User login

Foreign-Body Reaction to Orthopedic Hardware a Decade After Implantation

To the Editor:

Cutaneous reactions to implantable devices, such as dental implants, intracoronary stents, prosthetic valves, endovascular prostheses, gynecologic devices, and spinal cord stimulator devices, occur with varying frequency and include infectious, hypersensitivity, allergic, and foreign-body reactions. Manifestations have included contact dermatitis; urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions; extrusion; and granuloma formation.1,2 Immune complex reactions around implants causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardwarealso have been reported.3,4 Most reported cutaneous reactions typically occur within the first weeks or months after implantation; a reaction rarely presents several years after implantation. We report a cutaneous reaction to an orthopedic appliance almost 10 years after implantation.

A 67-year-old man presented with 2 painful nodules on the right clavicle that were present for several months. The patient denied fever, chills, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes, or night sweats. Approximately 10 years prior to the appearance of the nodules, the patient fractured the right clavicle and underwent placement of a metal plate. His medical history included resection of the right tonsil and soft-palate carcinoma with radical neck dissection and postoperative radiation, which was completed approximately 4 years prior to placement of the metal plate. The patient recently completed 4 to 6 weeks of fluorouracil for shave biopsy–proven actinic keratosis overlying the entire irradiated area.

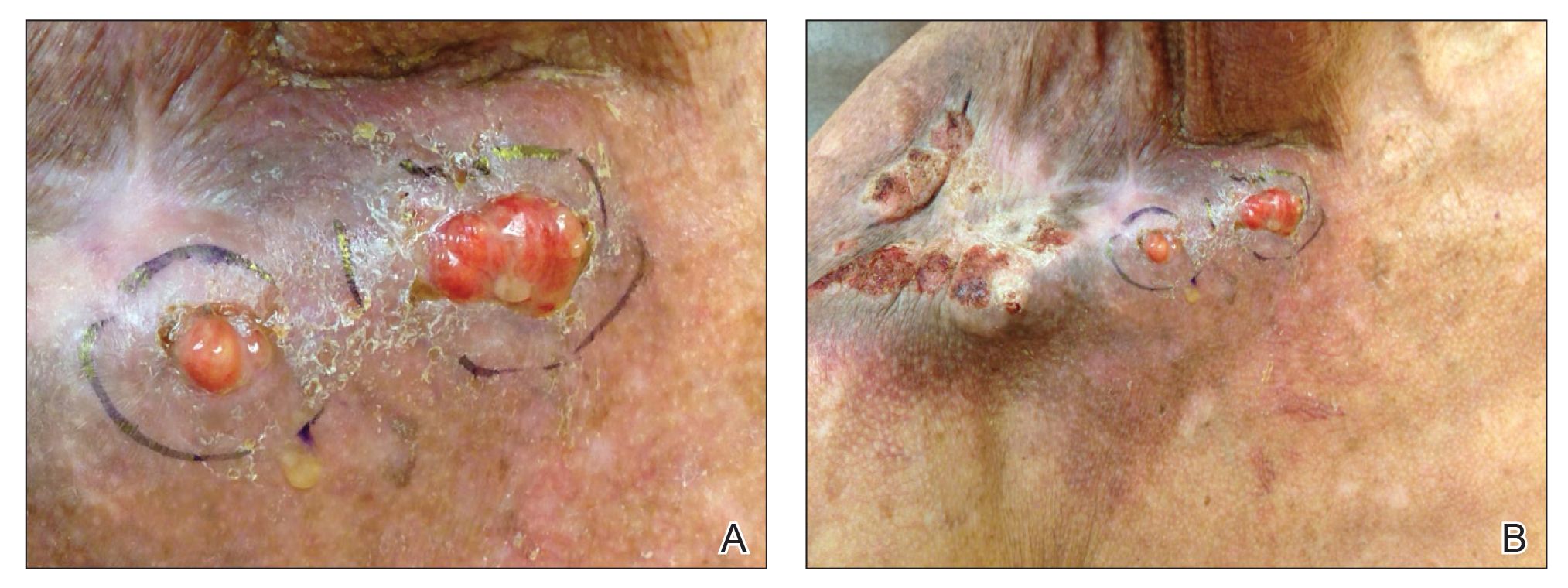

Physical examination revealed 2 pink friable nodules measuring 1.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter and leaking serous fluid within the irradiated area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, cutaneous recurrent metastasis, and atypical basal cell carcinoma. A skin biopsy specimen showed hemorrhagic ulcerated skin with acute and chronic inflammation and abscess.

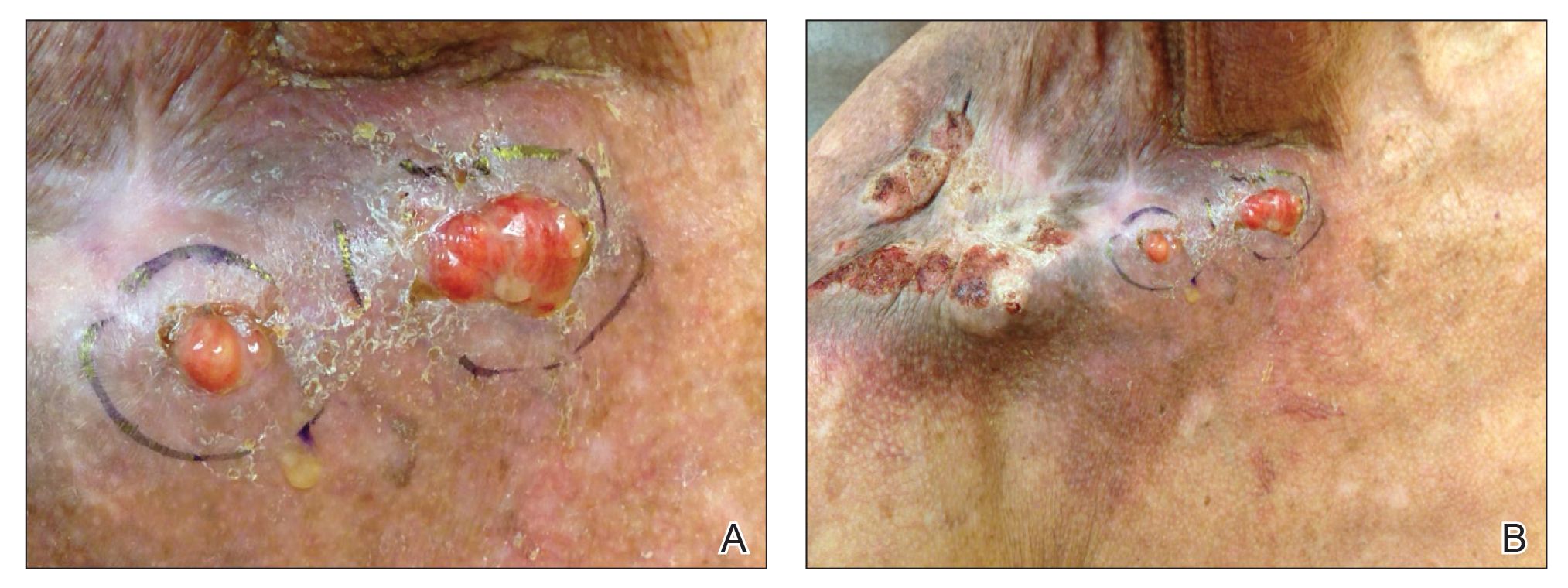

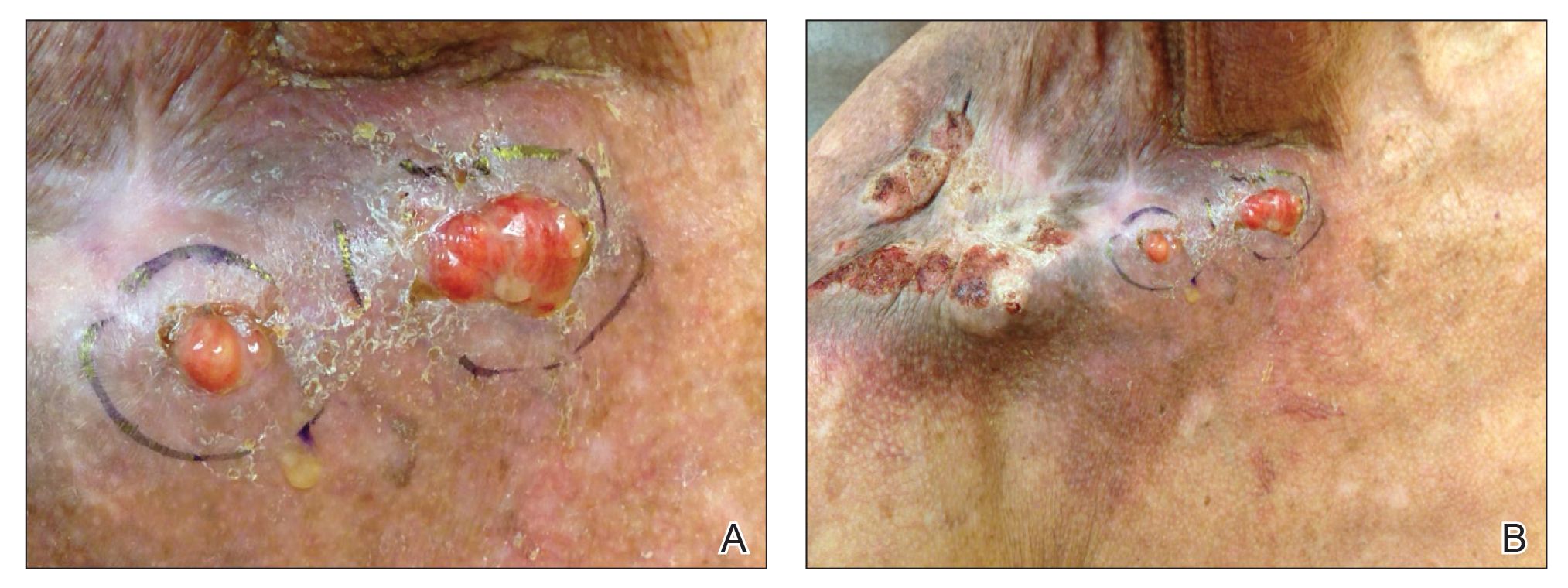

The patient presented for excisional biopsy of these areas on the right medial clavicle 1 week later. Physical examination revealed the 2 nodules had decreased in diameter; now, however, the patient had 4 discrete lesions measuring 4 to 7 mm in diameter, which were similar in appearance to the earlier nodules (Figure 2). He reported a low-grade fever, erythema, and increased tenderness of the area.

Underlying loosened orthopedic hardware screws were revealed upon punch biopsies of the involved areas (Figure 3). Wound cultures showed abundant Staphylococcus aureus and moderate group B Streptococcus; cultures for Mycobacterium were negative. The C-reactive protein level was elevated (5.47 mg/dL [reference range, ≤0.7 mg/dL]), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased (68 mm/h [reference range, 0–15 mm/h]). A complete blood cell count was within reference range, except for a mildly elevated eosinophil count (6.7% [reference range, 0%–5%]). The patient was admitted to the hospital, and antibiotics were started. Two days later, the orthopedic surgery service removed the hardware. At 3-week follow-up, physical examination revealed near closure of the wounds.

Cutaneous reactions to orthopedic implants include dermatitis, as well as urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions. Immune complex reactions can develop around implants, causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardware.1,3 Most inflammatory reactions take place within several months after implantation.3 Our patient’s reaction to hardware 10 years after implantation highlights the importance of taking a detailedand thorough history that includes queries about distant surgery.

- Basko-Plluska JL, Thyssen JP, Schalock PC. Cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants. Dermatitis. 2011;22:65-79.

- Chaudhry ZA, Najib U, Bajwa ZH, et al. Detailed analysis of allergic cutaneous reactions to spinal cord stimulator devices. J Pain Res. 2013;6:617-623.

- Huber M, Reinisch G, Trettenhahn G, et al. Presence of corrosion products and hypersensitivity-associated reactions in periprosthetic tissue after aseptic loosening of total hip replacements with metal bearing surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:172-180.

- Poncet-Wallet C, Ormezzano Y, Ernst E, et al. Study of a case of cochlear implant with recurrent cutaneous extrusion. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2009;126:264-268.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous reactions to implantable devices, such as dental implants, intracoronary stents, prosthetic valves, endovascular prostheses, gynecologic devices, and spinal cord stimulator devices, occur with varying frequency and include infectious, hypersensitivity, allergic, and foreign-body reactions. Manifestations have included contact dermatitis; urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions; extrusion; and granuloma formation.1,2 Immune complex reactions around implants causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardwarealso have been reported.3,4 Most reported cutaneous reactions typically occur within the first weeks or months after implantation; a reaction rarely presents several years after implantation. We report a cutaneous reaction to an orthopedic appliance almost 10 years after implantation.

A 67-year-old man presented with 2 painful nodules on the right clavicle that were present for several months. The patient denied fever, chills, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes, or night sweats. Approximately 10 years prior to the appearance of the nodules, the patient fractured the right clavicle and underwent placement of a metal plate. His medical history included resection of the right tonsil and soft-palate carcinoma with radical neck dissection and postoperative radiation, which was completed approximately 4 years prior to placement of the metal plate. The patient recently completed 4 to 6 weeks of fluorouracil for shave biopsy–proven actinic keratosis overlying the entire irradiated area.

Physical examination revealed 2 pink friable nodules measuring 1.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter and leaking serous fluid within the irradiated area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, cutaneous recurrent metastasis, and atypical basal cell carcinoma. A skin biopsy specimen showed hemorrhagic ulcerated skin with acute and chronic inflammation and abscess.

The patient presented for excisional biopsy of these areas on the right medial clavicle 1 week later. Physical examination revealed the 2 nodules had decreased in diameter; now, however, the patient had 4 discrete lesions measuring 4 to 7 mm in diameter, which were similar in appearance to the earlier nodules (Figure 2). He reported a low-grade fever, erythema, and increased tenderness of the area.

Underlying loosened orthopedic hardware screws were revealed upon punch biopsies of the involved areas (Figure 3). Wound cultures showed abundant Staphylococcus aureus and moderate group B Streptococcus; cultures for Mycobacterium were negative. The C-reactive protein level was elevated (5.47 mg/dL [reference range, ≤0.7 mg/dL]), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased (68 mm/h [reference range, 0–15 mm/h]). A complete blood cell count was within reference range, except for a mildly elevated eosinophil count (6.7% [reference range, 0%–5%]). The patient was admitted to the hospital, and antibiotics were started. Two days later, the orthopedic surgery service removed the hardware. At 3-week follow-up, physical examination revealed near closure of the wounds.

Cutaneous reactions to orthopedic implants include dermatitis, as well as urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions. Immune complex reactions can develop around implants, causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardware.1,3 Most inflammatory reactions take place within several months after implantation.3 Our patient’s reaction to hardware 10 years after implantation highlights the importance of taking a detailedand thorough history that includes queries about distant surgery.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous reactions to implantable devices, such as dental implants, intracoronary stents, prosthetic valves, endovascular prostheses, gynecologic devices, and spinal cord stimulator devices, occur with varying frequency and include infectious, hypersensitivity, allergic, and foreign-body reactions. Manifestations have included contact dermatitis; urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions; extrusion; and granuloma formation.1,2 Immune complex reactions around implants causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardwarealso have been reported.3,4 Most reported cutaneous reactions typically occur within the first weeks or months after implantation; a reaction rarely presents several years after implantation. We report a cutaneous reaction to an orthopedic appliance almost 10 years after implantation.

A 67-year-old man presented with 2 painful nodules on the right clavicle that were present for several months. The patient denied fever, chills, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes, or night sweats. Approximately 10 years prior to the appearance of the nodules, the patient fractured the right clavicle and underwent placement of a metal plate. His medical history included resection of the right tonsil and soft-palate carcinoma with radical neck dissection and postoperative radiation, which was completed approximately 4 years prior to placement of the metal plate. The patient recently completed 4 to 6 weeks of fluorouracil for shave biopsy–proven actinic keratosis overlying the entire irradiated area.

Physical examination revealed 2 pink friable nodules measuring 1.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter and leaking serous fluid within the irradiated area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, cutaneous recurrent metastasis, and atypical basal cell carcinoma. A skin biopsy specimen showed hemorrhagic ulcerated skin with acute and chronic inflammation and abscess.

The patient presented for excisional biopsy of these areas on the right medial clavicle 1 week later. Physical examination revealed the 2 nodules had decreased in diameter; now, however, the patient had 4 discrete lesions measuring 4 to 7 mm in diameter, which were similar in appearance to the earlier nodules (Figure 2). He reported a low-grade fever, erythema, and increased tenderness of the area.

Underlying loosened orthopedic hardware screws were revealed upon punch biopsies of the involved areas (Figure 3). Wound cultures showed abundant Staphylococcus aureus and moderate group B Streptococcus; cultures for Mycobacterium were negative. The C-reactive protein level was elevated (5.47 mg/dL [reference range, ≤0.7 mg/dL]), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased (68 mm/h [reference range, 0–15 mm/h]). A complete blood cell count was within reference range, except for a mildly elevated eosinophil count (6.7% [reference range, 0%–5%]). The patient was admitted to the hospital, and antibiotics were started. Two days later, the orthopedic surgery service removed the hardware. At 3-week follow-up, physical examination revealed near closure of the wounds.

