User login

Granulomatous Dermatitis in a Patient With Cholangiocarcinoma Treated With BRAF and MEK Inhibitors

To the Editor:

Granulomatous dermatitis (GD) has been described as a rare side effect of MEK and BRAF inhibitor use in the treatment of BRAF V600E mutation–positive metastatic melanoma. As the utilization of BRAF and MEK inhibitors increases for the treatment of a variety of cancers, it is essential that clinicians and pathologists recognize GD as a potential cutaneous manifestation. We present the case of a 52-year-old woman who developed GD while being treated with vemurafenib and cobimetinib for BRAF V600E mutation–positive metastatic cholangiocarcinoma.

A 52-year-old White woman presented with faint patches of nonpalpable violaceous mottling that extended distally to proximally from the ankles to the thighs on the medial aspects of both legs. She was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma 10 months prior, with metastases to the lung, liver, and sternum. She underwent treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin therapy. Computed tomography after several treatment cycles revealed progressive disease with multiple pulmonary nodules as well as metastatic intrathoracic and abdominal adenopathy. Treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin failed to produce a favorable response and was discontinued after 6 treatment cycles.

Genomic testing performed at the time of diagnosis revealed a positive mutation for BRAF V600E. The patient subsequently enrolled in a clinical trial and started treatment with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib and the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib. She developed sun sensitivity and multiple sunburns after starting these therapies. The patient tolerated the next few cycles of therapy well with only moderate concerns of dry sensitive skin.

