User login

The COVID-19 pandemic and changes in pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses

The COVID-19 pandemic upended the U.S. health care market and disrupted much of what was thought to be consistent and necessary hospital-based care for children. Early in the pandemic, clinics closed, elective surgeries were delayed, and well visits were postponed. Mitigation strategies were launched nationwide to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 including mask mandates, social distancing, shelter-in-place orders, and school closures. While these measures were enacted to target COVID-19, a potential off-target effect was reductions in transmission of other respiratory illness, and potentially nonrespiratory infectious illnesses and conditions exacerbated by acute infections.1 These measures have heavily impacted the pediatric population, wherein respiratory infections are common, and also because daycares and school can be hubs for disease transmission.2

To evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric health care utilization, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study of 44 children’s hospitals using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database.3 Children aged 2 months to 18 years discharged from a PHIS hospital with nonsurgical diagnoses from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30 over a 4-year period (2017-2020) were included in the study. The primary exposure was the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which was divided into three study periods: pre–COVID-19 (January–February 2020), early COVID-19 (March-April 2020), and COVID-19 (May-September 2020). The primary outcomes were the observed-to-expected ratio of respiratory and nonrespiratory illness encounters of the study period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic. For these calculations, the expected encounters for each period was derived from the same calendar periods from prepandemic years (2017-2019).

A total of 9,051,980 pediatric encounters were included in the analyses: 6,811,799 with nonrespiratory illnesses and 2,240,181 with respiratory illnesses. We found a 42% reduction in overall encounters during the COVID-19 period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic, with a greater reduction in respiratory, compared with nonrespiratory illnesses, which decreased 62% and 38%, respectively. These reductions were consistent across geographic and encounter type (ED vs. hospitalization). The frequency of hospital-based encounters for common pediatric respiratory illnesses was substantially reduced, with reductions in asthma exacerbations (down 76%), pneumonia (down 81%), croup (down 84%), influenza (down 87%) and bronchiolitis (down 91%). Differences in both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses varied by age, with larger reductions found in children aged less than 12 years. While adolescent (children aged over 12 years) encounters diminished during the early COVID period for both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses, their encounters returned to previous levels faster than those from younger children. For respiratory illnesses, hospital-based adolescents encounters had returned to prepandemic levels by the end of the study period (September 2020).

These findings warrant consideration as relaxation of SARS-CoV-2 mitigation are contemplated. Encounters for respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses declined less and recovered faster in adolescents, compared with younger children. The underlying contributors to this trend are likely multifactorial. For example, respiratory illnesses such as croup and bronchiolitis are more common in younger children and adolescents may be more likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2, compared with younger age groups.4,5 However, adolescents may have had less strict adherence to social distancing measures.6 Future efforts to halt transmission of SARS-CoV-2, as well as other respiratory pathogens, should inform mitigation efforts in the adolescent population with considerations of the intensity of social mixing in different pediatric age groups.

While reductions in encounters caused by respiratory illnesses were substantial, more modest but similar age-based trends were seen in nonrespiratory illnesses. Yet, reduced transmission of infectious agents may not fully explain these findings. For example, it is possible that families sought care for mild to moderate nonrespiratory illness in clinics or via telehealth rather than the EDs.7 Provided there were no unintended negative consequences, such transition of care to non-ED settings would suggest there was overutilization of hospital resources prior to the pandemic. Additional assessments would be helpful to examine this more closely and to clarify the long-term impact of those transitions.

It is also possible that the pandemic effects on financial, social, and family stress may have led to increases in some pediatric health care encounters, such as those for mental health conditions,8 nonaccidental trauma or inability to adhere to treatment because of lack of resources.9,10 Additional study on the evolution and distribution of social and stress-related illnesses is critical to maintain and improve the health of children and adolescents.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in rapid and marked changes to both communicable and noncommunicable illnesses and care-seeking behaviors. Some of these findings are encouraging, such as large reductions in respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses. However, other trends may be harbingers of negative health consequences of the pandemic, such as increases in health care utilization later in the pandemic. Further study of the evolving pandemic’s effects on disease and health care utilization is needed to benefit our children now and during the next pandemic.

Dr. Antoon is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University and a pediatric hospitalist at the Monroe Carroll Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, both in Nashville, Tenn.

References

1. Kenyon CC et al. Initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric asthma emergency department utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Sep;8(8):2774-6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.045.

2. Luca G et al. The impact of regular school closure on seasonal influenza epidemics: A data-driven spatial transmission model for Belgium. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2934-3.

3. Antoon JW et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021 Mar 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3608.

4. Park YJ et al. Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;26(10):2465-8. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315.

5. Davies NG et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020 Aug;26(8):1205-11. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9.

6. Andrews JL et al. Peer influence in adolescence: Public health implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020;24(8):585-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001.

7. Taquechel K et al. Pediatric asthma healthcare utilization, viral testing, and air pollution changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Nov-Dec;8(10):3378-87.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.057.

8. Hill RM et al. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020029280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280.

9. Sharma S et al. COVID-19: Differences in sentinel injury and child abuse reporting during a pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020 Dec;110:104709. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709.

10. Lauren BN et al. Predictors of households at risk for food insecurity in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000355.

The COVID-19 pandemic upended the U.S. health care market and disrupted much of what was thought to be consistent and necessary hospital-based care for children. Early in the pandemic, clinics closed, elective surgeries were delayed, and well visits were postponed. Mitigation strategies were launched nationwide to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 including mask mandates, social distancing, shelter-in-place orders, and school closures. While these measures were enacted to target COVID-19, a potential off-target effect was reductions in transmission of other respiratory illness, and potentially nonrespiratory infectious illnesses and conditions exacerbated by acute infections.1 These measures have heavily impacted the pediatric population, wherein respiratory infections are common, and also because daycares and school can be hubs for disease transmission.2

To evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric health care utilization, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study of 44 children’s hospitals using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database.3 Children aged 2 months to 18 years discharged from a PHIS hospital with nonsurgical diagnoses from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30 over a 4-year period (2017-2020) were included in the study. The primary exposure was the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which was divided into three study periods: pre–COVID-19 (January–February 2020), early COVID-19 (March-April 2020), and COVID-19 (May-September 2020). The primary outcomes were the observed-to-expected ratio of respiratory and nonrespiratory illness encounters of the study period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic. For these calculations, the expected encounters for each period was derived from the same calendar periods from prepandemic years (2017-2019).

A total of 9,051,980 pediatric encounters were included in the analyses: 6,811,799 with nonrespiratory illnesses and 2,240,181 with respiratory illnesses. We found a 42% reduction in overall encounters during the COVID-19 period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic, with a greater reduction in respiratory, compared with nonrespiratory illnesses, which decreased 62% and 38%, respectively. These reductions were consistent across geographic and encounter type (ED vs. hospitalization). The frequency of hospital-based encounters for common pediatric respiratory illnesses was substantially reduced, with reductions in asthma exacerbations (down 76%), pneumonia (down 81%), croup (down 84%), influenza (down 87%) and bronchiolitis (down 91%). Differences in both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses varied by age, with larger reductions found in children aged less than 12 years. While adolescent (children aged over 12 years) encounters diminished during the early COVID period for both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses, their encounters returned to previous levels faster than those from younger children. For respiratory illnesses, hospital-based adolescents encounters had returned to prepandemic levels by the end of the study period (September 2020).

These findings warrant consideration as relaxation of SARS-CoV-2 mitigation are contemplated. Encounters for respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses declined less and recovered faster in adolescents, compared with younger children. The underlying contributors to this trend are likely multifactorial. For example, respiratory illnesses such as croup and bronchiolitis are more common in younger children and adolescents may be more likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2, compared with younger age groups.4,5 However, adolescents may have had less strict adherence to social distancing measures.6 Future efforts to halt transmission of SARS-CoV-2, as well as other respiratory pathogens, should inform mitigation efforts in the adolescent population with considerations of the intensity of social mixing in different pediatric age groups.

