User login

Systems modeling advances precision medicine in alopecia

PORTLAND – Alopecia areata can resist treatment stubbornly, but dermatologists might soon have better tools to predict response to therapy.

Personalized gene sequencing is key to this type of precision medicine, but conventional sequencing can be “extremely cumbersome and clinically impractical,” James C. Chen, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

During alopecia trials at Columbia, researchers routinely perform RNA sequencing of scalp biopsies to analyze therapeutic response on a molecular level. Using these RNAseq data from patients with untreated alopecia areata and gene regulatory network analysis data from the Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks, Dr. Chen and his associates modeled the molecular mechanisms of action of the pan–Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib, the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, the CTLA4 inhibitor abatacept, and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (IL-TAC). Heat maps of molecular responses to treatment showed distinct mechanisms of action between IL-TAC and abatacept, Dr. Chen said.

Furthermore, these therapies showed distinct and much less robust molecular effects than either ruxolitinib or tofacitinib. A Venn diagram of the biosignatures and molecular mechanisms of action of all four therapies showed little overlap. In fact, the probability of so little overlap between tofacitinib and IL-TAC occurring by chance was 0.023. The lack of overlap between the two JAK inhibitors was even more pronounced (P = 2.21 x 10–11).

Only 5-10 transcription factors are needed to capture these molecular mechanisms of action, which could greatly streamline precision dermatology in the future, according to Dr. Chen. “Systems biology offers a foundation for developing precision medicine strategies and selecting treatments for patients based on their individual molecular pathology,” he concluded. “Even when patients with alopecia areata have the same clinical phenotype, the molecular pathways they take to get there are not necessarily the same. We need to define those paths to maximize our chances of matching drugs to patients.”

Dr. Chen acknowledged support from the National Institutes of Health, epiCURE, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. He had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND – Alopecia areata can resist treatment stubbornly, but dermatologists might soon have better tools to predict response to therapy.

Personalized gene sequencing is key to this type of precision medicine, but conventional sequencing can be “extremely cumbersome and clinically impractical,” James C. Chen, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

During alopecia trials at Columbia, researchers routinely perform RNA sequencing of scalp biopsies to analyze therapeutic response on a molecular level. Using these RNAseq data from patients with untreated alopecia areata and gene regulatory network analysis data from the Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks, Dr. Chen and his associates modeled the molecular mechanisms of action of the pan–Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib, the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, the CTLA4 inhibitor abatacept, and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (IL-TAC). Heat maps of molecular responses to treatment showed distinct mechanisms of action between IL-TAC and abatacept, Dr. Chen said.

Furthermore, these therapies showed distinct and much less robust molecular effects than either ruxolitinib or tofacitinib. A Venn diagram of the biosignatures and molecular mechanisms of action of all four therapies showed little overlap. In fact, the probability of so little overlap between tofacitinib and IL-TAC occurring by chance was 0.023. The lack of overlap between the two JAK inhibitors was even more pronounced (P = 2.21 x 10–11).

Only 5-10 transcription factors are needed to capture these molecular mechanisms of action, which could greatly streamline precision dermatology in the future, according to Dr. Chen. “Systems biology offers a foundation for developing precision medicine strategies and selecting treatments for patients based on their individual molecular pathology,” he concluded. “Even when patients with alopecia areata have the same clinical phenotype, the molecular pathways they take to get there are not necessarily the same. We need to define those paths to maximize our chances of matching drugs to patients.”

Dr. Chen acknowledged support from the National Institutes of Health, epiCURE, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. He had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND – Alopecia areata can resist treatment stubbornly, but dermatologists might soon have better tools to predict response to therapy.

Personalized gene sequencing is key to this type of precision medicine, but conventional sequencing can be “extremely cumbersome and clinically impractical,” James C. Chen, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

During alopecia trials at Columbia, researchers routinely perform RNA sequencing of scalp biopsies to analyze therapeutic response on a molecular level. Using these RNAseq data from patients with untreated alopecia areata and gene regulatory network analysis data from the Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks, Dr. Chen and his associates modeled the molecular mechanisms of action of the pan–Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib, the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, the CTLA4 inhibitor abatacept, and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (IL-TAC). Heat maps of molecular responses to treatment showed distinct mechanisms of action between IL-TAC and abatacept, Dr. Chen said.

Furthermore, these therapies showed distinct and much less robust molecular effects than either ruxolitinib or tofacitinib. A Venn diagram of the biosignatures and molecular mechanisms of action of all four therapies showed little overlap. In fact, the probability of so little overlap between tofacitinib and IL-TAC occurring by chance was 0.023. The lack of overlap between the two JAK inhibitors was even more pronounced (P = 2.21 x 10–11).

Only 5-10 transcription factors are needed to capture these molecular mechanisms of action, which could greatly streamline precision dermatology in the future, according to Dr. Chen. “Systems biology offers a foundation for developing precision medicine strategies and selecting treatments for patients based on their individual molecular pathology,” he concluded. “Even when patients with alopecia areata have the same clinical phenotype, the molecular pathways they take to get there are not necessarily the same. We need to define those paths to maximize our chances of matching drugs to patients.”

Dr. Chen acknowledged support from the National Institutes of Health, epiCURE, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. He had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SID 2017

Gray hair

Besides skin wrinkling, volume shifts, and photoaging, graying hair can also be a telltale sign of aging. While it was recently a fashionable trend for younger persons to dye their hair white or gray, graying hair can make a younger person appear older, even in those with naturally premature graying of the hair.

In a study recently published in Genes & Development, researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, identified hair shaft progenitors in the matrix that are specific to the hair shaft and not to follicular epithelial cells.1 These hair shaft progenitors express transcription factor KROX20, which expresses stem cell growth factor necessary for hair pigmentation by maintenance of differentiated melanocytes. When KROX20+ is depleted, hair growth is halted and hair turns gray, proving its important role in both hair growth and graying pathways.

Other mechanisms for hair graying include oxidative stress to the hair, at the level of the melanocyte stem cell or at the end-stage of the hair melanocyte, resulting in follicular melanocyte death. With aging and certain genetic mutations (such as that seen in Chediak-Higashi syndrome), reduction of catalase and sometimes downregulation of antioxidant proteins such as BCL-2 and TRP-2 are reduced, resulting in higher reactive oxygen species (ROS) that lead to bulbar melanocyte malfunction and death.

Last year, for the first time, researchers at University College of London identified a gene involved in gray hair, the interferon regulatory factor 4 gene (IRF4).2 The IRF4 gene is involved in regulating production and storage of melanin.

Besides photoprotection and vitamin antioxidants as a preventive measure, therapies that have been developed to target the reduction of ROS in hair have been largely unsatisfactory in treating gray hair. Most people either allow their hair to gray or dye their hair, which can be time consuming and costly and is required on a more frequent basis over time – not to mention the distress related to allergic contact dermatitis caused by some components of some hair dyes, including paraphenylenediamine, which we sometimes see in our profession.

Knowledge of KROX20+, the IRF4 gene, and other pathways involved may be useful in developing novel treatments to prevent or treat graying hair. Information regarding the use of platelet rich plasma (PRP) for hair growth is increasingly being published in the literature. While some physicians purport seeing a reversal in graying with scalp PRP injections, the majority say the results are not universal.

Currently, there are no published studies evaluating the effects of PRP on gray hair. Perhaps providing stem cell factors via injections of PRP or other growth factors may aid not only in hair regrowth but in preserving pigmentation and repigmentation.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References:

1. Genes Dev. 2017 May 2. doi: 10.1101/gad.298703.117.

2. Nat Commun. 2016 Mar 1;7:10815.

Besides skin wrinkling, volume shifts, and photoaging, graying hair can also be a telltale sign of aging. While it was recently a fashionable trend for younger persons to dye their hair white or gray, graying hair can make a younger person appear older, even in those with naturally premature graying of the hair.

In a study recently published in Genes & Development, researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, identified hair shaft progenitors in the matrix that are specific to the hair shaft and not to follicular epithelial cells.1 These hair shaft progenitors express transcription factor KROX20, which expresses stem cell growth factor necessary for hair pigmentation by maintenance of differentiated melanocytes. When KROX20+ is depleted, hair growth is halted and hair turns gray, proving its important role in both hair growth and graying pathways.