Cutaneous reactions to orthopedic implants include dermatitis, as well as urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions. Immune complex reactions can develop around implants, causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardware.1,3 Most inflammatory reactions take place within several months after implantation.3 Our patient’s reaction to hardware 10 years after implantation highlights the importance of taking a detailedand thorough history that includes queries about distant surgery.

- Basko-Plluska JL, Thyssen JP, Schalock PC. Cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants. Dermatitis. 2011;22:65-79.

- Chaudhry ZA, Najib U, Bajwa ZH, et al. Detailed analysis of allergic cutaneous reactions to spinal cord stimulator devices. J Pain Res. 2013;6:617-623.

- Huber M, Reinisch G, Trettenhahn G, et al. Presence of corrosion products and hypersensitivity-associated reactions in periprosthetic tissue after aseptic loosening of total hip replacements with metal bearing surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:172-180.

- Poncet-Wallet C, Ormezzano Y, Ernst E, et al. Study of a case of cochlear implant with recurrent cutaneous extrusion. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2009;126:264-268.

- Basko-Plluska JL, Thyssen JP, Schalock PC. Cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants. Dermatitis. 2011;22:65-79.

- Chaudhry ZA, Najib U, Bajwa ZH, et al. Detailed analysis of allergic cutaneous reactions to spinal cord stimulator devices. J Pain Res. 2013;6:617-623.

- Huber M, Reinisch G, Trettenhahn G, et al. Presence of corrosion products and hypersensitivity-associated reactions in periprosthetic tissue after aseptic loosening of total hip replacements with metal bearing surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:172-180.

- Poncet-Wallet C, Ormezzano Y, Ernst E, et al. Study of a case of cochlear implant with recurrent cutaneous extrusion. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2009;126:264-268.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous reactions to implantable devices occur with varying frequency and include infectious, hypersensitivity, allergic, and foreign-body reactions.

- Most reactions typically occur within the first weeks or months after implantation; however, a reaction rarely may present several years after implantation.

Recurrent Cutaneous Exophiala Phaeohyphomycosis in an Immunosuppressed Patient

To the Editor:

