User login

20-year-old woman • 2 syncopal episodes • nausea • dizziness • Dx?

THE CASE

A 20-year-old woman presented to clinic with a chief complaint of 2 syncopal episodes within 10 minutes of each other. She reported that in both cases, she felt nauseated and dizzy before losing consciousness. She lost consciousness for a few seconds during the first episode and a few minutes during the second episode. Both episodes were unwitnessed.

The patient denied any fasting, vomiting, diarrhea, palpitations, chest pain, incontinence, oral trauma, headaches, fevers, chills, or tremors. Her last menstrual period started 3 days prior to presentation. The patient was taking sertraline 25 mg once daily for anxiety and depression and norethindrone acetate–ethinyl estradiol tablets 20 µg daily for birth control. She also was finishing a 7-day course of metronidazole for bacterial vaginosis. She reported having started the sertraline about 10 days prior to the syncopal episodes. She denied any personal history of drug or alcohol use, syncope, seizures, or any other medical conditions. Family history was negative for any cardiac or neurologic conditions.

The patient appeared euvolemic on exam. Overall, the review of the respiratory, cardiac, and neurologic systems was unremarkable. An electrocardiogram, obtained in clinic, showed a normal sinus rhythm and QT interval. Orthostatic blood pressure and heart rate measurements were as follows: supine, 122/83 mm Hg and 67 beats/min; seated, 118/87 mm Hg and 60 beats/min; and standing, 123/83 mm Hg and 95 beats/min. In addition to the increase in pulse between sitting and standing, the patient reported feeling nauseated when transitioning to a standing position.

Laboratory work-up included a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, and thyroid-stimulating hormone test. The results showed mild erythrocytosis with a hematocrit and hemoglobin of 46.1% and 15.6 g/dL respectively, as well as mild hypercalcemia (10.4 mg/dL).

THE DIAGNOSIS

An increase in heart rate of more than 30 beats/min when the patient went from a sitting to a standing position pointed to a diagnosis of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). This prompted us to stop the sertraline.

DISCUSSION

POTS is a type of intolerance to orthostasis related to a significant increase in pulse without resulting hypotension upon standing. Other symptoms that accompany this change in position include dizziness, lightheadedness, blurry vision, and fatigue. Syncope occurs in about 40% of patients with POTS, which may be more frequent than for patients with orthostatic hypotension.1

The overall prevalence of POTS is 0.2% to 1%; however, it is generally seen in a 5:1 female-to-male ratio.2,3 POTS is often idiopathic. That said, it can also be caused by medication adverse effects, hypovolemia, and stressors, including vaccinations, viral infections, trauma, and emotional triggers. On physical exam, this patient did not appear to be hypovolemic, and she reported normal oral intake prior to this visit. Since the patient had started taking sertraline about 10 days prior to her syncopal episodes, we suspected POTS secondary to sertraline use was the likely etiology in this otherwise healthy young woman.

Continue to: Syncope could indicate a larger cardiovascular problem

Syncope could indicate a larger cardiovascular problem

The differential diagnosis of dizziness with loss of consciousness includes anemia, vasovagal syncope, orthostatic hypotension, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, arrhythmia, prolonged QT syndrome, cardiac valve or structure abnormality, and seizure. Most of these differentials can be ruled out from basic laboratory tests or cardiac imaging. In POTS, the diagnostic work-up is essentially normal compared to other causes of syncope. Orthostatic hypotension, for example, is similar; however, there is an additional change in the arterial blood pressure.

Unintended adverse effects

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline, are known to have fewer cardiovascular adverse effects compared to older antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors.4 However, case reports have shown an association between SSRIs and syncope.4-6 SSRIs have also been tied to increased heart rate variability.7

Nearly 2 weeks after stopping sertraline, our patient presented to clinic and was given a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis. She said she’d had no additional syncopal episodes. Twenty days after sertraline cessation, the patient returned for follow-up. Her blood pressure and heart rate were as follows: supine, 112/68 mm Hg and 61 beats/min; seated, 113/74 mm Hg and 87 beats/min; and standing, 108/74 mm Hg and 78 beats/min.

Thus, after cessation of sertraline, her orthostatic heart rate changes were smaller than when she was first examined. Her vital signs showed an increase in pulse of 26 beats/min between lying and sitting, without any reports of nausea. She had no further complaints of dizziness or syncopal episodes.

THE TAKEAWAY

We don’t always know how a patient will respond to a newly prescribed medication or lifestyle change. A proper review of a patient’s history and medication use is a pivotal first step in making any diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Courtney Lynn Dominguez, MD, 4220 North Roxboro Street, Durham, NC 27704; [email protected]

1. Ojha A, McNeeley K, Heller E, et al. Orthostatic syndromes differ in syncope frequency. Am J Med. 2010;123:245-249. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.018

2. Arnold AC, Ng J, Raj SR. Postural tachycardia syndrome—diagnosis, physiology, and prognosis. Auton Neurosci. 2018;215:3-11. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2018.02.005

3. Fedorowski A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J Intern Med. 2018;285:352-366. doi:10.1111/joim.12852

4. Pacher P, Ungvari Z, Kecskemeti V, et al. Review of cardiovascular effects of fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, compared to tricyclic antidepressants. Curr Med Chem. 1998;5:381-390.

5. Feder R. Bradycardia and syncope induced by fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:139.

6. Ellison JM, Milofsky JE, Ely E. Fluoxetine-induced bradycardia and syncope in two patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:385-386.

7. Tucker P, Adamson P, Miranda R Jr, et al. Paroxetine increases heart rate variability in panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:370-376. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199710000-00006

THE CASE

A 20-year-old woman presented to clinic with a chief complaint of 2 syncopal episodes within 10 minutes of each other. She reported that in both cases, she felt nauseated and dizzy before losing consciousness. She lost consciousness for a few seconds during the first episode and a few minutes during the second episode. Both episodes were unwitnessed.

The patient denied any fasting, vomiting, diarrhea, palpitations, chest pain, incontinence, oral trauma, headaches, fevers, chills, or tremors. Her last menstrual period started 3 days prior to presentation. The patient was taking sertraline 25 mg once daily for anxiety and depression and norethindrone acetate–ethinyl estradiol tablets 20 µg daily for birth control. She also was finishing a 7-day course of metronidazole for bacterial vaginosis. She reported having started the sertraline about 10 days prior to the syncopal episodes. She denied any personal history of drug or alcohol use, syncope, seizures, or any other medical conditions. Family history was negative for any cardiac or neurologic conditions.

The patient appeared euvolemic on exam. Overall, the review of the respiratory, cardiac, and neurologic systems was unremarkable. An electrocardiogram, obtained in clinic, showed a normal sinus rhythm and QT interval. Orthostatic blood pressure and heart rate measurements were as follows: supine, 122/83 mm Hg and 67 beats/min; seated, 118/87 mm Hg and 60 beats/min; and standing, 123/83 mm Hg and 95 beats/min. In addition to the increase in pulse between sitting and standing, the patient reported feeling nauseated when transitioning to a standing position.

Laboratory work-up included a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, and thyroid-stimulating hormone test. The results showed mild erythrocytosis with a hematocrit and hemoglobin of 46.1% and 15.6 g/dL respectively, as well as mild hypercalcemia (10.4 mg/dL).

THE DIAGNOSIS

An increase in heart rate of more than 30 beats/min when the patient went from a sitting to a standing position pointed to a diagnosis of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). This prompted us to stop the sertraline.

DISCUSSION

POTS is a type of intolerance to orthostasis related to a significant increase in pulse without resulting hypotension upon standing. Other symptoms that accompany this change in position include dizziness, lightheadedness, blurry vision, and fatigue. Syncope occurs in about 40% of patients with POTS, which may be more frequent than for patients with orthostatic hypotension.1

The overall prevalence of POTS is 0.2% to 1%; however, it is generally seen in a 5:1 female-to-male ratio.2,3 POTS is often idiopathic. That said, it can also be caused by medication adverse effects, hypovolemia, and stressors, including vaccinations, viral infections, trauma, and emotional triggers. On physical exam, this patient did not appear to be hypovolemic, and she reported normal oral intake prior to this visit. Since the patient had started taking sertraline about 10 days prior to her syncopal episodes, we suspected POTS secondary to sertraline use was the likely etiology in this otherwise healthy young woman.

Continue to: Syncope could indicate a larger cardiovascular problem

Syncope could indicate a larger cardiovascular problem

The differential diagnosis of dizziness with loss of consciousness includes anemia, vasovagal syncope, orthostatic hypotension, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, arrhythmia, prolonged QT syndrome, cardiac valve or structure abnormality, and seizure. Most of these differentials can be ruled out from basic laboratory tests or cardiac imaging. In POTS, the diagnostic work-up is essentially normal compared to other causes of syncope. Orthostatic hypotension, for example, is similar; however, there is an additional change in the arterial blood pressure.

Unintended adverse effects

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline, are known to have fewer cardiovascular adverse effects compared to older antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors.4 However, case reports have shown an association between SSRIs and syncope.4-6 SSRIs have also been tied to increased heart rate variability.7

Nearly 2 weeks after stopping sertraline, our patient presented to clinic and was given a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis. She said she’d had no additional syncopal episodes. Twenty days after sertraline cessation, the patient returned for follow-up. Her blood pressure and heart rate were as follows: supine, 112/68 mm Hg and 61 beats/min; seated, 113/74 mm Hg and 87 beats/min; and standing, 108/74 mm Hg and 78 beats/min.

Thus, after cessation of sertraline, her orthostatic heart rate changes were smaller than when she was first examined. Her vital signs showed an increase in pulse of 26 beats/min between lying and sitting, without any reports of nausea. She had no further complaints of dizziness or syncopal episodes.

THE TAKEAWAY

We don’t always know how a patient will respond to a newly prescribed medication or lifestyle change. A proper review of a patient’s history and medication use is a pivotal first step in making any diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Courtney Lynn Dominguez, MD, 4220 North Roxboro Street, Durham, NC 27704; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 20-year-old woman presented to clinic with a chief complaint of 2 syncopal episodes within 10 minutes of each other. She reported that in both cases, she felt nauseated and dizzy before losing consciousness. She lost consciousness for a few seconds during the first episode and a few minutes during the second episode. Both episodes were unwitnessed.

The patient denied any fasting, vomiting, diarrhea, palpitations, chest pain, incontinence, oral trauma, headaches, fevers, chills, or tremors. Her last menstrual period started 3 days prior to presentation. The patient was taking sertraline 25 mg once daily for anxiety and depression and norethindrone acetate–ethinyl estradiol tablets 20 µg daily for birth control. She also was finishing a 7-day course of metronidazole for bacterial vaginosis. She reported having started the sertraline about 10 days prior to the syncopal episodes. She denied any personal history of drug or alcohol use, syncope, seizures, or any other medical conditions. Family history was negative for any cardiac or neurologic conditions.

The patient appeared euvolemic on exam. Overall, the review of the respiratory, cardiac, and neurologic systems was unremarkable. An electrocardiogram, obtained in clinic, showed a normal sinus rhythm and QT interval. Orthostatic blood pressure and heart rate measurements were as follows: supine, 122/83 mm Hg and 67 beats/min; seated, 118/87 mm Hg and 60 beats/min; and standing, 123/83 mm Hg and 95 beats/min. In addition to the increase in pulse between sitting and standing, the patient reported feeling nauseated when transitioning to a standing position.

Laboratory work-up included a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, and thyroid-stimulating hormone test. The results showed mild erythrocytosis with a hematocrit and hemoglobin of 46.1% and 15.6 g/dL respectively, as well as mild hypercalcemia (10.4 mg/dL).

THE DIAGNOSIS

An increase in heart rate of more than 30 beats/min when the patient went from a sitting to a standing position pointed to a diagnosis of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). This prompted us to stop the sertraline.

DISCUSSION

POTS is a type of intolerance to orthostasis related to a significant increase in pulse without resulting hypotension upon standing. Other symptoms that accompany this change in position include dizziness, lightheadedness, blurry vision, and fatigue. Syncope occurs in about 40% of patients with POTS, which may be more frequent than for patients with orthostatic hypotension.1

The overall prevalence of POTS is 0.2% to 1%; however, it is generally seen in a 5:1 female-to-male ratio.2,3 POTS is often idiopathic. That said, it can also be caused by medication adverse effects, hypovolemia, and stressors, including vaccinations, viral infections, trauma, and emotional triggers. On physical exam, this patient did not appear to be hypovolemic, and she reported normal oral intake prior to this visit. Since the patient had started taking sertraline about 10 days prior to her syncopal episodes, we suspected POTS secondary to sertraline use was the likely etiology in this otherwise healthy young woman.

Continue to: Syncope could indicate a larger cardiovascular problem

Syncope could indicate a larger cardiovascular problem

The differential diagnosis of dizziness with loss of consciousness includes anemia, vasovagal syncope, orthostatic hypotension, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, arrhythmia, prolonged QT syndrome, cardiac valve or structure abnormality, and seizure. Most of these differentials can be ruled out from basic laboratory tests or cardiac imaging. In POTS, the diagnostic work-up is essentially normal compared to other causes of syncope. Orthostatic hypotension, for example, is similar; however, there is an additional change in the arterial blood pressure.

Unintended adverse effects

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline, are known to have fewer cardiovascular adverse effects compared to older antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors.4 However, case reports have shown an association between SSRIs and syncope.4-6 SSRIs have also been tied to increased heart rate variability.7

Nearly 2 weeks after stopping sertraline, our patient presented to clinic and was given a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis. She said she’d had no additional syncopal episodes. Twenty days after sertraline cessation, the patient returned for follow-up. Her blood pressure and heart rate were as follows: supine, 112/68 mm Hg and 61 beats/min; seated, 113/74 mm Hg and 87 beats/min; and standing, 108/74 mm Hg and 78 beats/min.

Thus, after cessation of sertraline, her orthostatic heart rate changes were smaller than when she was first examined. Her vital signs showed an increase in pulse of 26 beats/min between lying and sitting, without any reports of nausea. She had no further complaints of dizziness or syncopal episodes.

THE TAKEAWAY

We don’t always know how a patient will respond to a newly prescribed medication or lifestyle change. A proper review of a patient’s history and medication use is a pivotal first step in making any diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Courtney Lynn Dominguez, MD, 4220 North Roxboro Street, Durham, NC 27704; [email protected]

1. Ojha A, McNeeley K, Heller E, et al. Orthostatic syndromes differ in syncope frequency. Am J Med. 2010;123:245-249. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.018

2. Arnold AC, Ng J, Raj SR. Postural tachycardia syndrome—diagnosis, physiology, and prognosis. Auton Neurosci. 2018;215:3-11. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2018.02.005

3. Fedorowski A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J Intern Med. 2018;285:352-366. doi:10.1111/joim.12852

4. Pacher P, Ungvari Z, Kecskemeti V, et al. Review of cardiovascular effects of fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, compared to tricyclic antidepressants. Curr Med Chem. 1998;5:381-390.

5. Feder R. Bradycardia and syncope induced by fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:139.

6. Ellison JM, Milofsky JE, Ely E. Fluoxetine-induced bradycardia and syncope in two patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:385-386.

7. Tucker P, Adamson P, Miranda R Jr, et al. Paroxetine increases heart rate variability in panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:370-376. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199710000-00006

1. Ojha A, McNeeley K, Heller E, et al. Orthostatic syndromes differ in syncope frequency. Am J Med. 2010;123:245-249. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.018

2. Arnold AC, Ng J, Raj SR. Postural tachycardia syndrome—diagnosis, physiology, and prognosis. Auton Neurosci. 2018;215:3-11. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2018.02.005

3. Fedorowski A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J Intern Med. 2018;285:352-366. doi:10.1111/joim.12852

4. Pacher P, Ungvari Z, Kecskemeti V, et al. Review of cardiovascular effects of fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, compared to tricyclic antidepressants. Curr Med Chem. 1998;5:381-390.

5. Feder R. Bradycardia and syncope induced by fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:139.

6. Ellison JM, Milofsky JE, Ely E. Fluoxetine-induced bradycardia and syncope in two patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:385-386.

7. Tucker P, Adamson P, Miranda R Jr, et al. Paroxetine increases heart rate variability in panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:370-376. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199710000-00006

Treating Hepatitis C Virus Reinfection With 8 Weeks of Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir Achieves Sustained Virologic Response

Three patients reinfected with hepatitis C virus after a sustained virologic response were considered treatment naïve and treated with a short-course direct acting antiviral regimen.

To decrease the incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the United States, hepatology experts, public health officials, and patient advocates agree that linkage to care is essential for treatment of people who inject drugs (PWID). The most recent surveillance report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that injection drug use accounts for the transmission of approximately 72% of new HCV infections.1,2

Although recent studies of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents have not been designed to investigate the long-term rates of reinfection in this population, various population-based studies in multiple countries have attempted to describe the rate of reinfection for this cohort.3-7 This rate varies widely based on the defined population of PWID, definition of reinfection, and the prevalence of HCV in a given PWID population. However, studies have consistently shown a relatively low historic rate of reinfection, which varies from 1 to 5 per 100 person-years in patients who have ever injected drugs, to 3 to 33 per 100 person-years in patients who continue injection drug use (IDU). Higher rates are found in those who engage in high-risk behaviors such as needle sharing.3-7 Yet, the US opioid crisis is attributable to a recent rise in both overall incidence and reinfections, highlighting the importance of determining the best treatment strategy for those who become reinfected.1

Current HCV guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases AASLD) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) encourage access to retreatment for PWID who become reinfected, stating that new reinfections should follow treatment-naïve therapy recommendations.8 However, to date this recommendation has not been validated by published clinical trials or patient case reports. This is likely due in part both to the small number of reinfections among PWID requiring retreatment and barriers to payment for treatment, particularly for individuals with substance use disorders.9 While this recommendation can be found under the key population section for the “Identification and Management of HCV in People Who Inject Drugs,” health care providers (HCPs) may easily miss this statement if they alternatively refer to the “Treatment-Experienced” section that recommends escalation to either sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in patients who are NS5A inhibitor DAA-experienced.8 Anecdotally, the first instinct for many HCPs when considering a treatment regimen for a reinfected patient is to refer to treatment-experienced regimen recommendations rather than appreciating the reinfected virus to be treatment naïve.

A treatment-escalation approach could have the consequence of limiting the number of times a patient could undergo treatment on successive reinfections. Additionally, these retreatment regimens often are more expensive, resulting in further cost barriers for payors approving retreatment for individuals with HCV reinfection. In contrast, demonstrating efficacy of a less costly short-course regimen would support increased access to initial and retreatment courses for PWID. The implications of enabling improved access to care is essential in the setting of the ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States.

Given the perspective that the virus should be considered treatment naïve for patients who become reinfected, we describe here 3 cases of patients previously achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) being retreated with the cost-effective 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir following reinfection.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 59-year-old male presented for his third treatment course for HCV genotype 1a. The patient initially underwent 76 weeks of interferon-based HCV treatment in 2007 and 2008, from which he was determined to have achieved SVR in 24 weeks (SVR24) in April 2009. His viral load remained undetected through February 2010 but subsequently had detectable virus again in 2011 following relapsed use of alcohol, cocaine, and injection drugs. The patient elected to await approval of DAAs and eventually completed an 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir from May to July 2016, achieving SVR24 in December 2016. The patient’s viral load was rechecked in October 2018 and he was again viremic following recent IDU, suggesting a second reinfection.

In preparation for his third HCV treatment, the patient was included in shared decision making to consider retreating his de novo infection as treatment naïve to provide a briefer (ie, 8 weeks) and more cost-effective treatment given his low likelihood of advanced fibrotic liver disease—his FibroScan score was 6.5 kPa, whereas scores ≥ 12.5 kPa in patients with chronic HCV suggest a higher likelihood of cirrhosis.10 At week 4, the patient’s viral load was undetected, he completed his 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir as planned and achieved SVR12 (Table). He had reported excellent adherence throughout treatment with assistance of a pill box and validated by a reported pill count.

Case 2

A 32-year-old male presented with HCV genotype 1a. Like case 1, this patient had a low FibroScan score of 4.7 kPa. He was previously infected with genotype 3 and completed a 12-week course of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in November 2016. He achieved SVR12 as evidenced by an undetected viral load in February 2017 despite questionable adherence throughout and relapsed use of heroin by the end of his regimen. He continued intermittent IDU and presented in October 2018 with a detectable viral load, now with genotype 1a. The patient similarly agreed to undergo an 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, considering his de novo infection to be treatment naïve. His viral load at treatment week 3 was quantitatively negative while qualitatively detectable at < 15 U/mL. He completed his treatment course in March 2019 and was determined to have achieved SVR24 in September 2019.

Case 3

A 51-year-old male presented with a history of HCV genotype 1a and a low FibroScan score (4.9 kPa ). The patient was previously infected with genotype 2 and had achieved SVR24 following a 12-week regimen of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in 2017. The patient subsequently was reinfected with genotype 1a and completed an 8-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in May 2019. The patient had his SVR12 lab drawn 9 days early and was undetectable at that time. He reported 0 missed doses during treatment and achieved an undetected viral load by treatment week 4.

Discussion

We demonstrate that HCV reinfection after treatment with previous interferon and/or DAA-based regimens can be treated with less costly 8-week treatment regimens. Current guidelines include a statement allowing for reinfected patients to follow initial treatment guidelines, but this statement has previously lacked published evidence and may be overlooked by HCPs who refer to recommendations for treatment-experienced patients. Given the increasing likelihood of HCPs encountering patients who have become reinfected with HCV after achieving SVR from a DAA regimen, further delineation may be needed in the recommendations for treatment-experienced patients to highlight the important nuance of recognizing that reinfections should follow initial treatment guidance.

While all 3 of these cases met criteria for the least costly and simplest 1 pill once daily 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, patients requiring retreatment with alternative genotypes or evidence of advanced fibrotic liver disease could benefit from a similar approach of using the least expensive and/or shortest duration regimen for which they meet eligibility. With this approach, coverage could be further expanded to the PWID population to help limit HCV transmission amid the opioid crisis.1

Studies have established that PWID are able to achieve similar SVR efficacy rates similar to that of the general population when treated in the setting of an interdisciplinary treatment team that offers collaborative management of complex psychosocial comorbidities and harm reduction strategies.11,12 These integrative patient-centric strategies may include personalized behavioral health pretreatment evaluations, access to substance use treatment, harm reduction counseling, needle exchange programs, and close follow-up by a case manager.2,13 Current DAA regimens combined with 1 or more of these strategies have demonstrated SVR12 rates of 90 to 95% for initial treatment regimens.11 These high SVR12 rates were even achieved in a recent study in which 74% (76/103) of participants had self-reported IDU within 30 days of HCV treatment start and similar IDU rates throughout treatment.12 A meta-analysis, including real-world studies of DAA treatment outcomes yielded a pooled SVR of 88% (95% CI, 83‐92%) for recent PWID and 91% (95% CI, 88‐95%) for individuals using opiate substitution therapy (OST).14 Additionally, linking PWID with OST also reduces risk for reinfection.14,15

For any patient with detectable HCV after completing the initial DAA regimen, it is important to distinguish between relapse and reinfection. SVR12 is generally synonymous with a clinical cure. Patients with ongoing risk factors posttreatment should continue to have their HCV viral load monitored for evidence of reinfection. Patients without known risk factors may benefit from repeat viral load only if there is clinical concern for reinfection, for example, a rise in liver enzymes.

We have shown that patients with ongoing risk factors who are reinfected can be treated successfully with cost-effective 8-week regimens. For comparison this 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir has an average wholesale price (AWP) of $28,800, while alternative regimens approved for treatment-naïve patients vary in AWP from $31,680 to $43,200, and regimens approved for retreatment of DAA failures have an AWP as high as $89,712.

An 8-week treatment regimen for both initial and reinfection regimens affords many advantages in medication adherence and both medication and provider resource cost-effectiveness. First, new HCV reinfections are disproportionally younger individuals often with complex psychosocial issues that impact retention in treatment. An 8-week course of treatment can be initiated concurrently with substance abuse treatment programs, including intensive outpatient programs and residential treatment programs that are usually at least 28 days. Many of these programs provide aftercare options that would extend the entire course of treatment. These opportunities afford individuals to receive HCV treatment in a setting that supports medication adherence, sobriety efforts, and education on harm reduction to reduce risk for reinfection.

Finally, statistical models indicate eradication of HCV will require scaling up the treatment of PWID in conjunction with harm reduction strategies such as OST and needle exchange programs.16 In contrast, there are low risks associated with retreatment given these medications are well-tolerated, treatment of PWID lowers the risk of further HCV transmission, and the understanding of these reinfections being treatment naïve disavows concerns of these patients having resistance to regimens that cleared their prior infections. The opportunity to provide retreatment without escalating regimen complexity or cost increases access to care for a vulnerable population while aiding in the eradication of HCV.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance - United States, 2018. Updated August 28, 2020. Accessed May 18, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2018surveillance/HepC.htm 2. Grebely J, Robaeys G, Bruggmann P, et al; International Network for Hepatitis in Substance Users. Recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):1028-1038. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.005

3. Marco A, Esteban JI, Solé C, et al. Hepatitis C virus reinfection among prisoners with sustained virological response after treatment for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):45-51. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.008

4. Midgard H, Bjøro B, Mæland A, et al. Hepatitis C reinfection after sustained virological response. J Hepatol. 2016;64(5):1020-1026. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.001

5. Currie SL, Ryan JC, Tracy D, et al. A prospective study to examine persistent HCV reinfection in injection drug users who have previously cleared the virus [published correction appears in Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Jul;96(1-2):192]. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(1-2):148-154. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.011

6. Grady BP, Vanhommerig JW, Schinkel J, et al. Low incidence of reinfection with the hepatitis C virus following treatment in active drug users in Amsterdam. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(11):1302-1307. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835702a8

7. Grebely J, Pham ST, Matthews GV, et al; ATAHC Study Group. Hepatitis C virus reinfection and superinfection among treated and untreated participants with recent infection. Hepatology. 2012;55(4):1058-1069. doi:10.1002/hep.24754

8. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.hcvguidelines.org

9. National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable, Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation, Harvard Law School. Hepatitis C: The State of Medicaid Access. 2017 National Summary Report. Updated October 23, 2017. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://hepcstage.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/State-of-HepC_2017_FINAL.pdf

10. Singh S, Muir AJ, Dieterich DT, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the role of elastography in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1544-1577. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.03.016

11. Dore GJ, Altice F, Litwin AH, et al; C-EDGE CO-STAR Study Group. Elbasvir-grazoprevir to treat hepatitis C virus infection in persons receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):625-634. doi:10.7326/M16-0816

12. Grebely J, Dalgard O, Conway B, et al; SIMPLIFY Study Group. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(3):153-161. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30404-1

13. Cos TA, Bartholomew TS, Huynh, KJ. Role of behavioral health providers in treating hepatitis C. Professional Psychol Res Pract. 2019;50(4):246–254. doi:10.1037/pro0000243

14. Latham NH, Doyle JS, Palmer AY, et al. Staying hepatitis C negative: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cure and reinfection in people who inject drugs. Liver Int. 2019;39(12):2244-2260. doi:10.1111/liv.14152

15. Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):CD012021. Published 2017 Sep 18. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012021.pub2

16. Fraser H, Martin NK, Brummer-Korvenkontio H, et al. Model projections on the impact of HCV treatment in the prevention of HCV transmission among people who inject drugs in Europe. J Hepatol. 2018;68(3):402-411. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.010

Three patients reinfected with hepatitis C virus after a sustained virologic response were considered treatment naïve and treated with a short-course direct acting antiviral regimen.

Three patients reinfected with hepatitis C virus after a sustained virologic response were considered treatment naïve and treated with a short-course direct acting antiviral regimen.

To decrease the incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the United States, hepatology experts, public health officials, and patient advocates agree that linkage to care is essential for treatment of people who inject drugs (PWID). The most recent surveillance report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that injection drug use accounts for the transmission of approximately 72% of new HCV infections.1,2

Although recent studies of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents have not been designed to investigate the long-term rates of reinfection in this population, various population-based studies in multiple countries have attempted to describe the rate of reinfection for this cohort.3-7 This rate varies widely based on the defined population of PWID, definition of reinfection, and the prevalence of HCV in a given PWID population. However, studies have consistently shown a relatively low historic rate of reinfection, which varies from 1 to 5 per 100 person-years in patients who have ever injected drugs, to 3 to 33 per 100 person-years in patients who continue injection drug use (IDU). Higher rates are found in those who engage in high-risk behaviors such as needle sharing.3-7 Yet, the US opioid crisis is attributable to a recent rise in both overall incidence and reinfections, highlighting the importance of determining the best treatment strategy for those who become reinfected.1

Current HCV guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases AASLD) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) encourage access to retreatment for PWID who become reinfected, stating that new reinfections should follow treatment-naïve therapy recommendations.8 However, to date this recommendation has not been validated by published clinical trials or patient case reports. This is likely due in part both to the small number of reinfections among PWID requiring retreatment and barriers to payment for treatment, particularly for individuals with substance use disorders.9 While this recommendation can be found under the key population section for the “Identification and Management of HCV in People Who Inject Drugs,” health care providers (HCPs) may easily miss this statement if they alternatively refer to the “Treatment-Experienced” section that recommends escalation to either sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in patients who are NS5A inhibitor DAA-experienced.8 Anecdotally, the first instinct for many HCPs when considering a treatment regimen for a reinfected patient is to refer to treatment-experienced regimen recommendations rather than appreciating the reinfected virus to be treatment naïve.

A treatment-escalation approach could have the consequence of limiting the number of times a patient could undergo treatment on successive reinfections. Additionally, these retreatment regimens often are more expensive, resulting in further cost barriers for payors approving retreatment for individuals with HCV reinfection. In contrast, demonstrating efficacy of a less costly short-course regimen would support increased access to initial and retreatment courses for PWID. The implications of enabling improved access to care is essential in the setting of the ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States.

Given the perspective that the virus should be considered treatment naïve for patients who become reinfected, we describe here 3 cases of patients previously achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) being retreated with the cost-effective 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir following reinfection.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 59-year-old male presented for his third treatment course for HCV genotype 1a. The patient initially underwent 76 weeks of interferon-based HCV treatment in 2007 and 2008, from which he was determined to have achieved SVR in 24 weeks (SVR24) in April 2009. His viral load remained undetected through February 2010 but subsequently had detectable virus again in 2011 following relapsed use of alcohol, cocaine, and injection drugs. The patient elected to await approval of DAAs and eventually completed an 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir from May to July 2016, achieving SVR24 in December 2016. The patient’s viral load was rechecked in October 2018 and he was again viremic following recent IDU, suggesting a second reinfection.

In preparation for his third HCV treatment, the patient was included in shared decision making to consider retreating his de novo infection as treatment naïve to provide a briefer (ie, 8 weeks) and more cost-effective treatment given his low likelihood of advanced fibrotic liver disease—his FibroScan score was 6.5 kPa, whereas scores ≥ 12.5 kPa in patients with chronic HCV suggest a higher likelihood of cirrhosis.10 At week 4, the patient’s viral load was undetected, he completed his 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir as planned and achieved SVR12 (Table). He had reported excellent adherence throughout treatment with assistance of a pill box and validated by a reported pill count.

Case 2

A 32-year-old male presented with HCV genotype 1a. Like case 1, this patient had a low FibroScan score of 4.7 kPa. He was previously infected with genotype 3 and completed a 12-week course of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in November 2016. He achieved SVR12 as evidenced by an undetected viral load in February 2017 despite questionable adherence throughout and relapsed use of heroin by the end of his regimen. He continued intermittent IDU and presented in October 2018 with a detectable viral load, now with genotype 1a. The patient similarly agreed to undergo an 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, considering his de novo infection to be treatment naïve. His viral load at treatment week 3 was quantitatively negative while qualitatively detectable at < 15 U/mL. He completed his treatment course in March 2019 and was determined to have achieved SVR24 in September 2019.

Case 3

A 51-year-old male presented with a history of HCV genotype 1a and a low FibroScan score (4.9 kPa ). The patient was previously infected with genotype 2 and had achieved SVR24 following a 12-week regimen of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in 2017. The patient subsequently was reinfected with genotype 1a and completed an 8-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in May 2019. The patient had his SVR12 lab drawn 9 days early and was undetectable at that time. He reported 0 missed doses during treatment and achieved an undetected viral load by treatment week 4.

Discussion

We demonstrate that HCV reinfection after treatment with previous interferon and/or DAA-based regimens can be treated with less costly 8-week treatment regimens. Current guidelines include a statement allowing for reinfected patients to follow initial treatment guidelines, but this statement has previously lacked published evidence and may be overlooked by HCPs who refer to recommendations for treatment-experienced patients. Given the increasing likelihood of HCPs encountering patients who have become reinfected with HCV after achieving SVR from a DAA regimen, further delineation may be needed in the recommendations for treatment-experienced patients to highlight the important nuance of recognizing that reinfections should follow initial treatment guidance.

While all 3 of these cases met criteria for the least costly and simplest 1 pill once daily 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, patients requiring retreatment with alternative genotypes or evidence of advanced fibrotic liver disease could benefit from a similar approach of using the least expensive and/or shortest duration regimen for which they meet eligibility. With this approach, coverage could be further expanded to the PWID population to help limit HCV transmission amid the opioid crisis.1

Studies have established that PWID are able to achieve similar SVR efficacy rates similar to that of the general population when treated in the setting of an interdisciplinary treatment team that offers collaborative management of complex psychosocial comorbidities and harm reduction strategies.11,12 These integrative patient-centric strategies may include personalized behavioral health pretreatment evaluations, access to substance use treatment, harm reduction counseling, needle exchange programs, and close follow-up by a case manager.2,13 Current DAA regimens combined with 1 or more of these strategies have demonstrated SVR12 rates of 90 to 95% for initial treatment regimens.11 These high SVR12 rates were even achieved in a recent study in which 74% (76/103) of participants had self-reported IDU within 30 days of HCV treatment start and similar IDU rates throughout treatment.12 A meta-analysis, including real-world studies of DAA treatment outcomes yielded a pooled SVR of 88% (95% CI, 83‐92%) for recent PWID and 91% (95% CI, 88‐95%) for individuals using opiate substitution therapy (OST).14 Additionally, linking PWID with OST also reduces risk for reinfection.14,15

For any patient with detectable HCV after completing the initial DAA regimen, it is important to distinguish between relapse and reinfection. SVR12 is generally synonymous with a clinical cure. Patients with ongoing risk factors posttreatment should continue to have their HCV viral load monitored for evidence of reinfection. Patients without known risk factors may benefit from repeat viral load only if there is clinical concern for reinfection, for example, a rise in liver enzymes.

We have shown that patients with ongoing risk factors who are reinfected can be treated successfully with cost-effective 8-week regimens. For comparison this 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir has an average wholesale price (AWP) of $28,800, while alternative regimens approved for treatment-naïve patients vary in AWP from $31,680 to $43,200, and regimens approved for retreatment of DAA failures have an AWP as high as $89,712.

An 8-week treatment regimen for both initial and reinfection regimens affords many advantages in medication adherence and both medication and provider resource cost-effectiveness. First, new HCV reinfections are disproportionally younger individuals often with complex psychosocial issues that impact retention in treatment. An 8-week course of treatment can be initiated concurrently with substance abuse treatment programs, including intensive outpatient programs and residential treatment programs that are usually at least 28 days. Many of these programs provide aftercare options that would extend the entire course of treatment. These opportunities afford individuals to receive HCV treatment in a setting that supports medication adherence, sobriety efforts, and education on harm reduction to reduce risk for reinfection.

Finally, statistical models indicate eradication of HCV will require scaling up the treatment of PWID in conjunction with harm reduction strategies such as OST and needle exchange programs.16 In contrast, there are low risks associated with retreatment given these medications are well-tolerated, treatment of PWID lowers the risk of further HCV transmission, and the understanding of these reinfections being treatment naïve disavows concerns of these patients having resistance to regimens that cleared their prior infections. The opportunity to provide retreatment without escalating regimen complexity or cost increases access to care for a vulnerable population while aiding in the eradication of HCV.

To decrease the incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the United States, hepatology experts, public health officials, and patient advocates agree that linkage to care is essential for treatment of people who inject drugs (PWID). The most recent surveillance report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that injection drug use accounts for the transmission of approximately 72% of new HCV infections.1,2

Although recent studies of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents have not been designed to investigate the long-term rates of reinfection in this population, various population-based studies in multiple countries have attempted to describe the rate of reinfection for this cohort.3-7 This rate varies widely based on the defined population of PWID, definition of reinfection, and the prevalence of HCV in a given PWID population. However, studies have consistently shown a relatively low historic rate of reinfection, which varies from 1 to 5 per 100 person-years in patients who have ever injected drugs, to 3 to 33 per 100 person-years in patients who continue injection drug use (IDU). Higher rates are found in those who engage in high-risk behaviors such as needle sharing.3-7 Yet, the US opioid crisis is attributable to a recent rise in both overall incidence and reinfections, highlighting the importance of determining the best treatment strategy for those who become reinfected.1

Current HCV guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases AASLD) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) encourage access to retreatment for PWID who become reinfected, stating that new reinfections should follow treatment-naïve therapy recommendations.8 However, to date this recommendation has not been validated by published clinical trials or patient case reports. This is likely due in part both to the small number of reinfections among PWID requiring retreatment and barriers to payment for treatment, particularly for individuals with substance use disorders.9 While this recommendation can be found under the key population section for the “Identification and Management of HCV in People Who Inject Drugs,” health care providers (HCPs) may easily miss this statement if they alternatively refer to the “Treatment-Experienced” section that recommends escalation to either sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in patients who are NS5A inhibitor DAA-experienced.8 Anecdotally, the first instinct for many HCPs when considering a treatment regimen for a reinfected patient is to refer to treatment-experienced regimen recommendations rather than appreciating the reinfected virus to be treatment naïve.

A treatment-escalation approach could have the consequence of limiting the number of times a patient could undergo treatment on successive reinfections. Additionally, these retreatment regimens often are more expensive, resulting in further cost barriers for payors approving retreatment for individuals with HCV reinfection. In contrast, demonstrating efficacy of a less costly short-course regimen would support increased access to initial and retreatment courses for PWID. The implications of enabling improved access to care is essential in the setting of the ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States.

Given the perspective that the virus should be considered treatment naïve for patients who become reinfected, we describe here 3 cases of patients previously achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) being retreated with the cost-effective 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir following reinfection.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 59-year-old male presented for his third treatment course for HCV genotype 1a. The patient initially underwent 76 weeks of interferon-based HCV treatment in 2007 and 2008, from which he was determined to have achieved SVR in 24 weeks (SVR24) in April 2009. His viral load remained undetected through February 2010 but subsequently had detectable virus again in 2011 following relapsed use of alcohol, cocaine, and injection drugs. The patient elected to await approval of DAAs and eventually completed an 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir from May to July 2016, achieving SVR24 in December 2016. The patient’s viral load was rechecked in October 2018 and he was again viremic following recent IDU, suggesting a second reinfection.

In preparation for his third HCV treatment, the patient was included in shared decision making to consider retreating his de novo infection as treatment naïve to provide a briefer (ie, 8 weeks) and more cost-effective treatment given his low likelihood of advanced fibrotic liver disease—his FibroScan score was 6.5 kPa, whereas scores ≥ 12.5 kPa in patients with chronic HCV suggest a higher likelihood of cirrhosis.10 At week 4, the patient’s viral load was undetected, he completed his 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir as planned and achieved SVR12 (Table). He had reported excellent adherence throughout treatment with assistance of a pill box and validated by a reported pill count.

Case 2

A 32-year-old male presented with HCV genotype 1a. Like case 1, this patient had a low FibroScan score of 4.7 kPa. He was previously infected with genotype 3 and completed a 12-week course of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in November 2016. He achieved SVR12 as evidenced by an undetected viral load in February 2017 despite questionable adherence throughout and relapsed use of heroin by the end of his regimen. He continued intermittent IDU and presented in October 2018 with a detectable viral load, now with genotype 1a. The patient similarly agreed to undergo an 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, considering his de novo infection to be treatment naïve. His viral load at treatment week 3 was quantitatively negative while qualitatively detectable at < 15 U/mL. He completed his treatment course in March 2019 and was determined to have achieved SVR24 in September 2019.

Case 3

A 51-year-old male presented with a history of HCV genotype 1a and a low FibroScan score (4.9 kPa ). The patient was previously infected with genotype 2 and had achieved SVR24 following a 12-week regimen of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in 2017. The patient subsequently was reinfected with genotype 1a and completed an 8-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir in May 2019. The patient had his SVR12 lab drawn 9 days early and was undetectable at that time. He reported 0 missed doses during treatment and achieved an undetected viral load by treatment week 4.

Discussion

We demonstrate that HCV reinfection after treatment with previous interferon and/or DAA-based regimens can be treated with less costly 8-week treatment regimens. Current guidelines include a statement allowing for reinfected patients to follow initial treatment guidelines, but this statement has previously lacked published evidence and may be overlooked by HCPs who refer to recommendations for treatment-experienced patients. Given the increasing likelihood of HCPs encountering patients who have become reinfected with HCV after achieving SVR from a DAA regimen, further delineation may be needed in the recommendations for treatment-experienced patients to highlight the important nuance of recognizing that reinfections should follow initial treatment guidance.

While all 3 of these cases met criteria for the least costly and simplest 1 pill once daily 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, patients requiring retreatment with alternative genotypes or evidence of advanced fibrotic liver disease could benefit from a similar approach of using the least expensive and/or shortest duration regimen for which they meet eligibility. With this approach, coverage could be further expanded to the PWID population to help limit HCV transmission amid the opioid crisis.1

Studies have established that PWID are able to achieve similar SVR efficacy rates similar to that of the general population when treated in the setting of an interdisciplinary treatment team that offers collaborative management of complex psychosocial comorbidities and harm reduction strategies.11,12 These integrative patient-centric strategies may include personalized behavioral health pretreatment evaluations, access to substance use treatment, harm reduction counseling, needle exchange programs, and close follow-up by a case manager.2,13 Current DAA regimens combined with 1 or more of these strategies have demonstrated SVR12 rates of 90 to 95% for initial treatment regimens.11 These high SVR12 rates were even achieved in a recent study in which 74% (76/103) of participants had self-reported IDU within 30 days of HCV treatment start and similar IDU rates throughout treatment.12 A meta-analysis, including real-world studies of DAA treatment outcomes yielded a pooled SVR of 88% (95% CI, 83‐92%) for recent PWID and 91% (95% CI, 88‐95%) for individuals using opiate substitution therapy (OST).14 Additionally, linking PWID with OST also reduces risk for reinfection.14,15

For any patient with detectable HCV after completing the initial DAA regimen, it is important to distinguish between relapse and reinfection. SVR12 is generally synonymous with a clinical cure. Patients with ongoing risk factors posttreatment should continue to have their HCV viral load monitored for evidence of reinfection. Patients without known risk factors may benefit from repeat viral load only if there is clinical concern for reinfection, for example, a rise in liver enzymes.

We have shown that patients with ongoing risk factors who are reinfected can be treated successfully with cost-effective 8-week regimens. For comparison this 8-week regimen of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir has an average wholesale price (AWP) of $28,800, while alternative regimens approved for treatment-naïve patients vary in AWP from $31,680 to $43,200, and regimens approved for retreatment of DAA failures have an AWP as high as $89,712.

An 8-week treatment regimen for both initial and reinfection regimens affords many advantages in medication adherence and both medication and provider resource cost-effectiveness. First, new HCV reinfections are disproportionally younger individuals often with complex psychosocial issues that impact retention in treatment. An 8-week course of treatment can be initiated concurrently with substance abuse treatment programs, including intensive outpatient programs and residential treatment programs that are usually at least 28 days. Many of these programs provide aftercare options that would extend the entire course of treatment. These opportunities afford individuals to receive HCV treatment in a setting that supports medication adherence, sobriety efforts, and education on harm reduction to reduce risk for reinfection.

Finally, statistical models indicate eradication of HCV will require scaling up the treatment of PWID in conjunction with harm reduction strategies such as OST and needle exchange programs.16 In contrast, there are low risks associated with retreatment given these medications are well-tolerated, treatment of PWID lowers the risk of further HCV transmission, and the understanding of these reinfections being treatment naïve disavows concerns of these patients having resistance to regimens that cleared their prior infections. The opportunity to provide retreatment without escalating regimen complexity or cost increases access to care for a vulnerable population while aiding in the eradication of HCV.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance - United States, 2018. Updated August 28, 2020. Accessed May 18, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2018surveillance/HepC.htm 2. Grebely J, Robaeys G, Bruggmann P, et al; International Network for Hepatitis in Substance Users. Recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):1028-1038. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.005

3. Marco A, Esteban JI, Solé C, et al. Hepatitis C virus reinfection among prisoners with sustained virological response after treatment for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):45-51. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.008

4. Midgard H, Bjøro B, Mæland A, et al. Hepatitis C reinfection after sustained virological response. J Hepatol. 2016;64(5):1020-1026. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.001

5. Currie SL, Ryan JC, Tracy D, et al. A prospective study to examine persistent HCV reinfection in injection drug users who have previously cleared the virus [published correction appears in Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Jul;96(1-2):192]. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(1-2):148-154. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.011

6. Grady BP, Vanhommerig JW, Schinkel J, et al. Low incidence of reinfection with the hepatitis C virus following treatment in active drug users in Amsterdam. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(11):1302-1307. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835702a8

7. Grebely J, Pham ST, Matthews GV, et al; ATAHC Study Group. Hepatitis C virus reinfection and superinfection among treated and untreated participants with recent infection. Hepatology. 2012;55(4):1058-1069. doi:10.1002/hep.24754

8. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.hcvguidelines.org

9. National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable, Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation, Harvard Law School. Hepatitis C: The State of Medicaid Access. 2017 National Summary Report. Updated October 23, 2017. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://hepcstage.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/State-of-HepC_2017_FINAL.pdf

10. Singh S, Muir AJ, Dieterich DT, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the role of elastography in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1544-1577. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.03.016

11. Dore GJ, Altice F, Litwin AH, et al; C-EDGE CO-STAR Study Group. Elbasvir-grazoprevir to treat hepatitis C virus infection in persons receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):625-634. doi:10.7326/M16-0816

12. Grebely J, Dalgard O, Conway B, et al; SIMPLIFY Study Group. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(3):153-161. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30404-1

13. Cos TA, Bartholomew TS, Huynh, KJ. Role of behavioral health providers in treating hepatitis C. Professional Psychol Res Pract. 2019;50(4):246–254. doi:10.1037/pro0000243

14. Latham NH, Doyle JS, Palmer AY, et al. Staying hepatitis C negative: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cure and reinfection in people who inject drugs. Liver Int. 2019;39(12):2244-2260. doi:10.1111/liv.14152

15. Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):CD012021. Published 2017 Sep 18. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012021.pub2

16. Fraser H, Martin NK, Brummer-Korvenkontio H, et al. Model projections on the impact of HCV treatment in the prevention of HCV transmission among people who inject drugs in Europe. J Hepatol. 2018;68(3):402-411. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.010

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance - United States, 2018. Updated August 28, 2020. Accessed May 18, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2018surveillance/HepC.htm 2. Grebely J, Robaeys G, Bruggmann P, et al; International Network for Hepatitis in Substance Users. Recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):1028-1038. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.005

3. Marco A, Esteban JI, Solé C, et al. Hepatitis C virus reinfection among prisoners with sustained virological response after treatment for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):45-51. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.008

4. Midgard H, Bjøro B, Mæland A, et al. Hepatitis C reinfection after sustained virological response. J Hepatol. 2016;64(5):1020-1026. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.001

5. Currie SL, Ryan JC, Tracy D, et al. A prospective study to examine persistent HCV reinfection in injection drug users who have previously cleared the virus [published correction appears in Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Jul;96(1-2):192]. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(1-2):148-154. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.011

6. Grady BP, Vanhommerig JW, Schinkel J, et al. Low incidence of reinfection with the hepatitis C virus following treatment in active drug users in Amsterdam. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(11):1302-1307. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835702a8

7. Grebely J, Pham ST, Matthews GV, et al; ATAHC Study Group. Hepatitis C virus reinfection and superinfection among treated and untreated participants with recent infection. Hepatology. 2012;55(4):1058-1069. doi:10.1002/hep.24754

8. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.hcvguidelines.org

9. National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable, Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation, Harvard Law School. Hepatitis C: The State of Medicaid Access. 2017 National Summary Report. Updated October 23, 2017. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://hepcstage.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/State-of-HepC_2017_FINAL.pdf

10. Singh S, Muir AJ, Dieterich DT, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the role of elastography in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1544-1577. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.03.016

11. Dore GJ, Altice F, Litwin AH, et al; C-EDGE CO-STAR Study Group. Elbasvir-grazoprevir to treat hepatitis C virus infection in persons receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):625-634. doi:10.7326/M16-0816

12. Grebely J, Dalgard O, Conway B, et al; SIMPLIFY Study Group. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(3):153-161. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30404-1

13. Cos TA, Bartholomew TS, Huynh, KJ. Role of behavioral health providers in treating hepatitis C. Professional Psychol Res Pract. 2019;50(4):246–254. doi:10.1037/pro0000243

14. Latham NH, Doyle JS, Palmer AY, et al. Staying hepatitis C negative: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cure and reinfection in people who inject drugs. Liver Int. 2019;39(12):2244-2260. doi:10.1111/liv.14152

15. Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):CD012021. Published 2017 Sep 18. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012021.pub2

16. Fraser H, Martin NK, Brummer-Korvenkontio H, et al. Model projections on the impact of HCV treatment in the prevention of HCV transmission among people who inject drugs in Europe. J Hepatol. 2018;68(3):402-411. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.010

Thinking Outside the ‘Cage’

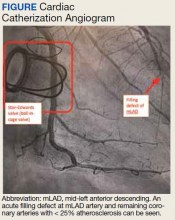

A 74-year-old male veteran presented at an urgent care clinic in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, with a sharp, nonradiating, left-sided precordial chest pain that started while cleaning his house and gardening. The patient described the pain as 9 on the 10-point Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, lasting about 5 to 10 minutes and was alleviated with rest. The patient’s medical history consisted of multiple comorbidities, including a mitral valve replacement with a Star-Edwards valve (ball in cage) in 1987. The electrocardiogram performed at the clinic showed no acute ischemic changes. Due to the persistent pain, the patient was transferred to Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for further evaluation and management. On arrival, the patient had an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.22; elevated high-sensitive troponin enzyme readings of 56 ng/L at 6:38 PM (0h); 61 ng/L at 7:38 PM (1h); and 83 ng/L at 9:47 PM (3h), reference range, 0-22 ng/L, and changes that prompted admission to the cardiac critical care unit. Two days later, a follow-up enzyme level was 52 ng/L. Cardiac catheterization revealed an acute filling defect at mid-left anterior descending artery and remaining coronary arteries with < 25% atherosclerosis (Figure). A myocardial perfusion study was performed for myocardial viability. The results showed a small, reversible perfusion defect involving the apical-septal wall with the remaining left ventricular myocardium appearing viable. Aspirin was added to the patient’s anticoagulation regimen of warfarin. Once target INR was reached, the patient was discharged home without recurrence of angina.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) consists of clinical suspicion of myocardial ischemia or laboratory confirmation of myocardial infarction (MI). ACS includes 3 major entities: non-ST elevation MI (NSTEMI), unstable angina, and ST-elevation MI (STEMI). ACS usually occurs as a result of a reduced supply of oxygenated blood to the myocardium, which is caused by restriction or occlusion of at least 1 of the coronary arteries. This alteration in blood flow is commonly secondary to a rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque or spontaneous dissection of a coronary artery. In rare cases, this reduction in blood flow is caused by a coronary embolism (CE) arising from a prosthetic heart valve.1,2

One of the first descriptions of CE was provided by Rudolf Virchow in the 1850s from postmortem autopsy findings.3 At that time, these coronary findings were associated with intracardiac mural thrombus or infective endocarditis. During the 1940s, CE was described in living patients who had survived a MI, and outcomes were not as catastrophic as originally believed. In the 1960s, a higher than usual association between prosthetic valves and CE was suspected and later confirmed by the invention and implementation of coronary angiography. Multiple studies have been published that confirm the association between prosthetic valves (especially in the mitral position), atrial fibrillation (AF), and a higher than usual rate of CEs.4,5

Discussion

The prevalence of this disease has varied during the years. Data from autopsies of patients with ACS and evidence of thromboembolic material in coronary arteries originally estimated a prevalence as high as 13%.6,7 After the invention of diagnostic angiography, consensus studies have established the prevalence to be approximately 3% in patient with ACS.1 The prevalence may be higher in patient with significant risk factors that may increase the probability of CEs, like prosthetic heart valves and AF.2

In 2015 Shibata and colleagues proposed a scoring system for the diagnosis of CE. The scoring system consisted of major and minor criteria.6 Diagnosis of CE is established by ≥ 2 major criteria; 1 major and 2 minor; or ≥ 3 minor criteria. This scoring system increases the diagnostic probability of the disease.1,6

The major criteria are angiographic evidence of coronary artery embolism and thrombosis without atherosclerotic components (met by this patient); concomitant coronary emboli in multiple coronary vascular territories; concomitant systemic embolization without left ventricular thrombus attributable to acute MI; histological evidence of venous origin of coronary embolic material; and evidence of an embolic source based on transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.1,6 The minor criteria are 25% stenosis on coronary angiography except for the culprit lesion (met by this patient); presence of emboli risk factors, such as prosthetic heart valve (met by this patient); and AF.1,6

Management of CE remains controversial; aspiration of thrombus may be considered in the acute setting and with evidence of a heavy thrombus formation. This may allow for restoration of flow and retrieval of thrombus formation for histopathologic evaluation. However, it is important to mention that in the setting of STEMI, aspiration has been shown to increase risk of stroke and lead to increased morbidity. If aspiration of thrombus provides good restoration of flow, there is no need for further percutaneous intervention. Benefits of aspiration in low thrombus burden are not well established and do not provide any additional benefit compared with those of anticoagulation.6-11

Anticoagulation should be initiated in patients with AF and low bleeding risk, even when CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, aged ≥ 75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke or transient ischemic attack, vascular disease, aged 65 to 74 years, sex category) score is low. In patients with prolonged immobilization, recent surgery, pregnancy, use of oral contraceptives/tamoxifen, or other reversible risks, 3 months of anticoagulation has been shown to be sufficient. In the setting of active cancer or known thrombophilia, prolonged anticoagulation is recommended. Thrombophilia testing is not recommended in the setting of CE.1

The America College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for valvular heart disease recommend that patients with mechanical prosthetic aortic valves should be started on a vitamin K antagonist with a target INR of 2 to 3. (Class 1A). Prosthetic mitral and high thromboembolic valves require a higher INR target above 3.0. The addition of antiplatelet agents, such as aspirin in doses of 75 to 100 mg, should be started to decrease risk of thromboembolic disease in all patients with prosthetic heart valves.12

CE is not a common cause of ACS. Nevertheless, it was considered in the differential diagnosis of this patient, and diagnostic criteria were reviewed. This patient met the diagnostic criteria for a definitive diagnosis of CE. These included 1 major and 2 minor criteria: angiographic evidence of coronary artery embolism and thrombosis without atherosclerotic components; < 25% stenosis on coronary angiography except for the culprit lesion; and presence of emboli risk factors (prosthetic heart valve).

CE is rare, and review of the literature reveals that it accounts for < 3% of all ACS cases. Despite its rarity, it is important to recognize its risk factors, which include prosthetic heart valves, valvuloplasty, vasculitis, AF, left ventricular aneurysm, and endocarditis. The difference in treatment between CE and the most frequently encountered etiologies of ACS reveals the importance in recognizing this syndrome. Management of CE remains controversial. Nevertheless, when the culprit lesion is located in a distal portion of the vessel involved, as was seen in our patient, and in cases where there is a low thrombi burden, anticoagulation instead of thrombectomy is usually preferred. Patients with prosthetic mechanical valves have a high incidence of thromboembolism. This sometimes leads to thrombi formation in uncommon locations. Guidelines of therapy in these patients recommend that all prosthetic mechanical valves should be treated with both antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapies to reduce the risk of thrombi formation.

Conclusion

Physicians involved in diagnosing ACS should be aware of the risk factors for CE and always consider it while evaluating patients and developing the differential diagnosis.

1. Raphael CE, Heit JA, Reeder GS, et al. Coronary embolus: an underappreciated cause of acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(2):172-180. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.057

2. Popovic B, Agrinier N, Bouchahda N, et al. Coronary embolism among ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients: mechanisms and management. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(1):e005587. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005587

3. Oakley C, Yusuf R, Hollman A. Coronary embolism and angina in mitral stenosis. Br Heart J. 1961;23(4):357-369. doi:10.1136/hrt.23.4.357

4. Charles RG, Epstein EJ. Diagnosis of coronary embolism: a review. J R Soc Med. 1983;76(10):863-869.

5. Bawell MB, Moragues V, Shrader EL. Coronary embolism. Circulation. 1956;14(6):1159-1163. doi:10.1161/01.cir.14.6.1159

6. Shibata T, Kawakami S, Noguchi T, et al. Prevalence, clinical features, and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction attributable to coronary artery embolism. Circulation. 2015;132(4):241-250. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015134

7. Prizel KR, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Coronary artery embolism and myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(2):155-161. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-155

8. Lacunza-Ruiz FJ, Muñoz-Esparza C, García-de-Lara J. Coronary embolism and thrombosis of prosthetic mitral valve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(10):e127-e128. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2014.02.025

9. Jolly SS, Cairns JA, Yusuf S, et al. Outcomes after thrombus aspiration for ST elevation myocardial infarction: 1-year follow-up of the prospective randomised TOTAL trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10014):127-135. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00448-1

10. Fröbert O, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, et al. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2014 Aug 21;371(8):786]. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(17):1587-1597. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1308789

11. Kalçık M, Yesin M, Gürsoy MO, Karakoyun S, Özkan M. Treatment strategies for prosthetic valve thrombosis-derived coronary embolism. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(5):756-757. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2014.11.019

12. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(25):e1159-e1195. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000503

A 74-year-old male veteran presented at an urgent care clinic in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, with a sharp, nonradiating, left-sided precordial chest pain that started while cleaning his house and gardening. The patient described the pain as 9 on the 10-point Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, lasting about 5 to 10 minutes and was alleviated with rest. The patient’s medical history consisted of multiple comorbidities, including a mitral valve replacement with a Star-Edwards valve (ball in cage) in 1987. The electrocardiogram performed at the clinic showed no acute ischemic changes. Due to the persistent pain, the patient was transferred to Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for further evaluation and management. On arrival, the patient had an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.22; elevated high-sensitive troponin enzyme readings of 56 ng/L at 6:38 PM (0h); 61 ng/L at 7:38 PM (1h); and 83 ng/L at 9:47 PM (3h), reference range, 0-22 ng/L, and changes that prompted admission to the cardiac critical care unit. Two days later, a follow-up enzyme level was 52 ng/L. Cardiac catheterization revealed an acute filling defect at mid-left anterior descending artery and remaining coronary arteries with < 25% atherosclerosis (Figure). A myocardial perfusion study was performed for myocardial viability. The results showed a small, reversible perfusion defect involving the apical-septal wall with the remaining left ventricular myocardium appearing viable. Aspirin was added to the patient’s anticoagulation regimen of warfarin. Once target INR was reached, the patient was discharged home without recurrence of angina.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?