User login

JAK inhibitors look good for severe alopecia areata treatment

said Lucy Yichu Liu, MD, and Brett Andrew King, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Standard medical therapies for alopecia areata – usually topical or injected corticosteroids and allergic contact sensitization – are not very effective for severe disease, particularly alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. The Janus kinase (JAK) pathway recently has been suggested as a target for treatment.

Dr. Liu and Dr. King reviewed several studies, including a retrospective cohort study of 13 patients aged 12-17 years, in which 7 patients had 100% hair loss and 6 had 20%-70% scalp hair loss. The adolescents were treated with the JAK1/3 inhibitor tofacitinib citrate 5 mg twice daily for 2-16 months (median, 5 months). That led to 93% median improvement in Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score (range, 1%-100%) from baseline. Nine patients experienced hair regrowth. There were mild adverse effects, such as upper respiratory infections and headaches.

In a retrospective cohort study of 90 adults taking tofacitinib at a dosage of 5-10 mg twice daily for 4 months or longer with or without prednisone (300 mg once monthly for three doses), patients were divided into those who were more or less likely to respond based on duration of disease. Of 65 patients with alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis that had lasted 10 years or less, or alopecia areata, 77% had some hair regrowth; 58% had more than 50% improvement from baseline, and 20% achieved full regrowth of hair, Dr. Liu and Dr. King reported in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings.

“Given the finding in adults that complete scalp hair loss for more than 10 years is less likely to respond to treatment, there may be merit to pursuing treatment, even if only intermittently, in adolescents or even younger patients with stable, severe alopecia areata, to prevent irreversible hair loss in the future,” they wrote.

A patient with alopecia universalis achieved partial scalp hair regrowth and complete eyebrow regrowth with compounded ruxolitinib, a topical JAK inhibitor, according to a 2016 case report. Dr. Liu and Dr. King reported that clinical trials with topical JAK inhibitors, including topical tofacitinib and topical ruxolitinib, currently are ongoing.

SOURCE: Liu LY et al. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2017.10.003.

said Lucy Yichu Liu, MD, and Brett Andrew King, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Standard medical therapies for alopecia areata – usually topical or injected corticosteroids and allergic contact sensitization – are not very effective for severe disease, particularly alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. The Janus kinase (JAK) pathway recently has been suggested as a target for treatment.

Dr. Liu and Dr. King reviewed several studies, including a retrospective cohort study of 13 patients aged 12-17 years, in which 7 patients had 100% hair loss and 6 had 20%-70% scalp hair loss. The adolescents were treated with the JAK1/3 inhibitor tofacitinib citrate 5 mg twice daily for 2-16 months (median, 5 months). That led to 93% median improvement in Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score (range, 1%-100%) from baseline. Nine patients experienced hair regrowth. There were mild adverse effects, such as upper respiratory infections and headaches.

In a retrospective cohort study of 90 adults taking tofacitinib at a dosage of 5-10 mg twice daily for 4 months or longer with or without prednisone (300 mg once monthly for three doses), patients were divided into those who were more or less likely to respond based on duration of disease. Of 65 patients with alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis that had lasted 10 years or less, or alopecia areata, 77% had some hair regrowth; 58% had more than 50% improvement from baseline, and 20% achieved full regrowth of hair, Dr. Liu and Dr. King reported in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings.

“Given the finding in adults that complete scalp hair loss for more than 10 years is less likely to respond to treatment, there may be merit to pursuing treatment, even if only intermittently, in adolescents or even younger patients with stable, severe alopecia areata, to prevent irreversible hair loss in the future,” they wrote.

A patient with alopecia universalis achieved partial scalp hair regrowth and complete eyebrow regrowth with compounded ruxolitinib, a topical JAK inhibitor, according to a 2016 case report. Dr. Liu and Dr. King reported that clinical trials with topical JAK inhibitors, including topical tofacitinib and topical ruxolitinib, currently are ongoing.

SOURCE: Liu LY et al. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2017.10.003.

said Lucy Yichu Liu, MD, and Brett Andrew King, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Standard medical therapies for alopecia areata – usually topical or injected corticosteroids and allergic contact sensitization – are not very effective for severe disease, particularly alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. The Janus kinase (JAK) pathway recently has been suggested as a target for treatment.

Dr. Liu and Dr. King reviewed several studies, including a retrospective cohort study of 13 patients aged 12-17 years, in which 7 patients had 100% hair loss and 6 had 20%-70% scalp hair loss. The adolescents were treated with the JAK1/3 inhibitor tofacitinib citrate 5 mg twice daily for 2-16 months (median, 5 months). That led to 93% median improvement in Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score (range, 1%-100%) from baseline. Nine patients experienced hair regrowth. There were mild adverse effects, such as upper respiratory infections and headaches.

In a retrospective cohort study of 90 adults taking tofacitinib at a dosage of 5-10 mg twice daily for 4 months or longer with or without prednisone (300 mg once monthly for three doses), patients were divided into those who were more or less likely to respond based on duration of disease. Of 65 patients with alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis that had lasted 10 years or less, or alopecia areata, 77% had some hair regrowth; 58% had more than 50% improvement from baseline, and 20% achieved full regrowth of hair, Dr. Liu and Dr. King reported in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings.

“Given the finding in adults that complete scalp hair loss for more than 10 years is less likely to respond to treatment, there may be merit to pursuing treatment, even if only intermittently, in adolescents or even younger patients with stable, severe alopecia areata, to prevent irreversible hair loss in the future,” they wrote.

A patient with alopecia universalis achieved partial scalp hair regrowth and complete eyebrow regrowth with compounded ruxolitinib, a topical JAK inhibitor, according to a 2016 case report. Dr. Liu and Dr. King reported that clinical trials with topical JAK inhibitors, including topical tofacitinib and topical ruxolitinib, currently are ongoing.

SOURCE: Liu LY et al. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2017.10.003.

FROM JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM PROCEEDINGS

Yellow-Orange Hairless Plaque on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceous

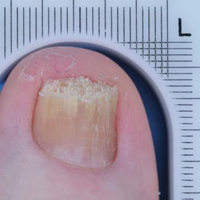

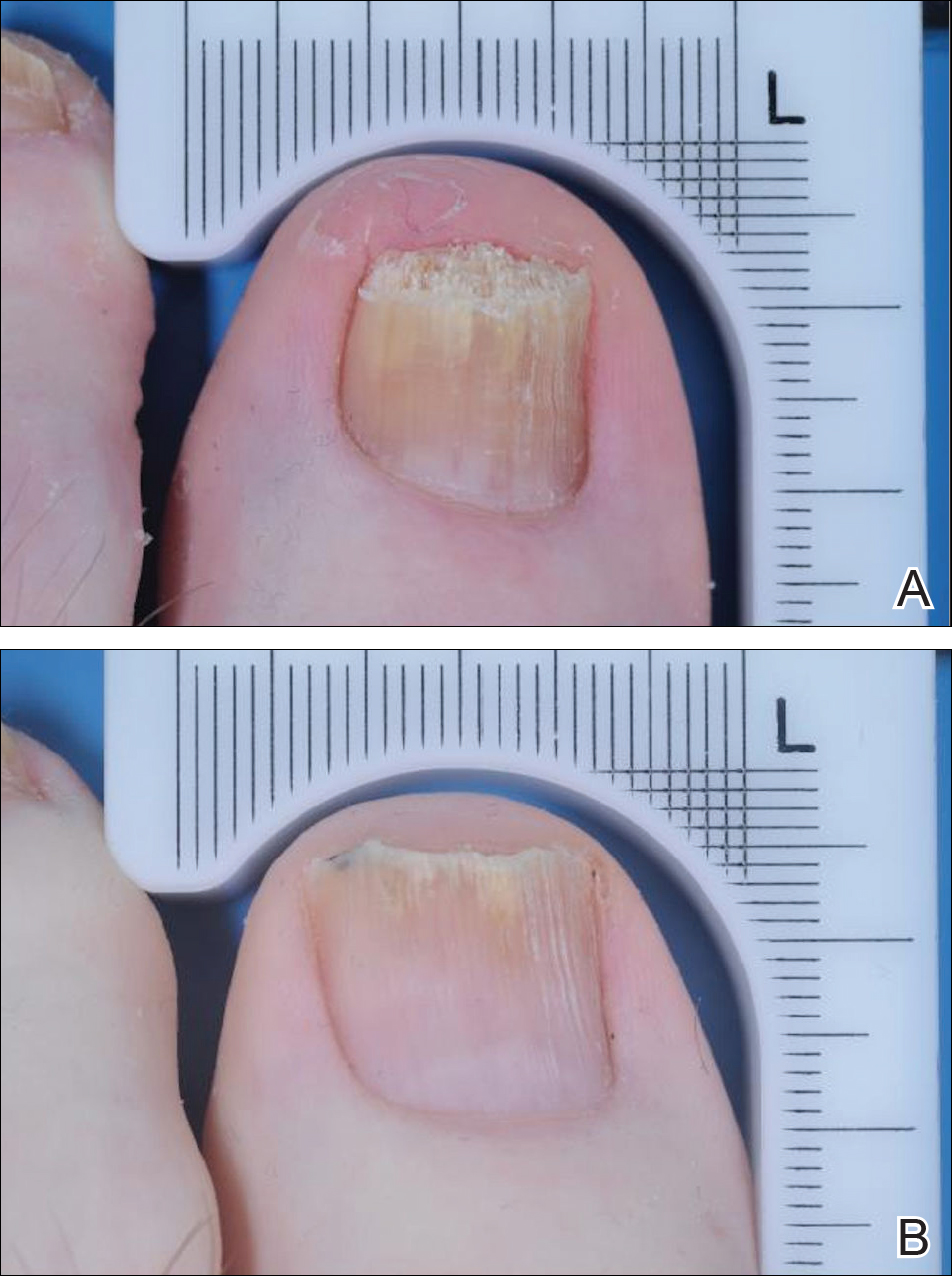

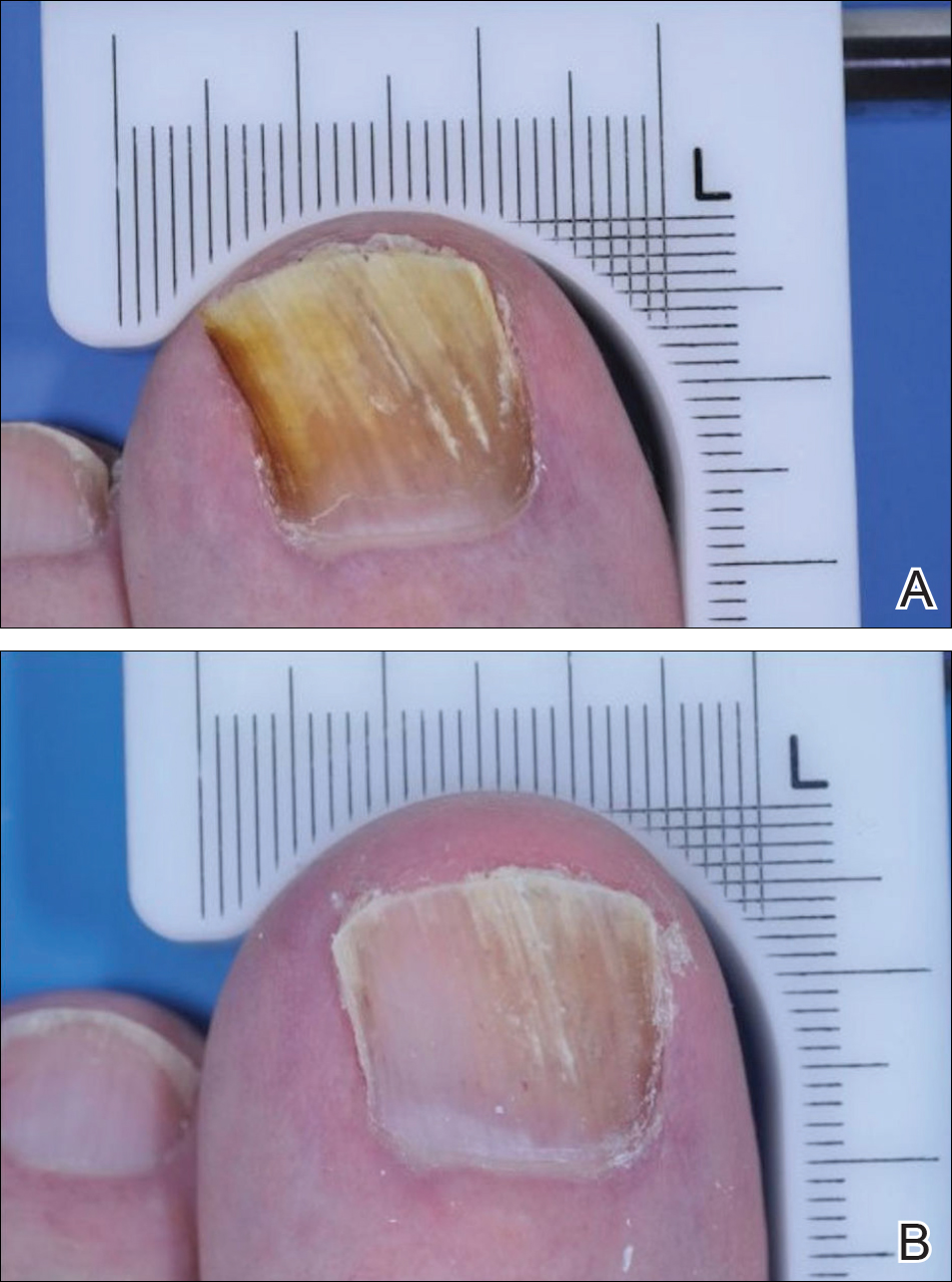

The patient presented with a typical solitary scalp lesion characteristic of nevus sebaceous (NS). The lesion was present at birth as a flat and smooth hairless plaque; however, over time it became more thickened and noticeable, which prompted the parents to seek medical advice.

Nevus sebaceous, also known as NS of Jadassohn, is a benign congenital hamartoma of the sebaceous gland that usually is present at birth and frequently involves the scalp and/or the face. The classic NS lesion is solitary and appears as a well-circumscribed, waxy, yellow-orange or tan, hairless plaque. Despite the presence of these lesions at birth, they may not be noted until early childhood or rarely until adulthood. Generally, the lesion tends to thicken and become more verrucous and velvety over time, particularly around the time of reaching puberty.1 Clinically, NS lesions vary in size from 1 cm to several centimeters. Lesions initially tend to grow proportionately with the child until puberty when they become notably thicker, greasier, and verrucous or nodular under hormonal influences. The yellow discoloration of the lesion is due to sebaceous gland secretion, and the characteristic color usually becomes less evident with age.

Nevus sebaceous occurs in approximately 0.3% of newborns and tends to be sporadic in nature; however, rare familial forms have been reported.2,3 Nevus sebaceous can present as multiple nevi that tend to be extensive and distributed along the Blaschko lines, and they usually are associated with neurologic, ocular, or skeletal defects. Involvement of the central nervous system frequently is associated with large sebaceous nevi located on the face or scalp. This association has been termed NS syndrome.4 Neurologic abnormalities associated with NS syndrome include seizures, mental retardation, and hemimegalencephaly.5 Ocular findings most communally associated with the syndrome are choristomas and colobomas.6-8

There are several benign and malignant epithelial neoplasms that may develop within sebaceous nevi. Benign tumors include trichoblastoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, trichilemmoma, sebaceoma, nodular hidradenoma, and hidrocystoma.1,8,9 Malignant neoplasms include basal cell carcinoma (BCC), apocrine carcinoma, sebaceous carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. The lifetime risk of malignancy in NS is unknown. In an extensive literature review by Moody et al10 of 4923 cases of NS for the development of secondary benign and malignant neoplasms, 16% developed benign tumors while 8% developed malignant tumors such as BCC. However, subsequent studies suggested that the incidence of BCC may have been overestimated due to misinterpretation of trichoblastoma and may be less than 1%.11-13

