User login

Exercise-Induced Vasculitis in a Patient With Negative Ultrasound Venous Reflux Study: A Mimic of Stasis Dermatitis

To the Editor:

The transient and generic appearance of exercise-induced vasculitis (EIV) makes it a commonly misdiagnosed condition. The lesion often is only encountered through photographs brought by the patient or by taking a thorough history. The lack of findings on clinical inspection and the generic appearance of EIV may lead to misdiagnosis as stasis dermatitis due to its presentation as erythematous lesions on the medial lower legs.

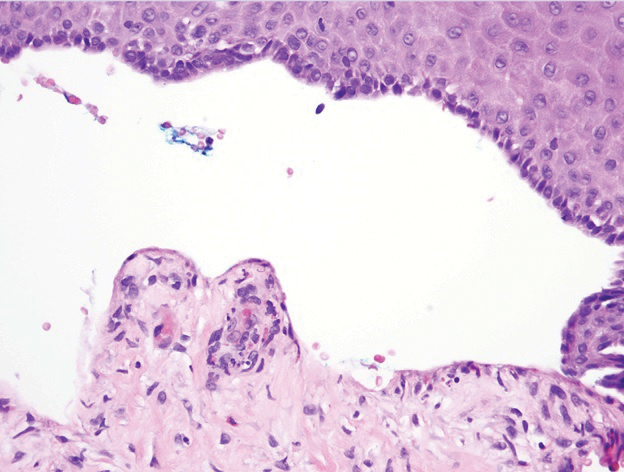

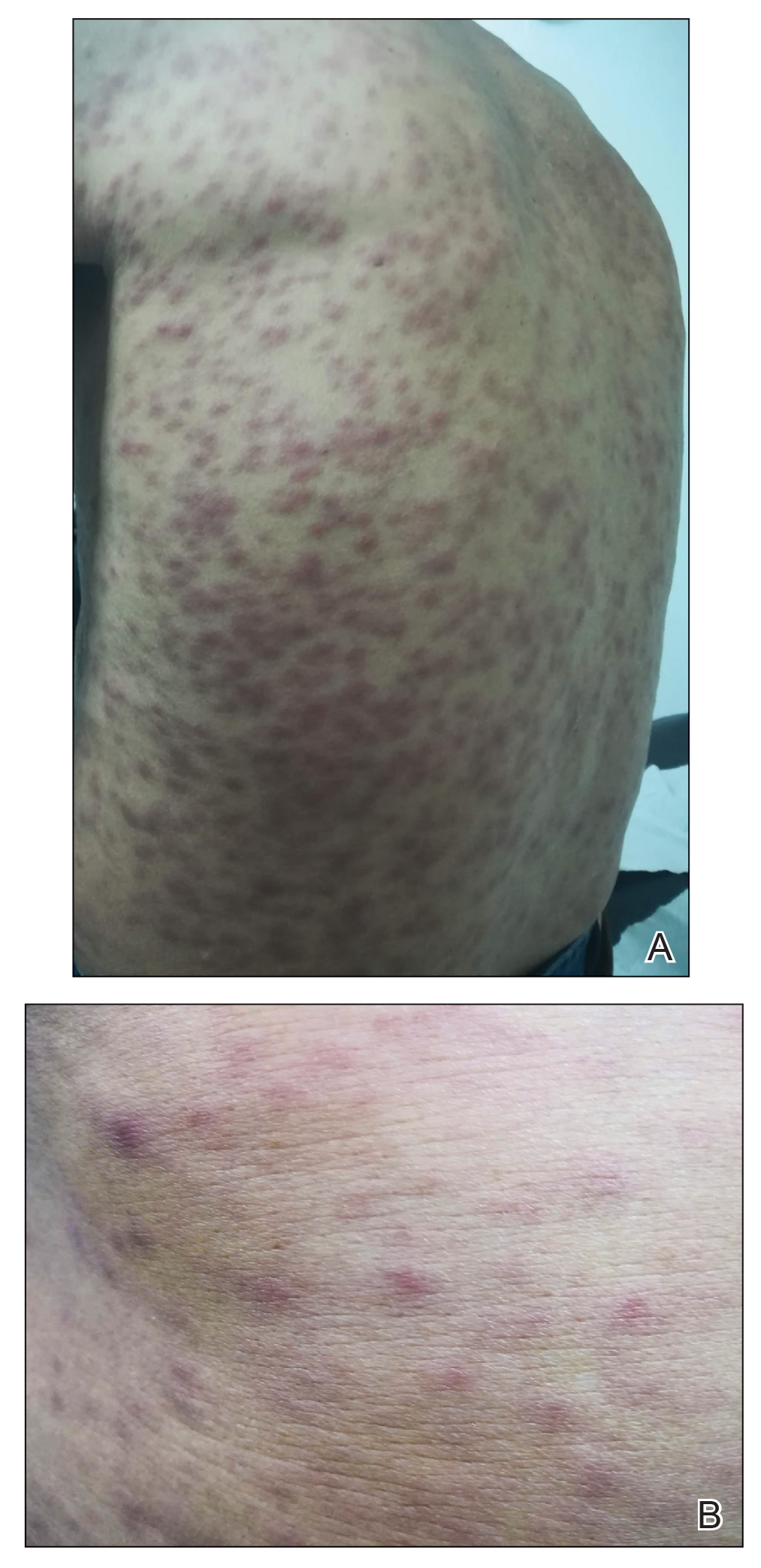

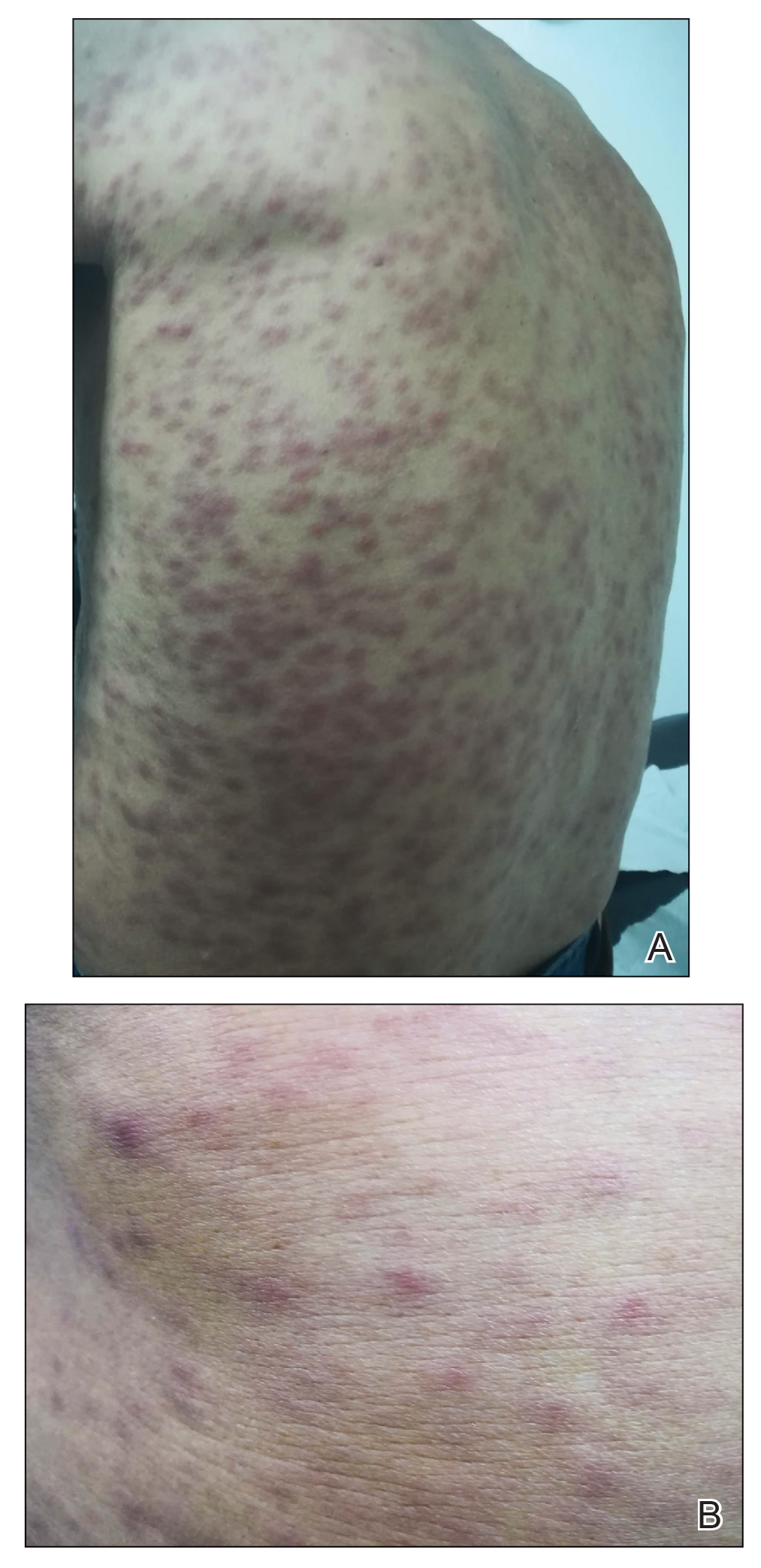

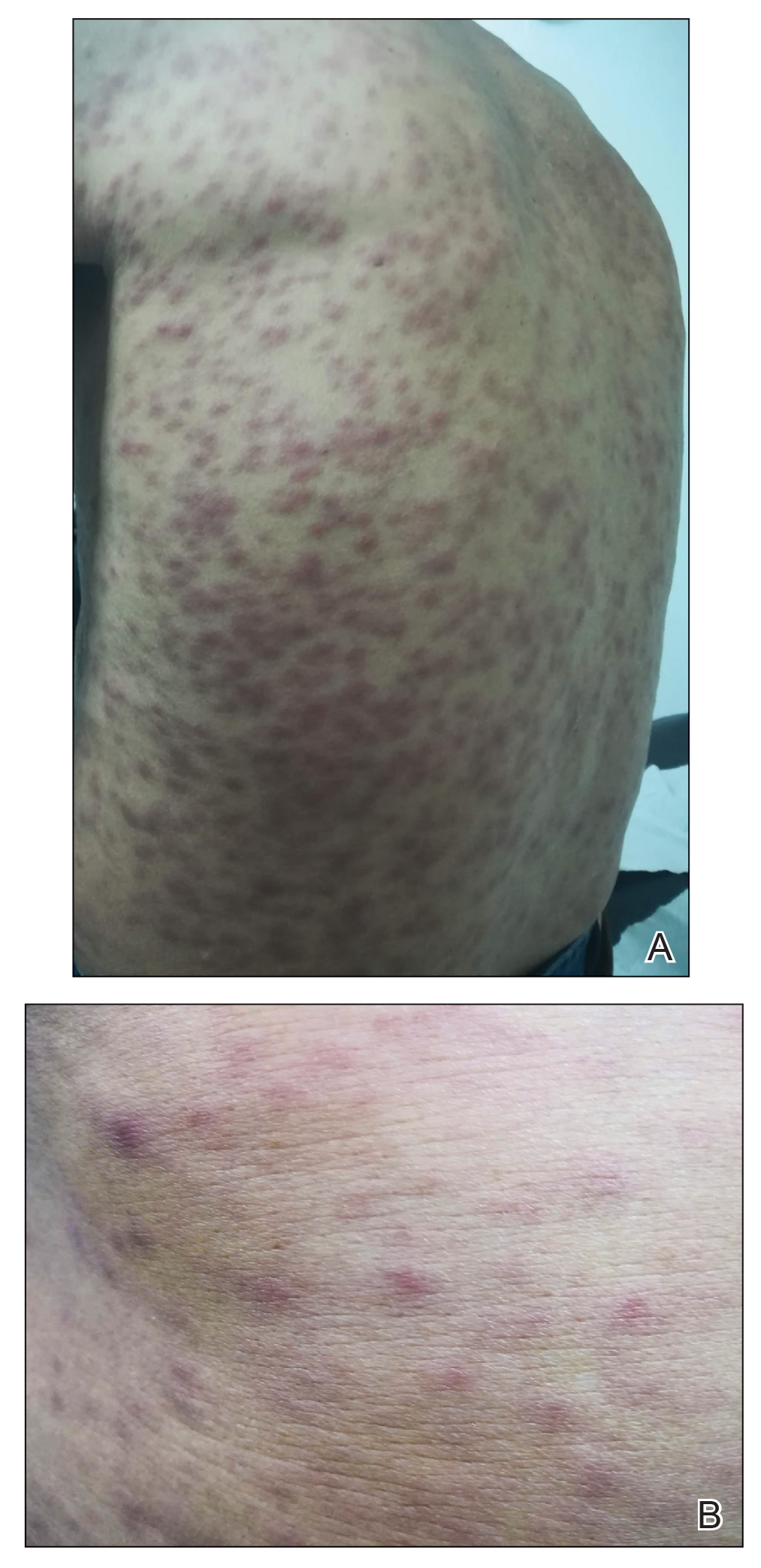

A 68-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our clinic for suspected stasis dermatitis. At presentation, no lesions were identified on the legs, but she brought photographs of an erythematous urticarial eruption on the medial lower legs, extending from just above the sock line to the mid-calves (Figure). The eruptions had occurred over the last 16 years, typically presenting suddenly after playing tennis or an extended period of walking and spontaneously resolving in 4 days. The lesions were painless, restricted to the calves, and were not pruritic, though the initial presentation 16 years prior included pruritic pigmented patches on the anterior thighs. Because the condition spontaneously improved within days, no treatment was attempted. An ultrasound venous reflux study ruled out venous reflux and stasis dermatitis.

Our patient stated that her 64-year-old sister had reported the same presentation over the last 8 years. Her physical activity was limited strictly to walking, and the lesions occurred after walking for many hours during the day in the heat, involving the medial aspects of the lower legs extending from the ankles to the full length of the calves. Her eruption was warm but was not painful or pruritic. It resolved spontaneously after 5 days with no therapy.

Our patient was advised to wear compression stockings as a preventative measure, but she did not adhere to these recommendations, stating it was impractical to wear compression garments while playing tennis.

Exercise-induced vasculitis most commonly is seen in the medial aspects of the lower extremities as an erythematous urticarial eruption or pigmented purpuric plaque rapidly occurring after a period of exercise.1,2 Lesions often are symmetric and can be pruritic and painful with a lack of systemic symptoms.3 These generic clinical manifestations may lead to a misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. One case report included initial treatment of presumptive cellulitis.4 Important clinical findings include a sparing of skin compressed by tight clothing such as socks, a lack of systemic symptoms, rapid appearance after exercise, and spontaneous resolution within a few days. No correlation with chronic venous disease has been demonstrated, as EIV can occur in patients with or without chronic venous insufficiency.5 Duplex ultrasound evaluation showed no venous reflux in our patient.

The pathophysiology of EIV remains unknown, but the concept of exercise-altered microcirculation has been proposed. Heat generated from exercise is normally dissipated by thermoregulatory mechanisms such as cutaneous vasodilation and sweat.1,6 When exercise is extended, done concomitantly in the heat, or performed in legs with preexisting edema or substantial adipose tissue that limit heat attenuation, the thermoregulatory capacity is overloaded and heat-induced muscle fiber breakdown occurs.1,7 Atrophy impairs the skeletal muscle’s ability to pump the increased venous return demanded by exercise to the heart, leading to backflow of venous return and eventual venous stasis.1 Reduction of venous return together with cutaneous vasodilation is thought to induce erythrocyte extravasation.

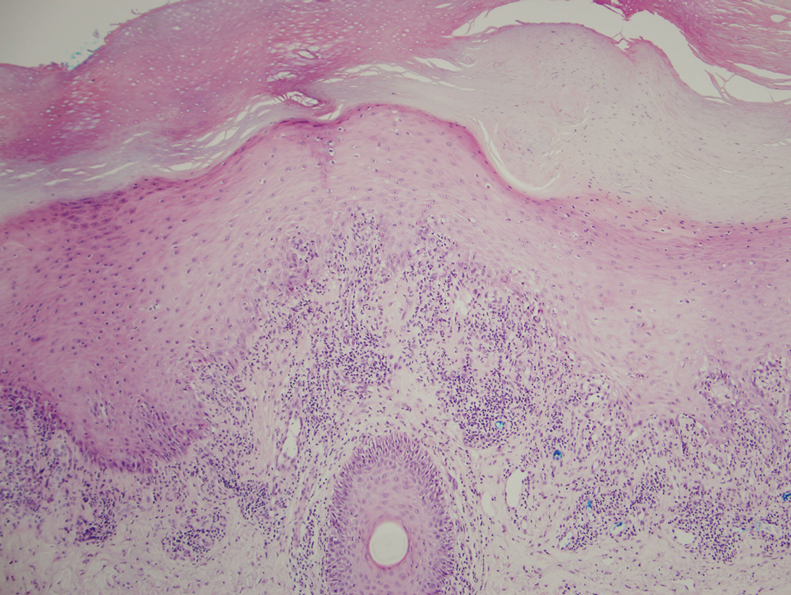

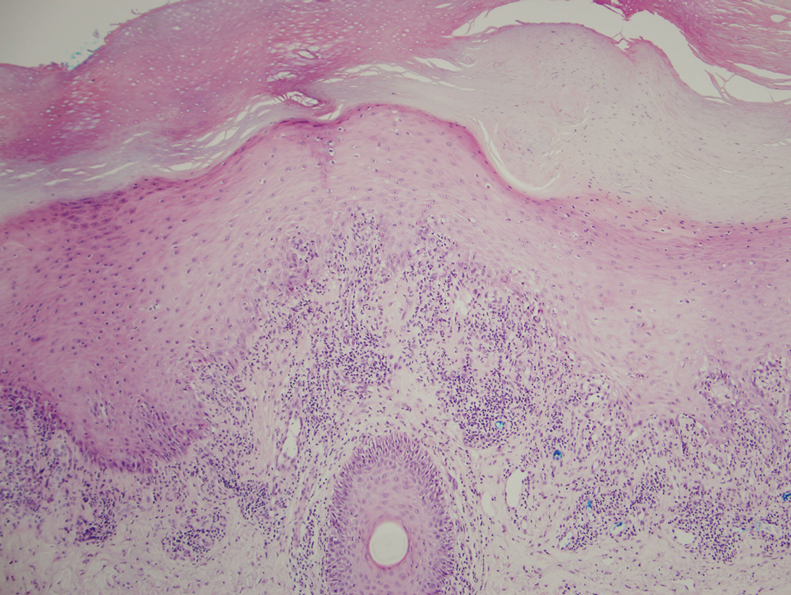

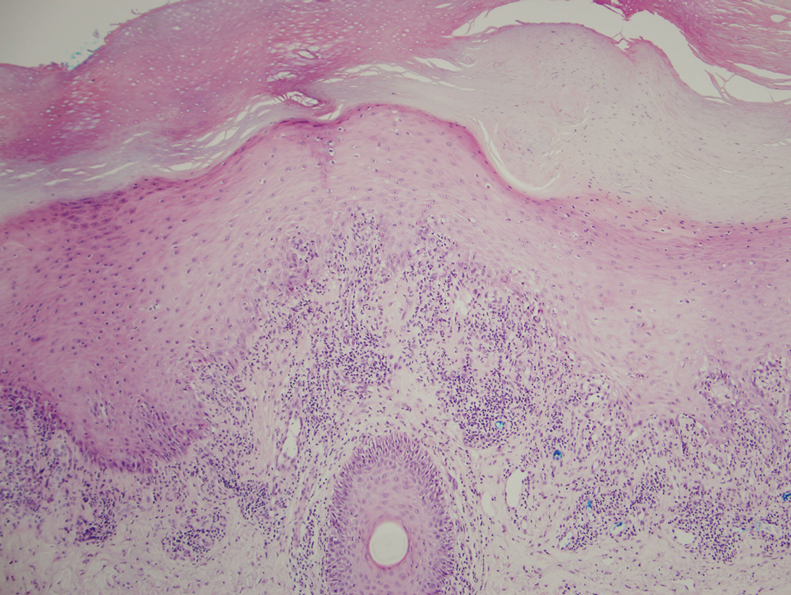

Histologic examination demonstrates features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with perivascular lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates.2 Erythrocyte extravasation, IgM deposits, and identification of C3 also have been reported.8,9 The spontaneous resolution of EIV has led to treatment efforts being focused on preventative measures. Several cases have reported some degree of success in preventing EIV with compression therapy, venoactive drugs, systemic steroids, and application of topical steroids before exercise.3

The clinical morphology and lower leg location of EIV leads to a common misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. Clinical history of a transient nature is the mainstay in the diagnosis of EIV, and ultrasound venous reflux study may be required in some cases. Preventative measures are superior to treatment and mainly include compression therapy.

- Ramelet AA. Exercise-induced vasculitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:423-427.

- Kelly RI, Opie J, Nixon R. Golfer’s vasculitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:11-14.

- Ramelet AA. Exercise-induced purpura. Dermatology. 2004;208:293-296.

- Cushman D, Rydberg L. A general rehabilitation inpatient with exercise-induced vasculitis. PM R. 2013;5:900-902.

- Veraart JC, Prins M, Hulsmans RF, et al. Influence of endurance exercise on the venous refilling time of the leg. Phlebology. 1994;23:120-123.

- Noakes T. Fluid replacement during marathon running. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:309-318.

- Armstrong RB. Muscle damage and endurance events. Sports Med. 1986;3:370-381.

- Prins M, Veraart JC, Vermeulen AH, et al. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis induced by prolonged exercise. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:915-918.

- Sagdeo A, Gormley RH, Wanat KA, et al. Purpuric eruption on the feet of a healthy young woman. “flip-flop vasculitis” (exercise-induced vasculitis). JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:751-756.

To the Editor:

The transient and generic appearance of exercise-induced vasculitis (EIV) makes it a commonly misdiagnosed condition. The lesion often is only encountered through photographs brought by the patient or by taking a thorough history. The lack of findings on clinical inspection and the generic appearance of EIV may lead to misdiagnosis as stasis dermatitis due to its presentation as erythematous lesions on the medial lower legs.

A 68-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our clinic for suspected stasis dermatitis. At presentation, no lesions were identified on the legs, but she brought photographs of an erythematous urticarial eruption on the medial lower legs, extending from just above the sock line to the mid-calves (Figure). The eruptions had occurred over the last 16 years, typically presenting suddenly after playing tennis or an extended period of walking and spontaneously resolving in 4 days. The lesions were painless, restricted to the calves, and were not pruritic, though the initial presentation 16 years prior included pruritic pigmented patches on the anterior thighs. Because the condition spontaneously improved within days, no treatment was attempted. An ultrasound venous reflux study ruled out venous reflux and stasis dermatitis.

Our patient stated that her 64-year-old sister had reported the same presentation over the last 8 years. Her physical activity was limited strictly to walking, and the lesions occurred after walking for many hours during the day in the heat, involving the medial aspects of the lower legs extending from the ankles to the full length of the calves. Her eruption was warm but was not painful or pruritic. It resolved spontaneously after 5 days with no therapy.

Our patient was advised to wear compression stockings as a preventative measure, but she did not adhere to these recommendations, stating it was impractical to wear compression garments while playing tennis.

Exercise-induced vasculitis most commonly is seen in the medial aspects of the lower extremities as an erythematous urticarial eruption or pigmented purpuric plaque rapidly occurring after a period of exercise.1,2 Lesions often are symmetric and can be pruritic and painful with a lack of systemic symptoms.3 These generic clinical manifestations may lead to a misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. One case report included initial treatment of presumptive cellulitis.4 Important clinical findings include a sparing of skin compressed by tight clothing such as socks, a lack of systemic symptoms, rapid appearance after exercise, and spontaneous resolution within a few days. No correlation with chronic venous disease has been demonstrated, as EIV can occur in patients with or without chronic venous insufficiency.5 Duplex ultrasound evaluation showed no venous reflux in our patient.

The pathophysiology of EIV remains unknown, but the concept of exercise-altered microcirculation has been proposed. Heat generated from exercise is normally dissipated by thermoregulatory mechanisms such as cutaneous vasodilation and sweat.1,6 When exercise is extended, done concomitantly in the heat, or performed in legs with preexisting edema or substantial adipose tissue that limit heat attenuation, the thermoregulatory capacity is overloaded and heat-induced muscle fiber breakdown occurs.1,7 Atrophy impairs the skeletal muscle’s ability to pump the increased venous return demanded by exercise to the heart, leading to backflow of venous return and eventual venous stasis.1 Reduction of venous return together with cutaneous vasodilation is thought to induce erythrocyte extravasation.

Histologic examination demonstrates features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with perivascular lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates.2 Erythrocyte extravasation, IgM deposits, and identification of C3 also have been reported.8,9 The spontaneous resolution of EIV has led to treatment efforts being focused on preventative measures. Several cases have reported some degree of success in preventing EIV with compression therapy, venoactive drugs, systemic steroids, and application of topical steroids before exercise.3

The clinical morphology and lower leg location of EIV leads to a common misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. Clinical history of a transient nature is the mainstay in the diagnosis of EIV, and ultrasound venous reflux study may be required in some cases. Preventative measures are superior to treatment and mainly include compression therapy.

To the Editor:

The transient and generic appearance of exercise-induced vasculitis (EIV) makes it a commonly misdiagnosed condition. The lesion often is only encountered through photographs brought by the patient or by taking a thorough history. The lack of findings on clinical inspection and the generic appearance of EIV may lead to misdiagnosis as stasis dermatitis due to its presentation as erythematous lesions on the medial lower legs.

A 68-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our clinic for suspected stasis dermatitis. At presentation, no lesions were identified on the legs, but she brought photographs of an erythematous urticarial eruption on the medial lower legs, extending from just above the sock line to the mid-calves (Figure). The eruptions had occurred over the last 16 years, typically presenting suddenly after playing tennis or an extended period of walking and spontaneously resolving in 4 days. The lesions were painless, restricted to the calves, and were not pruritic, though the initial presentation 16 years prior included pruritic pigmented patches on the anterior thighs. Because the condition spontaneously improved within days, no treatment was attempted. An ultrasound venous reflux study ruled out venous reflux and stasis dermatitis.

Our patient stated that her 64-year-old sister had reported the same presentation over the last 8 years. Her physical activity was limited strictly to walking, and the lesions occurred after walking for many hours during the day in the heat, involving the medial aspects of the lower legs extending from the ankles to the full length of the calves. Her eruption was warm but was not painful or pruritic. It resolved spontaneously after 5 days with no therapy.

Our patient was advised to wear compression stockings as a preventative measure, but she did not adhere to these recommendations, stating it was impractical to wear compression garments while playing tennis.

Exercise-induced vasculitis most commonly is seen in the medial aspects of the lower extremities as an erythematous urticarial eruption or pigmented purpuric plaque rapidly occurring after a period of exercise.1,2 Lesions often are symmetric and can be pruritic and painful with a lack of systemic symptoms.3 These generic clinical manifestations may lead to a misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. One case report included initial treatment of presumptive cellulitis.4 Important clinical findings include a sparing of skin compressed by tight clothing such as socks, a lack of systemic symptoms, rapid appearance after exercise, and spontaneous resolution within a few days. No correlation with chronic venous disease has been demonstrated, as EIV can occur in patients with or without chronic venous insufficiency.5 Duplex ultrasound evaluation showed no venous reflux in our patient.

The pathophysiology of EIV remains unknown, but the concept of exercise-altered microcirculation has been proposed. Heat generated from exercise is normally dissipated by thermoregulatory mechanisms such as cutaneous vasodilation and sweat.1,6 When exercise is extended, done concomitantly in the heat, or performed in legs with preexisting edema or substantial adipose tissue that limit heat attenuation, the thermoregulatory capacity is overloaded and heat-induced muscle fiber breakdown occurs.1,7 Atrophy impairs the skeletal muscle’s ability to pump the increased venous return demanded by exercise to the heart, leading to backflow of venous return and eventual venous stasis.1 Reduction of venous return together with cutaneous vasodilation is thought to induce erythrocyte extravasation.

Histologic examination demonstrates features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with perivascular lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates.2 Erythrocyte extravasation, IgM deposits, and identification of C3 also have been reported.8,9 The spontaneous resolution of EIV has led to treatment efforts being focused on preventative measures. Several cases have reported some degree of success in preventing EIV with compression therapy, venoactive drugs, systemic steroids, and application of topical steroids before exercise.3

The clinical morphology and lower leg location of EIV leads to a common misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. Clinical history of a transient nature is the mainstay in the diagnosis of EIV, and ultrasound venous reflux study may be required in some cases. Preventative measures are superior to treatment and mainly include compression therapy.

- Ramelet AA. Exercise-induced vasculitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:423-427.

- Kelly RI, Opie J, Nixon R. Golfer’s vasculitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:11-14.

- Ramelet AA. Exercise-induced purpura. Dermatology. 2004;208:293-296.

- Cushman D, Rydberg L. A general rehabilitation inpatient with exercise-induced vasculitis. PM R. 2013;5:900-902.

- Veraart JC, Prins M, Hulsmans RF, et al. Influence of endurance exercise on the venous refilling time of the leg. Phlebology. 1994;23:120-123.

- Noakes T. Fluid replacement during marathon running. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:309-318.

- Armstrong RB. Muscle damage and endurance events. Sports Med. 1986;3:370-381.

- Prins M, Veraart JC, Vermeulen AH, et al. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis induced by prolonged exercise. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:915-918.

- Sagdeo A, Gormley RH, Wanat KA, et al. Purpuric eruption on the feet of a healthy young woman. “flip-flop vasculitis” (exercise-induced vasculitis). JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:751-756.

- Ramelet AA. Exercise-induced vasculitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:423-427.

- Kelly RI, Opie J, Nixon R. Golfer’s vasculitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:11-14.

- Ramelet AA. Exercise-induced purpura. Dermatology. 2004;208:293-296.

- Cushman D, Rydberg L. A general rehabilitation inpatient with exercise-induced vasculitis. PM R. 2013;5:900-902.

- Veraart JC, Prins M, Hulsmans RF, et al. Influence of endurance exercise on the venous refilling time of the leg. Phlebology. 1994;23:120-123.

- Noakes T. Fluid replacement during marathon running. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:309-318.

- Armstrong RB. Muscle damage and endurance events. Sports Med. 1986;3:370-381.

- Prins M, Veraart JC, Vermeulen AH, et al. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis induced by prolonged exercise. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:915-918.

- Sagdeo A, Gormley RH, Wanat KA, et al. Purpuric eruption on the feet of a healthy young woman. “flip-flop vasculitis” (exercise-induced vasculitis). JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:751-756.

Practice Points

- Clinical history of a transient nature is the mainstay in the diagnosis of exercise-induced vasculitis.

- Exercise-induced vasculitis largely is documented in photographs or by history and may be misdiagnosed as stasis dermatitis due to its clinical morphology and lower leg location.

- Dermatologists should be aware of this disorder and consider performing further workup to rule out stasis dermatitis and diagnose this mimic.

- Preventative measures are superior to treatment and mainly include compression therapy.

Unilateral Nail Clubbing in a Hemiparetic Patient

To the Editor:

Few cases of unilateral nail changes affecting only the hemiplegic side after a stroke have been reported. We present a case of acquired unilateral nail clubbing and longitudinal melanonychia in a hemiparetic patient.

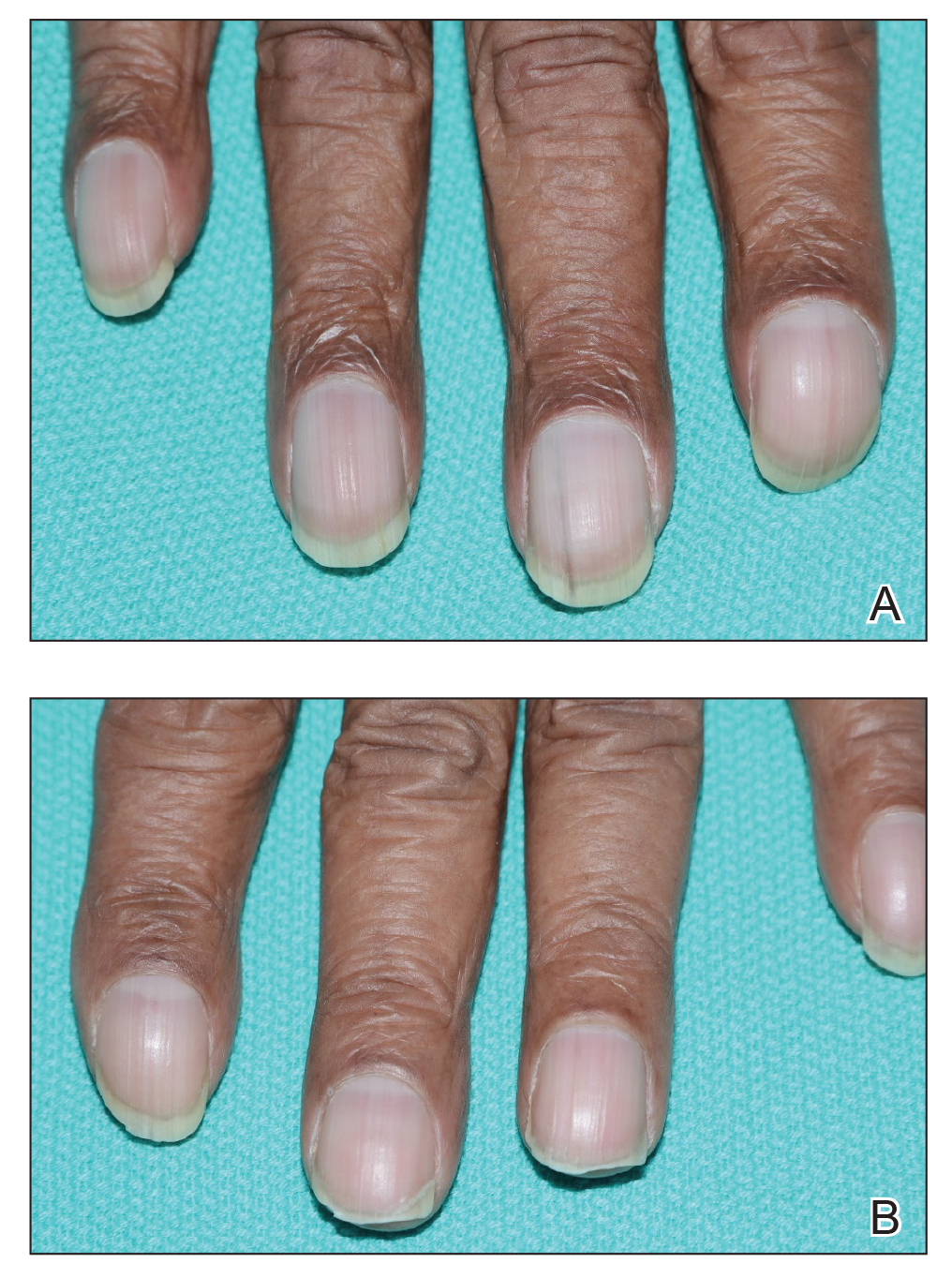

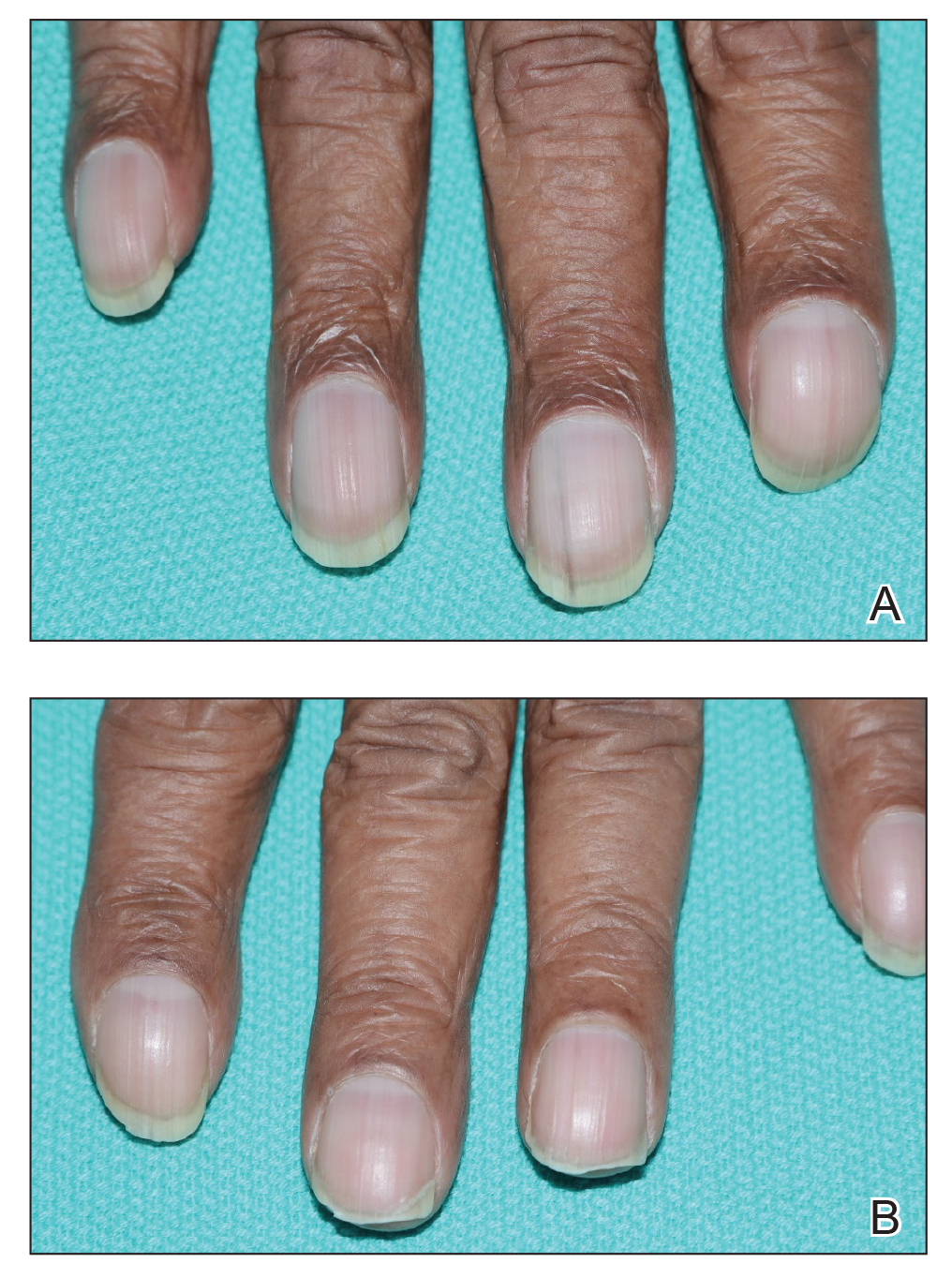

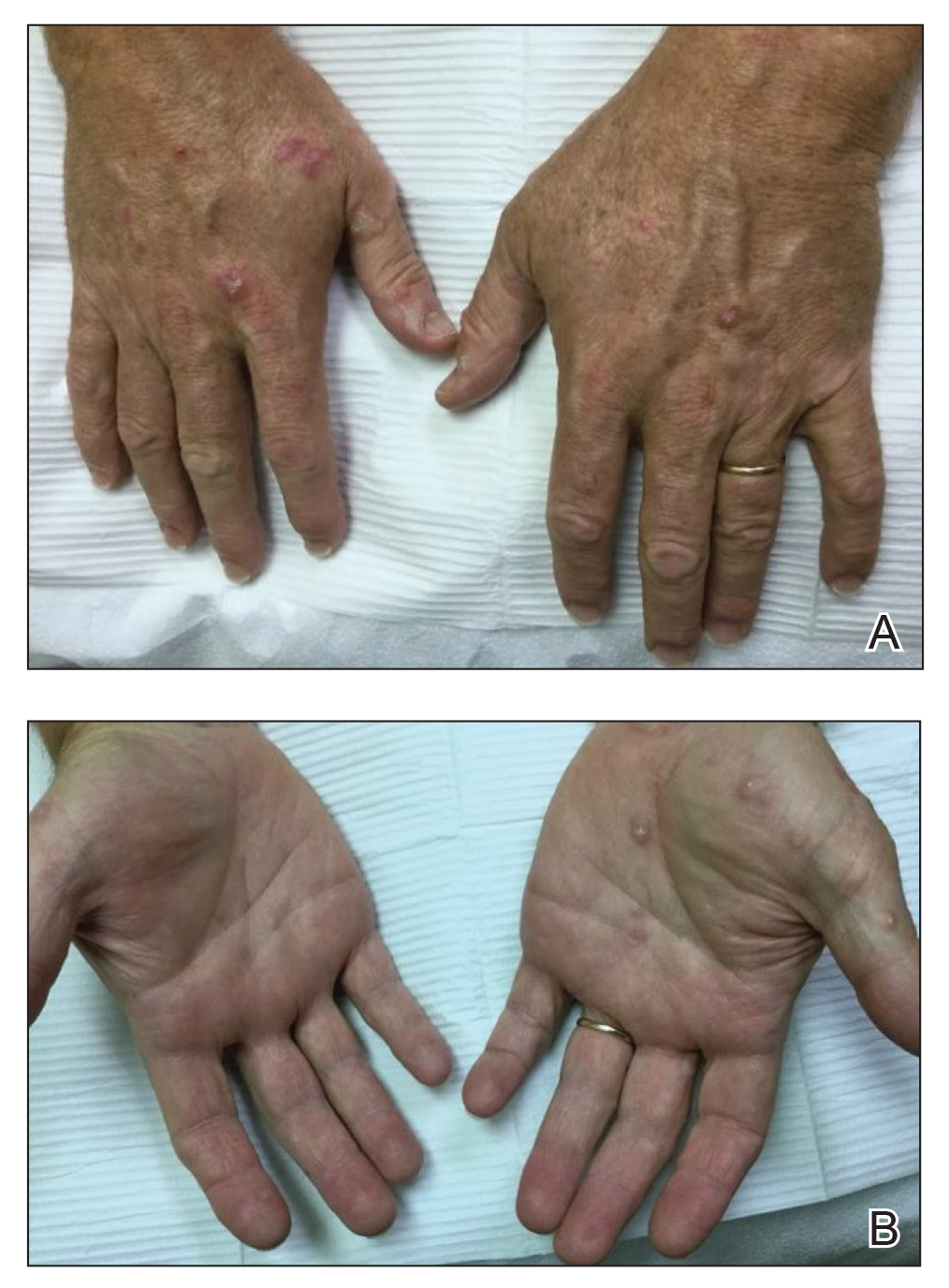

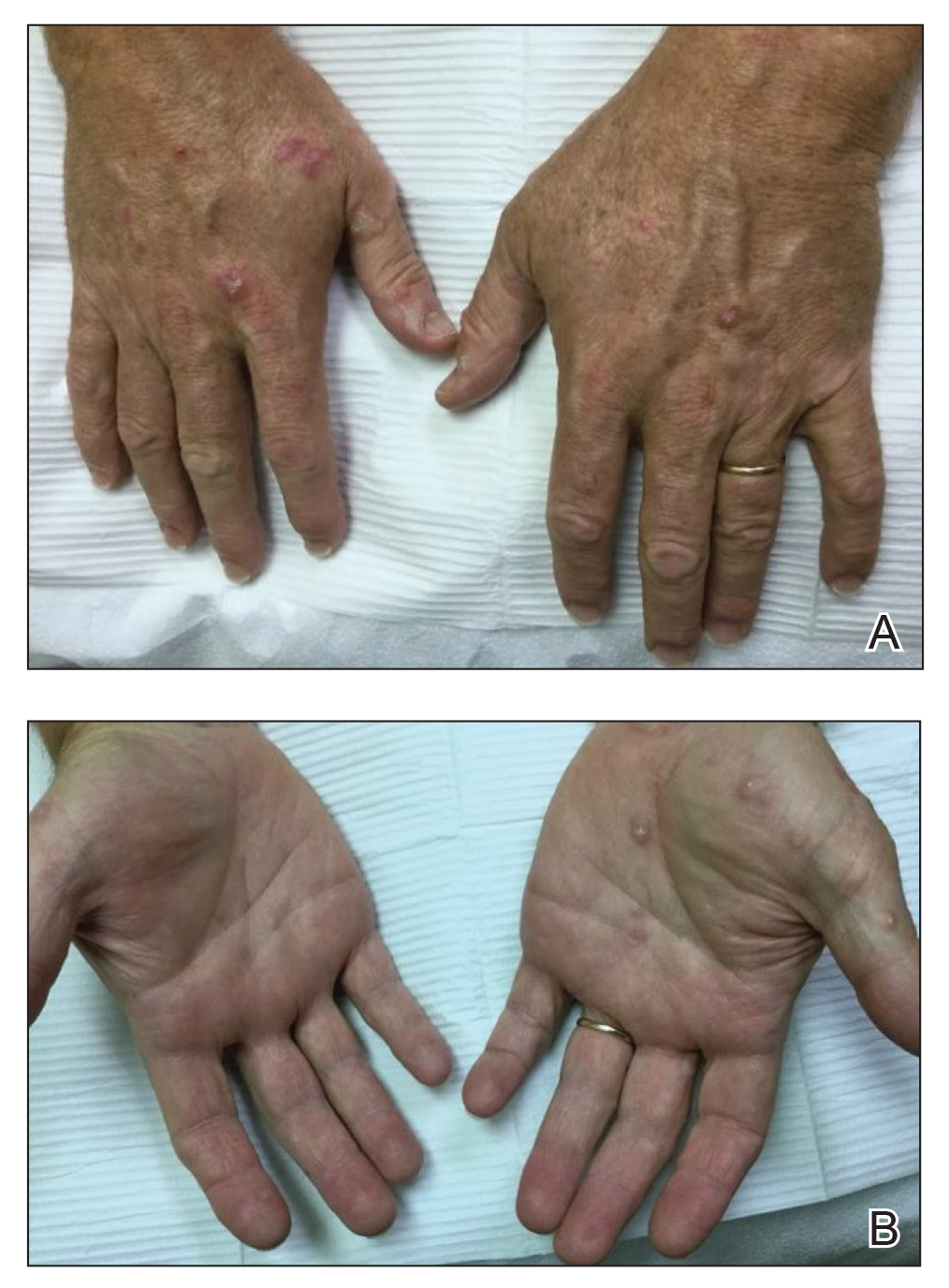

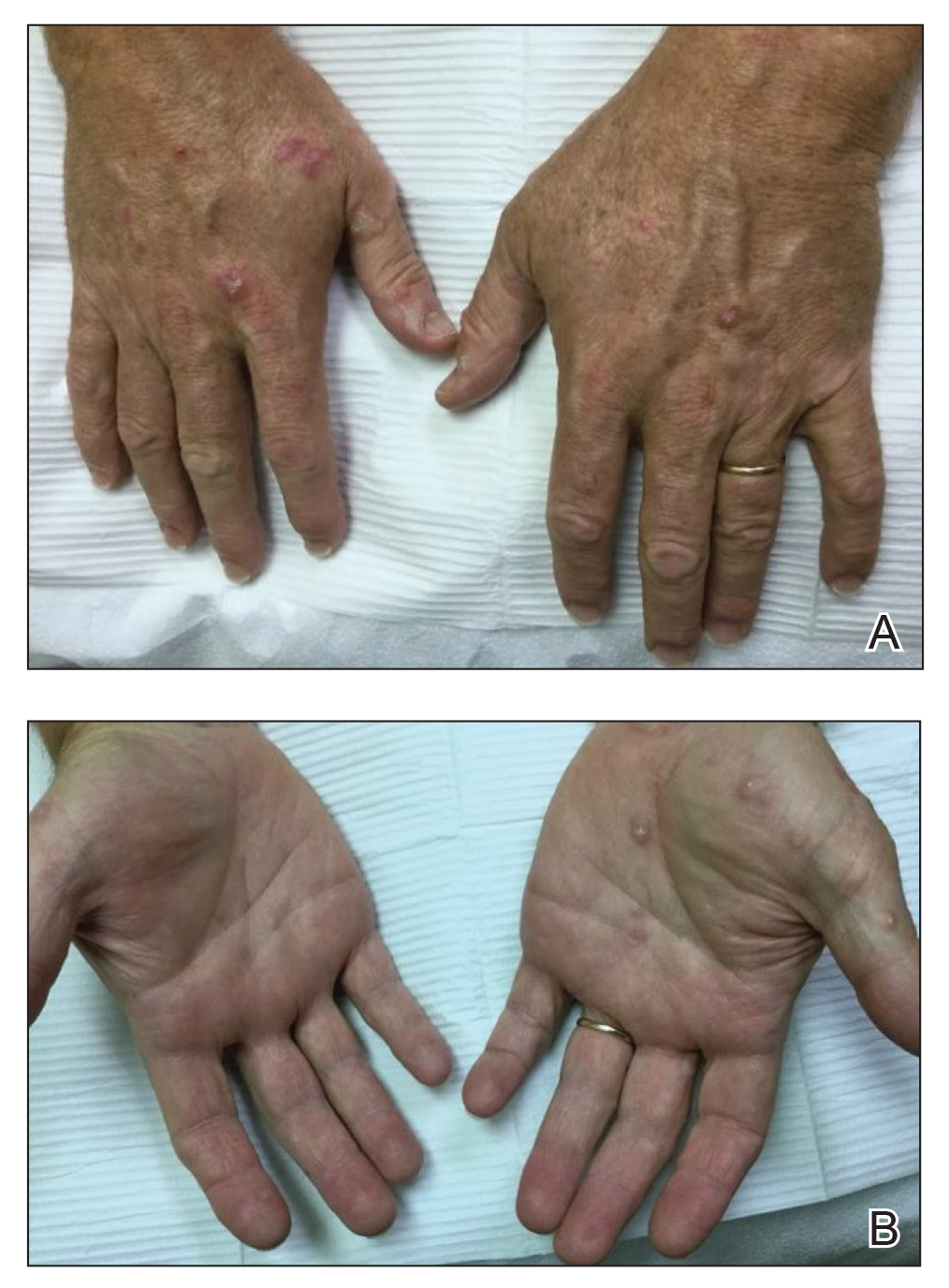

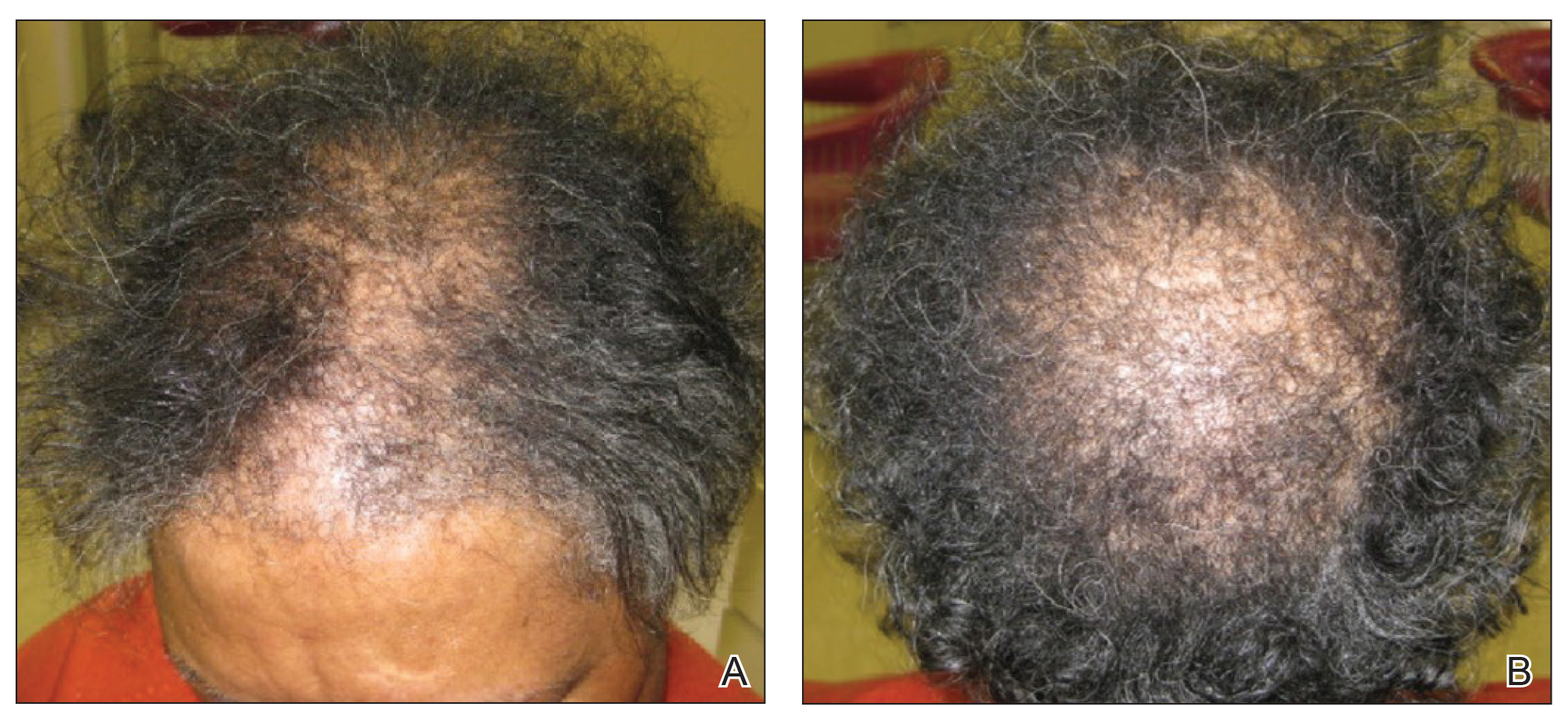

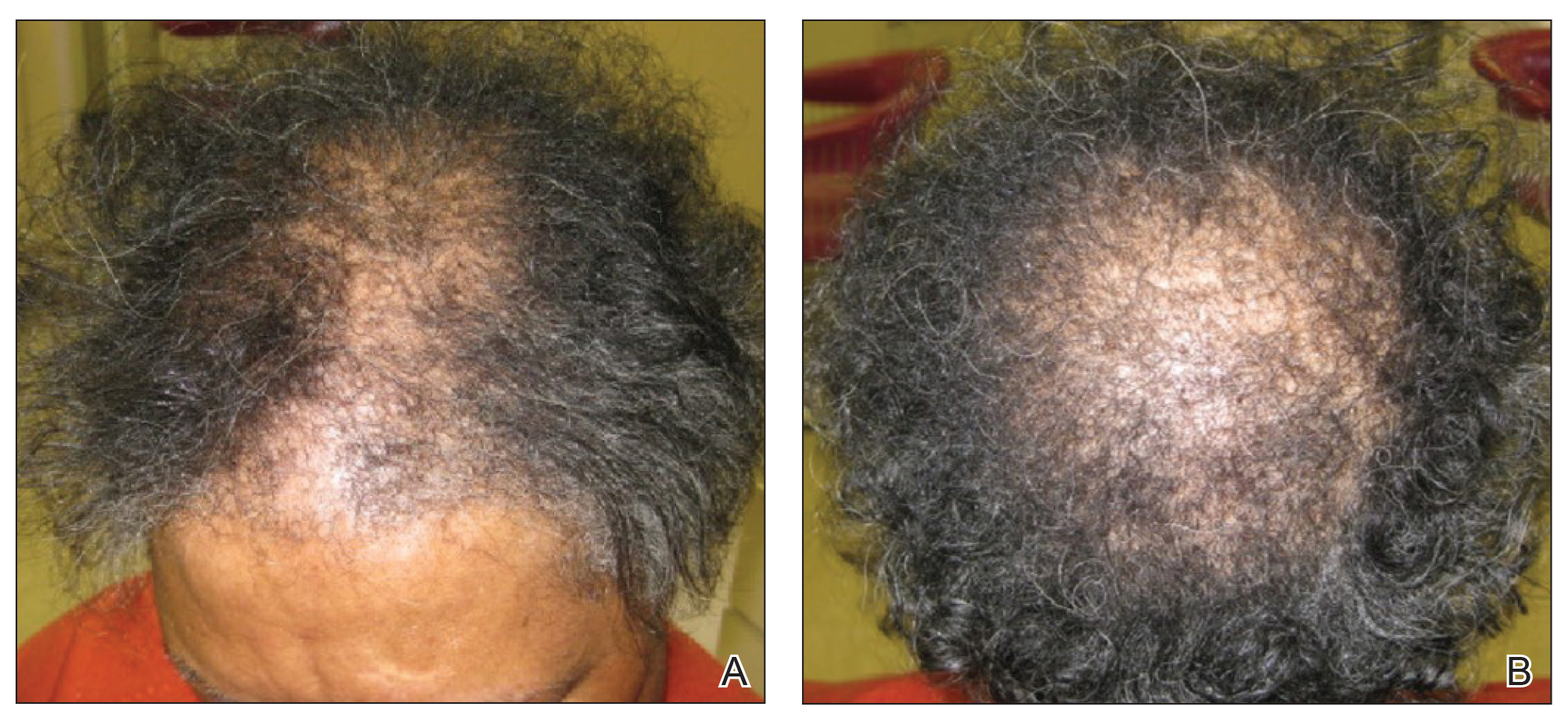

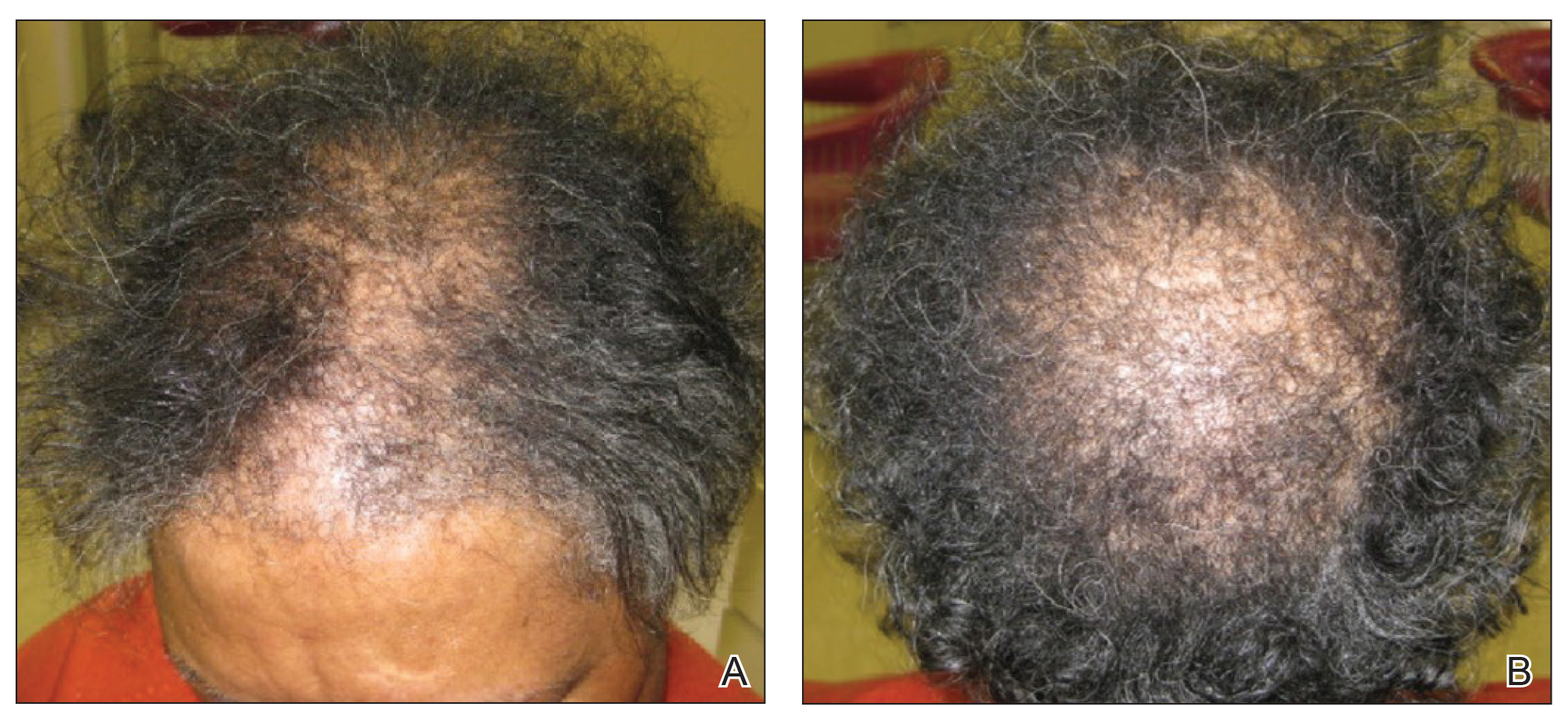

A 79-year-old Black man with a history of smoking and stroke presented with concerns of discoloration of the fingernails. His medical history was notable for congestive heart failure; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; hypercholesterolemia; and stroke 11 years prior, which resulted in right-sided hemiparesis. Physical examination revealed longitudinal, even hyperpigmentation of several fingernails on the hands, in addition to whitening of the nail beds, sparing the tips (Terry nails). Clubbing was noted only on the fingernails of the right hand; the fingernails of the left hand exhibited normal curvature (Figure). Pulse oximetry was conducted and demonstrated the following readings: unaffected left index finger, 98%; unaffected left middle finger, 100%; affected right index finger, 95%; and affected right middle finger, 97%. The patient was diagnosed with benign longitudinal melanonychia secondary to ethnic variation, Terry nails without underlying anemia or hypoalbuminemic state, and unilateral right-sided clubbing of the fingernails in the setting of right-sided hemiparesis.

Prior reports have documented the occurrence of nail pathologies after stroke and affecting hemiplegic limbs. Unilateral digital nail clubbing following a stroke was first reported in 19751; 2 reports concluded clubbing developed in all digits affected by the stroke, and the severity of clubbing was associated with the duration of the stroke.1,2 One study noted longitudinal reddish striation, Neapolitan nails, and unilateral clubbing more commonly in hemiplegic patients.3 Longitudinal reddish striation was the most frequent condition observed in this population, always affecting the entire thumbnail of the hemiplegic limb.3 A similar report observed clubbing only on the fingernails of the hemiplegic side.4

Digital clubbing describes an exaggerated nail curvature and bulbous overgrowth of the fingertips due to an expansion of connective tissue between the nail plate and the nail bed.3,5 Clubbed fingers are found in various chronic conditions affecting the heart, lungs, and liver. Although the pathogenesis of clubbing remains unknown, many hypothesize that it is a state of proliferation in response to digital hypoxia.5 Fittingly, our patient exhibited a relative hypoperfusion of the clubbed fingers in comparison to the unaffected side.

This case provides additional support for the phenomenon of unilateral nail changes limited to hemiplegic or hemiparetic limbs. The unique presentation of longitudinal melanonychia, clubbing, and a lowered pulse oximetry reading only affecting the hemiparetic side demonstrates the possible connection between hypoxia and nail clubbing in this patient population.

- Denham M, Hodkinson H, Wright B. Unilateral clubbing in hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:7-12.

- Alveraz A, McNair D, Wildman J, et al. Unilateral clubbing of the fingernails in patients with hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:1-6.

- Siragusa M, Schepis C, Cosentino F, et al. Nail pathology in patients with hemiplegia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:557-560.

- Gül Ü, Çakmak S, Özel S, et al. Skin disorders in patients with hemiplegia and paraplegia. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:681-683.

- Sarkar M, Mahesh D, Madabhavi I. Digital clubbing. Lung India. 2012;29:354-362.

To the Editor:

Few cases of unilateral nail changes affecting only the hemiplegic side after a stroke have been reported. We present a case of acquired unilateral nail clubbing and longitudinal melanonychia in a hemiparetic patient.

A 79-year-old Black man with a history of smoking and stroke presented with concerns of discoloration of the fingernails. His medical history was notable for congestive heart failure; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; hypercholesterolemia; and stroke 11 years prior, which resulted in right-sided hemiparesis. Physical examination revealed longitudinal, even hyperpigmentation of several fingernails on the hands, in addition to whitening of the nail beds, sparing the tips (Terry nails). Clubbing was noted only on the fingernails of the right hand; the fingernails of the left hand exhibited normal curvature (Figure). Pulse oximetry was conducted and demonstrated the following readings: unaffected left index finger, 98%; unaffected left middle finger, 100%; affected right index finger, 95%; and affected right middle finger, 97%. The patient was diagnosed with benign longitudinal melanonychia secondary to ethnic variation, Terry nails without underlying anemia or hypoalbuminemic state, and unilateral right-sided clubbing of the fingernails in the setting of right-sided hemiparesis.

Prior reports have documented the occurrence of nail pathologies after stroke and affecting hemiplegic limbs. Unilateral digital nail clubbing following a stroke was first reported in 19751; 2 reports concluded clubbing developed in all digits affected by the stroke, and the severity of clubbing was associated with the duration of the stroke.1,2 One study noted longitudinal reddish striation, Neapolitan nails, and unilateral clubbing more commonly in hemiplegic patients.3 Longitudinal reddish striation was the most frequent condition observed in this population, always affecting the entire thumbnail of the hemiplegic limb.3 A similar report observed clubbing only on the fingernails of the hemiplegic side.4

