User login

Locus Minoris Resistentiae: Mycobacterium chelonae in Striae Distensae

To the Editor:

Immunosuppressed patients are at particular risk for disseminated mycobacterial infections. A locus minoris resistentiae offers less resistance to the infectious spread of these microorganisms. We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae infection preferentially involving striae distensae.

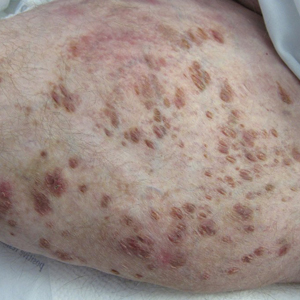

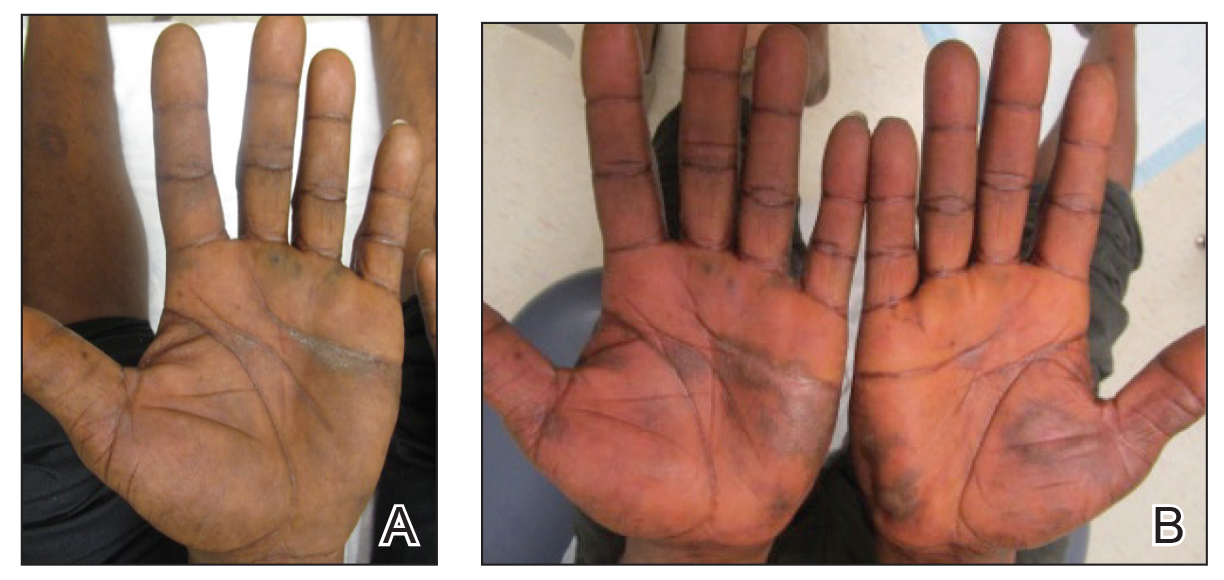

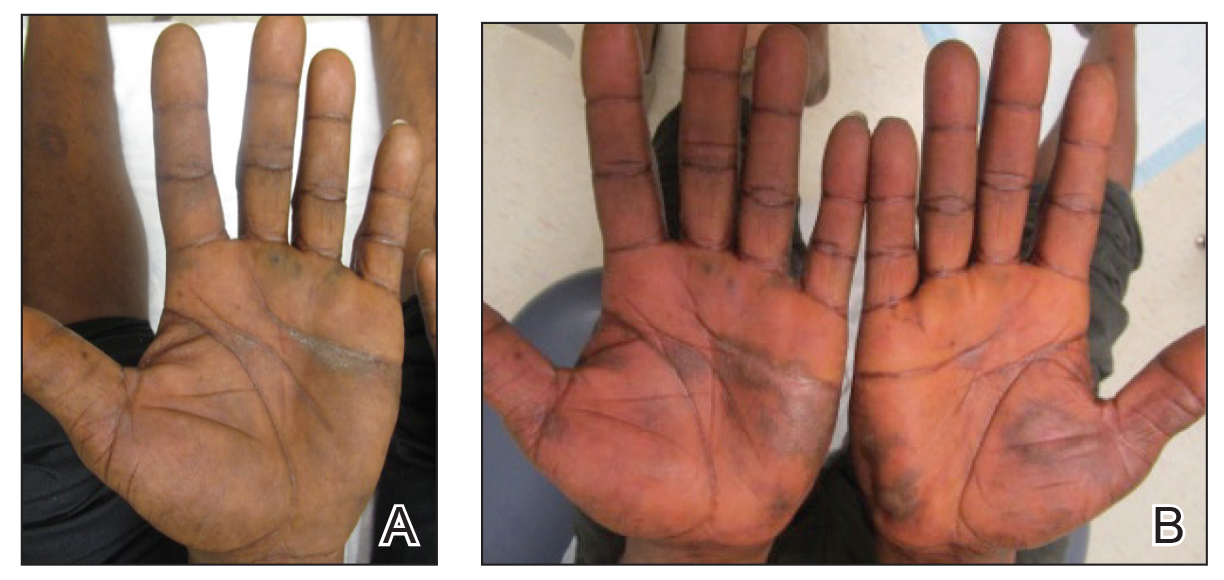

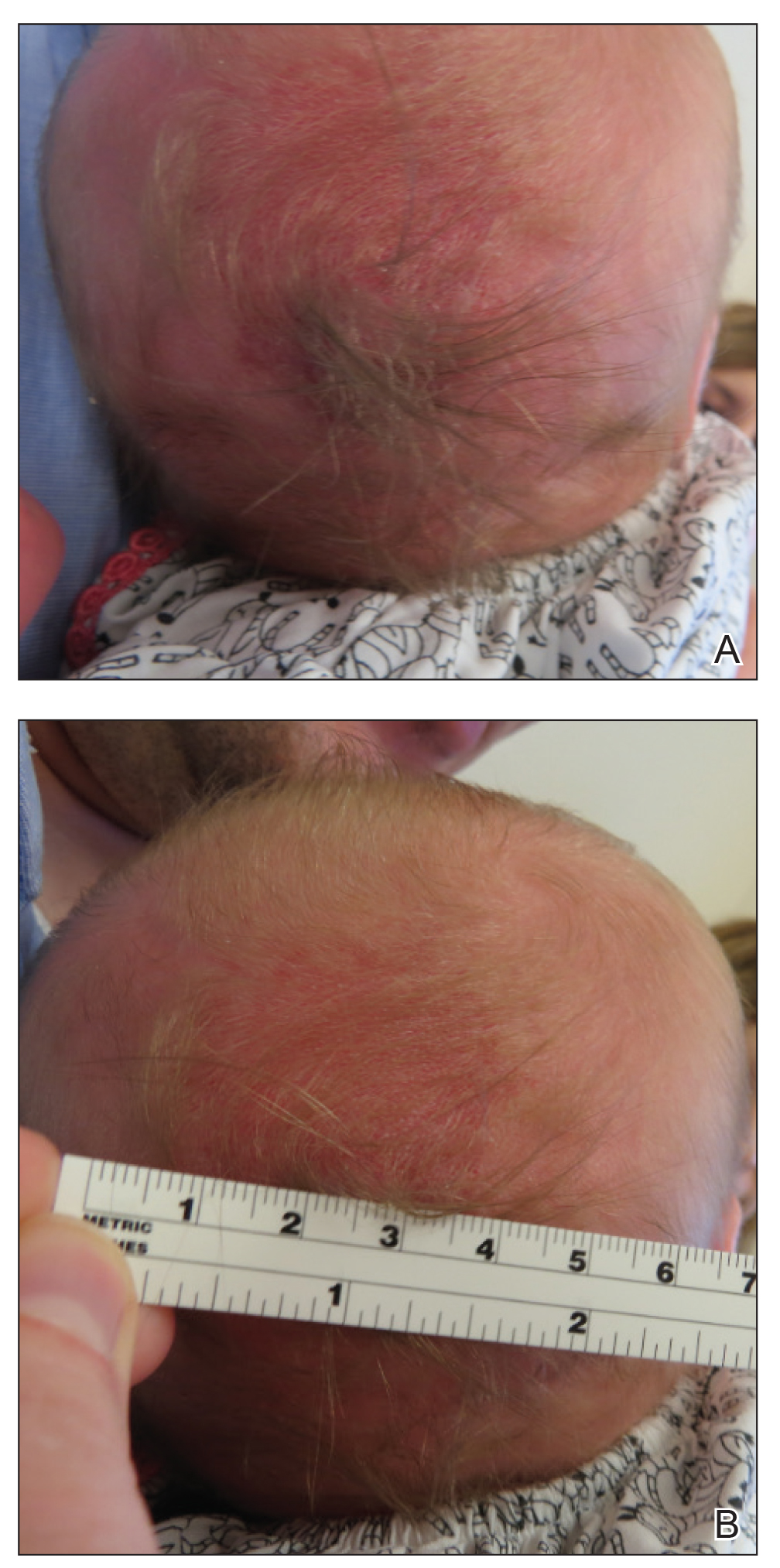

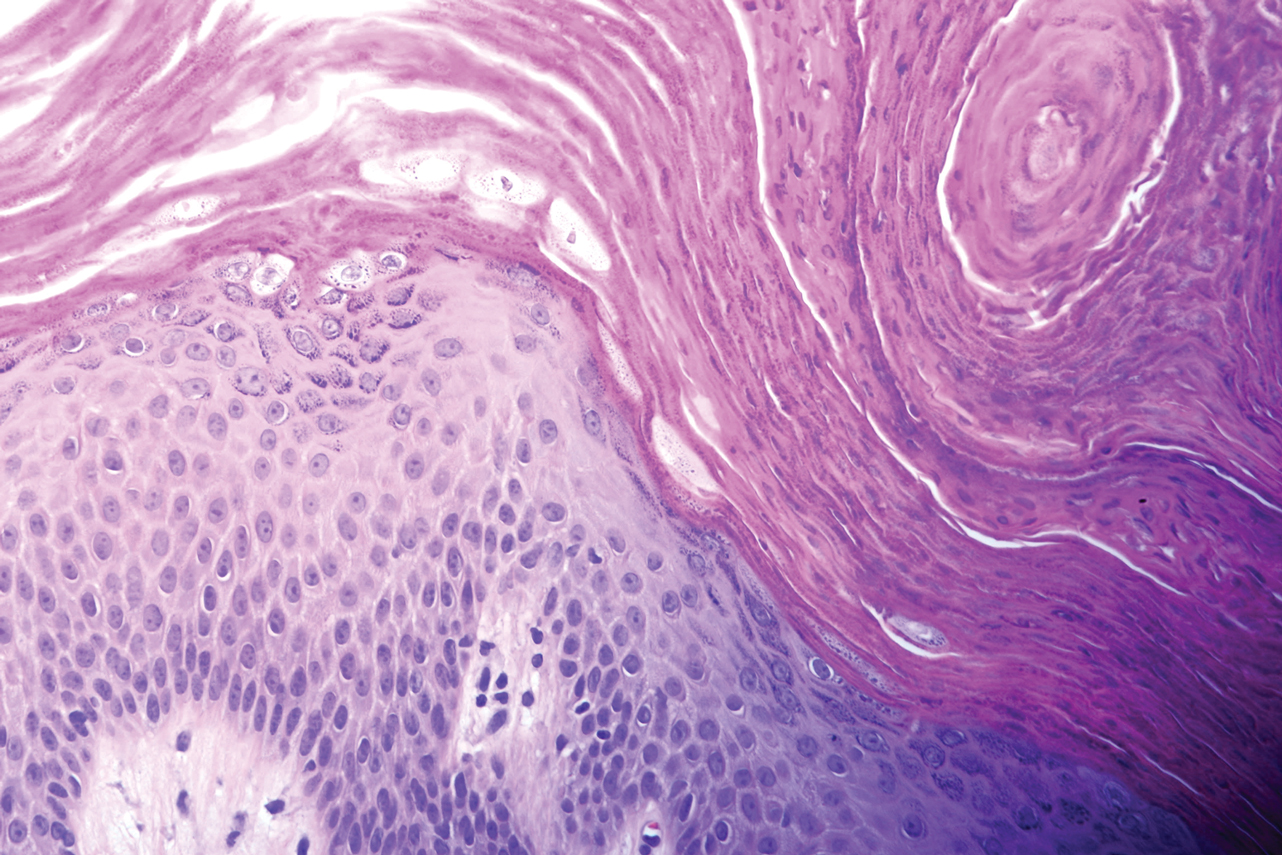

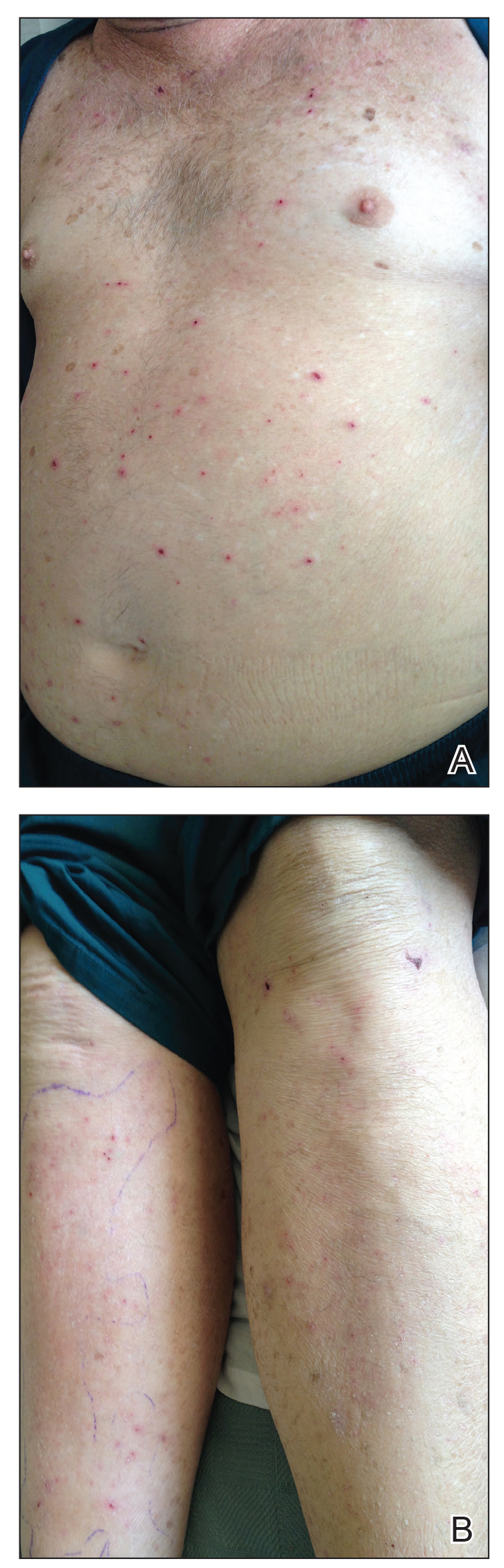

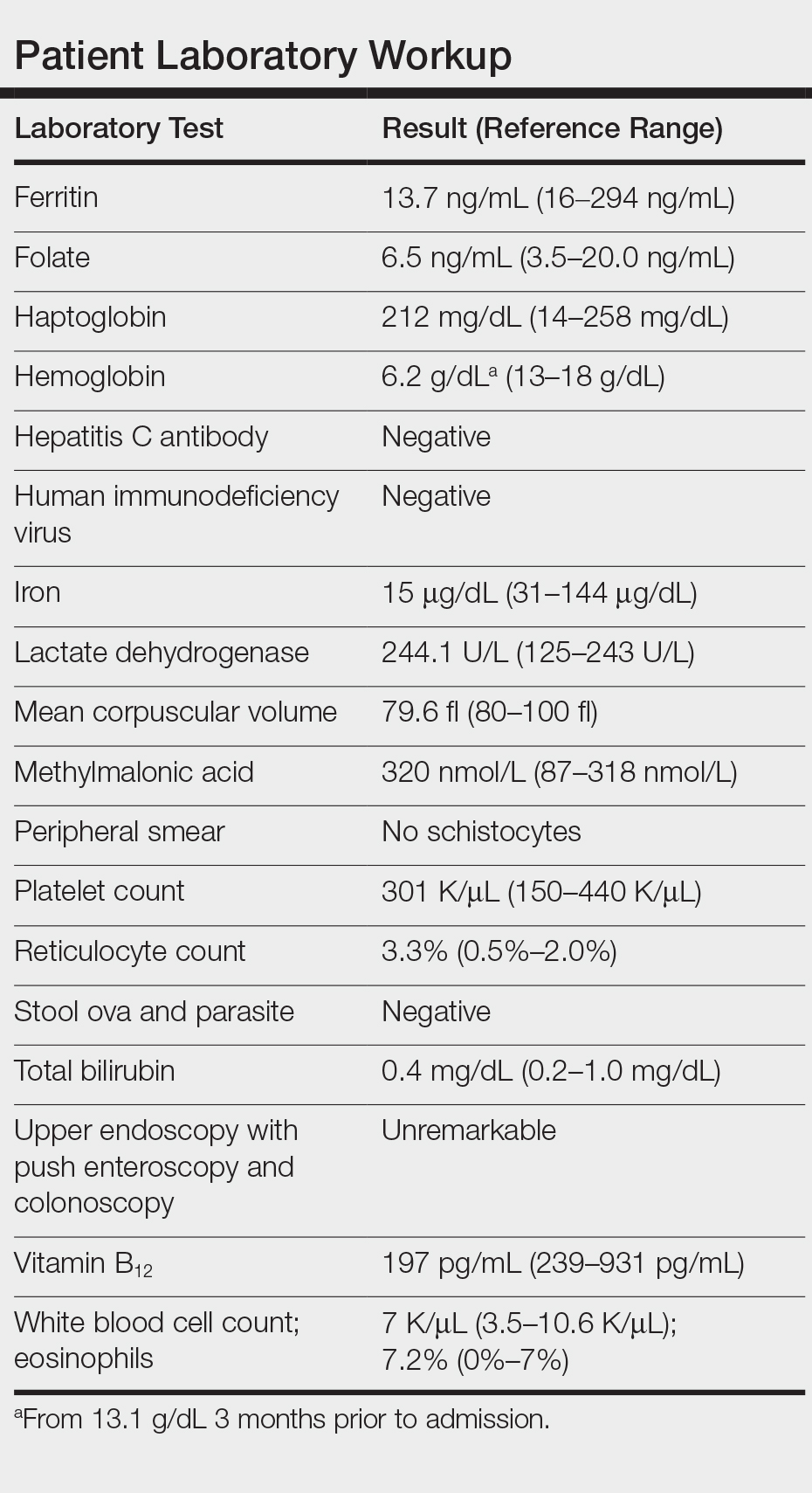

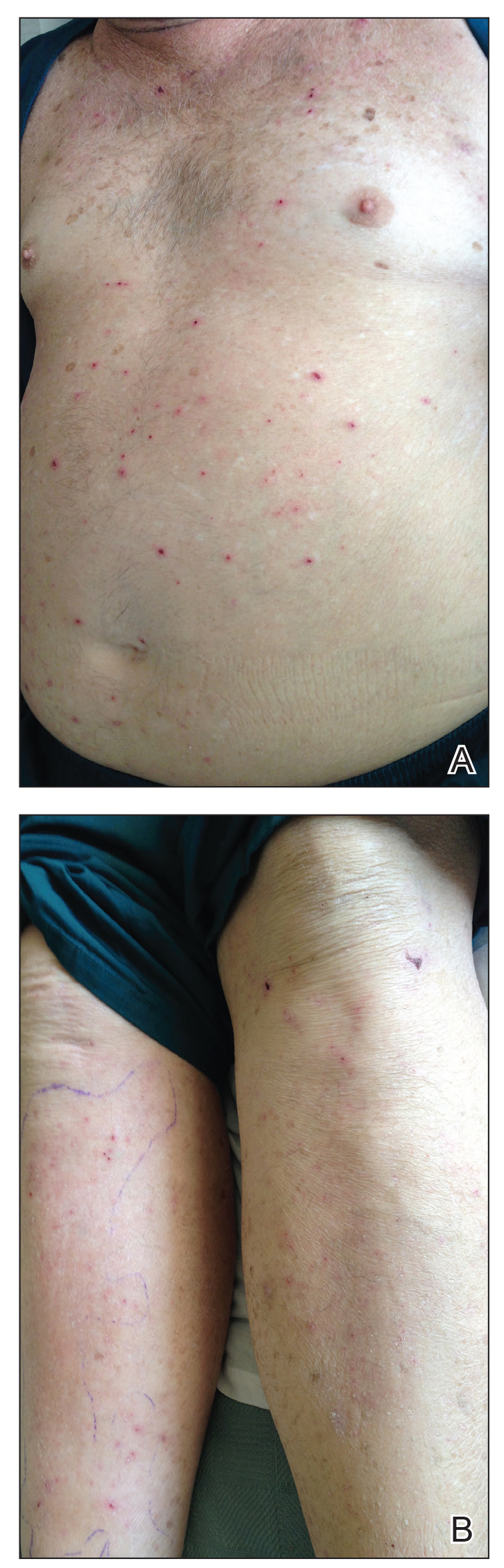

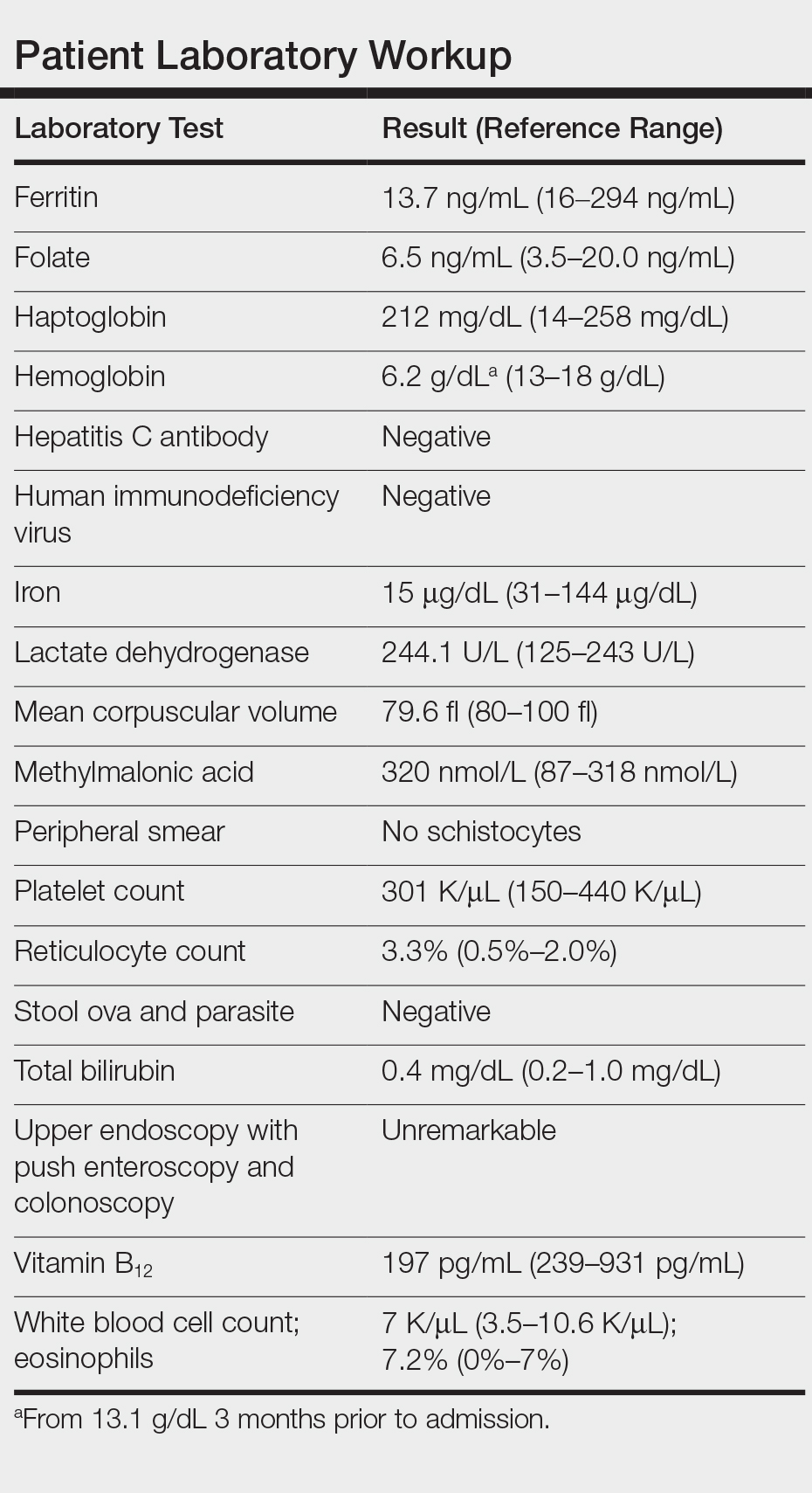

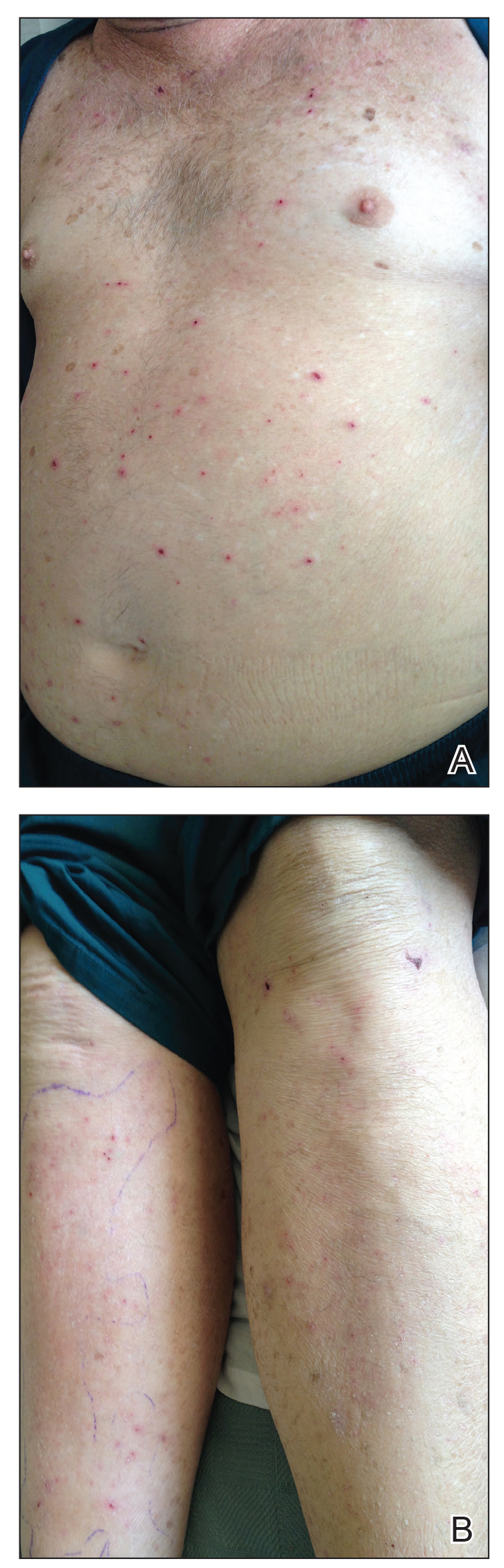

A 30-year-old man with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia requiring high-dose corticosteroid therapy presented with widespread skin lesions. He reported no history of cutaneous trauma or aquatic activities. Physical examination revealed the patient was markedly cushingoid with generalized cutaneous atrophy and widespread striae. Multiple erythematous papules surrounded a large ulceration on the dorsal aspect of the left hand. Depressed erythematous plaques and several small crusted erosions extended up the left lower leg (Figure 1) to the knee. Strikingly, numerous brown and pink papules and small plaques on the left thigh were primarily confined within striae (Figure 2).

