User login

Children and COVID: Vaccination trends beginning to diverge

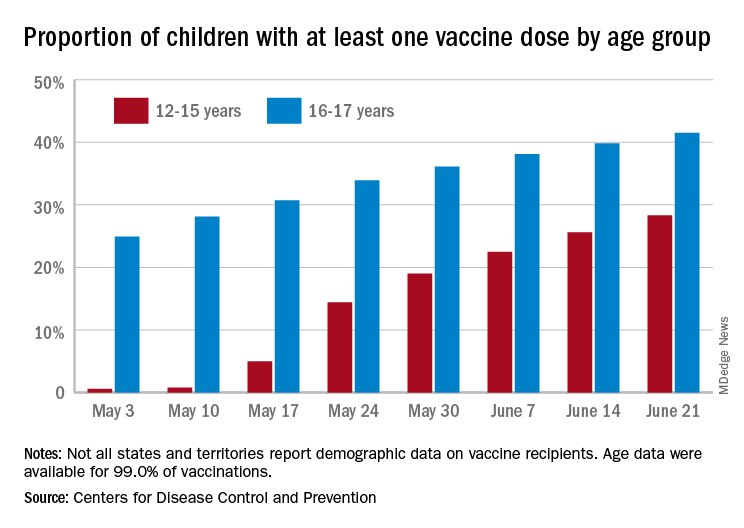

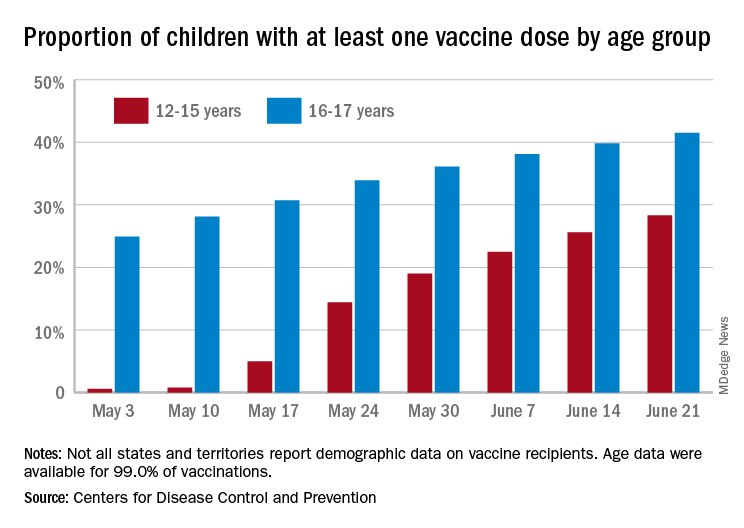

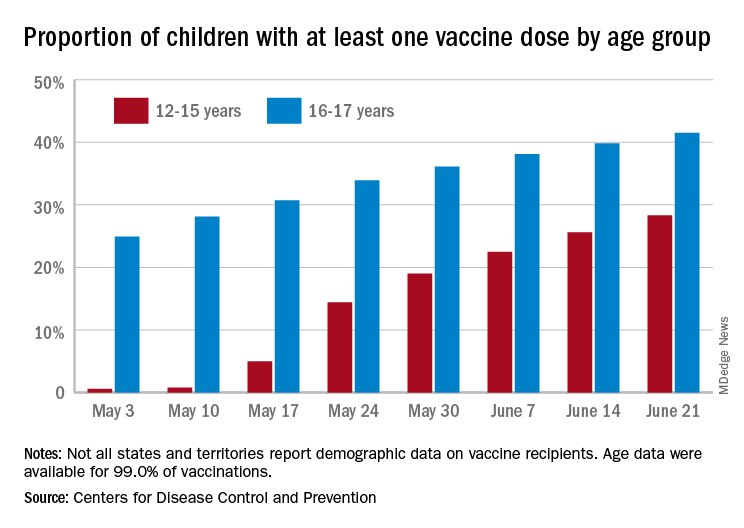

As more adolescents became eligible for a second dose of the Pfizer vaccine since it received approval from the Food and Drug Administration in mid-May, the share of 12- to 15-year-olds considered fully vaccinated rose from 11.4% on June 14 to 17.8% on June 28, an increase of 56%, the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker indicated June 22.

For children aged 16-17 years, who have been receiving the vaccine since early April, full vaccination rose by 9.6% in that same week, going from 29.1% on June 14 to 31.9% on June 21. The cumulative numbers for first vaccinations are higher, of course, but are rising more slowly in both age groups: 41.5% of those aged 16-17 had received at least one dose by June 21 (up by 4.3%), with the 12- to 15-year-olds at 28.3% (up by 10.5%), based on the CDC data.

Limiting the time frame to just the last 2 weeks, however, shows the opposite of rising among the younger children. During the 2 weeks ending June 7, 17.9% of those initiating a first dose were 12-15 years old, but that 2-week figure slipped to 17.1% as of June 14 and was down to 16.0% on June 21. The older group was slow but steady over that time: 4.8%, 4.7%, and 4.8%, the CDC said. To give those figures some context, those aged 25-39 years represented 23.7% of past-2-week initiations on June 7 and 24.3% on June 21.

Although no COVID-19 vaccine has been approved for children under 12 years, about 0.4% of that age group – just over 167,000 children – have received a first dose and almost 91,000 are fully vaccinated, according to CDC data.

As more adolescents became eligible for a second dose of the Pfizer vaccine since it received approval from the Food and Drug Administration in mid-May, the share of 12- to 15-year-olds considered fully vaccinated rose from 11.4% on June 14 to 17.8% on June 28, an increase of 56%, the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker indicated June 22.

For children aged 16-17 years, who have been receiving the vaccine since early April, full vaccination rose by 9.6% in that same week, going from 29.1% on June 14 to 31.9% on June 21. The cumulative numbers for first vaccinations are higher, of course, but are rising more slowly in both age groups: 41.5% of those aged 16-17 had received at least one dose by June 21 (up by 4.3%), with the 12- to 15-year-olds at 28.3% (up by 10.5%), based on the CDC data.

Limiting the time frame to just the last 2 weeks, however, shows the opposite of rising among the younger children. During the 2 weeks ending June 7, 17.9% of those initiating a first dose were 12-15 years old, but that 2-week figure slipped to 17.1% as of June 14 and was down to 16.0% on June 21. The older group was slow but steady over that time: 4.8%, 4.7%, and 4.8%, the CDC said. To give those figures some context, those aged 25-39 years represented 23.7% of past-2-week initiations on June 7 and 24.3% on June 21.