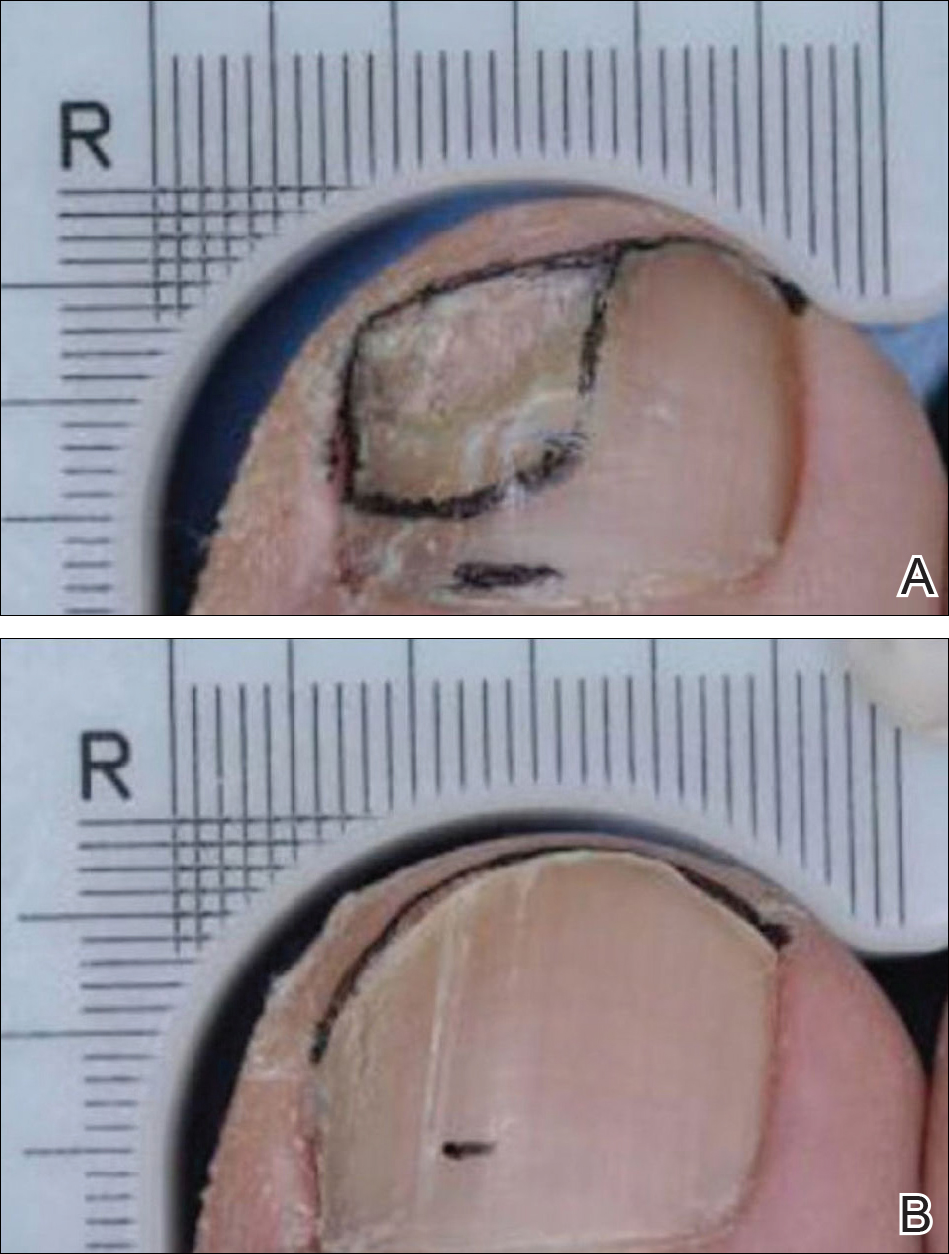

Usually the diagnosis of NS is made clinically and rarely a biopsy for histopathologic confirmation may be needed when the diagnosis is uncertain. Typically, these histopathologic findings include immature hair follicles, hyperplastic immature sebaceous glands, dilated apocrine glands, and epidermal hyperplasia.9 For patients with suspected NS syndrome, additional neurologic and ophthalmologic evaluations should be performed including neuroimaging studies, skeletal radiography, and analysis of liver and renal function.14

The current standard of care in treating NS is full-thickness excision. However, the decision should be individualized based on patient age, extension and location of the lesion, concerns about the cosmetic appearance, and the risk for malignancy.

The 2 main reasons to excise NS include concern about malignancy and undesirable cosmetic appearance. Once a malignant lesion develops within NS, it generally is agreed that the tumor and the entire nevus should be removed; however, recommendations vary for excising NS prophylactically to decrease the risk for malignant growths. Because the risk for malignant transformation seems to be lower than previously thought, observation can be a reasonable choice for lesions that are not associated with cosmetic concern.12,13

Photodynamic therapy, CO2 laser resurfacing, and dermabrasion have been reported as alternative therapeutic approaches. However, there is a growing concern on how effective these treatment modalities are in completely removing the lesion and whether the risk for recurrence and potential for neoplasm development remains.1,9

This patient was healthy with normal development and growth and no signs of neurologic or ocular involvement. The parents were counseled about the risk for malignancy and the long-term cosmetic appearance of the lesion. They opted for surgical excision of the lesion at 18 months of age.

- Eisen DB, Michael DJ. Sebaceous lesions and their associated syndromes: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:549-560; quiz 561-562.

- Happle R, König A. Familial naevus sebaceus may be explained by paradominant transmission. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:377.

- Hughes SM, Wilkerson AE, Winfield HL, et al. Familial nevus sebaceus in dizygotic male twins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S47-S48.

- Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:221-230.

- Davies D, Rogers M. Review of neurological manifestations in 196 patients with sebaceous naevi. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:20-23.

- Trivedi N, Nehete G. Complex limbal choristoma in linear nevus sebaceous syndrome managed with scleral grafting. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64:692-694.

- Nema N, Singh K, Verma A. Complex limbal choristoma in nevus sebaceous syndrome [published online February 14, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:227-229.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Kim J, et al. Epibulbar complex choristoma and hemimegalencephaly in linear sebaceous naevus syndrome [published online July 2, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E686-E689.

- Simi CM, Rajalakshmi T, Correa M. Clinicopathologic analysis of 21 cases of nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:625-627.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH. Nevus sebaceous revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:15-23.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268.

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660.

- Rosen H, Schmidt B, Lam HP, et al. Management of nevus sebaceous and the risk of basal cell carcinoma: an 18-year review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:676-681.

- Brandling-Bennett HA, Morel KD. Epidermal nevi. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1177-1198.

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceous

The patient presented with a typical solitary scalp lesion characteristic of nevus sebaceous (NS). The lesion was present at birth as a flat and smooth hairless plaque; however, over time it became more thickened and noticeable, which prompted the parents to seek medical advice.

Nevus sebaceous, also known as NS of Jadassohn, is a benign congenital hamartoma of the sebaceous gland that usually is present at birth and frequently involves the scalp and/or the face. The classic NS lesion is solitary and appears as a well-circumscribed, waxy, yellow-orange or tan, hairless plaque. Despite the presence of these lesions at birth, they may not be noted until early childhood or rarely until adulthood. Generally, the lesion tends to thicken and become more verrucous and velvety over time, particularly around the time of reaching puberty.1 Clinically, NS lesions vary in size from 1 cm to several centimeters. Lesions initially tend to grow proportionately with the child until puberty when they become notably thicker, greasier, and verrucous or nodular under hormonal influences. The yellow discoloration of the lesion is due to sebaceous gland secretion, and the characteristic color usually becomes less evident with age.

Nevus sebaceous occurs in approximately 0.3% of newborns and tends to be sporadic in nature; however, rare familial forms have been reported.2,3 Nevus sebaceous can present as multiple nevi that tend to be extensive and distributed along the Blaschko lines, and they usually are associated with neurologic, ocular, or skeletal defects. Involvement of the central nervous system frequently is associated with large sebaceous nevi located on the face or scalp. This association has been termed NS syndrome.4 Neurologic abnormalities associated with NS syndrome include seizures, mental retardation, and hemimegalencephaly.5 Ocular findings most communally associated with the syndrome are choristomas and colobomas.6-8

There are several benign and malignant epithelial neoplasms that may develop within sebaceous nevi. Benign tumors include trichoblastoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, trichilemmoma, sebaceoma, nodular hidradenoma, and hidrocystoma.1,8,9 Malignant neoplasms include basal cell carcinoma (BCC), apocrine carcinoma, sebaceous carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. The lifetime risk of malignancy in NS is unknown. In an extensive literature review by Moody et al10 of 4923 cases of NS for the development of secondary benign and malignant neoplasms, 16% developed benign tumors while 8% developed malignant tumors such as BCC. However, subsequent studies suggested that the incidence of BCC may have been overestimated due to misinterpretation of trichoblastoma and may be less than 1%.11-13

Usually the diagnosis of NS is made clinically and rarely a biopsy for histopathologic confirmation may be needed when the diagnosis is uncertain. Typically, these histopathologic findings include immature hair follicles, hyperplastic immature sebaceous glands, dilated apocrine glands, and epidermal hyperplasia.9 For patients with suspected NS syndrome, additional neurologic and ophthalmologic evaluations should be performed including neuroimaging studies, skeletal radiography, and analysis of liver and renal function.14

The current standard of care in treating NS is full-thickness excision. However, the decision should be individualized based on patient age, extension and location of the lesion, concerns about the cosmetic appearance, and the risk for malignancy.

The 2 main reasons to excise NS include concern about malignancy and undesirable cosmetic appearance. Once a malignant lesion develops within NS, it generally is agreed that the tumor and the entire nevus should be removed; however, recommendations vary for excising NS prophylactically to decrease the risk for malignant growths. Because the risk for malignant transformation seems to be lower than previously thought, observation can be a reasonable choice for lesions that are not associated with cosmetic concern.12,13

Photodynamic therapy, CO2 laser resurfacing, and dermabrasion have been reported as alternative therapeutic approaches. However, there is a growing concern on how effective these treatment modalities are in completely removing the lesion and whether the risk for recurrence and potential for neoplasm development remains.1,9

This patient was healthy with normal development and growth and no signs of neurologic or ocular involvement. The parents were counseled about the risk for malignancy and the long-term cosmetic appearance of the lesion. They opted for surgical excision of the lesion at 18 months of age.

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceous

The patient presented with a typical solitary scalp lesion characteristic of nevus sebaceous (NS). The lesion was present at birth as a flat and smooth hairless plaque; however, over time it became more thickened and noticeable, which prompted the parents to seek medical advice.

Nevus sebaceous, also known as NS of Jadassohn, is a benign congenital hamartoma of the sebaceous gland that usually is present at birth and frequently involves the scalp and/or the face. The classic NS lesion is solitary and appears as a well-circumscribed, waxy, yellow-orange or tan, hairless plaque. Despite the presence of these lesions at birth, they may not be noted until early childhood or rarely until adulthood. Generally, the lesion tends to thicken and become more verrucous and velvety over time, particularly around the time of reaching puberty.1 Clinically, NS lesions vary in size from 1 cm to several centimeters. Lesions initially tend to grow proportionately with the child until puberty when they become notably thicker, greasier, and verrucous or nodular under hormonal influences. The yellow discoloration of the lesion is due to sebaceous gland secretion, and the characteristic color usually becomes less evident with age.