Other mechanisms for hair graying include oxidative stress to the hair, at the level of the melanocyte stem cell or at the end-stage of the hair melanocyte, resulting in follicular melanocyte death. With aging and certain genetic mutations (such as that seen in Chediak-Higashi syndrome), reduction of catalase and sometimes downregulation of antioxidant proteins such as BCL-2 and TRP-2 are reduced, resulting in higher reactive oxygen species (ROS) that lead to bulbar melanocyte malfunction and death.

Last year, for the first time, researchers at University College of London identified a gene involved in gray hair, the interferon regulatory factor 4 gene (IRF4).2 The IRF4 gene is involved in regulating production and storage of melanin.

Besides photoprotection and vitamin antioxidants as a preventive measure, therapies that have been developed to target the reduction of ROS in hair have been largely unsatisfactory in treating gray hair. Most people either allow their hair to gray or dye their hair, which can be time consuming and costly and is required on a more frequent basis over time – not to mention the distress related to allergic contact dermatitis caused by some components of some hair dyes, including paraphenylenediamine, which we sometimes see in our profession.

Knowledge of KROX20+, the IRF4 gene, and other pathways involved may be useful in developing novel treatments to prevent or treat graying hair. Information regarding the use of platelet rich plasma (PRP) for hair growth is increasingly being published in the literature. While some physicians purport seeing a reversal in graying with scalp PRP injections, the majority say the results are not universal.

Currently, there are no published studies evaluating the effects of PRP on gray hair. Perhaps providing stem cell factors via injections of PRP or other growth factors may aid not only in hair regrowth but in preserving pigmentation and repigmentation.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References:

1. Genes Dev. 2017 May 2. doi: 10.1101/gad.298703.117.

2. Nat Commun. 2016 Mar 1;7:10815.

Besides skin wrinkling, volume shifts, and photoaging, graying hair can also be a telltale sign of aging. While it was recently a fashionable trend for younger persons to dye their hair white or gray, graying hair can make a younger person appear older, even in those with naturally premature graying of the hair.

In a study recently published in Genes & Development, researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, identified hair shaft progenitors in the matrix that are specific to the hair shaft and not to follicular epithelial cells.1 These hair shaft progenitors express transcription factor KROX20, which expresses stem cell growth factor necessary for hair pigmentation by maintenance of differentiated melanocytes. When KROX20+ is depleted, hair growth is halted and hair turns gray, proving its important role in both hair growth and graying pathways.

Other mechanisms for hair graying include oxidative stress to the hair, at the level of the melanocyte stem cell or at the end-stage of the hair melanocyte, resulting in follicular melanocyte death. With aging and certain genetic mutations (such as that seen in Chediak-Higashi syndrome), reduction of catalase and sometimes downregulation of antioxidant proteins such as BCL-2 and TRP-2 are reduced, resulting in higher reactive oxygen species (ROS) that lead to bulbar melanocyte malfunction and death.

Last year, for the first time, researchers at University College of London identified a gene involved in gray hair, the interferon regulatory factor 4 gene (IRF4).2 The IRF4 gene is involved in regulating production and storage of melanin.

Besides photoprotection and vitamin antioxidants as a preventive measure, therapies that have been developed to target the reduction of ROS in hair have been largely unsatisfactory in treating gray hair. Most people either allow their hair to gray or dye their hair, which can be time consuming and costly and is required on a more frequent basis over time – not to mention the distress related to allergic contact dermatitis caused by some components of some hair dyes, including paraphenylenediamine, which we sometimes see in our profession.

Knowledge of KROX20+, the IRF4 gene, and other pathways involved may be useful in developing novel treatments to prevent or treat graying hair. Information regarding the use of platelet rich plasma (PRP) for hair growth is increasingly being published in the literature. While some physicians purport seeing a reversal in graying with scalp PRP injections, the majority say the results are not universal.

Currently, there are no published studies evaluating the effects of PRP on gray hair. Perhaps providing stem cell factors via injections of PRP or other growth factors may aid not only in hair regrowth but in preserving pigmentation and repigmentation.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References:

1. Genes Dev. 2017 May 2. doi: 10.1101/gad.298703.117.

2. Nat Commun. 2016 Mar 1;7:10815.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia can affect adolescents

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) can affect adolescents, and a study of six biopsy-proven cases indicates CCCA has a genetic component, Ariana N. Eginli and her colleagues report in Pediatric Dermatology.

CCCA, a scarring alopecia that disproportionately affects middle-aged women of African descent, has been attributed to hair care and styling practices. In this series, however, five of the six patients had a maternal history of CCCA, and only one had used chemical products or styling tools. “Specifically, the early onset of CCCA in these patients with natural virgin hair raises the possibility of genetic anticipation,” wrote Ms. Eginli of Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., and her coauthors. “Therefore, recognizing that CCCA can present in children, particularly in those with a positive family history, is of utmost importance in controlling further disease progression and improving their quality of life.”

Two patients had previously undergone scalp surgery, specifically ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement, years before their hair loss began. The authors speculated that the scalp surgery may have contributed to the early development of CCCA.

“We recommend that clinicians check for early signs of CCCA when there are complaints of hair loss on the scalp of offspring of affected women of African descent,” they wrote. “If there is any clinical suspicion of CCCA or any scarring alopecia, a scalp biopsy should be performed.”

Ms. Eginli had no disclosures. One of her colleagues is a consultant for and has received grant support from various drug companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) can affect adolescents, and a study of six biopsy-proven cases indicates CCCA has a genetic component, Ariana N. Eginli and her colleagues report in Pediatric Dermatology.

CCCA, a scarring alopecia that disproportionately affects middle-aged women of African descent, has been attributed to hair care and styling practices. In this series, however, five of the six patients had a maternal history of CCCA, and only one had used chemical products or styling tools. “Specifically, the early onset of CCCA in these patients with natural virgin hair raises the possibility of genetic anticipation,” wrote Ms. Eginli of Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., and her coauthors. “Therefore, recognizing that CCCA can present in children, particularly in those with a positive family history, is of utmost importance in controlling further disease progression and improving their quality of life.”

Two patients had previously undergone scalp surgery, specifically ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement, years before their hair loss began. The authors speculated that the scalp surgery may have contributed to the early development of CCCA.

“We recommend that clinicians check for early signs of CCCA when there are complaints of hair loss on the scalp of offspring of affected women of African descent,” they wrote. “If there is any clinical suspicion of CCCA or any scarring alopecia, a scalp biopsy should be performed.”

Ms. Eginli had no disclosures. One of her colleagues is a consultant for and has received grant support from various drug companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) can affect adolescents, and a study of six biopsy-proven cases indicates CCCA has a genetic component, Ariana N. Eginli and her colleagues report in Pediatric Dermatology.

CCCA, a scarring alopecia that disproportionately affects middle-aged women of African descent, has been attributed to hair care and styling practices. In this series, however, five of the six patients had a maternal history of CCCA, and only one had used chemical products or styling tools. “Specifically, the early onset of CCCA in these patients with natural virgin hair raises the possibility of genetic anticipation,” wrote Ms. Eginli of Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., and her coauthors. “Therefore, recognizing that CCCA can present in children, particularly in those with a positive family history, is of utmost importance in controlling further disease progression and improving their quality of life.”

Two patients had previously undergone scalp surgery, specifically ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement, years before their hair loss began. The authors speculated that the scalp surgery may have contributed to the early development of CCCA.

“We recommend that clinicians check for early signs of CCCA when there are complaints of hair loss on the scalp of offspring of affected women of African descent,” they wrote. “If there is any clinical suspicion of CCCA or any scarring alopecia, a scalp biopsy should be performed.”

Ms. Eginli had no disclosures. One of her colleagues is a consultant for and has received grant support from various drug companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of six pediatric patients with biopsy-proven CCCA, five had a family history of CCCA and only one had used chemical products or styling tools.

Data source: A case series of six pediatric patients with biopsy-confirmed CCCA.

Disclosures: Ms. Eginli had no disclosures. One of her colleagues is a consultant for and has received grant support from various drug companies.

