User login

Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma and Other Slow-Growing Tumors in Acral Areas

First described by Fetsch et al1 in 2001, superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) is a rare fibromyxoid mesenchymal tumor that typically affects the fingers and toes with frequent involvement of the nail unit. It is not widely recognized and remains poorly understood. We describe a series of 3 cases of SAFM encountered at our institution and provide a review of the literature on this unique tumor.

Case Reports

Patient 1

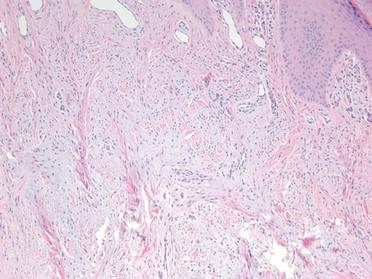

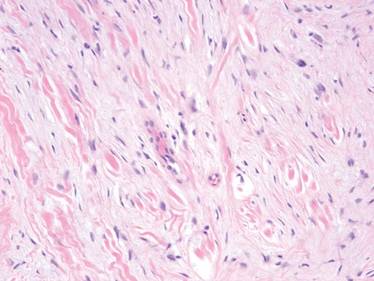

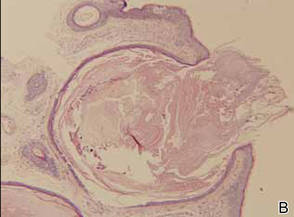

A 35-year-old man presented for treatment of a “wart” on the right fifth toe that had increased in size over the last year. He reported that the lesion was mildly painful and occasionally bled or drained clear fluid. He also noted cracking of the nail plate on the same toe. Physical examination revealed a firm, flesh-colored, 3-mm dermal papule on the proximal nail fold of the right fifth toe with subtle flattening of the underlying nail plate (Figure 1). The patient underwent biopsy of the involved proximal nail fold. Histopathology revealed a proliferation of small oval and spindle cells arranged in fascicles and bundles in the dermis (Figure 2). There was extensive mucin deposition associated with the spindle cell proliferation. Additionally, spindle cells and mucin surrounded and entrapped collagen bundles on the periphery of the lesion. Lesional cells were diffusely positive for CD34 and extended to the deep surgical margin (Figure 3). S-100 and factor XIIIa stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

|

Patient 2

A 47-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic growth on the left fourth toe that had increased in size over the last year. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, firm, fleshy, flesh-colored, smooth and slightly pedunculated papule on the distal aspect of the left fourth toe. The nail plate and periungual region were not involved. A shave biopsy of the papule was obtained. Histopathology demonstrated dermal stellate spindle cells arranged in a loose fascicular pattern with marked mucin deposition throughout the dermis (Figure 4). Lesional cells were positive for CD34. An S-100 stain highlighted dermal dendritic cells, but lesional cells were negative. No further excision was undertaken, and there was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Patient 3

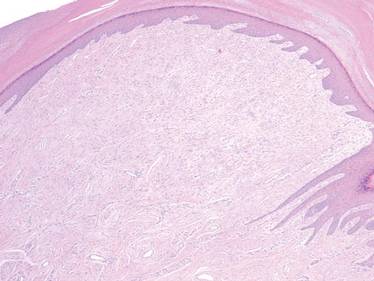

A 45-year-old woman presented with asymptomatic distal onycholysis of the right thumbnail of 1 year’s duration. She denied any history of trauma, and no bleeding or pigmentary changes were noted. Physical examination revealed a 5-mm flesh-colored papule on the hyponychium of the right thumb with focal onycholysis (Figure 5). A wedge biopsy of the lesion was performed. Histopathology showed an intradermal nodular proliferation of bland spindle cells arranged in loose fascicles and bundles and embedded in a myxoid stroma (Figure 6). CD34 staining strongly highlighted lesional cells. S-100 and neurofilament stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Comment

Clinically, SAFM typically presents as a slow-growing solitary nodule on the distal fingers or toes. The great toe is the most commonly affected digit, and the tumor may be subungual in up to two-thirds of cases.1 Unusual locations, such as the heel, also have been reported.2 Onset typically occurs in the fifth or sixth decade, and there is an approximately 2-fold higher incidence in men than women.1-3

Histopathologically, SAFM is a characteristically well-circumscribed but unencapsulated dermal tumor composed of spindle and stellate cells in a loose storiform or fascicular arrangement embedded in a myxoid, myxocollagenous, or collagenous stroma.4 The tumor often occupies the entire dermis and may extend into the subcutis or occasionally the underlying fascia and bone.4,5 Mast cells often are prominent, and microvascular accentuation also may be seen. Inflammatory infiltrates and multinucleated giant cells typically are not seen.6 Although 2 cases of atypical SAFM have been described,2 cellular atypia is not a characteristic feature of SAFM.

The immunohistochemical profile of SAFM is characterized by diffuse or focal expression of CD34, focal expression of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD99 expression, and varying numbers of factor XIIIa–positive histiocytes.2,3 Positive staining for vimentin also is common. Staining typically is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, keratin, smooth muscle actin, and desmin.

The standard treatment of SAFM is complete local resection of the tumor, though some patients have been treated with partial excision or biopsy and partial or complete digital amputation.1 Local recurrence may occur in up to 20% of cases; however, approximately two-thirds of the reported recurrences in the literature occurred after incomplete tumor excision.1,2 It may be more appropriate to consider these cases as persistent rather than recurrent tumors. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is considered a benign tumor, with no known cases of metastases.4

|

A broad differential diagnosis exists for SAFM and it can be difficult to differentiate it from a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors that may be seen on the nail unit and distal extremities (Table). Myxoid neurofibromas typically present as solitary lesions on the hands and feet. Similar to SAFM, myxoid neurofibromas are unencapsulated dermal tumors composed of spindle-shaped cells in which mast cells often are conspicuous.2,7 However, tumor cells in myxoid neurofibromas are S-100 positive, and the lesions typically do not show vasculature accentuation.4,7

Sclerosing perineuriomas are benign fibrous tumors of the fingers and palms. Histopathologically, bland spindle cells arranged in fascicles and whorls are observed in a hyalinized collagen matrix.8 Immunohistochemically, sclerosing perineuriomas are positive for EMA and negative for S-100, but unlike SAFM, these tumors usually are CD34 negative.8

Superficial angiomyxomas typically are located on the head and neck but also may be found in other locations such as the trunk. They present as cutaneous papules or polypoid lesions. Histopathologically, superficial angiomyxomas are poorly circumscribed with a lobular pattern. Spindle-shaped fibroblasts exist in a myxoid matrix with neutrophils and thin-walled capillaries. The fibroblasts are variably positive for CD34 but also are S-100 positive.1,9

Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, locally aggressive, mesenchymal tumor of the skin and subcutis2 that typically presents on the trunk, proximal extremities, or head and neck; occurrence on the fingers or toes is exceedingly rare.2,10 Histopathologically, a myxoid stroma contains sheets of bland spindle-shaped cells with minimal to no atypia, sometimes arranged in a storiform pattern. The tumor characteristically invades deeply into the subcutaneous tissues. CD34 is characteristically positive and S-100 is negative.2,10

Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma is a soft tissue sarcoma easily confused with other spindle cell tumors. It is one of the most common sarcomas in adults but rarely arises in acral areas.2 It is characterized by a nodular growth pattern with marked nuclear atypia and perivascular clustering of tumor cells. CD34 staining may be positive in some cases.11

Similar to SAFM, myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma has a predilection for the extremities.4 However, it typically presents as a subcutaneous mass and has no documented tendency for nail bed involvement. Also unlike SAFM, it has a remarkable inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic virocyte or Reed-Sternberg cells.12

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas are benign neoplasms that occur on fingers and toes; the classic clinical presentation is a solitary smooth nodule or dome, often with a characteristic projecting configuration and horn shape.1 Histopathologically, these tumors are paucicellular with thick, vertically oriented, interwoven collagen bundles; cells may be positive for CD34 but are negative for EMA.1,13 Related to acquired digital fibrokeratomas are Koenen tumors, which share a similar histology but are distinguished by their clinical characteristics. For example, Koenen tumors tend to be multifocal and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis. These tumors also have a tendency to recur.1

Conclusion

Our report of 3 typical cases of SAFM highlights the need to keep this increasingly recognized and well-defined clinicopathological entity in the differential for slow-growing tumors in acral locations, particularly those in the periungual and subungual regions.

