User login

Erythematous Friable Papule Under the Great Toenail

The Diagnosis: Subungual Eccrine Poroma

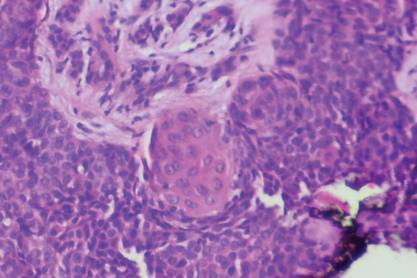

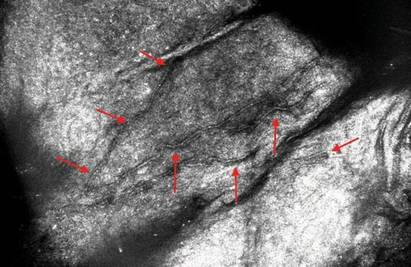

Histologic examination revealed a solitary papule (Figure 1). The epidermis was replaced with a well-defined proliferation of cuboidal and poroid cells. These cells demonstrated a downgrowth into the dermis in broad anastomosing bands that were surrounded by a fibrovascular stroma. Notably, there were few scattered foci of maturation into the ductal lumina of eccrine origin, which confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 2).

|

First described in 1956 by Goldman et al,1 eccrine poromas are benign, slow-growing tumors that account for approximately 10% of sweat gland neoplasms.2 Onset is typically in mid to late adulthood, and there is no ethnic or gender predilection. Classically, eccrine poromas present as soft, sessile, reddish papules or nodules measuring less than 2 cm that protrude from a well-circumscribed depression.

Although eccrine poromas can develop on hair-bearing regions, they most commonly arise on acral skin. In acral locations, bleeding, discharge, rapid growth, and localized pain can occur. These symptoms are even more common in this lesion’s malignant counterpart, eccrine porocarcinoma.3

Solar damage, radiation exposure, trauma, and human papillomavirus have been indicated in the pathogenesis of eccrine poroma; however, the exact etiology has yet to be defined.2,4 The differential diagnosis includes nevus, pyogenic granu-loma, acrochordon, basal cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris.5

Histologically, eccrine poromas consist of a combination of 5 distinct features: poroid cells, cuticular cells, intracytoplasmic or intercellular vacuolization en route to duct formation, massive necrosis or necrosis en masse, and nuclear monomorphism of the poroid and cuticular cells.6 However, all 5 histologic features do not have to be present for the diagnosis. Classically, there is a sharp demarcation of the lesion from the surrounding epidermis.7

Treatment of choice is complete excision to prevent recurrence and risk for malignant transformation in long-standing lesions. One study of eccrine porocarcinomas found that 18% (11/62) arose from a benign preexistent poroma.8 These malignant lesions are found more commonly on the extremities and tend to show a slight female predominance.9

Although there have been 2 reported cases of subungual eccrine porocarcinomas9,10 and 1 case of periungual eccrine porocarcinoma,11 according to an Ovid search using the terms porocarcinoma and nail, the benign subungual eccrine poroma is more rare.

1. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:511-521.

2. Orlandi C, Arcangeli F, Patrizi A, et al. Eccrine poroma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:279-280.

3. Casper DJ, Glass LF, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:227-229.

4. Kang MC, Kim SA, Lee KS, et al. A case of an unusual eccrine poroma on the left forearm area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:250-253.

5. Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

6. Chen CC, Chang YT, Liu HN. Clinical and histological characteristics of poroid neoplasms: a study of 25 cases in Taiwan. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:722-727.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, et al. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:84-86.

8. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

9. Moussallem CD, Abi Hatem NE, El-Khoury ZN.Malignant porocarcinoma of the nail fold: a tricky diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

10. Requena L, Sánchez M, Aguilar A, et al. Periungual porocarcinoma. Dermatologica. 1990;180:177-180.

11. van Gorp J, van der Putte SC. Periungual eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatology. 1993;187:67-70.

The Diagnosis: Subungual Eccrine Poroma

Histologic examination revealed a solitary papule (Figure 1). The epidermis was replaced with a well-defined proliferation of cuboidal and poroid cells. These cells demonstrated a downgrowth into the dermis in broad anastomosing bands that were surrounded by a fibrovascular stroma. Notably, there were few scattered foci of maturation into the ductal lumina of eccrine origin, which confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 2).

|

First described in 1956 by Goldman et al,1 eccrine poromas are benign, slow-growing tumors that account for approximately 10% of sweat gland neoplasms.2 Onset is typically in mid to late adulthood, and there is no ethnic or gender predilection. Classically, eccrine poromas present as soft, sessile, reddish papules or nodules measuring less than 2 cm that protrude from a well-circumscribed depression.

Although eccrine poromas can develop on hair-bearing regions, they most commonly arise on acral skin. In acral locations, bleeding, discharge, rapid growth, and localized pain can occur. These symptoms are even more common in this lesion’s malignant counterpart, eccrine porocarcinoma.3

Solar damage, radiation exposure, trauma, and human papillomavirus have been indicated in the pathogenesis of eccrine poroma; however, the exact etiology has yet to be defined.2,4 The differential diagnosis includes nevus, pyogenic granu-loma, acrochordon, basal cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris.5

Histologically, eccrine poromas consist of a combination of 5 distinct features: poroid cells, cuticular cells, intracytoplasmic or intercellular vacuolization en route to duct formation, massive necrosis or necrosis en masse, and nuclear monomorphism of the poroid and cuticular cells.6 However, all 5 histologic features do not have to be present for the diagnosis. Classically, there is a sharp demarcation of the lesion from the surrounding epidermis.7

Treatment of choice is complete excision to prevent recurrence and risk for malignant transformation in long-standing lesions. One study of eccrine porocarcinomas found that 18% (11/62) arose from a benign preexistent poroma.8 These malignant lesions are found more commonly on the extremities and tend to show a slight female predominance.9

Although there have been 2 reported cases of subungual eccrine porocarcinomas9,10 and 1 case of periungual eccrine porocarcinoma,11 according to an Ovid search using the terms porocarcinoma and nail, the benign subungual eccrine poroma is more rare.

The Diagnosis: Subungual Eccrine Poroma

Histologic examination revealed a solitary papule (Figure 1). The epidermis was replaced with a well-defined proliferation of cuboidal and poroid cells. These cells demonstrated a downgrowth into the dermis in broad anastomosing bands that were surrounded by a fibrovascular stroma. Notably, there were few scattered foci of maturation into the ductal lumina of eccrine origin, which confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 2).

|

First described in 1956 by Goldman et al,1 eccrine poromas are benign, slow-growing tumors that account for approximately 10% of sweat gland neoplasms.2 Onset is typically in mid to late adulthood, and there is no ethnic or gender predilection. Classically, eccrine poromas present as soft, sessile, reddish papules or nodules measuring less than 2 cm that protrude from a well-circumscribed depression.

Although eccrine poromas can develop on hair-bearing regions, they most commonly arise on acral skin. In acral locations, bleeding, discharge, rapid growth, and localized pain can occur. These symptoms are even more common in this lesion’s malignant counterpart, eccrine porocarcinoma.3

Solar damage, radiation exposure, trauma, and human papillomavirus have been indicated in the pathogenesis of eccrine poroma; however, the exact etiology has yet to be defined.2,4 The differential diagnosis includes nevus, pyogenic granu-loma, acrochordon, basal cell carcinoma, and verruca vulgaris.5

Histologically, eccrine poromas consist of a combination of 5 distinct features: poroid cells, cuticular cells, intracytoplasmic or intercellular vacuolization en route to duct formation, massive necrosis or necrosis en masse, and nuclear monomorphism of the poroid and cuticular cells.6 However, all 5 histologic features do not have to be present for the diagnosis. Classically, there is a sharp demarcation of the lesion from the surrounding epidermis.7

Treatment of choice is complete excision to prevent recurrence and risk for malignant transformation in long-standing lesions. One study of eccrine porocarcinomas found that 18% (11/62) arose from a benign preexistent poroma.8 These malignant lesions are found more commonly on the extremities and tend to show a slight female predominance.9

Although there have been 2 reported cases of subungual eccrine porocarcinomas9,10 and 1 case of periungual eccrine porocarcinoma,11 according to an Ovid search using the terms porocarcinoma and nail, the benign subungual eccrine poroma is more rare.

1. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:511-521.

