User login

Phytophotodermatitis in a Butterfly Enthusiast Induced by Common Rue

To the Editor:

Phytophotodermatitis is common in dermatology during the summer months, especially in individuals who spend time outdoors; however, identification of the offending plant can be challenging. We report a case of phytophotodermatitis in which the causative plant, common rue, was not identified until it was revealed that the patient was a butterfly enthusiast.

A 60-year-old woman presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic in late summer for a routine skin examination. An eruption was noted over the right thigh and knee that had first appeared approximately 2 weeks prior. The rash started as pruritic blisters but gradually progressed to erythema and then eventually to brown markings, which were observed at the current presentation. Physical examination revealed hyperpigmented, brown, streaky, linear patches and plaques over the right thigh, knee, and lower leg (Figure). When asked about her hobbies, the patient reported an affinity for butterflies and noted that she attracts them with specific species of plants in her garden. She recalled recently planting the herb of grace, or common rue, to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes). Upon further inquiry, she remembered working in the garden on her knees and digging up roots near the common rue plant while wearing shorts approximately 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. Given the streaky linear pattern of the eruption along with recent sun exposure and exposure to the common rue plant, a diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made. No further treatment was sought, as the eruption was not bothersome to her. She was intrigued that the common rue plant had caused the dermatitis and planned on taking proper precautions when working near the plant in the future.

In this case, the observed phototoxic skin findings resulted from exposure to common rue (Ruta graveolens),a pungently scented evergreen shrub native to the Mediterranean region and a member of the Rutaceae family. Extracts have been used in homeopathic practices for bruises, sprains, headache, neck stiffness, rheumatologic pain, neuralgia, stomach problems, and phlebitis, as well as in seasonings, soaps, creams, and perfumes.1 The most commonly encountered plants known to cause phytophotodermatitis belong to the Apiaceae and Rutaceae families.2 Members of Apiaceae include angelica, celery, dill, fennel, hogweed, parsley, and parsnip. Aside from the common rue plant, the Rutaceae family also includes bergamot orange, bitter orange, burning bush (or gas plant), grapefruit, lemon, and lime. Other potential offending agents are fig, mustard, buttercup, St. John’s wort, and scurfpea. The phototoxic properties are due to furocoumarins, which include psoralens and angelicins. They are inert until activated by UVA radiation, which inflicts direct cellular damage, causing vacuolization and apoptosis of keratinocytes, similar to a sunburn.3 Clinical findings typically present 24 hours after sun exposure with erythema, edema, pain, and occasionally vesicles or bullae in severe cases. Unlike sunburn, lesions often present in linear, streaky, or bizarre patterns, reflective of the direct contact with the plant. The lesions eventually transition to hyperpigmentation, which may take months to years to resolve.

Other considerations in cases of suspected phytophotodermatitis include polymorphic light eruption, actinic prurigo, hydroa vacciniforme, chronic actinic dermatitis, solar urticaria, drug reactions, porphyria, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis.4 Clinicians should suspect phytophotodermatitis with phototoxic findings in bartenders, citrus farm workers, gardeners, chefs, and kitchen workers, especially those handling limes and celery. As in our case, phytophotodermatitis also should be considered in butterfly enthusiasts trying to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly. The caterpillars feed on the leaves of the common rue plant, one of a select few plants that giant swallowtail butterflies use as a host due to its bitter leaves that aid in avoiding predators.5

This case illustrates a unique perspective of phytophotodermatitis, as butterfly enthusiasm is not commonly reported in association with the common rue plant with respect to phytophotodermatitis. This case underscores the importance of inquiring about patients’ professions and hobbies, both in dermatology and other specialties.

- Atta AH, Alkofahi A. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of some Jordanian medicinal plant extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;60:117-124.

- McGovern TW. Dermatoses due to plants. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby; 2007:265-283.

- Hawk JLM, Calonje E. The photosensitivity disorders. In: Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005:345-353.

- Lim HW. Abnormal responses to ultraviolet radiation: photosensitivity induced by exogenous agents. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:1066-1074.

- McAuslane H. Giant swallowtail. University of Florida Department of Entomology and Nematology Featured Creatures website. http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/citrus/giantswallowtail.htm. Revised January 2018. Accessed April 10, 2020.

To the Editor:

Phytophotodermatitis is common in dermatology during the summer months, especially in individuals who spend time outdoors; however, identification of the offending plant can be challenging. We report a case of phytophotodermatitis in which the causative plant, common rue, was not identified until it was revealed that the patient was a butterfly enthusiast.

A 60-year-old woman presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic in late summer for a routine skin examination. An eruption was noted over the right thigh and knee that had first appeared approximately 2 weeks prior. The rash started as pruritic blisters but gradually progressed to erythema and then eventually to brown markings, which were observed at the current presentation. Physical examination revealed hyperpigmented, brown, streaky, linear patches and plaques over the right thigh, knee, and lower leg (Figure). When asked about her hobbies, the patient reported an affinity for butterflies and noted that she attracts them with specific species of plants in her garden. She recalled recently planting the herb of grace, or common rue, to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes). Upon further inquiry, she remembered working in the garden on her knees and digging up roots near the common rue plant while wearing shorts approximately 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. Given the streaky linear pattern of the eruption along with recent sun exposure and exposure to the common rue plant, a diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made. No further treatment was sought, as the eruption was not bothersome to her. She was intrigued that the common rue plant had caused the dermatitis and planned on taking proper precautions when working near the plant in the future.

In this case, the observed phototoxic skin findings resulted from exposure to common rue (Ruta graveolens),a pungently scented evergreen shrub native to the Mediterranean region and a member of the Rutaceae family. Extracts have been used in homeopathic practices for bruises, sprains, headache, neck stiffness, rheumatologic pain, neuralgia, stomach problems, and phlebitis, as well as in seasonings, soaps, creams, and perfumes.1 The most commonly encountered plants known to cause phytophotodermatitis belong to the Apiaceae and Rutaceae families.2 Members of Apiaceae include angelica, celery, dill, fennel, hogweed, parsley, and parsnip. Aside from the common rue plant, the Rutaceae family also includes bergamot orange, bitter orange, burning bush (or gas plant), grapefruit, lemon, and lime. Other potential offending agents are fig, mustard, buttercup, St. John’s wort, and scurfpea. The phototoxic properties are due to furocoumarins, which include psoralens and angelicins. They are inert until activated by UVA radiation, which inflicts direct cellular damage, causing vacuolization and apoptosis of keratinocytes, similar to a sunburn.3 Clinical findings typically present 24 hours after sun exposure with erythema, edema, pain, and occasionally vesicles or bullae in severe cases. Unlike sunburn, lesions often present in linear, streaky, or bizarre patterns, reflective of the direct contact with the plant. The lesions eventually transition to hyperpigmentation, which may take months to years to resolve.

Other considerations in cases of suspected phytophotodermatitis include polymorphic light eruption, actinic prurigo, hydroa vacciniforme, chronic actinic dermatitis, solar urticaria, drug reactions, porphyria, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis.4 Clinicians should suspect phytophotodermatitis with phototoxic findings in bartenders, citrus farm workers, gardeners, chefs, and kitchen workers, especially those handling limes and celery. As in our case, phytophotodermatitis also should be considered in butterfly enthusiasts trying to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly. The caterpillars feed on the leaves of the common rue plant, one of a select few plants that giant swallowtail butterflies use as a host due to its bitter leaves that aid in avoiding predators.5

This case illustrates a unique perspective of phytophotodermatitis, as butterfly enthusiasm is not commonly reported in association with the common rue plant with respect to phytophotodermatitis. This case underscores the importance of inquiring about patients’ professions and hobbies, both in dermatology and other specialties.

To the Editor:

Phytophotodermatitis is common in dermatology during the summer months, especially in individuals who spend time outdoors; however, identification of the offending plant can be challenging. We report a case of phytophotodermatitis in which the causative plant, common rue, was not identified until it was revealed that the patient was a butterfly enthusiast.

A 60-year-old woman presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic in late summer for a routine skin examination. An eruption was noted over the right thigh and knee that had first appeared approximately 2 weeks prior. The rash started as pruritic blisters but gradually progressed to erythema and then eventually to brown markings, which were observed at the current presentation. Physical examination revealed hyperpigmented, brown, streaky, linear patches and plaques over the right thigh, knee, and lower leg (Figure). When asked about her hobbies, the patient reported an affinity for butterflies and noted that she attracts them with specific species of plants in her garden. She recalled recently planting the herb of grace, or common rue, to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly (Papilio cresphontes). Upon further inquiry, she remembered working in the garden on her knees and digging up roots near the common rue plant while wearing shorts approximately 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. Given the streaky linear pattern of the eruption along with recent sun exposure and exposure to the common rue plant, a diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis was made. No further treatment was sought, as the eruption was not bothersome to her. She was intrigued that the common rue plant had caused the dermatitis and planned on taking proper precautions when working near the plant in the future.

In this case, the observed phototoxic skin findings resulted from exposure to common rue (Ruta graveolens),a pungently scented evergreen shrub native to the Mediterranean region and a member of the Rutaceae family. Extracts have been used in homeopathic practices for bruises, sprains, headache, neck stiffness, rheumatologic pain, neuralgia, stomach problems, and phlebitis, as well as in seasonings, soaps, creams, and perfumes.1 The most commonly encountered plants known to cause phytophotodermatitis belong to the Apiaceae and Rutaceae families.2 Members of Apiaceae include angelica, celery, dill, fennel, hogweed, parsley, and parsnip. Aside from the common rue plant, the Rutaceae family also includes bergamot orange, bitter orange, burning bush (or gas plant), grapefruit, lemon, and lime. Other potential offending agents are fig, mustard, buttercup, St. John’s wort, and scurfpea. The phototoxic properties are due to furocoumarins, which include psoralens and angelicins. They are inert until activated by UVA radiation, which inflicts direct cellular damage, causing vacuolization and apoptosis of keratinocytes, similar to a sunburn.3 Clinical findings typically present 24 hours after sun exposure with erythema, edema, pain, and occasionally vesicles or bullae in severe cases. Unlike sunburn, lesions often present in linear, streaky, or bizarre patterns, reflective of the direct contact with the plant. The lesions eventually transition to hyperpigmentation, which may take months to years to resolve.