While reductions in encounters caused by respiratory illnesses were substantial, more modest but similar age-based trends were seen in nonrespiratory illnesses. Yet, reduced transmission of infectious agents may not fully explain these findings. For example, it is possible that families sought care for mild to moderate nonrespiratory illness in clinics or via telehealth rather than the EDs.7 Provided there were no unintended negative consequences, such transition of care to non-ED settings would suggest there was overutilization of hospital resources prior to the pandemic. Additional assessments would be helpful to examine this more closely and to clarify the long-term impact of those transitions.

It is also possible that the pandemic effects on financial, social, and family stress may have led to increases in some pediatric health care encounters, such as those for mental health conditions,8 nonaccidental trauma or inability to adhere to treatment because of lack of resources.9,10 Additional study on the evolution and distribution of social and stress-related illnesses is critical to maintain and improve the health of children and adolescents.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in rapid and marked changes to both communicable and noncommunicable illnesses and care-seeking behaviors. Some of these findings are encouraging, such as large reductions in respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses. However, other trends may be harbingers of negative health consequences of the pandemic, such as increases in health care utilization later in the pandemic. Further study of the evolving pandemic’s effects on disease and health care utilization is needed to benefit our children now and during the next pandemic.

Dr. Antoon is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University and a pediatric hospitalist at the Monroe Carroll Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, both in Nashville, Tenn.

References

1. Kenyon CC et al. Initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric asthma emergency department utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Sep;8(8):2774-6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.045.

2. Luca G et al. The impact of regular school closure on seasonal influenza epidemics: A data-driven spatial transmission model for Belgium. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2934-3.

3. Antoon JW et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021 Mar 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3608.

4. Park YJ et al. Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;26(10):2465-8. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315.

5. Davies NG et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020 Aug;26(8):1205-11. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9.

6. Andrews JL et al. Peer influence in adolescence: Public health implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020;24(8):585-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001.

7. Taquechel K et al. Pediatric asthma healthcare utilization, viral testing, and air pollution changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Nov-Dec;8(10):3378-87.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.057.

8. Hill RM et al. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020029280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280.

9. Sharma S et al. COVID-19: Differences in sentinel injury and child abuse reporting during a pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020 Dec;110:104709. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709.

10. Lauren BN et al. Predictors of households at risk for food insecurity in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000355.

The COVID-19 pandemic upended the U.S. health care market and disrupted much of what was thought to be consistent and necessary hospital-based care for children. Early in the pandemic, clinics closed, elective surgeries were delayed, and well visits were postponed. Mitigation strategies were launched nationwide to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 including mask mandates, social distancing, shelter-in-place orders, and school closures. While these measures were enacted to target COVID-19, a potential off-target effect was reductions in transmission of other respiratory illness, and potentially nonrespiratory infectious illnesses and conditions exacerbated by acute infections.1 These measures have heavily impacted the pediatric population, wherein respiratory infections are common, and also because daycares and school can be hubs for disease transmission.2

To evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric health care utilization, we performed a multicenter, cross-sectional study of 44 children’s hospitals using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database.3 Children aged 2 months to 18 years discharged from a PHIS hospital with nonsurgical diagnoses from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30 over a 4-year period (2017-2020) were included in the study. The primary exposure was the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which was divided into three study periods: pre–COVID-19 (January–February 2020), early COVID-19 (March-April 2020), and COVID-19 (May-September 2020). The primary outcomes were the observed-to-expected ratio of respiratory and nonrespiratory illness encounters of the study period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic. For these calculations, the expected encounters for each period was derived from the same calendar periods from prepandemic years (2017-2019).

A total of 9,051,980 pediatric encounters were included in the analyses: 6,811,799 with nonrespiratory illnesses and 2,240,181 with respiratory illnesses. We found a 42% reduction in overall encounters during the COVID-19 period, compared with the 3 years prior to the pandemic, with a greater reduction in respiratory, compared with nonrespiratory illnesses, which decreased 62% and 38%, respectively. These reductions were consistent across geographic and encounter type (ED vs. hospitalization). The frequency of hospital-based encounters for common pediatric respiratory illnesses was substantially reduced, with reductions in asthma exacerbations (down 76%), pneumonia (down 81%), croup (down 84%), influenza (down 87%) and bronchiolitis (down 91%). Differences in both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses varied by age, with larger reductions found in children aged less than 12 years. While adolescent (children aged over 12 years) encounters diminished during the early COVID period for both respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses, their encounters returned to previous levels faster than those from younger children. For respiratory illnesses, hospital-based adolescents encounters had returned to prepandemic levels by the end of the study period (September 2020).

These findings warrant consideration as relaxation of SARS-CoV-2 mitigation are contemplated. Encounters for respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses declined less and recovered faster in adolescents, compared with younger children. The underlying contributors to this trend are likely multifactorial. For example, respiratory illnesses such as croup and bronchiolitis are more common in younger children and adolescents may be more likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2, compared with younger age groups.4,5 However, adolescents may have had less strict adherence to social distancing measures.6 Future efforts to halt transmission of SARS-CoV-2, as well as other respiratory pathogens, should inform mitigation efforts in the adolescent population with considerations of the intensity of social mixing in different pediatric age groups.

While reductions in encounters caused by respiratory illnesses were substantial, more modest but similar age-based trends were seen in nonrespiratory illnesses. Yet, reduced transmission of infectious agents may not fully explain these findings. For example, it is possible that families sought care for mild to moderate nonrespiratory illness in clinics or via telehealth rather than the EDs.7 Provided there were no unintended negative consequences, such transition of care to non-ED settings would suggest there was overutilization of hospital resources prior to the pandemic. Additional assessments would be helpful to examine this more closely and to clarify the long-term impact of those transitions.

It is also possible that the pandemic effects on financial, social, and family stress may have led to increases in some pediatric health care encounters, such as those for mental health conditions,8 nonaccidental trauma or inability to adhere to treatment because of lack of resources.9,10 Additional study on the evolution and distribution of social and stress-related illnesses is critical to maintain and improve the health of children and adolescents.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in rapid and marked changes to both communicable and noncommunicable illnesses and care-seeking behaviors. Some of these findings are encouraging, such as large reductions in respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses. However, other trends may be harbingers of negative health consequences of the pandemic, such as increases in health care utilization later in the pandemic. Further study of the evolving pandemic’s effects on disease and health care utilization is needed to benefit our children now and during the next pandemic.

Dr. Antoon is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University and a pediatric hospitalist at the Monroe Carroll Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, both in Nashville, Tenn.

References

1. Kenyon CC et al. Initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric asthma emergency department utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Sep;8(8):2774-6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.045.

2. Luca G et al. The impact of regular school closure on seasonal influenza epidemics: A data-driven spatial transmission model for Belgium. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2934-3.

3. Antoon JW et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and changes in healthcare utilization for pediatric respiratory and nonrespiratory illnesses in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2021 Mar 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3608.

4. Park YJ et al. Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;26(10):2465-8. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315.

5. Davies NG et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020 Aug;26(8):1205-11. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9.

6. Andrews JL et al. Peer influence in adolescence: Public health implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020;24(8):585-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001.

7. Taquechel K et al. Pediatric asthma healthcare utilization, viral testing, and air pollution changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Nov-Dec;8(10):3378-87.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.057.

8. Hill RM et al. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020029280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280.

9. Sharma S et al. COVID-19: Differences in sentinel injury and child abuse reporting during a pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020 Dec;110:104709. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709.

10. Lauren BN et al. Predictors of households at risk for food insecurity in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000355.

Pandemic colonoscopy restrictions may lead to worse CRC outcomes

For veterans, changes in colonoscopy screening caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased risks of delayed colorectal cancer (CRC) diagnosis and could lead to worse CRC outcomes, based on data from more than 33,000 patients in the Veterans Health Administration.