Although no COVID-19 vaccine has been approved for children under 12 years, about 0.4% of that age group – just over 167,000 children – have received a first dose and almost 91,000 are fully vaccinated, according to CDC data.

As more adolescents became eligible for a second dose of the Pfizer vaccine since it received approval from the Food and Drug Administration in mid-May, the share of 12- to 15-year-olds considered fully vaccinated rose from 11.4% on June 14 to 17.8% on June 28, an increase of 56%, the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker indicated June 22.

For children aged 16-17 years, who have been receiving the vaccine since early April, full vaccination rose by 9.6% in that same week, going from 29.1% on June 14 to 31.9% on June 21. The cumulative numbers for first vaccinations are higher, of course, but are rising more slowly in both age groups: 41.5% of those aged 16-17 had received at least one dose by June 21 (up by 4.3%), with the 12- to 15-year-olds at 28.3% (up by 10.5%), based on the CDC data.

Limiting the time frame to just the last 2 weeks, however, shows the opposite of rising among the younger children. During the 2 weeks ending June 7, 17.9% of those initiating a first dose were 12-15 years old, but that 2-week figure slipped to 17.1% as of June 14 and was down to 16.0% on June 21. The older group was slow but steady over that time: 4.8%, 4.7%, and 4.8%, the CDC said. To give those figures some context, those aged 25-39 years represented 23.7% of past-2-week initiations on June 7 and 24.3% on June 21.

Although no COVID-19 vaccine has been approved for children under 12 years, about 0.4% of that age group – just over 167,000 children – have received a first dose and almost 91,000 are fully vaccinated, according to CDC data.

AAP updates guidance for return to sports and physical activities

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data on COVID-19’s cognitive fallout

Investigators found cognitive changes, depression, and PTSD in infected patients, both in the subacute phase and 10 months after hospital discharge.

“We showed that cognitive and behavioral alterations are associated with COVID-19 infection within 2 months from hospital discharge and that they partially persist in the post-COVID phase,” study investigator Elisa Canu, PhD, neuroimaging research unit, division of neuroscience, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, told a press briefing.

The findings were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

Executive dysfunction

Previous research suggests about 30% of COVID-19 survivors have cognitive disturbances and 30%-40% have psychopathological disorders including anxiety and depression, said Dr. Canu.

These disturbances have been associated with the severity of acute-phase respiratory symptoms, infection-triggered neuroinflammation, cerebrovascular alterations, and/or neurodegeneration.

However, it’s unclear whether these disturbances persist in the post-COVID phase.

To investigate, the researchers explored cognitive and psychopathological features in 49 patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted to a hospital ED. They examined these factors at 2 months (subacute phase) and at 10 months (post-COVID phase).

Participants had an average age of 61 years (age range, 40-75 years) and 73% were men. Most had at least one cardiovascular risk factor such as hypertension (55%), smoking (22%), and dyslipidemia (18%).

At hospital admission, 71% had an abnormal neurologic exam, 59% had hypogeusia (reduced sense of taste), 45% hyposmia (reduced sense of smell), 39% headache, and 20% confusion or drowsiness. During hospitalization, 27% had noninvasive ventilation.

In addition to cognitive and neurologic assessments, participants underwent MRI 2 months after hospital discharge. Researchers obtained data on gray matter, white matter, and total brain volume.

At 2 months post discharge, 53% of patients presented with at least one cognitive deficit. Many deficits related to executive function including difficulty planning, attention, and problem solving (16%).

However, some participants had memory issues (6%) or visuospatial disturbances (6%). Almost a quarter (23%) presented with a combination of symptoms related to executive dysfunction.

Low oxygen tied to more cognitive deficits

More than one-third of patients experienced symptoms of depression (16%) or PTSD (18%).

Patients younger than 50 years had more executive dysfunction, with these symptoms affecting 75% of younger patients. “Our explanation for that is that younger people had a milder clinical profile regarding COVID, so they were cared for at home,” said Dr. Canu.

While in hospital, patients may be on “continued alert” and receive structured interventions for cognitive and behavioral issues, she said.

More severe respiratory symptoms at hospital admission were significantly associated with deficits during the subacute phase (P = .002 for information processing).

“Low levels of oxygen in the brain could lead to confusion, headache, and brain fog, and cause the cognitive disturbances that we see,” said Dr. Canu.

White-matter hyperintensities were linked to cognitive deficits during this phase (P < .001 for verbal memory and delayed recall).

“These white-matter lesions are probably preexisting due to cardiovascular risk factors that were present in our population and may have amplified the memory disturbances we saw,” commented Dr. Canu.

The investigators did not find a significant relationship between cognitive performance and brain volume. Dr. Canu noted that cognitive and psychopathological disturbances are linked. For instance, she said, a patient with PTSD or depression may also have problems with attention or memory.

In the post-COVID phase, cognitive symptoms were reduced from 53% to 36%; again, the most common deficit was combined executive dysfunction symptoms. Depression persisted in 15% of patients and PTSD in 18%.

“We still don’t know if these alterations are a consequence of the infection,” said Dr. Canu. “And we don’t know whether the deficits are reversible or are part of a neurodegenerative process.”

The researchers plan to follow these patients further. “We definitely need longer follow-up and bigger populations, if possible, to see if these cognitive and psychopathological disturbances can improve in some way,” said Dr. Canu.

The study results underline the need for neuropsychological and neurologic monitoring in COVID patients. Cognitive stimulation training and physical activity, preferably outdoors, could be beneficial, Dr. Canu added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found cognitive changes, depression, and PTSD in infected patients, both in the subacute phase and 10 months after hospital discharge.

“We showed that cognitive and behavioral alterations are associated with COVID-19 infection within 2 months from hospital discharge and that they partially persist in the post-COVID phase,” study investigator Elisa Canu, PhD, neuroimaging research unit, division of neuroscience, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, told a press briefing.

The findings were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

Executive dysfunction

Previous research suggests about 30% of COVID-19 survivors have cognitive disturbances and 30%-40% have psychopathological disorders including anxiety and depression, said Dr. Canu.

These disturbances have been associated with the severity of acute-phase respiratory symptoms, infection-triggered neuroinflammation, cerebrovascular alterations, and/or neurodegeneration.

However, it’s unclear whether these disturbances persist in the post-COVID phase.