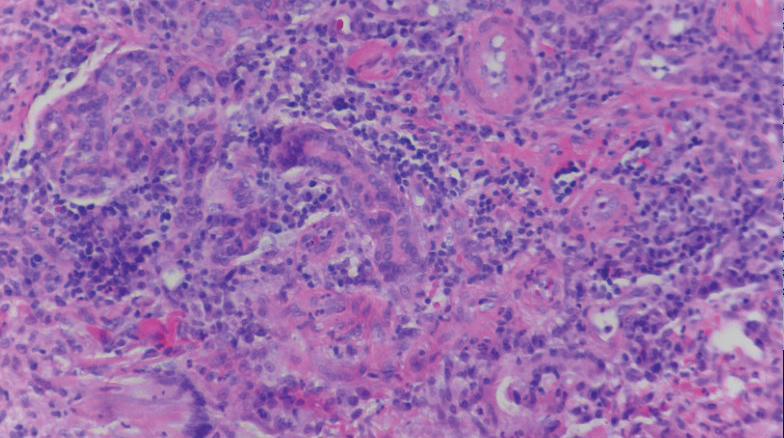

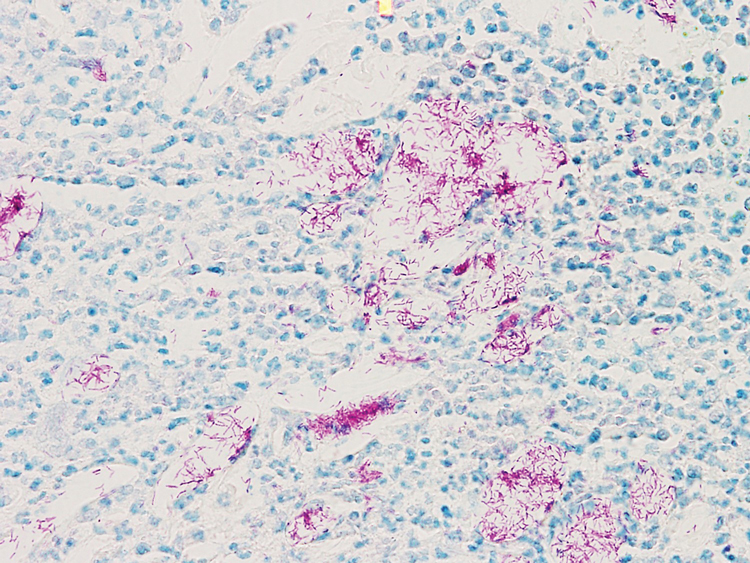

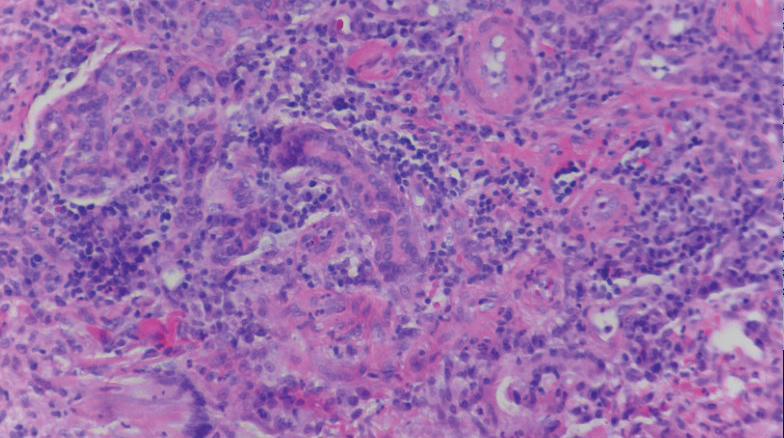

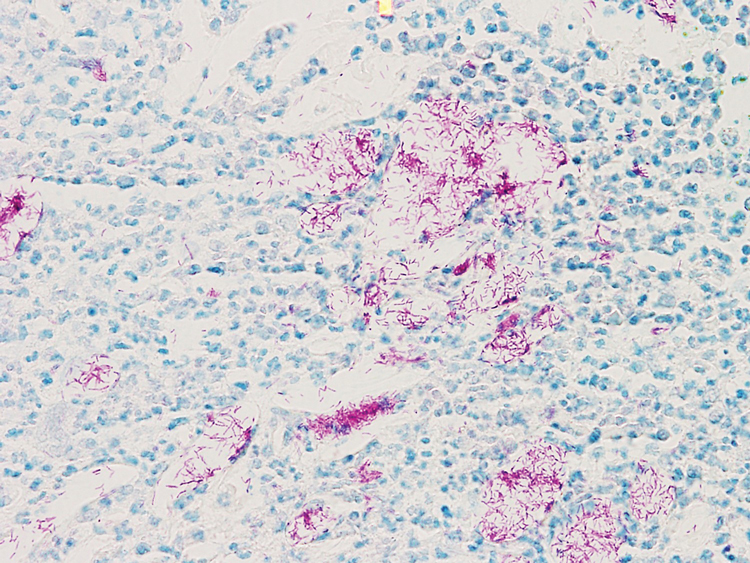

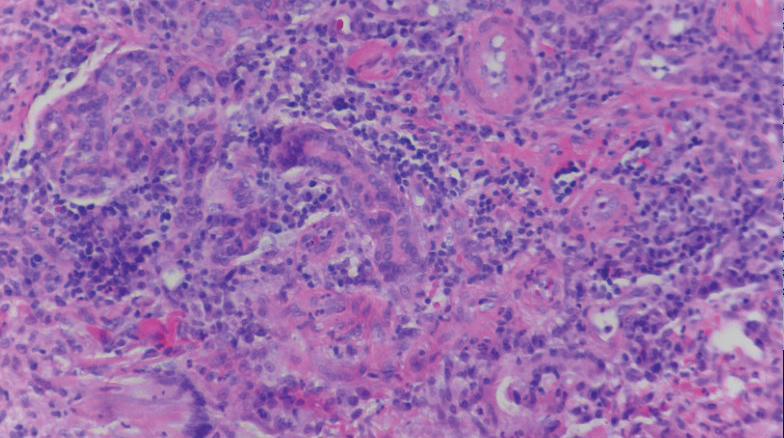

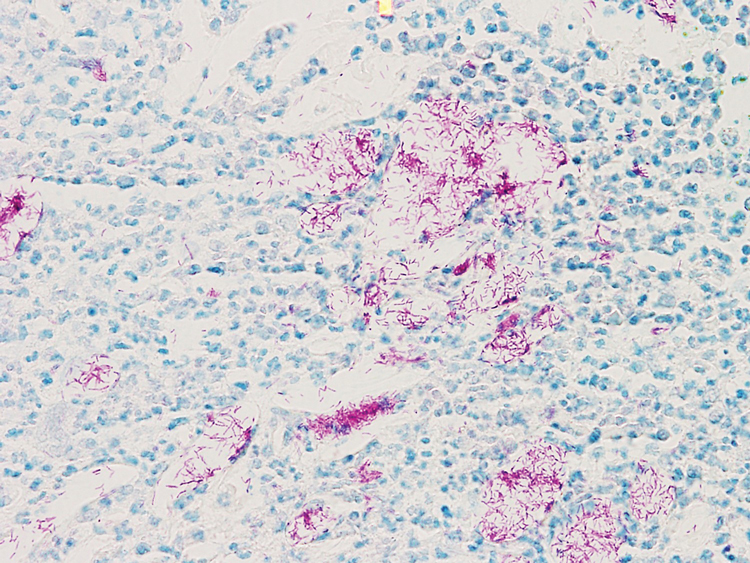

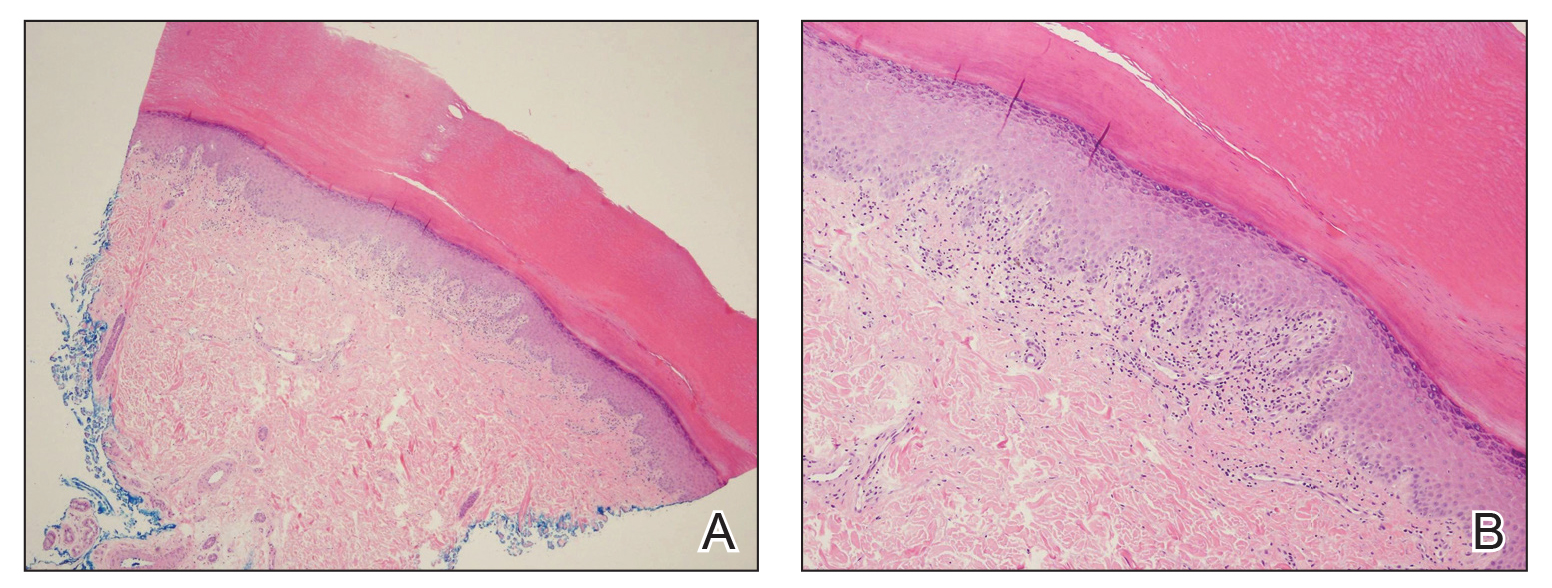

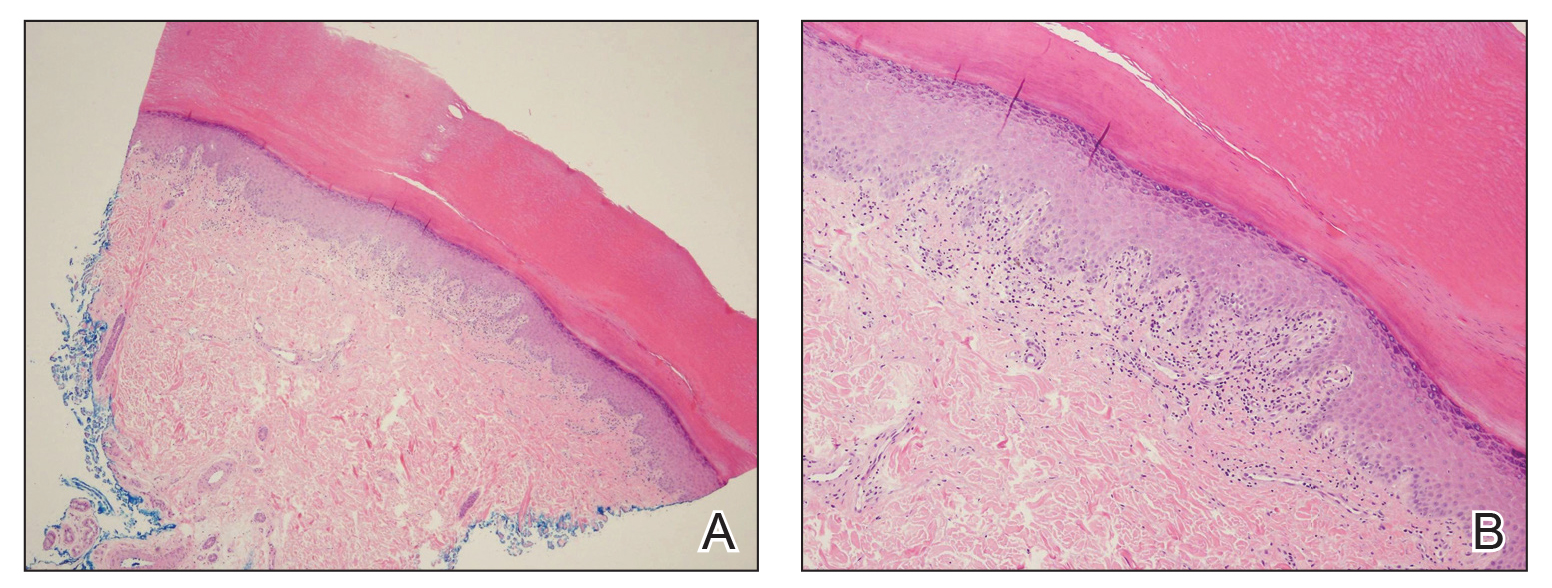

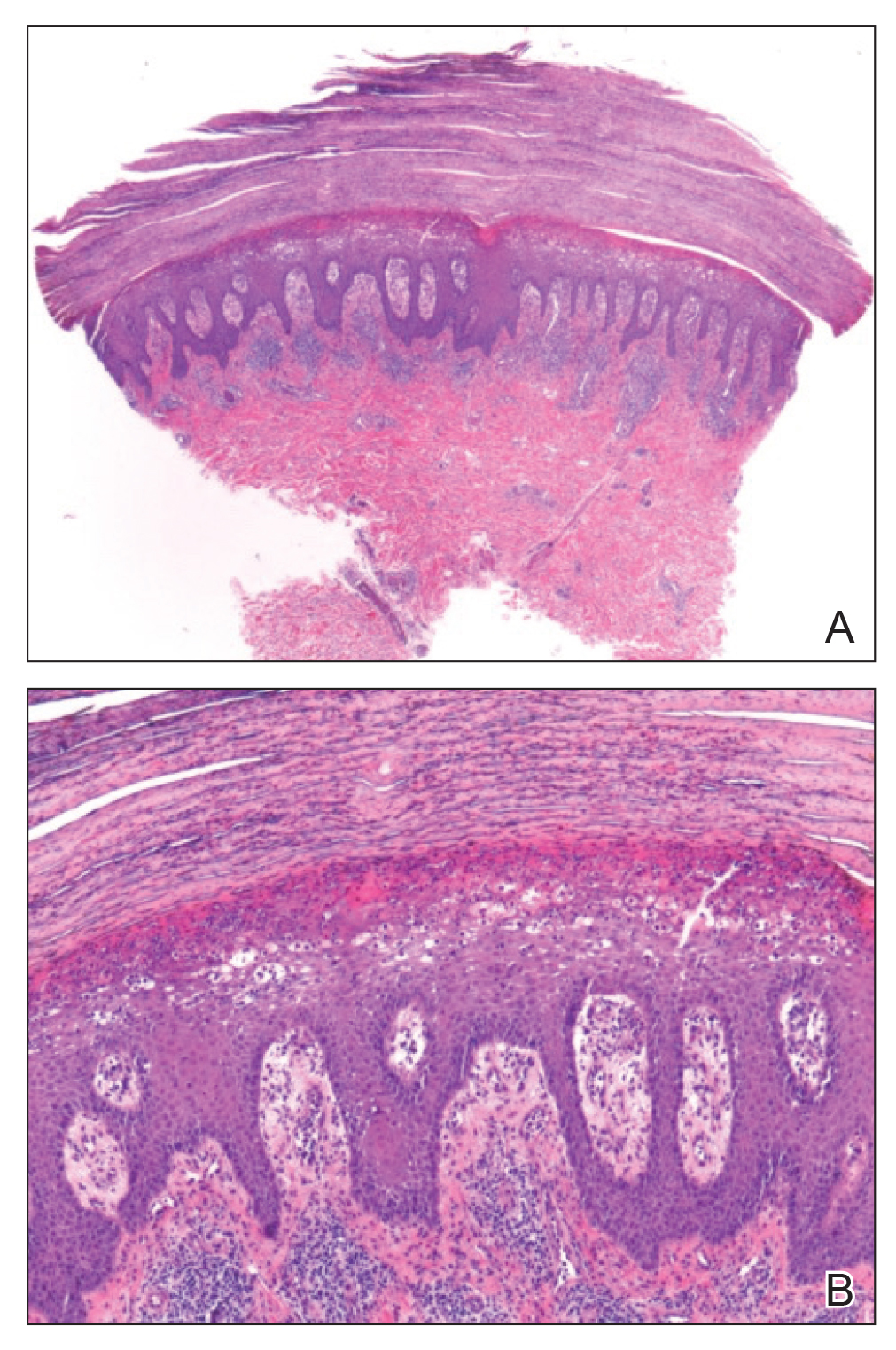

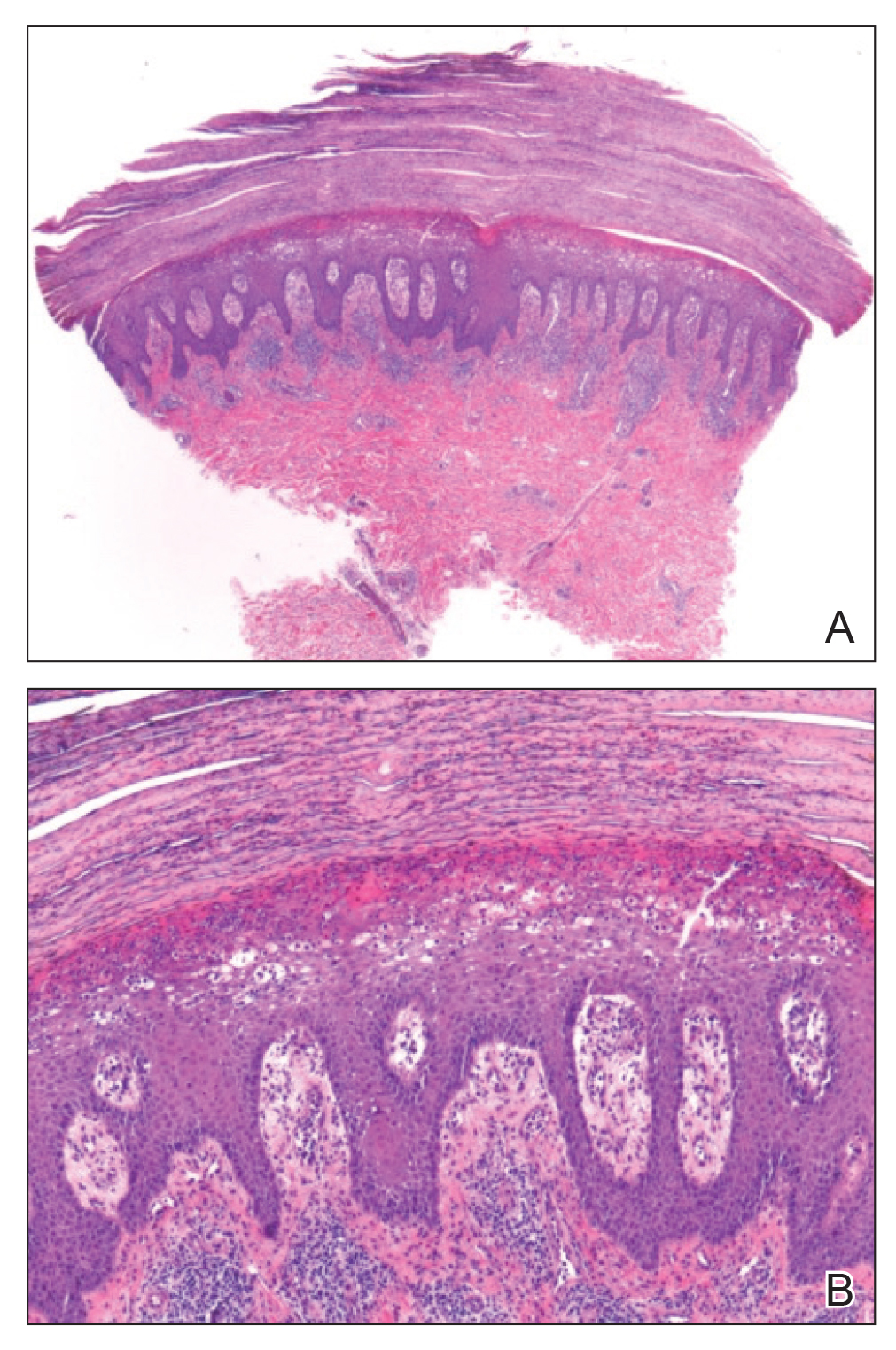

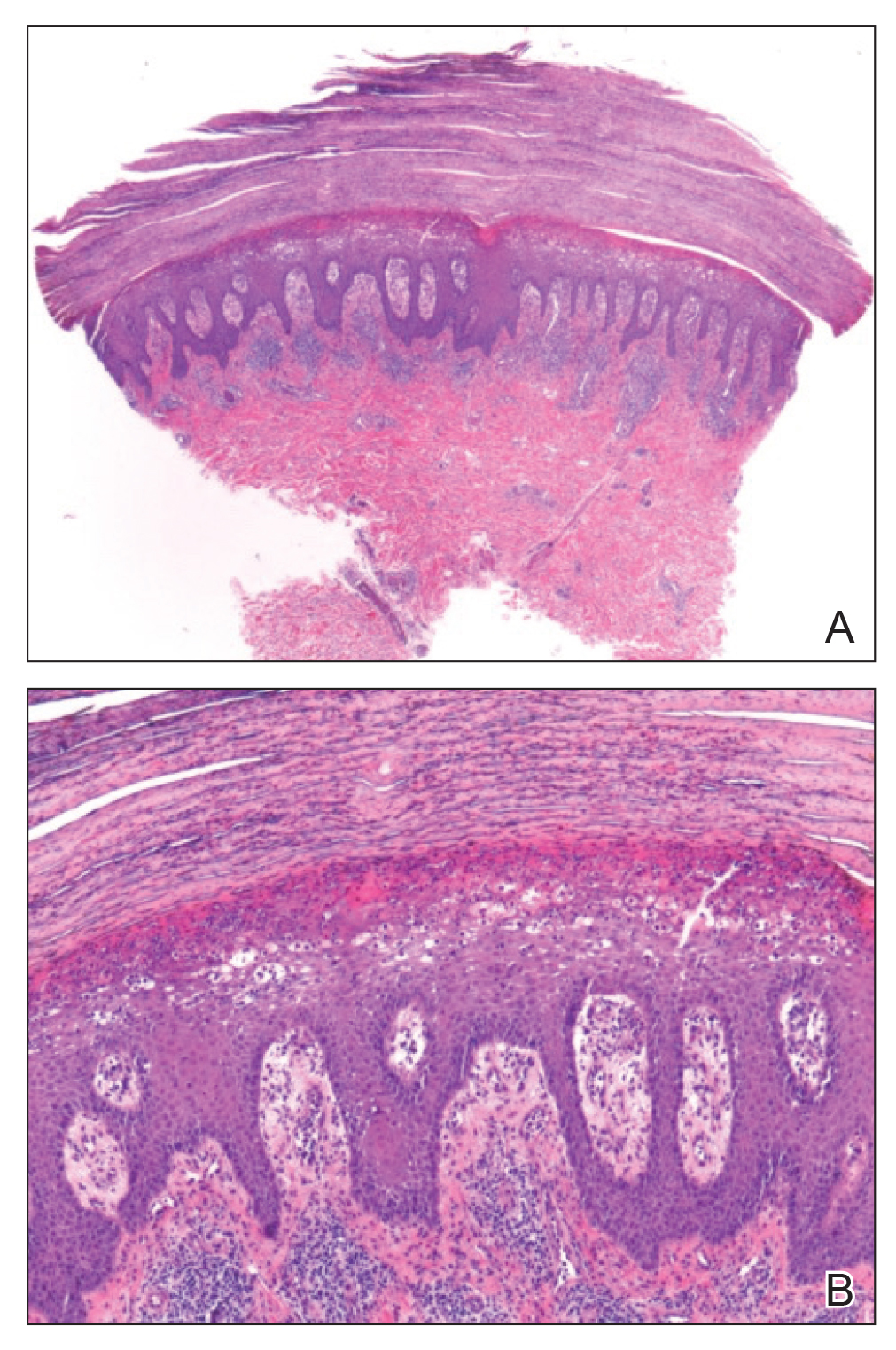

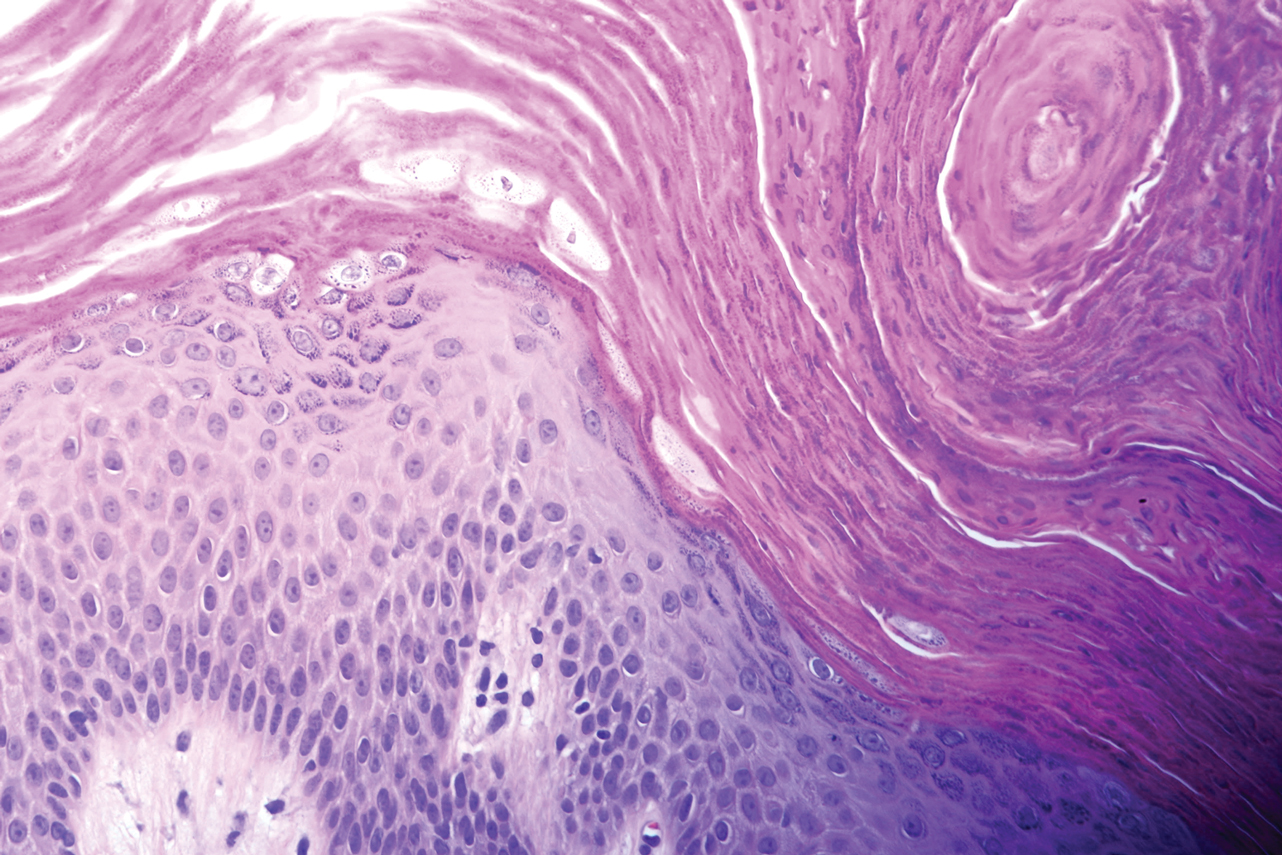

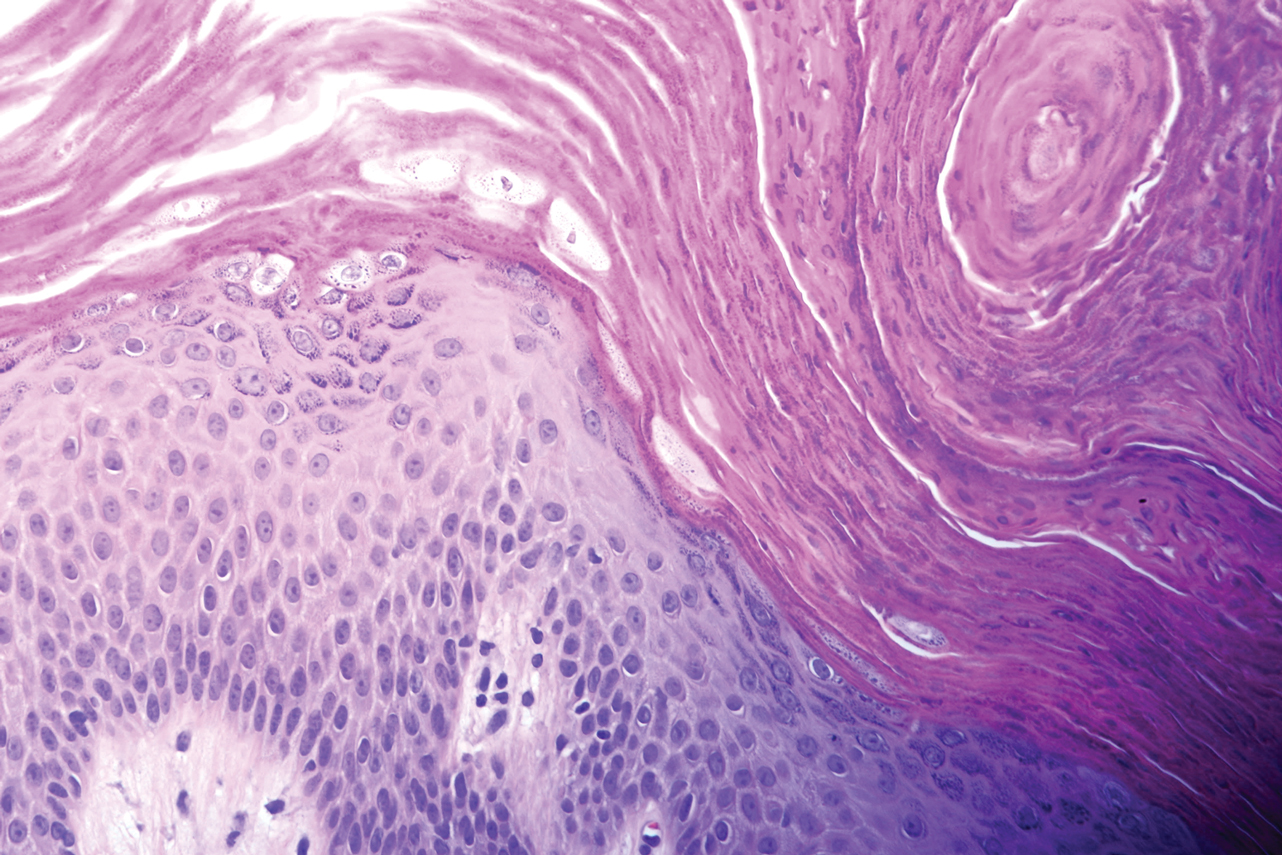

A biopsy of the left thigh revealed granulomatous inflammation (Figure 3) with numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 4). Broad-spectrum coverage for fast-growing acid-fast bacilli with amikacin, ceftriaxone, levofloxacin, and clarithromycin was initiated with steady improvement of the eruption. Tissue culture subsequently grew Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae, and therapy was narrowed to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin.

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing mycobacteria isolated from soil and water worldwide, and human skin is a commensal organism. Cutaneous infections have been associated with traumatic injury, tattooing, surgery, cosmetic procedures, vascular access sites, and acupuncture.1 Most cases of cutaneous M chelonae infection begin as a violaceous nodule. Over weeks to months, the localized infection progresses to multiple papules, nodules, draining abscesses, or ulcers. Infections tend to disseminate in immunosuppressed patients, and granulomatous inflammation may not be seen.1

Atypical mycobacterial infection occurring within striae distensae is an example of locus minoris resistentiae—a place of less resistance. Wolf et al2 hypothesized that locus minoris resistentiae could explain the occurrence of an isotopic response or the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed skin condition. They suggested that the same site could be affected by 2 unrelated diseases at different times due to an inherited or acquired susceptibility in the area.2 Herpes zoster serves as a primary example of Wolf phenomenon, as numerous conditions including granuloma annulare, pseudolymphoma, Bowen disease, and acne have reportedly emerged in its wake.3

Although locus minoris resistentiae does not specifically involve traumatized skin, it must be distinguished from the Koebner phenomenon, characterized by the appearance of isomorphic lesions in areas of otherwise healthy skin subjected to cutaneous injury, as well as the pseudo-Koebner phenomenon, a similar process involving infectious agents.3

In our patient, striae distensae represented areas of increased predisposition to infection. The catabolic effect of high corticosteroid levels on fibroblast activity decreased collagen deposition in the dermal matrix, leading to the formation of linear bands of atrophic skin.4 The elastic fiber network in striae distensae is reduced and reorganized compared to normal skin, in which an intertwining elastic system forms a continuum from the dermoepidermal junction to the deep dermis.5 The number of vertically oriented fibrillin microfibrils subjacent to the dermoepidermal junction and elastin fibers in the papillary dermis is comparatively diminished such that the elastin and fibrillin fibers in the deep dermis run more horizontally compared to normal skin.4 Consequently, collagen alignment in striae distensae demonstrates more anisotropy, or directionally dependent variability, and the dermal matrix is looser and more floccular than the surrounding skin.6 These alterations of dermal architecture likely provide a mechanical advantage for intradermal spread of M chelonae within striae.

Other dermatoses have been observed to occur within striae distensae, specifically leukemia cutis, urticarial vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, keloids, linear focal elastosis, chronic graft-vs-host disease, psoriasis, gestational pemphigoid, and vitiligo.7 Given the dissimilarities of these conditions, the distinctive milieu of striae must provide an invitation—a locus minoris resistentiae—for secondary pathology.

Chronic corticosteroid use leads to both immunosuppression and striae distensae, effectively creating a perfect storm for an atypical mycobacterial skin infection demonstrating locus minoris resistentiae. The immunosuppressed state makes patients more susceptible to infection, and striae distensae may serve as a conduit for the offending organisms.

Acknowledgments—We are indebted to Letty Peterson, MD (Vidalia, Georgia), for her referral of this case, and to Stephen Mullins, MD (Augusta, Georgia), for his dermatopathology services.

- Hay RJ. Mycobacterium chelonae—a growing problem in soft tissue infection. Cur Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:99-101.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Medeiros do Santos Camargo C, Brotas AM, Ramos-e-Silva M, et al. Isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:741-749.

- Watson REB, Parry EJ, Humphries JD, et al. Fibrillin microfibrils are reduced in skin exhibiting striae distensae. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:931-397.

- Bertin C, A Lopes-DaCunha, Nkengne A, et al. Striae distensae are characterized by distinct microstructural features as measured by non-invasive methods in vivo. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:81-86.

- Elsaie ML, Baumann LS, Elsaaiee LT. Striae distensae (stretch marks) and different modalities of therapy: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:563-573.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

To the Editor:

Immunosuppressed patients are at particular risk for disseminated mycobacterial infections. A locus minoris resistentiae offers less resistance to the infectious spread of these microorganisms. We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae infection preferentially involving striae distensae.

A 30-year-old man with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia requiring high-dose corticosteroid therapy presented with widespread skin lesions. He reported no history of cutaneous trauma or aquatic activities. Physical examination revealed the patient was markedly cushingoid with generalized cutaneous atrophy and widespread striae. Multiple erythematous papules surrounded a large ulceration on the dorsal aspect of the left hand. Depressed erythematous plaques and several small crusted erosions extended up the left lower leg (Figure 1) to the knee. Strikingly, numerous brown and pink papules and small plaques on the left thigh were primarily confined within striae (Figure 2).

A biopsy of the left thigh revealed granulomatous inflammation (Figure 3) with numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 4). Broad-spectrum coverage for fast-growing acid-fast bacilli with amikacin, ceftriaxone, levofloxacin, and clarithromycin was initiated with steady improvement of the eruption. Tissue culture subsequently grew Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae, and therapy was narrowed to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin.

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing mycobacteria isolated from soil and water worldwide, and human skin is a commensal organism. Cutaneous infections have been associated with traumatic injury, tattooing, surgery, cosmetic procedures, vascular access sites, and acupuncture.1 Most cases of cutaneous M chelonae infection begin as a violaceous nodule. Over weeks to months, the localized infection progresses to multiple papules, nodules, draining abscesses, or ulcers. Infections tend to disseminate in immunosuppressed patients, and granulomatous inflammation may not be seen.1