JAK inhibitors and alopecia: After positive early data, various trials now underway

PORTLAND, ORE. – Janus kinase inhibitors are relatively safe and can produce a full head of hair in patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata (AA), although patients tend to shed hair after stopping treatment, Julian Mackay-Wiggan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

“At this point, there are 17 publications in the literature, from clinical trials to case reports, looking at JAK [Janus kinase] inhibitors in patients with alopecia areata,” said Dr. Mackay-Wiggan of the department of dermatology, Columbia University, New York, where she specializes in hair disorders. “Pretty much all report very positive findings. It definitely appears that Janus kinase inhibitors can play a very significant role in treatment.”

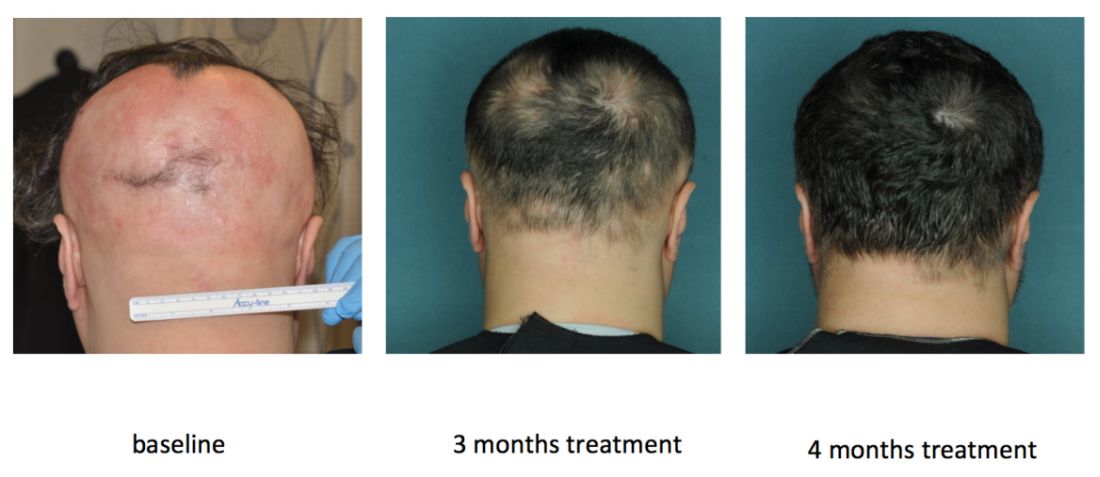

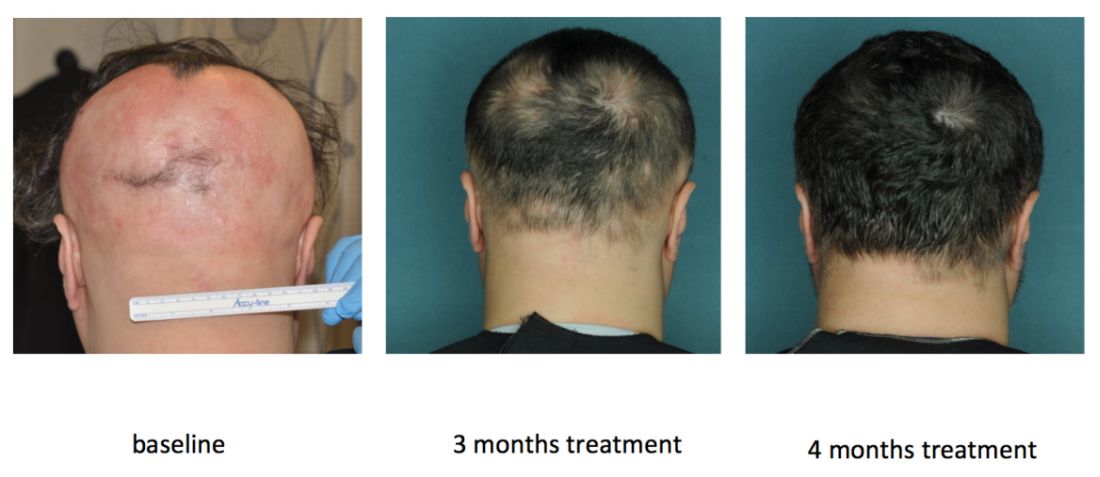

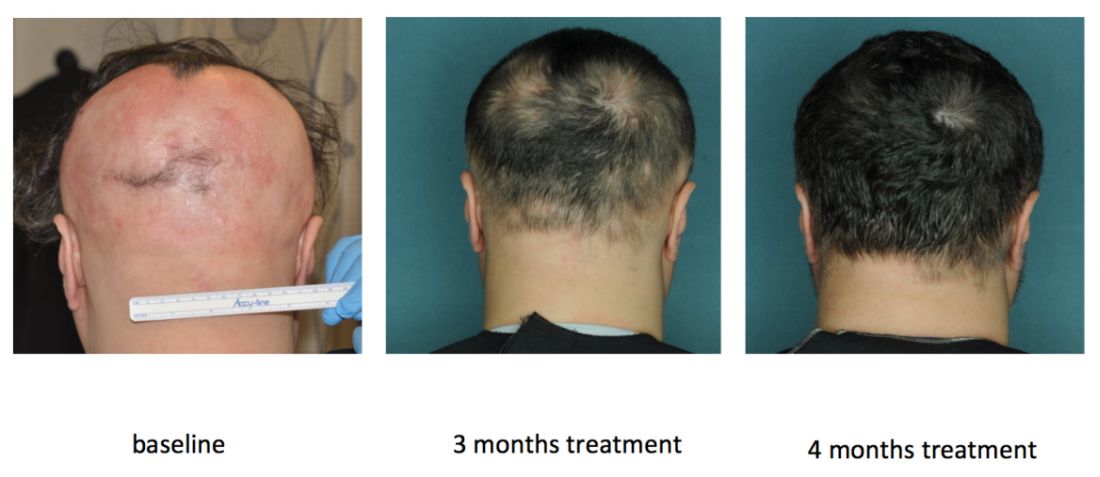

In an open label, uncontrolled pilot study at Columbia, 9 of 12 (75%) patients with moderate to severe AA improved by at least 50% on the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) after receiving 20 mg ruxolitinib twice daily for 3 to 6 months (JCI Insight. 2016 Sep 22;1[15]:e89790). Responses started with the first month, and all but one responder achieved at least 50% hair regrowth by week 12, said Dr. Mackay-Wiggan, who is also the director of the Dermatology Clinical Research Unit at Columbia.

By the end of treatment, seven of nine responders achieved more than 95% regrowth, one achieved 85% regrowth, and one achieved 55% regrowth. Importantly, none of these relatively healthy patients experienced serious adverse events on ruxolitinib, and none needed to stop treatment, although one patient experienced declining hemoglobin levels that resolved after dose modification.

Columbia researchers are also conducting an uncontrolled, open label pilot trial of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (Xeljanz) in 12 patients, of whom seven have moderate to severe patchy AA and five have alopecia totalis or universalis. Tofacitinib is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis at a dose of 5 mg twice daily, but patients have needed up to 10 mg twice daily to achieve hair regrowth, Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. To date, 11 (92%) have achieved at least some hair regrowth, and 8 (67%) have achieved at least 50% regrowth. So far, there have been no serious adverse events over 6 to 16 months of treatment, although one patient stopped treatment after developing hypertension, a known adverse effect of tofacitinib.

In this study, heatmaps of RNA sequencing of CD8+ T cell populations clearly showed pathogenic signatures for AA and a “robust molecular response to treatment,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. “These two signatures also overlapped statistically, producing 114 genes that may be targetable mediators of disease.” But as with ruxolitinib, regrowth started to decline as patients were taken off treatment.

Research indicates that inhibiting the JAK-STAT signaling pathway induces anagen and subsequent hair growth, but activating STAT 5 in the dermal papilla is also important to induce the growth phase of the hair follicle, according to Dr. Mackay-Wiggan. “Bottom line, it’s complicated,” she added. “The mode of delivery – topical versus systemic – may be important, and the timing of delivery may be crucial.”

Other studies point to a role for JAK inhibition in treating AA. In an uncontrolled, retrospective study of 90 adults with alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, or moderate to severe AA, 58% had SALT scores of 50% or better after receiving 5 mg tofacitinib twice daily for 4 to 18 months. Patients with AA improved more than those with alopecia totalis or universalis. There were no severe adverse effects, although nearly a third of patients developed upper respiratory tract infections. In another uncontrolled study of 13 patients with AA, totalis, or universalis, 9 (70%) patients achieved full regrowth and there were no serious adverse effects, although patients experienced headaches, upper respiratory infections, and mild increases in liver transaminase levels.

