User login

Delta variant key to breakthrough infections in vaccinated Israelis

Israeli officials are reporting a 30% decrease in the effectiveness of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and mild to moderate cases of COVID-19. At the same time, protection against hospitalization and severe illness remains robust.

The country’s Ministry of Health data cited high levels of circulating Delta variant and a relaxation of public health measures in early June for the drop in the vaccine’s prevention of “breakthrough” cases from 94% to 64% in recent weeks.

However, it is important to consider the findings in context, experts cautioned.

“My overall take on this that the vaccine is highly protective against the endpoints that matter – hospitalization and severe disease,” Anna Durbin, MD, told this news organization.

“I was very pleasantly surprised with the very high efficacy against hospitalization and severe disease – even against the Delta variant,” added Dr. Durbin, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, agreed that the high degree of protection against severe outcomes should be the focus.

“That’s the whole idea. You want to defend against COVID-19. So even if someone is infected, they don’t end up in the hospital or in the morgue,” he said in an interview.

Compared with an earlier report, the efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine against hospitalization fell slightly from 98% to 93%.

“For me, the fact that there is increased infection from the Delta variant after the vaccines such as Pfizer is of course a concern. But the positive news is that there is 93% prevention against severe disease or mortality,” added Dr. Mokdad, who is also professor of global health at University of Washington.

In addition, the absolute numbers remain relatively small. The Ministry of Health data show that, of the 63 Israelis hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide on July 3, 34 were in critical condition.

Unrealistic expectations?

People may have unrealistic expectations regarding breakthrough infections, Dr. Durbin said. “It seems that people are almost expecting ‘sterilizing immunity’ from these vaccines,” she said, explaining that would mean complete protection from infection.

Expectations may be high “because these vaccines have been so effective,” added Dr. Durbin, who is also affiliated with the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health.

The higher the number of vaccinated residents, the more breakthrough cases will be reported, epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences at the University of Texas Science Center at Houston, wrote in her “Your Local Epidemiologist” blog.

This could apply to Israel, with an estimated 60% of adults in Israel fully vaccinated and 65% receiving at least one dose as of July 5, Our World in Data figures show.

How the updated figures were reported could be confusing, Dr. Jetelina said. Israel’s Health Minister Chezy Levy noted that “55% of the newly infected had been vaccinated” in a radio interview announcing the results.

“This language is important because it’s very different than ‘half of vaccinated people were infected,’ ” Dr. Jetelina noted.

Israel had a 7-day rolling average of 324 new confirmed COVID-19 cases as of July 5. Assuming 55% of these cases were among vaccinated people, that would mean 178 people experienced breakthrough infections.

In contrast, almost 6 million people in Israel are fully vaccinated. If 55% of them experienced breakthrough infections, the number would be much higher – more than 3 million.

Dr. Jetelina added that more details about the new Israel figures would be helpful, including the severity of COVID-19 among the vaccinated cases and breakdown of infections between adults and children.

Next steps

Israeli health officials are weighing the necessity of a third or booster dose of the vaccine. Whether they will reinstate public health measures to prevent spread of COVID-19 also remains unknown.

Going forward, Israel intends to study whether factors such as age, comorbidities, or time since immunization affect risk for breakthrough infections among people vaccinated against COVID-19.

“We want to prevent people from getting hospitalized, seriously ill, and of course, dying. It’s encouraging these vaccines will be able to have a high impact on those outcomes,” Dr. Durbin said. “We just need to get people vaccinated.”

A call for better global surveillance

A global surveillance system is a potential solution to track and respond to the growing threat of the Delta variant and other variants of concern, Scott P. Layne, MD, and Jeffery K. Taubenberger, MD, PhD, wrote in a July 7, 2021, editorial in Science Translational Medicine.

One goal, Dr. Layne said in an interview, is to highlight “the compelling need for a new global COVID-19 program of surveillance and offer a blueprint for building it.” A second aim is to promote global cooperation among key advisers and leaders in the G7, G20, and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation nations.

“It’s an uphill struggle with superpower discords, global warming, cybersecurity, and pandemics all competing for finite attention,” Dr. Layne said. “However, what other options do we have for taming the so-called forever virus?”

Dr. Mokdad and Dr. Jetelina had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Durban disclosed she was the site primary investigator for the phase 3 AstraZeneca vaccine trial and an investigator on the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Israeli officials are reporting a 30% decrease in the effectiveness of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and mild to moderate cases of COVID-19. At the same time, protection against hospitalization and severe illness remains robust.

The country’s Ministry of Health data cited high levels of circulating Delta variant and a relaxation of public health measures in early June for the drop in the vaccine’s prevention of “breakthrough” cases from 94% to 64% in recent weeks.

However, it is important to consider the findings in context, experts cautioned.

“My overall take on this that the vaccine is highly protective against the endpoints that matter – hospitalization and severe disease,” Anna Durbin, MD, told this news organization.

“I was very pleasantly surprised with the very high efficacy against hospitalization and severe disease – even against the Delta variant,” added Dr. Durbin, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, agreed that the high degree of protection against severe outcomes should be the focus.

“That’s the whole idea. You want to defend against COVID-19. So even if someone is infected, they don’t end up in the hospital or in the morgue,” he said in an interview.

Compared with an earlier report, the efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine against hospitalization fell slightly from 98% to 93%.

“For me, the fact that there is increased infection from the Delta variant after the vaccines such as Pfizer is of course a concern. But the positive news is that there is 93% prevention against severe disease or mortality,” added Dr. Mokdad, who is also professor of global health at University of Washington.

In addition, the absolute numbers remain relatively small. The Ministry of Health data show that, of the 63 Israelis hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide on July 3, 34 were in critical condition.

Unrealistic expectations?

People may have unrealistic expectations regarding breakthrough infections, Dr. Durbin said. “It seems that people are almost expecting ‘sterilizing immunity’ from these vaccines,” she said, explaining that would mean complete protection from infection.

Expectations may be high “because these vaccines have been so effective,” added Dr. Durbin, who is also affiliated with the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health.

The higher the number of vaccinated residents, the more breakthrough cases will be reported, epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences at the University of Texas Science Center at Houston, wrote in her “Your Local Epidemiologist” blog.

This could apply to Israel, with an estimated 60% of adults in Israel fully vaccinated and 65% receiving at least one dose as of July 5, Our World in Data figures show.

How the updated figures were reported could be confusing, Dr. Jetelina said. Israel’s Health Minister Chezy Levy noted that “55% of the newly infected had been vaccinated” in a radio interview announcing the results.

“This language is important because it’s very different than ‘half of vaccinated people were infected,’ ” Dr. Jetelina noted.

Israel had a 7-day rolling average of 324 new confirmed COVID-19 cases as of July 5. Assuming 55% of these cases were among vaccinated people, that would mean 178 people experienced breakthrough infections.

In contrast, almost 6 million people in Israel are fully vaccinated. If 55% of them experienced breakthrough infections, the number would be much higher – more than 3 million.

Dr. Jetelina added that more details about the new Israel figures would be helpful, including the severity of COVID-19 among the vaccinated cases and breakdown of infections between adults and children.

Next steps

Israeli health officials are weighing the necessity of a third or booster dose of the vaccine. Whether they will reinstate public health measures to prevent spread of COVID-19 also remains unknown.

Going forward, Israel intends to study whether factors such as age, comorbidities, or time since immunization affect risk for breakthrough infections among people vaccinated against COVID-19.

“We want to prevent people from getting hospitalized, seriously ill, and of course, dying. It’s encouraging these vaccines will be able to have a high impact on those outcomes,” Dr. Durbin said. “We just need to get people vaccinated.”

A call for better global surveillance

A global surveillance system is a potential solution to track and respond to the growing threat of the Delta variant and other variants of concern, Scott P. Layne, MD, and Jeffery K. Taubenberger, MD, PhD, wrote in a July 7, 2021, editorial in Science Translational Medicine.

One goal, Dr. Layne said in an interview, is to highlight “the compelling need for a new global COVID-19 program of surveillance and offer a blueprint for building it.” A second aim is to promote global cooperation among key advisers and leaders in the G7, G20, and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation nations.

“It’s an uphill struggle with superpower discords, global warming, cybersecurity, and pandemics all competing for finite attention,” Dr. Layne said. “However, what other options do we have for taming the so-called forever virus?”

Dr. Mokdad and Dr. Jetelina had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Durban disclosed she was the site primary investigator for the phase 3 AstraZeneca vaccine trial and an investigator on the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Israeli officials are reporting a 30% decrease in the effectiveness of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and mild to moderate cases of COVID-19. At the same time, protection against hospitalization and severe illness remains robust.

The country’s Ministry of Health data cited high levels of circulating Delta variant and a relaxation of public health measures in early June for the drop in the vaccine’s prevention of “breakthrough” cases from 94% to 64% in recent weeks.

However, it is important to consider the findings in context, experts cautioned.

“My overall take on this that the vaccine is highly protective against the endpoints that matter – hospitalization and severe disease,” Anna Durbin, MD, told this news organization.

“I was very pleasantly surprised with the very high efficacy against hospitalization and severe disease – even against the Delta variant,” added Dr. Durbin, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, agreed that the high degree of protection against severe outcomes should be the focus.

“That’s the whole idea. You want to defend against COVID-19. So even if someone is infected, they don’t end up in the hospital or in the morgue,” he said in an interview.

Compared with an earlier report, the efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine against hospitalization fell slightly from 98% to 93%.

“For me, the fact that there is increased infection from the Delta variant after the vaccines such as Pfizer is of course a concern. But the positive news is that there is 93% prevention against severe disease or mortality,” added Dr. Mokdad, who is also professor of global health at University of Washington.

In addition, the absolute numbers remain relatively small. The Ministry of Health data show that, of the 63 Israelis hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide on July 3, 34 were in critical condition.

Unrealistic expectations?

People may have unrealistic expectations regarding breakthrough infections, Dr. Durbin said. “It seems that people are almost expecting ‘sterilizing immunity’ from these vaccines,” she said, explaining that would mean complete protection from infection.

Expectations may be high “because these vaccines have been so effective,” added Dr. Durbin, who is also affiliated with the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health.

The higher the number of vaccinated residents, the more breakthrough cases will be reported, epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences at the University of Texas Science Center at Houston, wrote in her “Your Local Epidemiologist” blog.

This could apply to Israel, with an estimated 60% of adults in Israel fully vaccinated and 65% receiving at least one dose as of July 5, Our World in Data figures show.

How the updated figures were reported could be confusing, Dr. Jetelina said. Israel’s Health Minister Chezy Levy noted that “55% of the newly infected had been vaccinated” in a radio interview announcing the results.

“This language is important because it’s very different than ‘half of vaccinated people were infected,’ ” Dr. Jetelina noted.

Israel had a 7-day rolling average of 324 new confirmed COVID-19 cases as of July 5. Assuming 55% of these cases were among vaccinated people, that would mean 178 people experienced breakthrough infections.

In contrast, almost 6 million people in Israel are fully vaccinated. If 55% of them experienced breakthrough infections, the number would be much higher – more than 3 million.

Dr. Jetelina added that more details about the new Israel figures would be helpful, including the severity of COVID-19 among the vaccinated cases and breakdown of infections between adults and children.

Next steps

Israeli health officials are weighing the necessity of a third or booster dose of the vaccine. Whether they will reinstate public health measures to prevent spread of COVID-19 also remains unknown.

Going forward, Israel intends to study whether factors such as age, comorbidities, or time since immunization affect risk for breakthrough infections among people vaccinated against COVID-19.

“We want to prevent people from getting hospitalized, seriously ill, and of course, dying. It’s encouraging these vaccines will be able to have a high impact on those outcomes,” Dr. Durbin said. “We just need to get people vaccinated.”

A call for better global surveillance

A global surveillance system is a potential solution to track and respond to the growing threat of the Delta variant and other variants of concern, Scott P. Layne, MD, and Jeffery K. Taubenberger, MD, PhD, wrote in a July 7, 2021, editorial in Science Translational Medicine.

One goal, Dr. Layne said in an interview, is to highlight “the compelling need for a new global COVID-19 program of surveillance and offer a blueprint for building it.” A second aim is to promote global cooperation among key advisers and leaders in the G7, G20, and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation nations.

“It’s an uphill struggle with superpower discords, global warming, cybersecurity, and pandemics all competing for finite attention,” Dr. Layne said. “However, what other options do we have for taming the so-called forever virus?”

Dr. Mokdad and Dr. Jetelina had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Durban disclosed she was the site primary investigator for the phase 3 AstraZeneca vaccine trial and an investigator on the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Extra COVID-19 vaccine could help immunocompromised people

People whose immune systems are compromised by therapy or disease may benefit from additional doses of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, researchers say.

In a study involving 101 people with solid-organ transplants, there was a significant boost in antibodies after the patients received third doses of the Pfizer vaccine, said Nassim Kamar, MD, PhD, professor of nephrology at Toulouse University Hospital, France.

None of the transplant patients had antibodies against the virus before their first dose of the vaccine, and only 4% produced antibodies after the first dose. That proportion rose to 40% after the second dose and to 68% after the third dose.

The effect is so strong that Dr. Kamar and colleagues at Toulouse University Hospital routinely administer three doses of mRNA vaccines to patients with solid-organ transplant without testing them for antibodies.

“When we observed that the second dose was not sufficient to have an immune response, the Francophone Society of Transplantation asked the National Health Authority to allow the third dose,” he told this news organization.

That agency on April 11 approved third doses of mRNA vaccines not only for people with solid-organ transplants but also for those with recent bone marrow transplants, those undergoing dialysis, and those with autoimmune diseases who were receiving strong immunosuppressive treatment, such as anti-CD20 or antimetabolites. Contrary to their procedure for people with solid-organ transplants, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital test these patients for antibodies and administer third doses of vaccine only to those who test negative or have very low titers.

The researchers’ findings, published on June 23 as a letter to the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, come as other researchers document more and more categories of patients whose responses to the vaccines typically fall short.

A study at the University of Pittsburgh that was published as a preprint on MedRxiv compared people with various health conditions to healthy health care workers. People with HIV who were taking antivirals against that virus responded almost as well as did the health care workers, said John Mellors, MD, chief of infectious diseases at the university. But people whose immune systems were compromised for other reasons fared less well.

“The areas of concern are hematological malignancy and solid-organ transplants, with the most nonresponsive groups being those who have had lung transplantation,” he said in an interview.

For patients with liver disease, mixed news came from the International Liver Congress (ILC) 2021 annual meeting.

In a study involving patients with liver disease who had received the Pfizer vaccine at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, antibody titers were lower in patients who had received liver transplants or who had advanced liver fibrosis, as reported by this news organization.

A multicenter study in China that was presented at the ILC meeting and that was also published in the Journal of Hepatology, provided a more optimistic picture. Among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who were immunized against SARS-CoV-2 with the Sinopharm vaccine, 95.5% had neutralizing antibodies; the median neutralizing antibody titer was 32.

In the Toulouse University Hospital study, for the 40 patients who were seropositive after the second dose, antibody titers increased from 36 before the third dose to 2,676 a month after the third dose, a statistically significant result (P < .001).

For patients whose immune systems are compromised for reasons other than having received a transplant, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital use a titer of 14 as the threshold below which they administer a third dose of mRNA vaccines. But Dr. Kamar acknowledged that the threshold is arbitrary and that the assays for antibodies with different vaccines in different populations can’t be compared head to head.

“We can’t tell you simply on the basis of the amount of antibody in your laboratory report how protected you are,” agreed William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who is a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Not enough research has been done to establish that relationship, and results vary from one laboratory to another, he said.

That doesn’t mean that antibody tests don’t help, Dr. Schaffner said. On the basis of views of other experts he has consulted, Dr. Schaffner recommends that people who are immunocompromised undergo an antibody test. If the test is positive – meaning they have some antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, however low the titers – patients can take fewer precautions than before they were vaccinated.

But they should still be more cautious than people with healthy immune systems, he said. “Would I be going to large indoor gatherings without a mask? No. Would I be outside without a mask? Yes. Would I gather with three other people who are vaccinated to play a game of bridge? Yes. You have to titrate things a little and use some common sense,” he added.

If the results are negative, such patients may still be protected. Much research remains to be done on T-cell immunity, a second line of defense against the virus. And the current assays often produce false negative results. But to be on the safe side, people with this result should assume that their vaccine is not protecting them, Dr. Schaffner said.

That suggestion contradicts the Food and Drug Administration, which issued a recommendation on May 19 against using antibody tests to check the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

The studies so far suggest that vaccines are safe for people whose immune systems are compromised, Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Kamar agreed. Dr. Kamar is aware of only two case reports of transplant patients rejecting their transplants after vaccination. One of these was his own patient, and the rejection occurred after her second dose. She has not needed dialysis, although her kidney function was impaired.

But the FDA has not approved additional doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to treat patients who are immunocompromised, and Dr. Kamar has not heard of any other national regulatory agencies that have.

In the United States, it may be difficult for anyone to obtain a third dose of vaccine outside of a clinical trial, Dr. Schaffner said, because vaccinators are likely to check databases and deny vaccination to anyone who has already received the recommended number.

Dr. Kamar, Dr. Mellors, and Dr. Schaffner have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People whose immune systems are compromised by therapy or disease may benefit from additional doses of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, researchers say.

In a study involving 101 people with solid-organ transplants, there was a significant boost in antibodies after the patients received third doses of the Pfizer vaccine, said Nassim Kamar, MD, PhD, professor of nephrology at Toulouse University Hospital, France.

None of the transplant patients had antibodies against the virus before their first dose of the vaccine, and only 4% produced antibodies after the first dose. That proportion rose to 40% after the second dose and to 68% after the third dose.

The effect is so strong that Dr. Kamar and colleagues at Toulouse University Hospital routinely administer three doses of mRNA vaccines to patients with solid-organ transplant without testing them for antibodies.

“When we observed that the second dose was not sufficient to have an immune response, the Francophone Society of Transplantation asked the National Health Authority to allow the third dose,” he told this news organization.

That agency on April 11 approved third doses of mRNA vaccines not only for people with solid-organ transplants but also for those with recent bone marrow transplants, those undergoing dialysis, and those with autoimmune diseases who were receiving strong immunosuppressive treatment, such as anti-CD20 or antimetabolites. Contrary to their procedure for people with solid-organ transplants, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital test these patients for antibodies and administer third doses of vaccine only to those who test negative or have very low titers.

The researchers’ findings, published on June 23 as a letter to the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, come as other researchers document more and more categories of patients whose responses to the vaccines typically fall short.

A study at the University of Pittsburgh that was published as a preprint on MedRxiv compared people with various health conditions to healthy health care workers. People with HIV who were taking antivirals against that virus responded almost as well as did the health care workers, said John Mellors, MD, chief of infectious diseases at the university. But people whose immune systems were compromised for other reasons fared less well.

“The areas of concern are hematological malignancy and solid-organ transplants, with the most nonresponsive groups being those who have had lung transplantation,” he said in an interview.

For patients with liver disease, mixed news came from the International Liver Congress (ILC) 2021 annual meeting.

In a study involving patients with liver disease who had received the Pfizer vaccine at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, antibody titers were lower in patients who had received liver transplants or who had advanced liver fibrosis, as reported by this news organization.

A multicenter study in China that was presented at the ILC meeting and that was also published in the Journal of Hepatology, provided a more optimistic picture. Among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who were immunized against SARS-CoV-2 with the Sinopharm vaccine, 95.5% had neutralizing antibodies; the median neutralizing antibody titer was 32.

In the Toulouse University Hospital study, for the 40 patients who were seropositive after the second dose, antibody titers increased from 36 before the third dose to 2,676 a month after the third dose, a statistically significant result (P < .001).

For patients whose immune systems are compromised for reasons other than having received a transplant, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital use a titer of 14 as the threshold below which they administer a third dose of mRNA vaccines. But Dr. Kamar acknowledged that the threshold is arbitrary and that the assays for antibodies with different vaccines in different populations can’t be compared head to head.

“We can’t tell you simply on the basis of the amount of antibody in your laboratory report how protected you are,” agreed William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who is a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Not enough research has been done to establish that relationship, and results vary from one laboratory to another, he said.

That doesn’t mean that antibody tests don’t help, Dr. Schaffner said. On the basis of views of other experts he has consulted, Dr. Schaffner recommends that people who are immunocompromised undergo an antibody test. If the test is positive – meaning they have some antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, however low the titers – patients can take fewer precautions than before they were vaccinated.

But they should still be more cautious than people with healthy immune systems, he said. “Would I be going to large indoor gatherings without a mask? No. Would I be outside without a mask? Yes. Would I gather with three other people who are vaccinated to play a game of bridge? Yes. You have to titrate things a little and use some common sense,” he added.

If the results are negative, such patients may still be protected. Much research remains to be done on T-cell immunity, a second line of defense against the virus. And the current assays often produce false negative results. But to be on the safe side, people with this result should assume that their vaccine is not protecting them, Dr. Schaffner said.

That suggestion contradicts the Food and Drug Administration, which issued a recommendation on May 19 against using antibody tests to check the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

The studies so far suggest that vaccines are safe for people whose immune systems are compromised, Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Kamar agreed. Dr. Kamar is aware of only two case reports of transplant patients rejecting their transplants after vaccination. One of these was his own patient, and the rejection occurred after her second dose. She has not needed dialysis, although her kidney function was impaired.

But the FDA has not approved additional doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to treat patients who are immunocompromised, and Dr. Kamar has not heard of any other national regulatory agencies that have.

In the United States, it may be difficult for anyone to obtain a third dose of vaccine outside of a clinical trial, Dr. Schaffner said, because vaccinators are likely to check databases and deny vaccination to anyone who has already received the recommended number.

Dr. Kamar, Dr. Mellors, and Dr. Schaffner have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People whose immune systems are compromised by therapy or disease may benefit from additional doses of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, researchers say.

In a study involving 101 people with solid-organ transplants, there was a significant boost in antibodies after the patients received third doses of the Pfizer vaccine, said Nassim Kamar, MD, PhD, professor of nephrology at Toulouse University Hospital, France.

None of the transplant patients had antibodies against the virus before their first dose of the vaccine, and only 4% produced antibodies after the first dose. That proportion rose to 40% after the second dose and to 68% after the third dose.

The effect is so strong that Dr. Kamar and colleagues at Toulouse University Hospital routinely administer three doses of mRNA vaccines to patients with solid-organ transplant without testing them for antibodies.

“When we observed that the second dose was not sufficient to have an immune response, the Francophone Society of Transplantation asked the National Health Authority to allow the third dose,” he told this news organization.

That agency on April 11 approved third doses of mRNA vaccines not only for people with solid-organ transplants but also for those with recent bone marrow transplants, those undergoing dialysis, and those with autoimmune diseases who were receiving strong immunosuppressive treatment, such as anti-CD20 or antimetabolites. Contrary to their procedure for people with solid-organ transplants, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital test these patients for antibodies and administer third doses of vaccine only to those who test negative or have very low titers.

The researchers’ findings, published on June 23 as a letter to the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, come as other researchers document more and more categories of patients whose responses to the vaccines typically fall short.

A study at the University of Pittsburgh that was published as a preprint on MedRxiv compared people with various health conditions to healthy health care workers. People with HIV who were taking antivirals against that virus responded almost as well as did the health care workers, said John Mellors, MD, chief of infectious diseases at the university. But people whose immune systems were compromised for other reasons fared less well.

“The areas of concern are hematological malignancy and solid-organ transplants, with the most nonresponsive groups being those who have had lung transplantation,” he said in an interview.

For patients with liver disease, mixed news came from the International Liver Congress (ILC) 2021 annual meeting.

In a study involving patients with liver disease who had received the Pfizer vaccine at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, antibody titers were lower in patients who had received liver transplants or who had advanced liver fibrosis, as reported by this news organization.

A multicenter study in China that was presented at the ILC meeting and that was also published in the Journal of Hepatology, provided a more optimistic picture. Among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who were immunized against SARS-CoV-2 with the Sinopharm vaccine, 95.5% had neutralizing antibodies; the median neutralizing antibody titer was 32.

In the Toulouse University Hospital study, for the 40 patients who were seropositive after the second dose, antibody titers increased from 36 before the third dose to 2,676 a month after the third dose, a statistically significant result (P < .001).

For patients whose immune systems are compromised for reasons other than having received a transplant, clinicians at Toulouse University Hospital use a titer of 14 as the threshold below which they administer a third dose of mRNA vaccines. But Dr. Kamar acknowledged that the threshold is arbitrary and that the assays for antibodies with different vaccines in different populations can’t be compared head to head.

“We can’t tell you simply on the basis of the amount of antibody in your laboratory report how protected you are,” agreed William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who is a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Not enough research has been done to establish that relationship, and results vary from one laboratory to another, he said.

That doesn’t mean that antibody tests don’t help, Dr. Schaffner said. On the basis of views of other experts he has consulted, Dr. Schaffner recommends that people who are immunocompromised undergo an antibody test. If the test is positive – meaning they have some antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, however low the titers – patients can take fewer precautions than before they were vaccinated.

But they should still be more cautious than people with healthy immune systems, he said. “Would I be going to large indoor gatherings without a mask? No. Would I be outside without a mask? Yes. Would I gather with three other people who are vaccinated to play a game of bridge? Yes. You have to titrate things a little and use some common sense,” he added.

If the results are negative, such patients may still be protected. Much research remains to be done on T-cell immunity, a second line of defense against the virus. And the current assays often produce false negative results. But to be on the safe side, people with this result should assume that their vaccine is not protecting them, Dr. Schaffner said.

That suggestion contradicts the Food and Drug Administration, which issued a recommendation on May 19 against using antibody tests to check the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

The studies so far suggest that vaccines are safe for people whose immune systems are compromised, Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Kamar agreed. Dr. Kamar is aware of only two case reports of transplant patients rejecting their transplants after vaccination. One of these was his own patient, and the rejection occurred after her second dose. She has not needed dialysis, although her kidney function was impaired.

But the FDA has not approved additional doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to treat patients who are immunocompromised, and Dr. Kamar has not heard of any other national regulatory agencies that have.

In the United States, it may be difficult for anyone to obtain a third dose of vaccine outside of a clinical trial, Dr. Schaffner said, because vaccinators are likely to check databases and deny vaccination to anyone who has already received the recommended number.

Dr. Kamar, Dr. Mellors, and Dr. Schaffner have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

California’s highest COVID infection rates shift to rural counties

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

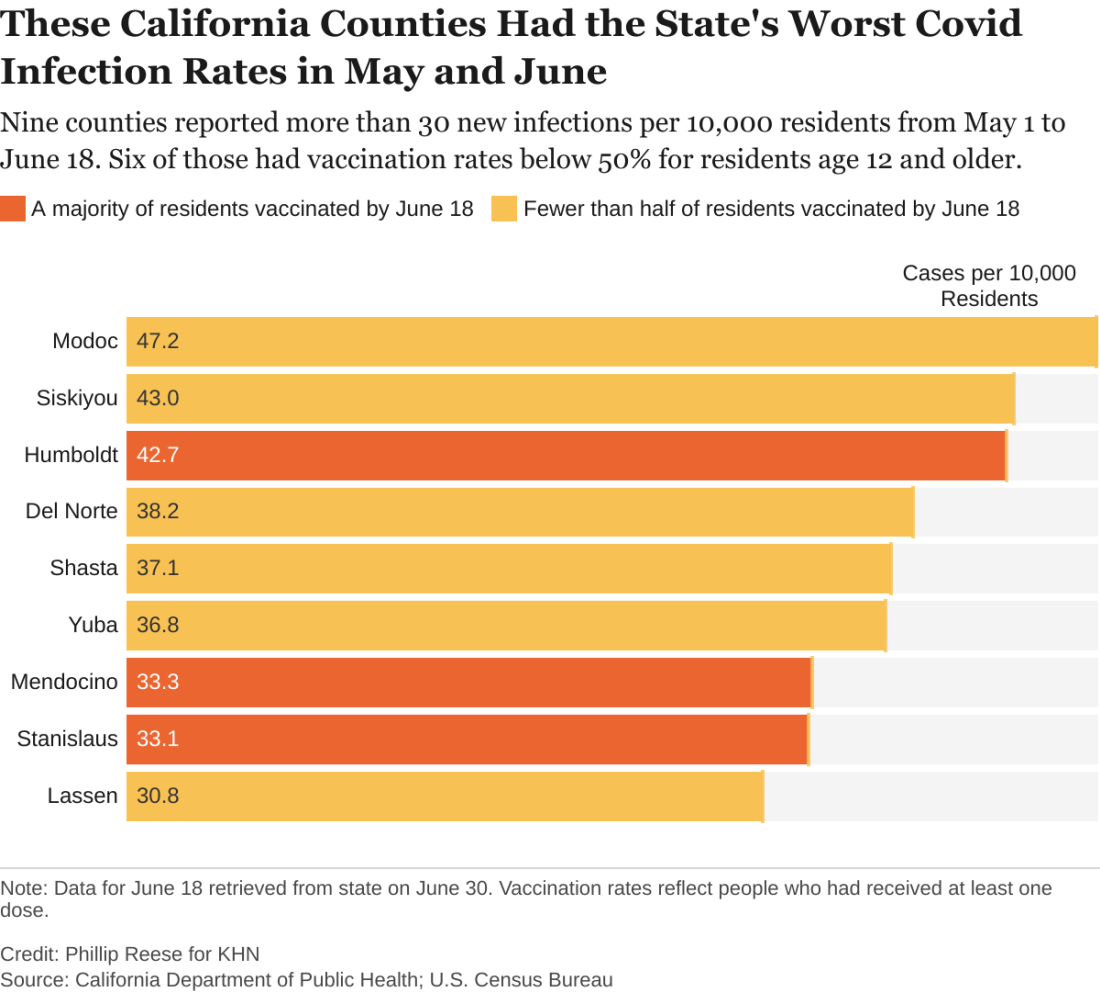

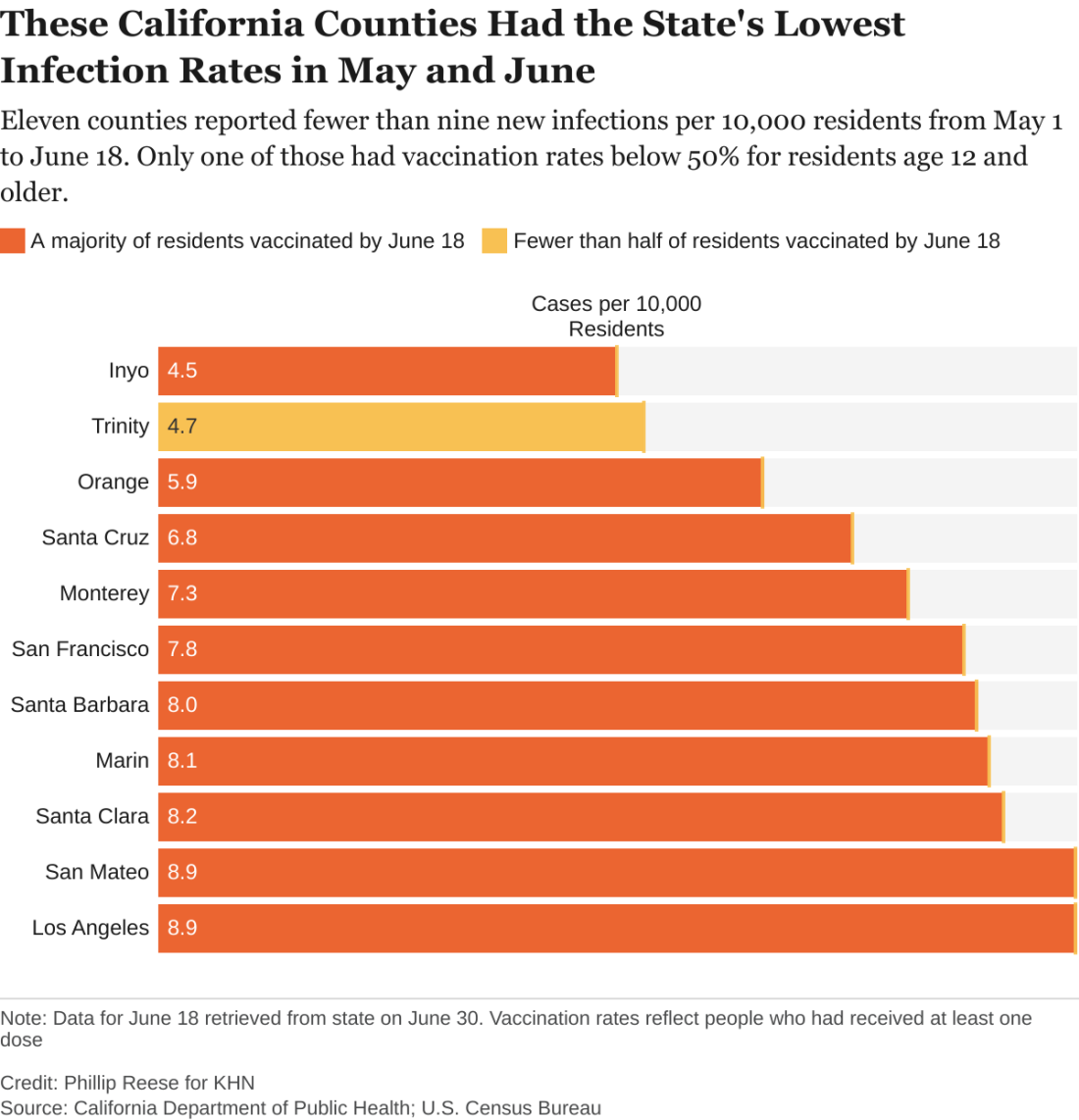