Digital clubbing describes an exaggerated nail curvature and bulbous overgrowth of the fingertips due to an expansion of connective tissue between the nail plate and the nail bed.3,5 Clubbed fingers are found in various chronic conditions affecting the heart, lungs, and liver. Although the pathogenesis of clubbing remains unknown, many hypothesize that it is a state of proliferation in response to digital hypoxia.5 Fittingly, our patient exhibited a relative hypoperfusion of the clubbed fingers in comparison to the unaffected side.

This case provides additional support for the phenomenon of unilateral nail changes limited to hemiplegic or hemiparetic limbs. The unique presentation of longitudinal melanonychia, clubbing, and a lowered pulse oximetry reading only affecting the hemiparetic side demonstrates the possible connection between hypoxia and nail clubbing in this patient population.

To the Editor:

Few cases of unilateral nail changes affecting only the hemiplegic side after a stroke have been reported. We present a case of acquired unilateral nail clubbing and longitudinal melanonychia in a hemiparetic patient.

A 79-year-old Black man with a history of smoking and stroke presented with concerns of discoloration of the fingernails. His medical history was notable for congestive heart failure; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; hypercholesterolemia; and stroke 11 years prior, which resulted in right-sided hemiparesis. Physical examination revealed longitudinal, even hyperpigmentation of several fingernails on the hands, in addition to whitening of the nail beds, sparing the tips (Terry nails). Clubbing was noted only on the fingernails of the right hand; the fingernails of the left hand exhibited normal curvature (Figure). Pulse oximetry was conducted and demonstrated the following readings: unaffected left index finger, 98%; unaffected left middle finger, 100%; affected right index finger, 95%; and affected right middle finger, 97%. The patient was diagnosed with benign longitudinal melanonychia secondary to ethnic variation, Terry nails without underlying anemia or hypoalbuminemic state, and unilateral right-sided clubbing of the fingernails in the setting of right-sided hemiparesis.

Prior reports have documented the occurrence of nail pathologies after stroke and affecting hemiplegic limbs. Unilateral digital nail clubbing following a stroke was first reported in 19751; 2 reports concluded clubbing developed in all digits affected by the stroke, and the severity of clubbing was associated with the duration of the stroke.1,2 One study noted longitudinal reddish striation, Neapolitan nails, and unilateral clubbing more commonly in hemiplegic patients.3 Longitudinal reddish striation was the most frequent condition observed in this population, always affecting the entire thumbnail of the hemiplegic limb.3 A similar report observed clubbing only on the fingernails of the hemiplegic side.4

Digital clubbing describes an exaggerated nail curvature and bulbous overgrowth of the fingertips due to an expansion of connective tissue between the nail plate and the nail bed.3,5 Clubbed fingers are found in various chronic conditions affecting the heart, lungs, and liver. Although the pathogenesis of clubbing remains unknown, many hypothesize that it is a state of proliferation in response to digital hypoxia.5 Fittingly, our patient exhibited a relative hypoperfusion of the clubbed fingers in comparison to the unaffected side.

This case provides additional support for the phenomenon of unilateral nail changes limited to hemiplegic or hemiparetic limbs. The unique presentation of longitudinal melanonychia, clubbing, and a lowered pulse oximetry reading only affecting the hemiparetic side demonstrates the possible connection between hypoxia and nail clubbing in this patient population.

- Denham M, Hodkinson H, Wright B. Unilateral clubbing in hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:7-12.

- Alveraz A, McNair D, Wildman J, et al. Unilateral clubbing of the fingernails in patients with hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:1-6.

- Siragusa M, Schepis C, Cosentino F, et al. Nail pathology in patients with hemiplegia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:557-560.

- Gül Ü, Çakmak S, Özel S, et al. Skin disorders in patients with hemiplegia and paraplegia. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:681-683.

- Sarkar M, Mahesh D, Madabhavi I. Digital clubbing. Lung India. 2012;29:354-362.

- Denham M, Hodkinson H, Wright B. Unilateral clubbing in hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:7-12.

- Alveraz A, McNair D, Wildman J, et al. Unilateral clubbing of the fingernails in patients with hemiplegia. Gerontology Clin (Basel). 1975;17:1-6.

- Siragusa M, Schepis C, Cosentino F, et al. Nail pathology in patients with hemiplegia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:557-560.

- Gül Ü, Çakmak S, Özel S, et al. Skin disorders in patients with hemiplegia and paraplegia. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:681-683.

- Sarkar M, Mahesh D, Madabhavi I. Digital clubbing. Lung India. 2012;29:354-362.

Practice Points

- Unilateral nail changes can be limited to hemiplegic or hemiparetic limbs.

- Lowered pulse oximetry reading only affecting the hemiparetic side demonstrates the possible connection between hypoxia and nail clubbing in this patient population.

Stump Pemphigoid Demonstrating Circulating Anti–BP180 and BP230 Antibodies

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a rare complication of lower limb amputation. Termed stump pemphigoid, it previously was described as a late complication arising on the stumps of leg amputees and tends to remain localized. We describe a case of stump pemphigoid presenting with an urticarial prodromal phase without generalized progression, confirmed by serum assay for circulating anti–basement membrane antibodies.

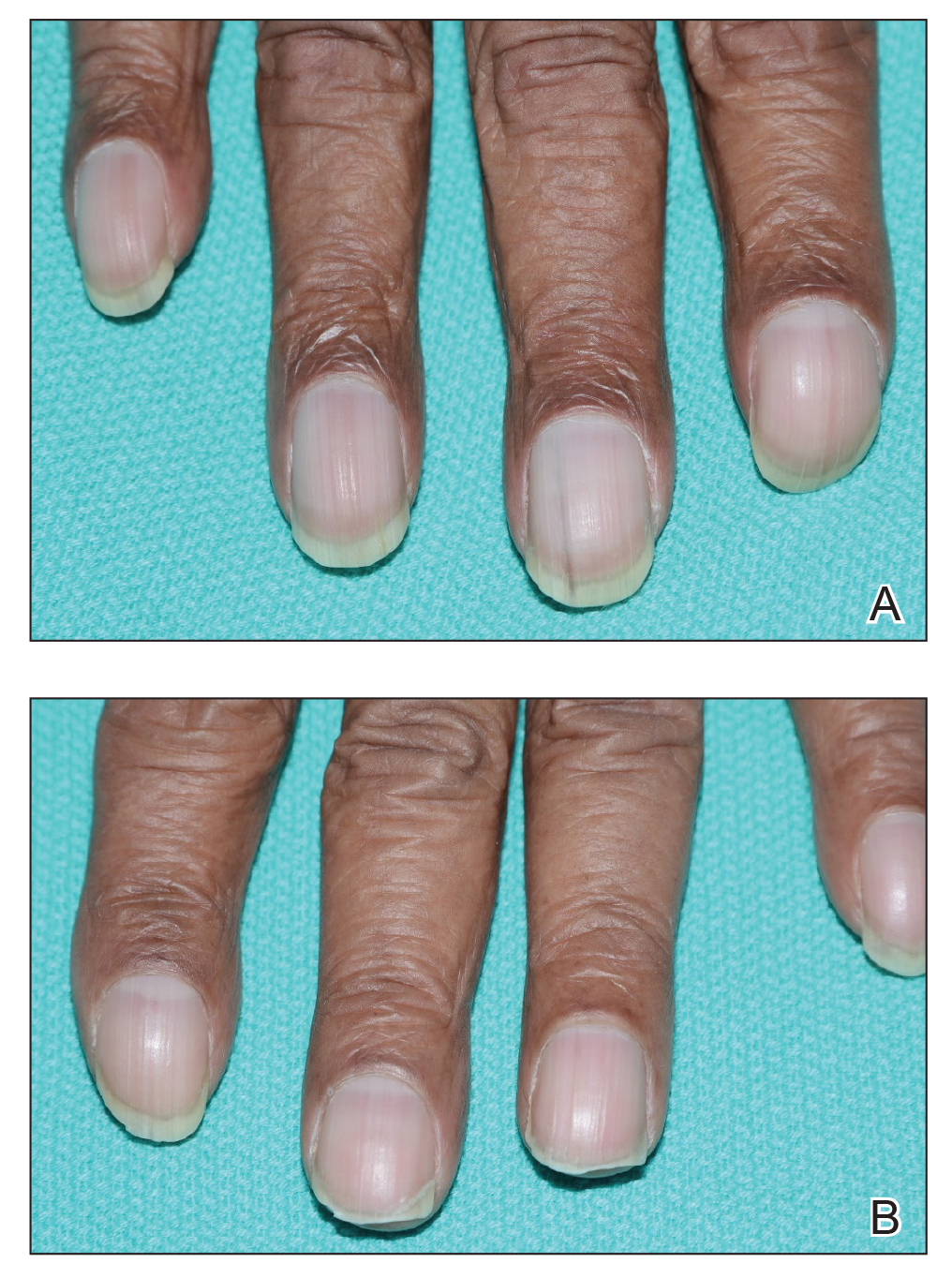

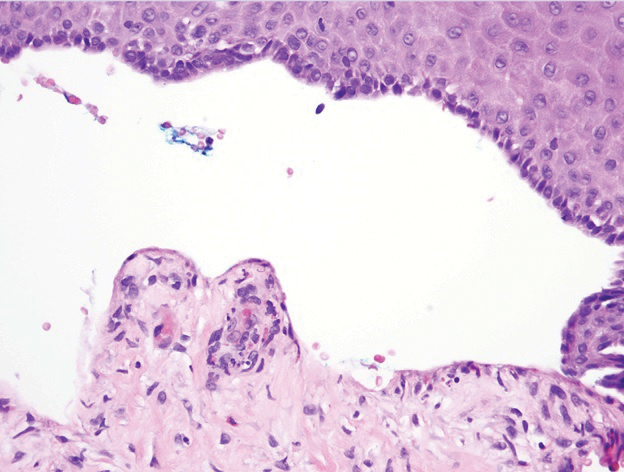

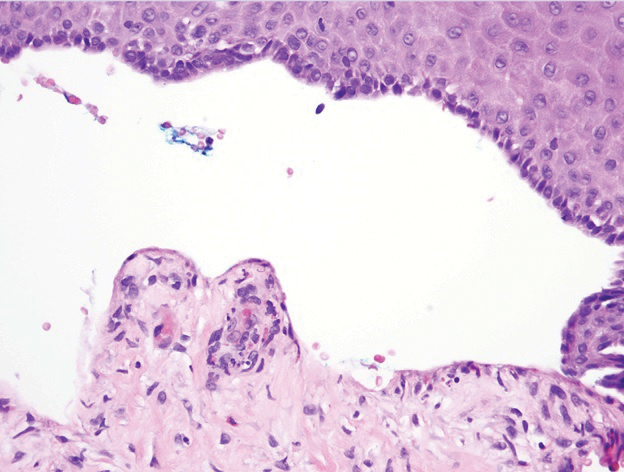

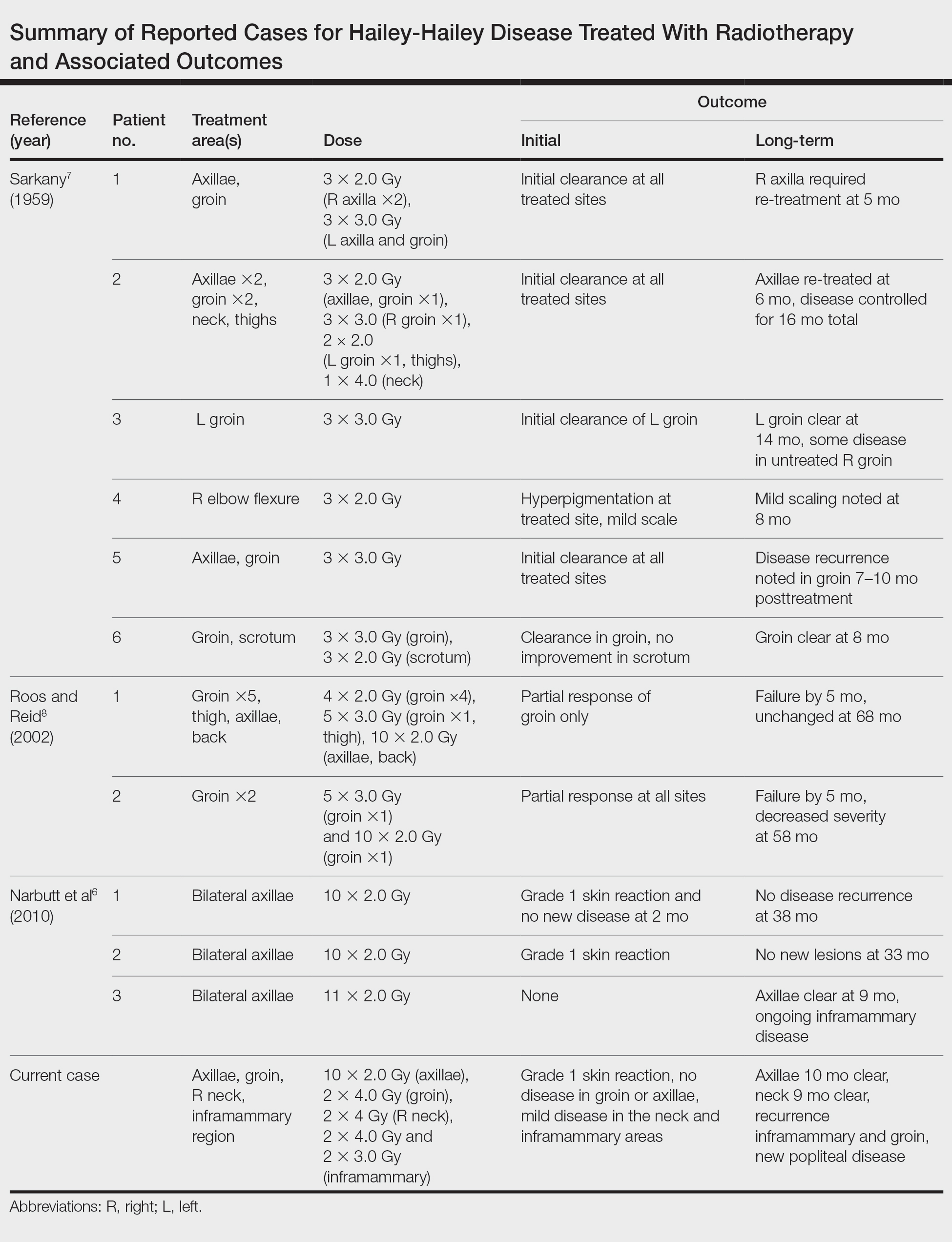

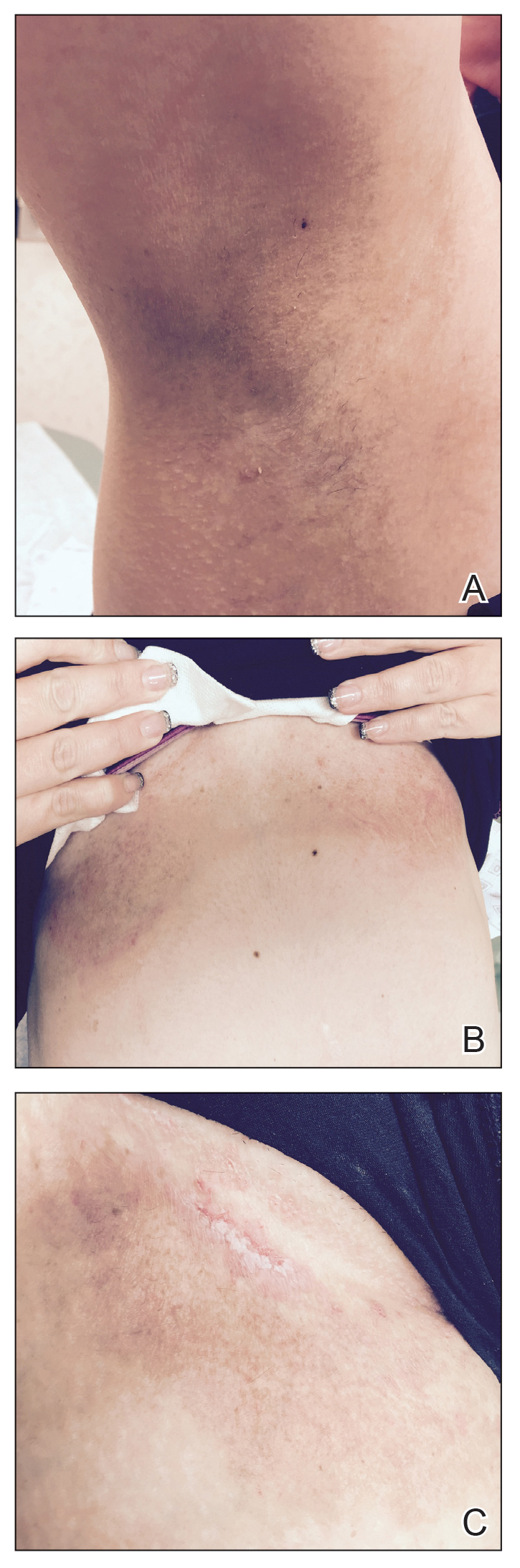

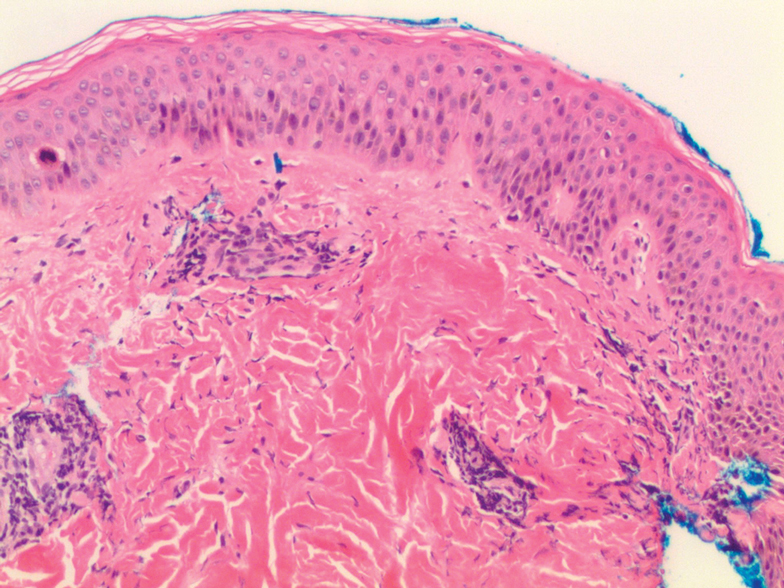

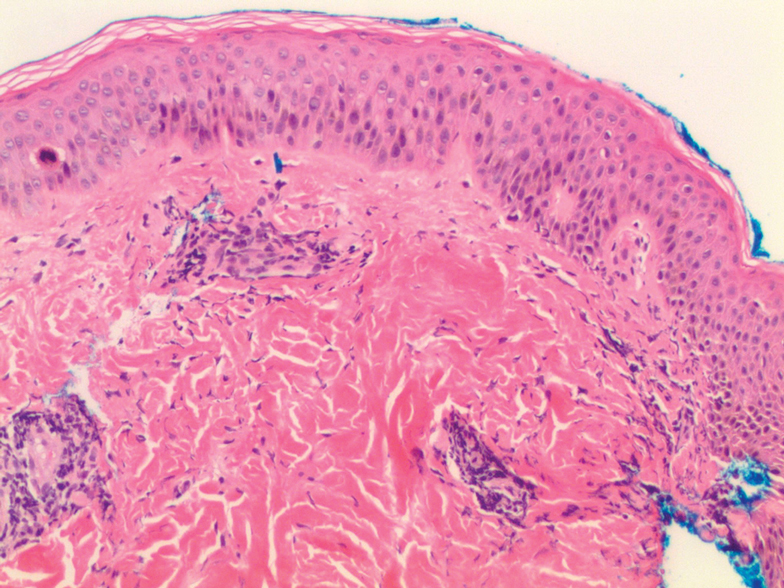

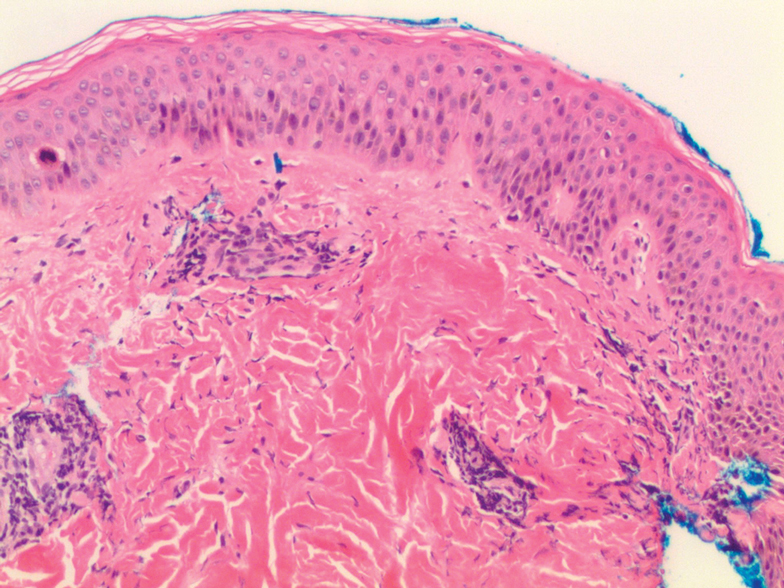

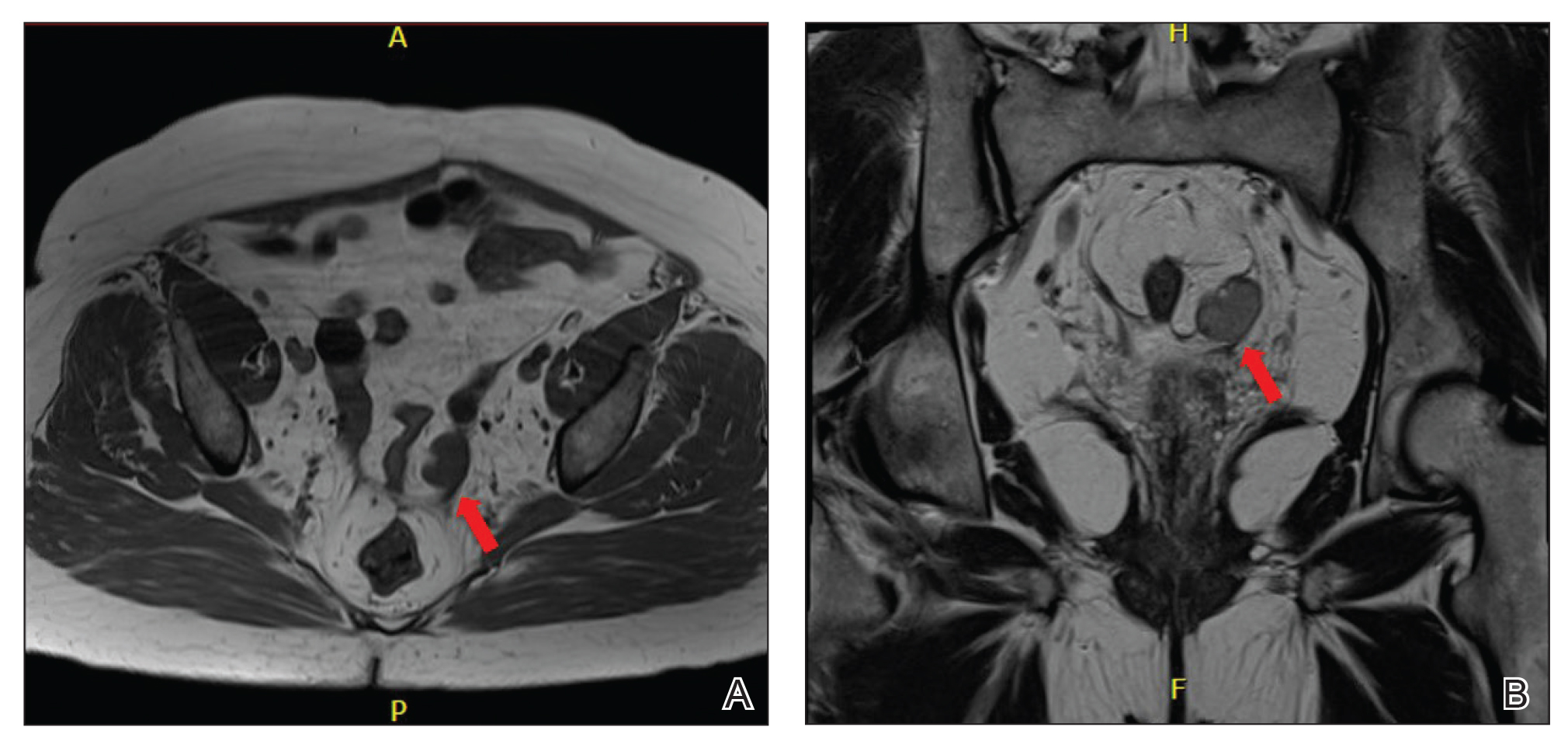

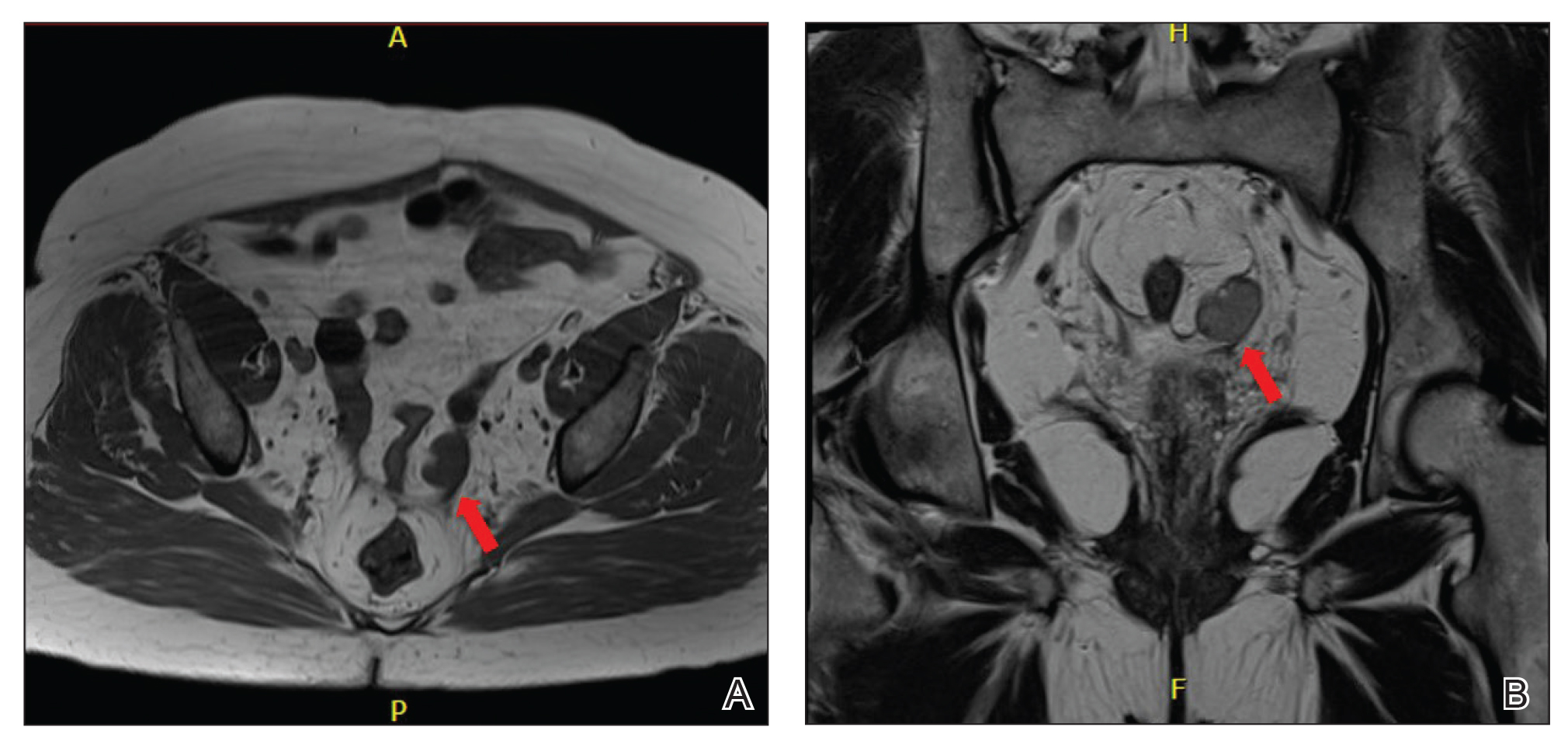

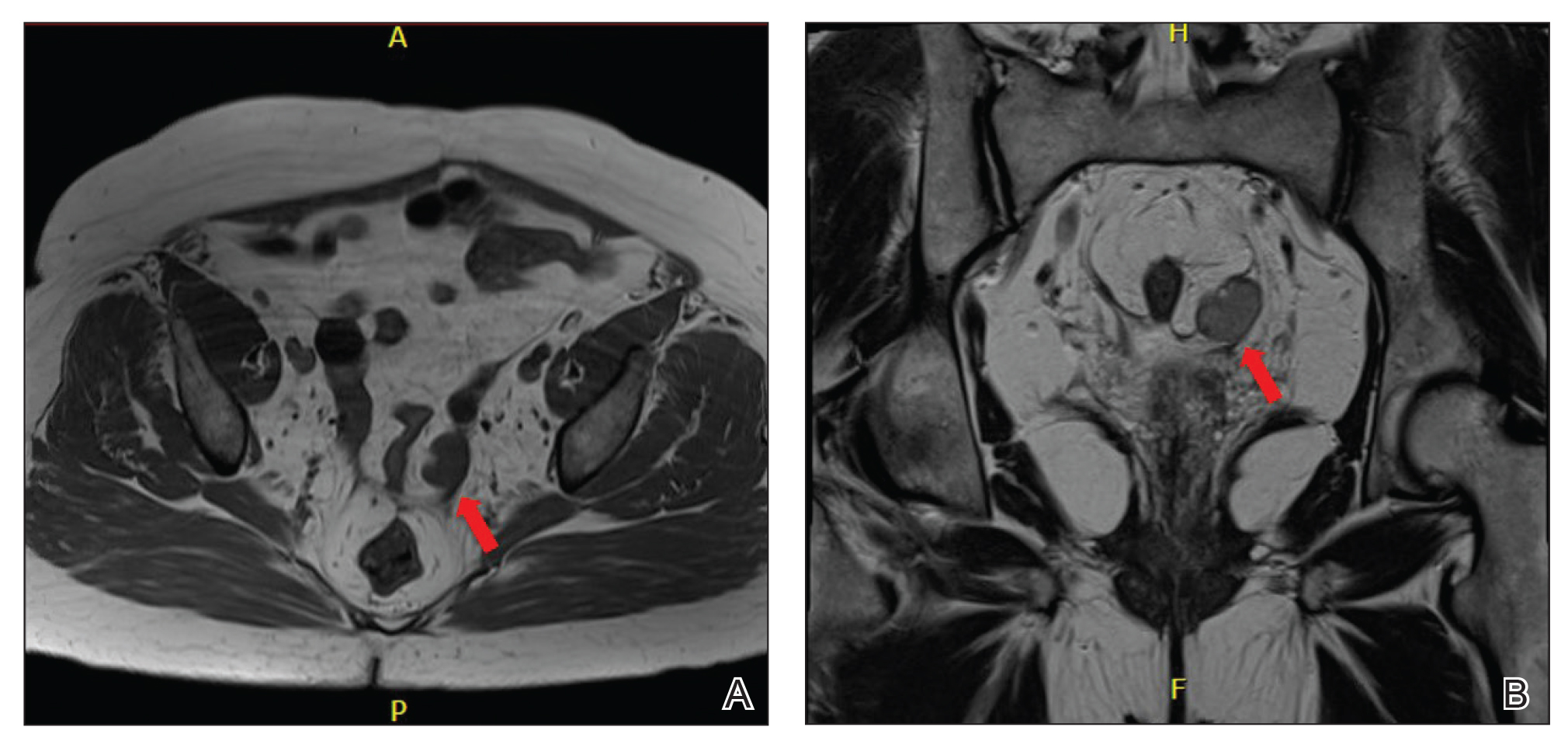

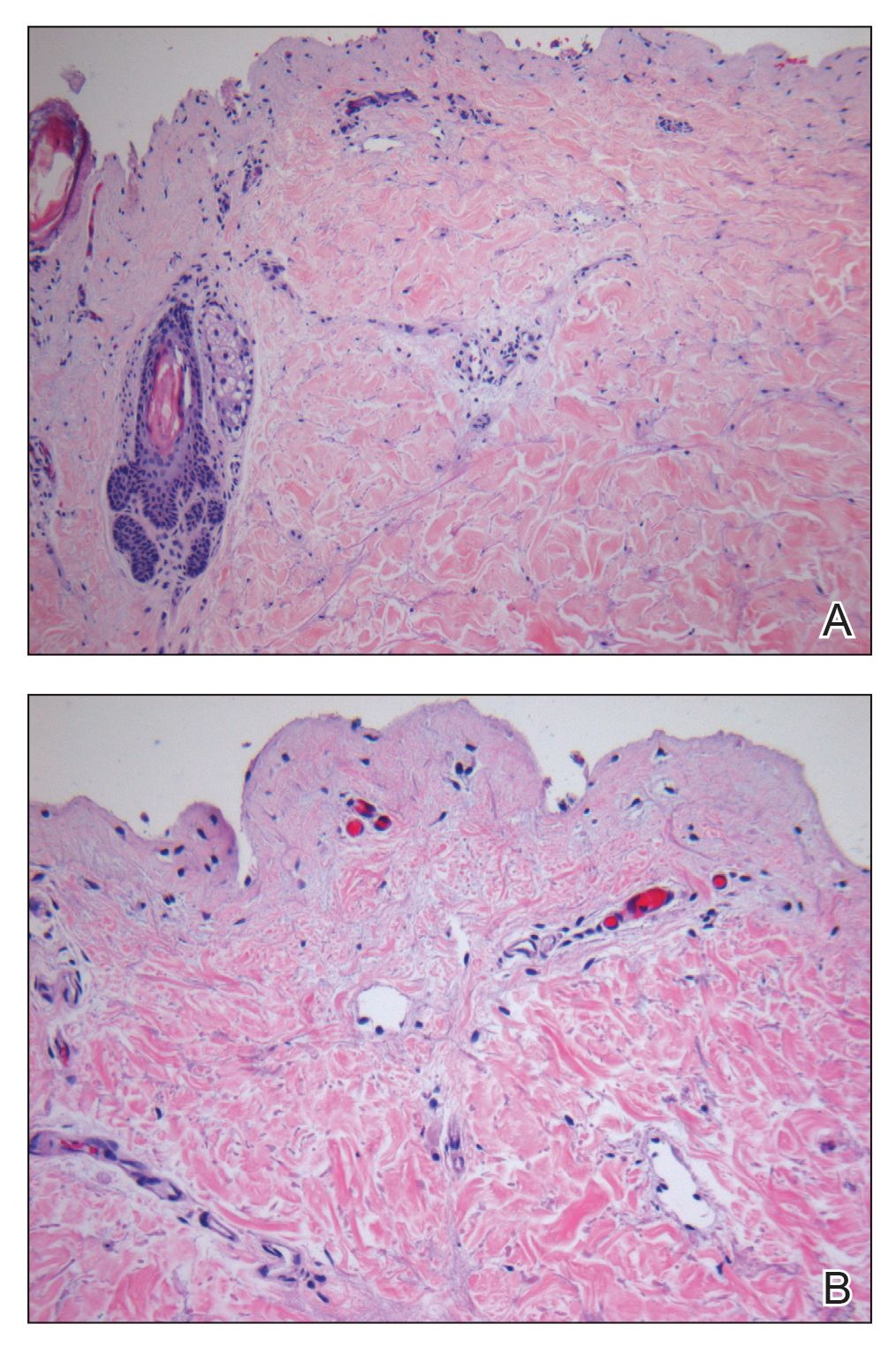

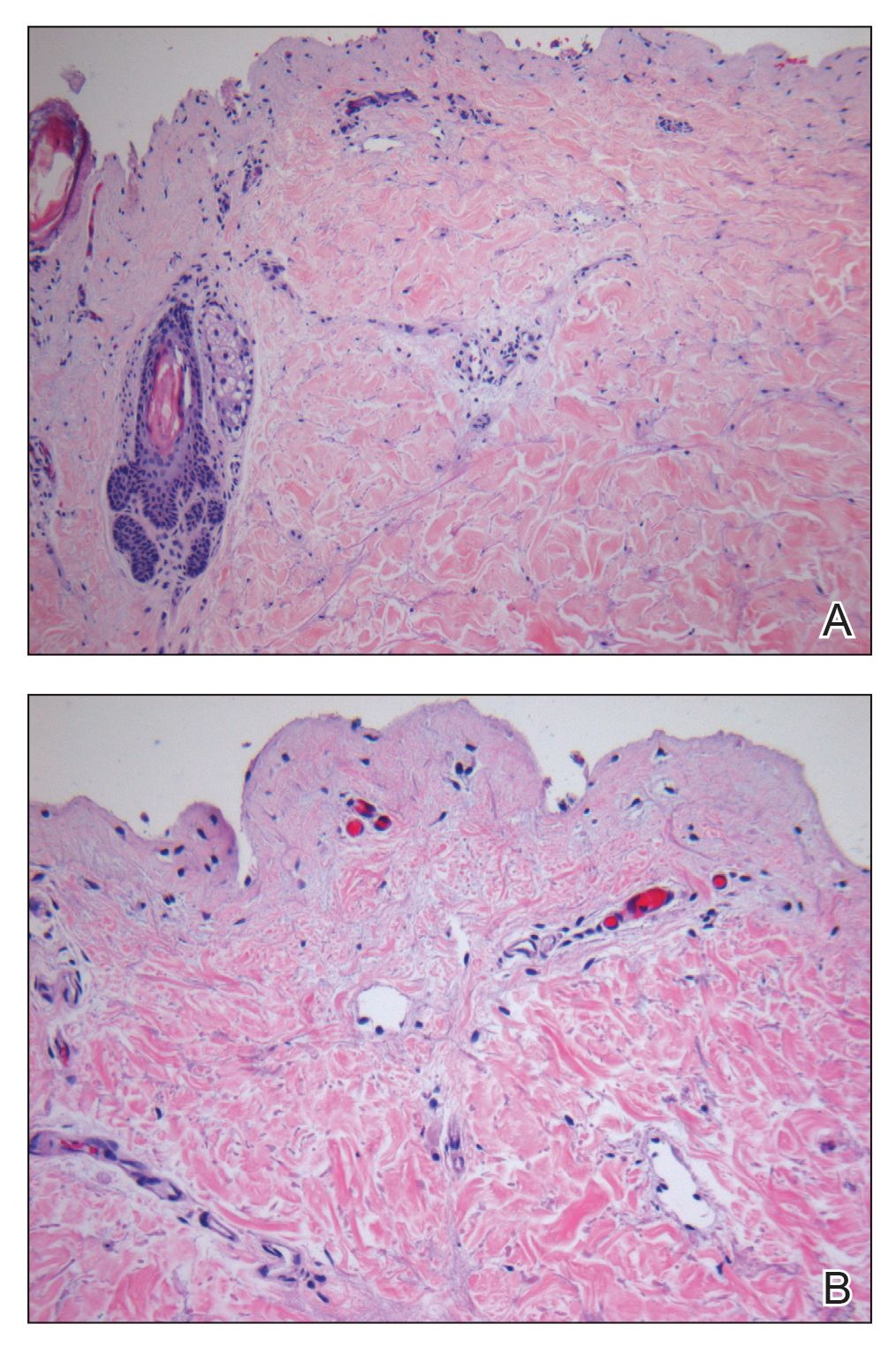

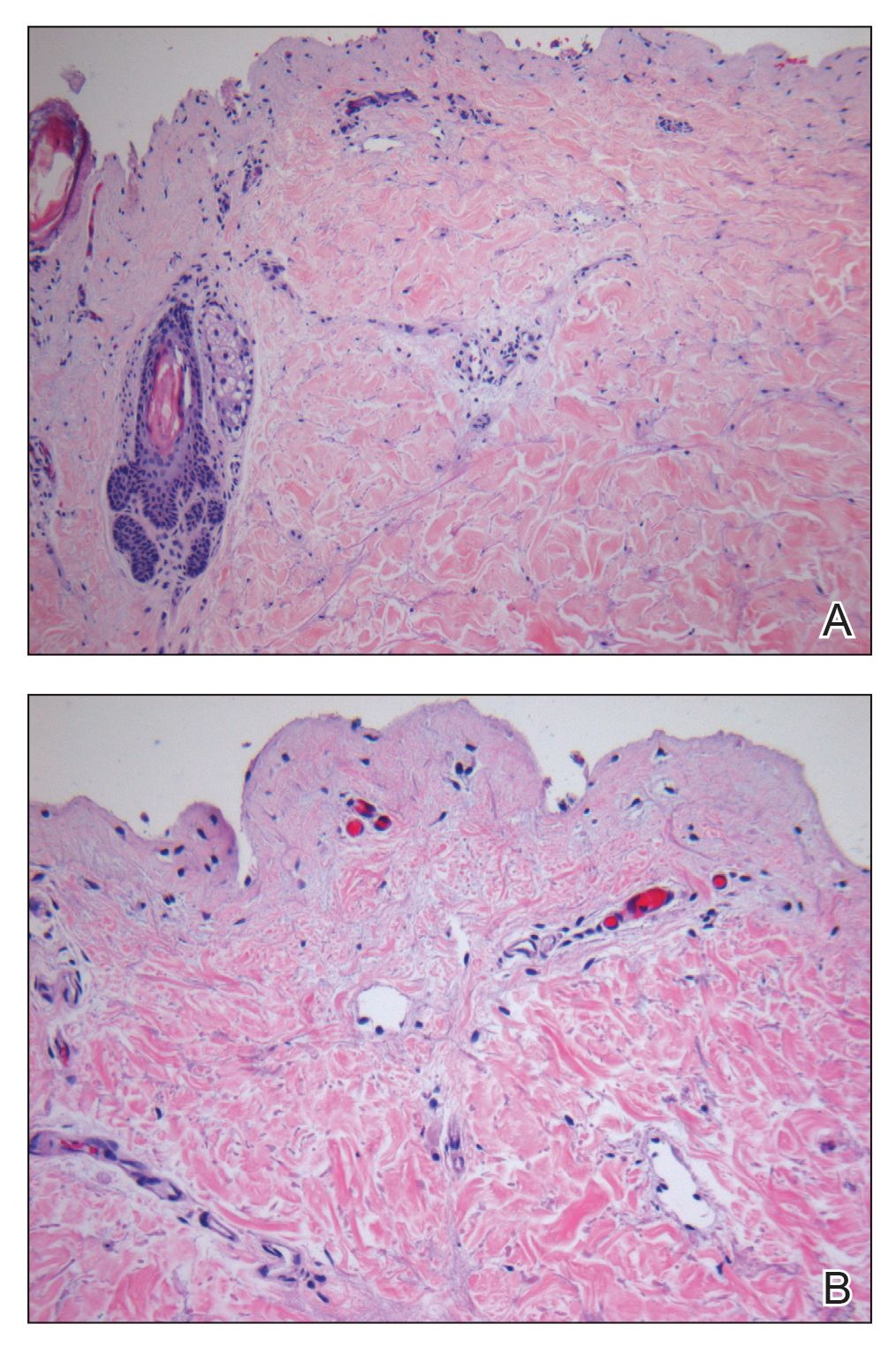

A 62-year-old man with a history of a right above-knee amputation initially presented with erythema as well as coalescing erosions and ulcers with fluid-filled vesicles and bullae on the amputation stump (Figure 1). The amputation was performed 15 years prior after a motorcycle accident. A skin biopsy of a vesicle on the amputation stump revealed subepidermal and focal intraepidermal clefting with hemorrhage and rare inflammatory cells composed of neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 2). A tissue direct immunofluorescence test demonstrated linear C3 and IgG deposition along the dermoepidermal junction. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) demonstrated an anti-BP180 IgG of 50.90 U/mL and anti-BP230 IgG of 129.40 U/mL (reference range, <9.00 U/mL [for both]).

Topical clobetasol led to only modest improvement of blistering on the stump. Minor frictional trauma related to his leg prosthesis continued to trigger new vesicles and bullae on the stump. Oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily was administered and tapered slowly over the course of 6 months. He also received oral niacinamide and doxycycline. He was completely clear after 3 weeks of initiating treatment and remained clear while prednisone was slowly tapered. One month after stopping prednisone he had recurrence of blisters on the stump only after he resumed wearing his prosthesis. Mycophenolate mofetil was started at a dosage of 1 g twice daily while he refrained from wearing the prosthesis. After 3 months he was able to wear the prosthesis without developing blisters. Two years after the initial presentation, repeat serum ELISA demonstrated normalization of the anti-BP180 IgG and anti-BP230 IgG titers. Thirty months after the initial presentation, mycophenolate mofetil was tapered and discontinued. The patient remained blisterfree and continued to wear his leg prosthesis without further blistering.

Amputees experience a high rate of skin complications on their stump,1 including friction blisters, shear injury, contact dermatitis, infections, and autoimmune blistering disorders (ie, BP, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita). The etiology of stump pemphigoid is not entirely understood but could be related to exposure of structural components of the hemidesmosome (eg, BP230, BP180), leading to autoantibody production as a consequence of either the underlying limb injury or from recurrent trauma related to limb prosthetics.2

Two previously reported cases of stump pemphigoid demonstrated a positive direct immunofluorescence antibody test.3,4 Another case demonstrated the presence of circulating IgG antibodies on indirect immunofluorescence to salt-split skin.5 We report a case of stump pemphigoid confirmed by presence of circulating anti–basement membrane antibodies on ELISA, supporting its use in the diagnostic workup and monitoring treatment response.

- Colgecen E, Korkmaz M, Ozyurt K, et al. A clinical evaluation of skin disorders of lower limb amputation sites. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:468-472.

- Lo Schiavo A, Ruocco E, Brancaccio G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: etiology, pathogenesis, and inducing factors: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:391-399.

- Reilly GD, Boulton AJ, Harrington CI. Stump pemphigoid: a new complication of the amputee. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:875-876.

- de Jong MC, Kardaun SH, Tupker RA, et al. Immunomapping in localized bullous pemphigoid. Hautarzt. 1989;40:226-230.

- Brodell RT, Korman NJ. Stump pemphigoid. Cutis. 1996;57:245-246.

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a rare complication of lower limb amputation. Termed stump pemphigoid, it previously was described as a late complication arising on the stumps of leg amputees and tends to remain localized. We describe a case of stump pemphigoid presenting with an urticarial prodromal phase without generalized progression, confirmed by serum assay for circulating anti–basement membrane antibodies.

A 62-year-old man with a history of a right above-knee amputation initially presented with erythema as well as coalescing erosions and ulcers with fluid-filled vesicles and bullae on the amputation stump (Figure 1). The amputation was performed 15 years prior after a motorcycle accident. A skin biopsy of a vesicle on the amputation stump revealed subepidermal and focal intraepidermal clefting with hemorrhage and rare inflammatory cells composed of neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 2). A tissue direct immunofluorescence test demonstrated linear C3 and IgG deposition along the dermoepidermal junction. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) demonstrated an anti-BP180 IgG of 50.90 U/mL and anti-BP230 IgG of 129.40 U/mL (reference range, <9.00 U/mL [for both]).

Topical clobetasol led to only modest improvement of blistering on the stump. Minor frictional trauma related to his leg prosthesis continued to trigger new vesicles and bullae on the stump. Oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily was administered and tapered slowly over the course of 6 months. He also received oral niacinamide and doxycycline. He was completely clear after 3 weeks of initiating treatment and remained clear while prednisone was slowly tapered. One month after stopping prednisone he had recurrence of blisters on the stump only after he resumed wearing his prosthesis. Mycophenolate mofetil was started at a dosage of 1 g twice daily while he refrained from wearing the prosthesis. After 3 months he was able to wear the prosthesis without developing blisters. Two years after the initial presentation, repeat serum ELISA demonstrated normalization of the anti-BP180 IgG and anti-BP230 IgG titers. Thirty months after the initial presentation, mycophenolate mofetil was tapered and discontinued. The patient remained blisterfree and continued to wear his leg prosthesis without further blistering.

Amputees experience a high rate of skin complications on their stump,1 including friction blisters, shear injury, contact dermatitis, infections, and autoimmune blistering disorders (ie, BP, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita). The etiology of stump pemphigoid is not entirely understood but could be related to exposure of structural components of the hemidesmosome (eg, BP230, BP180), leading to autoantibody production as a consequence of either the underlying limb injury or from recurrent trauma related to limb prosthetics.2

Two previously reported cases of stump pemphigoid demonstrated a positive direct immunofluorescence antibody test.3,4 Another case demonstrated the presence of circulating IgG antibodies on indirect immunofluorescence to salt-split skin.5 We report a case of stump pemphigoid confirmed by presence of circulating anti–basement membrane antibodies on ELISA, supporting its use in the diagnostic workup and monitoring treatment response.

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a rare complication of lower limb amputation. Termed stump pemphigoid, it previously was described as a late complication arising on the stumps of leg amputees and tends to remain localized. We describe a case of stump pemphigoid presenting with an urticarial prodromal phase without generalized progression, confirmed by serum assay for circulating anti–basement membrane antibodies.

A 62-year-old man with a history of a right above-knee amputation initially presented with erythema as well as coalescing erosions and ulcers with fluid-filled vesicles and bullae on the amputation stump (Figure 1). The amputation was performed 15 years prior after a motorcycle accident. A skin biopsy of a vesicle on the amputation stump revealed subepidermal and focal intraepidermal clefting with hemorrhage and rare inflammatory cells composed of neutrophils and eosinophils (Figure 2). A tissue direct immunofluorescence test demonstrated linear C3 and IgG deposition along the dermoepidermal junction. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) demonstrated an anti-BP180 IgG of 50.90 U/mL and anti-BP230 IgG of 129.40 U/mL (reference range, <9.00 U/mL [for both]).

Topical clobetasol led to only modest improvement of blistering on the stump. Minor frictional trauma related to his leg prosthesis continued to trigger new vesicles and bullae on the stump. Oral prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily was administered and tapered slowly over the course of 6 months. He also received oral niacinamide and doxycycline. He was completely clear after 3 weeks of initiating treatment and remained clear while prednisone was slowly tapered. One month after stopping prednisone he had recurrence of blisters on the stump only after he resumed wearing his prosthesis. Mycophenolate mofetil was started at a dosage of 1 g twice daily while he refrained from wearing the prosthesis. After 3 months he was able to wear the prosthesis without developing blisters. Two years after the initial presentation, repeat serum ELISA demonstrated normalization of the anti-BP180 IgG and anti-BP230 IgG titers. Thirty months after the initial presentation, mycophenolate mofetil was tapered and discontinued. The patient remained blisterfree and continued to wear his leg prosthesis without further blistering.

Amputees experience a high rate of skin complications on their stump,1 including friction blisters, shear injury, contact dermatitis, infections, and autoimmune blistering disorders (ie, BP, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita). The etiology of stump pemphigoid is not entirely understood but could be related to exposure of structural components of the hemidesmosome (eg, BP230, BP180), leading to autoantibody production as a consequence of either the underlying limb injury or from recurrent trauma related to limb prosthetics.2

Two previously reported cases of stump pemphigoid demonstrated a positive direct immunofluorescence antibody test.3,4 Another case demonstrated the presence of circulating IgG antibodies on indirect immunofluorescence to salt-split skin.5 We report a case of stump pemphigoid confirmed by presence of circulating anti–basement membrane antibodies on ELISA, supporting its use in the diagnostic workup and monitoring treatment response.

- Colgecen E, Korkmaz M, Ozyurt K, et al. A clinical evaluation of skin disorders of lower limb amputation sites. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:468-472.

- Lo Schiavo A, Ruocco E, Brancaccio G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: etiology, pathogenesis, and inducing factors: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:391-399.

- Reilly GD, Boulton AJ, Harrington CI. Stump pemphigoid: a new complication of the amputee. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:875-876.

- de Jong MC, Kardaun SH, Tupker RA, et al. Immunomapping in localized bullous pemphigoid. Hautarzt. 1989;40:226-230.

- Brodell RT, Korman NJ. Stump pemphigoid. Cutis. 1996;57:245-246.

- Colgecen E, Korkmaz M, Ozyurt K, et al. A clinical evaluation of skin disorders of lower limb amputation sites. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:468-472.

- Lo Schiavo A, Ruocco E, Brancaccio G, et al. Bullous pemphigoid: etiology, pathogenesis, and inducing factors: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:391-399.

- Reilly GD, Boulton AJ, Harrington CI. Stump pemphigoid: a new complication of the amputee. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:875-876.

- de Jong MC, Kardaun SH, Tupker RA, et al. Immunomapping in localized bullous pemphigoid. Hautarzt. 1989;40:226-230.

- Brodell RT, Korman NJ. Stump pemphigoid. Cutis. 1996;57:245-246.

Practice Points

- Bullous pemphigoid (BP) can mimic friction blisters and should be considered in amputees who present with vesicles and bullae on their amputation stump.

- Circulating anti–basement membrane antibodies BP230 and BP180 IgG may aid in diagnosis when skin biopsy results are equivocal and also may be helpful in gauging treatment response.

Scrub Typhus in Chile

To the Editor:

Scrub typhus (ST) is an infection caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi (genus Rickettsia), which is transmitted by the larvae of trombiculid mites, commonly called chiggers. The disease mainly has been described in Asia in an area known as the Tsutsugamushi Triangle, delineated by Pakistan, eastern Russia, and northern Australia. Although this classic distribution remains, recent reports have documented 1 case in the Arabian Peninsula1 and more than 16 cases in southern Chile.2-4 The first case in Chile was published in 2011 from Chiloé Island.2 To date, no other cases have been reported in the Americas.1-6

We describe a new case of ST from Chiloé Island and compare it to the first case reported in Chile in 2011.2 Both patients showed the typical clinical manifestation, but because ST has become an increasingly suspected disease in southern regions of Chile, new cases are now easily diagnosed. This infection is diagnosed mainly by skin lesions; therefore, dermatologists should be aware of this diagnosis when presented with a febrile rash.

A 67-year-old man from the city of Punta Arenas presented to the emergency department with a dark necrotic lesion on the right foot of 1 week’s duration. The patient later developed a generalized pruritic rash and fever. He also reported muscle pain, headache, cough, night sweats, and odynophagia. He reported recent travel to a rural area in the northern part of Chiloé Island, where he came into contact with firewood and participated in outdoor activities. He had no other relevant medical history.

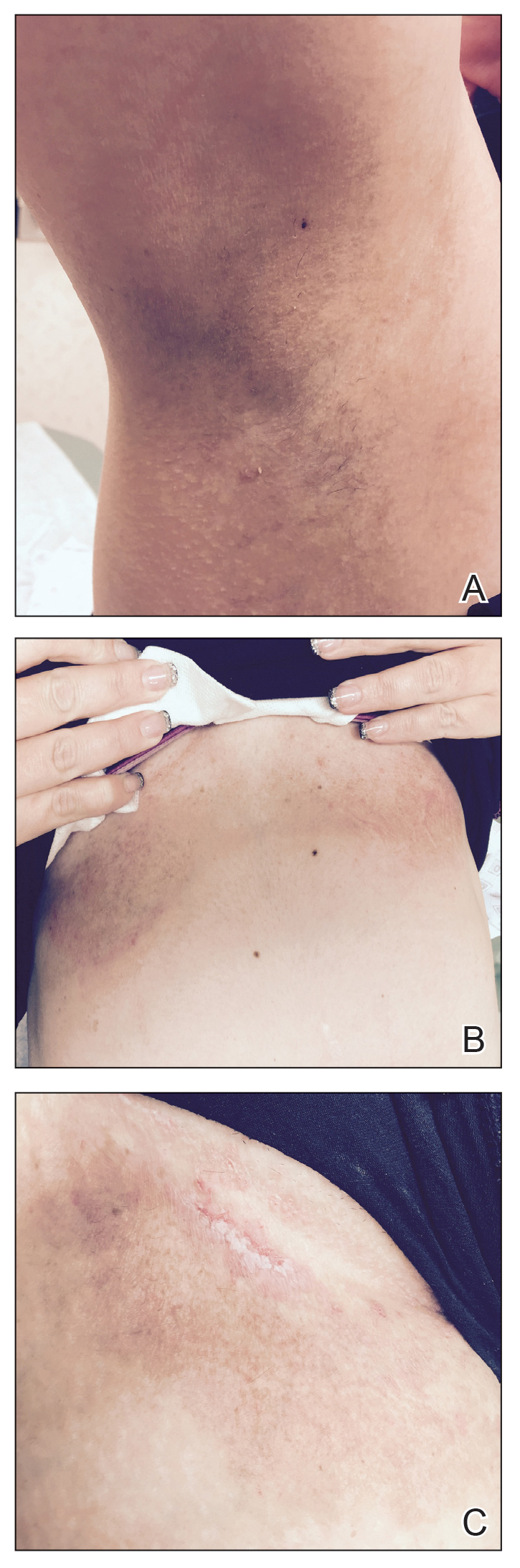

Physical examination revealed a temperature of 38 °C and a macular rash, with some papules distributed mainly on the face, trunk, and proximal extremities (Figure 1). He had a necrotic eschar on the dorsum of the right foot, with an erythematous halo (tache noire)(Figure 2).

A complete blood cell count, urinalysis, and tests of hepatic and renal function were normal. C-reactive protein was elevated 18 times the normal value. Because of high awareness of ST in the region, eschar samples were taken and submitted for serologic testing and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting the 16S rRNA Orientia gene. Empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started. Polymerase chain reaction analysis showed the presence of Orientia species, confirming the diagnosis of ST. The rash and eschar diminished considerably after 7 days of antibiotic treatment.

Scrub typhus is a high-impact disease in Asia, described mainly in an area known as the Tsutsugamushi Triangle. Recent reports show important epidemiologic changes in the distribution of the disease, with new published reports of cases outside this endemic area—1 in the Arabian peninsula1 and more than 16 in southern Chile.2-4

The disease begins with a painless, erythematous, and usually unnoticed papule at the site of the bite. After 48 to 72 hours, the papule changes to a necrotic form (tache noire), surrounded by a red halo that often is small, similar to a cigarette burn. This lesion is described in 20% to 90% of infected patients in different series.7 Two or 3 days later (1 to 3 weeks after exposure), high fever suddenly develops. Along with fever, a maculopapular rash distributed centrifugally develops, without compromise of the palms or soles. Patients frequently report headache and night sweating. Sometimes, ST is accompanied by muscle or joint pain, red eye, cough, and abdominal pain. Hearing loss and altered mental status less frequently have been reported.5,8

Common laboratory tests can be of use in diagnosis. An elevated C-reactive protein level and a slight to moderate increase in hepatic transaminases should be expected. Thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and elevation of the lactate dehydrogenase level less frequently are present.5,9

Our case de1monstrated a typical presentation. The patient developed a febrile syndrome with a generalized rash and a tache noire–type eschar associated with muscle pain, headache, cough, night sweats, and odynophagia. Because of epidemiologic changes in the area, the familiar clinical findings, and laboratory confirmation, histologic studies were unnecessary. In cases in which the diagnosis is not evident, skin biopsy could be useful, as in the first case reported in Chile.2

In that first case, the patient initially was hospitalized because of a febrile syndrome; eventually, a necrotic eschar was noticed on his leg. He had been staying on Chiloé Island and reported being bitten by leeches on multiple occasions. Laboratory findings revealed only slightly raised levels of hepatic transaminases and alkaline phosphatase. After a more precise dermatologic evaluation, the eschar of a tache noire, combined with other clinical and laboratory findings, raised suspicion of ST. Because this entity had never been described in Chile, biopsy of the eschar was taken to consider other entities in the differential diagnosis. Biopsy showed necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, perivascular inflammatory infiltrates comprising lymphocytes and macrophages, and rickettsial microorganisms inside endothelial cells under electron microscopic examination. The specimen was tested for the 16S ribosomal RNA Orientia gene; its presence confirmed the diagnosis.2

Classically, histology from the eschar shows signs of vasculitis and rickettsial microorganisms inside endothelial cells on electron microscopy.2,10 More recent publications describe important necrotic changes within keratinocytes as well as an inflammatory infiltrate comprising antigen-presenting cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Using high-resolution thin sections with confocal laser scanning microscopy and staining of specific monoclonal antibodies against 56 kDa type-specific surface antigens, the bacteria were found inside antigen-presenting cells, many of them located perivascularly or passing through the endothelium.11

The causal agent in Asia is O tsutsugamushi, an obligate intracellular bacterium (genus Rickettsia). Orientia species are transmitted by larvae of trombiculid mites, commonly called chiggers. The reservoir is believed to be the same as with chiggers, in which some vertebrates become infected and trombiculid mites feed on them.12 Recent studies of Chilean cases have revealed the presence of a novel Orientia species, Candidatus Orientia chiloensis and its vector, trombiculid mites from the Herpetacarus species, Quadraseta species, and Paratrombicula species genera.13,14

A high seroprevalence of Orientia species in dogs was reported in the main cities of Chiloé Island. Rates were higher in rural settings and older dogs. Of 202 specimens, 21.3% were positive for IgG against Orientia species.15

In Chile, most cases of ST came from Chiloé Island; some reports of cases from continental Chilean regions have been published.6 Most cases have occurred in the context of activities that brought the patients in contact with plants and firewood in rural areas during the summer.3-6

The diagnosis of ST is eminently clinical, based on the triad of fever, macular or papular rash, and an inoculation necrotic eschar. The diagnosis is supported by epidemiologic facts and fast recovery after treatment is initiated.16 Although the diagnosis can be established based on a quick recovery in endemic countries, in areas such as Chile where incidence and distribution are not completely known, it is better to confirm the diagnosis with laboratory tests without delaying treatment. Several testing options exist, including serologic techniques (immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), culture, and detection of the genetic material of Orientia species by PCR. Usually, IgM titers initially are negative, and IgG testing requires paired samples (acute and convalescent) to demonstrate seroconversion and therefore acute infection.17 Because culture requires a highly specialized laboratory, it is not frequently used. Polymerase chain reaction is recognized as the best confirmation method due to its high sensitivity and because it remains positive for a few days after treatment has been initiated. The specimen of choice is the eschar because of its high bacterial load. The base of the scar and the buffy coat are useful specimens when the eschar is unavailable.5,17-19

Due to potential complications of ST, empirical treatment with an antibiotic should be started based on clinical facts and never delayed because of diagnostic tests.18 Classically, ST is treated with a member of the tetracycline family, such as doxycycline, which provides a cure rate of 63% to 100% in ST.5

A 2017 systematic review of treatment options for this infection examined 11 studies from Southeast Asia, China, and South Korea (N=957).16 The review mainly compared doxycycline with azithromycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline. No significant difference in cure rate was noted in comparing doxycycline with any of the other 3 antibiotics; most of the studies examined were characterized by a moderate level of evidence. Regarding adverse effects, doxycycline showed a few more cases of gastrointestinal intolerance, and in 2 of 4 studies with chloramphenicol, patients presented with leukopenia.16 Several studies compared standard treatment (doxycycline) with rifampicin, telithromycin, erythromycin, and levofloxacin individually; similar cure rates were noted between doxycycline and each of those 4 agents.

Therapeutic failure in ST has been reported in several cases with the use of levofloxacin.20 Evidence for this novel antibiotic is still insufficient. Further studies are needed before rifampicin, telithromycin, erythromycin, or levofloxacin can be considered as options.Scrub typhus usually resolves within a few weeks. Left untreated, the disease can cause complications such as pneumonia, meningoencephalitis, renal failure, and even multiorgan failure and death. Without treatment, mortality is variable. A 2015 systematic review of mortality from untreated ST showed, on average, mortality of 6% (range, 0%–70%).21 When ST is treated, mortality falls to 0% to 30%.22 Cases reported in Chile have neither been lethal nor presented with severe complications.4,5

Scrub typhus is an infectious disease common in Asia, caused by O tsutsugamushi and transmitted by chiggers. It should be suspected when a febrile macular or papular rash and a tache noire appear. The diagnosis can be supported by laboratory findings, such as an elevated C-reactive protein level or a slight increase in the levels of hepatic transaminases, and response to treatment. The diagnosis is confirmed by serology or PCR of a specimen of the eschar. Empiric therapy with antibiotics is mandatory; doxycycline is the first option.

First described in Chile in 2011,2 ST was seen in a patient in whom disease was suspected because of clinical characteristics, laboratory and histologic findings, absence of prior reporting in South America, and confirmation with PCR targeting the 16S ribosomal RNA Orientia gene from specimens of the eschar. By 2020, 60 cases have been confirmed in Chile, not all of them published; there are no other reported cases in South America.

When comparing the first case in Chile2 with our case, we noted that both described classic clinical findings; however, the management approach and diagnostic challenges have evolved over time. Nowadays, ST is highly suspected, so it can be largely recognized and treated, which also provides better understanding of the nature of this disease in Chile. Because this infection is diagnosed mainly by characteristic cutaneous lesions, dermatologists should be aware of its epidemiology, clinical features, and transmission, and they should stay open to the possibility of this (until now) unusual diagnosis in South America.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Chilean Rickettsia & Zoonosis Research Group (Thomas Weitzel, MD [Santiago, Chile]; Constanza Martínez-Valdebenito [Santiago, Chile]; and Gerardo Acosta-Jammet, DSc [Valdivia, Chile]), whose study in execution in the country allowed the detection of the case and confirmation by PCR. The authors also thank Juan Carlos Román, MD (Chiloé, Chile) who was part of the team that detected this case.

- Izzard L, Fuller A, Blacksell SD, et al. Isolation of a novel Orientia species (O. chuto sp. nov.) from a patient infected in Dubai. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4404-4409.

- Balcells ME, Rabagliati R, García P, et al. Endemic scrub typhus-like illness, Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1659-1663.

- Weitzel T, Dittrich S, López J, et al. Endemic scrub typhus in South America. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:954-961.

- Weitzel T, Acosta-Jamett G, Martínez-Valdebenito C, et al. Scrub typhus risk in travelers to southern Chile. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2019;29:78-79.

- Abarca K, Weitzel T, Martínez-Valdebenito C, et al. Scrub typhus, an emerging infectious disease in Chile. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2018;35:696-699.

- Weitzel T, Martínez-Valdebenito C, Acosta-Jamett G, et al. Scrub typhus in continental Chile, 2016-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1214-1217.

- Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF, eds. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2011.

- Mahara F. Rickettsioses in Japan and the Far East. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:60-73.

- Salje J. Orientia tsutsugamushi: a neglected but fascinating obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006657.

- Lee JS, Park MY, Kim YJ, et al. Histopathological features in both the eschar and erythematous lesions of tsutsugamushi disease: identification of CD30+ cell infiltration in tsutsugamushi disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:551-556.

- Paris DH, Phetsouvanh R, Tanganuchitcharnchai A, et al. Orientia tsutsugamushi in human scrub typhus eschars shows tropism for dendritic cells and monocytes rather than endothelium. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:E1466.

- Walker DH. Scrub typhus—scientific neglect, ever-widening impact. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:913-915.

- Acosta-Jamett G, Martínez-Valdebenito C, Beltrami E, et al. Identification of trombiculid mites (Acari: Trombiculidae) on rodents from Chiloé Island and molecular evidence of infection with Orientia species [published online January 23, 2020]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007619

- Martínez-Valdebenito C, Angulo J, et al. Molecular description of a novel Orientia species causing scrub typhus in Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2148-2156.

- Weitzel T, Jiang J, Acosta-Jamett G, et al. Canine seroprevalence to Orientia species in southern Chile: a cross-sectional survey on the Chiloé Island. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200362.

- Wee I, Lo A, Rodrigo C. Drug treatment of scrub typhus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2017;111:336-344.

- Koh GCKW, Maude RJ, Paris DH, et al. Diagnosis of scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:368-370.

- Weitzel T, Aylwin M, Martínez-Valdebenito C, et al. Imported scrub typhus: first case in South America and review of the literature. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2018;4:10.

- Le Viet N, Laroche M, Thi Pham HL, et al. Use of eschar swabbing for the molecular diagnosis and genotyping of Orientia tsutsugamushi causing scrub typhus in Quang Nam province, Vietnam. 2017;11:e0005397.

- Jang HC, Choi SM, Jang MO, et al. Inappropriateness of quinolone in scrub typhus treatment due to gyrA mutation in Orientia tsutsugamushi Boryong strain. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:667-671.

- Taylor AJ, Paris DH, Newton PN. A systematic review of mortality from untreated scrub typhus (Orientia tsutsugamushi). PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003971.

- Bonell A, Lubell Y, Newton PN, et al. Estimating the burden of scrub typhus: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005838.

To the Editor:

Scrub typhus (ST) is an infection caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi (genus Rickettsia), which is transmitted by the larvae of trombiculid mites, commonly called chiggers. The disease mainly has been described in Asia in an area known as the Tsutsugamushi Triangle, delineated by Pakistan, eastern Russia, and northern Australia. Although this classic distribution remains, recent reports have documented 1 case in the Arabian Peninsula1 and more than 16 cases in southern Chile.2-4 The first case in Chile was published in 2011 from Chiloé Island.2 To date, no other cases have been reported in the Americas.1-6

We describe a new case of ST from Chiloé Island and compare it to the first case reported in Chile in 2011.2 Both patients showed the typical clinical manifestation, but because ST has become an increasingly suspected disease in southern regions of Chile, new cases are now easily diagnosed. This infection is diagnosed mainly by skin lesions; therefore, dermatologists should be aware of this diagnosis when presented with a febrile rash.

A 67-year-old man from the city of Punta Arenas presented to the emergency department with a dark necrotic lesion on the right foot of 1 week’s duration. The patient later developed a generalized pruritic rash and fever. He also reported muscle pain, headache, cough, night sweats, and odynophagia. He reported recent travel to a rural area in the northern part of Chiloé Island, where he came into contact with firewood and participated in outdoor activities. He had no other relevant medical history.

Physical examination revealed a temperature of 38 °C and a macular rash, with some papules distributed mainly on the face, trunk, and proximal extremities (Figure 1). He had a necrotic eschar on the dorsum of the right foot, with an erythematous halo (tache noire)(Figure 2).

A complete blood cell count, urinalysis, and tests of hepatic and renal function were normal. C-reactive protein was elevated 18 times the normal value. Because of high awareness of ST in the region, eschar samples were taken and submitted for serologic testing and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting the 16S rRNA Orientia gene. Empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started. Polymerase chain reaction analysis showed the presence of Orientia species, confirming the diagnosis of ST. The rash and eschar diminished considerably after 7 days of antibiotic treatment.

Scrub typhus is a high-impact disease in Asia, described mainly in an area known as the Tsutsugamushi Triangle. Recent reports show important epidemiologic changes in the distribution of the disease, with new published reports of cases outside this endemic area—1 in the Arabian peninsula1 and more than 16 in southern Chile.2-4

The disease begins with a painless, erythematous, and usually unnoticed papule at the site of the bite. After 48 to 72 hours, the papule changes to a necrotic form (tache noire), surrounded by a red halo that often is small, similar to a cigarette burn. This lesion is described in 20% to 90% of infected patients in different series.7 Two or 3 days later (1 to 3 weeks after exposure), high fever suddenly develops. Along with fever, a maculopapular rash distributed centrifugally develops, without compromise of the palms or soles. Patients frequently report headache and night sweating. Sometimes, ST is accompanied by muscle or joint pain, red eye, cough, and abdominal pain. Hearing loss and altered mental status less frequently have been reported.5,8

Common laboratory tests can be of use in diagnosis. An elevated C-reactive protein level and a slight to moderate increase in hepatic transaminases should be expected. Thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and elevation of the lactate dehydrogenase level less frequently are present.5,9

Our case de1monstrated a typical presentation. The patient developed a febrile syndrome with a generalized rash and a tache noire–type eschar associated with muscle pain, headache, cough, night sweats, and odynophagia. Because of epidemiologic changes in the area, the familiar clinical findings, and laboratory confirmation, histologic studies were unnecessary. In cases in which the diagnosis is not evident, skin biopsy could be useful, as in the first case reported in Chile.2

In that first case, the patient initially was hospitalized because of a febrile syndrome; eventually, a necrotic eschar was noticed on his leg. He had been staying on Chiloé Island and reported being bitten by leeches on multiple occasions. Laboratory findings revealed only slightly raised levels of hepatic transaminases and alkaline phosphatase. After a more precise dermatologic evaluation, the eschar of a tache noire, combined with other clinical and laboratory findings, raised suspicion of ST. Because this entity had never been described in Chile, biopsy of the eschar was taken to consider other entities in the differential diagnosis. Biopsy showed necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, perivascular inflammatory infiltrates comprising lymphocytes and macrophages, and rickettsial microorganisms inside endothelial cells under electron microscopic examination. The specimen was tested for the 16S ribosomal RNA Orientia gene; its presence confirmed the diagnosis.2

Classically, histology from the eschar shows signs of vasculitis and rickettsial microorganisms inside endothelial cells on electron microscopy.2,10 More recent publications describe important necrotic changes within keratinocytes as well as an inflammatory infiltrate comprising antigen-presenting cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Using high-resolution thin sections with confocal laser scanning microscopy and staining of specific monoclonal antibodies against 56 kDa type-specific surface antigens, the bacteria were found inside antigen-presenting cells, many of them located perivascularly or passing through the endothelium.11

The causal agent in Asia is O tsutsugamushi, an obligate intracellular bacterium (genus Rickettsia). Orientia species are transmitted by larvae of trombiculid mites, commonly called chiggers. The reservoir is believed to be the same as with chiggers, in which some vertebrates become infected and trombiculid mites feed on them.12 Recent studies of Chilean cases have revealed the presence of a novel Orientia species, Candidatus Orientia chiloensis and its vector, trombiculid mites from the Herpetacarus species, Quadraseta species, and Paratrombicula species genera.13,14

A high seroprevalence of Orientia species in dogs was reported in the main cities of Chiloé Island. Rates were higher in rural settings and older dogs. Of 202 specimens, 21.3% were positive for IgG against Orientia species.15

In Chile, most cases of ST came from Chiloé Island; some reports of cases from continental Chilean regions have been published.6 Most cases have occurred in the context of activities that brought the patients in contact with plants and firewood in rural areas during the summer.3-6

The diagnosis of ST is eminently clinical, based on the triad of fever, macular or papular rash, and an inoculation necrotic eschar. The diagnosis is supported by epidemiologic facts and fast recovery after treatment is initiated.16 Although the diagnosis can be established based on a quick recovery in endemic countries, in areas such as Chile where incidence and distribution are not completely known, it is better to confirm the diagnosis with laboratory tests without delaying treatment. Several testing options exist, including serologic techniques (immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), culture, and detection of the genetic material of Orientia species by PCR. Usually, IgM titers initially are negative, and IgG testing requires paired samples (acute and convalescent) to demonstrate seroconversion and therefore acute infection.17 Because culture requires a highly specialized laboratory, it is not frequently used. Polymerase chain reaction is recognized as the best confirmation method due to its high sensitivity and because it remains positive for a few days after treatment has been initiated. The specimen of choice is the eschar because of its high bacterial load. The base of the scar and the buffy coat are useful specimens when the eschar is unavailable.5,17-19

Due to potential complications of ST, empirical treatment with an antibiotic should be started based on clinical facts and never delayed because of diagnostic tests.18 Classically, ST is treated with a member of the tetracycline family, such as doxycycline, which provides a cure rate of 63% to 100% in ST.5

A 2017 systematic review of treatment options for this infection examined 11 studies from Southeast Asia, China, and South Korea (N=957).16 The review mainly compared doxycycline with azithromycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline. No significant difference in cure rate was noted in comparing doxycycline with any of the other 3 antibiotics; most of the studies examined were characterized by a moderate level of evidence. Regarding adverse effects, doxycycline showed a few more cases of gastrointestinal intolerance, and in 2 of 4 studies with chloramphenicol, patients presented with leukopenia.16 Several studies compared standard treatment (doxycycline) with rifampicin, telithromycin, erythromycin, and levofloxacin individually; similar cure rates were noted between doxycycline and each of those 4 agents.

Therapeutic failure in ST has been reported in several cases with the use of levofloxacin.20 Evidence for this novel antibiotic is still insufficient. Further studies are needed before rifampicin, telithromycin, erythromycin, or levofloxacin can be considered as options.Scrub typhus usually resolves within a few weeks. Left untreated, the disease can cause complications such as pneumonia, meningoencephalitis, renal failure, and even multiorgan failure and death. Without treatment, mortality is variable. A 2015 systematic review of mortality from untreated ST showed, on average, mortality of 6% (range, 0%–70%).21 When ST is treated, mortality falls to 0% to 30%.22 Cases reported in Chile have neither been lethal nor presented with severe complications.4,5

Scrub typhus is an infectious disease common in Asia, caused by O tsutsugamushi and transmitted by chiggers. It should be suspected when a febrile macular or papular rash and a tache noire appear. The diagnosis can be supported by laboratory findings, such as an elevated C-reactive protein level or a slight increase in the levels of hepatic transaminases, and response to treatment. The diagnosis is confirmed by serology or PCR of a specimen of the eschar. Empiric therapy with antibiotics is mandatory; doxycycline is the first option.

First described in Chile in 2011,2 ST was seen in a patient in whom disease was suspected because of clinical characteristics, laboratory and histologic findings, absence of prior reporting in South America, and confirmation with PCR targeting the 16S ribosomal RNA Orientia gene from specimens of the eschar. By 2020, 60 cases have been confirmed in Chile, not all of them published; there are no other reported cases in South America.

When comparing the first case in Chile2 with our case, we noted that both described classic clinical findings; however, the management approach and diagnostic challenges have evolved over time. Nowadays, ST is highly suspected, so it can be largely recognized and treated, which also provides better understanding of the nature of this disease in Chile. Because this infection is diagnosed mainly by characteristic cutaneous lesions, dermatologists should be aware of its epidemiology, clinical features, and transmission, and they should stay open to the possibility of this (until now) unusual diagnosis in South America.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Chilean Rickettsia & Zoonosis Research Group (Thomas Weitzel, MD [Santiago, Chile]; Constanza Martínez-Valdebenito [Santiago, Chile]; and Gerardo Acosta-Jammet, DSc [Valdivia, Chile]), whose study in execution in the country allowed the detection of the case and confirmation by PCR. The authors also thank Juan Carlos Román, MD (Chiloé, Chile) who was part of the team that detected this case.

To the Editor:

Scrub typhus (ST) is an infection caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi (genus Rickettsia), which is transmitted by the larvae of trombiculid mites, commonly called chiggers. The disease mainly has been described in Asia in an area known as the Tsutsugamushi Triangle, delineated by Pakistan, eastern Russia, and northern Australia. Although this classic distribution remains, recent reports have documented 1 case in the Arabian Peninsula1 and more than 16 cases in southern Chile.2-4 The first case in Chile was published in 2011 from Chiloé Island.2 To date, no other cases have been reported in the Americas.1-6

We describe a new case of ST from Chiloé Island and compare it to the first case reported in Chile in 2011.2 Both patients showed the typical clinical manifestation, but because ST has become an increasingly suspected disease in southern regions of Chile, new cases are now easily diagnosed. This infection is diagnosed mainly by skin lesions; therefore, dermatologists should be aware of this diagnosis when presented with a febrile rash.

A 67-year-old man from the city of Punta Arenas presented to the emergency department with a dark necrotic lesion on the right foot of 1 week’s duration. The patient later developed a generalized pruritic rash and fever. He also reported muscle pain, headache, cough, night sweats, and odynophagia. He reported recent travel to a rural area in the northern part of Chiloé Island, where he came into contact with firewood and participated in outdoor activities. He had no other relevant medical history.

Physical examination revealed a temperature of 38 °C and a macular rash, with some papules distributed mainly on the face, trunk, and proximal extremities (Figure 1). He had a necrotic eschar on the dorsum of the right foot, with an erythematous halo (tache noire)(Figure 2).

A complete blood cell count, urinalysis, and tests of hepatic and renal function were normal. C-reactive protein was elevated 18 times the normal value. Because of high awareness of ST in the region, eschar samples were taken and submitted for serologic testing and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting the 16S rRNA Orientia gene. Empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started. Polymerase chain reaction analysis showed the presence of Orientia species, confirming the diagnosis of ST. The rash and eschar diminished considerably after 7 days of antibiotic treatment.

Scrub typhus is a high-impact disease in Asia, described mainly in an area known as the Tsutsugamushi Triangle. Recent reports show important epidemiologic changes in the distribution of the disease, with new published reports of cases outside this endemic area—1 in the Arabian peninsula1 and more than 16 in southern Chile.2-4

The disease begins with a painless, erythematous, and usually unnoticed papule at the site of the bite. After 48 to 72 hours, the papule changes to a necrotic form (tache noire), surrounded by a red halo that often is small, similar to a cigarette burn. This lesion is described in 20% to 90% of infected patients in different series.7 Two or 3 days later (1 to 3 weeks after exposure), high fever suddenly develops. Along with fever, a maculopapular rash distributed centrifugally develops, without compromise of the palms or soles. Patients frequently report headache and night sweating. Sometimes, ST is accompanied by muscle or joint pain, red eye, cough, and abdominal pain. Hearing loss and altered mental status less frequently have been reported.5,8

Common laboratory tests can be of use in diagnosis. An elevated C-reactive protein level and a slight to moderate increase in hepatic transaminases should be expected. Thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and elevation of the lactate dehydrogenase level less frequently are present.5,9

Our case de1monstrated a typical presentation. The patient developed a febrile syndrome with a generalized rash and a tache noire–type eschar associated with muscle pain, headache, cough, night sweats, and odynophagia. Because of epidemiologic changes in the area, the familiar clinical findings, and laboratory confirmation, histologic studies were unnecessary. In cases in which the diagnosis is not evident, skin biopsy could be useful, as in the first case reported in Chile.2

In that first case, the patient initially was hospitalized because of a febrile syndrome; eventually, a necrotic eschar was noticed on his leg. He had been staying on Chiloé Island and reported being bitten by leeches on multiple occasions. Laboratory findings revealed only slightly raised levels of hepatic transaminases and alkaline phosphatase. After a more precise dermatologic evaluation, the eschar of a tache noire, combined with other clinical and laboratory findings, raised suspicion of ST. Because this entity had never been described in Chile, biopsy of the eschar was taken to consider other entities in the differential diagnosis. Biopsy showed necrotizing leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, perivascular inflammatory infiltrates comprising lymphocytes and macrophages, and rickettsial microorganisms inside endothelial cells under electron microscopic examination. The specimen was tested for the 16S ribosomal RNA Orientia gene; its presence confirmed the diagnosis.2

Classically, histology from the eschar shows signs of vasculitis and rickettsial microorganisms inside endothelial cells on electron microscopy.2,10 More recent publications describe important necrotic changes within keratinocytes as well as an inflammatory infiltrate comprising antigen-presenting cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Using high-resolution thin sections with confocal laser scanning microscopy and staining of specific monoclonal antibodies against 56 kDa type-specific surface antigens, the bacteria were found inside antigen-presenting cells, many of them located perivascularly or passing through the endothelium.11

The causal agent in Asia is O tsutsugamushi, an obligate intracellular bacterium (genus Rickettsia). Orientia species are transmitted by larvae of trombiculid mites, commonly called chiggers. The reservoir is believed to be the same as with chiggers, in which some vertebrates become infected and trombiculid mites feed on them.12 Recent studies of Chilean cases have revealed the presence of a novel Orientia species, Candidatus Orientia chiloensis and its vector, trombiculid mites from the Herpetacarus species, Quadraseta species, and Paratrombicula species genera.13,14

A high seroprevalence of Orientia species in dogs was reported in the main cities of Chiloé Island. Rates were higher in rural settings and older dogs. Of 202 specimens, 21.3% were positive for IgG against Orientia species.15

In Chile, most cases of ST came from Chiloé Island; some reports of cases from continental Chilean regions have been published.6 Most cases have occurred in the context of activities that brought the patients in contact with plants and firewood in rural areas during the summer.3-6

The diagnosis of ST is eminently clinical, based on the triad of fever, macular or papular rash, and an inoculation necrotic eschar. The diagnosis is supported by epidemiologic facts and fast recovery after treatment is initiated.16 Although the diagnosis can be established based on a quick recovery in endemic countries, in areas such as Chile where incidence and distribution are not completely known, it is better to confirm the diagnosis with laboratory tests without delaying treatment. Several testing options exist, including serologic techniques (immunofluorescence or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), culture, and detection of the genetic material of Orientia species by PCR. Usually, IgM titers initially are negative, and IgG testing requires paired samples (acute and convalescent) to demonstrate seroconversion and therefore acute infection.17 Because culture requires a highly specialized laboratory, it is not frequently used. Polymerase chain reaction is recognized as the best confirmation method due to its high sensitivity and because it remains positive for a few days after treatment has been initiated. The specimen of choice is the eschar because of its high bacterial load. The base of the scar and the buffy coat are useful specimens when the eschar is unavailable.5,17-19

Due to potential complications of ST, empirical treatment with an antibiotic should be started based on clinical facts and never delayed because of diagnostic tests.18 Classically, ST is treated with a member of the tetracycline family, such as doxycycline, which provides a cure rate of 63% to 100% in ST.5

A 2017 systematic review of treatment options for this infection examined 11 studies from Southeast Asia, China, and South Korea (N=957).16 The review mainly compared doxycycline with azithromycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline. No significant difference in cure rate was noted in comparing doxycycline with any of the other 3 antibiotics; most of the studies examined were characterized by a moderate level of evidence. Regarding adverse effects, doxycycline showed a few more cases of gastrointestinal intolerance, and in 2 of 4 studies with chloramphenicol, patients presented with leukopenia.16 Several studies compared standard treatment (doxycycline) with rifampicin, telithromycin, erythromycin, and levofloxacin individually; similar cure rates were noted between doxycycline and each of those 4 agents.

Therapeutic failure in ST has been reported in several cases with the use of levofloxacin.20 Evidence for this novel antibiotic is still insufficient. Further studies are needed before rifampicin, telithromycin, erythromycin, or levofloxacin can be considered as options.Scrub typhus usually resolves within a few weeks. Left untreated, the disease can cause complications such as pneumonia, meningoencephalitis, renal failure, and even multiorgan failure and death. Without treatment, mortality is variable. A 2015 systematic review of mortality from untreated ST showed, on average, mortality of 6% (range, 0%–70%).21 When ST is treated, mortality falls to 0% to 30%.22 Cases reported in Chile have neither been lethal nor presented with severe complications.4,5