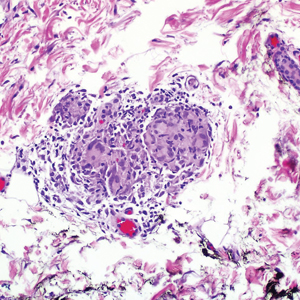

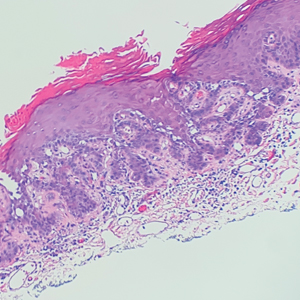

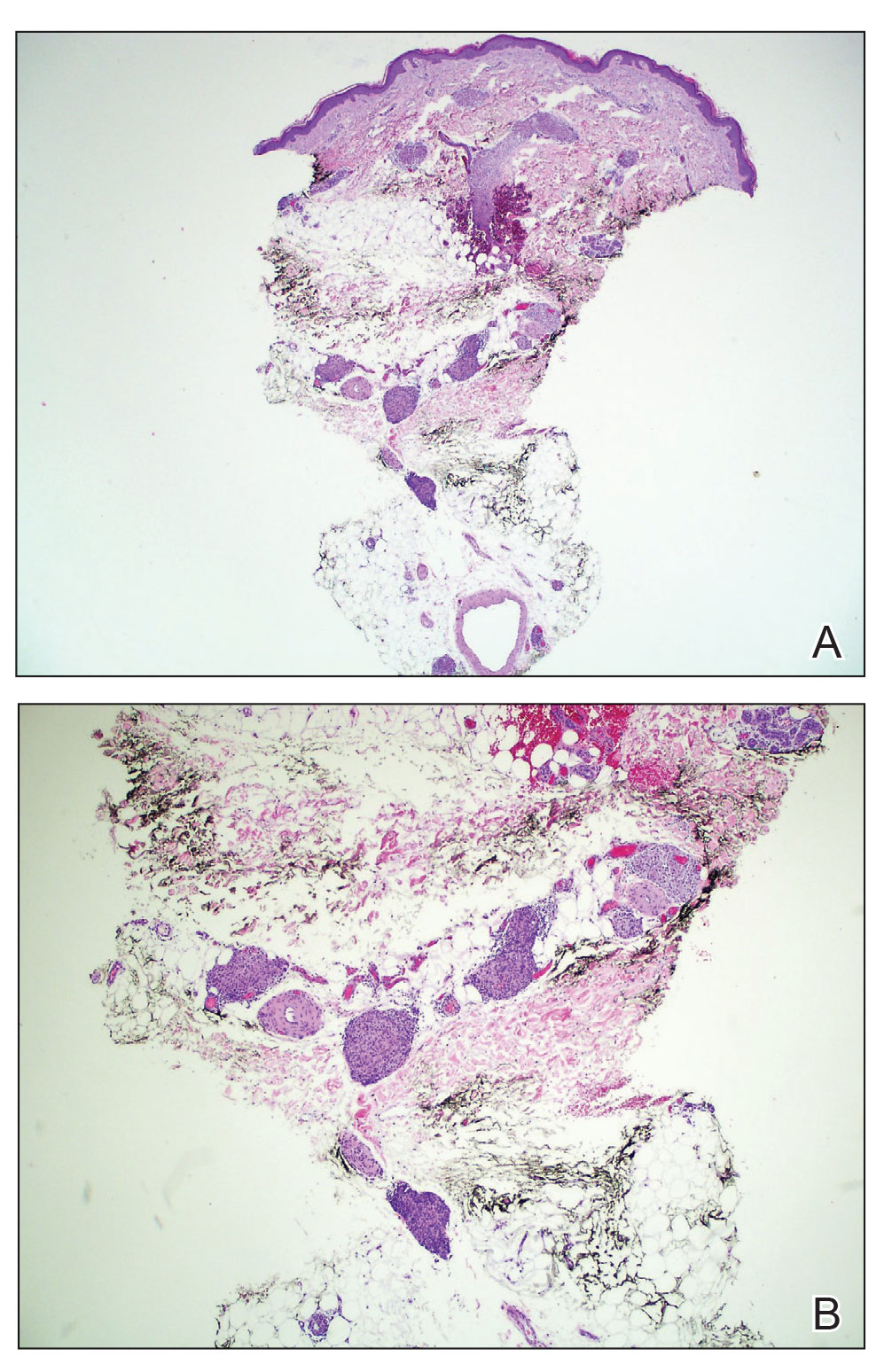

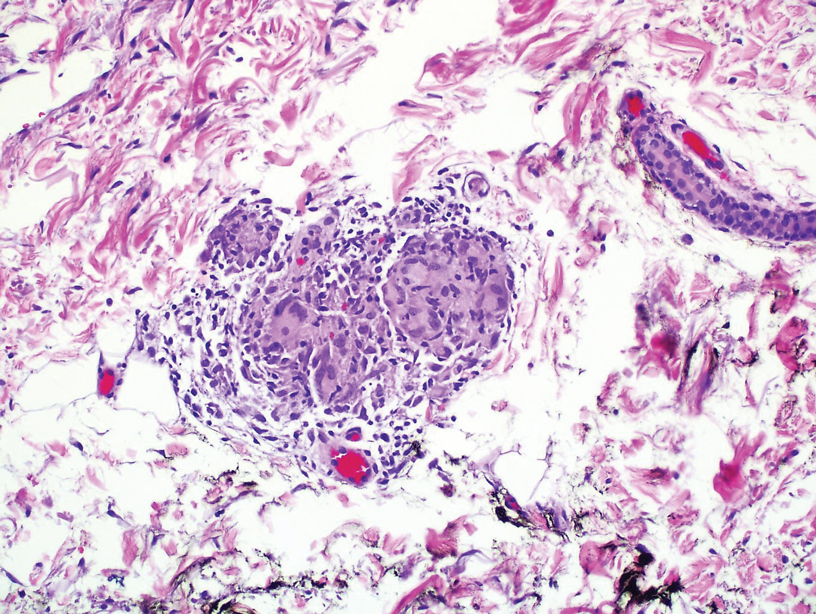

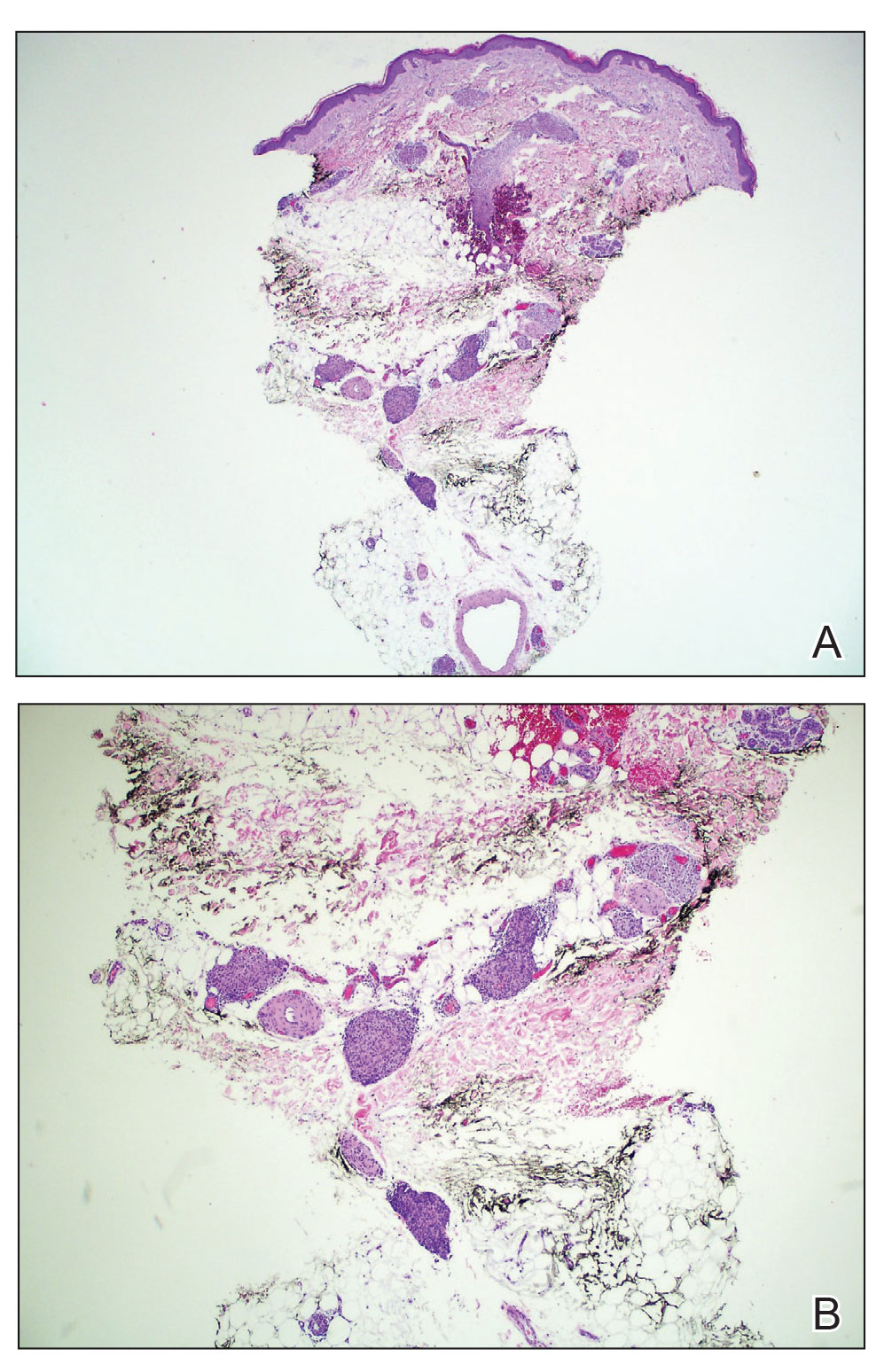

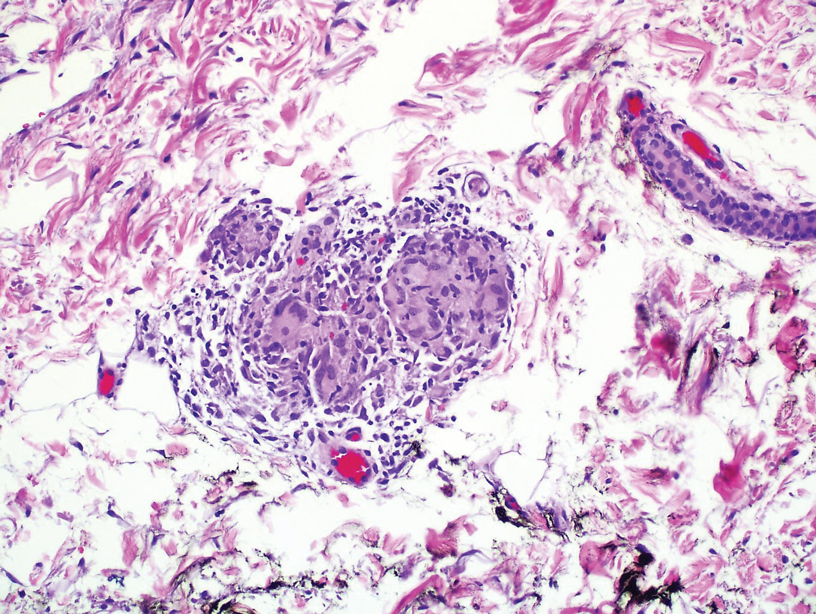

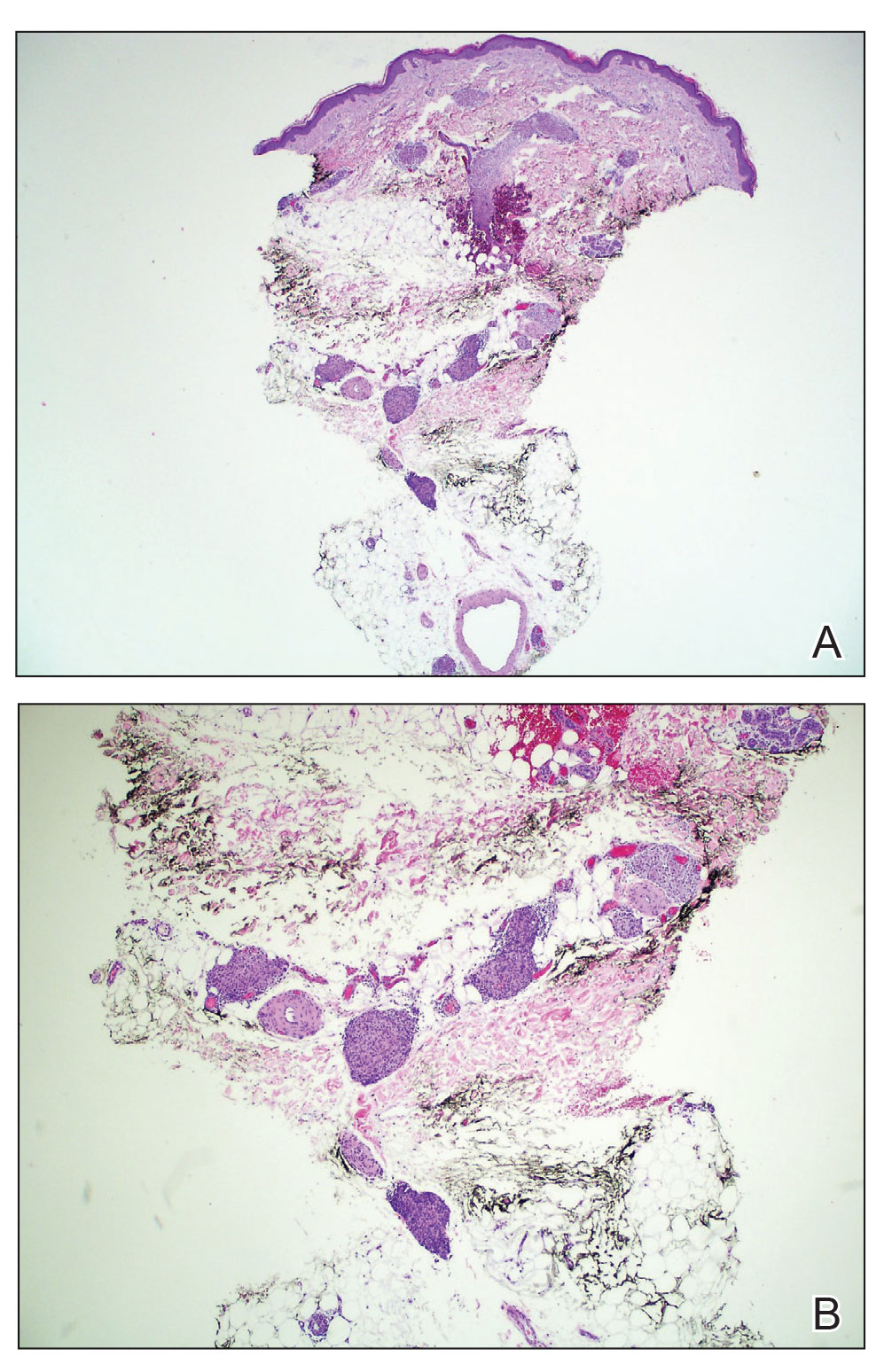

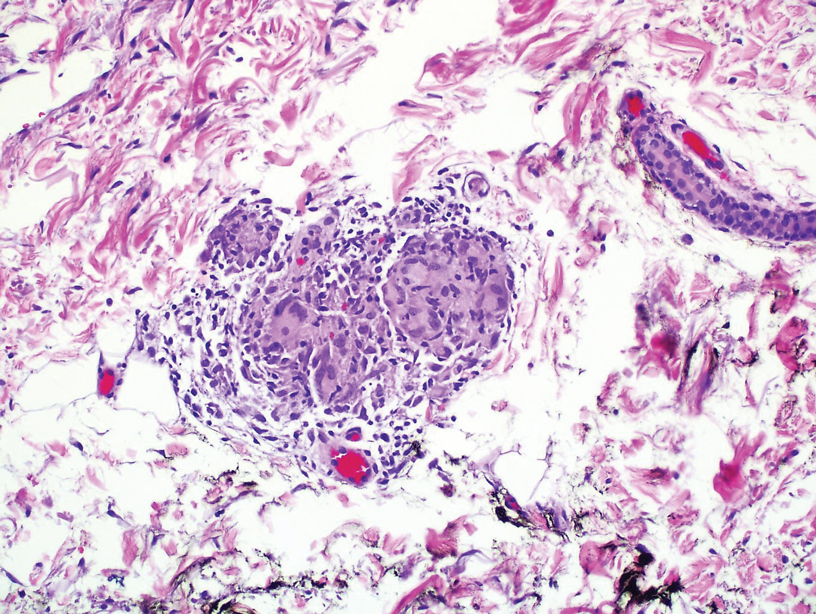

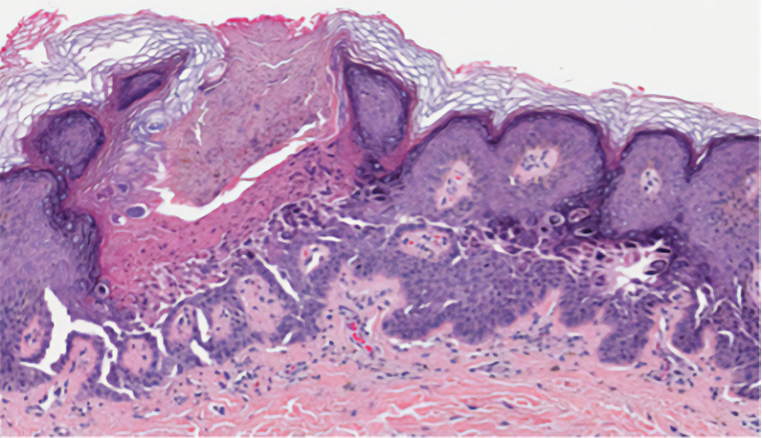

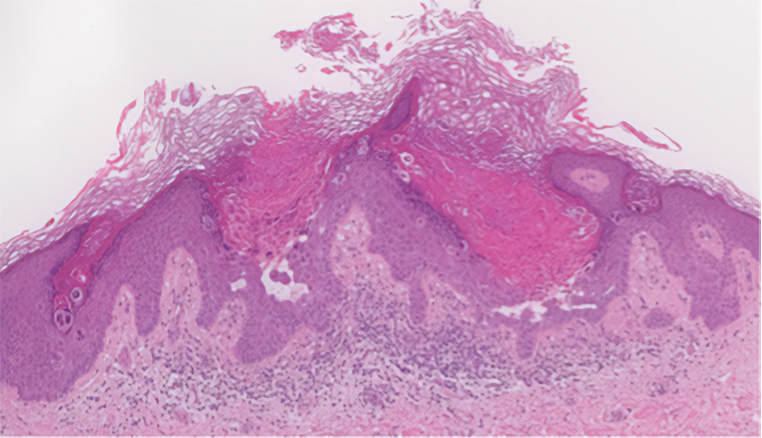

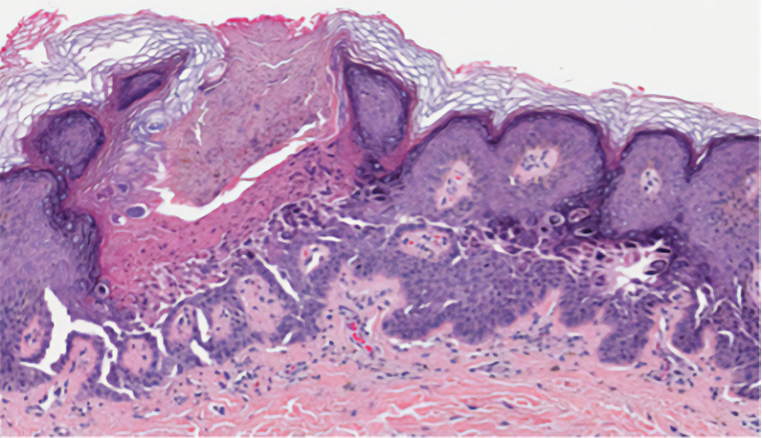

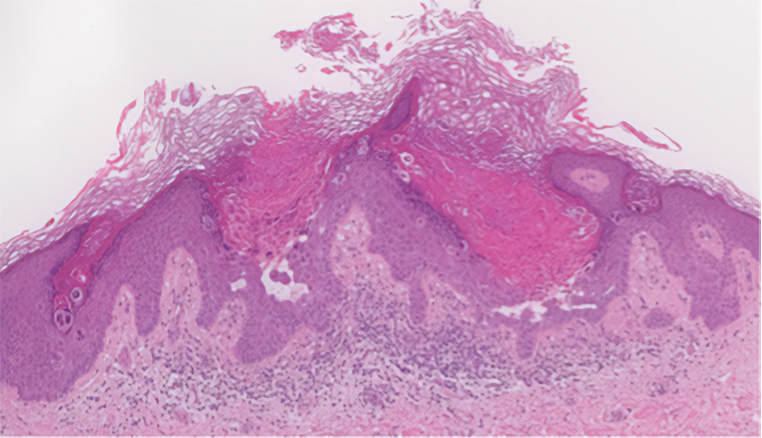

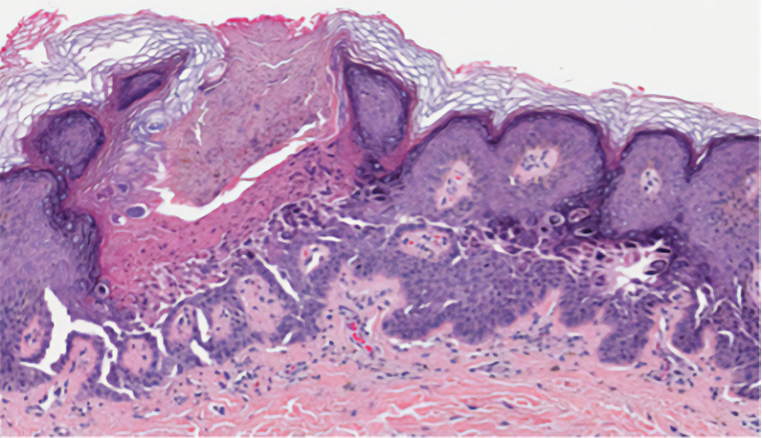

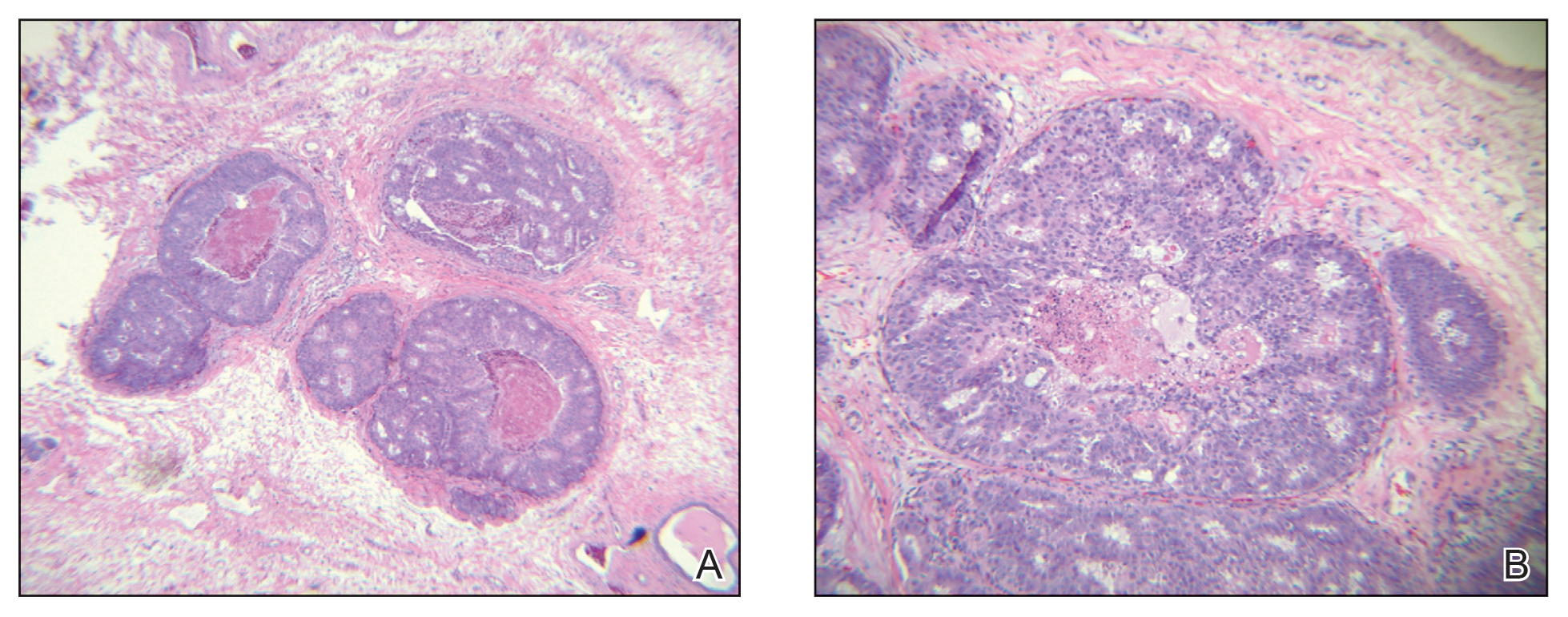

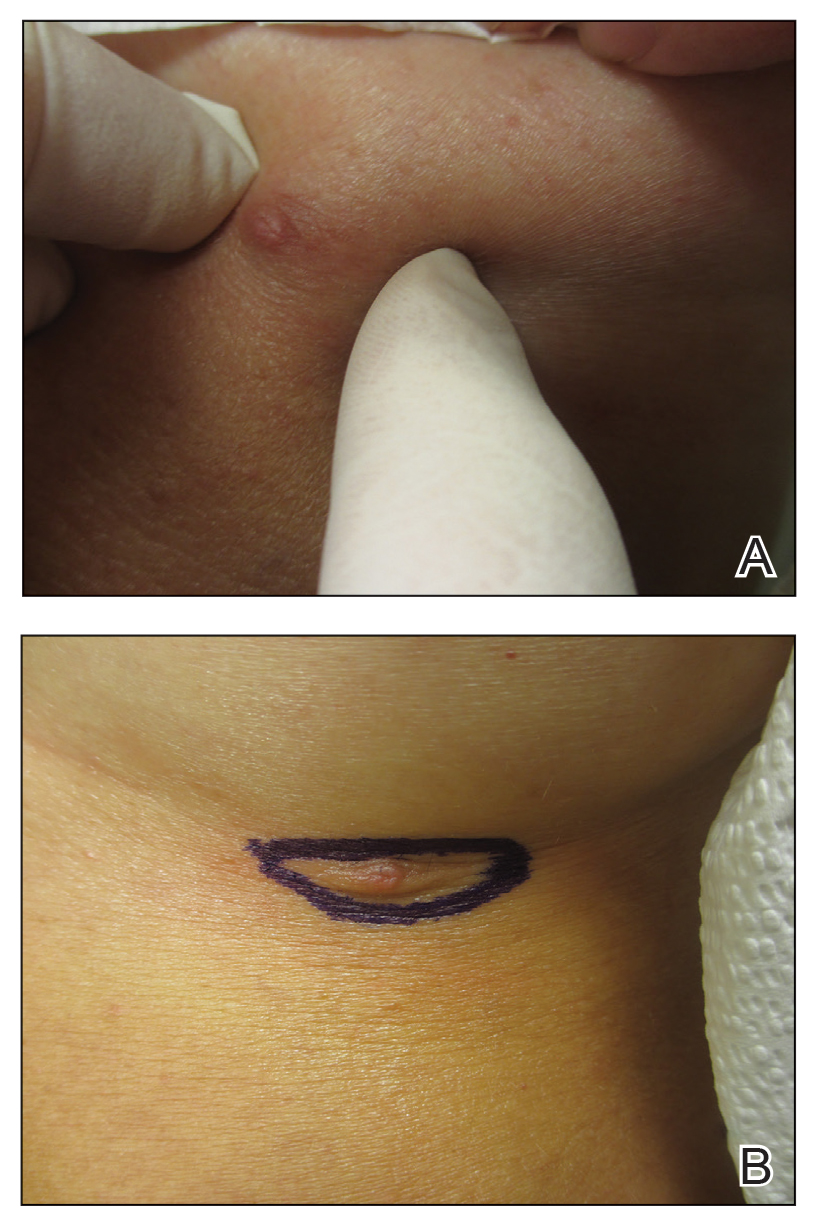

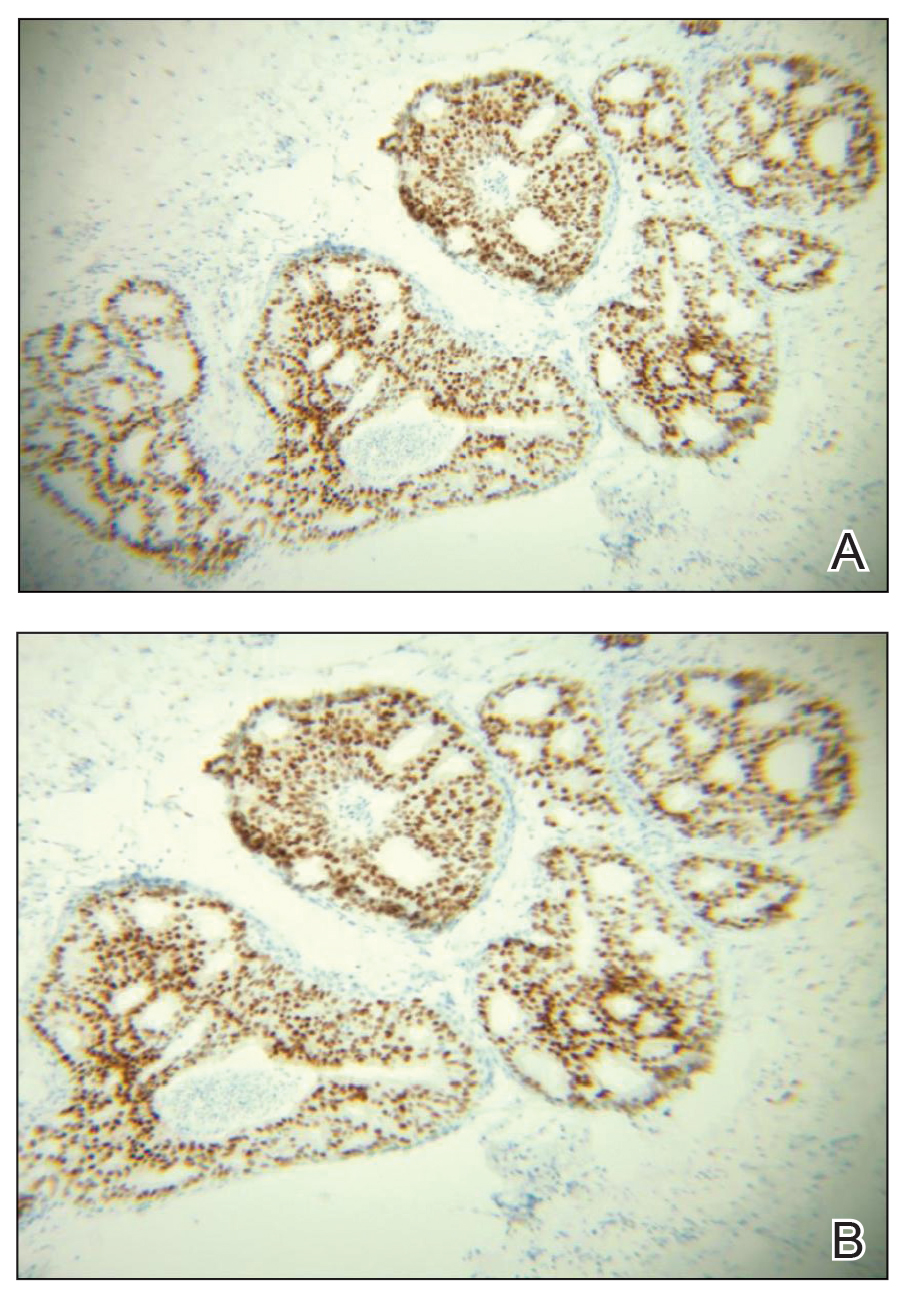

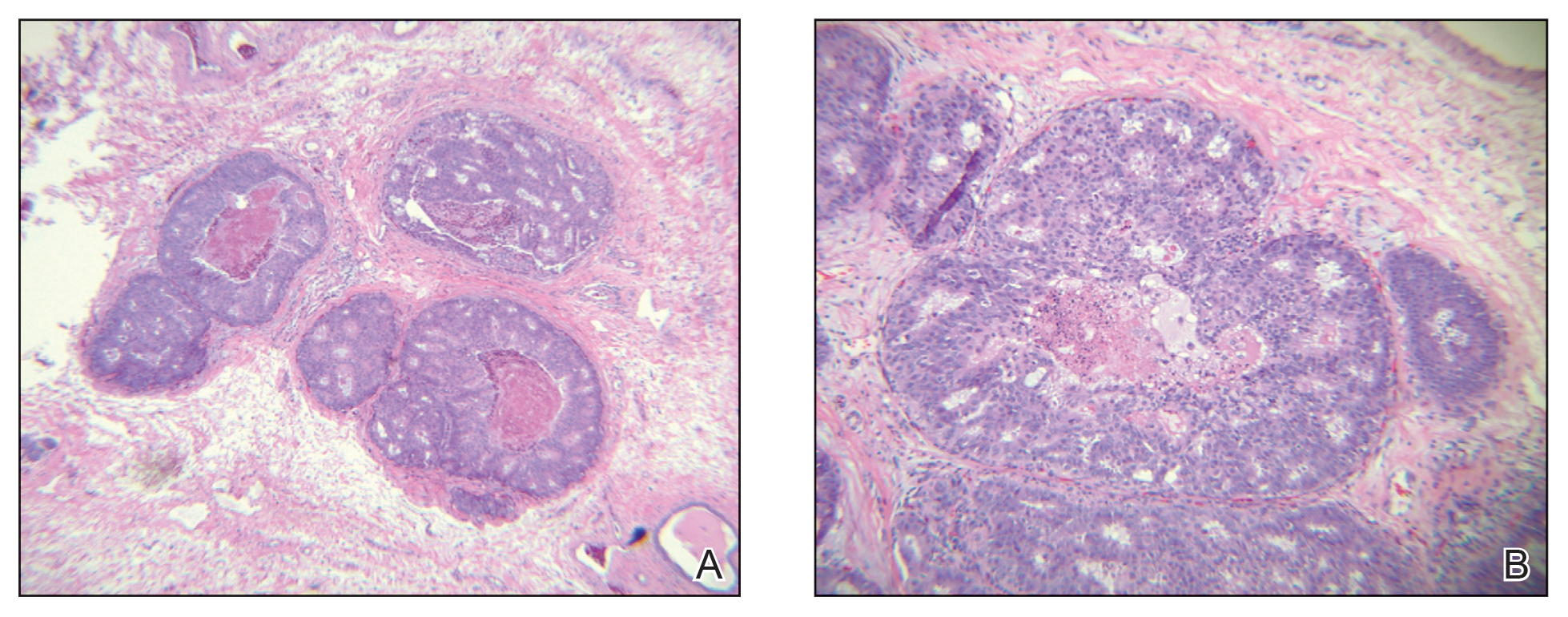

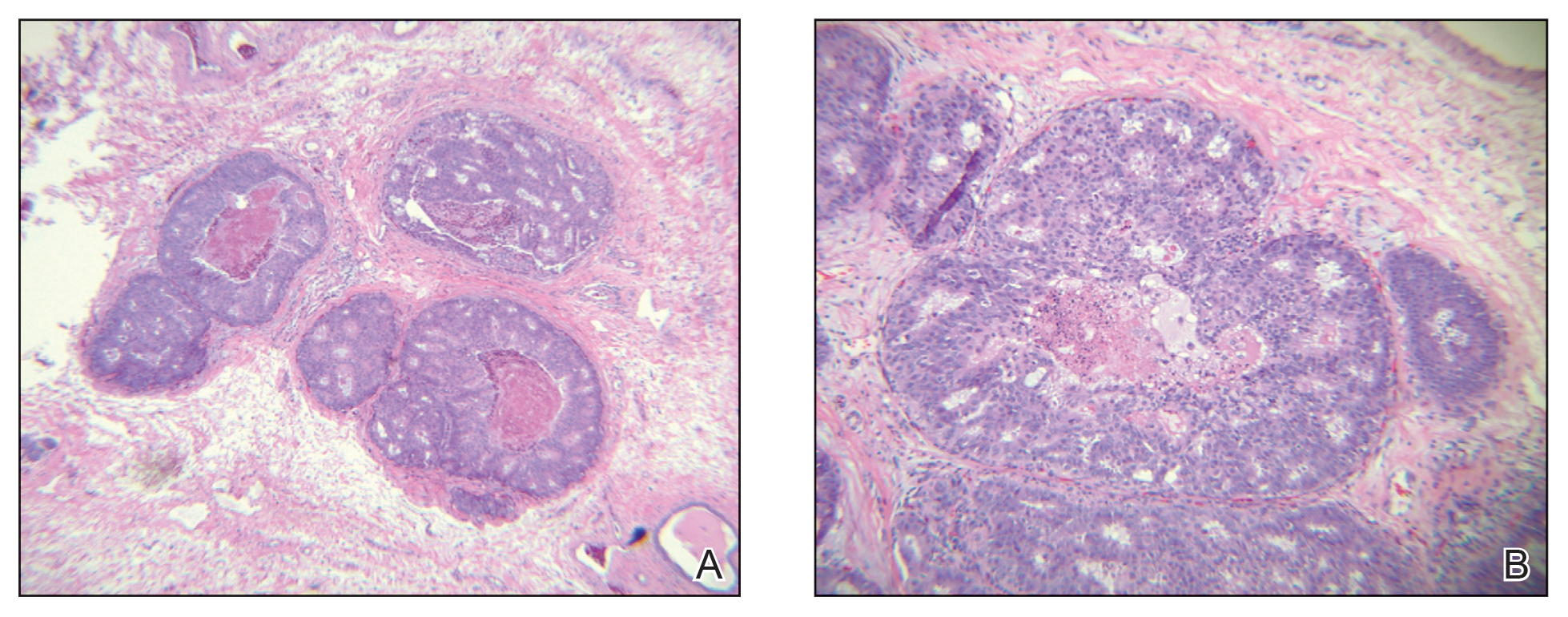

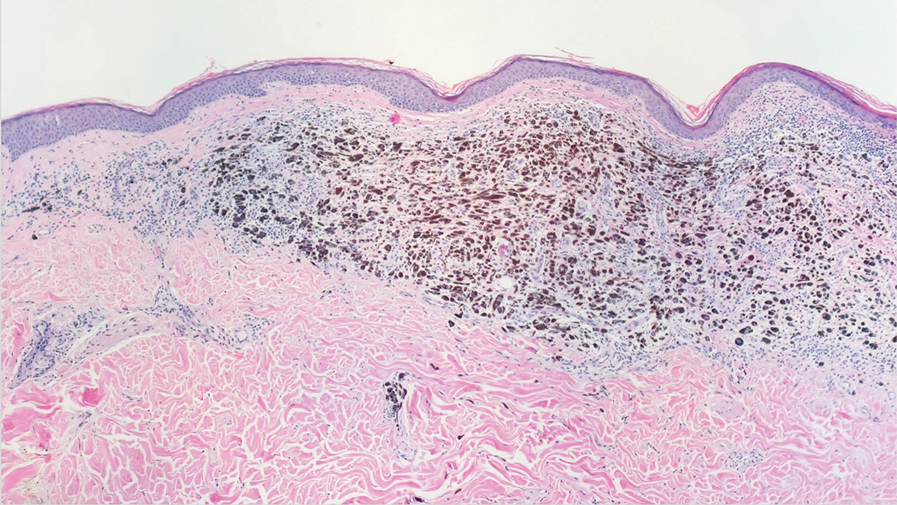

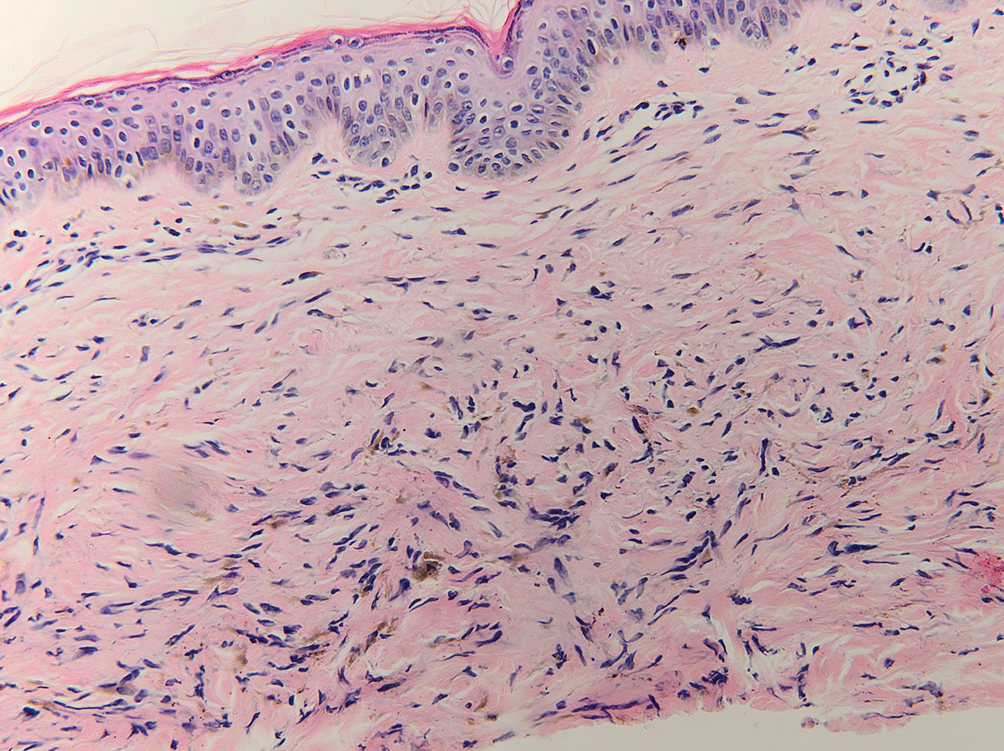

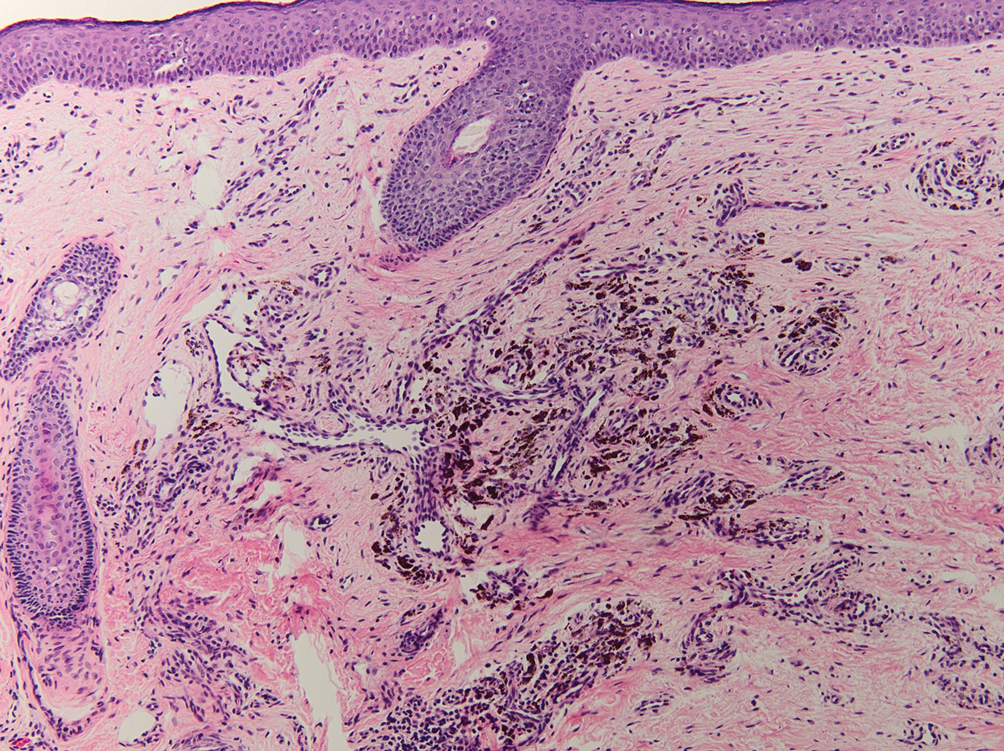

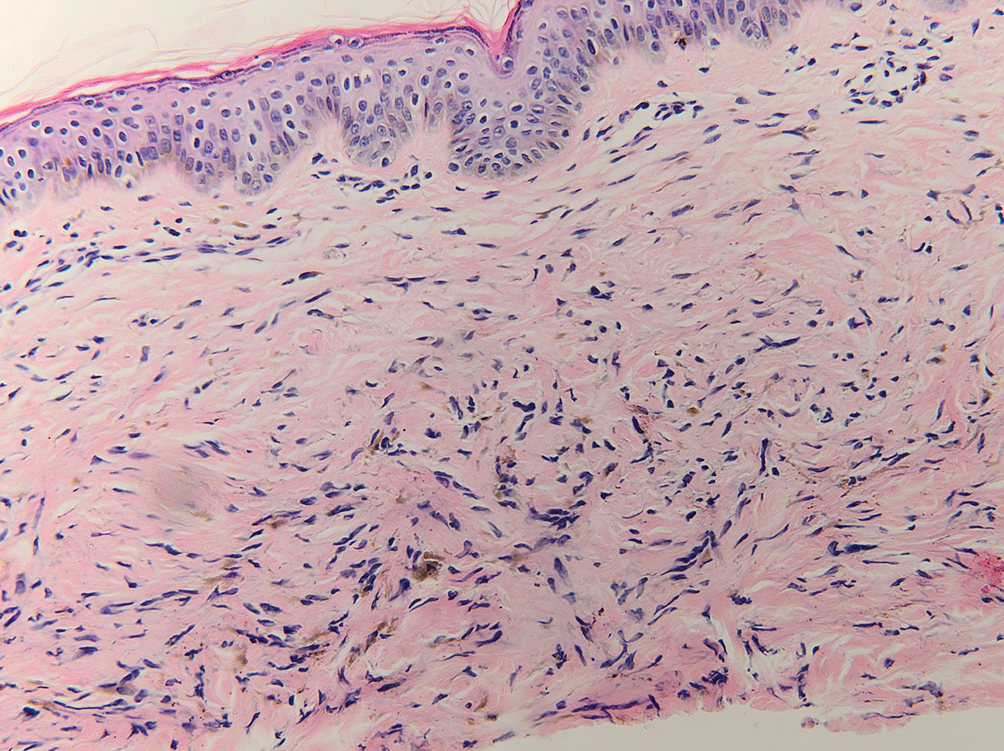

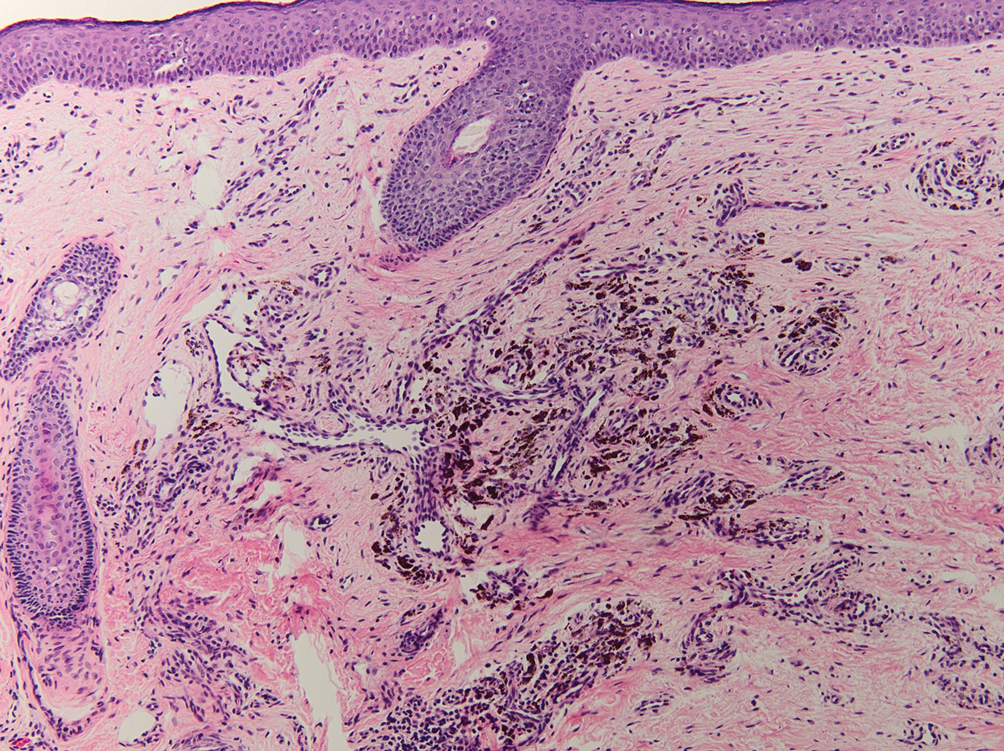

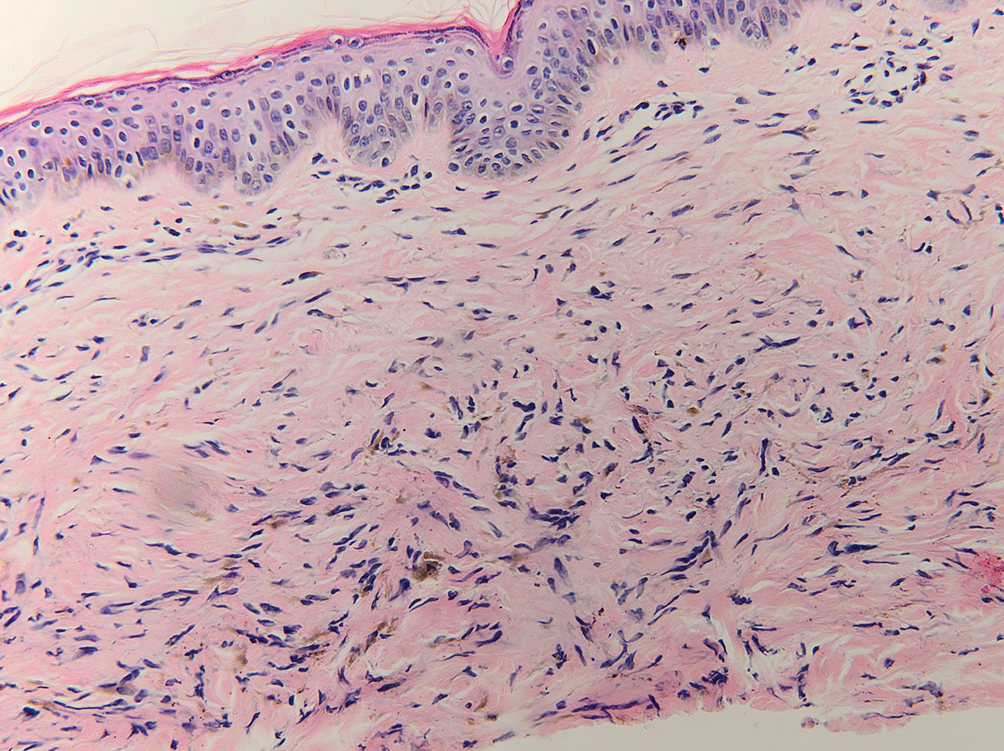

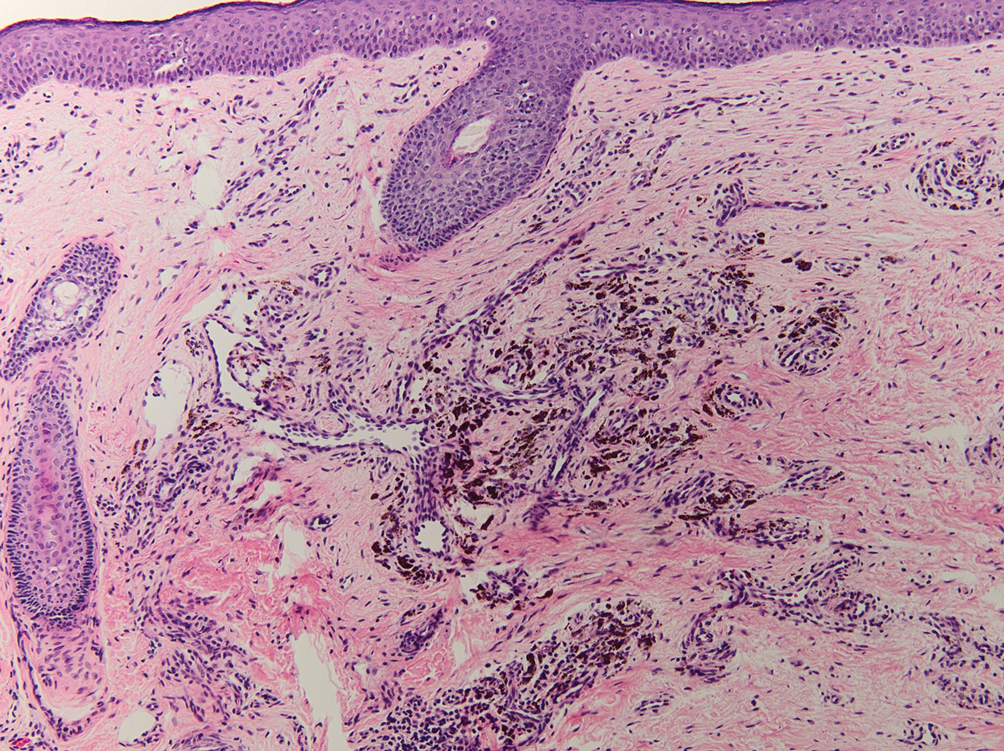

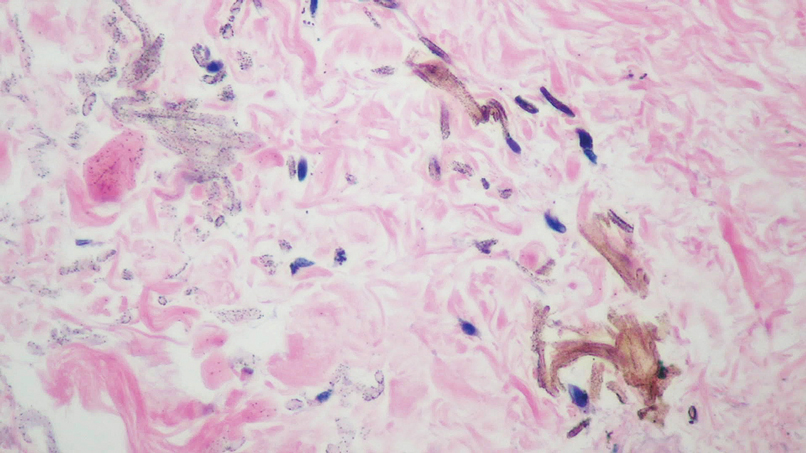

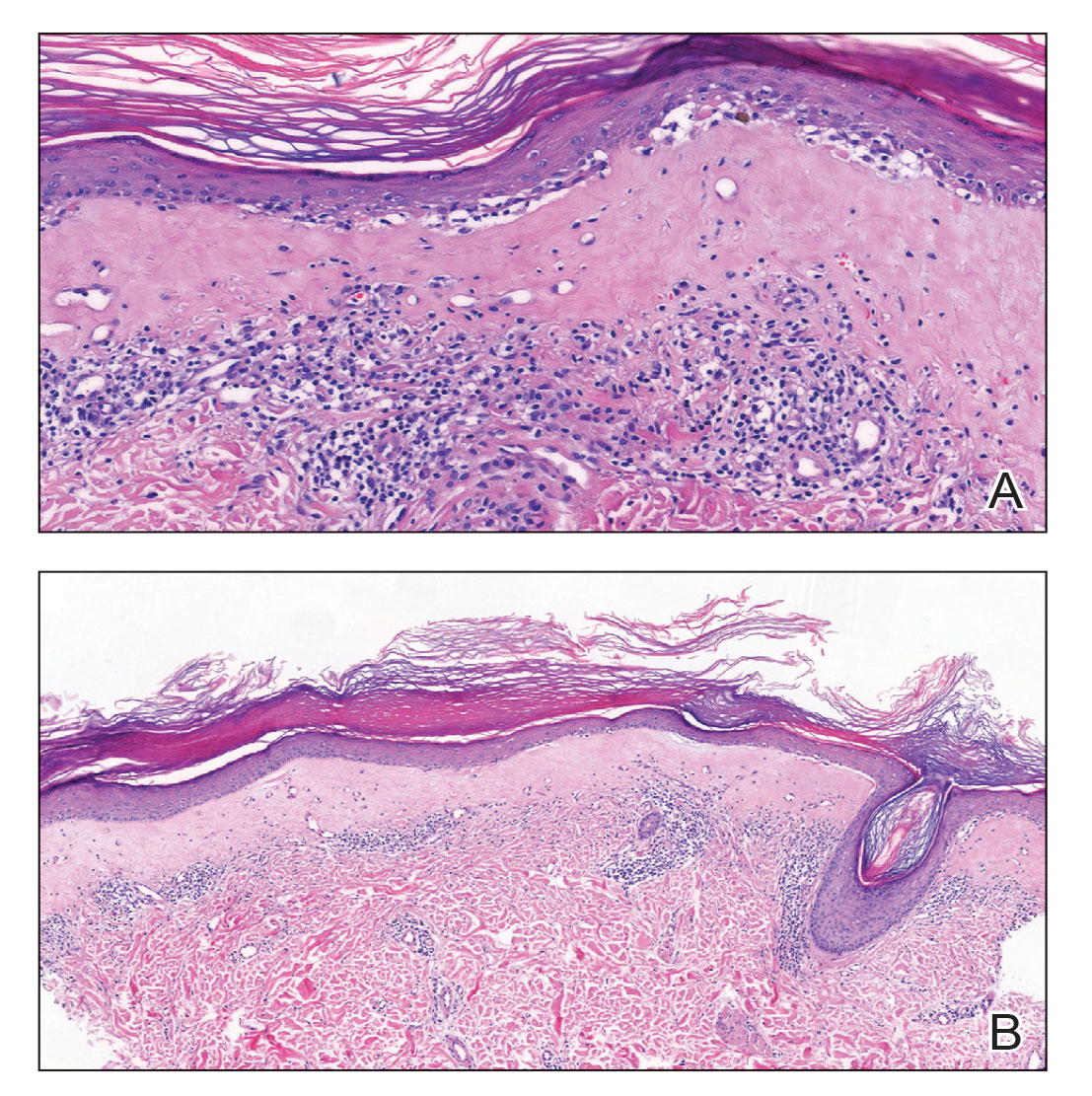

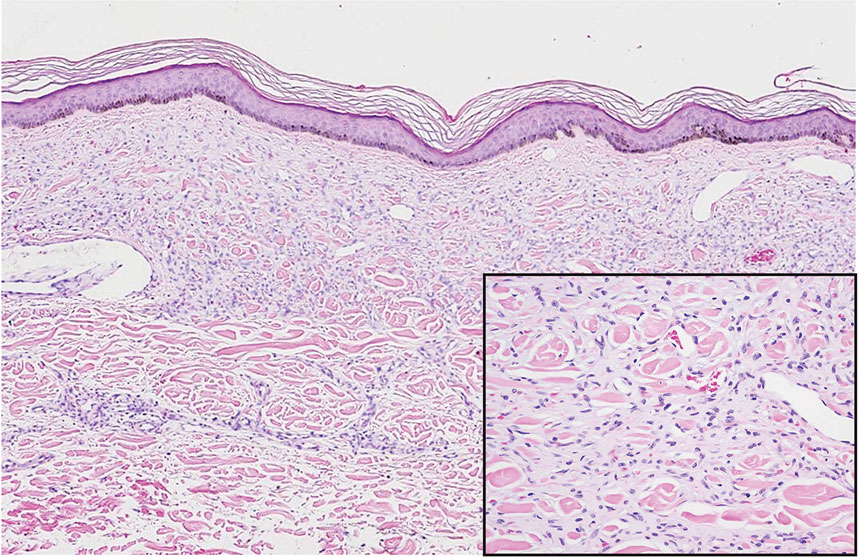

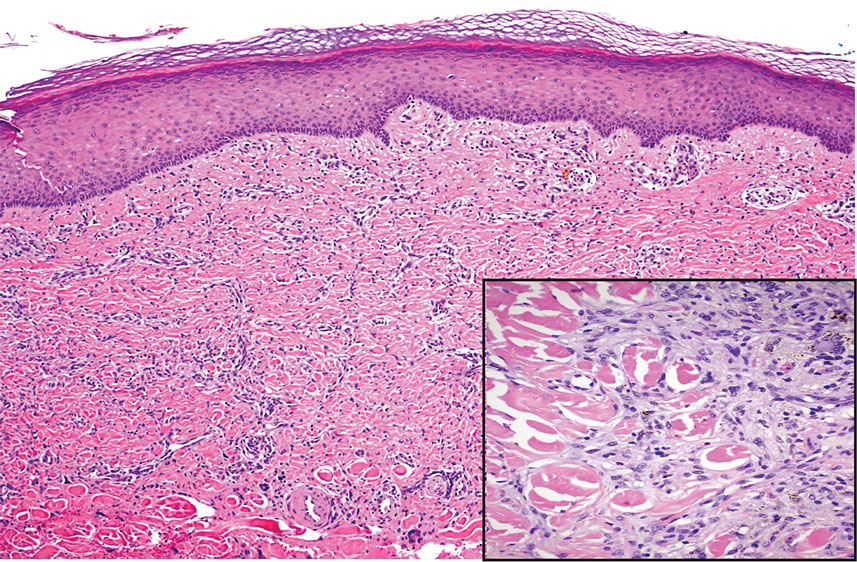

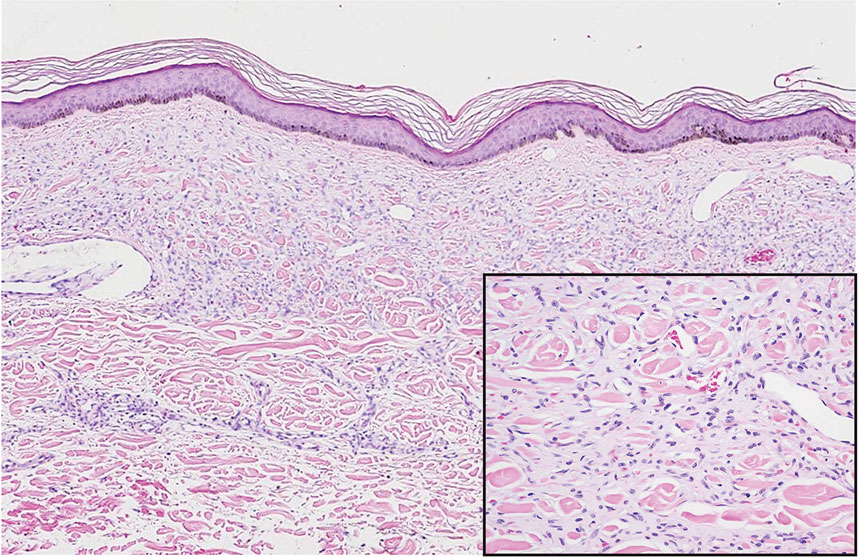

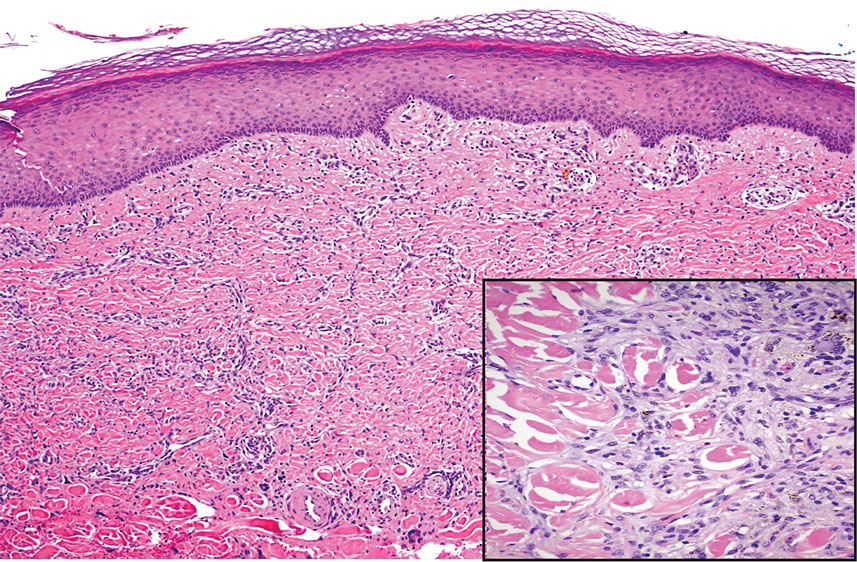

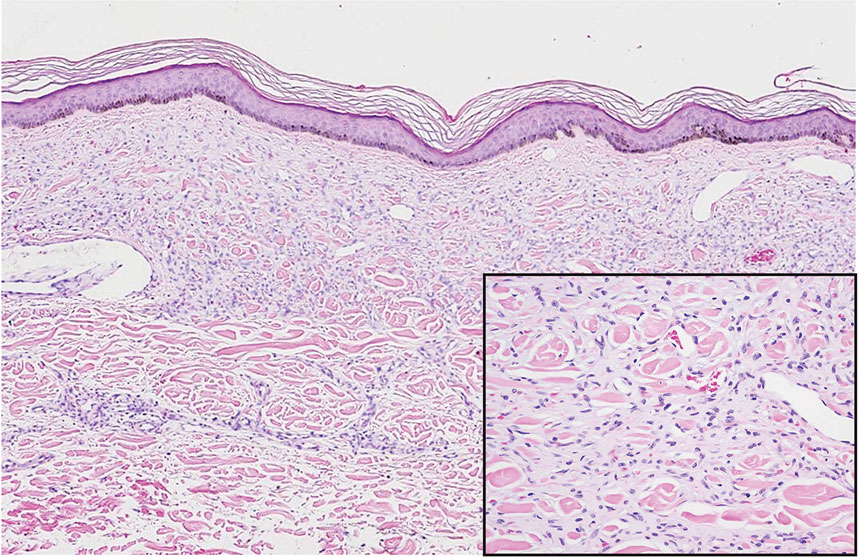

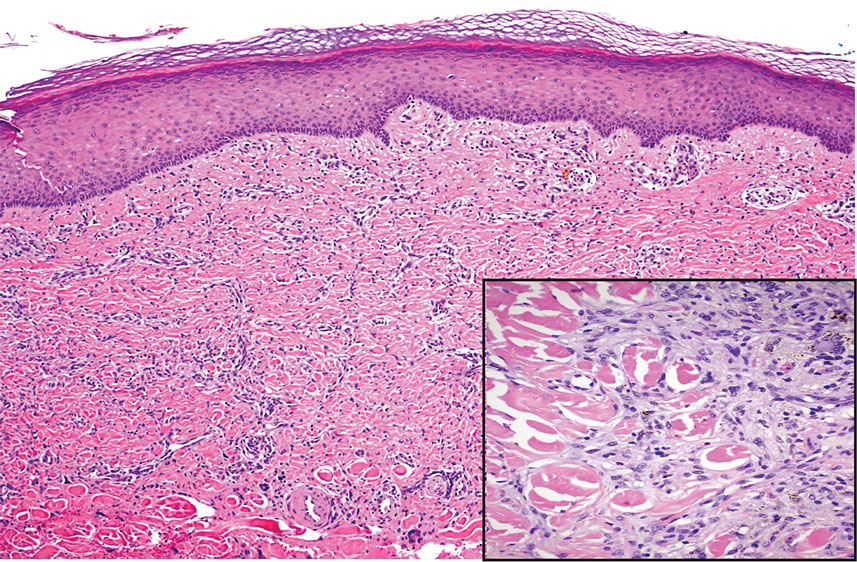

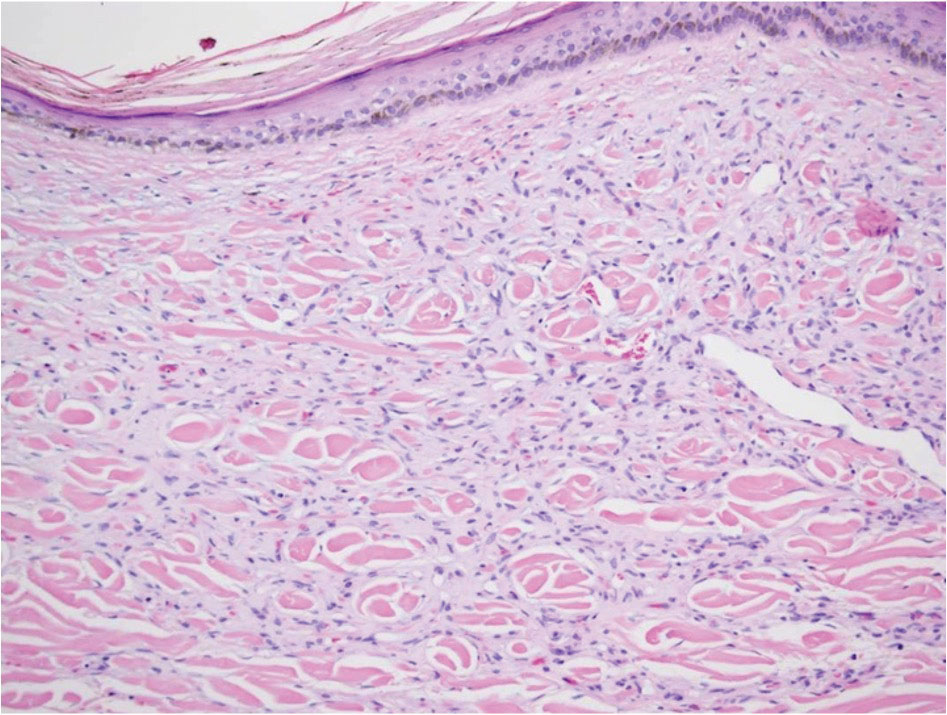

During the sixth cycle of therapy, she presented to dermatology after developing a rash. Over the next 2 weeks, similar lesions appeared on the arms. The patient denied the use of any new lotions, soaps, or other medications. Punch biopsies of the right forearm and right medial thigh revealed nonnecrotizing granulomas in the superficial dermis that extended into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 1). Surrounding chronic inflammation was scant, and the presence of rare eosinophils was noted (Figure 2). The histiocytes were highlighted by a CD68 immunohistochemical stain. An auramine-O special stain test was negative for acid-fast bacilli, and a Grocott methenamine-silver special stain test for fungal organisms was negative. These findings were consistent with GD. Computed tomography of the chest performed 2 months prior and 1 month after biopsy of the skin lesions revealed no axillary, mediastinal, or hilar lymphadenopathy. The calcium level at the time of skin biopsy was within reference range.

A topical steroid was prescribed; however, it was not utilized by the patient. Within 2 months of onset, the GD lesions resolved with no treatment. The GD lesions did not affect the patient’s enrollment in the clinical trial, and no dose reductions were made. Due to progressive disease with metastases to the brain, the patient eventually discontinued the clinical trial.