Other considerations in cases of suspected phytophotodermatitis include polymorphic light eruption, actinic prurigo, hydroa vacciniforme, chronic actinic dermatitis, solar urticaria, drug reactions, porphyria, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis.4 Clinicians should suspect phytophotodermatitis with phototoxic findings in bartenders, citrus farm workers, gardeners, chefs, and kitchen workers, especially those handling limes and celery. As in our case, phytophotodermatitis also should be considered in butterfly enthusiasts trying to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly. The caterpillars feed on the leaves of the common rue plant, one of a select few plants that giant swallowtail butterflies use as a host due to its bitter leaves that aid in avoiding predators.5

This case illustrates a unique perspective of phytophotodermatitis, as butterfly enthusiasm is not commonly reported in association with the common rue plant with respect to phytophotodermatitis. This case underscores the importance of inquiring about patients’ professions and hobbies, both in dermatology and other specialties.

- Atta AH, Alkofahi A. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of some Jordanian medicinal plant extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;60:117-124.

- McGovern TW. Dermatoses due to plants. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby; 2007:265-283.

- Hawk JLM, Calonje E. The photosensitivity disorders. In: Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005:345-353.

- Lim HW. Abnormal responses to ultraviolet radiation: photosensitivity induced by exogenous agents. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:1066-1074.

- McAuslane H. Giant swallowtail. University of Florida Department of Entomology and Nematology Featured Creatures website. http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/citrus/giantswallowtail.htm. Revised January 2018. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- Atta AH, Alkofahi A. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of some Jordanian medicinal plant extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;60:117-124.

- McGovern TW. Dermatoses due to plants. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby; 2007:265-283.

- Hawk JLM, Calonje E. The photosensitivity disorders. In: Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005:345-353.

- Lim HW. Abnormal responses to ultraviolet radiation: photosensitivity induced by exogenous agents. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:1066-1074.

- McAuslane H. Giant swallowtail. University of Florida Department of Entomology and Nematology Featured Creatures website. http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/citrus/giantswallowtail.htm. Revised January 2018. Accessed April 10, 2020.

Practice Points

- It is important to inquire about patients’ professions and hobbies, which may lead to the diagnosis, as in this case of a butterfly enthusiast trying to attract the giant swallowtail butterfly with the common rue plant.

- One should suspect phytophotodermatitis with phototoxic findings in bartenders, citrus farm workers, gardeners, chefs, and kitchen workers, especially those handling limes and celery

Sunless Tanner Caused Persistent Hyperpigmented Patches on the Hands

To the Editor:

The use of sunless tanners has become an alternative for individuals who wish to have tan skin without exposure to UV radiation.1 We present a case of a patient who experienced persistent hyperpigmented patches on the hands months after the use of a sunless tanner containing dihydroxyacetone (DHA), a carbohydrate that reacts with amino acids in the stratum corneum to produce pigments called melanoidins. The hyperpigmentation caused by DHA is due to the Maillard reaction, which is the nonenzymatic glycation of amino groups of proteins by the carbonyl groups of sugar.2 Many sunless tanners contain DHA at varying concentrations. Dermatologists should be aware of the benefits and potential side effects of these alternative products so that they can appropriately counsel patients.

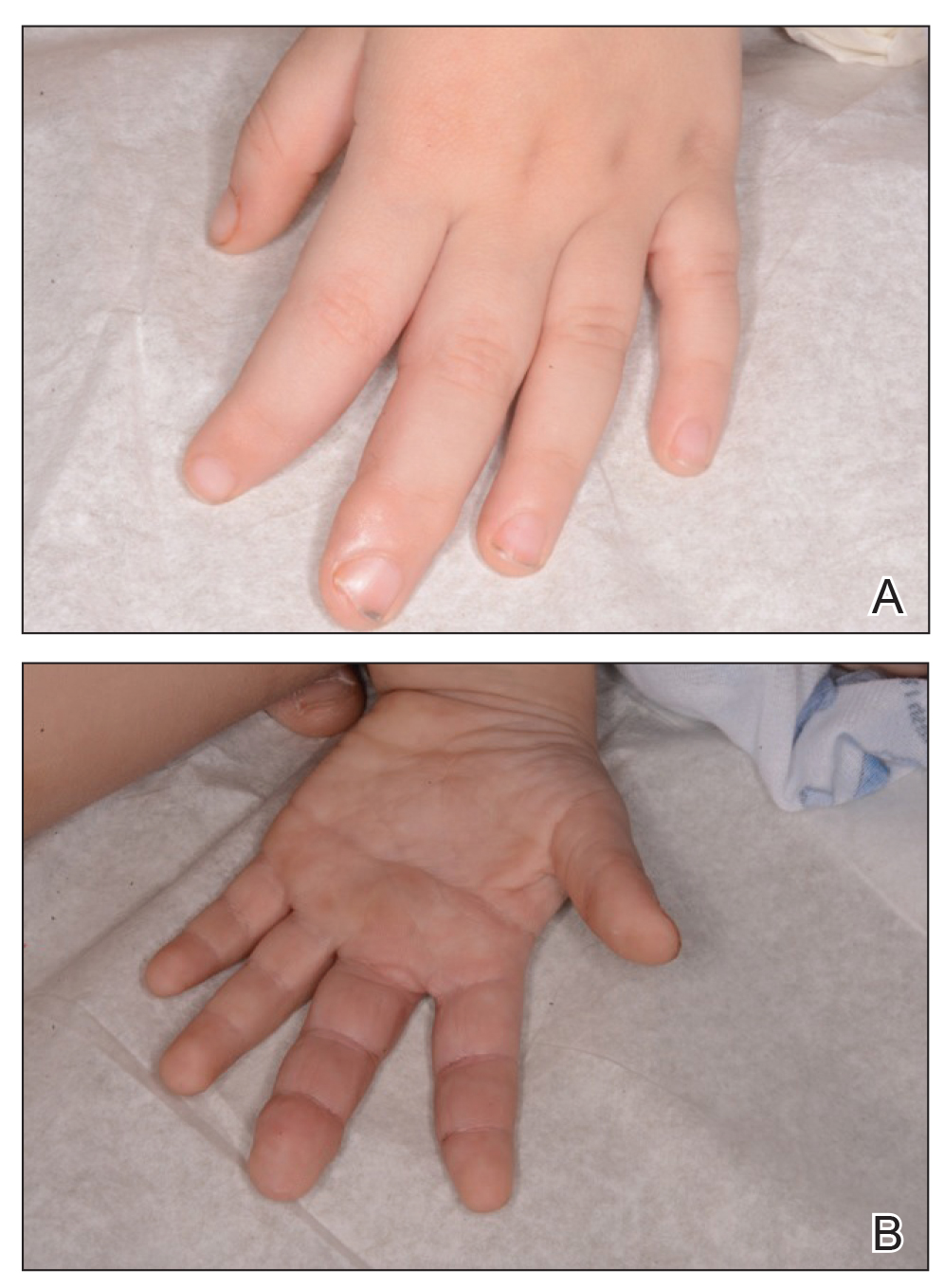

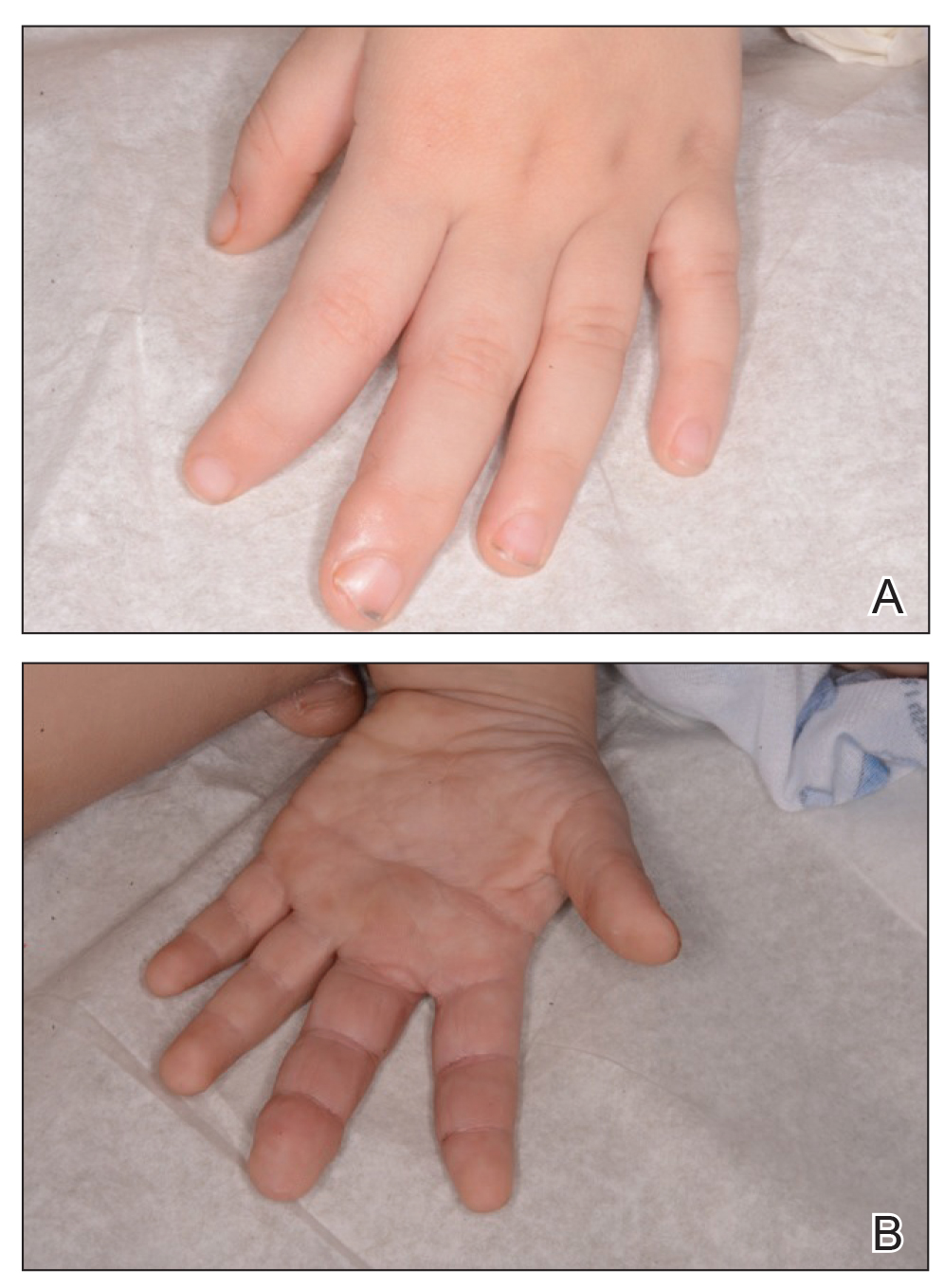

A 20-year-old woman with no history of skin disease presented for evaluation of hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal hands of several months’ duration. Physical examination revealed ill-defined hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal fingers without associated scale or erythema (Figure 1). She had a remote history of Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and was in remission for 5 years prior to the current presentation. Her hematologists referred her to dermatology for evaluation, as they did not believe the patches could be related to her chemotherapy given that she had completed the treatment years before.

