User login

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

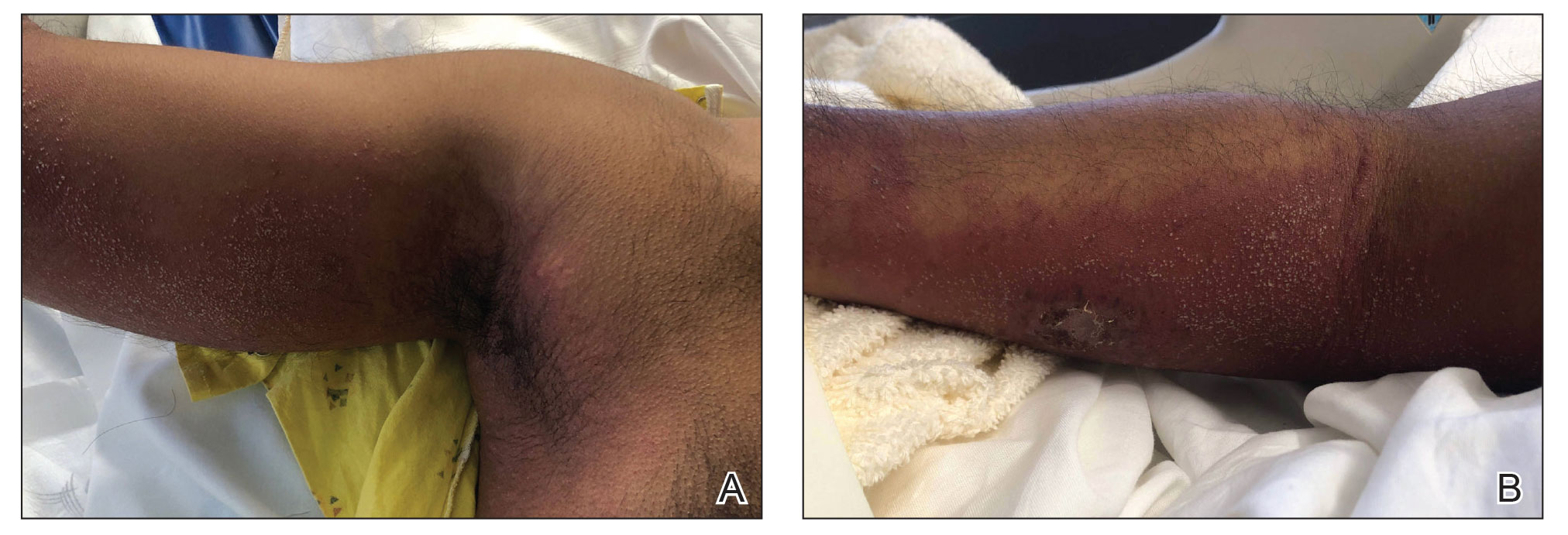

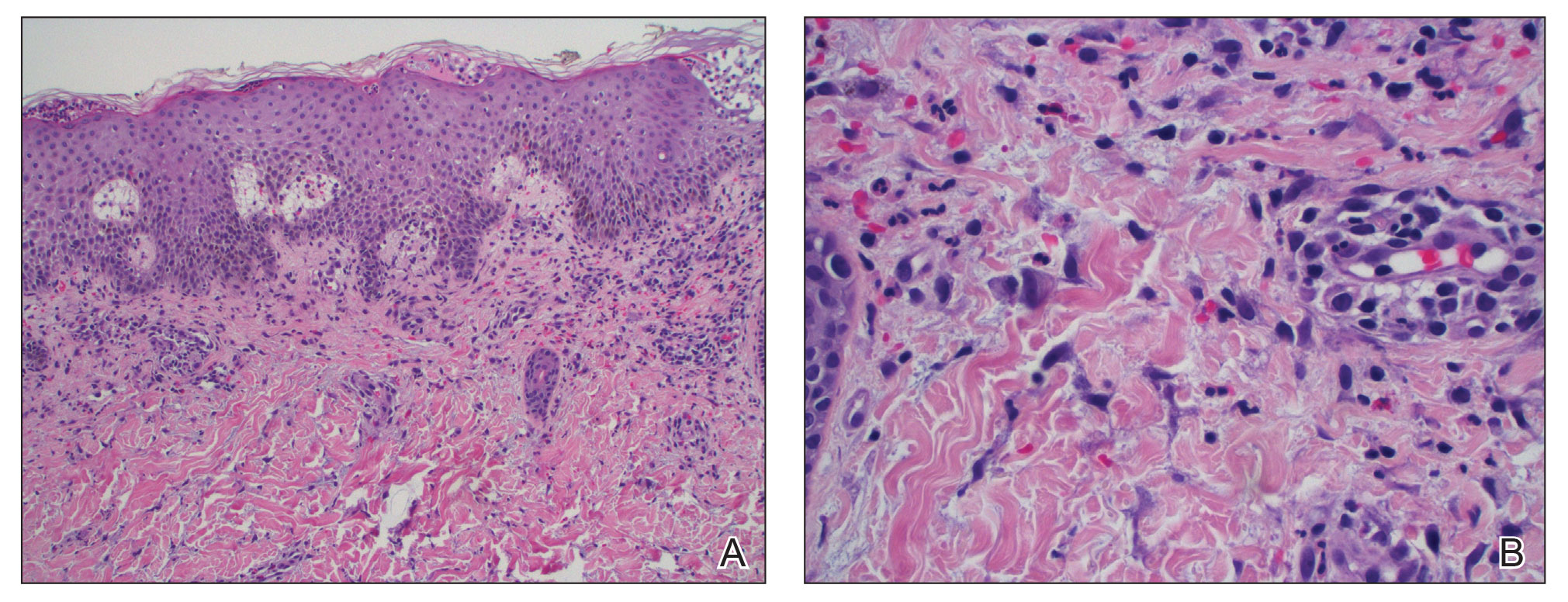

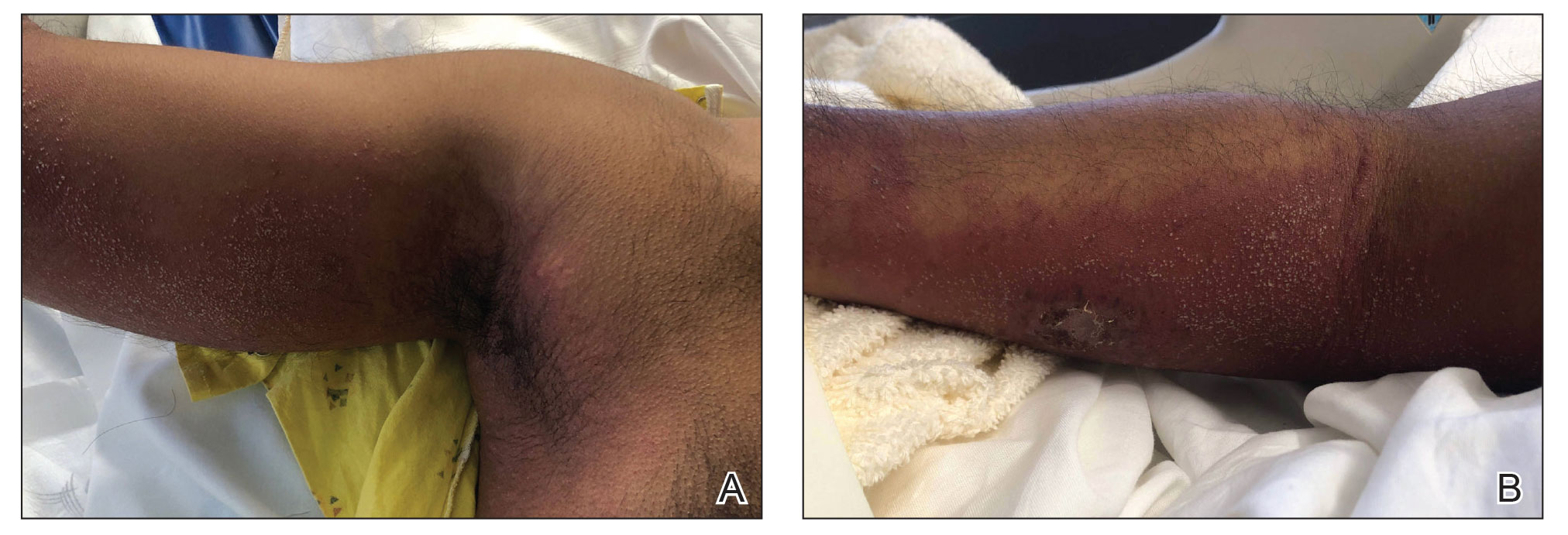

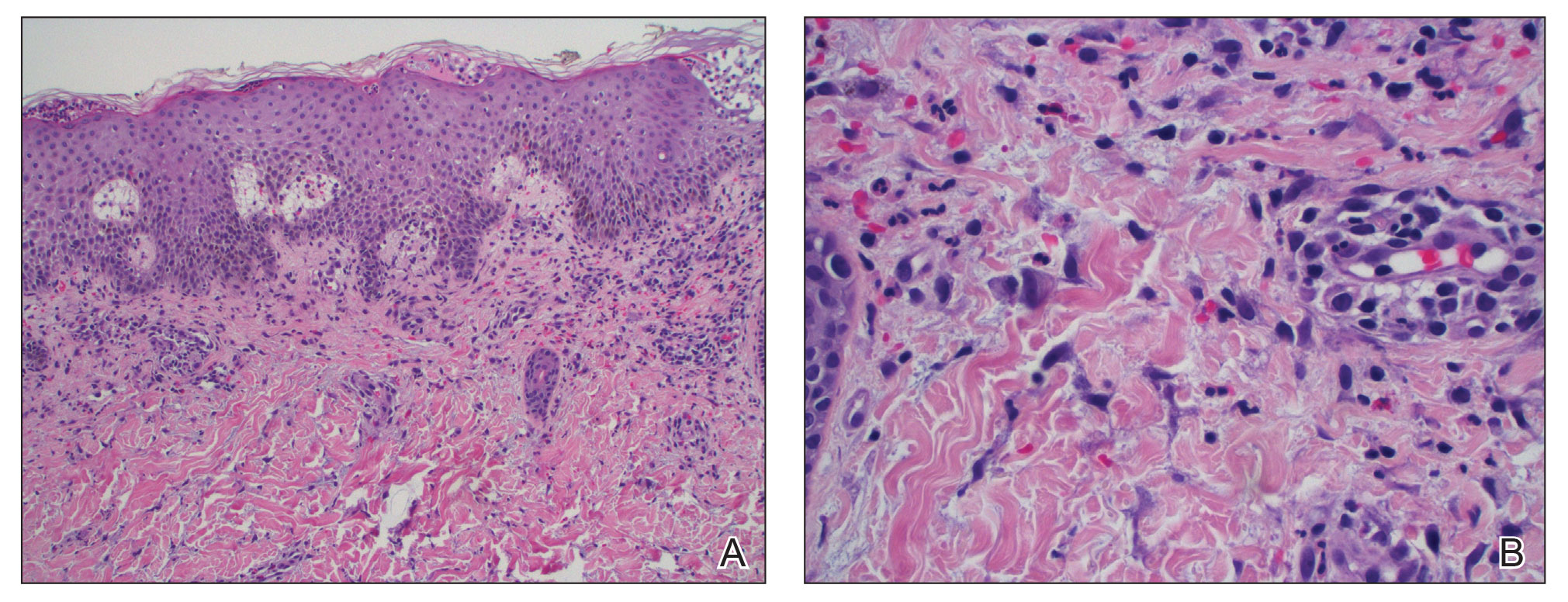

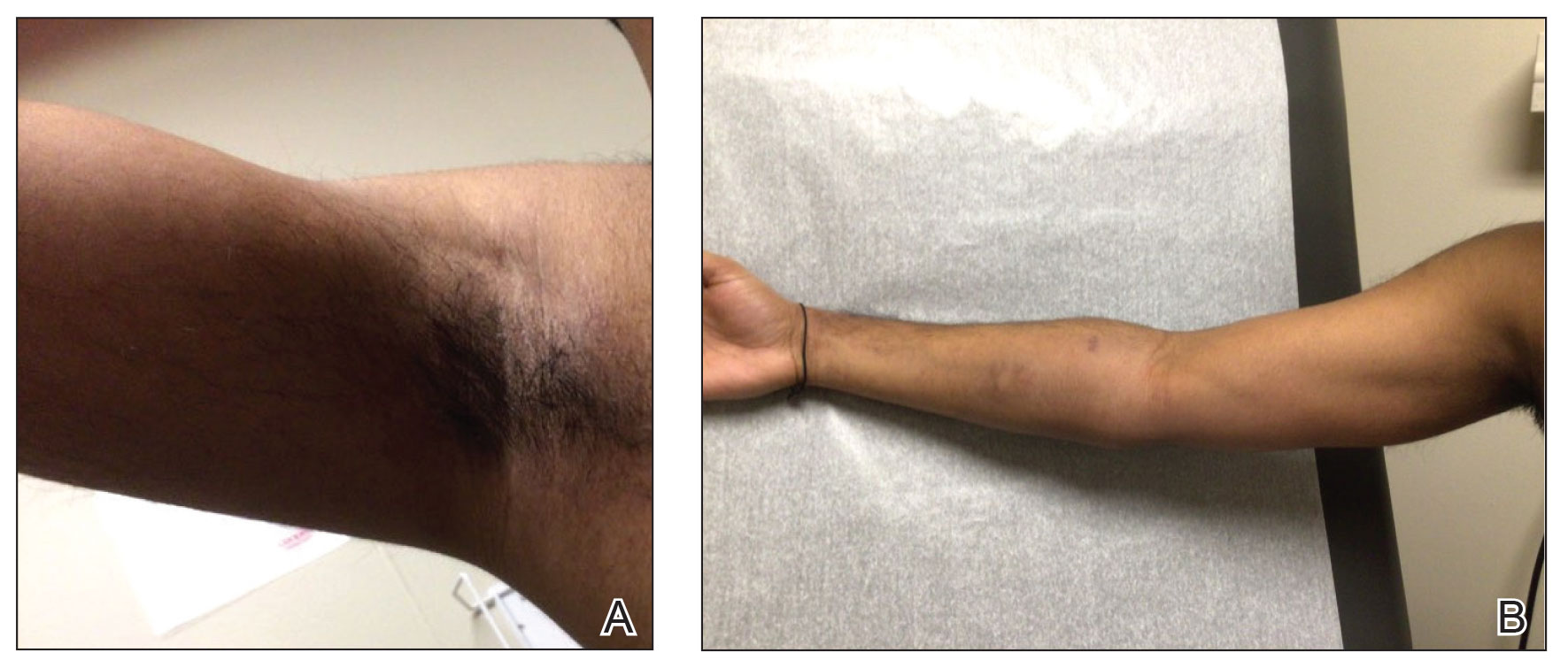

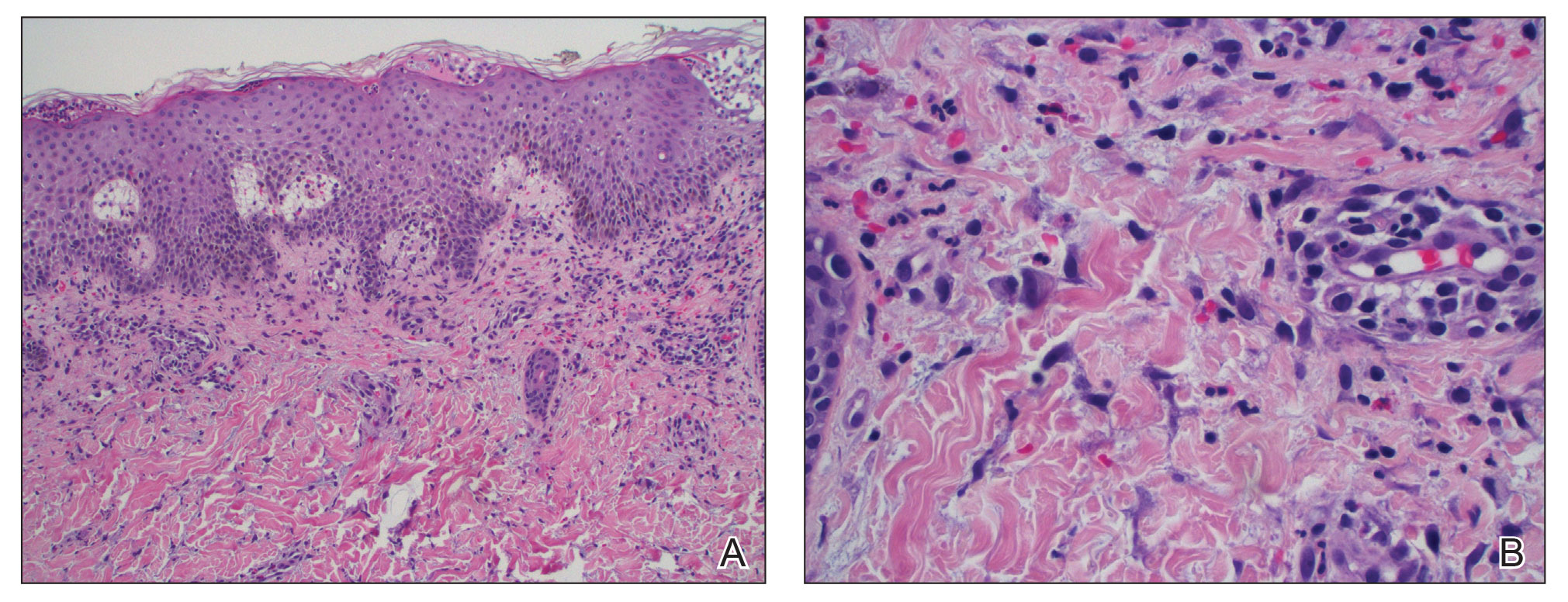

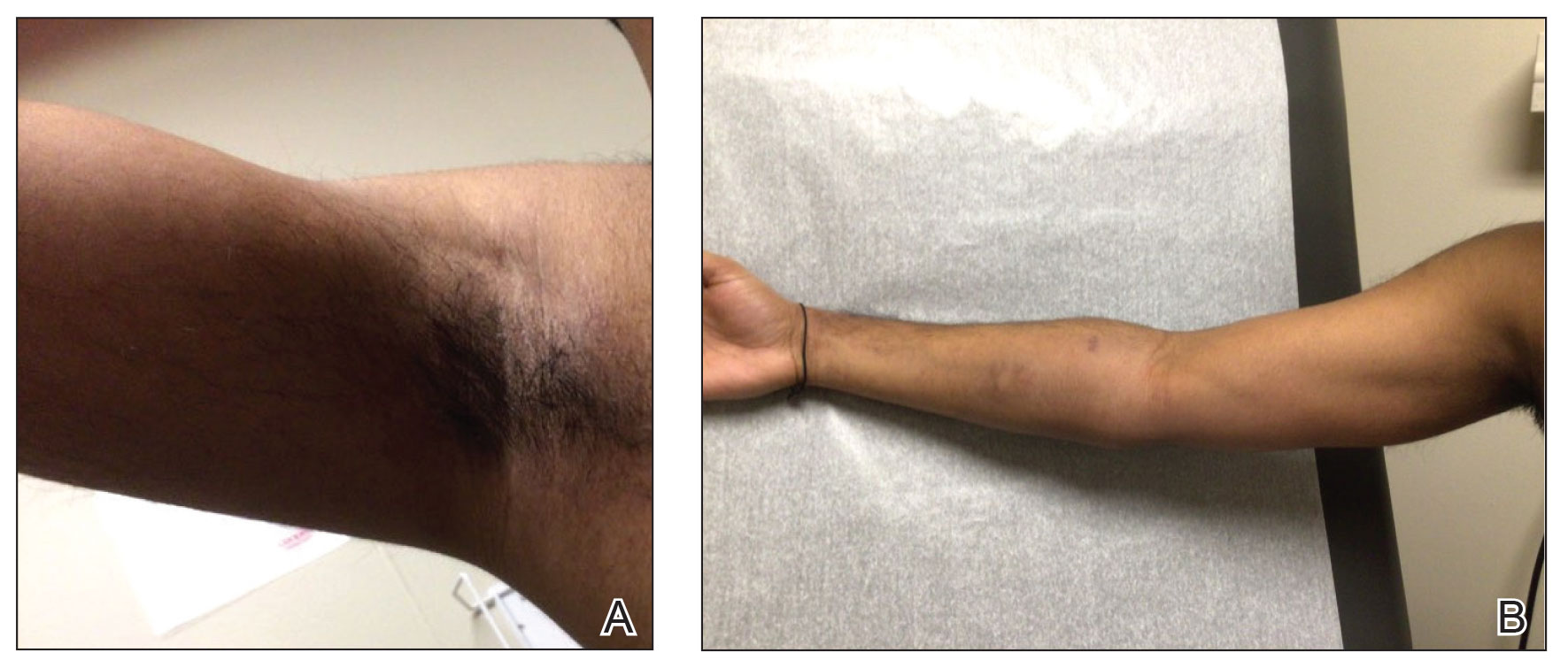

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

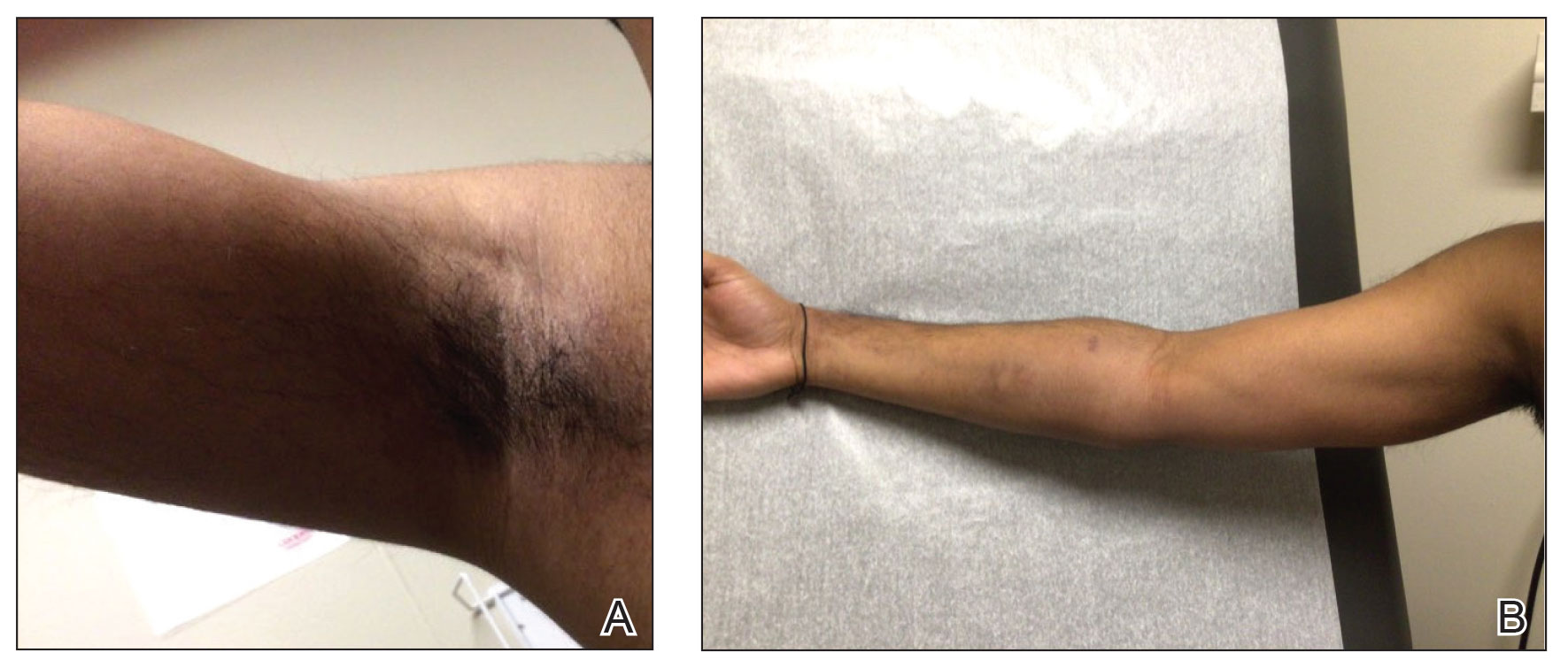

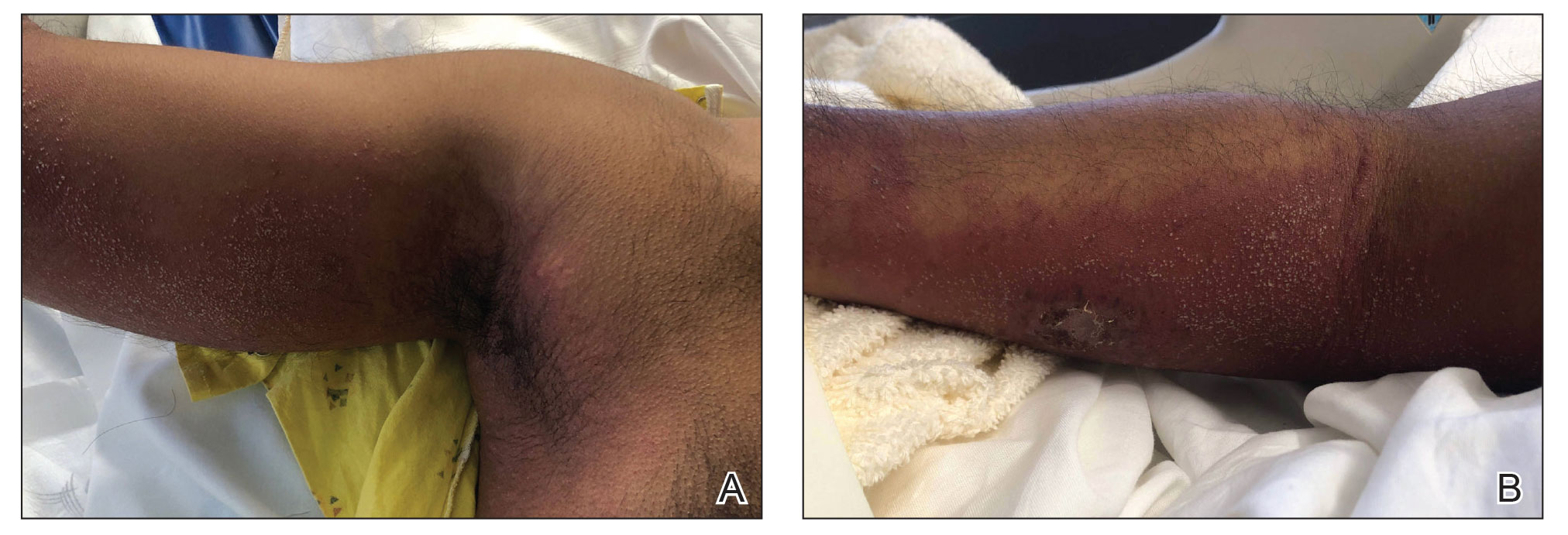

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

To the Editor:

For many years, topical treatment of plaque psoriasis was limited to steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, coal tar products, and anthralin. In recent years, 2 new nonsteroidal treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action, roflumilast 0.3% and tapinarof 1%, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.1 Roflumilast 0.3%, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, was shown in phase 3 clinical trials to reach an Investigator Global Assessment response of 37.5% to 42.2% in 8 weeks using once-daily application with minimal cutaneous adverse effects.1 Furthermore, it has demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas in subset analyses.1 Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that suppresses Th17 cell differentiation by downregulating IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23.1 In phase 3 clinical trials, 35% to 40% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% once daily demonstrated improvement in psoriasis compared with 6% who used the vehicle alone.2 In these studies, 18% to 24% of patients who used tapinarof cream 1% experienced folliculitis.2

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a nonfollicular pustular drug reaction with systemic symptoms that typically occurs within 2 weeks of exposure to an inciting medication. Systemic antibiotics are the most commonly reported cause of AGEP.3 There are few reports in the literature of AGEP induced by topical agents.4,5 We report a case of AGEP in a young man following the use of tapinarof cream 1%.

A 23-year-old man with a history of psoriasis presented to the emergency department with fever and a pustular rash. One week prior to presentation, he developed a pustular eruption around plaques of psoriasis on the arms and legs. The patient had been prescribed tapinarof cream 1% by an outside dermatologist and was applying the medication to the affected areas once daily for 1 month prior to onset of symptoms. He discontinued tapinarof a few days prior to the eruption starting, but the rash progressed centrifugally and was associated with fevers and fatigue despite treatment with a brief course of empiric cephalexin prescribed by his primary care provider.

At presentation to our institution, the patient had widespread erythematous patches studded with pustules located on the arms, legs, and flexural areas as well as plaques of psoriasis involving approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Furthermore, the patient was noted to have large noninflammatory bullae along the legs. The new eruption occurred on areas that were both treated and spared from the tapinarof cream 1%. Laboratory evaluation showed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 15.9×103/µL [reference range, 4.0-11.0×103/µL]; absolute neutrophil count, 10.3×103/µL [reference range, 1.5-8.0×103/µL]), absolute eosinophilia (1930/µL [reference range, 0-0.5×103/µL]), hypocalcemia (8.4 mg/dL [reference range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL]), and a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase, 37 IU/L [reference range, 10-40 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU/L [reference range, 7-56 U/L]). Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules and mixed dermal inflammation containing eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence revealed mild granular staining of C3 at the basement membrane zone.

The patient was started on 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered over 20 days, and he rapidly improved. Alanine aminotransferase levels peaked at 120 IU/L 2 weeks later. At that time, he had complete resolution of the original eruption and was transitioned to topical steroids for continued management of the psoriasis (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis for our patient included AGEP, generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), miliaria pustulosa, generalized cutaneous candidiasis, exuberant allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD). Based on the clinical manifestations, laboratory results, and histopathologic evaluation, we made the diagnosis of AGEP secondary to tapinarof with systemic absorption. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis has been reported with topical use of morphine and diphenhydramine, among other agents.4,5 To our knowledge, AGEP due to tapinarof cream 1% has not been reported. In the original clinical trials of tapinarof, folliculitis was contained to sites of application.2 Our patient developed pustules at sites distant to areas of application, as well as systemic symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, indicating a systemic reaction. It can be difficult to distinguish AGEP clinically and histologically from GPP. Both conditions can manifest with fever, hypocalcemia, and sterile pustules on a background of erythema that favors intertriginous areas.6 Infection, rapid oral steroid withdrawal, pregnancy, and rarely oral medications have been reported causes of GPP.6 Our patient did not have any of these exposures. There is overlap in the histology of AGEP and GPP. One retrospective series compared histologic samples to help distinguish these 2 entities. Reliable markers that favored AGEP over GPP included eosinophilic spongiosis, interface dermatitis, and dermal eosinophilia (>2/mm2).7 In contrast, the presence of CD161 positivity in the dermis with at least 10 cells favored a diagnosis of GPP.7 In our case, the presence of spongiosis with eosinophils in the dermis favored a diagnosis of AGEP over GPP.

Miliaria pustulosa is a benign condition caused by the occlusion of the epidermal portion of eccrine glands related to either high fever or hot and humid environmental conditions. While it can be present in intertriginous areas like AGEP, miliaria pustulosa can be seen extensively on the back, most commonly in immobile hospitalized patients.8 Generalized cutaneous candidiasis usually is caused by the yeast Candida albicans and can take on multiple morphologies, including folliculitis.9 The eruption may be disseminated but often is accentuated in intertriginous areas and the anogenital folds. Predisposing factors include immunosuppression, endocrinopathies, recent use of systemic antibiotics or steroids, chemotherapy, and indwelling catheters.9 Outside of recent antibiotic use, our patient did not have any risk factors for miliaria pustulosa, making this diagnosis unlikely.

Given the presence of overlapping bullae along the lower extremities, an exuberant ACD and LABD were considered. Bullae formation can occur in ACD secondary to robust inflammation and edema leading to acantholysis.10 While a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to topical tapinarof cream 1% was considered given that the patient used the medication for approximately 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, it would be unlikely for ACD to present with a concomitant pustular eruption. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune blistering disease in which antibodies target bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, and there is characteristically linear deposition of IgA at the dermal-epidermal junction that leads to subepidermal blistering.11 This often manifests clinically as widespread tense vesicles in an annular or string-of-pearls appearance. However, morphologies can vary, and large bullae may be seen. In adults, LABD typically is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or medications, notably vancomycin.11,12 Our patient did not have any of these predisposing factors, and his biopsy for direct immunofluorescence did not reveal the classic pattern described above.

Interestingly, there have been reports in the literature of bullous AGEP in the setting of oral anti-infectives. One report described a 62-year-old woman who developed widespread nonfollicular pustules with multiple tense serous blisters 24 hours after taking oral terbinafine.13 Another case described an 80-year-old woman with a similar presentation following a course of ciprofloxacin (although the timeline of medication administration was not described).14 In this case, patch testing to the culprit medication reproduced the response.14 In both cases, a biopsy revealed subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules with marked dermal edema.13,14 As previously described, spongiosis is a common feature of AGEP. We hypothesize that, similar to these reports, our patient had a robust inflammatory response leading to spongiosis, acantholysis, and blister formation secondary to AGEP.

Dermatologists should be aware of this case of AGEP secondary to tapinarof cream 1%, as reports in the literature are rare and it is a reminder that topical medications can cause serious systemic reactions.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.15632

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017

- Ghazawi FM, Colantonio S, Bradshaw S, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical morphine and confirmed by patch testing. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E22-E23. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000573

- Hanafusa T, Igawa K, Azukizawa H, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical diphenhydramine. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:994-995. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1500

- Reynolds KA, Pithadia DJ, Lee EB, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations,diagnosis, and treatment. Cutis. 2022;110:19-25. doi:10.12788/cutis.0579

- Isom J, Braswell DS, Siroy A, et al. Clinical and histopathologic features differentiating acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and pustular psoriasis: a retrospective series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:265-267. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.015

- Fealey RD, Hebert AA. Disorders of the eccrine sweat glands and sweating. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:946.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Marchiony Hunt K, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1329-1363.

- Elmas ÖF, Akdeniz N, Atasoy M, et al. Contact dermatitis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:176-192. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.10.003

- Hull CM, Zone JZ. Dermatitis herpetiforms and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:527-537.

- Yamagami J, Nakamura Y, Nagao K, et al. Vancomycin mediates IgA autoreactivity in drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1473-1480.

- Bullous acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.468

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280. doi:10.1159/000087024

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Secondary to Application of Tapinarof Cream 1%

PRACTICE POINTS

- Tapinarof cream 1% can be absorbed systemically and cause acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP).

- Clinical configuration and histology can be useful to distinguish AGEP from mimickers.

- Topical application of drugs in general, particularly over large body surface areas, may lead to systemic drug eruptions.

Bullous Amyloidosis Masquerading as Pseudoporphyria

Cutaneous amyloidosis encompasses a variety of clinical presentations. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis result from keratin deposits, while nodular amyloidosis results from cutaneous infiltration of plasma cells.2 Primary systemic amyloidosis is due to a plasma cell dyscrasia, particularly multiple myeloma, while secondary systemic amyloidosis occurs in the setting of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, renal dysfunction, or chronic inflammation, as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and various autoinflammatory disorders.2 Plasma cell proliferative disorders are associated with various skin disorders, which may result from aggregated misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins, indicating light chain–related systemic amyloidosis. Mucocutaneous lesions can occur in 30% to 40% of cases of primary systemic amyloidosis and may present as purpura, ecchymoses, waxy thickening, plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and/or bullae.3,4 When blistering is present, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes autoimmune bullous disease, drug eruptions, enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, deposition diseases, allergic contact dermatitis, bullous cellulitis, bullous bite reactions, neutrophilic dermatosis, and bullous lichen sclerosus.5 Herein, we present a case of a woman with a bullous skin eruption who eventually was diagnosed with bullous amyloidosis subsequent to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of well-demarcated, hemorrhagic, flaccid vesicles and focal erosions with a rim of erythema on the distal forearms and hands. A shave biopsy from the right forearm showed cell-poor subepidermal vesicular dermatitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 as well as urinary porphyrins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed granular IgM at the basement membrane zone around vessels and cytoid bodies. At this time, a preliminary diagnosis of pseudoporphyria was suspected, though no classic medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, antibiotics) or exogenous trigger factors (eg, UV light exposure, dialysis) were temporally related. Three months later, the patient presented with a large hemorrhagic bulla on the distal left forearm (Figure 1) and healing erosions on the dorsal fingers and upper back. Clobetasol ointment was initiated, as an autoimmune bullous dermatosis was suspected.

Approximately 1 year after she was first seen in our outpatient clinic, the patient was hospitalized for induction of chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone—for a new diagnosis of stage III multiple myeloma. A workup for back pain revealed multiple compression fractures and a plasma cell neoplasm with elevated λ light chains, which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy. During an inpatient dermatology consultation, we noted the development of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and worsening generalization of the hemorrhagic bullae, with healing erosions and intact hemorrhagic bullae on the dorsal hands, fingers (Figure 2), and upper back.

A repeat biopsy displayed bullous amyloidosis. Histopathologic examination revealed an ulcerated subepidermal blister with fibrin deposition at the ulcer base. A periadnexal, scant, eosinophilic deposition with extravasated red blood cells was appreciated. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits were found within the detached fragment of the epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate. A Congo red stain highlighted these areas with a salmon pink–colored material. Congo red staining showed a moderate amount of pale, apple green, birefringent deposit within these areas on polarized light examination.

A few months later, the patient was re-admitted, and the amount of skin detachment prompted the primary team to ask for another consultation. Although the extensive skin sloughing resembled toxic epidermal necrolysis, a repeat biopsy confirmed bullous amyloidosis.

Comment

Amyloidosis Histopathology—Amyloidoses represent a wide array of disorders with deposition of β-pleated sheets or amyloid fibrils, often with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 Primary systemic amyloidosis has been associated with underlying dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.6 In such cases, the skin lesions of multiple myeloma may result from a collection of misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments, as in light chain–related systemic amyloidosis.3 Histopathologically, both systemic and cutaneous amyloidosis appear similar and display deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic, fissured amyloid material in the dermis. Congo red stains the material orange-red and will display a characteristic apple green birefringence under polarized light.4 Although bullous amyloid lesions are rare, the cutaneous forms of these lesions can be an important sign of plasma cell dyscrasia.7

Presentation of Bullous Amyloidosis—Bullous manifestations rarely have been noted in the primary cutaneous forms of amyloidosis.5,8,9 Importantly, cutaneous blistering more often is linked to systemic forms of amyloidosis with multiorgan involvement, including primary systemic and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.5,10 However, patients with localized bullous cutaneous amyloidosis without systemic involvement also have been seen.10,11 Bullae may occur at any time, with contents that frequently are hemorrhagic due to capillary fragility.12,13 Bullous manifestations raise the differential diagnoses of bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, linear IgA disease, porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, bullous drug eruption, bullous eruption of renal dialysis, or bullous lupus erythematosus.5,13-17

In our patient, the acral distribution of bullae, presence of hemorrhage, chronicity of symptoms, and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay initially suggested a diagnosis of pseudoporphyria. However, the presence of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and subsequent confirmatory pathology aided in differentiating bullous amyloidosis from pseudoporphyria. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare form of skin-restricted amyloidoses, can coexist with bullous lesions. Of note, reported cases of nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis did not result in development of multiple myeloma.5,10

Bullae are located either subepidermally or intradermally, and bullous lesions of cutaneous amyloidosis typically demonstrate subepidermal or superficial intradermal clefting on light microscopy.5,10,12 Histopathology of bullous amyloidosis shows intradermal or subepidermal blister formation and amorphous eosinophilic material showing apple green birefringence with Congo red staining deposited in the dermis and/or around the adipocytes and blood vessel walls.12,18-20 In prior cases, direct immunofluorescence of bullous amyloidosis revealed absent immunoglobulin (IgG, IgA, IgM) or complement (C3 and C9) deposits in the basement membrane zone or dermis.13,21,22 In these cases, electron microscopy was useful in diagnosis, as it showed the presence of amyloid deposits.21,22

Cause of Bullae—Various mechanisms are thought to trigger the blister formation in amyloidosis. Bullae created from trauma or friction often present as tense painful blisters that commonly are hemorrhagic.10,23 Amyloid deposits in the walls of blood vessels and the affinity of dermal amyloid in blood vessel walls to surrounding collagen likely leads to increased fragility of capillaries and the dermal matrix, hemorrhagic tendency, and infrapapillary blisters, thus creating hemorrhagic bullous eruptions.24,25 Specifically, close proximity of immunoglobulin-derived amyloid oligomers to epidermal keratinocytes may be toxic and therefore could trigger subepidermal bullous change.5 Additionally, alteration in the physicochemical properties of the amyloidal protein might explain bullous eruption.9 Trauma or rubbing of the hands and feet may precipitate the acral blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.5,11

Due to deposition of these amyloid fibrils, skin bleeding in these patients is called amyloid or pinch purpura. Vessel wall fragility and damage by amyloid are the principal causes of periorbital and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.26 Destruction of the lamina densa and widening of the intercellular space between keratinocytes by amyloid globules induce skin fragility.11

Although uncommon, various cases of bullous amyloidosis have been reported in the literature. Multiple myeloma patients represent the majority of those reported to have bullous amyloidosis.6,7,13,24,27-30 Plasmacytoma-associated bullous amyloid purpura and paraproteinemia also have been noted.25 Multiple myeloma with secondary AL amyloidosis has been seen with amyloid purpura and atraumatic ecchymoses of the face, highlighting the hemorrhage noted in these patients.26

Management of Amyloidosis—Various treatment options have been attempted for primary cutaneous amyloidosis, including oral retinoids, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, amitriptyline, colchicine, cepharanthin, tacrolimus, dimethyl sulfoxide, vitamin D3 analogs, capsaicin, menthol, hydrocolloid dressings, surgical modalities, laser treatment, and phototherapy.1 There is no clear consensus for therapeutic modalities except for treating the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia in primary systemic amyloidosis.

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient displaying signs of pseudoporphyria that ultimately proved to be bullous amyloidosis, or what we termed pseudopseudoporphyria. Bullous amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnoses of hemorrhagic bullous skin eruptions. Particular attention should be given to a systemic workup for multiple myeloma when hemorrhagic vesicles/bullae are chronic and coexist with purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue/weight loss, and/or macroglossia.

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Amyloidosis. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:341-345.

- Bhutani M, Shahid Z, Schnebelen A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell proliferative disorders. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:395-400.

- Terushkin V, Boyd KP, Patel RR, et al. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20711.

- LaChance A, Phelps A, Finch J, et al. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:344-347.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Kanoh T. Bullous amyloidosis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34:1050-1052.

- Johnson TM, Rapini RP, Hebert AA, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Cutis. 1989;43:346-352.

- Houman MH, Smiti KM, Ben Ghorbel I, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:299-302.

- Sanusi T, Li Y, Qian Y, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with bullous lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:400-402.

- Ochiai T, Morishima T, Hao T, et al. Bullous amyloidosis: the mechanism of blister formation revealed by electron microscopy. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:407-411.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Wang XD, Shen H, Liu ZH. Diffuse haemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis with multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:94-96.

- Biswas P, Aggarwal I, Sen D, et al. Bullous pemphigoid clinically presenting as lichen amyloidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:544-546.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous dermatosis vs amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:252.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous amyloidosis vs epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. JAMA. 1981;245:32.

- Murphy GM, Wright J, Nicholls DS, et al. Sunbed-induced pseudoporphyria. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:555-562.

- Pramatarov K, Lazarova A, Mateev G, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic primary systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:211-213.

- Bieber T, Ruzicka T, Linke RP, et al. Hemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis. a histologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study of two patients. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1683-1686.

- Khoo BP, Tay YK. Lichen amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:105-107.

- Asahina A, Hasegawa K, Ishiyama M, et al. Bullous amyloidosis mimicking bullous pemphigoid: usefulness of electron microscopic examination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:427-428.

- Schmutz JL, Barbaud A, Cuny JF, et al. Bullous amyloidosis [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:295-301.

- Lachmann HJ, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis of the skin. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:1574-1583.

- Grundmann JU, Bonnekoh B, Gollnick H. Extensive haemorrhagic-bullous skin manifestation of systemic AA-amyloidosis associated with IgG lambda-myeloma. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:139-142.

- Hödl S, Turek TD, Kerl H. Plasmocytoma-associated bullous hemorrhagic amyloidosis of the skin [in German]. Hautarzt. 1982;33:556-558.

- Colucci G, Alberio L, Demarmels Biasiutti F, et al. Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses. an often missed sign of amyloid purpura. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:249-252.

- Behera B, Pattnaik M, Sahu B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:668-671.

- Fujita Y, Tsuji-Abe Y, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Nail dystrophy and blisters as sole manifestations in myeloma-associated amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:712-714.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Winzer M, Ruppert M, Baretton G, et al. Bullous poikilodermatitic amyloidosis of the skin with junctional bulla development in IgG light chain plasmacytoma of the lambda type. histology, immunohistology and electron microscopy [in German]. Hautarzt. 1992;43:199-204.

Cutaneous amyloidosis encompasses a variety of clinical presentations. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis result from keratin deposits, while nodular amyloidosis results from cutaneous infiltration of plasma cells.2 Primary systemic amyloidosis is due to a plasma cell dyscrasia, particularly multiple myeloma, while secondary systemic amyloidosis occurs in the setting of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, renal dysfunction, or chronic inflammation, as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and various autoinflammatory disorders.2 Plasma cell proliferative disorders are associated with various skin disorders, which may result from aggregated misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins, indicating light chain–related systemic amyloidosis. Mucocutaneous lesions can occur in 30% to 40% of cases of primary systemic amyloidosis and may present as purpura, ecchymoses, waxy thickening, plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and/or bullae.3,4 When blistering is present, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes autoimmune bullous disease, drug eruptions, enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, deposition diseases, allergic contact dermatitis, bullous cellulitis, bullous bite reactions, neutrophilic dermatosis, and bullous lichen sclerosus.5 Herein, we present a case of a woman with a bullous skin eruption who eventually was diagnosed with bullous amyloidosis subsequent to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of well-demarcated, hemorrhagic, flaccid vesicles and focal erosions with a rim of erythema on the distal forearms and hands. A shave biopsy from the right forearm showed cell-poor subepidermal vesicular dermatitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 as well as urinary porphyrins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed granular IgM at the basement membrane zone around vessels and cytoid bodies. At this time, a preliminary diagnosis of pseudoporphyria was suspected, though no classic medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, antibiotics) or exogenous trigger factors (eg, UV light exposure, dialysis) were temporally related. Three months later, the patient presented with a large hemorrhagic bulla on the distal left forearm (Figure 1) and healing erosions on the dorsal fingers and upper back. Clobetasol ointment was initiated, as an autoimmune bullous dermatosis was suspected.

Approximately 1 year after she was first seen in our outpatient clinic, the patient was hospitalized for induction of chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone—for a new diagnosis of stage III multiple myeloma. A workup for back pain revealed multiple compression fractures and a plasma cell neoplasm with elevated λ light chains, which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy. During an inpatient dermatology consultation, we noted the development of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and worsening generalization of the hemorrhagic bullae, with healing erosions and intact hemorrhagic bullae on the dorsal hands, fingers (Figure 2), and upper back.

A repeat biopsy displayed bullous amyloidosis. Histopathologic examination revealed an ulcerated subepidermal blister with fibrin deposition at the ulcer base. A periadnexal, scant, eosinophilic deposition with extravasated red blood cells was appreciated. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits were found within the detached fragment of the epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate. A Congo red stain highlighted these areas with a salmon pink–colored material. Congo red staining showed a moderate amount of pale, apple green, birefringent deposit within these areas on polarized light examination.

A few months later, the patient was re-admitted, and the amount of skin detachment prompted the primary team to ask for another consultation. Although the extensive skin sloughing resembled toxic epidermal necrolysis, a repeat biopsy confirmed bullous amyloidosis.

Comment

Amyloidosis Histopathology—Amyloidoses represent a wide array of disorders with deposition of β-pleated sheets or amyloid fibrils, often with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 Primary systemic amyloidosis has been associated with underlying dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.6 In such cases, the skin lesions of multiple myeloma may result from a collection of misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments, as in light chain–related systemic amyloidosis.3 Histopathologically, both systemic and cutaneous amyloidosis appear similar and display deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic, fissured amyloid material in the dermis. Congo red stains the material orange-red and will display a characteristic apple green birefringence under polarized light.4 Although bullous amyloid lesions are rare, the cutaneous forms of these lesions can be an important sign of plasma cell dyscrasia.7

Presentation of Bullous Amyloidosis—Bullous manifestations rarely have been noted in the primary cutaneous forms of amyloidosis.5,8,9 Importantly, cutaneous blistering more often is linked to systemic forms of amyloidosis with multiorgan involvement, including primary systemic and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.5,10 However, patients with localized bullous cutaneous amyloidosis without systemic involvement also have been seen.10,11 Bullae may occur at any time, with contents that frequently are hemorrhagic due to capillary fragility.12,13 Bullous manifestations raise the differential diagnoses of bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, linear IgA disease, porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, bullous drug eruption, bullous eruption of renal dialysis, or bullous lupus erythematosus.5,13-17

In our patient, the acral distribution of bullae, presence of hemorrhage, chronicity of symptoms, and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay initially suggested a diagnosis of pseudoporphyria. However, the presence of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and subsequent confirmatory pathology aided in differentiating bullous amyloidosis from pseudoporphyria. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare form of skin-restricted amyloidoses, can coexist with bullous lesions. Of note, reported cases of nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis did not result in development of multiple myeloma.5,10

Bullae are located either subepidermally or intradermally, and bullous lesions of cutaneous amyloidosis typically demonstrate subepidermal or superficial intradermal clefting on light microscopy.5,10,12 Histopathology of bullous amyloidosis shows intradermal or subepidermal blister formation and amorphous eosinophilic material showing apple green birefringence with Congo red staining deposited in the dermis and/or around the adipocytes and blood vessel walls.12,18-20 In prior cases, direct immunofluorescence of bullous amyloidosis revealed absent immunoglobulin (IgG, IgA, IgM) or complement (C3 and C9) deposits in the basement membrane zone or dermis.13,21,22 In these cases, electron microscopy was useful in diagnosis, as it showed the presence of amyloid deposits.21,22

Cause of Bullae—Various mechanisms are thought to trigger the blister formation in amyloidosis. Bullae created from trauma or friction often present as tense painful blisters that commonly are hemorrhagic.10,23 Amyloid deposits in the walls of blood vessels and the affinity of dermal amyloid in blood vessel walls to surrounding collagen likely leads to increased fragility of capillaries and the dermal matrix, hemorrhagic tendency, and infrapapillary blisters, thus creating hemorrhagic bullous eruptions.24,25 Specifically, close proximity of immunoglobulin-derived amyloid oligomers to epidermal keratinocytes may be toxic and therefore could trigger subepidermal bullous change.5 Additionally, alteration in the physicochemical properties of the amyloidal protein might explain bullous eruption.9 Trauma or rubbing of the hands and feet may precipitate the acral blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.5,11

Due to deposition of these amyloid fibrils, skin bleeding in these patients is called amyloid or pinch purpura. Vessel wall fragility and damage by amyloid are the principal causes of periorbital and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.26 Destruction of the lamina densa and widening of the intercellular space between keratinocytes by amyloid globules induce skin fragility.11

Although uncommon, various cases of bullous amyloidosis have been reported in the literature. Multiple myeloma patients represent the majority of those reported to have bullous amyloidosis.6,7,13,24,27-30 Plasmacytoma-associated bullous amyloid purpura and paraproteinemia also have been noted.25 Multiple myeloma with secondary AL amyloidosis has been seen with amyloid purpura and atraumatic ecchymoses of the face, highlighting the hemorrhage noted in these patients.26

Management of Amyloidosis—Various treatment options have been attempted for primary cutaneous amyloidosis, including oral retinoids, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, amitriptyline, colchicine, cepharanthin, tacrolimus, dimethyl sulfoxide, vitamin D3 analogs, capsaicin, menthol, hydrocolloid dressings, surgical modalities, laser treatment, and phototherapy.1 There is no clear consensus for therapeutic modalities except for treating the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia in primary systemic amyloidosis.

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient displaying signs of pseudoporphyria that ultimately proved to be bullous amyloidosis, or what we termed pseudopseudoporphyria. Bullous amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnoses of hemorrhagic bullous skin eruptions. Particular attention should be given to a systemic workup for multiple myeloma when hemorrhagic vesicles/bullae are chronic and coexist with purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue/weight loss, and/or macroglossia.

Cutaneous amyloidosis encompasses a variety of clinical presentations. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis result from keratin deposits, while nodular amyloidosis results from cutaneous infiltration of plasma cells.2 Primary systemic amyloidosis is due to a plasma cell dyscrasia, particularly multiple myeloma, while secondary systemic amyloidosis occurs in the setting of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, renal dysfunction, or chronic inflammation, as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and various autoinflammatory disorders.2 Plasma cell proliferative disorders are associated with various skin disorders, which may result from aggregated misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins, indicating light chain–related systemic amyloidosis. Mucocutaneous lesions can occur in 30% to 40% of cases of primary systemic amyloidosis and may present as purpura, ecchymoses, waxy thickening, plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and/or bullae.3,4 When blistering is present, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes autoimmune bullous disease, drug eruptions, enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, deposition diseases, allergic contact dermatitis, bullous cellulitis, bullous bite reactions, neutrophilic dermatosis, and bullous lichen sclerosus.5 Herein, we present a case of a woman with a bullous skin eruption who eventually was diagnosed with bullous amyloidosis subsequent to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of well-demarcated, hemorrhagic, flaccid vesicles and focal erosions with a rim of erythema on the distal forearms and hands. A shave biopsy from the right forearm showed cell-poor subepidermal vesicular dermatitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 as well as urinary porphyrins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed granular IgM at the basement membrane zone around vessels and cytoid bodies. At this time, a preliminary diagnosis of pseudoporphyria was suspected, though no classic medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, antibiotics) or exogenous trigger factors (eg, UV light exposure, dialysis) were temporally related. Three months later, the patient presented with a large hemorrhagic bulla on the distal left forearm (Figure 1) and healing erosions on the dorsal fingers and upper back. Clobetasol ointment was initiated, as an autoimmune bullous dermatosis was suspected.

Approximately 1 year after she was first seen in our outpatient clinic, the patient was hospitalized for induction of chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone—for a new diagnosis of stage III multiple myeloma. A workup for back pain revealed multiple compression fractures and a plasma cell neoplasm with elevated λ light chains, which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy. During an inpatient dermatology consultation, we noted the development of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and worsening generalization of the hemorrhagic bullae, with healing erosions and intact hemorrhagic bullae on the dorsal hands, fingers (Figure 2), and upper back.

A repeat biopsy displayed bullous amyloidosis. Histopathologic examination revealed an ulcerated subepidermal blister with fibrin deposition at the ulcer base. A periadnexal, scant, eosinophilic deposition with extravasated red blood cells was appreciated. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits were found within the detached fragment of the epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate. A Congo red stain highlighted these areas with a salmon pink–colored material. Congo red staining showed a moderate amount of pale, apple green, birefringent deposit within these areas on polarized light examination.

A few months later, the patient was re-admitted, and the amount of skin detachment prompted the primary team to ask for another consultation. Although the extensive skin sloughing resembled toxic epidermal necrolysis, a repeat biopsy confirmed bullous amyloidosis.

Comment

Amyloidosis Histopathology—Amyloidoses represent a wide array of disorders with deposition of β-pleated sheets or amyloid fibrils, often with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 Primary systemic amyloidosis has been associated with underlying dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.6 In such cases, the skin lesions of multiple myeloma may result from a collection of misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments, as in light chain–related systemic amyloidosis.3 Histopathologically, both systemic and cutaneous amyloidosis appear similar and display deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic, fissured amyloid material in the dermis. Congo red stains the material orange-red and will display a characteristic apple green birefringence under polarized light.4 Although bullous amyloid lesions are rare, the cutaneous forms of these lesions can be an important sign of plasma cell dyscrasia.7

Presentation of Bullous Amyloidosis—Bullous manifestations rarely have been noted in the primary cutaneous forms of amyloidosis.5,8,9 Importantly, cutaneous blistering more often is linked to systemic forms of amyloidosis with multiorgan involvement, including primary systemic and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.5,10 However, patients with localized bullous cutaneous amyloidosis without systemic involvement also have been seen.10,11 Bullae may occur at any time, with contents that frequently are hemorrhagic due to capillary fragility.12,13 Bullous manifestations raise the differential diagnoses of bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, linear IgA disease, porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, bullous drug eruption, bullous eruption of renal dialysis, or bullous lupus erythematosus.5,13-17

In our patient, the acral distribution of bullae, presence of hemorrhage, chronicity of symptoms, and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay initially suggested a diagnosis of pseudoporphyria. However, the presence of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and subsequent confirmatory pathology aided in differentiating bullous amyloidosis from pseudoporphyria. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare form of skin-restricted amyloidoses, can coexist with bullous lesions. Of note, reported cases of nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis did not result in development of multiple myeloma.5,10

Bullae are located either subepidermally or intradermally, and bullous lesions of cutaneous amyloidosis typically demonstrate subepidermal or superficial intradermal clefting on light microscopy.5,10,12 Histopathology of bullous amyloidosis shows intradermal or subepidermal blister formation and amorphous eosinophilic material showing apple green birefringence with Congo red staining deposited in the dermis and/or around the adipocytes and blood vessel walls.12,18-20 In prior cases, direct immunofluorescence of bullous amyloidosis revealed absent immunoglobulin (IgG, IgA, IgM) or complement (C3 and C9) deposits in the basement membrane zone or dermis.13,21,22 In these cases, electron microscopy was useful in diagnosis, as it showed the presence of amyloid deposits.21,22

Cause of Bullae—Various mechanisms are thought to trigger the blister formation in amyloidosis. Bullae created from trauma or friction often present as tense painful blisters that commonly are hemorrhagic.10,23 Amyloid deposits in the walls of blood vessels and the affinity of dermal amyloid in blood vessel walls to surrounding collagen likely leads to increased fragility of capillaries and the dermal matrix, hemorrhagic tendency, and infrapapillary blisters, thus creating hemorrhagic bullous eruptions.24,25 Specifically, close proximity of immunoglobulin-derived amyloid oligomers to epidermal keratinocytes may be toxic and therefore could trigger subepidermal bullous change.5 Additionally, alteration in the physicochemical properties of the amyloidal protein might explain bullous eruption.9 Trauma or rubbing of the hands and feet may precipitate the acral blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.5,11

Due to deposition of these amyloid fibrils, skin bleeding in these patients is called amyloid or pinch purpura. Vessel wall fragility and damage by amyloid are the principal causes of periorbital and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.26 Destruction of the lamina densa and widening of the intercellular space between keratinocytes by amyloid globules induce skin fragility.11

Although uncommon, various cases of bullous amyloidosis have been reported in the literature. Multiple myeloma patients represent the majority of those reported to have bullous amyloidosis.6,7,13,24,27-30 Plasmacytoma-associated bullous amyloid purpura and paraproteinemia also have been noted.25 Multiple myeloma with secondary AL amyloidosis has been seen with amyloid purpura and atraumatic ecchymoses of the face, highlighting the hemorrhage noted in these patients.26

Management of Amyloidosis—Various treatment options have been attempted for primary cutaneous amyloidosis, including oral retinoids, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, amitriptyline, colchicine, cepharanthin, tacrolimus, dimethyl sulfoxide, vitamin D3 analogs, capsaicin, menthol, hydrocolloid dressings, surgical modalities, laser treatment, and phototherapy.1 There is no clear consensus for therapeutic modalities except for treating the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia in primary systemic amyloidosis.

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient displaying signs of pseudoporphyria that ultimately proved to be bullous amyloidosis, or what we termed pseudopseudoporphyria. Bullous amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnoses of hemorrhagic bullous skin eruptions. Particular attention should be given to a systemic workup for multiple myeloma when hemorrhagic vesicles/bullae are chronic and coexist with purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue/weight loss, and/or macroglossia.

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Amyloidosis. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:341-345.

- Bhutani M, Shahid Z, Schnebelen A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell proliferative disorders. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:395-400.

- Terushkin V, Boyd KP, Patel RR, et al. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20711.

- LaChance A, Phelps A, Finch J, et al. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:344-347.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Kanoh T. Bullous amyloidosis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34:1050-1052.

- Johnson TM, Rapini RP, Hebert AA, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Cutis. 1989;43:346-352.

- Houman MH, Smiti KM, Ben Ghorbel I, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:299-302.

- Sanusi T, Li Y, Qian Y, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with bullous lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:400-402.

- Ochiai T, Morishima T, Hao T, et al. Bullous amyloidosis: the mechanism of blister formation revealed by electron microscopy. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:407-411.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Wang XD, Shen H, Liu ZH. Diffuse haemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis with multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:94-96.

- Biswas P, Aggarwal I, Sen D, et al. Bullous pemphigoid clinically presenting as lichen amyloidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:544-546.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous dermatosis vs amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:252.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous amyloidosis vs epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. JAMA. 1981;245:32.

- Murphy GM, Wright J, Nicholls DS, et al. Sunbed-induced pseudoporphyria. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:555-562.

- Pramatarov K, Lazarova A, Mateev G, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic primary systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:211-213.

- Bieber T, Ruzicka T, Linke RP, et al. Hemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis. a histologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study of two patients. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1683-1686.

- Khoo BP, Tay YK. Lichen amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:105-107.

- Asahina A, Hasegawa K, Ishiyama M, et al. Bullous amyloidosis mimicking bullous pemphigoid: usefulness of electron microscopic examination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:427-428.

- Schmutz JL, Barbaud A, Cuny JF, et al. Bullous amyloidosis [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:295-301.

- Lachmann HJ, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis of the skin. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:1574-1583.

- Grundmann JU, Bonnekoh B, Gollnick H. Extensive haemorrhagic-bullous skin manifestation of systemic AA-amyloidosis associated with IgG lambda-myeloma. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:139-142.

- Hödl S, Turek TD, Kerl H. Plasmocytoma-associated bullous hemorrhagic amyloidosis of the skin [in German]. Hautarzt. 1982;33:556-558.

- Colucci G, Alberio L, Demarmels Biasiutti F, et al. Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses. an often missed sign of amyloid purpura. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:249-252.

- Behera B, Pattnaik M, Sahu B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:668-671.

- Fujita Y, Tsuji-Abe Y, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Nail dystrophy and blisters as sole manifestations in myeloma-associated amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:712-714.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Winzer M, Ruppert M, Baretton G, et al. Bullous poikilodermatitic amyloidosis of the skin with junctional bulla development in IgG light chain plasmacytoma of the lambda type. histology, immunohistology and electron microscopy [in German]. Hautarzt. 1992;43:199-204.

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Amyloidosis. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:341-345.

- Bhutani M, Shahid Z, Schnebelen A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell proliferative disorders. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:395-400.

- Terushkin V, Boyd KP, Patel RR, et al. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20711.

- LaChance A, Phelps A, Finch J, et al. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:344-347.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Kanoh T. Bullous amyloidosis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34:1050-1052.

- Johnson TM, Rapini RP, Hebert AA, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Cutis. 1989;43:346-352.

- Houman MH, Smiti KM, Ben Ghorbel I, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:299-302.

- Sanusi T, Li Y, Qian Y, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with bullous lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:400-402.

- Ochiai T, Morishima T, Hao T, et al. Bullous amyloidosis: the mechanism of blister formation revealed by electron microscopy. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:407-411.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Wang XD, Shen H, Liu ZH. Diffuse haemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis with multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:94-96.

- Biswas P, Aggarwal I, Sen D, et al. Bullous pemphigoid clinically presenting as lichen amyloidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:544-546.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous dermatosis vs amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:252.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous amyloidosis vs epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. JAMA. 1981;245:32.

- Murphy GM, Wright J, Nicholls DS, et al. Sunbed-induced pseudoporphyria. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:555-562.

- Pramatarov K, Lazarova A, Mateev G, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic primary systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:211-213.

- Bieber T, Ruzicka T, Linke RP, et al. Hemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis. a histologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study of two patients. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1683-1686.

- Khoo BP, Tay YK. Lichen amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:105-107.

- Asahina A, Hasegawa K, Ishiyama M, et al. Bullous amyloidosis mimicking bullous pemphigoid: usefulness of electron microscopic examination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:427-428.

- Schmutz JL, Barbaud A, Cuny JF, et al. Bullous amyloidosis [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:295-301.

- Lachmann HJ, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis of the skin. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:1574-1583.

- Grundmann JU, Bonnekoh B, Gollnick H. Extensive haemorrhagic-bullous skin manifestation of systemic AA-amyloidosis associated with IgG lambda-myeloma. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:139-142.

- Hödl S, Turek TD, Kerl H. Plasmocytoma-associated bullous hemorrhagic amyloidosis of the skin [in German]. Hautarzt. 1982;33:556-558.

- Colucci G, Alberio L, Demarmels Biasiutti F, et al. Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses. an often missed sign of amyloid purpura. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:249-252.

- Behera B, Pattnaik M, Sahu B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:668-671.

- Fujita Y, Tsuji-Abe Y, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Nail dystrophy and blisters as sole manifestations in myeloma-associated amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:712-714.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Winzer M, Ruppert M, Baretton G, et al. Bullous poikilodermatitic amyloidosis of the skin with junctional bulla development in IgG light chain plasmacytoma of the lambda type. histology, immunohistology and electron microscopy [in German]. Hautarzt. 1992;43:199-204.

Practice Points

- Primary systemic amyloidosis, including the rare cutaneous bullous amyloidosis, often is difficult to diagnose and has been associated with underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.

- When evaluating patients with initially convincing signs of pseudoporphyria, it is imperative to consider the diagnosis of bullous amyloidosis, which additionally can present with intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and have confirmatory histopathologic features.

- Further investigation for multiple myeloma is warranted when patients with a chronic hemorrhagic bullous condition also present with symptoms of purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue, weight loss, and/or macroglossia. Accurate diagnosis of bullous amyloidosis and timely treatment of its underlying cause will contribute to better, more proactive patient care.