User login

Aberrant Expression of CD56 in Metastatic Malignant Melanoma

To the Editor:

Many types of neoplasms can show aberrant immunoreactivity or unexpected expression of markers.1 Malignant melanoma is a tumor that can show not only aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns but also notable histologic diversity,1,2 which often makes the diagnosis of melanoma challenging and ultimately can lead to diagnostic uncertainty.2

The incidence of malignant melanoma continues to grow.3 Maintaining a high degree of suspicion for this disease, recognizing its heterogeneity and divergent differentiation, and knowing potential aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns are imperative for accurate diagnosis.

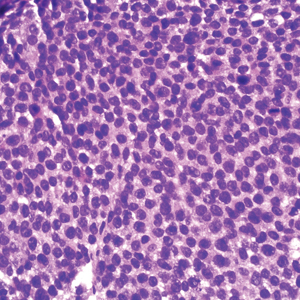

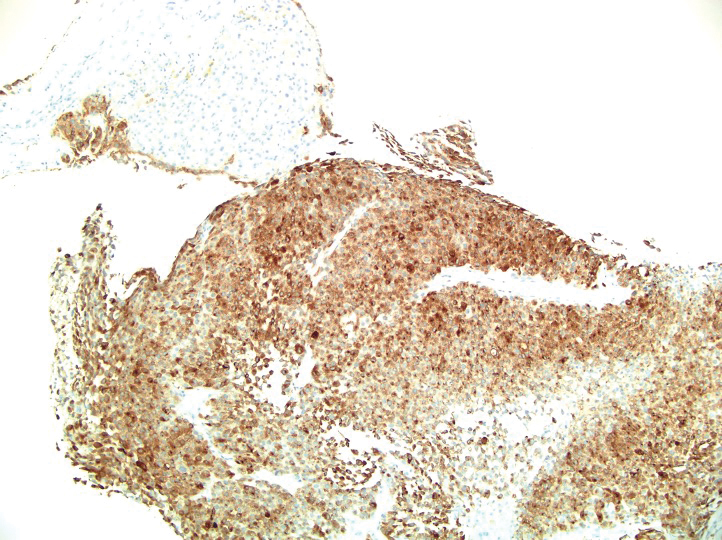

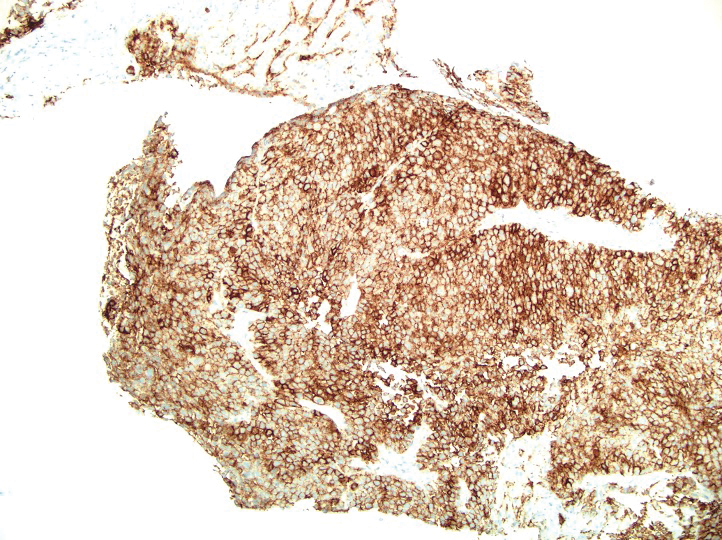

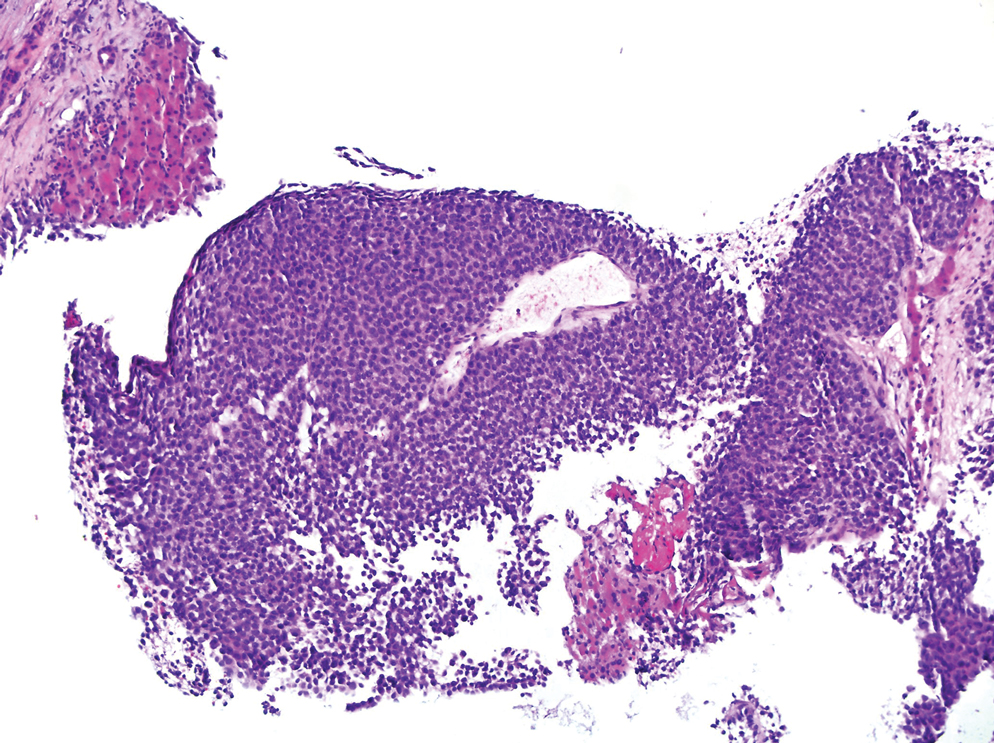

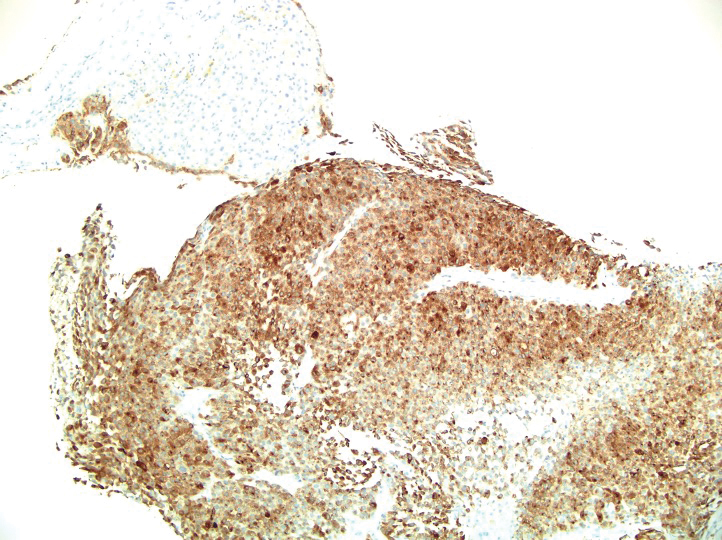

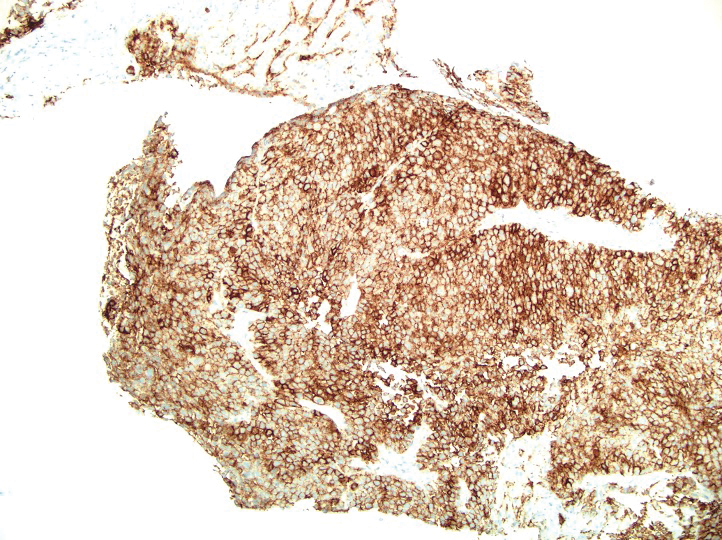

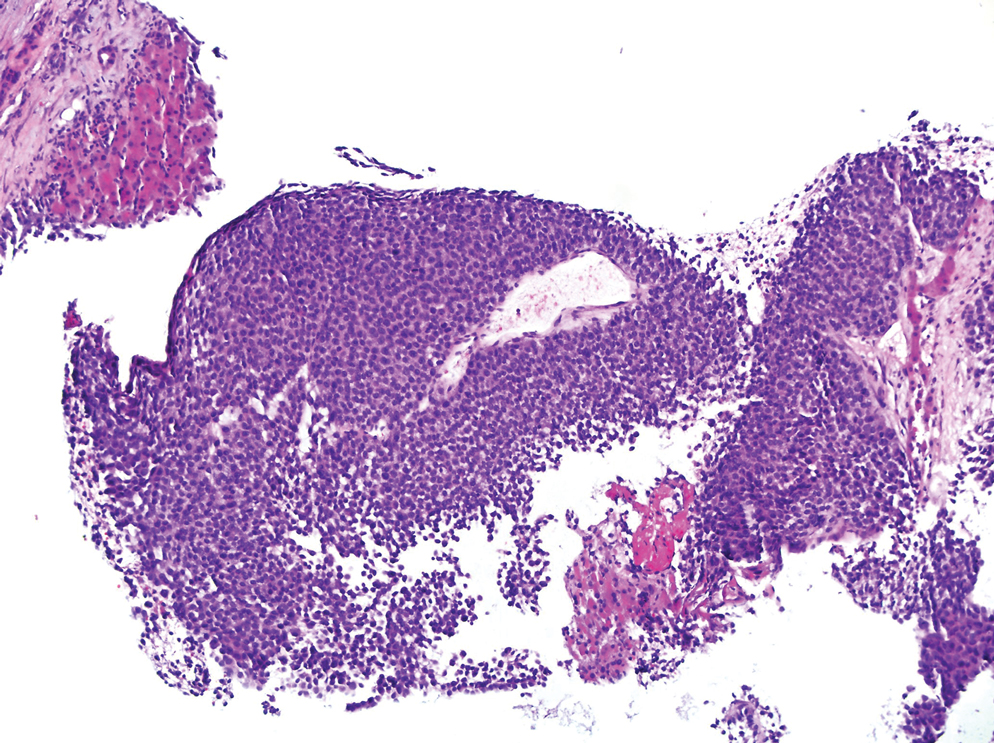

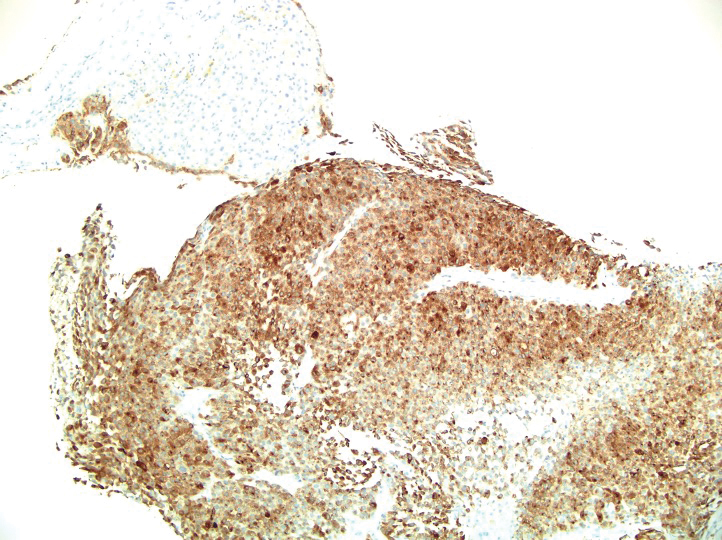

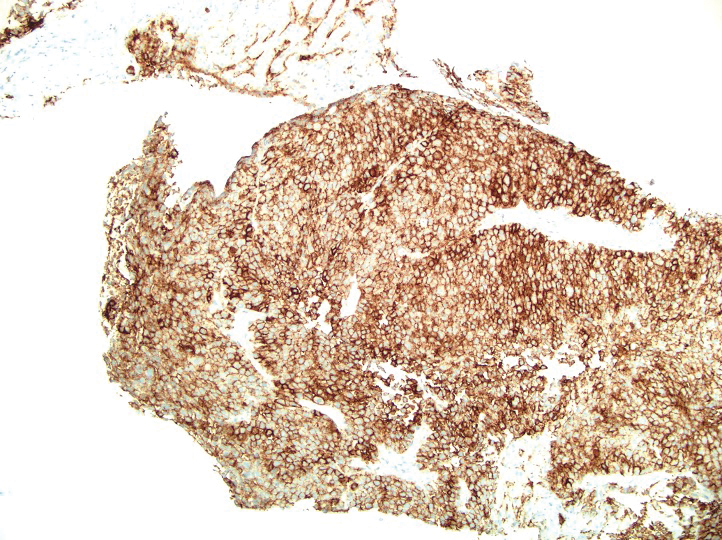

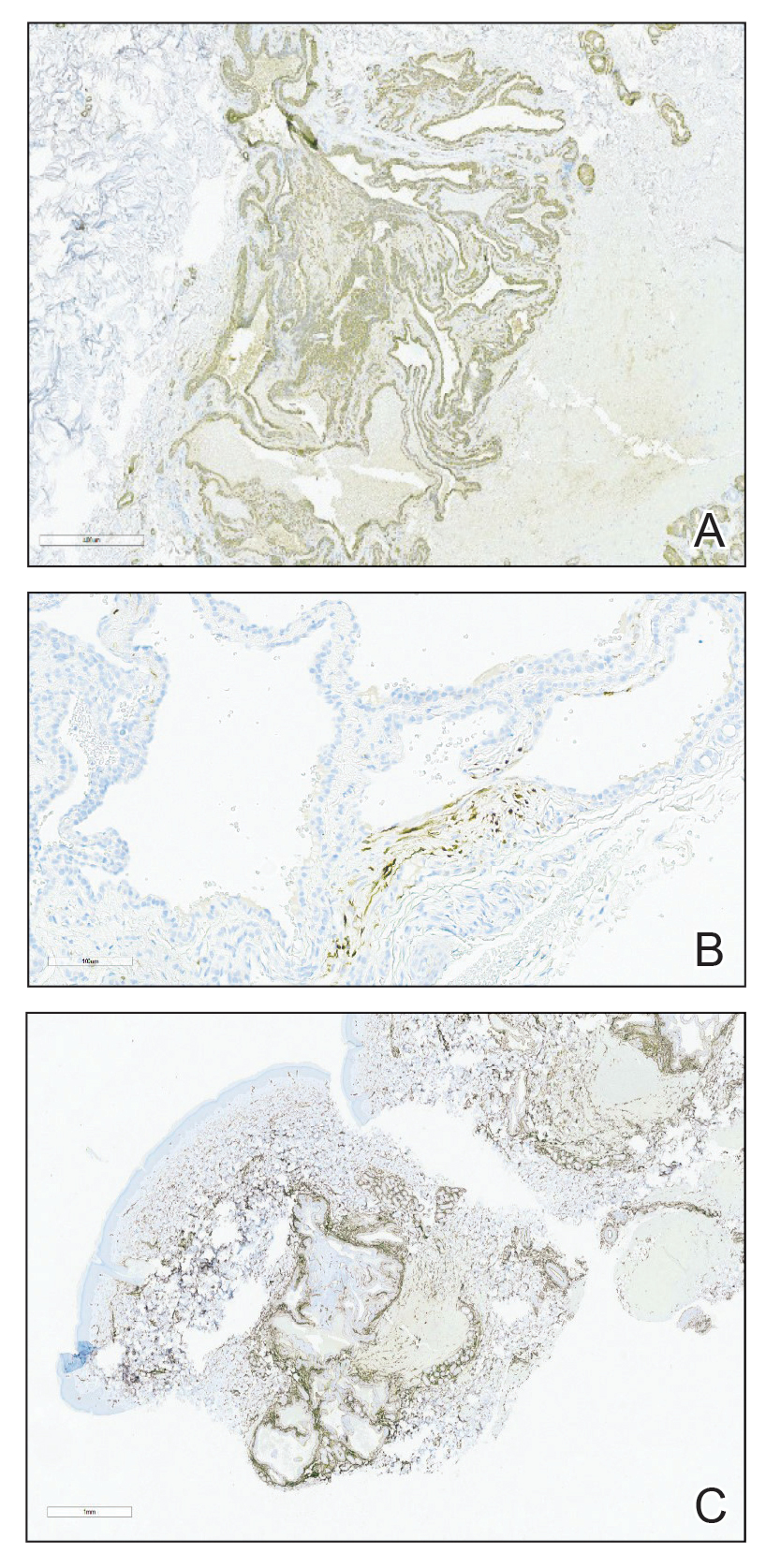

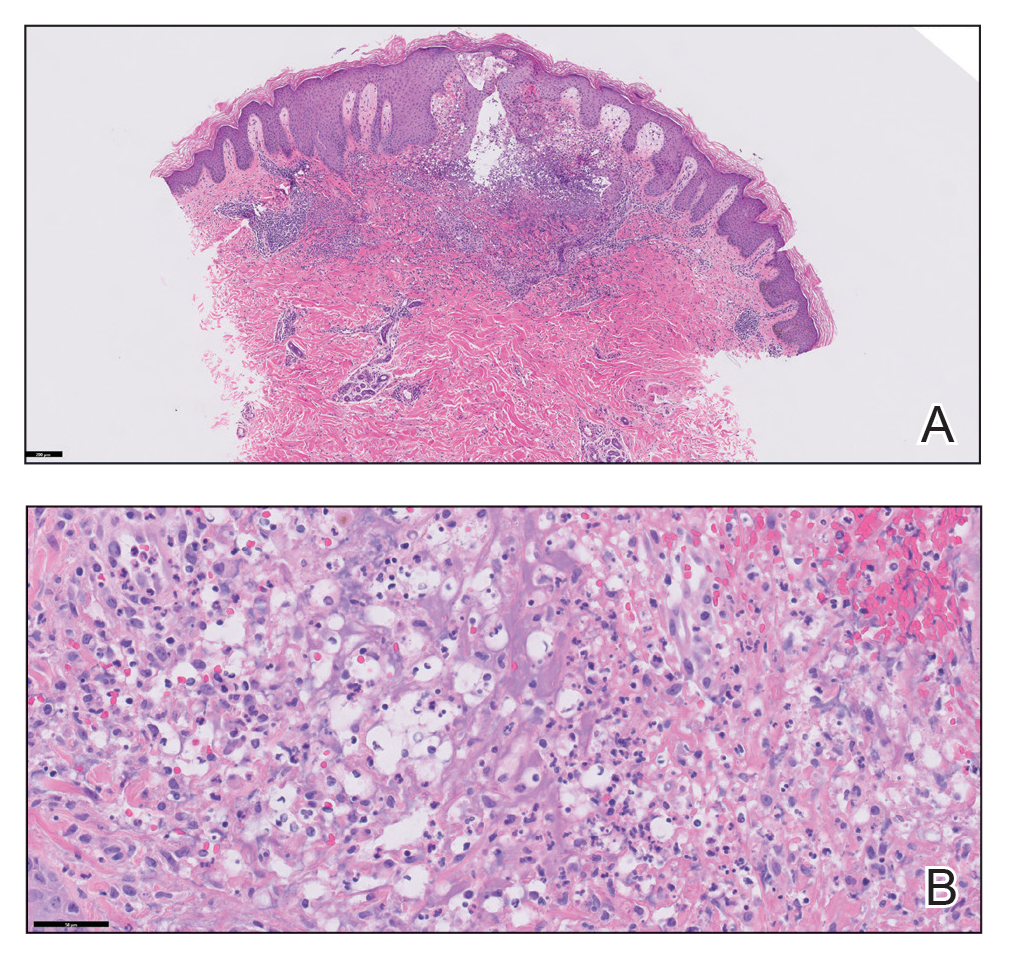

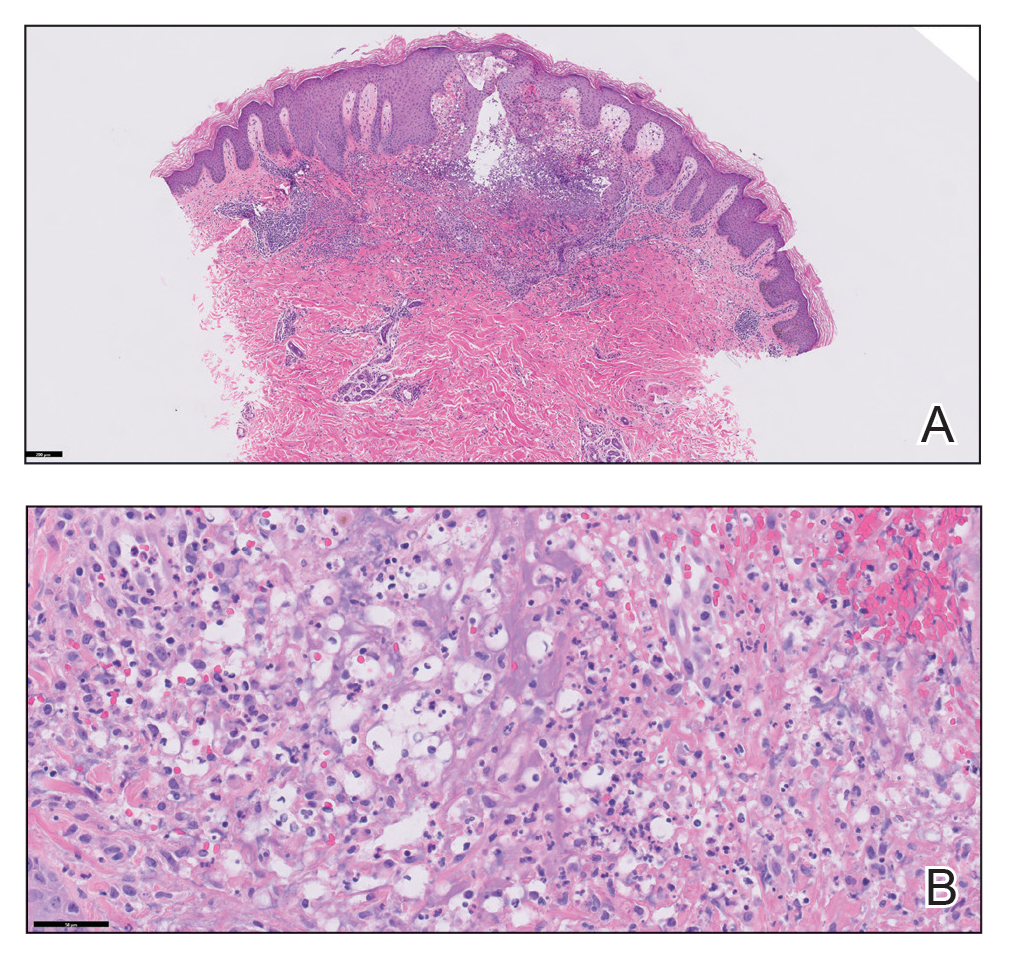

A 36-year-old man presented to a primary care physician with right-sided chest pain, upper and lower back aches, bilateral hip pain, neck pain, headache, night sweats, chills, and nausea. After infectious causes were ruled out, he was placed on a steroid taper without improvement. He presented to the emergency department a few days later with muscle spasms and was found to also have diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding. The patient’s medical history was noncontributory; he was a lifelong nonsmoker. Laboratory studies revealed elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase and C-reactive protein. Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed innumerable liver and lung lesions that were suspicious for metastatic malignancy. A liver biopsy revealed nests and sheets of metastatic tumor with pleomorphic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and areas of intranuclear clearing (Figures 1 and 2). Immunohistochemical staining was performed to further characterize the tumor. Neoplastic cells were positive for MART-1 (also known as Melan-A and melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells)(Figure 3), SOX10, S-100, HMB-45, and vimentin. Nonspecific staining with CD56 (Figure 4), a neuroendocrine marker, also was noted; however, the neoplasm was negative for synaptophysin, another neuroendocrine marker. Other markers for which staining was negative included pan-keratin, CD138 (syndecan-1), desmin, placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), inhibin, OCT-4, cytokeratin 7, and cytokeratin 20. This staining pattern was compatible with metastatic melanoma with aberrant CD56 expression.

BRAF V600E immunohistochemical staining also was performed and showed strong and diffuse positivity within neoplastic cells. A subsequent positron emission tomography scan revealed widespread metastatic disease involving the lungs, liver, spleen, and bones. The patient did not have a history of an excised skin lesion; no primary cutaneous or mucosal lesions were identified.

The patient was started on targeted therapy with trametinib, a mitogen-activated extracellular signal-related kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor, and dabrafenib, a BRAF inhibitor. The disease continued to progress; he developed extensive leptomeningeal metastatic disease for which palliative radiation therapy was administered. The patient died 4 months after the initial diagnosis.

More than 90% of melanoma cases are of cutaneous origin; however, 4% to 8% of cases present as a metastatic lesion in the absence of an identified primary lesion,4 similar to our patient. The diagnosis of melanoma often is challenging; the tumor can show notable histologic diversity and has the potential to express aberrant immunophenotypes.1,2 The histologic diversity of melanoma includes a variety of architectural patterns (eg, nests, trabeculae, fascicular, pseudoglandular, pseudopapillary, or pseudorosette patterns), cytomorphologic features, and stromal changes. Cytomorphologic features of melanoma can be large pleomorphic cells; small cells; spindle cells; clear cells; signet-ring cells; and rhabdoid, plasmacytoid, and balloon cells.5

Melanoma can mimic carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, benign stromal tumors, plasmacytoma, and germ-cell tumors.5 Nuclei can binucleated, multinucleated, or lobated and may contain inclusions or grooves. Stroma may become myxoid or desmoplastic in appearance or rarely show granulomatous inflammation or osteoclastic giant cells.5 These variations render the diagnosis of melanoma challenging and ultimately can lead to diagnostic uncertainty.

Melanomas typically express MART-1, HMB-45, S-100, tyrosinase, NK1C3, vimentin, and neuron-specific enolase. However, melanoma is among the many neoplasms that sometimes exhibit aberrant immunoreactivity and differentiation toward nonmelanocytic elements.6 The most commonly expressed immunophenotypic aberration is cytokeratin, especially the low-molecular-weight keratin marker CAM5.2.5 CAM5.2 positivity also is seen more often in metastatic melanoma. Melanomas rarely express other intermediate filaments, including desmin, neurofilament protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein; expression of smooth-muscle actin is rare.5

Only a few cases of melanoma showing expression of neuroendocrine markers have been reported. However, one study reported synaptophysin positivity in 29% (10/34) of cases of primary and metastatic melanoma, making the stain a relatively common finding.1

In contrast, expression of CD56 (also known as neural-cell adhesion molecule 1) in melanoma has been reported only rarely. CD56 is a nonspecific neuroendocrine marker that normally is expressed on neurons, glial tissue, skeletal muscle, and natural killer cells. Riddle and Bui7 reported a case of metastatic malignant melanoma with focal CD56 positivity and no expression of other neuroendocrine markers, similar to our patient. Suzuki and colleagues4 also reported a case of melanoma metastatic to bone marrow that showed CD56 expression in true nonhematologic tumor cells and negative immunoreactivity with synaptophysin and chromogranin A.

It is important to document cases of melanoma that express neuroendocrine markers to prevent an incorrect diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor.1 In some cases, distinguishing amelanotic melanoma from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, and lymphoma can be difficult.5

The term neuroendocrine differentiation is reserved for cases of melanoma that show areas of ultrastructural change consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor.2 Neuroendocrine differentiation in melanoma is not common; its prognostic significance is unknown.8 We do not consider our case to be true neuroendocrine differentiation, as the tumor lacked the morphologic changes of a neuroendocrine tumor. Furthermore, CD56 is a nonspecific neuroendocrine marker, and the tumor was negative for synaptophysin.

Melanoma has the potential to show notable histologic diversity as well as aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns.1,2 Our patient had metastatic melanoma with aberrant neuroendocrine expression of CD56, which could have been a potential diagnostic pitfall. Because expression of CD56 in melanoma is rare, it is imperative to recognize this potential aberrant staining pattern to ensure the accurate diagnosis of melanoma and appropriate provision of care.

1. Romano RC, Carter JM, Folpe AL. Aberrant intermediate filament and synaptophysin expression is a frequent event in malignant melanoma: an immunohistochemical study of 73 cases. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1033-1042. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2015.62

2. Eyden B, Pandit D, Banerjee SS. Malignant melanoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: clinical, histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features of three cases. Histopathology. 2005;47:402-409. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02240.x

3. Katerji H, Childs JM, Bratton LE, et al. Primary esophageal melanoma with aberrant CD56 expression: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Case Rep Pathol. 2017;2017:9052637. doi:10.1155/2017/9052637

4. Suzuki T, Kusumoto S, Iida S, et al. Amelanotic malignant melanoma of unknown primary origin metastasizing to the bone marrow: a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2014;53:325-328. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1412

5. Banerjee SS, Harris M. Morphological and immunophenotypic variations in malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 2000;36:387-402. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00894.x

6. Banerjee SS, Eyden B. Divergent differentiation in malignant melanomas: a review. Histopathology. 2008;52:119-129. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02823.x

7. Riddle ND, Bui MM. When melanoma is negative for S100: diagnostic pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:237-239. doi:10.5858/arpa.2011-0405-LE

8. Ilardi G, Caroppo D, Varricchio S, et al. Anal melanoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: report of a case. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:329-332. doi:10.1177/1066896915573568

To the Editor:

Many types of neoplasms can show aberrant immunoreactivity or unexpected expression of markers.1 Malignant melanoma is a tumor that can show not only aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns but also notable histologic diversity,1,2 which often makes the diagnosis of melanoma challenging and ultimately can lead to diagnostic uncertainty.2

The incidence of malignant melanoma continues to grow.3 Maintaining a high degree of suspicion for this disease, recognizing its heterogeneity and divergent differentiation, and knowing potential aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns are imperative for accurate diagnosis.

A 36-year-old man presented to a primary care physician with right-sided chest pain, upper and lower back aches, bilateral hip pain, neck pain, headache, night sweats, chills, and nausea. After infectious causes were ruled out, he was placed on a steroid taper without improvement. He presented to the emergency department a few days later with muscle spasms and was found to also have diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding. The patient’s medical history was noncontributory; he was a lifelong nonsmoker. Laboratory studies revealed elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase and C-reactive protein. Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed innumerable liver and lung lesions that were suspicious for metastatic malignancy. A liver biopsy revealed nests and sheets of metastatic tumor with pleomorphic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and areas of intranuclear clearing (Figures 1 and 2). Immunohistochemical staining was performed to further characterize the tumor. Neoplastic cells were positive for MART-1 (also known as Melan-A and melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells)(Figure 3), SOX10, S-100, HMB-45, and vimentin. Nonspecific staining with CD56 (Figure 4), a neuroendocrine marker, also was noted; however, the neoplasm was negative for synaptophysin, another neuroendocrine marker. Other markers for which staining was negative included pan-keratin, CD138 (syndecan-1), desmin, placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), inhibin, OCT-4, cytokeratin 7, and cytokeratin 20. This staining pattern was compatible with metastatic melanoma with aberrant CD56 expression.