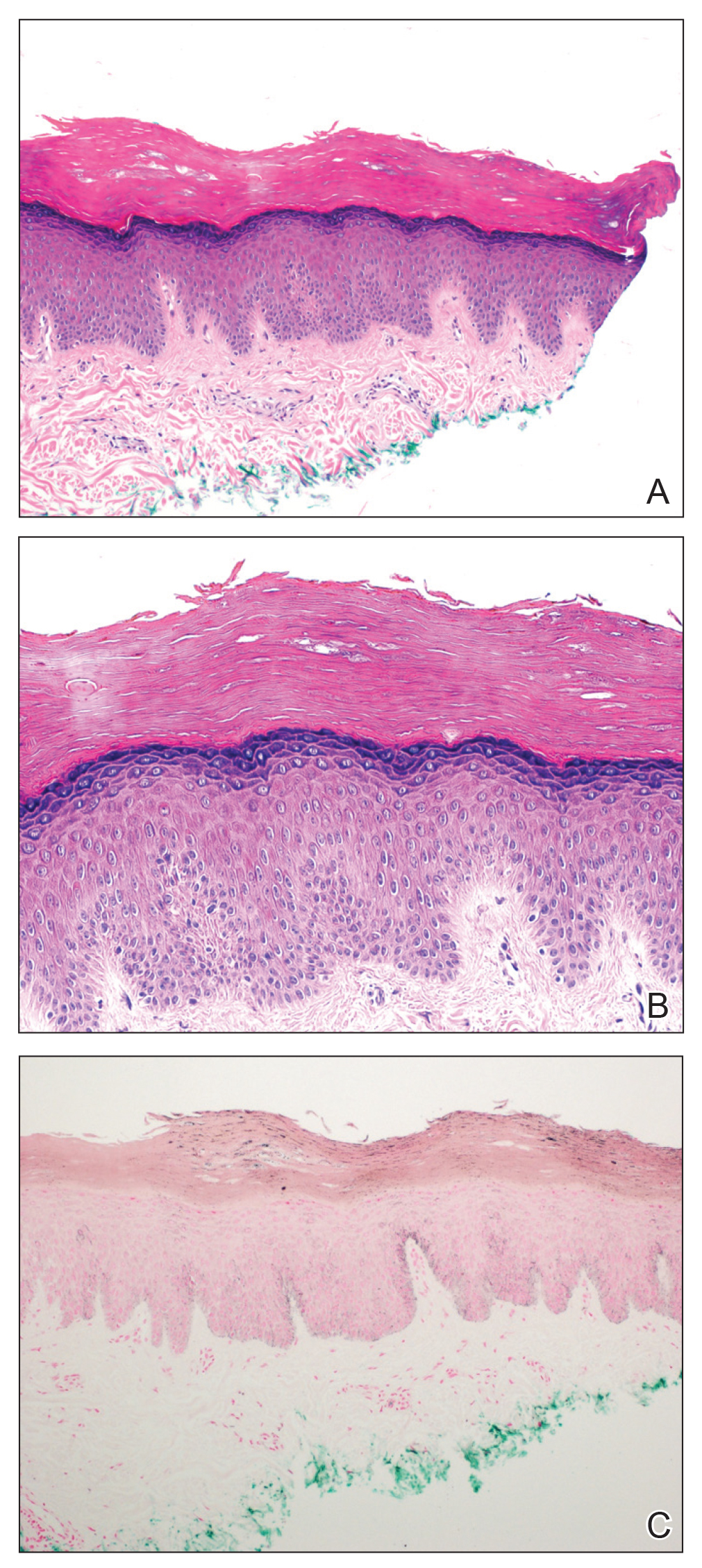

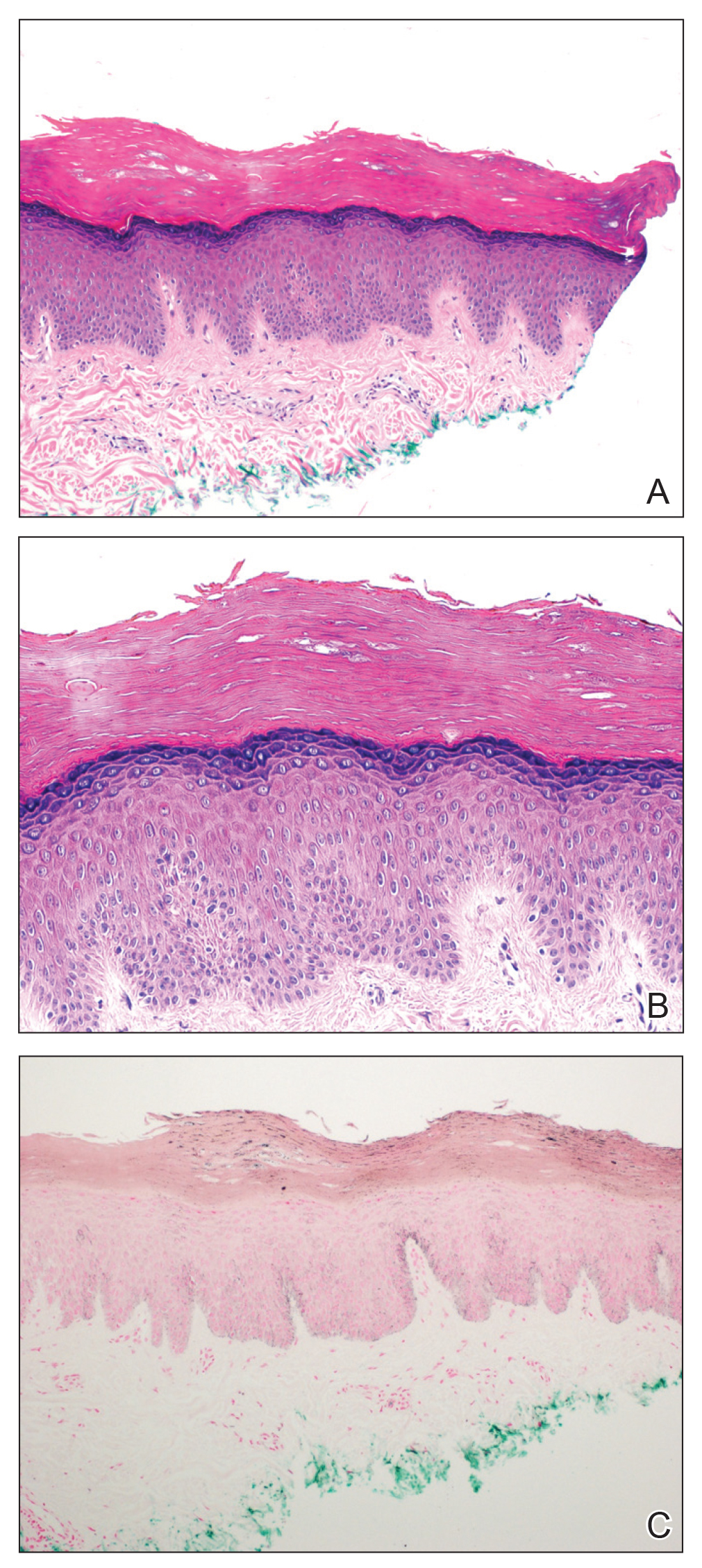

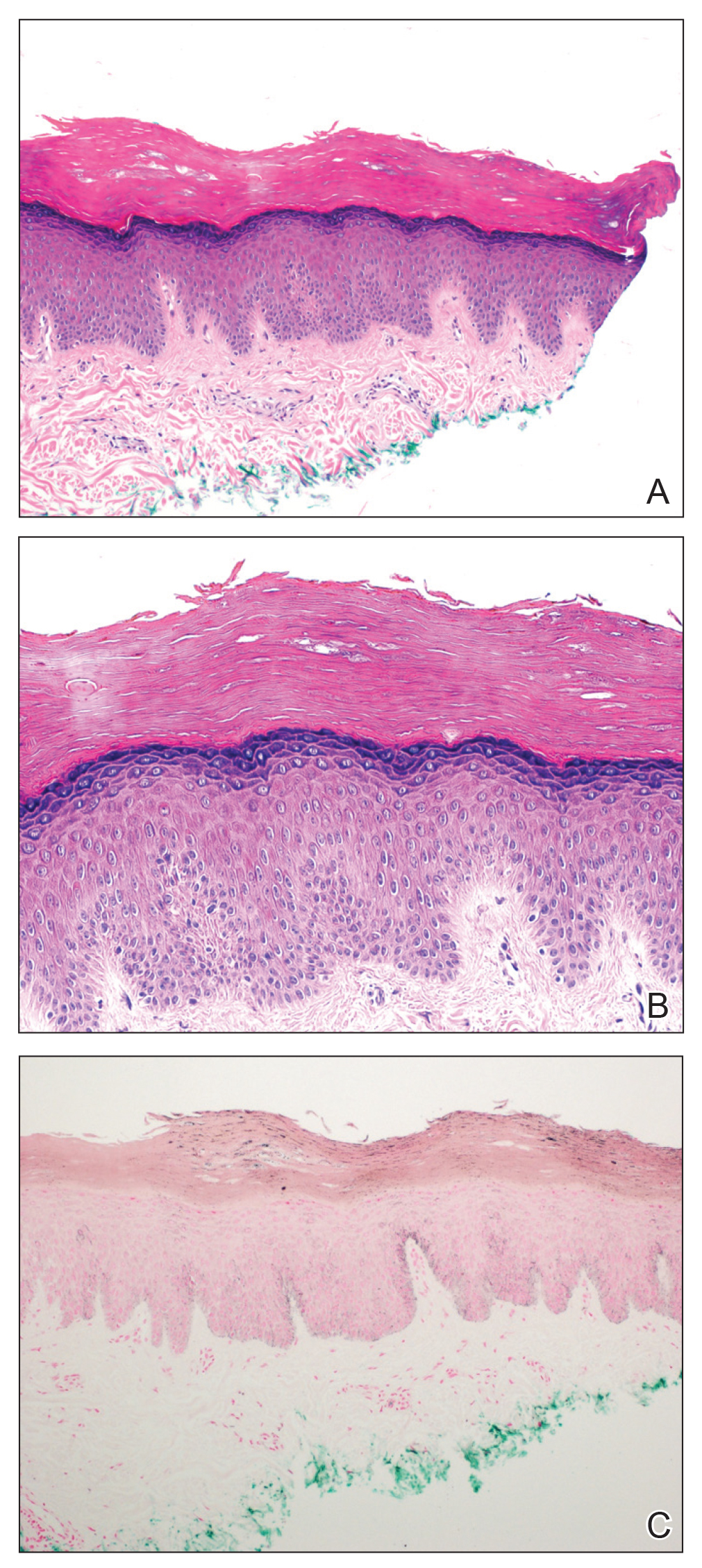

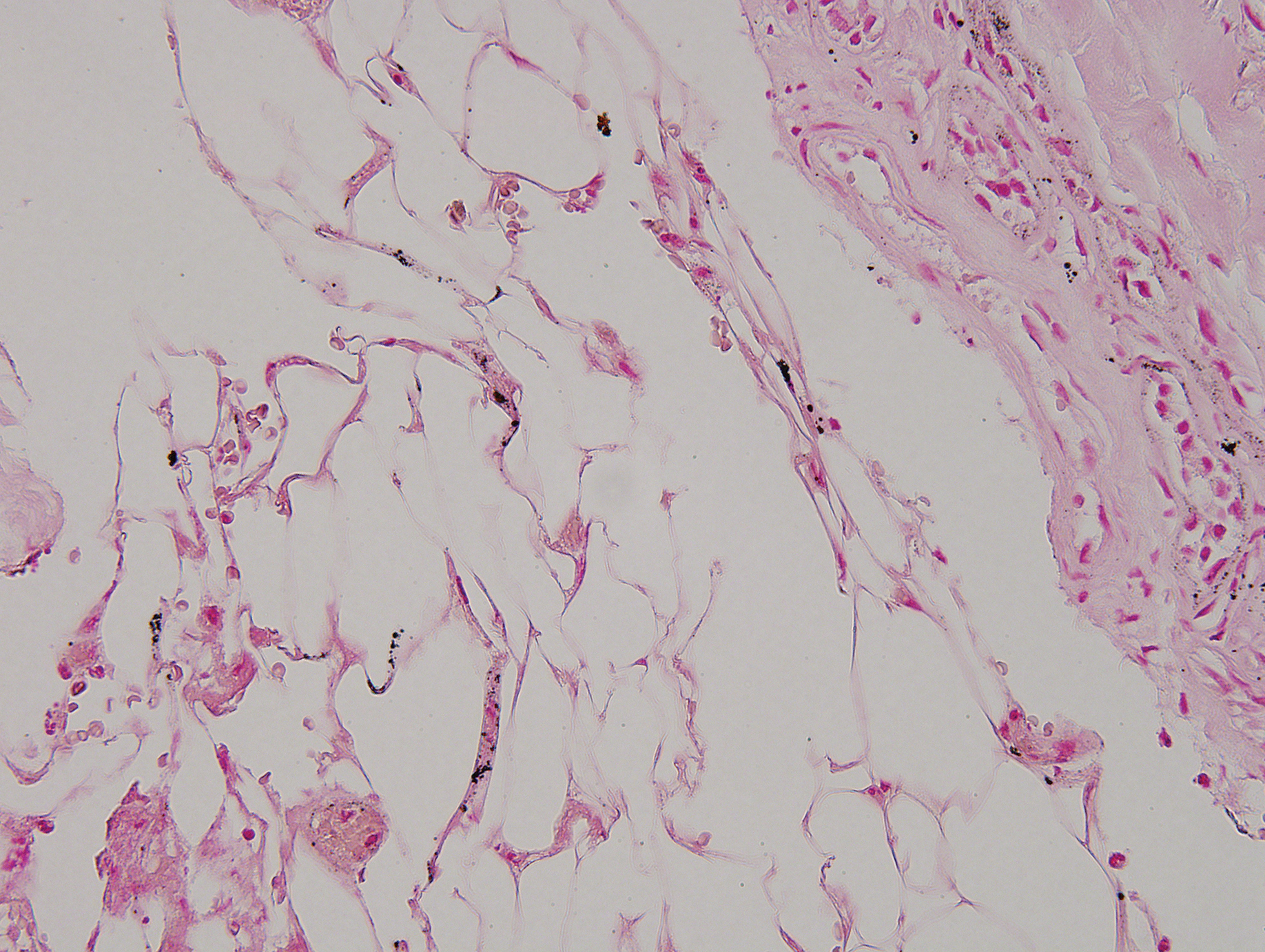

A punch biopsy of one of the patches was obtained to elucidate the origin of the hyperpigmentation, which had no obvious triggers according to the patient. Histopathologic examination revealed hyperpigmented parakeratosis and lentiginous hyperplasia along with pigmentation of the stratum corneum (Figures 2A and 2B) with black pigment, which stained positive with Fontana-Masson (Figure 2C).

Upon further questioning, it was revealed that our patient had used a sunless tanner 3 months prior to the development of the pigmented patches. She also used urea cream to hasten exfoliation, which resulted in lighter but still apparent hyperpigmentation at follow-up 6 months after the initial presentation.

There has been a rapid growth of the sunless tanning industry in the last several years due to effective public education against UV tanning. Generally, patients apply the sunless tanner and notice an increase in tan within the following 48 hours. Typically, the tan progressively fades with the normal skin exfoliation over the span of weeks. Although most of the DHA binds proteins in the stratum corneum, the US Food and Drug Administration released a report speculating that approximately 11% of the compound reaches the epidermis and dermis.3 There are limited data regarding the effects of the compound should it pass the stratum corneum into the living skin cells.

Products with DHA only confer a sun protection factor of approximately 34; although patients may appear tan, they have no actual decreased risk for sunburn after use. Reports have shown that the use of sunless tanners containing DHA can alter the appearance of melanocytic lesions clinically and has caused pseudochromhidrosis on the palms.3,5,6 A study performed on a human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT, showed that DHA can induce DNA damage, cell-cycle block, and apoptosis.7 In addition, as described in our case, patients may experience prolonged hyperpigmentation after use.

This case demonstrates the potential for persistent hyperpigmentation months after the use of sunless tanners containing DHA. Asking patients specific questions regarding their history of tanning product use is essential in identifying the pathology. Although a skin biopsy may not be strictly indicated, it may aid diagnosis, especially when the history is unclear. As more dermatologists support the use of sunless tanner, we must be aware of this possible outcome, especially on more cosmetically sensitive areas such as the fingers in this patient. Clinicians should be aware that the US Food and Drug Administration recommends avoiding contact with mucous membranes when applying products containing DHA and also recommends use of a test spot prior to treating the entire body with the product.8 Patients must not only be educated on the benefits of using sunless tanners but on the potential side effects with use of these products as well.

- Garone M, Howard J, Fabrikant J. A review of common tanning methods. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:43-47.

- Finot PA. Nonenzymatic browning products: physiologic effects and metabolic transit in relation to chemical structure. a review. Diabetes. 1982;31:22-28.

- Yourick JJ, Koenig ML, Yourick DL, et al. Fate of chemicals in skin after dermal application: does the in vitro skin reservoir affect the estimate of systemic absorption? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;195:309-320.

- Nguyen B, Kochevar I. Influence of hydration on dihydroxyacetone-induced pigmentation of stratum corneum. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:655-661.

- Takita Y, Ichimiya M, Yamaguchi M, et al. A case of pseudochromhidrosis due to dihydroxyacetone. J Dermatol. 2006;33:230-231.

- Yoshida R, Kobayashi S, Amagai M, et al. Brown palm pseudochromhidrosis. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:237-238.

- Petersen AB, Wulf HC, Gniadecki R, et al. Dihydroxyacetone, the active browning ingredient in sunless tanning lotions, induces DNA damage, cell-cycle block and apoptosis in cultured HaCaT keratinocytes. Mutat Res. 2004;560:173-186.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Sunless tanners & bronzers. FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/ProductsIngredients

/Products/ucm134064.htm. Updated March 6, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2020

To the Editor:

The use of sunless tanners has become an alternative for individuals who wish to have tan skin without exposure to UV radiation.1 We present a case of a patient who experienced persistent hyperpigmented patches on the hands months after the use of a sunless tanner containing dihydroxyacetone (DHA), a carbohydrate that reacts with amino acids in the stratum corneum to produce pigments called melanoidins. The hyperpigmentation caused by DHA is due to the Maillard reaction, which is the nonenzymatic glycation of amino groups of proteins by the carbonyl groups of sugar.2 Many sunless tanners contain DHA at varying concentrations. Dermatologists should be aware of the benefits and potential side effects of these alternative products so that they can appropriately counsel patients.

A 20-year-old woman with no history of skin disease presented for evaluation of hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal hands of several months’ duration. Physical examination revealed ill-defined hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal fingers without associated scale or erythema (Figure 1). She had a remote history of Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and was in remission for 5 years prior to the current presentation. Her hematologists referred her to dermatology for evaluation, as they did not believe the patches could be related to her chemotherapy given that she had completed the treatment years before.

A punch biopsy of one of the patches was obtained to elucidate the origin of the hyperpigmentation, which had no obvious triggers according to the patient. Histopathologic examination revealed hyperpigmented parakeratosis and lentiginous hyperplasia along with pigmentation of the stratum corneum (Figures 2A and 2B) with black pigment, which stained positive with Fontana-Masson (Figure 2C).

Upon further questioning, it was revealed that our patient had used a sunless tanner 3 months prior to the development of the pigmented patches. She also used urea cream to hasten exfoliation, which resulted in lighter but still apparent hyperpigmentation at follow-up 6 months after the initial presentation.

There has been a rapid growth of the sunless tanning industry in the last several years due to effective public education against UV tanning. Generally, patients apply the sunless tanner and notice an increase in tan within the following 48 hours. Typically, the tan progressively fades with the normal skin exfoliation over the span of weeks. Although most of the DHA binds proteins in the stratum corneum, the US Food and Drug Administration released a report speculating that approximately 11% of the compound reaches the epidermis and dermis.3 There are limited data regarding the effects of the compound should it pass the stratum corneum into the living skin cells.

Products with DHA only confer a sun protection factor of approximately 34; although patients may appear tan, they have no actual decreased risk for sunburn after use. Reports have shown that the use of sunless tanners containing DHA can alter the appearance of melanocytic lesions clinically and has caused pseudochromhidrosis on the palms.3,5,6 A study performed on a human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT, showed that DHA can induce DNA damage, cell-cycle block, and apoptosis.7 In addition, as described in our case, patients may experience prolonged hyperpigmentation after use.

This case demonstrates the potential for persistent hyperpigmentation months after the use of sunless tanners containing DHA. Asking patients specific questions regarding their history of tanning product use is essential in identifying the pathology. Although a skin biopsy may not be strictly indicated, it may aid diagnosis, especially when the history is unclear. As more dermatologists support the use of sunless tanner, we must be aware of this possible outcome, especially on more cosmetically sensitive areas such as the fingers in this patient. Clinicians should be aware that the US Food and Drug Administration recommends avoiding contact with mucous membranes when applying products containing DHA and also recommends use of a test spot prior to treating the entire body with the product.8 Patients must not only be educated on the benefits of using sunless tanners but on the potential side effects with use of these products as well.

To the Editor:

The use of sunless tanners has become an alternative for individuals who wish to have tan skin without exposure to UV radiation.1 We present a case of a patient who experienced persistent hyperpigmented patches on the hands months after the use of a sunless tanner containing dihydroxyacetone (DHA), a carbohydrate that reacts with amino acids in the stratum corneum to produce pigments called melanoidins. The hyperpigmentation caused by DHA is due to the Maillard reaction, which is the nonenzymatic glycation of amino groups of proteins by the carbonyl groups of sugar.2 Many sunless tanners contain DHA at varying concentrations. Dermatologists should be aware of the benefits and potential side effects of these alternative products so that they can appropriately counsel patients.

A 20-year-old woman with no history of skin disease presented for evaluation of hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal hands of several months’ duration. Physical examination revealed ill-defined hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal fingers without associated scale or erythema (Figure 1). She had a remote history of Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and was in remission for 5 years prior to the current presentation. Her hematologists referred her to dermatology for evaluation, as they did not believe the patches could be related to her chemotherapy given that she had completed the treatment years before.

A punch biopsy of one of the patches was obtained to elucidate the origin of the hyperpigmentation, which had no obvious triggers according to the patient. Histopathologic examination revealed hyperpigmented parakeratosis and lentiginous hyperplasia along with pigmentation of the stratum corneum (Figures 2A and 2B) with black pigment, which stained positive with Fontana-Masson (Figure 2C).

Upon further questioning, it was revealed that our patient had used a sunless tanner 3 months prior to the development of the pigmented patches. She also used urea cream to hasten exfoliation, which resulted in lighter but still apparent hyperpigmentation at follow-up 6 months after the initial presentation.

There has been a rapid growth of the sunless tanning industry in the last several years due to effective public education against UV tanning. Generally, patients apply the sunless tanner and notice an increase in tan within the following 48 hours. Typically, the tan progressively fades with the normal skin exfoliation over the span of weeks. Although most of the DHA binds proteins in the stratum corneum, the US Food and Drug Administration released a report speculating that approximately 11% of the compound reaches the epidermis and dermis.3 There are limited data regarding the effects of the compound should it pass the stratum corneum into the living skin cells.

Products with DHA only confer a sun protection factor of approximately 34; although patients may appear tan, they have no actual decreased risk for sunburn after use. Reports have shown that the use of sunless tanners containing DHA can alter the appearance of melanocytic lesions clinically and has caused pseudochromhidrosis on the palms.3,5,6 A study performed on a human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT, showed that DHA can induce DNA damage, cell-cycle block, and apoptosis.7 In addition, as described in our case, patients may experience prolonged hyperpigmentation after use.

This case demonstrates the potential for persistent hyperpigmentation months after the use of sunless tanners containing DHA. Asking patients specific questions regarding their history of tanning product use is essential in identifying the pathology. Although a skin biopsy may not be strictly indicated, it may aid diagnosis, especially when the history is unclear. As more dermatologists support the use of sunless tanner, we must be aware of this possible outcome, especially on more cosmetically sensitive areas such as the fingers in this patient. Clinicians should be aware that the US Food and Drug Administration recommends avoiding contact with mucous membranes when applying products containing DHA and also recommends use of a test spot prior to treating the entire body with the product.8 Patients must not only be educated on the benefits of using sunless tanners but on the potential side effects with use of these products as well.

- Garone M, Howard J, Fabrikant J. A review of common tanning methods. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:43-47.

- Finot PA. Nonenzymatic browning products: physiologic effects and metabolic transit in relation to chemical structure. a review. Diabetes. 1982;31:22-28.

- Yourick JJ, Koenig ML, Yourick DL, et al. Fate of chemicals in skin after dermal application: does the in vitro skin reservoir affect the estimate of systemic absorption? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;195:309-320.

- Nguyen B, Kochevar I. Influence of hydration on dihydroxyacetone-induced pigmentation of stratum corneum. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:655-661.

- Takita Y, Ichimiya M, Yamaguchi M, et al. A case of pseudochromhidrosis due to dihydroxyacetone. J Dermatol. 2006;33:230-231.

- Yoshida R, Kobayashi S, Amagai M, et al. Brown palm pseudochromhidrosis. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:237-238.

- Petersen AB, Wulf HC, Gniadecki R, et al. Dihydroxyacetone, the active browning ingredient in sunless tanning lotions, induces DNA damage, cell-cycle block and apoptosis in cultured HaCaT keratinocytes. Mutat Res. 2004;560:173-186.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Sunless tanners & bronzers. FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/ProductsIngredients

/Products/ucm134064.htm. Updated March 6, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2020

- Garone M, Howard J, Fabrikant J. A review of common tanning methods. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:43-47.

- Finot PA. Nonenzymatic browning products: physiologic effects and metabolic transit in relation to chemical structure. a review. Diabetes. 1982;31:22-28.

- Yourick JJ, Koenig ML, Yourick DL, et al. Fate of chemicals in skin after dermal application: does the in vitro skin reservoir affect the estimate of systemic absorption? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;195:309-320.

- Nguyen B, Kochevar I. Influence of hydration on dihydroxyacetone-induced pigmentation of stratum corneum. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:655-661.

- Takita Y, Ichimiya M, Yamaguchi M, et al. A case of pseudochromhidrosis due to dihydroxyacetone. J Dermatol. 2006;33:230-231.

- Yoshida R, Kobayashi S, Amagai M, et al. Brown palm pseudochromhidrosis. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:237-238.

- Petersen AB, Wulf HC, Gniadecki R, et al. Dihydroxyacetone, the active browning ingredient in sunless tanning lotions, induces DNA damage, cell-cycle block and apoptosis in cultured HaCaT keratinocytes. Mutat Res. 2004;560:173-186.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Sunless tanners & bronzers. FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/ProductsIngredients

/Products/ucm134064.htm. Updated March 6, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2020

Practice Points

- Patient education on the benefits and risks associated with sunless tanners is critical when using these products.

- Sunless tanners containing dihydroxyacetone potentially can lead to persistent hyperpigmented patches on areas of contact.

- Skin biopsy showing hyperpigmented parakeratosis along with pigmentation of the stratum corneum can aid in diagnosis.

Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia Arising From Purple Tattoo Pigment

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

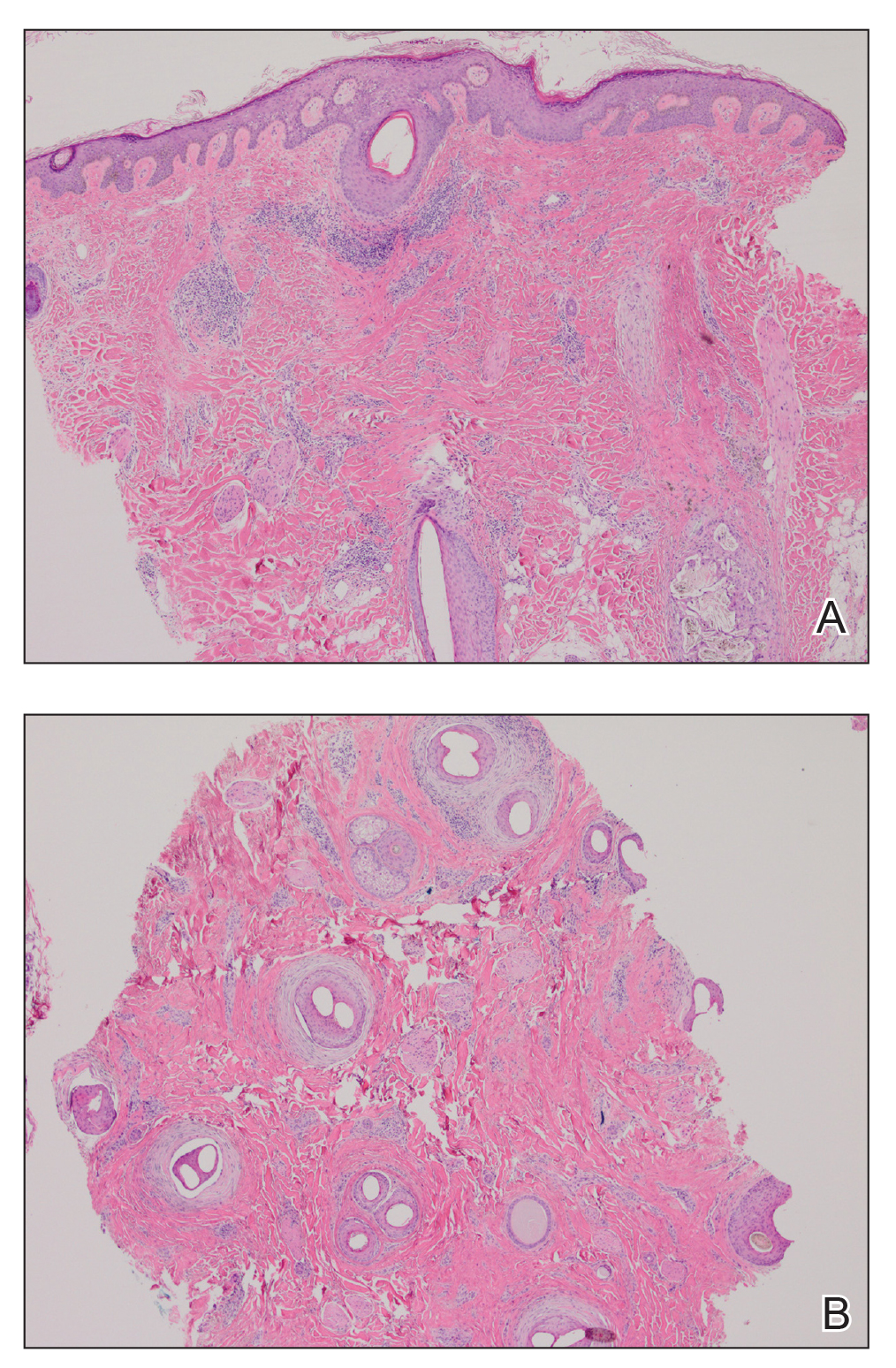

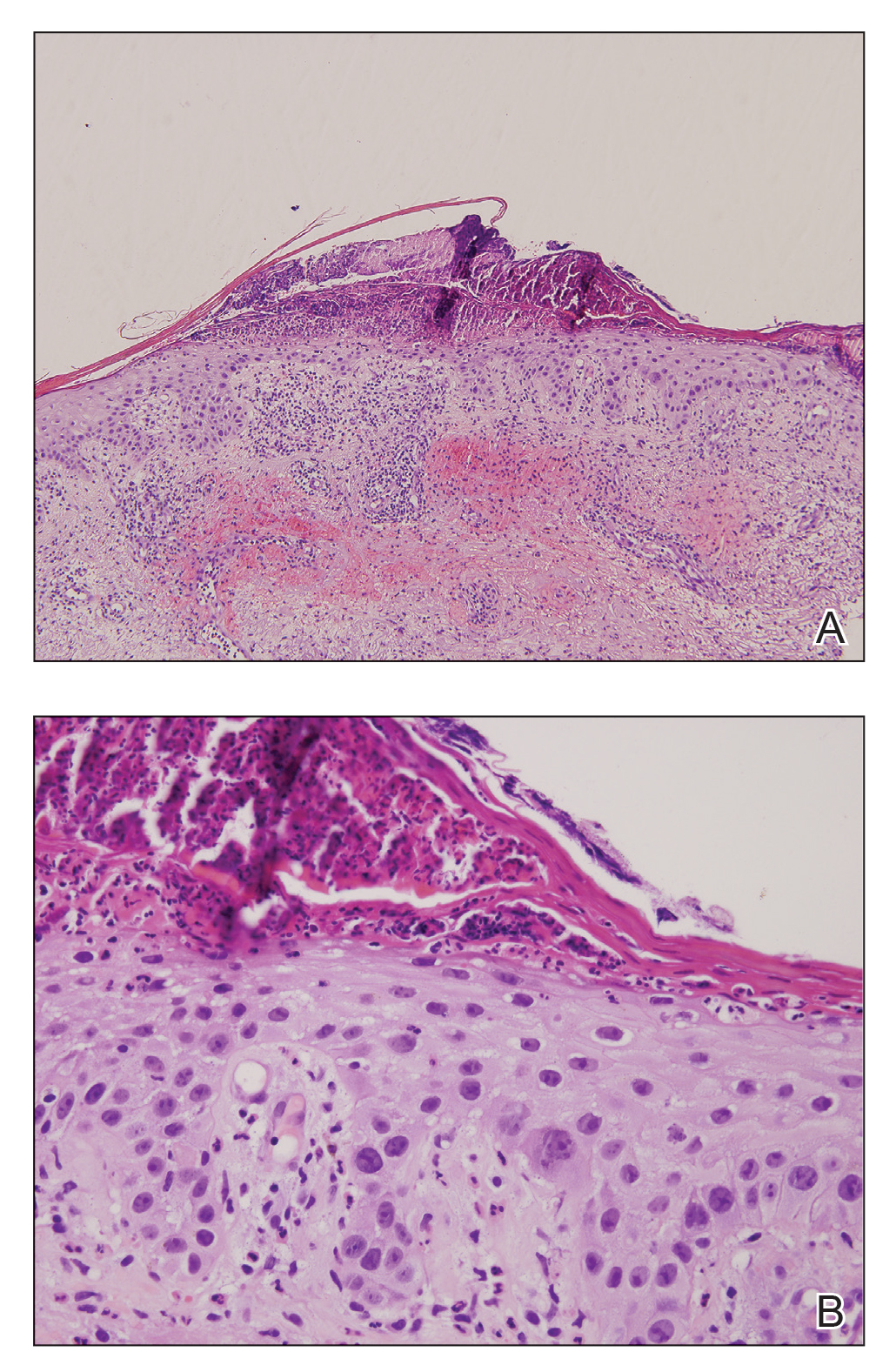

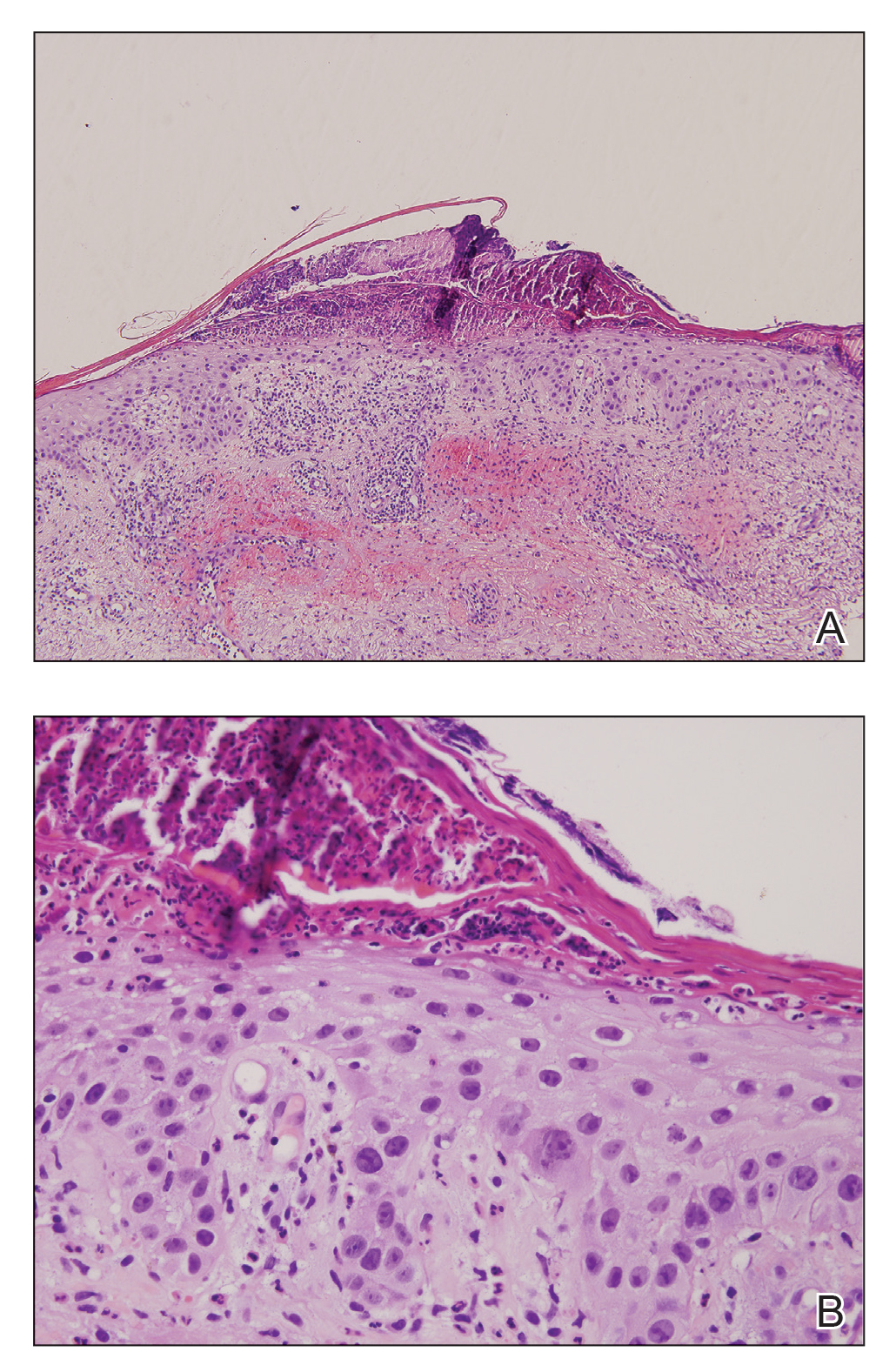

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

Practice Points

- Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is a rare benign condition that can arise in response to multiple underlying triggers such as tattoo pigment.

- Histopathologic evaluation is essential for diagnosis and shows characteristic hyperplasia of the epidermis.

- Clinicians should consider intralesional steroids in the treatment of PEH once atypical mycobacterial and deep fungal infections have been ruled out.

Lichen Planopilaris in a Patient Treated With Bexarotene for Lymphomatoid Papulosis

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

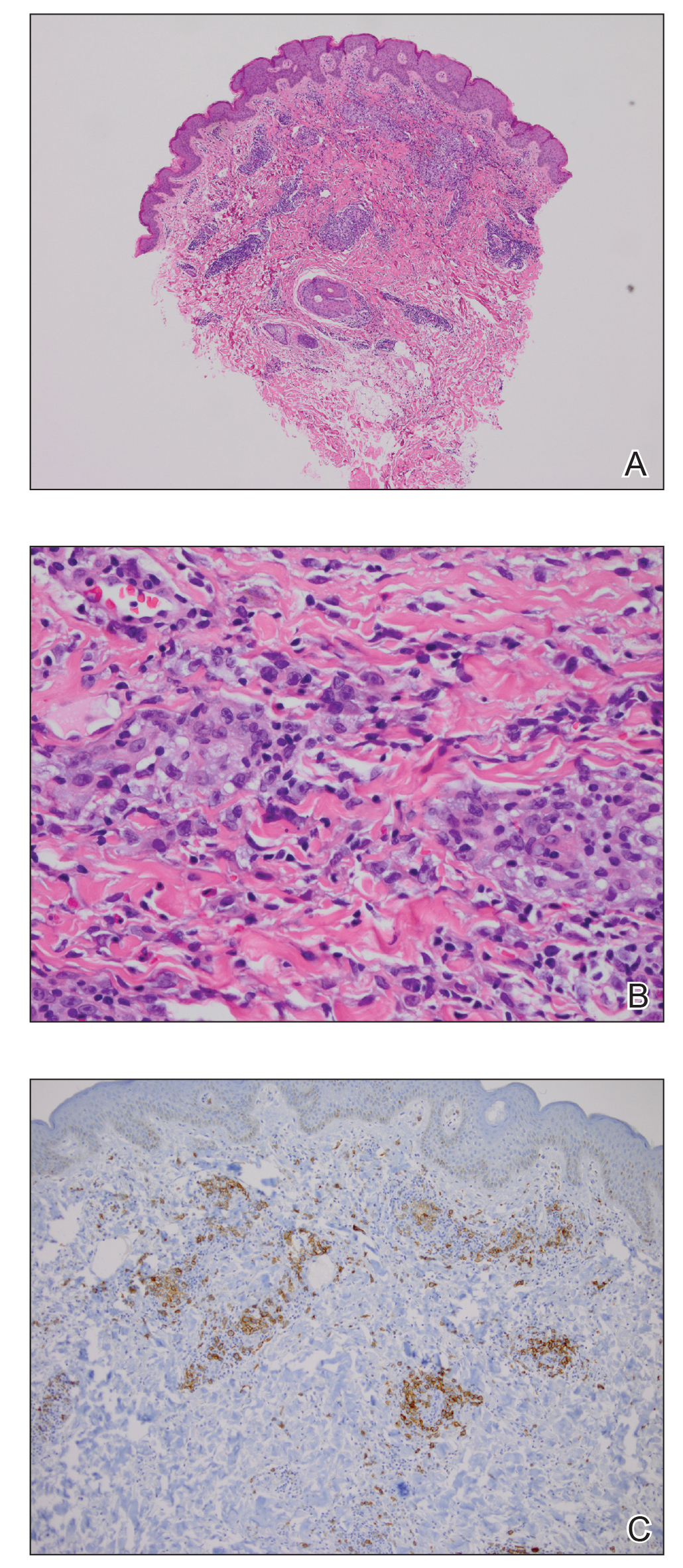

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

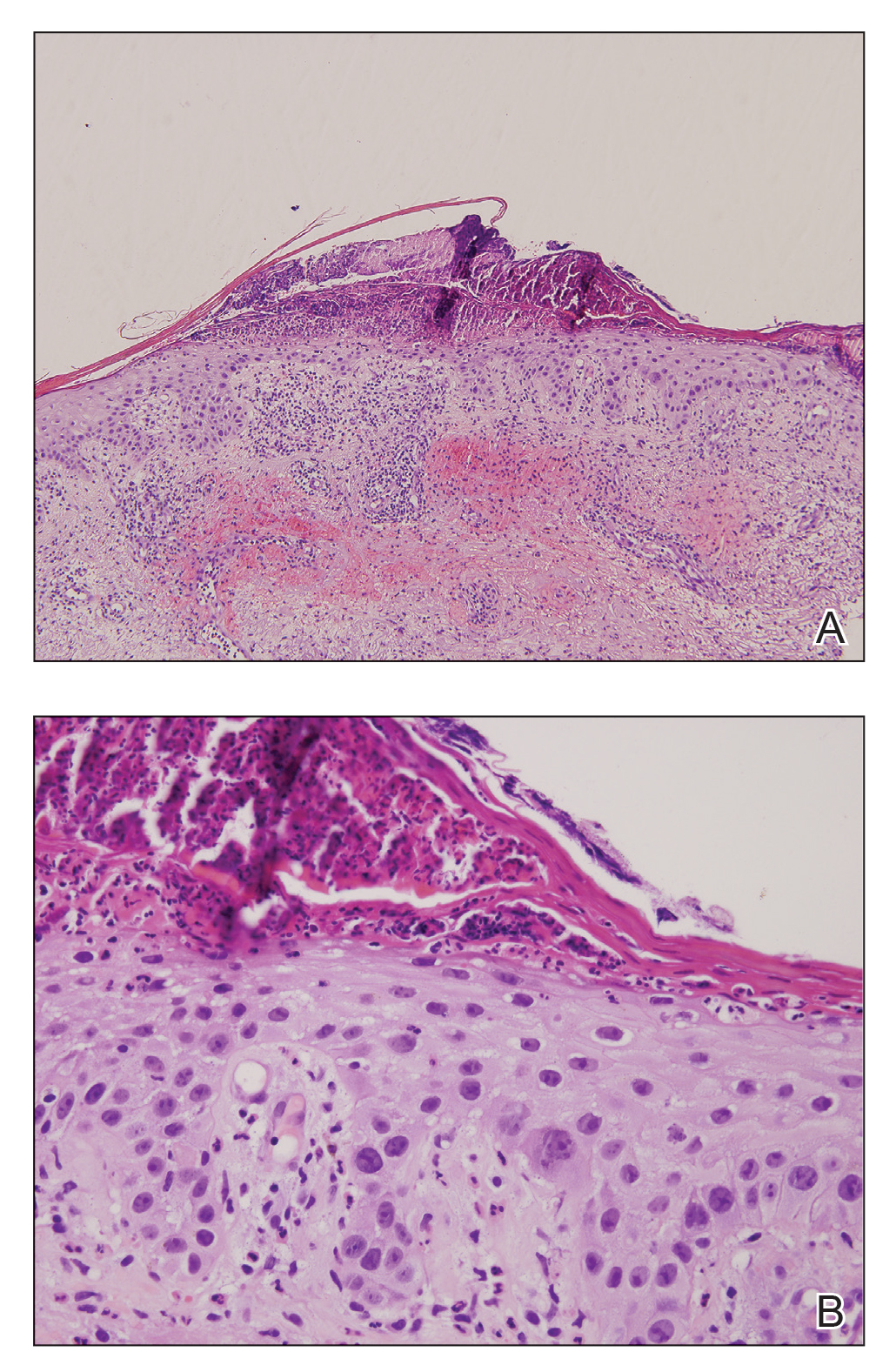

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent, self-healing crops of papulonodular eruptions, often resembling cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Oral bexarotene, a retinoid X receptor–selective retinoid, can be used to control the disease.2,3 Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is a type of cicatricial alopecia characterized by irreversible hair loss, perifollicular inflammation, and follicular hyperkeratosis, commonly affecting the scalp vertex in adults.4 We report a case of a patient with lymphomatoid papulosis who was treated with bexarotene and subsequently developed LPP. We also discuss a proposed mechanism by which bexarotene may have influenced the onset of LPP.

A 35-year-old woman who was previously healthy initially presented with recurrent pruritic papular eruptions on the flank, axillae, and groin of several months’ duration. The lesions appeared as 2-mm, flat-topped, violaceous papules. The patient had no known drug allergies, no medical or family history of skin disease, and was only taking 3000 mg/d of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil). Histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen from the inner thigh showed enlarged, atypical, dermal lymphocytes that were CD30+ (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. As she had undergone tubal ligation several years prior, she was prescribed oral bexarotene 300 mg once daily in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily, as needed. Symptoms were well controlled on this regimen.

Six months later the patient returned, presenting with a new central patch of scarring alopecia on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 2). Adjacent to the area of hair loss were areas of prominent perifollicular scale that were slightly violaceous in color. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the scalp showed dermal scarring with perifollicular lamellar fibrosis surrounded by a rim of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 3). Sebaceous glands were found to be reduced in number. These findings were consistent with cicatricial alopecia, which was further classified as LPP in conjunction with the clinical findings. No CD30+ lymphocytes were identified in these specimens.

Baseline fasting triglycerides were 123 mg/dL (desirable: <150 mg/dL; borderline: 150–199 mg/dL; high: ≥200 mg/dL) and were stable over the first 4 months on bexarotene. After 5 months of therapy, the triglycerides increased to a high of 255 mg/dL, which corresponded with the onset of LPP. She was treated for the hypertriglyceridemia with omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), and subsequent triglyceride levels have normalized and been stable. Her alopecia has not progressed but is persistent. She continues to have central hypothyroidism due to bexarotene and is on levothyroxine. The lymphomatoid papulosis also remains stable with no signs of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Although the exact mechanism of LPP is not fully understood, studies have suggested that cellular lipid metabolism may be responsible for the inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit.4-11 Hyperlipidemia is the most common side effect of oral bexarotene, typically occurring within the first 2 to 4 weeks of treatment.3,12 Considering the insights into the role of lipid regulation on LPP pathogenesis, it is reasonable to suspect that the dyslipidemia caused by bexarotene may have triggered the onset of LPP in our patient. The patient’s lipid values mostly remained within reference range throughout the course of treatment, though she did have elevation of triglycerides around the onset of LPP. Dyslipidemia has been reported in patients with lichen planus but not in patients with LPP. One case-control study showed no dyslipidemia in patients with LPP, but the triglyceride levels were not tracked over time and patients had varying durations since onset of disease at presentation.9-11,13 In our case, we were fortunate to have this information, and it may suggest an interaction between lipid dysregulation and the development of LPP. It would be interesting to explore this further in a larger patient population and to evaluate if control of dyslipidemia reduces progression of disease as it appears to have done for our patient.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

- Karp DL, Horn TD. Lymphomatoid papulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:379-395; quiz 396-398.

- Krathen RA, Ward S, Duvic M. Bexarotene is a new treatment option for lymphomatoid papulosis. Dermatology. 2003;206:142-147.

- Targretin (bexarotene) capsule [package insert]. St. Petersburg, FL: Cardinal Health; 2003. http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=63656f64-e240-4855-8df9-ca1655863735. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3-10.

- Dogra S, Sarangal R. What’s new in cicatricial alopecia? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:576-90.

- Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, et al. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268-270.

- Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, et al. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067-2075.

- Karnik P, Tekeste Z, McCormick TS, et al. Hair follicle stem cell-specific PPARgamma deletion causes scarring alopecia. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1243-157.

- López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Rodríguez-Martínes MA. Alterations in serum lipid profile patterns in oral lichen planus: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:399-404.

- Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Aneiros-Fernández J, et al. Lipid levels in patients with lichen planus: a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1398-1401.

- Dreiher J, Shapiro J, Cohen AD. Lichen planus and dyslipidaemia: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:626-629.

- de Vries-van der Weij J, de Haan W, Hu L, et al. Bexarotene induces dyslipidemia by increased very low-density lipoprotein production and cholesteryl ester transfer protein-mediated reduction of high-density lipoprotein. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2368-2375.

- Conic RRZ, Piliang M, Bergfeld W, et al. Association of lichen planopilaris with dyslipidemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1088-1089.

Practice Points

- Oral retinoids may be associated with development of lichen planopilaris (LPP).

- Hypertriglyceridemia may be associated with onset of LPP.

Tuberous Sclerosis With Segmental Overgrowth

To the Editor:

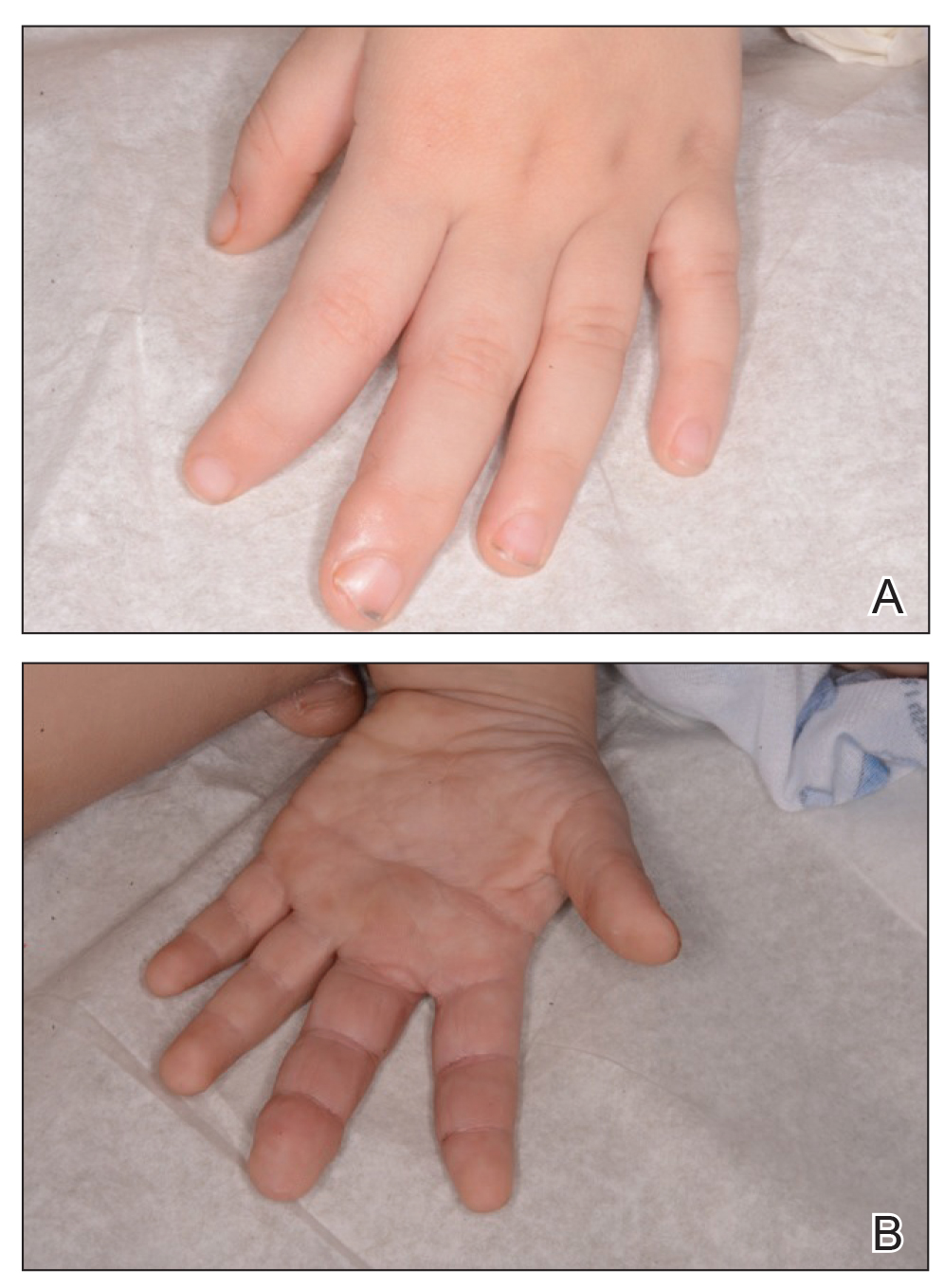

A 3-year-old boy with a history of tuberous sclerosis presented to our clinic for evaluation of bumps on the second and third fingers of the left hand. Physical examination revealed firm rubbery nodules on the palmar third metacarpophalangeal joint extending to the palm and the lateral aspect of the distal third dorsal finger. There also was asymmetric overgrowth of the left second and third digits consistent with bony segmental overgrowth (Figure).

Tuberous sclerosis and overgrowth syndromes including Proteus syndrome have mutations that share a common pathway, namely the PI3K/AKT/mTOR (phosphoinositide 3-kinase/alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway.1 The mutations in tuberous sclerosis involve the loss of TSC1 (TSC complex subunit 1) on chromosome 9 or TSC2 (TSC complex subunit 2) on chromosome 16.2 The protein products of these genes, hamartin and tuberin, act together as a tumor suppressor complex.3 The inheritance pattern of tuberous sclerosis is autosomal dominant, though two-thirds of cases are due to de novo germline mutations.4 The second copy of the gene must be lost spontaneously in any particular cell for the deleterious effects of the disease to manifest. The mutation in overgrowth syndromes including Proteus syndrome involves the activation of AKT1 (AKT serine/threonine kinase 1) on chromosome 14. This mutation occurs in somatic cells as opposed to germ cells, as in tuberous sclerosis. This difference accounts for the mosaic expression of segmental overgrowth syndromes. This concept has been demonstrated in overgrowth syndromes such as Proteus syndrome, with cells from unaffected areas having different genetic makeup than those from affected tissues.5 These mutations, though different, result in the downstream effects of unchecked messenger RNA translation and dysregulated cellular growth.

In our patient, we hypothesized that a small proportion of his postfertilization somatic cells underwent a second de novo mutation in the AKT1 pathway, resulting in the bony overgrowth seen on the left hand. We suspected that this second mutation could be an activation of AKT1, the mutation seen in Proteus syndrome. Sequencing of the tissue may be performed in the future, especially if segmental overgrowth continues and necessitates therapy.

- Wu Y, Zhou BP. Kinases meet at TSC. Cell Res. 2007;17:971-973.

- Roach SE, Sparagana SP. Diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:643-649.

- Barker KT, Houlston RS. Overgrowth syndromes: is dysfunctional PI3-kinase signaling a unifying mechanism? Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:665-670.

- Nothrup H, Koenig MK, Au KS. Tuberous sclerosis complex. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1999.

- Lindhurst MJ, Parker VE, Payne F, et al. Mosaic overgrowth with fibroadipose hyperplasia is caused by somatic activating mutations in PIK3CA. Nat Genet. 2012;44:928-933.

To the Editor:

A 3-year-old boy with a history of tuberous sclerosis presented to our clinic for evaluation of bumps on the second and third fingers of the left hand. Physical examination revealed firm rubbery nodules on the palmar third metacarpophalangeal joint extending to the palm and the lateral aspect of the distal third dorsal finger. There also was asymmetric overgrowth of the left second and third digits consistent with bony segmental overgrowth (Figure).

Tuberous sclerosis and overgrowth syndromes including Proteus syndrome have mutations that share a common pathway, namely the PI3K/AKT/mTOR (phosphoinositide 3-kinase/alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway.1 The mutations in tuberous sclerosis involve the loss of TSC1 (TSC complex subunit 1) on chromosome 9 or TSC2 (TSC complex subunit 2) on chromosome 16.2 The protein products of these genes, hamartin and tuberin, act together as a tumor suppressor complex.3 The inheritance pattern of tuberous sclerosis is autosomal dominant, though two-thirds of cases are due to de novo germline mutations.4 The second copy of the gene must be lost spontaneously in any particular cell for the deleterious effects of the disease to manifest. The mutation in overgrowth syndromes including Proteus syndrome involves the activation of AKT1 (AKT serine/threonine kinase 1) on chromosome 14. This mutation occurs in somatic cells as opposed to germ cells, as in tuberous sclerosis. This difference accounts for the mosaic expression of segmental overgrowth syndromes. This concept has been demonstrated in overgrowth syndromes such as Proteus syndrome, with cells from unaffected areas having different genetic makeup than those from affected tissues.5 These mutations, though different, result in the downstream effects of unchecked messenger RNA translation and dysregulated cellular growth.

In our patient, we hypothesized that a small proportion of his postfertilization somatic cells underwent a second de novo mutation in the AKT1 pathway, resulting in the bony overgrowth seen on the left hand. We suspected that this second mutation could be an activation of AKT1, the mutation seen in Proteus syndrome. Sequencing of the tissue may be performed in the future, especially if segmental overgrowth continues and necessitates therapy.

To the Editor: