User login

Managing Patients With Alopecia

What does the patient need to know at the first visit?

When I communicate with alopecia patients at the first visit, I make sure they know that I’m there to help them—that I won’t minimize their concerns and that I understand how important their condition is to them. Alopecia can be frustrating for both the patient and the physician, and there often is a confounding background of psychosocial stress and/or a history of physicians who have dismissed the patient’s concerns about his or her hair loss as trivial. Establishing an effective doctor-patient relationship is key in treating alopecia. Physicians sometimes may be left feeling like the patient wants to keep them in the room until his or her hair regrows, but in reality you simply need to reassure the patient that you are comfortable with the evaluation and treatment of alopecia and that several steps will be required but you will get started today.

How do you use punch biopsies to determine the best treatment options?

My most important tips regarding alopecia diagnosis relate to scalp biopsies, which usually are required in distinguishing chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other scarring alopecias. First, an absorbable gelatin compressed sponge is your best friend. A small strip inserted into the punch biopsy wound results in prompt hemostasis without the need for sutures, and the resulting scar often looks as good or better than that produced by suturing. Next, don’t biopsy the active advancing borders of an alopecia patch, as the findings usually are nonspecific. Instead, biopsy a well-established portion that has been present for at least 4 to 6 months but is still active. In inconclusive cases, a biopsy of a scarred area stained with Verhoeff elastic stain can demonstrate characteristic patterns of elastic tissue loss and often establish a diagnosis. It is important to distinguish chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other forms of scarring alopecia, as it is more likely to respond to antimalarials.

What are your go-to treatments? Are your recommendations anecdotal or evidence based?

There isn’t an extensive arsenal of evidence-based therapy for refractory scarring alopecia, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have effective therapies; it simply means that our treatments are based on experience without accompanying randomized controlled trials. We need to produce more evidence, but patients with severe disease still need to be treated in the meantime. It’s important to remember that therapeutic complacency can result in permanent irreversible scarring. The presence of easily extractable anagen hairs is a sign of active disease. This simple test is helpful to monitor therapeutic progress.

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids can be extremely useful and often are underused. In general, the risk of scarring and atrophy from untreated disease is much greater than that from the corticosteroid. On the scalp, atrophy often presents as erythema, which should not be confused with erythema related to active disease. Dermoscopy is useful to demonstrate that the redness represents dermal atrophy with prominence of the subpapillary plexus of vessels.

When systemic therapy is required, antimalarials, retinoids, dapsone, thalidomide, sulfasalazine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have all been used successfully in the setting of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, while topical tazarotene and topical calcineurin inhibitors are generally disappointing.

For the treatment of lichen planopilaris, intralesional corticosteroids, oral retinoids, and excimer laser can be effective. In contrast, antimalarials usually are not effective in preventing disease progression. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist pioglitazone can be effective, but reported results vary widely. In my experience, mycophenolate mofetil is generally reliable in patients with refractory disease. Dutasteride can be effective as a first-line therapy in the setting of frontal fibrosing alopecia, although some of the noted improvement may relate to the nonscarring portion of the disease in patients with a background of pattern alopecia.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Again, the key to treatment compliance is to establish an effective doctor-patient relationship. Whenever possible, begin with adequately potent therapy to give patients an early response. Don’t hesitate to use prednisone initially for inflammatory scarring alopecia. Patients need to see signs of progress in order to stay compliant with treatment, and long trials of ineffective therapies destroy trust. Adequate doses of intralesional or oral corticosteroids often are appropriate to ensure an early response with subsequent transition to steroid-sparing agents.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Try to find out why—often it’s simply fear of side effects. Patient education is key, and it can help tremendously to share with them the number of patients you have treated safely with the medication in question and assure them that you know how to monitor for the important side effects.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is helpful to keep a handy list of patient advocacy Web sites. Well-established support groups such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (https://www.naaf.org) and the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org) provide excellent information for patients and help to support research to improve outcomes for these difficult disorders.

What does the patient need to know at the first visit?

When I communicate with alopecia patients at the first visit, I make sure they know that I’m there to help them—that I won’t minimize their concerns and that I understand how important their condition is to them. Alopecia can be frustrating for both the patient and the physician, and there often is a confounding background of psychosocial stress and/or a history of physicians who have dismissed the patient’s concerns about his or her hair loss as trivial. Establishing an effective doctor-patient relationship is key in treating alopecia. Physicians sometimes may be left feeling like the patient wants to keep them in the room until his or her hair regrows, but in reality you simply need to reassure the patient that you are comfortable with the evaluation and treatment of alopecia and that several steps will be required but you will get started today.

How do you use punch biopsies to determine the best treatment options?

My most important tips regarding alopecia diagnosis relate to scalp biopsies, which usually are required in distinguishing chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other scarring alopecias. First, an absorbable gelatin compressed sponge is your best friend. A small strip inserted into the punch biopsy wound results in prompt hemostasis without the need for sutures, and the resulting scar often looks as good or better than that produced by suturing. Next, don’t biopsy the active advancing borders of an alopecia patch, as the findings usually are nonspecific. Instead, biopsy a well-established portion that has been present for at least 4 to 6 months but is still active. In inconclusive cases, a biopsy of a scarred area stained with Verhoeff elastic stain can demonstrate characteristic patterns of elastic tissue loss and often establish a diagnosis. It is important to distinguish chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other forms of scarring alopecia, as it is more likely to respond to antimalarials.

What are your go-to treatments? Are your recommendations anecdotal or evidence based?

There isn’t an extensive arsenal of evidence-based therapy for refractory scarring alopecia, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have effective therapies; it simply means that our treatments are based on experience without accompanying randomized controlled trials. We need to produce more evidence, but patients with severe disease still need to be treated in the meantime. It’s important to remember that therapeutic complacency can result in permanent irreversible scarring. The presence of easily extractable anagen hairs is a sign of active disease. This simple test is helpful to monitor therapeutic progress.

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids can be extremely useful and often are underused. In general, the risk of scarring and atrophy from untreated disease is much greater than that from the corticosteroid. On the scalp, atrophy often presents as erythema, which should not be confused with erythema related to active disease. Dermoscopy is useful to demonstrate that the redness represents dermal atrophy with prominence of the subpapillary plexus of vessels.

When systemic therapy is required, antimalarials, retinoids, dapsone, thalidomide, sulfasalazine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have all been used successfully in the setting of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, while topical tazarotene and topical calcineurin inhibitors are generally disappointing.

For the treatment of lichen planopilaris, intralesional corticosteroids, oral retinoids, and excimer laser can be effective. In contrast, antimalarials usually are not effective in preventing disease progression. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist pioglitazone can be effective, but reported results vary widely. In my experience, mycophenolate mofetil is generally reliable in patients with refractory disease. Dutasteride can be effective as a first-line therapy in the setting of frontal fibrosing alopecia, although some of the noted improvement may relate to the nonscarring portion of the disease in patients with a background of pattern alopecia.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Again, the key to treatment compliance is to establish an effective doctor-patient relationship. Whenever possible, begin with adequately potent therapy to give patients an early response. Don’t hesitate to use prednisone initially for inflammatory scarring alopecia. Patients need to see signs of progress in order to stay compliant with treatment, and long trials of ineffective therapies destroy trust. Adequate doses of intralesional or oral corticosteroids often are appropriate to ensure an early response with subsequent transition to steroid-sparing agents.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Try to find out why—often it’s simply fear of side effects. Patient education is key, and it can help tremendously to share with them the number of patients you have treated safely with the medication in question and assure them that you know how to monitor for the important side effects.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is helpful to keep a handy list of patient advocacy Web sites. Well-established support groups such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (https://www.naaf.org) and the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org) provide excellent information for patients and help to support research to improve outcomes for these difficult disorders.

What does the patient need to know at the first visit?

When I communicate with alopecia patients at the first visit, I make sure they know that I’m there to help them—that I won’t minimize their concerns and that I understand how important their condition is to them. Alopecia can be frustrating for both the patient and the physician, and there often is a confounding background of psychosocial stress and/or a history of physicians who have dismissed the patient’s concerns about his or her hair loss as trivial. Establishing an effective doctor-patient relationship is key in treating alopecia. Physicians sometimes may be left feeling like the patient wants to keep them in the room until his or her hair regrows, but in reality you simply need to reassure the patient that you are comfortable with the evaluation and treatment of alopecia and that several steps will be required but you will get started today.

