User login

75-year-old woman • right-side rib pain • radiating shoulder pain • history of hypertension & hypercholesterolemia • Dx?

THE CASE

A 75-year-old woman presented to the primary care clinic with right-side rib pain. The patient said the pain started 1 week earlier, after she ate fried chicken for dinner, and had since been exacerbated by rich meals, lying supine, and taking a deep inspiratory breath. She also said that prior to coming to the clinic that day, the pain had been radiating to her right shoulder.

The patient denied experiencing associated fevers, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, or changes in stool color. She had a history of hypertension, for which she was taking lisinopril 20 mg/d, and hypercholesterolemia, for which she was on simvastatin 10 mg/d. She was additionally using timolol ophthalmic solution for her glaucoma.

During the examination, the patient’s vital signs were stable, with a pulse of 80 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The patient had no abdominal tenderness upon palpation, and the physical exam revealed no abnormalities. An in-office electrocardiogram was performed, with normal results. Additionally, a comprehensive metabolic panel, lipase test, and

THE DIAGNOSIS

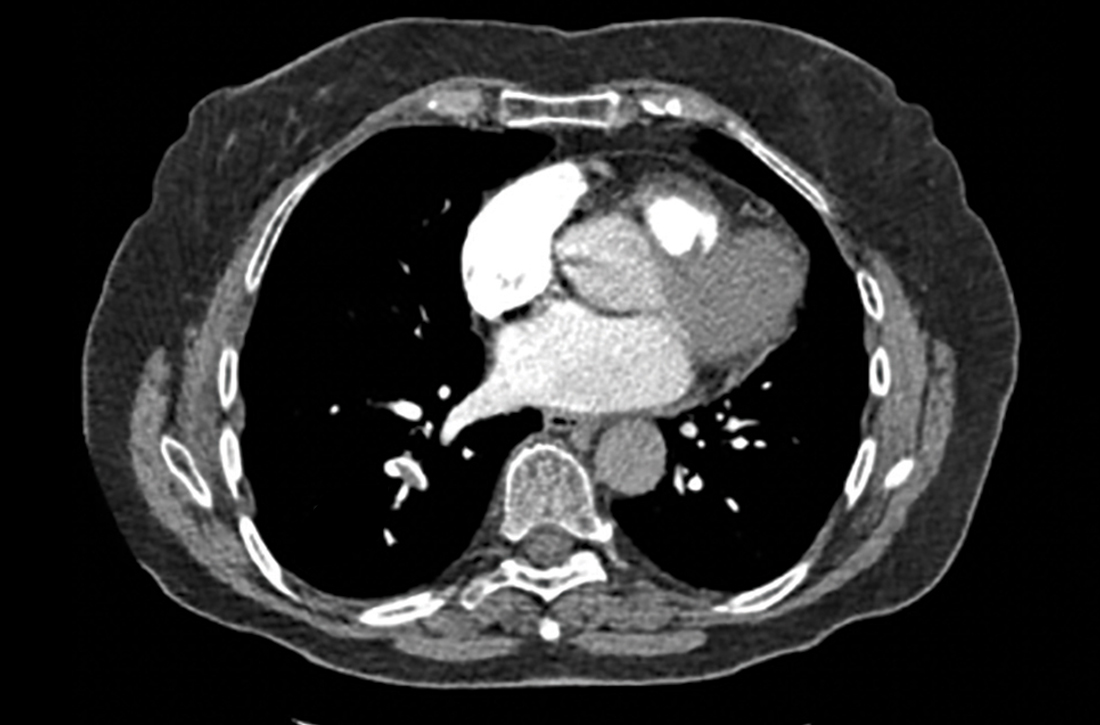

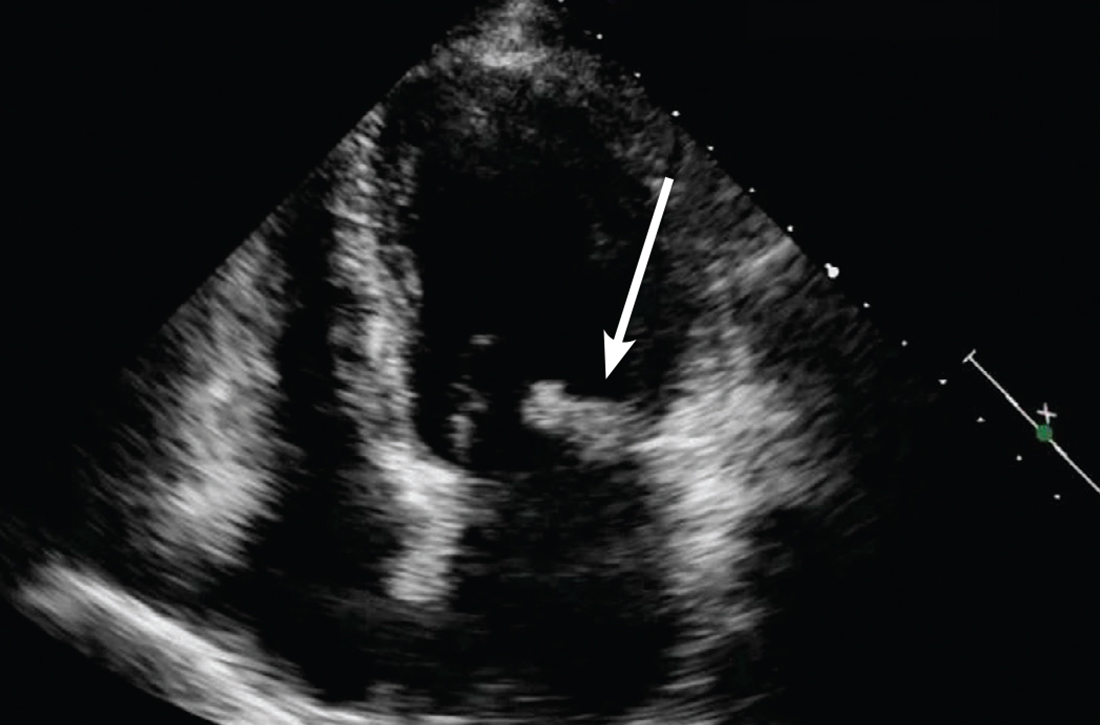

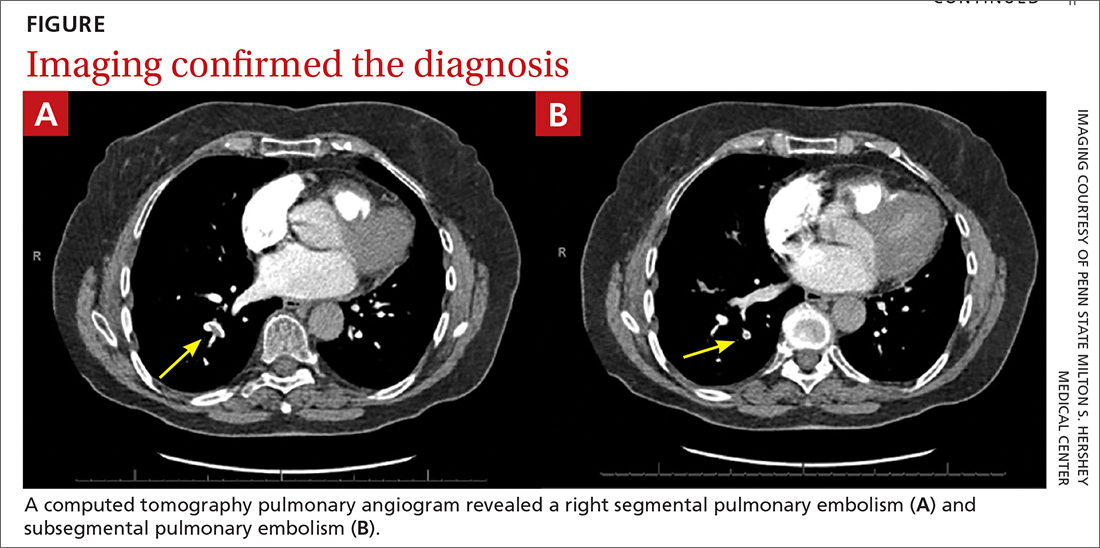

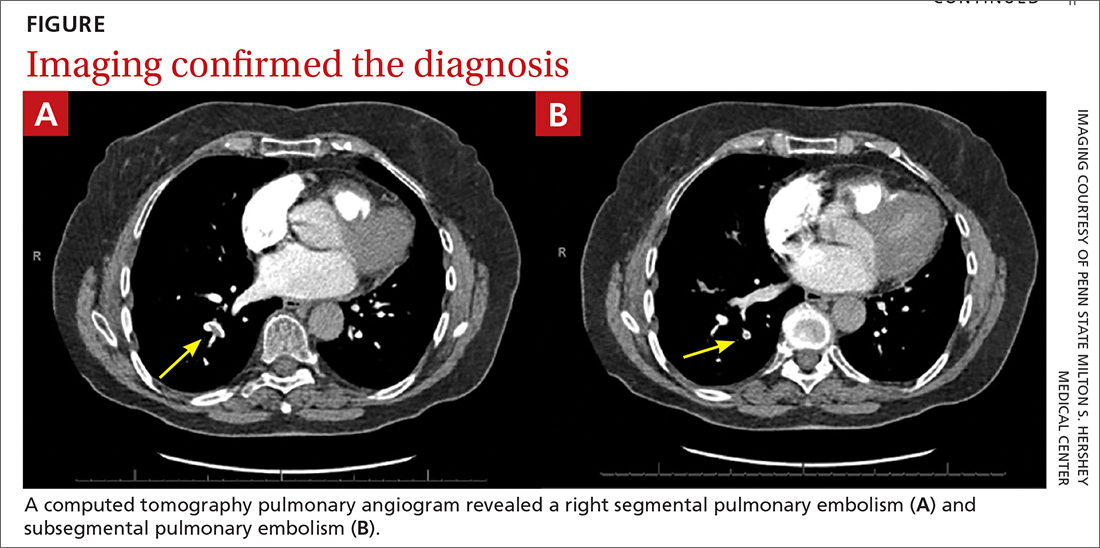

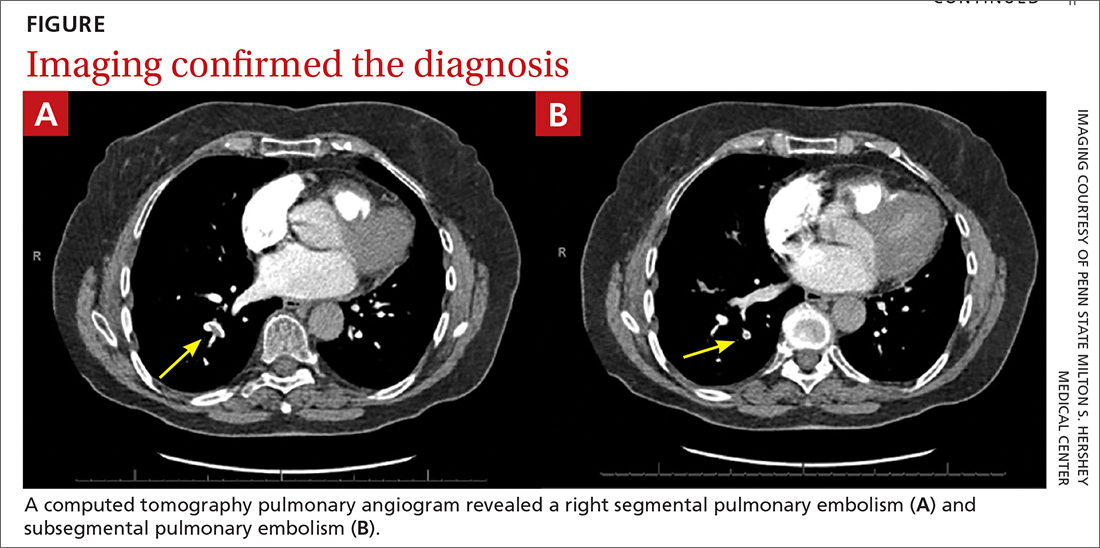

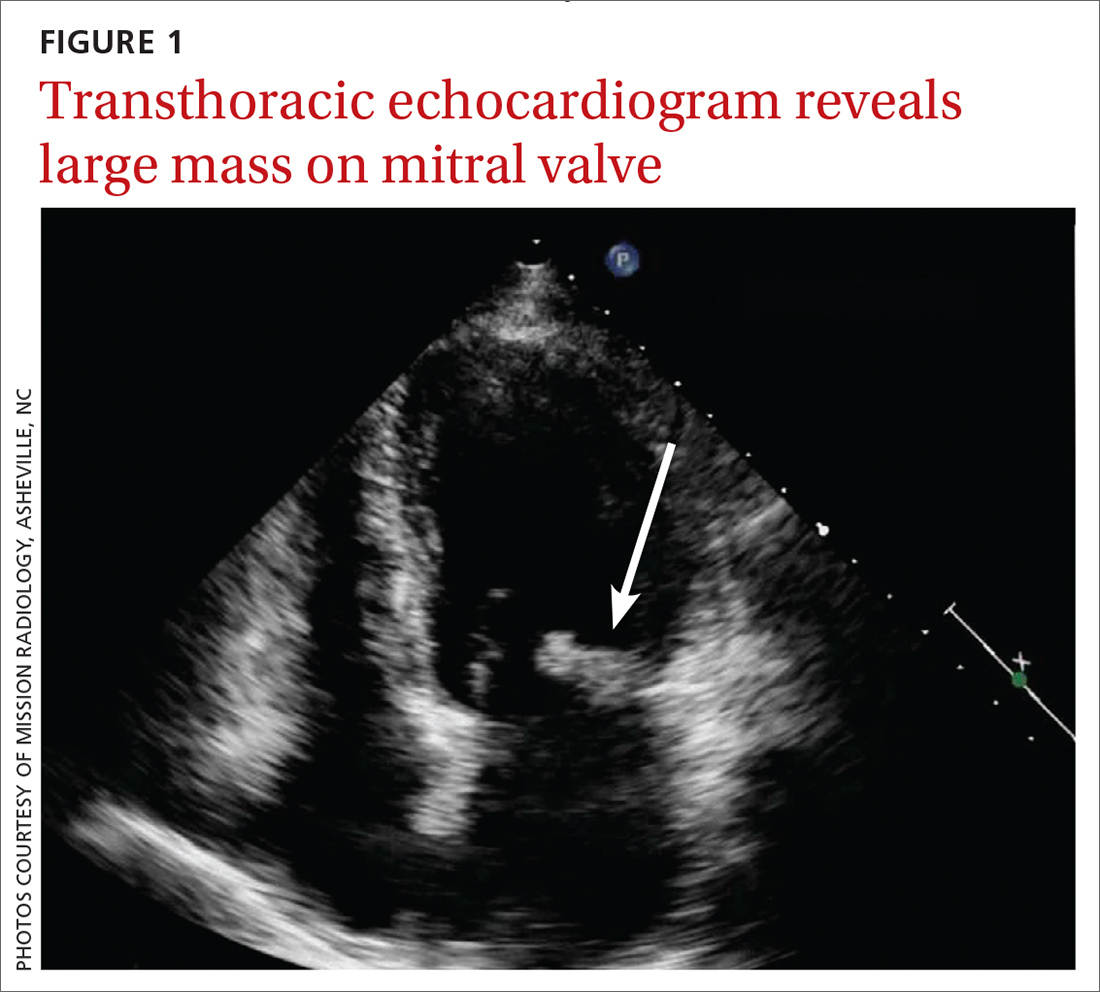

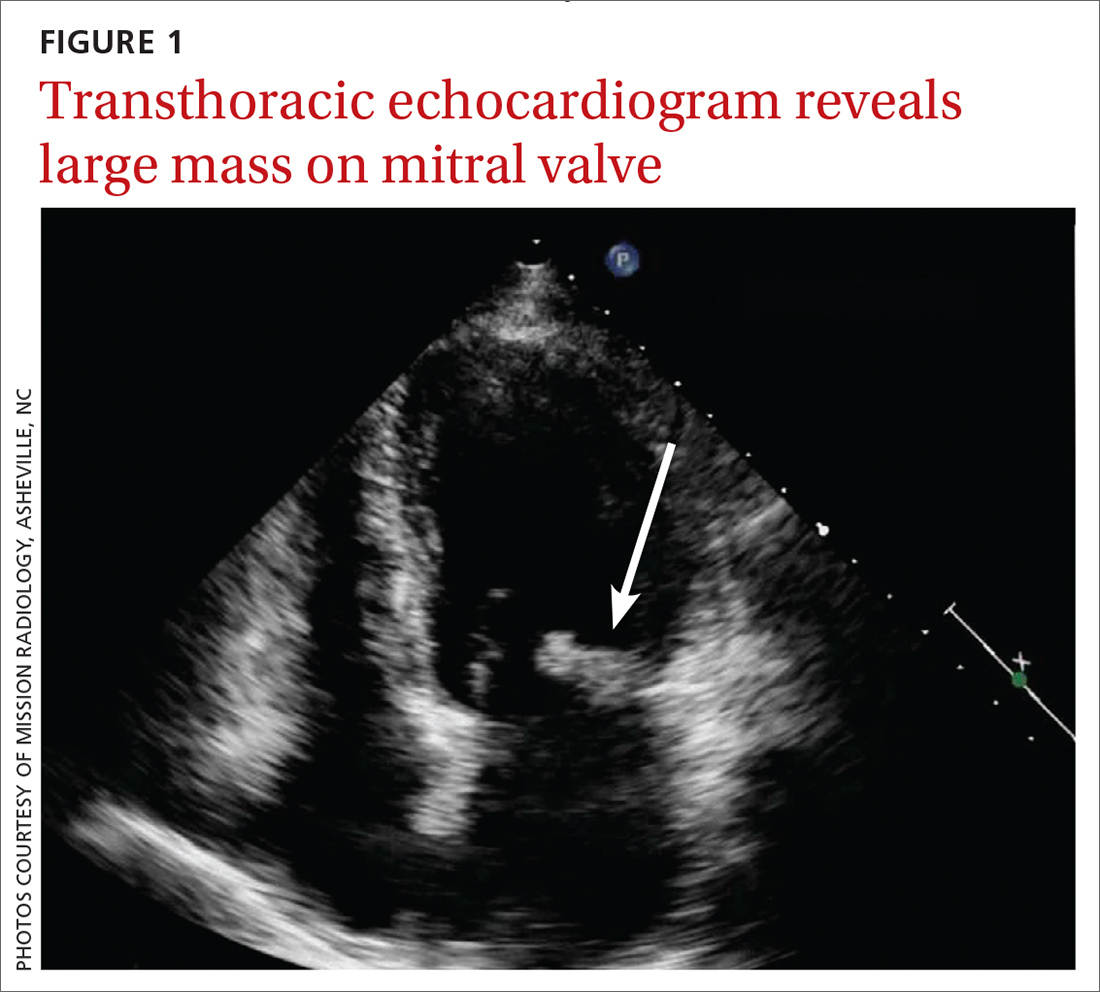

Based on the lab results, a stat computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was ordered and showed a right segmental and subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE; FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

PE shares pathophysiologic mechanisms with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and together these comprise venous thromboembolism (VTE). Risk factors for VTE include hypercoagulable disorders, use of estrogens, active malignancy, and immobilization.1 Unprovoked VTE occurs in the absence of identifiable risk factors and carries a higher risk of recurrence.2,3 While PE is classically thought to occur in the setting of a DVT, there is increasing literature describing de novo PE that can occur independent of a DVT.4

Common symptoms of PE include tachycardia, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain.5 Abdominal pain is a rare symptom described in some case reports.6,7 Thus, a high clinical suspicion is needed for diagnosis of PE.

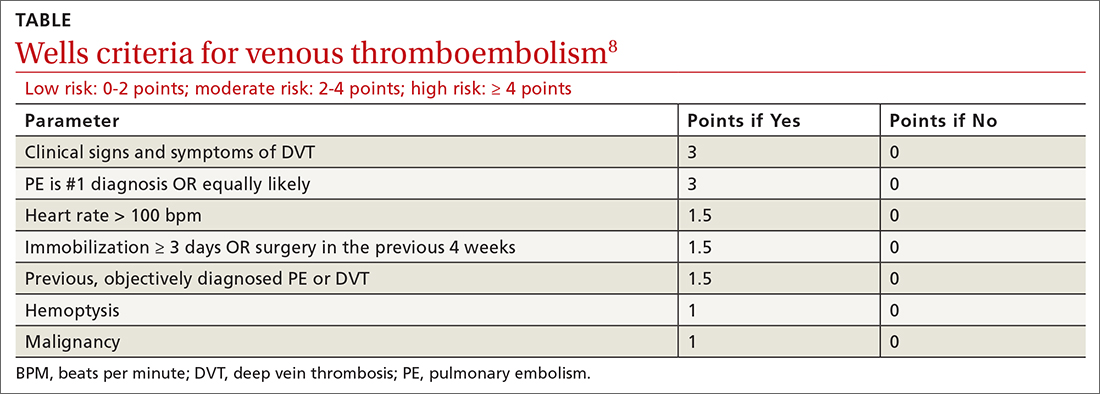

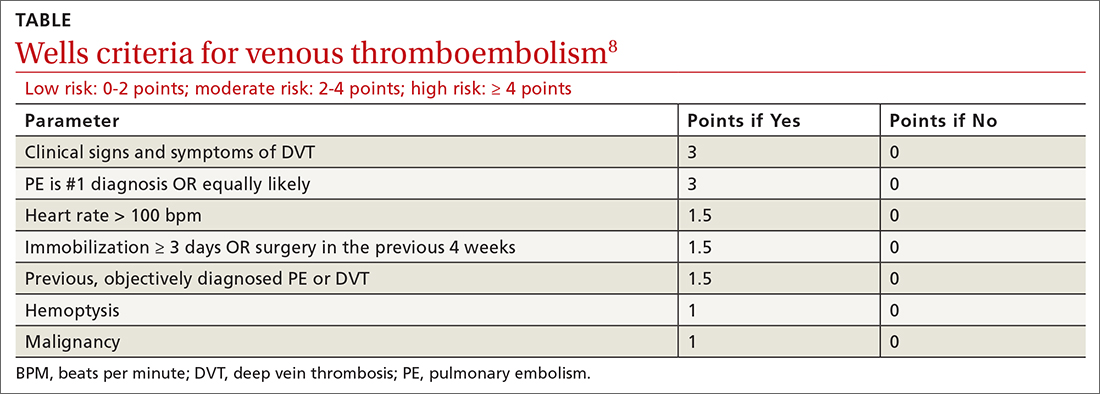

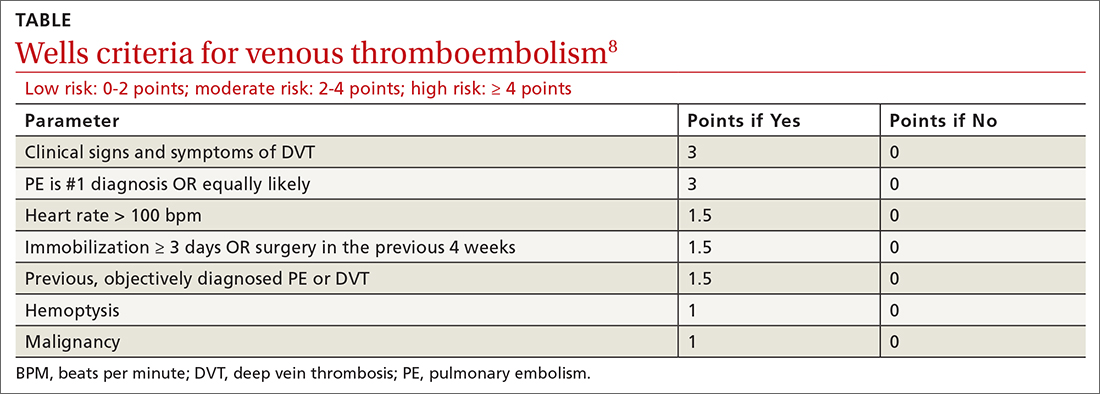

The Wells criteria is an established model for risk stratifying patients presenting with possible VTE (TABLE).8 For patients with low pretest probability, as in this case, a

Continue to: Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

The cornerstone treatment for stable patients with VTE is therapeutic anticoagulation. The new oral anticoagulants, which directly inhibit factor Xa or thrombin, have become increasingly popular for management of VTE, in part because they don’t require INR testing and monitoring.2

The duration of anticoagulation, particularly in unprovoked PE, is debatable. As noted earlier, patients with an unprovoked PE are at higher risk of recurrence than those with a reversible cause, so the question becomes whether these patients should have indefinite anticoagulation.2,3 Studies examining risk stratification of patients with a first, unprovoked VTE have found that men have the highest risk of recurrence, followed by women who were not taking estrogen during the index VTE, and lastly women who were taking estrogen therapy during the index VTE and subsequently discontinued it.2,3,10

Thus, it is reasonable to give women the option to discontinue anticoagulation in the setting of a negative

Our patient was directed to the emergency department for further monitoring following CT confirmation. She was discharged home after being deemed stable and prescribed apixaban 10 mg/d. A venous duplex ultrasound performed 12 days later for knee pain revealed no venous thrombosis. A CT of the abdomen performed 3 months later for other reasons revealed a normal gallbladder with no visible stones.

Apixaban was continued for 3 months and discontinued after discussion of risks and benefits of therapy cessation in the setting of a normal

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

PE carries a significantly high mortality rate and can manifest with nonspecific and masquerading signs. A high index of suspicion is required to place PE on the differential diagnosis and carry out appropriate testing. Our patient presented with a history consistent with biliary colic but with pleuritic chest pain that warranted consideration of a PE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Alyssa Anderson, MD, 1 Continental Drive, Elizabethtown, PA 17022; [email protected]

1. Israel HL, Goldstein F. The varied clinical manifestations of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1957;47:202-226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-47-2-202

2. Rehman H, John E, Parikh P. Pulmonary embolism presenting as abdominal pain: an atypical presentation of a common diagnosis. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2016;2016:1-3. doi: 10.1155/2016/7832895

3. Park ES, Cho JY, Seo J-H, et al. Pulmonary embolism presenting with acute abdominal pain in a girl with stable ankle fracture and inherited antithrombin deficiency. Blood Res. 2018;53:81-83. doi: 10.5045/br.2018.53.1.81

4. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1037-1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072753

5. Agrawal V, Kim ESH. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after an initial episode: risk stratification and implications for long-term treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:24. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1111-2

6. Kearon C, Parpia S, Spencer FA, et al. Long‐term risk of recurrence in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism managed according to d‐dimer results; A cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:1144-1152. doi: 10.1111/jth.14458

7. Van Gent J-M, Zander AL, Olson EJ, et al. Pulmonary embolism without deep venous thrombosis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1270-1274. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000233

8. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010

9. Kline JA. Diagnosis and exclusion of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2018;163:207-220. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.06.002

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest. 2016;149:315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

THE CASE

A 75-year-old woman presented to the primary care clinic with right-side rib pain. The patient said the pain started 1 week earlier, after she ate fried chicken for dinner, and had since been exacerbated by rich meals, lying supine, and taking a deep inspiratory breath. She also said that prior to coming to the clinic that day, the pain had been radiating to her right shoulder.

The patient denied experiencing associated fevers, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, or changes in stool color. She had a history of hypertension, for which she was taking lisinopril 20 mg/d, and hypercholesterolemia, for which she was on simvastatin 10 mg/d. She was additionally using timolol ophthalmic solution for her glaucoma.

During the examination, the patient’s vital signs were stable, with a pulse of 80 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The patient had no abdominal tenderness upon palpation, and the physical exam revealed no abnormalities. An in-office electrocardiogram was performed, with normal results. Additionally, a comprehensive metabolic panel, lipase test, and

THE DIAGNOSIS

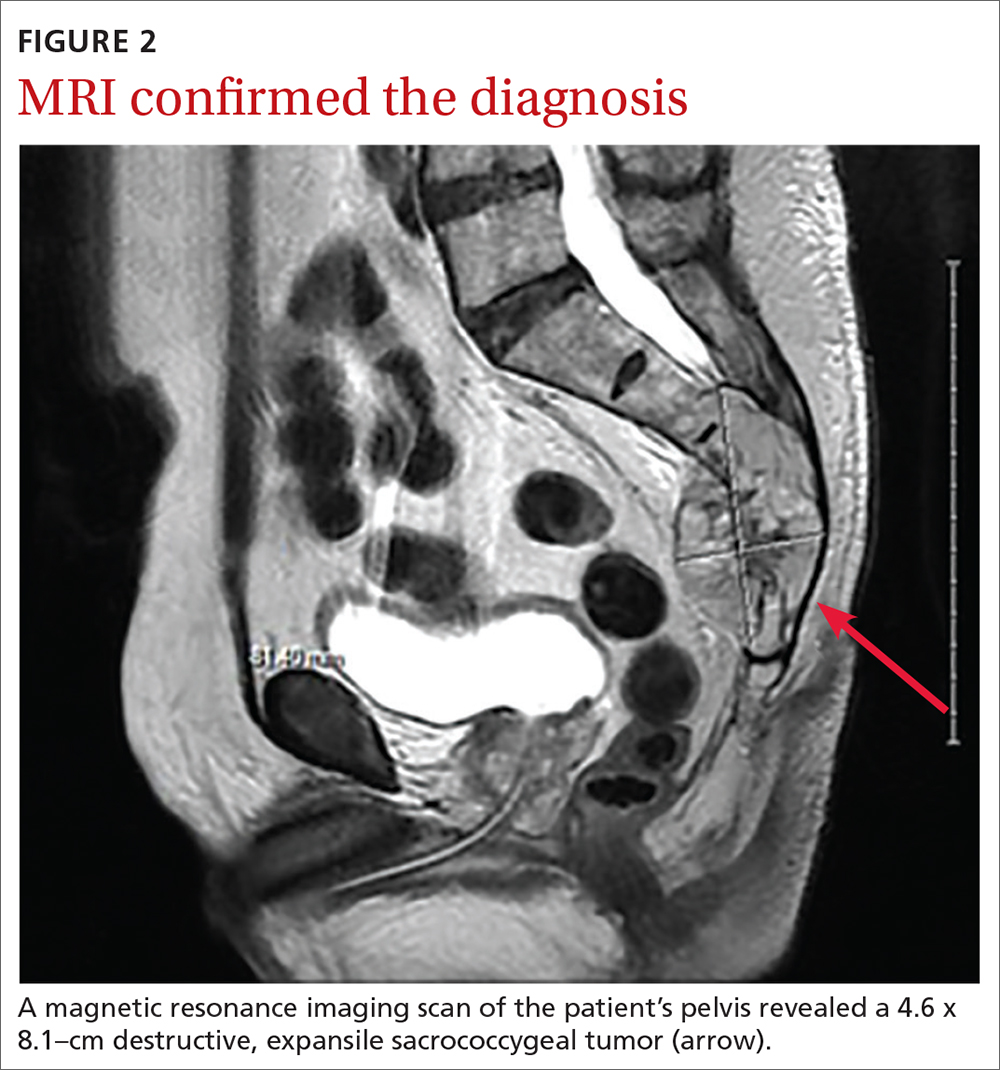

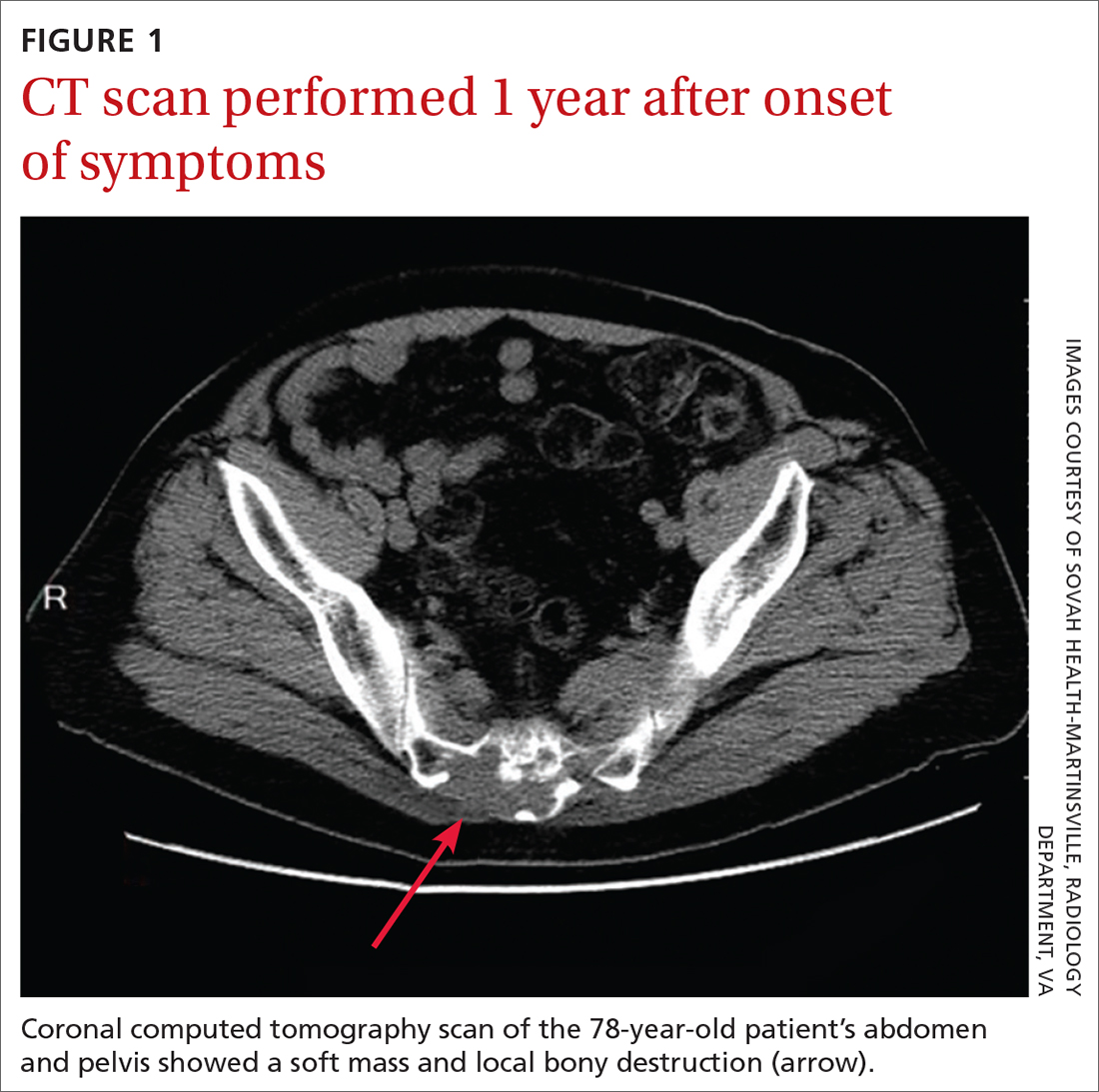

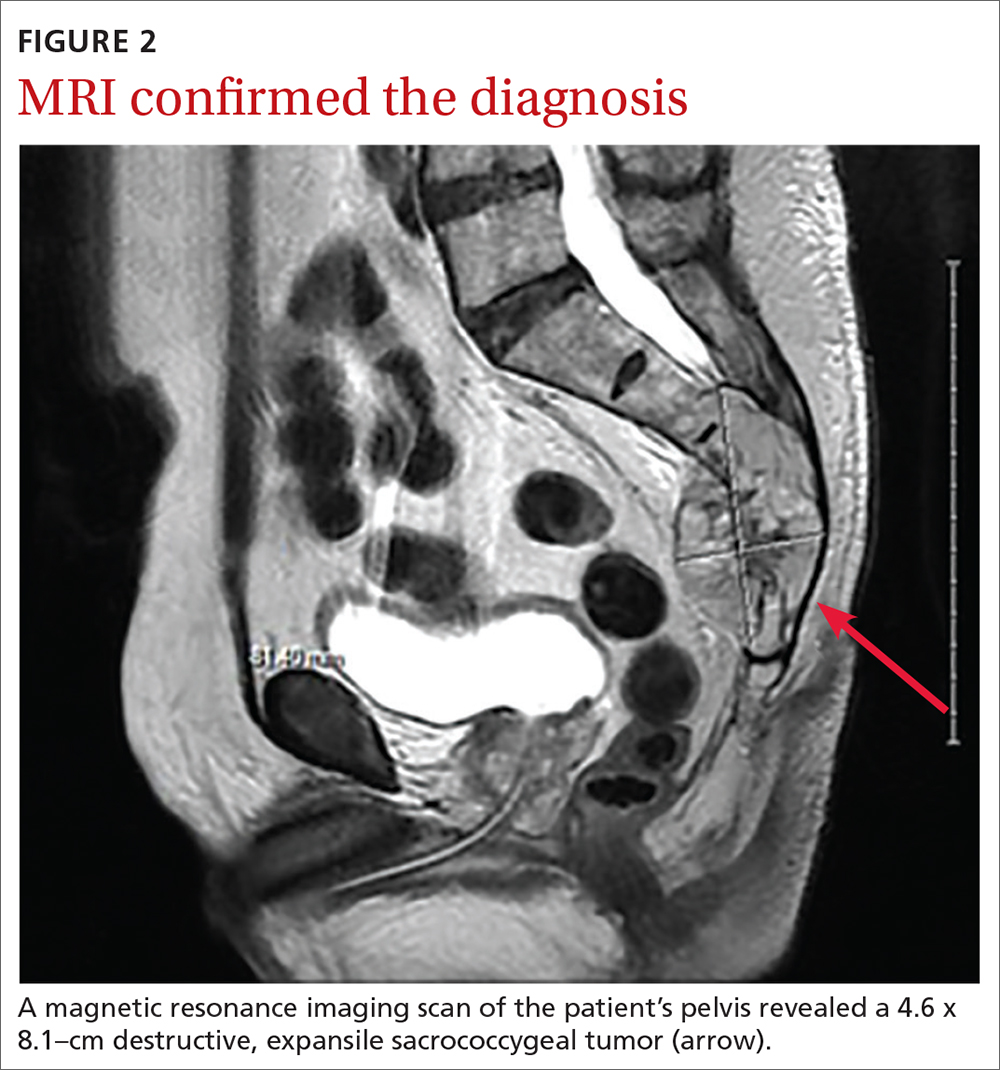

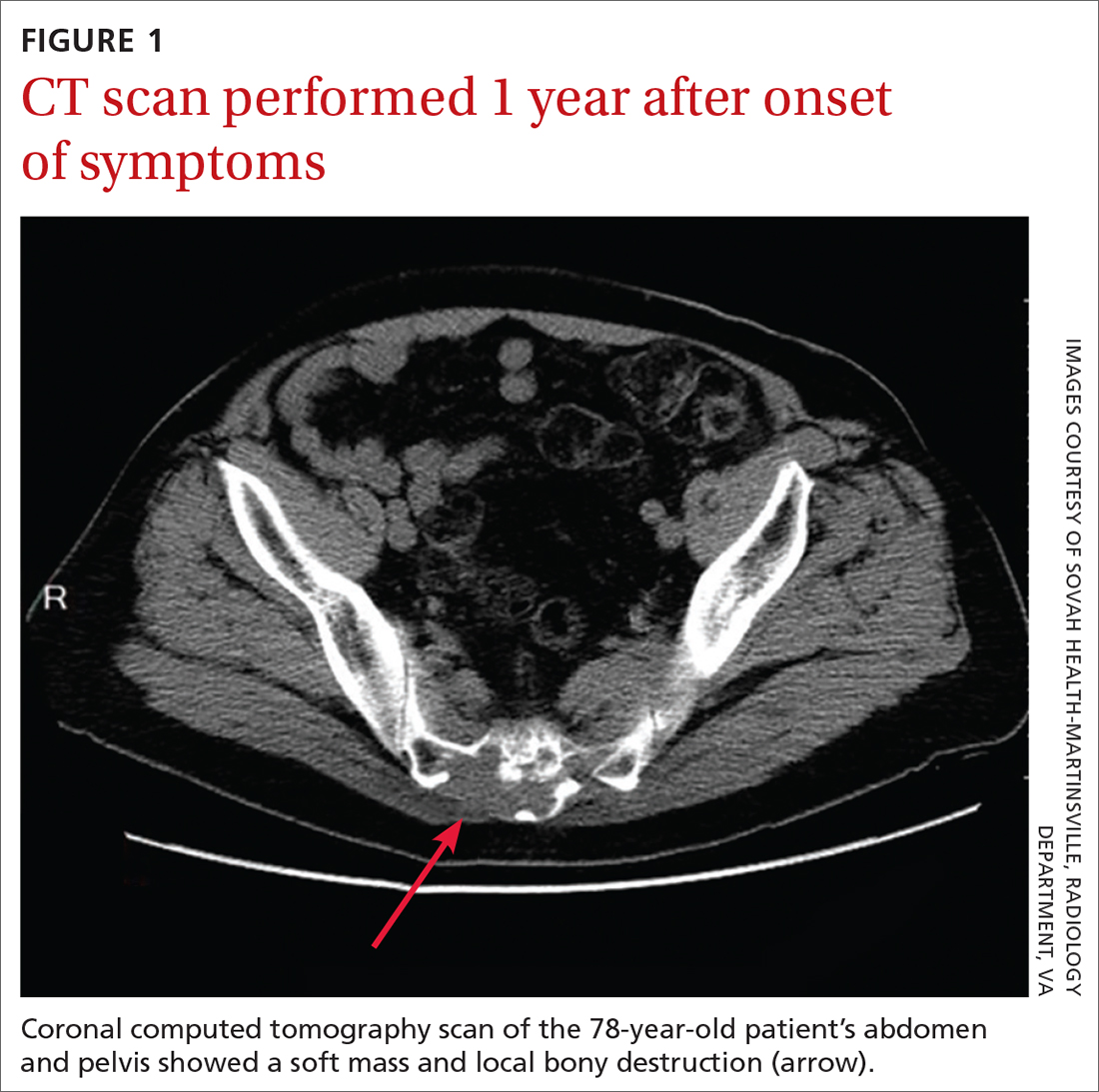

Based on the lab results, a stat computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was ordered and showed a right segmental and subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE; FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

PE shares pathophysiologic mechanisms with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and together these comprise venous thromboembolism (VTE). Risk factors for VTE include hypercoagulable disorders, use of estrogens, active malignancy, and immobilization.1 Unprovoked VTE occurs in the absence of identifiable risk factors and carries a higher risk of recurrence.2,3 While PE is classically thought to occur in the setting of a DVT, there is increasing literature describing de novo PE that can occur independent of a DVT.4

Common symptoms of PE include tachycardia, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain.5 Abdominal pain is a rare symptom described in some case reports.6,7 Thus, a high clinical suspicion is needed for diagnosis of PE.

The Wells criteria is an established model for risk stratifying patients presenting with possible VTE (TABLE).8 For patients with low pretest probability, as in this case, a

Continue to: Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

The cornerstone treatment for stable patients with VTE is therapeutic anticoagulation. The new oral anticoagulants, which directly inhibit factor Xa or thrombin, have become increasingly popular for management of VTE, in part because they don’t require INR testing and monitoring.2

The duration of anticoagulation, particularly in unprovoked PE, is debatable. As noted earlier, patients with an unprovoked PE are at higher risk of recurrence than those with a reversible cause, so the question becomes whether these patients should have indefinite anticoagulation.2,3 Studies examining risk stratification of patients with a first, unprovoked VTE have found that men have the highest risk of recurrence, followed by women who were not taking estrogen during the index VTE, and lastly women who were taking estrogen therapy during the index VTE and subsequently discontinued it.2,3,10

Thus, it is reasonable to give women the option to discontinue anticoagulation in the setting of a negative

Our patient was directed to the emergency department for further monitoring following CT confirmation. She was discharged home after being deemed stable and prescribed apixaban 10 mg/d. A venous duplex ultrasound performed 12 days later for knee pain revealed no venous thrombosis. A CT of the abdomen performed 3 months later for other reasons revealed a normal gallbladder with no visible stones.

Apixaban was continued for 3 months and discontinued after discussion of risks and benefits of therapy cessation in the setting of a normal

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

PE carries a significantly high mortality rate and can manifest with nonspecific and masquerading signs. A high index of suspicion is required to place PE on the differential diagnosis and carry out appropriate testing. Our patient presented with a history consistent with biliary colic but with pleuritic chest pain that warranted consideration of a PE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Alyssa Anderson, MD, 1 Continental Drive, Elizabethtown, PA 17022; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 75-year-old woman presented to the primary care clinic with right-side rib pain. The patient said the pain started 1 week earlier, after she ate fried chicken for dinner, and had since been exacerbated by rich meals, lying supine, and taking a deep inspiratory breath. She also said that prior to coming to the clinic that day, the pain had been radiating to her right shoulder.

The patient denied experiencing associated fevers, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, or changes in stool color. She had a history of hypertension, for which she was taking lisinopril 20 mg/d, and hypercholesterolemia, for which she was on simvastatin 10 mg/d. She was additionally using timolol ophthalmic solution for her glaucoma.

During the examination, the patient’s vital signs were stable, with a pulse of 80 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The patient had no abdominal tenderness upon palpation, and the physical exam revealed no abnormalities. An in-office electrocardiogram was performed, with normal results. Additionally, a comprehensive metabolic panel, lipase test, and

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the lab results, a stat computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was ordered and showed a right segmental and subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE; FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

PE shares pathophysiologic mechanisms with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and together these comprise venous thromboembolism (VTE). Risk factors for VTE include hypercoagulable disorders, use of estrogens, active malignancy, and immobilization.1 Unprovoked VTE occurs in the absence of identifiable risk factors and carries a higher risk of recurrence.2,3 While PE is classically thought to occur in the setting of a DVT, there is increasing literature describing de novo PE that can occur independent of a DVT.4

Common symptoms of PE include tachycardia, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain.5 Abdominal pain is a rare symptom described in some case reports.6,7 Thus, a high clinical suspicion is needed for diagnosis of PE.

The Wells criteria is an established model for risk stratifying patients presenting with possible VTE (TABLE).8 For patients with low pretest probability, as in this case, a

Continue to: Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

The cornerstone treatment for stable patients with VTE is therapeutic anticoagulation. The new oral anticoagulants, which directly inhibit factor Xa or thrombin, have become increasingly popular for management of VTE, in part because they don’t require INR testing and monitoring.2

The duration of anticoagulation, particularly in unprovoked PE, is debatable. As noted earlier, patients with an unprovoked PE are at higher risk of recurrence than those with a reversible cause, so the question becomes whether these patients should have indefinite anticoagulation.2,3 Studies examining risk stratification of patients with a first, unprovoked VTE have found that men have the highest risk of recurrence, followed by women who were not taking estrogen during the index VTE, and lastly women who were taking estrogen therapy during the index VTE and subsequently discontinued it.2,3,10

Thus, it is reasonable to give women the option to discontinue anticoagulation in the setting of a negative

Our patient was directed to the emergency department for further monitoring following CT confirmation. She was discharged home after being deemed stable and prescribed apixaban 10 mg/d. A venous duplex ultrasound performed 12 days later for knee pain revealed no venous thrombosis. A CT of the abdomen performed 3 months later for other reasons revealed a normal gallbladder with no visible stones.

Apixaban was continued for 3 months and discontinued after discussion of risks and benefits of therapy cessation in the setting of a normal

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

PE carries a significantly high mortality rate and can manifest with nonspecific and masquerading signs. A high index of suspicion is required to place PE on the differential diagnosis and carry out appropriate testing. Our patient presented with a history consistent with biliary colic but with pleuritic chest pain that warranted consideration of a PE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Alyssa Anderson, MD, 1 Continental Drive, Elizabethtown, PA 17022; [email protected]

1. Israel HL, Goldstein F. The varied clinical manifestations of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1957;47:202-226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-47-2-202

2. Rehman H, John E, Parikh P. Pulmonary embolism presenting as abdominal pain: an atypical presentation of a common diagnosis. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2016;2016:1-3. doi: 10.1155/2016/7832895

3. Park ES, Cho JY, Seo J-H, et al. Pulmonary embolism presenting with acute abdominal pain in a girl with stable ankle fracture and inherited antithrombin deficiency. Blood Res. 2018;53:81-83. doi: 10.5045/br.2018.53.1.81

4. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1037-1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072753

5. Agrawal V, Kim ESH. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after an initial episode: risk stratification and implications for long-term treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:24. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1111-2

6. Kearon C, Parpia S, Spencer FA, et al. Long‐term risk of recurrence in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism managed according to d‐dimer results; A cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:1144-1152. doi: 10.1111/jth.14458

7. Van Gent J-M, Zander AL, Olson EJ, et al. Pulmonary embolism without deep venous thrombosis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1270-1274. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000233

8. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010

9. Kline JA. Diagnosis and exclusion of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2018;163:207-220. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.06.002

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest. 2016;149:315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

1. Israel HL, Goldstein F. The varied clinical manifestations of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1957;47:202-226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-47-2-202

2. Rehman H, John E, Parikh P. Pulmonary embolism presenting as abdominal pain: an atypical presentation of a common diagnosis. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2016;2016:1-3. doi: 10.1155/2016/7832895

3. Park ES, Cho JY, Seo J-H, et al. Pulmonary embolism presenting with acute abdominal pain in a girl with stable ankle fracture and inherited antithrombin deficiency. Blood Res. 2018;53:81-83. doi: 10.5045/br.2018.53.1.81

4. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1037-1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072753

5. Agrawal V, Kim ESH. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after an initial episode: risk stratification and implications for long-term treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:24. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1111-2

6. Kearon C, Parpia S, Spencer FA, et al. Long‐term risk of recurrence in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism managed according to d‐dimer results; A cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:1144-1152. doi: 10.1111/jth.14458

7. Van Gent J-M, Zander AL, Olson EJ, et al. Pulmonary embolism without deep venous thrombosis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1270-1274. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000233

8. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010

9. Kline JA. Diagnosis and exclusion of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2018;163:207-220. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.06.002

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest. 2016;149:315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

Acyclovir-Resistant Cutaneous Herpes Simplex Virus in DOCK8 Deficiency

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

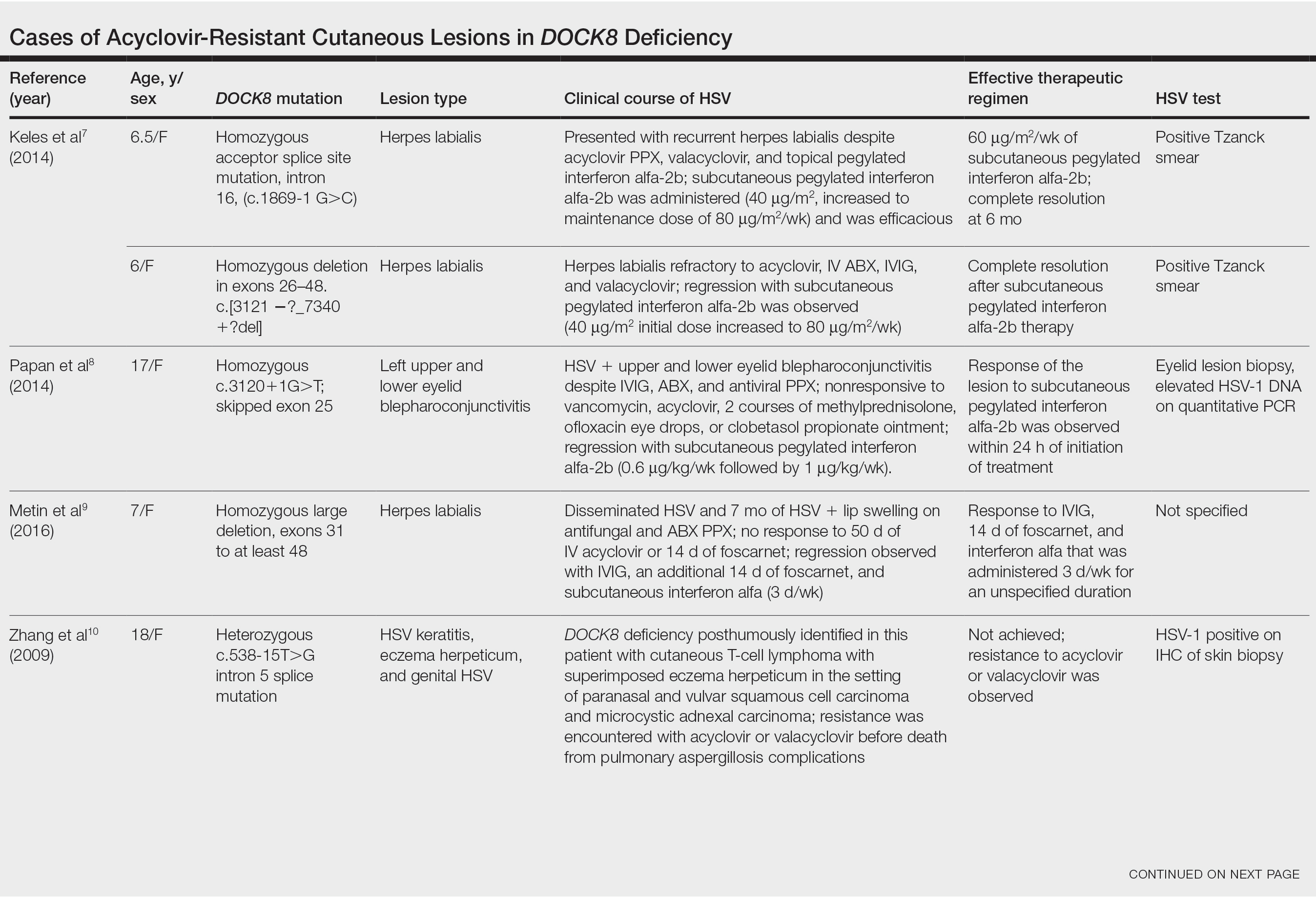

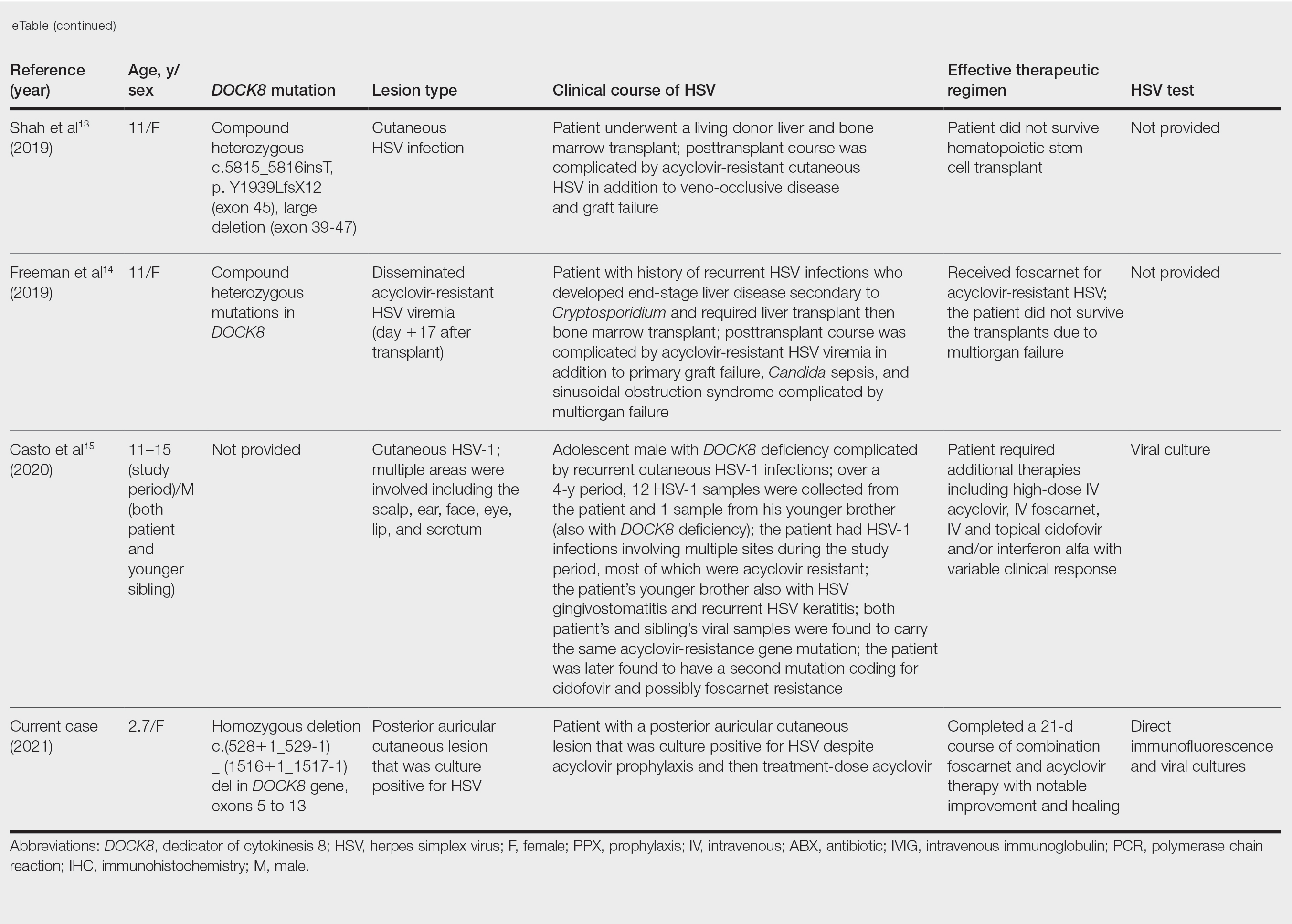

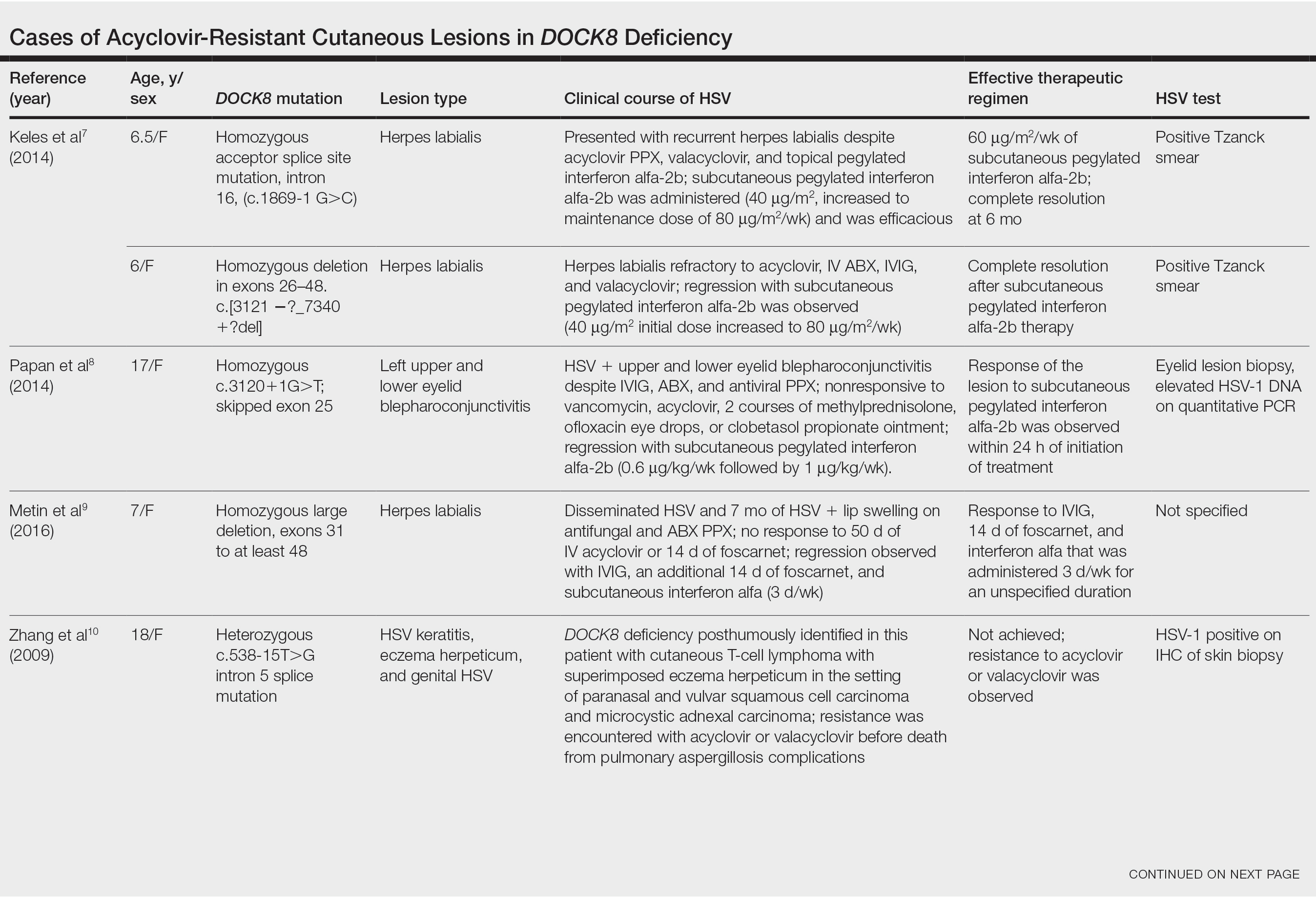

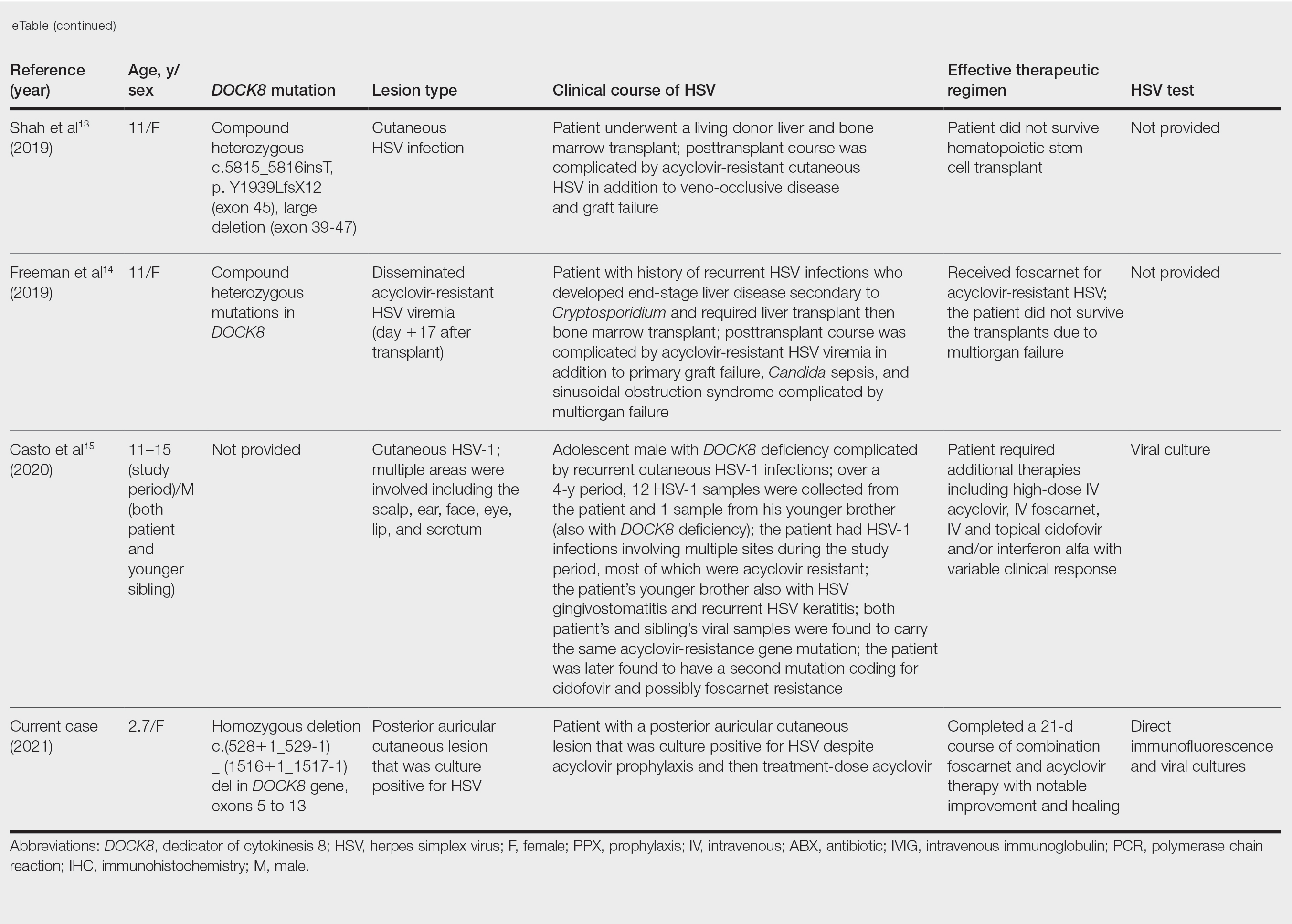

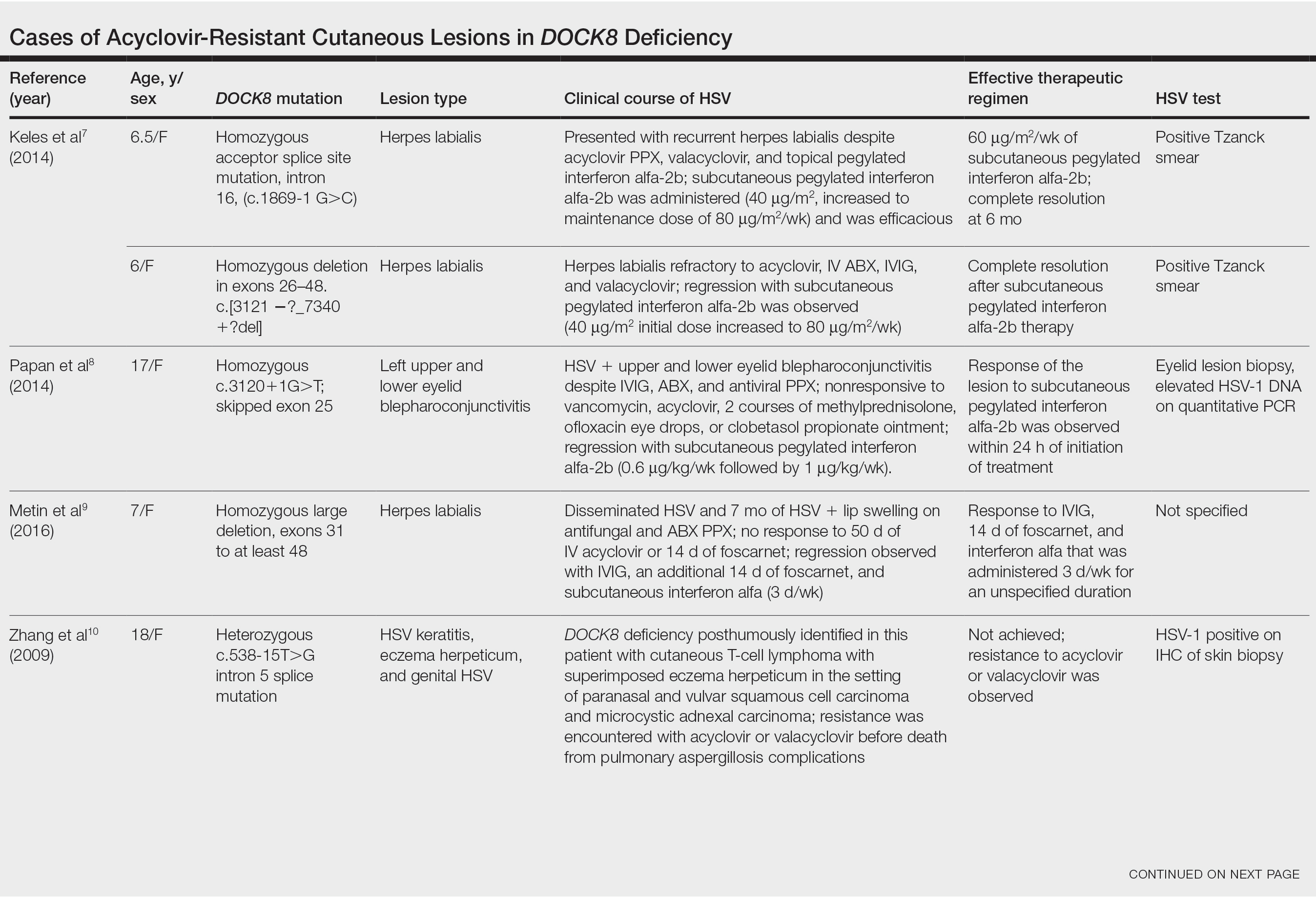

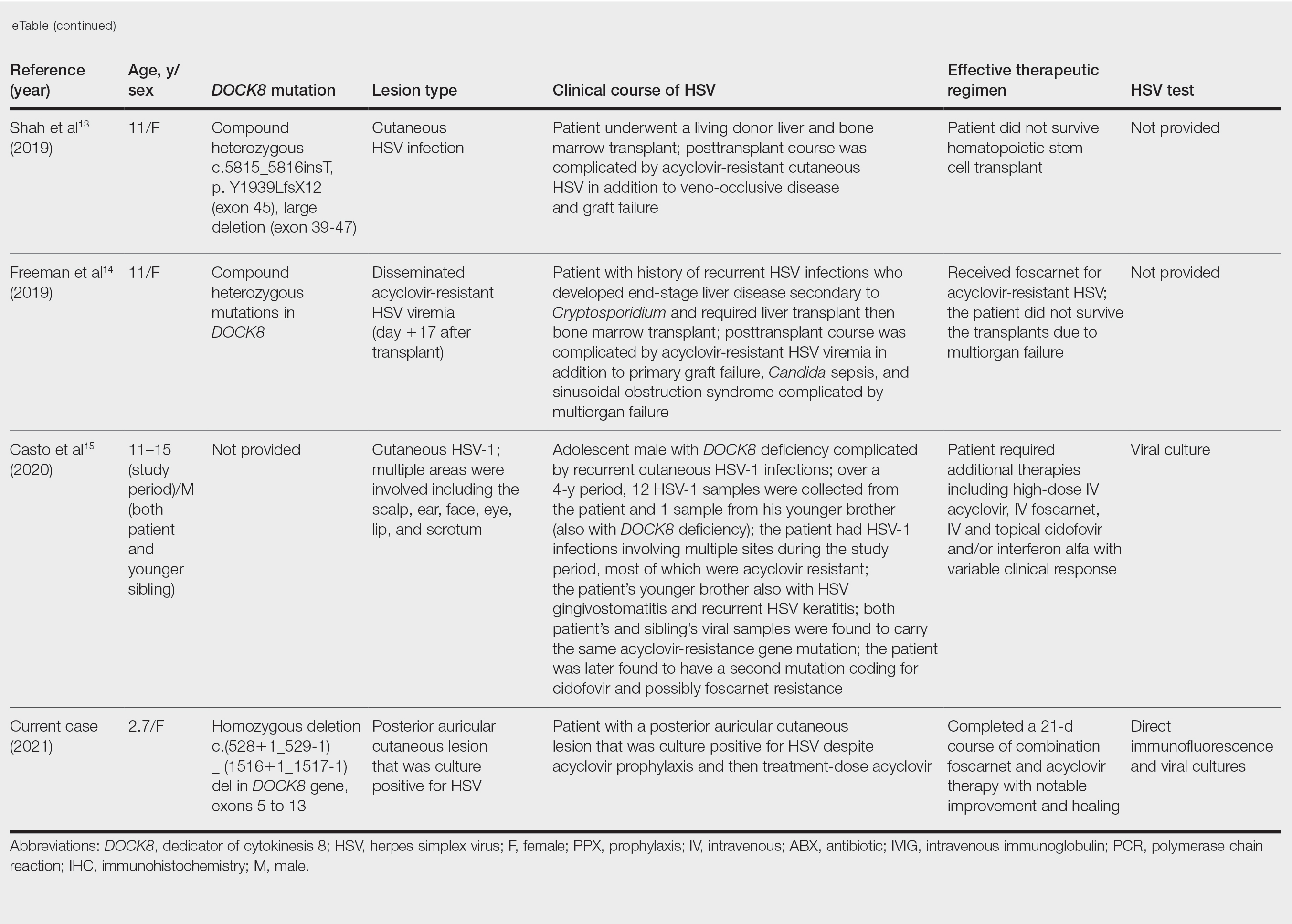

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

Practice Points

- Patients with dedicator of cytokinesis 8 ( DOCK 8 ) deficiency are susceptible to development of severe recalcitrant viral cutaneous infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Dermatologists should be aware that prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression in the setting of severe immunodeficiency.

- Acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV lesions require escalation of therapy, which may include addition of foscarnet, cidofovir, or subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b to the therapeutic regimen.

- Viral culture should be performed on suspicious lesions in DOCK 8 -deficient patients despite acyclovir prophylaxis, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low.

Bullous Amyloidosis Masquerading as Pseudoporphyria

Cutaneous amyloidosis encompasses a variety of clinical presentations. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis result from keratin deposits, while nodular amyloidosis results from cutaneous infiltration of plasma cells.2 Primary systemic amyloidosis is due to a plasma cell dyscrasia, particularly multiple myeloma, while secondary systemic amyloidosis occurs in the setting of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, renal dysfunction, or chronic inflammation, as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and various autoinflammatory disorders.2 Plasma cell proliferative disorders are associated with various skin disorders, which may result from aggregated misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins, indicating light chain–related systemic amyloidosis. Mucocutaneous lesions can occur in 30% to 40% of cases of primary systemic amyloidosis and may present as purpura, ecchymoses, waxy thickening, plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and/or bullae.3,4 When blistering is present, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes autoimmune bullous disease, drug eruptions, enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, deposition diseases, allergic contact dermatitis, bullous cellulitis, bullous bite reactions, neutrophilic dermatosis, and bullous lichen sclerosus.5 Herein, we present a case of a woman with a bullous skin eruption who eventually was diagnosed with bullous amyloidosis subsequent to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Case Report

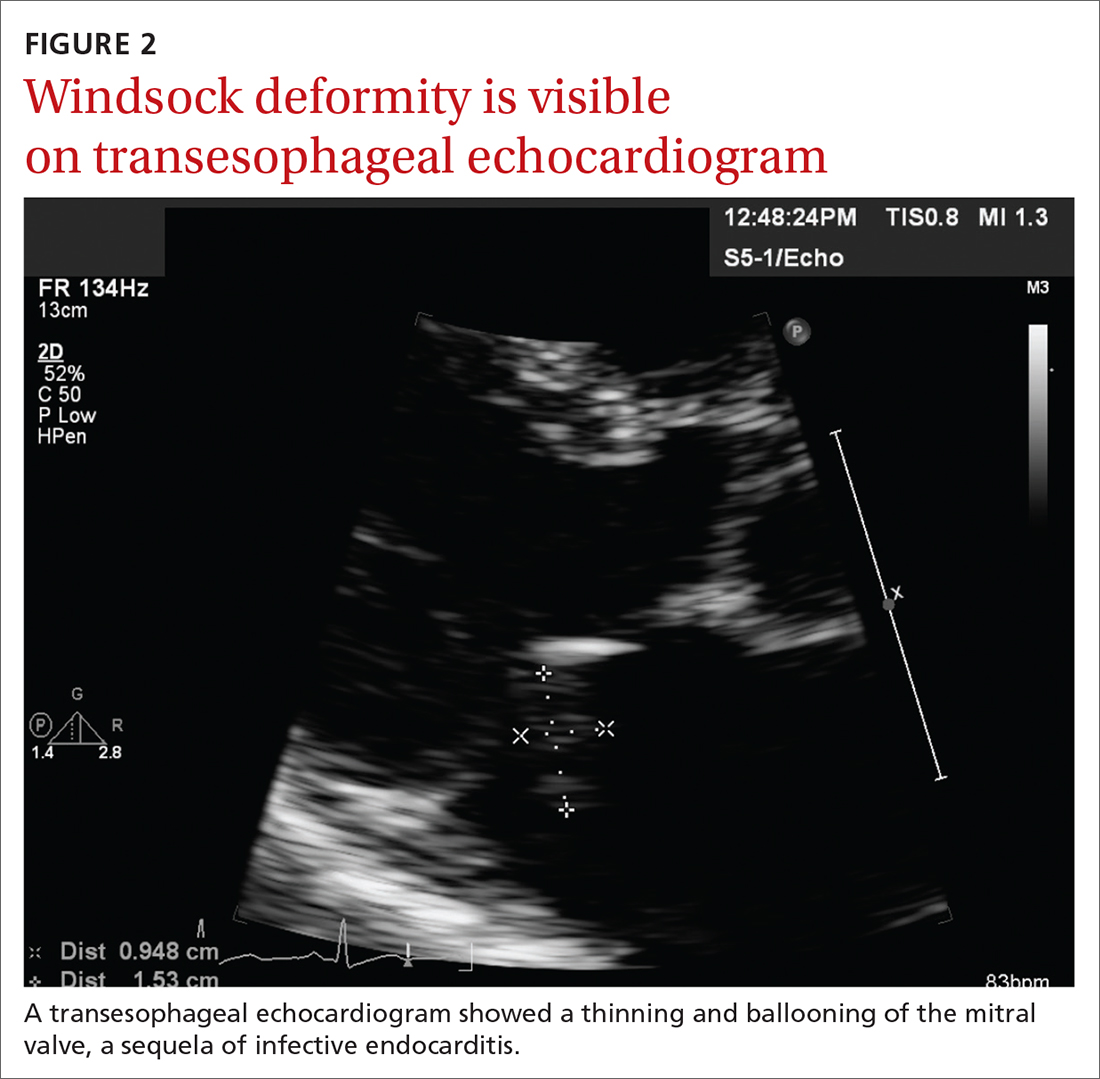

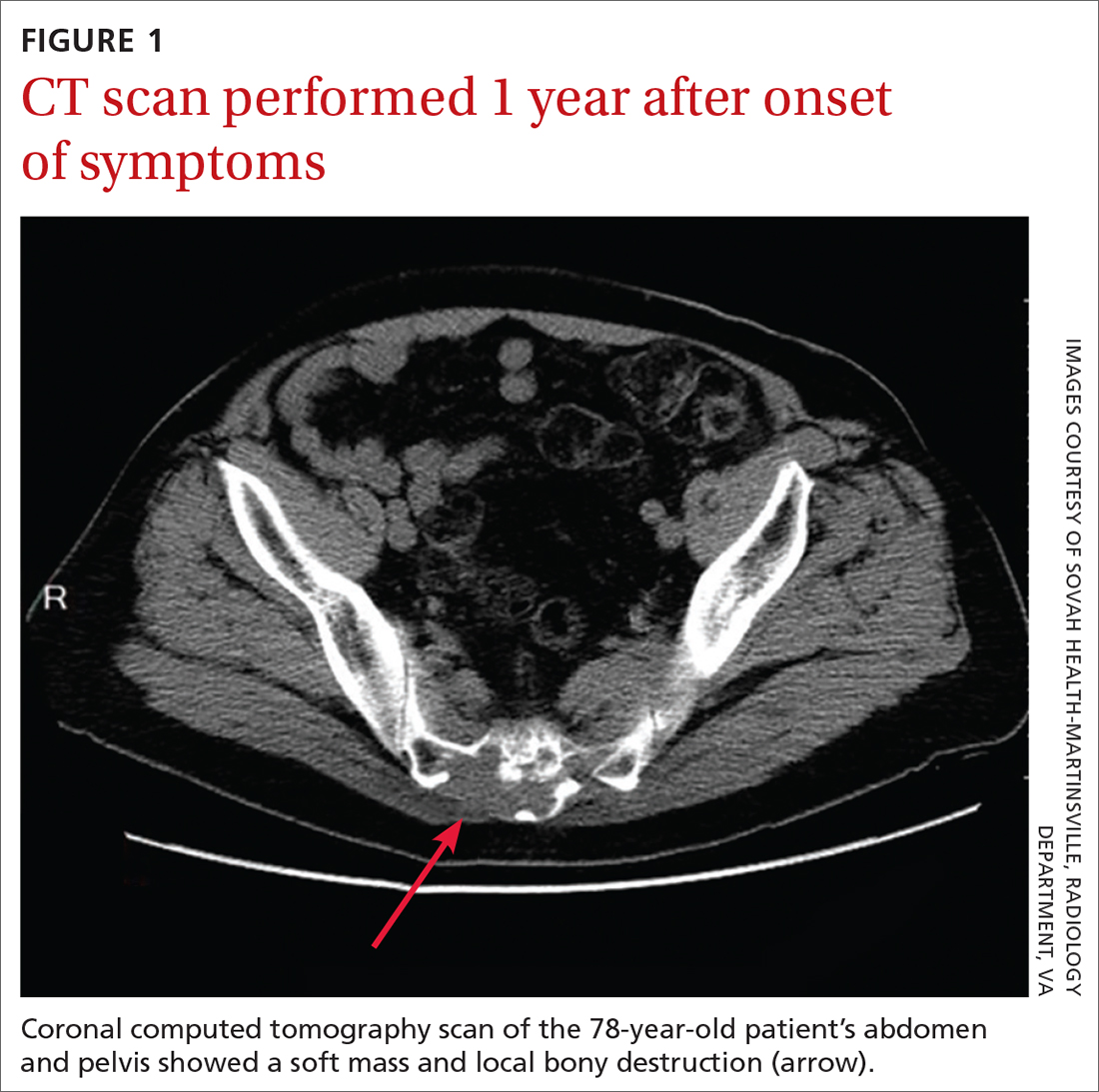

A 70-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of well-demarcated, hemorrhagic, flaccid vesicles and focal erosions with a rim of erythema on the distal forearms and hands. A shave biopsy from the right forearm showed cell-poor subepidermal vesicular dermatitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 as well as urinary porphyrins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed granular IgM at the basement membrane zone around vessels and cytoid bodies. At this time, a preliminary diagnosis of pseudoporphyria was suspected, though no classic medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, antibiotics) or exogenous trigger factors (eg, UV light exposure, dialysis) were temporally related. Three months later, the patient presented with a large hemorrhagic bulla on the distal left forearm (Figure 1) and healing erosions on the dorsal fingers and upper back. Clobetasol ointment was initiated, as an autoimmune bullous dermatosis was suspected.

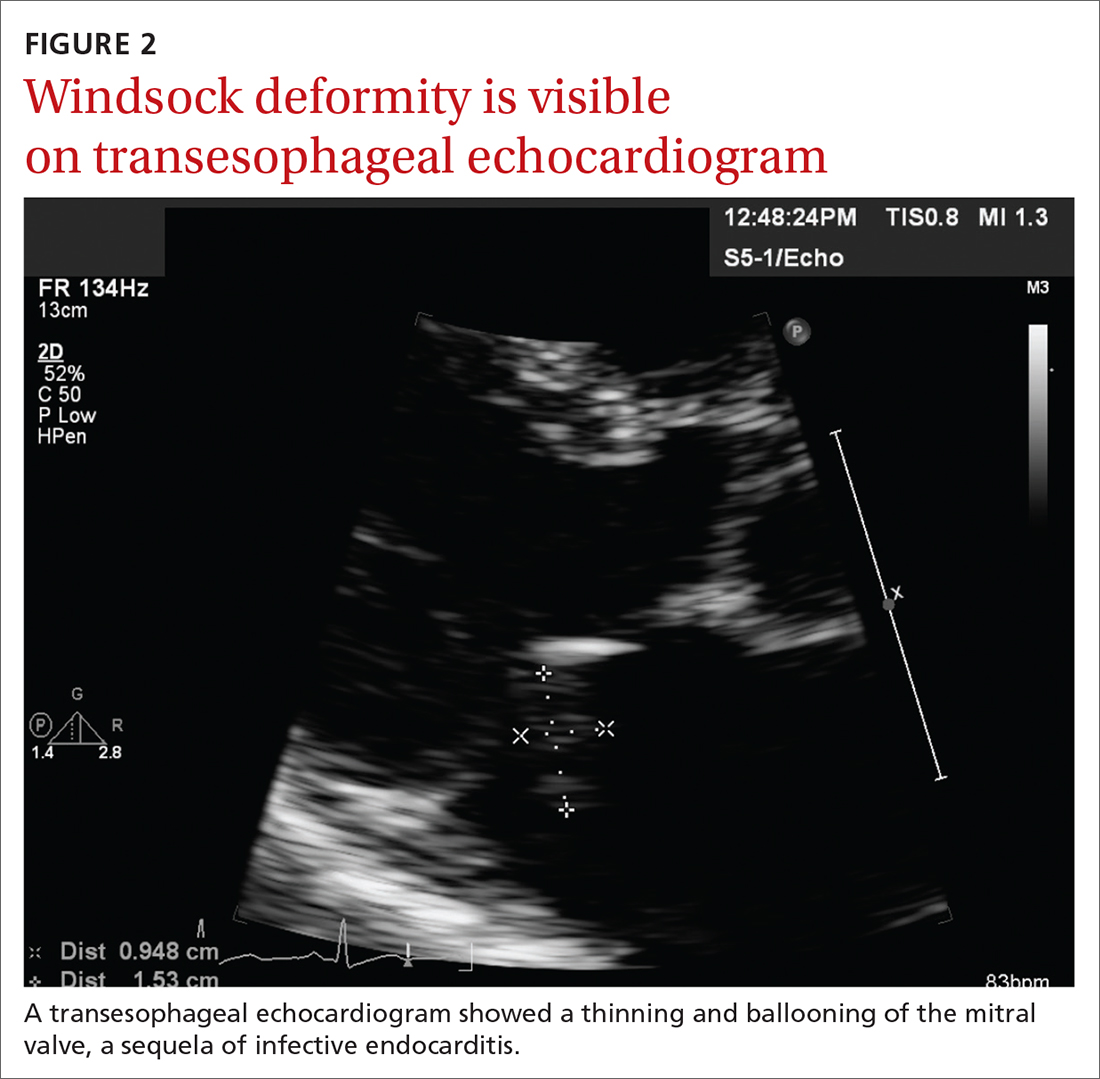

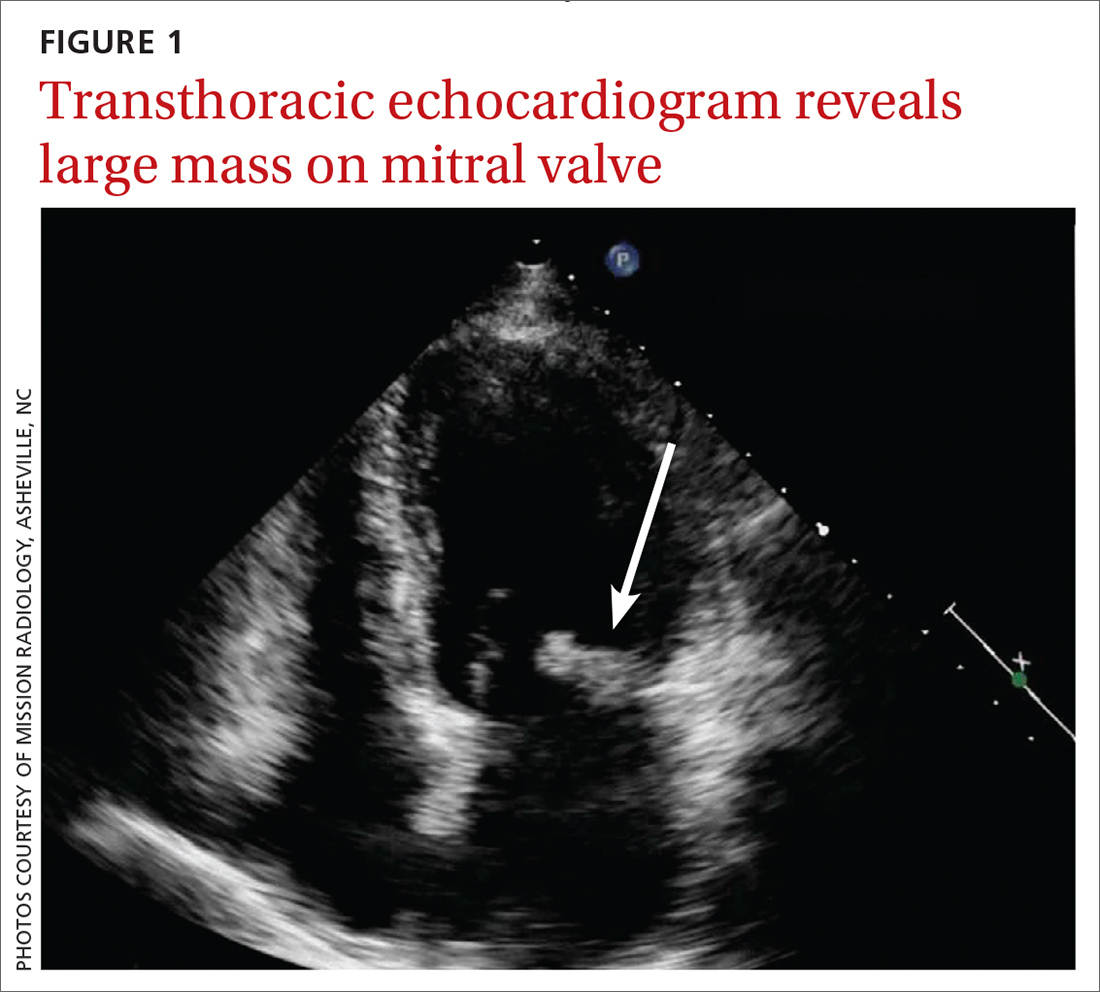

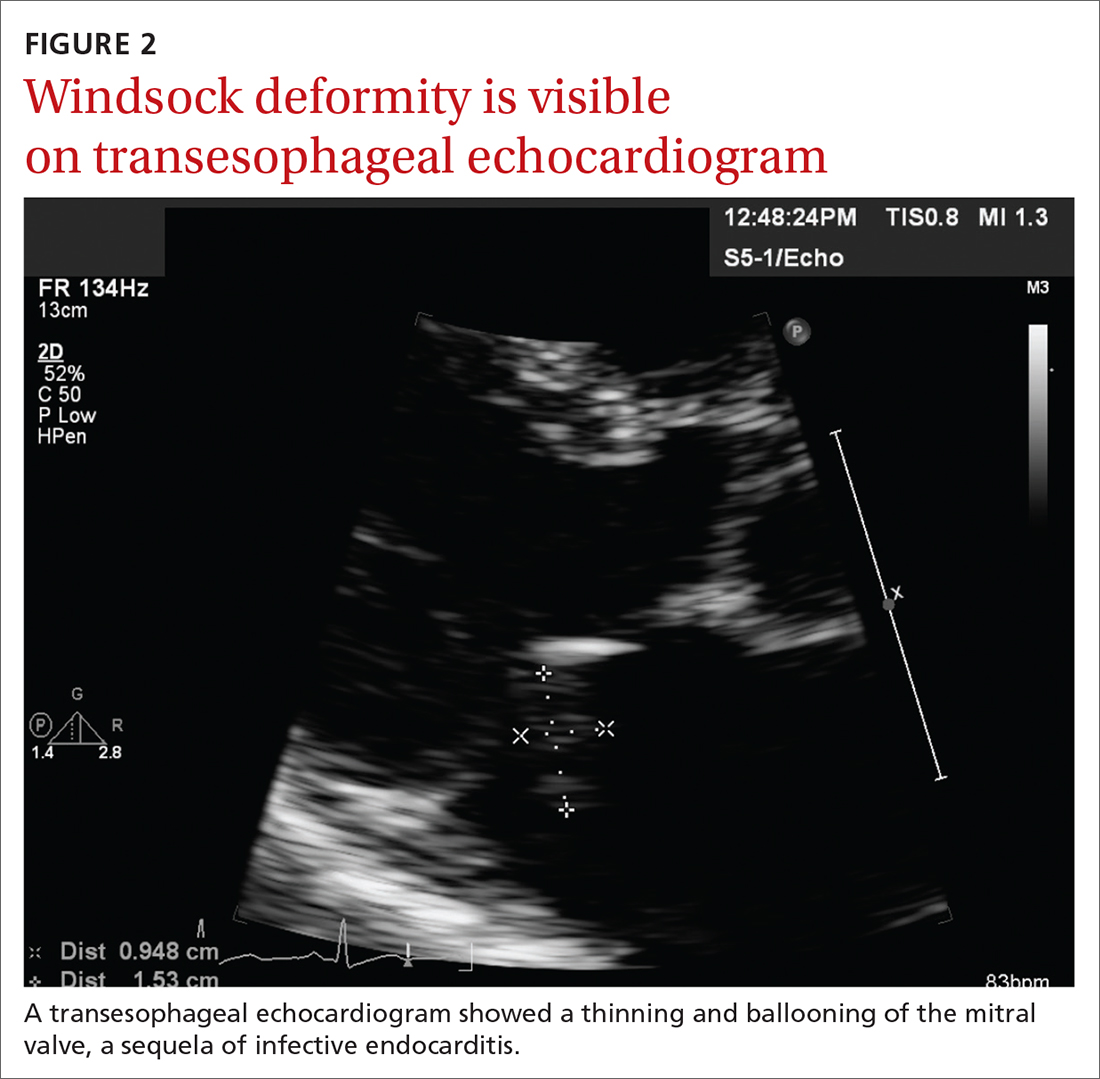

Approximately 1 year after she was first seen in our outpatient clinic, the patient was hospitalized for induction of chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone—for a new diagnosis of stage III multiple myeloma. A workup for back pain revealed multiple compression fractures and a plasma cell neoplasm with elevated λ light chains, which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy. During an inpatient dermatology consultation, we noted the development of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and worsening generalization of the hemorrhagic bullae, with healing erosions and intact hemorrhagic bullae on the dorsal hands, fingers (Figure 2), and upper back.

A repeat biopsy displayed bullous amyloidosis. Histopathologic examination revealed an ulcerated subepidermal blister with fibrin deposition at the ulcer base. A periadnexal, scant, eosinophilic deposition with extravasated red blood cells was appreciated. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits were found within the detached fragment of the epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate. A Congo red stain highlighted these areas with a salmon pink–colored material. Congo red staining showed a moderate amount of pale, apple green, birefringent deposit within these areas on polarized light examination.

A few months later, the patient was re-admitted, and the amount of skin detachment prompted the primary team to ask for another consultation. Although the extensive skin sloughing resembled toxic epidermal necrolysis, a repeat biopsy confirmed bullous amyloidosis.

Comment

Amyloidosis Histopathology—Amyloidoses represent a wide array of disorders with deposition of β-pleated sheets or amyloid fibrils, often with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 Primary systemic amyloidosis has been associated with underlying dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.6 In such cases, the skin lesions of multiple myeloma may result from a collection of misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments, as in light chain–related systemic amyloidosis.3 Histopathologically, both systemic and cutaneous amyloidosis appear similar and display deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic, fissured amyloid material in the dermis. Congo red stains the material orange-red and will display a characteristic apple green birefringence under polarized light.4 Although bullous amyloid lesions are rare, the cutaneous forms of these lesions can be an important sign of plasma cell dyscrasia.7

Presentation of Bullous Amyloidosis—Bullous manifestations rarely have been noted in the primary cutaneous forms of amyloidosis.5,8,9 Importantly, cutaneous blistering more often is linked to systemic forms of amyloidosis with multiorgan involvement, including primary systemic and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.5,10 However, patients with localized bullous cutaneous amyloidosis without systemic involvement also have been seen.10,11 Bullae may occur at any time, with contents that frequently are hemorrhagic due to capillary fragility.12,13 Bullous manifestations raise the differential diagnoses of bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, linear IgA disease, porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, bullous drug eruption, bullous eruption of renal dialysis, or bullous lupus erythematosus.5,13-17

In our patient, the acral distribution of bullae, presence of hemorrhage, chronicity of symptoms, and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay initially suggested a diagnosis of pseudoporphyria. However, the presence of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and subsequent confirmatory pathology aided in differentiating bullous amyloidosis from pseudoporphyria. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare form of skin-restricted amyloidoses, can coexist with bullous lesions. Of note, reported cases of nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis did not result in development of multiple myeloma.5,10

Bullae are located either subepidermally or intradermally, and bullous lesions of cutaneous amyloidosis typically demonstrate subepidermal or superficial intradermal clefting on light microscopy.5,10,12 Histopathology of bullous amyloidosis shows intradermal or subepidermal blister formation and amorphous eosinophilic material showing apple green birefringence with Congo red staining deposited in the dermis and/or around the adipocytes and blood vessel walls.12,18-20 In prior cases, direct immunofluorescence of bullous amyloidosis revealed absent immunoglobulin (IgG, IgA, IgM) or complement (C3 and C9) deposits in the basement membrane zone or dermis.13,21,22 In these cases, electron microscopy was useful in diagnosis, as it showed the presence of amyloid deposits.21,22

Cause of Bullae—Various mechanisms are thought to trigger the blister formation in amyloidosis. Bullae created from trauma or friction often present as tense painful blisters that commonly are hemorrhagic.10,23 Amyloid deposits in the walls of blood vessels and the affinity of dermal amyloid in blood vessel walls to surrounding collagen likely leads to increased fragility of capillaries and the dermal matrix, hemorrhagic tendency, and infrapapillary blisters, thus creating hemorrhagic bullous eruptions.24,25 Specifically, close proximity of immunoglobulin-derived amyloid oligomers to epidermal keratinocytes may be toxic and therefore could trigger subepidermal bullous change.5 Additionally, alteration in the physicochemical properties of the amyloidal protein might explain bullous eruption.9 Trauma or rubbing of the hands and feet may precipitate the acral blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.5,11

Due to deposition of these amyloid fibrils, skin bleeding in these patients is called amyloid or pinch purpura. Vessel wall fragility and damage by amyloid are the principal causes of periorbital and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.26 Destruction of the lamina densa and widening of the intercellular space between keratinocytes by amyloid globules induce skin fragility.11

Although uncommon, various cases of bullous amyloidosis have been reported in the literature. Multiple myeloma patients represent the majority of those reported to have bullous amyloidosis.6,7,13,24,27-30 Plasmacytoma-associated bullous amyloid purpura and paraproteinemia also have been noted.25 Multiple myeloma with secondary AL amyloidosis has been seen with amyloid purpura and atraumatic ecchymoses of the face, highlighting the hemorrhage noted in these patients.26

Management of Amyloidosis—Various treatment options have been attempted for primary cutaneous amyloidosis, including oral retinoids, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, amitriptyline, colchicine, cepharanthin, tacrolimus, dimethyl sulfoxide, vitamin D3 analogs, capsaicin, menthol, hydrocolloid dressings, surgical modalities, laser treatment, and phototherapy.1 There is no clear consensus for therapeutic modalities except for treating the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia in primary systemic amyloidosis.

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient displaying signs of pseudoporphyria that ultimately proved to be bullous amyloidosis, or what we termed pseudopseudoporphyria. Bullous amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnoses of hemorrhagic bullous skin eruptions. Particular attention should be given to a systemic workup for multiple myeloma when hemorrhagic vesicles/bullae are chronic and coexist with purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue/weight loss, and/or macroglossia.

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Amyloidosis. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:341-345.

- Bhutani M, Shahid Z, Schnebelen A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell proliferative disorders. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:395-400.

- Terushkin V, Boyd KP, Patel RR, et al. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20711.

- LaChance A, Phelps A, Finch J, et al. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:344-347.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Kanoh T. Bullous amyloidosis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34:1050-1052.

- Johnson TM, Rapini RP, Hebert AA, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Cutis. 1989;43:346-352.

- Houman MH, Smiti KM, Ben Ghorbel I, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:299-302.

- Sanusi T, Li Y, Qian Y, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with bullous lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:400-402.

- Ochiai T, Morishima T, Hao T, et al. Bullous amyloidosis: the mechanism of blister formation revealed by electron microscopy. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:407-411.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Wang XD, Shen H, Liu ZH. Diffuse haemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis with multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:94-96.

- Biswas P, Aggarwal I, Sen D, et al. Bullous pemphigoid clinically presenting as lichen amyloidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:544-546.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous dermatosis vs amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:252.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous amyloidosis vs epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. JAMA. 1981;245:32.

- Murphy GM, Wright J, Nicholls DS, et al. Sunbed-induced pseudoporphyria. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:555-562.

- Pramatarov K, Lazarova A, Mateev G, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic primary systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:211-213.

- Bieber T, Ruzicka T, Linke RP, et al. Hemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis. a histologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study of two patients. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1683-1686.

- Khoo BP, Tay YK. Lichen amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:105-107.

- Asahina A, Hasegawa K, Ishiyama M, et al. Bullous amyloidosis mimicking bullous pemphigoid: usefulness of electron microscopic examination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:427-428.

- Schmutz JL, Barbaud A, Cuny JF, et al. Bullous amyloidosis [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:295-301.

- Lachmann HJ, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis of the skin. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:1574-1583.

- Grundmann JU, Bonnekoh B, Gollnick H. Extensive haemorrhagic-bullous skin manifestation of systemic AA-amyloidosis associated with IgG lambda-myeloma. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:139-142.

- Hödl S, Turek TD, Kerl H. Plasmocytoma-associated bullous hemorrhagic amyloidosis of the skin [in German]. Hautarzt. 1982;33:556-558.

- Colucci G, Alberio L, Demarmels Biasiutti F, et al. Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses. an often missed sign of amyloid purpura. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:249-252.

- Behera B, Pattnaik M, Sahu B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:668-671.

- Fujita Y, Tsuji-Abe Y, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Nail dystrophy and blisters as sole manifestations in myeloma-associated amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:712-714.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Winzer M, Ruppert M, Baretton G, et al. Bullous poikilodermatitic amyloidosis of the skin with junctional bulla development in IgG light chain plasmacytoma of the lambda type. histology, immunohistology and electron microscopy [in German]. Hautarzt. 1992;43:199-204.

Cutaneous amyloidosis encompasses a variety of clinical presentations. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis result from keratin deposits, while nodular amyloidosis results from cutaneous infiltration of plasma cells.2 Primary systemic amyloidosis is due to a plasma cell dyscrasia, particularly multiple myeloma, while secondary systemic amyloidosis occurs in the setting of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, renal dysfunction, or chronic inflammation, as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and various autoinflammatory disorders.2 Plasma cell proliferative disorders are associated with various skin disorders, which may result from aggregated misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins, indicating light chain–related systemic amyloidosis. Mucocutaneous lesions can occur in 30% to 40% of cases of primary systemic amyloidosis and may present as purpura, ecchymoses, waxy thickening, plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and/or bullae.3,4 When blistering is present, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes autoimmune bullous disease, drug eruptions, enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, deposition diseases, allergic contact dermatitis, bullous cellulitis, bullous bite reactions, neutrophilic dermatosis, and bullous lichen sclerosus.5 Herein, we present a case of a woman with a bullous skin eruption who eventually was diagnosed with bullous amyloidosis subsequent to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of well-demarcated, hemorrhagic, flaccid vesicles and focal erosions with a rim of erythema on the distal forearms and hands. A shave biopsy from the right forearm showed cell-poor subepidermal vesicular dermatitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 as well as urinary porphyrins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed granular IgM at the basement membrane zone around vessels and cytoid bodies. At this time, a preliminary diagnosis of pseudoporphyria was suspected, though no classic medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, antibiotics) or exogenous trigger factors (eg, UV light exposure, dialysis) were temporally related. Three months later, the patient presented with a large hemorrhagic bulla on the distal left forearm (Figure 1) and healing erosions on the dorsal fingers and upper back. Clobetasol ointment was initiated, as an autoimmune bullous dermatosis was suspected.

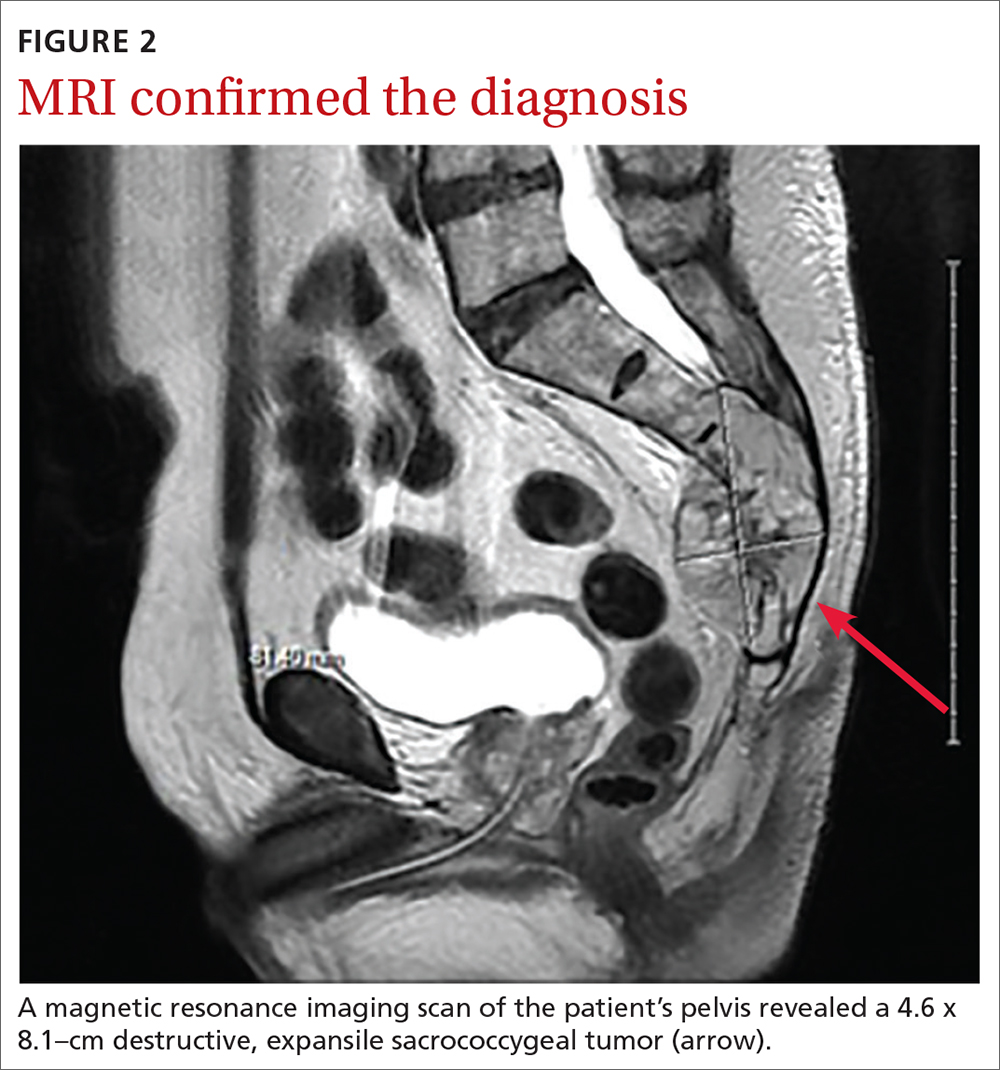

Approximately 1 year after she was first seen in our outpatient clinic, the patient was hospitalized for induction of chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone—for a new diagnosis of stage III multiple myeloma. A workup for back pain revealed multiple compression fractures and a plasma cell neoplasm with elevated λ light chains, which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy. During an inpatient dermatology consultation, we noted the development of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and worsening generalization of the hemorrhagic bullae, with healing erosions and intact hemorrhagic bullae on the dorsal hands, fingers (Figure 2), and upper back.

A repeat biopsy displayed bullous amyloidosis. Histopathologic examination revealed an ulcerated subepidermal blister with fibrin deposition at the ulcer base. A periadnexal, scant, eosinophilic deposition with extravasated red blood cells was appreciated. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits were found within the detached fragment of the epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate. A Congo red stain highlighted these areas with a salmon pink–colored material. Congo red staining showed a moderate amount of pale, apple green, birefringent deposit within these areas on polarized light examination.

A few months later, the patient was re-admitted, and the amount of skin detachment prompted the primary team to ask for another consultation. Although the extensive skin sloughing resembled toxic epidermal necrolysis, a repeat biopsy confirmed bullous amyloidosis.

Comment

Amyloidosis Histopathology—Amyloidoses represent a wide array of disorders with deposition of β-pleated sheets or amyloid fibrils, often with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 Primary systemic amyloidosis has been associated with underlying dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.6 In such cases, the skin lesions of multiple myeloma may result from a collection of misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments, as in light chain–related systemic amyloidosis.3 Histopathologically, both systemic and cutaneous amyloidosis appear similar and display deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic, fissured amyloid material in the dermis. Congo red stains the material orange-red and will display a characteristic apple green birefringence under polarized light.4 Although bullous amyloid lesions are rare, the cutaneous forms of these lesions can be an important sign of plasma cell dyscrasia.7

Presentation of Bullous Amyloidosis—Bullous manifestations rarely have been noted in the primary cutaneous forms of amyloidosis.5,8,9 Importantly, cutaneous blistering more often is linked to systemic forms of amyloidosis with multiorgan involvement, including primary systemic and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.5,10 However, patients with localized bullous cutaneous amyloidosis without systemic involvement also have been seen.10,11 Bullae may occur at any time, with contents that frequently are hemorrhagic due to capillary fragility.12,13 Bullous manifestations raise the differential diagnoses of bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, linear IgA disease, porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, bullous drug eruption, bullous eruption of renal dialysis, or bullous lupus erythematosus.5,13-17

In our patient, the acral distribution of bullae, presence of hemorrhage, chronicity of symptoms, and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay initially suggested a diagnosis of pseudoporphyria. However, the presence of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and subsequent confirmatory pathology aided in differentiating bullous amyloidosis from pseudoporphyria. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare form of skin-restricted amyloidoses, can coexist with bullous lesions. Of note, reported cases of nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis did not result in development of multiple myeloma.5,10