User login

Cancer immunotherapy seen repigmenting gray hair

Patients on immunotherapy treatments for lung cancer have experienced repigmentation of their formerly gray hair, according to a new report. Moreover, researchers say, all but one of the patients experiencing this effect also responded well to the therapy, suggesting that hair repigmentation could potentially serve as a marker of treatment response.

In a case series published online July 12 in JAMA Dermatology (2017. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2106), Noelia Rivera, MD, of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and her colleagues report findings from 14 patients (13 male, mean age 65) receiving anti–programmed cell death 1 (anti–PD-1) and anti–programmed cell death ligand 1 (anti–PD-L1) therapies to treat squamous cell lung cancer or lung adenocarcinoma, with most (11) receiving nivolumab (Opdivo). All but one patient experienced a diffuse darkening of the hair to resemble its previous color, while the remaining patient’s repigmentation occurred in patches.

Dr. Rivera and her colleagues wrote in their analysis that gray hair follicles “still preserve a reduced number of differentiated and functioning melanocytes located in the hair bulb. This reduced number of melanocytes may explain the possibility of [repigmentation] under appropriate conditions.” But, there are competing theories as to why this should occur with cancer immunotherapy, they noted. One is that the drugs’ inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines acts as negative regulators of melanogenesis. Another is that melanocytes in hair follicles are activated through inflammatory mediators. Of the patients with hair repigmentation in the study, only one, who was being treated with nivolumab for lung squamous cell carcinoma, had disease progression. This patient was discontinued after four treatment sessions and died. The other 13 patients saw either stable disease or a partial response.

The study received no outside funding, but two investigators disclosed financial relationships with pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Patients on immunotherapy treatments for lung cancer have experienced repigmentation of their formerly gray hair, according to a new report. Moreover, researchers say, all but one of the patients experiencing this effect also responded well to the therapy, suggesting that hair repigmentation could potentially serve as a marker of treatment response.

In a case series published online July 12 in JAMA Dermatology (2017. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2106), Noelia Rivera, MD, of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and her colleagues report findings from 14 patients (13 male, mean age 65) receiving anti–programmed cell death 1 (anti–PD-1) and anti–programmed cell death ligand 1 (anti–PD-L1) therapies to treat squamous cell lung cancer or lung adenocarcinoma, with most (11) receiving nivolumab (Opdivo). All but one patient experienced a diffuse darkening of the hair to resemble its previous color, while the remaining patient’s repigmentation occurred in patches.

Dr. Rivera and her colleagues wrote in their analysis that gray hair follicles “still preserve a reduced number of differentiated and functioning melanocytes located in the hair bulb. This reduced number of melanocytes may explain the possibility of [repigmentation] under appropriate conditions.” But, there are competing theories as to why this should occur with cancer immunotherapy, they noted. One is that the drugs’ inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines acts as negative regulators of melanogenesis. Another is that melanocytes in hair follicles are activated through inflammatory mediators. Of the patients with hair repigmentation in the study, only one, who was being treated with nivolumab for lung squamous cell carcinoma, had disease progression. This patient was discontinued after four treatment sessions and died. The other 13 patients saw either stable disease or a partial response.

The study received no outside funding, but two investigators disclosed financial relationships with pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Patients on immunotherapy treatments for lung cancer have experienced repigmentation of their formerly gray hair, according to a new report. Moreover, researchers say, all but one of the patients experiencing this effect also responded well to the therapy, suggesting that hair repigmentation could potentially serve as a marker of treatment response.

In a case series published online July 12 in JAMA Dermatology (2017. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2106), Noelia Rivera, MD, of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and her colleagues report findings from 14 patients (13 male, mean age 65) receiving anti–programmed cell death 1 (anti–PD-1) and anti–programmed cell death ligand 1 (anti–PD-L1) therapies to treat squamous cell lung cancer or lung adenocarcinoma, with most (11) receiving nivolumab (Opdivo). All but one patient experienced a diffuse darkening of the hair to resemble its previous color, while the remaining patient’s repigmentation occurred in patches.

Dr. Rivera and her colleagues wrote in their analysis that gray hair follicles “still preserve a reduced number of differentiated and functioning melanocytes located in the hair bulb. This reduced number of melanocytes may explain the possibility of [repigmentation] under appropriate conditions.” But, there are competing theories as to why this should occur with cancer immunotherapy, they noted. One is that the drugs’ inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines acts as negative regulators of melanogenesis. Another is that melanocytes in hair follicles are activated through inflammatory mediators. Of the patients with hair repigmentation in the study, only one, who was being treated with nivolumab for lung squamous cell carcinoma, had disease progression. This patient was discontinued after four treatment sessions and died. The other 13 patients saw either stable disease or a partial response.

The study received no outside funding, but two investigators disclosed financial relationships with pharmaceutical manufacturers.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 52 patients, 14 patients saw a diffuse restoration of their original hair color during the course of treatment. All but 1 of these also saw a robust treatment response.

Data source: A case series drawn from a single-center cohort of 52 lung cancer patients treated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 and monitored for cutaneous effects.

Disclosures: Two coauthors disclosed financial relationships with several drug manufacturers.

Temporal Triangular Alopecia Acquired in Adulthood

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

To the Editor:

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), a condition first described by Sabouraud1 in 1905, is a circumscribed nonscarring form of alopecia. Also referred to as congenital triangular alopecia, TTA presents as a triangular or lancet-shaped area of hair loss involving the frontotemporal hairline. Temporal triangular alopecia is characterized histologically by a normal number of miniaturized hair follicles without notable inflammation.2 Although the majority of cases arise between birth and 9 years of age,3,4 rare cases of adult-onset TTA also have been reported.5,6 Adult-onset cases can cause notable diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment, as reported in our patient.

A 25-year-old woman with a history of Hashimoto thyroiditis presented with hair loss affecting the right temporal scalp of 3 years' duration that was first noticed by her husband. The lesion was an asymptomatic, 6×8-cm, roughly lancet-shaped patch of alopecia located on the right temporal scalp, bordering on the frontal hairline (Figure 1). Centrally, the patch appeared almost hairless with a few retained terminal hairs. The frontal hairline was thinned but still present. There was no scaling or erythema, and fine vellus hairs and a few isolated terminal hairs covered the area. The corresponding skin on the contralateral temporal scalp showed normal hair density. The patient insisted that she had normal hair at the affected area until 22 years of age, and she denied a history of trauma or tight hairstyles. Initially diagnosed with alopecia areata by her primary care provider, the patient was treated with topical corticosteroids for 6 months without benefit. She was subsequently referred to a dermatologist who again offered a diagnosis of alopecia areata and treated the lesions with 2 intralesional corticosteroid injections without benefit. No biopsies of the affected area were performed, and the patient was given a trial of topical minoxidil.

The patient consulted a new primary care provider and was diagnosed with scarring alopecia. She was referred to our dermatology department for further treatment. An initial biopsy at the edge of the affected area was interpreted as normal, but after failing additional intralesional corticosteroid injections, she was referred to our hair clinic where another biopsy was performed in the central portion of the lesion. A 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimen revealed a normal epidermis and dermis; however, in the lower dermis only a single terminal follicle was seen (Figure 2). Sections through the upper dermis (Figure 3) showed that the total number of hairs was normal or nearly normal with at least 22 follicles, but most were vellus and indeterminate hairs with only a single terminal hair. The dermal architecture was otherwise normal. Given the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of TTA was made. Subsequent to the diagnosis, the patient did not pursue any additional treatment options and preferred to style her hair so that the area of TTA remained covered.

The differential diagnosis in adults presenting with a patch of localized alopecia includes alopecia areata, trichotillomania, pressure-induced alopecia, traction alopecia, lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, and rarely TTA. Temporal triangular alopecia is a fairly common, if underreported, nonscarring form of alopecia that mainly affects young children. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms temporal triangular alopecia or congenital triangular alopecia or triangular alopecia documented only 76 cases of TTA including our own, with the majority of patients diagnosed before 9 years of age. Only 2 cases of adult-onset TTA have been reported,5,6 possibly leading to misdiagnosis of adult patients who present with similar areas of hair loss. As with some prior cases of TTA,5,7 our patient was misdiagnosed with alopecia areata and scarring alopecia, both treated unsuccessfully before a diagnosis of TTA was considered. Clues to the diagnosis included the location, the lack of change in size and shape, the lack of response to intralesional corticosteroids, and the presence of numerous vellus hairs on the surface. A biopsy of the visibly hairless zone was confirmatory. The normal or nearly normal number of miniaturized hairs in specimens of TTA suggest that topical minoxidil therapy (eg, 5% solution twice daily for at least 6 months) might be useful, but the authors have tried it on a few other patients with clinically typical TTA without discernible benefit. When lesions are small, excision provides a fast and permanent solution to the problem, albeit with the usual risks of minor surgery.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

- Sabouraud RJA. Manuel Élémentaire de Dermatologie Topographique Régionale. Paris, France: Masson & Cie; 1905:197.

- Trakimas C, Sperling LC, Skelton HG 3rd, et al. Clinical and histologic findings in temporal triangular alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:205-209.

- Yamazaki M, Irisawa R, Tsuboi R. Temporal triangular alopecia and a review of 52 past cases. J Dermatol. 2010;37:360-362.

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C, et al. Prevalence of scalp disorders and hair loss in children. Cutis. 2012;90:225-229.

- Trakimas CA, Sperling LC. Temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:842-844.

- Akan IM, Yildirim S, Avci G, et al. Bilateral temporal triangular alopecia acquired in adulthood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1616-1617.

- Gupta LK, Khare AK, Garg A, et al. Congenital triangular alopecia--a close mimicker of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:40-41.

Practice Points

- Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA) in adults often is confused with alopecia areata.

- An acquired, persistent, unchanging, circumscribed hairless spot in an adult that does not respond to intralesional corticosteroids may represent TTA.

- Hair miniaturization without peribulbar inflammation is consistent with a diagnosis of TTA.

How to get through the tough talks about alopecia areata

CHICAGO – If you can’t set the temptation to hurry aside and take the time to listen, things may not go well, said Neil Prose, MD.

With the caveat that Janus kinase inhibitors show promise, Dr. Prose said that “most children who are destined to lose their hair will probably do so despite all of our best efforts.” Figuring out how to engage children and parents and frame a positive conversation about alopecia can present a real challenge, especially in the context of a busy practice, said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology and medical director of Patterson Place Pediatric Dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“These are very culturally-specific suggestions, but see which ones work for you,” said Dr. Prose, speaking to an international audience at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Prose depicted two opposing images. In one, he said, the patient and you are sitting on opposite sides of the table, with the prospect of hair loss looming between them. By contrast, “imagine what it would take to be on the same side of the table, looking at the problem together,” he said.

There are many barriers that stand in the way of getting you and the patient on the same side of the issue of dealing with severe alopecia areata. The high emotional content of the discussion can be big factor, not just for the patient and family members, but also for you.

“We are often dealing with patient disappointment and, frankly, with our own sense of personal failure” when there isn’t always a good set of options, said Dr. Prose. Other specific aspects of severe pediatric alopecia areata that make the conversation difficult include the high degree of uncertainty that any particular treatment will succeed and a knowledge of how to give patients and family members hope without raising expectations unrealistically.

Coming back to the important first steps of not rushing the visit and being sure to listen, Dr. Prose said that, for him, the process begins before he enters the room, when he takes a moment to clear his mind. “It starts for me just before I open the door to the examining room. As human beings, we are infinitely distractible. It’s very hard for us to simply pay attention.”

Yet, this is vitally important, he said, because families need to be heard. Citing the oft-quoted statistic that, on average, a physician interrupts a patient in the first 17 seconds of the office visit, Dr. Prose said, “Many of us are ‘explainaholics,’ ’’ spending precious visit time talking about what the physician thinks is important.

Still, it’s important to validate parents’ concerns and to alleviate guilt. “Patients’ families sometimes feel guilty because they are so upset and worried – and it’s not cancer,” said Dr. Prose. Potential impacts on quality of life are still huge, and all parents want the best for their children, he pointed out.

One way he likes to begin a follow-up visit is simply to ask, “So, how’s everyone doing?” This opens the door to allow the child and the family to talk about what’s important to them. These may be symptom-related, but social issues also may be what’s looming largest.

In order to decipher how hair loss is affecting a particular child, Dr. Prose said he likes to say, “I need to understand how this is affecting you, so we can decide together where to go from here.” This gives the family control in setting the agenda and begins the process of bringing you to the same side of the table.

Specific prompts that can help you understand how alopecia is affecting a child can include asking about how things are going at school, what the child’s friends know about his or her alopecia, whether there is mocking or bullying occurring, and how the patient, family, and teachers are addressing the global picture.

Parents can be asked whether they are noticing changes in behavior, and it’s a good idea to check in on how parents are coping as well, said Dr. Prose.

To ensure that families feel they’re being heard, and to make sure you are understanding correctly, it’s useful to mirror what’s been said, beginning with a phrase like, “So, what you’re saying is …” Putting a name to the emotions that emerge during the visit also can be useful, using phrases like, “I can imagine that this has been disappointing,” or “It feels like everyone is very worried.”

But, said Dr. Prose, don’t forget about opportunities to praise patients and their families when they’ve come through a tough time well. This validation is important, he said.

When treatment isn’t working, a first place to start is to acknowledge that you, along with the family, wish that things were turning out differently. Then, said Dr. Prose, it can be really important to reappraise treatment goals. After taking the emotional temperature of the room, it may be appropriate to ask, “Is it time to talk about not doing any more treatments?” This question can be put within the framework that hair may or may not regrow spontaneously anyway and that new treatments are emerging that may help in future.

When giving advice or talking about difficult issues, it can be helpful to ask permission, said Dr. Prose. He likes to begin with, “Would it be okay if I ...?” Then, he said, the door can be opened to give advice about school issues, to ask about difficult treatment decisions, or even to share tips learned from other families’ coping methods.

Don’t forget, said Dr. Prose, to refer patients to high-quality information and online support resources, such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. The Internet is full of inaccurate and scary information, and patients and families need help with this navigation, he said.

The very last question Dr. Prose asks during a visit is “What other questions do you have?” The question is always framed exactly like this, he said, because it assumes there will be more questions, and it gives families permission to ask more. Although most of the time there aren’t any further questions, Dr. Prose said, “Do not ask the question with your hand on the doorknob!”

Dr. Prose had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – If you can’t set the temptation to hurry aside and take the time to listen, things may not go well, said Neil Prose, MD.

With the caveat that Janus kinase inhibitors show promise, Dr. Prose said that “most children who are destined to lose their hair will probably do so despite all of our best efforts.” Figuring out how to engage children and parents and frame a positive conversation about alopecia can present a real challenge, especially in the context of a busy practice, said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology and medical director of Patterson Place Pediatric Dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“These are very culturally-specific suggestions, but see which ones work for you,” said Dr. Prose, speaking to an international audience at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Prose depicted two opposing images. In one, he said, the patient and you are sitting on opposite sides of the table, with the prospect of hair loss looming between them. By contrast, “imagine what it would take to be on the same side of the table, looking at the problem together,” he said.

There are many barriers that stand in the way of getting you and the patient on the same side of the issue of dealing with severe alopecia areata. The high emotional content of the discussion can be big factor, not just for the patient and family members, but also for you.

“We are often dealing with patient disappointment and, frankly, with our own sense of personal failure” when there isn’t always a good set of options, said Dr. Prose. Other specific aspects of severe pediatric alopecia areata that make the conversation difficult include the high degree of uncertainty that any particular treatment will succeed and a knowledge of how to give patients and family members hope without raising expectations unrealistically.

Coming back to the important first steps of not rushing the visit and being sure to listen, Dr. Prose said that, for him, the process begins before he enters the room, when he takes a moment to clear his mind. “It starts for me just before I open the door to the examining room. As human beings, we are infinitely distractible. It’s very hard for us to simply pay attention.”

Yet, this is vitally important, he said, because families need to be heard. Citing the oft-quoted statistic that, on average, a physician interrupts a patient in the first 17 seconds of the office visit, Dr. Prose said, “Many of us are ‘explainaholics,’ ’’ spending precious visit time talking about what the physician thinks is important.

Still, it’s important to validate parents’ concerns and to alleviate guilt. “Patients’ families sometimes feel guilty because they are so upset and worried – and it’s not cancer,” said Dr. Prose. Potential impacts on quality of life are still huge, and all parents want the best for their children, he pointed out.

One way he likes to begin a follow-up visit is simply to ask, “So, how’s everyone doing?” This opens the door to allow the child and the family to talk about what’s important to them. These may be symptom-related, but social issues also may be what’s looming largest.

In order to decipher how hair loss is affecting a particular child, Dr. Prose said he likes to say, “I need to understand how this is affecting you, so we can decide together where to go from here.” This gives the family control in setting the agenda and begins the process of bringing you to the same side of the table.

Specific prompts that can help you understand how alopecia is affecting a child can include asking about how things are going at school, what the child’s friends know about his or her alopecia, whether there is mocking or bullying occurring, and how the patient, family, and teachers are addressing the global picture.

Parents can be asked whether they are noticing changes in behavior, and it’s a good idea to check in on how parents are coping as well, said Dr. Prose.

To ensure that families feel they’re being heard, and to make sure you are understanding correctly, it’s useful to mirror what’s been said, beginning with a phrase like, “So, what you’re saying is …” Putting a name to the emotions that emerge during the visit also can be useful, using phrases like, “I can imagine that this has been disappointing,” or “It feels like everyone is very worried.”

But, said Dr. Prose, don’t forget about opportunities to praise patients and their families when they’ve come through a tough time well. This validation is important, he said.

When treatment isn’t working, a first place to start is to acknowledge that you, along with the family, wish that things were turning out differently. Then, said Dr. Prose, it can be really important to reappraise treatment goals. After taking the emotional temperature of the room, it may be appropriate to ask, “Is it time to talk about not doing any more treatments?” This question can be put within the framework that hair may or may not regrow spontaneously anyway and that new treatments are emerging that may help in future.

When giving advice or talking about difficult issues, it can be helpful to ask permission, said Dr. Prose. He likes to begin with, “Would it be okay if I ...?” Then, he said, the door can be opened to give advice about school issues, to ask about difficult treatment decisions, or even to share tips learned from other families’ coping methods.

Don’t forget, said Dr. Prose, to refer patients to high-quality information and online support resources, such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. The Internet is full of inaccurate and scary information, and patients and families need help with this navigation, he said.

The very last question Dr. Prose asks during a visit is “What other questions do you have?” The question is always framed exactly like this, he said, because it assumes there will be more questions, and it gives families permission to ask more. Although most of the time there aren’t any further questions, Dr. Prose said, “Do not ask the question with your hand on the doorknob!”

Dr. Prose had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – If you can’t set the temptation to hurry aside and take the time to listen, things may not go well, said Neil Prose, MD.

With the caveat that Janus kinase inhibitors show promise, Dr. Prose said that “most children who are destined to lose their hair will probably do so despite all of our best efforts.” Figuring out how to engage children and parents and frame a positive conversation about alopecia can present a real challenge, especially in the context of a busy practice, said Dr. Prose, professor of dermatology and medical director of Patterson Place Pediatric Dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

“These are very culturally-specific suggestions, but see which ones work for you,” said Dr. Prose, speaking to an international audience at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology.

Dr. Prose depicted two opposing images. In one, he said, the patient and you are sitting on opposite sides of the table, with the prospect of hair loss looming between them. By contrast, “imagine what it would take to be on the same side of the table, looking at the problem together,” he said.

There are many barriers that stand in the way of getting you and the patient on the same side of the issue of dealing with severe alopecia areata. The high emotional content of the discussion can be big factor, not just for the patient and family members, but also for you.

“We are often dealing with patient disappointment and, frankly, with our own sense of personal failure” when there isn’t always a good set of options, said Dr. Prose. Other specific aspects of severe pediatric alopecia areata that make the conversation difficult include the high degree of uncertainty that any particular treatment will succeed and a knowledge of how to give patients and family members hope without raising expectations unrealistically.

Coming back to the important first steps of not rushing the visit and being sure to listen, Dr. Prose said that, for him, the process begins before he enters the room, when he takes a moment to clear his mind. “It starts for me just before I open the door to the examining room. As human beings, we are infinitely distractible. It’s very hard for us to simply pay attention.”

Yet, this is vitally important, he said, because families need to be heard. Citing the oft-quoted statistic that, on average, a physician interrupts a patient in the first 17 seconds of the office visit, Dr. Prose said, “Many of us are ‘explainaholics,’ ’’ spending precious visit time talking about what the physician thinks is important.

Still, it’s important to validate parents’ concerns and to alleviate guilt. “Patients’ families sometimes feel guilty because they are so upset and worried – and it’s not cancer,” said Dr. Prose. Potential impacts on quality of life are still huge, and all parents want the best for their children, he pointed out.

One way he likes to begin a follow-up visit is simply to ask, “So, how’s everyone doing?” This opens the door to allow the child and the family to talk about what’s important to them. These may be symptom-related, but social issues also may be what’s looming largest.

In order to decipher how hair loss is affecting a particular child, Dr. Prose said he likes to say, “I need to understand how this is affecting you, so we can decide together where to go from here.” This gives the family control in setting the agenda and begins the process of bringing you to the same side of the table.

Specific prompts that can help you understand how alopecia is affecting a child can include asking about how things are going at school, what the child’s friends know about his or her alopecia, whether there is mocking or bullying occurring, and how the patient, family, and teachers are addressing the global picture.

Parents can be asked whether they are noticing changes in behavior, and it’s a good idea to check in on how parents are coping as well, said Dr. Prose.

To ensure that families feel they’re being heard, and to make sure you are understanding correctly, it’s useful to mirror what’s been said, beginning with a phrase like, “So, what you’re saying is …” Putting a name to the emotions that emerge during the visit also can be useful, using phrases like, “I can imagine that this has been disappointing,” or “It feels like everyone is very worried.”

But, said Dr. Prose, don’t forget about opportunities to praise patients and their families when they’ve come through a tough time well. This validation is important, he said.

When treatment isn’t working, a first place to start is to acknowledge that you, along with the family, wish that things were turning out differently. Then, said Dr. Prose, it can be really important to reappraise treatment goals. After taking the emotional temperature of the room, it may be appropriate to ask, “Is it time to talk about not doing any more treatments?” This question can be put within the framework that hair may or may not regrow spontaneously anyway and that new treatments are emerging that may help in future.

When giving advice or talking about difficult issues, it can be helpful to ask permission, said Dr. Prose. He likes to begin with, “Would it be okay if I ...?” Then, he said, the door can be opened to give advice about school issues, to ask about difficult treatment decisions, or even to share tips learned from other families’ coping methods.

Don’t forget, said Dr. Prose, to refer patients to high-quality information and online support resources, such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. The Internet is full of inaccurate and scary information, and patients and families need help with this navigation, he said.

The very last question Dr. Prose asks during a visit is “What other questions do you have?” The question is always framed exactly like this, he said, because it assumes there will be more questions, and it gives families permission to ask more. Although most of the time there aren’t any further questions, Dr. Prose said, “Do not ask the question with your hand on the doorknob!”

Dr. Prose had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCPD 2017

New one-time treatment for head lice found safe for children

CHICAGO – A novel one-time topical treatment for head lice, abametapir, was well tolerated in children as young as 6 months, according to pooled results from 11 clinical trials.

The pooled safety data included results from 11 clinical trials including 1,372 patients. Of these, 700 were aged 6 months to 17 years, and patients were exposed to the novel metalloproteinase inhibitor for 10-20 minutes.

In examining safety data from the pooled trials, Lydie Hazan, MD, of Axis Clinical Trials and her collaborators found that for pediatric patients, most treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were skin and subcutaneous tissue-related. The most common AEs were erythema, rash, a burning sensation on the skin, and contact dermatitis.

Data for the three phase II pharmacokinetic trials, the phase II ovicidal efficacy trial, and the two phase III trials were reported separately by Dr. Hazan and her coauthors in a poster presentation at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in the studies ranged from 20% to 29% for patients in the active arms of the trials. For patients who received the vehicle lotion only, the incidence of AEs ranged from 16% to 57%.

Of the 11 trials, 6 involved pediatric patients, with one phase IIB trial, one phase II ovicidal trial, two maximal-use open-label trials, and two phase III randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials. Of the 920 patients, in most of the trials they received a 10-minute exposure to the study drug (489 received abametapir lotion 0.74%, 431 received vehicle lotion).

Looking just at the phase III trials, 24% of patients in the abametapir arm reported AEs, while 19% of those receiving vehicle reported any AE.

In the two maximal-use pediatric trials, drug exposure ranged from 3.3 g to 200.8 g; AEs in these two trials occurred in 23% of participants.

Safety data collected for all studies also included vital signs, results of physical exams, and laboratory tests; no “clinically meaningful” changes were seen in any of the trials for any of these values, according to Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

“AEs were mild, not age-related, and primarily in the system organ class of skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders,” said Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

Abematapir 0.74% lotion had previously been shown to be an effective ovicidal treatment for head lice when used in a single application; the lotion is intended to be applied at home by the patient or caregiver (J Med Entomol. 2017. 54[1]:167-72).*

Dr. Hazan is employed by Axis clinical trials. Other study authors were employed by Hatchtech, which developed abametapir, and by Promius Pharma/Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, which plans to market abametapir lotion.

*Correction, 8/7/17: An earlier version of this article had an incorrect citation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – A novel one-time topical treatment for head lice, abametapir, was well tolerated in children as young as 6 months, according to pooled results from 11 clinical trials.

The pooled safety data included results from 11 clinical trials including 1,372 patients. Of these, 700 were aged 6 months to 17 years, and patients were exposed to the novel metalloproteinase inhibitor for 10-20 minutes.

In examining safety data from the pooled trials, Lydie Hazan, MD, of Axis Clinical Trials and her collaborators found that for pediatric patients, most treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were skin and subcutaneous tissue-related. The most common AEs were erythema, rash, a burning sensation on the skin, and contact dermatitis.

Data for the three phase II pharmacokinetic trials, the phase II ovicidal efficacy trial, and the two phase III trials were reported separately by Dr. Hazan and her coauthors in a poster presentation at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in the studies ranged from 20% to 29% for patients in the active arms of the trials. For patients who received the vehicle lotion only, the incidence of AEs ranged from 16% to 57%.

Of the 11 trials, 6 involved pediatric patients, with one phase IIB trial, one phase II ovicidal trial, two maximal-use open-label trials, and two phase III randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials. Of the 920 patients, in most of the trials they received a 10-minute exposure to the study drug (489 received abametapir lotion 0.74%, 431 received vehicle lotion).

Looking just at the phase III trials, 24% of patients in the abametapir arm reported AEs, while 19% of those receiving vehicle reported any AE.

In the two maximal-use pediatric trials, drug exposure ranged from 3.3 g to 200.8 g; AEs in these two trials occurred in 23% of participants.

Safety data collected for all studies also included vital signs, results of physical exams, and laboratory tests; no “clinically meaningful” changes were seen in any of the trials for any of these values, according to Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

“AEs were mild, not age-related, and primarily in the system organ class of skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders,” said Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

Abematapir 0.74% lotion had previously been shown to be an effective ovicidal treatment for head lice when used in a single application; the lotion is intended to be applied at home by the patient or caregiver (J Med Entomol. 2017. 54[1]:167-72).*

Dr. Hazan is employed by Axis clinical trials. Other study authors were employed by Hatchtech, which developed abametapir, and by Promius Pharma/Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, which plans to market abametapir lotion.

*Correction, 8/7/17: An earlier version of this article had an incorrect citation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – A novel one-time topical treatment for head lice, abametapir, was well tolerated in children as young as 6 months, according to pooled results from 11 clinical trials.

The pooled safety data included results from 11 clinical trials including 1,372 patients. Of these, 700 were aged 6 months to 17 years, and patients were exposed to the novel metalloproteinase inhibitor for 10-20 minutes.

In examining safety data from the pooled trials, Lydie Hazan, MD, of Axis Clinical Trials and her collaborators found that for pediatric patients, most treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were skin and subcutaneous tissue-related. The most common AEs were erythema, rash, a burning sensation on the skin, and contact dermatitis.

Data for the three phase II pharmacokinetic trials, the phase II ovicidal efficacy trial, and the two phase III trials were reported separately by Dr. Hazan and her coauthors in a poster presentation at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in the studies ranged from 20% to 29% for patients in the active arms of the trials. For patients who received the vehicle lotion only, the incidence of AEs ranged from 16% to 57%.

Of the 11 trials, 6 involved pediatric patients, with one phase IIB trial, one phase II ovicidal trial, two maximal-use open-label trials, and two phase III randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials. Of the 920 patients, in most of the trials they received a 10-minute exposure to the study drug (489 received abametapir lotion 0.74%, 431 received vehicle lotion).

Looking just at the phase III trials, 24% of patients in the abametapir arm reported AEs, while 19% of those receiving vehicle reported any AE.

In the two maximal-use pediatric trials, drug exposure ranged from 3.3 g to 200.8 g; AEs in these two trials occurred in 23% of participants.

Safety data collected for all studies also included vital signs, results of physical exams, and laboratory tests; no “clinically meaningful” changes were seen in any of the trials for any of these values, according to Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

“AEs were mild, not age-related, and primarily in the system organ class of skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders,” said Dr. Hazan and her coauthors.

Abematapir 0.74% lotion had previously been shown to be an effective ovicidal treatment for head lice when used in a single application; the lotion is intended to be applied at home by the patient or caregiver (J Med Entomol. 2017. 54[1]:167-72).*

Dr. Hazan is employed by Axis clinical trials. Other study authors were employed by Hatchtech, which developed abametapir, and by Promius Pharma/Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, which plans to market abametapir lotion.

*Correction, 8/7/17: An earlier version of this article had an incorrect citation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT WCPD 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In pooled clinical trial data, pediatric patients had adverse events at the same rate as adult patients, with overall rates ranging from 20% to 57%.

Data source: Pooled data from 11 clinical trials including 1,372 patients, 700 of whom were aged 6 months to 17 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Hazan is employed by Axis Clinical Trials. Other study authors were employed by Hatchtech, which developed abametapir, and by Promius Pharma/Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, which plans to market abametapir lotion.

Black Adherence Nodules on the Scalp Hair Shaft

The Diagnosis: Piedra

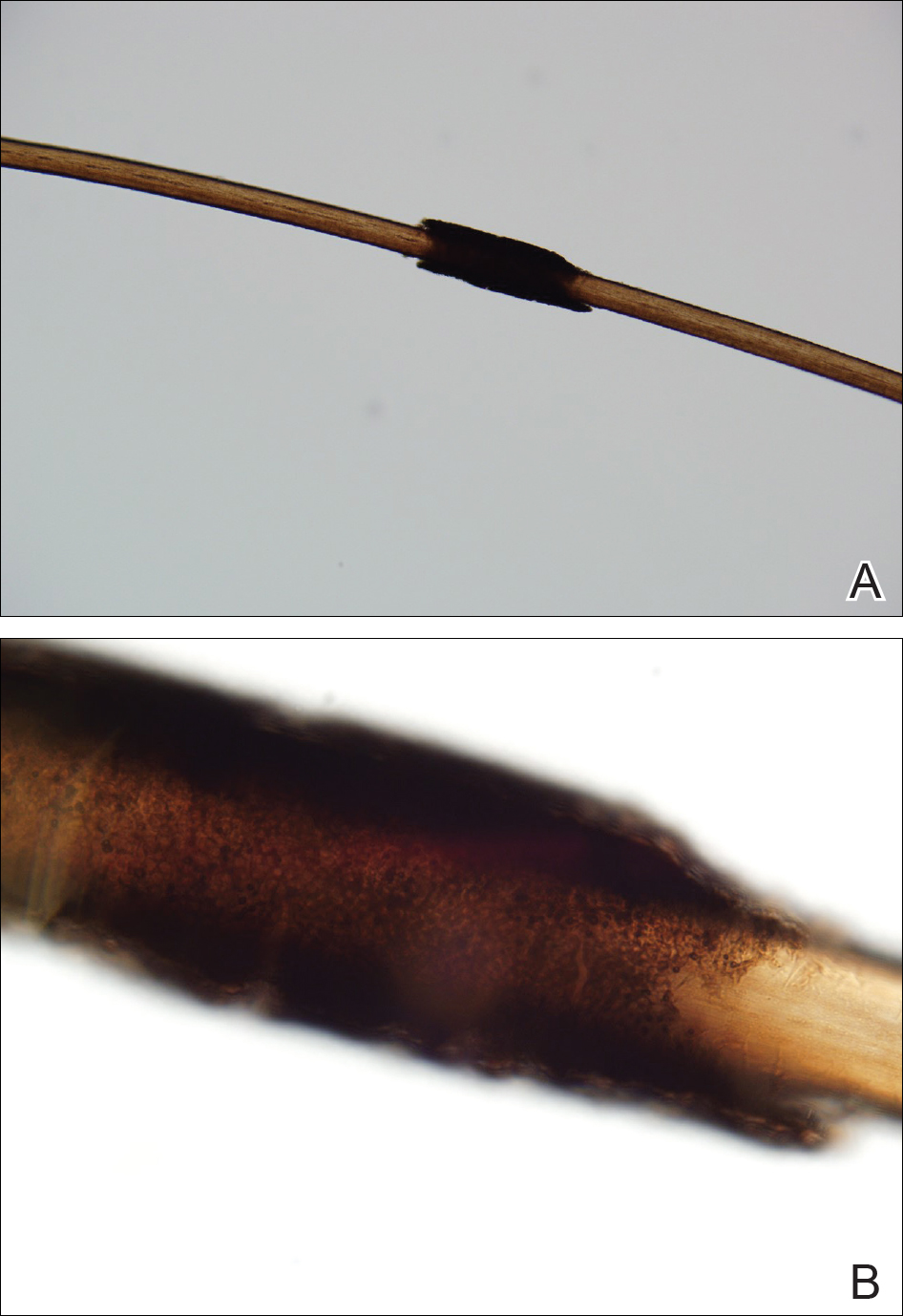

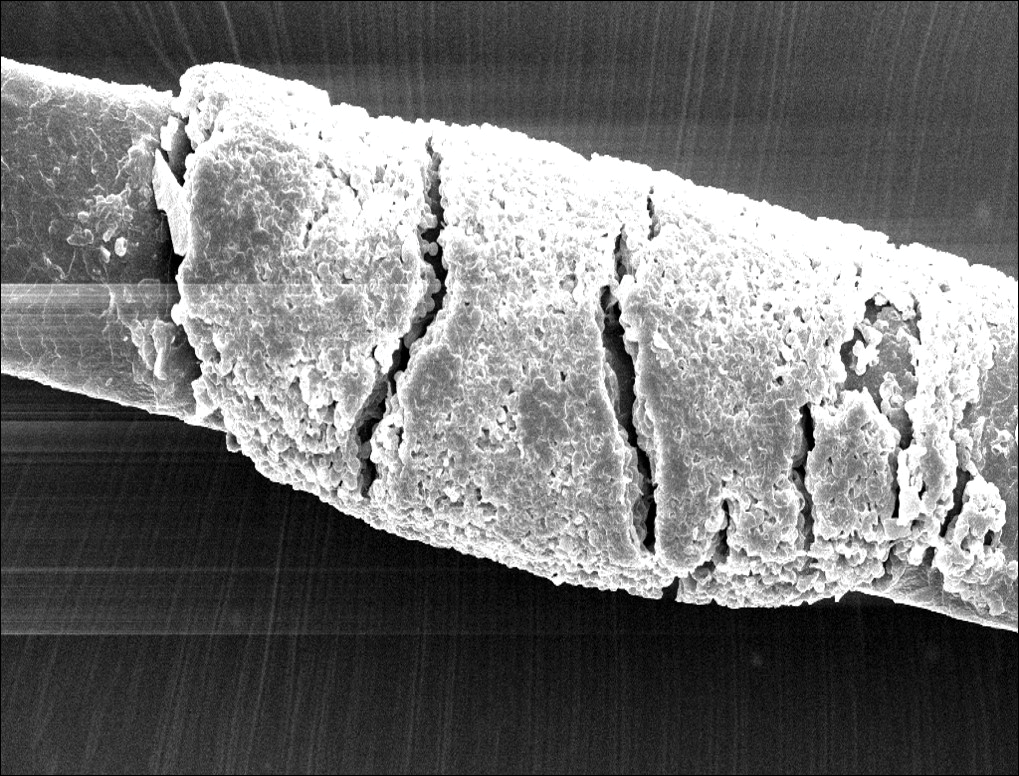

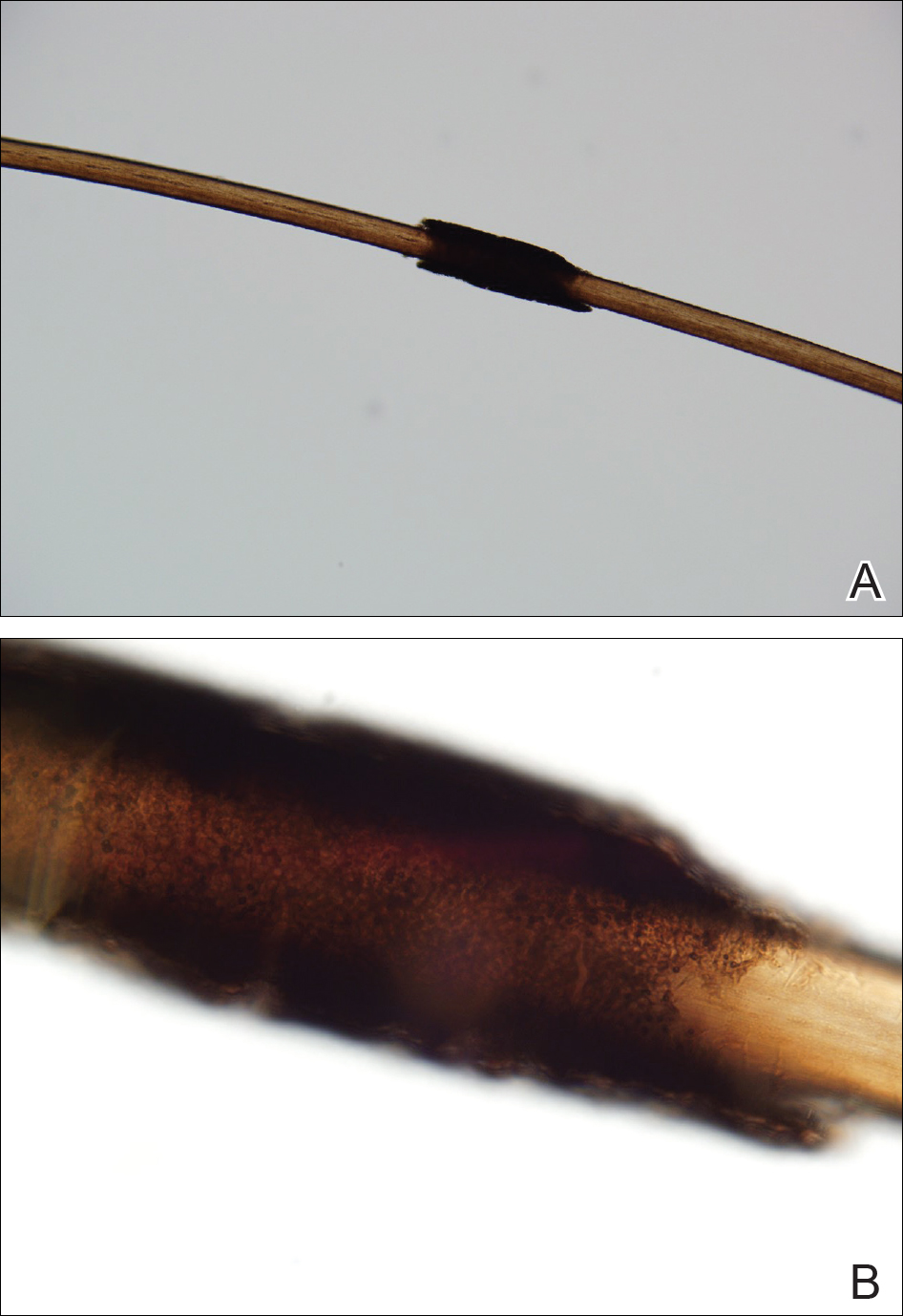

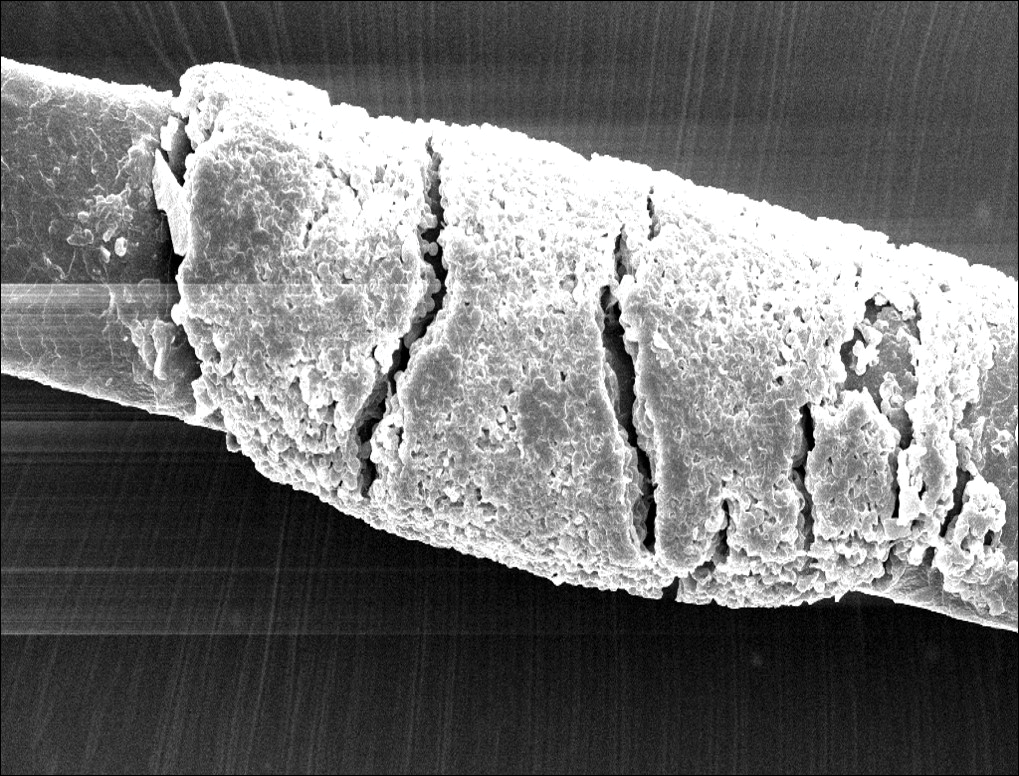

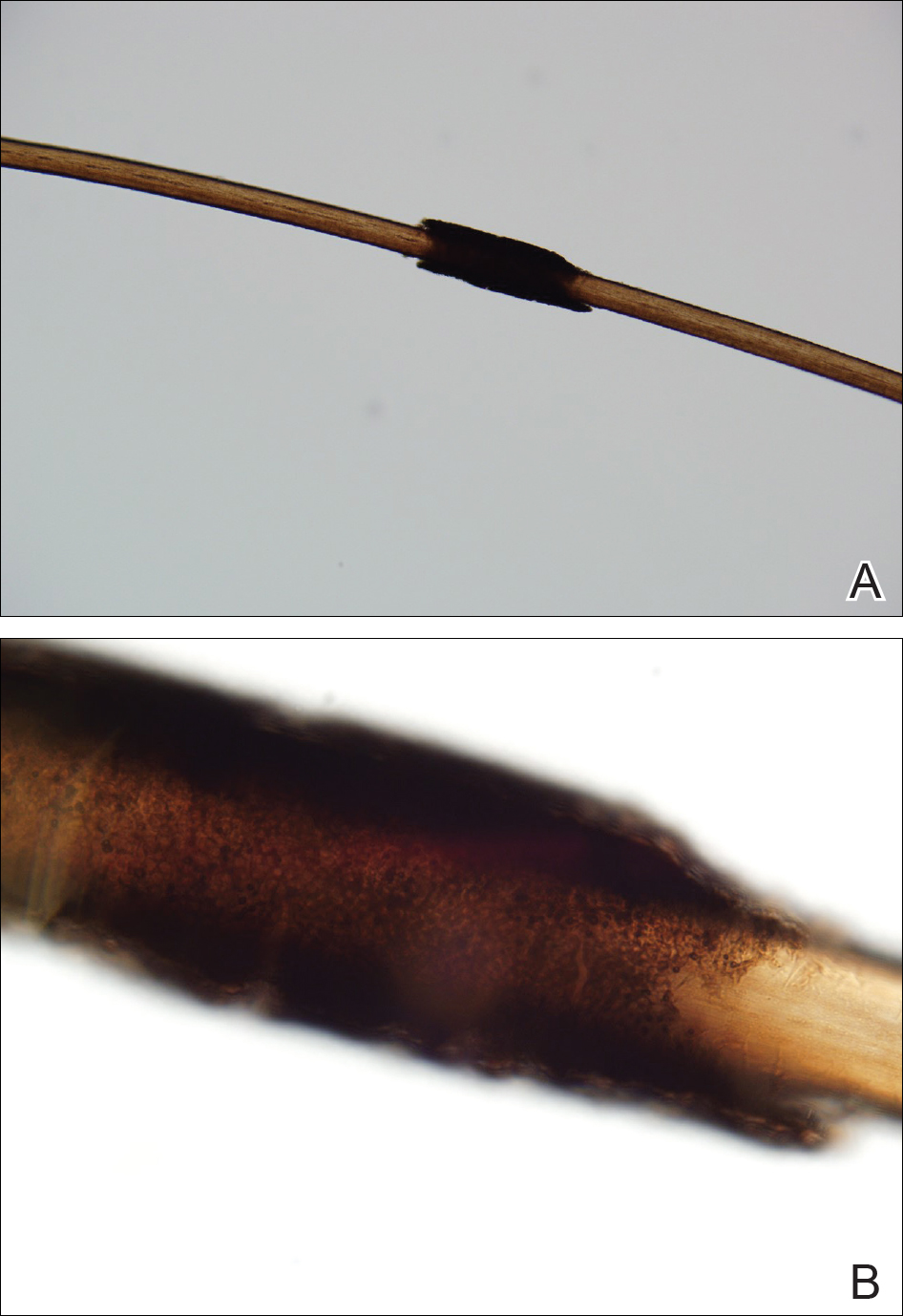

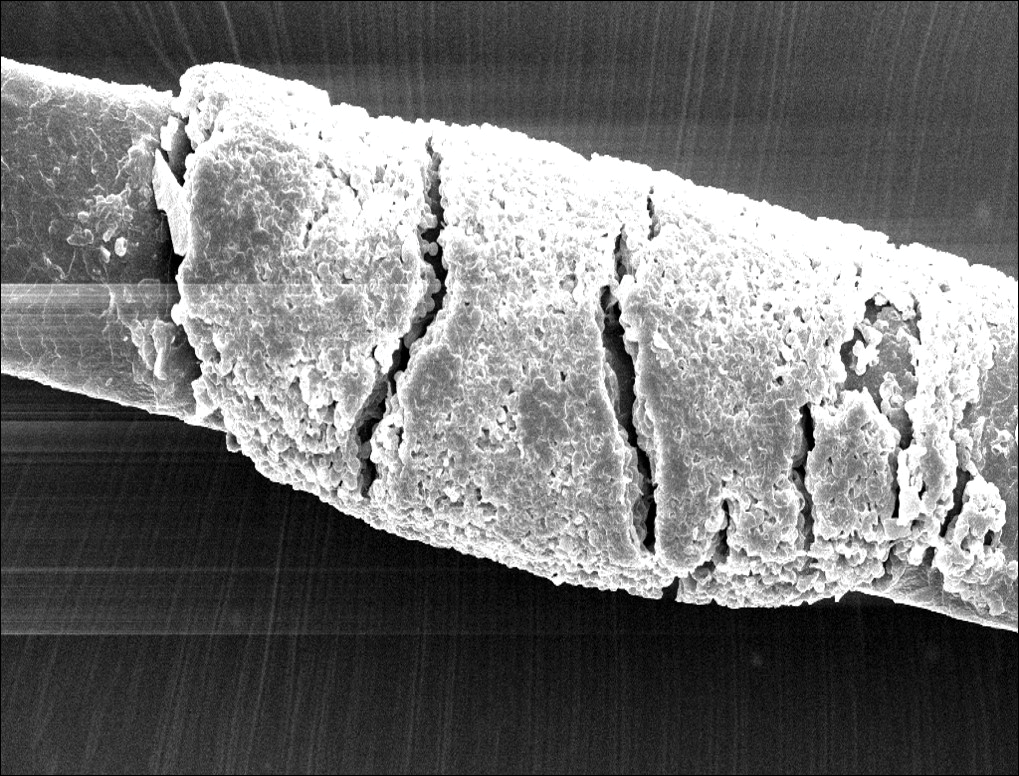

Microscopic examination of the hair shafts revealed brown to black, firmly adherent concretions (Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy of the nodules was performed, which allowed for greater definition of the constituent hyphae and arthrospores (Figure 2).

Fungal cultures grew Trichosporon inkin along with other dematiaceous molds. The patient initially was treated with a combination of ketoconazole shampoo and weekly application of topical terbinafine. She trimmed 15.2 cm of the hair of her own volition. At 2-month follow-up the nodules were still present, though smaller and less numerous. Repeat cultures were obtained, which again grew T inkin. She then began taking oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks.

This case of piedra is unique in that our patient presented with black nodules clinically, but cultures grew only the causative agent of white piedra, T inkin. A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms black piedra, white piedra, or piedra, and mixed infection or coinfection yielded one other similar case.1 Kanitakis et al1 speculated that perhaps there was coinfection of black and white piedra and that Piedraia hortae, the causative agent of black piedra, was unable to flourish in culture facing competition from other fungi. This scenario also could apply to our patient. However, the original culture taken from our patient also grew other dematiaceous molds including Cladosporium and Exophiala species. It also is possible that these other fungi could have contributed pigment to the nodules, giving it the appearance of black piedra when only T inkin was present as the true pathogen.

White piedra is a rare fungal infection of the hair shaft caused by organisms of the genus Trichosporon, with Trichosporon ovoides most likely to infect the scalp.2 Black piedra is a similar fungal infection caused by P hortae. Piedra means stone in Spanish, reflecting the appearance of these organisms on the hair shaft. It is common in tropical regions of the world such as Southeast Asia and South America, flourishing in the high temperatures and humidity.2 Both infectious agents are found in the soil or in standing water.3 White piedra most commonly is found in facial, axilla, or pubic hair, while black piedra most often is found in the hair of the scalp.2,4 Local cultural practices may contribute to transfer of Trichosporon or P hortae to the scalp, including the use of Brazilian plant oils in the hair or tying a veil or hijab to wet hair. Interestingly, some groups intentionally introduce the fungus to their hair for cosmetic reasons in endemic areas.2,3,5

Patients with white or black piedra generally are asymptomatic.4 Some may notice a rough texture to the hair or hear a characteristic metallic rattling sound as the nodules make contact with brush bristles.2,3 On inspection of the scalp, white piedra will appear to be white to light brown nodules, while black piedra presents as brown to black in color. The nodules are often firm on palpation.2,3 The nodules of white piedra generally are easy to remove in contrast to black piedra, which involves nodules that securely attach to the hair shaft but can be removed with pressure.3,5 Piedra has natural keratolytic activities and with prolonged infection can penetrate the hair cuticle, causing weakness and eventual breakage of the hair. This invasion into the hair cortex also can complicate treatment regimens, contributing to the chronic course of these infections.6

Diagnosis is based on clinical and microscopic findings. Nodules on hair shafts can be prepared with potassium hydroxide and placed on glass slides for examination.4 Dyes such as toluidine blue or chlorazol black E stain can be used to assist in identifying fungal structures.2 Sabouraud agar with cycloheximide may be the best choice for culture medium.2 Black piedra slowly grows into small dome-shaped colonies. White piedra will grow more quickly into cream-colored colonies with wrinkles and sometimes mucinous characteristics.3

The best treatment of black or white piedra is to cut the hair, thereby eliminating the fungi,7 which is not an easy option for many patients, such as ours, because of the aesthetic implications. Alternative treatments include azole shampoos such as ketoconazole.2,4 Treatment with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks has been successfully used for black piedra.7 Patients must be careful to thoroughly clean or discard hairbrushes, as they can serve as reservoirs of fungi to reinfect patients or spread to others.5,7

- Kanitakis J, Persat F, Piens MA, et al. Black piedra: report of a French case associated with Trichosporon asahii. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1258-1260.

- Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

- Khatu SS, Poojary SA, Nagpur NG. Nodules on the hair: a rare case of mixed piedra. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:220-223.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Sobera JO, et al. Fungal diseases. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012:1251-1284.

- Desai DH, Nadkarni NJ. Piedra: an ethnicity-related trichosis? Int J Dermatol. 2013;53:1008-1011.

- Figueras M, Guarro J, Zaror L. New findings in black piedra infection. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:157-158.

- Gip L. Black piedra: the first case treated with terbinafine (Lamisil). Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(suppl 43):26-28.

The Diagnosis: Piedra

Microscopic examination of the hair shafts revealed brown to black, firmly adherent concretions (Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy of the nodules was performed, which allowed for greater definition of the constituent hyphae and arthrospores (Figure 2).

Fungal cultures grew Trichosporon inkin along with other dematiaceous molds. The patient initially was treated with a combination of ketoconazole shampoo and weekly application of topical terbinafine. She trimmed 15.2 cm of the hair of her own volition. At 2-month follow-up the nodules were still present, though smaller and less numerous. Repeat cultures were obtained, which again grew T inkin. She then began taking oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks.

This case of piedra is unique in that our patient presented with black nodules clinically, but cultures grew only the causative agent of white piedra, T inkin. A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms black piedra, white piedra, or piedra, and mixed infection or coinfection yielded one other similar case.1 Kanitakis et al1 speculated that perhaps there was coinfection of black and white piedra and that Piedraia hortae, the causative agent of black piedra, was unable to flourish in culture facing competition from other fungi. This scenario also could apply to our patient. However, the original culture taken from our patient also grew other dematiaceous molds including Cladosporium and Exophiala species. It also is possible that these other fungi could have contributed pigment to the nodules, giving it the appearance of black piedra when only T inkin was present as the true pathogen.

White piedra is a rare fungal infection of the hair shaft caused by organisms of the genus Trichosporon, with Trichosporon ovoides most likely to infect the scalp.2 Black piedra is a similar fungal infection caused by P hortae. Piedra means stone in Spanish, reflecting the appearance of these organisms on the hair shaft. It is common in tropical regions of the world such as Southeast Asia and South America, flourishing in the high temperatures and humidity.2 Both infectious agents are found in the soil or in standing water.3 White piedra most commonly is found in facial, axilla, or pubic hair, while black piedra most often is found in the hair of the scalp.2,4 Local cultural practices may contribute to transfer of Trichosporon or P hortae to the scalp, including the use of Brazilian plant oils in the hair or tying a veil or hijab to wet hair. Interestingly, some groups intentionally introduce the fungus to their hair for cosmetic reasons in endemic areas.2,3,5

Patients with white or black piedra generally are asymptomatic.4 Some may notice a rough texture to the hair or hear a characteristic metallic rattling sound as the nodules make contact with brush bristles.2,3 On inspection of the scalp, white piedra will appear to be white to light brown nodules, while black piedra presents as brown to black in color. The nodules are often firm on palpation.2,3 The nodules of white piedra generally are easy to remove in contrast to black piedra, which involves nodules that securely attach to the hair shaft but can be removed with pressure.3,5 Piedra has natural keratolytic activities and with prolonged infection can penetrate the hair cuticle, causing weakness and eventual breakage of the hair. This invasion into the hair cortex also can complicate treatment regimens, contributing to the chronic course of these infections.6

Diagnosis is based on clinical and microscopic findings. Nodules on hair shafts can be prepared with potassium hydroxide and placed on glass slides for examination.4 Dyes such as toluidine blue or chlorazol black E stain can be used to assist in identifying fungal structures.2 Sabouraud agar with cycloheximide may be the best choice for culture medium.2 Black piedra slowly grows into small dome-shaped colonies. White piedra will grow more quickly into cream-colored colonies with wrinkles and sometimes mucinous characteristics.3

The best treatment of black or white piedra is to cut the hair, thereby eliminating the fungi,7 which is not an easy option for many patients, such as ours, because of the aesthetic implications. Alternative treatments include azole shampoos such as ketoconazole.2,4 Treatment with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks has been successfully used for black piedra.7 Patients must be careful to thoroughly clean or discard hairbrushes, as they can serve as reservoirs of fungi to reinfect patients or spread to others.5,7

The Diagnosis: Piedra

Microscopic examination of the hair shafts revealed brown to black, firmly adherent concretions (Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy of the nodules was performed, which allowed for greater definition of the constituent hyphae and arthrospores (Figure 2).

Fungal cultures grew Trichosporon inkin along with other dematiaceous molds. The patient initially was treated with a combination of ketoconazole shampoo and weekly application of topical terbinafine. She trimmed 15.2 cm of the hair of her own volition. At 2-month follow-up the nodules were still present, though smaller and less numerous. Repeat cultures were obtained, which again grew T inkin. She then began taking oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks.

This case of piedra is unique in that our patient presented with black nodules clinically, but cultures grew only the causative agent of white piedra, T inkin. A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms black piedra, white piedra, or piedra, and mixed infection or coinfection yielded one other similar case.1 Kanitakis et al1 speculated that perhaps there was coinfection of black and white piedra and that Piedraia hortae, the causative agent of black piedra, was unable to flourish in culture facing competition from other fungi. This scenario also could apply to our patient. However, the original culture taken from our patient also grew other dematiaceous molds including Cladosporium and Exophiala species. It also is possible that these other fungi could have contributed pigment to the nodules, giving it the appearance of black piedra when only T inkin was present as the true pathogen.

White piedra is a rare fungal infection of the hair shaft caused by organisms of the genus Trichosporon, with Trichosporon ovoides most likely to infect the scalp.2 Black piedra is a similar fungal infection caused by P hortae. Piedra means stone in Spanish, reflecting the appearance of these organisms on the hair shaft. It is common in tropical regions of the world such as Southeast Asia and South America, flourishing in the high temperatures and humidity.2 Both infectious agents are found in the soil or in standing water.3 White piedra most commonly is found in facial, axilla, or pubic hair, while black piedra most often is found in the hair of the scalp.2,4 Local cultural practices may contribute to transfer of Trichosporon or P hortae to the scalp, including the use of Brazilian plant oils in the hair or tying a veil or hijab to wet hair. Interestingly, some groups intentionally introduce the fungus to their hair for cosmetic reasons in endemic areas.2,3,5

Patients with white or black piedra generally are asymptomatic.4 Some may notice a rough texture to the hair or hear a characteristic metallic rattling sound as the nodules make contact with brush bristles.2,3 On inspection of the scalp, white piedra will appear to be white to light brown nodules, while black piedra presents as brown to black in color. The nodules are often firm on palpation.2,3 The nodules of white piedra generally are easy to remove in contrast to black piedra, which involves nodules that securely attach to the hair shaft but can be removed with pressure.3,5 Piedra has natural keratolytic activities and with prolonged infection can penetrate the hair cuticle, causing weakness and eventual breakage of the hair. This invasion into the hair cortex also can complicate treatment regimens, contributing to the chronic course of these infections.6

Diagnosis is based on clinical and microscopic findings. Nodules on hair shafts can be prepared with potassium hydroxide and placed on glass slides for examination.4 Dyes such as toluidine blue or chlorazol black E stain can be used to assist in identifying fungal structures.2 Sabouraud agar with cycloheximide may be the best choice for culture medium.2 Black piedra slowly grows into small dome-shaped colonies. White piedra will grow more quickly into cream-colored colonies with wrinkles and sometimes mucinous characteristics.3

The best treatment of black or white piedra is to cut the hair, thereby eliminating the fungi,7 which is not an easy option for many patients, such as ours, because of the aesthetic implications. Alternative treatments include azole shampoos such as ketoconazole.2,4 Treatment with oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks has been successfully used for black piedra.7 Patients must be careful to thoroughly clean or discard hairbrushes, as they can serve as reservoirs of fungi to reinfect patients or spread to others.5,7

- Kanitakis J, Persat F, Piens MA, et al. Black piedra: report of a French case associated with Trichosporon asahii. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1258-1260.

- Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

- Khatu SS, Poojary SA, Nagpur NG. Nodules on the hair: a rare case of mixed piedra. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:220-223.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Sobera JO, et al. Fungal diseases. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012:1251-1284.

- Desai DH, Nadkarni NJ. Piedra: an ethnicity-related trichosis? Int J Dermatol. 2013;53:1008-1011.

- Figueras M, Guarro J, Zaror L. New findings in black piedra infection. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:157-158.

- Gip L. Black piedra: the first case treated with terbinafine (Lamisil). Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(suppl 43):26-28.

- Kanitakis J, Persat F, Piens MA, et al. Black piedra: report of a French case associated with Trichosporon asahii. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1258-1260.

- Schwartz RA. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173-1182.

- Khatu SS, Poojary SA, Nagpur NG. Nodules on the hair: a rare case of mixed piedra. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:220-223.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Sobera JO, et al. Fungal diseases. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012:1251-1284.

- Desai DH, Nadkarni NJ. Piedra: an ethnicity-related trichosis? Int J Dermatol. 2013;53:1008-1011.

- Figueras M, Guarro J, Zaror L. New findings in black piedra infection. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:157-158.

- Gip L. Black piedra: the first case treated with terbinafine (Lamisil). Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(suppl 43):26-28.

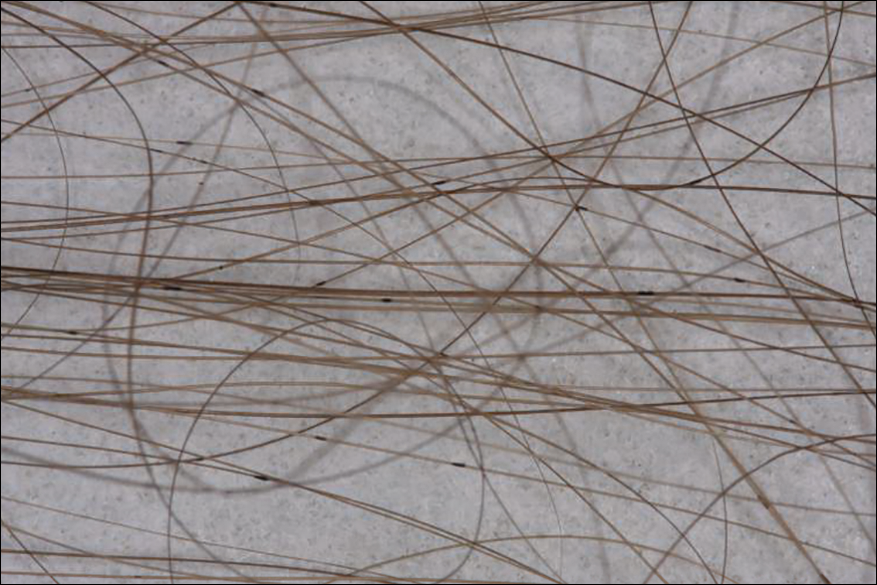

A 21-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with what she described as small black dots in her hair that she first noted 3 months prior to presentation. The black nodules were asymptomatic, but the patient noted that they seemed to be moving up the hair shaft. They were firmly attached and great effort was required to remove them. The patient's sister recently developed similar nodules. The patient and her sister work as missionaries and had spent time in India, Southeast Asia, and Central America within the last few years. Physical examination revealed firmly adherent black nodules involving the mid to distal portions of the hair shafts on the scalp. There were no nail or skin findings. Cultures were obtained, and microscopic examination was performed.

Hair and Scalp Disorders in Adult and Pediatric Patients With Skin of Color

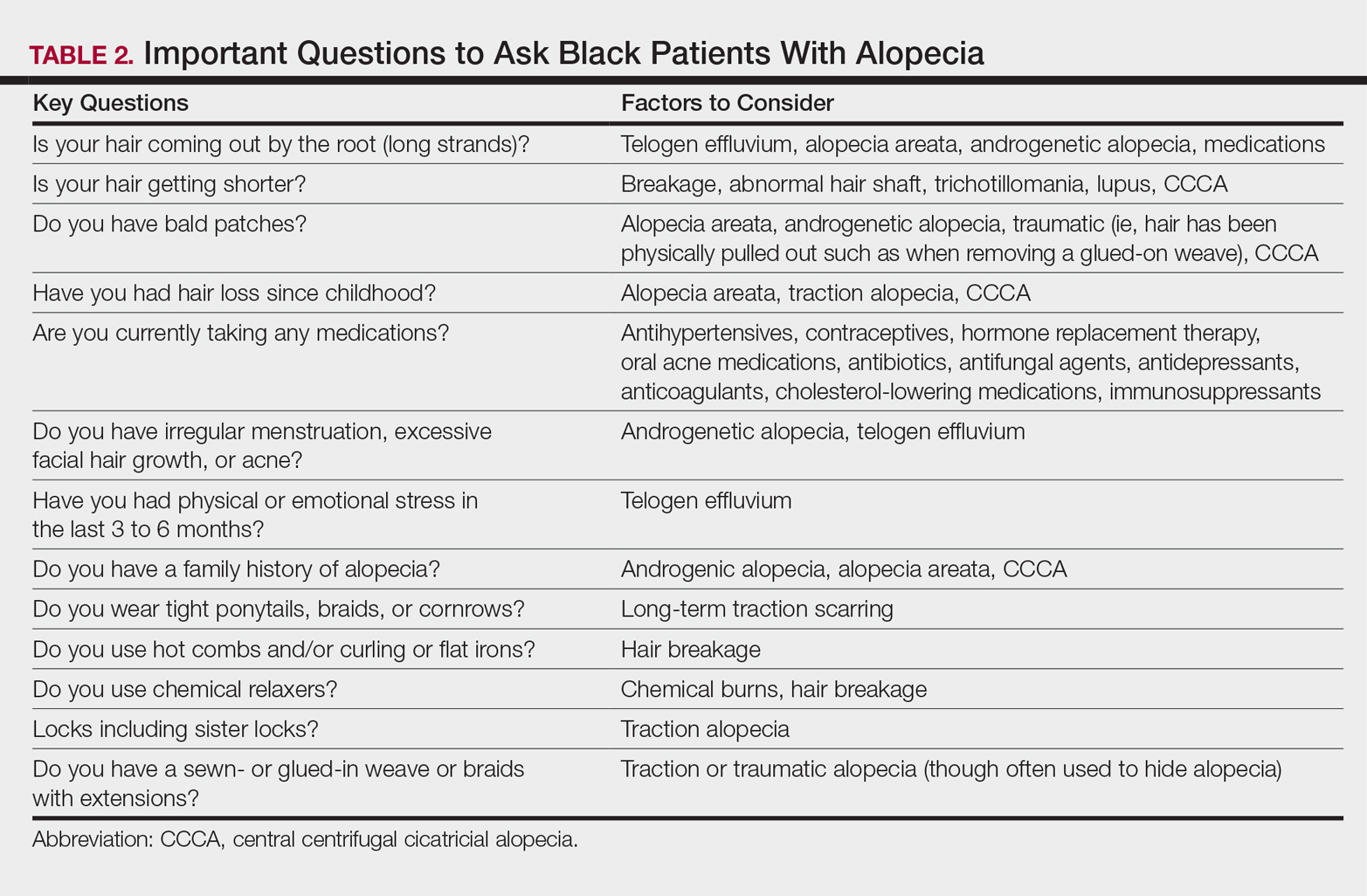

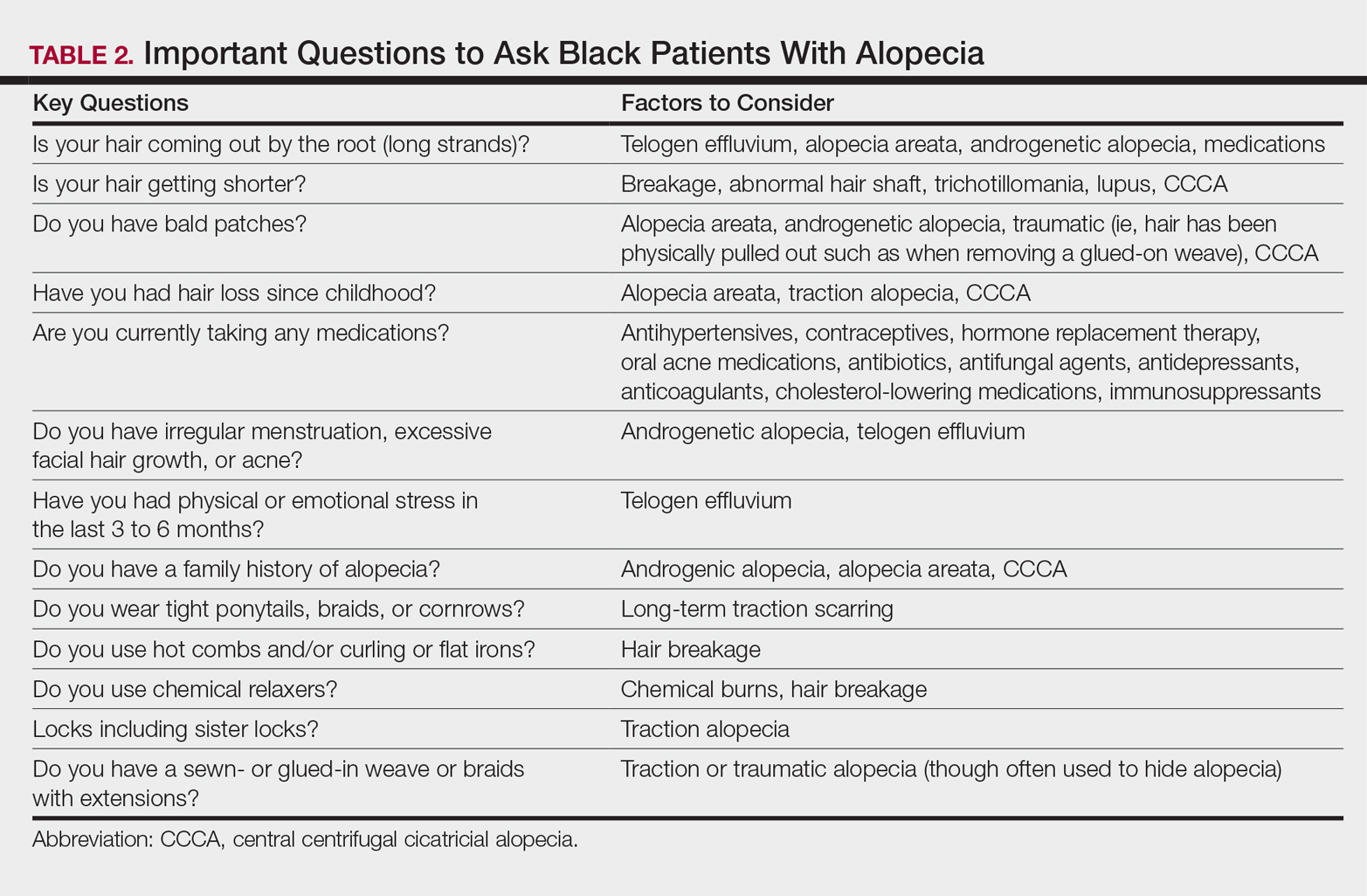

One of the most common concerns among black patients is hair- and scalp-related disease. As increasing numbers of black patients opt to see dermatologists, it is imperative that all dermatologists be adequately trained to address the concerns of this patient population. When patients ask for help with common skin diseases of the hair and scalp, there are details that must be included in diagnosis, treatment, and hair care recommendations to reach goals for excellence in patient care. Herein, we provide must-know information to effectively approach this patient population.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

A study utilizing data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 1993 to 2009 revealed seborrheic dermatitis (SD) as the second most common diagnosis for black patients who visit a dermatologist.1 Prevalence data from a population of 1408 white, black, and Chinese patients from the United States and China revealed scalp flaking in 81% to 95% of black patients, 66% to 82% in white patients, and 30% to 42% in Chinese patients.2 Seborrheic dermatitis has a notable prevalence in black women and often is considered normal by patients. It can be exacerbated by infrequent shampooing (ranging from once per month or longer in between shampoos) and the inappropriate use of hair oils and pomades; it also has been associated with hair breakage, lichen simplex chronicus, and folliculitis. Seborrheic dermatitis must be distinguished from other disorders including sarcoidosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus erythematosus, tinea capitis, and lichen simplex chronicus.

Although there is a paucity of literature on the treatment of SD in black patients, components of treatment are similar to those recommended for other populations. Black women are advised to carefully utilize antidandruff shampoos containing zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide, or tar to avoid hair shaft damage and dryness. Ketoconazole shampoo rarely is recommended and may be more appropriately used in men and boys, as hair fragility is less of a concern for them. The shampoo should be applied directly to the scalp rather than the hair shafts to minimize dryness, with no particular elongated contact time needed for these medicated shampoos to be effective. Because conditioners can wash off the active ingredients in therapeutic shampoos, antidandruff conditioners are recommended. Potent or ultrapotent topical corticosteroids applied to the scalp 3 to 4 times weekly initially will control the symptoms of itching as well as scaling, and mid-potency topical corticosteroid oil may be used at weekly intervals.

Hairline and facial involvement of SD often co-occurs, and low-potency topical steroids may be applied to the affected areas twice daily for 3 to 4 weeks, which may be repeated for flares. Topical calcineurin inhibitors or antifungal creams such as ketoconazole or econazole may then provide effective control. Encouraging patients to increase shampooing to once weekly or every 2 weeks and discontinue use of scalp pomades and oils also is recommended. Patients must know that an itchy scaly scalp represents a treatable disorder.

Acquired Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Hair fragility and breakage is common and multifactorial in black patients. Hair shaft breakage can occur on the vertex scalp in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), with random localized breakage due to scratching in SD. Heat, hair colorants, and chemical relaxers may result in diffuse damage and breakage.3 Sodium-, potassium-, and guanine hydroxide–containing chemical relaxers change the physical properties of the hair by rearranging disulfide bonds. They remove the monomolecular layer of fatty acids covalently bound to the cuticle that help prevent penetration of water into the hair shaft. Additionally, chemical relaxers weaken the hair shaft and decrease tensile strength.

Unlike hair relaxers, colorants are less likely to lead to catastrophic hair breakage after a single use and require frequent use, which leads to cumulative damage. Thermal straightening is another cause of hair-shaft weakening in black patients.4,5 Flat irons and curling irons can cause substantially more damage than blow-dryers due to the amount of heat generated. Flat irons may reach a high temperature of 230ºC (450ºF) as compared to 100°C (210°F) for a blow-dryer. Even the simple act of combing the hair can cause hair breakage, as demonstrated in African volunteers whose hair remained short in contrast to white and Asian volunteers, despite the fact that they had not cut their hair for 1 or more years.6,7 These volunteers had many hair strand knots that led to breakage during combing and hair grooming.6

There is no known prevalence data for acquired trichorrhexis nodosa, though a study of 30 white and black women demonstrated that broken hairs were significantly increased in black women (P=.0001).8 Another study by Hall et al9 of 103 black women showed that 55% of the women reported breakage of hair shafts with normal styling. Khumalo et al6 investigated hair shaft fragility and reported no trichothiodystrophy; the authors concluded that the cause of the hair fragility likely was physical trauma or an undiscovered structural abnormality. Franbourg et al10 examined the structure of hair fibers in white, Asian, and black patients and found no differences, but microfractures were only present in black patients and were determined to be the cause of hair breakage. These studies underscore the need for specific questioning of the patient on hair care including combing, washing, drying, and using products and chemicals.

The approach to the treatment of hair breakage involves correcting underlying abnormalities (eg, iron deficiency, hypothyroidism, nutritional deficiencies). Patients should “give their hair a rest” by discontinuing use of heat, colorants, and chemical relaxers. For patients who are unable to comply, advising them to stop these processes for 6 to 12 months will allow for repair of the hair shaft. To minimize damage from colorants, recommend semipermanent, demipermanent, or temporary dyes. Patients should be counseled to stop bleaching their hair or using permanent colorants. The use of heat protectant products on the hair before styling as well as layering moisturizing regimens starting with a moisturizing shampoo followed by a leave-in, dimethicone-containing conditioner marketed for dry damaged hair is suggested. Dimethicone thinly coats the hair shaft to restore hydrophobicity, smoothes cuticular scales, decreases frizz, and protects the hair from damage. Use of a 2-in-1 shampoo and conditioner containing anionic surfactants and wide-toothed, smooth (no jagged edges in the grooves) combs along with rare brushing are recommended. The hair may be worn in its natural state, but straightening with heat should be avoided. Air drying the hair can minimize breakage, but if thermal styling is necessary, patients should turn the temperature setting of the flat or curling iron down. Protective hair care practices may include placing a loosely sewn-in hair weave that will allow for good hair care, wearing loose braids, or using a wig. Serial trimming of the hair every 6 to 8 weeks is recommended. Improvement may take time, and patients should be advised of this timeline to prevent frustration.

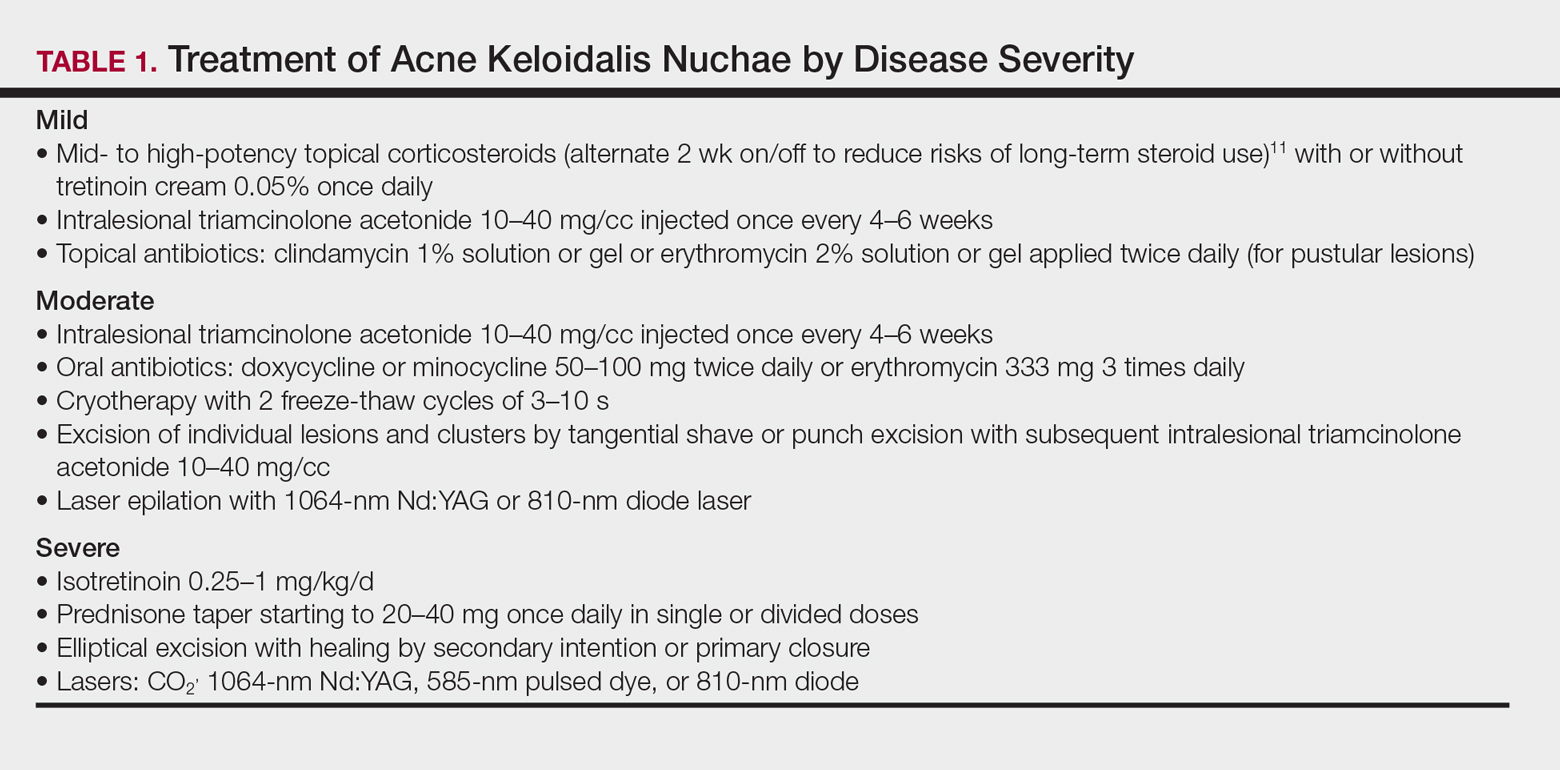

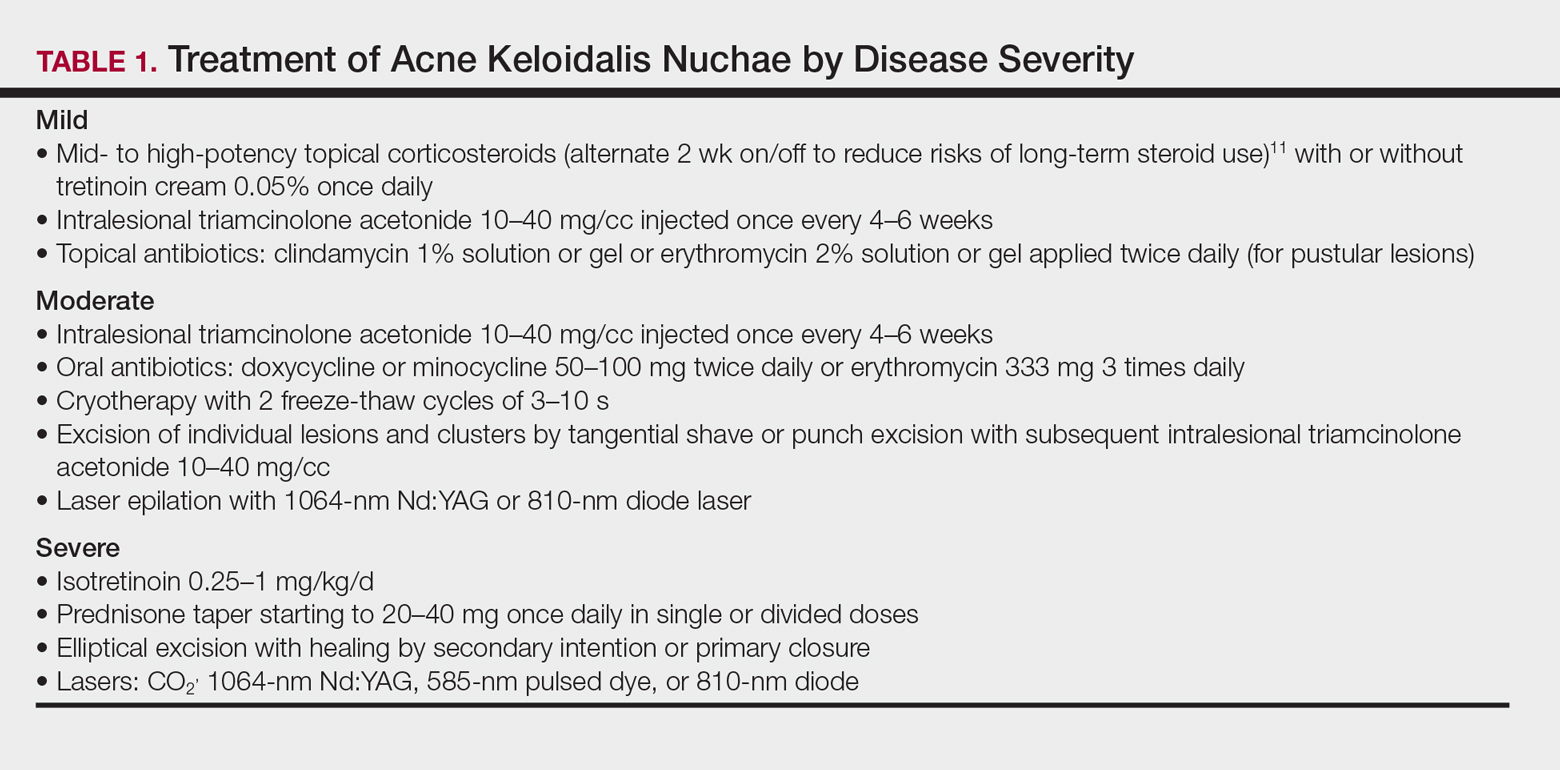

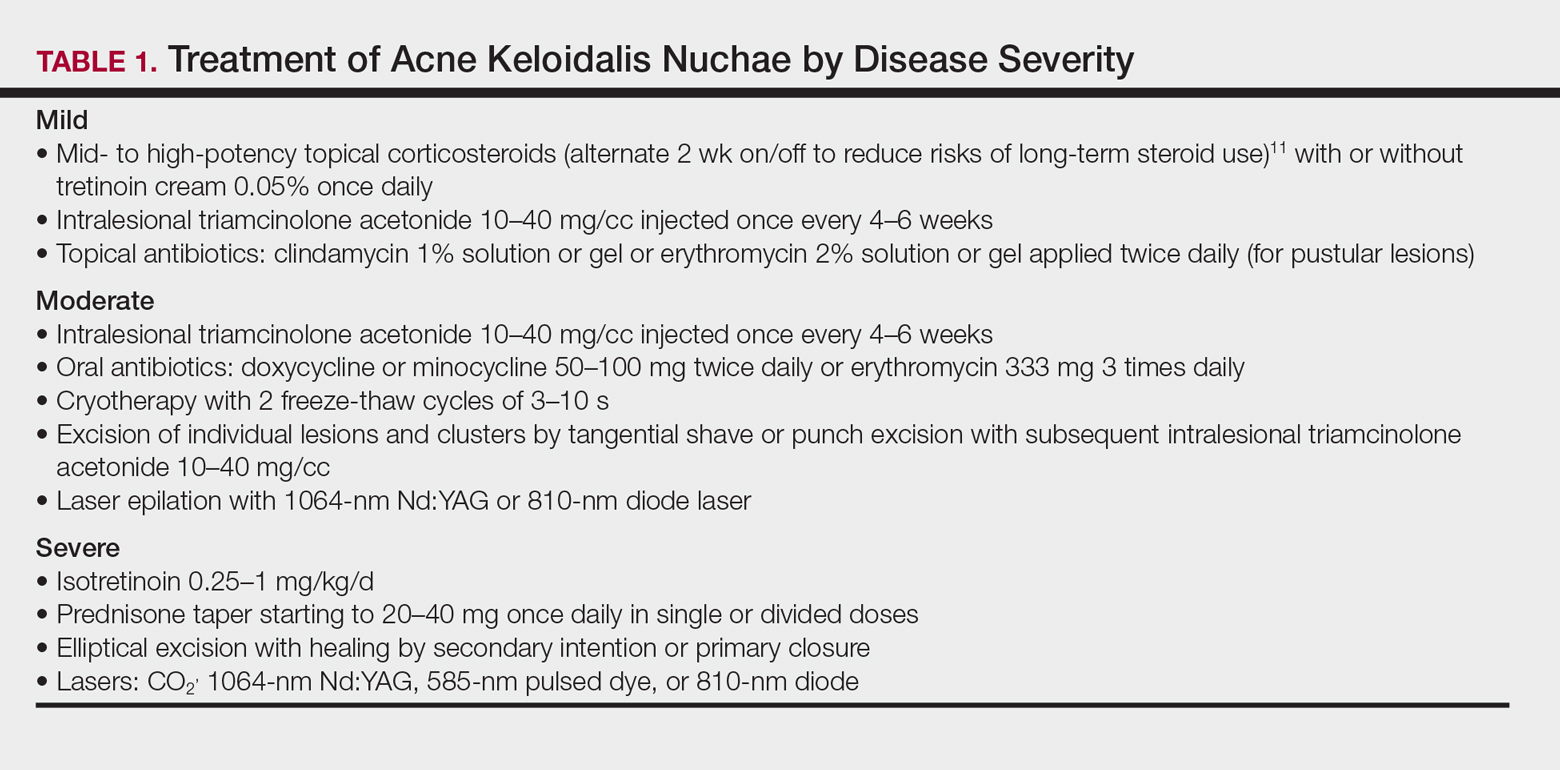

Acne Keloidalis Nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is characterized by papules and pustules located on the occipital scalp and/or the nape of the neck, which may result in keloidal papules and plaques. The etiology is unknown, but ingrown hairs, genetics, trauma, infection, inflammation, and androgen hormones have been proposed to play a role.11 Although AKN may occur in black women, it is primarily a disorder in black men. The diagnosis is made based primarily on clinical findings, and a history of short haircuts may support the diagnosis. Treatment is tailored to the severity of the disease (Table 1). Avoidance of short haircuts and irritation from shirt collars may be helpful. Patients should be advised that the condition is controllable but not curable.

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) is characterized by papules and pustules in the beard region that may result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloidal scar formation, and/or linear scarring. The coarse curled hairs characteristic of black men penetrate the follicle before exiting the skin and penetrate the skin after exiting the follicle, resulting in inflammation. Shaving methods and genetics also may contribute to the development of PFB. As with AKN, diagnosis is made clinically and does not require a skin biopsy. Important components of the patient’s history that should be obtained are hair removal practices and the use of over-the-counter products (eg, shave [pre and post] moisturizers, exfoliants, shaving creams or gels, keratin-softening agents containing α- or β-hydroxy acids). A bacterial culture may be appropriate if a notable pustular component is present. The patient should be advised to discontinue shaving if possible, which may require a physician’s letter explaining the necessity to the patient’s employer. Pseudofolliculitis barbae often can be prevented or lessened with the right hair removal strategy. Because there is not one optimal hair removal strategy that suits every patient, encourage the patient to experiment with different hair removal techniques, from depilatories to electric shavers, foil-guard razors, and multiple-blade razors. Preshave hydration and postshave moisturiza-tion also should be encouraged.12 Benzoyl peroxide–containing shave gels and cleansers, as well as moisturizers containing glycolic, salicylic, and phytic acids, may minimize ingrown hairs, papules, and inflammation.