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

3. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

4. André J, Theunis A, Richert B, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: clinical and pathological features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:472-474.

5. Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Burg G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

6. Meyerle JH, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

7. Graadt van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC, Fletcher CD. Myxoid tumours of soft tissue. Histopathology. 1999;35:291-312.

8. Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

9. Calonje E, Guerin D, McCormick D, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series of distinctive but poorly recognized cutaneous tumors with tendency for recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:910-917.

10. Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

11. Wada T, Hasegawa T, Nagoya S, et al. Myxofibrosarcoma with an infiltrative growth pattern: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:458-462.

12. Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a low-grade tumor of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:911-924.

13. Bart RS, Andrade R, Kopf AW, et al. Acquired digital fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:120-129.

First described by Fetsch et al1 in 2001, superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) is a rare fibromyxoid mesenchymal tumor that typically affects the fingers and toes with frequent involvement of the nail unit. It is not widely recognized and remains poorly understood. We describe a series of 3 cases of SAFM encountered at our institution and provide a review of the literature on this unique tumor.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 35-year-old man presented for treatment of a “wart” on the right fifth toe that had increased in size over the last year. He reported that the lesion was mildly painful and occasionally bled or drained clear fluid. He also noted cracking of the nail plate on the same toe. Physical examination revealed a firm, flesh-colored, 3-mm dermal papule on the proximal nail fold of the right fifth toe with subtle flattening of the underlying nail plate (Figure 1). The patient underwent biopsy of the involved proximal nail fold. Histopathology revealed a proliferation of small oval and spindle cells arranged in fascicles and bundles in the dermis (Figure 2). There was extensive mucin deposition associated with the spindle cell proliferation. Additionally, spindle cells and mucin surrounded and entrapped collagen bundles on the periphery of the lesion. Lesional cells were diffusely positive for CD34 and extended to the deep surgical margin (Figure 3). S-100 and factor XIIIa stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

|

Patient 2

A 47-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic growth on the left fourth toe that had increased in size over the last year. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, firm, fleshy, flesh-colored, smooth and slightly pedunculated papule on the distal aspect of the left fourth toe. The nail plate and periungual region were not involved. A shave biopsy of the papule was obtained. Histopathology demonstrated dermal stellate spindle cells arranged in a loose fascicular pattern with marked mucin deposition throughout the dermis (Figure 4). Lesional cells were positive for CD34. An S-100 stain highlighted dermal dendritic cells, but lesional cells were negative. No further excision was undertaken, and there was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Patient 3

A 45-year-old woman presented with asymptomatic distal onycholysis of the right thumbnail of 1 year’s duration. She denied any history of trauma, and no bleeding or pigmentary changes were noted. Physical examination revealed a 5-mm flesh-colored papule on the hyponychium of the right thumb with focal onycholysis (Figure 5). A wedge biopsy of the lesion was performed. Histopathology showed an intradermal nodular proliferation of bland spindle cells arranged in loose fascicles and bundles and embedded in a myxoid stroma (Figure 6). CD34 staining strongly highlighted lesional cells. S-100 and neurofilament stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Comment

Clinically, SAFM typically presents as a slow-growing solitary nodule on the distal fingers or toes. The great toe is the most commonly affected digit, and the tumor may be subungual in up to two-thirds of cases.1 Unusual locations, such as the heel, also have been reported.2 Onset typically occurs in the fifth or sixth decade, and there is an approximately 2-fold higher incidence in men than women.1-3

Histopathologically, SAFM is a characteristically well-circumscribed but unencapsulated dermal tumor composed of spindle and stellate cells in a loose storiform or fascicular arrangement embedded in a myxoid, myxocollagenous, or collagenous stroma.4 The tumor often occupies the entire dermis and may extend into the subcutis or occasionally the underlying fascia and bone.4,5 Mast cells often are prominent, and microvascular accentuation also may be seen. Inflammatory infiltrates and multinucleated giant cells typically are not seen.6 Although 2 cases of atypical SAFM have been described,2 cellular atypia is not a characteristic feature of SAFM.

The immunohistochemical profile of SAFM is characterized by diffuse or focal expression of CD34, focal expression of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD99 expression, and varying numbers of factor XIIIa–positive histiocytes.2,3 Positive staining for vimentin also is common. Staining typically is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, keratin, smooth muscle actin, and desmin.

The standard treatment of SAFM is complete local resection of the tumor, though some patients have been treated with partial excision or biopsy and partial or complete digital amputation.1 Local recurrence may occur in up to 20% of cases; however, approximately two-thirds of the reported recurrences in the literature occurred after incomplete tumor excision.1,2 It may be more appropriate to consider these cases as persistent rather than recurrent tumors. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is considered a benign tumor, with no known cases of metastases.4

|

A broad differential diagnosis exists for SAFM and it can be difficult to differentiate it from a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors that may be seen on the nail unit and distal extremities (Table). Myxoid neurofibromas typically present as solitary lesions on the hands and feet. Similar to SAFM, myxoid neurofibromas are unencapsulated dermal tumors composed of spindle-shaped cells in which mast cells often are conspicuous.2,7 However, tumor cells in myxoid neurofibromas are S-100 positive, and the lesions typically do not show vasculature accentuation.4,7

Sclerosing perineuriomas are benign fibrous tumors of the fingers and palms. Histopathologically, bland spindle cells arranged in fascicles and whorls are observed in a hyalinized collagen matrix.8 Immunohistochemically, sclerosing perineuriomas are positive for EMA and negative for S-100, but unlike SAFM, these tumors usually are CD34 negative.8

Superficial angiomyxomas typically are located on the head and neck but also may be found in other locations such as the trunk. They present as cutaneous papules or polypoid lesions. Histopathologically, superficial angiomyxomas are poorly circumscribed with a lobular pattern. Spindle-shaped fibroblasts exist in a myxoid matrix with neutrophils and thin-walled capillaries. The fibroblasts are variably positive for CD34 but also are S-100 positive.1,9

Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, locally aggressive, mesenchymal tumor of the skin and subcutis2 that typically presents on the trunk, proximal extremities, or head and neck; occurrence on the fingers or toes is exceedingly rare.2,10 Histopathologically, a myxoid stroma contains sheets of bland spindle-shaped cells with minimal to no atypia, sometimes arranged in a storiform pattern. The tumor characteristically invades deeply into the subcutaneous tissues. CD34 is characteristically positive and S-100 is negative.2,10

Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma is a soft tissue sarcoma easily confused with other spindle cell tumors. It is one of the most common sarcomas in adults but rarely arises in acral areas.2 It is characterized by a nodular growth pattern with marked nuclear atypia and perivascular clustering of tumor cells. CD34 staining may be positive in some cases.11

Similar to SAFM, myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma has a predilection for the extremities.4 However, it typically presents as a subcutaneous mass and has no documented tendency for nail bed involvement. Also unlike SAFM, it has a remarkable inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic virocyte or Reed-Sternberg cells.12

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas are benign neoplasms that occur on fingers and toes; the classic clinical presentation is a solitary smooth nodule or dome, often with a characteristic projecting configuration and horn shape.1 Histopathologically, these tumors are paucicellular with thick, vertically oriented, interwoven collagen bundles; cells may be positive for CD34 but are negative for EMA.1,13 Related to acquired digital fibrokeratomas are Koenen tumors, which share a similar histology but are distinguished by their clinical characteristics. For example, Koenen tumors tend to be multifocal and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis. These tumors also have a tendency to recur.1

Conclusion

Our report of 3 typical cases of SAFM highlights the need to keep this increasingly recognized and well-defined clinicopathological entity in the differential for slow-growing tumors in acral locations, particularly those in the periungual and subungual regions.

First described by Fetsch et al1 in 2001, superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) is a rare fibromyxoid mesenchymal tumor that typically affects the fingers and toes with frequent involvement of the nail unit. It is not widely recognized and remains poorly understood. We describe a series of 3 cases of SAFM encountered at our institution and provide a review of the literature on this unique tumor.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 35-year-old man presented for treatment of a “wart” on the right fifth toe that had increased in size over the last year. He reported that the lesion was mildly painful and occasionally bled or drained clear fluid. He also noted cracking of the nail plate on the same toe. Physical examination revealed a firm, flesh-colored, 3-mm dermal papule on the proximal nail fold of the right fifth toe with subtle flattening of the underlying nail plate (Figure 1). The patient underwent biopsy of the involved proximal nail fold. Histopathology revealed a proliferation of small oval and spindle cells arranged in fascicles and bundles in the dermis (Figure 2). There was extensive mucin deposition associated with the spindle cell proliferation. Additionally, spindle cells and mucin surrounded and entrapped collagen bundles on the periphery of the lesion. Lesional cells were diffusely positive for CD34 and extended to the deep surgical margin (Figure 3). S-100 and factor XIIIa stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

|

Patient 2

A 47-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic growth on the left fourth toe that had increased in size over the last year. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, firm, fleshy, flesh-colored, smooth and slightly pedunculated papule on the distal aspect of the left fourth toe. The nail plate and periungual region were not involved. A shave biopsy of the papule was obtained. Histopathology demonstrated dermal stellate spindle cells arranged in a loose fascicular pattern with marked mucin deposition throughout the dermis (Figure 4). Lesional cells were positive for CD34. An S-100 stain highlighted dermal dendritic cells, but lesional cells were negative. No further excision was undertaken, and there was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Patient 3

A 45-year-old woman presented with asymptomatic distal onycholysis of the right thumbnail of 1 year’s duration. She denied any history of trauma, and no bleeding or pigmentary changes were noted. Physical examination revealed a 5-mm flesh-colored papule on the hyponychium of the right thumb with focal onycholysis (Figure 5). A wedge biopsy of the lesion was performed. Histopathology showed an intradermal nodular proliferation of bland spindle cells arranged in loose fascicles and bundles and embedded in a myxoid stroma (Figure 6). CD34 staining strongly highlighted lesional cells. S-100 and neurofilament stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Comment

Clinically, SAFM typically presents as a slow-growing solitary nodule on the distal fingers or toes. The great toe is the most commonly affected digit, and the tumor may be subungual in up to two-thirds of cases.1 Unusual locations, such as the heel, also have been reported.2 Onset typically occurs in the fifth or sixth decade, and there is an approximately 2-fold higher incidence in men than women.1-3

Histopathologically, SAFM is a characteristically well-circumscribed but unencapsulated dermal tumor composed of spindle and stellate cells in a loose storiform or fascicular arrangement embedded in a myxoid, myxocollagenous, or collagenous stroma.4 The tumor often occupies the entire dermis and may extend into the subcutis or occasionally the underlying fascia and bone.4,5 Mast cells often are prominent, and microvascular accentuation also may be seen. Inflammatory infiltrates and multinucleated giant cells typically are not seen.6 Although 2 cases of atypical SAFM have been described,2 cellular atypia is not a characteristic feature of SAFM.

The immunohistochemical profile of SAFM is characterized by diffuse or focal expression of CD34, focal expression of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD99 expression, and varying numbers of factor XIIIa–positive histiocytes.2,3 Positive staining for vimentin also is common. Staining typically is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, keratin, smooth muscle actin, and desmin.

The standard treatment of SAFM is complete local resection of the tumor, though some patients have been treated with partial excision or biopsy and partial or complete digital amputation.1 Local recurrence may occur in up to 20% of cases; however, approximately two-thirds of the reported recurrences in the literature occurred after incomplete tumor excision.1,2 It may be more appropriate to consider these cases as persistent rather than recurrent tumors. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is considered a benign tumor, with no known cases of metastases.4

|

A broad differential diagnosis exists for SAFM and it can be difficult to differentiate it from a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors that may be seen on the nail unit and distal extremities (Table). Myxoid neurofibromas typically present as solitary lesions on the hands and feet. Similar to SAFM, myxoid neurofibromas are unencapsulated dermal tumors composed of spindle-shaped cells in which mast cells often are conspicuous.2,7 However, tumor cells in myxoid neurofibromas are S-100 positive, and the lesions typically do not show vasculature accentuation.4,7

Sclerosing perineuriomas are benign fibrous tumors of the fingers and palms. Histopathologically, bland spindle cells arranged in fascicles and whorls are observed in a hyalinized collagen matrix.8 Immunohistochemically, sclerosing perineuriomas are positive for EMA and negative for S-100, but unlike SAFM, these tumors usually are CD34 negative.8

Superficial angiomyxomas typically are located on the head and neck but also may be found in other locations such as the trunk. They present as cutaneous papules or polypoid lesions. Histopathologically, superficial angiomyxomas are poorly circumscribed with a lobular pattern. Spindle-shaped fibroblasts exist in a myxoid matrix with neutrophils and thin-walled capillaries. The fibroblasts are variably positive for CD34 but also are S-100 positive.1,9

Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, locally aggressive, mesenchymal tumor of the skin and subcutis2 that typically presents on the trunk, proximal extremities, or head and neck; occurrence on the fingers or toes is exceedingly rare.2,10 Histopathologically, a myxoid stroma contains sheets of bland spindle-shaped cells with minimal to no atypia, sometimes arranged in a storiform pattern. The tumor characteristically invades deeply into the subcutaneous tissues. CD34 is characteristically positive and S-100 is negative.2,10

Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma is a soft tissue sarcoma easily confused with other spindle cell tumors. It is one of the most common sarcomas in adults but rarely arises in acral areas.2 It is characterized by a nodular growth pattern with marked nuclear atypia and perivascular clustering of tumor cells. CD34 staining may be positive in some cases.11

Similar to SAFM, myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma has a predilection for the extremities.4 However, it typically presents as a subcutaneous mass and has no documented tendency for nail bed involvement. Also unlike SAFM, it has a remarkable inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic virocyte or Reed-Sternberg cells.12

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas are benign neoplasms that occur on fingers and toes; the classic clinical presentation is a solitary smooth nodule or dome, often with a characteristic projecting configuration and horn shape.1 Histopathologically, these tumors are paucicellular with thick, vertically oriented, interwoven collagen bundles; cells may be positive for CD34 but are negative for EMA.1,13 Related to acquired digital fibrokeratomas are Koenen tumors, which share a similar histology but are distinguished by their clinical characteristics. For example, Koenen tumors tend to be multifocal and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis. These tumors also have a tendency to recur.1

Conclusion

Our report of 3 typical cases of SAFM highlights the need to keep this increasingly recognized and well-defined clinicopathological entity in the differential for slow-growing tumors in acral locations, particularly those in the periungual and subungual regions.

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

3. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

4. André J, Theunis A, Richert B, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: clinical and pathological features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:472-474.

5. Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Burg G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

6. Meyerle JH, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

7. Graadt van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC, Fletcher CD. Myxoid tumours of soft tissue. Histopathology. 1999;35:291-312.

8. Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

9. Calonje E, Guerin D, McCormick D, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series of distinctive but poorly recognized cutaneous tumors with tendency for recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:910-917.

10. Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

11. Wada T, Hasegawa T, Nagoya S, et al. Myxofibrosarcoma with an infiltrative growth pattern: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:458-462.

12. Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a low-grade tumor of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:911-924.

13. Bart RS, Andrade R, Kopf AW, et al. Acquired digital fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:120-129.

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

3. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

4. André J, Theunis A, Richert B, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: clinical and pathological features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:472-474.

5. Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Burg G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

6. Meyerle JH, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

7. Graadt van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC, Fletcher CD. Myxoid tumours of soft tissue. Histopathology. 1999;35:291-312.

8. Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

9. Calonje E, Guerin D, McCormick D, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series of distinctive but poorly recognized cutaneous tumors with tendency for recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:910-917.

10. Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

11. Wada T, Hasegawa T, Nagoya S, et al. Myxofibrosarcoma with an infiltrative growth pattern: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:458-462.

12. Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a low-grade tumor of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:911-924.

13. Bart RS, Andrade R, Kopf AW, et al. Acquired digital fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:120-129.

Practice Points

- Superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) is a rare but distinct tumor that may affect the nail bed and nail plate, and it may clinically or histopathologically mimic other tumors of the distal extremities.

- Although SAFM is considered a benign tumor, it frequently persists or recurs after incomplete excision, and therefore complete local resection may be recommended, particularly for symptomatic lesions.

Subungual exostosis masquerades as nail fungus

ORLANDO – In a patient presenting with a tender, firm lesion under the nail, think subungual exostosis, Dr. Phoebe Rich advised.

Subungual exostosis is a benign bony growth that can cause discomfort by pressing up from the nail bed. It can be mistaken for onychomycosis, but keep in mind that only 50% of those presenting with nail disorders will have onychomycosis, so it is important to consider other diagnoses, Dr. Rich, director of the Nail Disorder Center at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

She described a teenager who presented with a growth under her nail, which the patient thought was nail fungus. The lesion developed after an injury experienced during a touch football game 2 months earlier.

An X-ray will aid in the diagnosis of such lesions, Dr. Rich said.

“You want to know that’s what it is … because you don’t want to just cut into it for a biopsy if you don’t know that it’s bone,” she said.

The diagnosis can be confirmed by removing the nail to take a look at the tumor.

“They are pretty characteristic. They are a bony growth. They’re actually composed of bone with a fibro-cartilaginous cap,” she said noting that tenderness is an important clue to the diagnosis.

Subungual exostosis occurs more often in toes than fingers, more often in girls than boys, and more often in children and young adults than older individuals, Dr. Rich noted.

Surgical removal is typically successful; the recurrence rate is about 10%, and recurrence is more common in children.

Presentation varies; some lesions can be quite obvious, with the growth protruding from under the nail, while others are more subtle. Dr. Rich described one young college student who presented with slight white spotting of the nail, and slight onycholysis. The patient had tenderness of the nail area when pressed, and the tumor peeked out from under the nail.

“If you see something like this, get an X-ray,” she said, adding: “You can be a hero and make the diagnosis. Don’t just treat it as though it’s a fungus.”

“If you’re very comfortable and expert at nails, great. Otherwise, make the diagnosis and send them to someone else, but you can really help these patients a lot,” she said.

Dr. Rich has participated in clinical trials with companies with antifungal/onychomycosis drugs, including Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

ORLANDO – In a patient presenting with a tender, firm lesion under the nail, think subungual exostosis, Dr. Phoebe Rich advised.

Subungual exostosis is a benign bony growth that can cause discomfort by pressing up from the nail bed. It can be mistaken for onychomycosis, but keep in mind that only 50% of those presenting with nail disorders will have onychomycosis, so it is important to consider other diagnoses, Dr. Rich, director of the Nail Disorder Center at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

She described a teenager who presented with a growth under her nail, which the patient thought was nail fungus. The lesion developed after an injury experienced during a touch football game 2 months earlier.

An X-ray will aid in the diagnosis of such lesions, Dr. Rich said.

“You want to know that’s what it is … because you don’t want to just cut into it for a biopsy if you don’t know that it’s bone,” she said.

The diagnosis can be confirmed by removing the nail to take a look at the tumor.

“They are pretty characteristic. They are a bony growth. They’re actually composed of bone with a fibro-cartilaginous cap,” she said noting that tenderness is an important clue to the diagnosis.

Subungual exostosis occurs more often in toes than fingers, more often in girls than boys, and more often in children and young adults than older individuals, Dr. Rich noted.

Surgical removal is typically successful; the recurrence rate is about 10%, and recurrence is more common in children.

Presentation varies; some lesions can be quite obvious, with the growth protruding from under the nail, while others are more subtle. Dr. Rich described one young college student who presented with slight white spotting of the nail, and slight onycholysis. The patient had tenderness of the nail area when pressed, and the tumor peeked out from under the nail.

“If you see something like this, get an X-ray,” she said, adding: “You can be a hero and make the diagnosis. Don’t just treat it as though it’s a fungus.”

“If you’re very comfortable and expert at nails, great. Otherwise, make the diagnosis and send them to someone else, but you can really help these patients a lot,” she said.

Dr. Rich has participated in clinical trials with companies with antifungal/onychomycosis drugs, including Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

ORLANDO – In a patient presenting with a tender, firm lesion under the nail, think subungual exostosis, Dr. Phoebe Rich advised.

Subungual exostosis is a benign bony growth that can cause discomfort by pressing up from the nail bed. It can be mistaken for onychomycosis, but keep in mind that only 50% of those presenting with nail disorders will have onychomycosis, so it is important to consider other diagnoses, Dr. Rich, director of the Nail Disorder Center at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

She described a teenager who presented with a growth under her nail, which the patient thought was nail fungus. The lesion developed after an injury experienced during a touch football game 2 months earlier.

An X-ray will aid in the diagnosis of such lesions, Dr. Rich said.

“You want to know that’s what it is … because you don’t want to just cut into it for a biopsy if you don’t know that it’s bone,” she said.

The diagnosis can be confirmed by removing the nail to take a look at the tumor.

“They are pretty characteristic. They are a bony growth. They’re actually composed of bone with a fibro-cartilaginous cap,” she said noting that tenderness is an important clue to the diagnosis.

Subungual exostosis occurs more often in toes than fingers, more often in girls than boys, and more often in children and young adults than older individuals, Dr. Rich noted.

Surgical removal is typically successful; the recurrence rate is about 10%, and recurrence is more common in children.

Presentation varies; some lesions can be quite obvious, with the growth protruding from under the nail, while others are more subtle. Dr. Rich described one young college student who presented with slight white spotting of the nail, and slight onycholysis. The patient had tenderness of the nail area when pressed, and the tumor peeked out from under the nail.

“If you see something like this, get an X-ray,” she said, adding: “You can be a hero and make the diagnosis. Don’t just treat it as though it’s a fungus.”

“If you’re very comfortable and expert at nails, great. Otherwise, make the diagnosis and send them to someone else, but you can really help these patients a lot,” she said.

Dr. Rich has participated in clinical trials with companies with antifungal/onychomycosis drugs, including Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE ODAC CONFERENCE

Antifungal treatment may cause DNA strain type switching in onychomycosis

Although DNA strain type switches are known to be a natural occurrence in patients with onychomycosis, increases in strain type switching that follow treatment failure could be an antifungal-induced response, according to the results of a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum is responsible for the majority (~80%) of [onychomycosis] cases, many of which frequently relapse after successful antifungal treatment,” noted the study authors, led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta of the University of Toronto. Despite several previous studies of various facets related to onychomycosis, “data outlining onychomycosis infections of T. rubrum with DNA strain type, treatments, outcome and geographical location are still warranted,” they added (Br. J. Dermatol. 2015;172:74-80).

