User login

Understanding Psychosis in a Veteran With a History of Combat and Multiple Sclerosis (FULL)

A patient with significant combat history and previous diagnoses of multiple sclerosis and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder was admitted with acute psychosis inconsistent with expected clinical presentations.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated neurodegenerative disease that affects > 700,000 people in the US.1 The hallmarks of MS pathology are axonal or neuronal loss, demyelination, and astrocytic gliosis. Of these, axonal or neuronal loss is the main underlying mechanism of permanent clinical disability.

MS also has been associated with an increased prevalence of psychiatric illnesses, with mood disorders affecting up to 40% to 60% of the population, and psychosis being reported in 2% to 4% of patients.2 The link between MS and mood disorders, including bipolar disorder and depression, was documented as early as 1926,with mood disorders hypothesized to be manifestations of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation.3 More recently, inflammation-driven microglia have been hypothesized to impair hippocampal connectivity and activate glucocorticoid-insensitive inflammatory cells that then overstimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4,5

Although the prevalence of psychosis in patients with MS is significantly rarer, averaging between 2% and 4%.6 A Canadian study by Patten and colleagues reviewed data from 2.45 million residents of Alberta and found that those who identified as having MS had a 2% to 3% prevalence of psychosis compared with 0.5% to 1% in the general population.7 The connection between psychosis and MS, similar to that between mood disorders and MS, has been described as a common regional demyelination process. Supporting this, MS manifesting as psychosis has been found to present with distinct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, such as diffuse periventricular lesions.8 Still, no conclusive criteria have been developed to distinguish MS presenting as psychosis from a primary psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia.

In patients with combat history, it is possible that both neurodegenerative and psychotic symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure. When soldiers were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, they may have been exposed to multiple toxicities, including depleted uranium, dust and fumes, and numerous infectious diseases.9 Gulf War illness (GWI) or chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) encompass a cluster of symptoms, such as chronic pain, chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, dermatitis, and seizures, as well as mental health issues such as depression and anxiety experienced following exposure to these combat environments.10,11

In light of this diagnostic uncertainty, the authors detail a case of a patient with significant combat history previously diagnosed with MS and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder (USS & OPD) presenting with acute psychosis.

Case Presentation

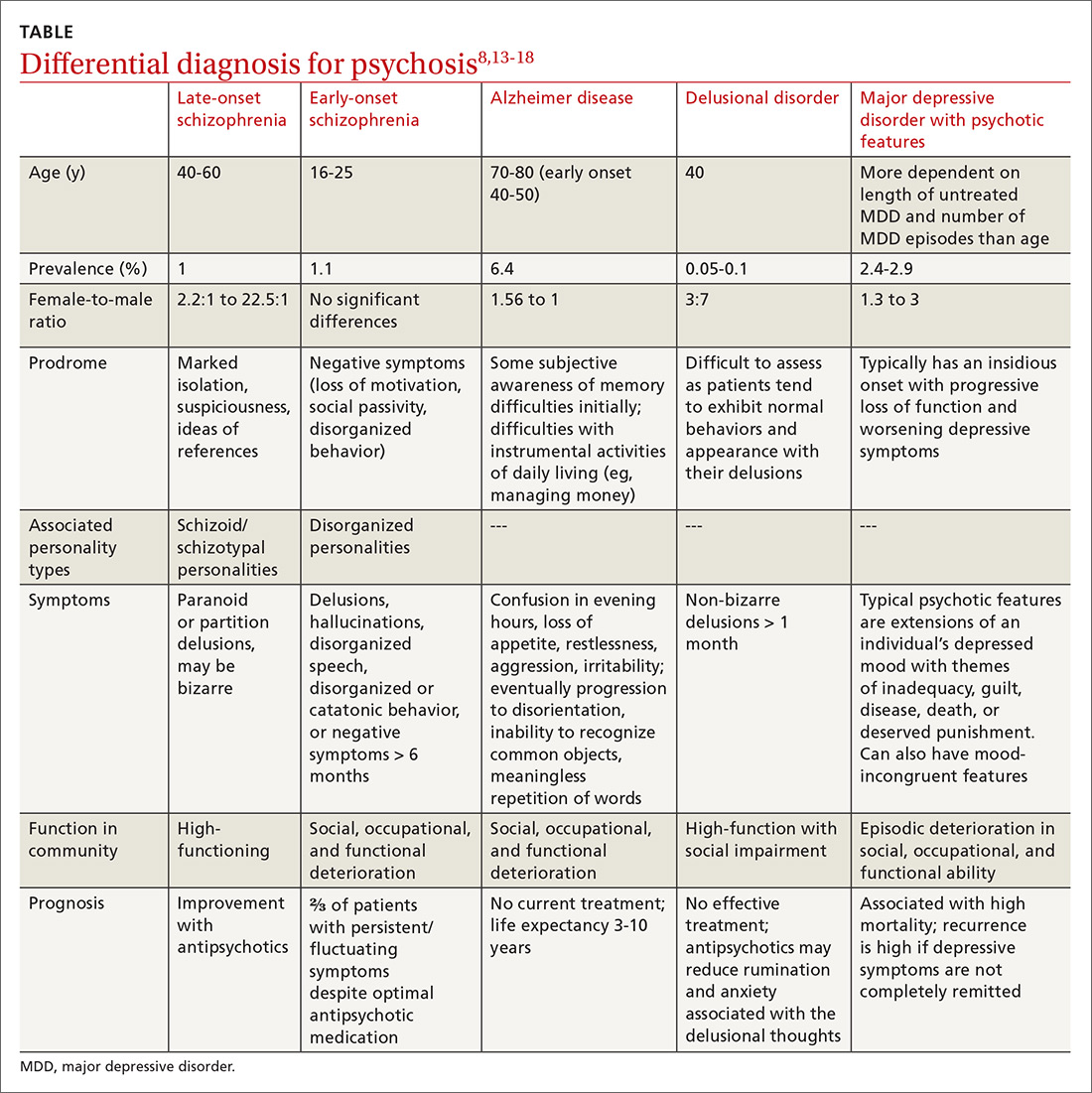

A 35-year-old male veteran, with a history of MS, USS & OPD, posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) was admitted to the psychiatric unit after being found by the police lying in the middle of a busy intersection, internally preoccupied. On admission, he reported a week of auditory hallucinations from birds with whom he had been communicating telepathically, and a recurrent visual hallucination of a tall man in white and purple robes. He had discontinued his antipsychotic medication, aripiprazole 10 mg, a few weeks prior for unknown reasons. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance, where he presented with disorganized thinking, tangential thought process, and active auditory and visual hallucinations. The differential diagnoses included USS & OPD, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and ruled out substance-induced psychotic disorder, and psychosis as a manifestation of MS.

The patient had 2 psychotic episodes prior to this presentation. He was hospitalized for his first psychotic break in 2015 at age 32, when he had tailed another car “to come back to reality” and ended up in a motor vehicle accident. During that admission, he reported weeks of thought broadcasting, conspiratorial delusions, and racing thoughts. Two years later, he was admitted to a psychiatric intensive care unit for his second episode of severe psychosis. After several trials of different antipsychotic medications, his most recent pharmacologic regimen was aripiprazole 10 mg once daily.

His medical history was complicated by 2 TBIs, in November 2014 and January 2015, with normal computed tomography (CT) scans. He was diagnosed with MS in December 2017, when he presented with intractable emesis, left facial numbness, right upper extremity ataxia, nystagmus, and imbalance. An MRI scan revealed multifocal bilateral hypodensities in his periventricular, subcortical, and brain stem white matter. Multiple areas of hyperintensity were visualized, including in the right periatrial region and left brachium pontis. More than 5 oligoclonal bands on lumbar puncture confirmed the diagnosis.

He was treated with IV methylprednisolone followed by a 2-week prednisone taper. Within 1 week, he returned to the psychiatric unit with worsening symptoms and received a second dose of IV steroids and plasma exchange treatment. In the following months, he completed a course of rituximab infusions and physical therapy for his dysarthria, gait abnormality, and vision impairment.

His social history was notable for multiple first-degree relatives with schizophrenia. He reported a history of sexual and verbal abuse and attempted suicide once at age 13 years by hanging himself with a bathrobe. He left home at age 18 years to serve in the Marine Corps (2001-2006). His service included deployment to Afghanistan, where he received a purple heart. Upon his return, he received BA and MS degrees. He married and had 2 daughters but became estranged from his wife. By his most recent admission, he was unemployed and living with his half-sister.

On the first day of this most recent psychiatric hospitalization, he was restarted on aripiprazole 10 mg daily, and a medicine consult was sought to evaluate the progression of his MS. No new onset neurologic symptoms were noted, but he had possible residual lower extremity hyperreflexia and tandem gait incoordination. The episodes of psychotic and neurologic symptoms appeared independent, given that his psychiatric history preceded the onset of his MS.

The patient reported no visual hallucinations starting day 2, and he no longer endorsed auditory hallucinations by day 3. However, he continued to appear internally preoccupied and was noticed to be pacing around the unit. On day 4 he presented with newly pressured speech and flights of ideas, while his affect remained euthymic and his sleep stayed consistent. In combination with his ongoing pacing, his newfound symptoms were hypothesized to be possibly akathisia, an adverse effect (AE) of aripiprazole. As such, on day 5 his dose was lowered to 5 mg daily. He continued to report no hallucinations and demonstrated progressively increased emotional range. A MRI scan was done on day 6 in case a new lesion could be identified, suggesting a primary MS flare-up; however, the scan identified no enhancing lesions, indicating no ongoing demyelination. After a neurology consult corroborated this conclusion, he was discharged in stable condition on day 7.

As is the case with the majority of patients with MS-induced psychosis, he continued to have relapsing psychiatric disease even after MS treatment had been started. Unfortunately, because this patient had stopped taking his atypical antipsychotic medication several weeks prior to his hospitalization, we cannot clarify whether his psychosis stems from a primary psychiatric vs MS process.

Discussion

Presently, treatment preferences for MS-related psychosis are divided between atypical antipsychotics and glucocorticoids. Some suggest that the treatment remains similar between MS-related psychosis and primary psychotic disorders in that atypical antipsychotics are the standard of care.12 A variety of atypical antipsychotics have been used successfully in case reports, including zipradisone, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole.13,14 First-generation antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs that can precipitate extra-pyramidal AEs are not recommended given their potential additive effect to motor deficits associated with MS.12 Alternatively, several case reports have found that MS-related psychotic symptoms respond to glucocorticoids more effectively, while cautioning that glucocorticoids can precipitate psychosis and depression.15,16 One review article found that 90% of patients who received corticosteroids saw an improvement in their psychotic symptoms.2

Finally, it is possible that our patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure during his time in Afghanistan. In a pilot study of veterans with GWI, Abou-Donia and colleagues found 2-to-9 fold increase in autoantibody reactivity levels of the following neuronal and glial-specific proteins relative to healthy controls: neurofilament triplet proteins, tubulin, microtubule-associated tau proteins, microtubule-associated protein-2, myelin basic protein, myelin-associated glycoprotein, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and calcium-calmodulin kinase II.17,18 Many of these autoantibodies are longstanding explicit markers for neurodegenerative disorders, given that they target proteins and antigens that support axonal transport and myelination. Still Gulf War veteran status has yet to be explicitly linked to an increased risk of MS,19 making this hypothesis less likely for our patient. Future research should address the clinical and therapeutic implications of different autoantibody levels in combat veterans with psychosis.

Conclusion

For patients with MS, mood disorder and psychotic symptoms should warrant a MRI given the possibility of a psychiatric manifestation of MS relapse. Ultimately, our patient’s presentation was inconsistent with the expected clinical presentations of both a primary psychotic disorder and psychosis as a manifestation of MS. His late age at his first psychotic break is atypical for primary psychotic disease, and the lack of MRI imaging done at his initial psychotic episodes cannot exclude a primary MS diagnosis. Still, his lack of MRI findings at his most recent hospitalization, negative symptomatology, and strong history of schizophrenia make a primary psychotic disorder likely.

Following his future clinical course will be necessary to determine the etiology of his psychotic episodes. Future episodes of psychosis with neurologic symptoms would suggest a primary MS diagnosis and potential benefit of immunosuppressant treatment, whereas repeated psychotic breaks with minimal temporal lobe involvement or demyelination as seen on MRI would be suspicious for separate MS and psychotic disease processes. Further research on treatment regimens for patients experiencing psychosis as a manifestation of MS is still necessary.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040.

2. Camara-Lemarroy CR, Ibarra-Yruegas BE, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Berrios-Morales I, Ionete C, Riskind P. The varieties of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:9-14.

3. Cottrel SS, Wilson SA. The affective symptomatology of disseminated sclerosis: a study of 100 cases. J Neurol Psychopathology. 1926;7(25):1-30.

4. Johansson V, Lundholm C, Hillert J, et al. Multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders: comorbidity and sibling risk in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Mult Scler. 2014;20(14):1881-1891.

5. Rossi S, Studer V, Motta C, et al. Neuroinflammation drives anxiety and depression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1338-1347.

6. Gilberthorpe TG, O’Connell KE, Carolan A, et al. The spectrum of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a clinical case series. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2017;13:303.

7. Patten SB, Svenson LW, Metz LM. Psychotic disorders in MS: population-based evidence of an association. Neurology 2005;65(7):1123-1125.

8. Kosmidis MH, Giannakou M, Messinis L, Papathanasopoulos P. Psychotic features associated with multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010; 22(1):55-66.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Public health: military exposures. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/. Updated April 16, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. DeBeer BB, Davidson D, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. The association between toxic exposures and chronic multisymptom illness in veterans of the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(1):54-60.

11. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

12. Murphy R, O’Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):697-708.

13. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar, M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):743-744.

14. Lo Fermo S, Barone R, Patti F, et al. Outcome of psychiatric symptoms presenting at onset of multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Mult Scler. 2010;16(6):742-748.

15. Enderami A, Fouladi R, Hosseini HS. First-episode psychosis as the initial presentation of multiple sclerosis: a case report. Int Medical Case Rep J. 2018;11:73-76.

16. Fragoso YD, Frota ER, Lopes JS, et al. Severe depression, suicide attempts, and ideation during the use of interferon beta by patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):312-316.

17. Abou-Donia MB, Conboy LA, Kokkotou E, et al. Screening for novel central nervous system biomarkers in veterans with Gulf War Illness. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017;61:36-46.

18. Abou-Donia MB, Lieberman A, Curtis L. Neural autoantibodies in patients with neurological symptoms and histories of chemical/mold exposures. Toxicol Ind Health. 2018;34(1):44-53.

19. Wallin MT, Kurtzke JF, Culpepper WJ, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Gulf War era veterans. 2. Military deployment and risk of multiple sclerosis in the first Gulf War. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42(4):226-234.

A patient with significant combat history and previous diagnoses of multiple sclerosis and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder was admitted with acute psychosis inconsistent with expected clinical presentations.

A patient with significant combat history and previous diagnoses of multiple sclerosis and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder was admitted with acute psychosis inconsistent with expected clinical presentations.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated neurodegenerative disease that affects > 700,000 people in the US.1 The hallmarks of MS pathology are axonal or neuronal loss, demyelination, and astrocytic gliosis. Of these, axonal or neuronal loss is the main underlying mechanism of permanent clinical disability.

MS also has been associated with an increased prevalence of psychiatric illnesses, with mood disorders affecting up to 40% to 60% of the population, and psychosis being reported in 2% to 4% of patients.2 The link between MS and mood disorders, including bipolar disorder and depression, was documented as early as 1926,with mood disorders hypothesized to be manifestations of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation.3 More recently, inflammation-driven microglia have been hypothesized to impair hippocampal connectivity and activate glucocorticoid-insensitive inflammatory cells that then overstimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4,5

Although the prevalence of psychosis in patients with MS is significantly rarer, averaging between 2% and 4%.6 A Canadian study by Patten and colleagues reviewed data from 2.45 million residents of Alberta and found that those who identified as having MS had a 2% to 3% prevalence of psychosis compared with 0.5% to 1% in the general population.7 The connection between psychosis and MS, similar to that between mood disorders and MS, has been described as a common regional demyelination process. Supporting this, MS manifesting as psychosis has been found to present with distinct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, such as diffuse periventricular lesions.8 Still, no conclusive criteria have been developed to distinguish MS presenting as psychosis from a primary psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia.

In patients with combat history, it is possible that both neurodegenerative and psychotic symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure. When soldiers were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, they may have been exposed to multiple toxicities, including depleted uranium, dust and fumes, and numerous infectious diseases.9 Gulf War illness (GWI) or chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) encompass a cluster of symptoms, such as chronic pain, chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, dermatitis, and seizures, as well as mental health issues such as depression and anxiety experienced following exposure to these combat environments.10,11

In light of this diagnostic uncertainty, the authors detail a case of a patient with significant combat history previously diagnosed with MS and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder (USS & OPD) presenting with acute psychosis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old male veteran, with a history of MS, USS & OPD, posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) was admitted to the psychiatric unit after being found by the police lying in the middle of a busy intersection, internally preoccupied. On admission, he reported a week of auditory hallucinations from birds with whom he had been communicating telepathically, and a recurrent visual hallucination of a tall man in white and purple robes. He had discontinued his antipsychotic medication, aripiprazole 10 mg, a few weeks prior for unknown reasons. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance, where he presented with disorganized thinking, tangential thought process, and active auditory and visual hallucinations. The differential diagnoses included USS & OPD, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and ruled out substance-induced psychotic disorder, and psychosis as a manifestation of MS.

The patient had 2 psychotic episodes prior to this presentation. He was hospitalized for his first psychotic break in 2015 at age 32, when he had tailed another car “to come back to reality” and ended up in a motor vehicle accident. During that admission, he reported weeks of thought broadcasting, conspiratorial delusions, and racing thoughts. Two years later, he was admitted to a psychiatric intensive care unit for his second episode of severe psychosis. After several trials of different antipsychotic medications, his most recent pharmacologic regimen was aripiprazole 10 mg once daily.

His medical history was complicated by 2 TBIs, in November 2014 and January 2015, with normal computed tomography (CT) scans. He was diagnosed with MS in December 2017, when he presented with intractable emesis, left facial numbness, right upper extremity ataxia, nystagmus, and imbalance. An MRI scan revealed multifocal bilateral hypodensities in his periventricular, subcortical, and brain stem white matter. Multiple areas of hyperintensity were visualized, including in the right periatrial region and left brachium pontis. More than 5 oligoclonal bands on lumbar puncture confirmed the diagnosis.

He was treated with IV methylprednisolone followed by a 2-week prednisone taper. Within 1 week, he returned to the psychiatric unit with worsening symptoms and received a second dose of IV steroids and plasma exchange treatment. In the following months, he completed a course of rituximab infusions and physical therapy for his dysarthria, gait abnormality, and vision impairment.

His social history was notable for multiple first-degree relatives with schizophrenia. He reported a history of sexual and verbal abuse and attempted suicide once at age 13 years by hanging himself with a bathrobe. He left home at age 18 years to serve in the Marine Corps (2001-2006). His service included deployment to Afghanistan, where he received a purple heart. Upon his return, he received BA and MS degrees. He married and had 2 daughters but became estranged from his wife. By his most recent admission, he was unemployed and living with his half-sister.

On the first day of this most recent psychiatric hospitalization, he was restarted on aripiprazole 10 mg daily, and a medicine consult was sought to evaluate the progression of his MS. No new onset neurologic symptoms were noted, but he had possible residual lower extremity hyperreflexia and tandem gait incoordination. The episodes of psychotic and neurologic symptoms appeared independent, given that his psychiatric history preceded the onset of his MS.

The patient reported no visual hallucinations starting day 2, and he no longer endorsed auditory hallucinations by day 3. However, he continued to appear internally preoccupied and was noticed to be pacing around the unit. On day 4 he presented with newly pressured speech and flights of ideas, while his affect remained euthymic and his sleep stayed consistent. In combination with his ongoing pacing, his newfound symptoms were hypothesized to be possibly akathisia, an adverse effect (AE) of aripiprazole. As such, on day 5 his dose was lowered to 5 mg daily. He continued to report no hallucinations and demonstrated progressively increased emotional range. A MRI scan was done on day 6 in case a new lesion could be identified, suggesting a primary MS flare-up; however, the scan identified no enhancing lesions, indicating no ongoing demyelination. After a neurology consult corroborated this conclusion, he was discharged in stable condition on day 7.

As is the case with the majority of patients with MS-induced psychosis, he continued to have relapsing psychiatric disease even after MS treatment had been started. Unfortunately, because this patient had stopped taking his atypical antipsychotic medication several weeks prior to his hospitalization, we cannot clarify whether his psychosis stems from a primary psychiatric vs MS process.

Discussion

Presently, treatment preferences for MS-related psychosis are divided between atypical antipsychotics and glucocorticoids. Some suggest that the treatment remains similar between MS-related psychosis and primary psychotic disorders in that atypical antipsychotics are the standard of care.12 A variety of atypical antipsychotics have been used successfully in case reports, including zipradisone, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole.13,14 First-generation antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs that can precipitate extra-pyramidal AEs are not recommended given their potential additive effect to motor deficits associated with MS.12 Alternatively, several case reports have found that MS-related psychotic symptoms respond to glucocorticoids more effectively, while cautioning that glucocorticoids can precipitate psychosis and depression.15,16 One review article found that 90% of patients who received corticosteroids saw an improvement in their psychotic symptoms.2

Finally, it is possible that our patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure during his time in Afghanistan. In a pilot study of veterans with GWI, Abou-Donia and colleagues found 2-to-9 fold increase in autoantibody reactivity levels of the following neuronal and glial-specific proteins relative to healthy controls: neurofilament triplet proteins, tubulin, microtubule-associated tau proteins, microtubule-associated protein-2, myelin basic protein, myelin-associated glycoprotein, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and calcium-calmodulin kinase II.17,18 Many of these autoantibodies are longstanding explicit markers for neurodegenerative disorders, given that they target proteins and antigens that support axonal transport and myelination. Still Gulf War veteran status has yet to be explicitly linked to an increased risk of MS,19 making this hypothesis less likely for our patient. Future research should address the clinical and therapeutic implications of different autoantibody levels in combat veterans with psychosis.

Conclusion

For patients with MS, mood disorder and psychotic symptoms should warrant a MRI given the possibility of a psychiatric manifestation of MS relapse. Ultimately, our patient’s presentation was inconsistent with the expected clinical presentations of both a primary psychotic disorder and psychosis as a manifestation of MS. His late age at his first psychotic break is atypical for primary psychotic disease, and the lack of MRI imaging done at his initial psychotic episodes cannot exclude a primary MS diagnosis. Still, his lack of MRI findings at his most recent hospitalization, negative symptomatology, and strong history of schizophrenia make a primary psychotic disorder likely.

Following his future clinical course will be necessary to determine the etiology of his psychotic episodes. Future episodes of psychosis with neurologic symptoms would suggest a primary MS diagnosis and potential benefit of immunosuppressant treatment, whereas repeated psychotic breaks with minimal temporal lobe involvement or demyelination as seen on MRI would be suspicious for separate MS and psychotic disease processes. Further research on treatment regimens for patients experiencing psychosis as a manifestation of MS is still necessary.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated neurodegenerative disease that affects > 700,000 people in the US.1 The hallmarks of MS pathology are axonal or neuronal loss, demyelination, and astrocytic gliosis. Of these, axonal or neuronal loss is the main underlying mechanism of permanent clinical disability.

MS also has been associated with an increased prevalence of psychiatric illnesses, with mood disorders affecting up to 40% to 60% of the population, and psychosis being reported in 2% to 4% of patients.2 The link between MS and mood disorders, including bipolar disorder and depression, was documented as early as 1926,with mood disorders hypothesized to be manifestations of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation.3 More recently, inflammation-driven microglia have been hypothesized to impair hippocampal connectivity and activate glucocorticoid-insensitive inflammatory cells that then overstimulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4,5

Although the prevalence of psychosis in patients with MS is significantly rarer, averaging between 2% and 4%.6 A Canadian study by Patten and colleagues reviewed data from 2.45 million residents of Alberta and found that those who identified as having MS had a 2% to 3% prevalence of psychosis compared with 0.5% to 1% in the general population.7 The connection between psychosis and MS, similar to that between mood disorders and MS, has been described as a common regional demyelination process. Supporting this, MS manifesting as psychosis has been found to present with distinct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, such as diffuse periventricular lesions.8 Still, no conclusive criteria have been developed to distinguish MS presenting as psychosis from a primary psychiatric illness, such as schizophrenia.

In patients with combat history, it is possible that both neurodegenerative and psychotic symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure. When soldiers were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, they may have been exposed to multiple toxicities, including depleted uranium, dust and fumes, and numerous infectious diseases.9 Gulf War illness (GWI) or chronic multisymptom illness (CMI) encompass a cluster of symptoms, such as chronic pain, chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, dermatitis, and seizures, as well as mental health issues such as depression and anxiety experienced following exposure to these combat environments.10,11

In light of this diagnostic uncertainty, the authors detail a case of a patient with significant combat history previously diagnosed with MS and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder (USS & OPD) presenting with acute psychosis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old male veteran, with a history of MS, USS & OPD, posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) was admitted to the psychiatric unit after being found by the police lying in the middle of a busy intersection, internally preoccupied. On admission, he reported a week of auditory hallucinations from birds with whom he had been communicating telepathically, and a recurrent visual hallucination of a tall man in white and purple robes. He had discontinued his antipsychotic medication, aripiprazole 10 mg, a few weeks prior for unknown reasons. He was brought to the hospital by ambulance, where he presented with disorganized thinking, tangential thought process, and active auditory and visual hallucinations. The differential diagnoses included USS & OPD, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and ruled out substance-induced psychotic disorder, and psychosis as a manifestation of MS.

The patient had 2 psychotic episodes prior to this presentation. He was hospitalized for his first psychotic break in 2015 at age 32, when he had tailed another car “to come back to reality” and ended up in a motor vehicle accident. During that admission, he reported weeks of thought broadcasting, conspiratorial delusions, and racing thoughts. Two years later, he was admitted to a psychiatric intensive care unit for his second episode of severe psychosis. After several trials of different antipsychotic medications, his most recent pharmacologic regimen was aripiprazole 10 mg once daily.

His medical history was complicated by 2 TBIs, in November 2014 and January 2015, with normal computed tomography (CT) scans. He was diagnosed with MS in December 2017, when he presented with intractable emesis, left facial numbness, right upper extremity ataxia, nystagmus, and imbalance. An MRI scan revealed multifocal bilateral hypodensities in his periventricular, subcortical, and brain stem white matter. Multiple areas of hyperintensity were visualized, including in the right periatrial region and left brachium pontis. More than 5 oligoclonal bands on lumbar puncture confirmed the diagnosis.

He was treated with IV methylprednisolone followed by a 2-week prednisone taper. Within 1 week, he returned to the psychiatric unit with worsening symptoms and received a second dose of IV steroids and plasma exchange treatment. In the following months, he completed a course of rituximab infusions and physical therapy for his dysarthria, gait abnormality, and vision impairment.

His social history was notable for multiple first-degree relatives with schizophrenia. He reported a history of sexual and verbal abuse and attempted suicide once at age 13 years by hanging himself with a bathrobe. He left home at age 18 years to serve in the Marine Corps (2001-2006). His service included deployment to Afghanistan, where he received a purple heart. Upon his return, he received BA and MS degrees. He married and had 2 daughters but became estranged from his wife. By his most recent admission, he was unemployed and living with his half-sister.

On the first day of this most recent psychiatric hospitalization, he was restarted on aripiprazole 10 mg daily, and a medicine consult was sought to evaluate the progression of his MS. No new onset neurologic symptoms were noted, but he had possible residual lower extremity hyperreflexia and tandem gait incoordination. The episodes of psychotic and neurologic symptoms appeared independent, given that his psychiatric history preceded the onset of his MS.

The patient reported no visual hallucinations starting day 2, and he no longer endorsed auditory hallucinations by day 3. However, he continued to appear internally preoccupied and was noticed to be pacing around the unit. On day 4 he presented with newly pressured speech and flights of ideas, while his affect remained euthymic and his sleep stayed consistent. In combination with his ongoing pacing, his newfound symptoms were hypothesized to be possibly akathisia, an adverse effect (AE) of aripiprazole. As such, on day 5 his dose was lowered to 5 mg daily. He continued to report no hallucinations and demonstrated progressively increased emotional range. A MRI scan was done on day 6 in case a new lesion could be identified, suggesting a primary MS flare-up; however, the scan identified no enhancing lesions, indicating no ongoing demyelination. After a neurology consult corroborated this conclusion, he was discharged in stable condition on day 7.

As is the case with the majority of patients with MS-induced psychosis, he continued to have relapsing psychiatric disease even after MS treatment had been started. Unfortunately, because this patient had stopped taking his atypical antipsychotic medication several weeks prior to his hospitalization, we cannot clarify whether his psychosis stems from a primary psychiatric vs MS process.

Discussion

Presently, treatment preferences for MS-related psychosis are divided between atypical antipsychotics and glucocorticoids. Some suggest that the treatment remains similar between MS-related psychosis and primary psychotic disorders in that atypical antipsychotics are the standard of care.12 A variety of atypical antipsychotics have been used successfully in case reports, including zipradisone, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole.13,14 First-generation antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs that can precipitate extra-pyramidal AEs are not recommended given their potential additive effect to motor deficits associated with MS.12 Alternatively, several case reports have found that MS-related psychotic symptoms respond to glucocorticoids more effectively, while cautioning that glucocorticoids can precipitate psychosis and depression.15,16 One review article found that 90% of patients who received corticosteroids saw an improvement in their psychotic symptoms.2

Finally, it is possible that our patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms can be explained by autoantibody formation in response to toxin exposure during his time in Afghanistan. In a pilot study of veterans with GWI, Abou-Donia and colleagues found 2-to-9 fold increase in autoantibody reactivity levels of the following neuronal and glial-specific proteins relative to healthy controls: neurofilament triplet proteins, tubulin, microtubule-associated tau proteins, microtubule-associated protein-2, myelin basic protein, myelin-associated glycoprotein, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and calcium-calmodulin kinase II.17,18 Many of these autoantibodies are longstanding explicit markers for neurodegenerative disorders, given that they target proteins and antigens that support axonal transport and myelination. Still Gulf War veteran status has yet to be explicitly linked to an increased risk of MS,19 making this hypothesis less likely for our patient. Future research should address the clinical and therapeutic implications of different autoantibody levels in combat veterans with psychosis.

Conclusion

For patients with MS, mood disorder and psychotic symptoms should warrant a MRI given the possibility of a psychiatric manifestation of MS relapse. Ultimately, our patient’s presentation was inconsistent with the expected clinical presentations of both a primary psychotic disorder and psychosis as a manifestation of MS. His late age at his first psychotic break is atypical for primary psychotic disease, and the lack of MRI imaging done at his initial psychotic episodes cannot exclude a primary MS diagnosis. Still, his lack of MRI findings at his most recent hospitalization, negative symptomatology, and strong history of schizophrenia make a primary psychotic disorder likely.

Following his future clinical course will be necessary to determine the etiology of his psychotic episodes. Future episodes of psychosis with neurologic symptoms would suggest a primary MS diagnosis and potential benefit of immunosuppressant treatment, whereas repeated psychotic breaks with minimal temporal lobe involvement or demyelination as seen on MRI would be suspicious for separate MS and psychotic disease processes. Further research on treatment regimens for patients experiencing psychosis as a manifestation of MS is still necessary.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040.

2. Camara-Lemarroy CR, Ibarra-Yruegas BE, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Berrios-Morales I, Ionete C, Riskind P. The varieties of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:9-14.

3. Cottrel SS, Wilson SA. The affective symptomatology of disseminated sclerosis: a study of 100 cases. J Neurol Psychopathology. 1926;7(25):1-30.

4. Johansson V, Lundholm C, Hillert J, et al. Multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders: comorbidity and sibling risk in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Mult Scler. 2014;20(14):1881-1891.

5. Rossi S, Studer V, Motta C, et al. Neuroinflammation drives anxiety and depression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1338-1347.

6. Gilberthorpe TG, O’Connell KE, Carolan A, et al. The spectrum of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a clinical case series. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2017;13:303.

7. Patten SB, Svenson LW, Metz LM. Psychotic disorders in MS: population-based evidence of an association. Neurology 2005;65(7):1123-1125.

8. Kosmidis MH, Giannakou M, Messinis L, Papathanasopoulos P. Psychotic features associated with multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010; 22(1):55-66.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Public health: military exposures. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/. Updated April 16, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. DeBeer BB, Davidson D, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. The association between toxic exposures and chronic multisymptom illness in veterans of the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(1):54-60.

11. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

12. Murphy R, O’Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):697-708.

13. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar, M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):743-744.

14. Lo Fermo S, Barone R, Patti F, et al. Outcome of psychiatric symptoms presenting at onset of multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Mult Scler. 2010;16(6):742-748.

15. Enderami A, Fouladi R, Hosseini HS. First-episode psychosis as the initial presentation of multiple sclerosis: a case report. Int Medical Case Rep J. 2018;11:73-76.

16. Fragoso YD, Frota ER, Lopes JS, et al. Severe depression, suicide attempts, and ideation during the use of interferon beta by patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):312-316.

17. Abou-Donia MB, Conboy LA, Kokkotou E, et al. Screening for novel central nervous system biomarkers in veterans with Gulf War Illness. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017;61:36-46.

18. Abou-Donia MB, Lieberman A, Curtis L. Neural autoantibodies in patients with neurological symptoms and histories of chemical/mold exposures. Toxicol Ind Health. 2018;34(1):44-53.

19. Wallin MT, Kurtzke JF, Culpepper WJ, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Gulf War era veterans. 2. Military deployment and risk of multiple sclerosis in the first Gulf War. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42(4):226-234.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040.

2. Camara-Lemarroy CR, Ibarra-Yruegas BE, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Berrios-Morales I, Ionete C, Riskind P. The varieties of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:9-14.

3. Cottrel SS, Wilson SA. The affective symptomatology of disseminated sclerosis: a study of 100 cases. J Neurol Psychopathology. 1926;7(25):1-30.

4. Johansson V, Lundholm C, Hillert J, et al. Multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders: comorbidity and sibling risk in a nationwide Swedish cohort. Mult Scler. 2014;20(14):1881-1891.

5. Rossi S, Studer V, Motta C, et al. Neuroinflammation drives anxiety and depression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1338-1347.

6. Gilberthorpe TG, O’Connell KE, Carolan A, et al. The spectrum of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a clinical case series. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2017;13:303.

7. Patten SB, Svenson LW, Metz LM. Psychotic disorders in MS: population-based evidence of an association. Neurology 2005;65(7):1123-1125.

8. Kosmidis MH, Giannakou M, Messinis L, Papathanasopoulos P. Psychotic features associated with multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010; 22(1):55-66.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Public health: military exposures. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/. Updated April 16, 2019. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. DeBeer BB, Davidson D, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. The association between toxic exposures and chronic multisymptom illness in veterans of the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(1):54-60.

11. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410.

12. Murphy R, O’Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):697-708.

13. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar, M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):743-744.

14. Lo Fermo S, Barone R, Patti F, et al. Outcome of psychiatric symptoms presenting at onset of multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Mult Scler. 2010;16(6):742-748.

15. Enderami A, Fouladi R, Hosseini HS. First-episode psychosis as the initial presentation of multiple sclerosis: a case report. Int Medical Case Rep J. 2018;11:73-76.

16. Fragoso YD, Frota ER, Lopes JS, et al. Severe depression, suicide attempts, and ideation during the use of interferon beta by patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(6):312-316.

17. Abou-Donia MB, Conboy LA, Kokkotou E, et al. Screening for novel central nervous system biomarkers in veterans with Gulf War Illness. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017;61:36-46.

18. Abou-Donia MB, Lieberman A, Curtis L. Neural autoantibodies in patients with neurological symptoms and histories of chemical/mold exposures. Toxicol Ind Health. 2018;34(1):44-53.

19. Wallin MT, Kurtzke JF, Culpepper WJ, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Gulf War era veterans. 2. Military deployment and risk of multiple sclerosis in the first Gulf War. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42(4):226-234.

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome With Severe Neurologic Complications in an Adult (FULL)

The case of a female presenting with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and hemolytic uremic syndrome highlights a severe neurologic complication that canbe associated with these conditions.

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a rare illness that can be acquired through the consumption of food products contaminated with strains of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (E coli; STEC).1 Between 6% and 15% of individuals infected with STEC develop HUS, with children affected more frequently than adults.2,3 This strain of E coli releases Shiga toxin into the systemic circulation, which causes a thrombotic microangiopathy resulting in the characteristic HUS triad of symptoms: acute renal insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic anemia.4-6

Although neurologic features are common in HUS, they have not been extensively studied, particularly in adults. We report a case of STEC 0157:H7 subtype HUS in an adult with severe neurologic complications. This case highlights the neurological sequelae in an adult with typical STEC-HUS. The use of treatment modalities, such as plasmapheresis and eculizumab, and their use in adult typical STEC-HUS also is explored.

Case

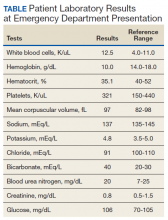

A 53-year-old white woman with no pertinent past medical history presented to the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Emergency Department with a 2-day history of abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, and bright bloody stools. She returned from a cruise to the Bahamas 3 days prior, where she ate local foods, including salads. She reported no fever, shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, and cognitive difficulties. She presented with a normal mental status and neurologic exam. Apart from leukocytosis and elevated glucose level, her laboratory results at initial presentation were normal, (Table). A stool sample showed occult blood with white blood cell counts (WBCs) but was negative for Clostridium difficile. She was started on ciprofloxacin 400 mg and metronidazole 500 mg on the day of admission.

Hematuria was found on hospital day 2. On hospital day 4, the patient exhibited word finding difficulties. Blood studies revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, and increasing blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine. A computed tomography scan of the head was normal. Laboratory analysis showed schistocytes in the peripheral blood smear.

The patient’s cognitive functioning deteriorated on hospital day 5. She was not oriented to time or place. Her laboratory results showed complement level C3 at 70 mg/dL (ref: 83-193 mg/dL) complement C4 at 12 mg/dL (ref: 15-57mg/dL). The patient exhibited oliguria and hyponatremia, as well as both metabolic and respiratory acidosis; dialysis was then initiated. Results from the stool sample that was collected on hospital day 1 were received and tested positive for Shiga toxin.

At this point, the patient’s presentation of hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia in the setting of acute bloody diarrheal illness with known Shiga toxin, schistocytes on blood smear, and lack of pertinent medical history for other causes of this presentation made STEC-HUS the leading differential diagnosis. Plasmapheresis was ordered and performed on hospital day 6 and 7. Shiga toxin was no longer detected in the stool and antibiotics were stopped on hospital day 7.

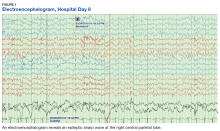

The patient’s progressive deterioration in mental status continued on hospital day 8. She was not oriented to time or place, unable to perform simple calculations, and could not spell the word “hand” backwards. Physicians observed repetitive jerking motions of the upper extremities that were worse on the left side. An electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed right hemispheric sharp waves that were thought to be epileptiform (Figure 1). The patient began taking levetiracetam 1500 mg IV with 750 mg bid maintenance for seizure control. Plasmapheresis was discontinued due to her continued neurologic deterioration on this therapy. Consequently, eculizumab 900 mg IV was given along with the Neisseria meningitidis (N meningitidis) vaccine and a 19-day course of azithromycin 250 mg po as prophylaxis for encapsulated bacteria.

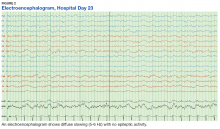

The patient continued to seize on hospital days 10 through 13. Oculocephalic maneuvers showed a tendency to keep her eyes deviated to the right. Her pupils continued to react to light. A repeat EEG showed diffuse slowing (5-6 Hz) with no epileptic activity seen (Figure 2). A second dose of eculizumab 900 mg IV was administered on hospital day 15. The patient experienced cardiac arrest on hospital day 16 and was successfully resuscitated. On hospital day 25 (10 days after receiving her second dose of eculizumab), the patient was able to speak and follow simple commands but exhibited difficulty concentrating and poor impulse control.

The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation on hospital day 28 (6 days after the third and final dose of eculizumab). A neurologic exam was significant only for a slight intention tremor. She was continued on levetiracetam with a plan to be maintained on the medication for the next 6 months for seizure control. She was discharged on hospital day 30.

Twenty-eight days postdischarge (57 days postadmission), the patient showed marked recovery. She had returned to her previous employment as a business administrator on a part-time basis and exhibited no deficiencies in executive functioning or handling activities of daily living. Although she had been very active prior to this illness, she now experienced decreased physical and mental endurance; however, this gradually improved with physical therapy. She planned on returning to work on a full-time basis when she had regained her stamina. She also noticed difficulties in retaining short term memory since her discharge but believed that these symptoms were remitting. On examination her mental status and neurologic exam was significant for inability to continue serial 7s, left sided 4/5 muscle strength in quadriceps and thumb to 5th metacarpal adduction, bilateral 1+ reflexes in muscle groups tested (triceps, biceps, brachioradialis, patellar, and Achilles), loss of dull pinprick sensation bilaterally at web of hands, deficit in tandem gait while looking away, and slight intention tremor on finger to nose testing bilaterally (with left hand tremor more pronounced than right). Her complete blood count was normal. Her recovery continues to be monitored in an outpatient setting.

Discussion

HUS is characterized by 3 core clinical features: microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury.4 Schistocytes are seen on peripheral blood smear and occur due to the passage of red blood cells over the microvascular thrombi induced by the disease. HUS can be classified as typical, atypical, or occurring with a coexisting disease. Typical HUS is associated with STEC 0157:H7 subtype, a bacterium known to be acquired through contaminated food and via human-to-human transmission.6-8 In the case of typical STEC 0157:H7, the bacterium releases a verotoxin that damages the vascular endothelium, thereby leading to activation of the coagulation cascade and eventually the formation of thrombi.4 It has been hypothesized that the Shiga toxin also activates the alternative complement pathway directly, which could contribute to thrombosis.9 This would explain the findings of low complement levels in our patient. Atypical HUS is primarily attributable to mutations in the alternative complement pathway. Causes for the third type of HUS can include Streptococcus pneumoniae, HIV, drug toxicity, and alterations in the metabolism of cobalamin C.

Epidemiologically, 15.3% of children aged < 5 years develop typical HUS after exposure to STEC compared with 1.2% of adults aged 18 to 59 years. The median age of patients who developed HUS from STEC exposure was 4 years compared with 16 years for those who did not develop HUS.2

Neurologic manifestations increase mortality for HUS patients.10 These have been described in the pediatric population as alteration in consciousness (85%), seizures (71%), pyramidal syndrome (52%), and extrapyramidal syndrome with hypertonia (42%).11 Brain imaging in children has demonstrated hemorrhagic lesions involving the pons, basal ganglia, and occipital cortex.11 Blood flow to areas such as the cerebellum, brainstem, and orbitofrontal area can be compromised.10 Adult patients with HUS can present without lesions on cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but instead with transient symmetric vasogenic edema of the central brain stem.12 Unfortunately in this case, MRI was not performed because it was thought to provide limited aid in diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary testing for the acutely ill patient.

The underlying pathophysiology of neurologic manifestations in patients may be due to a metabolic disturbance, toxin-mediated damage of the vascular endothelium, or toxin-induced cytokine release resulting in death of neural cells and subsequent neuroinflammation. However, the most likely mechanism is parenchymal ischemic changes related to microangiopathy.11,13 Pediatric patients often experience seizures and altered mental status, and their EEGs display delta waves.13 This patient’s diffuse slowing on her second EEG and altered mental status suggests that the neuropathologic mechanisms for typical HUS in adults may be similar to those in children.

HUS Treatment

The treatment and management of adults with typical STEC-HUS is evolving. The patient was first suspected to have an infectious colitis and empiric antibiotics were initiated. Some studies suggest that antibiotic administration may worsen the course of HUS in children as it may lead to release and subsequent absorption of Shiga toxin in the intestine.9,14 However, there is little evidence to suggest harm or efficacy of administration in adults. It is unclear what role antibiotic administration played in the recovery time of HUS given the co-administration of other treatments such as eculizumab and plasmapheresis, but it does appear to have helped with the initial E coli infection.

Plasmapheresis was subsequently administered, due to its documented benefit in the treatment of HUS.15 However, it should be noted that even though plasmapheresis is currently used in patients with CNS involvement, it remains unproven with conflicting information on its efficacy.3,16 The mechanism of action is unclear, but it has been hypothesized that plasmapheresis prevents microangiopathy caused by microthrombi.3,16 For this reason, eculizumab is becoming the mainstay for treatment of STEC-HUS with neurologic complications given the lack of well researched alternative treatments. In this case study, the use of plasmapheresis did not result in clinical improvement, and was abandoned after 2 days of treatment.

Eculizumab is a humanized, recombinant monoclonal IgG antibody that is a terminal complement inhibitor of the alternative complement system at the final step to cleave C5.17 The Shiga toxin may directly activate the complement system via the alternative pathway, which can result in uncontrolled platelet and white blood cell activation and depletion, endothelial cell damage, and hemolysis. The galvanized complement system leads to a series of cascading events that contribute to organ damage and death.9 Eculizumab is FDA approved for use in atypical HUS.18 It also can be used off-label to treat typical-HUS in adults with neurologic complications.

Eculizumab interferes with the immune response against encapsulated bacteria because it inhibits the alternative complement pathway. Thus, vaccination against N meningitides is recommended 2 weeks prior to the administration of eculizumab. However, in situations where the risks of delaying eculizumab for 2 weeks are greater than the risk of developing an N meningitides infection, eculizumab may be given without delay.18 Given the rapid deterioration of our patient’s condition, the vaccine and eculizumab were given together with prophylactic azithromycin. Although penicillin is the standard for prophylaxis in this situation, the patient’s penicillin allergy led to the use of azithromycin 250 mg po once a day. Literature also suggests azithromycin reduces the carriage duration of E coli-induced colitis.19 As such, it is possible that some improvement in the patient’s condition could be attributed to the elimination of the pathogen and toxin.

Conclusion

Three doses of eculizumab were administered at weekly intervals, with the first dose on hospital day 8 and the final dose on hospital day 22. Prior to the first dose, the patient displayed significant decline in mental status with EEG findings of right hemisphere epileptogenic discharges. After her third dose, she was found to have a drastically improved mental status exam and a normal EEG. One week later, she was discharged home. At the time of her 1-month follow-up, she was independent in all activities of daily living and had returned to part-time work. Apart from subtle cognitive changes, the remainder of her neurologic exam was normal.

There is evidence that supports the efficacy of eculizumab in children with HUS with neurologic symptoms on dialysis.20 However, its use in adults is not well established.21 This patient required dialysis and had neurologic symptoms similar to pediatric patients described in the literature, and responded similarly to the eculizumab. The rationale for the use of eculizumab in STEC-HUS also is evidenced by in vitro demonstrations of complement activation in STEC-HUS.22-25 This case report adds to the literature supporting the use of eculizumab in adult patients with typical HUS with neurological complications. Further research is necessary to develop guidelines in the treatment of adult STEC-HUS with regards to neurologic complications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Pete DiStaso, REEGT for his work on obtaining the electroencephalograms and Anthony Rinaldi, PsyD; Julie Cessnapalas, PsyD; and Syed Faizan Sagheer for proof-reading the article.

1. Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1073-1086.

2. Gould LH, Demma L, Jones TF, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome and death in persons with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection, foodborne diseases active surveillance network sites, 2000-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(10):1480-1485.

3. Boyce TG, Swerdlow DL, Griffin PM. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(6):364-368.

4. Rondeau E, Peraldi MN. Escherichia coli and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(9):660-662.

5. Te Loo DM, van Hinsbergh VW, van den Heuvel LP, Monnens LA. Detection of verocytotoxin bound to circulating polymorphonuclear leukocytes of patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(4):800-806.

6. Tran SL, Jenkins C, Livrelli V, Schüller S. Shiga toxin 2 translocation across intestinal epithelium is linked to virulence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in humans. Microbiology. 2018;164(4):509-516.

7. Jokiranta TS. HUS and atypical HUS. Blood. 2017;129(21):2847-2856.

8. Ferens WA, Hovde CJ. Escherichia coli O157:H7: animal reservoir and sources of human infection. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8(4):465-487.

9. Percheron L, Gramada R, Tellier S, et al. Eculizumab treatment in severe pediatric STEC-HUS: a multicenter retrospective study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(8):1385-1394.

10. Hosaka T, Nakamagoe K, Tamaoka A. Hemolytic uremic syndrome-associated encephalopathy successfully treated with corticosteroids. Intern Med. 2017;56(21):2937-2941.

11. Nathanson S, Kwon T, Elmaleh M, et al. Acute neurological involvement in diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(7):1218-1228.

12. Wengenroth M, Hoeltje J, Repenthin J, et al. Central nervous system involvement in adults with epidemic hemolytic uremic syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(5):1016-1021, S1.

13. Eriksson KJ, Boyd SG, Tasker RC. Acute neurology and neurophysiology of haemolytic-uraemic syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84(5):434-435.

14. Wong CS, Jelacic S, Habeeb RL, Watkins SL, Tarr PI. The risk of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(26):1930-1936.

15. Nguyen TC, Kiss JE, Goldman JR, Carcillo JA. The role of plasmapheresis in critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28(3):453-468, vii.

16. Loos S, Ahlenstiel T, Kranz B, et al. An outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 hemolytic uremic syndrome in Germany: presentation and short-term outcome in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(6):753-759.

17. Hossain MA, Cheema A, Kalathil S, et al. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: Laboratory characteristics, complement-amplifying conditions, renal biopsy, and genetic mutations. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29(2):276-283.

18. Soliris (eculizumab) [package insert]. Cheshire, CT: Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2011.

19. Keenswijk W, Raes A, Vande Walle J. Is eculizumab efficacious in Shigatoxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome? A narrative review of current evidence. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(3):311-318.

20. Lapeyraque AL, Malina M, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, et al. Eculizumab in severe Shiga-toxin-associated HUS. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2561-2563.

21. Pape L, Hartmann H, Bange FC, Suerbaum S, Bueltmann E, Ahlenstiel-Grunow T. Eculizumab in typical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) with neurological involvement. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(24):e1000.

22. Kim Y, Miller K, Michael AF. Breakdown products of C3 and factor B in hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Lab Clin Med. 1977;89(4):845-850.

23. Monnens L, Molenaar J, Lambert PH, Proesmans W, van Munster P. The complement system in hemolytic-uremic syndrome in childhood. Clin Nephrol. 1980;13(4):168-171.

24. Thurman JM, Marians R, Emlen W, et al. Alternative pathway of complement in children with diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(12):1920-1924.

25. Ståhl AL, Sartz L, Karpman D. Complement activation on platelet-leukocyte complexes and microparticles in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood. 2011;117(20):5503-5513.

The case of a female presenting with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and hemolytic uremic syndrome highlights a severe neurologic complication that canbe associated with these conditions.

The case of a female presenting with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and hemolytic uremic syndrome highlights a severe neurologic complication that canbe associated with these conditions.

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a rare illness that can be acquired through the consumption of food products contaminated with strains of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (E coli; STEC).1 Between 6% and 15% of individuals infected with STEC develop HUS, with children affected more frequently than adults.2,3 This strain of E coli releases Shiga toxin into the systemic circulation, which causes a thrombotic microangiopathy resulting in the characteristic HUS triad of symptoms: acute renal insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic anemia.4-6

Although neurologic features are common in HUS, they have not been extensively studied, particularly in adults. We report a case of STEC 0157:H7 subtype HUS in an adult with severe neurologic complications. This case highlights the neurological sequelae in an adult with typical STEC-HUS. The use of treatment modalities, such as plasmapheresis and eculizumab, and their use in adult typical STEC-HUS also is explored.

Case

A 53-year-old white woman with no pertinent past medical history presented to the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Emergency Department with a 2-day history of abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, and bright bloody stools. She returned from a cruise to the Bahamas 3 days prior, where she ate local foods, including salads. She reported no fever, shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, and cognitive difficulties. She presented with a normal mental status and neurologic exam. Apart from leukocytosis and elevated glucose level, her laboratory results at initial presentation were normal, (Table). A stool sample showed occult blood with white blood cell counts (WBCs) but was negative for Clostridium difficile. She was started on ciprofloxacin 400 mg and metronidazole 500 mg on the day of admission.

Hematuria was found on hospital day 2. On hospital day 4, the patient exhibited word finding difficulties. Blood studies revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, and increasing blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine. A computed tomography scan of the head was normal. Laboratory analysis showed schistocytes in the peripheral blood smear.

The patient’s cognitive functioning deteriorated on hospital day 5. She was not oriented to time or place. Her laboratory results showed complement level C3 at 70 mg/dL (ref: 83-193 mg/dL) complement C4 at 12 mg/dL (ref: 15-57mg/dL). The patient exhibited oliguria and hyponatremia, as well as both metabolic and respiratory acidosis; dialysis was then initiated. Results from the stool sample that was collected on hospital day 1 were received and tested positive for Shiga toxin.

At this point, the patient’s presentation of hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia in the setting of acute bloody diarrheal illness with known Shiga toxin, schistocytes on blood smear, and lack of pertinent medical history for other causes of this presentation made STEC-HUS the leading differential diagnosis. Plasmapheresis was ordered and performed on hospital day 6 and 7. Shiga toxin was no longer detected in the stool and antibiotics were stopped on hospital day 7.

The patient’s progressive deterioration in mental status continued on hospital day 8. She was not oriented to time or place, unable to perform simple calculations, and could not spell the word “hand” backwards. Physicians observed repetitive jerking motions of the upper extremities that were worse on the left side. An electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed right hemispheric sharp waves that were thought to be epileptiform (Figure 1). The patient began taking levetiracetam 1500 mg IV with 750 mg bid maintenance for seizure control. Plasmapheresis was discontinued due to her continued neurologic deterioration on this therapy. Consequently, eculizumab 900 mg IV was given along with the Neisseria meningitidis (N meningitidis) vaccine and a 19-day course of azithromycin 250 mg po as prophylaxis for encapsulated bacteria.

The patient continued to seize on hospital days 10 through 13. Oculocephalic maneuvers showed a tendency to keep her eyes deviated to the right. Her pupils continued to react to light. A repeat EEG showed diffuse slowing (5-6 Hz) with no epileptic activity seen (Figure 2). A second dose of eculizumab 900 mg IV was administered on hospital day 15. The patient experienced cardiac arrest on hospital day 16 and was successfully resuscitated. On hospital day 25 (10 days after receiving her second dose of eculizumab), the patient was able to speak and follow simple commands but exhibited difficulty concentrating and poor impulse control.

The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, time, and situation on hospital day 28 (6 days after the third and final dose of eculizumab). A neurologic exam was significant only for a slight intention tremor. She was continued on levetiracetam with a plan to be maintained on the medication for the next 6 months for seizure control. She was discharged on hospital day 30.

Twenty-eight days postdischarge (57 days postadmission), the patient showed marked recovery. She had returned to her previous employment as a business administrator on a part-time basis and exhibited no deficiencies in executive functioning or handling activities of daily living. Although she had been very active prior to this illness, she now experienced decreased physical and mental endurance; however, this gradually improved with physical therapy. She planned on returning to work on a full-time basis when she had regained her stamina. She also noticed difficulties in retaining short term memory since her discharge but believed that these symptoms were remitting. On examination her mental status and neurologic exam was significant for inability to continue serial 7s, left sided 4/5 muscle strength in quadriceps and thumb to 5th metacarpal adduction, bilateral 1+ reflexes in muscle groups tested (triceps, biceps, brachioradialis, patellar, and Achilles), loss of dull pinprick sensation bilaterally at web of hands, deficit in tandem gait while looking away, and slight intention tremor on finger to nose testing bilaterally (with left hand tremor more pronounced than right). Her complete blood count was normal. Her recovery continues to be monitored in an outpatient setting.

Discussion

HUS is characterized by 3 core clinical features: microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury.4 Schistocytes are seen on peripheral blood smear and occur due to the passage of red blood cells over the microvascular thrombi induced by the disease. HUS can be classified as typical, atypical, or occurring with a coexisting disease. Typical HUS is associated with STEC 0157:H7 subtype, a bacterium known to be acquired through contaminated food and via human-to-human transmission.6-8 In the case of typical STEC 0157:H7, the bacterium releases a verotoxin that damages the vascular endothelium, thereby leading to activation of the coagulation cascade and eventually the formation of thrombi.4 It has been hypothesized that the Shiga toxin also activates the alternative complement pathway directly, which could contribute to thrombosis.9 This would explain the findings of low complement levels in our patient. Atypical HUS is primarily attributable to mutations in the alternative complement pathway. Causes for the third type of HUS can include Streptococcus pneumoniae, HIV, drug toxicity, and alterations in the metabolism of cobalamin C.

Epidemiologically, 15.3% of children aged < 5 years develop typical HUS after exposure to STEC compared with 1.2% of adults aged 18 to 59 years. The median age of patients who developed HUS from STEC exposure was 4 years compared with 16 years for those who did not develop HUS.2

Neurologic manifestations increase mortality for HUS patients.10 These have been described in the pediatric population as alteration in consciousness (85%), seizures (71%), pyramidal syndrome (52%), and extrapyramidal syndrome with hypertonia (42%).11 Brain imaging in children has demonstrated hemorrhagic lesions involving the pons, basal ganglia, and occipital cortex.11 Blood flow to areas such as the cerebellum, brainstem, and orbitofrontal area can be compromised.10 Adult patients with HUS can present without lesions on cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but instead with transient symmetric vasogenic edema of the central brain stem.12 Unfortunately in this case, MRI was not performed because it was thought to provide limited aid in diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary testing for the acutely ill patient.

The underlying pathophysiology of neurologic manifestations in patients may be due to a metabolic disturbance, toxin-mediated damage of the vascular endothelium, or toxin-induced cytokine release resulting in death of neural cells and subsequent neuroinflammation. However, the most likely mechanism is parenchymal ischemic changes related to microangiopathy.11,13 Pediatric patients often experience seizures and altered mental status, and their EEGs display delta waves.13 This patient’s diffuse slowing on her second EEG and altered mental status suggests that the neuropathologic mechanisms for typical HUS in adults may be similar to those in children.

HUS Treatment

The treatment and management of adults with typical STEC-HUS is evolving. The patient was first suspected to have an infectious colitis and empiric antibiotics were initiated. Some studies suggest that antibiotic administration may worsen the course of HUS in children as it may lead to release and subsequent absorption of Shiga toxin in the intestine.9,14 However, there is little evidence to suggest harm or efficacy of administration in adults. It is unclear what role antibiotic administration played in the recovery time of HUS given the co-administration of other treatments such as eculizumab and plasmapheresis, but it does appear to have helped with the initial E coli infection.

Plasmapheresis was subsequently administered, due to its documented benefit in the treatment of HUS.15 However, it should be noted that even though plasmapheresis is currently used in patients with CNS involvement, it remains unproven with conflicting information on its efficacy.3,16 The mechanism of action is unclear, but it has been hypothesized that plasmapheresis prevents microangiopathy caused by microthrombi.3,16 For this reason, eculizumab is becoming the mainstay for treatment of STEC-HUS with neurologic complications given the lack of well researched alternative treatments. In this case study, the use of plasmapheresis did not result in clinical improvement, and was abandoned after 2 days of treatment.

Eculizumab is a humanized, recombinant monoclonal IgG antibody that is a terminal complement inhibitor of the alternative complement system at the final step to cleave C5.17 The Shiga toxin may directly activate the complement system via the alternative pathway, which can result in uncontrolled platelet and white blood cell activation and depletion, endothelial cell damage, and hemolysis. The galvanized complement system leads to a series of cascading events that contribute to organ damage and death.9 Eculizumab is FDA approved for use in atypical HUS.18 It also can be used off-label to treat typical-HUS in adults with neurologic complications.

Eculizumab interferes with the immune response against encapsulated bacteria because it inhibits the alternative complement pathway. Thus, vaccination against N meningitides is recommended 2 weeks prior to the administration of eculizumab. However, in situations where the risks of delaying eculizumab for 2 weeks are greater than the risk of developing an N meningitides infection, eculizumab may be given without delay.18 Given the rapid deterioration of our patient’s condition, the vaccine and eculizumab were given together with prophylactic azithromycin. Although penicillin is the standard for prophylaxis in this situation, the patient’s penicillin allergy led to the use of azithromycin 250 mg po once a day. Literature also suggests azithromycin reduces the carriage duration of E coli-induced colitis.19 As such, it is possible that some improvement in the patient’s condition could be attributed to the elimination of the pathogen and toxin.

Conclusion

Three doses of eculizumab were administered at weekly intervals, with the first dose on hospital day 8 and the final dose on hospital day 22. Prior to the first dose, the patient displayed significant decline in mental status with EEG findings of right hemisphere epileptogenic discharges. After her third dose, she was found to have a drastically improved mental status exam and a normal EEG. One week later, she was discharged home. At the time of her 1-month follow-up, she was independent in all activities of daily living and had returned to part-time work. Apart from subtle cognitive changes, the remainder of her neurologic exam was normal.

There is evidence that supports the efficacy of eculizumab in children with HUS with neurologic symptoms on dialysis.20 However, its use in adults is not well established.21 This patient required dialysis and had neurologic symptoms similar to pediatric patients described in the literature, and responded similarly to the eculizumab. The rationale for the use of eculizumab in STEC-HUS also is evidenced by in vitro demonstrations of complement activation in STEC-HUS.22-25 This case report adds to the literature supporting the use of eculizumab in adult patients with typical HUS with neurological complications. Further research is necessary to develop guidelines in the treatment of adult STEC-HUS with regards to neurologic complications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Pete DiStaso, REEGT for his work on obtaining the electroencephalograms and Anthony Rinaldi, PsyD; Julie Cessnapalas, PsyD; and Syed Faizan Sagheer for proof-reading the article.

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a rare illness that can be acquired through the consumption of food products contaminated with strains of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (E coli; STEC).1 Between 6% and 15% of individuals infected with STEC develop HUS, with children affected more frequently than adults.2,3 This strain of E coli releases Shiga toxin into the systemic circulation, which causes a thrombotic microangiopathy resulting in the characteristic HUS triad of symptoms: acute renal insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic anemia.4-6

Although neurologic features are common in HUS, they have not been extensively studied, particularly in adults. We report a case of STEC 0157:H7 subtype HUS in an adult with severe neurologic complications. This case highlights the neurological sequelae in an adult with typical STEC-HUS. The use of treatment modalities, such as plasmapheresis and eculizumab, and their use in adult typical STEC-HUS also is explored.

Case

A 53-year-old white woman with no pertinent past medical history presented to the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Emergency Department with a 2-day history of abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, and bright bloody stools. She returned from a cruise to the Bahamas 3 days prior, where she ate local foods, including salads. She reported no fever, shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, and cognitive difficulties. She presented with a normal mental status and neurologic exam. Apart from leukocytosis and elevated glucose level, her laboratory results at initial presentation were normal, (Table). A stool sample showed occult blood with white blood cell counts (WBCs) but was negative for Clostridium difficile. She was started on ciprofloxacin 400 mg and metronidazole 500 mg on the day of admission.

Hematuria was found on hospital day 2. On hospital day 4, the patient exhibited word finding difficulties. Blood studies revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, and increasing blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine. A computed tomography scan of the head was normal. Laboratory analysis showed schistocytes in the peripheral blood smear.