User login

Evaluation of Gender as a Clinically Relevant Outcome Variable in the Treatment of Onychomycosis With Efinaconazole Topical Solution 10%

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disease in adults, representing up to 50% of all nail disorders, and is nearly always associated with tinea pedis.1,2 Moreover, toenail onychomycosis frequently involves several nails3 and can be more challenging to treat because of the slow growth rate of nails and the difficult delivery of antifungal agents to the nail bed.3,4

The most prevalent predisposing risk factor for developing onychomycosis is advanced age, with a reported prevalence of 18.2% in patients aged 60 to 79 years compared to 0.7% in patients younger than 19 years.2 Men are up to 3 times more likely to develop onychomycosis than women, though the reasons for this gender difference are less clear.2,5 It has been hypothesized that occupational factors may play a role,2 with increased use of occlusive footwear and more frequent nail injuries contributing to a higher incidence of onychomycosis in males.6

Differences in hormone levels associated with gender also may result in different capacities to inhibit the growth of dermatophytes.2 The risk for developing onychomycosis increases with age at a similar rate in both genders.7

Although onychomycosis is more common in men, the disease has been shown to have a greater impact on quality of life (QOL) in women. Studies have shown that onychomycosis was more likely to cause embarrassment in women than in men (83% vs 71%; N=258), and women with onychomycosis felt severely embarrassed more often than men (44% vs 26%; N=258).8,9 Additionally, one study (N=43,593) showed statistically significant differences associated with gender among onychomycosis patients who reported experiencing pain (33.7% of women vs 26.7% of men; P<.001), discomfort in walking (43.1% vs 36.4%; P<.001), and embarrassment (28.8% vs 25.1%; P<.001).10 Severe cases of onychomycosis even appear to have a negative impact on patients’ intimate relationships, and lower self-esteem has been reported in female patients due to unsightly and contagious-looking nail plates.11,12 Socks and stockings frequently may be damaged due to the constant friction from diseased nails that are sharp and dystrophic.13,14 In one study, treatment satisfaction was related to improvement in nail condition; however, males tended to be more satisfied with the improvement than females. Females were significantly less satisfied than males based on QOL scores for discomfort in wearing shoes (61.5 vs 86.3; P=.001), restrictions in shoe options (59.0 vs 82.8; P=.001), and the need to conceal toenails (73.3 vs 89.3; P<.01).15

Numerous studies have assessed the effectiveness of antifungal drugs in treating onychomycosis; however, there are limited data available on the impact of gender on outcome variables. Results from 2 identical 52-week, prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies of a total of 1655 participants (age range, 18–70 years) assessing the safety and efficacy of efinaconazole topical solution 10% in the treatment of onychomycosis were reported in 2013.16 Here, a gender subgroup analysis for male and female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis is presented.

Methods

Two 52-week, prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies were designed to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of efinaconazole topical solution 10% versus vehicle in 1655 participants aged 18 to 70 years with mild to moderate toenail onychomycosis. Participants who presented with 20% to 50% clinical involvement of the target toenail were randomized (3:1 ratio) to once-daily application of a blinded study drug on the toenails for 48 weeks, followed by a 4-week follow-up period.16

Efficacy Evaluation

The primary efficacy end point was complete cure, defined as 0% clinical involvement of target toenail and mycologic cure based on negative potassium hydroxide examination and negative fungal culture at week 52.16 Secondary and supportive efficacy end points included mycologic cure, treatment success (<10% clinical involvement of the target toenail), complete or almost complete cure (≤5% clinical involvement and mycologic cure), and change in QOL based on a self-administered QOL questionnaire. All secondary end points were assessed at week 52.16 All items in the QOL questionnaire were transferred to a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating better functioning.17

In both studies, treatment compliance was assessed through participant diaries that detailed all drug applications as well as the weight of returned product bottles. Participants were considered noncompliant if they missed more than 14 cumulative applications of the study drug in the 28 days leading up to the visit at week 48, if they missed more than 20% of the total number of expected study drug applications during the treatment period, and/or if they missed 28 or more consecutive applications of the study drug during the total treatment period.

Safety Evaluation

Safety assessments included monitoring and recording adverse events (AEs) until week 52.16

Results

The 2 studies included a total of 1275 (77.2%) male and 376 (22.8%) female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis (intention-to-treat population). Pooled results are provided in this analysis.

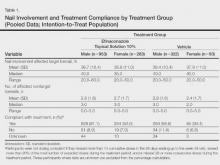

At baseline, the mean area of target toenail involvement among male and female participants in the efinaconazole treatment group was 36.7% and 35.6%, respectively, compared to 36.4% and 37.9%, respectively, in the vehicle group. The mean number of affected nontarget toenails was 2.8 and 2.7 among male and female participants, respectively, in the efinaconazole group compared to 2.9 and 2.4, respectively, in the vehicle group (Table 1).

Female participants tended to be somewhat more compliant with treatment than male participants at study end. At week 52, 93.0% and 93.4% of female participants in the efinaconazole and vehicle groups, respectively, were considered compliant with treatment compared to 91.1% and 88.6% of male participants, respectively (Table 1).

Primary Efficacy End Point (Observed Case)

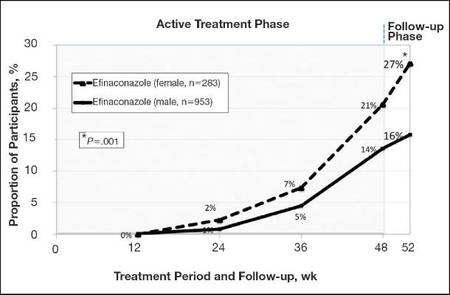

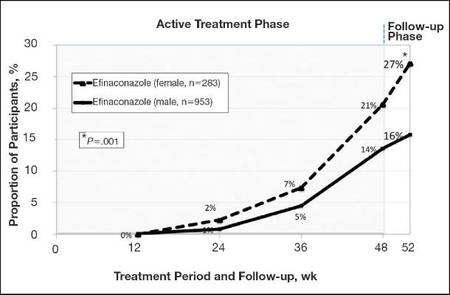

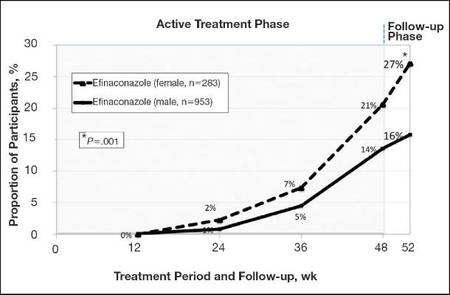

At week 52, 15.8% of male and 27.1% of female participants in the efinaconazole treatment group had a complete cure compared to 4.2% and 6.3%, respectively, of those in the vehicle group (both P<.001). Efinaconazole topical solution 10% was significantly more effective than vehicle from week 48 (P<.001 male and P=.004 female).

The differences in complete cure rates reported for male (15.8%) and female (27.1%) participants treated with efinaconazole topical solution 10% were significant at week 52 (P=.001)(Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Proportion of male and female participants treated with once-daily application of efinaconazole topical solution 10% who achieved complete cure from weeks 12 to 52 (observed case; intention-to-treat population; pooled data). |

|

| Figure 2. Treatment success (defined as ≤10% clinical involvement of the target toenail) at week 52. Comparison of results with efinaconazole topical solution 10% and vehicle (observed case; intention-to-treat population; pooled data). |

Secondary and Supportive Efficacy End Points (Observed Case)

At week 52, 53.7% of male participants and 64.8% of female participants in the efinaconazole group achieved mycologic cure compared to 14.8% and 22.5%, respectively, of those in the vehicle group (both P<.001). Mycologic cure in the efinaconazole group versus the vehicle group became statistically significant at week 12 in male participants (P=.002) and at week 24 in female participants (P<.001).