Dr. Gupta and his associates examined 50 adults infected with T. rubrum, determined via analysis of toenail specimens from onychomycosis patients in southwest Ontario. The patients were divided into cohorts based on the treatment they received: oral terbinafine, laser, or placebo (no terbinafine and no laser). Typing of DNA strains was done only in culture-positive samples before and after treatment, leaving a study population of six in the terbinafine group, nine in the laser group, and eight in the placebo group.

Half of the terbinafine subjects were prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/day for 12 weeks, while the other three received oral terbinafine 250 mg/day pulse therapy at on/off intervals of 2 weeks up to 12 weeks.

The investigators also used three DNA strains known to be common in Europe for comparison and found that six distinct strains, labeled A-F, accounted for 94% of the T. rubrum strains – these strains corresponded to the European ones. However, three other strains (6% of strains) were found that investigators concluded were native to North America.

Strain type switching occurred in five (83%) of the terbinafine subjects, five (56%) of the laser cohort subjects, and two (25%) of those in the placebo cohort. Roughly half of the type switches noted in the terbinafine cohort were associated with mycological cures and were followed by relapse shortly thereafter. Dr. Gupta and his associates also found that all DNA strains in this cohort were susceptible to terbinafine while in vitro. Strain types in the laser and placebo cohorts did not show any signs of intermittent cures.

The patients were sampled at intervals of 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 weeks of treatment, and T. rubrum DNA strain types were determined at week 0 (n = 6) and week 48 (n = 1) or 72 (n = 5). Patients in the laser cohort were treated at weeks 0, 8, and 16 and sampled at weeks 0, 8, 16, 24, and 48, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 9) and week 24 (n = 5) or 48 (n = 4). Finally, placebo patients were sampled at the same regularity as those in the laser cohort, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 8) and week 24 (n = 1) or 48 (n = 7), they reported.

“The T. rubrum DNA strain type switches observed in ongoing infections among all treatment groups could be attributed to microevolution or coinfections of DNA strains,” the researchers noted. “The presence of coinfecting T. rubrum DNA strains that flux with environmental conditions or local niches could account for the DNA strain type switches observed in all treatment groups, where only the relatively stable types are able to propagate in culture,” they added.

Dr. Gupta and his associates did not disclose any source of funding or any relevant conflicts of interest.

Although DNA strain type switches are known to be a natural occurrence in patients with onychomycosis, increases in strain type switching that follow treatment failure could be an antifungal-induced response, according to the results of a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum is responsible for the majority (~80%) of [onychomycosis] cases, many of which frequently relapse after successful antifungal treatment,” noted the study authors, led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta of the University of Toronto. Despite several previous studies of various facets related to onychomycosis, “data outlining onychomycosis infections of T. rubrum with DNA strain type, treatments, outcome and geographical location are still warranted,” they added (Br. J. Dermatol. 2015;172:74-80).

Dr. Gupta and his associates examined 50 adults infected with T. rubrum, determined via analysis of toenail specimens from onychomycosis patients in southwest Ontario. The patients were divided into cohorts based on the treatment they received: oral terbinafine, laser, or placebo (no terbinafine and no laser). Typing of DNA strains was done only in culture-positive samples before and after treatment, leaving a study population of six in the terbinafine group, nine in the laser group, and eight in the placebo group.

Half of the terbinafine subjects were prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/day for 12 weeks, while the other three received oral terbinafine 250 mg/day pulse therapy at on/off intervals of 2 weeks up to 12 weeks.

The investigators also used three DNA strains known to be common in Europe for comparison and found that six distinct strains, labeled A-F, accounted for 94% of the T. rubrum strains – these strains corresponded to the European ones. However, three other strains (6% of strains) were found that investigators concluded were native to North America.

Strain type switching occurred in five (83%) of the terbinafine subjects, five (56%) of the laser cohort subjects, and two (25%) of those in the placebo cohort. Roughly half of the type switches noted in the terbinafine cohort were associated with mycological cures and were followed by relapse shortly thereafter. Dr. Gupta and his associates also found that all DNA strains in this cohort were susceptible to terbinafine while in vitro. Strain types in the laser and placebo cohorts did not show any signs of intermittent cures.

The patients were sampled at intervals of 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 weeks of treatment, and T. rubrum DNA strain types were determined at week 0 (n = 6) and week 48 (n = 1) or 72 (n = 5). Patients in the laser cohort were treated at weeks 0, 8, and 16 and sampled at weeks 0, 8, 16, 24, and 48, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 9) and week 24 (n = 5) or 48 (n = 4). Finally, placebo patients were sampled at the same regularity as those in the laser cohort, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 8) and week 24 (n = 1) or 48 (n = 7), they reported.

“The T. rubrum DNA strain type switches observed in ongoing infections among all treatment groups could be attributed to microevolution or coinfections of DNA strains,” the researchers noted. “The presence of coinfecting T. rubrum DNA strains that flux with environmental conditions or local niches could account for the DNA strain type switches observed in all treatment groups, where only the relatively stable types are able to propagate in culture,” they added.

Dr. Gupta and his associates did not disclose any source of funding or any relevant conflicts of interest.

Although DNA strain type switches are known to be a natural occurrence in patients with onychomycosis, increases in strain type switching that follow treatment failure could be an antifungal-induced response, according to the results of a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum is responsible for the majority (~80%) of [onychomycosis] cases, many of which frequently relapse after successful antifungal treatment,” noted the study authors, led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta of the University of Toronto. Despite several previous studies of various facets related to onychomycosis, “data outlining onychomycosis infections of T. rubrum with DNA strain type, treatments, outcome and geographical location are still warranted,” they added (Br. J. Dermatol. 2015;172:74-80).

Dr. Gupta and his associates examined 50 adults infected with T. rubrum, determined via analysis of toenail specimens from onychomycosis patients in southwest Ontario. The patients were divided into cohorts based on the treatment they received: oral terbinafine, laser, or placebo (no terbinafine and no laser). Typing of DNA strains was done only in culture-positive samples before and after treatment, leaving a study population of six in the terbinafine group, nine in the laser group, and eight in the placebo group.

Half of the terbinafine subjects were prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/day for 12 weeks, while the other three received oral terbinafine 250 mg/day pulse therapy at on/off intervals of 2 weeks up to 12 weeks.

The investigators also used three DNA strains known to be common in Europe for comparison and found that six distinct strains, labeled A-F, accounted for 94% of the T. rubrum strains – these strains corresponded to the European ones. However, three other strains (6% of strains) were found that investigators concluded were native to North America.

Strain type switching occurred in five (83%) of the terbinafine subjects, five (56%) of the laser cohort subjects, and two (25%) of those in the placebo cohort. Roughly half of the type switches noted in the terbinafine cohort were associated with mycological cures and were followed by relapse shortly thereafter. Dr. Gupta and his associates also found that all DNA strains in this cohort were susceptible to terbinafine while in vitro. Strain types in the laser and placebo cohorts did not show any signs of intermittent cures.

The patients were sampled at intervals of 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 weeks of treatment, and T. rubrum DNA strain types were determined at week 0 (n = 6) and week 48 (n = 1) or 72 (n = 5). Patients in the laser cohort were treated at weeks 0, 8, and 16 and sampled at weeks 0, 8, 16, 24, and 48, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 9) and week 24 (n = 5) or 48 (n = 4). Finally, placebo patients were sampled at the same regularity as those in the laser cohort, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 8) and week 24 (n = 1) or 48 (n = 7), they reported.

“The T. rubrum DNA strain type switches observed in ongoing infections among all treatment groups could be attributed to microevolution or coinfections of DNA strains,” the researchers noted. “The presence of coinfecting T. rubrum DNA strains that flux with environmental conditions or local niches could account for the DNA strain type switches observed in all treatment groups, where only the relatively stable types are able to propagate in culture,” they added.

Dr. Gupta and his associates did not disclose any source of funding or any relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Antifungal treatment of onychomycosis could induce higher rates of DNA strain type switching in certain patients.

Major finding: Strain type switching occurred in 83% of the terbinafine group, 56% of the laser group, and 25% of the placebo group.

Data source: Cohort study of 23 individuals selected from 50 adults with onychomycosis who contributed samples to determine strain types.

Disclosures: The study authors did not disclose any source of funding or any relevant conflicts of interest.

Efinaconazole earns top marks for effectiveness in onychomycosis treatment

Topical treatment of toenail onychomycosis is effective with several antifungals, Dr. Aditya Gupta of the University of Toronto and his associates reported in an evidence-based review.

The researchers identified 28 relevant studies, 13 of which were of high quality. Four antifungals were an effective cure for mild to moderate toenail onychomycosis: amorolfine, ciclopirox, tavaborole, and efinaconazole. Efinaconazole was the most effective, but in all cases, outcomes were improved with longer treatment times and follow-ups.

Oral treatments are usually more effective for toenail onychomycosis, but are not always possible because of drug interactions, so topical treatments are important in certain patient populations, the investigators noted in the article abstract.

The article abstract can be found online in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0096-2).

Topical treatment of toenail onychomycosis is effective with several antifungals, Dr. Aditya Gupta of the University of Toronto and his associates reported in an evidence-based review.

The researchers identified 28 relevant studies, 13 of which were of high quality. Four antifungals were an effective cure for mild to moderate toenail onychomycosis: amorolfine, ciclopirox, tavaborole, and efinaconazole. Efinaconazole was the most effective, but in all cases, outcomes were improved with longer treatment times and follow-ups.

Oral treatments are usually more effective for toenail onychomycosis, but are not always possible because of drug interactions, so topical treatments are important in certain patient populations, the investigators noted in the article abstract.

The article abstract can be found online in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0096-2).

Topical treatment of toenail onychomycosis is effective with several antifungals, Dr. Aditya Gupta of the University of Toronto and his associates reported in an evidence-based review.

The researchers identified 28 relevant studies, 13 of which were of high quality. Four antifungals were an effective cure for mild to moderate toenail onychomycosis: amorolfine, ciclopirox, tavaborole, and efinaconazole. Efinaconazole was the most effective, but in all cases, outcomes were improved with longer treatment times and follow-ups.

Oral treatments are usually more effective for toenail onychomycosis, but are not always possible because of drug interactions, so topical treatments are important in certain patient populations, the investigators noted in the article abstract.

The article abstract can be found online in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0096-2).

PACT shows promise against onychomycosis

Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy is an effective option for treatment of in vitro onychomycosis, according to Dr. Tarun Mehra of Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany, and his associates.

In both a microdilution assay and a onychomycosis model, photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy (PACT) was effective in suppressing Trichophyton rubrum in conjunction with toluidine blue O (TBO) and LED irradiation. In another test, a patient diagnosed with distolateral onychomycosis was treated with TBO and PACT and experienced a significant improvement in nail health over the next 6 months while receiving no other treatments.

The long-term normalization of the patients’ nails suggests that PACT is a persistent cure, but patients with more than 50% of the nail affected may be more difficult to treat with PACT, the researchers said.

Read the full article online in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (doi:10:1111/jdv.12467).

Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy is an effective option for treatment of in vitro onychomycosis, according to Dr. Tarun Mehra of Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany, and his associates.

In both a microdilution assay and a onychomycosis model, photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy (PACT) was effective in suppressing Trichophyton rubrum in conjunction with toluidine blue O (TBO) and LED irradiation. In another test, a patient diagnosed with distolateral onychomycosis was treated with TBO and PACT and experienced a significant improvement in nail health over the next 6 months while receiving no other treatments.

The long-term normalization of the patients’ nails suggests that PACT is a persistent cure, but patients with more than 50% of the nail affected may be more difficult to treat with PACT, the researchers said.

Read the full article online in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (doi:10:1111/jdv.12467).

Photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy is an effective option for treatment of in vitro onychomycosis, according to Dr. Tarun Mehra of Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany, and his associates.

In both a microdilution assay and a onychomycosis model, photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy (PACT) was effective in suppressing Trichophyton rubrum in conjunction with toluidine blue O (TBO) and LED irradiation. In another test, a patient diagnosed with distolateral onychomycosis was treated with TBO and PACT and experienced a significant improvement in nail health over the next 6 months while receiving no other treatments.

The long-term normalization of the patients’ nails suggests that PACT is a persistent cure, but patients with more than 50% of the nail affected may be more difficult to treat with PACT, the researchers said.

Read the full article online in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (doi:10:1111/jdv.12467).

Incidence and Epidemiology of Onychomycosis in Patients Visiting a Tertiary Care Hospital in India

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nails. Dermatophytes are the most common etiologic agents, but yeasts and nondermatophyte molds also constitute a substantial number of cases.1 An accumulation of debris under distorted, deformed, thickened, and discolored nails, particularly with ragged and furrowed edges, strongly suggests tinea unguium.2 Candidal onychomycosis (CO) lacks gross distortion and accumulated detritus and mainly affects fingernails.3 Nondermatophytic molds cause 1.5% to 6% of cases of onychomycosis, mostly seen in toenails of elderly individuals with a history of trauma.4 Onychomycosis affects 5.5% of the world population5 and represents 20% to 40% of all onychopathies and approximately 30% of cutaneous mycotic infections.6

The incidence of onychomycosis ranges from 0.5% to 5% in the general population in India.7 The incidence is particularly high in warm humid climates such as India.8 Researchers have found certain habits of the population in the Indian subcontinent (eg, walking with bare feet, wearing ill-fitting shoes, nail-biting [eg, onychophagia], working with chemicals) to be contributing factors for onychomycosis.9 Several studies have shown that the prevalence of onychomycosis increases with age, possibly due to poor peripheral circulation, diabetes mellitus, repeated nail trauma, prolonged exposure to pathogenic fungi, suboptimal immune function, inactivity, or inability to trim the toenails and care for the feet.10 Nail infection is a cosmetic problem with serious physical and psychological morbidity and also serves as the fungal reservoir for skin infections. Besides destruction and disfigurement of the nail plate, onychomycosis can lead to self-consciousness and impairment of daily functioning.11

Nail dystrophy occurs secondary to various systemic disorders or can be associated with other dermatologic conditions. Nail discoloration and other onychia should be differentiated from onychomycosis by classifying nail lesions as distal lateral subungual onychomycosis, proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO), CO, white superficial onychomycosis (WSO), and total dystrophic onychomycosis.12 Laboratory investigation is necessary to accurately differentiate between fungal infections and other skin diseases before starting treatment. Our hospital-based study sought to determine the incidence and epidemiology of onychomycosis with an analysis of 134 participants with clinically suspected onychomycosis. We evaluated prevalence based on age, sex, and occupation, as well as the most common pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

The study population consisted of 134 patients with clinically suspected onychomycosis who visited the dermatology department at the Veer Chandra Singh Garhwali Government Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Institute in Uttarakhand, India (October 2010 to October 2011). A thorough history was obtained and a detailed examination of the distorted nails was conducted in the microbiology laboratory. Patient history and demographic factors such as age, sex, occupation, and related history of risk factors for onychomycosis were recorded pro forma. Some of the details such as itching, family history of fungal infection, and prior cutaneous infections were recorded. Patients who were undergoing treatment with systemic or topical antifungal agents in the 4 weeks preceding the study period were excluded to rule out false-negative cases and to avoid the influence of antifungal agents on the disease course.

Assessments

Two samples were taken from each patient on different days. Participants were divided into 4 groups based on occupation: farmer, housewife, student, and other (eg, clerk, shopkeeper, painter). Clinical presentation of discoloration, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and nail thickening affecting the distal and/or lateral nail plate was defined as distal lateral subungual onychomycosis; discoloration and onycholysis affecting the proximal part of the nail was defined as PSO; association with paronychia and distal and lateral onycholysis was defined as CO; white opaque patches on the nail surface were defined as WSO; and end-stage nail disease was defined as total dystrophic onychomycosis.

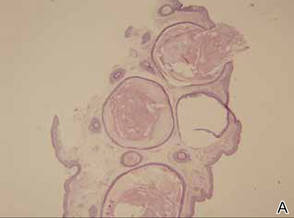

Prior to sampling, the nails were cleaned with a 70% alcohol solution. Nail clippings were obtained using presterilized nail clippers and a blunt no. 15 scalpel blade and were placed on sterilized black paper. Each nail sample was divided into 2 parts: one for direct microscopy and one for culture. Nail clippings were subjected to microscopic examination after clearing in 20% potassium hydroxide solution. The slides were examined for fungal hyphae, arthrospores, yeasts, and pseudohyphal forms. Culture was done with Emmons modification of Sabouraud dextrose agar (incubated at 27°C for molds and 37°C for yeasts) as well as with 0.4% chloramphenicol and 5% cycloheximide (incubated at 27°C). Culture tubes were examined daily for the first week and on alternate days thereafter for 4 weeks of incubation.

Dermatophytes were identified based on the colony morphology, growth rate, texture, border, and pigmentation in the obverse and reverse of culture media and microscopic examination using lactophenol cotton blue tease mount. Yeast colonies were identified microscopically with Gram stain, and species were identified by germ tube, carbohydrate assimilation, and fermentation tests.13 Nondermatophyte molds were identified by colony morphology, microscopic examination, and slide culture. Molds were considered as pathogens in the presence of the following criteria: (1) absence of other fungal growth in the same culture tube; (2) presence of mold growth in all 3 samples; and (3) presence of filaments identified on direct examination.

Results

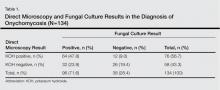

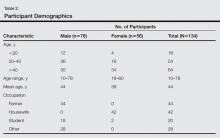

Of 134 clinically suspected cases of onychomycosis, 78 (58.2%) were from fingernails and 56 (41.8%) from toenails. Clinical diagnosis was confirmed in 96 (71.6%) cases by both fungal culture and direct microscopy but was confirmed by direct microscopy alone in only 76 (56.7%) cases. False-negative results were found in 23.9% (32/134) of participants with direct microscopy and 9.0% (12/134) with fungal cultures. The results of direct microscopy and fungal culture are outlined in Table 1. The study included 78 (58.2%) males and 56 (41.8%) females with a mean age of 44 years. Highest prevalence (47.8%) was seen in participants older than 40 years and lowest prevalence (11.9%) in participants younger than 20 years. In total, 32.8% of participants were farmers, 31.3% were housewives, 14.9% were students, and 20.9% performed other occupations. Disease history at the time of first presentation varied from 1 month to more than 2 years; 33.6% of participants had a 1- to 6-month history of disease, while only 3.7% had a disease history of less than 1 month at presentation. The demographic data are further outlined in Table 2.

Distal lateral subungual onychomycosis was the most prevalent clinical pattern found in 66 (49.3%) participants; fungal isolates were found in 60 of these participants. The next most prevalent clinical pattern was PSO, which was found in 34 (25.4%) participants, 12 showing fungal growth. A clinical pattern of CO was noted in 28 (20.9%) participants, 22 showing fungal growth; WSO was noted in 10 (7.5%) participants, 2 showing fungal growth.

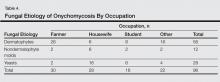

Of 96 culture-positive cases, dermatophytes were the most common pathogens isolated in 56 (58.3%) participants, followed by Candida species in 28 (29.2%) participants. Nondermatophyte molds were isolated in 12 (12.5%) participants. The various dermatophytes, Candida species, and nondermatophyte molds that were isolated on fungal culture are outlined in Table 3. Of the 96 participants with positive fungal cultures, 30 (31.2%) were farmers working with soil, 28 (29.2%) were housewives associated with wet work, 16 (16.7%) were students associated with increased physical exercise from extracurricular activity, and 22 (22.9%) were in other occupations (Table 4).

Comment

The term onychomycosis is derived from onyx, the Greek word for nail, and mykes, the Greek word for fungus. Onychomycosis is a chronic mycotic infection of the fingernails and toenails that can have a serious impact on patients’ quality of life. The fungi known to cause onychomycosis vary among geographic areas, primarily due to differences in climate.14 The isolation rate of onychomycosis in our hospital-based study was 71.6%, which is in accordance with various studies in India and abroad, including 60% in Karnataka, India5; 82.3% in Sikkim, India6; and 86.9% in Turkey.1 However, other studies have shown lower isolation rates of 39.5% in Central Delhi, India,15 and 37.6% in Himachal Pradesh, India.16 Some patients with onychomycosis may not seek medical attention, which may explain the difference in the prevalence of onychomycosis observed worldwide.17 The prevalence of onychomycosis by age also varies. In our study, participants older than 40 years showed the highest prevalence (47.8%), which is in accordance with other studies from India18 and abroad.19,20 In contrast, some Indian studies15,21,22 have reported a higher prevalence in younger adults (ie, 21–30 years), which may be attributed to greater self-consciousness about nail discoloration and disfigurement as well as increased physical activity and different shoe-wearing habits. A higher prevalence in older adults, as observed in our study as well some other studies,19,21 may be due to poor peripheral circulation, diabetes mellitus, repeated nail trauma, longer exposure to pathogenic fungi, suboptimal immune function, inactivity, and poor hygiene.10

In our study, suspected onychomycosis was more common in males (58.2%) than in females (41.8%). These results are in accordance with many of the studies in the worldwide literature.1,10,11,15,16,23-25 A higher isolation rate in males worldwide may be due to common use of occlusive footwear, more exposure to outdoor conditions, and increased physical activity, leading to an increased likelihood of trauma. The importance of trauma to the nails as a predisposing factor for onychomycosis is well established.24 In our study, the majority of males wore shoes regardless of occupation. Perspiration of the feet when wearing socks and/or shoes can generate a warm moist environment that promotes the growth of fungi and predisposes patients to onychomycosis. Similar observations have been reported by other investigators.21,22,25,26

The incidence of onychomycosis was almost evenly distributed among farmers, housewives, and the miscellaneous group, whereas a high isolation rate was noted among students. Of 20 students included in our study, onychomycosis was confirmed in 16, which may be related to an increased use of synthetic sports shoes and socks that retain sweat as well as vigorous physical activity frequently resulting in nail injuries among this patient population.11 Younger patients may be more conscious of their appearance and therefore may be more likely to seek treatment. Similar observations have been reported by other researchers.15,21,22

In our study, dermatophytes were the most commonly found pathogens (58.3%), which is comparable to other studies.15,18,22Trichophyton mentagrophytes was the most frequently isolated dermatophyte from cultures, which was in concordance with a study from Delhi.15 In some studies,18,20,22Trichophyton rubrum has been reported as the most prevalent dermatophyte, but we identified Trichophyton rubrum in only 18 participants, which can be attributed to variations in epidemiology based on geographic region. Nondermatophyte molds were isolated in 12.5% of participants, with Aspergillus niger being the most common isolate found in 8 cases. Other isolated species were Alternaria alternata and Fusarium solani found in 2 cases each. Aspergillus niger has been reported in worldwide studies as an important cause of onychomycosis.15,18,19,21,22

In 28 cases (29.2%) involving Candida species, Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida tropicalis were the most common pathogens, respectively, which is in accordance with many studies.15,20-22,25 In 28 cases of CO, females (n=16) were affected more than males (n=12). All of the females were housewives and C albicans was predominantly isolated from the fingernails. Household responsibilities involving kitchen work (eg, cutting and peeling vegetables, washing utensils, cleaning the house/laundry) may chronically expose housewives to moist environments and make them more prone to injury, thus facilitating easy entry of fungal agents.

Distal lateral subungual onychomycosis was the most prevalent clinical type found (n=66), which is comparable to other reports.20,22,25 Proximal subungual onychomycosis was the second most common type; however, a greater incidence has been reported by some researchers,23,24 while others have reported a lower incidence.20,21 Candidial onychomycosis and WSO were not common in our study, and PSO was not associated with any immunodeficiency disease, as reported by other researchers.15,20

Of 134 suspected cases of onychomycosis, 71.6% were confirmed by both direct microscopy and fungal culture, but only 56.7% were confirmed by direct microscopy alone. If we had relied on microscopy with potassium hydroxide only, we would have missed 23.9% of cases. Therefore, nail scrapings should always be subjected to fungal culture as well as direct microscopy, as both are necessary for accurate diagnosis and treatment of onychomycosis. If onychomycosis is not successfully treated, it can act as a reservoir of fungal infection affecting other parts of the body with the potential to pass infection on to others.

Conclusion

Clinical examination alone is not sufficient for diagnosing onychomycosis14,18,20; in many cases of suspected onychomycosis with nail changes, mycologic examination does not confirm fungal infection. In our study, only 71.6% of participants with nail changes proved to be of fungal etiology. Other researchers from different geographic locations have reported similar results with lower incidence (eg, 39.5%,15 37.6%,16 51.7%,18 45.3%21) of fungal etiology in such cases. Therefore, both clinical and mycologic examinations are important for establishing the diagnosis and selecting the most suitable antifungal agent, which is possible only if the underlying pathogen is correctly identified.

1. Yenişehirli G, Bulut Y, Sezer E, et al. Onychomycosis infections in the Middle Black Sea Region, Turkey. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:956-959.

2. Kouskoukis CE, Scher RK, Ackerman AB. What histologic finding distinguishes onychomycosis and psoriasis? Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:501-503.

3. Rippon JW. Medical mycology. In: Wonsiewicz M, ed. The Pathogenic Fungi and the Pathogenic Actinomycetes. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1988:169-275.

4. Greer DL. Evolving role of nondermatophytes in onychomycosis. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:521-524.

5. Murray SC, Dawber RP. Onychomycosis of toenails: orthopaedic and podiatric considerations. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:105-112.

6. Achten G, Wanet-Rouard J. Onychomycoses in the laboratory. Mykosen Suppl. 1978;1:125-127.

7. Sobhanadri C, Rao DT, Babu KS. Clinical and mycological study of superficial fungal infections at Government General Hospital: guntur and their response to treatment with hamycin, dermostatin and dermamycin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol. 1970;36:209-214.

8. Jain S, Sehgal VN. Commentary: onychomycosis: an epidemio-etiologic perspective. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:100-103.

9. Sehgal VN, Aggarwal AK, Srivastava G, et al. Onychomycosis: a 3 year clinicomycologic hospital-based study. Skinmed. 2007;6:11-17.

10. Elewski BE, Charif MA. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for the other conditions. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1172-1173.

11. Scher RK. Onychomycosis is more than a cosmetic problem. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(suppl 43):S15.

12. Godoy-Martinez PG, Nunes FG, Tomimori-Yamashita J, et al. Onychomycosis in São Paulo, Brazil [published online ahead of print May 8, 2009]. Mycopathologia. 2009;168:111-116.

13. Larone DH. Medically Important Fungi: A Guide to Identification. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2002.

14. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Dogra S, et al. Onychomycosis: an Asian perspective. Skinmed. 2010;8:37-45.

15. Sanjiv A, Shalini M, Charoo H. Etiological agents of onychomycosis from a tertiary care hospital in Central Delhi, India. Indian J Fund Appl Life Science. 2011;1:11-14.

16. Gupta M, Sharma NL, Kanga AK, et al. Onychomycosis: clinic-mycologic study of 130 patients from Himachal Pradesh, India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:389-392.

17. Eleweski BE. Diagnostic techniques for confirming onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 2):S6-S9.

18. Das NK, Ghosh P, Das S, et al. A study on the etiological agent and clinico-mycological correlation of fingernail onychomycosis in eastern India. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:75-79.

19. Bassiri-Jahromi S, Khaksar AA. Nondermatophytic moulds as a causative agent of onychomycosis in Tehran. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:140-143.

20. Bokhari MA, Hussain I, Jahangir M, et al. Onychomycosis in Lahore, Pakistan. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:591-595.

21. Jesudanam TM, Rao GR, Lakshmi DJ, et al. Onychomycosis: a significant medical problem. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:326-329.

22. Ahmad M, Gupta S, Gupte S. A clinico-mycological study of onychomycosis. EDOJ. 2010;6:1-9.

23. Vinod S, Grover S, Dash K, et al. A clinico-mycological evaluation of onychomycosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2000;66:238-240.

24. Veer P, Patwardhan NS, Damle AS. Study of onychomycosis: prevailing fungi and pattern of infection. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:53-56.

25. Garg A, Venkatesh V, Singh M, et al. Onychomycosis in central India: a clinicoetiologic correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:498-502.

26. Adhikari L, Das Gupta A, Pal R, et al. Clinico-etiologic correlates of onychomycosis in Sikkim. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:194-197.

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nails. Dermatophytes are the most common etiologic agents, but yeasts and nondermatophyte molds also constitute a substantial number of cases.1 An accumulation of debris under distorted, deformed, thickened, and discolored nails, particularly with ragged and furrowed edges, strongly suggests tinea unguium.2 Candidal onychomycosis (CO) lacks gross distortion and accumulated detritus and mainly affects fingernails.3 Nondermatophytic molds cause 1.5% to 6% of cases of onychomycosis, mostly seen in toenails of elderly individuals with a history of trauma.4 Onychomycosis affects 5.5% of the world population5 and represents 20% to 40% of all onychopathies and approximately 30% of cutaneous mycotic infections.6

The incidence of onychomycosis ranges from 0.5% to 5% in the general population in India.7 The incidence is particularly high in warm humid climates such as India.8 Researchers have found certain habits of the population in the Indian subcontinent (eg, walking with bare feet, wearing ill-fitting shoes, nail-biting [eg, onychophagia], working with chemicals) to be contributing factors for onychomycosis.9 Several studies have shown that the prevalence of onychomycosis increases with age, possibly due to poor peripheral circulation, diabetes mellitus, repeated nail trauma, prolonged exposure to pathogenic fungi, suboptimal immune function, inactivity, or inability to trim the toenails and care for the feet.10 Nail infection is a cosmetic problem with serious physical and psychological morbidity and also serves as the fungal reservoir for skin infections. Besides destruction and disfigurement of the nail plate, onychomycosis can lead to self-consciousness and impairment of daily functioning.11

Nail dystrophy occurs secondary to various systemic disorders or can be associated with other dermatologic conditions. Nail discoloration and other onychia should be differentiated from onychomycosis by classifying nail lesions as distal lateral subungual onychomycosis, proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO), CO, white superficial onychomycosis (WSO), and total dystrophic onychomycosis.12 Laboratory investigation is necessary to accurately differentiate between fungal infections and other skin diseases before starting treatment. Our hospital-based study sought to determine the incidence and epidemiology of onychomycosis with an analysis of 134 participants with clinically suspected onychomycosis. We evaluated prevalence based on age, sex, and occupation, as well as the most common pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants