User login

THE CASE

A 75-year-old woman presented to the primary care clinic with right-side rib pain. The patient said the pain started 1 week earlier, after she ate fried chicken for dinner, and had since been exacerbated by rich meals, lying supine, and taking a deep inspiratory breath. She also said that prior to coming to the clinic that day, the pain had been radiating to her right shoulder.

The patient denied experiencing associated fevers, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, or changes in stool color. She had a history of hypertension, for which she was taking lisinopril 20 mg/d, and hypercholesterolemia, for which she was on simvastatin 10 mg/d. She was additionally using timolol ophthalmic solution for her glaucoma.

During the examination, the patient’s vital signs were stable, with a pulse of 80 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The patient had no abdominal tenderness upon palpation, and the physical exam revealed no abnormalities. An in-office electrocardiogram was performed, with normal results. Additionally, a comprehensive metabolic panel, lipase test, and

THE DIAGNOSIS

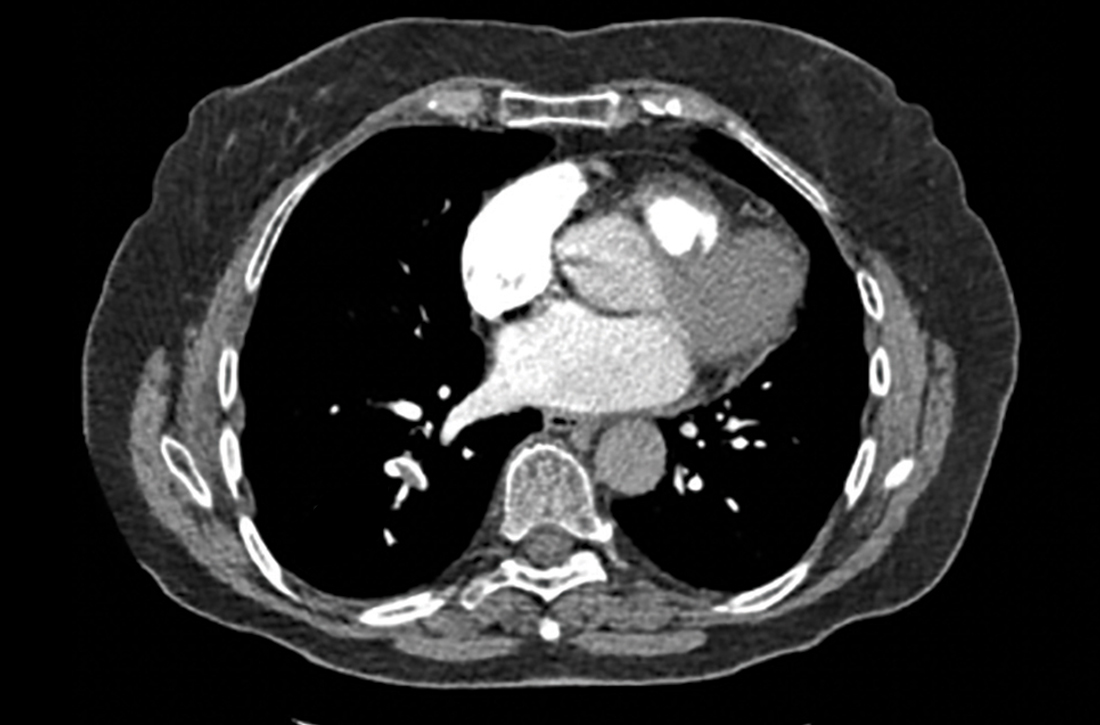

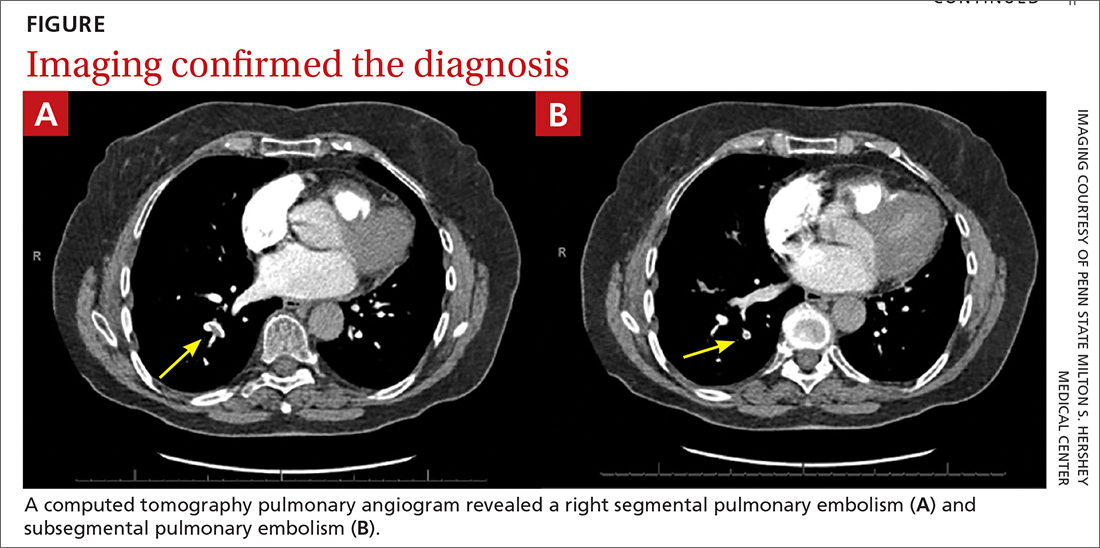

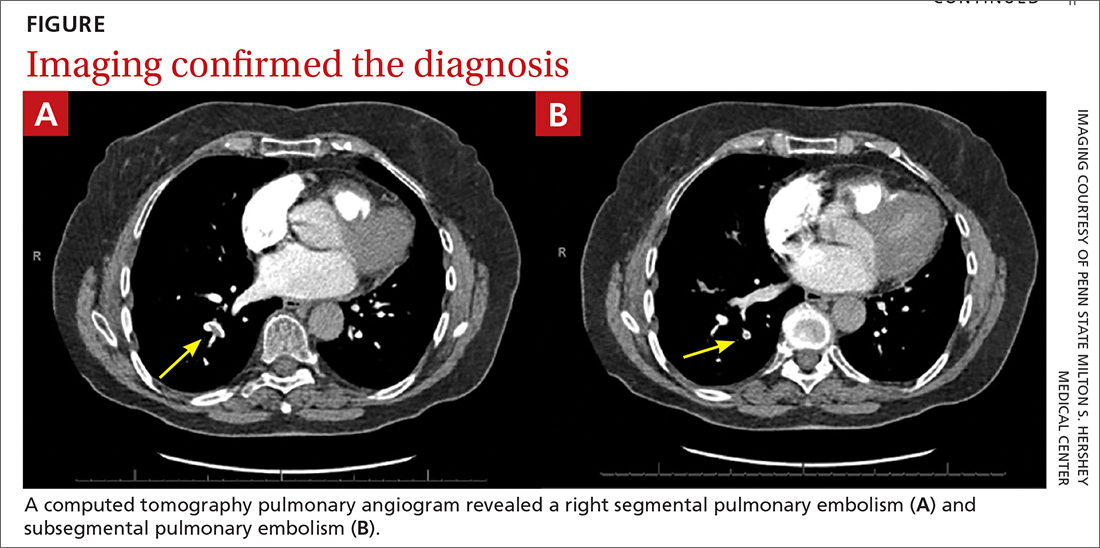

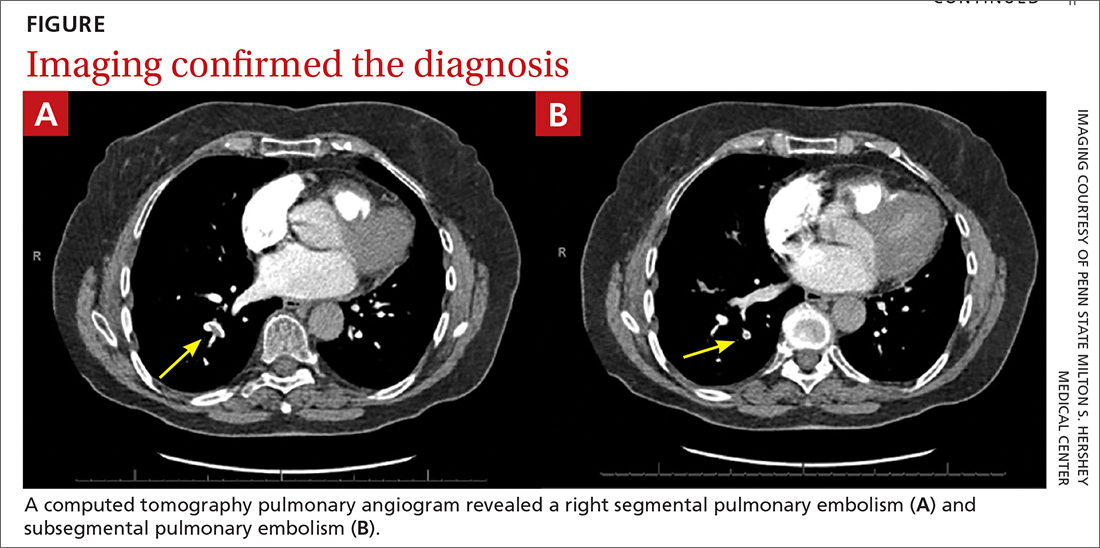

Based on the lab results, a stat computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was ordered and showed a right segmental and subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE; FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

PE shares pathophysiologic mechanisms with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and together these comprise venous thromboembolism (VTE). Risk factors for VTE include hypercoagulable disorders, use of estrogens, active malignancy, and immobilization.1 Unprovoked VTE occurs in the absence of identifiable risk factors and carries a higher risk of recurrence.2,3 While PE is classically thought to occur in the setting of a DVT, there is increasing literature describing de novo PE that can occur independent of a DVT.4

Common symptoms of PE include tachycardia, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain.5 Abdominal pain is a rare symptom described in some case reports.6,7 Thus, a high clinical suspicion is needed for diagnosis of PE.

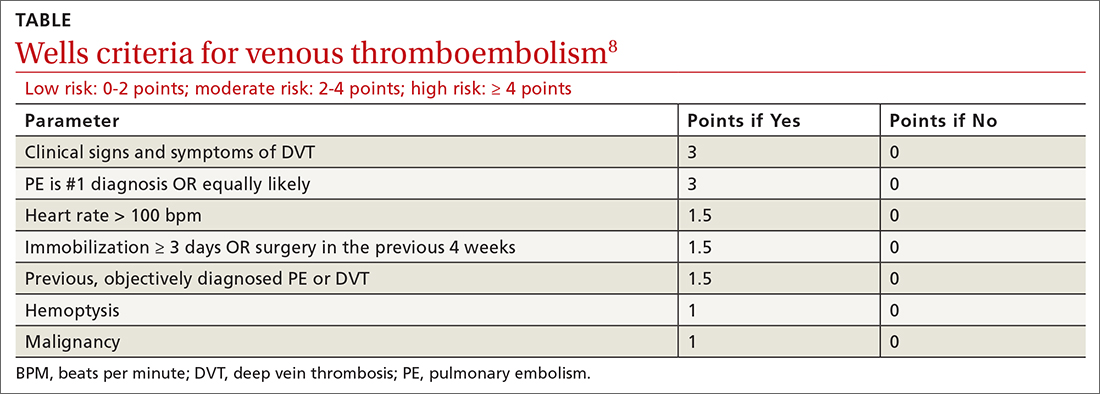

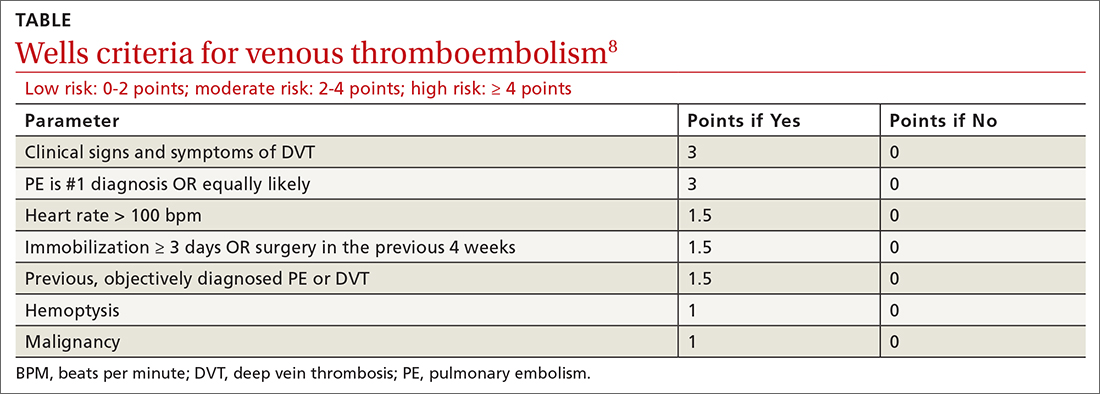

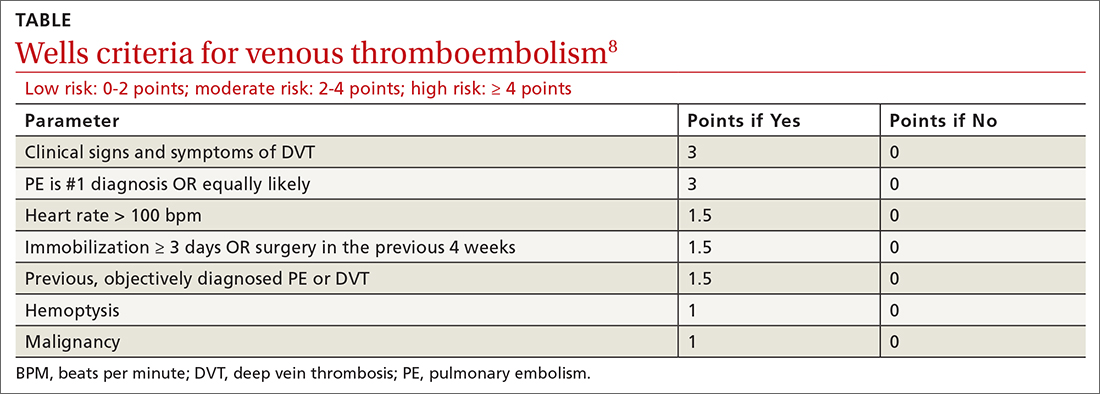

The Wells criteria is an established model for risk stratifying patients presenting with possible VTE (TABLE).8 For patients with low pretest probability, as in this case, a

Continue to: Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

The cornerstone treatment for stable patients with VTE is therapeutic anticoagulation. The new oral anticoagulants, which directly inhibit factor Xa or thrombin, have become increasingly popular for management of VTE, in part because they don’t require INR testing and monitoring.2

The duration of anticoagulation, particularly in unprovoked PE, is debatable. As noted earlier, patients with an unprovoked PE are at higher risk of recurrence than those with a reversible cause, so the question becomes whether these patients should have indefinite anticoagulation.2,3 Studies examining risk stratification of patients with a first, unprovoked VTE have found that men have the highest risk of recurrence, followed by women who were not taking estrogen during the index VTE, and lastly women who were taking estrogen therapy during the index VTE and subsequently discontinued it.2,3,10

Thus, it is reasonable to give women the option to discontinue anticoagulation in the setting of a negative

Our patient was directed to the emergency department for further monitoring following CT confirmation. She was discharged home after being deemed stable and prescribed apixaban 10 mg/d. A venous duplex ultrasound performed 12 days later for knee pain revealed no venous thrombosis. A CT of the abdomen performed 3 months later for other reasons revealed a normal gallbladder with no visible stones.

Apixaban was continued for 3 months and discontinued after discussion of risks and benefits of therapy cessation in the setting of a normal

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

PE carries a significantly high mortality rate and can manifest with nonspecific and masquerading signs. A high index of suspicion is required to place PE on the differential diagnosis and carry out appropriate testing. Our patient presented with a history consistent with biliary colic but with pleuritic chest pain that warranted consideration of a PE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Alyssa Anderson, MD, 1 Continental Drive, Elizabethtown, PA 17022; [email protected]

1. Israel HL, Goldstein F. The varied clinical manifestations of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1957;47:202-226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-47-2-202

2. Rehman H, John E, Parikh P. Pulmonary embolism presenting as abdominal pain: an atypical presentation of a common diagnosis. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2016;2016:1-3. doi: 10.1155/2016/7832895

3. Park ES, Cho JY, Seo J-H, et al. Pulmonary embolism presenting with acute abdominal pain in a girl with stable ankle fracture and inherited antithrombin deficiency. Blood Res. 2018;53:81-83. doi: 10.5045/br.2018.53.1.81

4. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1037-1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072753

5. Agrawal V, Kim ESH. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after an initial episode: risk stratification and implications for long-term treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:24. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1111-2

6. Kearon C, Parpia S, Spencer FA, et al. Long‐term risk of recurrence in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism managed according to d‐dimer results; A cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:1144-1152. doi: 10.1111/jth.14458

7. Van Gent J-M, Zander AL, Olson EJ, et al. Pulmonary embolism without deep venous thrombosis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1270-1274. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000233

8. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010

9. Kline JA. Diagnosis and exclusion of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2018;163:207-220. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.06.002

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest. 2016;149:315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

THE CASE

A 75-year-old woman presented to the primary care clinic with right-side rib pain. The patient said the pain started 1 week earlier, after she ate fried chicken for dinner, and had since been exacerbated by rich meals, lying supine, and taking a deep inspiratory breath. She also said that prior to coming to the clinic that day, the pain had been radiating to her right shoulder.

The patient denied experiencing associated fevers, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, or changes in stool color. She had a history of hypertension, for which she was taking lisinopril 20 mg/d, and hypercholesterolemia, for which she was on simvastatin 10 mg/d. She was additionally using timolol ophthalmic solution for her glaucoma.

During the examination, the patient’s vital signs were stable, with a pulse of 80 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The patient had no abdominal tenderness upon palpation, and the physical exam revealed no abnormalities. An in-office electrocardiogram was performed, with normal results. Additionally, a comprehensive metabolic panel, lipase test, and

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the lab results, a stat computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was ordered and showed a right segmental and subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE; FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

PE shares pathophysiologic mechanisms with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and together these comprise venous thromboembolism (VTE). Risk factors for VTE include hypercoagulable disorders, use of estrogens, active malignancy, and immobilization.1 Unprovoked VTE occurs in the absence of identifiable risk factors and carries a higher risk of recurrence.2,3 While PE is classically thought to occur in the setting of a DVT, there is increasing literature describing de novo PE that can occur independent of a DVT.4

Common symptoms of PE include tachycardia, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain.5 Abdominal pain is a rare symptom described in some case reports.6,7 Thus, a high clinical suspicion is needed for diagnosis of PE.

The Wells criteria is an established model for risk stratifying patients presenting with possible VTE (TABLE).8 For patients with low pretest probability, as in this case, a

Continue to: Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

The cornerstone treatment for stable patients with VTE is therapeutic anticoagulation. The new oral anticoagulants, which directly inhibit factor Xa or thrombin, have become increasingly popular for management of VTE, in part because they don’t require INR testing and monitoring.2

The duration of anticoagulation, particularly in unprovoked PE, is debatable. As noted earlier, patients with an unprovoked PE are at higher risk of recurrence than those with a reversible cause, so the question becomes whether these patients should have indefinite anticoagulation.2,3 Studies examining risk stratification of patients with a first, unprovoked VTE have found that men have the highest risk of recurrence, followed by women who were not taking estrogen during the index VTE, and lastly women who were taking estrogen therapy during the index VTE and subsequently discontinued it.2,3,10

Thus, it is reasonable to give women the option to discontinue anticoagulation in the setting of a negative

Our patient was directed to the emergency department for further monitoring following CT confirmation. She was discharged home after being deemed stable and prescribed apixaban 10 mg/d. A venous duplex ultrasound performed 12 days later for knee pain revealed no venous thrombosis. A CT of the abdomen performed 3 months later for other reasons revealed a normal gallbladder with no visible stones.

Apixaban was continued for 3 months and discontinued after discussion of risks and benefits of therapy cessation in the setting of a normal

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

PE carries a significantly high mortality rate and can manifest with nonspecific and masquerading signs. A high index of suspicion is required to place PE on the differential diagnosis and carry out appropriate testing. Our patient presented with a history consistent with biliary colic but with pleuritic chest pain that warranted consideration of a PE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Alyssa Anderson, MD, 1 Continental Drive, Elizabethtown, PA 17022; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 75-year-old woman presented to the primary care clinic with right-side rib pain. The patient said the pain started 1 week earlier, after she ate fried chicken for dinner, and had since been exacerbated by rich meals, lying supine, and taking a deep inspiratory breath. She also said that prior to coming to the clinic that day, the pain had been radiating to her right shoulder.

The patient denied experiencing associated fevers, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, or changes in stool color. She had a history of hypertension, for which she was taking lisinopril 20 mg/d, and hypercholesterolemia, for which she was on simvastatin 10 mg/d. She was additionally using timolol ophthalmic solution for her glaucoma.

During the examination, the patient’s vital signs were stable, with a pulse of 80 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The patient had no abdominal tenderness upon palpation, and the physical exam revealed no abnormalities. An in-office electrocardiogram was performed, with normal results. Additionally, a comprehensive metabolic panel, lipase test, and

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the lab results, a stat computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was ordered and showed a right segmental and subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE; FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

PE shares pathophysiologic mechanisms with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and together these comprise venous thromboembolism (VTE). Risk factors for VTE include hypercoagulable disorders, use of estrogens, active malignancy, and immobilization.1 Unprovoked VTE occurs in the absence of identifiable risk factors and carries a higher risk of recurrence.2,3 While PE is classically thought to occur in the setting of a DVT, there is increasing literature describing de novo PE that can occur independent of a DVT.4

Common symptoms of PE include tachycardia, tachypnea, and pleuritic chest pain.5 Abdominal pain is a rare symptom described in some case reports.6,7 Thus, a high clinical suspicion is needed for diagnosis of PE.

The Wells criteria is an established model for risk stratifying patients presenting with possible VTE (TABLE).8 For patients with low pretest probability, as in this case, a

Continue to: Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

Length of treatment depends on gender and etiology

The cornerstone treatment for stable patients with VTE is therapeutic anticoagulation. The new oral anticoagulants, which directly inhibit factor Xa or thrombin, have become increasingly popular for management of VTE, in part because they don’t require INR testing and monitoring.2

The duration of anticoagulation, particularly in unprovoked PE, is debatable. As noted earlier, patients with an unprovoked PE are at higher risk of recurrence than those with a reversible cause, so the question becomes whether these patients should have indefinite anticoagulation.2,3 Studies examining risk stratification of patients with a first, unprovoked VTE have found that men have the highest risk of recurrence, followed by women who were not taking estrogen during the index VTE, and lastly women who were taking estrogen therapy during the index VTE and subsequently discontinued it.2,3,10

Thus, it is reasonable to give women the option to discontinue anticoagulation in the setting of a negative

Our patient was directed to the emergency department for further monitoring following CT confirmation. She was discharged home after being deemed stable and prescribed apixaban 10 mg/d. A venous duplex ultrasound performed 12 days later for knee pain revealed no venous thrombosis. A CT of the abdomen performed 3 months later for other reasons revealed a normal gallbladder with no visible stones.

Apixaban was continued for 3 months and discontinued after discussion of risks and benefits of therapy cessation in the setting of a normal

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

PE carries a significantly high mortality rate and can manifest with nonspecific and masquerading signs. A high index of suspicion is required to place PE on the differential diagnosis and carry out appropriate testing. Our patient presented with a history consistent with biliary colic but with pleuritic chest pain that warranted consideration of a PE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Alyssa Anderson, MD, 1 Continental Drive, Elizabethtown, PA 17022; [email protected]

1. Israel HL, Goldstein F. The varied clinical manifestations of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1957;47:202-226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-47-2-202

2. Rehman H, John E, Parikh P. Pulmonary embolism presenting as abdominal pain: an atypical presentation of a common diagnosis. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2016;2016:1-3. doi: 10.1155/2016/7832895

3. Park ES, Cho JY, Seo J-H, et al. Pulmonary embolism presenting with acute abdominal pain in a girl with stable ankle fracture and inherited antithrombin deficiency. Blood Res. 2018;53:81-83. doi: 10.5045/br.2018.53.1.81

4. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1037-1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072753

5. Agrawal V, Kim ESH. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after an initial episode: risk stratification and implications for long-term treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:24. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1111-2

6. Kearon C, Parpia S, Spencer FA, et al. Long‐term risk of recurrence in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism managed according to d‐dimer results; A cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:1144-1152. doi: 10.1111/jth.14458

7. Van Gent J-M, Zander AL, Olson EJ, et al. Pulmonary embolism without deep venous thrombosis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1270-1274. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000233

8. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010

9. Kline JA. Diagnosis and exclusion of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2018;163:207-220. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.06.002

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest. 2016;149:315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

1. Israel HL, Goldstein F. The varied clinical manifestations of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1957;47:202-226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-47-2-202

2. Rehman H, John E, Parikh P. Pulmonary embolism presenting as abdominal pain: an atypical presentation of a common diagnosis. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2016;2016:1-3. doi: 10.1155/2016/7832895

3. Park ES, Cho JY, Seo J-H, et al. Pulmonary embolism presenting with acute abdominal pain in a girl with stable ankle fracture and inherited antithrombin deficiency. Blood Res. 2018;53:81-83. doi: 10.5045/br.2018.53.1.81

4. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1037-1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072753

5. Agrawal V, Kim ESH. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after an initial episode: risk stratification and implications for long-term treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:24. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1111-2

6. Kearon C, Parpia S, Spencer FA, et al. Long‐term risk of recurrence in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism managed according to d‐dimer results; A cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:1144-1152. doi: 10.1111/jth.14458

7. Van Gent J-M, Zander AL, Olson EJ, et al. Pulmonary embolism without deep venous thrombosis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1270-1274. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000233

8. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98-107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010

9. Kline JA. Diagnosis and exclusion of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2018;163:207-220. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.06.002

10. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Chest. 2016;149:315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026