To investigate, the researchers explored cognitive and psychopathological features in 49 patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted to a hospital ED. They examined these factors at 2 months (subacute phase) and at 10 months (post-COVID phase).

Participants had an average age of 61 years (age range, 40-75 years) and 73% were men. Most had at least one cardiovascular risk factor such as hypertension (55%), smoking (22%), and dyslipidemia (18%).

At hospital admission, 71% had an abnormal neurologic exam, 59% had hypogeusia (reduced sense of taste), 45% hyposmia (reduced sense of smell), 39% headache, and 20% confusion or drowsiness. During hospitalization, 27% had noninvasive ventilation.

In addition to cognitive and neurologic assessments, participants underwent MRI 2 months after hospital discharge. Researchers obtained data on gray matter, white matter, and total brain volume.

At 2 months post discharge, 53% of patients presented with at least one cognitive deficit. Many deficits related to executive function including difficulty planning, attention, and problem solving (16%).

However, some participants had memory issues (6%) or visuospatial disturbances (6%). Almost a quarter (23%) presented with a combination of symptoms related to executive dysfunction.

Low oxygen tied to more cognitive deficits

More than one-third of patients experienced symptoms of depression (16%) or PTSD (18%).

Patients younger than 50 years had more executive dysfunction, with these symptoms affecting 75% of younger patients. “Our explanation for that is that younger people had a milder clinical profile regarding COVID, so they were cared for at home,” said Dr. Canu.

While in hospital, patients may be on “continued alert” and receive structured interventions for cognitive and behavioral issues, she said.

More severe respiratory symptoms at hospital admission were significantly associated with deficits during the subacute phase (P = .002 for information processing).

“Low levels of oxygen in the brain could lead to confusion, headache, and brain fog, and cause the cognitive disturbances that we see,” said Dr. Canu.

White-matter hyperintensities were linked to cognitive deficits during this phase (P < .001 for verbal memory and delayed recall).

“These white-matter lesions are probably preexisting due to cardiovascular risk factors that were present in our population and may have amplified the memory disturbances we saw,” commented Dr. Canu.

The investigators did not find a significant relationship between cognitive performance and brain volume. Dr. Canu noted that cognitive and psychopathological disturbances are linked. For instance, she said, a patient with PTSD or depression may also have problems with attention or memory.

In the post-COVID phase, cognitive symptoms were reduced from 53% to 36%; again, the most common deficit was combined executive dysfunction symptoms. Depression persisted in 15% of patients and PTSD in 18%.

“We still don’t know if these alterations are a consequence of the infection,” said Dr. Canu. “And we don’t know whether the deficits are reversible or are part of a neurodegenerative process.”

The researchers plan to follow these patients further. “We definitely need longer follow-up and bigger populations, if possible, to see if these cognitive and psychopathological disturbances can improve in some way,” said Dr. Canu.

The study results underline the need for neuropsychological and neurologic monitoring in COVID patients. Cognitive stimulation training and physical activity, preferably outdoors, could be beneficial, Dr. Canu added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found cognitive changes, depression, and PTSD in infected patients, both in the subacute phase and 10 months after hospital discharge.

“We showed that cognitive and behavioral alterations are associated with COVID-19 infection within 2 months from hospital discharge and that they partially persist in the post-COVID phase,” study investigator Elisa Canu, PhD, neuroimaging research unit, division of neuroscience, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, told a press briefing.

The findings were presented at the annual congress of the European Academy of Neurology.

Executive dysfunction

Previous research suggests about 30% of COVID-19 survivors have cognitive disturbances and 30%-40% have psychopathological disorders including anxiety and depression, said Dr. Canu.

These disturbances have been associated with the severity of acute-phase respiratory symptoms, infection-triggered neuroinflammation, cerebrovascular alterations, and/or neurodegeneration.

However, it’s unclear whether these disturbances persist in the post-COVID phase.

To investigate, the researchers explored cognitive and psychopathological features in 49 patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted to a hospital ED. They examined these factors at 2 months (subacute phase) and at 10 months (post-COVID phase).

Participants had an average age of 61 years (age range, 40-75 years) and 73% were men. Most had at least one cardiovascular risk factor such as hypertension (55%), smoking (22%), and dyslipidemia (18%).

At hospital admission, 71% had an abnormal neurologic exam, 59% had hypogeusia (reduced sense of taste), 45% hyposmia (reduced sense of smell), 39% headache, and 20% confusion or drowsiness. During hospitalization, 27% had noninvasive ventilation.

In addition to cognitive and neurologic assessments, participants underwent MRI 2 months after hospital discharge. Researchers obtained data on gray matter, white matter, and total brain volume.

At 2 months post discharge, 53% of patients presented with at least one cognitive deficit. Many deficits related to executive function including difficulty planning, attention, and problem solving (16%).

However, some participants had memory issues (6%) or visuospatial disturbances (6%). Almost a quarter (23%) presented with a combination of symptoms related to executive dysfunction.

Low oxygen tied to more cognitive deficits

More than one-third of patients experienced symptoms of depression (16%) or PTSD (18%).

Patients younger than 50 years had more executive dysfunction, with these symptoms affecting 75% of younger patients. “Our explanation for that is that younger people had a milder clinical profile regarding COVID, so they were cared for at home,” said Dr. Canu.

While in hospital, patients may be on “continued alert” and receive structured interventions for cognitive and behavioral issues, she said.

More severe respiratory symptoms at hospital admission were significantly associated with deficits during the subacute phase (P = .002 for information processing).

“Low levels of oxygen in the brain could lead to confusion, headache, and brain fog, and cause the cognitive disturbances that we see,” said Dr. Canu.

White-matter hyperintensities were linked to cognitive deficits during this phase (P < .001 for verbal memory and delayed recall).

“These white-matter lesions are probably preexisting due to cardiovascular risk factors that were present in our population and may have amplified the memory disturbances we saw,” commented Dr. Canu.

The investigators did not find a significant relationship between cognitive performance and brain volume. Dr. Canu noted that cognitive and psychopathological disturbances are linked. For instance, she said, a patient with PTSD or depression may also have problems with attention or memory.

In the post-COVID phase, cognitive symptoms were reduced from 53% to 36%; again, the most common deficit was combined executive dysfunction symptoms. Depression persisted in 15% of patients and PTSD in 18%.

“We still don’t know if these alterations are a consequence of the infection,” said Dr. Canu. “And we don’t know whether the deficits are reversible or are part of a neurodegenerative process.”

