User login

Reckoning with America’s alarming rise in anti-Asian hate

On March 16, the world was witness to a horrific act of violence when a gunman killed six Asian American women and two others at spas in the Atlanta, Georgia area. The attack prompted a national outcry and protests against the rising levels of hate and violence directed at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), a community that has experienced a profound and disturbing legacy of racism in American history.

Despite this fact, my own understanding and awareness of the hate and racism experienced by the AAPI community, then and now, would be described as limited at best. Was I aware on some level? Perhaps. But if I’m being honest, I have not fully appreciated the unique experiences of AAPI colleagues, friends, and students.

That changed when I attended a White Coats Against Asian Hate & Racism rally, held by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences 2 months after the Atlanta killings. Hearing my colleagues speak of their personal experiences, I quickly realized my lack of education on the subject of how systemic racism has long affected Asian Americans in this country.

Measuring the alarming rise in anti-Asian hate

The data supporting a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes have been staring us in the face for decades but have drawn increasing attention since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when these already distressingly high numbers experienced a steep rise.

Before looking at these figures, though, we must begin by defining what is considered a hate crime versus a hate incident. The National Asian Pacific American Bar Association and Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum have produced a beneficial summary document on precisely what separates these terms:

- A hate crime is a crime committed on the basis of the victim’s perceived or actual race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability. It differs from “regular” crime in that its victims include the immediate crime target and others like them. Hate crimes affect families, communities, and, at times, an entire nation.

- A hate incident describes acts of prejudice that are not crimes and do not involve violence, threats, or property damage. The most common examples are isolated forms of speech, such as racial slurs.

Stop AAPI Hate (SAH) was founded in March 2020 as a coalition to track and analyze incidents of hate against this community. SAH’s 2020-2021 national report details 3,795 hate incidents that occurred from March 19, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021. In a notable parallel to the Georgia killings, SAH found that Asian American women reported hate incidents 2.3 times more often than men and that businesses were the primary site of discrimination.

This rise in hate incidents has occurred in parallel with an increase in Asian American hate crimes. Recently, the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism (CSUSB) released its Report to the Nation: Anti-Asian Prejudice & Hate Crime. I re-read that data point multiple times, thinking it must be in error. If you’re asking exactly why I was having difficulty accepting this data, you have to appreciate these two critical points:

- Per the CSUSB, anti-Asian hate crimes were already surging by 146% in 2020.

- This surge occurred while overall hate crimes dropped by 7%.

So, if 2020 was a surge, the first quarter of 2021 is a hurricane. What’s perhaps most concerning is that these data only capture reported cases and therefore are a fraction of the total.

Undoubtedly, we are living through an unprecedented rise in anti-Asian hate incidents and hate crimes since the start of the pandemic. This rise in hate-related events paralleled the many pandemic-related stressors (disease, isolation, economics, mental health, etc.). Should anyone have been surprised when this most recent deadly spike of anti-Asian hate occurred in the first quarter of 2021?

Hate’s toll on mental health

As a psychiatrist, I’ve spent my entire career working with dedicated teams to treat patients with mental health disorders. Currently, hate is not classified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a mental illness. However, I can’t think of another emotion that is a better candidate for further research and scientific instigation, if for no other reason than to better understand when prejudice and bias transform into hatred and crime.

Surprisingly, there has been relatively little research on the topic of hate in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. I’d be willing to wager that if you asked a typical graduating class of medical students to give you an actual working definition of the emotion of hate, most would be at a loss for words.

Dr. Fischer and Dr. Halperin published a helpful article that gives a functional perspective on hate. The authors cover a great deal of research on hate and offer the following four starting points valuable in considering it:

- “Hate is different from anger because an anger target is appraised as someone whose behavior can be influenced and changed.”

- “A hate target, on the contrary, implies appraisals of the other’s malevolent nature and malicious intent.”

- “Hate is characterized by appraisals that imply a stable perception of a person or group and thus the incapability to change the extremely negative characteristics attributed to the target of hate.”

- “Everyday observations also suggest that hate is so powerful that it does, not just temporarily but permanently, destroy relations between individuals or groups.”

When I view hate with these insights in mind, it completely changes how I choose to utilize the word or concept. Hate is an emotion whose goal/action tendency is to eliminate groups (not just people or obstacles) and destroy any current or future relationships. We can take this a step further in noting that hate spreads, not only to the intended targets but potentially my “own” group. Similar to secondhand smoke, there is no risk-free exposure to hate or racism.