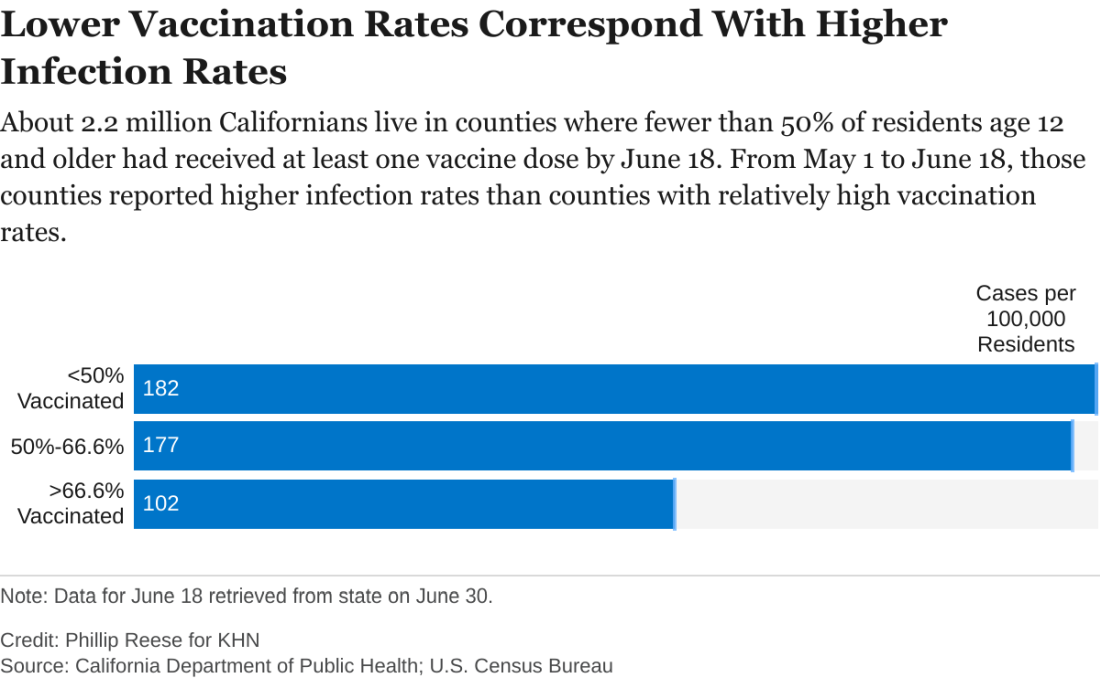

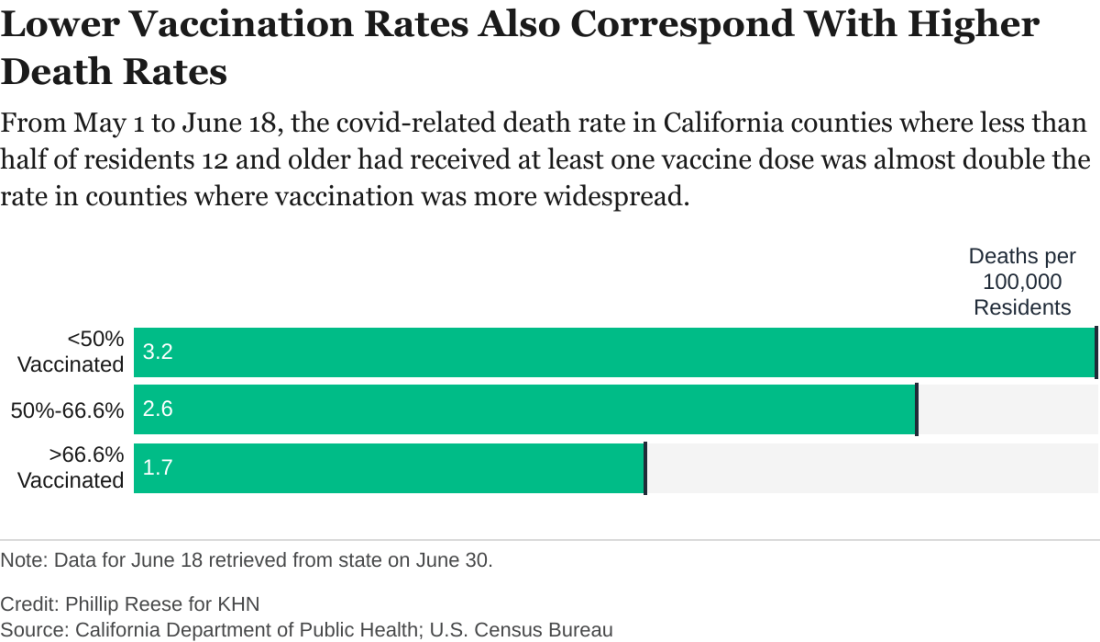

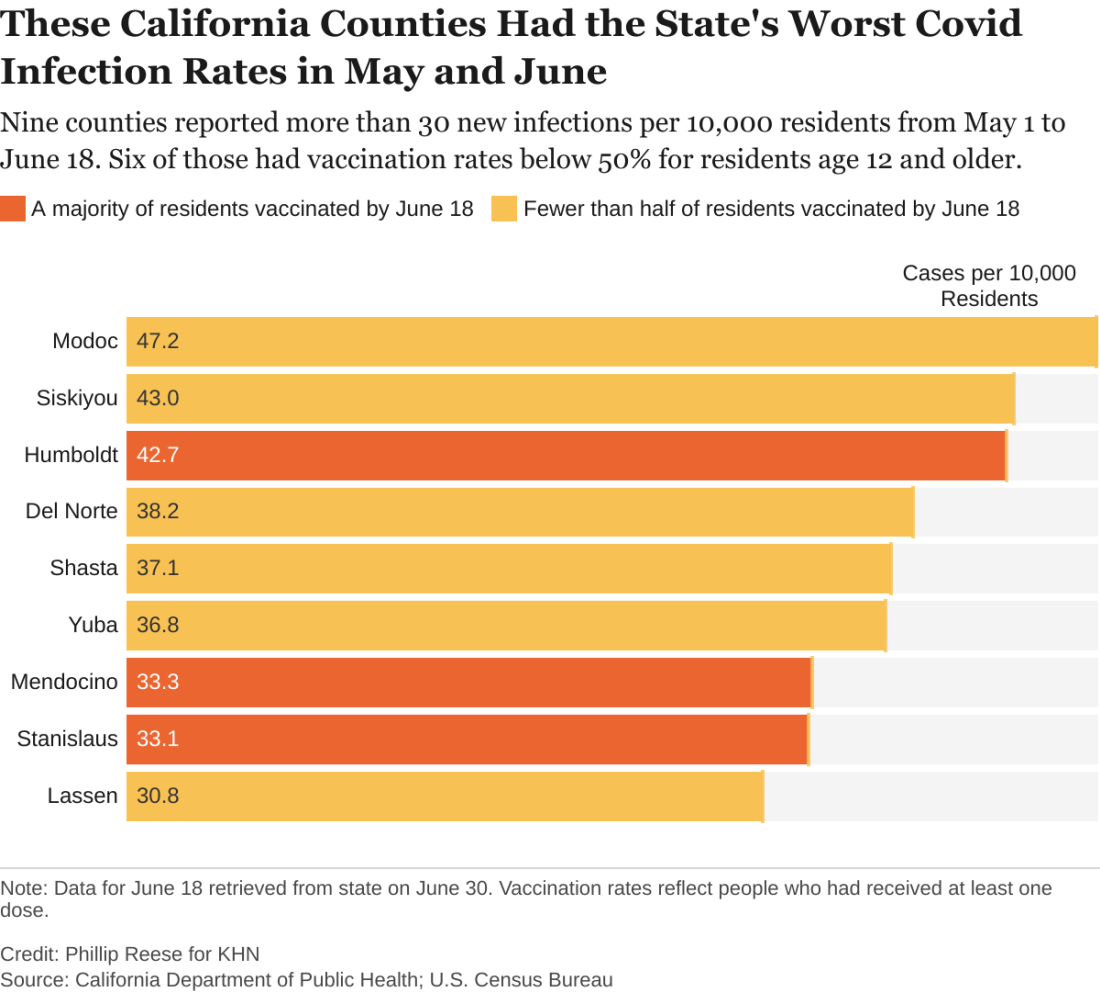

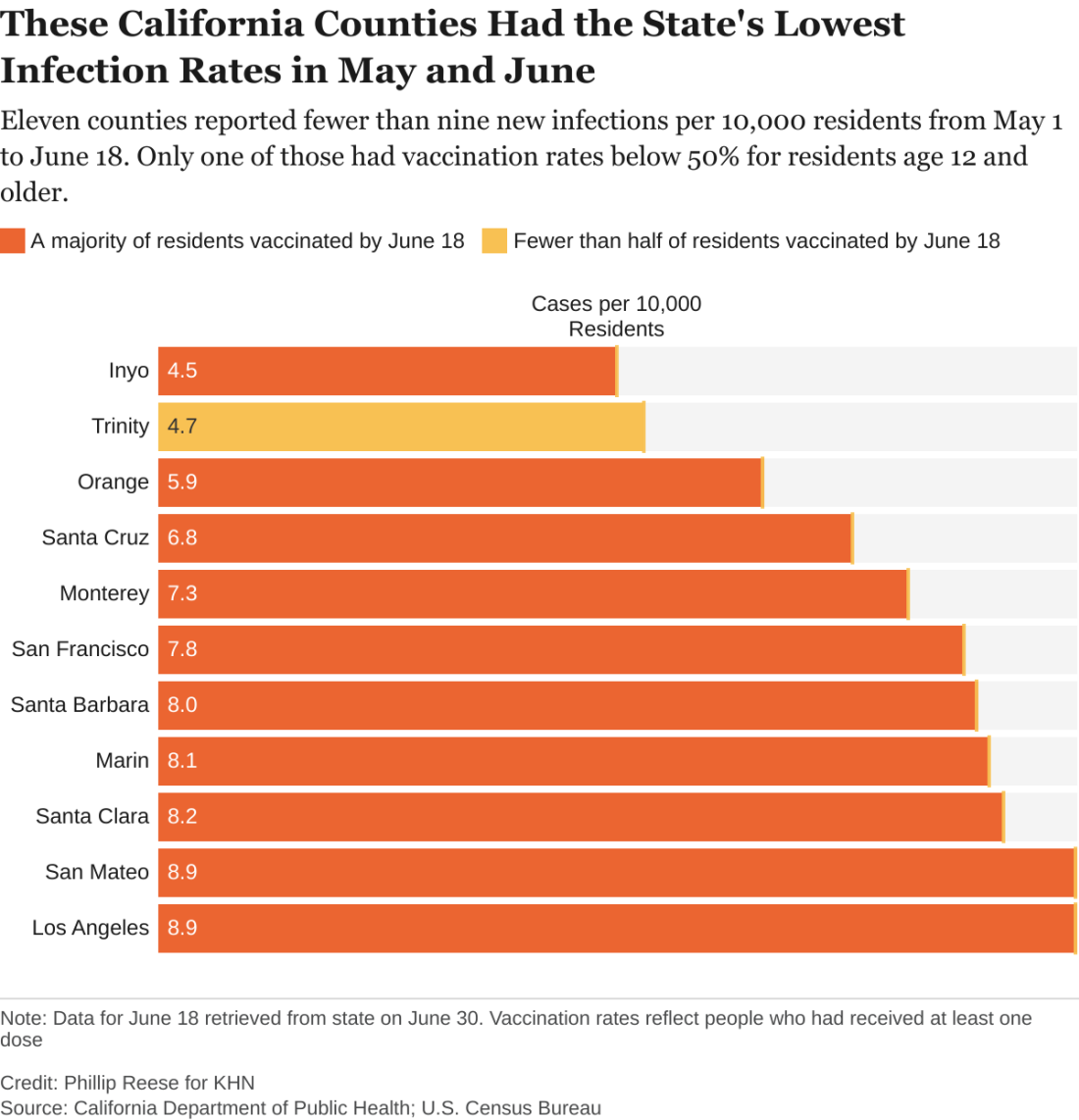

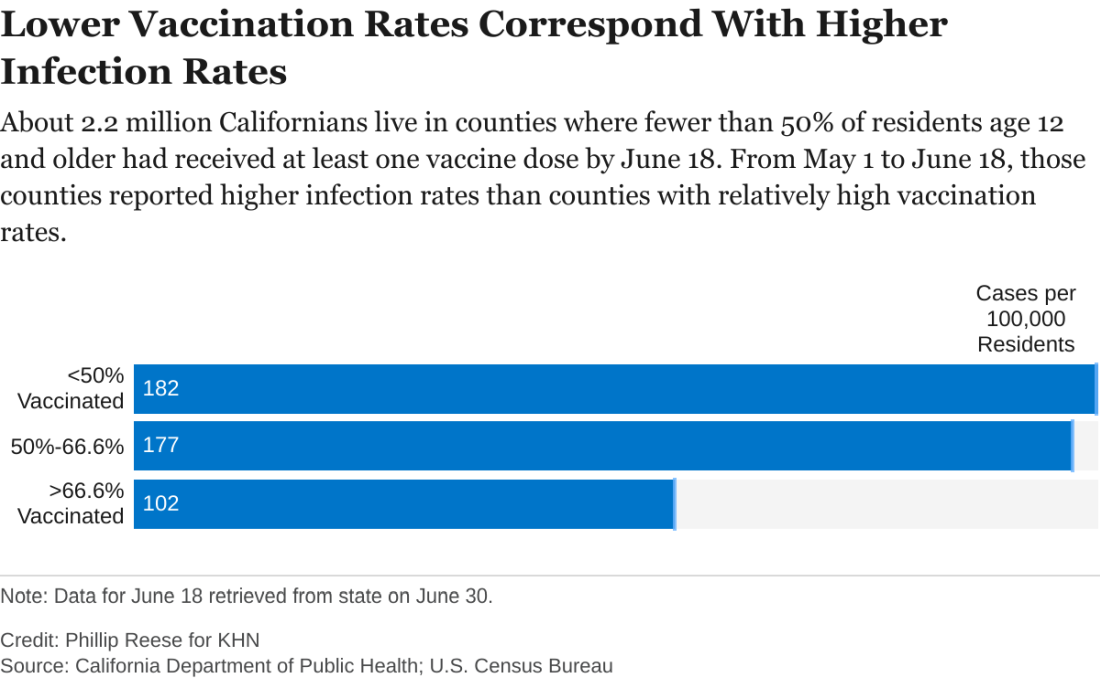

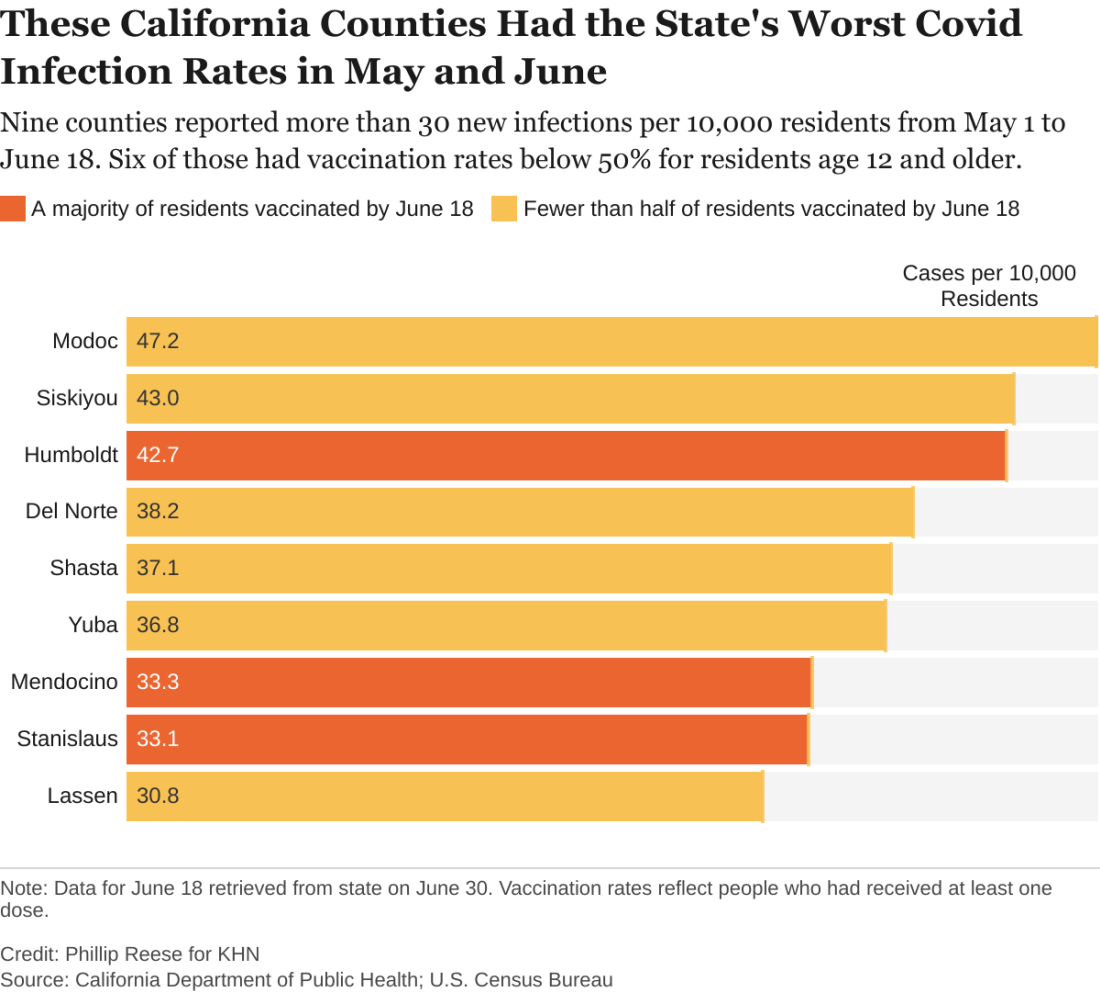

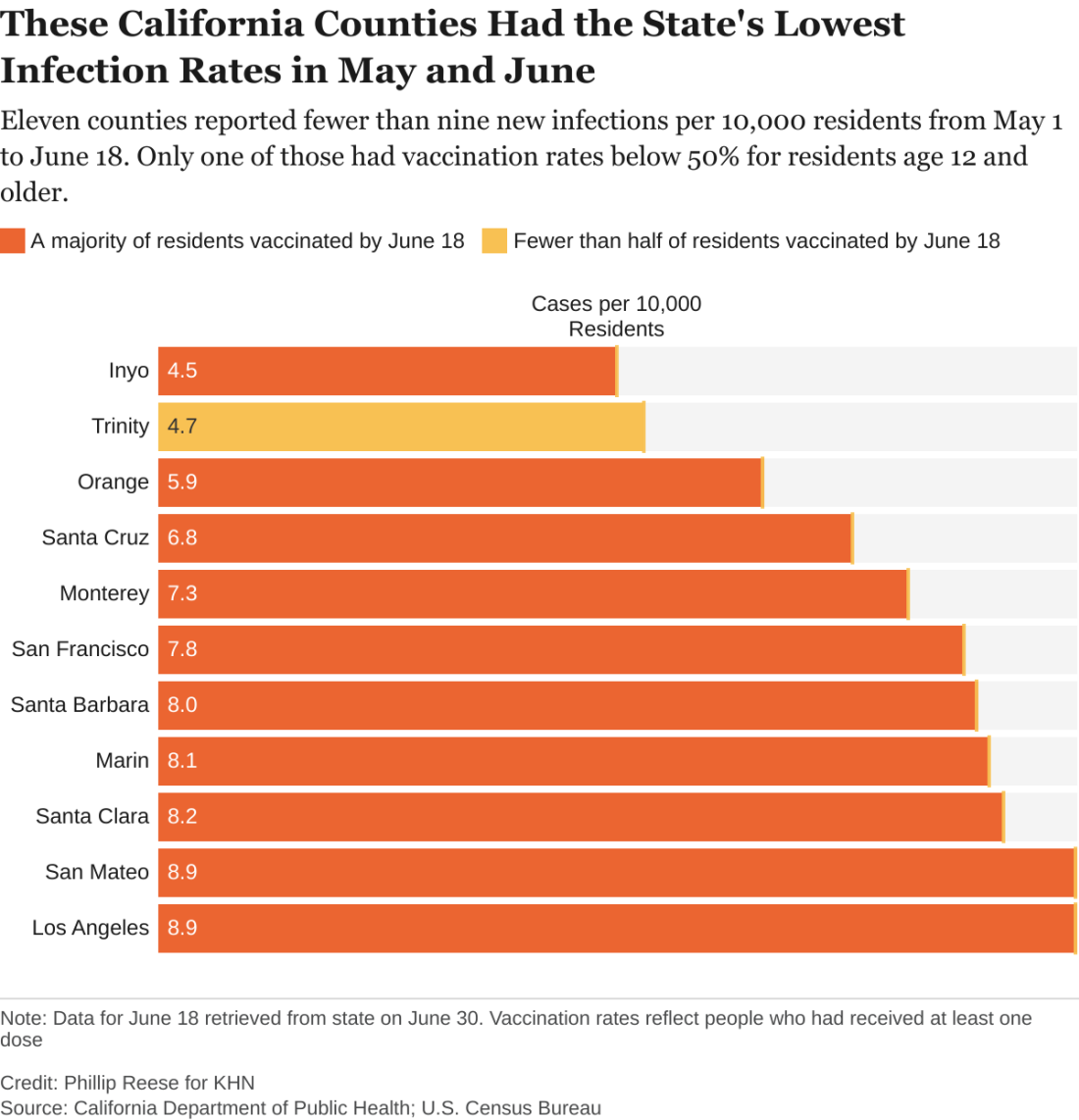

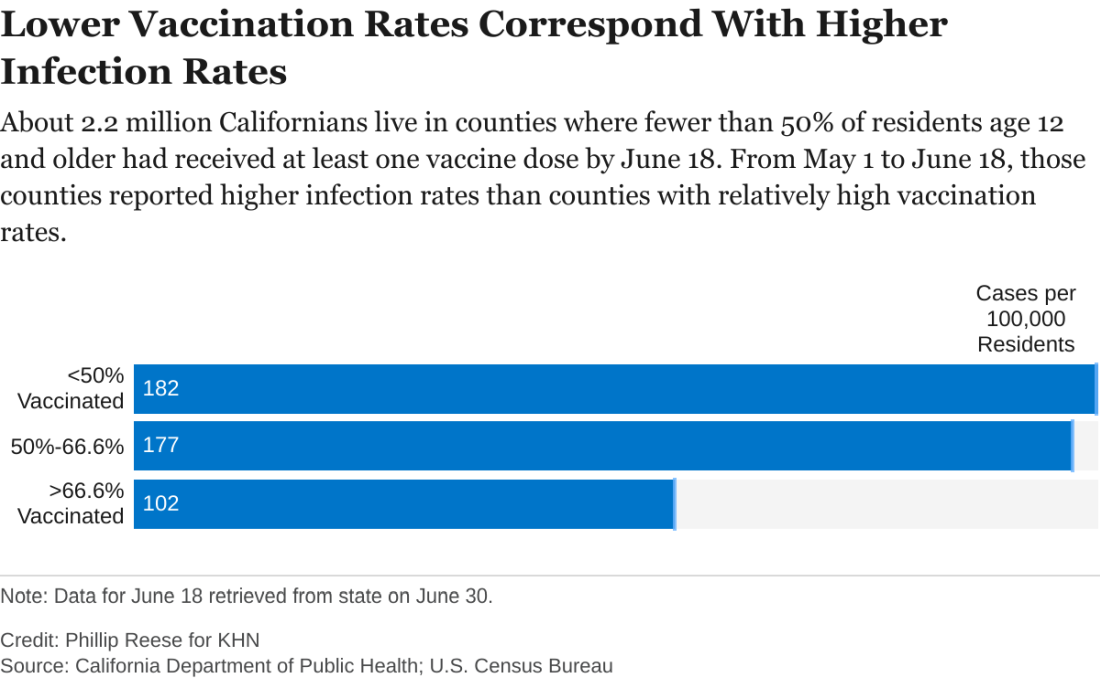

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

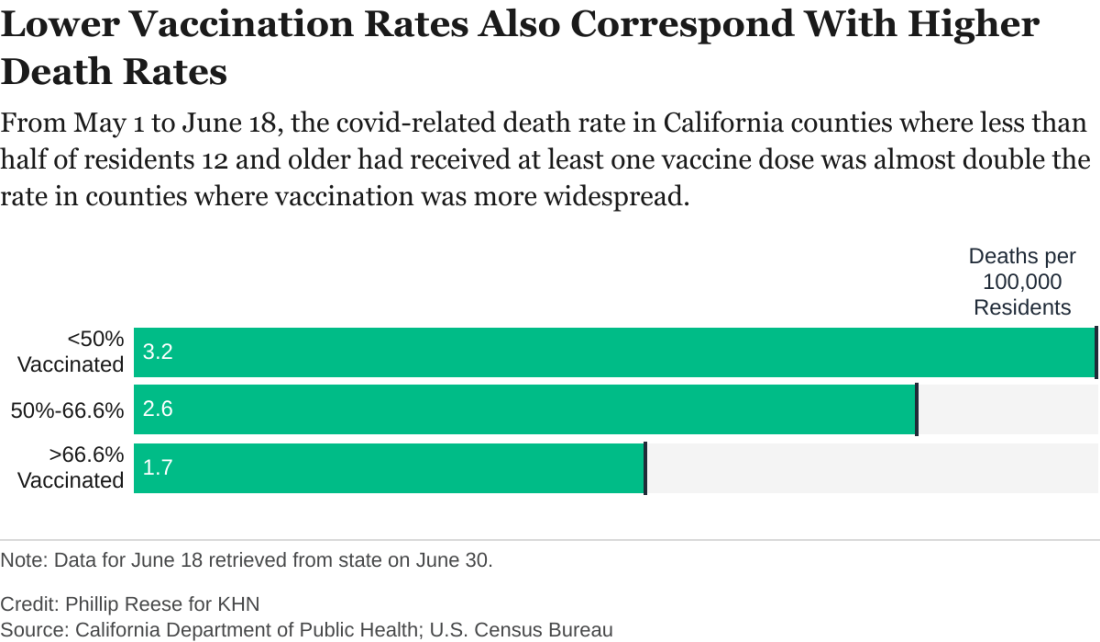

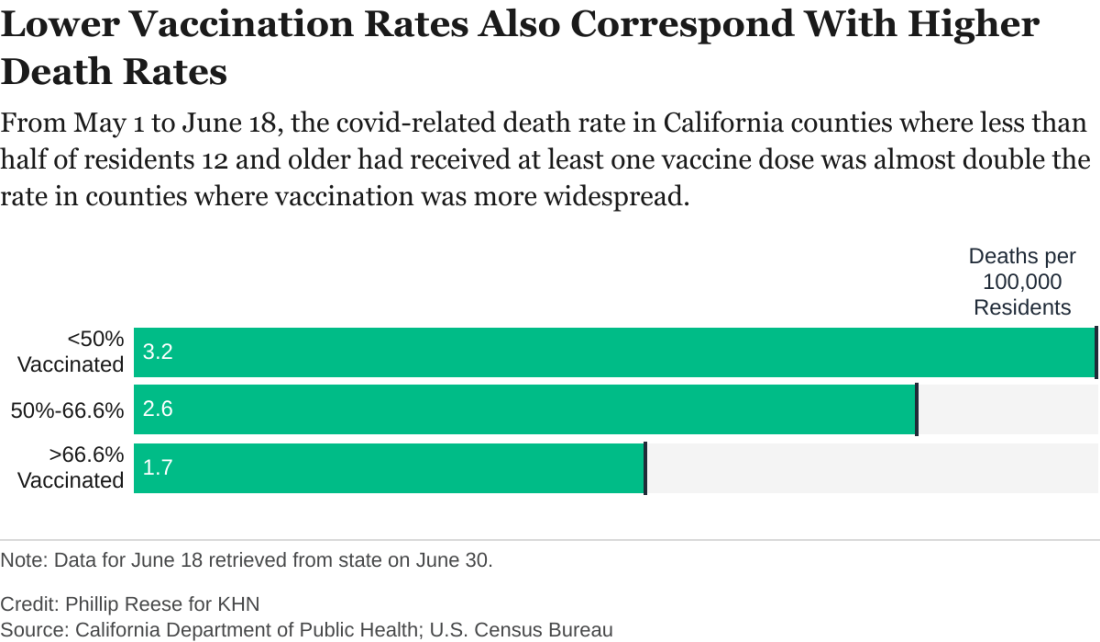

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Delta becomes dominant coronavirus variant in U.S.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pandemic upped telemedicine use 100-fold in type 2 diabetes

The COVID-19 pandemic jump-started a significant role for telemedicine in the routine follow-up of U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes, based on insurance claims records for more than 2.7 million American adults during 2019 and 2020.

