User login

Pseudobulbar affect: No laughing matter

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

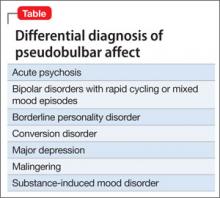

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Pathological laughter and crying— pseudobulbar affect (PBA)—is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of laughter or crying without an environmental trigger. Persons with PBA are at an increased risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms associated with an inappropriate outburst of emotion1; such emotional acts might be incongruent with their underlying emotional state.

When should you consider PBA?

Consider PBA in patients with new-onset emotional lability in the presence of certain neurologic conditions. PBA is most common in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and stroke, in which an incidence of >50% has been estimated.2 Other conditions associated with PBA include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, normal pressure hydrocephalus, progressive supranuclear palsy, Wilson disease, and neurosyphilis.3

Avoid PBA misdiagnosis

Depression is the most common PBA misdiagnosis (Table). However, many clinical features distinguish PBA episodes from depressive symptoms; the most prominent difference is duration. Depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, typically last weeks to months, but a PBA episode lasts seconds or minutes. In addition, crying, as a symptom of PBA, might be unrelated or exaggerated relative to the patient’s mood, but crying is congruent with subjective mood in depression. Other symptoms of depression—fatigue, anorexia, insomnia, anhedonia, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt— are not associated with pseudobulbar affect.

PBA also can be differentiated from bipolar disorder (BD) with rapid cycling or mixed mood episodes because of PBA’s relatively brief duration of laughing or crying episodes—with no mood disturbance between episodes—compared with the sustained changes in mood, cognition, and behavior seen in BD.

Options for treating PBA

Serotonergic therapies, such as amitriptyline and fluoxetine, may exert effects by increasing serotonin in the synapse; dextromethorphan may act via antiglutamatergic effects at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors and sigma-1 receptors.4 Dextromethorphan binding is most prominent in the brainstem and cerebellum, brain areas known to be rich in sigma-1 receptors and key sites implicated in the pathophysiology of PBA. Although the precise mechanisms by which dextromethorphan ameliorates PBA are unknown, modulation of excessive glutamatergic transmission within corticopontine-cerebellar circuits may contribute to its benefits.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.

1. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16(4):426-434.

2. Miller A, Pratt H, Schiffer RB. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(7):1077-1088.

3. Haiman G, Pratt H, Miller A. Brain responses to verbal stimuli among multiple sclerosis patients with pseudobulbar affect. J Neurol Sci. 2008;271(1-2):137-147.

4. Werling LL, Keller A, Frank JG, et al. A comparison of the binding profiles of dextromethorphan, memantine, fluoxetine and amitriptyline: treatment of involuntary emotional expression disorder. Exp Neurol. 2007;207(2): 248-257.

The first of 2 parts: A practical approach to subtyping depression among your patients

Depression carries a wide differential diagnosis. Practitioners sometimes think polarity is the fundamental distinction when they conceptualize depression as a clinical entity; in fact, many nosologic frameworks have been described for defining and subtyping clinically meaningful forms of depression, and each waxed and waned in popularity.

Kraepelin, writing in the early 20th century, linked manic-depressive illness with “the greater part of the morbid states termed melancholia,”1 but many features other than polarity remain important components of depression, and those features often carry implications for how individual patients respond to treatment.

In this 2-part article [April and May 2014 issues], I summarize information about clinically distinct subtypes of depression, as they are recognized within diagnostic systems or as descriptors of treatment outcomes for particular subgroups of patients. My focus is on practical considerations for assessing and managing depression. Because many forms of the disorder respond inadequately to initial antidepressant treatment, optimal “next-step” pharmacotherapy, after nonresponse or partial response, often hinges on clinical subtyping.

The first part of this article examines major depressive disorder (MDD), minor depression, chronic depression, depression in bipolar disorder, depression that is severe or mild, and psychotic depression. Treatments for these subtypes for which there is evidence, or a clinical rationale, are given in the Table.

The subtypes of depression that I’ll discuss in the second part of the article are listed on page 47.

Major and minor depression

MDD has been the focus of most drug trials seeking FDA approval. As a syndrome, MDD is defined by a constellation of features that are related not only to mood but also to sleep, energy, cognition, motivation, and motor behavior, persisting for ≥2 weeks.

DSM-5 has imposed few changes to the basic definition of MDD:

• bereavement (the aftermath of death of a loved one), formerly an exclusion criterion, no longer precludes making a diagnosis of MDD when syndromal criteria are otherwise fulfilled

• “with anxious distress” is a new course specifier that designates prominent anxiety features (feeling worried, restless, tense, or keyed up; fearful of losing control or something terrible happening)

• “with mixed features” is a new course specifier pertinent when ≥3 mania or hypomania symptoms coexist (that is, might be a subsyndromal mania or hypomania) with a depressive syndrome; the mixed features specifier can be applied to depressed patients whether or not they have ever had a manic or hypomanic episode, but MDD—rather than bipolar disorder— remains the overarching diagnosis, unless criteria have ever been met for a full mania or hypomania.

More than 2 dozen medications are FDA-approved to treat MDD. Evidence-based psychotherapies (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT] and interpersonal therapy), as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy, further improve outcomes, but with only modest additional effect.2

Minor depression. Depressive states that involve 2 to 4 associated symptoms lasting ≥2 weeks but <2 years are sometimes described as minor depression, captured within DSM-5 as “depression not elsewhere defined.” The terminology of so-called “minor depression” generally is shunned, in part because it might wrongly connote low severity and therefore discourage treatment—even though it confers more than a 5-fold increase in risk of MDD.3

Chronicity

DSM-IV-TR identified long-standing depression by 2 constructs:

• chronic major depression (an episode of MDD lasting ≥2 years in adults, ≥1 year in children and adolescents)

• dysthymic disorder (2 to 4 depressive symptoms for ≥2 years in adults and ≥1 year in children and adolescents), affecting 3% to 6% of adults and carrying a 2-fold increased risk of MDD, eventually.4

Depression that begins as dysthymic disorder and blossoms into syndromal MDD is described as “double depression”—although it is not recognized as a unique condition in any edition of the DSM. Subsequent incomplete recovery may revert to dysthymic disorder. DSM-5 has subsumed chronic major depression and dysthymia under the unified heading of persistent depressive disorder.

There are no FDA-approved drugs for treating dysthymia. A meta-analysis of 9 controlled trials of off-label use of antidepressants to treat dysthymia revealed an overall response rate of 52.4%, compared with 29.9% for placebo.5 Notably, although the active drug response rate in these studies is comparable to what seen in MDD, the placebo response rate was approximately 10% lower than what was seen in major depression.

Positive therapeutic findings (typically, treatment for 6 to 12 weeks) have been reported in so-called “pure” dysthymic disorder with sertraline, fluoxetine, imipramine, ritanserin, moclobemide (not approved for use in the United States), and phenelzine; the results of additional, positive placebo-controlled studies support the utility of duloxetine6 and paroxetine.7 Randomized trials have reported negative findings for desipramine,8 fluoxetine,9 and escitalopram10 escitalopram10—although the sample size in these latter studies might have been too small to detect a drug-placebo difference.

In dysthymic and minor-depressive middle-age and older adult men who have a low serum level of testosterone, hormone replacement was shown to be superior to placebo in several randomized trials.11 Studies of adjunctive atypical antipsychotics for dysthymic disorder are scarce; a Cochrane review identified controlled data only with amisulpride (not approved for use in the United States), which yielded a modest therapeutic effect.12

Polarity

In recent years, depression in bipolar disorder (BD) has been contrasted with unipolar MDD based on a difference in:

• duration (briefer in BD)

• severity (worse in BD)

• risk of suicide (higher)

• comorbidity (more extensive)

• family history (often present for BD and highly recurrent depression)

• treatment outcome (generally less favorable).

DSM-5 has at least somewhat blurred the distinctions in polarity by way of the new construct of “major depression with mixed features” (see the discussion of MDD above), identifiable even when a person has never had a full manic or hypomanic episode.

No randomized trials have been conducted to identify the best treatments for such presentations, which has invited extrapolation from the literature in regard to bipolar mixed episodes, and suggesting that 1) some mood stabilizers (eg, divalproex) might have value and 2) antidepressants might exacerbate manic symptoms.

Perhaps most noteworthy in regard to treating bipolar depression is the unresolved, but hotly debated, controversy over whether and, if so, when, an antidepressant is inappropriate (based on concerns about possible induction or exacerbation of manic symptoms). In addition, nearly all of the large, randomized controlled trials of antidepressants for bipolar depression have shown that they offer no advantage over placebo.

Some authors argue that a lack of response to antidepressants might, itself, be a “soft” indicator of “bipolarity.” However, nonresponse to antidepressants should prompt a wider assessment of features other than polarity—including psychosis, anxiety, substance abuse, a personality disorder, psychiatric adverse effects from concomitant medications, medical comor bidity, adequacy of trials of medical therapy, and potential non-adherence to such trials—to account for poor antidepressant outcomes.

Severity

Severity of depression warrants consideration when formulating impressions about the nature and treatment of all presentations of depression.

High-severity forms prompt decisions about treatment setting (inpatient or outpatient); suicide assessment; and therapeutic modalities (eg, electroconvulsive therapy is more appropriate than psychotherapy for catatonic depression).

Mild forms. A recent meta-analysis of 6 randomized trials (each of >6 weeks’ duration) of antidepressants for mild depression demonstrated that these agents exert only a modest effect compared with placebo, owing largely to higher placebo-responsivity in mild depressive episodes than in moderate and severe episodes.13 In contrast, another meta-analysis of subjects who had “mild” baseline depression severity scores found that antidepressant medication had greater efficacy than placebo in 4 of 6 randomized trials.14 Higher depression severity levels typically diminish the placebo response rate but also reduce the magnitude of drug efficacy.

Psychosis

Before DSM-III, psychotic (as opposed to neurotic) depression was perhaps the key nosologic distinction when characterizing forms of depression. The presence of psychosis and related components (eg, mood-congruence) is closely linked with the severity of depression (high) and prognosis and longitudinal outcome (poorer), and has implications for treatment (Table).

Bottom Line

Depressive disorders comprise a range of conditions that can be viewed along many dimensions, including polarity, chronicity, recurrence, psychosis, treatment resistance, comorbidity, and atypicality, among other classifications. Clinical characteristics vary across subtypes—and so do corresponding preferred treatments, which should be tailored to the needs of each of your patients.

Related Resources

• Goldberg JF, Thase ME. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors revisited: what you should know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(2):189-191.

• Goldberg JF. Antidepressants in bipolar disorder: 7 myths and realities. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):41-49.

• Ketamine cousin rapidly lifts depression without side effects. National Institute of Mental Health. http://www. nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2013/ketamine-cousin-rapidly-lifts-depression-without-side-effects.shtml. Published May 23, 2013. Accessed March 20, 2014.

• Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). National Institute of Mental Health. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/index.shtml?u tm_ source = govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign= govdelivery. Accessed March 20, 2014.

Drug Brand Names

Amisulpride • Amazeo, Lurasidone • Latuda

Amival, Amipride, Sulpitax Mirtazapine • Remeron

Aripiprazole • Abilify Moclobemide • Amira,

Armodafinil • Nuvigil Aurorix, Clobemix,

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Depnil, Manerix

Desipramine • Norpramin Modafinil • Provigil

Divalproex • Depakote, Olanzapine/fluoxetine

Depakene • Symbyax

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Paroxetine • Paxil

Escitalopram • Lexapro Phenelzine • Nardil

Fluoxetine • Prozac Pramipexole • Mirapex

Imipramine • Tofranil Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ketamine • Ketalar Riluzole • Rilutek

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Sertraline • Zoloft

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Vortioxetine • Brintellix

Disclosure

Dr. Goldberg has been a consultant to Avanir Pharmaceuticals and Merck; has served on the speakers’ bureau for AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, Sunovion

Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda and Lundbeck; and has received royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing and honoraria from Medscape and WebMD.

Editor’s note: The second part of Dr. Goldberg’s review of depression subtypes—focusing on “situational,” treatment-resistant, melancholic, agitated, anxious, and atypical depression; depression occurring with a substance use disorder; premenstrual dysphoric disorder; and seasonal affective disorder—will appear in the May 2014 issue of Current Psychiatry.

1. Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. Robertson GM, ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: E&S Livingstone; 1921:1.

2. Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, et al. Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1219-1229.

3. Fogel J, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Minor depression as a predictor of the first onset of major depressive disorder over a 15-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006; 113(1):36-43.

4. Cuijpers P, de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S. Minor depression: risk profiles, functional disability, health care use and risk of developing major depression. J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1-3):71-79.

5. Levkovitz Y, Tedeschini E, Papakostas GI. Efficacy of antidepressants for dysthymia: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(4):509-514.

6. Hellerstein DJ, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of nonmajor chronic depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(7):984-991.

7. Ravindran AV, Cameron C, Bhatla R, et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of dysthymic disorder without co-morbidities: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose study. Asian J Psychiatry. 2013;6(2):157-161.

8. Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Liebowitz MR, et al. Treatment outcome validation of DSM-III depressive subtypes. Clinical usefulness in outpatients with mild to moderate depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(12):1148-1153.

9. Serrano-Blanco A, Gabarron E, Garcia-Bayo I, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in primary health care: a six-month randomised study comparing fluoxetine to imipramine. J Affect Disord. 2006;91(2-3):153-163.

10. Hellerstein DJ, Batchelder ST, Hyler S, et al. Escitalopram versus placebo in the treatment of dysthymic disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(3):143-148.

11. Seidman SN, Orr G, Raviv G, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement in middle-aged men with dysthymia: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(3):216-221.

12. Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, et al. Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; 8:(12):CD008121.

13. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollom SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47-53.

14. Stewart JA, Deliyannides DA, Hellerstein DJ, et al. Can people with nonsevere major depression benefit from antidepressant medication? J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(4):518-525.

Depression carries a wide differential diagnosis. Practitioners sometimes think polarity is the fundamental distinction when they conceptualize depression as a clinical entity; in fact, many nosologic frameworks have been described for defining and subtyping clinically meaningful forms of depression, and each waxed and waned in popularity.

Kraepelin, writing in the early 20th century, linked manic-depressive illness with “the greater part of the morbid states termed melancholia,”1 but many features other than polarity remain important components of depression, and those features often carry implications for how individual patients respond to treatment.

In this 2-part article [April and May 2014 issues], I summarize information about clinically distinct subtypes of depression, as they are recognized within diagnostic systems or as descriptors of treatment outcomes for particular subgroups of patients. My focus is on practical considerations for assessing and managing depression. Because many forms of the disorder respond inadequately to initial antidepressant treatment, optimal “next-step” pharmacotherapy, after nonresponse or partial response, often hinges on clinical subtyping.

The first part of this article examines major depressive disorder (MDD), minor depression, chronic depression, depression in bipolar disorder, depression that is severe or mild, and psychotic depression. Treatments for these subtypes for which there is evidence, or a clinical rationale, are given in the Table.

The subtypes of depression that I’ll discuss in the second part of the article are listed on page 47.

Major and minor depression

MDD has been the focus of most drug trials seeking FDA approval. As a syndrome, MDD is defined by a constellation of features that are related not only to mood but also to sleep, energy, cognition, motivation, and motor behavior, persisting for ≥2 weeks.

DSM-5 has imposed few changes to the basic definition of MDD:

• bereavement (the aftermath of death of a loved one), formerly an exclusion criterion, no longer precludes making a diagnosis of MDD when syndromal criteria are otherwise fulfilled

• “with anxious distress” is a new course specifier that designates prominent anxiety features (feeling worried, restless, tense, or keyed up; fearful of losing control or something terrible happening)

• “with mixed features” is a new course specifier pertinent when ≥3 mania or hypomania symptoms coexist (that is, might be a subsyndromal mania or hypomania) with a depressive syndrome; the mixed features specifier can be applied to depressed patients whether or not they have ever had a manic or hypomanic episode, but MDD—rather than bipolar disorder— remains the overarching diagnosis, unless criteria have ever been met for a full mania or hypomania.

More than 2 dozen medications are FDA-approved to treat MDD. Evidence-based psychotherapies (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT] and interpersonal therapy), as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy, further improve outcomes, but with only modest additional effect.2

Minor depression. Depressive states that involve 2 to 4 associated symptoms lasting ≥2 weeks but <2 years are sometimes described as minor depression, captured within DSM-5 as “depression not elsewhere defined.” The terminology of so-called “minor depression” generally is shunned, in part because it might wrongly connote low severity and therefore discourage treatment—even though it confers more than a 5-fold increase in risk of MDD.3

Chronicity

DSM-IV-TR identified long-standing depression by 2 constructs:

• chronic major depression (an episode of MDD lasting ≥2 years in adults, ≥1 year in children and adolescents)

• dysthymic disorder (2 to 4 depressive symptoms for ≥2 years in adults and ≥1 year in children and adolescents), affecting 3% to 6% of adults and carrying a 2-fold increased risk of MDD, eventually.4

Depression that begins as dysthymic disorder and blossoms into syndromal MDD is described as “double depression”—although it is not recognized as a unique condition in any edition of the DSM. Subsequent incomplete recovery may revert to dysthymic disorder. DSM-5 has subsumed chronic major depression and dysthymia under the unified heading of persistent depressive disorder.

There are no FDA-approved drugs for treating dysthymia. A meta-analysis of 9 controlled trials of off-label use of antidepressants to treat dysthymia revealed an overall response rate of 52.4%, compared with 29.9% for placebo.5 Notably, although the active drug response rate in these studies is comparable to what seen in MDD, the placebo response rate was approximately 10% lower than what was seen in major depression.

Positive therapeutic findings (typically, treatment for 6 to 12 weeks) have been reported in so-called “pure” dysthymic disorder with sertraline, fluoxetine, imipramine, ritanserin, moclobemide (not approved for use in the United States), and phenelzine; the results of additional, positive placebo-controlled studies support the utility of duloxetine6 and paroxetine.7 Randomized trials have reported negative findings for desipramine,8 fluoxetine,9 and escitalopram10 escitalopram10—although the sample size in these latter studies might have been too small to detect a drug-placebo difference.

In dysthymic and minor-depressive middle-age and older adult men who have a low serum level of testosterone, hormone replacement was shown to be superior to placebo in several randomized trials.11 Studies of adjunctive atypical antipsychotics for dysthymic disorder are scarce; a Cochrane review identified controlled data only with amisulpride (not approved for use in the United States), which yielded a modest therapeutic effect.12

Polarity

In recent years, depression in bipolar disorder (BD) has been contrasted with unipolar MDD based on a difference in:

• duration (briefer in BD)

• severity (worse in BD)

• risk of suicide (higher)

• comorbidity (more extensive)

• family history (often present for BD and highly recurrent depression)

• treatment outcome (generally less favorable).

DSM-5 has at least somewhat blurred the distinctions in polarity by way of the new construct of “major depression with mixed features” (see the discussion of MDD above), identifiable even when a person has never had a full manic or hypomanic episode.

No randomized trials have been conducted to identify the best treatments for such presentations, which has invited extrapolation from the literature in regard to bipolar mixed episodes, and suggesting that 1) some mood stabilizers (eg, divalproex) might have value and 2) antidepressants might exacerbate manic symptoms.

Perhaps most noteworthy in regard to treating bipolar depression is the unresolved, but hotly debated, controversy over whether and, if so, when, an antidepressant is inappropriate (based on concerns about possible induction or exacerbation of manic symptoms). In addition, nearly all of the large, randomized controlled trials of antidepressants for bipolar depression have shown that they offer no advantage over placebo.

Some authors argue that a lack of response to antidepressants might, itself, be a “soft” indicator of “bipolarity.” However, nonresponse to antidepressants should prompt a wider assessment of features other than polarity—including psychosis, anxiety, substance abuse, a personality disorder, psychiatric adverse effects from concomitant medications, medical comor bidity, adequacy of trials of medical therapy, and potential non-adherence to such trials—to account for poor antidepressant outcomes.

Severity

Severity of depression warrants consideration when formulating impressions about the nature and treatment of all presentations of depression.

High-severity forms prompt decisions about treatment setting (inpatient or outpatient); suicide assessment; and therapeutic modalities (eg, electroconvulsive therapy is more appropriate than psychotherapy for catatonic depression).

Mild forms. A recent meta-analysis of 6 randomized trials (each of >6 weeks’ duration) of antidepressants for mild depression demonstrated that these agents exert only a modest effect compared with placebo, owing largely to higher placebo-responsivity in mild depressive episodes than in moderate and severe episodes.13 In contrast, another meta-analysis of subjects who had “mild” baseline depression severity scores found that antidepressant medication had greater efficacy than placebo in 4 of 6 randomized trials.14 Higher depression severity levels typically diminish the placebo response rate but also reduce the magnitude of drug efficacy.

Psychosis

Before DSM-III, psychotic (as opposed to neurotic) depression was perhaps the key nosologic distinction when characterizing forms of depression. The presence of psychosis and related components (eg, mood-congruence) is closely linked with the severity of depression (high) and prognosis and longitudinal outcome (poorer), and has implications for treatment (Table).

Bottom Line

Depressive disorders comprise a range of conditions that can be viewed along many dimensions, including polarity, chronicity, recurrence, psychosis, treatment resistance, comorbidity, and atypicality, among other classifications. Clinical characteristics vary across subtypes—and so do corresponding preferred treatments, which should be tailored to the needs of each of your patients.

Related Resources

• Goldberg JF, Thase ME. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors revisited: what you should know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(2):189-191.

• Goldberg JF. Antidepressants in bipolar disorder: 7 myths and realities. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):41-49.

• Ketamine cousin rapidly lifts depression without side effects. National Institute of Mental Health. http://www. nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2013/ketamine-cousin-rapidly-lifts-depression-without-side-effects.shtml. Published May 23, 2013. Accessed March 20, 2014.

• Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). National Institute of Mental Health. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/index.shtml?u tm_ source = govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign= govdelivery. Accessed March 20, 2014.

Drug Brand Names

Amisulpride • Amazeo, Lurasidone • Latuda

Amival, Amipride, Sulpitax Mirtazapine • Remeron

Aripiprazole • Abilify Moclobemide • Amira,

Armodafinil • Nuvigil Aurorix, Clobemix,

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Depnil, Manerix

Desipramine • Norpramin Modafinil • Provigil

Divalproex • Depakote, Olanzapine/fluoxetine

Depakene • Symbyax

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Paroxetine • Paxil

Escitalopram • Lexapro Phenelzine • Nardil

Fluoxetine • Prozac Pramipexole • Mirapex

Imipramine • Tofranil Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ketamine • Ketalar Riluzole • Rilutek

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Sertraline • Zoloft

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Vortioxetine • Brintellix

Disclosure

Dr. Goldberg has been a consultant to Avanir Pharmaceuticals and Merck; has served on the speakers’ bureau for AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, Sunovion

Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda and Lundbeck; and has received royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing and honoraria from Medscape and WebMD.

Editor’s note: The second part of Dr. Goldberg’s review of depression subtypes—focusing on “situational,” treatment-resistant, melancholic, agitated, anxious, and atypical depression; depression occurring with a substance use disorder; premenstrual dysphoric disorder; and seasonal affective disorder—will appear in the May 2014 issue of Current Psychiatry.

Depression carries a wide differential diagnosis. Practitioners sometimes think polarity is the fundamental distinction when they conceptualize depression as a clinical entity; in fact, many nosologic frameworks have been described for defining and subtyping clinically meaningful forms of depression, and each waxed and waned in popularity.

Kraepelin, writing in the early 20th century, linked manic-depressive illness with “the greater part of the morbid states termed melancholia,”1 but many features other than polarity remain important components of depression, and those features often carry implications for how individual patients respond to treatment.

In this 2-part article [April and May 2014 issues], I summarize information about clinically distinct subtypes of depression, as they are recognized within diagnostic systems or as descriptors of treatment outcomes for particular subgroups of patients. My focus is on practical considerations for assessing and managing depression. Because many forms of the disorder respond inadequately to initial antidepressant treatment, optimal “next-step” pharmacotherapy, after nonresponse or partial response, often hinges on clinical subtyping.

The first part of this article examines major depressive disorder (MDD), minor depression, chronic depression, depression in bipolar disorder, depression that is severe or mild, and psychotic depression. Treatments for these subtypes for which there is evidence, or a clinical rationale, are given in the Table.

The subtypes of depression that I’ll discuss in the second part of the article are listed on page 47.

Major and minor depression

MDD has been the focus of most drug trials seeking FDA approval. As a syndrome, MDD is defined by a constellation of features that are related not only to mood but also to sleep, energy, cognition, motivation, and motor behavior, persisting for ≥2 weeks.

DSM-5 has imposed few changes to the basic definition of MDD:

• bereavement (the aftermath of death of a loved one), formerly an exclusion criterion, no longer precludes making a diagnosis of MDD when syndromal criteria are otherwise fulfilled

• “with anxious distress” is a new course specifier that designates prominent anxiety features (feeling worried, restless, tense, or keyed up; fearful of losing control or something terrible happening)

• “with mixed features” is a new course specifier pertinent when ≥3 mania or hypomania symptoms coexist (that is, might be a subsyndromal mania or hypomania) with a depressive syndrome; the mixed features specifier can be applied to depressed patients whether or not they have ever had a manic or hypomanic episode, but MDD—rather than bipolar disorder— remains the overarching diagnosis, unless criteria have ever been met for a full mania or hypomania.

More than 2 dozen medications are FDA-approved to treat MDD. Evidence-based psychotherapies (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT] and interpersonal therapy), as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy, further improve outcomes, but with only modest additional effect.2

Minor depression. Depressive states that involve 2 to 4 associated symptoms lasting ≥2 weeks but <2 years are sometimes described as minor depression, captured within DSM-5 as “depression not elsewhere defined.” The terminology of so-called “minor depression” generally is shunned, in part because it might wrongly connote low severity and therefore discourage treatment—even though it confers more than a 5-fold increase in risk of MDD.3

Chronicity

DSM-IV-TR identified long-standing depression by 2 constructs:

• chronic major depression (an episode of MDD lasting ≥2 years in adults, ≥1 year in children and adolescents)

• dysthymic disorder (2 to 4 depressive symptoms for ≥2 years in adults and ≥1 year in children and adolescents), affecting 3% to 6% of adults and carrying a 2-fold increased risk of MDD, eventually.4

Depression that begins as dysthymic disorder and blossoms into syndromal MDD is described as “double depression”—although it is not recognized as a unique condition in any edition of the DSM. Subsequent incomplete recovery may revert to dysthymic disorder. DSM-5 has subsumed chronic major depression and dysthymia under the unified heading of persistent depressive disorder.

There are no FDA-approved drugs for treating dysthymia. A meta-analysis of 9 controlled trials of off-label use of antidepressants to treat dysthymia revealed an overall response rate of 52.4%, compared with 29.9% for placebo.5 Notably, although the active drug response rate in these studies is comparable to what seen in MDD, the placebo response rate was approximately 10% lower than what was seen in major depression.

Positive therapeutic findings (typically, treatment for 6 to 12 weeks) have been reported in so-called “pure” dysthymic disorder with sertraline, fluoxetine, imipramine, ritanserin, moclobemide (not approved for use in the United States), and phenelzine; the results of additional, positive placebo-controlled studies support the utility of duloxetine6 and paroxetine.7 Randomized trials have reported negative findings for desipramine,8 fluoxetine,9 and escitalopram10 escitalopram10—although the sample size in these latter studies might have been too small to detect a drug-placebo difference.

In dysthymic and minor-depressive middle-age and older adult men who have a low serum level of testosterone, hormone replacement was shown to be superior to placebo in several randomized trials.11 Studies of adjunctive atypical antipsychotics for dysthymic disorder are scarce; a Cochrane review identified controlled data only with amisulpride (not approved for use in the United States), which yielded a modest therapeutic effect.12

Polarity

In recent years, depression in bipolar disorder (BD) has been contrasted with unipolar MDD based on a difference in:

• duration (briefer in BD)

• severity (worse in BD)

• risk of suicide (higher)

• comorbidity (more extensive)

• family history (often present for BD and highly recurrent depression)

• treatment outcome (generally less favorable).

DSM-5 has at least somewhat blurred the distinctions in polarity by way of the new construct of “major depression with mixed features” (see the discussion of MDD above), identifiable even when a person has never had a full manic or hypomanic episode.

No randomized trials have been conducted to identify the best treatments for such presentations, which has invited extrapolation from the literature in regard to bipolar mixed episodes, and suggesting that 1) some mood stabilizers (eg, divalproex) might have value and 2) antidepressants might exacerbate manic symptoms.

Perhaps most noteworthy in regard to treating bipolar depression is the unresolved, but hotly debated, controversy over whether and, if so, when, an antidepressant is inappropriate (based on concerns about possible induction or exacerbation of manic symptoms). In addition, nearly all of the large, randomized controlled trials of antidepressants for bipolar depression have shown that they offer no advantage over placebo.

Some authors argue that a lack of response to antidepressants might, itself, be a “soft” indicator of “bipolarity.” However, nonresponse to antidepressants should prompt a wider assessment of features other than polarity—including psychosis, anxiety, substance abuse, a personality disorder, psychiatric adverse effects from concomitant medications, medical comor bidity, adequacy of trials of medical therapy, and potential non-adherence to such trials—to account for poor antidepressant outcomes.

Severity

Severity of depression warrants consideration when formulating impressions about the nature and treatment of all presentations of depression.

High-severity forms prompt decisions about treatment setting (inpatient or outpatient); suicide assessment; and therapeutic modalities (eg, electroconvulsive therapy is more appropriate than psychotherapy for catatonic depression).

Mild forms. A recent meta-analysis of 6 randomized trials (each of >6 weeks’ duration) of antidepressants for mild depression demonstrated that these agents exert only a modest effect compared with placebo, owing largely to higher placebo-responsivity in mild depressive episodes than in moderate and severe episodes.13 In contrast, another meta-analysis of subjects who had “mild” baseline depression severity scores found that antidepressant medication had greater efficacy than placebo in 4 of 6 randomized trials.14 Higher depression severity levels typically diminish the placebo response rate but also reduce the magnitude of drug efficacy.

Psychosis

Before DSM-III, psychotic (as opposed to neurotic) depression was perhaps the key nosologic distinction when characterizing forms of depression. The presence of psychosis and related components (eg, mood-congruence) is closely linked with the severity of depression (high) and prognosis and longitudinal outcome (poorer), and has implications for treatment (Table).

Bottom Line

Depressive disorders comprise a range of conditions that can be viewed along many dimensions, including polarity, chronicity, recurrence, psychosis, treatment resistance, comorbidity, and atypicality, among other classifications. Clinical characteristics vary across subtypes—and so do corresponding preferred treatments, which should be tailored to the needs of each of your patients.

Related Resources

• Goldberg JF, Thase ME. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors revisited: what you should know. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(2):189-191.

• Goldberg JF. Antidepressants in bipolar disorder: 7 myths and realities. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):41-49.

• Ketamine cousin rapidly lifts depression without side effects. National Institute of Mental Health. http://www. nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2013/ketamine-cousin-rapidly-lifts-depression-without-side-effects.shtml. Published May 23, 2013. Accessed March 20, 2014.

• Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). National Institute of Mental Health. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/index.shtml?u tm_ source = govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign= govdelivery. Accessed March 20, 2014.

Drug Brand Names

Amisulpride • Amazeo, Lurasidone • Latuda

Amival, Amipride, Sulpitax Mirtazapine • Remeron

Aripiprazole • Abilify Moclobemide • Amira,

Armodafinil • Nuvigil Aurorix, Clobemix,

Bupropion • Wellbutrin Depnil, Manerix

Desipramine • Norpramin Modafinil • Provigil

Divalproex • Depakote, Olanzapine/fluoxetine

Depakene • Symbyax

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Paroxetine • Paxil

Escitalopram • Lexapro Phenelzine • Nardil

Fluoxetine • Prozac Pramipexole • Mirapex

Imipramine • Tofranil Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ketamine • Ketalar Riluzole • Rilutek

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Sertraline • Zoloft

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid Vortioxetine • Brintellix

Disclosure

Dr. Goldberg has been a consultant to Avanir Pharmaceuticals and Merck; has served on the speakers’ bureau for AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, Sunovion

Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda and Lundbeck; and has received royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing and honoraria from Medscape and WebMD.

Editor’s note: The second part of Dr. Goldberg’s review of depression subtypes—focusing on “situational,” treatment-resistant, melancholic, agitated, anxious, and atypical depression; depression occurring with a substance use disorder; premenstrual dysphoric disorder; and seasonal affective disorder—will appear in the May 2014 issue of Current Psychiatry.

1. Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. Robertson GM, ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: E&S Livingstone; 1921:1.

2. Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, et al. Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1219-1229.

3. Fogel J, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Minor depression as a predictor of the first onset of major depressive disorder over a 15-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006; 113(1):36-43.

4. Cuijpers P, de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S. Minor depression: risk profiles, functional disability, health care use and risk of developing major depression. J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1-3):71-79.

5. Levkovitz Y, Tedeschini E, Papakostas GI. Efficacy of antidepressants for dysthymia: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(4):509-514.

6. Hellerstein DJ, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of nonmajor chronic depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(7):984-991.

7. Ravindran AV, Cameron C, Bhatla R, et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of dysthymic disorder without co-morbidities: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose study. Asian J Psychiatry. 2013;6(2):157-161.

8. Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Liebowitz MR, et al. Treatment outcome validation of DSM-III depressive subtypes. Clinical usefulness in outpatients with mild to moderate depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(12):1148-1153.

9. Serrano-Blanco A, Gabarron E, Garcia-Bayo I, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in primary health care: a six-month randomised study comparing fluoxetine to imipramine. J Affect Disord. 2006;91(2-3):153-163.

10. Hellerstein DJ, Batchelder ST, Hyler S, et al. Escitalopram versus placebo in the treatment of dysthymic disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(3):143-148.

11. Seidman SN, Orr G, Raviv G, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement in middle-aged men with dysthymia: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(3):216-221.

12. Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, et al. Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; 8:(12):CD008121.

13. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollom SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47-53.

14. Stewart JA, Deliyannides DA, Hellerstein DJ, et al. Can people with nonsevere major depression benefit from antidepressant medication? J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(4):518-525.

1. Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. Robertson GM, ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: E&S Livingstone; 1921:1.

2. Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, et al. Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1219-1229.

3. Fogel J, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Minor depression as a predictor of the first onset of major depressive disorder over a 15-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006; 113(1):36-43.

4. Cuijpers P, de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S. Minor depression: risk profiles, functional disability, health care use and risk of developing major depression. J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1-3):71-79.

5. Levkovitz Y, Tedeschini E, Papakostas GI. Efficacy of antidepressants for dysthymia: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(4):509-514.

6. Hellerstein DJ, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of nonmajor chronic depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(7):984-991.

7. Ravindran AV, Cameron C, Bhatla R, et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of dysthymic disorder without co-morbidities: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose study. Asian J Psychiatry. 2013;6(2):157-161.

8. Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Liebowitz MR, et al. Treatment outcome validation of DSM-III depressive subtypes. Clinical usefulness in outpatients with mild to moderate depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(12):1148-1153.

9. Serrano-Blanco A, Gabarron E, Garcia-Bayo I, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in primary health care: a six-month randomised study comparing fluoxetine to imipramine. J Affect Disord. 2006;91(2-3):153-163.

10. Hellerstein DJ, Batchelder ST, Hyler S, et al. Escitalopram versus placebo in the treatment of dysthymic disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(3):143-148.

11. Seidman SN, Orr G, Raviv G, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement in middle-aged men with dysthymia: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(3):216-221.

12. Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, et al. Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; 8:(12):CD008121.

13. Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollom SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47-53.

14. Stewart JA, Deliyannides DA, Hellerstein DJ, et al. Can people with nonsevere major depression benefit from antidepressant medication? J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(4):518-525.

To prevent depression recurrence, interpersonal psychotherapy is a first-line treatment with long-term benefits

Major depressive disorder (MDD) frequently is recurrent, with new episodes causing substantial social and economic impairment1 and increasing the likelihood of future episodes.2 For this reason, contemporary psychiatric practitioners think of depression treatment as long-term and plan thoughtfully for maintenance therapy.

Recognizing the importance of engaging depressed individuals beyond the initial response,3 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines conceptualize depression treatment as 3 phases:

• acute treatment, with the aim of remission (symptom removal)

• continuation treatment, with the aim of preventing relapse (symptom return)

• maintenance treatment, with the aim of preventing recurrence (new episodes).4

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is an evidence-based psychosocial treatment that adheres to this model.5 As a time-limited, manual-driven6,7 approach, IPT focuses on interpersonal distresses as precipitating and perpetuating factors of depression.8

Acute IPT’s efficacy is well-established across >200 empirical studies—making it an evidence-based, first-line treatment for adult depression.4,9,10 Meta-analyses show that acute IPT is superior to placebo and no-treatment controls, and largely comparable to antidepressant medication and other active, first-line psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).11,12

Although this review, as well as the literature, focuses largely on adult outpatients with depression, evidence of IPT’s general efficacy exists for adolescents,13 chronically depressed patients,11 and depressed inpatients.14 This article presents a case study to describe the structure of IPT when used to treat depressed adults. We also present evidence of IPT’s acute and long-term efficacy in preventing depression recurrence and data to guide its use in practice.

CASE REPORT

‘Safe’ but depressed

Timothy, age 18, is a first-year college student who presents for outpatient psychotherapy to address recurrent depression. He reports general unhappiness, loss of interest in things, low energy, sleep problems, poor academic and work functioning, and low self-esteem. He experienced at least 3 similar depressive episodes while in high school.

The therapist’s diagnostic and interpersonal assessment suggests that Timothy’s depression is interpersonally driven. Timothy longs for relational intimacy but fears he will fail or burden people with his needs. He has difficulty gauging appropriate levels of enmeshment with others and either becomes overdependent or stays at a distance. This “safe” approach to relationships contributes to boredom, loneliness, and isolation. His recent transition to college away from home and the failure of a romantic relationship have compounded these experiences.

Interpersonal model of IPT

IPT conceptualizes depression as involving predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating biopsychosocial factors, including:

• underlying biological and social vulnerability, such as insecure attach ment (ie, tenuous and often negative views of self and others)

• current interpersonal life stressors

• inadequate social supports.15,16

For example, poor early attachment to caregivers can give rise to despair, isolation, and low mood. In turn, this can be exacerbated by poor social and communication skills that promote further rejection and withdrawal of social support and thus, intensified despair, isolation, and low mood. As in Timothy’s case, this vicious cycle underscores psychosocial stressors as a causal factor, maintaining factor, and result of depression. Specifically, IPT conceptualizes 4 main biopsychosocial problem domains:

• grief and loss

• interpersonal disputes

• role transitions

• interpersonal/communication deficits (often connected to isolation).

Working within 1 or 2 of the most salient problem domains, IPT centers on strategies for helping patients solve interpersonal problems based on the notion that modified relationships, revised interpersonal expectations, improved communications, and increased social support will lead to symptom reduction.15-17

Many techniques are utilized in IPT (Table 1) to help patients modify their interpersonal relationships as a mechanism for decreasing their distress. IPT is problem-focused, aiming to improve patients’ relationships by drawing on their assets and helping to build skills around shortcomings. Therefore, IPT focuses on observable interpersonal patterns, as opposed to latent personality dynamics.

CASE CONTINUED

Setting goals

When the clinical explains in the non-technical terms the data supporting IPT’s efficacy for depression, including with young adults, Timothy agrees to teeatment with acute IPT. The therapist behins with consciousness-raising techniques to help Timothy adopt the “sick role” by viewing depressing as an illness to be cured. Collaboratively, they establish treatment goals that fit the IPT formulation of depression— ie, revising current relationships and expectations of them, increasing social support, improving communication skills, and solving problems within 1 or 2 of the IPT problem domains.

For Timothy, the most pressing psychosocial problems seem to be interpersonal deficits and role transitions. He appears to be insecurely attached to others, which is a risk factor for poor facilitation of, and boundaries around, good relationships. A transition to a new and intimidating interpersonal context—living on a college campus—compounded his vulnerabilities and increased his depression.

Acute treatment. The acute phase of IPT is time-limited—often, 12 to 16 sessions with gradual tapering toward the end (akin to a continuation phase). The time limit’s purpose is to focus both patient and therapist on the specific goal of removing the acute “illness” of depression. The IPT clinician takes an interpersonal inventory to learn about the patient’s most important relationships and hones in on the IPT domain foci. Working collaboratively, the therapist might help the patient mourn a loss, reconstruct a narrative with a deceased loved one, consider ways to increase social contact, develop assertiveness, label feelings and needs, resolve an impasse with a significant other, and so forth.

The IPT therapist is an advocate for the patient and adopts an active stance laced with empathy and warmth. However, the therapist is more than unconditionally accepting as depression is viewed as a problem to be actively resolved.

CASE CONTINUED

Creating new patterns

The therapist uses various IPT strategies to work collaboratively with Timothy. She attempts to develop a strong working alliance by building interpersonal safety and trust— which take time with an insecurely attached patient. She tries to provide a new model for how close relationships can develop, while also focusing on current relationships. She and Timothy address his romantic desire for a coworker and work on developing realistic expectations and effective methods for conveying his interest.

When Timothy approaches his coworker, she does not reject him—as he expected— but wants to pursue friendship before possibly dating. The therapist then works with Timothy’s emotional reaction and explores ways to effectively convey his emotions to this young woman. Drawing on communication analysis and problem-solving strategies, Timothy is able to sustain this friendship—a shift from his typical retreat when relationships have not gone as hoped or expected.

Timothy develops confidence to take more risks in initiating social encounters and starts to confide in his roommates when he feels upset. After 3 months of treatment, his expanded social network and improved interpersonal skills result in decreased depression. When Timothy suggests termination, he and the therapist agree to end acute IPT but—given his history of depression—to continue maintenance sessions.

Limited data exist on variables that relate to IPT’s acute success or conditions under which it works best. Although process research lags behind acute IPT outcome research, some findings can help guide the IPT practitioner. For example, variables shown to predict outcomes of acute IPT for depression include a positive therapeutic alliance, therapist warmth, and psycho psychotherapist use of exploratory techniques (Table 2).

Similarly, IPT has been shown to be more effective in some patients than others, depending on various moderators of depression. For example:

• For patients with high cognitive dysfunction, IPT outperforms CBT.

• For patients with higher need for medical reassurance, IPT outperforms selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) pharmacotherapy.

• For patients with severe depression, CBT outperforms IPT.

• For patients with low psychomotor activation, response is more rapid with an SSRI than with IPT (Table 3).18

Durability of acute IPT

One way to understand recurrence prevention is to examine the durability of a treatment’s acute effect in the absence of a specific maintenance plan. In theory, patients will continue to apply the skills learned in acute IPT to maintain gains and prevent recurrences, even after they stop seeing the psychotherapist.

Initial findings. Some research speaks to IPT’s acute-phase durability. The inaugural clinical trial of IPT by Weissman et al19 included 4 months of acute treatment and a 1-year uncontrolled naturalistic follow-up assessment. At follow-up, depression and global clinical symptoms were the same, whether patients had been acutely treated with IPT alone, pharmacotherapy alone (amitriptyline), combined IPT and pharmacotherapy, or nonscheduled treatment with a psychiatrist.

Some patients continued to function well, whereas others did not fully maintain acute treatment gains. Patients who received IPT acutely, either singly or with medication, showed better social functioning at follow-up compared with patients who did not receive IPT. This long-term durability of social improvements was an obvious target of IPT.

Support from TDCRP. In the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Project (TDCRP),20 patients in the acute phase of depression were assigned to 16 weeks of IPT, CBT, pharmacotherapy (imipramine) and clinical management (CM), or placebo plus CM. Among those who recovered by acute treatment’s end, MDD relapse rates at 18-month naturalistic follow-up were 33% for IPT, 36% for CBT, 50% for imipramine, and 33% for placebo. Between-group differences were not statistically significant.

Because acute responders to different types of treatment might have different inherent relapse tendencies, these data do not support causal attributions about the enduring effects of acute-phase treatment. The relapse rates do suggest, however, that 16 weeks of acute treatment, irrespective of kind, was insufficient for some patients to achieve full recovery and lasting remission. Consistent with the initial IPT trial,19 IPT (and CBT) outperformed medi cation and placebo in maintaining relationship quality.21

Long-term benefits. A more recent trial by Zobel et al22 examined the durability of benefits from 5 weeks of acute IPT plus pharmacotherapy and pharmacotherapy plus CM for inpatients with MDD. Although caution is required in interpreting naturalistic follow-up studies, patients in both groups showed decreased depression from baseline to 5-year follow-up. Early symptom reduction was more rapid for patients in the IPT plus pharmacotherapy group, but no significant difference existed at 5 years. More IPT patients than CM patients showed sustained remission (28% vs 11%, respectively). These rates demonstrate a need for longer-term potency of acute treatments and more targeted maintenance treatments.

IPT-M for preventing recurrence

A second way to understand recurrence prevention is to examine the efficacy of a treatment’s maintenance protocol added to an acute treatment phase. IPT has been adapted as a maintenance treatment (IPT-M), with emphasis on keeping patients well. With this revised focus, IPT-M differs somewhat from acute IPT. Although treatment continues to center on interpersonal functioning, IPT-M favors:

• vigilance for possible triggers of new depressive episodes

• longer-term contact with a therapist

• reinforcing skills learned

• addressing an expanded number of interpersonal problem areas (given that such problems can be addressed more efficiently relative to acute treatment).

Efficacy of IPT-M. In the initial trial, Frank et al23 compared the efficacy of IPT-M with that of pharmacotherapy (imipramine) in preventing depressive relapse among patients with recurrent depression who had responded to ≥16 sessions of acute IPT and imipramine and remained well during a 17- week continuation phase. For maintenance, patients were assigned to IPT-M alone, imipramine alone, placebo alone, IPT-M plus imipramine, or IPT-M plus placebo. Maintenance imipramine was continued at the acute dosage (target 200 mg/d; up to 400 mg/d was allowed). Maintenance IPT was monthly sessions. Patients remained in the trial for 3 years or until depression recurred.

On its own, IPT-M showed some efficacy in preventing recurrence, as the mean time to recurrence was 82 weeks for IPT-M alone and 74 weeks for IPT-M plus placebo. The prophylactic effect of imipramine was stronger, however. The mean time to recurrence for imipramine with IPT was 131 weeks, and the mean time to recurrence for imipramine without IPT was 124 weeks. Therefore, whereas monthly IPT-M can certainly help prolong wellness and delay recurrence, IPT maintenance treatment with acute doses of imipramine might be even more effective— if the patient is willing to take medication. These findings must be considered with caution because of the inherent inequity between imipramine and IPT-M in regard to maintenance dosage strength.

Frequency of treatment. In another trial, Frank et al24 examined whether the frequency of maintenance IPT sessions played a role in its prophylactic effect. Adult women who had achieved depression remission with acute IPT (alone or in combination with SSRI pharmacotherapy) were randomized to weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly IPT-M alone for 2 years or until recurrence. Depression recurred during IPT-M in:

• 26% of patients who had received acute IPT alone

• 50% of those who had received acute IPT plus an SSRI.

Frequency of IPT-M sessions did not affect time to recurrence. Thus, for women who can achieve remission with IPT alone, varied frequencies of IPT-M can be good prophylaxis. For women who need an SSRI to augment acute IPT, IPT-M alone at varied dosages is less effective in preventing depression recurrence. Therefore, acute treatment response patterns can inform maintenance plans, with the most prudent maintenance strategy being to maintain the acute treatment strategy over a longer period.

IPT-M for late-life depression. A trial by Reynolds et al25 examined the efficacy of maintenance nortriptyline and IPT-M in preventing depression recurrence in patients age ≥59 who initially recovered after combined acute and continuation IPT plus nortriptyline. The 4 conditions (with their recurrence rates) were:

• monthly IPT-M with nortriptyline (20%)

• monthly IPT-M with placebo (64%)

• nortriptyline plus medication visits (43%)

• placebo plus medication visits (90%).

Clearly, the combined active treatments outperformed placebo and antidepressant alone in terms of delaying or preventing recurrence, which suggests an optimal maintenance strategy with this population.

IPT-M for later life. Another trial by the same group26 enrolled patients age ≥70 with MDD that responded to acute IPT plus paroxetine. The maintenance treatments to which they were randomly assigned (and recurrence rates within 2 years) were:

• paroxetine plus IPT-M (35%)

• placebo plus IPT-M (68%)

• paroxetine plus clinical management (37%)

• placebo plus clinical management (58%).

Recurrence rates were the same for patients receiving medication plus IPT-M and medication plus clinical management, and depression was 2.4 times more likely to recur in patients receiving placebo vs active medication. Therefore, for later life depression, the optimal maintenance strategy was the SSRI.

Secondary analyses of data from these seminal trials of IPT-M point to other predictors of how and for whom maintenance IPT may work (Table 4). For example:

• Greater variability of depression symptoms during all forms of maintenance treatment is related to a greater risk of recurrence.

• Persistent insomnia is related to greater risk of recurrent depression.

• High interpersonal focus in IPT-M sessions is related to longer time to recurrence.

Bottom Line

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is efficacious for acute depression and for preventing recurrences. Patients treated successfully with acute IPT alone benefit from varied doses of maintenance IPT. Combining IPT-M with antidepressant medication can be more potent than IPT-M alone. For late-life depression, medication appears to be most effective for maintenance treatment.

Related Resources

Media

• Video demonstration, role-play transcripts, lesson plans, and quizzes. In: Appendices in and DVD companion to Ravitz P, Watson P, Grigoriadas S. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. New York, NY: Norton; 2013.

• Video demonstration of IPT sessions. In: DVD companion to Dewan, M, Steenbarger, B, Greenberg, R, eds. The art and science of brief psychotherapies: An illustrated guide. 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2012.

Text

• Stuart S, Robertson M. Interpersonal psychotherapy: a clinician’s guide. London, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis; 2012.

• Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2000.

• Weissman M, Markowitz J, Klerman GL. Clinician’s quick guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Websites

• Interpersonal Psychotherapy Institute. http://iptinstitute.com.

• International Society for Interpersonal Psychotherapy. http://interpersonalpsychotherapy.org.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Imipramine • Tofranil Paroxetine • Paxil

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Samantha L. Bernecker, MS, and Nicholas R. Morrison for their assistance with the research review.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. ten Doesschate MC, Koeter MW, Bockting CL, et al. Health related quality of life in recurrent depression: a comparison with a general population sample. J Affect Disord. 2010; 120(1-3):126-132.

2. Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, et al. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(3):184-91.

3. Arnow BA, Constantino MJ. Effectiveness of psychotherapy and combination treatment for chronic depression. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59(8):893-905.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2010.

5. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1984.

6. Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman G. Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2000.

7. Weissman M, Markowitz J, Klerman G. Clinician’s quick guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

8. Brakemeier EL, Frase L. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) in major depressive disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(suppl 2):S117-1121.

9. Depression in adults (update): NICE guideline CG90). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2009). http://www.nice.org.uk/cg90. Updated October 2009. Accessed March 5, 2014.

10. Depression. National Institutes of Mental Health. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/ index.shtml. Revised 2011. Accessed March 5, 2014.

11. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G, et al. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(6):909-922.

12. Cuijpers P, Geraedts AS, van Oppen P, et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis [Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):652]. Am J Psychiatry. 2011; 168(6):581-592.

13. Mufson L, Dorta K, Wickramaratne P, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(6): 577-584.

14. Schramm E, Schneider D, Zobel I, et al. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy in chronically depressed inpatients. J Affect Disord. 2008; 109(1-2):65-73.

15. Bernecker SL. How and for whom does interpersonal psychotherapy work? Psychotherapy Bulletin. 2012;47(2):13-17.

16. Stuart S. Interpersonal psychotherapy. In: Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP, eds. The art and science of brief psychotherapies: an illustrated guide. 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2012: 157-193.

17. Grigoriadas S, Watson P, Maunder R, eds. Psychotherapy essentials to go: Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.; 2013.

18. Bleiberg KL, Markowitz JC. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. In: Barlow D, ed. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a step-by-step treatment manual. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008:306-327.

19. Weissman MM, Klerman GL, Prusoff BA, et al. Depressed outpatients. Results one year after treatment with drugs and/or interpersonal psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(1):51-55.

20. Shea MT, Elkin I, Imber SD, et al. Course of depressive symptoms over follow-up. Findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):782-787.

21. Blatt S, Zuroff D, Bondi C, et al. Short- and long-term effect of medication and psychotherapy in the brief treatment of depression: further analyses of data from the NIMH TDCRP. Psychother Res. 2000;10(2):215-234.

22. Zobel I, Kech S, van Calker D, et al. Long-term effect of combined interpersonal psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in a randomized trial of depressed patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123(4):276-282.

23. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, et al. Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(12):1093-1099.

24. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Buysse DJ, et al. Randomized trial of weekly, twice-monthly, and monthly interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance treatment for women with recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(5): 761-767.

25. Reynolds CF 3rd, Frank E, Perel JM, et al. Nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression: a randomized controlled trial in patients older than 59 years. JAMA. 1999;281(1): 39-45.

26. Reynolds CF 3rd, Dew MA, Pollock BG, et al. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1130-1138.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) frequently is recurrent, with new episodes causing substantial social and economic impairment1 and increasing the likelihood of future episodes.2 For this reason, contemporary psychiatric practitioners think of depression treatment as long-term and plan thoughtfully for maintenance therapy.

Recognizing the importance of engaging depressed individuals beyond the initial response,3 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines conceptualize depression treatment as 3 phases:

• acute treatment, with the aim of remission (symptom removal)

• continuation treatment, with the aim of preventing relapse (symptom return)

• maintenance treatment, with the aim of preventing recurrence (new episodes).4

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is an evidence-based psychosocial treatment that adheres to this model.5 As a time-limited, manual-driven6,7 approach, IPT focuses on interpersonal distresses as precipitating and perpetuating factors of depression.8

Acute IPT’s efficacy is well-established across >200 empirical studies—making it an evidence-based, first-line treatment for adult depression.4,9,10 Meta-analyses show that acute IPT is superior to placebo and no-treatment controls, and largely comparable to antidepressant medication and other active, first-line psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).11,12