2. Orlandi C, Arcangeli F, Patrizi A, et al. Eccrine poroma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:279-280.

3. Casper DJ, Glass LF, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:227-229.

4. Kang MC, Kim SA, Lee KS, et al. A case of an unusual eccrine poroma on the left forearm area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:250-253.

5. Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

6. Chen CC, Chang YT, Liu HN. Clinical and histological characteristics of poroid neoplasms: a study of 25 cases in Taiwan. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:722-727.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, et al. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:84-86.

8. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

9. Moussallem CD, Abi Hatem NE, El-Khoury ZN.Malignant porocarcinoma of the nail fold: a tricky diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

10. Requena L, Sánchez M, Aguilar A, et al. Periungual porocarcinoma. Dermatologica. 1990;180:177-180.

11. van Gorp J, van der Putte SC. Periungual eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatology. 1993;187:67-70.

1. Goldman P, Pinkus H, Rogin JR. Eccrine poroma; tumors exhibiting features of the epidermal sweat duct unit. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:511-521.

2. Orlandi C, Arcangeli F, Patrizi A, et al. Eccrine poroma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:279-280.

3. Casper DJ, Glass LF, Shenefelt PD. An unusually large eccrine poroma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2011;88:227-229.

4. Kang MC, Kim SA, Lee KS, et al. A case of an unusual eccrine poroma on the left forearm area. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:250-253.

5. Moore TO, Orman HL, Orman SK, et al. Poromas of the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:48-52.

6. Chen CC, Chang YT, Liu HN. Clinical and histological characteristics of poroid neoplasms: a study of 25 cases in Taiwan. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:722-727.

7. Smith EV, Madan V, Joshi A, et al. A pigmented lesion on the foot. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:84-86.

8. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

9. Moussallem CD, Abi Hatem NE, El-Khoury ZN.Malignant porocarcinoma of the nail fold: a tricky diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

10. Requena L, Sánchez M, Aguilar A, et al. Periungual porocarcinoma. Dermatologica. 1990;180:177-180.

11. van Gorp J, van der Putte SC. Periungual eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatology. 1993;187:67-70.

A 20-year-old woman presented with a subungual growth of 1 year’s duration that would intermittently bleed. Despite treatment with silver nitrate in 2 sequential treatments, the lesion continued to increase in size. Physical examination revealed a 6×7-mm erythematous, friable, well-defined papule under the medial aspect of the distal great toenail. Complete surgical excision of the lesion was performed.

Dreadlocks

The Diagnosis: “Pseudonits”

Dreadlocks are matted hairs formed into thick ropelike strands (Figure 1). As a chosen hairstyle dreadlocks are worn by individuals of many different ethnic groups but are most commonly associated with members of the Rastafarian movement, or Rastas. Various techniques are used to form dreadlocks including backcombing (also known as teasing) in which the hair is combed toward the scalp to facilitate tangles and knotting or the neglect method in which the hair is not combed, brushed, or cut, becoming tangled and twisted as it grows long. Manicuring and perming techniques may be used to create the starting point for dreadlocks.

Telogen hairs are the hairs shed as part of normal hair cycling. The average person is estimated to lose 50 telogen hairs per day.1 With dreadlocks, the hairs are entangled distally, so when telogen hairs are released from scalp follicles, the shed hairs remain part of the locks. These “club” hairs have a bulbous white tip situated at the proximal end of the hair shaft (Figure 2) and should not be mistaken for the eggs of Pediculus humanus var capitis, hence the designation pseudonits.2 Hair casts, keratinous material surrounding the hair shafts when there is infundibular or perifollicular hyperkeratosis, also may resemble nits.3 Hair cast pseudonits can be distinguished from true nits by one’s ability to slide the hair casts freely along the hair shaft, whereas lice ova are cemented to the hair shaft and fixed in place.

Figure 2. “Club” hairs with a bulbous white tip situated at the

proximal end of the hair shaft (“pseudonits”).

1. Sperling LC. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. New York, NY: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 2003.

2. Salih S, Bowling JC. Pseudonits in dreadlocked hair: A louse-y case of nits. Dermatology. 2006;213:245.

3. Lam M, Crutchfield CE 3rd, Lewis EJ. Hair casts: a case of pseudonits. Cutis. 1997;60:251-252.

The Diagnosis: “Pseudonits”

Dreadlocks are matted hairs formed into thick ropelike strands (Figure 1). As a chosen hairstyle dreadlocks are worn by individuals of many different ethnic groups but are most commonly associated with members of the Rastafarian movement, or Rastas. Various techniques are used to form dreadlocks including backcombing (also known as teasing) in which the hair is combed toward the scalp to facilitate tangles and knotting or the neglect method in which the hair is not combed, brushed, or cut, becoming tangled and twisted as it grows long. Manicuring and perming techniques may be used to create the starting point for dreadlocks.

Telogen hairs are the hairs shed as part of normal hair cycling. The average person is estimated to lose 50 telogen hairs per day.1 With dreadlocks, the hairs are entangled distally, so when telogen hairs are released from scalp follicles, the shed hairs remain part of the locks. These “club” hairs have a bulbous white tip situated at the proximal end of the hair shaft (Figure 2) and should not be mistaken for the eggs of Pediculus humanus var capitis, hence the designation pseudonits.2 Hair casts, keratinous material surrounding the hair shafts when there is infundibular or perifollicular hyperkeratosis, also may resemble nits.3 Hair cast pseudonits can be distinguished from true nits by one’s ability to slide the hair casts freely along the hair shaft, whereas lice ova are cemented to the hair shaft and fixed in place.

Figure 2. “Club” hairs with a bulbous white tip situated at the

proximal end of the hair shaft (“pseudonits”).

The Diagnosis: “Pseudonits”

Dreadlocks are matted hairs formed into thick ropelike strands (Figure 1). As a chosen hairstyle dreadlocks are worn by individuals of many different ethnic groups but are most commonly associated with members of the Rastafarian movement, or Rastas. Various techniques are used to form dreadlocks including backcombing (also known as teasing) in which the hair is combed toward the scalp to facilitate tangles and knotting or the neglect method in which the hair is not combed, brushed, or cut, becoming tangled and twisted as it grows long. Manicuring and perming techniques may be used to create the starting point for dreadlocks.

Telogen hairs are the hairs shed as part of normal hair cycling. The average person is estimated to lose 50 telogen hairs per day.1 With dreadlocks, the hairs are entangled distally, so when telogen hairs are released from scalp follicles, the shed hairs remain part of the locks. These “club” hairs have a bulbous white tip situated at the proximal end of the hair shaft (Figure 2) and should not be mistaken for the eggs of Pediculus humanus var capitis, hence the designation pseudonits.2 Hair casts, keratinous material surrounding the hair shafts when there is infundibular or perifollicular hyperkeratosis, also may resemble nits.3 Hair cast pseudonits can be distinguished from true nits by one’s ability to slide the hair casts freely along the hair shaft, whereas lice ova are cemented to the hair shaft and fixed in place.

Figure 2. “Club” hairs with a bulbous white tip situated at the

proximal end of the hair shaft (“pseudonits”).

1. Sperling LC. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. New York, NY: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 2003.

2. Salih S, Bowling JC. Pseudonits in dreadlocked hair: A louse-y case of nits. Dermatology. 2006;213:245.

3. Lam M, Crutchfield CE 3rd, Lewis EJ. Hair casts: a case of pseudonits. Cutis. 1997;60:251-252.

1. Sperling LC. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. New York, NY: The Parthenon Publishing Group; 2003.

2. Salih S, Bowling JC. Pseudonits in dreadlocked hair: A louse-y case of nits. Dermatology. 2006;213:245.

3. Lam M, Crutchfield CE 3rd, Lewis EJ. Hair casts: a case of pseudonits. Cutis. 1997;60:251-252.

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to our dermatology office with dreadlocks that were unrelated to the reason for her visit. She had mild scalp pruritus. Close inspection of the hair and scalp was performed.

