User login

Atypical Fibroxanthoma Arising Within Erosive Pustular Dermatosis of the Scalp

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a low-grade dermal malignancy comprised of atypical spindle cells.1 Classified as a superficial fibrohistiocytic tumor with intermediate malignant potential, AFX has an incidence of approximately 0.24% worldwide.2 The tumor appears mainly on the head and neck in sun-exposed areas but can occur less frequently on the trunk and limbs in non–sun-exposed areas. There is a 70% to 80% predominance in men aged 69 to 77 years, with lesions primarily occurring in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck.3 A median period of 4 months between time of onset and time of diagnosis has been previously established.4

When AFX does occur in non–sun-exposed areas, it tends to be in a younger patient population. Clinically, it presents as a rather nondescript, firm, erythematous papule or nodule less than 2 cm in diameter. Atypical fibroxanthoma most often presents asymptomatically, but the tumor may ulcerate and bleed, though pain and pruritus are uncommon.5 Findings are nonspecific, and the diagnosis must be confirmed with biopsy, as it can resemble other common dermatological lesions. The pathogenesis of AFX has been controversial. Two different studies looked at AFX using electron microscopy and concluded that the tumor most closely resembled a myofibroblast,6,7 which is consistent with current thinking today.

Atypical fibroxanthoma is believed to be associated with p53 mutation and is closely linked with exposure to UV radiation due to its predominance in sun-exposed areas. Other predisposing factors may include prior exposure to UV radiation, history of organ transplantation, immunosuppression, advanced age in men, and xeroderma pigmentosum. The differential diagnosis for AFX encompasses basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, adnexal tumor, and pyogenic granuloma.

Case Report

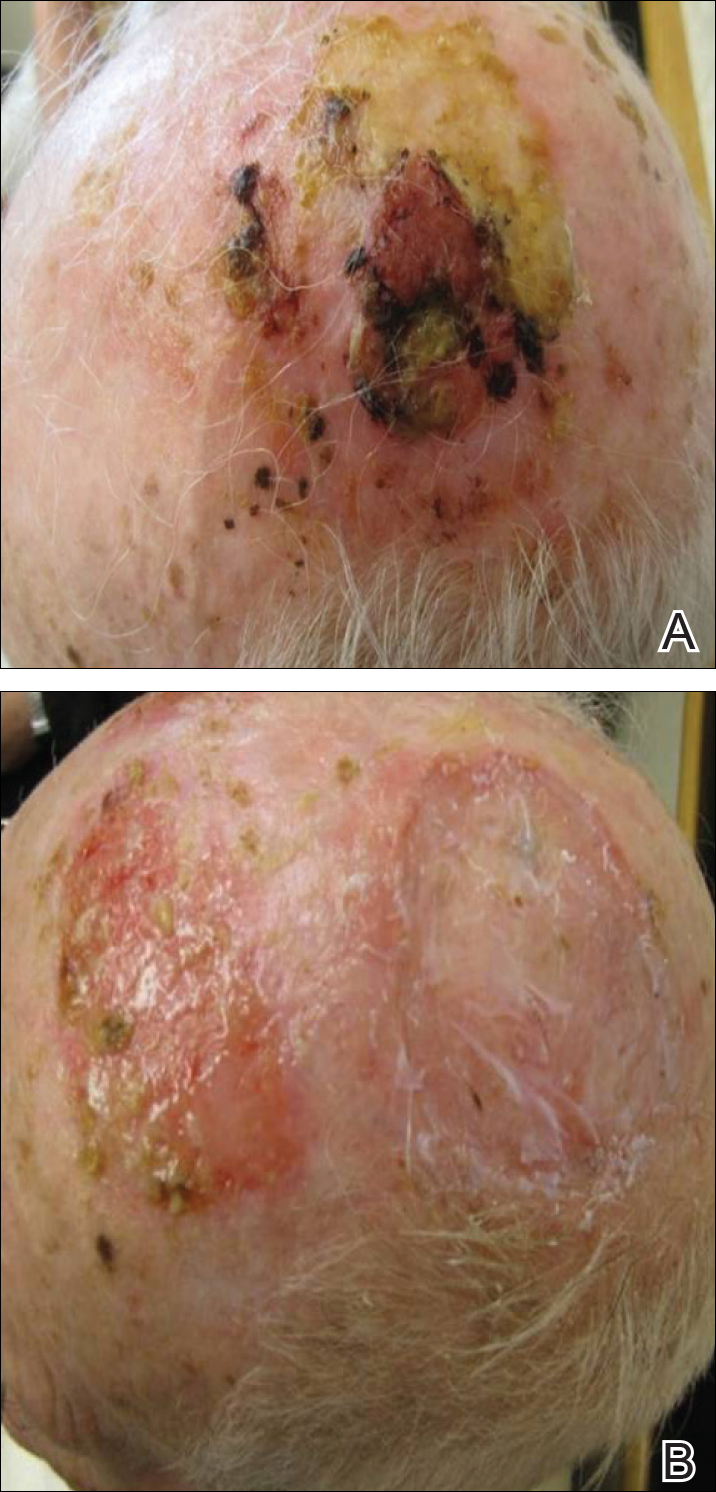

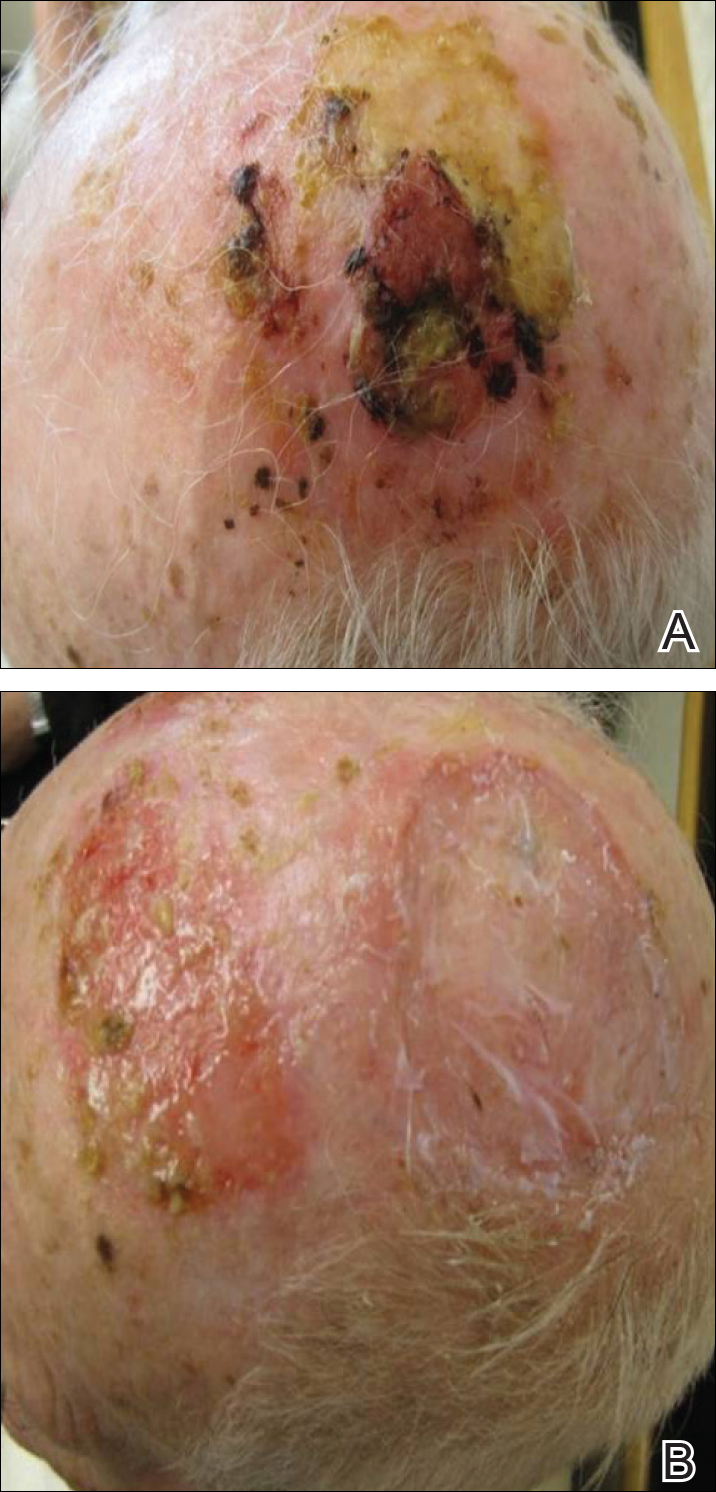

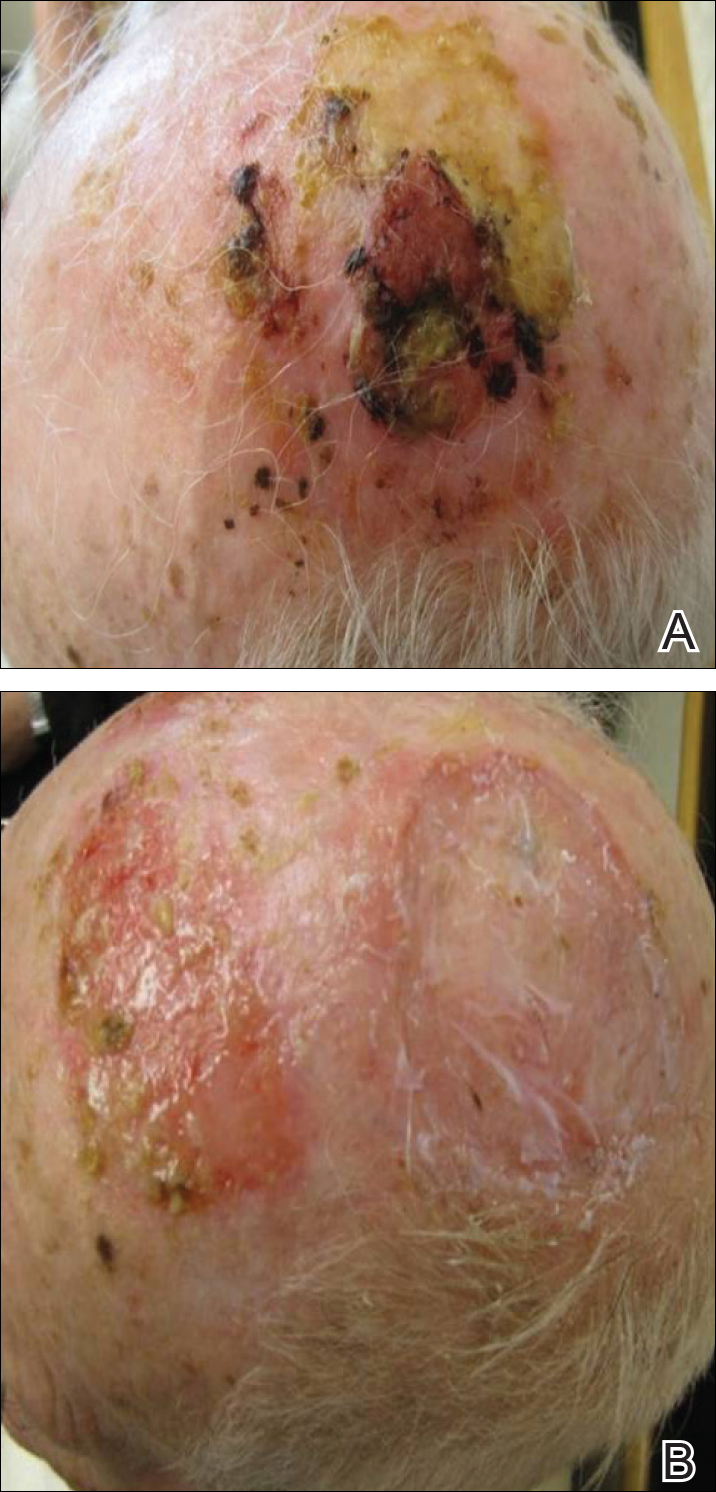

On physical examination, the lesions appeared erosive with crusting and granulation tissue (Figure 1A). The presentation was consistent with erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp. Biopsy revealed granulation tissue. The patient underwent PDT and prednisone treatment with improvement. Additional biopsies revealed AKs. His condition improved with 2 PDT sessions but never fully cleared. During the PDT sessions, the patient reported intense unilateral headaches without visual changes. The headaches were intermittent and not apparently related to the treatments. He was referred for a temporal artery biopsy and rebiopsy of the remaining lesion on the scalp. The temporal artery biopsy was negative. The lesion that remained was a large nodule on the vertex scalp, and biopsy revealed AFX.

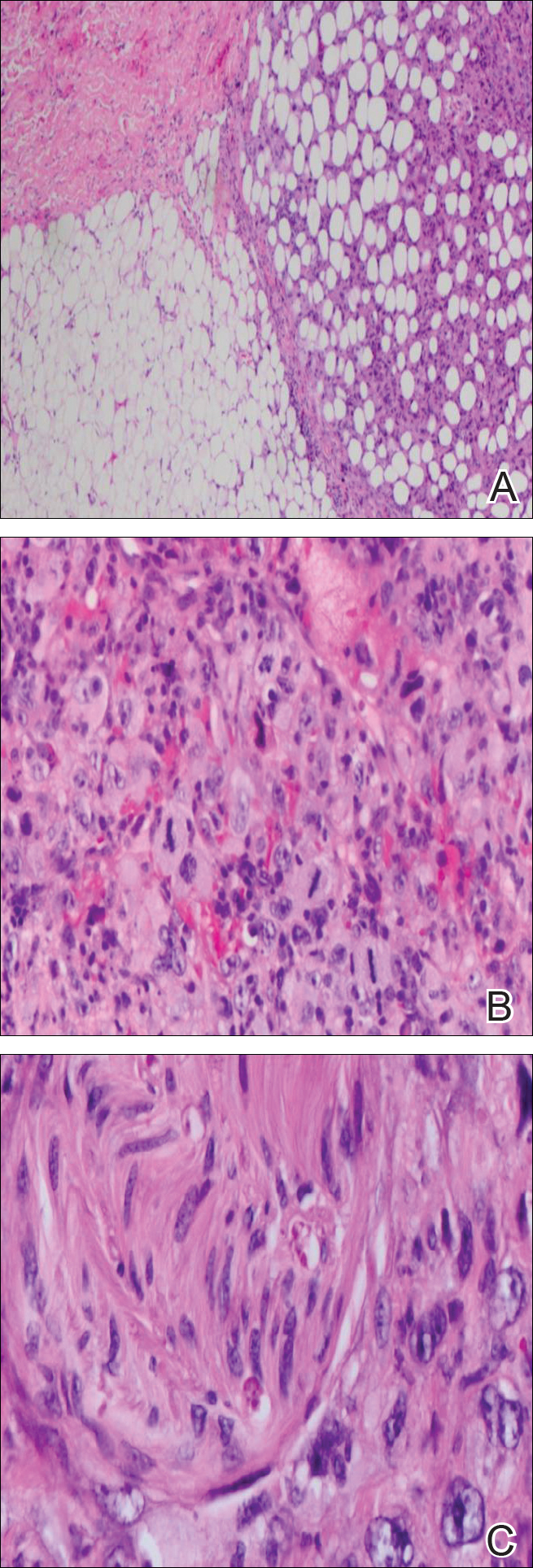

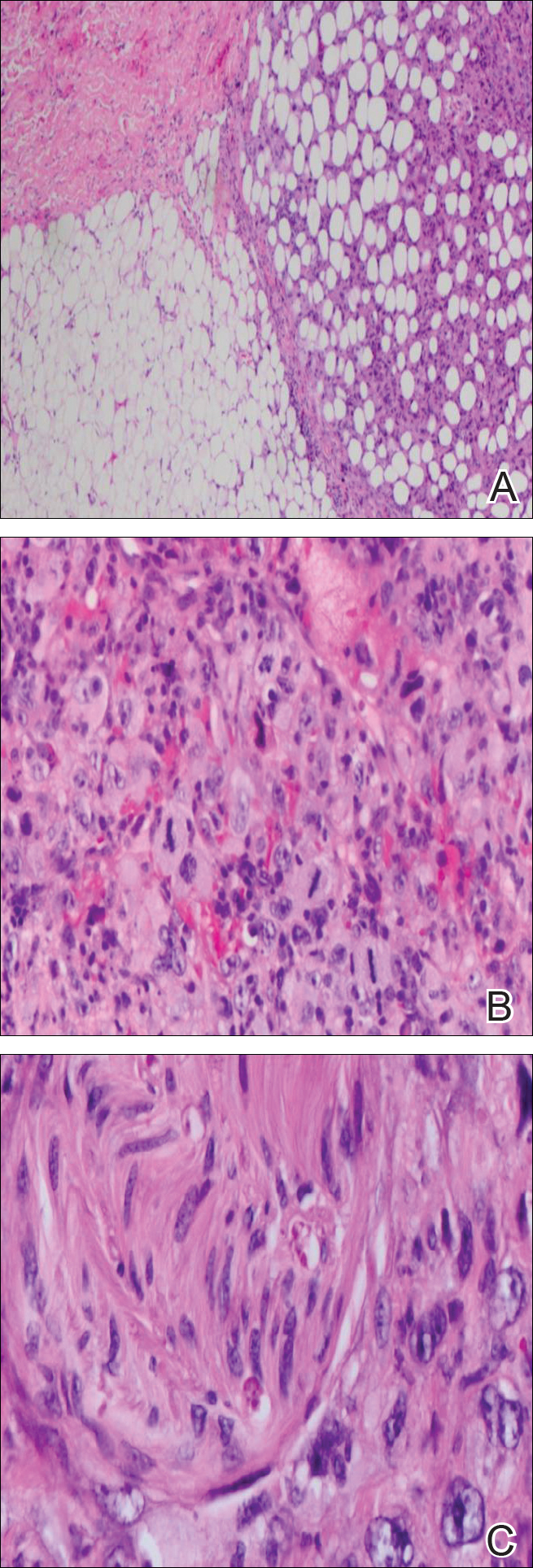

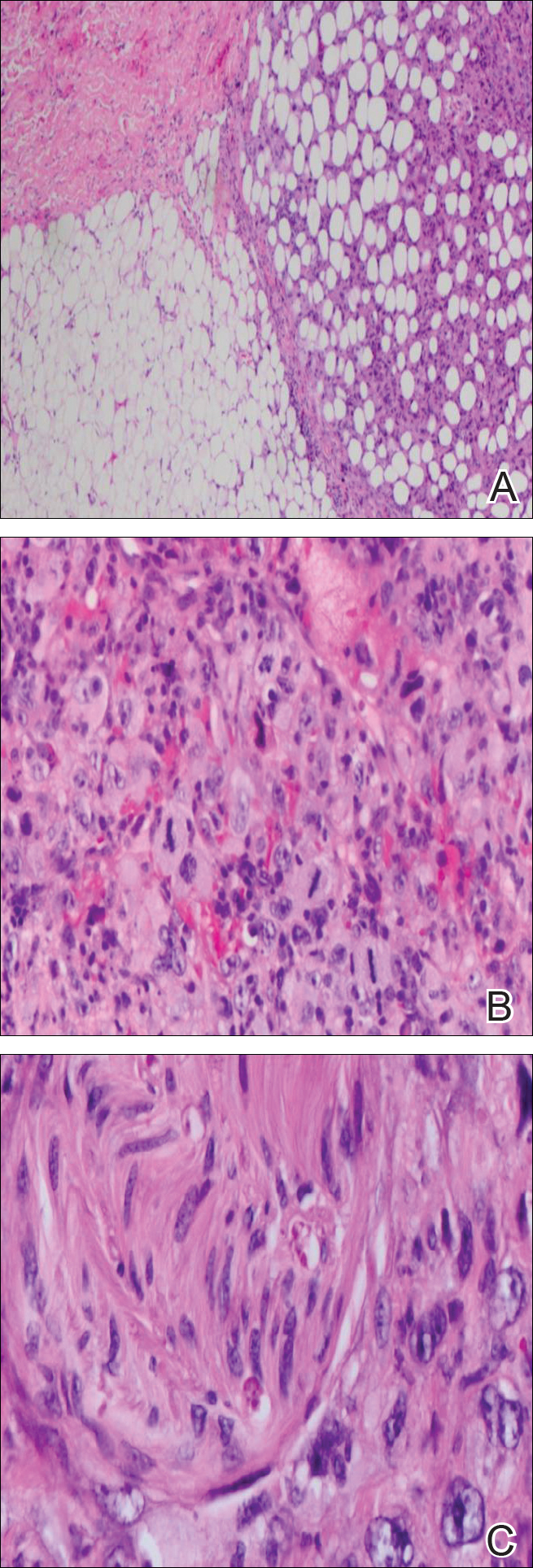

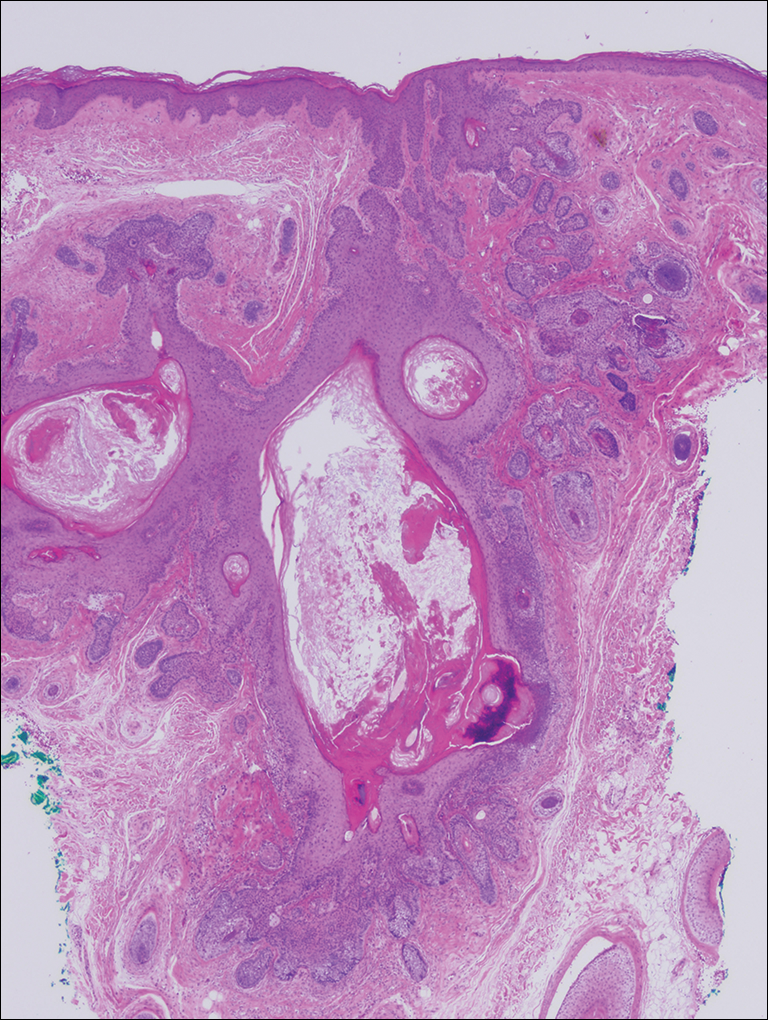

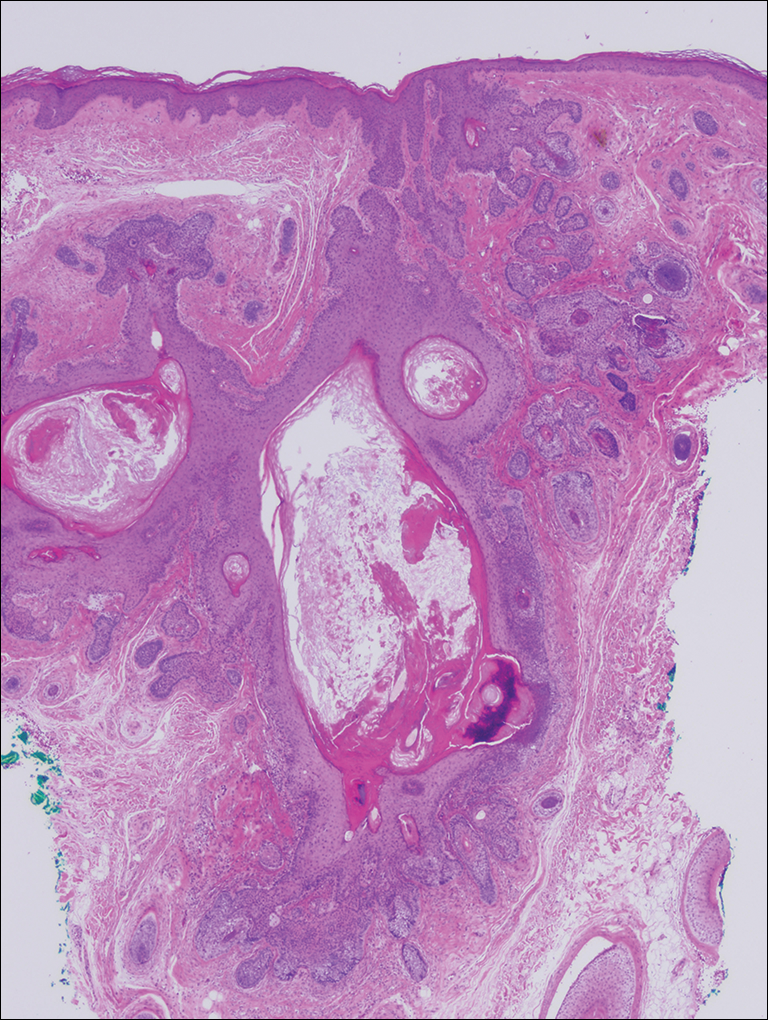

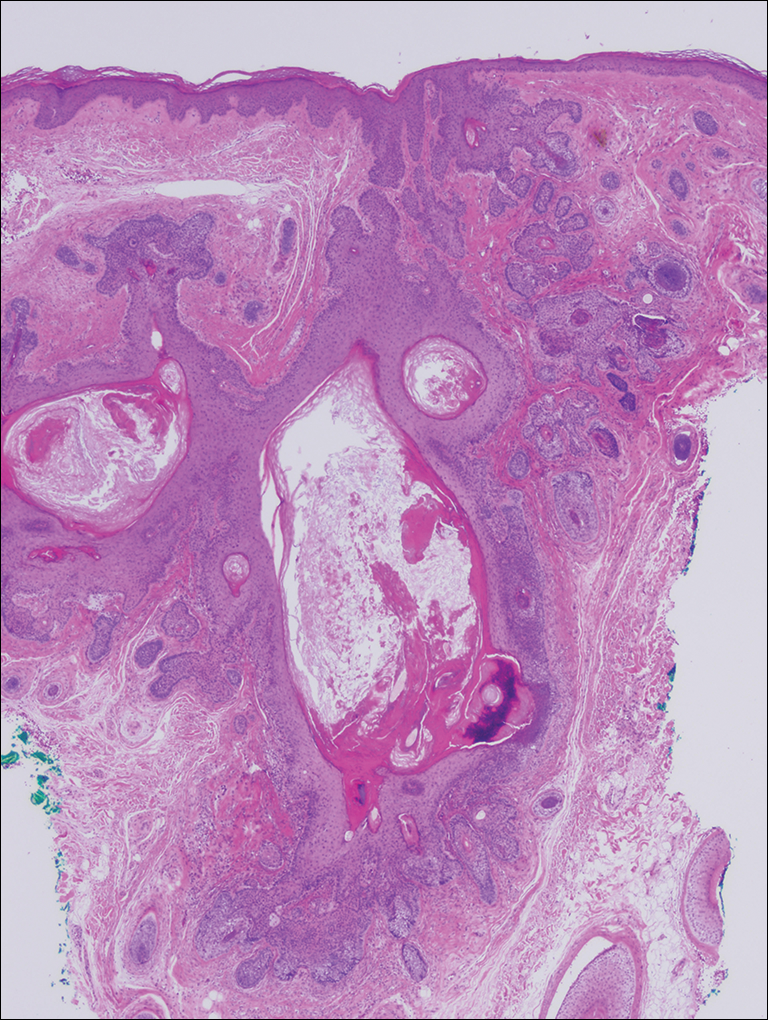

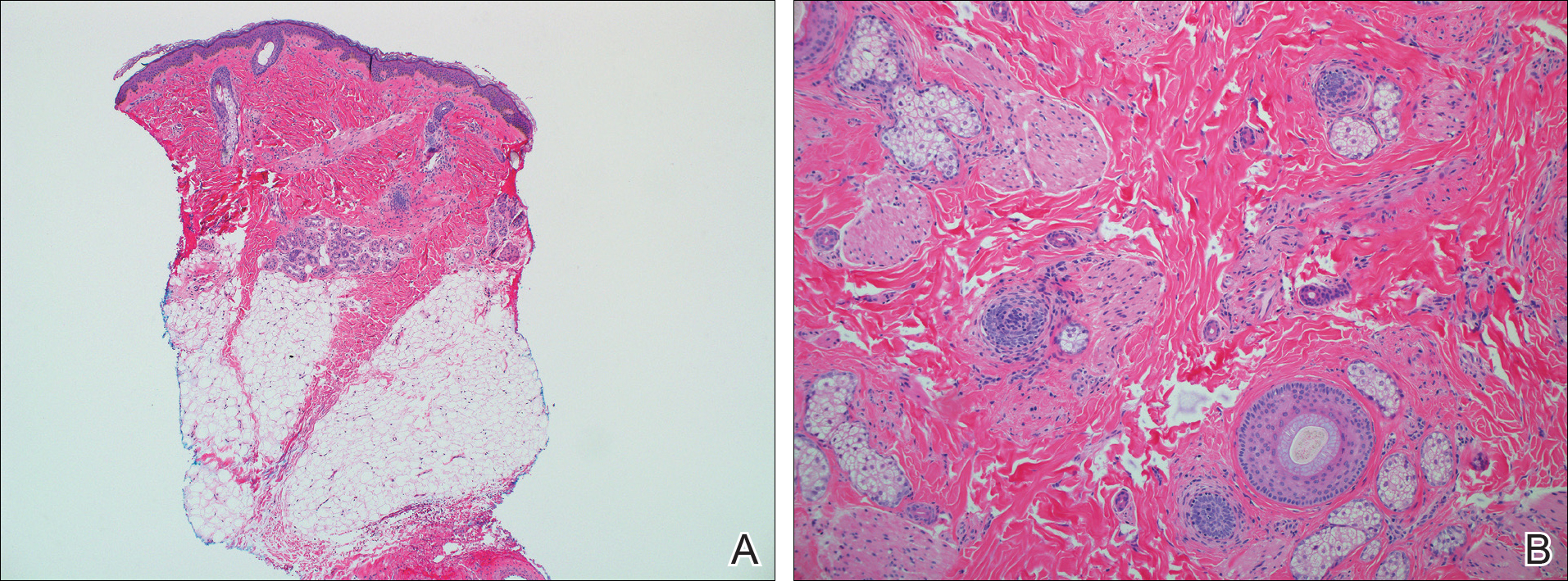

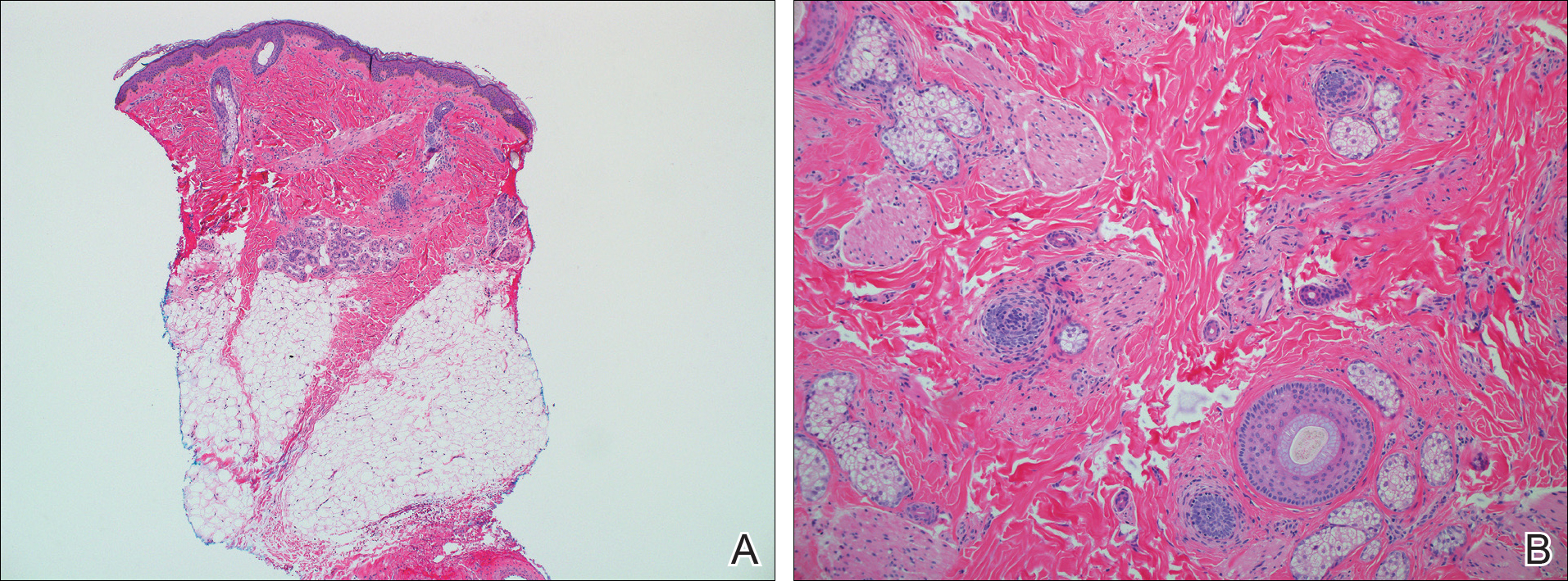

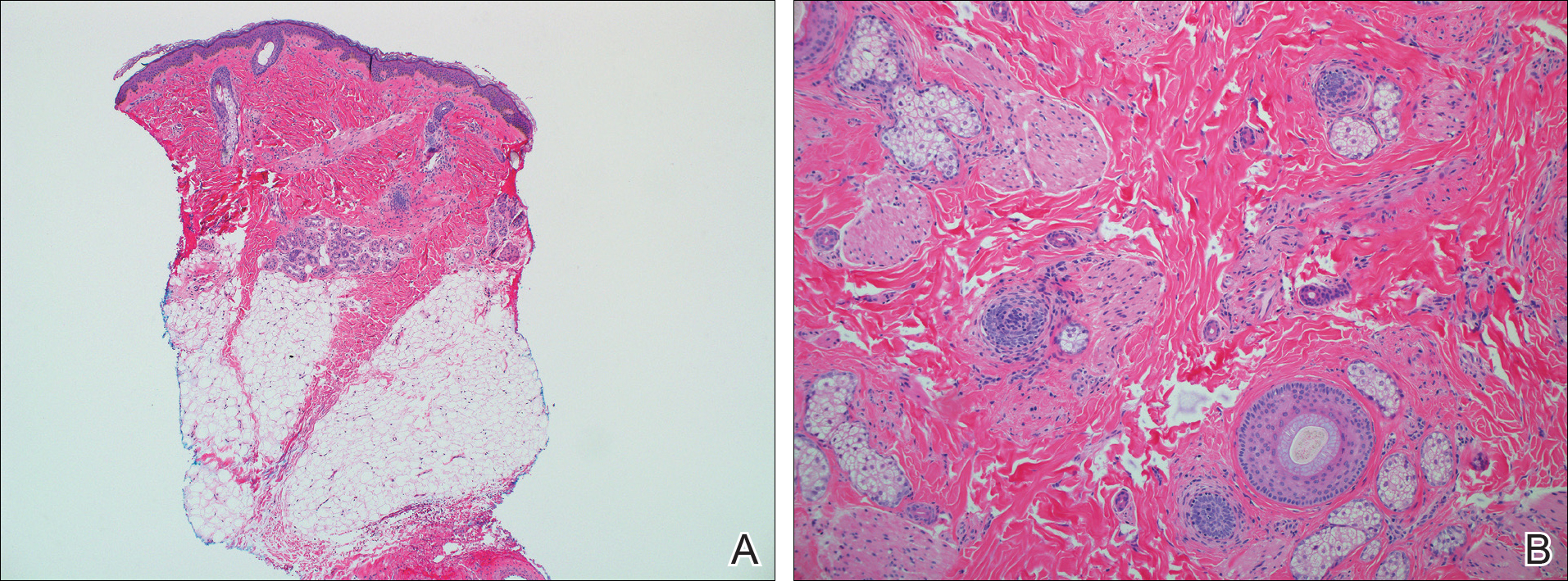

Immunohistochemical marker studies for S-100 and cytokeratin were negative. Invasion into subcutaneous fat was encountered (Figure 2A). Highly atypical spindle cells and mitoses were present (Figure 2B). Neoplastic cells were noted adjacent to nerve (Figure 2C). Excision of the lesion was curative, and his symptoms of pain and erosive pustular dermatosis resolved weeks thereafter (Figure 1B). The area of erosive pustular dermatosis was not excised, but symptoms resolved weeks following excision of the AFX.

Comment

Our case of AFX is unique due to the patient’s atypical presentation of severe pain. Because AFX usually presents asymptomatically, pain is an uncommon symptom. Based on the histologic findings in our case, we suspected that neural involvement of the tumor most likely explained the intense pain that our patient experienced.

The presence of erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp also is interesting in our case. This elderly man had an extensive history of actinic damage and had reported pustules, scaling, itching, and scabbing of the scalp. It is possible that erosive pustular dermatosis was superimposed over the tumor and could have been the reason that multiple biopsies were needed to eventually arrive at a diagnosis. The coexistence of the 2 entities suggests that the chronic actinic damage played a role in the etiology of both.

Classification

There is a question regarding nomenclature when discussing AFX. Atypical fibroxanthoma has been referred to as a variant of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, which is a type of soft tissue sarcoma. Atypical fibroxanthoma can be referred to as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma if it is more than 2 cm in diameter, if it involves the fascia or subcutaneous tissue, or if there is evidence of necrosis.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma generally is confined to the head and neck region and usually is less than 2 cm in diameter. In this patient, the presentation was consistent with AFX, as there was evidence of necrosis and invasion into the subcutaneous fat. The fact that the lesion also appeared on the scalp further supported the diagnosis of AFX.

Pathology

Biopsy of AFX typically reveals a spindle cell proliferation that usually arises in the setting of profound actinic damage. The epidermis may or may not be ulcerated, and in most cases, it is seen in close proximity to the overlying epidermis but not arising from it.8 Classic AFX is composed of highly atypical histiocytelike (epithelioid) cells admixed with pleomorphic spindle cells and giant cells, all showing frequent mitoses including atypical ones.9 Several histologic subtypes of AFX have been described, including clear cell, granular cell, pigmented cell, chondroid, osteoid, osteoclastic, and the most common spindle cell subtype.9 Features that indicate potential aggressive behavior include infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, vascular invasion, and presence of necrosis. A diagnosis of AFX is made by exclusion of other malignant neoplasms with similar morphology, namely spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell melanoma, and leiomyoscarcoma.9 As such, immunohistochemistry plays a critical role in distinguishing these lesions, as they arise as part of the differential diagnosis. A panel of immunohistochemical stains is helpful for diagnosis and commonly includes but is not limited to S-100, Melan-A, smooth muscle actin, desmin, and cytokeratin.

Sampling error is an inherent flaw in any biopsy specimen. The eventual diagnosis of AFX in our case supports the argument for multiple biopsies of an unknown lesion, seeing as the affected area was interpreted as both granulation tissue and AK prior to the eventual diagnosis. Repeat biopsies, especially if a lesion is nonhealing, often can help clinicians arrive at a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment

Different treatment options have been used to manage AFX. Mohs micrographic surgery is most often used because of its tissue-sparing potential, often giving the most cosmetically appealing result. Wide local excision is another surgical technique utilized, generally with fixed margins of at least 1 cm.10 Radiation at the tumor site is used as a treatment method but most often during cases of reoccurrence. Cryotherapy as well as electrodesiccation and curettage are possible treatment options but are not the standard of care.

- Helwig EB. Atypical fibroxanthoma, in tumor seminar. proceedings of 18th Annual Seminar of San Antonio Society of Pathologists, 1961. Tex State J Med. 1963;59:664-667.

- Anderson HL, Joseph AK. A pilot feasibility study of a rare skin tumor database. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:693-696.

- Iorizzo LJ 3rd, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

- Fretzin DF, Helwig EB. Atypical fibroxanthoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic study of 140 cases. Cancer. 1973;31:1541-1552.

- Vandergriff TW, Reed JA, Orengo IF. An unusual presentation of atypical fibroxanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Weedon D, Kerr JF. Atypical fibroxanthoma of skin: an electron microscope study. Pathology. 1975;7:173-177.

- Woyke S, Domagala W, Olszewski W, et al. Pseudosarcoma of the skin. an electron microscopic study and comparison with the fine structure of spindle-cell variant of squamous carcinoma. Cancer. 1974;33:970-980.

- Edward S, Yung A. Essential Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Morphologic and immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical fibroxanthoma with a special emphasis on potential diagnostic pitfalls: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:301-309.

- González-García R, Nam-Cha SH, Muñoz-Guerra MF, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma of the head and neck: report of 5 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:526-531.

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a low-grade dermal malignancy comprised of atypical spindle cells.1 Classified as a superficial fibrohistiocytic tumor with intermediate malignant potential, AFX has an incidence of approximately 0.24% worldwide.2 The tumor appears mainly on the head and neck in sun-exposed areas but can occur less frequently on the trunk and limbs in non–sun-exposed areas. There is a 70% to 80% predominance in men aged 69 to 77 years, with lesions primarily occurring in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck.3 A median period of 4 months between time of onset and time of diagnosis has been previously established.4

When AFX does occur in non–sun-exposed areas, it tends to be in a younger patient population. Clinically, it presents as a rather nondescript, firm, erythematous papule or nodule less than 2 cm in diameter. Atypical fibroxanthoma most often presents asymptomatically, but the tumor may ulcerate and bleed, though pain and pruritus are uncommon.5 Findings are nonspecific, and the diagnosis must be confirmed with biopsy, as it can resemble other common dermatological lesions. The pathogenesis of AFX has been controversial. Two different studies looked at AFX using electron microscopy and concluded that the tumor most closely resembled a myofibroblast,6,7 which is consistent with current thinking today.

Atypical fibroxanthoma is believed to be associated with p53 mutation and is closely linked with exposure to UV radiation due to its predominance in sun-exposed areas. Other predisposing factors may include prior exposure to UV radiation, history of organ transplantation, immunosuppression, advanced age in men, and xeroderma pigmentosum. The differential diagnosis for AFX encompasses basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, adnexal tumor, and pyogenic granuloma.

Case Report

On physical examination, the lesions appeared erosive with crusting and granulation tissue (Figure 1A). The presentation was consistent with erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp. Biopsy revealed granulation tissue. The patient underwent PDT and prednisone treatment with improvement. Additional biopsies revealed AKs. His condition improved with 2 PDT sessions but never fully cleared. During the PDT sessions, the patient reported intense unilateral headaches without visual changes. The headaches were intermittent and not apparently related to the treatments. He was referred for a temporal artery biopsy and rebiopsy of the remaining lesion on the scalp. The temporal artery biopsy was negative. The lesion that remained was a large nodule on the vertex scalp, and biopsy revealed AFX.

Immunohistochemical marker studies for S-100 and cytokeratin were negative. Invasion into subcutaneous fat was encountered (Figure 2A). Highly atypical spindle cells and mitoses were present (Figure 2B). Neoplastic cells were noted adjacent to nerve (Figure 2C). Excision of the lesion was curative, and his symptoms of pain and erosive pustular dermatosis resolved weeks thereafter (Figure 1B). The area of erosive pustular dermatosis was not excised, but symptoms resolved weeks following excision of the AFX.

Comment

Our case of AFX is unique due to the patient’s atypical presentation of severe pain. Because AFX usually presents asymptomatically, pain is an uncommon symptom. Based on the histologic findings in our case, we suspected that neural involvement of the tumor most likely explained the intense pain that our patient experienced.

The presence of erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp also is interesting in our case. This elderly man had an extensive history of actinic damage and had reported pustules, scaling, itching, and scabbing of the scalp. It is possible that erosive pustular dermatosis was superimposed over the tumor and could have been the reason that multiple biopsies were needed to eventually arrive at a diagnosis. The coexistence of the 2 entities suggests that the chronic actinic damage played a role in the etiology of both.

Classification

There is a question regarding nomenclature when discussing AFX. Atypical fibroxanthoma has been referred to as a variant of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, which is a type of soft tissue sarcoma. Atypical fibroxanthoma can be referred to as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma if it is more than 2 cm in diameter, if it involves the fascia or subcutaneous tissue, or if there is evidence of necrosis.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma generally is confined to the head and neck region and usually is less than 2 cm in diameter. In this patient, the presentation was consistent with AFX, as there was evidence of necrosis and invasion into the subcutaneous fat. The fact that the lesion also appeared on the scalp further supported the diagnosis of AFX.

Pathology

Biopsy of AFX typically reveals a spindle cell proliferation that usually arises in the setting of profound actinic damage. The epidermis may or may not be ulcerated, and in most cases, it is seen in close proximity to the overlying epidermis but not arising from it.8 Classic AFX is composed of highly atypical histiocytelike (epithelioid) cells admixed with pleomorphic spindle cells and giant cells, all showing frequent mitoses including atypical ones.9 Several histologic subtypes of AFX have been described, including clear cell, granular cell, pigmented cell, chondroid, osteoid, osteoclastic, and the most common spindle cell subtype.9 Features that indicate potential aggressive behavior include infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, vascular invasion, and presence of necrosis. A diagnosis of AFX is made by exclusion of other malignant neoplasms with similar morphology, namely spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell melanoma, and leiomyoscarcoma.9 As such, immunohistochemistry plays a critical role in distinguishing these lesions, as they arise as part of the differential diagnosis. A panel of immunohistochemical stains is helpful for diagnosis and commonly includes but is not limited to S-100, Melan-A, smooth muscle actin, desmin, and cytokeratin.

Sampling error is an inherent flaw in any biopsy specimen. The eventual diagnosis of AFX in our case supports the argument for multiple biopsies of an unknown lesion, seeing as the affected area was interpreted as both granulation tissue and AK prior to the eventual diagnosis. Repeat biopsies, especially if a lesion is nonhealing, often can help clinicians arrive at a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment

Different treatment options have been used to manage AFX. Mohs micrographic surgery is most often used because of its tissue-sparing potential, often giving the most cosmetically appealing result. Wide local excision is another surgical technique utilized, generally with fixed margins of at least 1 cm.10 Radiation at the tumor site is used as a treatment method but most often during cases of reoccurrence. Cryotherapy as well as electrodesiccation and curettage are possible treatment options but are not the standard of care.

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a low-grade dermal malignancy comprised of atypical spindle cells.1 Classified as a superficial fibrohistiocytic tumor with intermediate malignant potential, AFX has an incidence of approximately 0.24% worldwide.2 The tumor appears mainly on the head and neck in sun-exposed areas but can occur less frequently on the trunk and limbs in non–sun-exposed areas. There is a 70% to 80% predominance in men aged 69 to 77 years, with lesions primarily occurring in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck.3 A median period of 4 months between time of onset and time of diagnosis has been previously established.4

When AFX does occur in non–sun-exposed areas, it tends to be in a younger patient population. Clinically, it presents as a rather nondescript, firm, erythematous papule or nodule less than 2 cm in diameter. Atypical fibroxanthoma most often presents asymptomatically, but the tumor may ulcerate and bleed, though pain and pruritus are uncommon.5 Findings are nonspecific, and the diagnosis must be confirmed with biopsy, as it can resemble other common dermatological lesions. The pathogenesis of AFX has been controversial. Two different studies looked at AFX using electron microscopy and concluded that the tumor most closely resembled a myofibroblast,6,7 which is consistent with current thinking today.

Atypical fibroxanthoma is believed to be associated with p53 mutation and is closely linked with exposure to UV radiation due to its predominance in sun-exposed areas. Other predisposing factors may include prior exposure to UV radiation, history of organ transplantation, immunosuppression, advanced age in men, and xeroderma pigmentosum. The differential diagnosis for AFX encompasses basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, adnexal tumor, and pyogenic granuloma.

Case Report

On physical examination, the lesions appeared erosive with crusting and granulation tissue (Figure 1A). The presentation was consistent with erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp. Biopsy revealed granulation tissue. The patient underwent PDT and prednisone treatment with improvement. Additional biopsies revealed AKs. His condition improved with 2 PDT sessions but never fully cleared. During the PDT sessions, the patient reported intense unilateral headaches without visual changes. The headaches were intermittent and not apparently related to the treatments. He was referred for a temporal artery biopsy and rebiopsy of the remaining lesion on the scalp. The temporal artery biopsy was negative. The lesion that remained was a large nodule on the vertex scalp, and biopsy revealed AFX.

Immunohistochemical marker studies for S-100 and cytokeratin were negative. Invasion into subcutaneous fat was encountered (Figure 2A). Highly atypical spindle cells and mitoses were present (Figure 2B). Neoplastic cells were noted adjacent to nerve (Figure 2C). Excision of the lesion was curative, and his symptoms of pain and erosive pustular dermatosis resolved weeks thereafter (Figure 1B). The area of erosive pustular dermatosis was not excised, but symptoms resolved weeks following excision of the AFX.

Comment

Our case of AFX is unique due to the patient’s atypical presentation of severe pain. Because AFX usually presents asymptomatically, pain is an uncommon symptom. Based on the histologic findings in our case, we suspected that neural involvement of the tumor most likely explained the intense pain that our patient experienced.

The presence of erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp also is interesting in our case. This elderly man had an extensive history of actinic damage and had reported pustules, scaling, itching, and scabbing of the scalp. It is possible that erosive pustular dermatosis was superimposed over the tumor and could have been the reason that multiple biopsies were needed to eventually arrive at a diagnosis. The coexistence of the 2 entities suggests that the chronic actinic damage played a role in the etiology of both.

Classification

There is a question regarding nomenclature when discussing AFX. Atypical fibroxanthoma has been referred to as a variant of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, which is a type of soft tissue sarcoma. Atypical fibroxanthoma can be referred to as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma if it is more than 2 cm in diameter, if it involves the fascia or subcutaneous tissue, or if there is evidence of necrosis.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma generally is confined to the head and neck region and usually is less than 2 cm in diameter. In this patient, the presentation was consistent with AFX, as there was evidence of necrosis and invasion into the subcutaneous fat. The fact that the lesion also appeared on the scalp further supported the diagnosis of AFX.

Pathology

Biopsy of AFX typically reveals a spindle cell proliferation that usually arises in the setting of profound actinic damage. The epidermis may or may not be ulcerated, and in most cases, it is seen in close proximity to the overlying epidermis but not arising from it.8 Classic AFX is composed of highly atypical histiocytelike (epithelioid) cells admixed with pleomorphic spindle cells and giant cells, all showing frequent mitoses including atypical ones.9 Several histologic subtypes of AFX have been described, including clear cell, granular cell, pigmented cell, chondroid, osteoid, osteoclastic, and the most common spindle cell subtype.9 Features that indicate potential aggressive behavior include infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue, vascular invasion, and presence of necrosis. A diagnosis of AFX is made by exclusion of other malignant neoplasms with similar morphology, namely spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell melanoma, and leiomyoscarcoma.9 As such, immunohistochemistry plays a critical role in distinguishing these lesions, as they arise as part of the differential diagnosis. A panel of immunohistochemical stains is helpful for diagnosis and commonly includes but is not limited to S-100, Melan-A, smooth muscle actin, desmin, and cytokeratin.

Sampling error is an inherent flaw in any biopsy specimen. The eventual diagnosis of AFX in our case supports the argument for multiple biopsies of an unknown lesion, seeing as the affected area was interpreted as both granulation tissue and AK prior to the eventual diagnosis. Repeat biopsies, especially if a lesion is nonhealing, often can help clinicians arrive at a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment

Different treatment options have been used to manage AFX. Mohs micrographic surgery is most often used because of its tissue-sparing potential, often giving the most cosmetically appealing result. Wide local excision is another surgical technique utilized, generally with fixed margins of at least 1 cm.10 Radiation at the tumor site is used as a treatment method but most often during cases of reoccurrence. Cryotherapy as well as electrodesiccation and curettage are possible treatment options but are not the standard of care.

- Helwig EB. Atypical fibroxanthoma, in tumor seminar. proceedings of 18th Annual Seminar of San Antonio Society of Pathologists, 1961. Tex State J Med. 1963;59:664-667.

- Anderson HL, Joseph AK. A pilot feasibility study of a rare skin tumor database. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:693-696.

- Iorizzo LJ 3rd, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

- Fretzin DF, Helwig EB. Atypical fibroxanthoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic study of 140 cases. Cancer. 1973;31:1541-1552.

- Vandergriff TW, Reed JA, Orengo IF. An unusual presentation of atypical fibroxanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Weedon D, Kerr JF. Atypical fibroxanthoma of skin: an electron microscope study. Pathology. 1975;7:173-177.

- Woyke S, Domagala W, Olszewski W, et al. Pseudosarcoma of the skin. an electron microscopic study and comparison with the fine structure of spindle-cell variant of squamous carcinoma. Cancer. 1974;33:970-980.

- Edward S, Yung A. Essential Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Morphologic and immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical fibroxanthoma with a special emphasis on potential diagnostic pitfalls: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:301-309.

- González-García R, Nam-Cha SH, Muñoz-Guerra MF, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma of the head and neck: report of 5 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:526-531.

- Helwig EB. Atypical fibroxanthoma, in tumor seminar. proceedings of 18th Annual Seminar of San Antonio Society of Pathologists, 1961. Tex State J Med. 1963;59:664-667.

- Anderson HL, Joseph AK. A pilot feasibility study of a rare skin tumor database. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:693-696.

- Iorizzo LJ 3rd, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

- Fretzin DF, Helwig EB. Atypical fibroxanthoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic study of 140 cases. Cancer. 1973;31:1541-1552.

- Vandergriff TW, Reed JA, Orengo IF. An unusual presentation of atypical fibroxanthoma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Weedon D, Kerr JF. Atypical fibroxanthoma of skin: an electron microscope study. Pathology. 1975;7:173-177.

- Woyke S, Domagala W, Olszewski W, et al. Pseudosarcoma of the skin. an electron microscopic study and comparison with the fine structure of spindle-cell variant of squamous carcinoma. Cancer. 1974;33:970-980.

- Edward S, Yung A. Essential Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Morphologic and immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical fibroxanthoma with a special emphasis on potential diagnostic pitfalls: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:301-309.

- González-García R, Nam-Cha SH, Muñoz-Guerra MF, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma of the head and neck: report of 5 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:526-531.

Practice Points

- Atypical fibroxanthoma predominantly occurs in older men on the head and neck.

- Erosive pustular dermatosis may be a benign entity, but if it does not resolve, continue to rebiopsy, as rare tumors may mimic this condition.

Platelet-rich plasma treatment for hair loss continues to be refined

SAN DIEGO – There is currently no standard protocol for injecting autologous platelet-rich plasma to stimulate hair growth, but the technique appears to be about 50% effective, according to Marc R. Avram, MD.

“I tell patients that this is not FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved, but we think it to be safe,” said Dr. Avram, clinical professor of dermatology at the Cornell University, New York, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “We don’t know how well it’s going to work. There are a lot of published data on it, but none of [them are] randomized or controlled long-term.”

In Dr. Avram’s experience, he has found that PRP is a good option for patients with difficult hair loss, such as those who had extensive hair loss after chemotherapy but the hair never grew back in the same fashion, or patients who have failed treatment with finasteride and minoxidil.

Currently, there is no standard protocol for using PRP to stimulate hair growth, but the approach Dr. Avram follows is modeled on his experience of injecting thousands of patients with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) for hair loss every 4-6 weeks. After drawing 20 ccs-30 ccs of blood from the patient, the vial is placed in a centrifuge for 10 minutes, a process that separates PRP from red blood cells. Next, the clinician injects PRP into the deep dermis/superficial subcutaneous tissue of the desired treatment area. An average of 4 ccs-8 ccs is injected during each session.

After three monthly treatments, patients follow up at 3 and 6 months after the last treatment to evaluate efficacy. “All patients are told if there is regrowth or thickening of terminal hair, maintenance treatments will be needed every 6-9 months,” he said.

Published clinical trials of PRP include a follow-up period of 3-12 months and most demonstrate an efficacy in the range of 50%-70%. “It seems to be more effective for earlier stages of hair loss, and there are no known side effects to date,” said Dr. Avram, who has authored five textbooks on hair and cosmetic dermatology. “I had one patient call up to say he thought he had an increase in hair loss 2-3 weeks after treatment, but that’s one patient in a couple hundred. This may be similar to the effect minoxidil has on some patients. I’ve had no other issues with side effects.”

In his opinion, future challenges in the use of PRP for restoring hair loss include better defining optimal candidates for the procedure and establishing a better treatment protocol. “How often should maintenance be done?” he asked. “Is this going to be helpful for alopecia areata and scarring alopecia? Also, we need to determine if finasteride, minoxidil, low-level light laser therapy, or any other medications can enhance PRP efficacy in combination. What’s the optimal combination for patients? We don’t know yet. But I think in the future we will.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he is a consultant for Restoration Robotics.

SAN DIEGO – There is currently no standard protocol for injecting autologous platelet-rich plasma to stimulate hair growth, but the technique appears to be about 50% effective, according to Marc R. Avram, MD.

“I tell patients that this is not FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved, but we think it to be safe,” said Dr. Avram, clinical professor of dermatology at the Cornell University, New York, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “We don’t know how well it’s going to work. There are a lot of published data on it, but none of [them are] randomized or controlled long-term.”

In Dr. Avram’s experience, he has found that PRP is a good option for patients with difficult hair loss, such as those who had extensive hair loss after chemotherapy but the hair never grew back in the same fashion, or patients who have failed treatment with finasteride and minoxidil.

Currently, there is no standard protocol for using PRP to stimulate hair growth, but the approach Dr. Avram follows is modeled on his experience of injecting thousands of patients with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) for hair loss every 4-6 weeks. After drawing 20 ccs-30 ccs of blood from the patient, the vial is placed in a centrifuge for 10 minutes, a process that separates PRP from red blood cells. Next, the clinician injects PRP into the deep dermis/superficial subcutaneous tissue of the desired treatment area. An average of 4 ccs-8 ccs is injected during each session.

After three monthly treatments, patients follow up at 3 and 6 months after the last treatment to evaluate efficacy. “All patients are told if there is regrowth or thickening of terminal hair, maintenance treatments will be needed every 6-9 months,” he said.

Published clinical trials of PRP include a follow-up period of 3-12 months and most demonstrate an efficacy in the range of 50%-70%. “It seems to be more effective for earlier stages of hair loss, and there are no known side effects to date,” said Dr. Avram, who has authored five textbooks on hair and cosmetic dermatology. “I had one patient call up to say he thought he had an increase in hair loss 2-3 weeks after treatment, but that’s one patient in a couple hundred. This may be similar to the effect minoxidil has on some patients. I’ve had no other issues with side effects.”

In his opinion, future challenges in the use of PRP for restoring hair loss include better defining optimal candidates for the procedure and establishing a better treatment protocol. “How often should maintenance be done?” he asked. “Is this going to be helpful for alopecia areata and scarring alopecia? Also, we need to determine if finasteride, minoxidil, low-level light laser therapy, or any other medications can enhance PRP efficacy in combination. What’s the optimal combination for patients? We don’t know yet. But I think in the future we will.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he is a consultant for Restoration Robotics.

SAN DIEGO – There is currently no standard protocol for injecting autologous platelet-rich plasma to stimulate hair growth, but the technique appears to be about 50% effective, according to Marc R. Avram, MD.

“I tell patients that this is not FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved, but we think it to be safe,” said Dr. Avram, clinical professor of dermatology at the Cornell University, New York, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “We don’t know how well it’s going to work. There are a lot of published data on it, but none of [them are] randomized or controlled long-term.”

In Dr. Avram’s experience, he has found that PRP is a good option for patients with difficult hair loss, such as those who had extensive hair loss after chemotherapy but the hair never grew back in the same fashion, or patients who have failed treatment with finasteride and minoxidil.

Currently, there is no standard protocol for using PRP to stimulate hair growth, but the approach Dr. Avram follows is modeled on his experience of injecting thousands of patients with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) for hair loss every 4-6 weeks. After drawing 20 ccs-30 ccs of blood from the patient, the vial is placed in a centrifuge for 10 minutes, a process that separates PRP from red blood cells. Next, the clinician injects PRP into the deep dermis/superficial subcutaneous tissue of the desired treatment area. An average of 4 ccs-8 ccs is injected during each session.

After three monthly treatments, patients follow up at 3 and 6 months after the last treatment to evaluate efficacy. “All patients are told if there is regrowth or thickening of terminal hair, maintenance treatments will be needed every 6-9 months,” he said.

Published clinical trials of PRP include a follow-up period of 3-12 months and most demonstrate an efficacy in the range of 50%-70%. “It seems to be more effective for earlier stages of hair loss, and there are no known side effects to date,” said Dr. Avram, who has authored five textbooks on hair and cosmetic dermatology. “I had one patient call up to say he thought he had an increase in hair loss 2-3 weeks after treatment, but that’s one patient in a couple hundred. This may be similar to the effect minoxidil has on some patients. I’ve had no other issues with side effects.”

In his opinion, future challenges in the use of PRP for restoring hair loss include better defining optimal candidates for the procedure and establishing a better treatment protocol. “How often should maintenance be done?” he asked. “Is this going to be helpful for alopecia areata and scarring alopecia? Also, we need to determine if finasteride, minoxidil, low-level light laser therapy, or any other medications can enhance PRP efficacy in combination. What’s the optimal combination for patients? We don’t know yet. But I think in the future we will.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he is a consultant for Restoration Robotics.

AT MOAS 2017

Alopecia patients share their struggles

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Alopecia areata patients struggle as much, if not more so, with the social and emotional challenges of the disease as with the physical challenges, according to patients and others who spoke at a public meeting on alopecia areata patient-focused drug development.

Alopecia areata affects as many as 6.8 million individuals in the United States, according to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF). However, the particulars of alopecia can vary widely from one person to another; some patients experience total hair loss (alopecia universalis), while others retain eyebrows, eyelashes, or some body hair.

The FDA meeting, held on Sept. 11, is part of the agency’s patient-focused drug development initiative. “We wanted to hear the broader patient’s voice,” Theresa M. Mullin, PhD, director of the FDA’s Office of Strategic Programs, said in her opening remarks. Gary Sherwood, communications director for NAAF, said that the meeting was the culmination of a 5-year effort, begun in 2012 when alopecia areata was named as one of 39 disease categories under consideration for such a meeting. “It is too early to know what the exact results will be … but if the past is any indication, they may be significant. The meeting held with psoriasis yielded FDA approval of a treatment previously denied,” he added in an interview.

Two panel presentations featured patients who discussed their experiences with alopecia; each was followed by a discussion period where patients and family members in the audience were invited to share their experiences.

The “Health Effects and Daily Impacts” panel allowed several patients and their family members the opportunity to identify specific issues that may surprise clinicians.

“One thing I learned was how much the patients are bothered by sweating of the scalp; this can affect what type of head covering, hair piece, or hat/helmet they are able to wear, and thus limits activities,” Dr. Marathe continued. “This is not something I had focused on previously. I will be more inclined to ask about sweating and offer treatments, such as scalp botulinum toxin or aluminum chloride now that I have been alerted to this concern. Also, the challenges of facial makeup such as pencil for eyebrows was another thing that the FDA session brought home for me; I’m more inclined to suggest things such as microblading for eyebrows, or to try treatments like latanoprost for eyebrows/lashes.”

The second panel, “Current Approaches to Treatment,” included a different group of patients who shared stories of treatments that had been successful and those that had not. “The patients at the FDA meeting expressed very eloquently what our patients feel – different treatments may work temporarily and then stop working, which leads to a roller coaster of emotions of hope and disappointment,” A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, also a dermatologist at Children’s National Health System, said in an interview. “Patients and physicians would be interested in a treatment option with a track record for predictable efficacy with durable and sustained hair regrowth and minimal side effects.”

Dr. Marathe noted that in her experience, those who develop alopecia totalis or universalis at a younger age tend to have more recalcitrant disease. “It is still very hard for me to predict which children will regrow their hair spontaneously, or with topical therapies, versus those with more resistant disease. I hope that continued study will allow us to offer a more realistic prognosis for these patients,” she said.

Discussion after the treatment panel included testimonials from patients who reported successful treatment with tofacitinib (Xeljanz), a Janus kinase inhibitor approved for rheumatoid arthritis, which is not approved for treatment of alopecia.

“I absolutely agree with the focus on JAK inhibitors and increasing our understanding of how they work, as well as what some of the long-term effects are,” said Dr. Marathe. “The better we are able to target the pathogenesis of this condition, the more easily we can treat in a more focused fashion and reduce side effects,” but more clinical trials are needed to determine safety and efficacy for children and teens, she noted.

One of her hesitations in prescribing tofacitinib to her patients is that she cannot provide them with a sense of how long they will need to be on the treatment. “Current data show that the hair growth on the medication is usually lost upon stopping it; the question I still struggle with is whether it is realistic to put a 4- or 5-year-old on a medication that has no estimated or anticipated stop date,” she said.

As for what she offers patients in terms of resources for emotional support, Dr. Kirkorian said the psychosocial aspects of alopecia areata are always discussed at patient visits. “Psychosocial needs vary based on age, personality, and personal philosophy. We offer the gamut of outside resources from local support groups, the National Alopecia Areata Foundation, referral to psychology/psychiatry and, very importantly, referral to Camp Discovery. Children have told us across the board how important and meaningful it was to them to be able to just be themselves around other children who look like them.”

Dr. Marathe and Dr. Kirkorian were attendees at the meeting; they had no relevant disclosures. They are members of the Dermatology News Editorial Advisory Board.

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Alopecia areata patients struggle as much, if not more so, with the social and emotional challenges of the disease as with the physical challenges, according to patients and others who spoke at a public meeting on alopecia areata patient-focused drug development.

Alopecia areata affects as many as 6.8 million individuals in the United States, according to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF). However, the particulars of alopecia can vary widely from one person to another; some patients experience total hair loss (alopecia universalis), while others retain eyebrows, eyelashes, or some body hair.

The FDA meeting, held on Sept. 11, is part of the agency’s patient-focused drug development initiative. “We wanted to hear the broader patient’s voice,” Theresa M. Mullin, PhD, director of the FDA’s Office of Strategic Programs, said in her opening remarks. Gary Sherwood, communications director for NAAF, said that the meeting was the culmination of a 5-year effort, begun in 2012 when alopecia areata was named as one of 39 disease categories under consideration for such a meeting. “It is too early to know what the exact results will be … but if the past is any indication, they may be significant. The meeting held with psoriasis yielded FDA approval of a treatment previously denied,” he added in an interview.

Two panel presentations featured patients who discussed their experiences with alopecia; each was followed by a discussion period where patients and family members in the audience were invited to share their experiences.

The “Health Effects and Daily Impacts” panel allowed several patients and their family members the opportunity to identify specific issues that may surprise clinicians.

“One thing I learned was how much the patients are bothered by sweating of the scalp; this can affect what type of head covering, hair piece, or hat/helmet they are able to wear, and thus limits activities,” Dr. Marathe continued. “This is not something I had focused on previously. I will be more inclined to ask about sweating and offer treatments, such as scalp botulinum toxin or aluminum chloride now that I have been alerted to this concern. Also, the challenges of facial makeup such as pencil for eyebrows was another thing that the FDA session brought home for me; I’m more inclined to suggest things such as microblading for eyebrows, or to try treatments like latanoprost for eyebrows/lashes.”

The second panel, “Current Approaches to Treatment,” included a different group of patients who shared stories of treatments that had been successful and those that had not. “The patients at the FDA meeting expressed very eloquently what our patients feel – different treatments may work temporarily and then stop working, which leads to a roller coaster of emotions of hope and disappointment,” A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, also a dermatologist at Children’s National Health System, said in an interview. “Patients and physicians would be interested in a treatment option with a track record for predictable efficacy with durable and sustained hair regrowth and minimal side effects.”

Dr. Marathe noted that in her experience, those who develop alopecia totalis or universalis at a younger age tend to have more recalcitrant disease. “It is still very hard for me to predict which children will regrow their hair spontaneously, or with topical therapies, versus those with more resistant disease. I hope that continued study will allow us to offer a more realistic prognosis for these patients,” she said.

Discussion after the treatment panel included testimonials from patients who reported successful treatment with tofacitinib (Xeljanz), a Janus kinase inhibitor approved for rheumatoid arthritis, which is not approved for treatment of alopecia.

“I absolutely agree with the focus on JAK inhibitors and increasing our understanding of how they work, as well as what some of the long-term effects are,” said Dr. Marathe. “The better we are able to target the pathogenesis of this condition, the more easily we can treat in a more focused fashion and reduce side effects,” but more clinical trials are needed to determine safety and efficacy for children and teens, she noted.

One of her hesitations in prescribing tofacitinib to her patients is that she cannot provide them with a sense of how long they will need to be on the treatment. “Current data show that the hair growth on the medication is usually lost upon stopping it; the question I still struggle with is whether it is realistic to put a 4- or 5-year-old on a medication that has no estimated or anticipated stop date,” she said.

As for what she offers patients in terms of resources for emotional support, Dr. Kirkorian said the psychosocial aspects of alopecia areata are always discussed at patient visits. “Psychosocial needs vary based on age, personality, and personal philosophy. We offer the gamut of outside resources from local support groups, the National Alopecia Areata Foundation, referral to psychology/psychiatry and, very importantly, referral to Camp Discovery. Children have told us across the board how important and meaningful it was to them to be able to just be themselves around other children who look like them.”

Dr. Marathe and Dr. Kirkorian were attendees at the meeting; they had no relevant disclosures. They are members of the Dermatology News Editorial Advisory Board.

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Alopecia areata patients struggle as much, if not more so, with the social and emotional challenges of the disease as with the physical challenges, according to patients and others who spoke at a public meeting on alopecia areata patient-focused drug development.

Alopecia areata affects as many as 6.8 million individuals in the United States, according to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF). However, the particulars of alopecia can vary widely from one person to another; some patients experience total hair loss (alopecia universalis), while others retain eyebrows, eyelashes, or some body hair.

The FDA meeting, held on Sept. 11, is part of the agency’s patient-focused drug development initiative. “We wanted to hear the broader patient’s voice,” Theresa M. Mullin, PhD, director of the FDA’s Office of Strategic Programs, said in her opening remarks. Gary Sherwood, communications director for NAAF, said that the meeting was the culmination of a 5-year effort, begun in 2012 when alopecia areata was named as one of 39 disease categories under consideration for such a meeting. “It is too early to know what the exact results will be … but if the past is any indication, they may be significant. The meeting held with psoriasis yielded FDA approval of a treatment previously denied,” he added in an interview.

Two panel presentations featured patients who discussed their experiences with alopecia; each was followed by a discussion period where patients and family members in the audience were invited to share their experiences.

The “Health Effects and Daily Impacts” panel allowed several patients and their family members the opportunity to identify specific issues that may surprise clinicians.

“One thing I learned was how much the patients are bothered by sweating of the scalp; this can affect what type of head covering, hair piece, or hat/helmet they are able to wear, and thus limits activities,” Dr. Marathe continued. “This is not something I had focused on previously. I will be more inclined to ask about sweating and offer treatments, such as scalp botulinum toxin or aluminum chloride now that I have been alerted to this concern. Also, the challenges of facial makeup such as pencil for eyebrows was another thing that the FDA session brought home for me; I’m more inclined to suggest things such as microblading for eyebrows, or to try treatments like latanoprost for eyebrows/lashes.”

The second panel, “Current Approaches to Treatment,” included a different group of patients who shared stories of treatments that had been successful and those that had not. “The patients at the FDA meeting expressed very eloquently what our patients feel – different treatments may work temporarily and then stop working, which leads to a roller coaster of emotions of hope and disappointment,” A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, also a dermatologist at Children’s National Health System, said in an interview. “Patients and physicians would be interested in a treatment option with a track record for predictable efficacy with durable and sustained hair regrowth and minimal side effects.”

Dr. Marathe noted that in her experience, those who develop alopecia totalis or universalis at a younger age tend to have more recalcitrant disease. “It is still very hard for me to predict which children will regrow their hair spontaneously, or with topical therapies, versus those with more resistant disease. I hope that continued study will allow us to offer a more realistic prognosis for these patients,” she said.

Discussion after the treatment panel included testimonials from patients who reported successful treatment with tofacitinib (Xeljanz), a Janus kinase inhibitor approved for rheumatoid arthritis, which is not approved for treatment of alopecia.

“I absolutely agree with the focus on JAK inhibitors and increasing our understanding of how they work, as well as what some of the long-term effects are,” said Dr. Marathe. “The better we are able to target the pathogenesis of this condition, the more easily we can treat in a more focused fashion and reduce side effects,” but more clinical trials are needed to determine safety and efficacy for children and teens, she noted.

One of her hesitations in prescribing tofacitinib to her patients is that she cannot provide them with a sense of how long they will need to be on the treatment. “Current data show that the hair growth on the medication is usually lost upon stopping it; the question I still struggle with is whether it is realistic to put a 4- or 5-year-old on a medication that has no estimated or anticipated stop date,” she said.

As for what she offers patients in terms of resources for emotional support, Dr. Kirkorian said the psychosocial aspects of alopecia areata are always discussed at patient visits. “Psychosocial needs vary based on age, personality, and personal philosophy. We offer the gamut of outside resources from local support groups, the National Alopecia Areata Foundation, referral to psychology/psychiatry and, very importantly, referral to Camp Discovery. Children have told us across the board how important and meaningful it was to them to be able to just be themselves around other children who look like them.”

Dr. Marathe and Dr. Kirkorian were attendees at the meeting; they had no relevant disclosures. They are members of the Dermatology News Editorial Advisory Board.

AT AN FDA PUBLIC MEETING

VIDEO: Alopecia areata patients seek emotional support

SILVER SPRING, MD. – The emotional challenges facing alopecia areata patients are as tough, or tougher, than the physical challenges, according to many patients participating in a public meeting on alopecia areata patient-focused drug development.

A panel of patients shared their experiences of living with alopecia areata, including Elizabeth DeCarlo of Wilmington, Delaware. In a video interview at the meeting, held at FDA headquarters on Sept. 11, Ms. DeCarlo elaborated on what she would like clinicians to understand about alopecia patients that might surprise them, and what matters to her as a patient.

“I would tell them to be more compassionate,” Ms. DeCarlo said. “It’s very emotional.” She also emphasized the value of giving alopecia patients information about local support groups, as well as national organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation.

Ms. DeCarlo had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SILVER SPRING, MD. – The emotional challenges facing alopecia areata patients are as tough, or tougher, than the physical challenges, according to many patients participating in a public meeting on alopecia areata patient-focused drug development.

A panel of patients shared their experiences of living with alopecia areata, including Elizabeth DeCarlo of Wilmington, Delaware. In a video interview at the meeting, held at FDA headquarters on Sept. 11, Ms. DeCarlo elaborated on what she would like clinicians to understand about alopecia patients that might surprise them, and what matters to her as a patient.

“I would tell them to be more compassionate,” Ms. DeCarlo said. “It’s very emotional.” She also emphasized the value of giving alopecia patients information about local support groups, as well as national organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation.

Ms. DeCarlo had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SILVER SPRING, MD. – The emotional challenges facing alopecia areata patients are as tough, or tougher, than the physical challenges, according to many patients participating in a public meeting on alopecia areata patient-focused drug development.

A panel of patients shared their experiences of living with alopecia areata, including Elizabeth DeCarlo of Wilmington, Delaware. In a video interview at the meeting, held at FDA headquarters on Sept. 11, Ms. DeCarlo elaborated on what she would like clinicians to understand about alopecia patients that might surprise them, and what matters to her as a patient.

“I would tell them to be more compassionate,” Ms. DeCarlo said. “It’s very emotional.” She also emphasized the value of giving alopecia patients information about local support groups, as well as national organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation.

Ms. DeCarlo had no financial conflicts to disclose.

AT AN FDA PUBLIC MEETING

Maintenance therapy typically required after laser hair removal

REPORTING FROM MOAS 2017

SAN DIEGO – Hair removal ranks as the most popular laser procedure performed in the United States, but patients with blond, red, or gray hairs are out of luck, since those threadlike strands lack a chromophore for the laser to respond to.

“For now, I recommend that these patients get electrolysis or use eflornithine cream,” Arisa Ortiz, MD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

Future treatment options for patients with light-colored hair look promising, however. One emerging technology combines laser hair removal with the insertion of a silver nanoparticle into the unpigmented hair follicle. “These are currently in pivotal trials, so we should be seeing them on the market very soon,” she said.

According to Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, there is still a place for nonlaser hair removal, including shaving, waxing, threading, and electrolysis, but laser hair removal is safe, effective in skilled hands, and permanent. Key factors in optimizing treatment include understanding laser safety and laser-tissue interaction, proper patient selection, preoperative preparation, parameter selection, and recognizing complications.

The first-degree target in laser hair removal is eumelanin contained in the bulb of hair follicles, she said, but the heat must diffuse to a secondary target – follicular stem cells in the bulge of the outer root sheath. “Pulse duration is important,” she said. “The thermal relaxation time of a terminal hair follicle is roughly 100 milliseconds. Longer pulse widths are going to be safer for darker skin types, and you want shorter pulse durations for fine hair, and longer pulse durations for thicker hair. Spot size is also important. Larger spot sizes are faster and create less pain and less epidermal damage.”

Indications include unwanted hair, hypertrichosis, and hirsutism/polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). “You want to counsel patients with PCOS properly, because they will require multiple treatments as they tend to make new hair follicles,” she said. Other indications include ingrown hairs, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and pilonidal cysts.

The best candidates for laser hair removal are patients who have a light skin color and dark hair, and those who have thick, coarse hair. “Be cautious when treating tanned patients, and adjust your setting to a longer pulse duration and a lower fluence,” she continued. “I tell (patients) they’ll likely need at least six treatments. You want to treat them every 6 to 8 weeks. If you do treatments sooner than that, it’s probably not cost effective for the patient, because of the way hair follicles cycle. It’s also important that they avoid the sun.”

Clinicians can achieve temporary hair removal with Q-switched lasers, which may be suitable for patients with pseudofolliculitis barbae but who may not want permanent hair removal. “This will just vaporize the actual hair follicle, but that heat is not extending to the stem cells, so it’s temporary hair removal, because the hair follicle transitions into the telogen phase,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “The hair will then grow back after a few months.”

Endpoints are the most important factor for laser hair removal. You want to see perifollicular erythema, perifollicular edema, or hair singeing. “Then you know you have an effective treatment setting,” she said. “Sometimes, however, it takes time for this erythema or edema to develop, so you don’t want to keep increasing your fluences to see this end point. If you’re not comfortable with the laser you’re using, I recommend waiting a few minutes after treatment, and looking for the end point. You could always go higher during the next treatment, if you need to.”

Higher fluences have been correlated with greater permanent hair removal, but also with more side effects. “The recommended treatment settings are going to be the highest possible tolerated fluence that yields the desired endpoint without any adverse effects,” Dr. Ortiz said.

The first hair removal laser to hit the market was the Ruby 694-nm laser, which is safe for Fitzpatrick skin types I-III. A long-term follow-up of the seminal study showed permanent posttreatment efficacy of up to 2 years (Arch Dermatol. 1998;134[7]:837-42). The Alexandrite 755-nm laser, meanwhile, penetrates deeper because it’s a longer wavelength, so there’s less melanin absorption, and it’s safer for darker skin types. “With a device like this, you want to make sure that you’re always holding the laser perpendicular to the skin surface so that your cryogen spray is firing at the same area as the laser. [That way] you don’t get a burn injury,” she said.

The diode at 800 nm and 810 nm penetrates even deeper, which results in less melanin absorption. “Originally these devices had smaller spot sizes, but now some of the newer devices have larger hand pieces and use contact cooling,” she said. “Some of the diode lasers cause singeing and char. The carbon actually sticks onto the sapphire window of the device, so you want to make sure you swipe the window after every few pulses so that you’re not putting the char onto the epidermis and causing an epidermal burn,” Dr. Ortiz advised.

She described the Nd:YAG 1,064-nm laser as the safest for skin types V and VI. It has the deepest penetration but the least melanin absorption. Intense pulsed light (IPL) can also be used for hair removal. IPLs “have a larger spot size, and you can use various cutoff filters to make them safer for darker skin types,” she said. “However, in head-to-head studies, usually laser hair removal does better than IPL.”

Potential complications from laser hair removal include paradoxical hypertrichosis; pigmentary alterations such as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation; infections/folliculitis, scarring, and eye injury. Dr. Ortiz underscored the importance of counseling patients about the need for maintenance treatments prior to initiating their first hair removal session. Laser hair removal removes about 85-90% of hairs permanently “so that leaves a significant number that remain, and new hairs may grow over time,” she said.

Authors of a recent study found that the plume release during laser hair removal should be considered a potential biohazard that warrants the use of smoke evacuators and good room ventilation (JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152[12]:1320-26). “We are learning that we should be more careful to evacuate the plume from laser hair removal or wear laser protective masks as the plume may contain harmful chemicals that we breathe in on a daily basis,” said Dr. Ortiz, who was not affiliated with the analysis.

She disclosed serving as a consultant to, receiving equipment from, and/or being a member of the scientific board of several device companies, including Alastin, Allergan, BTL, Cutera, InMode, Merz, Revance, Rodan and Fields, Sciton, and Sienna Biopharmaceuticals.

-[email protected]

REPORTING FROM MOAS 2017

SAN DIEGO – Hair removal ranks as the most popular laser procedure performed in the United States, but patients with blond, red, or gray hairs are out of luck, since those threadlike strands lack a chromophore for the laser to respond to.

“For now, I recommend that these patients get electrolysis or use eflornithine cream,” Arisa Ortiz, MD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

Future treatment options for patients with light-colored hair look promising, however. One emerging technology combines laser hair removal with the insertion of a silver nanoparticle into the unpigmented hair follicle. “These are currently in pivotal trials, so we should be seeing them on the market very soon,” she said.

According to Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, there is still a place for nonlaser hair removal, including shaving, waxing, threading, and electrolysis, but laser hair removal is safe, effective in skilled hands, and permanent. Key factors in optimizing treatment include understanding laser safety and laser-tissue interaction, proper patient selection, preoperative preparation, parameter selection, and recognizing complications.

The first-degree target in laser hair removal is eumelanin contained in the bulb of hair follicles, she said, but the heat must diffuse to a secondary target – follicular stem cells in the bulge of the outer root sheath. “Pulse duration is important,” she said. “The thermal relaxation time of a terminal hair follicle is roughly 100 milliseconds. Longer pulse widths are going to be safer for darker skin types, and you want shorter pulse durations for fine hair, and longer pulse durations for thicker hair. Spot size is also important. Larger spot sizes are faster and create less pain and less epidermal damage.”

Indications include unwanted hair, hypertrichosis, and hirsutism/polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). “You want to counsel patients with PCOS properly, because they will require multiple treatments as they tend to make new hair follicles,” she said. Other indications include ingrown hairs, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and pilonidal cysts.

The best candidates for laser hair removal are patients who have a light skin color and dark hair, and those who have thick, coarse hair. “Be cautious when treating tanned patients, and adjust your setting to a longer pulse duration and a lower fluence,” she continued. “I tell (patients) they’ll likely need at least six treatments. You want to treat them every 6 to 8 weeks. If you do treatments sooner than that, it’s probably not cost effective for the patient, because of the way hair follicles cycle. It’s also important that they avoid the sun.”

Clinicians can achieve temporary hair removal with Q-switched lasers, which may be suitable for patients with pseudofolliculitis barbae but who may not want permanent hair removal. “This will just vaporize the actual hair follicle, but that heat is not extending to the stem cells, so it’s temporary hair removal, because the hair follicle transitions into the telogen phase,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “The hair will then grow back after a few months.”

Endpoints are the most important factor for laser hair removal. You want to see perifollicular erythema, perifollicular edema, or hair singeing. “Then you know you have an effective treatment setting,” she said. “Sometimes, however, it takes time for this erythema or edema to develop, so you don’t want to keep increasing your fluences to see this end point. If you’re not comfortable with the laser you’re using, I recommend waiting a few minutes after treatment, and looking for the end point. You could always go higher during the next treatment, if you need to.”

Higher fluences have been correlated with greater permanent hair removal, but also with more side effects. “The recommended treatment settings are going to be the highest possible tolerated fluence that yields the desired endpoint without any adverse effects,” Dr. Ortiz said.

The first hair removal laser to hit the market was the Ruby 694-nm laser, which is safe for Fitzpatrick skin types I-III. A long-term follow-up of the seminal study showed permanent posttreatment efficacy of up to 2 years (Arch Dermatol. 1998;134[7]:837-42). The Alexandrite 755-nm laser, meanwhile, penetrates deeper because it’s a longer wavelength, so there’s less melanin absorption, and it’s safer for darker skin types. “With a device like this, you want to make sure that you’re always holding the laser perpendicular to the skin surface so that your cryogen spray is firing at the same area as the laser. [That way] you don’t get a burn injury,” she said.

The diode at 800 nm and 810 nm penetrates even deeper, which results in less melanin absorption. “Originally these devices had smaller spot sizes, but now some of the newer devices have larger hand pieces and use contact cooling,” she said. “Some of the diode lasers cause singeing and char. The carbon actually sticks onto the sapphire window of the device, so you want to make sure you swipe the window after every few pulses so that you’re not putting the char onto the epidermis and causing an epidermal burn,” Dr. Ortiz advised.

She described the Nd:YAG 1,064-nm laser as the safest for skin types V and VI. It has the deepest penetration but the least melanin absorption. Intense pulsed light (IPL) can also be used for hair removal. IPLs “have a larger spot size, and you can use various cutoff filters to make them safer for darker skin types,” she said. “However, in head-to-head studies, usually laser hair removal does better than IPL.”

Potential complications from laser hair removal include paradoxical hypertrichosis; pigmentary alterations such as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation; infections/folliculitis, scarring, and eye injury. Dr. Ortiz underscored the importance of counseling patients about the need for maintenance treatments prior to initiating their first hair removal session. Laser hair removal removes about 85-90% of hairs permanently “so that leaves a significant number that remain, and new hairs may grow over time,” she said.

Authors of a recent study found that the plume release during laser hair removal should be considered a potential biohazard that warrants the use of smoke evacuators and good room ventilation (JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152[12]:1320-26). “We are learning that we should be more careful to evacuate the plume from laser hair removal or wear laser protective masks as the plume may contain harmful chemicals that we breathe in on a daily basis,” said Dr. Ortiz, who was not affiliated with the analysis.

She disclosed serving as a consultant to, receiving equipment from, and/or being a member of the scientific board of several device companies, including Alastin, Allergan, BTL, Cutera, InMode, Merz, Revance, Rodan and Fields, Sciton, and Sienna Biopharmaceuticals.

-[email protected]

REPORTING FROM MOAS 2017

SAN DIEGO – Hair removal ranks as the most popular laser procedure performed in the United States, but patients with blond, red, or gray hairs are out of luck, since those threadlike strands lack a chromophore for the laser to respond to.

“For now, I recommend that these patients get electrolysis or use eflornithine cream,” Arisa Ortiz, MD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium.

Future treatment options for patients with light-colored hair look promising, however. One emerging technology combines laser hair removal with the insertion of a silver nanoparticle into the unpigmented hair follicle. “These are currently in pivotal trials, so we should be seeing them on the market very soon,” she said.

According to Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, there is still a place for nonlaser hair removal, including shaving, waxing, threading, and electrolysis, but laser hair removal is safe, effective in skilled hands, and permanent. Key factors in optimizing treatment include understanding laser safety and laser-tissue interaction, proper patient selection, preoperative preparation, parameter selection, and recognizing complications.

The first-degree target in laser hair removal is eumelanin contained in the bulb of hair follicles, she said, but the heat must diffuse to a secondary target – follicular stem cells in the bulge of the outer root sheath. “Pulse duration is important,” she said. “The thermal relaxation time of a terminal hair follicle is roughly 100 milliseconds. Longer pulse widths are going to be safer for darker skin types, and you want shorter pulse durations for fine hair, and longer pulse durations for thicker hair. Spot size is also important. Larger spot sizes are faster and create less pain and less epidermal damage.”

Indications include unwanted hair, hypertrichosis, and hirsutism/polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). “You want to counsel patients with PCOS properly, because they will require multiple treatments as they tend to make new hair follicles,” she said. Other indications include ingrown hairs, pseudofolliculitis barbae, and pilonidal cysts.

The best candidates for laser hair removal are patients who have a light skin color and dark hair, and those who have thick, coarse hair. “Be cautious when treating tanned patients, and adjust your setting to a longer pulse duration and a lower fluence,” she continued. “I tell (patients) they’ll likely need at least six treatments. You want to treat them every 6 to 8 weeks. If you do treatments sooner than that, it’s probably not cost effective for the patient, because of the way hair follicles cycle. It’s also important that they avoid the sun.”

Clinicians can achieve temporary hair removal with Q-switched lasers, which may be suitable for patients with pseudofolliculitis barbae but who may not want permanent hair removal. “This will just vaporize the actual hair follicle, but that heat is not extending to the stem cells, so it’s temporary hair removal, because the hair follicle transitions into the telogen phase,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “The hair will then grow back after a few months.”

Endpoints are the most important factor for laser hair removal. You want to see perifollicular erythema, perifollicular edema, or hair singeing. “Then you know you have an effective treatment setting,” she said. “Sometimes, however, it takes time for this erythema or edema to develop, so you don’t want to keep increasing your fluences to see this end point. If you’re not comfortable with the laser you’re using, I recommend waiting a few minutes after treatment, and looking for the end point. You could always go higher during the next treatment, if you need to.”

Higher fluences have been correlated with greater permanent hair removal, but also with more side effects. “The recommended treatment settings are going to be the highest possible tolerated fluence that yields the desired endpoint without any adverse effects,” Dr. Ortiz said.

The first hair removal laser to hit the market was the Ruby 694-nm laser, which is safe for Fitzpatrick skin types I-III. A long-term follow-up of the seminal study showed permanent posttreatment efficacy of up to 2 years (Arch Dermatol. 1998;134[7]:837-42). The Alexandrite 755-nm laser, meanwhile, penetrates deeper because it’s a longer wavelength, so there’s less melanin absorption, and it’s safer for darker skin types. “With a device like this, you want to make sure that you’re always holding the laser perpendicular to the skin surface so that your cryogen spray is firing at the same area as the laser. [That way] you don’t get a burn injury,” she said.

The diode at 800 nm and 810 nm penetrates even deeper, which results in less melanin absorption. “Originally these devices had smaller spot sizes, but now some of the newer devices have larger hand pieces and use contact cooling,” she said. “Some of the diode lasers cause singeing and char. The carbon actually sticks onto the sapphire window of the device, so you want to make sure you swipe the window after every few pulses so that you’re not putting the char onto the epidermis and causing an epidermal burn,” Dr. Ortiz advised.

She described the Nd:YAG 1,064-nm laser as the safest for skin types V and VI. It has the deepest penetration but the least melanin absorption. Intense pulsed light (IPL) can also be used for hair removal. IPLs “have a larger spot size, and you can use various cutoff filters to make them safer for darker skin types,” she said. “However, in head-to-head studies, usually laser hair removal does better than IPL.”

Potential complications from laser hair removal include paradoxical hypertrichosis; pigmentary alterations such as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation; infections/folliculitis, scarring, and eye injury. Dr. Ortiz underscored the importance of counseling patients about the need for maintenance treatments prior to initiating their first hair removal session. Laser hair removal removes about 85-90% of hairs permanently “so that leaves a significant number that remain, and new hairs may grow over time,” she said.

Authors of a recent study found that the plume release during laser hair removal should be considered a potential biohazard that warrants the use of smoke evacuators and good room ventilation (JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152[12]:1320-26). “We are learning that we should be more careful to evacuate the plume from laser hair removal or wear laser protective masks as the plume may contain harmful chemicals that we breathe in on a daily basis,” said Dr. Ortiz, who was not affiliated with the analysis.

She disclosed serving as a consultant to, receiving equipment from, and/or being a member of the scientific board of several device companies, including Alastin, Allergan, BTL, Cutera, InMode, Merz, Revance, Rodan and Fields, Sciton, and Sienna Biopharmaceuticals.

-[email protected]

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Men’s Products

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on men’s products. Consideration must be given to:

- bareMinerals SPF 30 Natural Sunscreen

Bare Escentuals Beauty, Inc

“I recommend this product to my male patients when they are not wearing a hat. It protects the scalp from UV damage without a heavy greasy finish.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

- Ducray Alopexy 5% For Men

Pierre Fabre Laboratories

“This dermatologist-dispensed product for men addresses chronic hair loss as well as thinning hair. It contains an optimal level of minoxidil 5% in an elegant unscented formulation and is designed to spray on smoothly and evenly.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, Great Neck, New York

- Facial Fuel Energizing Scrub

Kiehl’s

“This product is great for oily skin and enlarged pores. The particles in the product allow one to get a deep-clean feeling.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50

SkinCeuticals

“For men I like to keep things simple. I recommend what I use with the single most important thing being daily sun protection. SkinCeuticals Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50 is my favorite and I use it after I shave. It goes on smoothly and has a natural tint along with a high SPF.”—Jerome Potozkin, MD, Danville, California

- Ultimate Brushless Shave Cream

Kiehl’s

“I recommend this product for men with frequent irritation from shaving. This cream-based product helps to provide a close shave without as much irritation from other gel-based products. A small amount goes a long way!”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments and cleansing devices will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on men’s products. Consideration must be given to:

- bareMinerals SPF 30 Natural Sunscreen

Bare Escentuals Beauty, Inc

“I recommend this product to my male patients when they are not wearing a hat. It protects the scalp from UV damage without a heavy greasy finish.”—Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

- Ducray Alopexy 5% For Men

Pierre Fabre Laboratories

“This dermatologist-dispensed product for men addresses chronic hair loss as well as thinning hair. It contains an optimal level of minoxidil 5% in an elegant unscented formulation and is designed to spray on smoothly and evenly.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, Great Neck, New York

- Facial Fuel Energizing Scrub

Kiehl’s

“This product is great for oily skin and enlarged pores. The particles in the product allow one to get a deep-clean feeling.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50

SkinCeuticals

“For men I like to keep things simple. I recommend what I use with the single most important thing being daily sun protection. SkinCeuticals Physical Matte UV Defense SPF 50 is my favorite and I use it after I shave. It goes on smoothly and has a natural tint along with a high SPF.”—Jerome Potozkin, MD, Danville, California

- Ultimate Brushless Shave Cream

Kiehl’s