JAK inhibition also has a potential role for treating some scarring alopecias, including lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia. These diseases are histologically “identical” and both exhibit perifollicular erythema, papules, and scale, all of which suggest active inflammation, Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. Hair follicles from affected patients show immune markers such as interferon-inducible chemokines, cytotoxic T cell responses, and expression of major histocompatibility complexes I and II. “The important message here is that JAK/STAT signaling may play a significant role in other types of hair loss other than alopecia areata,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. “These diseases may also be autoimmune diseases, and may also be treatable with JAK inhibitors.”

Studies continue to evaluate JAK inhibitors for treating alopecia and its variants. Investigators at Yale and Stanford are conducting three uncontrolled trials of oral or topical tofacitinib, while Incyte, the manufacturer of ruxolitinib, is sponsoring a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib phosphate cream for adults with AA, with topline results expected in May 2018. Concert Pharmaceuticals also is recruiting for a trial of a modified, investigational form of ruxolitinib called CTP-543 for treating moderate to severe AA. “Many more trials are in development,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan noted.

The ruxolitinib pilot study was funded by the Locks of Love Foundation, the Alopecia Areata Initiative, NIH/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and by an Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research/Columbia University Medical Center Clinical and Translational Science Award. The ongoing tofacitinib pilot study is sponsored by Dr. Mackay-Wiggan, Locks of Love, and Columbia University.

Dr. Mackay-Wiggan also acknowledged support from the Alopecia Areata Initiative – the Gates Foundation, the National Alopecia Areata Registry, and the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. She had no other relevant financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Janus kinase inhibitors are relatively safe and can produce a full head of hair in patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata (AA), although patients tend to shed hair after stopping treatment, Julian Mackay-Wiggan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

“At this point, there are 17 publications in the literature, from clinical trials to case reports, looking at JAK [Janus kinase] inhibitors in patients with alopecia areata,” said Dr. Mackay-Wiggan of the department of dermatology, Columbia University, New York, where she specializes in hair disorders. “Pretty much all report very positive findings. It definitely appears that Janus kinase inhibitors can play a very significant role in treatment.”

In an open label, uncontrolled pilot study at Columbia, 9 of 12 (75%) patients with moderate to severe AA improved by at least 50% on the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) after receiving 20 mg ruxolitinib twice daily for 3 to 6 months (JCI Insight. 2016 Sep 22;1[15]:e89790). Responses started with the first month, and all but one responder achieved at least 50% hair regrowth by week 12, said Dr. Mackay-Wiggan, who is also the director of the Dermatology Clinical Research Unit at Columbia.

By the end of treatment, seven of nine responders achieved more than 95% regrowth, one achieved 85% regrowth, and one achieved 55% regrowth. Importantly, none of these relatively healthy patients experienced serious adverse events on ruxolitinib, and none needed to stop treatment, although one patient experienced declining hemoglobin levels that resolved after dose modification.

Columbia researchers are also conducting an uncontrolled, open label pilot trial of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (Xeljanz) in 12 patients, of whom seven have moderate to severe patchy AA and five have alopecia totalis or universalis. Tofacitinib is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis at a dose of 5 mg twice daily, but patients have needed up to 10 mg twice daily to achieve hair regrowth, Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. To date, 11 (92%) have achieved at least some hair regrowth, and 8 (67%) have achieved at least 50% regrowth. So far, there have been no serious adverse events over 6 to 16 months of treatment, although one patient stopped treatment after developing hypertension, a known adverse effect of tofacitinib.

In this study, heatmaps of RNA sequencing of CD8+ T cell populations clearly showed pathogenic signatures for AA and a “robust molecular response to treatment,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. “These two signatures also overlapped statistically, producing 114 genes that may be targetable mediators of disease.” But as with ruxolitinib, regrowth started to decline as patients were taken off treatment.

Research indicates that inhibiting the JAK-STAT signaling pathway induces anagen and subsequent hair growth, but activating STAT 5 in the dermal papilla is also important to induce the growth phase of the hair follicle, according to Dr. Mackay-Wiggan. “Bottom line, it’s complicated,” she added. “The mode of delivery – topical versus systemic – may be important, and the timing of delivery may be crucial.”

Other studies point to a role for JAK inhibition in treating AA. In an uncontrolled, retrospective study of 90 adults with alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, or moderate to severe AA, 58% had SALT scores of 50% or better after receiving 5 mg tofacitinib twice daily for 4 to 18 months. Patients with AA improved more than those with alopecia totalis or universalis. There were no severe adverse effects, although nearly a third of patients developed upper respiratory tract infections. In another uncontrolled study of 13 patients with AA, totalis, or universalis, 9 (70%) patients achieved full regrowth and there were no serious adverse effects, although patients experienced headaches, upper respiratory infections, and mild increases in liver transaminase levels.

JAK inhibition also has a potential role for treating some scarring alopecias, including lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia. These diseases are histologically “identical” and both exhibit perifollicular erythema, papules, and scale, all of which suggest active inflammation, Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. Hair follicles from affected patients show immune markers such as interferon-inducible chemokines, cytotoxic T cell responses, and expression of major histocompatibility complexes I and II. “The important message here is that JAK/STAT signaling may play a significant role in other types of hair loss other than alopecia areata,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. “These diseases may also be autoimmune diseases, and may also be treatable with JAK inhibitors.”

Studies continue to evaluate JAK inhibitors for treating alopecia and its variants. Investigators at Yale and Stanford are conducting three uncontrolled trials of oral or topical tofacitinib, while Incyte, the manufacturer of ruxolitinib, is sponsoring a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib phosphate cream for adults with AA, with topline results expected in May 2018. Concert Pharmaceuticals also is recruiting for a trial of a modified, investigational form of ruxolitinib called CTP-543 for treating moderate to severe AA. “Many more trials are in development,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan noted.

The ruxolitinib pilot study was funded by the Locks of Love Foundation, the Alopecia Areata Initiative, NIH/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and by an Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research/Columbia University Medical Center Clinical and Translational Science Award. The ongoing tofacitinib pilot study is sponsored by Dr. Mackay-Wiggan, Locks of Love, and Columbia University.

Dr. Mackay-Wiggan also acknowledged support from the Alopecia Areata Initiative – the Gates Foundation, the National Alopecia Areata Registry, and the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. She had no other relevant financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Janus kinase inhibitors are relatively safe and can produce a full head of hair in patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata (AA), although patients tend to shed hair after stopping treatment, Julian Mackay-Wiggan, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

“At this point, there are 17 publications in the literature, from clinical trials to case reports, looking at JAK [Janus kinase] inhibitors in patients with alopecia areata,” said Dr. Mackay-Wiggan of the department of dermatology, Columbia University, New York, where she specializes in hair disorders. “Pretty much all report very positive findings. It definitely appears that Janus kinase inhibitors can play a very significant role in treatment.”

In an open label, uncontrolled pilot study at Columbia, 9 of 12 (75%) patients with moderate to severe AA improved by at least 50% on the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) after receiving 20 mg ruxolitinib twice daily for 3 to 6 months (JCI Insight. 2016 Sep 22;1[15]:e89790). Responses started with the first month, and all but one responder achieved at least 50% hair regrowth by week 12, said Dr. Mackay-Wiggan, who is also the director of the Dermatology Clinical Research Unit at Columbia.

By the end of treatment, seven of nine responders achieved more than 95% regrowth, one achieved 85% regrowth, and one achieved 55% regrowth. Importantly, none of these relatively healthy patients experienced serious adverse events on ruxolitinib, and none needed to stop treatment, although one patient experienced declining hemoglobin levels that resolved after dose modification.

Columbia researchers are also conducting an uncontrolled, open label pilot trial of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (Xeljanz) in 12 patients, of whom seven have moderate to severe patchy AA and five have alopecia totalis or universalis. Tofacitinib is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis at a dose of 5 mg twice daily, but patients have needed up to 10 mg twice daily to achieve hair regrowth, Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. To date, 11 (92%) have achieved at least some hair regrowth, and 8 (67%) have achieved at least 50% regrowth. So far, there have been no serious adverse events over 6 to 16 months of treatment, although one patient stopped treatment after developing hypertension, a known adverse effect of tofacitinib.

In this study, heatmaps of RNA sequencing of CD8+ T cell populations clearly showed pathogenic signatures for AA and a “robust molecular response to treatment,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. “These two signatures also overlapped statistically, producing 114 genes that may be targetable mediators of disease.” But as with ruxolitinib, regrowth started to decline as patients were taken off treatment.

Research indicates that inhibiting the JAK-STAT signaling pathway induces anagen and subsequent hair growth, but activating STAT 5 in the dermal papilla is also important to induce the growth phase of the hair follicle, according to Dr. Mackay-Wiggan. “Bottom line, it’s complicated,” she added. “The mode of delivery – topical versus systemic – may be important, and the timing of delivery may be crucial.”

Other studies point to a role for JAK inhibition in treating AA. In an uncontrolled, retrospective study of 90 adults with alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, or moderate to severe AA, 58% had SALT scores of 50% or better after receiving 5 mg tofacitinib twice daily for 4 to 18 months. Patients with AA improved more than those with alopecia totalis or universalis. There were no severe adverse effects, although nearly a third of patients developed upper respiratory tract infections. In another uncontrolled study of 13 patients with AA, totalis, or universalis, 9 (70%) patients achieved full regrowth and there were no serious adverse effects, although patients experienced headaches, upper respiratory infections, and mild increases in liver transaminase levels.

JAK inhibition also has a potential role for treating some scarring alopecias, including lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia. These diseases are histologically “identical” and both exhibit perifollicular erythema, papules, and scale, all of which suggest active inflammation, Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. Hair follicles from affected patients show immune markers such as interferon-inducible chemokines, cytotoxic T cell responses, and expression of major histocompatibility complexes I and II. “The important message here is that JAK/STAT signaling may play a significant role in other types of hair loss other than alopecia areata,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan said. “These diseases may also be autoimmune diseases, and may also be treatable with JAK inhibitors.”

Studies continue to evaluate JAK inhibitors for treating alopecia and its variants. Investigators at Yale and Stanford are conducting three uncontrolled trials of oral or topical tofacitinib, while Incyte, the manufacturer of ruxolitinib, is sponsoring a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib phosphate cream for adults with AA, with topline results expected in May 2018. Concert Pharmaceuticals also is recruiting for a trial of a modified, investigational form of ruxolitinib called CTP-543 for treating moderate to severe AA. “Many more trials are in development,” Dr. Mackay-Wiggan noted.

The ruxolitinib pilot study was funded by the Locks of Love Foundation, the Alopecia Areata Initiative, NIH/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and by an Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research/Columbia University Medical Center Clinical and Translational Science Award. The ongoing tofacitinib pilot study is sponsored by Dr. Mackay-Wiggan, Locks of Love, and Columbia University.

Dr. Mackay-Wiggan also acknowledged support from the Alopecia Areata Initiative – the Gates Foundation, the National Alopecia Areata Registry, and the National Alopecia Areata Foundation. She had no other relevant financial disclosures.

AT SID 2017

Transverse Melanonychia and Palmar Hyperpigmentation Secondary to Hydroxyurea Therapy

To the Editor:

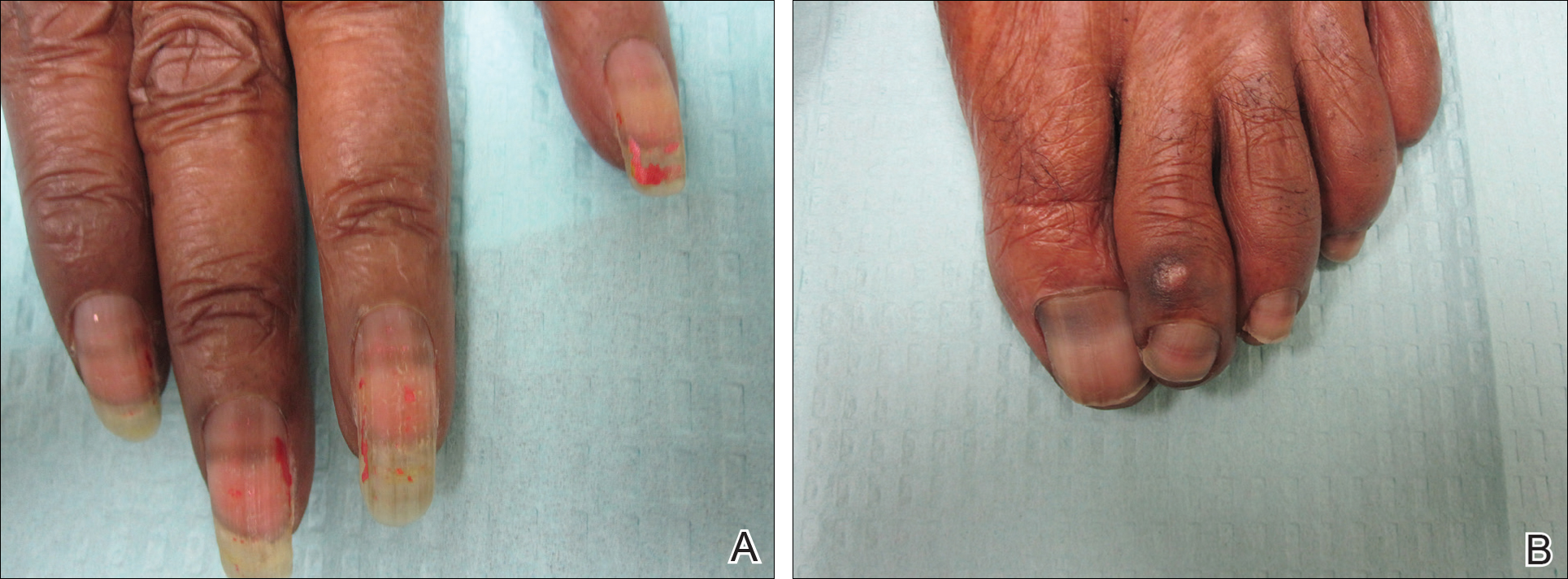

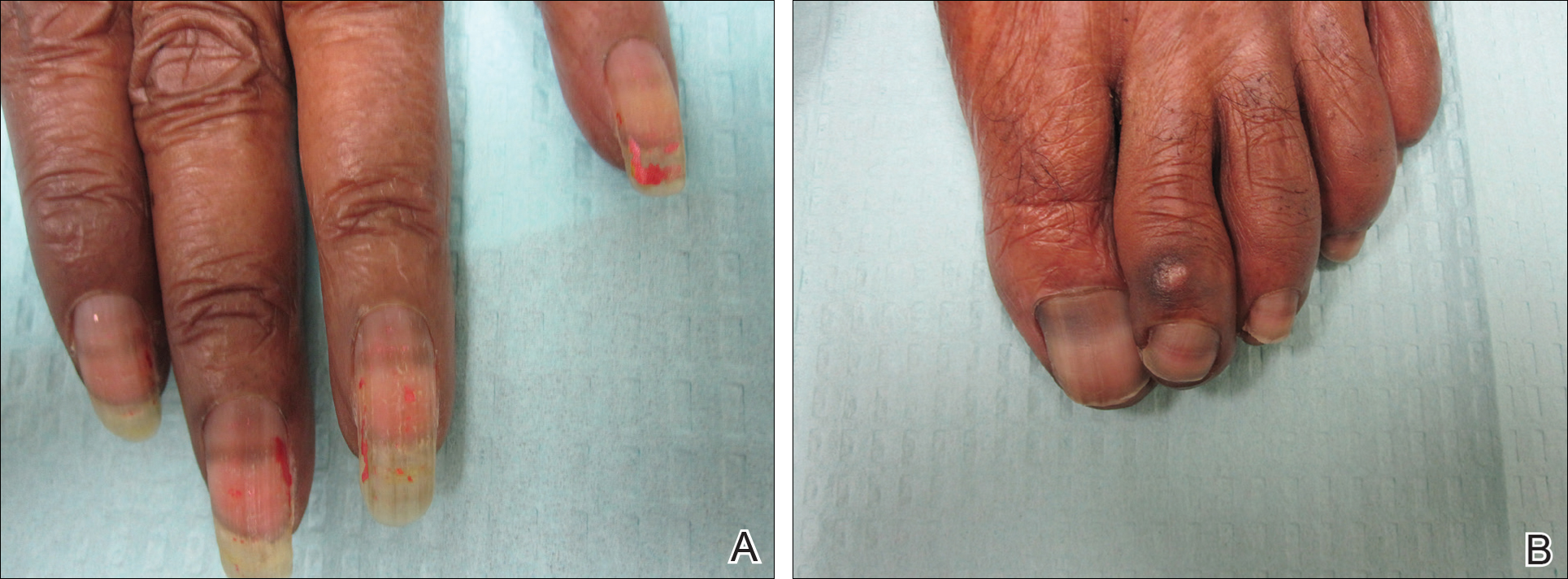

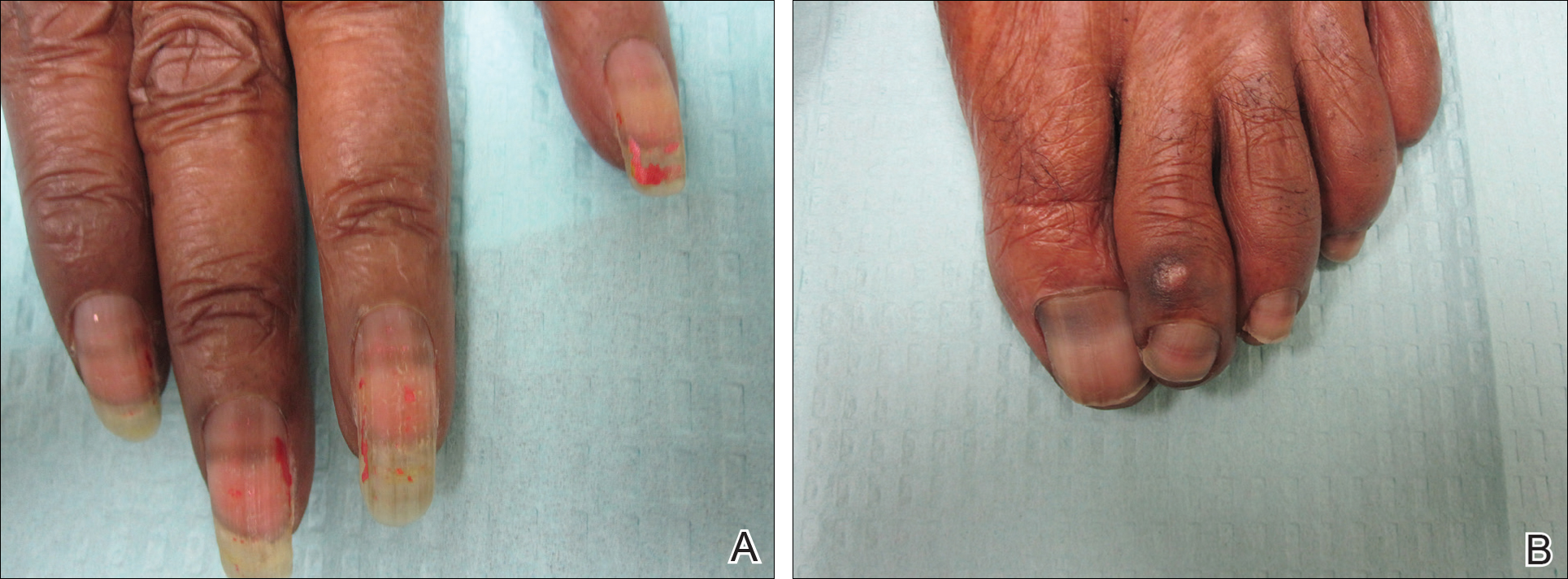

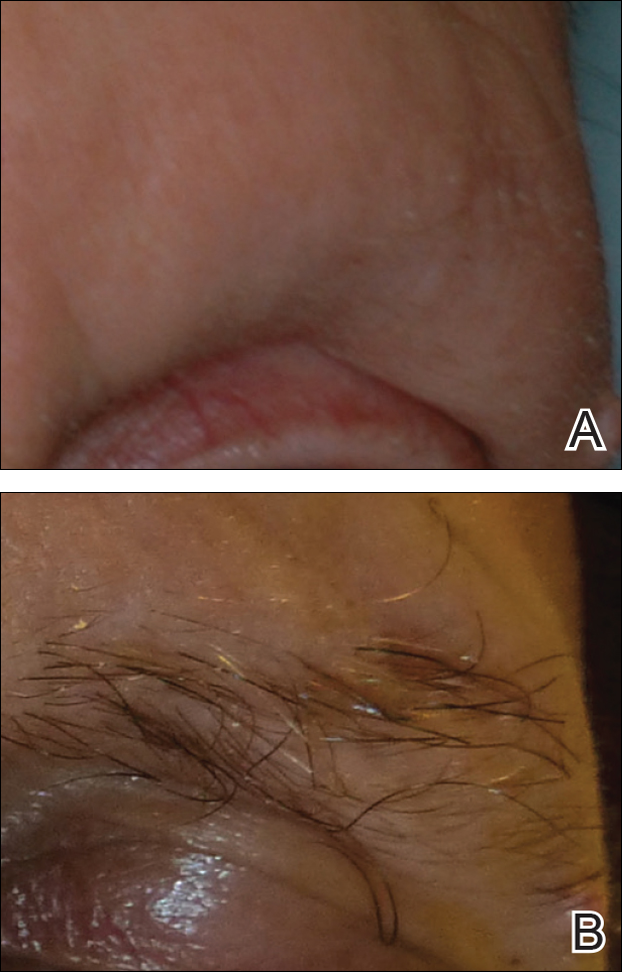

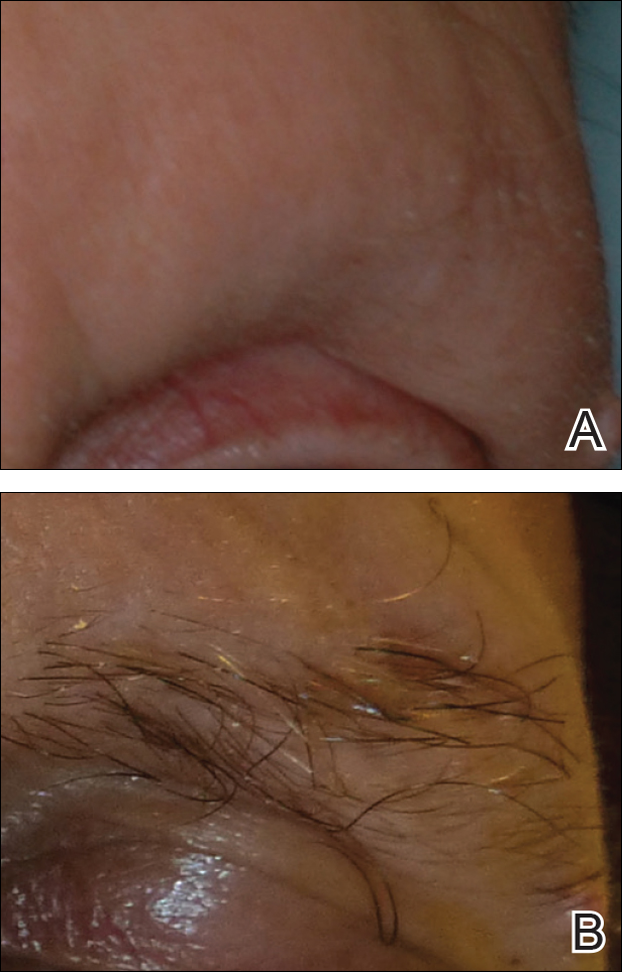

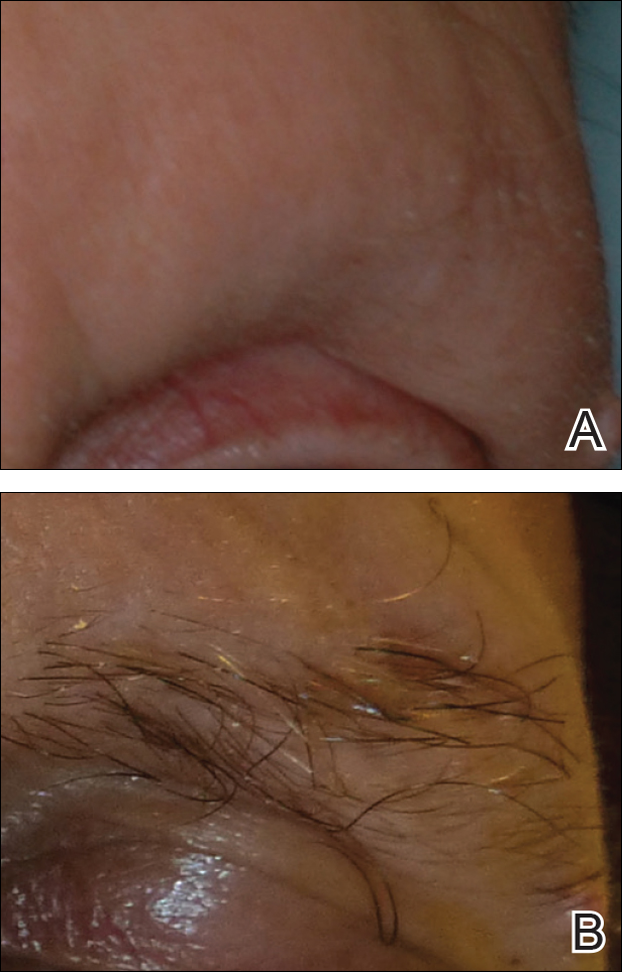

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

Practice Points

- Transverse melanonychia may result as a side effect of hydroxyurea.

- Discontinuation of hydroxyurea typically results in a resolution of symptoms. If the medication cannot be stopped, however, pigmentary changes may precede the development of severe mucocutaneous side effects and close monitoring is warranted.

- Patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.

Recovery of Hair in the Psoriatic Plaques of a Patient With Coexistent Alopecia Universalis

To the Editor:

Both alopecia areata (AA) and psoriasis vulgaris are chronic relapsing autoimmune diseases, with AA causing nonscarring hair loss in approximately 0.1% to 0.2%1 of the population with a lifetime risk of 1.7%,2 and psoriasis more broadly impacting 1.5% to 2% of the population.3 The helper T cell (TH1) cytokine milieu is pathogenic in both conditions.4-6 IFN-γ knockout mice, unlike their wild-type counterparts, do not exhibit AA.7 Psoriasis is notably improved by IL-10 injections, which dampen the TH1 response.8 Distinct from AA, TH17 and TH22 cells have been implicated as key players in psoriasis pathogenesis, along with the associated IL-17 and IL-22 cytokines.9-12

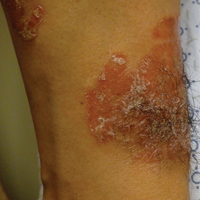

Few cases of patients with concurrent AA and psoriasis have been described. Interestingly, these cases document normal hair regrowth in the areas of psoriasis.13-16 These cases may offer unique insight into the immune factors driving each disease. We describe a case of a man with both alopecia universalis (AU) and psoriasis who developed hair regrowth in some of the psoriatic plaques.

A 34-year-old man with concurrent AU and psoriasis who had not used any systemic or topical medication for either condition in the last year presented to our clinic seeking treatment. The patient had a history of alopecia totalis as a toddler that completely resolved by 4 years of age with the use of squaric acid dibutylester (SADBE). At 31 years of age, the alopecia recurred and was localized to the scalp. It was partially responsive to intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. The patient’s alopecia worsened over the 2 years following recurrence, ultimately progressing to AU. Two months after the alopecia recurrence, he developed the first psoriatic plaques. As the plaque psoriasis progressed, systemic therapy was initiated, first methotrexate and then etanercept. Shortly after developing AU, he lost his health insurance and discontinued all therapy. The patient’s psoriasis began to recur approximately 3 months after stopping etanercept. He was not using any other psoriasis medications. At that time, he noted terminal hair regrowth within some of the psoriatic plaques. No terminal hairs grew outside of the psoriatic plaques, and all regions with growth had previously been without hair for an extended period of time. The patient presented to our clinic approximately 1 year later. He had no other medical conditions and no relevant family history.

On initial physical examination, he had nonscarring hair loss involving nearly 100% of the body with psoriatic plaques on approximately 30% of the body surface area. Regions of terminal hair growth were confined to some but not all of the psoriatic plaques (Figure). Interestingly, the terminal hairs were primarily localized to the thickest central regions of the plaques. The patient’s psoriasis was treated with a combination of topical clobetasol and calcipotriene. In addition, he was started on tacrolimus ointment to the face and eyebrows for the AA. Maintenance of terminal hair within a region of topically treated psoriasis on the forearm persisted at the 2-month follow-up despite complete clearance of the corresponding psoriatic plaque. A small psoriatic plaque on the scalp cleared early with topical therapy without noticeable hair regrowth. The patient subsequently was started on contact immunotherapy with SADBE and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide for the scalp alopecia without satisfactory response. He decided to discontinue further attempts at treating the alopecia and requested to be restarted on etanercept therapy for recalcitrant psoriatic plaques. His psoriasis responded well to this therapy and he continues to be followed in our psoriasis clinic. One year after clearance of the treated psoriatic plaques, the corresponding terminal hairs persist.

