User login

Clinical and Sonographic Evaluation of Bicortical Button for Proximal Biceps Tenodesis

The long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon is a recognized source of shoulder pain. LHB tendon pathology is commonly associated with other shoulder conditions, such as superior labral tears, rotator cuff tears, or subacromial impingement, whereas isolated pathology, such as traumatic ruptures, tendinosis, or medial subluxation, is rare.1 Treatment of LHB pathology ranges from conservative measures to surgical measures, including tenotomy or tenodesis.2 LHB tenodesis offers the advantage of maintaining the length–tension relationship of the biceps muscle to prevent atrophy and avoid the Popeye deformity incurred from tenotomy alone. Tenodesis also prevents muscle cramping associated with contracted biceps muscle and better maintains elbow flexion and supination strength, which may be decreased with tenotomy.3 In addition, when a subpectoral biceps tenodesis technique is used, pain from LHB tendinopathy in the intertubercular groove may be reduced.4

Open subpectoral biceps tenodesis is a reproducible, efficient method for LHB tenodesis.4,5 A variety of fixation devices has been used: bone tunnels,6 keyhole fixation,7 suture anchors,6-9 and interference screws.6-8,10,11 More recently, a bicortical button has been used for LHB tendon tenodesis.12 Biomechanical studies have shown that load to failure is comparable for bicortical button fixation and interference screw fixation.13,14 In other models of tendon repair, the bicortical button has strength and stability comparable to those of interference screw fixation and enables earlier rehabilitation.15-17 However, there is concern that bicortical button fixation may result in axillary nerve (AN) or posterior circumflex humeral artery (PCHA) compromise because of the proximity of these neurovascular structures to the bicortical button.13,18-21

We conducted a study to functionally and sonographically assess the outcomes of patients who underwent open subpectoral biceps tenodesis with a bicortical button. Functional outcomes were assessed with patient-reported outcomes and physician-reported outcomes. Sonographic studies were used to evaluate the integrity of the tenodesis and determine the proximity of the button to the AN and the PCHA along the posterior proximal humerus.

Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we retrospectively identified 28 consecutive patients who had proximal biceps tenodesis performed by a single surgeon (Dr. K.E. Swanson) using a mini-open subpectoral biceps tenodesis technique with a bicortical button between March 2011 and January 2013. All 28 patients were asked to participate in the study. Twenty-four (86%) agreed to complete 2 surgical outcome surveys, and 18 (64%) completed a 3-part clinical examination at minimum 12-month follow-up.

One of the surveys was Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (QuickDASH), a validated comprehensive disability survey that scores upper extremity functionality on a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 100 (extreme difficulty).22,23 The other survey scored pain on a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 100 (worst pain).

The clinical examination was completed during a single visit by an orthopedic surgeon (Dr. Meadows or Dr. Diesselhorst) different from the primary surgeon (Dr. K.E. Swanson) and by a clinician-sonologist (Dr. Finnoff). The examination’s 3 parts were physical examination of arm, biceps supination strength test, and ultrasonographic evaluation.

Physical Examination of Arm. Physical examination included palpation of bicipital groove, range of motion (ROM) of shoulder and elbow, and clinical deformity of biceps. Patients were questioned regarding symptoms of AN damage, including sensory and motor findings. Bicipital groove tenderness was assessed with a visual analog scale rating pain 0 to 10. ROM was measured in degrees and was presented as a percentage of full elbow ROM (150°) and full shoulder ROM (180°).

Biceps Supination Strength Test. Biceps supination strength was tested with a baseline hydraulic wrist dynamometer with door handle attachment. Patients were seated with the elbow bent 90° and the forearm in a neutral position. In a series of 3 trials, the patient maintained grip of the dynamometer doorknob while supinating the forearm. The tenodesed (operated) arm and contralateral unaffected (nonoperated) arm were tested in random order and recorded in pounds.

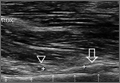

Ultrasonographic Evaluation. Ultrasonography was used to evaluate the tenodesis site. In each case, the biceps tendon was assessed to determine the location of the bicortical button in relation to the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle. Whereas nerves are difficult to visualize with ultrasonography, arteries are readily seen. Dr. Finnoff used a CX50 ultrasound machine (Philips Medical Systems) with either a 12-3 MHz linear array or a 5-1 MHz curvilinear array transducer to measure the shortest distance from the PCHA to the button.

Each patient was placed in a lateral decubitus or prone position, and the skin of the upper arm was exposed. Tendon integrity was deemed either intact (continuity between biceps tendon and cortical button) or disrupted (lack of continuity between tendon and cortical button). The transducer was then placed in an anatomical sagittal plane over the posterior aspect of the proximal humerus. Power Doppler and cephalad and caudad transducer glides were used to identify the location of the PCHA. The transducer was then glided laterally and anteriorly around the humerus, following the course of the PCHA, until the cortical button was located. The narrowest interval between the PCHA and the cortical button was measured using the ultrasound machine’s software. A still image of each measurement was saved.

Surgical Technique

Biceps tenodesis indications included high-demand heavy laborers, athletes, and patients who preferred the cosmetic results of tenodesis over tenotomy. Most patients had acute symptomatic tears of the superior labrum with instability of the biceps anchor complex. Others had fraying and tenosynovitis of the LHB tendon. Any associated pathology was addressed during the same surgical period.

The surgical technique used was similar to that described by Snir and colleagues.12 Each patient was placed in the lateral decubitus position. Once pathology confirmed biceps tenodesis, the biceps tendon was tenotomized at the base of the superior labrum. A 3-cm incision was made along the axillary fold centered over the inferior border of the pectoralis major tendon. Blunt dissection was performed to define the inferior border of the pectoralis major tendon and to palpate the underlying biceps tendon as it exited the intertubercular groove. The LHB tendon was removed and prepared with No. 2 Fiberwire (Arthrex) in Krackow fashion starting 2 cm proximal to the musculotendinous junction. The excess tendon was excised.

A 3.2-mm guide wire was centered along the most distal aspect of the biceps groove and then drilled through the anterior cortex and just through the posterior cortex. A cannulated reamer, selected on the basis of the biceps tendon diameter (typically, 5-7 mm), was then drilled over the guide wire through the anterior cortex only. The Food and Drug Administration–approved cortical button (BicepsButton; Arthrex) was then loaded by passing the tendon suture ends through each side of the button in alternating fashion, thus allowing the button to slide along the sutures.

The button was loaded onto the BicepsButton deployment device and inserted through the drilled tunnel of the anterior cortex and just through the posterior cortex. The deployment device was then removed, and 1 suture end was pulled to allow the button to engage the posterior humeral cortex. Pulling on both sutures allowed the biceps tendon to slide through the anterior cortex hole of the humerus until the tendon reached the posterior humeral cortex. Tension was verified, and the sutures were tied over the tendon. The wound was then irrigated and closed.

Rehabilitation Program

Patients completed a standard rehabilitation protocol for biceps tenodesis24 along with rehabilitation protocols for any additional procedures performed. In phase 1 (weeks 0-2), they focused on gradual restoration of passive ROM and remained in a sling. In phase 2 (weeks 2-6), they focused on gradual restoration of active ROM, and by week 3 were weaned out of the sling. In phase 3 (weeks 6-8), they continued ROM and strengthening exercises to normalize strength, endurance, and neuromuscular control. In phase 4 (weeks 8-12), they focused on advanced strengthening exercises and return to activities.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included means, medians, and SDs. Comparisons between operated and nonoperated arms and between dominant and nondominant arms were performed by a statistician using paired t tests with P = .05. Confidence intervals were calculated for operated and nonoperated arms and for dominant and nondominant arms by using the differences between them.

Results

Functional Outcomes

Surgical outcome scores and pain scores were obtained from 24 patients (86%) at minimum 12-month follow-up. Mean (SD) DASH score was 15.15 (17.6; median, 9), and mean (median) pain score was 12.61 (7).

Eighteen patients (64%) completed the clinical examination: 16 men (88.9%) and 2 women (11.1%). Mean age was 48.3 years (age range, 33-59 years). Of these 18 patients, 9 (50%) had surgery on the dominant arm, and the other 9 had surgery on the nondominant arm. All patients were right-hand–dominant. In 3 patients, biceps tenodesis was performed with only minimal arthroscopic débridement (20%); in the other 15, biceps tenodesis was performed concomitantly with 1 or more additional arthroscopic procedures: acromioplasty (73%), rotator cuff repair (47%), distal clavicle resection (33%), subacromial bursectomy (13%), microfracture of glenoid (13%), and posterior labral repair (7%).