Atypical mycobacterial infection occurring within striae distensae is an example of locus minoris resistentiae—a place of less resistance. Wolf et al2 hypothesized that locus minoris resistentiae could explain the occurrence of an isotopic response or the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed skin condition. They suggested that the same site could be affected by 2 unrelated diseases at different times due to an inherited or acquired susceptibility in the area.2 Herpes zoster serves as a primary example of Wolf phenomenon, as numerous conditions including granuloma annulare, pseudolymphoma, Bowen disease, and acne have reportedly emerged in its wake.3

Although locus minoris resistentiae does not specifically involve traumatized skin, it must be distinguished from the Koebner phenomenon, characterized by the appearance of isomorphic lesions in areas of otherwise healthy skin subjected to cutaneous injury, as well as the pseudo-Koebner phenomenon, a similar process involving infectious agents.3

In our patient, striae distensae represented areas of increased predisposition to infection. The catabolic effect of high corticosteroid levels on fibroblast activity decreased collagen deposition in the dermal matrix, leading to the formation of linear bands of atrophic skin.4 The elastic fiber network in striae distensae is reduced and reorganized compared to normal skin, in which an intertwining elastic system forms a continuum from the dermoepidermal junction to the deep dermis.5 The number of vertically oriented fibrillin microfibrils subjacent to the dermoepidermal junction and elastin fibers in the papillary dermis is comparatively diminished such that the elastin and fibrillin fibers in the deep dermis run more horizontally compared to normal skin.4 Consequently, collagen alignment in striae distensae demonstrates more anisotropy, or directionally dependent variability, and the dermal matrix is looser and more floccular than the surrounding skin.6 These alterations of dermal architecture likely provide a mechanical advantage for intradermal spread of M chelonae within striae.

Other dermatoses have been observed to occur within striae distensae, specifically leukemia cutis, urticarial vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, keloids, linear focal elastosis, chronic graft-vs-host disease, psoriasis, gestational pemphigoid, and vitiligo.7 Given the dissimilarities of these conditions, the distinctive milieu of striae must provide an invitation—a locus minoris resistentiae—for secondary pathology.

Chronic corticosteroid use leads to both immunosuppression and striae distensae, effectively creating a perfect storm for an atypical mycobacterial skin infection demonstrating locus minoris resistentiae. The immunosuppressed state makes patients more susceptible to infection, and striae distensae may serve as a conduit for the offending organisms.

Acknowledgments—We are indebted to Letty Peterson, MD (Vidalia, Georgia), for her referral of this case, and to Stephen Mullins, MD (Augusta, Georgia), for his dermatopathology services.

To the Editor:

Immunosuppressed patients are at particular risk for disseminated mycobacterial infections. A locus minoris resistentiae offers less resistance to the infectious spread of these microorganisms. We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae infection preferentially involving striae distensae.

A 30-year-old man with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia requiring high-dose corticosteroid therapy presented with widespread skin lesions. He reported no history of cutaneous trauma or aquatic activities. Physical examination revealed the patient was markedly cushingoid with generalized cutaneous atrophy and widespread striae. Multiple erythematous papules surrounded a large ulceration on the dorsal aspect of the left hand. Depressed erythematous plaques and several small crusted erosions extended up the left lower leg (Figure 1) to the knee. Strikingly, numerous brown and pink papules and small plaques on the left thigh were primarily confined within striae (Figure 2).

A biopsy of the left thigh revealed granulomatous inflammation (Figure 3) with numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 4). Broad-spectrum coverage for fast-growing acid-fast bacilli with amikacin, ceftriaxone, levofloxacin, and clarithromycin was initiated with steady improvement of the eruption. Tissue culture subsequently grew Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae, and therapy was narrowed to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin.

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing mycobacteria isolated from soil and water worldwide, and human skin is a commensal organism. Cutaneous infections have been associated with traumatic injury, tattooing, surgery, cosmetic procedures, vascular access sites, and acupuncture.1 Most cases of cutaneous M chelonae infection begin as a violaceous nodule. Over weeks to months, the localized infection progresses to multiple papules, nodules, draining abscesses, or ulcers. Infections tend to disseminate in immunosuppressed patients, and granulomatous inflammation may not be seen.1

Atypical mycobacterial infection occurring within striae distensae is an example of locus minoris resistentiae—a place of less resistance. Wolf et al2 hypothesized that locus minoris resistentiae could explain the occurrence of an isotopic response or the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed skin condition. They suggested that the same site could be affected by 2 unrelated diseases at different times due to an inherited or acquired susceptibility in the area.2 Herpes zoster serves as a primary example of Wolf phenomenon, as numerous conditions including granuloma annulare, pseudolymphoma, Bowen disease, and acne have reportedly emerged in its wake.3

Although locus minoris resistentiae does not specifically involve traumatized skin, it must be distinguished from the Koebner phenomenon, characterized by the appearance of isomorphic lesions in areas of otherwise healthy skin subjected to cutaneous injury, as well as the pseudo-Koebner phenomenon, a similar process involving infectious agents.3

In our patient, striae distensae represented areas of increased predisposition to infection. The catabolic effect of high corticosteroid levels on fibroblast activity decreased collagen deposition in the dermal matrix, leading to the formation of linear bands of atrophic skin.4 The elastic fiber network in striae distensae is reduced and reorganized compared to normal skin, in which an intertwining elastic system forms a continuum from the dermoepidermal junction to the deep dermis.5 The number of vertically oriented fibrillin microfibrils subjacent to the dermoepidermal junction and elastin fibers in the papillary dermis is comparatively diminished such that the elastin and fibrillin fibers in the deep dermis run more horizontally compared to normal skin.4 Consequently, collagen alignment in striae distensae demonstrates more anisotropy, or directionally dependent variability, and the dermal matrix is looser and more floccular than the surrounding skin.6 These alterations of dermal architecture likely provide a mechanical advantage for intradermal spread of M chelonae within striae.

Other dermatoses have been observed to occur within striae distensae, specifically leukemia cutis, urticarial vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, keloids, linear focal elastosis, chronic graft-vs-host disease, psoriasis, gestational pemphigoid, and vitiligo.7 Given the dissimilarities of these conditions, the distinctive milieu of striae must provide an invitation—a locus minoris resistentiae—for secondary pathology.

Chronic corticosteroid use leads to both immunosuppression and striae distensae, effectively creating a perfect storm for an atypical mycobacterial skin infection demonstrating locus minoris resistentiae. The immunosuppressed state makes patients more susceptible to infection, and striae distensae may serve as a conduit for the offending organisms.

