User login

New ACC guidance on cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19

The American College of Cardiology has issued an expert consensus clinical guidance document for the evaluation and management of adults with key cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19.

The document makes recommendations on how to evaluate and manage COVID-associated myocarditis and long COVID and gives advice on resumption of exercise following COVID-19 infection.

The clinical guidance was published online March 16 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“The best means to diagnose and treat myocarditis and long COVID following SARS-CoV-2 infection continues to evolve,” said Ty Gluckman, MD, MHA, cochair of the expert consensus decision pathway. “This document attempts to provide key recommendations for how to evaluate and manage adults with these conditions, including guidance for safe return to play for both competitive and noncompetitive athletes.”

The authors of the guidance note that COVID-19 can be associated with various abnormalities in cardiac testing and a wide range of cardiovascular complications. For some patients, cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and palpitations persist, lasting months after the initial illness, and evidence of myocardial injury has also been observed in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, as well as after receipt of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine.

“For clinicians treating these individuals, a growing number of questions exist related to evaluation and management of these conditions, as well as safe resumption of physical activity,” they say. This report is intended to provide practical guidance on these issues.

Myocarditis

The report states that myocarditis has been recognized as a rare but serious complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection as well as COVID-19 mRNA vaccination.

It defines myocarditis as: 1.cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, or syncope; 2. elevated cardiac troponin; and 3. abnormal electrocardiographic, echocardiographic, cardiac MRI, and/or histopathologic findings on biopsy.

The document makes the following recommendations in regard to COVID-related myocarditis:

When there is increased suspicion for cardiac involvement with COVID-19, initial testing should consist of an ECG, measurement of cardiac troponin, and an echocardiogram. Cardiology consultation is recommended for those with a rising cardiac troponin and/or echocardiographic abnormalities. Cardiac MRI is recommended in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected myocarditis.

Hospitalization is recommended for patients with definite myocarditis, ideally at an advanced heart failure center. Patients with fulminant myocarditis should be managed at centers with an expertise in advanced heart failure, mechanical circulatory support, and other advanced therapies.

Patients with myocarditis and COVID-19 pneumonia (with an ongoing need for supplemental oxygen) should be treated with corticosteroids. For patients with suspected pericardial involvement, treatment with NSAIDs, colchicine, and/or prednisone is reasonable. Intravenous corticosteroids may be considered in those with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 myocarditis with hemodynamic compromise or MIS-A (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults). Empiric use of corticosteroids may also be considered in those with biopsy evidence of severe myocardial infiltrates or fulminant myocarditis, balanced against infection risk.

As appropriate, guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure should be initiated and continued after discharge.

The document notes that myocarditis following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination is rare, with highest rates seen in young males after the second vaccine dose. As of May 22, 2021, the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System noted rates of 40.6 cases per million after the second vaccine dose among male individuals aged 12-29 years and 2.4 cases per million among male individuals aged 30 and older. Corresponding rates in female individuals were 4.2 and 1 cases per million, respectively.

But the report says that COVID-19 vaccination is associated with “a very favorable benefit-to-risk ratio” for all age and sex groups evaluated thus far.

In general, vaccine-associated myocarditis should be diagnosed, categorized, and treated in a manner analogous to myocarditis following SARS-CoV-2 infection, the guidance advises.

Long COVID

The document refers to long COVID as postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), and reports that this condition is experienced by up to 10%-30% of infected individuals. It is defined by a constellation of new, returning, or persistent health problems experienced by individuals 4 or more weeks after COVID-19 infection.

Although individuals with this condition may experience wide-ranging symptoms, the symptoms that draw increased attention to the cardiovascular system include tachycardia, exercise intolerance, chest pain, and shortness of breath.

Nicole Bhave, MD, cochair of the expert consensus decision pathway, says: “There appears to be a ‘downward spiral’ for long-COVID patients. Fatigue and decreased exercise capacity lead to diminished activity and bed rest, in turn leading to worsening symptoms and decreased quality of life.” She adds that “the writing committee recommends a basic cardiopulmonary evaluation performed up front to determine if further specialty care and formalized medical therapy is needed for these patients.”

The authors propose two terms to better understand potential etiologies for those with cardiovascular symptoms:

PASC-CVD, or PASC-cardiovascular disease, refers to a broad group of cardiovascular conditions (including myocarditis) that manifest at least 4 weeks after COVID-19 infection.

PASC-CVS, or PASC-cardiovascular syndrome, includes a wide range of cardiovascular symptoms without objective evidence of cardiovascular disease following standard diagnostic testing.

The document makes the following recommendations for the management of PASC-CVD and PASC-CVS.

For patients with cardiovascular symptoms and suspected PASC, the authors suggest that a reasonable initial testing approach includes basic laboratory testing, including cardiac troponin, an ECG, an echocardiogram, an ambulatory rhythm monitor, chest imaging, and/or pulmonary function tests.

Cardiology consultation is recommended for patients with PASC who have abnormal cardiac test results, known cardiovascular disease with new or worsening symptoms, documented cardiac complications during SARS-CoV-2 infection, and/or persistent cardiopulmonary symptoms that are not otherwise explained.

Recumbent or semirecumbent exercise (for example, rowing, swimming, or cycling) is recommended initially for PASC-CVS patients with tachycardia, exercise/orthostatic intolerance, and/or deconditioning, with transition to upright exercise as orthostatic intolerance improves. Exercise duration should also be short (5-10 minutes/day) initially, with gradual increases as functional capacity improves.

Salt and fluid loading represent nonpharmacologic interventions that may provide symptomatic relief for patients with tachycardia, palpitations, and/or orthostatic hypotension.

Beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, ivabradine, fludrocortisone, and midodrine may be used empirically as well.

Return to play for athletes

The authors note that concerns about possible cardiac injury after COVID-19 fueled early apprehension regarding the safety of competitive sports for athletes recovering from the infection.

But they say that subsequent data from large registries have demonstrated an overall low prevalence of clinical myocarditis, without a rise in the rate of adverse cardiac events. Based on this, updated guidance is provided with a practical, evidence-based framework to guide resumption of athletics and intense exercise training.

They make the following recommendations:

- For athletes recovering from COVID-19 with ongoing cardiopulmonary symptoms (chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, lightheadedness) or those requiring hospitalization with increased suspicion for cardiac involvement, further evaluation with triad testing – an ECG, measurement of cardiac troponin, and an echocardiogram – should be performed.

- For those with abnormal test results, further evaluation with cardiac MRI should be considered. Individuals diagnosed with clinical myocarditis should abstain from exercise for 3-6 months.

- Cardiac testing is not recommended for asymptomatic individuals following COVID-19 infection. Individuals should abstain from training for 3 days to ensure that symptoms do not develop.

- For those with mild or moderate noncardiopulmonary symptoms (fever, lethargy, muscle aches), training may resume after symptom resolution.

- For those with remote infection (≥3 months) without ongoing cardiopulmonary symptoms, a gradual increase in exercise is recommended without the need for cardiac testing.

Based on the low prevalence of myocarditis observed in competitive athletes with COVID-19, the authors note that these recommendations can be reasonably applied to high-school athletes (aged 14 and older) along with adult recreational exercise enthusiasts.

Future study is needed, however, to better understand how long cardiac abnormalities persist following COVID-19 infection and the role of exercise training in long COVID.

The authors conclude that the current guidance is intended to help clinicians understand not only when testing may be warranted, but also when it is not.

“Given that it reflects the current state of knowledge through early 2022, it is anticipated that recommendations will change over time as our understanding evolves,” they say.

The 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19: Myocarditis, Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC), and Return to Play will be discussed in a session at the American College of Cardiology’s annual scientific session meeting in Washington in April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Cardiology has issued an expert consensus clinical guidance document for the evaluation and management of adults with key cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19.

The document makes recommendations on how to evaluate and manage COVID-associated myocarditis and long COVID and gives advice on resumption of exercise following COVID-19 infection.

The clinical guidance was published online March 16 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“The best means to diagnose and treat myocarditis and long COVID following SARS-CoV-2 infection continues to evolve,” said Ty Gluckman, MD, MHA, cochair of the expert consensus decision pathway. “This document attempts to provide key recommendations for how to evaluate and manage adults with these conditions, including guidance for safe return to play for both competitive and noncompetitive athletes.”

The authors of the guidance note that COVID-19 can be associated with various abnormalities in cardiac testing and a wide range of cardiovascular complications. For some patients, cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and palpitations persist, lasting months after the initial illness, and evidence of myocardial injury has also been observed in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, as well as after receipt of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine.

“For clinicians treating these individuals, a growing number of questions exist related to evaluation and management of these conditions, as well as safe resumption of physical activity,” they say. This report is intended to provide practical guidance on these issues.

Myocarditis

The report states that myocarditis has been recognized as a rare but serious complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection as well as COVID-19 mRNA vaccination.

It defines myocarditis as: 1.cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, or syncope; 2. elevated cardiac troponin; and 3. abnormal electrocardiographic, echocardiographic, cardiac MRI, and/or histopathologic findings on biopsy.

The document makes the following recommendations in regard to COVID-related myocarditis:

When there is increased suspicion for cardiac involvement with COVID-19, initial testing should consist of an ECG, measurement of cardiac troponin, and an echocardiogram. Cardiology consultation is recommended for those with a rising cardiac troponin and/or echocardiographic abnormalities. Cardiac MRI is recommended in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected myocarditis.

Hospitalization is recommended for patients with definite myocarditis, ideally at an advanced heart failure center. Patients with fulminant myocarditis should be managed at centers with an expertise in advanced heart failure, mechanical circulatory support, and other advanced therapies.

Patients with myocarditis and COVID-19 pneumonia (with an ongoing need for supplemental oxygen) should be treated with corticosteroids. For patients with suspected pericardial involvement, treatment with NSAIDs, colchicine, and/or prednisone is reasonable. Intravenous corticosteroids may be considered in those with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 myocarditis with hemodynamic compromise or MIS-A (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults). Empiric use of corticosteroids may also be considered in those with biopsy evidence of severe myocardial infiltrates or fulminant myocarditis, balanced against infection risk.

As appropriate, guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure should be initiated and continued after discharge.

The document notes that myocarditis following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination is rare, with highest rates seen in young males after the second vaccine dose. As of May 22, 2021, the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System noted rates of 40.6 cases per million after the second vaccine dose among male individuals aged 12-29 years and 2.4 cases per million among male individuals aged 30 and older. Corresponding rates in female individuals were 4.2 and 1 cases per million, respectively.

But the report says that COVID-19 vaccination is associated with “a very favorable benefit-to-risk ratio” for all age and sex groups evaluated thus far.

In general, vaccine-associated myocarditis should be diagnosed, categorized, and treated in a manner analogous to myocarditis following SARS-CoV-2 infection, the guidance advises.

Long COVID

The document refers to long COVID as postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), and reports that this condition is experienced by up to 10%-30% of infected individuals. It is defined by a constellation of new, returning, or persistent health problems experienced by individuals 4 or more weeks after COVID-19 infection.

Although individuals with this condition may experience wide-ranging symptoms, the symptoms that draw increased attention to the cardiovascular system include tachycardia, exercise intolerance, chest pain, and shortness of breath.

Nicole Bhave, MD, cochair of the expert consensus decision pathway, says: “There appears to be a ‘downward spiral’ for long-COVID patients. Fatigue and decreased exercise capacity lead to diminished activity and bed rest, in turn leading to worsening symptoms and decreased quality of life.” She adds that “the writing committee recommends a basic cardiopulmonary evaluation performed up front to determine if further specialty care and formalized medical therapy is needed for these patients.”

The authors propose two terms to better understand potential etiologies for those with cardiovascular symptoms:

PASC-CVD, or PASC-cardiovascular disease, refers to a broad group of cardiovascular conditions (including myocarditis) that manifest at least 4 weeks after COVID-19 infection.

PASC-CVS, or PASC-cardiovascular syndrome, includes a wide range of cardiovascular symptoms without objective evidence of cardiovascular disease following standard diagnostic testing.

The document makes the following recommendations for the management of PASC-CVD and PASC-CVS.

For patients with cardiovascular symptoms and suspected PASC, the authors suggest that a reasonable initial testing approach includes basic laboratory testing, including cardiac troponin, an ECG, an echocardiogram, an ambulatory rhythm monitor, chest imaging, and/or pulmonary function tests.

Cardiology consultation is recommended for patients with PASC who have abnormal cardiac test results, known cardiovascular disease with new or worsening symptoms, documented cardiac complications during SARS-CoV-2 infection, and/or persistent cardiopulmonary symptoms that are not otherwise explained.

Recumbent or semirecumbent exercise (for example, rowing, swimming, or cycling) is recommended initially for PASC-CVS patients with tachycardia, exercise/orthostatic intolerance, and/or deconditioning, with transition to upright exercise as orthostatic intolerance improves. Exercise duration should also be short (5-10 minutes/day) initially, with gradual increases as functional capacity improves.

Salt and fluid loading represent nonpharmacologic interventions that may provide symptomatic relief for patients with tachycardia, palpitations, and/or orthostatic hypotension.

Beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, ivabradine, fludrocortisone, and midodrine may be used empirically as well.

Return to play for athletes

The authors note that concerns about possible cardiac injury after COVID-19 fueled early apprehension regarding the safety of competitive sports for athletes recovering from the infection.

But they say that subsequent data from large registries have demonstrated an overall low prevalence of clinical myocarditis, without a rise in the rate of adverse cardiac events. Based on this, updated guidance is provided with a practical, evidence-based framework to guide resumption of athletics and intense exercise training.

They make the following recommendations:

- For athletes recovering from COVID-19 with ongoing cardiopulmonary symptoms (chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, lightheadedness) or those requiring hospitalization with increased suspicion for cardiac involvement, further evaluation with triad testing – an ECG, measurement of cardiac troponin, and an echocardiogram – should be performed.

- For those with abnormal test results, further evaluation with cardiac MRI should be considered. Individuals diagnosed with clinical myocarditis should abstain from exercise for 3-6 months.

- Cardiac testing is not recommended for asymptomatic individuals following COVID-19 infection. Individuals should abstain from training for 3 days to ensure that symptoms do not develop.

- For those with mild or moderate noncardiopulmonary symptoms (fever, lethargy, muscle aches), training may resume after symptom resolution.

- For those with remote infection (≥3 months) without ongoing cardiopulmonary symptoms, a gradual increase in exercise is recommended without the need for cardiac testing.

Based on the low prevalence of myocarditis observed in competitive athletes with COVID-19, the authors note that these recommendations can be reasonably applied to high-school athletes (aged 14 and older) along with adult recreational exercise enthusiasts.

Future study is needed, however, to better understand how long cardiac abnormalities persist following COVID-19 infection and the role of exercise training in long COVID.

The authors conclude that the current guidance is intended to help clinicians understand not only when testing may be warranted, but also when it is not.

“Given that it reflects the current state of knowledge through early 2022, it is anticipated that recommendations will change over time as our understanding evolves,” they say.

The 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19: Myocarditis, Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC), and Return to Play will be discussed in a session at the American College of Cardiology’s annual scientific session meeting in Washington in April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Cardiology has issued an expert consensus clinical guidance document for the evaluation and management of adults with key cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19.

The document makes recommendations on how to evaluate and manage COVID-associated myocarditis and long COVID and gives advice on resumption of exercise following COVID-19 infection.

The clinical guidance was published online March 16 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“The best means to diagnose and treat myocarditis and long COVID following SARS-CoV-2 infection continues to evolve,” said Ty Gluckman, MD, MHA, cochair of the expert consensus decision pathway. “This document attempts to provide key recommendations for how to evaluate and manage adults with these conditions, including guidance for safe return to play for both competitive and noncompetitive athletes.”

The authors of the guidance note that COVID-19 can be associated with various abnormalities in cardiac testing and a wide range of cardiovascular complications. For some patients, cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and palpitations persist, lasting months after the initial illness, and evidence of myocardial injury has also been observed in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, as well as after receipt of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine.

“For clinicians treating these individuals, a growing number of questions exist related to evaluation and management of these conditions, as well as safe resumption of physical activity,” they say. This report is intended to provide practical guidance on these issues.

Myocarditis

The report states that myocarditis has been recognized as a rare but serious complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection as well as COVID-19 mRNA vaccination.

It defines myocarditis as: 1.cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, or syncope; 2. elevated cardiac troponin; and 3. abnormal electrocardiographic, echocardiographic, cardiac MRI, and/or histopathologic findings on biopsy.

The document makes the following recommendations in regard to COVID-related myocarditis:

When there is increased suspicion for cardiac involvement with COVID-19, initial testing should consist of an ECG, measurement of cardiac troponin, and an echocardiogram. Cardiology consultation is recommended for those with a rising cardiac troponin and/or echocardiographic abnormalities. Cardiac MRI is recommended in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected myocarditis.

Hospitalization is recommended for patients with definite myocarditis, ideally at an advanced heart failure center. Patients with fulminant myocarditis should be managed at centers with an expertise in advanced heart failure, mechanical circulatory support, and other advanced therapies.

Patients with myocarditis and COVID-19 pneumonia (with an ongoing need for supplemental oxygen) should be treated with corticosteroids. For patients with suspected pericardial involvement, treatment with NSAIDs, colchicine, and/or prednisone is reasonable. Intravenous corticosteroids may be considered in those with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 myocarditis with hemodynamic compromise or MIS-A (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults). Empiric use of corticosteroids may also be considered in those with biopsy evidence of severe myocardial infiltrates or fulminant myocarditis, balanced against infection risk.

As appropriate, guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure should be initiated and continued after discharge.

The document notes that myocarditis following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination is rare, with highest rates seen in young males after the second vaccine dose. As of May 22, 2021, the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System noted rates of 40.6 cases per million after the second vaccine dose among male individuals aged 12-29 years and 2.4 cases per million among male individuals aged 30 and older. Corresponding rates in female individuals were 4.2 and 1 cases per million, respectively.

But the report says that COVID-19 vaccination is associated with “a very favorable benefit-to-risk ratio” for all age and sex groups evaluated thus far.

In general, vaccine-associated myocarditis should be diagnosed, categorized, and treated in a manner analogous to myocarditis following SARS-CoV-2 infection, the guidance advises.

Long COVID

The document refers to long COVID as postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), and reports that this condition is experienced by up to 10%-30% of infected individuals. It is defined by a constellation of new, returning, or persistent health problems experienced by individuals 4 or more weeks after COVID-19 infection.

Although individuals with this condition may experience wide-ranging symptoms, the symptoms that draw increased attention to the cardiovascular system include tachycardia, exercise intolerance, chest pain, and shortness of breath.

Nicole Bhave, MD, cochair of the expert consensus decision pathway, says: “There appears to be a ‘downward spiral’ for long-COVID patients. Fatigue and decreased exercise capacity lead to diminished activity and bed rest, in turn leading to worsening symptoms and decreased quality of life.” She adds that “the writing committee recommends a basic cardiopulmonary evaluation performed up front to determine if further specialty care and formalized medical therapy is needed for these patients.”

The authors propose two terms to better understand potential etiologies for those with cardiovascular symptoms:

PASC-CVD, or PASC-cardiovascular disease, refers to a broad group of cardiovascular conditions (including myocarditis) that manifest at least 4 weeks after COVID-19 infection.

PASC-CVS, or PASC-cardiovascular syndrome, includes a wide range of cardiovascular symptoms without objective evidence of cardiovascular disease following standard diagnostic testing.

The document makes the following recommendations for the management of PASC-CVD and PASC-CVS.

For patients with cardiovascular symptoms and suspected PASC, the authors suggest that a reasonable initial testing approach includes basic laboratory testing, including cardiac troponin, an ECG, an echocardiogram, an ambulatory rhythm monitor, chest imaging, and/or pulmonary function tests.

Cardiology consultation is recommended for patients with PASC who have abnormal cardiac test results, known cardiovascular disease with new or worsening symptoms, documented cardiac complications during SARS-CoV-2 infection, and/or persistent cardiopulmonary symptoms that are not otherwise explained.

Recumbent or semirecumbent exercise (for example, rowing, swimming, or cycling) is recommended initially for PASC-CVS patients with tachycardia, exercise/orthostatic intolerance, and/or deconditioning, with transition to upright exercise as orthostatic intolerance improves. Exercise duration should also be short (5-10 minutes/day) initially, with gradual increases as functional capacity improves.

Salt and fluid loading represent nonpharmacologic interventions that may provide symptomatic relief for patients with tachycardia, palpitations, and/or orthostatic hypotension.

Beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, ivabradine, fludrocortisone, and midodrine may be used empirically as well.

Return to play for athletes

The authors note that concerns about possible cardiac injury after COVID-19 fueled early apprehension regarding the safety of competitive sports for athletes recovering from the infection.

But they say that subsequent data from large registries have demonstrated an overall low prevalence of clinical myocarditis, without a rise in the rate of adverse cardiac events. Based on this, updated guidance is provided with a practical, evidence-based framework to guide resumption of athletics and intense exercise training.

They make the following recommendations:

- For athletes recovering from COVID-19 with ongoing cardiopulmonary symptoms (chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, lightheadedness) or those requiring hospitalization with increased suspicion for cardiac involvement, further evaluation with triad testing – an ECG, measurement of cardiac troponin, and an echocardiogram – should be performed.

- For those with abnormal test results, further evaluation with cardiac MRI should be considered. Individuals diagnosed with clinical myocarditis should abstain from exercise for 3-6 months.

- Cardiac testing is not recommended for asymptomatic individuals following COVID-19 infection. Individuals should abstain from training for 3 days to ensure that symptoms do not develop.

- For those with mild or moderate noncardiopulmonary symptoms (fever, lethargy, muscle aches), training may resume after symptom resolution.

- For those with remote infection (≥3 months) without ongoing cardiopulmonary symptoms, a gradual increase in exercise is recommended without the need for cardiac testing.

Based on the low prevalence of myocarditis observed in competitive athletes with COVID-19, the authors note that these recommendations can be reasonably applied to high-school athletes (aged 14 and older) along with adult recreational exercise enthusiasts.

Future study is needed, however, to better understand how long cardiac abnormalities persist following COVID-19 infection and the role of exercise training in long COVID.

The authors conclude that the current guidance is intended to help clinicians understand not only when testing may be warranted, but also when it is not.

“Given that it reflects the current state of knowledge through early 2022, it is anticipated that recommendations will change over time as our understanding evolves,” they say.

The 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19: Myocarditis, Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC), and Return to Play will be discussed in a session at the American College of Cardiology’s annual scientific session meeting in Washington in April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

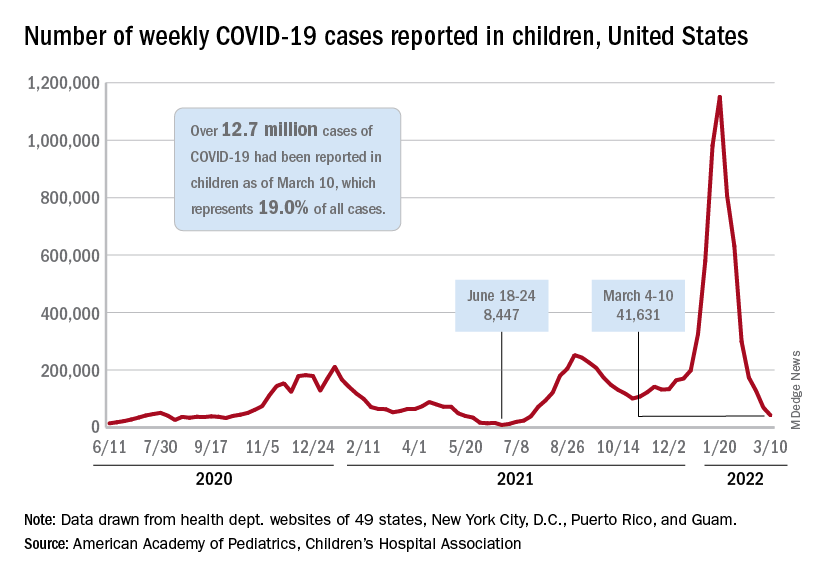

Children and COVID: Decline in new cases reaches 7th week

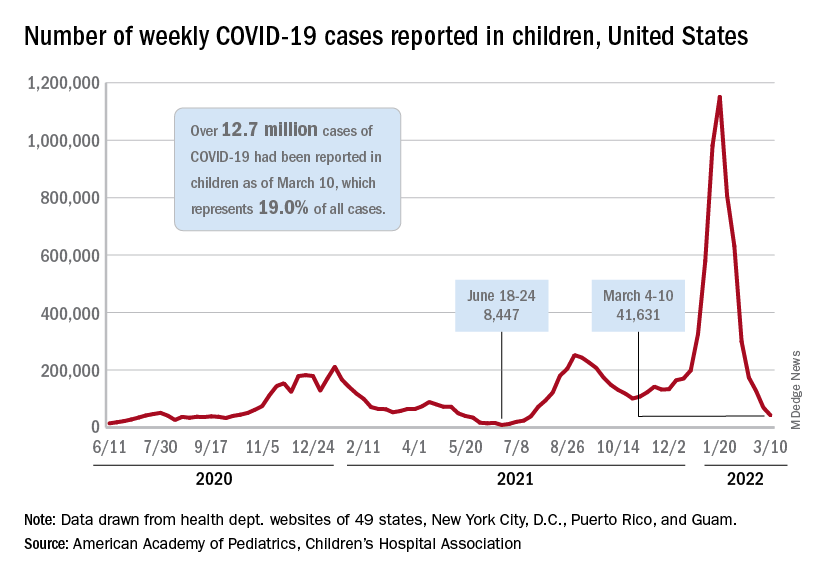

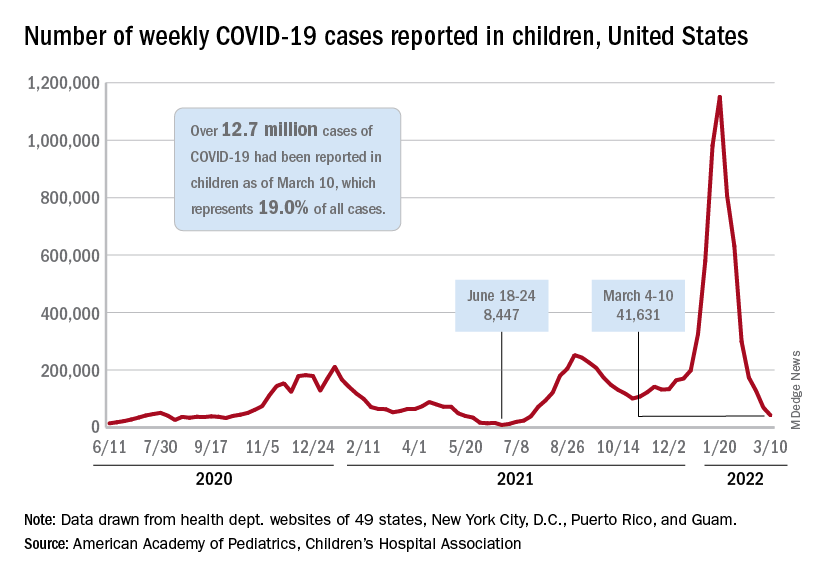

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children have fallen to their lowest level since the beginning of the Delta surge in July of 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

. Over those 7 weeks, new cases dropped over 96% from the 1.15 million reported for Jan. 14-20, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

The last time that the weekly count was below 42,000 was July 16-22, 2021, when almost 39,000 cases were reported in the midst of the Delta upsurge. That was shortly after cases had reached their lowest point, 8,447, since the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is now up to 12.7 million, while the overall proportion of cases occurring in children held steady at 19.0% for the 4th week in a row, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using an age range of 0-18 versus the states’ variety of ages, puts total cases at 11.7 million and deaths at 1,656 as of March 14.

Data from the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network show that hospitalizations with laboratory-confirmed infection were down by 50% in children aged 0-4 years, by 63% among 5- to 11-year-olds, and by 58% in those aged 12-17 years for the week of Feb. 27 to March 5, compared with the week before.

The pace of vaccination continues to follow a similar trend, as the declines seen through February have continued into March. Cumulatively, 33.7% of children aged 5-11 have received at least one dose, and 26.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding numbers of 68.0% and 58.0% for children aged 12-17, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

State-level data show that children aged 5-11 in Vermont, with a rate of 65%, are the most likely to have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, while just 15% of 5- to 11-year-olds in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi have gotten their first dose. Among children aged 12-17, that rate ranges from 40% in Wyoming to 94% in Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, the AAP said in a separate report based on CDC data.

In a recent report involving 1,364 children aged 5-15 years, two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine reduced the risk of infection from the Omicron variant by 31% in children aged 5-11 years and by 59% among children aged 12-15 years, said Ashley L. Fowlkes, ScD, of the CDC’s COVID-19 Emergency Response Team, and associates (MMWR 2022 Mar 11;71).

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children have fallen to their lowest level since the beginning of the Delta surge in July of 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

. Over those 7 weeks, new cases dropped over 96% from the 1.15 million reported for Jan. 14-20, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

The last time that the weekly count was below 42,000 was July 16-22, 2021, when almost 39,000 cases were reported in the midst of the Delta upsurge. That was shortly after cases had reached their lowest point, 8,447, since the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is now up to 12.7 million, while the overall proportion of cases occurring in children held steady at 19.0% for the 4th week in a row, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using an age range of 0-18 versus the states’ variety of ages, puts total cases at 11.7 million and deaths at 1,656 as of March 14.

Data from the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network show that hospitalizations with laboratory-confirmed infection were down by 50% in children aged 0-4 years, by 63% among 5- to 11-year-olds, and by 58% in those aged 12-17 years for the week of Feb. 27 to March 5, compared with the week before.

The pace of vaccination continues to follow a similar trend, as the declines seen through February have continued into March. Cumulatively, 33.7% of children aged 5-11 have received at least one dose, and 26.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding numbers of 68.0% and 58.0% for children aged 12-17, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

State-level data show that children aged 5-11 in Vermont, with a rate of 65%, are the most likely to have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, while just 15% of 5- to 11-year-olds in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi have gotten their first dose. Among children aged 12-17, that rate ranges from 40% in Wyoming to 94% in Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, the AAP said in a separate report based on CDC data.

In a recent report involving 1,364 children aged 5-15 years, two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine reduced the risk of infection from the Omicron variant by 31% in children aged 5-11 years and by 59% among children aged 12-15 years, said Ashley L. Fowlkes, ScD, of the CDC’s COVID-19 Emergency Response Team, and associates (MMWR 2022 Mar 11;71).

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children have fallen to their lowest level since the beginning of the Delta surge in July of 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

. Over those 7 weeks, new cases dropped over 96% from the 1.15 million reported for Jan. 14-20, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

The last time that the weekly count was below 42,000 was July 16-22, 2021, when almost 39,000 cases were reported in the midst of the Delta upsurge. That was shortly after cases had reached their lowest point, 8,447, since the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is now up to 12.7 million, while the overall proportion of cases occurring in children held steady at 19.0% for the 4th week in a row, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using an age range of 0-18 versus the states’ variety of ages, puts total cases at 11.7 million and deaths at 1,656 as of March 14.

Data from the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network show that hospitalizations with laboratory-confirmed infection were down by 50% in children aged 0-4 years, by 63% among 5- to 11-year-olds, and by 58% in those aged 12-17 years for the week of Feb. 27 to March 5, compared with the week before.

The pace of vaccination continues to follow a similar trend, as the declines seen through February have continued into March. Cumulatively, 33.7% of children aged 5-11 have received at least one dose, and 26.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding numbers of 68.0% and 58.0% for children aged 12-17, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

State-level data show that children aged 5-11 in Vermont, with a rate of 65%, are the most likely to have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, while just 15% of 5- to 11-year-olds in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi have gotten their first dose. Among children aged 12-17, that rate ranges from 40% in Wyoming to 94% in Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, the AAP said in a separate report based on CDC data.

In a recent report involving 1,364 children aged 5-15 years, two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine reduced the risk of infection from the Omicron variant by 31% in children aged 5-11 years and by 59% among children aged 12-15 years, said Ashley L. Fowlkes, ScD, of the CDC’s COVID-19 Emergency Response Team, and associates (MMWR 2022 Mar 11;71).

Air trapping common in patients with long COVID

, according to a prospective study that compared 100 COVID-19 survivors who had persistent symptoms and 106 healthy control persons.

“Something is going on in the distal airways related to either inflammation or fibrosis that is giving us a signal of air trapping,” noted senior author Alejandro P. Comellas, MD, in a press release. The study was stimulated by reports from University of Iowa clinicians noting that many patients with initial SARS-CoV-2 infection who were either hospitalized or were treated in the ambulatory setting later reported shortness of breath and other respiratory symptoms indicative of chronic lung disease.

Study results

Investigators classified patients (mean age, 48 years; 66 women) with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 according to whether they were ambulatory (67%), hospitalized (17%), or required treatment in the intensive care unit (16%). They then compared CT findings of patients who had COVID-19 and persistent symptoms with those of a healthy control group.

COVID-19 severity did not affect the percentage of cases of lung with air trapping among these patients. Air trapping occurred at rates of 25.4% among ambulatory patients, 34.6% in hospitalized patients, and in 27.3% of those requiring intensive care (P = .10). The percentage of lungs affected by air trapping in ambulatory participants was sharply and significantly higher than in healthy controls (25.4% vs. 7.2%; P < .001). Also, air trapping persisted; it was still present in 8 of 9 participants who underwent imaging more than 200 days post diagnosis.

Qualitative analysis of chest CT images showed that the most common imaging abnormality was air trapping (58%); ground glass opacities (GGOs) were found in 51% (46/91), note Dr. Comellas and coauthors. This suggests ongoing lung inflammation, edema, or fibrosis. These symptoms are often observed during acute COVID-19, frequently in an organizing pneumonia pattern, and have been shown to persist for months after infection in survivors of severe disease. The mean percentage of total lung classified as having regional GGOs on chest CT scans was 13.2% and 28.7%, respectively, in the hospitalized and ICU groups, both very much higher than in the ambulatory group, at 3.7% (P < .001 for both). Among healthy controls, the GGO rate on chest CT was only 0.06% (P < .001).

In addition, air trapping correlated with the ratio of residual volume to total lung capacity (r = 0.6; P < .001) but not with spirometry results. In fact, the investigators did not observe airflow obstruction by spirometry in any group, suggesting that air trapping in these patients involves only small rather than large airways and that these small airways contribute little to total airway resistance. Only when a large percentage, perhaps 75% or more, of all small airways are obstructed will spirometry pick up small airways disease, the authors observe.

Continuing disease

The findings taken together suggest that functional small airways disease and air trapping are a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to Dr. Comellas. “If a portion of patients continues to have small airways disease, then we need to think about the mechanisms behind it,” he said. “It could be something related to inflammation that’s reversible, or it may be something related to a scar that is irreversible, and then we need to look at ways to prevent further progression of the disease.” Furthermore, “studies aimed at determining the natural history of functional small airways disease in patients with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 and the biological mechanisms that underlie these findings are urgently needed to identify therapeutic and preventative interventions,” Dr. Comellas, professor of internal medicine at Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, concluded.

The study limitations, the authors state, include the fact that theirs was a single-center study that enrolled participants infected early during the COVID-19 pandemic and did not include patients with Delta or Omicron variants, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings.

The study was published in Radiology.

The reported findings “indicate a long-term impact on bronchiolar obstruction,” states Brett M. Elicker, MD, professor of clinical radiology, University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial . Because collagen may be absorbed for months after an acute insult, it is not entirely clear whether the abnormalities seen in the current study will be permanent. He said further, “the presence of ground glass opacity and/or fibrosis on CT were most common in the patients admitted to the ICU and likely correspond to post-organizing pneumonia and/or post-diffuse alveolar damage fibrosis.”

Dr. Elicker also pointed out that organizing pneumonia is especially common among patients with COVID-19 and is usually highly steroid-responsive. The opacities improve or resolve with treatment, but sometimes residual fibrosis occurs. “Longer-term studies assessing the clinical and imaging manifestations 1-2 years after the initial infection are needed to fully ascertain the permanent manifestations of post-COVID fibrosis.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Elicker have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a prospective study that compared 100 COVID-19 survivors who had persistent symptoms and 106 healthy control persons.

“Something is going on in the distal airways related to either inflammation or fibrosis that is giving us a signal of air trapping,” noted senior author Alejandro P. Comellas, MD, in a press release. The study was stimulated by reports from University of Iowa clinicians noting that many patients with initial SARS-CoV-2 infection who were either hospitalized or were treated in the ambulatory setting later reported shortness of breath and other respiratory symptoms indicative of chronic lung disease.

Study results

Investigators classified patients (mean age, 48 years; 66 women) with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 according to whether they were ambulatory (67%), hospitalized (17%), or required treatment in the intensive care unit (16%). They then compared CT findings of patients who had COVID-19 and persistent symptoms with those of a healthy control group.

COVID-19 severity did not affect the percentage of cases of lung with air trapping among these patients. Air trapping occurred at rates of 25.4% among ambulatory patients, 34.6% in hospitalized patients, and in 27.3% of those requiring intensive care (P = .10). The percentage of lungs affected by air trapping in ambulatory participants was sharply and significantly higher than in healthy controls (25.4% vs. 7.2%; P < .001). Also, air trapping persisted; it was still present in 8 of 9 participants who underwent imaging more than 200 days post diagnosis.

Qualitative analysis of chest CT images showed that the most common imaging abnormality was air trapping (58%); ground glass opacities (GGOs) were found in 51% (46/91), note Dr. Comellas and coauthors. This suggests ongoing lung inflammation, edema, or fibrosis. These symptoms are often observed during acute COVID-19, frequently in an organizing pneumonia pattern, and have been shown to persist for months after infection in survivors of severe disease. The mean percentage of total lung classified as having regional GGOs on chest CT scans was 13.2% and 28.7%, respectively, in the hospitalized and ICU groups, both very much higher than in the ambulatory group, at 3.7% (P < .001 for both). Among healthy controls, the GGO rate on chest CT was only 0.06% (P < .001).

In addition, air trapping correlated with the ratio of residual volume to total lung capacity (r = 0.6; P < .001) but not with spirometry results. In fact, the investigators did not observe airflow obstruction by spirometry in any group, suggesting that air trapping in these patients involves only small rather than large airways and that these small airways contribute little to total airway resistance. Only when a large percentage, perhaps 75% or more, of all small airways are obstructed will spirometry pick up small airways disease, the authors observe.

Continuing disease

The findings taken together suggest that functional small airways disease and air trapping are a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to Dr. Comellas. “If a portion of patients continues to have small airways disease, then we need to think about the mechanisms behind it,” he said. “It could be something related to inflammation that’s reversible, or it may be something related to a scar that is irreversible, and then we need to look at ways to prevent further progression of the disease.” Furthermore, “studies aimed at determining the natural history of functional small airways disease in patients with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 and the biological mechanisms that underlie these findings are urgently needed to identify therapeutic and preventative interventions,” Dr. Comellas, professor of internal medicine at Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, concluded.

The study limitations, the authors state, include the fact that theirs was a single-center study that enrolled participants infected early during the COVID-19 pandemic and did not include patients with Delta or Omicron variants, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings.

The study was published in Radiology.

The reported findings “indicate a long-term impact on bronchiolar obstruction,” states Brett M. Elicker, MD, professor of clinical radiology, University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial . Because collagen may be absorbed for months after an acute insult, it is not entirely clear whether the abnormalities seen in the current study will be permanent. He said further, “the presence of ground glass opacity and/or fibrosis on CT were most common in the patients admitted to the ICU and likely correspond to post-organizing pneumonia and/or post-diffuse alveolar damage fibrosis.”

Dr. Elicker also pointed out that organizing pneumonia is especially common among patients with COVID-19 and is usually highly steroid-responsive. The opacities improve or resolve with treatment, but sometimes residual fibrosis occurs. “Longer-term studies assessing the clinical and imaging manifestations 1-2 years after the initial infection are needed to fully ascertain the permanent manifestations of post-COVID fibrosis.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Elicker have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a prospective study that compared 100 COVID-19 survivors who had persistent symptoms and 106 healthy control persons.

“Something is going on in the distal airways related to either inflammation or fibrosis that is giving us a signal of air trapping,” noted senior author Alejandro P. Comellas, MD, in a press release. The study was stimulated by reports from University of Iowa clinicians noting that many patients with initial SARS-CoV-2 infection who were either hospitalized or were treated in the ambulatory setting later reported shortness of breath and other respiratory symptoms indicative of chronic lung disease.

Study results

Investigators classified patients (mean age, 48 years; 66 women) with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 according to whether they were ambulatory (67%), hospitalized (17%), or required treatment in the intensive care unit (16%). They then compared CT findings of patients who had COVID-19 and persistent symptoms with those of a healthy control group.

COVID-19 severity did not affect the percentage of cases of lung with air trapping among these patients. Air trapping occurred at rates of 25.4% among ambulatory patients, 34.6% in hospitalized patients, and in 27.3% of those requiring intensive care (P = .10). The percentage of lungs affected by air trapping in ambulatory participants was sharply and significantly higher than in healthy controls (25.4% vs. 7.2%; P < .001). Also, air trapping persisted; it was still present in 8 of 9 participants who underwent imaging more than 200 days post diagnosis.

Qualitative analysis of chest CT images showed that the most common imaging abnormality was air trapping (58%); ground glass opacities (GGOs) were found in 51% (46/91), note Dr. Comellas and coauthors. This suggests ongoing lung inflammation, edema, or fibrosis. These symptoms are often observed during acute COVID-19, frequently in an organizing pneumonia pattern, and have been shown to persist for months after infection in survivors of severe disease. The mean percentage of total lung classified as having regional GGOs on chest CT scans was 13.2% and 28.7%, respectively, in the hospitalized and ICU groups, both very much higher than in the ambulatory group, at 3.7% (P < .001 for both). Among healthy controls, the GGO rate on chest CT was only 0.06% (P < .001).

In addition, air trapping correlated with the ratio of residual volume to total lung capacity (r = 0.6; P < .001) but not with spirometry results. In fact, the investigators did not observe airflow obstruction by spirometry in any group, suggesting that air trapping in these patients involves only small rather than large airways and that these small airways contribute little to total airway resistance. Only when a large percentage, perhaps 75% or more, of all small airways are obstructed will spirometry pick up small airways disease, the authors observe.

Continuing disease

The findings taken together suggest that functional small airways disease and air trapping are a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to Dr. Comellas. “If a portion of patients continues to have small airways disease, then we need to think about the mechanisms behind it,” he said. “It could be something related to inflammation that’s reversible, or it may be something related to a scar that is irreversible, and then we need to look at ways to prevent further progression of the disease.” Furthermore, “studies aimed at determining the natural history of functional small airways disease in patients with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 and the biological mechanisms that underlie these findings are urgently needed to identify therapeutic and preventative interventions,” Dr. Comellas, professor of internal medicine at Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, concluded.

The study limitations, the authors state, include the fact that theirs was a single-center study that enrolled participants infected early during the COVID-19 pandemic and did not include patients with Delta or Omicron variants, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings.

The study was published in Radiology.

The reported findings “indicate a long-term impact on bronchiolar obstruction,” states Brett M. Elicker, MD, professor of clinical radiology, University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial . Because collagen may be absorbed for months after an acute insult, it is not entirely clear whether the abnormalities seen in the current study will be permanent. He said further, “the presence of ground glass opacity and/or fibrosis on CT were most common in the patients admitted to the ICU and likely correspond to post-organizing pneumonia and/or post-diffuse alveolar damage fibrosis.”

Dr. Elicker also pointed out that organizing pneumonia is especially common among patients with COVID-19 and is usually highly steroid-responsive. The opacities improve or resolve with treatment, but sometimes residual fibrosis occurs. “Longer-term studies assessing the clinical and imaging manifestations 1-2 years after the initial infection are needed to fully ascertain the permanent manifestations of post-COVID fibrosis.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Elicker have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM RADIOLOGY

COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy: What’s the latest?

COVID-19 vaccination is recommended for all reproductive-aged women, regardless of pregnancy status.1 Yet, national vaccination rates in pregnancy remain woefully low—lower than vaccine coverage rates for other recommended vaccines during pregnancy.2,3 COVID-19 infection has clearly documented risks for maternal and fetal health, and data continue to accumulate on the maternal and neonatal benefits of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy, as well as the safety of vaccination during pregnancy.

Maternal and neonatal benefits of COVID-19 vaccination

Does vaccination in pregnancy result in decreased rates of severe COVID-19 infection? Results from a study from a Louisiana health system comparing maternal outcomes between fully vaccinated (defined as 2 weeks after the final vaccine dose) and unvaccinated or partially vaccinated pregnant women during the delta variant—predominant COVID-19 surge clearly answer this question. Vaccination in pregnancy resulted in a 90% risk reduction in severe or critical COVID-19 infection and a 70% risk reduction in COVID-19 infection of any severity among fully vaccinated women. The study also provides some useful absolute numbers for patient counseling: Although none of the 1,332 vaccinated pregnant women in the study required supplemental oxygen or intensive care unit (ICU) admission, there was 1 maternal death, 5 ICU admissions, and 6 stillbirths among the 8,760 unvaccinated pregnant women.4

A larger population-based data set from Scotland and Israel demonstrated similar findings.5 Most importantly, the Scotland data, with most patients having had an mRNA-based vaccine, showed that, while 77% of all COVID-19 infections occurred in unvaccinated pregnant women, 91% of all hospital admissions occurred in unvaccinated women, and 98% of all critical care admissions occurred in unvaccinated women. Furthermore, although 13% of all COVID-19 hospitalizations in pregnancy occurred among vaccinated women, only 2% of critical care admissions occurred among vaccinated women. The Israeli experience (which identified nearly 30,000 eligible pregnancies from 1 of 4 state-mandated health funds in the country), demonstrated that the efficacy of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine to prevent a SARS-CoV-2 infection of any severity once fully vaccinated is more than 80%.6

Breakthrough infections, which were more prevalent during the omicron surge, have caused some patients to question the utility of COVID-19 vaccination. Recent data from South Africa, where the omicron variant was first identified, noted that efficacy of the Pfizer/ BioNTech vaccine to prevent hospitalization with COVID-19 infection during an omicron-predominant period was 70%—versus 93% efficacy in a delta-predominant period.7 These data, however, were in the absence of a booster dose, and in vitro studies suggest increased vaccine efficacy with a booster dose.8

Continue to: Counseling women on vaccination benefits and risks...

Counseling women on vaccination benefits and risks. No matter the specific numeric rate of efficacy against a COVID-19 infection, it is important to counsel women that the goal of vaccination is to prevent severe or critical COVID-19 infections, and these data all demonstrate that COVID-19 vaccination meets this goal. However, women may have additional questions regarding both fetal/neonatal benefits and safety with immunization in pregnancy.

Let us address the question of benefit first. In a large cohort of more than 1,300 women vaccinated during pregnancy and delivering at >34 weeks’ gestation, a few observations are worth noting.9 The first is that women who were fully vaccinated by the time of delivery had detectable antibodies at birth, even with first trimester vaccination, and these antibodies did cross the placenta to the neonate. Although higher maternal and neonatal antibody levels are achieved with early third trimester vaccination, it is key that women interpret this finding in light of 2 important points:

- women cannot know what gestational age they will deliver, thus waiting until the early third trimester for vaccination to optimize neonatal antibody levels could result in delivery prior to planned vaccination, with benefit for neither the woman nor the baby

- partial vaccination in the early third trimester resulted in lower maternal and neonatal antibody levels than full vaccination in the first trimester.

In addition, while the data were limited, a booster dose in the third trimester results in the highest antibody levels at delivery. Given the recommendation to initiate a booster dose 5 months after the completion of the primary vaccine series,10 many women will be eligible for a booster prior to delivery and thus can achieve the goals of high maternal and neonatal antibody levels simultaneously. One caveat to these data is that, while higher antibody levels seem comforting and may be better, we do not yet know the level of neonatal antibody necessary to decrease risks of COVID-19 infection in early newborn life.9 Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide real-world evidence that maternal vaccination decreases the risk of hospitalization from COVID-19 for infants aged <6 months, with vaccine efficacy estimated to be 61% during a period of both Delta and Omicron predominance.11

The evidence is clear—the time for COVID-19 vaccination is now. There is no “optimal” time of vaccination in pregnancy for neonatal benefit that would be worth risking any amount of time a woman is susceptible to COVID-19, especially given the promising data regarding maternal and neonatal antibody levels achieved after a booster dose.

Although the COVID-19 vaccine is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for ages 5 and above, Pfizer-BioNTech has plans to submit for approval for their vaccine’s use among kids as young as 6 months.1 Assuming that this approval occurs, this will leave newborns as the only group without possible vaccination against COVID-19. But can vaccination during pregnancy protect these infants against infection, as vaccination with the flu vaccine during pregnancy confers protective benefit to newborns?2

In a recent research letter published in Journal of the American Medical Association, Shook and colleagues present their data on antibody levels against COVID-19 present in newborns of women who were either naturally infected with COVID-19 at 20 to 32 weeks’ gestation (12 women) or who received mRNA vaccination during pregnancy at 20 to 32 weeks’ gestation (77 women).3 (They chose the 20- to 32-week timeframe during pregnancy because it had “demonstrated superior transplacental transfer of antibodies during this window.”)

They found that COVID-19 antibody levels were higher in both maternal and cord blood at birth in the women who were vaccinated versus the women who had infection. At 6 months, 16 of the 28 infants from the vaccinated-mother group had detectable antibodies compared with 1 of 12 infants from the infected-mother group. The researchers pointed out that the “antibody titer known to be protective against COVID-19 in infants is unknown;” however, they say that their findings provide further supportive evidence for COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant women.3

References

- Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine for children under 5 could be available by the end of February, people with knowledge say. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com /health/2022/01/31/coronavirus-vaccine-children-under-5/. Accessed February 11, 2022.

- Sakala IG, Honda-Okubo Y, Fung J, et al. Influenza immunization during pregnancy: benefits for mother and infant. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:3065-3071. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016 .1215392.

- Shook LL, Atyeo CG, Yonker LM, et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 vaccination or natural infection. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.1206.

Safety of COVID-19 vaccination: Current data

Risks for pregnancy loss, birth defects, and preterm delivery often are concerns of pregnant women considering a COVID-19 vaccination. Data from more than 2,400 women who submitted their information to the v-SAFE registry demonstrated a 14% risk for pregnancy loss between 6 and 20 weeks’ gestation—well within the expected rate of pregnancy loss in this gestational age range.12

Data from more than 46,000 pregnancies included in the Vaccine Safety Datalink, which includes data from health care organizations in 6 states, demonstrated a preterm birth rate of 6.6% and a small-for-gestational-age rate of 8.2% among fully vaccinated women, rates that were no different among unvaccinated women. There were no differences in the outcomes by trimester of vaccination, and these rates are comparable to the expected rates of these outcomes.13

Women also worry about the risks of vaccine side effects, such as fever or rare adverse events. Although all adverse events (ie, Guillain-Barre syndrome, pericarditis/myocarditis, thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome [TTS]) are very rare, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does recommend that women get an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, as the Johnson & Johnson/Janssen vaccine is associated with TTS, which occurred more commonly (although still rare) in women of reproductive age.14

Two large studies of typical side effects experienced after COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy are incredibly reassuring. In the first, authors of a large study of more than 12,000 pregnant women enrolled in the v-SAFE registry reported that the most common side effect after each mRNA dose was injection site pain (88% after dose 1, 92% after dose 2).15 Self-reported fever occurred in 4% of women after dose 1 and 35% after dose 2. Although this frequency may seem high, a fever of 38.0°C (100.4°F) or higher only occurred among 8% of all participants.

In another study of almost 8,000 women self-reporting side effects (some of whom also may have contributed data to the v-SAFE study), fever occurred in approximately 5% after dose 1 and in about 20% after dose 2.16 In this study, the highest mean temperature was 38.1°C (100.6°F) after dose 1 and 38.2°C (100.7°F) after dose 2. Although it is a reasonable expectation for fever to follow COVID-19 vaccination, particularly after the second dose, the typical fever is a low-grade temperature that will not harm a developing fetus and will be responsive to acetaminophen administration. Moreover, if the fever were the harbinger of harm, then it might stand to reason that an increased signal of preterm delivery may be observed, but data from nearly 10,000 pregnant women vaccinated during the second or third trimesters showed no association with preterm birth (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.91; 95% confidence interval, 0.82–1.01).13

The bottom line

The data are clear. COVID-19 vaccination decreases the risks of severe infection in pregnancy, confers antibodies to neonates with at least some level of protection, and has no demonstrated harmful side effects in pregnancy. ●

- Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines. CDC website. Published January 24, 2022. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html

- Cumulative data: percent of pregnant people aged 18-49 years receiving at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy overall, by race/ethnicity, and date reported to CDC—Vaccine Safety Datalink, United States. CDC website. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/Cumulative-Data-Percent-of-Pregnant-People-aged-18/4ht3-nbmd/data

- Razzaghi H, Kahn KE, Black CL, et al. Influenza and Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant women—United States, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1391-1397.

- Morgan JA, Biggio JRJ, Martin JK, et al. Maternal outcomes after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in vaccinated compared with unvaccinated pregnant patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:107-109.

- Stock SJ, Carruthers J, Calvert C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland [published online January 13, 2022]. Nat Med. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01666-2

- Goldshtein I, Nevo D, Steinberg DM, et al. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women. JAMA. 2021;326:728-735.

- Collie S, Champion J, Moultrie H, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 vaccine against omicron variant in South Africa [published online December 29, 2021]. N Engl J Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2119270

- Nemet I, Kliker L, Lustig Y, et al. Third BNT162b2 vaccination neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 omicron infection [published online December 29, 2021]. N Engl J Med. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2119358

- Yang YJ, Murphy EA, Singh S, et al. Association of gestational age at coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination, history of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and a vaccine booster dose with maternal and umbilical cord antibody levels at delivery [published online December 28, 2021]. Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004693

- COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/booster-shot.html. Accessed March 2, 2022.

- Effectiveness of maternal vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy against COVID-19–associated hospitalization in infants aged <6 months—17 states, July 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:264–270. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7107e3external icon.

- Zauche LH, Wallace B, Smoots AN, et al. Receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and risk of spontaneous abortion. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1533-1535.

- Lipkind HS. Receipt of COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy and preterm or small-for-gestational-age at birth—eight integrated health care organizations, United States, December 15, 2020–July 22, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7101e1

- COVID-19 vaccination considerations for obstetric-gynecologic care. ACOG website. Updated February 8, 2022. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/covid-19-vaccination-considerations-for-obstetric-gynecologic-care

- Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2273-2282.

- Kachikis A, Englund JA, Singleton M, et al. Short-term reactions among pregnant and lactating individuals in the first wave of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:E2121310.

COVID-19 vaccination is recommended for all reproductive-aged women, regardless of pregnancy status.1 Yet, national vaccination rates in pregnancy remain woefully low—lower than vaccine coverage rates for other recommended vaccines during pregnancy.2,3 COVID-19 infection has clearly documented risks for maternal and fetal health, and data continue to accumulate on the maternal and neonatal benefits of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy, as well as the safety of vaccination during pregnancy.

Maternal and neonatal benefits of COVID-19 vaccination

Does vaccination in pregnancy result in decreased rates of severe COVID-19 infection? Results from a study from a Louisiana health system comparing maternal outcomes between fully vaccinated (defined as 2 weeks after the final vaccine dose) and unvaccinated or partially vaccinated pregnant women during the delta variant—predominant COVID-19 surge clearly answer this question. Vaccination in pregnancy resulted in a 90% risk reduction in severe or critical COVID-19 infection and a 70% risk reduction in COVID-19 infection of any severity among fully vaccinated women. The study also provides some useful absolute numbers for patient counseling: Although none of the 1,332 vaccinated pregnant women in the study required supplemental oxygen or intensive care unit (ICU) admission, there was 1 maternal death, 5 ICU admissions, and 6 stillbirths among the 8,760 unvaccinated pregnant women.4

A larger population-based data set from Scotland and Israel demonstrated similar findings.5 Most importantly, the Scotland data, with most patients having had an mRNA-based vaccine, showed that, while 77% of all COVID-19 infections occurred in unvaccinated pregnant women, 91% of all hospital admissions occurred in unvaccinated women, and 98% of all critical care admissions occurred in unvaccinated women. Furthermore, although 13% of all COVID-19 hospitalizations in pregnancy occurred among vaccinated women, only 2% of critical care admissions occurred among vaccinated women. The Israeli experience (which identified nearly 30,000 eligible pregnancies from 1 of 4 state-mandated health funds in the country), demonstrated that the efficacy of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine to prevent a SARS-CoV-2 infection of any severity once fully vaccinated is more than 80%.6

Breakthrough infections, which were more prevalent during the omicron surge, have caused some patients to question the utility of COVID-19 vaccination. Recent data from South Africa, where the omicron variant was first identified, noted that efficacy of the Pfizer/ BioNTech vaccine to prevent hospitalization with COVID-19 infection during an omicron-predominant period was 70%—versus 93% efficacy in a delta-predominant period.7 These data, however, were in the absence of a booster dose, and in vitro studies suggest increased vaccine efficacy with a booster dose.8

Continue to: Counseling women on vaccination benefits and risks...

Counseling women on vaccination benefits and risks. No matter the specific numeric rate of efficacy against a COVID-19 infection, it is important to counsel women that the goal of vaccination is to prevent severe or critical COVID-19 infections, and these data all demonstrate that COVID-19 vaccination meets this goal. However, women may have additional questions regarding both fetal/neonatal benefits and safety with immunization in pregnancy.

Let us address the question of benefit first. In a large cohort of more than 1,300 women vaccinated during pregnancy and delivering at >34 weeks’ gestation, a few observations are worth noting.9 The first is that women who were fully vaccinated by the time of delivery had detectable antibodies at birth, even with first trimester vaccination, and these antibodies did cross the placenta to the neonate. Although higher maternal and neonatal antibody levels are achieved with early third trimester vaccination, it is key that women interpret this finding in light of 2 important points:

- women cannot know what gestational age they will deliver, thus waiting until the early third trimester for vaccination to optimize neonatal antibody levels could result in delivery prior to planned vaccination, with benefit for neither the woman nor the baby

- partial vaccination in the early third trimester resulted in lower maternal and neonatal antibody levels than full vaccination in the first trimester.

In addition, while the data were limited, a booster dose in the third trimester results in the highest antibody levels at delivery. Given the recommendation to initiate a booster dose 5 months after the completion of the primary vaccine series,10 many women will be eligible for a booster prior to delivery and thus can achieve the goals of high maternal and neonatal antibody levels simultaneously. One caveat to these data is that, while higher antibody levels seem comforting and may be better, we do not yet know the level of neonatal antibody necessary to decrease risks of COVID-19 infection in early newborn life.9 Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide real-world evidence that maternal vaccination decreases the risk of hospitalization from COVID-19 for infants aged <6 months, with vaccine efficacy estimated to be 61% during a period of both Delta and Omicron predominance.11

The evidence is clear—the time for COVID-19 vaccination is now. There is no “optimal” time of vaccination in pregnancy for neonatal benefit that would be worth risking any amount of time a woman is susceptible to COVID-19, especially given the promising data regarding maternal and neonatal antibody levels achieved after a booster dose.

Although the COVID-19 vaccine is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for ages 5 and above, Pfizer-BioNTech has plans to submit for approval for their vaccine’s use among kids as young as 6 months.1 Assuming that this approval occurs, this will leave newborns as the only group without possible vaccination against COVID-19. But can vaccination during pregnancy protect these infants against infection, as vaccination with the flu vaccine during pregnancy confers protective benefit to newborns?2

In a recent research letter published in Journal of the American Medical Association, Shook and colleagues present their data on antibody levels against COVID-19 present in newborns of women who were either naturally infected with COVID-19 at 20 to 32 weeks’ gestation (12 women) or who received mRNA vaccination during pregnancy at 20 to 32 weeks’ gestation (77 women).3 (They chose the 20- to 32-week timeframe during pregnancy because it had “demonstrated superior transplacental transfer of antibodies during this window.”)

They found that COVID-19 antibody levels were higher in both maternal and cord blood at birth in the women who were vaccinated versus the women who had infection. At 6 months, 16 of the 28 infants from the vaccinated-mother group had detectable antibodies compared with 1 of 12 infants from the infected-mother group. The researchers pointed out that the “antibody titer known to be protective against COVID-19 in infants is unknown;” however, they say that their findings provide further supportive evidence for COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant women.3

References

- Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine for children under 5 could be available by the end of February, people with knowledge say. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com /health/2022/01/31/coronavirus-vaccine-children-under-5/. Accessed February 11, 2022.

- Sakala IG, Honda-Okubo Y, Fung J, et al. Influenza immunization during pregnancy: benefits for mother and infant. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:3065-3071. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016 .1215392.

- Shook LL, Atyeo CG, Yonker LM, et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 vaccination or natural infection. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.1206.

Safety of COVID-19 vaccination: Current data

Risks for pregnancy loss, birth defects, and preterm delivery often are concerns of pregnant women considering a COVID-19 vaccination. Data from more than 2,400 women who submitted their information to the v-SAFE registry demonstrated a 14% risk for pregnancy loss between 6 and 20 weeks’ gestation—well within the expected rate of pregnancy loss in this gestational age range.12

Data from more than 46,000 pregnancies included in the Vaccine Safety Datalink, which includes data from health care organizations in 6 states, demonstrated a preterm birth rate of 6.6% and a small-for-gestational-age rate of 8.2% among fully vaccinated women, rates that were no different among unvaccinated women. There were no differences in the outcomes by trimester of vaccination, and these rates are comparable to the expected rates of these outcomes.13

Women also worry about the risks of vaccine side effects, such as fever or rare adverse events. Although all adverse events (ie, Guillain-Barre syndrome, pericarditis/myocarditis, thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome [TTS]) are very rare, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does recommend that women get an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, as the Johnson & Johnson/Janssen vaccine is associated with TTS, which occurred more commonly (although still rare) in women of reproductive age.14