The researchers plan to follow these patients further. “We definitely need longer follow-up and bigger populations, if possible, to see if these cognitive and psychopathological disturbances can improve in some way,” said Dr. Canu.

The study results underline the need for neuropsychological and neurologic monitoring in COVID patients. Cognitive stimulation training and physical activity, preferably outdoors, could be beneficial, Dr. Canu added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective for patients with migraine

according to a presentation at the American Headache Society’s 2021 annual meeting.

Amy Gelfand, MD, director of pediatric headache at University of California, San Francisco, reviewed common concerns migraine patients or their clinicians might have related any of the three vaccines, starting with a review of how the vaccines work – by targeting the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

“The vaccines induce response to that protein, but only that protein, so there’s no reason to think they’re going to cause the body to produce neutralizing antibodies against any of our migraine therapeutics,” Dr. Gelfand said. She added that the phase 3 clinical trials included participants from a wide range of ages and comorbidities, so there were likely many people in the trials who have migraine, though no subgroup analyses have been performed for this group or are likely to be performed.

Common questions

The two treatments people have the most questions about concerning the COVID-19 vaccine are onabotulinumtoxinA and CGRP pathway monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), likely because both of these are injections, as is the vaccine, Dr. Gelfand said. First, she reminded attendees that onabotulinumtoxinA is not a dermal filler, since some reports following administration of the Moderna vaccine suggested that some people with dermal fillers had swelling in those areas after vaccination.

In addition, “there’s no reason to think the onabotulinumtoxinA would influence our body’s immune response to any vaccine, so there’s no need to retime the onabotulinumtoxinA injections around COVID-19 vaccine administration,” Dr. Gelfand said.

Regarding mAbs, she acknowledged that some white blood cells have CGRP receptors, which may have a pro- or anti-inflammatory role, but clinical trials of mAbs did not show any evidence of being immunosuppressive or myelosuppressive.

“The monoclonal antibodies themselves have undergone engineering so that they are just going after their one target,” Dr. Gelfand said. “They’re not going to be expected to bind to anything else outside of their targets, so I don’t think there’s anything there to make us retime the monoclonal antibody administration relative to the COVID-19 vaccine.”

She did note that patients who choose to get mAbs injections in their arm instead of their thigh or abdomen may want to receive it in the opposite arm than they one they have gotten or will get the vaccine in since the vaccine can cause discomfort.

The other common question patients may have is whether taking any NSAIDs or acetaminophen before getting the COVID-19 vaccine will reduce their immune response to the vaccination. This concern arises because of past evidence showing that some infants tended to have lower immunologic responses when they received acetaminophen after their primary vaccines’ series, but the clinical significance of those reduced responses is not clear since they still had strong responses. Further, this effect was not seen with booster shots, suggesting it’s an age-dependent effect.

During the clinical trials of the AstraZeneca vaccine, several sites gave prophylactic paracetamol without any apparent detrimental effect on antibody response, Dr. Gelfand said. Further, the mRNA and adenovirus-vectored vaccines appear to induce antibodies far above what many believe is needed for protection.

“Even if there were a slight decrease, it’s not clear that that would have any kind of clinical significance for that person in terms of their level of protection against COVID-19,” she said. “Bottom line, it’s fine for patients to use either of these after administration of the COVID-19 vaccine.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention doesn’t recommend it prophylactically beforehand, but it’s fine to take it for a fever, aches or headache after getting the vaccine.

Migraine or vaccine reaction?

Dr. Gelfand then addressed whether it should affect physicians’ headache differential if seeing a patient who recently received an adenovirus-vectored vaccine, such as the Johnson & Johnson or AstraZeneca vaccines. The question relates to the discovery of a very rare potential adverse event from these vaccines: cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) with thrombocytopenia and thromboses in other major vessels, together called thrombosis thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS). No TTS cases have been reported following mRNA vaccines.

TTS’s mechanism appears similar to autoimmune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, where the body produces platelet-activating antibodies. TTS currently has three diagnostic criteria: new-onset thrombocytopenia (<150,000/microliter) without evidence of platelet clumping, venous or arterial thrombosis, and absence of prior exposure to heparin.

So far, TTS has been limited only to the vaccines that use an adenovirus vector. One male clinical trial participant experienced CVST with thrombocytopenia in Johnson & Johnson phase 3 trials, and 12 cases out of approximately 8 million Johnson & Johnson doses were reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System between March 2 and April 21, 2021. Three TTS more cases followed these, resulting in 15 TTS events per 8 million doses.

In terms of clinical features, all 15 cases were females under age 60, mostly white, and all 11 who were tested were positive for the heparin-platelet factor 4 antibody test. TTS occurred 6-15 days after vaccination for these cases, and all but one had a headache. Their platelet count was 9,000-127,000. None were pregnant or postpartum.

“For us, as headache clinicians, the epidemiology of TTS overlaps with the epidemiology of migraine – they’re happening to the same group of patients,” Dr. Gelfand said. Most of the cases occurred in women aged 30-39 years, while the estimated incidence in women aged 50 or older is 0.9 cases per million doses.

The CDC has proceeded with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine because a risk-benefit analysis revealed that use of the vaccine will result in fewer hospitalization and deaths from COVID-19, compared with adverse events from the vaccine, Dr. Gelfand explained. However, the CDC notes that “women younger than 50 years old should be made aware of a rare risk of blood clots with low platelets following vaccination and the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines where this risk has not been observed.”

For clinicians, the existence of TTS raises a question when patients with a history of migraine call after having received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, Dr. Gelfand said: “How do we know if this is a spontaneous attack, if it’s a headache provoked by receiving the vaccine, or they have one of these rare cases of [TTS]?”

Three things help with this differential, she said: timing, epidemiology, and headache phenotype. Headache after a vaccine is very common, but it usually happens within the first couple of hours or days after the vaccine. By day 4 after vaccination, few people had headaches in the clinical trials. Since TTS requires production of antibodies, a headache within a few hours of vaccination should not raise concerns about TTS. It should be considered, however, for patients who experience a headache within a week or 2 after vaccination.

Then consider the epidemiology: If it’s a woman between ages 18 and49 calling, the risk is higher than if it’s a male over age 50. Then consider whether there are any unusual headache features, positionality, encephalopathy, or clinical features that could suggest clots in other parts of the body, such as abdominal pain, shortness of breath, or pain in the legs.