After COVID-19 screening policies were implemented, a significantly lower rate of veterans with red-flag signs or symptoms for CRC underwent colonoscopy, lead author Joshua Demb, PhD, a cancer epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

“As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Veterans Health Administration enacted risk mitigation and management strategies in March 2020, including postponement of nearly all colonoscopies,” the investigators reported. “Notably, this included veterans with red flag signs or symptoms for CRC, among whom delays in workup could increase risk for later-stage and fatal CRC, if present.”

To measure the effects of this policy change, Dr. Demb and colleagues performed a cohort study involving 33,804 veterans with red-flag signs or symptoms for CRC, including hematochezia, iron deficiency anemia, or abnormal guaiac fecal occult blood test or fecal immunochemical test (FIT). Veterans were divided into two cohorts based on date of first red flag diagnosis: either before the COVID-19 policy was implemented (April to October 2019; n = 19,472) or after (April to October 2020; n = 14,332), with an intervening 6-month washout period.

Primary outcomes were proportion completing colonoscopy and time to colonoscopy completion. Multivariable logistic regression incorporated a number of demographic and medical covariates, including race/ethnicity, sex, age, number of red-flag signs/symptoms, first red-flag sign/symptom, and others.

Before the COVID-19 policy change, 44% of individuals with red-flag signs or symptoms received a colonoscopy, compared with 32% after the policy was introduced (P < .01). Adjusted models showed that veterans in the COVID policy group were 42% less likely to receive a diagnostic colonoscopy than those in the prepolicy group (odds ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.55-0.61). While these findings showed greater likelihood of receiving a screening before the pandemic, postpolicy colonoscopies were conducted sooner, with a median time to procedure of 41 days, compared with 65 days before the pandemic (P < .01). Similar differences in screening rates between pre- and postpandemic groups were observed across all types of red flag signs and symptoms.

“Lower colonoscopy uptake was observed among individuals with red-flag signs/symptoms for CRC post- versus preimplementation of COVID-19 policies, suggesting increased future risk for delayed CRC diagnosis and adverse CRC outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Prioritization may be needed to overcome backlog of colonoscopies

Jill Tinmouth, MD, PhD, lead scientist for ColonCancerCheck, Ontario’s organized colorectal cancer screening program, and a gastroenterologist and scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, shared similar concerns about delayed diagnoses.

“We might expect these cancers to present ... at a more advanced stage, and that, as a result, the outcomes from these cancers could be worse,” Dr. Tinmouth said in an interview.

She also noted the change in colonoscopy timing.

“A particularly interesting finding was that, when a colonoscopy occurred, the time to colonoscopy was shorter during the COVID era than in the pre-COVID era,” Dr. Tinmouth said. “The authors suggested that this might be as a result of Veterans Health Administration policies implemented as a result of the pandemic that led to prioritization of more urgent procedures.”

According to Dr. Tinmouth, similar prioritization may be needed to catch up with the backlog of colonoscopies created by pandemic-related policy changes. In a recent study comparing two backlog management techniques, Dr. Tinmouth and colleagues concluded that redirecting low-yield colonoscopies to FIT without increasing hospital colonoscopy capacity could reduce time to recovery by more than half.

Even so, screening programs may be facing a long road to recovery.

“Recovery of the colonoscopy backlog is going to be a challenge that will take a while – maybe even years – to resolve,” Dr. Tinmouth said. “Jurisdictions/institutions that have a strong centralized intake or triage will likely be most successful in resolving the backlog quickly as they will be able to prioritize the most urgent cases, such as persons with an abnormal FIT or with symptoms, and to redirect persons scheduled for a ‘low-yield’ colonoscopy to have a FIT instead.” Ontario defines low-yield colonoscopies as primary screening for average-risk individuals and follow-up colonoscopies for patients with low-risk adenomas at baseline.

When asked about strategies to address future pandemics, Dr. Tinmouth said, “I think that two key learnings for me from this [pandemic] are: one, not to let our guard down, and to remain vigilant and prepared – in terms of monitoring, supply chain, equipment, etc.] ... and two to create a nimble and agile health system so that we are able to assess the challenges that the next pandemic brings and address them as quickly as possible.”The investigators and Dr. Tinmouth reported no conflicts of interest.

For veterans, changes in colonoscopy screening caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased risks of delayed colorectal cancer (CRC) diagnosis and could lead to worse CRC outcomes, based on data from more than 33,000 patients in the Veterans Health Administration.

After COVID-19 screening policies were implemented, a significantly lower rate of veterans with red-flag signs or symptoms for CRC underwent colonoscopy, lead author Joshua Demb, PhD, a cancer epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

“As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Veterans Health Administration enacted risk mitigation and management strategies in March 2020, including postponement of nearly all colonoscopies,” the investigators reported. “Notably, this included veterans with red flag signs or symptoms for CRC, among whom delays in workup could increase risk for later-stage and fatal CRC, if present.”

To measure the effects of this policy change, Dr. Demb and colleagues performed a cohort study involving 33,804 veterans with red-flag signs or symptoms for CRC, including hematochezia, iron deficiency anemia, or abnormal guaiac fecal occult blood test or fecal immunochemical test (FIT). Veterans were divided into two cohorts based on date of first red flag diagnosis: either before the COVID-19 policy was implemented (April to October 2019; n = 19,472) or after (April to October 2020; n = 14,332), with an intervening 6-month washout period.

Primary outcomes were proportion completing colonoscopy and time to colonoscopy completion. Multivariable logistic regression incorporated a number of demographic and medical covariates, including race/ethnicity, sex, age, number of red-flag signs/symptoms, first red-flag sign/symptom, and others.

Before the COVID-19 policy change, 44% of individuals with red-flag signs or symptoms received a colonoscopy, compared with 32% after the policy was introduced (P < .01). Adjusted models showed that veterans in the COVID policy group were 42% less likely to receive a diagnostic colonoscopy than those in the prepolicy group (odds ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.55-0.61). While these findings showed greater likelihood of receiving a screening before the pandemic, postpolicy colonoscopies were conducted sooner, with a median time to procedure of 41 days, compared with 65 days before the pandemic (P < .01). Similar differences in screening rates between pre- and postpandemic groups were observed across all types of red flag signs and symptoms.

“Lower colonoscopy uptake was observed among individuals with red-flag signs/symptoms for CRC post- versus preimplementation of COVID-19 policies, suggesting increased future risk for delayed CRC diagnosis and adverse CRC outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Prioritization may be needed to overcome backlog of colonoscopies

Jill Tinmouth, MD, PhD, lead scientist for ColonCancerCheck, Ontario’s organized colorectal cancer screening program, and a gastroenterologist and scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, shared similar concerns about delayed diagnoses.

“We might expect these cancers to present ... at a more advanced stage, and that, as a result, the outcomes from these cancers could be worse,” Dr. Tinmouth said in an interview.

She also noted the change in colonoscopy timing.

“A particularly interesting finding was that, when a colonoscopy occurred, the time to colonoscopy was shorter during the COVID era than in the pre-COVID era,” Dr. Tinmouth said. “The authors suggested that this might be as a result of Veterans Health Administration policies implemented as a result of the pandemic that led to prioritization of more urgent procedures.”

According to Dr. Tinmouth, similar prioritization may be needed to catch up with the backlog of colonoscopies created by pandemic-related policy changes. In a recent study comparing two backlog management techniques, Dr. Tinmouth and colleagues concluded that redirecting low-yield colonoscopies to FIT without increasing hospital colonoscopy capacity could reduce time to recovery by more than half.

Even so, screening programs may be facing a long road to recovery.

“Recovery of the colonoscopy backlog is going to be a challenge that will take a while – maybe even years – to resolve,” Dr. Tinmouth said. “Jurisdictions/institutions that have a strong centralized intake or triage will likely be most successful in resolving the backlog quickly as they will be able to prioritize the most urgent cases, such as persons with an abnormal FIT or with symptoms, and to redirect persons scheduled for a ‘low-yield’ colonoscopy to have a FIT instead.” Ontario defines low-yield colonoscopies as primary screening for average-risk individuals and follow-up colonoscopies for patients with low-risk adenomas at baseline.

When asked about strategies to address future pandemics, Dr. Tinmouth said, “I think that two key learnings for me from this [pandemic] are: one, not to let our guard down, and to remain vigilant and prepared – in terms of monitoring, supply chain, equipment, etc.] ... and two to create a nimble and agile health system so that we are able to assess the challenges that the next pandemic brings and address them as quickly as possible.”The investigators and Dr. Tinmouth reported no conflicts of interest.

For veterans, changes in colonoscopy screening caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased risks of delayed colorectal cancer (CRC) diagnosis and could lead to worse CRC outcomes, based on data from more than 33,000 patients in the Veterans Health Administration.

After COVID-19 screening policies were implemented, a significantly lower rate of veterans with red-flag signs or symptoms for CRC underwent colonoscopy, lead author Joshua Demb, PhD, a cancer epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, reported at the annual Digestive Disease Week® (DDW).

“As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Veterans Health Administration enacted risk mitigation and management strategies in March 2020, including postponement of nearly all colonoscopies,” the investigators reported. “Notably, this included veterans with red flag signs or symptoms for CRC, among whom delays in workup could increase risk for later-stage and fatal CRC, if present.”

To measure the effects of this policy change, Dr. Demb and colleagues performed a cohort study involving 33,804 veterans with red-flag signs or symptoms for CRC, including hematochezia, iron deficiency anemia, or abnormal guaiac fecal occult blood test or fecal immunochemical test (FIT). Veterans were divided into two cohorts based on date of first red flag diagnosis: either before the COVID-19 policy was implemented (April to October 2019; n = 19,472) or after (April to October 2020; n = 14,332), with an intervening 6-month washout period.

Primary outcomes were proportion completing colonoscopy and time to colonoscopy completion. Multivariable logistic regression incorporated a number of demographic and medical covariates, including race/ethnicity, sex, age, number of red-flag signs/symptoms, first red-flag sign/symptom, and others.

Before the COVID-19 policy change, 44% of individuals with red-flag signs or symptoms received a colonoscopy, compared with 32% after the policy was introduced (P < .01). Adjusted models showed that veterans in the COVID policy group were 42% less likely to receive a diagnostic colonoscopy than those in the prepolicy group (odds ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.55-0.61). While these findings showed greater likelihood of receiving a screening before the pandemic, postpolicy colonoscopies were conducted sooner, with a median time to procedure of 41 days, compared with 65 days before the pandemic (P < .01). Similar differences in screening rates between pre- and postpandemic groups were observed across all types of red flag signs and symptoms.

“Lower colonoscopy uptake was observed among individuals with red-flag signs/symptoms for CRC post- versus preimplementation of COVID-19 policies, suggesting increased future risk for delayed CRC diagnosis and adverse CRC outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Prioritization may be needed to overcome backlog of colonoscopies

Jill Tinmouth, MD, PhD, lead scientist for ColonCancerCheck, Ontario’s organized colorectal cancer screening program, and a gastroenterologist and scientist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, shared similar concerns about delayed diagnoses.

“We might expect these cancers to present ... at a more advanced stage, and that, as a result, the outcomes from these cancers could be worse,” Dr. Tinmouth said in an interview.

She also noted the change in colonoscopy timing.

“A particularly interesting finding was that, when a colonoscopy occurred, the time to colonoscopy was shorter during the COVID era than in the pre-COVID era,” Dr. Tinmouth said. “The authors suggested that this might be as a result of Veterans Health Administration policies implemented as a result of the pandemic that led to prioritization of more urgent procedures.”

According to Dr. Tinmouth, similar prioritization may be needed to catch up with the backlog of colonoscopies created by pandemic-related policy changes. In a recent study comparing two backlog management techniques, Dr. Tinmouth and colleagues concluded that redirecting low-yield colonoscopies to FIT without increasing hospital colonoscopy capacity could reduce time to recovery by more than half.

Even so, screening programs may be facing a long road to recovery.

“Recovery of the colonoscopy backlog is going to be a challenge that will take a while – maybe even years – to resolve,” Dr. Tinmouth said. “Jurisdictions/institutions that have a strong centralized intake or triage will likely be most successful in resolving the backlog quickly as they will be able to prioritize the most urgent cases, such as persons with an abnormal FIT or with symptoms, and to redirect persons scheduled for a ‘low-yield’ colonoscopy to have a FIT instead.” Ontario defines low-yield colonoscopies as primary screening for average-risk individuals and follow-up colonoscopies for patients with low-risk adenomas at baseline.

When asked about strategies to address future pandemics, Dr. Tinmouth said, “I think that two key learnings for me from this [pandemic] are: one, not to let our guard down, and to remain vigilant and prepared – in terms of monitoring, supply chain, equipment, etc.] ... and two to create a nimble and agile health system so that we are able to assess the challenges that the next pandemic brings and address them as quickly as possible.”The investigators and Dr. Tinmouth reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM DDW 2021

Lower SARS-CoV-2 vaccine responses seen in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

Ten percent of patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) fail to respond properly to COVID-19 vaccinations regardless of medication, researchers report, and small new studies suggest those on methotrexate and rituximab may be especially vulnerable to vaccine failure.

Even so, it’s still crucially vital for patients with IMIDs to get vaccinated and for clinicians to follow recommendations to temporarily withhold certain medications around the time of vaccination, rheumatologist Anne R. Bass, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine and the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said in an interview. “We’re not making any significant adjustments,” added Dr. Bass, a coauthor of the American College of Rheumatology’s COVID-19 vaccination guidelines for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases.

The findings appear in a trio of studies in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. The most recent study, which appeared May 25, 2021, found that more than one-third of patients with IMIDs who took methotrexate didn’t produce adequate antibody levels after vaccination versus 10% of those in other groups. (P < .001) A May 11 study found that 20 of 30 patients with rheumatic diseases on rituximab failed to respond to vaccination. And a May 6 study reported that immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 are “somewhat delayed and reduced” in patients with IMID, with 99.5% of a control group developing neutralizing antibody activity after vaccination versus 90% of those with IMID (P = .0008).

Development of neutralizing antibodies somewhat delayed and reduced

Team members were surprised by the high number of vaccine nonresponders in the May 6 IMID study, coauthor Georg Schett, MD, of Germany’s Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg and University Hospital Erlangen, said in an interview.

The researchers compared two groups of patients who had no history of COVID-19 and received COVID-19 vaccinations, mostly two shots of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (96%): 84 with IMID (mean age, 53.1 years; 65.5% females) and 182 healthy controls (mean age, 40.8 years; 57.1% females).

The patients with IMID most commonly had spondyloarthritis (32.1%), RA (29.8%), inflammatory bowel disease (9.5%), and psoriasis (9.5%). Nearly 43% of the patients were treated with biologic and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and 23.9% with conventional synthetic DMARDSs. Another 29% were not treated.

All of the controls developed anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG, but 6% of the patients with IMID did not (P = .003). The gap in development of neutralizing antibodies was even higher: 99.5% of the controls developed neutralizing antibody activity versus 90% of the IMID group. “Neutralizing antibodies are more relevant because the test shows how much the antibodies interfere with the binding of SARS-CoV-2 proteins to the receptor,” Dr. Schett said.

The study authors concluded that “our study provides evidence that, while vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is well tolerated and even associated with lower incidence of side effects in patients with IMID, its efficacy is somewhat delayed and reduced. Nonetheless, the data also show that, in principle, patients with IMID respond to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, supporting an aggressive vaccination strategy.”

Lowered antibody response to vaccination for some methotrexate users

In the newer study, led by Rebecca H. Haberman, MD, of New York University Langone Health, researchers examined COVID-19 vaccine response in cohorts in New York City and Erlangen, Germany.

The New York cohort included 25 patients with IMID who were taking methotrexate by itself or with other immunomodulatory medications (mean age, 63.2 years), 26 with IMID who were on anticytokine therapy and/or other oral immunomodulators (mean age, 49.1 years) and 26 healthy controls (mean age, 49.2 years). Most patients with IMID had psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis or RA.

The German validation cohort included 182 healthy subjects (mean age, 45.0 years), 11 subjects with IMID who received TNF inhibitor monotherapy (mean age, 40.8 years), and 20 subjects with IMID on methotrexate monotherapy (mean age, 54.5 years).

In the New York cohort, 96.1% of healthy controls showed “adequate humoral immune response,” along with 92.3% of patients with IMID who weren’t taking methotrexate. However, those on methotrexate had a lower rate of adequate response (72.0%), and the gap persisted even after researchers removed those who showed signs of previous COVID-19 infection (P = .045).

In the German cohort, 98.3% of healthy cohorts and 90.9% of patients with IMID who didn’t receive methotrexate reached an “adequate” humoral response versus just half (50.0%) of those who were taking methotrexate.

When both cohorts are combined, over 90% of the healthy subjects and the patients with IMID on biologic treatments (mainly TNF blockers, n = 37) showed “robust” antibody response. However, only 62% of patients with IMID who took methotrexate (n = 45) reached an “adequate” level of response. The methotrexate gap remained after researchers accounted for differences in age among the cohorts.

What’s going on? “We think that the underlying chronic immune stimulation in autoimmune patients may cause T-cell exhaustion and thus blunts the immune response,” said Dr. Schett, who’s also a coauthor of this study. “In addition, specific drugs such as methotrexate could additionally impair the immune response.”

Still, the findings “reiterate that vaccinations are safe and effective, which is what the recommendations state,” he said, adding that more testing of vaccination immune response is wise.

Insights into vaccine response while on rituximab

Two more reports, also published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, offer insight into vaccine response in patients with IMID who take rituximab.

In one report, published May 11, U.S. researchers retrospectively tracked 89 rheumatic disease patients (76% female; mean age, 61) at a single clinic who’d received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Of those, 21 patients showed no sign of vaccine antibody response, and 20 of them were in the group taking rituximab. (The other patient was taking belimumab.) Another 10 patients taking rituximab did show a response.

“Longer duration from most recent rituximab exposure was associated with a greater likelihood of response,” the report’s authors wrote. “The results suggest that time from last rituximab exposure is an important consideration in maximizing the likelihood of a serological response, but this likely is related to the substantial variation in the period of B-cell depletion following rituximab.”

Finally, an Austrian report published May 6 examined COVID-19 vaccine immune response in five patients who were taking rituximab (four with other drugs such as methotrexate and prednisone). Researchers compared them with eight healthy controls, half who’d been vaccinated.

The researchers found evidence that rituximab “may not have to preclude SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, since a cellular immune response will be mounted even in the absence of circulating B cells. Alternatively, in patients with stable disease, delaying [rituximab] treatment until after the second vaccination may be warranted and, therefore, vaccines with a short interval between first and second vaccination or those showing full protection after a single vaccination may be preferable. Importantly, in the presence of circulating B cells also a humoral immune response may be expected despite prior [rituximab] therapy.”

Dr. Bass said the findings reflect growing awareness that “patients with autoimmune disease, especially when they’re on immunosuppressant medications, don’t quite have as optimal responses to the vaccinations.” However, she said, the vaccines are so potent that they’re likely to still have significant efficacy in these patients even if there’s a reduction in response.

What’s next? Dr. Schett said “testing immune response to vaccination is important for patients with autoimmune disease. Some of them may need a third vaccination.”

The American College of Rheumatology’s COVID-19 vaccination guidelines do not recommend third vaccinations or postvaccination immune testing at this time. However, Dr. Bass, one of the coauthors of the recommendations, said it’s likely that postvaccination immune testing and booster shots will become routine.

Dr. Bass reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Schett reported receiving consulting fees from AbbVie. The May 6 German vaccine study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, the ERC Synergy grant 4D Nanoscope, the IMI funded project RTCure, the Emerging Fields Initiative MIRACLE of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, the Schreiber Stiftung, and the Else Kröner-Memorial Scholarship. The study authors reported no disclosures. The May 25 study of German and American cohorts was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskletal and Skin Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Rheumatology Research Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies COVID-19 Initiative, Pfizer COVID-19 Competitive Grant Program, Beatrice Snyder Foundation, Riley Family Foundation, National Psoriasis Foundation, and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. The authors reported a range of financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. No specific funding was reported for the other two studies mentioned.

Ten percent of patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) fail to respond properly to COVID-19 vaccinations regardless of medication, researchers report, and small new studies suggest those on methotrexate and rituximab may be especially vulnerable to vaccine failure.

Even so, it’s still crucially vital for patients with IMIDs to get vaccinated and for clinicians to follow recommendations to temporarily withhold certain medications around the time of vaccination, rheumatologist Anne R. Bass, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine and the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said in an interview. “We’re not making any significant adjustments,” added Dr. Bass, a coauthor of the American College of Rheumatology’s COVID-19 vaccination guidelines for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases.

The findings appear in a trio of studies in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. The most recent study, which appeared May 25, 2021, found that more than one-third of patients with IMIDs who took methotrexate didn’t produce adequate antibody levels after vaccination versus 10% of those in other groups. (P < .001) A May 11 study found that 20 of 30 patients with rheumatic diseases on rituximab failed to respond to vaccination. And a May 6 study reported that immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 are “somewhat delayed and reduced” in patients with IMID, with 99.5% of a control group developing neutralizing antibody activity after vaccination versus 90% of those with IMID (P = .0008).

Development of neutralizing antibodies somewhat delayed and reduced

Team members were surprised by the high number of vaccine nonresponders in the May 6 IMID study, coauthor Georg Schett, MD, of Germany’s Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg and University Hospital Erlangen, said in an interview.

The researchers compared two groups of patients who had no history of COVID-19 and received COVID-19 vaccinations, mostly two shots of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (96%): 84 with IMID (mean age, 53.1 years; 65.5% females) and 182 healthy controls (mean age, 40.8 years; 57.1% females).

The patients with IMID most commonly had spondyloarthritis (32.1%), RA (29.8%), inflammatory bowel disease (9.5%), and psoriasis (9.5%). Nearly 43% of the patients were treated with biologic and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and 23.9% with conventional synthetic DMARDSs. Another 29% were not treated.

All of the controls developed anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG, but 6% of the patients with IMID did not (P = .003). The gap in development of neutralizing antibodies was even higher: 99.5% of the controls developed neutralizing antibody activity versus 90% of the IMID group. “Neutralizing antibodies are more relevant because the test shows how much the antibodies interfere with the binding of SARS-CoV-2 proteins to the receptor,” Dr. Schett said.

The study authors concluded that “our study provides evidence that, while vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is well tolerated and even associated with lower incidence of side effects in patients with IMID, its efficacy is somewhat delayed and reduced. Nonetheless, the data also show that, in principle, patients with IMID respond to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, supporting an aggressive vaccination strategy.”

Lowered antibody response to vaccination for some methotrexate users

In the newer study, led by Rebecca H. Haberman, MD, of New York University Langone Health, researchers examined COVID-19 vaccine response in cohorts in New York City and Erlangen, Germany.

The New York cohort included 25 patients with IMID who were taking methotrexate by itself or with other immunomodulatory medications (mean age, 63.2 years), 26 with IMID who were on anticytokine therapy and/or other oral immunomodulators (mean age, 49.1 years) and 26 healthy controls (mean age, 49.2 years). Most patients with IMID had psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis or RA.

The German validation cohort included 182 healthy subjects (mean age, 45.0 years), 11 subjects with IMID who received TNF inhibitor monotherapy (mean age, 40.8 years), and 20 subjects with IMID on methotrexate monotherapy (mean age, 54.5 years).

In the New York cohort, 96.1% of healthy controls showed “adequate humoral immune response,” along with 92.3% of patients with IMID who weren’t taking methotrexate. However, those on methotrexate had a lower rate of adequate response (72.0%), and the gap persisted even after researchers removed those who showed signs of previous COVID-19 infection (P = .045).

In the German cohort, 98.3% of healthy cohorts and 90.9% of patients with IMID who didn’t receive methotrexate reached an “adequate” humoral response versus just half (50.0%) of those who were taking methotrexate.

When both cohorts are combined, over 90% of the healthy subjects and the patients with IMID on biologic treatments (mainly TNF blockers, n = 37) showed “robust” antibody response. However, only 62% of patients with IMID who took methotrexate (n = 45) reached an “adequate” level of response. The methotrexate gap remained after researchers accounted for differences in age among the cohorts.

What’s going on? “We think that the underlying chronic immune stimulation in autoimmune patients may cause T-cell exhaustion and thus blunts the immune response,” said Dr. Schett, who’s also a coauthor of this study. “In addition, specific drugs such as methotrexate could additionally impair the immune response.”

Still, the findings “reiterate that vaccinations are safe and effective, which is what the recommendations state,” he said, adding that more testing of vaccination immune response is wise.

Insights into vaccine response while on rituximab

Two more reports, also published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, offer insight into vaccine response in patients with IMID who take rituximab.

In one report, published May 11, U.S. researchers retrospectively tracked 89 rheumatic disease patients (76% female; mean age, 61) at a single clinic who’d received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Of those, 21 patients showed no sign of vaccine antibody response, and 20 of them were in the group taking rituximab. (The other patient was taking belimumab.) Another 10 patients taking rituximab did show a response.

“Longer duration from most recent rituximab exposure was associated with a greater likelihood of response,” the report’s authors wrote. “The results suggest that time from last rituximab exposure is an important consideration in maximizing the likelihood of a serological response, but this likely is related to the substantial variation in the period of B-cell depletion following rituximab.”

Finally, an Austrian report published May 6 examined COVID-19 vaccine immune response in five patients who were taking rituximab (four with other drugs such as methotrexate and prednisone). Researchers compared them with eight healthy controls, half who’d been vaccinated.

The researchers found evidence that rituximab “may not have to preclude SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, since a cellular immune response will be mounted even in the absence of circulating B cells. Alternatively, in patients with stable disease, delaying [rituximab] treatment until after the second vaccination may be warranted and, therefore, vaccines with a short interval between first and second vaccination or those showing full protection after a single vaccination may be preferable. Importantly, in the presence of circulating B cells also a humoral immune response may be expected despite prior [rituximab] therapy.”

Dr. Bass said the findings reflect growing awareness that “patients with autoimmune disease, especially when they’re on immunosuppressant medications, don’t quite have as optimal responses to the vaccinations.” However, she said, the vaccines are so potent that they’re likely to still have significant efficacy in these patients even if there’s a reduction in response.

What’s next? Dr. Schett said “testing immune response to vaccination is important for patients with autoimmune disease. Some of them may need a third vaccination.”

The American College of Rheumatology’s COVID-19 vaccination guidelines do not recommend third vaccinations or postvaccination immune testing at this time. However, Dr. Bass, one of the coauthors of the recommendations, said it’s likely that postvaccination immune testing and booster shots will become routine.

Dr. Bass reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Schett reported receiving consulting fees from AbbVie. The May 6 German vaccine study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, the ERC Synergy grant 4D Nanoscope, the IMI funded project RTCure, the Emerging Fields Initiative MIRACLE of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, the Schreiber Stiftung, and the Else Kröner-Memorial Scholarship. The study authors reported no disclosures. The May 25 study of German and American cohorts was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskletal and Skin Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Rheumatology Research Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies COVID-19 Initiative, Pfizer COVID-19 Competitive Grant Program, Beatrice Snyder Foundation, Riley Family Foundation, National Psoriasis Foundation, and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. The authors reported a range of financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. No specific funding was reported for the other two studies mentioned.

Ten percent of patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) fail to respond properly to COVID-19 vaccinations regardless of medication, researchers report, and small new studies suggest those on methotrexate and rituximab may be especially vulnerable to vaccine failure.

Even so, it’s still crucially vital for patients with IMIDs to get vaccinated and for clinicians to follow recommendations to temporarily withhold certain medications around the time of vaccination, rheumatologist Anne R. Bass, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine and the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said in an interview. “We’re not making any significant adjustments,” added Dr. Bass, a coauthor of the American College of Rheumatology’s COVID-19 vaccination guidelines for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases.

The findings appear in a trio of studies in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. The most recent study, which appeared May 25, 2021, found that more than one-third of patients with IMIDs who took methotrexate didn’t produce adequate antibody levels after vaccination versus 10% of those in other groups. (P < .001) A May 11 study found that 20 of 30 patients with rheumatic diseases on rituximab failed to respond to vaccination. And a May 6 study reported that immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 are “somewhat delayed and reduced” in patients with IMID, with 99.5% of a control group developing neutralizing antibody activity after vaccination versus 90% of those with IMID (P = .0008).

Development of neutralizing antibodies somewhat delayed and reduced

Team members were surprised by the high number of vaccine nonresponders in the May 6 IMID study, coauthor Georg Schett, MD, of Germany’s Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg and University Hospital Erlangen, said in an interview.

The researchers compared two groups of patients who had no history of COVID-19 and received COVID-19 vaccinations, mostly two shots of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (96%): 84 with IMID (mean age, 53.1 years; 65.5% females) and 182 healthy controls (mean age, 40.8 years; 57.1% females).

The patients with IMID most commonly had spondyloarthritis (32.1%), RA (29.8%), inflammatory bowel disease (9.5%), and psoriasis (9.5%). Nearly 43% of the patients were treated with biologic and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and 23.9% with conventional synthetic DMARDSs. Another 29% were not treated.

All of the controls developed anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG, but 6% of the patients with IMID did not (P = .003). The gap in development of neutralizing antibodies was even higher: 99.5% of the controls developed neutralizing antibody activity versus 90% of the IMID group. “Neutralizing antibodies are more relevant because the test shows how much the antibodies interfere with the binding of SARS-CoV-2 proteins to the receptor,” Dr. Schett said.

The study authors concluded that “our study provides evidence that, while vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is well tolerated and even associated with lower incidence of side effects in patients with IMID, its efficacy is somewhat delayed and reduced. Nonetheless, the data also show that, in principle, patients with IMID respond to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, supporting an aggressive vaccination strategy.”

Lowered antibody response to vaccination for some methotrexate users

In the newer study, led by Rebecca H. Haberman, MD, of New York University Langone Health, researchers examined COVID-19 vaccine response in cohorts in New York City and Erlangen, Germany.

The New York cohort included 25 patients with IMID who were taking methotrexate by itself or with other immunomodulatory medications (mean age, 63.2 years), 26 with IMID who were on anticytokine therapy and/or other oral immunomodulators (mean age, 49.1 years) and 26 healthy controls (mean age, 49.2 years). Most patients with IMID had psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis or RA.

The German validation cohort included 182 healthy subjects (mean age, 45.0 years), 11 subjects with IMID who received TNF inhibitor monotherapy (mean age, 40.8 years), and 20 subjects with IMID on methotrexate monotherapy (mean age, 54.5 years).

In the New York cohort, 96.1% of healthy controls showed “adequate humoral immune response,” along with 92.3% of patients with IMID who weren’t taking methotrexate. However, those on methotrexate had a lower rate of adequate response (72.0%), and the gap persisted even after researchers removed those who showed signs of previous COVID-19 infection (P = .045).