Nevus sebaceous occurs in approximately 0.3% of newborns and tends to be sporadic in nature; however, rare familial forms have been reported.2,3 Nevus sebaceous can present as multiple nevi that tend to be extensive and distributed along the Blaschko lines, and they usually are associated with neurologic, ocular, or skeletal defects. Involvement of the central nervous system frequently is associated with large sebaceous nevi located on the face or scalp. This association has been termed NS syndrome.4 Neurologic abnormalities associated with NS syndrome include seizures, mental retardation, and hemimegalencephaly.5 Ocular findings most communally associated with the syndrome are choristomas and colobomas.6-8

There are several benign and malignant epithelial neoplasms that may develop within sebaceous nevi. Benign tumors include trichoblastoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, trichilemmoma, sebaceoma, nodular hidradenoma, and hidrocystoma.1,8,9 Malignant neoplasms include basal cell carcinoma (BCC), apocrine carcinoma, sebaceous carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. The lifetime risk of malignancy in NS is unknown. In an extensive literature review by Moody et al10 of 4923 cases of NS for the development of secondary benign and malignant neoplasms, 16% developed benign tumors while 8% developed malignant tumors such as BCC. However, subsequent studies suggested that the incidence of BCC may have been overestimated due to misinterpretation of trichoblastoma and may be less than 1%.11-13

Usually the diagnosis of NS is made clinically and rarely a biopsy for histopathologic confirmation may be needed when the diagnosis is uncertain. Typically, these histopathologic findings include immature hair follicles, hyperplastic immature sebaceous glands, dilated apocrine glands, and epidermal hyperplasia.9 For patients with suspected NS syndrome, additional neurologic and ophthalmologic evaluations should be performed including neuroimaging studies, skeletal radiography, and analysis of liver and renal function.14

The current standard of care in treating NS is full-thickness excision. However, the decision should be individualized based on patient age, extension and location of the lesion, concerns about the cosmetic appearance, and the risk for malignancy.

The 2 main reasons to excise NS include concern about malignancy and undesirable cosmetic appearance. Once a malignant lesion develops within NS, it generally is agreed that the tumor and the entire nevus should be removed; however, recommendations vary for excising NS prophylactically to decrease the risk for malignant growths. Because the risk for malignant transformation seems to be lower than previously thought, observation can be a reasonable choice for lesions that are not associated with cosmetic concern.12,13

Photodynamic therapy, CO2 laser resurfacing, and dermabrasion have been reported as alternative therapeutic approaches. However, there is a growing concern on how effective these treatment modalities are in completely removing the lesion and whether the risk for recurrence and potential for neoplasm development remains.1,9

This patient was healthy with normal development and growth and no signs of neurologic or ocular involvement. The parents were counseled about the risk for malignancy and the long-term cosmetic appearance of the lesion. They opted for surgical excision of the lesion at 18 months of age.

- Eisen DB, Michael DJ. Sebaceous lesions and their associated syndromes: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:549-560; quiz 561-562.

- Happle R, König A. Familial naevus sebaceus may be explained by paradominant transmission. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:377.

- Hughes SM, Wilkerson AE, Winfield HL, et al. Familial nevus sebaceus in dizygotic male twins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S47-S48.

- Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:221-230.

- Davies D, Rogers M. Review of neurological manifestations in 196 patients with sebaceous naevi. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:20-23.

- Trivedi N, Nehete G. Complex limbal choristoma in linear nevus sebaceous syndrome managed with scleral grafting. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64:692-694.

- Nema N, Singh K, Verma A. Complex limbal choristoma in nevus sebaceous syndrome [published online February 14, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:227-229.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Kim J, et al. Epibulbar complex choristoma and hemimegalencephaly in linear sebaceous naevus syndrome [published online July 2, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E686-E689.

- Simi CM, Rajalakshmi T, Correa M. Clinicopathologic analysis of 21 cases of nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:625-627.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH. Nevus sebaceous revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:15-23.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268.

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660.

- Rosen H, Schmidt B, Lam HP, et al. Management of nevus sebaceous and the risk of basal cell carcinoma: an 18-year review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:676-681.

- Brandling-Bennett HA, Morel KD. Epidermal nevi. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1177-1198.

- Eisen DB, Michael DJ. Sebaceous lesions and their associated syndromes: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:549-560; quiz 561-562.

- Happle R, König A. Familial naevus sebaceus may be explained by paradominant transmission. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:377.

- Hughes SM, Wilkerson AE, Winfield HL, et al. Familial nevus sebaceus in dizygotic male twins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S47-S48.

- Sugarman JL. Epidermal nevus syndromes. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:221-230.

- Davies D, Rogers M. Review of neurological manifestations in 196 patients with sebaceous naevi. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:20-23.

- Trivedi N, Nehete G. Complex limbal choristoma in linear nevus sebaceous syndrome managed with scleral grafting. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64:692-694.

- Nema N, Singh K, Verma A. Complex limbal choristoma in nevus sebaceous syndrome [published online February 14, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:227-229.

- Park JM, Kim DS, Kim J, et al. Epibulbar complex choristoma and hemimegalencephaly in linear sebaceous naevus syndrome [published online July 2, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E686-E689.

- Simi CM, Rajalakshmi T, Correa M. Clinicopathologic analysis of 21 cases of nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:625-627.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH. Nevus sebaceous revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:15-23.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268.

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660.

- Rosen H, Schmidt B, Lam HP, et al. Management of nevus sebaceous and the risk of basal cell carcinoma: an 18-year review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:676-681.

- Brandling-Bennett HA, Morel KD. Epidermal nevi. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1177-1198.

An otherwise healthy 13-month-old boy presented with a well-circumscribed, 3×4-cm, yellow-orange plaque with a verrucous velvety surface on the right side of the posterior scalp. The patient was born at 33 weeks' gestation and had an uneventful perinatal course with a normal head ultrasound at 4 days of age. The lesion had been present since birth and initially was comprised of waxy, yellow-orange, hairless plaques that became more thickened and noticeable over time. The mother recalled that the surface of the plaque initially was flat and smooth but gradually became bumpier and greasier in consistency in the months prior to presentation. The patient was otherwise asymptomatic.

Alopecia tied to nearly fivefold increase in fibroids in African American women

based on data from more than 400,000 women.

In a study published in JAMA Dermatology, researchers reviewed data from 487,104 black women seen at a single center between Aug. 1, 2013, and Aug. 1, 2017. Overall, 14% of women with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) also had a history of uterine fibroids, compared with 3% percent of black women without CCCA.

“Alopecia is more than just a cosmetic problem. … It could signal an increased risk of developing other conditions,” corresponding author Crystal Aguh, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore said in an interview. “To our knowledge, this is the first time that an association has been noted between these two conditions. We believe that the fact that both are related to excess scarring and fibrous tissue deposition may reflect similarities in how both [conditions] develop, but this is still unknown.”

Overall, 62 of 447 women who met criteria for CCCA also had fibroids, representing a nearly fivefold increase in fibroid risk for women with CCCA.

“I was definitely surprised by the findings,” said Dr. Aguh. “I thought it would be interesting to look at any possible correlation between the two diseases, but did not expect to see such a large difference between black women with and without this form of hair loss,” she noted.

As fibroids are often asymptomatic, “physicians should screen their patients with CCCA for symptoms of fibroids such as painful menstrual cycles, heavy bleeding, unexplained anemia, or difficulty conceiving,” said Dr. Aguh. “In those patients who may not know they have fibroids, early recognition that allows for treatment will be especially beneficial.”

The findings were limited by the retrospective nature of the study. “I believe that larger studies are warranted to help us fully understand how these two conditions are connected,” Dr. Aguh said.

Lead author Yemisi Dina of Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tenn., is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The other researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dina Y et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5163

based on data from more than 400,000 women.

In a study published in JAMA Dermatology, researchers reviewed data from 487,104 black women seen at a single center between Aug. 1, 2013, and Aug. 1, 2017. Overall, 14% of women with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) also had a history of uterine fibroids, compared with 3% percent of black women without CCCA.

“Alopecia is more than just a cosmetic problem. … It could signal an increased risk of developing other conditions,” corresponding author Crystal Aguh, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore said in an interview. “To our knowledge, this is the first time that an association has been noted between these two conditions. We believe that the fact that both are related to excess scarring and fibrous tissue deposition may reflect similarities in how both [conditions] develop, but this is still unknown.”

Overall, 62 of 447 women who met criteria for CCCA also had fibroids, representing a nearly fivefold increase in fibroid risk for women with CCCA.

“I was definitely surprised by the findings,” said Dr. Aguh. “I thought it would be interesting to look at any possible correlation between the two diseases, but did not expect to see such a large difference between black women with and without this form of hair loss,” she noted.

As fibroids are often asymptomatic, “physicians should screen their patients with CCCA for symptoms of fibroids such as painful menstrual cycles, heavy bleeding, unexplained anemia, or difficulty conceiving,” said Dr. Aguh. “In those patients who may not know they have fibroids, early recognition that allows for treatment will be especially beneficial.”

The findings were limited by the retrospective nature of the study. “I believe that larger studies are warranted to help us fully understand how these two conditions are connected,” Dr. Aguh said.

Lead author Yemisi Dina of Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tenn., is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The other researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dina Y et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5163

based on data from more than 400,000 women.

In a study published in JAMA Dermatology, researchers reviewed data from 487,104 black women seen at a single center between Aug. 1, 2013, and Aug. 1, 2017. Overall, 14% of women with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) also had a history of uterine fibroids, compared with 3% percent of black women without CCCA.

“Alopecia is more than just a cosmetic problem. … It could signal an increased risk of developing other conditions,” corresponding author Crystal Aguh, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore said in an interview. “To our knowledge, this is the first time that an association has been noted between these two conditions. We believe that the fact that both are related to excess scarring and fibrous tissue deposition may reflect similarities in how both [conditions] develop, but this is still unknown.”

Overall, 62 of 447 women who met criteria for CCCA also had fibroids, representing a nearly fivefold increase in fibroid risk for women with CCCA.

“I was definitely surprised by the findings,” said Dr. Aguh. “I thought it would be interesting to look at any possible correlation between the two diseases, but did not expect to see such a large difference between black women with and without this form of hair loss,” she noted.

As fibroids are often asymptomatic, “physicians should screen their patients with CCCA for symptoms of fibroids such as painful menstrual cycles, heavy bleeding, unexplained anemia, or difficulty conceiving,” said Dr. Aguh. “In those patients who may not know they have fibroids, early recognition that allows for treatment will be especially beneficial.”

The findings were limited by the retrospective nature of the study. “I believe that larger studies are warranted to help us fully understand how these two conditions are connected,” Dr. Aguh said.

Lead author Yemisi Dina of Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tenn., is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The other researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dina Y et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5163

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Dermatologists should screen patients with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia for potential fibroids.

Major finding: Women with CCCA were nearly five times more likely to have fibroids, compared with controls.

Data source: The data come from a review of 487,104 black women seen at a single center between Aug. 1, 2013, and Aug. 1, 2017.

Disclosures: Lead author Yemisi Dina of Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tenn., is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The other researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Dina Y et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5163.

No Sulfates, No Parabens, and the “No-Poo” Method: A New Patient Perspective on Common Shampoo Ingredients

Shampoo is a staple in hair grooming that is ever-evolving along with cultural trends. The global shampoo market is expected to reach an estimated value of $25.73 billion by 2019. A major driver of this upward trend in market growth is the increasing demand for natural and organic hair shampoos.1 Society today has a growing fixation on healthy living practices, and as of late, the ingredients in shampoos and other cosmetic products have become one of the latest targets in the health-consciousness craze. In the age of the Internet where information—and misinformation—is widely accessible and dispersed, the general public often strives to self-educate on specialized matters that are out of their expertise. As a result, individuals have developed an aversion to using certain shampoos out of fear that the ingredients, often referred to as “chemicals” by patients due to their complex names, are unnatural and therefore unhealthy.1,2 Product developers are working to meet the demand by reformulating shampoos with labels that indicate sulfate free or paraben free, despite the lack of proof that these formulations are an improvement over traditional approaches to hair health. Additionally, alternative methods of cleansing the hair and scalp, also known as the no-shampoo or “no-poo” method, have begun to gain popularity.2,3

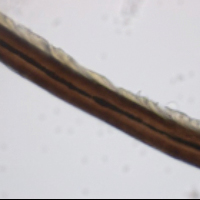

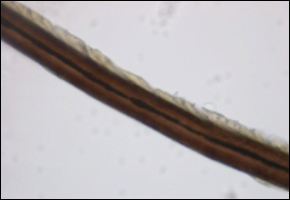

It is essential that dermatologists acknowledge the concerns that their patients have about common shampoo ingredients to dispel the myths that may misinform patient decision-making. This article reviews the controversy surrounding the use of sulfates and parabens in shampoos as well as commonly used shampoo alternatives. Due to the increased prevalence of dry hair shafts in the skin of color population, especially black women, this group is particularly interested in products that will minimize breakage and dryness of the hair. To that end, this population has great interest in the removal of chemical ingredients that may cause damage to the hair shafts, despite the lack of data to support sulfates and paraben damage to hair shafts or scalp skin. Blogs and uninformed hairstylists may propagate these beliefs in a group of consumers who are desperate for new approaches to hair fragility and breakage.

Surfactants and Sulfates

The cleansing ability of a shampoo depends on the surface activity of its detergents. Surface-active ingredients, or surfactants, reduce the surface tension between water and dirt, thus facilitating the removal of environmental dirt from the hair and scalp,4 which is achieved by a molecular structure containing both a hydrophilic and a lipophilic group. Sebum and dirt are bound by the lipophilic ends of the surfactant, becoming the center of a micelle structure with the hydrophilic molecule ends pointing outward. Dirt particles become water soluble and are removed from the scalp and hair shaft upon rinsing with water.4

Surfactants are classified according to the electric charge of the hydrophilic polar group as either anionic, cationic, amphoteric (zwitterionic), or nonionic.5 Each possesses different hair conditioning and cleansing qualities, and multiple surfactants are used in shampoos in differing ratios to accommodate different hair types. In most shampoos, the base consists of anionic and amphoteric surfactants. Depending on individual product requirements, nonionic and cationic surfactants are used to either modify the effects of the surfactants or as conditioning agents.4,5

One subcategory of surfactants that receives much attention is the group of anionic surfactants known as sulfates. Sulfates, particularly sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), recently have developed a negative reputation as cosmetic ingredients, as reports from various unscientific sources have labeled them as hazardous to one’s health; SLS has been described as a skin and scalp irritant, has been linked to cataract formation, and has even been wrongly labeled as carcinogenic.6 The origins of some of these claims are not clear, though they likely arose from the misinterpretation of complex scientific studies that are easily accessible to laypeople. The link between SLS and ocular irritation or cataract formation is a good illustration of this unsubstantiated fear. A study by Green et al7 showed that corneal exposure to extremely high concentrations of SLS following physical or chemical damage to the eye can result in a slowed healing process. The results of this study have since been wrongly quoted to state that SLS-containing products lead to blindness or severe corneal damage.8 A different study tested for possible ocular irritation in vivo by submerging the lens of an eye into a 20% SLS solution, which accurately approximates the concentration of SLS in rinse-off consumer products.9 However, to achieve ocular irritation, the eyes of laboratory animals were exposed to SLS constantly for 14 days, which would not occur in practical use.9 Similarly, a third study achieved cataract formation in a laboratory only by immersing the lens of an eye into a highly concentrated solution of SLS.10 Such studies are not appropriate representations of how SLS-containing products are used by consumers and have unfortunately been vulnerable to misinterpretation by the general public.

There is no known study that has shown SLS to be carcinogenic. One possible origin of this idea may be from the wrongful interpretation of studies that used SLS as a vehicle substance to test agents that were deemed to be carcinogenic.11 Another possible source of the idea that SLS is carcinogenic comes from its association with 1,4-dioxane, a by-product of the synthesis of certain sulfates such as sodium laureth sulfate due to a process known as ethoxylation.6,12 Although SLS does not undergo this process in its formation and is not linked to 1,4-dioxane, there is potential for cross-contamination of SLS with 1,4-dioxane, which cannot be overlooked. 1,4-Dioxane is classified as “possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B)” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer,13 but screening of SLS for this substance prior to its use in commercial products is standard.

Sulfates are inexpensive detergents that are responsible for lather formation in shampoos as well as in many household cleaning agents.5 Sulfates, similar to all anionic surfactants, are characterized by a negatively charged hydrophilic polar group. The best-known and most commonly used anionic surfactants are sulfated fatty alcohols, alkyl sulfates, and their polyethoxylated analogues alkyl ether sulfates.5,6 Sodium lauryl sulfate (also known as sodium laurilsulfate or sodium dodecyl sulfate) is the most common of them all, found in shampoo and conditioner formulations. Ammonium lauryl sulfate and sodium laureth sulfate are other sulfates commonly used in shampoos and household cleansing products. Sodium lauryl sulfate is a nonvolatile, water-soluble compound. Its partition coefficient (P0), a measure of a substance’s hydrophilic or lipophilic nature, is low at 1.6, making it a rather hydrophilic substance.6 Hydrophilic substances tend to have low bioaccumulation profiles in the body. Additionally, SLS is readily biodegradable. It can be derived from both synthetic and naturally occurring sources; for example, palm kernel oil, petrolatum, and coconut oil are all sources of lauric acid, the starting ingredient used to synthesize SLS. Sodium lauryl sulfate is created by reacting lauryl alcohol with sulfur trioxide gas, followed by neutralization with sodium carbonate (also a naturally occurring compound).6 Sodium lauryl sulfate and other sulfate-containing shampoos widely replaced the usage of traditional soaps formulated from animal or vegetable fats, as these latter formations created a film of insoluble calcium salts on the hair strands upon contact with water, resulting in tangled, dull-appearing hair.5 Additionally, sulfates were preferred to the alkaline pH of traditional soap, which can be harsh on hair strands and cause irritation of the skin and mucous membranes.14 Because they are highly water soluble, sulfates enable the formulation of clear shampoos. They exhibit remarkable cleaning properties and lather formation.5,14

Because sulfates are potent surfactants, they can remove dirt and debris as well as naturally produced healthy oils from the hair and scalp. As a result, sulfates can leave the hair feeling dry and stripped of moisture.4,5 Sulfates are used as the primary detergents in the formulation of deep-cleaning shampoos, which are designed for people who accumulate a heavy buildup of dirt, sebum, and debris from frequent use of styling products. Due to their potent detergency, these shampoos typically are not used on a daily basis but rather at longer intervals.15 A downside to sulfates is that they can have cosmetically unpleasant properties, which can be compensated for by including appropriate softening additives in shampoo formulations.4 A number of anionic surfactants such as olefin sulfonate, alkyl sulfosuccinate, acyl peptides, and alkyl ether carboxylates are well tolerated by the skin and are used together with other anionic and amphoteric surfactants to optimize shampoo properties. Alternatively, sulfate-free shampoos are cleansers compounded by the removal of the anionic group and switched for surfactants with less detergency.4,5

Preservatives and Parabens

Parabens refer to a group of esters of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid commonly used as preservatives in foods, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics whose widespread use dates back to 1923.16 Concerns over the presence of parabens in shampoos and other cosmetics have been raised by patients for their reputed estrogenic and antiandrogenic effects and suspected involvement in carcinogenesis via endocrine modulation.16,17 In in vitro studies done on yeast assays, parabens have shown weak estrogenic activity that increases in proportion to both the length and increased branching of the alkyl side chains in the paraben’s molecular structure.18 They are 10,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol. In in vivo animal studies, parabens show weak estrogenic activity and are 100,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol.18 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, a common metabolite, showed no estrogenic activity when tested both in vitro and in vivo.19 Some concerning research has implicated a link between parabens used in underarm cosmetics, such as deodorants and antiperspirants, and breast cancer16; however, the studies have been conflicting, and there is simply not enough data to assert that parabens cause breast cancer.

The Cosmetic Ingredient Review expert panel first reviewed parabens in 1984 and concluded that “methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben are safe as cosmetic ingredients in the present practices of use.”20 They extended this statement to include isopropylparaben and isobutylparaben in a later review.21 In 2005, the Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (now known as the Scientific Committee for Consumer Safety) in Europe stated that methylparaben and ethylparaben can be used at levels up to 0.4% in products.22 This decision was reached due to reports of decreased sperm counts and testosterone levels in male juvenile rats exposed to these parabens; however, these reults were not successfully replicated in larger studies.16,22 In 2010, the Scientific Committee for Consumer Safety revisited its stance on parabens, and they then revised their recommendations to say that concentrations of propylparaben and butylparaben should not exceed concentrations of 0.19%, based on “the conservative choice for the calculation of the [Margin-of-Safety] of butyl- and propylparaben.”23 However, in 2011 the use of propylparaben and butylparaben was banned in Denmark for cosmetic products used in children 3 years or younger,16 and the European Commission subsequently amended their directive in 2014, banning isopropylparaben, isobutylparaben, phenylparaben, benzylparaben, and pentylparaben due to lack of data available to evaluate the human risk of these products.24

Contrary to the trends in Europe, there currently are no regulations against the use of parabens in shampoos or other cosmetics in the United States. The American Cancer Society found that there is no evidence to suggest that the current levels of parabens in cosmetic products (eg, antiperspirants) increase one’s risk of breast cancer.25 Parabens are readily absorbed into the body both transdermally and through ingestion but also are believed to be rapidly transformed into harmless and nonspecific metabolites; they are readily metabolized by the liver and excreted in urine, and there is no measured accumulation in tissues.17

Parabens continue to be the most widely used preservatives in personal care products, usually in conjunction with other preservatives. Parabens are good biocides; short-chain esters (eg, methylparabens, ethylparabens) are effective against gram-positive bacteria and are weakly effective against gram-negative bacteria. Long-chain paraben esters (eg, propylparabens, butylparabens) are effective against mold and yeast. The addition of other preservatives creates a broad spectrum of antimicrobial defense in consumer products. Other preservatives include formaldehyde releasers or phenoxyethanol, as well as chelating agents such as EDTA, which improve the stability of these cosmetic products when exposed to air.16 Parabens are naturally occurring substances found in foods such as blueberries, barley, strawberries, yeast, olives, and grapes. As a colorless, odorless, and inexpensive substance, their use has been heavily favored in cosmetic and food products.16

Shampoo Alternatives and the No-Poo Method

Although research has not demonstrated any long-term danger to using shampoo, certain chemicals found in shampoos have the potential to irritate the scalp. Commonly cited allergens in shampoos include cocamidopropyl betaine, propylene glycol, vitamin E (tocopherol), parabens, and benzophenones.5 Additionally, the rising use of formaldehyde-releasing preservatives and isothiazolinones due to mounting pressures to move away from parabens has led to an increase in cases of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).16 However, the irritability (rather than allergenicity) of these substances often is established during patch testing, a method of detecting delayed-type allergic reactions, which is important to note because patch testing requires a substance to be exposed to the skin for 24 to 48 hours, whereas exposure to shampoo ingredients may last a matter of minutes at most and occur in lesser concentrations because the ingredients are diluted by water in the rinsing process. Given these differences, it is unlikely that a patient would develop a true allergic response from regular shampoo use. Nevertheless, in patients who are already sensitized, exposure could conceivably trigger ACD, and patients must be cognizant of the composition of their shampoos.16

The no-poo method refers to the avoidance of commercial shampoo products when cleansing the hair and scalp and encompasses different methods of cleansing the hair, such as the use of household items (eg, baking soda, apple cider vinegar [ACV]), the use of conditioners to wash the hair (also known as conditioner-only washing or co-washing), treating the scalp with tea tree oil, or simply rinsing the hair with water. Proponents of the no-poo method believe that abstaining from shampoo use leads to healthier hair, retained natural oils, and less exposure to supposedly dangerous chemicals such as parabens or sulfates.2,3,26-28 However, there are no known studies in the literature that assess or support the hypotheses of the no-poo method.

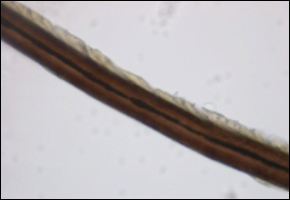

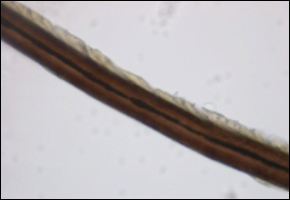

Baking Soda and ACV

Baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) is a substance commonly found in the average household. It has been used in toothpaste formulas and cosmetic products and is known for its acid-neutralizing properties. Baking soda has been shown to have some antifungal and viricidal properties through an unknown mechanism of action.28 It has gained popularity for its use as a means of reducing the appearance of excessive greasiness of the hair shafts. Users also have reported that when washing their hair with baking soda, they are able to achieve a clean scalp and hair that feels soft to the touch.2,3,26,27,29 Despite these reports, users must beware of using baking soda without adequately diluting it with water. Baking soda is a known alkaline irritant.26,30 With a pH of 9, baking soda causes the cuticle layer of the hair fiber to open, increasing the capacity for water absorption. Water penetrates the scales that open, breaking the hydrogen bonds of the keratin molecule.31 Keratin is a spiral helical molecule that keeps its shape due to hydrogen, disulfide, and ionic bonds, as well as Van der Waals force.30 Hydrolysis of these bonds due to exposure to baking soda lowers the elasticity of the hair and increases the negative electrical net charge of the hair fiber surface, which leads to increased friction between fibers, cuticle damage, hair fragility, and fiber breakage.32,33

Apple cider vinegar is an apple-derived acetic acid solution with a pH ranging from 3.1 to 5.28 The pH range of ACV is considered to be ideal for hair by no-poo proponents, as it is similar to the natural pH of the scalp. Its acidic properties are responsible for its antimicrobial abilities, particularly its effectiveness against gram-negative bacteria.30 The acetic acid of ACV can partially interrupt oil interfaces, which contributes to its mild ability to remove product residue and scalp buildup from the hair shaft; the acetic acid also tightens the cuticles on hair fibers.33 Apple cider vinegar is used as a means of cleansing the hair and scalp by no-poo proponents2,3,26; other uses for ACV include using it as a rinse following washing and/or conditioning of the hair or as a means of preserving color in color-treated hair. There also is evidence that ACV may have antifungal properties.28 However, consumers must be aware that if it is not diluted in water, ACV may be too caustic for direct application to the hair and may lead to damage; it can be irritating to eyes, mucus membranes, and acutely inflamed skin. Also, vinegar rinses used on processed or chemically damaged hair may lead to increased hair fragility.2,3

Hair fibers have a pH of 3.67, while the scalp has a pH between 4.5 and 6.2. This slightly acidic film acts as a barrier to viruses, bacteria, and other potential contaminants.33 Studies have shown that the pH of skin increases in proportion to the pH of the cleanser used.34 Therefore, due to the naturally acidic pH of the scalp, acid-balanced shampoos generally are recommended. Shampoos should not have a pH higher than 5.5, as hair shafts can swell due to alkalinization, which can be prevented by pH balancing the shampoo through the addition of an acidic substance (eg, glycolic acid, citric acid) to lower the pH down to approximately 5.5. Apple cider vinegar often is used for this purpose. However, one study revealed that 82% of shampoos already have an acidic pH.34

Conditioner-Only Washing (Co-washing)

Conditioner-only washing, or co-washing, is a widely practiced method of hair grooming. It is popular among individuals who find that commercial shampoos strip too much of the natural hair oils away, leaving the hair rough or unmanageable. Co-washing is not harmful to the hair; however, the molecular structure and function of a conditioner and that of a shampoo are very different.5,35,36 Conditioners are not formulated to remove dirt and buildup in the hair but rather to add substances to the hair, and thus cannot provide extensive cleansing of the hair and scalp; therefore, it is inappropriate to use co-washing as a replacement for shampooing. Quaternary conditioning agents are an exception because they contain amphoteric detergents comprised of both anionic and cationic groups, which allow them both the ability to remove dirt and sebum with its anionic group, typically found in shampoos, as well as the ability to coat and condition the hair due to the high affinity of the cationic group for the negatively charged hair fibers.36,37 Amphoteric detergents are commonly found in 2-in-1 conditioning cleansers, among other ingredients, such as hydrolyzed animal proteins that temporarily plug surface defects on the hair fiber, and dimethicone, a synthetic oil that creates a thin film over the hair shaft, increasing shine and manageability. Of note, these conditioning shampoos are ideal for individuals with minimal product buildup on the hair and scalp and are not adequate scalp cleansers for individuals who either wash their hair infrequently or who regularly use hairstyling products.36,37

Tea Tree Oil

Tea tree oil is an essential oil extracted from the Melaleuca alternifolia plant of the Myrtaceae family. It is native to the coast of northeastern Australia. A holy grail of natural cosmetics, tea tree oil is widely known for its antiviral, antifungal, and antiseptic properties.38 Although not used as a stand-alone cleanser, it is often added to a number of cosmetic products, including shampoos and co-washes. Although deemed safe for topical use, it has been shown to be quite toxic when ingested. Symptoms of ingestion include nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, and coma. The common concern with tea tree oil is its ability to cause ACD. In particular, it is believed that the oxidation products of tea tree oil are allergenic rather than the tea tree oil itself. The evaluation of tea tree oil as a potential contact allergen has been quite difficult; it consists of more than 100 distinct compounds and is often mislabeled, or does not meet the guidelines of the International Organization for Standardization. Nonetheless, the prevalence of ACD due to tea tree oil is low (approximately 1.4%). Despite its low prevalence, tea tree oil should remain in the differential as an ACD-inducing agent. Patch testing with the patient’s supply of tea tree oil is advised when possible.38

Conclusion

It is customary that the ingredients used in shampoos undergo periodic testing and monitoring to assure the safety of their use. Although it is encouraging that patients are proactive in their efforts to stay abreast of the literature, it is still important that cosmetic scientists, dermatologists, and other experts remain at the forefront of educating the public about these substances. Not doing so can result in the propagation of misinformation and unnecessary fears, which can lead to the adaptation of unhygienic or even unsafe hair care practices. As dermatologists, we must ensure that patients are educated about the benefits and hazards of off-label use of household ingredients to the extent that evidence-based medicine permits. Patients must be informed that not all synthetic substances are harmful, and likewise not all naturally occurring substances are safe.

- The global shampoo market 2014-2019 trends, forecast, and opportunity analysis [press release]. New York, NY: Reportlinker; May 21, 2015.

- Is the ‘no shampoo’ trend healthy or harmful? Mercola website. Published January 16, 2016. Accessed December 8, 2017.

- Feltman R. The science (or lack thereof) behind the ‘no-poo’ hair trend. Washington Post. March 10, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2016/03/10/the-science-or-lack-thereof-behind-the-no-poo-hair-trend/?utm_term=.9a61edf3fd5a. Accessed December 11, 2017.

- Bouillon C. Shampoos. Clin Dermatol. 1996;14:113-121.

- Trueb RM. Shampoos: ingredients, efficacy, and adverse effects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:356-365.

- Bondi CA, Marks JL, Wroblewski LB, et al. Human and environmental toxicity of sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS): evidence for safe use in household cleaning products. Environ Health Insights. 2015;9:27-32.

- Green K, Johnson RE, Chapman JM, et al. Preservative effects on the healing rate of rabbit corneal epithelium. Lens Eye Toxic Res. 1989;6:37-41.

- Sodium lauryl sulphate. Healthy Choices website. http://www.healthychoices.co.uk/sls.html. Accessed December 8, 2017.

- Tekbas¸ ÖF, Uysal Y, Og˘ur R, et al. Non-irritant baby shampoos may cause cataract development. TSK Koruyucu Hekimlik Bülteni. 2008;1:1-6.

- Cater KC, Harbell JW. Prediction of eye irritation potential of surfactant-based rinse-off personal care formulations by the bovine corneal opacity and permeability (BCOP) assay. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2006;25:217-233.

- Birt DF, Lawson TA, Julius AD, et al. Inhibition by dietary selenium of colon cancer induced in the rat by bis(2-oxopropyl) nitrosamine. Cancer Res. 1982;42:4455-4459.

- Rastogi SC. Headspace analysis of 1,4-dioxane in products containing polyethoxylated surfactants by GC-MS. Chromatographia. 1990;29:441-445.

- 1,4-Dioxane. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1999;71, pt 2:589-602.

- Trueb RM. Dermocosmetic aspects of hair and scalp. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:289-292.

- D’Souza P, Rathi SK. Shampoo and conditioners: what a dermatologist should know? Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:248-254.

- Sasseville D, Alfalah M, Lacroix JP. “Parabenoia” debunked, or “who’s afraid of parabens?” Dermatitis. 2015;26:254-259.

- Krowka JF, Loretz L, Geis PA, et al. Preserving the facts on parabens: an overview of these important tools of the trade. Cosmetics & Toiletries. http://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/research/chemistry/Preserving-the-Facts-on-Parabens-An-Overview-of-These-Important-Tools-of-the Trade-425784294.html. Published June 1, 2017. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, et al. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12Y19.

- Hossaini A, Larsen JJ, Larsen JC. Lack of oestrogenic effects of food preservatives (parabens) in uterotrophic assays. Food Chem Toxicol. 2000;38:319-323.

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review. Final report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben and butylparaben. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1984;3:147-209.

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review. Final report on the safety assessment of isobutylparaben and isopropylparaben. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1995;14:364-372.

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Products. Extended Opinion on the Safety Evaluation of Parabens. European Commission website. https://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_risk/committees/04_sccp/docs/sccp_o_019.pdf. Published January 28, 2005. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Products. Opinion on Parabens. European Commission website. http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/docs/sccs_o_041.pdf. Revised March 22, 2011. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) No 258/2014 of 9 April 2014 amending Annexes II and V to Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on cosmetic products. EUR-Lex website. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2014.107.01.0005.01.ENG. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- American Cancer Society. Antiperspirants and breast cancer risk. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/antiperspirants-and-breast-cancer-risk.html#references. Revised October 14, 2014. Accessed January 2, 2018.

- MacMillan A. Cutting back on shampoo? 15 things you should know. Health. February 25, 2014. http://www.health.com/health/gallery/0,,20788089,00.html#should-you-go-no-poo--1. Accessed December 10, 2017.

- The ‘no poo’ method. https://www.nopoomethod.com/. Accessed December 10, 2017.

- Fong, D, Gaulin C, Le M, et al. Effectiveness of alternative antimicrobial agents for disinfection of hard surfaces. National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health website. http://www.ncceh.ca/sites/default/files/Alternative_Antimicrobial_Agents_Aug_2014.pdf. Published August 2014. Accessed December 10, 2017.

- Is baking soda too harsh for natural hair? Black Girl With Long Hair website. http://blackgirllonghair.com/2012/02/is-baking-soda-too-harsh-for-hair/2/. Published February 5, 2012. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- O’Lenick T. Anionic/cationic complexes in hair care. J Cosmet Sci. 2011;62:209-228.

- Gavazzoni Dias MF, de Almeida AM, Cecato PM, et al. The shampoo pH can affect the hair: myth or reality? Int J Trichology. 2014;6:95-99.

- Goodman H. The acid mantle of the skin surface. Ind Med Surg. 1958;27:105-108.

- Korting HC, Kober M, Mueller M, et al. Influence of repeated washings with soap and synthetic detergents on pH and resident flora of the skin of forehead and forearm. results of a cross-over trial in health probationers. Acta Derm Venereol. 1987;67:41-47.

- Tarun J, Susan J, Suria J, et al. Evaluation of pH of bathing soaps and shampoos for skin and hair care. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:442-444.

- Corbett JF. The chemistry of hair-care products. J Soc Dyers Colour. 1976;92:285-303.

- McMichael AJ, Hordinsky M. Hair Diseases: Medical, Surgical, and Cosmetic Treatments. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2008:59-72.

- Allardice A, Gummo G. Hair conditioning: quaternary ammonium compounds on various hair types. Cosmet Toiletries. 1993;108:107-109.

- Larson D, Jacob SE. Tea tree oil. Dermatitis. 2012;23:48-49.

Shampoo is a staple in hair grooming that is ever-evolving along with cultural trends. The global shampoo market is expected to reach an estimated value of $25.73 billion by 2019. A major driver of this upward trend in market growth is the increasing demand for natural and organic hair shampoos.1 Society today has a growing fixation on healthy living practices, and as of late, the ingredients in shampoos and other cosmetic products have become one of the latest targets in the health-consciousness craze. In the age of the Internet where information—and misinformation—is widely accessible and dispersed, the general public often strives to self-educate on specialized matters that are out of their expertise. As a result, individuals have developed an aversion to using certain shampoos out of fear that the ingredients, often referred to as “chemicals” by patients due to their complex names, are unnatural and therefore unhealthy.1,2 Product developers are working to meet the demand by reformulating shampoos with labels that indicate sulfate free or paraben free, despite the lack of proof that these formulations are an improvement over traditional approaches to hair health. Additionally, alternative methods of cleansing the hair and scalp, also known as the no-shampoo or “no-poo” method, have begun to gain popularity.2,3

It is essential that dermatologists acknowledge the concerns that their patients have about common shampoo ingredients to dispel the myths that may misinform patient decision-making. This article reviews the controversy surrounding the use of sulfates and parabens in shampoos as well as commonly used shampoo alternatives. Due to the increased prevalence of dry hair shafts in the skin of color population, especially black women, this group is particularly interested in products that will minimize breakage and dryness of the hair. To that end, this population has great interest in the removal of chemical ingredients that may cause damage to the hair shafts, despite the lack of data to support sulfates and paraben damage to hair shafts or scalp skin. Blogs and uninformed hairstylists may propagate these beliefs in a group of consumers who are desperate for new approaches to hair fragility and breakage.

Surfactants and Sulfates

The cleansing ability of a shampoo depends on the surface activity of its detergents. Surface-active ingredients, or surfactants, reduce the surface tension between water and dirt, thus facilitating the removal of environmental dirt from the hair and scalp,4 which is achieved by a molecular structure containing both a hydrophilic and a lipophilic group. Sebum and dirt are bound by the lipophilic ends of the surfactant, becoming the center of a micelle structure with the hydrophilic molecule ends pointing outward. Dirt particles become water soluble and are removed from the scalp and hair shaft upon rinsing with water.4

Surfactants are classified according to the electric charge of the hydrophilic polar group as either anionic, cationic, amphoteric (zwitterionic), or nonionic.5 Each possesses different hair conditioning and cleansing qualities, and multiple surfactants are used in shampoos in differing ratios to accommodate different hair types. In most shampoos, the base consists of anionic and amphoteric surfactants. Depending on individual product requirements, nonionic and cationic surfactants are used to either modify the effects of the surfactants or as conditioning agents.4,5

One subcategory of surfactants that receives much attention is the group of anionic surfactants known as sulfates. Sulfates, particularly sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), recently have developed a negative reputation as cosmetic ingredients, as reports from various unscientific sources have labeled them as hazardous to one’s health; SLS has been described as a skin and scalp irritant, has been linked to cataract formation, and has even been wrongly labeled as carcinogenic.6 The origins of some of these claims are not clear, though they likely arose from the misinterpretation of complex scientific studies that are easily accessible to laypeople. The link between SLS and ocular irritation or cataract formation is a good illustration of this unsubstantiated fear. A study by Green et al7 showed that corneal exposure to extremely high concentrations of SLS following physical or chemical damage to the eye can result in a slowed healing process. The results of this study have since been wrongly quoted to state that SLS-containing products lead to blindness or severe corneal damage.8 A different study tested for possible ocular irritation in vivo by submerging the lens of an eye into a 20% SLS solution, which accurately approximates the concentration of SLS in rinse-off consumer products.9 However, to achieve ocular irritation, the eyes of laboratory animals were exposed to SLS constantly for 14 days, which would not occur in practical use.9 Similarly, a third study achieved cataract formation in a laboratory only by immersing the lens of an eye into a highly concentrated solution of SLS.10 Such studies are not appropriate representations of how SLS-containing products are used by consumers and have unfortunately been vulnerable to misinterpretation by the general public.

There is no known study that has shown SLS to be carcinogenic. One possible origin of this idea may be from the wrongful interpretation of studies that used SLS as a vehicle substance to test agents that were deemed to be carcinogenic.11 Another possible source of the idea that SLS is carcinogenic comes from its association with 1,4-dioxane, a by-product of the synthesis of certain sulfates such as sodium laureth sulfate due to a process known as ethoxylation.6,12 Although SLS does not undergo this process in its formation and is not linked to 1,4-dioxane, there is potential for cross-contamination of SLS with 1,4-dioxane, which cannot be overlooked. 1,4-Dioxane is classified as “possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B)” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer,13 but screening of SLS for this substance prior to its use in commercial products is standard.

Sulfates are inexpensive detergents that are responsible for lather formation in shampoos as well as in many household cleaning agents.5 Sulfates, similar to all anionic surfactants, are characterized by a negatively charged hydrophilic polar group. The best-known and most commonly used anionic surfactants are sulfated fatty alcohols, alkyl sulfates, and their polyethoxylated analogues alkyl ether sulfates.5,6 Sodium lauryl sulfate (also known as sodium laurilsulfate or sodium dodecyl sulfate) is the most common of them all, found in shampoo and conditioner formulations. Ammonium lauryl sulfate and sodium laureth sulfate are other sulfates commonly used in shampoos and household cleansing products. Sodium lauryl sulfate is a nonvolatile, water-soluble compound. Its partition coefficient (P0), a measure of a substance’s hydrophilic or lipophilic nature, is low at 1.6, making it a rather hydrophilic substance.6 Hydrophilic substances tend to have low bioaccumulation profiles in the body. Additionally, SLS is readily biodegradable. It can be derived from both synthetic and naturally occurring sources; for example, palm kernel oil, petrolatum, and coconut oil are all sources of lauric acid, the starting ingredient used to synthesize SLS. Sodium lauryl sulfate is created by reacting lauryl alcohol with sulfur trioxide gas, followed by neutralization with sodium carbonate (also a naturally occurring compound).6 Sodium lauryl sulfate and other sulfate-containing shampoos widely replaced the usage of traditional soaps formulated from animal or vegetable fats, as these latter formations created a film of insoluble calcium salts on the hair strands upon contact with water, resulting in tangled, dull-appearing hair.5 Additionally, sulfates were preferred to the alkaline pH of traditional soap, which can be harsh on hair strands and cause irritation of the skin and mucous membranes.14 Because they are highly water soluble, sulfates enable the formulation of clear shampoos. They exhibit remarkable cleaning properties and lather formation.5,14

Because sulfates are potent surfactants, they can remove dirt and debris as well as naturally produced healthy oils from the hair and scalp. As a result, sulfates can leave the hair feeling dry and stripped of moisture.4,5 Sulfates are used as the primary detergents in the formulation of deep-cleaning shampoos, which are designed for people who accumulate a heavy buildup of dirt, sebum, and debris from frequent use of styling products. Due to their potent detergency, these shampoos typically are not used on a daily basis but rather at longer intervals.15 A downside to sulfates is that they can have cosmetically unpleasant properties, which can be compensated for by including appropriate softening additives in shampoo formulations.4 A number of anionic surfactants such as olefin sulfonate, alkyl sulfosuccinate, acyl peptides, and alkyl ether carboxylates are well tolerated by the skin and are used together with other anionic and amphoteric surfactants to optimize shampoo properties. Alternatively, sulfate-free shampoos are cleansers compounded by the removal of the anionic group and switched for surfactants with less detergency.4,5

Preservatives and Parabens

Parabens refer to a group of esters of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid commonly used as preservatives in foods, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics whose widespread use dates back to 1923.16 Concerns over the presence of parabens in shampoos and other cosmetics have been raised by patients for their reputed estrogenic and antiandrogenic effects and suspected involvement in carcinogenesis via endocrine modulation.16,17 In in vitro studies done on yeast assays, parabens have shown weak estrogenic activity that increases in proportion to both the length and increased branching of the alkyl side chains in the paraben’s molecular structure.18 They are 10,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol. In in vivo animal studies, parabens show weak estrogenic activity and are 100,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol.18 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, a common metabolite, showed no estrogenic activity when tested both in vitro and in vivo.19 Some concerning research has implicated a link between parabens used in underarm cosmetics, such as deodorants and antiperspirants, and breast cancer16; however, the studies have been conflicting, and there is simply not enough data to assert that parabens cause breast cancer.

The Cosmetic Ingredient Review expert panel first reviewed parabens in 1984 and concluded that “methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben are safe as cosmetic ingredients in the present practices of use.”20 They extended this statement to include isopropylparaben and isobutylparaben in a later review.21 In 2005, the Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (now known as the Scientific Committee for Consumer Safety) in Europe stated that methylparaben and ethylparaben can be used at levels up to 0.4% in products.22 This decision was reached due to reports of decreased sperm counts and testosterone levels in male juvenile rats exposed to these parabens; however, these reults were not successfully replicated in larger studies.16,22 In 2010, the Scientific Committee for Consumer Safety revisited its stance on parabens, and they then revised their recommendations to say that concentrations of propylparaben and butylparaben should not exceed concentrations of 0.19%, based on “the conservative choice for the calculation of the [Margin-of-Safety] of butyl- and propylparaben.”23 However, in 2011 the use of propylparaben and butylparaben was banned in Denmark for cosmetic products used in children 3 years or younger,16 and the European Commission subsequently amended their directive in 2014, banning isopropylparaben, isobutylparaben, phenylparaben, benzylparaben, and pentylparaben due to lack of data available to evaluate the human risk of these products.24

Contrary to the trends in Europe, there currently are no regulations against the use of parabens in shampoos or other cosmetics in the United States. The American Cancer Society found that there is no evidence to suggest that the current levels of parabens in cosmetic products (eg, antiperspirants) increase one’s risk of breast cancer.25 Parabens are readily absorbed into the body both transdermally and through ingestion but also are believed to be rapidly transformed into harmless and nonspecific metabolites; they are readily metabolized by the liver and excreted in urine, and there is no measured accumulation in tissues.17

Parabens continue to be the most widely used preservatives in personal care products, usually in conjunction with other preservatives. Parabens are good biocides; short-chain esters (eg, methylparabens, ethylparabens) are effective against gram-positive bacteria and are weakly effective against gram-negative bacteria. Long-chain paraben esters (eg, propylparabens, butylparabens) are effective against mold and yeast. The addition of other preservatives creates a broad spectrum of antimicrobial defense in consumer products. Other preservatives include formaldehyde releasers or phenoxyethanol, as well as chelating agents such as EDTA, which improve the stability of these cosmetic products when exposed to air.16 Parabens are naturally occurring substances found in foods such as blueberries, barley, strawberries, yeast, olives, and grapes. As a colorless, odorless, and inexpensive substance, their use has been heavily favored in cosmetic and food products.16

Shampoo Alternatives and the No-Poo Method