During 2019, 0.3% of 1,357,029 adults with type 2 diabetes in a U.S. claims database, OptumLabs Data Warehouse, had one or more telemedicine visits. During 2020, this jumped to 29% of a similar group of U.S. adults once the pandemic kicked in, a nearly 100-fold increase, Sadiq Y. Patel, PhD, and coauthors wrote in a research letter published July 6, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The data show that telemedicine visits didn’t seem to negatively impact care, with hemoglobin A1c levels and medication fills remaining constant across the year.

But Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, chief science and medical officer for the American Diabetes Association, said these results, while reassuring, seem “quite surprising” relative to anecdotal reports from colleagues around the United States.

It’s possible they may only apply to the specific patients included in this study – which was limited to those with either commercial or Medicare Advantage health insurance – he noted in an interview.

Diabetes well-suited to telemedicine

Dr. Patel, of the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors said the information from their study showed “no evidence of a negative association with medication fills or glycemic control” among these patients during the pandemic in 2020, compared with the prepandemic year 2019.

During the first 48 weeks in 2020, A1c levels averaged 7.16% among patients with type 2 diabetes, compared with an average of 7.14% for patients with type 2 diabetes during the first 48 weeks of 2019. Fill rates for prescription medications were 64% during 2020 and 62% during 2019.

A1c levels and medication fill rates “are important markers of the quality of diabetes care, but obviously not the only important things,” said Ateev Mehrotra, MD, corresponding author for the study and a researcher in the same department as Dr. Patel.

“Limited to the metrics we looked at and in this population we did not see any substantial negative impact of the pandemic on the care for patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Mehrotra said in an interview.

“The pandemic catalyzed a tremendous shift to telemedicine among patients with diabetes. Because it is a chronic illness that requires frequent check-ins, diabetes is particularly well suited to using telemedicine,” he added.

Telemedicine not a complete replacement for in-patient visits

Dr. Gabbay agreed that “providers and patients have found telemedicine to be a helpful tool for managing patients with diabetes.”

But “most people do not think of this as a complete replacement for in-person visits, and most [U.S.] institutions have started to have more in-person visits. It’s probably about 50/50 at this point,” he said in an interview.

“It represents an impressive effort by the health care community to pivot toward telehealth to ensure that patients with diabetes continue to get care.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Gabbay added that “despite the success of telemedicine many patients still prefer to see their providers in person. I have a number of patients who were overjoyed to come in and be seen in person even when I offered telemedicine as an alternative. There is a relationship and trust piece that is more profound in person.”

And he cautioned that, although A1c “is a helpful measure, it may not fully demonstrate the percentage of patients at high risk.”

The data in the study by Dr. Patel and coauthors showing a steady level of medication refills during the pandemic “is encouraging,” he said, speculating that “people may have had more time [during the pandemic] to focus on medication adherence.”

More evidence of telemedicine’s leap

Other U.S. sites that follow patients with type 2 diabetes have recently reported similar findings, albeit on a much more localized level.

At Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., telemedicine consultations for patients with diabetes or other endocrinology disorders spurted from essentially none prior to March 2020 to a peak of nearly 700 visits/week in early May 2020, and then maintained a rate of roughly 500 telemedicine consultations weekly through the end of 2020, said Michelle L. Griffth, MD, during a talk at the 2021 annual ADA scientific sessions.

“We’ve made telehealth a permanent part of our practice,” said Dr. Griffith, medical director of telehealth ambulatory services at Vanderbilt. “We can use this boom in telehealth as a catalyst for diabetes-practice evolution,” she suggested.

It was a similar story at Scripps Health in southern California. During March and April 2020, video telemedicine consultations jumped from a prior rate of about 60/month to about 13,000/week, and then settled back to a monthly rate of about 25,000-30,000 during the balance of 2020, said Athena Philis-Tsimikas, MD, an endocrinologist and vice president of the Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute in La Jolla, Calif. (These numbers include all telehealth consultations for patients at Scripps, not just patients with diabetes.)

“COVID sped up the process of integrating digital technology into health care,” concluded Dr. Philis-Tsimikas. A big factor driving this transition was the decision of many insurers to reimburse for telemedicine visits, something not done prepandemic.

The study received no commercial support. Dr. Patel, Dr. Mehrotra, Dr. Griffith, Dr. Philis-Tsimikas, and Dr. Gabbay reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic jump-started a significant role for telemedicine in the routine follow-up of U.S. patients with type 2 diabetes, based on insurance claims records for more than 2.7 million American adults during 2019 and 2020.

During 2019, 0.3% of 1,357,029 adults with type 2 diabetes in a U.S. claims database, OptumLabs Data Warehouse, had one or more telemedicine visits. During 2020, this jumped to 29% of a similar group of U.S. adults once the pandemic kicked in, a nearly 100-fold increase, Sadiq Y. Patel, PhD, and coauthors wrote in a research letter published July 6, 2021, in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The data show that telemedicine visits didn’t seem to negatively impact care, with hemoglobin A1c levels and medication fills remaining constant across the year.

But Robert A. Gabbay, MD, PhD, chief science and medical officer for the American Diabetes Association, said these results, while reassuring, seem “quite surprising” relative to anecdotal reports from colleagues around the United States.

It’s possible they may only apply to the specific patients included in this study – which was limited to those with either commercial or Medicare Advantage health insurance – he noted in an interview.

Diabetes well-suited to telemedicine

Dr. Patel, of the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors said the information from their study showed “no evidence of a negative association with medication fills or glycemic control” among these patients during the pandemic in 2020, compared with the prepandemic year 2019.

During the first 48 weeks in 2020, A1c levels averaged 7.16% among patients with type 2 diabetes, compared with an average of 7.14% for patients with type 2 diabetes during the first 48 weeks of 2019. Fill rates for prescription medications were 64% during 2020 and 62% during 2019.

A1c levels and medication fill rates “are important markers of the quality of diabetes care, but obviously not the only important things,” said Ateev Mehrotra, MD, corresponding author for the study and a researcher in the same department as Dr. Patel.

“Limited to the metrics we looked at and in this population we did not see any substantial negative impact of the pandemic on the care for patients with type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Mehrotra said in an interview.

“The pandemic catalyzed a tremendous shift to telemedicine among patients with diabetes. Because it is a chronic illness that requires frequent check-ins, diabetes is particularly well suited to using telemedicine,” he added.

Telemedicine not a complete replacement for in-patient visits

Dr. Gabbay agreed that “providers and patients have found telemedicine to be a helpful tool for managing patients with diabetes.”

But “most people do not think of this as a complete replacement for in-person visits, and most [U.S.] institutions have started to have more in-person visits. It’s probably about 50/50 at this point,” he said in an interview.

“It represents an impressive effort by the health care community to pivot toward telehealth to ensure that patients with diabetes continue to get care.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Gabbay added that “despite the success of telemedicine many patients still prefer to see their providers in person. I have a number of patients who were overjoyed to come in and be seen in person even when I offered telemedicine as an alternative. There is a relationship and trust piece that is more profound in person.”

And he cautioned that, although A1c “is a helpful measure, it may not fully demonstrate the percentage of patients at high risk.”

The data in the study by Dr. Patel and coauthors showing a steady level of medication refills during the pandemic “is encouraging,” he said, speculating that “people may have had more time [during the pandemic] to focus on medication adherence.”

More evidence of telemedicine’s leap

Other U.S. sites that follow patients with type 2 diabetes have recently reported similar findings, albeit on a much more localized level.

At Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., telemedicine consultations for patients with diabetes or other endocrinology disorders spurted from essentially none prior to March 2020 to a peak of nearly 700 visits/week in early May 2020, and then maintained a rate of roughly 500 telemedicine consultations weekly through the end of 2020, said Michelle L. Griffth, MD, during a talk at the 2021 annual ADA scientific sessions.

“We’ve made telehealth a permanent part of our practice,” said Dr. Griffith, medical director of telehealth ambulatory services at Vanderbilt. “We can use this boom in telehealth as a catalyst for diabetes-practice evolution,” she suggested.