Contact immunotherapy, most commonly with diphenylcyclopropenone or SADBE, is reported to have a 50% to 60% success rate in extensive AA, with a broad range of 9% to 87%17; however, randomized controlled trials testing the efficacy of contact immunotherapy are lacking. Although the mechanism of action of these topical sensitizers is not clearly delineated, it has been postulated that by inducing a new type of inflammatory response in the region, the immunologic milieu is changed, allowing the hair to grow. Some proposed mechanisms include promoting perifollicular lymphocyte apoptosis, preventing new recruitment of autoreactive lymphocytes, and allowing for the correction of aberrant major histocompatibility complex expression on the hair matrix epithelium to regain follicle immune privilege.18-20

Iatrogenic immunotherapy may work analogously to the natural immune system deviation demonstrated in our patient. Psoriasis and AA are believed to form competing immune cells and cytokine milieus, thus explaining how an individual with AA could regain normal hair growth in areas of psoriasis.15,16 The Renbök phenomenon, or reverse Köbner phenomenon, coined by Happle et al13 can be used to describe both the iatrogenic and natural cases of dermatologic disease improvement in response to secondary insults.14

A complex cascade of immune cells and cytokines coordinate AA pathogenesis. In the acute stage of AA, an inflammatory infiltrate of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and antigen-presenting cells target anagen phase follicles, with a higher CD4+:CD8+ ratio in clinically active disease.21-23 Subcutaneous injections of either CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocyte subsets from mice with AA into normal-haired mice induces disease. However, CD8+ T cell injections rapidly produce apparent hair loss, whereas CD4+ T cells cause hair loss after several weeks, suggesting that CD8+ T cells directly modulate AA hair loss and CD4+ T cells act as an aide.24 The growth, differentiation, and survival of CD8+ T cells are stimulated by IL-2 and IFN-γ. Alopecia areata biopsies demonstrate a prevalence of TH1 cytokines, and patients with localized AA, alopecia totalis, and AU have notably higher serum IFN-γ levels compared to controls.25 In murine models, IL-1α and IL-1β increase during the catagen phase of the hair cycle and peak during the telogen phase.26 Excessive IL-1β expression is detected in the early stages of human disease, and certain IL-1β polymorphisms are associated with severe forms of AA.26 The role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α in AA is not well understood. In vitro studies show it inhibits hair growth, suggesting the cytokine may play a role in AA.27 However, anti–TNF-α therapy is not effective in AA, and case reports propose these therapies rarely induce AA.28-31

The TH1 response is likewise critical to psoriatic plaque development. IFN-γ and TNF-α are overexpressed in psoriatic plaques.32 IFN-γ has an antiproliferative and differentiation-inducing effect on normal keratinocytes, but psoriatic epithelial cells in vitro respond differently to the cytokine with a notably diminished growth inhibition.33,34 One explanation for the role of IFN-γ is that it stimulates dendritic cells to produce IL-1 and IL-23.35 IL-23 activates TH17 cells36; TH1 and TH17 conditions produce IL-22 whose serum level correlates with disease severity.37-39 IL-22 induces keratinocyte proliferation and migration and inhibits keratinocyte differentiation, helping account for hallmarks of the disease.40 Patients with psoriasis have increased levels of TH1, TH17, and TH22 cells, as well as their associated cytokines, in the skin and blood compared to controls.4,11,32,39,41

Alopecia areata and psoriasis are regulated by complex and still not entirely understood immune interactions. The fact that many of the same therapies are used to treat both diseases emphasizes both their overlapping characteristics and the lack of targeted therapy. It is unclear if and how the topical or systemic therapies used in our patient to treat one disease affected the natural history of the other condition. It is important to highlight, however, that the patient had not been treated for months when he developed the psoriatic plaques with hair regrowth. Other case reports also document hair regrowth in untreated plaques,13,16 making it unlikely to be a side effect of the medication regimen. For both psoriasis and AA, the immune cell composition and cytokine levels in the skin or serum vary throughout a patient’s disease course depending on severity of disease or response to treatment.6,39,42,43 Therefore, we hypothesize that the 2 conditions interact in a similarly distinct manner based on each disease’s stage and intensity in the patient. Both our patient’s course thus far and the various presentations described by other groups support this hypothesis. Our patient had a small region of psoriasis on the scalp that cleared without any terminal hair growth. He also had larger plaques on the forearms that developed hair growth most predominantly within the thicker regions of the plaques. His unique presentation highlights the fluidity of the immune factors driving psoriasis vulgaris and AA.

- Safavi K. Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:702.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Austin LM, Ozawa M, Kikuchi T, et al. The majority of epidermal T cells in psoriasis vulgaris lesions can produce type 1 cytokines, interferon-gamma, interleukin-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, defining TC1 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte) and TH1 effector populations: a type 1 differentiation bias is also measured in circulating blood T cells in psoriatic patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:752-759.

- Ghoreishi M, Martinka M, Dutz JP. Type 1 interferon signature in the scalp lesions of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:57-62.

- Rossi A, Cantisani C, Carlesimo M, et al. Serum concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α in patients with alopecia areata. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:781-788.

- Freyschmidt-Paul P, McElwee KJ, Hoffmann R, et al. Interferon-gamma-deficient mice are resistant to the development of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:515-521.

- Reich K, Garbe C, Blaschke V, et al. Response of psoriasis to interleukin-10 is associated with suppression of cutaneous type 1 inflammation, downregulation of the epidermal interleukin-8/CXCR2 pathway and normalization of keratinocyte maturation. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:319-329.

- Teunissen MB, Koomen CW, de Waal Malefyt R, et al. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma synergize in the enhancement of proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:645-649.

- Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648-651.

- Boniface K, Guignouard E, Pedretti N, et al. A role for T cell-derived interleukin 22 in psoriatic skin inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:407-415.

- Zaba LC, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with etanercept is linked to suppression of IL-17 signaling, not immediate response TNF genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1022-1030.e395.

- Happle R, van der Steen PHM, Perret CM. The Renbök phenomenon: an inverse Köebner reaction observed in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 1991;2:39-40.

- Ito T, Hashizume H, Takigawa M. Contact immunotherapy-induced Renbök phenomenon in a patient with alopecia areata and psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:126-127.

- Criado PR, Valente NY, Michalany NS, et al. An unusual association between scalp psoriasis and ophiasic alopecia areata: the Renbök phenomenon. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:320-321.

- Harris JE, Seykora JT, Lee RA. Renbök phenomenon and contact sensitization in a patient with alopecia universalis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:422-425.

- Alkhalifah A. Topical and intralesional therapies for alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:355-363.

- Herbst V, Zöller M, Kissling S, et al. Diphenylcyclopropenone treatment of alopecia areata induces apoptosis of perifollicular lymphocytes. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:537-542.

- Zöller M, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Vitacolonna M, et al. Chronic delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction as a means to treat alopecia areata. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:398-408.

- Bröcker EB, Echternacht-Happle K, Hamm H, et al. Abnormal expression of class I and class II major histocompatibility antigens in alopecia areata: modulation by topical immunotherapy. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:564-568.

- Todes-Taylor N, Turner R, Wood GS, et al. T cell subpopulations in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:216-223.

- Perret C, Wiesner-Menzel L, Happle R. Immunohistochemical analysis of T-cell subsets in the peribulbar and intrabulbar infiltrates of alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 1984;64:26-30.

- Wiesner-Menzel L, Happle R. Intrabulbar and peribulbar accumulation of dendritic OKT 6-positive cells in alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol Res. 1984;276:333-334.

- McElwee KJ, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Hoffmann R, et al. Transfer of CD8+ cells induces localized hair loss whereas CD4+/CD25– cells promote systemic alopecia areata and CD4+/CD25+ cells blockade disease onset in the C3H/HeJ mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:947-957.

- Arca E, Muşabak U, Akar A, et al. Interferon-gamma in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:33-36.

- Hoffmann R. The potential role of cytokines and T cells in alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:235-238.

- Philpott MP, Sanders DA, Bowen J, et al. Effects of interleukins, colony-stimulating factor and tumour necrosis factor on human hair follicle growth in vitro: a possible role for interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:942-948.

- Le Bidre E, Chaby G, Martin L, et al. Alopecia areata during anti-TNF alpha therapy: nine cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:285-293.

- Ferran M, Calvet J, Almirall M, et al. Alopecia areata as another immune-mediated disease developed in patients treated with tumour necrosis factor-α blocker agents: report of five cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:479-484.

- Pan Y, Rao NA. Alopecia areata during etanercept therapy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:127-129.

- Pelivani N, Hassan AS, Braathen LR, et al. Alopecia areata universalis elicited during treatment with adalimumab. Dermatology. 2008;216:320-323.

- Uyemura K, Yamamura M, Fivenson DF, et al. The cytokine network in lesional and lesion-free psoriatic skin is characterized by a T-helper type 1 cell-mediated response. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:701-705.

- Baker BS, Powles AV, Valdimarsson H, et al. An altered response by psoriatic keratinocytes to gamma interferon. Scan J Immunol. 1988;28:735-740.

- Jackson M, Howie SE, Weller R, et al. Psoriatic keratinocytes show reduced IRF-1 and STAT-1alpha activation in response to gamma-IFN. FASEB J. 1999;13:495-502.

- Perera GK, Di Meglio P, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:385-422.

- McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314-324.

- Volpe E, Servant N, Zollinger R, et al. A critical function for transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin 23 and proinflammatory cytokines in driving and modulating human T(H)-17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:650-657.

- Boniface K, Blumenschein WM, Brovont-Porth K, et al. Human Th17 cells comprise heterogeneous subsets including IFN-gamma-producing cells with distinct properties from the Th1 lineage. J Immunol. 2010;185:679-687.

- Kagami S, Rizzo HL, Lee JJ, et al. Circulating Th17, Th22, and Th1 cells are increased in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1373-1383.

- Boniface K, Bernard FX, Garcia M, et al. IL-22 inhibits epidermal differentiation and induces proinflammatory gene expression and migration of human keratinocytes. J Immunol. 2005;174:3695-3702.

- Harper EG, Guo C, Rizzo H, et al. Th17 cytokines stimulate CCL20 expression in keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo: implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2175-2183.

- Bowcock AM, Krueger JG. Getting under the skin: the immunogenetics of psoriasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:699-711.

- Hoffmann R, Wenzel E, Huth A, et al. Cytokine mRNA levels in alopecia areata before and after treatment with the contact allergen diphenylcyclopropenone. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:530-533.

To the Editor:

Both alopecia areata (AA) and psoriasis vulgaris are chronic relapsing autoimmune diseases, with AA causing nonscarring hair loss in approximately 0.1% to 0.2%1 of the population with a lifetime risk of 1.7%,2 and psoriasis more broadly impacting 1.5% to 2% of the population.3 The helper T cell (TH1) cytokine milieu is pathogenic in both conditions.4-6 IFN-γ knockout mice, unlike their wild-type counterparts, do not exhibit AA.7 Psoriasis is notably improved by IL-10 injections, which dampen the TH1 response.8 Distinct from AA, TH17 and TH22 cells have been implicated as key players in psoriasis pathogenesis, along with the associated IL-17 and IL-22 cytokines.9-12

Few cases of patients with concurrent AA and psoriasis have been described. Interestingly, these cases document normal hair regrowth in the areas of psoriasis.13-16 These cases may offer unique insight into the immune factors driving each disease. We describe a case of a man with both alopecia universalis (AU) and psoriasis who developed hair regrowth in some of the psoriatic plaques.