BRAF inhibitors are US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma to deactivate the serine-threonine kinase BRAF gene mutation, which leads to decreased generation and survival of melanoma cells.1,2 Vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib are the only BRAF inhibitors approved in the United States.3 The most common side effects of vemurafenib include arthralgia, fatigue, rash, and photosensitivity.1,4 There are 4 MEK inhibitors currently available in the United States: cobimetinib, trametinib, selumetinib and binimetinib. The addition of a MEK inhibitor to BRAF inhibitor therapy has shown increased patient response rates and prolonged survival in 3 phase 3 studies.5-10

Response rates remain low in the treatment of advanced cholangiocarcinoma with standard chemotherapy. Recent research has explored if targeted therapies at the molecular level would be of benefit.11 Our patient was enrolled in the American Society of Clinical Oncology Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) trial, a phase 2, prospective, nonrandomized trial that matches eligible participants to US Food and Drug Administration–approved study medications based on specific data from their molecular testing results.12 Some of the most common mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma include HER2, KRAS, MET, and BRAF.13-17 Our patient’s molecular test results were positive for a BRAF V600E–positive mutation, and she subsequently started therapy with vemurafenib and cobimetinib. The use of personalized genomic treatment approaches for BRAF V600E mutation–positive cholangiocarcinoma has produced a dramatic patient response to BRAF and MEK inhibitor combination therapies.11,18-20

Drug-induced GD most likely is caused by vascular insults that lead to deposition of immune complexes in vessels causing inflammation and a consequent granulomatous infiltrate.21,22 Although cordlike lesions in the subcutaneous tissue on the trunk commonly are reported, the presentation of GD can vary considerably. Other presentations include areas of violaceous or erythematous patches or plaques on the limbs, intertriginous areas, and upper trunk. Diffuse macular erythema or small flesh-colored papules also can be observed.23

Granulomatous dermatitis secondary to drug reactions can have varying morphologies. The infiltrate often can have an interstitial appearance with the presence of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells.24 These findings can be confused with interstitial granuloma annulare. Other cases, such as in our patient, can have discrete granulomata formation with a sarcoidlike appearance. These naked granulomas lack surrounding inflammation and suggest a differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis and infection. Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (CIs) and kinase inhibitors has been proven to cause sarcoidosislike reactions.25 The development of granulomatous/sarcoidlike lesions associated with the use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors may clinically and radiographically mimic disease recurrence. An awareness of this type of reaction by clinicians and pathologists is important to ensure appropriate management in patients who develop GD.26

Checkpoint inhibitor–induced GD that remains asymptomatic does not necessarily warrant treatment; however, corticosteroid use and elimination of CI therapies have resolved GD in prior cases. Responsiveness of the cancer to CI therapy and severity of GD symptoms should be considered before discontinuation of a CI trial.25

One case report described complete resolution of a GD eruption without interruption of the scheduled BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapies for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. There was no reported use of a steroidal cream or other topical medication to aid in controlling the eruption.27 The exact mechanism of how GD resolves while continuing therapy is unknown; however, it has been suggested that a GD eruption may be the consequence of a BRAF and MEK inhibitor–mediated immune response against a subclinical area of metastatic melanoma.28 If the immune response successfully eliminates the subclinical tumor, one could postulate that the inflammatory response and granulomatous eruption would resolve. Future studies are necessary to further elucidate the exact mechanisms involved.

There have been several case reports of GD with vemurafenib treatment,29,30 1 report of GD and erythema induratum with vemurafenib and cobimetinib treatment,31 2 reports of GD with dabrafenib treatment,27,30 and a few reports of GD with the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib combined with the MEK inhibitor trametinib,28,32,33 all for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Additionally, a report described a 3-year-old boy who developed GD secondary to vemurafenib for the treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis.34 We present a unique case of BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy–induced GD in the treatment of metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with vemurafenib and cobimetinib.

BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy is used in patients with metastatic melanomas with a positive BRAF V600E mutation. Due to advancements in next-generation DNA sequencing, these therapies also are being tested in clinical trials for use in the treatment of other cancers with the same checkpoint mutation, such as metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cutaneous reactions frequently are documented side effects that occur during treatment with BRAF and MEK inhibitors; GD is an uncommon finding. As the utilization of BRAF and MEK inhibitors increases for the treatment of a variety of other cancers, it is essential that clinicians and pathologists recognize GD as a potential cutaneous manifestation.

- Mackiewicz J, Mackiewicz A. BRAF and MEK inhibitors in the era of immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Comtemp Oncol (Pozn). 2018;22:68-72.

- Jovanovic B, Krockel D, Linden D, et al. Lack of cytoplasmic ERK activation is an independent adverse prognostic factor in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2696-2704.

- Alqathama A. BRAF in malignant melanoma progression and metastasis: potentials and challenges. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:1103-1114.

- Zimmer L, Hillen U, Livingstone E, et al. Atypical melanocytic proliferations and new primary melanomas in patients with advanced melanoma undergoing selective BRAF inhibition. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2375-2383.

- Casey D, Demko S, Sinha A, et al. FDA approval summary: selumetinib for plexiform neurofibroma. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27;4142-4146

- Flaherty K, Davies MA, Grob JJ, et al. Genomic analysis and 3-y efficacy and safety update of COMBI-d: a phase 3 study of dabrafenib (D) fl trametinib (T) vs D monotherapy in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K-mutant cutaneous melanoma. Abstract presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 3-7, 2016; Chicago, IL. P9502.

- Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:30-39.

- Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Three-year estimate of overall survival in COMBI-v, a randomized phase 3 study evaluating first-line dabrafenib (D) + trametinib (T) in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K–mutant cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 6):vi552-vi587.

- Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1867-1876.

- Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dréno B, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advance BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Once. 2016;17:1248-1260.

- Kocsis J, Árokszállási A, András C, et al. Combined dabrafenib and trametinib treatment in a case of chemotherapy-refractory extrahepatic BRAF V600E mutant cholangiocarcinoma: dramatic clinical and radiological response with a confusing synchronic new liver lesion. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:E32-E38.

- Mangat PK, Halabi S, Bruinooge SS, et al. Rationale and design of the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) Study [published online July 11, 2018]. JCO Precis Oncol. doi:10.1200/PO.18.00122

- Terada T, Ashida K, Endo K, et al. c-erbB-2 protein is expressed in hepatolithiasis and cholangiocarcinoma. Histopathology. 1998;33:325-331.

- Tannapfel A, Benicke M, Katalinic A, et al. Frequency of p16INK4A alterations and K-ras mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of the liver. Gut. 2000;47:721-727.

- Momoi H, Itoh T, Nozaki Y, et al. Microsatellite instability and alternative genetic pathway in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2001;35:235-244.

- Terada T, Nakanuma Y, Sirica AE. Immunohistochemical demonstration of MET overexpression in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and in hepatolithiasis. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:175-180.

- Tannapfel A, Sommerer F, Benicke M, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in cholangiocarcinoma but not in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2003;52:706-712.

- Bunyatov T, Zhao A, Kovalenko J, et al. Personalised approach in combined treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: a case report of healing from cholangiocellular carcinoma at stage IV. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:815-820.

- Lavingia V, Fakih M. Impressive response to dual BRAF and MEK inhibition in patients with BRAF mutant intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma-2 case reports and a brief review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:E98-E102.

- Loaiza-Bonilla A, Clayton E, Furth E, et al. Dramatic response to dabrafenib and trametinib combination in a BRAF V600E-mutated cholangiocarcinoma: implementation of a molecular tumour board and next-generation sequencing for personalized medicine. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:479.

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol 2012;166:775-783.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, Billings S. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. In: McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. China: Elsevier Limited: 2018;7:241-282.

- Gkiozos I, Kopitopoulou A, Kalkanis A, et al. Sarcoidosis-like reactions induced by checkpoint inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1076-1082.

- Tetzlaff MT, Nelson KC, Diab A, et al. Granulomatous/sarcoid-like lesions associated with checkpoint inhibitors: a marker of therapy response in a subset of melanoma patients. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:14.

- Garrido MC, Gutiérrez C, Riveiro-Falkenbach E, et al. BRAF inhibitor-induced antitumoral granulomatous dermatitis eruption in advanced melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:795-798.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307‐311.

- Ong ELH, Sinha R, Jmor S, et al. BRAF inhibitor-associated granulomatous dermatitis: a report of 3 cases. Am J of Dermatopathol. 2019;41:214-217.

- Wali GN, Stonard C, Espinosa O, et al. Persistent granulomatous cutaneous drug eruption to a BRAF inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(suppl 1):AB195.

- Aj lafolla M, Ramsay J, Wismer J, et al. Cobimetinib- and vemurafenib-induced granulomatous dermatitis and erythema induratum: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847358

- Jansen YJ, Janssens P, Hoorens A, et al. Granulomatous nephritis and dermatitis in a patient with BRAF V600E mutant metastatic melanoma treated with dabrafenib and trametinib. Melanoma Res. 2015;25:550‐554.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell J. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

- Chen L, His A, Kothari A, et al. Granulomatous dermatitis secondary to vemurafenib in a child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E402-E403.

To the Editor:

Granulomatous dermatitis (GD) has been described as a rare side effect of MEK and BRAF inhibitor use in the treatment of BRAF V600E mutation–positive metastatic melanoma. As the utilization of BRAF and MEK inhibitors increases for the treatment of a variety of cancers, it is essential that clinicians and pathologists recognize GD as a potential cutaneous manifestation. We present the case of a 52-year-old woman who developed GD while being treated with vemurafenib and cobimetinib for BRAF V600E mutation–positive metastatic cholangiocarcinoma.

A 52-year-old White woman presented with faint patches of nonpalpable violaceous mottling that extended distally to proximally from the ankles to the thighs on the medial aspects of both legs. She was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma 10 months prior, with metastases to the lung, liver, and sternum. She underwent treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin therapy. Computed tomography after several treatment cycles revealed progressive disease with multiple pulmonary nodules as well as metastatic intrathoracic and abdominal adenopathy. Treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin failed to produce a favorable response and was discontinued after 6 treatment cycles.

Genomic testing performed at the time of diagnosis revealed a positive mutation for BRAF V600E. The patient subsequently enrolled in a clinical trial and started treatment with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib and the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib. She developed sun sensitivity and multiple sunburns after starting these therapies. The patient tolerated the next few cycles of therapy well with only moderate concerns of dry sensitive skin.

During the sixth cycle of therapy, she presented to dermatology after developing a rash. Over the next 2 weeks, similar lesions appeared on the arms. The patient denied the use of any new lotions, soaps, or other medications. Punch biopsies of the right forearm and right medial thigh revealed nonnecrotizing granulomas in the superficial dermis that extended into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 1). Surrounding chronic inflammation was scant, and the presence of rare eosinophils was noted (Figure 2). The histiocytes were highlighted by a CD68 immunohistochemical stain. An auramine-O special stain test was negative for acid-fast bacilli, and a Grocott methenamine-silver special stain test for fungal organisms was negative. These findings were consistent with GD. Computed tomography of the chest performed 2 months prior and 1 month after biopsy of the skin lesions revealed no axillary, mediastinal, or hilar lymphadenopathy. The calcium level at the time of skin biopsy was within reference range.

A topical steroid was prescribed; however, it was not utilized by the patient. Within 2 months of onset, the GD lesions resolved with no treatment. The GD lesions did not affect the patient’s enrollment in the clinical trial, and no dose reductions were made. Due to progressive disease with metastases to the brain, the patient eventually discontinued the clinical trial.

BRAF inhibitors are US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma to deactivate the serine-threonine kinase BRAF gene mutation, which leads to decreased generation and survival of melanoma cells.1,2 Vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib are the only BRAF inhibitors approved in the United States.3 The most common side effects of vemurafenib include arthralgia, fatigue, rash, and photosensitivity.1,4 There are 4 MEK inhibitors currently available in the United States: cobimetinib, trametinib, selumetinib and binimetinib. The addition of a MEK inhibitor to BRAF inhibitor therapy has shown increased patient response rates and prolonged survival in 3 phase 3 studies.5-10

Response rates remain low in the treatment of advanced cholangiocarcinoma with standard chemotherapy. Recent research has explored if targeted therapies at the molecular level would be of benefit.11 Our patient was enrolled in the American Society of Clinical Oncology Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) trial, a phase 2, prospective, nonrandomized trial that matches eligible participants to US Food and Drug Administration–approved study medications based on specific data from their molecular testing results.12 Some of the most common mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma include HER2, KRAS, MET, and BRAF.13-17 Our patient’s molecular test results were positive for a BRAF V600E–positive mutation, and she subsequently started therapy with vemurafenib and cobimetinib. The use of personalized genomic treatment approaches for BRAF V600E mutation–positive cholangiocarcinoma has produced a dramatic patient response to BRAF and MEK inhibitor combination therapies.11,18-20

Drug-induced GD most likely is caused by vascular insults that lead to deposition of immune complexes in vessels causing inflammation and a consequent granulomatous infiltrate.21,22 Although cordlike lesions in the subcutaneous tissue on the trunk commonly are reported, the presentation of GD can vary considerably. Other presentations include areas of violaceous or erythematous patches or plaques on the limbs, intertriginous areas, and upper trunk. Diffuse macular erythema or small flesh-colored papules also can be observed.23

Granulomatous dermatitis secondary to drug reactions can have varying morphologies. The infiltrate often can have an interstitial appearance with the presence of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells.24 These findings can be confused with interstitial granuloma annulare. Other cases, such as in our patient, can have discrete granulomata formation with a sarcoidlike appearance. These naked granulomas lack surrounding inflammation and suggest a differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis and infection. Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (CIs) and kinase inhibitors has been proven to cause sarcoidosislike reactions.25 The development of granulomatous/sarcoidlike lesions associated with the use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors may clinically and radiographically mimic disease recurrence. An awareness of this type of reaction by clinicians and pathologists is important to ensure appropriate management in patients who develop GD.26

Checkpoint inhibitor–induced GD that remains asymptomatic does not necessarily warrant treatment; however, corticosteroid use and elimination of CI therapies have resolved GD in prior cases. Responsiveness of the cancer to CI therapy and severity of GD symptoms should be considered before discontinuation of a CI trial.25

One case report described complete resolution of a GD eruption without interruption of the scheduled BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapies for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. There was no reported use of a steroidal cream or other topical medication to aid in controlling the eruption.27 The exact mechanism of how GD resolves while continuing therapy is unknown; however, it has been suggested that a GD eruption may be the consequence of a BRAF and MEK inhibitor–mediated immune response against a subclinical area of metastatic melanoma.28 If the immune response successfully eliminates the subclinical tumor, one could postulate that the inflammatory response and granulomatous eruption would resolve. Future studies are necessary to further elucidate the exact mechanisms involved.

There have been several case reports of GD with vemurafenib treatment,29,30 1 report of GD and erythema induratum with vemurafenib and cobimetinib treatment,31 2 reports of GD with dabrafenib treatment,27,30 and a few reports of GD with the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib combined with the MEK inhibitor trametinib,28,32,33 all for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Additionally, a report described a 3-year-old boy who developed GD secondary to vemurafenib for the treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis.34 We present a unique case of BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy–induced GD in the treatment of metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with vemurafenib and cobimetinib.

BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy is used in patients with metastatic melanomas with a positive BRAF V600E mutation. Due to advancements in next-generation DNA sequencing, these therapies also are being tested in clinical trials for use in the treatment of other cancers with the same checkpoint mutation, such as metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cutaneous reactions frequently are documented side effects that occur during treatment with BRAF and MEK inhibitors; GD is an uncommon finding. As the utilization of BRAF and MEK inhibitors increases for the treatment of a variety of other cancers, it is essential that clinicians and pathologists recognize GD as a potential cutaneous manifestation.

To the Editor:

Granulomatous dermatitis (GD) has been described as a rare side effect of MEK and BRAF inhibitor use in the treatment of BRAF V600E mutation–positive metastatic melanoma. As the utilization of BRAF and MEK inhibitors increases for the treatment of a variety of cancers, it is essential that clinicians and pathologists recognize GD as a potential cutaneous manifestation. We present the case of a 52-year-old woman who developed GD while being treated with vemurafenib and cobimetinib for BRAF V600E mutation–positive metastatic cholangiocarcinoma.

A 52-year-old White woman presented with faint patches of nonpalpable violaceous mottling that extended distally to proximally from the ankles to the thighs on the medial aspects of both legs. She was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma 10 months prior, with metastases to the lung, liver, and sternum. She underwent treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin therapy. Computed tomography after several treatment cycles revealed progressive disease with multiple pulmonary nodules as well as metastatic intrathoracic and abdominal adenopathy. Treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin failed to produce a favorable response and was discontinued after 6 treatment cycles.

Genomic testing performed at the time of diagnosis revealed a positive mutation for BRAF V600E. The patient subsequently enrolled in a clinical trial and started treatment with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib and the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib. She developed sun sensitivity and multiple sunburns after starting these therapies. The patient tolerated the next few cycles of therapy well with only moderate concerns of dry sensitive skin.

During the sixth cycle of therapy, she presented to dermatology after developing a rash. Over the next 2 weeks, similar lesions appeared on the arms. The patient denied the use of any new lotions, soaps, or other medications. Punch biopsies of the right forearm and right medial thigh revealed nonnecrotizing granulomas in the superficial dermis that extended into the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 1). Surrounding chronic inflammation was scant, and the presence of rare eosinophils was noted (Figure 2). The histiocytes were highlighted by a CD68 immunohistochemical stain. An auramine-O special stain test was negative for acid-fast bacilli, and a Grocott methenamine-silver special stain test for fungal organisms was negative. These findings were consistent with GD. Computed tomography of the chest performed 2 months prior and 1 month after biopsy of the skin lesions revealed no axillary, mediastinal, or hilar lymphadenopathy. The calcium level at the time of skin biopsy was within reference range.

A topical steroid was prescribed; however, it was not utilized by the patient. Within 2 months of onset, the GD lesions resolved with no treatment. The GD lesions did not affect the patient’s enrollment in the clinical trial, and no dose reductions were made. Due to progressive disease with metastases to the brain, the patient eventually discontinued the clinical trial.

BRAF inhibitors are US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma to deactivate the serine-threonine kinase BRAF gene mutation, which leads to decreased generation and survival of melanoma cells.1,2 Vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib are the only BRAF inhibitors approved in the United States.3 The most common side effects of vemurafenib include arthralgia, fatigue, rash, and photosensitivity.1,4 There are 4 MEK inhibitors currently available in the United States: cobimetinib, trametinib, selumetinib and binimetinib. The addition of a MEK inhibitor to BRAF inhibitor therapy has shown increased patient response rates and prolonged survival in 3 phase 3 studies.5-10

Response rates remain low in the treatment of advanced cholangiocarcinoma with standard chemotherapy. Recent research has explored if targeted therapies at the molecular level would be of benefit.11 Our patient was enrolled in the American Society of Clinical Oncology Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) trial, a phase 2, prospective, nonrandomized trial that matches eligible participants to US Food and Drug Administration–approved study medications based on specific data from their molecular testing results.12 Some of the most common mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma include HER2, KRAS, MET, and BRAF.13-17 Our patient’s molecular test results were positive for a BRAF V600E–positive mutation, and she subsequently started therapy with vemurafenib and cobimetinib. The use of personalized genomic treatment approaches for BRAF V600E mutation–positive cholangiocarcinoma has produced a dramatic patient response to BRAF and MEK inhibitor combination therapies.11,18-20

Drug-induced GD most likely is caused by vascular insults that lead to deposition of immune complexes in vessels causing inflammation and a consequent granulomatous infiltrate.21,22 Although cordlike lesions in the subcutaneous tissue on the trunk commonly are reported, the presentation of GD can vary considerably. Other presentations include areas of violaceous or erythematous patches or plaques on the limbs, intertriginous areas, and upper trunk. Diffuse macular erythema or small flesh-colored papules also can be observed.23

Granulomatous dermatitis secondary to drug reactions can have varying morphologies. The infiltrate often can have an interstitial appearance with the presence of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells.24 These findings can be confused with interstitial granuloma annulare. Other cases, such as in our patient, can have discrete granulomata formation with a sarcoidlike appearance. These naked granulomas lack surrounding inflammation and suggest a differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis and infection. Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (CIs) and kinase inhibitors has been proven to cause sarcoidosislike reactions.25 The development of granulomatous/sarcoidlike lesions associated with the use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors may clinically and radiographically mimic disease recurrence. An awareness of this type of reaction by clinicians and pathologists is important to ensure appropriate management in patients who develop GD.26

Checkpoint inhibitor–induced GD that remains asymptomatic does not necessarily warrant treatment; however, corticosteroid use and elimination of CI therapies have resolved GD in prior cases. Responsiveness of the cancer to CI therapy and severity of GD symptoms should be considered before discontinuation of a CI trial.25

One case report described complete resolution of a GD eruption without interruption of the scheduled BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapies for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. There was no reported use of a steroidal cream or other topical medication to aid in controlling the eruption.27 The exact mechanism of how GD resolves while continuing therapy is unknown; however, it has been suggested that a GD eruption may be the consequence of a BRAF and MEK inhibitor–mediated immune response against a subclinical area of metastatic melanoma.28 If the immune response successfully eliminates the subclinical tumor, one could postulate that the inflammatory response and granulomatous eruption would resolve. Future studies are necessary to further elucidate the exact mechanisms involved.

There have been several case reports of GD with vemurafenib treatment,29,30 1 report of GD and erythema induratum with vemurafenib and cobimetinib treatment,31 2 reports of GD with dabrafenib treatment,27,30 and a few reports of GD with the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib combined with the MEK inhibitor trametinib,28,32,33 all for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Additionally, a report described a 3-year-old boy who developed GD secondary to vemurafenib for the treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis.34 We present a unique case of BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy–induced GD in the treatment of metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with vemurafenib and cobimetinib.

BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapy is used in patients with metastatic melanomas with a positive BRAF V600E mutation. Due to advancements in next-generation DNA sequencing, these therapies also are being tested in clinical trials for use in the treatment of other cancers with the same checkpoint mutation, such as metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cutaneous reactions frequently are documented side effects that occur during treatment with BRAF and MEK inhibitors; GD is an uncommon finding. As the utilization of BRAF and MEK inhibitors increases for the treatment of a variety of other cancers, it is essential that clinicians and pathologists recognize GD as a potential cutaneous manifestation.

- Mackiewicz J, Mackiewicz A. BRAF and MEK inhibitors in the era of immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Comtemp Oncol (Pozn). 2018;22:68-72.

- Jovanovic B, Krockel D, Linden D, et al. Lack of cytoplasmic ERK activation is an independent adverse prognostic factor in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2696-2704.

- Alqathama A. BRAF in malignant melanoma progression and metastasis: potentials and challenges. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:1103-1114.

- Zimmer L, Hillen U, Livingstone E, et al. Atypical melanocytic proliferations and new primary melanomas in patients with advanced melanoma undergoing selective BRAF inhibition. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2375-2383.

- Casey D, Demko S, Sinha A, et al. FDA approval summary: selumetinib for plexiform neurofibroma. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27;4142-4146

- Flaherty K, Davies MA, Grob JJ, et al. Genomic analysis and 3-y efficacy and safety update of COMBI-d: a phase 3 study of dabrafenib (D) fl trametinib (T) vs D monotherapy in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K-mutant cutaneous melanoma. Abstract presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 3-7, 2016; Chicago, IL. P9502.

- Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:30-39.

- Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Three-year estimate of overall survival in COMBI-v, a randomized phase 3 study evaluating first-line dabrafenib (D) + trametinib (T) in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K–mutant cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 6):vi552-vi587.

- Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1867-1876.

- Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dréno B, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advance BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Once. 2016;17:1248-1260.

- Kocsis J, Árokszállási A, András C, et al. Combined dabrafenib and trametinib treatment in a case of chemotherapy-refractory extrahepatic BRAF V600E mutant cholangiocarcinoma: dramatic clinical and radiological response with a confusing synchronic new liver lesion. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:E32-E38.

- Mangat PK, Halabi S, Bruinooge SS, et al. Rationale and design of the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) Study [published online July 11, 2018]. JCO Precis Oncol. doi:10.1200/PO.18.00122

- Terada T, Ashida K, Endo K, et al. c-erbB-2 protein is expressed in hepatolithiasis and cholangiocarcinoma. Histopathology. 1998;33:325-331.

- Tannapfel A, Benicke M, Katalinic A, et al. Frequency of p16INK4A alterations and K-ras mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of the liver. Gut. 2000;47:721-727.

- Momoi H, Itoh T, Nozaki Y, et al. Microsatellite instability and alternative genetic pathway in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2001;35:235-244.

- Terada T, Nakanuma Y, Sirica AE. Immunohistochemical demonstration of MET overexpression in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and in hepatolithiasis. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:175-180.

- Tannapfel A, Sommerer F, Benicke M, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in cholangiocarcinoma but not in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2003;52:706-712.

- Bunyatov T, Zhao A, Kovalenko J, et al. Personalised approach in combined treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: a case report of healing from cholangiocellular carcinoma at stage IV. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:815-820.

- Lavingia V, Fakih M. Impressive response to dual BRAF and MEK inhibition in patients with BRAF mutant intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma-2 case reports and a brief review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:E98-E102.

- Loaiza-Bonilla A, Clayton E, Furth E, et al. Dramatic response to dabrafenib and trametinib combination in a BRAF V600E-mutated cholangiocarcinoma: implementation of a molecular tumour board and next-generation sequencing for personalized medicine. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:479.

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol 2012;166:775-783.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, Billings S. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. In: McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. China: Elsevier Limited: 2018;7:241-282.

- Gkiozos I, Kopitopoulou A, Kalkanis A, et al. Sarcoidosis-like reactions induced by checkpoint inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1076-1082.

- Tetzlaff MT, Nelson KC, Diab A, et al. Granulomatous/sarcoid-like lesions associated with checkpoint inhibitors: a marker of therapy response in a subset of melanoma patients. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:14.

- Garrido MC, Gutiérrez C, Riveiro-Falkenbach E, et al. BRAF inhibitor-induced antitumoral granulomatous dermatitis eruption in advanced melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:795-798.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307‐311.

- Ong ELH, Sinha R, Jmor S, et al. BRAF inhibitor-associated granulomatous dermatitis: a report of 3 cases. Am J of Dermatopathol. 2019;41:214-217.

