User login

Secretan Syndrome: A Fluctuating Case of Factitious Lymphedema

Secretan syndrome (SS) represents a recurrent or chronic form of factitious lymphedema, usually affecting the dorsal aspect of the hand.1-3 It is accepted as a subtype of Munchausen syndrome whereby the patient self-inflicts and simulates lymphedema.1,2 Historically, many of the cases reported with the term Charcot’s oedème bleu are now believed to represent clinical variants of SS.4-6

Case Report

A 38-year-old Turkish woman presented with progressive swelling of the right hand of 2 years’ duration that had caused difficulty in manual work and reduction in manual dexterity. She previously had sought medical treatment for this condition by visiting several hospitals. According to her medical record, the following laboratory or radiologic tests had revealed negative or normal findings, except for obvious soft-tissue edema: bacterial and fungal cultures, plain radiography, Doppler ultrasonography, lymphoscintigraphy, magnetic resonance imaging, fine needle aspiration, and punch biopsy. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, compartment syndrome, filariasis, tuberculosis, and lymphatic and venous obstruction were all excluded by appropriate testing. Our patient was in good health prior to onset of this disorder, and her medical history was unremarkable. There was no family history of a similar condition.

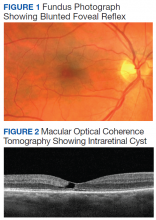

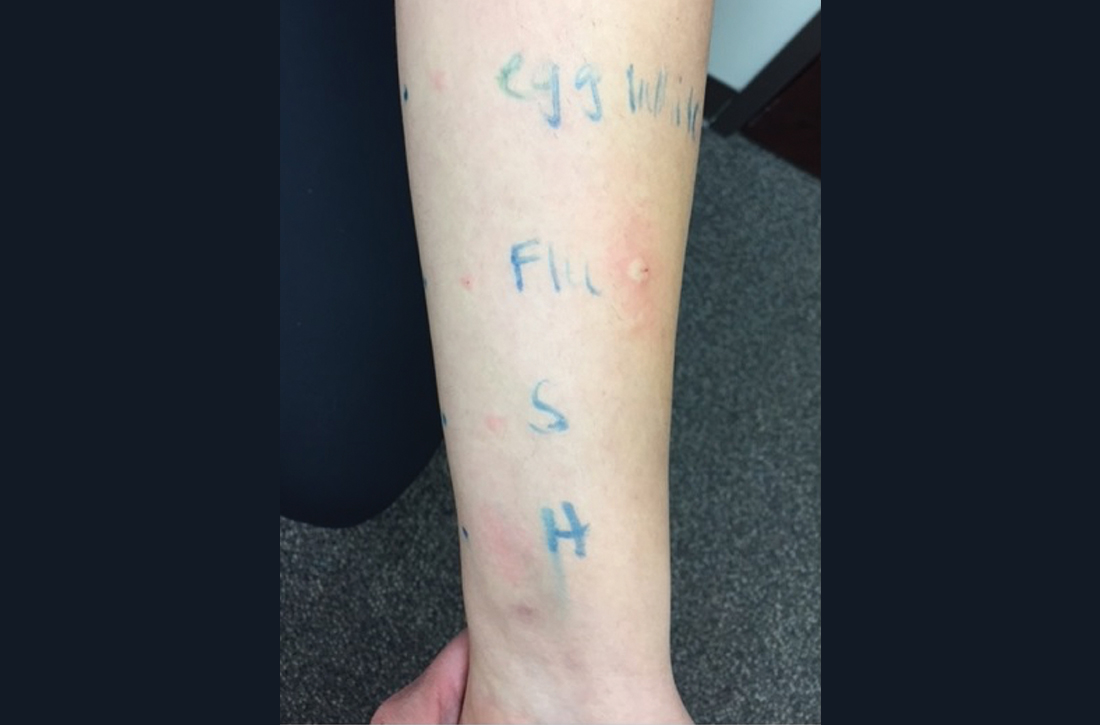

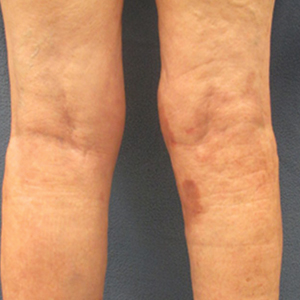

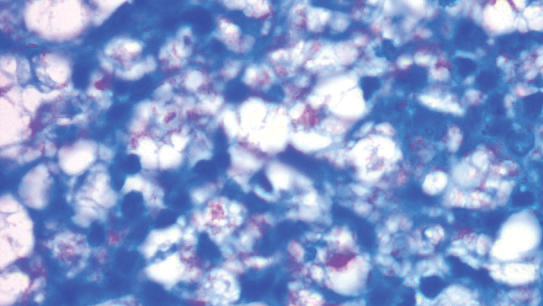

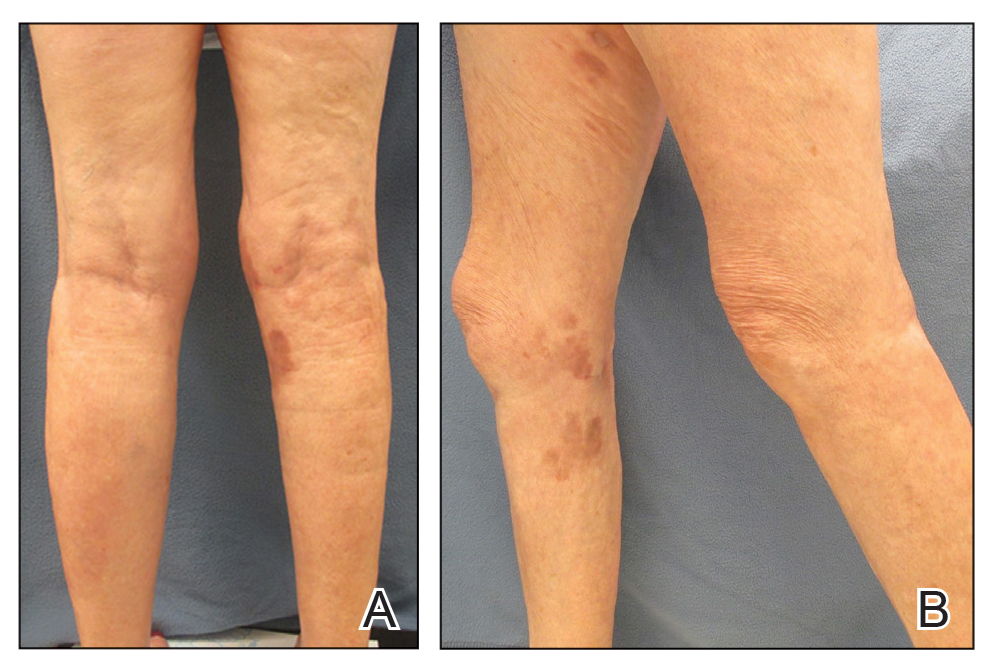

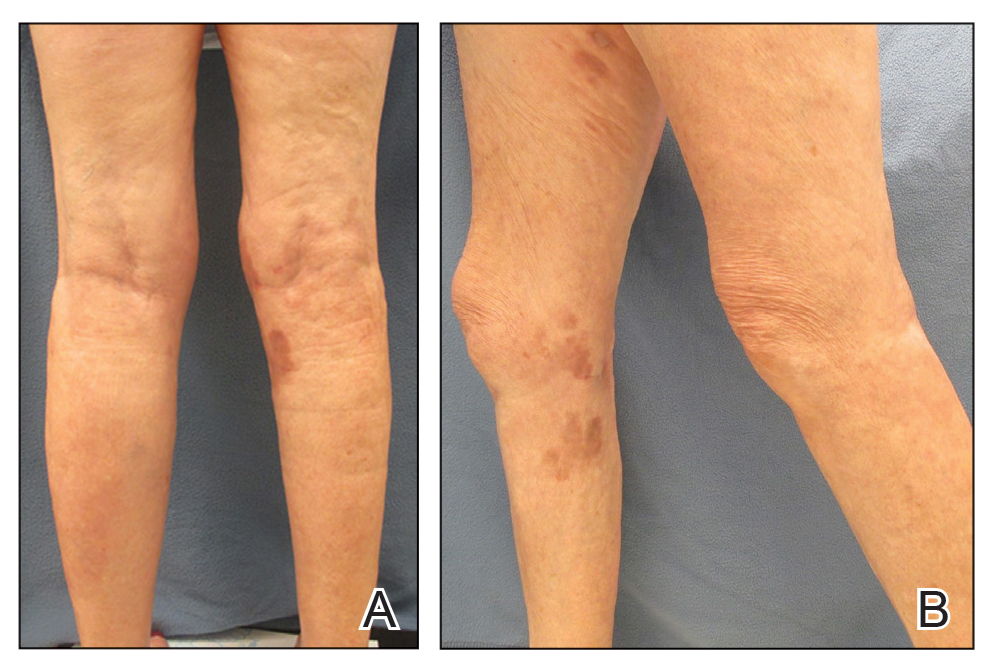

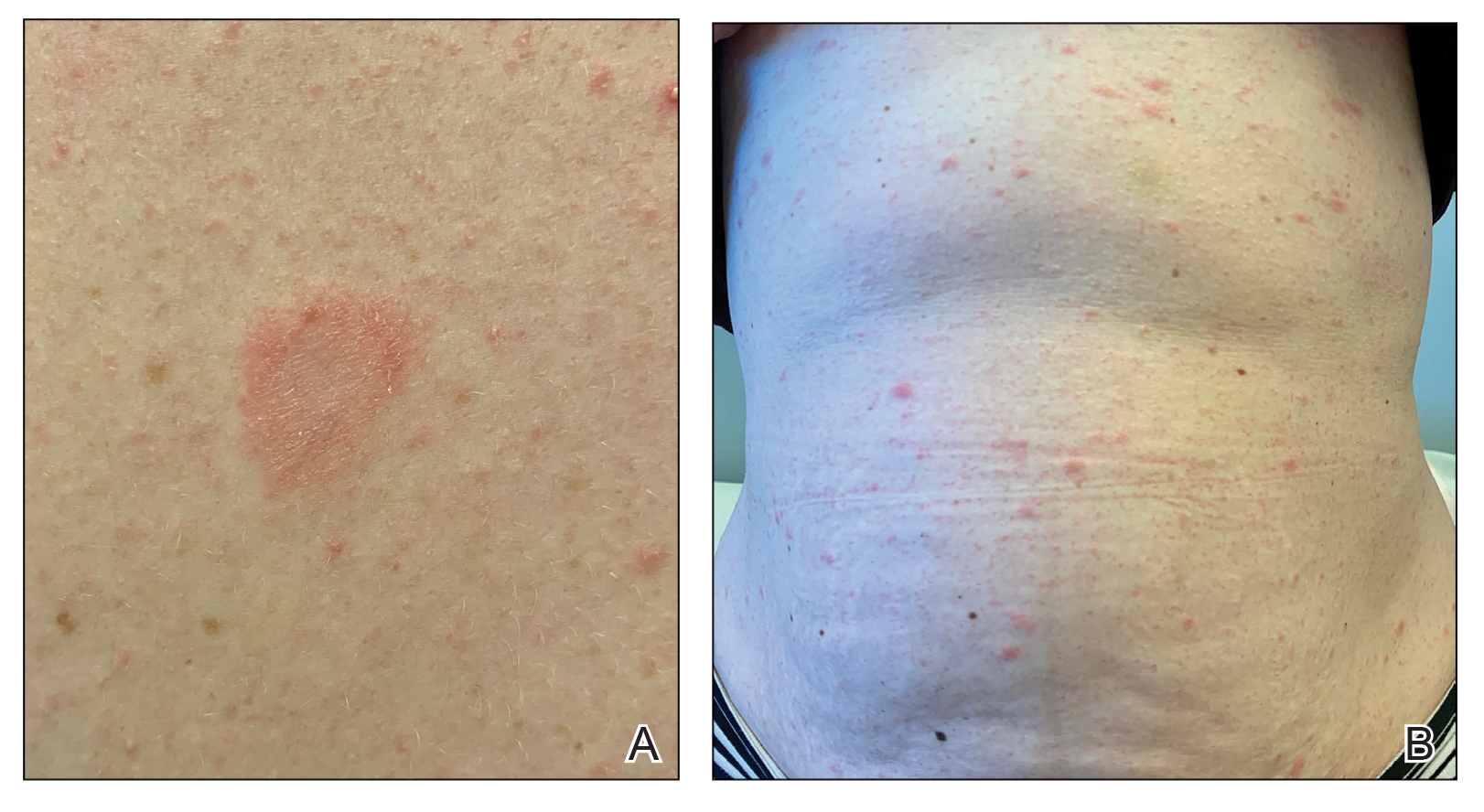

Dermatologic examination revealed brawny, soft, pitting edema; erythema; and crusts affecting the dorsal aspect of the right hand and proximal parts of the fingers (Figure 1). The yellow discoloration of the skin and nails was attributed to potassium permanganate wet dressings. Under an elastic bandage at the wrist, which the patient unrolled herself, a sharp line of demarcation was evident, separating the lymphedematous and normal parts of the arm. There was no axillary lymphadenopathy.

The patient’s affect was discordant to the manifestation of the cutaneous findings. She wanted to show every physician in the department how swollen her hand was and seemed to be happy with this condition. Although she displayed no signs of disturbance when the affected extremity was touched or handled, she reported severe pain and tenderness as well as difficulty in housework. She noted that she normally resided in a city and that the swelling had started at the time she had relocated to a rural village to take care of her bedridden mother-in-law. She was under an intensive workload in the village, and the condition of the hand was impeding manual work.

Factitious lymphedema was considered, and hospitalization was recommended. The patient was then lost to follow-up; however, one of her relatives noted that the patient had returned to the city. When she presented again 1 year later, almost all physical signs had disappeared (Figure 2), and a psychiatric referral was recommended. A Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory test yielded an invalid result due to the patient’s exaggeration of her preexisting physical symptoms. Further psychiatric workup was rejected by the patient.

Almost a year after the psychiatric referral, the patient’s follow-up photographs revealed that the lymphedema recurred when she went to visit her mother-in-law in the rural village and that it was completely ameliorated when she returned to the city. Thus, a positive “mother-in-law provocation test” was accepted as final proof of the self-inflicted nature of the condition.

Comment

In 1901, Henri Francois Secretan, a Swiss physician, reported workmen who had persistent hard swellings on the dorsal aspect of the hands after minor work-related trauma for which they had compensation claims.7 In his original report, Secretan did not suggest self-inflicted trauma in the etiology of this disorder.5,8,9 In 1890, Jean Martin Charcot, a French neurologist, described oedème bleu, a term that is now believed to denote a condition similar to SS.4-6 Currently, SS is attributed to self-inflicted injury and is considered a form of factitious lymphedema.9 As in dermatitis artefacta, most patients with SS are young women, and male patients with the condition tend to be older.3,8

The mechanism used to provoke this factitious lymphedema might be of traumatic or obstructive nature. Secretan syndrome either is induced by intermittent or constant application of a tourniquet, ligature, cord, elastic bandage, scarf, kerchief, rubber band, or compress around the affected extremity, or by repetitive blunt trauma, force, or skin irritation.1,4,5,8-10 There was an underlying psychopathology in all reported cases.1,8,11 Factitious lymphedema is unconsciously motivated and consciously produced.4,12 The affected patient often is experiencing a serious emotional conflict and is unlikely to be a malingerer, although exaggeration of symptoms may occur, as in our patient.12 Psychiatric evaluation in SS may uncover neurosis, hysteria, frank psychosis, schizophrenia, masochism, depression, or an abnormal personality disorder.1,12

Patients with SS present with recurrent or chronic lymphedema, usually affecting the dominant hand.1 Involvement usually is unilateral; bilateral cases are rare.3,6 Secretan syndrome is not solely limited to the hands; it also may involve the upper and lower extremities, including the feet.3,11 There may be a clear line of demarcation, a ring, sulcus, distinct circumferential linear bands of erythema, discoloration, or ecchymoses, separating the normal and lymphedematous parts of the extremity.1,4,6,8-10,12 Patients usually attempt to hide the constricted areas from sight.1 Over time, flexion contractures may develop due to peritendinous fibrosis.6 Histopathology displays a hematoma with adhesions to the extensor tendons; a hematoma surrounded by a thickened scar; or changes similar to ganglion tissue with cystic areas of mucin, fibrosis, and myxoid degeneration.4,6

Factitious lymphedema can only be definitively diagnosed when the patient confesses or is caught self-inflicting the injury. Nevertheless, a diagnosis by exclusion is possible.4 Lymphangiography, lymphoscintigraphy, vascular Doppler ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in excluding congenital and acquired causes of lymphedema and venous obstruction.1,3,9,11 Magnetic resonance imaging may show soft tissue and tendon edema as well as diffuse peritendinous fibrosis extending to the fascia of the dorsal interosseous muscles.3,4

Factitious lymphedema should be suspected in all patients with recurrent or chronic unilateral lymphedema without an explicable or apparent predisposing factor.4,11,12 Patients with SS typically visit several hospitals or institutions; see many physicians; and willingly accept, request, and undergo unnecessary extensive, invasive, and costly diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and prolonged hospitalizations.1,2,5,12 The disorder promptly responds to immobilization and elevation of the limb.2,4 Plaster casts may prove useful in prevention of compression and thus amelioration of the lymphedema.1,4,6 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, direct confrontation should be avoided and ideally the patient should be referred for psychiatric evaluation.1,2,4,5,8,12 If the patient admits self-inflicting behavior, psychotherapy and/or behavior modification therapy along with psychotropic medications may be helpful to relieve emotional and behavioral symptoms.12 Unfortunately, if the patient denies a self-inflicting role in the occurrence of lymphedema and persists in self-injurious behavior, psychotherapy or psychotropic medications will be futile.9

1. Miyamoto Y, Hamanaka T, Yokoyama S, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the upper limb. Kawasaki Med J. 1979;5:39-45.

2. de Oliveira RK, Bayer LR, Lauxen D, et al. Factitious lesions of the hand. Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48:381-386.

3. Hahm MH, Yi JH. A case report of Secretan’s disease in both hands. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;68:511-514.

4. Eldridge MP, Grunert BK, Matloub HS. Streamlined classification of psychopathological hand disorders: a literature review. Hand (NY). 2008;3:118-128.

5. Ostlere LS, Harris D, Denton C, et al. Boxing-glove hand: an unusual presentation of dermatitis artefacta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:120-122.

6. Winkelmann RK, Barker SM. Factitial traumatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:988-994.

7. Secretan H. Oederne dur et hyperplasie traumatique du metacarpe dorsal. RevMed Suisse Romande. 1901;21:409-416.

8. Barth JH, Pegum JS. The case of the speckled band: acquired lymphedema due to constriction bands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:296-297.

9. Birman MV, Lee DH. Factitious disorders of the upper extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:78-85.

10. Nwaejike N, Archbold H, Wilson DS. Factitious lymphoedema as a psychiatric condition mimicking reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:216.

11. De Fátima Guerreiro Godoy M, Pereira De Godoy JM. Factitious lymphedema of the arm: case report and review of publications. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:337-339.

12. Abhari SAA, Alimalayeri N, Abhari SSA, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the hand. Iran J Psychiatry. 2006;1:166-168.

Secretan syndrome (SS) represents a recurrent or chronic form of factitious lymphedema, usually affecting the dorsal aspect of the hand.1-3 It is accepted as a subtype of Munchausen syndrome whereby the patient self-inflicts and simulates lymphedema.1,2 Historically, many of the cases reported with the term Charcot’s oedème bleu are now believed to represent clinical variants of SS.4-6

Case Report

A 38-year-old Turkish woman presented with progressive swelling of the right hand of 2 years’ duration that had caused difficulty in manual work and reduction in manual dexterity. She previously had sought medical treatment for this condition by visiting several hospitals. According to her medical record, the following laboratory or radiologic tests had revealed negative or normal findings, except for obvious soft-tissue edema: bacterial and fungal cultures, plain radiography, Doppler ultrasonography, lymphoscintigraphy, magnetic resonance imaging, fine needle aspiration, and punch biopsy. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, compartment syndrome, filariasis, tuberculosis, and lymphatic and venous obstruction were all excluded by appropriate testing. Our patient was in good health prior to onset of this disorder, and her medical history was unremarkable. There was no family history of a similar condition.

Dermatologic examination revealed brawny, soft, pitting edema; erythema; and crusts affecting the dorsal aspect of the right hand and proximal parts of the fingers (Figure 1). The yellow discoloration of the skin and nails was attributed to potassium permanganate wet dressings. Under an elastic bandage at the wrist, which the patient unrolled herself, a sharp line of demarcation was evident, separating the lymphedematous and normal parts of the arm. There was no axillary lymphadenopathy.

The patient’s affect was discordant to the manifestation of the cutaneous findings. She wanted to show every physician in the department how swollen her hand was and seemed to be happy with this condition. Although she displayed no signs of disturbance when the affected extremity was touched or handled, she reported severe pain and tenderness as well as difficulty in housework. She noted that she normally resided in a city and that the swelling had started at the time she had relocated to a rural village to take care of her bedridden mother-in-law. She was under an intensive workload in the village, and the condition of the hand was impeding manual work.

Factitious lymphedema was considered, and hospitalization was recommended. The patient was then lost to follow-up; however, one of her relatives noted that the patient had returned to the city. When she presented again 1 year later, almost all physical signs had disappeared (Figure 2), and a psychiatric referral was recommended. A Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory test yielded an invalid result due to the patient’s exaggeration of her preexisting physical symptoms. Further psychiatric workup was rejected by the patient.

Almost a year after the psychiatric referral, the patient’s follow-up photographs revealed that the lymphedema recurred when she went to visit her mother-in-law in the rural village and that it was completely ameliorated when she returned to the city. Thus, a positive “mother-in-law provocation test” was accepted as final proof of the self-inflicted nature of the condition.

Comment

In 1901, Henri Francois Secretan, a Swiss physician, reported workmen who had persistent hard swellings on the dorsal aspect of the hands after minor work-related trauma for which they had compensation claims.7 In his original report, Secretan did not suggest self-inflicted trauma in the etiology of this disorder.5,8,9 In 1890, Jean Martin Charcot, a French neurologist, described oedème bleu, a term that is now believed to denote a condition similar to SS.4-6 Currently, SS is attributed to self-inflicted injury and is considered a form of factitious lymphedema.9 As in dermatitis artefacta, most patients with SS are young women, and male patients with the condition tend to be older.3,8

The mechanism used to provoke this factitious lymphedema might be of traumatic or obstructive nature. Secretan syndrome either is induced by intermittent or constant application of a tourniquet, ligature, cord, elastic bandage, scarf, kerchief, rubber band, or compress around the affected extremity, or by repetitive blunt trauma, force, or skin irritation.1,4,5,8-10 There was an underlying psychopathology in all reported cases.1,8,11 Factitious lymphedema is unconsciously motivated and consciously produced.4,12 The affected patient often is experiencing a serious emotional conflict and is unlikely to be a malingerer, although exaggeration of symptoms may occur, as in our patient.12 Psychiatric evaluation in SS may uncover neurosis, hysteria, frank psychosis, schizophrenia, masochism, depression, or an abnormal personality disorder.1,12

Patients with SS present with recurrent or chronic lymphedema, usually affecting the dominant hand.1 Involvement usually is unilateral; bilateral cases are rare.3,6 Secretan syndrome is not solely limited to the hands; it also may involve the upper and lower extremities, including the feet.3,11 There may be a clear line of demarcation, a ring, sulcus, distinct circumferential linear bands of erythema, discoloration, or ecchymoses, separating the normal and lymphedematous parts of the extremity.1,4,6,8-10,12 Patients usually attempt to hide the constricted areas from sight.1 Over time, flexion contractures may develop due to peritendinous fibrosis.6 Histopathology displays a hematoma with adhesions to the extensor tendons; a hematoma surrounded by a thickened scar; or changes similar to ganglion tissue with cystic areas of mucin, fibrosis, and myxoid degeneration.4,6

Factitious lymphedema can only be definitively diagnosed when the patient confesses or is caught self-inflicting the injury. Nevertheless, a diagnosis by exclusion is possible.4 Lymphangiography, lymphoscintigraphy, vascular Doppler ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in excluding congenital and acquired causes of lymphedema and venous obstruction.1,3,9,11 Magnetic resonance imaging may show soft tissue and tendon edema as well as diffuse peritendinous fibrosis extending to the fascia of the dorsal interosseous muscles.3,4

Factitious lymphedema should be suspected in all patients with recurrent or chronic unilateral lymphedema without an explicable or apparent predisposing factor.4,11,12 Patients with SS typically visit several hospitals or institutions; see many physicians; and willingly accept, request, and undergo unnecessary extensive, invasive, and costly diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and prolonged hospitalizations.1,2,5,12 The disorder promptly responds to immobilization and elevation of the limb.2,4 Plaster casts may prove useful in prevention of compression and thus amelioration of the lymphedema.1,4,6 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, direct confrontation should be avoided and ideally the patient should be referred for psychiatric evaluation.1,2,4,5,8,12 If the patient admits self-inflicting behavior, psychotherapy and/or behavior modification therapy along with psychotropic medications may be helpful to relieve emotional and behavioral symptoms.12 Unfortunately, if the patient denies a self-inflicting role in the occurrence of lymphedema and persists in self-injurious behavior, psychotherapy or psychotropic medications will be futile.9

Secretan syndrome (SS) represents a recurrent or chronic form of factitious lymphedema, usually affecting the dorsal aspect of the hand.1-3 It is accepted as a subtype of Munchausen syndrome whereby the patient self-inflicts and simulates lymphedema.1,2 Historically, many of the cases reported with the term Charcot’s oedème bleu are now believed to represent clinical variants of SS.4-6

Case Report

A 38-year-old Turkish woman presented with progressive swelling of the right hand of 2 years’ duration that had caused difficulty in manual work and reduction in manual dexterity. She previously had sought medical treatment for this condition by visiting several hospitals. According to her medical record, the following laboratory or radiologic tests had revealed negative or normal findings, except for obvious soft-tissue edema: bacterial and fungal cultures, plain radiography, Doppler ultrasonography, lymphoscintigraphy, magnetic resonance imaging, fine needle aspiration, and punch biopsy. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, compartment syndrome, filariasis, tuberculosis, and lymphatic and venous obstruction were all excluded by appropriate testing. Our patient was in good health prior to onset of this disorder, and her medical history was unremarkable. There was no family history of a similar condition.

Dermatologic examination revealed brawny, soft, pitting edema; erythema; and crusts affecting the dorsal aspect of the right hand and proximal parts of the fingers (Figure 1). The yellow discoloration of the skin and nails was attributed to potassium permanganate wet dressings. Under an elastic bandage at the wrist, which the patient unrolled herself, a sharp line of demarcation was evident, separating the lymphedematous and normal parts of the arm. There was no axillary lymphadenopathy.

The patient’s affect was discordant to the manifestation of the cutaneous findings. She wanted to show every physician in the department how swollen her hand was and seemed to be happy with this condition. Although she displayed no signs of disturbance when the affected extremity was touched or handled, she reported severe pain and tenderness as well as difficulty in housework. She noted that she normally resided in a city and that the swelling had started at the time she had relocated to a rural village to take care of her bedridden mother-in-law. She was under an intensive workload in the village, and the condition of the hand was impeding manual work.

Factitious lymphedema was considered, and hospitalization was recommended. The patient was then lost to follow-up; however, one of her relatives noted that the patient had returned to the city. When she presented again 1 year later, almost all physical signs had disappeared (Figure 2), and a psychiatric referral was recommended. A Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory test yielded an invalid result due to the patient’s exaggeration of her preexisting physical symptoms. Further psychiatric workup was rejected by the patient.

Almost a year after the psychiatric referral, the patient’s follow-up photographs revealed that the lymphedema recurred when she went to visit her mother-in-law in the rural village and that it was completely ameliorated when she returned to the city. Thus, a positive “mother-in-law provocation test” was accepted as final proof of the self-inflicted nature of the condition.

Comment

In 1901, Henri Francois Secretan, a Swiss physician, reported workmen who had persistent hard swellings on the dorsal aspect of the hands after minor work-related trauma for which they had compensation claims.7 In his original report, Secretan did not suggest self-inflicted trauma in the etiology of this disorder.5,8,9 In 1890, Jean Martin Charcot, a French neurologist, described oedème bleu, a term that is now believed to denote a condition similar to SS.4-6 Currently, SS is attributed to self-inflicted injury and is considered a form of factitious lymphedema.9 As in dermatitis artefacta, most patients with SS are young women, and male patients with the condition tend to be older.3,8

The mechanism used to provoke this factitious lymphedema might be of traumatic or obstructive nature. Secretan syndrome either is induced by intermittent or constant application of a tourniquet, ligature, cord, elastic bandage, scarf, kerchief, rubber band, or compress around the affected extremity, or by repetitive blunt trauma, force, or skin irritation.1,4,5,8-10 There was an underlying psychopathology in all reported cases.1,8,11 Factitious lymphedema is unconsciously motivated and consciously produced.4,12 The affected patient often is experiencing a serious emotional conflict and is unlikely to be a malingerer, although exaggeration of symptoms may occur, as in our patient.12 Psychiatric evaluation in SS may uncover neurosis, hysteria, frank psychosis, schizophrenia, masochism, depression, or an abnormal personality disorder.1,12

Patients with SS present with recurrent or chronic lymphedema, usually affecting the dominant hand.1 Involvement usually is unilateral; bilateral cases are rare.3,6 Secretan syndrome is not solely limited to the hands; it also may involve the upper and lower extremities, including the feet.3,11 There may be a clear line of demarcation, a ring, sulcus, distinct circumferential linear bands of erythema, discoloration, or ecchymoses, separating the normal and lymphedematous parts of the extremity.1,4,6,8-10,12 Patients usually attempt to hide the constricted areas from sight.1 Over time, flexion contractures may develop due to peritendinous fibrosis.6 Histopathology displays a hematoma with adhesions to the extensor tendons; a hematoma surrounded by a thickened scar; or changes similar to ganglion tissue with cystic areas of mucin, fibrosis, and myxoid degeneration.4,6

Factitious lymphedema can only be definitively diagnosed when the patient confesses or is caught self-inflicting the injury. Nevertheless, a diagnosis by exclusion is possible.4 Lymphangiography, lymphoscintigraphy, vascular Doppler ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in excluding congenital and acquired causes of lymphedema and venous obstruction.1,3,9,11 Magnetic resonance imaging may show soft tissue and tendon edema as well as diffuse peritendinous fibrosis extending to the fascia of the dorsal interosseous muscles.3,4

Factitious lymphedema should be suspected in all patients with recurrent or chronic unilateral lymphedema without an explicable or apparent predisposing factor.4,11,12 Patients with SS typically visit several hospitals or institutions; see many physicians; and willingly accept, request, and undergo unnecessary extensive, invasive, and costly diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and prolonged hospitalizations.1,2,5,12 The disorder promptly responds to immobilization and elevation of the limb.2,4 Plaster casts may prove useful in prevention of compression and thus amelioration of the lymphedema.1,4,6 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, direct confrontation should be avoided and ideally the patient should be referred for psychiatric evaluation.1,2,4,5,8,12 If the patient admits self-inflicting behavior, psychotherapy and/or behavior modification therapy along with psychotropic medications may be helpful to relieve emotional and behavioral symptoms.12 Unfortunately, if the patient denies a self-inflicting role in the occurrence of lymphedema and persists in self-injurious behavior, psychotherapy or psychotropic medications will be futile.9

1. Miyamoto Y, Hamanaka T, Yokoyama S, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the upper limb. Kawasaki Med J. 1979;5:39-45.

2. de Oliveira RK, Bayer LR, Lauxen D, et al. Factitious lesions of the hand. Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48:381-386.

3. Hahm MH, Yi JH. A case report of Secretan’s disease in both hands. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;68:511-514.

4. Eldridge MP, Grunert BK, Matloub HS. Streamlined classification of psychopathological hand disorders: a literature review. Hand (NY). 2008;3:118-128.

5. Ostlere LS, Harris D, Denton C, et al. Boxing-glove hand: an unusual presentation of dermatitis artefacta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:120-122.

6. Winkelmann RK, Barker SM. Factitial traumatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:988-994.

7. Secretan H. Oederne dur et hyperplasie traumatique du metacarpe dorsal. RevMed Suisse Romande. 1901;21:409-416.

8. Barth JH, Pegum JS. The case of the speckled band: acquired lymphedema due to constriction bands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:296-297.

9. Birman MV, Lee DH. Factitious disorders of the upper extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:78-85.

10. Nwaejike N, Archbold H, Wilson DS. Factitious lymphoedema as a psychiatric condition mimicking reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:216.

11. De Fátima Guerreiro Godoy M, Pereira De Godoy JM. Factitious lymphedema of the arm: case report and review of publications. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:337-339.

12. Abhari SAA, Alimalayeri N, Abhari SSA, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the hand. Iran J Psychiatry. 2006;1:166-168.

1. Miyamoto Y, Hamanaka T, Yokoyama S, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the upper limb. Kawasaki Med J. 1979;5:39-45.

2. de Oliveira RK, Bayer LR, Lauxen D, et al. Factitious lesions of the hand. Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48:381-386.

3. Hahm MH, Yi JH. A case report of Secretan’s disease in both hands. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;68:511-514.

4. Eldridge MP, Grunert BK, Matloub HS. Streamlined classification of psychopathological hand disorders: a literature review. Hand (NY). 2008;3:118-128.

5. Ostlere LS, Harris D, Denton C, et al. Boxing-glove hand: an unusual presentation of dermatitis artefacta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:120-122.

6. Winkelmann RK, Barker SM. Factitial traumatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:988-994.

7. Secretan H. Oederne dur et hyperplasie traumatique du metacarpe dorsal. RevMed Suisse Romande. 1901;21:409-416.

8. Barth JH, Pegum JS. The case of the speckled band: acquired lymphedema due to constriction bands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:296-297.

9. Birman MV, Lee DH. Factitious disorders of the upper extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:78-85.

10. Nwaejike N, Archbold H, Wilson DS. Factitious lymphoedema as a psychiatric condition mimicking reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:216.

11. De Fátima Guerreiro Godoy M, Pereira De Godoy JM. Factitious lymphedema of the arm: case report and review of publications. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:337-339.

12. Abhari SAA, Alimalayeri N, Abhari SSA, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the hand. Iran J Psychiatry. 2006;1:166-168.

Practice Points

- Secretan syndrome is a recurrent or chronic form of factitious lymphedema that usually affects the dorsal aspect of the hand; it is accepted as a subtype of Munchausen syndrome.

- Secretan syndrome usually is induced by compression of the extremity by tourniquets, ligatures, cords, or similar equipment.

- This unconsciously motivated and consciously produced lymphedema is an expression of underlying psychiatric disease.

Not All Pulmonary Nodules in Smokers are Lung Cancer

Identification of pulmonary nodules in older adults who smoke immediately brings concern for malignancy in the mind of clinicians. This is particularly the case in patients with significant smoking history. According to the National Cancer Institute in 2019, 12.9% of all new cancer cases were lung cancers.1 Screening for lung cancer, especially in patients with increased risk from smoking, is imperative to early detection and treatment. However, 20% of patients will be overdiagnosed by lung cancer-screening techniques.2 The rate of malignancy noted on a patient’s first screening computed tomography (CT) scan was between 3.7% and 5.5%.3

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune inflammatory condition that mainly affects the joints. Extraarticular manifestations can arise in various locations throughout the body, however. These manifestations are commonly observed in the skin, heart, and lungs.4 Prevalence of pulmonary rheumatoid nodules ranges from < 0.4% in radiologic studies to 32% in lung biopsies of patients with RA and nodules.5

Furthermore, there is a strong association between the risk of rheumatoid nodules in patients with positive serum rheumatoid factor (RF) and smoking history.6 Solitary pulmonary nodules in patients with RA can coexist with bronchogenic carcinoma, making their diagnosis more important.7

Case Presentation

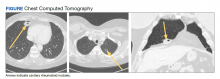

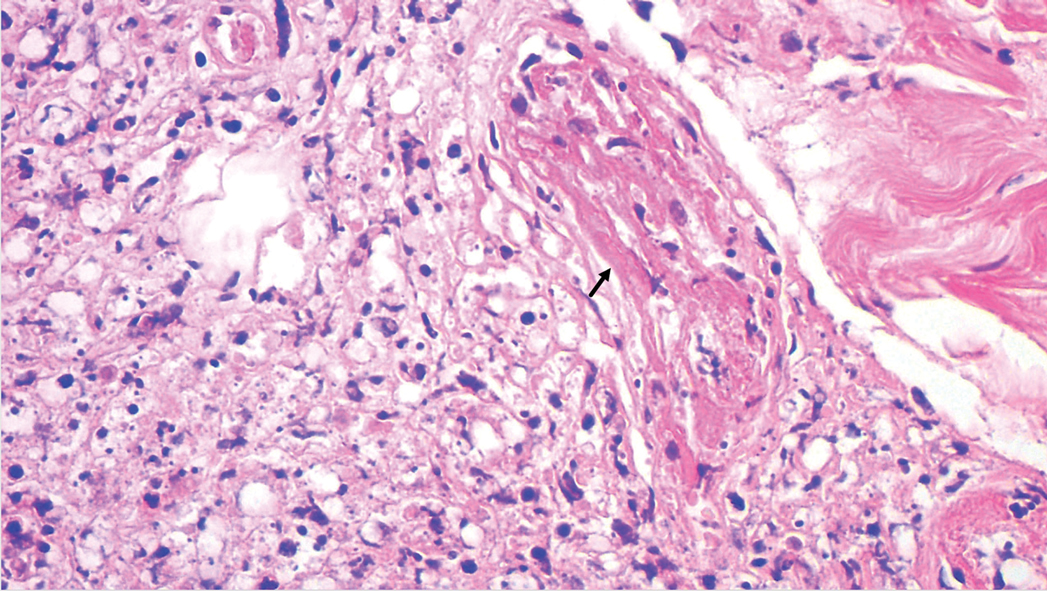

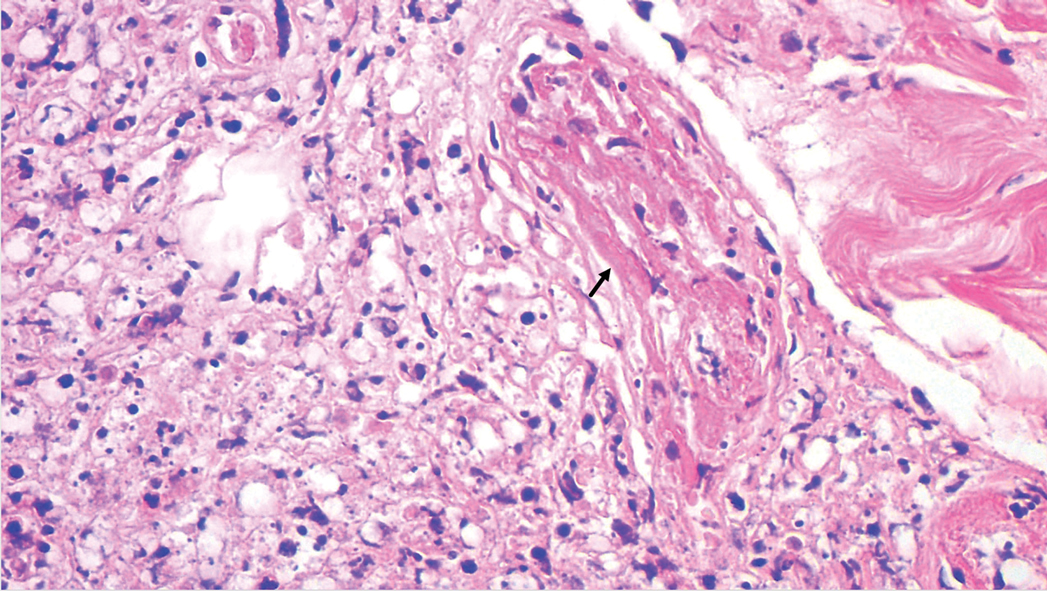

A 54-year-old woman with a 30 pack-year smoking history and history of RA initially presented to the emergency department for cough and dyspnea for 5-day duration. Her initial diagnosis was bronchitis based on presenting symptom profile. A chest CT demonstrated 3 cavitary pulmonary nodules, 1 measuring 2.4 x 2.0 cm in the right middle lobe, and 2 additional nodules, measuring 1.8 x 1.4 and 1.5 x 1.4 in the left upper lobe (Figure). She had no improvement of symptoms after a 7-day course of doxycycline. The patient was taking methotrexate 15 mg weekly and golimumab 50 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks as treatment for RA, prescribed by her rheumatologist.

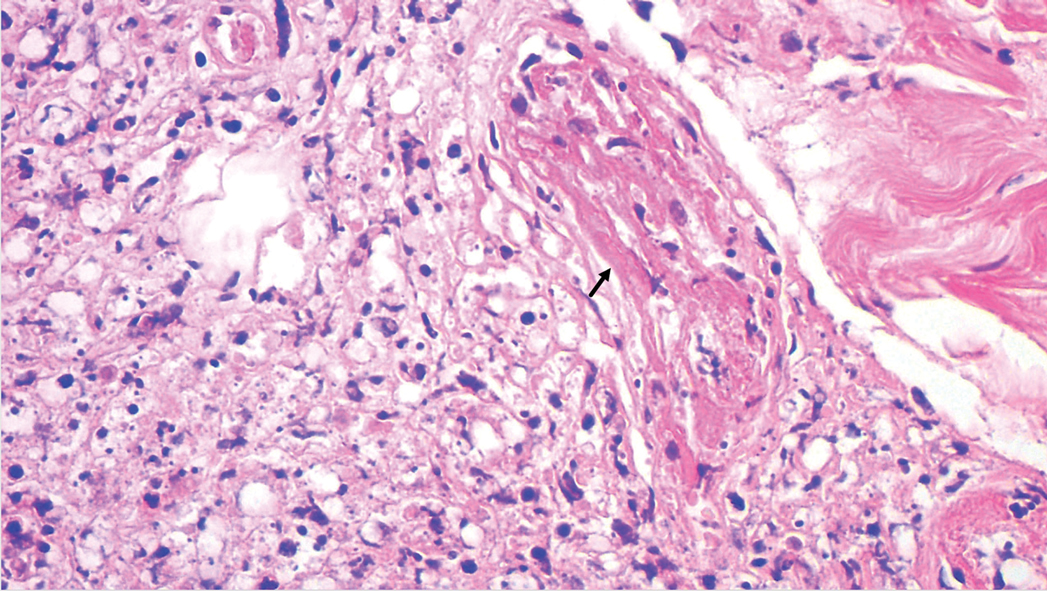

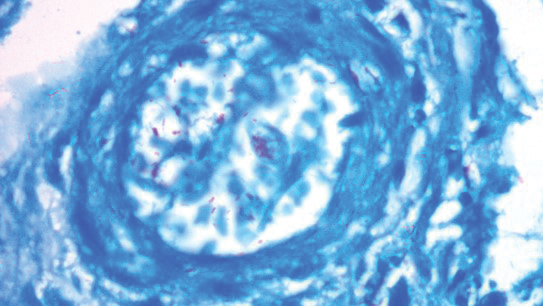

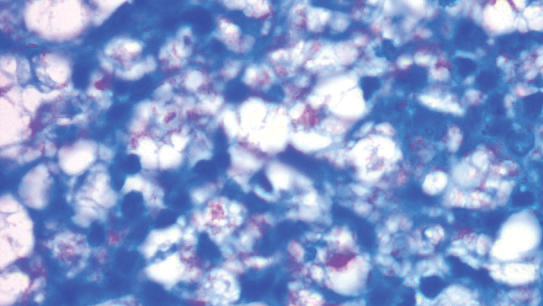

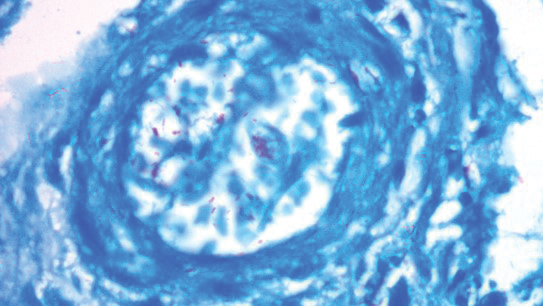

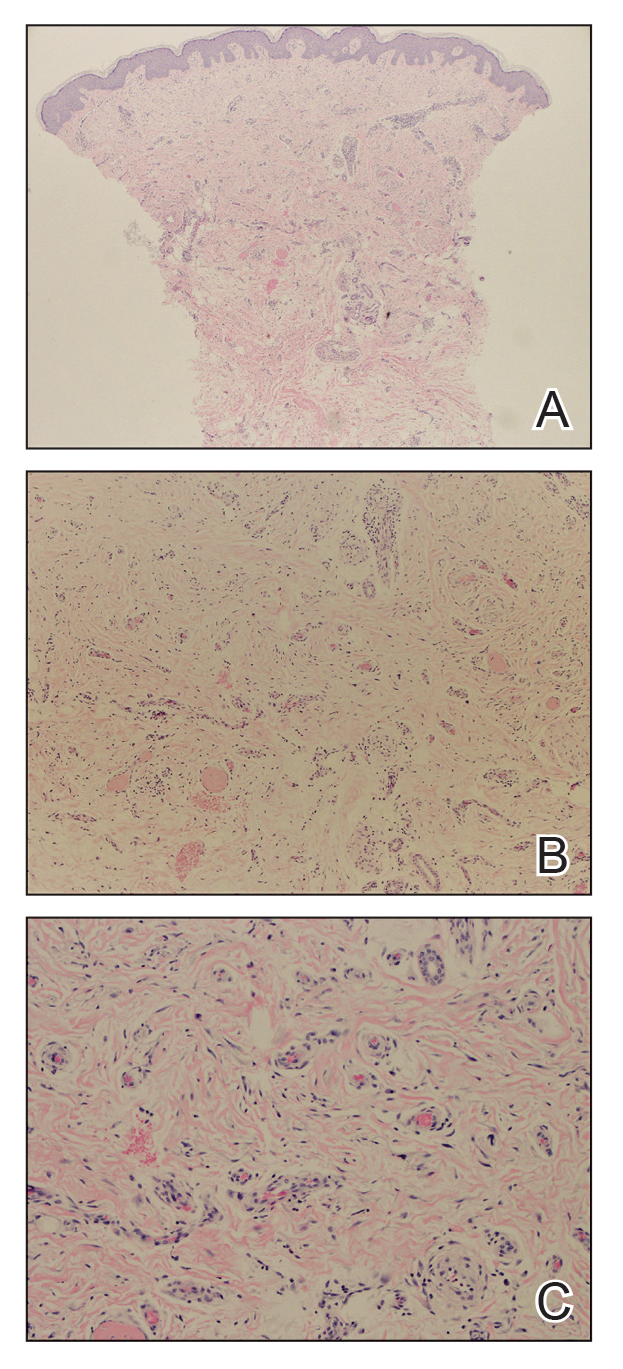

Pulmonology was consulted and a positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) confirmed several cavitary pulmonary nodules involving both lungs with no suspicious fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake. The largest lesion was in the right middle lobe with FDG uptake of 1.9. Additional nodules were found in the left upper lobe, measuring 1.8 x 1.4 cm with FDG of 4.01, and in the left lung apex, measuring 1.5 x 1.4 cm with uptake of 3.53. CTguided percutaneous fine needle aspiration (PFNA) of the right middle lobe lung nodule demonstrated granuloma with central inflammatory debris. Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) stain was negative for fungal organism, acid-fast bacteria (AFB) stain was negative for acid-fast bacilli, and CD20 and CD3 immunostaining demonstrated mixed B- and T-cell populations. There was no evidence of atypia or malignancy. The biopsy demonstrated granuloma with central inflammatory debris on a background of densely fibrotic tissue and lympho-plasmatic inflammation. This finding confirmed the diagnosis of RA with pulmonary involvement.

Outpatient follow-up was established with a pulmonologist and rheumatologist. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly and golimumab subcutaneously 50 mg every 4 weeks were prescribed for the patient. The nodules are being monitored based on Fleischer guidelines with CT imaging 3 to 6 months following initial presentation. Further imaging will be considered at 18 to 24 months as well to further assess stability of the nodules and monitor for changes in size, shape, and necrosis. The patient also was encouraged to quit smoking. Her clinical course since the diagnosis has been stable.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis for new multiple pulmonary nodules on imaging studies is broad and includes infectious processes, such as tuberculosis, as well as other mycobacterial, fungal, and bacterial infections. Noninfectious causes of lung disease are an even broader category of consideration. Noninfectious pulmonary nodules differential includes sarcoidosis, granulomatous with polyangiitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, methotrexate drug reaction, pulmonary manifestations of systemic conditions, such as RA chronic granulomatous disease and malignancy.8 Bronchogenic carcinoma was suspected in this patient due to her smoking history. Squamous cell carcinoma was also considered as the lesion was cavitary. AFB and GMS stains were negative for fungi. Langerhans cell histiocytosis were considered but ruled out as these lesions contain larger numbers of eosinophils than described in the pathology report. Histoplasma and coccidiosis laboratory tests were obtained as the patient lived in a region endemic to both these fungi but were negative (Table). A diagnosis of rheumatoid nodule was made based on the clinical setting, typical radiographic, histopathology features, and negative cultures.

This case is unique due to the quality and location of the rheumatoid nodules within the lungs. Pulmonary manifestations of RA are usually subcutaneous or subpleural, solid, and peripherally located.9 This patient’s nodules were necrobiotic and located within the lung parenchyma. There was significant cavitation. These factors are atypical features of pulmonary RA.

Pulmonary RA can have many associated symptoms and remains an important factor in patient mortality. Estimates demonstrate that 10 to 20% of RA-related deaths are secondary to pulmonary manifestations.10 There are a wide array of symptoms and presentations to be aware of clinically. These symptoms are often nondescript, widely sensitive to many disease processes, and nonspecific to pulmonary RA. These symptoms include dyspnea, wheezing, and nonproductive cough.10 Bronchiectasis is a common symptom as well as small airway obstruction.10 Consolidated necrobiotic lesions are present in up to 20% of pulmonary RA cases.10 Generally these lesions are asymptomatic but can also be associated with pneumothorax, hemoptysis, and airway obstruction.10 Awareness of these symptoms is important for diagnosis and monitoring clinical improvement in patients.

Further workup is necessary to differentiate malignancy-related pulmonary nodules and other causes; if the index of suspicion is high for malignancy as in our case, the workup should be more aggressive. Biopsy is mandatory in such cases to rule out infections and malignancy, as it is highly sensitive and specific. The main problem hindering management is when a clinician fails to include this in their differential diagnosis. This further elucidates the importance of awareness of this diagnosis. Suspicious lesions in a proper clinical setting should be followed up by imaging studies and confirmatory histopathological diagnosis. Typical follow-up is 3 months after initial presentation to assess stability and possibly 18 to 24 months as well based on Fleischer guidelines.

Various treatment modalities have been tried as per literature, including tocilizumab and rituximab. 11,12 Our patient is currently being treated with golimumab based on outpatient rheumatologist recommendations.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates the importance of a careful workup to narrow a broad differential. Medical diagnosis of pulmonary nodules requires an in-depth workup, including clinical evaluation, laboratory and pulmonary functions tests, as well as various imaging studies.

1. Lung and Bronchus Cancer - Cancer Stat Facts. SEER. Accessed February 2, 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov /statfacts/html/lungb.html

2. Shaughnessy AF. One in Five Patients Overdiagnosed with Lung Cancer Screening. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Jul 15;90(2):112.

3. McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med. 2013;369;910-919. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214726

4. Stamp LK, Cleland LG. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Thompson LU, Ward WE, eds. Optimizing Women’s Health through Nutrition. CRC Press; 2008; 279-320.

5. Yousem SA, Colby TV, Carrington CB. Lung biopsy in rheumatoid arthritis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131(5):770-777. doi:10.1164/arrd.1985.131.5.770

6. Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, Turesson C; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(5):601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

7. Shenberger KN, Schned AR, Taylor TH. Rheumatoid disease and bronchogenic carcinoma—case report and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1984;11:226–228.

8. Mukhopadhyay S, Wilcox BE, Myers JL, et al. Pulmonary necrotizing granulomas of unknown cause clinical and pathologic analysis of 131 patients with completely resected nodules. Chest. 2013;144(3):813-824. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2113

9. Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: Number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26(145):170012. Published 2017 Aug 9. doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

10. Brown KK. Rheumatoid lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(5):443-448. doi:10.1513/pats.200703-045MS

11. Braun MG, Wagener P. Regression von peripheren und pulmonalen Rheumaknoten unter Rituximab-Therapie [Regression of peripheral and pulmonary rheumatoid nodules under therapy with rituximab]. Z Rheumatol. 2013;72(2):166-171. doi:10.1007/s00393-012-1054-0

12. Andres M, Vela P, Romera C. Marked improvement of lung rheumatoid nodules after treatment with tocilizumab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(6):1132-1134. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker455

Identification of pulmonary nodules in older adults who smoke immediately brings concern for malignancy in the mind of clinicians. This is particularly the case in patients with significant smoking history. According to the National Cancer Institute in 2019, 12.9% of all new cancer cases were lung cancers.1 Screening for lung cancer, especially in patients with increased risk from smoking, is imperative to early detection and treatment. However, 20% of patients will be overdiagnosed by lung cancer-screening techniques.2 The rate of malignancy noted on a patient’s first screening computed tomography (CT) scan was between 3.7% and 5.5%.3

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune inflammatory condition that mainly affects the joints. Extraarticular manifestations can arise in various locations throughout the body, however. These manifestations are commonly observed in the skin, heart, and lungs.4 Prevalence of pulmonary rheumatoid nodules ranges from < 0.4% in radiologic studies to 32% in lung biopsies of patients with RA and nodules.5

Furthermore, there is a strong association between the risk of rheumatoid nodules in patients with positive serum rheumatoid factor (RF) and smoking history.6 Solitary pulmonary nodules in patients with RA can coexist with bronchogenic carcinoma, making their diagnosis more important.7

Case Presentation

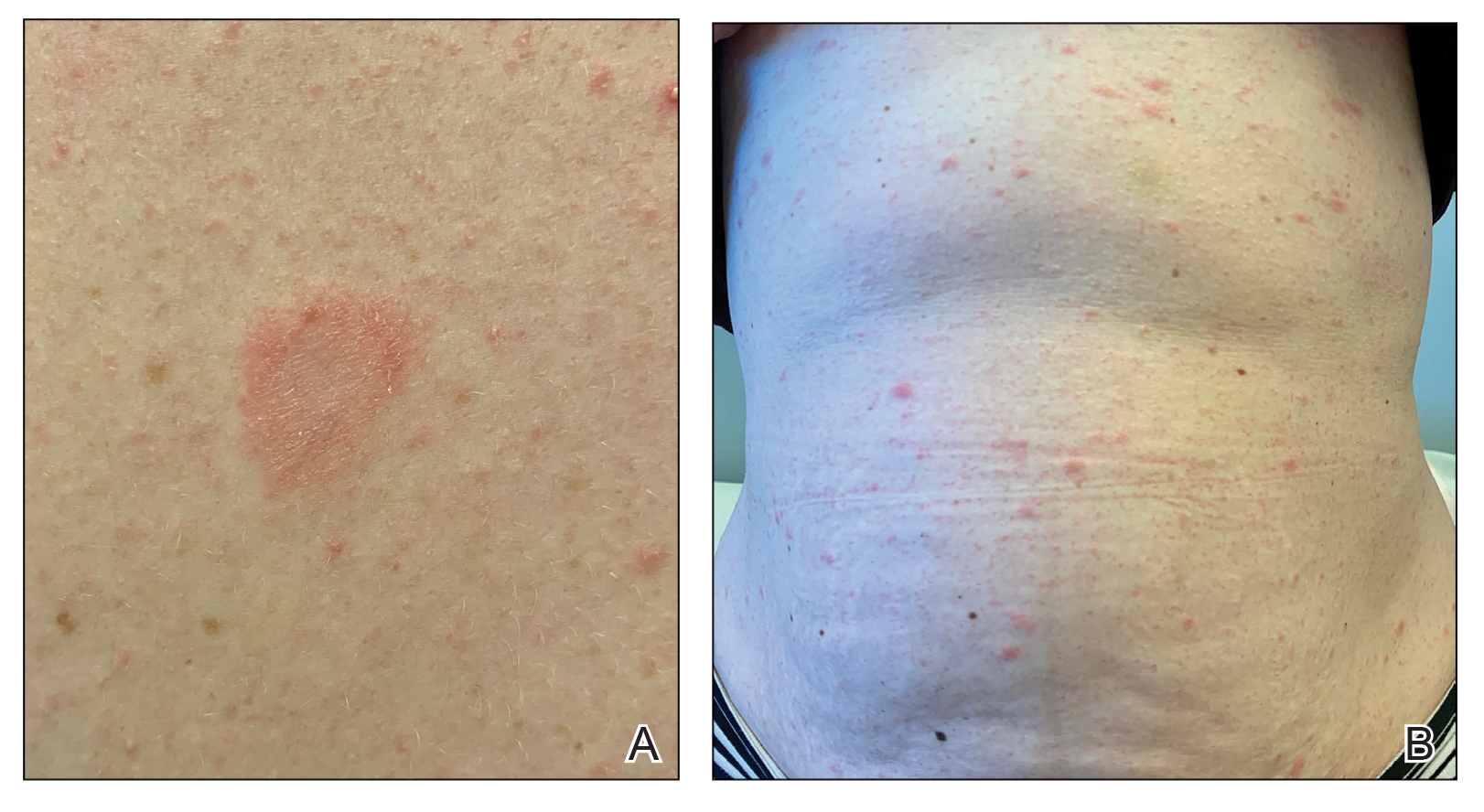

A 54-year-old woman with a 30 pack-year smoking history and history of RA initially presented to the emergency department for cough and dyspnea for 5-day duration. Her initial diagnosis was bronchitis based on presenting symptom profile. A chest CT demonstrated 3 cavitary pulmonary nodules, 1 measuring 2.4 x 2.0 cm in the right middle lobe, and 2 additional nodules, measuring 1.8 x 1.4 and 1.5 x 1.4 in the left upper lobe (Figure). She had no improvement of symptoms after a 7-day course of doxycycline. The patient was taking methotrexate 15 mg weekly and golimumab 50 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks as treatment for RA, prescribed by her rheumatologist.

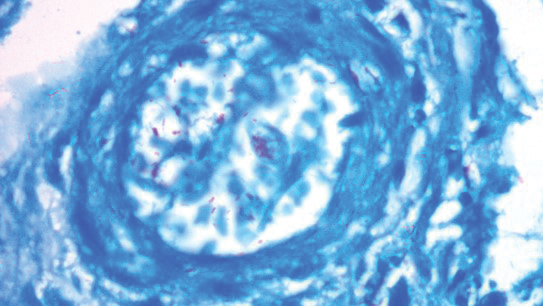

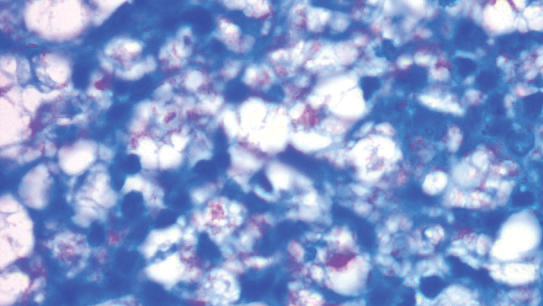

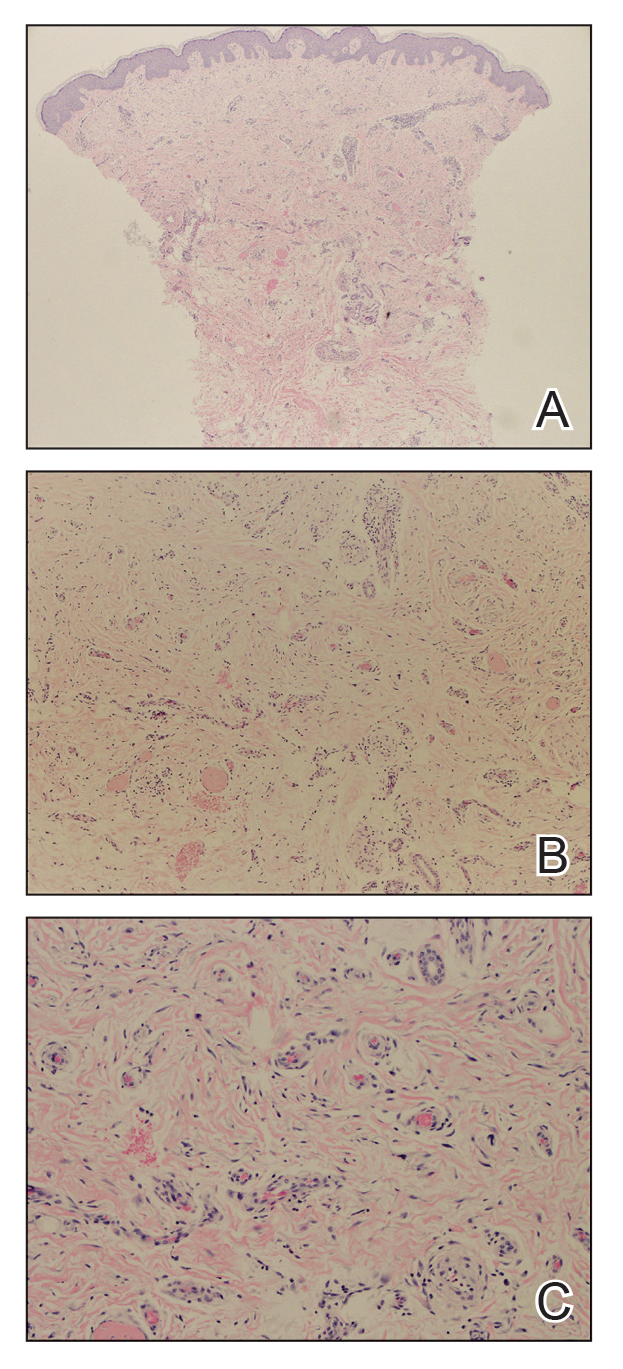

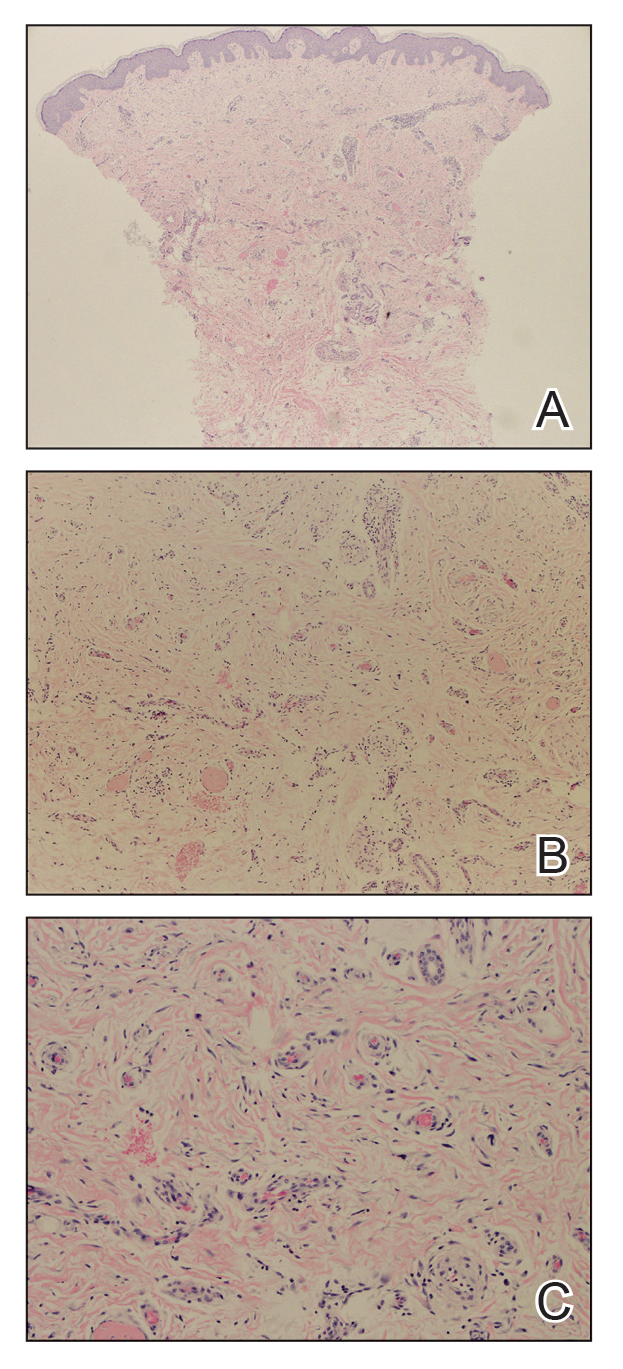

Pulmonology was consulted and a positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) confirmed several cavitary pulmonary nodules involving both lungs with no suspicious fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake. The largest lesion was in the right middle lobe with FDG uptake of 1.9. Additional nodules were found in the left upper lobe, measuring 1.8 x 1.4 cm with FDG of 4.01, and in the left lung apex, measuring 1.5 x 1.4 cm with uptake of 3.53. CTguided percutaneous fine needle aspiration (PFNA) of the right middle lobe lung nodule demonstrated granuloma with central inflammatory debris. Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) stain was negative for fungal organism, acid-fast bacteria (AFB) stain was negative for acid-fast bacilli, and CD20 and CD3 immunostaining demonstrated mixed B- and T-cell populations. There was no evidence of atypia or malignancy. The biopsy demonstrated granuloma with central inflammatory debris on a background of densely fibrotic tissue and lympho-plasmatic inflammation. This finding confirmed the diagnosis of RA with pulmonary involvement.

Outpatient follow-up was established with a pulmonologist and rheumatologist. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly and golimumab subcutaneously 50 mg every 4 weeks were prescribed for the patient. The nodules are being monitored based on Fleischer guidelines with CT imaging 3 to 6 months following initial presentation. Further imaging will be considered at 18 to 24 months as well to further assess stability of the nodules and monitor for changes in size, shape, and necrosis. The patient also was encouraged to quit smoking. Her clinical course since the diagnosis has been stable.

Discussion

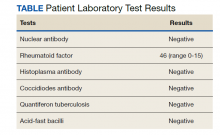

The differential diagnosis for new multiple pulmonary nodules on imaging studies is broad and includes infectious processes, such as tuberculosis, as well as other mycobacterial, fungal, and bacterial infections. Noninfectious causes of lung disease are an even broader category of consideration. Noninfectious pulmonary nodules differential includes sarcoidosis, granulomatous with polyangiitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, methotrexate drug reaction, pulmonary manifestations of systemic conditions, such as RA chronic granulomatous disease and malignancy.8 Bronchogenic carcinoma was suspected in this patient due to her smoking history. Squamous cell carcinoma was also considered as the lesion was cavitary. AFB and GMS stains were negative for fungi. Langerhans cell histiocytosis were considered but ruled out as these lesions contain larger numbers of eosinophils than described in the pathology report. Histoplasma and coccidiosis laboratory tests were obtained as the patient lived in a region endemic to both these fungi but were negative (Table). A diagnosis of rheumatoid nodule was made based on the clinical setting, typical radiographic, histopathology features, and negative cultures.

This case is unique due to the quality and location of the rheumatoid nodules within the lungs. Pulmonary manifestations of RA are usually subcutaneous or subpleural, solid, and peripherally located.9 This patient’s nodules were necrobiotic and located within the lung parenchyma. There was significant cavitation. These factors are atypical features of pulmonary RA.

Pulmonary RA can have many associated symptoms and remains an important factor in patient mortality. Estimates demonstrate that 10 to 20% of RA-related deaths are secondary to pulmonary manifestations.10 There are a wide array of symptoms and presentations to be aware of clinically. These symptoms are often nondescript, widely sensitive to many disease processes, and nonspecific to pulmonary RA. These symptoms include dyspnea, wheezing, and nonproductive cough.10 Bronchiectasis is a common symptom as well as small airway obstruction.10 Consolidated necrobiotic lesions are present in up to 20% of pulmonary RA cases.10 Generally these lesions are asymptomatic but can also be associated with pneumothorax, hemoptysis, and airway obstruction.10 Awareness of these symptoms is important for diagnosis and monitoring clinical improvement in patients.

Further workup is necessary to differentiate malignancy-related pulmonary nodules and other causes; if the index of suspicion is high for malignancy as in our case, the workup should be more aggressive. Biopsy is mandatory in such cases to rule out infections and malignancy, as it is highly sensitive and specific. The main problem hindering management is when a clinician fails to include this in their differential diagnosis. This further elucidates the importance of awareness of this diagnosis. Suspicious lesions in a proper clinical setting should be followed up by imaging studies and confirmatory histopathological diagnosis. Typical follow-up is 3 months after initial presentation to assess stability and possibly 18 to 24 months as well based on Fleischer guidelines.

Various treatment modalities have been tried as per literature, including tocilizumab and rituximab. 11,12 Our patient is currently being treated with golimumab based on outpatient rheumatologist recommendations.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates the importance of a careful workup to narrow a broad differential. Medical diagnosis of pulmonary nodules requires an in-depth workup, including clinical evaluation, laboratory and pulmonary functions tests, as well as various imaging studies.

Identification of pulmonary nodules in older adults who smoke immediately brings concern for malignancy in the mind of clinicians. This is particularly the case in patients with significant smoking history. According to the National Cancer Institute in 2019, 12.9% of all new cancer cases were lung cancers.1 Screening for lung cancer, especially in patients with increased risk from smoking, is imperative to early detection and treatment. However, 20% of patients will be overdiagnosed by lung cancer-screening techniques.2 The rate of malignancy noted on a patient’s first screening computed tomography (CT) scan was between 3.7% and 5.5%.3

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune inflammatory condition that mainly affects the joints. Extraarticular manifestations can arise in various locations throughout the body, however. These manifestations are commonly observed in the skin, heart, and lungs.4 Prevalence of pulmonary rheumatoid nodules ranges from < 0.4% in radiologic studies to 32% in lung biopsies of patients with RA and nodules.5

Furthermore, there is a strong association between the risk of rheumatoid nodules in patients with positive serum rheumatoid factor (RF) and smoking history.6 Solitary pulmonary nodules in patients with RA can coexist with bronchogenic carcinoma, making their diagnosis more important.7

Case Presentation

A 54-year-old woman with a 30 pack-year smoking history and history of RA initially presented to the emergency department for cough and dyspnea for 5-day duration. Her initial diagnosis was bronchitis based on presenting symptom profile. A chest CT demonstrated 3 cavitary pulmonary nodules, 1 measuring 2.4 x 2.0 cm in the right middle lobe, and 2 additional nodules, measuring 1.8 x 1.4 and 1.5 x 1.4 in the left upper lobe (Figure). She had no improvement of symptoms after a 7-day course of doxycycline. The patient was taking methotrexate 15 mg weekly and golimumab 50 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks as treatment for RA, prescribed by her rheumatologist.

Pulmonology was consulted and a positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) confirmed several cavitary pulmonary nodules involving both lungs with no suspicious fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake. The largest lesion was in the right middle lobe with FDG uptake of 1.9. Additional nodules were found in the left upper lobe, measuring 1.8 x 1.4 cm with FDG of 4.01, and in the left lung apex, measuring 1.5 x 1.4 cm with uptake of 3.53. CTguided percutaneous fine needle aspiration (PFNA) of the right middle lobe lung nodule demonstrated granuloma with central inflammatory debris. Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) stain was negative for fungal organism, acid-fast bacteria (AFB) stain was negative for acid-fast bacilli, and CD20 and CD3 immunostaining demonstrated mixed B- and T-cell populations. There was no evidence of atypia or malignancy. The biopsy demonstrated granuloma with central inflammatory debris on a background of densely fibrotic tissue and lympho-plasmatic inflammation. This finding confirmed the diagnosis of RA with pulmonary involvement.

Outpatient follow-up was established with a pulmonologist and rheumatologist. Methotrexate 15 mg weekly and golimumab subcutaneously 50 mg every 4 weeks were prescribed for the patient. The nodules are being monitored based on Fleischer guidelines with CT imaging 3 to 6 months following initial presentation. Further imaging will be considered at 18 to 24 months as well to further assess stability of the nodules and monitor for changes in size, shape, and necrosis. The patient also was encouraged to quit smoking. Her clinical course since the diagnosis has been stable.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis for new multiple pulmonary nodules on imaging studies is broad and includes infectious processes, such as tuberculosis, as well as other mycobacterial, fungal, and bacterial infections. Noninfectious causes of lung disease are an even broader category of consideration. Noninfectious pulmonary nodules differential includes sarcoidosis, granulomatous with polyangiitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, methotrexate drug reaction, pulmonary manifestations of systemic conditions, such as RA chronic granulomatous disease and malignancy.8 Bronchogenic carcinoma was suspected in this patient due to her smoking history. Squamous cell carcinoma was also considered as the lesion was cavitary. AFB and GMS stains were negative for fungi. Langerhans cell histiocytosis were considered but ruled out as these lesions contain larger numbers of eosinophils than described in the pathology report. Histoplasma and coccidiosis laboratory tests were obtained as the patient lived in a region endemic to both these fungi but were negative (Table). A diagnosis of rheumatoid nodule was made based on the clinical setting, typical radiographic, histopathology features, and negative cultures.

This case is unique due to the quality and location of the rheumatoid nodules within the lungs. Pulmonary manifestations of RA are usually subcutaneous or subpleural, solid, and peripherally located.9 This patient’s nodules were necrobiotic and located within the lung parenchyma. There was significant cavitation. These factors are atypical features of pulmonary RA.

Pulmonary RA can have many associated symptoms and remains an important factor in patient mortality. Estimates demonstrate that 10 to 20% of RA-related deaths are secondary to pulmonary manifestations.10 There are a wide array of symptoms and presentations to be aware of clinically. These symptoms are often nondescript, widely sensitive to many disease processes, and nonspecific to pulmonary RA. These symptoms include dyspnea, wheezing, and nonproductive cough.10 Bronchiectasis is a common symptom as well as small airway obstruction.10 Consolidated necrobiotic lesions are present in up to 20% of pulmonary RA cases.10 Generally these lesions are asymptomatic but can also be associated with pneumothorax, hemoptysis, and airway obstruction.10 Awareness of these symptoms is important for diagnosis and monitoring clinical improvement in patients.

Further workup is necessary to differentiate malignancy-related pulmonary nodules and other causes; if the index of suspicion is high for malignancy as in our case, the workup should be more aggressive. Biopsy is mandatory in such cases to rule out infections and malignancy, as it is highly sensitive and specific. The main problem hindering management is when a clinician fails to include this in their differential diagnosis. This further elucidates the importance of awareness of this diagnosis. Suspicious lesions in a proper clinical setting should be followed up by imaging studies and confirmatory histopathological diagnosis. Typical follow-up is 3 months after initial presentation to assess stability and possibly 18 to 24 months as well based on Fleischer guidelines.

Various treatment modalities have been tried as per literature, including tocilizumab and rituximab. 11,12 Our patient is currently being treated with golimumab based on outpatient rheumatologist recommendations.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates the importance of a careful workup to narrow a broad differential. Medical diagnosis of pulmonary nodules requires an in-depth workup, including clinical evaluation, laboratory and pulmonary functions tests, as well as various imaging studies.

1. Lung and Bronchus Cancer - Cancer Stat Facts. SEER. Accessed February 2, 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov /statfacts/html/lungb.html

2. Shaughnessy AF. One in Five Patients Overdiagnosed with Lung Cancer Screening. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Jul 15;90(2):112.

3. McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med. 2013;369;910-919. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214726

4. Stamp LK, Cleland LG. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Thompson LU, Ward WE, eds. Optimizing Women’s Health through Nutrition. CRC Press; 2008; 279-320.

5. Yousem SA, Colby TV, Carrington CB. Lung biopsy in rheumatoid arthritis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131(5):770-777. doi:10.1164/arrd.1985.131.5.770

6. Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, Turesson C; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(5):601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

7. Shenberger KN, Schned AR, Taylor TH. Rheumatoid disease and bronchogenic carcinoma—case report and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1984;11:226–228.

8. Mukhopadhyay S, Wilcox BE, Myers JL, et al. Pulmonary necrotizing granulomas of unknown cause clinical and pathologic analysis of 131 patients with completely resected nodules. Chest. 2013;144(3):813-824. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2113

9. Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: Number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26(145):170012. Published 2017 Aug 9. doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

10. Brown KK. Rheumatoid lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(5):443-448. doi:10.1513/pats.200703-045MS

11. Braun MG, Wagener P. Regression von peripheren und pulmonalen Rheumaknoten unter Rituximab-Therapie [Regression of peripheral and pulmonary rheumatoid nodules under therapy with rituximab]. Z Rheumatol. 2013;72(2):166-171. doi:10.1007/s00393-012-1054-0

12. Andres M, Vela P, Romera C. Marked improvement of lung rheumatoid nodules after treatment with tocilizumab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(6):1132-1134. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker455

1. Lung and Bronchus Cancer - Cancer Stat Facts. SEER. Accessed February 2, 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov /statfacts/html/lungb.html

2. Shaughnessy AF. One in Five Patients Overdiagnosed with Lung Cancer Screening. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Jul 15;90(2):112.

3. McWilliams A, Tammemagi MC, Mayo JR, et al. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med. 2013;369;910-919. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214726

4. Stamp LK, Cleland LG. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Thompson LU, Ward WE, eds. Optimizing Women’s Health through Nutrition. CRC Press; 2008; 279-320.

5. Yousem SA, Colby TV, Carrington CB. Lung biopsy in rheumatoid arthritis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131(5):770-777. doi:10.1164/arrd.1985.131.5.770

6. Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, Turesson C; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(5):601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

7. Shenberger KN, Schned AR, Taylor TH. Rheumatoid disease and bronchogenic carcinoma—case report and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1984;11:226–228.

8. Mukhopadhyay S, Wilcox BE, Myers JL, et al. Pulmonary necrotizing granulomas of unknown cause clinical and pathologic analysis of 131 patients with completely resected nodules. Chest. 2013;144(3):813-824. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2113

9. Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: Number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26(145):170012. Published 2017 Aug 9. doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

10. Brown KK. Rheumatoid lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(5):443-448. doi:10.1513/pats.200703-045MS

11. Braun MG, Wagener P. Regression von peripheren und pulmonalen Rheumaknoten unter Rituximab-Therapie [Regression of peripheral and pulmonary rheumatoid nodules under therapy with rituximab]. Z Rheumatol. 2013;72(2):166-171. doi:10.1007/s00393-012-1054-0

12. Andres M, Vela P, Romera C. Marked improvement of lung rheumatoid nodules after treatment with tocilizumab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(6):1132-1134. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker455

Pheochromocytoma: An Incidental Finding in an Asymptomatic Older Adult With Renal Oncocytoma

A high index of suspicion for pheochromocytoma is necessary during the workup of secondary hypertension as untreated pheochromocytoma may lead to significant morbidity and mortality, especially in patients who require any surgical treatment.

Pheochromocytoma is a rare catecholamine-secreting tumor of chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla or sympathetic ganglia, occurring in about 0.2 to 0.5% of patients with hypertension.1-3 However, in a review of 54 autopsy-proven cases of pheochromocytoma, about 50% of the patients with hypertension were not clinically suspected for pheochromocytoma.4

Pheochromocytoma is usually diagnosed based on symptoms of hyperadrenergic spells, resistant hypertension, especially in the young, with a pressor response to the anesthesia stress test and adrenal incidentaloma.

The classic triad of symptoms associated with pheochromocytoma includes episodic headache (90%), sweating (60-70%), and palpitations (70%).2,5 Sustained or paroxysmal hypertension is the most common symptom reported in about 95% of patients with pheochromocytoma. Other symptoms include pallor, tremors, dyspnea, generalized weakness, orthostatic hypotension, cardiomyopathy, or hyperglycemia.6 However, about 10% of patients with pheochromocytoma are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic.7 Secondary causes of hypertension are usually suspected in multidrug resistant or sudden early onset of hypertension.8

Approximately 10% of catecholamine-secreting tumors are malignant.9-11 Benign and malignant pheochromocytoma have a similar biochemical and histologic presentation and are differentiated based on local invasion into the surrounding tissues and organs (eg, kidney, liver) or distant metastasis.

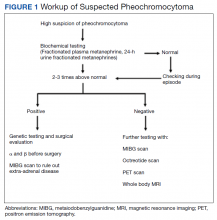

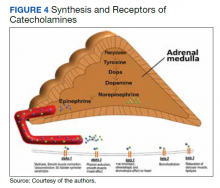

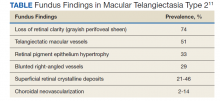

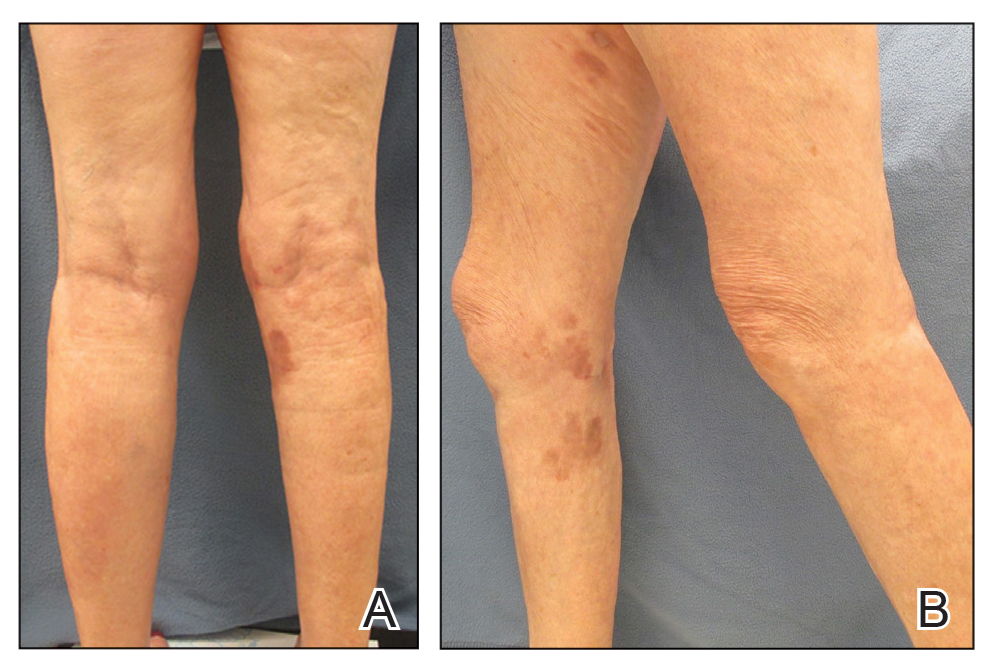

A typical workup of a suspected patient with pheochromocytoma includes biochemical tests, including measurements of urinary and fractionated plasma metanephrines and catecholamine. Patients with positive biochemical tests should undergo localization of the tumor with an imaging study either with an adrenal/abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scan. If a patient has paraganglioma or an adrenal mass > 10 cm or negative abdominal imaging with a positive biochemical test, further imaging with an iobenguane I-123 scan is needed (Figure 1).

In this article, we present an unusual case of asymptomatic pheochromocytoma in a patient with right-sided renal oncocytoma who underwent an uneventful nephrectomy and adrenalectomy.

Case Presentation

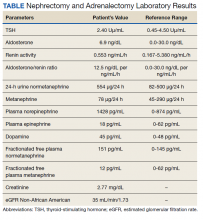

A 72-year-old male with a medical history of diabetes, hypertension, sensory neuropathy, benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) status posttransurethral resection of the prostate, and chronic renal failure presented to establish care with the Arizona Kidney Disease and Hypertension Center. His medications included losartan 50 mg by mouth daily, diltiazem 180 mg extended-release by mouth daily, carvedilol 6.25 mg by mouth twice a day, and tamsulosin 0.4 mg by mouth daily. His presenting vitals were blood pressure (BP), 112/74 left arm sitting, pulse, 63/beats per min, and body mass index, 34. On physical examination, the patient was alert and oriented, and the chest was clear to auscultation without wheeze or rhonchi. On cardiac examination, heart rate and rhythm were regular; S1 and S2 were normal with no added murmurs, rubs or gallops, and no jugular venous distension. The abdomen was soft, nontender, with no palpable mass. His laboratory results showed sodium, 142 mmol/L; potassium, 5.3 mmol/L; chloride, 101 mmol/L; carbon dioxide, 24 mmol/L; albumin, 4.3 g/dL; creatinine, 1.89 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 29 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate non-African American, 35 mL/min/1.73; 24-h urine creatinine clearance, 105 mL/min; protein, 1306 mg/24 h (Table).

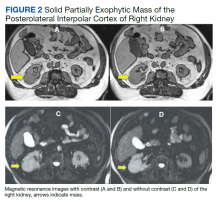

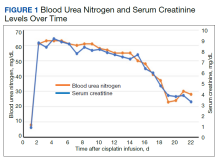

His renal ultrasound showed an exophytic isoechoic mass or complex cyst at the lateral aspect of the lower pole of the right kidney, measuring 45 mm in diameter. An MRI of the abdomen with and without contrast showed a solid partially exophytic mass of the posterolateral interpolar cortex of the right kidney, measuring 5.9 cm in the greatest dimension (Figure 2). No definite involvement of Gerota fascia was noted, a 1-cm metastasis to the right adrenal gland was present, renal veins were patent, and there was no upper retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient underwent right-hand-assisted lap-aroscopic radical nephrectomy and right adre-nalectomy without any complications. However, the surgical pathology report showed oncocytoma of the kidney (5.7 cm), pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland (1.4 cm), and papillary adenoma of the kidney (0.7 cm). Right kidney nephrectomy showed non-neoplastic renal parenchyma, diabetic glomerulosclerosis (Renal Pathology Society 2010 diabetic nephropathy class IIb), severe mesangial expansion, moderate interstitial fibrosis, moderate arteriosclerosis, and mild arteriolosclerosis.

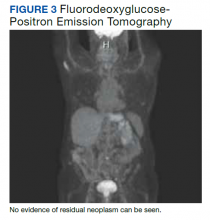

A fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan was significant for right nephrectomy and adrenalectomy and showed no significant evidence of residual neoplasm or local or distant metastases. A nuclear medicine (iobenguane I-123) tumor and single positron emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan showed normal activity throughout the body and no evidence of abnormal activity (Figure 3).

Discussion

Pheochromocytoma is a rare cause of secondary hypertension. However, the real numbers are thought to be > 0.2 to 0.5%.1,2,4 Patients with pheochromocytoma should undergo surgical adrenal resection after appropriate medical preparation. Patients with pheochromocytoma who are not diagnosed preoperatively have increased surgical mortality rates due to fatal hypertensive crises, malignant arrhythmia, and multiorgan failure as a result of hypertensive crisis.15 Anesthetic drugs during surgery also can exacerbate the cardiotoxic effects of catecholamines. Short-acting anesthetic agents, such as fentanyl, are used in patients with pheochromocytoma.16

This case of pheochromocytoma illustrated no classic symptoms of episodic headache, sweating, and tachycardia, and the patient was otherwise asymptomatic. BP was well controlled with losartan, diltiazem, and a β-blocker with α-blocking activity (carvedilol). As the patient was not known to have pheochromocytoma, he did not undergo preoperative medical therapy. Figure 4 illustrates the receptors stimulate catecholamines, and the drugs blocking these receptors prevent hypertensive crisis during surgery. However, the surgery was without potential complications (ie, hypertensive crisis, malignant arrhythmia, or multiorgan failure). The patient was diagnosed incidentally on histopathology after right radical nephrectomy and adrenalectomy due to solid partially exophytic right renal mass (5.9 cm) with right adrenal metastasis. About 10% of patients are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic.7 Sometimes, the symptoms may be ignored because of the episodic nature. Other possible reasons can be small, nonfunctional tumors or the use of antihypertensive medications suppressing the symptoms.7

The adrenal mass that was initially thought to be a metastasis of right kidney mass was later confirmed as pheochromocytoma. One possible explanation for uneventful surgery could be the use of β-blocker with α-blocking activity (carvedilol), α-1 adrenergic blocker (tamsulosin) along with nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (diltiazem) as part of the patient’s antihypertensive and BPH medication regimen. Another possible explanation could be silent or episodically secreting pheochromocytoma with a small functional portion.

Subsequent workup after adrenalectomy, including urinary and fractionated plasma metanephrines and catecholamines, were not consistent with catecholamine hypersecretion. A 24-hour urine fractionated metanephrines test has about 98% sensitivity and 98% specificity. Elevated plasma norepinephrine was thought to be due to renal failure because it was < 3-fold the upper limit of normal, which is considered to be a possible indication of pheochromocytoma.17,18 The nuclear medicine (iobenguane I-123) tumor, SPECT, and FDG-PET CT studies were negative for residual pheochromocytoma. Other imaging studies to consider in patients with suspected catecholamine-secreting tumor with positive biochemical test and negative abdominal imaging are a whole-body MRI scan, 68-Ga DOTATATE (gallium 68 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10 tetraacetic acid-octreotate) or FDG-PET scan.19

In a review of 54 autopsy-proven pheochromocytoma cases by Sutton and colleagues in 1981, 74% of the patients were not clinically suspected for pheochromocytoma in their life.4 Similarly, in a retrospective study of hospital autopsies by McNeil and colleagues, one incidental pheochromocytoma was detected in every 2031 autopsies (0.05%).20 In another case series of 41 patients with pheochromocytoma-related adrenalectomy, almost 50% of the pheochromocytomas were detected incidentally on imaging studies.21 Although the number of incidental findings are decreasing due to advances in screening techniques, a significant number of patients remain undiagnosed. Multiple cases of diagnosis of pheochromocytoma on autopsy of patients who died of hemodynamic instability (ie, hypertensive crisis, hypotension crisis precipitated by surgery for adrenal or nonadrenal conditions) are reported.3 To the best of our knowledge, there are no case reports published on the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma after adrenalectomy in an asymptomatic patient without intraoperative complications.

The goal of preoperative medical therapy includes BP control, prevention of tachycardia, and volume expansion. The preoperative medications regimens are combined α- and β-adrenergic blockade, calcium channel blockers, and metyrosine. According to clinical practice guidelines of the Endocrine Society in 2014, the α-adrenergic blockers should be started first at least 7 days before surgery to control BP and to cause vasodilation. Early use of α-blockers is required to prevent cardiotoxicity. The β-adrenergic blockers should be started after the adequate α-adrenergic blockade, typically 2 to 3 days before surgery, as early use can cause vasoconstriction in patients with pheochromocytoma. The α-adrenergic blockers include phenoxybenzamine (nonselective long-acting nonspecific α-adrenergic blocking agent), and selective α-1 adrenergic blockers (doxazosin, prazosin, terazosin). The β-adrenergic blocker (ie, propranolol, metoprolol) should be started cautiously with a low dose and slowly titrated to control heart rate. A high sodium diet and increased fluid intake also are recommended 7 to 14 days before surgery. A sudden drop in catecholamines can cause hypotension during an operation. Continuous fluid infusions are given to prevent hypotension.22 Similarly, anesthetic agents also should be modified to prevent cardiotoxic effects. Rocuronium and vecuronium are less cardiotoxic compared with other sympathomimetic muscle relaxants. Short-acting anesthetic agents, such as fentanyl, are preferred. α-blockers are continued throughout the operation. Biochemical testing with fractionated metanephrines is performed about 1 to 2 weeks postoperatively to look for recurrence of the disease.23

Secondary causes of hypertension are suspected in multidrug resistant or sudden early onset of hypertension before aged 40 years. Pheochromocytoma is a rare cause of secondary hypertension, and older adult patients are rarely diagnosed with pheochromocytoma.24 In this report, pheochromocytoma was detected in a 72-year-old hypertensive patient. Therefore, a pheochromocytoma diagnosis should not be ignored in the older adult patient with adrenal mass and hypertension treated with more than one drug. The authors recommend any patient undergoing surgery with adrenal lesion should be considered for the screening of possible pheochromocytoma and prepared preoperatively, especially any patient with renal cell carcinoma with adrenal metastasis.

Conclusions

Asymptomatic pheochromocytoma is an unusual but serious condition, especially for patients undergoing a surgical procedure. An adrenal mass may be ignored in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic older adult patients and is mostly considered as adrenal metastasis when present with other malignancies. Fortunately, the nephrectomy and adrenalectomy in our case of asymptomatic pheochromocytoma was uneventful, but pheochromocytoma should be ruled out before a surgical procedure, as an absence of medical pretreatment can lead to serious consequences. Therefore, we suggest a more careful screening of pheochromocytoma in patients with an adrenal mass (primary or metastatic) and hypertension treated with multiple antihypertensive drugs, even in older adult patients.

1. Omura M, Saito J, Yamaguchi K, Kakuta Y, Nishikawa T. Prospective study on the prevalence of secondary hypertension among hypertensive patients visiting a general outpatient clinic in Japan. Hypertens Res. 2004;27(3):193-202. doi:10.1291/hypres.27.193

2. Stein PP, Black HR. A simplified diagnostic approach to pheochromocytoma: a review of the literature and report of one institution’s experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70(1):46-66. doi:10.1097/00005792-199101000-00004

3. Beard CM, Sheps SG, Kurland LT, Carney JA, Lie JT. Occurrence of pheochromocytoma in Rochester, Minnesota, 1950 through 1979. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58(12):802-804.

4. Sutton MG, Sheps SG, Lie JT. Prevalence of clinically unsuspected pheochromocytoma: review of a 50-year autopsy series. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56(6):354-360.

5. Manger WM, Gifford RW Jr. Pheochromocytoma. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2002;4(1):62-72. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.01452.x

6. Kassim TA, Clarke DD, Mai VQ, Clyde PW, Mohamed Shakir KM. Catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy. Endocr Pract. 2008;14(9):1137-1149. doi:10.4158/EP.14.9.1137

7. Kudva YC, Young WF, Thompson GB, Grant CS, Van Heerden JA. Adrenal incidentaloma: an important component of the clinical presentation spectrum of benign sporadic adrenal pheochromocytoma. The Endocrinologist. 1999;9(2):77-80. doi:10.1097/00019616-199903000-00002

8. Puar TH, Mok Y, Debajyoti R, Khoo J, How CH, Ng AK. Secondary hypertension in adults. Singapore Med J. 2016;57(5):228-232. doi:10.11622/smedj.2016087

9. Bravo EL. Pheochromocytoma: new concepts and future trends. Kidney Int. 1991;40(3):544-556. doi:10.1038/ki.1991.244

10. Plouin PF, Chatellier G, Fofol I, Corvol P. Tumor recurrence and hypertension persistence after successful pheochromocytoma operation. Hypertension. 1997;29(5):1133-1139. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.29.5.1133

11. Hamidi O, Young WF Jr, Iñiguez-Ariza NM, et al. Malignant pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: 272 patients over 55 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(9):3296-3305. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-00992

12. Kenny L, Rizzo V, Trevis J, Assimakopoulou E, Timon D. The unexpected diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma in the anaesthetic room. Ann Card Anaesth. 2018;21(3):307-310. doi:10.4103/aca.ACA_206_17

13. Johnston PC, Silversides JA, Wallace H, et al. Phaeochromocytoma crisis: two cases of undiagnosed phaeochromocytoma presenting after elective nonrelated surgical procedures. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2013;2013:514714. doi:10.1155/2013/514714

14. Shen SJ, Cheng HM, Chiu AW, Chou CW, Chen JY. Perioperative hypertensive crisis in clinically silent pheochromocytomas: report of four cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2005;28(1):44-50.

15. Lo CY, Lam KY, Wat MS, Lam KS. Adrenal pheochromocytoma remains a frequently overlooked diagnosis. Am J Surg. 2000;179(3):212-215. doi:10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00296-8

16. Myklejord DJ. Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma: the anesthesiologist nightmare. Clin Med Res. 2004;2(1):59-62. doi:10.3121/cmr.2.1.59

17. Stumvoll M, Radjaipour M, Seif F. Diagnostic considerations in pheochromocytoma and chronic hemodialysis: case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol. 1995;15(2):147-151. doi:10.1159/000168820

18. Morioka M, Yuihama S, Nakajima T, et al. Incidentally discovered pheochromocytoma in long-term hemodialysis patients. Int J Urol. 2002;9(12):700-703. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00553.x

19. ˇCtvrtlík F, Koranda P, Schovánek J, Škarda J, Hartmann I, Tüdös Z. Current diagnostic imaging of pheochromocytomas and implications for therapeutic strategy. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15(4):3151-3160. doi:10.3892/etm.2018.5871

20. McNeil AR, Blok BH, Koelmeyer TD, Burke MP, Hilton JM. Phaeochromocytomas discovered during coronial autopsies in Sydney, Melbourne and Auckland. Aust N Z J Med. 2000;30(6):648-652. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2000.tb04358.x

21. Baguet JP, Hammer L, Mazzuco TL, et al. Circumstances of discovery of phaeochromocytoma: a retrospective study of 41 consecutive patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150(5):681-686. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1500681

22. Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):1915-1942. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-1498

23. Dortzbach K, Gainsburg DM, Frost EA. Variants of pheochromocytoma and their anesthetic implications--a case report and literature review. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2010;20(6):897-905.

24. Januszewicz W, Chodakowska J, Styczy´nski G. Secondary hypertension in the elderly. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12(9):603-606. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1000673

A high index of suspicion for pheochromocytoma is necessary during the workup of secondary hypertension as untreated pheochromocytoma may lead to significant morbidity and mortality, especially in patients who require any surgical treatment.

A high index of suspicion for pheochromocytoma is necessary during the workup of secondary hypertension as untreated pheochromocytoma may lead to significant morbidity and mortality, especially in patients who require any surgical treatment.

Pheochromocytoma is a rare catecholamine-secreting tumor of chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla or sympathetic ganglia, occurring in about 0.2 to 0.5% of patients with hypertension.1-3 However, in a review of 54 autopsy-proven cases of pheochromocytoma, about 50% of the patients with hypertension were not clinically suspected for pheochromocytoma.4

Pheochromocytoma is usually diagnosed based on symptoms of hyperadrenergic spells, resistant hypertension, especially in the young, with a pressor response to the anesthesia stress test and adrenal incidentaloma.

The classic triad of symptoms associated with pheochromocytoma includes episodic headache (90%), sweating (60-70%), and palpitations (70%).2,5 Sustained or paroxysmal hypertension is the most common symptom reported in about 95% of patients with pheochromocytoma. Other symptoms include pallor, tremors, dyspnea, generalized weakness, orthostatic hypotension, cardiomyopathy, or hyperglycemia.6 However, about 10% of patients with pheochromocytoma are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic.7 Secondary causes of hypertension are usually suspected in multidrug resistant or sudden early onset of hypertension.8

Approximately 10% of catecholamine-secreting tumors are malignant.9-11 Benign and malignant pheochromocytoma have a similar biochemical and histologic presentation and are differentiated based on local invasion into the surrounding tissues and organs (eg, kidney, liver) or distant metastasis.

A typical workup of a suspected patient with pheochromocytoma includes biochemical tests, including measurements of urinary and fractionated plasma metanephrines and catecholamine. Patients with positive biochemical tests should undergo localization of the tumor with an imaging study either with an adrenal/abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scan. If a patient has paraganglioma or an adrenal mass > 10 cm or negative abdominal imaging with a positive biochemical test, further imaging with an iobenguane I-123 scan is needed (Figure 1).

In this article, we present an unusual case of asymptomatic pheochromocytoma in a patient with right-sided renal oncocytoma who underwent an uneventful nephrectomy and adrenalectomy.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male with a medical history of diabetes, hypertension, sensory neuropathy, benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) status posttransurethral resection of the prostate, and chronic renal failure presented to establish care with the Arizona Kidney Disease and Hypertension Center. His medications included losartan 50 mg by mouth daily, diltiazem 180 mg extended-release by mouth daily, carvedilol 6.25 mg by mouth twice a day, and tamsulosin 0.4 mg by mouth daily. His presenting vitals were blood pressure (BP), 112/74 left arm sitting, pulse, 63/beats per min, and body mass index, 34. On physical examination, the patient was alert and oriented, and the chest was clear to auscultation without wheeze or rhonchi. On cardiac examination, heart rate and rhythm were regular; S1 and S2 were normal with no added murmurs, rubs or gallops, and no jugular venous distension. The abdomen was soft, nontender, with no palpable mass. His laboratory results showed sodium, 142 mmol/L; potassium, 5.3 mmol/L; chloride, 101 mmol/L; carbon dioxide, 24 mmol/L; albumin, 4.3 g/dL; creatinine, 1.89 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 29 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate non-African American, 35 mL/min/1.73; 24-h urine creatinine clearance, 105 mL/min; protein, 1306 mg/24 h (Table).

His renal ultrasound showed an exophytic isoechoic mass or complex cyst at the lateral aspect of the lower pole of the right kidney, measuring 45 mm in diameter. An MRI of the abdomen with and without contrast showed a solid partially exophytic mass of the posterolateral interpolar cortex of the right kidney, measuring 5.9 cm in the greatest dimension (Figure 2). No definite involvement of Gerota fascia was noted, a 1-cm metastasis to the right adrenal gland was present, renal veins were patent, and there was no upper retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.

Treatment and Follow-up