User login

Inverted Appendix in a Patient With Weakness and Occult Bleeding

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (AMNs) are rare tumors of the appendix that can be asymptomatic or present with acute right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain mimicking appendicitis. Due to their potential to cause either no symptoms or nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting, AMNs are often found incidentally during appendectomies or, even more rarely, colonoscopies. Most AMNs grow slowly and have little metastatic potential. However, due to potential complications, such as bowel obstruction and rupture, timely detection and removal of AMN is essential. We describe the case of a patient who appeared to have acute appendicitis complicated by rupture on imaging who was found instead to have a perforated low-grade AMN during surgery.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 72 years with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and aortic stenosis, but no prior abdominal surgery, presented with a chief concern of generalized weakness. As part of the workup for his weakness, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed which showed an RLQ phlegmon and mild fat stranding in the area. Imaging also revealed an asymptomatic gallstone measuring 1.5 cm with no evidence of cholecystitis. The patient had no fever and reported no abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel habits. On physical examination, the patient’s abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended with normoactive bowel sounds and no rebound or guarding.

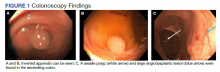

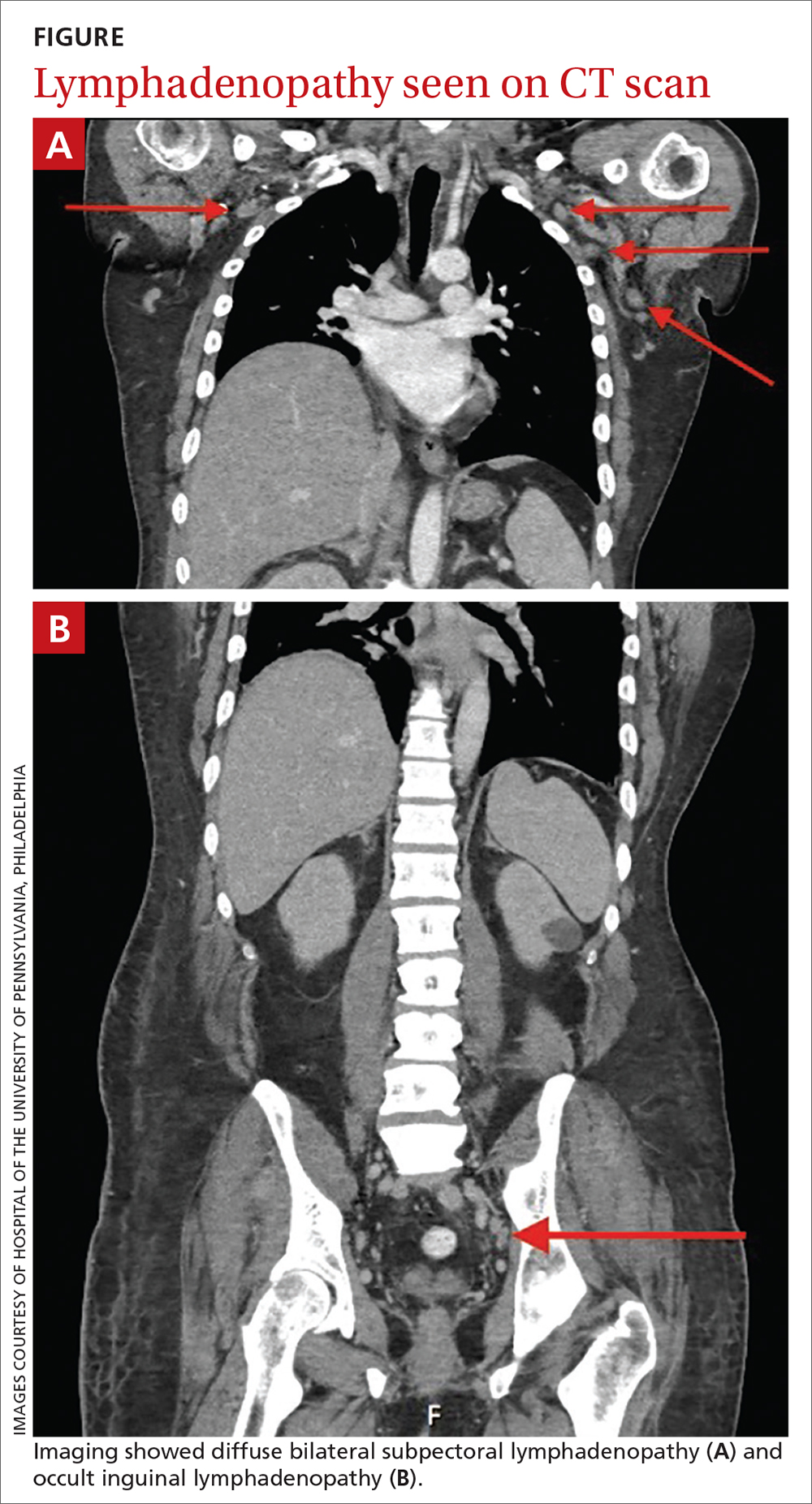

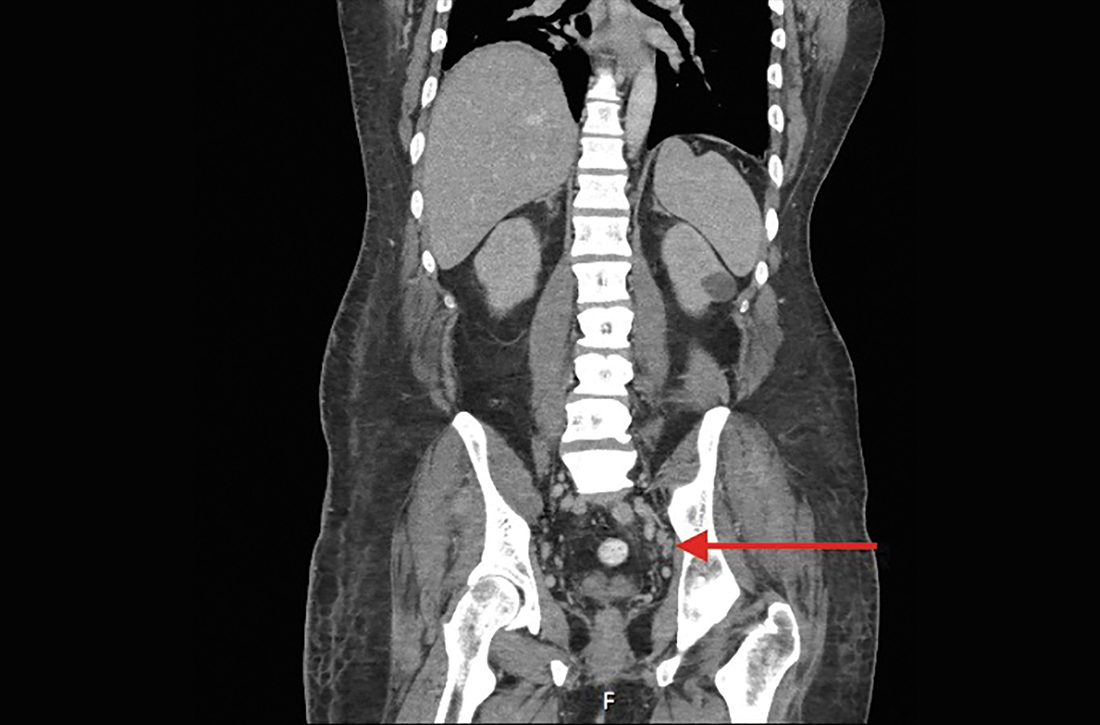

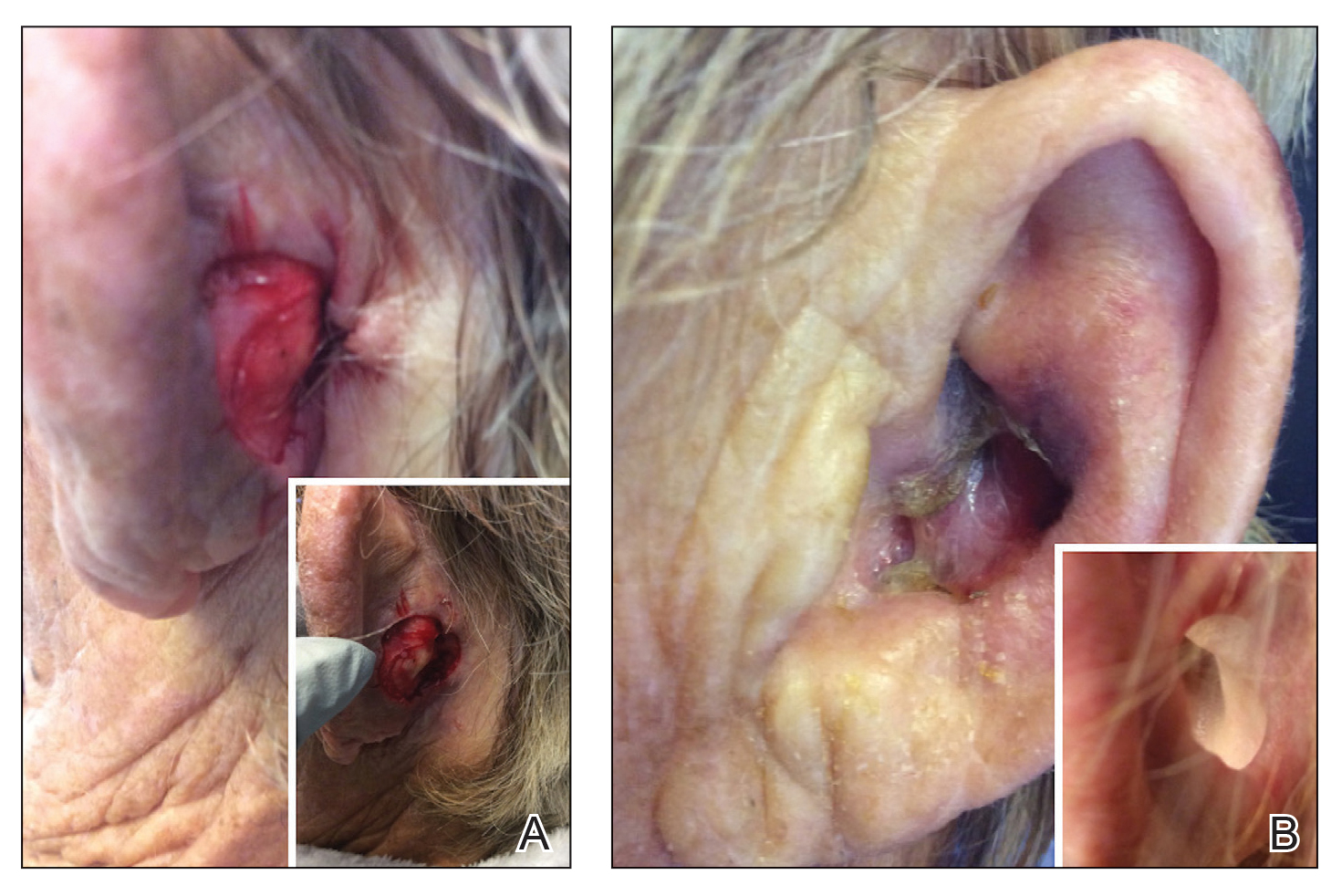

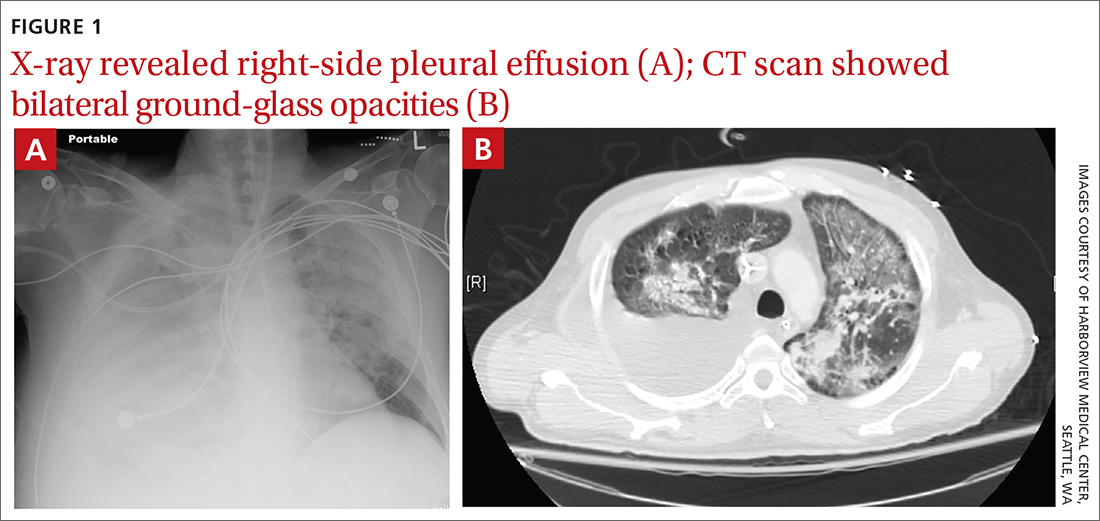

To manage the appendicitis, the patient started a 2-week course of amoxicillin clavulanate 875 mg twice daily and was instructed to schedule an interval appendectomy in the coming months. Four days later, during a follow-up with his primary care physician, he was found to be asymptomatic. However, at this visit his stool was found to be positive for occult blood. Given this finding and the lack of a previous colonoscopy, the patient underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed bulging at the appendiceal orifice, consistent with an inverted appendix. Portions of the appendix were biopsied (Figure 1). Histologic analysis of the appendiceal biopsies revealed no dysplasia or malignancy. The colonoscopy also revealed an 8-mm sessile polyp in the ascending colon which was resected, and histologic analysis of this polyp revealed a low-grade tubular adenoma. Additionally, a large angiodysplastic lesion was found in the ascending colon as well as external and medium-sized internal hemorrhoids.

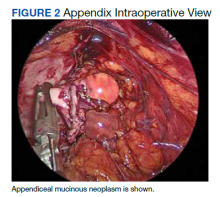

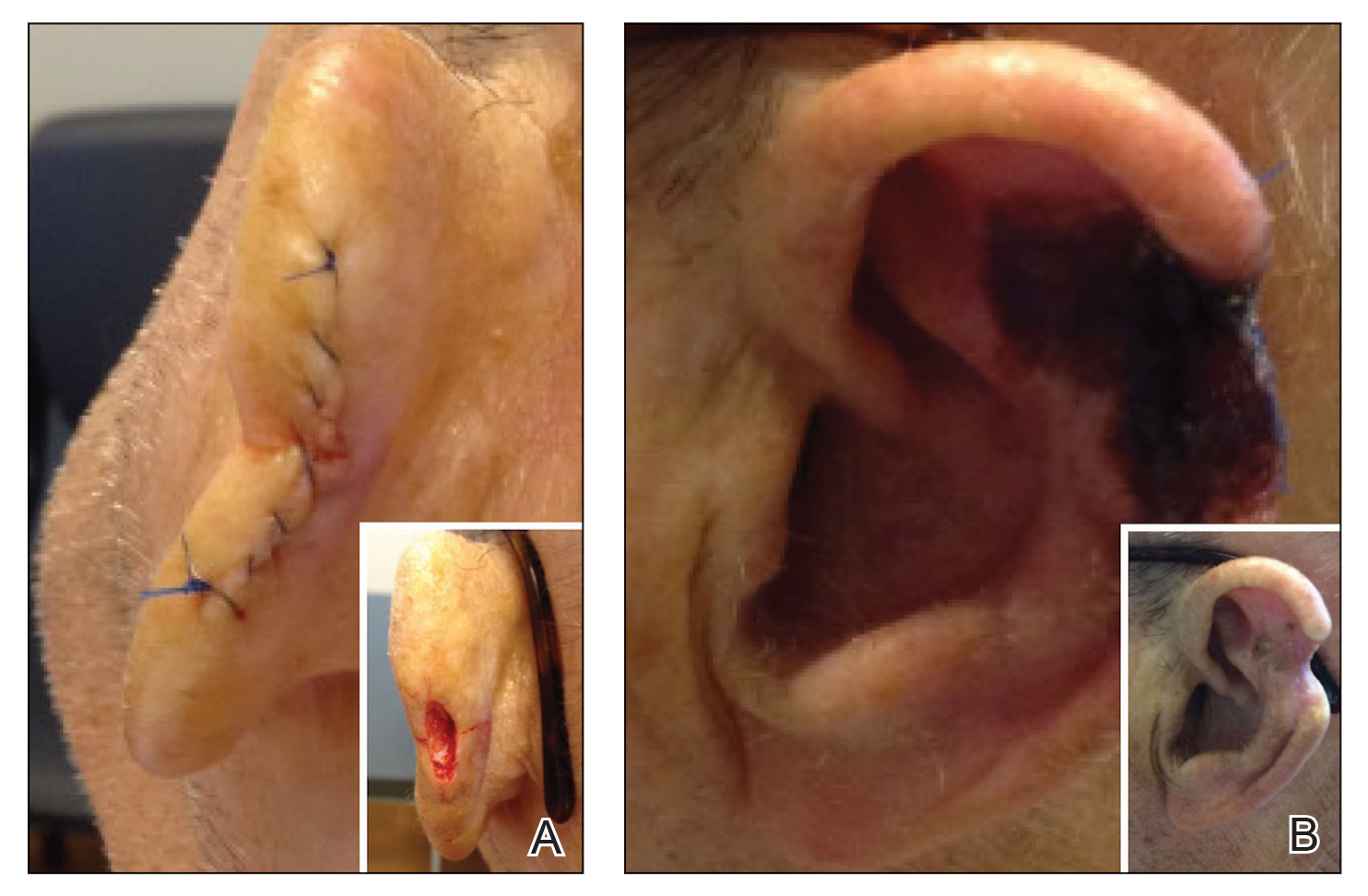

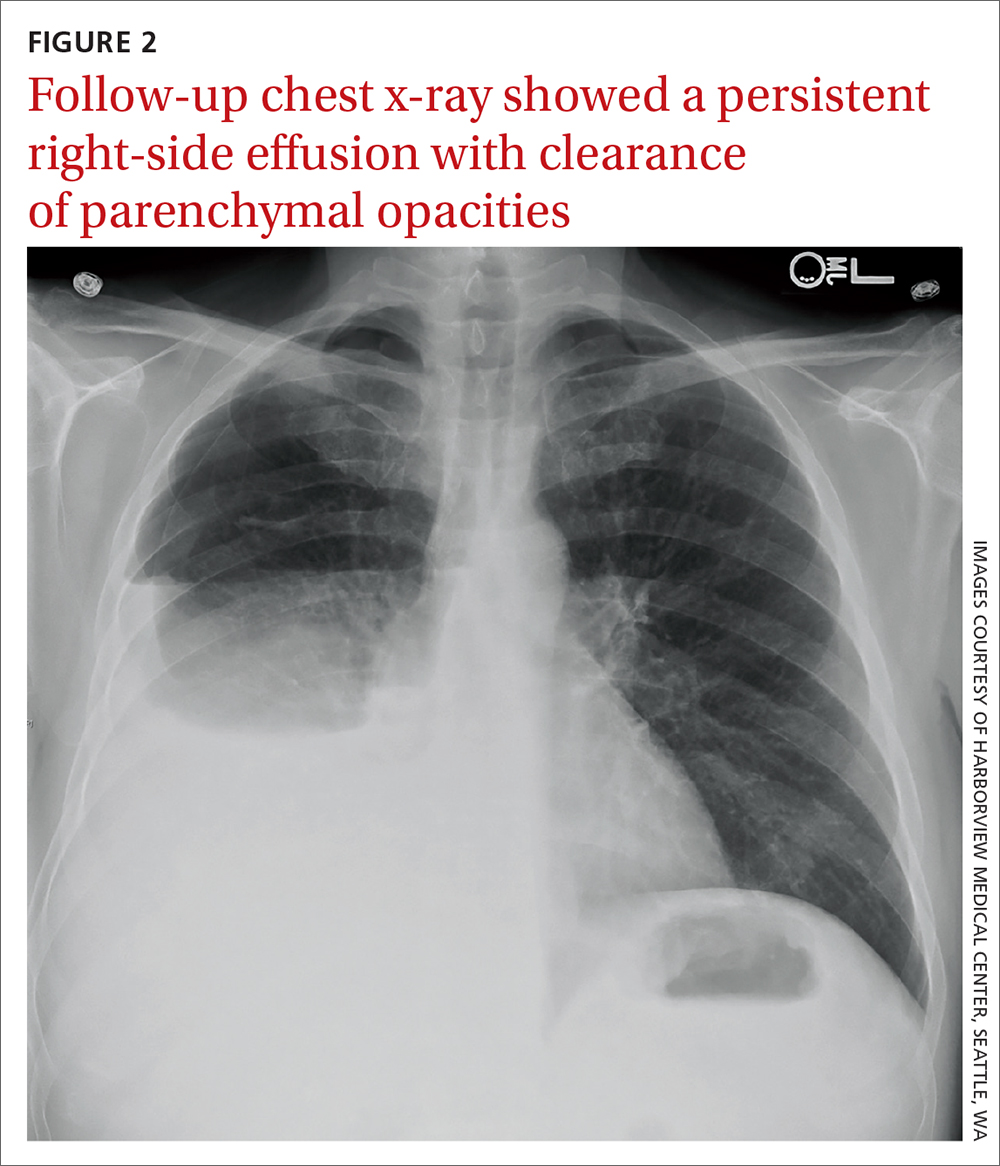

Six weeks after the colonoscopy, the patient was taken to the operating room for a laparoscopic appendectomy. Upon entry of the abdomen, extensive adhesions throughout the RLQ were found which required adhesiolysis. A calcified fecalith adherent to the mesentery of the small intestine in the RLQ was also found and resected. After lysis of the adhesions, the appendix and fibrotic tissue surrounding it could be seen (Figure 2). The appendix was dilated and the tip showed perforation. During dissection of the appendix, clear gelatinous material was found coming from the appendiceal lumen as well as from the fibrotic tissue around the appendix. On postoperative day 1 the appendix was resected and the patient was discharged.

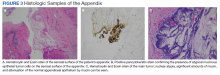

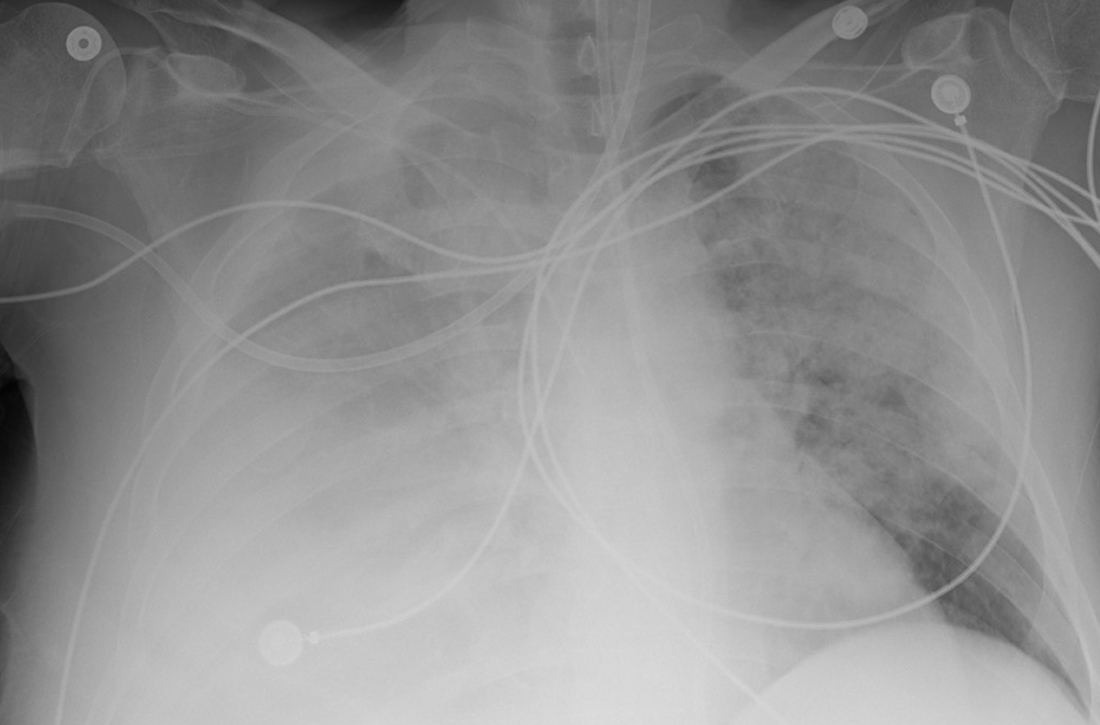

Histologic specimens of the appendix were notable for evidence of perforation and neoplasia leading to a diagnosis of low-grade AMN. The presence of atypical mucinous epithelial cells on the serosal surface of the appendix, confirmed with a positive pancytokeratin stain, provided histologic evidence of appendiceal perforation (Figure 3). The presence of nuclear atypia demonstrated that the appendix was involved by a neoplastic process. Additionally, attenuation of the normal appendiceal epithelium, evidence of a chronic process, further helped to differentiate the AMN from complicated appendicitis. The presence of mucin involving the serosa of the appendix led to the classification of this patient’s neoplasm as grade pT4a. Of note, histologic examination demonstrated that the surgical margins contained tumor cells.

Given the positive margins of the resected AMN and the relatively large size of the neoplasm, a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy was performed 2 months later. Although multiple adhesions were found in the terminal ileum, cecum, and ascending colon during the hemicolectomy, no mucinous lesions were observed grossly. Histologic analysis showed no residual neoplasm as well as no lymph node involvement. On postoperative day 3 the patient was discharged and had an uneventful recovery. At his first surveillance visit 6 months after his hemicolectomy, the patient appeared to be doing well and reported no abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, change in bowel habits, or any blood in the stool.

Discussion

AMNs are rare tumors with an annual age-adjusted incidence of approximately 0.12 per 1,000,000 people.1 These neoplasms can present as acute or chronic abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal obstruction, or acute abdomen.2-4 Most AMNs, however, are asymptomatic and are usually found incidentally during appendectomies for appendicitis, and can even be found during colonoscopies,such as in this case.5,6

Low-grade AMNs are distinguished from appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas by their lack of wall invasion.7 Additionally, low-grade AMNs have a very good prognosis as even neoplasms that have spread outside of the appendix have a 5-year overall survival rate of 79 to 86%.8 These low-grade neoplasms also have extremely low rates of recurrence after resection.9 In contrast, appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas have a much worse prognosis with a 5-year overall survival rate of 53.6%.10

Treatment of AMNs depends on the extent of their spread. Neoplasms that are confined to the appendix can typically be treated with appendectomy alone, while those that have spread beyond the appendix may require cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy, namely, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), in addition to appendectomy.11 Cases in which neoplasms are not confined to the appendix also require more frequent surveillance for recurrence as compared to appendix-restricted neoplasms.11

Appendiceal inversion is a rare finding in adults with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%.6 Not only is appendiceal inversion rare in and of itself, it is even more rarely found in combination with appendiceal neoplasms.6 Other causes of appendiceal inversion include intussusception, acute appendicitis, appendiceal nodule, or even iatrogenic due to appendectomy.12-14 While appendiceal inversion can be completely benign, because these morphological changes of the appendix can resemble a polyp, these lesions are often biopsied and/or resected.15 However, lesion resection may be quite problematic due to high risk of bleeding and perforation.15 In order to avoid the risks associated with resection of a potentially benign finding, biopsy should be performed prior to any attempted resection of inverted appendices.15

Another interesting aspect of this case is the finding of fecal occult blood. The differential for fecal occult blood is quite broad and the patient had multiple conditions that could have led to the finding of occult blood in his stool. Hemorrhoids can cause a positive result on a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) although this is relatively uncommon, and hemorrhoids are more likely to cause frank blood to be seen.16 The sessile polyp found in the patient’s colon may also have caused the FOBT to be positive. This patient was also found to have an angiodysplasia (a finding that is associated with aortic stenosis, which this patient has a history of) which can also cause gastrointestinal bleeding.17 Lastly, AMNs may also cause gastrointestinal bleeding and thus a positive FOBT, although bleeding is a relatively uncommon presentation of AMNs, especially those that are low-grade as in this case.18

This case also highlights the association between appendiceal neoplasms and colonic neoplastic lesions. Patients with appendiceal neoplasms are more likely to have colonic neoplastic lesions than patients without appendiceal neoplasms.19 Studies have found that approximately 13 to 42% of patients with appendiceal neoplasms also have colonic neoplastic lesions.19 The majority of these lesions in the colon were right-sided and this finding was also seen in this case as the patient’s polyp was located in the ascending colon.19 Due to this association between appendiceal and colorectal neoplasia, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons strongly recommends that patients with appendiceal neoplasms or who are suspected of having them receive a colonoscopy.19

Additionally, perforation of an AMN, as was seen in this case, is a finding that should raise significant concern. Perforation of an AMN allows for the spread of malignant mucinous epithelial cells throughout the abdomen. The finding of extensive adhesions throughout the patient’s RLQ was unexpected as abdominal adhesions are most often seen in patients with a history of abdominal surgeries. Considering the lack of any prior abdominal surgeries in this patient, these adhesions were most likely the result of the spread and proliferation of malignant mucinous epithelial cells from the perforated AMN in the RLQ.20 The adhesiolysis performed in this case was thus not only important in order to visualize the appendix, but also for preventing future complications of abdominal adhesions such as bowel obstruction.20 Perforated AMN is also so concerning because it can potentially lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei—a condition in which malignant mucinous epithelial cells accumulate in the abdomen.21 Pseudomyxoma peritonei is extremely rare with an incidence of approximately 1 to 2 cases per million per year.22 Early recognition of AMNs and surgical referral are critically important as pseudomyxoma peritonei is difficult to treat, has a high rate of recurrence, and can be fatal.23

Lastly, this case highlights how findings of a ruptured appendix and/or mucin surrounding the appendix on imaging should warrant laparoscopy because only pathologic analysis of the appendix can definitively rule out AMNs. The utility of laparoscopic evaluation of the appendix is especially apparent as nonsurgical treatment of appendicitis using antibiotics is gaining favor for treating even complicated appendicitis.24 Appendicitis is much more common than AMNs. However, had the patient in this case only been given antibiotics for his suspected complicated appendicitis without any colonoscopy or appendectomy, the neoplasm in his appendix would have gone undetected and continued to grow, causing significant complications. The patient’s age at presentation in this case also necessitated laparoscopic evaluation of the appendix as the incidence of AMNs is highest among patients aged > 60 years.25 Additionally, because appendiceal inversion may be seen with AMNs,the patient’s inverted appendix seen during his colonoscopy was another compelling reason for laparoscopic evaluation of his appendix.6

Conclusions

AMNs can present with nonspecific symptoms or can be completely asymptomatic and are often found incidentally during colonoscopies or appendectomies for acute appendicitis. While it is true that AMNs have low metastatic potential and grow slowly, AMNs can rupture leading to pseudomyxoma peritonei or even cause bowel obstruction warranting timely identification and removal of these neoplasms. Laparoscopic evaluation in cases of ruptured appendices is critical not only for treatment, but also for determining the presence of a potential underlying appendiceal malignancy. Although AMNs are a rare pathology, physicians should still consider the possibility of these neoplasms even when imaging findings suggest appendicitis. Having AMNs as part of the differential diagnosis is especially necessary in cases, such as this one, in which the patient has appendiceal inversion, is aged > 50 years, and has concurrent colorectal neoplasms.

1. Shaib WL, Goodman M, Chen Z, et al. Incidence and survival of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a SEER analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017;40(6):569-573. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000210

2. Kehagias I, Zygomalas A, Markopoulos G, Papandreou T, Kraniotis P. Diagnosis and treatment of mucinous appendiceal neoplasm presented as acute appendicitis. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2016;3:1-6. doi:10.1155/2016/2161952

3. Karatas M, Simsek C, Gunay S, et al. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to low-grade mucinous neoplasm of appendix. Acta Chir Belg. 2020;120(4):1-4. doi:10.1080/00015458.2020.1860397

4. Mourad FH, Hussein M, Bahlawan M, Haddad M, Tawil A. Intestinal obstruction secondary to appendiceal mucocele. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44(8):1594-1599. doi:10.1023/a:1026615010989

5. Benabe SH, Leeman R, Brady AC, Hirzel A, Langshaw AH. Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in an adolescent patient with untreated Crohn’s disease. ACG Case Reports J. 2020;7(3). doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000338

6. Liu X, Liu G, Liu Y, et al. Complete appendiceal inversion with local high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in an adult female: A case report. BMC Surg. 2019;19(1). doi:10.1186/s12893-019-0632-3

7. Gündog˘ar ÖS, Kımılog˘lu ES, Komut NS, et al. The evaluation of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms with a new classification system. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29(5):532-542. doi:10.5152/tjg.2018.17605

8. Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM, Balis UJ, Young RH. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(8):1089-1103. doi:10.1097/00000478-200308000-00006

9. Pai RK, Beck AH, Norton JA, Longacre TA. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: clinicopathologic study of 116 cases with analysis of factors predicting recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(10):1425-1439. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181af6067

10. Asare EA, Compton CC, Hanna NN, et al. The impact of stage, grade, and mucinous histology on the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the appendix: analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2015;122(2):213-221. doi:10.1002/cncr.29744

11. Shaib WL, Assi R, Shamseddine A, et al. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: diagnosis and management. Oncologist. 2018;23(1):137. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0081erratum

12. Tran C, Sakioka J, Nguyen E, Beutler BD, Hsu J. An inverted appendix found on routine colonoscopy: a case report with discussion of imaging findings. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14(8):952-955. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2019.05.022

13. Shafi A, Azab M. A case of everted appendix with benign appendiceal nodule masquerading as appendiceal mucocele: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S1436. doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-02585

14. Pokhrel B, Chang M, Anand G, Savides T, Fehmi S. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in an inverted appendix found on prior colonoscopy. VideoGIE. 2020;5(1):34-36. doi:10.1016/j.vgie.2019.09.013

15. Johnson EK, Arcila ME, Steele SR. Appendiceal inversion: a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. JSLS. 2009;13(1):92-95.

16. van Turenhout ST, Oort FA, sive Droste JST, et al. Hemorrhoids detected at colonoscopy: an infrequent cause of false-positive fecal immunochemical test results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(1):136-143. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.169

17. Hudzik B, Wilczek K, Gasior M. Heyde syndrome: Gastrointestinal bleeding and aortic stenosis. CMAJ. 2016;188(2):135-138. doi:10.1503/cmaj.150194

18. Leonards LM, Pahwa A, Patel MK, Petersen J, Nguyen MJ, Jude CM. Neoplasms of the appendix: pictorial review with clinical and pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2017;37(4):1059-1083. doi:10.1148/rg.2017160150

19. Glasgow SC, Gaertner W, Stewart D, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, clinical practice guidelines for the management of appendiceal neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(12):1425-1438. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000001530

20. Panagopoulos P, Tsokaki T, Misiakos E, et al. Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm presenting as an adnexal mass. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;2017:1-3. doi:10.1155/2017/7165321

21. Ramaswamy V. Pathology of mucinous appendiceal tumors and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2016;7(2):258-267. doi:10.1007/s13193-016-0516-2.

22. Bevan KE, Mohamed F, Moran BJ. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2(1):44-50. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v2.i1.44

23. Mercier F, Dagbert F, Pocard M, et al. Recurrence of pseudomyxoma peritonei after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. BJS Open. 2018;3(2):195-202. doi:10.1002/bjs5.97

24. David A, Dodgion C, Eddine SBZ, Davila D, Webb TP, Trevino CM. Perforated appendicitis: Short duration antibiotics are noninferior to traditional long duration antibiotics. Surgery. 2020;167(2):475-477. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2019.08.007

25. Raijman I, Leong S, Hassaram S, Marcon NE. Appendiceal mucocele: Endoscopic appearance. Endoscopy. 1994;26(3):326-328. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1008979

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (AMNs) are rare tumors of the appendix that can be asymptomatic or present with acute right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain mimicking appendicitis. Due to their potential to cause either no symptoms or nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting, AMNs are often found incidentally during appendectomies or, even more rarely, colonoscopies. Most AMNs grow slowly and have little metastatic potential. However, due to potential complications, such as bowel obstruction and rupture, timely detection and removal of AMN is essential. We describe the case of a patient who appeared to have acute appendicitis complicated by rupture on imaging who was found instead to have a perforated low-grade AMN during surgery.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 72 years with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and aortic stenosis, but no prior abdominal surgery, presented with a chief concern of generalized weakness. As part of the workup for his weakness, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed which showed an RLQ phlegmon and mild fat stranding in the area. Imaging also revealed an asymptomatic gallstone measuring 1.5 cm with no evidence of cholecystitis. The patient had no fever and reported no abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel habits. On physical examination, the patient’s abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended with normoactive bowel sounds and no rebound or guarding.

To manage the appendicitis, the patient started a 2-week course of amoxicillin clavulanate 875 mg twice daily and was instructed to schedule an interval appendectomy in the coming months. Four days later, during a follow-up with his primary care physician, he was found to be asymptomatic. However, at this visit his stool was found to be positive for occult blood. Given this finding and the lack of a previous colonoscopy, the patient underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed bulging at the appendiceal orifice, consistent with an inverted appendix. Portions of the appendix were biopsied (Figure 1). Histologic analysis of the appendiceal biopsies revealed no dysplasia or malignancy. The colonoscopy also revealed an 8-mm sessile polyp in the ascending colon which was resected, and histologic analysis of this polyp revealed a low-grade tubular adenoma. Additionally, a large angiodysplastic lesion was found in the ascending colon as well as external and medium-sized internal hemorrhoids.

Six weeks after the colonoscopy, the patient was taken to the operating room for a laparoscopic appendectomy. Upon entry of the abdomen, extensive adhesions throughout the RLQ were found which required adhesiolysis. A calcified fecalith adherent to the mesentery of the small intestine in the RLQ was also found and resected. After lysis of the adhesions, the appendix and fibrotic tissue surrounding it could be seen (Figure 2). The appendix was dilated and the tip showed perforation. During dissection of the appendix, clear gelatinous material was found coming from the appendiceal lumen as well as from the fibrotic tissue around the appendix. On postoperative day 1 the appendix was resected and the patient was discharged.

Histologic specimens of the appendix were notable for evidence of perforation and neoplasia leading to a diagnosis of low-grade AMN. The presence of atypical mucinous epithelial cells on the serosal surface of the appendix, confirmed with a positive pancytokeratin stain, provided histologic evidence of appendiceal perforation (Figure 3). The presence of nuclear atypia demonstrated that the appendix was involved by a neoplastic process. Additionally, attenuation of the normal appendiceal epithelium, evidence of a chronic process, further helped to differentiate the AMN from complicated appendicitis. The presence of mucin involving the serosa of the appendix led to the classification of this patient’s neoplasm as grade pT4a. Of note, histologic examination demonstrated that the surgical margins contained tumor cells.

Given the positive margins of the resected AMN and the relatively large size of the neoplasm, a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy was performed 2 months later. Although multiple adhesions were found in the terminal ileum, cecum, and ascending colon during the hemicolectomy, no mucinous lesions were observed grossly. Histologic analysis showed no residual neoplasm as well as no lymph node involvement. On postoperative day 3 the patient was discharged and had an uneventful recovery. At his first surveillance visit 6 months after his hemicolectomy, the patient appeared to be doing well and reported no abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, change in bowel habits, or any blood in the stool.

Discussion

AMNs are rare tumors with an annual age-adjusted incidence of approximately 0.12 per 1,000,000 people.1 These neoplasms can present as acute or chronic abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal obstruction, or acute abdomen.2-4 Most AMNs, however, are asymptomatic and are usually found incidentally during appendectomies for appendicitis, and can even be found during colonoscopies,such as in this case.5,6

Low-grade AMNs are distinguished from appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas by their lack of wall invasion.7 Additionally, low-grade AMNs have a very good prognosis as even neoplasms that have spread outside of the appendix have a 5-year overall survival rate of 79 to 86%.8 These low-grade neoplasms also have extremely low rates of recurrence after resection.9 In contrast, appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas have a much worse prognosis with a 5-year overall survival rate of 53.6%.10

Treatment of AMNs depends on the extent of their spread. Neoplasms that are confined to the appendix can typically be treated with appendectomy alone, while those that have spread beyond the appendix may require cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy, namely, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), in addition to appendectomy.11 Cases in which neoplasms are not confined to the appendix also require more frequent surveillance for recurrence as compared to appendix-restricted neoplasms.11

Appendiceal inversion is a rare finding in adults with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%.6 Not only is appendiceal inversion rare in and of itself, it is even more rarely found in combination with appendiceal neoplasms.6 Other causes of appendiceal inversion include intussusception, acute appendicitis, appendiceal nodule, or even iatrogenic due to appendectomy.12-14 While appendiceal inversion can be completely benign, because these morphological changes of the appendix can resemble a polyp, these lesions are often biopsied and/or resected.15 However, lesion resection may be quite problematic due to high risk of bleeding and perforation.15 In order to avoid the risks associated with resection of a potentially benign finding, biopsy should be performed prior to any attempted resection of inverted appendices.15

Another interesting aspect of this case is the finding of fecal occult blood. The differential for fecal occult blood is quite broad and the patient had multiple conditions that could have led to the finding of occult blood in his stool. Hemorrhoids can cause a positive result on a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) although this is relatively uncommon, and hemorrhoids are more likely to cause frank blood to be seen.16 The sessile polyp found in the patient’s colon may also have caused the FOBT to be positive. This patient was also found to have an angiodysplasia (a finding that is associated with aortic stenosis, which this patient has a history of) which can also cause gastrointestinal bleeding.17 Lastly, AMNs may also cause gastrointestinal bleeding and thus a positive FOBT, although bleeding is a relatively uncommon presentation of AMNs, especially those that are low-grade as in this case.18

This case also highlights the association between appendiceal neoplasms and colonic neoplastic lesions. Patients with appendiceal neoplasms are more likely to have colonic neoplastic lesions than patients without appendiceal neoplasms.19 Studies have found that approximately 13 to 42% of patients with appendiceal neoplasms also have colonic neoplastic lesions.19 The majority of these lesions in the colon were right-sided and this finding was also seen in this case as the patient’s polyp was located in the ascending colon.19 Due to this association between appendiceal and colorectal neoplasia, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons strongly recommends that patients with appendiceal neoplasms or who are suspected of having them receive a colonoscopy.19

Additionally, perforation of an AMN, as was seen in this case, is a finding that should raise significant concern. Perforation of an AMN allows for the spread of malignant mucinous epithelial cells throughout the abdomen. The finding of extensive adhesions throughout the patient’s RLQ was unexpected as abdominal adhesions are most often seen in patients with a history of abdominal surgeries. Considering the lack of any prior abdominal surgeries in this patient, these adhesions were most likely the result of the spread and proliferation of malignant mucinous epithelial cells from the perforated AMN in the RLQ.20 The adhesiolysis performed in this case was thus not only important in order to visualize the appendix, but also for preventing future complications of abdominal adhesions such as bowel obstruction.20 Perforated AMN is also so concerning because it can potentially lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei—a condition in which malignant mucinous epithelial cells accumulate in the abdomen.21 Pseudomyxoma peritonei is extremely rare with an incidence of approximately 1 to 2 cases per million per year.22 Early recognition of AMNs and surgical referral are critically important as pseudomyxoma peritonei is difficult to treat, has a high rate of recurrence, and can be fatal.23

Lastly, this case highlights how findings of a ruptured appendix and/or mucin surrounding the appendix on imaging should warrant laparoscopy because only pathologic analysis of the appendix can definitively rule out AMNs. The utility of laparoscopic evaluation of the appendix is especially apparent as nonsurgical treatment of appendicitis using antibiotics is gaining favor for treating even complicated appendicitis.24 Appendicitis is much more common than AMNs. However, had the patient in this case only been given antibiotics for his suspected complicated appendicitis without any colonoscopy or appendectomy, the neoplasm in his appendix would have gone undetected and continued to grow, causing significant complications. The patient’s age at presentation in this case also necessitated laparoscopic evaluation of the appendix as the incidence of AMNs is highest among patients aged > 60 years.25 Additionally, because appendiceal inversion may be seen with AMNs,the patient’s inverted appendix seen during his colonoscopy was another compelling reason for laparoscopic evaluation of his appendix.6

Conclusions

AMNs can present with nonspecific symptoms or can be completely asymptomatic and are often found incidentally during colonoscopies or appendectomies for acute appendicitis. While it is true that AMNs have low metastatic potential and grow slowly, AMNs can rupture leading to pseudomyxoma peritonei or even cause bowel obstruction warranting timely identification and removal of these neoplasms. Laparoscopic evaluation in cases of ruptured appendices is critical not only for treatment, but also for determining the presence of a potential underlying appendiceal malignancy. Although AMNs are a rare pathology, physicians should still consider the possibility of these neoplasms even when imaging findings suggest appendicitis. Having AMNs as part of the differential diagnosis is especially necessary in cases, such as this one, in which the patient has appendiceal inversion, is aged > 50 years, and has concurrent colorectal neoplasms.

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (AMNs) are rare tumors of the appendix that can be asymptomatic or present with acute right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain mimicking appendicitis. Due to their potential to cause either no symptoms or nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting, AMNs are often found incidentally during appendectomies or, even more rarely, colonoscopies. Most AMNs grow slowly and have little metastatic potential. However, due to potential complications, such as bowel obstruction and rupture, timely detection and removal of AMN is essential. We describe the case of a patient who appeared to have acute appendicitis complicated by rupture on imaging who was found instead to have a perforated low-grade AMN during surgery.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 72 years with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and aortic stenosis, but no prior abdominal surgery, presented with a chief concern of generalized weakness. As part of the workup for his weakness, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed which showed an RLQ phlegmon and mild fat stranding in the area. Imaging also revealed an asymptomatic gallstone measuring 1.5 cm with no evidence of cholecystitis. The patient had no fever and reported no abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or change in bowel habits. On physical examination, the patient’s abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended with normoactive bowel sounds and no rebound or guarding.

To manage the appendicitis, the patient started a 2-week course of amoxicillin clavulanate 875 mg twice daily and was instructed to schedule an interval appendectomy in the coming months. Four days later, during a follow-up with his primary care physician, he was found to be asymptomatic. However, at this visit his stool was found to be positive for occult blood. Given this finding and the lack of a previous colonoscopy, the patient underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed bulging at the appendiceal orifice, consistent with an inverted appendix. Portions of the appendix were biopsied (Figure 1). Histologic analysis of the appendiceal biopsies revealed no dysplasia or malignancy. The colonoscopy also revealed an 8-mm sessile polyp in the ascending colon which was resected, and histologic analysis of this polyp revealed a low-grade tubular adenoma. Additionally, a large angiodysplastic lesion was found in the ascending colon as well as external and medium-sized internal hemorrhoids.

Six weeks after the colonoscopy, the patient was taken to the operating room for a laparoscopic appendectomy. Upon entry of the abdomen, extensive adhesions throughout the RLQ were found which required adhesiolysis. A calcified fecalith adherent to the mesentery of the small intestine in the RLQ was also found and resected. After lysis of the adhesions, the appendix and fibrotic tissue surrounding it could be seen (Figure 2). The appendix was dilated and the tip showed perforation. During dissection of the appendix, clear gelatinous material was found coming from the appendiceal lumen as well as from the fibrotic tissue around the appendix. On postoperative day 1 the appendix was resected and the patient was discharged.

Histologic specimens of the appendix were notable for evidence of perforation and neoplasia leading to a diagnosis of low-grade AMN. The presence of atypical mucinous epithelial cells on the serosal surface of the appendix, confirmed with a positive pancytokeratin stain, provided histologic evidence of appendiceal perforation (Figure 3). The presence of nuclear atypia demonstrated that the appendix was involved by a neoplastic process. Additionally, attenuation of the normal appendiceal epithelium, evidence of a chronic process, further helped to differentiate the AMN from complicated appendicitis. The presence of mucin involving the serosa of the appendix led to the classification of this patient’s neoplasm as grade pT4a. Of note, histologic examination demonstrated that the surgical margins contained tumor cells.

Given the positive margins of the resected AMN and the relatively large size of the neoplasm, a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy was performed 2 months later. Although multiple adhesions were found in the terminal ileum, cecum, and ascending colon during the hemicolectomy, no mucinous lesions were observed grossly. Histologic analysis showed no residual neoplasm as well as no lymph node involvement. On postoperative day 3 the patient was discharged and had an uneventful recovery. At his first surveillance visit 6 months after his hemicolectomy, the patient appeared to be doing well and reported no abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, change in bowel habits, or any blood in the stool.

Discussion

AMNs are rare tumors with an annual age-adjusted incidence of approximately 0.12 per 1,000,000 people.1 These neoplasms can present as acute or chronic abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal obstruction, or acute abdomen.2-4 Most AMNs, however, are asymptomatic and are usually found incidentally during appendectomies for appendicitis, and can even be found during colonoscopies,such as in this case.5,6

Low-grade AMNs are distinguished from appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas by their lack of wall invasion.7 Additionally, low-grade AMNs have a very good prognosis as even neoplasms that have spread outside of the appendix have a 5-year overall survival rate of 79 to 86%.8 These low-grade neoplasms also have extremely low rates of recurrence after resection.9 In contrast, appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas have a much worse prognosis with a 5-year overall survival rate of 53.6%.10

Treatment of AMNs depends on the extent of their spread. Neoplasms that are confined to the appendix can typically be treated with appendectomy alone, while those that have spread beyond the appendix may require cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy, namely, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), in addition to appendectomy.11 Cases in which neoplasms are not confined to the appendix also require more frequent surveillance for recurrence as compared to appendix-restricted neoplasms.11

Appendiceal inversion is a rare finding in adults with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%.6 Not only is appendiceal inversion rare in and of itself, it is even more rarely found in combination with appendiceal neoplasms.6 Other causes of appendiceal inversion include intussusception, acute appendicitis, appendiceal nodule, or even iatrogenic due to appendectomy.12-14 While appendiceal inversion can be completely benign, because these morphological changes of the appendix can resemble a polyp, these lesions are often biopsied and/or resected.15 However, lesion resection may be quite problematic due to high risk of bleeding and perforation.15 In order to avoid the risks associated with resection of a potentially benign finding, biopsy should be performed prior to any attempted resection of inverted appendices.15

Another interesting aspect of this case is the finding of fecal occult blood. The differential for fecal occult blood is quite broad and the patient had multiple conditions that could have led to the finding of occult blood in his stool. Hemorrhoids can cause a positive result on a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) although this is relatively uncommon, and hemorrhoids are more likely to cause frank blood to be seen.16 The sessile polyp found in the patient’s colon may also have caused the FOBT to be positive. This patient was also found to have an angiodysplasia (a finding that is associated with aortic stenosis, which this patient has a history of) which can also cause gastrointestinal bleeding.17 Lastly, AMNs may also cause gastrointestinal bleeding and thus a positive FOBT, although bleeding is a relatively uncommon presentation of AMNs, especially those that are low-grade as in this case.18

This case also highlights the association between appendiceal neoplasms and colonic neoplastic lesions. Patients with appendiceal neoplasms are more likely to have colonic neoplastic lesions than patients without appendiceal neoplasms.19 Studies have found that approximately 13 to 42% of patients with appendiceal neoplasms also have colonic neoplastic lesions.19 The majority of these lesions in the colon were right-sided and this finding was also seen in this case as the patient’s polyp was located in the ascending colon.19 Due to this association between appendiceal and colorectal neoplasia, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons strongly recommends that patients with appendiceal neoplasms or who are suspected of having them receive a colonoscopy.19

Additionally, perforation of an AMN, as was seen in this case, is a finding that should raise significant concern. Perforation of an AMN allows for the spread of malignant mucinous epithelial cells throughout the abdomen. The finding of extensive adhesions throughout the patient’s RLQ was unexpected as abdominal adhesions are most often seen in patients with a history of abdominal surgeries. Considering the lack of any prior abdominal surgeries in this patient, these adhesions were most likely the result of the spread and proliferation of malignant mucinous epithelial cells from the perforated AMN in the RLQ.20 The adhesiolysis performed in this case was thus not only important in order to visualize the appendix, but also for preventing future complications of abdominal adhesions such as bowel obstruction.20 Perforated AMN is also so concerning because it can potentially lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei—a condition in which malignant mucinous epithelial cells accumulate in the abdomen.21 Pseudomyxoma peritonei is extremely rare with an incidence of approximately 1 to 2 cases per million per year.22 Early recognition of AMNs and surgical referral are critically important as pseudomyxoma peritonei is difficult to treat, has a high rate of recurrence, and can be fatal.23

Lastly, this case highlights how findings of a ruptured appendix and/or mucin surrounding the appendix on imaging should warrant laparoscopy because only pathologic analysis of the appendix can definitively rule out AMNs. The utility of laparoscopic evaluation of the appendix is especially apparent as nonsurgical treatment of appendicitis using antibiotics is gaining favor for treating even complicated appendicitis.24 Appendicitis is much more common than AMNs. However, had the patient in this case only been given antibiotics for his suspected complicated appendicitis without any colonoscopy or appendectomy, the neoplasm in his appendix would have gone undetected and continued to grow, causing significant complications. The patient’s age at presentation in this case also necessitated laparoscopic evaluation of the appendix as the incidence of AMNs is highest among patients aged > 60 years.25 Additionally, because appendiceal inversion may be seen with AMNs,the patient’s inverted appendix seen during his colonoscopy was another compelling reason for laparoscopic evaluation of his appendix.6

Conclusions

AMNs can present with nonspecific symptoms or can be completely asymptomatic and are often found incidentally during colonoscopies or appendectomies for acute appendicitis. While it is true that AMNs have low metastatic potential and grow slowly, AMNs can rupture leading to pseudomyxoma peritonei or even cause bowel obstruction warranting timely identification and removal of these neoplasms. Laparoscopic evaluation in cases of ruptured appendices is critical not only for treatment, but also for determining the presence of a potential underlying appendiceal malignancy. Although AMNs are a rare pathology, physicians should still consider the possibility of these neoplasms even when imaging findings suggest appendicitis. Having AMNs as part of the differential diagnosis is especially necessary in cases, such as this one, in which the patient has appendiceal inversion, is aged > 50 years, and has concurrent colorectal neoplasms.

1. Shaib WL, Goodman M, Chen Z, et al. Incidence and survival of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a SEER analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017;40(6):569-573. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000210

2. Kehagias I, Zygomalas A, Markopoulos G, Papandreou T, Kraniotis P. Diagnosis and treatment of mucinous appendiceal neoplasm presented as acute appendicitis. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2016;3:1-6. doi:10.1155/2016/2161952

3. Karatas M, Simsek C, Gunay S, et al. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to low-grade mucinous neoplasm of appendix. Acta Chir Belg. 2020;120(4):1-4. doi:10.1080/00015458.2020.1860397

4. Mourad FH, Hussein M, Bahlawan M, Haddad M, Tawil A. Intestinal obstruction secondary to appendiceal mucocele. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44(8):1594-1599. doi:10.1023/a:1026615010989

5. Benabe SH, Leeman R, Brady AC, Hirzel A, Langshaw AH. Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in an adolescent patient with untreated Crohn’s disease. ACG Case Reports J. 2020;7(3). doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000338

6. Liu X, Liu G, Liu Y, et al. Complete appendiceal inversion with local high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in an adult female: A case report. BMC Surg. 2019;19(1). doi:10.1186/s12893-019-0632-3

7. Gündog˘ar ÖS, Kımılog˘lu ES, Komut NS, et al. The evaluation of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms with a new classification system. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29(5):532-542. doi:10.5152/tjg.2018.17605

8. Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM, Balis UJ, Young RH. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(8):1089-1103. doi:10.1097/00000478-200308000-00006

9. Pai RK, Beck AH, Norton JA, Longacre TA. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: clinicopathologic study of 116 cases with analysis of factors predicting recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(10):1425-1439. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181af6067

10. Asare EA, Compton CC, Hanna NN, et al. The impact of stage, grade, and mucinous histology on the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the appendix: analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2015;122(2):213-221. doi:10.1002/cncr.29744

11. Shaib WL, Assi R, Shamseddine A, et al. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: diagnosis and management. Oncologist. 2018;23(1):137. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0081erratum

12. Tran C, Sakioka J, Nguyen E, Beutler BD, Hsu J. An inverted appendix found on routine colonoscopy: a case report with discussion of imaging findings. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14(8):952-955. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2019.05.022

13. Shafi A, Azab M. A case of everted appendix with benign appendiceal nodule masquerading as appendiceal mucocele: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S1436. doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-02585

14. Pokhrel B, Chang M, Anand G, Savides T, Fehmi S. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in an inverted appendix found on prior colonoscopy. VideoGIE. 2020;5(1):34-36. doi:10.1016/j.vgie.2019.09.013

15. Johnson EK, Arcila ME, Steele SR. Appendiceal inversion: a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. JSLS. 2009;13(1):92-95.

16. van Turenhout ST, Oort FA, sive Droste JST, et al. Hemorrhoids detected at colonoscopy: an infrequent cause of false-positive fecal immunochemical test results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(1):136-143. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.169

17. Hudzik B, Wilczek K, Gasior M. Heyde syndrome: Gastrointestinal bleeding and aortic stenosis. CMAJ. 2016;188(2):135-138. doi:10.1503/cmaj.150194

18. Leonards LM, Pahwa A, Patel MK, Petersen J, Nguyen MJ, Jude CM. Neoplasms of the appendix: pictorial review with clinical and pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2017;37(4):1059-1083. doi:10.1148/rg.2017160150

19. Glasgow SC, Gaertner W, Stewart D, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, clinical practice guidelines for the management of appendiceal neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(12):1425-1438. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000001530

20. Panagopoulos P, Tsokaki T, Misiakos E, et al. Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm presenting as an adnexal mass. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;2017:1-3. doi:10.1155/2017/7165321

21. Ramaswamy V. Pathology of mucinous appendiceal tumors and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2016;7(2):258-267. doi:10.1007/s13193-016-0516-2.

22. Bevan KE, Mohamed F, Moran BJ. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2(1):44-50. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v2.i1.44

23. Mercier F, Dagbert F, Pocard M, et al. Recurrence of pseudomyxoma peritonei after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. BJS Open. 2018;3(2):195-202. doi:10.1002/bjs5.97

24. David A, Dodgion C, Eddine SBZ, Davila D, Webb TP, Trevino CM. Perforated appendicitis: Short duration antibiotics are noninferior to traditional long duration antibiotics. Surgery. 2020;167(2):475-477. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2019.08.007

25. Raijman I, Leong S, Hassaram S, Marcon NE. Appendiceal mucocele: Endoscopic appearance. Endoscopy. 1994;26(3):326-328. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1008979

1. Shaib WL, Goodman M, Chen Z, et al. Incidence and survival of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a SEER analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017;40(6):569-573. doi:10.1097/COC.0000000000000210

2. Kehagias I, Zygomalas A, Markopoulos G, Papandreou T, Kraniotis P. Diagnosis and treatment of mucinous appendiceal neoplasm presented as acute appendicitis. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2016;3:1-6. doi:10.1155/2016/2161952

3. Karatas M, Simsek C, Gunay S, et al. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to low-grade mucinous neoplasm of appendix. Acta Chir Belg. 2020;120(4):1-4. doi:10.1080/00015458.2020.1860397

4. Mourad FH, Hussein M, Bahlawan M, Haddad M, Tawil A. Intestinal obstruction secondary to appendiceal mucocele. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44(8):1594-1599. doi:10.1023/a:1026615010989

5. Benabe SH, Leeman R, Brady AC, Hirzel A, Langshaw AH. Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in an adolescent patient with untreated Crohn’s disease. ACG Case Reports J. 2020;7(3). doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000338

6. Liu X, Liu G, Liu Y, et al. Complete appendiceal inversion with local high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in an adult female: A case report. BMC Surg. 2019;19(1). doi:10.1186/s12893-019-0632-3

7. Gündog˘ar ÖS, Kımılog˘lu ES, Komut NS, et al. The evaluation of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms with a new classification system. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29(5):532-542. doi:10.5152/tjg.2018.17605

8. Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM, Balis UJ, Young RH. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(8):1089-1103. doi:10.1097/00000478-200308000-00006

9. Pai RK, Beck AH, Norton JA, Longacre TA. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: clinicopathologic study of 116 cases with analysis of factors predicting recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(10):1425-1439. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181af6067

10. Asare EA, Compton CC, Hanna NN, et al. The impact of stage, grade, and mucinous histology on the efficacy of systemic chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the appendix: analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 2015;122(2):213-221. doi:10.1002/cncr.29744

11. Shaib WL, Assi R, Shamseddine A, et al. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: diagnosis and management. Oncologist. 2018;23(1):137. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0081erratum

12. Tran C, Sakioka J, Nguyen E, Beutler BD, Hsu J. An inverted appendix found on routine colonoscopy: a case report with discussion of imaging findings. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14(8):952-955. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2019.05.022

13. Shafi A, Azab M. A case of everted appendix with benign appendiceal nodule masquerading as appendiceal mucocele: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S1436. doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-02585

14. Pokhrel B, Chang M, Anand G, Savides T, Fehmi S. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasm in an inverted appendix found on prior colonoscopy. VideoGIE. 2020;5(1):34-36. doi:10.1016/j.vgie.2019.09.013

15. Johnson EK, Arcila ME, Steele SR. Appendiceal inversion: a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. JSLS. 2009;13(1):92-95.

16. van Turenhout ST, Oort FA, sive Droste JST, et al. Hemorrhoids detected at colonoscopy: an infrequent cause of false-positive fecal immunochemical test results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(1):136-143. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.169

17. Hudzik B, Wilczek K, Gasior M. Heyde syndrome: Gastrointestinal bleeding and aortic stenosis. CMAJ. 2016;188(2):135-138. doi:10.1503/cmaj.150194

18. Leonards LM, Pahwa A, Patel MK, Petersen J, Nguyen MJ, Jude CM. Neoplasms of the appendix: pictorial review with clinical and pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2017;37(4):1059-1083. doi:10.1148/rg.2017160150

19. Glasgow SC, Gaertner W, Stewart D, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, clinical practice guidelines for the management of appendiceal neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(12):1425-1438. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000001530

20. Panagopoulos P, Tsokaki T, Misiakos E, et al. Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm presenting as an adnexal mass. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;2017:1-3. doi:10.1155/2017/7165321

21. Ramaswamy V. Pathology of mucinous appendiceal tumors and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2016;7(2):258-267. doi:10.1007/s13193-016-0516-2.

22. Bevan KE, Mohamed F, Moran BJ. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2(1):44-50. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v2.i1.44

23. Mercier F, Dagbert F, Pocard M, et al. Recurrence of pseudomyxoma peritonei after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. BJS Open. 2018;3(2):195-202. doi:10.1002/bjs5.97

24. David A, Dodgion C, Eddine SBZ, Davila D, Webb TP, Trevino CM. Perforated appendicitis: Short duration antibiotics are noninferior to traditional long duration antibiotics. Surgery. 2020;167(2):475-477. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2019.08.007

25. Raijman I, Leong S, Hassaram S, Marcon NE. Appendiceal mucocele: Endoscopic appearance. Endoscopy. 1994;26(3):326-328. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1008979

Caregiver Support in a Case of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Lewy Body Dementia

Caregiving for a person with dementia in the community can be extremely difficult work. Much of this work falls on unpaid or informal caregivers. Sixty-three percent of older adults with dementia depend completely on unpaid caregivers, and an additional 26% receive some combination of paid and unpaid support, together comprising nearly 90% of the more than 3 million older Americans with dementia.1 In-home care is preferable for these patients. For veterans, the Caregiver Support Program (CSP) is the only US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) program that exclusively supports caregivers. Although the CSP is not a nursing home diversion or cost savings program, successfully enabling at-home living in lieu of facility living also has the potential to reduce overall cost of care, and most importantly, to enable veterans who desire it to age at home.2,3

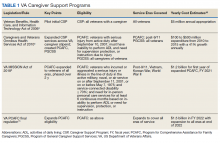

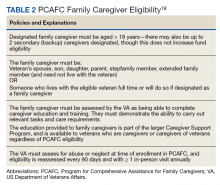

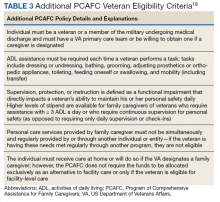

The CSP has 2 unique programs for caregivers of eligible veterans. The Program of General Caregiver Support Services (PGCSS) provides resources, education, and support to caregivers of all veterans enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) provides education and training, access to health care insurance if eligible, mental health counseling, access to a monthly caregiver stipend, enhanced respite care, wellness contacts, and travel compensation for VA health care appointments (Table 1).4,5

Patients undergo a rigorous assessment and highly specialized and individualized clinical decision-making process to confirm the service is appropriate for the patient. PCAFC was restructured and expanded on October 1, 2020.6 Currently, veterans who incurred or aggravated a serious injury (defined by a single or combined service-connection rating of ≥ 70%) in active military service before May 8, 1975, or after September 10, 2001, are eligible for PCAFC.6 Most notably, these changes opened eligibility in the PCAFC to caregivers of veterans from the Vietnam, Korean, and World War II eras of conflict and veterans with dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) due to a wider variety of illnesses, including dementia.6 The PCAFC is set to further expand to caregivers of otherwise eligible veterans of all eras of service on October 1, 2022, 2 years after the initial expansion, as laid out in the 2018 VA MISSION Act.6 Additional information on the history of the PGCSS and PCAFC and eligibility criteria for veterans and their family caregivers can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and cognitive impairment are 2 common causes of disability among veterans who receive VHA care. Among older veterans, rates of lifetime development of PTSD reach up to 30%.7 Dementia diagnosis is also more common in older veterans compared with age-matched civilians.8 Furthermore, a prior diagnosis of PTSD has been associated with nearly a 2-fold increase in risk of development of dementia in older age.7 These conditions are also linked to high degrees of service connection. PTSD is the third most prevalent service-connected disability for veterans receiving compensation and cognitive limitation is the third most prevalent category of service-connected disability among veterans.9

We present a case of a Vietnam-era veteran with a history of combat exposure and service-connected PTSD, and a later diagnosis of Lewy body dementia (LBD). Through combination of VHA geriatric services, the CSP, and the expanded PCAFC, the veteran’s primary family caregiver received the materials, support, and financial resources necessary to enable at-home living for the veteran, despite his illness and later complications.

Case Presentation

A male combat veteran presented to his primary care practitioner (PCP) with concerns of several years of progressive changes in gait, forgetfulness, and a gradual decline in the ability to live independently without assistance. At that time, his medical history was notable for PTSD (50% service connection), which had been diagnosed over a decade prior (but for which the veteran had refused medication or therapy on multiple occasions, stating he preferred to “breathe through” his intrusive symptom flare-ups), localized prostate cancer with a radical prostatectomy (100% service connection), multiple kidney stones with persistent left ureteral inflammation, and arteriosclerotic heart disease (10% service connection). A Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS) performed by the PCP was notable for a score of 9/30, in the dementia range. A computed tomography of the brain demonstrated scattered foci of hypoattenuation attributable to normal aging without any other pathology noted.

The veteran was referred to the Cognitive Care clinic, a local longitudinal multidisciplinary dementia care clinic, along with his spouse/caregiver. Cognitive testing was performed by a licensed clinical psychologist in the clinic and was notable for a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 18/30, also in the dementia range, and a more robust neuropsychiatric battery demonstrated borderline intact memory and language function but impairments in executive function and visuospatial skills. The patient’s clinical history included functional loss over time, with total dependence in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), or tasks necessary to be fully independent or manage a household, including inability to manage finances, and some need for assistance in ADL, or personal care tasks such as dressing or grooming, including bathing. Physical examination was notable for bradykinesia, a shuffling gait, and rare episodes of speaking to someone who was not in the room, thought to be due to mild nondistressing hallucinations.

A diagnosis of LBD was made. At time of diagnosis, the patient met criteria for probable dementia with Lewy bodies, with 2 of 4 core clinical features (hallucinations and Parkinsonism), and multiple supportive features (gait disturbance, sensory disturbance, and altered mood).10,11 The veteran continued to develop more supportive features for diagnosis of LBD over time, including evidence of autonomic instability.

The veteran and his caregiver were educated on his diagnosis, and longitudinal support was offered. The veteran was no longer driving, and due to the severity of his symptoms, the importance of driving cessation was reinforced by the care team. Over the course of the next year, his illness progressed, with more frequent behaviors and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). He began to exhibit nighttime wandering throughout the house and became more anxious and restless during the day. He lost the ability to make his own health care decisions, and his spouse became his activated health care power of attorney (HCPOA). His BPSD became more disruptive to daily life and was accompanied by a change in the character of his hallucinations, with prior nondistressing visions of other people being replaced with visions of war, burning bodies, and violence, much of it related to combat experiences in Vietnam. The BPSD began to include hiding behind furniture, running out of the house, and shouting and crying in response to hallucinations. At times, his BPSD became violent, lashing out in fear against his hallucinations and caregiver.

The veteran’s change in BPSD was concerning for a new baseline, rather than being clearly related to an underlying unmet physical need, such as pain, hunger, sleep, or discomfort. Multiple hospital admissions during that year involved IV hydration and treatment for urinary tract infections (UTI) for several days of inpatient stay at a time, but these behaviors persisted despite infection treatment and hydration. The patient’s changes in BPSD were thought to be secondary to uncovered and intensified PTSD in the setting of progressive dementia. Due to the clear danger the patient posed to himself and others, potential treatment options for these PTSD-related hallucinations were discussed with his caregiver. The caregiver shared that the patient’s BPSD and hallucinations were so distressing that “he would never want to live like this,” and that things had progressed to the point that “he has no quality of life.”

Oral aripiprazole 2 mg twice daily was prescribed after the risks of infection, cardiac complications, and exacerbation of movement disorder symptoms, such as increased stiffness and falls, were discussed with the caregiver. The caregiver was employed and relied on continued employment for income, but the patient could not be safely left alone. As the patient and his caregiver had reached a crisis point and living at home no longer appeared to be safe, the patient was referred to a VA-contracted skilled nursing facility (SNF) for long-term care. The patient’s caregiver was also referred to CSP for support during this transition. Due to the patient’s level of service connection and personal needs, as well as the patient and caregiver’s preference for the veteran to remain in his home, they were evaluated for the PCAFC for enhanced support to enable home as an alternative to facility living, should the patient respond to the antipsychotic therapy sufficiently, which was evaluated on a regular basis.

After several months, the patient’s BPSD had improved significantly, and he was no longer experiencing distressing hallucinations. However, his mobility also declined, and he became fully dependent in most ADL, including transfers, hygiene, and toileting. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, visitation was limited, which was difficult for both the patient and his caregiver. The veteran and caregiver were approved for PCAFC due to the veteran’s combination of service-connected illnesses > 70%, dependence for most ADLs, and need for continuous supervision. A transfer home from the SNF was arranged.

The PCAFC allowed the veteran’s caregiver and family members to provide in-home full-time caregiving, as an alternative to facility placement. The caregiver received a variety of support, including access to peer support, instruction on ways to assist in his toileting, hygiene, and transfers, and a caregiving stipend. In addition to offsetting lost wages, the stipend also helped offset the cost of care supplies which were not provided or were not readily available from the VA, which at the time included the patient’s preferred nutritional supplement and some supplies for personal care.

The veteran’s care needs continued to escalate. A fall at home resulted in a hip fracture, which was treated with surgical pinning. Postfracture physical therapy in a facility was considered, but ultimately was provided at home. The patient also experienced multiple UTIs and resulting delirium, with accompanying agitation and hallucinations. These episodes improved with IV antibiotics and hydration during short hospital stays. Ultimately, a computed tomography demonstrated overflow incontinence likely related to urologic damage from prior kidney stones and stent placement was recommended.

Visiting skilled nurses for the patient’s area were difficult to coordinate but were eventually arranged. The patient continued residing in his home with the support of his caregiver, the PCAFC, and the local VA medical center geriatric and transitional care services. The patient was also referred to the palliative care outpatient specialty clinic for discussion of goals of care and assistance with advance care planning as his illness progressed. Mental health and geriatric psychiatry consult teams were considered for this case but not utilized.

Discussion

Older adult Americans are at high risk of poor financial wellbeing, with nearly one quarter of Americans aged > 62 years experiencing financial insecurity.12 Even in this case with health care provided by the VA, successful in-home care was challenging and required a dedicated live-in caregiver, care coordination resources, and financial support. As part of its mission of caring for veterans, the VA has instituted CSP, whose mission is to promote the health and well-being of family caregivers through education, support, and services.

PCAFC offers enhanced clinical support for caregivers of eligible veterans who are seriously injured. This includes resources, education, support, financial stipends, health insurance (if eligible), and beneficiary travel (if eligible) to primary caregivers of eligible veterans. PCAFC was originally reserved for veterans who had onset of service-related disability after September 11, 2001, with an associated personal care need. In this population, PCAFC demonstrated an increased usage of clinical resources, likely related to increased ease in accessing care.13

The cohort of post-9/11 veterans is very different from the cohort of veterans and their caregivers who may now qualify for the PCAFC after its October 2020 expansion. Veterans from the Vietnam, Korean, and World War II eras of conflict have rates of service-connected disability 2 to 3 times higher than those of post-9/11 era veterans and are at greater risk for dementia.9 Veterans aged ≥ 75 years who have service connection also report higher rates of difficulty with independent living and self-care compared with their younger peers.9 Since dementia and PTSD are common causes of service connection and disability it is likely that a significant proportion of older veterans will be eligible to apply for the newly expanded PCAFC.

To be eligible for PCAFC, a veteran must have a service-connected disability rating of ≥ 70% and must need in-person care services for ≥ 6 continuous months, based on either an inability to perform an ADL, or a need for supervision, protection, or instruction.

It is not clear how CSP use or increased access to PCAFC will impact costs. However, the PCAFC monthly stipend is scaled to the median wage of a home health aide and to the location of the caregiver, which is considerably less than the cost of recurrent hospitalization or a year of facility-level care.15 The CSP may eventually be a successful long-term investment in cost savings. In order to ensure the process for PCAFC approval is uniform and prompt as the program expands, CSP has restructured, increasing the number of employees, improving the patient review process, and expanding staff training.16 The VA plans to continually re-assess CSP using the infrastructure of the Caregiver Record Management Application as it continues to expand.17

Conclusions

Dementia and PTSD commonly coexist and are a significant source of disability in the service-connected veteran population. This case brings attention to the recent expansion of PCAFC, which now has the potential to support eligible veterans from the World War II, Korean, and Vietnam-era conflicts, in whom these illnesses are more common. In this case, in-home care was preferred by the veteran and primary caregiver but would not have been possible without a complex intervention. There is still more research to be done on the best way to meet the needs of older adults with dementia, the impact of in-home care, and the system-wide implications of PCAFC, especially as the program grows. However, in-home care is preferable to SNF living for many veterans and caregivers, and CSP will continue to be an essential element of providing care for this population.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. The authors would also like to thank the members of the Veterans Affairs Central Office and National Caregiver Support Program Office, including Elyse Kaplan, Melinda Hogue, Beth Wolfsohn, Colleen Richardson, and Timothy Jobin, for their thorough review of the work and edits to ensure accurate program description.

1. Chi W, Graf E, Hughes L, et al. Community-dwelling older adults with dementia and their caregivers: key indicators from the National Health and Aging Trends study. Published January 29, 2019. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//186501/DemChartbook.pdf

2. Rapaport P, Burton A, Leverton M, et al. “I just keep thinking that I don’t want to rely on people.” A qualitative study of how people living with dementia achieve and maintain independence at home: stakeholder perspectives. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1-11. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1406-6

3. Miller EA, Gidmark S, Gadbois E, Rudolph JL, Intrator O. Nursing home referral within the Veterans Health Administration: practice variation by payment source and facility type. Res Aging. 2018;40(7):687-711. doi:10.1177/0164027517730383

4. Veterans Benefits, Health Care, and Information Technology Act of 2006, Pub L No. 109-461, 120 Stat. 3403.

5. Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010, Pub L No. 111-163, 115 Stat 552.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018. 38 CFR § 17.

7. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61

8. Krishnan LL, Petersen NJ, Snow AL, et al. Prevalence of dementia among Veterans Affairs medical care system users. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20(4):245-253. doi:10.1159/000087345

9. Holder, KA. The Disability of Veterans. Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, US Census Bureau; 2014. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2016/demo/Holder-2016-01.pdf

10. Sanford AM. Lewy body dementia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(4):603-615. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2018.06.007

11. Armstrong MJ. Lewy body dementias. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25(1):128-146. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000685

12. Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection. Financial well-being of older Americans. Published December 2018. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/bcfp_financial-well-being-older-americans_report.pdf

13. Van Houtven CH, Smith VA, Stechuchak KM, et al. Comprehensive support for family caregivers: impact on veteran health care utilization and costs. Med Care Res Rev. 2019;76(1):89-114. doi:10.1177/1077558717697015

14. Boland L, Légaré F, Perez MMB, et al. Impact of home care versus alternative locations of care on elder health outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):20. doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0395-y

15. Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers Improvements and Amendments Under the VA MISSION Act of 2018. 85 FR § 13356.

16. Extension of Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers Eligibility for Legacy Participants and Legacy Applicants. 86 FR § 52614.

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020. Certification of the Implementation of the Caregiver Records Management Application (CARMA). 85 FR § 63358.

18. Sussman, JS. Department of Veterans Affairs: Caregiver Support. Congressional Research Service Report No. R46282. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20200324_R46282_656f1e8338af12a2a676c471be3b3c13b2fcb0bb.pdf

19. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Affairs Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers Eligibility Criteria Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2020. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.caregiver.va.gov/pdfs/MissionAct/EligibilityCriteriaFactsheet_Chapter2_Launch_Approved_Final_100120.pdf

Caregiving for a person with dementia in the community can be extremely difficult work. Much of this work falls on unpaid or informal caregivers. Sixty-three percent of older adults with dementia depend completely on unpaid caregivers, and an additional 26% receive some combination of paid and unpaid support, together comprising nearly 90% of the more than 3 million older Americans with dementia.1 In-home care is preferable for these patients. For veterans, the Caregiver Support Program (CSP) is the only US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) program that exclusively supports caregivers. Although the CSP is not a nursing home diversion or cost savings program, successfully enabling at-home living in lieu of facility living also has the potential to reduce overall cost of care, and most importantly, to enable veterans who desire it to age at home.2,3

The CSP has 2 unique programs for caregivers of eligible veterans. The Program of General Caregiver Support Services (PGCSS) provides resources, education, and support to caregivers of all veterans enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) provides education and training, access to health care insurance if eligible, mental health counseling, access to a monthly caregiver stipend, enhanced respite care, wellness contacts, and travel compensation for VA health care appointments (Table 1).4,5

Patients undergo a rigorous assessment and highly specialized and individualized clinical decision-making process to confirm the service is appropriate for the patient. PCAFC was restructured and expanded on October 1, 2020.6 Currently, veterans who incurred or aggravated a serious injury (defined by a single or combined service-connection rating of ≥ 70%) in active military service before May 8, 1975, or after September 10, 2001, are eligible for PCAFC.6 Most notably, these changes opened eligibility in the PCAFC to caregivers of veterans from the Vietnam, Korean, and World War II eras of conflict and veterans with dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) due to a wider variety of illnesses, including dementia.6 The PCAFC is set to further expand to caregivers of otherwise eligible veterans of all eras of service on October 1, 2022, 2 years after the initial expansion, as laid out in the 2018 VA MISSION Act.6 Additional information on the history of the PGCSS and PCAFC and eligibility criteria for veterans and their family caregivers can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and cognitive impairment are 2 common causes of disability among veterans who receive VHA care. Among older veterans, rates of lifetime development of PTSD reach up to 30%.7 Dementia diagnosis is also more common in older veterans compared with age-matched civilians.8 Furthermore, a prior diagnosis of PTSD has been associated with nearly a 2-fold increase in risk of development of dementia in older age.7 These conditions are also linked to high degrees of service connection. PTSD is the third most prevalent service-connected disability for veterans receiving compensation and cognitive limitation is the third most prevalent category of service-connected disability among veterans.9

We present a case of a Vietnam-era veteran with a history of combat exposure and service-connected PTSD, and a later diagnosis of Lewy body dementia (LBD). Through combination of VHA geriatric services, the CSP, and the expanded PCAFC, the veteran’s primary family caregiver received the materials, support, and financial resources necessary to enable at-home living for the veteran, despite his illness and later complications.

Case Presentation

A male combat veteran presented to his primary care practitioner (PCP) with concerns of several years of progressive changes in gait, forgetfulness, and a gradual decline in the ability to live independently without assistance. At that time, his medical history was notable for PTSD (50% service connection), which had been diagnosed over a decade prior (but for which the veteran had refused medication or therapy on multiple occasions, stating he preferred to “breathe through” his intrusive symptom flare-ups), localized prostate cancer with a radical prostatectomy (100% service connection), multiple kidney stones with persistent left ureteral inflammation, and arteriosclerotic heart disease (10% service connection). A Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS) performed by the PCP was notable for a score of 9/30, in the dementia range. A computed tomography of the brain demonstrated scattered foci of hypoattenuation attributable to normal aging without any other pathology noted.

The veteran was referred to the Cognitive Care clinic, a local longitudinal multidisciplinary dementia care clinic, along with his spouse/caregiver. Cognitive testing was performed by a licensed clinical psychologist in the clinic and was notable for a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score of 18/30, also in the dementia range, and a more robust neuropsychiatric battery demonstrated borderline intact memory and language function but impairments in executive function and visuospatial skills. The patient’s clinical history included functional loss over time, with total dependence in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), or tasks necessary to be fully independent or manage a household, including inability to manage finances, and some need for assistance in ADL, or personal care tasks such as dressing or grooming, including bathing. Physical examination was notable for bradykinesia, a shuffling gait, and rare episodes of speaking to someone who was not in the room, thought to be due to mild nondistressing hallucinations.

A diagnosis of LBD was made. At time of diagnosis, the patient met criteria for probable dementia with Lewy bodies, with 2 of 4 core clinical features (hallucinations and Parkinsonism), and multiple supportive features (gait disturbance, sensory disturbance, and altered mood).10,11 The veteran continued to develop more supportive features for diagnosis of LBD over time, including evidence of autonomic instability.

The veteran and his caregiver were educated on his diagnosis, and longitudinal support was offered. The veteran was no longer driving, and due to the severity of his symptoms, the importance of driving cessation was reinforced by the care team. Over the course of the next year, his illness progressed, with more frequent behaviors and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). He began to exhibit nighttime wandering throughout the house and became more anxious and restless during the day. He lost the ability to make his own health care decisions, and his spouse became his activated health care power of attorney (HCPOA). His BPSD became more disruptive to daily life and was accompanied by a change in the character of his hallucinations, with prior nondistressing visions of other people being replaced with visions of war, burning bodies, and violence, much of it related to combat experiences in Vietnam. The BPSD began to include hiding behind furniture, running out of the house, and shouting and crying in response to hallucinations. At times, his BPSD became violent, lashing out in fear against his hallucinations and caregiver.

The veteran’s change in BPSD was concerning for a new baseline, rather than being clearly related to an underlying unmet physical need, such as pain, hunger, sleep, or discomfort. Multiple hospital admissions during that year involved IV hydration and treatment for urinary tract infections (UTI) for several days of inpatient stay at a time, but these behaviors persisted despite infection treatment and hydration. The patient’s changes in BPSD were thought to be secondary to uncovered and intensified PTSD in the setting of progressive dementia. Due to the clear danger the patient posed to himself and others, potential treatment options for these PTSD-related hallucinations were discussed with his caregiver. The caregiver shared that the patient’s BPSD and hallucinations were so distressing that “he would never want to live like this,” and that things had progressed to the point that “he has no quality of life.”