- Wali GN, Stonard C, Espinosa O, et al. Persistent granulomatous cutaneous drug eruption to a BRAF inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(suppl 1):AB195.

- Aj lafolla M, Ramsay J, Wismer J, et al. Cobimetinib- and vemurafenib-induced granulomatous dermatitis and erythema induratum: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847358

- Jansen YJ, Janssens P, Hoorens A, et al. Granulomatous nephritis and dermatitis in a patient with BRAF V600E mutant metastatic melanoma treated with dabrafenib and trametinib. Melanoma Res. 2015;25:550‐554.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell J. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

- Chen L, His A, Kothari A, et al. Granulomatous dermatitis secondary to vemurafenib in a child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E402-E403.

- Mackiewicz J, Mackiewicz A. BRAF and MEK inhibitors in the era of immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Comtemp Oncol (Pozn). 2018;22:68-72.

- Jovanovic B, Krockel D, Linden D, et al. Lack of cytoplasmic ERK activation is an independent adverse prognostic factor in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2696-2704.

- Alqathama A. BRAF in malignant melanoma progression and metastasis: potentials and challenges. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:1103-1114.

- Zimmer L, Hillen U, Livingstone E, et al. Atypical melanocytic proliferations and new primary melanomas in patients with advanced melanoma undergoing selective BRAF inhibition. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2375-2383.

- Casey D, Demko S, Sinha A, et al. FDA approval summary: selumetinib for plexiform neurofibroma. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27;4142-4146

- Flaherty K, Davies MA, Grob JJ, et al. Genomic analysis and 3-y efficacy and safety update of COMBI-d: a phase 3 study of dabrafenib (D) fl trametinib (T) vs D monotherapy in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K-mutant cutaneous melanoma. Abstract presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 3-7, 2016; Chicago, IL. P9502.

- Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:30-39.

- Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Three-year estimate of overall survival in COMBI-v, a randomized phase 3 study evaluating first-line dabrafenib (D) + trametinib (T) in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K–mutant cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 6):vi552-vi587.

- Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1867-1876.

- Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dréno B, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advance BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Once. 2016;17:1248-1260.

- Kocsis J, Árokszállási A, András C, et al. Combined dabrafenib and trametinib treatment in a case of chemotherapy-refractory extrahepatic BRAF V600E mutant cholangiocarcinoma: dramatic clinical and radiological response with a confusing synchronic new liver lesion. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:E32-E38.

- Mangat PK, Halabi S, Bruinooge SS, et al. Rationale and design of the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) Study [published online July 11, 2018]. JCO Precis Oncol. doi:10.1200/PO.18.00122

- Terada T, Ashida K, Endo K, et al. c-erbB-2 protein is expressed in hepatolithiasis and cholangiocarcinoma. Histopathology. 1998;33:325-331.

- Tannapfel A, Benicke M, Katalinic A, et al. Frequency of p16INK4A alterations and K-ras mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of the liver. Gut. 2000;47:721-727.

- Momoi H, Itoh T, Nozaki Y, et al. Microsatellite instability and alternative genetic pathway in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2001;35:235-244.

- Terada T, Nakanuma Y, Sirica AE. Immunohistochemical demonstration of MET overexpression in human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and in hepatolithiasis. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:175-180.

- Tannapfel A, Sommerer F, Benicke M, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in cholangiocarcinoma but not in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2003;52:706-712.

- Bunyatov T, Zhao A, Kovalenko J, et al. Personalised approach in combined treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: a case report of healing from cholangiocellular carcinoma at stage IV. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:815-820.

- Lavingia V, Fakih M. Impressive response to dual BRAF and MEK inhibition in patients with BRAF mutant intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma-2 case reports and a brief review. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:E98-E102.

- Loaiza-Bonilla A, Clayton E, Furth E, et al. Dramatic response to dabrafenib and trametinib combination in a BRAF V600E-mutated cholangiocarcinoma: implementation of a molecular tumour board and next-generation sequencing for personalized medicine. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:479.

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol 2012;166:775-783.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, Billings S. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. In: McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. China: Elsevier Limited: 2018;7:241-282.

- Gkiozos I, Kopitopoulou A, Kalkanis A, et al. Sarcoidosis-like reactions induced by checkpoint inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1076-1082.

- Tetzlaff MT, Nelson KC, Diab A, et al. Granulomatous/sarcoid-like lesions associated with checkpoint inhibitors: a marker of therapy response in a subset of melanoma patients. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:14.

- Garrido MC, Gutiérrez C, Riveiro-Falkenbach E, et al. BRAF inhibitor-induced antitumoral granulomatous dermatitis eruption in advanced melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:795-798.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307‐311.

- Ong ELH, Sinha R, Jmor S, et al. BRAF inhibitor-associated granulomatous dermatitis: a report of 3 cases. Am J of Dermatopathol. 2019;41:214-217.

- Wali GN, Stonard C, Espinosa O, et al. Persistent granulomatous cutaneous drug eruption to a BRAF inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(suppl 1):AB195.

- Aj lafolla M, Ramsay J, Wismer J, et al. Cobimetinib- and vemurafenib-induced granulomatous dermatitis and erythema induratum: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19847358

- Jansen YJ, Janssens P, Hoorens A, et al. Granulomatous nephritis and dermatitis in a patient with BRAF V600E mutant metastatic melanoma treated with dabrafenib and trametinib. Melanoma Res. 2015;25:550‐554.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell J. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

- Chen L, His A, Kothari A, et al. Granulomatous dermatitis secondary to vemurafenib in a child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E402-E403.

Practice Points

- Granulomatous dermatitis (GD) is a potential rare side effect of the use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors for the treatment of BRAF V600 mutation–positive cancers, including metastatic cholangiocarcinoma.

- Granulomatous dermatitis can resolve despite continuation of BRAF and MEK inhibitor therapies.

- Histologically, GD can appear similar to disease recurrence. It is imperative that clinicians and pathologists recognize the cutaneous manifestations of BRAF and MEK inhibitors.

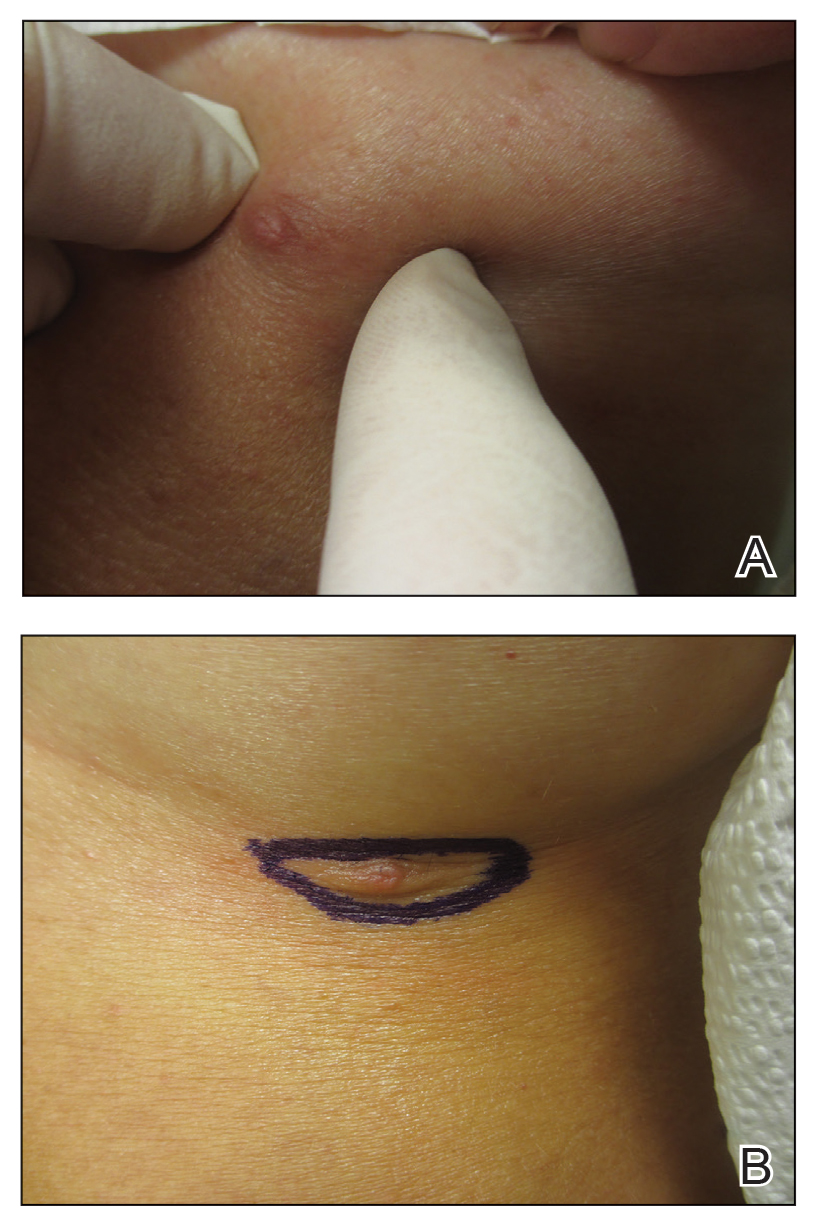

Pruritic Papules in the Perianal and Gluteal Cleft Regions

The Diagnosis: Papular Acantholytic Dyskeratosis

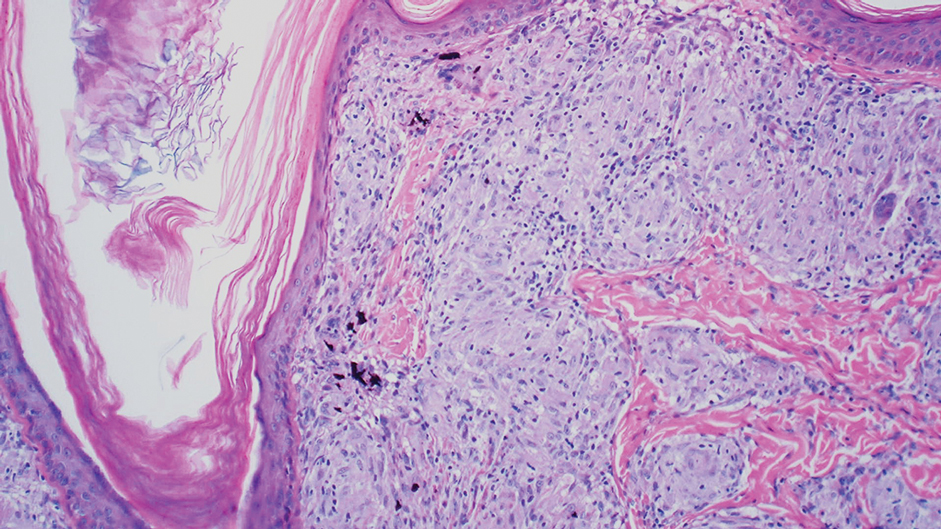

The shave biopsy revealed suprabasal clefts associated with acantholytic and dyskeratotic cells as well as overlying hyperkeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative. Based on the combined clinical and histological findings, the patient was diagnosed with papular acantholytic dyskeratosis (PAD), a rare disease that clinically presents as small whitishgreyish papules with the potential to coalesce into larger plaques.1,2 The condition predominantly manifests without symptoms, though pruritus and burning have been reported in affected sites. Most cases of PAD have been reported in older adults rather than in children or adolescents; it is more prevalent in women than in men. Lesions generally are localized to the penis, vulva, scrotum, inguinal folds, and perianal region.3 More specific terms have been used to describe this presentation such as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the anogenital region and papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genital-crural region. Histologic findings of PAD include epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis (quiz image).

The histologic differential diagnosis of PAD is broad due to its overlapping features with other diseases such as pemphigus vulgaris, Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), Darier disease, and Grover disease. The acantholytic pathophysiology of these conditions involves dysfunction in cell adhesion markers. The correct diagnosis can be made by considering both the clinical location of involvement and histopathologic clues.

