User login

Liquid albuterol shortage effects reduced by alternative drugs, similar shortages may be increasingly common

The shortage of 0.5% albuterol sulfate inhalation solution, first reported by the FDA last October, gained increasing attention earlier this month when Akorn Pharmaceuticals – one of just two companies making the product – shut down after years of financial and regulatory troubles.

The other manufacturer, Nephron Pharmaceuticals, is producing 0.5% albuterol “as fast as possible” to overcome the shortage, CEO Lou Kennedy said in a written comment.

Meanwhile, the more commonly used version of liquid albuterol, with a concentration of 0.083%, remains in “good supply from several manufacturers,” according to an FDA spokesperson.

Still, headlines concerning the shortage have caused “a bit of a panic” for patients with asthma and parents with asthmatic children, according to David R. Stukus, MD, professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of allergy and immunology at Nationwide Children’s, Columbus, Ohio.

Much of the media coverage has lacked context, causing unnecessary worry, he said, as the shortage only affects one type of albuterol generally reserved for inpatient and emergency use.

“The shortage has not impacted our albuterol inhalers thus far,” Dr. Stukus said in an interview. “So I certainly don’t want people with asthma to panic that they’re going to run out of their inhaler anytime soon.”

Even infants and toddlers can use inhalers

Although Dr. Stukus noted that certain patients do require nebulizers, such as those with conditions that physically limit their breathing, like muscular dystrophy, most patients can use inhalers just fine. He said it’s a “pretty common misconception, even among medical professionals,” that infants and toddlers need nebulizers instead.

“In our institution, for example, we rarely ever start babies on a nebulizer when we diagnose them with asthma,” Dr. Stukus said. “We often just start right away with an inhaler with a spacer and a face mask.”

The shortage of liquid albuterol may therefore have a silver lining, he suggested, as it prompts clinicians to reconsider their routine practice.

“When situations like this arise, it’s a great opportunity for all of us to just take a step back and reevaluate the way we do things,” Dr. Stukus said. “Sometimes we just get caught up with inertia and we continue to do things the same way even though new options are available, or evidence has changed to the contrary.”

Nathan Rabinovitch, MD, professor of pediatrics in the division of pediatric allergy and clinical immunology at National Jewish Health, Denver, said that his center had trouble obtaining liquid albuterol about 2 weeks ago, so they pivoted to the more expensive levalbuterol for about a week and a half, until their albuterol supply was restored.

While Dr. Rabinovitch agreed that most children don’t need a nebulizer, he said about 5%-10% of kids with severe asthma should have one on hand in case their inhaler fails to control an exacerbation.

Personal preferences may also considered, he added.

“If [a parent] says, ‘I like to use the nebulizer. The kid likes it,’ I’m fine if they just use a nebulizer.”

One possible downside of relying on a nebulizer, however, is portability, according to Kelly O’Shea, MD, assistant professor in the division of allergy and clinical immunology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“If you’re out at the park or out at a soccer game with your kids, and they are having trouble breathing ... and they need their albuterol, you don’t have that ability if you are tied to a nebulizer,” Dr. O’Shea said in an interview. “As long as a parent feels comfortable – they feel like [their child] can get deep breaths in, I agree that you can use [an inhaler] in the infant and toddler population.”

She also agreed that a nebulizer may serve as a kind of second step if an inhaler isn’t controlling an exacerbation; however, she emphasized that a nebulizer should not be considered a replacement for professional care, and should not give a false sense of security.

“I caution parents to make sure that when they need it, they also take the next step and head over to the emergency room,” Dr. O’Shea said.

Generic drug shortages becoming more common

While the present scarcity of liquid albuterol appears relatively mild in terms of clinical impact, it brings up broader concerns about generic drug supply, and why shortages like this are becoming more common, according to Katie J. Suda, PharmD, MS, professor of medicine and pharmacy, and associate director, center for pharmaceutical policy and prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh.

“Drug shortages continue to increase in frequency, and the duration and severity of the shortages are also getting worse,” Dr. Suda said in an interview.

The reasons for these shortages can be elusive, according to 2022 report by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, which found that more than half of shortages came with no explanation from manufacturers.

The same report showed that only 5% of shortages were due to a “business decision,” but this factor is likely more central than publicly stated.

A recent FDA analysis on drug shortages, for instance, lists “lack of incentives to produce less profitable drugs,” as the first “root cause,” and Dr. Suda agrees.

“It’s important that we have generic medicines to decrease costs to our health systems, as well as for our patients,” Dr. Suda said. “But frequently, with those generic products, the price is driven so low that it increases the risk of a shortage.”

The drive to maintain profit margins may motivate companies to cut corners in production, Dr. Suda explained. She emphasized that this connection is speculative, because motivations are effectively unknowable, but the rationale is supported by past and present shortages.

Akorn Pharmaceuticals, for example, received a warning letter from the FDA in 2019 because of a variety of manufacturing issues, including defective bottles, questionable data, and metal shavings on aseptic filling equipment.

When a manufacturer like Akorn fails, the effects can be far-reaching, Dr. Suda said, noting their broad catalog of agents. Beyond liquid albuterol, Akorn was producing cardiac drugs, antibiotics, vitamins, local anesthetics, eye products, and others.

Drug shortages cause “a significant strain on our health care system,” Dr. Suda said, and substituting other medications increases risk of medical errors.

Fortunately, the increasing number of drug shortages is not going unnoticed, according to Dr. Suda. The FDA and multiple other organizations, including the ASHP, American Medical Association, and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, are all taking steps to ensure that essential medicines are in steady supply, including moves to gather more data from manufacturers.

“I hope that a lot of the efforts that are moving forward ... will help us decrease the impact of shortages on our patients,” Dr. Suda said.

Lou Kennedy is the CEO of Nephron Pharmaceuticals, which commercially produces liquid albuterol. The other interviewees disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

The shortage of 0.5% albuterol sulfate inhalation solution, first reported by the FDA last October, gained increasing attention earlier this month when Akorn Pharmaceuticals – one of just two companies making the product – shut down after years of financial and regulatory troubles.

The other manufacturer, Nephron Pharmaceuticals, is producing 0.5% albuterol “as fast as possible” to overcome the shortage, CEO Lou Kennedy said in a written comment.

Meanwhile, the more commonly used version of liquid albuterol, with a concentration of 0.083%, remains in “good supply from several manufacturers,” according to an FDA spokesperson.

Still, headlines concerning the shortage have caused “a bit of a panic” for patients with asthma and parents with asthmatic children, according to David R. Stukus, MD, professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of allergy and immunology at Nationwide Children’s, Columbus, Ohio.

Much of the media coverage has lacked context, causing unnecessary worry, he said, as the shortage only affects one type of albuterol generally reserved for inpatient and emergency use.

“The shortage has not impacted our albuterol inhalers thus far,” Dr. Stukus said in an interview. “So I certainly don’t want people with asthma to panic that they’re going to run out of their inhaler anytime soon.”

Even infants and toddlers can use inhalers

Although Dr. Stukus noted that certain patients do require nebulizers, such as those with conditions that physically limit their breathing, like muscular dystrophy, most patients can use inhalers just fine. He said it’s a “pretty common misconception, even among medical professionals,” that infants and toddlers need nebulizers instead.

“In our institution, for example, we rarely ever start babies on a nebulizer when we diagnose them with asthma,” Dr. Stukus said. “We often just start right away with an inhaler with a spacer and a face mask.”

The shortage of liquid albuterol may therefore have a silver lining, he suggested, as it prompts clinicians to reconsider their routine practice.

“When situations like this arise, it’s a great opportunity for all of us to just take a step back and reevaluate the way we do things,” Dr. Stukus said. “Sometimes we just get caught up with inertia and we continue to do things the same way even though new options are available, or evidence has changed to the contrary.”

Nathan Rabinovitch, MD, professor of pediatrics in the division of pediatric allergy and clinical immunology at National Jewish Health, Denver, said that his center had trouble obtaining liquid albuterol about 2 weeks ago, so they pivoted to the more expensive levalbuterol for about a week and a half, until their albuterol supply was restored.

While Dr. Rabinovitch agreed that most children don’t need a nebulizer, he said about 5%-10% of kids with severe asthma should have one on hand in case their inhaler fails to control an exacerbation.

Personal preferences may also considered, he added.

“If [a parent] says, ‘I like to use the nebulizer. The kid likes it,’ I’m fine if they just use a nebulizer.”

One possible downside of relying on a nebulizer, however, is portability, according to Kelly O’Shea, MD, assistant professor in the division of allergy and clinical immunology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“If you’re out at the park or out at a soccer game with your kids, and they are having trouble breathing ... and they need their albuterol, you don’t have that ability if you are tied to a nebulizer,” Dr. O’Shea said in an interview. “As long as a parent feels comfortable – they feel like [their child] can get deep breaths in, I agree that you can use [an inhaler] in the infant and toddler population.”

She also agreed that a nebulizer may serve as a kind of second step if an inhaler isn’t controlling an exacerbation; however, she emphasized that a nebulizer should not be considered a replacement for professional care, and should not give a false sense of security.

“I caution parents to make sure that when they need it, they also take the next step and head over to the emergency room,” Dr. O’Shea said.

Generic drug shortages becoming more common

While the present scarcity of liquid albuterol appears relatively mild in terms of clinical impact, it brings up broader concerns about generic drug supply, and why shortages like this are becoming more common, according to Katie J. Suda, PharmD, MS, professor of medicine and pharmacy, and associate director, center for pharmaceutical policy and prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh.

“Drug shortages continue to increase in frequency, and the duration and severity of the shortages are also getting worse,” Dr. Suda said in an interview.

The reasons for these shortages can be elusive, according to 2022 report by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, which found that more than half of shortages came with no explanation from manufacturers.

The same report showed that only 5% of shortages were due to a “business decision,” but this factor is likely more central than publicly stated.

A recent FDA analysis on drug shortages, for instance, lists “lack of incentives to produce less profitable drugs,” as the first “root cause,” and Dr. Suda agrees.

“It’s important that we have generic medicines to decrease costs to our health systems, as well as for our patients,” Dr. Suda said. “But frequently, with those generic products, the price is driven so low that it increases the risk of a shortage.”

The drive to maintain profit margins may motivate companies to cut corners in production, Dr. Suda explained. She emphasized that this connection is speculative, because motivations are effectively unknowable, but the rationale is supported by past and present shortages.

Akorn Pharmaceuticals, for example, received a warning letter from the FDA in 2019 because of a variety of manufacturing issues, including defective bottles, questionable data, and metal shavings on aseptic filling equipment.

When a manufacturer like Akorn fails, the effects can be far-reaching, Dr. Suda said, noting their broad catalog of agents. Beyond liquid albuterol, Akorn was producing cardiac drugs, antibiotics, vitamins, local anesthetics, eye products, and others.

Drug shortages cause “a significant strain on our health care system,” Dr. Suda said, and substituting other medications increases risk of medical errors.

Fortunately, the increasing number of drug shortages is not going unnoticed, according to Dr. Suda. The FDA and multiple other organizations, including the ASHP, American Medical Association, and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, are all taking steps to ensure that essential medicines are in steady supply, including moves to gather more data from manufacturers.

“I hope that a lot of the efforts that are moving forward ... will help us decrease the impact of shortages on our patients,” Dr. Suda said.

Lou Kennedy is the CEO of Nephron Pharmaceuticals, which commercially produces liquid albuterol. The other interviewees disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

The shortage of 0.5% albuterol sulfate inhalation solution, first reported by the FDA last October, gained increasing attention earlier this month when Akorn Pharmaceuticals – one of just two companies making the product – shut down after years of financial and regulatory troubles.

The other manufacturer, Nephron Pharmaceuticals, is producing 0.5% albuterol “as fast as possible” to overcome the shortage, CEO Lou Kennedy said in a written comment.

Meanwhile, the more commonly used version of liquid albuterol, with a concentration of 0.083%, remains in “good supply from several manufacturers,” according to an FDA spokesperson.

Still, headlines concerning the shortage have caused “a bit of a panic” for patients with asthma and parents with asthmatic children, according to David R. Stukus, MD, professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of allergy and immunology at Nationwide Children’s, Columbus, Ohio.

Much of the media coverage has lacked context, causing unnecessary worry, he said, as the shortage only affects one type of albuterol generally reserved for inpatient and emergency use.

“The shortage has not impacted our albuterol inhalers thus far,” Dr. Stukus said in an interview. “So I certainly don’t want people with asthma to panic that they’re going to run out of their inhaler anytime soon.”

Even infants and toddlers can use inhalers

Although Dr. Stukus noted that certain patients do require nebulizers, such as those with conditions that physically limit their breathing, like muscular dystrophy, most patients can use inhalers just fine. He said it’s a “pretty common misconception, even among medical professionals,” that infants and toddlers need nebulizers instead.

“In our institution, for example, we rarely ever start babies on a nebulizer when we diagnose them with asthma,” Dr. Stukus said. “We often just start right away with an inhaler with a spacer and a face mask.”

The shortage of liquid albuterol may therefore have a silver lining, he suggested, as it prompts clinicians to reconsider their routine practice.

“When situations like this arise, it’s a great opportunity for all of us to just take a step back and reevaluate the way we do things,” Dr. Stukus said. “Sometimes we just get caught up with inertia and we continue to do things the same way even though new options are available, or evidence has changed to the contrary.”

Nathan Rabinovitch, MD, professor of pediatrics in the division of pediatric allergy and clinical immunology at National Jewish Health, Denver, said that his center had trouble obtaining liquid albuterol about 2 weeks ago, so they pivoted to the more expensive levalbuterol for about a week and a half, until their albuterol supply was restored.

While Dr. Rabinovitch agreed that most children don’t need a nebulizer, he said about 5%-10% of kids with severe asthma should have one on hand in case their inhaler fails to control an exacerbation.

Personal preferences may also considered, he added.

“If [a parent] says, ‘I like to use the nebulizer. The kid likes it,’ I’m fine if they just use a nebulizer.”

One possible downside of relying on a nebulizer, however, is portability, according to Kelly O’Shea, MD, assistant professor in the division of allergy and clinical immunology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“If you’re out at the park or out at a soccer game with your kids, and they are having trouble breathing ... and they need their albuterol, you don’t have that ability if you are tied to a nebulizer,” Dr. O’Shea said in an interview. “As long as a parent feels comfortable – they feel like [their child] can get deep breaths in, I agree that you can use [an inhaler] in the infant and toddler population.”

She also agreed that a nebulizer may serve as a kind of second step if an inhaler isn’t controlling an exacerbation; however, she emphasized that a nebulizer should not be considered a replacement for professional care, and should not give a false sense of security.

“I caution parents to make sure that when they need it, they also take the next step and head over to the emergency room,” Dr. O’Shea said.

Generic drug shortages becoming more common

While the present scarcity of liquid albuterol appears relatively mild in terms of clinical impact, it brings up broader concerns about generic drug supply, and why shortages like this are becoming more common, according to Katie J. Suda, PharmD, MS, professor of medicine and pharmacy, and associate director, center for pharmaceutical policy and prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh.

“Drug shortages continue to increase in frequency, and the duration and severity of the shortages are also getting worse,” Dr. Suda said in an interview.

The reasons for these shortages can be elusive, according to 2022 report by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, which found that more than half of shortages came with no explanation from manufacturers.

The same report showed that only 5% of shortages were due to a “business decision,” but this factor is likely more central than publicly stated.

A recent FDA analysis on drug shortages, for instance, lists “lack of incentives to produce less profitable drugs,” as the first “root cause,” and Dr. Suda agrees.

“It’s important that we have generic medicines to decrease costs to our health systems, as well as for our patients,” Dr. Suda said. “But frequently, with those generic products, the price is driven so low that it increases the risk of a shortage.”

The drive to maintain profit margins may motivate companies to cut corners in production, Dr. Suda explained. She emphasized that this connection is speculative, because motivations are effectively unknowable, but the rationale is supported by past and present shortages.

Akorn Pharmaceuticals, for example, received a warning letter from the FDA in 2019 because of a variety of manufacturing issues, including defective bottles, questionable data, and metal shavings on aseptic filling equipment.

When a manufacturer like Akorn fails, the effects can be far-reaching, Dr. Suda said, noting their broad catalog of agents. Beyond liquid albuterol, Akorn was producing cardiac drugs, antibiotics, vitamins, local anesthetics, eye products, and others.

Drug shortages cause “a significant strain on our health care system,” Dr. Suda said, and substituting other medications increases risk of medical errors.

Fortunately, the increasing number of drug shortages is not going unnoticed, according to Dr. Suda. The FDA and multiple other organizations, including the ASHP, American Medical Association, and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, are all taking steps to ensure that essential medicines are in steady supply, including moves to gather more data from manufacturers.

“I hope that a lot of the efforts that are moving forward ... will help us decrease the impact of shortages on our patients,” Dr. Suda said.

Lou Kennedy is the CEO of Nephron Pharmaceuticals, which commercially produces liquid albuterol. The other interviewees disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

New hope for MDS, with AML treatments

Until just over a year ago, Pat Trueman, an 82-year-old in New Hampshire, had always been a “go-go-go” kind of person. Then she started feeling tired easily, even while doing basic housework.

“I had no stamina,” Ms. Trueman said. “I didn’t feel that bad, but I just couldn’t do anything.” She had also begun noticing black and blue bruises appearing on her body, so she met with her cardiologist. But when switching medications and getting a pacemaker didn’t rid Ms. Trueman of the symptoms, her doctor referred her to a hematologist oncologist.

A bone marrow biopsy eventually revealed that Ms. Trueman had myelodysplastic neoplasms, or MDS, a blood cancer affecting an estimated 60,000-170,000 people in the United States, mostly over age 60. MDS includes several bone marrow disorders in which the bone marrow does not produce enough healthy, normal blood cells. Cytopenias are therefore a key feature of MDS, whether it’s anemia (in Ms. Trueman’s case), neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia.

Jamie Koprivnikar, MD, a hematologist oncologist at Hackensack (N.J) University Medical Center, describes the condition to her patients using a factory metaphor: “Our bone marrow is the factory where the red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets are made, and MDS is where the machinery of the factory is broken, so the factory is making defective parts and not enough parts.”

The paradox of MDS is that too many cells are in the bone marrow while too few are in the blood, since most in the marrow die before reaching the blood, explained Azra Raza, MD, a professor of medicine and director of the MDS Center at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and author of The First Cell (New York: Basic Books, 2019).

“We’re looking at taking a lot of the therapies that we’ve used to treat AML and then trying to apply them to MDS,” Dr. Koprivnikar said. “With all the improvement that we’re seeing there with leukemia, we’re definitely expecting this trickle-down effect to also help our high-risk MDS patients.”

Workup begins with risk stratification

While different types of MDS exist, based on morphology of the blood cells, after diagnosis the most important determination to make is of the patient’s risk level, based on the International Prognostic Scoring System–Revised (IPSS-R), updated in 2022.

While there are six MDS risk levels, patients generally fall into the high-risk and low-risk categories. The risk-level workup includes “a bone marrow biopsy with morphology, looking at how many blasts they have, looking for dysplasia, cytogenetics, and a full spectrum myeloid mutation testing, or molecular testing,” according to Anna Halpern, MD, an assistant professor of hematology in the clinical research division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle. ”I use that information and along with their age, in some cases to calculate an IPSS-M or IPPS-R score, and what goes into that risk stratification includes how low their blood counts are as well as any adverse risks features we might see in their marrow, like adverse risk genetics, adverse risk mutations or increased blasts.”

Treatment decisions then turn on whether a patient is high risk – about a third of MDS patients – or low risk, because those treatment goals differ.

“With low-risk, the goal is to improve quality of life,” Dr. Raza said. “For higher-risk MDS, the goal is to prolong survival and delay progression to acute leukemia” since nearly a third of MDS patients will eventually develop AML.

More specifically, the aim with low-risk MDS is “to foster transfusion independence, either to prevent transfusions or to decrease the need for transfusions in people already receiving them,” explained Ellen Ritchie, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and hematologist-oncologist at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. “We’re not hoping so much to cure the myelofibrosis at that point, but rather to improve blood counts.”

Sometimes, Dr. Halpern said, such treatment means active surveillance monitoring of blood counts, and at other times, it means treating cytopenia – most often anemia. The erythropoiesis-stimulating agents used to treat anemia are epoetin alfa (Epogen/Procrit) or darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp).

Ms. Trueman, whose MDS is low risk, started taking Aranesp, but she didn’t feel well on the drug and didn’t think it was helping much. She was taken off that drug and now relies only on transfusions for treatment, when her blood counts fall too low.

A newer anemia medication, luspatercept (Reblozyl), was approved in 2020 but is reserved primarily for those who fail one of the other erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and have a subtype of MDS with ring sideroblasts. Although white blood cell and platelet growth factors exist for other cytopenias, they’re rarely used because they offer little survival benefit and carry risks, Dr. Halpern said. The only other medication typically used for low-risk MDS is lenalidomide (Revlimid), which is reserved only for those with 5q-deletion syndrome.

The goal of treating high-risk MDS, on the other hand, is to cure it – when possible.

“The only curative approach for MDS is an allogeneic stem cell transplant or bone marrow transplant,” Dr. Halpern said, but transplants carry high rates of morbidity and mortality and therefore require a base level of physical fitness for a patient to consider it.

Dr. Koprivnikar observed that “MDS is certainly a disease of the elderly, and with each increasing decade of life, incidence increases. So there are a lot of patients who do not qualify for transplant.”

Age is not the sole determining factor, however. Dr. Ritchie noted that transplants can be offered to patients up to age 75 and sometimes older, depending on their physical condition. “It all depends upon the patient, their fitness, how much caretaker support they have, and what their comorbid illnesses are.”

If a transplant isn’t an option, Dr. Halpern and Dr. Raza said, they steer patients toward clinical trial participation. Otherwise, the first-line treatment is chemotherapy with hypomethylating agents to hopefully put patients in remission, Dr. Ritchie said.

The main chemo agents for high-risk patients ineligible for transplant are azacitidine (Vidaza) or decitabine (Dacogen), offered indefinitely until patients stop responding or experience progression or intolerance, Dr. Koprivnikar said. The only recently approved drug in this space is Inqovi, which is not a new agent, but it provides decitabine and cedazuridine in an oral pill form, so that patients can avoid infusions.

Treatment gaps

Few treatments options currently exist for patients with MDS, beyond erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for low-risk MDS and chemotherapy or transplant for high-risk MDS, as well as lenalidomide and luspatercept for specific subpopulations. With few breakthroughs occurring, Dr. Halpern expects that progress will only happen gradually, with new treatments coming primarily in the form of AML therapies.

“The biggest gap in our MDS regimen is treatment that can successfully treat or alter the natural history of TP53-mutated disease,” said Dr. Halpern, referring to an adverse risk mutation that can occur spontaneously or as a result of exposure to chemotherapy or radiation. “TP53-mutated MDS is very challenging to treat, and we have not had any successful therapy, so that is the biggest area of need.”

The most promising possibility in that area is an anti-CD47 drug called magrolimab, a drug being tested in a trial of which Dr. Halpern is a principal investigator. Not yet approved, magrolimab has been showing promise for AML when given with azacitidine (Vidaza) and venetoclax (Venclexta).

Venetoclax, currently used for AML, is another drug that Dr. Halpern expects to be approved for MDS soon. A phase 1b trial presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Hematology Society found that more than three-quarters of patients with high-risk MDS responded to the combination of venetoclax and azacitidine.

Unlike so many other cancers, MDS has seen little success with immunotherapy, which tends to have too much toxicity for patients with MDS. While Dr. Halpern sees potential for more exploration in this realm, she doesn’t anticipate immunotherapy or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy becoming treatments for MDS in the near future.

“What I do think is, hopefully, we will have better treatment for TP53-mutated disease,” she said, while adding that there are currently no standard options for patients who stopped responding or don’t respond to hypomethylating agents.

Similarly, few new treatments have emerged for low-risk MDS, but there a couple of possibilities on the horizon.

“For a while, low-risk, transfusion-dependent MDS was an area that was being overlooked, and we are starting to see more activity in that area as well, with more drugs being developed,” Dr. Koprivnikar said. Drugs showing promise include imetelstat – an investigative telomerase inhibitor – and IRAK inhibitors. A phase 3 trial of imetelstat recently met its primary endpoint of 8 weeks of transfusion independence in low-risk MDS patients who aren’t responding to or cannot take erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, like Ms. Trueman. If effective and approved, a drug like imetelstat may allow patients like Ms. Trueman to resume some activities that she misses now.

“I have so much energy in my head, and I want to do so much, but I can’t,” Ms. Trueman said. “Now I think I’m getting lazy and I don’t like it because I’m not that kind of person. It’s pretty hard.”

Dr. Raza disclosed relationships with Epizyme, Grail, Vor, Taiho, RareCells, and TFC Therapeutics. Dr Ritchie reported ties with Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Takeda, Incyte, AbbVie, Astellas, and Imago Biosciences. Dr. Halpern disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Notable Labs, Imago, Bayer, Gilead, Jazz, Incyte, Karyopharm, and Disc Medicine.

Until just over a year ago, Pat Trueman, an 82-year-old in New Hampshire, had always been a “go-go-go” kind of person. Then she started feeling tired easily, even while doing basic housework.

“I had no stamina,” Ms. Trueman said. “I didn’t feel that bad, but I just couldn’t do anything.” She had also begun noticing black and blue bruises appearing on her body, so she met with her cardiologist. But when switching medications and getting a pacemaker didn’t rid Ms. Trueman of the symptoms, her doctor referred her to a hematologist oncologist.

A bone marrow biopsy eventually revealed that Ms. Trueman had myelodysplastic neoplasms, or MDS, a blood cancer affecting an estimated 60,000-170,000 people in the United States, mostly over age 60. MDS includes several bone marrow disorders in which the bone marrow does not produce enough healthy, normal blood cells. Cytopenias are therefore a key feature of MDS, whether it’s anemia (in Ms. Trueman’s case), neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia.

Jamie Koprivnikar, MD, a hematologist oncologist at Hackensack (N.J) University Medical Center, describes the condition to her patients using a factory metaphor: “Our bone marrow is the factory where the red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets are made, and MDS is where the machinery of the factory is broken, so the factory is making defective parts and not enough parts.”

The paradox of MDS is that too many cells are in the bone marrow while too few are in the blood, since most in the marrow die before reaching the blood, explained Azra Raza, MD, a professor of medicine and director of the MDS Center at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and author of The First Cell (New York: Basic Books, 2019).

“We’re looking at taking a lot of the therapies that we’ve used to treat AML and then trying to apply them to MDS,” Dr. Koprivnikar said. “With all the improvement that we’re seeing there with leukemia, we’re definitely expecting this trickle-down effect to also help our high-risk MDS patients.”

Workup begins with risk stratification

While different types of MDS exist, based on morphology of the blood cells, after diagnosis the most important determination to make is of the patient’s risk level, based on the International Prognostic Scoring System–Revised (IPSS-R), updated in 2022.

While there are six MDS risk levels, patients generally fall into the high-risk and low-risk categories. The risk-level workup includes “a bone marrow biopsy with morphology, looking at how many blasts they have, looking for dysplasia, cytogenetics, and a full spectrum myeloid mutation testing, or molecular testing,” according to Anna Halpern, MD, an assistant professor of hematology in the clinical research division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle. ”I use that information and along with their age, in some cases to calculate an IPSS-M or IPPS-R score, and what goes into that risk stratification includes how low their blood counts are as well as any adverse risks features we might see in their marrow, like adverse risk genetics, adverse risk mutations or increased blasts.”

Treatment decisions then turn on whether a patient is high risk – about a third of MDS patients – or low risk, because those treatment goals differ.

“With low-risk, the goal is to improve quality of life,” Dr. Raza said. “For higher-risk MDS, the goal is to prolong survival and delay progression to acute leukemia” since nearly a third of MDS patients will eventually develop AML.

More specifically, the aim with low-risk MDS is “to foster transfusion independence, either to prevent transfusions or to decrease the need for transfusions in people already receiving them,” explained Ellen Ritchie, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and hematologist-oncologist at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. “We’re not hoping so much to cure the myelofibrosis at that point, but rather to improve blood counts.”

Sometimes, Dr. Halpern said, such treatment means active surveillance monitoring of blood counts, and at other times, it means treating cytopenia – most often anemia. The erythropoiesis-stimulating agents used to treat anemia are epoetin alfa (Epogen/Procrit) or darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp).

Ms. Trueman, whose MDS is low risk, started taking Aranesp, but she didn’t feel well on the drug and didn’t think it was helping much. She was taken off that drug and now relies only on transfusions for treatment, when her blood counts fall too low.

A newer anemia medication, luspatercept (Reblozyl), was approved in 2020 but is reserved primarily for those who fail one of the other erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and have a subtype of MDS with ring sideroblasts. Although white blood cell and platelet growth factors exist for other cytopenias, they’re rarely used because they offer little survival benefit and carry risks, Dr. Halpern said. The only other medication typically used for low-risk MDS is lenalidomide (Revlimid), which is reserved only for those with 5q-deletion syndrome.

The goal of treating high-risk MDS, on the other hand, is to cure it – when possible.

“The only curative approach for MDS is an allogeneic stem cell transplant or bone marrow transplant,” Dr. Halpern said, but transplants carry high rates of morbidity and mortality and therefore require a base level of physical fitness for a patient to consider it.

Dr. Koprivnikar observed that “MDS is certainly a disease of the elderly, and with each increasing decade of life, incidence increases. So there are a lot of patients who do not qualify for transplant.”

Age is not the sole determining factor, however. Dr. Ritchie noted that transplants can be offered to patients up to age 75 and sometimes older, depending on their physical condition. “It all depends upon the patient, their fitness, how much caretaker support they have, and what their comorbid illnesses are.”

If a transplant isn’t an option, Dr. Halpern and Dr. Raza said, they steer patients toward clinical trial participation. Otherwise, the first-line treatment is chemotherapy with hypomethylating agents to hopefully put patients in remission, Dr. Ritchie said.

The main chemo agents for high-risk patients ineligible for transplant are azacitidine (Vidaza) or decitabine (Dacogen), offered indefinitely until patients stop responding or experience progression or intolerance, Dr. Koprivnikar said. The only recently approved drug in this space is Inqovi, which is not a new agent, but it provides decitabine and cedazuridine in an oral pill form, so that patients can avoid infusions.

Treatment gaps

Few treatments options currently exist for patients with MDS, beyond erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for low-risk MDS and chemotherapy or transplant for high-risk MDS, as well as lenalidomide and luspatercept for specific subpopulations. With few breakthroughs occurring, Dr. Halpern expects that progress will only happen gradually, with new treatments coming primarily in the form of AML therapies.

“The biggest gap in our MDS regimen is treatment that can successfully treat or alter the natural history of TP53-mutated disease,” said Dr. Halpern, referring to an adverse risk mutation that can occur spontaneously or as a result of exposure to chemotherapy or radiation. “TP53-mutated MDS is very challenging to treat, and we have not had any successful therapy, so that is the biggest area of need.”

The most promising possibility in that area is an anti-CD47 drug called magrolimab, a drug being tested in a trial of which Dr. Halpern is a principal investigator. Not yet approved, magrolimab has been showing promise for AML when given with azacitidine (Vidaza) and venetoclax (Venclexta).

Venetoclax, currently used for AML, is another drug that Dr. Halpern expects to be approved for MDS soon. A phase 1b trial presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Hematology Society found that more than three-quarters of patients with high-risk MDS responded to the combination of venetoclax and azacitidine.

Unlike so many other cancers, MDS has seen little success with immunotherapy, which tends to have too much toxicity for patients with MDS. While Dr. Halpern sees potential for more exploration in this realm, she doesn’t anticipate immunotherapy or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy becoming treatments for MDS in the near future.

“What I do think is, hopefully, we will have better treatment for TP53-mutated disease,” she said, while adding that there are currently no standard options for patients who stopped responding or don’t respond to hypomethylating agents.

Similarly, few new treatments have emerged for low-risk MDS, but there a couple of possibilities on the horizon.

“For a while, low-risk, transfusion-dependent MDS was an area that was being overlooked, and we are starting to see more activity in that area as well, with more drugs being developed,” Dr. Koprivnikar said. Drugs showing promise include imetelstat – an investigative telomerase inhibitor – and IRAK inhibitors. A phase 3 trial of imetelstat recently met its primary endpoint of 8 weeks of transfusion independence in low-risk MDS patients who aren’t responding to or cannot take erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, like Ms. Trueman. If effective and approved, a drug like imetelstat may allow patients like Ms. Trueman to resume some activities that she misses now.

“I have so much energy in my head, and I want to do so much, but I can’t,” Ms. Trueman said. “Now I think I’m getting lazy and I don’t like it because I’m not that kind of person. It’s pretty hard.”

Dr. Raza disclosed relationships with Epizyme, Grail, Vor, Taiho, RareCells, and TFC Therapeutics. Dr Ritchie reported ties with Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Takeda, Incyte, AbbVie, Astellas, and Imago Biosciences. Dr. Halpern disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Notable Labs, Imago, Bayer, Gilead, Jazz, Incyte, Karyopharm, and Disc Medicine.

Until just over a year ago, Pat Trueman, an 82-year-old in New Hampshire, had always been a “go-go-go” kind of person. Then she started feeling tired easily, even while doing basic housework.

“I had no stamina,” Ms. Trueman said. “I didn’t feel that bad, but I just couldn’t do anything.” She had also begun noticing black and blue bruises appearing on her body, so she met with her cardiologist. But when switching medications and getting a pacemaker didn’t rid Ms. Trueman of the symptoms, her doctor referred her to a hematologist oncologist.

A bone marrow biopsy eventually revealed that Ms. Trueman had myelodysplastic neoplasms, or MDS, a blood cancer affecting an estimated 60,000-170,000 people in the United States, mostly over age 60. MDS includes several bone marrow disorders in which the bone marrow does not produce enough healthy, normal blood cells. Cytopenias are therefore a key feature of MDS, whether it’s anemia (in Ms. Trueman’s case), neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia.

Jamie Koprivnikar, MD, a hematologist oncologist at Hackensack (N.J) University Medical Center, describes the condition to her patients using a factory metaphor: “Our bone marrow is the factory where the red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets are made, and MDS is where the machinery of the factory is broken, so the factory is making defective parts and not enough parts.”

The paradox of MDS is that too many cells are in the bone marrow while too few are in the blood, since most in the marrow die before reaching the blood, explained Azra Raza, MD, a professor of medicine and director of the MDS Center at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and author of The First Cell (New York: Basic Books, 2019).

“We’re looking at taking a lot of the therapies that we’ve used to treat AML and then trying to apply them to MDS,” Dr. Koprivnikar said. “With all the improvement that we’re seeing there with leukemia, we’re definitely expecting this trickle-down effect to also help our high-risk MDS patients.”

Workup begins with risk stratification

While different types of MDS exist, based on morphology of the blood cells, after diagnosis the most important determination to make is of the patient’s risk level, based on the International Prognostic Scoring System–Revised (IPSS-R), updated in 2022.

While there are six MDS risk levels, patients generally fall into the high-risk and low-risk categories. The risk-level workup includes “a bone marrow biopsy with morphology, looking at how many blasts they have, looking for dysplasia, cytogenetics, and a full spectrum myeloid mutation testing, or molecular testing,” according to Anna Halpern, MD, an assistant professor of hematology in the clinical research division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle. ”I use that information and along with their age, in some cases to calculate an IPSS-M or IPPS-R score, and what goes into that risk stratification includes how low their blood counts are as well as any adverse risks features we might see in their marrow, like adverse risk genetics, adverse risk mutations or increased blasts.”

Treatment decisions then turn on whether a patient is high risk – about a third of MDS patients – or low risk, because those treatment goals differ.

“With low-risk, the goal is to improve quality of life,” Dr. Raza said. “For higher-risk MDS, the goal is to prolong survival and delay progression to acute leukemia” since nearly a third of MDS patients will eventually develop AML.

More specifically, the aim with low-risk MDS is “to foster transfusion independence, either to prevent transfusions or to decrease the need for transfusions in people already receiving them,” explained Ellen Ritchie, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and hematologist-oncologist at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. “We’re not hoping so much to cure the myelofibrosis at that point, but rather to improve blood counts.”

Sometimes, Dr. Halpern said, such treatment means active surveillance monitoring of blood counts, and at other times, it means treating cytopenia – most often anemia. The erythropoiesis-stimulating agents used to treat anemia are epoetin alfa (Epogen/Procrit) or darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp).

Ms. Trueman, whose MDS is low risk, started taking Aranesp, but she didn’t feel well on the drug and didn’t think it was helping much. She was taken off that drug and now relies only on transfusions for treatment, when her blood counts fall too low.

A newer anemia medication, luspatercept (Reblozyl), was approved in 2020 but is reserved primarily for those who fail one of the other erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and have a subtype of MDS with ring sideroblasts. Although white blood cell and platelet growth factors exist for other cytopenias, they’re rarely used because they offer little survival benefit and carry risks, Dr. Halpern said. The only other medication typically used for low-risk MDS is lenalidomide (Revlimid), which is reserved only for those with 5q-deletion syndrome.

The goal of treating high-risk MDS, on the other hand, is to cure it – when possible.

“The only curative approach for MDS is an allogeneic stem cell transplant or bone marrow transplant,” Dr. Halpern said, but transplants carry high rates of morbidity and mortality and therefore require a base level of physical fitness for a patient to consider it.

Dr. Koprivnikar observed that “MDS is certainly a disease of the elderly, and with each increasing decade of life, incidence increases. So there are a lot of patients who do not qualify for transplant.”

Age is not the sole determining factor, however. Dr. Ritchie noted that transplants can be offered to patients up to age 75 and sometimes older, depending on their physical condition. “It all depends upon the patient, their fitness, how much caretaker support they have, and what their comorbid illnesses are.”

If a transplant isn’t an option, Dr. Halpern and Dr. Raza said, they steer patients toward clinical trial participation. Otherwise, the first-line treatment is chemotherapy with hypomethylating agents to hopefully put patients in remission, Dr. Ritchie said.

The main chemo agents for high-risk patients ineligible for transplant are azacitidine (Vidaza) or decitabine (Dacogen), offered indefinitely until patients stop responding or experience progression or intolerance, Dr. Koprivnikar said. The only recently approved drug in this space is Inqovi, which is not a new agent, but it provides decitabine and cedazuridine in an oral pill form, so that patients can avoid infusions.

Treatment gaps

Few treatments options currently exist for patients with MDS, beyond erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for low-risk MDS and chemotherapy or transplant for high-risk MDS, as well as lenalidomide and luspatercept for specific subpopulations. With few breakthroughs occurring, Dr. Halpern expects that progress will only happen gradually, with new treatments coming primarily in the form of AML therapies.

“The biggest gap in our MDS regimen is treatment that can successfully treat or alter the natural history of TP53-mutated disease,” said Dr. Halpern, referring to an adverse risk mutation that can occur spontaneously or as a result of exposure to chemotherapy or radiation. “TP53-mutated MDS is very challenging to treat, and we have not had any successful therapy, so that is the biggest area of need.”

The most promising possibility in that area is an anti-CD47 drug called magrolimab, a drug being tested in a trial of which Dr. Halpern is a principal investigator. Not yet approved, magrolimab has been showing promise for AML when given with azacitidine (Vidaza) and venetoclax (Venclexta).

Venetoclax, currently used for AML, is another drug that Dr. Halpern expects to be approved for MDS soon. A phase 1b trial presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Hematology Society found that more than three-quarters of patients with high-risk MDS responded to the combination of venetoclax and azacitidine.

Unlike so many other cancers, MDS has seen little success with immunotherapy, which tends to have too much toxicity for patients with MDS. While Dr. Halpern sees potential for more exploration in this realm, she doesn’t anticipate immunotherapy or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy becoming treatments for MDS in the near future.

“What I do think is, hopefully, we will have better treatment for TP53-mutated disease,” she said, while adding that there are currently no standard options for patients who stopped responding or don’t respond to hypomethylating agents.

Similarly, few new treatments have emerged for low-risk MDS, but there a couple of possibilities on the horizon.

“For a while, low-risk, transfusion-dependent MDS was an area that was being overlooked, and we are starting to see more activity in that area as well, with more drugs being developed,” Dr. Koprivnikar said. Drugs showing promise include imetelstat – an investigative telomerase inhibitor – and IRAK inhibitors. A phase 3 trial of imetelstat recently met its primary endpoint of 8 weeks of transfusion independence in low-risk MDS patients who aren’t responding to or cannot take erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, like Ms. Trueman. If effective and approved, a drug like imetelstat may allow patients like Ms. Trueman to resume some activities that she misses now.

“I have so much energy in my head, and I want to do so much, but I can’t,” Ms. Trueman said. “Now I think I’m getting lazy and I don’t like it because I’m not that kind of person. It’s pretty hard.”

Dr. Raza disclosed relationships with Epizyme, Grail, Vor, Taiho, RareCells, and TFC Therapeutics. Dr Ritchie reported ties with Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Takeda, Incyte, AbbVie, Astellas, and Imago Biosciences. Dr. Halpern disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Notable Labs, Imago, Bayer, Gilead, Jazz, Incyte, Karyopharm, and Disc Medicine.

California picks generic drug company Civica to produce low-cost insulin

Gov. Gavin Newsom on March 18 announced the selection of Utah-based generic drug manufacturer Civica to produce low-cost insulin for California, an unprecedented move that makes good on his promise to put state government in direct competition with the brand-name drug companies that dominate the market.

“People should not be forced to go into debt to get lifesaving prescriptions,” Gov. Newsom said. “Californians will have access to some of the most inexpensive insulin available, helping them save thousands of dollars each year.”

The contract, with an initial cost of $50 million that Gov. Newsom and his fellow Democratic lawmakers approved last year, calls for Civica to manufacture state-branded insulin and make the lifesaving drug available to any Californian who needs it, regardless of insurance coverage, by mail order and at local pharmacies. But insulin is just the beginning. Gov. Newsom said the state will also look to produce the opioid overdose reversal drug naloxone.

Allan Coukell, Civica’s senior vice president of public policy, said in an interview that the nonprofit drugmaker is also in talks with the Newsom administration to potentially produce other generic medications, but he declined to elaborate, saying the company is focused on making cheap insulin widely available first.

“We are very excited about this partnership with the state of California,” Mr. Coukell said. “We’re not looking to have 100% of the market, but we do want 100% of people to have access to fair insulin prices.”

As insulin costs for consumers have soared, Democratic lawmakers and activists have called on the industry to rein in prices. Just weeks after President Joe Biden attacked Big Pharma for jacking up insulin prices, the three drugmakers that control the insulin market – Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi – announced they would slash the list prices of some products.

Gov. Newsom, who has previously accused the pharmaceutical industry of gouging Californians with “sky-high prices,” argued that the launch of the state’s generic drug label, CalRx, will add competition and apply pressure on the industry. Administration officials declined to say when California’s insulin products would be available, but experts say it could be as soon as 2025. Mr. Coukell said the state-branded medication will still require approval from the Food and Drug Administration, which can take roughly 10 months.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, which lobbies on behalf of brand-name companies, blasted California’s move. Reid Porter, senior director of state public affairs for PhRMA, said Gov. Newsom just “wants to score political points.”

“If the governor wants to impact what patients pay for insulins and other medicines meaningfully, he should expand his focus to others in the system that often make patients pay more than they do for medicines,” Mr. Porter said, blaming pharmaceutical go-between companies, known as pharmacy benefit managers, that negotiate with manufacturers on behalf of insurers for rebates and discounts on drugs.

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, which represents pharmacy benefit managers argued in turn that it’s pharmaceutical companies that are to blame for high prices.

Drug pricing experts, however, say pharmacy benefit managers and drugmakers share the blame.

Gov. Newsom administration officials say that inflated insulin costs force some to pay as much as $300 per vial or $500 for a box of injectable pens, and that too many Californians with diabetes skip or ration their medication. Doing so can lead to blindness, amputations, and life-threatening conditions such as heart disease and kidney failure. Nearly 10% of California adults have diabetes.

Civica is developing three types of generic insulin, known as a biosimilar, which will be available both in vials and in injectable pens. They are expected to be interchangeable with brand-name products including Lantus, Humalog, and NovoLog. Mr. Coukell said the company would make the drug available for no more than $30 a vial, or $55 for five injectable pens.

Gov. Newsom said the state’s insulin will save many patients $2,000-$4,000 a year, though critical questions about how California would get the products into the hands of consumers remain unanswered, including how it would persuade pharmacies, insurers, and retailers to distribute the drugs.

In 2022, Gov. Newsom also secured $50 million in seed money to build a facility to manufacture insulin; Mr. Coukell said Civica is exploring building a plant in California.

California’s move, though never previously tried by a state government, could be blunted by recent industry decisions to lower insulin prices. In March, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi vowed to cut prices, with Lilly offering a vial at $25 per month, Novo Nordisk promising major reductions that would bring the price of a particular generic vial to $48, and Sanofi pegging one vial at $64.

The governor’s office said it will cost the state $30 per vial to manufacture and distribute insulin and it will be sold at that price. Doing so, the administration argued, “will prevent the egregious cost-shifting that happens in traditional pharmaceutical price games.”

Drug pricing experts said generic production in California could further lower costs for insulin, and benefit people with high-deductible health insurance plans or no insurance.

“This is an extraordinary move in the pharmaceutical industry, not just for insulin but potentially for all kinds of drugs,” said Robin Feldman, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco. “It’s a very difficult industry to disrupt, but California is poised to do just that.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Gov. Gavin Newsom on March 18 announced the selection of Utah-based generic drug manufacturer Civica to produce low-cost insulin for California, an unprecedented move that makes good on his promise to put state government in direct competition with the brand-name drug companies that dominate the market.

“People should not be forced to go into debt to get lifesaving prescriptions,” Gov. Newsom said. “Californians will have access to some of the most inexpensive insulin available, helping them save thousands of dollars each year.”

The contract, with an initial cost of $50 million that Gov. Newsom and his fellow Democratic lawmakers approved last year, calls for Civica to manufacture state-branded insulin and make the lifesaving drug available to any Californian who needs it, regardless of insurance coverage, by mail order and at local pharmacies. But insulin is just the beginning. Gov. Newsom said the state will also look to produce the opioid overdose reversal drug naloxone.

Allan Coukell, Civica’s senior vice president of public policy, said in an interview that the nonprofit drugmaker is also in talks with the Newsom administration to potentially produce other generic medications, but he declined to elaborate, saying the company is focused on making cheap insulin widely available first.

“We are very excited about this partnership with the state of California,” Mr. Coukell said. “We’re not looking to have 100% of the market, but we do want 100% of people to have access to fair insulin prices.”

As insulin costs for consumers have soared, Democratic lawmakers and activists have called on the industry to rein in prices. Just weeks after President Joe Biden attacked Big Pharma for jacking up insulin prices, the three drugmakers that control the insulin market – Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi – announced they would slash the list prices of some products.

Gov. Newsom, who has previously accused the pharmaceutical industry of gouging Californians with “sky-high prices,” argued that the launch of the state’s generic drug label, CalRx, will add competition and apply pressure on the industry. Administration officials declined to say when California’s insulin products would be available, but experts say it could be as soon as 2025. Mr. Coukell said the state-branded medication will still require approval from the Food and Drug Administration, which can take roughly 10 months.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, which lobbies on behalf of brand-name companies, blasted California’s move. Reid Porter, senior director of state public affairs for PhRMA, said Gov. Newsom just “wants to score political points.”

“If the governor wants to impact what patients pay for insulins and other medicines meaningfully, he should expand his focus to others in the system that often make patients pay more than they do for medicines,” Mr. Porter said, blaming pharmaceutical go-between companies, known as pharmacy benefit managers, that negotiate with manufacturers on behalf of insurers for rebates and discounts on drugs.

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, which represents pharmacy benefit managers argued in turn that it’s pharmaceutical companies that are to blame for high prices.

Drug pricing experts, however, say pharmacy benefit managers and drugmakers share the blame.

Gov. Newsom administration officials say that inflated insulin costs force some to pay as much as $300 per vial or $500 for a box of injectable pens, and that too many Californians with diabetes skip or ration their medication. Doing so can lead to blindness, amputations, and life-threatening conditions such as heart disease and kidney failure. Nearly 10% of California adults have diabetes.

Civica is developing three types of generic insulin, known as a biosimilar, which will be available both in vials and in injectable pens. They are expected to be interchangeable with brand-name products including Lantus, Humalog, and NovoLog. Mr. Coukell said the company would make the drug available for no more than $30 a vial, or $55 for five injectable pens.

Gov. Newsom said the state’s insulin will save many patients $2,000-$4,000 a year, though critical questions about how California would get the products into the hands of consumers remain unanswered, including how it would persuade pharmacies, insurers, and retailers to distribute the drugs.

In 2022, Gov. Newsom also secured $50 million in seed money to build a facility to manufacture insulin; Mr. Coukell said Civica is exploring building a plant in California.

California’s move, though never previously tried by a state government, could be blunted by recent industry decisions to lower insulin prices. In March, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi vowed to cut prices, with Lilly offering a vial at $25 per month, Novo Nordisk promising major reductions that would bring the price of a particular generic vial to $48, and Sanofi pegging one vial at $64.

The governor’s office said it will cost the state $30 per vial to manufacture and distribute insulin and it will be sold at that price. Doing so, the administration argued, “will prevent the egregious cost-shifting that happens in traditional pharmaceutical price games.”

Drug pricing experts said generic production in California could further lower costs for insulin, and benefit people with high-deductible health insurance plans or no insurance.

“This is an extraordinary move in the pharmaceutical industry, not just for insulin but potentially for all kinds of drugs,” said Robin Feldman, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco. “It’s a very difficult industry to disrupt, but California is poised to do just that.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Gov. Gavin Newsom on March 18 announced the selection of Utah-based generic drug manufacturer Civica to produce low-cost insulin for California, an unprecedented move that makes good on his promise to put state government in direct competition with the brand-name drug companies that dominate the market.

“People should not be forced to go into debt to get lifesaving prescriptions,” Gov. Newsom said. “Californians will have access to some of the most inexpensive insulin available, helping them save thousands of dollars each year.”

The contract, with an initial cost of $50 million that Gov. Newsom and his fellow Democratic lawmakers approved last year, calls for Civica to manufacture state-branded insulin and make the lifesaving drug available to any Californian who needs it, regardless of insurance coverage, by mail order and at local pharmacies. But insulin is just the beginning. Gov. Newsom said the state will also look to produce the opioid overdose reversal drug naloxone.

Allan Coukell, Civica’s senior vice president of public policy, said in an interview that the nonprofit drugmaker is also in talks with the Newsom administration to potentially produce other generic medications, but he declined to elaborate, saying the company is focused on making cheap insulin widely available first.

“We are very excited about this partnership with the state of California,” Mr. Coukell said. “We’re not looking to have 100% of the market, but we do want 100% of people to have access to fair insulin prices.”

As insulin costs for consumers have soared, Democratic lawmakers and activists have called on the industry to rein in prices. Just weeks after President Joe Biden attacked Big Pharma for jacking up insulin prices, the three drugmakers that control the insulin market – Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi – announced they would slash the list prices of some products.

Gov. Newsom, who has previously accused the pharmaceutical industry of gouging Californians with “sky-high prices,” argued that the launch of the state’s generic drug label, CalRx, will add competition and apply pressure on the industry. Administration officials declined to say when California’s insulin products would be available, but experts say it could be as soon as 2025. Mr. Coukell said the state-branded medication will still require approval from the Food and Drug Administration, which can take roughly 10 months.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, which lobbies on behalf of brand-name companies, blasted California’s move. Reid Porter, senior director of state public affairs for PhRMA, said Gov. Newsom just “wants to score political points.”

“If the governor wants to impact what patients pay for insulins and other medicines meaningfully, he should expand his focus to others in the system that often make patients pay more than they do for medicines,” Mr. Porter said, blaming pharmaceutical go-between companies, known as pharmacy benefit managers, that negotiate with manufacturers on behalf of insurers for rebates and discounts on drugs.

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, which represents pharmacy benefit managers argued in turn that it’s pharmaceutical companies that are to blame for high prices.

Drug pricing experts, however, say pharmacy benefit managers and drugmakers share the blame.

Gov. Newsom administration officials say that inflated insulin costs force some to pay as much as $300 per vial or $500 for a box of injectable pens, and that too many Californians with diabetes skip or ration their medication. Doing so can lead to blindness, amputations, and life-threatening conditions such as heart disease and kidney failure. Nearly 10% of California adults have diabetes.

Civica is developing three types of generic insulin, known as a biosimilar, which will be available both in vials and in injectable pens. They are expected to be interchangeable with brand-name products including Lantus, Humalog, and NovoLog. Mr. Coukell said the company would make the drug available for no more than $30 a vial, or $55 for five injectable pens.

Gov. Newsom said the state’s insulin will save many patients $2,000-$4,000 a year, though critical questions about how California would get the products into the hands of consumers remain unanswered, including how it would persuade pharmacies, insurers, and retailers to distribute the drugs.

In 2022, Gov. Newsom also secured $50 million in seed money to build a facility to manufacture insulin; Mr. Coukell said Civica is exploring building a plant in California.

California’s move, though never previously tried by a state government, could be blunted by recent industry decisions to lower insulin prices. In March, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi vowed to cut prices, with Lilly offering a vial at $25 per month, Novo Nordisk promising major reductions that would bring the price of a particular generic vial to $48, and Sanofi pegging one vial at $64.

The governor’s office said it will cost the state $30 per vial to manufacture and distribute insulin and it will be sold at that price. Doing so, the administration argued, “will prevent the egregious cost-shifting that happens in traditional pharmaceutical price games.”

Drug pricing experts said generic production in California could further lower costs for insulin, and benefit people with high-deductible health insurance plans or no insurance.

“This is an extraordinary move in the pharmaceutical industry, not just for insulin but potentially for all kinds of drugs,” said Robin Feldman, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco. “It’s a very difficult industry to disrupt, but California is poised to do just that.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Match Day: Record number of residencies offered

Baily Nagle, vice president of her graduating class at Harvard Medical School, Boston, celebrated “the luck of the Irish” on St. Patrick’s Day that allowed her to match into her chosen specialty and top choice of residency programs: anesthesia at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“I am feeling very excited and relieved – I matched,” she said in an interview upon hearing her good fortune on Match Monday, March 13. She had a similar reaction on Match Day, March 17. “After a lot of long nights and hard work, happy to have it pay off.”

Ms. Nagle was so determined to match into her specialty that she didn’t have any other specialties in mind as a backup.

The annual process of matching medical school graduates with compatible residency programs is an emotional roller coaster for all applicants, their personal March Madness, so to speak. But Ms. Nagle was one of the more fortunate applicants. She didn’t have to confront the heartbreak other applicants felt when the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) announced results of the main residency match and the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program (SOAP), which offers alternate programs for unfilled positions or unmatched applicants.

During the 2023 Match process, this news organization has been following a handful of students, checking in with them periodically for updates on their progress. Most of them matched successfully, but at least one international medical graduate (IMG) did not. What the others have in common is that their hearts were set on a chosen specialty. Like Ms. Nagle, another student banked on landing his chosen specialty without a backup plan, whereas another said that she’d continue through the SOAP if she didn’t match successfully.

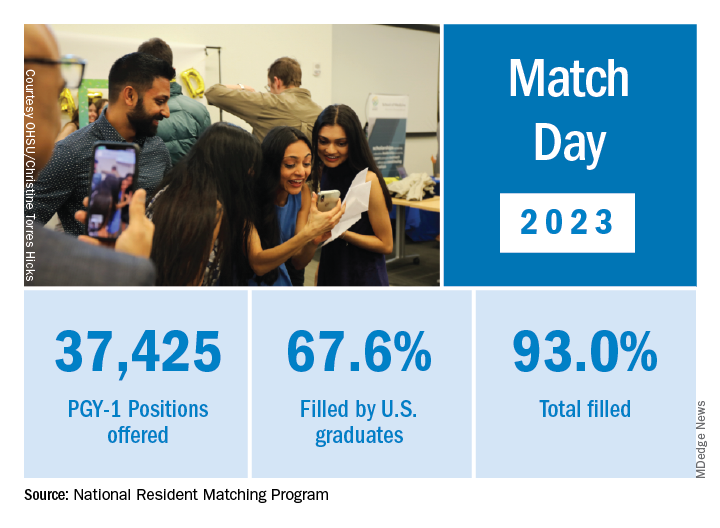

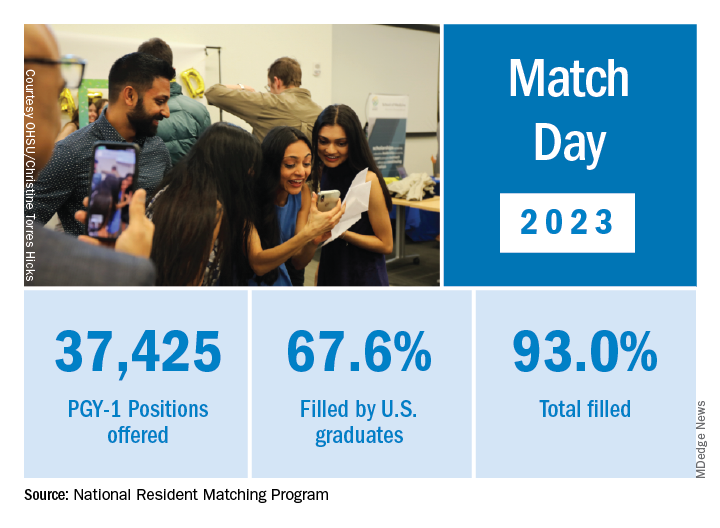

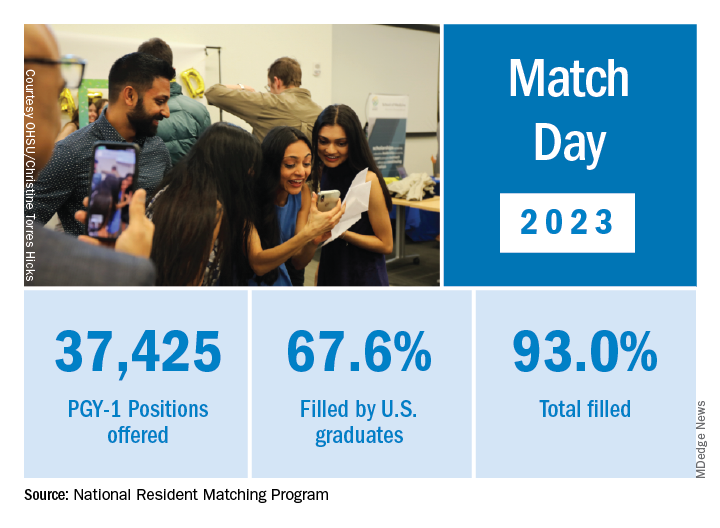

Overall, Match Day resulted in a record number of residency positions offered, most notably in primary care, which “hit an all-time high,” according to NRMP President and CEO Donna L. Lamb, DHSc, MBA, BSN. The number of positions has “consistently increased over the past 5 years, and most importantly the fill rate for primary care has remained steady,” Dr.. Lamb noted in the NRMP release of Match Day results. The release coincided with students learning through emails at noon Eastern Time to which residency or supplemental programs they were matched.

Though more applicants registered for the Match in 2023 than in 2022 – driven primarily by non-U.S. IMGs – the NRMP stated that it was surprised by the decrease in U.S. MD senior applicants.

U.S. MD seniors had a nearly 94% Match rate, a small increase over 2022. U.S. citizen IMGs saw a nearly 68% Match rate, which NRMP reported as an “all-time high” and about six percentage points over in 2022, whereas non-U.S. IMGs had a nearly 60% Match rate, a 1.3 percentage point increase over 2022.

Among the specialties that filled all available positions in 2023 were orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery (integrated), and radiology – diagnostic and thoracic surgery.

Not everyone matches

On March 13, the American College of Emergency Physicians issued a joint statement with other emergency medicine (EM) organizations about a high rate of unfilled EM positions expected in 2023.

NRMP acknowledged March 17 that 554 positions remained unfilled, an increase of 335 more unfilled positions than 2022. NRMP attributed the increase in unfilled positions in part to a decrease in the number of U.S. MD and U.S. DO seniors who submitted ranks for the specialty, which “could reflect changing applicant interests or projections about workforce opportunities post residency.”

Applicants who didn’t match usually try to obtain an unfilled position through SOAP. In 2023, 2,685 positions were unfilled after the matching algorithm was processed, an increase of nearly 19% over 2022. The vast majority of those positions were placed in SOAP, an increase of 17.5% over 2022.

Asim Ansari was one of the unlucky ones. Mr. Ansari was trying to match for the fifth time. He was unsuccessful in doing so again in 2023 in the Match and SOAP. Still, he was offered and accepted a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship at Kansas University Medical Center in Kansas City. Psychiatry was his chosen specialty, so he was “feeling good. It’s a nice place to go to do the next 2 years.”

Mr. Ansari, who started the #MatchMadness support group for unmatched doctors on Twitter Spaces, was quick to cheer on his fellow matching peers on March 13 while revealing his own fate: “Congratulations to everyone who matched!!! Y’all are amazing. So proud of each one of you!!! I didn’t.”

Soon after the results, #MatchMadness held a #Soap2023 support session, and Mr. Ansari sought advice for those willing to review SOAP applications. Elsewhere on Twitter Match Day threads, a few doctors offered their support to those who planned to SOAP, students announced their matches, and others either congratulated or encouraged those still trying to match.

Couples match

Not everyone who matched considered the alternative. Before March 13, William Boyer said that he hadn’t given much thought to what would happen if he didn’t match because he was “optimistically confident” he would match into his chosen EM specialty. But he did and got his top choice of programs: Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital.

“I feel great,” he said in an interview. “I was definitely nervous opening the envelope” that revealed his residency program, “but there was a rush of relief” when he saw he landed Yale.

Earlier in the match cycle, he said in an interview that he “interviewed at a few ‘reach’ programs, so I hope I don’t match lower than expected on my rank list.”

Mr. Boyer considers himself “a mature applicant,” entering the University of South Carolina, Columbia, after 4 years as an insurance broker.

“I am celebrating today by playing pickleball with a few close medical friends who also matched this morning,” Mr. Boyer said on March 13. “I definitely had periods of nervousness leading up to this morning though that quickly turned into joy and relief” after learning he matched.

Mr. Boyer believes that his professional experience in the insurance industry and health care lobbying efforts with the National Association of Health Underwriters set him apart from other applicants.

“I changed careers to pursue this aspiration, which demonstrates my full dedication to the medical profession.”

He applied to 48 programs and was offered interviews to nearly half. Mr. Boyer visited the majority of those virtually. He said he targeted programs close to where his and his partner’s families are located: Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Texas. “My partner, who I met in medical school, matched into ortho as well so the whole household is very happy,” Mr. Boyer said.

She matched into her top choice as well on March 17, though a distance away at UT Health in San Antonio, he said. “We are both ecstatic. We both got our no. 1 choice. That was the plan going into it. We will make it work. I have 4 weeks of vacation.”

In his program choices, Mr. Boyer prioritized access to nature, minimal leadership turnover, a mix of clinical training sites, and adequate elective rotations and fellowship opportunities, such as in wilderness medicine and health policy.

NRMP reported that there were 1,239 couples participating in the Match; 1,095 had both partners match, and 114 had one partner match to residency training programs for a match rate of 93%.

Like Mr. Boyer, Hannah Hedriana matched into EM, one of the more popular despite the reported unfilled positions. In the past few years, it has consistently been one of the fastest-growing specialties, according to the NRMP.

Still Ms. Hedriana had a fall-back plan. “If I don’t match, then I do plan on going through SOAP. With the number of EM spots that were unfilled in 2022, there’s a chance I could still be an EM physician, but if not, then that’s okay with me.”

Her reaction on March 13, after learning she matched? “Super excited, celebrating with my friends right now.” On Match Day, she said she was “ecstatic” to be matched into Lakeland (Fla.) Regional Health. “This was my first choice so now I can stay close to family and friends,” she said in an interview soon after the results were released.

A first-generation, Filipino American student from the University of South Florida, Tampa, Ms. Hedriana comes from a family of health care professionals. Her father is a respiratory therapist turned physical therapist; her mother a registered nurse. Her sister is a patient care technician applying to nursing school.

Ms. Hedriana applied to 70 programs and interviewed mostly online with 24. Her goal was to stay on the East Coast.

“My partner is a licensed dentist in the state of Florida, and so for his career it would be more practical to stay in state, rather than get relicensed in another state, which could take months,” she said earlier in the matching cycle. “However, when we discussed choosing a residency program, he ultimately left it up to me and wanted me to pick where I thought I’d flourish best,” Ms. Hedriana said, adding that her family lives in Florida, too.