User login

Successful accelerated taper for sleeping aid

THE CASE

A 49-year-old man with chronic insomnia was referred to the pharmacist authors (LF and DP) to initiate and manage the tapering of nightly zolpidem use. Per chart review, the patient had complaints of insomnia for more than 30 years. His care had been transferred to a Nebraska clinic 5 years earlier, with a medication list that included zolpidem controlled release (CR) 12.5 mg nightly. Since then, multiple interventions to achieve cessation had been tried, including counseling on sleep hygiene, adjunct antidepressant use, and abrupt discontinuation. Each of these methods was unsuccessful. So, his family physician (SS) reached out to the pharmacist authors (LF and DP).

THE APPROACH

Due to the patient’s long history of zolpidem use, a lack of literature on the topic, and worry for withdrawal symptoms, a taper schedule was designed utilizing various benzodiazepine taper resources for guidance. The proposed taper utilized 5-mg immediate release (IR) tablets to ensure ease of tapering. The taper ranged from 20% to 43% weekly reductions based on the ability to split the zolpidem tablet in half.

DISCUSSION

Zolpidem is a sedative-hypnotic medication indicated for the treatment of insomnia when used at therapeutic dosing (ie, 5 to 10 mg nightly). Anecdotal efficacy, accompanied by weak chronic insomnia guideline recommendations, has led prescribers to use zolpidem as a chronic medication to treat insomnia.1,2 There is evidence of dependence and possible seizures from supratherapeutic zolpidem doses in the hundreds of milligrams, raising safety concerns regarding abuse, dependence, and withdrawal seizures in chronic use.2,3

Additionally, there is limited evidence regarding the appropriate process of discontinuing zolpidem after chronic use.2 Often a taper schedule—similar to those used with benzodiazepine medications—is used as a reference for discontinuation.1 The hypothetical goal of a taper is to prevent withdrawal effects such as rebound insomnia, anxiety, palpitations, and seizures.3 However, an extended taper may not actually be necessary with chronic zolpidem patients.

Tapering with minimal adverse effects

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies have suggested minimal, if not complete, absence of rebound or withdrawal effects with short-term zolpidem use.4 The same appears to be true of patients with long-term use. In a study, Roehrs and colleagues5 explored whether long-term treatment (defined as 8 months) caused rebound insomnia upon abrupt withdrawal. The investigators concluded that people with primary insomnia do not experience rebound insomnia or withdrawal symptoms with chronic, therapeutic dosing.

Another study involving 92 elderly patients on long-term treatment of zolpidem (defined as > 1 month, with average around 9.9 ± 6.2 years) experienced only 1 or 2 nights of rebound insomnia during a month-long taper.1,6 Following that, they experienced improvements in initiation and staying asleep.

A possible explanation for the lack of dependence or withdrawal symptoms in patients chronically treated with zolpidem is the pharmacokinetic profile. While the selectivity of the binding sites differentiates this medication from benzodiazepines, the additional fact of a short half-life, and no repeated dosing throughout the day, likely limit the risk of experiencing withdrawal symptoms.1 The daily periods of minimal zolpidem exposure in the body may limit the amount of physical dependence.

Continue to: Discontinuation of zolpidem

Discontinuation of zolpidem

The 49-year-old man had a history of failed abrupt discontinuation of zolpidem in the past (without noted withdrawal symptoms). Thus, various benzodiazepine taper resources were consulted to develop a taper schedule.

We switched our patient from the zolpidem CR 12.5 mg nightly to 10 mg of the IR formulation, and the pharmacists proposed 20% to 43% weekly decreases in dosing based on dosage strengths. At the initial 3-day follow-up (having taken 10 mg nightly for 3 days), the patient reported a quicker onset of sleep but an inability to sleep through the night. The patient denied withdrawal symptoms or any significant impact to his daily routines. These results encouraged a progression to the next step of the taper. For the next 9 days, the patient took 5 mg nightly, rather than the pharmacist-advised dosing of alternating 5 mg and 10 mg nightly, and reported similar outcomes at his next visit.

This success led to the discontinuation of scheduled zolpidem. The patient was also given a prescription of 2.5 mg, as needed, if insomnia rebounded. No adverse effects were noted despite the accelerated taper. Based on patient response and motivation, the taper had progressed more quickly than scheduled, resulting in 3 days of 10 mg, 9 days of 5 mg, and 1 final day of 2.5 mg that was used when the patient had trouble falling asleep. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient informed the physician that he had neither experienced insomnia nor used any further medication.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case documents a successfully accelerated taper for a patient with a chronic history (> 5 years) of zolpidem use. Although withdrawal is often patient specific, this case suggests the risk is low despite the chronic usage. This further adds to the literature suggesting against the need for an extended taper, and possibly a taper at all, when using recommended doses of chronic zolpidem. This is a significant difference compared to past practices that drew from literature-based benzodiazepine tapers.6 This case serves as an observational point of reference for clinicians who are assisting patients with chronic zolpidem tapers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Logan Franck, PharmD, 986145 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-6145; [email protected]

1. Lähteenmäki R, Neuvonen PJ, Puustinen J, et al. Withdrawal from long-term use of zopiclone, zolpidem and temazepam may improve perceived sleep and quality of life in older adults with primary insomnia. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;124:330-340. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13144

2. Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:307-349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470

3. Haji Seyed Javadi SA, Hajiali F, Nassiri-Asl M. Zolpidem dependency and withdrawal seizure: a case report study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e19926. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19926

4. Salvà P, Costa J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem. Therapeutic implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29:142-153. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199529030-00002

5. Roehrs TA, Randall S, Harris E, et al. Twelve months of nightly zolpidem does not lead to rebound insomnia or withdrawal symptoms: a prospective placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:1088-1095. doi: 10.1177/0269881111424455

6. Lader M. Benzodiazepine harm: how can it be reduced? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77:295-301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04418.x

THE CASE

A 49-year-old man with chronic insomnia was referred to the pharmacist authors (LF and DP) to initiate and manage the tapering of nightly zolpidem use. Per chart review, the patient had complaints of insomnia for more than 30 years. His care had been transferred to a Nebraska clinic 5 years earlier, with a medication list that included zolpidem controlled release (CR) 12.5 mg nightly. Since then, multiple interventions to achieve cessation had been tried, including counseling on sleep hygiene, adjunct antidepressant use, and abrupt discontinuation. Each of these methods was unsuccessful. So, his family physician (SS) reached out to the pharmacist authors (LF and DP).

THE APPROACH

Due to the patient’s long history of zolpidem use, a lack of literature on the topic, and worry for withdrawal symptoms, a taper schedule was designed utilizing various benzodiazepine taper resources for guidance. The proposed taper utilized 5-mg immediate release (IR) tablets to ensure ease of tapering. The taper ranged from 20% to 43% weekly reductions based on the ability to split the zolpidem tablet in half.

DISCUSSION

Zolpidem is a sedative-hypnotic medication indicated for the treatment of insomnia when used at therapeutic dosing (ie, 5 to 10 mg nightly). Anecdotal efficacy, accompanied by weak chronic insomnia guideline recommendations, has led prescribers to use zolpidem as a chronic medication to treat insomnia.1,2 There is evidence of dependence and possible seizures from supratherapeutic zolpidem doses in the hundreds of milligrams, raising safety concerns regarding abuse, dependence, and withdrawal seizures in chronic use.2,3

Additionally, there is limited evidence regarding the appropriate process of discontinuing zolpidem after chronic use.2 Often a taper schedule—similar to those used with benzodiazepine medications—is used as a reference for discontinuation.1 The hypothetical goal of a taper is to prevent withdrawal effects such as rebound insomnia, anxiety, palpitations, and seizures.3 However, an extended taper may not actually be necessary with chronic zolpidem patients.

Tapering with minimal adverse effects

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies have suggested minimal, if not complete, absence of rebound or withdrawal effects with short-term zolpidem use.4 The same appears to be true of patients with long-term use. In a study, Roehrs and colleagues5 explored whether long-term treatment (defined as 8 months) caused rebound insomnia upon abrupt withdrawal. The investigators concluded that people with primary insomnia do not experience rebound insomnia or withdrawal symptoms with chronic, therapeutic dosing.

Another study involving 92 elderly patients on long-term treatment of zolpidem (defined as > 1 month, with average around 9.9 ± 6.2 years) experienced only 1 or 2 nights of rebound insomnia during a month-long taper.1,6 Following that, they experienced improvements in initiation and staying asleep.

A possible explanation for the lack of dependence or withdrawal symptoms in patients chronically treated with zolpidem is the pharmacokinetic profile. While the selectivity of the binding sites differentiates this medication from benzodiazepines, the additional fact of a short half-life, and no repeated dosing throughout the day, likely limit the risk of experiencing withdrawal symptoms.1 The daily periods of minimal zolpidem exposure in the body may limit the amount of physical dependence.

Continue to: Discontinuation of zolpidem

Discontinuation of zolpidem

The 49-year-old man had a history of failed abrupt discontinuation of zolpidem in the past (without noted withdrawal symptoms). Thus, various benzodiazepine taper resources were consulted to develop a taper schedule.

We switched our patient from the zolpidem CR 12.5 mg nightly to 10 mg of the IR formulation, and the pharmacists proposed 20% to 43% weekly decreases in dosing based on dosage strengths. At the initial 3-day follow-up (having taken 10 mg nightly for 3 days), the patient reported a quicker onset of sleep but an inability to sleep through the night. The patient denied withdrawal symptoms or any significant impact to his daily routines. These results encouraged a progression to the next step of the taper. For the next 9 days, the patient took 5 mg nightly, rather than the pharmacist-advised dosing of alternating 5 mg and 10 mg nightly, and reported similar outcomes at his next visit.

This success led to the discontinuation of scheduled zolpidem. The patient was also given a prescription of 2.5 mg, as needed, if insomnia rebounded. No adverse effects were noted despite the accelerated taper. Based on patient response and motivation, the taper had progressed more quickly than scheduled, resulting in 3 days of 10 mg, 9 days of 5 mg, and 1 final day of 2.5 mg that was used when the patient had trouble falling asleep. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient informed the physician that he had neither experienced insomnia nor used any further medication.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case documents a successfully accelerated taper for a patient with a chronic history (> 5 years) of zolpidem use. Although withdrawal is often patient specific, this case suggests the risk is low despite the chronic usage. This further adds to the literature suggesting against the need for an extended taper, and possibly a taper at all, when using recommended doses of chronic zolpidem. This is a significant difference compared to past practices that drew from literature-based benzodiazepine tapers.6 This case serves as an observational point of reference for clinicians who are assisting patients with chronic zolpidem tapers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Logan Franck, PharmD, 986145 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-6145; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 49-year-old man with chronic insomnia was referred to the pharmacist authors (LF and DP) to initiate and manage the tapering of nightly zolpidem use. Per chart review, the patient had complaints of insomnia for more than 30 years. His care had been transferred to a Nebraska clinic 5 years earlier, with a medication list that included zolpidem controlled release (CR) 12.5 mg nightly. Since then, multiple interventions to achieve cessation had been tried, including counseling on sleep hygiene, adjunct antidepressant use, and abrupt discontinuation. Each of these methods was unsuccessful. So, his family physician (SS) reached out to the pharmacist authors (LF and DP).

THE APPROACH

Due to the patient’s long history of zolpidem use, a lack of literature on the topic, and worry for withdrawal symptoms, a taper schedule was designed utilizing various benzodiazepine taper resources for guidance. The proposed taper utilized 5-mg immediate release (IR) tablets to ensure ease of tapering. The taper ranged from 20% to 43% weekly reductions based on the ability to split the zolpidem tablet in half.

DISCUSSION

Zolpidem is a sedative-hypnotic medication indicated for the treatment of insomnia when used at therapeutic dosing (ie, 5 to 10 mg nightly). Anecdotal efficacy, accompanied by weak chronic insomnia guideline recommendations, has led prescribers to use zolpidem as a chronic medication to treat insomnia.1,2 There is evidence of dependence and possible seizures from supratherapeutic zolpidem doses in the hundreds of milligrams, raising safety concerns regarding abuse, dependence, and withdrawal seizures in chronic use.2,3

Additionally, there is limited evidence regarding the appropriate process of discontinuing zolpidem after chronic use.2 Often a taper schedule—similar to those used with benzodiazepine medications—is used as a reference for discontinuation.1 The hypothetical goal of a taper is to prevent withdrawal effects such as rebound insomnia, anxiety, palpitations, and seizures.3 However, an extended taper may not actually be necessary with chronic zolpidem patients.

Tapering with minimal adverse effects

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies have suggested minimal, if not complete, absence of rebound or withdrawal effects with short-term zolpidem use.4 The same appears to be true of patients with long-term use. In a study, Roehrs and colleagues5 explored whether long-term treatment (defined as 8 months) caused rebound insomnia upon abrupt withdrawal. The investigators concluded that people with primary insomnia do not experience rebound insomnia or withdrawal symptoms with chronic, therapeutic dosing.

Another study involving 92 elderly patients on long-term treatment of zolpidem (defined as > 1 month, with average around 9.9 ± 6.2 years) experienced only 1 or 2 nights of rebound insomnia during a month-long taper.1,6 Following that, they experienced improvements in initiation and staying asleep.

A possible explanation for the lack of dependence or withdrawal symptoms in patients chronically treated with zolpidem is the pharmacokinetic profile. While the selectivity of the binding sites differentiates this medication from benzodiazepines, the additional fact of a short half-life, and no repeated dosing throughout the day, likely limit the risk of experiencing withdrawal symptoms.1 The daily periods of minimal zolpidem exposure in the body may limit the amount of physical dependence.

Continue to: Discontinuation of zolpidem

Discontinuation of zolpidem

The 49-year-old man had a history of failed abrupt discontinuation of zolpidem in the past (without noted withdrawal symptoms). Thus, various benzodiazepine taper resources were consulted to develop a taper schedule.

We switched our patient from the zolpidem CR 12.5 mg nightly to 10 mg of the IR formulation, and the pharmacists proposed 20% to 43% weekly decreases in dosing based on dosage strengths. At the initial 3-day follow-up (having taken 10 mg nightly for 3 days), the patient reported a quicker onset of sleep but an inability to sleep through the night. The patient denied withdrawal symptoms or any significant impact to his daily routines. These results encouraged a progression to the next step of the taper. For the next 9 days, the patient took 5 mg nightly, rather than the pharmacist-advised dosing of alternating 5 mg and 10 mg nightly, and reported similar outcomes at his next visit.

This success led to the discontinuation of scheduled zolpidem. The patient was also given a prescription of 2.5 mg, as needed, if insomnia rebounded. No adverse effects were noted despite the accelerated taper. Based on patient response and motivation, the taper had progressed more quickly than scheduled, resulting in 3 days of 10 mg, 9 days of 5 mg, and 1 final day of 2.5 mg that was used when the patient had trouble falling asleep. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient informed the physician that he had neither experienced insomnia nor used any further medication.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case documents a successfully accelerated taper for a patient with a chronic history (> 5 years) of zolpidem use. Although withdrawal is often patient specific, this case suggests the risk is low despite the chronic usage. This further adds to the literature suggesting against the need for an extended taper, and possibly a taper at all, when using recommended doses of chronic zolpidem. This is a significant difference compared to past practices that drew from literature-based benzodiazepine tapers.6 This case serves as an observational point of reference for clinicians who are assisting patients with chronic zolpidem tapers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Logan Franck, PharmD, 986145 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-6145; [email protected]

1. Lähteenmäki R, Neuvonen PJ, Puustinen J, et al. Withdrawal from long-term use of zopiclone, zolpidem and temazepam may improve perceived sleep and quality of life in older adults with primary insomnia. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;124:330-340. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13144

2. Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:307-349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470

3. Haji Seyed Javadi SA, Hajiali F, Nassiri-Asl M. Zolpidem dependency and withdrawal seizure: a case report study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e19926. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19926

4. Salvà P, Costa J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem. Therapeutic implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29:142-153. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199529030-00002

5. Roehrs TA, Randall S, Harris E, et al. Twelve months of nightly zolpidem does not lead to rebound insomnia or withdrawal symptoms: a prospective placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:1088-1095. doi: 10.1177/0269881111424455

6. Lader M. Benzodiazepine harm: how can it be reduced? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77:295-301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04418.x

1. Lähteenmäki R, Neuvonen PJ, Puustinen J, et al. Withdrawal from long-term use of zopiclone, zolpidem and temazepam may improve perceived sleep and quality of life in older adults with primary insomnia. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;124:330-340. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13144

2. Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:307-349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470

3. Haji Seyed Javadi SA, Hajiali F, Nassiri-Asl M. Zolpidem dependency and withdrawal seizure: a case report study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e19926. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19926

4. Salvà P, Costa J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem. Therapeutic implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29:142-153. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199529030-00002

5. Roehrs TA, Randall S, Harris E, et al. Twelve months of nightly zolpidem does not lead to rebound insomnia or withdrawal symptoms: a prospective placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:1088-1095. doi: 10.1177/0269881111424455

6. Lader M. Benzodiazepine harm: how can it be reduced? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77:295-301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04418.x

Long QT and Cardiac Arrest After Symptomatic Improvement of Pulmonary Edema

A case of extreme QT prolongation induced following symptomatic resolution of acute pulmonary edema is both relatively unknown and poorly understood.

Abnormalities in the T-wave morphology of an electrocardiogram (ECG) are classically attributed to ischemic cardiac disease. However, these changes can be seen in a variety of other etiologies, including noncardiac pathology, which should be considered whenever reviewing an ECG: central nervous system disease, including stroke and subarachnoid hemorrhage; hypothermia; pulmonary disease, such as pulmonary embolism or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; myopericarditis; drug effects; and electrolyte abnormalities.

Prolongation of the QT interval, on the other hand, can be precipitated by medications, metabolic derangements, or genetic phenotypes. The QT interval is measured from the beginning of the QRS complex to the termination of the T wave and represents the total time for ventricular depolarization and repolarization. The QT interval must be corrected based on the patient’s heart rate, known as the QTc. As the QTc interval lengthens, there is increased risk of R-on-T phenomena, which may result in Torsades de Pointes (TdP). Typical features of TdP include an antecedent prolonged QTc, cyclic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia on the surface ECG, and either a short-lived spontaneously terminating course or degeneration into ventricular fibrillation (VF) and sudden cardiac death.1 These dysrhythmias become more likely as the QTc interval exceeds 500 msec.2

The combination of new-onset global T-wave inversions with prolongation of the QT interval has been reported in only a few limited conditions. Some known causes of these QT T changes include cardiac ischemia, status epilepticus, pheochromocytoma, and acute cocaine intoxication.3 One uncommon and rarely reported cause of extreme QT prolongation and T-wave inversion is acute pulmonary edema. The ECG findings are not present on initial patient presentation; rather the dynamic changes occur after resolution of the pulmonary symptoms. Despite significant ECG changes, all prior reported cases describe ECG normalization without significant morbidity.4,5 We report a case of extreme QT prolongation following acute pulmonary edema that resulted in cardiac arrest secondary to VF.

Case Presentation

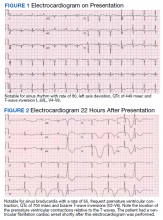

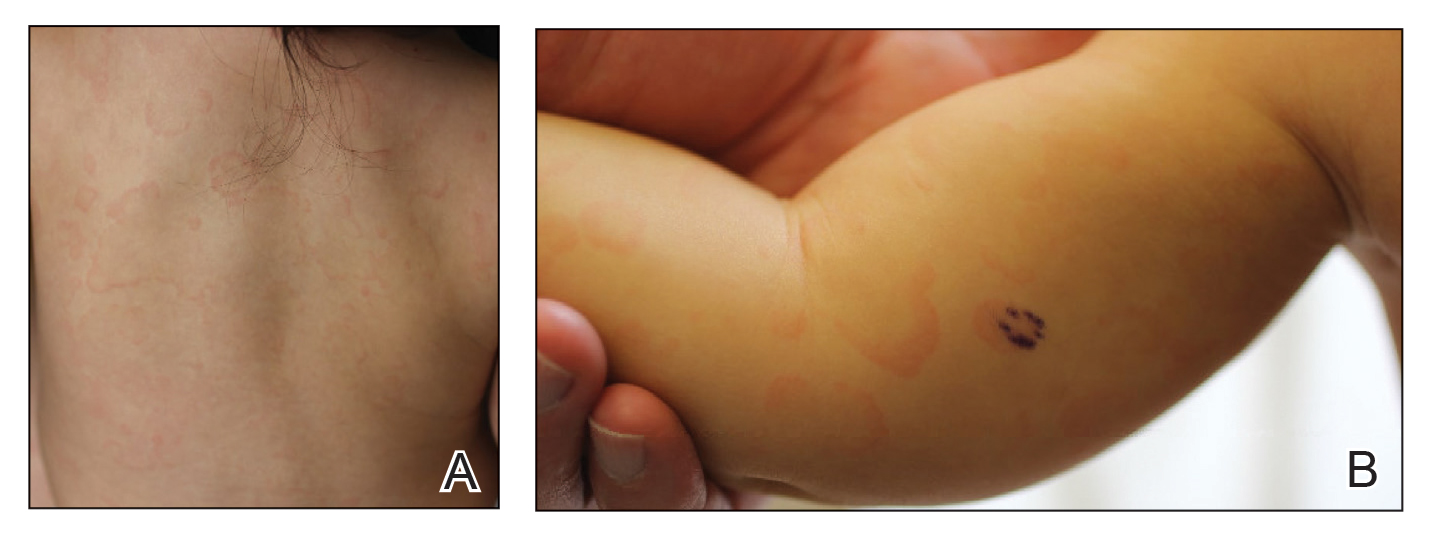

A 72-year-old male with medical history of combined systolic and diastolic heart failure, ischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, cerebral vascular accident, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and tobacco dependence presented to the emergency department (ED) by emergency medical services after awaking with acute onset of dyspnea and diaphoresis. On arrival at the ED, the patient was noted to be in respiratory distress (ie, unable to speak single words) and was extremely diaphoretic. His initial vital signs included blood pressure, 186/113 mm Hg, heart rate, 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate, 40 breaths per minute, and temperature, 36.4 °C. The patient was quickly placed on bilevel positive airway pressure and given sublingual nitroglycerin followed by transdermal nitroglycerin with a single dose of 40 mg IV furosemide, which improved his respiratory status. A chest X-ray was consistent with pulmonary edema, and his brain natriuretic peptide was 1654 pg/mL. An ECG demonstrated new T-wave inversions, and his troponin increased from 0.04 to 0.24 ng/mL during his ED stay (Figure 1). He was started on a heparin infusion and admitted to the hospital for hypertensive emergency with presumed acute decompensated heart failure and non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction.

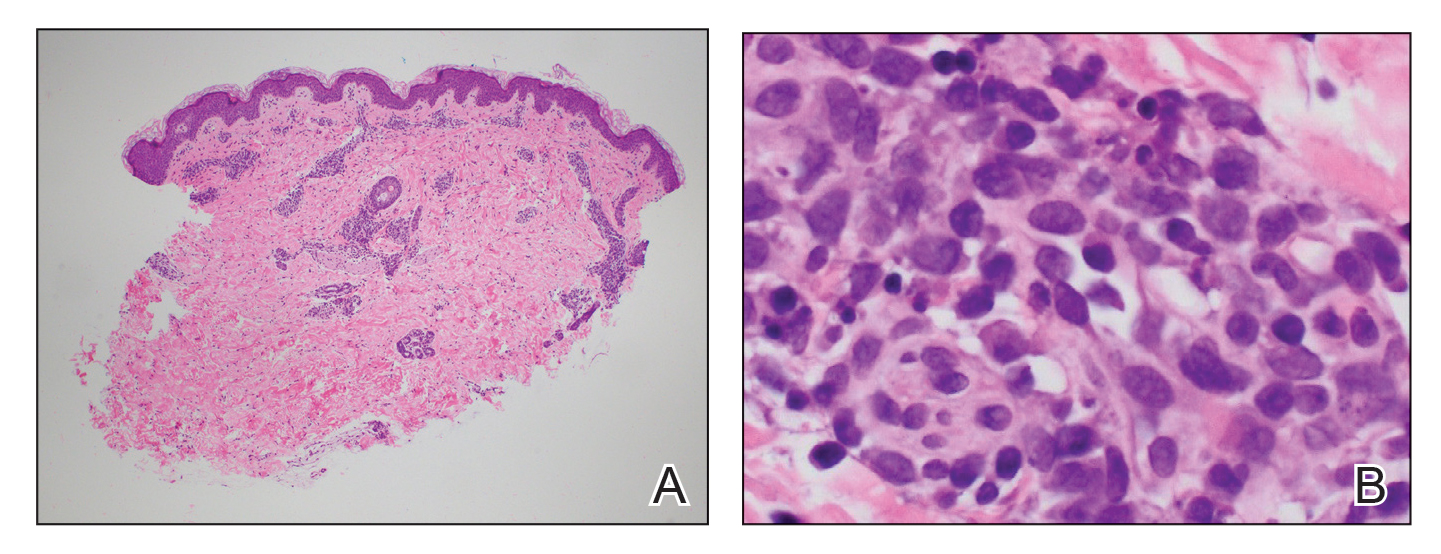

Throughout the patient’s first night, the troponin level started to down-trend after peaking at 0.24 ng/mL, and his oxygen requirements decreased allowing transition to nasal cannula. However, his repeat ECGs demonstrated significant T-wave abnormalities, new premature ventricular contractions, bradycardia, and a prolonging QTc interval to 703 msec (Figure 2). At this time, the patient’s electrolytes were normal, specifically a potassium level of 4.4 mEq/L, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, magnesium 2.0 mg/dL, and phosphorus 2.6 mg/dL. Given the worsening ECG changes, a computed tomography scan of his head was ordered to rule out intracranial pathology. While in the scanner, the patient went into pulseless VF, prompting defibrillation with 200 J. In addition, he was given 75 mg IV lidocaine, 2 g IV magnesium, and 1 ampule of both calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate. With treatment, he had return of spontaneous circulation and was taken promptly to cardiac catheterization. The catheterization showed no significant obstructive coronary artery disease, and no interventions were performed. The patient was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit for continued care.

During his course in the intensive care unit, the patient’s potassium and magnesium levels were maintained at high-normal levels. The patient was started on a dobutamine infusion to increase his heart rate and attempt to decrease his QTc. The patient also underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate for possible myocarditis, which showed no evidence of acute inflammation. Echocardiogram demonstrated an ejection fraction of 40% and global hypokinesis but no specific regional abnormalities and no change from prior echocardiogram performed 1 year earlier. Over the course of 3 days, his ECG normalized and his QTc shortened to 477 msec. Genetic testing was performed and did not reveal any mutations associated with long QT syndrome. Ultimately, an automated internal cardiac defibrillator (AICD) was placed, and the patient was discharged home.

Over the 2 years since his initial event, the patient has not experienced recurrent VF and his AICD has not fired. The patient continues to have ED presentations for heart-failure symptoms, though he has been stable from an electrophysiologic standpoint and his QTc remains less than 500 msec.

Discussion

Prolongation of the QT interval as a result of deep, global T-wave inversions after resolution of acute pulmonary edema has been minimally reported.4,5 This phenomenon has been described in the cardiology literature but has not been discussed in the emergency medicine literature and bears consideration in this case.4,5 As noted, an extensive evaluation did not reveal another cause of QTc prolongation. The patient had normal electrolytes and temperature, his neurologic examination and computed tomography were not remarkable. The patient had no obstructive coronary artery disease on catheterization, no evidence of acute myocarditis on cardiac MRI, no prescribed medications associated with QT prolongation, and no evidence of genetic mutations associated with QT prolongation on testing. The minimal troponin elevation was felt to represent a type II myocardial infarction related to ischemia due to supply-demand mismatch rather than acute plaque rupture.

Littmann published a case series of 9 cases of delayed onset T-wave inversion and extreme QTc prolongation in the 24 to 48 hours following treatment and symptomatic improvement in acute pulmonary edema.4 In each of his patients, an ischemic cardiac insult was ruled out as the etiology of the pulmonary edema by laboratory assessment, echocardiography, and left heart catheterization.All of the patients in this case series recovered without incident and with normalization of the QTc interval.4 Similarly, in our patient, significant QT T changes occurred approximately 22 hours after presentation and with resolution of symptoms of pulmonary edema. Pascale and colleagues also published a series of 3 patients developing similar ECG patterns following a hypertensive crisis with resolution of ECG findings and without any morbidity.5 In contrast, our patient experienced significant morbidity secondary to the extreme QTc prolongation.

Conclusions

We believe this is the first reported case of excessive prolongation of the QTc with VF arrest secondary to resolution of acute pulmonary edema. The pattern observed in our patient follows the patterns outlined in the previous case series—patients present with acute pulmonary edema and hypertensive crisis but develop significant ECG abnormalities about 24 hours after the resolution of the high catecholamine state. Our patient did have a history of prior cardiac insult, given the QTc changes developed acutely, with frequent premature ventricular contractions, and the cardiac arrest occurred at maximal QTc prolongation, yet after resolution of the high catecholamine state, the treatment team felt there was likely an uncaptured and short-lived episode of TdP that degenerated into VF. This theory is further supported by the lack of recurrent VF episodes, confirmed by AICD interrogation, after normalization of the QTc in our patient.

1. Passman R, Kadish A. Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, long Q-T syndrome, and torsades de pointes. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(2):321-341. doi:10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70318-7

2. Kallergis EM, Goudis CA, Simantirakis EN, Kochiadakis GE, Vardas PE. Mechanisms, risk factors, and management of acquired long QT syndrome: a comprehensive review. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:212178. doi:10.1100/2012/212178

3. Miller MA, Elmariah S, Fischer A. Giant T-wave inversions and extreme QT prolongation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(6):e42-e43. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.108.825729

4. Littmann L. Large T wave inversion and QT prolongation associated with pulmonary edema: a report of nine cases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(4):1106-1110. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00311-3

5. Pascale P, Quartenoud B, Stauffer JC. Isolated large inverted T wave in pulmonary edema due to hypertensive crisis: a novel electrocardiographic phenomenon mimicking ischemia?. Clin Res Cardiol. 2007;96(5):288-294. doi:10.1007/s00392-007-0504-1

A case of extreme QT prolongation induced following symptomatic resolution of acute pulmonary edema is both relatively unknown and poorly understood.

A case of extreme QT prolongation induced following symptomatic resolution of acute pulmonary edema is both relatively unknown and poorly understood.

Abnormalities in the T-wave morphology of an electrocardiogram (ECG) are classically attributed to ischemic cardiac disease. However, these changes can be seen in a variety of other etiologies, including noncardiac pathology, which should be considered whenever reviewing an ECG: central nervous system disease, including stroke and subarachnoid hemorrhage; hypothermia; pulmonary disease, such as pulmonary embolism or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; myopericarditis; drug effects; and electrolyte abnormalities.

Prolongation of the QT interval, on the other hand, can be precipitated by medications, metabolic derangements, or genetic phenotypes. The QT interval is measured from the beginning of the QRS complex to the termination of the T wave and represents the total time for ventricular depolarization and repolarization. The QT interval must be corrected based on the patient’s heart rate, known as the QTc. As the QTc interval lengthens, there is increased risk of R-on-T phenomena, which may result in Torsades de Pointes (TdP). Typical features of TdP include an antecedent prolonged QTc, cyclic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia on the surface ECG, and either a short-lived spontaneously terminating course or degeneration into ventricular fibrillation (VF) and sudden cardiac death.1 These dysrhythmias become more likely as the QTc interval exceeds 500 msec.2

The combination of new-onset global T-wave inversions with prolongation of the QT interval has been reported in only a few limited conditions. Some known causes of these QT T changes include cardiac ischemia, status epilepticus, pheochromocytoma, and acute cocaine intoxication.3 One uncommon and rarely reported cause of extreme QT prolongation and T-wave inversion is acute pulmonary edema. The ECG findings are not present on initial patient presentation; rather the dynamic changes occur after resolution of the pulmonary symptoms. Despite significant ECG changes, all prior reported cases describe ECG normalization without significant morbidity.4,5 We report a case of extreme QT prolongation following acute pulmonary edema that resulted in cardiac arrest secondary to VF.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male with medical history of combined systolic and diastolic heart failure, ischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, cerebral vascular accident, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and tobacco dependence presented to the emergency department (ED) by emergency medical services after awaking with acute onset of dyspnea and diaphoresis. On arrival at the ED, the patient was noted to be in respiratory distress (ie, unable to speak single words) and was extremely diaphoretic. His initial vital signs included blood pressure, 186/113 mm Hg, heart rate, 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate, 40 breaths per minute, and temperature, 36.4 °C. The patient was quickly placed on bilevel positive airway pressure and given sublingual nitroglycerin followed by transdermal nitroglycerin with a single dose of 40 mg IV furosemide, which improved his respiratory status. A chest X-ray was consistent with pulmonary edema, and his brain natriuretic peptide was 1654 pg/mL. An ECG demonstrated new T-wave inversions, and his troponin increased from 0.04 to 0.24 ng/mL during his ED stay (Figure 1). He was started on a heparin infusion and admitted to the hospital for hypertensive emergency with presumed acute decompensated heart failure and non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction.

Throughout the patient’s first night, the troponin level started to down-trend after peaking at 0.24 ng/mL, and his oxygen requirements decreased allowing transition to nasal cannula. However, his repeat ECGs demonstrated significant T-wave abnormalities, new premature ventricular contractions, bradycardia, and a prolonging QTc interval to 703 msec (Figure 2). At this time, the patient’s electrolytes were normal, specifically a potassium level of 4.4 mEq/L, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, magnesium 2.0 mg/dL, and phosphorus 2.6 mg/dL. Given the worsening ECG changes, a computed tomography scan of his head was ordered to rule out intracranial pathology. While in the scanner, the patient went into pulseless VF, prompting defibrillation with 200 J. In addition, he was given 75 mg IV lidocaine, 2 g IV magnesium, and 1 ampule of both calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate. With treatment, he had return of spontaneous circulation and was taken promptly to cardiac catheterization. The catheterization showed no significant obstructive coronary artery disease, and no interventions were performed. The patient was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit for continued care.

During his course in the intensive care unit, the patient’s potassium and magnesium levels were maintained at high-normal levels. The patient was started on a dobutamine infusion to increase his heart rate and attempt to decrease his QTc. The patient also underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate for possible myocarditis, which showed no evidence of acute inflammation. Echocardiogram demonstrated an ejection fraction of 40% and global hypokinesis but no specific regional abnormalities and no change from prior echocardiogram performed 1 year earlier. Over the course of 3 days, his ECG normalized and his QTc shortened to 477 msec. Genetic testing was performed and did not reveal any mutations associated with long QT syndrome. Ultimately, an automated internal cardiac defibrillator (AICD) was placed, and the patient was discharged home.

Over the 2 years since his initial event, the patient has not experienced recurrent VF and his AICD has not fired. The patient continues to have ED presentations for heart-failure symptoms, though he has been stable from an electrophysiologic standpoint and his QTc remains less than 500 msec.

Discussion

Prolongation of the QT interval as a result of deep, global T-wave inversions after resolution of acute pulmonary edema has been minimally reported.4,5 This phenomenon has been described in the cardiology literature but has not been discussed in the emergency medicine literature and bears consideration in this case.4,5 As noted, an extensive evaluation did not reveal another cause of QTc prolongation. The patient had normal electrolytes and temperature, his neurologic examination and computed tomography were not remarkable. The patient had no obstructive coronary artery disease on catheterization, no evidence of acute myocarditis on cardiac MRI, no prescribed medications associated with QT prolongation, and no evidence of genetic mutations associated with QT prolongation on testing. The minimal troponin elevation was felt to represent a type II myocardial infarction related to ischemia due to supply-demand mismatch rather than acute plaque rupture.

Littmann published a case series of 9 cases of delayed onset T-wave inversion and extreme QTc prolongation in the 24 to 48 hours following treatment and symptomatic improvement in acute pulmonary edema.4 In each of his patients, an ischemic cardiac insult was ruled out as the etiology of the pulmonary edema by laboratory assessment, echocardiography, and left heart catheterization.All of the patients in this case series recovered without incident and with normalization of the QTc interval.4 Similarly, in our patient, significant QT T changes occurred approximately 22 hours after presentation and with resolution of symptoms of pulmonary edema. Pascale and colleagues also published a series of 3 patients developing similar ECG patterns following a hypertensive crisis with resolution of ECG findings and without any morbidity.5 In contrast, our patient experienced significant morbidity secondary to the extreme QTc prolongation.

Conclusions

We believe this is the first reported case of excessive prolongation of the QTc with VF arrest secondary to resolution of acute pulmonary edema. The pattern observed in our patient follows the patterns outlined in the previous case series—patients present with acute pulmonary edema and hypertensive crisis but develop significant ECG abnormalities about 24 hours after the resolution of the high catecholamine state. Our patient did have a history of prior cardiac insult, given the QTc changes developed acutely, with frequent premature ventricular contractions, and the cardiac arrest occurred at maximal QTc prolongation, yet after resolution of the high catecholamine state, the treatment team felt there was likely an uncaptured and short-lived episode of TdP that degenerated into VF. This theory is further supported by the lack of recurrent VF episodes, confirmed by AICD interrogation, after normalization of the QTc in our patient.

Abnormalities in the T-wave morphology of an electrocardiogram (ECG) are classically attributed to ischemic cardiac disease. However, these changes can be seen in a variety of other etiologies, including noncardiac pathology, which should be considered whenever reviewing an ECG: central nervous system disease, including stroke and subarachnoid hemorrhage; hypothermia; pulmonary disease, such as pulmonary embolism or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; myopericarditis; drug effects; and electrolyte abnormalities.

Prolongation of the QT interval, on the other hand, can be precipitated by medications, metabolic derangements, or genetic phenotypes. The QT interval is measured from the beginning of the QRS complex to the termination of the T wave and represents the total time for ventricular depolarization and repolarization. The QT interval must be corrected based on the patient’s heart rate, known as the QTc. As the QTc interval lengthens, there is increased risk of R-on-T phenomena, which may result in Torsades de Pointes (TdP). Typical features of TdP include an antecedent prolonged QTc, cyclic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia on the surface ECG, and either a short-lived spontaneously terminating course or degeneration into ventricular fibrillation (VF) and sudden cardiac death.1 These dysrhythmias become more likely as the QTc interval exceeds 500 msec.2

The combination of new-onset global T-wave inversions with prolongation of the QT interval has been reported in only a few limited conditions. Some known causes of these QT T changes include cardiac ischemia, status epilepticus, pheochromocytoma, and acute cocaine intoxication.3 One uncommon and rarely reported cause of extreme QT prolongation and T-wave inversion is acute pulmonary edema. The ECG findings are not present on initial patient presentation; rather the dynamic changes occur after resolution of the pulmonary symptoms. Despite significant ECG changes, all prior reported cases describe ECG normalization without significant morbidity.4,5 We report a case of extreme QT prolongation following acute pulmonary edema that resulted in cardiac arrest secondary to VF.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male with medical history of combined systolic and diastolic heart failure, ischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, cerebral vascular accident, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and tobacco dependence presented to the emergency department (ED) by emergency medical services after awaking with acute onset of dyspnea and diaphoresis. On arrival at the ED, the patient was noted to be in respiratory distress (ie, unable to speak single words) and was extremely diaphoretic. His initial vital signs included blood pressure, 186/113 mm Hg, heart rate, 104 beats per minute, respiratory rate, 40 breaths per minute, and temperature, 36.4 °C. The patient was quickly placed on bilevel positive airway pressure and given sublingual nitroglycerin followed by transdermal nitroglycerin with a single dose of 40 mg IV furosemide, which improved his respiratory status. A chest X-ray was consistent with pulmonary edema, and his brain natriuretic peptide was 1654 pg/mL. An ECG demonstrated new T-wave inversions, and his troponin increased from 0.04 to 0.24 ng/mL during his ED stay (Figure 1). He was started on a heparin infusion and admitted to the hospital for hypertensive emergency with presumed acute decompensated heart failure and non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction.

Throughout the patient’s first night, the troponin level started to down-trend after peaking at 0.24 ng/mL, and his oxygen requirements decreased allowing transition to nasal cannula. However, his repeat ECGs demonstrated significant T-wave abnormalities, new premature ventricular contractions, bradycardia, and a prolonging QTc interval to 703 msec (Figure 2). At this time, the patient’s electrolytes were normal, specifically a potassium level of 4.4 mEq/L, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, magnesium 2.0 mg/dL, and phosphorus 2.6 mg/dL. Given the worsening ECG changes, a computed tomography scan of his head was ordered to rule out intracranial pathology. While in the scanner, the patient went into pulseless VF, prompting defibrillation with 200 J. In addition, he was given 75 mg IV lidocaine, 2 g IV magnesium, and 1 ampule of both calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate. With treatment, he had return of spontaneous circulation and was taken promptly to cardiac catheterization. The catheterization showed no significant obstructive coronary artery disease, and no interventions were performed. The patient was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit for continued care.

During his course in the intensive care unit, the patient’s potassium and magnesium levels were maintained at high-normal levels. The patient was started on a dobutamine infusion to increase his heart rate and attempt to decrease his QTc. The patient also underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate for possible myocarditis, which showed no evidence of acute inflammation. Echocardiogram demonstrated an ejection fraction of 40% and global hypokinesis but no specific regional abnormalities and no change from prior echocardiogram performed 1 year earlier. Over the course of 3 days, his ECG normalized and his QTc shortened to 477 msec. Genetic testing was performed and did not reveal any mutations associated with long QT syndrome. Ultimately, an automated internal cardiac defibrillator (AICD) was placed, and the patient was discharged home.

Over the 2 years since his initial event, the patient has not experienced recurrent VF and his AICD has not fired. The patient continues to have ED presentations for heart-failure symptoms, though he has been stable from an electrophysiologic standpoint and his QTc remains less than 500 msec.

Discussion

Prolongation of the QT interval as a result of deep, global T-wave inversions after resolution of acute pulmonary edema has been minimally reported.4,5 This phenomenon has been described in the cardiology literature but has not been discussed in the emergency medicine literature and bears consideration in this case.4,5 As noted, an extensive evaluation did not reveal another cause of QTc prolongation. The patient had normal electrolytes and temperature, his neurologic examination and computed tomography were not remarkable. The patient had no obstructive coronary artery disease on catheterization, no evidence of acute myocarditis on cardiac MRI, no prescribed medications associated with QT prolongation, and no evidence of genetic mutations associated with QT prolongation on testing. The minimal troponin elevation was felt to represent a type II myocardial infarction related to ischemia due to supply-demand mismatch rather than acute plaque rupture.

Littmann published a case series of 9 cases of delayed onset T-wave inversion and extreme QTc prolongation in the 24 to 48 hours following treatment and symptomatic improvement in acute pulmonary edema.4 In each of his patients, an ischemic cardiac insult was ruled out as the etiology of the pulmonary edema by laboratory assessment, echocardiography, and left heart catheterization.All of the patients in this case series recovered without incident and with normalization of the QTc interval.4 Similarly, in our patient, significant QT T changes occurred approximately 22 hours after presentation and with resolution of symptoms of pulmonary edema. Pascale and colleagues also published a series of 3 patients developing similar ECG patterns following a hypertensive crisis with resolution of ECG findings and without any morbidity.5 In contrast, our patient experienced significant morbidity secondary to the extreme QTc prolongation.

Conclusions

We believe this is the first reported case of excessive prolongation of the QTc with VF arrest secondary to resolution of acute pulmonary edema. The pattern observed in our patient follows the patterns outlined in the previous case series—patients present with acute pulmonary edema and hypertensive crisis but develop significant ECG abnormalities about 24 hours after the resolution of the high catecholamine state. Our patient did have a history of prior cardiac insult, given the QTc changes developed acutely, with frequent premature ventricular contractions, and the cardiac arrest occurred at maximal QTc prolongation, yet after resolution of the high catecholamine state, the treatment team felt there was likely an uncaptured and short-lived episode of TdP that degenerated into VF. This theory is further supported by the lack of recurrent VF episodes, confirmed by AICD interrogation, after normalization of the QTc in our patient.

1. Passman R, Kadish A. Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, long Q-T syndrome, and torsades de pointes. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(2):321-341. doi:10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70318-7

2. Kallergis EM, Goudis CA, Simantirakis EN, Kochiadakis GE, Vardas PE. Mechanisms, risk factors, and management of acquired long QT syndrome: a comprehensive review. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:212178. doi:10.1100/2012/212178

3. Miller MA, Elmariah S, Fischer A. Giant T-wave inversions and extreme QT prolongation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(6):e42-e43. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.108.825729

4. Littmann L. Large T wave inversion and QT prolongation associated with pulmonary edema: a report of nine cases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(4):1106-1110. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00311-3

5. Pascale P, Quartenoud B, Stauffer JC. Isolated large inverted T wave in pulmonary edema due to hypertensive crisis: a novel electrocardiographic phenomenon mimicking ischemia?. Clin Res Cardiol. 2007;96(5):288-294. doi:10.1007/s00392-007-0504-1

1. Passman R, Kadish A. Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, long Q-T syndrome, and torsades de pointes. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(2):321-341. doi:10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70318-7

2. Kallergis EM, Goudis CA, Simantirakis EN, Kochiadakis GE, Vardas PE. Mechanisms, risk factors, and management of acquired long QT syndrome: a comprehensive review. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:212178. doi:10.1100/2012/212178

3. Miller MA, Elmariah S, Fischer A. Giant T-wave inversions and extreme QT prolongation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(6):e42-e43. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.108.825729

4. Littmann L. Large T wave inversion and QT prolongation associated with pulmonary edema: a report of nine cases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(4):1106-1110. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00311-3

5. Pascale P, Quartenoud B, Stauffer JC. Isolated large inverted T wave in pulmonary edema due to hypertensive crisis: a novel electrocardiographic phenomenon mimicking ischemia?. Clin Res Cardiol. 2007;96(5):288-294. doi:10.1007/s00392-007-0504-1

Emphysematous Aortitis due to Klebsiella Pneumoniae in a Patient With Poorly Controlled Diabetes Mellitus

Patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and an infectious source can be predisposed to infectious aortitis.

Aortitis is the all-encompassing term ascribed to the inflammatory process in the aortic wall that can be either infective or noninfective in origin, commonly autoimmune or inflammatory large-vessel vasculitis.1 Infectious aortitis, also known as bacterial, microbial, or cryptogenic aortitis, as well as mycotic or infected aneurysm, is a rare entity in the current antibiotic era but potentially a life-threatening disorder.2 The potential complications of infectious aortitis include emphysematous aortitis (EA), pseudoaneurysm, aortic rupture, septic emboli, and fistula formation (eg, aorto-enteric fistula).2,3

EA is a rare but serious inflammatory condition of the aorta with a nonspecific clinical presentation associated with high morbidity and mortality.2-6 The condition is characterized by a localized collection of gas and purulent exudate at the aortic wall.1,3 A few cases of EA have previously been reported; however, no known cases have been reported in the literature due to Klebsiella pneumoniae (K pneumoniae).

The pathophysiology of EA is the presence of underlying damage to the arterial wall caused by a hematogenously inoculated gas-producing organism.2,3 Most reported cases of EA are due to endovascular graft complications. Under normal circumstances, the aortic intima is highly resistant to infectious pathogens; however, certain risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), atherosclerotic disease, preexisting aneurysm, cystic medial necrosis, vascular malformation, presence of medical devices, surgery, or impaired immunity can alter the integrity of the aortic intimal layer and predispose the aortic intima to infection.1,4-7 Bacteria are the most common causative organisms that can infect the aorta, especially Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Salmonella, and spirochete Treponema pallidum (syphilis).1,2,4,8 The site of the primary infection remains unclear in some patients.2,3,5,6 Infection of the aorta can arise by several mechanisms: direct extension of a local infection to an existing intimal injury or atherosclerotic plaque (the most common mechanism), septic embolism from endocarditis, direct bacterial inoculation from traumatic contamination, contiguous infection extending to the aorta wall, or a distant source of bacteremia.2,3

Clinical manifestations of EA depend on the site and the extent of infection. The diagnosis should be considered in patients with atherosclerosis, fever, abdominal pain, and leukocytosis.2,4-8 The differential diagnosis for EA includes (1) noninfective causes of aortitis, including rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus; (2) tuberculous aortitis; (3) syphilitic aortitis; and (4) idiopathic isolated aortitis. Establishing an early diagnosis of infectious aortitis is extremely important because this condition is associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality secondary to aortic rupture.2-7

Imaging is critical for a reliable and quick diagnosis of acute aortic pathology. Noninvasive cross-sectional imaging modalities, such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, nuclear medicine, or positron emission tomography, are used for both the initial diagnosis and follow-up of aortitis.1 CT is the primary imaging method in most medical centers because it is widely available with short acquisition time in critically ill patients.3 CT allows rapid detection of abnormalities in wall thickness, diameter, and density, and enhancement of periaortic structures, enabling reliable exclusion of other aortic pathologies that may resemble acute aortitis. Also, CT aids in planning the optimal therapeutic approach.1,3,5-8

This case illustrates EA associated with infection by K pneumoniae in a patient with poorly controlled type 2 DM (T2DM). In this single case, our patient presented to the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (BPVAHS) in Florida with recent superficial soft tissue injury, severe hyperglycemia, worsening abdominal pain, and leukocytosis without fever or chills. The correct diagnosis of EA was confirmed by characteristic CT findings.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male with a history of T2DM, hypertension, atherosclerotic vascular disease, obstructive lung disease, and smoking 1.5 packs per day for 40 years presented with diabetic ketoacidosis, a urinary tract infection, and abdominal pain of 1-week duration that started to worsen the morning he arrived at the BPVAHS emergency department. He reported no nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, chest pain, shortness of breath, fever, chills, fatigue, or dysuria. He had a nonhealing laceration on his left medial foot that occurred 18 days before admission and was treated at an outside hospital.

The patient’s surgical history included a left common femoral endarterectomy and a left femoral popliteal above-knee reverse saphenous vein bypass 4 years ago for severe critical limb ischemia due to occlusion of his left superficial femoral artery with distal embolization to the first and fifth toes. About 6 months later, he developed disabling claudication in his left lower extremity due to distal popliteal artery occlusion and had another bypass surgery to the below-knee popliteal artery with a reverse saphenous vein graft harvested from the right thigh.

On initial examination, his vital signs were within normal limits except for a blood pressure of 177/87 mm Hg. His physical examination demonstrated a nondistended abdomen with normal bowel sounds, mild lower quadrant tenderness on the left more than on the right, intermittent abdominal pain located around umbilicus with radiation to the back, and a negative psoas sign. His left medial foot had a nonhealing laceration with black sutures in place, with minimal erythema in the surrounding tissue and scab formation. He also had mild costovertebral tenderness on the left.

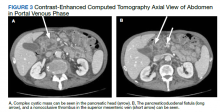

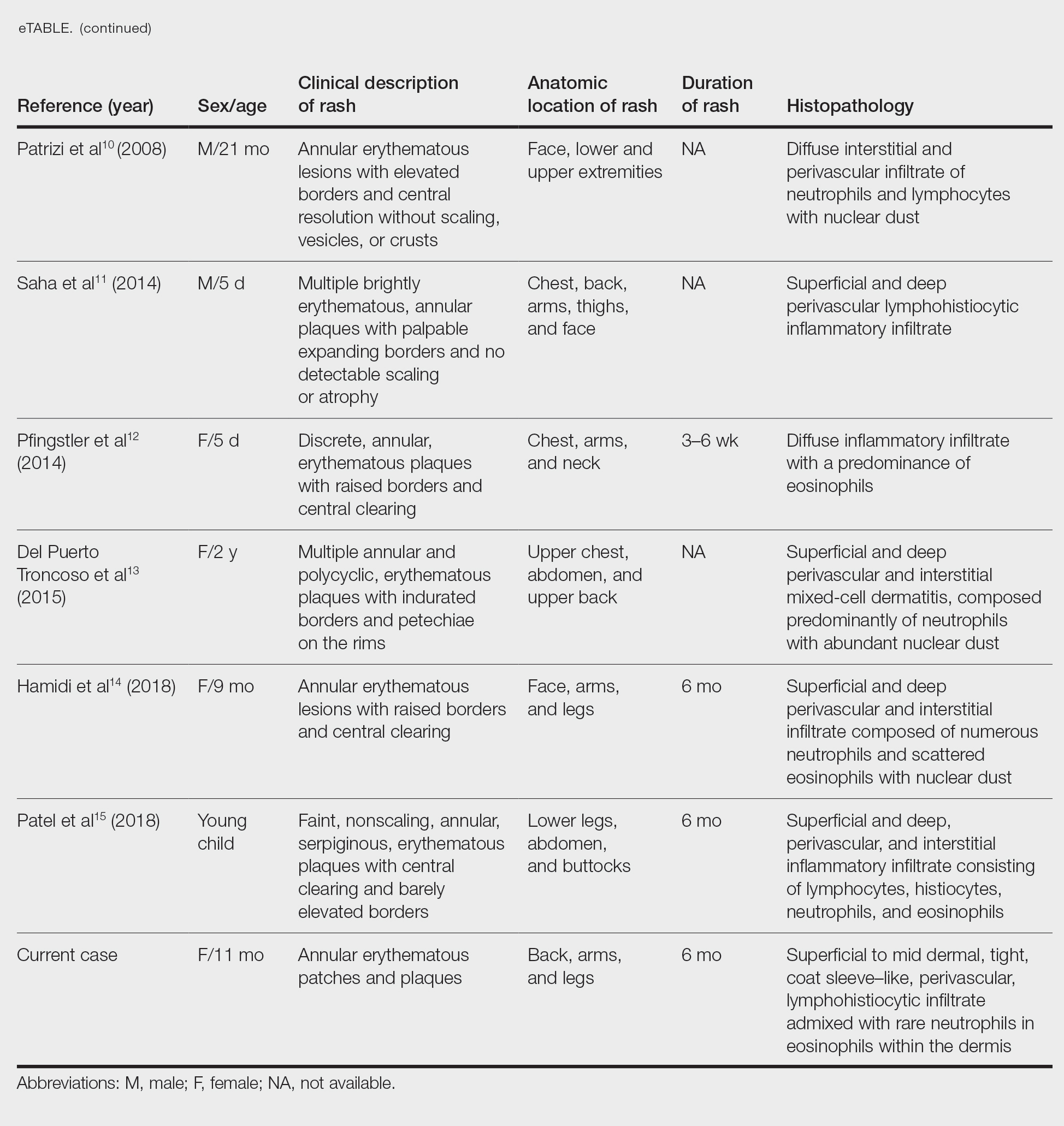

Initial laboratory investigation results were notable for a glucose level of 609 mg/dL and a white blood cell count of 14.6 × 103 cells/mcL with 86.5% of neutrophils. A CT scan of his abdomen revealed extensive atherosclerosis of the abdominal aorta and periaortic aneurysmal fluid collection with multiple foci of gas (Figure 1). Additionally, the aneurysmal fluid collection involved the proximal segment of the left common femoral artery, suspicious for left femoral arteritis (Figure 2). The patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, morphine, and an insulin drip. Both urine and blood cultures were positive for K pneumoniae susceptible to multiple antibiotics. He was transferred to a tertiary medical center and was referred for a vascular surgery consultation.

The patient underwent surgical resection of the infected infrarenal EA and infected left common femoral artery with right axillary-bifemoral bypass with an 8-mm PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) graft. During the surgery, excision of the wall of the left common femoral artery and infrarenal aorta revealed frank pus with purulent fluid, which was sent to cytology for analysis and culture. His intraoperative cultures grew K pneumoniae sensitive to multiple antibiotics, including ceftriaxone, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and ampicillin/sulbactam. The vascular surgery team recommended inpatient admission and administration of 6 weeks of IV antibiotics postoperatively with ceftriaxone, followed by outpatient oral suppression therapy after discharge. The patient tolerated the surgery well and was discharged after 6 weeks of IV ceftriaxone followed by outpatient oral suppression therapy. However, the patient was transferred back to BPVAHS for continued care and rehabilitation placement.

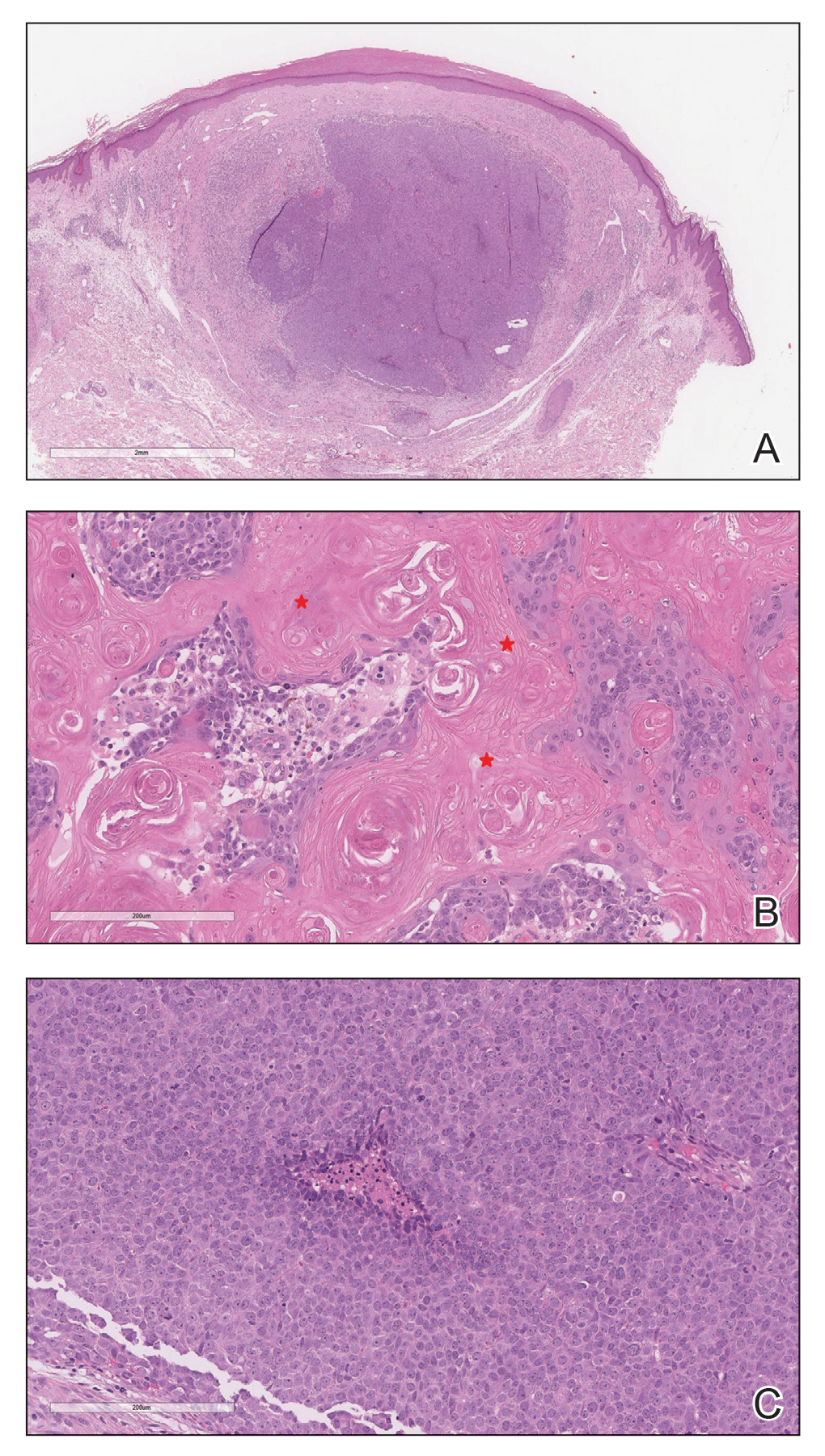

The patient’s subsequent course was complicated by multiple hospital admissions, including aspiration pneumonia, hypoglycemia, diarrhea, and anemia. On one of his CT abdomen/pelvic examinations, a cysticlike mass was noted in the pancreatic head with a possible pancreatic duodenal fistula (this mass was not mentioned on the initial presurgical CT, although it can be seen in retrospect (Figure 3). Gastroenterology was consulted.

An upper endoscopy was performed that confirmed the fistula at the second portion of the duodenum. Findings from an endoscopic ultrasonography performed at an outside institution were concerning for a main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) with fistula, with biopsy results pending.

Discussion

This case contributes to the evidence that poorly controlled T2DM can be a predisposing factor for multiple vascular complications, including the infection of the aortic wall with progression to EA. Klebsiella species are considered opportunistic, Gram-negative pathogens that may disseminate to other tissues, causing life-threatening infections, including pneumonia, UTIs, bacteremia, and sepsis.9K pneumoniae infections are particularly challenging in neonates, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals.9 CT is sensitive and specific in the detection of this pathologic entity.1,3 In patients with a suspected infectious etiology, the presence of foci of gas on CT in solid organ tissues is usually associated with an anaerobic infection. Gas can also be produced by Gram-negative facultative anaerobes that can ferment glucose in necrotic tissues.9

Although any microorganism can infect the aorta, K pneumoniae cultured from the blood specimen, urine culture, and intraoperative specimens in our patient was responsible for the formed gas in the aortic wall. Occurrence of spontaneous gas by this microorganism is usually associated with conditions leading to either increased vulnerability to infections and/or enhanced bacterial virulence.9 Although a relationship between EA and T2DM has not been proved, it is well known that patients with T2DM have a defect in their host-defense mechanisms, making them more susceptible to infections such as EA. Furthermore, because patients with T2DM are prone to the development of Gram-negative sepsis, organisms such as K pneumoniae would tend to emerge. Patients with poorly controlled T2DM and the presence of an infectious source can be predisposed to infectious aortitis, eventually leading to a gas-forming infection of the aorta.5,7

We postulate that the hematogenous spread of bacteria from a laceration in the leg as well as the presence of the pancreaticoduodenal fistula was likely the cause of the infectious EA in this case, considering the patient’s underlying uncontrolled T2DM. The patient’s prior left lower extremity vascular graft also may have provided a nidus for spreading to the aorta. Other reported underlying diseases of EA include aortic atherosclerosis, T2DM, diverticulitis, colon cancer, underlying aneurysm, immune-compromised status, and the presence of a medical device or open surgery.4-7,9

To our knowledge, this is the first case of EA associated with a pancreaticoduodenal fistula related to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). Fistulation of a main duct IPMN is rare, occurring in just 6.6% of cases.10 It can occur both before and after malignant degeneration.

EA requires rapid diagnosis, antibiotic therapy, and consultation with a vascular surgeon for immediate resection of the infected artery and graft bypass. The initial treatment of suspected infectious aortitis is IV antibiotics with broad antimicrobial coverage of the most likely pathologic organisms, particularly staphylococcal species and Gram-negative rods. Surgical debridement and revascularization should be completed early because of the high mortality rate of this condition. The intent of surgery is to control sepsis and reconstruct the arterial vasculature. Patients should remain on parenteral or oral antibiotics for at least 6 weeks to ensure full clearance of the infection.8 They should be followed up closely with serial blood cultures and CT scans.8 The rarity of the disorder, low level of awareness, varying presentations, and lack of evidence delineating pathogenesis and causality contribute to the challenge of recognizing, diagnosing, and treating EA in patients with T2DM and inflammation.

Conclusions

This case report can help bring awareness of this rare and potentially life-threatening condition in patients with T2DM. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of AE, particularly in patients with several additional risk factors: recent skin/soft tissue trauma, prior vascular graft surgery, and an underlying pancreatic mass. CT is the imaging method of choice that helps to rapidly choose a necessary emergent treatment approach.

1. Litmanovich DE, Yıldırım A, Bankier AA. Insights into imaging of aortitis. Insights Imaging. 2012;3(6):545-560. doi:10.1007/s13244-012-0192-x

2. Lopes RJ, Almeida J, Dias PJ, Pinho P, Maciel MJ. Infectious thoracic aortitis: a literature review. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(9):488-490. doi:10.1002/clc.20578

3. Murphy DJ, Keraliya AR, Agrawal MD, Aghayev A, Steigner ML. Cross-sectional imaging of aortic infections. Insights Imaging. 2016;7(6):801-818. doi:10.1007/s13244-016-0522-5

4. Md Noh MSF, Abdul Rashid AM, Ar A, B N, Mohammed Y, A RE. Emphysematous aortitis: report of two cases and CT imaging findings. BJR Case Rep. 2017;3(3):20170006. doi:10.1259/bjrcr.20170006

5. Harris C, Geffen J, Rizg K, et al. A rare report of infectious emphysematous aortitis secondary to Clostridium septicum without prior vascular intervention. Case Rep Vasc Med. 2017;2017:4984325. doi:10.1155/2017/4984325

6. Ito F, Inokuchi R, Matsumoto A, et al. Presence of periaortic gas in Clostridium septicum-infected aortic aneurysm aids in early diagnosis: a case report and systematic review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11(1):268. doi:10.1186/s13256-017-1422-0

7. Urgiles S, Matos-Casano H, Win KZ, Berardo J, Bhatt U, Shah J. Emphysematous aortitis due to Clostridium septicum in an 89-year-old female with ileus. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2019;2019:1094837. doi:10.1155/2019/1094837

8. Foote EA, Postier RG, Greenfield RA, Bronze MS. Infectious aortitis. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2005;7(2):89-97. doi:10.1007/s11936-005-0010-6

9. Paczosa MK, Mecsas J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80(3):629-661. doi:10.1128/mmbr.00078-15

10. Kobayashi G, Fujita N, Noda Y, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas showing fistula formation into other organs. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(10):1080-1089. doi:10.1007/s00535-010-0263-z

Patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and an infectious source can be predisposed to infectious aortitis.

Patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and an infectious source can be predisposed to infectious aortitis.

Aortitis is the all-encompassing term ascribed to the inflammatory process in the aortic wall that can be either infective or noninfective in origin, commonly autoimmune or inflammatory large-vessel vasculitis.1 Infectious aortitis, also known as bacterial, microbial, or cryptogenic aortitis, as well as mycotic or infected aneurysm, is a rare entity in the current antibiotic era but potentially a life-threatening disorder.2 The potential complications of infectious aortitis include emphysematous aortitis (EA), pseudoaneurysm, aortic rupture, septic emboli, and fistula formation (eg, aorto-enteric fistula).2,3

EA is a rare but serious inflammatory condition of the aorta with a nonspecific clinical presentation associated with high morbidity and mortality.2-6 The condition is characterized by a localized collection of gas and purulent exudate at the aortic wall.1,3 A few cases of EA have previously been reported; however, no known cases have been reported in the literature due to Klebsiella pneumoniae (K pneumoniae).

The pathophysiology of EA is the presence of underlying damage to the arterial wall caused by a hematogenously inoculated gas-producing organism.2,3 Most reported cases of EA are due to endovascular graft complications. Under normal circumstances, the aortic intima is highly resistant to infectious pathogens; however, certain risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), atherosclerotic disease, preexisting aneurysm, cystic medial necrosis, vascular malformation, presence of medical devices, surgery, or impaired immunity can alter the integrity of the aortic intimal layer and predispose the aortic intima to infection.1,4-7 Bacteria are the most common causative organisms that can infect the aorta, especially Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Salmonella, and spirochete Treponema pallidum (syphilis).1,2,4,8 The site of the primary infection remains unclear in some patients.2,3,5,6 Infection of the aorta can arise by several mechanisms: direct extension of a local infection to an existing intimal injury or atherosclerotic plaque (the most common mechanism), septic embolism from endocarditis, direct bacterial inoculation from traumatic contamination, contiguous infection extending to the aorta wall, or a distant source of bacteremia.2,3

Clinical manifestations of EA depend on the site and the extent of infection. The diagnosis should be considered in patients with atherosclerosis, fever, abdominal pain, and leukocytosis.2,4-8 The differential diagnosis for EA includes (1) noninfective causes of aortitis, including rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus; (2) tuberculous aortitis; (3) syphilitic aortitis; and (4) idiopathic isolated aortitis. Establishing an early diagnosis of infectious aortitis is extremely important because this condition is associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality secondary to aortic rupture.2-7

Imaging is critical for a reliable and quick diagnosis of acute aortic pathology. Noninvasive cross-sectional imaging modalities, such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, nuclear medicine, or positron emission tomography, are used for both the initial diagnosis and follow-up of aortitis.1 CT is the primary imaging method in most medical centers because it is widely available with short acquisition time in critically ill patients.3 CT allows rapid detection of abnormalities in wall thickness, diameter, and density, and enhancement of periaortic structures, enabling reliable exclusion of other aortic pathologies that may resemble acute aortitis. Also, CT aids in planning the optimal therapeutic approach.1,3,5-8

This case illustrates EA associated with infection by K pneumoniae in a patient with poorly controlled type 2 DM (T2DM). In this single case, our patient presented to the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (BPVAHS) in Florida with recent superficial soft tissue injury, severe hyperglycemia, worsening abdominal pain, and leukocytosis without fever or chills. The correct diagnosis of EA was confirmed by characteristic CT findings.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male with a history of T2DM, hypertension, atherosclerotic vascular disease, obstructive lung disease, and smoking 1.5 packs per day for 40 years presented with diabetic ketoacidosis, a urinary tract infection, and abdominal pain of 1-week duration that started to worsen the morning he arrived at the BPVAHS emergency department. He reported no nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, chest pain, shortness of breath, fever, chills, fatigue, or dysuria. He had a nonhealing laceration on his left medial foot that occurred 18 days before admission and was treated at an outside hospital.

The patient’s surgical history included a left common femoral endarterectomy and a left femoral popliteal above-knee reverse saphenous vein bypass 4 years ago for severe critical limb ischemia due to occlusion of his left superficial femoral artery with distal embolization to the first and fifth toes. About 6 months later, he developed disabling claudication in his left lower extremity due to distal popliteal artery occlusion and had another bypass surgery to the below-knee popliteal artery with a reverse saphenous vein graft harvested from the right thigh.

On initial examination, his vital signs were within normal limits except for a blood pressure of 177/87 mm Hg. His physical examination demonstrated a nondistended abdomen with normal bowel sounds, mild lower quadrant tenderness on the left more than on the right, intermittent abdominal pain located around umbilicus with radiation to the back, and a negative psoas sign. His left medial foot had a nonhealing laceration with black sutures in place, with minimal erythema in the surrounding tissue and scab formation. He also had mild costovertebral tenderness on the left.

Initial laboratory investigation results were notable for a glucose level of 609 mg/dL and a white blood cell count of 14.6 × 103 cells/mcL with 86.5% of neutrophils. A CT scan of his abdomen revealed extensive atherosclerosis of the abdominal aorta and periaortic aneurysmal fluid collection with multiple foci of gas (Figure 1). Additionally, the aneurysmal fluid collection involved the proximal segment of the left common femoral artery, suspicious for left femoral arteritis (Figure 2). The patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, morphine, and an insulin drip. Both urine and blood cultures were positive for K pneumoniae susceptible to multiple antibiotics. He was transferred to a tertiary medical center and was referred for a vascular surgery consultation.

The patient underwent surgical resection of the infected infrarenal EA and infected left common femoral artery with right axillary-bifemoral bypass with an 8-mm PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) graft. During the surgery, excision of the wall of the left common femoral artery and infrarenal aorta revealed frank pus with purulent fluid, which was sent to cytology for analysis and culture. His intraoperative cultures grew K pneumoniae sensitive to multiple antibiotics, including ceftriaxone, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and ampicillin/sulbactam. The vascular surgery team recommended inpatient admission and administration of 6 weeks of IV antibiotics postoperatively with ceftriaxone, followed by outpatient oral suppression therapy after discharge. The patient tolerated the surgery well and was discharged after 6 weeks of IV ceftriaxone followed by outpatient oral suppression therapy. However, the patient was transferred back to BPVAHS for continued care and rehabilitation placement.

The patient’s subsequent course was complicated by multiple hospital admissions, including aspiration pneumonia, hypoglycemia, diarrhea, and anemia. On one of his CT abdomen/pelvic examinations, a cysticlike mass was noted in the pancreatic head with a possible pancreatic duodenal fistula (this mass was not mentioned on the initial presurgical CT, although it can be seen in retrospect (Figure 3). Gastroenterology was consulted.

An upper endoscopy was performed that confirmed the fistula at the second portion of the duodenum. Findings from an endoscopic ultrasonography performed at an outside institution were concerning for a main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) with fistula, with biopsy results pending.

Discussion

This case contributes to the evidence that poorly controlled T2DM can be a predisposing factor for multiple vascular complications, including the infection of the aortic wall with progression to EA. Klebsiella species are considered opportunistic, Gram-negative pathogens that may disseminate to other tissues, causing life-threatening infections, including pneumonia, UTIs, bacteremia, and sepsis.9K pneumoniae infections are particularly challenging in neonates, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals.9 CT is sensitive and specific in the detection of this pathologic entity.1,3 In patients with a suspected infectious etiology, the presence of foci of gas on CT in solid organ tissues is usually associated with an anaerobic infection. Gas can also be produced by Gram-negative facultative anaerobes that can ferment glucose in necrotic tissues.9

Although any microorganism can infect the aorta, K pneumoniae cultured from the blood specimen, urine culture, and intraoperative specimens in our patient was responsible for the formed gas in the aortic wall. Occurrence of spontaneous gas by this microorganism is usually associated with conditions leading to either increased vulnerability to infections and/or enhanced bacterial virulence.9 Although a relationship between EA and T2DM has not been proved, it is well known that patients with T2DM have a defect in their host-defense mechanisms, making them more susceptible to infections such as EA. Furthermore, because patients with T2DM are prone to the development of Gram-negative sepsis, organisms such as K pneumoniae would tend to emerge. Patients with poorly controlled T2DM and the presence of an infectious source can be predisposed to infectious aortitis, eventually leading to a gas-forming infection of the aorta.5,7

We postulate that the hematogenous spread of bacteria from a laceration in the leg as well as the presence of the pancreaticoduodenal fistula was likely the cause of the infectious EA in this case, considering the patient’s underlying uncontrolled T2DM. The patient’s prior left lower extremity vascular graft also may have provided a nidus for spreading to the aorta. Other reported underlying diseases of EA include aortic atherosclerosis, T2DM, diverticulitis, colon cancer, underlying aneurysm, immune-compromised status, and the presence of a medical device or open surgery.4-7,9

To our knowledge, this is the first case of EA associated with a pancreaticoduodenal fistula related to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). Fistulation of a main duct IPMN is rare, occurring in just 6.6% of cases.10 It can occur both before and after malignant degeneration.

EA requires rapid diagnosis, antibiotic therapy, and consultation with a vascular surgeon for immediate resection of the infected artery and graft bypass. The initial treatment of suspected infectious aortitis is IV antibiotics with broad antimicrobial coverage of the most likely pathologic organisms, particularly staphylococcal species and Gram-negative rods. Surgical debridement and revascularization should be completed early because of the high mortality rate of this condition. The intent of surgery is to control sepsis and reconstruct the arterial vasculature. Patients should remain on parenteral or oral antibiotics for at least 6 weeks to ensure full clearance of the infection.8 They should be followed up closely with serial blood cultures and CT scans.8 The rarity of the disorder, low level of awareness, varying presentations, and lack of evidence delineating pathogenesis and causality contribute to the challenge of recognizing, diagnosing, and treating EA in patients with T2DM and inflammation.

Conclusions

This case report can help bring awareness of this rare and potentially life-threatening condition in patients with T2DM. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of AE, particularly in patients with several additional risk factors: recent skin/soft tissue trauma, prior vascular graft surgery, and an underlying pancreatic mass. CT is the imaging method of choice that helps to rapidly choose a necessary emergent treatment approach.

Aortitis is the all-encompassing term ascribed to the inflammatory process in the aortic wall that can be either infective or noninfective in origin, commonly autoimmune or inflammatory large-vessel vasculitis.1 Infectious aortitis, also known as bacterial, microbial, or cryptogenic aortitis, as well as mycotic or infected aneurysm, is a rare entity in the current antibiotic era but potentially a life-threatening disorder.2 The potential complications of infectious aortitis include emphysematous aortitis (EA), pseudoaneurysm, aortic rupture, septic emboli, and fistula formation (eg, aorto-enteric fistula).2,3