In the German cohort, 98.3% of healthy cohorts and 90.9% of patients with IMID who didn’t receive methotrexate reached an “adequate” humoral response versus just half (50.0%) of those who were taking methotrexate.

When both cohorts are combined, over 90% of the healthy subjects and the patients with IMID on biologic treatments (mainly TNF blockers, n = 37) showed “robust” antibody response. However, only 62% of patients with IMID who took methotrexate (n = 45) reached an “adequate” level of response. The methotrexate gap remained after researchers accounted for differences in age among the cohorts.

What’s going on? “We think that the underlying chronic immune stimulation in autoimmune patients may cause T-cell exhaustion and thus blunts the immune response,” said Dr. Schett, who’s also a coauthor of this study. “In addition, specific drugs such as methotrexate could additionally impair the immune response.”

Still, the findings “reiterate that vaccinations are safe and effective, which is what the recommendations state,” he said, adding that more testing of vaccination immune response is wise.

Insights into vaccine response while on rituximab

Two more reports, also published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, offer insight into vaccine response in patients with IMID who take rituximab.

In one report, published May 11, U.S. researchers retrospectively tracked 89 rheumatic disease patients (76% female; mean age, 61) at a single clinic who’d received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Of those, 21 patients showed no sign of vaccine antibody response, and 20 of them were in the group taking rituximab. (The other patient was taking belimumab.) Another 10 patients taking rituximab did show a response.

“Longer duration from most recent rituximab exposure was associated with a greater likelihood of response,” the report’s authors wrote. “The results suggest that time from last rituximab exposure is an important consideration in maximizing the likelihood of a serological response, but this likely is related to the substantial variation in the period of B-cell depletion following rituximab.”

Finally, an Austrian report published May 6 examined COVID-19 vaccine immune response in five patients who were taking rituximab (four with other drugs such as methotrexate and prednisone). Researchers compared them with eight healthy controls, half who’d been vaccinated.

The researchers found evidence that rituximab “may not have to preclude SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, since a cellular immune response will be mounted even in the absence of circulating B cells. Alternatively, in patients with stable disease, delaying [rituximab] treatment until after the second vaccination may be warranted and, therefore, vaccines with a short interval between first and second vaccination or those showing full protection after a single vaccination may be preferable. Importantly, in the presence of circulating B cells also a humoral immune response may be expected despite prior [rituximab] therapy.”

Dr. Bass said the findings reflect growing awareness that “patients with autoimmune disease, especially when they’re on immunosuppressant medications, don’t quite have as optimal responses to the vaccinations.” However, she said, the vaccines are so potent that they’re likely to still have significant efficacy in these patients even if there’s a reduction in response.

What’s next? Dr. Schett said “testing immune response to vaccination is important for patients with autoimmune disease. Some of them may need a third vaccination.”

The American College of Rheumatology’s COVID-19 vaccination guidelines do not recommend third vaccinations or postvaccination immune testing at this time. However, Dr. Bass, one of the coauthors of the recommendations, said it’s likely that postvaccination immune testing and booster shots will become routine.

Dr. Bass reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Schett reported receiving consulting fees from AbbVie. The May 6 German vaccine study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, the ERC Synergy grant 4D Nanoscope, the IMI funded project RTCure, the Emerging Fields Initiative MIRACLE of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, the Schreiber Stiftung, and the Else Kröner-Memorial Scholarship. The study authors reported no disclosures. The May 25 study of German and American cohorts was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskletal and Skin Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Rheumatology Research Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies COVID-19 Initiative, Pfizer COVID-19 Competitive Grant Program, Beatrice Snyder Foundation, Riley Family Foundation, National Psoriasis Foundation, and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. The authors reported a range of financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. No specific funding was reported for the other two studies mentioned.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

COVID-19 vaccination rate rising quickly among adolescents

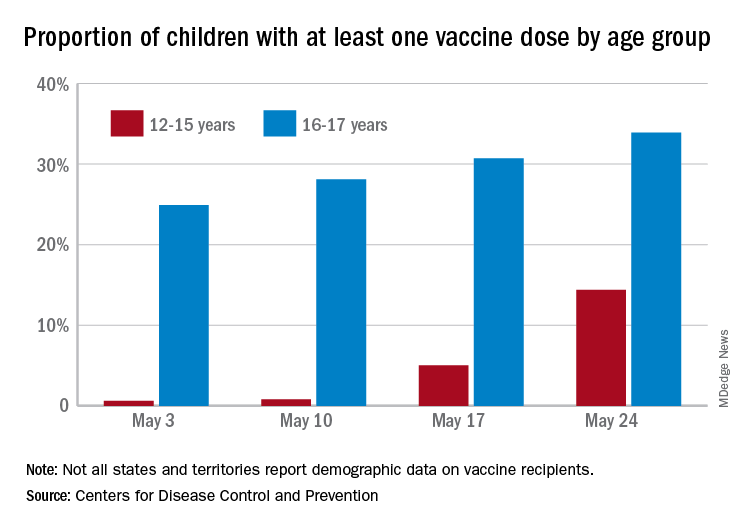

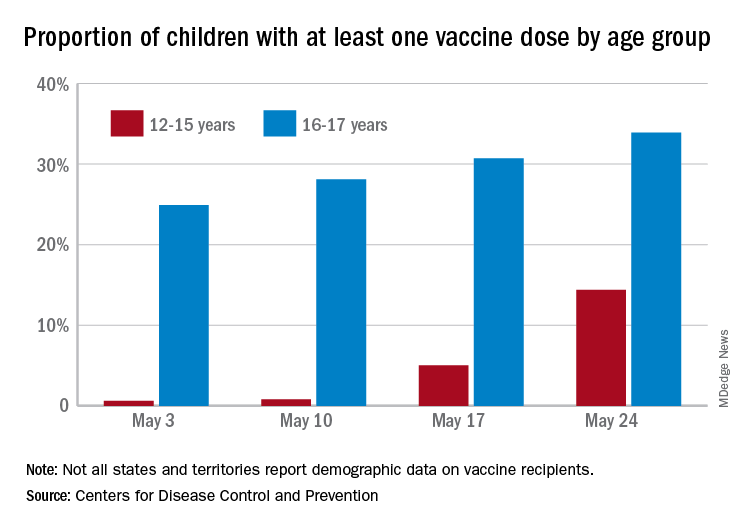

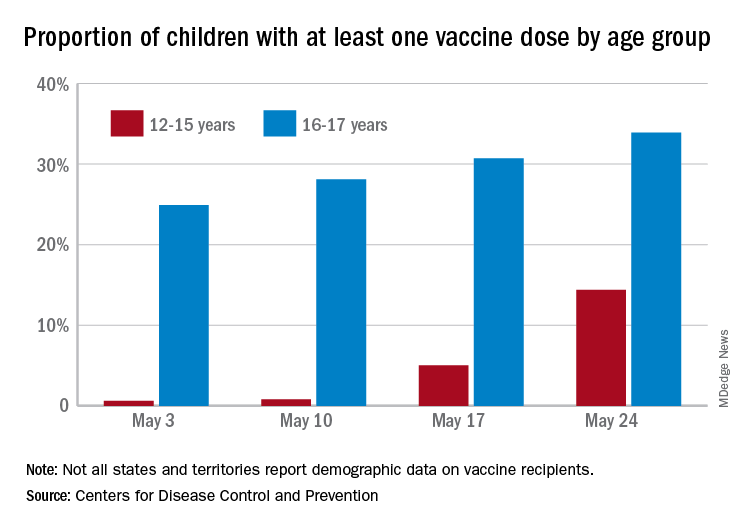

With nearly half of all Americans having received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, the youngest eligible group is beginning to overcome its late start, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of May 24, 49.4% of the U.S. population – that’s almost 164 million people – has received at least one dose of vaccine. The corresponding figure for children aged 12-15 years is 14.4%, but that’s up from only 0.6% just 3 weeks before. Among children aged 16-17, who’ve been getting vaccinated since early April in some states, the proportion receiving at least one dose went from 24.9% to 33.9% over those same 3 weeks, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker site.

The comparatively rapid increase among the younger group of eligible children can be seen over the last 14 days. To put that into perspective, only those aged 25-39 years were higher at 21.9%, while 18-24 (12.1%), 40-49 (13.4%), 50-64 (18.2%), 65-74 (5.3%), and ≥75 (2.9%) were all lower.

The 12- to 15-year-olds are further behind when it comes to full vaccination status, however, with just 0.6% having received both doses of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of the single-shot variety, compared with 21.6% for those aged 16-17 years. Children aged 12-15 make up 5% of the total U.S. population but just 0.1% of all those who have been fully vaccinated versus 2.5% and 1.4%, respectively, for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

With nearly half of all Americans having received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, the youngest eligible group is beginning to overcome its late start, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of May 24, 49.4% of the U.S. population – that’s almost 164 million people – has received at least one dose of vaccine. The corresponding figure for children aged 12-15 years is 14.4%, but that’s up from only 0.6% just 3 weeks before. Among children aged 16-17, who’ve been getting vaccinated since early April in some states, the proportion receiving at least one dose went from 24.9% to 33.9% over those same 3 weeks, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker site.

The comparatively rapid increase among the younger group of eligible children can be seen over the last 14 days. To put that into perspective, only those aged 25-39 years were higher at 21.9%, while 18-24 (12.1%), 40-49 (13.4%), 50-64 (18.2%), 65-74 (5.3%), and ≥75 (2.9%) were all lower.

The 12- to 15-year-olds are further behind when it comes to full vaccination status, however, with just 0.6% having received both doses of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of the single-shot variety, compared with 21.6% for those aged 16-17 years. Children aged 12-15 make up 5% of the total U.S. population but just 0.1% of all those who have been fully vaccinated versus 2.5% and 1.4%, respectively, for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

With nearly half of all Americans having received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, the youngest eligible group is beginning to overcome its late start, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of May 24, 49.4% of the U.S. population – that’s almost 164 million people – has received at least one dose of vaccine. The corresponding figure for children aged 12-15 years is 14.4%, but that’s up from only 0.6% just 3 weeks before. Among children aged 16-17, who’ve been getting vaccinated since early April in some states, the proportion receiving at least one dose went from 24.9% to 33.9% over those same 3 weeks, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker site.

The comparatively rapid increase among the younger group of eligible children can be seen over the last 14 days. To put that into perspective, only those aged 25-39 years were higher at 21.9%, while 18-24 (12.1%), 40-49 (13.4%), 50-64 (18.2%), 65-74 (5.3%), and ≥75 (2.9%) were all lower.

The 12- to 15-year-olds are further behind when it comes to full vaccination status, however, with just 0.6% having received both doses of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of the single-shot variety, compared with 21.6% for those aged 16-17 years. Children aged 12-15 make up 5% of the total U.S. population but just 0.1% of all those who have been fully vaccinated versus 2.5% and 1.4%, respectively, for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy: Benefits outweigh the risks, for now

Vaccines have been a lifesaving public health measure since 1000 CE, when the Chinese first used smallpox inoculations to induce immunity.1 Work by pioneers such as Edward Jenner, Louis Pasteur, and Maurice Hilleman has averted countless millions of vaccine-preventable illnesses and deaths, and vaccines have become a routine part of health maintenance throughout the human life cycle.

Pregnant patients who receive vaccines often have an added benefit of protection provided to their infants through passive transfer of antibodies. Several vaccine platforms have been utilized in pregnancy with well-documented improvements in maternal and obstetric outcomes as well as improved neonatal outcomes in the first several months of life.

Risks of COVID-19 in pregnancy

The COVID-19 pandemic placed a spotlight on medically at-risk groups. Pregnant women are 3 times more likely to require admission to the intensive care unit, have increased requirement for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment, and are up to 70% more likely to die than nonpregnant peers—and this risk increases with the presence of additional comorbidities.

In the case of COVID-19, vaccination trials that have shaped worldwide clinical practice unfortunately followed the historical trend of excluding pregnant patients from participation. This has required clinicians to guide their patients through the decision of whether or not to accept vaccination without having the same reassurances regarding safety and effectiveness afforded to their nonpregnant counterparts. With more than 86,000 pregnant women infected with COVID-19 through April 19, 2021, this lack of information regarding vaccine safety in pregnancy is a significant public health gap.2

COVID-19 vaccines

The current COVID-19 vaccines approved for use in the United States under an Emergency Use Authorization issued by the US Food and Drug Administration are nonreplicating and thus cannot cause infection in the mother or fetus. These are the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine, the Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine, and the Janssen Biotech Inc. monovalent vaccine. Furthermore, in animal studies that included the Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, or Janssen COVID-19 vaccines, no fetal, embryonal, female reproductive, or postnatal development safety concerns were demonstrated.

As of April 19, 2021, 94,335 pregnant women had received a COVID-19 vaccination, and 4,622 of these enrolled in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) V-safe Vaccine Pregnancy Registry.3 The data reported noted no unexpected pregnancy or infant outcomes related to COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Adverse effects of the vaccine were similar to those in nonpregnant cohorts. Additionally, emerging data suggest passage of immunity to neonates, with maternal antibodies demonstrated in cord blood at time of delivery as well as in breast milk.4 To date, these data mainly have come from women immunized with the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccines.

Counseling pregnant patients

Our counseling aligns with that of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in that COVID-19 vaccination should not be withheld from pregnant patients or patients who want to become pregnant. In pregnant patients with comorbidities that place them at higher risk for severe COVID-19 infection, all available formulations of the COVID-19 vaccination should be strongly considered.

As evidence for vaccination safety continues to emerge, patients should continue to discuss their individual needs for vaccination in a shared decision-making format with their obstetric providers.

Boylston A. The origins of inoculation. J R Soc Med. 2012;105:309-313.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. Data on COVID-19 during pregnancy: severity of maternal illness. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#pregnant-population. Accessed April 19, 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. V-safe COVID-19 Vaccine Pregnancy Registry. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- ncov/vaccines/safety/vsafepregnancyregistry.html. Updated May 3, 2021. Accessed April 19, 2021.

Gray KJ, Bordt EA, Atyeo C, et al. COVID-19 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;S0002-9378(21)00187-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.023

Vaccines have been a lifesaving public health measure since 1000 CE, when the Chinese first used smallpox inoculations to induce immunity.1 Work by pioneers such as Edward Jenner, Louis Pasteur, and Maurice Hilleman has averted countless millions of vaccine-preventable illnesses and deaths, and vaccines have become a routine part of health maintenance throughout the human life cycle.

Pregnant patients who receive vaccines often have an added benefit of protection provided to their infants through passive transfer of antibodies. Several vaccine platforms have been utilized in pregnancy with well-documented improvements in maternal and obstetric outcomes as well as improved neonatal outcomes in the first several months of life.

Risks of COVID-19 in pregnancy

The COVID-19 pandemic placed a spotlight on medically at-risk groups. Pregnant women are 3 times more likely to require admission to the intensive care unit, have increased requirement for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment, and are up to 70% more likely to die than nonpregnant peers—and this risk increases with the presence of additional comorbidities.

In the case of COVID-19, vaccination trials that have shaped worldwide clinical practice unfortunately followed the historical trend of excluding pregnant patients from participation. This has required clinicians to guide their patients through the decision of whether or not to accept vaccination without having the same reassurances regarding safety and effectiveness afforded to their nonpregnant counterparts. With more than 86,000 pregnant women infected with COVID-19 through April 19, 2021, this lack of information regarding vaccine safety in pregnancy is a significant public health gap.2

COVID-19 vaccines