User login

Dupilumab-Induced Facial Flushing After Alcohol Consumption

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

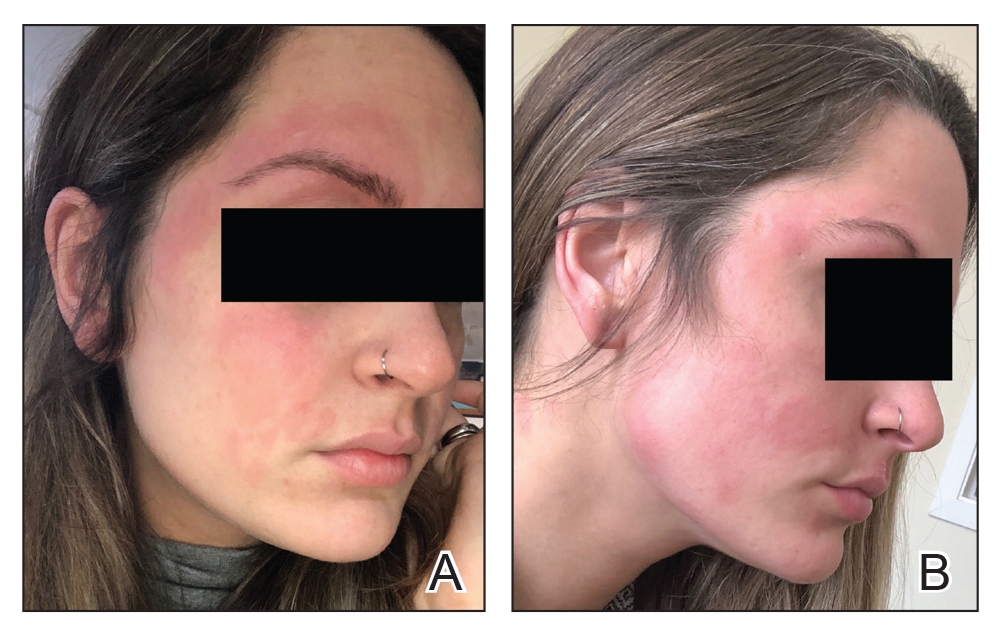

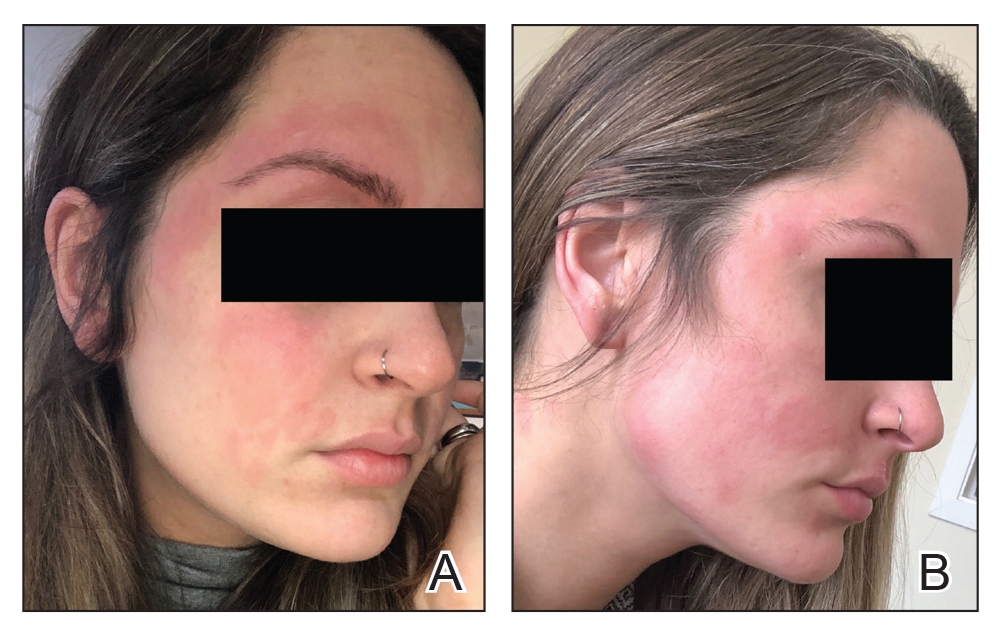

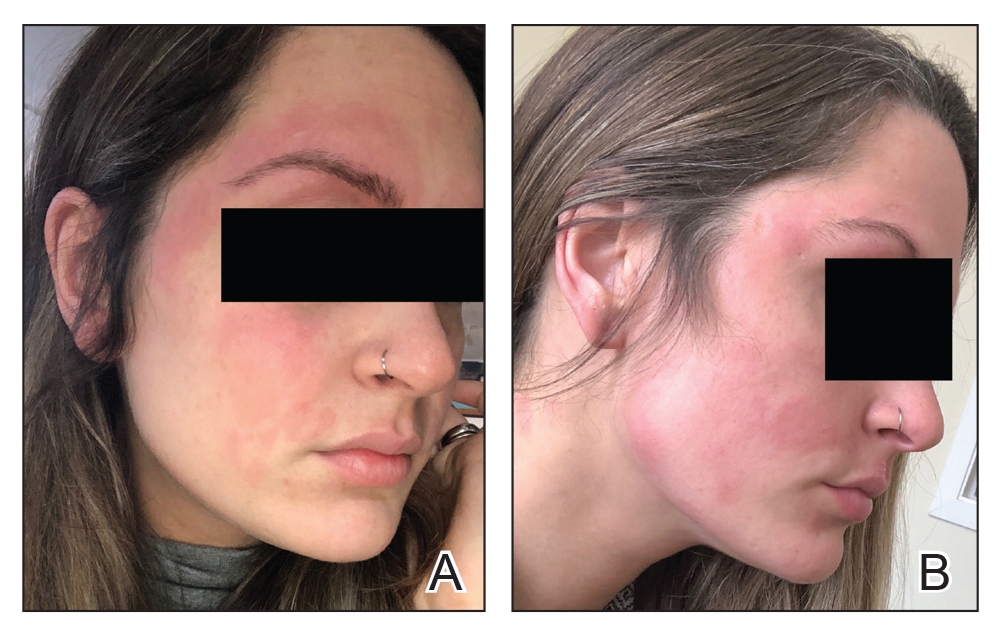

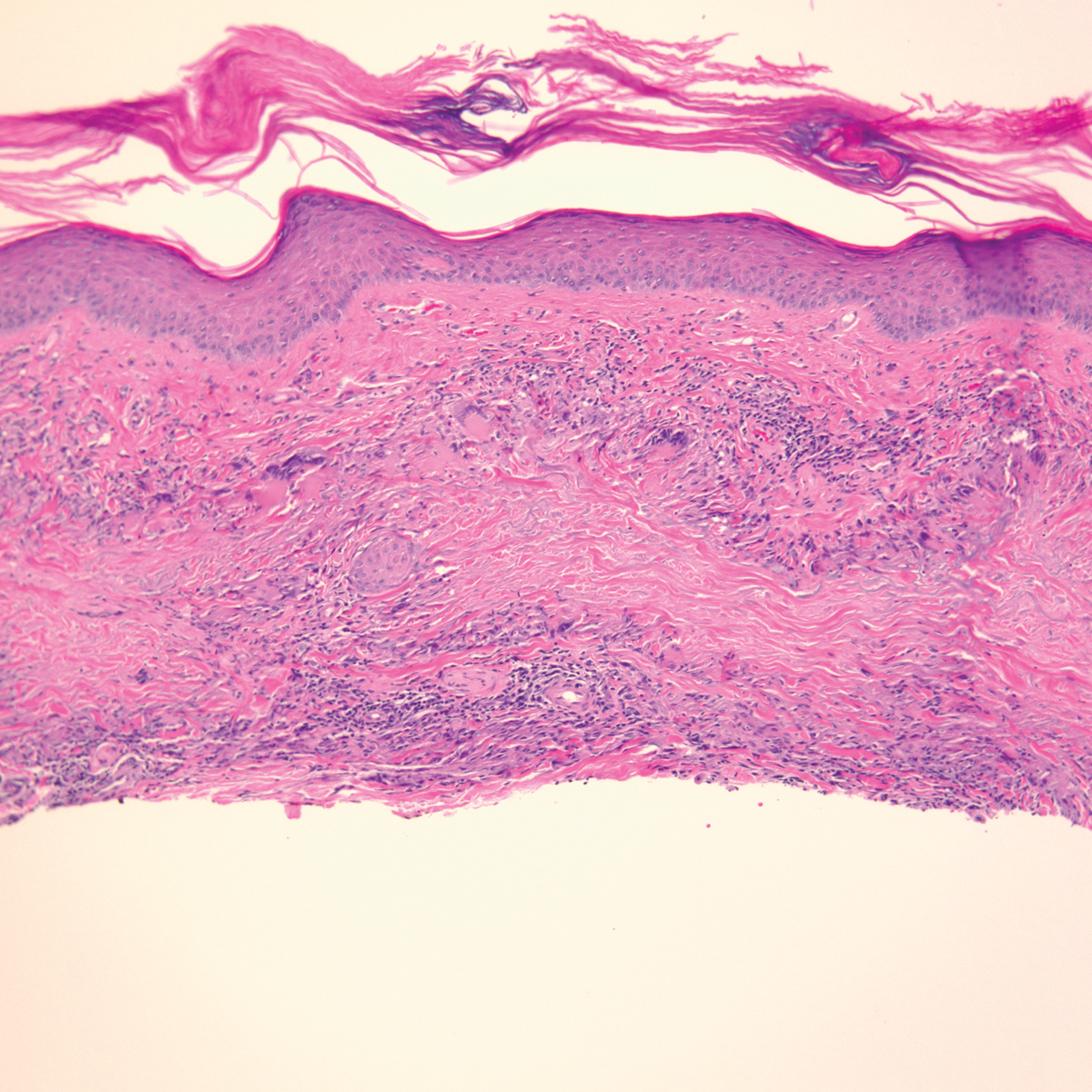

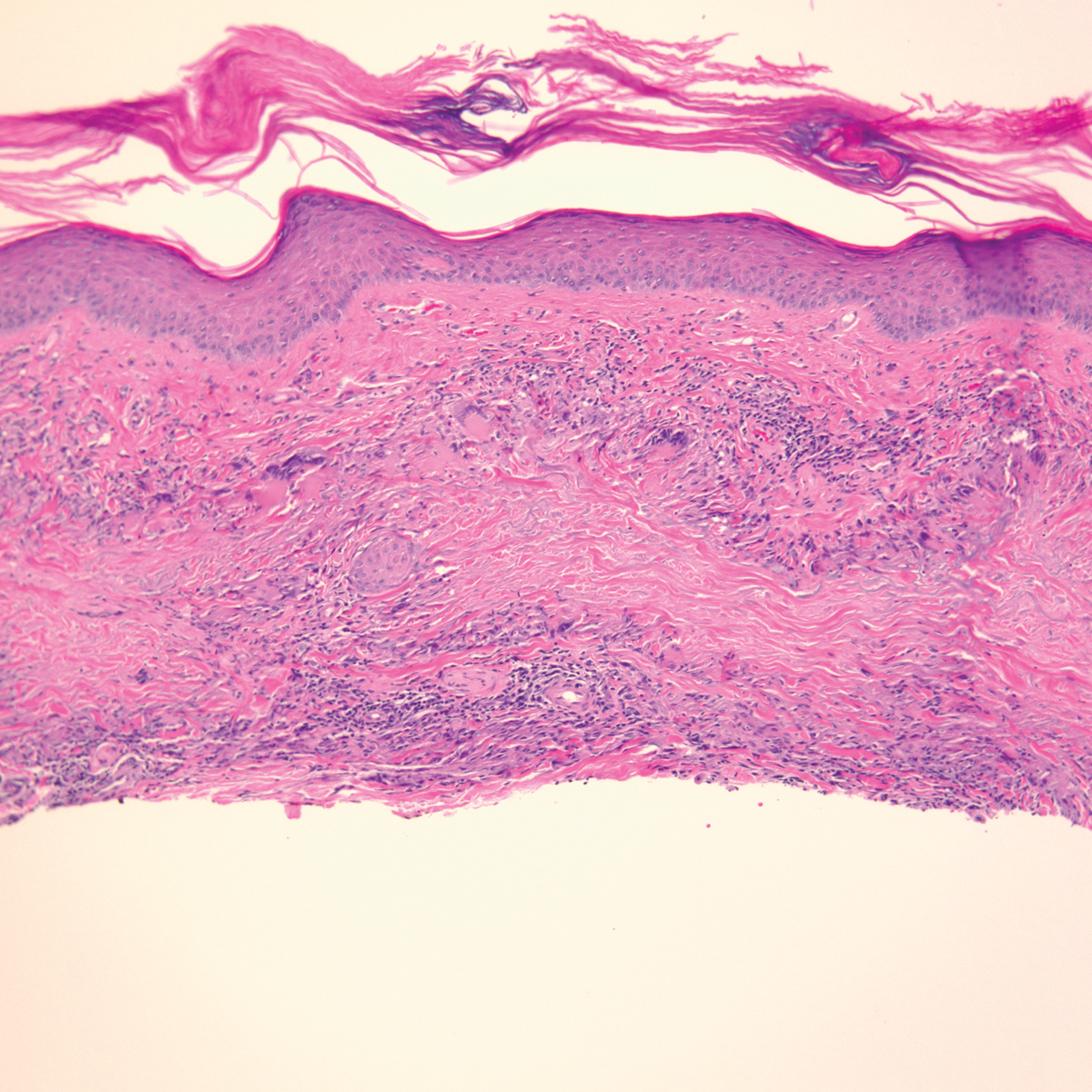

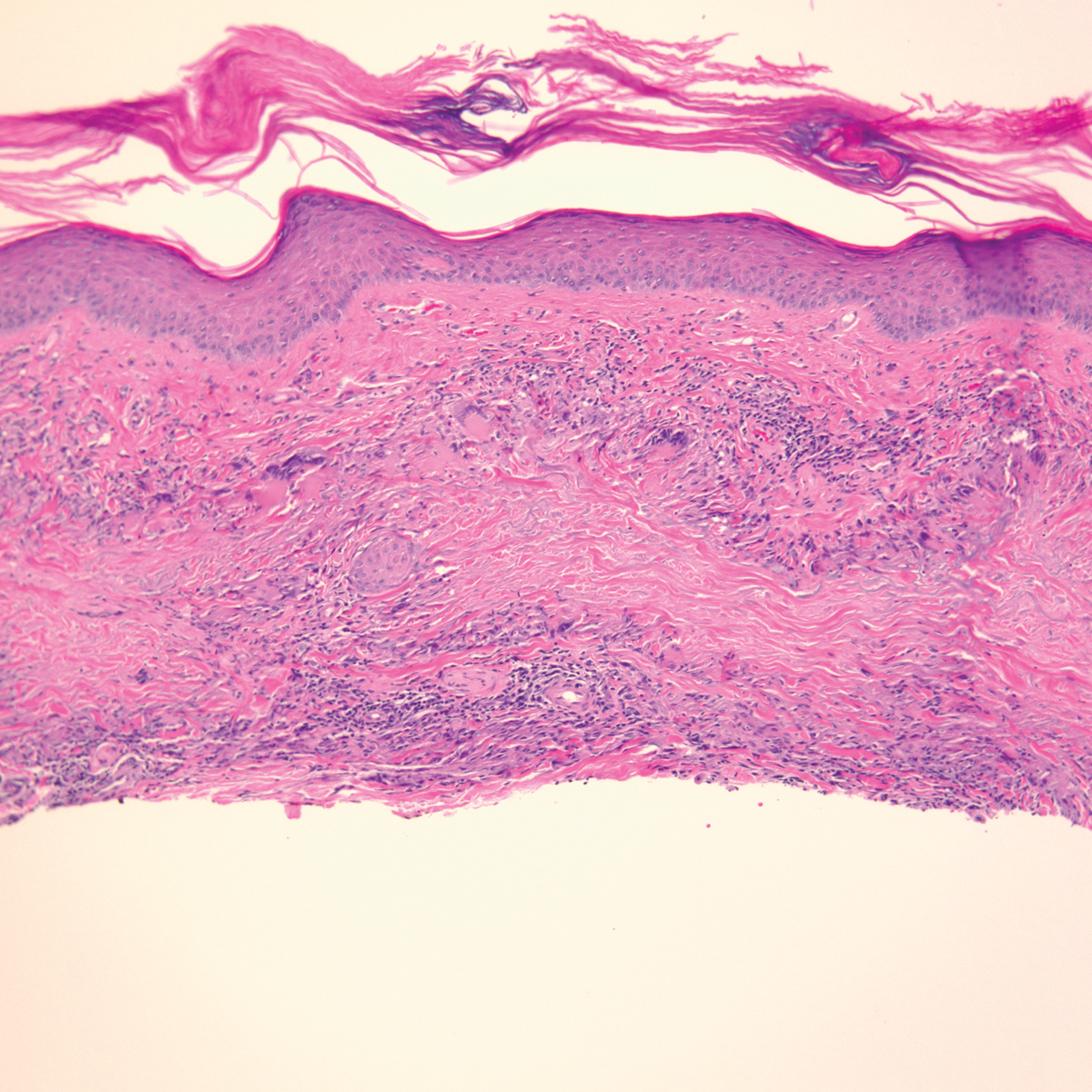

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

Practice Points

- Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits the action of IL-4 and IL-13. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

- Facial flushing after alcohol consumption may be an emerging side effect of dupilumab.

- Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Myasthenic Crisis After Recurrent COVID-19 Infection

A patient with myasthenia gravis who survived 2 COVID-19 infections required plasmapheresis to recover from an acute crisis.

COVID-19 is still in the early stages of understanding, although it is known to be complicated by individual patient comorbidities. The management and treatment of COVID-19 continues to quickly evolve as more is discovered regarding the virus. Multiple treatments have been preliminarily tested and used under a Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) determination. The long-term success of these therapies, however, is yet to be determined. Additionally, if a patient has a second clinical presentation for COVID-19, it is not known whether this represents latency with subsequent reactivation from the previous infection or a second de novo infection. The uncertainty calls into question the duration of immunity, if any, following a primary infection.

COVID-19 management becomes more complicated when patients have complex medical conditions, such as myasthenia gravis (MG). This autoimmune neuromuscular disorder can present with varying weakness, and many patients are on immunomodulator medications. The weakness can worsen into a myasthenic crisis (MC), resulting in profound weakness of the respiratory muscles. Therefore, patients with MG are at increased risk for COVID-19 and may have a more complicated course when infected.

Our patient with MG presented for severe COVID-19 symptoms twice and later developed MC. He received 2 treatment modalities available under an EUA (remdesivir and convalescent plasma) for COVID-19, resulting in symptom resolution and a negative polymerize chain reaction (PCR) test result for the virus. However, after receiving his typical maintenance therapy of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) for his MG, he again developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19 and tested positive. After recovering from the second episode of COVID-19, the patient went into MC requiring plasmapheresis.

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old male, US Army veteran presented to Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center emergency department (ED) 6 days after testing positive for COVID-19, with worsening sputum, cough, congestion, dyspnea, and fever. Due to his MG, the patient had a home oxygen monitor and reported that his oxygenation saturation dropped below 90% with minimal exertion. His medical history was significant for MG, status postthymectomy and radiation treatment, left hemidiaphragm paralysis secondary to phrenic nerve injury, and corticosteroid-induced insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. His current home medications included pyridostigmine 60 mg 3 times a day, mycophenolate (MMF) 1500 mg twice daily, IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) every 3 weeks, insulin aspart up to 16 U per meal, insulin glargine 30 U twice a day, dulaglutide 0.75 mg every week, and metformin 1000 mg twice daily.

On initial examination, the patient’s heart rate (HR) was 111 beats/min, respiratory rate (RR), 22 breaths/min, blood pressure (BP), 138/88 mm Hg, temperature, 100.9 oF, and his initial pulse oximetry, 91% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was tachypneic, though without other signs of respiratory distress. Lung auscultation revealed no adventitial lung sounds. His cardiac examination was notable only for tachycardia. His neurologic examination demonstrated intact cranial nerves, with 5 out of 5 (scale 1 to 5) strength throughout the upper and lower extremities, sensation was intact to light touch, and he had normal cerebellar function. The rest of the examination was normal.

Initial laboratory investigation was notable for a white blood cell count of 14.15x103 cells/mcL with 84% neutrophils, and 6% lymphocytes. Additional tests revealed a C-reactive protein (CRP) level, 17.97 mg/dL (reference range, 0-0.5 mg/dL), ferritin level, 647 ng/mL (reference range, 22-274 ng/mL), d-dimer, 0.64 mcg/mL (reference range, 0-0.47mcg/mL), and a repeated positive COVID-19 PCR test. A portable chest X-ray showed bibasilar opacities (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). In the ICU, the patient received 1 U of convalescent plasma (CP) and started on a course of IV remdesivir 100 mg/d consistent with the EUA. He also received a 5-day course of ceftriaxone and azithromycin for possible community acquired pneumonia (CAP). As part of the patient’s MG maintenance medications, he received IVIG 4 g while in the ICU. Throughout his ICU stay, he required supplemental nasal cannula oxygenation to maintain his oxygen saturation > 93%. After 8 days in the ICU, his oxygen requirements decreased, and the patient was transferred out of the ICU and remdesivir was discontinued. On hospital day 10, a repeat COVID-19 PCR test was negative, inflammatory markers returned to within normal limits, and a repeat chest X-ray showed improvement from admission (Figure 2). Having recovered significantly, he was discharged home.

Three weeks later, the patient again presented to the MTF with 3 days of dyspnea, cough, fever, nausea, and vomiting. One day before symptom onset, he had received his maintenance IVIG infusion. The patient reported that his home oxygen saturation was 82% with minimal exertion. On ED presentation his HR was 107 beats/min, RR, 28 breaths/min, temperature, 98.1 oF, BP 118/71 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation, 92% on 2L nasal cannula. His examination was most notable for tachypnea with accessory muscle use. At this time, his neurologic examination was unchanged from prior admission with grossly intact cranial nerves and symmetric 5 of 5 motor strength in all extremities.

At this second ED visit, laboratory results demonstrated a CRP of 3.44 mg/dL, ferritin 2019 ng/mL, d-dimer, 3.39 mcg/mL, and a positive COVID-19 PCR result. His chest X-ray demonstrated new peripheral opacities compared with the X-ray at discharge (Figure 3). He required ICU admission again for his COVID-19 symptoms.

During his ICU course he continued to require supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, though never required intubation. This second admission, he was again treated empirically for CAP with levofloxacin 750 mg daily for 5 days. He was discharged after 14 days with symptom resolution and down trending of inflammatory markers, though he was not retested for COVID-19.

Four days after his second discharge, he presented to the ED for a third time with diffuse weakness, dysphagia, and dysarthria of 1 day. His HR was 87/beats/min; RR, 17 breaths/min; temperature, 98.7 oF; BP, 144/81 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 98% on room air. His examination was significant for slurred speech, bilateral ptosis, 3 of 5 strength in bilateral finger flexion/abduction, wrist extension, knee and ankle flexion/extension; 4 of 5 strength in bilateral proximal muscle testing of deltoid, and hip; normal sensation, cerebellar function and reflexes. His negative inspiratory force (NIF) maximal effort was −30 cmH2O. He was determined to be in MC without evidence of COIVD-19 symptoms, and laboratory results were within normal limits, including a negative COVID-19 PCR. As he received IVIG as maintenance therapy, plasmapheresis was recommended to treat his MC, which required transfer to an outside civilian facility.

At the outside hospital, the patient underwent 5 rounds of plasmapheresis over 10 days. By the third treatment his strength had returned with resolution of the bulbar symptoms and no supplemental oxygen requirements. The patient was discharged and continued his original dosages of MMF and pyridostigmine. At 3 months, he remained asymptomatic from a COVID-19 standpoint and stable from a MG standpoint.

Discussion

Reinfection with the COVID-19 has been continuously debated with alternative explanations suggested for a positive test after a previous negative PCR test in the setting of symptom resolution.1,2 Proposed causes include dynamic PCR results due to prolonged viral shedding and inaccurate or poorly sensitive tests. The repeat positive cases in these scenarios, however, occurred in asymptomatic patients.1,2 COVID-19 shedding averages 20 to 22 days after symptom onset but has been seen up to 36 days after symptom resolution.2,3 This would suggest that fluctuating results during the immediate postsymptom period may be due to variations in viral shedding load and or sampling error—especially in asymptomatic patients. On the other hand, patients who experience return of symptoms days to weeks after previous convalescence leave clinicians wondering whether this represents clinical latency with reactivation or COVID-19 reinfection. A separate case of initial COVID-19 in a patient that had subsequent clinical recovery with a negative PCR developed recurrent respiratory symptoms and had a positive PCR test only 10 days later, further highlighting the reinfection vs reactivation issue of COVID-19.2 Further understanding of this issue may have implications on the extent of natural immunity following primary infection; potential vaccine dosage schedules; and global public health policies.

Although reactivation may be plausible given his immunomodulatory therapy, our patient’s second COVID-19 symptoms started 40 days after the initial symptoms, and 26 days after the initial course resolution; previous cases of return of severe symptoms occurred between 3 and 6 days.1 Given our patient’s time course between resolution and return of symptoms, if latency is the mechanism at play, this case demonstrates an exceptionally longer latency period than the ones that have been reported. Additionally, if latency is an issue in COVID-19, using remdesivir as a treatment further complicates the understanding of this disease.

Remdesivir, a nucleoside analogue antiviral, was shown to benefit recovery in patients with severe symptoms in the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial-1 study.4 Our patient had originally been placed on a 10-day course; however, on treatment day 8, his symptoms resolved and the remdesivir was discontinued. This is a similar finding to half the patients in the 10-day arm of the study by McCreary and colleagues.5 Although our patient was asymptomatic 4 weeks after the start of remdesivir, consistent with the majority of patients in the McCreary 10-day study arm, further comparison of the presented patient is limited due to study length and follow-up considerations.5 No previous data exist on reactivation, reinfection, or long-term mortality after being treated with remdesivir for COVID-19 infection.

IVIG is being studied in the treatment of COVID-19 and bears consideration as it relates to our patient. There is no evidence that IVIG used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases increases the risk of infection compared with that of other medications used in the treatment of such diseases. Furthermore, the current guidance from the MG expert panel does not suggest that IVIG increases the risk of contracting COVID-19 aside from the risks of exposure to hospital infrastructure.6 Yet the guidance does not discuss the use of IVIG for MG in patients who are already symptomatic from COVID-19 or for patients recovering from the clinical disease or does it discuss a possible compounding risk of thromboembolic events associated with IVIG and COVID-19.6,7 Our patient received his maintenance IVIG during his first admission without any worsening of symptoms or increased oxygen requirements. The day following our patient’s next scheduled IVIG infusion—while asymptomatic—he again developed respiratory symptoms; this could suggest that IVIG did not contribute to his second clinical course nor protect against.

CP is a treatment modality that has been used and studied in previous infectious outbreaks such as the first severe acute respiratory syndrome, and the H1N1 influenza virus.8 Current data on CP for COVID-19 are limited, but early descriptive studies have shown a benefit in improvement of symptoms 5 days sooner in those requiring supplemental oxygen, but no benefit for those requiring mechanical ventilation.9 Like patients that benefitted in these studies, our patient received CP early, 6 days after first testing positive and onset of symptoms. This patient’s reinfection or return of symptoms draws into question the hindrance or even prevention of long-term immunity from administration of CP.

COVID-19 presents many challenges when managing this patient’s coexisting MG, especially as the patient was already being treated with immunosuppressing therapies. The guidance does recommend continuation of standard MG therapies during hospitalizations, including immunosuppression medications such as MMF.6 Immunosuppression is associated with worsened severity of COVID-19 symptoms, although no relation exists to degree of immunosuppression and severity.7,10 To the best of our knowledge there has been no case report of reinfection or reactivation of COVID-19 associated with immunosuppressive agents used in the treatment of MG.

Our patient also was taking pyridostigmine for the treatment of his MG. There is no evidence this medication increases the risk of infection; but the cholinergic activity can increase bronchial secretions, which could theoretically worsen the COVID-19 respiratory symptoms.6,11 During both ICU admissions, our patient continued pyridostigmine use, observing complete return to baseline after discharge. Given the possible association with worsened respiratory outcomes after the second ICU admission, the balance between managing MG symptoms and COVID-19 symptoms needs further examination.

The patient was in MC during his third presentation to the ED. Although respiratory symptoms may be difficult to differentiate from COVID-19, the additional neurologic symptoms seen in this patient allowed for quick determination of the need for MC treatment. There are many potential etiologies contributing to the development of the MC presented here, and it was likely due to multifactorial precipitants. A common cause of MC is viral upper respiratory infections, further challenging the care of these patients during this pandemic.12 Many medications have been cited as causing a MC, 2 of which our patient received during admission for COVID-19: azithromycin and levoquin.12 Although the patient did not receive hydroxychloroquine, which was still being considered as an appropriate COVID-19 treatment at the time, it also is a drug known for precipitating MC and its use scrutinized in patients with MG.12

A key aspect to diagnosing and guiding therapies in myasthenic crisis in addition to the clinical symptoms of acute weakness is respiratory assessment through the nonaerosolizing NIF test.12 Our patient’s NIF measured < 30 cmH2O when in MC, while the reference range is < 75 cmH2O, and for mechanical ventilation is recommended at 20 cmH2O. Although the patient was maintaining O2 saturation > 95%, his NIF value was concerning, and preparations were made in case of precipitous decline. Compounding the NIF assessment in this patient is his history of left phrenic nerve palsy. Without a documented baseline NIF, results were limited in determining his diaphragm strength.13 Treatment for MC includes IVIG or plasmapheresis, since this patient had failed his maintenance therapy IVIG, plasmapheresis was coordinated for definitive therapy.

Conclusions

Federal facilities have seen an increase in the amount of respiratory complaints over the past months. Although COVID-19 is a concerning diagnosis, it is crucial to consider comorbidities in the diagnostic workup of each, even with a previous recent diagnosis of COVID-19. As treatment recommendations for COVID-19 continue to fluctuate coupled with the limitations and difficulties associated with MG patients, so too treatment and evaluation must be carefully considered at each presentation.

1. Gousseff M, Penot P, Gallay L, et al. Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? J Infect. 2020;81(5):816-846. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.073

2. Duggan NM, Ludy SM, Shannon BC, Reisner AT, Wilcox SR. Is novel coronavirus 2019 reinfection possible? Interpreting dynamic SARS-CoV-2 test results. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;39:256.e1-256.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.079

3. Li J, Zhang L, Liu B, Song D. Case report: viral shedding for 60 days in a woman with COVID-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(6):1210-1213. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0275

4. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - preliminary report. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):994. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2022236

5. McCreary EK, Angus DC. Efficacy of remdesivir in COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1041-1042. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.16337

6. International MG/COVID-19 Working Group; Jacob S, Muppidi S, Gordon A, et al. Guidance for the management of myasthenia gravis (MG) and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurol Sci. 2020;412:116803. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2020.116803

7. Anand P, Slama MCC, Kaku M, et al. COVID-19 in patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2020;62(2):254-258. doi:10.1002/mus.26918

8. Wooding DJ, Bach H. Treatment of COVID-19 with convalescent plasma: lessons from past coronavirus outbreaks. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(10):1436-1446. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.005

9. Salazar E, Perez KK, Ashraf M, et al. Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) patients with convalescent plasma. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(8):1680-1690. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.05.014

10. Ryan C, Minc A, Caceres J, et al. Predicting severe outcomes in Covid-19 related illness using only patient demographics, comorbidities and symptoms [published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 9]. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;S0735-6757(20)30809-3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.017

11. Singh S, Govindarajan R. COVID-19 and generalized myasthenia gravis exacerbation: a case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;196:106045. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106045

12. Wendell LC, Levine JM. Myasthenic crisis. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(1):16-22. doi:10.1177/1941875210382918

13. Dubé BP, Dres M. Diaphragm dysfunction: diagnostic approaches and management strategies. J Clin Med. 2016;5(12):113. Published 2016 Dec 5. doi:10.3390/jcm5120113

A patient with myasthenia gravis who survived 2 COVID-19 infections required plasmapheresis to recover from an acute crisis.

A patient with myasthenia gravis who survived 2 COVID-19 infections required plasmapheresis to recover from an acute crisis.

COVID-19 is still in the early stages of understanding, although it is known to be complicated by individual patient comorbidities. The management and treatment of COVID-19 continues to quickly evolve as more is discovered regarding the virus. Multiple treatments have been preliminarily tested and used under a Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) determination. The long-term success of these therapies, however, is yet to be determined. Additionally, if a patient has a second clinical presentation for COVID-19, it is not known whether this represents latency with subsequent reactivation from the previous infection or a second de novo infection. The uncertainty calls into question the duration of immunity, if any, following a primary infection.

COVID-19 management becomes more complicated when patients have complex medical conditions, such as myasthenia gravis (MG). This autoimmune neuromuscular disorder can present with varying weakness, and many patients are on immunomodulator medications. The weakness can worsen into a myasthenic crisis (MC), resulting in profound weakness of the respiratory muscles. Therefore, patients with MG are at increased risk for COVID-19 and may have a more complicated course when infected.

Our patient with MG presented for severe COVID-19 symptoms twice and later developed MC. He received 2 treatment modalities available under an EUA (remdesivir and convalescent plasma) for COVID-19, resulting in symptom resolution and a negative polymerize chain reaction (PCR) test result for the virus. However, after receiving his typical maintenance therapy of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) for his MG, he again developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19 and tested positive. After recovering from the second episode of COVID-19, the patient went into MC requiring plasmapheresis.

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old male, US Army veteran presented to Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center emergency department (ED) 6 days after testing positive for COVID-19, with worsening sputum, cough, congestion, dyspnea, and fever. Due to his MG, the patient had a home oxygen monitor and reported that his oxygenation saturation dropped below 90% with minimal exertion. His medical history was significant for MG, status postthymectomy and radiation treatment, left hemidiaphragm paralysis secondary to phrenic nerve injury, and corticosteroid-induced insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. His current home medications included pyridostigmine 60 mg 3 times a day, mycophenolate (MMF) 1500 mg twice daily, IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) every 3 weeks, insulin aspart up to 16 U per meal, insulin glargine 30 U twice a day, dulaglutide 0.75 mg every week, and metformin 1000 mg twice daily.

On initial examination, the patient’s heart rate (HR) was 111 beats/min, respiratory rate (RR), 22 breaths/min, blood pressure (BP), 138/88 mm Hg, temperature, 100.9 oF, and his initial pulse oximetry, 91% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was tachypneic, though without other signs of respiratory distress. Lung auscultation revealed no adventitial lung sounds. His cardiac examination was notable only for tachycardia. His neurologic examination demonstrated intact cranial nerves, with 5 out of 5 (scale 1 to 5) strength throughout the upper and lower extremities, sensation was intact to light touch, and he had normal cerebellar function. The rest of the examination was normal.

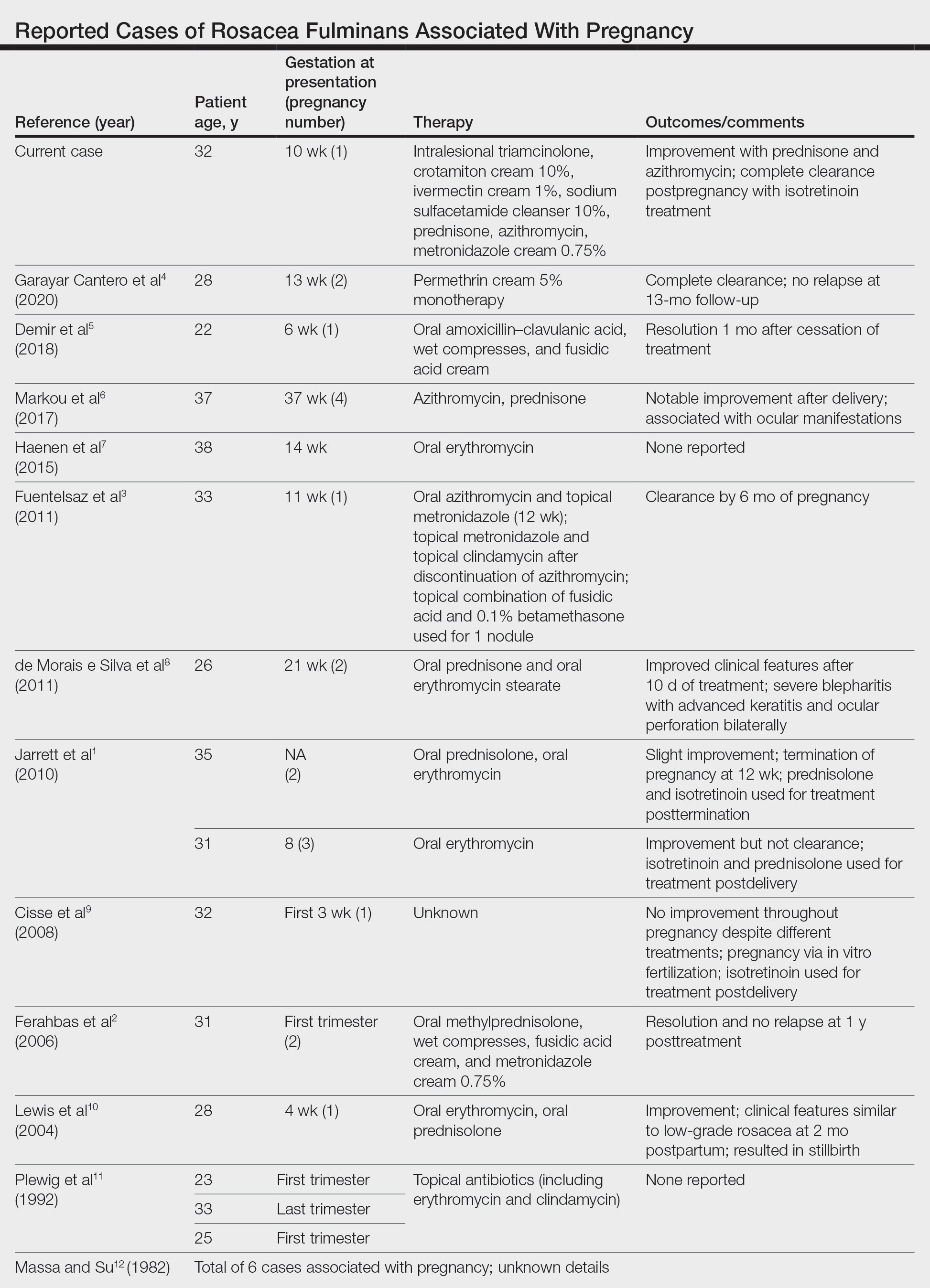

Initial laboratory investigation was notable for a white blood cell count of 14.15x103 cells/mcL with 84% neutrophils, and 6% lymphocytes. Additional tests revealed a C-reactive protein (CRP) level, 17.97 mg/dL (reference range, 0-0.5 mg/dL), ferritin level, 647 ng/mL (reference range, 22-274 ng/mL), d-dimer, 0.64 mcg/mL (reference range, 0-0.47mcg/mL), and a repeated positive COVID-19 PCR test. A portable chest X-ray showed bibasilar opacities (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). In the ICU, the patient received 1 U of convalescent plasma (CP) and started on a course of IV remdesivir 100 mg/d consistent with the EUA. He also received a 5-day course of ceftriaxone and azithromycin for possible community acquired pneumonia (CAP). As part of the patient’s MG maintenance medications, he received IVIG 4 g while in the ICU. Throughout his ICU stay, he required supplemental nasal cannula oxygenation to maintain his oxygen saturation > 93%. After 8 days in the ICU, his oxygen requirements decreased, and the patient was transferred out of the ICU and remdesivir was discontinued. On hospital day 10, a repeat COVID-19 PCR test was negative, inflammatory markers returned to within normal limits, and a repeat chest X-ray showed improvement from admission (Figure 2). Having recovered significantly, he was discharged home.

Three weeks later, the patient again presented to the MTF with 3 days of dyspnea, cough, fever, nausea, and vomiting. One day before symptom onset, he had received his maintenance IVIG infusion. The patient reported that his home oxygen saturation was 82% with minimal exertion. On ED presentation his HR was 107 beats/min, RR, 28 breaths/min, temperature, 98.1 oF, BP 118/71 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation, 92% on 2L nasal cannula. His examination was most notable for tachypnea with accessory muscle use. At this time, his neurologic examination was unchanged from prior admission with grossly intact cranial nerves and symmetric 5 of 5 motor strength in all extremities.

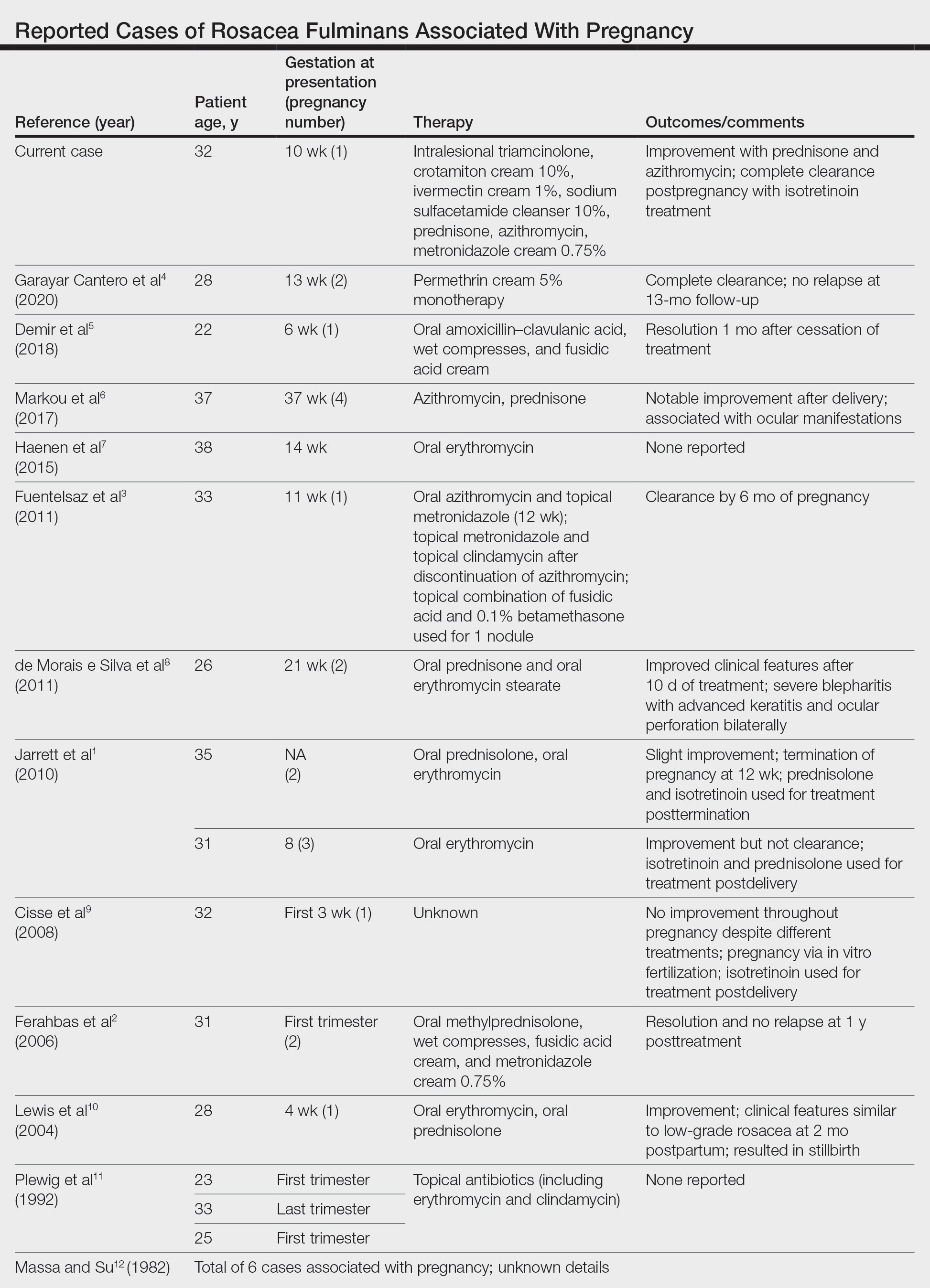

At this second ED visit, laboratory results demonstrated a CRP of 3.44 mg/dL, ferritin 2019 ng/mL, d-dimer, 3.39 mcg/mL, and a positive COVID-19 PCR result. His chest X-ray demonstrated new peripheral opacities compared with the X-ray at discharge (Figure 3). He required ICU admission again for his COVID-19 symptoms.

During his ICU course he continued to require supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, though never required intubation. This second admission, he was again treated empirically for CAP with levofloxacin 750 mg daily for 5 days. He was discharged after 14 days with symptom resolution and down trending of inflammatory markers, though he was not retested for COVID-19.

Four days after his second discharge, he presented to the ED for a third time with diffuse weakness, dysphagia, and dysarthria of 1 day. His HR was 87/beats/min; RR, 17 breaths/min; temperature, 98.7 oF; BP, 144/81 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 98% on room air. His examination was significant for slurred speech, bilateral ptosis, 3 of 5 strength in bilateral finger flexion/abduction, wrist extension, knee and ankle flexion/extension; 4 of 5 strength in bilateral proximal muscle testing of deltoid, and hip; normal sensation, cerebellar function and reflexes. His negative inspiratory force (NIF) maximal effort was −30 cmH2O. He was determined to be in MC without evidence of COIVD-19 symptoms, and laboratory results were within normal limits, including a negative COVID-19 PCR. As he received IVIG as maintenance therapy, plasmapheresis was recommended to treat his MC, which required transfer to an outside civilian facility.

At the outside hospital, the patient underwent 5 rounds of plasmapheresis over 10 days. By the third treatment his strength had returned with resolution of the bulbar symptoms and no supplemental oxygen requirements. The patient was discharged and continued his original dosages of MMF and pyridostigmine. At 3 months, he remained asymptomatic from a COVID-19 standpoint and stable from a MG standpoint.

Discussion

Reinfection with the COVID-19 has been continuously debated with alternative explanations suggested for a positive test after a previous negative PCR test in the setting of symptom resolution.1,2 Proposed causes include dynamic PCR results due to prolonged viral shedding and inaccurate or poorly sensitive tests. The repeat positive cases in these scenarios, however, occurred in asymptomatic patients.1,2 COVID-19 shedding averages 20 to 22 days after symptom onset but has been seen up to 36 days after symptom resolution.2,3 This would suggest that fluctuating results during the immediate postsymptom period may be due to variations in viral shedding load and or sampling error—especially in asymptomatic patients. On the other hand, patients who experience return of symptoms days to weeks after previous convalescence leave clinicians wondering whether this represents clinical latency with reactivation or COVID-19 reinfection. A separate case of initial COVID-19 in a patient that had subsequent clinical recovery with a negative PCR developed recurrent respiratory symptoms and had a positive PCR test only 10 days later, further highlighting the reinfection vs reactivation issue of COVID-19.2 Further understanding of this issue may have implications on the extent of natural immunity following primary infection; potential vaccine dosage schedules; and global public health policies.

Although reactivation may be plausible given his immunomodulatory therapy, our patient’s second COVID-19 symptoms started 40 days after the initial symptoms, and 26 days after the initial course resolution; previous cases of return of severe symptoms occurred between 3 and 6 days.1 Given our patient’s time course between resolution and return of symptoms, if latency is the mechanism at play, this case demonstrates an exceptionally longer latency period than the ones that have been reported. Additionally, if latency is an issue in COVID-19, using remdesivir as a treatment further complicates the understanding of this disease.

Remdesivir, a nucleoside analogue antiviral, was shown to benefit recovery in patients with severe symptoms in the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial-1 study.4 Our patient had originally been placed on a 10-day course; however, on treatment day 8, his symptoms resolved and the remdesivir was discontinued. This is a similar finding to half the patients in the 10-day arm of the study by McCreary and colleagues.5 Although our patient was asymptomatic 4 weeks after the start of remdesivir, consistent with the majority of patients in the McCreary 10-day study arm, further comparison of the presented patient is limited due to study length and follow-up considerations.5 No previous data exist on reactivation, reinfection, or long-term mortality after being treated with remdesivir for COVID-19 infection.

IVIG is being studied in the treatment of COVID-19 and bears consideration as it relates to our patient. There is no evidence that IVIG used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases increases the risk of infection compared with that of other medications used in the treatment of such diseases. Furthermore, the current guidance from the MG expert panel does not suggest that IVIG increases the risk of contracting COVID-19 aside from the risks of exposure to hospital infrastructure.6 Yet the guidance does not discuss the use of IVIG for MG in patients who are already symptomatic from COVID-19 or for patients recovering from the clinical disease or does it discuss a possible compounding risk of thromboembolic events associated with IVIG and COVID-19.6,7 Our patient received his maintenance IVIG during his first admission without any worsening of symptoms or increased oxygen requirements. The day following our patient’s next scheduled IVIG infusion—while asymptomatic—he again developed respiratory symptoms; this could suggest that IVIG did not contribute to his second clinical course nor protect against.

CP is a treatment modality that has been used and studied in previous infectious outbreaks such as the first severe acute respiratory syndrome, and the H1N1 influenza virus.8 Current data on CP for COVID-19 are limited, but early descriptive studies have shown a benefit in improvement of symptoms 5 days sooner in those requiring supplemental oxygen, but no benefit for those requiring mechanical ventilation.9 Like patients that benefitted in these studies, our patient received CP early, 6 days after first testing positive and onset of symptoms. This patient’s reinfection or return of symptoms draws into question the hindrance or even prevention of long-term immunity from administration of CP.

COVID-19 presents many challenges when managing this patient’s coexisting MG, especially as the patient was already being treated with immunosuppressing therapies. The guidance does recommend continuation of standard MG therapies during hospitalizations, including immunosuppression medications such as MMF.6 Immunosuppression is associated with worsened severity of COVID-19 symptoms, although no relation exists to degree of immunosuppression and severity.7,10 To the best of our knowledge there has been no case report of reinfection or reactivation of COVID-19 associated with immunosuppressive agents used in the treatment of MG.

Our patient also was taking pyridostigmine for the treatment of his MG. There is no evidence this medication increases the risk of infection; but the cholinergic activity can increase bronchial secretions, which could theoretically worsen the COVID-19 respiratory symptoms.6,11 During both ICU admissions, our patient continued pyridostigmine use, observing complete return to baseline after discharge. Given the possible association with worsened respiratory outcomes after the second ICU admission, the balance between managing MG symptoms and COVID-19 symptoms needs further examination.

The patient was in MC during his third presentation to the ED. Although respiratory symptoms may be difficult to differentiate from COVID-19, the additional neurologic symptoms seen in this patient allowed for quick determination of the need for MC treatment. There are many potential etiologies contributing to the development of the MC presented here, and it was likely due to multifactorial precipitants. A common cause of MC is viral upper respiratory infections, further challenging the care of these patients during this pandemic.12 Many medications have been cited as causing a MC, 2 of which our patient received during admission for COVID-19: azithromycin and levoquin.12 Although the patient did not receive hydroxychloroquine, which was still being considered as an appropriate COVID-19 treatment at the time, it also is a drug known for precipitating MC and its use scrutinized in patients with MG.12

A key aspect to diagnosing and guiding therapies in myasthenic crisis in addition to the clinical symptoms of acute weakness is respiratory assessment through the nonaerosolizing NIF test.12 Our patient’s NIF measured < 30 cmH2O when in MC, while the reference range is < 75 cmH2O, and for mechanical ventilation is recommended at 20 cmH2O. Although the patient was maintaining O2 saturation > 95%, his NIF value was concerning, and preparations were made in case of precipitous decline. Compounding the NIF assessment in this patient is his history of left phrenic nerve palsy. Without a documented baseline NIF, results were limited in determining his diaphragm strength.13 Treatment for MC includes IVIG or plasmapheresis, since this patient had failed his maintenance therapy IVIG, plasmapheresis was coordinated for definitive therapy.

Conclusions

Federal facilities have seen an increase in the amount of respiratory complaints over the past months. Although COVID-19 is a concerning diagnosis, it is crucial to consider comorbidities in the diagnostic workup of each, even with a previous recent diagnosis of COVID-19. As treatment recommendations for COVID-19 continue to fluctuate coupled with the limitations and difficulties associated with MG patients, so too treatment and evaluation must be carefully considered at each presentation.

COVID-19 is still in the early stages of understanding, although it is known to be complicated by individual patient comorbidities. The management and treatment of COVID-19 continues to quickly evolve as more is discovered regarding the virus. Multiple treatments have been preliminarily tested and used under a Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) determination. The long-term success of these therapies, however, is yet to be determined. Additionally, if a patient has a second clinical presentation for COVID-19, it is not known whether this represents latency with subsequent reactivation from the previous infection or a second de novo infection. The uncertainty calls into question the duration of immunity, if any, following a primary infection.

COVID-19 management becomes more complicated when patients have complex medical conditions, such as myasthenia gravis (MG). This autoimmune neuromuscular disorder can present with varying weakness, and many patients are on immunomodulator medications. The weakness can worsen into a myasthenic crisis (MC), resulting in profound weakness of the respiratory muscles. Therefore, patients with MG are at increased risk for COVID-19 and may have a more complicated course when infected.

Our patient with MG presented for severe COVID-19 symptoms twice and later developed MC. He received 2 treatment modalities available under an EUA (remdesivir and convalescent plasma) for COVID-19, resulting in symptom resolution and a negative polymerize chain reaction (PCR) test result for the virus. However, after receiving his typical maintenance therapy of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) for his MG, he again developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19 and tested positive. After recovering from the second episode of COVID-19, the patient went into MC requiring plasmapheresis.

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old male, US Army veteran presented to Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center emergency department (ED) 6 days after testing positive for COVID-19, with worsening sputum, cough, congestion, dyspnea, and fever. Due to his MG, the patient had a home oxygen monitor and reported that his oxygenation saturation dropped below 90% with minimal exertion. His medical history was significant for MG, status postthymectomy and radiation treatment, left hemidiaphragm paralysis secondary to phrenic nerve injury, and corticosteroid-induced insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. His current home medications included pyridostigmine 60 mg 3 times a day, mycophenolate (MMF) 1500 mg twice daily, IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) every 3 weeks, insulin aspart up to 16 U per meal, insulin glargine 30 U twice a day, dulaglutide 0.75 mg every week, and metformin 1000 mg twice daily.

On initial examination, the patient’s heart rate (HR) was 111 beats/min, respiratory rate (RR), 22 breaths/min, blood pressure (BP), 138/88 mm Hg, temperature, 100.9 oF, and his initial pulse oximetry, 91% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was tachypneic, though without other signs of respiratory distress. Lung auscultation revealed no adventitial lung sounds. His cardiac examination was notable only for tachycardia. His neurologic examination demonstrated intact cranial nerves, with 5 out of 5 (scale 1 to 5) strength throughout the upper and lower extremities, sensation was intact to light touch, and he had normal cerebellar function. The rest of the examination was normal.

Initial laboratory investigation was notable for a white blood cell count of 14.15x103 cells/mcL with 84% neutrophils, and 6% lymphocytes. Additional tests revealed a C-reactive protein (CRP) level, 17.97 mg/dL (reference range, 0-0.5 mg/dL), ferritin level, 647 ng/mL (reference range, 22-274 ng/mL), d-dimer, 0.64 mcg/mL (reference range, 0-0.47mcg/mL), and a repeated positive COVID-19 PCR test. A portable chest X-ray showed bibasilar opacities (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). In the ICU, the patient received 1 U of convalescent plasma (CP) and started on a course of IV remdesivir 100 mg/d consistent with the EUA. He also received a 5-day course of ceftriaxone and azithromycin for possible community acquired pneumonia (CAP). As part of the patient’s MG maintenance medications, he received IVIG 4 g while in the ICU. Throughout his ICU stay, he required supplemental nasal cannula oxygenation to maintain his oxygen saturation > 93%. After 8 days in the ICU, his oxygen requirements decreased, and the patient was transferred out of the ICU and remdesivir was discontinued. On hospital day 10, a repeat COVID-19 PCR test was negative, inflammatory markers returned to within normal limits, and a repeat chest X-ray showed improvement from admission (Figure 2). Having recovered significantly, he was discharged home.

Three weeks later, the patient again presented to the MTF with 3 days of dyspnea, cough, fever, nausea, and vomiting. One day before symptom onset, he had received his maintenance IVIG infusion. The patient reported that his home oxygen saturation was 82% with minimal exertion. On ED presentation his HR was 107 beats/min, RR, 28 breaths/min, temperature, 98.1 oF, BP 118/71 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation, 92% on 2L nasal cannula. His examination was most notable for tachypnea with accessory muscle use. At this time, his neurologic examination was unchanged from prior admission with grossly intact cranial nerves and symmetric 5 of 5 motor strength in all extremities.

At this second ED visit, laboratory results demonstrated a CRP of 3.44 mg/dL, ferritin 2019 ng/mL, d-dimer, 3.39 mcg/mL, and a positive COVID-19 PCR result. His chest X-ray demonstrated new peripheral opacities compared with the X-ray at discharge (Figure 3). He required ICU admission again for his COVID-19 symptoms.

During his ICU course he continued to require supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, though never required intubation. This second admission, he was again treated empirically for CAP with levofloxacin 750 mg daily for 5 days. He was discharged after 14 days with symptom resolution and down trending of inflammatory markers, though he was not retested for COVID-19.

Four days after his second discharge, he presented to the ED for a third time with diffuse weakness, dysphagia, and dysarthria of 1 day. His HR was 87/beats/min; RR, 17 breaths/min; temperature, 98.7 oF; BP, 144/81 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation, 98% on room air. His examination was significant for slurred speech, bilateral ptosis, 3 of 5 strength in bilateral finger flexion/abduction, wrist extension, knee and ankle flexion/extension; 4 of 5 strength in bilateral proximal muscle testing of deltoid, and hip; normal sensation, cerebellar function and reflexes. His negative inspiratory force (NIF) maximal effort was −30 cmH2O. He was determined to be in MC without evidence of COIVD-19 symptoms, and laboratory results were within normal limits, including a negative COVID-19 PCR. As he received IVIG as maintenance therapy, plasmapheresis was recommended to treat his MC, which required transfer to an outside civilian facility.

At the outside hospital, the patient underwent 5 rounds of plasmapheresis over 10 days. By the third treatment his strength had returned with resolution of the bulbar symptoms and no supplemental oxygen requirements. The patient was discharged and continued his original dosages of MMF and pyridostigmine. At 3 months, he remained asymptomatic from a COVID-19 standpoint and stable from a MG standpoint.

Discussion

Reinfection with the COVID-19 has been continuously debated with alternative explanations suggested for a positive test after a previous negative PCR test in the setting of symptom resolution.1,2 Proposed causes include dynamic PCR results due to prolonged viral shedding and inaccurate or poorly sensitive tests. The repeat positive cases in these scenarios, however, occurred in asymptomatic patients.1,2 COVID-19 shedding averages 20 to 22 days after symptom onset but has been seen up to 36 days after symptom resolution.2,3 This would suggest that fluctuating results during the immediate postsymptom period may be due to variations in viral shedding load and or sampling error—especially in asymptomatic patients. On the other hand, patients who experience return of symptoms days to weeks after previous convalescence leave clinicians wondering whether this represents clinical latency with reactivation or COVID-19 reinfection. A separate case of initial COVID-19 in a patient that had subsequent clinical recovery with a negative PCR developed recurrent respiratory symptoms and had a positive PCR test only 10 days later, further highlighting the reinfection vs reactivation issue of COVID-19.2 Further understanding of this issue may have implications on the extent of natural immunity following primary infection; potential vaccine dosage schedules; and global public health policies.

Although reactivation may be plausible given his immunomodulatory therapy, our patient’s second COVID-19 symptoms started 40 days after the initial symptoms, and 26 days after the initial course resolution; previous cases of return of severe symptoms occurred between 3 and 6 days.1 Given our patient’s time course between resolution and return of symptoms, if latency is the mechanism at play, this case demonstrates an exceptionally longer latency period than the ones that have been reported. Additionally, if latency is an issue in COVID-19, using remdesivir as a treatment further complicates the understanding of this disease.

Remdesivir, a nucleoside analogue antiviral, was shown to benefit recovery in patients with severe symptoms in the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial-1 study.4 Our patient had originally been placed on a 10-day course; however, on treatment day 8, his symptoms resolved and the remdesivir was discontinued. This is a similar finding to half the patients in the 10-day arm of the study by McCreary and colleagues.5 Although our patient was asymptomatic 4 weeks after the start of remdesivir, consistent with the majority of patients in the McCreary 10-day study arm, further comparison of the presented patient is limited due to study length and follow-up considerations.5 No previous data exist on reactivation, reinfection, or long-term mortality after being treated with remdesivir for COVID-19 infection.

IVIG is being studied in the treatment of COVID-19 and bears consideration as it relates to our patient. There is no evidence that IVIG used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases increases the risk of infection compared with that of other medications used in the treatment of such diseases. Furthermore, the current guidance from the MG expert panel does not suggest that IVIG increases the risk of contracting COVID-19 aside from the risks of exposure to hospital infrastructure.6 Yet the guidance does not discuss the use of IVIG for MG in patients who are already symptomatic from COVID-19 or for patients recovering from the clinical disease or does it discuss a possible compounding risk of thromboembolic events associated with IVIG and COVID-19.6,7 Our patient received his maintenance IVIG during his first admission without any worsening of symptoms or increased oxygen requirements. The day following our patient’s next scheduled IVIG infusion—while asymptomatic—he again developed respiratory symptoms; this could suggest that IVIG did not contribute to his second clinical course nor protect against.

CP is a treatment modality that has been used and studied in previous infectious outbreaks such as the first severe acute respiratory syndrome, and the H1N1 influenza virus.8 Current data on CP for COVID-19 are limited, but early descriptive studies have shown a benefit in improvement of symptoms 5 days sooner in those requiring supplemental oxygen, but no benefit for those requiring mechanical ventilation.9 Like patients that benefitted in these studies, our patient received CP early, 6 days after first testing positive and onset of symptoms. This patient’s reinfection or return of symptoms draws into question the hindrance or even prevention of long-term immunity from administration of CP.

COVID-19 presents many challenges when managing this patient’s coexisting MG, especially as the patient was already being treated with immunosuppressing therapies. The guidance does recommend continuation of standard MG therapies during hospitalizations, including immunosuppression medications such as MMF.6 Immunosuppression is associated with worsened severity of COVID-19 symptoms, although no relation exists to degree of immunosuppression and severity.7,10 To the best of our knowledge there has been no case report of reinfection or reactivation of COVID-19 associated with immunosuppressive agents used in the treatment of MG.

Our patient also was taking pyridostigmine for the treatment of his MG. There is no evidence this medication increases the risk of infection; but the cholinergic activity can increase bronchial secretions, which could theoretically worsen the COVID-19 respiratory symptoms.6,11 During both ICU admissions, our patient continued pyridostigmine use, observing complete return to baseline after discharge. Given the possible association with worsened respiratory outcomes after the second ICU admission, the balance between managing MG symptoms and COVID-19 symptoms needs further examination.

The patient was in MC during his third presentation to the ED. Although respiratory symptoms may be difficult to differentiate from COVID-19, the additional neurologic symptoms seen in this patient allowed for quick determination of the need for MC treatment. There are many potential etiologies contributing to the development of the MC presented here, and it was likely due to multifactorial precipitants. A common cause of MC is viral upper respiratory infections, further challenging the care of these patients during this pandemic.12 Many medications have been cited as causing a MC, 2 of which our patient received during admission for COVID-19: azithromycin and levoquin.12 Although the patient did not receive hydroxychloroquine, which was still being considered as an appropriate COVID-19 treatment at the time, it also is a drug known for precipitating MC and its use scrutinized in patients with MG.12

A key aspect to diagnosing and guiding therapies in myasthenic crisis in addition to the clinical symptoms of acute weakness is respiratory assessment through the nonaerosolizing NIF test.12 Our patient’s NIF measured < 30 cmH2O when in MC, while the reference range is < 75 cmH2O, and for mechanical ventilation is recommended at 20 cmH2O. Although the patient was maintaining O2 saturation > 95%, his NIF value was concerning, and preparations were made in case of precipitous decline. Compounding the NIF assessment in this patient is his history of left phrenic nerve palsy. Without a documented baseline NIF, results were limited in determining his diaphragm strength.13 Treatment for MC includes IVIG or plasmapheresis, since this patient had failed his maintenance therapy IVIG, plasmapheresis was coordinated for definitive therapy.

Conclusions

Federal facilities have seen an increase in the amount of respiratory complaints over the past months. Although COVID-19 is a concerning diagnosis, it is crucial to consider comorbidities in the diagnostic workup of each, even with a previous recent diagnosis of COVID-19. As treatment recommendations for COVID-19 continue to fluctuate coupled with the limitations and difficulties associated with MG patients, so too treatment and evaluation must be carefully considered at each presentation.

1. Gousseff M, Penot P, Gallay L, et al. Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? J Infect. 2020;81(5):816-846. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.073

2. Duggan NM, Ludy SM, Shannon BC, Reisner AT, Wilcox SR. Is novel coronavirus 2019 reinfection possible? Interpreting dynamic SARS-CoV-2 test results. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;39:256.e1-256.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.079

3. Li J, Zhang L, Liu B, Song D. Case report: viral shedding for 60 days in a woman with COVID-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(6):1210-1213. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0275

4. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - preliminary report. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):994. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2022236

5. McCreary EK, Angus DC. Efficacy of remdesivir in COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1041-1042. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.16337

6. International MG/COVID-19 Working Group; Jacob S, Muppidi S, Gordon A, et al. Guidance for the management of myasthenia gravis (MG) and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurol Sci. 2020;412:116803. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2020.116803

7. Anand P, Slama MCC, Kaku M, et al. COVID-19 in patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2020;62(2):254-258. doi:10.1002/mus.26918

8. Wooding DJ, Bach H. Treatment of COVID-19 with convalescent plasma: lessons from past coronavirus outbreaks. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(10):1436-1446. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.005

9. Salazar E, Perez KK, Ashraf M, et al. Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) patients with convalescent plasma. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(8):1680-1690. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.05.014

10. Ryan C, Minc A, Caceres J, et al. Predicting severe outcomes in Covid-19 related illness using only patient demographics, comorbidities and symptoms [published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 9]. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;S0735-6757(20)30809-3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.017

11. Singh S, Govindarajan R. COVID-19 and generalized myasthenia gravis exacerbation: a case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;196:106045. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106045

12. Wendell LC, Levine JM. Myasthenic crisis. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(1):16-22. doi:10.1177/1941875210382918

13. Dubé BP, Dres M. Diaphragm dysfunction: diagnostic approaches and management strategies. J Clin Med. 2016;5(12):113. Published 2016 Dec 5. doi:10.3390/jcm5120113

1. Gousseff M, Penot P, Gallay L, et al. Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? J Infect. 2020;81(5):816-846. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.073

2. Duggan NM, Ludy SM, Shannon BC, Reisner AT, Wilcox SR. Is novel coronavirus 2019 reinfection possible? Interpreting dynamic SARS-CoV-2 test results. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;39:256.e1-256.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.079

3. Li J, Zhang L, Liu B, Song D. Case report: viral shedding for 60 days in a woman with COVID-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(6):1210-1213. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0275

4. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - preliminary report. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):994. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2022236

5. McCreary EK, Angus DC. Efficacy of remdesivir in COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1041-1042. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.16337

6. International MG/COVID-19 Working Group; Jacob S, Muppidi S, Gordon A, et al. Guidance for the management of myasthenia gravis (MG) and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurol Sci. 2020;412:116803. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2020.116803

7. Anand P, Slama MCC, Kaku M, et al. COVID-19 in patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2020;62(2):254-258. doi:10.1002/mus.26918

8. Wooding DJ, Bach H. Treatment of COVID-19 with convalescent plasma: lessons from past coronavirus outbreaks. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(10):1436-1446. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.005

9. Salazar E, Perez KK, Ashraf M, et al. Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) patients with convalescent plasma. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(8):1680-1690. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.05.014

10. Ryan C, Minc A, Caceres J, et al. Predicting severe outcomes in Covid-19 related illness using only patient demographics, comorbidities and symptoms [published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 9]. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;S0735-6757(20)30809-3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.017

11. Singh S, Govindarajan R. COVID-19 and generalized myasthenia gravis exacerbation: a case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;196:106045. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106045

12. Wendell LC, Levine JM. Myasthenic crisis. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(1):16-22. doi:10.1177/1941875210382918

13. Dubé BP, Dres M. Diaphragm dysfunction: diagnostic approaches and management strategies. J Clin Med. 2016;5(12):113. Published 2016 Dec 5. doi:10.3390/jcm5120113

27-year-old woman • postpartum seizures • PTSD • history of depression • Dx?

THE CASE

A 27-year-old woman presented to the family medicine clinic to establish care for a recent onset of seizures, for which she had previously been admitted, 4 months after delivering her first child. Her pregnancy was complicated by type 1 diabetes and poor glycemic control. Labor was induced at 37 weeks; however, vaginal delivery was impeded by arrest of dilation. An emergency cesarean section was performed under general anesthesia, resulting in a healthy newborn male.

Six weeks after giving birth, the patient was started on sertraline 50 mg/d for postpartum depression. Her history was significant for depression 8 years prior that was controlled with psychotherapy, and treated prior to coming to our clinic. She had not experienced any depressive symptoms during pregnancy.