Onychomycosis Treatment in the United States

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophyte molds, and yeasts, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common causative organism.1-3 Onychomycosis affects approximately 2% to 26% of different populations worldwide. It represents 20% to 50% of onychopathies and approximately 30% of fungal cutaneous infections.4-9 Less than 30% of infected persons seek medical advice or treatment even in developed areas of the world.10 Onychomycosis may be a source of more widespread fungal skin infections or give rise to complications such as cellulitis. Chronic, long-lasting infection may result in nail dystrophy and can lead to pain, absence from work, and decreased quality of life.1,11 Because the dermatophyte can contaminate communal bathing facilities and spread to others,12 it is important to effectively target and treat patients with onychomycosis, thus reducing the rate of related morbidities.1,9

The primary aim of onychomycosis treatment is to cure the infection and prevent relapse. Both topical and oral agents are available for the treatment of fungal nail infections. Generally, systemic therapy for onychomycosis is more successful than topical treatment, likely due to poor penetration of topical medications into the nail plate.1,2,9 However, newer topical drugs have shown promising results in treating some types of onychomycosis.13 In its guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis, the British Association of Dermatologists recommends use of topical treatment under the following conditions: (1) when there is not extensive involvement of the nail plate (eg, candidal paronychia, superficial white onychomycosis, early stages of distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis), (2) when systemic therapy is contraindicated, or (3) in combination with systemic therapy.1 Although there are multiple treatments for fungal nail infections, there are limited reports on the ways in which physicians actually use these treatments or the frequency with which they prescribe them.

This study provides a representative portrayal of onychomycosis visits in the US outpatient setting using a large nationally sampled survey. In particular, we aimed to assess the number of visits related to onychomycosis, the demographics of patients, and the treatments being prescribed for onychomycosis.

Methods

Study Design

Data from January 1, 1993, to December 31, 2010, were collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an ongoing survey of nonfederal employed US office-based physicians who are primarily engaged in direct patient care. The NAMCS has been conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics every year since 1989 to estimate the utilization of ambulatory care services in the United States. Since 1989 including 1993 to 2010, the NAMCS sampled approximately 30,000 visits per year. For each visit sampled, a 1-page patient log including demographic data, physicians’ diagnoses, services provided, and medications was completed. In the NAMCS survey, visits were divided into 2 groups: (1) visits from established patients that have been seen in that office before for any reason, and (2) visits for new (ie, first-time) patients. The current study included all visits in which fungal nail infection (code 110.1 according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]) was listed as 1 of 3 possible diagnoses.

Statistical Analysis

Sampling weights were applied to data to produce estimates for the total US outpatient setting.14 Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2, and SAS survey analysis procedures were used to account for the clustered sampling of the survey. The total numbers of visits for which onychomycosis was 1 of 3 possible diagnoses and for which it was the sole diagnosis were reported. Visit rates per population by demographic characteristics (ie, patient sex, age, race, and ethnicity) were calculated. Population estimates were based on the 2001 NAMCS Public Micro-Data File Documentation records of the US census estimates for noninstitutionalized civilian persons.15 Trends in proportion of visits linked with an onychomycosis diagnosis over time were evaluated using the SAS SURVEYREG procedure. Types of physicians who attended to these visits as well as leading comorbidities that had been diagnosed and documented in the medical record were characterized. Onychomycosis-related medications prescribed at these visits were reported and prescribing trends over time were evaluated. Differences in the treatment prescribed according to the type of visit (ie, first-time or return visit); physician specialty; and patients’ gender, race, and health conditions (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus) were examined. To exclude the possibility that fluconazole and other broad-spectrum antifungals were being used for secondary diagnoses, we determined the number of visits that had an additional diagnosis of either candidiasis (ICD-9 codes 112.0–112.9) or “other specified erythematous conditions” (ICD-9 code 695.89).

Results

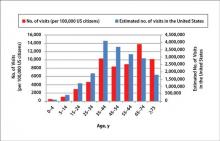

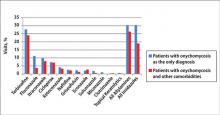

During the 18-year study period, 636 visits with a diagnosis of onychomycosis were recorded in the NAMCS database. This unweighted number of visits corresponded with approximately 19,350,000 visits (an average of 1,075,000 visits per year) to physicians’ offices with a diagnosis of onychomycosis in the United States during this period. Among these visits, there were an estimated 4,250,000 visits with fungal nail infection as the only diagnosis (no other comorbidities recorded). The recorded visits included more female (57.6%) than male (42.4%) patients, and 85% of patients were white (Table). Patients aged 35 to 44 years accounted for the largest number of visits; however, the estimated rate of onychomycosis visits per 100,000 US citizens was highest among those aged 65 to 74 years (Figure 1).

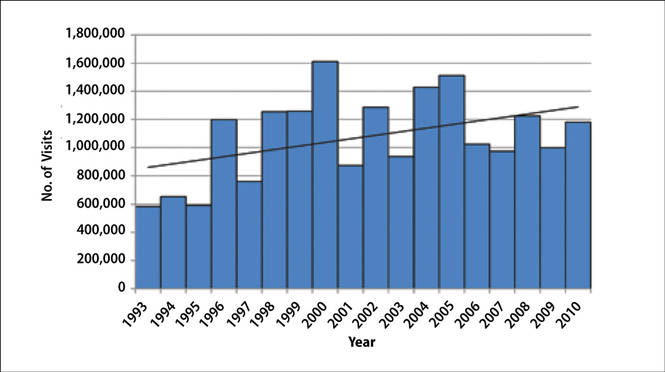

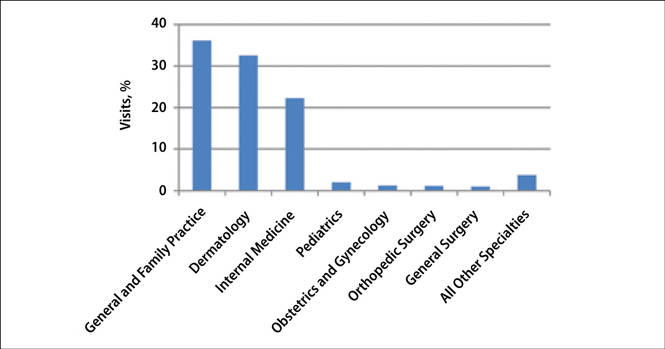

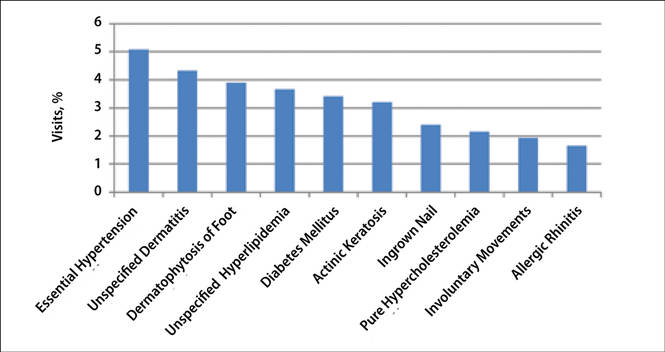

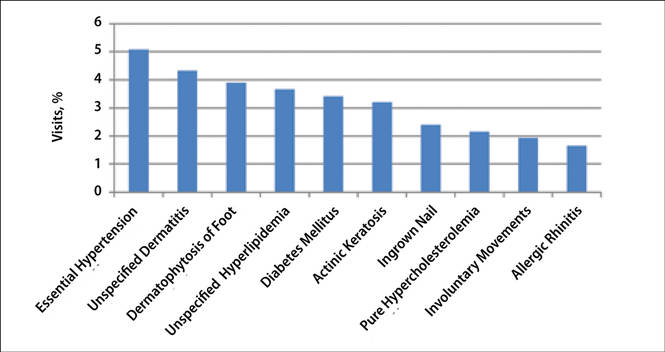

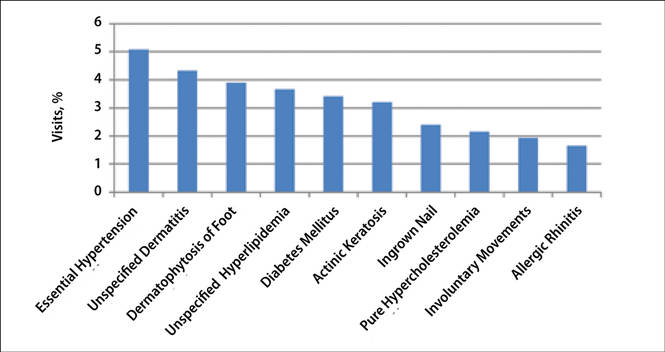

The number of US outpatient visits with a recorded diagnosis of onychomycosis increased from 1993 to 2010 (Figure 2); however, there was no change in the ratio of onychomycosis visits to the total number of recorded visits in NAMCS database during the study period (P=.9). A combined total of 91% of onychomycosis visits were to general and family practitioners, dermatologists, or internal medicine practitioners (Figure 3). Although cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus accounted for a large proportion of comorbidities, conditions affecting the feet (eg, tinea pedis, ingrown nails) also were among the most common comorbidities (Figure 4).

|

In both topical and systemic form, terbinafine was the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent, followed by systemic fluconazole, systemic itraconazole, and topical ciclopirox (Figure 5). Over the 18-year study period, there was an increasing trend in the frequency of terbinafine prescription (regression coefficient [r]=0.01319; P=.004); a decreasing trend for fluconazole (r=-0.0053851; P=.04), itraconazole (r=-0.0113988; P<.001), griseofulvin (r=-0.0073942; P<.001), and econazole prescription (r=-0.0032405; P=.01); and no significant trend for ketoconazole (r=-0.0034553; P=.1), naftifine (r=-0.0029067; P=.06), sulconazole (r=-0.0001619; P=.8), ciclopirox (r=0.0032684; P=.1), and miconazole prescription (r=0.0002074; P=.5).