BRAF V600E immunohistochemical staining also was performed and showed strong and diffuse positivity within neoplastic cells. A subsequent positron emission tomography scan revealed widespread metastatic disease involving the lungs, liver, spleen, and bones. The patient did not have a history of an excised skin lesion; no primary cutaneous or mucosal lesions were identified.

The patient was started on targeted therapy with trametinib, a mitogen-activated extracellular signal-related kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor, and dabrafenib, a BRAF inhibitor. The disease continued to progress; he developed extensive leptomeningeal metastatic disease for which palliative radiation therapy was administered. The patient died 4 months after the initial diagnosis.

More than 90% of melanoma cases are of cutaneous origin; however, 4% to 8% of cases present as a metastatic lesion in the absence of an identified primary lesion,4 similar to our patient. The diagnosis of melanoma often is challenging; the tumor can show notable histologic diversity and has the potential to express aberrant immunophenotypes.1,2 The histologic diversity of melanoma includes a variety of architectural patterns (eg, nests, trabeculae, fascicular, pseudoglandular, pseudopapillary, or pseudorosette patterns), cytomorphologic features, and stromal changes. Cytomorphologic features of melanoma can be large pleomorphic cells; small cells; spindle cells; clear cells; signet-ring cells; and rhabdoid, plasmacytoid, and balloon cells.5

Melanoma can mimic carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, benign stromal tumors, plasmacytoma, and germ-cell tumors.5 Nuclei can binucleated, multinucleated, or lobated and may contain inclusions or grooves. Stroma may become myxoid or desmoplastic in appearance or rarely show granulomatous inflammation or osteoclastic giant cells.5 These variations render the diagnosis of melanoma challenging and ultimately can lead to diagnostic uncertainty.

Melanomas typically express MART-1, HMB-45, S-100, tyrosinase, NK1C3, vimentin, and neuron-specific enolase. However, melanoma is among the many neoplasms that sometimes exhibit aberrant immunoreactivity and differentiation toward nonmelanocytic elements.6 The most commonly expressed immunophenotypic aberration is cytokeratin, especially the low-molecular-weight keratin marker CAM5.2.5 CAM5.2 positivity also is seen more often in metastatic melanoma. Melanomas rarely express other intermediate filaments, including desmin, neurofilament protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein; expression of smooth-muscle actin is rare.5

Only a few cases of melanoma showing expression of neuroendocrine markers have been reported. However, one study reported synaptophysin positivity in 29% (10/34) of cases of primary and metastatic melanoma, making the stain a relatively common finding.1

In contrast, expression of CD56 (also known as neural-cell adhesion molecule 1) in melanoma has been reported only rarely. CD56 is a nonspecific neuroendocrine marker that normally is expressed on neurons, glial tissue, skeletal muscle, and natural killer cells. Riddle and Bui7 reported a case of metastatic malignant melanoma with focal CD56 positivity and no expression of other neuroendocrine markers, similar to our patient. Suzuki and colleagues4 also reported a case of melanoma metastatic to bone marrow that showed CD56 expression in true nonhematologic tumor cells and negative immunoreactivity with synaptophysin and chromogranin A.

It is important to document cases of melanoma that express neuroendocrine markers to prevent an incorrect diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor.1 In some cases, distinguishing amelanotic melanoma from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, and lymphoma can be difficult.5

The term neuroendocrine differentiation is reserved for cases of melanoma that show areas of ultrastructural change consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor.2 Neuroendocrine differentiation in melanoma is not common; its prognostic significance is unknown.8 We do not consider our case to be true neuroendocrine differentiation, as the tumor lacked the morphologic changes of a neuroendocrine tumor. Furthermore, CD56 is a nonspecific neuroendocrine marker, and the tumor was negative for synaptophysin.

Melanoma has the potential to show notable histologic diversity as well as aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns.1,2 Our patient had metastatic melanoma with aberrant neuroendocrine expression of CD56, which could have been a potential diagnostic pitfall. Because expression of CD56 in melanoma is rare, it is imperative to recognize this potential aberrant staining pattern to ensure the accurate diagnosis of melanoma and appropriate provision of care.

To the Editor:

Many types of neoplasms can show aberrant immunoreactivity or unexpected expression of markers.1 Malignant melanoma is a tumor that can show not only aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns but also notable histologic diversity,1,2 which often makes the diagnosis of melanoma challenging and ultimately can lead to diagnostic uncertainty.2

The incidence of malignant melanoma continues to grow.3 Maintaining a high degree of suspicion for this disease, recognizing its heterogeneity and divergent differentiation, and knowing potential aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns are imperative for accurate diagnosis.

A 36-year-old man presented to a primary care physician with right-sided chest pain, upper and lower back aches, bilateral hip pain, neck pain, headache, night sweats, chills, and nausea. After infectious causes were ruled out, he was placed on a steroid taper without improvement. He presented to the emergency department a few days later with muscle spasms and was found to also have diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding. The patient’s medical history was noncontributory; he was a lifelong nonsmoker. Laboratory studies revealed elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase and C-reactive protein. Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed innumerable liver and lung lesions that were suspicious for metastatic malignancy. A liver biopsy revealed nests and sheets of metastatic tumor with pleomorphic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and areas of intranuclear clearing (Figures 1 and 2). Immunohistochemical staining was performed to further characterize the tumor. Neoplastic cells were positive for MART-1 (also known as Melan-A and melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells)(Figure 3), SOX10, S-100, HMB-45, and vimentin. Nonspecific staining with CD56 (Figure 4), a neuroendocrine marker, also was noted; however, the neoplasm was negative for synaptophysin, another neuroendocrine marker. Other markers for which staining was negative included pan-keratin, CD138 (syndecan-1), desmin, placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), inhibin, OCT-4, cytokeratin 7, and cytokeratin 20. This staining pattern was compatible with metastatic melanoma with aberrant CD56 expression.

BRAF V600E immunohistochemical staining also was performed and showed strong and diffuse positivity within neoplastic cells. A subsequent positron emission tomography scan revealed widespread metastatic disease involving the lungs, liver, spleen, and bones. The patient did not have a history of an excised skin lesion; no primary cutaneous or mucosal lesions were identified.

The patient was started on targeted therapy with trametinib, a mitogen-activated extracellular signal-related kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor, and dabrafenib, a BRAF inhibitor. The disease continued to progress; he developed extensive leptomeningeal metastatic disease for which palliative radiation therapy was administered. The patient died 4 months after the initial diagnosis.

More than 90% of melanoma cases are of cutaneous origin; however, 4% to 8% of cases present as a metastatic lesion in the absence of an identified primary lesion,4 similar to our patient. The diagnosis of melanoma often is challenging; the tumor can show notable histologic diversity and has the potential to express aberrant immunophenotypes.1,2 The histologic diversity of melanoma includes a variety of architectural patterns (eg, nests, trabeculae, fascicular, pseudoglandular, pseudopapillary, or pseudorosette patterns), cytomorphologic features, and stromal changes. Cytomorphologic features of melanoma can be large pleomorphic cells; small cells; spindle cells; clear cells; signet-ring cells; and rhabdoid, plasmacytoid, and balloon cells.5

Melanoma can mimic carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, benign stromal tumors, plasmacytoma, and germ-cell tumors.5 Nuclei can binucleated, multinucleated, or lobated and may contain inclusions or grooves. Stroma may become myxoid or desmoplastic in appearance or rarely show granulomatous inflammation or osteoclastic giant cells.5 These variations render the diagnosis of melanoma challenging and ultimately can lead to diagnostic uncertainty.

Melanomas typically express MART-1, HMB-45, S-100, tyrosinase, NK1C3, vimentin, and neuron-specific enolase. However, melanoma is among the many neoplasms that sometimes exhibit aberrant immunoreactivity and differentiation toward nonmelanocytic elements.6 The most commonly expressed immunophenotypic aberration is cytokeratin, especially the low-molecular-weight keratin marker CAM5.2.5 CAM5.2 positivity also is seen more often in metastatic melanoma. Melanomas rarely express other intermediate filaments, including desmin, neurofilament protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein; expression of smooth-muscle actin is rare.5

Only a few cases of melanoma showing expression of neuroendocrine markers have been reported. However, one study reported synaptophysin positivity in 29% (10/34) of cases of primary and metastatic melanoma, making the stain a relatively common finding.1

In contrast, expression of CD56 (also known as neural-cell adhesion molecule 1) in melanoma has been reported only rarely. CD56 is a nonspecific neuroendocrine marker that normally is expressed on neurons, glial tissue, skeletal muscle, and natural killer cells. Riddle and Bui7 reported a case of metastatic malignant melanoma with focal CD56 positivity and no expression of other neuroendocrine markers, similar to our patient. Suzuki and colleagues4 also reported a case of melanoma metastatic to bone marrow that showed CD56 expression in true nonhematologic tumor cells and negative immunoreactivity with synaptophysin and chromogranin A.

It is important to document cases of melanoma that express neuroendocrine markers to prevent an incorrect diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor.1 In some cases, distinguishing amelanotic melanoma from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, and lymphoma can be difficult.5

The term neuroendocrine differentiation is reserved for cases of melanoma that show areas of ultrastructural change consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor.2 Neuroendocrine differentiation in melanoma is not common; its prognostic significance is unknown.8 We do not consider our case to be true neuroendocrine differentiation, as the tumor lacked the morphologic changes of a neuroendocrine tumor. Furthermore, CD56 is a nonspecific neuroendocrine marker, and the tumor was negative for synaptophysin.

Melanoma has the potential to show notable histologic diversity as well as aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns.1,2 Our patient had metastatic melanoma with aberrant neuroendocrine expression of CD56, which could have been a potential diagnostic pitfall. Because expression of CD56 in melanoma is rare, it is imperative to recognize this potential aberrant staining pattern to ensure the accurate diagnosis of melanoma and appropriate provision of care.

