User login

Why misinformation spreads

Over the past 16 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted not only our vulnerability to disease outbreaks but also our susceptibility to misinformation and the dangers of “fake news.”

In fact, COVID-19 is not a pandemic but rather a syndemic of viral disease and misinformation. In the current digital age, there is an abundance of information at our fingertips. This has resulted in a surplus of accurate as well as inaccurate information – information that is subject to the various biases we humans are subject to.

Our decision making and cognition are colored by our internal and external environmental biases, whether through our emotions, societal influences, or cues from the “machines” that are now such an omnipresent part of our lives.

Let’s break them down:

- Emotional bias: We’re only human, and our emotions often overwhelm objective judgment. Even when the evidence is of low quality, emotional attachments can deter us from rational thinking. This kind of bias can be rooted in personal experiences.

- Societal bias: Thoughts, opinions, or perspectives of peers are powerful forces that may influence our decisions and viewpoints. We can conceptualize our social networks as partisan circles and “echo chambers.” This bias is perhaps most evident in various online social media platforms.

- Machine bias: Our online platforms are laced with algorithms that tailor the content we see. Accordingly, the curated content we see (and, by extension, the less diverse content we view) may reinforce existing biases, such as confirmation bias.

- Although bias plays a significant role in decision making, we should also consider intuition versus deliberation – and whether the “gut” is a reliable source of information.

Intuition versus deliberation: The power of reasoning

The dual process theory suggests that thought may be categorized in two ways: System 1, referred to as rapid, intuitive, or automatic thinking (which may be a result of personal experience); and system 2, referred to as deliberate or controlled thinking (for example, reasoned thinking). System 1 versus system 2 may be conceptualized as fast versus slow thinking.

Let’s use the Cognitive Reflection Test to illustrate the dual process theory. This test measures the ability to reflect and deliberate on a question and to forgo an intuitive, rapid response. One of the questions asks: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” A common answer is that the ball costs $0.10. However, the ball actually costs $0.05. The common response is a “gut” response, rather than an analytic or deliberate response.

This example can be extrapolated to social media behavior, such as when individuals endorse beliefs and behaviors that may be far from the truth (for example, conspiracy ideation). It is not uncommon for individuals to rely on intuition, which may be incorrect, as a driving source of truth. Although one’s intuition can be correct, it’s important to be careful and to deliberate.

But would deliberate engagement lead to more politically valenced perspectives? One hypothesis posits that system 2 can lead to false claims and worsening discernment of truth. Another, and more popular, account of classical reasoning says that more thoughtful engagement (regardless of one’s political beliefs) is less susceptible to false news (for example, hyperpartisan news).

Additionally, having good literacy (political, scientific, or general) is important for discerning the truth, especially regarding events in which the information and/or claims of knowledge have been heavily manipulated.

Are believing and sharing the same?

Interestingly, believing in a headline and sharing it are not the same. A study that investigated the difference between the two found that although individuals were able to discern the validity of headlines, the veracity of those headlines was not a determining factor in sharing the story on social media.

It has been suggested that social media context may distract individuals from engaging in deliberate thinking that would enhance their ability to determine the accuracy of the content. The dissociation between truthfulness and sharing may be a result of the “attention economy,” which refers to user engagement of likes, comments, shares, and so forth. As such, social media behavior and content consumption may not necessarily reflect one’s beliefs and may be influenced by what others value.

To combat the spread of misinformation, it has been suggested that proactive interventions – “prebunking” or “inoculation” – are necessary. This idea is in accordance with the inoculation theory, which suggests that pre-exposure can confer resistance to challenge. This line of thinking is aligned with the use of vaccines to counter medical illnesses. Increasing awareness of individual vulnerability to manipulation and misinformation has also been proposed as a strategy to resist persuasion.

The age old tale of what others think of us versus what we believe to be true has existed long before the viral overtake of social media. The main difference today is that social media acts as a catalyst for pockets of misinformation. Although social media outlets are cracking down on “false news,” we must consider what criteria should be employed to identify false information. Should external bodies regulate our content consumption? We are certainly entering a gray zone of “wrong” versus “right.” With the overabundance of information available online, it may be the case of “them” versus “us” – that is, those who do not believe in the existence of misinformation versus those who do.

Leanna M. W. Lui, HBSc, completed an HBSc global health specialist degree at the University of Toronto, where she is now an MSc candidate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the past 16 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted not only our vulnerability to disease outbreaks but also our susceptibility to misinformation and the dangers of “fake news.”

In fact, COVID-19 is not a pandemic but rather a syndemic of viral disease and misinformation. In the current digital age, there is an abundance of information at our fingertips. This has resulted in a surplus of accurate as well as inaccurate information – information that is subject to the various biases we humans are subject to.

Our decision making and cognition are colored by our internal and external environmental biases, whether through our emotions, societal influences, or cues from the “machines” that are now such an omnipresent part of our lives.

Let’s break them down:

- Emotional bias: We’re only human, and our emotions often overwhelm objective judgment. Even when the evidence is of low quality, emotional attachments can deter us from rational thinking. This kind of bias can be rooted in personal experiences.

- Societal bias: Thoughts, opinions, or perspectives of peers are powerful forces that may influence our decisions and viewpoints. We can conceptualize our social networks as partisan circles and “echo chambers.” This bias is perhaps most evident in various online social media platforms.

- Machine bias: Our online platforms are laced with algorithms that tailor the content we see. Accordingly, the curated content we see (and, by extension, the less diverse content we view) may reinforce existing biases, such as confirmation bias.

- Although bias plays a significant role in decision making, we should also consider intuition versus deliberation – and whether the “gut” is a reliable source of information.

Intuition versus deliberation: The power of reasoning

The dual process theory suggests that thought may be categorized in two ways: System 1, referred to as rapid, intuitive, or automatic thinking (which may be a result of personal experience); and system 2, referred to as deliberate or controlled thinking (for example, reasoned thinking). System 1 versus system 2 may be conceptualized as fast versus slow thinking.

Let’s use the Cognitive Reflection Test to illustrate the dual process theory. This test measures the ability to reflect and deliberate on a question and to forgo an intuitive, rapid response. One of the questions asks: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” A common answer is that the ball costs $0.10. However, the ball actually costs $0.05. The common response is a “gut” response, rather than an analytic or deliberate response.

This example can be extrapolated to social media behavior, such as when individuals endorse beliefs and behaviors that may be far from the truth (for example, conspiracy ideation). It is not uncommon for individuals to rely on intuition, which may be incorrect, as a driving source of truth. Although one’s intuition can be correct, it’s important to be careful and to deliberate.

But would deliberate engagement lead to more politically valenced perspectives? One hypothesis posits that system 2 can lead to false claims and worsening discernment of truth. Another, and more popular, account of classical reasoning says that more thoughtful engagement (regardless of one’s political beliefs) is less susceptible to false news (for example, hyperpartisan news).

Additionally, having good literacy (political, scientific, or general) is important for discerning the truth, especially regarding events in which the information and/or claims of knowledge have been heavily manipulated.

Are believing and sharing the same?

Interestingly, believing in a headline and sharing it are not the same. A study that investigated the difference between the two found that although individuals were able to discern the validity of headlines, the veracity of those headlines was not a determining factor in sharing the story on social media.

It has been suggested that social media context may distract individuals from engaging in deliberate thinking that would enhance their ability to determine the accuracy of the content. The dissociation between truthfulness and sharing may be a result of the “attention economy,” which refers to user engagement of likes, comments, shares, and so forth. As such, social media behavior and content consumption may not necessarily reflect one’s beliefs and may be influenced by what others value.

To combat the spread of misinformation, it has been suggested that proactive interventions – “prebunking” or “inoculation” – are necessary. This idea is in accordance with the inoculation theory, which suggests that pre-exposure can confer resistance to challenge. This line of thinking is aligned with the use of vaccines to counter medical illnesses. Increasing awareness of individual vulnerability to manipulation and misinformation has also been proposed as a strategy to resist persuasion.

The age old tale of what others think of us versus what we believe to be true has existed long before the viral overtake of social media. The main difference today is that social media acts as a catalyst for pockets of misinformation. Although social media outlets are cracking down on “false news,” we must consider what criteria should be employed to identify false information. Should external bodies regulate our content consumption? We are certainly entering a gray zone of “wrong” versus “right.” With the overabundance of information available online, it may be the case of “them” versus “us” – that is, those who do not believe in the existence of misinformation versus those who do.

Leanna M. W. Lui, HBSc, completed an HBSc global health specialist degree at the University of Toronto, where she is now an MSc candidate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the past 16 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted not only our vulnerability to disease outbreaks but also our susceptibility to misinformation and the dangers of “fake news.”

In fact, COVID-19 is not a pandemic but rather a syndemic of viral disease and misinformation. In the current digital age, there is an abundance of information at our fingertips. This has resulted in a surplus of accurate as well as inaccurate information – information that is subject to the various biases we humans are subject to.

Our decision making and cognition are colored by our internal and external environmental biases, whether through our emotions, societal influences, or cues from the “machines” that are now such an omnipresent part of our lives.

Let’s break them down:

- Emotional bias: We’re only human, and our emotions often overwhelm objective judgment. Even when the evidence is of low quality, emotional attachments can deter us from rational thinking. This kind of bias can be rooted in personal experiences.

- Societal bias: Thoughts, opinions, or perspectives of peers are powerful forces that may influence our decisions and viewpoints. We can conceptualize our social networks as partisan circles and “echo chambers.” This bias is perhaps most evident in various online social media platforms.

- Machine bias: Our online platforms are laced with algorithms that tailor the content we see. Accordingly, the curated content we see (and, by extension, the less diverse content we view) may reinforce existing biases, such as confirmation bias.

- Although bias plays a significant role in decision making, we should also consider intuition versus deliberation – and whether the “gut” is a reliable source of information.

Intuition versus deliberation: The power of reasoning

The dual process theory suggests that thought may be categorized in two ways: System 1, referred to as rapid, intuitive, or automatic thinking (which may be a result of personal experience); and system 2, referred to as deliberate or controlled thinking (for example, reasoned thinking). System 1 versus system 2 may be conceptualized as fast versus slow thinking.

Let’s use the Cognitive Reflection Test to illustrate the dual process theory. This test measures the ability to reflect and deliberate on a question and to forgo an intuitive, rapid response. One of the questions asks: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” A common answer is that the ball costs $0.10. However, the ball actually costs $0.05. The common response is a “gut” response, rather than an analytic or deliberate response.

This example can be extrapolated to social media behavior, such as when individuals endorse beliefs and behaviors that may be far from the truth (for example, conspiracy ideation). It is not uncommon for individuals to rely on intuition, which may be incorrect, as a driving source of truth. Although one’s intuition can be correct, it’s important to be careful and to deliberate.

But would deliberate engagement lead to more politically valenced perspectives? One hypothesis posits that system 2 can lead to false claims and worsening discernment of truth. Another, and more popular, account of classical reasoning says that more thoughtful engagement (regardless of one’s political beliefs) is less susceptible to false news (for example, hyperpartisan news).

Additionally, having good literacy (political, scientific, or general) is important for discerning the truth, especially regarding events in which the information and/or claims of knowledge have been heavily manipulated.

Are believing and sharing the same?

Interestingly, believing in a headline and sharing it are not the same. A study that investigated the difference between the two found that although individuals were able to discern the validity of headlines, the veracity of those headlines was not a determining factor in sharing the story on social media.

It has been suggested that social media context may distract individuals from engaging in deliberate thinking that would enhance their ability to determine the accuracy of the content. The dissociation between truthfulness and sharing may be a result of the “attention economy,” which refers to user engagement of likes, comments, shares, and so forth. As such, social media behavior and content consumption may not necessarily reflect one’s beliefs and may be influenced by what others value.

To combat the spread of misinformation, it has been suggested that proactive interventions – “prebunking” or “inoculation” – are necessary. This idea is in accordance with the inoculation theory, which suggests that pre-exposure can confer resistance to challenge. This line of thinking is aligned with the use of vaccines to counter medical illnesses. Increasing awareness of individual vulnerability to manipulation and misinformation has also been proposed as a strategy to resist persuasion.

The age old tale of what others think of us versus what we believe to be true has existed long before the viral overtake of social media. The main difference today is that social media acts as a catalyst for pockets of misinformation. Although social media outlets are cracking down on “false news,” we must consider what criteria should be employed to identify false information. Should external bodies regulate our content consumption? We are certainly entering a gray zone of “wrong” versus “right.” With the overabundance of information available online, it may be the case of “them” versus “us” – that is, those who do not believe in the existence of misinformation versus those who do.

Leanna M. W. Lui, HBSc, completed an HBSc global health specialist degree at the University of Toronto, where she is now an MSc candidate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A boy went to a COVID-swamped ER. He waited for hours. Then his appendix burst.

Seth was finally diagnosed with appendicitis more than six hours after arriving at Cleveland Clinic Martin Health North Hospital in late July. Around midnight, he was taken by ambulance to a sister hospital about a half-hour away that was better equipped to perform pediatric emergency surgery, his father said.

But by the time the doctor operated in the early morning hours, Seth’s appendix had burst – a potentially fatal complication.

They, too, need emergency care, but the sheer number of COVID-19 cases is crowding them out. Treatment has often been delayed as ERs scramble to find a bed that may be hundreds of miles away.

Some health officials now worry about looming ethical decisions. Last week, Idaho activated a “crisis standard of care,” which one official described as a “last resort.” It allows overwhelmed hospitals to ration care, including “in rare cases, ventilator (breathing machines) or intensive care unit (ICU) beds may need to be used for those who are most likely to survive, while patients who are not likely to survive may not be able to receive one,” the state’s website said.

The federal government’s latest data shows Alabama is at 100% of its intensive care unit capacity, with Texas, Georgia, Mississippi and Arkansas at more than 90% ICU capacity. Florida is just under 90%.

It’s the COVID-19 cases that are dominating. In Georgia, 62% of the ICU beds are now filled with just COVID-19 patients. In Texas, the percentage is nearly half.

To have so many ICU beds pressed into service for a single diagnosis is “unheard of,” said Dr. Hasan Kakli, an emergency room physician at Bellville Medical Center in Bellville, Texas, about an hour from Houston. “It’s approaching apocalyptic.”

In Texas, state data released Monday showed there were only 319 adult and 104 pediatric staffed ICU beds available across a state of 29 million people.

Hospitals need to hold some ICU beds for other patients, such as those recovering from major surgery or other critical conditions such as stroke, trauma or heart failure.

“This is not just a COVID issue,” said Dr. Normaliz Rodriguez, pediatric emergency physician at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida. “This is an everyone issue.”

While the latest hospital crisis echoes previous pandemic spikes, there are troubling differences this time around.

Before, localized COVID-19 hot spots led to bed shortages, but there were usually hospitals in the region not as affected that could accept a transfer.

Now, as the highly contagious delta variant envelops swaths of low-vaccination states all at once, it becomes harder to find nearby hospitals that are not slammed.

“Wait times can now be measured in days,” said Darrell Pile, CEO of the SouthEast Texas Regional Advisory Council, which helps coordinate patient transfers across a 25-county region.

Recently, Dr. Cedric Dark, a Houston emergency physician and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, said he saw a critically ill COVID-19 patient waiting in the emergency room for an ICU bed to open. The doctor worked eight hours, went home and came in the next day. The patient was still waiting.

Holding a seriously ill patient in an emergency room while waiting for an in-patient bed to open is known as boarding. The longer the wait, the more dangerous it can be for the patient, studies have found.

Not only do patients ultimately end up staying in the hospital or the ICU longer, some research suggests that long waits for a bed will worsen their condition and may increase the risk of in-hospital death.

That’s what happened last month in Texas.

On Aug. 21, around 11:30 a.m., Michelle Puget took her adult son, Daniel Wilkinson, to the Bellville Medical Center’s emergency room as a pain in his abdomen became unbearable. “Mama,” he said, “take me to the hospital.”

Wilkinson, a 46-year-old decorated Army veteran who did two tours of duty in Afghanistan, was ushered into an exam room about half an hour later. Kakli, the emergency room physician there, diagnosed gallstone pancreatitis, a serious but treatable condition that required a specialist to perform a surgical procedure and an ICU bed.

In other times, the transfer to a larger facility would be easy. But soon Kakli found himself on a frantic, six-hour quest to find a bed for his patient. Not only did he call hospitals across Texas, but he also tried Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and Colorado. It was like throwing darts at a map and hoping to get lucky, he told ProPublica. But no one could or would take the transfer.

By 2:30 p.m., Wilkinson’s condition was deteriorating. Kakli told Puget to come back to the hospital. “I have to tell you,” she said he told her, “Your son is a very, very sick man. If he doesn’t get this procedure he will die.” She began to weep.

Two hours later, Wilkinson’s blood pressure was dropping, signaling his organs were failing, she said.

Kakli went on Facebook and posted an all-caps plea to physician groups around the nation: “GETTING REJECTED BY ALL HOSPITALS IN TEXAS DUE TO NO ICU BEDS. PLEASE HELP. MESSAGE ME IF YOU HAVE A BED. PATIENT IS IN ER NOW. I AM THE ER DOC. WILL FLY ANYWHERE.”

The doctor tried Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston for a second time. This time he found a bed.

Around 7 p.m., Wilkinson, still conscious but in grave condition, was flown by helicopter to the hospital. He was put in a medically induced coma. Through the night and into the next morning, medical teams worked to stabilize him enough to perform the procedure. They could not.

Doctors told his family the internal damage was catastrophic. “We made the decision we had to let him go,” Puget said.

Time of death: 1:37 p.m. Aug. 22 – 26 hours after he first arrived in the emergency room.

The story was first reported by CBS News. Kakli told ProPublica last week he still sometimes does the math in his head: It should have been 40 minutes from diagnosis in Bellville to transfer to the ICU in Houston. “If he had 40 minutes to wait instead of six hours, I strongly believe he would have had a different outcome.”

Another difference with the latest surge is how it’s affecting children.

Last year, schools were closed, and children were more protected because they were mostly isolated at home. In fact, children’s hospitals were often so empty during previous spikes they opened beds to adult patients.

Now, families are out more. Schools have reopened, some with mask mandates, some without. Vaccines are not yet available to those under 12. Suddenly the numbers of hospitalized children are on the rise, setting up the same type of competition for resources between young COVID-19 patients and those with other illnesses such as new onset diabetes, trauma, pneumonia or appendicitis.

Dr. Rafael Santiago, a pediatric emergency physician in Central Florida, said at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center, the average number of children coming into the emergency room is around 130 per day. During the lockdown last spring, that number dropped to 33. Last month – “the busiest month ever” – the average daily number of children in the emergency room was 160.

Pediatric transfers are not yet as fraught as adult ones, Santiago said, but it does take more calls than it once did to secure a bed.

Seth Osborn, the 12-year-old whose appendix burst after a long wait, spent five days and four nights in the hospital as doctors pumped his body full of antibiotics to stave off infection from the rupture. The typical hospitalization for a routine appendectomy is about 24 hours.

The initial hospital bill for the stay came to more than $48,000, Nathaniel Osborn said. Although insurance paid for most of it, he said the family still borrowed against its house to cover the more than $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs so far.

While the hospital system where Seth was treated declined to comment about his case because of patient privacy laws, it did email a statement about the strain the pandemic is creating.

“Since July 2021, we have seen a tremendous spike in COVID-19 patients needing care and hospitalization. In mid-August, we saw the highest number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 across the Cleveland Clinic Florida region, a total of 395 COVID-19 patients in four hospitals. Those hospitals have approximately 1,000 total beds,” the email to ProPublica said. “We strongly encourage vaccination. Approximately 90% of our patients hospitalized due to COVID-19 are unvaccinated.”

On Sunday, The Washington Post reported that a hospital in Alabama called 43 others across three states before finding a bed for Ray DeMonia, a critically ill heart patient who later died. In his obituary his family wrote: “In honor of Ray, please get vaccinated if you have not, in an effort to free up resources for non COVID related emergencies. ... He would not want any other family to go through what his did.”

Today, Seth is mostly recovered. “Twelve-year-old boys bounce back,” his father said. Still, the experience has left Nathaniel Osborn shaken.

The high school history teacher said he likes to stay upbeat and apolitical in his social media musings, posting about Florida wildlife preservation and favorite books. But on Sept. 7, he tweeted: “My 12-year-old had appendicitis. The ER was overwhelmed with unvaccinated Covid patients and we had to wait 6+ hours. While waiting, his appendix ruptured and had to spend 5 days in hospital. ... So yeah, your decision to not vaccinate does affect others.”

It was retweeted 34,700 times, with 143,000 likes. Most comments were sympathetic and wished his child a speedy recovery. Some, though, went straight to hate, apparently triggered by his last line. He was attacked personally and accused of making up the story: “Good try with the guilt, jerk.”

Osborn, who is vaccinated, as are his wife and son, told ProPublica he only shared Seth’s story on Twitter to encourage vaccinations.

“I have no ill will towards the hospitals or the care received at either hospital,” he said this week, “but had these hospitals not been so crowded with COVID patients, we wouldn’t have had to wait so long and perhaps my son’s appendix would not have burst.”

This story was originally published on ProPublica. ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive their biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Seth was finally diagnosed with appendicitis more than six hours after arriving at Cleveland Clinic Martin Health North Hospital in late July. Around midnight, he was taken by ambulance to a sister hospital about a half-hour away that was better equipped to perform pediatric emergency surgery, his father said.

But by the time the doctor operated in the early morning hours, Seth’s appendix had burst – a potentially fatal complication.

They, too, need emergency care, but the sheer number of COVID-19 cases is crowding them out. Treatment has often been delayed as ERs scramble to find a bed that may be hundreds of miles away.

Some health officials now worry about looming ethical decisions. Last week, Idaho activated a “crisis standard of care,” which one official described as a “last resort.” It allows overwhelmed hospitals to ration care, including “in rare cases, ventilator (breathing machines) or intensive care unit (ICU) beds may need to be used for those who are most likely to survive, while patients who are not likely to survive may not be able to receive one,” the state’s website said.

The federal government’s latest data shows Alabama is at 100% of its intensive care unit capacity, with Texas, Georgia, Mississippi and Arkansas at more than 90% ICU capacity. Florida is just under 90%.

It’s the COVID-19 cases that are dominating. In Georgia, 62% of the ICU beds are now filled with just COVID-19 patients. In Texas, the percentage is nearly half.

To have so many ICU beds pressed into service for a single diagnosis is “unheard of,” said Dr. Hasan Kakli, an emergency room physician at Bellville Medical Center in Bellville, Texas, about an hour from Houston. “It’s approaching apocalyptic.”

In Texas, state data released Monday showed there were only 319 adult and 104 pediatric staffed ICU beds available across a state of 29 million people.

Hospitals need to hold some ICU beds for other patients, such as those recovering from major surgery or other critical conditions such as stroke, trauma or heart failure.

“This is not just a COVID issue,” said Dr. Normaliz Rodriguez, pediatric emergency physician at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida. “This is an everyone issue.”

While the latest hospital crisis echoes previous pandemic spikes, there are troubling differences this time around.

Before, localized COVID-19 hot spots led to bed shortages, but there were usually hospitals in the region not as affected that could accept a transfer.

Now, as the highly contagious delta variant envelops swaths of low-vaccination states all at once, it becomes harder to find nearby hospitals that are not slammed.

“Wait times can now be measured in days,” said Darrell Pile, CEO of the SouthEast Texas Regional Advisory Council, which helps coordinate patient transfers across a 25-county region.

Recently, Dr. Cedric Dark, a Houston emergency physician and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, said he saw a critically ill COVID-19 patient waiting in the emergency room for an ICU bed to open. The doctor worked eight hours, went home and came in the next day. The patient was still waiting.

Holding a seriously ill patient in an emergency room while waiting for an in-patient bed to open is known as boarding. The longer the wait, the more dangerous it can be for the patient, studies have found.

Not only do patients ultimately end up staying in the hospital or the ICU longer, some research suggests that long waits for a bed will worsen their condition and may increase the risk of in-hospital death.

That’s what happened last month in Texas.

On Aug. 21, around 11:30 a.m., Michelle Puget took her adult son, Daniel Wilkinson, to the Bellville Medical Center’s emergency room as a pain in his abdomen became unbearable. “Mama,” he said, “take me to the hospital.”

Wilkinson, a 46-year-old decorated Army veteran who did two tours of duty in Afghanistan, was ushered into an exam room about half an hour later. Kakli, the emergency room physician there, diagnosed gallstone pancreatitis, a serious but treatable condition that required a specialist to perform a surgical procedure and an ICU bed.

In other times, the transfer to a larger facility would be easy. But soon Kakli found himself on a frantic, six-hour quest to find a bed for his patient. Not only did he call hospitals across Texas, but he also tried Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and Colorado. It was like throwing darts at a map and hoping to get lucky, he told ProPublica. But no one could or would take the transfer.

By 2:30 p.m., Wilkinson’s condition was deteriorating. Kakli told Puget to come back to the hospital. “I have to tell you,” she said he told her, “Your son is a very, very sick man. If he doesn’t get this procedure he will die.” She began to weep.

Two hours later, Wilkinson’s blood pressure was dropping, signaling his organs were failing, she said.

Kakli went on Facebook and posted an all-caps plea to physician groups around the nation: “GETTING REJECTED BY ALL HOSPITALS IN TEXAS DUE TO NO ICU BEDS. PLEASE HELP. MESSAGE ME IF YOU HAVE A BED. PATIENT IS IN ER NOW. I AM THE ER DOC. WILL FLY ANYWHERE.”

The doctor tried Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston for a second time. This time he found a bed.

Around 7 p.m., Wilkinson, still conscious but in grave condition, was flown by helicopter to the hospital. He was put in a medically induced coma. Through the night and into the next morning, medical teams worked to stabilize him enough to perform the procedure. They could not.

Doctors told his family the internal damage was catastrophic. “We made the decision we had to let him go,” Puget said.

Time of death: 1:37 p.m. Aug. 22 – 26 hours after he first arrived in the emergency room.

The story was first reported by CBS News. Kakli told ProPublica last week he still sometimes does the math in his head: It should have been 40 minutes from diagnosis in Bellville to transfer to the ICU in Houston. “If he had 40 minutes to wait instead of six hours, I strongly believe he would have had a different outcome.”

Another difference with the latest surge is how it’s affecting children.

Last year, schools were closed, and children were more protected because they were mostly isolated at home. In fact, children’s hospitals were often so empty during previous spikes they opened beds to adult patients.

Now, families are out more. Schools have reopened, some with mask mandates, some without. Vaccines are not yet available to those under 12. Suddenly the numbers of hospitalized children are on the rise, setting up the same type of competition for resources between young COVID-19 patients and those with other illnesses such as new onset diabetes, trauma, pneumonia or appendicitis.

Dr. Rafael Santiago, a pediatric emergency physician in Central Florida, said at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center, the average number of children coming into the emergency room is around 130 per day. During the lockdown last spring, that number dropped to 33. Last month – “the busiest month ever” – the average daily number of children in the emergency room was 160.

Pediatric transfers are not yet as fraught as adult ones, Santiago said, but it does take more calls than it once did to secure a bed.

Seth Osborn, the 12-year-old whose appendix burst after a long wait, spent five days and four nights in the hospital as doctors pumped his body full of antibiotics to stave off infection from the rupture. The typical hospitalization for a routine appendectomy is about 24 hours.

The initial hospital bill for the stay came to more than $48,000, Nathaniel Osborn said. Although insurance paid for most of it, he said the family still borrowed against its house to cover the more than $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs so far.

While the hospital system where Seth was treated declined to comment about his case because of patient privacy laws, it did email a statement about the strain the pandemic is creating.

“Since July 2021, we have seen a tremendous spike in COVID-19 patients needing care and hospitalization. In mid-August, we saw the highest number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 across the Cleveland Clinic Florida region, a total of 395 COVID-19 patients in four hospitals. Those hospitals have approximately 1,000 total beds,” the email to ProPublica said. “We strongly encourage vaccination. Approximately 90% of our patients hospitalized due to COVID-19 are unvaccinated.”

On Sunday, The Washington Post reported that a hospital in Alabama called 43 others across three states before finding a bed for Ray DeMonia, a critically ill heart patient who later died. In his obituary his family wrote: “In honor of Ray, please get vaccinated if you have not, in an effort to free up resources for non COVID related emergencies. ... He would not want any other family to go through what his did.”

Today, Seth is mostly recovered. “Twelve-year-old boys bounce back,” his father said. Still, the experience has left Nathaniel Osborn shaken.

The high school history teacher said he likes to stay upbeat and apolitical in his social media musings, posting about Florida wildlife preservation and favorite books. But on Sept. 7, he tweeted: “My 12-year-old had appendicitis. The ER was overwhelmed with unvaccinated Covid patients and we had to wait 6+ hours. While waiting, his appendix ruptured and had to spend 5 days in hospital. ... So yeah, your decision to not vaccinate does affect others.”

It was retweeted 34,700 times, with 143,000 likes. Most comments were sympathetic and wished his child a speedy recovery. Some, though, went straight to hate, apparently triggered by his last line. He was attacked personally and accused of making up the story: “Good try with the guilt, jerk.”

Osborn, who is vaccinated, as are his wife and son, told ProPublica he only shared Seth’s story on Twitter to encourage vaccinations.

“I have no ill will towards the hospitals or the care received at either hospital,” he said this week, “but had these hospitals not been so crowded with COVID patients, we wouldn’t have had to wait so long and perhaps my son’s appendix would not have burst.”

This story was originally published on ProPublica. ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive their biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Seth was finally diagnosed with appendicitis more than six hours after arriving at Cleveland Clinic Martin Health North Hospital in late July. Around midnight, he was taken by ambulance to a sister hospital about a half-hour away that was better equipped to perform pediatric emergency surgery, his father said.

But by the time the doctor operated in the early morning hours, Seth’s appendix had burst – a potentially fatal complication.

They, too, need emergency care, but the sheer number of COVID-19 cases is crowding them out. Treatment has often been delayed as ERs scramble to find a bed that may be hundreds of miles away.

Some health officials now worry about looming ethical decisions. Last week, Idaho activated a “crisis standard of care,” which one official described as a “last resort.” It allows overwhelmed hospitals to ration care, including “in rare cases, ventilator (breathing machines) or intensive care unit (ICU) beds may need to be used for those who are most likely to survive, while patients who are not likely to survive may not be able to receive one,” the state’s website said.

The federal government’s latest data shows Alabama is at 100% of its intensive care unit capacity, with Texas, Georgia, Mississippi and Arkansas at more than 90% ICU capacity. Florida is just under 90%.

It’s the COVID-19 cases that are dominating. In Georgia, 62% of the ICU beds are now filled with just COVID-19 patients. In Texas, the percentage is nearly half.

To have so many ICU beds pressed into service for a single diagnosis is “unheard of,” said Dr. Hasan Kakli, an emergency room physician at Bellville Medical Center in Bellville, Texas, about an hour from Houston. “It’s approaching apocalyptic.”

In Texas, state data released Monday showed there were only 319 adult and 104 pediatric staffed ICU beds available across a state of 29 million people.

Hospitals need to hold some ICU beds for other patients, such as those recovering from major surgery or other critical conditions such as stroke, trauma or heart failure.

“This is not just a COVID issue,” said Dr. Normaliz Rodriguez, pediatric emergency physician at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida. “This is an everyone issue.”

While the latest hospital crisis echoes previous pandemic spikes, there are troubling differences this time around.

Before, localized COVID-19 hot spots led to bed shortages, but there were usually hospitals in the region not as affected that could accept a transfer.

Now, as the highly contagious delta variant envelops swaths of low-vaccination states all at once, it becomes harder to find nearby hospitals that are not slammed.

“Wait times can now be measured in days,” said Darrell Pile, CEO of the SouthEast Texas Regional Advisory Council, which helps coordinate patient transfers across a 25-county region.

Recently, Dr. Cedric Dark, a Houston emergency physician and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, said he saw a critically ill COVID-19 patient waiting in the emergency room for an ICU bed to open. The doctor worked eight hours, went home and came in the next day. The patient was still waiting.

Holding a seriously ill patient in an emergency room while waiting for an in-patient bed to open is known as boarding. The longer the wait, the more dangerous it can be for the patient, studies have found.

Not only do patients ultimately end up staying in the hospital or the ICU longer, some research suggests that long waits for a bed will worsen their condition and may increase the risk of in-hospital death.

That’s what happened last month in Texas.

On Aug. 21, around 11:30 a.m., Michelle Puget took her adult son, Daniel Wilkinson, to the Bellville Medical Center’s emergency room as a pain in his abdomen became unbearable. “Mama,” he said, “take me to the hospital.”

Wilkinson, a 46-year-old decorated Army veteran who did two tours of duty in Afghanistan, was ushered into an exam room about half an hour later. Kakli, the emergency room physician there, diagnosed gallstone pancreatitis, a serious but treatable condition that required a specialist to perform a surgical procedure and an ICU bed.

In other times, the transfer to a larger facility would be easy. But soon Kakli found himself on a frantic, six-hour quest to find a bed for his patient. Not only did he call hospitals across Texas, but he also tried Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and Colorado. It was like throwing darts at a map and hoping to get lucky, he told ProPublica. But no one could or would take the transfer.

By 2:30 p.m., Wilkinson’s condition was deteriorating. Kakli told Puget to come back to the hospital. “I have to tell you,” she said he told her, “Your son is a very, very sick man. If he doesn’t get this procedure he will die.” She began to weep.

Two hours later, Wilkinson’s blood pressure was dropping, signaling his organs were failing, she said.

Kakli went on Facebook and posted an all-caps plea to physician groups around the nation: “GETTING REJECTED BY ALL HOSPITALS IN TEXAS DUE TO NO ICU BEDS. PLEASE HELP. MESSAGE ME IF YOU HAVE A BED. PATIENT IS IN ER NOW. I AM THE ER DOC. WILL FLY ANYWHERE.”

The doctor tried Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston for a second time. This time he found a bed.

Around 7 p.m., Wilkinson, still conscious but in grave condition, was flown by helicopter to the hospital. He was put in a medically induced coma. Through the night and into the next morning, medical teams worked to stabilize him enough to perform the procedure. They could not.

Doctors told his family the internal damage was catastrophic. “We made the decision we had to let him go,” Puget said.

Time of death: 1:37 p.m. Aug. 22 – 26 hours after he first arrived in the emergency room.

The story was first reported by CBS News. Kakli told ProPublica last week he still sometimes does the math in his head: It should have been 40 minutes from diagnosis in Bellville to transfer to the ICU in Houston. “If he had 40 minutes to wait instead of six hours, I strongly believe he would have had a different outcome.”

Another difference with the latest surge is how it’s affecting children.

Last year, schools were closed, and children were more protected because they were mostly isolated at home. In fact, children’s hospitals were often so empty during previous spikes they opened beds to adult patients.

Now, families are out more. Schools have reopened, some with mask mandates, some without. Vaccines are not yet available to those under 12. Suddenly the numbers of hospitalized children are on the rise, setting up the same type of competition for resources between young COVID-19 patients and those with other illnesses such as new onset diabetes, trauma, pneumonia or appendicitis.

Dr. Rafael Santiago, a pediatric emergency physician in Central Florida, said at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center, the average number of children coming into the emergency room is around 130 per day. During the lockdown last spring, that number dropped to 33. Last month – “the busiest month ever” – the average daily number of children in the emergency room was 160.

Pediatric transfers are not yet as fraught as adult ones, Santiago said, but it does take more calls than it once did to secure a bed.

Seth Osborn, the 12-year-old whose appendix burst after a long wait, spent five days and four nights in the hospital as doctors pumped his body full of antibiotics to stave off infection from the rupture. The typical hospitalization for a routine appendectomy is about 24 hours.

The initial hospital bill for the stay came to more than $48,000, Nathaniel Osborn said. Although insurance paid for most of it, he said the family still borrowed against its house to cover the more than $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs so far.

While the hospital system where Seth was treated declined to comment about his case because of patient privacy laws, it did email a statement about the strain the pandemic is creating.

“Since July 2021, we have seen a tremendous spike in COVID-19 patients needing care and hospitalization. In mid-August, we saw the highest number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 across the Cleveland Clinic Florida region, a total of 395 COVID-19 patients in four hospitals. Those hospitals have approximately 1,000 total beds,” the email to ProPublica said. “We strongly encourage vaccination. Approximately 90% of our patients hospitalized due to COVID-19 are unvaccinated.”

On Sunday, The Washington Post reported that a hospital in Alabama called 43 others across three states before finding a bed for Ray DeMonia, a critically ill heart patient who later died. In his obituary his family wrote: “In honor of Ray, please get vaccinated if you have not, in an effort to free up resources for non COVID related emergencies. ... He would not want any other family to go through what his did.”

Today, Seth is mostly recovered. “Twelve-year-old boys bounce back,” his father said. Still, the experience has left Nathaniel Osborn shaken.

The high school history teacher said he likes to stay upbeat and apolitical in his social media musings, posting about Florida wildlife preservation and favorite books. But on Sept. 7, he tweeted: “My 12-year-old had appendicitis. The ER was overwhelmed with unvaccinated Covid patients and we had to wait 6+ hours. While waiting, his appendix ruptured and had to spend 5 days in hospital. ... So yeah, your decision to not vaccinate does affect others.”

It was retweeted 34,700 times, with 143,000 likes. Most comments were sympathetic and wished his child a speedy recovery. Some, though, went straight to hate, apparently triggered by his last line. He was attacked personally and accused of making up the story: “Good try with the guilt, jerk.”

Osborn, who is vaccinated, as are his wife and son, told ProPublica he only shared Seth’s story on Twitter to encourage vaccinations.

“I have no ill will towards the hospitals or the care received at either hospital,” he said this week, “but had these hospitals not been so crowded with COVID patients, we wouldn’t have had to wait so long and perhaps my son’s appendix would not have burst.”

This story was originally published on ProPublica. ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive their biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

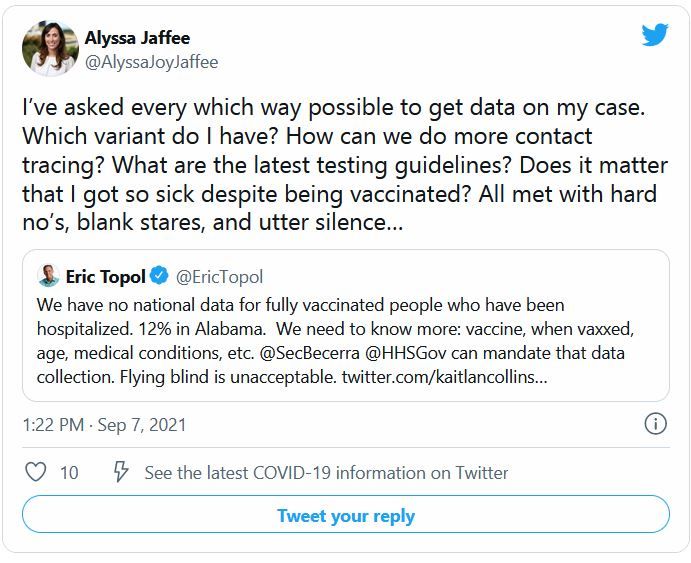

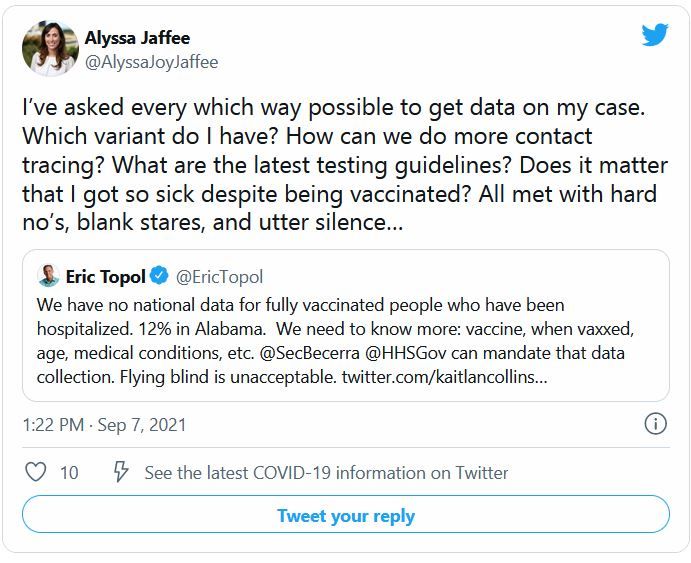

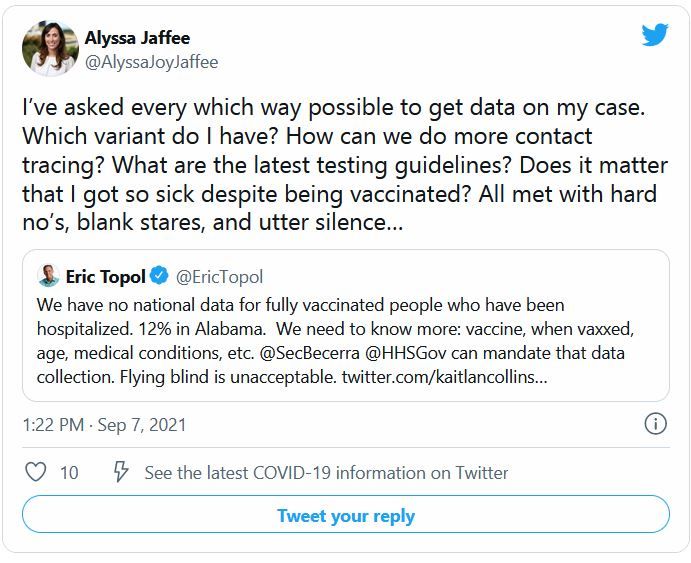

Want to see what COVID strain you have? The government says no

Every day, more than 140,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with COVID-19. But no matter how curious they are about which variant they are fighting, none of them will find out.

The country is dotted with labs that sequence the genomes of COVID-19 cases, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks those results. But federal rules say those results are not allowed to make their way back to patients or doctors.

According to public health and infectious disease experts, this is unlikely to change any time soon.

“I know people want to know – I’ve had a lot of friends or family who’ve asked me how they can find out,” says Aubree Gordon, PhD, an epidemiology specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “I think it’s an interesting thing to find out, for sure. And it would certainly be nice to know. But because it probably isn’t necessary, there is little motivation to change the rules.”

Because the tests that are used have not been approved as diagnostic tools under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program, which is overseen by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they can only be used for research purposes.

In fact, the scientists doing the sequencing rarely have any patient information, Dr. Gordon says. For example, the Lauring Lab at University of Michigan – run by Adam Lauring, MD – focuses on viral evolution and currently tests for variants. But this is not done for the sake of the patient or the doctors treating the patient.

“The samples come in ... and they’ve been de-identified,”Dr. Gordon says. “This is just for research purposes. Not much patient information is shared with the researchers.”

But as of now, aside from sheer curiosity, there is not a reason to change this, says Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at University of California, Los Angeles.

Although there are emerging variants – including the new Mu variant, also known as B.1.621 and recently classified as a “variant of interest” – the Delta variant accounts for about 99% of U.S. cases.

In addition, Dr. Brewer says, treatments are the same for all COVID-19 patients, regardless of the variant.

“There would have to be some clinical significance for there to be a good reason to give this information,” he says. “That would mean we would be doing something different treatment-wise depending on the variant. As of now, that is not the case.”

There is a loophole that allows labs to release variant information: They can develop their own tests. But they then must go through a lengthy validation process that proves their tests are as effective as the gold standard, says Mark Pandori, PhD, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory.

But even with validation, it is too time-consuming and costly to sequence large numbers of cases, he says.

“The reason we’re not doing it routinely is there’s no way to do the genomic analysis on all the positives,” Dr. Pandori says. “It is about $110 dollars to do a sequence. It’s not like a standard PCR test.”

There is a hypothetical situation that may warrant the release of these results, Dr. Brewer says: If a variant emerges that evades vaccines.

“That would be a real public health issue,” he says. “You want to make sure there aren’t variants emerging somewhere that are escaping immunity.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Every day, more than 140,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with COVID-19. But no matter how curious they are about which variant they are fighting, none of them will find out.

The country is dotted with labs that sequence the genomes of COVID-19 cases, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks those results. But federal rules say those results are not allowed to make their way back to patients or doctors.

According to public health and infectious disease experts, this is unlikely to change any time soon.

“I know people want to know – I’ve had a lot of friends or family who’ve asked me how they can find out,” says Aubree Gordon, PhD, an epidemiology specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “I think it’s an interesting thing to find out, for sure. And it would certainly be nice to know. But because it probably isn’t necessary, there is little motivation to change the rules.”

Because the tests that are used have not been approved as diagnostic tools under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program, which is overseen by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they can only be used for research purposes.

In fact, the scientists doing the sequencing rarely have any patient information, Dr. Gordon says. For example, the Lauring Lab at University of Michigan – run by Adam Lauring, MD – focuses on viral evolution and currently tests for variants. But this is not done for the sake of the patient or the doctors treating the patient.

“The samples come in ... and they’ve been de-identified,”Dr. Gordon says. “This is just for research purposes. Not much patient information is shared with the researchers.”

But as of now, aside from sheer curiosity, there is not a reason to change this, says Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at University of California, Los Angeles.

Although there are emerging variants – including the new Mu variant, also known as B.1.621 and recently classified as a “variant of interest” – the Delta variant accounts for about 99% of U.S. cases.

In addition, Dr. Brewer says, treatments are the same for all COVID-19 patients, regardless of the variant.

“There would have to be some clinical significance for there to be a good reason to give this information,” he says. “That would mean we would be doing something different treatment-wise depending on the variant. As of now, that is not the case.”

There is a loophole that allows labs to release variant information: They can develop their own tests. But they then must go through a lengthy validation process that proves their tests are as effective as the gold standard, says Mark Pandori, PhD, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory.

But even with validation, it is too time-consuming and costly to sequence large numbers of cases, he says.

“The reason we’re not doing it routinely is there’s no way to do the genomic analysis on all the positives,” Dr. Pandori says. “It is about $110 dollars to do a sequence. It’s not like a standard PCR test.”

There is a hypothetical situation that may warrant the release of these results, Dr. Brewer says: If a variant emerges that evades vaccines.

“That would be a real public health issue,” he says. “You want to make sure there aren’t variants emerging somewhere that are escaping immunity.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Every day, more than 140,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with COVID-19. But no matter how curious they are about which variant they are fighting, none of them will find out.

The country is dotted with labs that sequence the genomes of COVID-19 cases, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks those results. But federal rules say those results are not allowed to make their way back to patients or doctors.

According to public health and infectious disease experts, this is unlikely to change any time soon.

“I know people want to know – I’ve had a lot of friends or family who’ve asked me how they can find out,” says Aubree Gordon, PhD, an epidemiology specialist at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “I think it’s an interesting thing to find out, for sure. And it would certainly be nice to know. But because it probably isn’t necessary, there is little motivation to change the rules.”

Because the tests that are used have not been approved as diagnostic tools under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program, which is overseen by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, they can only be used for research purposes.

In fact, the scientists doing the sequencing rarely have any patient information, Dr. Gordon says. For example, the Lauring Lab at University of Michigan – run by Adam Lauring, MD – focuses on viral evolution and currently tests for variants. But this is not done for the sake of the patient or the doctors treating the patient.

“The samples come in ... and they’ve been de-identified,”Dr. Gordon says. “This is just for research purposes. Not much patient information is shared with the researchers.”

But as of now, aside from sheer curiosity, there is not a reason to change this, says Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at University of California, Los Angeles.

Although there are emerging variants – including the new Mu variant, also known as B.1.621 and recently classified as a “variant of interest” – the Delta variant accounts for about 99% of U.S. cases.

In addition, Dr. Brewer says, treatments are the same for all COVID-19 patients, regardless of the variant.

“There would have to be some clinical significance for there to be a good reason to give this information,” he says. “That would mean we would be doing something different treatment-wise depending on the variant. As of now, that is not the case.”

There is a loophole that allows labs to release variant information: They can develop their own tests. But they then must go through a lengthy validation process that proves their tests are as effective as the gold standard, says Mark Pandori, PhD, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory.

But even with validation, it is too time-consuming and costly to sequence large numbers of cases, he says.

“The reason we’re not doing it routinely is there’s no way to do the genomic analysis on all the positives,” Dr. Pandori says. “It is about $110 dollars to do a sequence. It’s not like a standard PCR test.”

There is a hypothetical situation that may warrant the release of these results, Dr. Brewer says: If a variant emerges that evades vaccines.

“That would be a real public health issue,” he says. “You want to make sure there aren’t variants emerging somewhere that are escaping immunity.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Low RA flare rate reported after Pfizer COVID vaccination

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission had a rate of flare following vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNtech COVID-19 vaccine that appears to be on par with rates seen with other vaccines in patients with RA, according to results from a small Italian cohort study.

“Our data show a very low flare rate [7.8% (6 of 77)] after the BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine in patients with RA in remission and are consistent with previous findings about varicella-zoster virus (6.7%) and hepatitis B virus (2.2%) vaccinations,” Riccardo Bixio, MD, and colleagues from University of Verona (Italy) Hospital Trust wrote in ACR Open Rheumatology. “Because remission is not commonly obtained in the real world, we are aware that our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with RA receiving COVID-19 vaccination.”

Other studies of flare rate after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with a variety of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases have reported rates ranging from 5% to 17%, they said.

The 77 consecutive patients from the University of Verona center that conducted the study were all in clinical remission in the 3 months before vaccination based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) of less than 2.6, and all had discontinued antirheumatic therapies according to American College of Rheumatology COVID-19 recommendations. The researchers defined flares as agreement between patient and rheumatologist assessments and a DAS28-CRP increase of more than 1.2.

Five of the six people with a flare had it occur after the second dose at a mean of 2.6 days later, and all flares were resolved within 2 weeks using glucocorticoids with or without anti-inflammatory drugs. One flare was called severe. The overall disease activity of the cohort after 3 months was not significantly changed after vaccination.

In noting that five out of the six patients with flares had withdrawn or delayed antirheumatic therapies around the time of vaccination according to ACR recommendations, the authors wrote that “Even if there is no direct evidence that holding therapies could occur in a higher proportion of disease flares, we suggest that clinicians consider this possibility when counseling patients about COVID-19 vaccination.”

The authors had no outside funding for the study and had no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission had a rate of flare following vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNtech COVID-19 vaccine that appears to be on par with rates seen with other vaccines in patients with RA, according to results from a small Italian cohort study.

“Our data show a very low flare rate [7.8% (6 of 77)] after the BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine in patients with RA in remission and are consistent with previous findings about varicella-zoster virus (6.7%) and hepatitis B virus (2.2%) vaccinations,” Riccardo Bixio, MD, and colleagues from University of Verona (Italy) Hospital Trust wrote in ACR Open Rheumatology. “Because remission is not commonly obtained in the real world, we are aware that our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with RA receiving COVID-19 vaccination.”

Other studies of flare rate after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with a variety of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases have reported rates ranging from 5% to 17%, they said.

The 77 consecutive patients from the University of Verona center that conducted the study were all in clinical remission in the 3 months before vaccination based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) of less than 2.6, and all had discontinued antirheumatic therapies according to American College of Rheumatology COVID-19 recommendations. The researchers defined flares as agreement between patient and rheumatologist assessments and a DAS28-CRP increase of more than 1.2.

Five of the six people with a flare had it occur after the second dose at a mean of 2.6 days later, and all flares were resolved within 2 weeks using glucocorticoids with or without anti-inflammatory drugs. One flare was called severe. The overall disease activity of the cohort after 3 months was not significantly changed after vaccination.

In noting that five out of the six patients with flares had withdrawn or delayed antirheumatic therapies around the time of vaccination according to ACR recommendations, the authors wrote that “Even if there is no direct evidence that holding therapies could occur in a higher proportion of disease flares, we suggest that clinicians consider this possibility when counseling patients about COVID-19 vaccination.”

The authors had no outside funding for the study and had no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission had a rate of flare following vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNtech COVID-19 vaccine that appears to be on par with rates seen with other vaccines in patients with RA, according to results from a small Italian cohort study.

“Our data show a very low flare rate [7.8% (6 of 77)] after the BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine in patients with RA in remission and are consistent with previous findings about varicella-zoster virus (6.7%) and hepatitis B virus (2.2%) vaccinations,” Riccardo Bixio, MD, and colleagues from University of Verona (Italy) Hospital Trust wrote in ACR Open Rheumatology. “Because remission is not commonly obtained in the real world, we are aware that our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with RA receiving COVID-19 vaccination.”

Other studies of flare rate after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with a variety of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases have reported rates ranging from 5% to 17%, they said.

The 77 consecutive patients from the University of Verona center that conducted the study were all in clinical remission in the 3 months before vaccination based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) of less than 2.6, and all had discontinued antirheumatic therapies according to American College of Rheumatology COVID-19 recommendations. The researchers defined flares as agreement between patient and rheumatologist assessments and a DAS28-CRP increase of more than 1.2.

Five of the six people with a flare had it occur after the second dose at a mean of 2.6 days later, and all flares were resolved within 2 weeks using glucocorticoids with or without anti-inflammatory drugs. One flare was called severe. The overall disease activity of the cohort after 3 months was not significantly changed after vaccination.

In noting that five out of the six patients with flares had withdrawn or delayed antirheumatic therapies around the time of vaccination according to ACR recommendations, the authors wrote that “Even if there is no direct evidence that holding therapies could occur in a higher proportion of disease flares, we suggest that clinicians consider this possibility when counseling patients about COVID-19 vaccination.”

The authors had no outside funding for the study and had no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM ACR OPEN RHEUMATOLOGY

Children and COVID: New cases down slightly from record high

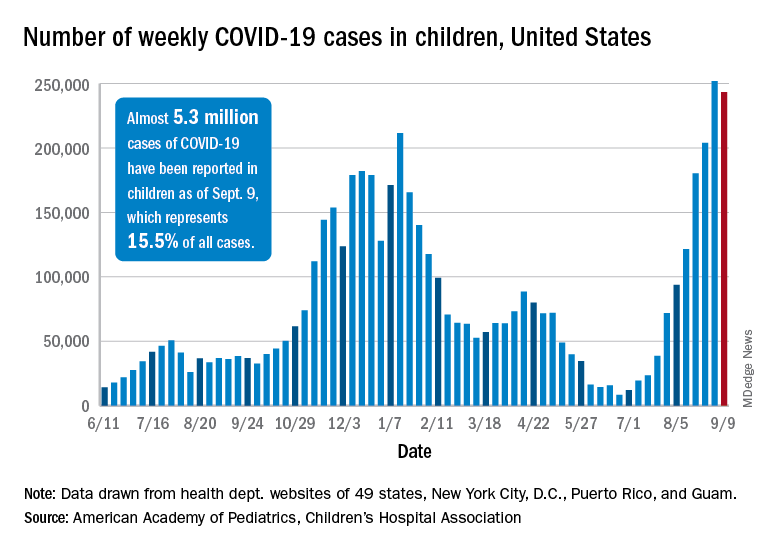

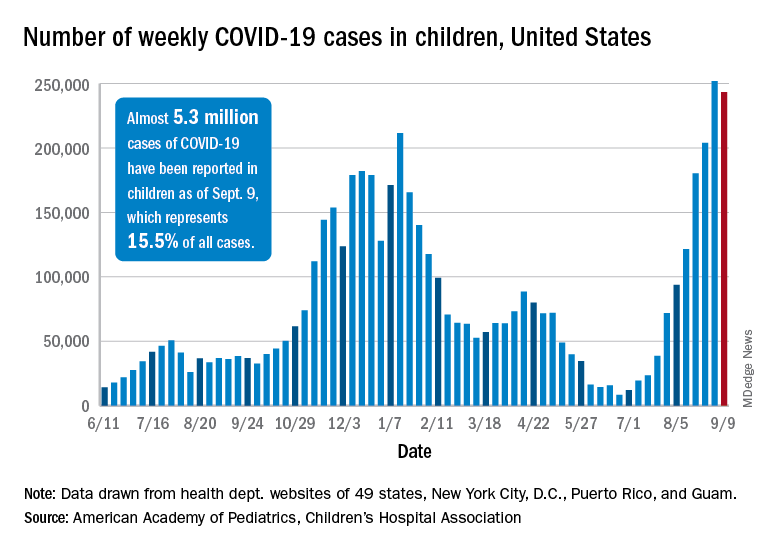

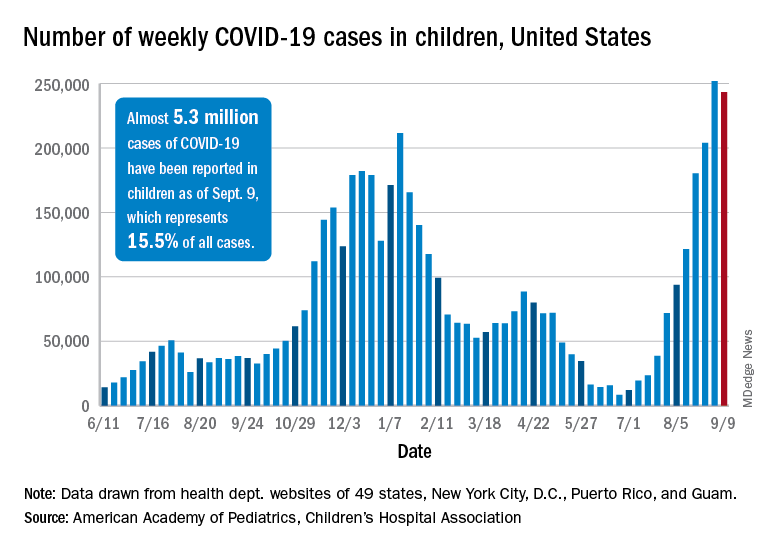

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children dropped for the first time since June, and daily hospitalizations appear to be falling, even as the pace of vaccinations continues to slow among the youngest eligible recipients, according to new data.

Despite the 3.3% decline from the previous week’s record high, the new-case count still topped 243,000 for the week of Sept. 3-9, putting the total number of cases in children at almost 5.3 million since the pandemic began.

Hospitalizations seem to have peaked on Sept. 4, when the rate for children aged 0-17 years reached 0.51 per 100,000 population. The admission rate for confirmed COVID-19 has dropped steadily since then and was down to 0.45 per 100,000 on Sept. 11, the last day for which preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were available.

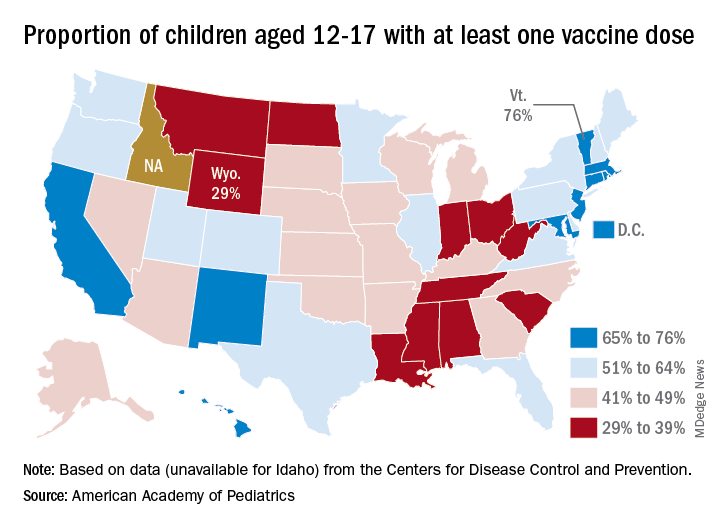

On the prevention side, fully vaccinated children aged 12-17 years represented 5.5% of all Americans who had completed the vaccine regimen as of Sept. 13. Vaccine initiation, however, has dropped for 5 consecutive weeks in 12- to 15-year-olds and in 4 of the last 5 weeks among 16- and 17-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Just under 199,000 children aged 12-15 received their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine during the week of Sept. 7-13. That’s down by 18.5% from the week before and by 51.6% since Aug. 9, the last week that vaccine initiation increased for the age group. Among 16- and 17-year-olds, the 83,000 new recipients that week was a decrease of 25.7% from the previous week and a decline of 47% since the summer peak of Aug. 9, the CDC data show.

Those newest recipients bring at-least-one-dose status to 52.0% of those aged 12-15 and 59.9% of the 16- and 17-year-olds, while 40.3% and 48.9% were fully vaccinated as of Sept. 13. Corresponding figures for some of the older groups are 61.6%/49.7% (age 18-24 years), 73.8%/63.1% (40-49 years), and 95.1%/84.5% (65-74 years), the CDC said.

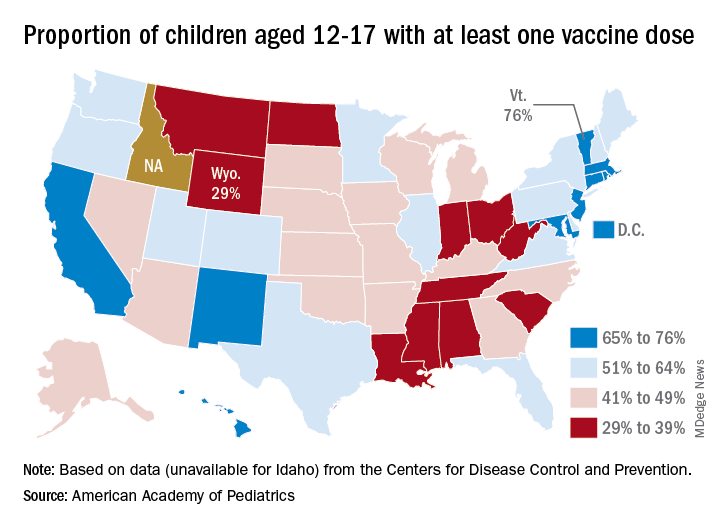

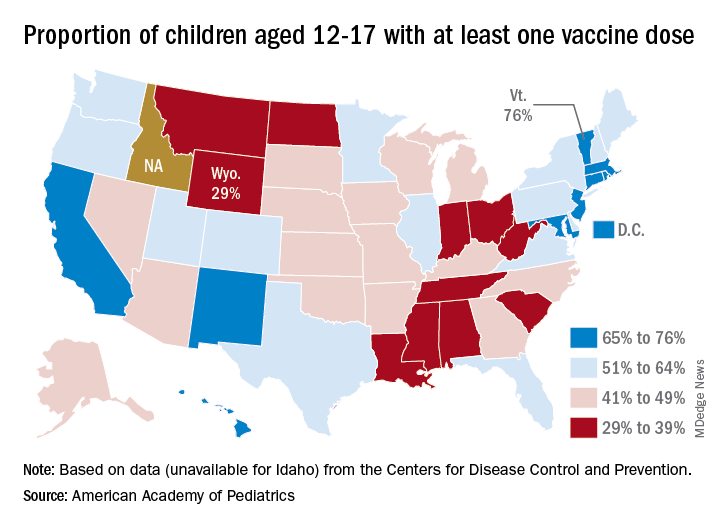

Vaccine coverage for children at the state level deviates considerably from the national averages. The highest rates for children aged 12-17 are to be found in Vermont, where 76% have received at least one dose, the AAP reported in a separate analysis. Massachusetts is just below that but also comes in at 76% by virtue of a rounding error. The other states in the top five are Connecticut (74%), Hawaii (73%), and Rhode Island (71%).

The lowest vaccination rate for children comes from Wyoming (29%), which is preceded by North Dakota (33%), West Virginia (33%), Alabama (33%), and Mississippi (34%). the AAP said based on data from the CDC, which does not include Idaho.

In a bit of a side note, West Virginia’s Republican governor, Jim Justice, recently said this about vaccine reluctance in his state: “For God’s sakes a livin’, how difficult is this to understand? Why in the world do we have to come up with these crazy ideas – and they’re crazy ideas – that the vaccine’s got something in it and it’s tracing people wherever they go? And the same very people that are saying that are carrying their cellphones around. I mean, come on. Come on.”

Over the last 3 weeks, the District of Columbia has had the largest increase in children having received at least one dose: 10 percentage points, as it went from 58% to 68%. The next-largest improvement – 7 percentage points – occurred in Georgia (34% to 41%), New Mexico (61% to 68%), New York (55% to 62%), and Washington (57% to 64%), the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children dropped for the first time since June, and daily hospitalizations appear to be falling, even as the pace of vaccinations continues to slow among the youngest eligible recipients, according to new data.

Despite the 3.3% decline from the previous week’s record high, the new-case count still topped 243,000 for the week of Sept. 3-9, putting the total number of cases in children at almost 5.3 million since the pandemic began.

Hospitalizations seem to have peaked on Sept. 4, when the rate for children aged 0-17 years reached 0.51 per 100,000 population. The admission rate for confirmed COVID-19 has dropped steadily since then and was down to 0.45 per 100,000 on Sept. 11, the last day for which preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were available.

On the prevention side, fully vaccinated children aged 12-17 years represented 5.5% of all Americans who had completed the vaccine regimen as of Sept. 13. Vaccine initiation, however, has dropped for 5 consecutive weeks in 12- to 15-year-olds and in 4 of the last 5 weeks among 16- and 17-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Just under 199,000 children aged 12-15 received their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine during the week of Sept. 7-13. That’s down by 18.5% from the week before and by 51.6% since Aug. 9, the last week that vaccine initiation increased for the age group. Among 16- and 17-year-olds, the 83,000 new recipients that week was a decrease of 25.7% from the previous week and a decline of 47% since the summer peak of Aug. 9, the CDC data show.

Those newest recipients bring at-least-one-dose status to 52.0% of those aged 12-15 and 59.9% of the 16- and 17-year-olds, while 40.3% and 48.9% were fully vaccinated as of Sept. 13. Corresponding figures for some of the older groups are 61.6%/49.7% (age 18-24 years), 73.8%/63.1% (40-49 years), and 95.1%/84.5% (65-74 years), the CDC said.

Vaccine coverage for children at the state level deviates considerably from the national averages. The highest rates for children aged 12-17 are to be found in Vermont, where 76% have received at least one dose, the AAP reported in a separate analysis. Massachusetts is just below that but also comes in at 76% by virtue of a rounding error. The other states in the top five are Connecticut (74%), Hawaii (73%), and Rhode Island (71%).

The lowest vaccination rate for children comes from Wyoming (29%), which is preceded by North Dakota (33%), West Virginia (33%), Alabama (33%), and Mississippi (34%). the AAP said based on data from the CDC, which does not include Idaho.

In a bit of a side note, West Virginia’s Republican governor, Jim Justice, recently said this about vaccine reluctance in his state: “For God’s sakes a livin’, how difficult is this to understand? Why in the world do we have to come up with these crazy ideas – and they’re crazy ideas – that the vaccine’s got something in it and it’s tracing people wherever they go? And the same very people that are saying that are carrying their cellphones around. I mean, come on. Come on.”

Over the last 3 weeks, the District of Columbia has had the largest increase in children having received at least one dose: 10 percentage points, as it went from 58% to 68%. The next-largest improvement – 7 percentage points – occurred in Georgia (34% to 41%), New Mexico (61% to 68%), New York (55% to 62%), and Washington (57% to 64%), the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children dropped for the first time since June, and daily hospitalizations appear to be falling, even as the pace of vaccinations continues to slow among the youngest eligible recipients, according to new data.

Despite the 3.3% decline from the previous week’s record high, the new-case count still topped 243,000 for the week of Sept. 3-9, putting the total number of cases in children at almost 5.3 million since the pandemic began.

Hospitalizations seem to have peaked on Sept. 4, when the rate for children aged 0-17 years reached 0.51 per 100,000 population. The admission rate for confirmed COVID-19 has dropped steadily since then and was down to 0.45 per 100,000 on Sept. 11, the last day for which preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were available.

On the prevention side, fully vaccinated children aged 12-17 years represented 5.5% of all Americans who had completed the vaccine regimen as of Sept. 13. Vaccine initiation, however, has dropped for 5 consecutive weeks in 12- to 15-year-olds and in 4 of the last 5 weeks among 16- and 17-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Just under 199,000 children aged 12-15 received their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine during the week of Sept. 7-13. That’s down by 18.5% from the week before and by 51.6% since Aug. 9, the last week that vaccine initiation increased for the age group. Among 16- and 17-year-olds, the 83,000 new recipients that week was a decrease of 25.7% from the previous week and a decline of 47% since the summer peak of Aug. 9, the CDC data show.

Those newest recipients bring at-least-one-dose status to 52.0% of those aged 12-15 and 59.9% of the 16- and 17-year-olds, while 40.3% and 48.9% were fully vaccinated as of Sept. 13. Corresponding figures for some of the older groups are 61.6%/49.7% (age 18-24 years), 73.8%/63.1% (40-49 years), and 95.1%/84.5% (65-74 years), the CDC said.

Vaccine coverage for children at the state level deviates considerably from the national averages. The highest rates for children aged 12-17 are to be found in Vermont, where 76% have received at least one dose, the AAP reported in a separate analysis. Massachusetts is just below that but also comes in at 76% by virtue of a rounding error. The other states in the top five are Connecticut (74%), Hawaii (73%), and Rhode Island (71%).

The lowest vaccination rate for children comes from Wyoming (29%), which is preceded by North Dakota (33%), West Virginia (33%), Alabama (33%), and Mississippi (34%). the AAP said based on data from the CDC, which does not include Idaho.

In a bit of a side note, West Virginia’s Republican governor, Jim Justice, recently said this about vaccine reluctance in his state: “For God’s sakes a livin’, how difficult is this to understand? Why in the world do we have to come up with these crazy ideas – and they’re crazy ideas – that the vaccine’s got something in it and it’s tracing people wherever they go? And the same very people that are saying that are carrying their cellphones around. I mean, come on. Come on.”

Over the last 3 weeks, the District of Columbia has had the largest increase in children having received at least one dose: 10 percentage points, as it went from 58% to 68%. The next-largest improvement – 7 percentage points – occurred in Georgia (34% to 41%), New Mexico (61% to 68%), New York (55% to 62%), and Washington (57% to 64%), the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

Man dies after 43 full ICUs turn him away

Ray Martin DeMonia, 73, of Cullman, Alabama, ran an antiques business for 40 years and served as an auctioneer at charity events, the obituary said.

He had a stroke in 2020 during the first months of the COVID pandemic and made sure to get vaccinated, his daughter, Raven DeMonia, told The Washington Post.

“He knew what the vaccine meant for his health and what it meant to staying alive,” she said. “He said, ‘I just want to get back to shaking hands with people, selling stuff, and talking antiques.’”

His daughter told the Post that her father went to Cullman Regional Medical Center on Aug. 23 with heart problems.

About 12 hours after he was admitted, her mother got a call from the hospital saying they’d called 43 hospitals and were unable to find a “specialized cardiac ICU bed” for him, Ms. DeMonia told the Post.

He was finally airlifted to Rush Foundation Hospital in Meridian, Mississippi, almost 200 miles from his home, but died there Sept. 1. His family decided to make a plea for increased vaccinations in his obituary.

“In honor of Ray, please get vaccinated if you have not, in an effort to free up resources for non COVID related emergencies,” the obit said. “Due to COVID 19, CRMC emergency staff contacted 43 hospitals in 3 states in search of a Cardiac ICU bed and finally located one in Meridian, MS. He would not want any other family to go through what his did.”

Mr. DeMonia is survived by his wife, daughter, grandson, and other family members.