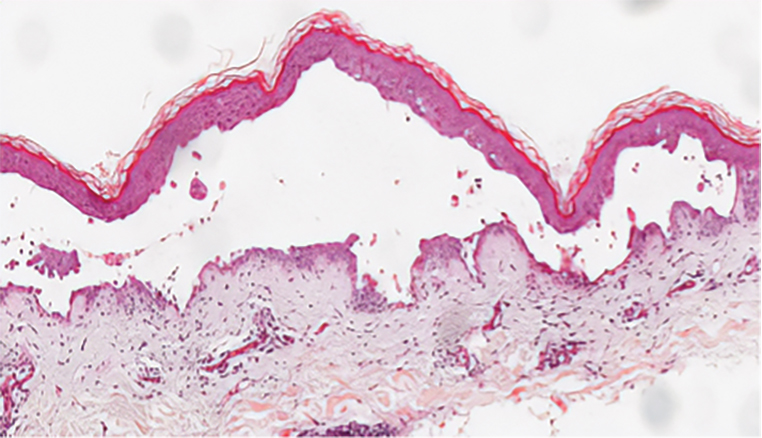

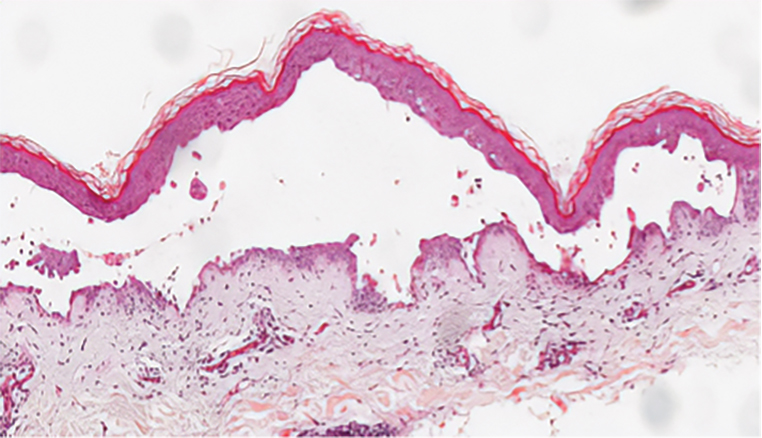

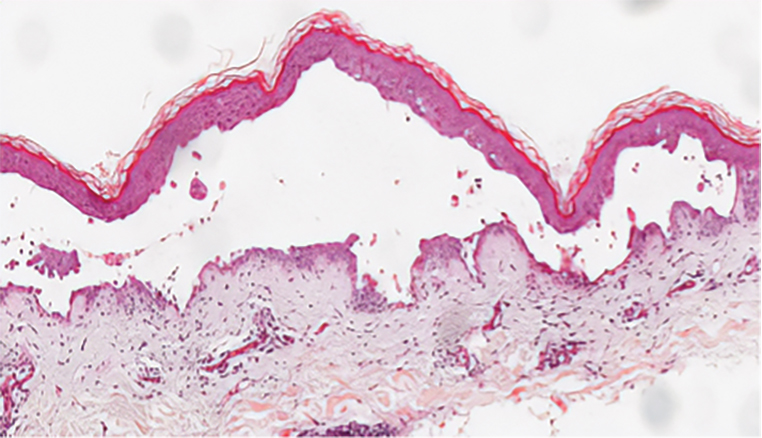

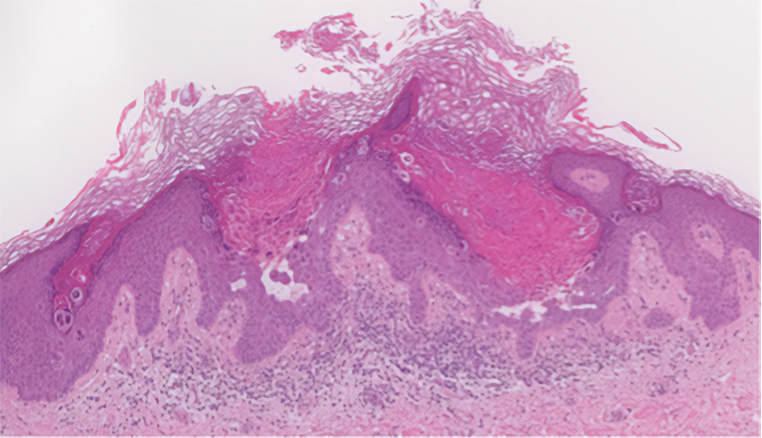

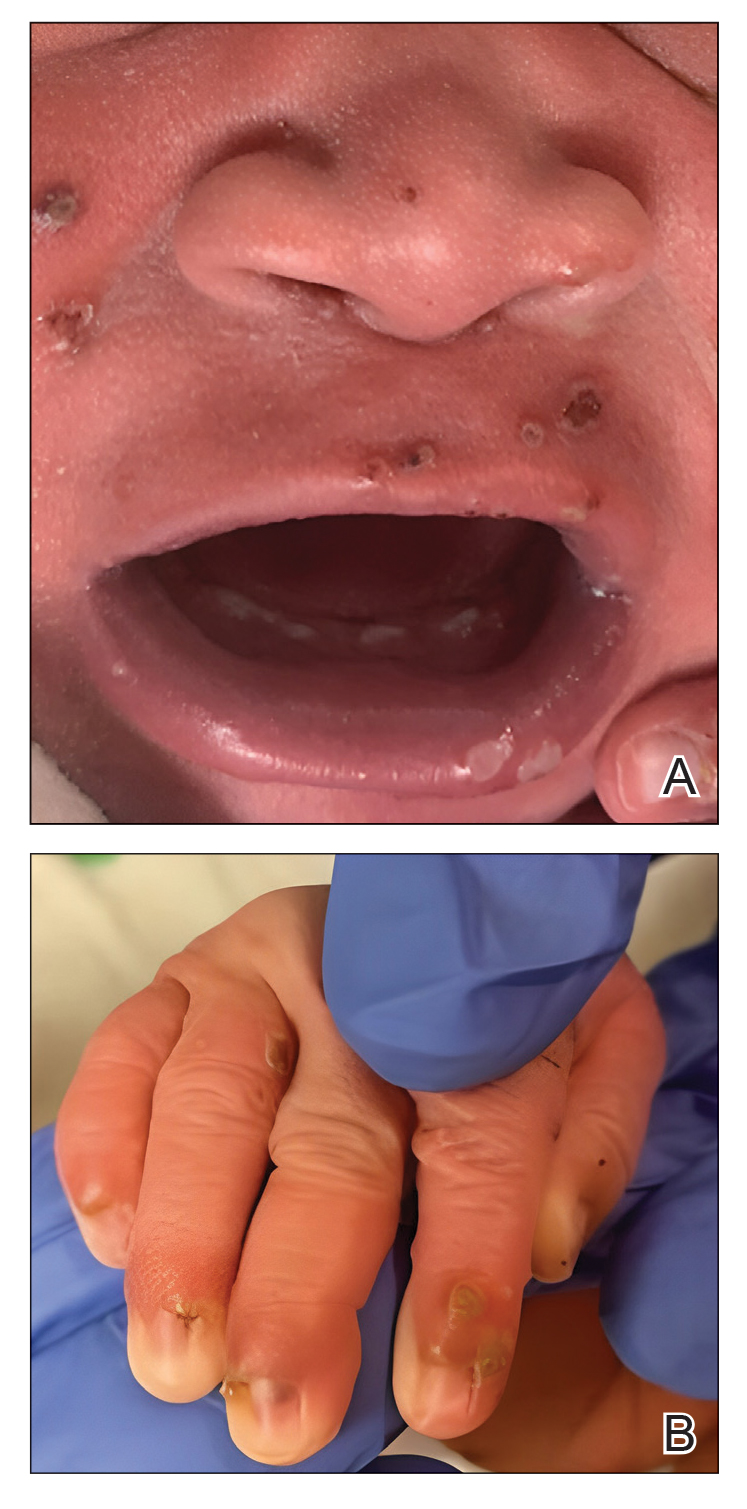

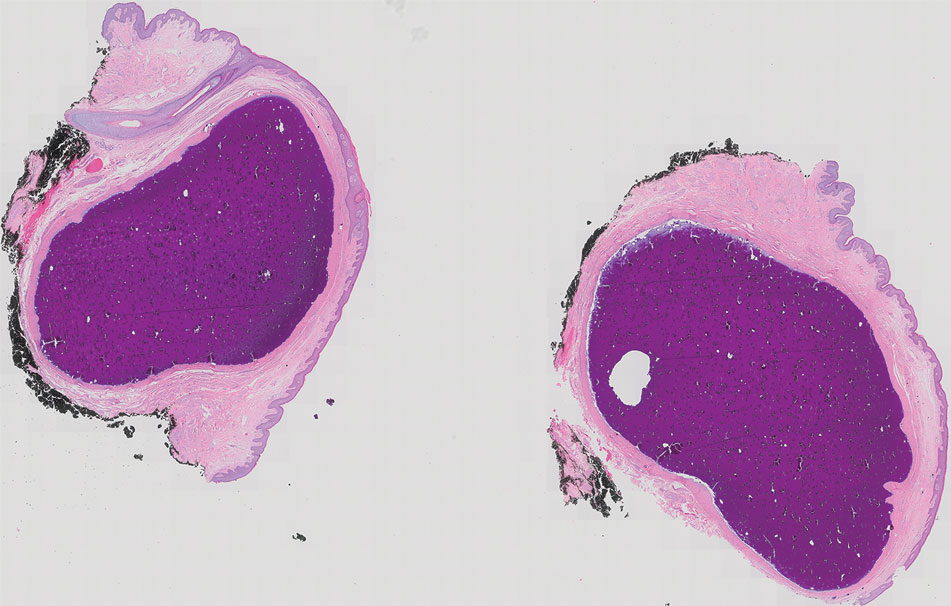

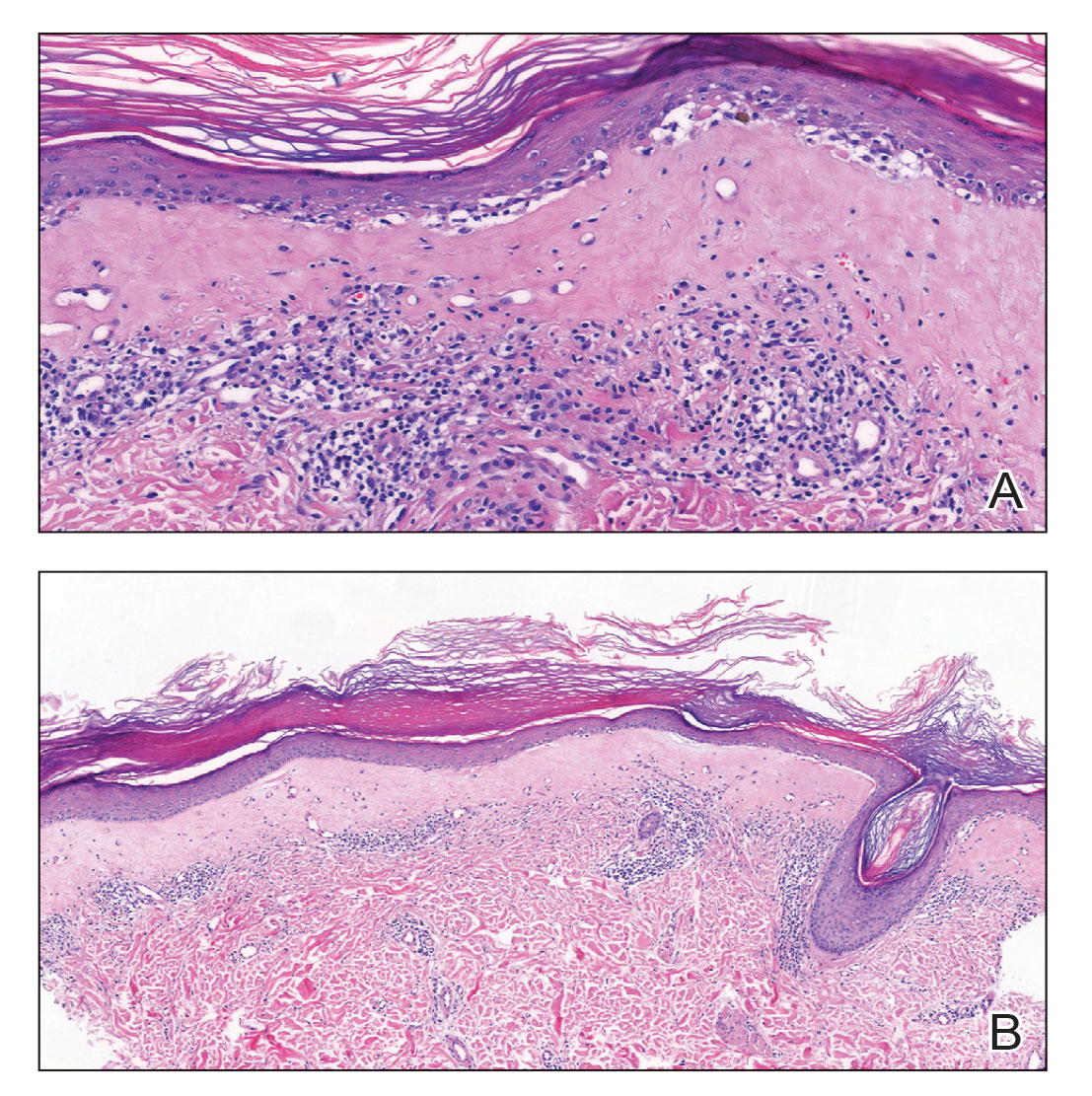

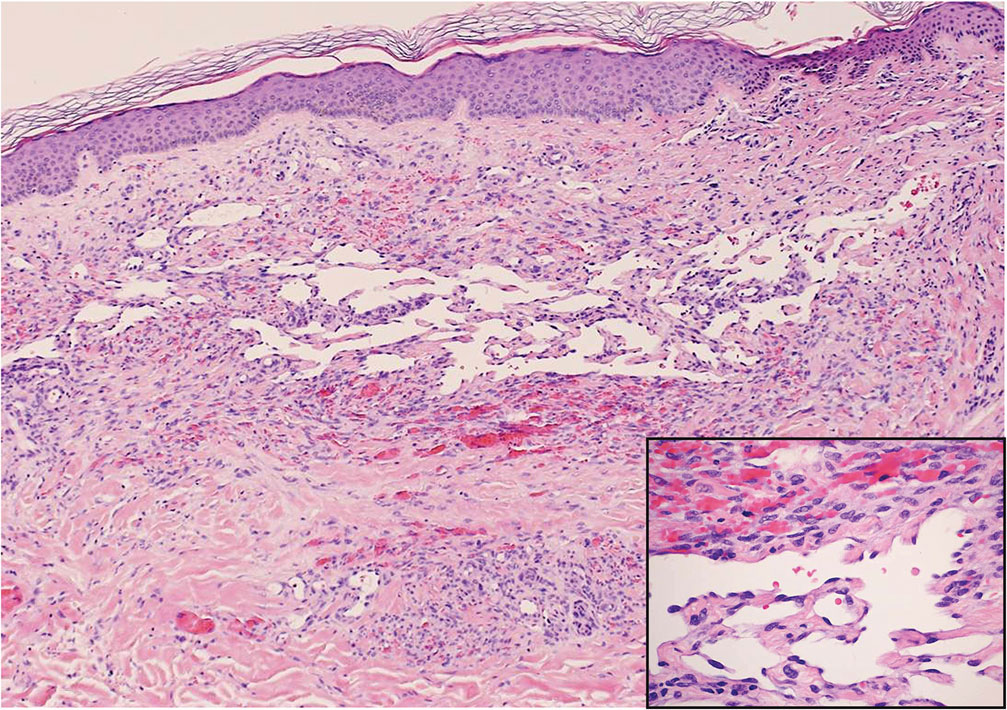

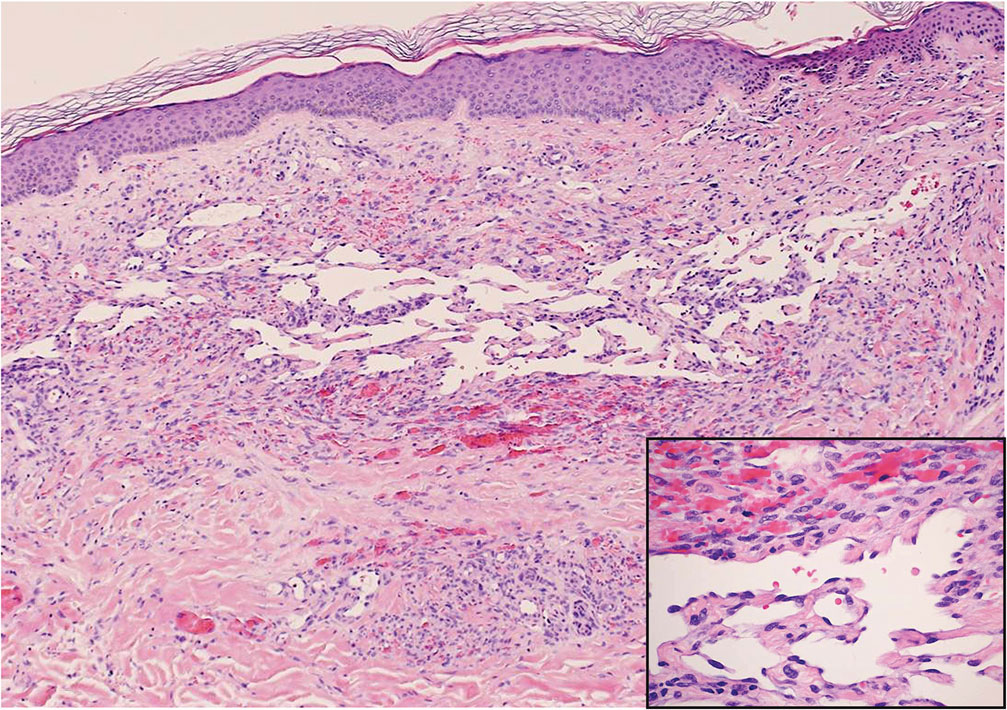

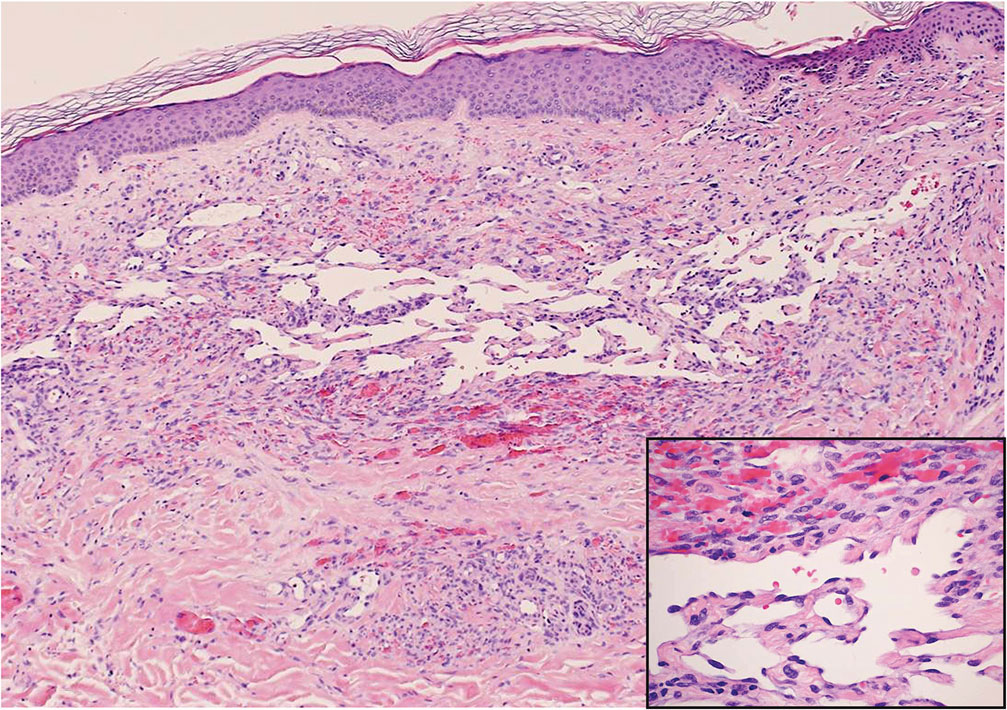

Pemphigus is a family of disorders involving mucocutaneous blistering of an autoimmune nature (Figure 1). Pemphigus vulgaris is the most prevalent variant of the pemphigus family, with symptomatically painful involvement of mucosal and cutaneous tissue. Autoantibodies to desmoglein 3 alone or both desmoglein 1 and 3 are present. Pemphigus vulgaris displays positive DIF findings with intercellular IgG and C3.

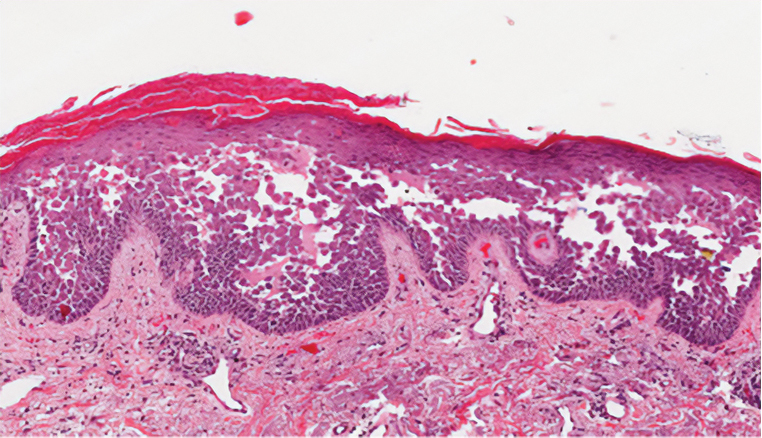

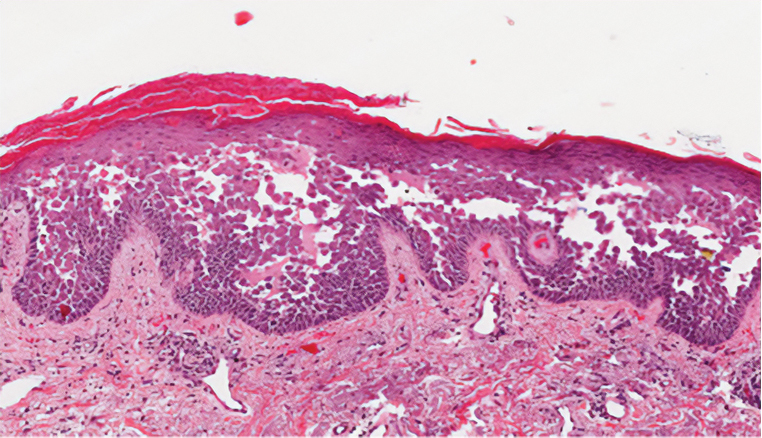

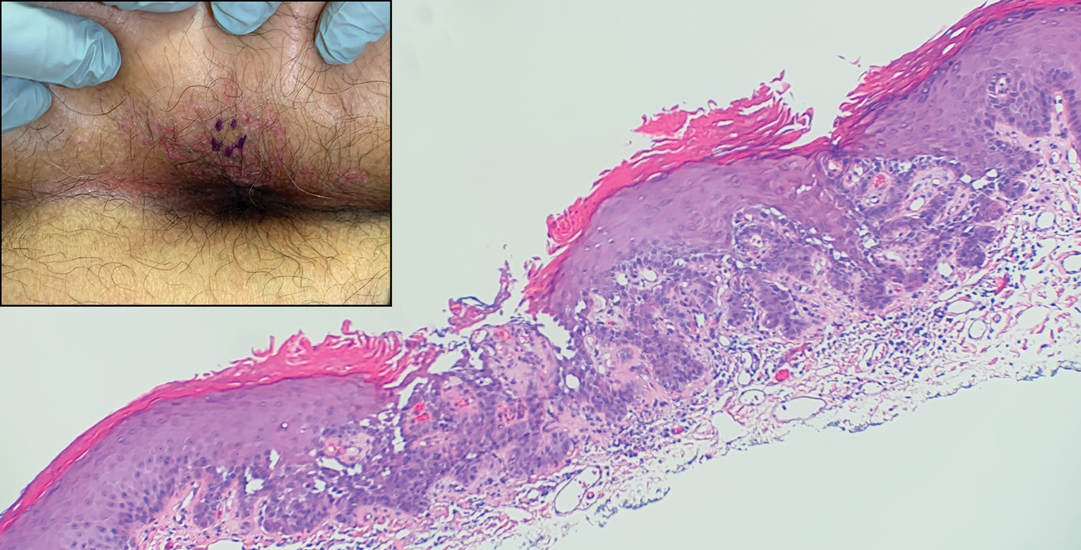

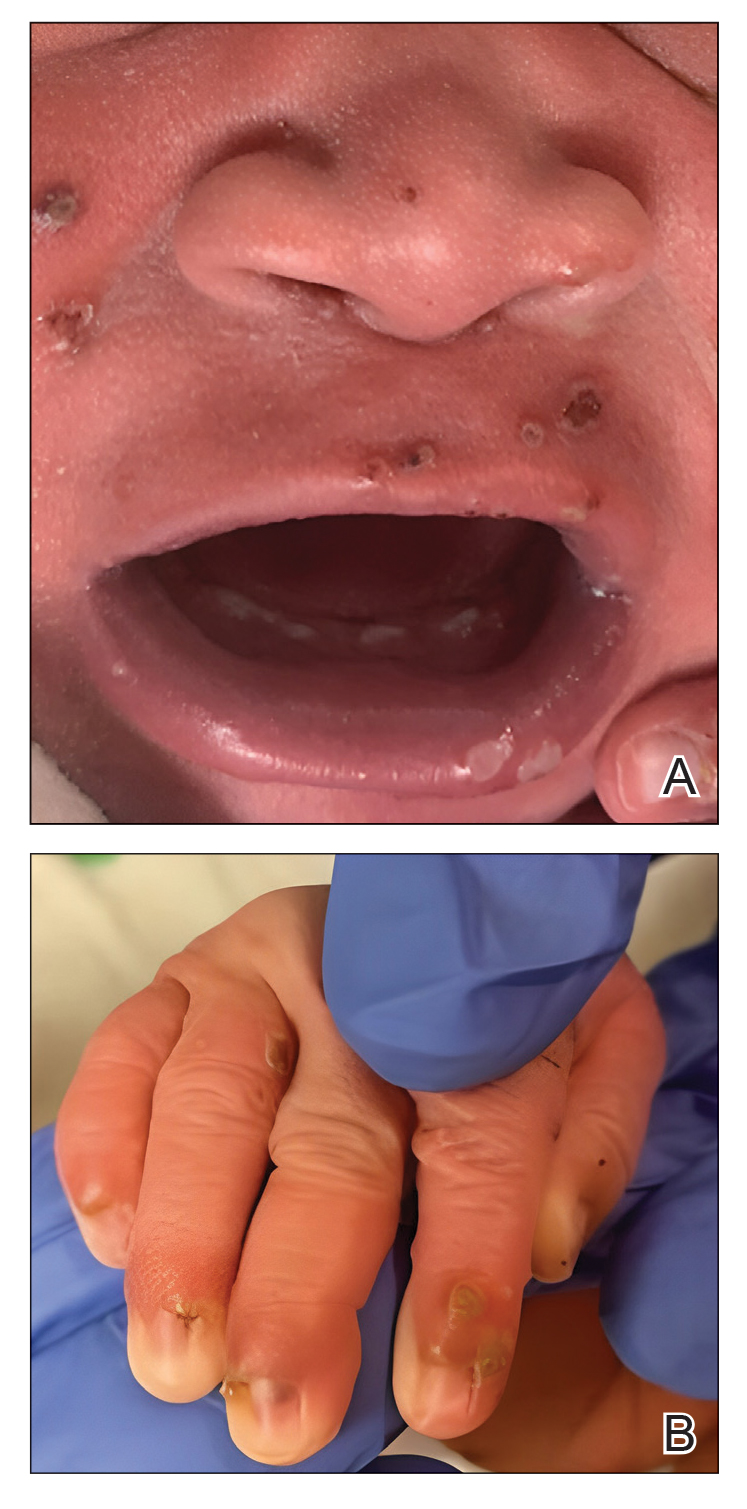

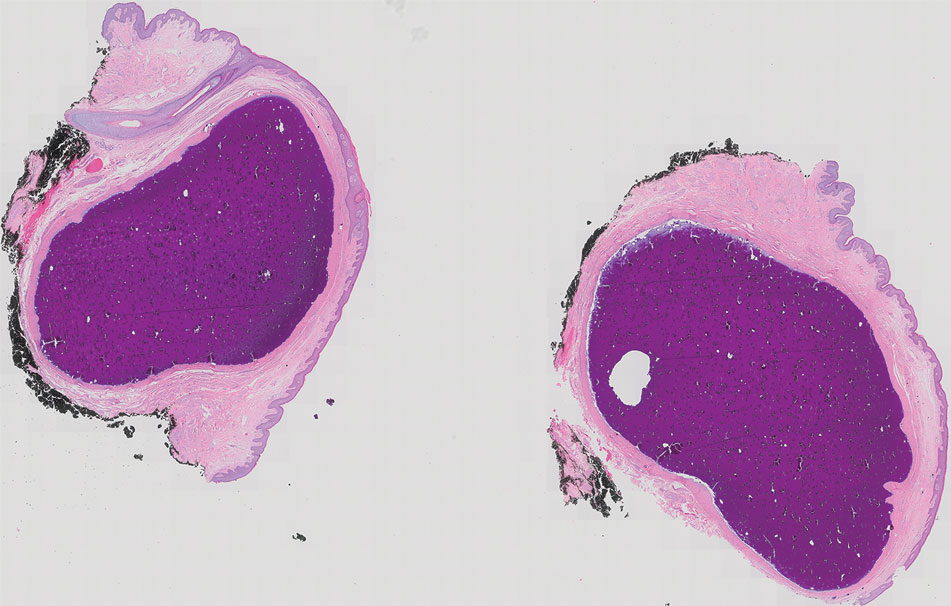

Hailey-Hailey disease (also known as benign familial pemphigus) is an autosomal-dominant disease that shares the acantholytic feature that is common in this class of diseases and caused by a defect in cell-cell adhesion as well as a loss of function in the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Blistering lesions typically appear in the neck, axillary, inguinal, or genital regions, and they can develop into crusted, exudate-filled lesions. No autoimmunity has been associated with this disease, unlike other diseases in the pemphigus family, and mutations in the ATP2C1 gene have been linked with dysregulation of cell-cell adhesion, particularly in cadherins and calcium-dependent cell adhesion processes. Histologically, HHD will show diffuse keratinocyte acantholysis with suprabasal clefting (Figure 2).4 Dyskeratosis is mild, if present at all, and dyskeratotic keratinocytes show a well-defined nucleus with cytoplasmic preservation. In contrast to HHD, PAD typically shows more dyskeratosis.