Eighty-six percent of visits were for established patients who had been seen in the related office with any diagnosis before the recorded visit and 14% of visits were for new (first-time) patients. Fluconazole was the most frequently used antifungal drug for new patients, while terbinafine was the most frequently used in other visits. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug by general and family practitioners, dermatologists, internal medicine practitioners, and all other specialties not listed.

Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug in both genders and in white and black patients. Itraconazole was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for Hispanic patients and those of other ethnicities not listed. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for patients with diabetes and obesity (ie, body mass index ≥30). In 19,330,000 of 19,350,000 total estimated visits included in this study, onychomycosis was the only diagnosis with a potential indication for an antifungal drug therapy, ruling out the possibility that fluconazole or other drugs were used for patients who also had candidiasis or “other specified erythematous conditions.”

Discussion

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails that is more prevalent in older age groups, with equal prevalence in both genders and a higher prevalence in males. The NAMCS data showed higher rates of onychomycosis visits among older age groups, which is in agreement with results from prior studies.16,17 In the current study, we observed a higher prevalence of onychomycosis visits among females as well as white and Hispanic patients. These results may be due to a higher prevalence of onychomycosis in these populations or simply a result of difference in socioeconomic level or importance of aesthetics. Although there are limited data regarding the prevalence of onychomycosis among different races and ethnicities in the United States, a high incidence of onychomycosis has been reported in Mexico.18

Repeated trauma to the great toenail from ill-fitting shoes is a predisposing factor for onychomycosis.16 In the current study, ingrown nails were among the most common comorbidities found in onychomycosis patients. Although nail dystrophy caused by onychomycosis may lead to ingrown nails, it also is possible that both conditions may be caused by trauma.

Patients with immunodeficiencies (eg, diabetes) may be predisposed to onychomycosis as well as its associated complications and morbidities (eg, cellulitis).16,19 Diabetes affects 4% to 22% of patients with onychomycosis in different populations, including Denmark, Mexico, and India.18,20,21 In our study, diabetes was among the most common recorded comorbidities reported during onychomycosis visits, with a prevalence of 3.4%. It is likely that many more visits involved patients with diabetes that had not been diagnosed or reported. With the increased risk for complications with diabetes, it is important for physicians to treat these patients when they have a nail infection.

The available systemic therapies for treatment of onychomycosis include griseofulvin, allylamines, and imidazoles. Comparison of griseofulvin with newer systemic antifungal agents such as terbinafine and itraconazole suggests that griseofulvin has lower efficacy and therefore is not a first-line treatment of onychomycosis.1 Terbinafine is the most active of the currently available antidermatophyte drugs both in vitro and in vivo, with synergistic effects with imidazoles and ciclopirox.1,22-27 A combination of topical and systemic therapies may improve cure rates of onychomycosis or possibly shorten the duration of therapy with the systemic agent.1,2 Treatment strategies can vary according to the specialty of the treating physician, with general practitioners often preferring monotherapies and dermatologists preferring combination therapies.28 In Europe, the most commonly prescribed medication for onychomycosis was topical amorolfine followed by systemic terbinafine and itraconazole.28 In the current study, we could not separate data for topical versus systemic terbinafine because the NAMCS uses similar names for reporting the drug; however, the rates of prescription for allylamines and imidazoles were nearly equal (Figure 5), with terbinafine showing an increased use over time as opposed to a decreased use of imidazoles. Although fluconazole is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of onychomycosis, oral fluconazole was the second most common treatment prescribed in our study. Griseofulvin, which is not considered as a drug of choice in onychomycosis,1 was prescribed in a small fraction of the visits, with a decreasing trend of usage over time.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the NAMCS data revealed that the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States is in accordance with recommendations in current guidelines. An encouraging finding was the notable downward trend in use of griseofulvin, suggesting that health care providers are changing practice to meet standard of care. Increased efforts must be made to uniformly modify practices in compliance with evidence-based recommendations and to minimize unnecessary risk and cost associated with use of drugs with lower efficacy.

1. Roberts DT, Taylor WD, Boyle J; British Association of Dermatologists. Guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:402-410.

2. Seebacher C, Brasch J, Abeck D, et al. Onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2007;50:321-327.

3. Summerbell RC, Kane J, Krajden S. Onychomycosis, tinea pedis and tinea manuum caused by non-dermatophytic filamentous fungi. Mycoses. 1989;32:609-619.

4. Murray SC, Dawber RP. Onychomycosis of toenails: orthopaedic and podiatric considerations. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:105-112.

5. Achten G, Wanet-Rouard J. Onychomycoses in the laboratory. Mykosen Suppl. 1978;1:125-127.

6. Haneke E, Roseeuw D. The scope of onychomycosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(suppl 2):7-12.

7. Haneke E. Fungal infections of the nail. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:41-53.

8. Karmakar S, Kalla G, Joshi KR, et al. Dermatophytoses in a desert district of Western Rajasthan. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:280-283.

9. Drake LA. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: onychomycosis. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:116-121.

10. Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(suppl 39):23-27.

11. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5 pt 1):702-704.

12. Detandt M, Nolard N. Fungal contamination of the floors of swimming pools, particularly subtropical swimming paradises. Mycoses. 1995;38:509-513.

13. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

14. Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Bradham DD. Office-based physician services provided by dermatologists in the United States in 1990. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:93-97.

15. 2001 NAMCS Micro-Data File Documentation. http://www.nber.org/namcs/docs/namcs2001.pdf. National Bureau of Economic Research Web site. Accessed April 27, 2015.

16. Williams HC. The epidemiology of onychomycosis in Britain. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:101-109.

17. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

18. Arenas R, Bonifaz A, Padilla MC, et al. Onychomycosis. a Mexican survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:611-614.

19. Faergemann J, Baran R. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):1-4.

20. Sarma S, Capoor MR, Deb M, et al. Epidemiologic and clinicomycologic profile of onychomycosis from north India. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:584-587.

21. Svejgaard EL, Nilsson J. Onychomycosis in Denmark: prevalence of fungal nail infection in general practice. Mycoses. 2004;47:131-135.

22. Santos DA, Hamdan JS. In vitro antifungal oral drug and drug-combination activity against onychomycosis causative dermatophytes. Med Mycol. 2006;44:357-362.

23. Gupta AK, Kohli Y. In vitro susceptibility testing of ciclopirox, terbinafine, ketoconazole and itraconazole against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, and in vitro evaluation of combination antifungal activity. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:296-305.

24. Gupta AK, Lynch LE. Management of onychomycosis: examining the role of monotherapy and dual, triple, or quadruple therapies. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 1):5-9.

25. Harman S, Ashbee HR, Evans EG. Testing of antifungal combinations against yeasts and dermatophytes. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:104-107.

26. Spader TB, Venturini TP, Rossato L, et al. Synergisms of voriconazole or itraconazole combined with other antifungal agents against Fusarium spp. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2013;30:200-204.

27. Biancalana FS, Lyra L, Moretti ML, et al. Susceptibility testing of terbinafine alone and in combination with amphotericin B, itraconazole, or voriconazole against conidia and hyphae of dematiaceous molds. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:378-385.

28. Effendy I, Lecha M, Feuilhade de CM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical classification of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 1):8-12.

