from hospital admission to reperfusion (P < .001). Multiple studies globally have found a similar increase in total ischemic times, including those conducted in China and Europe.13-15 Every level of potential delay must be considered, including pre-hospital, triage and emergency department, and/or reperfusion team. Pre-hospital sources of delays that have been suggested include “stay-at-home” orders and apprehension to seek medical care due to concern about contracting the virus or overwhelming the health care facilities. There was a clinically significant 4-fold decrease in the number of walk-in acute STEMI cases in the study period. In 2019, there were 8 walk-in cases compared to 2 cases in 2020 (P = .065). However, this change was not statistically significant. In-hospital/systemic sources of delays have been mentioned in other studies; they include increased time taken to rule out COVID-19 (nasopharyngeal swab/chest x-ray) and increased time due to the need for intensive gowning and gloving procedures by staff. It was difficult to objectively determine the sources of system delay by the reperfusion team due to a lack of quantitative data.

In the current study, we found a significant increase in in-hospital mortality during the COVID-19 period compared to a parallel time frame in 2019. This finding is contrary to a multicenter study from Spain that reported no difference in in-hospital outcomes or mortality rates among all acute coronary syndrome cases.16 The worsening outcomes and prognosis may simply be a result of increased ischemic time; however, the virus that causes COVID-19 itself may play a role as well. Studies have found that SARS-Cov-2 infection places patients at greater risk for cardiovascular conditions such as hypercoagulability, myocarditis, and arrhythmias.17 In our study, however, there were no acute STEMI patients who tested positive for COVID-19. Therefore, we cannot discuss the impact of increased thrombus burden in patients with COVID-19. Piedmont Healthcare published a STEMI treatment protocol in May 2020 that advised increased use of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in COVID-19-positive cases; during the study period, however, there were no occasions when tPA use was deemed appropriate based on clinical judgment.

Our findings align with previous studies that describe an increase in combined in-hospital adverse outcomes during the COVID-19 era. Previous studies detected a higher rate of complications in the COVID-19 cohort, but in the current study, the adverse in-hospital course is unrelated to underlying infection.18,19 This study reports a higher incidence of major in-hospital outcomes, including a 65% increase in the rate of combined in-hospital outcomes, which is similar to a multicenter study conducted in Israel.19 There was a 2.3-fold numerical increase in sustained ventricular arrhythmias and a 2.5-fold numerical increase in the incidence of cardiac arrest in the study period. This phenomenon was observed despite a similar rate of reperfusion procedures in both groups.

Acute STEMI is a highly fatal condition with an incidence of 8.5 in 10,000 annually in the United States. While studies across the world have shown a 25% to 40% reduction in the rate of hospitalized acute coronary syndrome cases during the COVID-19 pandemic, the decrease from 34 to 30 STEMI admissions at PAR is not statistically significant.20 Possible reasons for the reduction globally include increased out-of-hospital mortality and decreased incidence of acute STEMI across the general population as a result of improved access to telemedicine or decreased levels of life stressors.20

In summary, there was an increase in ischemic time to reperfusion, in-hospital mortality, and combined in-hospital outcomes for acute STEMI patients at PAR during the COVID period.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. This is a single-center study, so the sample size is small and may not be generalizable to a larger population. This is a retrospective observational study, so causation cannot be inferred. This study analyzed ischemic time parameters as average rates over time rather than in an interrupted time series. Post-reperfusion outcomes were limited to hospital stay. Post-hospital follow-up would provide a better picture of the effects of STEMI intervention. There is no account of patients who died out-of-hospital secondary to acute STEMI. COVID-19 testing was not introduced until midway in our study period. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility of the SARS-Cov-2 virus inciting acute STEMI and subsequently leading to worse outcomes and poor prognosis.

Conclusions

This study provides an analysis of the incidence, characteristics, and clinical outcomes of patients presenting with acute STEMI during the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic. In-hospital mortality and ischemic time to reperfusion increased while combined in-hospital outcomes worsened.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Piedmont Athens Regional IRB for approving this project and allowing access to patient data.

Corresponding author: Syed H. Ali; Department of Medicine, Medical College of Georgia at the Augusta University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership, 30606, Athens, GA; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi:10.12788/jcom.0085

1. Bhatt AS, Moscone A, McElrath EE, et al. Fewer hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(3):280-288. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.038

2. Metzler B, Siostrzonek P, Binder RK, Bauer A, Reinstadler SJR. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of Covid-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1852-1853. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa314

3. De Rosa S, Spaccarotella C, Basso C, et al. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the Covid-19 era. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(22):2083-2088.

4. Wilson SJ, Connolly MJ, Elghamry Z, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction presentations and in-hospital outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020; 13(7):e009438. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.009438

5. Mafham MM, Spata E, Goldacre R, et al. Covid-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet. 2020;396 (10248):381-389. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31356-8

6. Bhatt AS, Moscone A, McElrath EE, et al. Fewer Hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(3):280-288. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.038

7. Tam CF, Cheung KS, Lam S, et al. Impact of Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) outbreak on ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(4):e006631. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631

8. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141:1648-1655. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941

9. Ebinger JE, Shah PK. Declining admissions for acute cardiovascular illness: The Covid-19 paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(3):289-291. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.039

10 Leor J, Poole WK, Kloner RA. Sudden cardiac death triggered by an earthquake. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(7):413-419. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602153340701

11. Hiramori K. Major causes of death from acute myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. Jpn Circ J. 1987;51(9):1041-1047. doi:10.1253/jcj.51.1041

12. Bui AH, Waks JW. Risk stratification of sudden cardiac death after acute myocardial infarction. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2018;9(2):3035-3049. doi:10.19102/icrm.2018.090201

13. Xiang D, Xiang X, Zhang W, et al. Management and outcomes of patients with STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(11):1318-1324. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.039

14. Hakim R, Motreff P, Rangé G. COVID-19 and STEMI. [Article in French]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 2020;69(6):355-359. doi:10.1016/j.ancard.2020.09.034

15. Soylu K, Coksevim M, Yanık A, Bugra Cerik I, Aksan G. Effect of Covid-19 pandemic process on STEMI patients timeline. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(5):e14005. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14005

16. Salinas P, Travieso A, Vergara-Uzcategui C, et al. Clinical profile and 30-day mortality of invasively managed patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int Heart J. 2021;62(2):274-281. doi:10.1536/ihj.20-574

17. Hu Y, Sun J, Dai Z, et al. Prevalence and severity of corona virus disease 2019 (Covid-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104371. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104371

18. Rodriguez-Leor O, Cid Alvarez AB, Perez de Prado A, et al. In-hospital outcomes of COVID-19 ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients. EuroIntervention. 2021;16(17):1426-1433. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-20-00935

19. Fardman A, Zahger D, Orvin K, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the Covid-19 era: incidence, clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes—A multicenter registry. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6): e0253524. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0253524

20. Pessoa-Amorim G, Camm CF, Gajendragadkar P, et al. Admission of patients with STEMI since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey by the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6(3):210-216. doi:10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa046

From the Department of Medicine, Medical College of Georgia at the Augusta University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership, Athens, GA (Syed H. Ali, Syed Hyder, and Dr. Murrow), and the Department of Cardiology, Piedmont Heart Institute, Piedmont Athens Regional, Athens, GA (Dr. Murrow and Mrs. Davis).

Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) during the early COVID-19 pandemic at Piedmont Athens Regional (PAR), a 330-bed tertiary referral center in Northeast Georgia.

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted at PAR to evaluate patients with acute STEMI admitted over an 8-week period during the initial COVID-19 outbreak. This study group was compared to patients admitted during the corresponding period in 2019. The primary endpoint of this study was defined as a composite of sustained ventricular arrhythmia, congestive heart failure (CHF) with pulmonary congestion, and/or in-hospital mortality.

Results: This study cohort was composed of 64 patients with acute STEMI; 30 patients (46.9%) were hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with STEMI in both the COVID-19 and control groups had similar comorbidities, Killip classification score, and clinical presentations. The median (interquartile range) time from symptom onset to reperfusion (total ischemic time) increased from 99.5 minutes (84.8-132) in 2019 to 149 minutes (96.3-231.8; P = .032) in 2020. Hospitalization during the COVID-19 period was associated with an increased risk for combined in-hospital outcome (odds ratio, 3.96; P = .046).

Conclusion: Patients with STEMI admitted during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak experienced longer total ischemic time and increased risk for combined in-hospital outcomes compared to patients admitted during the corresponding period in 2019.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, hospitalization, outcomes.

The emergence of the SARS-Cov-2 virus in December 2019 caused a worldwide shift in resource allocation and the restructuring of health care systems within the span of a few months. With the rapid spread of infection, the World Health Organization officially declared a pandemic in March 2020. The pandemic led to the deferral and cancellation of in-person patient visits, routine diagnostic studies, and nonessential surgeries and procedures. This response occurred secondary to a joint effort to reduce transmission via stay-at-home mandates and appropriate social distancing.1

Alongside the reduction in elective procedures and health care visits, significant reductions in hospitalization rates due to decreases in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and catheterization laboratory utilization have been reported in many studies from around the world.2-7 Comprehensive data demonstrating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on acute STEMI patient characteristics, clinical presentation, and in-hospital outcomes are lacking. Although patients with previously diagnosed cardiovascular disease are more likely to encounter worse outcomes in the setting of COVID-19, there may also be an indirect impact of the pandemic on high-risk patients, including those without the infection.8 Several theories have been hypothesized to explain this phenomenon. One theory postulates that the fear of contracting the virus during hospitalization is great enough to prevent patients from seeking care.2 Another theory suggests that the increased utilization of telemedicine prevents exacerbation of chronic conditions and the need for hospitalization.9 Contrary to this trend, previous studies have shown an increased incidence of acute STEMI following stressful events such as natural disasters.10

The aim of this study was to describe trends pertaining to clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute STEMI during the early COVID-19 pandemic at Piedmont Athens Regional (PAR), a 330-bed tertiary referral center in Northeast Georgia.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at PAR to evaluate patients with STEMI admitted to the cardiovascular intensive care unit over an 8-week period (March 5 to May 5, 2020) during the COVID-19 outbreak. COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020, in the United States. The institutional review board at PAR approved the study; the need for individual consent was waived under the condition that participant data would undergo de-identification and be strictly safeguarded.

Data Collection

Because there are seasonal variations in cardiovascular admissions, patient data from a control period (March 9 to May 9, 2019) were obtained to compare with data from the 2020 period. The number of patients with the diagnosis of acute STEMI during the COVID-19 period was recorded. Demographic data, clinical characteristics, and primary angiographic findings were gathered for all patients. Time from symptom onset to hospital admission and time from hospital admission to reperfusion (defined as door-to-balloon time) were documented for each patient. Killip classification was used to assess patients’ clinical status on admission. Length of stay was determined as days from hospital admission to discharge or death (if occurring during the same hospitalization).

Adverse in-hospital complications were also recorded. These were selected based on inclusion of the following categories of acute STEMI complications: ischemic, mechanical, arrhythmic, embolic, and inflammatory. The following complications occurred in our patient cohort: sustained ventricular arrhythmia, congestive heart failure (CHF) defined as congestion requiring intravenous diuretics, re-infarction, mechanical complications (free-wall rupture, ventricular septal defect, or mitral regurgitation), second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, atrial fibrillation, stroke, mechanical ventilation, major bleeding, pericarditis, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, and in-hospital mortality. The primary outcome of this study was defined as a composite of sustained ventricular arrhythmia, CHF with congestion requiring intravenous diuretics, and/or in-hospital mortality. Ventricular arrythmia and CHF were included in the composite outcome because they are defined as the 2 most common causes of sudden cardiac death following acute STEMI.11,12

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables and categorical variables were compared using the paired t-test. A 2-sided P value <.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Mean admission rates for acute STEMI hospitalizations were determined by dividing the number of admissions by the number of days in each time period. The daily rate of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 individuals was obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 database. All data analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 64 patients, of whom 30 (46.9%) were hospitalized between March 5 and May 5, 2020, and 34 (53.1%) who were admitted during the analogous time period in 2019. This reflected a 6% decrease in STEMI admissions at PAR in the COVID-19 cohort.

Acute STEMI Hospitalization Rates and COVID-19 Incidence

The mean daily acute STEMI admission rate was 0.50 during the study period compared to 0.57 during the control period. During the study period in 2020 in the state of Georgia, the daily rate of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases ranged from 0.194 per 100,000 on March 5 to 8.778 per 100,000 on May 5. Results of COVID-19 testing were available for 9 STEMI patients, and of these 0 tests were positive.

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the acute STEMI cohorts are presented in Table 1. Approximately 75% were male; median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was 60 (51-72) years. There were no significant differences in age and gender between the study periods. Three-quarters of patients had a history of hypertension, and 87.5% had a history of dyslipidemia. There was no significant difference in baseline comorbidity profiles between the 2 study periods; therefore, our sample populations shared similar characteristics.

Clinical Presentation

Significant differences were observed regarding the time intervals of STEMI patients in the COVID-19 period and the control period (Table 2). Median time from symptom onset to hospital admission (patient delay) was extended from 57.5 minutes (IQR, 40.3-106) in 2019 to 93 minutes (IQR, 48.8-132) in 2020; however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .697). Median time from hospital admission to reperfusion (system delay) was prolonged from 45 minutes (IQR, 28-61) in 2019 to 78 minutes (IQR, 50-110) in 2020 (P < .001). Overall time from symptom onset to reperfusion (total ischemic time) increased from 99.5 minutes (IQR, 84.8-132) in 2019 to 149 minutes (IQR, 96.3-231.8) in 2020 (P = .032).

Regarding mode of transportation, 23.5% of patients in 2019 were walk-in admissions to the emergency department. During the COVID-19 period, walk-in admissions decreased to 6.7% (P = .065). There were no significant differences between emergency medical service, transfer, or in-patient admissions for STEMI cases between the 2 study periods.

Killip classification scores were calculated for all patients on admission; 90.6% of patients were classified as Killip Class 1. There was no significant difference between hemodynamic presentations during the COVID-19 period compared to the control period.

Angiographic Data

Overall, 53 (82.8%) patients admitted with acute STEMI underwent coronary angiography during their hospital stay. The proportion of patients who underwent primary reperfusion was greater in the control period than in the COVID-19 period (85.3% vs 80%; P = .582). Angiographic characteristics and findings were similar between the 2 study groups (Table 2).

In-Hospital Outcomes

In-hospital outcome data were available for all patients. As shown in Table 3, hospitalization during the COVID-19 period was independently associated with an increased risk for combined in-hospital outcome (odds ratio, 3.96; P = .046). The rate of in-hospital mortality was greater in the COVID-19 period (P = .013). We found no significant difference when comparing secondary outcomes from admissions during the COVID-19 period and the control period in 2019. For the 5 patients who died during the study period, the primary diagnosis at death was acute STEMI complicated by CHF (3 patients) or cardiogenic shock (2 patients).

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study at PAR looks at the impact of COVID-19 on hospitalizations for acute STEMI during the initial peak of the pandemic. The key findings of this study show a significant increase in ischemic time parameters (symptom onset to reperfusion, hospital admission to reperfusion), in-hospital mortality, and combined in-hospital outcomes.

There was a 49.5-minute increase in total ischemic time noted in this study (P = .032). Though there was a numerical increase in time of symptom onset to hospital admission by 23.5 minutes, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .697). However, this study observed a statistically significant 33-minute increase in ischemic time from hospital admission to reperfusion (P < .001). Multiple studies globally have found a similar increase in total ischemic times, including those conducted in China and Europe.13-15 Every level of potential delay must be considered, including pre-hospital, triage and emergency department, and/or reperfusion team. Pre-hospital sources of delays that have been suggested include “stay-at-home” orders and apprehension to seek medical care due to concern about contracting the virus or overwhelming the health care facilities. There was a clinically significant 4-fold decrease in the number of walk-in acute STEMI cases in the study period. In 2019, there were 8 walk-in cases compared to 2 cases in 2020 (P = .065). However, this change was not statistically significant. In-hospital/systemic sources of delays have been mentioned in other studies; they include increased time taken to rule out COVID-19 (nasopharyngeal swab/chest x-ray) and increased time due to the need for intensive gowning and gloving procedures by staff. It was difficult to objectively determine the sources of system delay by the reperfusion team due to a lack of quantitative data.

In the current study, we found a significant increase in in-hospital mortality during the COVID-19 period compared to a parallel time frame in 2019. This finding is contrary to a multicenter study from Spain that reported no difference in in-hospital outcomes or mortality rates among all acute coronary syndrome cases.16 The worsening outcomes and prognosis may simply be a result of increased ischemic time; however, the virus that causes COVID-19 itself may play a role as well. Studies have found that SARS-Cov-2 infection places patients at greater risk for cardiovascular conditions such as hypercoagulability, myocarditis, and arrhythmias.17 In our study, however, there were no acute STEMI patients who tested positive for COVID-19. Therefore, we cannot discuss the impact of increased thrombus burden in patients with COVID-19. Piedmont Healthcare published a STEMI treatment protocol in May 2020 that advised increased use of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in COVID-19-positive cases; during the study period, however, there were no occasions when tPA use was deemed appropriate based on clinical judgment.

Our findings align with previous studies that describe an increase in combined in-hospital adverse outcomes during the COVID-19 era. Previous studies detected a higher rate of complications in the COVID-19 cohort, but in the current study, the adverse in-hospital course is unrelated to underlying infection.18,19 This study reports a higher incidence of major in-hospital outcomes, including a 65% increase in the rate of combined in-hospital outcomes, which is similar to a multicenter study conducted in Israel.19 There was a 2.3-fold numerical increase in sustained ventricular arrhythmias and a 2.5-fold numerical increase in the incidence of cardiac arrest in the study period. This phenomenon was observed despite a similar rate of reperfusion procedures in both groups.

Acute STEMI is a highly fatal condition with an incidence of 8.5 in 10,000 annually in the United States. While studies across the world have shown a 25% to 40% reduction in the rate of hospitalized acute coronary syndrome cases during the COVID-19 pandemic, the decrease from 34 to 30 STEMI admissions at PAR is not statistically significant.20 Possible reasons for the reduction globally include increased out-of-hospital mortality and decreased incidence of acute STEMI across the general population as a result of improved access to telemedicine or decreased levels of life stressors.20

In summary, there was an increase in ischemic time to reperfusion, in-hospital mortality, and combined in-hospital outcomes for acute STEMI patients at PAR during the COVID period.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. This is a single-center study, so the sample size is small and may not be generalizable to a larger population. This is a retrospective observational study, so causation cannot be inferred. This study analyzed ischemic time parameters as average rates over time rather than in an interrupted time series. Post-reperfusion outcomes were limited to hospital stay. Post-hospital follow-up would provide a better picture of the effects of STEMI intervention. There is no account of patients who died out-of-hospital secondary to acute STEMI. COVID-19 testing was not introduced until midway in our study period. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility of the SARS-Cov-2 virus inciting acute STEMI and subsequently leading to worse outcomes and poor prognosis.

Conclusions

This study provides an analysis of the incidence, characteristics, and clinical outcomes of patients presenting with acute STEMI during the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic. In-hospital mortality and ischemic time to reperfusion increased while combined in-hospital outcomes worsened.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Piedmont Athens Regional IRB for approving this project and allowing access to patient data.

Corresponding author: Syed H. Ali; Department of Medicine, Medical College of Georgia at the Augusta University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership, 30606, Athens, GA; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

doi:10.12788/jcom.0085

From the Department of Medicine, Medical College of Georgia at the Augusta University-University of Georgia Medical Partnership, Athens, GA (Syed H. Ali, Syed Hyder, and Dr. Murrow), and the Department of Cardiology, Piedmont Heart Institute, Piedmont Athens Regional, Athens, GA (Dr. Murrow and Mrs. Davis).

Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) during the early COVID-19 pandemic at Piedmont Athens Regional (PAR), a 330-bed tertiary referral center in Northeast Georgia.

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted at PAR to evaluate patients with acute STEMI admitted over an 8-week period during the initial COVID-19 outbreak. This study group was compared to patients admitted during the corresponding period in 2019. The primary endpoint of this study was defined as a composite of sustained ventricular arrhythmia, congestive heart failure (CHF) with pulmonary congestion, and/or in-hospital mortality.

Results: This study cohort was composed of 64 patients with acute STEMI; 30 patients (46.9%) were hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with STEMI in both the COVID-19 and control groups had similar comorbidities, Killip classification score, and clinical presentations. The median (interquartile range) time from symptom onset to reperfusion (total ischemic time) increased from 99.5 minutes (84.8-132) in 2019 to 149 minutes (96.3-231.8; P = .032) in 2020. Hospitalization during the COVID-19 period was associated with an increased risk for combined in-hospital outcome (odds ratio, 3.96; P = .046).

Conclusion: Patients with STEMI admitted during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak experienced longer total ischemic time and increased risk for combined in-hospital outcomes compared to patients admitted during the corresponding period in 2019.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, hospitalization, outcomes.

The emergence of the SARS-Cov-2 virus in December 2019 caused a worldwide shift in resource allocation and the restructuring of health care systems within the span of a few months. With the rapid spread of infection, the World Health Organization officially declared a pandemic in March 2020. The pandemic led to the deferral and cancellation of in-person patient visits, routine diagnostic studies, and nonessential surgeries and procedures. This response occurred secondary to a joint effort to reduce transmission via stay-at-home mandates and appropriate social distancing.1