User login

Four-branched arch replacement gets acceptable results

NEW YORK – A total aortic arch replacement approach that uses a four-branched graft with antegrade cerebral perfusion can be done with low rates of in-hospital death and complications, a large series from two institutions in Japan showed.

Kenji Minatoya, MD, of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in Osaka, Japan, reported that his institution’s approach for total arch replacement (TAR) had an in-hospital death rate of 5.2%.

Dr. Minatoya and his colleagues started using four-branch TAR in the 1980s, switching from retrograde to antegrade cerebral perfusion to protect the brain later on. “The study purpose was to investigate the results of total arch replacement using the four-branch graft as a benchmark in the endovascular era,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

The study involved 1,005 cases of total arch replacement performed at Dr. Minatoya’s center and at Tokyo Medical University from 2001 to 2016.

The study population included a cohort of 152 people in their 80s. The in-hospital death rate in this group was 11.8%, Dr. Minatoya said. The over-80 group mostly underwent thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) beginning in 2008, he said, but in recent years some had open total arch replacement operations.

The univariate analysis showed that chronic kidney disease, long operation times, long durations for coronary bypass and circulatory arrest, and extended time on mechanical ventilation were risk factors for in-hospital death in octogenarians, Dr. Minatoya said. The multivariate analysis showed that male gender along with extended mechanical ventilation were risk factors for in-hospital death in this group, he said.

The overall population included 252 emergent operations, 224 of which were for acute aortic dissections, Dr. Minatoya said. The in-hospital death rate was 4.5% for elective operations and 7.1% for emergent cases, he said. The death rate for isolated, elective total arch replacement was 3.4%.

Focusing on acute aortic dissections, Dr. Minatoya said, “We have adopted an aggressive strategy for entry-site resection, including total arch replacement, in patients with arch tears.” Almost 50% of patients with acute aortic dissection had total arch replacement, he said, with identical 4.9% rates for in-hospital mortality rate and permanent neurological deficit in this group.

The leading overall causes of in-hospital death were low-output syndrome (38.5%), sepsis (25%), respiratory failure (21%) and rupture of the residual aneurysm (9%), Dr. Minatoya said.

Fifteen patients (1.5%) underwent second operations for arch grafts, he said: 11 for pseudoaneurysm; three for hemolysis and one for infection. Other overall measures in the analysis were a permanent neurological dysfunction rate of 3.6%, a temporary neurological dysfunction rate of 6.4%, and no spinal cord complications. Overall 5-year survival was 80.7% and 10-year survival was 63.1%, Dr. Minatoya said.

A total of 311 patients had concomitant procedures. They included aortic valve operations (64); aortic root replacement (38); mitral valve replacement (13); and coronary artery bypass grafting (196).

The typical operation in the study population took about 8 hours, Dr. Minatoya said (482 minutes). Timing of key operative steps were cardiopulmonary time of 254 minutes, cardiac arrest time of 146 minutes, antegrade cerebral perfusion time of 160 minutes and lower-body circulatory arrest time of 62 minutes.

“Since the mean age was 70 years old, we think the survival rate was acceptable,” Dr. Minatoya said, regarding overall study results. Overall risk factors for in-hospital death were short stature, long pump time, chronic kidney disease, and age of 80 and up, he said. Short stature was a risk factor for permanent neurological deficit, and males over age 80 had a higher risk for total arch replacement.

“Total arch replacement using the four-branched graft with antegrade cerebral perfusion could be accomplished with acceptable early and late results,” Dr. Minatoya said. “The branched-arch TEVAR may be a good option for octogenarians and patients with chronic kidney disease.”

Dr. Minatoya had no financial relationships to disclose.

NEW YORK – A total aortic arch replacement approach that uses a four-branched graft with antegrade cerebral perfusion can be done with low rates of in-hospital death and complications, a large series from two institutions in Japan showed.

Kenji Minatoya, MD, of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in Osaka, Japan, reported that his institution’s approach for total arch replacement (TAR) had an in-hospital death rate of 5.2%.

Dr. Minatoya and his colleagues started using four-branch TAR in the 1980s, switching from retrograde to antegrade cerebral perfusion to protect the brain later on. “The study purpose was to investigate the results of total arch replacement using the four-branch graft as a benchmark in the endovascular era,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

The study involved 1,005 cases of total arch replacement performed at Dr. Minatoya’s center and at Tokyo Medical University from 2001 to 2016.

The study population included a cohort of 152 people in their 80s. The in-hospital death rate in this group was 11.8%, Dr. Minatoya said. The over-80 group mostly underwent thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) beginning in 2008, he said, but in recent years some had open total arch replacement operations.

The univariate analysis showed that chronic kidney disease, long operation times, long durations for coronary bypass and circulatory arrest, and extended time on mechanical ventilation were risk factors for in-hospital death in octogenarians, Dr. Minatoya said. The multivariate analysis showed that male gender along with extended mechanical ventilation were risk factors for in-hospital death in this group, he said.

The overall population included 252 emergent operations, 224 of which were for acute aortic dissections, Dr. Minatoya said. The in-hospital death rate was 4.5% for elective operations and 7.1% for emergent cases, he said. The death rate for isolated, elective total arch replacement was 3.4%.

Focusing on acute aortic dissections, Dr. Minatoya said, “We have adopted an aggressive strategy for entry-site resection, including total arch replacement, in patients with arch tears.” Almost 50% of patients with acute aortic dissection had total arch replacement, he said, with identical 4.9% rates for in-hospital mortality rate and permanent neurological deficit in this group.

The leading overall causes of in-hospital death were low-output syndrome (38.5%), sepsis (25%), respiratory failure (21%) and rupture of the residual aneurysm (9%), Dr. Minatoya said.

Fifteen patients (1.5%) underwent second operations for arch grafts, he said: 11 for pseudoaneurysm; three for hemolysis and one for infection. Other overall measures in the analysis were a permanent neurological dysfunction rate of 3.6%, a temporary neurological dysfunction rate of 6.4%, and no spinal cord complications. Overall 5-year survival was 80.7% and 10-year survival was 63.1%, Dr. Minatoya said.

A total of 311 patients had concomitant procedures. They included aortic valve operations (64); aortic root replacement (38); mitral valve replacement (13); and coronary artery bypass grafting (196).

The typical operation in the study population took about 8 hours, Dr. Minatoya said (482 minutes). Timing of key operative steps were cardiopulmonary time of 254 minutes, cardiac arrest time of 146 minutes, antegrade cerebral perfusion time of 160 minutes and lower-body circulatory arrest time of 62 minutes.

“Since the mean age was 70 years old, we think the survival rate was acceptable,” Dr. Minatoya said, regarding overall study results. Overall risk factors for in-hospital death were short stature, long pump time, chronic kidney disease, and age of 80 and up, he said. Short stature was a risk factor for permanent neurological deficit, and males over age 80 had a higher risk for total arch replacement.

“Total arch replacement using the four-branched graft with antegrade cerebral perfusion could be accomplished with acceptable early and late results,” Dr. Minatoya said. “The branched-arch TEVAR may be a good option for octogenarians and patients with chronic kidney disease.”

Dr. Minatoya had no financial relationships to disclose.

NEW YORK – A total aortic arch replacement approach that uses a four-branched graft with antegrade cerebral perfusion can be done with low rates of in-hospital death and complications, a large series from two institutions in Japan showed.

Kenji Minatoya, MD, of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in Osaka, Japan, reported that his institution’s approach for total arch replacement (TAR) had an in-hospital death rate of 5.2%.

Dr. Minatoya and his colleagues started using four-branch TAR in the 1980s, switching from retrograde to antegrade cerebral perfusion to protect the brain later on. “The study purpose was to investigate the results of total arch replacement using the four-branch graft as a benchmark in the endovascular era,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

The study involved 1,005 cases of total arch replacement performed at Dr. Minatoya’s center and at Tokyo Medical University from 2001 to 2016.

The study population included a cohort of 152 people in their 80s. The in-hospital death rate in this group was 11.8%, Dr. Minatoya said. The over-80 group mostly underwent thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) beginning in 2008, he said, but in recent years some had open total arch replacement operations.

The univariate analysis showed that chronic kidney disease, long operation times, long durations for coronary bypass and circulatory arrest, and extended time on mechanical ventilation were risk factors for in-hospital death in octogenarians, Dr. Minatoya said. The multivariate analysis showed that male gender along with extended mechanical ventilation were risk factors for in-hospital death in this group, he said.

The overall population included 252 emergent operations, 224 of which were for acute aortic dissections, Dr. Minatoya said. The in-hospital death rate was 4.5% for elective operations and 7.1% for emergent cases, he said. The death rate for isolated, elective total arch replacement was 3.4%.

Focusing on acute aortic dissections, Dr. Minatoya said, “We have adopted an aggressive strategy for entry-site resection, including total arch replacement, in patients with arch tears.” Almost 50% of patients with acute aortic dissection had total arch replacement, he said, with identical 4.9% rates for in-hospital mortality rate and permanent neurological deficit in this group.

The leading overall causes of in-hospital death were low-output syndrome (38.5%), sepsis (25%), respiratory failure (21%) and rupture of the residual aneurysm (9%), Dr. Minatoya said.

Fifteen patients (1.5%) underwent second operations for arch grafts, he said: 11 for pseudoaneurysm; three for hemolysis and one for infection. Other overall measures in the analysis were a permanent neurological dysfunction rate of 3.6%, a temporary neurological dysfunction rate of 6.4%, and no spinal cord complications. Overall 5-year survival was 80.7% and 10-year survival was 63.1%, Dr. Minatoya said.

A total of 311 patients had concomitant procedures. They included aortic valve operations (64); aortic root replacement (38); mitral valve replacement (13); and coronary artery bypass grafting (196).

The typical operation in the study population took about 8 hours, Dr. Minatoya said (482 minutes). Timing of key operative steps were cardiopulmonary time of 254 minutes, cardiac arrest time of 146 minutes, antegrade cerebral perfusion time of 160 minutes and lower-body circulatory arrest time of 62 minutes.

“Since the mean age was 70 years old, we think the survival rate was acceptable,” Dr. Minatoya said, regarding overall study results. Overall risk factors for in-hospital death were short stature, long pump time, chronic kidney disease, and age of 80 and up, he said. Short stature was a risk factor for permanent neurological deficit, and males over age 80 had a higher risk for total arch replacement.

“Total arch replacement using the four-branched graft with antegrade cerebral perfusion could be accomplished with acceptable early and late results,” Dr. Minatoya said. “The branched-arch TEVAR may be a good option for octogenarians and patients with chronic kidney disease.”

Dr. Minatoya had no financial relationships to disclose.

AT THE AATS AORTIC SYMPOSIUM 2016

Key clinical point: Four-branched total aortic arch replacement can achieve acceptable early and late results.

Major finding: Overall in-hospital mortality was 5.2% and 5-year survival was 80.7%.

Data source: Consecutive series of 1,005 patients who had total arch replacement between 2001 and 2016 at two centers in Japan.

Disclosures: Dr. Minatoya reported having no financial disclosures.

Pediatric autologous aortic repair built to last

NEW YORK – With more than 1 million adults living today with congenital aortic disease, cardiovascular surgeons must think of outcomes in terms of decades, not years, when performing aortic arch repair in newborns, infants, and children, according to Charles D. Fraser Jr., M.D.

To that end, an all-autologous approach to aortic arch repair is key in preserving problem-free aortic function in adulthood, said Dr. Fraser, surgeon-in-chief at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Dr. Fraser reported on his center’s experience with all-autologous aortic arch repair techniques. He reviewed the following five principles that guide aortic arch repair in newborns, infants, and children at Texas Children’s Hospital:

• Use of autologous tissue reconstruction and avoidance of prosthetic material.

• Concomitant intracardiac repair.

• Use of anatomic reconstruction.

• Optimization of ventriculoarterial coupling.

• Preservation of laryngeal nerve function.

“The principles we developed at Texas Children’s Hospital we hope will translate into fewer of these patients that surgeons caring for adults with aortic disease will have to take care of later in life,” Dr. Fraser said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. He reviewed cases in which he explained techniques he and his colleagues developed to address long-term outcomes.

The first challenge is to determine when to perform aortic repair in pediatric patients. “A question often asked is how small is too small when assessing the aortic arch in association with significant periductal coarctation?” he said. “Our rule of thumb has been that the arch diameter measured in millimeters should be at least the patient’s weight in kilograms plus one.” In other words, a 3-kg baby should have an aortic arch of at least 4 mm in diameter, he said.

He described the case of a 3.8-kg male baby on prostaglandin E1 who had aortic arch advancement repair and closure of atrial and ventricular septal defects at 8 days of age. The patient had an early origin of the left common carotid artery and a small proximal aortic arch. “This is the kind of patient in which we would do a complete aortic arch reconstruction, again with the autologous technique,” Dr. Fraser said.

In such a patient, Dr. Fraser and his colleagues at Texas Children’s Hospital support the circulation to the brain with antegrade cerebral perfusion, using transcranial Doppler and near-infrared spectroscopy to guide their profusion strategy, before putting the child on cardiac bypass and “profound” hypothermia. Careful planning before cannulation is important to perform the aortic transection at the correct level, he said

He also explained the ascending sliding arch aortoplasty, also known as the “Texas slide,” first described by E. Dean McKenzie, M.D., at Texas Children’s Hospital in 2011 (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;91:805-10) This technique involves sliding a tongue-shaped piece of the ascending aorta underneath the aortic arch to construct an all-autologous repair.

“In patients with bicuspid aortic valves, we often observe that the ascending aorta is extremely elongated,” he said. “The idea is to take advantage of that and slide the ascending aorta completely up underneath the aortic arch and construct an all-autologous arch advancement type of repair.”

He presented the case of a 4-year-old boy with coarctation of the aorta in whom the Texas slide was indicated. “If this patient were treated with a simple coarctectomy, the patient would be subject to a life with a moderately hypoplastic aortic arch, and over the course of time, this could be problematic,” Dr. Fraser said. “The sliding reconstruction has relevance not only to the status of the aortic arch over the long term but it also has a profound effect on ventricular function.”

He noted a single-center, retrospective study from the United Kingdom that demonstrated that the quality of the aortic arch reconstruction, and the related opportunity for ventricular arterial coupling, directly correlate with long-term performance of the aortic arch in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1526-33).

“This is very important as part of the growing population of these patients who need long-term management, most of whom we’re anticipating managing not just for years, but for decades,” Dr. Fraser said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – With more than 1 million adults living today with congenital aortic disease, cardiovascular surgeons must think of outcomes in terms of decades, not years, when performing aortic arch repair in newborns, infants, and children, according to Charles D. Fraser Jr., M.D.

To that end, an all-autologous approach to aortic arch repair is key in preserving problem-free aortic function in adulthood, said Dr. Fraser, surgeon-in-chief at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Dr. Fraser reported on his center’s experience with all-autologous aortic arch repair techniques. He reviewed the following five principles that guide aortic arch repair in newborns, infants, and children at Texas Children’s Hospital:

• Use of autologous tissue reconstruction and avoidance of prosthetic material.

• Concomitant intracardiac repair.

• Use of anatomic reconstruction.

• Optimization of ventriculoarterial coupling.

• Preservation of laryngeal nerve function.

“The principles we developed at Texas Children’s Hospital we hope will translate into fewer of these patients that surgeons caring for adults with aortic disease will have to take care of later in life,” Dr. Fraser said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. He reviewed cases in which he explained techniques he and his colleagues developed to address long-term outcomes.

The first challenge is to determine when to perform aortic repair in pediatric patients. “A question often asked is how small is too small when assessing the aortic arch in association with significant periductal coarctation?” he said. “Our rule of thumb has been that the arch diameter measured in millimeters should be at least the patient’s weight in kilograms plus one.” In other words, a 3-kg baby should have an aortic arch of at least 4 mm in diameter, he said.

He described the case of a 3.8-kg male baby on prostaglandin E1 who had aortic arch advancement repair and closure of atrial and ventricular septal defects at 8 days of age. The patient had an early origin of the left common carotid artery and a small proximal aortic arch. “This is the kind of patient in which we would do a complete aortic arch reconstruction, again with the autologous technique,” Dr. Fraser said.

In such a patient, Dr. Fraser and his colleagues at Texas Children’s Hospital support the circulation to the brain with antegrade cerebral perfusion, using transcranial Doppler and near-infrared spectroscopy to guide their profusion strategy, before putting the child on cardiac bypass and “profound” hypothermia. Careful planning before cannulation is important to perform the aortic transection at the correct level, he said

He also explained the ascending sliding arch aortoplasty, also known as the “Texas slide,” first described by E. Dean McKenzie, M.D., at Texas Children’s Hospital in 2011 (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;91:805-10) This technique involves sliding a tongue-shaped piece of the ascending aorta underneath the aortic arch to construct an all-autologous repair.

“In patients with bicuspid aortic valves, we often observe that the ascending aorta is extremely elongated,” he said. “The idea is to take advantage of that and slide the ascending aorta completely up underneath the aortic arch and construct an all-autologous arch advancement type of repair.”

He presented the case of a 4-year-old boy with coarctation of the aorta in whom the Texas slide was indicated. “If this patient were treated with a simple coarctectomy, the patient would be subject to a life with a moderately hypoplastic aortic arch, and over the course of time, this could be problematic,” Dr. Fraser said. “The sliding reconstruction has relevance not only to the status of the aortic arch over the long term but it also has a profound effect on ventricular function.”

He noted a single-center, retrospective study from the United Kingdom that demonstrated that the quality of the aortic arch reconstruction, and the related opportunity for ventricular arterial coupling, directly correlate with long-term performance of the aortic arch in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1526-33).

“This is very important as part of the growing population of these patients who need long-term management, most of whom we’re anticipating managing not just for years, but for decades,” Dr. Fraser said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – With more than 1 million adults living today with congenital aortic disease, cardiovascular surgeons must think of outcomes in terms of decades, not years, when performing aortic arch repair in newborns, infants, and children, according to Charles D. Fraser Jr., M.D.

To that end, an all-autologous approach to aortic arch repair is key in preserving problem-free aortic function in adulthood, said Dr. Fraser, surgeon-in-chief at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Dr. Fraser reported on his center’s experience with all-autologous aortic arch repair techniques. He reviewed the following five principles that guide aortic arch repair in newborns, infants, and children at Texas Children’s Hospital:

• Use of autologous tissue reconstruction and avoidance of prosthetic material.

• Concomitant intracardiac repair.

• Use of anatomic reconstruction.

• Optimization of ventriculoarterial coupling.

• Preservation of laryngeal nerve function.

“The principles we developed at Texas Children’s Hospital we hope will translate into fewer of these patients that surgeons caring for adults with aortic disease will have to take care of later in life,” Dr. Fraser said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. He reviewed cases in which he explained techniques he and his colleagues developed to address long-term outcomes.

The first challenge is to determine when to perform aortic repair in pediatric patients. “A question often asked is how small is too small when assessing the aortic arch in association with significant periductal coarctation?” he said. “Our rule of thumb has been that the arch diameter measured in millimeters should be at least the patient’s weight in kilograms plus one.” In other words, a 3-kg baby should have an aortic arch of at least 4 mm in diameter, he said.

He described the case of a 3.8-kg male baby on prostaglandin E1 who had aortic arch advancement repair and closure of atrial and ventricular septal defects at 8 days of age. The patient had an early origin of the left common carotid artery and a small proximal aortic arch. “This is the kind of patient in which we would do a complete aortic arch reconstruction, again with the autologous technique,” Dr. Fraser said.

In such a patient, Dr. Fraser and his colleagues at Texas Children’s Hospital support the circulation to the brain with antegrade cerebral perfusion, using transcranial Doppler and near-infrared spectroscopy to guide their profusion strategy, before putting the child on cardiac bypass and “profound” hypothermia. Careful planning before cannulation is important to perform the aortic transection at the correct level, he said

He also explained the ascending sliding arch aortoplasty, also known as the “Texas slide,” first described by E. Dean McKenzie, M.D., at Texas Children’s Hospital in 2011 (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;91:805-10) This technique involves sliding a tongue-shaped piece of the ascending aorta underneath the aortic arch to construct an all-autologous repair.

“In patients with bicuspid aortic valves, we often observe that the ascending aorta is extremely elongated,” he said. “The idea is to take advantage of that and slide the ascending aorta completely up underneath the aortic arch and construct an all-autologous arch advancement type of repair.”

He presented the case of a 4-year-old boy with coarctation of the aorta in whom the Texas slide was indicated. “If this patient were treated with a simple coarctectomy, the patient would be subject to a life with a moderately hypoplastic aortic arch, and over the course of time, this could be problematic,” Dr. Fraser said. “The sliding reconstruction has relevance not only to the status of the aortic arch over the long term but it also has a profound effect on ventricular function.”

He noted a single-center, retrospective study from the United Kingdom that demonstrated that the quality of the aortic arch reconstruction, and the related opportunity for ventricular arterial coupling, directly correlate with long-term performance of the aortic arch in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1526-33).

“This is very important as part of the growing population of these patients who need long-term management, most of whom we’re anticipating managing not just for years, but for decades,” Dr. Fraser said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AATS AORTIC SYMPOSIUM 2016

Key clinical point: Surgeons must think of outcomes for operations to correct aortic arch disease in children in the context of decades, not years.

Major finding: Five principles should guide autologous aortic arch repair in newborns, infants, and children.

Data source: Case studies from Texas Children’s Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Fraser reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Protective hypothermia during arch surgery lacked benefit, study shows

NEW YORK – Deep hypothermia may affect long-term survival in individuals who have aortic arch surgery with antegrade cerebral perfusion (ACP), but not short-term outcomes in terms of death and major morbidities, according to a Baylor College of Medicine study.

The study evaluated outcomes of 544 consecutive patients who had proximal and total aortic arch surgery and received ACP for more than 30 minutes over a 10-year period, said lead investigator Ourania Preventza, MD, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the college in Houston. The researchers compared results of three different hypothermia levels: deep hypothermia at 14.1°-20° C; low-moderate at 20.1°-23.9° C; and high-moderate at 24°-28° C. The study also classified ACP time in two levels: 31-45 minutes for 238 patients (43.8%); and 45 minutes or more in 306 patients (56.3%).

“The different temperature levels did not significantly affect the short-term mortality and major morbidity rates,” Dr. Preventza said. “Reoperation for bleeding was associated with lower temperature (14.1°-20° C). The long-term survival rate in patients who underwent proximal arch surgery involving ACP for more than 30 minutes and use of moderate hypothermia (20.1°-28° C) were actually improved.”

While the outcomes showed small variations between the three groups, with deep hypothermia being associated with a higher percentage of adverse outcomes, Dr. Preventza said the differences were not statistically significant. The overall operative mortality rate was 12.5% (68 patients): 15.5% (18 patients) in the deep-hypothermia group; 11.8% (31 patients) in the low-moderate group; and 11.5% (19 patients) in the high-moderate group (P = 0.54).

The patients who underwent deep hypothermia were more likely to receive unilateral ACP, and those who underwent moderate hypothermia were more likely to have bilateral ACP, Dr. Preventza said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. The deep-hypothermia group had higher transfusion rates, but, again, the researchers did not consider this variation to be statistically significant.

In the deep-hypothermia group, 20.9% of patients had a reoperation for bleeding, compared with 11.3% in the overall group and 7.7% and 10.2% in the low- and high-moderate groups, respectively, Dr. Preventza reported. Multivariate analysis revealed that higher temperature was associated with less bleeding, with an odds ratio of 0.61 (P = 0.015).

Deep hypothermia was related to statistically significant differences in the rates of permanent stroke and permanent neurologic events in the univariate analysis only, Dr. Preventza said: 6.3% and 7.2%, respectively, in the overall analysis vs. 12.2% for both events in the deep-hypothermia group. In the propensity score analysis, the rates of permanent stroke and permanent neurologic events in the moderate-hypothermia group were 7.6% and 8.5%, respectively, vs. 11.3% for both events in the deep-hypothermia group, a nonsignificant difference.

“With regard to permanent stoke and permanent neurological events, the multivariate analysis showed that preoperatively a neurologic deficit as well as acute type I aortic dissection were associated with adverse neurological events,” she said.

“However,” Dr. Preventza added, “the surprising thing is that when we looked at long-term survival for the entire cohort, we saw that the patients with moderate hypothermia did better.”

Kaplan-Meier analysis for the propensity pairs showed that the probability of survival at 8 years was 55.3% for the deep-hypothermia group vs. 68.5% for the moderate-hypothermia group.

The approach the Baylor researchers used involved cannulating the axillary or innominate artery in most patients before administering ACP, although a few patients had femoral or direct aortic cannulation, Dr. Preventza said. For bilateral ACP, the researchers delivered cerebral perfusion via a 9-French Pruitt balloon-tip catheter (LeMaitre Vascular) in the left common carotid artery. To protect the brain, they administered perfusion at 8-12 cc/kg per min and maintained a perfusion pressure of 50-70 mm Hg, as measured via the radial arterial line and guided by near-infrared spectroscopy.

Dr. Preventza had no relevant disclosures.

NEW YORK – Deep hypothermia may affect long-term survival in individuals who have aortic arch surgery with antegrade cerebral perfusion (ACP), but not short-term outcomes in terms of death and major morbidities, according to a Baylor College of Medicine study.

The study evaluated outcomes of 544 consecutive patients who had proximal and total aortic arch surgery and received ACP for more than 30 minutes over a 10-year period, said lead investigator Ourania Preventza, MD, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the college in Houston. The researchers compared results of three different hypothermia levels: deep hypothermia at 14.1°-20° C; low-moderate at 20.1°-23.9° C; and high-moderate at 24°-28° C. The study also classified ACP time in two levels: 31-45 minutes for 238 patients (43.8%); and 45 minutes or more in 306 patients (56.3%).

“The different temperature levels did not significantly affect the short-term mortality and major morbidity rates,” Dr. Preventza said. “Reoperation for bleeding was associated with lower temperature (14.1°-20° C). The long-term survival rate in patients who underwent proximal arch surgery involving ACP for more than 30 minutes and use of moderate hypothermia (20.1°-28° C) were actually improved.”

While the outcomes showed small variations between the three groups, with deep hypothermia being associated with a higher percentage of adverse outcomes, Dr. Preventza said the differences were not statistically significant. The overall operative mortality rate was 12.5% (68 patients): 15.5% (18 patients) in the deep-hypothermia group; 11.8% (31 patients) in the low-moderate group; and 11.5% (19 patients) in the high-moderate group (P = 0.54).

The patients who underwent deep hypothermia were more likely to receive unilateral ACP, and those who underwent moderate hypothermia were more likely to have bilateral ACP, Dr. Preventza said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. The deep-hypothermia group had higher transfusion rates, but, again, the researchers did not consider this variation to be statistically significant.

In the deep-hypothermia group, 20.9% of patients had a reoperation for bleeding, compared with 11.3% in the overall group and 7.7% and 10.2% in the low- and high-moderate groups, respectively, Dr. Preventza reported. Multivariate analysis revealed that higher temperature was associated with less bleeding, with an odds ratio of 0.61 (P = 0.015).

Deep hypothermia was related to statistically significant differences in the rates of permanent stroke and permanent neurologic events in the univariate analysis only, Dr. Preventza said: 6.3% and 7.2%, respectively, in the overall analysis vs. 12.2% for both events in the deep-hypothermia group. In the propensity score analysis, the rates of permanent stroke and permanent neurologic events in the moderate-hypothermia group were 7.6% and 8.5%, respectively, vs. 11.3% for both events in the deep-hypothermia group, a nonsignificant difference.

“With regard to permanent stoke and permanent neurological events, the multivariate analysis showed that preoperatively a neurologic deficit as well as acute type I aortic dissection were associated with adverse neurological events,” she said.

“However,” Dr. Preventza added, “the surprising thing is that when we looked at long-term survival for the entire cohort, we saw that the patients with moderate hypothermia did better.”

Kaplan-Meier analysis for the propensity pairs showed that the probability of survival at 8 years was 55.3% for the deep-hypothermia group vs. 68.5% for the moderate-hypothermia group.

The approach the Baylor researchers used involved cannulating the axillary or innominate artery in most patients before administering ACP, although a few patients had femoral or direct aortic cannulation, Dr. Preventza said. For bilateral ACP, the researchers delivered cerebral perfusion via a 9-French Pruitt balloon-tip catheter (LeMaitre Vascular) in the left common carotid artery. To protect the brain, they administered perfusion at 8-12 cc/kg per min and maintained a perfusion pressure of 50-70 mm Hg, as measured via the radial arterial line and guided by near-infrared spectroscopy.

Dr. Preventza had no relevant disclosures.

NEW YORK – Deep hypothermia may affect long-term survival in individuals who have aortic arch surgery with antegrade cerebral perfusion (ACP), but not short-term outcomes in terms of death and major morbidities, according to a Baylor College of Medicine study.

The study evaluated outcomes of 544 consecutive patients who had proximal and total aortic arch surgery and received ACP for more than 30 minutes over a 10-year period, said lead investigator Ourania Preventza, MD, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the college in Houston. The researchers compared results of three different hypothermia levels: deep hypothermia at 14.1°-20° C; low-moderate at 20.1°-23.9° C; and high-moderate at 24°-28° C. The study also classified ACP time in two levels: 31-45 minutes for 238 patients (43.8%); and 45 minutes or more in 306 patients (56.3%).

“The different temperature levels did not significantly affect the short-term mortality and major morbidity rates,” Dr. Preventza said. “Reoperation for bleeding was associated with lower temperature (14.1°-20° C). The long-term survival rate in patients who underwent proximal arch surgery involving ACP for more than 30 minutes and use of moderate hypothermia (20.1°-28° C) were actually improved.”

While the outcomes showed small variations between the three groups, with deep hypothermia being associated with a higher percentage of adverse outcomes, Dr. Preventza said the differences were not statistically significant. The overall operative mortality rate was 12.5% (68 patients): 15.5% (18 patients) in the deep-hypothermia group; 11.8% (31 patients) in the low-moderate group; and 11.5% (19 patients) in the high-moderate group (P = 0.54).

The patients who underwent deep hypothermia were more likely to receive unilateral ACP, and those who underwent moderate hypothermia were more likely to have bilateral ACP, Dr. Preventza said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. The deep-hypothermia group had higher transfusion rates, but, again, the researchers did not consider this variation to be statistically significant.

In the deep-hypothermia group, 20.9% of patients had a reoperation for bleeding, compared with 11.3% in the overall group and 7.7% and 10.2% in the low- and high-moderate groups, respectively, Dr. Preventza reported. Multivariate analysis revealed that higher temperature was associated with less bleeding, with an odds ratio of 0.61 (P = 0.015).

Deep hypothermia was related to statistically significant differences in the rates of permanent stroke and permanent neurologic events in the univariate analysis only, Dr. Preventza said: 6.3% and 7.2%, respectively, in the overall analysis vs. 12.2% for both events in the deep-hypothermia group. In the propensity score analysis, the rates of permanent stroke and permanent neurologic events in the moderate-hypothermia group were 7.6% and 8.5%, respectively, vs. 11.3% for both events in the deep-hypothermia group, a nonsignificant difference.

“With regard to permanent stoke and permanent neurological events, the multivariate analysis showed that preoperatively a neurologic deficit as well as acute type I aortic dissection were associated with adverse neurological events,” she said.

“However,” Dr. Preventza added, “the surprising thing is that when we looked at long-term survival for the entire cohort, we saw that the patients with moderate hypothermia did better.”

Kaplan-Meier analysis for the propensity pairs showed that the probability of survival at 8 years was 55.3% for the deep-hypothermia group vs. 68.5% for the moderate-hypothermia group.

The approach the Baylor researchers used involved cannulating the axillary or innominate artery in most patients before administering ACP, although a few patients had femoral or direct aortic cannulation, Dr. Preventza said. For bilateral ACP, the researchers delivered cerebral perfusion via a 9-French Pruitt balloon-tip catheter (LeMaitre Vascular) in the left common carotid artery. To protect the brain, they administered perfusion at 8-12 cc/kg per min and maintained a perfusion pressure of 50-70 mm Hg, as measured via the radial arterial line and guided by near-infrared spectroscopy.

Dr. Preventza had no relevant disclosures.

AT AATS AORTIC SYMPOSIUM 2016

Key clinical point: Differing temperatures of hypothermia did not affect death or morbidity in patients who had aortic arch surgery with more than 30 minutes of antegrade cerebral perfusion.

Major finding: The overall operative death rate in the study was 12.4% with no statistically significant differences between three different hypothermia groups.

Data source: Series of 510 consecutive patients who had proximal and total arch surgery and received antegrade cerebral perfusion for more than 30 minutes over a 10-year period.

Disclosures: Dr. Preventza reported having no financial disclosures.

Surgery for acute type A dissection shows 20-year shift to valve sparing, biological valves

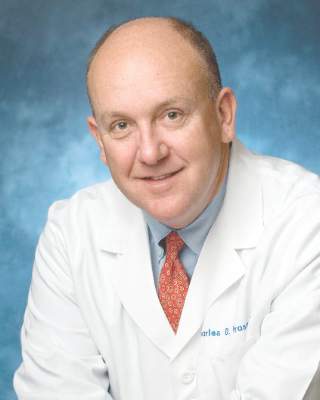

NEW YORK – A study of an international database of individuals who have had open repair for acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) has revealed that in the past 20 years, cardiovascular surgeons have widely embraced valve-sparing procedures, bioprosthetic valves, and cerebral profusion strategies, according to a report here on the latest analysis of the database.

The most telling result is the decline in overall mortality, Santi Trimarchi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan IRCCS Policlinico San Donato in Italy reported on behalf of the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Interventional Cohort (IVC). The cohort analyzed surgery techniques and outcomes of 1,732 patients who had open repair from 1996 to 2016, clustering results in three time intervals: 1996-2003; 2004-2009; and 2010-2015.

“We noted in the registry that the overall in-hospital mortality rate was 14.3%, and this mortality decreased over time from 17.5% in the first six-year time span to 12.2% in the last six years,” Dr. Trimarchi said.

Among other trends the study identified are greater reliance on biological vs. mechanical valves, an increase in valve-sparing procedures, and steady use of Bentall procedures throughout the study period. “Operative techniques for redo aortic valve repair have been improving over the time, and that’s why we see more frequent use of biologic valves,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

“Cerebral profusion management has been widely adopted,” Dr. Trimarchi said. “Also there is an important trend showing an increasing utilization of antegrade cerebral profusion while we see a negative trend of the utilization of retrograde brain protection.”

Dr. Trimarchi attributed the detail the study generated to the survey form sent to the 26 IRAD-IVC sites around the world. The form measures 131 different variables, he said.

“Using this new specific surgical data form, we think we can address some surgical issues and report better data from the IRAD registry results on acute dissection,” he said. “These analyses have shown there have been significant changes in operative strategy over time in terms of managing such patients, and more importantly, a significant decrease in in-hospital mortality was observed in a 20-year time period.”

Dr. Trimarchi disclosed that he has received speaking and consulting fees and research support from W.L. Gore & Associates and Medtronic. IRAD is supported by W.L. Gore, Active Sites, Medtronic, Varbedian Aortic Research Fund, the Hewlett Foundation, the Mardigian Foundation, UM Faculty Group Practice, Terumo, and Ann and Bob Aikens.

NEW YORK – A study of an international database of individuals who have had open repair for acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) has revealed that in the past 20 years, cardiovascular surgeons have widely embraced valve-sparing procedures, bioprosthetic valves, and cerebral profusion strategies, according to a report here on the latest analysis of the database.

The most telling result is the decline in overall mortality, Santi Trimarchi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan IRCCS Policlinico San Donato in Italy reported on behalf of the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Interventional Cohort (IVC). The cohort analyzed surgery techniques and outcomes of 1,732 patients who had open repair from 1996 to 2016, clustering results in three time intervals: 1996-2003; 2004-2009; and 2010-2015.

“We noted in the registry that the overall in-hospital mortality rate was 14.3%, and this mortality decreased over time from 17.5% in the first six-year time span to 12.2% in the last six years,” Dr. Trimarchi said.

Among other trends the study identified are greater reliance on biological vs. mechanical valves, an increase in valve-sparing procedures, and steady use of Bentall procedures throughout the study period. “Operative techniques for redo aortic valve repair have been improving over the time, and that’s why we see more frequent use of biologic valves,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

“Cerebral profusion management has been widely adopted,” Dr. Trimarchi said. “Also there is an important trend showing an increasing utilization of antegrade cerebral profusion while we see a negative trend of the utilization of retrograde brain protection.”

Dr. Trimarchi attributed the detail the study generated to the survey form sent to the 26 IRAD-IVC sites around the world. The form measures 131 different variables, he said.

“Using this new specific surgical data form, we think we can address some surgical issues and report better data from the IRAD registry results on acute dissection,” he said. “These analyses have shown there have been significant changes in operative strategy over time in terms of managing such patients, and more importantly, a significant decrease in in-hospital mortality was observed in a 20-year time period.”

Dr. Trimarchi disclosed that he has received speaking and consulting fees and research support from W.L. Gore & Associates and Medtronic. IRAD is supported by W.L. Gore, Active Sites, Medtronic, Varbedian Aortic Research Fund, the Hewlett Foundation, the Mardigian Foundation, UM Faculty Group Practice, Terumo, and Ann and Bob Aikens.

NEW YORK – A study of an international database of individuals who have had open repair for acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) has revealed that in the past 20 years, cardiovascular surgeons have widely embraced valve-sparing procedures, bioprosthetic valves, and cerebral profusion strategies, according to a report here on the latest analysis of the database.

The most telling result is the decline in overall mortality, Santi Trimarchi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan IRCCS Policlinico San Donato in Italy reported on behalf of the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Interventional Cohort (IVC). The cohort analyzed surgery techniques and outcomes of 1,732 patients who had open repair from 1996 to 2016, clustering results in three time intervals: 1996-2003; 2004-2009; and 2010-2015.

“We noted in the registry that the overall in-hospital mortality rate was 14.3%, and this mortality decreased over time from 17.5% in the first six-year time span to 12.2% in the last six years,” Dr. Trimarchi said.

Among other trends the study identified are greater reliance on biological vs. mechanical valves, an increase in valve-sparing procedures, and steady use of Bentall procedures throughout the study period. “Operative techniques for redo aortic valve repair have been improving over the time, and that’s why we see more frequent use of biologic valves,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

“Cerebral profusion management has been widely adopted,” Dr. Trimarchi said. “Also there is an important trend showing an increasing utilization of antegrade cerebral profusion while we see a negative trend of the utilization of retrograde brain protection.”

Dr. Trimarchi attributed the detail the study generated to the survey form sent to the 26 IRAD-IVC sites around the world. The form measures 131 different variables, he said.

“Using this new specific surgical data form, we think we can address some surgical issues and report better data from the IRAD registry results on acute dissection,” he said. “These analyses have shown there have been significant changes in operative strategy over time in terms of managing such patients, and more importantly, a significant decrease in in-hospital mortality was observed in a 20-year time period.”

Dr. Trimarchi disclosed that he has received speaking and consulting fees and research support from W.L. Gore & Associates and Medtronic. IRAD is supported by W.L. Gore, Active Sites, Medtronic, Varbedian Aortic Research Fund, the Hewlett Foundation, the Mardigian Foundation, UM Faculty Group Practice, Terumo, and Ann and Bob Aikens.

AT AATS AORTIC SYMPOSIUM 2016

Key clinical point: Operations for acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) have seen significant changes in technique over the past 20 years.

Major finding: Use of biological valves increased from 35.6% of procedures to 52% over the study period while reliance of mechanical valves declined from 57.6% to 45.4%.

Data source: Interventional Cohort database of 1,732 patients enrolled in the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection database who had open surgery for ATAAD from February 1996 to March 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Trimarchi disclosed having receive speaking and consulting fees from W.L. Gore & Associates and Medtronic as well as research support from the two companies. IRAD is supported by W.L. Gore, Active Sites, Medtronic, Varbedian Aortic Research Fund, the Hewlett Foundation, the Mardigian Foundation, UM Faculty Group Practice, Terumo, and Ann and Bob Aikens.

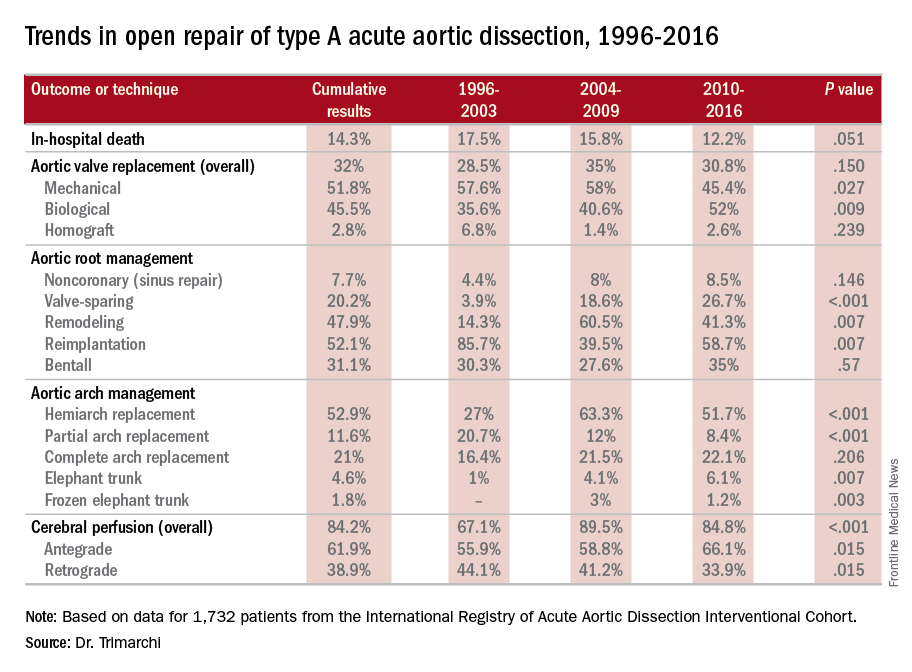

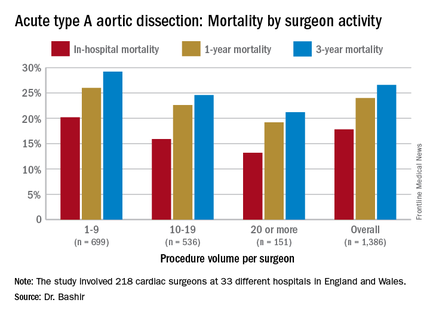

Study quantifies volume disparities for ATAD repair in the U.K.

NEW YORK – Mastery is the product of repetition, and it has long been taken for granted that surgeons and centers that perform a high volume of an operation will have better results than those who don’t do the operation as often, but a study out of the United Kingdom has determined just how much better high-volume centers are when it comes to repair of acute type A aortic dissection (ATAD) – and what the in-hospital mortality odds ratio is for lower-volume surgeons.

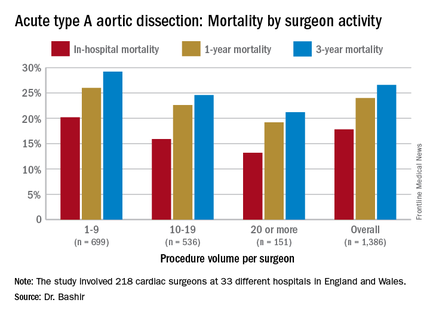

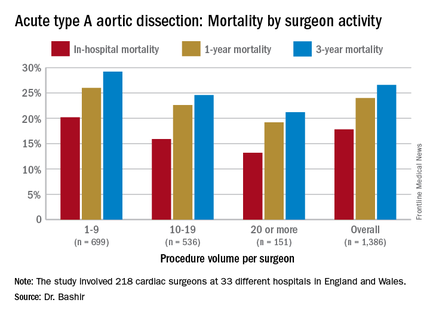

Specifically, that odds ratio is 1.64 (P = .030), Mohamad Bashir, MD, PhD, MRCS, a research fellow at Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital, said in reporting early results of the study here. Lower-volume surgeons had worse outcomes in 12 of 14 different operative metrics the study evaluated, most notably in-hospital mortality: 20.2% for lower-volume surgeons vs. 15.2% for higher-volume surgeons. “There is an initiative in the U.K. to change the trend,” Dr. Bashir said. Full study results will be published in an upcoming issue of BMJ, he said.

“In-hospital mortality for surgeons who operate on 20 or more procedures is very good at 13.2%, and the same follows for 90-day mortality, one-year mortality and three-year mortality,” Dr. Bashir said.

The study evaluated 1,386 ATAD procedures in the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research database by 218 different cardiac surgeons at 33 different hospitals in England and Wales from April 2007 to March 2013. That would make the average number of procedures per surgeon 6.4, Dr. Bashir said, but a closer look at each surgeon’s case load reveals some disconcerting trends: almost 80% of the surgeons performed fewer than 10 ATAD repairs in the 6-year span of the study, and 34 surgeons, or about 15%, just did a single procedure in that time. The highest-volume surgeon did 32 procedures. The minimum hospital volume was 8 ATAD operations and the maximum was 103.

The study stratified lower- and higher-volume surgeon groups by characteristics of the patients they operated on. “The differences between these two groups are pretty interesting because we noticed that the lower-volume surgeons are actually operating on patients who are diabetic, who are smokers, who use inotropic support prior to anesthesia and who also have an injection fraction that is significant,” Dr. Bashir said.

In drilling down into those characteristics, people with diabetes made up 6% of the lower-volume surgeons’ cases vs. 3.1% of the higher-volume surgeons’ cases, despite an almost 50-50 split in share of procedures between the two surgeon groups. Current smokers comprised 20.5% of the lower-volume surgeons’ patients vs. 15.5% of their high-volume counterparts’ patients. Operative characteristics in terms of urgency of surgery were similar between the two groups. However Dr. Bashir noted, lower-volume surgeons had longer times for cardiopulmonary bypass, aortic cross-clamping, and circulatory arrest.

The study investigators applied a multivariable logistic regression model to determine predictors of in-hospital mortality for ATAD. “The odds ratio (OR) of mortality for lower-volume surgeons is 1.64, which is statistically significant,” Dr. Bashir said. Odds ratios for other predictors are: previous cardiac surgery, 2.51; peripheral vascular disease, 2.15; preoperative cardiogenic shock, 2.05; salvage operation, 5.57; and concomitant coronary artery bypass procedure, 2.98. For 5-year mortality, the odds ratio was 1.37 for the lower-volume surgeons.

Dr. Bashir laid out how the National Health Service can use the study results. “Concentration of expertise and volume to the appropriate surgeons and centers who perform increasingly more work and more complex aortic cases would be required to change the paradigm of acute type A aortic dissection outcomes in the U.K.,” he said. “It is reasonable to suggest that there should be a national standardization mandate and a quality-improvement framework of acute aortic dissection treatment.”

Dr. Bashir had no financial relationships to disclose.

NEW YORK – Mastery is the product of repetition, and it has long been taken for granted that surgeons and centers that perform a high volume of an operation will have better results than those who don’t do the operation as often, but a study out of the United Kingdom has determined just how much better high-volume centers are when it comes to repair of acute type A aortic dissection (ATAD) – and what the in-hospital mortality odds ratio is for lower-volume surgeons.

Specifically, that odds ratio is 1.64 (P = .030), Mohamad Bashir, MD, PhD, MRCS, a research fellow at Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital, said in reporting early results of the study here. Lower-volume surgeons had worse outcomes in 12 of 14 different operative metrics the study evaluated, most notably in-hospital mortality: 20.2% for lower-volume surgeons vs. 15.2% for higher-volume surgeons. “There is an initiative in the U.K. to change the trend,” Dr. Bashir said. Full study results will be published in an upcoming issue of BMJ, he said.

“In-hospital mortality for surgeons who operate on 20 or more procedures is very good at 13.2%, and the same follows for 90-day mortality, one-year mortality and three-year mortality,” Dr. Bashir said.

The study evaluated 1,386 ATAD procedures in the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research database by 218 different cardiac surgeons at 33 different hospitals in England and Wales from April 2007 to March 2013. That would make the average number of procedures per surgeon 6.4, Dr. Bashir said, but a closer look at each surgeon’s case load reveals some disconcerting trends: almost 80% of the surgeons performed fewer than 10 ATAD repairs in the 6-year span of the study, and 34 surgeons, or about 15%, just did a single procedure in that time. The highest-volume surgeon did 32 procedures. The minimum hospital volume was 8 ATAD operations and the maximum was 103.

The study stratified lower- and higher-volume surgeon groups by characteristics of the patients they operated on. “The differences between these two groups are pretty interesting because we noticed that the lower-volume surgeons are actually operating on patients who are diabetic, who are smokers, who use inotropic support prior to anesthesia and who also have an injection fraction that is significant,” Dr. Bashir said.

In drilling down into those characteristics, people with diabetes made up 6% of the lower-volume surgeons’ cases vs. 3.1% of the higher-volume surgeons’ cases, despite an almost 50-50 split in share of procedures between the two surgeon groups. Current smokers comprised 20.5% of the lower-volume surgeons’ patients vs. 15.5% of their high-volume counterparts’ patients. Operative characteristics in terms of urgency of surgery were similar between the two groups. However Dr. Bashir noted, lower-volume surgeons had longer times for cardiopulmonary bypass, aortic cross-clamping, and circulatory arrest.

The study investigators applied a multivariable logistic regression model to determine predictors of in-hospital mortality for ATAD. “The odds ratio (OR) of mortality for lower-volume surgeons is 1.64, which is statistically significant,” Dr. Bashir said. Odds ratios for other predictors are: previous cardiac surgery, 2.51; peripheral vascular disease, 2.15; preoperative cardiogenic shock, 2.05; salvage operation, 5.57; and concomitant coronary artery bypass procedure, 2.98. For 5-year mortality, the odds ratio was 1.37 for the lower-volume surgeons.

Dr. Bashir laid out how the National Health Service can use the study results. “Concentration of expertise and volume to the appropriate surgeons and centers who perform increasingly more work and more complex aortic cases would be required to change the paradigm of acute type A aortic dissection outcomes in the U.K.,” he said. “It is reasonable to suggest that there should be a national standardization mandate and a quality-improvement framework of acute aortic dissection treatment.”

Dr. Bashir had no financial relationships to disclose.

NEW YORK – Mastery is the product of repetition, and it has long been taken for granted that surgeons and centers that perform a high volume of an operation will have better results than those who don’t do the operation as often, but a study out of the United Kingdom has determined just how much better high-volume centers are when it comes to repair of acute type A aortic dissection (ATAD) – and what the in-hospital mortality odds ratio is for lower-volume surgeons.

Specifically, that odds ratio is 1.64 (P = .030), Mohamad Bashir, MD, PhD, MRCS, a research fellow at Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital, said in reporting early results of the study here. Lower-volume surgeons had worse outcomes in 12 of 14 different operative metrics the study evaluated, most notably in-hospital mortality: 20.2% for lower-volume surgeons vs. 15.2% for higher-volume surgeons. “There is an initiative in the U.K. to change the trend,” Dr. Bashir said. Full study results will be published in an upcoming issue of BMJ, he said.

“In-hospital mortality for surgeons who operate on 20 or more procedures is very good at 13.2%, and the same follows for 90-day mortality, one-year mortality and three-year mortality,” Dr. Bashir said.

The study evaluated 1,386 ATAD procedures in the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research database by 218 different cardiac surgeons at 33 different hospitals in England and Wales from April 2007 to March 2013. That would make the average number of procedures per surgeon 6.4, Dr. Bashir said, but a closer look at each surgeon’s case load reveals some disconcerting trends: almost 80% of the surgeons performed fewer than 10 ATAD repairs in the 6-year span of the study, and 34 surgeons, or about 15%, just did a single procedure in that time. The highest-volume surgeon did 32 procedures. The minimum hospital volume was 8 ATAD operations and the maximum was 103.

The study stratified lower- and higher-volume surgeon groups by characteristics of the patients they operated on. “The differences between these two groups are pretty interesting because we noticed that the lower-volume surgeons are actually operating on patients who are diabetic, who are smokers, who use inotropic support prior to anesthesia and who also have an injection fraction that is significant,” Dr. Bashir said.

In drilling down into those characteristics, people with diabetes made up 6% of the lower-volume surgeons’ cases vs. 3.1% of the higher-volume surgeons’ cases, despite an almost 50-50 split in share of procedures between the two surgeon groups. Current smokers comprised 20.5% of the lower-volume surgeons’ patients vs. 15.5% of their high-volume counterparts’ patients. Operative characteristics in terms of urgency of surgery were similar between the two groups. However Dr. Bashir noted, lower-volume surgeons had longer times for cardiopulmonary bypass, aortic cross-clamping, and circulatory arrest.

The study investigators applied a multivariable logistic regression model to determine predictors of in-hospital mortality for ATAD. “The odds ratio (OR) of mortality for lower-volume surgeons is 1.64, which is statistically significant,” Dr. Bashir said. Odds ratios for other predictors are: previous cardiac surgery, 2.51; peripheral vascular disease, 2.15; preoperative cardiogenic shock, 2.05; salvage operation, 5.57; and concomitant coronary artery bypass procedure, 2.98. For 5-year mortality, the odds ratio was 1.37 for the lower-volume surgeons.

Dr. Bashir laid out how the National Health Service can use the study results. “Concentration of expertise and volume to the appropriate surgeons and centers who perform increasingly more work and more complex aortic cases would be required to change the paradigm of acute type A aortic dissection outcomes in the U.K.,” he said. “It is reasonable to suggest that there should be a national standardization mandate and a quality-improvement framework of acute aortic dissection treatment.”

Dr. Bashir had no financial relationships to disclose.

AT THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THORACIC SURGERY AORTIC SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Patients undergoing repair of acute type A aortic dissection (ATAD) by lower-volume surgeons have high mortality in comparison with those undergoing repair by the highest-volume surgeons.

Major finding: In-hospital mortality for ATAD repair was 20.2% for lower-volume surgeons and 15.3% for higher-volume surgeons.

Data source: Analysis of 1,386 ATAD procedures from April 2007 to March 2013 in the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research data.

Disclosures: Dr. Bashir reported having no financial disclosures.

Guideline tweak addresses conflicting recommendations on BAV

NEW YORK – While overall guidelines for aortic repair surgery have not changed significantly in the past 5 years, guidelines for the timing of surgery in patients with bicuspid aortic valves and enlarged aortas have undergone some updating in an attempt to clear up disparities in different guidelines on when to operate on those patients.

Lars G. Svensson, MD, PhD, chairman of the Cleveland Clinic Heart and Vascular Institute, coauthor of the clarification statement by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:959-66), reported on the guidelines clarification at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. He noted that five different clinical guidelines between 2010 and 2014 recommended five different size thresholds for prophylactic aortic root or ascending aortic surgery in the setting of bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), ranging from 4 cm to greater than 5.5 cm. “This created a bit of a quandary and controversy between different guidelines and time periods,” he said.

Dr. Svensson and Loren Hiratzka, MD, medical director of cardiac surgery for TriHealth in Cincinnati, and their colleagues drafted the guideline clarification that makes the following recommendations for aortic root and ascending aorta repair or replacement when patients have BAV (strength of recommendation):

• Surgery is indicated to replace the aortic root or ascending aorta in asymptomatic patients with BAV if the diameter of the aortic root or ascending aorta is 5.5 cm or greater (Class 1).

• Surgical repair is indicated for asymptomatic patients with BAV if the root or ascending aorta diameter is 5 cm or greater in two scenarios: if the patient has an additional risk factor for dissection, such as family history or excessive aortic growth rate; or if the patient is a low surgical risk and has access to an experienced surgeon at a high-volume center (Class IIa).

The guideline update also addresses BAV in patients with Turner syndrome. The 2010 joint guidelines of 10 societies left some questions with regard to surgery in these patients, Dr. Svensson said. The established guidelines included a Class IIb recommendation for imaging of the heart and aorta to help determine the aorta risk in patients with Turner syndrome who had additional risk factors, including BAV, aortic coarctation and/or hypertension, or were planning a pregnancy.

The updated guideline includes Class IIa recommendation that in short-statured patients with Turner syndrome and BAV, measurement of the aortic root or ascending aorta diameter may not predict the dissection risk as well as aortic diameter index greater than 2.5 cm/m2. The updated recommendations also draw on one study that reported that in patients with BAV, a maximum aortic cross-sectional area-to-height ratio of 10 cm2/m or greater was also predictive of aortic dissection. (Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1666-73)

The updated recommendations for open surgery for ascending aortic aneurysm include separate valve and ascending aortic replacement in patients without significant aortic root dilatation or in elderly patients, or in younger patients with minimal dilatation who have aortic valve disease; and excision of the sinuses of Valsalva with a modified David reimplantation when technically feasible in patients with connective tissue disease and others with dilatation of the aortic root and sinuses. For patients in whom the latter procedure is not feasible, root replacement with valved graft conduit would be indicated, Dr. Svensson said.

Dr. Svensson also reported on recent studies that validated recommendations in established guidelines.

Studies of circulatory arrest practices in aortic arch surgery as prescribed by established guidelines showed confirmatory results, he said. “The one point I would make about circulatory arrest is that we found in a fairly large study of 1,352 circulatory arrest patients that we reduced the risk of stroke by 40% when we used the axillary artery with a side a graft,” he said (Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1274-84). His own institution’s clinical trial of 121 patients who received antegrade or retrograde brain perfusion showed rates of 0.8% for each stroke and operative death, he said (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1140-7).

“What was also of interest there was no difference in outcomes with antegrade vs. retrograde brain profusion,” he said. “I think protection of the brain is pretty good if you follow the fundamental principles of brain protection.”

He also reported on a recent study at his institution that documented the benefits of intrathecal papaverine (IP) for spinal cord protection during descending open and endovascular aortic repairs. In 398 aortic repairs from 2001-2009, the rates of spinal cord injury were 23% in the non-IP group vs. 7% in the IP group (P = .07) in a matched cohort.

He noted that the clinical guidelines of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery as well as AATS/Society of Thoracic Surgeons joint guidelines are open to input. “If you have areas where you think guideline should be written about, please let me or other members of the committee know,” he said.

Dr. Svensson had no disclosures relevant to his presentation.

NEW YORK – While overall guidelines for aortic repair surgery have not changed significantly in the past 5 years, guidelines for the timing of surgery in patients with bicuspid aortic valves and enlarged aortas have undergone some updating in an attempt to clear up disparities in different guidelines on when to operate on those patients.

Lars G. Svensson, MD, PhD, chairman of the Cleveland Clinic Heart and Vascular Institute, coauthor of the clarification statement by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:959-66), reported on the guidelines clarification at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. He noted that five different clinical guidelines between 2010 and 2014 recommended five different size thresholds for prophylactic aortic root or ascending aortic surgery in the setting of bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), ranging from 4 cm to greater than 5.5 cm. “This created a bit of a quandary and controversy between different guidelines and time periods,” he said.

Dr. Svensson and Loren Hiratzka, MD, medical director of cardiac surgery for TriHealth in Cincinnati, and their colleagues drafted the guideline clarification that makes the following recommendations for aortic root and ascending aorta repair or replacement when patients have BAV (strength of recommendation):

• Surgery is indicated to replace the aortic root or ascending aorta in asymptomatic patients with BAV if the diameter of the aortic root or ascending aorta is 5.5 cm or greater (Class 1).

• Surgical repair is indicated for asymptomatic patients with BAV if the root or ascending aorta diameter is 5 cm or greater in two scenarios: if the patient has an additional risk factor for dissection, such as family history or excessive aortic growth rate; or if the patient is a low surgical risk and has access to an experienced surgeon at a high-volume center (Class IIa).

The guideline update also addresses BAV in patients with Turner syndrome. The 2010 joint guidelines of 10 societies left some questions with regard to surgery in these patients, Dr. Svensson said. The established guidelines included a Class IIb recommendation for imaging of the heart and aorta to help determine the aorta risk in patients with Turner syndrome who had additional risk factors, including BAV, aortic coarctation and/or hypertension, or were planning a pregnancy.

The updated guideline includes Class IIa recommendation that in short-statured patients with Turner syndrome and BAV, measurement of the aortic root or ascending aorta diameter may not predict the dissection risk as well as aortic diameter index greater than 2.5 cm/m2. The updated recommendations also draw on one study that reported that in patients with BAV, a maximum aortic cross-sectional area-to-height ratio of 10 cm2/m or greater was also predictive of aortic dissection. (Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1666-73)

The updated recommendations for open surgery for ascending aortic aneurysm include separate valve and ascending aortic replacement in patients without significant aortic root dilatation or in elderly patients, or in younger patients with minimal dilatation who have aortic valve disease; and excision of the sinuses of Valsalva with a modified David reimplantation when technically feasible in patients with connective tissue disease and others with dilatation of the aortic root and sinuses. For patients in whom the latter procedure is not feasible, root replacement with valved graft conduit would be indicated, Dr. Svensson said.

Dr. Svensson also reported on recent studies that validated recommendations in established guidelines.

Studies of circulatory arrest practices in aortic arch surgery as prescribed by established guidelines showed confirmatory results, he said. “The one point I would make about circulatory arrest is that we found in a fairly large study of 1,352 circulatory arrest patients that we reduced the risk of stroke by 40% when we used the axillary artery with a side a graft,” he said (Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1274-84). His own institution’s clinical trial of 121 patients who received antegrade or retrograde brain perfusion showed rates of 0.8% for each stroke and operative death, he said (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1140-7).

“What was also of interest there was no difference in outcomes with antegrade vs. retrograde brain profusion,” he said. “I think protection of the brain is pretty good if you follow the fundamental principles of brain protection.”

He also reported on a recent study at his institution that documented the benefits of intrathecal papaverine (IP) for spinal cord protection during descending open and endovascular aortic repairs. In 398 aortic repairs from 2001-2009, the rates of spinal cord injury were 23% in the non-IP group vs. 7% in the IP group (P = .07) in a matched cohort.

He noted that the clinical guidelines of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery as well as AATS/Society of Thoracic Surgeons joint guidelines are open to input. “If you have areas where you think guideline should be written about, please let me or other members of the committee know,” he said.

Dr. Svensson had no disclosures relevant to his presentation.

NEW YORK – While overall guidelines for aortic repair surgery have not changed significantly in the past 5 years, guidelines for the timing of surgery in patients with bicuspid aortic valves and enlarged aortas have undergone some updating in an attempt to clear up disparities in different guidelines on when to operate on those patients.

Lars G. Svensson, MD, PhD, chairman of the Cleveland Clinic Heart and Vascular Institute, coauthor of the clarification statement by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:959-66), reported on the guidelines clarification at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. He noted that five different clinical guidelines between 2010 and 2014 recommended five different size thresholds for prophylactic aortic root or ascending aortic surgery in the setting of bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), ranging from 4 cm to greater than 5.5 cm. “This created a bit of a quandary and controversy between different guidelines and time periods,” he said.

Dr. Svensson and Loren Hiratzka, MD, medical director of cardiac surgery for TriHealth in Cincinnati, and their colleagues drafted the guideline clarification that makes the following recommendations for aortic root and ascending aorta repair or replacement when patients have BAV (strength of recommendation):

• Surgery is indicated to replace the aortic root or ascending aorta in asymptomatic patients with BAV if the diameter of the aortic root or ascending aorta is 5.5 cm or greater (Class 1).

• Surgical repair is indicated for asymptomatic patients with BAV if the root or ascending aorta diameter is 5 cm or greater in two scenarios: if the patient has an additional risk factor for dissection, such as family history or excessive aortic growth rate; or if the patient is a low surgical risk and has access to an experienced surgeon at a high-volume center (Class IIa).

The guideline update also addresses BAV in patients with Turner syndrome. The 2010 joint guidelines of 10 societies left some questions with regard to surgery in these patients, Dr. Svensson said. The established guidelines included a Class IIb recommendation for imaging of the heart and aorta to help determine the aorta risk in patients with Turner syndrome who had additional risk factors, including BAV, aortic coarctation and/or hypertension, or were planning a pregnancy.

The updated guideline includes Class IIa recommendation that in short-statured patients with Turner syndrome and BAV, measurement of the aortic root or ascending aorta diameter may not predict the dissection risk as well as aortic diameter index greater than 2.5 cm/m2. The updated recommendations also draw on one study that reported that in patients with BAV, a maximum aortic cross-sectional area-to-height ratio of 10 cm2/m or greater was also predictive of aortic dissection. (Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1666-73)

The updated recommendations for open surgery for ascending aortic aneurysm include separate valve and ascending aortic replacement in patients without significant aortic root dilatation or in elderly patients, or in younger patients with minimal dilatation who have aortic valve disease; and excision of the sinuses of Valsalva with a modified David reimplantation when technically feasible in patients with connective tissue disease and others with dilatation of the aortic root and sinuses. For patients in whom the latter procedure is not feasible, root replacement with valved graft conduit would be indicated, Dr. Svensson said.

Dr. Svensson also reported on recent studies that validated recommendations in established guidelines.

Studies of circulatory arrest practices in aortic arch surgery as prescribed by established guidelines showed confirmatory results, he said. “The one point I would make about circulatory arrest is that we found in a fairly large study of 1,352 circulatory arrest patients that we reduced the risk of stroke by 40% when we used the axillary artery with a side a graft,” he said (Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1274-84). His own institution’s clinical trial of 121 patients who received antegrade or retrograde brain perfusion showed rates of 0.8% for each stroke and operative death, he said (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1140-7).

“What was also of interest there was no difference in outcomes with antegrade vs. retrograde brain profusion,” he said. “I think protection of the brain is pretty good if you follow the fundamental principles of brain protection.”

He also reported on a recent study at his institution that documented the benefits of intrathecal papaverine (IP) for spinal cord protection during descending open and endovascular aortic repairs. In 398 aortic repairs from 2001-2009, the rates of spinal cord injury were 23% in the non-IP group vs. 7% in the IP group (P = .07) in a matched cohort.

He noted that the clinical guidelines of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery as well as AATS/Society of Thoracic Surgeons joint guidelines are open to input. “If you have areas where you think guideline should be written about, please let me or other members of the committee know,” he said.

Dr. Svensson had no disclosures relevant to his presentation.

AT THE AATS AORTIC SYMPOSIUM 2016

Key clinical point: Various clinical guidelines provided five different recommendations for the timing of aortic repair surgery in patients with bicuspid aortic valves.

Major finding: Recent updates in guidelines provide clarity on when an aortic repair is needed in the setting of aortic bicuspid valve.