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophyte molds, and yeasts, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common causative organism.1-3 Onychomycosis affects approximately 2% to 26% of different populations worldwide. It represents 20% to 50% of onychopathies and approximately 30% of fungal cutaneous infections.4-9 Less than 30% of infected persons seek medical advice or treatment even in developed areas of the world.10 Onychomycosis may be a source of more widespread fungal skin infections or give rise to complications such as cellulitis. Chronic, long-lasting infection may result in nail dystrophy and can lead to pain, absence from work, and decreased quality of life.1,11 Because the dermatophyte can contaminate communal bathing facilities and spread to others,12 it is important to effectively target and treat patients with onychomycosis, thus reducing the rate of related morbidities.1,9

The primary aim of onychomycosis treatment is to cure the infection and prevent relapse. Both topical and oral agents are available for the treatment of fungal nail infections. Generally, systemic therapy for onychomycosis is more successful than topical treatment, likely due to poor penetration of topical medications into the nail plate.1,2,9 However, newer topical drugs have shown promising results in treating some types of onychomycosis.13 In its guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis, the British Association of Dermatologists recommends use of topical treatment under the following conditions: (1) when there is not extensive involvement of the nail plate (eg, candidal paronychia, superficial white onychomycosis, early stages of distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis), (2) when systemic therapy is contraindicated, or (3) in combination with systemic therapy.1 Although there are multiple treatments for fungal nail infections, there are limited reports on the ways in which physicians actually use these treatments or the frequency with which they prescribe them.

This study provides a representative portrayal of onychomycosis visits in the US outpatient setting using a large nationally sampled survey. In particular, we aimed to assess the number of visits related to onychomycosis, the demographics of patients, and the treatments being prescribed for onychomycosis.

Methods

Study Design

Data from January 1, 1993, to December 31, 2010, were collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an ongoing survey of nonfederal employed US office-based physicians who are primarily engaged in direct patient care. The NAMCS has been conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics every year since 1989 to estimate the utilization of ambulatory care services in the United States. Since 1989 including 1993 to 2010, the NAMCS sampled approximately 30,000 visits per year. For each visit sampled, a 1-page patient log including demographic data, physicians’ diagnoses, services provided, and medications was completed. In the NAMCS survey, visits were divided into 2 groups: (1) visits from established patients that have been seen in that office before for any reason, and (2) visits for new (ie, first-time) patients. The current study included all visits in which fungal nail infection (code 110.1 according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]) was listed as 1 of 3 possible diagnoses.

Statistical Analysis

Sampling weights were applied to data to produce estimates for the total US outpatient setting.14 Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2, and SAS survey analysis procedures were used to account for the clustered sampling of the survey. The total numbers of visits for which onychomycosis was 1 of 3 possible diagnoses and for which it was the sole diagnosis were reported. Visit rates per population by demographic characteristics (ie, patient sex, age, race, and ethnicity) were calculated. Population estimates were based on the 2001 NAMCS Public Micro-Data File Documentation records of the US census estimates for noninstitutionalized civilian persons.15 Trends in proportion of visits linked with an onychomycosis diagnosis over time were evaluated using the SAS SURVEYREG procedure. Types of physicians who attended to these visits as well as leading comorbidities that had been diagnosed and documented in the medical record were characterized. Onychomycosis-related medications prescribed at these visits were reported and prescribing trends over time were evaluated. Differences in the treatment prescribed according to the type of visit (ie, first-time or return visit); physician specialty; and patients’ gender, race, and health conditions (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus) were examined. To exclude the possibility that fluconazole and other broad-spectrum antifungals were being used for secondary diagnoses, we determined the number of visits that had an additional diagnosis of either candidiasis (ICD-9 codes 112.0–112.9) or “other specified erythematous conditions” (ICD-9 code 695.89).

Results

During the 18-year study period, 636 visits with a diagnosis of onychomycosis were recorded in the NAMCS database. This unweighted number of visits corresponded with approximately 19,350,000 visits (an average of 1,075,000 visits per year) to physicians’ offices with a diagnosis of onychomycosis in the United States during this period. Among these visits, there were an estimated 4,250,000 visits with fungal nail infection as the only diagnosis (no other comorbidities recorded). The recorded visits included more female (57.6%) than male (42.4%) patients, and 85% of patients were white (Table). Patients aged 35 to 44 years accounted for the largest number of visits; however, the estimated rate of onychomycosis visits per 100,000 US citizens was highest among those aged 65 to 74 years (Figure 1).

The number of US outpatient visits with a recorded diagnosis of onychomycosis increased from 1993 to 2010 (Figure 2); however, there was no change in the ratio of onychomycosis visits to the total number of recorded visits in NAMCS database during the study period (P=.9). A combined total of 91% of onychomycosis visits were to general and family practitioners, dermatologists, or internal medicine practitioners (Figure 3). Although cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus accounted for a large proportion of comorbidities, conditions affecting the feet (eg, tinea pedis, ingrown nails) also were among the most common comorbidities (Figure 4).

|

In both topical and systemic form, terbinafine was the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent, followed by systemic fluconazole, systemic itraconazole, and topical ciclopirox (Figure 5). Over the 18-year study period, there was an increasing trend in the frequency of terbinafine prescription (regression coefficient [r]=0.01319; P=.004); a decreasing trend for fluconazole (r=-0.0053851; P=.04), itraconazole (r=-0.0113988; P<.001), griseofulvin (r=-0.0073942; P<.001), and econazole prescription (r=-0.0032405; P=.01); and no significant trend for ketoconazole (r=-0.0034553; P=.1), naftifine (r=-0.0029067; P=.06), sulconazole (r=-0.0001619; P=.8), ciclopirox (r=0.0032684; P=.1), and miconazole prescription (r=0.0002074; P=.5).

Eighty-six percent of visits were for established patients who had been seen in the related office with any diagnosis before the recorded visit and 14% of visits were for new (first-time) patients. Fluconazole was the most frequently used antifungal drug for new patients, while terbinafine was the most frequently used in other visits. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug by general and family practitioners, dermatologists, internal medicine practitioners, and all other specialties not listed.

Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug in both genders and in white and black patients. Itraconazole was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for Hispanic patients and those of other ethnicities not listed. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for patients with diabetes and obesity (ie, body mass index ≥30). In 19,330,000 of 19,350,000 total estimated visits included in this study, onychomycosis was the only diagnosis with a potential indication for an antifungal drug therapy, ruling out the possibility that fluconazole or other drugs were used for patients who also had candidiasis or “other specified erythematous conditions.”

Discussion

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails that is more prevalent in older age groups, with equal prevalence in both genders and a higher prevalence in males. The NAMCS data showed higher rates of onychomycosis visits among older age groups, which is in agreement with results from prior studies.16,17 In the current study, we observed a higher prevalence of onychomycosis visits among females as well as white and Hispanic patients. These results may be due to a higher prevalence of onychomycosis in these populations or simply a result of difference in socioeconomic level or importance of aesthetics. Although there are limited data regarding the prevalence of onychomycosis among different races and ethnicities in the United States, a high incidence of onychomycosis has been reported in Mexico.18

Repeated trauma to the great toenail from ill-fitting shoes is a predisposing factor for onychomycosis.16 In the current study, ingrown nails were among the most common comorbidities found in onychomycosis patients. Although nail dystrophy caused by onychomycosis may lead to ingrown nails, it also is possible that both conditions may be caused by trauma.

Patients with immunodeficiencies (eg, diabetes) may be predisposed to onychomycosis as well as its associated complications and morbidities (eg, cellulitis).16,19 Diabetes affects 4% to 22% of patients with onychomycosis in different populations, including Denmark, Mexico, and India.18,20,21 In our study, diabetes was among the most common recorded comorbidities reported during onychomycosis visits, with a prevalence of 3.4%. It is likely that many more visits involved patients with diabetes that had not been diagnosed or reported. With the increased risk for complications with diabetes, it is important for physicians to treat these patients when they have a nail infection.

The available systemic therapies for treatment of onychomycosis include griseofulvin, allylamines, and imidazoles. Comparison of griseofulvin with newer systemic antifungal agents such as terbinafine and itraconazole suggests that griseofulvin has lower efficacy and therefore is not a first-line treatment of onychomycosis.1 Terbinafine is the most active of the currently available antidermatophyte drugs both in vitro and in vivo, with synergistic effects with imidazoles and ciclopirox.1,22-27 A combination of topical and systemic therapies may improve cure rates of onychomycosis or possibly shorten the duration of therapy with the systemic agent.1,2 Treatment strategies can vary according to the specialty of the treating physician, with general practitioners often preferring monotherapies and dermatologists preferring combination therapies.28 In Europe, the most commonly prescribed medication for onychomycosis was topical amorolfine followed by systemic terbinafine and itraconazole.28 In the current study, we could not separate data for topical versus systemic terbinafine because the NAMCS uses similar names for reporting the drug; however, the rates of prescription for allylamines and imidazoles were nearly equal (Figure 5), with terbinafine showing an increased use over time as opposed to a decreased use of imidazoles. Although fluconazole is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of onychomycosis, oral fluconazole was the second most common treatment prescribed in our study. Griseofulvin, which is not considered as a drug of choice in onychomycosis,1 was prescribed in a small fraction of the visits, with a decreasing trend of usage over time.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the NAMCS data revealed that the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States is in accordance with recommendations in current guidelines. An encouraging finding was the notable downward trend in use of griseofulvin, suggesting that health care providers are changing practice to meet standard of care. Increased efforts must be made to uniformly modify practices in compliance with evidence-based recommendations and to minimize unnecessary risk and cost associated with use of drugs with lower efficacy.

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophyte molds, and yeasts, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common causative organism.1-3 Onychomycosis affects approximately 2% to 26% of different populations worldwide. It represents 20% to 50% of onychopathies and approximately 30% of fungal cutaneous infections.4-9 Less than 30% of infected persons seek medical advice or treatment even in developed areas of the world.10 Onychomycosis may be a source of more widespread fungal skin infections or give rise to complications such as cellulitis. Chronic, long-lasting infection may result in nail dystrophy and can lead to pain, absence from work, and decreased quality of life.1,11 Because the dermatophyte can contaminate communal bathing facilities and spread to others,12 it is important to effectively target and treat patients with onychomycosis, thus reducing the rate of related morbidities.1,9

The primary aim of onychomycosis treatment is to cure the infection and prevent relapse. Both topical and oral agents are available for the treatment of fungal nail infections. Generally, systemic therapy for onychomycosis is more successful than topical treatment, likely due to poor penetration of topical medications into the nail plate.1,2,9 However, newer topical drugs have shown promising results in treating some types of onychomycosis.13 In its guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis, the British Association of Dermatologists recommends use of topical treatment under the following conditions: (1) when there is not extensive involvement of the nail plate (eg, candidal paronychia, superficial white onychomycosis, early stages of distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis), (2) when systemic therapy is contraindicated, or (3) in combination with systemic therapy.1 Although there are multiple treatments for fungal nail infections, there are limited reports on the ways in which physicians actually use these treatments or the frequency with which they prescribe them.

This study provides a representative portrayal of onychomycosis visits in the US outpatient setting using a large nationally sampled survey. In particular, we aimed to assess the number of visits related to onychomycosis, the demographics of patients, and the treatments being prescribed for onychomycosis.

Methods

Study Design

Data from January 1, 1993, to December 31, 2010, were collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an ongoing survey of nonfederal employed US office-based physicians who are primarily engaged in direct patient care. The NAMCS has been conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics every year since 1989 to estimate the utilization of ambulatory care services in the United States. Since 1989 including 1993 to 2010, the NAMCS sampled approximately 30,000 visits per year. For each visit sampled, a 1-page patient log including demographic data, physicians’ diagnoses, services provided, and medications was completed. In the NAMCS survey, visits were divided into 2 groups: (1) visits from established patients that have been seen in that office before for any reason, and (2) visits for new (ie, first-time) patients. The current study included all visits in which fungal nail infection (code 110.1 according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]) was listed as 1 of 3 possible diagnoses.

Statistical Analysis

Sampling weights were applied to data to produce estimates for the total US outpatient setting.14 Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2, and SAS survey analysis procedures were used to account for the clustered sampling of the survey. The total numbers of visits for which onychomycosis was 1 of 3 possible diagnoses and for which it was the sole diagnosis were reported. Visit rates per population by demographic characteristics (ie, patient sex, age, race, and ethnicity) were calculated. Population estimates were based on the 2001 NAMCS Public Micro-Data File Documentation records of the US census estimates for noninstitutionalized civilian persons.15 Trends in proportion of visits linked with an onychomycosis diagnosis over time were evaluated using the SAS SURVEYREG procedure. Types of physicians who attended to these visits as well as leading comorbidities that had been diagnosed and documented in the medical record were characterized. Onychomycosis-related medications prescribed at these visits were reported and prescribing trends over time were evaluated. Differences in the treatment prescribed according to the type of visit (ie, first-time or return visit); physician specialty; and patients’ gender, race, and health conditions (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus) were examined. To exclude the possibility that fluconazole and other broad-spectrum antifungals were being used for secondary diagnoses, we determined the number of visits that had an additional diagnosis of either candidiasis (ICD-9 codes 112.0–112.9) or “other specified erythematous conditions” (ICD-9 code 695.89).

Results

During the 18-year study period, 636 visits with a diagnosis of onychomycosis were recorded in the NAMCS database. This unweighted number of visits corresponded with approximately 19,350,000 visits (an average of 1,075,000 visits per year) to physicians’ offices with a diagnosis of onychomycosis in the United States during this period. Among these visits, there were an estimated 4,250,000 visits with fungal nail infection as the only diagnosis (no other comorbidities recorded). The recorded visits included more female (57.6%) than male (42.4%) patients, and 85% of patients were white (Table). Patients aged 35 to 44 years accounted for the largest number of visits; however, the estimated rate of onychomycosis visits per 100,000 US citizens was highest among those aged 65 to 74 years (Figure 1).

The number of US outpatient visits with a recorded diagnosis of onychomycosis increased from 1993 to 2010 (Figure 2); however, there was no change in the ratio of onychomycosis visits to the total number of recorded visits in NAMCS database during the study period (P=.9). A combined total of 91% of onychomycosis visits were to general and family practitioners, dermatologists, or internal medicine practitioners (Figure 3). Although cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus accounted for a large proportion of comorbidities, conditions affecting the feet (eg, tinea pedis, ingrown nails) also were among the most common comorbidities (Figure 4).

|

In both topical and systemic form, terbinafine was the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent, followed by systemic fluconazole, systemic itraconazole, and topical ciclopirox (Figure 5). Over the 18-year study period, there was an increasing trend in the frequency of terbinafine prescription (regression coefficient [r]=0.01319; P=.004); a decreasing trend for fluconazole (r=-0.0053851; P=.04), itraconazole (r=-0.0113988; P<.001), griseofulvin (r=-0.0073942; P<.001), and econazole prescription (r=-0.0032405; P=.01); and no significant trend for ketoconazole (r=-0.0034553; P=.1), naftifine (r=-0.0029067; P=.06), sulconazole (r=-0.0001619; P=.8), ciclopirox (r=0.0032684; P=.1), and miconazole prescription (r=0.0002074; P=.5).

Eighty-six percent of visits were for established patients who had been seen in the related office with any diagnosis before the recorded visit and 14% of visits were for new (first-time) patients. Fluconazole was the most frequently used antifungal drug for new patients, while terbinafine was the most frequently used in other visits. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug by general and family practitioners, dermatologists, internal medicine practitioners, and all other specialties not listed.

Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug in both genders and in white and black patients. Itraconazole was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for Hispanic patients and those of other ethnicities not listed. Terbinafine was the most frequently prescribed antifungal drug for patients with diabetes and obesity (ie, body mass index ≥30). In 19,330,000 of 19,350,000 total estimated visits included in this study, onychomycosis was the only diagnosis with a potential indication for an antifungal drug therapy, ruling out the possibility that fluconazole or other drugs were used for patients who also had candidiasis or “other specified erythematous conditions.”

Discussion

Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails that is more prevalent in older age groups, with equal prevalence in both genders and a higher prevalence in males. The NAMCS data showed higher rates of onychomycosis visits among older age groups, which is in agreement with results from prior studies.16,17 In the current study, we observed a higher prevalence of onychomycosis visits among females as well as white and Hispanic patients. These results may be due to a higher prevalence of onychomycosis in these populations or simply a result of difference in socioeconomic level or importance of aesthetics. Although there are limited data regarding the prevalence of onychomycosis among different races and ethnicities in the United States, a high incidence of onychomycosis has been reported in Mexico.18

Repeated trauma to the great toenail from ill-fitting shoes is a predisposing factor for onychomycosis.16 In the current study, ingrown nails were among the most common comorbidities found in onychomycosis patients. Although nail dystrophy caused by onychomycosis may lead to ingrown nails, it also is possible that both conditions may be caused by trauma.

Patients with immunodeficiencies (eg, diabetes) may be predisposed to onychomycosis as well as its associated complications and morbidities (eg, cellulitis).16,19 Diabetes affects 4% to 22% of patients with onychomycosis in different populations, including Denmark, Mexico, and India.18,20,21 In our study, diabetes was among the most common recorded comorbidities reported during onychomycosis visits, with a prevalence of 3.4%. It is likely that many more visits involved patients with diabetes that had not been diagnosed or reported. With the increased risk for complications with diabetes, it is important for physicians to treat these patients when they have a nail infection.

The available systemic therapies for treatment of onychomycosis include griseofulvin, allylamines, and imidazoles. Comparison of griseofulvin with newer systemic antifungal agents such as terbinafine and itraconazole suggests that griseofulvin has lower efficacy and therefore is not a first-line treatment of onychomycosis.1 Terbinafine is the most active of the currently available antidermatophyte drugs both in vitro and in vivo, with synergistic effects with imidazoles and ciclopirox.1,22-27 A combination of topical and systemic therapies may improve cure rates of onychomycosis or possibly shorten the duration of therapy with the systemic agent.1,2 Treatment strategies can vary according to the specialty of the treating physician, with general practitioners often preferring monotherapies and dermatologists preferring combination therapies.28 In Europe, the most commonly prescribed medication for onychomycosis was topical amorolfine followed by systemic terbinafine and itraconazole.28 In the current study, we could not separate data for topical versus systemic terbinafine because the NAMCS uses similar names for reporting the drug; however, the rates of prescription for allylamines and imidazoles were nearly equal (Figure 5), with terbinafine showing an increased use over time as opposed to a decreased use of imidazoles. Although fluconazole is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of onychomycosis, oral fluconazole was the second most common treatment prescribed in our study. Griseofulvin, which is not considered as a drug of choice in onychomycosis,1 was prescribed in a small fraction of the visits, with a decreasing trend of usage over time.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the NAMCS data revealed that the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States is in accordance with recommendations in current guidelines. An encouraging finding was the notable downward trend in use of griseofulvin, suggesting that health care providers are changing practice to meet standard of care. Increased efforts must be made to uniformly modify practices in compliance with evidence-based recommendations and to minimize unnecessary risk and cost associated with use of drugs with lower efficacy.

1. Roberts DT, Taylor WD, Boyle J; British Association of Dermatologists. Guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:402-410.

2. Seebacher C, Brasch J, Abeck D, et al. Onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2007;50:321-327.

3. Summerbell RC, Kane J, Krajden S. Onychomycosis, tinea pedis and tinea manuum caused by non-dermatophytic filamentous fungi. Mycoses. 1989;32:609-619.

4. Murray SC, Dawber RP. Onychomycosis of toenails: orthopaedic and podiatric considerations. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:105-112.

5. Achten G, Wanet-Rouard J. Onychomycoses in the laboratory. Mykosen Suppl. 1978;1:125-127.

6. Haneke E, Roseeuw D. The scope of onychomycosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(suppl 2):7-12.

7. Haneke E. Fungal infections of the nail. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:41-53.

8. Karmakar S, Kalla G, Joshi KR, et al. Dermatophytoses in a desert district of Western Rajasthan. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:280-283.

9. Drake LA. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: onychomycosis. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:116-121.

10. Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(suppl 39):23-27.

11. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5 pt 1):702-704.

12. Detandt M, Nolard N. Fungal contamination of the floors of swimming pools, particularly subtropical swimming paradises. Mycoses. 1995;38:509-513.

13. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

14. Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Bradham DD. Office-based physician services provided by dermatologists in the United States in 1990. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:93-97.

15. 2001 NAMCS Micro-Data File Documentation. http://www.nber.org/namcs/docs/namcs2001.pdf. National Bureau of Economic Research Web site. Accessed April 27, 2015.

16. Williams HC. The epidemiology of onychomycosis in Britain. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:101-109.

17. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

18. Arenas R, Bonifaz A, Padilla MC, et al. Onychomycosis. a Mexican survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:611-614.

19. Faergemann J, Baran R. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):1-4.

20. Sarma S, Capoor MR, Deb M, et al. Epidemiologic and clinicomycologic profile of onychomycosis from north India. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:584-587.

21. Svejgaard EL, Nilsson J. Onychomycosis in Denmark: prevalence of fungal nail infection in general practice. Mycoses. 2004;47:131-135.

22. Santos DA, Hamdan JS. In vitro antifungal oral drug and drug-combination activity against onychomycosis causative dermatophytes. Med Mycol. 2006;44:357-362.

23. Gupta AK, Kohli Y. In vitro susceptibility testing of ciclopirox, terbinafine, ketoconazole and itraconazole against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, and in vitro evaluation of combination antifungal activity. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:296-305.

24. Gupta AK, Lynch LE. Management of onychomycosis: examining the role of monotherapy and dual, triple, or quadruple therapies. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 1):5-9.

25. Harman S, Ashbee HR, Evans EG. Testing of antifungal combinations against yeasts and dermatophytes. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:104-107.

26. Spader TB, Venturini TP, Rossato L, et al. Synergisms of voriconazole or itraconazole combined with other antifungal agents against Fusarium spp. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2013;30:200-204.

27. Biancalana FS, Lyra L, Moretti ML, et al. Susceptibility testing of terbinafine alone and in combination with amphotericin B, itraconazole, or voriconazole against conidia and hyphae of dematiaceous molds. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:378-385.

28. Effendy I, Lecha M, Feuilhade de CM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical classification of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 1):8-12.

1. Roberts DT, Taylor WD, Boyle J; British Association of Dermatologists. Guidelines for treatment of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:402-410.

2. Seebacher C, Brasch J, Abeck D, et al. Onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2007;50:321-327.

3. Summerbell RC, Kane J, Krajden S. Onychomycosis, tinea pedis and tinea manuum caused by non-dermatophytic filamentous fungi. Mycoses. 1989;32:609-619.

4. Murray SC, Dawber RP. Onychomycosis of toenails: orthopaedic and podiatric considerations. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:105-112.

5. Achten G, Wanet-Rouard J. Onychomycoses in the laboratory. Mykosen Suppl. 1978;1:125-127.

6. Haneke E, Roseeuw D. The scope of onychomycosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38(suppl 2):7-12.

7. Haneke E. Fungal infections of the nail. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:41-53.

8. Karmakar S, Kalla G, Joshi KR, et al. Dermatophytoses in a desert district of Western Rajasthan. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:280-283.

9. Drake LA. Guidelines of care for superficial mycotic infections of the skin: onychomycosis. Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:116-121.

10. Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(suppl 39):23-27.

11. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5 pt 1):702-704.

12. Detandt M, Nolard N. Fungal contamination of the floors of swimming pools, particularly subtropical swimming paradises. Mycoses. 1995;38:509-513.

13. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

14. Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Bradham DD. Office-based physician services provided by dermatologists in the United States in 1990. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:93-97.

15. 2001 NAMCS Micro-Data File Documentation. http://www.nber.org/namcs/docs/namcs2001.pdf. National Bureau of Economic Research Web site. Accessed April 27, 2015.

16. Williams HC. The epidemiology of onychomycosis in Britain. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:101-109.

17. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

18. Arenas R, Bonifaz A, Padilla MC, et al. Onychomycosis. a Mexican survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:611-614.

19. Faergemann J, Baran R. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 65):1-4.

20. Sarma S, Capoor MR, Deb M, et al. Epidemiologic and clinicomycologic profile of onychomycosis from north India. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:584-587.

21. Svejgaard EL, Nilsson J. Onychomycosis in Denmark: prevalence of fungal nail infection in general practice. Mycoses. 2004;47:131-135.

22. Santos DA, Hamdan JS. In vitro antifungal oral drug and drug-combination activity against onychomycosis causative dermatophytes. Med Mycol. 2006;44:357-362.

23. Gupta AK, Kohli Y. In vitro susceptibility testing of ciclopirox, terbinafine, ketoconazole and itraconazole against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, and in vitro evaluation of combination antifungal activity. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:296-305.

24. Gupta AK, Lynch LE. Management of onychomycosis: examining the role of monotherapy and dual, triple, or quadruple therapies. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 1):5-9.

25. Harman S, Ashbee HR, Evans EG. Testing of antifungal combinations against yeasts and dermatophytes. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:104-107.

26. Spader TB, Venturini TP, Rossato L, et al. Synergisms of voriconazole or itraconazole combined with other antifungal agents against Fusarium spp. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2013;30:200-204.

27. Biancalana FS, Lyra L, Moretti ML, et al. Susceptibility testing of terbinafine alone and in combination with amphotericin B, itraconazole, or voriconazole against conidia and hyphae of dematiaceous molds. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:378-385.

28. Effendy I, Lecha M, Feuilhade de CM, et al. Epidemiology and clinical classification of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(suppl 1):8-12.

Practice Points

- Onychomycosis is a common progressive infection of the nails that may result in remarkable morbidity. Effective treatment may reduce the rate of transmission and related morbidities.

- Onychomycosis is most commonly found in patients older than 35 years.

- Terbinafine has been the most commonly prescribed antifungal agent for onychomycosis in the United States between 1993 and 2010, followed by systemic fluconazole, systemic itraconazole, and topical ciclopirox.

Combine topicals, orals for onychomycosis

MIAMI BEACH – Two new topical solutions approved in 2014 for the treatment of distal subungual onychomycosis don’t eliminate the need for oral treatment, but they do represent improvement in the options available to patients, according to Dr. Boni E. Elewski.

Oral treatments, including terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole are still of value – either alone or in combination with the new solutions or other agents – for this type of onychomycosis, which is “essentially a nail bed dermatophytosis,” she said at the South Beach Symposium.

Terbinafine has been used for 2 decades, and is probably the most commonly used treatment for onychomycosis. It is approved as a once-daily pill given for 90 days, and reportedly has a cure rate just under 40%, she said.

Itraconazole is approved as a 200-mg daily dose for 12 weeks, although most physicians use pulse dosing, prescribing 400 mg daily for a week, then for 1 week each month.

“I like this drug for my nondermatophyte patients … if you have something that you don’t think is a dermatophyte, or if they’ve failed terbinafine, this is an excellent option,” she said.

Fluconazole, her “personal favorite,” is used off label for onychomycosis, but has been shown to have good cure rates with once-weekly treatment, said Dr. Elewski of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“I’ll confess, I like this drug because I feel comfortable with it,” she said adding that she tells her patients to think about “Fungal Fridays” or “Toesdays” as a way to remember to take their weekly treatments.

The cure rates are quite good, she said, noting that because the nails grow so slowly, the pace of the treatment matches patient expectations. They don’t finish treatment and still have a “cruddy-looking” nail, she explained.

If any of these oral drugs are used, laboratory monitoring and periodic assessments are necessary, so treatment is a bit complicated. Adverse events remain a concern – particularly drug-drug interactions, drug eruption, cardiac issues (with itraconazole), and loss of taste (with terbinafine).

“So we do have to worry about some of these conditions, which is why having other treatments is so nice,” Dr. Elewski said.

Another reason it’s good to have more options is that no matter which drug you choose, it won’t cure everyone, she noted. Sometimes that’s because the condition is severe; patients with a dermatophyte abscess, those with very thick nails, and those with complete nail involvement associated with a nondermatophyte mold, for example, will have a poorer prognosis, regardless of which oral treatment given. Also, the condition is often complicated by concomitant disorders such as psoriasis. About 5% of patients with psoriasis have nail-only disease, and about a third of them also have onychomycosis. Others are misdiagnosed as having onychomycosis.

Alternatives that can be used alone or in combination with the oral therapies, include the two new topical solutions: efinaconazole and tavaborole, Dr. Elewski said.

Solutions are good, because you can apply them on, under, and around the nail. Both of the drugs have demonstrated effective penetration of the nail plate, allowing penetration to the nail bed where the infection exists, she noted.

The mycological cure rate with efinaconazole yields outcomes comparable to those with oral drugs.

“I think [the mycological cure] is actually the most important endpoint. Because when you want to get rid of the fungus, what do you do? You want to kill the fungus,” said Dr. Elewski, adding that mycological cure is the first sign a patient will go on to experience complete cure.

The complete cure rate is lower, but that appears to be a time-related factor. The nail takes a long time to grow, so the complete cure rate will lag behind the mycological cure rate, Dr. Elewski explained.

The other topical solution – tavaborole – is a new molecule that contains boron. Mycological cure rates in studies of the drug were in the mid-30% range, and it appears able to be used with nail polish without issues to the polish or the outcomes, she said.

In Dr. Elewski’s experience, these topicals work better than expected in clinical practice, based on the clinical trials. One patient who wasn’t eligible for the clinical trials because of a dermatophytosis, for example, was nearly clear within 5 months, and is now totally cured, she said.

“So these treatments are effective as monotherapy, but could be used as an adjunct with systemic therapy, and perhaps also in nondermatophyte cases of onychomycosis,” Dr. Elewski noted. “I think it would be a better option to pick one of these topical drugs than putting someone on a prolonged course of itraconazole if at all possible.” The safety issue would be more favorable with the topical antifungal solution, she said.

A treatment that should never be used is ketoconazole, she noted, explaining that although the drug was never approved specifically for onychomycosis, it was often prescribed for the treatment of tinea versicolor. Because of safety concerns, the FDA removed its indication for all cutaneous fungal infections in 2013.

Dr. Elewski is a consultant for Valeant Pharmaceuticals and a contracted researcher for Anacor Pharmaceuticals.

MIAMI BEACH – Two new topical solutions approved in 2014 for the treatment of distal subungual onychomycosis don’t eliminate the need for oral treatment, but they do represent improvement in the options available to patients, according to Dr. Boni E. Elewski.

Oral treatments, including terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole are still of value – either alone or in combination with the new solutions or other agents – for this type of onychomycosis, which is “essentially a nail bed dermatophytosis,” she said at the South Beach Symposium.

Terbinafine has been used for 2 decades, and is probably the most commonly used treatment for onychomycosis. It is approved as a once-daily pill given for 90 days, and reportedly has a cure rate just under 40%, she said.

Itraconazole is approved as a 200-mg daily dose for 12 weeks, although most physicians use pulse dosing, prescribing 400 mg daily for a week, then for 1 week each month.

“I like this drug for my nondermatophyte patients … if you have something that you don’t think is a dermatophyte, or if they’ve failed terbinafine, this is an excellent option,” she said.

Fluconazole, her “personal favorite,” is used off label for onychomycosis, but has been shown to have good cure rates with once-weekly treatment, said Dr. Elewski of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“I’ll confess, I like this drug because I feel comfortable with it,” she said adding that she tells her patients to think about “Fungal Fridays” or “Toesdays” as a way to remember to take their weekly treatments.

The cure rates are quite good, she said, noting that because the nails grow so slowly, the pace of the treatment matches patient expectations. They don’t finish treatment and still have a “cruddy-looking” nail, she explained.

If any of these oral drugs are used, laboratory monitoring and periodic assessments are necessary, so treatment is a bit complicated. Adverse events remain a concern – particularly drug-drug interactions, drug eruption, cardiac issues (with itraconazole), and loss of taste (with terbinafine).

“So we do have to worry about some of these conditions, which is why having other treatments is so nice,” Dr. Elewski said.

Another reason it’s good to have more options is that no matter which drug you choose, it won’t cure everyone, she noted. Sometimes that’s because the condition is severe; patients with a dermatophyte abscess, those with very thick nails, and those with complete nail involvement associated with a nondermatophyte mold, for example, will have a poorer prognosis, regardless of which oral treatment given. Also, the condition is often complicated by concomitant disorders such as psoriasis. About 5% of patients with psoriasis have nail-only disease, and about a third of them also have onychomycosis. Others are misdiagnosed as having onychomycosis.

Alternatives that can be used alone or in combination with the oral therapies, include the two new topical solutions: efinaconazole and tavaborole, Dr. Elewski said.

Solutions are good, because you can apply them on, under, and around the nail. Both of the drugs have demonstrated effective penetration of the nail plate, allowing penetration to the nail bed where the infection exists, she noted.

The mycological cure rate with efinaconazole yields outcomes comparable to those with oral drugs.

“I think [the mycological cure] is actually the most important endpoint. Because when you want to get rid of the fungus, what do you do? You want to kill the fungus,” said Dr. Elewski, adding that mycological cure is the first sign a patient will go on to experience complete cure.

The complete cure rate is lower, but that appears to be a time-related factor. The nail takes a long time to grow, so the complete cure rate will lag behind the mycological cure rate, Dr. Elewski explained.