1. Romano RC, Carter JM, Folpe AL. Aberrant intermediate filament and synaptophysin expression is a frequent event in malignant melanoma: an immunohistochemical study of 73 cases. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1033-1042. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2015.62

2. Eyden B, Pandit D, Banerjee SS. Malignant melanoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: clinical, histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features of three cases. Histopathology. 2005;47:402-409. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02240.x

3. Katerji H, Childs JM, Bratton LE, et al. Primary esophageal melanoma with aberrant CD56 expression: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Case Rep Pathol. 2017;2017:9052637. doi:10.1155/2017/9052637

4. Suzuki T, Kusumoto S, Iida S, et al. Amelanotic malignant melanoma of unknown primary origin metastasizing to the bone marrow: a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2014;53:325-328. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1412

5. Banerjee SS, Harris M. Morphological and immunophenotypic variations in malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 2000;36:387-402. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00894.x

6. Banerjee SS, Eyden B. Divergent differentiation in malignant melanomas: a review. Histopathology. 2008;52:119-129. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02823.x

7. Riddle ND, Bui MM. When melanoma is negative for S100: diagnostic pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:237-239. doi:10.5858/arpa.2011-0405-LE

8. Ilardi G, Caroppo D, Varricchio S, et al. Anal melanoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: report of a case. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:329-332. doi:10.1177/1066896915573568

1. Romano RC, Carter JM, Folpe AL. Aberrant intermediate filament and synaptophysin expression is a frequent event in malignant melanoma: an immunohistochemical study of 73 cases. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1033-1042. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2015.62

2. Eyden B, Pandit D, Banerjee SS. Malignant melanoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: clinical, histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features of three cases. Histopathology. 2005;47:402-409. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02240.x

3. Katerji H, Childs JM, Bratton LE, et al. Primary esophageal melanoma with aberrant CD56 expression: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Case Rep Pathol. 2017;2017:9052637. doi:10.1155/2017/9052637

4. Suzuki T, Kusumoto S, Iida S, et al. Amelanotic malignant melanoma of unknown primary origin metastasizing to the bone marrow: a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2014;53:325-328. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1412

5. Banerjee SS, Harris M. Morphological and immunophenotypic variations in malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 2000;36:387-402. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00894.x

6. Banerjee SS, Eyden B. Divergent differentiation in malignant melanomas: a review. Histopathology. 2008;52:119-129. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02823.x

7. Riddle ND, Bui MM. When melanoma is negative for S100: diagnostic pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:237-239. doi:10.5858/arpa.2011-0405-LE

8. Ilardi G, Caroppo D, Varricchio S, et al. Anal melanoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: report of a case. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:329-332. doi:10.1177/1066896915573568

Practice Points

- The diagnosis of melanoma often is challenging as tumors can show notable histologic diversity and have the potential to express aberrant immunophenotypes including CD56 expression.

- Because expression of CD56 in melanoma is rare, it is important to be aware of this potential aberrant staining pattern.

- Recognizing this heterogeneity and divergent differentiation as well as knowing potential aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns are imperative for accurate and timely diagnosis.

Specialty-trained pathologists more likely to make higher-grade diagnoses for melanocytic lesions

, results from an exploratory study showed.

The findings “could in part play a role in the rising incidence of early-stage melanoma with low risk of progression or patient morbidity, thereby contributing to increasing rates of overdiagnosis,” researchers led by co–senior authors Joann G. Elmore, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Raymond L. Barnhill, MD, MBA, of the Institut Curie, Paris, wrote in their study, published online in JAMA Dermatology.

To investigate the characteristics associated with rendering higher-grade diagnoses, including invasive melanoma, the researchers drew from two national data sets: the Melanoma Pathology (M-Path) study, conducted from July 2013 to May 2016, and the Reducing Errors in Melanocytic Interpretations (REMI) study, conducted from August 2018 to March 2021. In both studies, pathologists who interpreted melanocytic lesions in their clinical practices interpreted study cases in glass slide format. For the current study, researchers used logistic regression to examine the association of pathologist characteristics with diagnosis of a study case as higher grade (including severely dysplastic and melanoma in situ) vs. lower grade (including mild to moderately dysplastic nevi) and diagnosis of invasive melanoma vs. any less severe diagnosis.

A total of 338 pathologists were included in the analysis. Of these, 113 were general pathologists and 225 were dermatopathologists (those who were board certified and/or fellowship trained in dermatopathology).

The researchers found that, compared with general pathologists, dermatopathologists were 2.63 times more likely to render higher-grade diagnoses and 1.95 times more likely to diagnose invasive melanoma (P < .001 for both associations). Diagnoses of stage pT1a melanomas with no mitotic activity completely accounted for the difference between dermatopathologists and general pathologists in diagnosing invasive melanoma.

For the analysis limited to the 225 dermatopathologists, those with a higher practice caseload of melanocytic lesions were more likely to assign higher-grade diagnoses (odds ratio for trend, 1.27; P = .02), while those affiliated with an academic center had lower odds of diagnosing invasive melanoma (OR, 0.61; P = .049).

The researchers acknowledged limitations of their analysis, including the lack of data on patient outcomes, “so we could not make conclusions about the clinical outcome of any particular diagnosis by a study participant,” they wrote. “While our analyses revealed pathologist characteristics associated with assigning more vs. less severe diagnoses of melanocytic lesions, we could not conclude that any particular diagnosis by a study participant was overcalling or undercalling. However, the epidemiologic evidence that melanoma is overdiagnosed suggests that overcalling by some pathologists may be contributing to increasing rates of low-risk melanoma diagnoses.”

In an accompanying editorial, authors Klaus J. Busam, MD, of the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, Pedram Gerami, MD, of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and Richard A. Scolyer, MD, of the Melanoma Institute, Wollstonecraft, Australia, wrote that the study findings “raise the question of whether subspecialization in dermatopathology may be a factor contributing to the epidemiologic phenomenon of overdiagnosis – that is, the discordance in the rise of melanoma incidence and relatively constant annual mortality rates over many decades. The findings also invite a discussion about strategies to minimize harm from overdiagnosis for both patients and the health care system.”

To minimize misdiagnoses, they continued, efforts to facilitate diagnostic accuracy should be encouraged. “Excisional (rather than partial) biopsies and provision of relevant clinical information would facilitate rendering of the correct histopathologic diagnosis,” they wrote. “When the diagnosis is uncertain, this is best acknowledged. If felt necessary, a reexcision of a lesion with an uncertain diagnosis can be recommended without upgrading the diagnosis.”

In addition, “improvements in prognosis are needed beyond American Joint Committee on Cancer staging,” they noted. “This will likely require a multimodal approach with novel methods, including artificial intelligence and biomarkers that help distinguish low-risk melanomas, for which a conservative approach may be appropriate, from those that require surgical intervention.”

The study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and by the National Institutes of Health. One author disclosed receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study, and another disclosed serving as editor in chief of Primary Care topics at UpToDate; other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Busam reported receiving nonfinancial support from the American Society of Dermatopathology. Dr. Gerami reported receiving consulting fees from Castle Biosciences. Dr. Scolyer reported receiving an investigator grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia during the conduct of the study and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

, results from an exploratory study showed.

The findings “could in part play a role in the rising incidence of early-stage melanoma with low risk of progression or patient morbidity, thereby contributing to increasing rates of overdiagnosis,” researchers led by co–senior authors Joann G. Elmore, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Raymond L. Barnhill, MD, MBA, of the Institut Curie, Paris, wrote in their study, published online in JAMA Dermatology.

To investigate the characteristics associated with rendering higher-grade diagnoses, including invasive melanoma, the researchers drew from two national data sets: the Melanoma Pathology (M-Path) study, conducted from July 2013 to May 2016, and the Reducing Errors in Melanocytic Interpretations (REMI) study, conducted from August 2018 to March 2021. In both studies, pathologists who interpreted melanocytic lesions in their clinical practices interpreted study cases in glass slide format. For the current study, researchers used logistic regression to examine the association of pathologist characteristics with diagnosis of a study case as higher grade (including severely dysplastic and melanoma in situ) vs. lower grade (including mild to moderately dysplastic nevi) and diagnosis of invasive melanoma vs. any less severe diagnosis.

A total of 338 pathologists were included in the analysis. Of these, 113 were general pathologists and 225 were dermatopathologists (those who were board certified and/or fellowship trained in dermatopathology).

The researchers found that, compared with general pathologists, dermatopathologists were 2.63 times more likely to render higher-grade diagnoses and 1.95 times more likely to diagnose invasive melanoma (P < .001 for both associations). Diagnoses of stage pT1a melanomas with no mitotic activity completely accounted for the difference between dermatopathologists and general pathologists in diagnosing invasive melanoma.

For the analysis limited to the 225 dermatopathologists, those with a higher practice caseload of melanocytic lesions were more likely to assign higher-grade diagnoses (odds ratio for trend, 1.27; P = .02), while those affiliated with an academic center had lower odds of diagnosing invasive melanoma (OR, 0.61; P = .049).

The researchers acknowledged limitations of their analysis, including the lack of data on patient outcomes, “so we could not make conclusions about the clinical outcome of any particular diagnosis by a study participant,” they wrote. “While our analyses revealed pathologist characteristics associated with assigning more vs. less severe diagnoses of melanocytic lesions, we could not conclude that any particular diagnosis by a study participant was overcalling or undercalling. However, the epidemiologic evidence that melanoma is overdiagnosed suggests that overcalling by some pathologists may be contributing to increasing rates of low-risk melanoma diagnoses.”

In an accompanying editorial, authors Klaus J. Busam, MD, of the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, Pedram Gerami, MD, of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and Richard A. Scolyer, MD, of the Melanoma Institute, Wollstonecraft, Australia, wrote that the study findings “raise the question of whether subspecialization in dermatopathology may be a factor contributing to the epidemiologic phenomenon of overdiagnosis – that is, the discordance in the rise of melanoma incidence and relatively constant annual mortality rates over many decades. The findings also invite a discussion about strategies to minimize harm from overdiagnosis for both patients and the health care system.”

To minimize misdiagnoses, they continued, efforts to facilitate diagnostic accuracy should be encouraged. “Excisional (rather than partial) biopsies and provision of relevant clinical information would facilitate rendering of the correct histopathologic diagnosis,” they wrote. “When the diagnosis is uncertain, this is best acknowledged. If felt necessary, a reexcision of a lesion with an uncertain diagnosis can be recommended without upgrading the diagnosis.”

In addition, “improvements in prognosis are needed beyond American Joint Committee on Cancer staging,” they noted. “This will likely require a multimodal approach with novel methods, including artificial intelligence and biomarkers that help distinguish low-risk melanomas, for which a conservative approach may be appropriate, from those that require surgical intervention.”

The study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and by the National Institutes of Health. One author disclosed receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study, and another disclosed serving as editor in chief of Primary Care topics at UpToDate; other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Busam reported receiving nonfinancial support from the American Society of Dermatopathology. Dr. Gerami reported receiving consulting fees from Castle Biosciences. Dr. Scolyer reported receiving an investigator grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia during the conduct of the study and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

, results from an exploratory study showed.

The findings “could in part play a role in the rising incidence of early-stage melanoma with low risk of progression or patient morbidity, thereby contributing to increasing rates of overdiagnosis,” researchers led by co–senior authors Joann G. Elmore, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Raymond L. Barnhill, MD, MBA, of the Institut Curie, Paris, wrote in their study, published online in JAMA Dermatology.

To investigate the characteristics associated with rendering higher-grade diagnoses, including invasive melanoma, the researchers drew from two national data sets: the Melanoma Pathology (M-Path) study, conducted from July 2013 to May 2016, and the Reducing Errors in Melanocytic Interpretations (REMI) study, conducted from August 2018 to March 2021. In both studies, pathologists who interpreted melanocytic lesions in their clinical practices interpreted study cases in glass slide format. For the current study, researchers used logistic regression to examine the association of pathologist characteristics with diagnosis of a study case as higher grade (including severely dysplastic and melanoma in situ) vs. lower grade (including mild to moderately dysplastic nevi) and diagnosis of invasive melanoma vs. any less severe diagnosis.

A total of 338 pathologists were included in the analysis. Of these, 113 were general pathologists and 225 were dermatopathologists (those who were board certified and/or fellowship trained in dermatopathology).

The researchers found that, compared with general pathologists, dermatopathologists were 2.63 times more likely to render higher-grade diagnoses and 1.95 times more likely to diagnose invasive melanoma (P < .001 for both associations). Diagnoses of stage pT1a melanomas with no mitotic activity completely accounted for the difference between dermatopathologists and general pathologists in diagnosing invasive melanoma.

For the analysis limited to the 225 dermatopathologists, those with a higher practice caseload of melanocytic lesions were more likely to assign higher-grade diagnoses (odds ratio for trend, 1.27; P = .02), while those affiliated with an academic center had lower odds of diagnosing invasive melanoma (OR, 0.61; P = .049).

The researchers acknowledged limitations of their analysis, including the lack of data on patient outcomes, “so we could not make conclusions about the clinical outcome of any particular diagnosis by a study participant,” they wrote. “While our analyses revealed pathologist characteristics associated with assigning more vs. less severe diagnoses of melanocytic lesions, we could not conclude that any particular diagnosis by a study participant was overcalling or undercalling. However, the epidemiologic evidence that melanoma is overdiagnosed suggests that overcalling by some pathologists may be contributing to increasing rates of low-risk melanoma diagnoses.”

In an accompanying editorial, authors Klaus J. Busam, MD, of the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, Pedram Gerami, MD, of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, and Richard A. Scolyer, MD, of the Melanoma Institute, Wollstonecraft, Australia, wrote that the study findings “raise the question of whether subspecialization in dermatopathology may be a factor contributing to the epidemiologic phenomenon of overdiagnosis – that is, the discordance in the rise of melanoma incidence and relatively constant annual mortality rates over many decades. The findings also invite a discussion about strategies to minimize harm from overdiagnosis for both patients and the health care system.”

To minimize misdiagnoses, they continued, efforts to facilitate diagnostic accuracy should be encouraged. “Excisional (rather than partial) biopsies and provision of relevant clinical information would facilitate rendering of the correct histopathologic diagnosis,” they wrote. “When the diagnosis is uncertain, this is best acknowledged. If felt necessary, a reexcision of a lesion with an uncertain diagnosis can be recommended without upgrading the diagnosis.”

In addition, “improvements in prognosis are needed beyond American Joint Committee on Cancer staging,” they noted. “This will likely require a multimodal approach with novel methods, including artificial intelligence and biomarkers that help distinguish low-risk melanomas, for which a conservative approach may be appropriate, from those that require surgical intervention.”

The study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and by the National Institutes of Health. One author disclosed receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study, and another disclosed serving as editor in chief of Primary Care topics at UpToDate; other authors had no disclosures. Dr. Busam reported receiving nonfinancial support from the American Society of Dermatopathology. Dr. Gerami reported receiving consulting fees from Castle Biosciences. Dr. Scolyer reported receiving an investigator grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia during the conduct of the study and personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

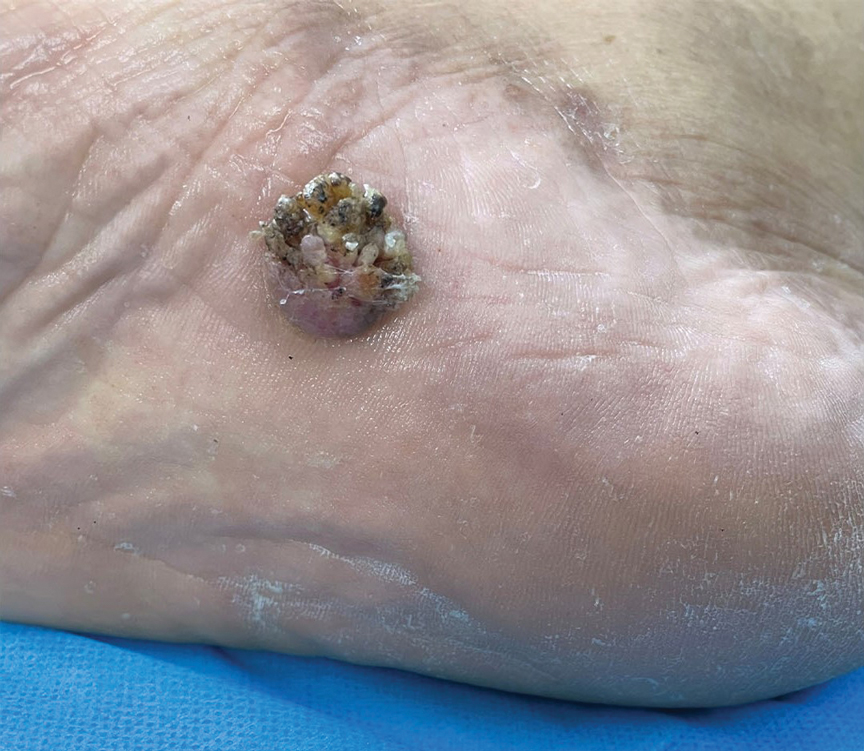

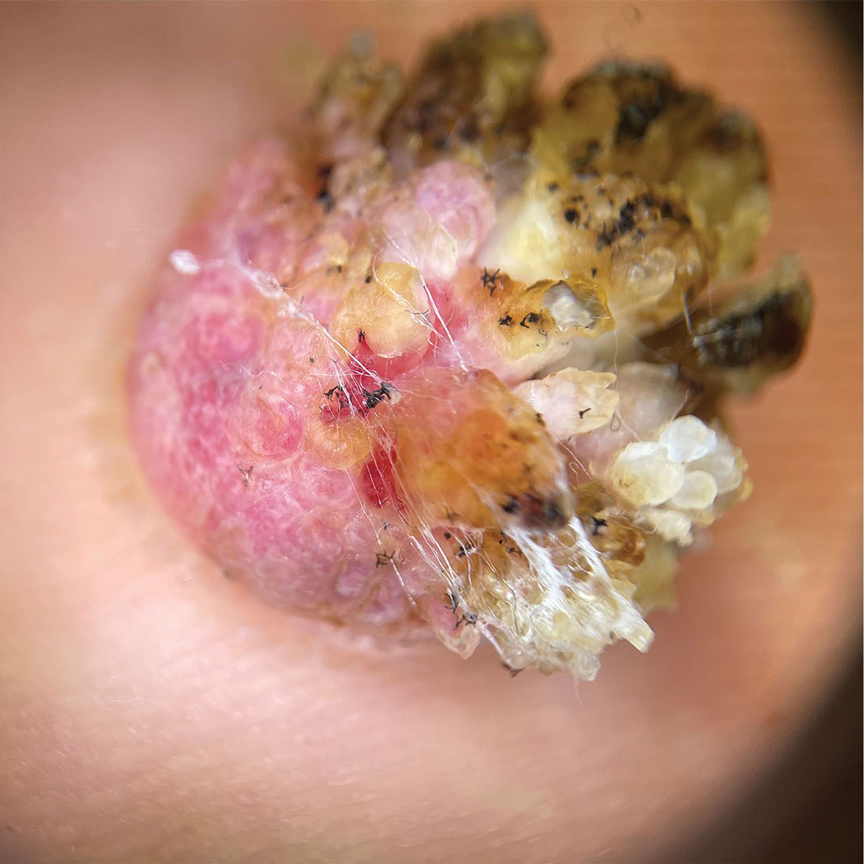

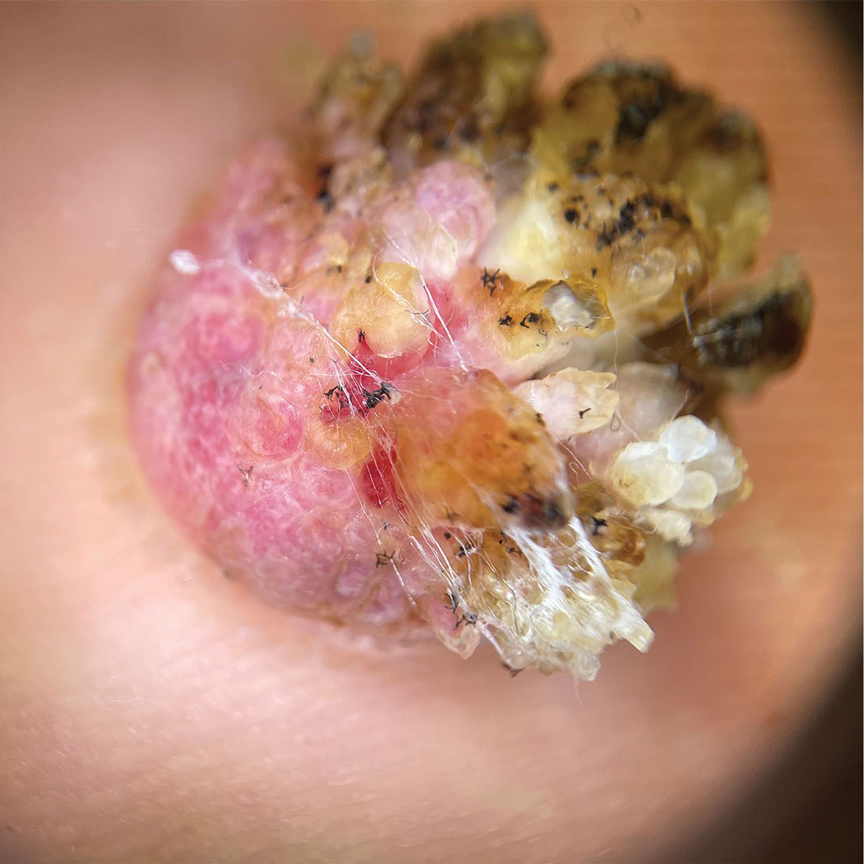

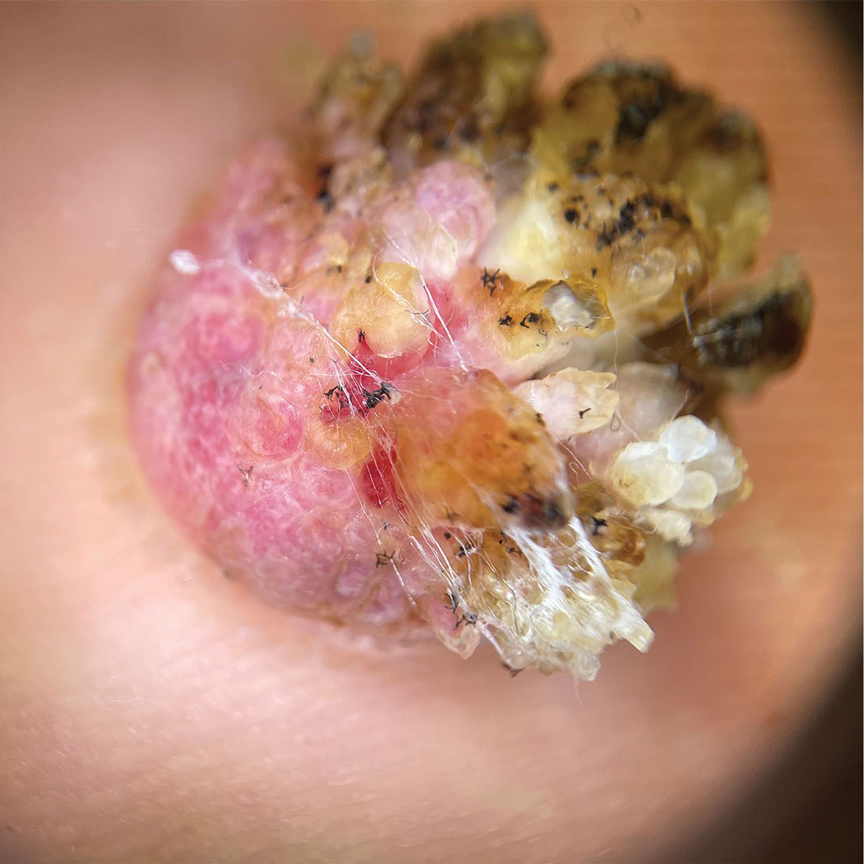

An 88-year-old Black woman presented with 3 months duration of asymptomatic, violaceous patches on the left breast

