User login

52-year-old man • hematemesis • history of cirrhosis • persistent fevers • Dx?

THE CASE

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department after vomiting a large volume of blood and was admitted to the intensive care unit. His past medical history was remarkable for untreated chronic hepatitis C resulting from injection drug use and cirrhosis without prior history of esophageal varices.

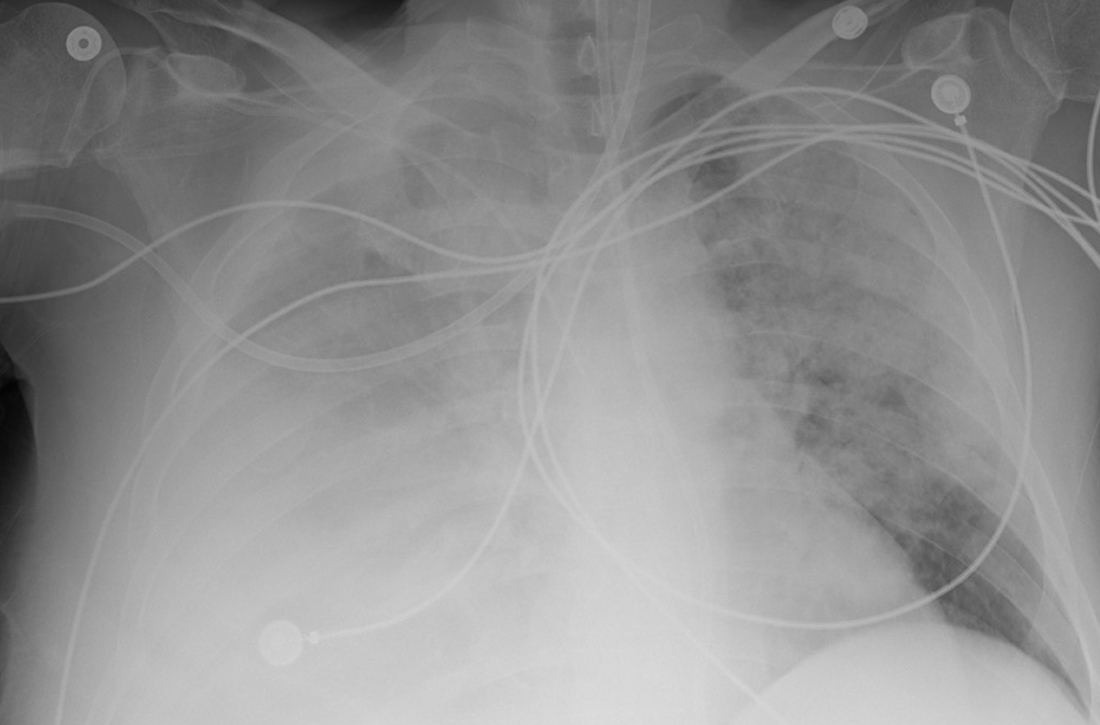

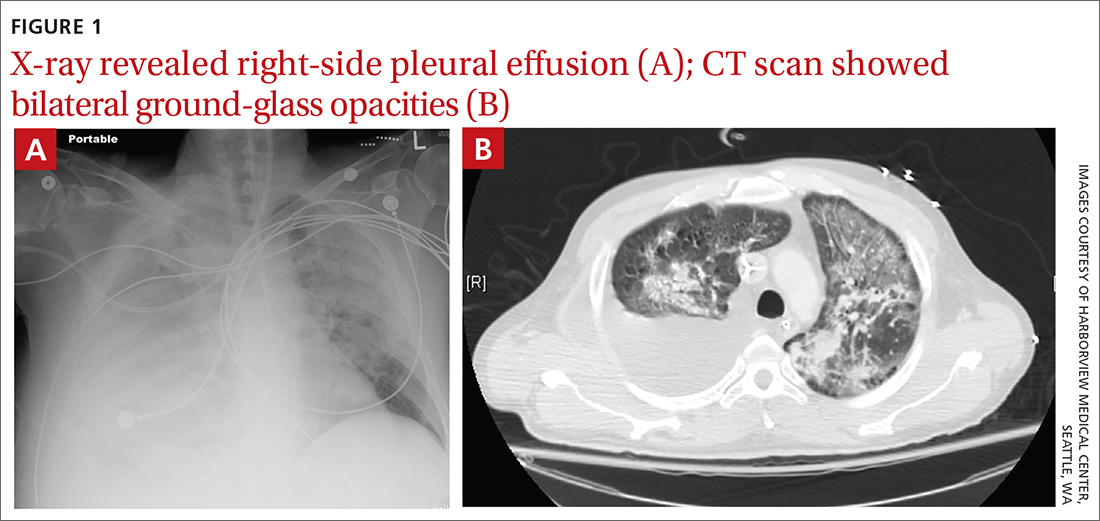

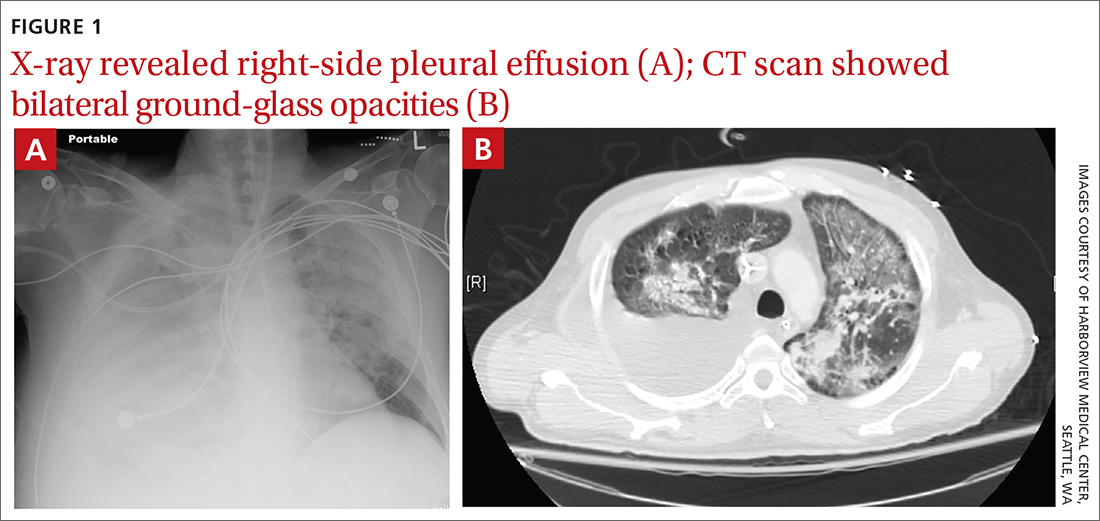

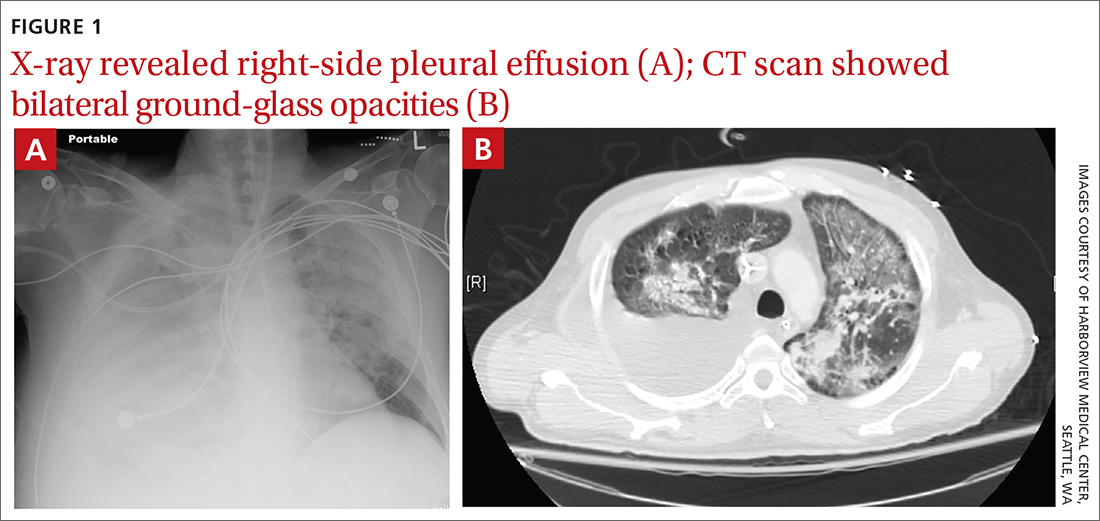

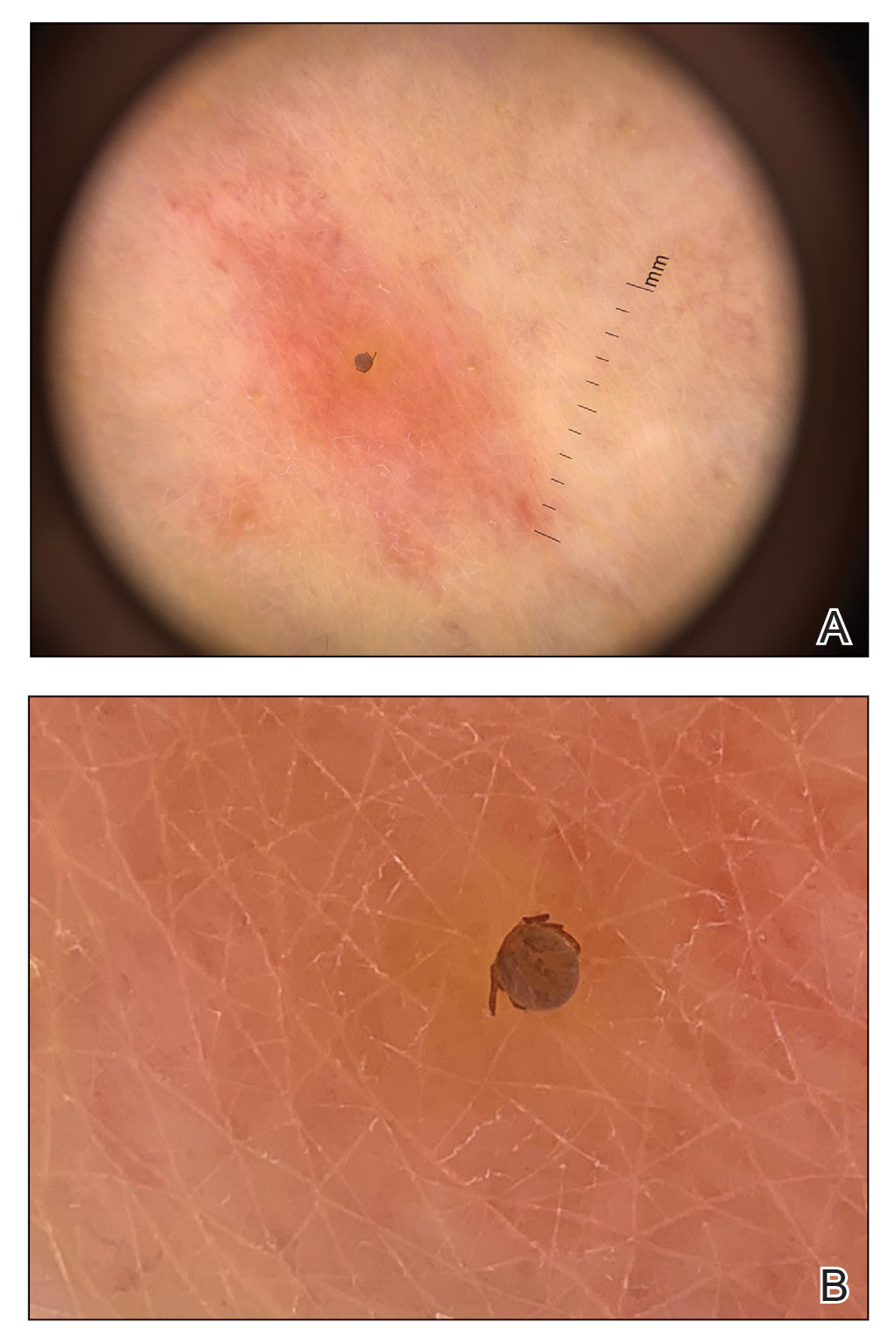

Due to ongoing hematemesis, he was intubated for airway protection and underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with banding of large esophageal varices on hospital day (HD) 1. He was extubated on HD 2 after clinical stability was achieved; however, he became encephalopathic over the subsequent days despite treatment with lactulose. On HD 4, the patient required re-intubation for progressive respiratory failure. Chest imaging revealed a large, simple-appearing right pleural effusion and extensive bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities (FIGURE 1).

Thoracentesis was ordered and revealed transudative pleural fluid; this finding, along with negative infectious studies, was consistent with hepatic hydrothorax. In the setting of initial decompensation, empiric treatment with vancomycin and meropenem was started for suspected hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The patient had persistent fevers that had developed during his hospital stay and pulmonary opacities, despite 72 hours of treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Thus, a diagnostic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. BAL cell count and differential revealed 363 nucleated cells/µL, with profound eosinophilia (42% eosinophils, 44% macrophages, 14% neutrophils).

Bacterial and fungal cultures and a viral polymerase chain reaction panel were negative. HIV antibody-antigen and RNA testing were also negative. The patient had no evidence or history of underlying malignancy, autoimmune disease, or recent immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids. Due to consistent imaging findings and lack of improvement with appropriate treatment for bacterial pneumonia, further work-up was pursued.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Given the consistent radiographic pattern, the differential diagnosis for this patient included pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), a potentially life-threatening opportunistic infection. Work-up therefore included direct fluorescent antibody testing, which was positive for Pneumocystis jirovecii, a fungus that can cause PCP.

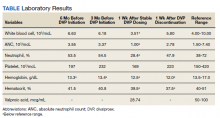

Of note, the patient’s white blood cell count was elevated on admission (11.44 × 103/µL) but low for much of his hospital stay (nadir = 1.97 × 103/µL), with associated lymphopenia (nadir = 0.22 × 103/µl). No peripheral eosinophilia was noted.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

PCP typically occurs in immunocompromised individuals and may be related to HIV infection, malignancy, or exposure to immunosuppressive therapies.1,2 While rare cases of PCP have been described in adults without predisposing factors, many of these cases occurred at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, prior to reliable HIV testing.3-5

Uncharted territory. We were confident in our diagnosis because immunofluorescence testing has very few false-positives and a high specificity.6-8 But there were informational gaps. The eosinophilia recorded on BAL is poorly described in HIV-negative patients with PCP but well-described in HIV-positive patients, with the level of eosinophilia associated with disease severity.9,10 Eosinophils are thought to contribute to pulmonary inflammation, which may explain the severity of our patient’s course.10

A first of its kind case?

To our knowledge, this is the first report of PCP in a patient with cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis C virus infection and no other predisposing conditions or preceding immunosuppressive therapy. We suspect that his lymphopenia, which was noted during his critical illness, predisposed him to PCP.

Lymphocytes (in particular CD4+ T cells) have been shown to play an important role, along with alveolar macrophages and neutrophils, in directing the host defense against

Typical risk factors for lymphopenia had not been observed in this patient. However, cirrhosis has been associated with low CD4+ T-cell counts and disruption of cell-mediated immunity, even in HIV-seronegative patients.14,15 There are several postulated mechanisms for low CD4+ T-cell counts in cirrhosis, including splenic sequestration, impaired T-cell production (due to impaired thymopoiesis), increased T-cell consumption, and apoptosis (due to persistent immune system activation from bacterial translocation and an overall pro-inflammatory state).16,17

Continue to: Predisposing factors guide treatment

Predisposing factors guide treatment

Routine treatment for PCP in patients without HIV is a 21-day course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). Dosing for patients with normal renal function is 15 to 20 mg/kg orally or intravenously per day. Patients with allergy to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole should ideally undergo desensitization, given its effectiveness against PCP.

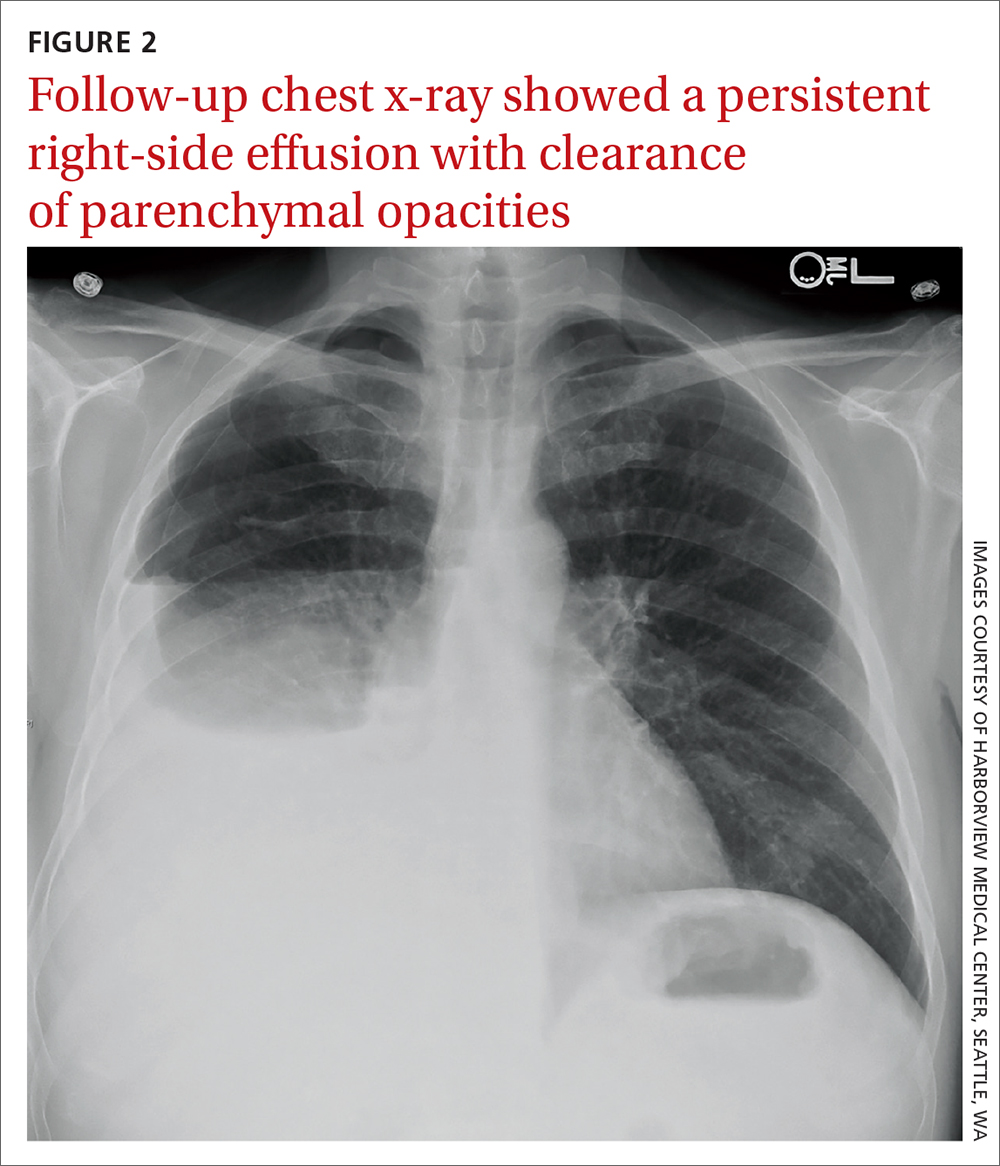

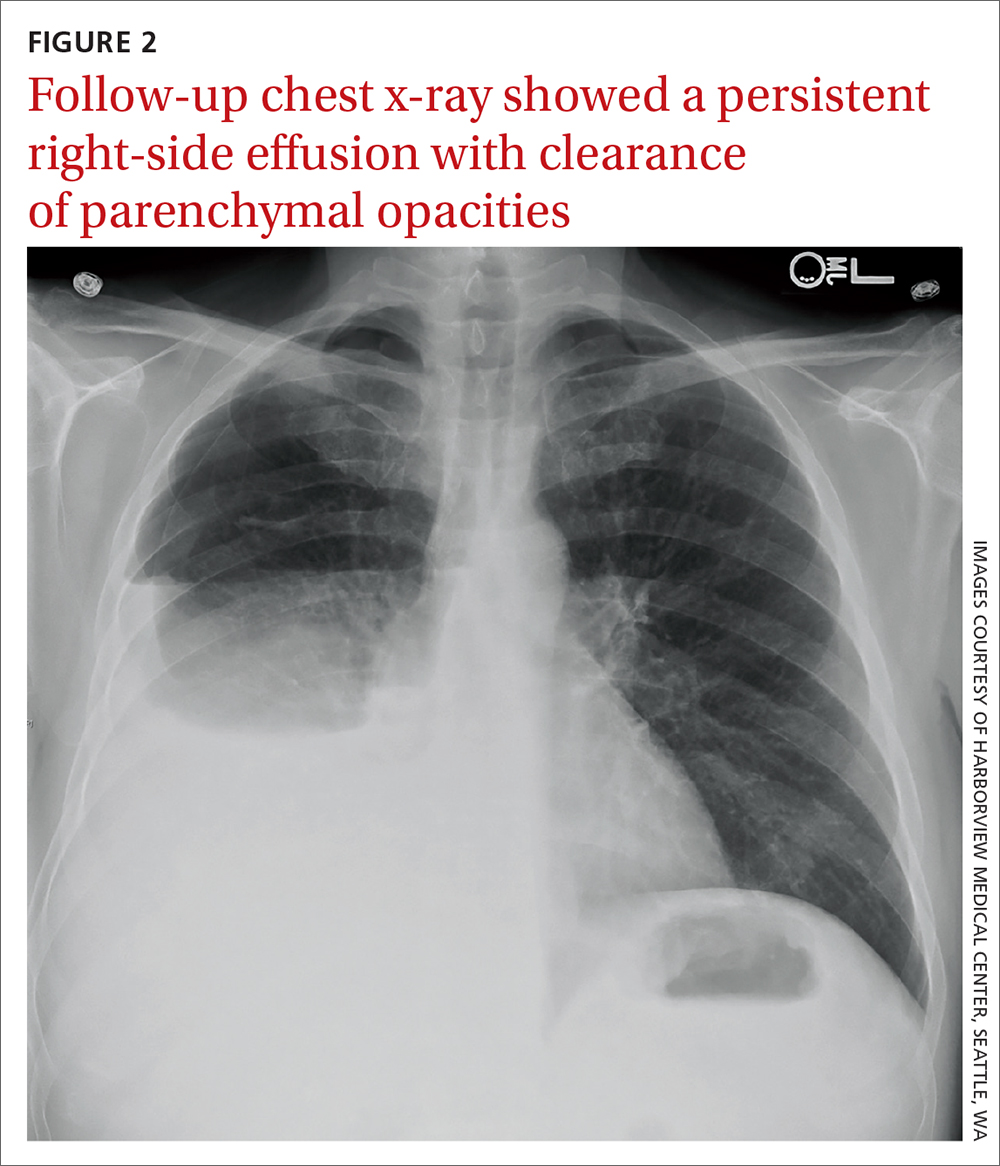

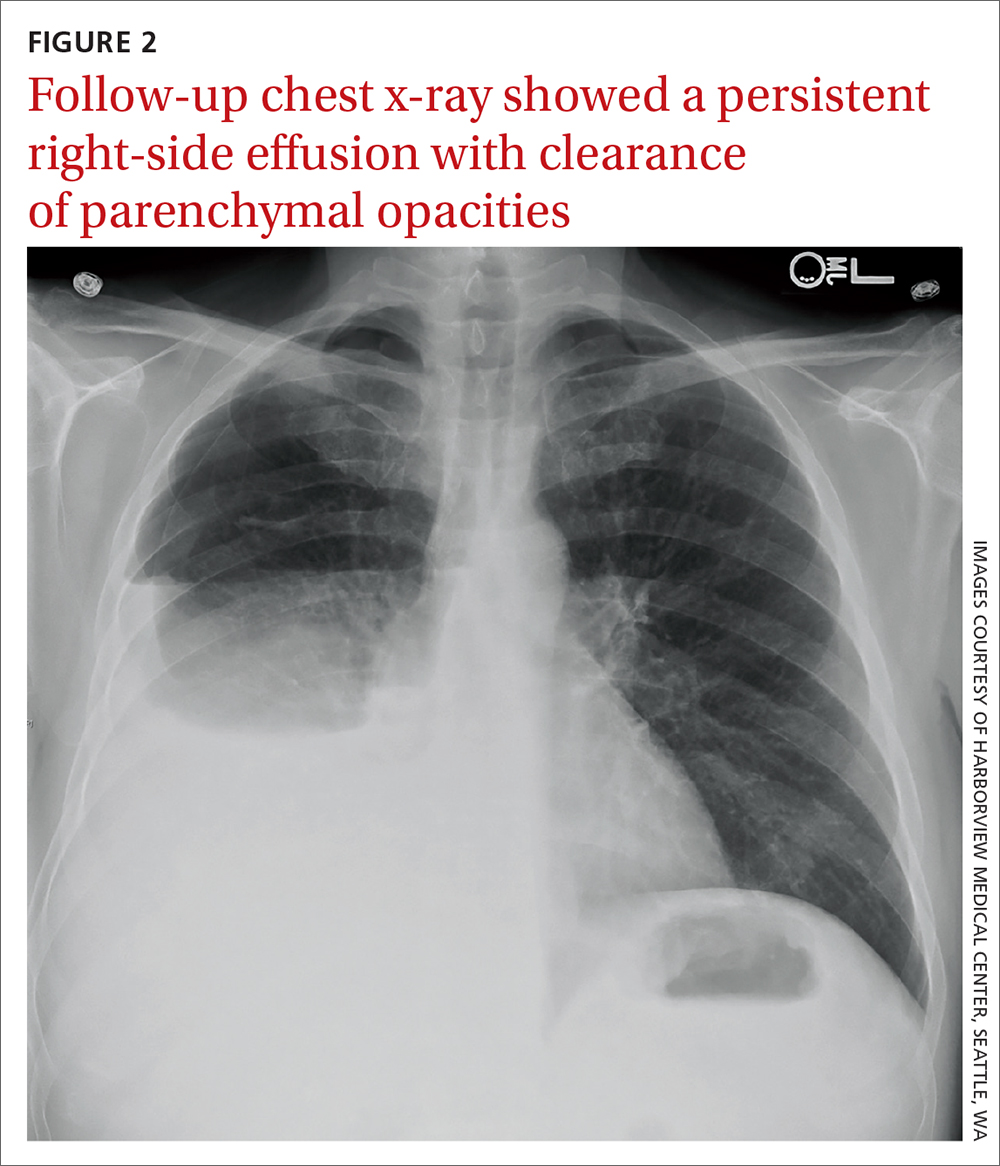

Due to a sulfonamide allergy, our patient was started on primaquine 30 mg/d, clindamycin 600 mg tid, and prednisone 40 mg bid. (The corticosteroid was added because of the severity of the disease.) Three days after starting treatment—and 10 days into his hospital stay—the patient had significant improvement in his respiratory status and was successfully extubated. He underwent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole desensitization and completed a 21-day course of treatment for PCP with complete resolution of respiratory symptoms. Follow-up chest radiograph 2 months later (FIGURE 2) confirmed clearance of opacities.

THE TAKEAWAY

PCP remains a rare disease in patients without the typical immunosuppressive risk factors. However, it should be considered in patients with cirrhosis who develop respiratory failure, especially those with compatible radiographic findings and negative microbiologic evaluation for other, more typical, organisms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tyler Albert, MD, VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, 1660 South Columbian Way, S-111-Pulm, Seattle, WA 98108; [email protected]

1. Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487-2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032588

2. Walzer PD, Perl DP, Krogstad DJ, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the United States. Epidemiologic, diagnostic, and clinical features. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:83-93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-1-83

3. Sepkowitz KA. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17 suppl 2:S416-422. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_2.s416

4. Al Soub H, Taha RY, El Deeb Y, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a patient without a predisposing illness: case report and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:618-621. doi: 10.1080/00365540410017608

5. Jacobs JL, Libby DM, Winters RA, et al. A cluster of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in adults without predisposing illnesses. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:246-250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101243240407

6. Ng VL, Yajko DM, McPhaul LW, et al. Evaluation of an indirect fluorescent-antibody stain for detection of Pneumocystis carinii in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:975-979. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.975-979.1990

7. Cregan P, Yamamoto A, Lum A, et al. Comparison of four methods for rapid detection of Pneumocystis carinii in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2432-2436. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2432-2436.1990

8. Turner D, Schwarz Y, Yust I. Induced sputum for diagnosing Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV patients: new data, new issues. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:204-208. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00035303

9. Smith RL, el-Sadr WM, Lewis ML. Correlation of bronchoalveolar lavage cell populations with clinical severity of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Chest. 1988;93:60-64. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.60

10. Fleury-Feith J, Van Nhieu JT, Picard C, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage eosinophilia associated with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonitis in AIDS patients. Comparative study with non-AIDS patients. Chest. 1989;95:1198-1201. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.6.1198

11. Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Current insights into the biology and pathogenesis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:298-308. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1621

12. Toh BH, Roberts-Thomson IC, Mathews JD, et al. Depression of cell-mediated immunity in old age and the immunopathic diseases, lupus erythematosus, chronic hepatitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;14:193-202.

13. Mansharamani NG, Balachandran D, Vernovsky I, et al. Peripheral blood CD4 + T-lymphocyte counts during Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in immunocompromised patients without HIV infection. Chest. 2000;118:712-720. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.712

14. McGovern BH, Golan Y, Lopez M, et al. The impact of cirrhosis on CD4+ T cell counts in HIV-seronegative patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:431-437. doi: 10.1086/509580

15. Bienvenu AL, Traore K, Plekhanova I, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia suspected cases in 604 non-HIV and HIV patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;46:11-17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.018

16. Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385-1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.010

17. Lario M, Muñoz L, Ubeda M, et al. Defective thymopoiesis and poor peripheral homeostatic replenishment of T-helper cells cause T-cell lymphopenia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;59:723-730. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.042

THE CASE

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department after vomiting a large volume of blood and was admitted to the intensive care unit. His past medical history was remarkable for untreated chronic hepatitis C resulting from injection drug use and cirrhosis without prior history of esophageal varices.

Due to ongoing hematemesis, he was intubated for airway protection and underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with banding of large esophageal varices on hospital day (HD) 1. He was extubated on HD 2 after clinical stability was achieved; however, he became encephalopathic over the subsequent days despite treatment with lactulose. On HD 4, the patient required re-intubation for progressive respiratory failure. Chest imaging revealed a large, simple-appearing right pleural effusion and extensive bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities (FIGURE 1).

Thoracentesis was ordered and revealed transudative pleural fluid; this finding, along with negative infectious studies, was consistent with hepatic hydrothorax. In the setting of initial decompensation, empiric treatment with vancomycin and meropenem was started for suspected hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The patient had persistent fevers that had developed during his hospital stay and pulmonary opacities, despite 72 hours of treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Thus, a diagnostic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. BAL cell count and differential revealed 363 nucleated cells/µL, with profound eosinophilia (42% eosinophils, 44% macrophages, 14% neutrophils).

Bacterial and fungal cultures and a viral polymerase chain reaction panel were negative. HIV antibody-antigen and RNA testing were also negative. The patient had no evidence or history of underlying malignancy, autoimmune disease, or recent immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids. Due to consistent imaging findings and lack of improvement with appropriate treatment for bacterial pneumonia, further work-up was pursued.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Given the consistent radiographic pattern, the differential diagnosis for this patient included pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), a potentially life-threatening opportunistic infection. Work-up therefore included direct fluorescent antibody testing, which was positive for Pneumocystis jirovecii, a fungus that can cause PCP.

Of note, the patient’s white blood cell count was elevated on admission (11.44 × 103/µL) but low for much of his hospital stay (nadir = 1.97 × 103/µL), with associated lymphopenia (nadir = 0.22 × 103/µl). No peripheral eosinophilia was noted.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

PCP typically occurs in immunocompromised individuals and may be related to HIV infection, malignancy, or exposure to immunosuppressive therapies.1,2 While rare cases of PCP have been described in adults without predisposing factors, many of these cases occurred at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, prior to reliable HIV testing.3-5

Uncharted territory. We were confident in our diagnosis because immunofluorescence testing has very few false-positives and a high specificity.6-8 But there were informational gaps. The eosinophilia recorded on BAL is poorly described in HIV-negative patients with PCP but well-described in HIV-positive patients, with the level of eosinophilia associated with disease severity.9,10 Eosinophils are thought to contribute to pulmonary inflammation, which may explain the severity of our patient’s course.10

A first of its kind case?

To our knowledge, this is the first report of PCP in a patient with cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis C virus infection and no other predisposing conditions or preceding immunosuppressive therapy. We suspect that his lymphopenia, which was noted during his critical illness, predisposed him to PCP.

Lymphocytes (in particular CD4+ T cells) have been shown to play an important role, along with alveolar macrophages and neutrophils, in directing the host defense against

Typical risk factors for lymphopenia had not been observed in this patient. However, cirrhosis has been associated with low CD4+ T-cell counts and disruption of cell-mediated immunity, even in HIV-seronegative patients.14,15 There are several postulated mechanisms for low CD4+ T-cell counts in cirrhosis, including splenic sequestration, impaired T-cell production (due to impaired thymopoiesis), increased T-cell consumption, and apoptosis (due to persistent immune system activation from bacterial translocation and an overall pro-inflammatory state).16,17

Continue to: Predisposing factors guide treatment

Predisposing factors guide treatment

Routine treatment for PCP in patients without HIV is a 21-day course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). Dosing for patients with normal renal function is 15 to 20 mg/kg orally or intravenously per day. Patients with allergy to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole should ideally undergo desensitization, given its effectiveness against PCP.

Due to a sulfonamide allergy, our patient was started on primaquine 30 mg/d, clindamycin 600 mg tid, and prednisone 40 mg bid. (The corticosteroid was added because of the severity of the disease.) Three days after starting treatment—and 10 days into his hospital stay—the patient had significant improvement in his respiratory status and was successfully extubated. He underwent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole desensitization and completed a 21-day course of treatment for PCP with complete resolution of respiratory symptoms. Follow-up chest radiograph 2 months later (FIGURE 2) confirmed clearance of opacities.

THE TAKEAWAY

PCP remains a rare disease in patients without the typical immunosuppressive risk factors. However, it should be considered in patients with cirrhosis who develop respiratory failure, especially those with compatible radiographic findings and negative microbiologic evaluation for other, more typical, organisms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tyler Albert, MD, VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, 1660 South Columbian Way, S-111-Pulm, Seattle, WA 98108; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department after vomiting a large volume of blood and was admitted to the intensive care unit. His past medical history was remarkable for untreated chronic hepatitis C resulting from injection drug use and cirrhosis without prior history of esophageal varices.

Due to ongoing hematemesis, he was intubated for airway protection and underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with banding of large esophageal varices on hospital day (HD) 1. He was extubated on HD 2 after clinical stability was achieved; however, he became encephalopathic over the subsequent days despite treatment with lactulose. On HD 4, the patient required re-intubation for progressive respiratory failure. Chest imaging revealed a large, simple-appearing right pleural effusion and extensive bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities (FIGURE 1).

Thoracentesis was ordered and revealed transudative pleural fluid; this finding, along with negative infectious studies, was consistent with hepatic hydrothorax. In the setting of initial decompensation, empiric treatment with vancomycin and meropenem was started for suspected hospital-acquired pneumonia.

The patient had persistent fevers that had developed during his hospital stay and pulmonary opacities, despite 72 hours of treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Thus, a diagnostic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. BAL cell count and differential revealed 363 nucleated cells/µL, with profound eosinophilia (42% eosinophils, 44% macrophages, 14% neutrophils).

Bacterial and fungal cultures and a viral polymerase chain reaction panel were negative. HIV antibody-antigen and RNA testing were also negative. The patient had no evidence or history of underlying malignancy, autoimmune disease, or recent immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids. Due to consistent imaging findings and lack of improvement with appropriate treatment for bacterial pneumonia, further work-up was pursued.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Given the consistent radiographic pattern, the differential diagnosis for this patient included pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), a potentially life-threatening opportunistic infection. Work-up therefore included direct fluorescent antibody testing, which was positive for Pneumocystis jirovecii, a fungus that can cause PCP.

Of note, the patient’s white blood cell count was elevated on admission (11.44 × 103/µL) but low for much of his hospital stay (nadir = 1.97 × 103/µL), with associated lymphopenia (nadir = 0.22 × 103/µl). No peripheral eosinophilia was noted.

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

PCP typically occurs in immunocompromised individuals and may be related to HIV infection, malignancy, or exposure to immunosuppressive therapies.1,2 While rare cases of PCP have been described in adults without predisposing factors, many of these cases occurred at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, prior to reliable HIV testing.3-5

Uncharted territory. We were confident in our diagnosis because immunofluorescence testing has very few false-positives and a high specificity.6-8 But there were informational gaps. The eosinophilia recorded on BAL is poorly described in HIV-negative patients with PCP but well-described in HIV-positive patients, with the level of eosinophilia associated with disease severity.9,10 Eosinophils are thought to contribute to pulmonary inflammation, which may explain the severity of our patient’s course.10

A first of its kind case?

To our knowledge, this is the first report of PCP in a patient with cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis C virus infection and no other predisposing conditions or preceding immunosuppressive therapy. We suspect that his lymphopenia, which was noted during his critical illness, predisposed him to PCP.

Lymphocytes (in particular CD4+ T cells) have been shown to play an important role, along with alveolar macrophages and neutrophils, in directing the host defense against

Typical risk factors for lymphopenia had not been observed in this patient. However, cirrhosis has been associated with low CD4+ T-cell counts and disruption of cell-mediated immunity, even in HIV-seronegative patients.14,15 There are several postulated mechanisms for low CD4+ T-cell counts in cirrhosis, including splenic sequestration, impaired T-cell production (due to impaired thymopoiesis), increased T-cell consumption, and apoptosis (due to persistent immune system activation from bacterial translocation and an overall pro-inflammatory state).16,17

Continue to: Predisposing factors guide treatment

Predisposing factors guide treatment

Routine treatment for PCP in patients without HIV is a 21-day course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). Dosing for patients with normal renal function is 15 to 20 mg/kg orally or intravenously per day. Patients with allergy to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole should ideally undergo desensitization, given its effectiveness against PCP.

Due to a sulfonamide allergy, our patient was started on primaquine 30 mg/d, clindamycin 600 mg tid, and prednisone 40 mg bid. (The corticosteroid was added because of the severity of the disease.) Three days after starting treatment—and 10 days into his hospital stay—the patient had significant improvement in his respiratory status and was successfully extubated. He underwent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole desensitization and completed a 21-day course of treatment for PCP with complete resolution of respiratory symptoms. Follow-up chest radiograph 2 months later (FIGURE 2) confirmed clearance of opacities.

THE TAKEAWAY

PCP remains a rare disease in patients without the typical immunosuppressive risk factors. However, it should be considered in patients with cirrhosis who develop respiratory failure, especially those with compatible radiographic findings and negative microbiologic evaluation for other, more typical, organisms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tyler Albert, MD, VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, 1660 South Columbian Way, S-111-Pulm, Seattle, WA 98108; [email protected]

1. Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487-2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032588

2. Walzer PD, Perl DP, Krogstad DJ, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the United States. Epidemiologic, diagnostic, and clinical features. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:83-93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-1-83

3. Sepkowitz KA. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17 suppl 2:S416-422. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_2.s416

4. Al Soub H, Taha RY, El Deeb Y, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a patient without a predisposing illness: case report and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:618-621. doi: 10.1080/00365540410017608

5. Jacobs JL, Libby DM, Winters RA, et al. A cluster of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in adults without predisposing illnesses. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:246-250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101243240407

6. Ng VL, Yajko DM, McPhaul LW, et al. Evaluation of an indirect fluorescent-antibody stain for detection of Pneumocystis carinii in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:975-979. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.975-979.1990

7. Cregan P, Yamamoto A, Lum A, et al. Comparison of four methods for rapid detection of Pneumocystis carinii in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2432-2436. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2432-2436.1990

8. Turner D, Schwarz Y, Yust I. Induced sputum for diagnosing Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV patients: new data, new issues. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:204-208. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00035303

9. Smith RL, el-Sadr WM, Lewis ML. Correlation of bronchoalveolar lavage cell populations with clinical severity of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Chest. 1988;93:60-64. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.60

10. Fleury-Feith J, Van Nhieu JT, Picard C, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage eosinophilia associated with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonitis in AIDS patients. Comparative study with non-AIDS patients. Chest. 1989;95:1198-1201. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.6.1198

11. Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Current insights into the biology and pathogenesis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:298-308. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1621

12. Toh BH, Roberts-Thomson IC, Mathews JD, et al. Depression of cell-mediated immunity in old age and the immunopathic diseases, lupus erythematosus, chronic hepatitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;14:193-202.

13. Mansharamani NG, Balachandran D, Vernovsky I, et al. Peripheral blood CD4 + T-lymphocyte counts during Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in immunocompromised patients without HIV infection. Chest. 2000;118:712-720. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.712

14. McGovern BH, Golan Y, Lopez M, et al. The impact of cirrhosis on CD4+ T cell counts in HIV-seronegative patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:431-437. doi: 10.1086/509580

15. Bienvenu AL, Traore K, Plekhanova I, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia suspected cases in 604 non-HIV and HIV patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;46:11-17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.018

16. Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385-1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.010

17. Lario M, Muñoz L, Ubeda M, et al. Defective thymopoiesis and poor peripheral homeostatic replenishment of T-helper cells cause T-cell lymphopenia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;59:723-730. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.042

1. Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487-2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032588

2. Walzer PD, Perl DP, Krogstad DJ, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the United States. Epidemiologic, diagnostic, and clinical features. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:83-93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-1-83

3. Sepkowitz KA. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17 suppl 2:S416-422. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_2.s416

4. Al Soub H, Taha RY, El Deeb Y, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a patient without a predisposing illness: case report and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:618-621. doi: 10.1080/00365540410017608

5. Jacobs JL, Libby DM, Winters RA, et al. A cluster of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in adults without predisposing illnesses. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:246-250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101243240407

6. Ng VL, Yajko DM, McPhaul LW, et al. Evaluation of an indirect fluorescent-antibody stain for detection of Pneumocystis carinii in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:975-979. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.975-979.1990

7. Cregan P, Yamamoto A, Lum A, et al. Comparison of four methods for rapid detection of Pneumocystis carinii in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2432-2436. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2432-2436.1990

8. Turner D, Schwarz Y, Yust I. Induced sputum for diagnosing Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV patients: new data, new issues. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:204-208. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00035303

9. Smith RL, el-Sadr WM, Lewis ML. Correlation of bronchoalveolar lavage cell populations with clinical severity of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Chest. 1988;93:60-64. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.60

10. Fleury-Feith J, Van Nhieu JT, Picard C, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage eosinophilia associated with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonitis in AIDS patients. Comparative study with non-AIDS patients. Chest. 1989;95:1198-1201. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.6.1198

11. Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. Current insights into the biology and pathogenesis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:298-308. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1621

12. Toh BH, Roberts-Thomson IC, Mathews JD, et al. Depression of cell-mediated immunity in old age and the immunopathic diseases, lupus erythematosus, chronic hepatitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;14:193-202.

13. Mansharamani NG, Balachandran D, Vernovsky I, et al. Peripheral blood CD4 + T-lymphocyte counts during Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in immunocompromised patients without HIV infection. Chest. 2000;118:712-720. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.712

14. McGovern BH, Golan Y, Lopez M, et al. The impact of cirrhosis on CD4+ T cell counts in HIV-seronegative patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:431-437. doi: 10.1086/509580

15. Bienvenu AL, Traore K, Plekhanova I, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia suspected cases in 604 non-HIV and HIV patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;46:11-17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.018

16. Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385-1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.010

17. Lario M, Muñoz L, Ubeda M, et al. Defective thymopoiesis and poor peripheral homeostatic replenishment of T-helper cells cause T-cell lymphopenia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;59:723-730. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.042

61-year-old woman • nausea • paresthesia • cold allodynia • Dx?

THE CASE

An active 61-year-old woman (140 lbs) in good health became ill during a sailing holiday in the Virgin Islands. During the trip, she ate various fish in local restaurants; after one lunch, she developed nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, and light-headedness. In the following days, she suffered “intense itching” in the ears, dizziness, malaise, a “fluttering feeling” throughout her body, genitourinary sensitivity, and a “rhythmic buzzing sensation near the rectum.”

She said that cold objects and beverages felt uncomfortably hot (cold allodynia). She noted heightened senses of smell and taste, as well as paresthesia down her spine, and described feeling “moody.” She reduced her workload, took many days off from work, and ceased consuming meat and alcohol because these items seemed to aggravate her symptoms.

The paresthesia persisted, and she consulted her family physician one month later. Laboratory tests—including a complete blood count, hematocrit, thyroid-stimulating hormone, antinuclear antibodies, and titers for Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Lyme disease, and Anaplasma phagocytophila—all yielded normal results. Her symptoms continued for 3 more months before referral to Medical Toxicology.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s symptoms and history were consistent with ciguatera poisoning. Features supporting this diagnosis included an acute gastrointestinal illness after eating fish caught in tropical waters and subsequent persistent paresthesia, including cold allodynia.1 Laboratory testing excluded acute infection, anemia, thyroid dysfunction, vitamin B12 deficiency, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, and anaplasmosis.

DISCUSSION

Ciguatera results from ciguatoxin, a class of heat-stable polycyclic toxins produced in warm tropical waters by microscopic dinoflagellates (most often Gambierdiscus toxicus).2,3 Small variations exist in the Caribbean, Pacific, and Indian Ocean forms. Ciguatoxin bio-accumulates in the food chain, and humans most often ingest it by eating larger fish (typically barracuda, snapper, grouper, or amberjack).4 Because ciguatoxin confers no characteristic taste or smell to the fish, people who prepare or eat contaminated seafood have no reliable means to detect and avoid it.

Ciguatoxin opens neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels and blocks delayed-rectifier potassium channels.5 These cause repetitive, spontaneous action potentials that explain the paresthesia. Sodium influx triggers an increase in intracellular calcium concentrations. Increased intracellular sodium and calcium concentrations draw water into the intracellular space and cause neuronal edema.

Death is rarely associated with ciguatera (< 0.1% in the largest observational study).1 Even without treatment (discussed shortly), symptoms of ciguatera will gradually resolve over several weeks to several months in most cases.1,4,5 However, after recovery, patients often briefly experience milder symptoms after consuming fish, alcohol, or nuts.6

Continue to: Treatment of ciguatera

Treatment of ciguatera may include intravenous (IV) mannitol infusion. Other treatments, such as amitriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin, and tocainide, have been used, but there is limited supporting evidence and they appear variably effective.7

Mannitol reverses the effects of ciguatoxin, with suppression of spontaneous action potentials and reversal of neuronal edema.8,9 It is reasonable to offer mannitol for acute or persistent symptoms of ciguatera fish poisoning even after a delay of several weeks.

A recent systematic review found that mannitol has the largest body of evidence supporting its use, although that evidence is generally of low quality (case reports and large case series).7 While these reports10-13 describe beneficial effects of mannitol, a single randomized trial suggested that mannitol is no more effective than normal saline.14 However, this study was underpowered and had inadequate treatment concealment; twice as many saline control patients as mannitol-treated patients requested a rescue dose of mannitol.14

Mannitol may be most effective when given early in the course of ciguatera but has shown some success when given later.5,12,13 In 1 large case series, the longest interval from symptom onset to successful treatment was 70 days, although most patients with satisfactory results received mannitol in the first few days.5

Our patient was administered an IV infusion of 100 g of 20% mannitol over 1 hour. She received the infusion 140 days after the onset of her symptoms and experienced rapid symptom relief.

Continue to: At a follow-up visit...

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, she described increased energy and further improvement in her paresthesia. She returned to a full work schedule and resumed all of her daily activities. However, she continued to avoid alcohol and proteins, as she had experienced a mild recurrence that she temporally related to eating meat and drinking alcohol.

At the 2-month follow-up, the patient reported continued improvement in her paresthesia but continued to experience occasional gastrointestinal symptoms and fatigue associated with meat and alcohol consumption.

The Takeaway

Ciguatera fish poisoning is largely a clinical diagnosis. It is based on early gastrointestinal symptoms followed by persistent paresthesia and cold allodynia after consumption of fish caught in tropical waters. Family physicians may see ciguatera in returning travelers or people who have consumed certain fish imported from endemic areas. Untreated symptoms may last for many weeks or months. IV mannitol may relieve symptoms of ciguatera poisoning even when administered several months after symptom onset.

We are grateful to our patient, who allowed us to share her story in the hope of helping other travelers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael E. Mullins, MD, Division of Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8072, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63110; [email protected]

1. Bagnis R, Kuberski T, Laugier S. Clinical Observations of 3,009 cases of ciguatera (fish poisoning) in the South Pacific. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:1067-1073. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.1067

2. Morris JG Jr, Lewin P, Smith CW, et al. Ciguatera fish poisoning: epidemiology of the disease on St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:574-578. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.574

3. Radke EG, Grattan LM, Cook RL, et al. Ciguatera incidence in the US Virgin Islands has not increased over a 30-year time period despite rising seawater temperatures. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:908-913. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0676

4. Goodman DM, Rogers J, Livingston EH. Ciguatera fish poisoning.

5. Blythe DG, De Sylva DP, Fleming LE, et al. Clinical experience with IV mannitol in the treatment of ciguatera. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1992;85:425-426.

6. Lewis, RJ. The changing face of ciguatera. Toxicon. 2001;39:97-106. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00161-6

7. Mullins ME, Hoffman RS. Is mannitol the treatment of choice for ciguatera fish poisoning? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55:947-955. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1327664

8. Nicholson GM, Lewis, RJ. Ciguatoxins: cyclic polyether modulators of voltage-gated ion channel function. Mar Drugs. 2006;4:82-118.

9. Mattei C, Molgo J, Marquais M, et al. Hyperosmolar D-mannitol reverses the increased membrane excitability and the nodal swelling caused by Caribbean ciguatoxin-1 in single frog myelinated neurons. Brain Res. 1999;847:50-58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02032-6

10. Palafox NA, Jain LG, Pinano AZ, et al. Successful treatment of ciguatera fish poisoning with intravenous mannitol. JAMA. 1988;259:2740-2742.

11. Pearn JH, Lewis RJ, Ruff T, et al. Ciguatera and mannitol: experience with a new treatment regimen. Med J Aust. 1989;151:77-80. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb101165.x

12. Eastaugh JA. Delayed use of intravenous mannitol in ciguatera (fish poisoning). Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:105-106. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70151-8

13. Schwarz ES, Mullins ME, Brooks CB. Ciguatera poisoning successfully treated with delayed mannitol. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:476-477. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.015

14. Schnorf H, Taurarii M, Cundy T. Ciguatera fish poisoning: a double-blind randomized trial of mannitol therapy. Neurology. 2002;58:873-880. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.6.873

THE CASE

An active 61-year-old woman (140 lbs) in good health became ill during a sailing holiday in the Virgin Islands. During the trip, she ate various fish in local restaurants; after one lunch, she developed nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, and light-headedness. In the following days, she suffered “intense itching” in the ears, dizziness, malaise, a “fluttering feeling” throughout her body, genitourinary sensitivity, and a “rhythmic buzzing sensation near the rectum.”

She said that cold objects and beverages felt uncomfortably hot (cold allodynia). She noted heightened senses of smell and taste, as well as paresthesia down her spine, and described feeling “moody.” She reduced her workload, took many days off from work, and ceased consuming meat and alcohol because these items seemed to aggravate her symptoms.

The paresthesia persisted, and she consulted her family physician one month later. Laboratory tests—including a complete blood count, hematocrit, thyroid-stimulating hormone, antinuclear antibodies, and titers for Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Lyme disease, and Anaplasma phagocytophila—all yielded normal results. Her symptoms continued for 3 more months before referral to Medical Toxicology.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s symptoms and history were consistent with ciguatera poisoning. Features supporting this diagnosis included an acute gastrointestinal illness after eating fish caught in tropical waters and subsequent persistent paresthesia, including cold allodynia.1 Laboratory testing excluded acute infection, anemia, thyroid dysfunction, vitamin B12 deficiency, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, and anaplasmosis.

DISCUSSION

Ciguatera results from ciguatoxin, a class of heat-stable polycyclic toxins produced in warm tropical waters by microscopic dinoflagellates (most often Gambierdiscus toxicus).2,3 Small variations exist in the Caribbean, Pacific, and Indian Ocean forms. Ciguatoxin bio-accumulates in the food chain, and humans most often ingest it by eating larger fish (typically barracuda, snapper, grouper, or amberjack).4 Because ciguatoxin confers no characteristic taste or smell to the fish, people who prepare or eat contaminated seafood have no reliable means to detect and avoid it.

Ciguatoxin opens neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels and blocks delayed-rectifier potassium channels.5 These cause repetitive, spontaneous action potentials that explain the paresthesia. Sodium influx triggers an increase in intracellular calcium concentrations. Increased intracellular sodium and calcium concentrations draw water into the intracellular space and cause neuronal edema.

Death is rarely associated with ciguatera (< 0.1% in the largest observational study).1 Even without treatment (discussed shortly), symptoms of ciguatera will gradually resolve over several weeks to several months in most cases.1,4,5 However, after recovery, patients often briefly experience milder symptoms after consuming fish, alcohol, or nuts.6

Continue to: Treatment of ciguatera

Treatment of ciguatera may include intravenous (IV) mannitol infusion. Other treatments, such as amitriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin, and tocainide, have been used, but there is limited supporting evidence and they appear variably effective.7

Mannitol reverses the effects of ciguatoxin, with suppression of spontaneous action potentials and reversal of neuronal edema.8,9 It is reasonable to offer mannitol for acute or persistent symptoms of ciguatera fish poisoning even after a delay of several weeks.

A recent systematic review found that mannitol has the largest body of evidence supporting its use, although that evidence is generally of low quality (case reports and large case series).7 While these reports10-13 describe beneficial effects of mannitol, a single randomized trial suggested that mannitol is no more effective than normal saline.14 However, this study was underpowered and had inadequate treatment concealment; twice as many saline control patients as mannitol-treated patients requested a rescue dose of mannitol.14

Mannitol may be most effective when given early in the course of ciguatera but has shown some success when given later.5,12,13 In 1 large case series, the longest interval from symptom onset to successful treatment was 70 days, although most patients with satisfactory results received mannitol in the first few days.5

Our patient was administered an IV infusion of 100 g of 20% mannitol over 1 hour. She received the infusion 140 days after the onset of her symptoms and experienced rapid symptom relief.

Continue to: At a follow-up visit...

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, she described increased energy and further improvement in her paresthesia. She returned to a full work schedule and resumed all of her daily activities. However, she continued to avoid alcohol and proteins, as she had experienced a mild recurrence that she temporally related to eating meat and drinking alcohol.

At the 2-month follow-up, the patient reported continued improvement in her paresthesia but continued to experience occasional gastrointestinal symptoms and fatigue associated with meat and alcohol consumption.

The Takeaway

Ciguatera fish poisoning is largely a clinical diagnosis. It is based on early gastrointestinal symptoms followed by persistent paresthesia and cold allodynia after consumption of fish caught in tropical waters. Family physicians may see ciguatera in returning travelers or people who have consumed certain fish imported from endemic areas. Untreated symptoms may last for many weeks or months. IV mannitol may relieve symptoms of ciguatera poisoning even when administered several months after symptom onset.

We are grateful to our patient, who allowed us to share her story in the hope of helping other travelers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael E. Mullins, MD, Division of Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8072, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63110; [email protected]

THE CASE

An active 61-year-old woman (140 lbs) in good health became ill during a sailing holiday in the Virgin Islands. During the trip, she ate various fish in local restaurants; after one lunch, she developed nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, and light-headedness. In the following days, she suffered “intense itching” in the ears, dizziness, malaise, a “fluttering feeling” throughout her body, genitourinary sensitivity, and a “rhythmic buzzing sensation near the rectum.”

She said that cold objects and beverages felt uncomfortably hot (cold allodynia). She noted heightened senses of smell and taste, as well as paresthesia down her spine, and described feeling “moody.” She reduced her workload, took many days off from work, and ceased consuming meat and alcohol because these items seemed to aggravate her symptoms.

The paresthesia persisted, and she consulted her family physician one month later. Laboratory tests—including a complete blood count, hematocrit, thyroid-stimulating hormone, antinuclear antibodies, and titers for Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Lyme disease, and Anaplasma phagocytophila—all yielded normal results. Her symptoms continued for 3 more months before referral to Medical Toxicology.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s symptoms and history were consistent with ciguatera poisoning. Features supporting this diagnosis included an acute gastrointestinal illness after eating fish caught in tropical waters and subsequent persistent paresthesia, including cold allodynia.1 Laboratory testing excluded acute infection, anemia, thyroid dysfunction, vitamin B12 deficiency, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, and anaplasmosis.

DISCUSSION

Ciguatera results from ciguatoxin, a class of heat-stable polycyclic toxins produced in warm tropical waters by microscopic dinoflagellates (most often Gambierdiscus toxicus).2,3 Small variations exist in the Caribbean, Pacific, and Indian Ocean forms. Ciguatoxin bio-accumulates in the food chain, and humans most often ingest it by eating larger fish (typically barracuda, snapper, grouper, or amberjack).4 Because ciguatoxin confers no characteristic taste or smell to the fish, people who prepare or eat contaminated seafood have no reliable means to detect and avoid it.

Ciguatoxin opens neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels and blocks delayed-rectifier potassium channels.5 These cause repetitive, spontaneous action potentials that explain the paresthesia. Sodium influx triggers an increase in intracellular calcium concentrations. Increased intracellular sodium and calcium concentrations draw water into the intracellular space and cause neuronal edema.

Death is rarely associated with ciguatera (< 0.1% in the largest observational study).1 Even without treatment (discussed shortly), symptoms of ciguatera will gradually resolve over several weeks to several months in most cases.1,4,5 However, after recovery, patients often briefly experience milder symptoms after consuming fish, alcohol, or nuts.6

Continue to: Treatment of ciguatera

Treatment of ciguatera may include intravenous (IV) mannitol infusion. Other treatments, such as amitriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin, and tocainide, have been used, but there is limited supporting evidence and they appear variably effective.7

Mannitol reverses the effects of ciguatoxin, with suppression of spontaneous action potentials and reversal of neuronal edema.8,9 It is reasonable to offer mannitol for acute or persistent symptoms of ciguatera fish poisoning even after a delay of several weeks.

A recent systematic review found that mannitol has the largest body of evidence supporting its use, although that evidence is generally of low quality (case reports and large case series).7 While these reports10-13 describe beneficial effects of mannitol, a single randomized trial suggested that mannitol is no more effective than normal saline.14 However, this study was underpowered and had inadequate treatment concealment; twice as many saline control patients as mannitol-treated patients requested a rescue dose of mannitol.14

Mannitol may be most effective when given early in the course of ciguatera but has shown some success when given later.5,12,13 In 1 large case series, the longest interval from symptom onset to successful treatment was 70 days, although most patients with satisfactory results received mannitol in the first few days.5

Our patient was administered an IV infusion of 100 g of 20% mannitol over 1 hour. She received the infusion 140 days after the onset of her symptoms and experienced rapid symptom relief.

Continue to: At a follow-up visit...

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, she described increased energy and further improvement in her paresthesia. She returned to a full work schedule and resumed all of her daily activities. However, she continued to avoid alcohol and proteins, as she had experienced a mild recurrence that she temporally related to eating meat and drinking alcohol.

At the 2-month follow-up, the patient reported continued improvement in her paresthesia but continued to experience occasional gastrointestinal symptoms and fatigue associated with meat and alcohol consumption.

The Takeaway

Ciguatera fish poisoning is largely a clinical diagnosis. It is based on early gastrointestinal symptoms followed by persistent paresthesia and cold allodynia after consumption of fish caught in tropical waters. Family physicians may see ciguatera in returning travelers or people who have consumed certain fish imported from endemic areas. Untreated symptoms may last for many weeks or months. IV mannitol may relieve symptoms of ciguatera poisoning even when administered several months after symptom onset.

We are grateful to our patient, who allowed us to share her story in the hope of helping other travelers.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael E. Mullins, MD, Division of Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8072, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63110; [email protected]

1. Bagnis R, Kuberski T, Laugier S. Clinical Observations of 3,009 cases of ciguatera (fish poisoning) in the South Pacific. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:1067-1073. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.1067

2. Morris JG Jr, Lewin P, Smith CW, et al. Ciguatera fish poisoning: epidemiology of the disease on St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:574-578. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.574

3. Radke EG, Grattan LM, Cook RL, et al. Ciguatera incidence in the US Virgin Islands has not increased over a 30-year time period despite rising seawater temperatures. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:908-913. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0676

4. Goodman DM, Rogers J, Livingston EH. Ciguatera fish poisoning.

5. Blythe DG, De Sylva DP, Fleming LE, et al. Clinical experience with IV mannitol in the treatment of ciguatera. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1992;85:425-426.

6. Lewis, RJ. The changing face of ciguatera. Toxicon. 2001;39:97-106. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00161-6

7. Mullins ME, Hoffman RS. Is mannitol the treatment of choice for ciguatera fish poisoning? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55:947-955. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1327664

8. Nicholson GM, Lewis, RJ. Ciguatoxins: cyclic polyether modulators of voltage-gated ion channel function. Mar Drugs. 2006;4:82-118.

9. Mattei C, Molgo J, Marquais M, et al. Hyperosmolar D-mannitol reverses the increased membrane excitability and the nodal swelling caused by Caribbean ciguatoxin-1 in single frog myelinated neurons. Brain Res. 1999;847:50-58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02032-6

10. Palafox NA, Jain LG, Pinano AZ, et al. Successful treatment of ciguatera fish poisoning with intravenous mannitol. JAMA. 1988;259:2740-2742.

11. Pearn JH, Lewis RJ, Ruff T, et al. Ciguatera and mannitol: experience with a new treatment regimen. Med J Aust. 1989;151:77-80. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb101165.x

12. Eastaugh JA. Delayed use of intravenous mannitol in ciguatera (fish poisoning). Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:105-106. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70151-8

13. Schwarz ES, Mullins ME, Brooks CB. Ciguatera poisoning successfully treated with delayed mannitol. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:476-477. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.015

14. Schnorf H, Taurarii M, Cundy T. Ciguatera fish poisoning: a double-blind randomized trial of mannitol therapy. Neurology. 2002;58:873-880. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.6.873

1. Bagnis R, Kuberski T, Laugier S. Clinical Observations of 3,009 cases of ciguatera (fish poisoning) in the South Pacific. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:1067-1073. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.1067

2. Morris JG Jr, Lewin P, Smith CW, et al. Ciguatera fish poisoning: epidemiology of the disease on St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:574-578. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.574

3. Radke EG, Grattan LM, Cook RL, et al. Ciguatera incidence in the US Virgin Islands has not increased over a 30-year time period despite rising seawater temperatures. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:908-913. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0676

4. Goodman DM, Rogers J, Livingston EH. Ciguatera fish poisoning.

5. Blythe DG, De Sylva DP, Fleming LE, et al. Clinical experience with IV mannitol in the treatment of ciguatera. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1992;85:425-426.

6. Lewis, RJ. The changing face of ciguatera. Toxicon. 2001;39:97-106. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00161-6

7. Mullins ME, Hoffman RS. Is mannitol the treatment of choice for ciguatera fish poisoning? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55:947-955. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1327664

8. Nicholson GM, Lewis, RJ. Ciguatoxins: cyclic polyether modulators of voltage-gated ion channel function. Mar Drugs. 2006;4:82-118.

9. Mattei C, Molgo J, Marquais M, et al. Hyperosmolar D-mannitol reverses the increased membrane excitability and the nodal swelling caused by Caribbean ciguatoxin-1 in single frog myelinated neurons. Brain Res. 1999;847:50-58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02032-6

10. Palafox NA, Jain LG, Pinano AZ, et al. Successful treatment of ciguatera fish poisoning with intravenous mannitol. JAMA. 1988;259:2740-2742.

11. Pearn JH, Lewis RJ, Ruff T, et al. Ciguatera and mannitol: experience with a new treatment regimen. Med J Aust. 1989;151:77-80. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb101165.x

12. Eastaugh JA. Delayed use of intravenous mannitol in ciguatera (fish poisoning). Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:105-106. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70151-8

13. Schwarz ES, Mullins ME, Brooks CB. Ciguatera poisoning successfully treated with delayed mannitol. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:476-477. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.015

14. Schnorf H, Taurarii M, Cundy T. Ciguatera fish poisoning: a double-blind randomized trial of mannitol therapy. Neurology. 2002;58:873-880. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.6.873

Elective Total Hip Arthroplasty: Which Surgical Approach Is Optimal?

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most successful orthopedic interventions performed today in terms of pain relief, cost effectiveness, and clinical outcomes.1 As a definitive treatment for end-stage arthritis of the hip, more than 330,000 procedures are performed in the Unites States each year. The number performed is growing by > 5% per year and is predicted to double by 2030, partly due to patients living longer, older individuals seeking a higher level of functionality than did previous generations, and better access to health care.2,3

The THA procedure also has become increasingly common in a younger population for posttraumatic fractures and conditions that lead to early-onset secondary arthritis, such as avascular necrosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, hip dysplasia, Perthes disease, and femoroacetabular impingement.4 Younger patients are more likely to need a revision. According to a study by Evans and colleagues using available arthroplasty registry data, about three-quarters of hip replacements last 15 to 20 years, and 58% of hip replacements last 25 years in patients with osteoarthritis.5

For decades, the THA procedure of choice has been a standard posterior approach (PA). The PA was used because it allowed excellent intraoperative exposure and was applicable to a wide range of hip problems.6 In the past several years, modified muscle-sparing surgical approaches have been introduced. Two performed frequently are the mini PA (MPA) and the direct anterior approach (DAA).

The MPA is a modification of the PA. Surgeons perform the THA through a small incision without cutting the abductor muscles that are critical to hip stability and gait. A study published in 2010 concluded that the MPA was associated with less pain, shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) (therefore, an economic saving), and an earlier return to walking postoperatively.7

The DAA has been around since the early days of THA. Carl Hueter first described the anterior approach to the hip in 1881 (referred to as the Hueter approach). Smith-Peterson is frequently credited with popularizing the DAA technique during his career after publishing his first description of the approach in 1917.8 About 10 years ago, the DAA showed a resurgence as another muscle-sparing alternative for THAs. The DAA is considered to be a true intermuscular approach that preserves the soft tissues around the hip joint, thereby preserving the stability of the joint.9-11 The optimal surgical approach is still the subject of debate.

We present a male with right hip end-stage degenerative joint disease (DJD) and review some medical literature. Although other approaches to THA can be used (lateral, anterolateral), the discussion focuses on 2 muscle-sparing approaches performed frequently, the MPA and the DAA, and can be of value to primary care practitioners in their discussion with patients.

Case Presentation

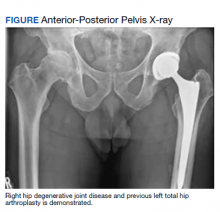

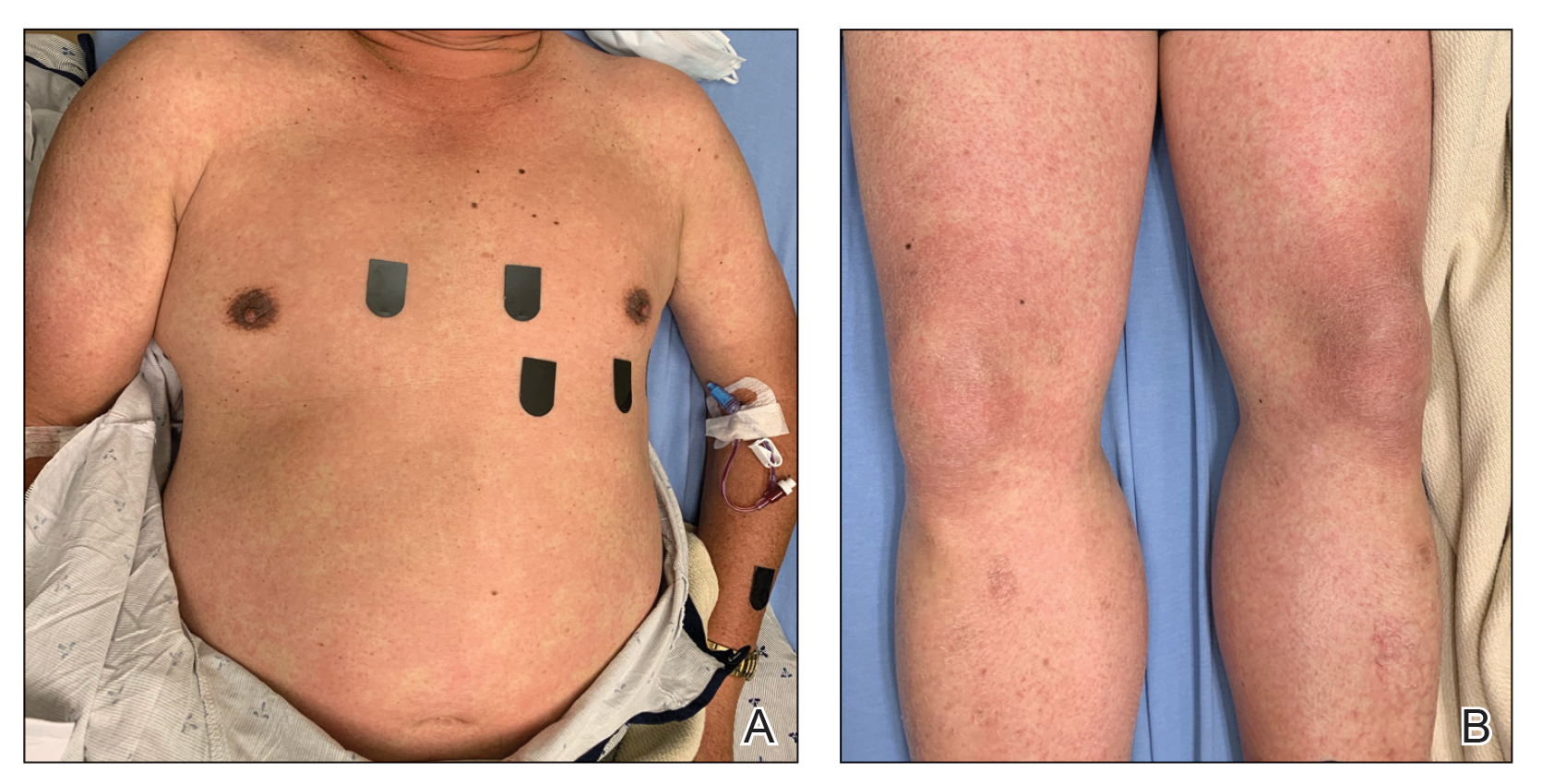

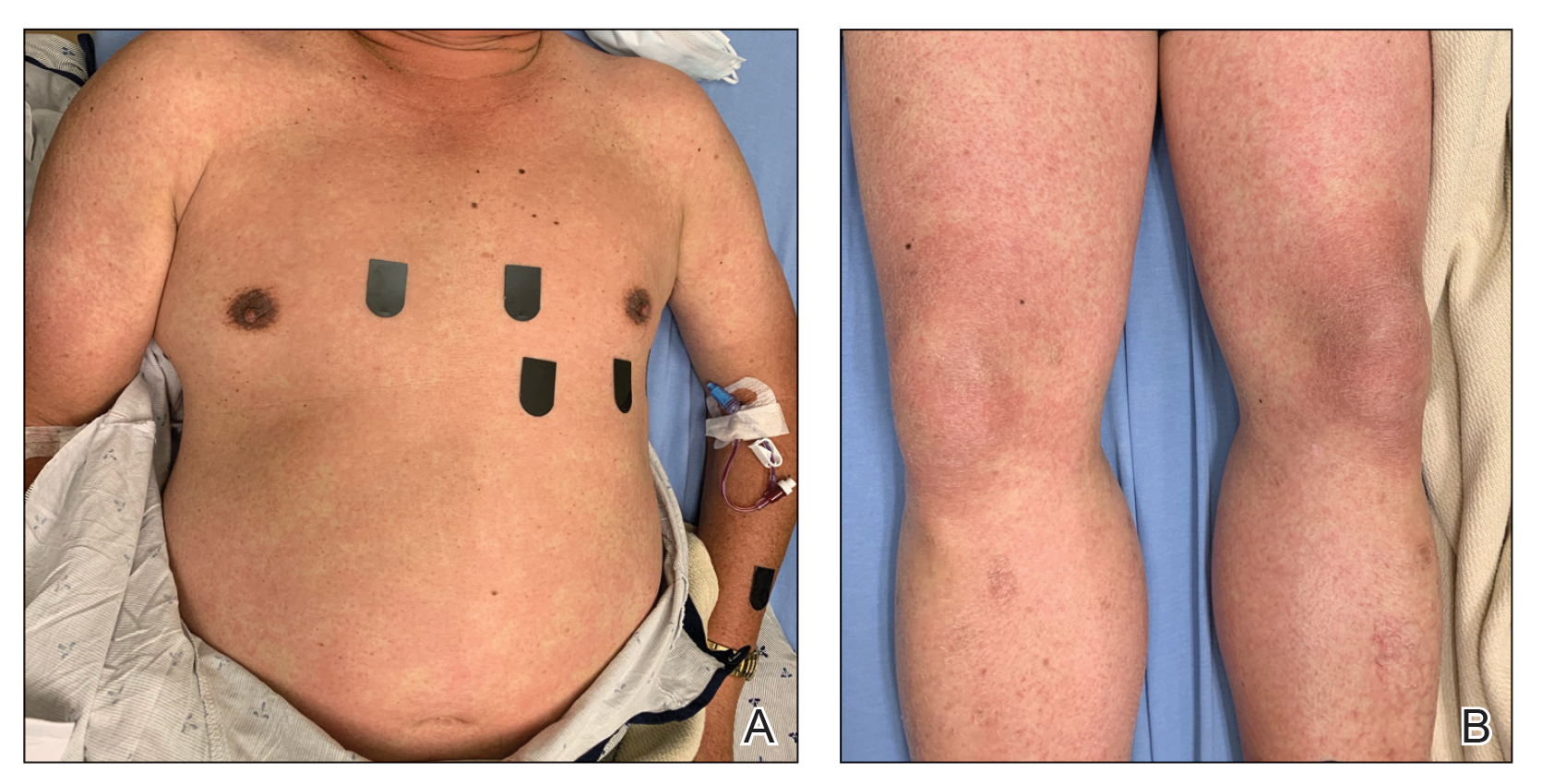

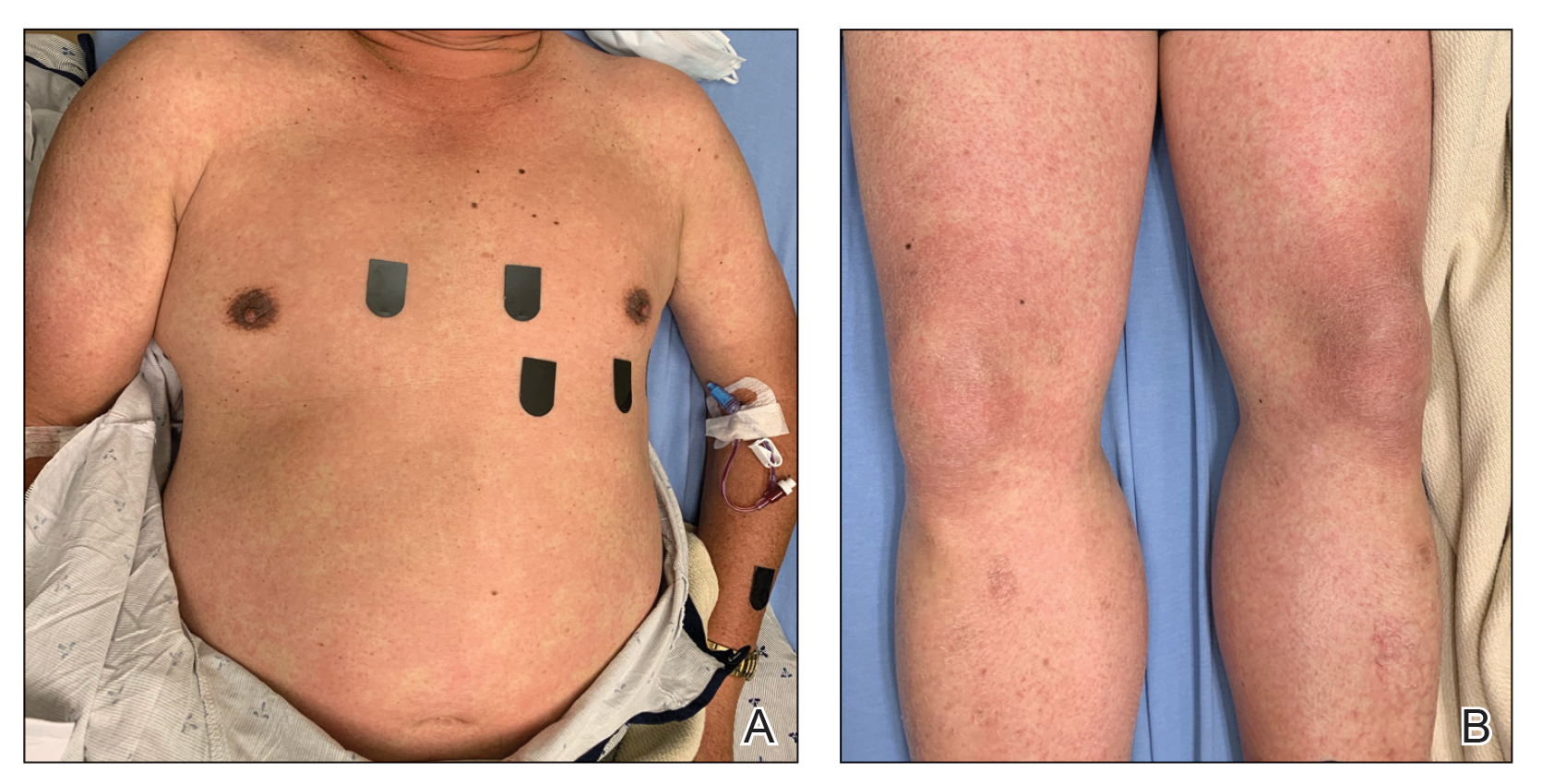

A 61-year-old male patient presented with progressive right hip pain. At age 37, he had a left THA via a PA due to hip dysplasia and a revision on the same hip at age 55 (the polyethylene liner was replaced and the cobalt chromium head was changed to ceramic), again through a PA. An orthopedic clinical evaluation and X-rays confirmed end-stage DJD of the right hip (Figure). He was informed to return to plan an elective THA when the “bad days were significantly greater than the good days” and/or when his functionality or quality of life was unacceptable. The orthopedic surgeon favored an MPA but offered a hand-off to colleagues who preferred the DAA. The patient was given information to review.

Discussion

No matter which approach is used, one study concluded that surgeons who perform > 50 hip replacements each year have better overall outcomes.12

The MPA emerged in the past decade as a muscle-sparing modification of the PA. The incision length (< 10 cm) is the simplest way of categorizing the surgery as an MPA. However, the amount of deep surgical dissection is a more important consideration for sparing muscle (for improved postoperative functionality, recovery, and joint stability) due to the gluteus maximus insertion, the quadratus femoris, and the piriformis tendons being left intact.13-16

Multiple studies have directly compared the MPA and PA, with variable results. One study concluded that the MPA was associated with lower surgical blood loss, lower pain at rest, and a faster recovery compared with that of the PA. Still, the study found no significant difference in postoperative laboratory values of possible markers of increased tissue damage and surgical invasiveness, such as creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) levels.15 Another randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 100 patients concluded that there was a trend for improved walking times and patient satisfaction at 6 weeks post-MPA vs PA.16 Other studies have found that the MPA and PA were essentially equivalent to each other regarding operative time, early postoperative outcomes, transfusion rate, hospital LOS, and postoperative complications.14 However, a recent meta-analysis found positive trends in favor of the MPA. The MPA was associated with a slight decrease in operating time, blood loss, hospital LOS, and earlier improvement in Harris hip scores. The meta-analysis found no significant decrease in the rate of dislocation or femoral fracture.13 Studies are still needed to evaluate long-term implant survival and outcomes for MPA and PA.

The DAA has received renewed attention as surgeons seek minimally invasive techniques and more rapid recoveries.6 The DAA involves a 3- to 4-inch incision on the front of the hip and enters the hip joint through the intermuscular interval between the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius muscles laterally and the sartorius muscle and rectus fascia medially.9 The DAA is considered a true intermuscular approach that preserves the soft tissues around the hip joint (including the posterior capsule), thereby presumably preserving the stability of the joint.9 The popularity for this approach has been attributed primarily to claims of improved recovery times, lower pain levels, improved patient satisfaction, as well as improved accuracy on both implant placement/alignment and leg length restoration.17 Orthopedic surgeons are increasingly being trained in the DAA during their residency and fellowship training.

There are many potential disadvantages to DAA. For example, DAA may present intraoperative radiation exposure for patients and surgeons during a fluoroscopy-assisted procedure. In addition, neuropraxia, particularly to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, can cause transient or permanent meralgia paresthetica. Wound healing may also present problems for female and obese patients, particularly those with a body mass index > 39 who are at increased risk of wound complications. DAA also increases time under anesthesia. Patients may experience proximal femoral fractures and dislocations and complex/challenging femoral exposure and bone preparation. Finally, sagittal malalignment of the stem could lead to loosening and an increased need for revision surgery.18

Another disadvantage of the DAA compared with the PA and MPA is the steep learning curve. Most studies find that the complication rate decreases only when the surgeon performs a significant number of DAA procedures. DeSteiger and colleagues noted a learning curve of 50 to 100 cases needed, and Masonis and colleagues concluded that at least 100 cases needed to be done to decrease operating and fluoroscopy times.19,20 Many orthopedic surgeons perform < 25 THA procedures a year.21

With the recent surge in popularity of the DAA, several studies have evaluated the DAA vs the MPA. A prospective RCT of 54 patients comparing the 2 approaches found that DAA patients walked without assistive devices sooner than did MPA patients: 22 days for DAA and 28 days for MPA.22 Improved cup position and a faster return of functionality were found in another study. DAA patients transitioned to a cane at 12 days vs 15.5 days for MPA patients and had a negative Trendelenburg sign at 16.7 days vs 24.8 days for MPA patients.23

Comparing DAA and MPA for inflammatory markers (serum CPK, C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, interleukin-1 β and tumor necrosis factor-α), the level of CPK postoperatively was 5.5 times higher in MPA patients, consistent with significantly more muscle damage. However, the overall physiologic burden as demonstrated by the measurement of all inflammatory markers was similar between the MPA and the DAA. This suggests that the inflammatory cascade associated with THA may be influenced more by the osteotomy and prosthesis implantation than by the surgical approach.24

Of note, some surgeons who perform the DAA recommend fewer postoperative precautions and suggest that physical therapy may not be necessary after discharge.25,26 Nevertheless, physiotherapeutic rehabilitation after all THA surgery is recommended as the standard treatment to minimize postoperative complications, such as hip dislocation, wound infection, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, and to maximize the patient’s functionality.27-29 RCTs are needed to look at long-term data on clinical outcomes between the MPA and DAA. Dislocation is a risk regardless of the approach used. Nevertheless, rates of dislocation, in general, are now very low, given the use of larger femoral head implants for all approaches.

Conclusions

THA is one of the most successful surgical procedures performed today. Patients desire hip pain relief and a return to function with as little interruption in their life as possible. Additionally, health care systems and insurers require THA procedures to be as efficient and cost-effective as possible. The debate regarding the most effective or preferable approach for THA continues. Although some prospective RCTs found that patients who underwent the DAA had objectively faster recovery than patients who had the MPA, it is also acknowledged that the results were dependent on surgeons who are very skilled in performing DAAs. The hope of both approaches is to get the individual moving as quickly and safely as possible to avoid a cascade of deterioration in the postoperative period. Factors other than the surgical approach, including patient selection, surgical volume and experience, careful preoperative assessments, attentive pain management, and rapid rehabilitation protocols, may be just as important as to which procedure is performed.30 The final decision should still be dependent on the patient-surgeon relationship and informed decision making.

In this case, the patient reviewed all the information he was given and independently researched the 2 procedures over many months. Ultimately, he decided to undergo a right THA via the DAA.

1. Elmallah RK, Chughtai M, Khlopas A. et al. Determining cost-effectiveness of total hip and knee arthroplasty using the Short Form-6D utility measure. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(2):351-354. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.006

2. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.00285

3. Kurtz, S, Ong KL, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00222

4. Sheahan WT, Parvataneni HK. Asymptomatic but time for a hip revision. Fed Pract. 2016;33(2):39-43.

5. Evans, JT, Evans JP, Walker RW, et al. How long does a hip replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2019;393(10172):647-654. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31665-9

6. Yang X, Huang H-F, Sun L , Yang Z, Deng C-Y, Tian XB. Direct anterior approach versus posterolateral approach in total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Orthop Surg. 2020;12:1065-1073. doi:10.1111/os.12669

7. Varela Egocheaga JR, Suárez-Suárez MA, Fernández-Villán M, González-Sastre V, Varela-Gómez JR, Murcia-Mazón A. Minimally invasive posterior approach in total hip arthroplasty. Prospective randomized trial. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2010:33(2):133-143. doi:10.4321/s1137-66272010000300002

8. Raxhbauer F, Kain MS, Leunig M. The history of the anterior approach to the hip. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40(3):311-320. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2009.02.007

9. Jia F, Guo B, Xu F, Hou Y, Tang X, Huang L. A comparison of clinical, radiographic and surgical outcomes of total hip arthroplasty between direct anterior and posterior approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hip Int. 2019;29(6):584-596. doi:10.1177/1120700018820652

10. Kennon RE Keggi JM, Wetmore RS, Zatorski LE, Huo MH, Keggi KJ. Total hip arthroplasty through a minimally invasive anterior surgical approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(suppl 4):39-48. doi:10.2106/00004623-200300004-00005

11. Bal BS, Vallurupalli S. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty with the anterior approach. Indian J Orthop. 2008;42(3):301-308. doi:10.4103/0019-5413.41853

12. Katz JN, Losina E, Barrett E. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and outcomes of total hip replacement in the United States Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(11):1622-1629. doi:10.2106/00004623-200111000-00002

13. Berstock JR, Blom AW, Beswick AD. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the standard versus mini-incision approach to a total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(10):1970-1982. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2014.05.021

14. Chimento GF, Pavone V, Sharrock S, Kahn K, Cahill J, Sculco TP. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(2):139-144. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.061

15. Fink B, Mittelstaedt A, Schulz MS, Sebena P, Sing J. Comparison of a minimally invasive posterior approach and the standard posterior approach for total hip arthroplasty. A prospective and comparative study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:46. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-5-46

16. Khan RJ, Maor D, Hofmann M, Haebich S. A comparison of a less invasive piriformis-sparing approach versus the standard approach to the hip: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:43-50. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B1.27001

17. Galakatos GR. Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. Missouri Med. 2018;115(6):537-541.

18. Flevas, DA, Tsantes AG, Mavrogenis, AE. Direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty revisited. JBJS Rev. 2020;8(4):e0144. doi:10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00144

19. DeSteiger RN, Lorimer M, Solomon M. What is the learning curve for the anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(12):3860-3866. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4565-6

20. Masonis J, Thompson C, Odum S. Safe and accurate: learning the direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2008;31(12)(suppl 2).

21. Bal BS. Clinical faceoff: anterior total hip versus mini-posterior: Which one is better? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(4):1192-1196. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3684-9

22. Taunton MJ, Mason JB, Odum SM, Bryan D, Springer BD. Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty yields more rapid voluntary cessation of all walking aids: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29;(suppl 9):169-172. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.05

23. Nakata K, Nishikawa M, Yamamoto K, Hirota S, Yoshikawa H. A clinical comparative study of the direct anterior with mini-posterior approach: two consecutive series. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(5):698-704. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.012

24. Bergin PF, Doppelt JD, Kephart CJ. Comparison of minimally invasive direct anterior versus posterior total hip arthroplasty based on inflammation and muscle damage markers. Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011; 93(15):1392-1398. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.00557

25. Carli AV, Poitras S, Clohisy JC, Beaule PE. Variation in use of postoperative precautions and equipment following total hip arthroplasty: a survey of the AAHKS and CAS membership. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3201-3205. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.05.043

26. Kavcˇicˇ G, Mirt PK, Tumpej J, Bedenčič. The direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty without specific table: surgical approach and our seven years of experience. Published June 14, 2019. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://crimsonăpublishers.com/rabs/fulltext/RABS.000520.php27. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Total hip replacement exercise guide. Published 2017. Updated February 2022. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/recovery/total-hip-replacement-exercise-guide

28. Medical Advisory Secretariat. Physiotherapy rehabilitation after total knee or hip replacement: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2005;5(8):1-91.

29. Pa˘unescu F, Didilescu A, Antonescu DM. Factors that may influence the functional outcome after primary total hip arthroplasty. Clujul Med. 2013;86(2):121-127.

30. Poehling-Monaghan KL, Kamath AF, Taunton MJ, Pagnano MW. Direct anterior versus miniposterior THA with the same advanced perioperative protocols: surprising early clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(2):623-631. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3827-z

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most successful orthopedic interventions performed today in terms of pain relief, cost effectiveness, and clinical outcomes.1 As a definitive treatment for end-stage arthritis of the hip, more than 330,000 procedures are performed in the Unites States each year. The number performed is growing by > 5% per year and is predicted to double by 2030, partly due to patients living longer, older individuals seeking a higher level of functionality than did previous generations, and better access to health care.2,3

The THA procedure also has become increasingly common in a younger population for posttraumatic fractures and conditions that lead to early-onset secondary arthritis, such as avascular necrosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, hip dysplasia, Perthes disease, and femoroacetabular impingement.4 Younger patients are more likely to need a revision. According to a study by Evans and colleagues using available arthroplasty registry data, about three-quarters of hip replacements last 15 to 20 years, and 58% of hip replacements last 25 years in patients with osteoarthritis.5

For decades, the THA procedure of choice has been a standard posterior approach (PA). The PA was used because it allowed excellent intraoperative exposure and was applicable to a wide range of hip problems.6 In the past several years, modified muscle-sparing surgical approaches have been introduced. Two performed frequently are the mini PA (MPA) and the direct anterior approach (DAA).

The MPA is a modification of the PA. Surgeons perform the THA through a small incision without cutting the abductor muscles that are critical to hip stability and gait. A study published in 2010 concluded that the MPA was associated with less pain, shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) (therefore, an economic saving), and an earlier return to walking postoperatively.7

The DAA has been around since the early days of THA. Carl Hueter first described the anterior approach to the hip in 1881 (referred to as the Hueter approach). Smith-Peterson is frequently credited with popularizing the DAA technique during his career after publishing his first description of the approach in 1917.8 About 10 years ago, the DAA showed a resurgence as another muscle-sparing alternative for THAs. The DAA is considered to be a true intermuscular approach that preserves the soft tissues around the hip joint, thereby preserving the stability of the joint.9-11 The optimal surgical approach is still the subject of debate.

We present a male with right hip end-stage degenerative joint disease (DJD) and review some medical literature. Although other approaches to THA can be used (lateral, anterolateral), the discussion focuses on 2 muscle-sparing approaches performed frequently, the MPA and the DAA, and can be of value to primary care practitioners in their discussion with patients.

Case Presentation

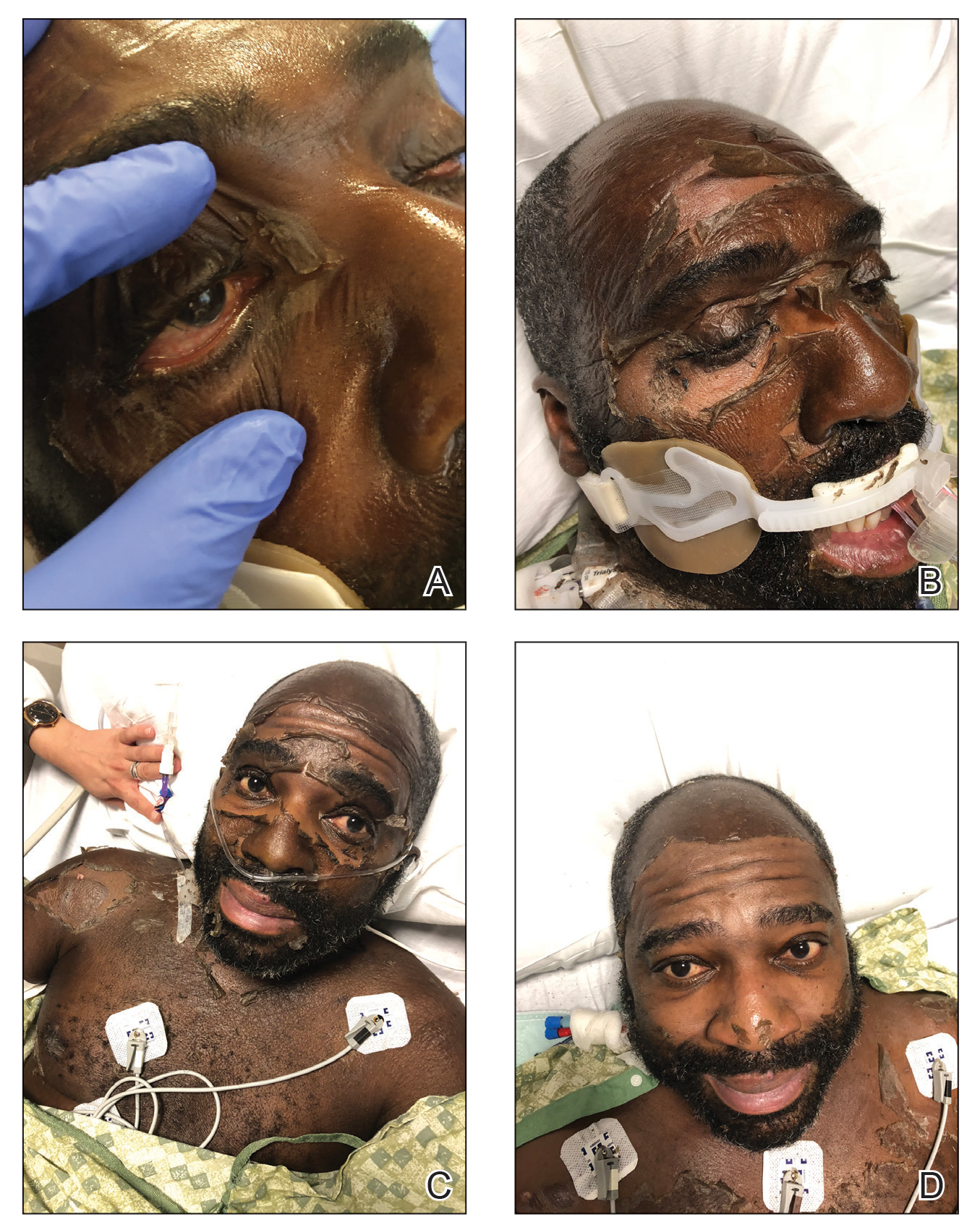

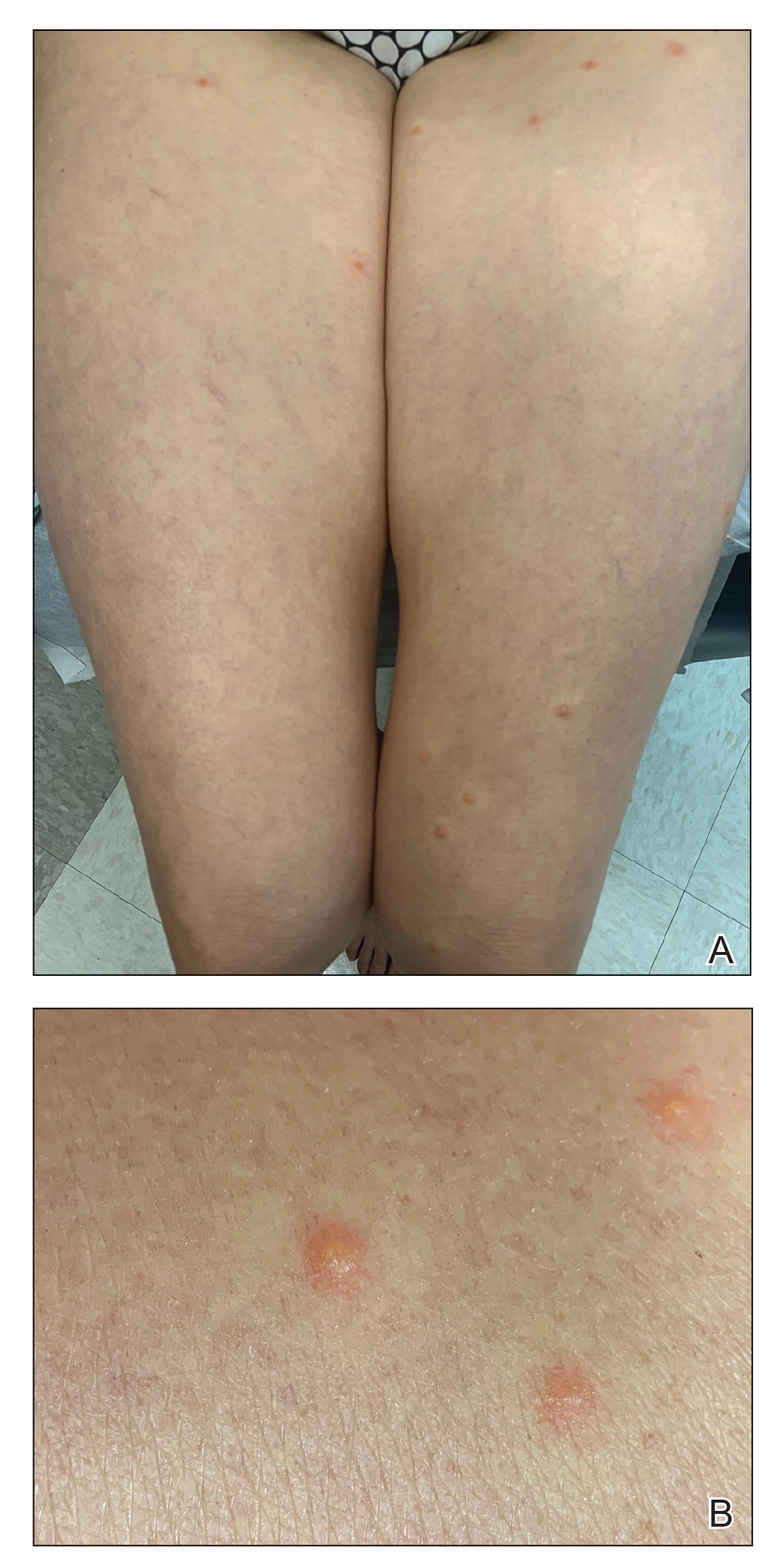

A 61-year-old male patient presented with progressive right hip pain. At age 37, he had a left THA via a PA due to hip dysplasia and a revision on the same hip at age 55 (the polyethylene liner was replaced and the cobalt chromium head was changed to ceramic), again through a PA. An orthopedic clinical evaluation and X-rays confirmed end-stage DJD of the right hip (Figure). He was informed to return to plan an elective THA when the “bad days were significantly greater than the good days” and/or when his functionality or quality of life was unacceptable. The orthopedic surgeon favored an MPA but offered a hand-off to colleagues who preferred the DAA. The patient was given information to review.

Discussion

No matter which approach is used, one study concluded that surgeons who perform > 50 hip replacements each year have better overall outcomes.12

The MPA emerged in the past decade as a muscle-sparing modification of the PA. The incision length (< 10 cm) is the simplest way of categorizing the surgery as an MPA. However, the amount of deep surgical dissection is a more important consideration for sparing muscle (for improved postoperative functionality, recovery, and joint stability) due to the gluteus maximus insertion, the quadratus femoris, and the piriformis tendons being left intact.13-16

Multiple studies have directly compared the MPA and PA, with variable results. One study concluded that the MPA was associated with lower surgical blood loss, lower pain at rest, and a faster recovery compared with that of the PA. Still, the study found no significant difference in postoperative laboratory values of possible markers of increased tissue damage and surgical invasiveness, such as creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) levels.15 Another randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 100 patients concluded that there was a trend for improved walking times and patient satisfaction at 6 weeks post-MPA vs PA.16 Other studies have found that the MPA and PA were essentially equivalent to each other regarding operative time, early postoperative outcomes, transfusion rate, hospital LOS, and postoperative complications.14 However, a recent meta-analysis found positive trends in favor of the MPA. The MPA was associated with a slight decrease in operating time, blood loss, hospital LOS, and earlier improvement in Harris hip scores. The meta-analysis found no significant decrease in the rate of dislocation or femoral fracture.13 Studies are still needed to evaluate long-term implant survival and outcomes for MPA and PA.

The DAA has received renewed attention as surgeons seek minimally invasive techniques and more rapid recoveries.6 The DAA involves a 3- to 4-inch incision on the front of the hip and enters the hip joint through the intermuscular interval between the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius muscles laterally and the sartorius muscle and rectus fascia medially.9 The DAA is considered a true intermuscular approach that preserves the soft tissues around the hip joint (including the posterior capsule), thereby presumably preserving the stability of the joint.9 The popularity for this approach has been attributed primarily to claims of improved recovery times, lower pain levels, improved patient satisfaction, as well as improved accuracy on both implant placement/alignment and leg length restoration.17 Orthopedic surgeons are increasingly being trained in the DAA during their residency and fellowship training.

There are many potential disadvantages to DAA. For example, DAA may present intraoperative radiation exposure for patients and surgeons during a fluoroscopy-assisted procedure. In addition, neuropraxia, particularly to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, can cause transient or permanent meralgia paresthetica. Wound healing may also present problems for female and obese patients, particularly those with a body mass index > 39 who are at increased risk of wound complications. DAA also increases time under anesthesia. Patients may experience proximal femoral fractures and dislocations and complex/challenging femoral exposure and bone preparation. Finally, sagittal malalignment of the stem could lead to loosening and an increased need for revision surgery.18