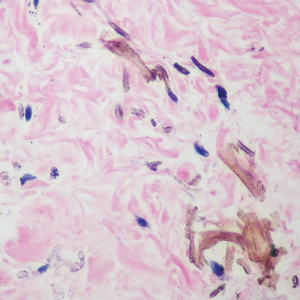

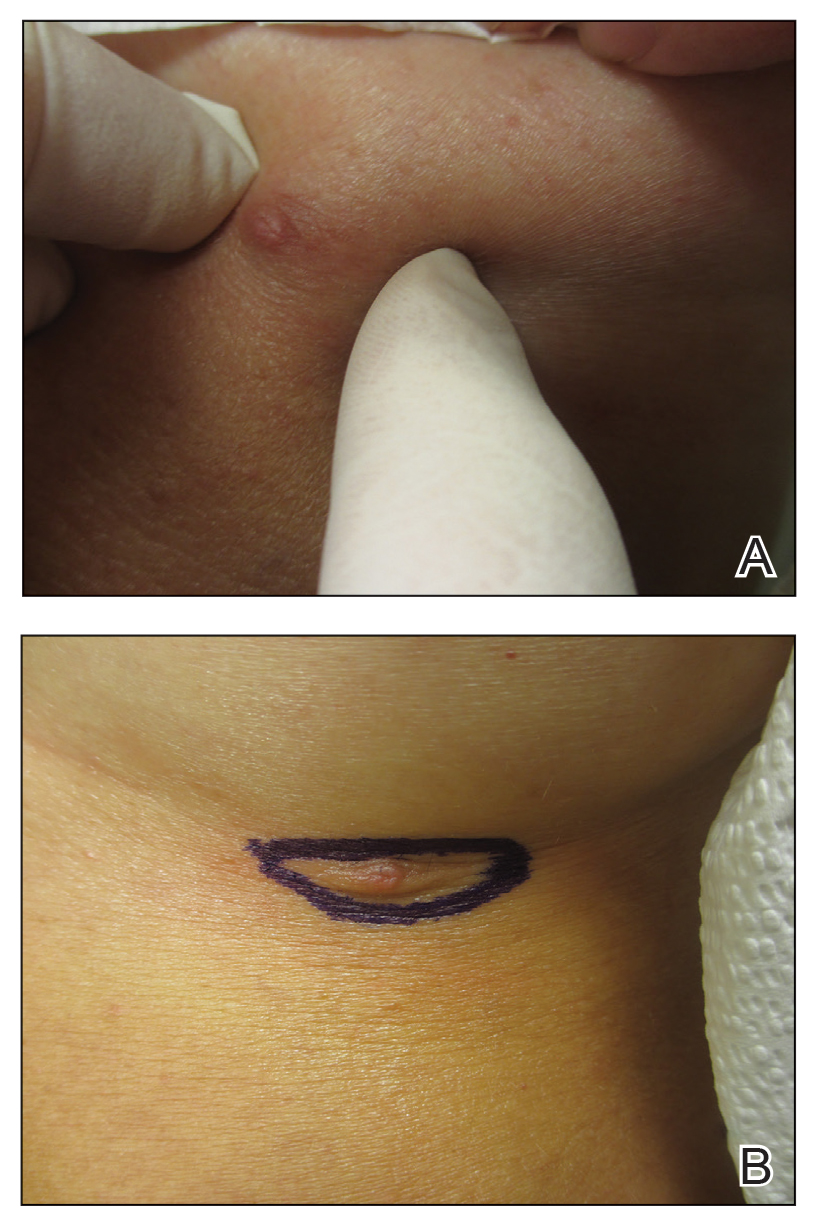

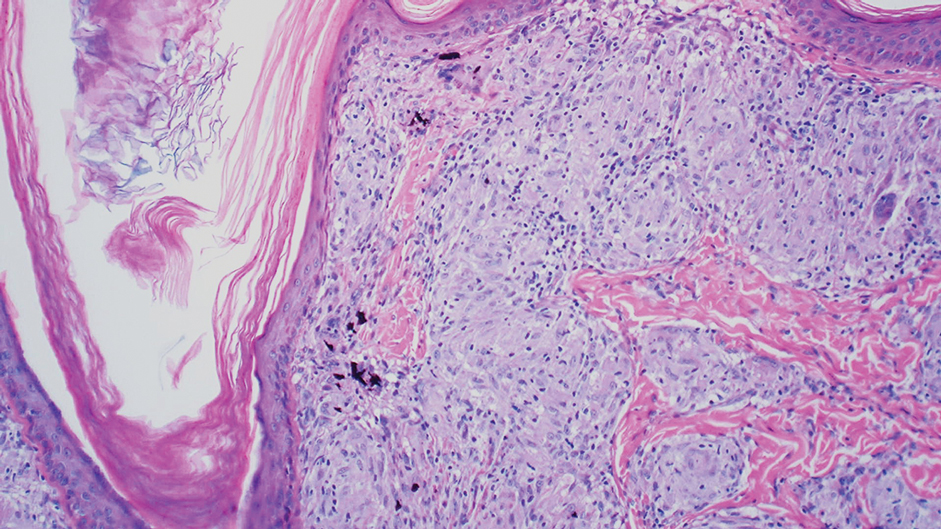

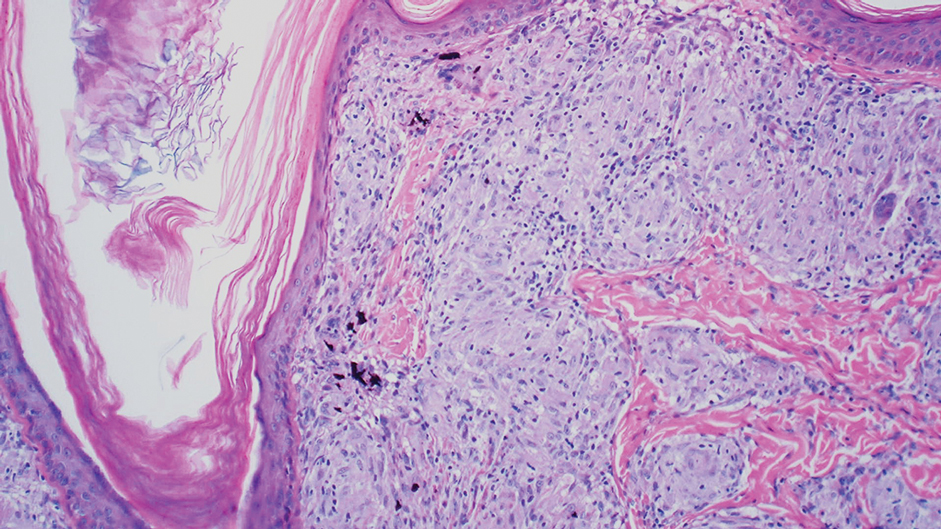

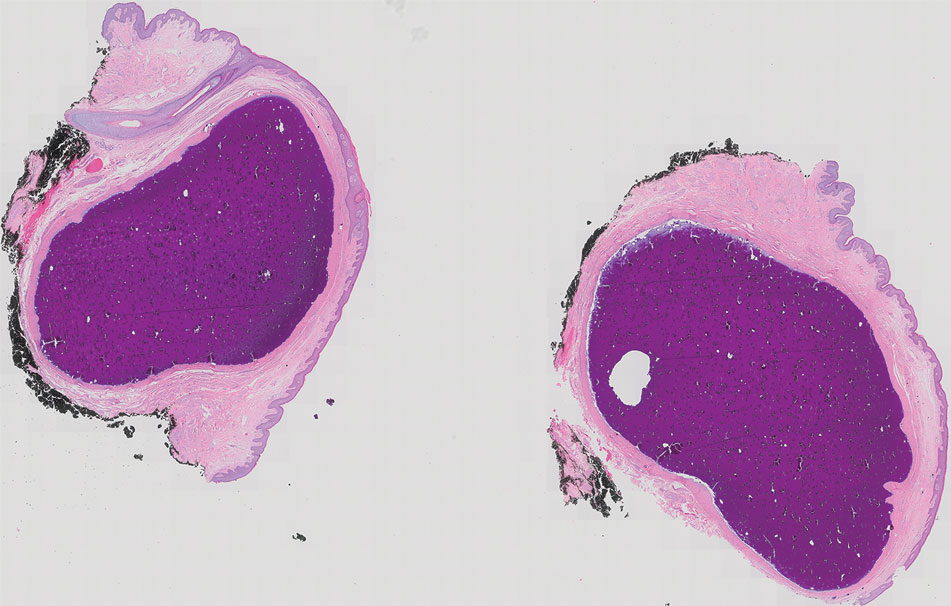

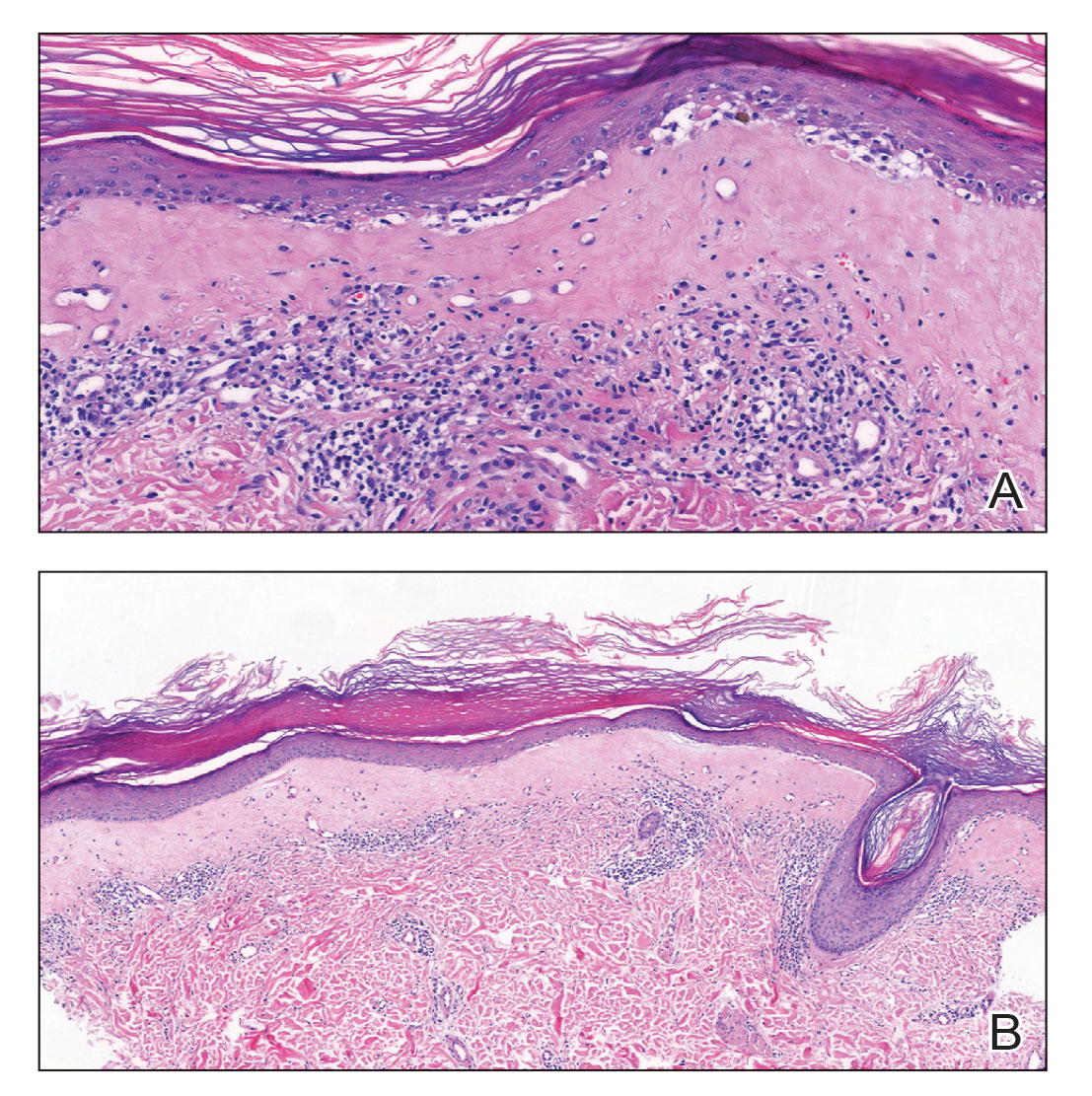

Darier disease (also known as keratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant condition that normally presents with seborrheic eruptions in intertriginous areas, usually with onset during adolescence. Darier disease is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the ATP2A2 gene found on chromosome 12q23-24.1 that encodes for the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium ATPase2 (SERCA2) enzymes involved in calcium-dependent transport of the endoplasmic reticulum within the cell. Due to calcium dysregulation, desmosomes are unable to carry out their function in cell-cell adhesion, resulting in keratinocyte acantholysis. Histopathology of Darier disease is identical to HHD but displays more dyskeratosis than HHD (Figure 3), possibly due to the endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores that are affected in Darier disease compared to the Golgi apparatus calcium stores that are implicated in HHD.5 The lowered endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores in Darier-White disease are associated with more pronounced dyskeratosis, which is seen histologically as corps ronds. Suprabasal hyperkeratosis also is found in Darier disease. The histopathologic findings of Darier disease and PAD can be identical, but the clinical presentations are distinct, with Darier disease typically manifesting as seborrheic eruptions appearing in adolescence and PAD presenting as small white papules in the anogenital or crural regions.

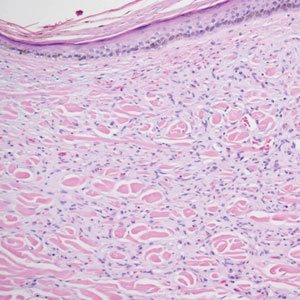

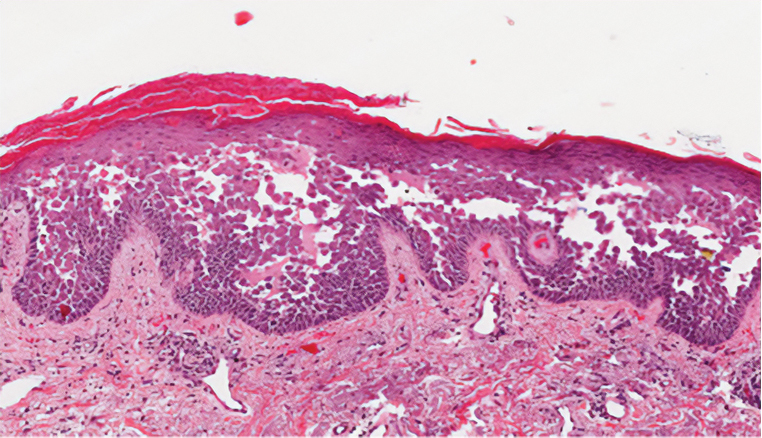

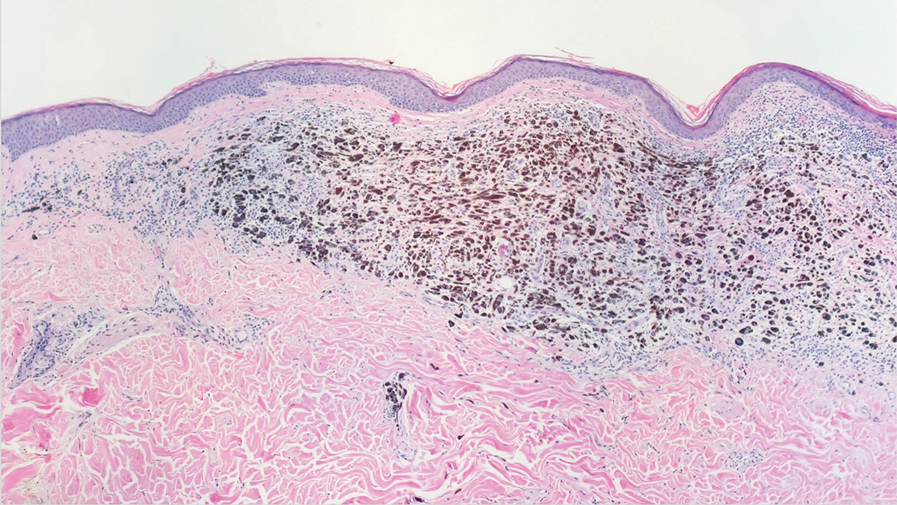

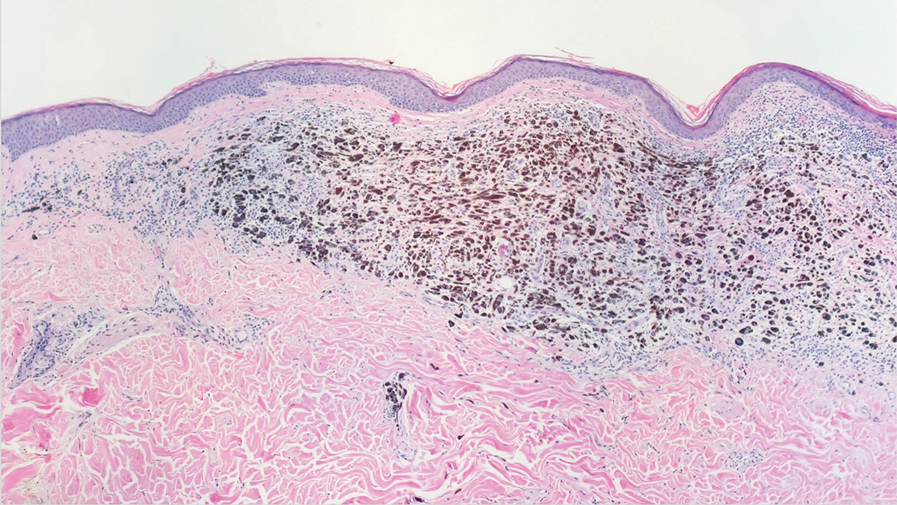

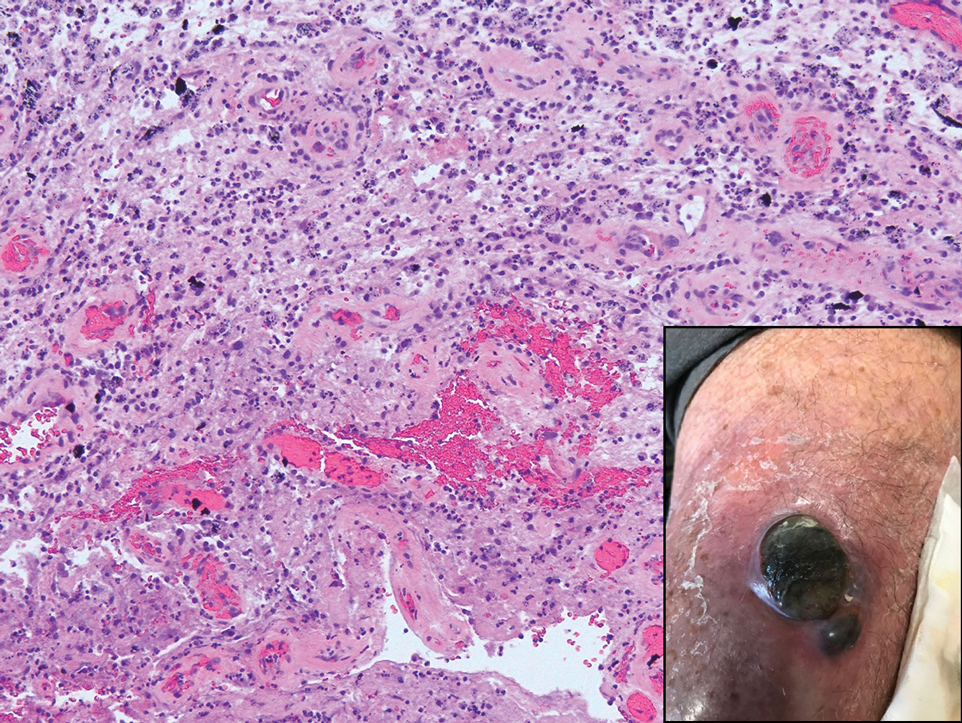

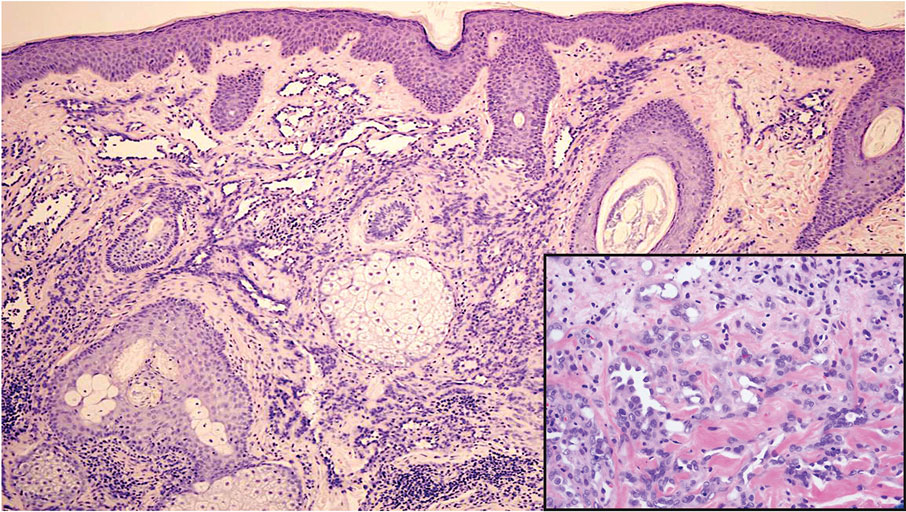

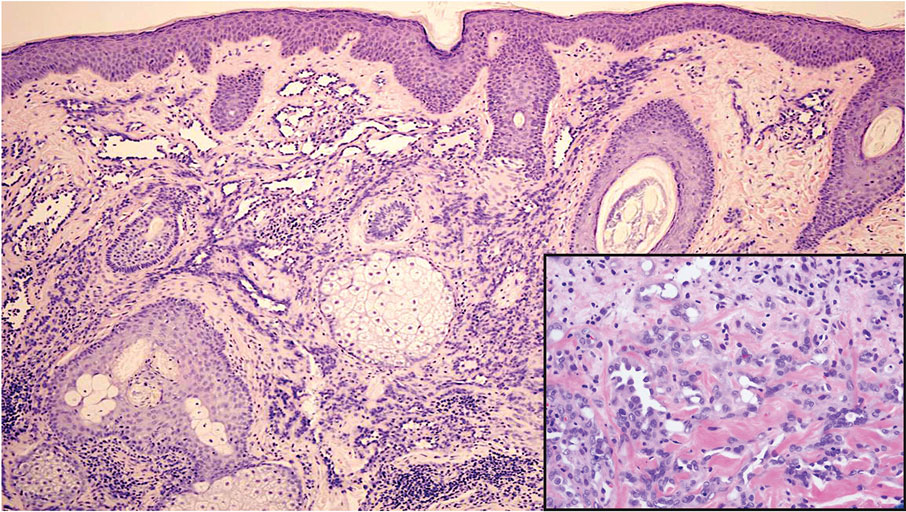

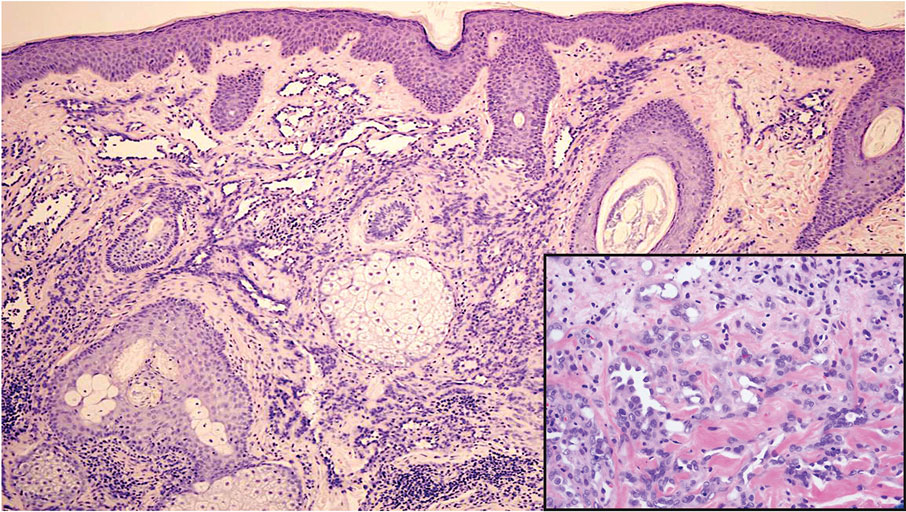

Grover disease (also referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis) has an idiopathic pathophysiology. It clinically manifests with eruptions of erythematous, pruritic, truncal papules on the chest or back. Grover disease has a predilection for White men older than 50 years, and symptoms may be exacerbated in heat and diaphoretic conditions. Histologically, Grover disease may show acantholytic features seen in pemphigus vulgaris, HHD, and Darier disease; the pattern can only follow a specific disease or consist of a combination of all disease features (Figure 4). The acantholytic pattern of Grover disease was found to be similar to pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pemphigus foliaceus, and HHD 47%, 18%, 9%, and 8% of the time, respectively. In 9% of cases, Grover disease will exhibit a mixed histopathology in which its acantholytic pattern will consist of a combination of features seen in the pemphigus family of diseases.6 Biopsy results showing mixed histologic patterns or a combination of different acantholytic features are suggestive of Grover disease over PAD. Moreover, the clinical distribution helps to differentiate Grover disease from PAD.

Because the histologic characteristics of these diseases overlap, certain nuances in clinical correlations and histology allow for distinction. In our patient, the diagnosis was most consistent with PAD based on the clinical manifestation of the disease and the biopsy results. Considering solely the clinical location of the lesions, Grover disease was a less likely diagnosis because our patient’s lesions were observed in the perianal region, not the truncal region as typically seen in Grover disease. Taking into account the DIF assay results in our patient, the pemphigus family of diseases also moved lower on the differential diagnosis. Finally, because the biopsy showed more dyskeratosis than would be present in HHD and also was inconsistent with the location and onset that would be expected to be seen in Darier disease, PAD was the most probable diagnosis. Interestingly, studies have shown mosaic mutations in ATP2A2 and ATP2C1 as possible causes of PAD, suggesting that this may be an allelic variant of Darier disease and HHD.7-9 No genetic testing was performed in our patient.

- Dowd ML, Ansell LH, Husain S, et al. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area: a rare unilateral asymptomatic intertrigo. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:132-134. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.11.003

- Konstantinou MP, Krasagakis K. Benign familial pemphigus (Hailey Hailey disease). StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585136/

- Montis-Palos MC, Acebo-Mariñas E, Catón-Santarén B, et al. Papular acantholytic dermatosis in the genito-crural region: a localized form of Darier disease or Hailey-Hailey disease? Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2013;104:170-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adengl.2012.02.008

- Verma SB. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis localized to the perineal and perianal area in a young male. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:393-395.

- Schmieder SJ, Rosario-Collazo JA. Keratosis follicularis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK519557/

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Knopp EA, Saraceni C, Moss J, et al. Somatic ATP2A2 mutation in a case of papular acantholytic dyskeratosis: mosaic Darier disease [published online August 12, 2015]. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:853-857. doi:10.1111/cup.12551

- Lipoff JB, Mudgil AV, Young S, et al. Acantholytic dermatosis of the crural folds with ATP2C1 mutation is a possible variant of Hailey-Hailey Disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:151.

- Vodo D, Malchin N, Furman M, et al. Identification of a recurrent mutation in ATP2C1 demonstrates that papular acantholytic dyskeratosis and Hailey-Hailey disease are allelic disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1001-1002.

The Diagnosis: Papular Acantholytic Dyskeratosis

The shave biopsy revealed suprabasal clefts associated with acantholytic and dyskeratotic cells as well as overlying hyperkeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative. Based on the combined clinical and histological findings, the patient was diagnosed with papular acantholytic dyskeratosis (PAD), a rare disease that clinically presents as small whitishgreyish papules with the potential to coalesce into larger plaques.1,2 The condition predominantly manifests without symptoms, though pruritus and burning have been reported in affected sites. Most cases of PAD have been reported in older adults rather than in children or adolescents; it is more prevalent in women than in men. Lesions generally are localized to the penis, vulva, scrotum, inguinal folds, and perianal region.3 More specific terms have been used to describe this presentation such as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the anogenital region and papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genital-crural region. Histologic findings of PAD include epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis (quiz image).

The histologic differential diagnosis of PAD is broad due to its overlapping features with other diseases such as pemphigus vulgaris, Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), Darier disease, and Grover disease. The acantholytic pathophysiology of these conditions involves dysfunction in cell adhesion markers. The correct diagnosis can be made by considering both the clinical location of involvement and histopathologic clues.

Pemphigus is a family of disorders involving mucocutaneous blistering of an autoimmune nature (Figure 1). Pemphigus vulgaris is the most prevalent variant of the pemphigus family, with symptomatically painful involvement of mucosal and cutaneous tissue. Autoantibodies to desmoglein 3 alone or both desmoglein 1 and 3 are present. Pemphigus vulgaris displays positive DIF findings with intercellular IgG and C3.

Hailey-Hailey disease (also known as benign familial pemphigus) is an autosomal-dominant disease that shares the acantholytic feature that is common in this class of diseases and caused by a defect in cell-cell adhesion as well as a loss of function in the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Blistering lesions typically appear in the neck, axillary, inguinal, or genital regions, and they can develop into crusted, exudate-filled lesions. No autoimmunity has been associated with this disease, unlike other diseases in the pemphigus family, and mutations in the ATP2C1 gene have been linked with dysregulation of cell-cell adhesion, particularly in cadherins and calcium-dependent cell adhesion processes. Histologically, HHD will show diffuse keratinocyte acantholysis with suprabasal clefting (Figure 2).4 Dyskeratosis is mild, if present at all, and dyskeratotic keratinocytes show a well-defined nucleus with cytoplasmic preservation. In contrast to HHD, PAD typically shows more dyskeratosis.

Darier disease (also known as keratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant condition that normally presents with seborrheic eruptions in intertriginous areas, usually with onset during adolescence. Darier disease is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the ATP2A2 gene found on chromosome 12q23-24.1 that encodes for the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium ATPase2 (SERCA2) enzymes involved in calcium-dependent transport of the endoplasmic reticulum within the cell. Due to calcium dysregulation, desmosomes are unable to carry out their function in cell-cell adhesion, resulting in keratinocyte acantholysis. Histopathology of Darier disease is identical to HHD but displays more dyskeratosis than HHD (Figure 3), possibly due to the endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores that are affected in Darier disease compared to the Golgi apparatus calcium stores that are implicated in HHD.5 The lowered endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores in Darier-White disease are associated with more pronounced dyskeratosis, which is seen histologically as corps ronds. Suprabasal hyperkeratosis also is found in Darier disease. The histopathologic findings of Darier disease and PAD can be identical, but the clinical presentations are distinct, with Darier disease typically manifesting as seborrheic eruptions appearing in adolescence and PAD presenting as small white papules in the anogenital or crural regions.

Grover disease (also referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis) has an idiopathic pathophysiology. It clinically manifests with eruptions of erythematous, pruritic, truncal papules on the chest or back. Grover disease has a predilection for White men older than 50 years, and symptoms may be exacerbated in heat and diaphoretic conditions. Histologically, Grover disease may show acantholytic features seen in pemphigus vulgaris, HHD, and Darier disease; the pattern can only follow a specific disease or consist of a combination of all disease features (Figure 4). The acantholytic pattern of Grover disease was found to be similar to pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pemphigus foliaceus, and HHD 47%, 18%, 9%, and 8% of the time, respectively. In 9% of cases, Grover disease will exhibit a mixed histopathology in which its acantholytic pattern will consist of a combination of features seen in the pemphigus family of diseases.6 Biopsy results showing mixed histologic patterns or a combination of different acantholytic features are suggestive of Grover disease over PAD. Moreover, the clinical distribution helps to differentiate Grover disease from PAD.