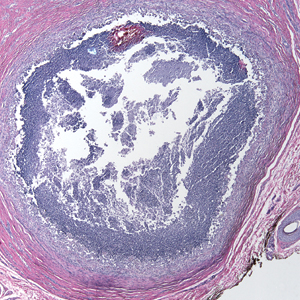

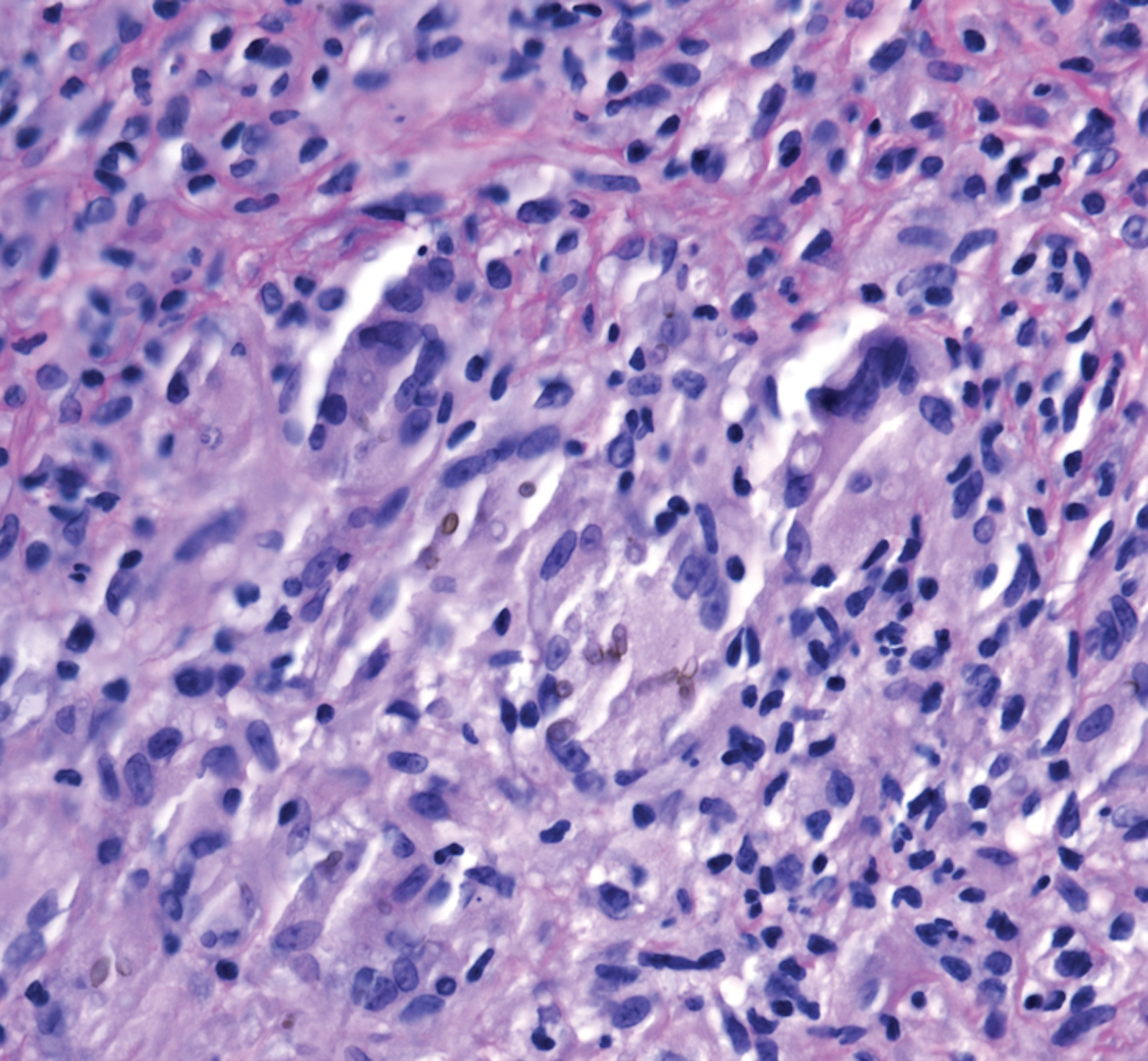

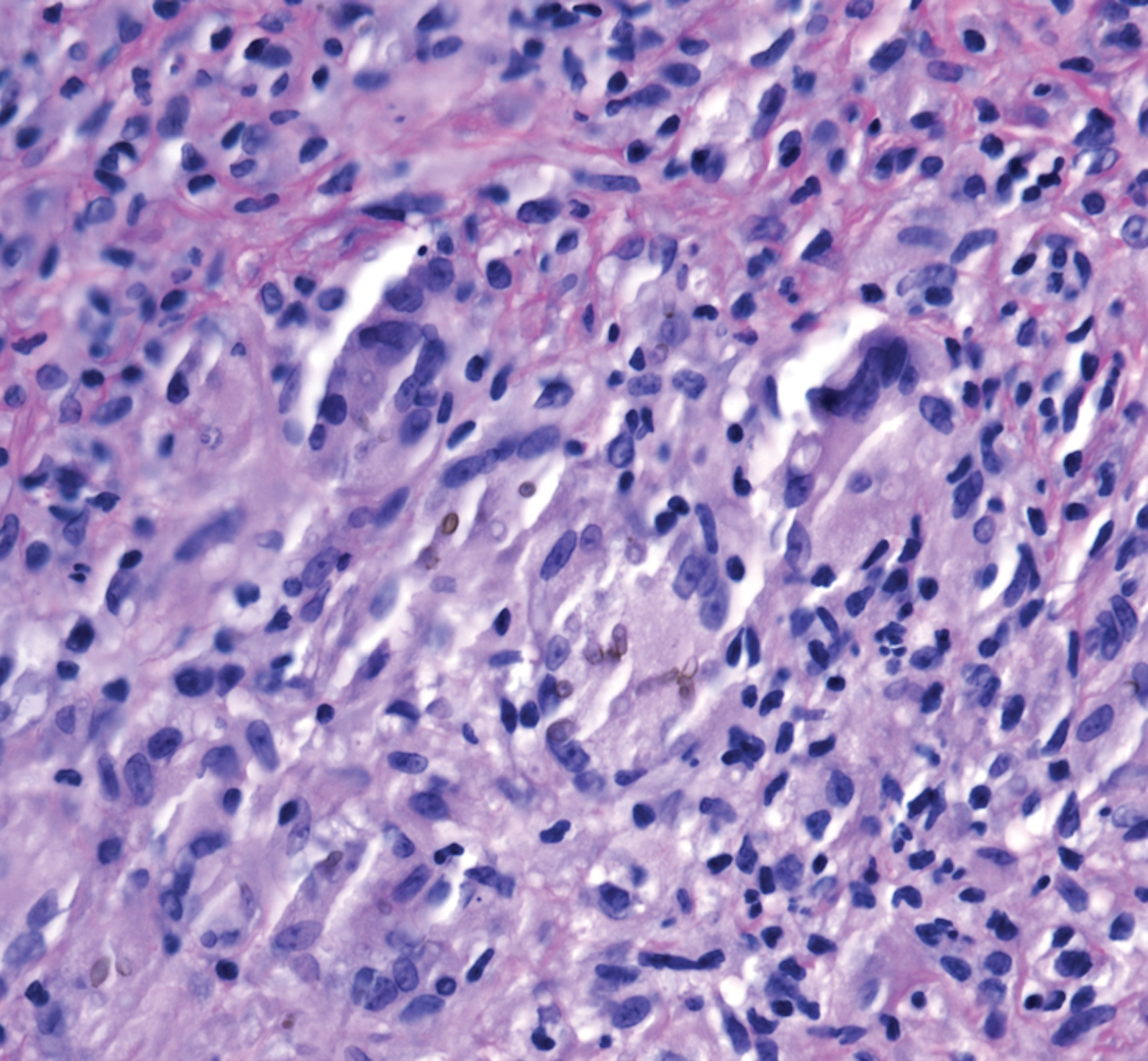

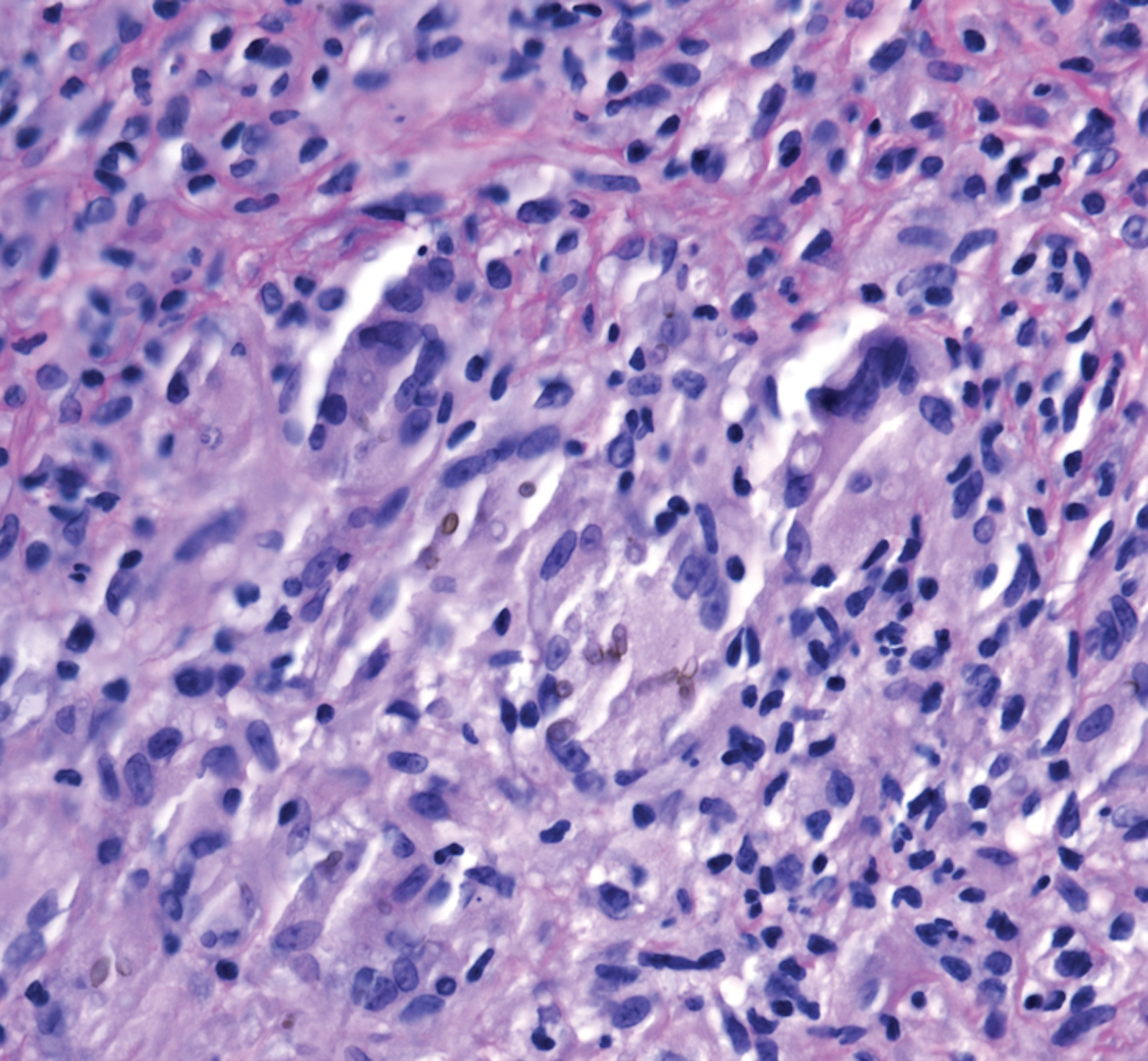

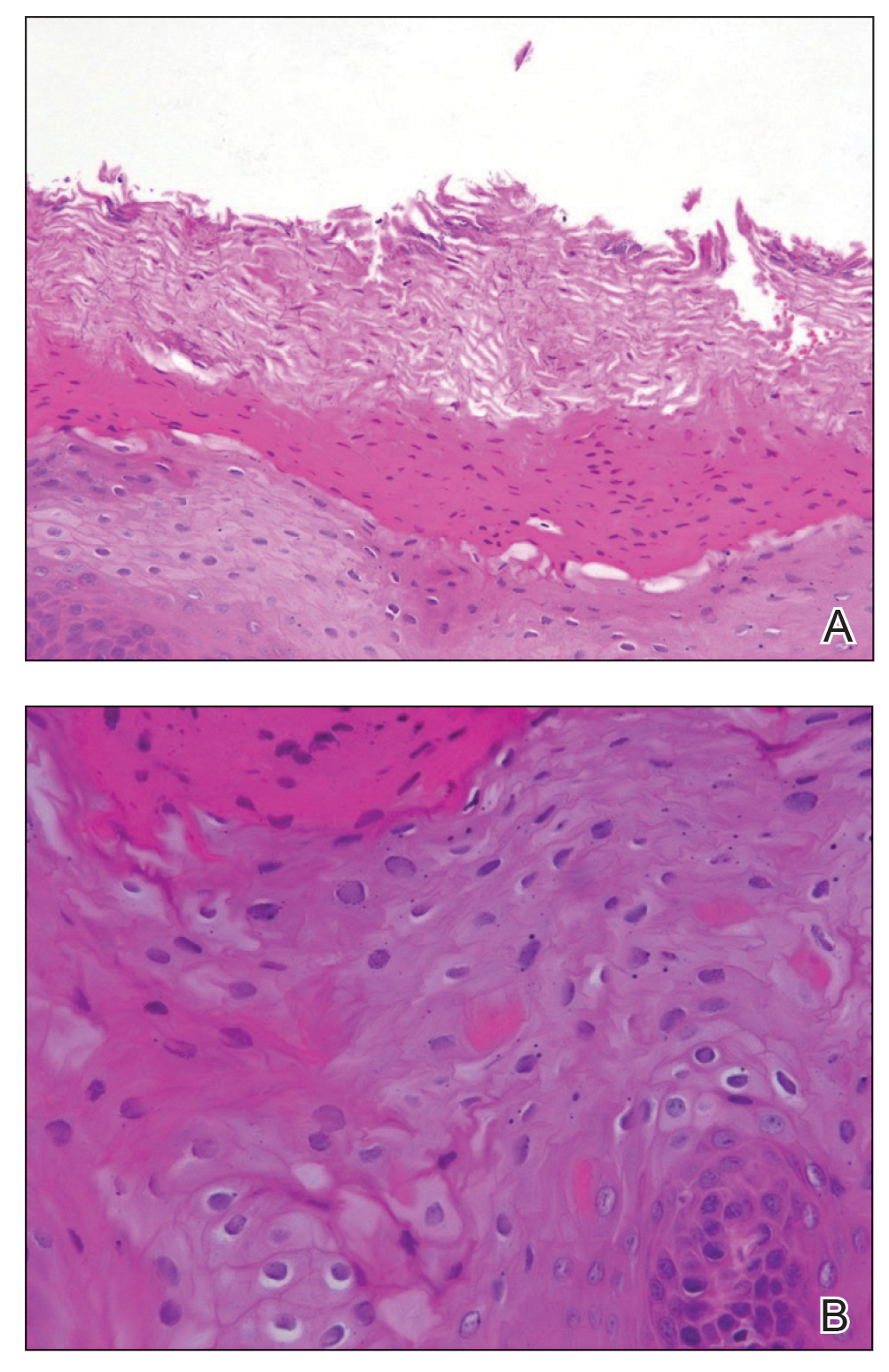

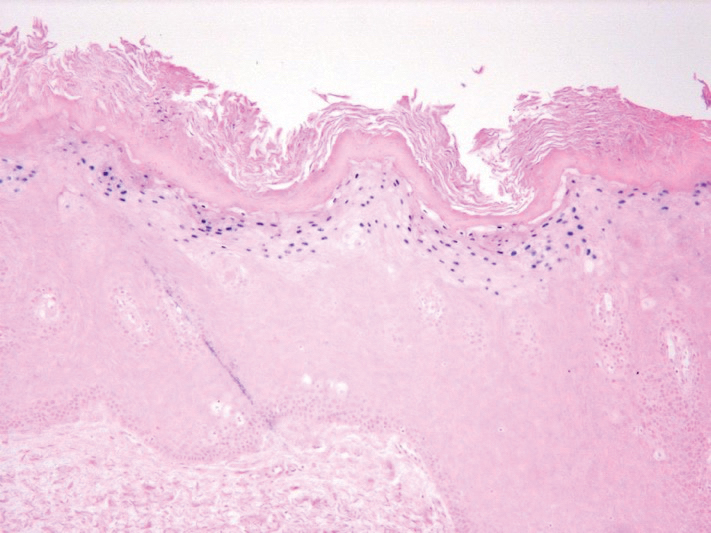

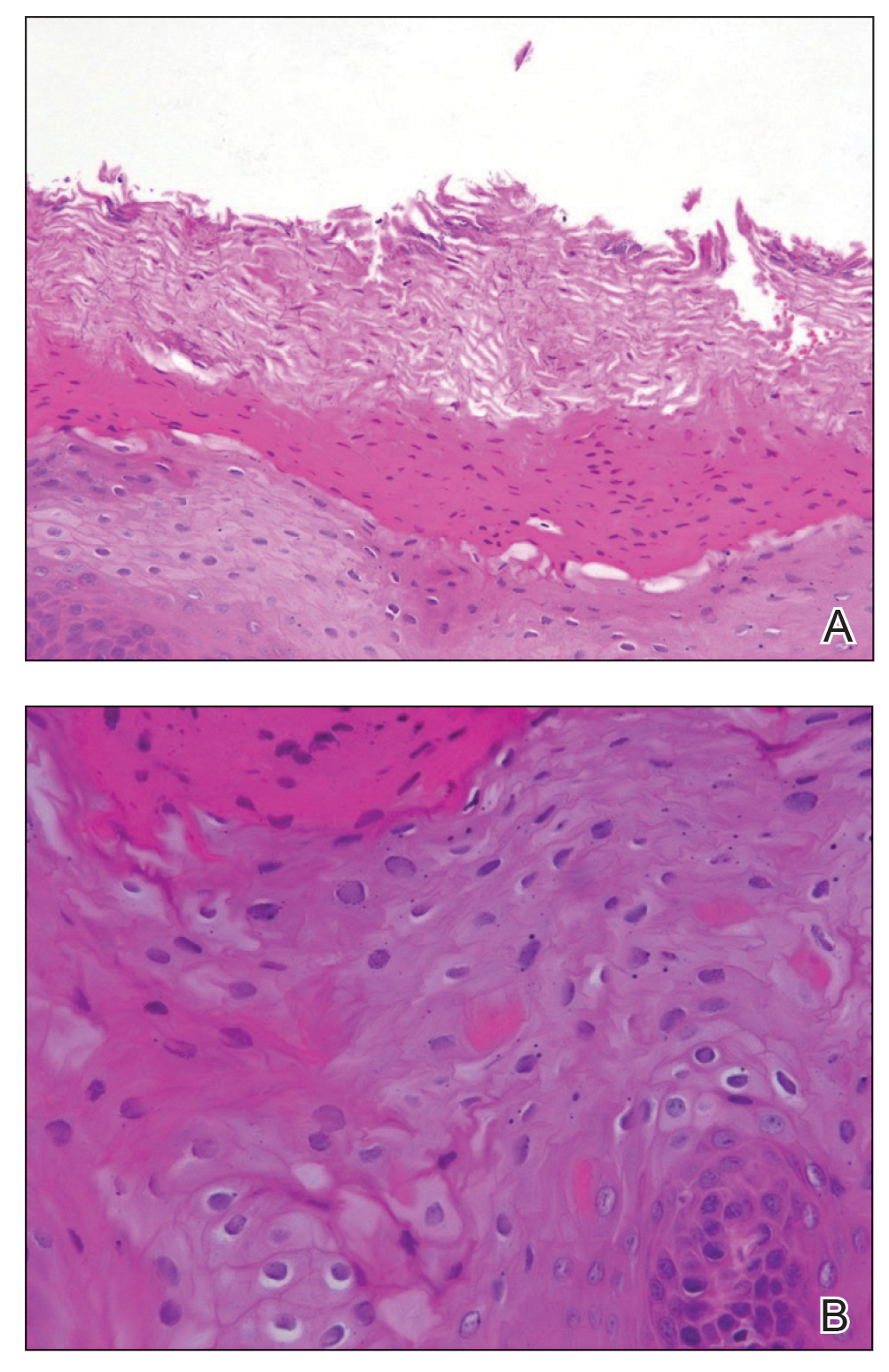

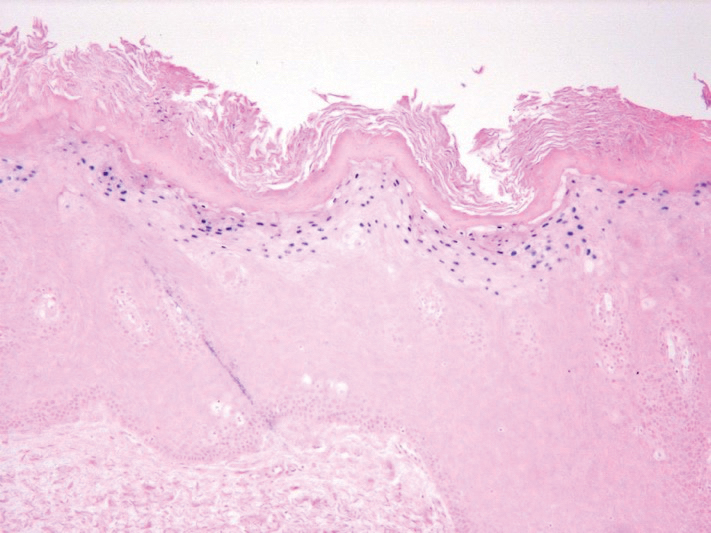

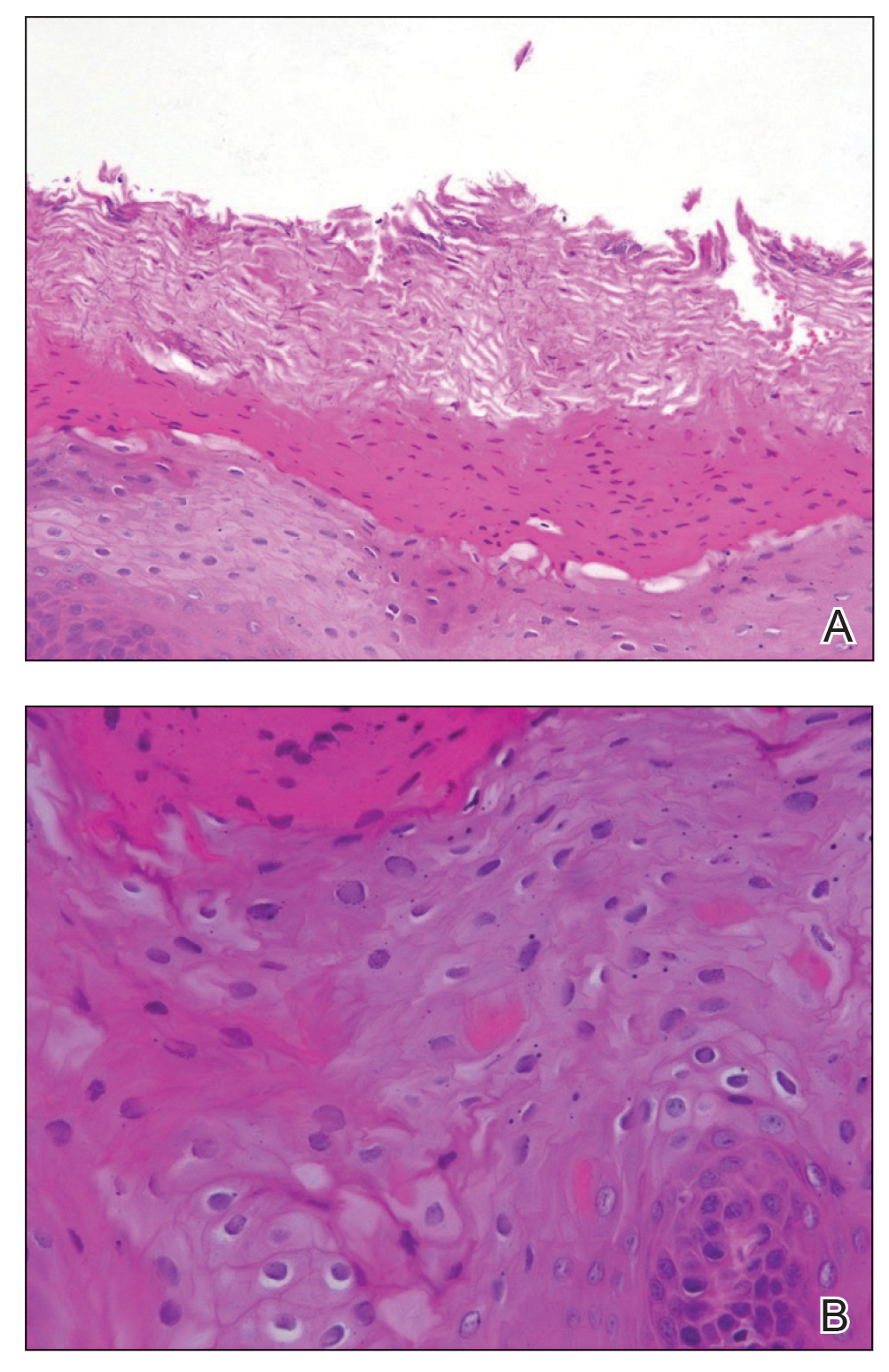

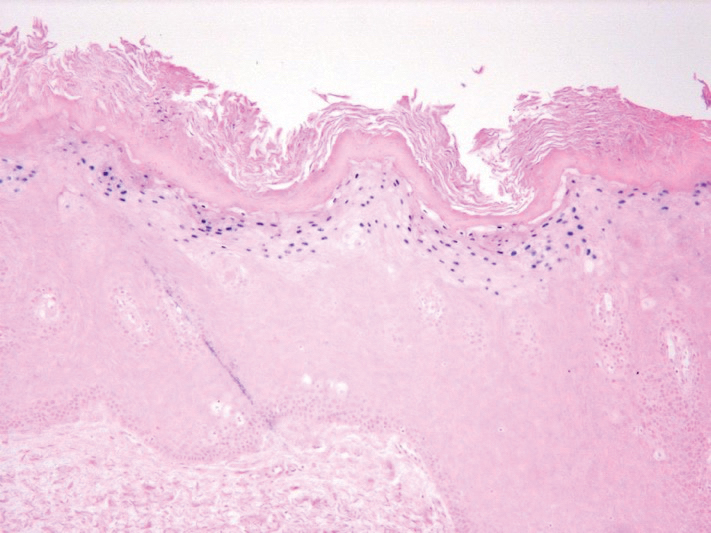

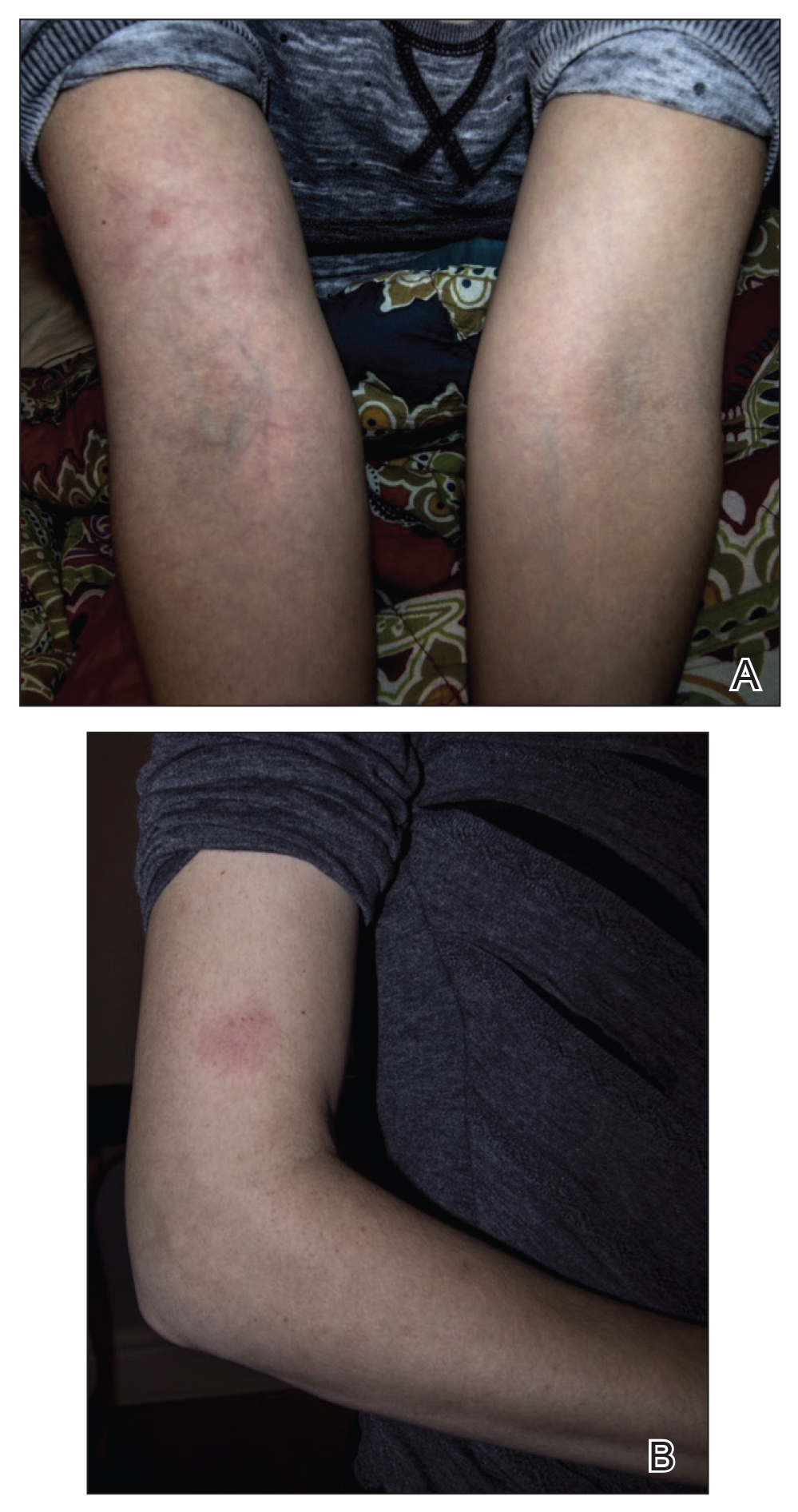

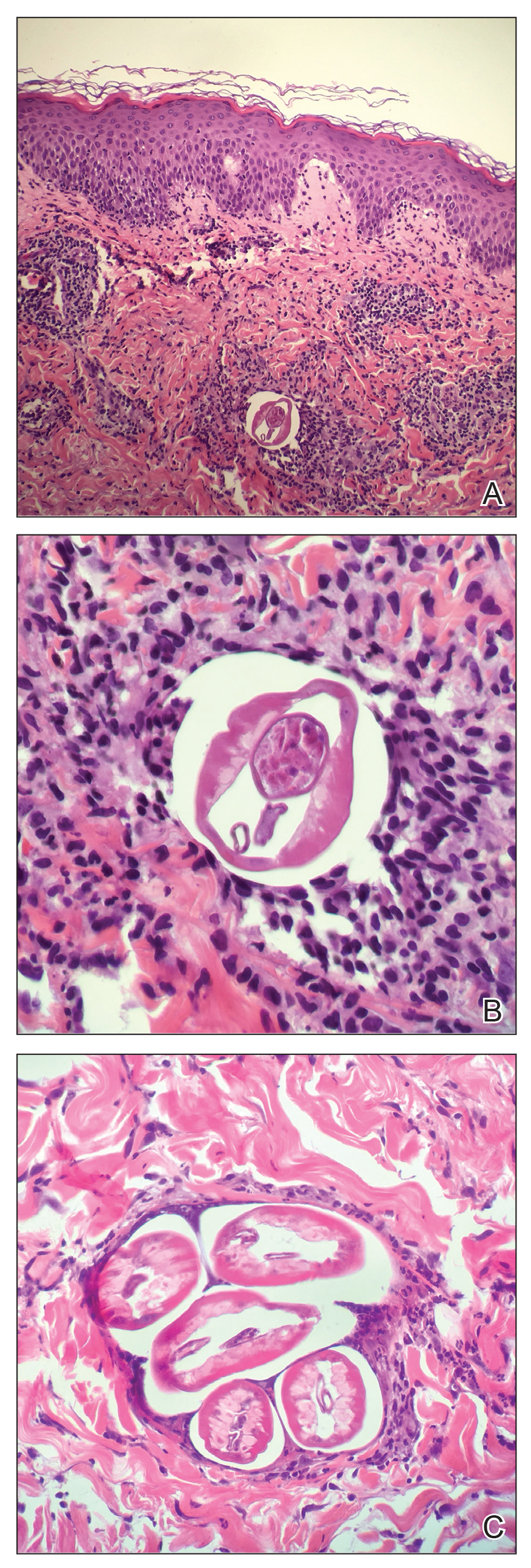

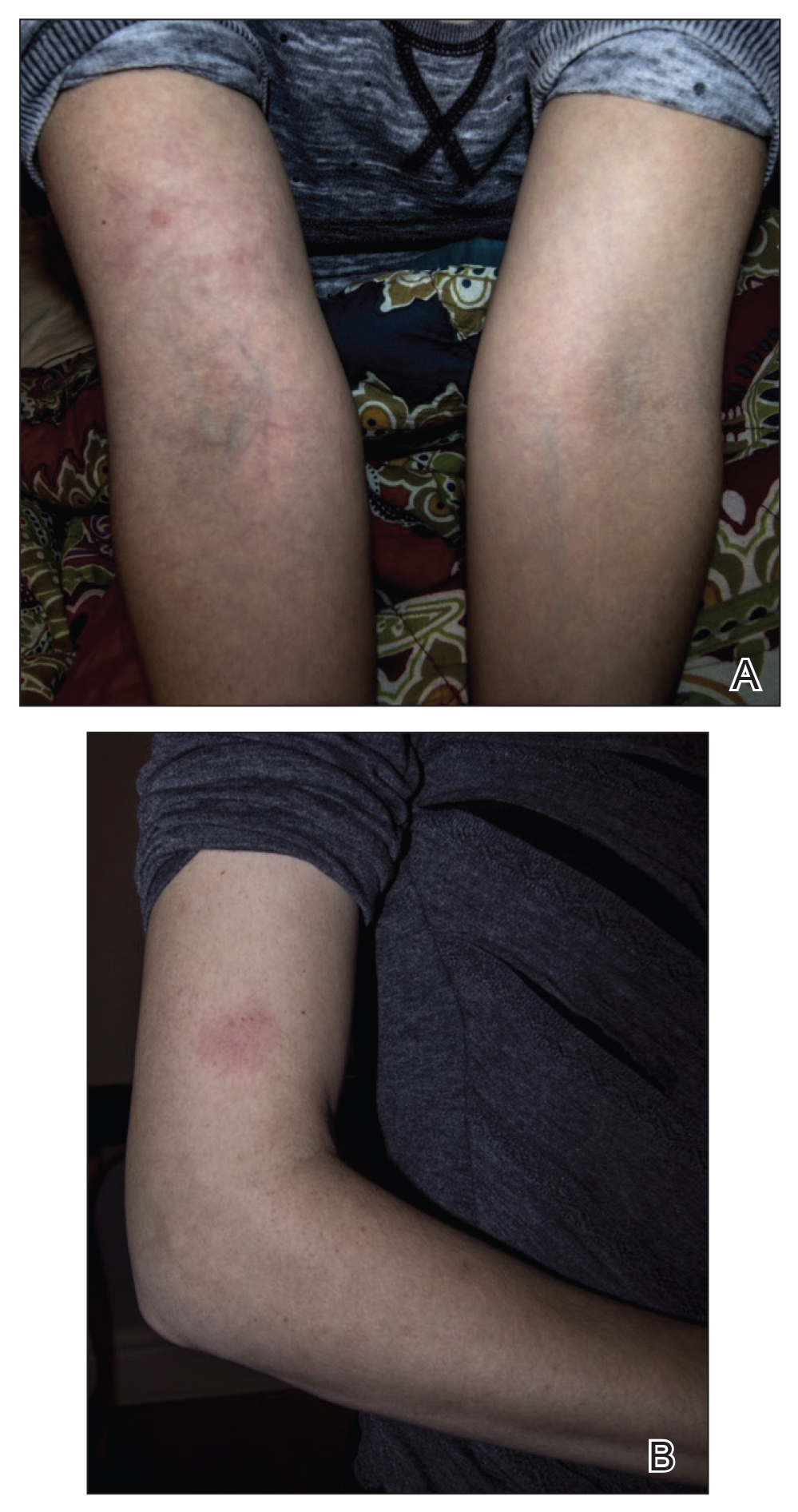

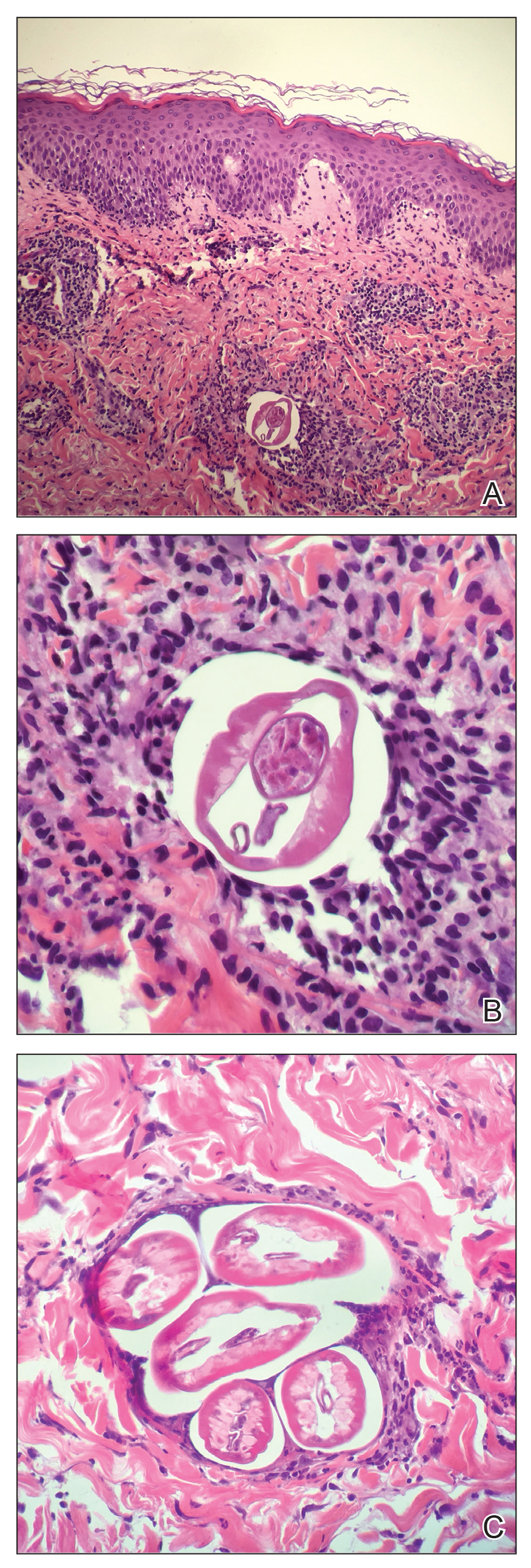

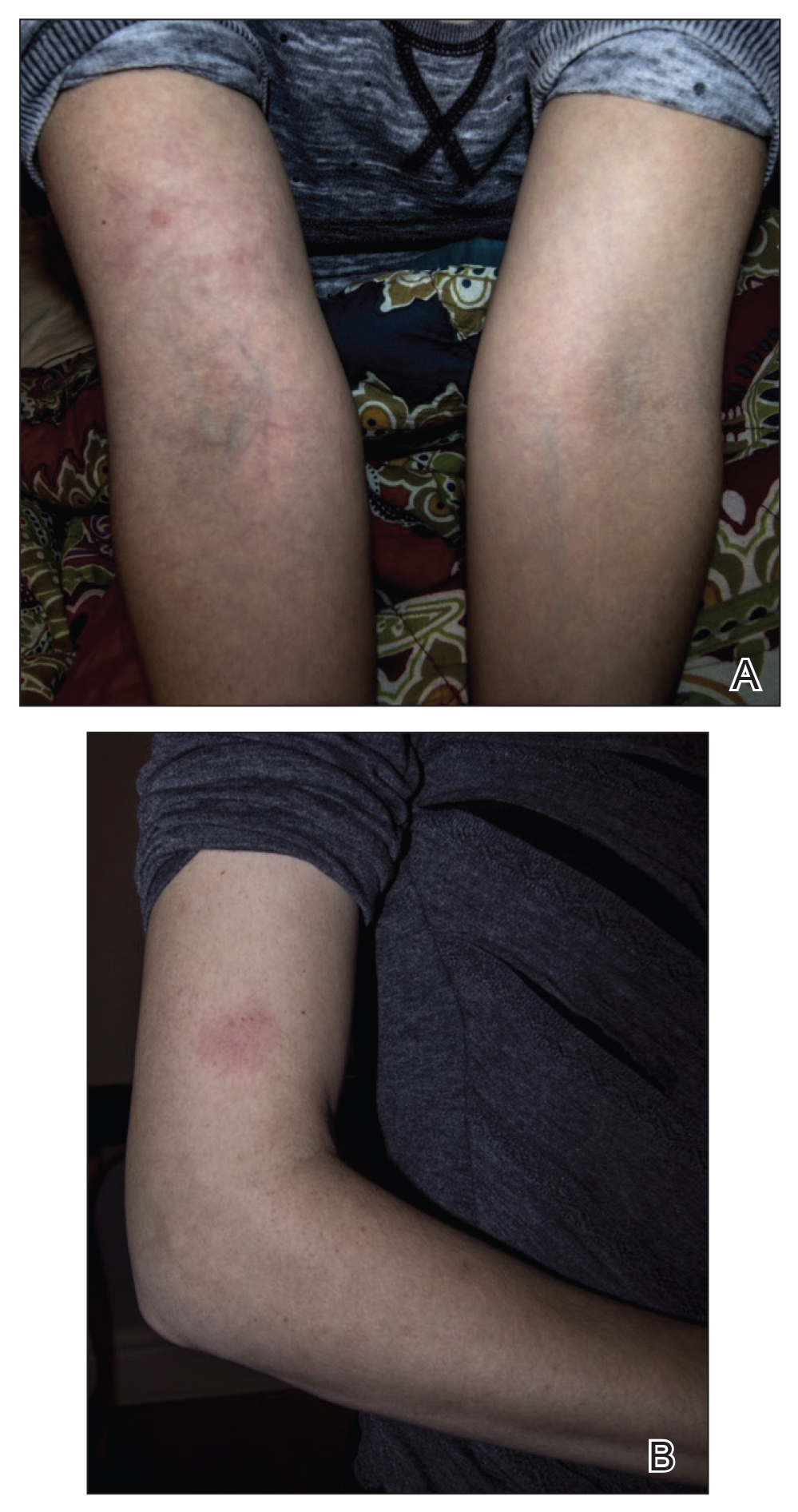

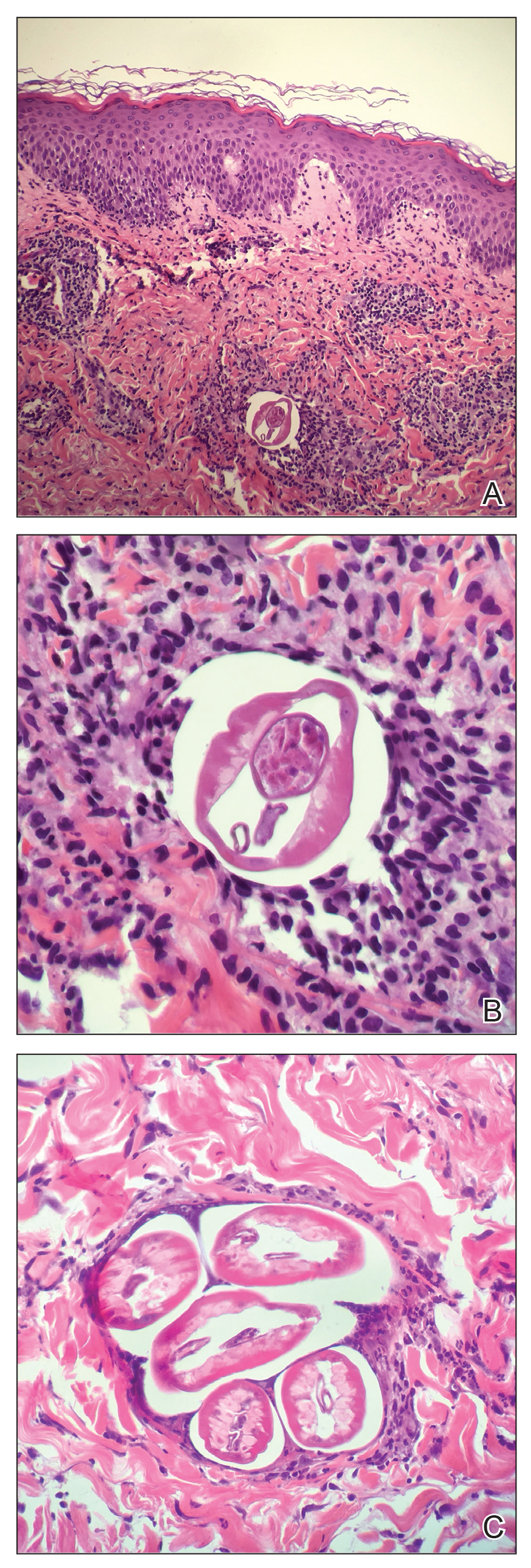

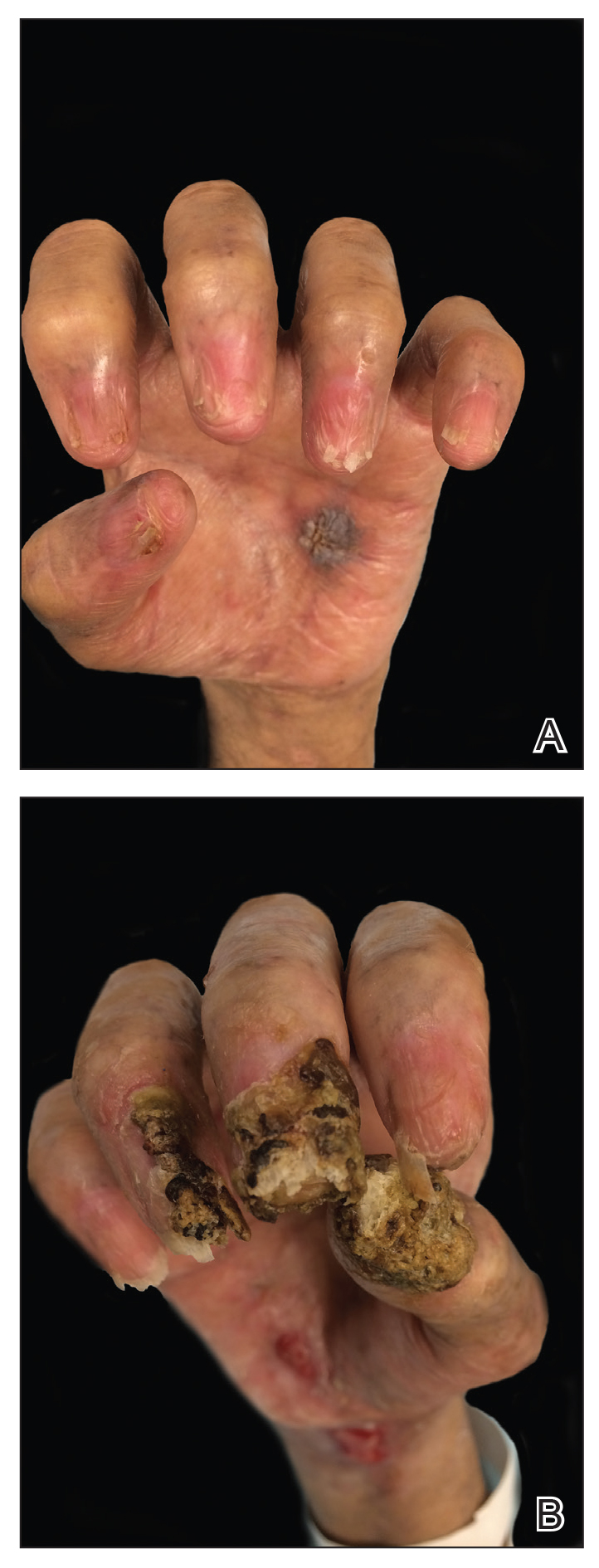

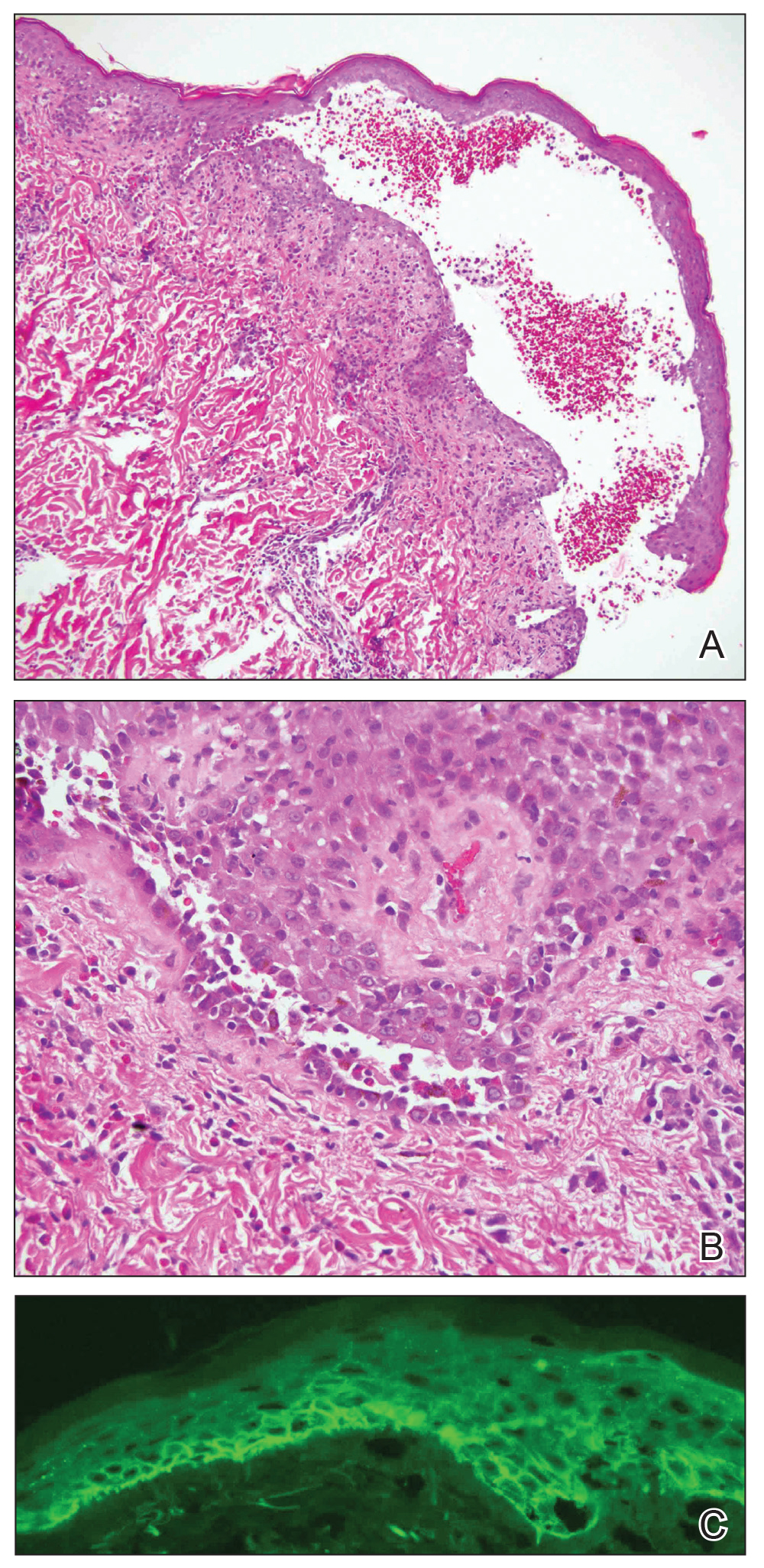

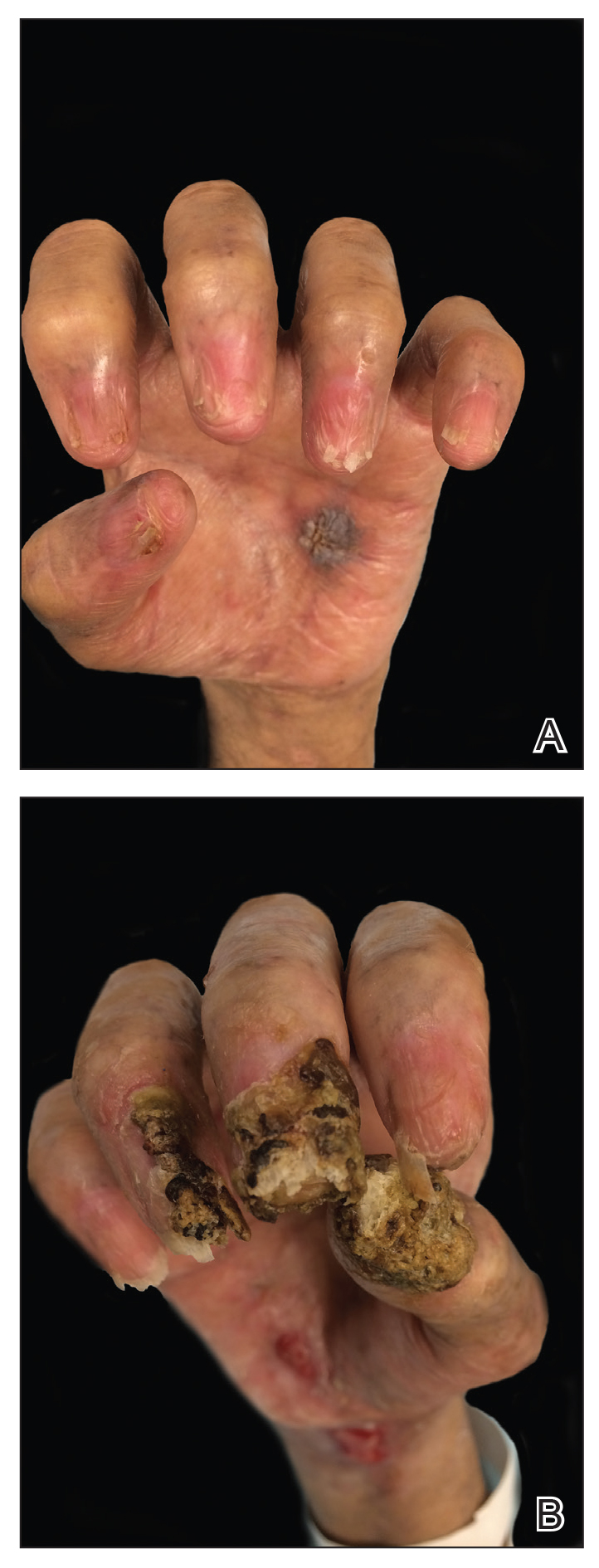

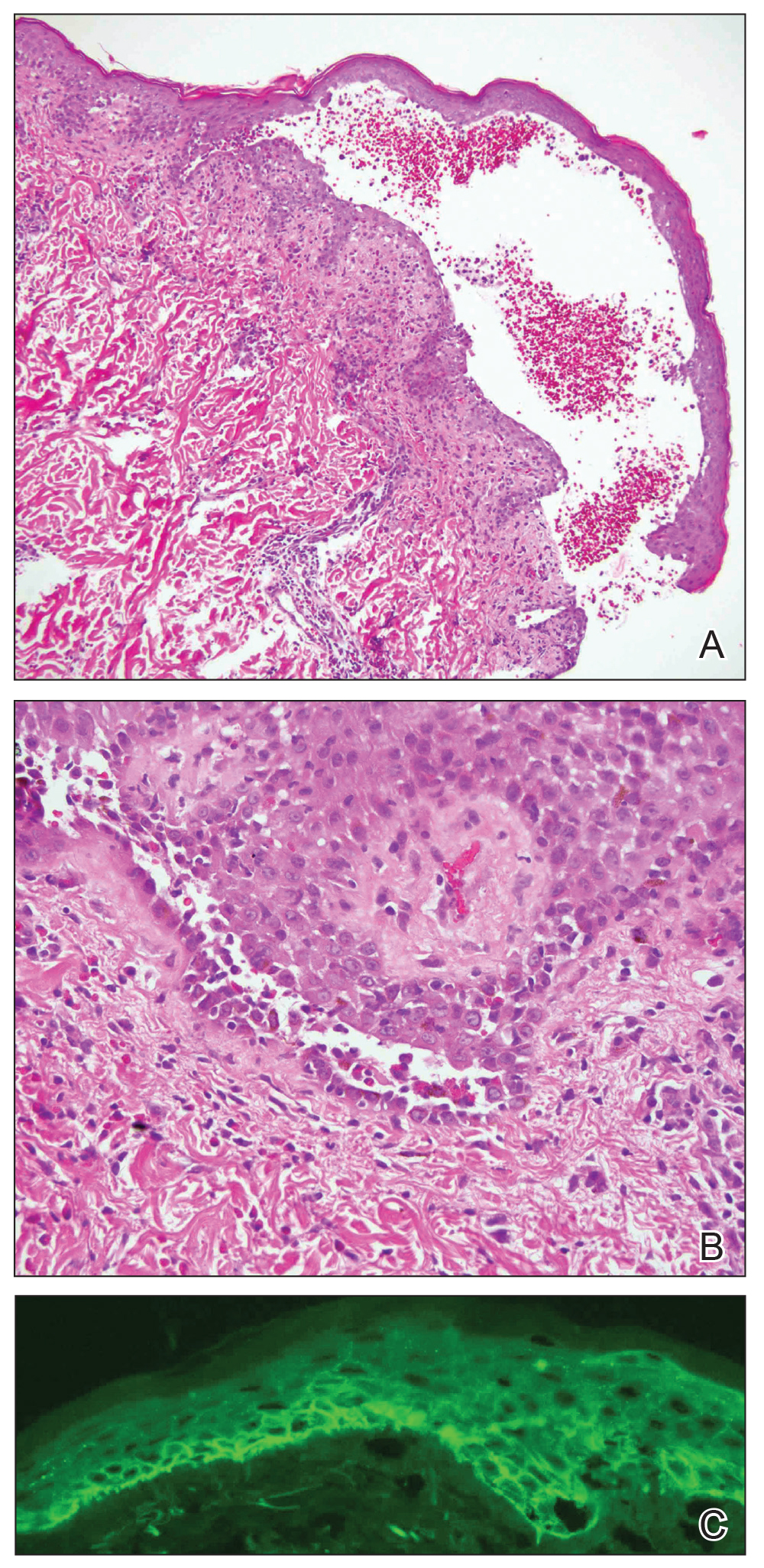

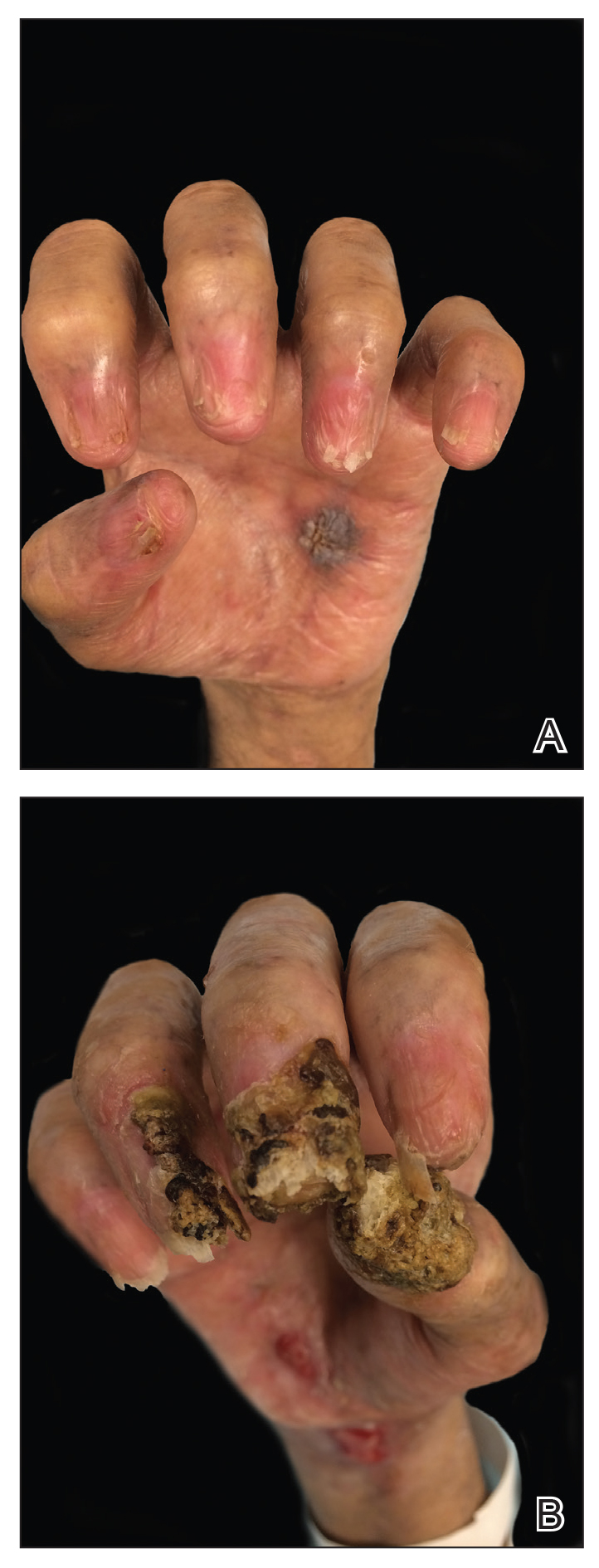

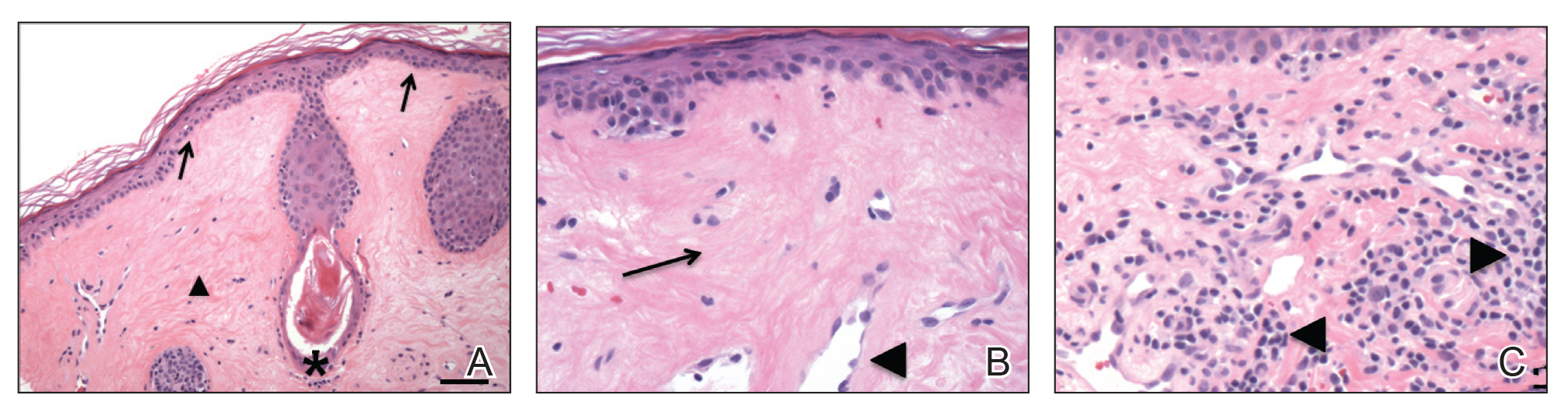

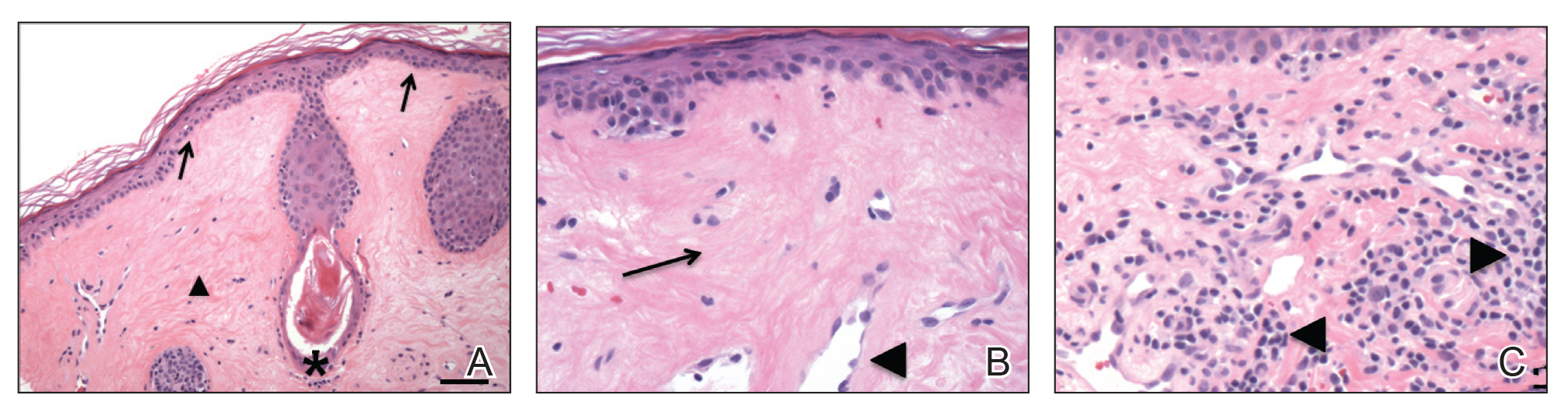

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

Practice Points

- Phaeohyphomycosis is an infection with dematiaceous fungi that most commonly affects immunosuppressed patients.

- Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis may present with nodulocystic lesions that recur over the course of years.

- Tissue fungal culture should be obtained when the diagnosis is suspected, as the risk for dissemination is related to the culprit organism.

- Surgical excision with close follow-up may be an appropriate management strategy for patients on immunosuppressive medications to avoid interactions with azole therapy.

Scalp Arteriovenous Fistula With Intracranial Communication

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old man presented with a nodule on the vertex of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had become soft and tender during the week prior to presentation. He noted that he was experiencing headaches and a buzzing sound in his head. He denied all other neurologic symptoms. The patient was given amoxicillin from a primary care physician and was referred to our institution for evaluation of a presumed inflamed cyst.

The patient’s medical history included an intracranial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to presentation, 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness, essential hypertension, and an aortic aneurysm. His medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, amoxicillin, a multivitamin, and grape seed extract.

Physical examination revealed a 2-cm, pink, somewhat rubbery, subcutaneous, nonmobile nodule on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 1). The lesion was not consistent with a common pilar cyst, and an excisional biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy. Upon superficial incision, the lesion bled moderately, and the procedure was immediately discontinued. Hemostasis was obtained, and the patient was sent for ultrasonography of the lesion.

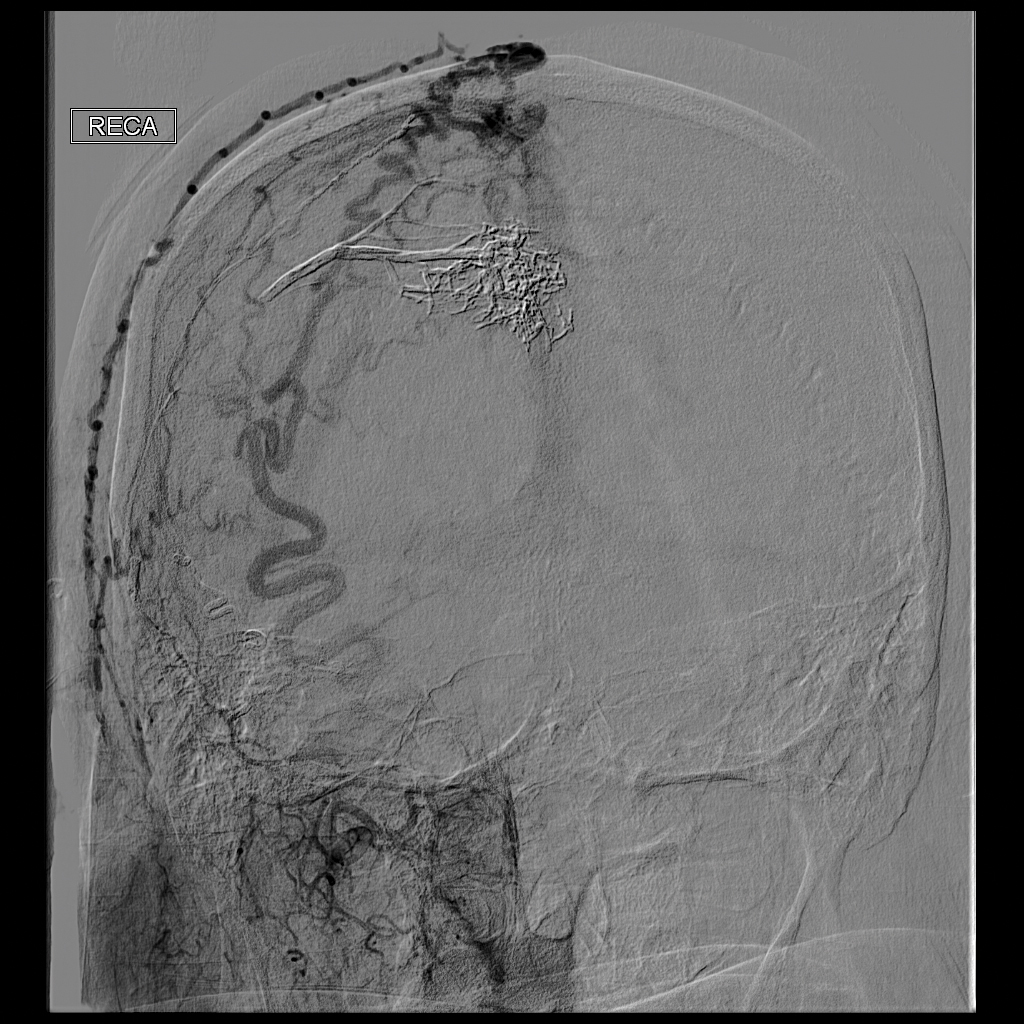

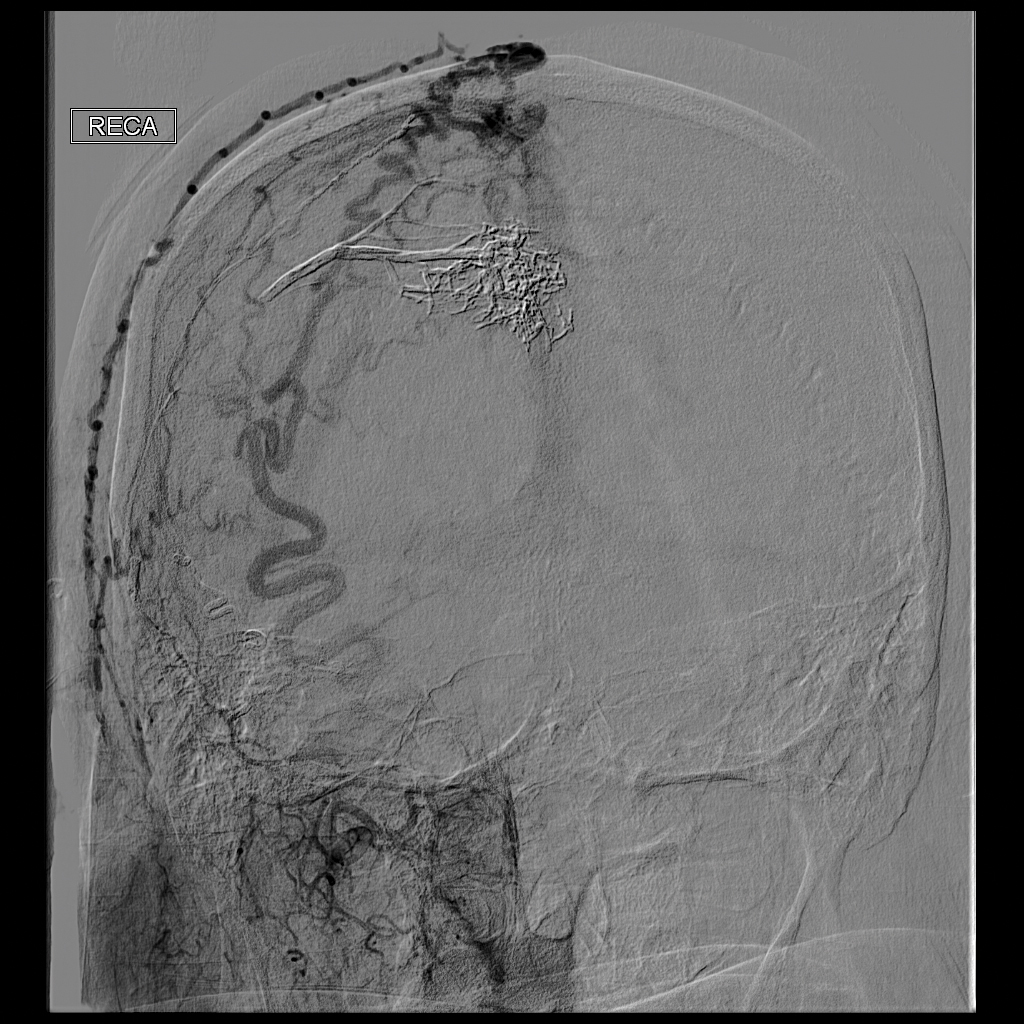

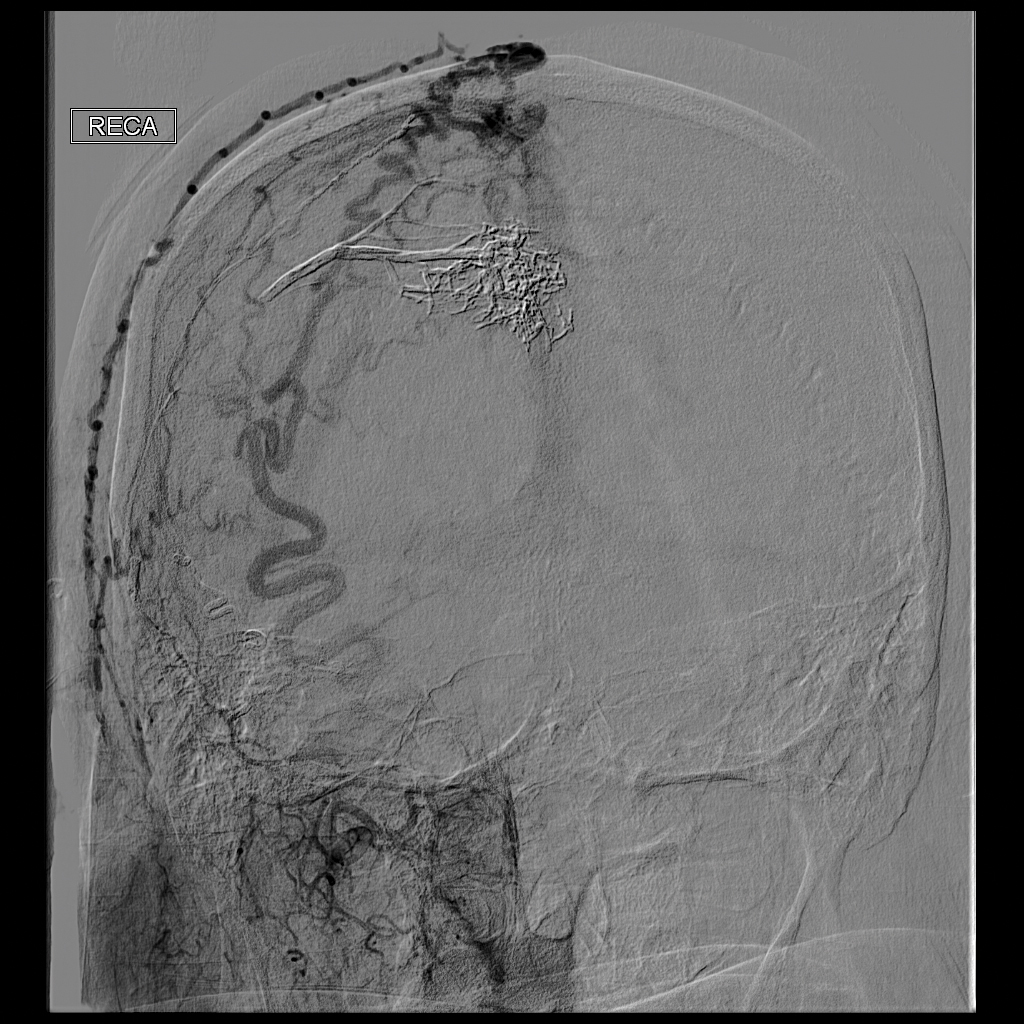

Ultrasonography demonstrated a small hypoechoic nodule measuring up to 0.5 cm containing a tangle of vessels in the subcutaneous soft tissue corresponding to the palpable abnormality. A cerebral angiogram demonstrated a dural AVF of the superior sagittal sinus with multifocal supply that connected with this scalp nodule (Figure 2). The patient was treated by interventional neuroradiology with endovascular embolization, which resulted in complete resolution of the scalp nodule.

Scalp arteriovenous fistulas (S-AVFs) are characterized by abnormal connections between supplying arteries and draining veins in the subcutaneous plane of the scalp.1,2 The veins of an S-AVF undergo progressive aneurysmal dilatation from abnormal hemodynamics.1-3 Scalp arteriovenous fistulas are rare and may present as either an innocuous-looking scalp nodule or a progressively enlarging pulsatile mass on the scalp.2-4 Associated symptoms often include headache, local pain, bruits, tinnitus, and thrill.1,3,4 Recurrent hemorrhage, scalp necrosis, congestive heart failure, epilepsy, mental retardation, and intracranial ischemia also may occur.4

Scalp AVFs may occur with or without intracranial communication.4 Spontaneous S-AVFs with intracranial communication are uncommon, and their etiology is unclear. They may form as congenital malformations or may be idiopathic. Factors increasing circulation through the S-AVF such as trauma, pregnancy, hormonal changes, and inflammation prompt the development of symptoms.4 Scalp AVFs also may be caused by trauma.3 Scalp AVFs without intracranial communication have been reported following hair transplantation.1 Scalp AVFs with intracranial communication have been reported months to years after skull fracture or craniotomy.2 True spontaneous S-AVFs are difficult to differentiate from traumatic S-AVFs other than by history alone.2

Increased venous pressure has been shown to generate AVFs in rats.5 It has been suggested that S-AVFs can become enlarged by capturing subcutaneous or intracranial feeder vessels and that the consequent hemodynamic stress may induce de novo aneurysms in S-AVFs. Additionally, intracranial AVFs may alter the intracranial hemodynamics, leading to increased venous pressure in the superior sagittal sinus and the formation of communicating S-AVFs.5 Interestingly, our patient had an intracranial AVF treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to the formation of the S-AVF. An angiogram at the time of this embolization procedure did not demonstrate any S-AVFs. Furthermore, our patient has a history of 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness. Perhaps these traumas initiated a channel through the cranium where an S-AVF with intracranial communication was able to form and may have only become clinically or radiographically detectable once it enlarged due to the altered hemodynamics caused by the intracranial AVF 1 year prior.

The diagnosis of an S-AVF is confirmed with imaging studies. Doppler ultrasonography initially will help to detect that a lesion is vascular in nature. Intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography is the gold-standard imaging technique and is necessary to delineate the feeding arteries and the draining channels as well as possible communication with intracranial vasculature.1,2 There is controversy regarding the appropriate treatment of S-AVFs.2 Each S-AVF possesses unique anatomic features that dictate appropriate management. The prognosis for an S-AVF is extremely variable, and the decision to treat is based on the patient’s symptoms and risk for exsanguinating hemorrhage.2,4 Neurosurgical approaches include ligation of the feeding arteries, surgical resection, electrothrombosis, direct intralesional injection of sclerosing agents, and endovascular embolization. Endovascular intervention increasingly is utilized as a primary treatment or as a preoperative adjunct to surgery.2,4 Large S-AVFs have a high risk for recurrence after treatment with endovascular embolization alone. In cases with intracranial communication, the intracranial component is treated first.2

This case emphasizes the importance of including S-AVFs on the dermatologic differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule, especially in patients with any history of intracranial AVF. A thorough history, detailed intake of potential signs and symptoms of AVF, and palpation for bruits is recommended as part of the surgical evaluation of a scalp nodule. Imaging of scalp nodules also should be considered for patients with any history of intracranial AVF; S-AVFs should be referred to neurosurgery or interventional neuroradiology for evaluation and possible treatment.

- Bernstein J, Podnos S, Leavitt M. Arteriovenous fistula following hair transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:873-875.

- Kumar R, Sharma G, Sharma BS. Management of scalp arterio-venous malformation: case series and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:371-377.

- Gurkanlar D, Gonul M, Solmaz I, et al. Cirsoid aneurysms of the scalp. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:208-212.

- Senoglu M, Yasim A, Gokce M, et al. Nontraumatic scalp arteriovenous fistula in an adult: technical report on an illustrative case. Surg Neurol. 2008;70:194-197.

- Lanzino G, Passacantilli E, Lemole G, et al. Scalp arteriovenous malformation draining into the superior sagittal sinus associated with an intracranial arteriovenous malformation: just a coincidence? case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:440-443.

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old man presented with a nodule on the vertex of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had become soft and tender during the week prior to presentation. He noted that he was experiencing headaches and a buzzing sound in his head. He denied all other neurologic symptoms. The patient was given amoxicillin from a primary care physician and was referred to our institution for evaluation of a presumed inflamed cyst.

The patient’s medical history included an intracranial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to presentation, 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness, essential hypertension, and an aortic aneurysm. His medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, amoxicillin, a multivitamin, and grape seed extract.

Physical examination revealed a 2-cm, pink, somewhat rubbery, subcutaneous, nonmobile nodule on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 1). The lesion was not consistent with a common pilar cyst, and an excisional biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy. Upon superficial incision, the lesion bled moderately, and the procedure was immediately discontinued. Hemostasis was obtained, and the patient was sent for ultrasonography of the lesion.

Ultrasonography demonstrated a small hypoechoic nodule measuring up to 0.5 cm containing a tangle of vessels in the subcutaneous soft tissue corresponding to the palpable abnormality. A cerebral angiogram demonstrated a dural AVF of the superior sagittal sinus with multifocal supply that connected with this scalp nodule (Figure 2). The patient was treated by interventional neuroradiology with endovascular embolization, which resulted in complete resolution of the scalp nodule.

Scalp arteriovenous fistulas (S-AVFs) are characterized by abnormal connections between supplying arteries and draining veins in the subcutaneous plane of the scalp.1,2 The veins of an S-AVF undergo progressive aneurysmal dilatation from abnormal hemodynamics.1-3 Scalp arteriovenous fistulas are rare and may present as either an innocuous-looking scalp nodule or a progressively enlarging pulsatile mass on the scalp.2-4 Associated symptoms often include headache, local pain, bruits, tinnitus, and thrill.1,3,4 Recurrent hemorrhage, scalp necrosis, congestive heart failure, epilepsy, mental retardation, and intracranial ischemia also may occur.4

Scalp AVFs may occur with or without intracranial communication.4 Spontaneous S-AVFs with intracranial communication are uncommon, and their etiology is unclear. They may form as congenital malformations or may be idiopathic. Factors increasing circulation through the S-AVF such as trauma, pregnancy, hormonal changes, and inflammation prompt the development of symptoms.4 Scalp AVFs also may be caused by trauma.3 Scalp AVFs without intracranial communication have been reported following hair transplantation.1 Scalp AVFs with intracranial communication have been reported months to years after skull fracture or craniotomy.2 True spontaneous S-AVFs are difficult to differentiate from traumatic S-AVFs other than by history alone.2

Increased venous pressure has been shown to generate AVFs in rats.5 It has been suggested that S-AVFs can become enlarged by capturing subcutaneous or intracranial feeder vessels and that the consequent hemodynamic stress may induce de novo aneurysms in S-AVFs. Additionally, intracranial AVFs may alter the intracranial hemodynamics, leading to increased venous pressure in the superior sagittal sinus and the formation of communicating S-AVFs.5 Interestingly, our patient had an intracranial AVF treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to the formation of the S-AVF. An angiogram at the time of this embolization procedure did not demonstrate any S-AVFs. Furthermore, our patient has a history of 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness. Perhaps these traumas initiated a channel through the cranium where an S-AVF with intracranial communication was able to form and may have only become clinically or radiographically detectable once it enlarged due to the altered hemodynamics caused by the intracranial AVF 1 year prior.

The diagnosis of an S-AVF is confirmed with imaging studies. Doppler ultrasonography initially will help to detect that a lesion is vascular in nature. Intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography is the gold-standard imaging technique and is necessary to delineate the feeding arteries and the draining channels as well as possible communication with intracranial vasculature.1,2 There is controversy regarding the appropriate treatment of S-AVFs.2 Each S-AVF possesses unique anatomic features that dictate appropriate management. The prognosis for an S-AVF is extremely variable, and the decision to treat is based on the patient’s symptoms and risk for exsanguinating hemorrhage.2,4 Neurosurgical approaches include ligation of the feeding arteries, surgical resection, electrothrombosis, direct intralesional injection of sclerosing agents, and endovascular embolization. Endovascular intervention increasingly is utilized as a primary treatment or as a preoperative adjunct to surgery.2,4 Large S-AVFs have a high risk for recurrence after treatment with endovascular embolization alone. In cases with intracranial communication, the intracranial component is treated first.2

This case emphasizes the importance of including S-AVFs on the dermatologic differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule, especially in patients with any history of intracranial AVF. A thorough history, detailed intake of potential signs and symptoms of AVF, and palpation for bruits is recommended as part of the surgical evaluation of a scalp nodule. Imaging of scalp nodules also should be considered for patients with any history of intracranial AVF; S-AVFs should be referred to neurosurgery or interventional neuroradiology for evaluation and possible treatment.

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old man presented with a nodule on the vertex of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had become soft and tender during the week prior to presentation. He noted that he was experiencing headaches and a buzzing sound in his head. He denied all other neurologic symptoms. The patient was given amoxicillin from a primary care physician and was referred to our institution for evaluation of a presumed inflamed cyst.

The patient’s medical history included an intracranial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to presentation, 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness, essential hypertension, and an aortic aneurysm. His medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, amoxicillin, a multivitamin, and grape seed extract.

Physical examination revealed a 2-cm, pink, somewhat rubbery, subcutaneous, nonmobile nodule on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 1). The lesion was not consistent with a common pilar cyst, and an excisional biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy. Upon superficial incision, the lesion bled moderately, and the procedure was immediately discontinued. Hemostasis was obtained, and the patient was sent for ultrasonography of the lesion.

Ultrasonography demonstrated a small hypoechoic nodule measuring up to 0.5 cm containing a tangle of vessels in the subcutaneous soft tissue corresponding to the palpable abnormality. A cerebral angiogram demonstrated a dural AVF of the superior sagittal sinus with multifocal supply that connected with this scalp nodule (Figure 2). The patient was treated by interventional neuroradiology with endovascular embolization, which resulted in complete resolution of the scalp nodule.

Scalp arteriovenous fistulas (S-AVFs) are characterized by abnormal connections between supplying arteries and draining veins in the subcutaneous plane of the scalp.1,2 The veins of an S-AVF undergo progressive aneurysmal dilatation from abnormal hemodynamics.1-3 Scalp arteriovenous fistulas are rare and may present as either an innocuous-looking scalp nodule or a progressively enlarging pulsatile mass on the scalp.2-4 Associated symptoms often include headache, local pain, bruits, tinnitus, and thrill.1,3,4 Recurrent hemorrhage, scalp necrosis, congestive heart failure, epilepsy, mental retardation, and intracranial ischemia also may occur.4

Scalp AVFs may occur with or without intracranial communication.4 Spontaneous S-AVFs with intracranial communication are uncommon, and their etiology is unclear. They may form as congenital malformations or may be idiopathic. Factors increasing circulation through the S-AVF such as trauma, pregnancy, hormonal changes, and inflammation prompt the development of symptoms.4 Scalp AVFs also may be caused by trauma.3 Scalp AVFs without intracranial communication have been reported following hair transplantation.1 Scalp AVFs with intracranial communication have been reported months to years after skull fracture or craniotomy.2 True spontaneous S-AVFs are difficult to differentiate from traumatic S-AVFs other than by history alone.2

Increased venous pressure has been shown to generate AVFs in rats.5 It has been suggested that S-AVFs can become enlarged by capturing subcutaneous or intracranial feeder vessels and that the consequent hemodynamic stress may induce de novo aneurysms in S-AVFs. Additionally, intracranial AVFs may alter the intracranial hemodynamics, leading to increased venous pressure in the superior sagittal sinus and the formation of communicating S-AVFs.5 Interestingly, our patient had an intracranial AVF treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to the formation of the S-AVF. An angiogram at the time of this embolization procedure did not demonstrate any S-AVFs. Furthermore, our patient has a history of 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness. Perhaps these traumas initiated a channel through the cranium where an S-AVF with intracranial communication was able to form and may have only become clinically or radiographically detectable once it enlarged due to the altered hemodynamics caused by the intracranial AVF 1 year prior.

The diagnosis of an S-AVF is confirmed with imaging studies. Doppler ultrasonography initially will help to detect that a lesion is vascular in nature. Intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography is the gold-standard imaging technique and is necessary to delineate the feeding arteries and the draining channels as well as possible communication with intracranial vasculature.1,2 There is controversy regarding the appropriate treatment of S-AVFs.2 Each S-AVF possesses unique anatomic features that dictate appropriate management. The prognosis for an S-AVF is extremely variable, and the decision to treat is based on the patient’s symptoms and risk for exsanguinating hemorrhage.2,4 Neurosurgical approaches include ligation of the feeding arteries, surgical resection, electrothrombosis, direct intralesional injection of sclerosing agents, and endovascular embolization. Endovascular intervention increasingly is utilized as a primary treatment or as a preoperative adjunct to surgery.2,4 Large S-AVFs have a high risk for recurrence after treatment with endovascular embolization alone. In cases with intracranial communication, the intracranial component is treated first.2

This case emphasizes the importance of including S-AVFs on the dermatologic differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule, especially in patients with any history of intracranial AVF. A thorough history, detailed intake of potential signs and symptoms of AVF, and palpation for bruits is recommended as part of the surgical evaluation of a scalp nodule. Imaging of scalp nodules also should be considered for patients with any history of intracranial AVF; S-AVFs should be referred to neurosurgery or interventional neuroradiology for evaluation and possible treatment.

- Bernstein J, Podnos S, Leavitt M. Arteriovenous fistula following hair transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:873-875.

- Kumar R, Sharma G, Sharma BS. Management of scalp arterio-venous malformation: case series and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:371-377.

- Gurkanlar D, Gonul M, Solmaz I, et al. Cirsoid aneurysms of the scalp. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:208-212.

- Senoglu M, Yasim A, Gokce M, et al. Nontraumatic scalp arteriovenous fistula in an adult: technical report on an illustrative case. Surg Neurol. 2008;70:194-197.

- Lanzino G, Passacantilli E, Lemole G, et al. Scalp arteriovenous malformation draining into the superior sagittal sinus associated with an intracranial arteriovenous malformation: just a coincidence? case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:440-443.

- Bernstein J, Podnos S, Leavitt M. Arteriovenous fistula following hair transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:873-875.

- Kumar R, Sharma G, Sharma BS. Management of scalp arterio-venous malformation: case series and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26:371-377.

- Gurkanlar D, Gonul M, Solmaz I, et al. Cirsoid aneurysms of the scalp. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:208-212.

- Senoglu M, Yasim A, Gokce M, et al. Nontraumatic scalp arteriovenous fistula in an adult: technical report on an illustrative case. Surg Neurol. 2008;70:194-197.

- Lanzino G, Passacantilli E, Lemole G, et al. Scalp arteriovenous malformation draining into the superior sagittal sinus associated with an intracranial arteriovenous malformation: just a coincidence? case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:440-443.

Practice Points

- Scalp arteriovenous fistulas may be traumatic or spontaneous and present as either an innocuous-looking scalp nodule or as a progressively enlarging pulsatile mass on the scalp.

- Clinical detection followed by appropriate imaging and referral to neurosurgery or interventional neuroradiology is vital to patient safety.

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia Associated With the Use of Adalimumab

To the Editor:

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–mediated mucocutaneous disease that often involves the lingual epithelium. The lateral portions of the tongue are the most commonly affected sites. The lesions often are described as asymptomatic, white, corrugated patches or plaques that are unable to be scraped off.1 Oral hairy leukoplakia was first identified in 1984 and was considered to be associated with AIDS.2 An association between the presence of OHL and the degree of immunosuppression as well as the severity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been reported.3 Although OHL initially was considered to be pathognomonic for HIV, it has since been described in multiple other immunosuppressive conditions.4 Numerous medical conditions and combinations of immunosuppressive medications have been associated with OHL in patients who were HIV negative.5

Adalimumab is an injectable human IgG1 recombinant antibody to tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).6 It currently is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult and pediatric Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, noninfectious uveitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and plaque psoriasis.7 We report a case of OHL associated with the use of adalimumab.

A 47-year-old woman initially presented with chronic plaque-type psoriasis. Her medical history was notable for bipolar disorder, migraines, hypertension, and tobacco use. The patient’s psoriasis initially was well controlled on a regimen of topical steroids and methotrexate; however, methotrexate was stopped after 2.5 years due to a mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase level, as well as an abnormal liver biopsy showing mildly active (grade 1 of 3) steatohepatitis with portal chronic inflammation, pericellular fibrosis, and portal and focal periportal fibrosis (stage 1-2 of 4). The patient and her dermatologist were uncomfortable continuing methotrexate with these findings. After baseline screening including a negative purified protein derivative skin test, adalimumab was initiated. A loading dose of 80 mg subcutaneously (SQ) was given, followed by adalimumab 40 mg SQ 1 week later and 40 mg every other week as maintenance.

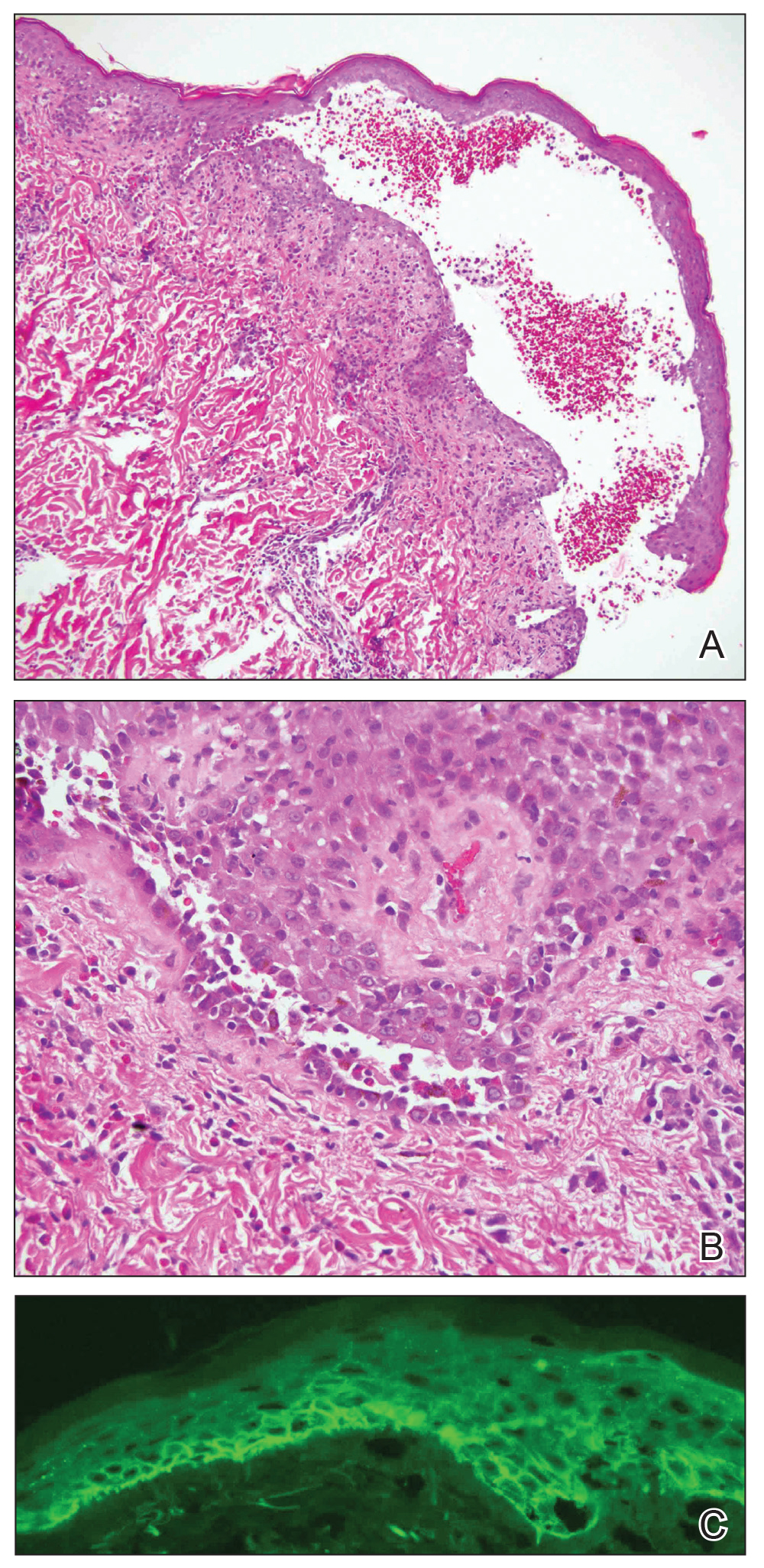

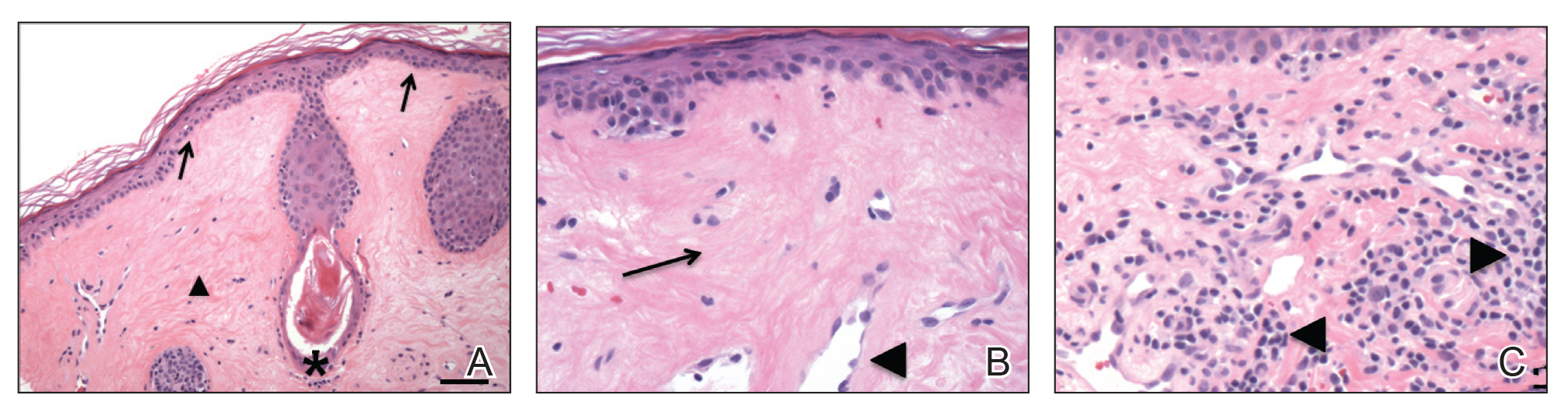

The patient’s psoriasis was well controlled with adalimumab for 22 months, but she then developed a thin white plaque on the right lateral tongue (Figure 1). An incisional biopsy of the tongue performed by an oral surgeon revealed hyperkeratosis with Candida colonization and viral cytopathic effect (Figure 2). An EBV DNA in situ hybridization stain revealed focal positivity within these cells (Figure 3), leading to a diagnosis of OHL. Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count with differential and liver panel as well as a negative HIV test. The patient otherwise felt well and denied fevers, lymphadenopathy, and weight loss.

We consulted with an infectious disease and immunodeficiency specialist regarding the patient’s case. Before conducting further evaluation beyond HIV screening for immunodeficiency states, adalimumab was discontinued to see if the OHL would spontaneously resolve. Three months after discontinuation of adalimumab, the white plaque on the right lateral tongue was notably improved. The OHL continued to disappear and was completely resolved 1 year after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient’s psoriasis had subsequently remained well controlled with diet and weight loss, smoking cessation, topical steroids, and apremilast without any recurrence of the OHL.

Oral hairy leukoplakia is associated with upregulated EBV replication and EBV-encoded proteins such as latent membrane protein 1.2 It often presents as white or gray patches on the lateral lingual margins with prominent folds and/or projections, giving a shaggy appearance. Oral hairy leukoplakia often is specific for HIV infection and rarely is associated with other immunodeficiencies.2 Prasad and Bilodeau5 performed a literature review of medical conditions and immunosuppressive medications associated with OHL in patients without HIV. Allogeneic transplant was associated with the highest incidence of OHL in HIV-negative patients (59.2% [45/76]).5 Various combinations of immunosuppressive medications (eg, prednisone, cyclosporine, azathioprine) also may be implicated in cases of HIV-negative patients with OHL. A case of OHL also has been reported with long-standing use of inhaled corticosteroids in an immunocompetent, HIV-negative patient.6 Another case was reported with long-term use of the aromatic antiepileptic lamotrigine, which resolved once stopping the medication.8 Although EBV is an oncovirus and has been associated with lymphoproliferative disorders and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, OHL is not considered to be a premalignant lesion.7 Despite the strong association between OHL and HIV, our patient was HIV negative. The only immunocompromising factor in our patient was the use of adalimumab to treat psoriasis. We did not conduct further testing for immunodeficiency states because the OHL spontaneously resolved when the adalimumab was discontinued.

PubMed and Ovid searches of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms adalimumab and oral hairy leukoplakia as well as TNF-alpha inhibitor and oral hairy leukoplakia with humans and English language as limitations revealed that no cases have been reported in the literature demonstrating an association between OHL and adalimumab or any other TNF-α inhibitor. However, Cetkovska et al9 reported a case of EBV hepatitis and subsequently chronic hepatitis as a complication of infliximab used for the treatment of chronic psoriasis. Because TNF-α and IFN-γ play an important role in controlling viral infections, there is an increased risk for reactivating a viral illness when depleting TNF through pharmacologic measures (ie, adalimumab, infliximab).8 Another case of EBV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma was reported after 1 year of adalimumab use in a patient with Crohn disease. The plasmablastic lymphoma resolved after 4 rounds of chemotherapy.10

The only contraindication for the use of adalimumab is a known hypersensitivity to the drug. Relative contraindications for use of adalimumab include active tuberculosis, demyelinating disease, hematologic diseases (ie, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia), lymphoma, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B.11 The most common adverse effect of adalimumab is an injection-site reaction. Additional reported adverse effects of TNF-α inhibitors as a class are lymphoma, melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, reactivation of latent tuberculosis, congestive heart failure, autoimmunity, and hematologic toxicity.11

This case demonstrates an association between adalimumab and OHL in an HIV-negative patient. Although the mechanism behind OHL and immunosuppression remains to be elucidated, this association is important to keep in mind when using adalimumab or other TNF-α inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis or other medical conditions.

- Triantos D, Porter SR, Scully C, et al. Oral hairy leukoplakia: clinicopathologic features, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical significance. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1392-1396.

- Greenspan D, Greenspan JS, Conant M, et al. Oral “hairy” leucoplakia in male homosexuals: evidence of association with both papillomavirus and a herpes-group virus. Lancet. 1984;2:831-834.

- Glick M, Muzyka BC, Lurie D, et al. Oral manifestations associated with HIV-related disease as marks for immune suppression and AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:344-349.

- Chambers AE, Conn B, Pemberton M, et al. Twenty-first-century oral hair leukoplakia—a non-HIV-associated entity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Patho Oral Radiol. 2015;119:326-332.

- Prasad JL, Bilodeau EA. Oral hairy leukoplakia in patients without HIV: presentation of 2 new cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118:E151-E160.

- Moffat M, Jauhar S, Jones ME, et al. Oral hairy leukoplakia in an HIV-negative, immunocompetent patient. Oral Biosci Med. 2005;2:282-284.

- Greenspan JS, Greenspan D. Oral hairy leukoplakia: diagnosis and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:396-403.

- Gordins P, Sloan P, Spickett GP, et al. Oral hairy leukoplakia in a patient on long-term anticonvulsant treatment with lamotrigine. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:E17-E23.

- Cetkovska P, Lomicova I, Mukensnabl P, et al. Anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment of severe psoriasis complicated by Epstein-Barr virus hepatitis and subsequently by chronic hepatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:369-372.

- Liu L, Charabaty A, Ozdemirli M. EBV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient with Crohn’s disease after adalimumab treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:E118-E119.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2018.

To the Editor:

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–mediated mucocutaneous disease that often involves the lingual epithelium. The lateral portions of the tongue are the most commonly affected sites. The lesions often are described as asymptomatic, white, corrugated patches or plaques that are unable to be scraped off.1 Oral hairy leukoplakia was first identified in 1984 and was considered to be associated with AIDS.2 An association between the presence of OHL and the degree of immunosuppression as well as the severity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been reported.3 Although OHL initially was considered to be pathognomonic for HIV, it has since been described in multiple other immunosuppressive conditions.4 Numerous medical conditions and combinations of immunosuppressive medications have been associated with OHL in patients who were HIV negative.5

Adalimumab is an injectable human IgG1 recombinant antibody to tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).6 It currently is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult and pediatric Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, noninfectious uveitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and plaque psoriasis.7 We report a case of OHL associated with the use of adalimumab.

A 47-year-old woman initially presented with chronic plaque-type psoriasis. Her medical history was notable for bipolar disorder, migraines, hypertension, and tobacco use. The patient’s psoriasis initially was well controlled on a regimen of topical steroids and methotrexate; however, methotrexate was stopped after 2.5 years due to a mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase level, as well as an abnormal liver biopsy showing mildly active (grade 1 of 3) steatohepatitis with portal chronic inflammation, pericellular fibrosis, and portal and focal periportal fibrosis (stage 1-2 of 4). The patient and her dermatologist were uncomfortable continuing methotrexate with these findings. After baseline screening including a negative purified protein derivative skin test, adalimumab was initiated. A loading dose of 80 mg subcutaneously (SQ) was given, followed by adalimumab 40 mg SQ 1 week later and 40 mg every other week as maintenance.

The patient’s psoriasis was well controlled with adalimumab for 22 months, but she then developed a thin white plaque on the right lateral tongue (Figure 1). An incisional biopsy of the tongue performed by an oral surgeon revealed hyperkeratosis with Candida colonization and viral cytopathic effect (Figure 2). An EBV DNA in situ hybridization stain revealed focal positivity within these cells (Figure 3), leading to a diagnosis of OHL. Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count with differential and liver panel as well as a negative HIV test. The patient otherwise felt well and denied fevers, lymphadenopathy, and weight loss.

We consulted with an infectious disease and immunodeficiency specialist regarding the patient’s case. Before conducting further evaluation beyond HIV screening for immunodeficiency states, adalimumab was discontinued to see if the OHL would spontaneously resolve. Three months after discontinuation of adalimumab, the white plaque on the right lateral tongue was notably improved. The OHL continued to disappear and was completely resolved 1 year after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient’s psoriasis had subsequently remained well controlled with diet and weight loss, smoking cessation, topical steroids, and apremilast without any recurrence of the OHL.

Oral hairy leukoplakia is associated with upregulated EBV replication and EBV-encoded proteins such as latent membrane protein 1.2 It often presents as white or gray patches on the lateral lingual margins with prominent folds and/or projections, giving a shaggy appearance. Oral hairy leukoplakia often is specific for HIV infection and rarely is associated with other immunodeficiencies.2 Prasad and Bilodeau5 performed a literature review of medical conditions and immunosuppressive medications associated with OHL in patients without HIV. Allogeneic transplant was associated with the highest incidence of OHL in HIV-negative patients (59.2% [45/76]).5 Various combinations of immunosuppressive medications (eg, prednisone, cyclosporine, azathioprine) also may be implicated in cases of HIV-negative patients with OHL. A case of OHL also has been reported with long-standing use of inhaled corticosteroids in an immunocompetent, HIV-negative patient.6 Another case was reported with long-term use of the aromatic antiepileptic lamotrigine, which resolved once stopping the medication.8 Although EBV is an oncovirus and has been associated with lymphoproliferative disorders and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, OHL is not considered to be a premalignant lesion.7 Despite the strong association between OHL and HIV, our patient was HIV negative. The only immunocompromising factor in our patient was the use of adalimumab to treat psoriasis. We did not conduct further testing for immunodeficiency states because the OHL spontaneously resolved when the adalimumab was discontinued.

PubMed and Ovid searches of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms adalimumab and oral hairy leukoplakia as well as TNF-alpha inhibitor and oral hairy leukoplakia with humans and English language as limitations revealed that no cases have been reported in the literature demonstrating an association between OHL and adalimumab or any other TNF-α inhibitor. However, Cetkovska et al9 reported a case of EBV hepatitis and subsequently chronic hepatitis as a complication of infliximab used for the treatment of chronic psoriasis. Because TNF-α and IFN-γ play an important role in controlling viral infections, there is an increased risk for reactivating a viral illness when depleting TNF through pharmacologic measures (ie, adalimumab, infliximab).8 Another case of EBV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma was reported after 1 year of adalimumab use in a patient with Crohn disease. The plasmablastic lymphoma resolved after 4 rounds of chemotherapy.10

The only contraindication for the use of adalimumab is a known hypersensitivity to the drug. Relative contraindications for use of adalimumab include active tuberculosis, demyelinating disease, hematologic diseases (ie, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia), lymphoma, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B.11 The most common adverse effect of adalimumab is an injection-site reaction. Additional reported adverse effects of TNF-α inhibitors as a class are lymphoma, melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, reactivation of latent tuberculosis, congestive heart failure, autoimmunity, and hematologic toxicity.11

This case demonstrates an association between adalimumab and OHL in an HIV-negative patient. Although the mechanism behind OHL and immunosuppression remains to be elucidated, this association is important to keep in mind when using adalimumab or other TNF-α inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis or other medical conditions.

To the Editor:

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–mediated mucocutaneous disease that often involves the lingual epithelium. The lateral portions of the tongue are the most commonly affected sites. The lesions often are described as asymptomatic, white, corrugated patches or plaques that are unable to be scraped off.1 Oral hairy leukoplakia was first identified in 1984 and was considered to be associated with AIDS.2 An association between the presence of OHL and the degree of immunosuppression as well as the severity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been reported.3 Although OHL initially was considered to be pathognomonic for HIV, it has since been described in multiple other immunosuppressive conditions.4 Numerous medical conditions and combinations of immunosuppressive medications have been associated with OHL in patients who were HIV negative.5

Adalimumab is an injectable human IgG1 recombinant antibody to tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).6 It currently is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult and pediatric Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, noninfectious uveitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and plaque psoriasis.7 We report a case of OHL associated with the use of adalimumab.

A 47-year-old woman initially presented with chronic plaque-type psoriasis. Her medical history was notable for bipolar disorder, migraines, hypertension, and tobacco use. The patient’s psoriasis initially was well controlled on a regimen of topical steroids and methotrexate; however, methotrexate was stopped after 2.5 years due to a mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase level, as well as an abnormal liver biopsy showing mildly active (grade 1 of 3) steatohepatitis with portal chronic inflammation, pericellular fibrosis, and portal and focal periportal fibrosis (stage 1-2 of 4). The patient and her dermatologist were uncomfortable continuing methotrexate with these findings. After baseline screening including a negative purified protein derivative skin test, adalimumab was initiated. A loading dose of 80 mg subcutaneously (SQ) was given, followed by adalimumab 40 mg SQ 1 week later and 40 mg every other week as maintenance.

The patient’s psoriasis was well controlled with adalimumab for 22 months, but she then developed a thin white plaque on the right lateral tongue (Figure 1). An incisional biopsy of the tongue performed by an oral surgeon revealed hyperkeratosis with Candida colonization and viral cytopathic effect (Figure 2). An EBV DNA in situ hybridization stain revealed focal positivity within these cells (Figure 3), leading to a diagnosis of OHL. Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count with differential and liver panel as well as a negative HIV test. The patient otherwise felt well and denied fevers, lymphadenopathy, and weight loss.

We consulted with an infectious disease and immunodeficiency specialist regarding the patient’s case. Before conducting further evaluation beyond HIV screening for immunodeficiency states, adalimumab was discontinued to see if the OHL would spontaneously resolve. Three months after discontinuation of adalimumab, the white plaque on the right lateral tongue was notably improved. The OHL continued to disappear and was completely resolved 1 year after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient’s psoriasis had subsequently remained well controlled with diet and weight loss, smoking cessation, topical steroids, and apremilast without any recurrence of the OHL.

Oral hairy leukoplakia is associated with upregulated EBV replication and EBV-encoded proteins such as latent membrane protein 1.2 It often presents as white or gray patches on the lateral lingual margins with prominent folds and/or projections, giving a shaggy appearance. Oral hairy leukoplakia often is specific for HIV infection and rarely is associated with other immunodeficiencies.2 Prasad and Bilodeau5 performed a literature review of medical conditions and immunosuppressive medications associated with OHL in patients without HIV. Allogeneic transplant was associated with the highest incidence of OHL in HIV-negative patients (59.2% [45/76]).5 Various combinations of immunosuppressive medications (eg, prednisone, cyclosporine, azathioprine) also may be implicated in cases of HIV-negative patients with OHL. A case of OHL also has been reported with long-standing use of inhaled corticosteroids in an immunocompetent, HIV-negative patient.6 Another case was reported with long-term use of the aromatic antiepileptic lamotrigine, which resolved once stopping the medication.8 Although EBV is an oncovirus and has been associated with lymphoproliferative disorders and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, OHL is not considered to be a premalignant lesion.7 Despite the strong association between OHL and HIV, our patient was HIV negative. The only immunocompromising factor in our patient was the use of adalimumab to treat psoriasis. We did not conduct further testing for immunodeficiency states because the OHL spontaneously resolved when the adalimumab was discontinued.

PubMed and Ovid searches of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms adalimumab and oral hairy leukoplakia as well as TNF-alpha inhibitor and oral hairy leukoplakia with humans and English language as limitations revealed that no cases have been reported in the literature demonstrating an association between OHL and adalimumab or any other TNF-α inhibitor. However, Cetkovska et al9 reported a case of EBV hepatitis and subsequently chronic hepatitis as a complication of infliximab used for the treatment of chronic psoriasis. Because TNF-α and IFN-γ play an important role in controlling viral infections, there is an increased risk for reactivating a viral illness when depleting TNF through pharmacologic measures (ie, adalimumab, infliximab).8 Another case of EBV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma was reported after 1 year of adalimumab use in a patient with Crohn disease. The plasmablastic lymphoma resolved after 4 rounds of chemotherapy.10

The only contraindication for the use of adalimumab is a known hypersensitivity to the drug. Relative contraindications for use of adalimumab include active tuberculosis, demyelinating disease, hematologic diseases (ie, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia), lymphoma, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B.11 The most common adverse effect of adalimumab is an injection-site reaction. Additional reported adverse effects of TNF-α inhibitors as a class are lymphoma, melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, reactivation of latent tuberculosis, congestive heart failure, autoimmunity, and hematologic toxicity.11

This case demonstrates an association between adalimumab and OHL in an HIV-negative patient. Although the mechanism behind OHL and immunosuppression remains to be elucidated, this association is important to keep in mind when using adalimumab or other TNF-α inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis or other medical conditions.

- Triantos D, Porter SR, Scully C, et al. Oral hairy leukoplakia: clinicopathologic features, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical significance. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1392-1396.

- Greenspan D, Greenspan JS, Conant M, et al. Oral “hairy” leucoplakia in male homosexuals: evidence of association with both papillomavirus and a herpes-group virus. Lancet. 1984;2:831-834.

- Glick M, Muzyka BC, Lurie D, et al. Oral manifestations associated with HIV-related disease as marks for immune suppression and AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:344-349.

- Chambers AE, Conn B, Pemberton M, et al. Twenty-first-century oral hair leukoplakia—a non-HIV-associated entity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Patho Oral Radiol. 2015;119:326-332.

- Prasad JL, Bilodeau EA. Oral hairy leukoplakia in patients without HIV: presentation of 2 new cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118:E151-E160.

- Moffat M, Jauhar S, Jones ME, et al. Oral hairy leukoplakia in an HIV-negative, immunocompetent patient. Oral Biosci Med. 2005;2:282-284.

- Greenspan JS, Greenspan D. Oral hairy leukoplakia: diagnosis and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:396-403.

- Gordins P, Sloan P, Spickett GP, et al. Oral hairy leukoplakia in a patient on long-term anticonvulsant treatment with lamotrigine. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:E17-E23.

- Cetkovska P, Lomicova I, Mukensnabl P, et al. Anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment of severe psoriasis complicated by Epstein-Barr virus hepatitis and subsequently by chronic hepatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:369-372.

- Liu L, Charabaty A, Ozdemirli M. EBV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient with Crohn’s disease after adalimumab treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:E118-E119.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2018.

- Triantos D, Porter SR, Scully C, et al. Oral hairy leukoplakia: clinicopathologic features, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical significance. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1392-1396.

- Greenspan D, Greenspan JS, Conant M, et al. Oral “hairy” leucoplakia in male homosexuals: evidence of association with both papillomavirus and a herpes-group virus. Lancet. 1984;2:831-834.

- Glick M, Muzyka BC, Lurie D, et al. Oral manifestations associated with HIV-related disease as marks for immune suppression and AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:344-349.

- Chambers AE, Conn B, Pemberton M, et al. Twenty-first-century oral hair leukoplakia—a non-HIV-associated entity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Patho Oral Radiol. 2015;119:326-332.

- Prasad JL, Bilodeau EA. Oral hairy leukoplakia in patients without HIV: presentation of 2 new cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118:E151-E160.

- Moffat M, Jauhar S, Jones ME, et al. Oral hairy leukoplakia in an HIV-negative, immunocompetent patient. Oral Biosci Med. 2005;2:282-284.

- Greenspan JS, Greenspan D. Oral hairy leukoplakia: diagnosis and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:396-403.