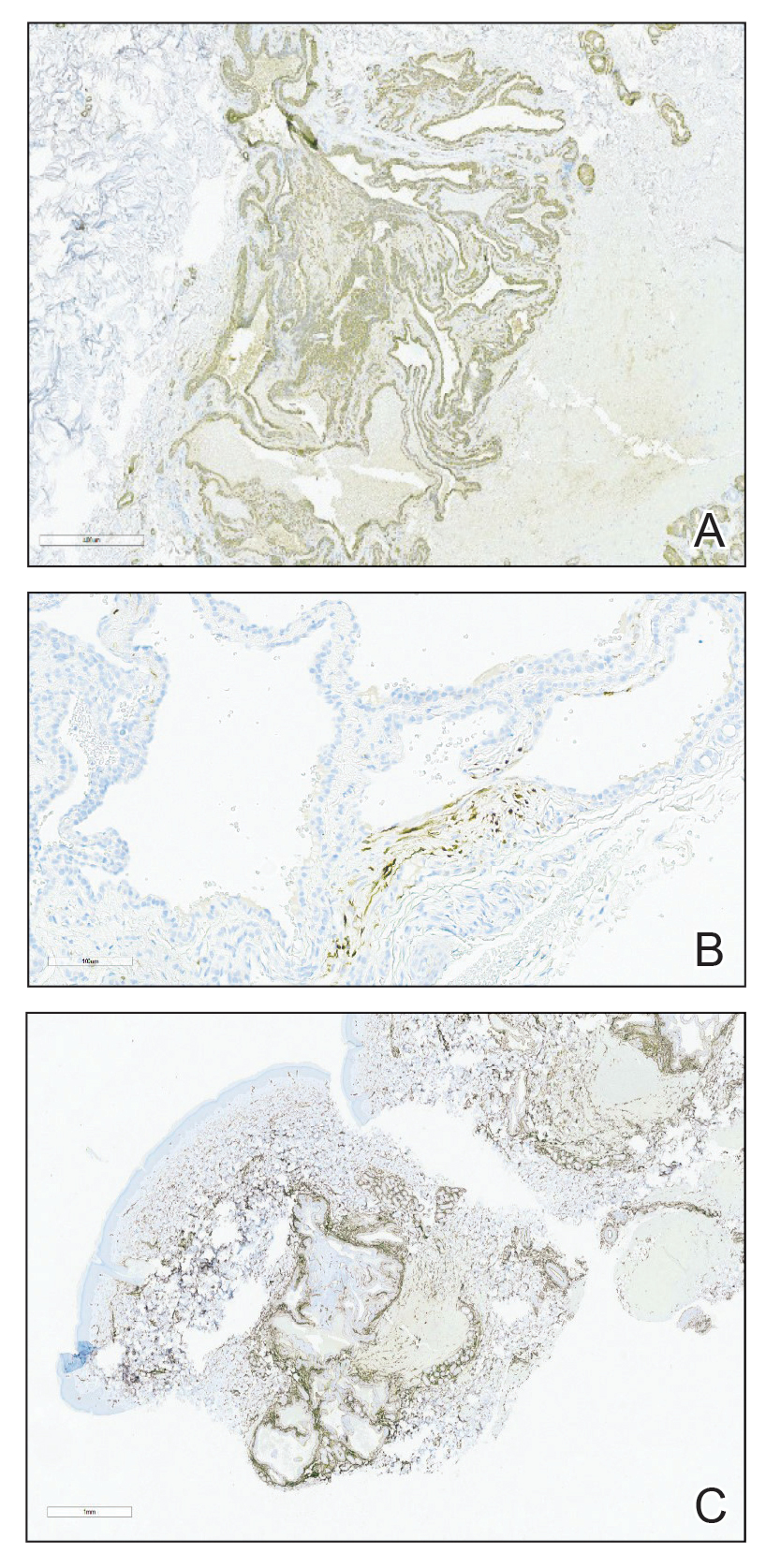

Angiosarcomas are uncommon, high-grade malignant tumors of endothelial cell origin that can arise via the lymphatics or vasculature. They typically occur spontaneously; however, there have been cases reported of benign vascular transformation. These tumors are more commonly found in elderly men on the head and neck in sun-damaged skin. . This is a late complication, typically occurring about 5-10 years after radiation. Stewart-Treves syndrome, chronic lymphedema occurring after breast cancer treatment with axillary node dissection, increases the risk of angiosarcoma. As a vascular tumor, angiosarcoma spreads hematogenously and carries a poor prognosis if not caught early. Differential diagnoses include other vascular tumors such as retiform hemangioendothelioma. In this specific patient, the differential diagnosis includes Paget’s disease, chronic radiation skin changes, and eczema.

Histopathologically, angiosarcomas exhibit abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells. As the tumor progresses, the cell architecture becomes more distorted and cells form layers with papillary projections into the vascular lumen. Malignant cells may stain positive for CD31, CD34, the oncogene ERG and the proto-oncogene FLI-1. Histology in this patient revealed radiation changes in the dermis, as well as few vascular channels lined by large endothelial cells with marked nuclear atypia, in the form of large nucleoli and variably coarse chromatin. The cells were positive for MYC.

Treatment of angiosarcoma involves a multidisciplinary approach. Resection with wide margins is generally the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is relatively common, which may be a result of microsatellite deposits of the tumor. Perioperative radiation is recommended, and adjuvant chemotherapy often is recommended for metastatic disease. Specifically, paclitaxel has been found to promote survival in some cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Metastatic disease may be treated with cytotoxic drugs such as anthracyclines and taxanes. Additionally, targeted therapy including anti-VEGF drugs and tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been tested.

The case and photo were submitted by Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Dr. Bilu Martin. The column was edited by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Cohen-Hallaleh RB et al. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2017 Aug 7:7:15.

Cozzi S et al. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2021 Sep 30;26(5):827-32.

Spiker AM, Mangla A, Ramsey ML. Angiosarcoma. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441983/

Angiosarcomas are uncommon, high-grade malignant tumors of endothelial cell origin that can arise via the lymphatics or vasculature. They typically occur spontaneously; however, there have been cases reported of benign vascular transformation. These tumors are more commonly found in elderly men on the head and neck in sun-damaged skin. . This is a late complication, typically occurring about 5-10 years after radiation. Stewart-Treves syndrome, chronic lymphedema occurring after breast cancer treatment with axillary node dissection, increases the risk of angiosarcoma. As a vascular tumor, angiosarcoma spreads hematogenously and carries a poor prognosis if not caught early. Differential diagnoses include other vascular tumors such as retiform hemangioendothelioma. In this specific patient, the differential diagnosis includes Paget’s disease, chronic radiation skin changes, and eczema.

Histopathologically, angiosarcomas exhibit abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells. As the tumor progresses, the cell architecture becomes more distorted and cells form layers with papillary projections into the vascular lumen. Malignant cells may stain positive for CD31, CD34, the oncogene ERG and the proto-oncogene FLI-1. Histology in this patient revealed radiation changes in the dermis, as well as few vascular channels lined by large endothelial cells with marked nuclear atypia, in the form of large nucleoli and variably coarse chromatin. The cells were positive for MYC.

Treatment of angiosarcoma involves a multidisciplinary approach. Resection with wide margins is generally the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is relatively common, which may be a result of microsatellite deposits of the tumor. Perioperative radiation is recommended, and adjuvant chemotherapy often is recommended for metastatic disease. Specifically, paclitaxel has been found to promote survival in some cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Metastatic disease may be treated with cytotoxic drugs such as anthracyclines and taxanes. Additionally, targeted therapy including anti-VEGF drugs and tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been tested.

The case and photo were submitted by Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Dr. Bilu Martin. The column was edited by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Cohen-Hallaleh RB et al. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2017 Aug 7:7:15.

Cozzi S et al. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2021 Sep 30;26(5):827-32.

Spiker AM, Mangla A, Ramsey ML. Angiosarcoma. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441983/

Angiosarcomas are uncommon, high-grade malignant tumors of endothelial cell origin that can arise via the lymphatics or vasculature. They typically occur spontaneously; however, there have been cases reported of benign vascular transformation. These tumors are more commonly found in elderly men on the head and neck in sun-damaged skin. . This is a late complication, typically occurring about 5-10 years after radiation. Stewart-Treves syndrome, chronic lymphedema occurring after breast cancer treatment with axillary node dissection, increases the risk of angiosarcoma. As a vascular tumor, angiosarcoma spreads hematogenously and carries a poor prognosis if not caught early. Differential diagnoses include other vascular tumors such as retiform hemangioendothelioma. In this specific patient, the differential diagnosis includes Paget’s disease, chronic radiation skin changes, and eczema.

Histopathologically, angiosarcomas exhibit abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells. As the tumor progresses, the cell architecture becomes more distorted and cells form layers with papillary projections into the vascular lumen. Malignant cells may stain positive for CD31, CD34, the oncogene ERG and the proto-oncogene FLI-1. Histology in this patient revealed radiation changes in the dermis, as well as few vascular channels lined by large endothelial cells with marked nuclear atypia, in the form of large nucleoli and variably coarse chromatin. The cells were positive for MYC.

Treatment of angiosarcoma involves a multidisciplinary approach. Resection with wide margins is generally the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is relatively common, which may be a result of microsatellite deposits of the tumor. Perioperative radiation is recommended, and adjuvant chemotherapy often is recommended for metastatic disease. Specifically, paclitaxel has been found to promote survival in some cases of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Metastatic disease may be treated with cytotoxic drugs such as anthracyclines and taxanes. Additionally, targeted therapy including anti-VEGF drugs and tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been tested.

The case and photo were submitted by Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Dr. Bilu Martin. The column was edited by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Cohen-Hallaleh RB et al. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2017 Aug 7:7:15.

Cozzi S et al. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2021 Sep 30;26(5):827-32.

Spiker AM, Mangla A, Ramsey ML. Angiosarcoma. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441983/

Keratotic Nodules in a Patient With End-Stage Renal Disease

The Diagnosis: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) is the most common type of primary perforating dermatosis and is characterized by the transepithelial elimination of collagen from the dermis. Although familial RPC usually presents in infancy or early childhood, the acquired form has a strong association with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic renal disease. Up to 10% of hemodialysis patients develop RPC.1 Patients with RPC develop red-brown, umbilicated, papulonodular lesions, often with a central keratotic crust and erythematous halo. The lesions are variable in shape and size (typically up to 10 mm in diameter) and commonly are located on the trunk or extensor aspects of the limbs. Pruritus is the primary concern, and the Koebner phenomenon commonly is seen.2

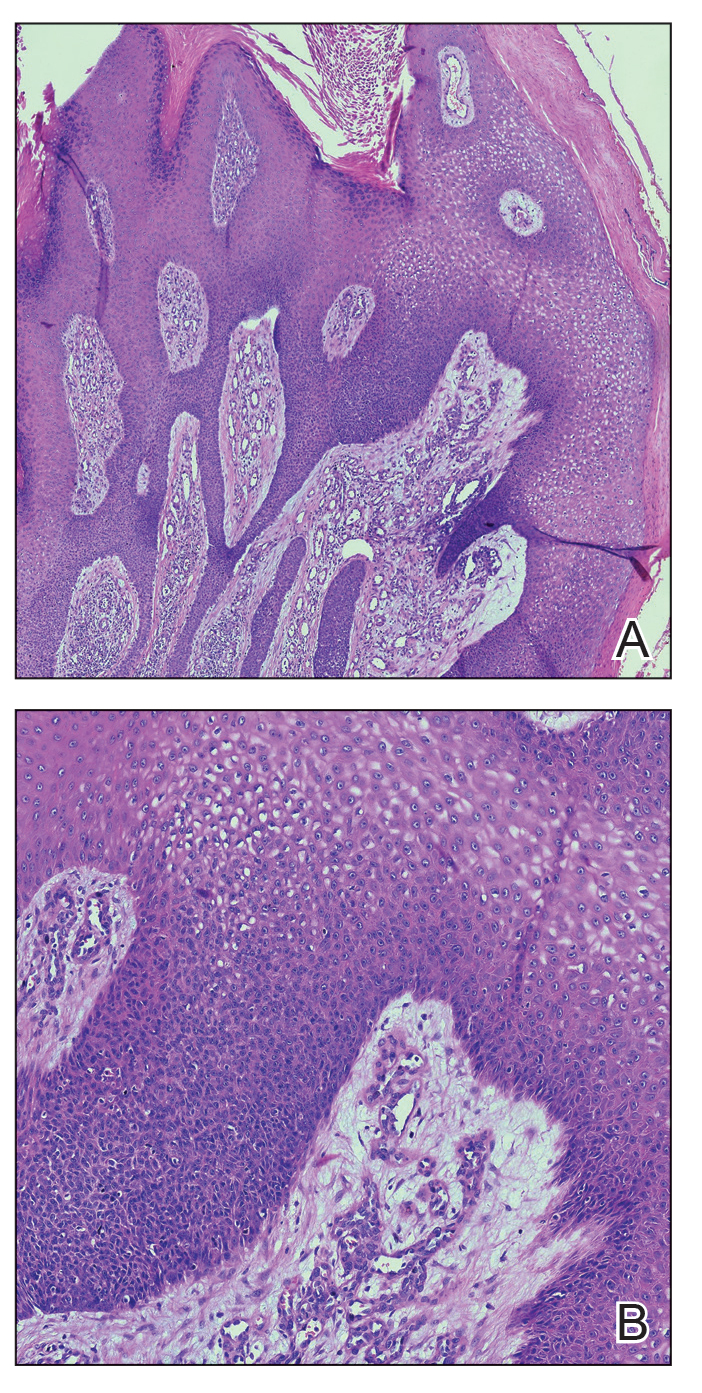

Although the histopathology can vary depending on the stage of the lesion, an invaginating epidermal process with prominent epidermal hyperplasia surrounding a central plug of keratin, basophilic inflammatory debris, and degenerated collagen are findings indicative of RPC. At the base of the invagination, the altered collagen perforates through the epidermis by the process of transepidermal elimination.3 Trichrome stains can highlight the collagen, while Verhoeff–van Gieson staining is negative (no elastic fiber elimination). Anecdotal reports have described a variety of successful therapies including retinoids, allopurinol, doxycycline, dupilumab, and phototherapy, with phototherapy being especially effective in patients with coexistent renal disease.4-8 Our patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg every other week and triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily (Monday through Friday) for itchy areas. The efficacy of the treatment was to be assessed at the next visit.

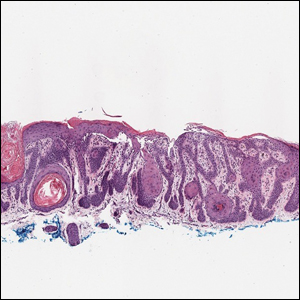

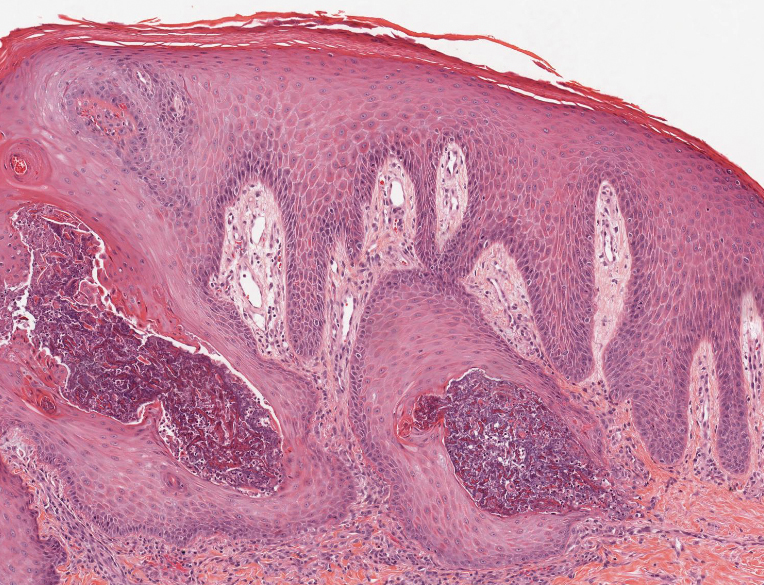

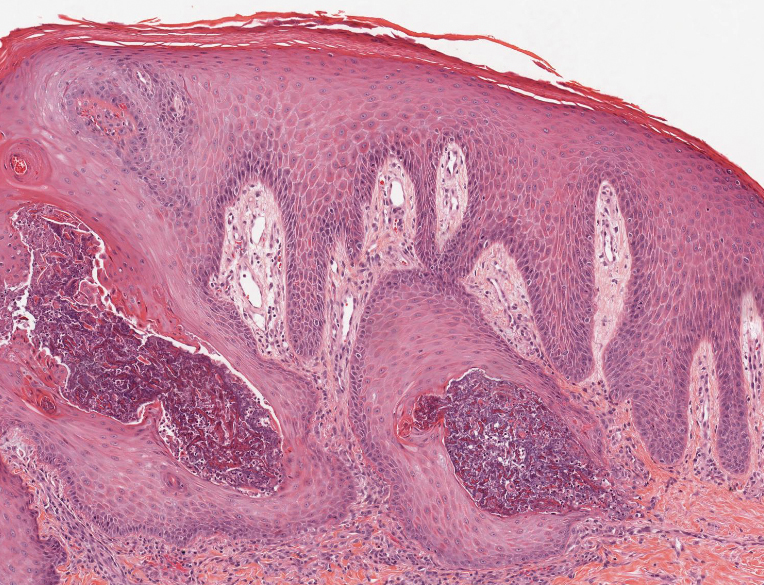

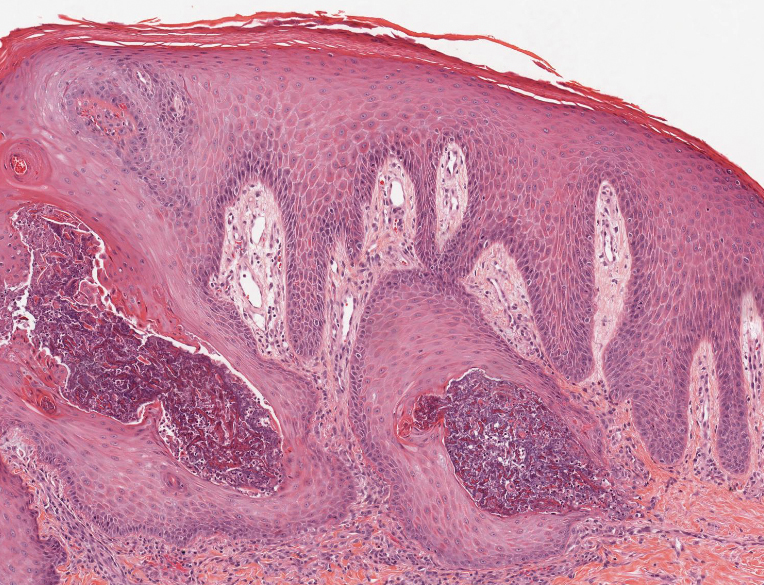

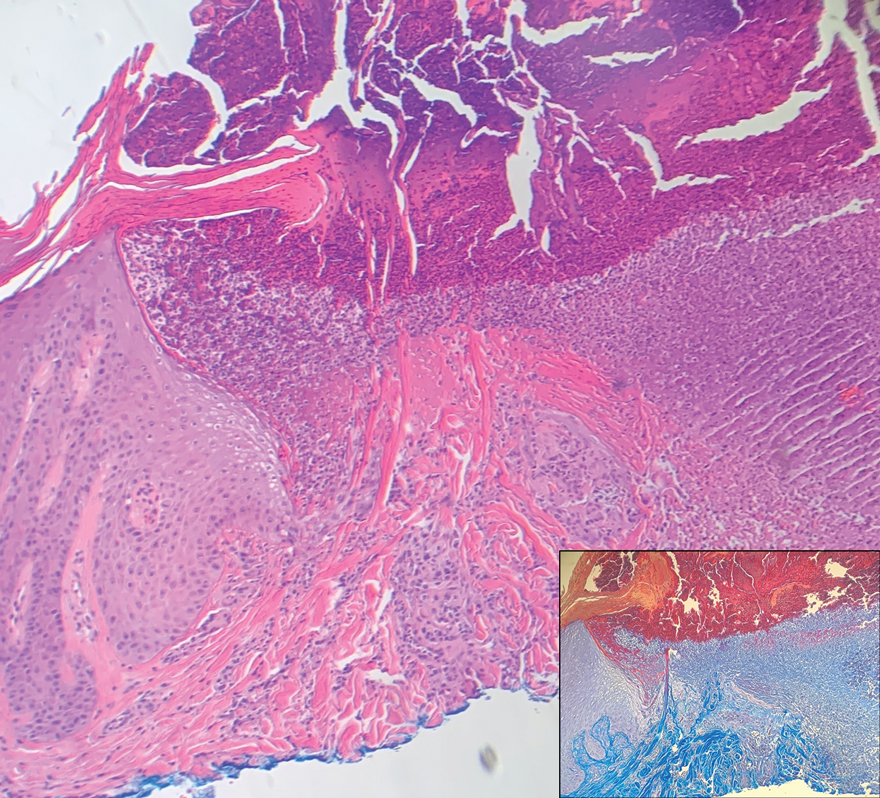

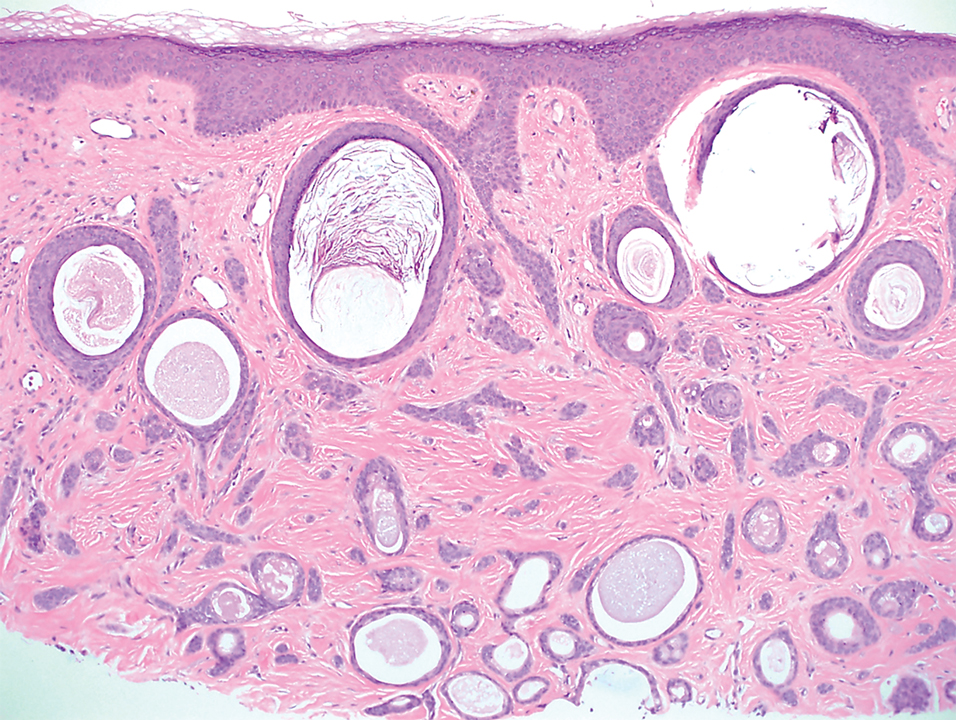

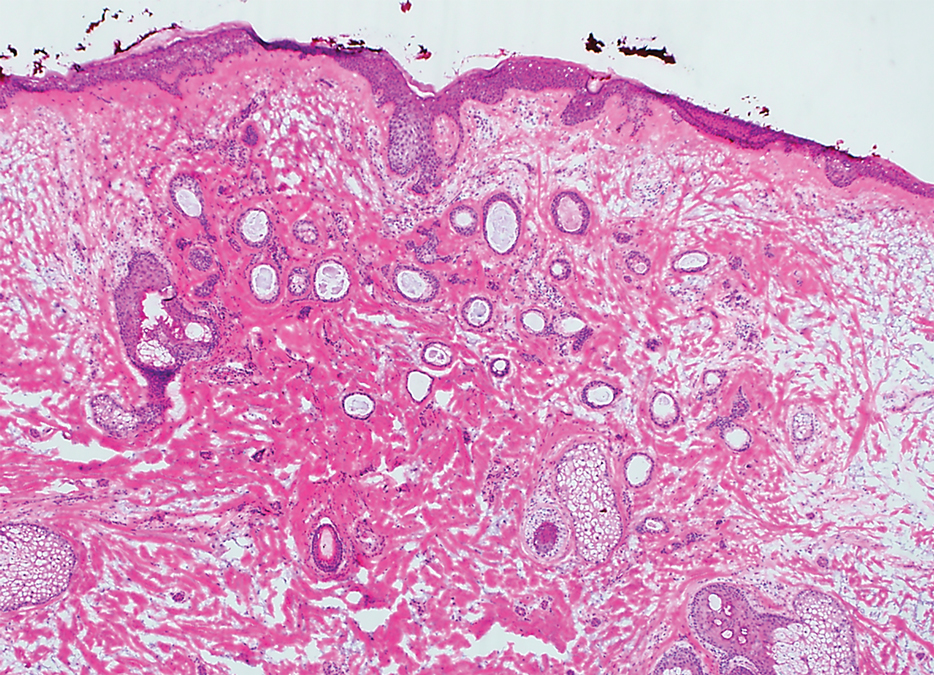

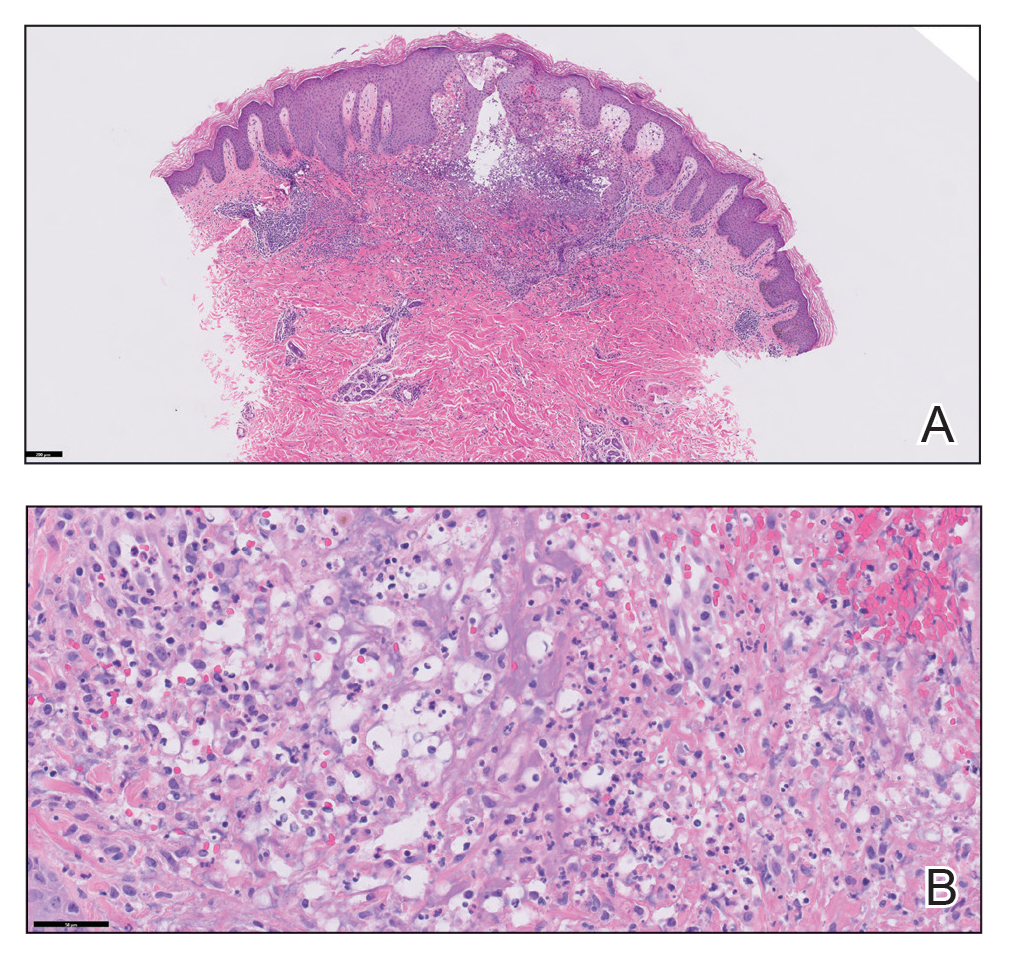

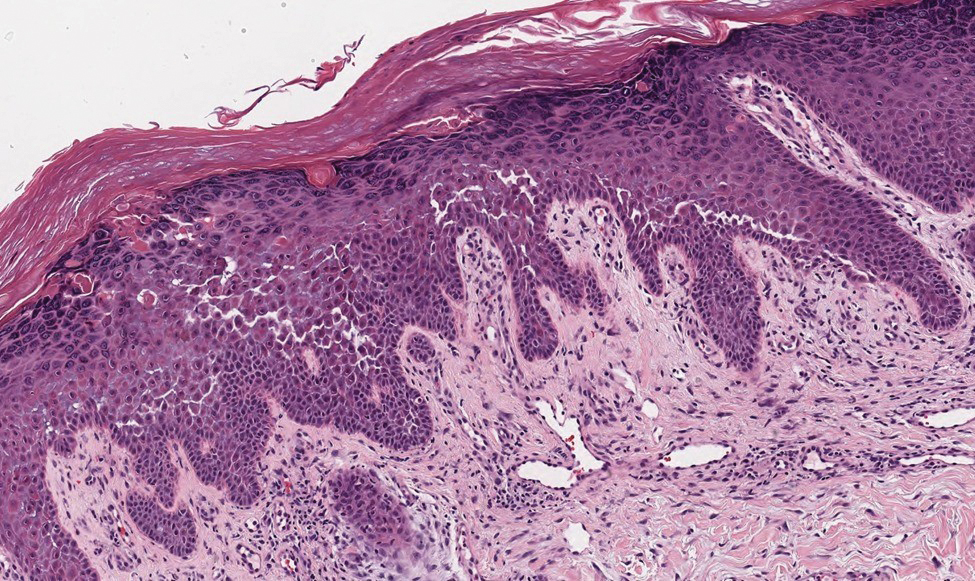

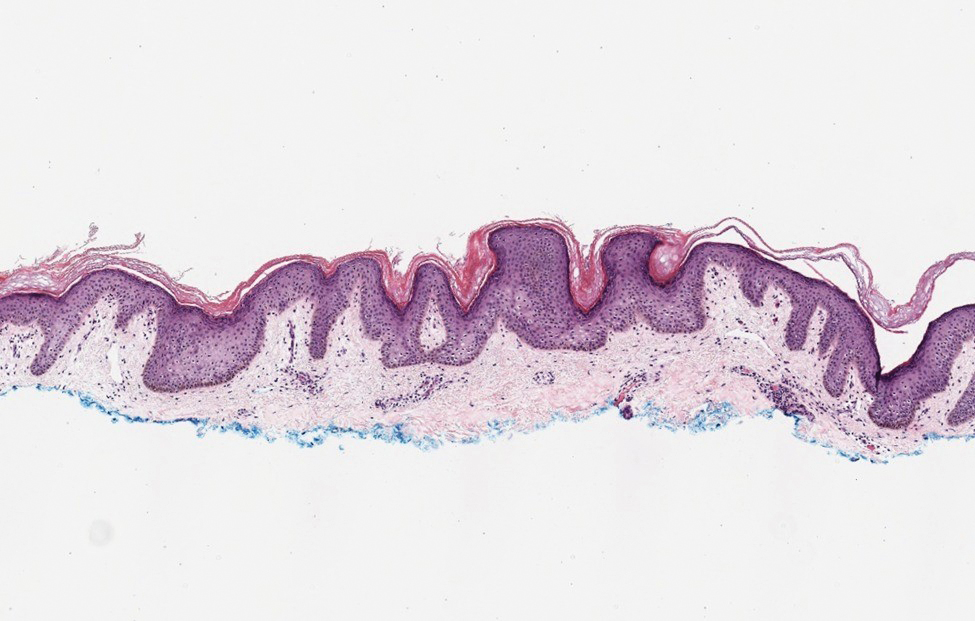

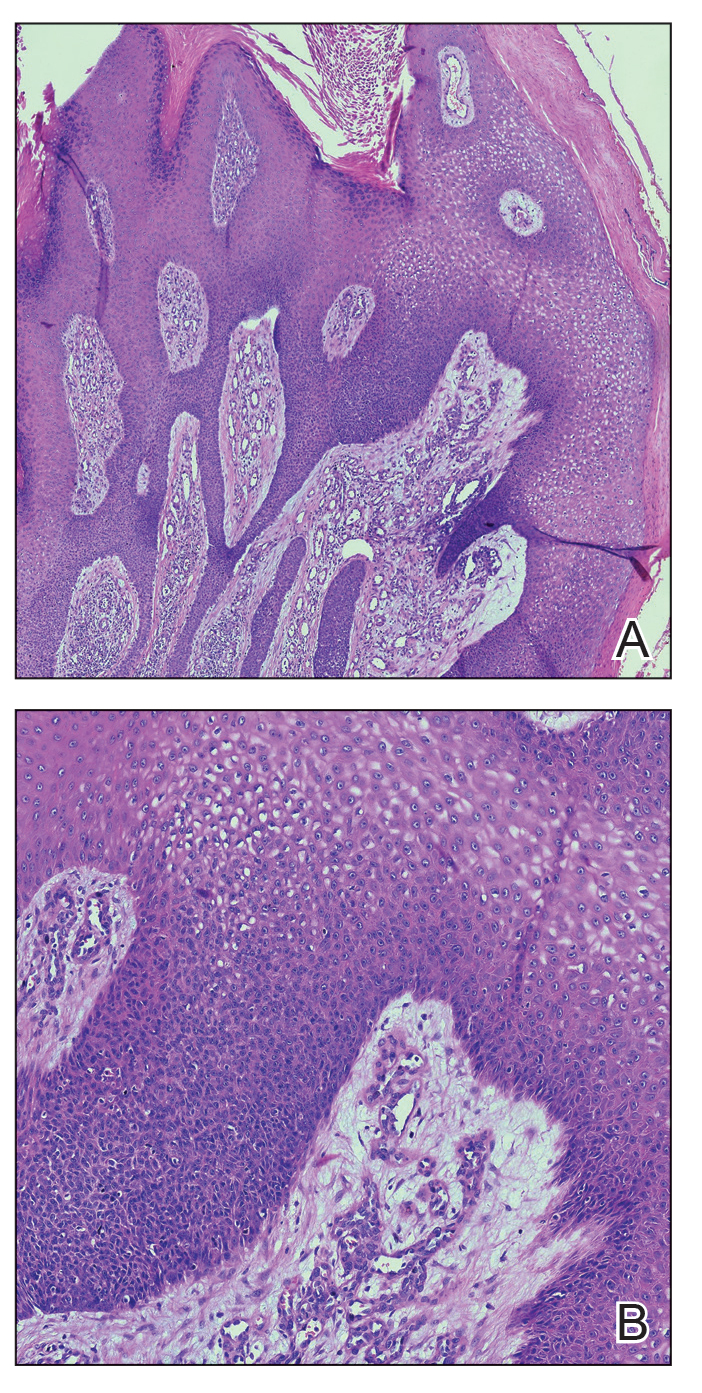

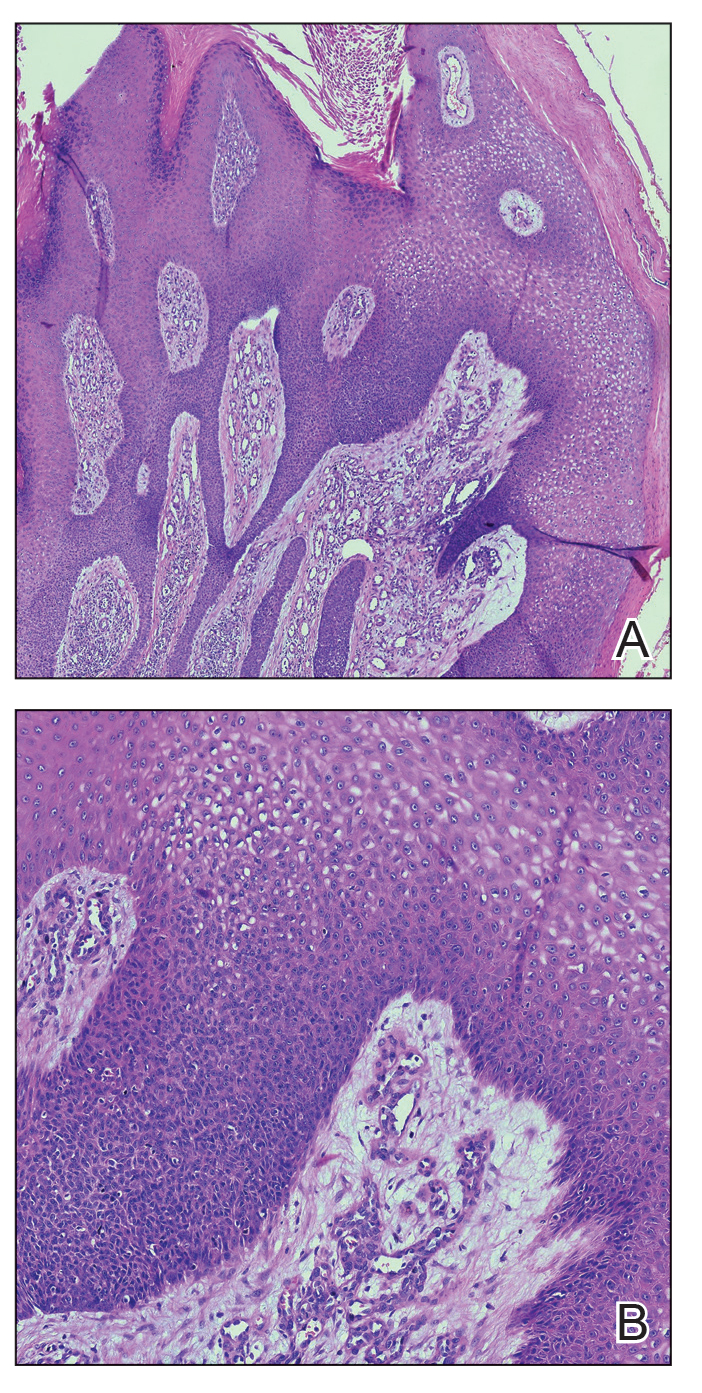

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) is a rare skin disease that presents as small papules arranged in serpiginous or annular patterns on the neck, face, arms, or other flexural areas in early adulthood. It more commonly is seen in males and can be associated with other inherited disorders such as Down syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Marfan syndrome. In rare instances, EPS has been linked to D-penicillamine.9 Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is characterized by focal dermal elastosis and transepithelial elimination of abnormal elastic fibers instead of collagen. The formation of narrow channels extending upward from the dermis in straight or corkscrew patterns commonly is seen (Figure 1). The dermis also may contain a chronic inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells.10 Verhoeff– van Gieson stain highlights the altered elastic fibers in the papillary dermis.

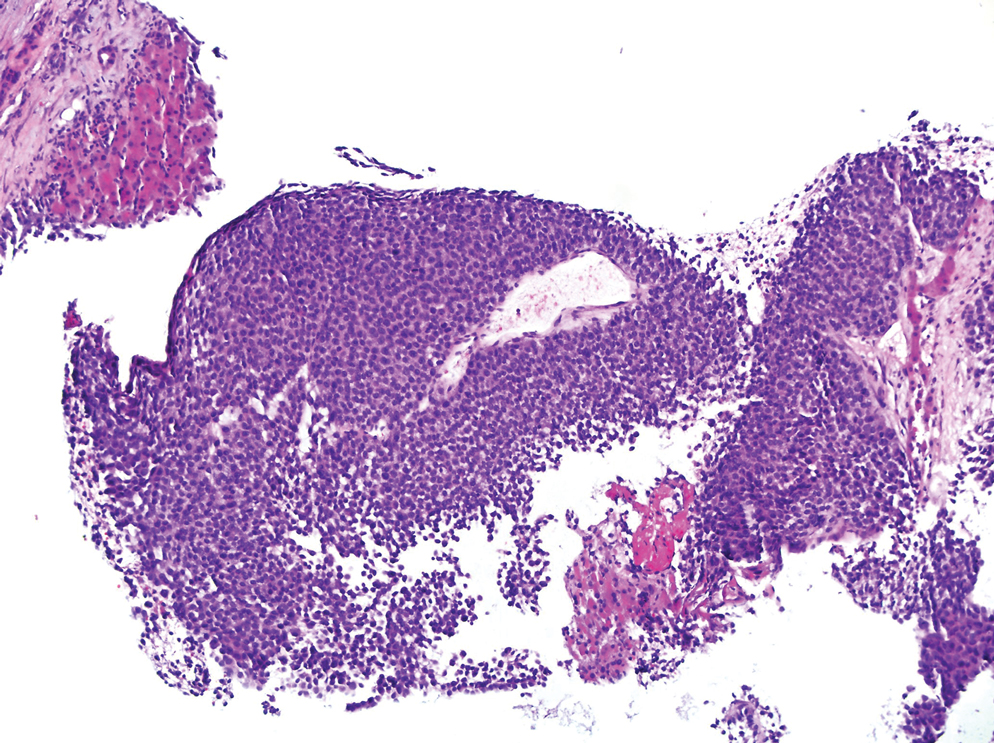

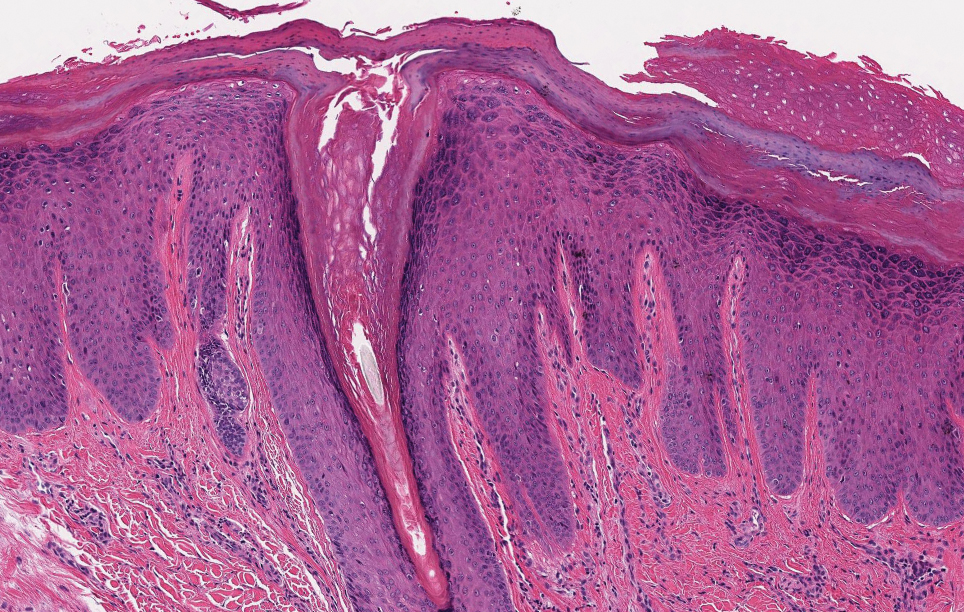

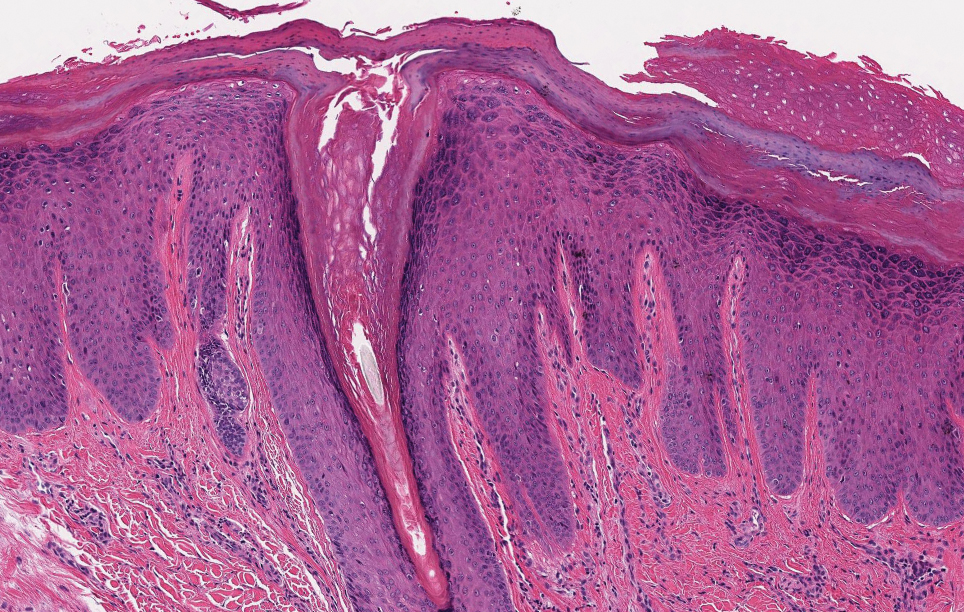

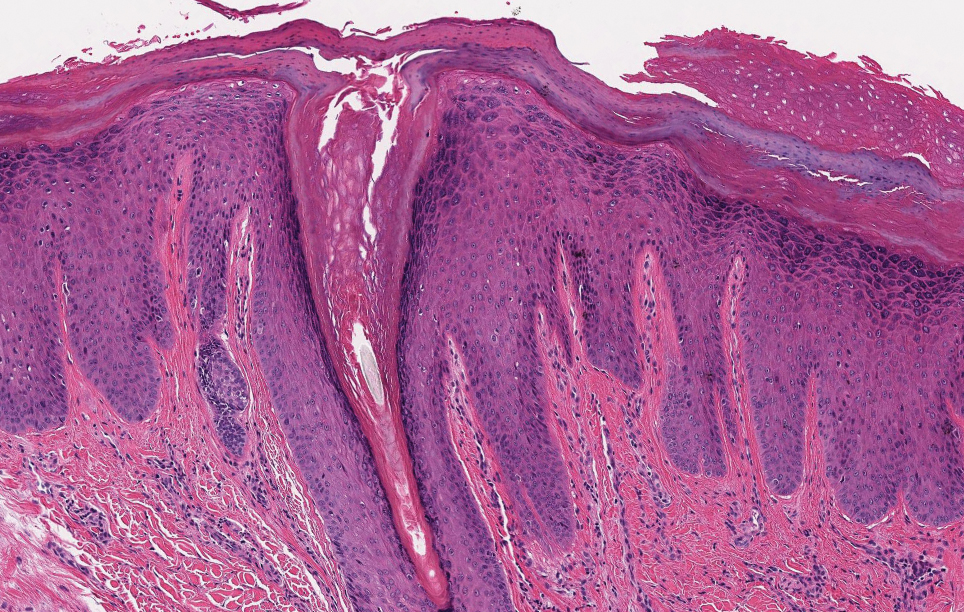

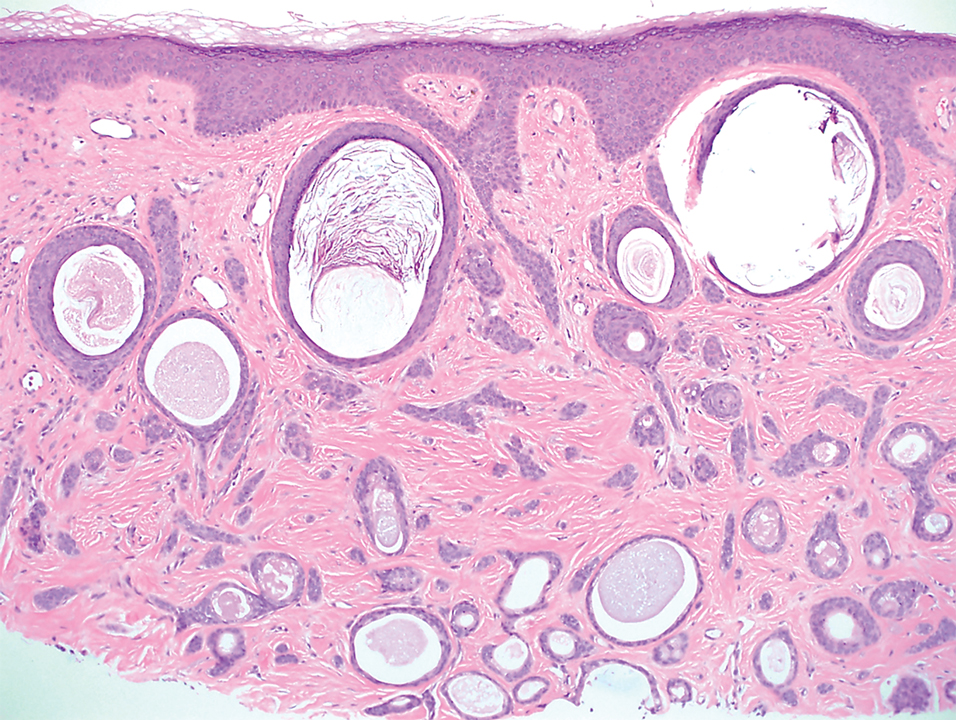

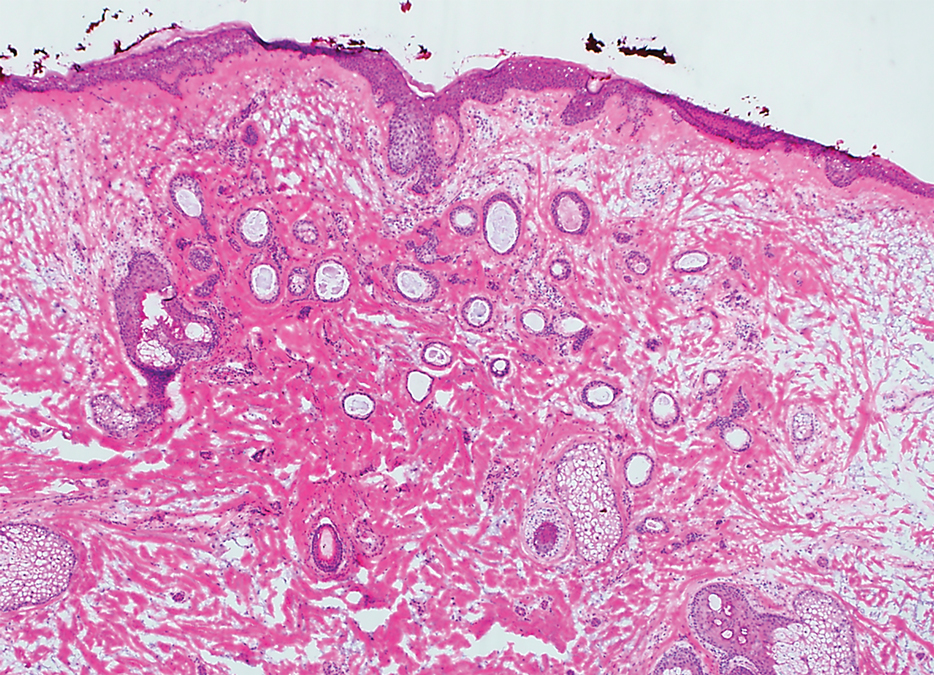

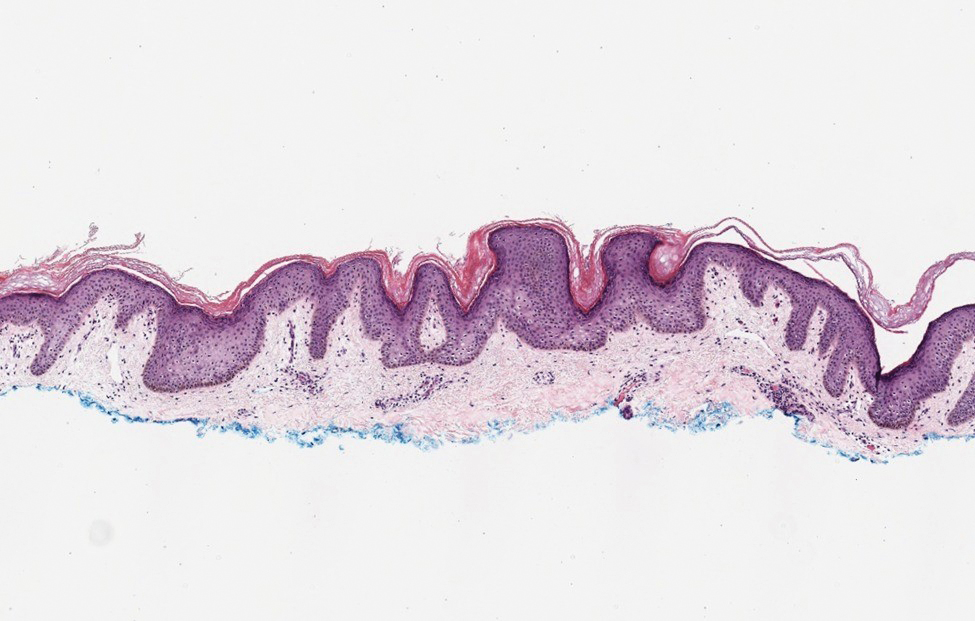

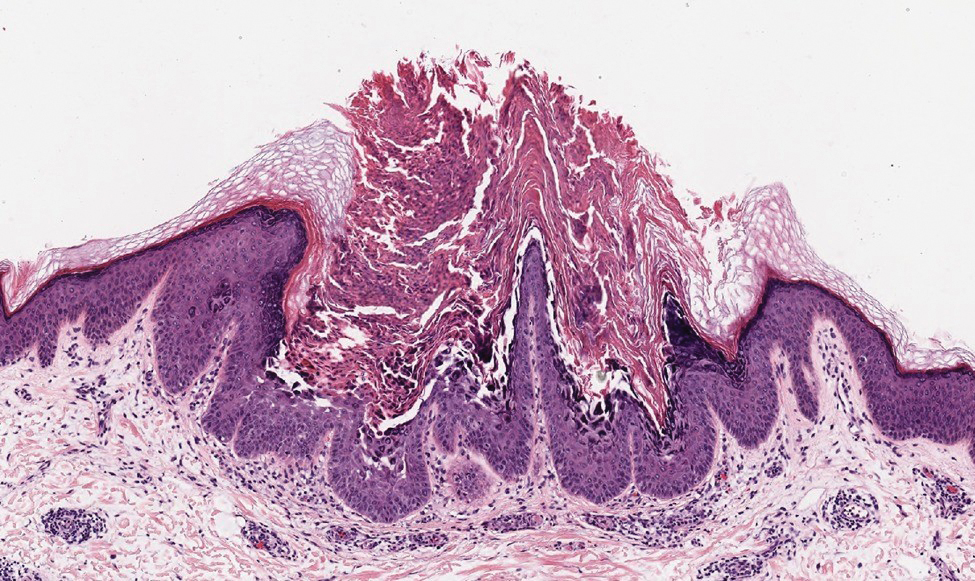

Prurigo nodularis involves chronic, intensely pruritic, lichenified, excoriated nodules that often present as grouped symmetric lesions predominantly on the extensor aspects of the distal extremities and occasionally the trunk. Histologically, prurigo nodularis appears similar to lichen simplex chronicus but in a nodular form with pronounced hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, sometimes to the degree of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2).11 Its features may resemble chronic eczema with mild spongiosis and focal parakeratosis. In the dermis, there is vascular hyperplasia surrounded by perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. Immunohistochemical staining for calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P may show a large increase of immunoreactive nerves in the lesional skin of nodular prurigo patients compared to the lichenified skin of eczema patients.12 However, neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in prurigo nodularis.13 Rarely, hyperplasic nerve trunks associated with Schwann cell proliferation may give rise to small neuromata that can be detected on electron microscopy.14 Screening for underlying systemic disease is recommended to rule out cancer, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, thyroid disorders, or HIV.

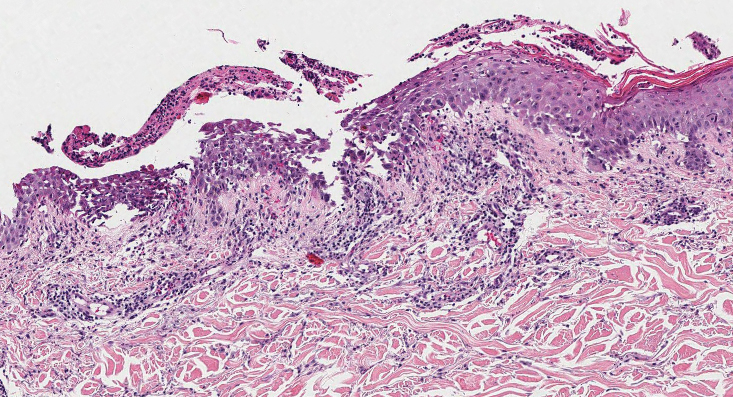

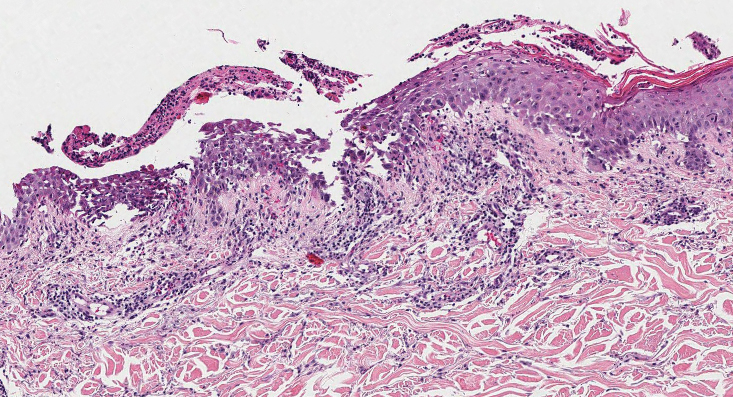

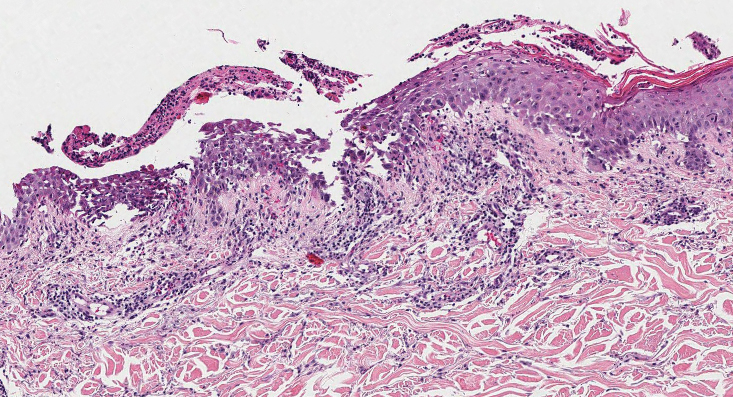

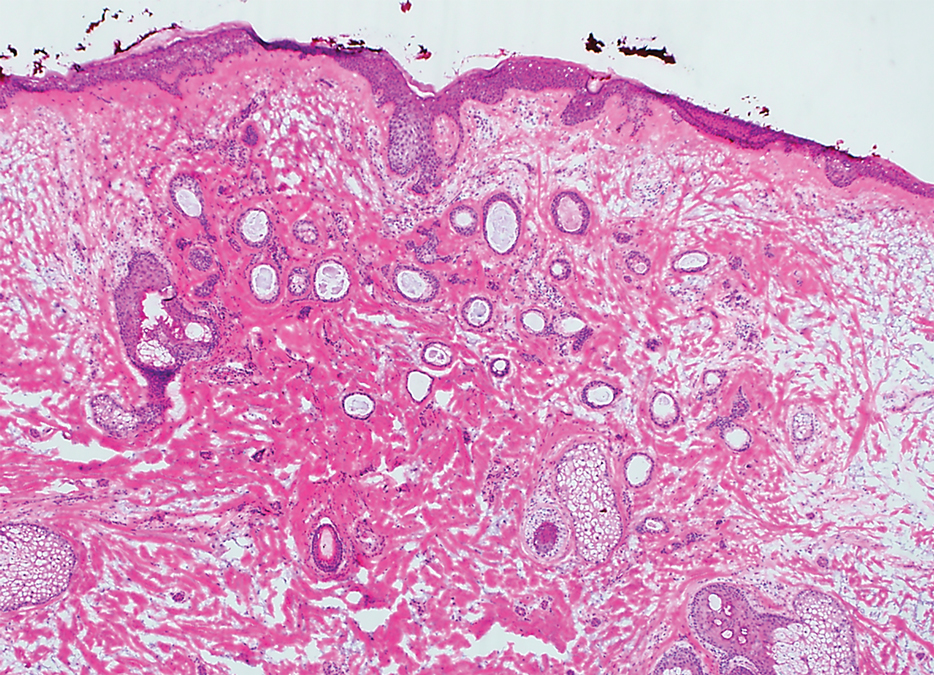

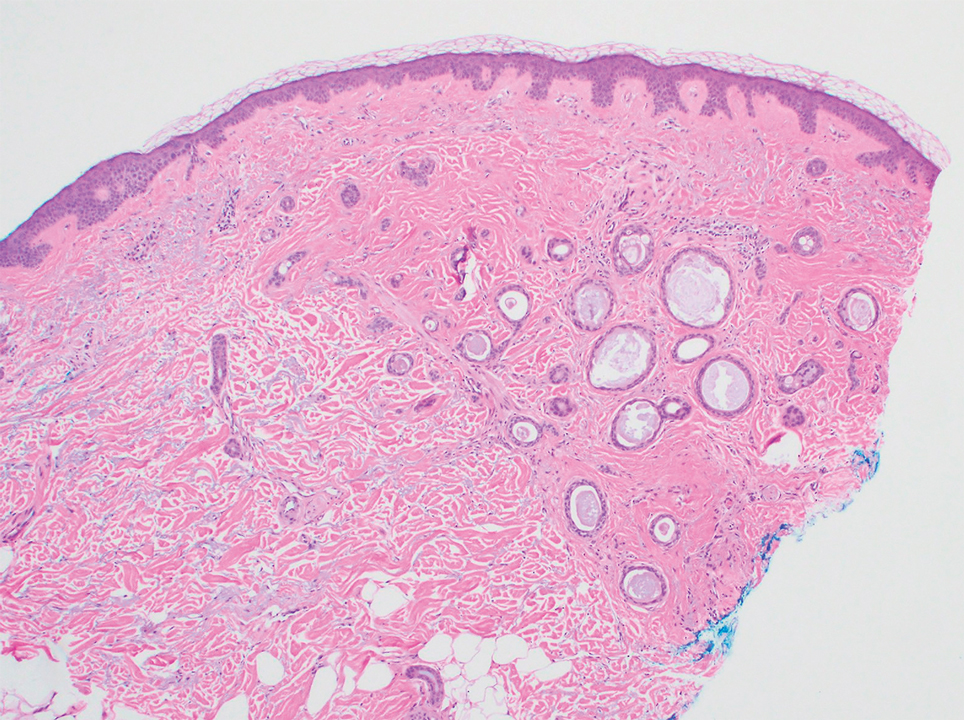

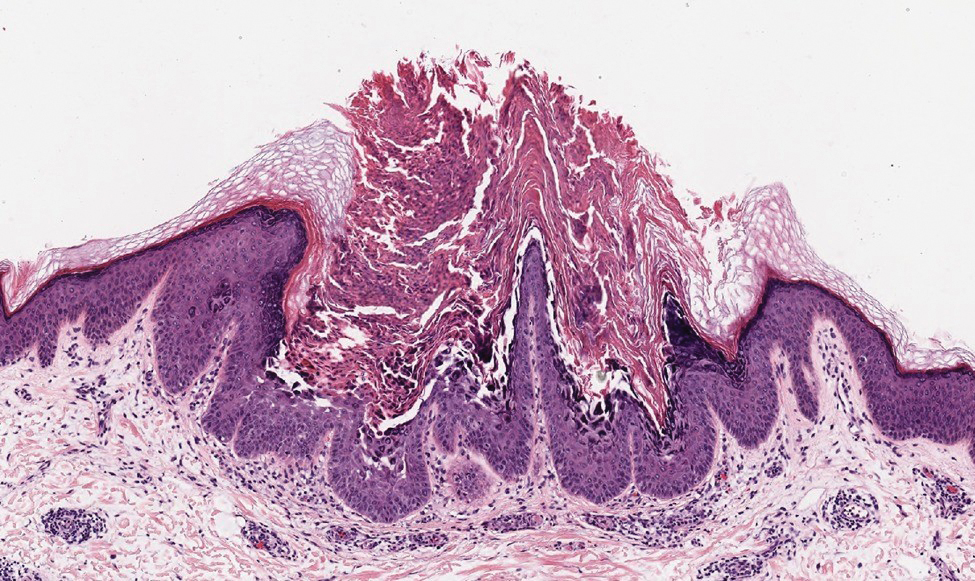

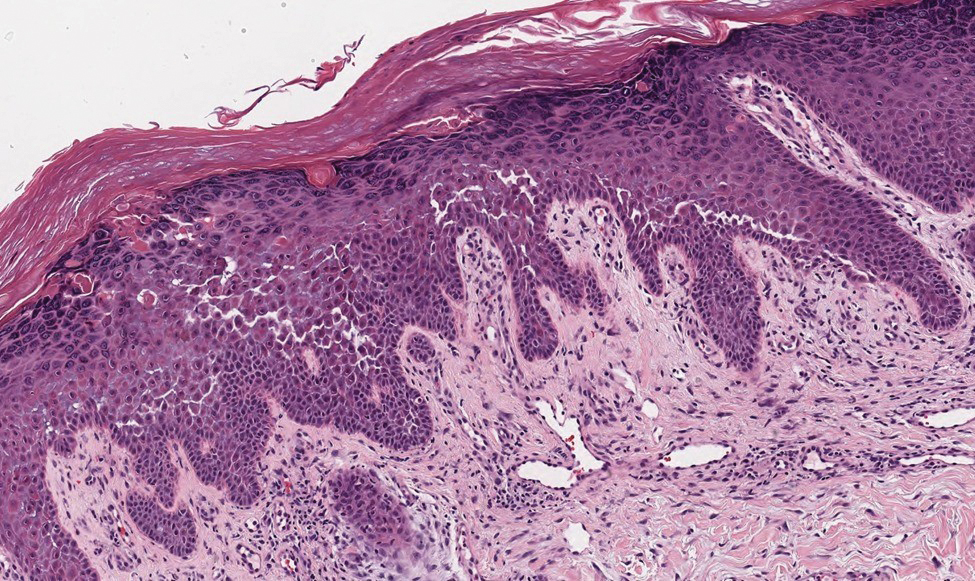

Ecthyma can affect children, adults, and especially immunocompromised patients at sites of trauma that allow entry of Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus. Histologically, there is ulceration of the epidermis with a thick overlying inflammatory crust (Figure 3). The heavy infiltrate of neutrophils in the reticular dermis forms the base of the ulcer, and gram-positive cocci may be detected within the inflammatory crust. Ecthyma lesions may resemble the excoriations and shallow ulcers that are seen in a variety of other pruritic conditions.15

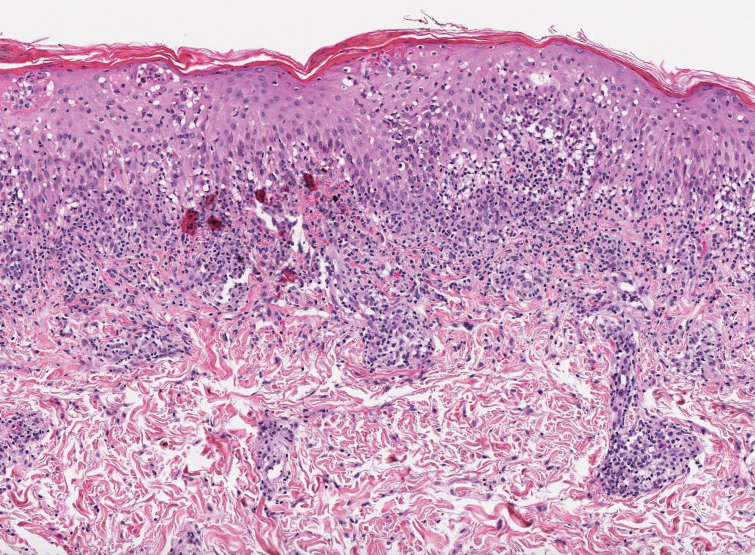

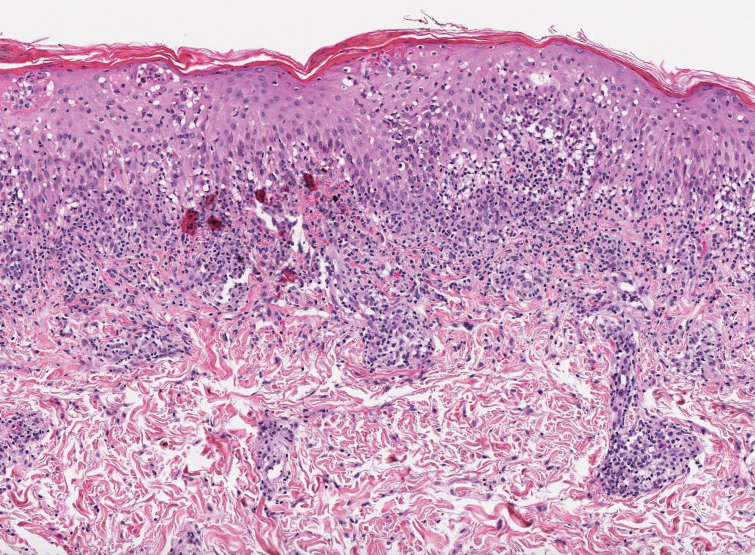

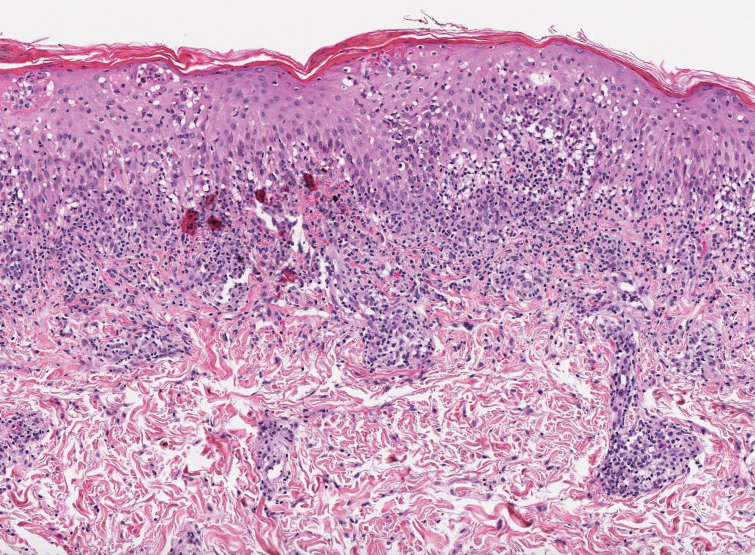

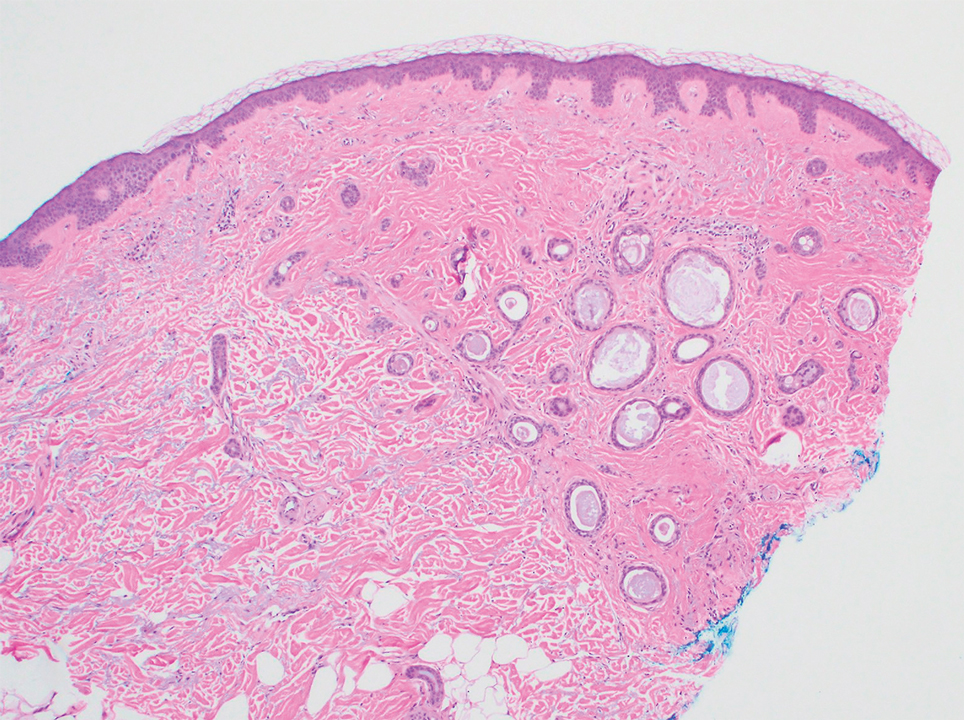

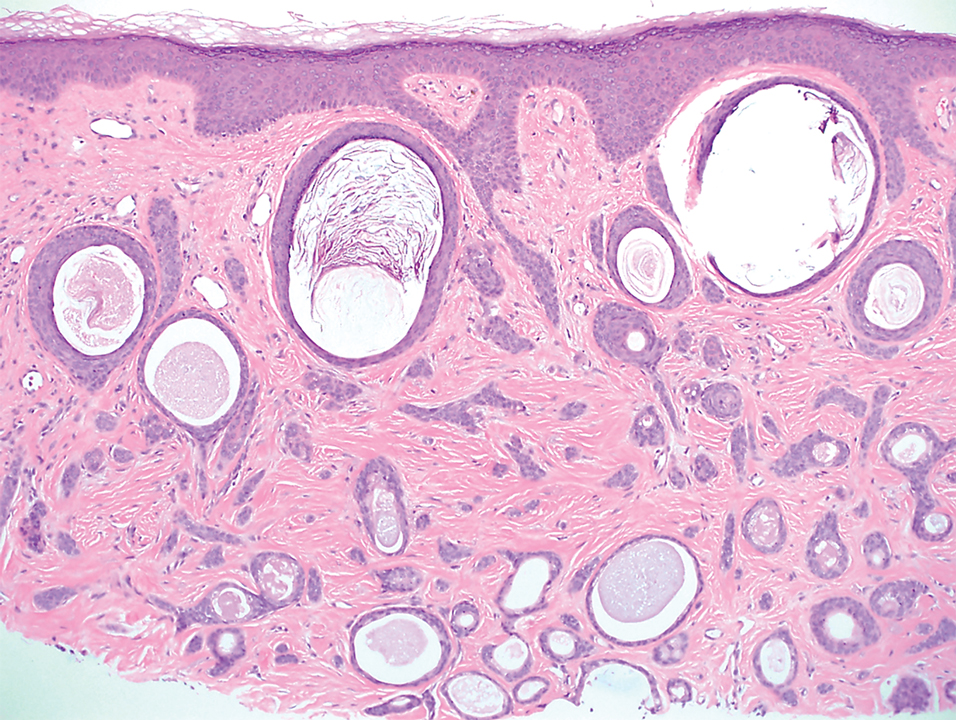

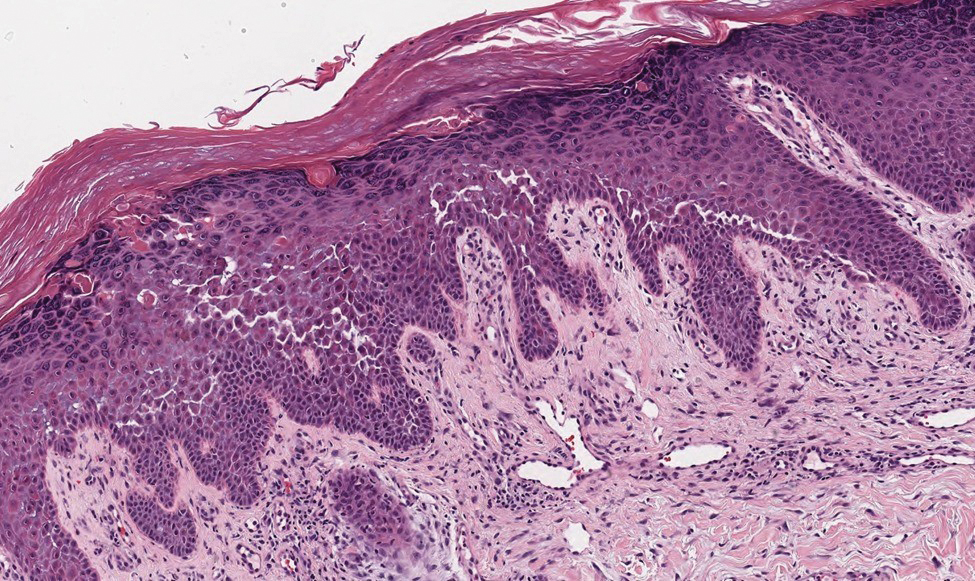

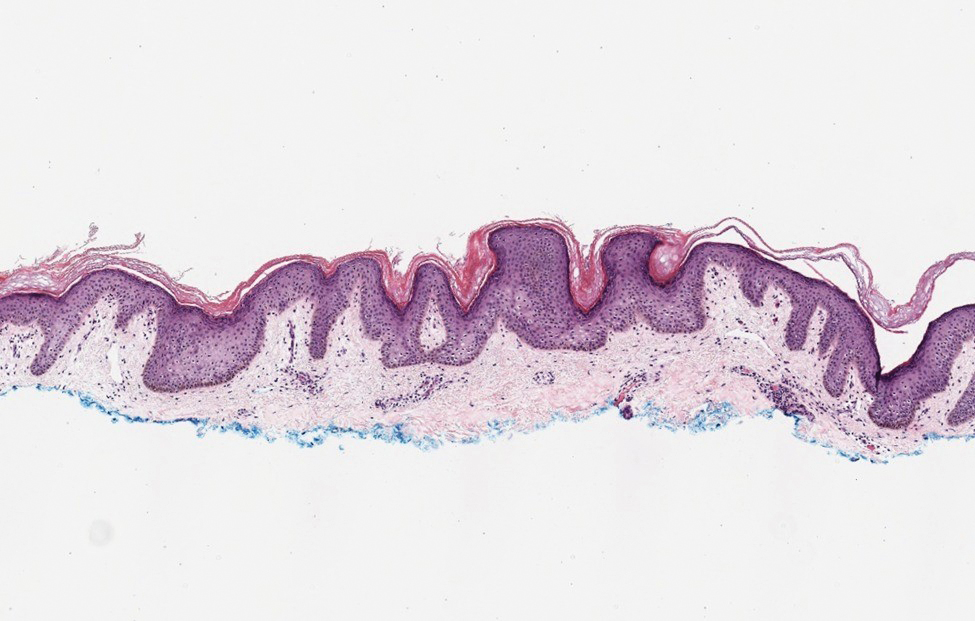

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a T-cell–mediated disease that is characterized by crops of lesions in varying sizes and stages including vesicular, hemorrhagic, ulcerated, and necrotic. It often results in varioliform scarring. Histologic findings can include parakeratosis, lichenoid inflammation, extravasation of red blood cells, vasculitis, and apoptotic keratinocytes (Figure 4).16

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288. doi:10.3346/jkms.2004.19.2.283

- Mullins TB, Sickinger M, Zito PM. Reactive perforating collagenosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritus! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Cullen SI. Successful treatment of reactive perforating collagenosis with tretinoin. Cutis. 1979;23:187-193.

- Tilz H, Becker JC, Legat F, et al. Allopurinol in the treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:94-97. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962013000100012

- Brinkmeier T, Schaller J, Herbst RA, et al. Successful treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with doxycycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:393-395. doi:10.1080/000155502320624249

- Gil-Lianes J, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Mascaró JM Jr. Reactive perforating collagenosis successfully treated with dupilumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:398-400. doi:10.1111/ajd.13874

- Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.018

- Na SY, Choi M, Kim MJ, et al. Penicillamine-induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa and cutis laxa in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:468-471. doi:10.5021/ad.2010.22.4.468

- Lee SH, Choi Y, Kim SC. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:103-106. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.1.103

- Weigelt N, Metze D, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis: systematic analysis of 58 histological criteria in 136 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:578-586. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01484.x

- Abadía Molina F, Burrows NP, Jones RR, et al. Increased sensory neuropeptides in nodular prurigo: a quantitative immunohistochemical analysis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:344-351. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00452.x

- Lindley RP, Payne CM. Neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in nodular prurigo. a controlled morphometric microscopic study of 26 biopsy specimens. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:14-18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1989.tb00003.x

- Feuerman EJ, Sandbank M. Prurigo nodularis. histological and electron microscopical study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:1472-1477. doi:10.1001/archderm.111.11.1472

- Weedon D, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2010. 16. Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Trowbridge RM. Clinical, dermatoscopic, and histological findings in a diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides [published online June 20, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E8725. doi:10.7759 /cureus.8725

The Diagnosis: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) is the most common type of primary perforating dermatosis and is characterized by the transepithelial elimination of collagen from the dermis. Although familial RPC usually presents in infancy or early childhood, the acquired form has a strong association with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic renal disease. Up to 10% of hemodialysis patients develop RPC.1 Patients with RPC develop red-brown, umbilicated, papulonodular lesions, often with a central keratotic crust and erythematous halo. The lesions are variable in shape and size (typically up to 10 mm in diameter) and commonly are located on the trunk or extensor aspects of the limbs. Pruritus is the primary concern, and the Koebner phenomenon commonly is seen.2

Although the histopathology can vary depending on the stage of the lesion, an invaginating epidermal process with prominent epidermal hyperplasia surrounding a central plug of keratin, basophilic inflammatory debris, and degenerated collagen are findings indicative of RPC. At the base of the invagination, the altered collagen perforates through the epidermis by the process of transepidermal elimination.3 Trichrome stains can highlight the collagen, while Verhoeff–van Gieson staining is negative (no elastic fiber elimination). Anecdotal reports have described a variety of successful therapies including retinoids, allopurinol, doxycycline, dupilumab, and phototherapy, with phototherapy being especially effective in patients with coexistent renal disease.4-8 Our patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg every other week and triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily (Monday through Friday) for itchy areas. The efficacy of the treatment was to be assessed at the next visit.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) is a rare skin disease that presents as small papules arranged in serpiginous or annular patterns on the neck, face, arms, or other flexural areas in early adulthood. It more commonly is seen in males and can be associated with other inherited disorders such as Down syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Marfan syndrome. In rare instances, EPS has been linked to D-penicillamine.9 Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is characterized by focal dermal elastosis and transepithelial elimination of abnormal elastic fibers instead of collagen. The formation of narrow channels extending upward from the dermis in straight or corkscrew patterns commonly is seen (Figure 1). The dermis also may contain a chronic inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells.10 Verhoeff– van Gieson stain highlights the altered elastic fibers in the papillary dermis.

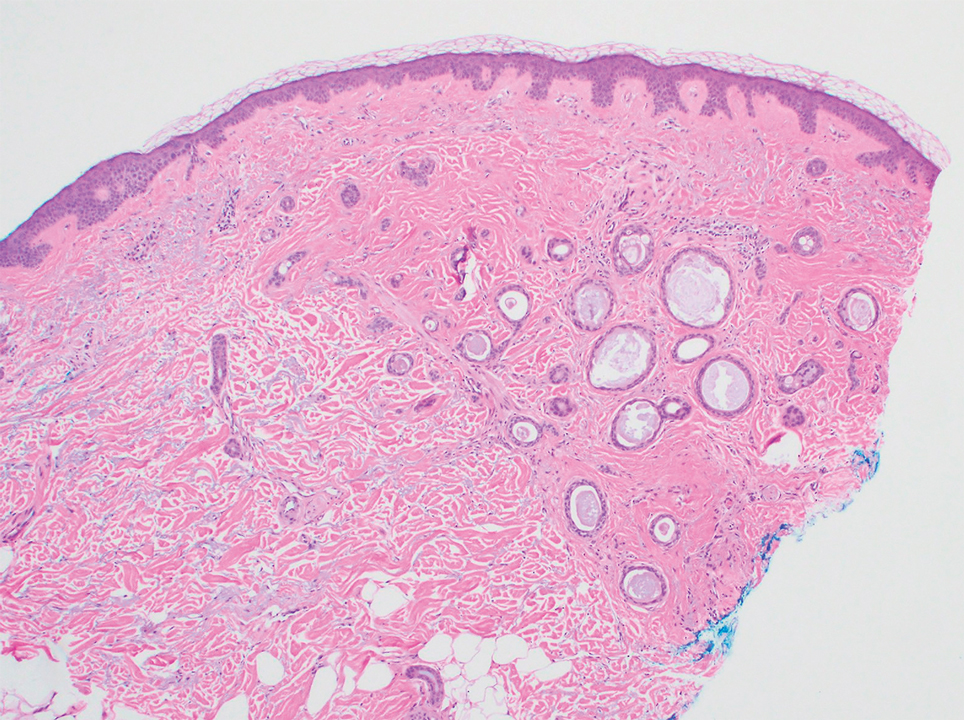

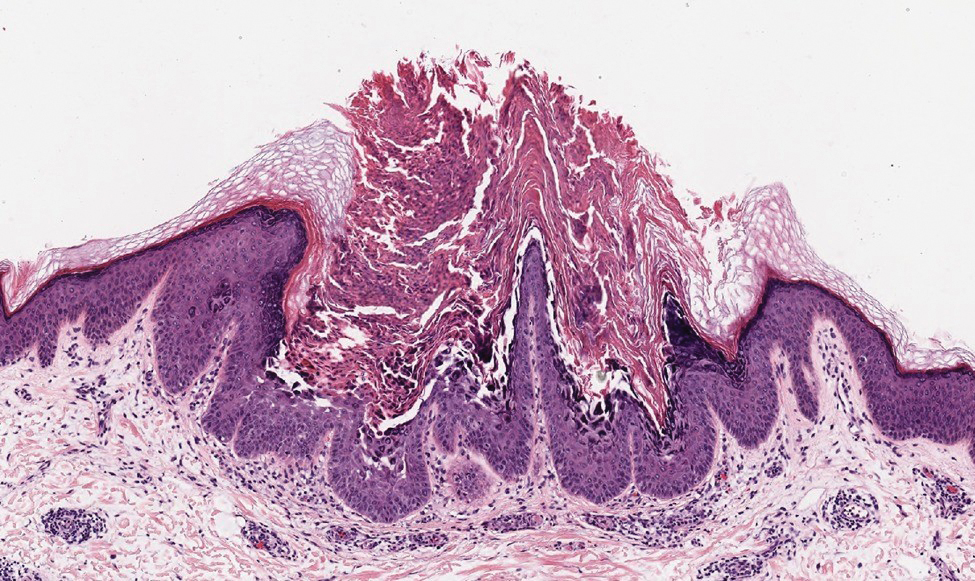

Prurigo nodularis involves chronic, intensely pruritic, lichenified, excoriated nodules that often present as grouped symmetric lesions predominantly on the extensor aspects of the distal extremities and occasionally the trunk. Histologically, prurigo nodularis appears similar to lichen simplex chronicus but in a nodular form with pronounced hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, sometimes to the degree of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2).11 Its features may resemble chronic eczema with mild spongiosis and focal parakeratosis. In the dermis, there is vascular hyperplasia surrounded by perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. Immunohistochemical staining for calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P may show a large increase of immunoreactive nerves in the lesional skin of nodular prurigo patients compared to the lichenified skin of eczema patients.12 However, neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in prurigo nodularis.13 Rarely, hyperplasic nerve trunks associated with Schwann cell proliferation may give rise to small neuromata that can be detected on electron microscopy.14 Screening for underlying systemic disease is recommended to rule out cancer, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, thyroid disorders, or HIV.

Ecthyma can affect children, adults, and especially immunocompromised patients at sites of trauma that allow entry of Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus. Histologically, there is ulceration of the epidermis with a thick overlying inflammatory crust (Figure 3). The heavy infiltrate of neutrophils in the reticular dermis forms the base of the ulcer, and gram-positive cocci may be detected within the inflammatory crust. Ecthyma lesions may resemble the excoriations and shallow ulcers that are seen in a variety of other pruritic conditions.15

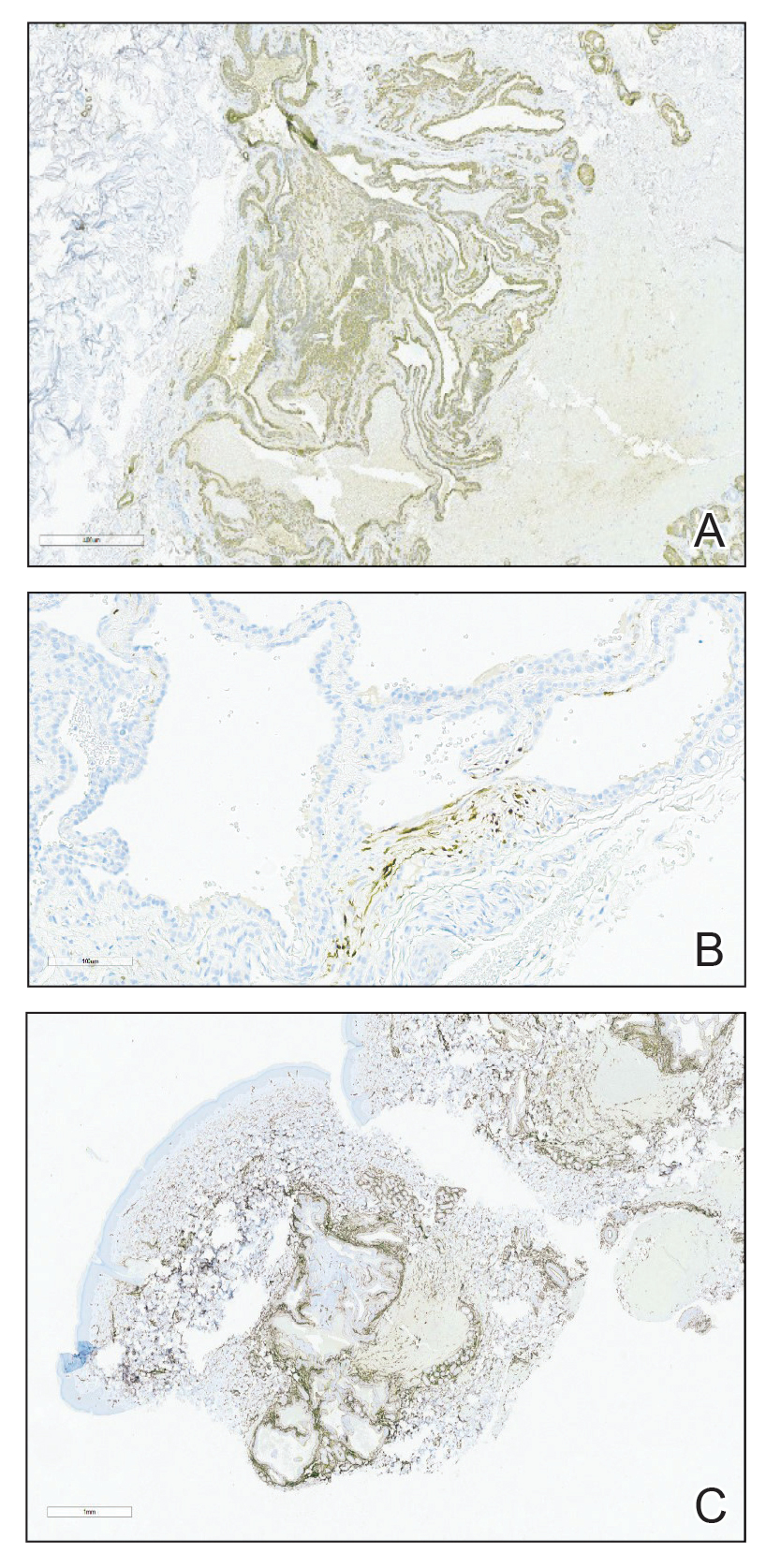

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a T-cell–mediated disease that is characterized by crops of lesions in varying sizes and stages including vesicular, hemorrhagic, ulcerated, and necrotic. It often results in varioliform scarring. Histologic findings can include parakeratosis, lichenoid inflammation, extravasation of red blood cells, vasculitis, and apoptotic keratinocytes (Figure 4).16

The Diagnosis: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) is the most common type of primary perforating dermatosis and is characterized by the transepithelial elimination of collagen from the dermis. Although familial RPC usually presents in infancy or early childhood, the acquired form has a strong association with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic renal disease. Up to 10% of hemodialysis patients develop RPC.1 Patients with RPC develop red-brown, umbilicated, papulonodular lesions, often with a central keratotic crust and erythematous halo. The lesions are variable in shape and size (typically up to 10 mm in diameter) and commonly are located on the trunk or extensor aspects of the limbs. Pruritus is the primary concern, and the Koebner phenomenon commonly is seen.2

Although the histopathology can vary depending on the stage of the lesion, an invaginating epidermal process with prominent epidermal hyperplasia surrounding a central plug of keratin, basophilic inflammatory debris, and degenerated collagen are findings indicative of RPC. At the base of the invagination, the altered collagen perforates through the epidermis by the process of transepidermal elimination.3 Trichrome stains can highlight the collagen, while Verhoeff–van Gieson staining is negative (no elastic fiber elimination). Anecdotal reports have described a variety of successful therapies including retinoids, allopurinol, doxycycline, dupilumab, and phototherapy, with phototherapy being especially effective in patients with coexistent renal disease.4-8 Our patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg every other week and triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily (Monday through Friday) for itchy areas. The efficacy of the treatment was to be assessed at the next visit.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) is a rare skin disease that presents as small papules arranged in serpiginous or annular patterns on the neck, face, arms, or other flexural areas in early adulthood. It more commonly is seen in males and can be associated with other inherited disorders such as Down syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Marfan syndrome. In rare instances, EPS has been linked to D-penicillamine.9 Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is characterized by focal dermal elastosis and transepithelial elimination of abnormal elastic fibers instead of collagen. The formation of narrow channels extending upward from the dermis in straight or corkscrew patterns commonly is seen (Figure 1). The dermis also may contain a chronic inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells.10 Verhoeff– van Gieson stain highlights the altered elastic fibers in the papillary dermis.

Prurigo nodularis involves chronic, intensely pruritic, lichenified, excoriated nodules that often present as grouped symmetric lesions predominantly on the extensor aspects of the distal extremities and occasionally the trunk. Histologically, prurigo nodularis appears similar to lichen simplex chronicus but in a nodular form with pronounced hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, sometimes to the degree of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2).11 Its features may resemble chronic eczema with mild spongiosis and focal parakeratosis. In the dermis, there is vascular hyperplasia surrounded by perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. Immunohistochemical staining for calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P may show a large increase of immunoreactive nerves in the lesional skin of nodular prurigo patients compared to the lichenified skin of eczema patients.12 However, neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in prurigo nodularis.13 Rarely, hyperplasic nerve trunks associated with Schwann cell proliferation may give rise to small neuromata that can be detected on electron microscopy.14 Screening for underlying systemic disease is recommended to rule out cancer, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, thyroid disorders, or HIV.

Ecthyma can affect children, adults, and especially immunocompromised patients at sites of trauma that allow entry of Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus. Histologically, there is ulceration of the epidermis with a thick overlying inflammatory crust (Figure 3). The heavy infiltrate of neutrophils in the reticular dermis forms the base of the ulcer, and gram-positive cocci may be detected within the inflammatory crust. Ecthyma lesions may resemble the excoriations and shallow ulcers that are seen in a variety of other pruritic conditions.15

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a T-cell–mediated disease that is characterized by crops of lesions in varying sizes and stages including vesicular, hemorrhagic, ulcerated, and necrotic. It often results in varioliform scarring. Histologic findings can include parakeratosis, lichenoid inflammation, extravasation of red blood cells, vasculitis, and apoptotic keratinocytes (Figure 4).16

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288. doi:10.3346/jkms.2004.19.2.283

- Mullins TB, Sickinger M, Zito PM. Reactive perforating collagenosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritus! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Cullen SI. Successful treatment of reactive perforating collagenosis with tretinoin. Cutis. 1979;23:187-193.

- Tilz H, Becker JC, Legat F, et al. Allopurinol in the treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:94-97. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962013000100012

- Brinkmeier T, Schaller J, Herbst RA, et al. Successful treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with doxycycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:393-395. doi:10.1080/000155502320624249

- Gil-Lianes J, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Mascaró JM Jr. Reactive perforating collagenosis successfully treated with dupilumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:398-400. doi:10.1111/ajd.13874

- Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.018

- Na SY, Choi M, Kim MJ, et al. Penicillamine-induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa and cutis laxa in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:468-471. doi:10.5021/ad.2010.22.4.468

- Lee SH, Choi Y, Kim SC. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:103-106. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.1.103

- Weigelt N, Metze D, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis: systematic analysis of 58 histological criteria in 136 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:578-586. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01484.x

- Abadía Molina F, Burrows NP, Jones RR, et al. Increased sensory neuropeptides in nodular prurigo: a quantitative immunohistochemical analysis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:344-351. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00452.x

- Lindley RP, Payne CM. Neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in nodular prurigo. a controlled morphometric microscopic study of 26 biopsy specimens. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:14-18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1989.tb00003.x

- Feuerman EJ, Sandbank M. Prurigo nodularis. histological and electron microscopical study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:1472-1477. doi:10.1001/archderm.111.11.1472

- Weedon D, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2010. 16. Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Trowbridge RM. Clinical, dermatoscopic, and histological findings in a diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides [published online June 20, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E8725. doi:10.7759 /cureus.8725

- Hong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, et al. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:283-288. doi:10.3346/jkms.2004.19.2.283

- Mullins TB, Sickinger M, Zito PM. Reactive perforating collagenosis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritus! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Cullen SI. Successful treatment of reactive perforating collagenosis with tretinoin. Cutis. 1979;23:187-193.

- Tilz H, Becker JC, Legat F, et al. Allopurinol in the treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:94-97. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962013000100012

- Brinkmeier T, Schaller J, Herbst RA, et al. Successful treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with doxycycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:393-395. doi:10.1080/000155502320624249

- Gil-Lianes J, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Mascaró JM Jr. Reactive perforating collagenosis successfully treated with dupilumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:398-400. doi:10.1111/ajd.13874

- Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis with narrowband ultraviolet B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.018

- Na SY, Choi M, Kim MJ, et al. Penicillamine-induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa and cutis laxa in a patient with Wilson’s disease. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:468-471. doi:10.5021/ad.2010.22.4.468

- Lee SH, Choi Y, Kim SC. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:103-106. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.1.103

- Weigelt N, Metze D, Ständer S. Prurigo nodularis: systematic analysis of 58 histological criteria in 136 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:578-586. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01484.x

- Abadía Molina F, Burrows NP, Jones RR, et al. Increased sensory neuropeptides in nodular prurigo: a quantitative immunohistochemical analysis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:344-351. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00452.x

- Lindley RP, Payne CM. Neural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in nodular prurigo. a controlled morphometric microscopic study of 26 biopsy specimens. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:14-18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1989.tb00003.x

- Feuerman EJ, Sandbank M. Prurigo nodularis. histological and electron microscopical study. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:1472-1477. doi:10.1001/archderm.111.11.1472

- Weedon D, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2010. 16. Clarey DD, Lauer SR, Trowbridge RM. Clinical, dermatoscopic, and histological findings in a diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides [published online June 20, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E8725. doi:10.7759 /cureus.8725

A 42-year-old man with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis presented with generalized body itching and nodules on the scalp and back of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination revealed diffuse, hyperpigmented, pruritic, keratotic nodules and macules on the scalp and back (top). A punch biopsy was performed (bottom).

Plaquelike Syringoma Mimicking Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma: A Potential Histologic Pitfall

To the Editor:

Plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma is a lesser-known variant of syringoma that can appear histologically indistinguishable from the superficial portion of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). The plaquelike variant of syringoma holds a benign clinical course, and no treatment is necessary. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is distinguished from plaquelike syringoma by an aggressive growth pattern with a high risk for local invasion and recurrence if inadequately treated. Thus, treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been recommended as the mainstay for MAC. If superficial biopsy specimens reveal suspicion for MAC and patients are referred for MMS, careful consideration should be made to differentiate MAC and plaquelike syringoma early to prevent unnecessary morbidity.

A 78-year-old woman was referred for MMS for a left forehead lesion that was diagnosed via shave biopsy as a desmoplastic and cystic adnexal neoplasm with suspicion for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma or MAC (Figure 1). Upon presentation for MMS, a well-healed, 1.0×0.9-cm scar at the biopsy site on the left forehead was observed (Figure 2A). One stage was obtained by standard MMS technique and sent for intraoperative processing (Figure 2B). Frozen section examination of the first stage demonstrated peripheral margin involvement with syringomatous change confined to the superficial and mid dermis (Figure 3). Before proceeding further, these findings were reviewed with an in-house dermatopathologist, and it was determined that no infiltrative tumor, perineural involvement, or other features to indicate malignancy were noted. A decision was made to refrain from obtaining any additional layers and to send excised Burow triangles for permanent section analysis. A primary linear closure was performed without complication, and the patient was discharged from the ambulatory surgery suite. Histopathologic examination of the Burow triangles later confirmed findings consistent with plaquelike syringoma with no evidence of malignancy (Figure 4).

Syringomas present as small flesh-colored papules in the periorbital areas. These benign neoplasms previously have been classified into 4 major clinical variants: localized, generalized, Down syndrome associated, and familial.1 The lesser-known plaquelike variant of syringoma was first described by Kikuchi et al2 in 1979. Aside from our report, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms plaquelike or plaque-type syringoma yielded 16 cases in the literature.2-14 Of these, 6 were referred to or encountered in the MMS setting.8,9,11,12,14 Plaquelike syringoma can be solitary or multiple in presentation.6 It most commonly involves the head and neck but also can present on the trunk, arms, legs, and groin areas. The clinical size of plaquelike syringoma is variable, with the largest reported cases extending several centimeters in diameter.2,6 Similar to reported associations with conventional syringoma, the plaquelike subtype of syringoma has been reported in association with Down syndrome.13