“At the end of the day, if it’s a person who’s in this epidemiological window and they’re calling a week or 2 out from the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, we may just need to work it up and see,” Dr. Gelfand said. Work-up involves a CBC, a platelet count to see if they’re thrombocytopenic, and perhaps imaging, preferentially using MRI/MRV over CT since it’s a younger population. Treatment for CVST with thrombocytopenia is a nonheparin anticoagulant, and platelet transfusion should not occur before consulting with hematology.

Continue to vaccinate

“The big take home is that we should continue to vaccinate patients with migraine and that your current therapies do not interfere with the vaccine working and that the vaccine does not interact with our therapies,” Brian D. Loftus, MD, BSChE, immediate past president of the Southern Headache Society and a neurologist at Bellaire (Pa.) Neurology, said of the presentation. He also felt it was helpful to know that NSAIDs likely have no impact on the vaccines’ effectiveness as well.

“The most important new information for me was that the median onset of the CSVT was 8 days post vaccine,” Dr. Loftus said. “Typically, postvaccine headache is seen much sooner, within 1-2 days, so this is a useful clinical feature to separate out who needs to closer follow-up and possible neuroimaging.”

Given the epidemiology of those most likely to have TTS, Dr. Loftus said he would advise his female patients younger than 60 to simply get the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine since they appear safer for this demographic.

Dr. Gelfand is editor of the journal Headache but has no industry disclosures. Her spouse has received clinical trial grant support from Genentech and honoraria for editorial work from Dynamed Plus. Dr. Loftus has received grants or fees from Teva, Amgen, Abbvie, and Biohaven.

according to a presentation at the American Headache Society’s 2021 annual meeting.

Amy Gelfand, MD, director of pediatric headache at University of California, San Francisco, reviewed common concerns migraine patients or their clinicians might have related any of the three vaccines, starting with a review of how the vaccines work – by targeting the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

“The vaccines induce response to that protein, but only that protein, so there’s no reason to think they’re going to cause the body to produce neutralizing antibodies against any of our migraine therapeutics,” Dr. Gelfand said. She added that the phase 3 clinical trials included participants from a wide range of ages and comorbidities, so there were likely many people in the trials who have migraine, though no subgroup analyses have been performed for this group or are likely to be performed.

Common questions

The two treatments people have the most questions about concerning the COVID-19 vaccine are onabotulinumtoxinA and CGRP pathway monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), likely because both of these are injections, as is the vaccine, Dr. Gelfand said. First, she reminded attendees that onabotulinumtoxinA is not a dermal filler, since some reports following administration of the Moderna vaccine suggested that some people with dermal fillers had swelling in those areas after vaccination.

In addition, “there’s no reason to think the onabotulinumtoxinA would influence our body’s immune response to any vaccine, so there’s no need to retime the onabotulinumtoxinA injections around COVID-19 vaccine administration,” Dr. Gelfand said.

Regarding mAbs, she acknowledged that some white blood cells have CGRP receptors, which may have a pro- or anti-inflammatory role, but clinical trials of mAbs did not show any evidence of being immunosuppressive or myelosuppressive.

“The monoclonal antibodies themselves have undergone engineering so that they are just going after their one target,” Dr. Gelfand said. “They’re not going to be expected to bind to anything else outside of their targets, so I don’t think there’s anything there to make us retime the monoclonal antibody administration relative to the COVID-19 vaccine.”

She did note that patients who choose to get mAbs injections in their arm instead of their thigh or abdomen may want to receive it in the opposite arm than they one they have gotten or will get the vaccine in since the vaccine can cause discomfort.

The other common question patients may have is whether taking any NSAIDs or acetaminophen before getting the COVID-19 vaccine will reduce their immune response to the vaccination. This concern arises because of past evidence showing that some infants tended to have lower immunologic responses when they received acetaminophen after their primary vaccines’ series, but the clinical significance of those reduced responses is not clear since they still had strong responses. Further, this effect was not seen with booster shots, suggesting it’s an age-dependent effect.

During the clinical trials of the AstraZeneca vaccine, several sites gave prophylactic paracetamol without any apparent detrimental effect on antibody response, Dr. Gelfand said. Further, the mRNA and adenovirus-vectored vaccines appear to induce antibodies far above what many believe is needed for protection.

“Even if there were a slight decrease, it’s not clear that that would have any kind of clinical significance for that person in terms of their level of protection against COVID-19,” she said. “Bottom line, it’s fine for patients to use either of these after administration of the COVID-19 vaccine.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention doesn’t recommend it prophylactically beforehand, but it’s fine to take it for a fever, aches or headache after getting the vaccine.

Migraine or vaccine reaction?

Dr. Gelfand then addressed whether it should affect physicians’ headache differential if seeing a patient who recently received an adenovirus-vectored vaccine, such as the Johnson & Johnson or AstraZeneca vaccines. The question relates to the discovery of a very rare potential adverse event from these vaccines: cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) with thrombocytopenia and thromboses in other major vessels, together called thrombosis thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS). No TTS cases have been reported following mRNA vaccines.

TTS’s mechanism appears similar to autoimmune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, where the body produces platelet-activating antibodies. TTS currently has three diagnostic criteria: new-onset thrombocytopenia (<150,000/microliter) without evidence of platelet clumping, venous or arterial thrombosis, and absence of prior exposure to heparin.

So far, TTS has been limited only to the vaccines that use an adenovirus vector. One male clinical trial participant experienced CVST with thrombocytopenia in Johnson & Johnson phase 3 trials, and 12 cases out of approximately 8 million Johnson & Johnson doses were reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System between March 2 and April 21, 2021. Three TTS more cases followed these, resulting in 15 TTS events per 8 million doses.

In terms of clinical features, all 15 cases were females under age 60, mostly white, and all 11 who were tested were positive for the heparin-platelet factor 4 antibody test. TTS occurred 6-15 days after vaccination for these cases, and all but one had a headache. Their platelet count was 9,000-127,000. None were pregnant or postpartum.

“For us, as headache clinicians, the epidemiology of TTS overlaps with the epidemiology of migraine – they’re happening to the same group of patients,” Dr. Gelfand said. Most of the cases occurred in women aged 30-39 years, while the estimated incidence in women aged 50 or older is 0.9 cases per million doses.

The CDC has proceeded with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine because a risk-benefit analysis revealed that use of the vaccine will result in fewer hospitalization and deaths from COVID-19, compared with adverse events from the vaccine, Dr. Gelfand explained. However, the CDC notes that “women younger than 50 years old should be made aware of a rare risk of blood clots with low platelets following vaccination and the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines where this risk has not been observed.”

For clinicians, the existence of TTS raises a question when patients with a history of migraine call after having received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, Dr. Gelfand said: “How do we know if this is a spontaneous attack, if it’s a headache provoked by receiving the vaccine, or they have one of these rare cases of [TTS]?”

Three things help with this differential, she said: timing, epidemiology, and headache phenotype. Headache after a vaccine is very common, but it usually happens within the first couple of hours or days after the vaccine. By day 4 after vaccination, few people had headaches in the clinical trials. Since TTS requires production of antibodies, a headache within a few hours of vaccination should not raise concerns about TTS. It should be considered, however, for patients who experience a headache within a week or 2 after vaccination.

Then consider the epidemiology: If it’s a woman between ages 18 and49 calling, the risk is higher than if it’s a male over age 50. Then consider whether there are any unusual headache features, positionality, encephalopathy, or clinical features that could suggest clots in other parts of the body, such as abdominal pain, shortness of breath, or pain in the legs.

“At the end of the day, if it’s a person who’s in this epidemiological window and they’re calling a week or 2 out from the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, we may just need to work it up and see,” Dr. Gelfand said. Work-up involves a CBC, a platelet count to see if they’re thrombocytopenic, and perhaps imaging, preferentially using MRI/MRV over CT since it’s a younger population. Treatment for CVST with thrombocytopenia is a nonheparin anticoagulant, and platelet transfusion should not occur before consulting with hematology.

Continue to vaccinate

“The big take home is that we should continue to vaccinate patients with migraine and that your current therapies do not interfere with the vaccine working and that the vaccine does not interact with our therapies,” Brian D. Loftus, MD, BSChE, immediate past president of the Southern Headache Society and a neurologist at Bellaire (Pa.) Neurology, said of the presentation. He also felt it was helpful to know that NSAIDs likely have no impact on the vaccines’ effectiveness as well.

“The most important new information for me was that the median onset of the CSVT was 8 days post vaccine,” Dr. Loftus said. “Typically, postvaccine headache is seen much sooner, within 1-2 days, so this is a useful clinical feature to separate out who needs to closer follow-up and possible neuroimaging.”

Given the epidemiology of those most likely to have TTS, Dr. Loftus said he would advise his female patients younger than 60 to simply get the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine since they appear safer for this demographic.

Dr. Gelfand is editor of the journal Headache but has no industry disclosures. Her spouse has received clinical trial grant support from Genentech and honoraria for editorial work from Dynamed Plus. Dr. Loftus has received grants or fees from Teva, Amgen, Abbvie, and Biohaven.

according to a presentation at the American Headache Society’s 2021 annual meeting.

Amy Gelfand, MD, director of pediatric headache at University of California, San Francisco, reviewed common concerns migraine patients or their clinicians might have related any of the three vaccines, starting with a review of how the vaccines work – by targeting the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

“The vaccines induce response to that protein, but only that protein, so there’s no reason to think they’re going to cause the body to produce neutralizing antibodies against any of our migraine therapeutics,” Dr. Gelfand said. She added that the phase 3 clinical trials included participants from a wide range of ages and comorbidities, so there were likely many people in the trials who have migraine, though no subgroup analyses have been performed for this group or are likely to be performed.

Common questions

The two treatments people have the most questions about concerning the COVID-19 vaccine are onabotulinumtoxinA and CGRP pathway monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), likely because both of these are injections, as is the vaccine, Dr. Gelfand said. First, she reminded attendees that onabotulinumtoxinA is not a dermal filler, since some reports following administration of the Moderna vaccine suggested that some people with dermal fillers had swelling in those areas after vaccination.

In addition, “there’s no reason to think the onabotulinumtoxinA would influence our body’s immune response to any vaccine, so there’s no need to retime the onabotulinumtoxinA injections around COVID-19 vaccine administration,” Dr. Gelfand said.

Regarding mAbs, she acknowledged that some white blood cells have CGRP receptors, which may have a pro- or anti-inflammatory role, but clinical trials of mAbs did not show any evidence of being immunosuppressive or myelosuppressive.

“The monoclonal antibodies themselves have undergone engineering so that they are just going after their one target,” Dr. Gelfand said. “They’re not going to be expected to bind to anything else outside of their targets, so I don’t think there’s anything there to make us retime the monoclonal antibody administration relative to the COVID-19 vaccine.”

She did note that patients who choose to get mAbs injections in their arm instead of their thigh or abdomen may want to receive it in the opposite arm than they one they have gotten or will get the vaccine in since the vaccine can cause discomfort.

The other common question patients may have is whether taking any NSAIDs or acetaminophen before getting the COVID-19 vaccine will reduce their immune response to the vaccination. This concern arises because of past evidence showing that some infants tended to have lower immunologic responses when they received acetaminophen after their primary vaccines’ series, but the clinical significance of those reduced responses is not clear since they still had strong responses. Further, this effect was not seen with booster shots, suggesting it’s an age-dependent effect.

During the clinical trials of the AstraZeneca vaccine, several sites gave prophylactic paracetamol without any apparent detrimental effect on antibody response, Dr. Gelfand said. Further, the mRNA and adenovirus-vectored vaccines appear to induce antibodies far above what many believe is needed for protection.

“Even if there were a slight decrease, it’s not clear that that would have any kind of clinical significance for that person in terms of their level of protection against COVID-19,” she said. “Bottom line, it’s fine for patients to use either of these after administration of the COVID-19 vaccine.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention doesn’t recommend it prophylactically beforehand, but it’s fine to take it for a fever, aches or headache after getting the vaccine.

Migraine or vaccine reaction?

Dr. Gelfand then addressed whether it should affect physicians’ headache differential if seeing a patient who recently received an adenovirus-vectored vaccine, such as the Johnson & Johnson or AstraZeneca vaccines. The question relates to the discovery of a very rare potential adverse event from these vaccines: cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) with thrombocytopenia and thromboses in other major vessels, together called thrombosis thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS). No TTS cases have been reported following mRNA vaccines.

TTS’s mechanism appears similar to autoimmune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, where the body produces platelet-activating antibodies. TTS currently has three diagnostic criteria: new-onset thrombocytopenia (<150,000/microliter) without evidence of platelet clumping, venous or arterial thrombosis, and absence of prior exposure to heparin.

So far, TTS has been limited only to the vaccines that use an adenovirus vector. One male clinical trial participant experienced CVST with thrombocytopenia in Johnson & Johnson phase 3 trials, and 12 cases out of approximately 8 million Johnson & Johnson doses were reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System between March 2 and April 21, 2021. Three TTS more cases followed these, resulting in 15 TTS events per 8 million doses.

In terms of clinical features, all 15 cases were females under age 60, mostly white, and all 11 who were tested were positive for the heparin-platelet factor 4 antibody test. TTS occurred 6-15 days after vaccination for these cases, and all but one had a headache. Their platelet count was 9,000-127,000. None were pregnant or postpartum.

“For us, as headache clinicians, the epidemiology of TTS overlaps with the epidemiology of migraine – they’re happening to the same group of patients,” Dr. Gelfand said. Most of the cases occurred in women aged 30-39 years, while the estimated incidence in women aged 50 or older is 0.9 cases per million doses.

The CDC has proceeded with the Johnson & Johnson vaccine because a risk-benefit analysis revealed that use of the vaccine will result in fewer hospitalization and deaths from COVID-19, compared with adverse events from the vaccine, Dr. Gelfand explained. However, the CDC notes that “women younger than 50 years old should be made aware of a rare risk of blood clots with low platelets following vaccination and the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines where this risk has not been observed.”

For clinicians, the existence of TTS raises a question when patients with a history of migraine call after having received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, Dr. Gelfand said: “How do we know if this is a spontaneous attack, if it’s a headache provoked by receiving the vaccine, or they have one of these rare cases of [TTS]?”

Three things help with this differential, she said: timing, epidemiology, and headache phenotype. Headache after a vaccine is very common, but it usually happens within the first couple of hours or days after the vaccine. By day 4 after vaccination, few people had headaches in the clinical trials. Since TTS requires production of antibodies, a headache within a few hours of vaccination should not raise concerns about TTS. It should be considered, however, for patients who experience a headache within a week or 2 after vaccination.

Then consider the epidemiology: If it’s a woman between ages 18 and49 calling, the risk is higher than if it’s a male over age 50. Then consider whether there are any unusual headache features, positionality, encephalopathy, or clinical features that could suggest clots in other parts of the body, such as abdominal pain, shortness of breath, or pain in the legs.

“At the end of the day, if it’s a person who’s in this epidemiological window and they’re calling a week or 2 out from the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, we may just need to work it up and see,” Dr. Gelfand said. Work-up involves a CBC, a platelet count to see if they’re thrombocytopenic, and perhaps imaging, preferentially using MRI/MRV over CT since it’s a younger population. Treatment for CVST with thrombocytopenia is a nonheparin anticoagulant, and platelet transfusion should not occur before consulting with hematology.

Continue to vaccinate

“The big take home is that we should continue to vaccinate patients with migraine and that your current therapies do not interfere with the vaccine working and that the vaccine does not interact with our therapies,” Brian D. Loftus, MD, BSChE, immediate past president of the Southern Headache Society and a neurologist at Bellaire (Pa.) Neurology, said of the presentation. He also felt it was helpful to know that NSAIDs likely have no impact on the vaccines’ effectiveness as well.

“The most important new information for me was that the median onset of the CSVT was 8 days post vaccine,” Dr. Loftus said. “Typically, postvaccine headache is seen much sooner, within 1-2 days, so this is a useful clinical feature to separate out who needs to closer follow-up and possible neuroimaging.”

Given the epidemiology of those most likely to have TTS, Dr. Loftus said he would advise his female patients younger than 60 to simply get the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine since they appear safer for this demographic.

Dr. Gelfand is editor of the journal Headache but has no industry disclosures. Her spouse has received clinical trial grant support from Genentech and honoraria for editorial work from Dynamed Plus. Dr. Loftus has received grants or fees from Teva, Amgen, Abbvie, and Biohaven.

FROM AHS 2021

Why getting a COVID-19 vaccine to children could take time

Testing COVID-19 vaccines in young children is going to be tricky. Deciding how to approve them and who should get them may be even more difficult.

So far, the vaccines available to Americans ages 12 and up have sailed through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory checks, taking advantage of an accelerated clearance process called an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

EUAs set a lower bar for effectiveness, saying the vaccines may be safe and effective based on just a few months of data.

But with COVID cases plummeting in the United States and children historically seeing far less serious disease than adults, a panel of expert advisors to the FDA was asked to deliberate on Thursday whether the agency could consider vaccines for this age group under the same standard.

Stated another way: Is COVID an emergency for kids?

There’s another wrinkle in the mix, too – heart inflammation, which appears to be a very rare emerging adverse event tied to vaccination. It seems to happen more often in teens and young adults. To date, cases of myocarditis and pericarditis appear to be happening in 16 to 30 people for every 1 million doses given.

But if it is conclusively linked to the shots, some wonder whether it might tip the balance between benefits and risks for kids.

That left some of the experts who sit on the FDA’s advisory committee for vaccines and related biological products urging the FDA to take its time and more thoroughly study the shots before they’re given to millions of children.

Vaccine studies different in children?

Clinical studies of the vaccines in teens and adults have thus far relied on some straightforward math. You take two groups of similar people. You give half the vaccine and half a placebo. Then you wait and see which group has more symptomatic infections. To date, the vaccines have dramatically cut the risk of getting severely ill with COVID for every age group tested.

But COVID infections are falling rapidly in the U.S., and that may make it more difficult for researchers to conduct a similar kind of experiment in children.

The FDA is considering different approaches to figure out whether a vaccine would be effective in kids, including something called an “immunobridging trial.”

In bridging trials, researchers don’t look for infections; rather, they look for proven signs that someone has developed immunity, like antibody levels. Those biomarkers are then compared to the immune responses of younger adults who have demonstrated good protection against infection.

The main advantage of bridging studies is speed. It’s possible to get a snapshot of how the immune system responds to a vaccine within weeks of the final dose.

The drawback is that researchers don’t know exactly what to look for to judge how well the shots are generating protection.

That’s made even more difficult because kids’ immune systems are still developing, so it may be tough to draw direct parallels to adults.

“We don’t know what the serologic correlate of immunity is now. We don’t know how much antibody you have to get in order to be protected. We don’t know what the role of T cells will be,” said H. Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

“I have so much sympathy for the FDA because these are enormous problems, and you have to make a decision,” said Dr. Meissner, who is a member of the FDA’s vaccines and related biological products advisory committee.

Speed vaccines to market, or gather more data?

The plummeting rate of infections in the United States also means that it may be more difficult for the FDA to justify allowing a vaccine on the market for emergency use for children under age 12.

In its recent advisory committee meeting, the agency asked the panel whether it should consider COVID vaccines for children under an EUA or a biologics license application (BLA), aka full approval.

A BLA typically means the agency considers a year or two of data on a new product, rather than just 2 months’ worth. Emergency use also allows products on the market under a looser standard – they “may be” safe and effective, instead of has been proven to be safe and effective.

Several committee members said they didn’t feel the United States was still in an emergency with COVID and couldn’t see the FDA allowing a vaccine to be used in kids that wasn’t given the agency’s highest level of scrutiny, particularly with reports of adverse events like myocarditis coming to light.

“I just want to be sure the price we pay for vaccinating millions of children justifies the side effects, and I don’t think we know that yet,” Dr. Meissner said.

Others acknowledged that there was little risk to kids now with infections on the decline but said that picture could change as variants spread, schools reopen, and colder temperatures force people indoors.

The FDA must decide whether to act based on where we are now or where we could be in a few months.

“I think it’s the million-dollar question right now,” said Hannah Kirking, MD, a medical epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who presented new and unpublished data on COVID’s impact in children to the FDA’s advisory committee.

She said prospective studies tracking the way COVID moves through a household with weekly testing from New York City and Utah had found that children catch and transmit COVID almost as readily as adults. But they don’t usually get as sick as adults do, so their cases are easy to miss.

She also presented the results of blood tests from samples around the country looking for evidence of past infection. In these seroprevalence studies, about 27% of children under age 17 had antibodies to COVID – the most of any age group. So more than 1 in 4 kids already has some natural immunity.

That means the main benefit of vaccinating children might be the protection of others, while they still bear the risks – however tiny.

Some experts felt that wasn’t enough reason to justify mass distribution of the vaccines to kids, and from a regulatory standpoint, it might not be permissible.

“FDA can only approve a medical product in a population if the benefits outweigh the risks in that population,” said Peter Doshi, PhD, assistant professor of pharmaceutical health services research in the University of Maryland’s school of pharmacy, Baltimore.

“If benefits don’t outweigh risks in children, it can’t be indicated for children. Full stop,” said Dr. Doshi, who is also an editor at the BMJ.

He said there’s another way to give children access to vaccines, through an expanded access or compassionate use program. Because most COVID deaths have been in children with underlying health conditions, Dr. Doshi and others said it might make sense to allow expanded access – which would get vaccines to children at high risk for complications – without turning them loose on millions before they are more thoroughly studied.

“It’s not a particularly attractive option for industry, because there’s no money to be made. Your medicine can’t be commercialized under expanded access. The most you can reap is manufacturing cost, which is not a lot,” he said.

Art Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University’s Langone medical center, said the argument for vaccinating children for flu falls along the same lines. The benefit-to-risk ratio is finely balanced in children. The main value of protecting them is to protect others.

“Flu rarely kills young folks. But you’re really trying to protect old folks and that’s the classic example,” he said.

What’s more, he said the idea that children would take on some risk with a vaccine for little personal benefit is oversimplified.

“Yes, you might get vaccinated to prevent harm to others, but those others are providing benefits to you. It’s not a one-way street. I think that’s a little morally distorted,” Mr. Caplan said. “Being able to keep society open benefits kids and adults alike.”

Other committee members felt like it was too early to sound the all-clear on COVID and said the FDA should authorize vaccines for children as quickly as it had for other age groups.

“We are still, I believe, in an emergency situation. I think that when this virus goes into our children, which is what it’s going to do, that will give it an incubator to change,” said Oveta Fuller, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Fuller said that for the good of the world, Americans needed to vaccinate children to prevent the virus from mutating and creating new and potentially more dangerous variants.

Weighing risk over safety

Beth Thielen, MD, PhD, pediatric infectious disease specialist and virologist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said she had not followed the committee’s discussions, but about once a month she treats kids who are very sick because of the virus – either because of a COVID infection or because of multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), an inflammatory reaction that strikes after infection.

She’s worried about how the virus has already changed. She said the kind of disease she’s seeing in kids now is different than what she saw in the early months of the pandemic.

“In the last couple of months, I’ve actually seen a few cases of severe pulmonary disease, more similar to adult disease in children,” Dr. Thielen said. “I see on the horizon that we could start seeing more significant disease in young people, and then the risks of being unvaccinated go up substantially.”

But she also knows nobody has a crystal ball, and right now, everything seems to be trending in the right direction with COVID. That makes the risk-to-benefit consideration murkier.

“The question in my mind is, what is the risk of side effects from the vaccine?” she said. “I think we really need to know what the safety profile of vaccine looks like in children because we do have a decent understanding now what risk from disease looks like, because it’s small, but we are seeing it.”

Dr. Thielen said she’ll be keeping an eye on the next meeting of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for more answers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Testing COVID-19 vaccines in young children is going to be tricky. Deciding how to approve them and who should get them may be even more difficult.

So far, the vaccines available to Americans ages 12 and up have sailed through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory checks, taking advantage of an accelerated clearance process called an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

EUAs set a lower bar for effectiveness, saying the vaccines may be safe and effective based on just a few months of data.

But with COVID cases plummeting in the United States and children historically seeing far less serious disease than adults, a panel of expert advisors to the FDA was asked to deliberate on Thursday whether the agency could consider vaccines for this age group under the same standard.

Stated another way: Is COVID an emergency for kids?

There’s another wrinkle in the mix, too – heart inflammation, which appears to be a very rare emerging adverse event tied to vaccination. It seems to happen more often in teens and young adults. To date, cases of myocarditis and pericarditis appear to be happening in 16 to 30 people for every 1 million doses given.

But if it is conclusively linked to the shots, some wonder whether it might tip the balance between benefits and risks for kids.

That left some of the experts who sit on the FDA’s advisory committee for vaccines and related biological products urging the FDA to take its time and more thoroughly study the shots before they’re given to millions of children.

Vaccine studies different in children?

Clinical studies of the vaccines in teens and adults have thus far relied on some straightforward math. You take two groups of similar people. You give half the vaccine and half a placebo. Then you wait and see which group has more symptomatic infections. To date, the vaccines have dramatically cut the risk of getting severely ill with COVID for every age group tested.

But COVID infections are falling rapidly in the U.S., and that may make it more difficult for researchers to conduct a similar kind of experiment in children.