User login

COVID-19: Guiding vaccinated patients through to the ‘new normal’

As COVID-related restrictions are lifting and the streets, restaurants, and events are filling back up, we must encourage our patients to take inventory. It is time to help them create posttraumatic growth.

As we help them navigate this part of the pandemic, encourage them to ask what they learned over the last year and how they plan to integrate what they’ve been through to successfully create the “new normal.”

The Biden administration had set a goal of getting at least one shot to 70% of American adults by July 4, and that goal will not be reached. That shortfall, combined with the increase of the highly transmissible Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 means that we and our patients must not let our guards completely down. At the same time, we can encourage our vaccinated patients to get back to their prepandemic lives – to the extent that they feel comfortable doing so.

Ultimately, this is about respecting physical and emotional boundaries. How do we greet vaccinated people now? Is it okay to shake hands, hug, or kiss to greet a friend or family member – or should we continue to elbow bump – or perhaps wave? Should we confront family members who have opted not to get vaccinated for reasons not related to health? Is it safe to visit with older relatives who are vaccinated? What about children under 12 who are not?

Those who were on the front lines of the pandemic faced unfathomable pain and suffering – and mental and physical exhaustion. And we know that the nightmare is not over. Several areas of the country with large numbers of unvaccinated people could face “very dense outbreaks,” in large part because of the Delta variant.

As we sort through the remaining challenges, I urge us all to reflect. We have been in this together and will emerge together. We know that the closer we were to the trauma, the longer recovery will take.

Ask patients to consider what is most important to resume and what can still wait. Some are eager to jump back into the deep end of the pool; others prefer to continue to wait cautiously. Families need to be on the same page as they assess risks and opportunities going forward, because household spread continues to be at the highest risk. Remind patients that the health of one of us affects the health of all of us.

Urge patients to take time to explore the following questions as they process the pandemic. We can also ask ourselves these same questions and share them with colleagues who are also rebuilding.

- Did you prioritize your family more? How can you continue to spend quality time them as other opportunities emerge?

- Did you have to withdraw from friends/coworkers and family members because of the pandemic? If so, how can you reincorporate them in our lives?

- Did you send more time caring for yourself with exercise and meditation? Can those new habits remain in place as life presents more options? How can you continue to make time for self-care while adding back other responsibilities?

- Did you eat better or worse in quarantine? Can you maintain the positive habits you developed as you venture back to restaurants, parties, and gatherings?

- What habits did you break that you are now better off without?

- What new habits or hobbies did you create that you want to continue?

- What hobbies should you resume that you missed during the last year?

- What new coping skills have you gained?

- Has your alcohol consumption declined or increased during the pandemic?

- Did you neglect/decide to forgo your medical and dental care? How quickly can you safely resume that care?

- How did your value system shift this year?

- Did the people you feel closest to change?

- How can you use this trauma to appreciate life more?

Life might get very busy this summer, so encourage patients to find time to answer these questions. Journaling can be a great way to think through all that we have experienced. Our brains will need to change again to adapt. Many of us have felt sad or anxious for a quite a while, and we want to move toward more positive feelings of safety, happiness, optimism, and joy. This will take effort. After all, we have lost more than 600,000 people to COVID, and much of the world is still in the middle of the pandemic. But this will get much easier as the threat of COVID-19 continues to recede. We must now work toward creating better times ahead.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

As COVID-related restrictions are lifting and the streets, restaurants, and events are filling back up, we must encourage our patients to take inventory. It is time to help them create posttraumatic growth.

As we help them navigate this part of the pandemic, encourage them to ask what they learned over the last year and how they plan to integrate what they’ve been through to successfully create the “new normal.”

The Biden administration had set a goal of getting at least one shot to 70% of American adults by July 4, and that goal will not be reached. That shortfall, combined with the increase of the highly transmissible Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 means that we and our patients must not let our guards completely down. At the same time, we can encourage our vaccinated patients to get back to their prepandemic lives – to the extent that they feel comfortable doing so.

Ultimately, this is about respecting physical and emotional boundaries. How do we greet vaccinated people now? Is it okay to shake hands, hug, or kiss to greet a friend or family member – or should we continue to elbow bump – or perhaps wave? Should we confront family members who have opted not to get vaccinated for reasons not related to health? Is it safe to visit with older relatives who are vaccinated? What about children under 12 who are not?

Those who were on the front lines of the pandemic faced unfathomable pain and suffering – and mental and physical exhaustion. And we know that the nightmare is not over. Several areas of the country with large numbers of unvaccinated people could face “very dense outbreaks,” in large part because of the Delta variant.

As we sort through the remaining challenges, I urge us all to reflect. We have been in this together and will emerge together. We know that the closer we were to the trauma, the longer recovery will take.

Ask patients to consider what is most important to resume and what can still wait. Some are eager to jump back into the deep end of the pool; others prefer to continue to wait cautiously. Families need to be on the same page as they assess risks and opportunities going forward, because household spread continues to be at the highest risk. Remind patients that the health of one of us affects the health of all of us.

Urge patients to take time to explore the following questions as they process the pandemic. We can also ask ourselves these same questions and share them with colleagues who are also rebuilding.

- Did you prioritize your family more? How can you continue to spend quality time them as other opportunities emerge?

- Did you have to withdraw from friends/coworkers and family members because of the pandemic? If so, how can you reincorporate them in our lives?

- Did you send more time caring for yourself with exercise and meditation? Can those new habits remain in place as life presents more options? How can you continue to make time for self-care while adding back other responsibilities?

- Did you eat better or worse in quarantine? Can you maintain the positive habits you developed as you venture back to restaurants, parties, and gatherings?

- What habits did you break that you are now better off without?

- What new habits or hobbies did you create that you want to continue?

- What hobbies should you resume that you missed during the last year?

- What new coping skills have you gained?

- Has your alcohol consumption declined or increased during the pandemic?

- Did you neglect/decide to forgo your medical and dental care? How quickly can you safely resume that care?

- How did your value system shift this year?

- Did the people you feel closest to change?

- How can you use this trauma to appreciate life more?

Life might get very busy this summer, so encourage patients to find time to answer these questions. Journaling can be a great way to think through all that we have experienced. Our brains will need to change again to adapt. Many of us have felt sad or anxious for a quite a while, and we want to move toward more positive feelings of safety, happiness, optimism, and joy. This will take effort. After all, we have lost more than 600,000 people to COVID, and much of the world is still in the middle of the pandemic. But this will get much easier as the threat of COVID-19 continues to recede. We must now work toward creating better times ahead.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

As COVID-related restrictions are lifting and the streets, restaurants, and events are filling back up, we must encourage our patients to take inventory. It is time to help them create posttraumatic growth.

As we help them navigate this part of the pandemic, encourage them to ask what they learned over the last year and how they plan to integrate what they’ve been through to successfully create the “new normal.”

The Biden administration had set a goal of getting at least one shot to 70% of American adults by July 4, and that goal will not be reached. That shortfall, combined with the increase of the highly transmissible Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 means that we and our patients must not let our guards completely down. At the same time, we can encourage our vaccinated patients to get back to their prepandemic lives – to the extent that they feel comfortable doing so.

Ultimately, this is about respecting physical and emotional boundaries. How do we greet vaccinated people now? Is it okay to shake hands, hug, or kiss to greet a friend or family member – or should we continue to elbow bump – or perhaps wave? Should we confront family members who have opted not to get vaccinated for reasons not related to health? Is it safe to visit with older relatives who are vaccinated? What about children under 12 who are not?

Those who were on the front lines of the pandemic faced unfathomable pain and suffering – and mental and physical exhaustion. And we know that the nightmare is not over. Several areas of the country with large numbers of unvaccinated people could face “very dense outbreaks,” in large part because of the Delta variant.

As we sort through the remaining challenges, I urge us all to reflect. We have been in this together and will emerge together. We know that the closer we were to the trauma, the longer recovery will take.

Ask patients to consider what is most important to resume and what can still wait. Some are eager to jump back into the deep end of the pool; others prefer to continue to wait cautiously. Families need to be on the same page as they assess risks and opportunities going forward, because household spread continues to be at the highest risk. Remind patients that the health of one of us affects the health of all of us.

Urge patients to take time to explore the following questions as they process the pandemic. We can also ask ourselves these same questions and share them with colleagues who are also rebuilding.

- Did you prioritize your family more? How can you continue to spend quality time them as other opportunities emerge?

- Did you have to withdraw from friends/coworkers and family members because of the pandemic? If so, how can you reincorporate them in our lives?

- Did you send more time caring for yourself with exercise and meditation? Can those new habits remain in place as life presents more options? How can you continue to make time for self-care while adding back other responsibilities?

- Did you eat better or worse in quarantine? Can you maintain the positive habits you developed as you venture back to restaurants, parties, and gatherings?

- What habits did you break that you are now better off without?

- What new habits or hobbies did you create that you want to continue?

- What hobbies should you resume that you missed during the last year?

- What new coping skills have you gained?

- Has your alcohol consumption declined or increased during the pandemic?

- Did you neglect/decide to forgo your medical and dental care? How quickly can you safely resume that care?

- How did your value system shift this year?

- Did the people you feel closest to change?

- How can you use this trauma to appreciate life more?

Life might get very busy this summer, so encourage patients to find time to answer these questions. Journaling can be a great way to think through all that we have experienced. Our brains will need to change again to adapt. Many of us have felt sad or anxious for a quite a while, and we want to move toward more positive feelings of safety, happiness, optimism, and joy. This will take effort. After all, we have lost more than 600,000 people to COVID, and much of the world is still in the middle of the pandemic. But this will get much easier as the threat of COVID-19 continues to recede. We must now work toward creating better times ahead.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

Stimulant reduces ‘sluggish cognitive tempo’ in adults with ADHD

A stimulant used in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder might prove useful for other comorbid symptoms, results of a randomized, crossover trial suggest.

In the trial, the investigators reported that lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) reduced self-reported symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) by 30%, in addition to lowering ADHD symptoms by more than 40%.

The drug also corrected deficits in executive brain function. Patients had fewer episodes of procrastination, were better able to prioritize, and showed improvements in keeping things in mind.

“These findings highlight the importance of assessing symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo and executive brain function in patients when they are initially diagnosed with ADHD,” Lenard A. Adler, MD, the lead author, said in a press release. The results were published June 29, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The trial is groundbreaking because it is the first treatment study for ADHD with SCT in adults, Dr. Adler, director of the adult ADHD program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. He said that Russell A. Barkley, PhD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, defines SCT as having nine cardinal symptoms: prone to daydreaming, easy boredom, trouble staying awake, feeling foggy, spaciness, lethargy, underachieving, less energy, and not processing information quickly or accurately.

Dr. Barkley, who studied more than 1,200 individuals with SCT, discovered that nearly half also had ADHD, Dr. Adler said. Those with the comorbid symptoms also had more impairment.

Whether or not the symptom set of SCT is a distinct disorder or a cotraveling symptom set that goes along with ADHD has been an area of investigation, said Dr. Adler, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University. Other known comorbid symptoms include executive function deficits and trouble with emotional control.

Stimulants to date have only shown success in children, as far as improving SCT. The goal of this study was to determine the efficacy of lisdexamfetamine on the nature and severity of ADHD symptoms and SCT behavioral indicators in adults with ADHD and SCT.

Two cohorts, alternating regimens

The investigators enrolled 38 adults with DSM-5 ADHD and SCT. Patients were recruited from two academic centers, New York University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The randomized 10-week crossover trial included two double-blind treatment periods, each 4 weeks long, with an intervening 2-week, single-blind placebo washout period.

“In crossover design, patients act as their own control, because they receive both treatments,” Dr. Adler said. Recruiting a smaller number of subjects helps to achieve significance in results.

For the first 4 weeks, participants received daily doses of either lisdexamfetamine (30-70 mg/day; mean, 59.1 mg/day) or a placebo sugar pill (mean, 66.6 mg/day). Researchers used standardized tests for SCT signs and symptoms, ADHD, and other measures of brain function to track psychiatric health on a weekly basis. After a month, the two cohorts switched regimens – those taking the placebo started the daily doses of lisdexamfetamine, and the other half stopped the drug and started taking the placebo.

Primary outcomes included the ADHD Rating Scale and Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV SCT subscale.

Compared with placebo, adults with ADHD and comorbid SCT showed significant improvement after taking lisdexamfetamine in ratings of SCT and total ADHD symptoms. This was also true of other comorbid symptoms, such as executive function deficits.

In the crossover design, patients who received the drug first hadn’t gone fully back to baseline by the time the investigators crossed them over into the placebo group. “So, we couldn’t combine the two treatment epochs,” Dr. Adler said. However, the effect of the drug versus placebo was comparable in both study arms.

SCT alone was not studied

The trial had some limitations, mainly that it was an initial study with a modest sample size, Dr. Adler said. It also did not examine SCT alone, “so we can’t really say whether the stimulant medicine would improve SCT in patients who don’t have ADHD. What’s notable is when you look at how much of the improvement in SCT was due to improvement in ADHD, it was just 25%.” This means the effects occurring on SCT symptoms were not solely caused by effects on ADHD.

he said.

Dr. Adler would like to see treatment studies of adults with ADHD and SCT in a larger sample, potentially with other stimulants. In addition, future trials could examine the effects of stimulants on adults with SCT that do not have ADHD.

The results of this trial underscore the importance of evaluating adults with ADHD for comorbid symptoms, such as executive function and emotional control, he continued. “Impairing SCT symptoms may very well fall under that umbrella,” Dr. Adler said. “If you don’t identify them, you can’t track them in terms of treatment.”

SCT as a ‘flavor’ of ADHD

The outcome of this study demonstrates that lisdexamfetamine significantly improves both ADHD symptoms and SCT symptoms, said David W. Goodman MD, LFAPA, an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Goodman, who was not involved in the study, agreed that clinicians should be aware of SCT when assessing adults with ADHD and conceptualize SCT as a “flavor” of ADHD. “SCT is not widely recognized by clinicians outside of the research arena but will likely become an important characteristic of ADHD presentation,” he said in an interview.

“Future studies in adult ADHD should further clarify the prevalence of SCT in the ADHD population and address more specific effective treatment options,” he said.

James M. Swanson, PhD, who also was not involved with the study, agreed in an interview that it documents the clear short-term benefit of stimulants on symptoms of SCT. The study “may be very timely, since adults who were affected by COVID-19 often have residual sequelae manifested as ‘brain fog,’ which resemble SCT,” said Dr. Swanson, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.

The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical, manufacturer of lisdexamfetamine. Dr. Adler has received grant/research support and has served as a consultant from Shire/Takeda and other companies. Dr. Goodman is a scientific consultant to Takeda and other pharmaceutical companies in the ADHD arena. Dr. Swanson had no disclosures.

A stimulant used in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder might prove useful for other comorbid symptoms, results of a randomized, crossover trial suggest.

In the trial, the investigators reported that lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) reduced self-reported symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) by 30%, in addition to lowering ADHD symptoms by more than 40%.

The drug also corrected deficits in executive brain function. Patients had fewer episodes of procrastination, were better able to prioritize, and showed improvements in keeping things in mind.

“These findings highlight the importance of assessing symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo and executive brain function in patients when they are initially diagnosed with ADHD,” Lenard A. Adler, MD, the lead author, said in a press release. The results were published June 29, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The trial is groundbreaking because it is the first treatment study for ADHD with SCT in adults, Dr. Adler, director of the adult ADHD program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. He said that Russell A. Barkley, PhD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, defines SCT as having nine cardinal symptoms: prone to daydreaming, easy boredom, trouble staying awake, feeling foggy, spaciness, lethargy, underachieving, less energy, and not processing information quickly or accurately.

Dr. Barkley, who studied more than 1,200 individuals with SCT, discovered that nearly half also had ADHD, Dr. Adler said. Those with the comorbid symptoms also had more impairment.

Whether or not the symptom set of SCT is a distinct disorder or a cotraveling symptom set that goes along with ADHD has been an area of investigation, said Dr. Adler, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University. Other known comorbid symptoms include executive function deficits and trouble with emotional control.

Stimulants to date have only shown success in children, as far as improving SCT. The goal of this study was to determine the efficacy of lisdexamfetamine on the nature and severity of ADHD symptoms and SCT behavioral indicators in adults with ADHD and SCT.

Two cohorts, alternating regimens

The investigators enrolled 38 adults with DSM-5 ADHD and SCT. Patients were recruited from two academic centers, New York University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The randomized 10-week crossover trial included two double-blind treatment periods, each 4 weeks long, with an intervening 2-week, single-blind placebo washout period.

“In crossover design, patients act as their own control, because they receive both treatments,” Dr. Adler said. Recruiting a smaller number of subjects helps to achieve significance in results.

For the first 4 weeks, participants received daily doses of either lisdexamfetamine (30-70 mg/day; mean, 59.1 mg/day) or a placebo sugar pill (mean, 66.6 mg/day). Researchers used standardized tests for SCT signs and symptoms, ADHD, and other measures of brain function to track psychiatric health on a weekly basis. After a month, the two cohorts switched regimens – those taking the placebo started the daily doses of lisdexamfetamine, and the other half stopped the drug and started taking the placebo.

Primary outcomes included the ADHD Rating Scale and Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV SCT subscale.

Compared with placebo, adults with ADHD and comorbid SCT showed significant improvement after taking lisdexamfetamine in ratings of SCT and total ADHD symptoms. This was also true of other comorbid symptoms, such as executive function deficits.

In the crossover design, patients who received the drug first hadn’t gone fully back to baseline by the time the investigators crossed them over into the placebo group. “So, we couldn’t combine the two treatment epochs,” Dr. Adler said. However, the effect of the drug versus placebo was comparable in both study arms.

SCT alone was not studied

The trial had some limitations, mainly that it was an initial study with a modest sample size, Dr. Adler said. It also did not examine SCT alone, “so we can’t really say whether the stimulant medicine would improve SCT in patients who don’t have ADHD. What’s notable is when you look at how much of the improvement in SCT was due to improvement in ADHD, it was just 25%.” This means the effects occurring on SCT symptoms were not solely caused by effects on ADHD.

he said.

Dr. Adler would like to see treatment studies of adults with ADHD and SCT in a larger sample, potentially with other stimulants. In addition, future trials could examine the effects of stimulants on adults with SCT that do not have ADHD.

The results of this trial underscore the importance of evaluating adults with ADHD for comorbid symptoms, such as executive function and emotional control, he continued. “Impairing SCT symptoms may very well fall under that umbrella,” Dr. Adler said. “If you don’t identify them, you can’t track them in terms of treatment.”

SCT as a ‘flavor’ of ADHD

The outcome of this study demonstrates that lisdexamfetamine significantly improves both ADHD symptoms and SCT symptoms, said David W. Goodman MD, LFAPA, an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Goodman, who was not involved in the study, agreed that clinicians should be aware of SCT when assessing adults with ADHD and conceptualize SCT as a “flavor” of ADHD. “SCT is not widely recognized by clinicians outside of the research arena but will likely become an important characteristic of ADHD presentation,” he said in an interview.

“Future studies in adult ADHD should further clarify the prevalence of SCT in the ADHD population and address more specific effective treatment options,” he said.

James M. Swanson, PhD, who also was not involved with the study, agreed in an interview that it documents the clear short-term benefit of stimulants on symptoms of SCT. The study “may be very timely, since adults who were affected by COVID-19 often have residual sequelae manifested as ‘brain fog,’ which resemble SCT,” said Dr. Swanson, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.

The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical, manufacturer of lisdexamfetamine. Dr. Adler has received grant/research support and has served as a consultant from Shire/Takeda and other companies. Dr. Goodman is a scientific consultant to Takeda and other pharmaceutical companies in the ADHD arena. Dr. Swanson had no disclosures.

A stimulant used in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder might prove useful for other comorbid symptoms, results of a randomized, crossover trial suggest.

In the trial, the investigators reported that lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) reduced self-reported symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) by 30%, in addition to lowering ADHD symptoms by more than 40%.

The drug also corrected deficits in executive brain function. Patients had fewer episodes of procrastination, were better able to prioritize, and showed improvements in keeping things in mind.

“These findings highlight the importance of assessing symptoms of sluggish cognitive tempo and executive brain function in patients when they are initially diagnosed with ADHD,” Lenard A. Adler, MD, the lead author, said in a press release. The results were published June 29, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The trial is groundbreaking because it is the first treatment study for ADHD with SCT in adults, Dr. Adler, director of the adult ADHD program at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. He said that Russell A. Barkley, PhD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, defines SCT as having nine cardinal symptoms: prone to daydreaming, easy boredom, trouble staying awake, feeling foggy, spaciness, lethargy, underachieving, less energy, and not processing information quickly or accurately.

Dr. Barkley, who studied more than 1,200 individuals with SCT, discovered that nearly half also had ADHD, Dr. Adler said. Those with the comorbid symptoms also had more impairment.

Whether or not the symptom set of SCT is a distinct disorder or a cotraveling symptom set that goes along with ADHD has been an area of investigation, said Dr. Adler, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University. Other known comorbid symptoms include executive function deficits and trouble with emotional control.

Stimulants to date have only shown success in children, as far as improving SCT. The goal of this study was to determine the efficacy of lisdexamfetamine on the nature and severity of ADHD symptoms and SCT behavioral indicators in adults with ADHD and SCT.

Two cohorts, alternating regimens

The investigators enrolled 38 adults with DSM-5 ADHD and SCT. Patients were recruited from two academic centers, New York University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The randomized 10-week crossover trial included two double-blind treatment periods, each 4 weeks long, with an intervening 2-week, single-blind placebo washout period.

“In crossover design, patients act as their own control, because they receive both treatments,” Dr. Adler said. Recruiting a smaller number of subjects helps to achieve significance in results.

For the first 4 weeks, participants received daily doses of either lisdexamfetamine (30-70 mg/day; mean, 59.1 mg/day) or a placebo sugar pill (mean, 66.6 mg/day). Researchers used standardized tests for SCT signs and symptoms, ADHD, and other measures of brain function to track psychiatric health on a weekly basis. After a month, the two cohorts switched regimens – those taking the placebo started the daily doses of lisdexamfetamine, and the other half stopped the drug and started taking the placebo.

Primary outcomes included the ADHD Rating Scale and Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV SCT subscale.

Compared with placebo, adults with ADHD and comorbid SCT showed significant improvement after taking lisdexamfetamine in ratings of SCT and total ADHD symptoms. This was also true of other comorbid symptoms, such as executive function deficits.

In the crossover design, patients who received the drug first hadn’t gone fully back to baseline by the time the investigators crossed them over into the placebo group. “So, we couldn’t combine the two treatment epochs,” Dr. Adler said. However, the effect of the drug versus placebo was comparable in both study arms.

SCT alone was not studied

The trial had some limitations, mainly that it was an initial study with a modest sample size, Dr. Adler said. It also did not examine SCT alone, “so we can’t really say whether the stimulant medicine would improve SCT in patients who don’t have ADHD. What’s notable is when you look at how much of the improvement in SCT was due to improvement in ADHD, it was just 25%.” This means the effects occurring on SCT symptoms were not solely caused by effects on ADHD.

he said.

Dr. Adler would like to see treatment studies of adults with ADHD and SCT in a larger sample, potentially with other stimulants. In addition, future trials could examine the effects of stimulants on adults with SCT that do not have ADHD.

The results of this trial underscore the importance of evaluating adults with ADHD for comorbid symptoms, such as executive function and emotional control, he continued. “Impairing SCT symptoms may very well fall under that umbrella,” Dr. Adler said. “If you don’t identify them, you can’t track them in terms of treatment.”

SCT as a ‘flavor’ of ADHD

The outcome of this study demonstrates that lisdexamfetamine significantly improves both ADHD symptoms and SCT symptoms, said David W. Goodman MD, LFAPA, an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Dr. Goodman, who was not involved in the study, agreed that clinicians should be aware of SCT when assessing adults with ADHD and conceptualize SCT as a “flavor” of ADHD. “SCT is not widely recognized by clinicians outside of the research arena but will likely become an important characteristic of ADHD presentation,” he said in an interview.

“Future studies in adult ADHD should further clarify the prevalence of SCT in the ADHD population and address more specific effective treatment options,” he said.

James M. Swanson, PhD, who also was not involved with the study, agreed in an interview that it documents the clear short-term benefit of stimulants on symptoms of SCT. The study “may be very timely, since adults who were affected by COVID-19 often have residual sequelae manifested as ‘brain fog,’ which resemble SCT,” said Dr. Swanson, professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.

The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical, manufacturer of lisdexamfetamine. Dr. Adler has received grant/research support and has served as a consultant from Shire/Takeda and other companies. Dr. Goodman is a scientific consultant to Takeda and other pharmaceutical companies in the ADHD arena. Dr. Swanson had no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

A pacemaker that 'just disappears' and a magnetic diet device

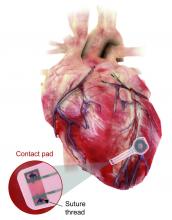

Ignore this pacemaker and it will go away

At some point – and now seems to be that point – we have to say enough is enough. The throwaway culture that produces phones, TVs, and computers that get tossed in the trash because they can’t be repaired has gone too far. That’s right, we’re looking at you, medical science!

This time, it’s a pacemaker that just disappears when it’s no longer needed. Some lazy heart surgeon decided that it was way too much trouble to do another surgery to remove the leads when a temporary pacemaker was no longer needed. You know the type: “It sure would be nice if the pacemaker components were biocompatible and were naturally absorbed by the body over the course of a few weeks and wouldn’t need to be surgically extracted.” Slacker.

Well, get a load of this. Researchers at Northwestern and George Washington universities say that they have come up with a transient pacemaker that “harvests energy from an external, remote antenna using near-field communication protocols – the same technology used in smartphones for electronic payments and in RFID tags.”

That means no batteries and no wires that have to be removed and can cause infections. Because the infectious disease docs also are too lazy to do their jobs, apparently.

The lack of onboard infrastructure means that the device can be very small – it weighs less than half a gram and is only 250 microns thick. And yes, it is bioresorbable and completely harmless. It fully degrades and disappears in 5-7 weeks through the body’s natural biologic processes, “thereby avoiding the need for physical removal of the pacemaker electrodes. This is potentially a major victory for postoperative patients,” said Dr. Rishi Arora, one of the investigators.

A victory for patients, he says. Not a word about the time and effort saved by the surgeons. Typical.

It’s a mask! No, it’s a COVID-19 test!

Mask wearing has gotten more lax as people get vaccinated for COVID-19, but as wearing masks for virus prevention is becoming more normalized in western society, some saw an opportunity to make them work for diagnosis.

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University have found a way to do just that with their wearable freeze-dried cell-free (wFDCF) technology. A single push of a button releases water from a reservoir in the mask that sequentially activates three different freeze-dried biological reactions, which detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the wearer’s breath.

Initially meant as a tool for the Zika outbreak in 2015, the team made a quick pivot in May 2020. But this isn’t just some run-of-the-mill, at-home test. The data prove that the wFDCF mask is comparable to polymerase chain reactions tests, the standard in COVID-19 detection. Plus there aren’t any extra factors to deal with, like room or instrument temperature to ensure accuracy. In just 90 minutes, the mask gives results on a readout in a way similar to that of a pregnancy test. Voilà! To have COVID-19 or not to have COVID-19 is an easily answered question.

At LOTME, we think this is a big improvement from having dogs, or even three-foot rats, sniffing out coronavirus.

But wait, there’s more. “In addition to face masks, our programmable biosensors can be integrated into other garments to provide on-the-go detection of dangerous substances including viruses, bacteria, toxins, and chemical agents,” said Peter Nguyen, PhD, study coauthor and research scientist at the Wyss Institute. The technology can be used on lab coats, scrubs, military uniforms, and uniforms of first responders who may come in contact with hazardous pathogens and toxins. Think of all the lives saved and possible avoidances.

If only it could diagnose bad breath.

Finally, an excuse for the all-beer diet

Weight loss is hard work. Extremely hard work, and, as evidenced by the constant inundation and advertisement of quick fixes, crash diets, and expensive gym memberships, there’s not really a solid, 100% solution to the issue. Until now, thanks to a team of doctors from New Zealand, who’ve decided that the best way to combat obesity is to leave you in constant agony.

The DentalSlim Diet Control device is certainly a radical yet comically logical attempt to combat obesity. The creators say that the biggest problem with dieting is compliance, and, well, it’s difficult to eat too much if you can’t actually open your mouth. The metal contraption is mounted onto your teeth and uses magnetic locks to prevent the user from opening their mouths more than 2 mm. That’s less than a tenth of an inch. Which is not a lot. So not a lot that essentially all you can consume is liquid.

Oh, and they’ve got results to back up their madness. In a small study, seven otherwise healthy obese women lost an average of 5.1% of their body weight after using the DentalSlim for 2 weeks, though they did complain that the device was difficult to use, caused discomfort and difficulty speaking, made them more tense, and in general made life “less satisfying.” And one participant was able to cheat the system and consume nonhealthy food like chocolate by melting it.

So, there you are, if you want a weight-loss solution that tortures you and has far bigger holes than the one it leaves for your mouth, try the DentalSlim. Or, you know, don’t eat that eighth slice of pizza and maybe go for a walk later. Your choice.

Ignore this pacemaker and it will go away

At some point – and now seems to be that point – we have to say enough is enough. The throwaway culture that produces phones, TVs, and computers that get tossed in the trash because they can’t be repaired has gone too far. That’s right, we’re looking at you, medical science!

This time, it’s a pacemaker that just disappears when it’s no longer needed. Some lazy heart surgeon decided that it was way too much trouble to do another surgery to remove the leads when a temporary pacemaker was no longer needed. You know the type: “It sure would be nice if the pacemaker components were biocompatible and were naturally absorbed by the body over the course of a few weeks and wouldn’t need to be surgically extracted.” Slacker.

Well, get a load of this. Researchers at Northwestern and George Washington universities say that they have come up with a transient pacemaker that “harvests energy from an external, remote antenna using near-field communication protocols – the same technology used in smartphones for electronic payments and in RFID tags.”

That means no batteries and no wires that have to be removed and can cause infections. Because the infectious disease docs also are too lazy to do their jobs, apparently.

The lack of onboard infrastructure means that the device can be very small – it weighs less than half a gram and is only 250 microns thick. And yes, it is bioresorbable and completely harmless. It fully degrades and disappears in 5-7 weeks through the body’s natural biologic processes, “thereby avoiding the need for physical removal of the pacemaker electrodes. This is potentially a major victory for postoperative patients,” said Dr. Rishi Arora, one of the investigators.

A victory for patients, he says. Not a word about the time and effort saved by the surgeons. Typical.

It’s a mask! No, it’s a COVID-19 test!

Mask wearing has gotten more lax as people get vaccinated for COVID-19, but as wearing masks for virus prevention is becoming more normalized in western society, some saw an opportunity to make them work for diagnosis.

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University have found a way to do just that with their wearable freeze-dried cell-free (wFDCF) technology. A single push of a button releases water from a reservoir in the mask that sequentially activates three different freeze-dried biological reactions, which detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the wearer’s breath.

Initially meant as a tool for the Zika outbreak in 2015, the team made a quick pivot in May 2020. But this isn’t just some run-of-the-mill, at-home test. The data prove that the wFDCF mask is comparable to polymerase chain reactions tests, the standard in COVID-19 detection. Plus there aren’t any extra factors to deal with, like room or instrument temperature to ensure accuracy. In just 90 minutes, the mask gives results on a readout in a way similar to that of a pregnancy test. Voilà! To have COVID-19 or not to have COVID-19 is an easily answered question.

At LOTME, we think this is a big improvement from having dogs, or even three-foot rats, sniffing out coronavirus.

But wait, there’s more. “In addition to face masks, our programmable biosensors can be integrated into other garments to provide on-the-go detection of dangerous substances including viruses, bacteria, toxins, and chemical agents,” said Peter Nguyen, PhD, study coauthor and research scientist at the Wyss Institute. The technology can be used on lab coats, scrubs, military uniforms, and uniforms of first responders who may come in contact with hazardous pathogens and toxins. Think of all the lives saved and possible avoidances.

If only it could diagnose bad breath.

Finally, an excuse for the all-beer diet

Weight loss is hard work. Extremely hard work, and, as evidenced by the constant inundation and advertisement of quick fixes, crash diets, and expensive gym memberships, there’s not really a solid, 100% solution to the issue. Until now, thanks to a team of doctors from New Zealand, who’ve decided that the best way to combat obesity is to leave you in constant agony.

The DentalSlim Diet Control device is certainly a radical yet comically logical attempt to combat obesity. The creators say that the biggest problem with dieting is compliance, and, well, it’s difficult to eat too much if you can’t actually open your mouth. The metal contraption is mounted onto your teeth and uses magnetic locks to prevent the user from opening their mouths more than 2 mm. That’s less than a tenth of an inch. Which is not a lot. So not a lot that essentially all you can consume is liquid.

Oh, and they’ve got results to back up their madness. In a small study, seven otherwise healthy obese women lost an average of 5.1% of their body weight after using the DentalSlim for 2 weeks, though they did complain that the device was difficult to use, caused discomfort and difficulty speaking, made them more tense, and in general made life “less satisfying.” And one participant was able to cheat the system and consume nonhealthy food like chocolate by melting it.

So, there you are, if you want a weight-loss solution that tortures you and has far bigger holes than the one it leaves for your mouth, try the DentalSlim. Or, you know, don’t eat that eighth slice of pizza and maybe go for a walk later. Your choice.

Ignore this pacemaker and it will go away

At some point – and now seems to be that point – we have to say enough is enough. The throwaway culture that produces phones, TVs, and computers that get tossed in the trash because they can’t be repaired has gone too far. That’s right, we’re looking at you, medical science!

This time, it’s a pacemaker that just disappears when it’s no longer needed. Some lazy heart surgeon decided that it was way too much trouble to do another surgery to remove the leads when a temporary pacemaker was no longer needed. You know the type: “It sure would be nice if the pacemaker components were biocompatible and were naturally absorbed by the body over the course of a few weeks and wouldn’t need to be surgically extracted.” Slacker.

Well, get a load of this. Researchers at Northwestern and George Washington universities say that they have come up with a transient pacemaker that “harvests energy from an external, remote antenna using near-field communication protocols – the same technology used in smartphones for electronic payments and in RFID tags.”

That means no batteries and no wires that have to be removed and can cause infections. Because the infectious disease docs also are too lazy to do their jobs, apparently.

The lack of onboard infrastructure means that the device can be very small – it weighs less than half a gram and is only 250 microns thick. And yes, it is bioresorbable and completely harmless. It fully degrades and disappears in 5-7 weeks through the body’s natural biologic processes, “thereby avoiding the need for physical removal of the pacemaker electrodes. This is potentially a major victory for postoperative patients,” said Dr. Rishi Arora, one of the investigators.

A victory for patients, he says. Not a word about the time and effort saved by the surgeons. Typical.

It’s a mask! No, it’s a COVID-19 test!

Mask wearing has gotten more lax as people get vaccinated for COVID-19, but as wearing masks for virus prevention is becoming more normalized in western society, some saw an opportunity to make them work for diagnosis.

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University have found a way to do just that with their wearable freeze-dried cell-free (wFDCF) technology. A single push of a button releases water from a reservoir in the mask that sequentially activates three different freeze-dried biological reactions, which detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the wearer’s breath.

Initially meant as a tool for the Zika outbreak in 2015, the team made a quick pivot in May 2020. But this isn’t just some run-of-the-mill, at-home test. The data prove that the wFDCF mask is comparable to polymerase chain reactions tests, the standard in COVID-19 detection. Plus there aren’t any extra factors to deal with, like room or instrument temperature to ensure accuracy. In just 90 minutes, the mask gives results on a readout in a way similar to that of a pregnancy test. Voilà! To have COVID-19 or not to have COVID-19 is an easily answered question.

At LOTME, we think this is a big improvement from having dogs, or even three-foot rats, sniffing out coronavirus.

But wait, there’s more. “In addition to face masks, our programmable biosensors can be integrated into other garments to provide on-the-go detection of dangerous substances including viruses, bacteria, toxins, and chemical agents,” said Peter Nguyen, PhD, study coauthor and research scientist at the Wyss Institute. The technology can be used on lab coats, scrubs, military uniforms, and uniforms of first responders who may come in contact with hazardous pathogens and toxins. Think of all the lives saved and possible avoidances.

If only it could diagnose bad breath.

Finally, an excuse for the all-beer diet

Weight loss is hard work. Extremely hard work, and, as evidenced by the constant inundation and advertisement of quick fixes, crash diets, and expensive gym memberships, there’s not really a solid, 100% solution to the issue. Until now, thanks to a team of doctors from New Zealand, who’ve decided that the best way to combat obesity is to leave you in constant agony.

The DentalSlim Diet Control device is certainly a radical yet comically logical attempt to combat obesity. The creators say that the biggest problem with dieting is compliance, and, well, it’s difficult to eat too much if you can’t actually open your mouth. The metal contraption is mounted onto your teeth and uses magnetic locks to prevent the user from opening their mouths more than 2 mm. That’s less than a tenth of an inch. Which is not a lot. So not a lot that essentially all you can consume is liquid.

Oh, and they’ve got results to back up their madness. In a small study, seven otherwise healthy obese women lost an average of 5.1% of their body weight after using the DentalSlim for 2 weeks, though they did complain that the device was difficult to use, caused discomfort and difficulty speaking, made them more tense, and in general made life “less satisfying.” And one participant was able to cheat the system and consume nonhealthy food like chocolate by melting it.

So, there you are, if you want a weight-loss solution that tortures you and has far bigger holes than the one it leaves for your mouth, try the DentalSlim. Or, you know, don’t eat that eighth slice of pizza and maybe go for a walk later. Your choice.

Two case reports identify Guillain-Barré variants after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare peripheral nerve disorder that can occur after certain types of viral and bacterial infections, has not to date been definitively linked to infection by SARS-CoV-2 or with vaccination against the virus, despite surveillance searching for such associations.

Spikes in Guillain-Barré syndrome incidence have previously, but rarely, been associated with outbreaks of other viral diseases, including Zika, but not with vaccination, except for a 1976-1977 swine influenza vaccine campaign in the United States that was seen associated with a slight elevation in risk, and was halted when that risk became known. Since then, all sorts of vaccines in the European Union and United States have come with warnings about Guillain-Barré syndrome in their package inserts – a fact that some Guillain-Barré syndrome experts lament as perpetuating the notion that vaccines cause Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Epidemiologic studies in the United Kingdom and Singapore did not detect increases in Guillain-Barré syndrome incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. And as mass vaccination against COVID-19 got underway early this year, experts cautioned against the temptation to attribute incident Guillain-Barré syndrome cases following vaccination to SARS-CoV-2 without careful statistical and epidemiological analysis. Until now reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome have been scant: clinical trials of a viral vector vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson saw one in the placebo arm and another in the intervention arm, while another case was reported following administration of a Pfizer mRNA SARS-Cov-2 vaccine.

Recent case reports

None of the patients had evidence of current SARS-CoV-2 infection.

From India, Boby V. Maramattom, MD, of Aster Medcity in Kochi, India, and colleagues reported on seven severe cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome occurring between 10 and 14 days after a first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine. All but one of the patients were women, all had bilateral facial paresis, all progressed to areflexic quadriplegia, and six required respiratory support. Patients’ ages ranged from 43 to 70. Four developed other cranial neuropathies, including abducens palsy and trigeminal sensory nerve involvement, which are rare in reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome from India, Dr. Maramattom and colleagues noted.

The authors argued that their findings “should prompt all physicians to be vigilant in recognizing Guillain-Barré syndrome in patients who have received the AstraZeneca vaccine. While the risk per patient (5.8 per million) may be relatively low, our observations suggest that this clinically distinct [Guillain-Barré syndrome] variant is more severe than usual and may require mechanical ventilation.”

The U.K. cases, reported by Christopher Martin Allen, MD, and colleagues at Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, describe bifacial weakness and normal facial sensation in four men between 11 and 22 days after their first doses of the Astra-Zeneca vaccine. This type of facial palsy, the authors wrote, was unusual Guillain-Barré syndrome variant that one rapid review found in 3 of 42 European patients diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Dr. Allen and colleagues acknowledged that causality could not be assumed from the temporal relationship of immunization to onset of bifacial weakness in their report, but argued that their findings argued for “robust postvaccination surveillance” and that “the report of a similar syndrome in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection suggests an immunologic response to the spike protein.” If the link is casual, they wrote, “it could be due to a cross-reactive immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and components of the peripheral immune system.”

‘The jury is still out’

Asked for comment, neurologist Anthony Amato, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that he did not see what the two new studies add to what is already known. “Guillain-Barré syndrome has already been reported temporally following COVID-19 along with accompanying editorials that such temporal occurrences do not imply causation and there is a need for surveillance and epidemiological studies.”

Robert Lisak, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and a longtime adviser to the GBS-CIDP Foundation International, commented that “the relationship between vaccines and association with Guillain-Barré syndrome continues to be controversial in part because Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare disorder, has many reported associated illnesses including infections. Many vaccines have been implicated but with the probable exception of the ‘swine flu’ vaccine in the 1970s, most have not stood up to scrutiny.”

With SARS-Cov-2 infection and vaccines, “the jury is still out,” Dr. Lisak said. “The report from the U.K. is intriguing since they report several cases of an uncommon variant, but the cases from India seem to be more of the usual forms of Guillain-Barré syndrome.”

Dr. Lisak noted that, even if an association turns out to be valid, “we are talking about a very low incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with COVID-19 vaccines,” one that would not justify avoiding them because of a possible association with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

The GBS-CIDP Foundation, which supports research into Guillain-Barré syndrome and related diseases, has likewise stressed the low risk presented by SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, noting on its website that “the risk of death or long-term complications from COVID in adults still far exceeds the risk of any possible risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome by several orders of magnitude.”

None of the study authors reported financial conflicts of interest related to their research. Dr. Amato is an adviser to the pharmaceutical firms Alexion and Argenx, while Dr. Lisak has received research support or honoraria from Alexion, Novartis, Hoffmann–La Roche, and others.

Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare peripheral nerve disorder that can occur after certain types of viral and bacterial infections, has not to date been definitively linked to infection by SARS-CoV-2 or with vaccination against the virus, despite surveillance searching for such associations.

Spikes in Guillain-Barré syndrome incidence have previously, but rarely, been associated with outbreaks of other viral diseases, including Zika, but not with vaccination, except for a 1976-1977 swine influenza vaccine campaign in the United States that was seen associated with a slight elevation in risk, and was halted when that risk became known. Since then, all sorts of vaccines in the European Union and United States have come with warnings about Guillain-Barré syndrome in their package inserts – a fact that some Guillain-Barré syndrome experts lament as perpetuating the notion that vaccines cause Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Epidemiologic studies in the United Kingdom and Singapore did not detect increases in Guillain-Barré syndrome incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. And as mass vaccination against COVID-19 got underway early this year, experts cautioned against the temptation to attribute incident Guillain-Barré syndrome cases following vaccination to SARS-CoV-2 without careful statistical and epidemiological analysis. Until now reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome have been scant: clinical trials of a viral vector vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson saw one in the placebo arm and another in the intervention arm, while another case was reported following administration of a Pfizer mRNA SARS-Cov-2 vaccine.

Recent case reports

None of the patients had evidence of current SARS-CoV-2 infection.

From India, Boby V. Maramattom, MD, of Aster Medcity in Kochi, India, and colleagues reported on seven severe cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome occurring between 10 and 14 days after a first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine. All but one of the patients were women, all had bilateral facial paresis, all progressed to areflexic quadriplegia, and six required respiratory support. Patients’ ages ranged from 43 to 70. Four developed other cranial neuropathies, including abducens palsy and trigeminal sensory nerve involvement, which are rare in reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome from India, Dr. Maramattom and colleagues noted.

The authors argued that their findings “should prompt all physicians to be vigilant in recognizing Guillain-Barré syndrome in patients who have received the AstraZeneca vaccine. While the risk per patient (5.8 per million) may be relatively low, our observations suggest that this clinically distinct [Guillain-Barré syndrome] variant is more severe than usual and may require mechanical ventilation.”

The U.K. cases, reported by Christopher Martin Allen, MD, and colleagues at Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, describe bifacial weakness and normal facial sensation in four men between 11 and 22 days after their first doses of the Astra-Zeneca vaccine. This type of facial palsy, the authors wrote, was unusual Guillain-Barré syndrome variant that one rapid review found in 3 of 42 European patients diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Dr. Allen and colleagues acknowledged that causality could not be assumed from the temporal relationship of immunization to onset of bifacial weakness in their report, but argued that their findings argued for “robust postvaccination surveillance” and that “the report of a similar syndrome in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection suggests an immunologic response to the spike protein.” If the link is casual, they wrote, “it could be due to a cross-reactive immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and components of the peripheral immune system.”

‘The jury is still out’

Asked for comment, neurologist Anthony Amato, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that he did not see what the two new studies add to what is already known. “Guillain-Barré syndrome has already been reported temporally following COVID-19 along with accompanying editorials that such temporal occurrences do not imply causation and there is a need for surveillance and epidemiological studies.”

Robert Lisak, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and a longtime adviser to the GBS-CIDP Foundation International, commented that “the relationship between vaccines and association with Guillain-Barré syndrome continues to be controversial in part because Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare disorder, has many reported associated illnesses including infections. Many vaccines have been implicated but with the probable exception of the ‘swine flu’ vaccine in the 1970s, most have not stood up to scrutiny.”

With SARS-Cov-2 infection and vaccines, “the jury is still out,” Dr. Lisak said. “The report from the U.K. is intriguing since they report several cases of an uncommon variant, but the cases from India seem to be more of the usual forms of Guillain-Barré syndrome.”

Dr. Lisak noted that, even if an association turns out to be valid, “we are talking about a very low incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with COVID-19 vaccines,” one that would not justify avoiding them because of a possible association with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

The GBS-CIDP Foundation, which supports research into Guillain-Barré syndrome and related diseases, has likewise stressed the low risk presented by SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, noting on its website that “the risk of death or long-term complications from COVID in adults still far exceeds the risk of any possible risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome by several orders of magnitude.”

None of the study authors reported financial conflicts of interest related to their research. Dr. Amato is an adviser to the pharmaceutical firms Alexion and Argenx, while Dr. Lisak has received research support or honoraria from Alexion, Novartis, Hoffmann–La Roche, and others.

Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare peripheral nerve disorder that can occur after certain types of viral and bacterial infections, has not to date been definitively linked to infection by SARS-CoV-2 or with vaccination against the virus, despite surveillance searching for such associations.

Spikes in Guillain-Barré syndrome incidence have previously, but rarely, been associated with outbreaks of other viral diseases, including Zika, but not with vaccination, except for a 1976-1977 swine influenza vaccine campaign in the United States that was seen associated with a slight elevation in risk, and was halted when that risk became known. Since then, all sorts of vaccines in the European Union and United States have come with warnings about Guillain-Barré syndrome in their package inserts – a fact that some Guillain-Barré syndrome experts lament as perpetuating the notion that vaccines cause Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Epidemiologic studies in the United Kingdom and Singapore did not detect increases in Guillain-Barré syndrome incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. And as mass vaccination against COVID-19 got underway early this year, experts cautioned against the temptation to attribute incident Guillain-Barré syndrome cases following vaccination to SARS-CoV-2 without careful statistical and epidemiological analysis. Until now reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome have been scant: clinical trials of a viral vector vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson saw one in the placebo arm and another in the intervention arm, while another case was reported following administration of a Pfizer mRNA SARS-Cov-2 vaccine.

Recent case reports

None of the patients had evidence of current SARS-CoV-2 infection.

From India, Boby V. Maramattom, MD, of Aster Medcity in Kochi, India, and colleagues reported on seven severe cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome occurring between 10 and 14 days after a first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine. All but one of the patients were women, all had bilateral facial paresis, all progressed to areflexic quadriplegia, and six required respiratory support. Patients’ ages ranged from 43 to 70. Four developed other cranial neuropathies, including abducens palsy and trigeminal sensory nerve involvement, which are rare in reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome from India, Dr. Maramattom and colleagues noted.

The authors argued that their findings “should prompt all physicians to be vigilant in recognizing Guillain-Barré syndrome in patients who have received the AstraZeneca vaccine. While the risk per patient (5.8 per million) may be relatively low, our observations suggest that this clinically distinct [Guillain-Barré syndrome] variant is more severe than usual and may require mechanical ventilation.”

The U.K. cases, reported by Christopher Martin Allen, MD, and colleagues at Nottingham (England) University Hospitals NHS Trust, describe bifacial weakness and normal facial sensation in four men between 11 and 22 days after their first doses of the Astra-Zeneca vaccine. This type of facial palsy, the authors wrote, was unusual Guillain-Barré syndrome variant that one rapid review found in 3 of 42 European patients diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Dr. Allen and colleagues acknowledged that causality could not be assumed from the temporal relationship of immunization to onset of bifacial weakness in their report, but argued that their findings argued for “robust postvaccination surveillance” and that “the report of a similar syndrome in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection suggests an immunologic response to the spike protein.” If the link is casual, they wrote, “it could be due to a cross-reactive immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and components of the peripheral immune system.”

‘The jury is still out’

Asked for comment, neurologist Anthony Amato, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that he did not see what the two new studies add to what is already known. “Guillain-Barré syndrome has already been reported temporally following COVID-19 along with accompanying editorials that such temporal occurrences do not imply causation and there is a need for surveillance and epidemiological studies.”

Robert Lisak, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and a longtime adviser to the GBS-CIDP Foundation International, commented that “the relationship between vaccines and association with Guillain-Barré syndrome continues to be controversial in part because Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare disorder, has many reported associated illnesses including infections. Many vaccines have been implicated but with the probable exception of the ‘swine flu’ vaccine in the 1970s, most have not stood up to scrutiny.”

With SARS-Cov-2 infection and vaccines, “the jury is still out,” Dr. Lisak said. “The report from the U.K. is intriguing since they report several cases of an uncommon variant, but the cases from India seem to be more of the usual forms of Guillain-Barré syndrome.”

Dr. Lisak noted that, even if an association turns out to be valid, “we are talking about a very low incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with COVID-19 vaccines,” one that would not justify avoiding them because of a possible association with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

The GBS-CIDP Foundation, which supports research into Guillain-Barré syndrome and related diseases, has likewise stressed the low risk presented by SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, noting on its website that “the risk of death or long-term complications from COVID in adults still far exceeds the risk of any possible risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome by several orders of magnitude.”

None of the study authors reported financial conflicts of interest related to their research. Dr. Amato is an adviser to the pharmaceutical firms Alexion and Argenx, while Dr. Lisak has received research support or honoraria from Alexion, Novartis, Hoffmann–La Roche, and others.

FROM ANNALS OF NEUROLOGY

The pandemic hurt patients with liver disease in many ways

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the health of patients with liver disease worldwide, researchers say.

Not only does liver disease make people more vulnerable to the virus that causes COVID-19, precautions to prevent its spread have delayed health care and worsened alcohol abuse.

At this year’s virtual International Liver Congress (ILC) 2021, experts from around the world documented this toll on their patients.

Surgeons have seen a surge in patients needing transplants because of alcoholic liver disease, the campaign to snuff out hepatitis C slowed down, and procedures such as endoscopy and ultrasound exams postponed, said Mario Mondelli, MD, PhD, a professor and consultant physician of infectious diseases at the University of Pavia, Italy.

“We were able to ensure only emergency treatments, not routine surveillance,” he said in an interview.

Of 1,994 people with chronic liver disease who responded to a survey through the Global Liver Registry, 11% reported that the pandemic had affected their liver health.

This proportion was not statistically different for the 165 patients (8.2%) who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 compared with those who had not. But many of those who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 reported that it severely affected them. They reported worse overall heath, more mental illness, and greater need for supportive service than those who evaded the virus. Thirty-three respondents (20.8%) were hospitalized.

The global effort to eradicate hepatitis C slowed as a result of the pandemic. Already in 2019, the United States was behind the World Health Organization schedule for eliminating this virus. In 2020, it slipped further, with 25% fewer patients starting treatment for hepatitis C than in 2019, according to researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Similar delays in eliminating hepatitis C occurred around the world, Dr. Mondelli said, noting that the majority of countries will not be able to reach the WHO objectives.

One striking result of the pandemic was an uptick of patients needing liver transplants as a result of alcoholic liver disease, said George Cholankeril, MD, a liver transplant surgeon at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Before the pandemic, he and his colleagues had noted an increase in the number of people needing liver transplants because of alcohol abuse. During the pandemic, that trend accelerated.

They defined the pre-COVID era as June 1, 2019, to Feb. 29, 2020, and the COVID era as after April 1, 2020. In the COVID era, alcoholic liver disease accounted for 40% of patients whom the hospital put on its list for liver transplant. Hepatitis C and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease combined accounted for only 36%.

The change has resulted in part from the effectiveness of hepatitis C treatments, which have reduced the number of patients with livers damaged by that virus. But the change also resulted from the increased severity of illness in the patients with alcoholic liver disease, Dr. Cholankeril said in an interview. Overall, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores – which are used to predict survival – worsened for patients with alcoholic liver disease but remained the same for patients with nonalcoholic liver disease.

In the pre-COVID era, patients with alcoholic liver disease had a 10% higher chance for undergoing transplant, compared with patients with nonalcoholic liver disease. In the COVID era, they had a 50% higher chance, a statistically significant change (P < .001).

The finding parallels those of other studies that have shown a spike in consults for alcohol-related gastrointestinal and liver diseases, as reported by this news organization.

“We feel that the increase in alcoholic hepatitis is possibly from binge drinking and alcoholic consumption during the pandemic,” said Dr. Cholankeril. “Anecdotally, I can’t tell you how many patients say that the video meetings for Alcoholic Anonymous just don’t work. It’s not the same as in person. They don’t feel that they’re getting the support that they need.”

In Europe, fewer of the people who need liver transplants may be receiving them, said Dr. Mondelli.

“There are several papers indicating, particularly in Italy, in France, and in the United Kingdom, that during the pandemic, the offer for organs significantly declined,” he said.

Other studies have shown increases in mortality from liver disease during the pandemic, Dr. Mondelli said. The same is true of myocardial infarction, cancer, and most other life-threatening illnesses, he pointed out.

“Because of the enormous tsunami that has affected hospital services during the peaks of the pandemic, there has been an increase in deceased patients from a variety of other diseases, not only liver disease,” he said.

But Dr. Mondelli also added that physicians had improved in their ability to safely care for their patients while protecting themselves over the course of the pandemic.

Dr. Mondelli and Dr. Cholankeril have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the health of patients with liver disease worldwide, researchers say.

Not only does liver disease make people more vulnerable to the virus that causes COVID-19, precautions to prevent its spread have delayed health care and worsened alcohol abuse.

At this year’s virtual International Liver Congress (ILC) 2021, experts from around the world documented this toll on their patients.

Surgeons have seen a surge in patients needing transplants because of alcoholic liver disease, the campaign to snuff out hepatitis C slowed down, and procedures such as endoscopy and ultrasound exams postponed, said Mario Mondelli, MD, PhD, a professor and consultant physician of infectious diseases at the University of Pavia, Italy.

“We were able to ensure only emergency treatments, not routine surveillance,” he said in an interview.

Of 1,994 people with chronic liver disease who responded to a survey through the Global Liver Registry, 11% reported that the pandemic had affected their liver health.

This proportion was not statistically different for the 165 patients (8.2%) who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 compared with those who had not. But many of those who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 reported that it severely affected them. They reported worse overall heath, more mental illness, and greater need for supportive service than those who evaded the virus. Thirty-three respondents (20.8%) were hospitalized.

The global effort to eradicate hepatitis C slowed as a result of the pandemic. Already in 2019, the United States was behind the World Health Organization schedule for eliminating this virus. In 2020, it slipped further, with 25% fewer patients starting treatment for hepatitis C than in 2019, according to researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Similar delays in eliminating hepatitis C occurred around the world, Dr. Mondelli said, noting that the majority of countries will not be able to reach the WHO objectives.

One striking result of the pandemic was an uptick of patients needing liver transplants as a result of alcoholic liver disease, said George Cholankeril, MD, a liver transplant surgeon at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Before the pandemic, he and his colleagues had noted an increase in the number of people needing liver transplants because of alcohol abuse. During the pandemic, that trend accelerated.

They defined the pre-COVID era as June 1, 2019, to Feb. 29, 2020, and the COVID era as after April 1, 2020. In the COVID era, alcoholic liver disease accounted for 40% of patients whom the hospital put on its list for liver transplant. Hepatitis C and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease combined accounted for only 36%.

The change has resulted in part from the effectiveness of hepatitis C treatments, which have reduced the number of patients with livers damaged by that virus. But the change also resulted from the increased severity of illness in the patients with alcoholic liver disease, Dr. Cholankeril said in an interview. Overall, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores – which are used to predict survival – worsened for patients with alcoholic liver disease but remained the same for patients with nonalcoholic liver disease.

In the pre-COVID era, patients with alcoholic liver disease had a 10% higher chance for undergoing transplant, compared with patients with nonalcoholic liver disease. In the COVID era, they had a 50% higher chance, a statistically significant change (P < .001).

The finding parallels those of other studies that have shown a spike in consults for alcohol-related gastrointestinal and liver diseases, as reported by this news organization.

“We feel that the increase in alcoholic hepatitis is possibly from binge drinking and alcoholic consumption during the pandemic,” said Dr. Cholankeril. “Anecdotally, I can’t tell you how many patients say that the video meetings for Alcoholic Anonymous just don’t work. It’s not the same as in person. They don’t feel that they’re getting the support that they need.”

In Europe, fewer of the people who need liver transplants may be receiving them, said Dr. Mondelli.

“There are several papers indicating, particularly in Italy, in France, and in the United Kingdom, that during the pandemic, the offer for organs significantly declined,” he said.

Other studies have shown increases in mortality from liver disease during the pandemic, Dr. Mondelli said. The same is true of myocardial infarction, cancer, and most other life-threatening illnesses, he pointed out.

“Because of the enormous tsunami that has affected hospital services during the peaks of the pandemic, there has been an increase in deceased patients from a variety of other diseases, not only liver disease,” he said.

But Dr. Mondelli also added that physicians had improved in their ability to safely care for their patients while protecting themselves over the course of the pandemic.

Dr. Mondelli and Dr. Cholankeril have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.