Acknowledgments—We are indebted to Letty Peterson, MD (Vidalia, Georgia), for her referral of this case, and to Stephen Mullins, MD (Augusta, Georgia), for his dermatopathology services.

- Hay RJ. Mycobacterium chelonae—a growing problem in soft tissue infection. Cur Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:99-101.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Medeiros do Santos Camargo C, Brotas AM, Ramos-e-Silva M, et al. Isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:741-749.

- Watson REB, Parry EJ, Humphries JD, et al. Fibrillin microfibrils are reduced in skin exhibiting striae distensae. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:931-397.

- Bertin C, A Lopes-DaCunha, Nkengne A, et al. Striae distensae are characterized by distinct microstructural features as measured by non-invasive methods in vivo. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:81-86.

- Elsaie ML, Baumann LS, Elsaaiee LT. Striae distensae (stretch marks) and different modalities of therapy: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:563-573.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Hay RJ. Mycobacterium chelonae—a growing problem in soft tissue infection. Cur Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:99-101.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Medeiros do Santos Camargo C, Brotas AM, Ramos-e-Silva M, et al. Isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:741-749.

- Watson REB, Parry EJ, Humphries JD, et al. Fibrillin microfibrils are reduced in skin exhibiting striae distensae. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:931-397.

- Bertin C, A Lopes-DaCunha, Nkengne A, et al. Striae distensae are characterized by distinct microstructural features as measured by non-invasive methods in vivo. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:81-86.

- Elsaie ML, Baumann LS, Elsaaiee LT. Striae distensae (stretch marks) and different modalities of therapy: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:563-573.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

Practice Points

- Striae distensae, seen frequently in the setting of chronic corticosteroid use, are at an increased risk for localized infection, particularly in immunocompromised patients. There should be a low threshold to biopsy striae distensae that demonstrate morphologic evolution.

- The Koebner reaction, also known as an isomorphic response, refers to the appearance of certain dermatoses in previously healthy skin subjected to cutaneous injury.

- Locus minoris resistentiae is an isotropic response that characterizes the presentation of a new dermatosis within an area previously affected by an unrelated skin condition that has healed.

Dystrophic Calcinosis Cutis: Treatment With Intravenous Sodium Thiosulfate

To the Editor:

Severe dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease with no universally accepted therapeutic options. This case demonstrates the benefit of intravenous (IV) sodium thiosulfate in alleviating the calcified lesions as well as the associated pain and disability. This application of IV sodium thiosulfate with a favorable outcome is new and should be considered for the treatment of generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis, especially when topical, procedural, or surgical options are not feasible.

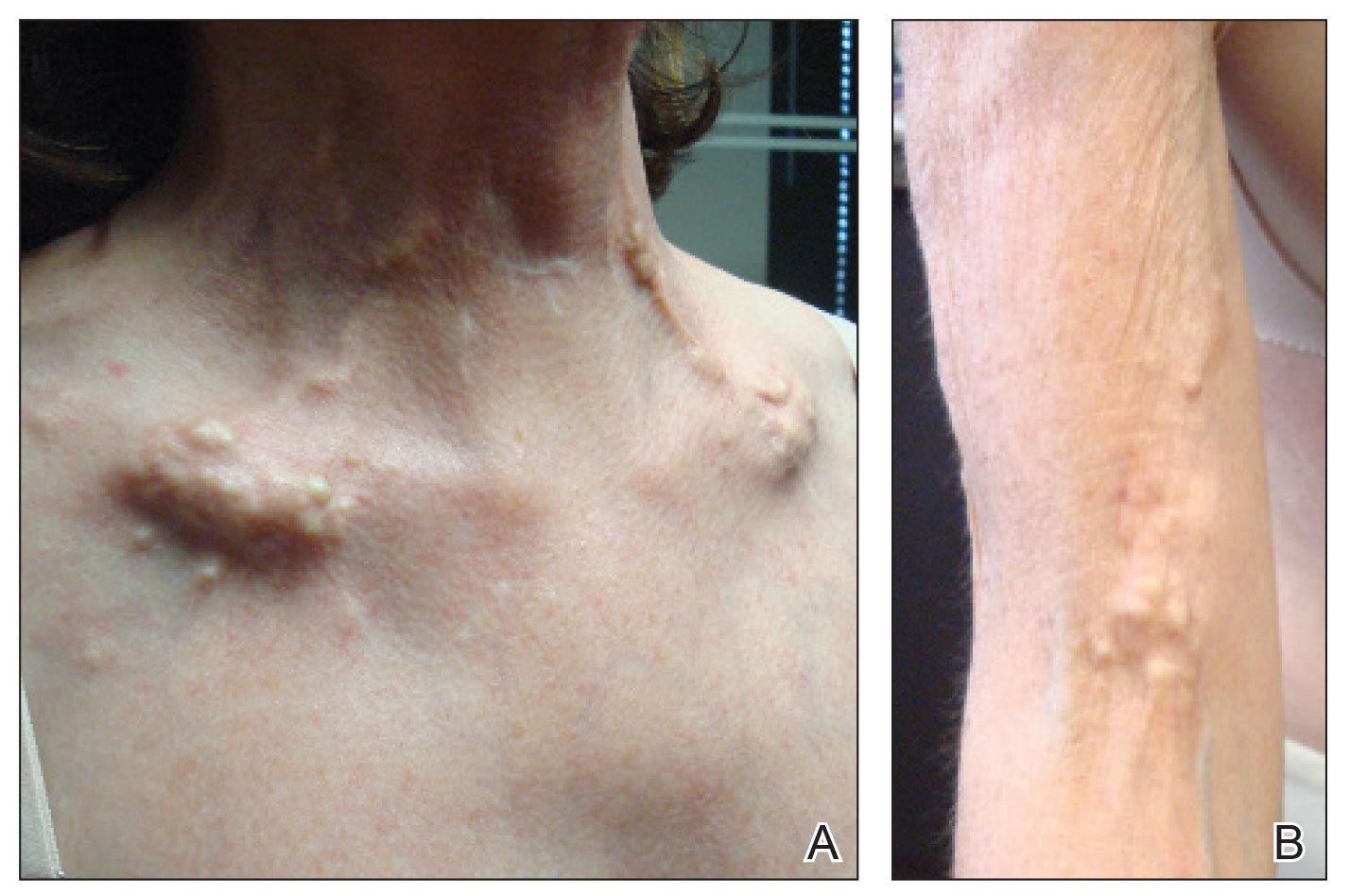

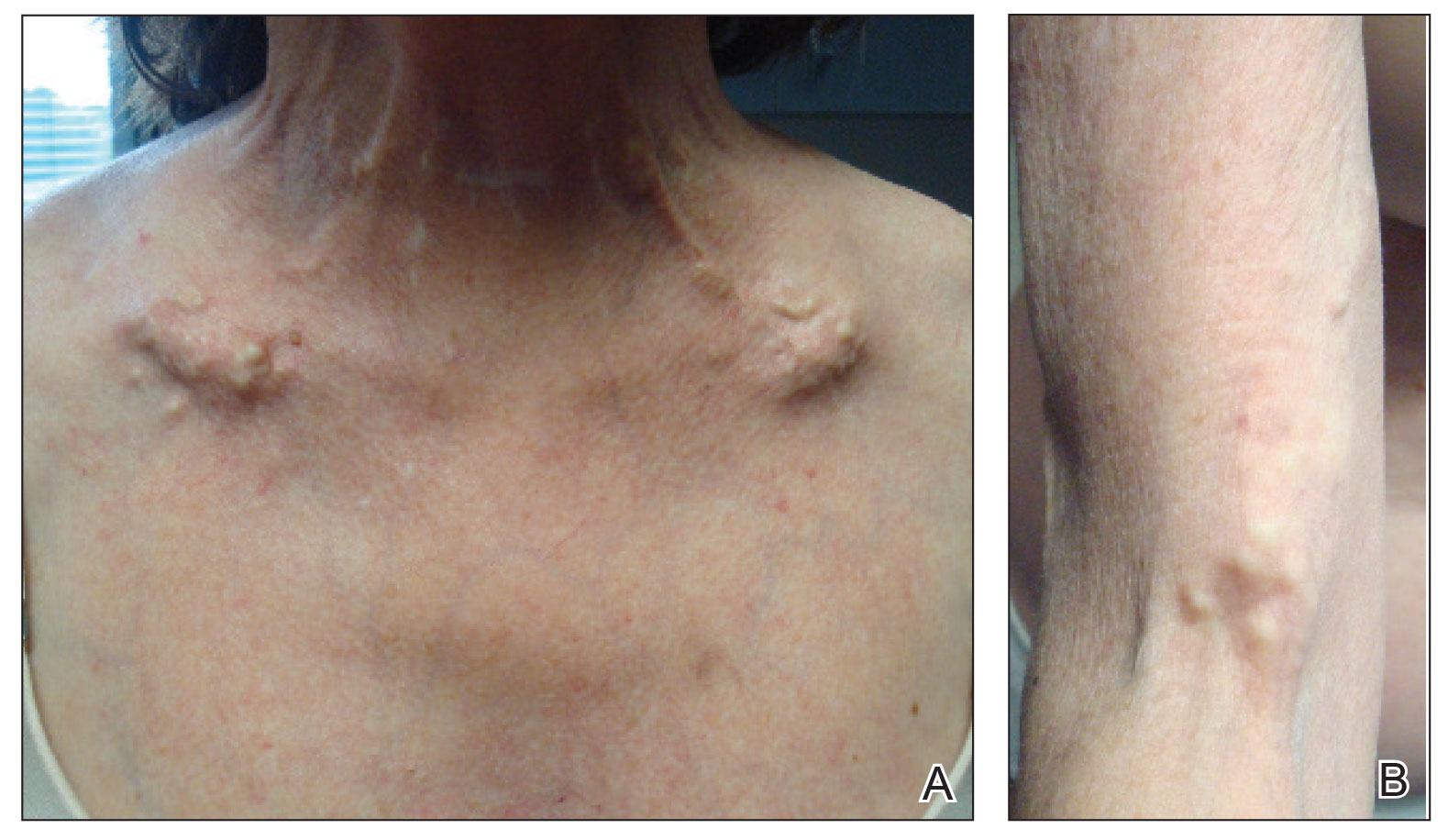

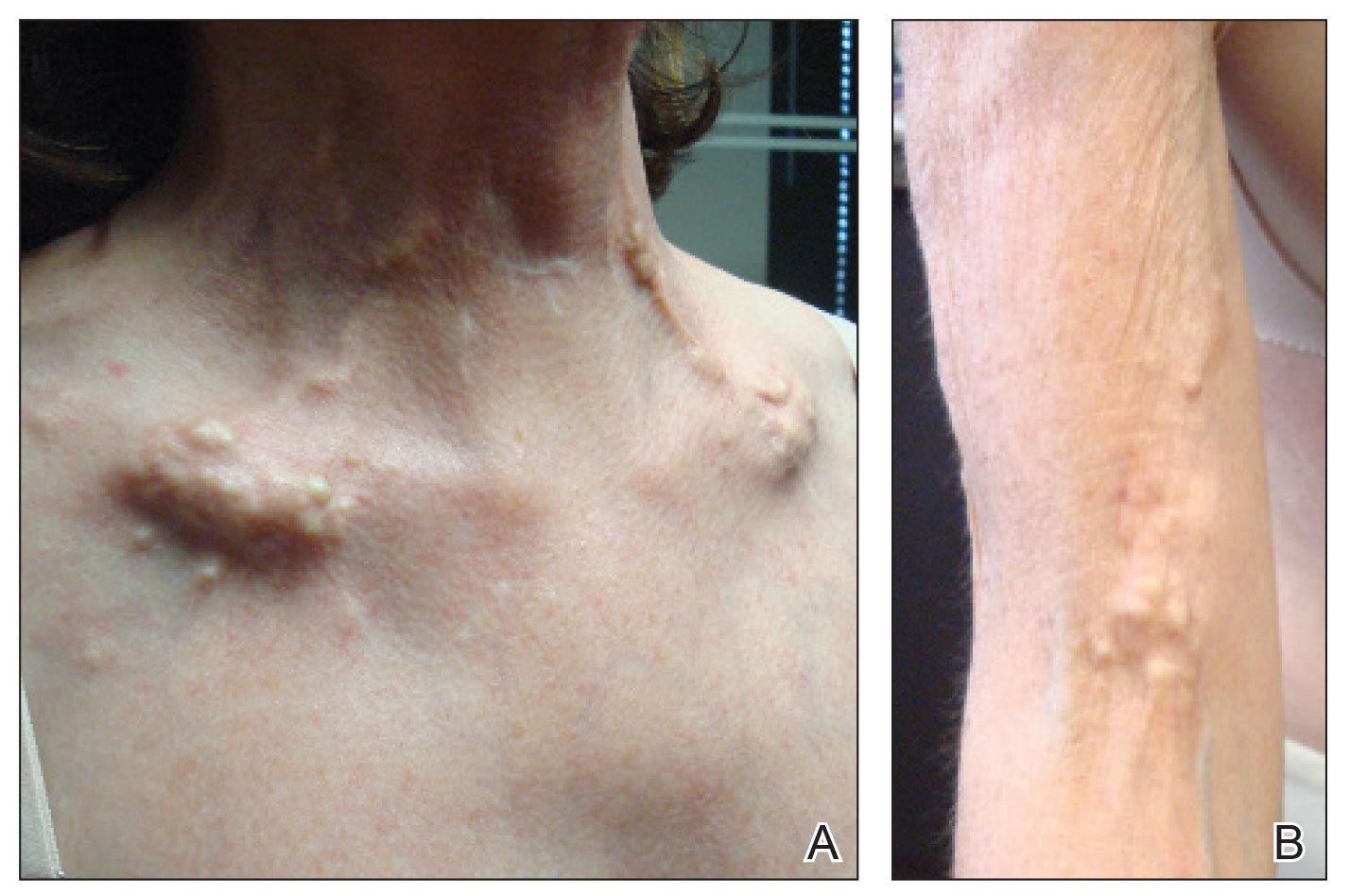

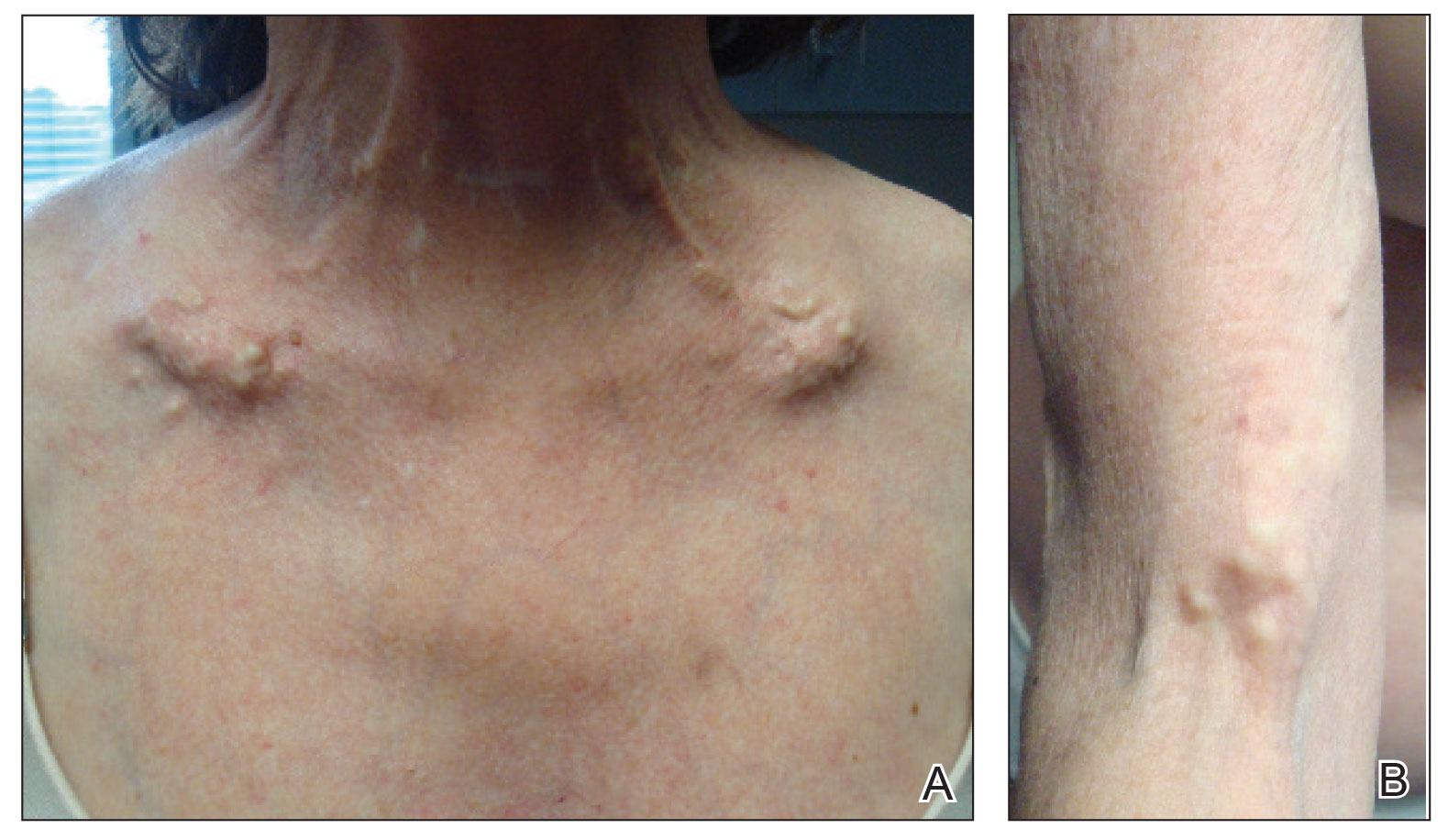

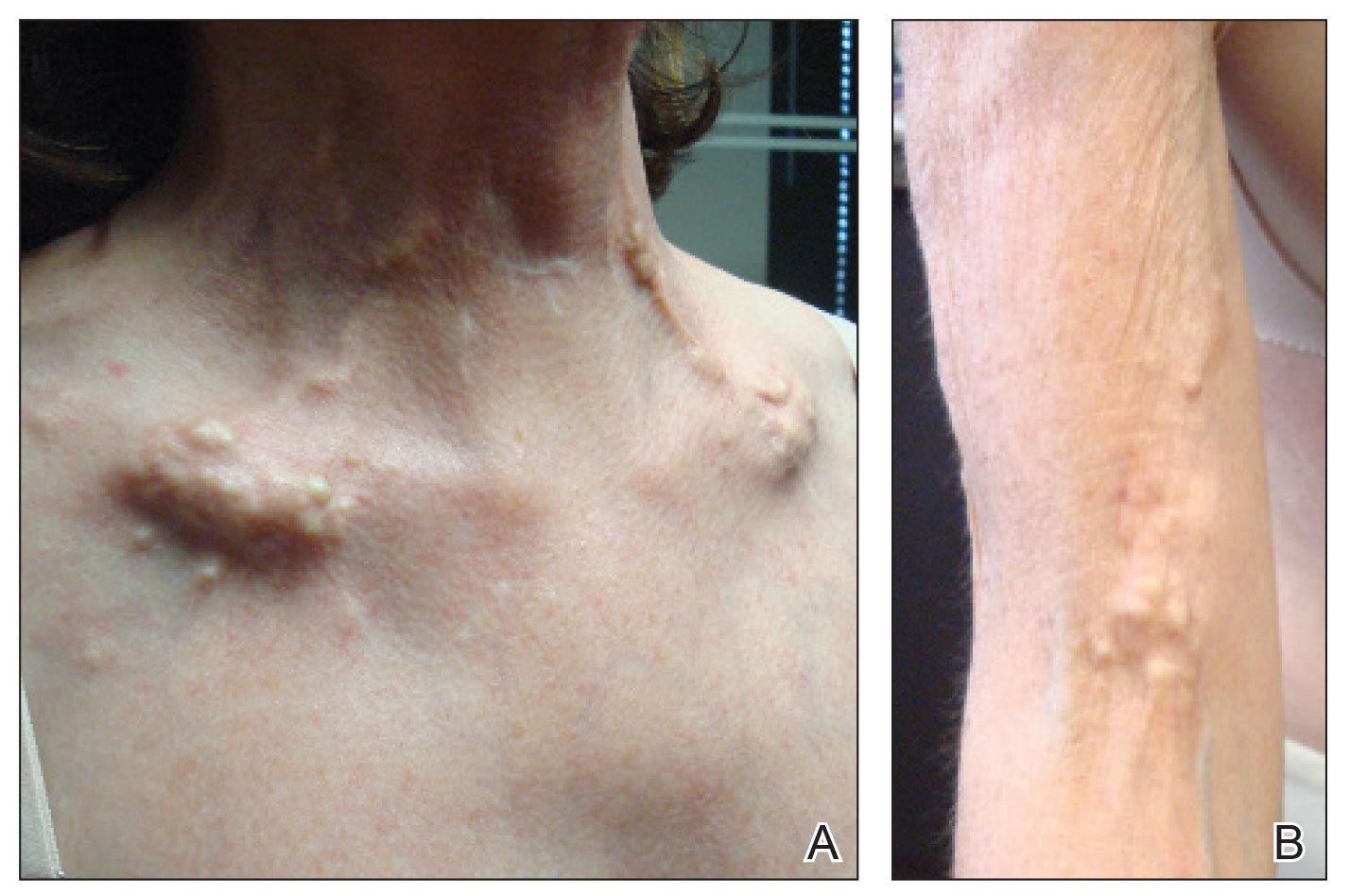

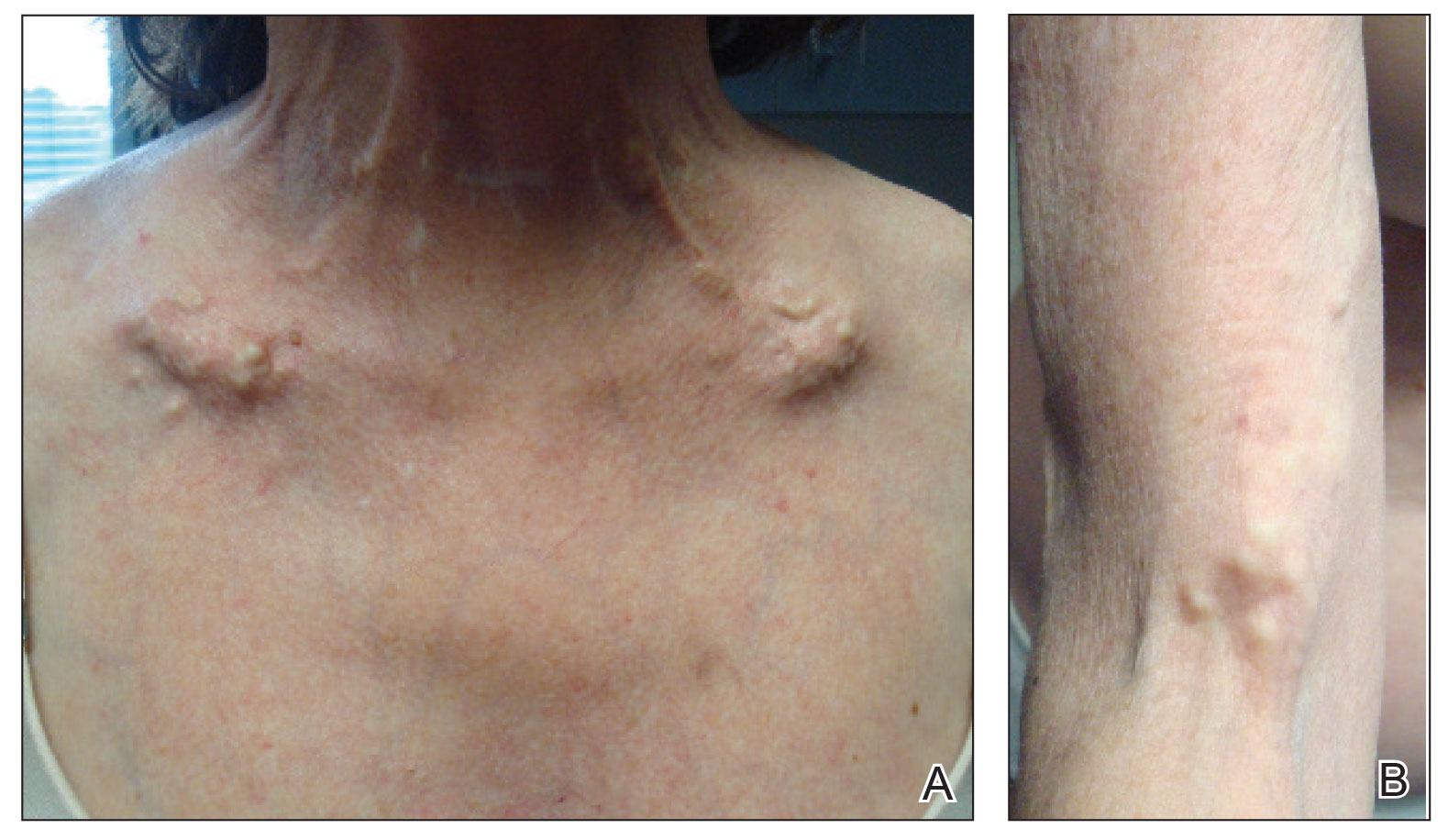

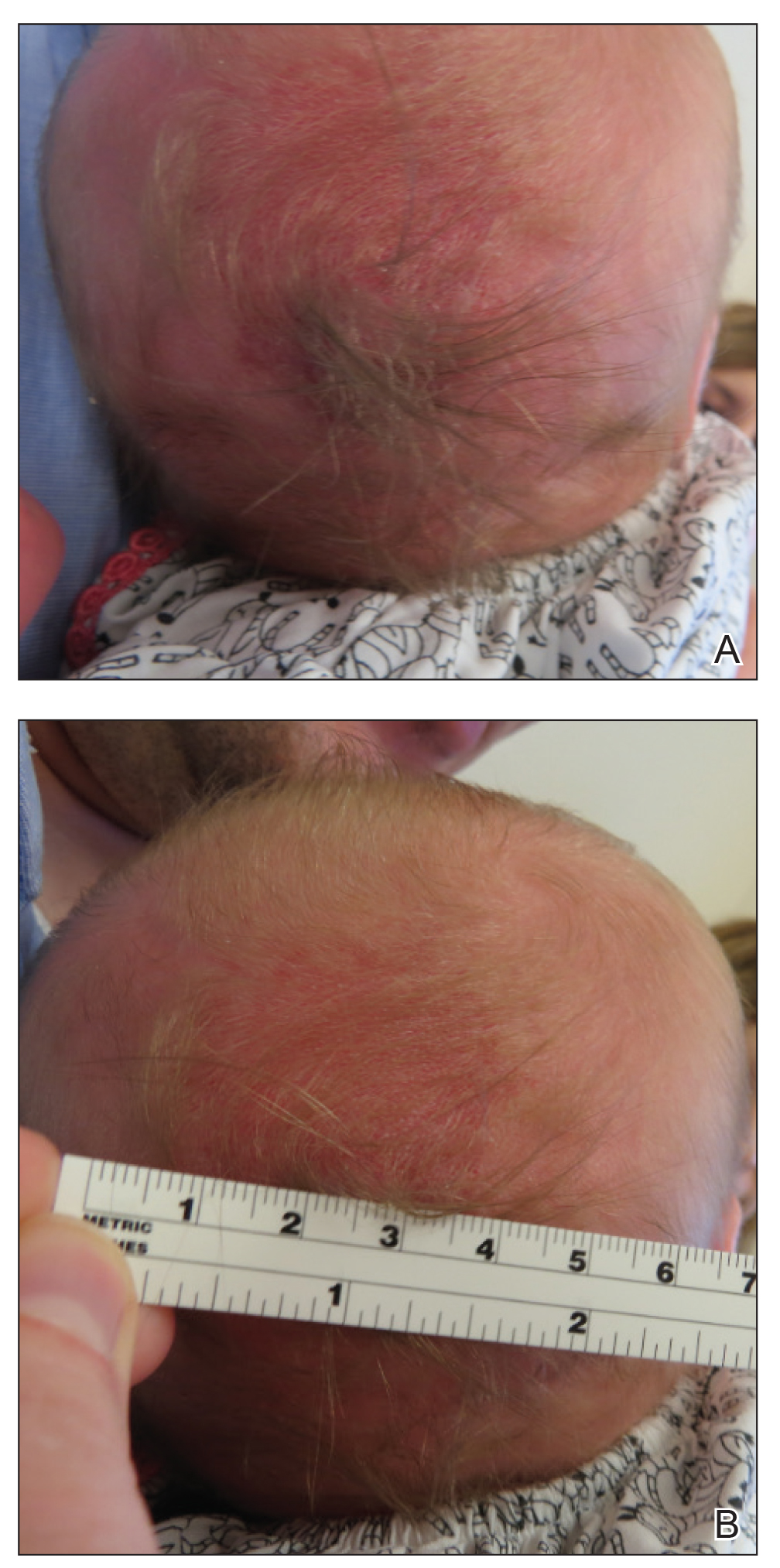

A 54-year-old woman with a history of well-controlled dermatomyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus presented with diffuse, hard, calcified lesions on the legs, arms, clavicular region, and neck that had slowly progressed over at least a 10-year period (Figure 1). The lesions were consistent with dystrophic calcinosis cutis. The patient was started on 12.5 g of IV sodium thiosulfate 3 times weekly infused over 30 minutes. Drastic diminution of the cutaneous calcification was observed at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2). She reported decreased pain and burning as well as increased overall functionality and improved sleep. The patient completed 8 months of therapy, but the treatment was stopped secondary to suspicion of a lupuslike flare, and the lesions recurred with more widespread involvement, including the trunk, tendons, bony prominences, and supraclavicular soft tissue. The patient reported burning pain and pruritus that resulted in impairment of daily activities such as getting dressed. Sodium thiosulfate was restarted once weekly, which again resulted in reduction of the dystrophic calcinosis cutis.

Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease that results in considerable morbidity and pain with major implications on quality of life. The pathophysiology is unclear; calcium and phosphate serum levels generally are normal. A proposed mechanism is that chronic inflammation causes tissue damage and defective collagen synthesis, resulting in a distorted architecture that facilitates calcium deposition in the skin and subcutaneous tissues.1 Dystrophic calcinosis cutis most commonly is associated with systemic sclerosis and dermatomyositis but also can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, panniculitis, and other connective tissue diseases. It also can occur with skin neoplasms, collagen and elastin disorders, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pancreatic panniculitis.1 Progression of dystrophic calcinosis cutis usually is independent of the associated disease status.

Treatment is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports, as there is no universally accepted pharmacologic or procedural intervention available for dystrophic calcinosis cutis. Medications that have been reported to be helpful to varying degrees include diltiazem, colchicine, minocycline, IV immunoglobulin, ceftriaxone, aluminum hydroxide, probenecid, alendronic acid, etidronate disodium, warfarin, intralesional corticosteroids, and sodium thiosulfate. Procedural interventions also have been reported, such as surgical excision, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and CO2 and erbium: YAG lasers.1 Surgical excision of dystrophic calcinosis cutis is widely implemented but outcomes are poor. Moreover, in patients with widely diffuse calcinosis, targeted procedural therapy is impractical.

Intravenous sodium thiosulfate has been widely used for the treatment of calciphylaxis secondary to end-stage renal failure and tumoral calcinosis.2 It also has been reported to be effective in iatrogenic calcinosis cutis secondary to extravasation of calcium-containing solutions in a patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3 However, reports of its use in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis are limited. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate—10 g 3 times weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 15 g twice weekly for the next 3 months—was used with abatacept for treatment of dystrophic calcinosis cutis in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis.4 Other formulations of sodium thiosulfate have been reported to result in clearance of calcified lesions, including a topical application compounded in zinc oxide5 and intradermal injection at the base of a nodule.6 We used 12.5 g over 30 minutes 3 times weekly; however, the dose can be increased to 25 g over 60 minutes if 3 to 4 treatments are tolerated, with nausea being the only notable side effect. Its mechanism of action in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis is unclear, but it likely is due to its ability to chelate and dissolve calcium deposits. Topical and intradermal therapy is impractical for widespread, dystrophic calcinosis cutis as in our patient.

Our case highlights the successful use of IV sodium thiosulfate as a stand-alone treatment modality for generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis in an adult patient. Both our patient and a child in a previously reported case who received the same treatment4 had dermatomyositis, but we suspect IV sodium thiosulfate also may be effective for dystrophic calcinosis cutis associated with other diseases. Sodium thiosulfate should be considered as a treatment for patients who experience tremendous pain and disability. It is safe, inexpensive, and easy to administer and is especially helpful in patients for whom topical, intradermal, or procedural therapy is not possible.

- Gutierrez A Jr, Wetter DA. Calcinosis cutis in autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:195-206.

- Mageau A, Guigonis V, Ratzimbasafy V, et al. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate for treating tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic disorders: report of four cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:341-344.

Raffaella C, Annapaola C, Tullio I, et al. Successful treatment of severe iatrogenic calcinosis cutis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate in a child affected by T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:311-315. - Arabshahi B, Silverman RA, Jones OY, et al. Abatacept and sodium thiosulfate for treatment of recalcitrant juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by ulceration and calcinosis. J Pediatrics. 2012;160:520-522.

- Bair B, Fivenson D. A novel treatment for ulcerative calcinosis cutis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1042-1044.

- Smith GP. Intradermal sodium thiosulfate for exophytic calcinosis cutis of connective tissue disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E146-E147.

To the Editor:

Severe dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease with no universally accepted therapeutic options. This case demonstrates the benefit of intravenous (IV) sodium thiosulfate in alleviating the calcified lesions as well as the associated pain and disability. This application of IV sodium thiosulfate with a favorable outcome is new and should be considered for the treatment of generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis, especially when topical, procedural, or surgical options are not feasible.

A 54-year-old woman with a history of well-controlled dermatomyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus presented with diffuse, hard, calcified lesions on the legs, arms, clavicular region, and neck that had slowly progressed over at least a 10-year period (Figure 1). The lesions were consistent with dystrophic calcinosis cutis. The patient was started on 12.5 g of IV sodium thiosulfate 3 times weekly infused over 30 minutes. Drastic diminution of the cutaneous calcification was observed at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2). She reported decreased pain and burning as well as increased overall functionality and improved sleep. The patient completed 8 months of therapy, but the treatment was stopped secondary to suspicion of a lupuslike flare, and the lesions recurred with more widespread involvement, including the trunk, tendons, bony prominences, and supraclavicular soft tissue. The patient reported burning pain and pruritus that resulted in impairment of daily activities such as getting dressed. Sodium thiosulfate was restarted once weekly, which again resulted in reduction of the dystrophic calcinosis cutis.

Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease that results in considerable morbidity and pain with major implications on quality of life. The pathophysiology is unclear; calcium and phosphate serum levels generally are normal. A proposed mechanism is that chronic inflammation causes tissue damage and defective collagen synthesis, resulting in a distorted architecture that facilitates calcium deposition in the skin and subcutaneous tissues.1 Dystrophic calcinosis cutis most commonly is associated with systemic sclerosis and dermatomyositis but also can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, panniculitis, and other connective tissue diseases. It also can occur with skin neoplasms, collagen and elastin disorders, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pancreatic panniculitis.1 Progression of dystrophic calcinosis cutis usually is independent of the associated disease status.

Treatment is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports, as there is no universally accepted pharmacologic or procedural intervention available for dystrophic calcinosis cutis. Medications that have been reported to be helpful to varying degrees include diltiazem, colchicine, minocycline, IV immunoglobulin, ceftriaxone, aluminum hydroxide, probenecid, alendronic acid, etidronate disodium, warfarin, intralesional corticosteroids, and sodium thiosulfate. Procedural interventions also have been reported, such as surgical excision, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and CO2 and erbium: YAG lasers.1 Surgical excision of dystrophic calcinosis cutis is widely implemented but outcomes are poor. Moreover, in patients with widely diffuse calcinosis, targeted procedural therapy is impractical.

Intravenous sodium thiosulfate has been widely used for the treatment of calciphylaxis secondary to end-stage renal failure and tumoral calcinosis.2 It also has been reported to be effective in iatrogenic calcinosis cutis secondary to extravasation of calcium-containing solutions in a patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3 However, reports of its use in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis are limited. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate—10 g 3 times weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 15 g twice weekly for the next 3 months—was used with abatacept for treatment of dystrophic calcinosis cutis in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis.4 Other formulations of sodium thiosulfate have been reported to result in clearance of calcified lesions, including a topical application compounded in zinc oxide5 and intradermal injection at the base of a nodule.6 We used 12.5 g over 30 minutes 3 times weekly; however, the dose can be increased to 25 g over 60 minutes if 3 to 4 treatments are tolerated, with nausea being the only notable side effect. Its mechanism of action in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis is unclear, but it likely is due to its ability to chelate and dissolve calcium deposits. Topical and intradermal therapy is impractical for widespread, dystrophic calcinosis cutis as in our patient.

Our case highlights the successful use of IV sodium thiosulfate as a stand-alone treatment modality for generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis in an adult patient. Both our patient and a child in a previously reported case who received the same treatment4 had dermatomyositis, but we suspect IV sodium thiosulfate also may be effective for dystrophic calcinosis cutis associated with other diseases. Sodium thiosulfate should be considered as a treatment for patients who experience tremendous pain and disability. It is safe, inexpensive, and easy to administer and is especially helpful in patients for whom topical, intradermal, or procedural therapy is not possible.

To the Editor:

Severe dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease with no universally accepted therapeutic options. This case demonstrates the benefit of intravenous (IV) sodium thiosulfate in alleviating the calcified lesions as well as the associated pain and disability. This application of IV sodium thiosulfate with a favorable outcome is new and should be considered for the treatment of generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis, especially when topical, procedural, or surgical options are not feasible.

A 54-year-old woman with a history of well-controlled dermatomyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus presented with diffuse, hard, calcified lesions on the legs, arms, clavicular region, and neck that had slowly progressed over at least a 10-year period (Figure 1). The lesions were consistent with dystrophic calcinosis cutis. The patient was started on 12.5 g of IV sodium thiosulfate 3 times weekly infused over 30 minutes. Drastic diminution of the cutaneous calcification was observed at 3-month follow-up (Figure 2). She reported decreased pain and burning as well as increased overall functionality and improved sleep. The patient completed 8 months of therapy, but the treatment was stopped secondary to suspicion of a lupuslike flare, and the lesions recurred with more widespread involvement, including the trunk, tendons, bony prominences, and supraclavicular soft tissue. The patient reported burning pain and pruritus that resulted in impairment of daily activities such as getting dressed. Sodium thiosulfate was restarted once weekly, which again resulted in reduction of the dystrophic calcinosis cutis.

Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a debilitating disease that results in considerable morbidity and pain with major implications on quality of life. The pathophysiology is unclear; calcium and phosphate serum levels generally are normal. A proposed mechanism is that chronic inflammation causes tissue damage and defective collagen synthesis, resulting in a distorted architecture that facilitates calcium deposition in the skin and subcutaneous tissues.1 Dystrophic calcinosis cutis most commonly is associated with systemic sclerosis and dermatomyositis but also can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, panniculitis, and other connective tissue diseases. It also can occur with skin neoplasms, collagen and elastin disorders, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pancreatic panniculitis.1 Progression of dystrophic calcinosis cutis usually is independent of the associated disease status.

Treatment is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports, as there is no universally accepted pharmacologic or procedural intervention available for dystrophic calcinosis cutis. Medications that have been reported to be helpful to varying degrees include diltiazem, colchicine, minocycline, IV immunoglobulin, ceftriaxone, aluminum hydroxide, probenecid, alendronic acid, etidronate disodium, warfarin, intralesional corticosteroids, and sodium thiosulfate. Procedural interventions also have been reported, such as surgical excision, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, and CO2 and erbium: YAG lasers.1 Surgical excision of dystrophic calcinosis cutis is widely implemented but outcomes are poor. Moreover, in patients with widely diffuse calcinosis, targeted procedural therapy is impractical.

Intravenous sodium thiosulfate has been widely used for the treatment of calciphylaxis secondary to end-stage renal failure and tumoral calcinosis.2 It also has been reported to be effective in iatrogenic calcinosis cutis secondary to extravasation of calcium-containing solutions in a patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.3 However, reports of its use in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis are limited. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate—10 g 3 times weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 15 g twice weekly for the next 3 months—was used with abatacept for treatment of dystrophic calcinosis cutis in a patient with juvenile dermatomyositis.4 Other formulations of sodium thiosulfate have been reported to result in clearance of calcified lesions, including a topical application compounded in zinc oxide5 and intradermal injection at the base of a nodule.6 We used 12.5 g over 30 minutes 3 times weekly; however, the dose can be increased to 25 g over 60 minutes if 3 to 4 treatments are tolerated, with nausea being the only notable side effect. Its mechanism of action in treating dystrophic calcinosis cutis is unclear, but it likely is due to its ability to chelate and dissolve calcium deposits. Topical and intradermal therapy is impractical for widespread, dystrophic calcinosis cutis as in our patient.

Our case highlights the successful use of IV sodium thiosulfate as a stand-alone treatment modality for generalized dystrophic calcinosis cutis in an adult patient. Both our patient and a child in a previously reported case who received the same treatment4 had dermatomyositis, but we suspect IV sodium thiosulfate also may be effective for dystrophic calcinosis cutis associated with other diseases. Sodium thiosulfate should be considered as a treatment for patients who experience tremendous pain and disability. It is safe, inexpensive, and easy to administer and is especially helpful in patients for whom topical, intradermal, or procedural therapy is not possible.

- Gutierrez A Jr, Wetter DA. Calcinosis cutis in autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:195-206.

- Mageau A, Guigonis V, Ratzimbasafy V, et al. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate for treating tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic disorders: report of four cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:341-344.

Raffaella C, Annapaola C, Tullio I, et al. Successful treatment of severe iatrogenic calcinosis cutis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate in a child affected by T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:311-315. - Arabshahi B, Silverman RA, Jones OY, et al. Abatacept and sodium thiosulfate for treatment of recalcitrant juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by ulceration and calcinosis. J Pediatrics. 2012;160:520-522.

- Bair B, Fivenson D. A novel treatment for ulcerative calcinosis cutis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1042-1044.

- Smith GP. Intradermal sodium thiosulfate for exophytic calcinosis cutis of connective tissue disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E146-E147.

- Gutierrez A Jr, Wetter DA. Calcinosis cutis in autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:195-206.

- Mageau A, Guigonis V, Ratzimbasafy V, et al. Intravenous sodium thiosulfate for treating tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic disorders: report of four cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84:341-344.

Raffaella C, Annapaola C, Tullio I, et al. Successful treatment of severe iatrogenic calcinosis cutis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate in a child affected by T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:311-315. - Arabshahi B, Silverman RA, Jones OY, et al. Abatacept and sodium thiosulfate for treatment of recalcitrant juvenile dermatomyositis complicated by ulceration and calcinosis. J Pediatrics. 2012;160:520-522.

- Bair B, Fivenson D. A novel treatment for ulcerative calcinosis cutis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1042-1044.

- Smith GP. Intradermal sodium thiosulfate for exophytic calcinosis cutis of connective tissue disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:E146-E147.

Practice Points

- Dystrophic calcinosis cutis is a potentially debilitating condition with limited effective therapies.

- Consider intravenous sodium thiosulfate in patients with diffuse and severe dystrophic calcinosis cutis.

Field Cancerization With Multiple Keratoacanthomas Successfully Treated With Topical and Intralesional 5-Fluorouracil

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

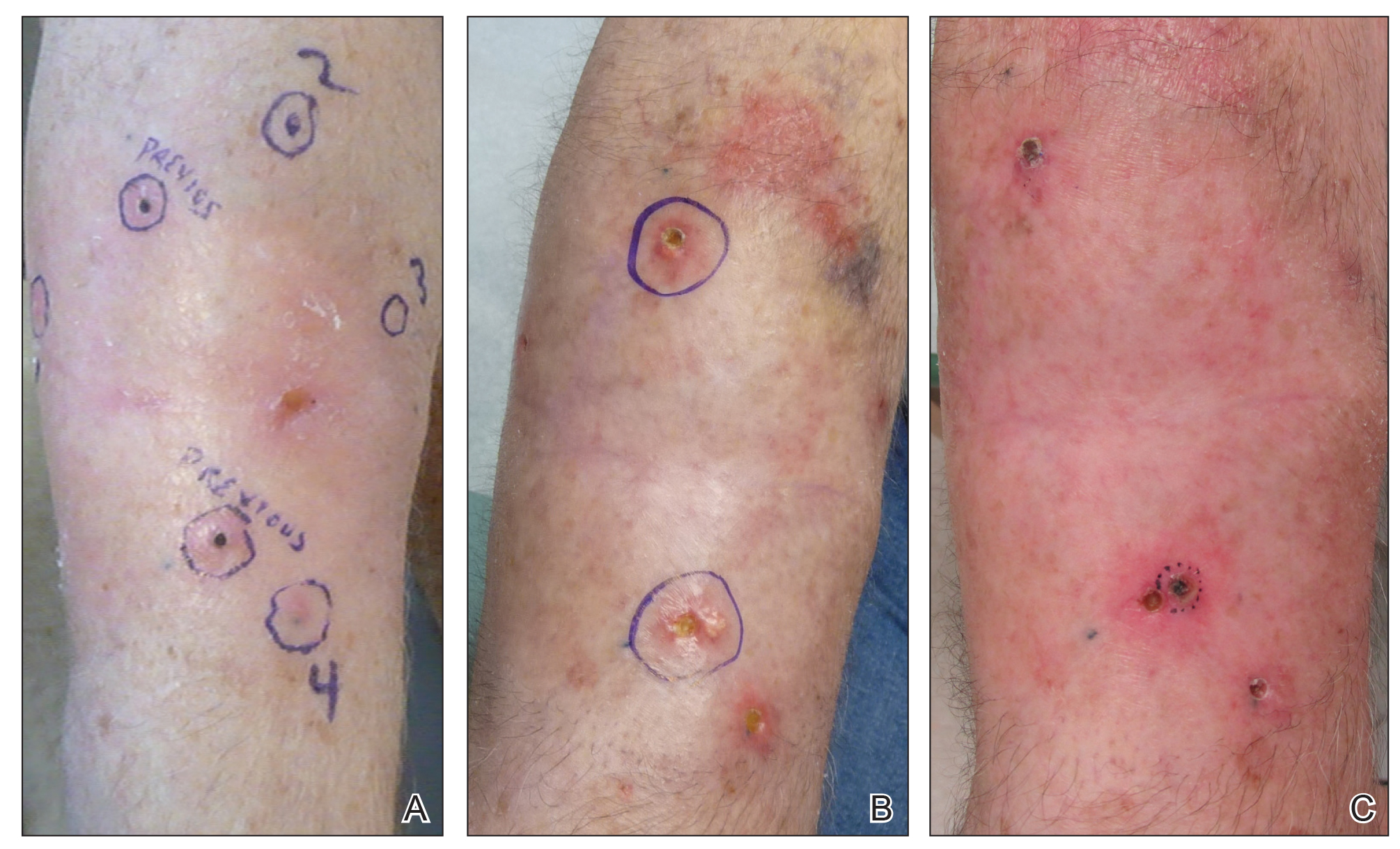

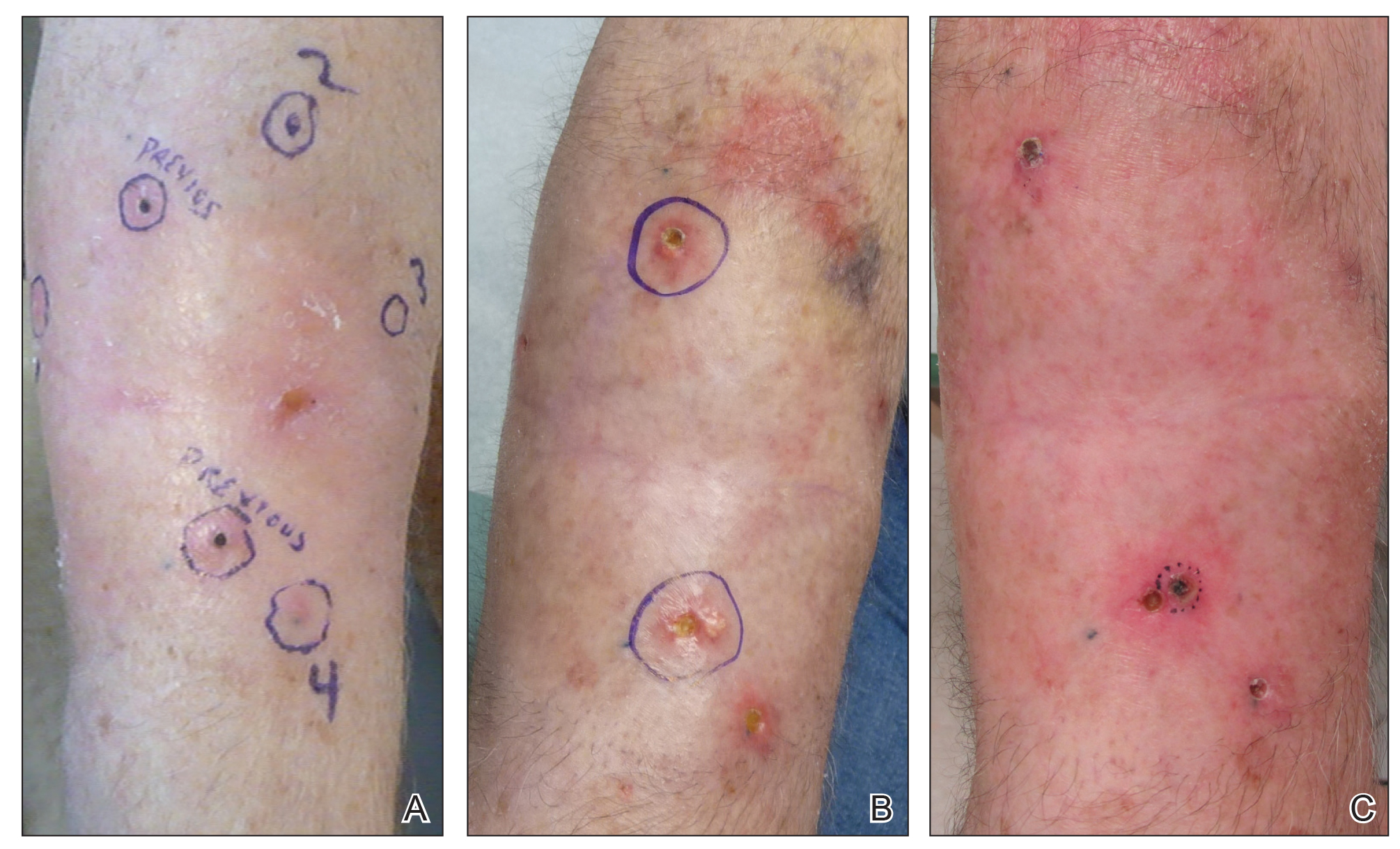

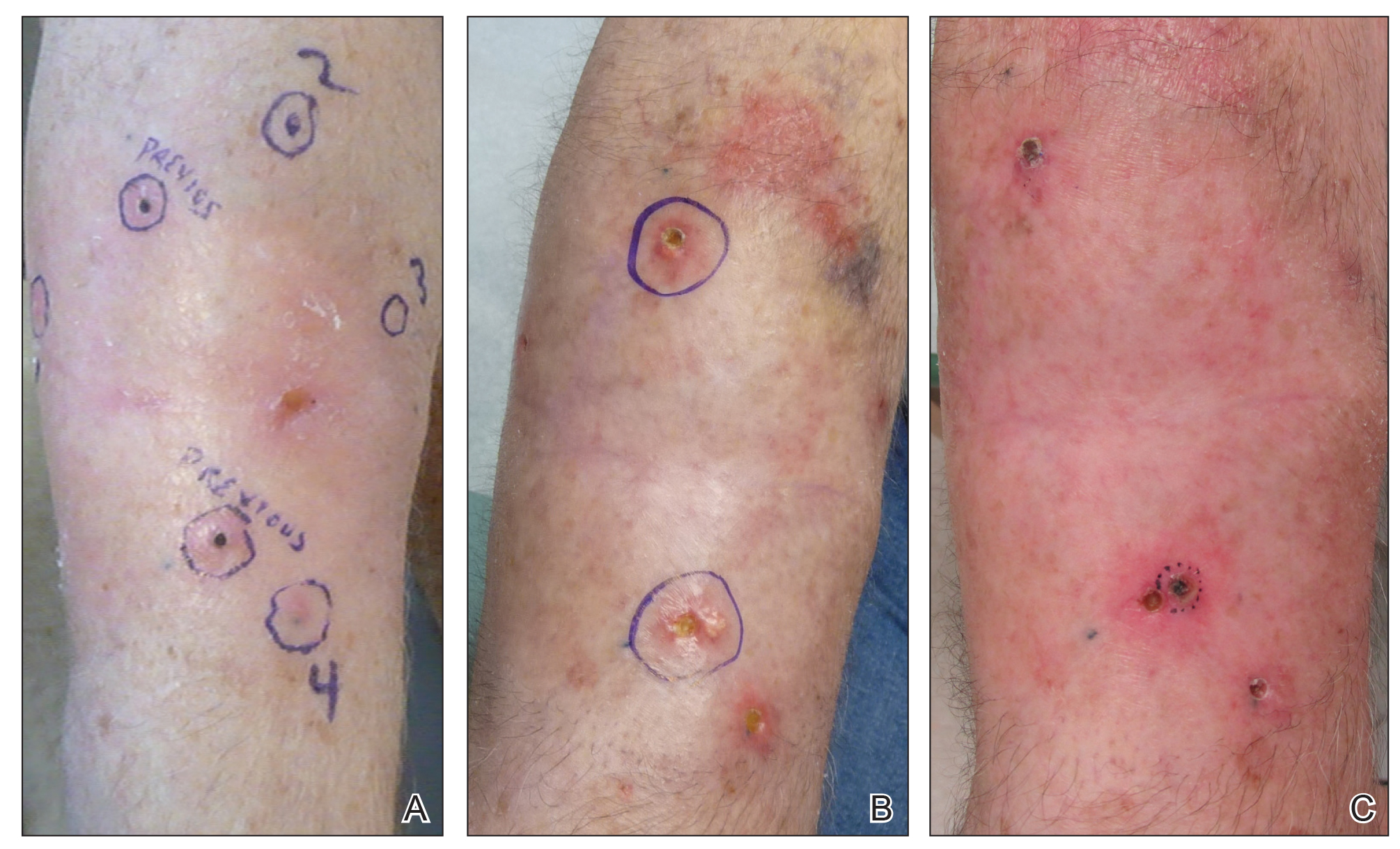

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

Methotrexate as a Treatment of Palmoplantar Lichen Planus

To the Editor:

Palmoplantar lichen planus (LP) is an uncommon variant of LP that involves the palms and soles. The prevalence of LP is approximately 0.1% to 2% in the general population. It can affect both mucosal and cutaneous surfaces.1 A study of 36 patients with LP showed that 25% (9/36) had palmar and/or plantar involvement.2 Palmoplantar LP is more commonly found in men than women, with an average age of onset of 38 to 65 years.3 It tends to affect the soles more often than the palms, with the most common site being the plantar arch. Itching generally is the most common symptom reported. Lesions often resolve over a few months, but relapses can occur in 10% to 29% of patients.2 The clinical morphology commonly is characterized as erythematous scaly plaques, hyperkeratotic plaques, or ulcerations.4 Due to its rare occurrence, palmoplantar LP often is misdiagnosed as psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, tinea nigra, or secondary syphilis, making pathology extremely helpful in making the diagnosis.1 Darker skin types can obscure defining characteristics, further impeding a timely diagnosis. We describe a novel case of palmoplantar LP that was successfully treated with methotrexate.

A 38-year-old man with no notable medical history presented for dermatologic evaluation of a palmar and plantar rash of 4 months' duration. The rash was accompanied by intense burning pain and pruritus. Prior to presentation, he had been treated with multiple prednisone tapers starting at 40 mg daily as well as combination therapy of a 2-week course of minocycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment twice daily for 4 months, with no notable improvement. Workup prior to presentation included a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation and a normal antinuclear antibody titer. A review of symptoms was negative for arthralgia, myalgia, photosensitivity, malar rash, Raynaud phenomenon, pleuritic pain, seizures, and psychosis.

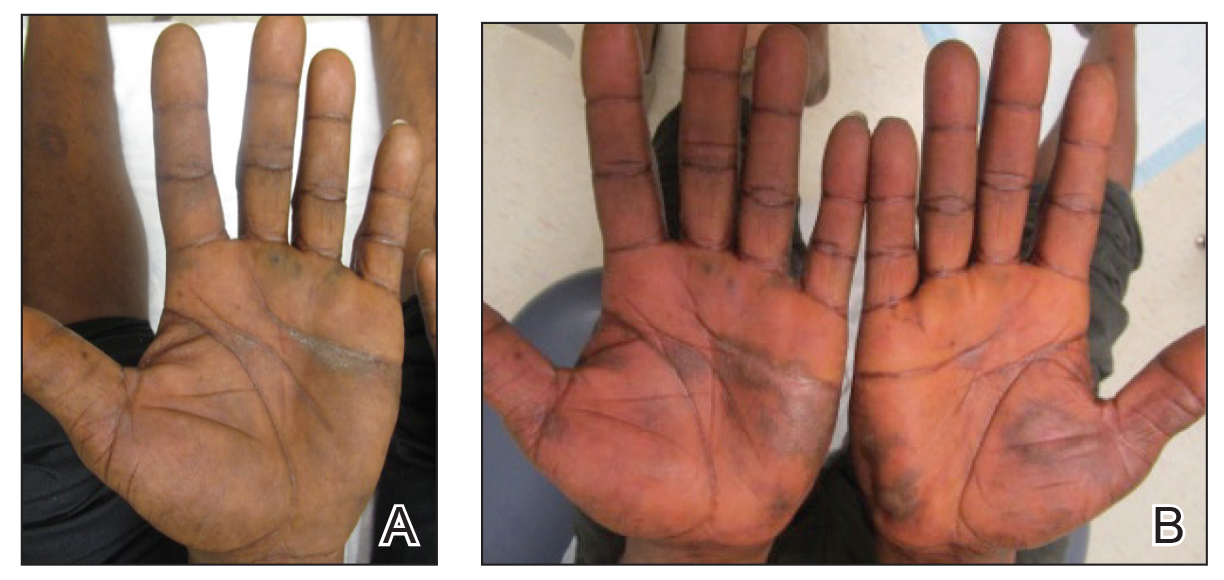

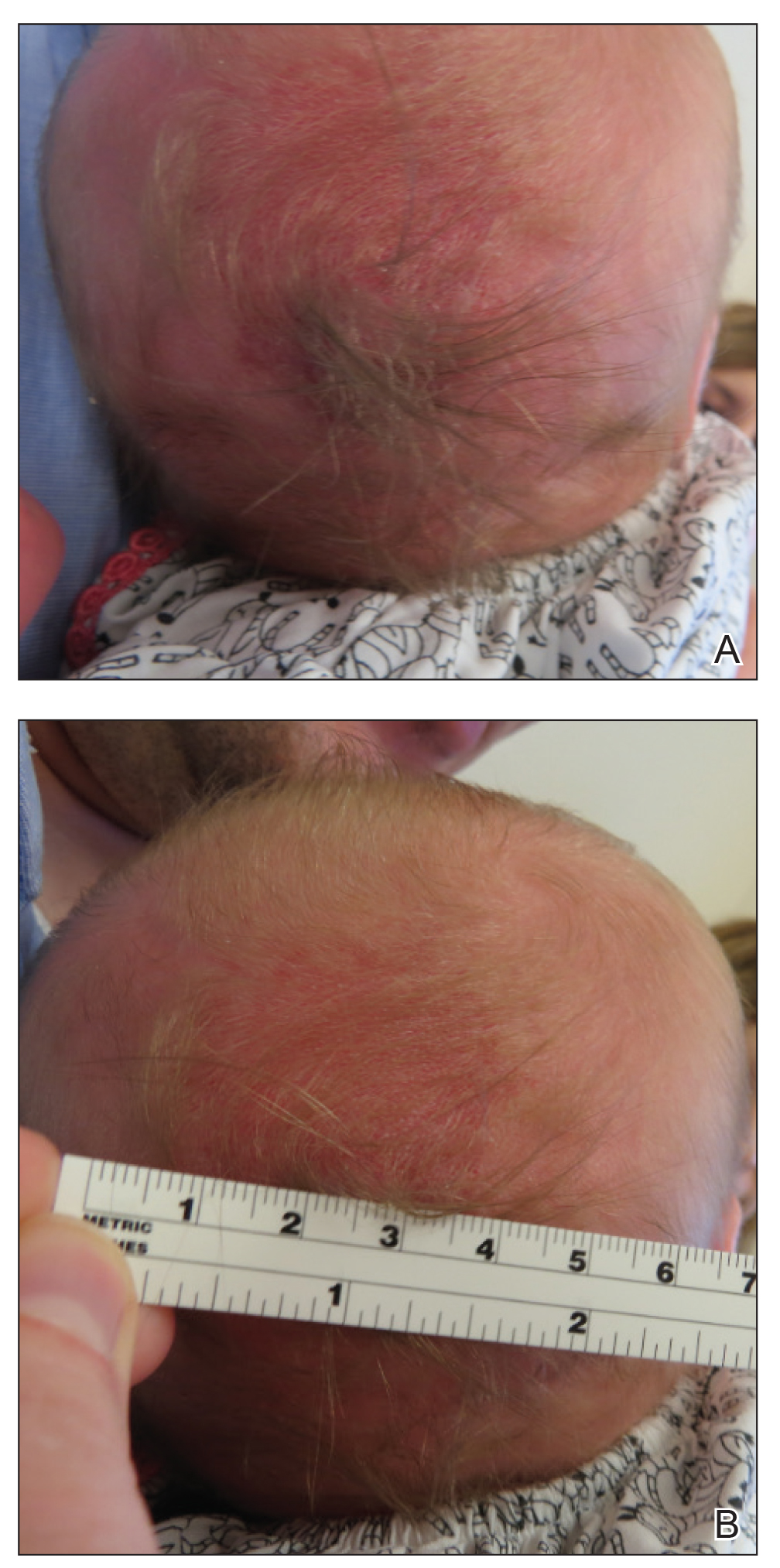

Physical examination revealed focal areas of mildly thick, hyperkeratotic scale with desquamation on the plantar and palmar surfaces of the feet and hands. The underlying skin of the feet consisted of dyspigmented patches of dark brown and hypopigmented skin with erythema, profound scaling, and sparing of the internal plantar arches (Figure 1A). On the palms, thin hyperkeratotic plaques with desquamation and erythematous maceration of the surrounding skin were observed (Figure 2A). Thin white plaques of the posterior bilateral buccal mucosa were appreciated as well as an erosion that extended to the lower lip.

The differential diagnosis included LP, psoriasis, acquired palmoplantar keratoderma, and discoid lupus erythematosus. Tinea pedis and tinea manuum were less likely in the setting of a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation.

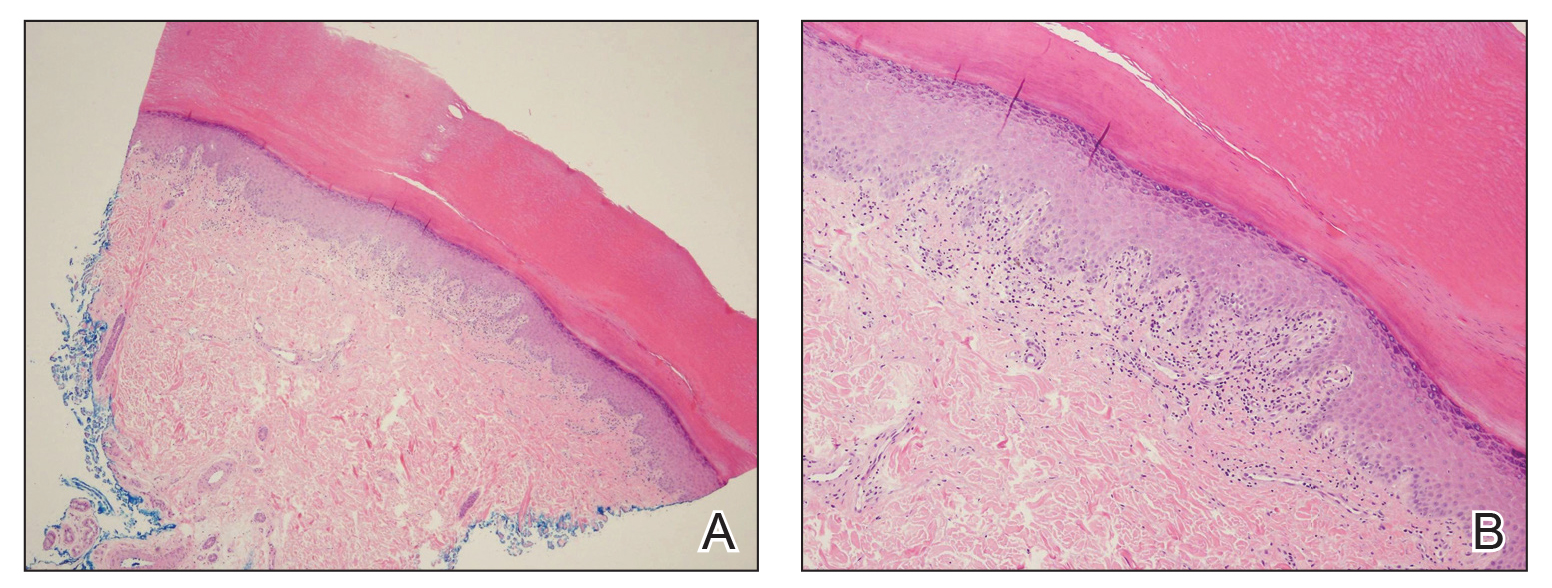

A biopsy of the lateral aspect of the left foot showed a cell-poor interface dermatitis that could resemble partially treated LP or a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 3). Given the clinical and pathologic findings, a diagnosis of palmoplantar LP was favored. The patient was on no medications or over-the-counter supplements prior to the appearance of the rash, making a lichenoid hypersensitivity rash less likely. The histology findings likely were muted, as they were done at the end of the prednisone taper.

Minocycline and clobetasol ointment were discontinued, and the prednisone taper was completed as originally prescribed. The patient was started on 25 mg daily of acitretin for 4 weeks, then increased to 35 mg daily. Notable improvement in the palmar and plantar lesions was noted after the initial 4 weeks of therapy; however, acitretin treatment was discontinued due to lack of adequate insurance coverage for the medication. The patient became symptomatic several weeks following acitretin cessation and was started on methotrexate 15 mg weekly with triamcinolone acetonide paste 0.1% for the oral lesions. Once again, improvement was seen on both the palmar and plantar surfaces after 4 weeks of therapy (Figures 1B and 2B).

Evidence for treatment of palmoplantar LP is limited to a few case reports and case series. Documented treatments for palmoplantar LP include topical and systemic steroids, tazarotene, acitretin, and immunosuppressive medications.4 One case report described a patient who responded well to prednisone therapy (1 mg/kg daily for 3 weeks, then reduced to 5 mg daily).5 Another report described a patient who responded favorably to cyclosporine 3.5 mg/kg daily for 4 weeks, then tapered over another 4 weeks for a total of 8 weeks of treatment.4 Although the most common treatments described in the literature consist of acitretin as well as topical and systemic steroids, few have discussed the efficacy of methotrexate. In one study, acitretin did not result in clearance, but the patient saw profound improvement with methotrexate (titrated up to 25 mg weekly) over 2 months.1

In our case, treatment with methotrexate was proven successful in a patient who responded to acitretin but was unable to afford treatment. This case highlights a rare variant of a common disease and the possibility of methotrexate as a cost-effective and useful treatment option for LP.

- Rieder E, Hale CS, Meehan SA, et al. Palmoplantar lichen planus. Dermatol Online J. 2015;20:13030/qt1vn9s55z.

- Sánchez-Pérez J, Rios Buceta L, Fraga J, et al. Lichen planus with lesions on the palms and/or soles: prevalence and clinicopathological study of 36 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:310-314.

- Gutte R, Khopkar U. Predominant palmoplantar lichen planus: a diagnostic challenge. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:343-347.

- Karakatsanis G, Patsatsi A, Kastoridou C, et al Palmoplantar lichen planus with umbilicated papules: an atypical case with rapid therapeutic response to cyclosporin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1006-1007.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Bennani Z, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: Effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

To the Editor:

Palmoplantar lichen planus (LP) is an uncommon variant of LP that involves the palms and soles. The prevalence of LP is approximately 0.1% to 2% in the general population. It can affect both mucosal and cutaneous surfaces.1 A study of 36 patients with LP showed that 25% (9/36) had palmar and/or plantar involvement.2 Palmoplantar LP is more commonly found in men than women, with an average age of onset of 38 to 65 years.3 It tends to affect the soles more often than the palms, with the most common site being the plantar arch. Itching generally is the most common symptom reported. Lesions often resolve over a few months, but relapses can occur in 10% to 29% of patients.2 The clinical morphology commonly is characterized as erythematous scaly plaques, hyperkeratotic plaques, or ulcerations.4 Due to its rare occurrence, palmoplantar LP often is misdiagnosed as psoriasis, eczematous dermatitis, tinea nigra, or secondary syphilis, making pathology extremely helpful in making the diagnosis.1 Darker skin types can obscure defining characteristics, further impeding a timely diagnosis. We describe a novel case of palmoplantar LP that was successfully treated with methotrexate.

A 38-year-old man with no notable medical history presented for dermatologic evaluation of a palmar and plantar rash of 4 months' duration. The rash was accompanied by intense burning pain and pruritus. Prior to presentation, he had been treated with multiple prednisone tapers starting at 40 mg daily as well as combination therapy of a 2-week course of minocycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment twice daily for 4 months, with no notable improvement. Workup prior to presentation included a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation and a normal antinuclear antibody titer. A review of symptoms was negative for arthralgia, myalgia, photosensitivity, malar rash, Raynaud phenomenon, pleuritic pain, seizures, and psychosis.

Physical examination revealed focal areas of mildly thick, hyperkeratotic scale with desquamation on the plantar and palmar surfaces of the feet and hands. The underlying skin of the feet consisted of dyspigmented patches of dark brown and hypopigmented skin with erythema, profound scaling, and sparing of the internal plantar arches (Figure 1A). On the palms, thin hyperkeratotic plaques with desquamation and erythematous maceration of the surrounding skin were observed (Figure 2A). Thin white plaques of the posterior bilateral buccal mucosa were appreciated as well as an erosion that extended to the lower lip.

The differential diagnosis included LP, psoriasis, acquired palmoplantar keratoderma, and discoid lupus erythematosus. Tinea pedis and tinea manuum were less likely in the setting of a negative potassium hydroxide fungal preparation.