User login

The Balance of Truth-Telling and Respect for Confidentiality: The Ethics of Case Reports

Medical case reports are as old as the healing profession itself.1 These ancient medical stories have a modern definition: “A case report is a narrative that describes, for medical, scientific or educational purposes, a medical problem experienced by one or more patients.”2 Case report experts describe the 3-fold purposes of this type of research: as a mainstay of education; a harbinger of emerging illnesses; and an appraiser of new interventions. Case-based education has long been a pillar of health professions education: Nurses, doctors, and allied health professionals are taught and learn through reading and discussing with their teachers and each other about cases of their own patients and of those in the literature.3 Case reports also have helped identify and raise awareness of new diseases and rare conditions, such as HIV.4 Finally, case reports have alerted regulatory agencies and the medical community about medication adverse effects, such as birth defects from thalidomide.5

Case reports also have been criticized on both scientific and ethical grounds. Critics argue that many case reports often lack the rigor and consistency of other types of research.6 Three recent trends in medical publication have strengthened the validity of these criticisms: the increase in the popularity of case reports; the corresponding increase in submissions to journals, including Federal Practitioner; and the rise of predatory publishers.7,8

The ethical scrutiny of case reports discussed in this column focuses on the tension between providing readers with adequate, accurate information to fulfil the goals of case reports while also protecting patient confidentiality. The latter issue during most of the history of medicine was not considered by health care professionals when the prevailing paternalism supported a professional-oriented approach to health care. The rise of bioethics in the 1960s and 1970s began the shift toward patient autonomy in medical decision making and patient rights to control their protected health information that rendered case reports ethically problematic.

To address both changes in ethical standards and scientific limitations, a committee of clinicians, researchers, and journal editors formed the Case Report (CARE) group.2,8 The group undertook an effort to improve the quality of case reports. From 2011 to 2012, they developed the CARE guidelines for clinical case reporting. The guidance took the form of a Statement and Checklist presented at the 2013 International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication. Since their presentation, multiple prestigious medical journals in many countries have implemented these recommendations.

As part of an overall effort to raise the ethical caliber of our own journal, Federal Practitioner will begin to implement the CARE guidelines for case reports for all future submissions. Use of the CARE recommendations will help prospective authors enhance the scientific value and ethical caliber of case reports submitted to the journal as well as assist the Federal Practitioner editorial team, editorial board, and peer reviewers to evaluate submissions more judiciously.

An essential part of the CARE guidelines is that the patient who is the subject of the case report provide informed consent for the publication of their personal narrative. The CARE group considers this an “ethical duty” of authors and editors alike. In “exceptional circumstances” such as if the patient is a minor or permanently incapacitated, a guardian or relative may grant consent. In the rare event that even with exhaustive attempts, if informed consent cannot be obtained from a patient or their representative, then the authors of the case report must submit a statement to this effect.4 Some journals may require that the authors obtain the approval of an institutional review board or the permission of an ethics or other institutional committee or a privacy officer.2

Requesting the patient’s consent is an extension of the shared decision making that is now a best practice in clinical care into the arena of research, making the patient or their representative a partner in the work. Ethicists have recommended inviting patients or relatives to read a draft of the case report and agree to its publication or request specific modifications to the manuscript. The CARE group rightly points out that with the rise of open notes in medical documentation, patients increasingly have access to their charts in near or real time.2 Gone are the days of Sir William Osler when only doctors read medical journals and all of these technical developments as well as standards of research and social changes in the practitioner-patient relationship make it imperative that writers and editors join together to make case reports more transparent, accurate, and consistent.7

An additional step to protect patient privacy is the requirement that authors either de-identify potentially identifiable health information, such as age, birth, death, admission, and discharge dates, or in some instances obtain separate consent for the release of that protected data.8 These restrictions constitute a challenge to case report authors who in some instances may consider these same facts critical to the integrity of the case presentation that have made some scholars doubt their continued viability. After all, the contribution of the case to the medical literature often lies in its very particularity. Conversely, no matter how frustrated we might become during writing a case report, we would not want to see our own protected health information or that of our family on a website or in print without our knowledge or approval. Indeed, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors states that “If identifying characteristics are de-identified, authors should provide assurance, and editors should so note, that such changes do not distort scientific meaning.”9

However, the exponential growth of the internet, the spread of social media, and the ubiquity of a plethora of electronic devices, which prior generations of writers and readers could not even imagine, make these limitations necessary to protect patient privacy and the public’s trust in health care professionals. The CARE guidelines can help authors of case reports hone the art of anonymizing the protected health information of subjects of case reports, such as ethnicity and occupation, while accurately conveying the clinical specifics of the case that make it valuable to students and colleagues.

We at Federal Practitioner recognize there is a real tension between truth-telling in case report publication and respect for patient confidentiality that will never be perfectly achieved, but is one that is important for medical knowledge, making it worthy of the continuous efforts of authors and editors to negotiate.

1. Nissen T, Wynn R. The history of the case report: a selective review. JRSM Open. 2014;5(4):2054270414523410. Published 2014 Mar 12. doi:10.1177/2054270414523410

2. Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201554. Published 2013 Oct 23. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201554

3. McLean SF. Case-based learning and its application in medical and health-care fields: a review of worldwide literature. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2016;3:JMECD.S20377. Published 2016 Apr 27. doi:10.4137/JMECD.S20377

4. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30(21):250-252.

5. McBride WG. Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. Lancet 1961;278(7216):1358. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)90927-8

6. Vandenbroucke JP. In defense of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(4):330-334. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-4-200102200-00017

7. Rosoff PM. Can the case report withstand ethical scrutiny? Hastings Cent Rep. 2019;49(6):17-21. doi:10.1002/hast.1065

8. Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:218-235. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026

9. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. Updated December 2021. Accessed January 31, 2022. http://www.icmje.org/news-and-editorials/new_journal_dec2021.html

Medical case reports are as old as the healing profession itself.1 These ancient medical stories have a modern definition: “A case report is a narrative that describes, for medical, scientific or educational purposes, a medical problem experienced by one or more patients.”2 Case report experts describe the 3-fold purposes of this type of research: as a mainstay of education; a harbinger of emerging illnesses; and an appraiser of new interventions. Case-based education has long been a pillar of health professions education: Nurses, doctors, and allied health professionals are taught and learn through reading and discussing with their teachers and each other about cases of their own patients and of those in the literature.3 Case reports also have helped identify and raise awareness of new diseases and rare conditions, such as HIV.4 Finally, case reports have alerted regulatory agencies and the medical community about medication adverse effects, such as birth defects from thalidomide.5

Case reports also have been criticized on both scientific and ethical grounds. Critics argue that many case reports often lack the rigor and consistency of other types of research.6 Three recent trends in medical publication have strengthened the validity of these criticisms: the increase in the popularity of case reports; the corresponding increase in submissions to journals, including Federal Practitioner; and the rise of predatory publishers.7,8

The ethical scrutiny of case reports discussed in this column focuses on the tension between providing readers with adequate, accurate information to fulfil the goals of case reports while also protecting patient confidentiality. The latter issue during most of the history of medicine was not considered by health care professionals when the prevailing paternalism supported a professional-oriented approach to health care. The rise of bioethics in the 1960s and 1970s began the shift toward patient autonomy in medical decision making and patient rights to control their protected health information that rendered case reports ethically problematic.

To address both changes in ethical standards and scientific limitations, a committee of clinicians, researchers, and journal editors formed the Case Report (CARE) group.2,8 The group undertook an effort to improve the quality of case reports. From 2011 to 2012, they developed the CARE guidelines for clinical case reporting. The guidance took the form of a Statement and Checklist presented at the 2013 International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication. Since their presentation, multiple prestigious medical journals in many countries have implemented these recommendations.

As part of an overall effort to raise the ethical caliber of our own journal, Federal Practitioner will begin to implement the CARE guidelines for case reports for all future submissions. Use of the CARE recommendations will help prospective authors enhance the scientific value and ethical caliber of case reports submitted to the journal as well as assist the Federal Practitioner editorial team, editorial board, and peer reviewers to evaluate submissions more judiciously.

An essential part of the CARE guidelines is that the patient who is the subject of the case report provide informed consent for the publication of their personal narrative. The CARE group considers this an “ethical duty” of authors and editors alike. In “exceptional circumstances” such as if the patient is a minor or permanently incapacitated, a guardian or relative may grant consent. In the rare event that even with exhaustive attempts, if informed consent cannot be obtained from a patient or their representative, then the authors of the case report must submit a statement to this effect.4 Some journals may require that the authors obtain the approval of an institutional review board or the permission of an ethics or other institutional committee or a privacy officer.2

Requesting the patient’s consent is an extension of the shared decision making that is now a best practice in clinical care into the arena of research, making the patient or their representative a partner in the work. Ethicists have recommended inviting patients or relatives to read a draft of the case report and agree to its publication or request specific modifications to the manuscript. The CARE group rightly points out that with the rise of open notes in medical documentation, patients increasingly have access to their charts in near or real time.2 Gone are the days of Sir William Osler when only doctors read medical journals and all of these technical developments as well as standards of research and social changes in the practitioner-patient relationship make it imperative that writers and editors join together to make case reports more transparent, accurate, and consistent.7

An additional step to protect patient privacy is the requirement that authors either de-identify potentially identifiable health information, such as age, birth, death, admission, and discharge dates, or in some instances obtain separate consent for the release of that protected data.8 These restrictions constitute a challenge to case report authors who in some instances may consider these same facts critical to the integrity of the case presentation that have made some scholars doubt their continued viability. After all, the contribution of the case to the medical literature often lies in its very particularity. Conversely, no matter how frustrated we might become during writing a case report, we would not want to see our own protected health information or that of our family on a website or in print without our knowledge or approval. Indeed, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors states that “If identifying characteristics are de-identified, authors should provide assurance, and editors should so note, that such changes do not distort scientific meaning.”9

However, the exponential growth of the internet, the spread of social media, and the ubiquity of a plethora of electronic devices, which prior generations of writers and readers could not even imagine, make these limitations necessary to protect patient privacy and the public’s trust in health care professionals. The CARE guidelines can help authors of case reports hone the art of anonymizing the protected health information of subjects of case reports, such as ethnicity and occupation, while accurately conveying the clinical specifics of the case that make it valuable to students and colleagues.

We at Federal Practitioner recognize there is a real tension between truth-telling in case report publication and respect for patient confidentiality that will never be perfectly achieved, but is one that is important for medical knowledge, making it worthy of the continuous efforts of authors and editors to negotiate.

Medical case reports are as old as the healing profession itself.1 These ancient medical stories have a modern definition: “A case report is a narrative that describes, for medical, scientific or educational purposes, a medical problem experienced by one or more patients.”2 Case report experts describe the 3-fold purposes of this type of research: as a mainstay of education; a harbinger of emerging illnesses; and an appraiser of new interventions. Case-based education has long been a pillar of health professions education: Nurses, doctors, and allied health professionals are taught and learn through reading and discussing with their teachers and each other about cases of their own patients and of those in the literature.3 Case reports also have helped identify and raise awareness of new diseases and rare conditions, such as HIV.4 Finally, case reports have alerted regulatory agencies and the medical community about medication adverse effects, such as birth defects from thalidomide.5

Case reports also have been criticized on both scientific and ethical grounds. Critics argue that many case reports often lack the rigor and consistency of other types of research.6 Three recent trends in medical publication have strengthened the validity of these criticisms: the increase in the popularity of case reports; the corresponding increase in submissions to journals, including Federal Practitioner; and the rise of predatory publishers.7,8

The ethical scrutiny of case reports discussed in this column focuses on the tension between providing readers with adequate, accurate information to fulfil the goals of case reports while also protecting patient confidentiality. The latter issue during most of the history of medicine was not considered by health care professionals when the prevailing paternalism supported a professional-oriented approach to health care. The rise of bioethics in the 1960s and 1970s began the shift toward patient autonomy in medical decision making and patient rights to control their protected health information that rendered case reports ethically problematic.

To address both changes in ethical standards and scientific limitations, a committee of clinicians, researchers, and journal editors formed the Case Report (CARE) group.2,8 The group undertook an effort to improve the quality of case reports. From 2011 to 2012, they developed the CARE guidelines for clinical case reporting. The guidance took the form of a Statement and Checklist presented at the 2013 International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication. Since their presentation, multiple prestigious medical journals in many countries have implemented these recommendations.

As part of an overall effort to raise the ethical caliber of our own journal, Federal Practitioner will begin to implement the CARE guidelines for case reports for all future submissions. Use of the CARE recommendations will help prospective authors enhance the scientific value and ethical caliber of case reports submitted to the journal as well as assist the Federal Practitioner editorial team, editorial board, and peer reviewers to evaluate submissions more judiciously.

An essential part of the CARE guidelines is that the patient who is the subject of the case report provide informed consent for the publication of their personal narrative. The CARE group considers this an “ethical duty” of authors and editors alike. In “exceptional circumstances” such as if the patient is a minor or permanently incapacitated, a guardian or relative may grant consent. In the rare event that even with exhaustive attempts, if informed consent cannot be obtained from a patient or their representative, then the authors of the case report must submit a statement to this effect.4 Some journals may require that the authors obtain the approval of an institutional review board or the permission of an ethics or other institutional committee or a privacy officer.2

Requesting the patient’s consent is an extension of the shared decision making that is now a best practice in clinical care into the arena of research, making the patient or their representative a partner in the work. Ethicists have recommended inviting patients or relatives to read a draft of the case report and agree to its publication or request specific modifications to the manuscript. The CARE group rightly points out that with the rise of open notes in medical documentation, patients increasingly have access to their charts in near or real time.2 Gone are the days of Sir William Osler when only doctors read medical journals and all of these technical developments as well as standards of research and social changes in the practitioner-patient relationship make it imperative that writers and editors join together to make case reports more transparent, accurate, and consistent.7

An additional step to protect patient privacy is the requirement that authors either de-identify potentially identifiable health information, such as age, birth, death, admission, and discharge dates, or in some instances obtain separate consent for the release of that protected data.8 These restrictions constitute a challenge to case report authors who in some instances may consider these same facts critical to the integrity of the case presentation that have made some scholars doubt their continued viability. After all, the contribution of the case to the medical literature often lies in its very particularity. Conversely, no matter how frustrated we might become during writing a case report, we would not want to see our own protected health information or that of our family on a website or in print without our knowledge or approval. Indeed, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors states that “If identifying characteristics are de-identified, authors should provide assurance, and editors should so note, that such changes do not distort scientific meaning.”9

However, the exponential growth of the internet, the spread of social media, and the ubiquity of a plethora of electronic devices, which prior generations of writers and readers could not even imagine, make these limitations necessary to protect patient privacy and the public’s trust in health care professionals. The CARE guidelines can help authors of case reports hone the art of anonymizing the protected health information of subjects of case reports, such as ethnicity and occupation, while accurately conveying the clinical specifics of the case that make it valuable to students and colleagues.

We at Federal Practitioner recognize there is a real tension between truth-telling in case report publication and respect for patient confidentiality that will never be perfectly achieved, but is one that is important for medical knowledge, making it worthy of the continuous efforts of authors and editors to negotiate.

1. Nissen T, Wynn R. The history of the case report: a selective review. JRSM Open. 2014;5(4):2054270414523410. Published 2014 Mar 12. doi:10.1177/2054270414523410

2. Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201554. Published 2013 Oct 23. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201554

3. McLean SF. Case-based learning and its application in medical and health-care fields: a review of worldwide literature. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2016;3:JMECD.S20377. Published 2016 Apr 27. doi:10.4137/JMECD.S20377

4. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30(21):250-252.

5. McBride WG. Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. Lancet 1961;278(7216):1358. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)90927-8

6. Vandenbroucke JP. In defense of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(4):330-334. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-4-200102200-00017

7. Rosoff PM. Can the case report withstand ethical scrutiny? Hastings Cent Rep. 2019;49(6):17-21. doi:10.1002/hast.1065

8. Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:218-235. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026

9. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. Updated December 2021. Accessed January 31, 2022. http://www.icmje.org/news-and-editorials/new_journal_dec2021.html

1. Nissen T, Wynn R. The history of the case report: a selective review. JRSM Open. 2014;5(4):2054270414523410. Published 2014 Mar 12. doi:10.1177/2054270414523410

2. Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201554. Published 2013 Oct 23. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201554

3. McLean SF. Case-based learning and its application in medical and health-care fields: a review of worldwide literature. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2016;3:JMECD.S20377. Published 2016 Apr 27. doi:10.4137/JMECD.S20377

4. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30(21):250-252.

5. McBride WG. Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. Lancet 1961;278(7216):1358. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)90927-8

6. Vandenbroucke JP. In defense of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(4):330-334. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-4-200102200-00017

7. Rosoff PM. Can the case report withstand ethical scrutiny? Hastings Cent Rep. 2019;49(6):17-21. doi:10.1002/hast.1065

8. Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:218-235. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026

9. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. Updated December 2021. Accessed January 31, 2022. http://www.icmje.org/news-and-editorials/new_journal_dec2021.html

Guttate Psoriasis Following COVID-19 Infection

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin condition affecting 1% to 5% of the world population. 1 Guttate psoriasis is a subgroup of psoriasis that most commonly presents as raindroplike, erythematous, silvery, scaly papules. There have been limited reports of guttate psoriasis caused by rhinovirus and COVID-19 infection, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term COVID-19 guttate psoriasis yielded only 3 documented cases of a psoriatic flare secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. 1-4 Herein, we detail a case in which a patient with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection who did not have a personal or family history of psoriasis experienced a moderate psoriatic flare 3 weeks after diagnosis of COVID-19.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman was diagnosed with COVID-19 after SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected from a nasopharyngeal swab. She reported moderate fatigue but no other symptoms. At the time of infection, she was not taking medications and reported neither a personal nor family history of psoriasis.

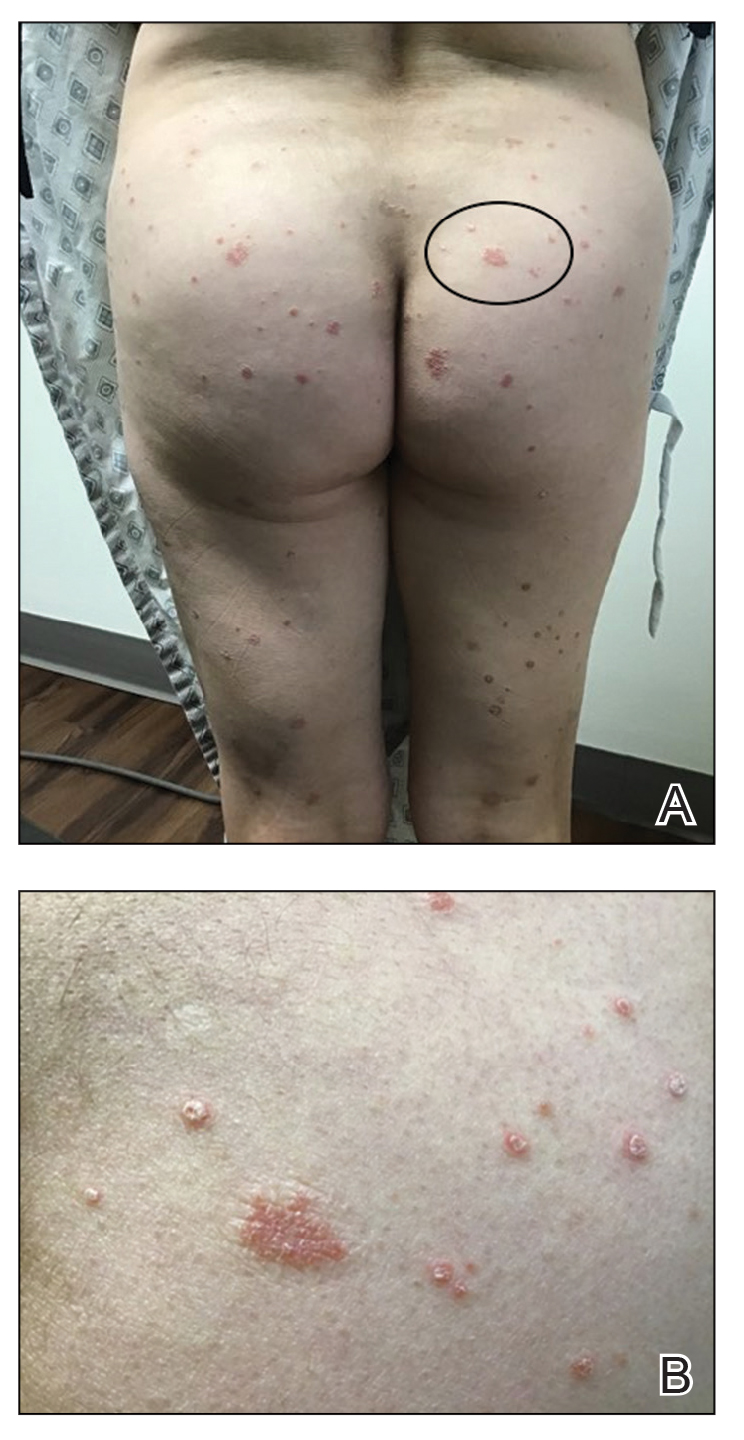

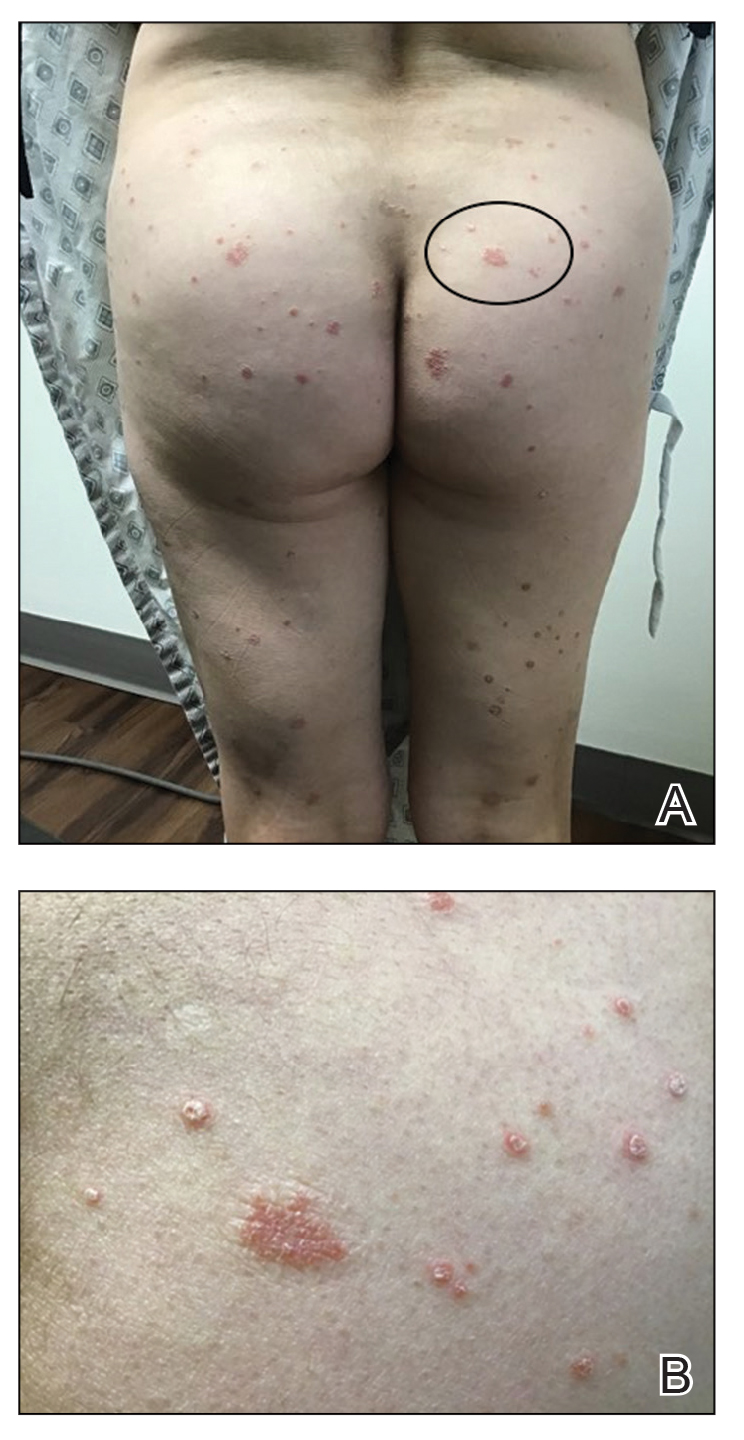

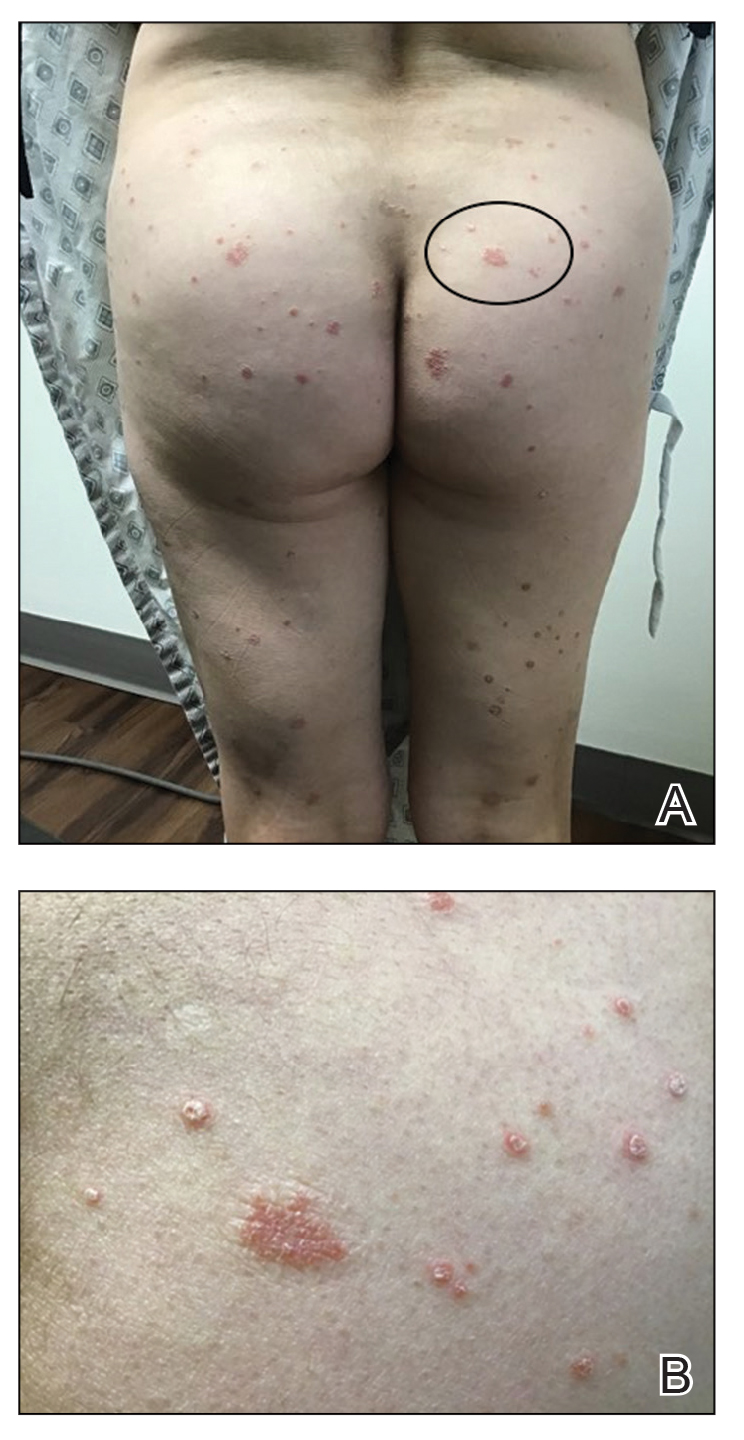

Three weeks after the COVID-19 diagnosis, she reported erythematous scaly papules only on the trunk and backs of the legs. Two months after the COVID-19 diagnosis, she was evaluated in our practice and diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. The patient refused biopsy. Physical examination revealed that the affected body surface area had increased to 5%; erythematous, silvery, scaly papules were found on the trunk, anterior and posterior legs, and lateral thighs (Figure). At the time of evaluation, she did not report joint pain or nail changes.

The patient was treated with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks. The guttate psoriasis resolved.

Comment

A sudden psoriatic flare can be linked to dysregulation of the innate immune response. Guttate psoriasis and generalized plaque-type psoriasis are postulated to have similar pathogenetic mechanisms, but guttate psoriasis is the only type of psoriasis that originates from viral infection. Initially, viral RNA will stimulate the toll-like receptor 3 protein, leading to increased production of the pathogenic cytokine IL-36γ and pathogenic chemokine CXCL8 (also known as IL-8), both of which are biomarkers for psoriasis.1 Specifically, IL-36γ and CXCL8 are known to further stimulate the proinflammatory cascade during the innate immune response displayed in guttate psoriasis.5,6

Our patient had a mild case of COVID-19, and she first reported the erythematous and scaly papules 3 weeks after infection. Dysregulation of proinflammatory cytokines must have started in the initial stages—within 7 days—of the viral infection. Guttate psoriasis arises within 3 weeks of infection with other viral and bacterial triggers, most commonly with streptococcal infections.1

Rodríguez et al7 described a phenomenon in which both SARS-CoV-2 and Middle East respiratory syndrome, both caused by a coronavirus, can lead to a reduction of type I interferon, which in turn leads to failure of control of viral replication during initial stages of a viral infection. This triggers an increase in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL‐36γ and CXCL8. This pathologic mechanism might apply to SARS-CoV-2, as demonstrated in our patient’s sudden psoriatic flare 3 weeks after the COVID-19 diagnosis. However, further investigation and quantification of the putatively involved cytokines is necessary for confirmation.

Conclusion

Psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory skin condition, has been linked predominantly to genetic and environmental factors. Guttate psoriasis as a secondary reaction after streptococcal tonsillar and respiratory infections has been reported.1

Our case is the fourth documented case of guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19 infection.2-4 However, it is the second documented case of a patient with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19 infection who had neither a personal nor family history of psoriasis.

Because SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus, the long-term effects of COVID-19 remain unclear. We report this case and its findings to introduce a novel clinical manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Sbidian E, Madrange M, Viguier M, et al. Respiratory virus infection triggers acute psoriasis flares across different clinical subtypes and genetic backgrounds. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1304-1306. doi:10.1111/bjd.18203

- Gananandan K, Sacks B, Ewing I. Guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e237367. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-237367

- Rouai M, Rabhi F, Mansouri N, et al. New-onset guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e04542. doi:10.1002/ccr3.4542

- Agarwal A, Tripathy T, Kar BR. Guttate flare in a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis following COVID-19 infection: a case report. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3064-3065. doi:10.1111/jocd.14396

- Madonna S, Girolomoni G, Dinarello CA, et al. The significance of IL-36 hyperactivation and IL-36R targeting in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3318. doi:10.3390/ijms20133318

- Nedoszytko B, Sokołowska-Wojdyło M, Ruckemann-Dziurdzin´ska K, et al. Chemokines and cytokines network in the pathogenesis of the inflammatory skin diseases: atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and skin mastocytosis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:84-91. doi:10.5114/pdia.2014.40920

- Rodríguez Y, Novelli L, Rojas M, et al. Autoinflammatory and autoimmune conditions at the crossroad of COVID-19. J Autoimmun. 2020;114:102506. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102506

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin condition affecting 1% to 5% of the world population. 1 Guttate psoriasis is a subgroup of psoriasis that most commonly presents as raindroplike, erythematous, silvery, scaly papules. There have been limited reports of guttate psoriasis caused by rhinovirus and COVID-19 infection, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term COVID-19 guttate psoriasis yielded only 3 documented cases of a psoriatic flare secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. 1-4 Herein, we detail a case in which a patient with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection who did not have a personal or family history of psoriasis experienced a moderate psoriatic flare 3 weeks after diagnosis of COVID-19.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman was diagnosed with COVID-19 after SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected from a nasopharyngeal swab. She reported moderate fatigue but no other symptoms. At the time of infection, she was not taking medications and reported neither a personal nor family history of psoriasis.

Three weeks after the COVID-19 diagnosis, she reported erythematous scaly papules only on the trunk and backs of the legs. Two months after the COVID-19 diagnosis, she was evaluated in our practice and diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. The patient refused biopsy. Physical examination revealed that the affected body surface area had increased to 5%; erythematous, silvery, scaly papules were found on the trunk, anterior and posterior legs, and lateral thighs (Figure). At the time of evaluation, she did not report joint pain or nail changes.

The patient was treated with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks. The guttate psoriasis resolved.

Comment

A sudden psoriatic flare can be linked to dysregulation of the innate immune response. Guttate psoriasis and generalized plaque-type psoriasis are postulated to have similar pathogenetic mechanisms, but guttate psoriasis is the only type of psoriasis that originates from viral infection. Initially, viral RNA will stimulate the toll-like receptor 3 protein, leading to increased production of the pathogenic cytokine IL-36γ and pathogenic chemokine CXCL8 (also known as IL-8), both of which are biomarkers for psoriasis.1 Specifically, IL-36γ and CXCL8 are known to further stimulate the proinflammatory cascade during the innate immune response displayed in guttate psoriasis.5,6

Our patient had a mild case of COVID-19, and she first reported the erythematous and scaly papules 3 weeks after infection. Dysregulation of proinflammatory cytokines must have started in the initial stages—within 7 days—of the viral infection. Guttate psoriasis arises within 3 weeks of infection with other viral and bacterial triggers, most commonly with streptococcal infections.1

Rodríguez et al7 described a phenomenon in which both SARS-CoV-2 and Middle East respiratory syndrome, both caused by a coronavirus, can lead to a reduction of type I interferon, which in turn leads to failure of control of viral replication during initial stages of a viral infection. This triggers an increase in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL‐36γ and CXCL8. This pathologic mechanism might apply to SARS-CoV-2, as demonstrated in our patient’s sudden psoriatic flare 3 weeks after the COVID-19 diagnosis. However, further investigation and quantification of the putatively involved cytokines is necessary for confirmation.

Conclusion

Psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory skin condition, has been linked predominantly to genetic and environmental factors. Guttate psoriasis as a secondary reaction after streptococcal tonsillar and respiratory infections has been reported.1

Our case is the fourth documented case of guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19 infection.2-4 However, it is the second documented case of a patient with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19 infection who had neither a personal nor family history of psoriasis.

Because SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus, the long-term effects of COVID-19 remain unclear. We report this case and its findings to introduce a novel clinical manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin condition affecting 1% to 5% of the world population. 1 Guttate psoriasis is a subgroup of psoriasis that most commonly presents as raindroplike, erythematous, silvery, scaly papules. There have been limited reports of guttate psoriasis caused by rhinovirus and COVID-19 infection, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term COVID-19 guttate psoriasis yielded only 3 documented cases of a psoriatic flare secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. 1-4 Herein, we detail a case in which a patient with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection who did not have a personal or family history of psoriasis experienced a moderate psoriatic flare 3 weeks after diagnosis of COVID-19.

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman was diagnosed with COVID-19 after SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected from a nasopharyngeal swab. She reported moderate fatigue but no other symptoms. At the time of infection, she was not taking medications and reported neither a personal nor family history of psoriasis.

Three weeks after the COVID-19 diagnosis, she reported erythematous scaly papules only on the trunk and backs of the legs. Two months after the COVID-19 diagnosis, she was evaluated in our practice and diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. The patient refused biopsy. Physical examination revealed that the affected body surface area had increased to 5%; erythematous, silvery, scaly papules were found on the trunk, anterior and posterior legs, and lateral thighs (Figure). At the time of evaluation, she did not report joint pain or nail changes.

The patient was treated with triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks. The guttate psoriasis resolved.

Comment

A sudden psoriatic flare can be linked to dysregulation of the innate immune response. Guttate psoriasis and generalized plaque-type psoriasis are postulated to have similar pathogenetic mechanisms, but guttate psoriasis is the only type of psoriasis that originates from viral infection. Initially, viral RNA will stimulate the toll-like receptor 3 protein, leading to increased production of the pathogenic cytokine IL-36γ and pathogenic chemokine CXCL8 (also known as IL-8), both of which are biomarkers for psoriasis.1 Specifically, IL-36γ and CXCL8 are known to further stimulate the proinflammatory cascade during the innate immune response displayed in guttate psoriasis.5,6

Our patient had a mild case of COVID-19, and she first reported the erythematous and scaly papules 3 weeks after infection. Dysregulation of proinflammatory cytokines must have started in the initial stages—within 7 days—of the viral infection. Guttate psoriasis arises within 3 weeks of infection with other viral and bacterial triggers, most commonly with streptococcal infections.1

Rodríguez et al7 described a phenomenon in which both SARS-CoV-2 and Middle East respiratory syndrome, both caused by a coronavirus, can lead to a reduction of type I interferon, which in turn leads to failure of control of viral replication during initial stages of a viral infection. This triggers an increase in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL‐36γ and CXCL8. This pathologic mechanism might apply to SARS-CoV-2, as demonstrated in our patient’s sudden psoriatic flare 3 weeks after the COVID-19 diagnosis. However, further investigation and quantification of the putatively involved cytokines is necessary for confirmation.

Conclusion

Psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory skin condition, has been linked predominantly to genetic and environmental factors. Guttate psoriasis as a secondary reaction after streptococcal tonsillar and respiratory infections has been reported.1

Our case is the fourth documented case of guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19 infection.2-4 However, it is the second documented case of a patient with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19 infection who had neither a personal nor family history of psoriasis.

Because SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus, the long-term effects of COVID-19 remain unclear. We report this case and its findings to introduce a novel clinical manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Sbidian E, Madrange M, Viguier M, et al. Respiratory virus infection triggers acute psoriasis flares across different clinical subtypes and genetic backgrounds. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1304-1306. doi:10.1111/bjd.18203

- Gananandan K, Sacks B, Ewing I. Guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e237367. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-237367

- Rouai M, Rabhi F, Mansouri N, et al. New-onset guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e04542. doi:10.1002/ccr3.4542

- Agarwal A, Tripathy T, Kar BR. Guttate flare in a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis following COVID-19 infection: a case report. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3064-3065. doi:10.1111/jocd.14396

- Madonna S, Girolomoni G, Dinarello CA, et al. The significance of IL-36 hyperactivation and IL-36R targeting in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3318. doi:10.3390/ijms20133318

- Nedoszytko B, Sokołowska-Wojdyło M, Ruckemann-Dziurdzin´ska K, et al. Chemokines and cytokines network in the pathogenesis of the inflammatory skin diseases: atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and skin mastocytosis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:84-91. doi:10.5114/pdia.2014.40920

- Rodríguez Y, Novelli L, Rojas M, et al. Autoinflammatory and autoimmune conditions at the crossroad of COVID-19. J Autoimmun. 2020;114:102506. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102506

- Sbidian E, Madrange M, Viguier M, et al. Respiratory virus infection triggers acute psoriasis flares across different clinical subtypes and genetic backgrounds. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1304-1306. doi:10.1111/bjd.18203

- Gananandan K, Sacks B, Ewing I. Guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e237367. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-237367

- Rouai M, Rabhi F, Mansouri N, et al. New-onset guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e04542. doi:10.1002/ccr3.4542

- Agarwal A, Tripathy T, Kar BR. Guttate flare in a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis following COVID-19 infection: a case report. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3064-3065. doi:10.1111/jocd.14396

- Madonna S, Girolomoni G, Dinarello CA, et al. The significance of IL-36 hyperactivation and IL-36R targeting in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3318. doi:10.3390/ijms20133318

- Nedoszytko B, Sokołowska-Wojdyło M, Ruckemann-Dziurdzin´ska K, et al. Chemokines and cytokines network in the pathogenesis of the inflammatory skin diseases: atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and skin mastocytosis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:84-91. doi:10.5114/pdia.2014.40920

- Rodríguez Y, Novelli L, Rojas M, et al. Autoinflammatory and autoimmune conditions at the crossroad of COVID-19. J Autoimmun. 2020;114:102506. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102506

Practice Points

- Guttate psoriasis is the only type of psoriasis that originates from viral infection.

- Dysregulation of proinflammatory cytokines during COVID-19 infection in our patient led to development of guttate psoriasis 3 weeks later.

Severe Acute Systemic Reaction After the First Injections of Ixekizumab

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with fatigue, malaise, a resolving rash, focal lymphadenopathy, increasing distal arthritis, dactylitis, resolving ecchymoses, and acute onycholysis of 1 week’s duration that developed 13 days after initiating ixekizumab. The patient had a history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis for more than 10 years. She had been successfully treated in the past for psoriasis with adalimumab for several years; however, adalimumab was discontinued after an episode of Clostridium difficile colitis. The patient had a negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test prior to starting biologics as she works in the health care field. Routine follow-up purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test was positive. She discontinued all therapy for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis prior to being appropriately treated for 6 months under the care of infectious disease physicians. She then had several pregnancies and chose to restart biologic treatment after weaning her third child from breastfeeding, as her skin and joint disease were notably flaring.

Ustekinumab was chosen to shift treatment away from tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors. The patient's condition was under relatively good control for 1 year; however, she experienced notable gastrointestinal tract upset (ie, intermittent diarrhea and constipation), despite multiple negative tests for C difficile. The patient was referred to see a gastroenterologist but never followed up. Due to long-term low-grade gastrointestinal problems, ustekinumab was discontinued, and the gastrointestinal symptoms resolved without treatment.

Given the side effects noted with TNF-α and IL-12/23 inhibitors and the fact that the patient’s cutaneous and joint disease were notable, the decision was made to start the IL-17A inhibitor ixekizumab. The patient administered 2 injections, one in each thigh. Within 12 hours, she experienced severe injection-site pain. The pain was so severe that it woke her from sleep the night of the first injections. She then developed severe pain in the right axilla that limited upper extremity mobility. Within 48 hours, she developed an erythematous, nonpruritic, nonscaly, mottled rash on the right breast that began to resolve within 24 hours without treatment. In addition, 3 days after the injections, she developed ecchymoses on the trunk and extremities without any identifiable trauma, severe acute onycholysis in several fingernails (Figure 1) and toenails, dactylitis such that she could not wear her wedding ring, and a flare of psoriatic arthritis in the fingers and ankles.

At the current presentation (2 weeks after the injections), the patient reported malaise, flulike symptoms, and low-grade intermittent fevers. Results from a hematology panel displayed leukopenia at 2.69×103/μL (reference range, 3.54–9.06×103/μL) and thrombocytopenia at 114×103/μL (reference range, 165–415×103/μL).1 Her most recent laboratory results before the ixekizumab injections displayed a white blood cell count level at 4.6×103/μL and platelet count at 159×103/μL. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within reference range. A shave biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fourth finger on the right hand displayed spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 2).

Interestingly, the psoriatic plaques on the scalp, trunk, and extremities had nearly completely resolved after only the first 2 injections. However, given the side effects, the second dose of ixekizumab was held, repeat laboratory tests were ordered to ensure normalization of cytopenia, and the patient was transitioned to pulse-dose topical steroids to control the remaining psoriatic plaques.

One week after presentation (3 weeks after the initial injections), the patient’s systemic symptoms had almost completely resolved, and she denied any further concerns. Her fingernails and toenails, however, continued to show the changes of onycholysis noted at the visit.

Comment

Ixekizumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-17A, one of the cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. The monoclonal antibody prevents its attachment to the IL-17 receptor, which inhibits the release of further cytokines and chemokines, decreasing the inflammatory and immune response.2

Ixekizumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis after 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—were performed. In UNCOVER-3, the most common side effects that occurred—nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, injection-site reaction, arthralgia, headache, and infections (specifically candidiasis)—generally were well tolerated. More serious adverse events included cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, inflammatory bowel disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer.3

Notable laboratory abnormalities that have been documented from ixekizumab include elevated liver function tests (eg, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase), as well as leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.4 Although short-term thrombocytopenia, as described in our patient, provides an explanation for the bruising noted on observation, it is unusual to note such notable ecchymoses within days of the first injection.

Onycholysis has not been documented as a side effect of ixekizumab; however, it has been reported as an adverse event from other biologic medications. Sfikakis et al5 reported 5 patients who developed psoriatic skin lesions after treatment with 3 different anti-TNF biologics—infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—fo

The exact pathophysiology of these adverse events has not been clearly understood, but it has been proposed that anti-TNF biologics may initiate an autoimmune reaction in the skin and nails, leading to paradoxical psoriasis and nail changes such as onycholysis. Tumor necrosis factor may have a regulatory role in the skin that prevents autoreactive T cells, such as cutaneous lymphocyte antigen–expressing T cells that promote the formation of psoriasiform lesions. By inhibiting TNF, there can be an underlying activation of autoreactive T cells that leads to tissue destruction in the skin and nails.6 Anti-TNF biologics also could increase CXCR3, a chemokine receptor that allows autoreactive T cells to enter the skin and cause pathology.7

IL-17A and IL-17F also have been shown to upregulate the expression of TNF receptor II in synoviocytes,8 which demonstrates that IL-17 works in synergy with TNF-α to promote an inflammatory reaction.9 Due to the inhibitory effects of ixekizumab, psoriatic arthritis should theoretically improve. However, if there is an alteration in the inflammatory sequence, then the regulatory role of TNF could be suppressed and psoriatic arthritis could become exacerbated. Additionally, its associated symptoms, such as dactylitis, could develop, as seen in our patient.4 Because psoriatic arthritis is closely associated with nail changes of psoriasis, it is conceivable that acute arthritic flares and acute onycholysis are both induced by the same cytokine dysregulation. Further studies and a larger patient population need to be evaluated to determine the exact cause of the acute exacerbation of psoriatic arthritis with concomitant nail changes as noted in our patient.

Acute onycholysis (within 72 hours) is a rare side effect of ixekizumab. It can be postulated that our patient’s severe acute onycholysis associated with a flare of psoriatic arthritis could be due to idiosyncratic immune dysregulation, promoting the activity of autoreactive T cells. The pharmacologic effects of ixekizumab occur through the inhibition of IL-17. We propose that by inhibiting IL-17 with associated TNF alterations, an altered inflammatory cascade could promote an autoimmune reaction leading to the described pathology.

- Kratz A, Pesce MA, Basner RC, et al. Laboratory values of clinical importance. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2014.

- Ixekizumab. Package insert. Eli Lilly & Co; 2017.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1190-1199.

- Sfikakis PP, Iliopoulos A, Elezoglou A, et al. Psoriasis induced by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: a paradoxical adverse reaction. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2513-2518.

- Berg EL, Yoshino T, Rott LS, et al. The cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is a skin lymphocyte homing receptor for the vascular lectin endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1461-1466.

- Flier J, Boorsma DM, van Beek PJ, et al. Differential expression of CXCR3 targeting chemokines CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 in different types of skin inflammation. J Pathol. 2001;194:398-405.

- Zrioual S, Ecochard R, Tournadre A, et al. Genome-wide comparison between IL-17A- and IL-17F-induced effects in human rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. J Immunol. 2009;182:3112-3120.

- Gaffen SL. The role of interleukin-17 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11:365-370.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with fatigue, malaise, a resolving rash, focal lymphadenopathy, increasing distal arthritis, dactylitis, resolving ecchymoses, and acute onycholysis of 1 week’s duration that developed 13 days after initiating ixekizumab. The patient had a history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis for more than 10 years. She had been successfully treated in the past for psoriasis with adalimumab for several years; however, adalimumab was discontinued after an episode of Clostridium difficile colitis. The patient had a negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test prior to starting biologics as she works in the health care field. Routine follow-up purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test was positive. She discontinued all therapy for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis prior to being appropriately treated for 6 months under the care of infectious disease physicians. She then had several pregnancies and chose to restart biologic treatment after weaning her third child from breastfeeding, as her skin and joint disease were notably flaring.

Ustekinumab was chosen to shift treatment away from tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors. The patient's condition was under relatively good control for 1 year; however, she experienced notable gastrointestinal tract upset (ie, intermittent diarrhea and constipation), despite multiple negative tests for C difficile. The patient was referred to see a gastroenterologist but never followed up. Due to long-term low-grade gastrointestinal problems, ustekinumab was discontinued, and the gastrointestinal symptoms resolved without treatment.

Given the side effects noted with TNF-α and IL-12/23 inhibitors and the fact that the patient’s cutaneous and joint disease were notable, the decision was made to start the IL-17A inhibitor ixekizumab. The patient administered 2 injections, one in each thigh. Within 12 hours, she experienced severe injection-site pain. The pain was so severe that it woke her from sleep the night of the first injections. She then developed severe pain in the right axilla that limited upper extremity mobility. Within 48 hours, she developed an erythematous, nonpruritic, nonscaly, mottled rash on the right breast that began to resolve within 24 hours without treatment. In addition, 3 days after the injections, she developed ecchymoses on the trunk and extremities without any identifiable trauma, severe acute onycholysis in several fingernails (Figure 1) and toenails, dactylitis such that she could not wear her wedding ring, and a flare of psoriatic arthritis in the fingers and ankles.

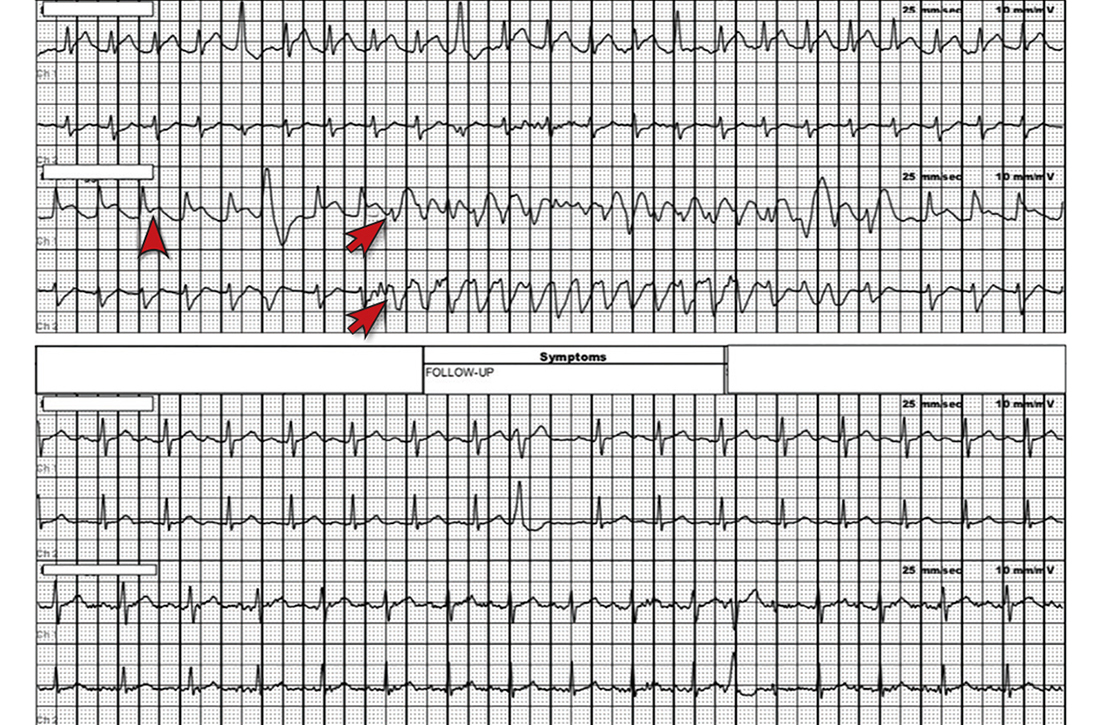

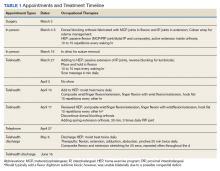

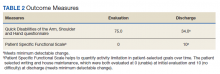

At the current presentation (2 weeks after the injections), the patient reported malaise, flulike symptoms, and low-grade intermittent fevers. Results from a hematology panel displayed leukopenia at 2.69×103/μL (reference range, 3.54–9.06×103/μL) and thrombocytopenia at 114×103/μL (reference range, 165–415×103/μL).1 Her most recent laboratory results before the ixekizumab injections displayed a white blood cell count level at 4.6×103/μL and platelet count at 159×103/μL. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within reference range. A shave biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fourth finger on the right hand displayed spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 2).

Interestingly, the psoriatic plaques on the scalp, trunk, and extremities had nearly completely resolved after only the first 2 injections. However, given the side effects, the second dose of ixekizumab was held, repeat laboratory tests were ordered to ensure normalization of cytopenia, and the patient was transitioned to pulse-dose topical steroids to control the remaining psoriatic plaques.

One week after presentation (3 weeks after the initial injections), the patient’s systemic symptoms had almost completely resolved, and she denied any further concerns. Her fingernails and toenails, however, continued to show the changes of onycholysis noted at the visit.

Comment

Ixekizumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-17A, one of the cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. The monoclonal antibody prevents its attachment to the IL-17 receptor, which inhibits the release of further cytokines and chemokines, decreasing the inflammatory and immune response.2

Ixekizumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis after 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—were performed. In UNCOVER-3, the most common side effects that occurred—nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, injection-site reaction, arthralgia, headache, and infections (specifically candidiasis)—generally were well tolerated. More serious adverse events included cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, inflammatory bowel disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer.3

Notable laboratory abnormalities that have been documented from ixekizumab include elevated liver function tests (eg, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase), as well as leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.4 Although short-term thrombocytopenia, as described in our patient, provides an explanation for the bruising noted on observation, it is unusual to note such notable ecchymoses within days of the first injection.

Onycholysis has not been documented as a side effect of ixekizumab; however, it has been reported as an adverse event from other biologic medications. Sfikakis et al5 reported 5 patients who developed psoriatic skin lesions after treatment with 3 different anti-TNF biologics—infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—fo

The exact pathophysiology of these adverse events has not been clearly understood, but it has been proposed that anti-TNF biologics may initiate an autoimmune reaction in the skin and nails, leading to paradoxical psoriasis and nail changes such as onycholysis. Tumor necrosis factor may have a regulatory role in the skin that prevents autoreactive T cells, such as cutaneous lymphocyte antigen–expressing T cells that promote the formation of psoriasiform lesions. By inhibiting TNF, there can be an underlying activation of autoreactive T cells that leads to tissue destruction in the skin and nails.6 Anti-TNF biologics also could increase CXCR3, a chemokine receptor that allows autoreactive T cells to enter the skin and cause pathology.7

IL-17A and IL-17F also have been shown to upregulate the expression of TNF receptor II in synoviocytes,8 which demonstrates that IL-17 works in synergy with TNF-α to promote an inflammatory reaction.9 Due to the inhibitory effects of ixekizumab, psoriatic arthritis should theoretically improve. However, if there is an alteration in the inflammatory sequence, then the regulatory role of TNF could be suppressed and psoriatic arthritis could become exacerbated. Additionally, its associated symptoms, such as dactylitis, could develop, as seen in our patient.4 Because psoriatic arthritis is closely associated with nail changes of psoriasis, it is conceivable that acute arthritic flares and acute onycholysis are both induced by the same cytokine dysregulation. Further studies and a larger patient population need to be evaluated to determine the exact cause of the acute exacerbation of psoriatic arthritis with concomitant nail changes as noted in our patient.

Acute onycholysis (within 72 hours) is a rare side effect of ixekizumab. It can be postulated that our patient’s severe acute onycholysis associated with a flare of psoriatic arthritis could be due to idiosyncratic immune dysregulation, promoting the activity of autoreactive T cells. The pharmacologic effects of ixekizumab occur through the inhibition of IL-17. We propose that by inhibiting IL-17 with associated TNF alterations, an altered inflammatory cascade could promote an autoimmune reaction leading to the described pathology.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with fatigue, malaise, a resolving rash, focal lymphadenopathy, increasing distal arthritis, dactylitis, resolving ecchymoses, and acute onycholysis of 1 week’s duration that developed 13 days after initiating ixekizumab. The patient had a history of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis for more than 10 years. She had been successfully treated in the past for psoriasis with adalimumab for several years; however, adalimumab was discontinued after an episode of Clostridium difficile colitis. The patient had a negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test prior to starting biologics as she works in the health care field. Routine follow-up purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test was positive. She discontinued all therapy for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis prior to being appropriately treated for 6 months under the care of infectious disease physicians. She then had several pregnancies and chose to restart biologic treatment after weaning her third child from breastfeeding, as her skin and joint disease were notably flaring.

Ustekinumab was chosen to shift treatment away from tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors. The patient's condition was under relatively good control for 1 year; however, she experienced notable gastrointestinal tract upset (ie, intermittent diarrhea and constipation), despite multiple negative tests for C difficile. The patient was referred to see a gastroenterologist but never followed up. Due to long-term low-grade gastrointestinal problems, ustekinumab was discontinued, and the gastrointestinal symptoms resolved without treatment.

Given the side effects noted with TNF-α and IL-12/23 inhibitors and the fact that the patient’s cutaneous and joint disease were notable, the decision was made to start the IL-17A inhibitor ixekizumab. The patient administered 2 injections, one in each thigh. Within 12 hours, she experienced severe injection-site pain. The pain was so severe that it woke her from sleep the night of the first injections. She then developed severe pain in the right axilla that limited upper extremity mobility. Within 48 hours, she developed an erythematous, nonpruritic, nonscaly, mottled rash on the right breast that began to resolve within 24 hours without treatment. In addition, 3 days after the injections, she developed ecchymoses on the trunk and extremities without any identifiable trauma, severe acute onycholysis in several fingernails (Figure 1) and toenails, dactylitis such that she could not wear her wedding ring, and a flare of psoriatic arthritis in the fingers and ankles.

At the current presentation (2 weeks after the injections), the patient reported malaise, flulike symptoms, and low-grade intermittent fevers. Results from a hematology panel displayed leukopenia at 2.69×103/μL (reference range, 3.54–9.06×103/μL) and thrombocytopenia at 114×103/μL (reference range, 165–415×103/μL).1 Her most recent laboratory results before the ixekizumab injections displayed a white blood cell count level at 4.6×103/μL and platelet count at 159×103/μL. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within reference range. A shave biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the proximal interphalangeal joint of the fourth finger on the right hand displayed spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 2).

Interestingly, the psoriatic plaques on the scalp, trunk, and extremities had nearly completely resolved after only the first 2 injections. However, given the side effects, the second dose of ixekizumab was held, repeat laboratory tests were ordered to ensure normalization of cytopenia, and the patient was transitioned to pulse-dose topical steroids to control the remaining psoriatic plaques.

One week after presentation (3 weeks after the initial injections), the patient’s systemic symptoms had almost completely resolved, and she denied any further concerns. Her fingernails and toenails, however, continued to show the changes of onycholysis noted at the visit.

Comment

Ixekizumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-17A, one of the cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. The monoclonal antibody prevents its attachment to the IL-17 receptor, which inhibits the release of further cytokines and chemokines, decreasing the inflammatory and immune response.2

Ixekizumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis after 3 clinical trials—UNCOVER-1, UNCOVER-2, and UNCOVER-3—were performed. In UNCOVER-3, the most common side effects that occurred—nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, injection-site reaction, arthralgia, headache, and infections (specifically candidiasis)—generally were well tolerated. More serious adverse events included cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, inflammatory bowel disease, and nonmelanoma skin cancer.3

Notable laboratory abnormalities that have been documented from ixekizumab include elevated liver function tests (eg, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase), as well as leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.4 Although short-term thrombocytopenia, as described in our patient, provides an explanation for the bruising noted on observation, it is unusual to note such notable ecchymoses within days of the first injection.

Onycholysis has not been documented as a side effect of ixekizumab; however, it has been reported as an adverse event from other biologic medications. Sfikakis et al5 reported 5 patients who developed psoriatic skin lesions after treatment with 3 different anti-TNF biologics—infliximab, adalimumab, or etanercept—fo

The exact pathophysiology of these adverse events has not been clearly understood, but it has been proposed that anti-TNF biologics may initiate an autoimmune reaction in the skin and nails, leading to paradoxical psoriasis and nail changes such as onycholysis. Tumor necrosis factor may have a regulatory role in the skin that prevents autoreactive T cells, such as cutaneous lymphocyte antigen–expressing T cells that promote the formation of psoriasiform lesions. By inhibiting TNF, there can be an underlying activation of autoreactive T cells that leads to tissue destruction in the skin and nails.6 Anti-TNF biologics also could increase CXCR3, a chemokine receptor that allows autoreactive T cells to enter the skin and cause pathology.7

IL-17A and IL-17F also have been shown to upregulate the expression of TNF receptor II in synoviocytes,8 which demonstrates that IL-17 works in synergy with TNF-α to promote an inflammatory reaction.9 Due to the inhibitory effects of ixekizumab, psoriatic arthritis should theoretically improve. However, if there is an alteration in the inflammatory sequence, then the regulatory role of TNF could be suppressed and psoriatic arthritis could become exacerbated. Additionally, its associated symptoms, such as dactylitis, could develop, as seen in our patient.4 Because psoriatic arthritis is closely associated with nail changes of psoriasis, it is conceivable that acute arthritic flares and acute onycholysis are both induced by the same cytokine dysregulation. Further studies and a larger patient population need to be evaluated to determine the exact cause of the acute exacerbation of psoriatic arthritis with concomitant nail changes as noted in our patient.

Acute onycholysis (within 72 hours) is a rare side effect of ixekizumab. It can be postulated that our patient’s severe acute onycholysis associated with a flare of psoriatic arthritis could be due to idiosyncratic immune dysregulation, promoting the activity of autoreactive T cells. The pharmacologic effects of ixekizumab occur through the inhibition of IL-17. We propose that by inhibiting IL-17 with associated TNF alterations, an altered inflammatory cascade could promote an autoimmune reaction leading to the described pathology.

- Kratz A, Pesce MA, Basner RC, et al. Laboratory values of clinical importance. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2014.

- Ixekizumab. Package insert. Eli Lilly & Co; 2017.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1190-1199.

- Sfikakis PP, Iliopoulos A, Elezoglou A, et al. Psoriasis induced by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: a paradoxical adverse reaction. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2513-2518.

- Berg EL, Yoshino T, Rott LS, et al. The cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is a skin lymphocyte homing receptor for the vascular lectin endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1461-1466.

- Flier J, Boorsma DM, van Beek PJ, et al. Differential expression of CXCR3 targeting chemokines CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 in different types of skin inflammation. J Pathol. 2001;194:398-405.

- Zrioual S, Ecochard R, Tournadre A, et al. Genome-wide comparison between IL-17A- and IL-17F-induced effects in human rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. J Immunol. 2009;182:3112-3120.

- Gaffen SL. The role of interleukin-17 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11:365-370.

- Kratz A, Pesce MA, Basner RC, et al. Laboratory values of clinical importance. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2014.

- Ixekizumab. Package insert. Eli Lilly & Co; 2017.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1190-1199.

- Sfikakis PP, Iliopoulos A, Elezoglou A, et al. Psoriasis induced by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: a paradoxical adverse reaction. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2513-2518.

- Berg EL, Yoshino T, Rott LS, et al. The cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is a skin lymphocyte homing receptor for the vascular lectin endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1461-1466.

- Flier J, Boorsma DM, van Beek PJ, et al. Differential expression of CXCR3 targeting chemokines CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 in different types of skin inflammation. J Pathol. 2001;194:398-405.

- Zrioual S, Ecochard R, Tournadre A, et al. Genome-wide comparison between IL-17A- and IL-17F-induced effects in human rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. J Immunol. 2009;182:3112-3120.

- Gaffen SL. The role of interleukin-17 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11:365-370.

Practice Points

- Psoriasis is an autoimmune disorder with a predominance of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that release cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor 11α and interleukins, which promote inflammation in the skin and joints and is associated with systemic inflammation predisposing patients to cardiovascular disease.

- Common adverse effects of most biologic medications for psoriasis include injection-site pain and rash, fever, malaise, back pain, urticaria and flushing, edema, dyspnea, and nausea.

- Ixekizumab is a humanized IL-17A antagonist intended for adults with moderate to severe psoriasis. Certain rare side effects specific to ixekizumab include inflammatory bowel disease, thrombocytopenia, severe injection-site reactions, and candidiasis.

- Acute onycholysis and acute exacerbation of arthritis/dactylitis are rare side effects of ixekizumab therapy.

58-year-old man • bilateral shoulder pain • history of prostate cancer • limited shoulder range of motion • Dx?

THE CASE

A 58-year-old African American man with a past medical history of prostate cancer, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease presented to our office to establish care with a new provider. He complained of bilateral shoulder pain, that was worse on the right side, for the past year. He denied any previous falls, trauma, or injury. He reported that lifting his grandkids was becoming increasingly difficult due to the pain but denied any weakness or neurologic symptoms. He had been using over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which provided minimal relief.

On physical examination, the overlying skin was normal and there was no tenderness to palpation. His shoulder range of motion was limited with complete flexion, but otherwise intact. Muscle strength was 5 out of 5 bilaterally, and neurovascular and sensory examinations were normal. On the right side, the Empty Can Test was positive, but the Neer and Apley tests were negative. All testing was negative on the left side.

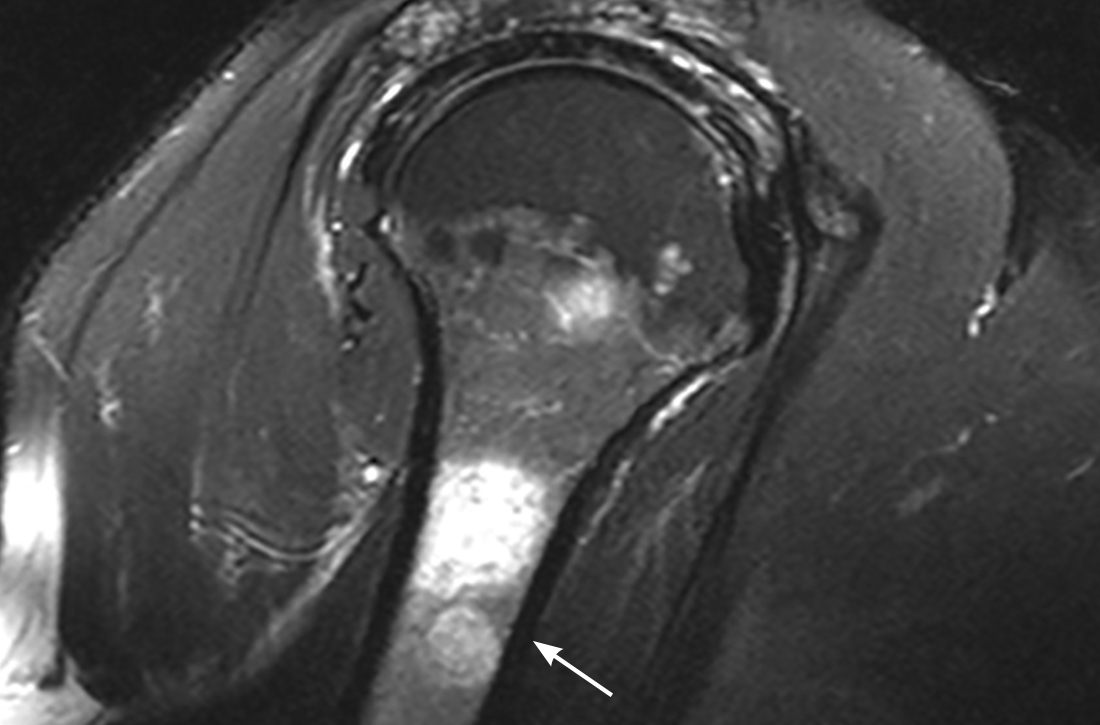

The patient was referred for 10 sessions of physical therapy, which he completed. His pain persisted, and an x-ray of his right shoulder was performed. The x-ray indicated a high-riding humeral head, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the right shoulder was recommended due to possible rotator cuff tendinopathy.

The MRI demonstrated a full-thickness tear of the distal supraspinatus tendon along with “metastatic lesions” (FIGURE). As a result, a bone scan was obtained and revealed activity in the proximal right humerus; however, it was nonconclusive for osteoblastic metastasis. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan was ordered, which revealed findings suggestive of bony metastasis in the proximal left tibia, distal shaft of the right tibia, and the right and left humeral heads. The patient was then scheduled for a bone biopsy; a chest, abdomen, and pelvis computed tomography (CT) scan with IV and oral contrast was also ordered.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A bone biopsy of the left tibia indicated prominent non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and stains were negative for microorganisms. The CT scan demonstrated peribronchial vascular reticulonodular opacities in the upper lung zones compatible with sarcoidosis; no metastatic lesions were identified. Laboratory studies were obtained and demonstrated an elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level consistent with sarcoidosis. The cumulative test results pointed to a diagnosis of osseous sarcoidosis.

DISCUSSION

Osseous sarcoidosis is a rare manifestation of larger systemic disease. It is estimated that bony lesions occur in only 3% to 13% of patients with sarcoidosis.1 Bone involvement is most common in African Americans and occurs primarily in the hands and feet.1-3

Osseous lesions are comprised of noncaseating granulomatous inflammation.4,5 They are often asymptomatic but can be painful and associated with overlying skin disease and soft-tissue swelling.1,4 Although it’s not typical, patients may present with symptoms such as pain, stiffness, or fractures. On CT imaging and MRI (as in this case), osseous lesions can be confused with metastatic bone disease, and biopsy may be required for diagnosis.4

Continue to: There are multiple patterns of bone involvement

There are multiple patterns of bone involvement in osseous sarcoidosis, ranging from large cystic lesions that can lead to stress fractures to “tunnels” or “lace-like” reticulated patterns found in the bones of the hands and feet. 2,3,5,6 Long bone involvement is typically limited to the proximal and distal thirds of the bone.6 Sarcoidosis is also known to involve the axial skeleton, and less commonly, the cranial vault.6 Although multiple variations may manifest over time, skin changes usually precede bone lesions3,6; however, that was not the case with this patient.

Treatment entails pain management

Up to 50% of patients with bone lesions are symptomatic and may require treatment.3,5 Treatment is reserved for these symptomatic patients, with the goal of pain reduction.2,3,7

Low- to moderate-dose corticosteroids have been shown to relieve soft-tissue swelling and decrease pain.2,3,7 A prolonged course of steroids is not recommended, due to the risk of osteoporosis and fractures, and does not normalize bone structure.3,7

Other options. NSAIDs, such as colchicine and indomethacin, have also been found to be effective in pain management.7 Treatments such as methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine may be considered for those cases that are refractory to steroids.2

Given the extent of our patient’s disease, he was referred to multiple specialists to rule out further organ involvement. He was found to have neurosarcoidosis on brain imaging and was subsequently treated with prednisone 10 mg/d. The patient is being routinely monitored for active disease at various intervals or as symptoms arise.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consideration for systemic diseases (eg, sarcoidosis) should be given to patients presenting with musculoskeletal complaints without a significant history of trauma or injury. In those with risk factors associated with a higher incidence of sarcoidosis, such as age and race, a work-up should include imaging and biopsy. Treatment (eg, corticosteroids, NSAIDs) is provided to those patients who are symptomatic, with the goal of symptom relief.3

1. Rao DA, Dellaripa PF. Extrapulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:277-297. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2013.02.007

2. Kobak S. Sarcoidosis: a rheumatologist’s perspective. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2015;7:196-205. doi: 10.1177/1759720X15591310

3. Bechman K, Christidis D, Walsh S, et al. A review of the musculoskeletal manifestations of sarcoidosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57:777-783. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex317

4. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071714

5. Yachoui R, Parker BJ, Nguyen TT. Bone and bone marrow involvement in sarcoidosis. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1917-1924. doi: 10.1007/s00296-015-3341-y

6. Aptel S, Lecocq-Teixeira S, Olivier P, et al. Multimodality evaluation of musculoskeletal sarcoidosis: Imaging findings and literature review. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97:5-18. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2014.11.038

7. Wilcox A, Bharadwaj P, Sharma OP. Bone sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:321-330. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200007000-00016

THE CASE

A 58-year-old African American man with a past medical history of prostate cancer, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease presented to our office to establish care with a new provider. He complained of bilateral shoulder pain, that was worse on the right side, for the past year. He denied any previous falls, trauma, or injury. He reported that lifting his grandkids was becoming increasingly difficult due to the pain but denied any weakness or neurologic symptoms. He had been using over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which provided minimal relief.