Because the histologic characteristics of these diseases overlap, certain nuances in clinical correlations and histology allow for distinction. In our patient, the diagnosis was most consistent with PAD based on the clinical manifestation of the disease and the biopsy results. Considering solely the clinical location of the lesions, Grover disease was a less likely diagnosis because our patient’s lesions were observed in the perianal region, not the truncal region as typically seen in Grover disease. Taking into account the DIF assay results in our patient, the pemphigus family of diseases also moved lower on the differential diagnosis. Finally, because the biopsy showed more dyskeratosis than would be present in HHD and also was inconsistent with the location and onset that would be expected to be seen in Darier disease, PAD was the most probable diagnosis. Interestingly, studies have shown mosaic mutations in ATP2A2 and ATP2C1 as possible causes of PAD, suggesting that this may be an allelic variant of Darier disease and HHD.7-9 No genetic testing was performed in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Papular Acantholytic Dyskeratosis

The shave biopsy revealed suprabasal clefts associated with acantholytic and dyskeratotic cells as well as overlying hyperkeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was negative. Based on the combined clinical and histological findings, the patient was diagnosed with papular acantholytic dyskeratosis (PAD), a rare disease that clinically presents as small whitishgreyish papules with the potential to coalesce into larger plaques.1,2 The condition predominantly manifests without symptoms, though pruritus and burning have been reported in affected sites. Most cases of PAD have been reported in older adults rather than in children or adolescents; it is more prevalent in women than in men. Lesions generally are localized to the penis, vulva, scrotum, inguinal folds, and perianal region.3 More specific terms have been used to describe this presentation such as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the anogenital region and papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genital-crural region. Histologic findings of PAD include epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis (quiz image).

The histologic differential diagnosis of PAD is broad due to its overlapping features with other diseases such as pemphigus vulgaris, Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), Darier disease, and Grover disease. The acantholytic pathophysiology of these conditions involves dysfunction in cell adhesion markers. The correct diagnosis can be made by considering both the clinical location of involvement and histopathologic clues.

Pemphigus is a family of disorders involving mucocutaneous blistering of an autoimmune nature (Figure 1). Pemphigus vulgaris is the most prevalent variant of the pemphigus family, with symptomatically painful involvement of mucosal and cutaneous tissue. Autoantibodies to desmoglein 3 alone or both desmoglein 1 and 3 are present. Pemphigus vulgaris displays positive DIF findings with intercellular IgG and C3.

Hailey-Hailey disease (also known as benign familial pemphigus) is an autosomal-dominant disease that shares the acantholytic feature that is common in this class of diseases and caused by a defect in cell-cell adhesion as well as a loss of function in the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Blistering lesions typically appear in the neck, axillary, inguinal, or genital regions, and they can develop into crusted, exudate-filled lesions. No autoimmunity has been associated with this disease, unlike other diseases in the pemphigus family, and mutations in the ATP2C1 gene have been linked with dysregulation of cell-cell adhesion, particularly in cadherins and calcium-dependent cell adhesion processes. Histologically, HHD will show diffuse keratinocyte acantholysis with suprabasal clefting (Figure 2).4 Dyskeratosis is mild, if present at all, and dyskeratotic keratinocytes show a well-defined nucleus with cytoplasmic preservation. In contrast to HHD, PAD typically shows more dyskeratosis.

Darier disease (also known as keratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant condition that normally presents with seborrheic eruptions in intertriginous areas, usually with onset during adolescence. Darier disease is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the ATP2A2 gene found on chromosome 12q23-24.1 that encodes for the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium ATPase2 (SERCA2) enzymes involved in calcium-dependent transport of the endoplasmic reticulum within the cell. Due to calcium dysregulation, desmosomes are unable to carry out their function in cell-cell adhesion, resulting in keratinocyte acantholysis. Histopathology of Darier disease is identical to HHD but displays more dyskeratosis than HHD (Figure 3), possibly due to the endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores that are affected in Darier disease compared to the Golgi apparatus calcium stores that are implicated in HHD.5 The lowered endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores in Darier-White disease are associated with more pronounced dyskeratosis, which is seen histologically as corps ronds. Suprabasal hyperkeratosis also is found in Darier disease. The histopathologic findings of Darier disease and PAD can be identical, but the clinical presentations are distinct, with Darier disease typically manifesting as seborrheic eruptions appearing in adolescence and PAD presenting as small white papules in the anogenital or crural regions.

Grover disease (also referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis) has an idiopathic pathophysiology. It clinically manifests with eruptions of erythematous, pruritic, truncal papules on the chest or back. Grover disease has a predilection for White men older than 50 years, and symptoms may be exacerbated in heat and diaphoretic conditions. Histologically, Grover disease may show acantholytic features seen in pemphigus vulgaris, HHD, and Darier disease; the pattern can only follow a specific disease or consist of a combination of all disease features (Figure 4). The acantholytic pattern of Grover disease was found to be similar to pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pemphigus foliaceus, and HHD 47%, 18%, 9%, and 8% of the time, respectively. In 9% of cases, Grover disease will exhibit a mixed histopathology in which its acantholytic pattern will consist of a combination of features seen in the pemphigus family of diseases.6 Biopsy results showing mixed histologic patterns or a combination of different acantholytic features are suggestive of Grover disease over PAD. Moreover, the clinical distribution helps to differentiate Grover disease from PAD.

Because the histologic characteristics of these diseases overlap, certain nuances in clinical correlations and histology allow for distinction. In our patient, the diagnosis was most consistent with PAD based on the clinical manifestation of the disease and the biopsy results. Considering solely the clinical location of the lesions, Grover disease was a less likely diagnosis because our patient’s lesions were observed in the perianal region, not the truncal region as typically seen in Grover disease. Taking into account the DIF assay results in our patient, the pemphigus family of diseases also moved lower on the differential diagnosis. Finally, because the biopsy showed more dyskeratosis than would be present in HHD and also was inconsistent with the location and onset that would be expected to be seen in Darier disease, PAD was the most probable diagnosis. Interestingly, studies have shown mosaic mutations in ATP2A2 and ATP2C1 as possible causes of PAD, suggesting that this may be an allelic variant of Darier disease and HHD.7-9 No genetic testing was performed in our patient.

- Dowd ML, Ansell LH, Husain S, et al. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area: a rare unilateral asymptomatic intertrigo. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:132-134. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.11.003

- Konstantinou MP, Krasagakis K. Benign familial pemphigus (Hailey Hailey disease). StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585136/

- Montis-Palos MC, Acebo-Mariñas E, Catón-Santarén B, et al. Papular acantholytic dermatosis in the genito-crural region: a localized form of Darier disease or Hailey-Hailey disease? Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2013;104:170-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adengl.2012.02.008

- Verma SB. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis localized to the perineal and perianal area in a young male. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:393-395.

- Schmieder SJ, Rosario-Collazo JA. Keratosis follicularis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK519557/

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Knopp EA, Saraceni C, Moss J, et al. Somatic ATP2A2 mutation in a case of papular acantholytic dyskeratosis: mosaic Darier disease [published online August 12, 2015]. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:853-857. doi:10.1111/cup.12551

- Lipoff JB, Mudgil AV, Young S, et al. Acantholytic dermatosis of the crural folds with ATP2C1 mutation is a possible variant of Hailey-Hailey Disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:151.

- Vodo D, Malchin N, Furman M, et al. Identification of a recurrent mutation in ATP2C1 demonstrates that papular acantholytic dyskeratosis and Hailey-Hailey disease are allelic disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1001-1002.

- Dowd ML, Ansell LH, Husain S, et al. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area: a rare unilateral asymptomatic intertrigo. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:132-134. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.11.003

- Konstantinou MP, Krasagakis K. Benign familial pemphigus (Hailey Hailey disease). StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585136/

- Montis-Palos MC, Acebo-Mariñas E, Catón-Santarén B, et al. Papular acantholytic dermatosis in the genito-crural region: a localized form of Darier disease or Hailey-Hailey disease? Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2013;104:170-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adengl.2012.02.008

- Verma SB. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis localized to the perineal and perianal area in a young male. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:393-395.

- Schmieder SJ, Rosario-Collazo JA. Keratosis follicularis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm .nih.gov/books/NBK519557/

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Knopp EA, Saraceni C, Moss J, et al. Somatic ATP2A2 mutation in a case of papular acantholytic dyskeratosis: mosaic Darier disease [published online August 12, 2015]. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:853-857. doi:10.1111/cup.12551

- Lipoff JB, Mudgil AV, Young S, et al. Acantholytic dermatosis of the crural folds with ATP2C1 mutation is a possible variant of Hailey-Hailey Disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:151.

- Vodo D, Malchin N, Furman M, et al. Identification of a recurrent mutation in ATP2C1 demonstrates that papular acantholytic dyskeratosis and Hailey-Hailey disease are allelic disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1001-1002.

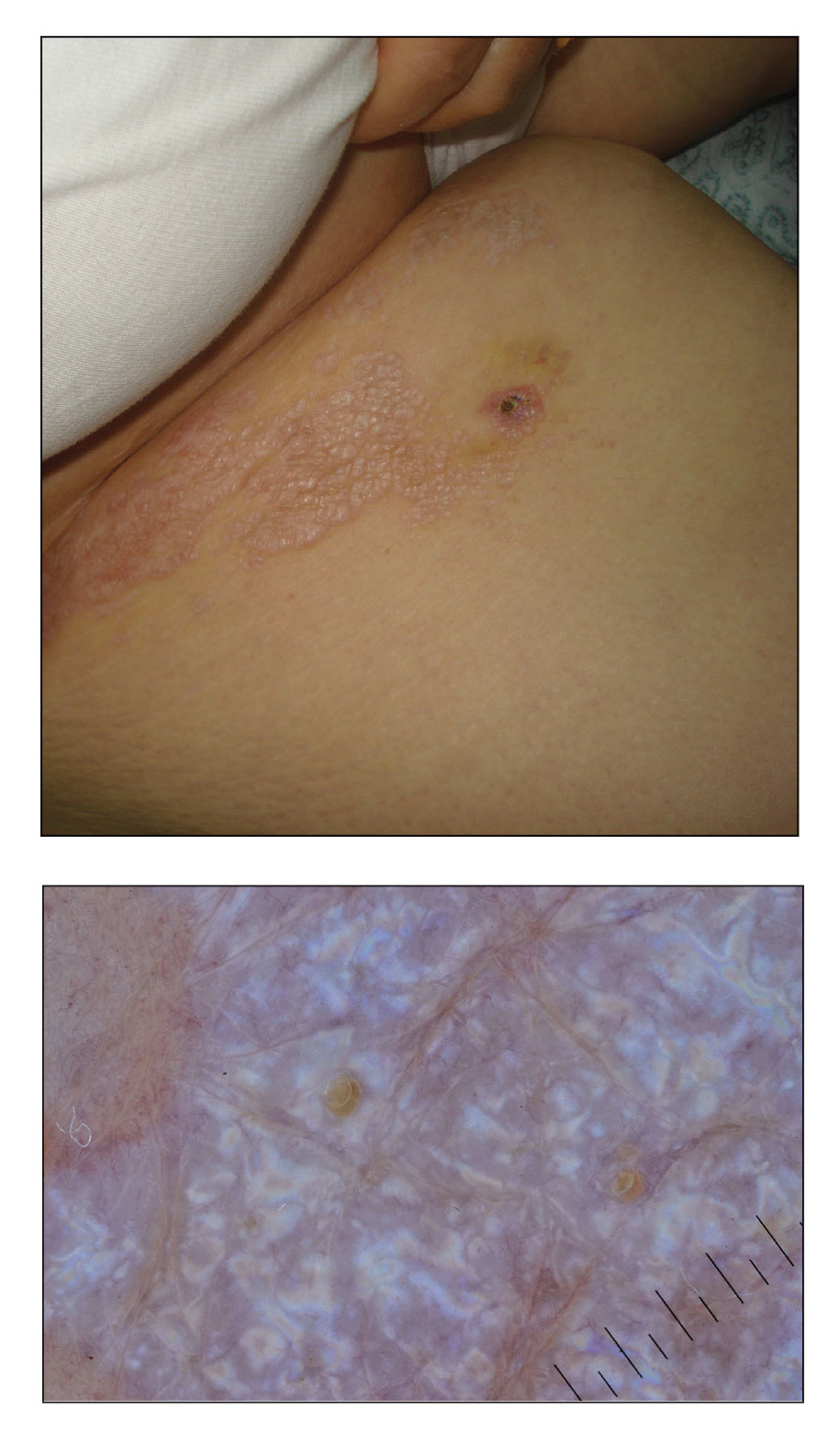

A 66-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with pruritus of the gluteal cleft and perianal region of several months’ duration. He had been prescribed permethrin by an outside physician, as well as oral acyclovir, triamcinolone-nystatin combination ointment, and topical zinc oxide prescribed by dermatology, without improvement. Physical examination showed several papules and erosions (<1 mm) in the perianal and gluteal cleft regions (inset). Hyperpigmented macules also were noted in the inguinal folds. A shave biopsy of a lesion from the perianal region was performed.

Disseminated Papules and Nodules on the Skin and Oral Mucosa in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Congenital Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

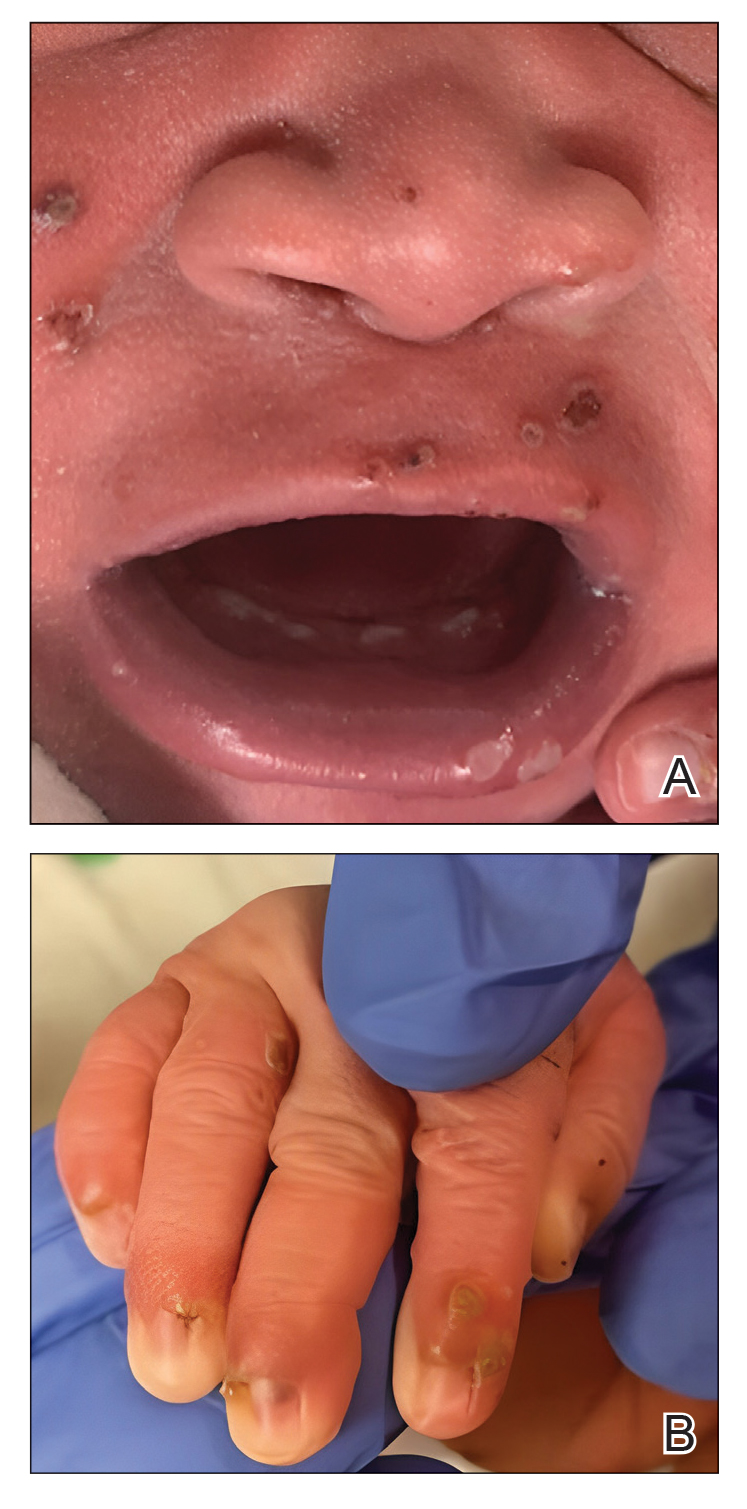

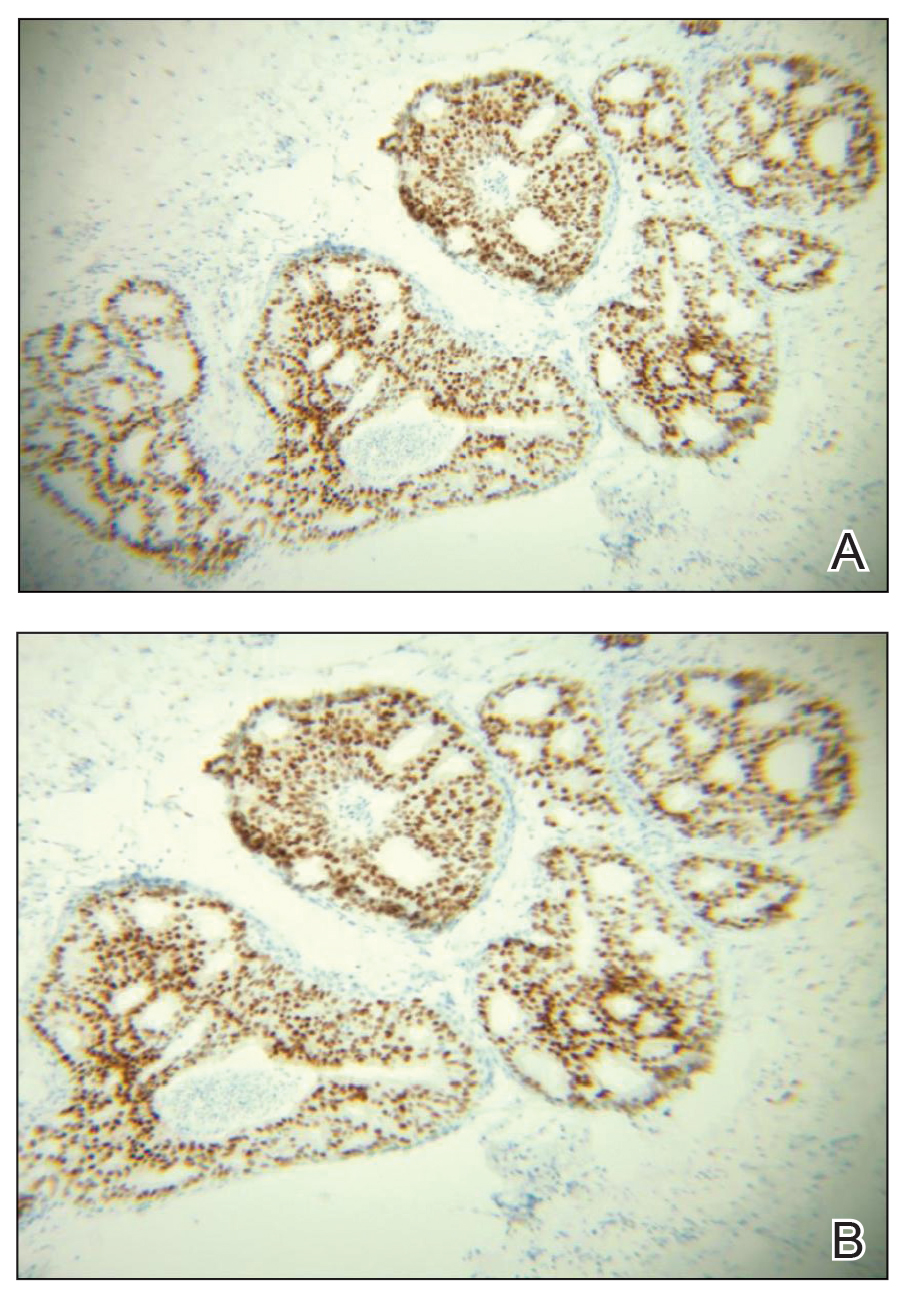

Although the infectious workup was positive for herpes simplex virus type 1 and cytomegalovirus antibodies, serologies for the rest of the TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other agents [syphilis, hepatitis B virus], rubella, cytomegalovirus) group of infections, as well as other bacterial, fungal, and viral infections, were negative. A skin biopsy from the right fifth toe showed a dense infiltrate of CD1a+ histiocytic cells with folded or kidney-shaped nuclei mixed with eosinophils, which was consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) (Figure 1). Skin lesions were treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% and progressively faded over a few weeks.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disorder with a variable clinical presentation depending on the sites affected and the extent of involvement. It can involve multiple organ systems, most commonly the skeletal system and the skin. Organ involvement is characterized by histiocyte infiltration. Acute disseminated multisystem disease most commonly is seen in children younger than 3 years.1

Congenital cutaneous LCH presents with variable skin lesions ranging from papules to vesicles, pustules, and ulcers, with onset at birth or in the neonatal period. Various morphologic traits of skin lesions have been described; the most common presentation is multiple red to yellow-brown, crusted papules with accompanying hemorrhage or erosion.1 Other cases have described an eczematous, seborrheic, diffuse eruption or erosive intertrigo. One case of a child with a solitary necrotic nodule on the scalp has been reported.2

Our patient presented with disseminated, nonblanching, purple to dark red papules and nodules of the skin and oral mucosa, as well as nail dystrophy (Figure 2). However, LCH in a neonate can mimic other causes of congenital papulonodular eruptions. Red-brown papules and nodules with or without crusting in a newborn can be mistaken for erythema toxicum neonatorum, transient neonatal pustular melanosis, congenital leukemia cutis, neonatal erythropoiesis, disseminated neonatal hemangiomatosis, infantile acropustulosis, or congenital TORCH infections such as rubella or syphilis. When LCH presents as vesicles or eroded papules or nodules in a newborn, the differential diagnosis includes incontinentia pigmenti and hereditary epidermolysis bullosa.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis may even present with a classic blueberry muffin rash that can lead clinicians to consider cutaneous metastasis from various hematologic malignancies or the more common TORCH infections. Several diagnostic tests can be performed to clarify the diagnosis, including bacterial and viral cultures and stains, serology, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, bone marrow aspiration, or skin biopsy.3 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is diagnosed with a combination of histology, immunohistochemistry, and clinical presentation; however, a skin biopsy is crucial. Tissue should be taken from the most easily accessible yet representative lesion. The characteristic appearance of LCH lesions is described as a dense infiltrate of histiocytic cells mixed with numerous eosinophils in the dermis.1 Histiocytes usually have folded nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm or kidney-shaped nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Positive CD1a and/or CD207 (Langerin) staining of the cells is required for definitive diagnosis.4 After diagnosis, it is important to obtain baseline laboratory and radiographic studies to determine the extent of systemic involvement.

Treatment of congenital LCH is tailored to the extent of organ involvement. The dermatologic manifestations resolve without medications in many cases. However, true self-resolving LCH can only be diagnosed retrospectively after a full evaluation for other sites of disease. Disseminated disease can be life-threatening and requires more active management. In cases of skin-limited disease, therapies include topical steroids, nitrogen mustard, or imiquimod; surgical resection of isolated lesions; phototherapy; or systemic therapies such as methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, vinblastine/vincristine, cladribine, and/or cytarabine. Symptomatic patients initially are treated with methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine.5 Asymptomatic infants with skin-limited involvement can be managed with topical treatments.

Our patient had skin-limited disease. Abdominal ultrasonography, skeletal survey, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed no abnormalities. The patient’s family was advised to monitor him for reoccurrence of the skin lesions and to continue close follow-up with hematology and dermatology. Although congenital LCH often is self-resolving, extensive skin involvement increases the risk for internal organ involvement for several years.6 These patients require long-term follow-up for potential musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, endocrine, hepatic, and/or pulmonary disease.

- Pan Y, Zeng X, Ge J, et al. Congenital self-healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis: clinical and pathological characteristics. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2275-2278.

- Morren MA, Vanden Broecke K, Vangeebergen L, et al. Diverse cutaneous presentations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:486-492. doi:10.1002/pbc.25834

- Krooks J, Minkov M, Weatherall AG. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment, sequelae, and standardized follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1047-1056. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.060

- Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:175-184. doi:10.1002/pbc.24367

- Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL. How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2015;126:26-35. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-12-569301

- Jezierska M, Stefanowicz J, Romanowicz G, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children—a disease with many faces. recent advances in pathogenesis, diagnostic examinations and treatment. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2018;35:6-17. doi:10.5114/pdia.2017.67095

The Diagnosis: Congenital Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis