User login

Ultrasound bests auscultation for ETT positioning

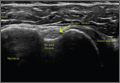

SAN DIEGO – Assessment of the trachea and pleura via point-of-care ultrasound is superior to auscultation in determining the exact location of the endotracheal tube, a randomized, single-center study found.

“It’s been reported that about 20% of the time the endotracheal tube is malpositioned,” study author Dr. Davinder S. Ramsingh said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. “Most of the time (the tube) is too deep, which can lead to severe complications.”

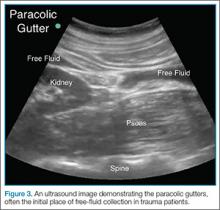

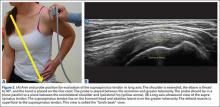

In a double-blinded, randomized study, Dr. Ramsingh and his associates assessed the accuracy of auscultation vs. point-of-care ultrasound in verifying the correct position of the endotracheal tube (ETT). They enrolled 42 adults who required general anesthesia with ETT and randomized them to right main bronchus, left main bronchus, or tracheal intubation, followed by fiber optically–guided visualization to place the ETT. Next, an anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used auscultation to assess the location of the ETT, while another anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used point-of-care ultrasound to assess the location of the ETT. The ultrasound exam consisted of assessing tracheal dilation via standard cuff inflation with air and evaluation of pleural lung sliding, explained Dr. Ramsingh of the department of anesthesiology and perioperative care at the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Ramsingh reported that in differentiating tracheal versus bronchial intubations, auscultation demonstrated a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 59%, while ultrasound demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96%. Chi-square comparison showed a statistically significant improvement with ultrasound (P = .0005), while inter-observer agreement of the ultrasound findings was 100%.

Limitations of the study, he said, include the fact that “we don’t know the incidence of malpositioned endotracheal tubes in the operating room and that this study was evaluating patients undergoing elective surgical procedures.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Assessment of the trachea and pleura via point-of-care ultrasound is superior to auscultation in determining the exact location of the endotracheal tube, a randomized, single-center study found.

“It’s been reported that about 20% of the time the endotracheal tube is malpositioned,” study author Dr. Davinder S. Ramsingh said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. “Most of the time (the tube) is too deep, which can lead to severe complications.”

In a double-blinded, randomized study, Dr. Ramsingh and his associates assessed the accuracy of auscultation vs. point-of-care ultrasound in verifying the correct position of the endotracheal tube (ETT). They enrolled 42 adults who required general anesthesia with ETT and randomized them to right main bronchus, left main bronchus, or tracheal intubation, followed by fiber optically–guided visualization to place the ETT. Next, an anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used auscultation to assess the location of the ETT, while another anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used point-of-care ultrasound to assess the location of the ETT. The ultrasound exam consisted of assessing tracheal dilation via standard cuff inflation with air and evaluation of pleural lung sliding, explained Dr. Ramsingh of the department of anesthesiology and perioperative care at the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Ramsingh reported that in differentiating tracheal versus bronchial intubations, auscultation demonstrated a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 59%, while ultrasound demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96%. Chi-square comparison showed a statistically significant improvement with ultrasound (P = .0005), while inter-observer agreement of the ultrasound findings was 100%.

Limitations of the study, he said, include the fact that “we don’t know the incidence of malpositioned endotracheal tubes in the operating room and that this study was evaluating patients undergoing elective surgical procedures.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Assessment of the trachea and pleura via point-of-care ultrasound is superior to auscultation in determining the exact location of the endotracheal tube, a randomized, single-center study found.

“It’s been reported that about 20% of the time the endotracheal tube is malpositioned,” study author Dr. Davinder S. Ramsingh said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. “Most of the time (the tube) is too deep, which can lead to severe complications.”

In a double-blinded, randomized study, Dr. Ramsingh and his associates assessed the accuracy of auscultation vs. point-of-care ultrasound in verifying the correct position of the endotracheal tube (ETT). They enrolled 42 adults who required general anesthesia with ETT and randomized them to right main bronchus, left main bronchus, or tracheal intubation, followed by fiber optically–guided visualization to place the ETT. Next, an anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used auscultation to assess the location of the ETT, while another anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used point-of-care ultrasound to assess the location of the ETT. The ultrasound exam consisted of assessing tracheal dilation via standard cuff inflation with air and evaluation of pleural lung sliding, explained Dr. Ramsingh of the department of anesthesiology and perioperative care at the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Ramsingh reported that in differentiating tracheal versus bronchial intubations, auscultation demonstrated a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 59%, while ultrasound demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96%. Chi-square comparison showed a statistically significant improvement with ultrasound (P = .0005), while inter-observer agreement of the ultrasound findings was 100%.

Limitations of the study, he said, include the fact that “we don’t know the incidence of malpositioned endotracheal tubes in the operating room and that this study was evaluating patients undergoing elective surgical procedures.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Using point-of-care ultrasound was superior to auscultation in determining the exact location of the endotracheal tube.

Major finding: In differentiating tracheal versus bronchial intubations, auscultation demonstrated a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 59%, while ultrasound demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96%.

Data source: An randomized study of 42 adults who required general anesthesia with ETT.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Optical coherence tomography for PCI gets boost in OPINION trial

PARIS – The first-ever head-to-head randomized trial comparing clinical outcomes of optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) for guidance of percutaneous coronary intervention with a second-generation drug-eluting stent has ended in a draw.

“The clinical outcomes in both OCT-guided PCI and IVUS-guided PCI were excellent in the OPINION study,” Dr. Takashi Kubo reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The form of OCT used in this randomized trial is called optimal frequency domain imaging (OFDI). On the strength of the OPINION results, OFDI deserves to get an upgrade in the PCI treatment guidelines, said Dr. Kubo of Wakayama (Japan) University.

He noted that the 2014 European Society of Cardiology guidelines give IVUS a Class IIa recommendation in selected patients to optimize stent implantation, with a Level of Evidence of B (Eur Heart J. 2014 Oct 1;35:2541-619). The guidelines give OCT (optimal coherence tomography), the more recent and less-studied technology, a Class IIb, Level of Evidence C.

“Our results might influence the next ESC guidelines,” according to Dr. Kubo. “OCT use during PCI should have a Class IIa recommendation.”

The OPINION trial was a prospective, 42-site Japanese study in which 800 patients scheduled for PCI with the Terumo Nobori biolimus-eluting resorbable polymer stent were randomized to an OFDI- or IVUS-guided procedure. All participants underwent follow-up coronary angiography at 8 months and clinical assessment at 12 months.

The primary study endpoint was target vessel failure at 12 months post-PCI, a composite comprising cardiac death, target vessel–related MI, or clinically driven target vessel revascularization. The rate was 5.2% in the OFDI group and statistically similar at 4.9% in the IVUS arm. No cases of contrast-induced nephropathy occurred in either study arm, and stroke rates in both groups were similarly low.

Also noteworthy was the finding that the two intracoronary imaging technologies resulted in similar rates of procedural change: 38% of patients in the OFDI group had a procedural change as result of the imaging findings, as did 36% of the IVUS group. Examples of these procedural changes included upsizing the pre- or postdilatation balloon size or pressure, addition of an another stent, or the use of a distal protection device.

In Japan, where both OCT and IVUS during PCI are routinely reimbursed, roughly 80% of PCI patients undergo one of the two intracoronary imaging procedures. In the United States and Europe, the situation is reversed, Dr. Kubo observed.

Discussant Dr. Ron Waksman agreed with Dr. Kubo that the OPINION results warrant reconsideration of OCT’s Class IIb recommendation in the ESC PCI guidelines. But he thinks the study has a major limitation.

“In my view, this was a missed opportunity to include an angiographically guided PCI arm to establish the superiority of invasive imaging over angiographically guided PCI,” said Dr. Waksman of the MedStar Heart Institute in Washington. While he noted that a recent meta-analysis of 20 studies in more than 29,000 patients concluded that IVUS-guided implantation of drug-eluting stents was associated with a 38% reduction in the risk of mortality, a 23% decrease in major adverse cardiovascular events, and a 41% reduction in stent thrombosis, compared with angiographically guided PCI (BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015 Nov 17;15:153), given the inherent limitations of meta-analyses he’s not convinced that cardiologists really need imaging guidance.

“ILUMIEN III, to my view, is the right study design because it randomizes patients to OCT guidance, IVUS guidance, or angiographic guidance to see if there are important differences. We will have to wait for the ILUMIEN III study results to prove the superiority of invasive imaging over angiographically guided PCI,” according to Dr. Waksman.

It’s anticipated that the ILUMIEN III trial will be ready for presentation at EuroPCR 2017.

The OPINION trial was sponsored by Terumo. Dr. Kubo is a consultant to and recipient of an institutional research grant from the company.

PARIS – The first-ever head-to-head randomized trial comparing clinical outcomes of optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) for guidance of percutaneous coronary intervention with a second-generation drug-eluting stent has ended in a draw.

“The clinical outcomes in both OCT-guided PCI and IVUS-guided PCI were excellent in the OPINION study,” Dr. Takashi Kubo reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The form of OCT used in this randomized trial is called optimal frequency domain imaging (OFDI). On the strength of the OPINION results, OFDI deserves to get an upgrade in the PCI treatment guidelines, said Dr. Kubo of Wakayama (Japan) University.

He noted that the 2014 European Society of Cardiology guidelines give IVUS a Class IIa recommendation in selected patients to optimize stent implantation, with a Level of Evidence of B (Eur Heart J. 2014 Oct 1;35:2541-619). The guidelines give OCT (optimal coherence tomography), the more recent and less-studied technology, a Class IIb, Level of Evidence C.

“Our results might influence the next ESC guidelines,” according to Dr. Kubo. “OCT use during PCI should have a Class IIa recommendation.”

The OPINION trial was a prospective, 42-site Japanese study in which 800 patients scheduled for PCI with the Terumo Nobori biolimus-eluting resorbable polymer stent were randomized to an OFDI- or IVUS-guided procedure. All participants underwent follow-up coronary angiography at 8 months and clinical assessment at 12 months.

The primary study endpoint was target vessel failure at 12 months post-PCI, a composite comprising cardiac death, target vessel–related MI, or clinically driven target vessel revascularization. The rate was 5.2% in the OFDI group and statistically similar at 4.9% in the IVUS arm. No cases of contrast-induced nephropathy occurred in either study arm, and stroke rates in both groups were similarly low.

Also noteworthy was the finding that the two intracoronary imaging technologies resulted in similar rates of procedural change: 38% of patients in the OFDI group had a procedural change as result of the imaging findings, as did 36% of the IVUS group. Examples of these procedural changes included upsizing the pre- or postdilatation balloon size or pressure, addition of an another stent, or the use of a distal protection device.

In Japan, where both OCT and IVUS during PCI are routinely reimbursed, roughly 80% of PCI patients undergo one of the two intracoronary imaging procedures. In the United States and Europe, the situation is reversed, Dr. Kubo observed.

Discussant Dr. Ron Waksman agreed with Dr. Kubo that the OPINION results warrant reconsideration of OCT’s Class IIb recommendation in the ESC PCI guidelines. But he thinks the study has a major limitation.

“In my view, this was a missed opportunity to include an angiographically guided PCI arm to establish the superiority of invasive imaging over angiographically guided PCI,” said Dr. Waksman of the MedStar Heart Institute in Washington. While he noted that a recent meta-analysis of 20 studies in more than 29,000 patients concluded that IVUS-guided implantation of drug-eluting stents was associated with a 38% reduction in the risk of mortality, a 23% decrease in major adverse cardiovascular events, and a 41% reduction in stent thrombosis, compared with angiographically guided PCI (BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015 Nov 17;15:153), given the inherent limitations of meta-analyses he’s not convinced that cardiologists really need imaging guidance.

“ILUMIEN III, to my view, is the right study design because it randomizes patients to OCT guidance, IVUS guidance, or angiographic guidance to see if there are important differences. We will have to wait for the ILUMIEN III study results to prove the superiority of invasive imaging over angiographically guided PCI,” according to Dr. Waksman.

It’s anticipated that the ILUMIEN III trial will be ready for presentation at EuroPCR 2017.

The OPINION trial was sponsored by Terumo. Dr. Kubo is a consultant to and recipient of an institutional research grant from the company.

PARIS – The first-ever head-to-head randomized trial comparing clinical outcomes of optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) for guidance of percutaneous coronary intervention with a second-generation drug-eluting stent has ended in a draw.

“The clinical outcomes in both OCT-guided PCI and IVUS-guided PCI were excellent in the OPINION study,” Dr. Takashi Kubo reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The form of OCT used in this randomized trial is called optimal frequency domain imaging (OFDI). On the strength of the OPINION results, OFDI deserves to get an upgrade in the PCI treatment guidelines, said Dr. Kubo of Wakayama (Japan) University.

He noted that the 2014 European Society of Cardiology guidelines give IVUS a Class IIa recommendation in selected patients to optimize stent implantation, with a Level of Evidence of B (Eur Heart J. 2014 Oct 1;35:2541-619). The guidelines give OCT (optimal coherence tomography), the more recent and less-studied technology, a Class IIb, Level of Evidence C.

“Our results might influence the next ESC guidelines,” according to Dr. Kubo. “OCT use during PCI should have a Class IIa recommendation.”

The OPINION trial was a prospective, 42-site Japanese study in which 800 patients scheduled for PCI with the Terumo Nobori biolimus-eluting resorbable polymer stent were randomized to an OFDI- or IVUS-guided procedure. All participants underwent follow-up coronary angiography at 8 months and clinical assessment at 12 months.

The primary study endpoint was target vessel failure at 12 months post-PCI, a composite comprising cardiac death, target vessel–related MI, or clinically driven target vessel revascularization. The rate was 5.2% in the OFDI group and statistically similar at 4.9% in the IVUS arm. No cases of contrast-induced nephropathy occurred in either study arm, and stroke rates in both groups were similarly low.

Also noteworthy was the finding that the two intracoronary imaging technologies resulted in similar rates of procedural change: 38% of patients in the OFDI group had a procedural change as result of the imaging findings, as did 36% of the IVUS group. Examples of these procedural changes included upsizing the pre- or postdilatation balloon size or pressure, addition of an another stent, or the use of a distal protection device.

In Japan, where both OCT and IVUS during PCI are routinely reimbursed, roughly 80% of PCI patients undergo one of the two intracoronary imaging procedures. In the United States and Europe, the situation is reversed, Dr. Kubo observed.

Discussant Dr. Ron Waksman agreed with Dr. Kubo that the OPINION results warrant reconsideration of OCT’s Class IIb recommendation in the ESC PCI guidelines. But he thinks the study has a major limitation.

“In my view, this was a missed opportunity to include an angiographically guided PCI arm to establish the superiority of invasive imaging over angiographically guided PCI,” said Dr. Waksman of the MedStar Heart Institute in Washington. While he noted that a recent meta-analysis of 20 studies in more than 29,000 patients concluded that IVUS-guided implantation of drug-eluting stents was associated with a 38% reduction in the risk of mortality, a 23% decrease in major adverse cardiovascular events, and a 41% reduction in stent thrombosis, compared with angiographically guided PCI (BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015 Nov 17;15:153), given the inherent limitations of meta-analyses he’s not convinced that cardiologists really need imaging guidance.

“ILUMIEN III, to my view, is the right study design because it randomizes patients to OCT guidance, IVUS guidance, or angiographic guidance to see if there are important differences. We will have to wait for the ILUMIEN III study results to prove the superiority of invasive imaging over angiographically guided PCI,” according to Dr. Waksman.

It’s anticipated that the ILUMIEN III trial will be ready for presentation at EuroPCR 2017.

The OPINION trial was sponsored by Terumo. Dr. Kubo is a consultant to and recipient of an institutional research grant from the company.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: A large, randomized trial shows PCI clinical outcomes are equivalent with optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound guidance.

Major finding: The composite rate of cardiac death, target vessel–related MI, or clinically driven target vessel revascularization within 12 months of PCI was 5.2% in the group whose procedure was guided by optical coherence tomography and statistically similar at 4.9% in patients whose PCI was guided by intravascular ultrasound.

Data source: This was a randomized, prospective, multicenter, 12-month follow-up trial of 800 Japanese patients scheduled for PCI under intracoronary imaging guidance provided by either IVUS or OCT.

Disclosures: The OPINION trial was sponsored by Terumo. The study presenter is a consultant to and recipient of an institutional research grant from the company.

Linea Aspera as Rotational Landmark for Tumor Endoprostheses: A Computed Tomography Study

The distal or proximal femur with tumor endoprosthesis is commonly replaced after segmental resections for bone tumors, complex trauma, or revision arthroplasty. In conventional joint replacements, correct rotational alignment of the component is referenced off anatomical landmarks in the proximal or distal femur. After tumor resection, however, these landmarks are often not available for rotational orientation. There are no reports of studies validating a particular method of establishing rotation in these cases.

To establish a guide for rotational alignment of tumor endoprostheses, we set out to define the natural location of the linea aspera (LA) based on axial computed tomography (CT) scans. The LA is often the most outstanding visible bony landmark on a cross-section of the femur during surgery, and it would be helpful to know its normal orientation in relation to the true anteroposterior (AP) axis of the femur and to the femoral version. We wanted to answer these 5 questions:

1. Is the prominence of the LA easily identifiable on cross-section at different levels of the femoral shaft?

2. Does an axis passing through the LA correspond to the AP axis of the femur?

3. If not, is this axis offset internally or externally and by how much?

4. Is this offset constant at all levels of the femoral shaft?

5. How does the LA axis relate to the femoral neck axis at these levels?

The answers determine if the LA can be reliably used for rotational alignment of tumor endoprostheses.

Materials and Methods

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed whole-body fluorine-18-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) studies performed in our hospital between 2003 and 2006 to identify those with full-length bilateral femur CT scans. These scans were available on the hospital’s computerized picture archiving system (General Electric). Patients could be included in the study as long as they were at least 18 years old at time of scan and did not have any pathology that deformed the femur, broke a cortex, or otherwise caused any gross asymmetry of the femur. Of the 72 patients with full-length femur CT scans, 3 were excluded: 1 with a congenital hip dysplasia, 1 with an old, malunited femoral fracture, and 1 who was 15 years old at time of scan.

Axial Slice Selection

For each patient, scout AP films were used to measure femoral shaft length from the top of the greater trochanter to the end of the lateral femoral condyle. The levels of the proximal third, midshaft, and distal third were then calculated based on this length. The LA was studied on the axial slices nearest these levels. Next, we scrolled through the scans to identify an axial slice that best showed the femoral neck axis. The literature on CT measurement of femoral anteversion is varied. Some articles describe a technique that uses 2 superimposed axial slices, and others describe a single axial slice.1-3 We used 1 axial slice to draw the femoral neck axis because our computer software could not superimpose 2 images on 1 screen and because the CT scans were not made under specific protocols to measure anteversion but rather were part of a cancer staging work-up. Axial cuts were made at 5-mm intervals, and not all scans included a single slice capturing the head, neck, and greater trochanter. Therefore, we used a (previously described) method in which the femoral neck axis is drawn on a slice that most captured the femoral neck, usually toward its base.4 Last, in order to draw the posterior condyle (PC) axis, we selected an axial slice that showed the posterior-most aspects of the femoral condyles at the intercondylar notch.

Determining Anteroposterior and Posterior Condyle Axes of Femur

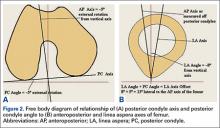

As we made all measurements for each femur off a single CT scan, we were able to use a straight horizontal line—drawn on-screen with a software tool—as a reference for measuring rotation. On a distal femur cut, the PC axis is drawn by connecting the posterior-most points of both condyles. The software calculates the angle formed—the PC angle (Figure 1). This angle, the degree to which the PC axis deviates from a straight horizontal line on-screen, can be used to account for gross rotation of the limb on comparison of images. The AP axis of the femur is the axis perpendicular to the PC axis. As such, the PC angle can also be used to determine degree of deviation of the AP axis from a straight vertical line on-screen. The AP axis was used when calculating the LA axis at the various levels of the femur (Figure 2).

Femoral Version

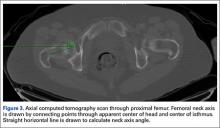

We used the software tool to draw the femoral neck axis. From the end of this line, a straight horizontal line is drawn on-screen (Figure 3). The software calculates the angle formed—the femoral neck axis angle. We assigned a positive value for a femoral head that pointed anteriorly on the image and a negative value for a head that pointed posteriorly. Adjusting for external rotation of the limb involved calculating the femoral version by subtracting the PC angle from the neck axis angle; adjusting for internal rotation involved adding these 2 angles.

Linea Aspera Morphology

After viewing the first 20 CT scans, we identified 3 types of LA morphology. Type I presents as a thickening on the posterior cortex with a sharp apex; type II presents as a flat-faced but distinct ridge of bone between the medial and lateral lips; and in type III there is no distinct cortical thickening with blunted medial and lateral lips; the latter is always more prominent.

Linea Aspera Axis Offset

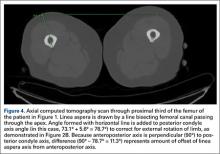

From the most posterior point of the LA, a line drawn forward bisecting the femoral canal defined the LA axis. In type I morphology, the posterior-most point was the apex; in type II, the middle of flat posterior surface was used as the starting point; in type III, the lateral lip was used, as it was sharper than the medial lip. This line is again referenced with a straight horizontal line across the image. The PC angle is then added to account for limb rotation, and the result is the LA angle. As the AP axis is perpendicular to the PC axis, the LA angle is subtracted from 90°; the difference represents the amount of offset of the LA axis from the AP axis. By convention, we assigned this a positive value for an LA lateral to the midpoint of the femur and a negative value for an LA medial to the midpoint (Figure 4).

Linea Aspera Axis and Femoral Neck Axis

The angle between the LA axis and the PC axis was measured. The femoral version angle was subtracted from that angle to obtain the arc between the LA axis and the femoral neck axis.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute). All tests were 2-sided and conducted at the .05 significance level. No adjustments were made for multiple testing. Statistical analysis was performed with nonparametric tests and without making assumptions about the distribution of the study population. Univariate analyses were performed to test for significant side-to-side differences in femoral length, femoral version angle, and LA torsion angles at each level. A multivariate analysis was performed to test for interactions between sex, side, and level. In all analyses, P < .05 was used as the cutoff value for statistical significance.

Results

Femoral lengths varied by side and sex. The left side was longer than the right by a mean of 1.3 mm (P = .008). With multivariate analysis taking into account sex and age (cumulated per decade), there was still a significant effect of side on femoral length. Sex also had a significant effect on femoral length, with females’ femurs shorter by 21.7 mm (standard error, 5.0 mm). Mean (SD) anteversion of the femoral neck was 7.9° (12.7°) on the left and 13.3° (13.0°) on the right; the difference between sides was significant (P < .001). In a multivariate analysis performed to identify potential predictors of femoral version, side still had a significant (P < .001) independent effect; sex and age did not have an effect.

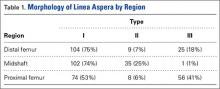

LA morphology varied according to femoral shaft level (Table 1). The morphology was type I in 75% of patients at the distal femur and 74% of patients at the midshaft femur, while only 53% of patients had a type I morphology at the proximal femur. The proportion of type III morphology was larger in the proximal femur (41%) than in the other locations.

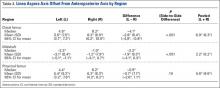

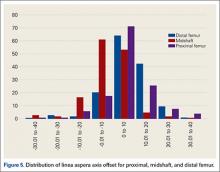

The LA axis of the femur did not correspond exactly to the AP axis at all femoral levels. At the distal femur, mean (SD) lateral offset of the LA axis was 5.5° (7.5°) on the left and 8.3° (8.9°) on the right. At the midshaft, mean (SD) medial offset of the LA axis was 3.1° (8.4°) on the left and 1.2° (7.9°) on the right. At the proximal femur, mean (SD) lateral offset of the LA axis was 5.4° (9.2°) on the left and 6.2° (8.3°) on the right. The side-to-side differences were statistically significant for the distal femur and midshaft but not the proximal femur. Table 2 lists the 95% confidence intervals for the mean values. As the range of differences was small (0.7°-2.8°), and the differences may not be clinically detected on gross inspection during surgery, we pooled both sides’ values to arrive at a single mean for each level. The LA axis was offset a mean (SD) of 6.9° (8.3°) laterally at the distal femur, 2.2° (8.2°) medially at the midshaft, and 5.8° (8.6°) laterally at the proximal femur. Figure 5 shows the frequency of distribution of LA axis offset.Offset of the LA axis from the AP axis of the femur was significantly (P < .001) different for each femoral level, even when a multivariate analysis was performed to determine the effect of sex, age, or side. Age and sex had no significant effect on mean offset of LA axis from AP axis.

We compared the mean arc between femoral neck axis and LA axis after referencing both off the PC axis. At the distal femur, mean (SD) arc between these 2 axes was 76.6° (13.1°) on the left and 68.3° (13.6°) on the right (mean difference, 8.3°); at the midshaft, mean (SD) arc was 85.2° (13.5°) on the left and 77.9° (13.1°) on the right (mean difference, 7.4°); at the proximal femur, mean (SD) arc was 76.7° (11.9°) on the left and 70.5° (12.8°) on the right (mean difference, 6.2°). The side-to-side differences were statistically significant (P < .001) for all locations.

In multivariate analysis, sex and age did not have an effect on mean arc between the 2 axes. Side and femoral level, however, had a significant effect (P < .001).

Discussion

In total hip arthroplasty, the goal is to restore femoral anteversion, usually referenced to the remaining femoral neck segment.3 In total knee arthroplasty (TKA), proper rotation preserves normal patellofemoral tracking.5 Various landmarks are used, such as the PCs or the epicondyles. After tumor resections, these landmarks are often lost.6 However, there are no reports of studies validating a particular method of achieving proper rotational orientation of tumor endoprostheses, though several methods are being used. One method involves inserting 2 drill bits before osteotomy—one proximal to the intended level of resection on the anterior femur, and the other on the anterior tibial shaft. The straight line formed can establish a plane of rotation (and length), which the surgeon must aim to restore when the components are placed. This method is useful for distal femur resections but not proximal femur resections. Another method, based on the LA’s anatomical position on the posterior aspect of the femur,4 uses the prominence of the LA to align the prosthesis. With this method, the LA is assumed to be directly posterior (6 o’clock) on the femur. However, this assumption has not been confirmed by any study. A third method, described by Heck and Carnesale,5 involves marking the anterior aspect of the femur after resection and aligning the components to it. The authors cautioned against using the LA as a landmark, saying that its course is highly variable.

The LA is a narrow, elevated length of bone, with medial and lateral lips, that serves as an attachment site for muscles in the posterior thigh. Proximally, the LA presents with lateral, medial, and intermediate lips. In the midshaft, it is often elevated by an underlying bony ridge or pilaster complex. Distally, it diverges into 2 ridges that form the triangular popliteal surface.1,7 For the LA to be a reliable landmark, first it must be clearly identifiable on viewing a femoral cross-section. The LA that presents with type I or II morphology is distinctly identifiable, and an axis from its apex and bisecting the canal can easily be constructed. In our study, the LA presented with type I or II morphology in 82% of distal femoral sections and 99% of midshaft femoral sections. Therefore, the LA is a conspicuous landmark at these levels. In the proximal femur, 59% had type I or II morphology. Type III morphology could be identified on cross-sections by the persisting prominence of the lateral lip. However, it may be difficult to appreciate the LA with this morphology at surgery.

Once the LA is identified, its normal cross-sectional position must be defined. One way to do this is to establish the relationship of its axis (LA axis) to the true AP axis. Based on mean values, the LA axis is laterally offset 7º at the distal third of the femur, medially offset 2º at the midshaft, and laterally offset 6º at the proximal third. Therefore, for ideal placement with the LA used for orientation, the component must be internally rotated 7º relative to the LA for femoral resection at the distal third, externally rotated 2º for resection at the midshaft, and internally rotated 6º for resection at the proximal third. Studies have demonstrated that joint contact forces and mechanical alignment of the lower limb can be altered with as little as 5º of femoral malrotation.8,9 Although such a small degree of malrotation is often asymptomatic, it can have long-term effects on soft-tissue tension and patellar tracking.10,11 Rotating-platform mobile-bearing TKA designs can compensate for femoral malrotation, but they may have little to no effect on patellar tracking.12 Therefore, we think aligning the components as near as possible to their natural orientation can prove beneficial in long-term patient management.

Another way of defining the normal cross-sectional position of the LA is to relate it to the femoral neck axis. We measured the difference between these 2 axes. Mean differences were 72º (distal femur), 81.5º (midshaft), and 73.5º (proximal third). Mean arc differences at all levels were larger on the left side—a reflection of the femoral neck being less anteverted on that side in our measurements. Standard deviations were smaller for measurements of LA axis offset from AP axis (range, 7.5°-9.2°) than for measurements of arc between LA axis and femoral neck axis (range, 11.9°-13.6°). This finding indicates there is less variation in the former method, making it preferable for defining the cross-sectional position of the LA.

It has been said that the course of the LA is variable, and our data provide confirmation. The LA does not lie directly posterior (6 o’clock), and it does not trace a straight longitudinal course along the posterior femur, as demonstrated by the different LA axis offsets at 3 levels. However, we may still use it as a landmark if we remain aware how much the LA is offset from the AP axis at each femoral level. Figures 6A-6D, which show CT scans of a patient who underwent distal femoral resection and replacement with an endoprosthesis, illustrate how the LA axis was measured before surgery and how proper prosthesis placement was confirmed after surgery.

In hip arthroplasty, restoration of normal femoral version is the reference for endoprosthetic placement. The literature on “normal” femoral anteversion varies with the method used. In a review of studies on CT-measured adult femoral version, reported values ranged from 6.3° to 40°.2 Mean femoral version in our study ranged from 8° to 13°. Orthopedics textbooks generally put the value at 10° to 15º, and this seems to be the range that surgeons target.6 However, we found a statistically significant mean side-to-side difference of 5.4°. This finding is possibly explained by our large sample—it was larger than the samples used in other studies of CT-measured femoral version. Other studies have found mean side-to-side differences of up to 4.0º.5 Another explanation for our finding is that the studies may differ methodologically. The studies that established values for femoral anteversion were based on CT protocols—thinner slices (1-5 mm), use of foot holders to standardize limb rotation, use of 2 axial cuts in proximal femur to establish femoral neck axis2,13—designed specifically for this measurement. As the CT scans reviewed in our study are not designed for this purpose, errors in femoral version measurement may have been introduced, which may also explain why there is larger variation in measurements of the arc between the LA axis and the femoral neck axis.

Conclusion

The LA does not lie directly on the posterior surface of the femur. It deviates 6.9° laterally at the distal femur, 2.2° medially at the midshaft, and 6.9° laterally at the proximal third. As the LA is an easily identifiable structure on cross-sections of the femoral shaft at the midshaft and distal third of the femur, it may be useful as a rotational landmark for resections at these levels if these deviations are considered during tumor endoprosthetic replacements.

1. Desai SC, Willson S. Radiology of the linea aspera. Australas Radiol. 1985;29(3):273-274.

2. Kuo TY, Skedros JG, Bloebaum RD. Measurement of femoral anteversion by biplane radiography and computed tomography imaging: comparison with an anatomic reference. Invest Radiol. 2003;38(4):221-229.

3. Wines AP, McNicol D. Computed tomography measurement of the accuracy of component version in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):696-701.

4. Gray H. Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1918.

5. Heck RK, Carnesale PG. General principles of tumors. In: Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. Vol 1. 10th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003:733-791.

6. Katz, MA, Beck TD, Silber JS, Seldes RM, Lotke PA. Determining femoral rotational alignment in total knee arthroplasty: reliability of techniques. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(3):301-305.

7. Pitt MJ. Radiology of the femoral linea aspera–pilaster complex: the track sign. Radiology. 1982;142(1):66.

8. Bretin P, O’Loughlin PF, Suero EM, et al. Influence of femoral malrotation on knee joint alignment and intra-articular contact pressures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(8):1115-1120.

9. Zihlmann MS, Stacoff A, Romero J, Quervain IK, Stüssi E. Biomechanical background and clinical observations of rotational malalignment in TKA: literature review and consequences. Clin Biomech. 2005;20(7):661-668.

10. Ghosh KM, Merican AM, Iranpour F, Deehan DJ, Amis AA. The effect of femoral component rotation on the extensor retinaculum of the knee. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(9):1136-1141.

11. Verlinden C, Uvin P, Labey L, Luyckx JP, Bellemans J, Vandenneucker H. The influence of malrotation of the femoral component in total knee replacement on the mechanics of patellofemoral contact during gait: an in vitro biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(5):737-742.

12. Kessler O, Patil S, Colwell CW Jr, D’Lima DD. The effect of femoral component malrotation on patellar biomechanics. J Biomech. 2008;41(16):3332-3339.

13. Strecker W, Keppler P, Gebhard F, Kinzl L. Length and torsion of the lower limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(6):1019-1023.

The distal or proximal femur with tumor endoprosthesis is commonly replaced after segmental resections for bone tumors, complex trauma, or revision arthroplasty. In conventional joint replacements, correct rotational alignment of the component is referenced off anatomical landmarks in the proximal or distal femur. After tumor resection, however, these landmarks are often not available for rotational orientation. There are no reports of studies validating a particular method of establishing rotation in these cases.

To establish a guide for rotational alignment of tumor endoprostheses, we set out to define the natural location of the linea aspera (LA) based on axial computed tomography (CT) scans. The LA is often the most outstanding visible bony landmark on a cross-section of the femur during surgery, and it would be helpful to know its normal orientation in relation to the true anteroposterior (AP) axis of the femur and to the femoral version. We wanted to answer these 5 questions:

1. Is the prominence of the LA easily identifiable on cross-section at different levels of the femoral shaft?

2. Does an axis passing through the LA correspond to the AP axis of the femur?

3. If not, is this axis offset internally or externally and by how much?

4. Is this offset constant at all levels of the femoral shaft?

5. How does the LA axis relate to the femoral neck axis at these levels?

The answers determine if the LA can be reliably used for rotational alignment of tumor endoprostheses.

Materials and Methods

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed whole-body fluorine-18-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) studies performed in our hospital between 2003 and 2006 to identify those with full-length bilateral femur CT scans. These scans were available on the hospital’s computerized picture archiving system (General Electric). Patients could be included in the study as long as they were at least 18 years old at time of scan and did not have any pathology that deformed the femur, broke a cortex, or otherwise caused any gross asymmetry of the femur. Of the 72 patients with full-length femur CT scans, 3 were excluded: 1 with a congenital hip dysplasia, 1 with an old, malunited femoral fracture, and 1 who was 15 years old at time of scan.

Axial Slice Selection

For each patient, scout AP films were used to measure femoral shaft length from the top of the greater trochanter to the end of the lateral femoral condyle. The levels of the proximal third, midshaft, and distal third were then calculated based on this length. The LA was studied on the axial slices nearest these levels. Next, we scrolled through the scans to identify an axial slice that best showed the femoral neck axis. The literature on CT measurement of femoral anteversion is varied. Some articles describe a technique that uses 2 superimposed axial slices, and others describe a single axial slice.1-3 We used 1 axial slice to draw the femoral neck axis because our computer software could not superimpose 2 images on 1 screen and because the CT scans were not made under specific protocols to measure anteversion but rather were part of a cancer staging work-up. Axial cuts were made at 5-mm intervals, and not all scans included a single slice capturing the head, neck, and greater trochanter. Therefore, we used a (previously described) method in which the femoral neck axis is drawn on a slice that most captured the femoral neck, usually toward its base.4 Last, in order to draw the posterior condyle (PC) axis, we selected an axial slice that showed the posterior-most aspects of the femoral condyles at the intercondylar notch.

Determining Anteroposterior and Posterior Condyle Axes of Femur

As we made all measurements for each femur off a single CT scan, we were able to use a straight horizontal line—drawn on-screen with a software tool—as a reference for measuring rotation. On a distal femur cut, the PC axis is drawn by connecting the posterior-most points of both condyles. The software calculates the angle formed—the PC angle (Figure 1). This angle, the degree to which the PC axis deviates from a straight horizontal line on-screen, can be used to account for gross rotation of the limb on comparison of images. The AP axis of the femur is the axis perpendicular to the PC axis. As such, the PC angle can also be used to determine degree of deviation of the AP axis from a straight vertical line on-screen. The AP axis was used when calculating the LA axis at the various levels of the femur (Figure 2).

Femoral Version

We used the software tool to draw the femoral neck axis. From the end of this line, a straight horizontal line is drawn on-screen (Figure 3). The software calculates the angle formed—the femoral neck axis angle. We assigned a positive value for a femoral head that pointed anteriorly on the image and a negative value for a head that pointed posteriorly. Adjusting for external rotation of the limb involved calculating the femoral version by subtracting the PC angle from the neck axis angle; adjusting for internal rotation involved adding these 2 angles.

Linea Aspera Morphology

After viewing the first 20 CT scans, we identified 3 types of LA morphology. Type I presents as a thickening on the posterior cortex with a sharp apex; type II presents as a flat-faced but distinct ridge of bone between the medial and lateral lips; and in type III there is no distinct cortical thickening with blunted medial and lateral lips; the latter is always more prominent.

Linea Aspera Axis Offset

From the most posterior point of the LA, a line drawn forward bisecting the femoral canal defined the LA axis. In type I morphology, the posterior-most point was the apex; in type II, the middle of flat posterior surface was used as the starting point; in type III, the lateral lip was used, as it was sharper than the medial lip. This line is again referenced with a straight horizontal line across the image. The PC angle is then added to account for limb rotation, and the result is the LA angle. As the AP axis is perpendicular to the PC axis, the LA angle is subtracted from 90°; the difference represents the amount of offset of the LA axis from the AP axis. By convention, we assigned this a positive value for an LA lateral to the midpoint of the femur and a negative value for an LA medial to the midpoint (Figure 4).

Linea Aspera Axis and Femoral Neck Axis

The angle between the LA axis and the PC axis was measured. The femoral version angle was subtracted from that angle to obtain the arc between the LA axis and the femoral neck axis.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute). All tests were 2-sided and conducted at the .05 significance level. No adjustments were made for multiple testing. Statistical analysis was performed with nonparametric tests and without making assumptions about the distribution of the study population. Univariate analyses were performed to test for significant side-to-side differences in femoral length, femoral version angle, and LA torsion angles at each level. A multivariate analysis was performed to test for interactions between sex, side, and level. In all analyses, P < .05 was used as the cutoff value for statistical significance.

Results

Femoral lengths varied by side and sex. The left side was longer than the right by a mean of 1.3 mm (P = .008). With multivariate analysis taking into account sex and age (cumulated per decade), there was still a significant effect of side on femoral length. Sex also had a significant effect on femoral length, with females’ femurs shorter by 21.7 mm (standard error, 5.0 mm). Mean (SD) anteversion of the femoral neck was 7.9° (12.7°) on the left and 13.3° (13.0°) on the right; the difference between sides was significant (P < .001). In a multivariate analysis performed to identify potential predictors of femoral version, side still had a significant (P < .001) independent effect; sex and age did not have an effect.

LA morphology varied according to femoral shaft level (Table 1). The morphology was type I in 75% of patients at the distal femur and 74% of patients at the midshaft femur, while only 53% of patients had a type I morphology at the proximal femur. The proportion of type III morphology was larger in the proximal femur (41%) than in the other locations.

The LA axis of the femur did not correspond exactly to the AP axis at all femoral levels. At the distal femur, mean (SD) lateral offset of the LA axis was 5.5° (7.5°) on the left and 8.3° (8.9°) on the right. At the midshaft, mean (SD) medial offset of the LA axis was 3.1° (8.4°) on the left and 1.2° (7.9°) on the right. At the proximal femur, mean (SD) lateral offset of the LA axis was 5.4° (9.2°) on the left and 6.2° (8.3°) on the right. The side-to-side differences were statistically significant for the distal femur and midshaft but not the proximal femur. Table 2 lists the 95% confidence intervals for the mean values. As the range of differences was small (0.7°-2.8°), and the differences may not be clinically detected on gross inspection during surgery, we pooled both sides’ values to arrive at a single mean for each level. The LA axis was offset a mean (SD) of 6.9° (8.3°) laterally at the distal femur, 2.2° (8.2°) medially at the midshaft, and 5.8° (8.6°) laterally at the proximal femur. Figure 5 shows the frequency of distribution of LA axis offset.Offset of the LA axis from the AP axis of the femur was significantly (P < .001) different for each femoral level, even when a multivariate analysis was performed to determine the effect of sex, age, or side. Age and sex had no significant effect on mean offset of LA axis from AP axis.

We compared the mean arc between femoral neck axis and LA axis after referencing both off the PC axis. At the distal femur, mean (SD) arc between these 2 axes was 76.6° (13.1°) on the left and 68.3° (13.6°) on the right (mean difference, 8.3°); at the midshaft, mean (SD) arc was 85.2° (13.5°) on the left and 77.9° (13.1°) on the right (mean difference, 7.4°); at the proximal femur, mean (SD) arc was 76.7° (11.9°) on the left and 70.5° (12.8°) on the right (mean difference, 6.2°). The side-to-side differences were statistically significant (P < .001) for all locations.

In multivariate analysis, sex and age did not have an effect on mean arc between the 2 axes. Side and femoral level, however, had a significant effect (P < .001).

Discussion

In total hip arthroplasty, the goal is to restore femoral anteversion, usually referenced to the remaining femoral neck segment.3 In total knee arthroplasty (TKA), proper rotation preserves normal patellofemoral tracking.5 Various landmarks are used, such as the PCs or the epicondyles. After tumor resections, these landmarks are often lost.6 However, there are no reports of studies validating a particular method of achieving proper rotational orientation of tumor endoprostheses, though several methods are being used. One method involves inserting 2 drill bits before osteotomy—one proximal to the intended level of resection on the anterior femur, and the other on the anterior tibial shaft. The straight line formed can establish a plane of rotation (and length), which the surgeon must aim to restore when the components are placed. This method is useful for distal femur resections but not proximal femur resections. Another method, based on the LA’s anatomical position on the posterior aspect of the femur,4 uses the prominence of the LA to align the prosthesis. With this method, the LA is assumed to be directly posterior (6 o’clock) on the femur. However, this assumption has not been confirmed by any study. A third method, described by Heck and Carnesale,5 involves marking the anterior aspect of the femur after resection and aligning the components to it. The authors cautioned against using the LA as a landmark, saying that its course is highly variable.

The LA is a narrow, elevated length of bone, with medial and lateral lips, that serves as an attachment site for muscles in the posterior thigh. Proximally, the LA presents with lateral, medial, and intermediate lips. In the midshaft, it is often elevated by an underlying bony ridge or pilaster complex. Distally, it diverges into 2 ridges that form the triangular popliteal surface.1,7 For the LA to be a reliable landmark, first it must be clearly identifiable on viewing a femoral cross-section. The LA that presents with type I or II morphology is distinctly identifiable, and an axis from its apex and bisecting the canal can easily be constructed. In our study, the LA presented with type I or II morphology in 82% of distal femoral sections and 99% of midshaft femoral sections. Therefore, the LA is a conspicuous landmark at these levels. In the proximal femur, 59% had type I or II morphology. Type III morphology could be identified on cross-sections by the persisting prominence of the lateral lip. However, it may be difficult to appreciate the LA with this morphology at surgery.

Once the LA is identified, its normal cross-sectional position must be defined. One way to do this is to establish the relationship of its axis (LA axis) to the true AP axis. Based on mean values, the LA axis is laterally offset 7º at the distal third of the femur, medially offset 2º at the midshaft, and laterally offset 6º at the proximal third. Therefore, for ideal placement with the LA used for orientation, the component must be internally rotated 7º relative to the LA for femoral resection at the distal third, externally rotated 2º for resection at the midshaft, and internally rotated 6º for resection at the proximal third. Studies have demonstrated that joint contact forces and mechanical alignment of the lower limb can be altered with as little as 5º of femoral malrotation.8,9 Although such a small degree of malrotation is often asymptomatic, it can have long-term effects on soft-tissue tension and patellar tracking.10,11 Rotating-platform mobile-bearing TKA designs can compensate for femoral malrotation, but they may have little to no effect on patellar tracking.12 Therefore, we think aligning the components as near as possible to their natural orientation can prove beneficial in long-term patient management.

Another way of defining the normal cross-sectional position of the LA is to relate it to the femoral neck axis. We measured the difference between these 2 axes. Mean differences were 72º (distal femur), 81.5º (midshaft), and 73.5º (proximal third). Mean arc differences at all levels were larger on the left side—a reflection of the femoral neck being less anteverted on that side in our measurements. Standard deviations were smaller for measurements of LA axis offset from AP axis (range, 7.5°-9.2°) than for measurements of arc between LA axis and femoral neck axis (range, 11.9°-13.6°). This finding indicates there is less variation in the former method, making it preferable for defining the cross-sectional position of the LA.

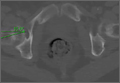

It has been said that the course of the LA is variable, and our data provide confirmation. The LA does not lie directly posterior (6 o’clock), and it does not trace a straight longitudinal course along the posterior femur, as demonstrated by the different LA axis offsets at 3 levels. However, we may still use it as a landmark if we remain aware how much the LA is offset from the AP axis at each femoral level. Figures 6A-6D, which show CT scans of a patient who underwent distal femoral resection and replacement with an endoprosthesis, illustrate how the LA axis was measured before surgery and how proper prosthesis placement was confirmed after surgery.

In hip arthroplasty, restoration of normal femoral version is the reference for endoprosthetic placement. The literature on “normal” femoral anteversion varies with the method used. In a review of studies on CT-measured adult femoral version, reported values ranged from 6.3° to 40°.2 Mean femoral version in our study ranged from 8° to 13°. Orthopedics textbooks generally put the value at 10° to 15º, and this seems to be the range that surgeons target.6 However, we found a statistically significant mean side-to-side difference of 5.4°. This finding is possibly explained by our large sample—it was larger than the samples used in other studies of CT-measured femoral version. Other studies have found mean side-to-side differences of up to 4.0º.5 Another explanation for our finding is that the studies may differ methodologically. The studies that established values for femoral anteversion were based on CT protocols—thinner slices (1-5 mm), use of foot holders to standardize limb rotation, use of 2 axial cuts in proximal femur to establish femoral neck axis2,13—designed specifically for this measurement. As the CT scans reviewed in our study are not designed for this purpose, errors in femoral version measurement may have been introduced, which may also explain why there is larger variation in measurements of the arc between the LA axis and the femoral neck axis.

Conclusion

The LA does not lie directly on the posterior surface of the femur. It deviates 6.9° laterally at the distal femur, 2.2° medially at the midshaft, and 6.9° laterally at the proximal third. As the LA is an easily identifiable structure on cross-sections of the femoral shaft at the midshaft and distal third of the femur, it may be useful as a rotational landmark for resections at these levels if these deviations are considered during tumor endoprosthetic replacements.

The distal or proximal femur with tumor endoprosthesis is commonly replaced after segmental resections for bone tumors, complex trauma, or revision arthroplasty. In conventional joint replacements, correct rotational alignment of the component is referenced off anatomical landmarks in the proximal or distal femur. After tumor resection, however, these landmarks are often not available for rotational orientation. There are no reports of studies validating a particular method of establishing rotation in these cases.

To establish a guide for rotational alignment of tumor endoprostheses, we set out to define the natural location of the linea aspera (LA) based on axial computed tomography (CT) scans. The LA is often the most outstanding visible bony landmark on a cross-section of the femur during surgery, and it would be helpful to know its normal orientation in relation to the true anteroposterior (AP) axis of the femur and to the femoral version. We wanted to answer these 5 questions:

1. Is the prominence of the LA easily identifiable on cross-section at different levels of the femoral shaft?

2. Does an axis passing through the LA correspond to the AP axis of the femur?

3. If not, is this axis offset internally or externally and by how much?

4. Is this offset constant at all levels of the femoral shaft?

5. How does the LA axis relate to the femoral neck axis at these levels?

The answers determine if the LA can be reliably used for rotational alignment of tumor endoprostheses.

Materials and Methods

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed whole-body fluorine-18-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) studies performed in our hospital between 2003 and 2006 to identify those with full-length bilateral femur CT scans. These scans were available on the hospital’s computerized picture archiving system (General Electric). Patients could be included in the study as long as they were at least 18 years old at time of scan and did not have any pathology that deformed the femur, broke a cortex, or otherwise caused any gross asymmetry of the femur. Of the 72 patients with full-length femur CT scans, 3 were excluded: 1 with a congenital hip dysplasia, 1 with an old, malunited femoral fracture, and 1 who was 15 years old at time of scan.

Axial Slice Selection

For each patient, scout AP films were used to measure femoral shaft length from the top of the greater trochanter to the end of the lateral femoral condyle. The levels of the proximal third, midshaft, and distal third were then calculated based on this length. The LA was studied on the axial slices nearest these levels. Next, we scrolled through the scans to identify an axial slice that best showed the femoral neck axis. The literature on CT measurement of femoral anteversion is varied. Some articles describe a technique that uses 2 superimposed axial slices, and others describe a single axial slice.1-3 We used 1 axial slice to draw the femoral neck axis because our computer software could not superimpose 2 images on 1 screen and because the CT scans were not made under specific protocols to measure anteversion but rather were part of a cancer staging work-up. Axial cuts were made at 5-mm intervals, and not all scans included a single slice capturing the head, neck, and greater trochanter. Therefore, we used a (previously described) method in which the femoral neck axis is drawn on a slice that most captured the femoral neck, usually toward its base.4 Last, in order to draw the posterior condyle (PC) axis, we selected an axial slice that showed the posterior-most aspects of the femoral condyles at the intercondylar notch.

Determining Anteroposterior and Posterior Condyle Axes of Femur

As we made all measurements for each femur off a single CT scan, we were able to use a straight horizontal line—drawn on-screen with a software tool—as a reference for measuring rotation. On a distal femur cut, the PC axis is drawn by connecting the posterior-most points of both condyles. The software calculates the angle formed—the PC angle (Figure 1). This angle, the degree to which the PC axis deviates from a straight horizontal line on-screen, can be used to account for gross rotation of the limb on comparison of images. The AP axis of the femur is the axis perpendicular to the PC axis. As such, the PC angle can also be used to determine degree of deviation of the AP axis from a straight vertical line on-screen. The AP axis was used when calculating the LA axis at the various levels of the femur (Figure 2).

Femoral Version

We used the software tool to draw the femoral neck axis. From the end of this line, a straight horizontal line is drawn on-screen (Figure 3). The software calculates the angle formed—the femoral neck axis angle. We assigned a positive value for a femoral head that pointed anteriorly on the image and a negative value for a head that pointed posteriorly. Adjusting for external rotation of the limb involved calculating the femoral version by subtracting the PC angle from the neck axis angle; adjusting for internal rotation involved adding these 2 angles.

Linea Aspera Morphology

After viewing the first 20 CT scans, we identified 3 types of LA morphology. Type I presents as a thickening on the posterior cortex with a sharp apex; type II presents as a flat-faced but distinct ridge of bone between the medial and lateral lips; and in type III there is no distinct cortical thickening with blunted medial and lateral lips; the latter is always more prominent.

Linea Aspera Axis Offset

From the most posterior point of the LA, a line drawn forward bisecting the femoral canal defined the LA axis. In type I morphology, the posterior-most point was the apex; in type II, the middle of flat posterior surface was used as the starting point; in type III, the lateral lip was used, as it was sharper than the medial lip. This line is again referenced with a straight horizontal line across the image. The PC angle is then added to account for limb rotation, and the result is the LA angle. As the AP axis is perpendicular to the PC axis, the LA angle is subtracted from 90°; the difference represents the amount of offset of the LA axis from the AP axis. By convention, we assigned this a positive value for an LA lateral to the midpoint of the femur and a negative value for an LA medial to the midpoint (Figure 4).

Linea Aspera Axis and Femoral Neck Axis

The angle between the LA axis and the PC axis was measured. The femoral version angle was subtracted from that angle to obtain the arc between the LA axis and the femoral neck axis.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute). All tests were 2-sided and conducted at the .05 significance level. No adjustments were made for multiple testing. Statistical analysis was performed with nonparametric tests and without making assumptions about the distribution of the study population. Univariate analyses were performed to test for significant side-to-side differences in femoral length, femoral version angle, and LA torsion angles at each level. A multivariate analysis was performed to test for interactions between sex, side, and level. In all analyses, P < .05 was used as the cutoff value for statistical significance.

Results

Femoral lengths varied by side and sex. The left side was longer than the right by a mean of 1.3 mm (P = .008). With multivariate analysis taking into account sex and age (cumulated per decade), there was still a significant effect of side on femoral length. Sex also had a significant effect on femoral length, with females’ femurs shorter by 21.7 mm (standard error, 5.0 mm). Mean (SD) anteversion of the femoral neck was 7.9° (12.7°) on the left and 13.3° (13.0°) on the right; the difference between sides was significant (P < .001). In a multivariate analysis performed to identify potential predictors of femoral version, side still had a significant (P < .001) independent effect; sex and age did not have an effect.

LA morphology varied according to femoral shaft level (Table 1). The morphology was type I in 75% of patients at the distal femur and 74% of patients at the midshaft femur, while only 53% of patients had a type I morphology at the proximal femur. The proportion of type III morphology was larger in the proximal femur (41%) than in the other locations.

The LA axis of the femur did not correspond exactly to the AP axis at all femoral levels. At the distal femur, mean (SD) lateral offset of the LA axis was 5.5° (7.5°) on the left and 8.3° (8.9°) on the right. At the midshaft, mean (SD) medial offset of the LA axis was 3.1° (8.4°) on the left and 1.2° (7.9°) on the right. At the proximal femur, mean (SD) lateral offset of the LA axis was 5.4° (9.2°) on the left and 6.2° (8.3°) on the right. The side-to-side differences were statistically significant for the distal femur and midshaft but not the proximal femur. Table 2 lists the 95% confidence intervals for the mean values. As the range of differences was small (0.7°-2.8°), and the differences may not be clinically detected on gross inspection during surgery, we pooled both sides’ values to arrive at a single mean for each level. The LA axis was offset a mean (SD) of 6.9° (8.3°) laterally at the distal femur, 2.2° (8.2°) medially at the midshaft, and 5.8° (8.6°) laterally at the proximal femur. Figure 5 shows the frequency of distribution of LA axis offset.Offset of the LA axis from the AP axis of the femur was significantly (P < .001) different for each femoral level, even when a multivariate analysis was performed to determine the effect of sex, age, or side. Age and sex had no significant effect on mean offset of LA axis from AP axis.

We compared the mean arc between femoral neck axis and LA axis after referencing both off the PC axis. At the distal femur, mean (SD) arc between these 2 axes was 76.6° (13.1°) on the left and 68.3° (13.6°) on the right (mean difference, 8.3°); at the midshaft, mean (SD) arc was 85.2° (13.5°) on the left and 77.9° (13.1°) on the right (mean difference, 7.4°); at the proximal femur, mean (SD) arc was 76.7° (11.9°) on the left and 70.5° (12.8°) on the right (mean difference, 6.2°). The side-to-side differences were statistically significant (P < .001) for all locations.

In multivariate analysis, sex and age did not have an effect on mean arc between the 2 axes. Side and femoral level, however, had a significant effect (P < .001).

Discussion

In total hip arthroplasty, the goal is to restore femoral anteversion, usually referenced to the remaining femoral neck segment.3 In total knee arthroplasty (TKA), proper rotation preserves normal patellofemoral tracking.5 Various landmarks are used, such as the PCs or the epicondyles. After tumor resections, these landmarks are often lost.6 However, there are no reports of studies validating a particular method of achieving proper rotational orientation of tumor endoprostheses, though several methods are being used. One method involves inserting 2 drill bits before osteotomy—one proximal to the intended level of resection on the anterior femur, and the other on the anterior tibial shaft. The straight line formed can establish a plane of rotation (and length), which the surgeon must aim to restore when the components are placed. This method is useful for distal femur resections but not proximal femur resections. Another method, based on the LA’s anatomical position on the posterior aspect of the femur,4 uses the prominence of the LA to align the prosthesis. With this method, the LA is assumed to be directly posterior (6 o’clock) on the femur. However, this assumption has not been confirmed by any study. A third method, described by Heck and Carnesale,5 involves marking the anterior aspect of the femur after resection and aligning the components to it. The authors cautioned against using the LA as a landmark, saying that its course is highly variable.

The LA is a narrow, elevated length of bone, with medial and lateral lips, that serves as an attachment site for muscles in the posterior thigh. Proximally, the LA presents with lateral, medial, and intermediate lips. In the midshaft, it is often elevated by an underlying bony ridge or pilaster complex. Distally, it diverges into 2 ridges that form the triangular popliteal surface.1,7 For the LA to be a reliable landmark, first it must be clearly identifiable on viewing a femoral cross-section. The LA that presents with type I or II morphology is distinctly identifiable, and an axis from its apex and bisecting the canal can easily be constructed. In our study, the LA presented with type I or II morphology in 82% of distal femoral sections and 99% of midshaft femoral sections. Therefore, the LA is a conspicuous landmark at these levels. In the proximal femur, 59% had type I or II morphology. Type III morphology could be identified on cross-sections by the persisting prominence of the lateral lip. However, it may be difficult to appreciate the LA with this morphology at surgery.

Once the LA is identified, its normal cross-sectional position must be defined. One way to do this is to establish the relationship of its axis (LA axis) to the true AP axis. Based on mean values, the LA axis is laterally offset 7º at the distal third of the femur, medially offset 2º at the midshaft, and laterally offset 6º at the proximal third. Therefore, for ideal placement with the LA used for orientation, the component must be internally rotated 7º relative to the LA for femoral resection at the distal third, externally rotated 2º for resection at the midshaft, and internally rotated 6º for resection at the proximal third. Studies have demonstrated that joint contact forces and mechanical alignment of the lower limb can be altered with as little as 5º of femoral malrotation.8,9 Although such a small degree of malrotation is often asymptomatic, it can have long-term effects on soft-tissue tension and patellar tracking.10,11 Rotating-platform mobile-bearing TKA designs can compensate for femoral malrotation, but they may have little to no effect on patellar tracking.12 Therefore, we think aligning the components as near as possible to their natural orientation can prove beneficial in long-term patient management.

Another way of defining the normal cross-sectional position of the LA is to relate it to the femoral neck axis. We measured the difference between these 2 axes. Mean differences were 72º (distal femur), 81.5º (midshaft), and 73.5º (proximal third). Mean arc differences at all levels were larger on the left side—a reflection of the femoral neck being less anteverted on that side in our measurements. Standard deviations were smaller for measurements of LA axis offset from AP axis (range, 7.5°-9.2°) than for measurements of arc between LA axis and femoral neck axis (range, 11.9°-13.6°). This finding indicates there is less variation in the former method, making it preferable for defining the cross-sectional position of the LA.

It has been said that the course of the LA is variable, and our data provide confirmation. The LA does not lie directly posterior (6 o’clock), and it does not trace a straight longitudinal course along the posterior femur, as demonstrated by the different LA axis offsets at 3 levels. However, we may still use it as a landmark if we remain aware how much the LA is offset from the AP axis at each femoral level. Figures 6A-6D, which show CT scans of a patient who underwent distal femoral resection and replacement with an endoprosthesis, illustrate how the LA axis was measured before surgery and how proper prosthesis placement was confirmed after surgery.

In hip arthroplasty, restoration of normal femoral version is the reference for endoprosthetic placement. The literature on “normal” femoral anteversion varies with the method used. In a review of studies on CT-measured adult femoral version, reported values ranged from 6.3° to 40°.2 Mean femoral version in our study ranged from 8° to 13°. Orthopedics textbooks generally put the value at 10° to 15º, and this seems to be the range that surgeons target.6 However, we found a statistically significant mean side-to-side difference of 5.4°. This finding is possibly explained by our large sample—it was larger than the samples used in other studies of CT-measured femoral version. Other studies have found mean side-to-side differences of up to 4.0º.5 Another explanation for our finding is that the studies may differ methodologically. The studies that established values for femoral anteversion were based on CT protocols—thinner slices (1-5 mm), use of foot holders to standardize limb rotation, use of 2 axial cuts in proximal femur to establish femoral neck axis2,13—designed specifically for this measurement. As the CT scans reviewed in our study are not designed for this purpose, errors in femoral version measurement may have been introduced, which may also explain why there is larger variation in measurements of the arc between the LA axis and the femoral neck axis.

Conclusion

The LA does not lie directly on the posterior surface of the femur. It deviates 6.9° laterally at the distal femur, 2.2° medially at the midshaft, and 6.9° laterally at the proximal third. As the LA is an easily identifiable structure on cross-sections of the femoral shaft at the midshaft and distal third of the femur, it may be useful as a rotational landmark for resections at these levels if these deviations are considered during tumor endoprosthetic replacements.

1. Desai SC, Willson S. Radiology of the linea aspera. Australas Radiol. 1985;29(3):273-274.

2. Kuo TY, Skedros JG, Bloebaum RD. Measurement of femoral anteversion by biplane radiography and computed tomography imaging: comparison with an anatomic reference. Invest Radiol. 2003;38(4):221-229.

3. Wines AP, McNicol D. Computed tomography measurement of the accuracy of component version in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):696-701.

4. Gray H. Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1918.

5. Heck RK, Carnesale PG. General principles of tumors. In: Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. Vol 1. 10th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003:733-791.

6. Katz, MA, Beck TD, Silber JS, Seldes RM, Lotke PA. Determining femoral rotational alignment in total knee arthroplasty: reliability of techniques. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(3):301-305.

7. Pitt MJ. Radiology of the femoral linea aspera–pilaster complex: the track sign. Radiology. 1982;142(1):66.

8. Bretin P, O’Loughlin PF, Suero EM, et al. Influence of femoral malrotation on knee joint alignment and intra-articular contact pressures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(8):1115-1120.

9. Zihlmann MS, Stacoff A, Romero J, Quervain IK, Stüssi E. Biomechanical background and clinical observations of rotational malalignment in TKA: literature review and consequences. Clin Biomech. 2005;20(7):661-668.

10. Ghosh KM, Merican AM, Iranpour F, Deehan DJ, Amis AA. The effect of femoral component rotation on the extensor retinaculum of the knee. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(9):1136-1141.

11. Verlinden C, Uvin P, Labey L, Luyckx JP, Bellemans J, Vandenneucker H. The influence of malrotation of the femoral component in total knee replacement on the mechanics of patellofemoral contact during gait: an in vitro biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(5):737-742.

12. Kessler O, Patil S, Colwell CW Jr, D’Lima DD. The effect of femoral component malrotation on patellar biomechanics. J Biomech. 2008;41(16):3332-3339.

13. Strecker W, Keppler P, Gebhard F, Kinzl L. Length and torsion of the lower limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(6):1019-1023.

1. Desai SC, Willson S. Radiology of the linea aspera. Australas Radiol. 1985;29(3):273-274.

2. Kuo TY, Skedros JG, Bloebaum RD. Measurement of femoral anteversion by biplane radiography and computed tomography imaging: comparison with an anatomic reference. Invest Radiol. 2003;38(4):221-229.

3. Wines AP, McNicol D. Computed tomography measurement of the accuracy of component version in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):696-701.

4. Gray H. Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1918.

5. Heck RK, Carnesale PG. General principles of tumors. In: Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. Vol 1. 10th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003:733-791.

6. Katz, MA, Beck TD, Silber JS, Seldes RM, Lotke PA. Determining femoral rotational alignment in total knee arthroplasty: reliability of techniques. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(3):301-305.

7. Pitt MJ. Radiology of the femoral linea aspera–pilaster complex: the track sign. Radiology. 1982;142(1):66.

8. Bretin P, O’Loughlin PF, Suero EM, et al. Influence of femoral malrotation on knee joint alignment and intra-articular contact pressures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(8):1115-1120.