User login

56-year-old woman • worsening pain in left upper arm • influenza vaccination in the arm a few days prior to pain onset • Dx?

THE CASE

A 56-year-old woman presented with a 3-day complaint of worsening left upper arm pain. She denied having any specific initiating factors but reported receiving an influenza vaccination in the arm a few days prior to the onset of pain. The patient did not have any associated numbness or tingling in the arm. She reported that the pain was worse with movement—especially abduction. The patient reported taking an over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) without much relief.

On physical examination, the patient had difficulty with active range of motion and had erythema, swelling, and tenderness to palpation along the subacromial space and the proximal deltoid. Further examination of the shoulder revealed a positive Neer Impingement Test and a positive Hawkins–Kennedy Test. (For more on these tests, visit “MSK Clinic: Evaluating shoulder pain using IPASS.”). The patient demonstrated full passive range of motion, but her pain was exacerbated with abduction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

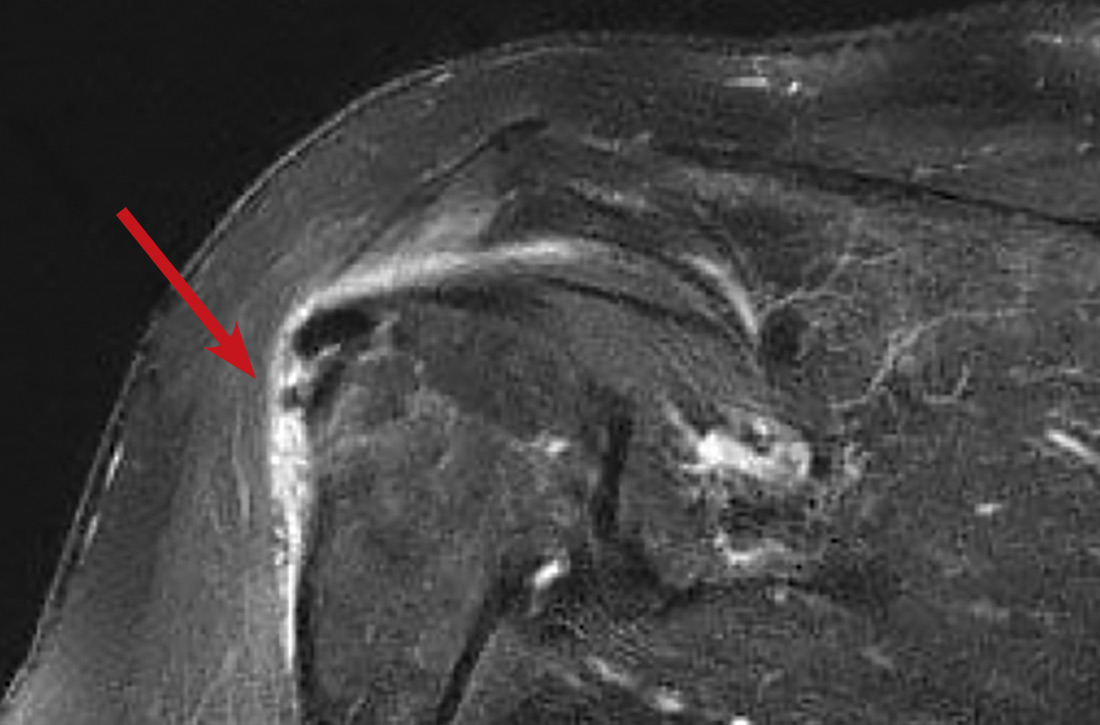

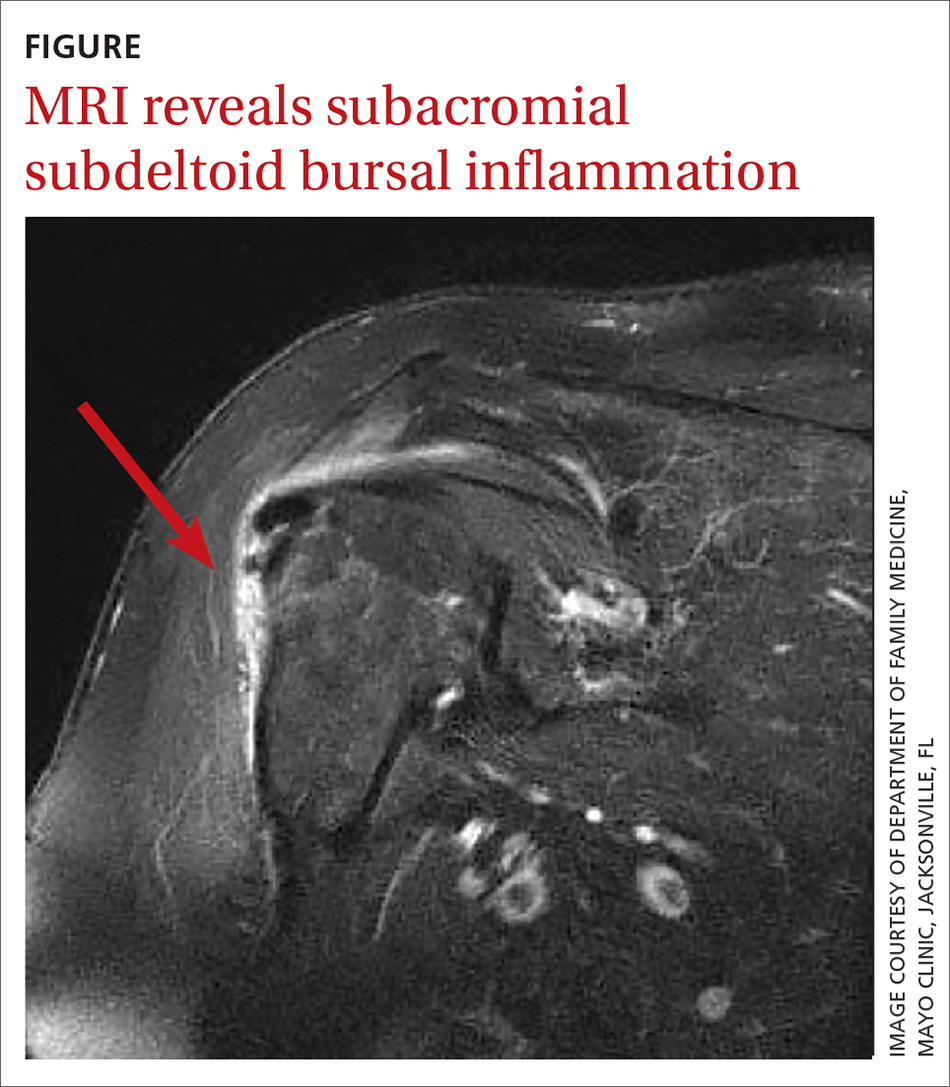

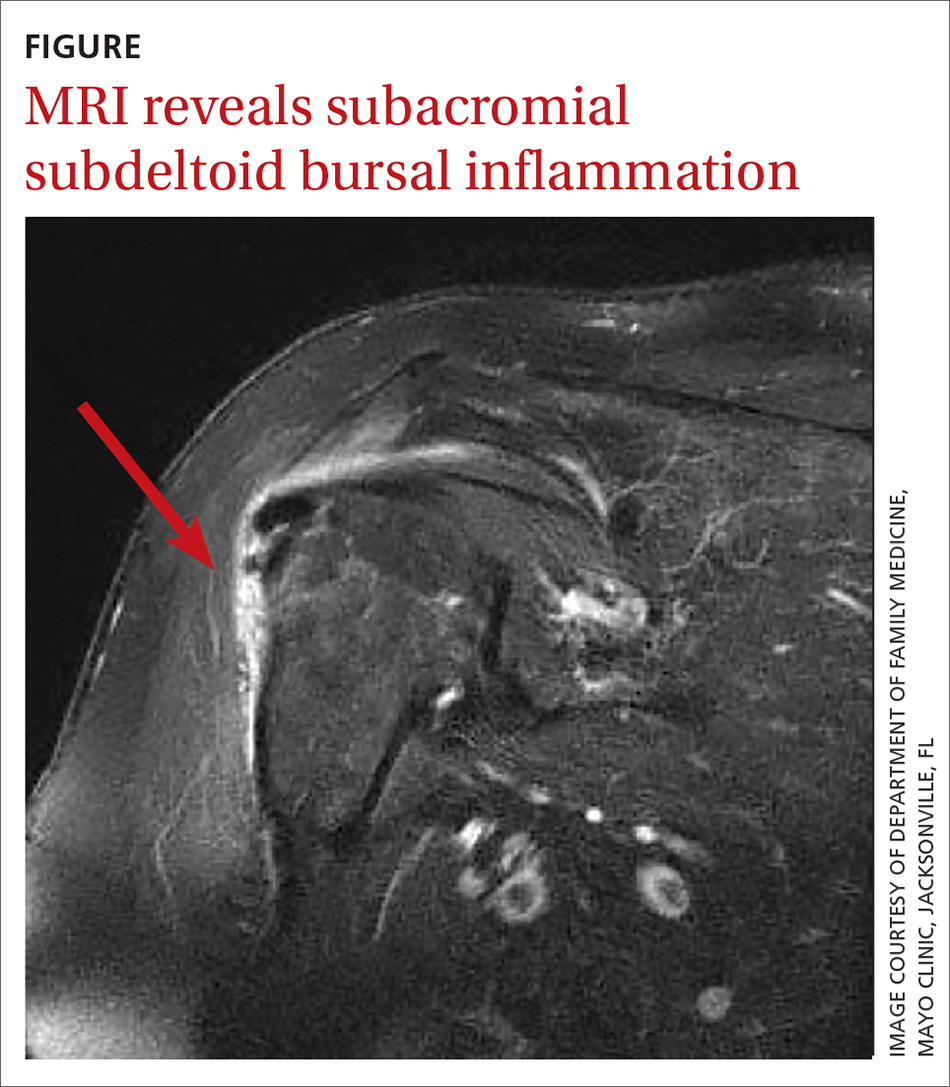

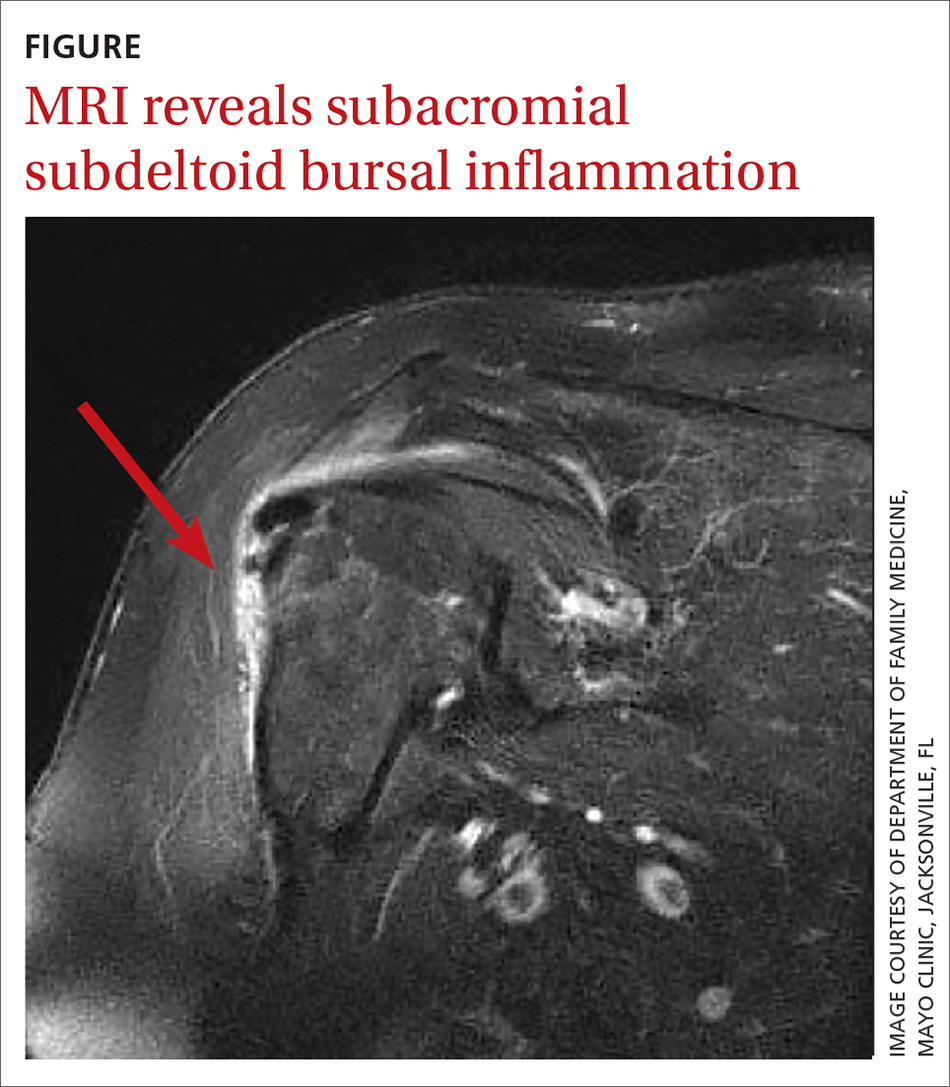

In light of the soft-tissue findings and the absence of trauma, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), rather than an x-ray, of the upper extremity was ordered. Imaging revealed subacromial subdeltoid bursal inflammation (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) is the result of accidental injection of a vaccine into the tissue lying underneath the deltoid muscle or joint space, leading to a suspected immune-mediated inflammatory reaction.

A report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee of the US Department of Health & Human Services showed an increase in the number of reported cases of SIRVA (59 reported cases in 2011-2014 and 202 cases reported in 2016).1 Additionally, in 2016 more than $29 million was awarded in compensation to patients with SIRVA.1,2 In a 2011 report, an Institute of Medicine committee found convincing evidence of a causal relationship between injection of vaccine, independent of the antigen involved, and deltoid bursitis, or frozen shoulder, characterized by shoulder pain and loss of motion.3

A review of 13 cases revealed that 50% of the patients reported pain immediately after the injection and 90% had developed pain within 24 hours.2 On physical exam, a limited range of motion and pain were the most common findings, while weakness and sensory changes were uncommon. In some cases, the pain lasted several years and 30% of the patients required surgery. Forty-six percent of the patients reported apprehension concerning the administration of the vaccine, specifically that the injection was administered “too high” into the deltoid.2

In the review of cases, routine x-rays of the shoulder did not provide beneficial diagnostic information; however, when an MRI was performed, it revealed fluid collections in the deep deltoid or overlying the rotator cuff tendons; bursitis; tendonitis; and rotator cuff tears.2

Continue to: Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA is similar to that of other shoulder injuries. Treatment may include icing the shoulder, NSAIDs, intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy. If conservative management does not resolve the patient’s pain and improve function, then a consult with an orthopedic surgeon is recommended to determine if surgical intervention is required.

Another case report from Japan reported that a 45-year-old woman developed acute pain following a third injection of Cervarix, the prophylactic human papillomavirus-16/18 vaccine. An x-ray was ordered and was normal, but an MRI revealed acute subacromial bursitis. In an attempt to relieve the pain and improve her mobility, multiple cortisone injections were administered and physical therapy was performed. Despite the conservative treatment efforts, she continued to have pain and limited mobility in the shoulder 6 months following the onset of symptoms. As a result, the patient underwent arthroscopic synovectomy and subacromial decompression. One week following the surgery, the patient’s pain improved and at 1 year she had no pain and full range of motion.4

Prevention of SIRVA

By using appropriate techniques when administering intramuscular vaccinations, SIRVA can be prevented. The manufacturer recommended route of administration is based on studies showing maximum safety and immunogenicity, and should therefore be followed by the individual administering the vaccine.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using a 22- to 25-gauge needle that is long enough to reach into the muscle and may range from ⅝" to 1½" depending on the patient’s weight.6 The vaccine should be injected at a 90° angle into the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle, about 2" below the acromion process and above the level of the axilla.5

Our patient’s outcome. The patient’s symptoms resolved within 10 days of receiving a steroid injection into the subacromial space. Although this case was the result of the influenza vaccine, any intramuscularly injected vaccine could lead to SIRVA.

THE TAKEAWAY

Inappropriate administration of routine intramuscularly injected vaccinations can lead to significant patient harm, including pain and disability. It is important for physicians to be aware of SIRVA and to be able to identify the signs and symptoms. Although an MRI of the shoulder is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, it is not necessary if the physician takes a thorough history and performs a comprehensive shoulder exam. Routine x-rays do not provide any beneficial clinical information.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bryan Farford, DO, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Davis Building, 4500 San Pablo Road South #358, Jacksonville, FL 32224; [email protected]

1. Nair N. Update on SIRVA National Vaccine Advisory Committee. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Nair_Special%20Highlight_SIRVA%20remediated.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

2. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, et al. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28:8049-8052.

3. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Uchida S, Sakai A, Nakamura T. Subacromial bursitis following human papilloma virus vaccine misinjection. Vaccine. 2012;31:27-30.

5. Meissner HC. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration reported more frequently. AAP News. September 1, 2017. www.aappublications.org/news/2017/09/01/IDSnapshot082917. Accessed January 14, 2020.

6. Immunization Action Coalition. How to administer intramuscular and subcutaneous vaccine injections to adults. https://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p2020a.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

THE CASE

A 56-year-old woman presented with a 3-day complaint of worsening left upper arm pain. She denied having any specific initiating factors but reported receiving an influenza vaccination in the arm a few days prior to the onset of pain. The patient did not have any associated numbness or tingling in the arm. She reported that the pain was worse with movement—especially abduction. The patient reported taking an over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) without much relief.

On physical examination, the patient had difficulty with active range of motion and had erythema, swelling, and tenderness to palpation along the subacromial space and the proximal deltoid. Further examination of the shoulder revealed a positive Neer Impingement Test and a positive Hawkins–Kennedy Test. (For more on these tests, visit “MSK Clinic: Evaluating shoulder pain using IPASS.”). The patient demonstrated full passive range of motion, but her pain was exacerbated with abduction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

In light of the soft-tissue findings and the absence of trauma, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), rather than an x-ray, of the upper extremity was ordered. Imaging revealed subacromial subdeltoid bursal inflammation (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) is the result of accidental injection of a vaccine into the tissue lying underneath the deltoid muscle or joint space, leading to a suspected immune-mediated inflammatory reaction.

A report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee of the US Department of Health & Human Services showed an increase in the number of reported cases of SIRVA (59 reported cases in 2011-2014 and 202 cases reported in 2016).1 Additionally, in 2016 more than $29 million was awarded in compensation to patients with SIRVA.1,2 In a 2011 report, an Institute of Medicine committee found convincing evidence of a causal relationship between injection of vaccine, independent of the antigen involved, and deltoid bursitis, or frozen shoulder, characterized by shoulder pain and loss of motion.3

A review of 13 cases revealed that 50% of the patients reported pain immediately after the injection and 90% had developed pain within 24 hours.2 On physical exam, a limited range of motion and pain were the most common findings, while weakness and sensory changes were uncommon. In some cases, the pain lasted several years and 30% of the patients required surgery. Forty-six percent of the patients reported apprehension concerning the administration of the vaccine, specifically that the injection was administered “too high” into the deltoid.2

In the review of cases, routine x-rays of the shoulder did not provide beneficial diagnostic information; however, when an MRI was performed, it revealed fluid collections in the deep deltoid or overlying the rotator cuff tendons; bursitis; tendonitis; and rotator cuff tears.2

Continue to: Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA is similar to that of other shoulder injuries. Treatment may include icing the shoulder, NSAIDs, intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy. If conservative management does not resolve the patient’s pain and improve function, then a consult with an orthopedic surgeon is recommended to determine if surgical intervention is required.

Another case report from Japan reported that a 45-year-old woman developed acute pain following a third injection of Cervarix, the prophylactic human papillomavirus-16/18 vaccine. An x-ray was ordered and was normal, but an MRI revealed acute subacromial bursitis. In an attempt to relieve the pain and improve her mobility, multiple cortisone injections were administered and physical therapy was performed. Despite the conservative treatment efforts, she continued to have pain and limited mobility in the shoulder 6 months following the onset of symptoms. As a result, the patient underwent arthroscopic synovectomy and subacromial decompression. One week following the surgery, the patient’s pain improved and at 1 year she had no pain and full range of motion.4

Prevention of SIRVA

By using appropriate techniques when administering intramuscular vaccinations, SIRVA can be prevented. The manufacturer recommended route of administration is based on studies showing maximum safety and immunogenicity, and should therefore be followed by the individual administering the vaccine.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using a 22- to 25-gauge needle that is long enough to reach into the muscle and may range from ⅝" to 1½" depending on the patient’s weight.6 The vaccine should be injected at a 90° angle into the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle, about 2" below the acromion process and above the level of the axilla.5

Our patient’s outcome. The patient’s symptoms resolved within 10 days of receiving a steroid injection into the subacromial space. Although this case was the result of the influenza vaccine, any intramuscularly injected vaccine could lead to SIRVA.

THE TAKEAWAY

Inappropriate administration of routine intramuscularly injected vaccinations can lead to significant patient harm, including pain and disability. It is important for physicians to be aware of SIRVA and to be able to identify the signs and symptoms. Although an MRI of the shoulder is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, it is not necessary if the physician takes a thorough history and performs a comprehensive shoulder exam. Routine x-rays do not provide any beneficial clinical information.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bryan Farford, DO, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Davis Building, 4500 San Pablo Road South #358, Jacksonville, FL 32224; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 56-year-old woman presented with a 3-day complaint of worsening left upper arm pain. She denied having any specific initiating factors but reported receiving an influenza vaccination in the arm a few days prior to the onset of pain. The patient did not have any associated numbness or tingling in the arm. She reported that the pain was worse with movement—especially abduction. The patient reported taking an over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) without much relief.

On physical examination, the patient had difficulty with active range of motion and had erythema, swelling, and tenderness to palpation along the subacromial space and the proximal deltoid. Further examination of the shoulder revealed a positive Neer Impingement Test and a positive Hawkins–Kennedy Test. (For more on these tests, visit “MSK Clinic: Evaluating shoulder pain using IPASS.”). The patient demonstrated full passive range of motion, but her pain was exacerbated with abduction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

In light of the soft-tissue findings and the absence of trauma, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), rather than an x-ray, of the upper extremity was ordered. Imaging revealed subacromial subdeltoid bursal inflammation (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) is the result of accidental injection of a vaccine into the tissue lying underneath the deltoid muscle or joint space, leading to a suspected immune-mediated inflammatory reaction.

A report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee of the US Department of Health & Human Services showed an increase in the number of reported cases of SIRVA (59 reported cases in 2011-2014 and 202 cases reported in 2016).1 Additionally, in 2016 more than $29 million was awarded in compensation to patients with SIRVA.1,2 In a 2011 report, an Institute of Medicine committee found convincing evidence of a causal relationship between injection of vaccine, independent of the antigen involved, and deltoid bursitis, or frozen shoulder, characterized by shoulder pain and loss of motion.3

A review of 13 cases revealed that 50% of the patients reported pain immediately after the injection and 90% had developed pain within 24 hours.2 On physical exam, a limited range of motion and pain were the most common findings, while weakness and sensory changes were uncommon. In some cases, the pain lasted several years and 30% of the patients required surgery. Forty-six percent of the patients reported apprehension concerning the administration of the vaccine, specifically that the injection was administered “too high” into the deltoid.2

In the review of cases, routine x-rays of the shoulder did not provide beneficial diagnostic information; however, when an MRI was performed, it revealed fluid collections in the deep deltoid or overlying the rotator cuff tendons; bursitis; tendonitis; and rotator cuff tears.2

Continue to: Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA is similar to that of other shoulder injuries. Treatment may include icing the shoulder, NSAIDs, intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy. If conservative management does not resolve the patient’s pain and improve function, then a consult with an orthopedic surgeon is recommended to determine if surgical intervention is required.

Another case report from Japan reported that a 45-year-old woman developed acute pain following a third injection of Cervarix, the prophylactic human papillomavirus-16/18 vaccine. An x-ray was ordered and was normal, but an MRI revealed acute subacromial bursitis. In an attempt to relieve the pain and improve her mobility, multiple cortisone injections were administered and physical therapy was performed. Despite the conservative treatment efforts, she continued to have pain and limited mobility in the shoulder 6 months following the onset of symptoms. As a result, the patient underwent arthroscopic synovectomy and subacromial decompression. One week following the surgery, the patient’s pain improved and at 1 year she had no pain and full range of motion.4

Prevention of SIRVA

By using appropriate techniques when administering intramuscular vaccinations, SIRVA can be prevented. The manufacturer recommended route of administration is based on studies showing maximum safety and immunogenicity, and should therefore be followed by the individual administering the vaccine.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using a 22- to 25-gauge needle that is long enough to reach into the muscle and may range from ⅝" to 1½" depending on the patient’s weight.6 The vaccine should be injected at a 90° angle into the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle, about 2" below the acromion process and above the level of the axilla.5

Our patient’s outcome. The patient’s symptoms resolved within 10 days of receiving a steroid injection into the subacromial space. Although this case was the result of the influenza vaccine, any intramuscularly injected vaccine could lead to SIRVA.

THE TAKEAWAY

Inappropriate administration of routine intramuscularly injected vaccinations can lead to significant patient harm, including pain and disability. It is important for physicians to be aware of SIRVA and to be able to identify the signs and symptoms. Although an MRI of the shoulder is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, it is not necessary if the physician takes a thorough history and performs a comprehensive shoulder exam. Routine x-rays do not provide any beneficial clinical information.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bryan Farford, DO, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Davis Building, 4500 San Pablo Road South #358, Jacksonville, FL 32224; [email protected]

1. Nair N. Update on SIRVA National Vaccine Advisory Committee. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Nair_Special%20Highlight_SIRVA%20remediated.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

2. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, et al. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28:8049-8052.

3. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Uchida S, Sakai A, Nakamura T. Subacromial bursitis following human papilloma virus vaccine misinjection. Vaccine. 2012;31:27-30.

5. Meissner HC. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration reported more frequently. AAP News. September 1, 2017. www.aappublications.org/news/2017/09/01/IDSnapshot082917. Accessed January 14, 2020.

6. Immunization Action Coalition. How to administer intramuscular and subcutaneous vaccine injections to adults. https://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p2020a.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

1. Nair N. Update on SIRVA National Vaccine Advisory Committee. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Nair_Special%20Highlight_SIRVA%20remediated.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

2. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, et al. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28:8049-8052.

3. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Uchida S, Sakai A, Nakamura T. Subacromial bursitis following human papilloma virus vaccine misinjection. Vaccine. 2012;31:27-30.

5. Meissner HC. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration reported more frequently. AAP News. September 1, 2017. www.aappublications.org/news/2017/09/01/IDSnapshot082917. Accessed January 14, 2020.

6. Immunization Action Coalition. How to administer intramuscular and subcutaneous vaccine injections to adults. https://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p2020a.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

33-year-old man • flaccid paralysis in limbs • 30-lb weight loss • thyromegaly without nodules • Dx?

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; [email protected].

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; [email protected].

THE CASE

A 33-year-old Hispanic man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with generalized flaccid paralysis in both arms and legs. Two days before, he had been working on a construction site in hot weather. The following day, he woke up with very little energy or strength to perform his daily activities, and he had pain in the inguinal area and both calves. He denied taking any medications or supplements.

The patient had complete muscle weakness and was unable to move his arms and legs. He reported dysphagia and an unintentional weight loss of 30 lb during the previous month.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were within the normal range, and mild thyromegaly without nodules was present. Neurologic examination revealed decreased deep tendon reflexes with intact sensation. Muscle strength in his arms and legs was 0/5.

Initial laboratory test results included a potassium level of 2.2 mEq/L (normal range, 3.5–5 mEq/L) and normal acid-basic status that was confirmed by an arterial blood gas measurement. Serum magnesium was 1.6 mg/dL (normal range, 1.6–2.5 mg/dL); phosphorus, 1.9 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7–4.5 mg/dL); and random urinary potassium, 16 mEq/L (normal range, 25–125 mEq/L). An initial chest x-ray was normal, and an electrocardiogram showed a prolonged QT interval, flattening of the T wave, and a prominent U wave consistent with hypokalemia.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The initial clinical diagnosis was hypokalemic paralysis. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) potassium chloride 40 mEq

Evaluation of the patient’s hypokalemia revealed the following: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, < 0.01 microIU/mL (normal range, 0.27–4.2 microIU/mL); free T4 (thyroxine) level, 4.47 ng/dL (normal range, 0.08–1.70 ng/dL); total T3 (triiodothyronine) level, 17.5 ng/dL (normal range, 2.6–4.4 ng/dL).

The patient was diagnosed with hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HPP) secondary to thyrotoxicosis, also known as thyrotoxicosis periodic paralysis (TPP). His hyperthyroidism was treated with oral atenolol 25 mg/d and oral methimazole 10 mg tid.

Continue to: Within a few hours...

Within a few hours of this treatment, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength and complete resolution of weakness in his arms and legs. Serial measurements of potassium levels normalized.

Further workup revealed that the patient’s thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was 4.2 on the TSI index (normal, ≤ 1.3) and his thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody level was 133.4 IU/mL (normal, < 34 IU/mL). Ultrasonography showed decreased echogenicity of the thyroid gland, consistent with the acute phase of Hashimoto thyroiditis or Graves disease.

The patient was unaware that he had any thyroid disorder previously. He was a private-pay, undocumented immigrant and did not have a regular primary care physician. On discharge, he was referred to a local primary care physician as well as an endocrinologist. He was discharged on atenolol and methimazole.

DISCUSSION

A rare neuromuscular disorder known as periodic paralysis can be precipitated by a hypokalemic or hyperkalemic state; HPP is more common and can be either familial (a defect in the gene) or acquired (secondary to thyrotoxicosis; TPP).1,2 In both forms of periodic paralysis, patients present with hypokalemia and paralysis. Physicians need to look closely at thyroid lab test results so as not to miss the cause of the paralysis.

TPP is most commonly seen in Asian populations, and 95% of cases reported occur in males, despite the higher incidence of hyperthyroidism in females.3 TPP can be precipitated by emotional stress, steroid use, beta-adrenergic bronchodilators, heavy exercise, fasting, or high-carbohydrate meals.2-4 In our patient, heavy exercise and fasting likely were the triggers.

Continue to: The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia...

The pathophysiology for the hypokalemia in TPP is thought to involve the sodium/potassium–adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+–ATPase) pump. This pump activity is increased in skeletal muscle and platelets in patients with TPP vs patients with thyrotoxicosis alone.3,5

The role of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis. Most acquired cases of TPP are mainly secondary to Graves disease with elevated levels of TSI and mildly elevated or normal levels of TPO. In this case, the patient was in the acute phase of Hashimoto thyrotoxicosis (“hashitoxicosis”) with elevated levels of TPO and only mildly elevated TSI.Imaging studies to support the diagnosis, such as a thyroid uptake scan or ultrasonography, are not necessary to determine the cause of thyrotoxicosis. In the absence of test results for TPO and TSI antibodies, however, a scan can be helpful.6,7

Treatment of TPP consists of early recognition and supportive management by correcting the potassium deficit; failure to do so could cause severe complications, such as respiratory failure and psychosis.8 Because of the risk for rebound hyperkalemia, serial potassium levels must be measured until a stable potassium level in the normal range is achieved.

Nonselective beta-blockers, such as propranolol (3 mg/kg) 4 times per day, have been reported to ameliorate the periodic paralysis and prevent rebound hyperkalemia.9 Finally, restoring a euthyroid state will prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks.

THE TAKEAWAY

Few medical conditions result in complete muscle paralysis in a matter of hours. Clinicians should consider the possibility of TPP in any patient who presents with acute onset of paralysis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jorge Luis Chavez, MD; 8405 E. San Pedro Drive, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; [email protected].

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

1. Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet. 2008;63:3-23.

2. Ober KP. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the United States. Report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).1992;71:109-120.

3. Lin YF, Wu CC, Pei D, et al. Diagnosing thyrotoxic periodic paralysis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:339-342.

4. Yu TS, Tseng CF, Chuang YY, et al. Potassium chloride supplementation alone may not improve hypokalemia in thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:263-265.

5. Chan A, Shinde R, Chow CC, et al. In vivo and in vitro sodium pump activity in subjects with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. BMJ. 1991;303:1096-1099.

6. Harsch IA, Hahn EG, Strobel D. Hashitoxicosis—three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Endocrinol. 2008;4:70-72. 7. Pou Ucha JL. Imaging in hyperthyroidism. In: Díaz-Soto G, ed. Thyroid Disorders: Focus on Hyperthyroidism. InTechOpen; 2014. www.intechopen.com/books/thyroid-disorders-focus-on-hyperthyroidism/imaging-in-hyperthyroidism. Accessed January 14, 2020.

8. Abbasi B, Sharif Z, Sprabery LR. Hypokalemic thyrotoxic periodic paralysis with thyrotoxic psychosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:147-153.

9. Lin SH, Lin YF. Propranolol rapidly reverses paralysis, hypokalemia, and hypophosphatemia in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:620-623.

Nonuremic Calciphylaxis Triggered by Rapid Weight Loss and Hypotension

Calciphylaxis, otherwise known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is characterized by calcification of the tunica media of the small- to medium-sized blood vessels of the dermis and subcutis, leading to ischemia and necrosis.1 It is a deadly disease with a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50%.2 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the most common risk factor for calciphylaxis, with a prevalence of 1% to 4% of hemodialysis patients with calciphylaxis in the United States.2-5 However, nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC) has been increasingly reported in the literature and has risk factors other than ESRD, including but not limited to obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, and underlying malignancy.3,6-9 Triggers for calciphylaxis in at-risk patients include use of corticosteroids or warfarin, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6,9-11 We report an unusual case of NUC that most likely was triggered by rapid weight loss and hypotension in a patient with multiple risk factors for calciphylaxis.

Case Report

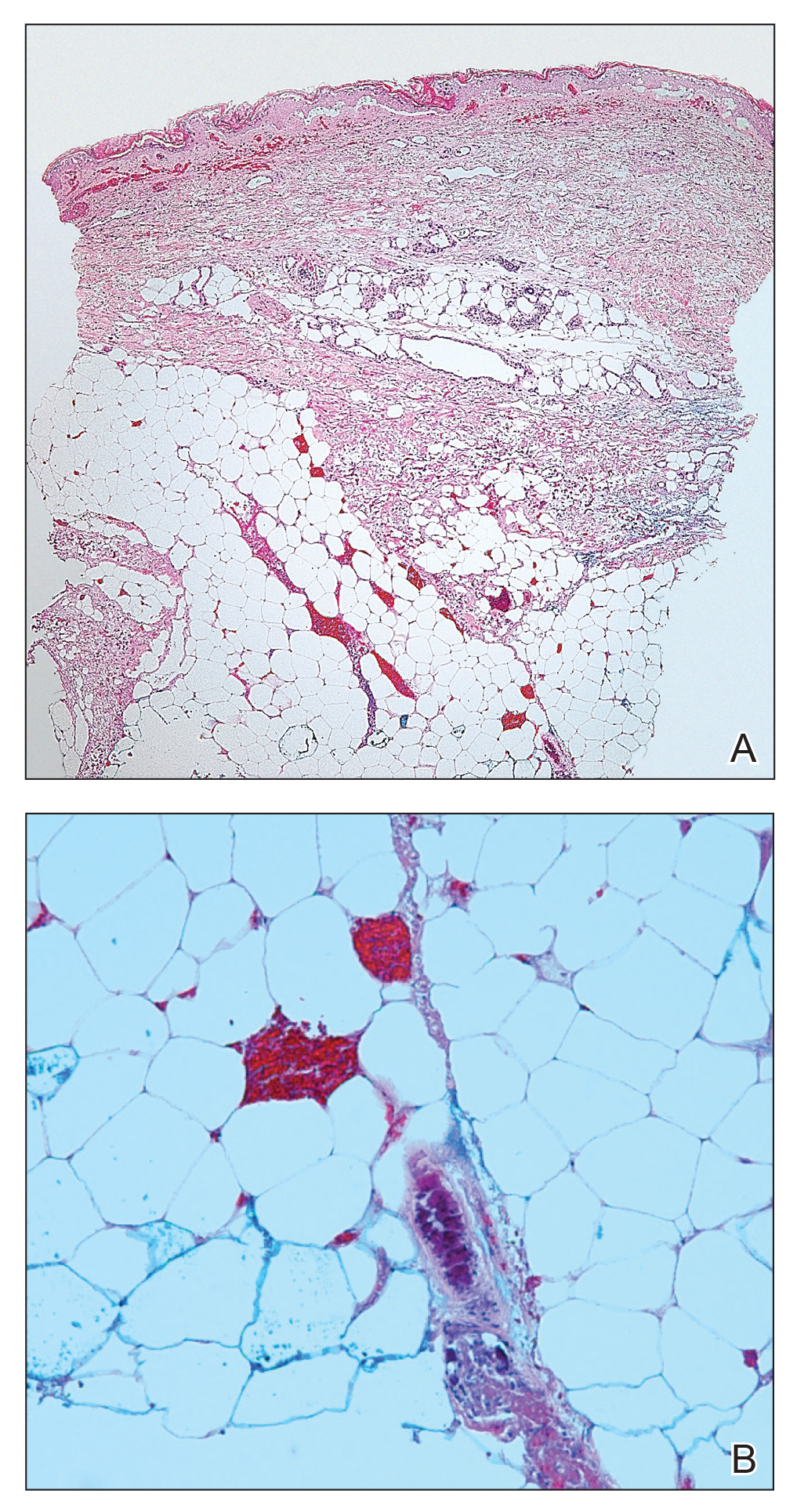

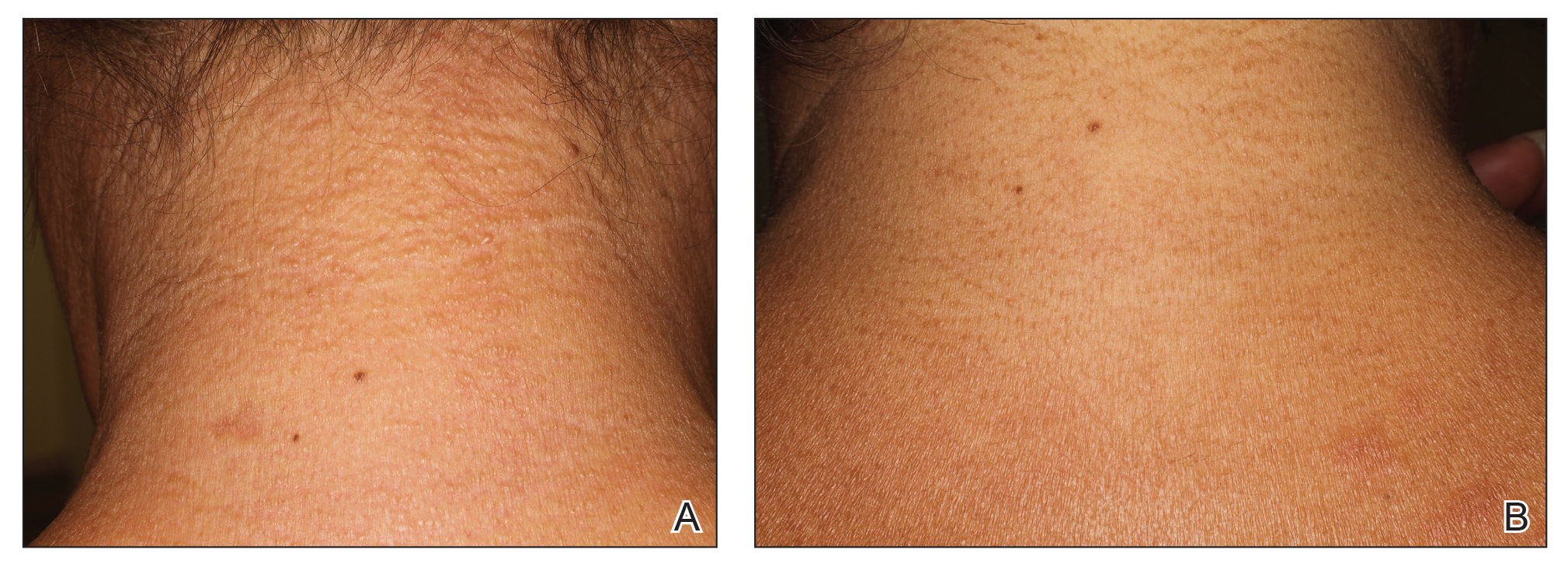

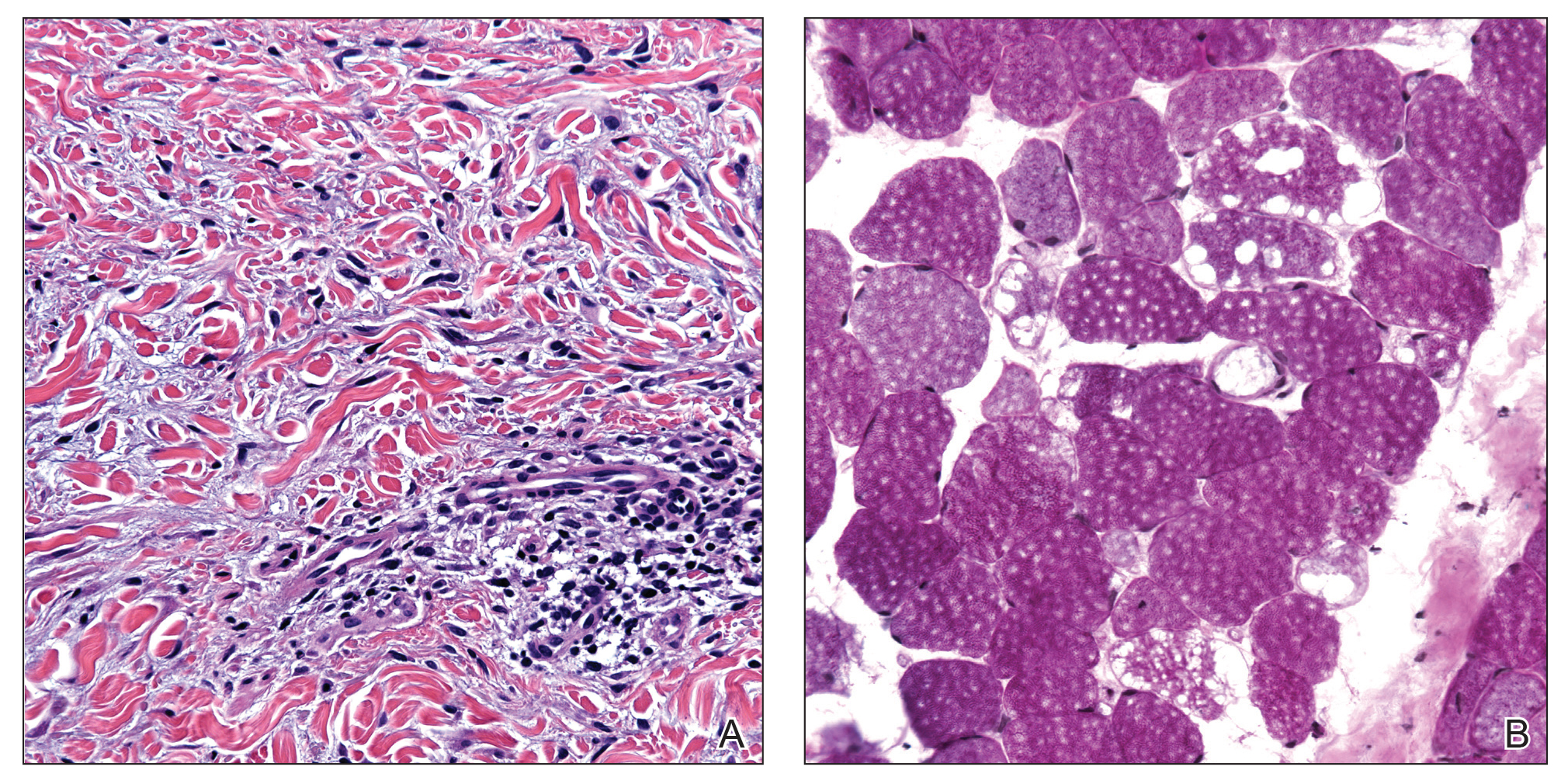

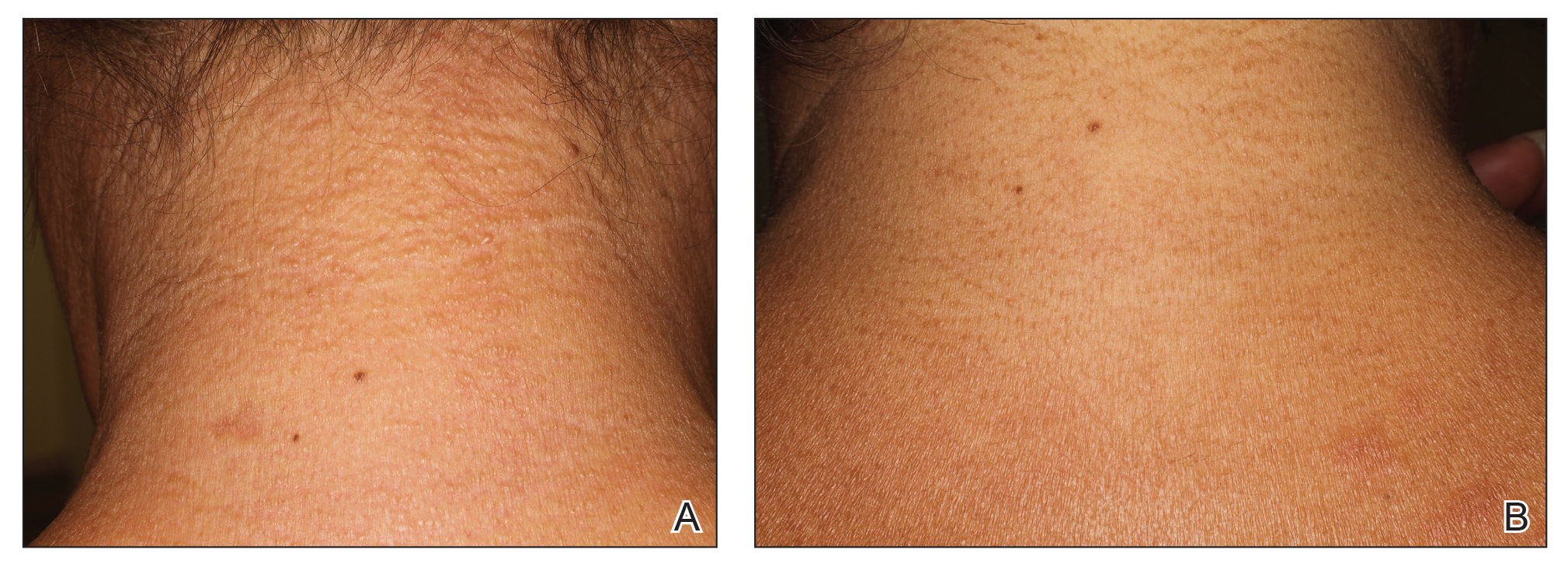

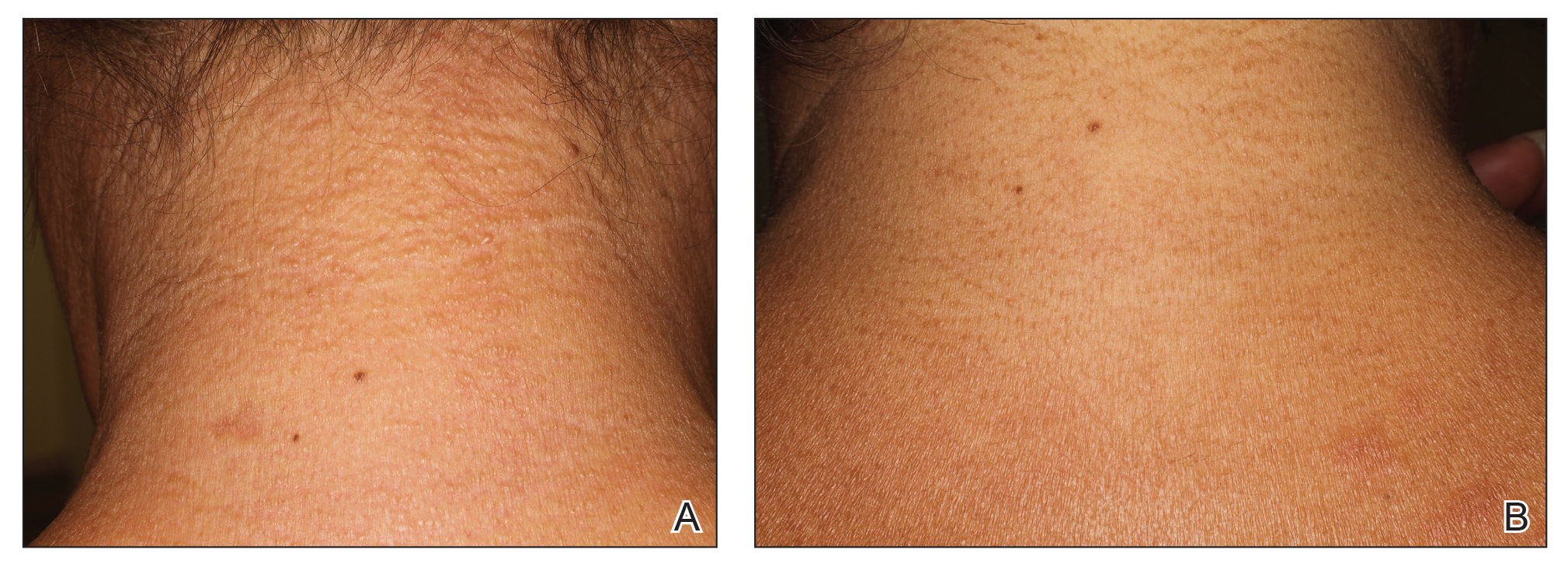

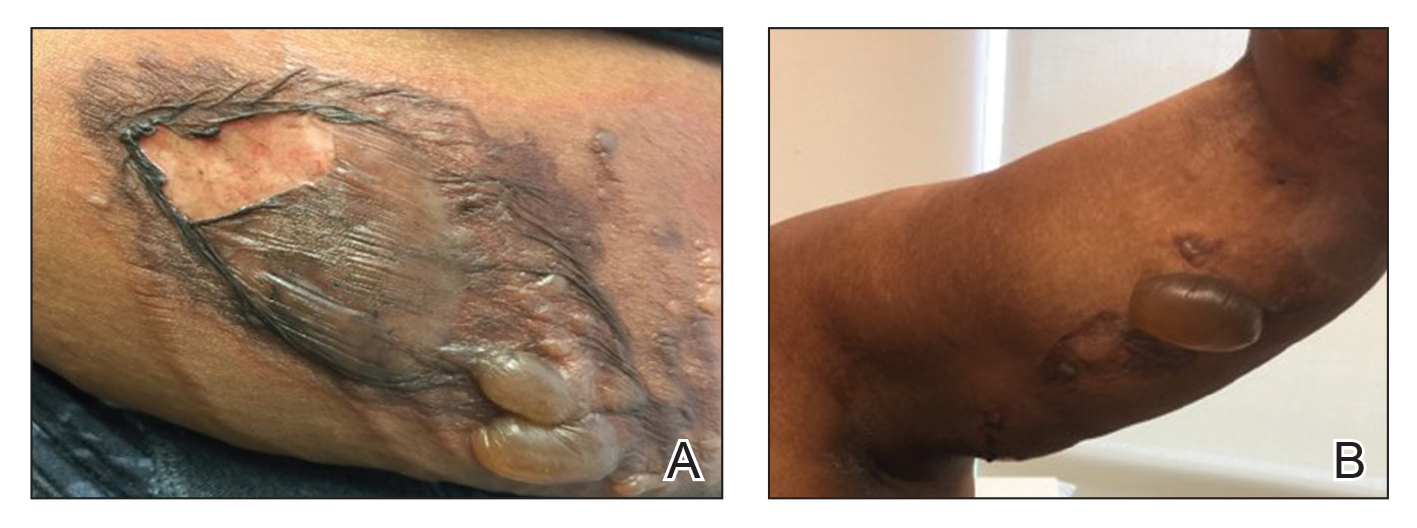

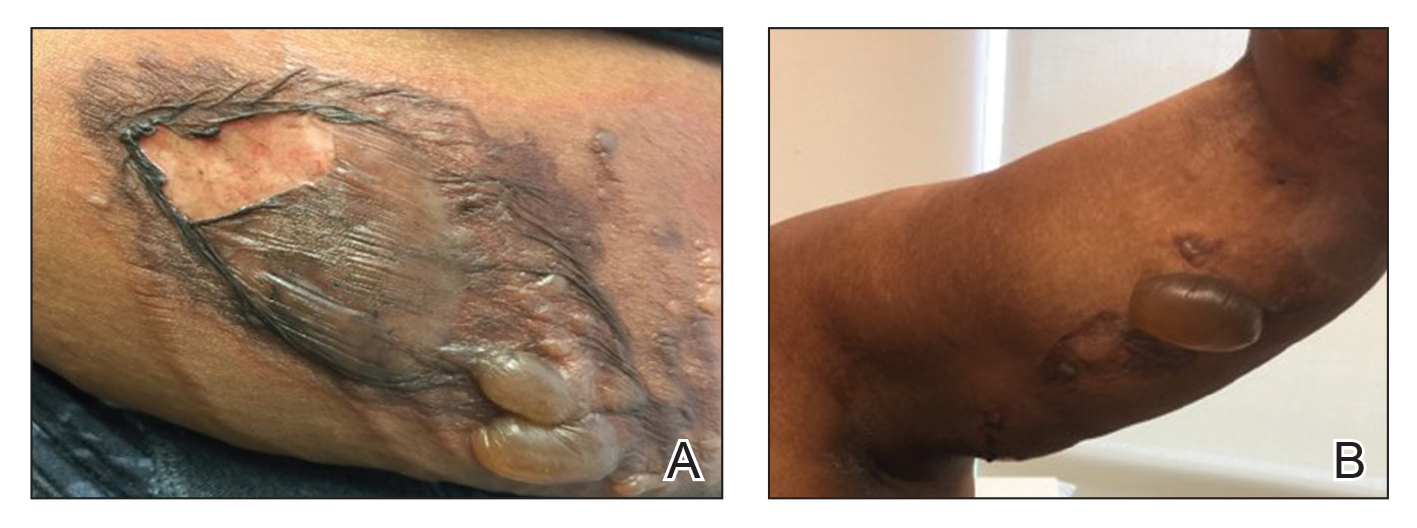

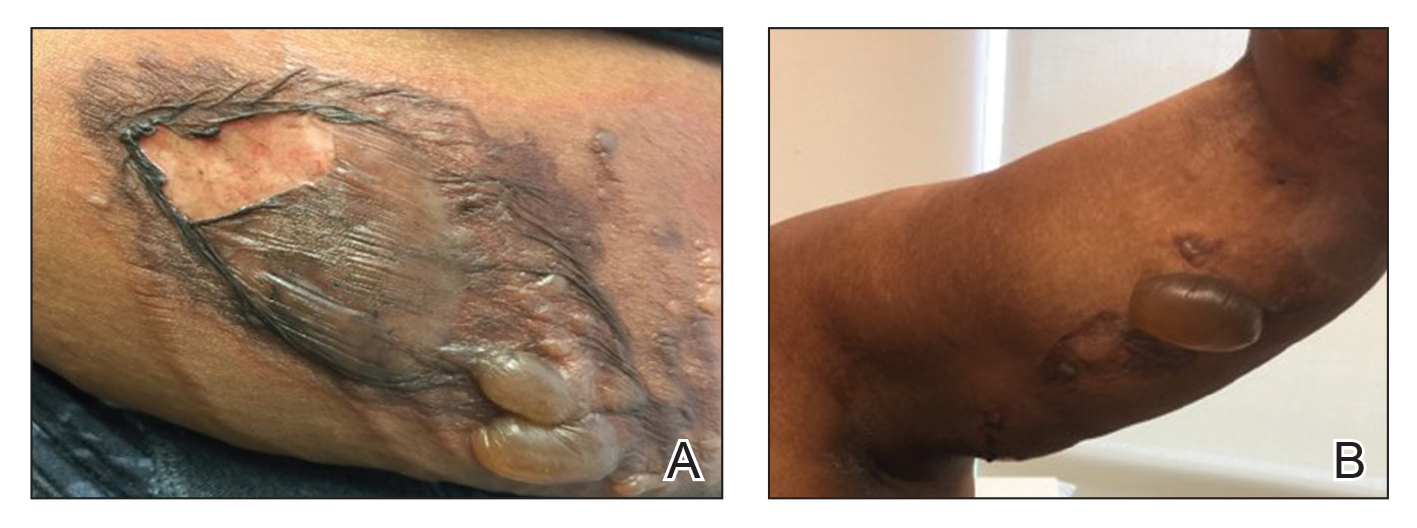

A 75-year-old white woman with history of morbid obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), unexplained weight loss of 70 lb over the last year, and polymyalgia rheumatica requiring chronic prednisone therapy presented with painful lesions on the thighs, buttocks, and right shoulder of 4 months’ duration. She had multiple hospital admissions preceding the onset of lesions for severe infections resulting in sepsis with hypotension, including Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase bacteremia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Physical examination revealed large well-demarcated ulcers and necrotic eschars with surrounding violaceous induration and stellate erythema on the anterior, medial, and posterior thighs and buttocks that were exquisitely tender (Figures 1 and 2).

Notable laboratory results included hypoalbuminemia (1.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5–5.0 g/dL]) with normal renal function, a corrected calcium level of 9.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL), a serum phosphorus level of 3.5 mg/dL (reference range, 2.3–4.7 mg/dL), a calcium-phosphate product of 27.3 mg2/dL2 (reference range, <55 mg2/dL2), and a parathyroid hormone level of 49.3 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL). Antinuclear antibodies were negative. A hypercoagulability evaluation showed normal protein C and S levels, negative lupus anticoagulant, and negative anticardiolipin antibodies.

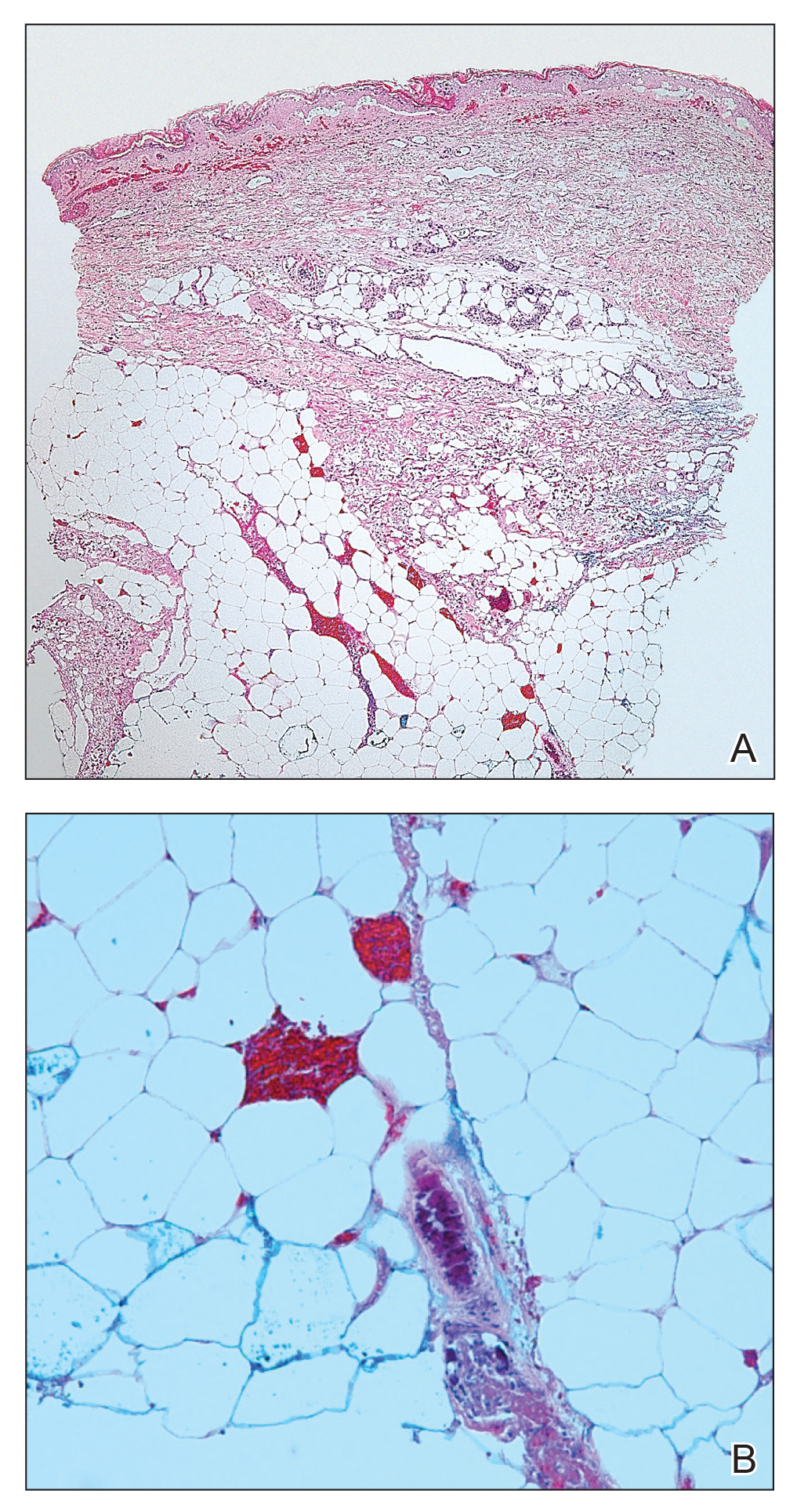

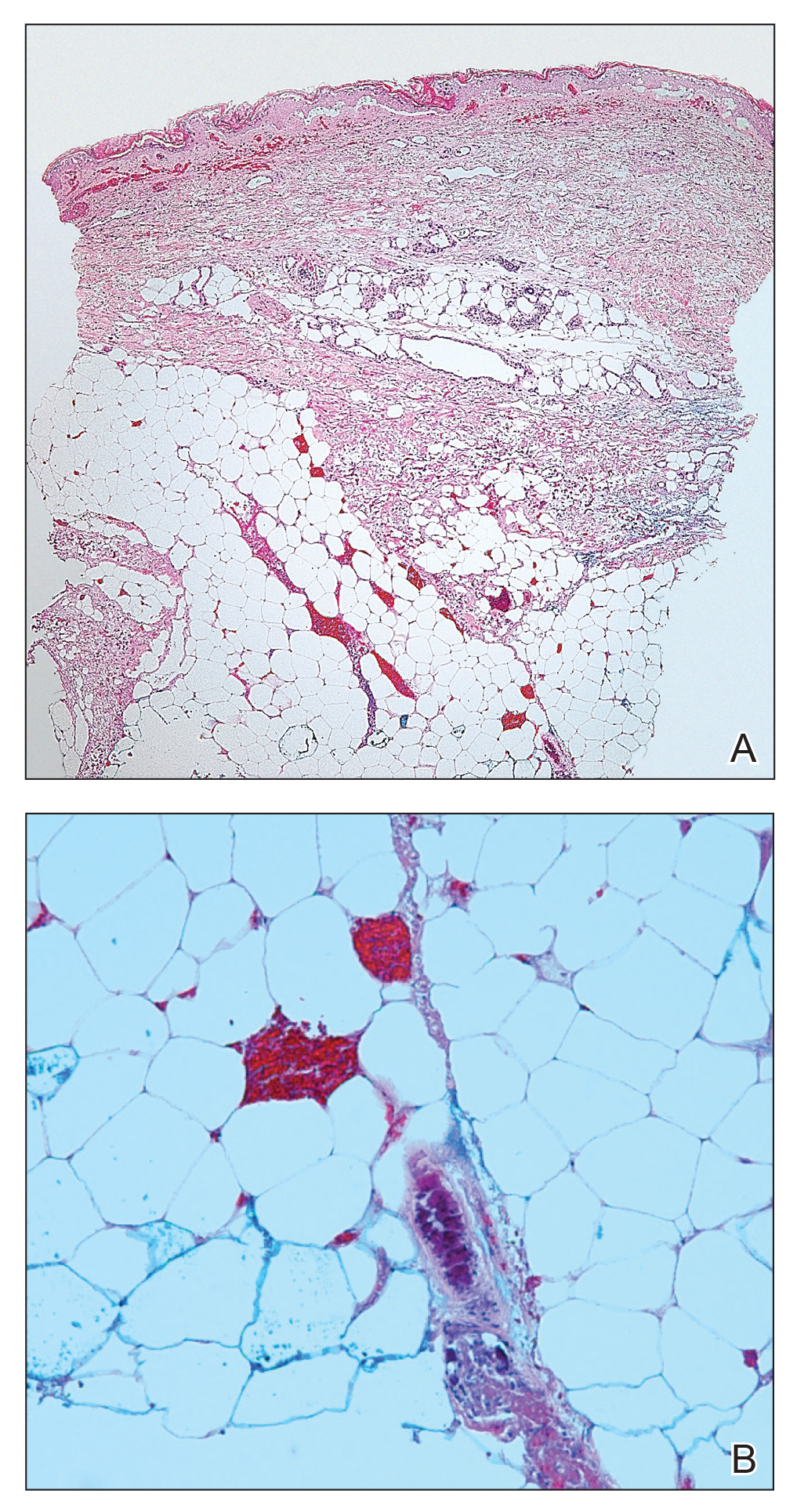

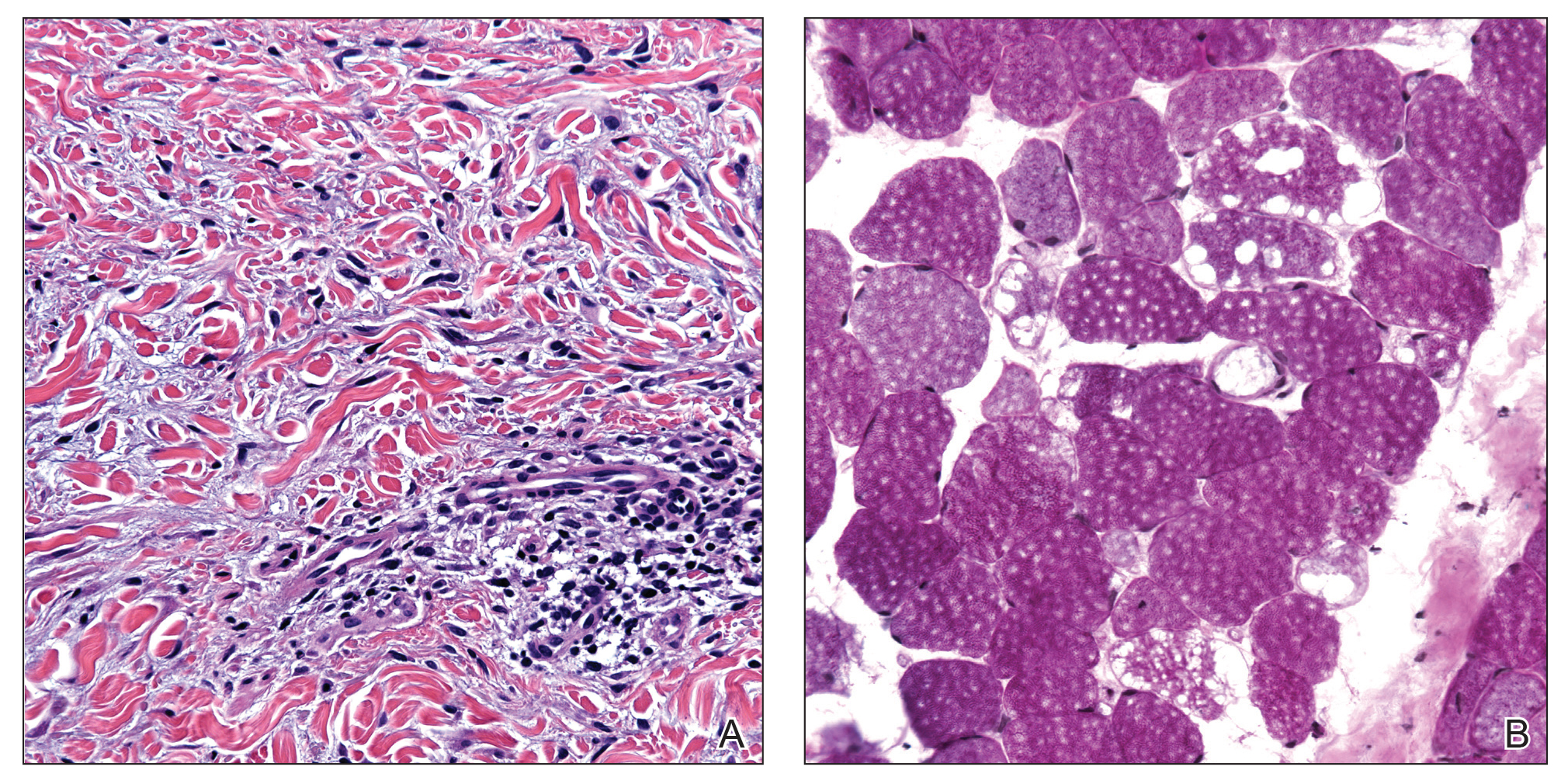

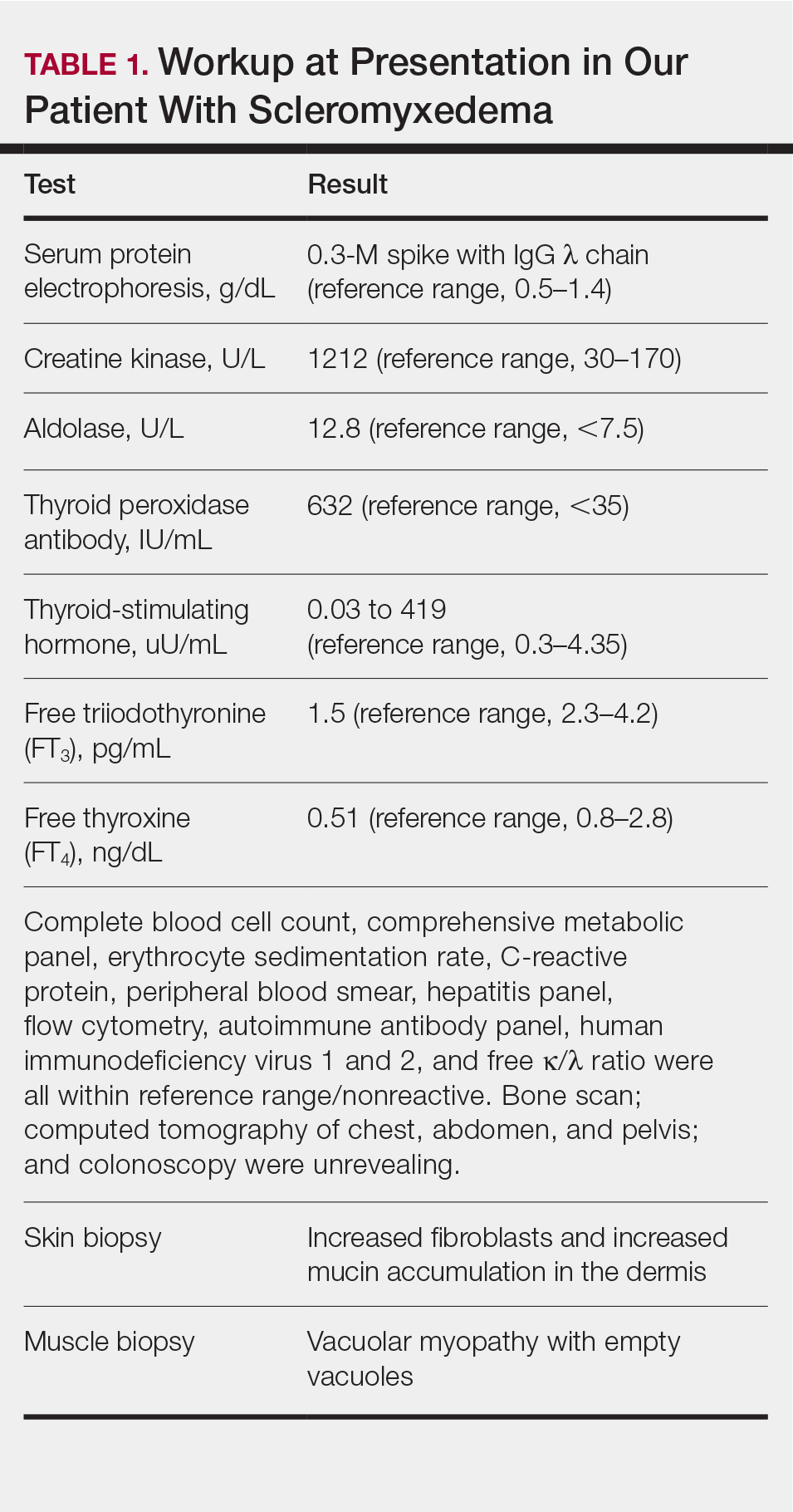

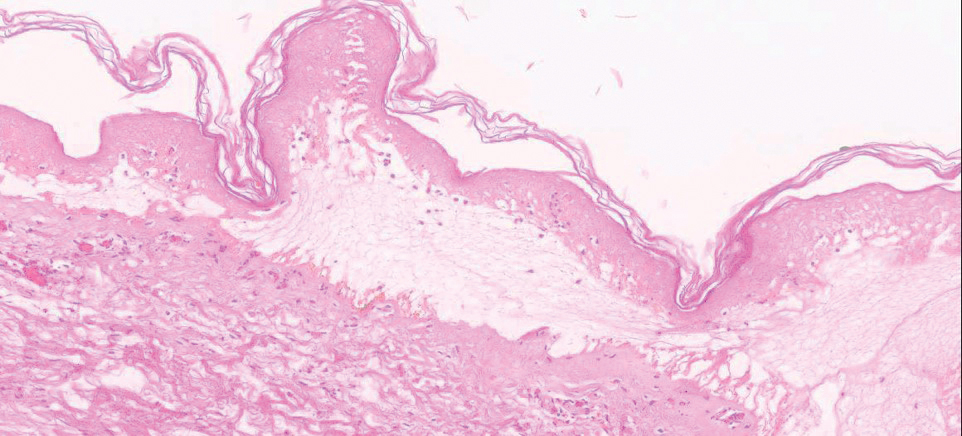

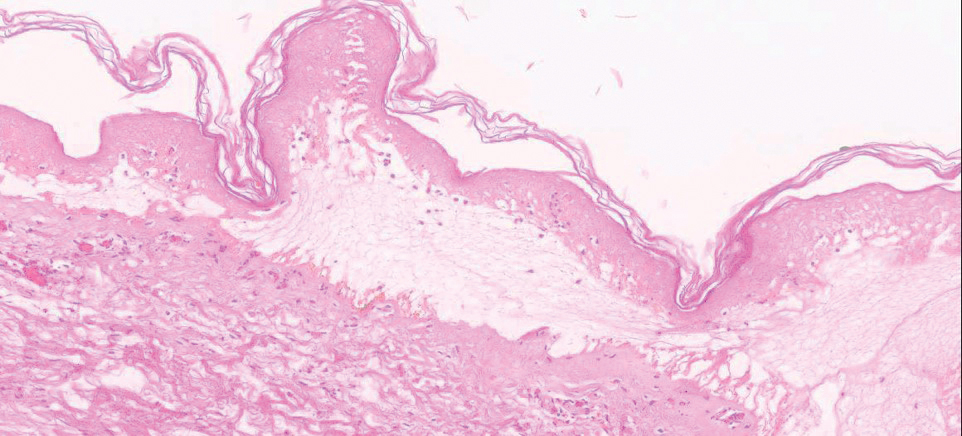

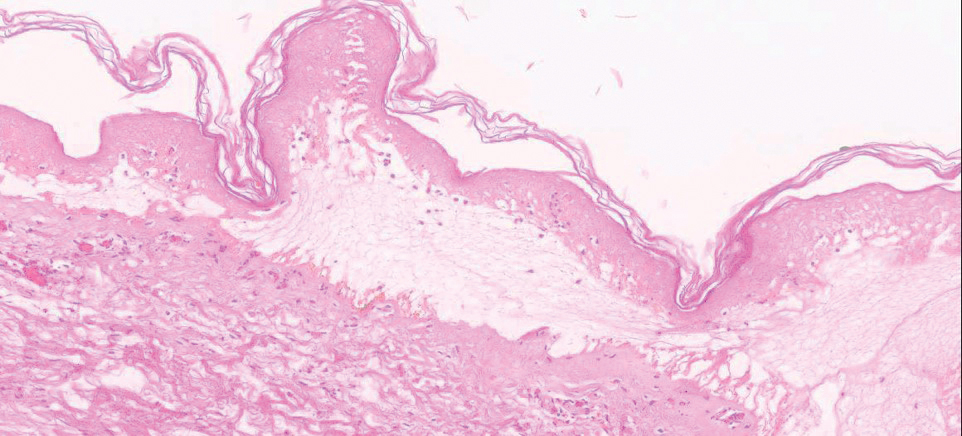

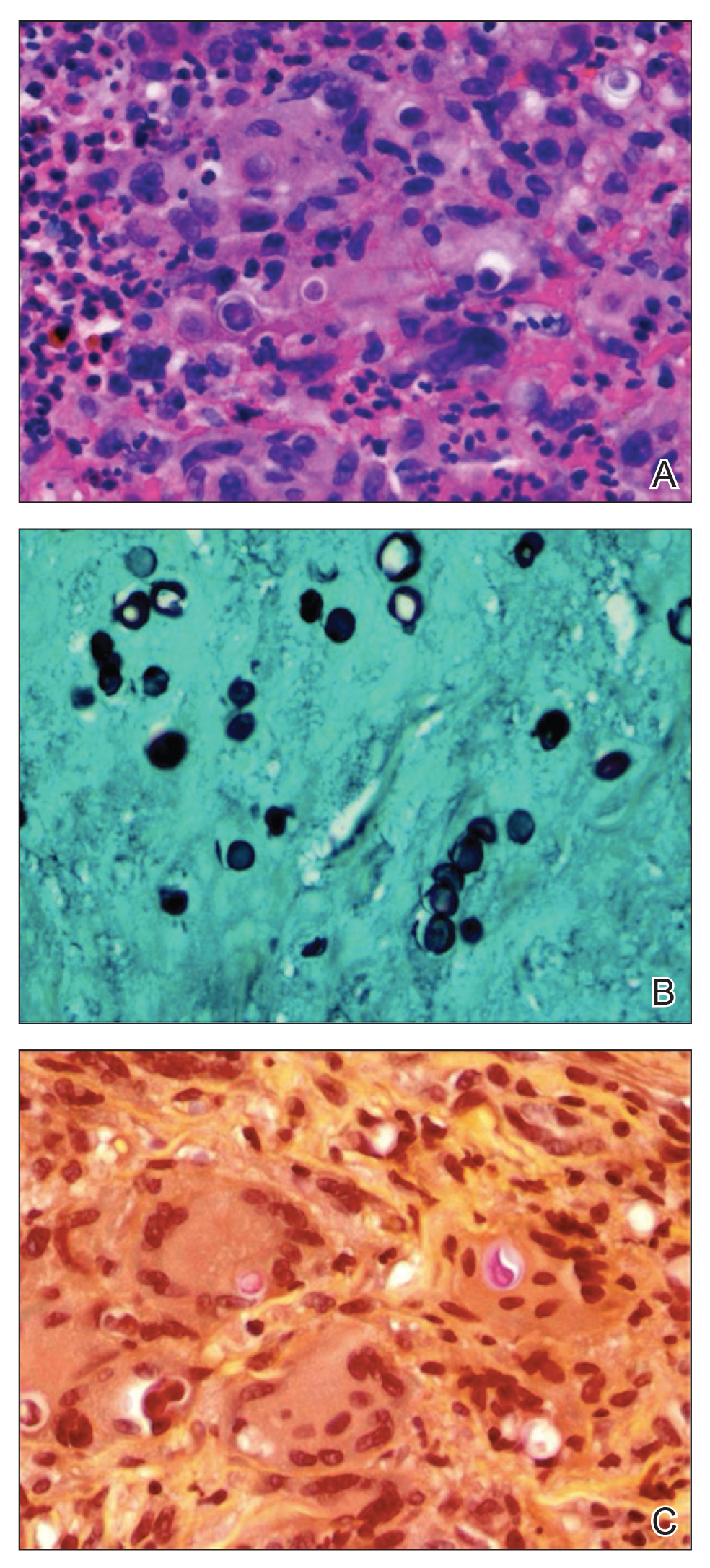

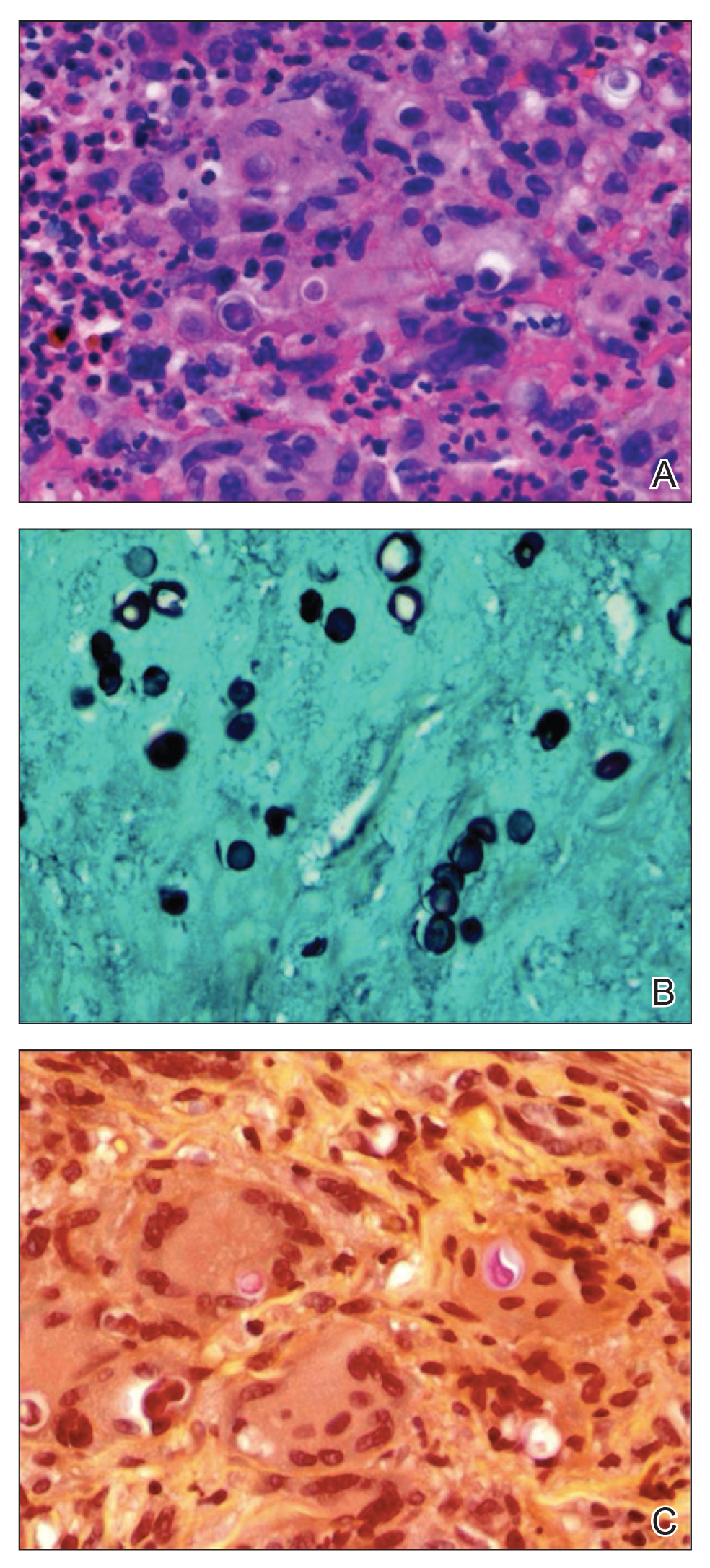

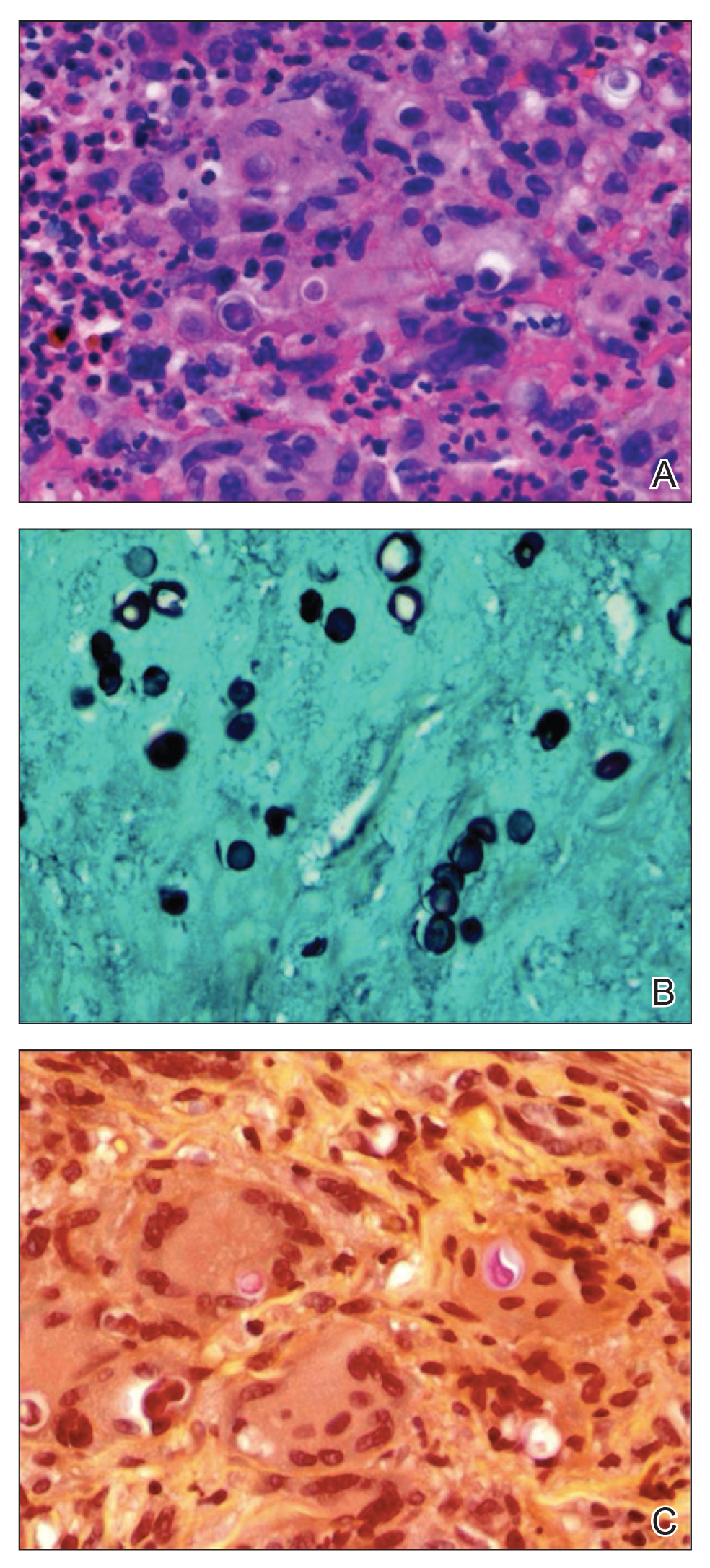

Telescoping punch biopsies of the indurated borders of the eschars showed prominent calcification of the small- and medium-sized vessels in the mid and deep dermis, intravascular thrombi, and necrosis of the epidermis and subcutaneous fat consistent with calciphylaxis (Figure 3).

After the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made, the patient was treated with intravenous sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and alendronate 70 mg weekly. Daily arterial blood gas studies did not detect metabolic acidosis during the patient’s sodium thiosulfate therapy. The wounds were debrided, and we attempted to slowly taper the patient off the oral prednisone. Unfortunately, her condition slowly deteriorated secondary to sepsis, resulting in septic shock. The patient died 3 weeks after the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made. At the time of diagnosis, the patient had a poor prognosis and notable risk for sepsis due to the large eschars on the thighs and abdomen as well as her relative immunosuppression due to chronic prednisone use.

Comment

Background on Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare but deadly disease that affects both ESRD patients receiving dialysis and patients without ESRD who have known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including female gender, white race, obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, underlying malignancy, protein C or S deficiency, corticosteroid use, warfarin use, diabetes, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6-9,11 Although the molecular pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not completely understood, it is believed to be caused by local deposition of calcium in the tunica media of small- to medium-sized arterioles and venules in the skin.12 This deposition leads to intimal proliferation and progressive narrowing of the vessels with resultant thrombosis, ischemia, and necrosis. The cutaneous manifestations and histopathology of calciphylaxis classically follow its pathogenesis. Calciphylaxis typically presents with livedo reticularis as vessels narrow and then progresses to purpura, bullae, necrosis, and eschar formation with the onset of acute thrombosis and ischemia. Histopathology is characterized by small- and medium-sized vessel calcification and thrombus, dermal necrosis, and septal panniculitis, though the histology can be highly variable.12 Unfortunately, the already poor prognosis for calciphylaxis worsens when lesions become either ulcerative or present on the proximal extremities and trunk.4,13 Sepsis is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis patients, affecting more than 50% of patients.2,3,14 The differential diagnoses for calciphylactic-appearing lesions include warfarin-induced skin necrosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pyoderma gangrenosum, cholesterol emboli, and various vasculitides and coagulopathies.

Risk Factors

Our case demonstrates the importance of risk factor minimization, trigger avoidance, and early intervention due to the high mortality rate of calciphylaxis. Selye et al15 coined the term calciphylaxis in 1961 based on experiments that induced calciphylaxis in rat models. Their research concluded that there were certain sensitizers (ie, risk factors) that predisposed patients to medial calcium deposition in blood vessels and other challengers (ie, triggers) that acted as inciting events to calcium deposition. Our patient presented with multiple known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), female gender, white race, hypoalbuminemia, and chronic corticosteroid use.16 In the presence of a milieu of risk factors, the patient’s rapid weight loss and episodes of hypotension likely were triggers for calciphylaxis.

Other case reports in the literature have suggested weight loss as a trigger for NUC. One morbidly obese patient with inactive rheumatoid arthritis had onset of calciphylaxis lesions after unintentional weight loss of approximately 50% body weight in 1 year17; however, the weight loss does not have to be drastic to trigger calciphylaxis. Another study of 16 patients with uremic calciphylaxis found that 7 of 16 (44%) patients lost 10 to 50 kg in the 6 months prior to calciphylaxis onset.14 One proposed mechanism by Munavalli et al10 is that elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases during catabolic weight loss states enhance the deposition of calcium into elastic fibers of small vessels. The authors found elevated serum levels of matrix metalloproteinases in their patients with NUC induced by rapid weight loss.10

A meta-analysis by Nigwekar et al3 found a history of prior corticosteroid use in 61% (22/36) of NUC cases reviewed. However, it is unclear whether it is the use of corticosteroids or chronic inflammation that is implicated in NUC pathogenesis. Chronic inflammation causes downregulation of anticalcification signaling pathways.18-20 The role of 2 vascular calcification inhibitors has been evaluated in the pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: fetuin-A and matrix gla protein (MGP).21 The activity of these proteins is decreased not only in calciphylaxis but also in other inflammatory states and chronic renal failure.18-20 One study found lower fetuin-A levels in 312 hemodialysis patients compared to healthy controls and an association between low fetuin-A levels and increased C-reactive protein levels.22 Reduced fetuin-A and MGP levels may be the result of several calciphylaxis risk factors. Warfarin is believed to trigger calciphylaxis via inhibition of gamma-carboxylation of MGP, which is necessary for its anticalcification activity.23 Hypoalbuminemia and alcoholic liver disease also are risk factors that may be explained by the fact that fetuin-A is synthesized in the liver.24 Therefore, liver disease results in decreased production of fetuin-A that is permissive to vascular calcification in calciphylaxis patients.

There have been other reports of calciphylaxis patients who were originally hospitalized due to hypotension, which may serve as a trigger for calciphylaxis onset.25 Because calciphylaxis lesions are more likely to occur in the fatty areas of the abdomen and proximal thighs where blood flow is slower, hypotension likely accentuates the slowing of blood flow and subsequent blood vessel calcification. This theory is supported by studies showing that established calciphylactic lesions worsen more quickly in the presence of systemic hypotension.26 One patient with ESRD and calciphylaxis of the breasts had consistent systolic blood pressure readings in the high 60s to low 70s between dialysis sessions.27 Due to this association, we recommend that patients with calciphylaxis have close blood pressure monitoring to aid in preventing disease progression.28

Management

Calciphylaxis treatment has not yet been standardized, as it is an uncommon disease whose pathogenesis is not fully understood. Current management strategies aim to normalize metabolic abnormalities such as hypercalcemia if they are present and remove inciting agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids.29 Other medical treatments that have been successfully used include sodium thiosulfate, oral steroids, and adjunctive bisphosphonates.29-31 Sodium thiosulfate is known to cause metabolic acidosis by generating thiosulfuric acid in vivo in patients with or without renal disease; therefore, patients on sodium thiosulfate therapy should be monitored for development of metabolic acidosis and treated with oral sodium bicarbonate or dialysis as needed.30,32 Wound care also is an important element of calciphylaxis treatment; however, the debridement of wounds is controversial. Some argue that dry intact eschars serve to protect against sepsis, which is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis.2,14,33 In contrast, a retrospective study of 63 calciphylaxis patients found a 1-year survival rate of 61.6% in 17 patients receiving wound debridement vs 27.4% in 46 patients who did not.2 The current consensus is that debridement should be considered on a case-by-case basis, factoring in the presence of wound infection, size of wounds, stability of eschars, and treatment goals of the patient.34 Future studies should be aimed at this issue, with special focus on how these factors and the decision to debride or not impact patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Calciphylaxis is a potentially fatal disease that impacts both patients with ESRD and those with nonuremic risk factors. The term calcific uremic arteriolopathy should be disregarded, as nonuremic causes are being reported with increased frequency in the literature. In such cases, patients often have multiple risk factors, including obesity, primary hyperparathyroidism, alcoholic liver disease, and underlying malignancy, among others. Certain triggers for onset of calciphylaxis should be avoided in at-risk patients, including the use of corticosteroids or warfarin; iron and albumin infusions; hypotension; and rapid weight loss. Our fatal case of NUC is a reminder to dermatologists treating at-risk patients to avoid these triggers and to keep calciphylaxis in the differential diagnosis when encountering early lesions such as livedo reticularis, as progression of these lesions has a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50% with the therapies being utilized at this time.

- Au S, Crawford RI. Three-dimensional analysis of a calciphylaxis plaque: clues to pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;47:53-57.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

- Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

- Angelis M, Wong LL, Myers SA, et al. Calciphylaxis in patients on hemodialysis: a prevalence study. Surgery. 1997;122:1083-1090.

- Chavel SM, Taraszka KS, Schaffer JV, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with acute, reversible renal failure in the setting of alcoholic cirrhosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:125-128.

- Bosler DS, Amin MB, Gulli F, et al. Unusual case of calciphylaxis associated with metastatic breast carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:400-403.

- Buxtorf K, Cerottini JP, Panizzon RG. Lower limb skin ulcerations, intravascular calcifications and sensorimotor polyneuropathy: calciphylaxis as part of a hyperparathyroidism? Dermatology. 1999;198:423-425.

- Brouns K, Verbeken E, Degreef H, et al. Fatal calciphylaxis in two patients with giant cell arteritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:836-840.

- Munavalli G, Reisenauer A, Moses M, et al. Weight loss-induced calciphylaxis: potential role of matrix metalloproteinases. J Dermatol. 2003;30:915-919.

- Bae GH, Nambudiri VE, Bach DQ, et al. Rapidly progressive nonuremic calciphylaxis in setting of warfarin. Am J Med. 2015;128:E19-E21.

- Essary LR, Wick MR. Cutaneous calciphylaxis. an underrecognized clinicopathologic entity. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:280-287.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:954-962.

- Coates T, Kirkland GS, Dymock RB, et al. Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:384-391.

- Selye H, Gentile G, Prioreschi P. Cutaneous molt induced by calciphylaxis in the rat. Science. 1961;134:1876-1877.

- Kalajian AH, Malhotra PS, Callen JP, et al. Calciphylaxis with normal renal and parathyroid function: not as rare as previously believed. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:451-458.

- Malabu U, Roberts L, Sangla K. Calciphylaxis in a morbidly obese woman with rheumatoid arthritis presenting with severe weight loss and vitamin D deficiency. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:104-108.

- Schäfer C, Heiss A, Schwarz A, et al. The serum protein alpha 2–Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:357-366.

- Cozzolino M, Galassi A, Biondi ML, et al. Serum fetuin-A levels link inflammation and cardiovascular calcification in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:423-429.

- Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386:78-81.

- Weenig RH. Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: Hans Selye to nuclear factor kappa-B. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:458-471.

- Ketteler M, Bongartz P, Westenfeld R, et al. Association of low fetuin-A (AHSG) concentrations in serum with cardiovascular mortality in patients on dialysis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2003;361:827-833.

- Wallin R, Cain D, Sane DC. Matrix Gla protein synthesis and gamma-carboxylation in the aortic vessel wall and proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells a cell system which resembles the system in bone cells. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1764-1767.

- Sowers KM, Hayden MR. Calcific uremic arteriolopathy: pathophysiology, reactive oxygen species and therapeutic approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3:109-121.

- Allegretti AS, Nazarian RM, Goverman J, et al. Calciphylaxis: a rare but fatal delayed complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:274-277.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial. 2002;15:172-186.

- Gupta D, Tadros R, Mazumdar A, et al. Breast lesions with intractable pain in end-stage renal disease: calciphylaxis with chronic hypotensive dermatopathy related watershed breast lesions. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:551-554.

- Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA, et al. Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:588-597.

- Jeong HS, Dominguez AR. Calciphylaxis: controversies in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351:217-227.

- Bourgeois P, De Haes P. Sodium thiosulfate as a treatment for calciphylaxis: a case series. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:520-524.

- Biswas A, Walsh NM, Tremaine R. A case of nonuremic calciphylaxis treated effectively with systemic corticosteroids. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:275-278.

- Selk N, Rodby, RA. Unexpectedly severe metabolic acidosis associated with sodium thiosulfate therapy in a patient with calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Semin Dial. 2011;24:85-88.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004:50:64-66, 68-70.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146.

Calciphylaxis, otherwise known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is characterized by calcification of the tunica media of the small- to medium-sized blood vessels of the dermis and subcutis, leading to ischemia and necrosis.1 It is a deadly disease with a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50%.2 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the most common risk factor for calciphylaxis, with a prevalence of 1% to 4% of hemodialysis patients with calciphylaxis in the United States.2-5 However, nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC) has been increasingly reported in the literature and has risk factors other than ESRD, including but not limited to obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, and underlying malignancy.3,6-9 Triggers for calciphylaxis in at-risk patients include use of corticosteroids or warfarin, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6,9-11 We report an unusual case of NUC that most likely was triggered by rapid weight loss and hypotension in a patient with multiple risk factors for calciphylaxis.

Case Report

A 75-year-old white woman with history of morbid obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), unexplained weight loss of 70 lb over the last year, and polymyalgia rheumatica requiring chronic prednisone therapy presented with painful lesions on the thighs, buttocks, and right shoulder of 4 months’ duration. She had multiple hospital admissions preceding the onset of lesions for severe infections resulting in sepsis with hypotension, including Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase bacteremia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Physical examination revealed large well-demarcated ulcers and necrotic eschars with surrounding violaceous induration and stellate erythema on the anterior, medial, and posterior thighs and buttocks that were exquisitely tender (Figures 1 and 2).

Notable laboratory results included hypoalbuminemia (1.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5–5.0 g/dL]) with normal renal function, a corrected calcium level of 9.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL), a serum phosphorus level of 3.5 mg/dL (reference range, 2.3–4.7 mg/dL), a calcium-phosphate product of 27.3 mg2/dL2 (reference range, <55 mg2/dL2), and a parathyroid hormone level of 49.3 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL). Antinuclear antibodies were negative. A hypercoagulability evaluation showed normal protein C and S levels, negative lupus anticoagulant, and negative anticardiolipin antibodies.

Telescoping punch biopsies of the indurated borders of the eschars showed prominent calcification of the small- and medium-sized vessels in the mid and deep dermis, intravascular thrombi, and necrosis of the epidermis and subcutaneous fat consistent with calciphylaxis (Figure 3).

After the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made, the patient was treated with intravenous sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and alendronate 70 mg weekly. Daily arterial blood gas studies did not detect metabolic acidosis during the patient’s sodium thiosulfate therapy. The wounds were debrided, and we attempted to slowly taper the patient off the oral prednisone. Unfortunately, her condition slowly deteriorated secondary to sepsis, resulting in septic shock. The patient died 3 weeks after the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made. At the time of diagnosis, the patient had a poor prognosis and notable risk for sepsis due to the large eschars on the thighs and abdomen as well as her relative immunosuppression due to chronic prednisone use.

Comment

Background on Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare but deadly disease that affects both ESRD patients receiving dialysis and patients without ESRD who have known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including female gender, white race, obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, underlying malignancy, protein C or S deficiency, corticosteroid use, warfarin use, diabetes, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6-9,11 Although the molecular pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not completely understood, it is believed to be caused by local deposition of calcium in the tunica media of small- to medium-sized arterioles and venules in the skin.12 This deposition leads to intimal proliferation and progressive narrowing of the vessels with resultant thrombosis, ischemia, and necrosis. The cutaneous manifestations and histopathology of calciphylaxis classically follow its pathogenesis. Calciphylaxis typically presents with livedo reticularis as vessels narrow and then progresses to purpura, bullae, necrosis, and eschar formation with the onset of acute thrombosis and ischemia. Histopathology is characterized by small- and medium-sized vessel calcification and thrombus, dermal necrosis, and septal panniculitis, though the histology can be highly variable.12 Unfortunately, the already poor prognosis for calciphylaxis worsens when lesions become either ulcerative or present on the proximal extremities and trunk.4,13 Sepsis is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis patients, affecting more than 50% of patients.2,3,14 The differential diagnoses for calciphylactic-appearing lesions include warfarin-induced skin necrosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pyoderma gangrenosum, cholesterol emboli, and various vasculitides and coagulopathies.

Risk Factors

Our case demonstrates the importance of risk factor minimization, trigger avoidance, and early intervention due to the high mortality rate of calciphylaxis. Selye et al15 coined the term calciphylaxis in 1961 based on experiments that induced calciphylaxis in rat models. Their research concluded that there were certain sensitizers (ie, risk factors) that predisposed patients to medial calcium deposition in blood vessels and other challengers (ie, triggers) that acted as inciting events to calcium deposition. Our patient presented with multiple known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), female gender, white race, hypoalbuminemia, and chronic corticosteroid use.16 In the presence of a milieu of risk factors, the patient’s rapid weight loss and episodes of hypotension likely were triggers for calciphylaxis.

Other case reports in the literature have suggested weight loss as a trigger for NUC. One morbidly obese patient with inactive rheumatoid arthritis had onset of calciphylaxis lesions after unintentional weight loss of approximately 50% body weight in 1 year17; however, the weight loss does not have to be drastic to trigger calciphylaxis. Another study of 16 patients with uremic calciphylaxis found that 7 of 16 (44%) patients lost 10 to 50 kg in the 6 months prior to calciphylaxis onset.14 One proposed mechanism by Munavalli et al10 is that elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases during catabolic weight loss states enhance the deposition of calcium into elastic fibers of small vessels. The authors found elevated serum levels of matrix metalloproteinases in their patients with NUC induced by rapid weight loss.10

A meta-analysis by Nigwekar et al3 found a history of prior corticosteroid use in 61% (22/36) of NUC cases reviewed. However, it is unclear whether it is the use of corticosteroids or chronic inflammation that is implicated in NUC pathogenesis. Chronic inflammation causes downregulation of anticalcification signaling pathways.18-20 The role of 2 vascular calcification inhibitors has been evaluated in the pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: fetuin-A and matrix gla protein (MGP).21 The activity of these proteins is decreased not only in calciphylaxis but also in other inflammatory states and chronic renal failure.18-20 One study found lower fetuin-A levels in 312 hemodialysis patients compared to healthy controls and an association between low fetuin-A levels and increased C-reactive protein levels.22 Reduced fetuin-A and MGP levels may be the result of several calciphylaxis risk factors. Warfarin is believed to trigger calciphylaxis via inhibition of gamma-carboxylation of MGP, which is necessary for its anticalcification activity.23 Hypoalbuminemia and alcoholic liver disease also are risk factors that may be explained by the fact that fetuin-A is synthesized in the liver.24 Therefore, liver disease results in decreased production of fetuin-A that is permissive to vascular calcification in calciphylaxis patients.

There have been other reports of calciphylaxis patients who were originally hospitalized due to hypotension, which may serve as a trigger for calciphylaxis onset.25 Because calciphylaxis lesions are more likely to occur in the fatty areas of the abdomen and proximal thighs where blood flow is slower, hypotension likely accentuates the slowing of blood flow and subsequent blood vessel calcification. This theory is supported by studies showing that established calciphylactic lesions worsen more quickly in the presence of systemic hypotension.26 One patient with ESRD and calciphylaxis of the breasts had consistent systolic blood pressure readings in the high 60s to low 70s between dialysis sessions.27 Due to this association, we recommend that patients with calciphylaxis have close blood pressure monitoring to aid in preventing disease progression.28

Management

Calciphylaxis treatment has not yet been standardized, as it is an uncommon disease whose pathogenesis is not fully understood. Current management strategies aim to normalize metabolic abnormalities such as hypercalcemia if they are present and remove inciting agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids.29 Other medical treatments that have been successfully used include sodium thiosulfate, oral steroids, and adjunctive bisphosphonates.29-31 Sodium thiosulfate is known to cause metabolic acidosis by generating thiosulfuric acid in vivo in patients with or without renal disease; therefore, patients on sodium thiosulfate therapy should be monitored for development of metabolic acidosis and treated with oral sodium bicarbonate or dialysis as needed.30,32 Wound care also is an important element of calciphylaxis treatment; however, the debridement of wounds is controversial. Some argue that dry intact eschars serve to protect against sepsis, which is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis.2,14,33 In contrast, a retrospective study of 63 calciphylaxis patients found a 1-year survival rate of 61.6% in 17 patients receiving wound debridement vs 27.4% in 46 patients who did not.2 The current consensus is that debridement should be considered on a case-by-case basis, factoring in the presence of wound infection, size of wounds, stability of eschars, and treatment goals of the patient.34 Future studies should be aimed at this issue, with special focus on how these factors and the decision to debride or not impact patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Calciphylaxis is a potentially fatal disease that impacts both patients with ESRD and those with nonuremic risk factors. The term calcific uremic arteriolopathy should be disregarded, as nonuremic causes are being reported with increased frequency in the literature. In such cases, patients often have multiple risk factors, including obesity, primary hyperparathyroidism, alcoholic liver disease, and underlying malignancy, among others. Certain triggers for onset of calciphylaxis should be avoided in at-risk patients, including the use of corticosteroids or warfarin; iron and albumin infusions; hypotension; and rapid weight loss. Our fatal case of NUC is a reminder to dermatologists treating at-risk patients to avoid these triggers and to keep calciphylaxis in the differential diagnosis when encountering early lesions such as livedo reticularis, as progression of these lesions has a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50% with the therapies being utilized at this time.

Calciphylaxis, otherwise known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is characterized by calcification of the tunica media of the small- to medium-sized blood vessels of the dermis and subcutis, leading to ischemia and necrosis.1 It is a deadly disease with a 1-year mortality rate of more than 50%.2 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the most common risk factor for calciphylaxis, with a prevalence of 1% to 4% of hemodialysis patients with calciphylaxis in the United States.2-5 However, nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC) has been increasingly reported in the literature and has risk factors other than ESRD, including but not limited to obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, and underlying malignancy.3,6-9 Triggers for calciphylaxis in at-risk patients include use of corticosteroids or warfarin, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6,9-11 We report an unusual case of NUC that most likely was triggered by rapid weight loss and hypotension in a patient with multiple risk factors for calciphylaxis.

Case Report

A 75-year-old white woman with history of morbid obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), unexplained weight loss of 70 lb over the last year, and polymyalgia rheumatica requiring chronic prednisone therapy presented with painful lesions on the thighs, buttocks, and right shoulder of 4 months’ duration. She had multiple hospital admissions preceding the onset of lesions for severe infections resulting in sepsis with hypotension, including Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase bacteremia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Physical examination revealed large well-demarcated ulcers and necrotic eschars with surrounding violaceous induration and stellate erythema on the anterior, medial, and posterior thighs and buttocks that were exquisitely tender (Figures 1 and 2).

Notable laboratory results included hypoalbuminemia (1.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5–5.0 g/dL]) with normal renal function, a corrected calcium level of 9.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL), a serum phosphorus level of 3.5 mg/dL (reference range, 2.3–4.7 mg/dL), a calcium-phosphate product of 27.3 mg2/dL2 (reference range, <55 mg2/dL2), and a parathyroid hormone level of 49.3 pg/mL (reference range, 10–65 pg/mL). Antinuclear antibodies were negative. A hypercoagulability evaluation showed normal protein C and S levels, negative lupus anticoagulant, and negative anticardiolipin antibodies.

Telescoping punch biopsies of the indurated borders of the eschars showed prominent calcification of the small- and medium-sized vessels in the mid and deep dermis, intravascular thrombi, and necrosis of the epidermis and subcutaneous fat consistent with calciphylaxis (Figure 3).

After the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made, the patient was treated with intravenous sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and alendronate 70 mg weekly. Daily arterial blood gas studies did not detect metabolic acidosis during the patient’s sodium thiosulfate therapy. The wounds were debrided, and we attempted to slowly taper the patient off the oral prednisone. Unfortunately, her condition slowly deteriorated secondary to sepsis, resulting in septic shock. The patient died 3 weeks after the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made. At the time of diagnosis, the patient had a poor prognosis and notable risk for sepsis due to the large eschars on the thighs and abdomen as well as her relative immunosuppression due to chronic prednisone use.

Comment

Background on Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is a rare but deadly disease that affects both ESRD patients receiving dialysis and patients without ESRD who have known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including female gender, white race, obesity, alcoholic liver disease, primary hyperparathyroidism, connective tissue disease, underlying malignancy, protein C or S deficiency, corticosteroid use, warfarin use, diabetes, iron or albumin infusions, and rapid weight loss.3,6-9,11 Although the molecular pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not completely understood, it is believed to be caused by local deposition of calcium in the tunica media of small- to medium-sized arterioles and venules in the skin.12 This deposition leads to intimal proliferation and progressive narrowing of the vessels with resultant thrombosis, ischemia, and necrosis. The cutaneous manifestations and histopathology of calciphylaxis classically follow its pathogenesis. Calciphylaxis typically presents with livedo reticularis as vessels narrow and then progresses to purpura, bullae, necrosis, and eschar formation with the onset of acute thrombosis and ischemia. Histopathology is characterized by small- and medium-sized vessel calcification and thrombus, dermal necrosis, and septal panniculitis, though the histology can be highly variable.12 Unfortunately, the already poor prognosis for calciphylaxis worsens when lesions become either ulcerative or present on the proximal extremities and trunk.4,13 Sepsis is the leading cause of death in calciphylaxis patients, affecting more than 50% of patients.2,3,14 The differential diagnoses for calciphylactic-appearing lesions include warfarin-induced skin necrosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pyoderma gangrenosum, cholesterol emboli, and various vasculitides and coagulopathies.

Risk Factors

Our case demonstrates the importance of risk factor minimization, trigger avoidance, and early intervention due to the high mortality rate of calciphylaxis. Selye et al15 coined the term calciphylaxis in 1961 based on experiments that induced calciphylaxis in rat models. Their research concluded that there were certain sensitizers (ie, risk factors) that predisposed patients to medial calcium deposition in blood vessels and other challengers (ie, triggers) that acted as inciting events to calcium deposition. Our patient presented with multiple known risk factors for calciphylaxis, including obesity (body mass index, 40 kg/m2), female gender, white race, hypoalbuminemia, and chronic corticosteroid use.16 In the presence of a milieu of risk factors, the patient’s rapid weight loss and episodes of hypotension likely were triggers for calciphylaxis.

Other case reports in the literature have suggested weight loss as a trigger for NUC. One morbidly obese patient with inactive rheumatoid arthritis had onset of calciphylaxis lesions after unintentional weight loss of approximately 50% body weight in 1 year17; however, the weight loss does not have to be drastic to trigger calciphylaxis. Another study of 16 patients with uremic calciphylaxis found that 7 of 16 (44%) patients lost 10 to 50 kg in the 6 months prior to calciphylaxis onset.14 One proposed mechanism by Munavalli et al10 is that elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases during catabolic weight loss states enhance the deposition of calcium into elastic fibers of small vessels. The authors found elevated serum levels of matrix metalloproteinases in their patients with NUC induced by rapid weight loss.10