In the past decade, a robust body of evidence has emerged that clearly illustrates the negative health impacts of racism. Dr. Paradies and colleagues performed a systematic meta-analysis explicitly focused on racism as a determinant of health, finding that it was associated with poorer mental health, including depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. Over the past two decades, researchers have increasingly looked at the effects of racial discrimination on the AAPI community. In their 2009 review article, Dr. Gee and colleagues identified 62 empirical articles assessing the relation between discrimination and health among Asian Americans. Most of the studies found that discrimination was associated with poorer health. Of the 40 studies focused on mental health, 37 reported that discrimination was associated with poorer outcomes.

SAH recently released its very illuminating Mental Health Report. Among several key findings, two in particular caught my attention. First, Asian Americans who have experienced racism are more stressed by anti-Asian hate than the pandemic itself. Second, one in five Asian Americans who have experienced racism display racial trauma, the psychological and emotional harm caused by racism. Given the rise in hate crimes, there must be concern regarding the level of trauma being inflicted upon the Asian American community.

A complete review of the health effects of racism is beyond this article’s scope. Still, the previously mentioned studies further support the need to treat racism in general, and specifically anti-Asian hate, as the urgent public health concern that it truly is. The U.S. government recently outlined an action plan to respond to anti-Asian violence, xenophobia, and bias. These are helpful first steps, but much more is required on a societal and individual level, given the mental health disparities faced by the AAPI community.

Determining the best ways to address this urgent public health concern can be overwhelming, exhausting, and outright demoralizing. The bottom line is that if we do nothing, communities and groups will continue to suffer the effects of racial hatred. These consequences are severe and transgenerational.

But we must start somewhere. For me, that begins by gaining a better understanding of the emotion of hate and my role in either facilitating or stopping it, and by listening, listening, and listening some more to AAPI colleagues, friends, and family about their lived experience with anti-Asian hate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On March 16, the world was witness to a horrific act of violence when a gunman killed six Asian American women and two others at spas in the Atlanta, Georgia area. The attack prompted a national outcry and protests against the rising levels of hate and violence directed at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), a community that has experienced a profound and disturbing legacy of racism in American history.

Despite this fact, my own understanding and awareness of the hate and racism experienced by the AAPI community, then and now, would be described as limited at best. Was I aware on some level? Perhaps. But if I’m being honest, I have not fully appreciated the unique experiences of AAPI colleagues, friends, and students.

That changed when I attended a White Coats Against Asian Hate & Racism rally, held by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences 2 months after the Atlanta killings. Hearing my colleagues speak of their personal experiences, I quickly realized my lack of education on the subject of how systemic racism has long affected Asian Americans in this country.

Measuring the alarming rise in anti-Asian hate

The data supporting a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes have been staring us in the face for decades but have drawn increasing attention since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when these already distressingly high numbers experienced a steep rise.

Before looking at these figures, though, we must begin by defining what is considered a hate crime versus a hate incident. The National Asian Pacific American Bar Association and Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum have produced a beneficial summary document on precisely what separates these terms:

- A hate crime is a crime committed on the basis of the victim’s perceived or actual race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability. It differs from “regular” crime in that its victims include the immediate crime target and others like them. Hate crimes affect families, communities, and, at times, an entire nation.

- A hate incident describes acts of prejudice that are not crimes and do not involve violence, threats, or property damage. The most common examples are isolated forms of speech, such as racial slurs.

Stop AAPI Hate (SAH) was founded in March 2020 as a coalition to track and analyze incidents of hate against this community. SAH’s 2020-2021 national report details 3,795 hate incidents that occurred from March 19, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021. In a notable parallel to the Georgia killings, SAH found that Asian American women reported hate incidents 2.3 times more often than men and that businesses were the primary site of discrimination.

This rise in hate incidents has occurred in parallel with an increase in Asian American hate crimes. Recently, the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism (CSUSB) released its Report to the Nation: Anti-Asian Prejudice & Hate Crime. I re-read that data point multiple times, thinking it must be in error. If you’re asking exactly why I was having difficulty accepting this data, you have to appreciate these two critical points:

- Per the CSUSB, anti-Asian hate crimes were already surging by 146% in 2020.

- This surge occurred while overall hate crimes dropped by 7%.

So, if 2020 was a surge, the first quarter of 2021 is a hurricane. What’s perhaps most concerning is that these data only capture reported cases and therefore are a fraction of the total.

Undoubtedly, we are living through an unprecedented rise in anti-Asian hate incidents and hate crimes since the start of the pandemic. This rise in hate-related events paralleled the many pandemic-related stressors (disease, isolation, economics, mental health, etc.). Should anyone have been surprised when this most recent deadly spike of anti-Asian hate occurred in the first quarter of 2021?

Hate’s toll on mental health

As a psychiatrist, I’ve spent my entire career working with dedicated teams to treat patients with mental health disorders. Currently, hate is not classified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a mental illness. However, I can’t think of another emotion that is a better candidate for further research and scientific instigation, if for no other reason than to better understand when prejudice and bias transform into hatred and crime.

Surprisingly, there has been relatively little research on the topic of hate in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. I’d be willing to wager that if you asked a typical graduating class of medical students to give you an actual working definition of the emotion of hate, most would be at a loss for words.

Dr. Fischer and Dr. Halperin published a helpful article that gives a functional perspective on hate. The authors cover a great deal of research on hate and offer the following four starting points valuable in considering it:

- “Hate is different from anger because an anger target is appraised as someone whose behavior can be influenced and changed.”

- “A hate target, on the contrary, implies appraisals of the other’s malevolent nature and malicious intent.”

- “Hate is characterized by appraisals that imply a stable perception of a person or group and thus the incapability to change the extremely negative characteristics attributed to the target of hate.”

- “Everyday observations also suggest that hate is so powerful that it does, not just temporarily but permanently, destroy relations between individuals or groups.”

When I view hate with these insights in mind, it completely changes how I choose to utilize the word or concept. Hate is an emotion whose goal/action tendency is to eliminate groups (not just people or obstacles) and destroy any current or future relationships. We can take this a step further in noting that hate spreads, not only to the intended targets but potentially my “own” group. Similar to secondhand smoke, there is no risk-free exposure to hate or racism.

In the past decade, a robust body of evidence has emerged that clearly illustrates the negative health impacts of racism. Dr. Paradies and colleagues performed a systematic meta-analysis explicitly focused on racism as a determinant of health, finding that it was associated with poorer mental health, including depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. Over the past two decades, researchers have increasingly looked at the effects of racial discrimination on the AAPI community. In their 2009 review article, Dr. Gee and colleagues identified 62 empirical articles assessing the relation between discrimination and health among Asian Americans. Most of the studies found that discrimination was associated with poorer health. Of the 40 studies focused on mental health, 37 reported that discrimination was associated with poorer outcomes.

SAH recently released its very illuminating Mental Health Report. Among several key findings, two in particular caught my attention. First, Asian Americans who have experienced racism are more stressed by anti-Asian hate than the pandemic itself. Second, one in five Asian Americans who have experienced racism display racial trauma, the psychological and emotional harm caused by racism. Given the rise in hate crimes, there must be concern regarding the level of trauma being inflicted upon the Asian American community.

A complete review of the health effects of racism is beyond this article’s scope. Still, the previously mentioned studies further support the need to treat racism in general, and specifically anti-Asian hate, as the urgent public health concern that it truly is. The U.S. government recently outlined an action plan to respond to anti-Asian violence, xenophobia, and bias. These are helpful first steps, but much more is required on a societal and individual level, given the mental health disparities faced by the AAPI community.

Determining the best ways to address this urgent public health concern can be overwhelming, exhausting, and outright demoralizing. The bottom line is that if we do nothing, communities and groups will continue to suffer the effects of racial hatred. These consequences are severe and transgenerational.

But we must start somewhere. For me, that begins by gaining a better understanding of the emotion of hate and my role in either facilitating or stopping it, and by listening, listening, and listening some more to AAPI colleagues, friends, and family about their lived experience with anti-Asian hate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On March 16, the world was witness to a horrific act of violence when a gunman killed six Asian American women and two others at spas in the Atlanta, Georgia area. The attack prompted a national outcry and protests against the rising levels of hate and violence directed at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), a community that has experienced a profound and disturbing legacy of racism in American history.

Despite this fact, my own understanding and awareness of the hate and racism experienced by the AAPI community, then and now, would be described as limited at best. Was I aware on some level? Perhaps. But if I’m being honest, I have not fully appreciated the unique experiences of AAPI colleagues, friends, and students.

That changed when I attended a White Coats Against Asian Hate & Racism rally, held by the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences 2 months after the Atlanta killings. Hearing my colleagues speak of their personal experiences, I quickly realized my lack of education on the subject of how systemic racism has long affected Asian Americans in this country.

Measuring the alarming rise in anti-Asian hate

The data supporting a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes have been staring us in the face for decades but have drawn increasing attention since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when these already distressingly high numbers experienced a steep rise.

Before looking at these figures, though, we must begin by defining what is considered a hate crime versus a hate incident. The National Asian Pacific American Bar Association and Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum have produced a beneficial summary document on precisely what separates these terms:

- A hate crime is a crime committed on the basis of the victim’s perceived or actual race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability. It differs from “regular” crime in that its victims include the immediate crime target and others like them. Hate crimes affect families, communities, and, at times, an entire nation.

- A hate incident describes acts of prejudice that are not crimes and do not involve violence, threats, or property damage. The most common examples are isolated forms of speech, such as racial slurs.

Stop AAPI Hate (SAH) was founded in March 2020 as a coalition to track and analyze incidents of hate against this community. SAH’s 2020-2021 national report details 3,795 hate incidents that occurred from March 19, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021. In a notable parallel to the Georgia killings, SAH found that Asian American women reported hate incidents 2.3 times more often than men and that businesses were the primary site of discrimination.

This rise in hate incidents has occurred in parallel with an increase in Asian American hate crimes. Recently, the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism (CSUSB) released its Report to the Nation: Anti-Asian Prejudice & Hate Crime. I re-read that data point multiple times, thinking it must be in error. If you’re asking exactly why I was having difficulty accepting this data, you have to appreciate these two critical points:

- Per the CSUSB, anti-Asian hate crimes were already surging by 146% in 2020.

- This surge occurred while overall hate crimes dropped by 7%.

So, if 2020 was a surge, the first quarter of 2021 is a hurricane. What’s perhaps most concerning is that these data only capture reported cases and therefore are a fraction of the total.

Undoubtedly, we are living through an unprecedented rise in anti-Asian hate incidents and hate crimes since the start of the pandemic. This rise in hate-related events paralleled the many pandemic-related stressors (disease, isolation, economics, mental health, etc.). Should anyone have been surprised when this most recent deadly spike of anti-Asian hate occurred in the first quarter of 2021?

Hate’s toll on mental health

As a psychiatrist, I’ve spent my entire career working with dedicated teams to treat patients with mental health disorders. Currently, hate is not classified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a mental illness. However, I can’t think of another emotion that is a better candidate for further research and scientific instigation, if for no other reason than to better understand when prejudice and bias transform into hatred and crime.

Surprisingly, there has been relatively little research on the topic of hate in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. I’d be willing to wager that if you asked a typical graduating class of medical students to give you an actual working definition of the emotion of hate, most would be at a loss for words.

Dr. Fischer and Dr. Halperin published a helpful article that gives a functional perspective on hate. The authors cover a great deal of research on hate and offer the following four starting points valuable in considering it:

- “Hate is different from anger because an anger target is appraised as someone whose behavior can be influenced and changed.”

- “A hate target, on the contrary, implies appraisals of the other’s malevolent nature and malicious intent.”

- “Hate is characterized by appraisals that imply a stable perception of a person or group and thus the incapability to change the extremely negative characteristics attributed to the target of hate.”

- “Everyday observations also suggest that hate is so powerful that it does, not just temporarily but permanently, destroy relations between individuals or groups.”

When I view hate with these insights in mind, it completely changes how I choose to utilize the word or concept. Hate is an emotion whose goal/action tendency is to eliminate groups (not just people or obstacles) and destroy any current or future relationships. We can take this a step further in noting that hate spreads, not only to the intended targets but potentially my “own” group. Similar to secondhand smoke, there is no risk-free exposure to hate or racism.

In the past decade, a robust body of evidence has emerged that clearly illustrates the negative health impacts of racism. Dr. Paradies and colleagues performed a systematic meta-analysis explicitly focused on racism as a determinant of health, finding that it was associated with poorer mental health, including depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. Over the past two decades, researchers have increasingly looked at the effects of racial discrimination on the AAPI community. In their 2009 review article, Dr. Gee and colleagues identified 62 empirical articles assessing the relation between discrimination and health among Asian Americans. Most of the studies found that discrimination was associated with poorer health. Of the 40 studies focused on mental health, 37 reported that discrimination was associated with poorer outcomes.

SAH recently released its very illuminating Mental Health Report. Among several key findings, two in particular caught my attention. First, Asian Americans who have experienced racism are more stressed by anti-Asian hate than the pandemic itself. Second, one in five Asian Americans who have experienced racism display racial trauma, the psychological and emotional harm caused by racism. Given the rise in hate crimes, there must be concern regarding the level of trauma being inflicted upon the Asian American community.

A complete review of the health effects of racism is beyond this article’s scope. Still, the previously mentioned studies further support the need to treat racism in general, and specifically anti-Asian hate, as the urgent public health concern that it truly is. The U.S. government recently outlined an action plan to respond to anti-Asian violence, xenophobia, and bias. These are helpful first steps, but much more is required on a societal and individual level, given the mental health disparities faced by the AAPI community.

Determining the best ways to address this urgent public health concern can be overwhelming, exhausting, and outright demoralizing. The bottom line is that if we do nothing, communities and groups will continue to suffer the effects of racial hatred. These consequences are severe and transgenerational.

But we must start somewhere. For me, that begins by gaining a better understanding of the emotion of hate and my role in either facilitating or stopping it, and by listening, listening, and listening some more to AAPI colleagues, friends, and family about their lived experience with anti-Asian hate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fulminant Hemorrhagic Bullae of the Upper Extremities Arising in the Setting of IV Placement During Severe COVID-19 Infection: Observations From a Major Consultative Practice

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

Practice Points

- Hemorrhagic bullae are an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 infection in hospitalized individuals.

- Although there is no reported treatment for COVID-19–associated hemorrhagic bullae, we recommend supportive care and management of underlying etiology.

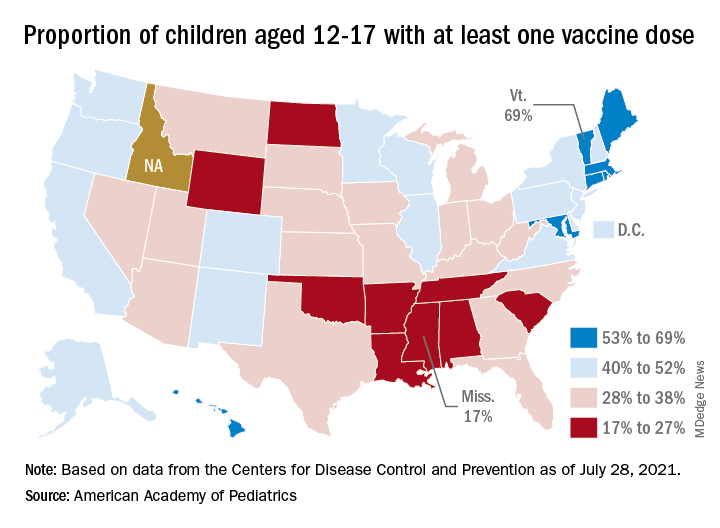

Delta variant could drive herd immunity threshold over 80%

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

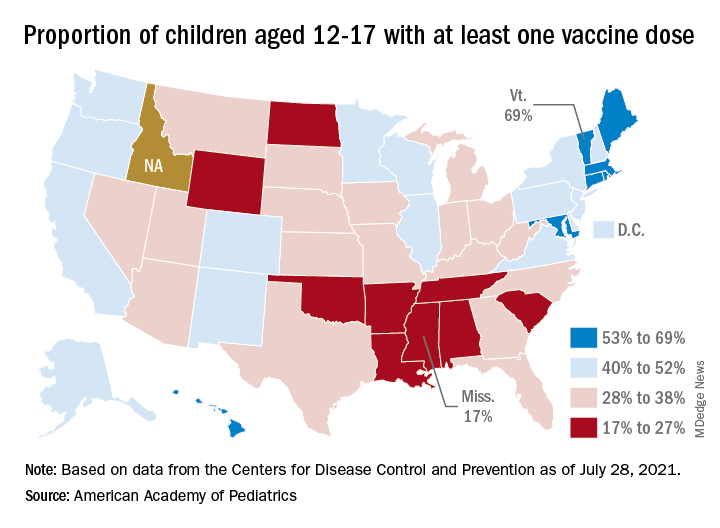

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

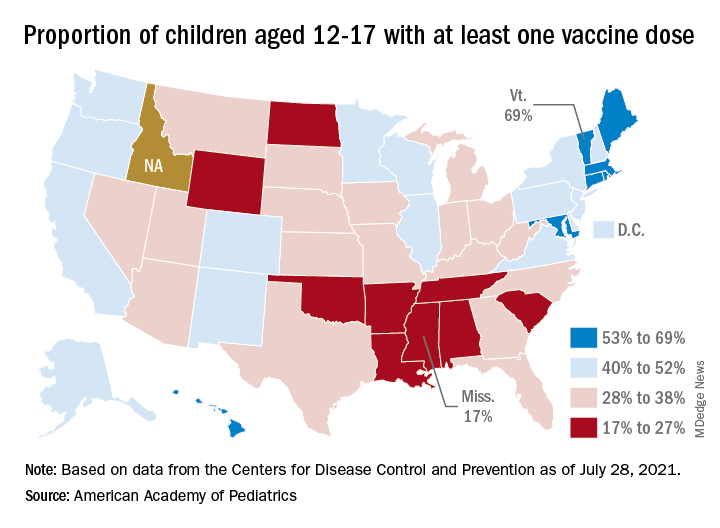

Because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 spreads more easily than the original virus, the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity could be upward of 80% or more, experts say.

Also, it could be time to consider wearing an N95 mask in public indoor spaces regardless of vaccination status, according to a media briefing on Aug. 3 sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Furthermore, giving booster shots to the fully vaccinated is not the top public health priority now. Instead, third vaccinations should be reserved for more vulnerable populations – and efforts should focus on getting first vaccinations to unvaccinated people in the United States and around the world.

“The problem here is that the Delta variant is ... more transmissible than the original virus. That pushes the overall population herd immunity threshold much higher,” Ricardo Franco, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said during the briefing.

“For Delta, those threshold estimates go well over 80% and may be approaching 90%,” he said.

To put that figure in context, the original SARS-CoV-2 virus required an estimated 67% of the population to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Also, measles has one of the highest herd immunity thresholds at 95%, Dr. Franco added.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people are immunized that the entire population gains protection. And it’s already happening. “Unvaccinated people are actually benefiting from greater herd immunity protection in high-vaccination counties compared to low-vaccination ones,” he said.

Maximize mask protection

Unlike early in the COVID-19 pandemic with widespread shortages of personal protective equipment, face masks are now readily available. This includes N95 masks, which offer enhanced protection against SARS-CoV-2, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, said during the briefing.

Following the July 27 CDC recommendation that most Americans wear masks indoors when in public places, “I do think we need to upgrade our masks,” said Dr. Emanuel, who is Diane v.S. Levy & Robert M. Levy professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It’s not just any mask,” he added. “Good masks make a big difference and are very important.”

Mask protection is about blocking 0.3-mcm particles, “and I think we need to make sure that people have masks that can filter that out,” he said. Although surgical masks are very good, he added, “they’re not quite as good as N95s.” As their name implies, N95s filter out 95% of these particles.

Dr. Emanuel acknowledged that people are tired of COVID-19 and complying with public health measures but urged perseverance. “We’ve sacrificed a lot. We should not throw it away in just a few months because we are tired. We’re all tired, but we do have to do the little bit extra getting vaccinated, wearing masks indoors, and protecting ourselves, our families, and our communities.”

Dealing with a disconnect

In response to a reporter’s question about the possibility that the large crowd at the Lollapalooza music festival in Chicago could become a superspreader event, Dr. Emanuel said, “it is worrisome.”

“I would say that, if you’re going to go to a gathering like that, wearing an N95 mask is wise, and not spending too long at any one place is also wise,” he said.

On the plus side, the event was held outdoors with lots of air circulation, Dr. Emanuel said.

However, “this is the kind of thing where we’ve got a sort of disconnect between people’s desire to get back to normal ... and the fact that we’re in the middle of this upsurge.”

Another potential problem is the event brought people together from many different locations, so when they travel home, they could be “potentially seeding lots of other communities.”

Boosters for some, for now

Even though not officially recommended, some fully vaccinated Americans are seeking a third or booster vaccination on their own.

Asked for his opinion, Dr. Emanuel said: “We’re probably going to have to be giving boosters to immunocompromised people and people who are susceptible. That’s where we are going to start.”

More research is needed regarding booster shots, he said. “There are very small studies – and the ‘very small’ should be emphasized – given that we’ve given shots to over 160 million people.”

“But it does appear that the boosters increase the antibodies and protection,” he said.

Instead of boosters, it is more important for people who haven’t been vaccinated to get fully vaccinated.

“We need to put our priorities in the right places,” he said.

Emanuel noted that, except for people in rural areas that might have to travel long distances, access to vaccines is no longer an issue. “It’s very hard not to find a vaccine if you want it.”

A remaining hurdle is “battling a major disinformation initiative. I don’t think this is misinformation. I think there’s very clear evidence that it is disinformation – false facts about the vaccines being spread,” Dr. Emanuel said.

The breakthrough infection dilemma

Breakthrough cases “remain the vast minority of infections at this time ... that is reassuring,” Dr. Franco said.

Also, tracking symptomatic breakthrough infections remains easier than studying fully vaccinated people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 but remain symptom free.

“We really don’t have a good handle on the frequency of asymptomatic cases,” Dr. Emanuel said. “If you’re missing breakthrough infections, a lot of them, you may be missing some [virus] evolution that would be very important for us to follow.” This missing information could include the emergence of new variants.

The asymptomatic breakthrough cases are the most worrisome group,” Dr. Emanuel said. “You get infected, you’re feeling fine. Maybe you’ve got a little sneeze or cough, but nothing unusual. And then you’re still able to transmit the Delta variant.”

The big picture

The upsurge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths is a major challenge, Dr. Emanuel said. “We need to address that by getting many more people vaccinated right now with what are very good vaccines.”

“But it also means that we have to stop being U.S. focused alone.” He pointed out that Delta and other variants originated overseas, “so getting the world vaccinated ... has to be a top priority.”

“We are obviously all facing a challenge as we move into the fall,” Dr. Emanuel said. “With schools opening and employers bringing their employees back together, even if these groups are vaccinated, there are going to be major challenges for all of us.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No higher risk of rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease flares seen after COVID-19 vaccination

Double-dose vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) doesn’t appear to boost the risk of flares, a new study shows. The risk of adverse effects after vaccination is high, just as it is in the general population, but no patients experienced allergic reactions.

“Our findings suggest that COVID-19 vaccines are safe in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Overall, rates of flare are low and mild, while local and systemic reactions should be anticipated,” lead author Caoilfhionn Connolly, MD, MSc, a rheumatology fellow at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview. “Many of our patients are at increased risk of severe infection and or complications from COVID-19. It has been shown that patients with RMDs are more willing to reconsider vaccination if it is recommended by a physician, and these data should help inform these critical discussions.”

The study appeared Aug. 4 in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

According to Dr. Connolly, the researchers launched their study to better understand the effect of two-dose SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccinations authorized for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration (Pfizer and Moderna vaccines) on immunosuppressed patients. As she noted, patients with RMDs were largely excluded from vaccine trials, and “studies have shown that some patients with RMDs are hesitant about vaccination due to the lack of safety data.”

Some data about this patient population have started to appear. A study published July 21 in Lancet Rheumatology found that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) reported few flares within a median of 3 days after receiving one or two doses of various COVID-19 vaccines. Side effects were common but were mainly mild or moderate.

For the new study, researchers surveyed 1,377 patients with RMDs who’d received two vaccination doses between December 2020 and April 2021. The patients had a median age of 47, 92% were female, and 10% were non-White. The patients had a variety of RMDs, including inflammatory arthritis (47%), SLE (20%), overlap connective tissue disease (20%), and Sjögren’s syndrome and myositis (each 5%).

A total of 11% said they’d experienced a flare that required treatment, but none were severe. In comparison, 56% of patients said they had experienced a flare of their RMD in the 6 months prior to their first vaccine dose. Several groups had a greater likelihood of flares, including those who’d had COVID-19 previously (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 2.09; P = .02). “COVID-19 can cause both acute and delayed inflammatory syndromes through activation of the immune system,” Dr. Connolly said. “Vaccination possibly triggered further activation of the immune system resulting in disease flare. This is an area that warrants further research.”

Patients who took combination immunomodulatory therapy were also more likely to flare after vaccination (IRR, 1.95; P < .001). And patients were more likely to report flares after vaccination if they experienced a flare in the 6 months preceding vaccination (IRR, 2.36; P < .001). “This may suggest more active disease at baseline,” Dr. Connolly said. “It is difficult to differentiate whether these patients would have experienced flare even without the vaccine.”

A number of factors didn’t appear to affect the likelihood of flares: gender, age, ethnicity, type of RMD, and type of vaccine.

Local and systemic side effects were frequently reported, including injection site pain (87% and 86% after first and second doses, respectively) and fatigue (60% and 80%, respectively). As is common among people receiving COVID-19 vaccines, side effects were more frequent after the second dose.

As for future research, “we are evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines in patients with RMDs,” study coauthor Julie J. Paik, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins, said in an interview. “We are also evaluating the impact of changes in immunosuppression around vaccination.”

The study was funded by the Ben-Dov family and grants from several institutes of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Connolly and Dr. Paik reported no relevant disclosures. Other study authors reported various financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Double-dose vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) doesn’t appear to boost the risk of flares, a new study shows. The risk of adverse effects after vaccination is high, just as it is in the general population, but no patients experienced allergic reactions.

“Our findings suggest that COVID-19 vaccines are safe in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Overall, rates of flare are low and mild, while local and systemic reactions should be anticipated,” lead author Caoilfhionn Connolly, MD, MSc, a rheumatology fellow at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview. “Many of our patients are at increased risk of severe infection and or complications from COVID-19. It has been shown that patients with RMDs are more willing to reconsider vaccination if it is recommended by a physician, and these data should help inform these critical discussions.”

The study appeared Aug. 4 in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

According to Dr. Connolly, the researchers launched their study to better understand the effect of two-dose SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccinations authorized for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration (Pfizer and Moderna vaccines) on immunosuppressed patients. As she noted, patients with RMDs were largely excluded from vaccine trials, and “studies have shown that some patients with RMDs are hesitant about vaccination due to the lack of safety data.”

Some data about this patient population have started to appear. A study published July 21 in Lancet Rheumatology found that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) reported few flares within a median of 3 days after receiving one or two doses of various COVID-19 vaccines. Side effects were common but were mainly mild or moderate.

For the new study, researchers surveyed 1,377 patients with RMDs who’d received two vaccination doses between December 2020 and April 2021. The patients had a median age of 47, 92% were female, and 10% were non-White. The patients had a variety of RMDs, including inflammatory arthritis (47%), SLE (20%), overlap connective tissue disease (20%), and Sjögren’s syndrome and myositis (each 5%).

A total of 11% said they’d experienced a flare that required treatment, but none were severe. In comparison, 56% of patients said they had experienced a flare of their RMD in the 6 months prior to their first vaccine dose. Several groups had a greater likelihood of flares, including those who’d had COVID-19 previously (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 2.09; P = .02). “COVID-19 can cause both acute and delayed inflammatory syndromes through activation of the immune system,” Dr. Connolly said. “Vaccination possibly triggered further activation of the immune system resulting in disease flare. This is an area that warrants further research.”

Patients who took combination immunomodulatory therapy were also more likely to flare after vaccination (IRR, 1.95; P < .001). And patients were more likely to report flares after vaccination if they experienced a flare in the 6 months preceding vaccination (IRR, 2.36; P < .001). “This may suggest more active disease at baseline,” Dr. Connolly said. “It is difficult to differentiate whether these patients would have experienced flare even without the vaccine.”

A number of factors didn’t appear to affect the likelihood of flares: gender, age, ethnicity, type of RMD, and type of vaccine.

Local and systemic side effects were frequently reported, including injection site pain (87% and 86% after first and second doses, respectively) and fatigue (60% and 80%, respectively). As is common among people receiving COVID-19 vaccines, side effects were more frequent after the second dose.

As for future research, “we are evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines in patients with RMDs,” study coauthor Julie J. Paik, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins, said in an interview. “We are also evaluating the impact of changes in immunosuppression around vaccination.”

The study was funded by the Ben-Dov family and grants from several institutes of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Connolly and Dr. Paik reported no relevant disclosures. Other study authors reported various financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Double-dose vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) doesn’t appear to boost the risk of flares, a new study shows. The risk of adverse effects after vaccination is high, just as it is in the general population, but no patients experienced allergic reactions.

“Our findings suggest that COVID-19 vaccines are safe in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Overall, rates of flare are low and mild, while local and systemic reactions should be anticipated,” lead author Caoilfhionn Connolly, MD, MSc, a rheumatology fellow at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview. “Many of our patients are at increased risk of severe infection and or complications from COVID-19. It has been shown that patients with RMDs are more willing to reconsider vaccination if it is recommended by a physician, and these data should help inform these critical discussions.”

The study appeared Aug. 4 in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

According to Dr. Connolly, the researchers launched their study to better understand the effect of two-dose SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccinations authorized for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration (Pfizer and Moderna vaccines) on immunosuppressed patients. As she noted, patients with RMDs were largely excluded from vaccine trials, and “studies have shown that some patients with RMDs are hesitant about vaccination due to the lack of safety data.”

Some data about this patient population have started to appear. A study published July 21 in Lancet Rheumatology found that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) reported few flares within a median of 3 days after receiving one or two doses of various COVID-19 vaccines. Side effects were common but were mainly mild or moderate.

For the new study, researchers surveyed 1,377 patients with RMDs who’d received two vaccination doses between December 2020 and April 2021. The patients had a median age of 47, 92% were female, and 10% were non-White. The patients had a variety of RMDs, including inflammatory arthritis (47%), SLE (20%), overlap connective tissue disease (20%), and Sjögren’s syndrome and myositis (each 5%).

A total of 11% said they’d experienced a flare that required treatment, but none were severe. In comparison, 56% of patients said they had experienced a flare of their RMD in the 6 months prior to their first vaccine dose. Several groups had a greater likelihood of flares, including those who’d had COVID-19 previously (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 2.09; P = .02). “COVID-19 can cause both acute and delayed inflammatory syndromes through activation of the immune system,” Dr. Connolly said. “Vaccination possibly triggered further activation of the immune system resulting in disease flare. This is an area that warrants further research.”

Patients who took combination immunomodulatory therapy were also more likely to flare after vaccination (IRR, 1.95; P < .001). And patients were more likely to report flares after vaccination if they experienced a flare in the 6 months preceding vaccination (IRR, 2.36; P < .001). “This may suggest more active disease at baseline,” Dr. Connolly said. “It is difficult to differentiate whether these patients would have experienced flare even without the vaccine.”

A number of factors didn’t appear to affect the likelihood of flares: gender, age, ethnicity, type of RMD, and type of vaccine.

Local and systemic side effects were frequently reported, including injection site pain (87% and 86% after first and second doses, respectively) and fatigue (60% and 80%, respectively). As is common among people receiving COVID-19 vaccines, side effects were more frequent after the second dose.