How do you use punch biopsies to determine the best treatment options?

My most important tips regarding alopecia diagnosis relate to scalp biopsies, which usually are required in distinguishing chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other scarring alopecias. First, an absorbable gelatin compressed sponge is your best friend. A small strip inserted into the punch biopsy wound results in prompt hemostasis without the need for sutures, and the resulting scar often looks as good or better than that produced by suturing. Next, don’t biopsy the active advancing borders of an alopecia patch, as the findings usually are nonspecific. Instead, biopsy a well-established portion that has been present for at least 4 to 6 months but is still active. In inconclusive cases, a biopsy of a scarred area stained with Verhoeff elastic stain can demonstrate characteristic patterns of elastic tissue loss and often establish a diagnosis. It is important to distinguish chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus from other forms of scarring alopecia, as it is more likely to respond to antimalarials.

What are your go-to treatments? Are your recommendations anecdotal or evidence based?

There isn’t an extensive arsenal of evidence-based therapy for refractory scarring alopecia, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have effective therapies; it simply means that our treatments are based on experience without accompanying randomized controlled trials. We need to produce more evidence, but patients with severe disease still need to be treated in the meantime. It’s important to remember that therapeutic complacency can result in permanent irreversible scarring. The presence of easily extractable anagen hairs is a sign of active disease. This simple test is helpful to monitor therapeutic progress.

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids can be extremely useful and often are underused. In general, the risk of scarring and atrophy from untreated disease is much greater than that from the corticosteroid. On the scalp, atrophy often presents as erythema, which should not be confused with erythema related to active disease. Dermoscopy is useful to demonstrate that the redness represents dermal atrophy with prominence of the subpapillary plexus of vessels.

When systemic therapy is required, antimalarials, retinoids, dapsone, thalidomide, sulfasalazine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have all been used successfully in the setting of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, while topical tazarotene and topical calcineurin inhibitors are generally disappointing.

For the treatment of lichen planopilaris, intralesional corticosteroids, oral retinoids, and excimer laser can be effective. In contrast, antimalarials usually are not effective in preventing disease progression. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist pioglitazone can be effective, but reported results vary widely. In my experience, mycophenolate mofetil is generally reliable in patients with refractory disease. Dutasteride can be effective as a first-line therapy in the setting of frontal fibrosing alopecia, although some of the noted improvement may relate to the nonscarring portion of the disease in patients with a background of pattern alopecia.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Again, the key to treatment compliance is to establish an effective doctor-patient relationship. Whenever possible, begin with adequately potent therapy to give patients an early response. Don’t hesitate to use prednisone initially for inflammatory scarring alopecia. Patients need to see signs of progress in order to stay compliant with treatment, and long trials of ineffective therapies destroy trust. Adequate doses of intralesional or oral corticosteroids often are appropriate to ensure an early response with subsequent transition to steroid-sparing agents.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Try to find out why—often it’s simply fear of side effects. Patient education is key, and it can help tremendously to share with them the number of patients you have treated safely with the medication in question and assure them that you know how to monitor for the important side effects.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

It is helpful to keep a handy list of patient advocacy Web sites. Well-established support groups such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (https://www.naaf.org) and the Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (http://www.carfintl.org) provide excellent information for patients and help to support research to improve outcomes for these difficult disorders.

New antifungals effective with shorter treatment course for tinea pedis

LAS VEGAS – Tinea pedis plagues millions of patients yearly, and treatment is lengthy, cumbersome, and often ineffective.

But two potent new antifungals promise an easier treatment regimen and a higher rate of successful treatment outcomes, according to Dr. David M. Pariser, who shared data about luliconazole and a new formulation of naftifine as topical treatments for tinea infections, at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar.

Dr. Pariser, professor in the department of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, pointed out that most antifungals currently approved for tinea pedis require at least daily – and sometimes twice daily – application for at least 4 weeks. Terbinafine and tolnaftate are the exceptions, with treatment periods ranging from 1-6 weeks for the two products, depending on clinical response.

A new formulation of naftifine hydrochloride 2%, (Naftin), a potent prescription topical allylamine antifungal available as a cream or a gel, has shown equivalent efficacy with just two weeks of treatment. Naftifine has lipophilic and keratinophilic properties; further, it has clinically significant anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects, in addition to its potent fungicidal and fungistatic effects against dermatophytes, Dr. Pariser said at the meeting. The preparations are currently approved for topical treatment of tinea pedis, tinea cruris, and tinea corporis.

Notably, naftifine maintains a “clinically relevant therapeutic reservoir effect after treatment completion, with naftifine detected in the stratum corneum for up to 4 weeks posttreatment,” he said. This reservoir effect permits a significantly easier treatment regimen, with topical application of either formulation daily for just 2 weeks.

The clinical trials of naftifine HCl 2% with daily administration for 2 weeks showed equivalence with the 1% formulation administered for 4 weeks; the higher concentration was well tolerated and was effective in both the moccasin and interdigital distributions of tinea pedis involvement. Trials also showed the mycologic and clinical cure rates of naftifine 2% to be equivalent or superior to those of terbinafine, econazole, clotrimazole, miconazole, and tolnaftate.

Clinical trials showed treatment effectiveness – defined as 90% improvement over baseline and achieving “essentially normal skin” – in 52% of patients receiving naftifine 2%, compared with 20% of patients receiving vehicle only. Overall clinical success – defined as mycologic cure and either clinical cure of effective clinical treatment – was seen in 78% of the naftifine 2% patients, compared with 49% of the vehicle patients.

The second antifungal Dr. Pariser discussed is luliconazole (Luzu), a prescription topical imidazole that is available as a 1% cream. Luliconazole is also a broad-spectrum, potent antifungal with effects that persist several weeks after treatment. The preparation is at least as effective as bifonazole, terbinafine, and lanoconazole, both in vitro and in vivo, Dr. Pariser said.

In two parallel clinical trials comparing luliconazole 1% cream to its vehicle, treatment was effective (at least 90% clearing and with normal-appearing skin) in 48% and 33% of patients receiving luliconazole, compared with 10% and 15% of patients receiving vehicle alone.

An advantage of the topical agents is that there are generally no major systemic side effects, since there is minimal systemic absorption, Dr. Pariser noted. Allergic contact dermatitis may be a local reaction, but tends to be mild and transient, he said.

Clinicians should always be alert for tinea pedis when treating onychomycosis, said Dr. Pariser, and untreated tinea can contribute to recurrence of nail fungus. “If you don’t look for tinea, you might not find it, and you’ve missed a treatment opportunity,” he said.

Dr. Pariser disclosed that he is an investigator and consultant for Valeant and an investigator for Anacor Pharmaceuticals.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Tinea pedis plagues millions of patients yearly, and treatment is lengthy, cumbersome, and often ineffective.

But two potent new antifungals promise an easier treatment regimen and a higher rate of successful treatment outcomes, according to Dr. David M. Pariser, who shared data about luliconazole and a new formulation of naftifine as topical treatments for tinea infections, at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar.

Dr. Pariser, professor in the department of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, pointed out that most antifungals currently approved for tinea pedis require at least daily – and sometimes twice daily – application for at least 4 weeks. Terbinafine and tolnaftate are the exceptions, with treatment periods ranging from 1-6 weeks for the two products, depending on clinical response.

A new formulation of naftifine hydrochloride 2%, (Naftin), a potent prescription topical allylamine antifungal available as a cream or a gel, has shown equivalent efficacy with just two weeks of treatment. Naftifine has lipophilic and keratinophilic properties; further, it has clinically significant anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects, in addition to its potent fungicidal and fungistatic effects against dermatophytes, Dr. Pariser said at the meeting. The preparations are currently approved for topical treatment of tinea pedis, tinea cruris, and tinea corporis.

Notably, naftifine maintains a “clinically relevant therapeutic reservoir effect after treatment completion, with naftifine detected in the stratum corneum for up to 4 weeks posttreatment,” he said. This reservoir effect permits a significantly easier treatment regimen, with topical application of either formulation daily for just 2 weeks.