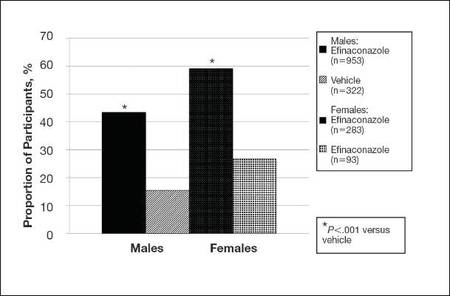

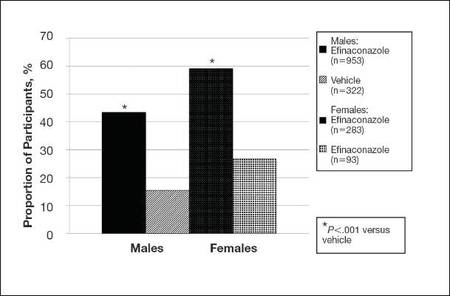

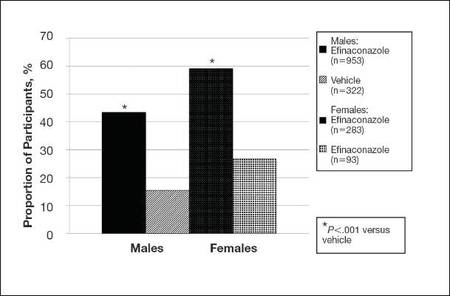

At week 52, more male and female participants in the efinaconazole group (24.9% and 36.8%, respectively) achieved complete or almost complete cure compared to those in the vehicle group (6.8% and 11.3%, respectively), and 43.5% and 59.1% of male and female participants, respectively, were considered treatment successes (≤10% clinical involvement of the target toenail) compared to 15.5% and 26.8%, respectively, in the vehicle group (all P<.001)(Figure 2).

Treatment satisfaction scores were higher among female participants. At week 52, the mean QOL assessment score among female participants in the efinaconazole group was 77.2 compared to 70.3 among male participants in the same group (43.0 and 41.2, respectively, in the vehicle group). All QOL assessment scores were lower (ie, worse) in female onychomycosis participants at baseline. Improvements in all QOL scores were much greater in female participants at week 52 (Table 2).

The total number of efinaconazole applications was similar among male and female participants (315.1 vs 316.7). The mean amount of efina- conazole applied was greater in male participants (50.4 g vs 45.6 g), and overall compliance rates, though similar, were slightly higher in females compared to males (efinaconazole only)(93.0% vs 91.1%).

Safety

Overall, AE rates for efinaconazole were similar to those reported for vehicle (65.3% vs 59.8%).16 Slightly more female participants reported 1 or more AE than males (71.3% vs 63.5%). Adverse events were generally mild (50.0% in females; 53.7% in males) or moderate (46.7% in females; 41.8% in males) in severity, were not related to the study drug (89.9% in females; 93.1% in males), and resolved without sequelae. The rate of discontinuation from AEs was low (2.8% in females; 2.5% in males).

Comment

Efinaconazole topical solution 10% was significantly more effective than vehicle in both male and female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis. It appears to be especially effective in female participants, with more than 27% of female participants achieving complete cure at week 52, and nearly 37% of female participants achieving complete or almost complete cure at week 52.

Mycologic cure is the only consistently defined efficacy parameter reported in toenail onychomycosis studies.18 It often is considered the main treatment goal, with complete cure occurring somewhat later as the nails grow out.19 Indeed, in this subgroup analysis the differences seen between the active and vehicle groups correlated well with the cure rates seen at week 52. Interestingly, significantly better mycologic cure rates (P=.002, active vs vehicle) were seen as early as week 12 in the male subgroup.

The current analysis suggests that male onychomycosis patients may be more difficult to treat, a finding noted by other investigators, though the reason is not clear.20 It is known that the prevalence of onychomycosis is higher in males,2,5 but data comparing cure rates by gender is lacking. It has been suggested that men more frequently undergo nail trauma and tend to seek help for more advanced disease.20 Treatment compliance also may be an issue. In our study, mean nail involvement was similar among male and female participants treated with efinaconazole (36.7% and 35.6%, respectively). Treatment compliance was higher among females compared to males (93.0% vs 91.1%), with the lowest compliance rates seen in males in the vehicle group (where complete cure rates also were the lowest). The amount of study drug used was greater in males, possibly due to larger toenails, though toenail surface area was not measured. Although there is no evidence to suggest that male toenails grow quicker, as many factors can impact nail growth, they tend to be thicker. Patients with thick toenails may be less likely to achieve complete cure.20 It also is possible that male toenails take longer to grow out fully, and they may require a longer treatment course. The 52-week duration of these studies may not have allowed for full regrowth of the nails, despite mycologic cure. Indeed, continued improvement in cure rates in onychomycosis patients with longer treatment courses have been noted by other investigators.21

The current analysis revealed much lower baseline QOL scores in female onychomycosis patients compared to male patients. Given that target nail involvement at baseline was similar across both groups, this finding may be indicative of greater concern about their condition among females, supporting other views that onychomycosis has a greater impact on QOL in female patients. Similar scores reported across genders at week 52 likely reflects the greater efficacy seen in females.

Conclusion

Based on this subgroup analysis, once-daily application of efinaconazole topical solution 10% may provide a useful option in the treatment of mild to moderate onychomycosis, particularly in female patients. The greater improvement in nail condition concomitantly among females translates to higher overall treatment satisfaction.

Acknowledgment—The author thanks Brian Bulley, MSc, of Inergy Limited, Lindfield, West Sussex, United Kingdom, for medical writing support. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America, LLC, funded Inergy’s activities pertaining to the manuscript.

1. Scher RK, Coppa LM. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of onychomycosis. Hosp Med. 1998;34:11-20.

2. Gupta AK, Jain HC, Lynde CW, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of onychomycosis in patients visiting physicians’ offices: a multicenter Canadian survey of 15,000 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:244-248.

3. Finch JJ, Warshaw EM. Toenail onychomycosis: current and future treatment options. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:31-46.

4. Kumar S, Kimball AB. New antifungal therapies for the treatment of onychomycosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:727-734.

5. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

6. Araujo AJG, Bastos OMP, Souza MAJ, et al. Occurrence of onychomycosis among patients attended in dermatology offices in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2003;78:299-308.

7. Pierard G. Onychomycosis and other superficial fungal infections of the foot in the elderly: a Pan-European Survey. Dermatology. 2001;202:220-224.

8. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5, pt 1):702-704.

9. Kowalczuk-Zieleniec E, Nowicki E, Majkowicz M. Onychomycosis changes quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(suppl 1):248.

10. Katsambas A, Abeck D, Haneke E, et al. The effects of foot disease on quality of life: results of the Achilles Project. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:191-195.

11. Salgo PL, Daniel CR, Gupta AK, et al. Onychomycosis disease management. Medical Crossfire: Debates, Peer Exchange and Insights in Medicine. 2003;4:1-17.

12. Elewski BE. The effect of toenail onychomycosis on patient quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:754-756.

13. Hay RJ. The future of onychomycosis therapy may involve a combination of approaches. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:3-8.

14. Whittam LR, Hay RJ. The impact of onychomycosis on quality of life. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:87-89.

15. Stier DM, Gause D, Joseph WS, et al. Patient satisfaction with oral versus nonoral therapeutic approaches in onychomycosis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:521-527.

16. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

17. Tosti A, Elewski BE. Treatment of onychomycosis with efinaconazole 10% topical solution and quality of life. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:25-30.

18. Werschler WP, Bondar G, Armstrong D. Assessing treatment outcomes in toenail onychomycosis clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:145-152.

19. Gupta AK. Treatment of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis in the United States: a pharmacoeconomic analysis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92:272-286.

20. Sigurgeirsson B. Prognostic factors for cure following treatment of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:679-684.

21. Epstein E. How often does oral treatment of toenail onychomycosis produce a disease-free nail? an analysis of published data. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1551-1554.

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disease in adults, representing up to 50% of all nail disorders, and is nearly always associated with tinea pedis.1,2 Moreover, toenail onychomycosis frequently involves several nails3 and can be more challenging to treat because of the slow growth rate of nails and the difficult delivery of antifungal agents to the nail bed.3,4

The most prevalent predisposing risk factor for developing onychomycosis is advanced age, with a reported prevalence of 18.2% in patients aged 60 to 79 years compared to 0.7% in patients younger than 19 years.2 Men are up to 3 times more likely to develop onychomycosis than women, though the reasons for this gender difference are less clear.2,5 It has been hypothesized that occupational factors may play a role,2 with increased use of occlusive footwear and more frequent nail injuries contributing to a higher incidence of onychomycosis in males.6

Differences in hormone levels associated with gender also may result in different capacities to inhibit the growth of dermatophytes.2 The risk for developing onychomycosis increases with age at a similar rate in both genders.7

Although onychomycosis is more common in men, the disease has been shown to have a greater impact on quality of life (QOL) in women. Studies have shown that onychomycosis was more likely to cause embarrassment in women than in men (83% vs 71%; N=258), and women with onychomycosis felt severely embarrassed more often than men (44% vs 26%; N=258).8,9 Additionally, one study (N=43,593) showed statistically significant differences associated with gender among onychomycosis patients who reported experiencing pain (33.7% of women vs 26.7% of men; P<.001), discomfort in walking (43.1% vs 36.4%; P<.001), and embarrassment (28.8% vs 25.1%; P<.001).10 Severe cases of onychomycosis even appear to have a negative impact on patients’ intimate relationships, and lower self-esteem has been reported in female patients due to unsightly and contagious-looking nail plates.11,12 Socks and stockings frequently may be damaged due to the constant friction from diseased nails that are sharp and dystrophic.13,14 In one study, treatment satisfaction was related to improvement in nail condition; however, males tended to be more satisfied with the improvement than females. Females were significantly less satisfied than males based on QOL scores for discomfort in wearing shoes (61.5 vs 86.3; P=.001), restrictions in shoe options (59.0 vs 82.8; P=.001), and the need to conceal toenails (73.3 vs 89.3; P<.01).15

Numerous studies have assessed the effectiveness of antifungal drugs in treating onychomycosis; however, there are limited data available on the impact of gender on outcome variables. Results from 2 identical 52-week, prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies of a total of 1655 participants (age range, 18–70 years) assessing the safety and efficacy of efinaconazole topical solution 10% in the treatment of onychomycosis were reported in 2013.16 Here, a gender subgroup analysis for male and female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis is presented.

Methods

Two 52-week, prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies were designed to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of efinaconazole topical solution 10% versus vehicle in 1655 participants aged 18 to 70 years with mild to moderate toenail onychomycosis. Participants who presented with 20% to 50% clinical involvement of the target toenail were randomized (3:1 ratio) to once-daily application of a blinded study drug on the toenails for 48 weeks, followed by a 4-week follow-up period.16

Efficacy Evaluation

The primary efficacy end point was complete cure, defined as 0% clinical involvement of target toenail and mycologic cure based on negative potassium hydroxide examination and negative fungal culture at week 52.16 Secondary and supportive efficacy end points included mycologic cure, treatment success (<10% clinical involvement of the target toenail), complete or almost complete cure (≤5% clinical involvement and mycologic cure), and change in QOL based on a self-administered QOL questionnaire. All secondary end points were assessed at week 52.16 All items in the QOL questionnaire were transferred to a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating better functioning.17

In both studies, treatment compliance was assessed through participant diaries that detailed all drug applications as well as the weight of returned product bottles. Participants were considered noncompliant if they missed more than 14 cumulative applications of the study drug in the 28 days leading up to the visit at week 48, if they missed more than 20% of the total number of expected study drug applications during the treatment period, and/or if they missed 28 or more consecutive applications of the study drug during the total treatment period.

Safety Evaluation

Safety assessments included monitoring and recording adverse events (AEs) until week 52.16

Results

The 2 studies included a total of 1275 (77.2%) male and 376 (22.8%) female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis (intention-to-treat population). Pooled results are provided in this analysis.

At baseline, the mean area of target toenail involvement among male and female participants in the efinaconazole treatment group was 36.7% and 35.6%, respectively, compared to 36.4% and 37.9%, respectively, in the vehicle group. The mean number of affected nontarget toenails was 2.8 and 2.7 among male and female participants, respectively, in the efinaconazole group compared to 2.9 and 2.4, respectively, in the vehicle group (Table 1).

Female participants tended to be somewhat more compliant with treatment than male participants at study end. At week 52, 93.0% and 93.4% of female participants in the efinaconazole and vehicle groups, respectively, were considered compliant with treatment compared to 91.1% and 88.6% of male participants, respectively (Table 1).

Primary Efficacy End Point (Observed Case)

At week 52, 15.8% of male and 27.1% of female participants in the efinaconazole treatment group had a complete cure compared to 4.2% and 6.3%, respectively, of those in the vehicle group (both P<.001). Efinaconazole topical solution 10% was significantly more effective than vehicle from week 48 (P<.001 male and P=.004 female).

The differences in complete cure rates reported for male (15.8%) and female (27.1%) participants treated with efinaconazole topical solution 10% were significant at week 52 (P=.001)(Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Proportion of male and female participants treated with once-daily application of efinaconazole topical solution 10% who achieved complete cure from weeks 12 to 52 (observed case; intention-to-treat population; pooled data). |

|

| Figure 2. Treatment success (defined as ≤10% clinical involvement of the target toenail) at week 52. Comparison of results with efinaconazole topical solution 10% and vehicle (observed case; intention-to-treat population; pooled data). |

Secondary and Supportive Efficacy End Points (Observed Case)

At week 52, 53.7% of male participants and 64.8% of female participants in the efinaconazole group achieved mycologic cure compared to 14.8% and 22.5%, respectively, of those in the vehicle group (both P<.001). Mycologic cure in the efinaconazole group versus the vehicle group became statistically significant at week 12 in male participants (P=.002) and at week 24 in female participants (P<.001).

At week 52, more male and female participants in the efinaconazole group (24.9% and 36.8%, respectively) achieved complete or almost complete cure compared to those in the vehicle group (6.8% and 11.3%, respectively), and 43.5% and 59.1% of male and female participants, respectively, were considered treatment successes (≤10% clinical involvement of the target toenail) compared to 15.5% and 26.8%, respectively, in the vehicle group (all P<.001)(Figure 2).

Treatment satisfaction scores were higher among female participants. At week 52, the mean QOL assessment score among female participants in the efinaconazole group was 77.2 compared to 70.3 among male participants in the same group (43.0 and 41.2, respectively, in the vehicle group). All QOL assessment scores were lower (ie, worse) in female onychomycosis participants at baseline. Improvements in all QOL scores were much greater in female participants at week 52 (Table 2).

The total number of efinaconazole applications was similar among male and female participants (315.1 vs 316.7). The mean amount of efina- conazole applied was greater in male participants (50.4 g vs 45.6 g), and overall compliance rates, though similar, were slightly higher in females compared to males (efinaconazole only)(93.0% vs 91.1%).

Safety

Overall, AE rates for efinaconazole were similar to those reported for vehicle (65.3% vs 59.8%).16 Slightly more female participants reported 1 or more AE than males (71.3% vs 63.5%). Adverse events were generally mild (50.0% in females; 53.7% in males) or moderate (46.7% in females; 41.8% in males) in severity, were not related to the study drug (89.9% in females; 93.1% in males), and resolved without sequelae. The rate of discontinuation from AEs was low (2.8% in females; 2.5% in males).

Comment

Efinaconazole topical solution 10% was significantly more effective than vehicle in both male and female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis. It appears to be especially effective in female participants, with more than 27% of female participants achieving complete cure at week 52, and nearly 37% of female participants achieving complete or almost complete cure at week 52.

Mycologic cure is the only consistently defined efficacy parameter reported in toenail onychomycosis studies.18 It often is considered the main treatment goal, with complete cure occurring somewhat later as the nails grow out.19 Indeed, in this subgroup analysis the differences seen between the active and vehicle groups correlated well with the cure rates seen at week 52. Interestingly, significantly better mycologic cure rates (P=.002, active vs vehicle) were seen as early as week 12 in the male subgroup.

The current analysis suggests that male onychomycosis patients may be more difficult to treat, a finding noted by other investigators, though the reason is not clear.20 It is known that the prevalence of onychomycosis is higher in males,2,5 but data comparing cure rates by gender is lacking. It has been suggested that men more frequently undergo nail trauma and tend to seek help for more advanced disease.20 Treatment compliance also may be an issue. In our study, mean nail involvement was similar among male and female participants treated with efinaconazole (36.7% and 35.6%, respectively). Treatment compliance was higher among females compared to males (93.0% vs 91.1%), with the lowest compliance rates seen in males in the vehicle group (where complete cure rates also were the lowest). The amount of study drug used was greater in males, possibly due to larger toenails, though toenail surface area was not measured. Although there is no evidence to suggest that male toenails grow quicker, as many factors can impact nail growth, they tend to be thicker. Patients with thick toenails may be less likely to achieve complete cure.20 It also is possible that male toenails take longer to grow out fully, and they may require a longer treatment course. The 52-week duration of these studies may not have allowed for full regrowth of the nails, despite mycologic cure. Indeed, continued improvement in cure rates in onychomycosis patients with longer treatment courses have been noted by other investigators.21

The current analysis revealed much lower baseline QOL scores in female onychomycosis patients compared to male patients. Given that target nail involvement at baseline was similar across both groups, this finding may be indicative of greater concern about their condition among females, supporting other views that onychomycosis has a greater impact on QOL in female patients. Similar scores reported across genders at week 52 likely reflects the greater efficacy seen in females.

Conclusion

Based on this subgroup analysis, once-daily application of efinaconazole topical solution 10% may provide a useful option in the treatment of mild to moderate onychomycosis, particularly in female patients. The greater improvement in nail condition concomitantly among females translates to higher overall treatment satisfaction.

Acknowledgment—The author thanks Brian Bulley, MSc, of Inergy Limited, Lindfield, West Sussex, United Kingdom, for medical writing support. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America, LLC, funded Inergy’s activities pertaining to the manuscript.

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disease in adults, representing up to 50% of all nail disorders, and is nearly always associated with tinea pedis.1,2 Moreover, toenail onychomycosis frequently involves several nails3 and can be more challenging to treat because of the slow growth rate of nails and the difficult delivery of antifungal agents to the nail bed.3,4

The most prevalent predisposing risk factor for developing onychomycosis is advanced age, with a reported prevalence of 18.2% in patients aged 60 to 79 years compared to 0.7% in patients younger than 19 years.2 Men are up to 3 times more likely to develop onychomycosis than women, though the reasons for this gender difference are less clear.2,5 It has been hypothesized that occupational factors may play a role,2 with increased use of occlusive footwear and more frequent nail injuries contributing to a higher incidence of onychomycosis in males.6

Differences in hormone levels associated with gender also may result in different capacities to inhibit the growth of dermatophytes.2 The risk for developing onychomycosis increases with age at a similar rate in both genders.7

Although onychomycosis is more common in men, the disease has been shown to have a greater impact on quality of life (QOL) in women. Studies have shown that onychomycosis was more likely to cause embarrassment in women than in men (83% vs 71%; N=258), and women with onychomycosis felt severely embarrassed more often than men (44% vs 26%; N=258).8,9 Additionally, one study (N=43,593) showed statistically significant differences associated with gender among onychomycosis patients who reported experiencing pain (33.7% of women vs 26.7% of men; P<.001), discomfort in walking (43.1% vs 36.4%; P<.001), and embarrassment (28.8% vs 25.1%; P<.001).10 Severe cases of onychomycosis even appear to have a negative impact on patients’ intimate relationships, and lower self-esteem has been reported in female patients due to unsightly and contagious-looking nail plates.11,12 Socks and stockings frequently may be damaged due to the constant friction from diseased nails that are sharp and dystrophic.13,14 In one study, treatment satisfaction was related to improvement in nail condition; however, males tended to be more satisfied with the improvement than females. Females were significantly less satisfied than males based on QOL scores for discomfort in wearing shoes (61.5 vs 86.3; P=.001), restrictions in shoe options (59.0 vs 82.8; P=.001), and the need to conceal toenails (73.3 vs 89.3; P<.01).15

Numerous studies have assessed the effectiveness of antifungal drugs in treating onychomycosis; however, there are limited data available on the impact of gender on outcome variables. Results from 2 identical 52-week, prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies of a total of 1655 participants (age range, 18–70 years) assessing the safety and efficacy of efinaconazole topical solution 10% in the treatment of onychomycosis were reported in 2013.16 Here, a gender subgroup analysis for male and female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis is presented.

Methods

Two 52-week, prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies were designed to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of efinaconazole topical solution 10% versus vehicle in 1655 participants aged 18 to 70 years with mild to moderate toenail onychomycosis. Participants who presented with 20% to 50% clinical involvement of the target toenail were randomized (3:1 ratio) to once-daily application of a blinded study drug on the toenails for 48 weeks, followed by a 4-week follow-up period.16

Efficacy Evaluation

The primary efficacy end point was complete cure, defined as 0% clinical involvement of target toenail and mycologic cure based on negative potassium hydroxide examination and negative fungal culture at week 52.16 Secondary and supportive efficacy end points included mycologic cure, treatment success (<10% clinical involvement of the target toenail), complete or almost complete cure (≤5% clinical involvement and mycologic cure), and change in QOL based on a self-administered QOL questionnaire. All secondary end points were assessed at week 52.16 All items in the QOL questionnaire were transferred to a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating better functioning.17

In both studies, treatment compliance was assessed through participant diaries that detailed all drug applications as well as the weight of returned product bottles. Participants were considered noncompliant if they missed more than 14 cumulative applications of the study drug in the 28 days leading up to the visit at week 48, if they missed more than 20% of the total number of expected study drug applications during the treatment period, and/or if they missed 28 or more consecutive applications of the study drug during the total treatment period.

Safety Evaluation

Safety assessments included monitoring and recording adverse events (AEs) until week 52.16

Results

The 2 studies included a total of 1275 (77.2%) male and 376 (22.8%) female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis (intention-to-treat population). Pooled results are provided in this analysis.

At baseline, the mean area of target toenail involvement among male and female participants in the efinaconazole treatment group was 36.7% and 35.6%, respectively, compared to 36.4% and 37.9%, respectively, in the vehicle group. The mean number of affected nontarget toenails was 2.8 and 2.7 among male and female participants, respectively, in the efinaconazole group compared to 2.9 and 2.4, respectively, in the vehicle group (Table 1).

Female participants tended to be somewhat more compliant with treatment than male participants at study end. At week 52, 93.0% and 93.4% of female participants in the efinaconazole and vehicle groups, respectively, were considered compliant with treatment compared to 91.1% and 88.6% of male participants, respectively (Table 1).

Primary Efficacy End Point (Observed Case)

At week 52, 15.8% of male and 27.1% of female participants in the efinaconazole treatment group had a complete cure compared to 4.2% and 6.3%, respectively, of those in the vehicle group (both P<.001). Efinaconazole topical solution 10% was significantly more effective than vehicle from week 48 (P<.001 male and P=.004 female).

The differences in complete cure rates reported for male (15.8%) and female (27.1%) participants treated with efinaconazole topical solution 10% were significant at week 52 (P=.001)(Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Proportion of male and female participants treated with once-daily application of efinaconazole topical solution 10% who achieved complete cure from weeks 12 to 52 (observed case; intention-to-treat population; pooled data). |

|

| Figure 2. Treatment success (defined as ≤10% clinical involvement of the target toenail) at week 52. Comparison of results with efinaconazole topical solution 10% and vehicle (observed case; intention-to-treat population; pooled data). |

Secondary and Supportive Efficacy End Points (Observed Case)

At week 52, 53.7% of male participants and 64.8% of female participants in the efinaconazole group achieved mycologic cure compared to 14.8% and 22.5%, respectively, of those in the vehicle group (both P<.001). Mycologic cure in the efinaconazole group versus the vehicle group became statistically significant at week 12 in male participants (P=.002) and at week 24 in female participants (P<.001).

At week 52, more male and female participants in the efinaconazole group (24.9% and 36.8%, respectively) achieved complete or almost complete cure compared to those in the vehicle group (6.8% and 11.3%, respectively), and 43.5% and 59.1% of male and female participants, respectively, were considered treatment successes (≤10% clinical involvement of the target toenail) compared to 15.5% and 26.8%, respectively, in the vehicle group (all P<.001)(Figure 2).

Treatment satisfaction scores were higher among female participants. At week 52, the mean QOL assessment score among female participants in the efinaconazole group was 77.2 compared to 70.3 among male participants in the same group (43.0 and 41.2, respectively, in the vehicle group). All QOL assessment scores were lower (ie, worse) in female onychomycosis participants at baseline. Improvements in all QOL scores were much greater in female participants at week 52 (Table 2).

The total number of efinaconazole applications was similar among male and female participants (315.1 vs 316.7). The mean amount of efina- conazole applied was greater in male participants (50.4 g vs 45.6 g), and overall compliance rates, though similar, were slightly higher in females compared to males (efinaconazole only)(93.0% vs 91.1%).

Safety

Overall, AE rates for efinaconazole were similar to those reported for vehicle (65.3% vs 59.8%).16 Slightly more female participants reported 1 or more AE than males (71.3% vs 63.5%). Adverse events were generally mild (50.0% in females; 53.7% in males) or moderate (46.7% in females; 41.8% in males) in severity, were not related to the study drug (89.9% in females; 93.1% in males), and resolved without sequelae. The rate of discontinuation from AEs was low (2.8% in females; 2.5% in males).

Comment

Efinaconazole topical solution 10% was significantly more effective than vehicle in both male and female participants with mild to moderate onychomycosis. It appears to be especially effective in female participants, with more than 27% of female participants achieving complete cure at week 52, and nearly 37% of female participants achieving complete or almost complete cure at week 52.

Mycologic cure is the only consistently defined efficacy parameter reported in toenail onychomycosis studies.18 It often is considered the main treatment goal, with complete cure occurring somewhat later as the nails grow out.19 Indeed, in this subgroup analysis the differences seen between the active and vehicle groups correlated well with the cure rates seen at week 52. Interestingly, significantly better mycologic cure rates (P=.002, active vs vehicle) were seen as early as week 12 in the male subgroup.

The current analysis suggests that male onychomycosis patients may be more difficult to treat, a finding noted by other investigators, though the reason is not clear.20 It is known that the prevalence of onychomycosis is higher in males,2,5 but data comparing cure rates by gender is lacking. It has been suggested that men more frequently undergo nail trauma and tend to seek help for more advanced disease.20 Treatment compliance also may be an issue. In our study, mean nail involvement was similar among male and female participants treated with efinaconazole (36.7% and 35.6%, respectively). Treatment compliance was higher among females compared to males (93.0% vs 91.1%), with the lowest compliance rates seen in males in the vehicle group (where complete cure rates also were the lowest). The amount of study drug used was greater in males, possibly due to larger toenails, though toenail surface area was not measured. Although there is no evidence to suggest that male toenails grow quicker, as many factors can impact nail growth, they tend to be thicker. Patients with thick toenails may be less likely to achieve complete cure.20 It also is possible that male toenails take longer to grow out fully, and they may require a longer treatment course. The 52-week duration of these studies may not have allowed for full regrowth of the nails, despite mycologic cure. Indeed, continued improvement in cure rates in onychomycosis patients with longer treatment courses have been noted by other investigators.21

The current analysis revealed much lower baseline QOL scores in female onychomycosis patients compared to male patients. Given that target nail involvement at baseline was similar across both groups, this finding may be indicative of greater concern about their condition among females, supporting other views that onychomycosis has a greater impact on QOL in female patients. Similar scores reported across genders at week 52 likely reflects the greater efficacy seen in females.

Conclusion

Based on this subgroup analysis, once-daily application of efinaconazole topical solution 10% may provide a useful option in the treatment of mild to moderate onychomycosis, particularly in female patients. The greater improvement in nail condition concomitantly among females translates to higher overall treatment satisfaction.

Acknowledgment—The author thanks Brian Bulley, MSc, of Inergy Limited, Lindfield, West Sussex, United Kingdom, for medical writing support. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America, LLC, funded Inergy’s activities pertaining to the manuscript.

1. Scher RK, Coppa LM. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of onychomycosis. Hosp Med. 1998;34:11-20.

2. Gupta AK, Jain HC, Lynde CW, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of onychomycosis in patients visiting physicians’ offices: a multicenter Canadian survey of 15,000 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:244-248.

3. Finch JJ, Warshaw EM. Toenail onychomycosis: current and future treatment options. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:31-46.

4. Kumar S, Kimball AB. New antifungal therapies for the treatment of onychomycosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:727-734.

5. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

6. Araujo AJG, Bastos OMP, Souza MAJ, et al. Occurrence of onychomycosis among patients attended in dermatology offices in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2003;78:299-308.

7. Pierard G. Onychomycosis and other superficial fungal infections of the foot in the elderly: a Pan-European Survey. Dermatology. 2001;202:220-224.

8. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5, pt 1):702-704.

9. Kowalczuk-Zieleniec E, Nowicki E, Majkowicz M. Onychomycosis changes quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(suppl 1):248.

10. Katsambas A, Abeck D, Haneke E, et al. The effects of foot disease on quality of life: results of the Achilles Project. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:191-195.

11. Salgo PL, Daniel CR, Gupta AK, et al. Onychomycosis disease management. Medical Crossfire: Debates, Peer Exchange and Insights in Medicine. 2003;4:1-17.

12. Elewski BE. The effect of toenail onychomycosis on patient quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:754-756.

13. Hay RJ. The future of onychomycosis therapy may involve a combination of approaches. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:3-8.

14. Whittam LR, Hay RJ. The impact of onychomycosis on quality of life. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:87-89.

15. Stier DM, Gause D, Joseph WS, et al. Patient satisfaction with oral versus nonoral therapeutic approaches in onychomycosis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:521-527.

16. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

17. Tosti A, Elewski BE. Treatment of onychomycosis with efinaconazole 10% topical solution and quality of life. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:25-30.

18. Werschler WP, Bondar G, Armstrong D. Assessing treatment outcomes in toenail onychomycosis clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:145-152.

19. Gupta AK. Treatment of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis in the United States: a pharmacoeconomic analysis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92:272-286.

20. Sigurgeirsson B. Prognostic factors for cure following treatment of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:679-684.

21. Epstein E. How often does oral treatment of toenail onychomycosis produce a disease-free nail? an analysis of published data. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1551-1554.

1. Scher RK, Coppa LM. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of onychomycosis. Hosp Med. 1998;34:11-20.

2. Gupta AK, Jain HC, Lynde CW, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of onychomycosis in patients visiting physicians’ offices: a multicenter Canadian survey of 15,000 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:244-248.

3. Finch JJ, Warshaw EM. Toenail onychomycosis: current and future treatment options. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:31-46.

4. Kumar S, Kimball AB. New antifungal therapies for the treatment of onychomycosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:727-734.

5. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

6. Araujo AJG, Bastos OMP, Souza MAJ, et al. Occurrence of onychomycosis among patients attended in dermatology offices in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2003;78:299-308.

7. Pierard G. Onychomycosis and other superficial fungal infections of the foot in the elderly: a Pan-European Survey. Dermatology. 2001;202:220-224.

8. Drake LA, Scher RK, Smith EB, et al. Effect of onychomycosis on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5, pt 1):702-704.

9. Kowalczuk-Zieleniec E, Nowicki E, Majkowicz M. Onychomycosis changes quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(suppl 1):248.

10. Katsambas A, Abeck D, Haneke E, et al. The effects of foot disease on quality of life: results of the Achilles Project. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:191-195.

11. Salgo PL, Daniel CR, Gupta AK, et al. Onychomycosis disease management. Medical Crossfire: Debates, Peer Exchange and Insights in Medicine. 2003;4:1-17.

12. Elewski BE. The effect of toenail onychomycosis on patient quality of life. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:754-756.

13. Hay RJ. The future of onychomycosis therapy may involve a combination of approaches. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:3-8.

14. Whittam LR, Hay RJ. The impact of onychomycosis on quality of life. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:87-89.

15. Stier DM, Gause D, Joseph WS, et al. Patient satisfaction with oral versus nonoral therapeutic approaches in onychomycosis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:521-527.

16. Elewski BE, Rich P, Pollak R, et al. Efinaconazole 10% solution in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: two phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:600-608.

17. Tosti A, Elewski BE. Treatment of onychomycosis with efinaconazole 10% topical solution and quality of life. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:25-30.

18. Werschler WP, Bondar G, Armstrong D. Assessing treatment outcomes in toenail onychomycosis clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:145-152.

19. Gupta AK. Treatment of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis in the United States: a pharmacoeconomic analysis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92:272-286.

20. Sigurgeirsson B. Prognostic factors for cure following treatment of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:679-684.

21. Epstein E. How often does oral treatment of toenail onychomycosis produce a disease-free nail? an analysis of published data. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1551-1554.

Practice Points

- Men, particularly as they age, are more likely to develop onychomycosis.

- Treatment adherence may be a bigger issue among male patients.

- Onychomycosis in males may be more difficult to treat for a variety of reasons.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on OTC Dandruff Treatments

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC dandruff treatments. Consideration must be given to:

- Head & Shoulders Shampoo

Procter & Gamble

“OTC dandruff products are more for maintenance rather than active treatment, which is why many consumers and patients become frustrated with their use. I recommend to soak [this product] on the scalp skin (not hair) for 5 minutes 2 to 3 times per week.”—Adam Friedman, MD, Washington, DC

- Moroccanoil Treatment

Moroccanoil

“I think it’s great to actually put [this product] directly onto the scalp after shampooing to get any remaining scales off.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena T/Gel Therapeutic Hair Care

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena T/Sal Therapeutic Shampoo

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Nizoral A-D Ketoconazole Shampoo 1%

McNeil-PPC, Inc

“I recommend to soak [this product] on the scalp skin (not hair) for 5 minutes 2 to 3 times per week.”—Adam Friedman, MD, Washington, DC

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Eye creams, men’s shaving products, and products for babies will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to [email protected].

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC dandruff treatments. Consideration must be given to:

- Head & Shoulders Shampoo

Procter & Gamble

“OTC dandruff products are more for maintenance rather than active treatment, which is why many consumers and patients become frustrated with their use. I recommend to soak [this product] on the scalp skin (not hair) for 5 minutes 2 to 3 times per week.”—Adam Friedman, MD, Washington, DC

- Moroccanoil Treatment

Moroccanoil

“I think it’s great to actually put [this product] directly onto the scalp after shampooing to get any remaining scales off.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena T/Gel Therapeutic Hair Care

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena T/Sal Therapeutic Shampoo

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Nizoral A-D Ketoconazole Shampoo 1%

McNeil-PPC, Inc

“I recommend to soak [this product] on the scalp skin (not hair) for 5 minutes 2 to 3 times per week.”—Adam Friedman, MD, Washington, DC

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Eye creams, men’s shaving products, and products for babies will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to [email protected].

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC dandruff treatments. Consideration must be given to:

- Head & Shoulders Shampoo

Procter & Gamble

“OTC dandruff products are more for maintenance rather than active treatment, which is why many consumers and patients become frustrated with their use. I recommend to soak [this product] on the scalp skin (not hair) for 5 minutes 2 to 3 times per week.”—Adam Friedman, MD, Washington, DC

- Moroccanoil Treatment

Moroccanoil

“I think it’s great to actually put [this product] directly onto the scalp after shampooing to get any remaining scales off.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena T/Gel Therapeutic Hair Care

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Neutrogena T/Sal Therapeutic Shampoo

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Nizoral A-D Ketoconazole Shampoo 1%

McNeil-PPC, Inc

“I recommend to soak [this product] on the scalp skin (not hair) for 5 minutes 2 to 3 times per week.”—Adam Friedman, MD, Washington, DC

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Eye creams, men’s shaving products, and products for babies will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to [email protected].

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Turn down the androgens to treat female pattern hair loss

NEW YORK – Antiandrogen hormones can help stabilize, and even improve, female pattern hair loss.

The pathophysiology of the disorder is unknown, but treatment is based on the assumption that women must be like men, at least when it comes to losing their hair. Intuitively, decreasing androgens should help correct the problem.

The answer, though, is a complicated mix of yes and maybe, Dr. Rochelle Torgerson said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“It used to be assumed that pattern hair loss in women was just the same as it is in men,” said Dr. Torgerson of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “Now there is some evidence that’s not true. In 2010, for example, this was seen in a woman with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, so in her, androgens were not affecting hair follicles. There must be a place for estrogen.”

Further complicating the picture is the fact that no hormonal medications have FDA approval for hair loss in women, and their use has a history of conflicting data in clinical studies. Still, they remain the cornerstone for treating this physically and emotionally challenging problem.

The initial challenge is simply what to label it at the first visit.

“I have no problem with term ‘androgenetic alopecia,’ since that is what women are seeing when they first look on the Internet for information. But I do try to transition them to ‘female pattern hair loss.’ And I never – ever – use the term ‘male pattern baldness.’ It has a huge impact on women.”

The disease is a progressive miniaturization of the hair follicle over time. The growing cycle slows and the resting phase lengthens. There is progressive thinning over the vertex. Some women may keep most of their frontal hairline, but the vast majority do say it’s thinner than it was.

Spironolactone and oral contraceptives with spironolactone analogues are Dr. Torgerson’s go-to medications for first-line treatment. For spironolactone, she prefers a dose of 100-200 mg/day. Some women experience gastrointestinal upset, dizziness, cramps, breast tenderness, and spotting with these medications.

Her choice for an oral contraceptive is the combination of 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol plus drospirenone, but any oral contraceptive approved for acne may work.

Finasteride and dutasteride are approved for pattern hair loss in men, but not in women. Both inhibit 5 alpha-reductase type II. Dutasteride is more potent that finasteride and also inhibits type 1 alpha-reductase; both of these enzymes convert testosterone into the more potent dihydrotestosterone. The side-effect profile is more moderate than that of spironolactone, but both of the drugs have had mixed results in clinical trials.

One problem with the finasteride trials has been the variation in dosing. The least positive studies used the lowest dose of 1.25 mg. As the dosage increased to 2.5 mg and 5 mg, the benefit increased.

Despite her support for hormonal therapies, Dr. Torgerson doesn’t rely upon them alone – she supports them with the direct action of a 5% minoxidil foam. In addition to prescribing effective therapy, she urges women to actually be patient and to have realistic expectations.

Most women expect dramatic improvement in a short time. “I have no idea where that expectation comes from. This is a slow progressive condition. I agree with them that it’s completely unsexy to have the head of hair they do at that time. But if, in 3 years, they have this same head of hair, that’s going to be an amazing success. And once they have that expectation in their mind, they are usually happy with any other results that they see.”

Dr. Torgerson had no financial conflicts with regard to her presentation.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

NEW YORK – Antiandrogen hormones can help stabilize, and even improve, female pattern hair loss.

The pathophysiology of the disorder is unknown, but treatment is based on the assumption that women must be like men, at least when it comes to losing their hair. Intuitively, decreasing androgens should help correct the problem.

The answer, though, is a complicated mix of yes and maybe, Dr. Rochelle Torgerson said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“It used to be assumed that pattern hair loss in women was just the same as it is in men,” said Dr. Torgerson of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “Now there is some evidence that’s not true. In 2010, for example, this was seen in a woman with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, so in her, androgens were not affecting hair follicles. There must be a place for estrogen.”

Further complicating the picture is the fact that no hormonal medications have FDA approval for hair loss in women, and their use has a history of conflicting data in clinical studies. Still, they remain the cornerstone for treating this physically and emotionally challenging problem.

The initial challenge is simply what to label it at the first visit.

“I have no problem with term ‘androgenetic alopecia,’ since that is what women are seeing when they first look on the Internet for information. But I do try to transition them to ‘female pattern hair loss.’ And I never – ever – use the term ‘male pattern baldness.’ It has a huge impact on women.”

The disease is a progressive miniaturization of the hair follicle over time. The growing cycle slows and the resting phase lengthens. There is progressive thinning over the vertex. Some women may keep most of their frontal hairline, but the vast majority do say it’s thinner than it was.

Spironolactone and oral contraceptives with spironolactone analogues are Dr. Torgerson’s go-to medications for first-line treatment. For spironolactone, she prefers a dose of 100-200 mg/day. Some women experience gastrointestinal upset, dizziness, cramps, breast tenderness, and spotting with these medications.

Her choice for an oral contraceptive is the combination of 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol plus drospirenone, but any oral contraceptive approved for acne may work.

Finasteride and dutasteride are approved for pattern hair loss in men, but not in women. Both inhibit 5 alpha-reductase type II. Dutasteride is more potent that finasteride and also inhibits type 1 alpha-reductase; both of these enzymes convert testosterone into the more potent dihydrotestosterone. The side-effect profile is more moderate than that of spironolactone, but both of the drugs have had mixed results in clinical trials.

One problem with the finasteride trials has been the variation in dosing. The least positive studies used the lowest dose of 1.25 mg. As the dosage increased to 2.5 mg and 5 mg, the benefit increased.

Despite her support for hormonal therapies, Dr. Torgerson doesn’t rely upon them alone – she supports them with the direct action of a 5% minoxidil foam. In addition to prescribing effective therapy, she urges women to actually be patient and to have realistic expectations.

Most women expect dramatic improvement in a short time. “I have no idea where that expectation comes from. This is a slow progressive condition. I agree with them that it’s completely unsexy to have the head of hair they do at that time. But if, in 3 years, they have this same head of hair, that’s going to be an amazing success. And once they have that expectation in their mind, they are usually happy with any other results that they see.”

Dr. Torgerson had no financial conflicts with regard to her presentation.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

NEW YORK – Antiandrogen hormones can help stabilize, and even improve, female pattern hair loss.

The pathophysiology of the disorder is unknown, but treatment is based on the assumption that women must be like men, at least when it comes to losing their hair. Intuitively, decreasing androgens should help correct the problem.

The answer, though, is a complicated mix of yes and maybe, Dr. Rochelle Torgerson said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“It used to be assumed that pattern hair loss in women was just the same as it is in men,” said Dr. Torgerson of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “Now there is some evidence that’s not true. In 2010, for example, this was seen in a woman with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, so in her, androgens were not affecting hair follicles. There must be a place for estrogen.”

Further complicating the picture is the fact that no hormonal medications have FDA approval for hair loss in women, and their use has a history of conflicting data in clinical studies. Still, they remain the cornerstone for treating this physically and emotionally challenging problem.

The initial challenge is simply what to label it at the first visit.

“I have no problem with term ‘androgenetic alopecia,’ since that is what women are seeing when they first look on the Internet for information. But I do try to transition them to ‘female pattern hair loss.’ And I never – ever – use the term ‘male pattern baldness.’ It has a huge impact on women.”

The disease is a progressive miniaturization of the hair follicle over time. The growing cycle slows and the resting phase lengthens. There is progressive thinning over the vertex. Some women may keep most of their frontal hairline, but the vast majority do say it’s thinner than it was.

Spironolactone and oral contraceptives with spironolactone analogues are Dr. Torgerson’s go-to medications for first-line treatment. For spironolactone, she prefers a dose of 100-200 mg/day. Some women experience gastrointestinal upset, dizziness, cramps, breast tenderness, and spotting with these medications.

Her choice for an oral contraceptive is the combination of 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol plus drospirenone, but any oral contraceptive approved for acne may work.

Finasteride and dutasteride are approved for pattern hair loss in men, but not in women. Both inhibit 5 alpha-reductase type II. Dutasteride is more potent that finasteride and also inhibits type 1 alpha-reductase; both of these enzymes convert testosterone into the more potent dihydrotestosterone. The side-effect profile is more moderate than that of spironolactone, but both of the drugs have had mixed results in clinical trials.

One problem with the finasteride trials has been the variation in dosing. The least positive studies used the lowest dose of 1.25 mg. As the dosage increased to 2.5 mg and 5 mg, the benefit increased.

Despite her support for hormonal therapies, Dr. Torgerson doesn’t rely upon them alone – she supports them with the direct action of a 5% minoxidil foam. In addition to prescribing effective therapy, she urges women to actually be patient and to have realistic expectations.

Most women expect dramatic improvement in a short time. “I have no idea where that expectation comes from. This is a slow progressive condition. I agree with them that it’s completely unsexy to have the head of hair they do at that time. But if, in 3 years, they have this same head of hair, that’s going to be an amazing success. And once they have that expectation in their mind, they are usually happy with any other results that they see.”

Dr. Torgerson had no financial conflicts with regard to her presentation.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AAD SUMMER ACADEMY 2015

Onychomatricoma: An Often Misdiagnosed Tumor of the Nails

Changes in the appearance of the nail apparatus can be produced by a variety of conditions. Onychomatricoma is an unusual benign tumor with specific clinical characteristics that was first described more than 2 decades ago.1 It is often and easily misdiagnosed because the condition rarely has been described. We report a case of onychomatricoma in a 54-year-old Colombian man who presented with a deformity of the nail plate on the right index finger that corresponded with the classic description of onychomatricoma. We emphasize the importance of reporting such lesions to prevent misdiagnosis and delay of proper treatment.

Case Report

A 54-year-old Colombian man presented with nail dystrophy involving the right index finger of 2 years’ duration. He did not recall any trauma prior to the onset of the nail abnormalities. Several topical treatments had previously been ineffective. Physical examination revealed a longitudinally banded thickening of the lateral half of the nail plate on the right index finger with yellowish brown discoloration, transverse overcurvature of the nail, longitudinal white lines, and splinter hemorrhages (Figure 1). Direct microscopy and fungal culture were performed to diagnose or rule out onychomycosis.

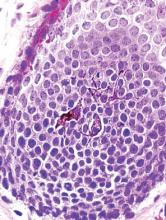

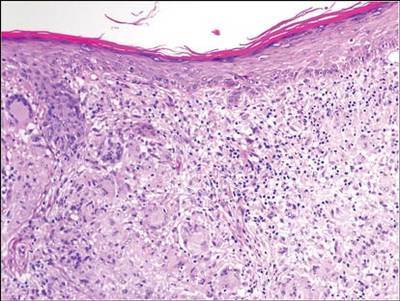

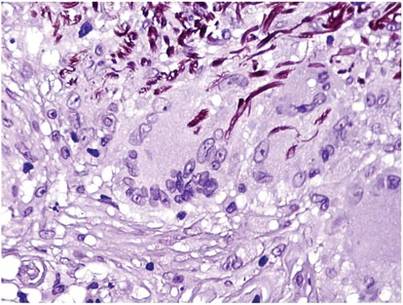

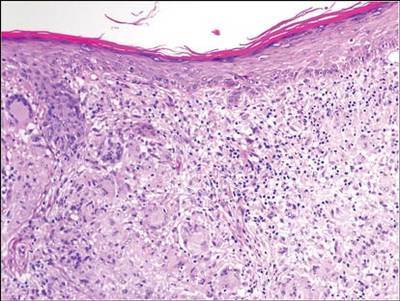

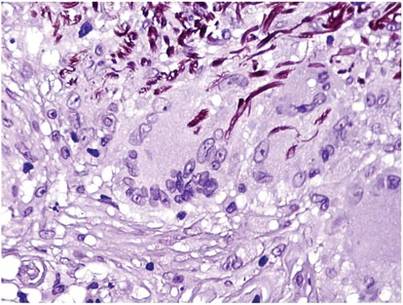

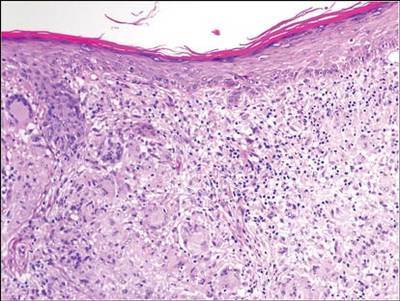

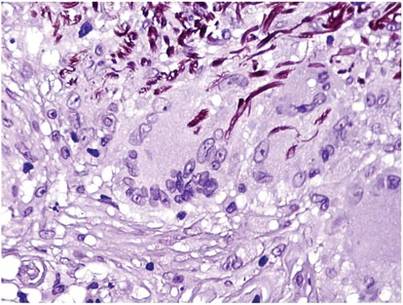

A clinical diagnosis of onychomatricoma was made, and the lesion was surgically removed and sent for histopathologic study (Figure 2). The radial half of the nail plate was avulsed, and the proximal part of the removed nail plate contained a large, firmly attached, filamentous tumor arising from the nail matrix (Figure 3) with multiple fine filiform projections (Figure 4). The nail bed was cleaned with a curette to remove any debris, the ulnar half of the nail plate and nail bed was left in place, and the radial border was reconstructed. Histology confirmed the clinical diagnosis (Figure 5). No recurrences of the tumor were seen 36 months following surgery.

|

|

Comment

Since the original report of this tumor,1 fewer than 10 cases of onychomatricoma have been reported in Latin America,2-5 with no more than 80 cases reported worldwide.6 Clinicians and academicians are becoming interested in the topic, which will result in better recognition and more reports in the literature.

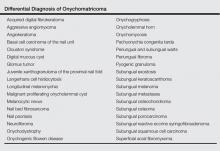

The clinical differential diagnosis of onycho-matricoma is extensive,7,8 but onychomatricoma has characteristic clinical and histopathologic features that allow its separation from other nail disorders and subungual tumors (Table).9 There are 4 cardinal clinical signs that suggest a diagnosis of onychomatricoma: (1) banded or diffuse thickening of the nail plate of variable widths; (2) yellowish discoloration of the involved nail plate, often showing fine splinter hemorrhages in the proximal nail portion; (3) transverse overcurvature of the nail; and (4) exposure of a filamentous tufted tumor emerging from the matrix in a funnel-shaped nail by avulsion.1

|

Histologic findings of onychomatricoma typically demonstrate a fibroepithelial tumor with a biphasic growth pattern mimicking normal nail matrix histology, including a proximal zone, which corresponds to the base of the fibroepithelial tumor, and a distal zone, which is composed of multiple epithelial digitations that extend into the small cavities present in the attached nail.10-12 Nevertheless, the anatomic tumor location, the often fragmented aspect of the tissue specimen, and the choice of the section planes may change the typical histologic features seen in onychomatricoma.13 Stromal prominence, cellularity, and atypia may vary in individual cases.10-12

The etiology of onychomatricoma is not yet known. Although it has been suggested that onychomatricoma could be an epithelial and connective tissue hamartoma simulating the nail matrix structure,1,10 the more recent concept of an epithelial onychogenic tumor with onychogenic mesenchyme will help to clarify its etiology because new histopathologic and immunohistochemical features suggest a neoplastic nature.14 On the other hand, predisposing factors such as trauma to the nail plate and onychomycosis may play a role,7 as the thumbs, index fingers, and great toes are more susceptible to onychomycosis and accidental trauma.

Conclusion

Our patient fulfilled the criteria of onychomatricoma.1 Onychomatricoma should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of subungual or periungual tumors to avoid misdiagnosis and erroneous treatments.

1. Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma: filamentous tufted tumor in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: a new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:510-515.

2. Estrada-Chavez G, Vega-Memije ME, Toussaint-Caire S, et al. Giant onychomatricoma: report of two cases with rare clinical presentation. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46: 634-636.

3. Soto R, Wortsman X, Corredoira Y. Onychomatricoma: clinical and sonographic findings. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1461-1462.

4. Tavares GT, Chiacchio NG, Chiacchio ND, et al. Onychomatricoma: a tumor unknown to dermatologists. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:265-267.

5. Fernández-Sánchez M, Saeb-Lima M, Charli-Joseph Y, et al. Onychomatricoma: an infrequent nail tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:382-383.

6. Tavares G, Di-Chiacchio N, Di-Santis E, et al. Onycho-matricoma: epidemiological and clinical findings in a large series of 30 cases [published online ahead of print May 12, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.13900.

7. Rashid RM, Swan J. Onychomatricoma: benign sporadic nail lesion or much more? Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:4.

8. Goutos I, Furniss D, Smith GD. Onychomatricoma: an unusual case of ungual pathology. case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:54-57.

9. Fraga GR, Patterson JW, McHargue CA. Onychomatricoma: report of a case and its comparison with fibrokeratoma of the nailbed. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:36-40.

10. Perrin C, Goettmann S, Baran R. Onychomatricoma: clinical and histopathologic findings in 12 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:560-564.

11. Gaertner EM, Gordon M, Reed T. Onychomatricoma: case report of an unusual subungual tumor with literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):S66-S69.

12. Perrin C, Baran R, Pisani A, et al. The onychomatricoma: additional histologic criteria and immunohistochemical study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:199-203.

13. Perrin C, Baran R, Balaguer T, et al. Onychomatricoma: new clinical and histological features. a review of 19 tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:1-8.

14. Perrin C, Langbein L, Schweizer J, et al. Onychomatricoma in the light of the microanatomy of the normal nail unit. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:131-139.

Changes in the appearance of the nail apparatus can be produced by a variety of conditions. Onychomatricoma is an unusual benign tumor with specific clinical characteristics that was first described more than 2 decades ago.1 It is often and easily misdiagnosed because the condition rarely has been described. We report a case of onychomatricoma in a 54-year-old Colombian man who presented with a deformity of the nail plate on the right index finger that corresponded with the classic description of onychomatricoma. We emphasize the importance of reporting such lesions to prevent misdiagnosis and delay of proper treatment.

Case Report

A 54-year-old Colombian man presented with nail dystrophy involving the right index finger of 2 years’ duration. He did not recall any trauma prior to the onset of the nail abnormalities. Several topical treatments had previously been ineffective. Physical examination revealed a longitudinally banded thickening of the lateral half of the nail plate on the right index finger with yellowish brown discoloration, transverse overcurvature of the nail, longitudinal white lines, and splinter hemorrhages (Figure 1). Direct microscopy and fungal culture were performed to diagnose or rule out onychomycosis.

A clinical diagnosis of onychomatricoma was made, and the lesion was surgically removed and sent for histopathologic study (Figure 2). The radial half of the nail plate was avulsed, and the proximal part of the removed nail plate contained a large, firmly attached, filamentous tumor arising from the nail matrix (Figure 3) with multiple fine filiform projections (Figure 4). The nail bed was cleaned with a curette to remove any debris, the ulnar half of the nail plate and nail bed was left in place, and the radial border was reconstructed. Histology confirmed the clinical diagnosis (Figure 5). No recurrences of the tumor were seen 36 months following surgery.

|

|

Comment

Since the original report of this tumor,1 fewer than 10 cases of onychomatricoma have been reported in Latin America,2-5 with no more than 80 cases reported worldwide.6 Clinicians and academicians are becoming interested in the topic, which will result in better recognition and more reports in the literature.

The clinical differential diagnosis of onycho-matricoma is extensive,7,8 but onychomatricoma has characteristic clinical and histopathologic features that allow its separation from other nail disorders and subungual tumors (Table).9 There are 4 cardinal clinical signs that suggest a diagnosis of onychomatricoma: (1) banded or diffuse thickening of the nail plate of variable widths; (2) yellowish discoloration of the involved nail plate, often showing fine splinter hemorrhages in the proximal nail portion; (3) transverse overcurvature of the nail; and (4) exposure of a filamentous tufted tumor emerging from the matrix in a funnel-shaped nail by avulsion.1

|

Histologic findings of onychomatricoma typically demonstrate a fibroepithelial tumor with a biphasic growth pattern mimicking normal nail matrix histology, including a proximal zone, which corresponds to the base of the fibroepithelial tumor, and a distal zone, which is composed of multiple epithelial digitations that extend into the small cavities present in the attached nail.10-12 Nevertheless, the anatomic tumor location, the often fragmented aspect of the tissue specimen, and the choice of the section planes may change the typical histologic features seen in onychomatricoma.13 Stromal prominence, cellularity, and atypia may vary in individual cases.10-12

The etiology of onychomatricoma is not yet known. Although it has been suggested that onychomatricoma could be an epithelial and connective tissue hamartoma simulating the nail matrix structure,1,10 the more recent concept of an epithelial onychogenic tumor with onychogenic mesenchyme will help to clarify its etiology because new histopathologic and immunohistochemical features suggest a neoplastic nature.14 On the other hand, predisposing factors such as trauma to the nail plate and onychomycosis may play a role,7 as the thumbs, index fingers, and great toes are more susceptible to onychomycosis and accidental trauma.

Conclusion

Our patient fulfilled the criteria of onychomatricoma.1 Onychomatricoma should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of subungual or periungual tumors to avoid misdiagnosis and erroneous treatments.

Changes in the appearance of the nail apparatus can be produced by a variety of conditions. Onychomatricoma is an unusual benign tumor with specific clinical characteristics that was first described more than 2 decades ago.1 It is often and easily misdiagnosed because the condition rarely has been described. We report a case of onychomatricoma in a 54-year-old Colombian man who presented with a deformity of the nail plate on the right index finger that corresponded with the classic description of onychomatricoma. We emphasize the importance of reporting such lesions to prevent misdiagnosis and delay of proper treatment.

Case Report

A 54-year-old Colombian man presented with nail dystrophy involving the right index finger of 2 years’ duration. He did not recall any trauma prior to the onset of the nail abnormalities. Several topical treatments had previously been ineffective. Physical examination revealed a longitudinally banded thickening of the lateral half of the nail plate on the right index finger with yellowish brown discoloration, transverse overcurvature of the nail, longitudinal white lines, and splinter hemorrhages (Figure 1). Direct microscopy and fungal culture were performed to diagnose or rule out onychomycosis.

A clinical diagnosis of onychomatricoma was made, and the lesion was surgically removed and sent for histopathologic study (Figure 2). The radial half of the nail plate was avulsed, and the proximal part of the removed nail plate contained a large, firmly attached, filamentous tumor arising from the nail matrix (Figure 3) with multiple fine filiform projections (Figure 4). The nail bed was cleaned with a curette to remove any debris, the ulnar half of the nail plate and nail bed was left in place, and the radial border was reconstructed. Histology confirmed the clinical diagnosis (Figure 5). No recurrences of the tumor were seen 36 months following surgery.

|

|

Comment