User login

Raynaud Phenomenon of the Nipple Successfully Treated With Nifedipine and Gabapentin

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon is characterized by vasospasm of arterioles causing intermittent ischemia of the digits. The characteristic triphasic color change presents first as a dramatic change in skin color from normal to white, as the vasoconstriction causes pallor secondary to ischemia. This change is followed by a blue appearance, as cyanosis results from the deoxygenated venous blood. Finally, reflex vasodilation and reperfusion manifest as a red color from erythema. Several cases have been reported describing Raynaud phenomenon affecting the nipples of breastfeeding women.1-5 This vasospasm results in episodic nipple pain manifesting from breastfeeding and exposure to cold. If it is not appropriately treated, the pain’s severity causes affected women to stop breastfeeding. We report a case of vasospasm of the nipple in which the patient experienced nipple pain and a separate lancinating pain that radiated through the breasts.

A 36-year-old woman presented with excruciating nipple and breast pain 3 weeks after delivering her first child. She had no history of smoking or Raynaud phenomenon. The nipple pain was triggered upon breastfeeding and exposure to cold. During these episodes, the nipples would initially blanch white, then turn purple and finally a deep red. The patient also experienced an episodic excruciating lancinating pain of the breast that would randomly and spontaneously radiate through either breast several times per day for 15 to 30 seconds. A workup including an antinuclear antibody test, complete blood cell count with differential, and comprehensive metabolic panel all were within reference range.

The patient was diagnosed with nipple vasospasm. Partial relief of nipple pain occurred after treatment with 30 mg daily of nifedipine; 60 mg daily resulted in complete control, allowing the patient to breastfeed without discomfort, but the lancinating pain continued unabated. The patient could not discontinue breastfeeding because her child was intolerant to formula. She became despondent, as she could find no relief from the pain that she found to be intolerable. Because the patient’s description was reminiscent of the lancinating pain seen in postherpetic neuralgia, a trial of pregabalin was prescribed. A dosage of 75 mg twice daily resulted in near-complete resolution of the pain. After 3 months, the patient successfully weaned her child from breast milk to formula, and the nipple and breast pain promptly resolved. The baby experienced no adverse effects from the patient’s use of pregabalin.

This condition was first described by Gunther1 in 1970 as initial blanching of the nipple followed by a mulberry color. It was termed psychosomatic sore nipples.1 Lawlor-Smith and Lawlor-Smith2 described the condition in 1997 and termed it vasospasm of the nipple. They reported 5 patients who experienced debilitating nipple pain as well as the triphasic color change of Raynaud phenomenon or a biphasic color change (white and blue). Two patients had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the digits before their first pregnancy.2 Anderson et al3 presented 12 breastfeeding women with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; only 1 patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon. In this series, all 6 women who chose to try nifedipine responded well to the drug.3

Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple also has been reported to be associated with the use of labetalol.4 In this case, the patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the toes and nipples on cold days. In 2 subsequent pregnancies she was treated with labetalol for pregnancy-induced hypertension, which resulted in severe nipple pain with each pregnancy unrelated to cold weather. Unlike other cases, this patient experienced antenatal symptoms in addition to the typical postnatal symptoms. The nipple pain resolved with discontinuation of the labetalol.4

Barrett et al5 conducted a retrospective review of medical records of 88 breastfeeding mothers who presented with nipple pain and dermatitis. They defined the criteria for Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple as chronic deep breast pain (in general lasting >4 weeks) that responded to therapy for the condition and had at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) observed or self-reported color changes of the nipple, especially with cold exposure (white, blue, or red); (2) cold sensitivity or color changes of the hands or feet with cold exposure; or (3) failed therapy with oral antifungals. Using these criteria, they diagnosed 22 women (25%) with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; 20 (91%) reported a history of cold sensitivity or color change of acral surfaces. Of 12 patients who received and tolerated nifedipine use, 10 (83%) reported decreased pain or complete resolution. This series described breast or nipple pain, whereas other reported cases only described nipple pain. The authors described a sharp, shooting, or stabbing pain—qualifications not previously noted.5 Our patient experienced both nipple pain and a lancinating breast pain consistent with the cases reported by Barrett et al.5

The nipple pain and treatment response in our patient was typical of previously reported cases of vasospasm of the nipple in breastfeeding women; however, Barrett et al5 did not describe individual patients who exhibited the dual nature of the pain described in our patient. The nipple pain experienced during breastfeeding in our patient was successfully treated with nifedipine. We report the successful treatment of the separate lancinating pain with pregabalin.

- Gunther M. Infant Feeding. London, United Kingdom: Methuen; 1970.

- Lawlor-Smith L, Lawlor-Smith C. Vasospasm of the nipple—a manifestation of Raynaud’s phenomenon: case reports. BMJ. 1997;314:644-645.

- Anderson JE, Held N, Wright K. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple: a treatable cause of painful breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2004;113:360-364.

- McGuinness N, Cording V. Raynaud’s phenomenon of the nipple associated with labetalol use. J Hum Lact. 2013;29:17-19.

- Barrett ME, Heller MM, Stone HF, et al. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple in breastfeeding mothers: an underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:300-306.

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon is characterized by vasospasm of arterioles causing intermittent ischemia of the digits. The characteristic triphasic color change presents first as a dramatic change in skin color from normal to white, as the vasoconstriction causes pallor secondary to ischemia. This change is followed by a blue appearance, as cyanosis results from the deoxygenated venous blood. Finally, reflex vasodilation and reperfusion manifest as a red color from erythema. Several cases have been reported describing Raynaud phenomenon affecting the nipples of breastfeeding women.1-5 This vasospasm results in episodic nipple pain manifesting from breastfeeding and exposure to cold. If it is not appropriately treated, the pain’s severity causes affected women to stop breastfeeding. We report a case of vasospasm of the nipple in which the patient experienced nipple pain and a separate lancinating pain that radiated through the breasts.

A 36-year-old woman presented with excruciating nipple and breast pain 3 weeks after delivering her first child. She had no history of smoking or Raynaud phenomenon. The nipple pain was triggered upon breastfeeding and exposure to cold. During these episodes, the nipples would initially blanch white, then turn purple and finally a deep red. The patient also experienced an episodic excruciating lancinating pain of the breast that would randomly and spontaneously radiate through either breast several times per day for 15 to 30 seconds. A workup including an antinuclear antibody test, complete blood cell count with differential, and comprehensive metabolic panel all were within reference range.

The patient was diagnosed with nipple vasospasm. Partial relief of nipple pain occurred after treatment with 30 mg daily of nifedipine; 60 mg daily resulted in complete control, allowing the patient to breastfeed without discomfort, but the lancinating pain continued unabated. The patient could not discontinue breastfeeding because her child was intolerant to formula. She became despondent, as she could find no relief from the pain that she found to be intolerable. Because the patient’s description was reminiscent of the lancinating pain seen in postherpetic neuralgia, a trial of pregabalin was prescribed. A dosage of 75 mg twice daily resulted in near-complete resolution of the pain. After 3 months, the patient successfully weaned her child from breast milk to formula, and the nipple and breast pain promptly resolved. The baby experienced no adverse effects from the patient’s use of pregabalin.

This condition was first described by Gunther1 in 1970 as initial blanching of the nipple followed by a mulberry color. It was termed psychosomatic sore nipples.1 Lawlor-Smith and Lawlor-Smith2 described the condition in 1997 and termed it vasospasm of the nipple. They reported 5 patients who experienced debilitating nipple pain as well as the triphasic color change of Raynaud phenomenon or a biphasic color change (white and blue). Two patients had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the digits before their first pregnancy.2 Anderson et al3 presented 12 breastfeeding women with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; only 1 patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon. In this series, all 6 women who chose to try nifedipine responded well to the drug.3

Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple also has been reported to be associated with the use of labetalol.4 In this case, the patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the toes and nipples on cold days. In 2 subsequent pregnancies she was treated with labetalol for pregnancy-induced hypertension, which resulted in severe nipple pain with each pregnancy unrelated to cold weather. Unlike other cases, this patient experienced antenatal symptoms in addition to the typical postnatal symptoms. The nipple pain resolved with discontinuation of the labetalol.4

Barrett et al5 conducted a retrospective review of medical records of 88 breastfeeding mothers who presented with nipple pain and dermatitis. They defined the criteria for Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple as chronic deep breast pain (in general lasting >4 weeks) that responded to therapy for the condition and had at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) observed or self-reported color changes of the nipple, especially with cold exposure (white, blue, or red); (2) cold sensitivity or color changes of the hands or feet with cold exposure; or (3) failed therapy with oral antifungals. Using these criteria, they diagnosed 22 women (25%) with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; 20 (91%) reported a history of cold sensitivity or color change of acral surfaces. Of 12 patients who received and tolerated nifedipine use, 10 (83%) reported decreased pain or complete resolution. This series described breast or nipple pain, whereas other reported cases only described nipple pain. The authors described a sharp, shooting, or stabbing pain—qualifications not previously noted.5 Our patient experienced both nipple pain and a lancinating breast pain consistent with the cases reported by Barrett et al.5

The nipple pain and treatment response in our patient was typical of previously reported cases of vasospasm of the nipple in breastfeeding women; however, Barrett et al5 did not describe individual patients who exhibited the dual nature of the pain described in our patient. The nipple pain experienced during breastfeeding in our patient was successfully treated with nifedipine. We report the successful treatment of the separate lancinating pain with pregabalin.

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon is characterized by vasospasm of arterioles causing intermittent ischemia of the digits. The characteristic triphasic color change presents first as a dramatic change in skin color from normal to white, as the vasoconstriction causes pallor secondary to ischemia. This change is followed by a blue appearance, as cyanosis results from the deoxygenated venous blood. Finally, reflex vasodilation and reperfusion manifest as a red color from erythema. Several cases have been reported describing Raynaud phenomenon affecting the nipples of breastfeeding women.1-5 This vasospasm results in episodic nipple pain manifesting from breastfeeding and exposure to cold. If it is not appropriately treated, the pain’s severity causes affected women to stop breastfeeding. We report a case of vasospasm of the nipple in which the patient experienced nipple pain and a separate lancinating pain that radiated through the breasts.

A 36-year-old woman presented with excruciating nipple and breast pain 3 weeks after delivering her first child. She had no history of smoking or Raynaud phenomenon. The nipple pain was triggered upon breastfeeding and exposure to cold. During these episodes, the nipples would initially blanch white, then turn purple and finally a deep red. The patient also experienced an episodic excruciating lancinating pain of the breast that would randomly and spontaneously radiate through either breast several times per day for 15 to 30 seconds. A workup including an antinuclear antibody test, complete blood cell count with differential, and comprehensive metabolic panel all were within reference range.

The patient was diagnosed with nipple vasospasm. Partial relief of nipple pain occurred after treatment with 30 mg daily of nifedipine; 60 mg daily resulted in complete control, allowing the patient to breastfeed without discomfort, but the lancinating pain continued unabated. The patient could not discontinue breastfeeding because her child was intolerant to formula. She became despondent, as she could find no relief from the pain that she found to be intolerable. Because the patient’s description was reminiscent of the lancinating pain seen in postherpetic neuralgia, a trial of pregabalin was prescribed. A dosage of 75 mg twice daily resulted in near-complete resolution of the pain. After 3 months, the patient successfully weaned her child from breast milk to formula, and the nipple and breast pain promptly resolved. The baby experienced no adverse effects from the patient’s use of pregabalin.

This condition was first described by Gunther1 in 1970 as initial blanching of the nipple followed by a mulberry color. It was termed psychosomatic sore nipples.1 Lawlor-Smith and Lawlor-Smith2 described the condition in 1997 and termed it vasospasm of the nipple. They reported 5 patients who experienced debilitating nipple pain as well as the triphasic color change of Raynaud phenomenon or a biphasic color change (white and blue). Two patients had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the digits before their first pregnancy.2 Anderson et al3 presented 12 breastfeeding women with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; only 1 patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon. In this series, all 6 women who chose to try nifedipine responded well to the drug.3

Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple also has been reported to be associated with the use of labetalol.4 In this case, the patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the toes and nipples on cold days. In 2 subsequent pregnancies she was treated with labetalol for pregnancy-induced hypertension, which resulted in severe nipple pain with each pregnancy unrelated to cold weather. Unlike other cases, this patient experienced antenatal symptoms in addition to the typical postnatal symptoms. The nipple pain resolved with discontinuation of the labetalol.4

Barrett et al5 conducted a retrospective review of medical records of 88 breastfeeding mothers who presented with nipple pain and dermatitis. They defined the criteria for Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple as chronic deep breast pain (in general lasting >4 weeks) that responded to therapy for the condition and had at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) observed or self-reported color changes of the nipple, especially with cold exposure (white, blue, or red); (2) cold sensitivity or color changes of the hands or feet with cold exposure; or (3) failed therapy with oral antifungals. Using these criteria, they diagnosed 22 women (25%) with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; 20 (91%) reported a history of cold sensitivity or color change of acral surfaces. Of 12 patients who received and tolerated nifedipine use, 10 (83%) reported decreased pain or complete resolution. This series described breast or nipple pain, whereas other reported cases only described nipple pain. The authors described a sharp, shooting, or stabbing pain—qualifications not previously noted.5 Our patient experienced both nipple pain and a lancinating breast pain consistent with the cases reported by Barrett et al.5

The nipple pain and treatment response in our patient was typical of previously reported cases of vasospasm of the nipple in breastfeeding women; however, Barrett et al5 did not describe individual patients who exhibited the dual nature of the pain described in our patient. The nipple pain experienced during breastfeeding in our patient was successfully treated with nifedipine. We report the successful treatment of the separate lancinating pain with pregabalin.

- Gunther M. Infant Feeding. London, United Kingdom: Methuen; 1970.

- Lawlor-Smith L, Lawlor-Smith C. Vasospasm of the nipple—a manifestation of Raynaud’s phenomenon: case reports. BMJ. 1997;314:644-645.

- Anderson JE, Held N, Wright K. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple: a treatable cause of painful breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2004;113:360-364.

- McGuinness N, Cording V. Raynaud’s phenomenon of the nipple associated with labetalol use. J Hum Lact. 2013;29:17-19.

- Barrett ME, Heller MM, Stone HF, et al. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple in breastfeeding mothers: an underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:300-306.

- Gunther M. Infant Feeding. London, United Kingdom: Methuen; 1970.

- Lawlor-Smith L, Lawlor-Smith C. Vasospasm of the nipple—a manifestation of Raynaud’s phenomenon: case reports. BMJ. 1997;314:644-645.

- Anderson JE, Held N, Wright K. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple: a treatable cause of painful breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2004;113:360-364.

- McGuinness N, Cording V. Raynaud’s phenomenon of the nipple associated with labetalol use. J Hum Lact. 2013;29:17-19.

- Barrett ME, Heller MM, Stone HF, et al. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple in breastfeeding mothers: an underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:300-306.

Practice Points

- Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple may be accompanied by lancinating pain of the breast in addition to nipple pain reminiscent of postherpetic neuralgia.

- Associated breast pain is particularly distressing for breastfeeding women, particularly primiparous mothers with children intolerant to formula.

- In women with Raynaud phenomenon accompanied by lancinating breast pain, consider a trial of pregabalin.

Radiation Recall Dermatitis Triggered by Prednisone

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

Practice Points

- Consider the diagnosis of radiation recall dermatitis for a skin eruption that occurs in the same location as prior radiation exposure.

- Prednisone may be a trigger for radiation recall dermatitis in patients with sensitization to cross-reactive topical steroids such as tixocortol pivalate.

- Radiation therapy may prime the skin for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines that persist after the conclusion of treatment.

Mycosis Fungoides Manifesting as a Morbilliform Eruption Mimicking a Viral Exanthem

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of primary cutaneous lymphoma, occurring in approximately 4 of 1 million individuals per year in the United States.1 It classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure2; however, MF is known to have variable presentations and has been reported to imitate at least 25 other dermatoses.3 This case describes MF as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

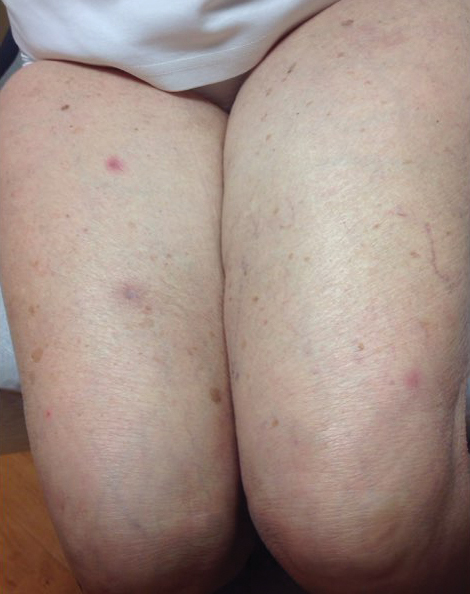

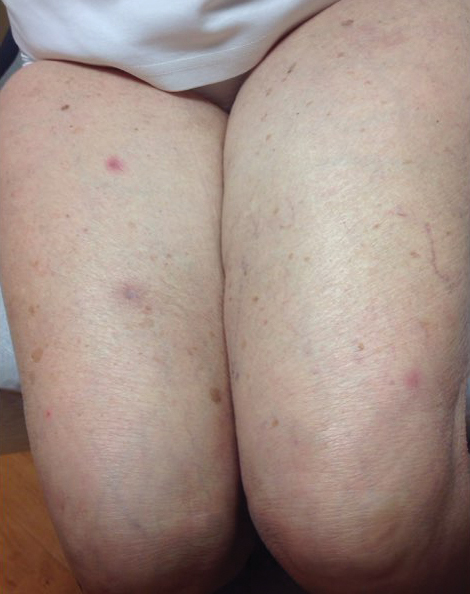

A 30-year-old man with a 12-year history of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) presented with a widespread rash of 2 weeks’ duration. At the time of diagnosis of HL, the patient had several slightly enlarged, hyperdense, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes seen on positron emission tomography–computed tomography. He achieved complete remission 11 years prior after 6 cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin-bleomycin-vinblastine-dacarbazine) chemotherapy. He initially presented to us prior to starting chemotherapy for evaluation of what he described as eczema on the bilateral arms and legs that had been present for 10 years. Findings from a skin biopsy of an erythematous scaling patch on the left lateral thigh were consistent with MF. One year later, new lesions on the left lateral thigh were clinically and histologically consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

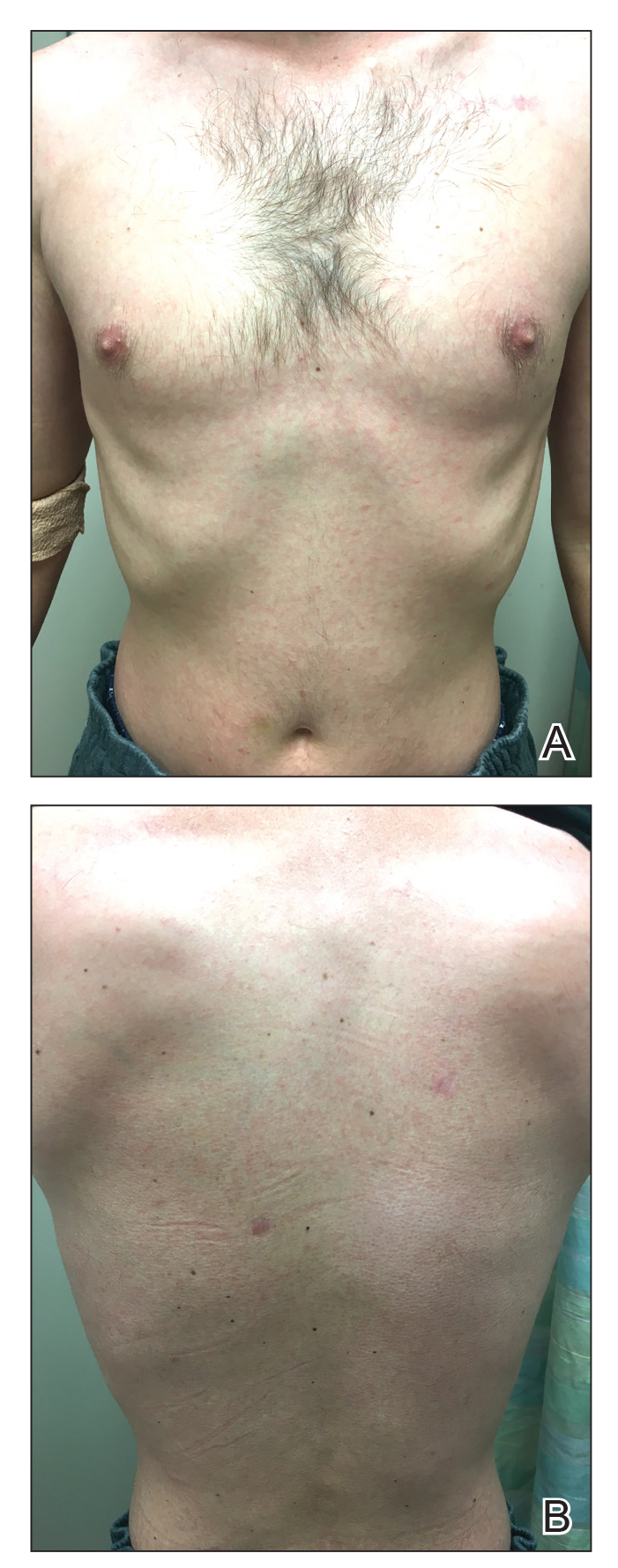

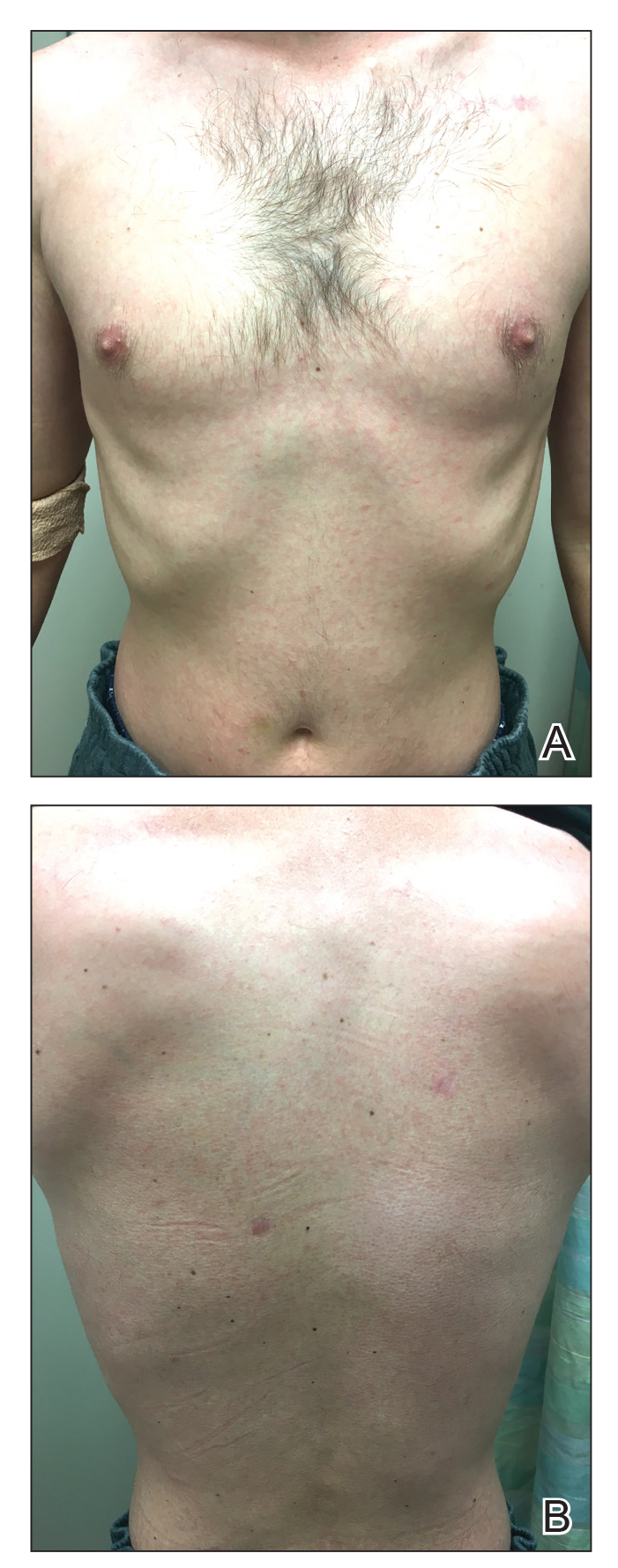

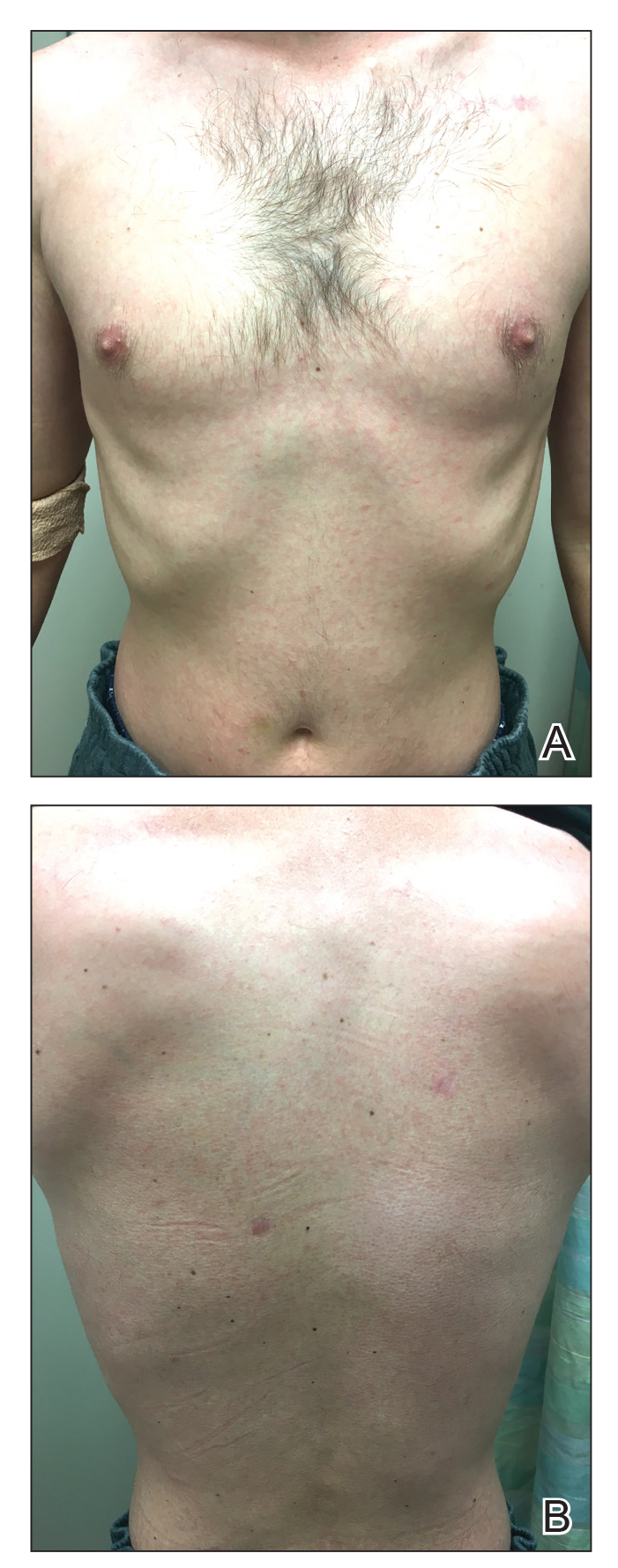

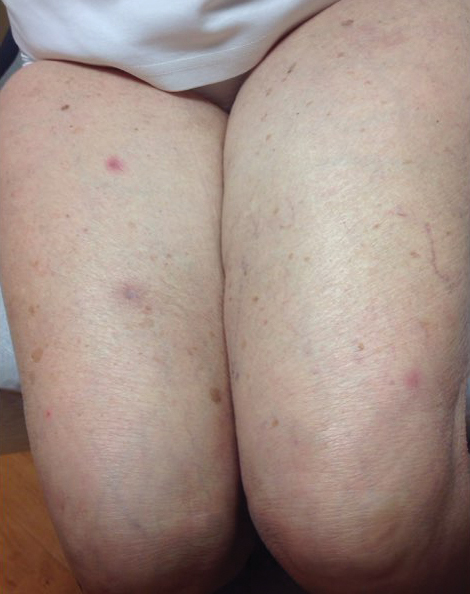

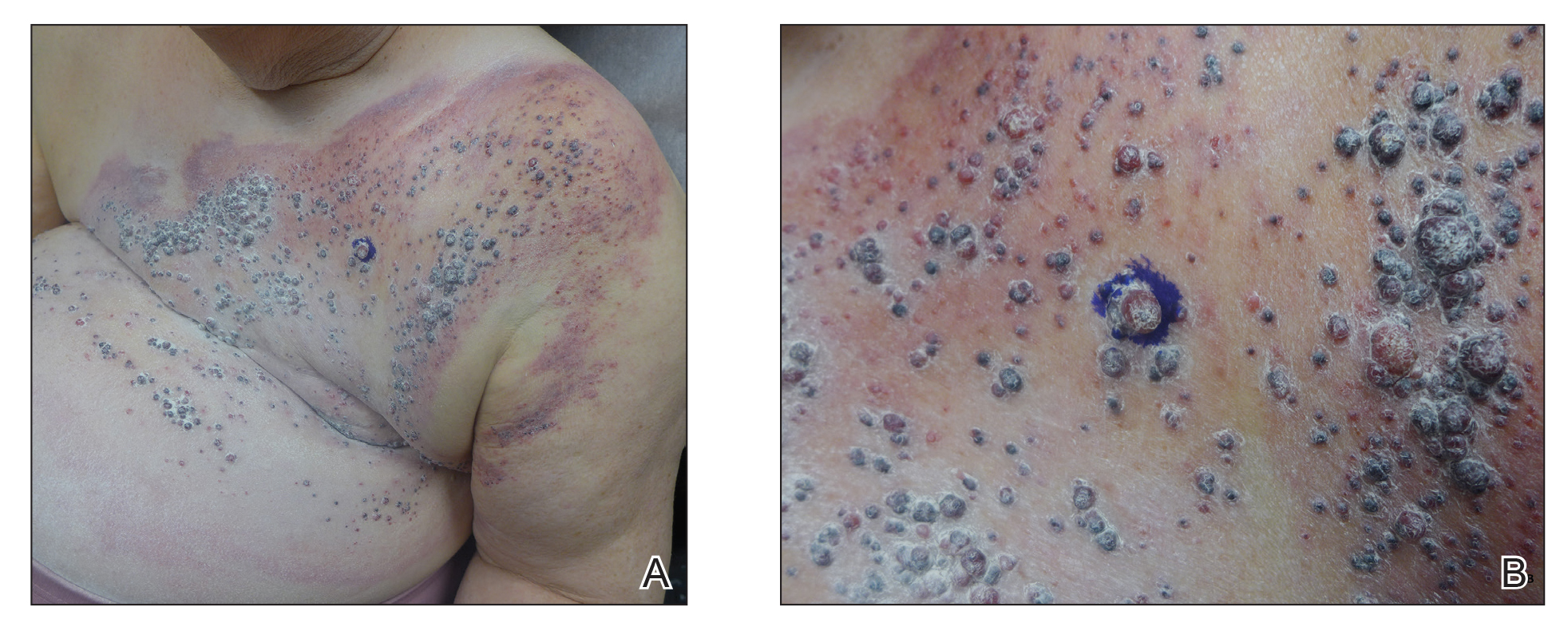

At the current presentation, the patient denied any changes in medications, which consisted of topical clobetasol, triamcinolone, and mupirocin; however, he reported that his young child had recently been diagnosed with bronchitis and impetigo. Physical examination revealed pink-orange macules and papules on the anterior and posterior trunk, medial upper arms, and bilateral legs involving 18% of the body surface area. A complete blood cell count showed no leukocytosis or left shift. A respiratory viral panel was positive for human metapneumovirus. Two weeks later, the patient noted improvement of the rash with use of topical triamcinolone.

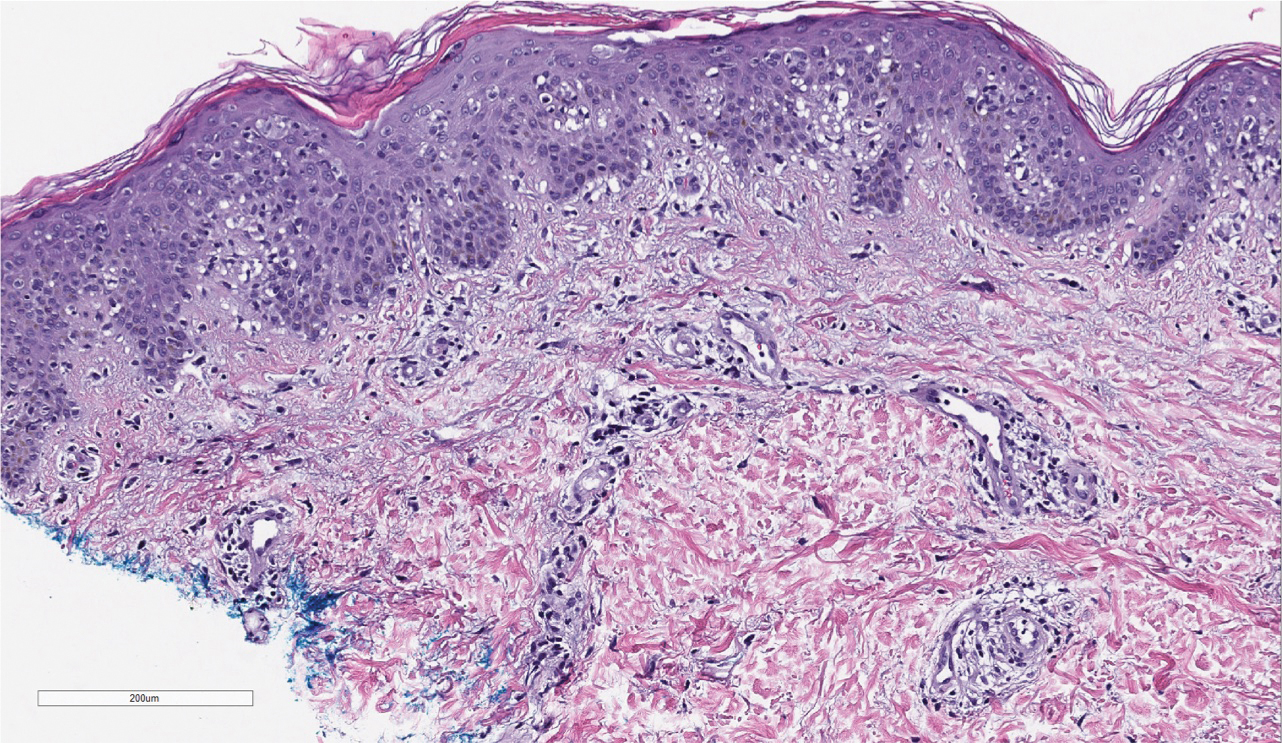

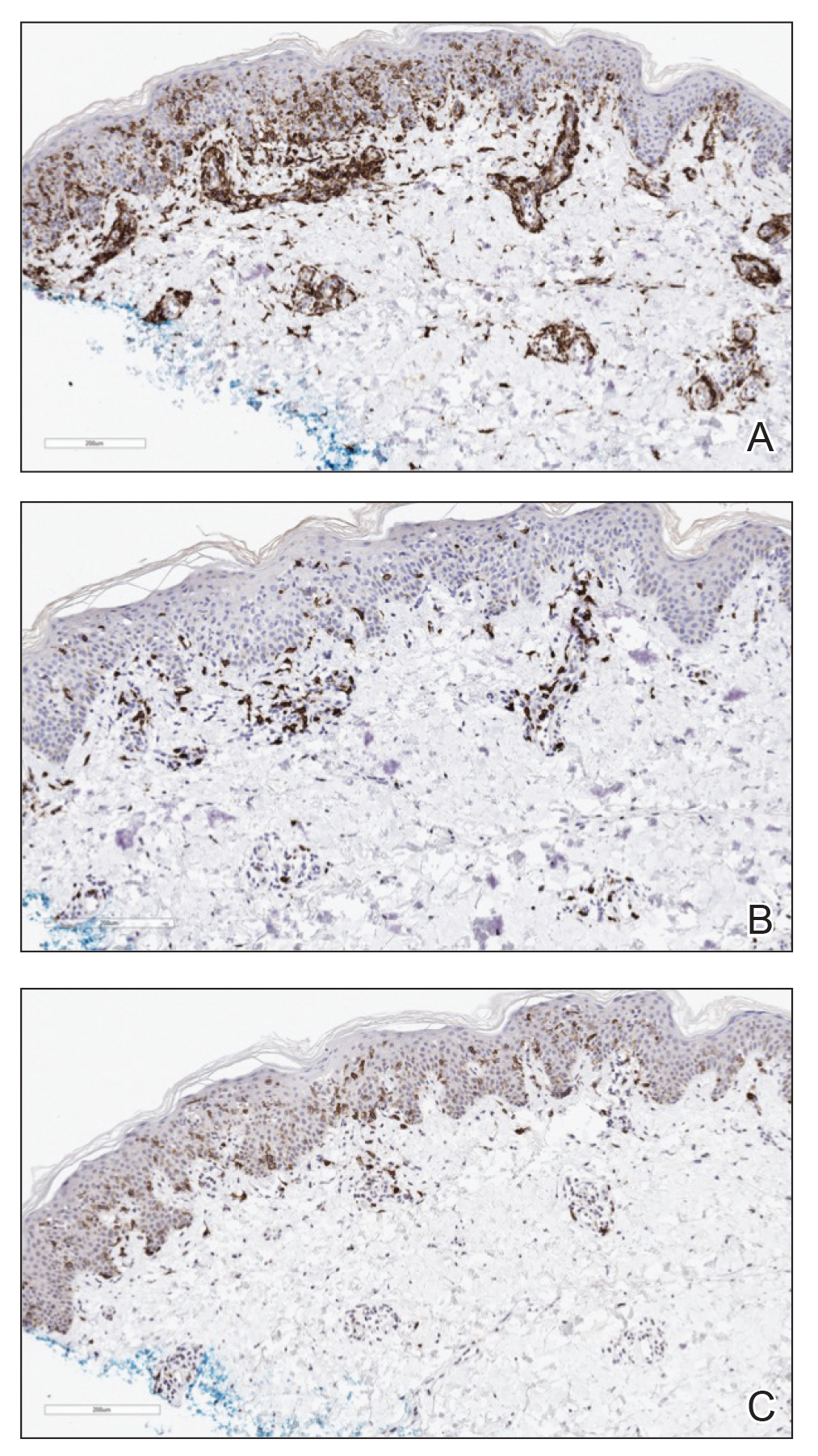

Four months later, the rash still had not completely resolved and now involved 50% of the body surface area. A punch biopsy of the left lower abdomen demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with focal epidermotropism and predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 4:1 ratio), and CD30 labeled rare cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the biopsy revealed monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma chain gene rearrangement. Taken together, the findings were consistent with MF. The patient started narrowband UVB phototherapy and completed a total of 25 treatments, reaching a maximum 4-minute dose, with minimal improvement.

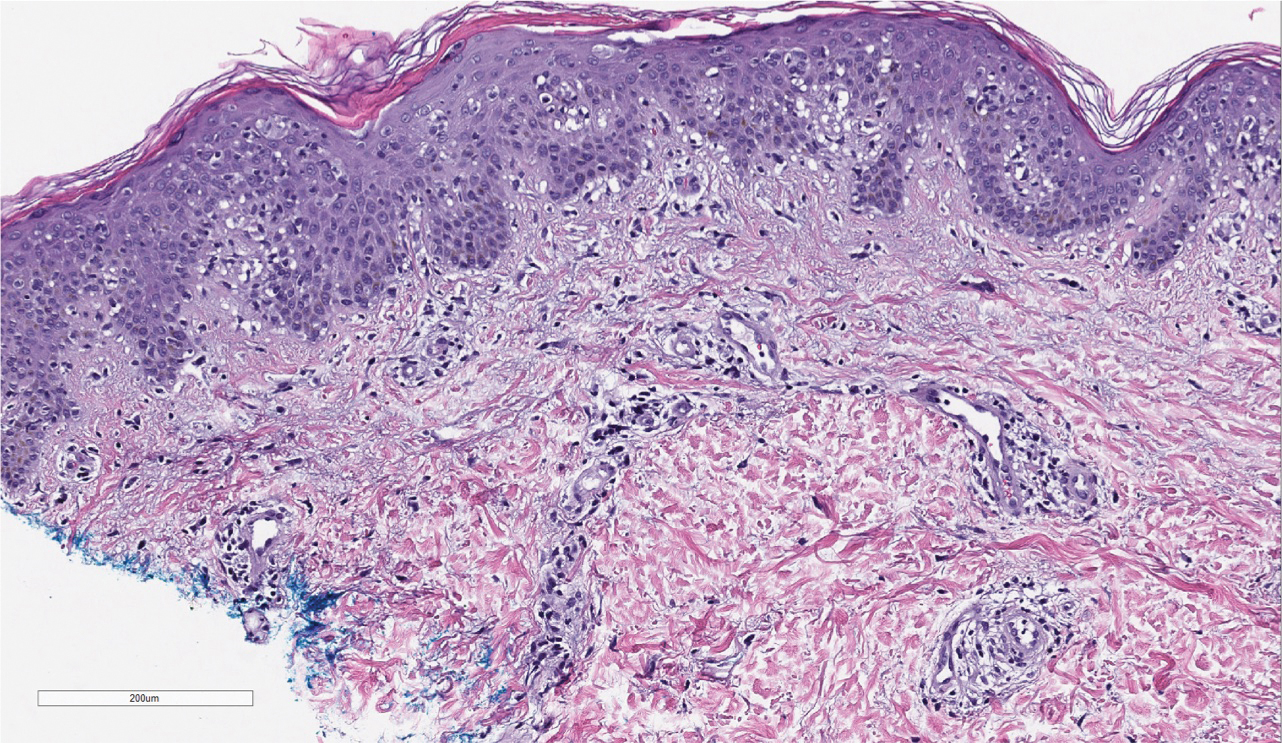

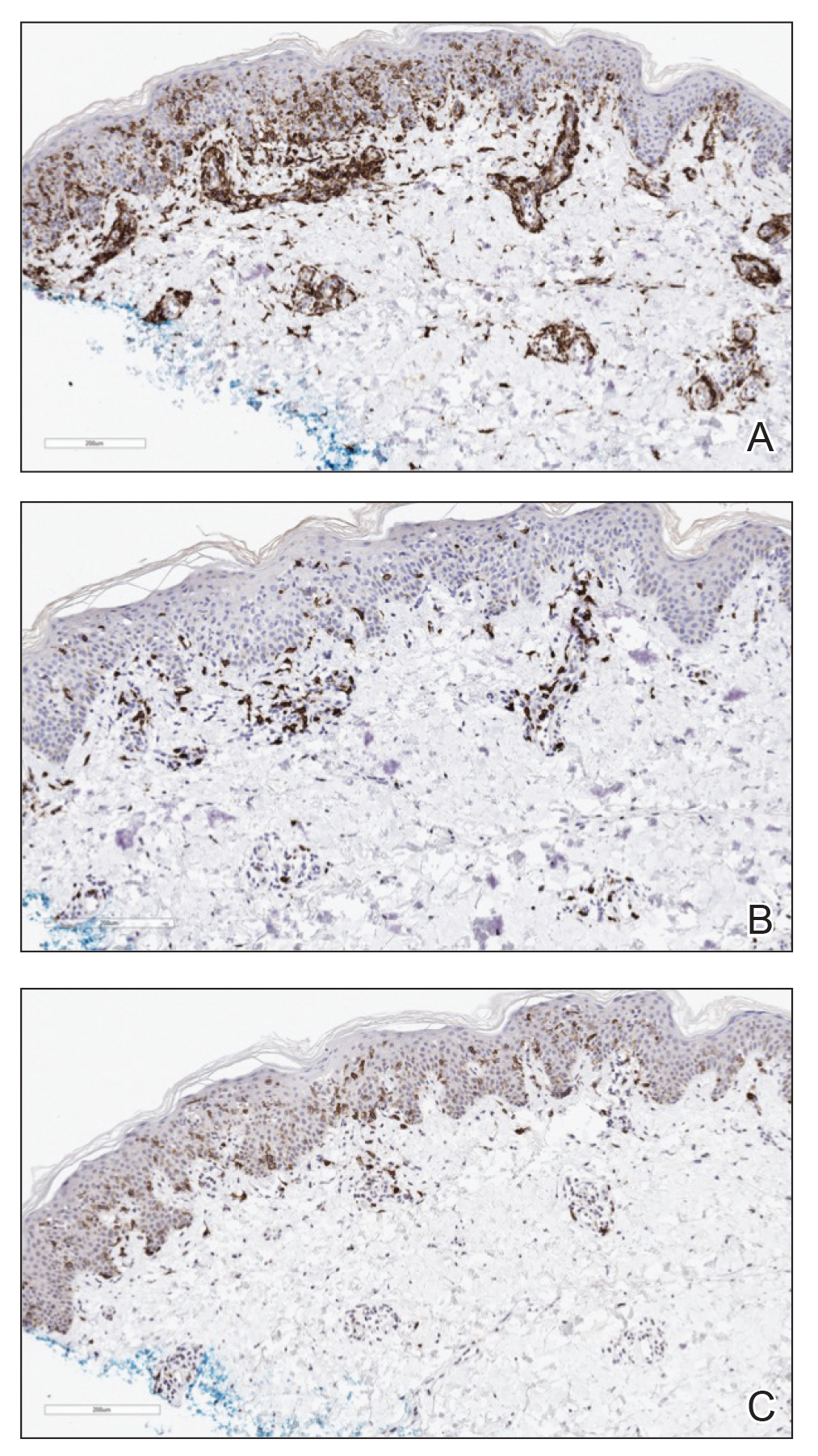

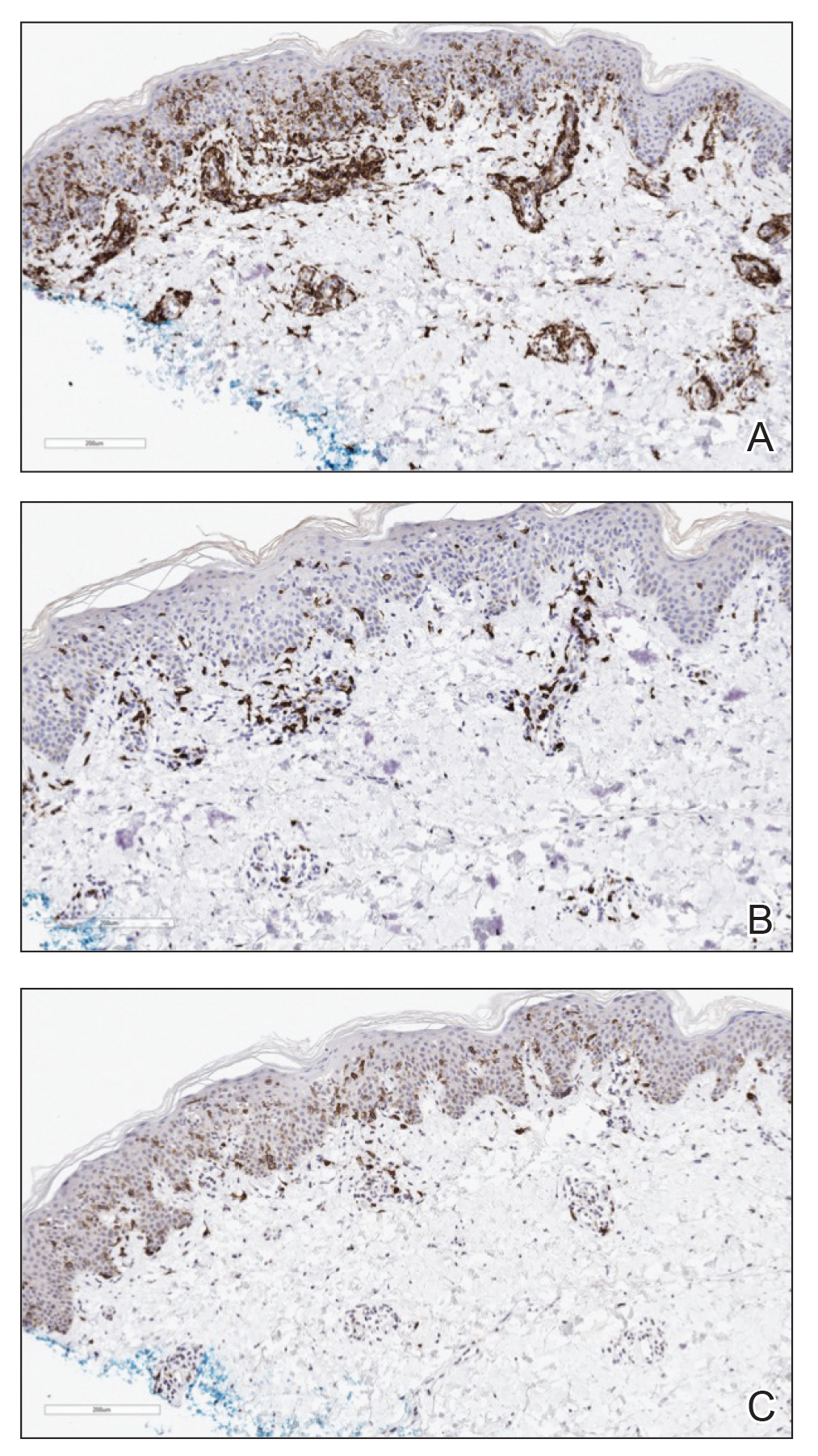

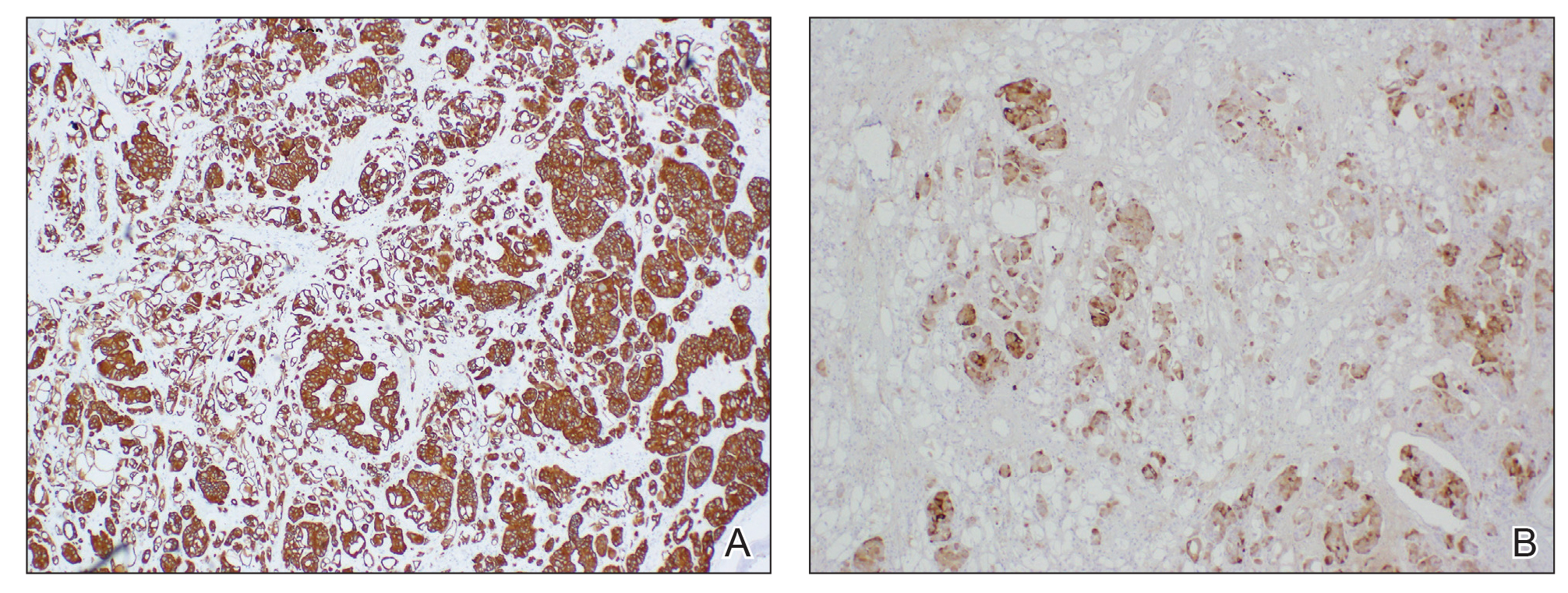

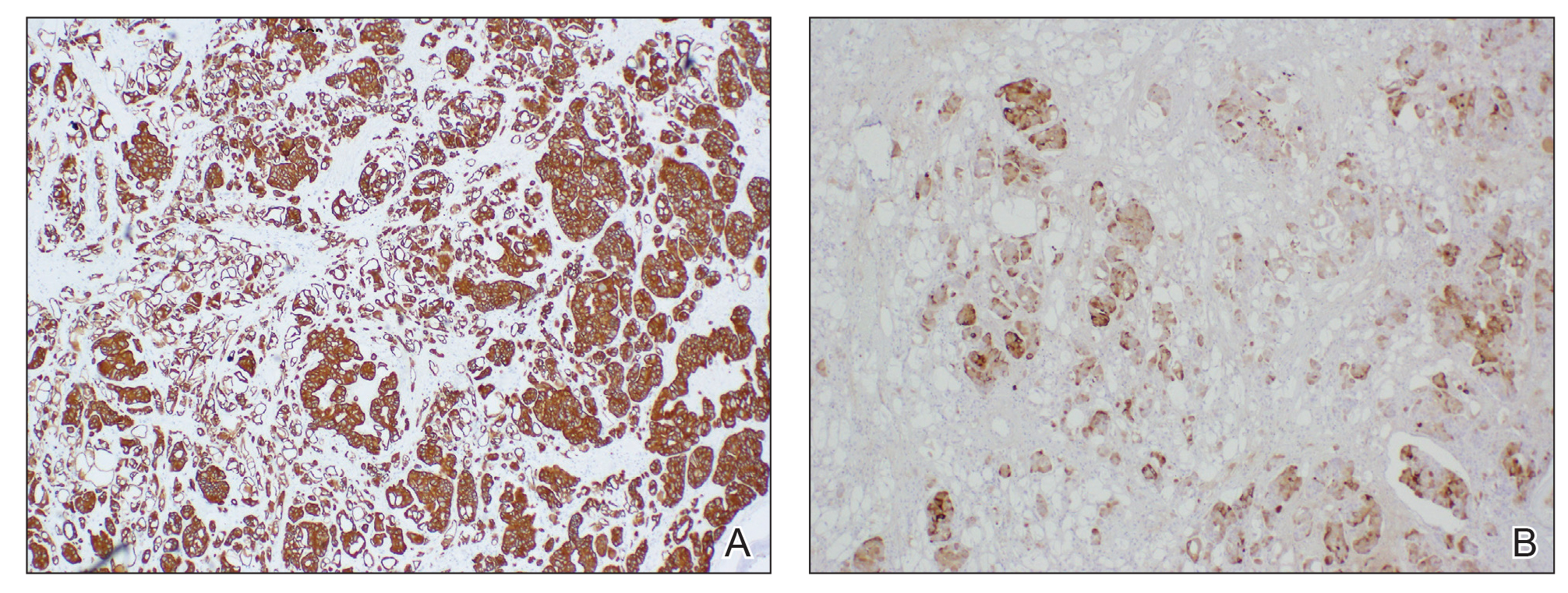

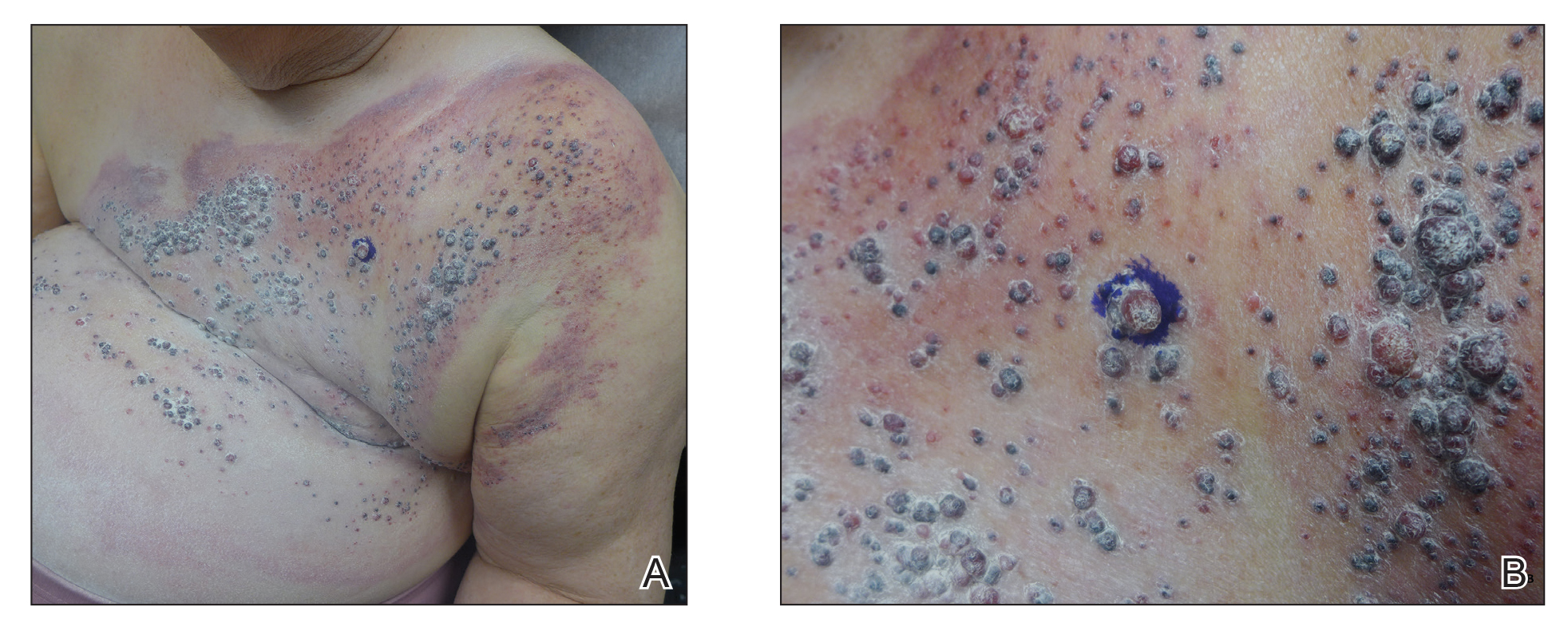

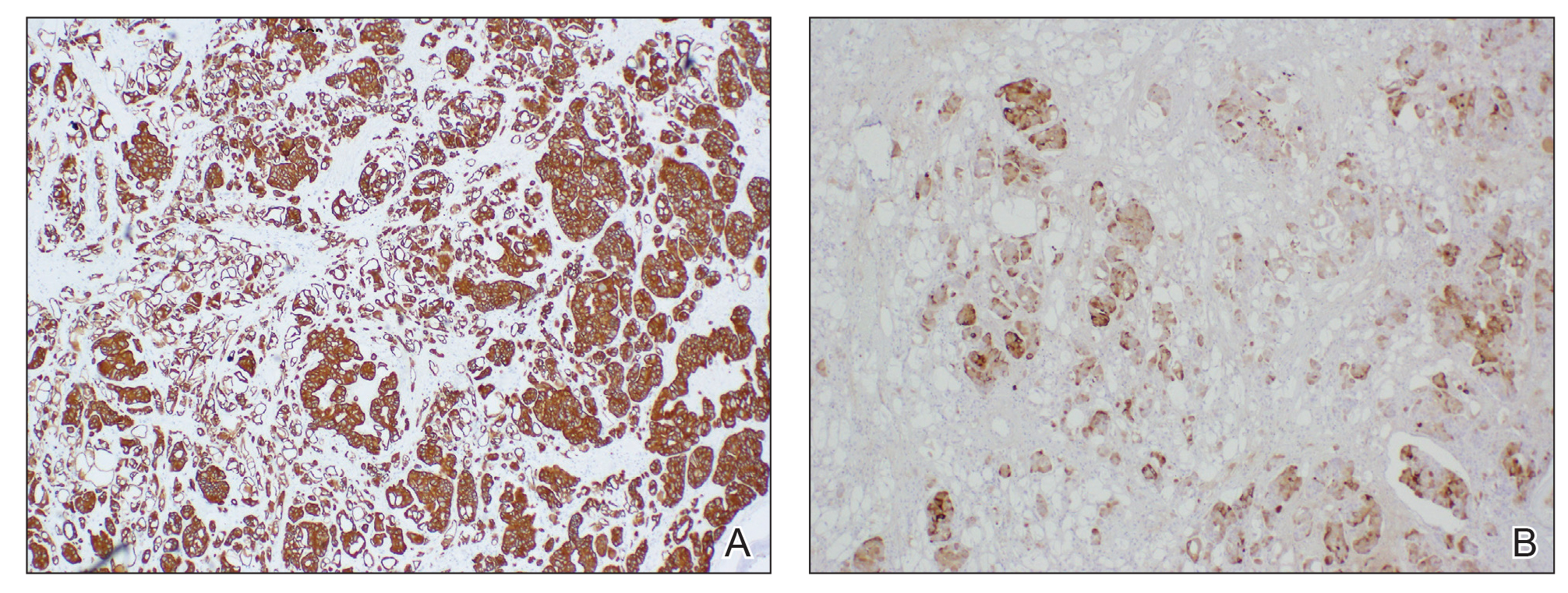

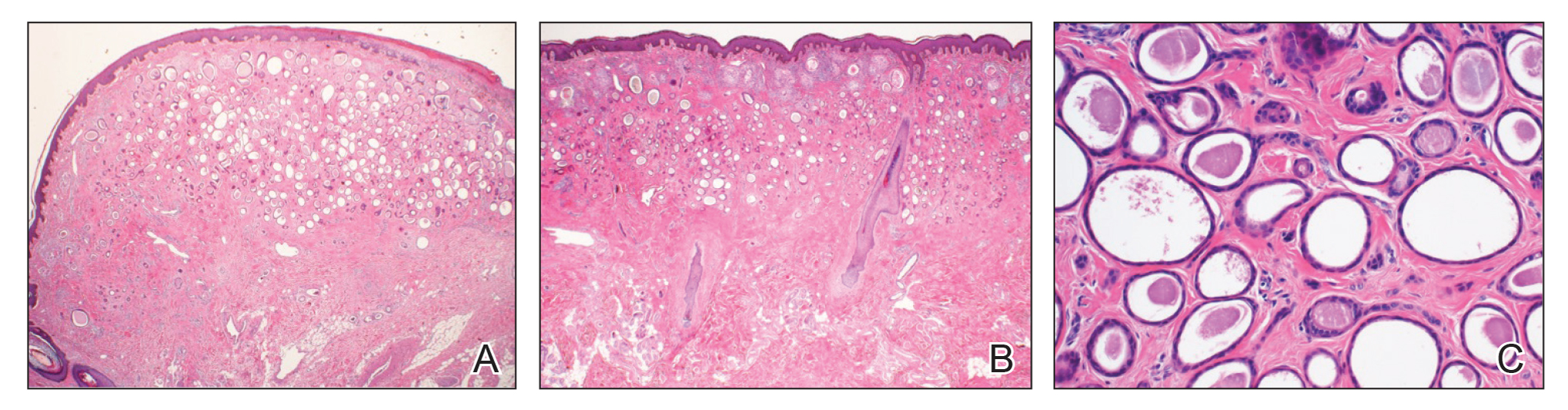

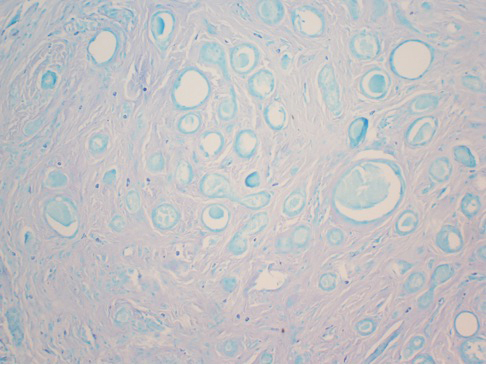

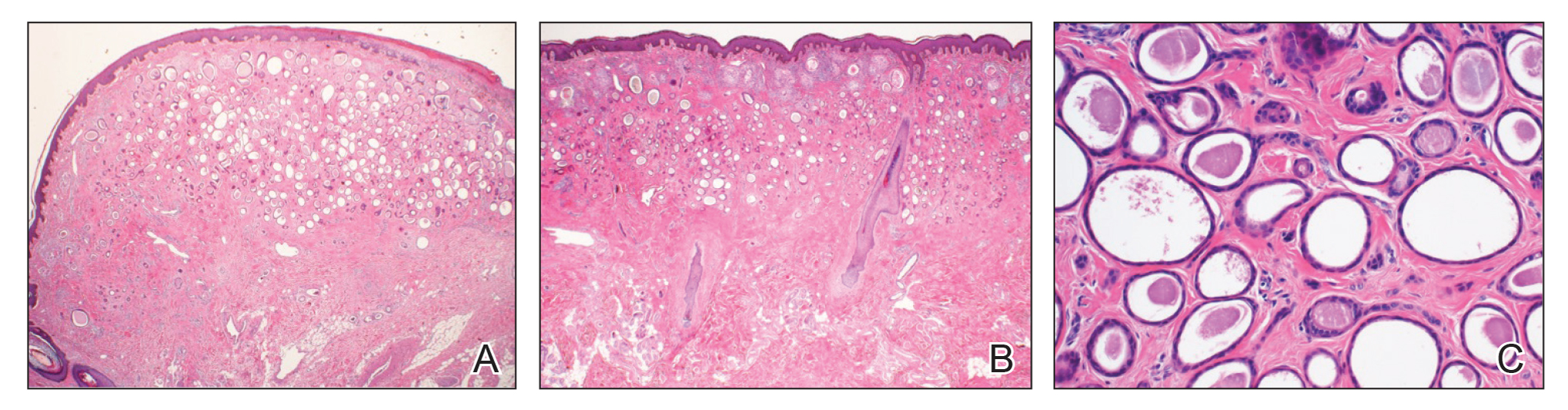

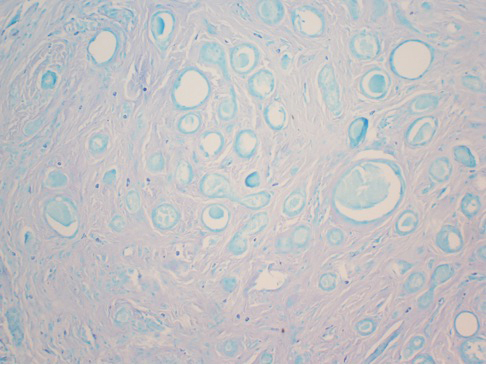

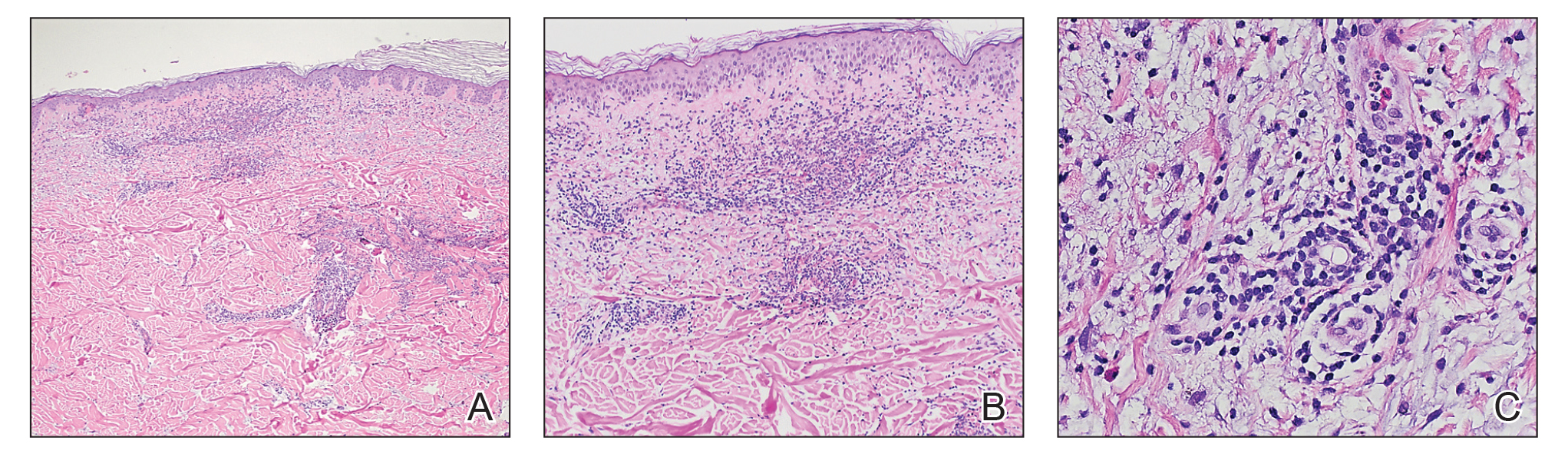

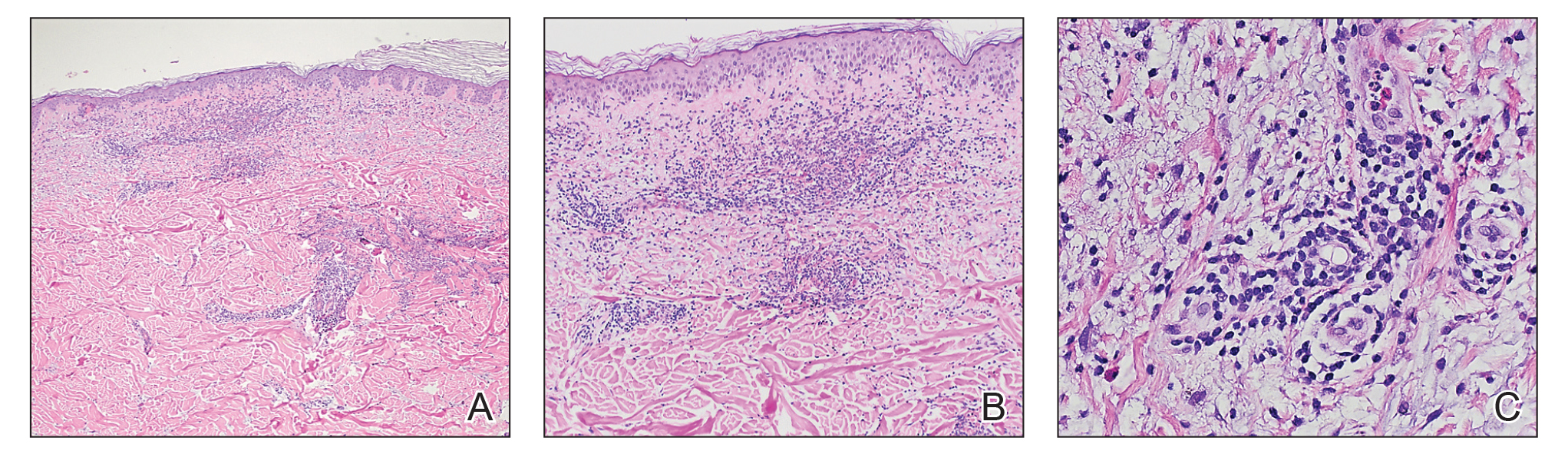

Three months later, the patient had 90% body surface area involvement and started treatment with intramuscular interferon alfa-2b at 1 million units 3 times weekly. He noticed improvement within the first week of treatment and reported that his skin was clear until 5 months later when he woke up one morning with a morbilliform eruption on the anterior trunk, thighs, and upper arms (Figure 1). Biopsy from the right thigh showed an infiltrate of CD3+ lymphocytes with a predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 6:1 ratio), both in the dermis and epidermis (Figure 2). CD30 highlighted approximately 10% of cells (Figure 3). Findings again were consistent with MF. Flow cytometry was negative for peripheral blood involvement.

Three months later, the patient reported enlargement of several left inguinal nodes. Fine needle aspiration of 1 node demonstrated an atypical lymphoid proliferation consistent with MF. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed several mildly enlarged inguinal lymph nodes, which were unchanged from the initial diagnosis of HL. There were no hypermetabolic lesions. One month later, the patient started extracorporeal electrophoresis in addition to interferon alfa-2b with notable improvement of the rash. The rash later recurred after completion of these treatments and continues to have a waxing and waning course. It is currently managed with triamcinolone cream only.

At the time of the initial diagnosis of MF, the patient’s lesions appeared as eczematous patches on the face, abdomen, buttocks, and legs. Based on the history of a sick child at home, viral panel positive for human metapneumovirus, and clinical appearance, a viral exanthem was considered to be a likely explanation for the patient’s new-onset morbilliform eruption rash occurring 12 years later. A drug reaction also was considered in the differential based on the appearance of the rash; however, it was deemed less likely because the patient reported no changes in his medications at the time of rash onset. Persistence of the eruption for many months was less consistent with a reactive condition. A biopsy demonstrated the rash to be histologically consistent with MF. This patient was a rare case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

Various inflammatory conditions, including drug eruptions and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, may mimic MF, not only based on their histophenotypic findings but also occasionally clonal proliferation by molecular study.4,5 In our patient, one consideration was the possibility of a viral infection mimicking MF; however, biopsies showed both definite histophenotypic features of MF and clonality. More importantly, subsequent biopsy also revealed similar findings by morphology, immunohistochemical study, and T-cell gene rearrangement study, confirming the diagnosis of MF.

Another interesting feature of our case was the occurrence of HL, LyP, and MF in the same patient. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic condition characterized by self-healing lesions and histologic features suggestive of malignancy that lies within a spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. There is a known association between LyP and an increased incidence of lymphomas, including MF and HL.1 In a 2016 study, lymphomas occurred in 52% of patients with LyP (N=180), with MF being the most frequently associated lymphoma.6 Notably, biopsies consistent with both HL and MF, respectively, in our patient were positive for the CD30 marker. Patients with HL also are at increased risk for developing other malignancies, with the risk of leukemias and non-HLs greater than that of solid tumors.5 There have been multiple reported cases of HL and MF occurring in the same patient and at least one prior reported case of LyP, HL, and MF occurring in the same patient.6,7

This case highlights the myriad presentations of MF and describes an unusual case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

- de la Garza Bravo MM, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin [published online December 31, 2014]. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

- Howard MS, Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: classic disease and variant presentations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:91-99.

- Zackheim HS, Mccalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

- Suchak R, Verdolini R, Robson A, et al. Extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus mimicking cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:982-986.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma: report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:536-551.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Sont JK, van Stiphout WA, Noordijk EM, et al. Increased risk of second cancers in managing Hodgkins disease: the 20-year Leiden experience. Ann Hematol. 1992;65:213-218.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of primary cutaneous lymphoma, occurring in approximately 4 of 1 million individuals per year in the United States.1 It classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure2; however, MF is known to have variable presentations and has been reported to imitate at least 25 other dermatoses.3 This case describes MF as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

A 30-year-old man with a 12-year history of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) presented with a widespread rash of 2 weeks’ duration. At the time of diagnosis of HL, the patient had several slightly enlarged, hyperdense, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes seen on positron emission tomography–computed tomography. He achieved complete remission 11 years prior after 6 cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin-bleomycin-vinblastine-dacarbazine) chemotherapy. He initially presented to us prior to starting chemotherapy for evaluation of what he described as eczema on the bilateral arms and legs that had been present for 10 years. Findings from a skin biopsy of an erythematous scaling patch on the left lateral thigh were consistent with MF. One year later, new lesions on the left lateral thigh were clinically and histologically consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

At the current presentation, the patient denied any changes in medications, which consisted of topical clobetasol, triamcinolone, and mupirocin; however, he reported that his young child had recently been diagnosed with bronchitis and impetigo. Physical examination revealed pink-orange macules and papules on the anterior and posterior trunk, medial upper arms, and bilateral legs involving 18% of the body surface area. A complete blood cell count showed no leukocytosis or left shift. A respiratory viral panel was positive for human metapneumovirus. Two weeks later, the patient noted improvement of the rash with use of topical triamcinolone.

Four months later, the rash still had not completely resolved and now involved 50% of the body surface area. A punch biopsy of the left lower abdomen demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with focal epidermotropism and predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 4:1 ratio), and CD30 labeled rare cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the biopsy revealed monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma chain gene rearrangement. Taken together, the findings were consistent with MF. The patient started narrowband UVB phototherapy and completed a total of 25 treatments, reaching a maximum 4-minute dose, with minimal improvement.

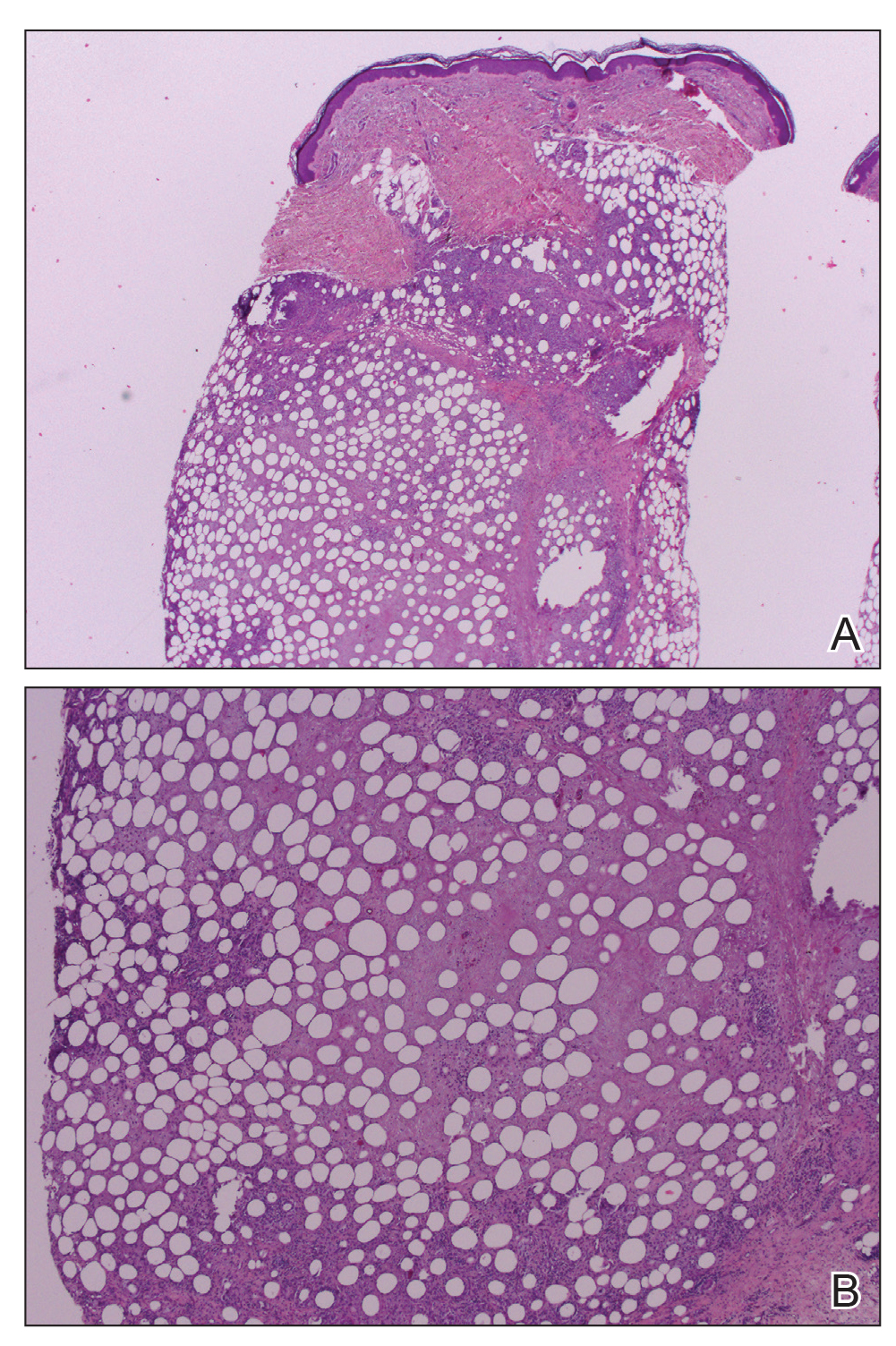

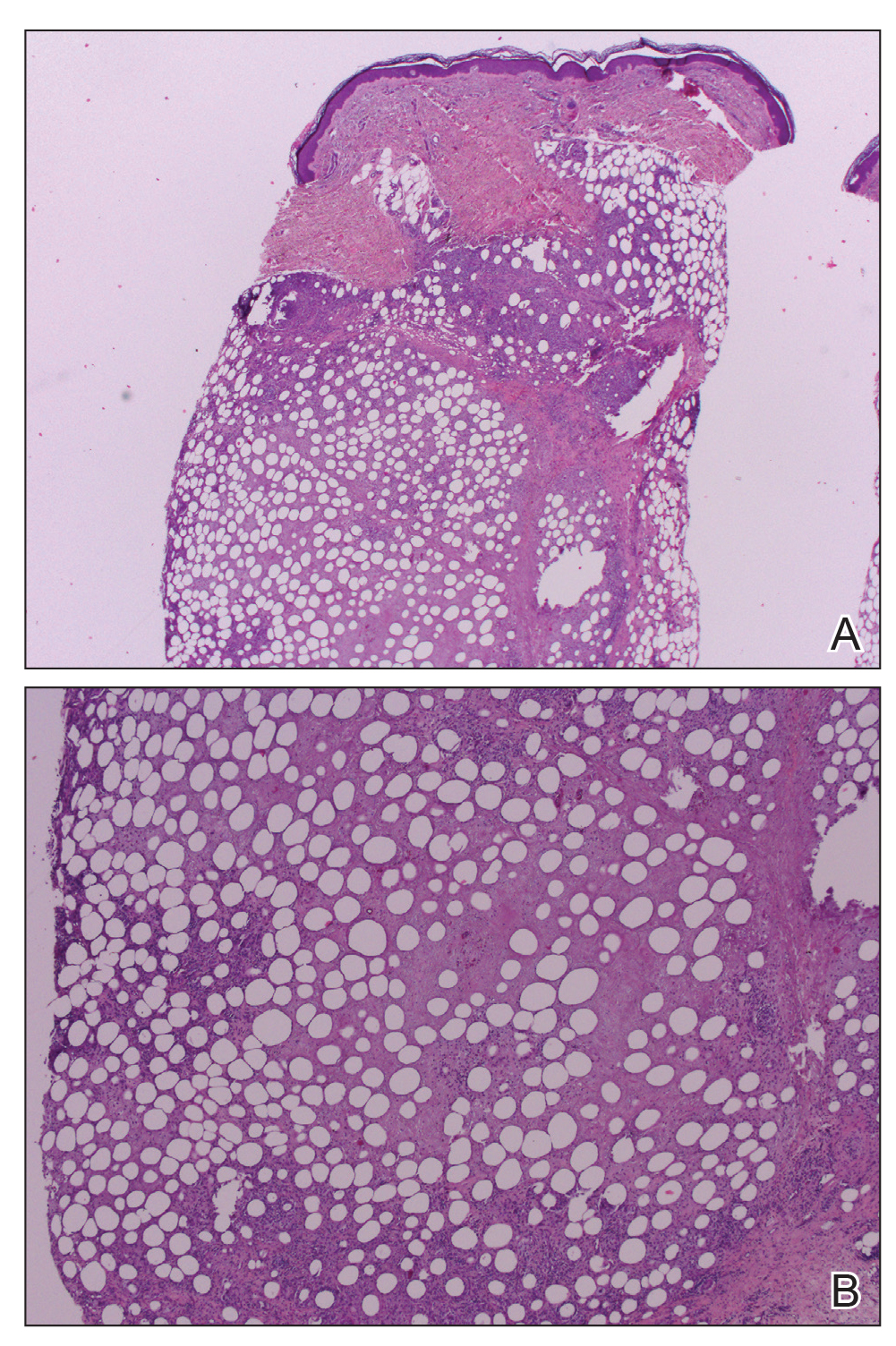

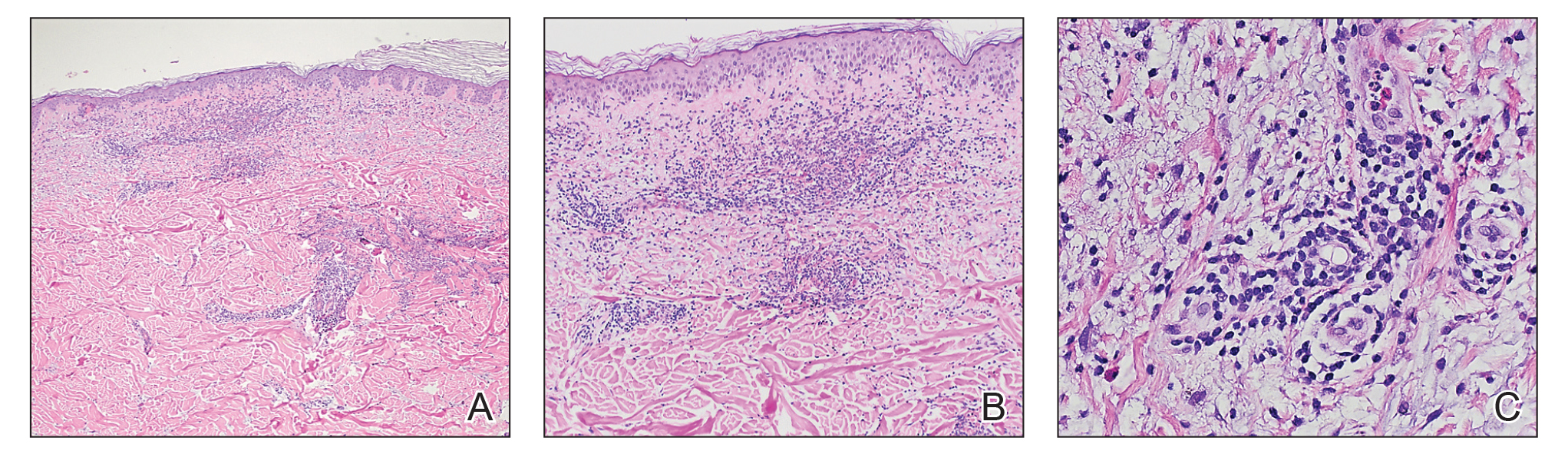

Three months later, the patient had 90% body surface area involvement and started treatment with intramuscular interferon alfa-2b at 1 million units 3 times weekly. He noticed improvement within the first week of treatment and reported that his skin was clear until 5 months later when he woke up one morning with a morbilliform eruption on the anterior trunk, thighs, and upper arms (Figure 1). Biopsy from the right thigh showed an infiltrate of CD3+ lymphocytes with a predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 6:1 ratio), both in the dermis and epidermis (Figure 2). CD30 highlighted approximately 10% of cells (Figure 3). Findings again were consistent with MF. Flow cytometry was negative for peripheral blood involvement.

Three months later, the patient reported enlargement of several left inguinal nodes. Fine needle aspiration of 1 node demonstrated an atypical lymphoid proliferation consistent with MF. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed several mildly enlarged inguinal lymph nodes, which were unchanged from the initial diagnosis of HL. There were no hypermetabolic lesions. One month later, the patient started extracorporeal electrophoresis in addition to interferon alfa-2b with notable improvement of the rash. The rash later recurred after completion of these treatments and continues to have a waxing and waning course. It is currently managed with triamcinolone cream only.

At the time of the initial diagnosis of MF, the patient’s lesions appeared as eczematous patches on the face, abdomen, buttocks, and legs. Based on the history of a sick child at home, viral panel positive for human metapneumovirus, and clinical appearance, a viral exanthem was considered to be a likely explanation for the patient’s new-onset morbilliform eruption rash occurring 12 years later. A drug reaction also was considered in the differential based on the appearance of the rash; however, it was deemed less likely because the patient reported no changes in his medications at the time of rash onset. Persistence of the eruption for many months was less consistent with a reactive condition. A biopsy demonstrated the rash to be histologically consistent with MF. This patient was a rare case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

Various inflammatory conditions, including drug eruptions and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, may mimic MF, not only based on their histophenotypic findings but also occasionally clonal proliferation by molecular study.4,5 In our patient, one consideration was the possibility of a viral infection mimicking MF; however, biopsies showed both definite histophenotypic features of MF and clonality. More importantly, subsequent biopsy also revealed similar findings by morphology, immunohistochemical study, and T-cell gene rearrangement study, confirming the diagnosis of MF.

Another interesting feature of our case was the occurrence of HL, LyP, and MF in the same patient. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic condition characterized by self-healing lesions and histologic features suggestive of malignancy that lies within a spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. There is a known association between LyP and an increased incidence of lymphomas, including MF and HL.1 In a 2016 study, lymphomas occurred in 52% of patients with LyP (N=180), with MF being the most frequently associated lymphoma.6 Notably, biopsies consistent with both HL and MF, respectively, in our patient were positive for the CD30 marker. Patients with HL also are at increased risk for developing other malignancies, with the risk of leukemias and non-HLs greater than that of solid tumors.5 There have been multiple reported cases of HL and MF occurring in the same patient and at least one prior reported case of LyP, HL, and MF occurring in the same patient.6,7

This case highlights the myriad presentations of MF and describes an unusual case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of primary cutaneous lymphoma, occurring in approximately 4 of 1 million individuals per year in the United States.1 It classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure2; however, MF is known to have variable presentations and has been reported to imitate at least 25 other dermatoses.3 This case describes MF as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

A 30-year-old man with a 12-year history of nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) presented with a widespread rash of 2 weeks’ duration. At the time of diagnosis of HL, the patient had several slightly enlarged, hyperdense, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes seen on positron emission tomography–computed tomography. He achieved complete remission 11 years prior after 6 cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin-bleomycin-vinblastine-dacarbazine) chemotherapy. He initially presented to us prior to starting chemotherapy for evaluation of what he described as eczema on the bilateral arms and legs that had been present for 10 years. Findings from a skin biopsy of an erythematous scaling patch on the left lateral thigh were consistent with MF. One year later, new lesions on the left lateral thigh were clinically and histologically consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

At the current presentation, the patient denied any changes in medications, which consisted of topical clobetasol, triamcinolone, and mupirocin; however, he reported that his young child had recently been diagnosed with bronchitis and impetigo. Physical examination revealed pink-orange macules and papules on the anterior and posterior trunk, medial upper arms, and bilateral legs involving 18% of the body surface area. A complete blood cell count showed no leukocytosis or left shift. A respiratory viral panel was positive for human metapneumovirus. Two weeks later, the patient noted improvement of the rash with use of topical triamcinolone.

Four months later, the rash still had not completely resolved and now involved 50% of the body surface area. A punch biopsy of the left lower abdomen demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with focal epidermotropism and predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 4:1 ratio), and CD30 labeled rare cells. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the biopsy revealed monoclonal T-cell receptor gamma chain gene rearrangement. Taken together, the findings were consistent with MF. The patient started narrowband UVB phototherapy and completed a total of 25 treatments, reaching a maximum 4-minute dose, with minimal improvement.

Three months later, the patient had 90% body surface area involvement and started treatment with intramuscular interferon alfa-2b at 1 million units 3 times weekly. He noticed improvement within the first week of treatment and reported that his skin was clear until 5 months later when he woke up one morning with a morbilliform eruption on the anterior trunk, thighs, and upper arms (Figure 1). Biopsy from the right thigh showed an infiltrate of CD3+ lymphocytes with a predominance of CD4 over CD8 cells (approximately 6:1 ratio), both in the dermis and epidermis (Figure 2). CD30 highlighted approximately 10% of cells (Figure 3). Findings again were consistent with MF. Flow cytometry was negative for peripheral blood involvement.

Three months later, the patient reported enlargement of several left inguinal nodes. Fine needle aspiration of 1 node demonstrated an atypical lymphoid proliferation consistent with MF. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed several mildly enlarged inguinal lymph nodes, which were unchanged from the initial diagnosis of HL. There were no hypermetabolic lesions. One month later, the patient started extracorporeal electrophoresis in addition to interferon alfa-2b with notable improvement of the rash. The rash later recurred after completion of these treatments and continues to have a waxing and waning course. It is currently managed with triamcinolone cream only.

At the time of the initial diagnosis of MF, the patient’s lesions appeared as eczematous patches on the face, abdomen, buttocks, and legs. Based on the history of a sick child at home, viral panel positive for human metapneumovirus, and clinical appearance, a viral exanthem was considered to be a likely explanation for the patient’s new-onset morbilliform eruption rash occurring 12 years later. A drug reaction also was considered in the differential based on the appearance of the rash; however, it was deemed less likely because the patient reported no changes in his medications at the time of rash onset. Persistence of the eruption for many months was less consistent with a reactive condition. A biopsy demonstrated the rash to be histologically consistent with MF. This patient was a rare case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

Various inflammatory conditions, including drug eruptions and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, may mimic MF, not only based on their histophenotypic findings but also occasionally clonal proliferation by molecular study.4,5 In our patient, one consideration was the possibility of a viral infection mimicking MF; however, biopsies showed both definite histophenotypic features of MF and clonality. More importantly, subsequent biopsy also revealed similar findings by morphology, immunohistochemical study, and T-cell gene rearrangement study, confirming the diagnosis of MF.

Another interesting feature of our case was the occurrence of HL, LyP, and MF in the same patient. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic condition characterized by self-healing lesions and histologic features suggestive of malignancy that lies within a spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. There is a known association between LyP and an increased incidence of lymphomas, including MF and HL.1 In a 2016 study, lymphomas occurred in 52% of patients with LyP (N=180), with MF being the most frequently associated lymphoma.6 Notably, biopsies consistent with both HL and MF, respectively, in our patient were positive for the CD30 marker. Patients with HL also are at increased risk for developing other malignancies, with the risk of leukemias and non-HLs greater than that of solid tumors.5 There have been multiple reported cases of HL and MF occurring in the same patient and at least one prior reported case of LyP, HL, and MF occurring in the same patient.6,7

This case highlights the myriad presentations of MF and describes an unusual case of MF manifesting as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.

- de la Garza Bravo MM, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin [published online December 31, 2014]. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

- Howard MS, Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: classic disease and variant presentations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:91-99.

- Zackheim HS, Mccalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

- Suchak R, Verdolini R, Robson A, et al. Extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus mimicking cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:982-986.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma: report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:536-551.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Sont JK, van Stiphout WA, Noordijk EM, et al. Increased risk of second cancers in managing Hodgkins disease: the 20-year Leiden experience. Ann Hematol. 1992;65:213-218.

- de la Garza Bravo MM, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin [published online December 31, 2014]. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

- Howard MS, Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: classic disease and variant presentations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:91-99.

- Zackheim HS, Mccalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:914-918.

- Suchak R, Verdolini R, Robson A, et al. Extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus mimicking cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:982-986.

- Sarantopoulos GP, Palla B, Said J, et al. Mimics of cutaneous lymphoma: report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:536-551.

- Wieser I, Oh CW, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Sont JK, van Stiphout WA, Noordijk EM, et al. Increased risk of second cancers in managing Hodgkins disease: the 20-year Leiden experience. Ann Hematol. 1992;65:213-218.

Practice Points

- Mycosis fungoides classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages, with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure; however, the condition may present atypically, mimicking a variety of other conditions.

- Lymphomatoid papulosis exists within a spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and is associated with increased incidence of lymphomas.

Disseminated Erythema Induratum in a Patient With a History of Tuberculosis

To the Editor:

Erythema induratum, also known as nodular vasculitis, is a panniculitis that usually affects the lower extremities in middle-aged women. Classically, it has been described as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as a tuberculid.1,2 Other infections, however, also have been implicated as causes of erythema induratum, including bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which commonly is used for tuberculosis vaccination. Medications also may cause erythema induratum. The characteristic distribution of the nodules on the posterior calves helps to distinguish erythema induratum from other panniculitides. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term disseminated erythema induratum revealed few case reports documenting nodules on the arms, thighs, or chest, and only 1 case report of disseminated erythema induratum.3-8 We describe a rare combination of disseminated erythema induratum in a patient with remote exposure to tuberculosis and recent BCG exposure.

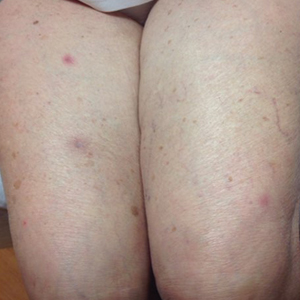

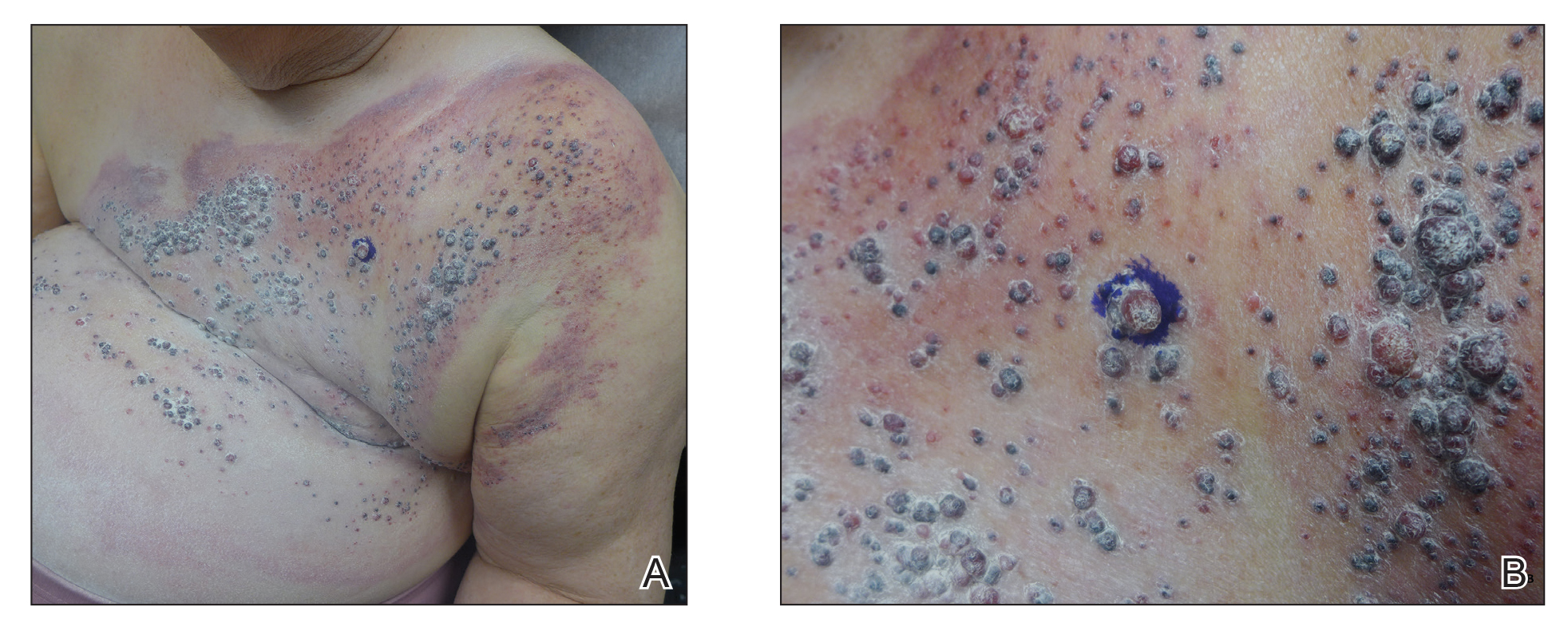

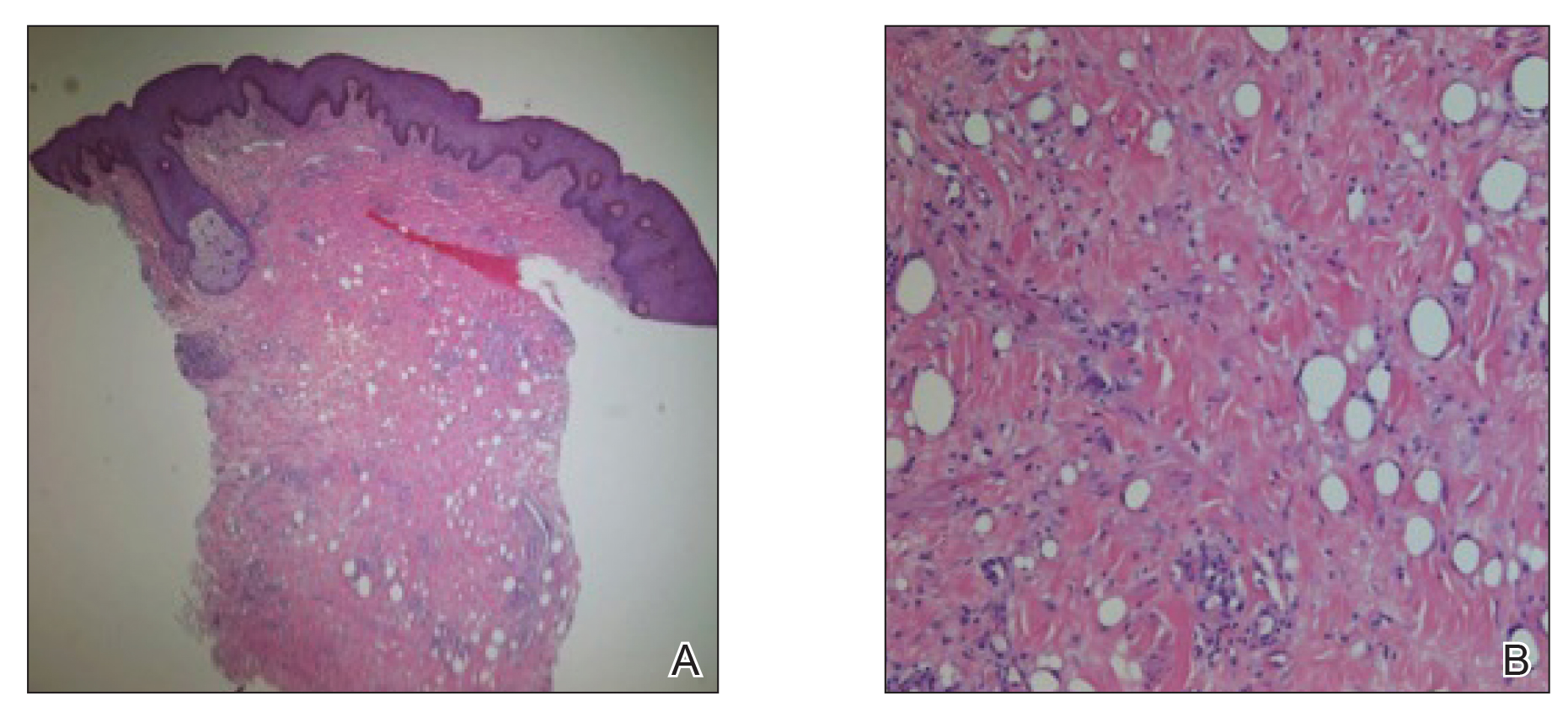

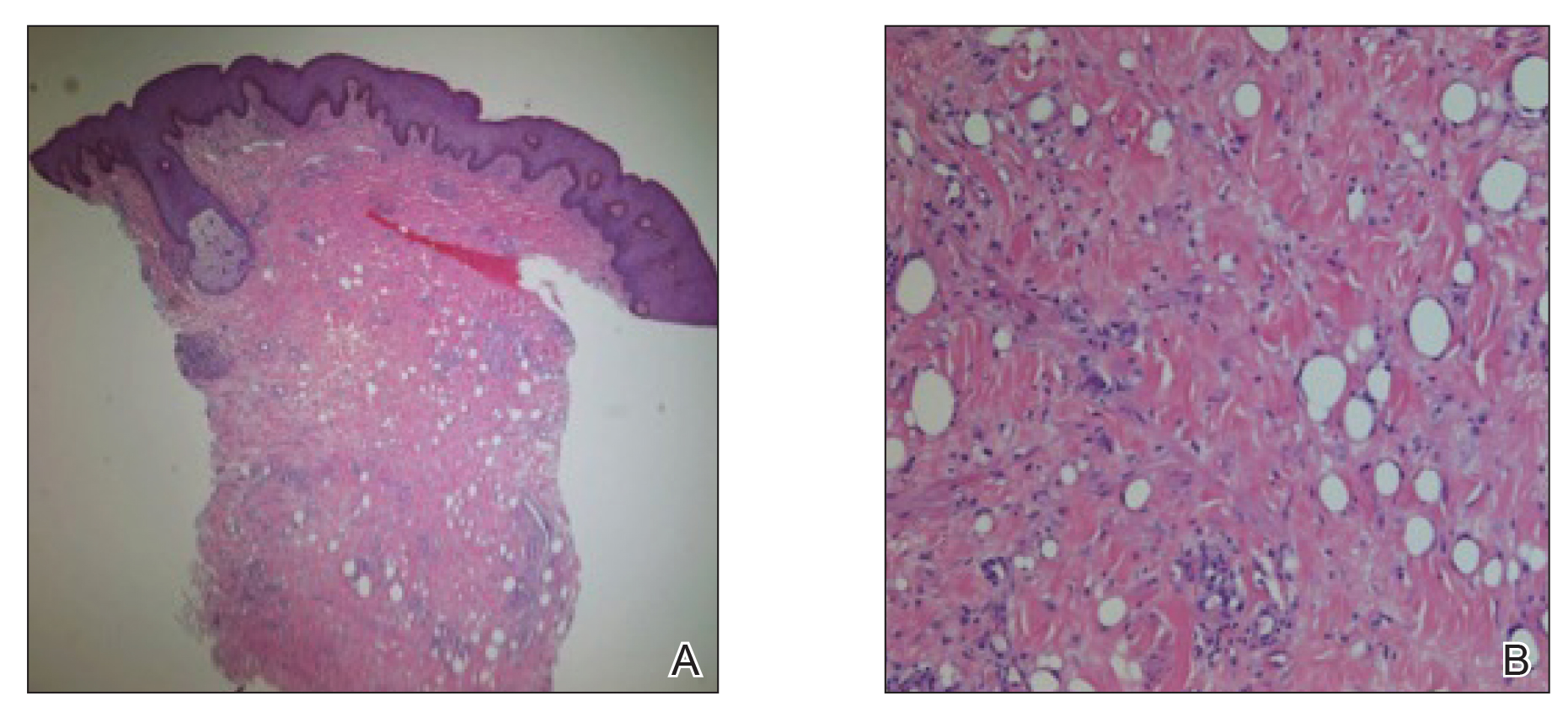

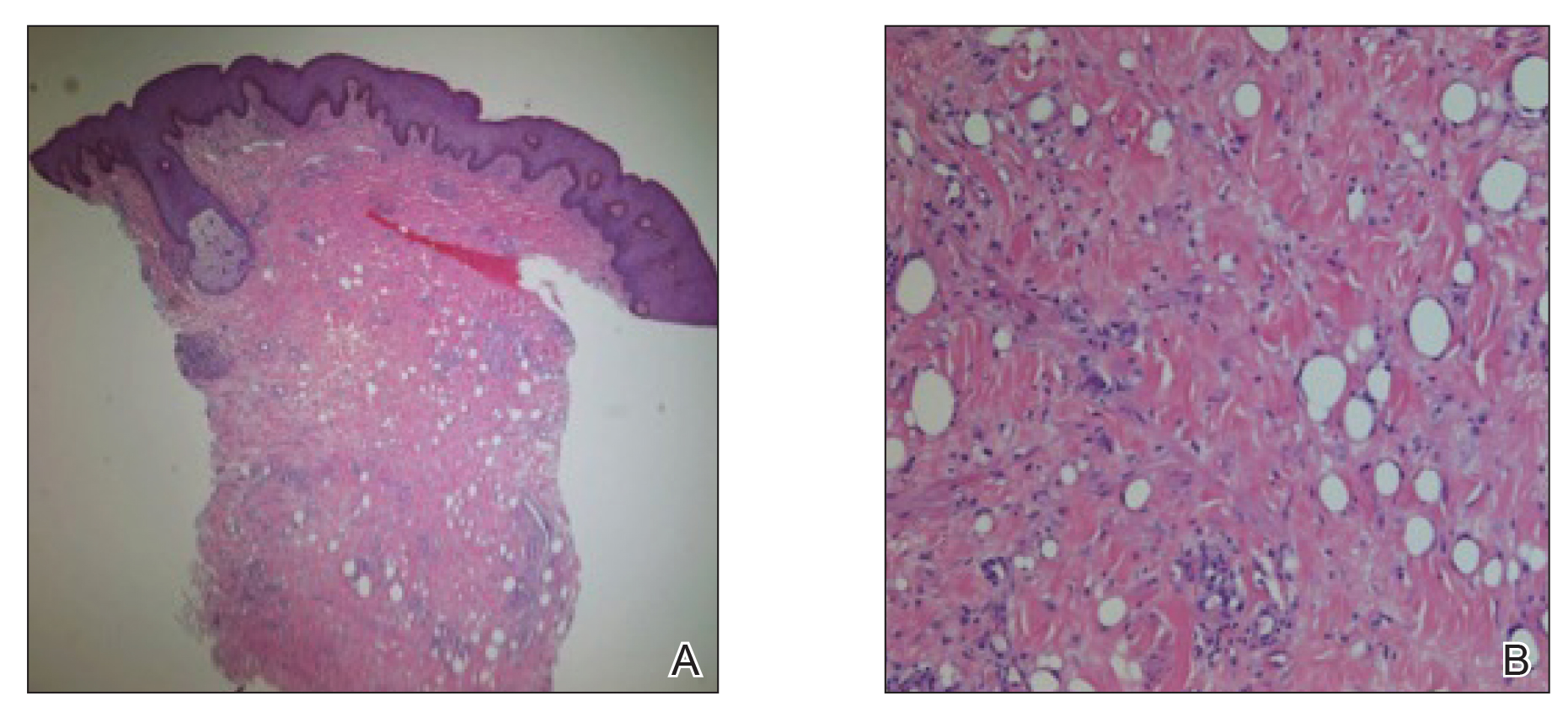

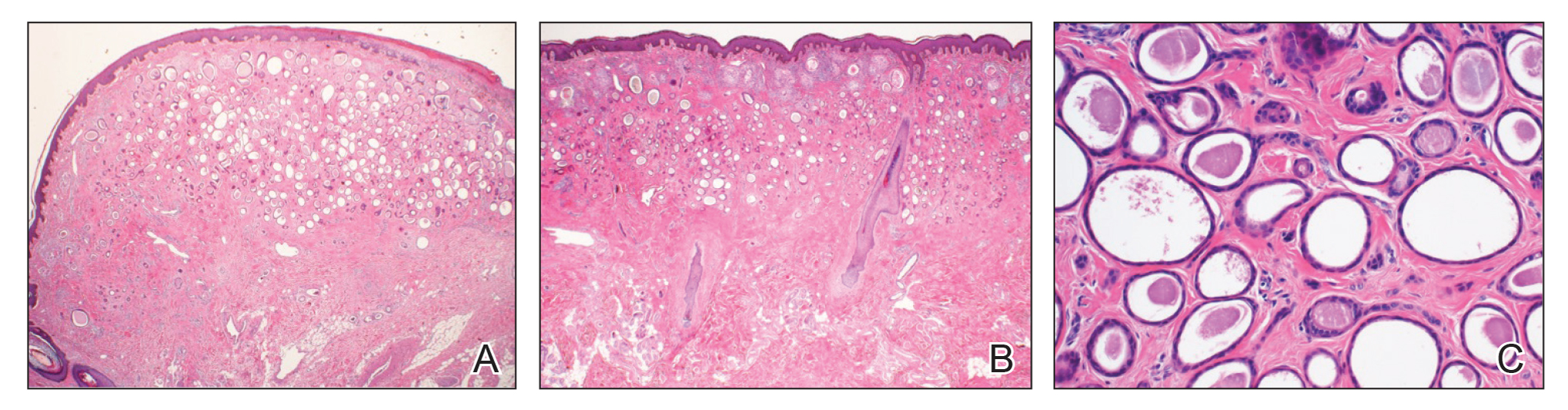

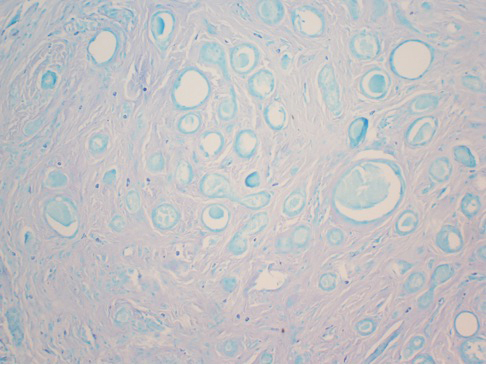

An 88-year-old woman presented for evaluation of violaceous, minimally tender, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodules on the legs, arms, and trunk of several weeks’ duration (Figure 1). She had a remote history of tuberculosis as a child, prior to the advent of modern antituberculosis regimens. Her medical history also included hypertension, breast cancer treated with lymph node dissection, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and bladder cancer treated with intravesical BCG 10 years prior to the onset of the nodules. She reported minimal coughing and a 25-lb weight loss over the last year, but she denied night sweats, fever, or chills.

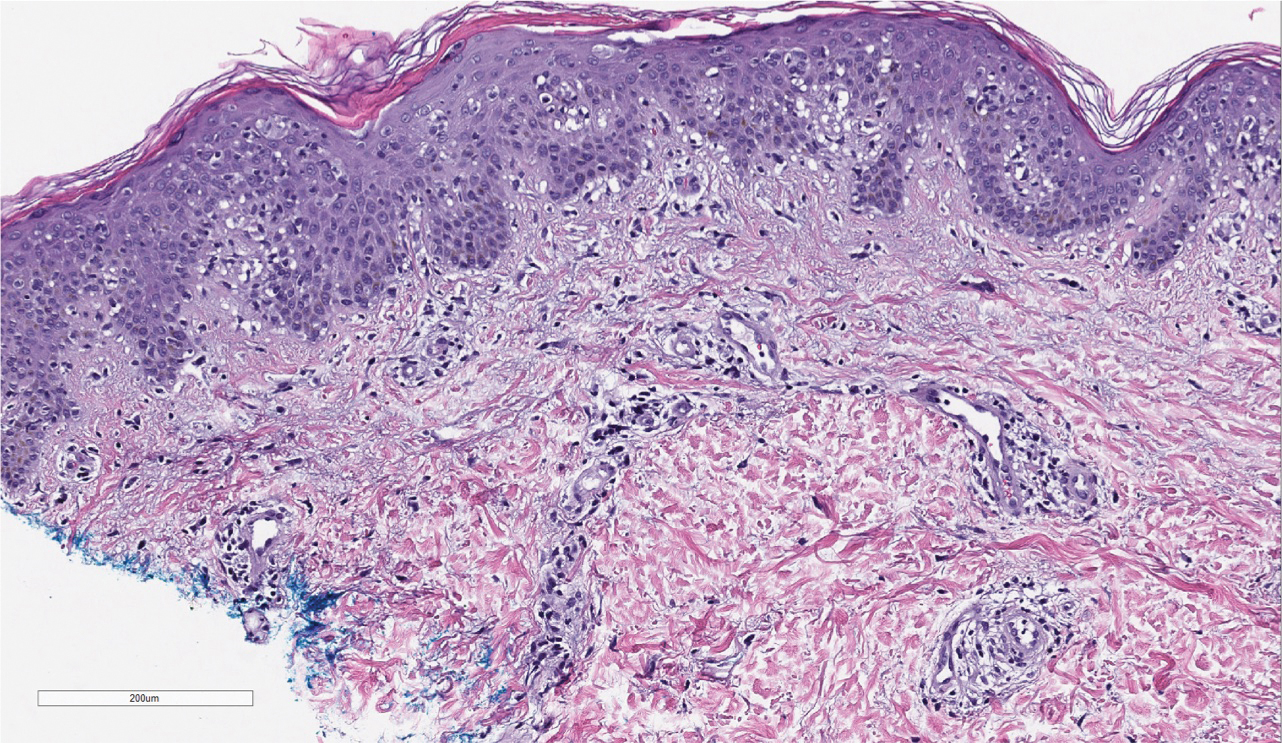

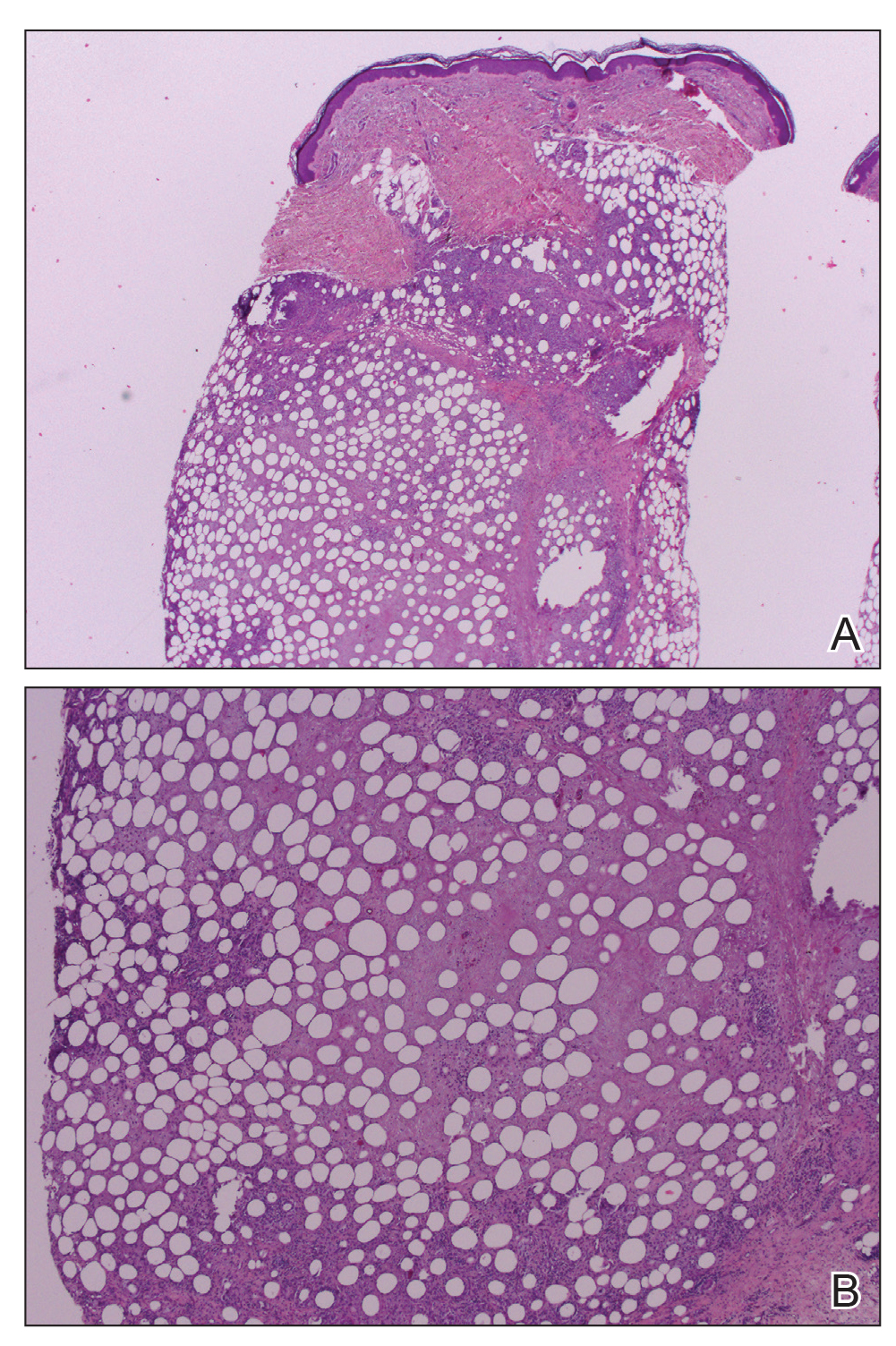

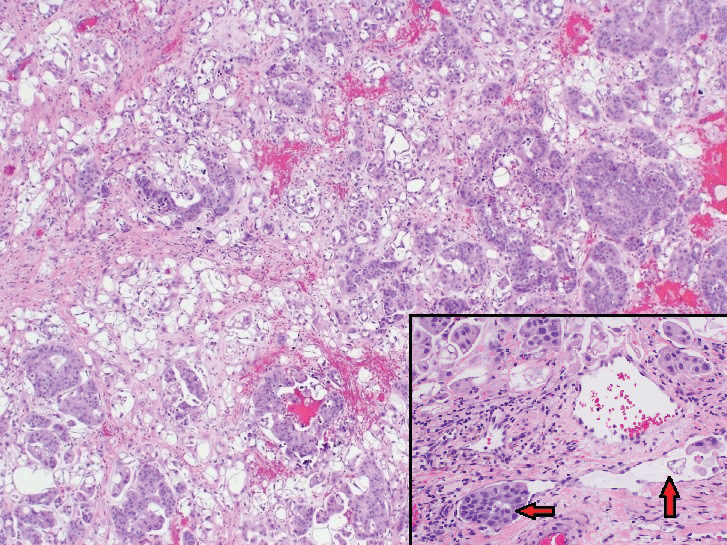

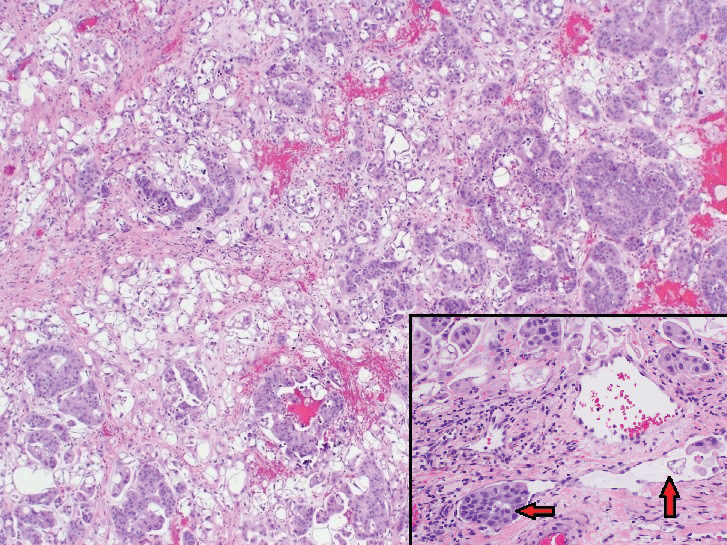

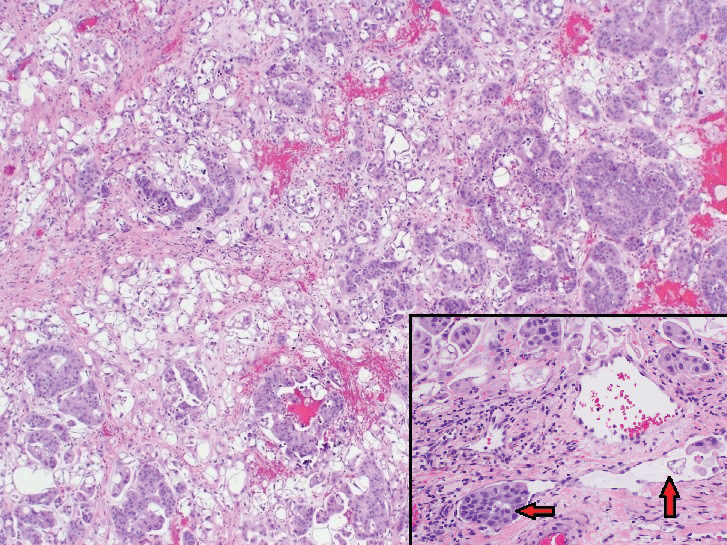

Workup included a biopsy, which showed a dense inflammatory infiltrate within the septae and lobules of the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2A). Foci of necrosis were seen within the fat lobules (Figure 2B). The histologic diagnosis was erythema induratum. Tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative. Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis also was negative. An IFN-γ release assay test was positive for infection with M tuberculosis, suggesting that the erythema induratum was due to tuberculosis rather than BCG exposure. A chest radiograph demonstrated a 22-mm nodule in the left lung (unchanged from a prior film) and a new 10-mm nodule in the left upper lobe.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred that the erythema induratum and the new lung nodule likely represented a reactivation of tuberculosis. Sputum samples were found to be smear and culture negative for mycobacteria, but due to high clinical suspicion, she was started on a 4-drug tuberculosis regimen of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Some lesions had started to improve prior to the institution of therapy; after initiation of treatment, all lesions resolved within 4 weeks of starting treatment without recurrence.

Erythema induratum was first described by Bazin9 in 1861. The disorder usually occurs in middle-aged women and is characterized by violaceous ulcerative plaques that classically present on the lower extremities, especially the calves. When the eruption occurs due to a nontuberculous etiology, the term nodular vasculitis is used.1,5 The distinction largely is historical, as most dermatologists today recognize erythema induratum and nodular vasculitis to be the same entity. Examples of nontuberculous causes include infections such as Nocardia, Pseudomonas, Fusarium, or other Mycobacterium species.10 Medications such as propylthiouracil also have been implicated.11 The classification of erythema induratum as a tuberculid suggests that the nodules are a reaction pattern rather than a primary infection, though the term tuberculid may be imprecise. The differential diagnosis of violaceous nodules on the lower extremities and trunk is broad and includes erythema nodosum, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, pancreatic panniculitis, subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and lupus profundus.1,11,12

Histologically, lesions classically demonstrate a mostly lobular panniculitis with varying degrees of septal fibrosis and focal necrosis. Neutrophils may predominate early, while adipocyte necrosis, epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes may be found in older lesions. The presence of vasculitis as a requisite diagnostic criterion remains controversial.1,12

The incidence of erythema induratum has decreased since multidrug tuberculosis treatment has become more widespread.3 Our case displayed the disseminated variant of erythema induratum, an even rarer clinical entity.8 Interestingly, our patient had a history of tuberculosis and exposure to BCG prior to the development of lesions. Case reports have documented erythema induratum after BCG exposure but less frequently than in cases associated with tuberculosis.3,13