The clinical trials of naftifine HCl 2% with daily administration for 2 weeks showed equivalence with the 1% formulation administered for 4 weeks; the higher concentration was well tolerated and was effective in both the moccasin and interdigital distributions of tinea pedis involvement. Trials also showed the mycologic and clinical cure rates of naftifine 2% to be equivalent or superior to those of terbinafine, econazole, clotrimazole, miconazole, and tolnaftate.

Clinical trials showed treatment effectiveness – defined as 90% improvement over baseline and achieving “essentially normal skin” – in 52% of patients receiving naftifine 2%, compared with 20% of patients receiving vehicle only. Overall clinical success – defined as mycologic cure and either clinical cure of effective clinical treatment – was seen in 78% of the naftifine 2% patients, compared with 49% of the vehicle patients.

The second antifungal Dr. Pariser discussed is luliconazole (Luzu), a prescription topical imidazole that is available as a 1% cream. Luliconazole is also a broad-spectrum, potent antifungal with effects that persist several weeks after treatment. The preparation is at least as effective as bifonazole, terbinafine, and lanoconazole, both in vitro and in vivo, Dr. Pariser said.

In two parallel clinical trials comparing luliconazole 1% cream to its vehicle, treatment was effective (at least 90% clearing and with normal-appearing skin) in 48% and 33% of patients receiving luliconazole, compared with 10% and 15% of patients receiving vehicle alone.

An advantage of the topical agents is that there are generally no major systemic side effects, since there is minimal systemic absorption, Dr. Pariser noted. Allergic contact dermatitis may be a local reaction, but tends to be mild and transient, he said.

Clinicians should always be alert for tinea pedis when treating onychomycosis, said Dr. Pariser, and untreated tinea can contribute to recurrence of nail fungus. “If you don’t look for tinea, you might not find it, and you’ve missed a treatment opportunity,” he said.

Dr. Pariser disclosed that he is an investigator and consultant for Valeant and an investigator for Anacor Pharmaceuticals.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Tinea pedis plagues millions of patients yearly, and treatment is lengthy, cumbersome, and often ineffective.

But two potent new antifungals promise an easier treatment regimen and a higher rate of successful treatment outcomes, according to Dr. David M. Pariser, who shared data about luliconazole and a new formulation of naftifine as topical treatments for tinea infections, at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar.

Dr. Pariser, professor in the department of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, pointed out that most antifungals currently approved for tinea pedis require at least daily – and sometimes twice daily – application for at least 4 weeks. Terbinafine and tolnaftate are the exceptions, with treatment periods ranging from 1-6 weeks for the two products, depending on clinical response.

A new formulation of naftifine hydrochloride 2%, (Naftin), a potent prescription topical allylamine antifungal available as a cream or a gel, has shown equivalent efficacy with just two weeks of treatment. Naftifine has lipophilic and keratinophilic properties; further, it has clinically significant anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects, in addition to its potent fungicidal and fungistatic effects against dermatophytes, Dr. Pariser said at the meeting. The preparations are currently approved for topical treatment of tinea pedis, tinea cruris, and tinea corporis.

Notably, naftifine maintains a “clinically relevant therapeutic reservoir effect after treatment completion, with naftifine detected in the stratum corneum for up to 4 weeks posttreatment,” he said. This reservoir effect permits a significantly easier treatment regimen, with topical application of either formulation daily for just 2 weeks.

The clinical trials of naftifine HCl 2% with daily administration for 2 weeks showed equivalence with the 1% formulation administered for 4 weeks; the higher concentration was well tolerated and was effective in both the moccasin and interdigital distributions of tinea pedis involvement. Trials also showed the mycologic and clinical cure rates of naftifine 2% to be equivalent or superior to those of terbinafine, econazole, clotrimazole, miconazole, and tolnaftate.

Clinical trials showed treatment effectiveness – defined as 90% improvement over baseline and achieving “essentially normal skin” – in 52% of patients receiving naftifine 2%, compared with 20% of patients receiving vehicle only. Overall clinical success – defined as mycologic cure and either clinical cure of effective clinical treatment – was seen in 78% of the naftifine 2% patients, compared with 49% of the vehicle patients.

The second antifungal Dr. Pariser discussed is luliconazole (Luzu), a prescription topical imidazole that is available as a 1% cream. Luliconazole is also a broad-spectrum, potent antifungal with effects that persist several weeks after treatment. The preparation is at least as effective as bifonazole, terbinafine, and lanoconazole, both in vitro and in vivo, Dr. Pariser said.

In two parallel clinical trials comparing luliconazole 1% cream to its vehicle, treatment was effective (at least 90% clearing and with normal-appearing skin) in 48% and 33% of patients receiving luliconazole, compared with 10% and 15% of patients receiving vehicle alone.

An advantage of the topical agents is that there are generally no major systemic side effects, since there is minimal systemic absorption, Dr. Pariser noted. Allergic contact dermatitis may be a local reaction, but tends to be mild and transient, he said.

Clinicians should always be alert for tinea pedis when treating onychomycosis, said Dr. Pariser, and untreated tinea can contribute to recurrence of nail fungus. “If you don’t look for tinea, you might not find it, and you’ve missed a treatment opportunity,” he said.

Dr. Pariser disclosed that he is an investigator and consultant for Valeant and an investigator for Anacor Pharmaceuticals.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

SDEF: Improved responses with newer topical onychomycosis treatments

LAS VEGAS – Better penetration through the nail is a key driver behind the increased efficacy of newer topical treatments for onychomycosis, affording a better chance for a clinical and mycologic cure without the potential for toxicity that comes with systemic treatments, according to Dr. David M. Pariser.

At the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar, Dr. Pariser, professor in the department of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, reviewed clinical trial data for 10% topical efinaconazole solution and 5% tavaborole topical solution, newer treatment options for the old problem of nail fungus. “New topical antifungals have improved the challenge of nail penetration,” which had been a key obstacle to efficacy with earlier topical treatments, he said.

Though topical treatments for onychomycosis avoid the risk of systemic side effects and the need for periodic blood tests to check liver function, historically, these treatments have not been very effective, he commented.

Ciclopirox (Penlac), one of the more efficacious treatments, achieves a cure rate of 5.5%-8.5%, and the buildup of the lacquer vehicle requires frequent nail debridement. Because of real or perceived risks, patients may be reluctant to take oral antifungals for onychomycosis, he said, noting that in addition to the potential for liver injury, use of these medications may also be limited by multiple drug-drug interactions.

The two new topical formulations he reviewed have a low molecular weight to allow better penetration through the dense, keratin-rich nail plate, Dr. Pariser said.

One of the topicals, 10% topical efinaconazole solution (Jublia), uses a formulation with low surface tension for good penetration with no surface buildup of vehicle material, achieving better nail penetration than do lacquer-based products, he noted.

A key efinaconazole study assessed clinical improvement in nail appearance in combination with mycologic cure, defined as negative findings on KOH prep exam and negative fungal culture. A complete cure was defined as a “totally clear target toenail and negative KOH/negative fungal culture,” and an “almost complete cure” was defined as mycologic cure, combined with no more than 5% clinically apparent involvement of the target toenail.

After double-blinded randomization into two parallel studies, patients applied either efinaconazole or the vehicle alone once daily at bedtime to the target toenail for 48 weeks. In the studies, 18% and 15% of those in the efinaconazole arm had achieved complete cure 52 weeks after beginning treatment, compared with 3% and 6% of the vehicle arm patients, respectively. However, for a pooled intent-to-treat population, the treatment arm saw a 28% cured or almost-cured rate, compared with 7% of the pooled vehicle-treated patients (P less than .001). Mycologic cure was achieved by 55% and 53% of the patients in the two efinaconazole arms, compared with 17% of the vehicle-only patients in each arm, according to Dr. Pariser.

Adverse events, similar between treatment arms, were mostly mild to moderate and localized, with dermatitis, vesicles, pain, and ingrown toenails the most commonly reported effects.

Tavaborole topical solution, 5% (Kerydin), is a boron-based compound that is highly water soluble, with broad antifungal activity that persists in the presence of keratin. As with efinaconazole, there is no product buildup, so nail debridement is not needed during treatment, Dr. Pariser said.

Two multicenter tavaborole trials compared the active tavaborole solution with a vehicle-only arm in a randomized, double-blind fashion, with product application daily for 48 weeks. The primary efficacy outcome for the trials was complete cure of the target great toenail at week 52. Secondary endpoints were a completely clear or almost clear (10% or less involvement of the target nail) target great toenail, as well as mycologic cure of the nail. Safety was measured by tracking adverse events, and local tolerability, as well as monitoring labs and ECG parameters.

A complete cure for the tavaborole trials required a completely clear nail on clinical exam, as well as negative mycology (negative KOH and negative fungal culture). At 52 weeks, 6.5% and 9.1% of the tavaborole-treated patients saw a complete cure, compared with 0.5% and 1.5% of vehicle-only patients in the two studies. Of those treated with tavaborole, 31.1% and 35.9% achieved mycologic cure, compared with 7.2% and 12.2% of those in the vehicle arm.

The rates of complete or almost complete clearing of the target great toenail for those in the tavaborole arms were 26.1% and 27.5%, compared with 9.3% and 14.6% in the vehicle arms. Predefined treatment success – a combination of mycologic cure and clear or almost clear target great toenail – was seen in 15.3% and 17.9% of the tavaborole-treated patients, compared with 1.5% and 3.9% of the vehicle-only patients (P less than or equal to .001 for all endpoints in both studies).

Treatment-related adverse events were generally mild and similar between the vehicle and treatment arms, with application site exfoliation, erythema, dermatitis, as well as ingrown toenails, the most commonly reported events for both arms.

Dr. Pariser noted that comparing efficacy of the newer agents directly is difficult, since the pivotal clinical trials for each had different designs, entry criteria, clinical assessments, and endpoints.

He disclosed that he is an investigator and consultant for Valeant, which manufactures the 10% topical efinaconazole solution, and an investigator for Anacor Pharmaceuticals, which markets tavaborole.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Better penetration through the nail is a key driver behind the increased efficacy of newer topical treatments for onychomycosis, affording a better chance for a clinical and mycologic cure without the potential for toxicity that comes with systemic treatments, according to Dr. David M. Pariser.

At the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar, Dr. Pariser, professor in the department of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, reviewed clinical trial data for 10% topical efinaconazole solution and 5% tavaborole topical solution, newer treatment options for the old problem of nail fungus. “New topical antifungals have improved the challenge of nail penetration,” which had been a key obstacle to efficacy with earlier topical treatments, he said.

Though topical treatments for onychomycosis avoid the risk of systemic side effects and the need for periodic blood tests to check liver function, historically, these treatments have not been very effective, he commented.

Ciclopirox (Penlac), one of the more efficacious treatments, achieves a cure rate of 5.5%-8.5%, and the buildup of the lacquer vehicle requires frequent nail debridement. Because of real or perceived risks, patients may be reluctant to take oral antifungals for onychomycosis, he said, noting that in addition to the potential for liver injury, use of these medications may also be limited by multiple drug-drug interactions.

The two new topical formulations he reviewed have a low molecular weight to allow better penetration through the dense, keratin-rich nail plate, Dr. Pariser said.

One of the topicals, 10% topical efinaconazole solution (Jublia), uses a formulation with low surface tension for good penetration with no surface buildup of vehicle material, achieving better nail penetration than do lacquer-based products, he noted.

A key efinaconazole study assessed clinical improvement in nail appearance in combination with mycologic cure, defined as negative findings on KOH prep exam and negative fungal culture. A complete cure was defined as a “totally clear target toenail and negative KOH/negative fungal culture,” and an “almost complete cure” was defined as mycologic cure, combined with no more than 5% clinically apparent involvement of the target toenail.

After double-blinded randomization into two parallel studies, patients applied either efinaconazole or the vehicle alone once daily at bedtime to the target toenail for 48 weeks. In the studies, 18% and 15% of those in the efinaconazole arm had achieved complete cure 52 weeks after beginning treatment, compared with 3% and 6% of the vehicle arm patients, respectively. However, for a pooled intent-to-treat population, the treatment arm saw a 28% cured or almost-cured rate, compared with 7% of the pooled vehicle-treated patients (P less than .001). Mycologic cure was achieved by 55% and 53% of the patients in the two efinaconazole arms, compared with 17% of the vehicle-only patients in each arm, according to Dr. Pariser.

Adverse events, similar between treatment arms, were mostly mild to moderate and localized, with dermatitis, vesicles, pain, and ingrown toenails the most commonly reported effects.

Tavaborole topical solution, 5% (Kerydin), is a boron-based compound that is highly water soluble, with broad antifungal activity that persists in the presence of keratin. As with efinaconazole, there is no product buildup, so nail debridement is not needed during treatment, Dr. Pariser said.

Two multicenter tavaborole trials compared the active tavaborole solution with a vehicle-only arm in a randomized, double-blind fashion, with product application daily for 48 weeks. The primary efficacy outcome for the trials was complete cure of the target great toenail at week 52. Secondary endpoints were a completely clear or almost clear (10% or less involvement of the target nail) target great toenail, as well as mycologic cure of the nail. Safety was measured by tracking adverse events, and local tolerability, as well as monitoring labs and ECG parameters.

A complete cure for the tavaborole trials required a completely clear nail on clinical exam, as well as negative mycology (negative KOH and negative fungal culture). At 52 weeks, 6.5% and 9.1% of the tavaborole-treated patients saw a complete cure, compared with 0.5% and 1.5% of vehicle-only patients in the two studies. Of those treated with tavaborole, 31.1% and 35.9% achieved mycologic cure, compared with 7.2% and 12.2% of those in the vehicle arm.

The rates of complete or almost complete clearing of the target great toenail for those in the tavaborole arms were 26.1% and 27.5%, compared with 9.3% and 14.6% in the vehicle arms. Predefined treatment success – a combination of mycologic cure and clear or almost clear target great toenail – was seen in 15.3% and 17.9% of the tavaborole-treated patients, compared with 1.5% and 3.9% of the vehicle-only patients (P less than or equal to .001 for all endpoints in both studies).

Treatment-related adverse events were generally mild and similar between the vehicle and treatment arms, with application site exfoliation, erythema, dermatitis, as well as ingrown toenails, the most commonly reported events for both arms.

Dr. Pariser noted that comparing efficacy of the newer agents directly is difficult, since the pivotal clinical trials for each had different designs, entry criteria, clinical assessments, and endpoints.

He disclosed that he is an investigator and consultant for Valeant, which manufactures the 10% topical efinaconazole solution, and an investigator for Anacor Pharmaceuticals, which markets tavaborole.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Better penetration through the nail is a key driver behind the increased efficacy of newer topical treatments for onychomycosis, affording a better chance for a clinical and mycologic cure without the potential for toxicity that comes with systemic treatments, according to Dr. David M. Pariser.

At the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar, Dr. Pariser, professor in the department of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, reviewed clinical trial data for 10% topical efinaconazole solution and 5% tavaborole topical solution, newer treatment options for the old problem of nail fungus. “New topical antifungals have improved the challenge of nail penetration,” which had been a key obstacle to efficacy with earlier topical treatments, he said.

Though topical treatments for onychomycosis avoid the risk of systemic side effects and the need for periodic blood tests to check liver function, historically, these treatments have not been very effective, he commented.

Ciclopirox (Penlac), one of the more efficacious treatments, achieves a cure rate of 5.5%-8.5%, and the buildup of the lacquer vehicle requires frequent nail debridement. Because of real or perceived risks, patients may be reluctant to take oral antifungals for onychomycosis, he said, noting that in addition to the potential for liver injury, use of these medications may also be limited by multiple drug-drug interactions.

The two new topical formulations he reviewed have a low molecular weight to allow better penetration through the dense, keratin-rich nail plate, Dr. Pariser said.

One of the topicals, 10% topical efinaconazole solution (Jublia), uses a formulation with low surface tension for good penetration with no surface buildup of vehicle material, achieving better nail penetration than do lacquer-based products, he noted.

A key efinaconazole study assessed clinical improvement in nail appearance in combination with mycologic cure, defined as negative findings on KOH prep exam and negative fungal culture. A complete cure was defined as a “totally clear target toenail and negative KOH/negative fungal culture,” and an “almost complete cure” was defined as mycologic cure, combined with no more than 5% clinically apparent involvement of the target toenail.

After double-blinded randomization into two parallel studies, patients applied either efinaconazole or the vehicle alone once daily at bedtime to the target toenail for 48 weeks. In the studies, 18% and 15% of those in the efinaconazole arm had achieved complete cure 52 weeks after beginning treatment, compared with 3% and 6% of the vehicle arm patients, respectively. However, for a pooled intent-to-treat population, the treatment arm saw a 28% cured or almost-cured rate, compared with 7% of the pooled vehicle-treated patients (P less than .001). Mycologic cure was achieved by 55% and 53% of the patients in the two efinaconazole arms, compared with 17% of the vehicle-only patients in each arm, according to Dr. Pariser.

Adverse events, similar between treatment arms, were mostly mild to moderate and localized, with dermatitis, vesicles, pain, and ingrown toenails the most commonly reported effects.

Tavaborole topical solution, 5% (Kerydin), is a boron-based compound that is highly water soluble, with broad antifungal activity that persists in the presence of keratin. As with efinaconazole, there is no product buildup, so nail debridement is not needed during treatment, Dr. Pariser said.

Two multicenter tavaborole trials compared the active tavaborole solution with a vehicle-only arm in a randomized, double-blind fashion, with product application daily for 48 weeks. The primary efficacy outcome for the trials was complete cure of the target great toenail at week 52. Secondary endpoints were a completely clear or almost clear (10% or less involvement of the target nail) target great toenail, as well as mycologic cure of the nail. Safety was measured by tracking adverse events, and local tolerability, as well as monitoring labs and ECG parameters.

A complete cure for the tavaborole trials required a completely clear nail on clinical exam, as well as negative mycology (negative KOH and negative fungal culture). At 52 weeks, 6.5% and 9.1% of the tavaborole-treated patients saw a complete cure, compared with 0.5% and 1.5% of vehicle-only patients in the two studies. Of those treated with tavaborole, 31.1% and 35.9% achieved mycologic cure, compared with 7.2% and 12.2% of those in the vehicle arm.

The rates of complete or almost complete clearing of the target great toenail for those in the tavaborole arms were 26.1% and 27.5%, compared with 9.3% and 14.6% in the vehicle arms. Predefined treatment success – a combination of mycologic cure and clear or almost clear target great toenail – was seen in 15.3% and 17.9% of the tavaborole-treated patients, compared with 1.5% and 3.9% of the vehicle-only patients (P less than or equal to .001 for all endpoints in both studies).

Treatment-related adverse events were generally mild and similar between the vehicle and treatment arms, with application site exfoliation, erythema, dermatitis, as well as ingrown toenails, the most commonly reported events for both arms.

Dr. Pariser noted that comparing efficacy of the newer agents directly is difficult, since the pivotal clinical trials for each had different designs, entry criteria, clinical assessments, and endpoints.

He disclosed that he is an investigator and consultant for Valeant, which manufactures the 10% topical efinaconazole solution, and an investigator for Anacor Pharmaceuticals, which markets tavaborole.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Recurrent Omphalitis Secondary to a Hair-Containing Umbilical Foreign Body

To the Editor:

We read with great interest the article, “Omphalith-Associated Relapsing Umbilical Cellulitis: Recurrent Omphalitis Secondary to a Hair-Containing Belly Button Bezoar” (Cutis. 2010;86:199-202), which introduced the terms omphalotrich and tricomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body in an 18-year-old man. We report a similar case.

A 38-year-old man presented with a 10-year history of an unusual odor in the umbilical region with recurrent discharge. He diligently maintained proper hygiene of the umbilicus using cotton swabs and had received recurrent cycles of oral antibiotics prescribed by his general practitioner with temporary improvement of the odor and amount of discharge. Physical examination revealed a normal umbilicus with a deep and tight umbilical cleft that required the use of curved mosquito forceps for further examination (Figure 1). A bezoar comprised of a compact collection of terminal hair shafts was noted deep in the umbilicus (Figure 2). A considerable amount of terminal hairs also were noted on the skin of the abdominal area. Following removal of the bezoar, no umbilical fistula was observed, and the presence of embryologic abnormalities (eg, omphalomesenteric duct remnants) was ruled out on magnetic resonance imaging. A diagnosis of recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing bezoar was made. Following extraction of the bezoar, the odor and discharge promptly resolved, thereby avoiding the need for oral antibiotics; however, a smaller bezoar comprised of a collection of terminal hair shafts was removed 4 months later.

|

| |

Figure 1. Deep and narrow umbilical cleft with serous exudate in the umbilicus after removal of the foreign body. | Figure 2. A section of the umbilical foreign body composed of a collection of terminal hair shafts. |

An omphalith is an umbilical foreign body that results from the accumulation of keratinous and amorphous sebaceous material.2 Several predisposing factors have been proposed for its pathogenesis, such as the anatomical disposition of the umbilicus and the patient’s hygiene. We hypothesize that a deep umbilicus and a large amount of terminal hairs in the abdominal area were predisposing factors in our patient. Cohen et al1 proposed the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body that did not have the characteristic stonelike presentation of a traditional omphalith. The authors also referred to the umbilical foreign body in their patient as a trichobezoar, a term used to describe exogenous foreign bodies composed of ingested hair in the gastrointestinal tract, given the embryologic origin of the umbilicus and epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract. We agree that the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith appropriately describe the current presentation; we also propose the terms omphalitrichia or thricomphalia to describe the findings seen in our patient, which should always be ruled out in patients with recurrent omphalitis that is unresponsive to antibiotics.

1. Cohen PR, Robinson FW, Gray JM. Omphalith-associated relapsing umbilical cellulitis: recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing belly button bezoar. Cutis. 2010;86:199-202.

2. Swanson SL, Woosley JT, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Umbilical mass. omphalith. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1267, 1270.

To the Editor:

We read with great interest the article, “Omphalith-Associated Relapsing Umbilical Cellulitis: Recurrent Omphalitis Secondary to a Hair-Containing Belly Button Bezoar” (Cutis. 2010;86:199-202), which introduced the terms omphalotrich and tricomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body in an 18-year-old man. We report a similar case.

A 38-year-old man presented with a 10-year history of an unusual odor in the umbilical region with recurrent discharge. He diligently maintained proper hygiene of the umbilicus using cotton swabs and had received recurrent cycles of oral antibiotics prescribed by his general practitioner with temporary improvement of the odor and amount of discharge. Physical examination revealed a normal umbilicus with a deep and tight umbilical cleft that required the use of curved mosquito forceps for further examination (Figure 1). A bezoar comprised of a compact collection of terminal hair shafts was noted deep in the umbilicus (Figure 2). A considerable amount of terminal hairs also were noted on the skin of the abdominal area. Following removal of the bezoar, no umbilical fistula was observed, and the presence of embryologic abnormalities (eg, omphalomesenteric duct remnants) was ruled out on magnetic resonance imaging. A diagnosis of recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing bezoar was made. Following extraction of the bezoar, the odor and discharge promptly resolved, thereby avoiding the need for oral antibiotics; however, a smaller bezoar comprised of a collection of terminal hair shafts was removed 4 months later.

|

| |

Figure 1. Deep and narrow umbilical cleft with serous exudate in the umbilicus after removal of the foreign body. | Figure 2. A section of the umbilical foreign body composed of a collection of terminal hair shafts. |

An omphalith is an umbilical foreign body that results from the accumulation of keratinous and amorphous sebaceous material.2 Several predisposing factors have been proposed for its pathogenesis, such as the anatomical disposition of the umbilicus and the patient’s hygiene. We hypothesize that a deep umbilicus and a large amount of terminal hairs in the abdominal area were predisposing factors in our patient. Cohen et al1 proposed the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body that did not have the characteristic stonelike presentation of a traditional omphalith. The authors also referred to the umbilical foreign body in their patient as a trichobezoar, a term used to describe exogenous foreign bodies composed of ingested hair in the gastrointestinal tract, given the embryologic origin of the umbilicus and epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract. We agree that the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith appropriately describe the current presentation; we also propose the terms omphalitrichia or thricomphalia to describe the findings seen in our patient, which should always be ruled out in patients with recurrent omphalitis that is unresponsive to antibiotics.

To the Editor:

We read with great interest the article, “Omphalith-Associated Relapsing Umbilical Cellulitis: Recurrent Omphalitis Secondary to a Hair-Containing Belly Button Bezoar” (Cutis. 2010;86:199-202), which introduced the terms omphalotrich and tricomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body in an 18-year-old man. We report a similar case.

A 38-year-old man presented with a 10-year history of an unusual odor in the umbilical region with recurrent discharge. He diligently maintained proper hygiene of the umbilicus using cotton swabs and had received recurrent cycles of oral antibiotics prescribed by his general practitioner with temporary improvement of the odor and amount of discharge. Physical examination revealed a normal umbilicus with a deep and tight umbilical cleft that required the use of curved mosquito forceps for further examination (Figure 1). A bezoar comprised of a compact collection of terminal hair shafts was noted deep in the umbilicus (Figure 2). A considerable amount of terminal hairs also were noted on the skin of the abdominal area. Following removal of the bezoar, no umbilical fistula was observed, and the presence of embryologic abnormalities (eg, omphalomesenteric duct remnants) was ruled out on magnetic resonance imaging. A diagnosis of recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing bezoar was made. Following extraction of the bezoar, the odor and discharge promptly resolved, thereby avoiding the need for oral antibiotics; however, a smaller bezoar comprised of a collection of terminal hair shafts was removed 4 months later.

|

| |

Figure 1. Deep and narrow umbilical cleft with serous exudate in the umbilicus after removal of the foreign body. | Figure 2. A section of the umbilical foreign body composed of a collection of terminal hair shafts. |

An omphalith is an umbilical foreign body that results from the accumulation of keratinous and amorphous sebaceous material.2 Several predisposing factors have been proposed for its pathogenesis, such as the anatomical disposition of the umbilicus and the patient’s hygiene. We hypothesize that a deep umbilicus and a large amount of terminal hairs in the abdominal area were predisposing factors in our patient. Cohen et al1 proposed the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith to describe the pilar composition of a hair-containing umbilical foreign body that did not have the characteristic stonelike presentation of a traditional omphalith. The authors also referred to the umbilical foreign body in their patient as a trichobezoar, a term used to describe exogenous foreign bodies composed of ingested hair in the gastrointestinal tract, given the embryologic origin of the umbilicus and epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract. We agree that the terms omphalotrich and trichomphalith appropriately describe the current presentation; we also propose the terms omphalitrichia or thricomphalia to describe the findings seen in our patient, which should always be ruled out in patients with recurrent omphalitis that is unresponsive to antibiotics.

1. Cohen PR, Robinson FW, Gray JM. Omphalith-associated relapsing umbilical cellulitis: recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing belly button bezoar. Cutis. 2010;86:199-202.

2. Swanson SL, Woosley JT, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Umbilical mass. omphalith. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1267, 1270.

1. Cohen PR, Robinson FW, Gray JM. Omphalith-associated relapsing umbilical cellulitis: recurrent omphalitis secondary to a hair-containing belly button bezoar. Cutis. 2010;86:199-202.

2. Swanson SL, Woosley JT, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Umbilical mass. omphalith. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1267, 1270.

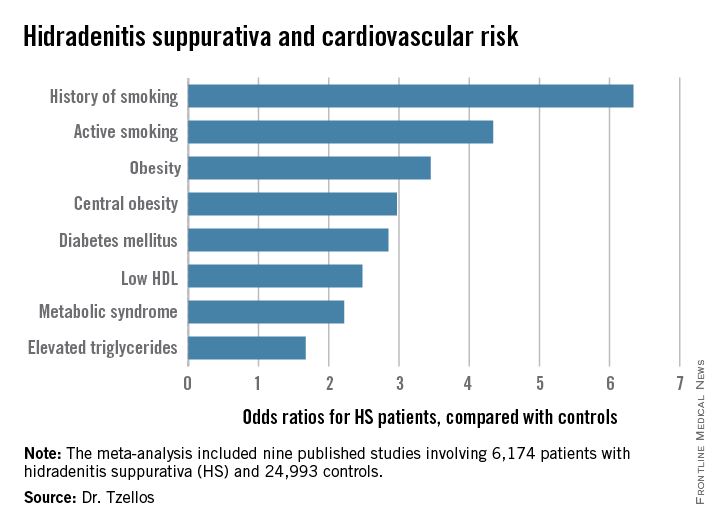

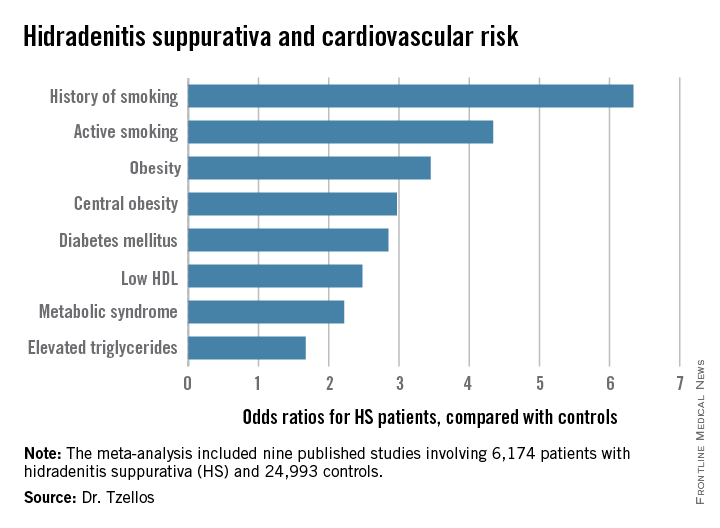

EADV: Hidradenitis suppurativa carries high cardiovascular risk

COPENHAGEN – Hidradenitis suppurativa, a common, chronic, inflammatory scarring skin disease of the hair follicles, is a red flag signaling elevated levels of multiple cardiovascular risk factors, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

“The need for screening of hidradenitis suppurativa patients for modifiable cardiovascular risk is emphasized,” Dr. Thrasyvoulos Tzellos said in presenting the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

For such a common and dramatically destructive disease, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) was underresearched until recently. Investigative interest grew as the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) underwent development as a novel therapy for what has been traditionally a notoriously difficult to treat disease. The biologic agent received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October as the first and only approved treatment for HS.

Dr. Tzellos’s meta-analysis included nine published studies totaling 6,174 HS patients and 24,993 controls. Five studies were case control, and the other four were cross sectional. An indicator of the recent explosive research interest in HS can be seen in the fact that 80% of all the HS patients included in the meta-analysis come from two studies published within just the last year, one from Massachusetts General Hospital (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Dec;71[6]:1144-50) and the other from Israel (Br J Dermatol. 2015 Aug;173[2]:464-70).

Not all the studies examined the same cardiovascular risk factors. For example, only six of nine studies looked at diabetes mellitus as an endpoint. Of those studies that did, diabetes occurred in 856 of 5,685 HS patients, a rate 2.85-fold higher than in controls, according to Dr. Tzellos of University Hospital of North Norway in Troms.

The only cardiovascular risk factor examined that was not significantly more common among patients with HS than controls was hypertension. The 1.57-fold increased likelihood of hypertension among HS patients didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Although patients whose HS was treated exclusively in outpatient settings had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors than did controls, risk levels were consistently higher still in patients who had been hospitalized for HS.

A meta-analysis such as this cannot address causality, leaving open the question of whether increased cardiovascular risk factors are intrinsic to HS, or the debilitating recurrent skin disease causes affected patients to take a defeatest attitude toward maintenance of a healthy lifestyle.

Dr. Tzellos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, carried out with academic funding.

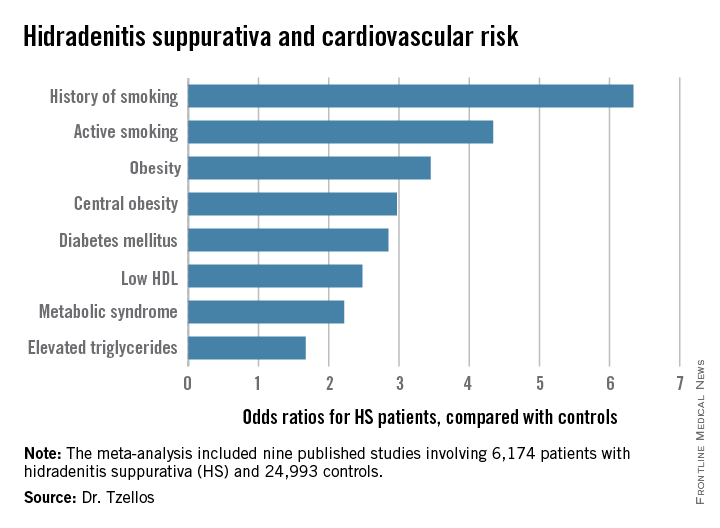

COPENHAGEN – Hidradenitis suppurativa, a common, chronic, inflammatory scarring skin disease of the hair follicles, is a red flag signaling elevated levels of multiple cardiovascular risk factors, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

“The need for screening of hidradenitis suppurativa patients for modifiable cardiovascular risk is emphasized,” Dr. Thrasyvoulos Tzellos said in presenting the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

For such a common and dramatically destructive disease, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) was underresearched until recently. Investigative interest grew as the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) underwent development as a novel therapy for what has been traditionally a notoriously difficult to treat disease. The biologic agent received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October as the first and only approved treatment for HS.

Dr. Tzellos’s meta-analysis included nine published studies totaling 6,174 HS patients and 24,993 controls. Five studies were case control, and the other four were cross sectional. An indicator of the recent explosive research interest in HS can be seen in the fact that 80% of all the HS patients included in the meta-analysis come from two studies published within just the last year, one from Massachusetts General Hospital (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Dec;71[6]:1144-50) and the other from Israel (Br J Dermatol. 2015 Aug;173[2]:464-70).

Not all the studies examined the same cardiovascular risk factors. For example, only six of nine studies looked at diabetes mellitus as an endpoint. Of those studies that did, diabetes occurred in 856 of 5,685 HS patients, a rate 2.85-fold higher than in controls, according to Dr. Tzellos of University Hospital of North Norway in Troms.

The only cardiovascular risk factor examined that was not significantly more common among patients with HS than controls was hypertension. The 1.57-fold increased likelihood of hypertension among HS patients didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Although patients whose HS was treated exclusively in outpatient settings had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors than did controls, risk levels were consistently higher still in patients who had been hospitalized for HS.

A meta-analysis such as this cannot address causality, leaving open the question of whether increased cardiovascular risk factors are intrinsic to HS, or the debilitating recurrent skin disease causes affected patients to take a defeatest attitude toward maintenance of a healthy lifestyle.

Dr. Tzellos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, carried out with academic funding.

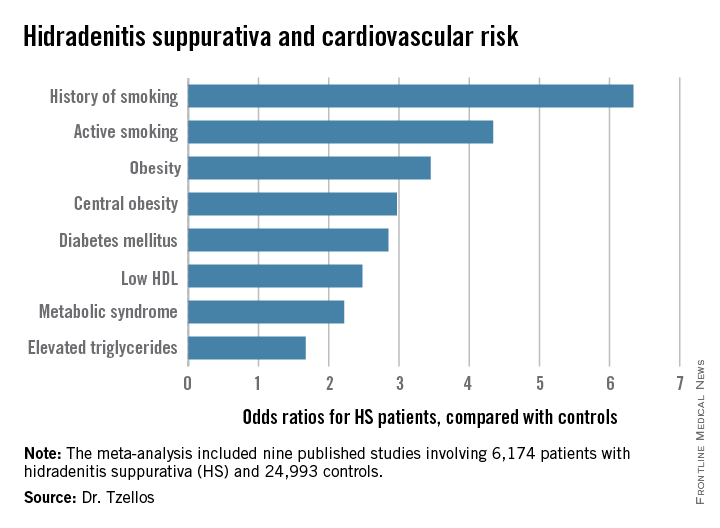

COPENHAGEN – Hidradenitis suppurativa, a common, chronic, inflammatory scarring skin disease of the hair follicles, is a red flag signaling elevated levels of multiple cardiovascular risk factors, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

“The need for screening of hidradenitis suppurativa patients for modifiable cardiovascular risk is emphasized,” Dr. Thrasyvoulos Tzellos said in presenting the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

For such a common and dramatically destructive disease, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) was underresearched until recently. Investigative interest grew as the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) underwent development as a novel therapy for what has been traditionally a notoriously difficult to treat disease. The biologic agent received Food and Drug Administration marketing approval in October as the first and only approved treatment for HS.

Dr. Tzellos’s meta-analysis included nine published studies totaling 6,174 HS patients and 24,993 controls. Five studies were case control, and the other four were cross sectional. An indicator of the recent explosive research interest in HS can be seen in the fact that 80% of all the HS patients included in the meta-analysis come from two studies published within just the last year, one from Massachusetts General Hospital (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Dec;71[6]:1144-50) and the other from Israel (Br J Dermatol. 2015 Aug;173[2]:464-70).

Not all the studies examined the same cardiovascular risk factors. For example, only six of nine studies looked at diabetes mellitus as an endpoint. Of those studies that did, diabetes occurred in 856 of 5,685 HS patients, a rate 2.85-fold higher than in controls, according to Dr. Tzellos of University Hospital of North Norway in Troms.

The only cardiovascular risk factor examined that was not significantly more common among patients with HS than controls was hypertension. The 1.57-fold increased likelihood of hypertension among HS patients didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Although patients whose HS was treated exclusively in outpatient settings had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors than did controls, risk levels were consistently higher still in patients who had been hospitalized for HS.

A meta-analysis such as this cannot address causality, leaving open the question of whether increased cardiovascular risk factors are intrinsic to HS, or the debilitating recurrent skin disease causes affected patients to take a defeatest attitude toward maintenance of a healthy lifestyle.

Dr. Tzellos reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, carried out with academic funding.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Be vigilant in screening for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Major finding: Hidradenitis suppurativa patients were 2.85-fold more likely than controls to have diabetes, 2.22-fold more likely to have metabolic syndrome, and 4.34-fold more likely to be active smokers.

Data source: A meta-analysis of nine published studies totaling 6,174 hidradenitis suppurativa patients and 24,993 controls.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, carried out with academic funding.

EADV: Comorbid spondyloarthropathy common in hidradenitis suppurativa

COPENHAGEN – Back pain is surprisingly common in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, and more than half of affected patients showed MRI evidence of axial spondyloarthropathy, Dr. Sylke Schneider-Burrus reported at the Annual Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Our study demonstrates that back pain and spondyloarthropathy are very common among hidradenitis suppurativa patients and that neither history nor clinical parameters provide any hints for the presence of spondyloarthropathy. Therefore, we strongly suggest that hidradenitis suppurativa patients should be evaluated for spondyloarthropathy and affected patients should be treated systemically with TNF-alpha blockers in order to avoid chronic joint alterations,” said Dr. Schneider-Burrus, a dermatologist at Charite University Hospital in Berlin.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, recurrent, scarring, inflammatory skin disease of the hair follicles. It causes painful, purulent, foul-smelling fistulating sinuses in the axillae, groin, and perianal region.

Because several other chronic inflammatory diseases affecting epithelial tissue have been associated with increased rates of axial spondyloarthropathy – notably, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and psoriasis – Dr. Schneider-Burrus and coinvestigators wondered whether that might true of HS as well.

She presented a survey of 100 HS patients. To her surprise, fully 71% indicated they suffer from back pain, with lower back complaints predominating.

Forty-eight HS patients with back pain consented to undergo a pelvic MRI exam. Fifteen of the 48 (32%) showed clear MRI evidence of spondyloarthropathy, including sacroiliac erosions and subchondral sclerosis, while another 12 showed active sacroiliac synovitis and other acute inflammatory changes.

No significant differences were found between HS patients with and without axial spondyloarthropathy in terms of age at onset of HS, disease duration, HS severity as reflected in Sartorius score, age at MRI, body mass index, or smoking status.

Dr. Schneider-Burrus reported serving as a paid investigator for and consultant to Novartis and AbbVie.

COPENHAGEN – Back pain is surprisingly common in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, and more than half of affected patients showed MRI evidence of axial spondyloarthropathy, Dr. Sylke Schneider-Burrus reported at the Annual Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Our study demonstrates that back pain and spondyloarthropathy are very common among hidradenitis suppurativa patients and that neither history nor clinical parameters provide any hints for the presence of spondyloarthropathy. Therefore, we strongly suggest that hidradenitis suppurativa patients should be evaluated for spondyloarthropathy and affected patients should be treated systemically with TNF-alpha blockers in order to avoid chronic joint alterations,” said Dr. Schneider-Burrus, a dermatologist at Charite University Hospital in Berlin.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, recurrent, scarring, inflammatory skin disease of the hair follicles. It causes painful, purulent, foul-smelling fistulating sinuses in the axillae, groin, and perianal region.

Because several other chronic inflammatory diseases affecting epithelial tissue have been associated with increased rates of axial spondyloarthropathy – notably, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and psoriasis – Dr. Schneider-Burrus and coinvestigators wondered whether that might true of HS as well.

She presented a survey of 100 HS patients. To her surprise, fully 71% indicated they suffer from back pain, with lower back complaints predominating.

Forty-eight HS patients with back pain consented to undergo a pelvic MRI exam. Fifteen of the 48 (32%) showed clear MRI evidence of spondyloarthropathy, including sacroiliac erosions and subchondral sclerosis, while another 12 showed active sacroiliac synovitis and other acute inflammatory changes.

No significant differences were found between HS patients with and without axial spondyloarthropathy in terms of age at onset of HS, disease duration, HS severity as reflected in Sartorius score, age at MRI, body mass index, or smoking status.

Dr. Schneider-Burrus reported serving as a paid investigator for and consultant to Novartis and AbbVie.

COPENHAGEN – Back pain is surprisingly common in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, and more than half of affected patients showed MRI evidence of axial spondyloarthropathy, Dr. Sylke Schneider-Burrus reported at the Annual Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Our study demonstrates that back pain and spondyloarthropathy are very common among hidradenitis suppurativa patients and that neither history nor clinical parameters provide any hints for the presence of spondyloarthropathy. Therefore, we strongly suggest that hidradenitis suppurativa patients should be evaluated for spondyloarthropathy and affected patients should be treated systemically with TNF-alpha blockers in order to avoid chronic joint alterations,” said Dr. Schneider-Burrus, a dermatologist at Charite University Hospital in Berlin.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, recurrent, scarring, inflammatory skin disease of the hair follicles. It causes painful, purulent, foul-smelling fistulating sinuses in the axillae, groin, and perianal region.

Because several other chronic inflammatory diseases affecting epithelial tissue have been associated with increased rates of axial spondyloarthropathy – notably, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and psoriasis – Dr. Schneider-Burrus and coinvestigators wondered whether that might true of HS as well.

She presented a survey of 100 HS patients. To her surprise, fully 71% indicated they suffer from back pain, with lower back complaints predominating.

Forty-eight HS patients with back pain consented to undergo a pelvic MRI exam. Fifteen of the 48 (32%) showed clear MRI evidence of spondyloarthropathy, including sacroiliac erosions and subchondral sclerosis, while another 12 showed active sacroiliac synovitis and other acute inflammatory changes.

No significant differences were found between HS patients with and without axial spondyloarthropathy in terms of age at onset of HS, disease duration, HS severity as reflected in Sartorius score, age at MRI, body mass index, or smoking status.

Dr. Schneider-Burrus reported serving as a paid investigator for and consultant to Novartis and AbbVie.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Axial spondyloarthropathy is extremely common in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Major finding: Seventy-one percent of surveyed hidradenitis suppurativa patients reported suffering from back pain, and 56% of affected patients showed MRI evidence of axial spondyloarthropathy.

Data source: A back pain survey of 100 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa along with pelvic MRI exams in the 48 who reported back pain.

Disclosures: The presenter reported serving as a paid investigator for and consultant to Novartis and AbbVie.

What’s Eating You? Ant-Induced Alopecia (Pheidole)

Case Report

An 18-year-old Iranian man presented to the dermatology clinic with hair loss of 1 night’s duration. He denied pruritus, pain, discharge, or flaking. The patient had no notable personal, family, or surgical history and was not currently taking any medications. He denied recent travel. The patient reported that he found hair on his pillow upon waking up in the morning prior to coming to the clinic. On physical examination, 2 ants (Figure 1) were found on the scalp and alopecia with a vertical linear distribution was noted (Figure 2). Hairs of various lengths were found on the scalp within the distribution of the alopecia. No excoriations, crusting, seborrhea, or other areas of hair loss were detected. Wood lamp examination was negative. Based on these findings, which were concordant with similar findings from prior reports,1-4 a diagnosis of ant-induced alopecia was made. Hair regrowth was noted within 1 week with full appearance of normal-length hair within 2.5 weeks.

Comment

Ant-induced alopecia is a form of localized hair loss caused by the Pheidole genus, the second largest genus of ants in the world.5 These ants can be found worldwide, but most cases of ant-induced alopecia have been from Iran, with at least 1 reported case from Turkey.1-4,6 An early case series of ant-induced alopecia was reported in 1999,6 but the causative species was not described at that time.

The majority of reported cases of ant-induced alopecia are attributed to the barber ant (Pheidole pallidula). This type of alopecia is caused by worker ants within the species hierarchy.1,4,6 The P pallidula worker ants are dimorphic and are classified as major and minor workers.7 Major workers have body lengths ranging up to 6 mm, whereas minor workers have body lengths ranging up to 4 mm. Major workers have larger heads and mandibles than minor workers and also have up to 2 pairs of denticles on the cranium.5 The minor workers are foragers and mainly collect food, whereas the major workers defend the nest and store food.8 These ants have widespread habitats with the ability to live in indoor and outdoor environments.

The presentation of hair loss caused by these ants is acute. Hair loss usually is confined to one specific area. Some patients may report pruritus or may present with erythematous lesions from ant stings or manual scratching.5 None of these signs or symptoms were seen in our patient. Some investigators have suggested that the barber ant is attracted to the hair of individuals with seborrheic dermatitis,1 but our patient had no medical history of seborrheic dermatitis. Most likely, ants are attracted to excess sebum on the scalp in select individuals in their search for food and cause localized hair destruction.

Localized hair loss, as depicted in our case, should warrant a thorough evaluation for alopecia areata, trichotillomania, and tinea capitis.9 Alopecia areata should be considered in individuals with multiple focal patches of hair loss that have a positive hair pull test from peripheral sites of active lesions. Tinea capitis usually has localized sites of hair loss with underlying scaling, crusting, pruritus, erythema, and discharge from lesions, with positive potassium hydroxide preparations or fungal cultures. Trichotillomania typically presents with a spared peripheral fringe of hair. Remaining hairs may be thick and hyperpigmented as a response to repeated pulling, and biopsy often demonstrates fracture or degeneration of the hair shaft. A psychiatric evaluation may be warranted in cases of trichotillomania. Other cases of arthropod-induced hair loss include tick bite alopecia10,11 and hair loss induced by numerous honeybee stings,12 and these diagnoses should be suspected in patients with a history of ants on their pillow or in those from endemic areas.

No specific treatment is indicated in cases of ant-induced alopecia because hair usually regrows to its normal length without intervention.

- Shamsadini S. Localized scalp hair shedding caused by Pheidole ants and overview of similar case reports. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:12.

- Aghaei S, Sodaifi M. Circumscribed scalp hair loss following multiple hair-cutter ant invasion. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:14.

- Mortazavi M, Mansouri P. Ant-induced alopecia: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Kapdağli S, Seçkin D, Baba M, et al. Localized hair breakage caused by ants. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:519-520.

- Ogata K. Toxonomy and biology of the genus Pheidole of Japan. Nature and Insects. 1981;16:17-22.

- Radmanesh M, Mousavipour M. Alopecia induced by ants. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:427.

- Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. The Ants. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990.

- Wilson EO. Pheidole in the New World: A Dominant Hyperdiverse Ant Genus. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; 2003.

- Veraldi S, Lunardon L, Francia C, et al. Alopecia caused by the “barber ant” Pheidole pallidula. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1329-1330.

- Marshall J. Alopecia after tick bite. S Afr Med J. 1966;40: 555-556.

- Heyl T. Tick bite alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1982;7: 537-542.

- Sharma AK, Sharma RC, Sharma NL. Diffuse hair loss following multiple honeybee stings. Dermatology. 1997;195:305.

Case Report