User login

Dog Walking Can Be Hazardous to Cutaneous Health

Studies have recommended dog walking as an activity designed to improve the overall health of older adults.1,2 Benefits purportedly associated with dog walking include lower body mass index, fewer chronic diseases, reduction in the number of physician visits, and decreased limitations of activities of daily living.2 The Arthritis Foundation even recommends dog walking to relieve arthritis symptoms.3 Of course, dogs also provide comfort in companionship, and dog walking can be an enjoyable way for a pet and owner to spend time together.

However, this seemingly benign activity poses a notable and perhaps grossly underrecognized risk for injury in older adults. The annual number of patients 65 years and older who presented to US emergency departments (EDs) for fractures directly associated with walking leashed dogs more than doubled from 2004 to 2017.4 Interestingly, this dramatic increase parallels a nationwide trend in dog ownership demographics. Between 2006 and 2016, the median age of dog owners in the United States rose from 46 to 49 years.5

These trends raise concern for more than just the health of older Americans’ bones. Intuitively, a dog- walking accident that results in a bone fracture will likely also lead to some degree of skin trauma. Older adults have thin fragile skin due to flattening of the dermoepidermal junction and disintegration or degeneration of dermal collagen and elastin.6 This loss of connective tissue as well as subcutaneous tissue in some body areas facilitates shearing injury; concurrently, weakened perivascular support increases the risk for vascular injury and bruising.7 Therefore, when an older person falls while walking a dog, trauma can easily damage delicate aged skin.

Older adults are particularly susceptible to falls, the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries in this age group.8 There are multiple risk factors for falls, including polypharmacy, impaired balance and gait, visual impairments, and cognitive decline, among others.9

Also, many older adults with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism take an anticoagulant drug to prevent stroke. The use of anticoagulants is associated with an increased risk for bleeding, ranging from minor cutaneous bleeding to fatal intracranial hemorrhage.10

A predisposition to falling and bleeding can be hazardous for a dog owner whose excited pet suddenly jumps, runs, or scratches. The use of a leash, mandatory in many urban jurisdictions, tethers the human to the dog, which expedites a fall associated with any sudden, forceful forward or lateral movement by the dog. The following case reports describe a variety of cutaneous injuries experienced by older adults while dog walking.

Case Reports

Patient 1

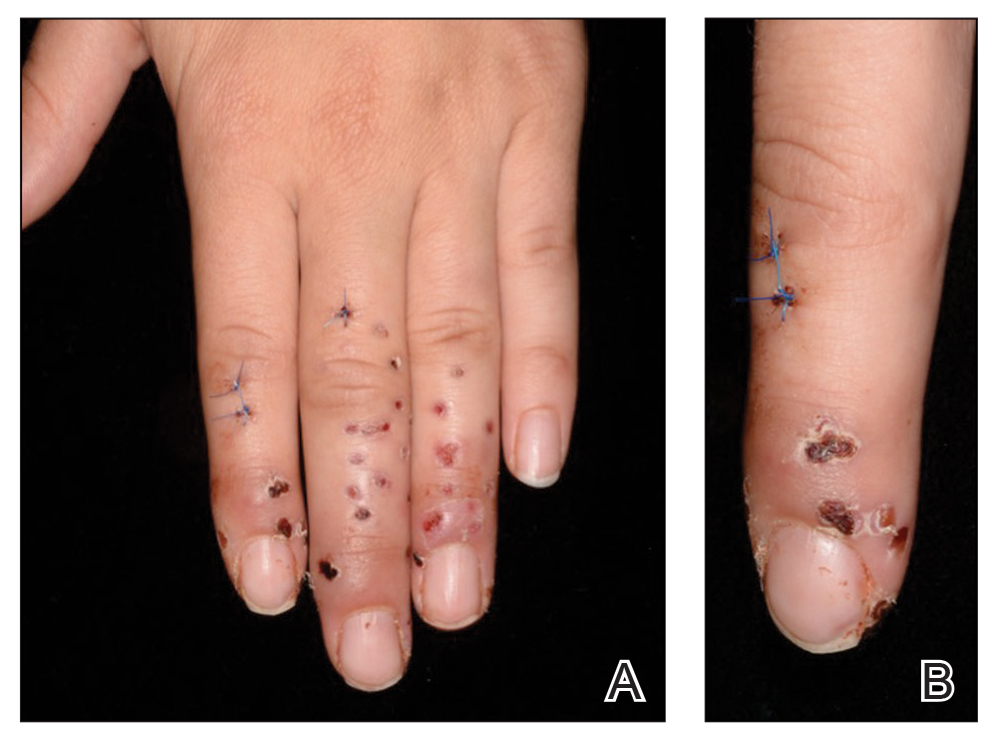

A 79-year-old woman was quietly walking her dog when the dog spotted a squirrel climbing a tree. The dog became excited, turned to the owner, and jumped on her, which caused the dog’s claws to dig into the owner’s fragile forearm skin, creating several superficial but painful abrasions and lacerations (Figure 1). These injuries healed well with conservative therapy including application of an occlusive ointment.

Patient 2

A 68-year-old woman was walking her dog when the dog saw a cat running across the street. The dog suddenly leaped toward the cat, causing the owner to fall forward as the animal’s momentum was transferred through the leash. The owner fell awkwardly on her side, leading to an extensive abrasion and contusion of the shoulder (Figure 2). The lesion healed well with conservative management, albeit with moderate postinflammatory hypochromia.

Patient 3

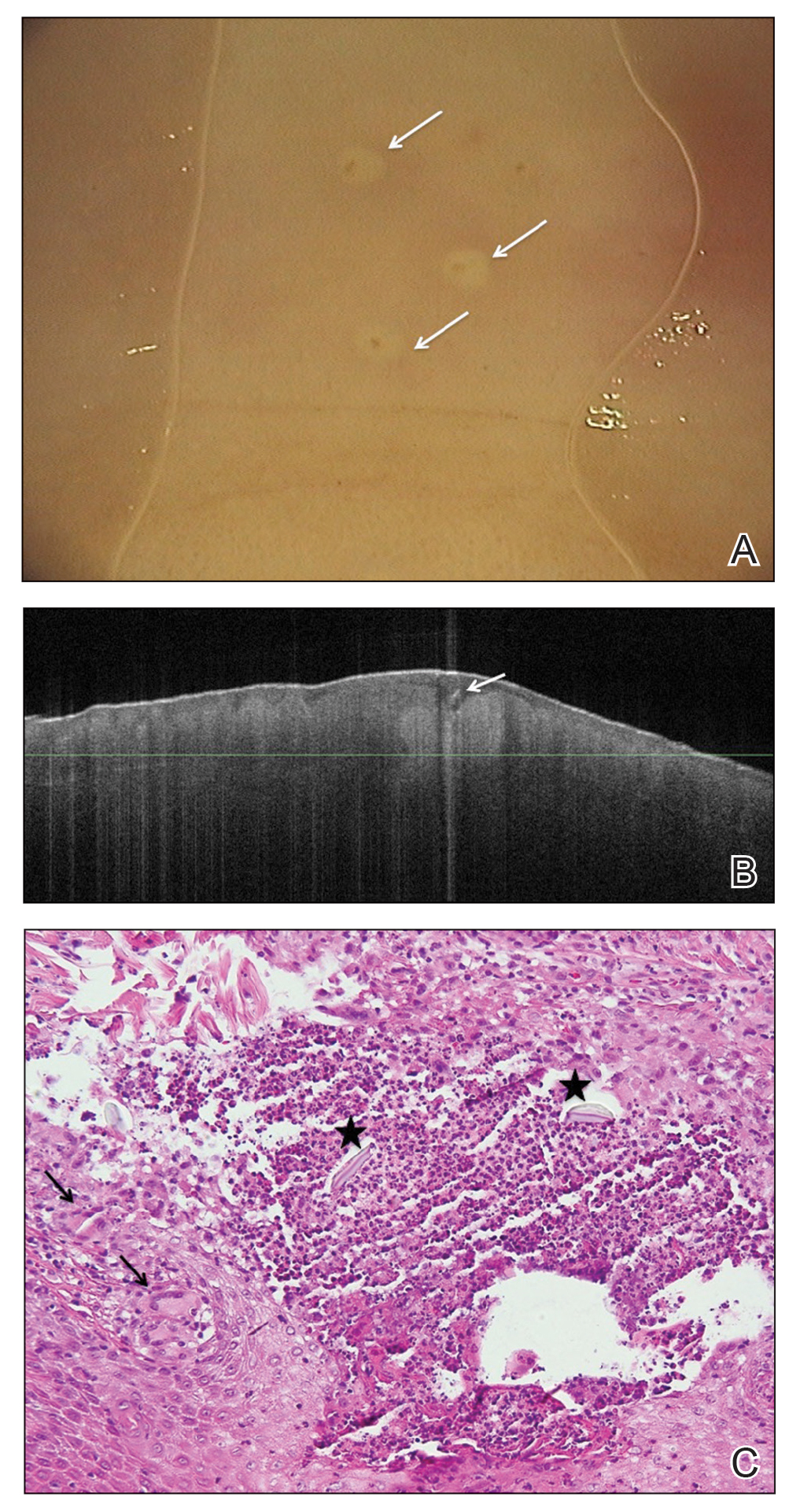

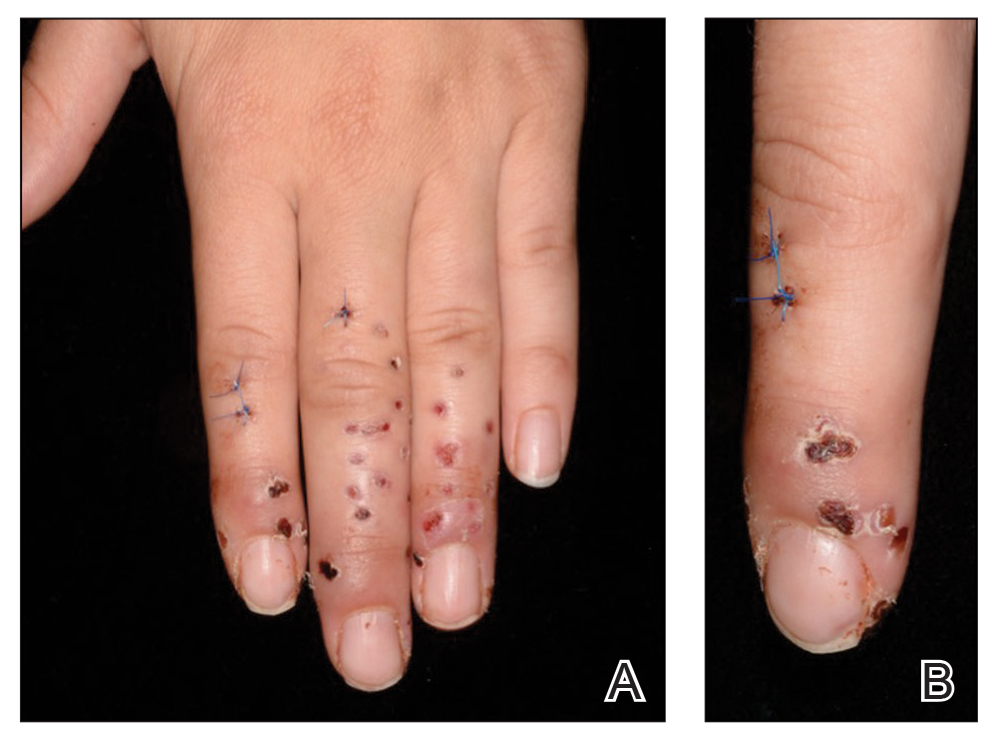

A 65-year-old woman was walking her dog and they heard a loud noise. The dog started to run forward—likely, startled. The owner did not fall, but the leash, which was wrapped around her hand, exerted enough force to avulse a 5×3-cm piece of skin from the dorsum of the hand (Figure 3). The painful abrasion and concomitant bruise eventually healed with conservative management but left a noticeable hemosiderin stain.

Patient 4

A 66-year-old man was walking a large Rottweiler when the dog lurched toward another dog that was being walked across the street. The owner, taken by surprise by this sudden motion, fell on the concrete sidewalk and was dragged several feet by the dog. This unexpected and off-balance fall caused multiple injuries, including bruises on the upper arm, a large avulsion of epidermal forearm skin (Figure 4), a gouge in the dermis down to fat, and a large abrasion of the contralateral knee. The patient received a tetanus booster and conservative therapy. The affected area healed with an atrophic hypopigmented scar.

Patient 5

An 82-year-old woman with known atrial fibrillation who was taking chronic anticoagulation medication was walking her dog. For no apparent reason, the dog sped up the pace. The woman lost her balance and fell face first onto the sidewalk. She did not lose consciousness but did develop a large bruise on the forehead with a tender fluctuant nodule in the center (Figure 5).

The patient presented the next day, requesting drainage of the forehead hematoma. However, a brief review of systems revealed a persistent severe headache and nausea with vomiting since the prior day. She was immediately transported to the nearest ED where complete neurologic workup revealed a moderate-sized subdural hematoma that was treated by trephination. Recovery was uneventful.

Comment

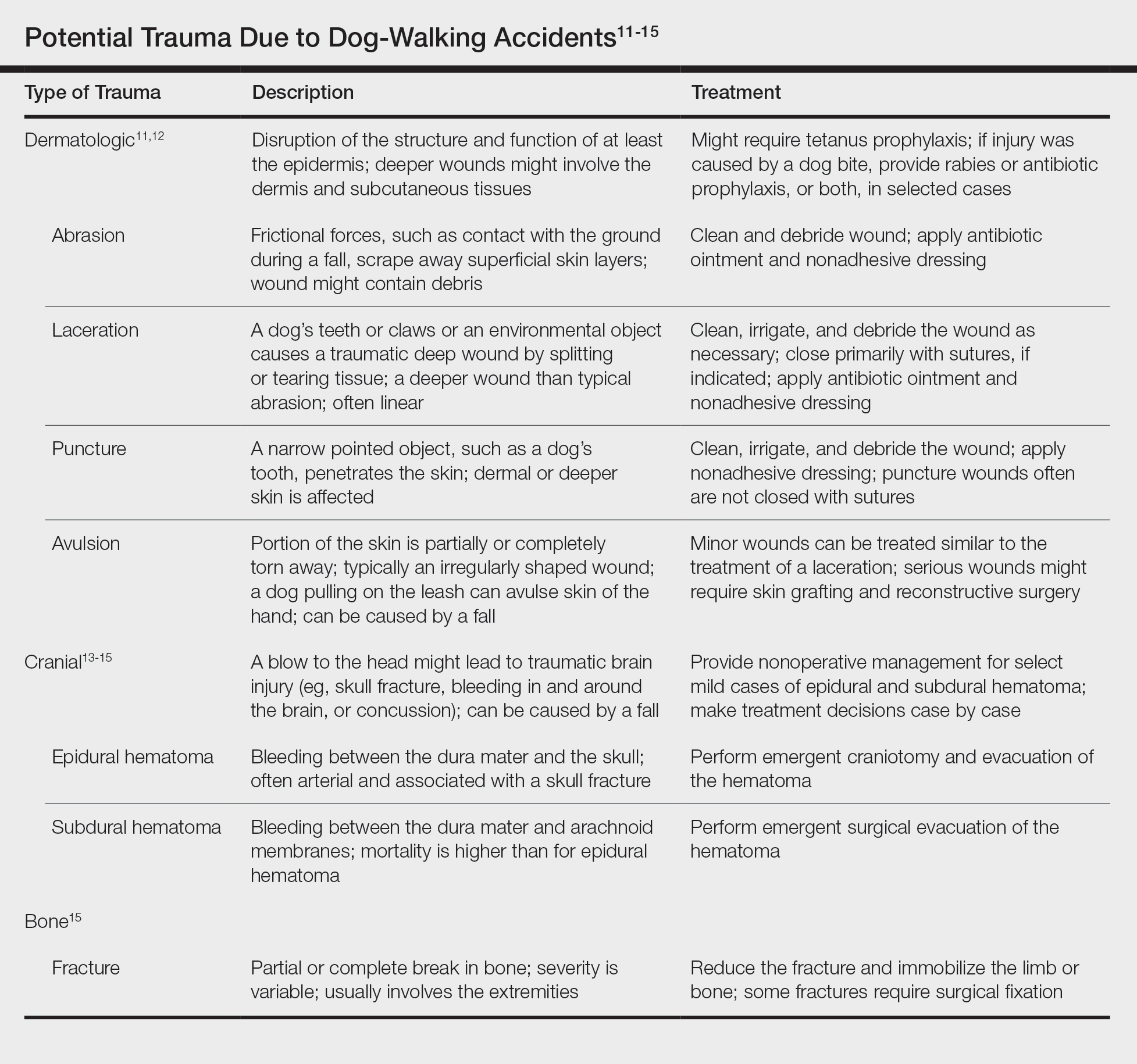

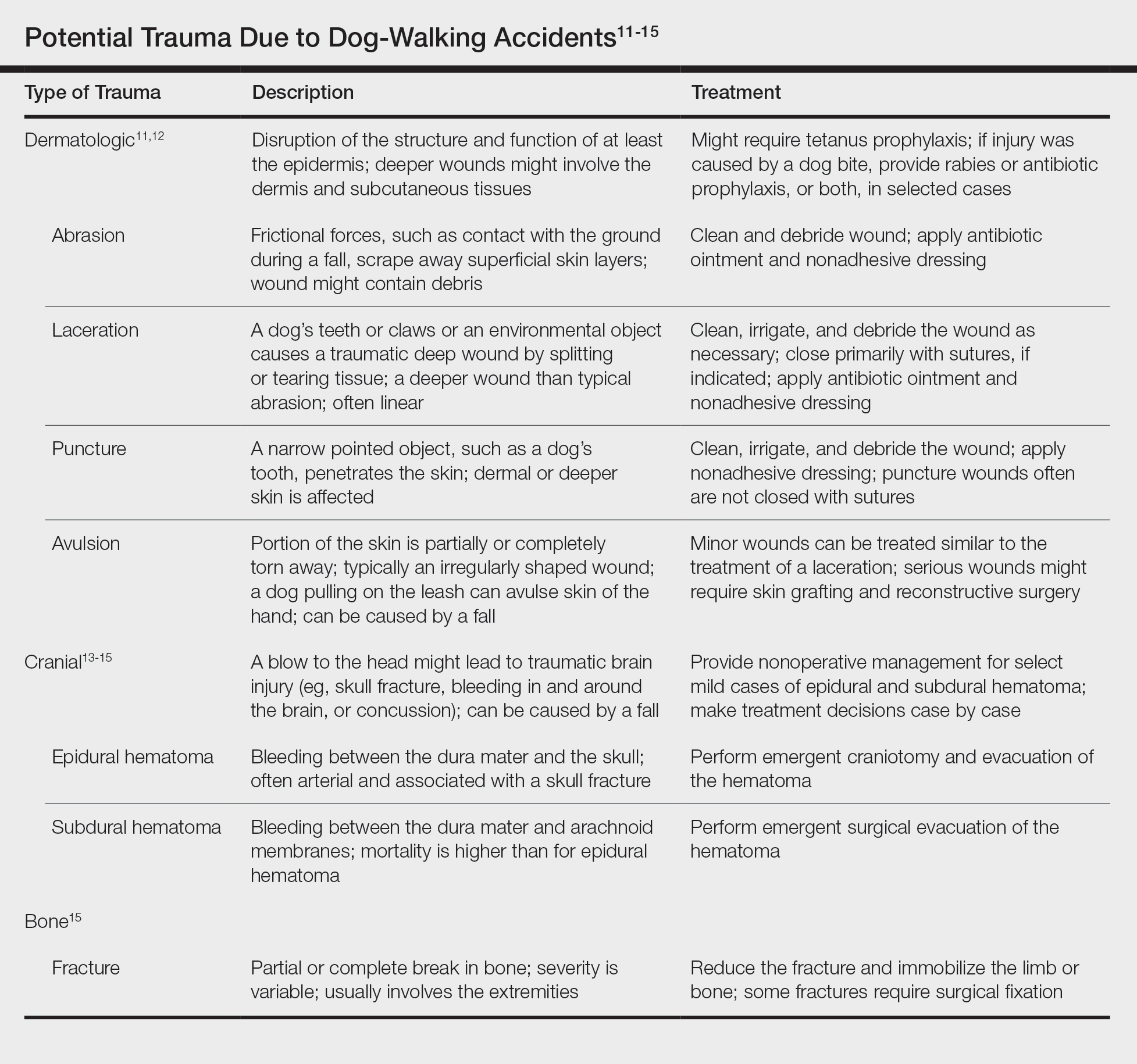

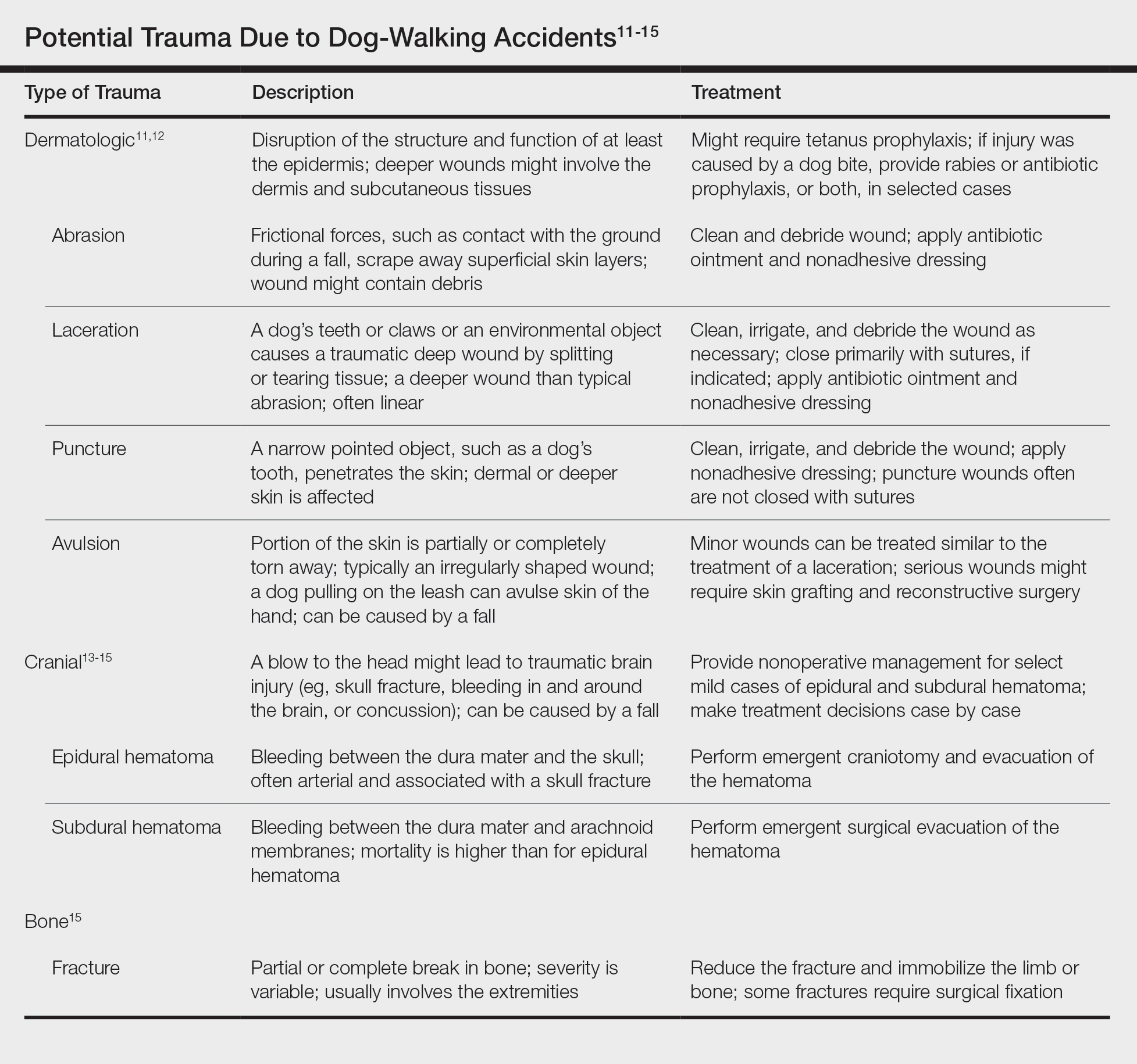

These 5 cases illustrate the notable skin (and neurologic) trauma that can occur due to a dog-walking accident (Table).11-15

Regrettably, obtaining an accurate national estimate of the annual incidence of cutaneous dog-walking injuries is difficult. Researchers who have described the rise in dog walking–associated bone fractures queried the US Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database for its numbers.4 This public database generates incidence estimates of activity- or product-related injuries based on data from a nationally representative sample of approximately 100 hospital EDs.16

We queried the same database for the diagnoses avulsion, abrasion or contusion, and laceration.17 These terms were searched in association with pet supplies, including leashes, and patients 65 years and older. This search yielded fewer than 800 total cases from 2008 to 2017, resulting in unreliable estimates for each year.

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database no doubt underestimates the true incidence of dog walking–related skin trauma; the great majority of patients with cutaneous injury, as illustrated here, likely never present to the ED, unlike patients with bone fracture. Moreover, data do not capture cases handled by providers outside the ED and self-treated injuries.

In the absence of accurate estimates of cutaneous morbidity related to dog-walking injury, the case reports here are clearly a cautionary tale. Physicians and older adults need to be cognizant of the hazards of this activity. Providers should discuss with older patients the potential risks of dog walking before recommending or condoning this exercise.

The presence of other comorbidities that could hamper a person’s ability to control a leashed dog warrants special consideration. Older prospective dog owners might consider adopting a small, easily manageable breed. These measures can help protect older adults’ fragile skin (and bones) from avoidable minor to potentially life-threatening trauma.

- Christian H, Bauman A, Epping JN, et al. Encouraging dog walking for health promotion and disease prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;12:233-243.

- Curl AL, Bibbo J, Johnson RA. Dog walking, the human–animal bond and older adults’ physical health. Gerontologist. 2017;57:930-939.

- Dunkin MA. Walking strategies. Arthritis Foundation website. https://arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/walking/5-walking-strategies. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Pirruccio K, Yoon YM, Ahn J. Fractures in elderly Americans associated with walking leashed dogs. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:458-459.

- Sprinkle D. Pet owner demographics get grayer, more golden. Petfood Industry website. https://www.petfoodindustry.com/articles/6315-pet-owner-demographics-get-grayer-more-golden?v=preview. Published March 10, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Quan T, Fisher GJ. Role of age-associated alterations of the dermal extracellular matrix microenvironment in human skin aging: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2015;61:427-434.

- Aging & painful skin. Cleveland Clinic website. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16725-aging--painful-skin. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:993-998.

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75:51-61.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; . 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:E1-E76.

- Armstrong DG, Meyr AJ. Basic principles of wound management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/basic-principles-of-wound-management. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Trott AT. Wounds and Lacerations: Emergency Care and Closure. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Head injuries in adults: what is it? Harvard Health Publishing website. www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/head-injury-in-adults-a-to-z. Published October 2018. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- McBride W. Intracranial epidural hematoma in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intracranial-epidural-hematoma-in-adults. Updated July 23, 2018. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- McBride W. Subdural hematoma in adults: prognosis and management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/subdural-hematoma-in-adults-prognosis-and-management. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Schroeder T, Ault K. The NEISS sample: design and implementation. Washington, DC: US Consumer Product Safety Commission, Division of Hazard and Injury Data Systems; June 2001. https://cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2001d011-6b6.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). Bethesda, MD: US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2018. https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data. Accessed March 16, 2020.

Studies have recommended dog walking as an activity designed to improve the overall health of older adults.1,2 Benefits purportedly associated with dog walking include lower body mass index, fewer chronic diseases, reduction in the number of physician visits, and decreased limitations of activities of daily living.2 The Arthritis Foundation even recommends dog walking to relieve arthritis symptoms.3 Of course, dogs also provide comfort in companionship, and dog walking can be an enjoyable way for a pet and owner to spend time together.

However, this seemingly benign activity poses a notable and perhaps grossly underrecognized risk for injury in older adults. The annual number of patients 65 years and older who presented to US emergency departments (EDs) for fractures directly associated with walking leashed dogs more than doubled from 2004 to 2017.4 Interestingly, this dramatic increase parallels a nationwide trend in dog ownership demographics. Between 2006 and 2016, the median age of dog owners in the United States rose from 46 to 49 years.5

These trends raise concern for more than just the health of older Americans’ bones. Intuitively, a dog- walking accident that results in a bone fracture will likely also lead to some degree of skin trauma. Older adults have thin fragile skin due to flattening of the dermoepidermal junction and disintegration or degeneration of dermal collagen and elastin.6 This loss of connective tissue as well as subcutaneous tissue in some body areas facilitates shearing injury; concurrently, weakened perivascular support increases the risk for vascular injury and bruising.7 Therefore, when an older person falls while walking a dog, trauma can easily damage delicate aged skin.

Older adults are particularly susceptible to falls, the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries in this age group.8 There are multiple risk factors for falls, including polypharmacy, impaired balance and gait, visual impairments, and cognitive decline, among others.9

Also, many older adults with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism take an anticoagulant drug to prevent stroke. The use of anticoagulants is associated with an increased risk for bleeding, ranging from minor cutaneous bleeding to fatal intracranial hemorrhage.10

A predisposition to falling and bleeding can be hazardous for a dog owner whose excited pet suddenly jumps, runs, or scratches. The use of a leash, mandatory in many urban jurisdictions, tethers the human to the dog, which expedites a fall associated with any sudden, forceful forward or lateral movement by the dog. The following case reports describe a variety of cutaneous injuries experienced by older adults while dog walking.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 79-year-old woman was quietly walking her dog when the dog spotted a squirrel climbing a tree. The dog became excited, turned to the owner, and jumped on her, which caused the dog’s claws to dig into the owner’s fragile forearm skin, creating several superficial but painful abrasions and lacerations (Figure 1). These injuries healed well with conservative therapy including application of an occlusive ointment.

Patient 2

A 68-year-old woman was walking her dog when the dog saw a cat running across the street. The dog suddenly leaped toward the cat, causing the owner to fall forward as the animal’s momentum was transferred through the leash. The owner fell awkwardly on her side, leading to an extensive abrasion and contusion of the shoulder (Figure 2). The lesion healed well with conservative management, albeit with moderate postinflammatory hypochromia.

Patient 3

A 65-year-old woman was walking her dog and they heard a loud noise. The dog started to run forward—likely, startled. The owner did not fall, but the leash, which was wrapped around her hand, exerted enough force to avulse a 5×3-cm piece of skin from the dorsum of the hand (Figure 3). The painful abrasion and concomitant bruise eventually healed with conservative management but left a noticeable hemosiderin stain.

Patient 4

A 66-year-old man was walking a large Rottweiler when the dog lurched toward another dog that was being walked across the street. The owner, taken by surprise by this sudden motion, fell on the concrete sidewalk and was dragged several feet by the dog. This unexpected and off-balance fall caused multiple injuries, including bruises on the upper arm, a large avulsion of epidermal forearm skin (Figure 4), a gouge in the dermis down to fat, and a large abrasion of the contralateral knee. The patient received a tetanus booster and conservative therapy. The affected area healed with an atrophic hypopigmented scar.

Patient 5

An 82-year-old woman with known atrial fibrillation who was taking chronic anticoagulation medication was walking her dog. For no apparent reason, the dog sped up the pace. The woman lost her balance and fell face first onto the sidewalk. She did not lose consciousness but did develop a large bruise on the forehead with a tender fluctuant nodule in the center (Figure 5).

The patient presented the next day, requesting drainage of the forehead hematoma. However, a brief review of systems revealed a persistent severe headache and nausea with vomiting since the prior day. She was immediately transported to the nearest ED where complete neurologic workup revealed a moderate-sized subdural hematoma that was treated by trephination. Recovery was uneventful.

Comment

These 5 cases illustrate the notable skin (and neurologic) trauma that can occur due to a dog-walking accident (Table).11-15

Regrettably, obtaining an accurate national estimate of the annual incidence of cutaneous dog-walking injuries is difficult. Researchers who have described the rise in dog walking–associated bone fractures queried the US Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database for its numbers.4 This public database generates incidence estimates of activity- or product-related injuries based on data from a nationally representative sample of approximately 100 hospital EDs.16

We queried the same database for the diagnoses avulsion, abrasion or contusion, and laceration.17 These terms were searched in association with pet supplies, including leashes, and patients 65 years and older. This search yielded fewer than 800 total cases from 2008 to 2017, resulting in unreliable estimates for each year.

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database no doubt underestimates the true incidence of dog walking–related skin trauma; the great majority of patients with cutaneous injury, as illustrated here, likely never present to the ED, unlike patients with bone fracture. Moreover, data do not capture cases handled by providers outside the ED and self-treated injuries.

In the absence of accurate estimates of cutaneous morbidity related to dog-walking injury, the case reports here are clearly a cautionary tale. Physicians and older adults need to be cognizant of the hazards of this activity. Providers should discuss with older patients the potential risks of dog walking before recommending or condoning this exercise.

The presence of other comorbidities that could hamper a person’s ability to control a leashed dog warrants special consideration. Older prospective dog owners might consider adopting a small, easily manageable breed. These measures can help protect older adults’ fragile skin (and bones) from avoidable minor to potentially life-threatening trauma.

Studies have recommended dog walking as an activity designed to improve the overall health of older adults.1,2 Benefits purportedly associated with dog walking include lower body mass index, fewer chronic diseases, reduction in the number of physician visits, and decreased limitations of activities of daily living.2 The Arthritis Foundation even recommends dog walking to relieve arthritis symptoms.3 Of course, dogs also provide comfort in companionship, and dog walking can be an enjoyable way for a pet and owner to spend time together.

However, this seemingly benign activity poses a notable and perhaps grossly underrecognized risk for injury in older adults. The annual number of patients 65 years and older who presented to US emergency departments (EDs) for fractures directly associated with walking leashed dogs more than doubled from 2004 to 2017.4 Interestingly, this dramatic increase parallels a nationwide trend in dog ownership demographics. Between 2006 and 2016, the median age of dog owners in the United States rose from 46 to 49 years.5

These trends raise concern for more than just the health of older Americans’ bones. Intuitively, a dog- walking accident that results in a bone fracture will likely also lead to some degree of skin trauma. Older adults have thin fragile skin due to flattening of the dermoepidermal junction and disintegration or degeneration of dermal collagen and elastin.6 This loss of connective tissue as well as subcutaneous tissue in some body areas facilitates shearing injury; concurrently, weakened perivascular support increases the risk for vascular injury and bruising.7 Therefore, when an older person falls while walking a dog, trauma can easily damage delicate aged skin.

Older adults are particularly susceptible to falls, the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries in this age group.8 There are multiple risk factors for falls, including polypharmacy, impaired balance and gait, visual impairments, and cognitive decline, among others.9

Also, many older adults with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism take an anticoagulant drug to prevent stroke. The use of anticoagulants is associated with an increased risk for bleeding, ranging from minor cutaneous bleeding to fatal intracranial hemorrhage.10

A predisposition to falling and bleeding can be hazardous for a dog owner whose excited pet suddenly jumps, runs, or scratches. The use of a leash, mandatory in many urban jurisdictions, tethers the human to the dog, which expedites a fall associated with any sudden, forceful forward or lateral movement by the dog. The following case reports describe a variety of cutaneous injuries experienced by older adults while dog walking.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 79-year-old woman was quietly walking her dog when the dog spotted a squirrel climbing a tree. The dog became excited, turned to the owner, and jumped on her, which caused the dog’s claws to dig into the owner’s fragile forearm skin, creating several superficial but painful abrasions and lacerations (Figure 1). These injuries healed well with conservative therapy including application of an occlusive ointment.

Patient 2

A 68-year-old woman was walking her dog when the dog saw a cat running across the street. The dog suddenly leaped toward the cat, causing the owner to fall forward as the animal’s momentum was transferred through the leash. The owner fell awkwardly on her side, leading to an extensive abrasion and contusion of the shoulder (Figure 2). The lesion healed well with conservative management, albeit with moderate postinflammatory hypochromia.

Patient 3

A 65-year-old woman was walking her dog and they heard a loud noise. The dog started to run forward—likely, startled. The owner did not fall, but the leash, which was wrapped around her hand, exerted enough force to avulse a 5×3-cm piece of skin from the dorsum of the hand (Figure 3). The painful abrasion and concomitant bruise eventually healed with conservative management but left a noticeable hemosiderin stain.

Patient 4

A 66-year-old man was walking a large Rottweiler when the dog lurched toward another dog that was being walked across the street. The owner, taken by surprise by this sudden motion, fell on the concrete sidewalk and was dragged several feet by the dog. This unexpected and off-balance fall caused multiple injuries, including bruises on the upper arm, a large avulsion of epidermal forearm skin (Figure 4), a gouge in the dermis down to fat, and a large abrasion of the contralateral knee. The patient received a tetanus booster and conservative therapy. The affected area healed with an atrophic hypopigmented scar.

Patient 5

An 82-year-old woman with known atrial fibrillation who was taking chronic anticoagulation medication was walking her dog. For no apparent reason, the dog sped up the pace. The woman lost her balance and fell face first onto the sidewalk. She did not lose consciousness but did develop a large bruise on the forehead with a tender fluctuant nodule in the center (Figure 5).

The patient presented the next day, requesting drainage of the forehead hematoma. However, a brief review of systems revealed a persistent severe headache and nausea with vomiting since the prior day. She was immediately transported to the nearest ED where complete neurologic workup revealed a moderate-sized subdural hematoma that was treated by trephination. Recovery was uneventful.

Comment

These 5 cases illustrate the notable skin (and neurologic) trauma that can occur due to a dog-walking accident (Table).11-15

Regrettably, obtaining an accurate national estimate of the annual incidence of cutaneous dog-walking injuries is difficult. Researchers who have described the rise in dog walking–associated bone fractures queried the US Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database for its numbers.4 This public database generates incidence estimates of activity- or product-related injuries based on data from a nationally representative sample of approximately 100 hospital EDs.16

We queried the same database for the diagnoses avulsion, abrasion or contusion, and laceration.17 These terms were searched in association with pet supplies, including leashes, and patients 65 years and older. This search yielded fewer than 800 total cases from 2008 to 2017, resulting in unreliable estimates for each year.

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database no doubt underestimates the true incidence of dog walking–related skin trauma; the great majority of patients with cutaneous injury, as illustrated here, likely never present to the ED, unlike patients with bone fracture. Moreover, data do not capture cases handled by providers outside the ED and self-treated injuries.

In the absence of accurate estimates of cutaneous morbidity related to dog-walking injury, the case reports here are clearly a cautionary tale. Physicians and older adults need to be cognizant of the hazards of this activity. Providers should discuss with older patients the potential risks of dog walking before recommending or condoning this exercise.

The presence of other comorbidities that could hamper a person’s ability to control a leashed dog warrants special consideration. Older prospective dog owners might consider adopting a small, easily manageable breed. These measures can help protect older adults’ fragile skin (and bones) from avoidable minor to potentially life-threatening trauma.

- Christian H, Bauman A, Epping JN, et al. Encouraging dog walking for health promotion and disease prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;12:233-243.

- Curl AL, Bibbo J, Johnson RA. Dog walking, the human–animal bond and older adults’ physical health. Gerontologist. 2017;57:930-939.

- Dunkin MA. Walking strategies. Arthritis Foundation website. https://arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/walking/5-walking-strategies. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Pirruccio K, Yoon YM, Ahn J. Fractures in elderly Americans associated with walking leashed dogs. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:458-459.

- Sprinkle D. Pet owner demographics get grayer, more golden. Petfood Industry website. https://www.petfoodindustry.com/articles/6315-pet-owner-demographics-get-grayer-more-golden?v=preview. Published March 10, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Quan T, Fisher GJ. Role of age-associated alterations of the dermal extracellular matrix microenvironment in human skin aging: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2015;61:427-434.

- Aging & painful skin. Cleveland Clinic website. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16725-aging--painful-skin. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:993-998.

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75:51-61.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; . 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:E1-E76.

- Armstrong DG, Meyr AJ. Basic principles of wound management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/basic-principles-of-wound-management. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Trott AT. Wounds and Lacerations: Emergency Care and Closure. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Head injuries in adults: what is it? Harvard Health Publishing website. www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/head-injury-in-adults-a-to-z. Published October 2018. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- McBride W. Intracranial epidural hematoma in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intracranial-epidural-hematoma-in-adults. Updated July 23, 2018. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- McBride W. Subdural hematoma in adults: prognosis and management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/subdural-hematoma-in-adults-prognosis-and-management. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Schroeder T, Ault K. The NEISS sample: design and implementation. Washington, DC: US Consumer Product Safety Commission, Division of Hazard and Injury Data Systems; June 2001. https://cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2001d011-6b6.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). Bethesda, MD: US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2018. https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Christian H, Bauman A, Epping JN, et al. Encouraging dog walking for health promotion and disease prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;12:233-243.

- Curl AL, Bibbo J, Johnson RA. Dog walking, the human–animal bond and older adults’ physical health. Gerontologist. 2017;57:930-939.

- Dunkin MA. Walking strategies. Arthritis Foundation website. https://arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/walking/5-walking-strategies. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Pirruccio K, Yoon YM, Ahn J. Fractures in elderly Americans associated with walking leashed dogs. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:458-459.

- Sprinkle D. Pet owner demographics get grayer, more golden. Petfood Industry website. https://www.petfoodindustry.com/articles/6315-pet-owner-demographics-get-grayer-more-golden?v=preview. Published March 10, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Quan T, Fisher GJ. Role of age-associated alterations of the dermal extracellular matrix microenvironment in human skin aging: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2015;61:427-434.

- Aging & painful skin. Cleveland Clinic website. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16725-aging--painful-skin. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:993-998.

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75:51-61.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; . 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:E1-E76.

- Armstrong DG, Meyr AJ. Basic principles of wound management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/basic-principles-of-wound-management. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Trott AT. Wounds and Lacerations: Emergency Care and Closure. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Head injuries in adults: what is it? Harvard Health Publishing website. www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/head-injury-in-adults-a-to-z. Published October 2018. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- McBride W. Intracranial epidural hematoma in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intracranial-epidural-hematoma-in-adults. Updated July 23, 2018. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- McBride W. Subdural hematoma in adults: prognosis and management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/subdural-hematoma-in-adults-prognosis-and-management. Updated July 11, 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- Schroeder T, Ault K. The NEISS sample: design and implementation. Washington, DC: US Consumer Product Safety Commission, Division of Hazard and Injury Data Systems; June 2001. https://cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2001d011-6b6.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). Bethesda, MD: US Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2018. https://www.cpsc.gov/Research--Statistics/NEISS-Injury-Data. Accessed March 16, 2020.

Practice Points

- Dog walking is a good source of exercise but can lead to serious skin/soft tissue injury.

- When evaluating cutaneous trauma related to dog walking, remember to consider the possibility of an underlying bone fracture.

- Cutaneous trauma may overlay serious internal injury, such as epidural or subdural hematoma.

Sharp lower back pain • left-side paraspinal tenderness • anterior thigh sensory loss • Dx?

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman with a history of late-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto thyroiditis, and scoliosis presented to the sports medicine clinic with acute-onset, sharp, nonradiating right lower back pain that began when she bent forward to apply lotion. At presentation, she denied fever, chills, numbness, tingling, aggravation of pain with movement, weakness, and incontinence. Her neuromuscular examination was unremarkable except for left-side paraspinal tenderness. She was prescribed cyclobenzaprine for symptomatic relief.

Two days later, she was seen for worsening pain. Her physical exam was unchanged. She was prescribed tramadol and advised to start physical therapy gradually. As the day progressed, however, she developed anterior thigh sensory loss, which gradually extended distally.

The following day, she was brought to the emergency department with severe left-side weakness without urinary incontinence. Her mental status and cranial nerve exams were normal. On examination, strength of the iliopsoas and quadriceps was 1/5 bilaterally, and of the peroneal tendon and gastrocnemius, 3/5 bilaterally. Reflexes of triceps, biceps, knee, and Achilles tendon were symmetric and 3+ with bilateral clonus of the ankle. The Babinski sign was positive bilaterally. The patient had diminished pain sensation bilaterally, extending down from the T11 dermatome (left more than right side) with diminished vibration sensation at the left ankle. Her perianal sensation, bilateral temperature sensation, and cerebellar examination were normal.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast of the lumbar spine demonstrated ischemia findings corresponding to T12-L1. Degenerative changes from L1-S1 were noted, with multiple osteophytes impinging on the neural foramina without cord compression.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial presentation was consistent with mechanical low back pain with signs of anterior spinal artery infarction and medial lemniscus pathway involvement 48 hours after initial presentation. Spinal cord infarction occurs more commonly in women and in the young than does cerebral infarction,1 with better reemployment rates.1,2 Similar to other strokes, long-term prognosis is primarily determined by the initial severity of motor impairment, which is linked to long-term immobility and need for bladder catheterization.3

Neurogenic pain developing years after spinal cord infarction is most often observed in anterior spinal artery infarction4 without functional limitations.

Initial treatment. Our patient was started on aspirin 325 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d. Her mean arterial blood pressure was maintained above 80 mm Hg. Computed tomography angiography of the abdomen and pelvis was negative for aortic dissection. Lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis was unremarkable. Results of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing, antinuclear antibody testing, a hepatitis panel, and an antiphospholipid panel were all negative. The patient was started on IV steroids with a plan for gradual tapering. The neurosurgical team agreed with medical management.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Possible etiologies for acute spinal cord infarction include spinal cord ischemia from compression of the vessels, fibrocartilaginous embolism, and arterial thrombosis or atherosclerosis, especially in patients with diabetes.5

The majority (86%) of spinal strokes are due to spontaneous occlusion of the vessels with no identifiable cause; much less frequently (9% of cases), hemorrhage is the causative factor.1 A retrospective study demonstrated that 10 of 27 patients with spinal stroke had an anterior spinal infarct. Of those 10 patients, 6 reported a mechanical triggering movement (similar to this case), indicating potential compression of the radicular arteries due to said movement.4

Fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE) is worth considering as a possible cause, because it accounts for 5.5% of all cases of acute spinal cord infarction.3 FCE is thought to arise after a precipitating event such as minor trauma, heavy lifting, physical exertion, or Valsalva maneuver causing embolization of the fragments of nucleus pulposus to the arterial system. In a case series of 8 patients, 2 had possible FCE with precipitating events occurring within the prior 24 hours. This was also demonstrated in another case series6 in which 7 of 9 patients had precipitating events.

Although FCE can only definitively be diagnosed postmortem, the researchers6 proposed clinical criteria for its diagnosis in living patients, based on 40 postmortem and 11 suspected antemortem cases of FCE. These criteria include a rapid evolution of symptoms consistent with vascular etiology, with or without preceding minor trauma or Valsalva maneuver; MRI changes consistent with ischemic myelopathy, with or without evidence of disc herniation; and no more than 2 vascular risk factors.

Our patient had no trauma (although there was a triggering movement), no signs of disc herniation, and 2 risk factors (> 60 years and diabetes mellitus). Also, a neurologically symptom-free interval between the painful movement and the onset of neurologic manifestations in our case parallels the clinical picture of FCE.

Continue to: The role of factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation

The role of factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation in arterial thrombosis is questionable. Previous reports demonstrate a risk for venous thrombosis 7 to 10 times higher with heterozygous FVL mutation and 100 times higher with homozygous mutation, with a less established role in arterial thrombosis.7 A retrospective Turkish study compared the incidence of FVL mutation in patients with arterial thrombosis vs healthy subjects; incidence was significantly higher in female patients than female controls (37.5% vs. 2%).7 A meta-analysis of published studies showed an association between arterial ischemic events and FVL mutation to be modest, with an odds ratio of 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.49).8

In contrast, a 3.4-year longitudinal health study of patients ages 65 and older found no significant difference in the occurrence of myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, stroke, or angina for more than 5000 patients with heterozygous FVL mutation compared to fewer than 500 controls.9 The case patient’s clinical course did not fit a thrombotic clinical picture.

Evaluating for “red flags” is crucial in any case of low back pain to exclude serious pathologies. Red flag symptoms include signs of myelopathy, signs of infection, history of trauma with focal tenderness to palpation, and steroid or anticoagulant use (to rule out medication adverse effects).10 Our patient lacked these classical signs, but she did have subjective pain out of proportion to the clinical exam findings.

Of note: The above red flags for low back pain are all based on expert opinion,11 and the positive predictive value of a red flag is always low because of the low prevalence of serious spinal pathologies.12

Striking a proper balance. This case emphasizes the necessity to keep uncommon causes—such as nontraumatic spinal stroke, which has a prevalence of about 5% to 8% of all acute myelopathies—in the differential diagnosis.3

Continue to: We recommend watchful...

We recommend watchful waiting coupled with communication with the patient regarding monitoring for changes in symptoms over time.11 Any changes in symptoms concerning for underlying spinal cord injury indicate necessity for transfer to a tertiary care center (if possible), along with immediate evaluation with imaging—including computed tomography angiography of the abdomen to rule out aortic dissection (1%-2% of all spinal cord infarcts), followed by a specialist consultation based on the findings.3

Our patient

Our patient was discharged to rehabilitation on hospital Day 5, after progressive return of lower extremity strength. At the 2-month follow-up visit, she demonstrated grade 4+ strength throughout her lower extremities bilaterally. Weakness was predominant at the hip flexors and ankle dorsiflexors, which was consistent with her status at discharge. She had burning pain in the distribution of the L1 dermatome that responded to ibuprofen.

Hypercoagulability work-up was positive for heterozygous FVL mutation without any previous history of venous thromboembolic disease. She was continued on aspirin 325 mg/d, as per American College of Chest Physicians antithrombotic guidelines.13

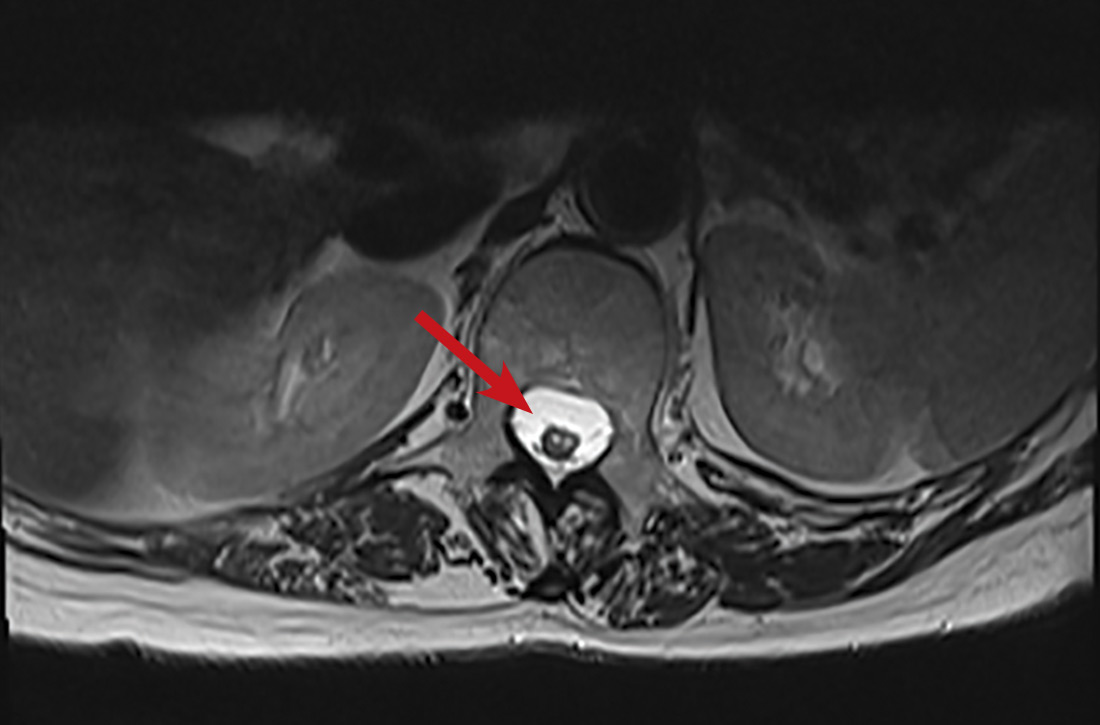

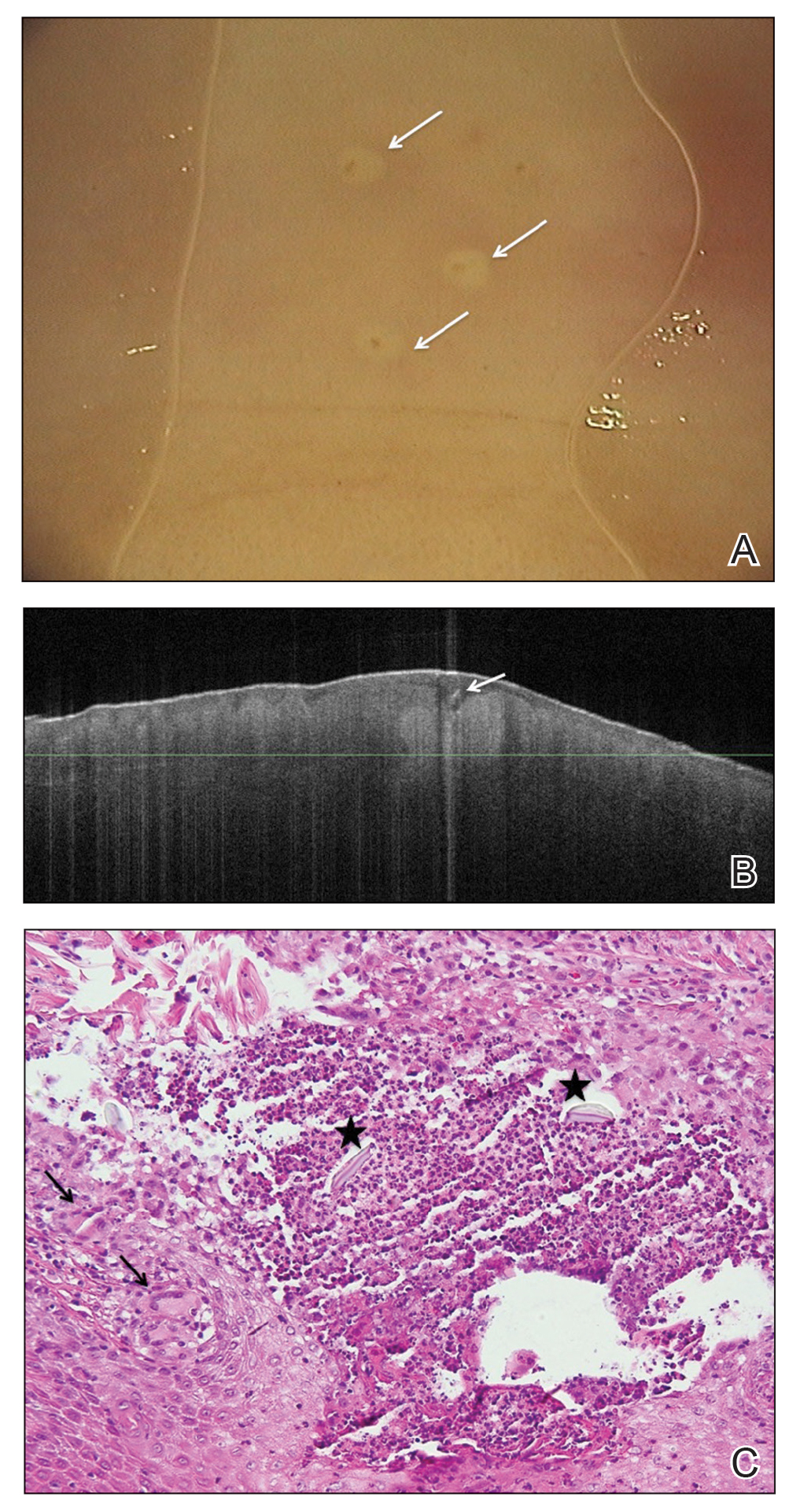

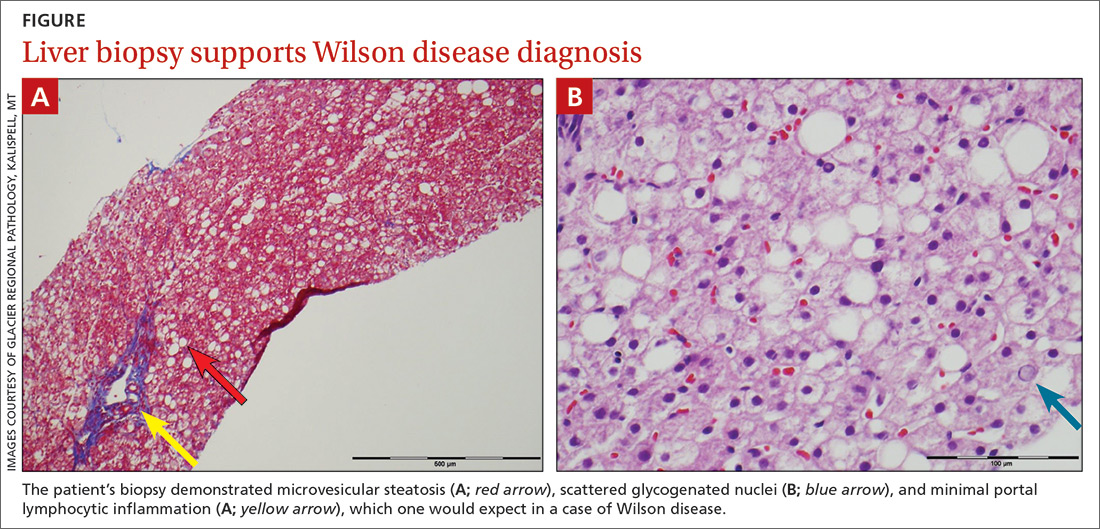

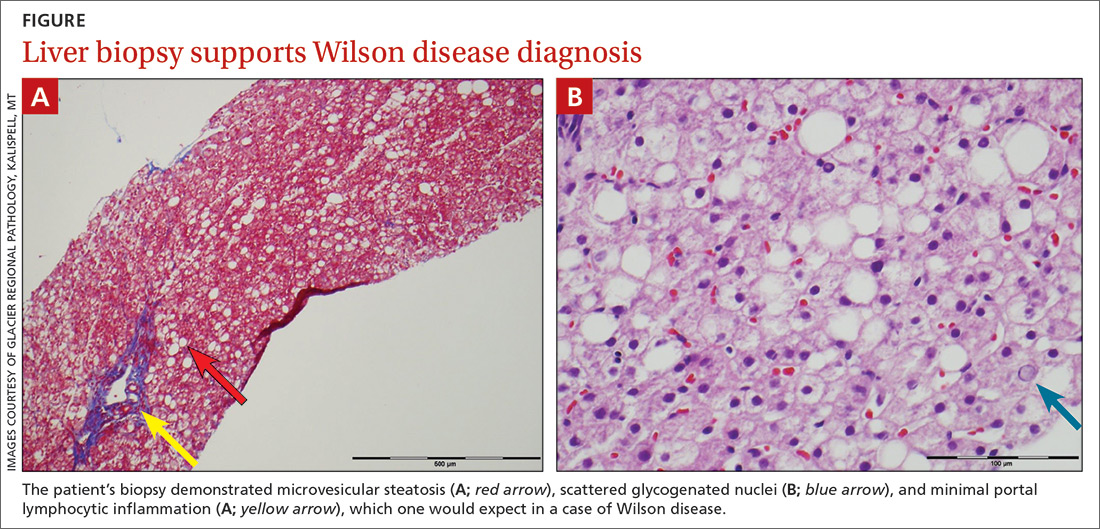

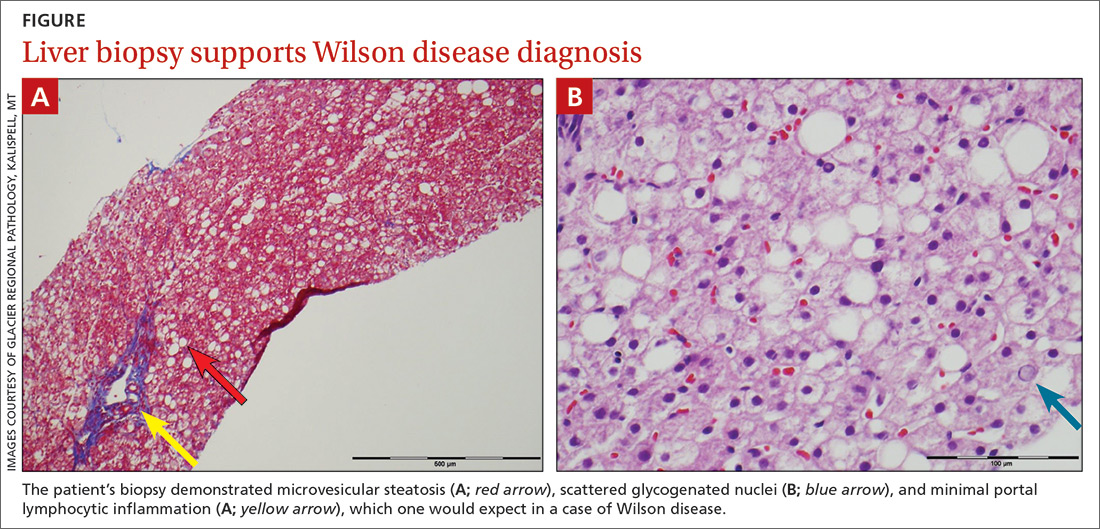

One year later, our patient underwent a follow-up MRI of the thoracic spine, which showed an “owl’s eye” hyperintensity in the anterior cord (FIGURE), a sign that’s often seen in bilateral spinal cord infarction

THE TAKEAWAY

Spinal stroke is rare, but a missed diagnosis and lack of treatment can result in long-term morbidity. Therefore, it is prudent to consider this diagnosis in the differential—especially when the patient’s subjective back pain is out of proportion to the clinical examination findings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Srikanth Nithyanandam, MBBS, MS, University of Kentucky Family and Community Medicine, 2195 Harrodsburg Road, Suite 125, Lexington, KY 40504-3504; [email protected].

1. Romi F, Naess H. Spinal cord infarction in clinical neurology: a review of characteristics and long-term prognosis in comparison to cerebral infarction. Eur Neurol. 2016;76:95-98.

2. Hanson SR, Romi F, Rekand T, et al. Long-term outcome after spinal cord infarctions. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;131:253-257.

3. Rigney L, Cappelen-Smith C, Sebire D, et al. Nontraumatic spinal cord ischaemic syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1544-1549.

4. Novy J, Carruzzo A, Maeder P, Bogousslavsky J. Spinal cord ischemia: clinical and imaging patterns, pathogenesis, and outcomes in 27 patients. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1113-1120.

5. Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, et al; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2006;113:e873-e923.

6. Mateen FJ, Monrad PA, Hunderfund AN, et al. Clinically suspected fibrocartilaginous embolism: clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:218-225.

7. Ozmen F, Ozmen MM, Ozalp N, et al. The prevalence of factor V (G1691A), MTHFR (C677T) and PT (G20210A) gene mutations in arterial thrombosis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:113-119.

8. Kim RJ, Becker RC. Association between factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A, and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutations and events of the arterial circulatory system: a meta-analysis of published studies. Am Heart J. 2003;146:948-957.

9. Cushman M, Rosendaal FR, Psaty BM, et al. Factor V Leiden is not a risk factor for arterial vascular disease in the elderly: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:912-915.

10. Strudwick K, McPhee M, Bell A, et al. Review article: best practice management of low back pain in the emergency department (part 1 of the musculoskeletal injuries rapid review series). Emerg Med Australas. 2018;30:18-35.

11. Cook CE, George SZ, Reiman MP. Red flag screening for low back pain: nothing to see here, move along: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:493-496.

12. Grunau GL, Darlow B, Flynn T, et al. Red flags or red herrings? Redefining the role of red flags in low back pain to reduce overimaging. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:488-489.

13. Lansberg MG, O’Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e601S-e636S.

14. Pikija S, Mutzenbach JS, Kunz AB, et al. Delayed hospital presentation and neuroimaging in non-surgical spinal cord infarction. Front Neurol. 2017;8:143.

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman with a history of late-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto thyroiditis, and scoliosis presented to the sports medicine clinic with acute-onset, sharp, nonradiating right lower back pain that began when she bent forward to apply lotion. At presentation, she denied fever, chills, numbness, tingling, aggravation of pain with movement, weakness, and incontinence. Her neuromuscular examination was unremarkable except for left-side paraspinal tenderness. She was prescribed cyclobenzaprine for symptomatic relief.

Two days later, she was seen for worsening pain. Her physical exam was unchanged. She was prescribed tramadol and advised to start physical therapy gradually. As the day progressed, however, she developed anterior thigh sensory loss, which gradually extended distally.

The following day, she was brought to the emergency department with severe left-side weakness without urinary incontinence. Her mental status and cranial nerve exams were normal. On examination, strength of the iliopsoas and quadriceps was 1/5 bilaterally, and of the peroneal tendon and gastrocnemius, 3/5 bilaterally. Reflexes of triceps, biceps, knee, and Achilles tendon were symmetric and 3+ with bilateral clonus of the ankle. The Babinski sign was positive bilaterally. The patient had diminished pain sensation bilaterally, extending down from the T11 dermatome (left more than right side) with diminished vibration sensation at the left ankle. Her perianal sensation, bilateral temperature sensation, and cerebellar examination were normal.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast of the lumbar spine demonstrated ischemia findings corresponding to T12-L1. Degenerative changes from L1-S1 were noted, with multiple osteophytes impinging on the neural foramina without cord compression.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial presentation was consistent with mechanical low back pain with signs of anterior spinal artery infarction and medial lemniscus pathway involvement 48 hours after initial presentation. Spinal cord infarction occurs more commonly in women and in the young than does cerebral infarction,1 with better reemployment rates.1,2 Similar to other strokes, long-term prognosis is primarily determined by the initial severity of motor impairment, which is linked to long-term immobility and need for bladder catheterization.3

Neurogenic pain developing years after spinal cord infarction is most often observed in anterior spinal artery infarction4 without functional limitations.

Initial treatment. Our patient was started on aspirin 325 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d. Her mean arterial blood pressure was maintained above 80 mm Hg. Computed tomography angiography of the abdomen and pelvis was negative for aortic dissection. Lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis was unremarkable. Results of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing, antinuclear antibody testing, a hepatitis panel, and an antiphospholipid panel were all negative. The patient was started on IV steroids with a plan for gradual tapering. The neurosurgical team agreed with medical management.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Possible etiologies for acute spinal cord infarction include spinal cord ischemia from compression of the vessels, fibrocartilaginous embolism, and arterial thrombosis or atherosclerosis, especially in patients with diabetes.5

The majority (86%) of spinal strokes are due to spontaneous occlusion of the vessels with no identifiable cause; much less frequently (9% of cases), hemorrhage is the causative factor.1 A retrospective study demonstrated that 10 of 27 patients with spinal stroke had an anterior spinal infarct. Of those 10 patients, 6 reported a mechanical triggering movement (similar to this case), indicating potential compression of the radicular arteries due to said movement.4

Fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE) is worth considering as a possible cause, because it accounts for 5.5% of all cases of acute spinal cord infarction.3 FCE is thought to arise after a precipitating event such as minor trauma, heavy lifting, physical exertion, or Valsalva maneuver causing embolization of the fragments of nucleus pulposus to the arterial system. In a case series of 8 patients, 2 had possible FCE with precipitating events occurring within the prior 24 hours. This was also demonstrated in another case series6 in which 7 of 9 patients had precipitating events.

Although FCE can only definitively be diagnosed postmortem, the researchers6 proposed clinical criteria for its diagnosis in living patients, based on 40 postmortem and 11 suspected antemortem cases of FCE. These criteria include a rapid evolution of symptoms consistent with vascular etiology, with or without preceding minor trauma or Valsalva maneuver; MRI changes consistent with ischemic myelopathy, with or without evidence of disc herniation; and no more than 2 vascular risk factors.

Our patient had no trauma (although there was a triggering movement), no signs of disc herniation, and 2 risk factors (> 60 years and diabetes mellitus). Also, a neurologically symptom-free interval between the painful movement and the onset of neurologic manifestations in our case parallels the clinical picture of FCE.

Continue to: The role of factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation

The role of factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation in arterial thrombosis is questionable. Previous reports demonstrate a risk for venous thrombosis 7 to 10 times higher with heterozygous FVL mutation and 100 times higher with homozygous mutation, with a less established role in arterial thrombosis.7 A retrospective Turkish study compared the incidence of FVL mutation in patients with arterial thrombosis vs healthy subjects; incidence was significantly higher in female patients than female controls (37.5% vs. 2%).7 A meta-analysis of published studies showed an association between arterial ischemic events and FVL mutation to be modest, with an odds ratio of 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.49).8

In contrast, a 3.4-year longitudinal health study of patients ages 65 and older found no significant difference in the occurrence of myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, stroke, or angina for more than 5000 patients with heterozygous FVL mutation compared to fewer than 500 controls.9 The case patient’s clinical course did not fit a thrombotic clinical picture.

Evaluating for “red flags” is crucial in any case of low back pain to exclude serious pathologies. Red flag symptoms include signs of myelopathy, signs of infection, history of trauma with focal tenderness to palpation, and steroid or anticoagulant use (to rule out medication adverse effects).10 Our patient lacked these classical signs, but she did have subjective pain out of proportion to the clinical exam findings.

Of note: The above red flags for low back pain are all based on expert opinion,11 and the positive predictive value of a red flag is always low because of the low prevalence of serious spinal pathologies.12

Striking a proper balance. This case emphasizes the necessity to keep uncommon causes—such as nontraumatic spinal stroke, which has a prevalence of about 5% to 8% of all acute myelopathies—in the differential diagnosis.3

Continue to: We recommend watchful...

We recommend watchful waiting coupled with communication with the patient regarding monitoring for changes in symptoms over time.11 Any changes in symptoms concerning for underlying spinal cord injury indicate necessity for transfer to a tertiary care center (if possible), along with immediate evaluation with imaging—including computed tomography angiography of the abdomen to rule out aortic dissection (1%-2% of all spinal cord infarcts), followed by a specialist consultation based on the findings.3

Our patient

Our patient was discharged to rehabilitation on hospital Day 5, after progressive return of lower extremity strength. At the 2-month follow-up visit, she demonstrated grade 4+ strength throughout her lower extremities bilaterally. Weakness was predominant at the hip flexors and ankle dorsiflexors, which was consistent with her status at discharge. She had burning pain in the distribution of the L1 dermatome that responded to ibuprofen.

Hypercoagulability work-up was positive for heterozygous FVL mutation without any previous history of venous thromboembolic disease. She was continued on aspirin 325 mg/d, as per American College of Chest Physicians antithrombotic guidelines.13

One year later, our patient underwent a follow-up MRI of the thoracic spine, which showed an “owl’s eye” hyperintensity in the anterior cord (FIGURE), a sign that’s often seen in bilateral spinal cord infarction

THE TAKEAWAY

Spinal stroke is rare, but a missed diagnosis and lack of treatment can result in long-term morbidity. Therefore, it is prudent to consider this diagnosis in the differential—especially when the patient’s subjective back pain is out of proportion to the clinical examination findings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Srikanth Nithyanandam, MBBS, MS, University of Kentucky Family and Community Medicine, 2195 Harrodsburg Road, Suite 125, Lexington, KY 40504-3504; [email protected].

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman with a history of late-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto thyroiditis, and scoliosis presented to the sports medicine clinic with acute-onset, sharp, nonradiating right lower back pain that began when she bent forward to apply lotion. At presentation, she denied fever, chills, numbness, tingling, aggravation of pain with movement, weakness, and incontinence. Her neuromuscular examination was unremarkable except for left-side paraspinal tenderness. She was prescribed cyclobenzaprine for symptomatic relief.

Two days later, she was seen for worsening pain. Her physical exam was unchanged. She was prescribed tramadol and advised to start physical therapy gradually. As the day progressed, however, she developed anterior thigh sensory loss, which gradually extended distally.

The following day, she was brought to the emergency department with severe left-side weakness without urinary incontinence. Her mental status and cranial nerve exams were normal. On examination, strength of the iliopsoas and quadriceps was 1/5 bilaterally, and of the peroneal tendon and gastrocnemius, 3/5 bilaterally. Reflexes of triceps, biceps, knee, and Achilles tendon were symmetric and 3+ with bilateral clonus of the ankle. The Babinski sign was positive bilaterally. The patient had diminished pain sensation bilaterally, extending down from the T11 dermatome (left more than right side) with diminished vibration sensation at the left ankle. Her perianal sensation, bilateral temperature sensation, and cerebellar examination were normal.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast of the lumbar spine demonstrated ischemia findings corresponding to T12-L1. Degenerative changes from L1-S1 were noted, with multiple osteophytes impinging on the neural foramina without cord compression.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial presentation was consistent with mechanical low back pain with signs of anterior spinal artery infarction and medial lemniscus pathway involvement 48 hours after initial presentation. Spinal cord infarction occurs more commonly in women and in the young than does cerebral infarction,1 with better reemployment rates.1,2 Similar to other strokes, long-term prognosis is primarily determined by the initial severity of motor impairment, which is linked to long-term immobility and need for bladder catheterization.3

Neurogenic pain developing years after spinal cord infarction is most often observed in anterior spinal artery infarction4 without functional limitations.

Initial treatment. Our patient was started on aspirin 325 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d. Her mean arterial blood pressure was maintained above 80 mm Hg. Computed tomography angiography of the abdomen and pelvis was negative for aortic dissection. Lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis was unremarkable. Results of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing, antinuclear antibody testing, a hepatitis panel, and an antiphospholipid panel were all negative. The patient was started on IV steroids with a plan for gradual tapering. The neurosurgical team agreed with medical management.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Possible etiologies for acute spinal cord infarction include spinal cord ischemia from compression of the vessels, fibrocartilaginous embolism, and arterial thrombosis or atherosclerosis, especially in patients with diabetes.5

The majority (86%) of spinal strokes are due to spontaneous occlusion of the vessels with no identifiable cause; much less frequently (9% of cases), hemorrhage is the causative factor.1 A retrospective study demonstrated that 10 of 27 patients with spinal stroke had an anterior spinal infarct. Of those 10 patients, 6 reported a mechanical triggering movement (similar to this case), indicating potential compression of the radicular arteries due to said movement.4

Fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE) is worth considering as a possible cause, because it accounts for 5.5% of all cases of acute spinal cord infarction.3 FCE is thought to arise after a precipitating event such as minor trauma, heavy lifting, physical exertion, or Valsalva maneuver causing embolization of the fragments of nucleus pulposus to the arterial system. In a case series of 8 patients, 2 had possible FCE with precipitating events occurring within the prior 24 hours. This was also demonstrated in another case series6 in which 7 of 9 patients had precipitating events.

Although FCE can only definitively be diagnosed postmortem, the researchers6 proposed clinical criteria for its diagnosis in living patients, based on 40 postmortem and 11 suspected antemortem cases of FCE. These criteria include a rapid evolution of symptoms consistent with vascular etiology, with or without preceding minor trauma or Valsalva maneuver; MRI changes consistent with ischemic myelopathy, with or without evidence of disc herniation; and no more than 2 vascular risk factors.

Our patient had no trauma (although there was a triggering movement), no signs of disc herniation, and 2 risk factors (> 60 years and diabetes mellitus). Also, a neurologically symptom-free interval between the painful movement and the onset of neurologic manifestations in our case parallels the clinical picture of FCE.

Continue to: The role of factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation

The role of factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation in arterial thrombosis is questionable. Previous reports demonstrate a risk for venous thrombosis 7 to 10 times higher with heterozygous FVL mutation and 100 times higher with homozygous mutation, with a less established role in arterial thrombosis.7 A retrospective Turkish study compared the incidence of FVL mutation in patients with arterial thrombosis vs healthy subjects; incidence was significantly higher in female patients than female controls (37.5% vs. 2%).7 A meta-analysis of published studies showed an association between arterial ischemic events and FVL mutation to be modest, with an odds ratio of 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99-1.49).8

In contrast, a 3.4-year longitudinal health study of patients ages 65 and older found no significant difference in the occurrence of myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, stroke, or angina for more than 5000 patients with heterozygous FVL mutation compared to fewer than 500 controls.9 The case patient’s clinical course did not fit a thrombotic clinical picture.

Evaluating for “red flags” is crucial in any case of low back pain to exclude serious pathologies. Red flag symptoms include signs of myelopathy, signs of infection, history of trauma with focal tenderness to palpation, and steroid or anticoagulant use (to rule out medication adverse effects).10 Our patient lacked these classical signs, but she did have subjective pain out of proportion to the clinical exam findings.

Of note: The above red flags for low back pain are all based on expert opinion,11 and the positive predictive value of a red flag is always low because of the low prevalence of serious spinal pathologies.12

Striking a proper balance. This case emphasizes the necessity to keep uncommon causes—such as nontraumatic spinal stroke, which has a prevalence of about 5% to 8% of all acute myelopathies—in the differential diagnosis.3

Continue to: We recommend watchful...

We recommend watchful waiting coupled with communication with the patient regarding monitoring for changes in symptoms over time.11 Any changes in symptoms concerning for underlying spinal cord injury indicate necessity for transfer to a tertiary care center (if possible), along with immediate evaluation with imaging—including computed tomography angiography of the abdomen to rule out aortic dissection (1%-2% of all spinal cord infarcts), followed by a specialist consultation based on the findings.3

Our patient

Our patient was discharged to rehabilitation on hospital Day 5, after progressive return of lower extremity strength. At the 2-month follow-up visit, she demonstrated grade 4+ strength throughout her lower extremities bilaterally. Weakness was predominant at the hip flexors and ankle dorsiflexors, which was consistent with her status at discharge. She had burning pain in the distribution of the L1 dermatome that responded to ibuprofen.

Hypercoagulability work-up was positive for heterozygous FVL mutation without any previous history of venous thromboembolic disease. She was continued on aspirin 325 mg/d, as per American College of Chest Physicians antithrombotic guidelines.13

One year later, our patient underwent a follow-up MRI of the thoracic spine, which showed an “owl’s eye” hyperintensity in the anterior cord (FIGURE), a sign that’s often seen in bilateral spinal cord infarction

THE TAKEAWAY

Spinal stroke is rare, but a missed diagnosis and lack of treatment can result in long-term morbidity. Therefore, it is prudent to consider this diagnosis in the differential—especially when the patient’s subjective back pain is out of proportion to the clinical examination findings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Srikanth Nithyanandam, MBBS, MS, University of Kentucky Family and Community Medicine, 2195 Harrodsburg Road, Suite 125, Lexington, KY 40504-3504; [email protected].

1. Romi F, Naess H. Spinal cord infarction in clinical neurology: a review of characteristics and long-term prognosis in comparison to cerebral infarction. Eur Neurol. 2016;76:95-98.

2. Hanson SR, Romi F, Rekand T, et al. Long-term outcome after spinal cord infarctions. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;131:253-257.

3. Rigney L, Cappelen-Smith C, Sebire D, et al. Nontraumatic spinal cord ischaemic syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1544-1549.

4. Novy J, Carruzzo A, Maeder P, Bogousslavsky J. Spinal cord ischemia: clinical and imaging patterns, pathogenesis, and outcomes in 27 patients. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1113-1120.

5. Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, et al; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2006;113:e873-e923.

6. Mateen FJ, Monrad PA, Hunderfund AN, et al. Clinically suspected fibrocartilaginous embolism: clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:218-225.

7. Ozmen F, Ozmen MM, Ozalp N, et al. The prevalence of factor V (G1691A), MTHFR (C677T) and PT (G20210A) gene mutations in arterial thrombosis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:113-119.

8. Kim RJ, Becker RC. Association between factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A, and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutations and events of the arterial circulatory system: a meta-analysis of published studies. Am Heart J. 2003;146:948-957.

9. Cushman M, Rosendaal FR, Psaty BM, et al. Factor V Leiden is not a risk factor for arterial vascular disease in the elderly: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:912-915.

10. Strudwick K, McPhee M, Bell A, et al. Review article: best practice management of low back pain in the emergency department (part 1 of the musculoskeletal injuries rapid review series). Emerg Med Australas. 2018;30:18-35.

11. Cook CE, George SZ, Reiman MP. Red flag screening for low back pain: nothing to see here, move along: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:493-496.

12. Grunau GL, Darlow B, Flynn T, et al. Red flags or red herrings? Redefining the role of red flags in low back pain to reduce overimaging. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:488-489.

13. Lansberg MG, O’Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e601S-e636S.

14. Pikija S, Mutzenbach JS, Kunz AB, et al. Delayed hospital presentation and neuroimaging in non-surgical spinal cord infarction. Front Neurol. 2017;8:143.

1. Romi F, Naess H. Spinal cord infarction in clinical neurology: a review of characteristics and long-term prognosis in comparison to cerebral infarction. Eur Neurol. 2016;76:95-98.

2. Hanson SR, Romi F, Rekand T, et al. Long-term outcome after spinal cord infarctions. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;131:253-257.

3. Rigney L, Cappelen-Smith C, Sebire D, et al. Nontraumatic spinal cord ischaemic syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1544-1549.

4. Novy J, Carruzzo A, Maeder P, Bogousslavsky J. Spinal cord ischemia: clinical and imaging patterns, pathogenesis, and outcomes in 27 patients. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1113-1120.

5. Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, et al; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2006;113:e873-e923.

6. Mateen FJ, Monrad PA, Hunderfund AN, et al. Clinically suspected fibrocartilaginous embolism: clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:218-225.

7. Ozmen F, Ozmen MM, Ozalp N, et al. The prevalence of factor V (G1691A), MTHFR (C677T) and PT (G20210A) gene mutations in arterial thrombosis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:113-119.

8. Kim RJ, Becker RC. Association between factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A, and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutations and events of the arterial circulatory system: a meta-analysis of published studies. Am Heart J. 2003;146:948-957.

9. Cushman M, Rosendaal FR, Psaty BM, et al. Factor V Leiden is not a risk factor for arterial vascular disease in the elderly: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:912-915.

10. Strudwick K, McPhee M, Bell A, et al. Review article: best practice management of low back pain in the emergency department (part 1 of the musculoskeletal injuries rapid review series). Emerg Med Australas. 2018;30:18-35.

11. Cook CE, George SZ, Reiman MP. Red flag screening for low back pain: nothing to see here, move along: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:493-496.

12. Grunau GL, Darlow B, Flynn T, et al. Red flags or red herrings? Redefining the role of red flags in low back pain to reduce overimaging. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:488-489.

13. Lansberg MG, O’Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e601S-e636S.

14. Pikija S, Mutzenbach JS, Kunz AB, et al. Delayed hospital presentation and neuroimaging in non-surgical spinal cord infarction. Front Neurol. 2017;8:143.

A Nervous Recipient of a “Tongue Lashing”

Self-injurious behaviors are common and can be either volitional or unintentional. Often people who perform these behaviors receive “tongue lashings” from family, friends, and loved ones. We recently treated a patient whose lesion in the oral cavity was thought to be caused by some form of self-injury, though the prognosis clearly depended on the true culprit. It is important for clinicians to identify the cause of the injury when encountering patients with oral cavity lesions.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white male with a medical history of bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, polysubstance abuse, and recently diagnosed temporomandibular joint (TMJ) syndrome was seen in outpatient primary care for a bleeding lesion in his mouth for the past 3 weeks. The lesion was under the surface of his right tongue. He first noted the lesion after he had burned himself tasting some homemade rice pudding while under the influence of marijuana. The next day, an impression was taken of his mouth by a dental assistant who was fitting him for an oral appliance for his TMJ syndrome; according to his history, she did not perform a visual inspection of his mouth nor could he recall his last dental examination. He had neither lost weight nor experienced dysphagia. He was not taking any prescribed medications, had an 8 pack-year history of smoking cigarettes, and had smoked crack cocaine intermittently for several years. The also patient had chewed one-half tin per day of chewing tobacco for 5 years, though he had quit 7 years before presentation. He was consuming 6 alcoholic drinks daily and had no history of chewing betel nuts.

On physical examination, the patient seemed extremely anxious, but his vital signs were unremarkable. The nasal dorsum was straight, and the nares were widely patent. There were no suspicious cutaneous lesions noted of the face, head, trunk, or extremities. The salivary glands were soft and showed no lesions or masses within the parotid or submandibular glands bilaterally. There was no obvious obstruction of Stenson or Wharton ducts bilaterally. He had normal lips and oral competence. The dentition was noted to be fair.

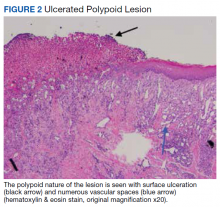

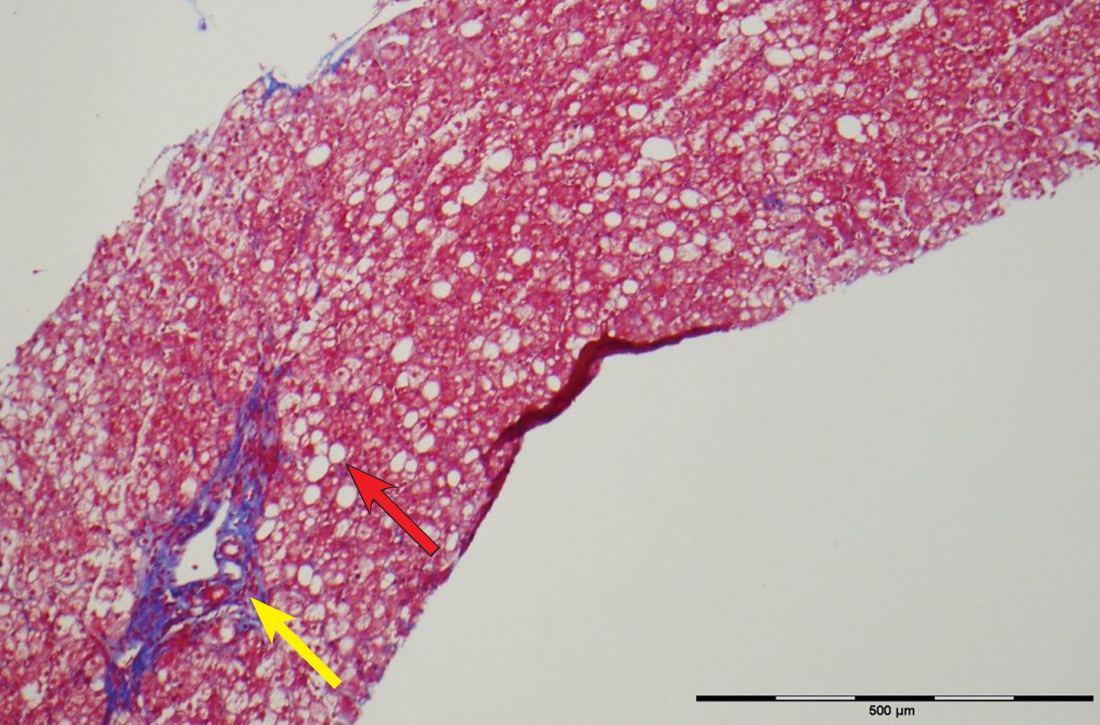

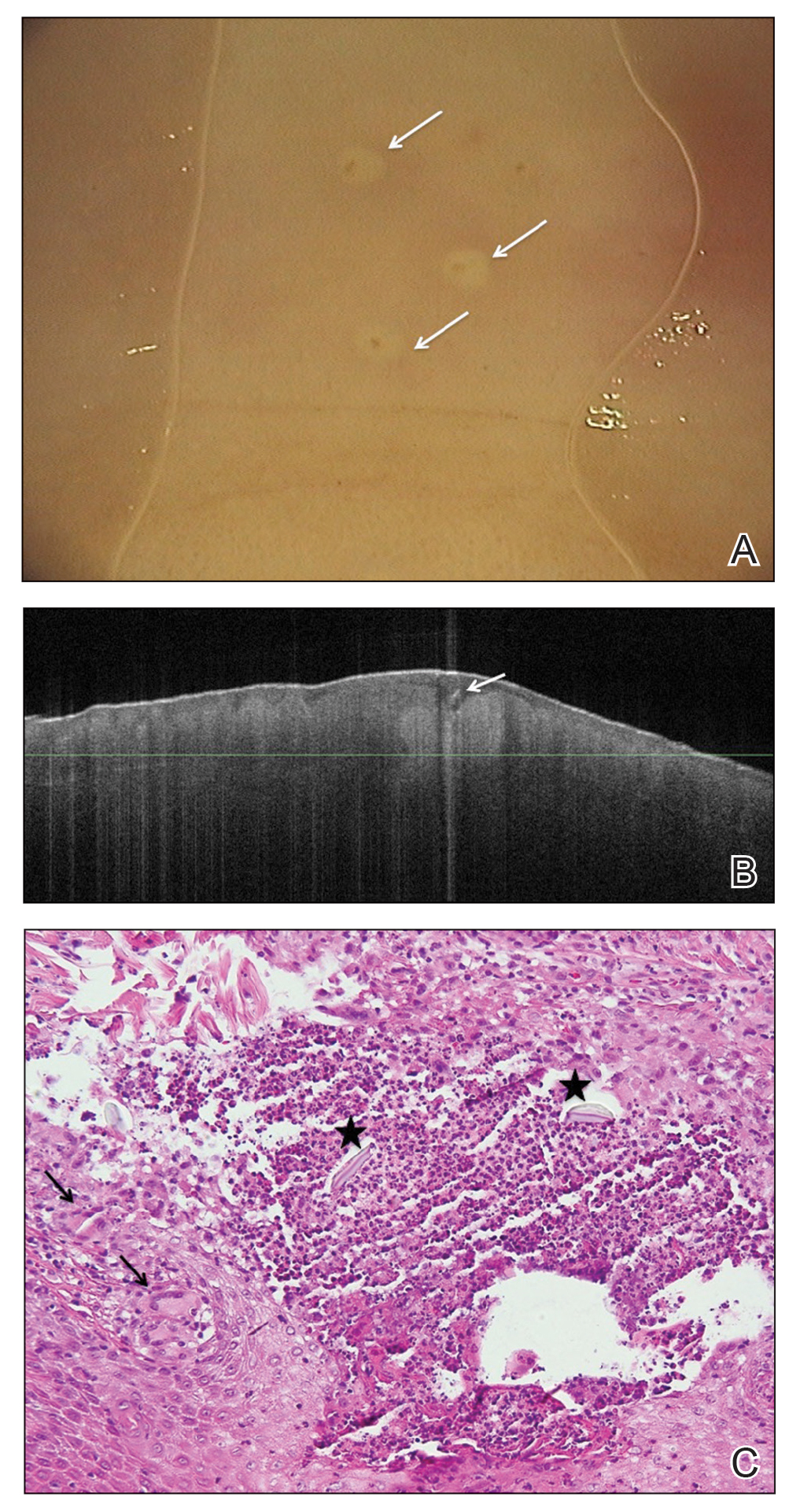

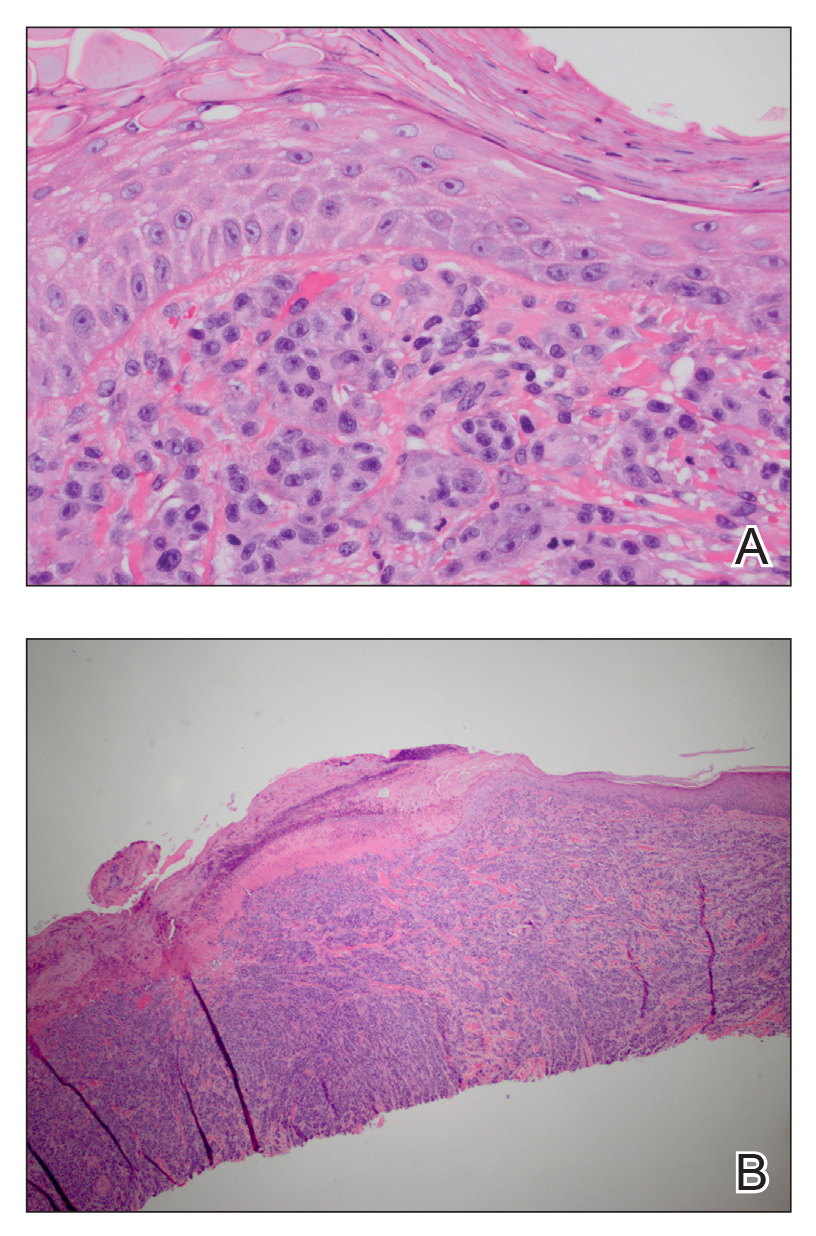

A nonfriable, 1.5 cm-wide lesion was found on the ventral surface of the right tongue (Figure 1). The tongue was mobile. The mouth floor was soft and without evidence of masses or lesions. The tonsils, tonsillar pillars, palate, and base of tongue did not show any concerning lesions or masses. The neck revealed a nonenlarged thyroid and no lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

Diagnosis

Given his risk factors of alcohol use disorder and a history of both inhaled and chewing tobacco, oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was considered. The differential diagnosis also included pyogenic granuloma, mucocele, sublingual fibroma, and metastasis to the oral soft tissue. Due to its implications with respect to morbidity and mortality, we thought it necessary to rule out SCC of the oral cavity. SCC comprises more than 90% of oral malignancies, and tobacco-related products, alcohol, and human papilloma virus are well-established risk factors.1

Pyogenic granuloma, also known as eruptive hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma, is a relatively common benign lesion of the skin and mucosal surfaces that often presents as a solitary, rapidly enlarging papule or nodule that is extremely friable.2 Interestingly, pyogenic granuloma is a misnomer, since it is neither infectious in origin nor granulomatous when visualized under the microscope and is thought to arise from an exuberant tissue response to localized irritation or trauma. An individual lesion can range in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters and generally reaches its maximum size within a matter of weeks; they often arise at sites of minor trauma.3 While the pathogenesis of pyogenic granuloma has not been clearly established, it seems to be related to an imbalance of angiogenesis secondary to overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor.4 While they can occur at any age, pyogenic granulomas are frequently seen in pediatric patients and during pregnancy.

A fibroma, also known as an irritation fibroma, is one of the more common fibrous tumorlike growths and is often caused by trauma or irritation. It usually presents as a smooth-surfaced, painless solid lesion, though it can be nodular and histopathologically shows collagen and connective tissue.5 While fibromas can occur anywhere in the oral cavity, they commonly arise on the buccal mucosa along the plane of occlusion between the maxillary and mandibular teeth.

Mucoceles are the most common benign lesions in the mouth and are commonly found on the lower lip and are mucus-filled cavities, arising from the accumulation of mucus from trauma or lip-biting and alteration of minor salivary glands.6 Our patient’s rapid evolution and history of trauma were consistent with a mucocele. Although the lower lip is the most common site of involvement, mucoceles also occur on the tongue, cheek, palate, and mouth floor.Metastases to the oral cavity are rare and comprise only 1% of all oral cavity malignancies.7 Although most commonly seen in the jaw, nearly one-third of oral cavity metastases are in the soft tissue.8 They generally occur late in the course of disease, and the time between appearance and death is usually short.8 Our patient’s lack of known primary malignancy and lack of weight loss rendered this diagnosis unlikely.

Other possibilities include peripheral giant cell granuloma, a reactive hyperplastic lesion of the oral cavity originating from the periosteum or periodontal membrane following local irritation or chronic trauma,9 and peripheral ossifying fibroma, a reactive soft tissue growth usually seen on the interdental papilla.10

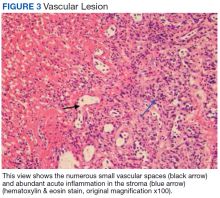

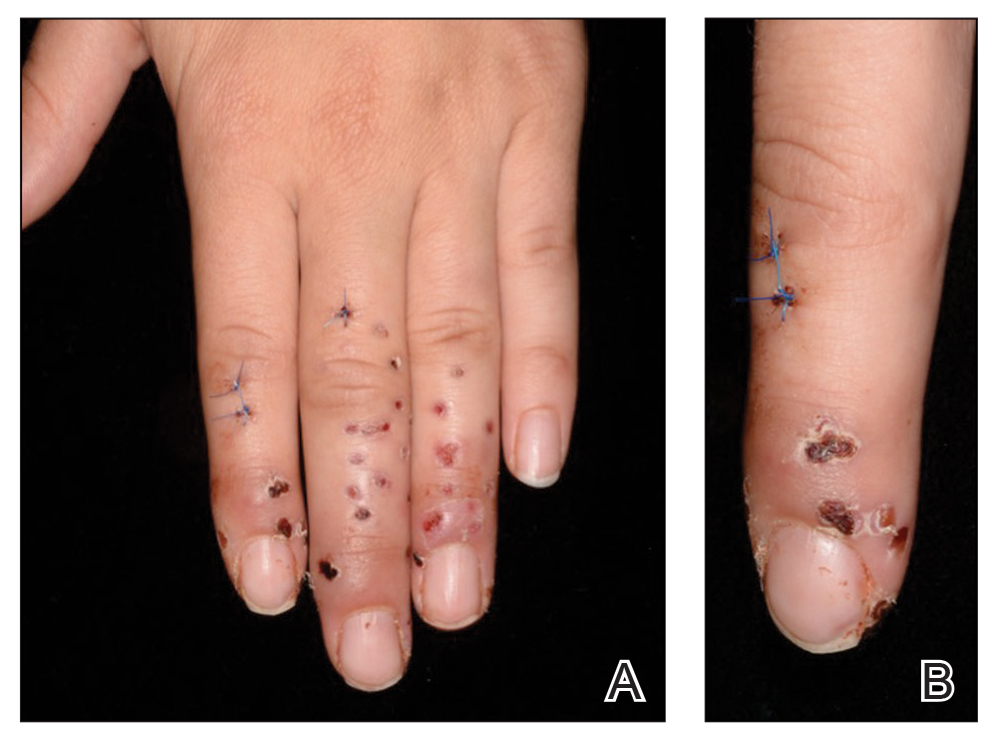

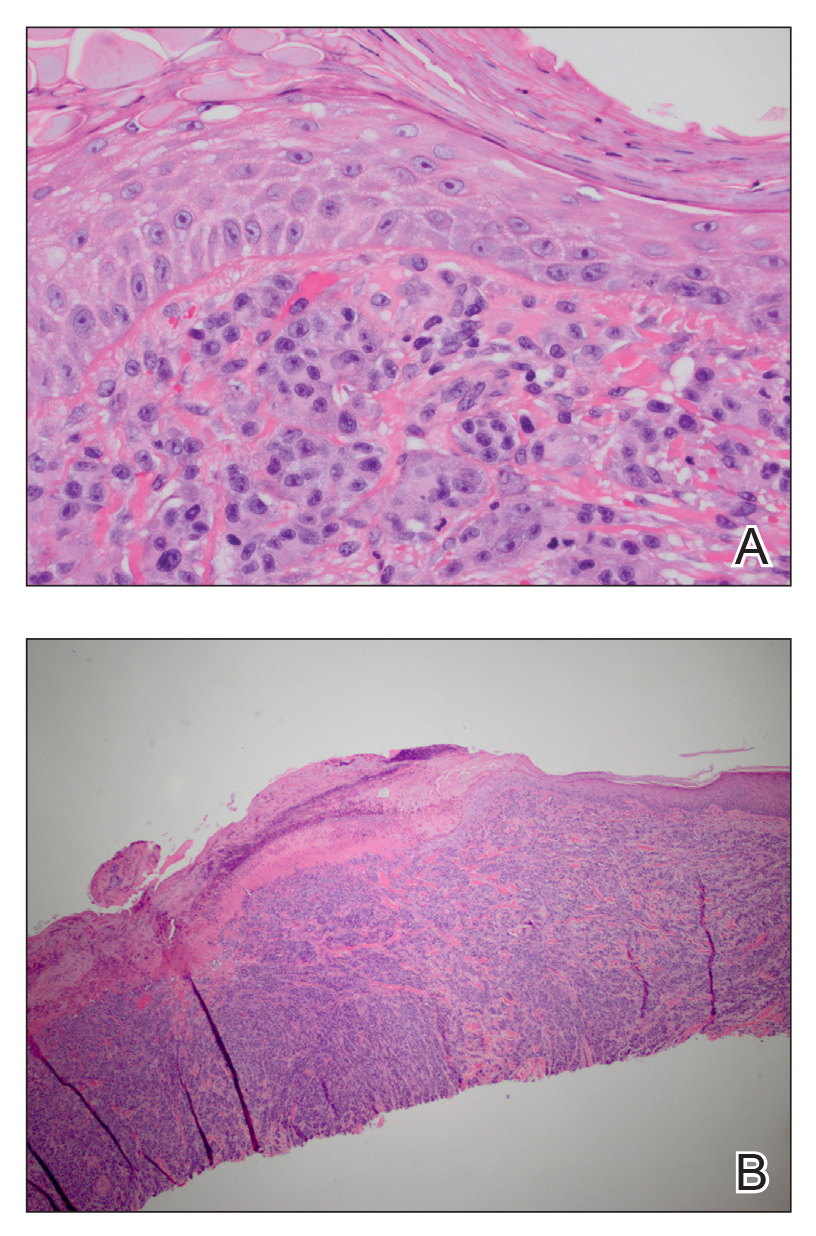

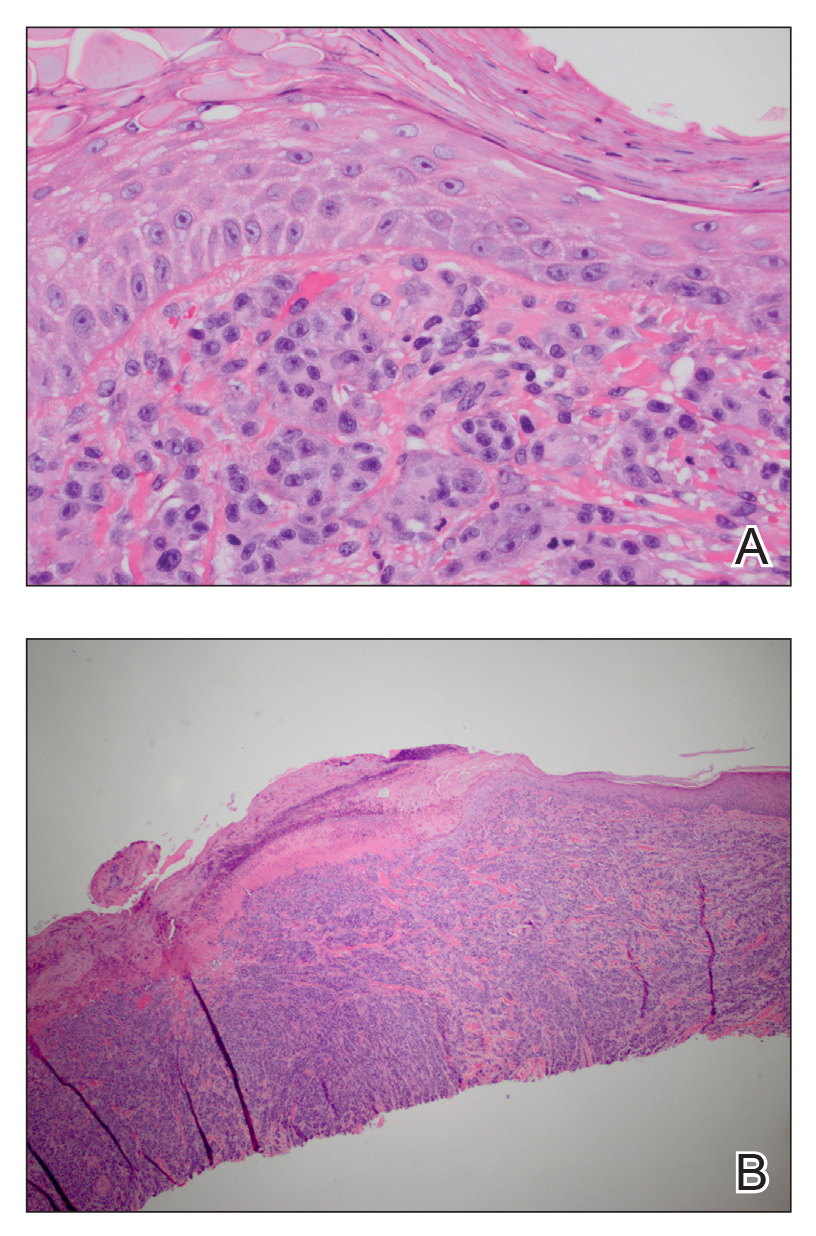

Surgical excision was performed and revealed reactive epidermal hyperplasia, ulceration, granulation tissue formation, and marked inflammation with reactive changes. There was no evidence of malignancy and was interpreted as consistent with pyogenic granuloma (Figures 2 and 3) likely due to the trauma from the thermal burn or poor dentition.

Management

The patient was relieved to be informed of the diagnosis of an unusual presentation of pyogenic granuloma with no evidence of cancer. Current treatment strategies for pyogenic granuloma include surgical excision, shave excision with cautery, cryotherapy, sclerotherapy, carbon dioxide or pulsed dye laser, as well as expectant management. However, recurrence after initial treatment can occur, with lower recurrence rates occurring with surgical excision.11

Although we wouldn’t state that we gave the patient a “tongue-lashing,” we strongly advised him that he return to his dentist and abstain from tobacco products, alcohol, illicit drugs, and taste-testing scalding food directly from the pot.

1. Khot KP, Deshmane S, Choudhari S. Human papilloma virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma-the enigma unraveled. Clin J Dent Res. 2016;19(1):17-23.

2. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Neoplasms of the skin. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1627-1901.

3. Tatusov M, Reddy S, Federman DG. Pyogenic granuloma: yet another motorcycle peril. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(6):124-126.

4. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71(5):701-709.

5. Krishnan V, Shunmugavelu K. A clinical challenging situation of intra oral fibroma mimicking pyogenic granuloma. J Pan African Med. 2015;22(1):263.

6. Nallasivam KU, Sudha BR. Oral mucocele: review of literature and a case report. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(suppl 2):S731-S733.

7. Zachariades N. Neoplasms metastatic to the mouth, jaws, and surrounding tissues. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17(6):283-290.

8. Irani S. Metastasis to the oral soft tissues: a review of 412 cases. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6(5):393-401.

9. Shadman N, Ebrahimi SF, Jafari S, Eslami M. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: a review of 123 cases. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2009;6(1):47-50.

10. Poonacha KS, Shigli AL, Shirol D. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: a clinical report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1(1):54-56.

11. Gilmore A, Kelsberg G, Safranek G. Clinical inquiries. What’s the best treatment for pyogenic granuloma? J Fam Pract. 2010;59(1):40-42.

Self-injurious behaviors are common and can be either volitional or unintentional. Often people who perform these behaviors receive “tongue lashings” from family, friends, and loved ones. We recently treated a patient whose lesion in the oral cavity was thought to be caused by some form of self-injury, though the prognosis clearly depended on the true culprit. It is important for clinicians to identify the cause of the injury when encountering patients with oral cavity lesions.

Case Presentation