The clinical examination was performed a mean of 15.2 months (range, 12-26 months) after surgery. Physical examination findings are listed in Table 1.

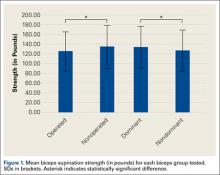

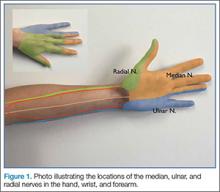

Forearm supination strength, averaged from 3 trials on each arm, was significantly (P = .01) greater in the nonoperated arm than in the operated arm (Table 2, Figure 1). A 95% confidence interval for the mean (SD) difference in strength was 9.35 (7.76) pounds, meaning that on average, the nonoperated arm will be 1.59 to 17.11 pounds stronger than the operated arm. In addition, strength of the dominant arm was greater than that of the nondominant arm (P = .05) regardless of which arm underwent surgery (Table 2, Figure 1). However, the mean (SD) difference in strength was 6.94 (8.39) pounds, indicating the observed difference was not statistically significant.

Sonographic Evaluation

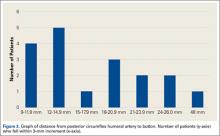

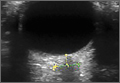

According to the sonographic evaluations, the tenodesis was intact in all 18 patients (Figure 2). Estimated mean (SD) distance from button to PCHA was 18.17 (9.0) mm (median, 16.1 mm; range, 9.4-48 mm) (Figure 2, Figure 3). No patient indicated any symptoms of AN damage.

Discussion

There are few studies of functional outcomes of biceps tenodesis. Pain is a common measure of patient satisfaction. Mazzocca and colleagues25 reported a mean follow-up pain score of 1.1 (range, 0.5-1.9) out of 10 for a group of 41 patients who had subpectoral tenodesis with an interference screw. Millett and colleagues26 reported a mean postoperative pain score of 2.5 out of 10 for patients who had subpectoral interference screw fixation. Our patients reported a mean pain score of 12.6 out of 100 after minimum 12-month follow-up. We also assessed for pain in the intertubercular groove during palpation. Although some studies have shown that groove pain was eliminated by subpectoral biceps tenodesis,5 3 patients in our study had pain on groove palpation. The cause of this residual pain is unclear, but some studies have suggested a chronic degenerative pathologic process that occurs while the tendon is within the biceps groove.27 Removing the tendon from the groove may not remove the underlying cause of pain.

Our patients’ mean DASH score was 15.15 (within the excellent range). Normative mean (SD) DASH score for the general population is 10.1 (14.68).28

Functional strength of forearm supination, shoulder ROM, and elbow ROM are objective measures of patient performance after fixation. On Cybex testing, Phillips and colleagues29 found no difference in forearm supination strength or elbow flexion (compared with contralateral arm) after biceps tenodesis or conservative treatment for proximal biceps ruptures. Shank and colleagues30 compared elbow flexion and supination strength of the affected and unaffected arms after suture anchor subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was no significant difference in Cybex results, but there was a 14% to 15% loss of average strength in the tenodesed versus nonsurgical arm. In the present study, we found a significant difference in forearm supination strength between the operated and nonoperated arms, but with only a 7% loss of average strength in the operated arms. The difference in strength ranged from 1.59 to 17.11 pounds, which may not be clinically significant, as supination strength ranged from 60 to 270 pounds.

Of the 18 patients in this study, 9 had surgery on the dominant arm, and the other 9 had surgery on the nondominant arm. Examining the effect of arm dominance on results revealed that patients with surgery on the nondominant arm tended to have substantially reduced supination strength in that arm vs the dominant arm. There was an 11% loss of average strength for nondominant vs dominant arms that had surgery. Examining nondominant arms only revealed a 13% loss of strength for operated vs nonoperated arms. There was no difference in forearm supination strengths between nonoperated arms (dominant vs nondominant) or between dominant arms (operated vs nonoperated). This suggests that, though hand dominance may not play a significant role in control patients’ forearm supination strength,30 it may have a substantial effect on surgical patients’ ability to regain strength when the nondominant arm is the surgical arm. One objective of this study was to measure the distance between the biceps cortical button on the posterior humeral cortex and the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle. The AN bundles with the PCHA posterior to the humeral neck.31-33 As the AN travels with the PCHA, and the PCHA has been reliably identified with Doppler ultrasonography,34-36 the PCHA was used as a marker for the AN in this study. Our bicortical button technique places the button on the posterior aspect of the humerus, making AN and PCHA the nearest at-risk neurovascular structures. None of our patients had symptoms of AN damage. However, 2 patients indicated pain in the posterior aspect of the humerus during deltoid activation. Distance from the neurovascular structures to the button was 48 mm in one patient and 13.6 mm in the other. DASH scores were 43 and 27, respectively. Both patients’ 1-year pain score was 30. The first patient underwent arthroscopic acromioplasty, distal clavicle resection, and microfracture of the glenoid surface in addition to the subpectoral biceps tenodesis; the second underwent subacromial decompression and distal clavicle resection in addition to the subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Whether the associated pathology contributed to their persistent pain is unknown. However, given the distance from AN/PCHA to button, it is unlikely that their pain was a result of neurovascular compromise from the procedure.

Advantages of the cortical button include the ability to drill a smaller hole in the humerus for fixation, compared with the hole drilled for an interference screw. Despite the biomechanical strength of the screw, large (8 mm) cortical violations have been associated with increased fracture risk of the proximal humerus.37,38 The tendon may experience less trauma than that caused by being twisted against an interference screw, the most common location of failure of which is the tendon–screw interface.39 In addition, tendon healing may be improved through circumferential healing in the cortical button tunnel.

A concern of using a bicortical button for fixation is drilling through the posterior cortex, because of the proximity of the posterior neurovascular structures. In a case in which the posterior cord was injured, Rhee and colleagues40 used a suture pullout technique whereby a Beath pin was passed out of the posterior humerus and soft tissues to then hold tension on the biceps tendon during the tenodesis. The radial nerve potentially could have been injured by pin overpenetration or by becoming wrapped up in the soft tissues as the pin was spinning through them. In our technique, the posterior humeral cortex is drilled cautiously to avoid overpenetration and possibly getting the posterior soft tissues wrapped up in the guide pin. No AN injuries have been reported with this technique. Mean distance from AN to posterior cortical button in this study was 18.17 mm. In 2 cadaver studies of bicortical drilling for subpectoral biceps tenodesis, the ANs were 25.1 mm and 36.7 mm from the posterior drill hole.41,21

Limitations of this study included its design (case series) and limited number of follow-up patients. Of the 28 consecutive patients identified for the study, 10 did not undergo the clinical examination, as they either lived more than 3 hours away (8 patients) or could not be contacted (2 patients). Another study limitation was the inability to directly image ANs with ultrasound. Therefore, measurements of the distance from the PCHA to the button were used to estimate the distance from the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle to the button.

In this study, functional outcomes were excellent, and there were no tenodesis failures or neurovascular complications. These preliminary findings indicate that subpectoral biceps tenodesis with a bicortical button is a viable treatment option for patients with the appropriate indications for this procedure.

1. Khazzam M, George MS, Churchill RS, Kuhn JE. Disorders of the long head of biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):136-145.

2. Geaney LE, Mazzocca AD. Biceps brachii tendon ruptures: a review of diagnosis and treatment of proximal and distal biceps tendon ruptures. Phys Sportsmed. 2010;38(2):117-125.

3. Kelly AM, Drakos MC, Fealy S, Taylor SA, O’Brien SJ. Arthroscopic release of the long head of the biceps tendon: functional outcome and clinical results. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(2):208-213.

4. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2008;16(3):170-176.

5. Nho SJ, Reiff SN, Verma NN, Slabaugh MA, Mazzocca AD, Romeo AA. Complications associated with subpectoral biceps tenodesis: low rates of incidence following surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):764-768.

6. Mazzocca AD, Bicos J, Santangelo S, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. The biomechanical evaluation of four fixation techniques for proximal biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1296-1306.

7. Ozalay, M, Akpinar S, Karaeminogullari O, et al. Mechanical strength of four different biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(8):992-998.

8. Golish RS, Caldwell PE, Miller MD, et al. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for subpectoral tenodesis of the proximal biceps tendon: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1103-1108.

9. Richards DP, Burkhart SS. A biomechanical analysis of two biceps tenodesis fixation techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):861-866.

10. Mazzocca AD, Rios CG, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):896.

11. Wolf RS, Zheng N, Weichel D. Long head biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a cadaveric biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(2):182-185.

12. Snir N, Hamula M, Wolfson T, Laible C, Sherman O. Long head of the biceps tenodesis with cortical button technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e95-e97.

13. Arora AS, Singh A, Koonce RC. Biomechanical evaluation of a unicortical button versus interference screw for subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):638-644.

14. Buchholz A, Martetschläger F, Siebenlist S, et al. Biomechanical comparison of intramedullary cortical button fixation and interference screw technique for subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(5):845-853.

15. Bain GI, Prem H, Heptinstall RJ, Verhellen R, Paix D. Repair of distal biceps tendon rupture: a new technique using the Endobutton. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(2):120-126.

16. Greenberg JA. Endobutton repair of distal biceps tendon ruptures. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1541-1548.

17. Heinzelmann AD, Savoie FH 3rd, Ramsey JR, Field LD, Mazzocca AD. A combined technique for distal biceps repair using a soft tissue button and biotenodesis interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):989-994.

18. DeAngelis JP, Chen A, Wexler M, et al. Biomechanical characterization of unicortical button fixation: a novel technique for proximal subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(5):1434-1441.

19. Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, Tintle SM, Giuliani J, Schaefer RA, Rue JP. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis: an anatomic study and evaluation of at-risk structures. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2337-2341.

20. Sethi PM, Rajaram A, Beitzel K, Hackett TR, Chowaniec DM, Mazzocca AD. Biomechanical performance of subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a comparison of interference screw fixation, cortical button fixation, and interference screw diameter. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):451-457.

21. Sethi PM, Vadasdi K, Greene RT, Vitale MA, Duong M, Miller SR. Safety of open suprapectoral and subpectoral biceps tenodesis: an anatomic assessment of risk for neurologic injury. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(1):138-142.

22. Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I. The shortened Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:44.

23. Schmidt CC, Brown BT, Sawardeker PJ, DeGravelle M Jr, Miller MC. Factors affecting supination strength after a distal biceps rupture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):68-75.

24. Brotzman SB, Wilk KE, eds. Handbook of Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

25. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

26. Millett PJ, Snaders B, Gobezie R, Braun S, Warner JP. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: does it matter? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9(121):1-6.

27. Streit JJ, Shishani Y, Rodgers M, Gobezie R. Tendinopathy of the long head of the biceps tendon: histopathologic analysis of the extra-articular biceps tendon and tenosynovium. Open Access J Sports Med. 2015;6:63-70.

28. Hunsaker FG, Cioffi DA, Amadio PC, Wright JG, Caughlin B. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons outcomes instruments: normative values from the general population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(2):208-215.

29. Phillips BB, Canale ST, Sisk TD, Stralka SW, Wyatt KP. Rupture of the proximal biceps tendon in middle-aged patients. Orthop Rev. 1993;22(3):349-353.

30. Shank JR, Singleton SB, Braun S, et al. A comparison of forearm supination and elbow flexion strength in patients with long head of the biceps tenotomy or tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(1):9-16.

31. Apaydin N, Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Duparc F. Review of the surgical anatomy of the axillary nerve and the anatomic basis of its iatrogenic and traumatic injury. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32(3):193-201.

32. Johnson D. Pectoral girdle and upper limp. In: Standring S, ed. Gray’s Anatomy. 40th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2008:814-821.

33. Tubbs RS, Tyler-Kabara EC, Aikens AC, et al. Surgical anatomy of the axillary nerve within the quadrangular space. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(5):912-914.

34. Kim YA, Yoon KB, Kwon TD, Kim DH, Yoon DM. Evaluation of anatomic landmarks for axillary nerve block in the quadrilateral space. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(5):567-571.

35. Robinson DJ, Marks P, Schneider-Kolsky ME. Ultrasound of the posterior circumflex humeral artery. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2010;54(3):219-223.

36. Rothe C, Asghar S, Andersen HL, Christensen JK, Lange KH. Ultrasound-guided block of the axillary nerve: a volunteer study of a new method. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(5):565-570.

37. Reiff SN, Nho SJ, Romeo AA. Proximal humerus fracture after keyhole biceps tenodesis. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(7):E61-E63.

38. Sears BW, Spencer EE, Getz CL. Humeral fracture following subpectoral biceps tenodesis in 2 active, healthy patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(6):e7-e11.

39. Koch BS, Burks RT. Failure of biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(5):735-740.

40. Rhee PC, Spinner RJ, Bishop AT, Shin AY. Iatrogenic brachial plexus injuries associated with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2048-2053.

41. Ding DY, Gupta A, Snir N, Wolfson T, Meislin RJ. Nerve proximity during bicortical drilling for subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(8):942-946.

The long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon is a recognized source of shoulder pain. LHB tendon pathology is commonly associated with other shoulder conditions, such as superior labral tears, rotator cuff tears, or subacromial impingement, whereas isolated pathology, such as traumatic ruptures, tendinosis, or medial subluxation, is rare.1 Treatment of LHB pathology ranges from conservative measures to surgical measures, including tenotomy or tenodesis.2 LHB tenodesis offers the advantage of maintaining the length–tension relationship of the biceps muscle to prevent atrophy and avoid the Popeye deformity incurred from tenotomy alone. Tenodesis also prevents muscle cramping associated with contracted biceps muscle and better maintains elbow flexion and supination strength, which may be decreased with tenotomy.3 In addition, when a subpectoral biceps tenodesis technique is used, pain from LHB tendinopathy in the intertubercular groove may be reduced.4

Open subpectoral biceps tenodesis is a reproducible, efficient method for LHB tenodesis.4,5 A variety of fixation devices has been used: bone tunnels,6 keyhole fixation,7 suture anchors,6-9 and interference screws.6-8,10,11 More recently, a bicortical button has been used for LHB tendon tenodesis.12 Biomechanical studies have shown that load to failure is comparable for bicortical button fixation and interference screw fixation.13,14 In other models of tendon repair, the bicortical button has strength and stability comparable to those of interference screw fixation and enables earlier rehabilitation.15-17 However, there is concern that bicortical button fixation may result in axillary nerve (AN) or posterior circumflex humeral artery (PCHA) compromise because of the proximity of these neurovascular structures to the bicortical button.13,18-21

We conducted a study to functionally and sonographically assess the outcomes of patients who underwent open subpectoral biceps tenodesis with a bicortical button. Functional outcomes were assessed with patient-reported outcomes and physician-reported outcomes. Sonographic studies were used to evaluate the integrity of the tenodesis and determine the proximity of the button to the AN and the PCHA along the posterior proximal humerus.

Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we retrospectively identified 28 consecutive patients who had proximal biceps tenodesis performed by a single surgeon (Dr. K.E. Swanson) using a mini-open subpectoral biceps tenodesis technique with a bicortical button between March 2011 and January 2013. All 28 patients were asked to participate in the study. Twenty-four (86%) agreed to complete 2 surgical outcome surveys, and 18 (64%) completed a 3-part clinical examination at minimum 12-month follow-up.

One of the surveys was Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (QuickDASH), a validated comprehensive disability survey that scores upper extremity functionality on a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 100 (extreme difficulty).22,23 The other survey scored pain on a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 100 (worst pain).

The clinical examination was completed during a single visit by an orthopedic surgeon (Dr. Meadows or Dr. Diesselhorst) different from the primary surgeon (Dr. K.E. Swanson) and by a clinician-sonologist (Dr. Finnoff). The examination’s 3 parts were physical examination of arm, biceps supination strength test, and ultrasonographic evaluation.

Physical Examination of Arm. Physical examination included palpation of bicipital groove, range of motion (ROM) of shoulder and elbow, and clinical deformity of biceps. Patients were questioned regarding symptoms of AN damage, including sensory and motor findings. Bicipital groove tenderness was assessed with a visual analog scale rating pain 0 to 10. ROM was measured in degrees and was presented as a percentage of full elbow ROM (150°) and full shoulder ROM (180°).

Biceps Supination Strength Test. Biceps supination strength was tested with a baseline hydraulic wrist dynamometer with door handle attachment. Patients were seated with the elbow bent 90° and the forearm in a neutral position. In a series of 3 trials, the patient maintained grip of the dynamometer doorknob while supinating the forearm. The tenodesed (operated) arm and contralateral unaffected (nonoperated) arm were tested in random order and recorded in pounds.

Ultrasonographic Evaluation. Ultrasonography was used to evaluate the tenodesis site. In each case, the biceps tendon was assessed to determine the location of the bicortical button in relation to the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle. Whereas nerves are difficult to visualize with ultrasonography, arteries are readily seen. Dr. Finnoff used a CX50 ultrasound machine (Philips Medical Systems) with either a 12-3 MHz linear array or a 5-1 MHz curvilinear array transducer to measure the shortest distance from the PCHA to the button.

Each patient was placed in a lateral decubitus or prone position, and the skin of the upper arm was exposed. Tendon integrity was deemed either intact (continuity between biceps tendon and cortical button) or disrupted (lack of continuity between tendon and cortical button). The transducer was then placed in an anatomical sagittal plane over the posterior aspect of the proximal humerus. Power Doppler and cephalad and caudad transducer glides were used to identify the location of the PCHA. The transducer was then glided laterally and anteriorly around the humerus, following the course of the PCHA, until the cortical button was located. The narrowest interval between the PCHA and the cortical button was measured using the ultrasound machine’s software. A still image of each measurement was saved.

Surgical Technique

Biceps tenodesis indications included high-demand heavy laborers, athletes, and patients who preferred the cosmetic results of tenodesis over tenotomy. Most patients had acute symptomatic tears of the superior labrum with instability of the biceps anchor complex. Others had fraying and tenosynovitis of the LHB tendon. Any associated pathology was addressed during the same surgical period.

The surgical technique used was similar to that described by Snir and colleagues.12 Each patient was placed in the lateral decubitus position. Once pathology confirmed biceps tenodesis, the biceps tendon was tenotomized at the base of the superior labrum. A 3-cm incision was made along the axillary fold centered over the inferior border of the pectoralis major tendon. Blunt dissection was performed to define the inferior border of the pectoralis major tendon and to palpate the underlying biceps tendon as it exited the intertubercular groove. The LHB tendon was removed and prepared with No. 2 Fiberwire (Arthrex) in Krackow fashion starting 2 cm proximal to the musculotendinous junction. The excess tendon was excised.

A 3.2-mm guide wire was centered along the most distal aspect of the biceps groove and then drilled through the anterior cortex and just through the posterior cortex. A cannulated reamer, selected on the basis of the biceps tendon diameter (typically, 5-7 mm), was then drilled over the guide wire through the anterior cortex only. The Food and Drug Administration–approved cortical button (BicepsButton; Arthrex) was then loaded by passing the tendon suture ends through each side of the button in alternating fashion, thus allowing the button to slide along the sutures.

The button was loaded onto the BicepsButton deployment device and inserted through the drilled tunnel of the anterior cortex and just through the posterior cortex. The deployment device was then removed, and 1 suture end was pulled to allow the button to engage the posterior humeral cortex. Pulling on both sutures allowed the biceps tendon to slide through the anterior cortex hole of the humerus until the tendon reached the posterior humeral cortex. Tension was verified, and the sutures were tied over the tendon. The wound was then irrigated and closed.

Rehabilitation Program

Patients completed a standard rehabilitation protocol for biceps tenodesis24 along with rehabilitation protocols for any additional procedures performed. In phase 1 (weeks 0-2), they focused on gradual restoration of passive ROM and remained in a sling. In phase 2 (weeks 2-6), they focused on gradual restoration of active ROM, and by week 3 were weaned out of the sling. In phase 3 (weeks 6-8), they continued ROM and strengthening exercises to normalize strength, endurance, and neuromuscular control. In phase 4 (weeks 8-12), they focused on advanced strengthening exercises and return to activities.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included means, medians, and SDs. Comparisons between operated and nonoperated arms and between dominant and nondominant arms were performed by a statistician using paired t tests with P = .05. Confidence intervals were calculated for operated and nonoperated arms and for dominant and nondominant arms by using the differences between them.

Results

Functional Outcomes

Surgical outcome scores and pain scores were obtained from 24 patients (86%) at minimum 12-month follow-up. Mean (SD) DASH score was 15.15 (17.6; median, 9), and mean (median) pain score was 12.61 (7).

Eighteen patients (64%) completed the clinical examination: 16 men (88.9%) and 2 women (11.1%). Mean age was 48.3 years (age range, 33-59 years). Of these 18 patients, 9 (50%) had surgery on the dominant arm, and the other 9 had surgery on the nondominant arm. All patients were right-hand–dominant. In 3 patients, biceps tenodesis was performed with only minimal arthroscopic débridement (20%); in the other 15, biceps tenodesis was performed concomitantly with 1 or more additional arthroscopic procedures: acromioplasty (73%), rotator cuff repair (47%), distal clavicle resection (33%), subacromial bursectomy (13%), microfracture of glenoid (13%), and posterior labral repair (7%).

The clinical examination was performed a mean of 15.2 months (range, 12-26 months) after surgery. Physical examination findings are listed in Table 1.

Forearm supination strength, averaged from 3 trials on each arm, was significantly (P = .01) greater in the nonoperated arm than in the operated arm (Table 2, Figure 1). A 95% confidence interval for the mean (SD) difference in strength was 9.35 (7.76) pounds, meaning that on average, the nonoperated arm will be 1.59 to 17.11 pounds stronger than the operated arm. In addition, strength of the dominant arm was greater than that of the nondominant arm (P = .05) regardless of which arm underwent surgery (Table 2, Figure 1). However, the mean (SD) difference in strength was 6.94 (8.39) pounds, indicating the observed difference was not statistically significant.

Sonographic Evaluation

According to the sonographic evaluations, the tenodesis was intact in all 18 patients (Figure 2). Estimated mean (SD) distance from button to PCHA was 18.17 (9.0) mm (median, 16.1 mm; range, 9.4-48 mm) (Figure 2, Figure 3). No patient indicated any symptoms of AN damage.

Discussion

There are few studies of functional outcomes of biceps tenodesis. Pain is a common measure of patient satisfaction. Mazzocca and colleagues25 reported a mean follow-up pain score of 1.1 (range, 0.5-1.9) out of 10 for a group of 41 patients who had subpectoral tenodesis with an interference screw. Millett and colleagues26 reported a mean postoperative pain score of 2.5 out of 10 for patients who had subpectoral interference screw fixation. Our patients reported a mean pain score of 12.6 out of 100 after minimum 12-month follow-up. We also assessed for pain in the intertubercular groove during palpation. Although some studies have shown that groove pain was eliminated by subpectoral biceps tenodesis,5 3 patients in our study had pain on groove palpation. The cause of this residual pain is unclear, but some studies have suggested a chronic degenerative pathologic process that occurs while the tendon is within the biceps groove.27 Removing the tendon from the groove may not remove the underlying cause of pain.

Our patients’ mean DASH score was 15.15 (within the excellent range). Normative mean (SD) DASH score for the general population is 10.1 (14.68).28

Functional strength of forearm supination, shoulder ROM, and elbow ROM are objective measures of patient performance after fixation. On Cybex testing, Phillips and colleagues29 found no difference in forearm supination strength or elbow flexion (compared with contralateral arm) after biceps tenodesis or conservative treatment for proximal biceps ruptures. Shank and colleagues30 compared elbow flexion and supination strength of the affected and unaffected arms after suture anchor subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was no significant difference in Cybex results, but there was a 14% to 15% loss of average strength in the tenodesed versus nonsurgical arm. In the present study, we found a significant difference in forearm supination strength between the operated and nonoperated arms, but with only a 7% loss of average strength in the operated arms. The difference in strength ranged from 1.59 to 17.11 pounds, which may not be clinically significant, as supination strength ranged from 60 to 270 pounds.

Of the 18 patients in this study, 9 had surgery on the dominant arm, and the other 9 had surgery on the nondominant arm. Examining the effect of arm dominance on results revealed that patients with surgery on the nondominant arm tended to have substantially reduced supination strength in that arm vs the dominant arm. There was an 11% loss of average strength for nondominant vs dominant arms that had surgery. Examining nondominant arms only revealed a 13% loss of strength for operated vs nonoperated arms. There was no difference in forearm supination strengths between nonoperated arms (dominant vs nondominant) or between dominant arms (operated vs nonoperated). This suggests that, though hand dominance may not play a significant role in control patients’ forearm supination strength,30 it may have a substantial effect on surgical patients’ ability to regain strength when the nondominant arm is the surgical arm. One objective of this study was to measure the distance between the biceps cortical button on the posterior humeral cortex and the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle. The AN bundles with the PCHA posterior to the humeral neck.31-33 As the AN travels with the PCHA, and the PCHA has been reliably identified with Doppler ultrasonography,34-36 the PCHA was used as a marker for the AN in this study. Our bicortical button technique places the button on the posterior aspect of the humerus, making AN and PCHA the nearest at-risk neurovascular structures. None of our patients had symptoms of AN damage. However, 2 patients indicated pain in the posterior aspect of the humerus during deltoid activation. Distance from the neurovascular structures to the button was 48 mm in one patient and 13.6 mm in the other. DASH scores were 43 and 27, respectively. Both patients’ 1-year pain score was 30. The first patient underwent arthroscopic acromioplasty, distal clavicle resection, and microfracture of the glenoid surface in addition to the subpectoral biceps tenodesis; the second underwent subacromial decompression and distal clavicle resection in addition to the subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Whether the associated pathology contributed to their persistent pain is unknown. However, given the distance from AN/PCHA to button, it is unlikely that their pain was a result of neurovascular compromise from the procedure.

Advantages of the cortical button include the ability to drill a smaller hole in the humerus for fixation, compared with the hole drilled for an interference screw. Despite the biomechanical strength of the screw, large (8 mm) cortical violations have been associated with increased fracture risk of the proximal humerus.37,38 The tendon may experience less trauma than that caused by being twisted against an interference screw, the most common location of failure of which is the tendon–screw interface.39 In addition, tendon healing may be improved through circumferential healing in the cortical button tunnel.

A concern of using a bicortical button for fixation is drilling through the posterior cortex, because of the proximity of the posterior neurovascular structures. In a case in which the posterior cord was injured, Rhee and colleagues40 used a suture pullout technique whereby a Beath pin was passed out of the posterior humerus and soft tissues to then hold tension on the biceps tendon during the tenodesis. The radial nerve potentially could have been injured by pin overpenetration or by becoming wrapped up in the soft tissues as the pin was spinning through them. In our technique, the posterior humeral cortex is drilled cautiously to avoid overpenetration and possibly getting the posterior soft tissues wrapped up in the guide pin. No AN injuries have been reported with this technique. Mean distance from AN to posterior cortical button in this study was 18.17 mm. In 2 cadaver studies of bicortical drilling for subpectoral biceps tenodesis, the ANs were 25.1 mm and 36.7 mm from the posterior drill hole.41,21

Limitations of this study included its design (case series) and limited number of follow-up patients. Of the 28 consecutive patients identified for the study, 10 did not undergo the clinical examination, as they either lived more than 3 hours away (8 patients) or could not be contacted (2 patients). Another study limitation was the inability to directly image ANs with ultrasound. Therefore, measurements of the distance from the PCHA to the button were used to estimate the distance from the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle to the button.

In this study, functional outcomes were excellent, and there were no tenodesis failures or neurovascular complications. These preliminary findings indicate that subpectoral biceps tenodesis with a bicortical button is a viable treatment option for patients with the appropriate indications for this procedure.

The long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon is a recognized source of shoulder pain. LHB tendon pathology is commonly associated with other shoulder conditions, such as superior labral tears, rotator cuff tears, or subacromial impingement, whereas isolated pathology, such as traumatic ruptures, tendinosis, or medial subluxation, is rare.1 Treatment of LHB pathology ranges from conservative measures to surgical measures, including tenotomy or tenodesis.2 LHB tenodesis offers the advantage of maintaining the length–tension relationship of the biceps muscle to prevent atrophy and avoid the Popeye deformity incurred from tenotomy alone. Tenodesis also prevents muscle cramping associated with contracted biceps muscle and better maintains elbow flexion and supination strength, which may be decreased with tenotomy.3 In addition, when a subpectoral biceps tenodesis technique is used, pain from LHB tendinopathy in the intertubercular groove may be reduced.4

Open subpectoral biceps tenodesis is a reproducible, efficient method for LHB tenodesis.4,5 A variety of fixation devices has been used: bone tunnels,6 keyhole fixation,7 suture anchors,6-9 and interference screws.6-8,10,11 More recently, a bicortical button has been used for LHB tendon tenodesis.12 Biomechanical studies have shown that load to failure is comparable for bicortical button fixation and interference screw fixation.13,14 In other models of tendon repair, the bicortical button has strength and stability comparable to those of interference screw fixation and enables earlier rehabilitation.15-17 However, there is concern that bicortical button fixation may result in axillary nerve (AN) or posterior circumflex humeral artery (PCHA) compromise because of the proximity of these neurovascular structures to the bicortical button.13,18-21

We conducted a study to functionally and sonographically assess the outcomes of patients who underwent open subpectoral biceps tenodesis with a bicortical button. Functional outcomes were assessed with patient-reported outcomes and physician-reported outcomes. Sonographic studies were used to evaluate the integrity of the tenodesis and determine the proximity of the button to the AN and the PCHA along the posterior proximal humerus.

Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for this study, we retrospectively identified 28 consecutive patients who had proximal biceps tenodesis performed by a single surgeon (Dr. K.E. Swanson) using a mini-open subpectoral biceps tenodesis technique with a bicortical button between March 2011 and January 2013. All 28 patients were asked to participate in the study. Twenty-four (86%) agreed to complete 2 surgical outcome surveys, and 18 (64%) completed a 3-part clinical examination at minimum 12-month follow-up.

One of the surveys was Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (QuickDASH), a validated comprehensive disability survey that scores upper extremity functionality on a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 100 (extreme difficulty).22,23 The other survey scored pain on a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 100 (worst pain).

The clinical examination was completed during a single visit by an orthopedic surgeon (Dr. Meadows or Dr. Diesselhorst) different from the primary surgeon (Dr. K.E. Swanson) and by a clinician-sonologist (Dr. Finnoff). The examination’s 3 parts were physical examination of arm, biceps supination strength test, and ultrasonographic evaluation.

Physical Examination of Arm. Physical examination included palpation of bicipital groove, range of motion (ROM) of shoulder and elbow, and clinical deformity of biceps. Patients were questioned regarding symptoms of AN damage, including sensory and motor findings. Bicipital groove tenderness was assessed with a visual analog scale rating pain 0 to 10. ROM was measured in degrees and was presented as a percentage of full elbow ROM (150°) and full shoulder ROM (180°).

Biceps Supination Strength Test. Biceps supination strength was tested with a baseline hydraulic wrist dynamometer with door handle attachment. Patients were seated with the elbow bent 90° and the forearm in a neutral position. In a series of 3 trials, the patient maintained grip of the dynamometer doorknob while supinating the forearm. The tenodesed (operated) arm and contralateral unaffected (nonoperated) arm were tested in random order and recorded in pounds.

Ultrasonographic Evaluation. Ultrasonography was used to evaluate the tenodesis site. In each case, the biceps tendon was assessed to determine the location of the bicortical button in relation to the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle. Whereas nerves are difficult to visualize with ultrasonography, arteries are readily seen. Dr. Finnoff used a CX50 ultrasound machine (Philips Medical Systems) with either a 12-3 MHz linear array or a 5-1 MHz curvilinear array transducer to measure the shortest distance from the PCHA to the button.

Each patient was placed in a lateral decubitus or prone position, and the skin of the upper arm was exposed. Tendon integrity was deemed either intact (continuity between biceps tendon and cortical button) or disrupted (lack of continuity between tendon and cortical button). The transducer was then placed in an anatomical sagittal plane over the posterior aspect of the proximal humerus. Power Doppler and cephalad and caudad transducer glides were used to identify the location of the PCHA. The transducer was then glided laterally and anteriorly around the humerus, following the course of the PCHA, until the cortical button was located. The narrowest interval between the PCHA and the cortical button was measured using the ultrasound machine’s software. A still image of each measurement was saved.

Surgical Technique

Biceps tenodesis indications included high-demand heavy laborers, athletes, and patients who preferred the cosmetic results of tenodesis over tenotomy. Most patients had acute symptomatic tears of the superior labrum with instability of the biceps anchor complex. Others had fraying and tenosynovitis of the LHB tendon. Any associated pathology was addressed during the same surgical period.

The surgical technique used was similar to that described by Snir and colleagues.12 Each patient was placed in the lateral decubitus position. Once pathology confirmed biceps tenodesis, the biceps tendon was tenotomized at the base of the superior labrum. A 3-cm incision was made along the axillary fold centered over the inferior border of the pectoralis major tendon. Blunt dissection was performed to define the inferior border of the pectoralis major tendon and to palpate the underlying biceps tendon as it exited the intertubercular groove. The LHB tendon was removed and prepared with No. 2 Fiberwire (Arthrex) in Krackow fashion starting 2 cm proximal to the musculotendinous junction. The excess tendon was excised.

A 3.2-mm guide wire was centered along the most distal aspect of the biceps groove and then drilled through the anterior cortex and just through the posterior cortex. A cannulated reamer, selected on the basis of the biceps tendon diameter (typically, 5-7 mm), was then drilled over the guide wire through the anterior cortex only. The Food and Drug Administration–approved cortical button (BicepsButton; Arthrex) was then loaded by passing the tendon suture ends through each side of the button in alternating fashion, thus allowing the button to slide along the sutures.

The button was loaded onto the BicepsButton deployment device and inserted through the drilled tunnel of the anterior cortex and just through the posterior cortex. The deployment device was then removed, and 1 suture end was pulled to allow the button to engage the posterior humeral cortex. Pulling on both sutures allowed the biceps tendon to slide through the anterior cortex hole of the humerus until the tendon reached the posterior humeral cortex. Tension was verified, and the sutures were tied over the tendon. The wound was then irrigated and closed.

Rehabilitation Program

Patients completed a standard rehabilitation protocol for biceps tenodesis24 along with rehabilitation protocols for any additional procedures performed. In phase 1 (weeks 0-2), they focused on gradual restoration of passive ROM and remained in a sling. In phase 2 (weeks 2-6), they focused on gradual restoration of active ROM, and by week 3 were weaned out of the sling. In phase 3 (weeks 6-8), they continued ROM and strengthening exercises to normalize strength, endurance, and neuromuscular control. In phase 4 (weeks 8-12), they focused on advanced strengthening exercises and return to activities.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included means, medians, and SDs. Comparisons between operated and nonoperated arms and between dominant and nondominant arms were performed by a statistician using paired t tests with P = .05. Confidence intervals were calculated for operated and nonoperated arms and for dominant and nondominant arms by using the differences between them.

Results

Functional Outcomes

Surgical outcome scores and pain scores were obtained from 24 patients (86%) at minimum 12-month follow-up. Mean (SD) DASH score was 15.15 (17.6; median, 9), and mean (median) pain score was 12.61 (7).

Eighteen patients (64%) completed the clinical examination: 16 men (88.9%) and 2 women (11.1%). Mean age was 48.3 years (age range, 33-59 years). Of these 18 patients, 9 (50%) had surgery on the dominant arm, and the other 9 had surgery on the nondominant arm. All patients were right-hand–dominant. In 3 patients, biceps tenodesis was performed with only minimal arthroscopic débridement (20%); in the other 15, biceps tenodesis was performed concomitantly with 1 or more additional arthroscopic procedures: acromioplasty (73%), rotator cuff repair (47%), distal clavicle resection (33%), subacromial bursectomy (13%), microfracture of glenoid (13%), and posterior labral repair (7%).

The clinical examination was performed a mean of 15.2 months (range, 12-26 months) after surgery. Physical examination findings are listed in Table 1.

Forearm supination strength, averaged from 3 trials on each arm, was significantly (P = .01) greater in the nonoperated arm than in the operated arm (Table 2, Figure 1). A 95% confidence interval for the mean (SD) difference in strength was 9.35 (7.76) pounds, meaning that on average, the nonoperated arm will be 1.59 to 17.11 pounds stronger than the operated arm. In addition, strength of the dominant arm was greater than that of the nondominant arm (P = .05) regardless of which arm underwent surgery (Table 2, Figure 1). However, the mean (SD) difference in strength was 6.94 (8.39) pounds, indicating the observed difference was not statistically significant.

Sonographic Evaluation

According to the sonographic evaluations, the tenodesis was intact in all 18 patients (Figure 2). Estimated mean (SD) distance from button to PCHA was 18.17 (9.0) mm (median, 16.1 mm; range, 9.4-48 mm) (Figure 2, Figure 3). No patient indicated any symptoms of AN damage.

Discussion

There are few studies of functional outcomes of biceps tenodesis. Pain is a common measure of patient satisfaction. Mazzocca and colleagues25 reported a mean follow-up pain score of 1.1 (range, 0.5-1.9) out of 10 for a group of 41 patients who had subpectoral tenodesis with an interference screw. Millett and colleagues26 reported a mean postoperative pain score of 2.5 out of 10 for patients who had subpectoral interference screw fixation. Our patients reported a mean pain score of 12.6 out of 100 after minimum 12-month follow-up. We also assessed for pain in the intertubercular groove during palpation. Although some studies have shown that groove pain was eliminated by subpectoral biceps tenodesis,5 3 patients in our study had pain on groove palpation. The cause of this residual pain is unclear, but some studies have suggested a chronic degenerative pathologic process that occurs while the tendon is within the biceps groove.27 Removing the tendon from the groove may not remove the underlying cause of pain.

Our patients’ mean DASH score was 15.15 (within the excellent range). Normative mean (SD) DASH score for the general population is 10.1 (14.68).28

Functional strength of forearm supination, shoulder ROM, and elbow ROM are objective measures of patient performance after fixation. On Cybex testing, Phillips and colleagues29 found no difference in forearm supination strength or elbow flexion (compared with contralateral arm) after biceps tenodesis or conservative treatment for proximal biceps ruptures. Shank and colleagues30 compared elbow flexion and supination strength of the affected and unaffected arms after suture anchor subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was no significant difference in Cybex results, but there was a 14% to 15% loss of average strength in the tenodesed versus nonsurgical arm. In the present study, we found a significant difference in forearm supination strength between the operated and nonoperated arms, but with only a 7% loss of average strength in the operated arms. The difference in strength ranged from 1.59 to 17.11 pounds, which may not be clinically significant, as supination strength ranged from 60 to 270 pounds.

Of the 18 patients in this study, 9 had surgery on the dominant arm, and the other 9 had surgery on the nondominant arm. Examining the effect of arm dominance on results revealed that patients with surgery on the nondominant arm tended to have substantially reduced supination strength in that arm vs the dominant arm. There was an 11% loss of average strength for nondominant vs dominant arms that had surgery. Examining nondominant arms only revealed a 13% loss of strength for operated vs nonoperated arms. There was no difference in forearm supination strengths between nonoperated arms (dominant vs nondominant) or between dominant arms (operated vs nonoperated). This suggests that, though hand dominance may not play a significant role in control patients’ forearm supination strength,30 it may have a substantial effect on surgical patients’ ability to regain strength when the nondominant arm is the surgical arm. One objective of this study was to measure the distance between the biceps cortical button on the posterior humeral cortex and the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle. The AN bundles with the PCHA posterior to the humeral neck.31-33 As the AN travels with the PCHA, and the PCHA has been reliably identified with Doppler ultrasonography,34-36 the PCHA was used as a marker for the AN in this study. Our bicortical button technique places the button on the posterior aspect of the humerus, making AN and PCHA the nearest at-risk neurovascular structures. None of our patients had symptoms of AN damage. However, 2 patients indicated pain in the posterior aspect of the humerus during deltoid activation. Distance from the neurovascular structures to the button was 48 mm in one patient and 13.6 mm in the other. DASH scores were 43 and 27, respectively. Both patients’ 1-year pain score was 30. The first patient underwent arthroscopic acromioplasty, distal clavicle resection, and microfracture of the glenoid surface in addition to the subpectoral biceps tenodesis; the second underwent subacromial decompression and distal clavicle resection in addition to the subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Whether the associated pathology contributed to their persistent pain is unknown. However, given the distance from AN/PCHA to button, it is unlikely that their pain was a result of neurovascular compromise from the procedure.

Advantages of the cortical button include the ability to drill a smaller hole in the humerus for fixation, compared with the hole drilled for an interference screw. Despite the biomechanical strength of the screw, large (8 mm) cortical violations have been associated with increased fracture risk of the proximal humerus.37,38 The tendon may experience less trauma than that caused by being twisted against an interference screw, the most common location of failure of which is the tendon–screw interface.39 In addition, tendon healing may be improved through circumferential healing in the cortical button tunnel.

A concern of using a bicortical button for fixation is drilling through the posterior cortex, because of the proximity of the posterior neurovascular structures. In a case in which the posterior cord was injured, Rhee and colleagues40 used a suture pullout technique whereby a Beath pin was passed out of the posterior humerus and soft tissues to then hold tension on the biceps tendon during the tenodesis. The radial nerve potentially could have been injured by pin overpenetration or by becoming wrapped up in the soft tissues as the pin was spinning through them. In our technique, the posterior humeral cortex is drilled cautiously to avoid overpenetration and possibly getting the posterior soft tissues wrapped up in the guide pin. No AN injuries have been reported with this technique. Mean distance from AN to posterior cortical button in this study was 18.17 mm. In 2 cadaver studies of bicortical drilling for subpectoral biceps tenodesis, the ANs were 25.1 mm and 36.7 mm from the posterior drill hole.41,21

Limitations of this study included its design (case series) and limited number of follow-up patients. Of the 28 consecutive patients identified for the study, 10 did not undergo the clinical examination, as they either lived more than 3 hours away (8 patients) or could not be contacted (2 patients). Another study limitation was the inability to directly image ANs with ultrasound. Therefore, measurements of the distance from the PCHA to the button were used to estimate the distance from the AN/PCHA neurovascular bundle to the button.

In this study, functional outcomes were excellent, and there were no tenodesis failures or neurovascular complications. These preliminary findings indicate that subpectoral biceps tenodesis with a bicortical button is a viable treatment option for patients with the appropriate indications for this procedure.

1. Khazzam M, George MS, Churchill RS, Kuhn JE. Disorders of the long head of biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):136-145.

2. Geaney LE, Mazzocca AD. Biceps brachii tendon ruptures: a review of diagnosis and treatment of proximal and distal biceps tendon ruptures. Phys Sportsmed. 2010;38(2):117-125.

3. Kelly AM, Drakos MC, Fealy S, Taylor SA, O’Brien SJ. Arthroscopic release of the long head of the biceps tendon: functional outcome and clinical results. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(2):208-213.

4. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2008;16(3):170-176.

5. Nho SJ, Reiff SN, Verma NN, Slabaugh MA, Mazzocca AD, Romeo AA. Complications associated with subpectoral biceps tenodesis: low rates of incidence following surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):764-768.

6. Mazzocca AD, Bicos J, Santangelo S, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. The biomechanical evaluation of four fixation techniques for proximal biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1296-1306.

7. Ozalay, M, Akpinar S, Karaeminogullari O, et al. Mechanical strength of four different biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(8):992-998.

8. Golish RS, Caldwell PE, Miller MD, et al. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for subpectoral tenodesis of the proximal biceps tendon: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1103-1108.

9. Richards DP, Burkhart SS. A biomechanical analysis of two biceps tenodesis fixation techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):861-866.

10. Mazzocca AD, Rios CG, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):896.

11. Wolf RS, Zheng N, Weichel D. Long head biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a cadaveric biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(2):182-185.

12. Snir N, Hamula M, Wolfson T, Laible C, Sherman O. Long head of the biceps tenodesis with cortical button technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e95-e97.

13. Arora AS, Singh A, Koonce RC. Biomechanical evaluation of a unicortical button versus interference screw for subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):638-644.

14. Buchholz A, Martetschläger F, Siebenlist S, et al. Biomechanical comparison of intramedullary cortical button fixation and interference screw technique for subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(5):845-853.

15. Bain GI, Prem H, Heptinstall RJ, Verhellen R, Paix D. Repair of distal biceps tendon rupture: a new technique using the Endobutton. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(2):120-126.

16. Greenberg JA. Endobutton repair of distal biceps tendon ruptures. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1541-1548.

17. Heinzelmann AD, Savoie FH 3rd, Ramsey JR, Field LD, Mazzocca AD. A combined technique for distal biceps repair using a soft tissue button and biotenodesis interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):989-994.

18. DeAngelis JP, Chen A, Wexler M, et al. Biomechanical characterization of unicortical button fixation: a novel technique for proximal subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(5):1434-1441.

19. Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, Tintle SM, Giuliani J, Schaefer RA, Rue JP. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis: an anatomic study and evaluation of at-risk structures. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2337-2341.

20. Sethi PM, Rajaram A, Beitzel K, Hackett TR, Chowaniec DM, Mazzocca AD. Biomechanical performance of subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a comparison of interference screw fixation, cortical button fixation, and interference screw diameter. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):451-457.

21. Sethi PM, Vadasdi K, Greene RT, Vitale MA, Duong M, Miller SR. Safety of open suprapectoral and subpectoral biceps tenodesis: an anatomic assessment of risk for neurologic injury. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(1):138-142.

22. Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I. The shortened Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:44.

23. Schmidt CC, Brown BT, Sawardeker PJ, DeGravelle M Jr, Miller MC. Factors affecting supination strength after a distal biceps rupture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):68-75.

24. Brotzman SB, Wilk KE, eds. Handbook of Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

25. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

26. Millett PJ, Snaders B, Gobezie R, Braun S, Warner JP. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: does it matter? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9(121):1-6.

27. Streit JJ, Shishani Y, Rodgers M, Gobezie R. Tendinopathy of the long head of the biceps tendon: histopathologic analysis of the extra-articular biceps tendon and tenosynovium. Open Access J Sports Med. 2015;6:63-70.

28. Hunsaker FG, Cioffi DA, Amadio PC, Wright JG, Caughlin B. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons outcomes instruments: normative values from the general population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(2):208-215.

29. Phillips BB, Canale ST, Sisk TD, Stralka SW, Wyatt KP. Rupture of the proximal biceps tendon in middle-aged patients. Orthop Rev. 1993;22(3):349-353.

30. Shank JR, Singleton SB, Braun S, et al. A comparison of forearm supination and elbow flexion strength in patients with long head of the biceps tenotomy or tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(1):9-16.

31. Apaydin N, Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Duparc F. Review of the surgical anatomy of the axillary nerve and the anatomic basis of its iatrogenic and traumatic injury. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32(3):193-201.

32. Johnson D. Pectoral girdle and upper limp. In: Standring S, ed. Gray’s Anatomy. 40th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2008:814-821.

33. Tubbs RS, Tyler-Kabara EC, Aikens AC, et al. Surgical anatomy of the axillary nerve within the quadrangular space. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(5):912-914.

34. Kim YA, Yoon KB, Kwon TD, Kim DH, Yoon DM. Evaluation of anatomic landmarks for axillary nerve block in the quadrilateral space. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(5):567-571.

35. Robinson DJ, Marks P, Schneider-Kolsky ME. Ultrasound of the posterior circumflex humeral artery. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2010;54(3):219-223.

36. Rothe C, Asghar S, Andersen HL, Christensen JK, Lange KH. Ultrasound-guided block of the axillary nerve: a volunteer study of a new method. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(5):565-570.

37. Reiff SN, Nho SJ, Romeo AA. Proximal humerus fracture after keyhole biceps tenodesis. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(7):E61-E63.

38. Sears BW, Spencer EE, Getz CL. Humeral fracture following subpectoral biceps tenodesis in 2 active, healthy patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(6):e7-e11.

39. Koch BS, Burks RT. Failure of biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(5):735-740.

40. Rhee PC, Spinner RJ, Bishop AT, Shin AY. Iatrogenic brachial plexus injuries associated with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2048-2053.

41. Ding DY, Gupta A, Snir N, Wolfson T, Meislin RJ. Nerve proximity during bicortical drilling for subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(8):942-946.

1. Khazzam M, George MS, Churchill RS, Kuhn JE. Disorders of the long head of biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):136-145.

2. Geaney LE, Mazzocca AD. Biceps brachii tendon ruptures: a review of diagnosis and treatment of proximal and distal biceps tendon ruptures. Phys Sportsmed. 2010;38(2):117-125.

3. Kelly AM, Drakos MC, Fealy S, Taylor SA, O’Brien SJ. Arthroscopic release of the long head of the biceps tendon: functional outcome and clinical results. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(2):208-213.

4. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2008;16(3):170-176.

5. Nho SJ, Reiff SN, Verma NN, Slabaugh MA, Mazzocca AD, Romeo AA. Complications associated with subpectoral biceps tenodesis: low rates of incidence following surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):764-768.

6. Mazzocca AD, Bicos J, Santangelo S, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. The biomechanical evaluation of four fixation techniques for proximal biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1296-1306.

7. Ozalay, M, Akpinar S, Karaeminogullari O, et al. Mechanical strength of four different biceps tenodesis techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(8):992-998.

8. Golish RS, Caldwell PE, Miller MD, et al. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for subpectoral tenodesis of the proximal biceps tendon: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(10):1103-1108.

9. Richards DP, Burkhart SS. A biomechanical analysis of two biceps tenodesis fixation techniques. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):861-866.

10. Mazzocca AD, Rios CG, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(7):896.

11. Wolf RS, Zheng N, Weichel D. Long head biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a cadaveric biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(2):182-185.

12. Snir N, Hamula M, Wolfson T, Laible C, Sherman O. Long head of the biceps tenodesis with cortical button technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e95-e97.

13. Arora AS, Singh A, Koonce RC. Biomechanical evaluation of a unicortical button versus interference screw for subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):638-644.

14. Buchholz A, Martetschläger F, Siebenlist S, et al. Biomechanical comparison of intramedullary cortical button fixation and interference screw technique for subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(5):845-853.

15. Bain GI, Prem H, Heptinstall RJ, Verhellen R, Paix D. Repair of distal biceps tendon rupture: a new technique using the Endobutton. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(2):120-126.

16. Greenberg JA. Endobutton repair of distal biceps tendon ruptures. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1541-1548.

17. Heinzelmann AD, Savoie FH 3rd, Ramsey JR, Field LD, Mazzocca AD. A combined technique for distal biceps repair using a soft tissue button and biotenodesis interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):989-994.

18. DeAngelis JP, Chen A, Wexler M, et al. Biomechanical characterization of unicortical button fixation: a novel technique for proximal subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(5):1434-1441.

19. Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, Tintle SM, Giuliani J, Schaefer RA, Rue JP. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis: an anatomic study and evaluation of at-risk structures. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2337-2341.

20. Sethi PM, Rajaram A, Beitzel K, Hackett TR, Chowaniec DM, Mazzocca AD. Biomechanical performance of subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a comparison of interference screw fixation, cortical button fixation, and interference screw diameter. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):451-457.

21. Sethi PM, Vadasdi K, Greene RT, Vitale MA, Duong M, Miller SR. Safety of open suprapectoral and subpectoral biceps tenodesis: an anatomic assessment of risk for neurologic injury. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(1):138-142.

22. Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I. The shortened Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:44.

23. Schmidt CC, Brown BT, Sawardeker PJ, DeGravelle M Jr, Miller MC. Factors affecting supination strength after a distal biceps rupture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):68-75.

24. Brotzman SB, Wilk KE, eds. Handbook of Orthopaedic Rehabilitation. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

25. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

26. Millett PJ, Snaders B, Gobezie R, Braun S, Warner JP. Interference screw versus suture anchor fixation for open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: does it matter? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9(121):1-6.

27. Streit JJ, Shishani Y, Rodgers M, Gobezie R. Tendinopathy of the long head of the biceps tendon: histopathologic analysis of the extra-articular biceps tendon and tenosynovium. Open Access J Sports Med. 2015;6:63-70.

28. Hunsaker FG, Cioffi DA, Amadio PC, Wright JG, Caughlin B. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons outcomes instruments: normative values from the general population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(2):208-215.

29. Phillips BB, Canale ST, Sisk TD, Stralka SW, Wyatt KP. Rupture of the proximal biceps tendon in middle-aged patients. Orthop Rev. 1993;22(3):349-353.

30. Shank JR, Singleton SB, Braun S, et al. A comparison of forearm supination and elbow flexion strength in patients with long head of the biceps tenotomy or tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(1):9-16.

31. Apaydin N, Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Duparc F. Review of the surgical anatomy of the axillary nerve and the anatomic basis of its iatrogenic and traumatic injury. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32(3):193-201.

32. Johnson D. Pectoral girdle and upper limp. In: Standring S, ed. Gray’s Anatomy. 40th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2008:814-821.

33. Tubbs RS, Tyler-Kabara EC, Aikens AC, et al. Surgical anatomy of the axillary nerve within the quadrangular space. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(5):912-914.

34. Kim YA, Yoon KB, Kwon TD, Kim DH, Yoon DM. Evaluation of anatomic landmarks for axillary nerve block in the quadrilateral space. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(5):567-571.

35. Robinson DJ, Marks P, Schneider-Kolsky ME. Ultrasound of the posterior circumflex humeral artery. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2010;54(3):219-223.

36. Rothe C, Asghar S, Andersen HL, Christensen JK, Lange KH. Ultrasound-guided block of the axillary nerve: a volunteer study of a new method. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(5):565-570.

37. Reiff SN, Nho SJ, Romeo AA. Proximal humerus fracture after keyhole biceps tenodesis. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(7):E61-E63.

38. Sears BW, Spencer EE, Getz CL. Humeral fracture following subpectoral biceps tenodesis in 2 active, healthy patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(6):e7-e11.

39. Koch BS, Burks RT. Failure of biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(5):735-740.

40. Rhee PC, Spinner RJ, Bishop AT, Shin AY. Iatrogenic brachial plexus injuries associated with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2048-2053.

41. Ding DY, Gupta A, Snir N, Wolfson T, Meislin RJ. Nerve proximity during bicortical drilling for subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(8):942-946.

Emergency Imaging: Shortness of breath

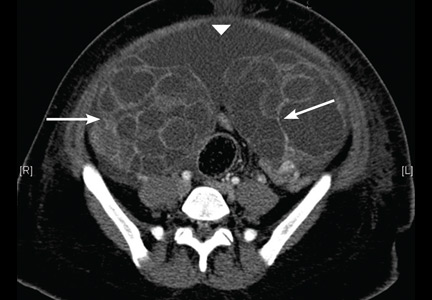

A 79-year-old woman presented to the ED with acute shortness of breath. Of note, she had been recently discharged from our hospital after an open reduction and internal fixation of an intertrochanteric fracture of the right hip. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated, and she was discharged home after a brief inpatient stay.

On physical examination, the patient was diaphoretic and tachypneic; oxygen saturation was 68% on room air, but increased to 100% saturation with supplemental oxygen through a nonrebreather mask. Radiographs from the patient’s inpatient hospital stay (Figure 1a) as well as ED visit (Figure 1b) were reviewed; representative images are shown above.

What is the diagnosis? What additional imaging tests may be useful to confirm the diagnosis?

Answer

The radiographs taken at the time of the patient’s discharge were normal. The radiograph of the chest obtained in the ED, however, demonstrated a distinct cut-off of the right mainstem bronchus, referred to as a bronchial cut-off sign (white arrow, Figure 2), with a rounded density projecting over the right mainstem bronchus (white asterisk, Figure 2). These radiographic appearances suggested the presence of an aspirated foreign body.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with contrast was performed to further evaluate the radiographic opacity and to exclude pulmonary embolism (PE), as this patient was at risk for such. The CT scan revealed no evidence of PE but confirmed the diagnosis of an aspirated foreign body. A high-density tablet (black asterisk, Figure 3) was noted to be completely occluding the right mainstem bronchus (white arrow, Figure 3) with resultant mild hyperinflation of the right lung. Upon further questioning, the patient stated that she had choked on a calcium tablet earlier in the day, but thought that the pill had finally “gone down.”

Since aspiration of foreign bodies is far more common in children,1,2 the diagnosis often is not considered in adults who present with acute onset of shortness of breath. In adults, the most significant predisposing factor to aspiration is alcoholism. However, foreign body aspiration may arise in various clinical scenarios, including in patients with structural abnormalities, in those with neuromuscular disease, and in the postoperative setting. The most common aspirated foreign bodies are food and broken tooth fragments/periodontal devices (eg, periodontal splint).2