User login

Incontinentia Pigmenti: Initial Presentation of Encephalopathy and Seizures

To the Editor:

A 7-day-old full-term infant presented to the neonatal intensive care unit with poor feeding and altered consciousness. She was born at 39 weeks and 3 days to a gravida 1 mother with a pregnancy history complicated by maternal chorioamnionitis and gestational diabetes. During labor, nonreassuring fetal heart tones and arrest of labor prompted an uncomplicated cesarean delivery with normal Apgar scores at birth. The infant’s family history revealed only beta thalassemia minor in her father. At 5 to 7 days of life, the mother noted difficulty with feeding and poor latch along with lethargy and depressed consciousness in the infant.

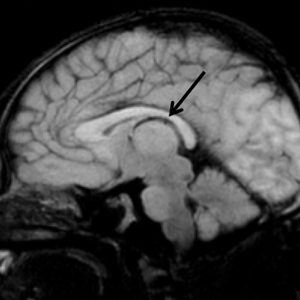

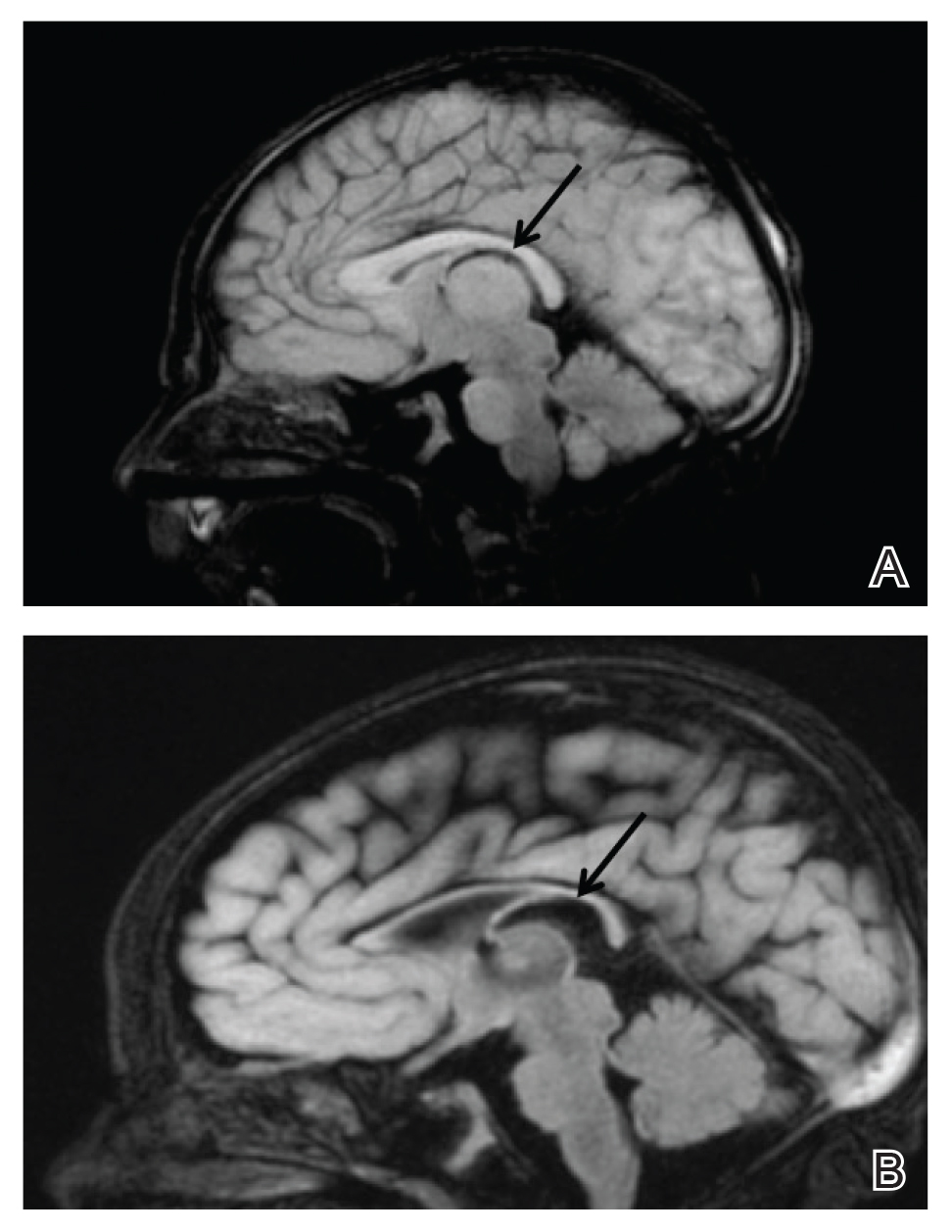

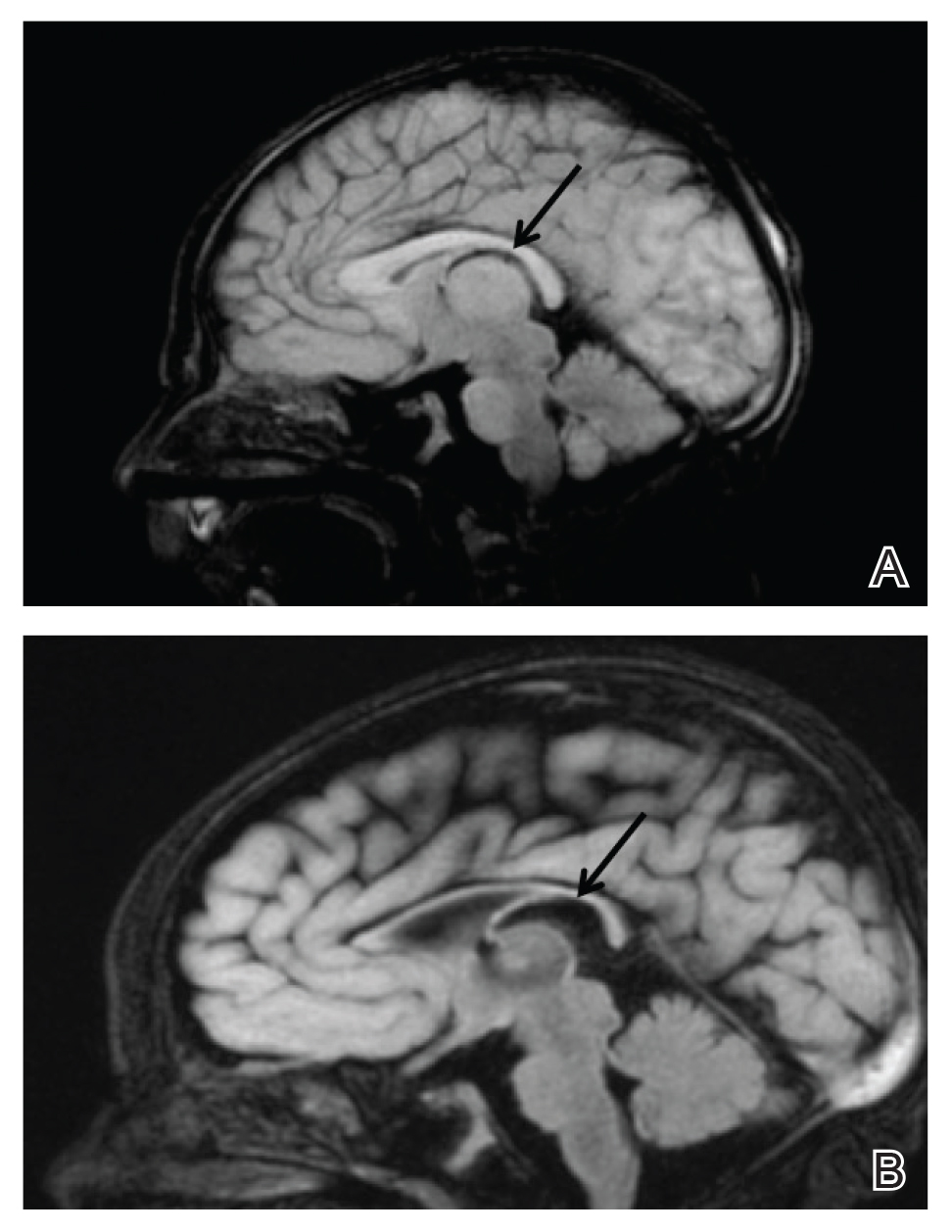

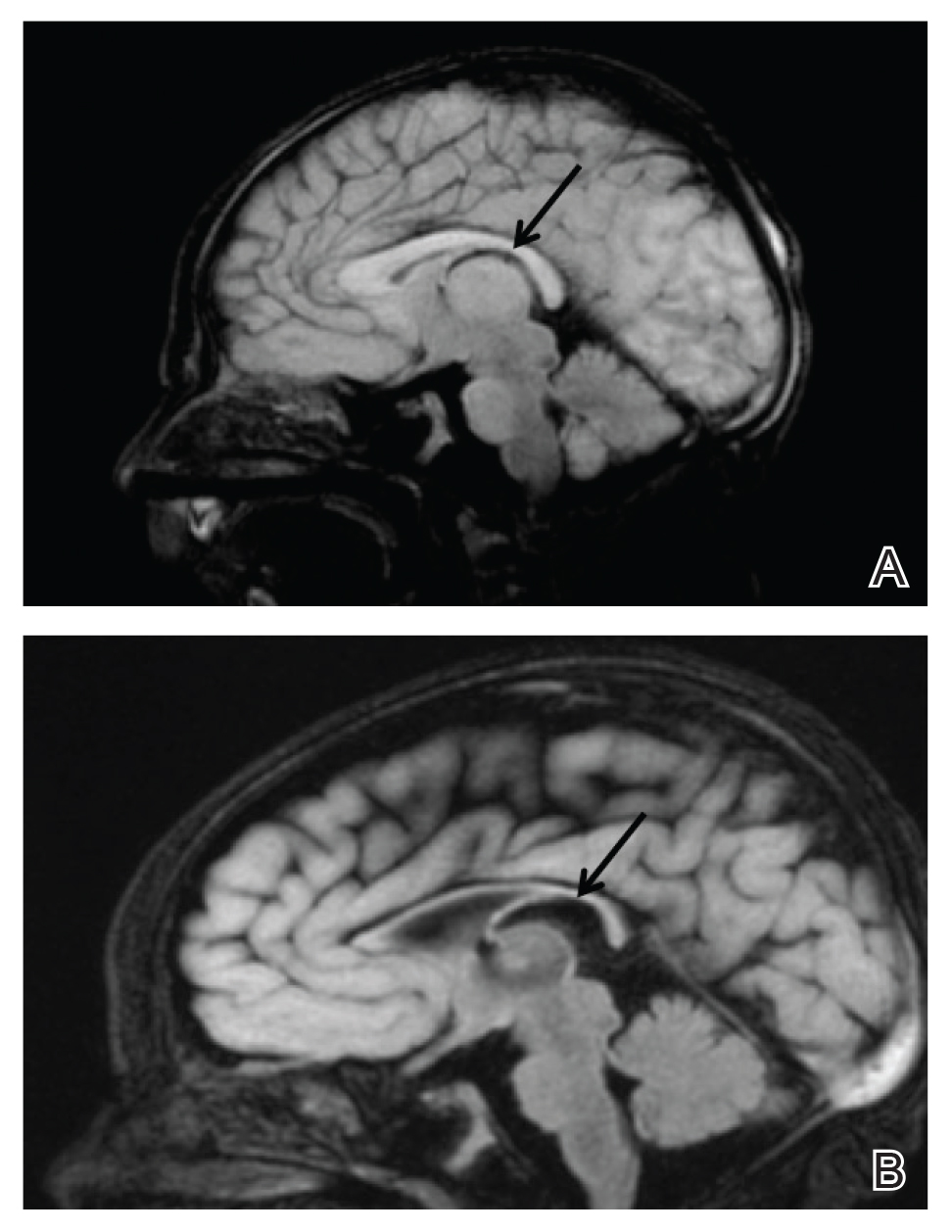

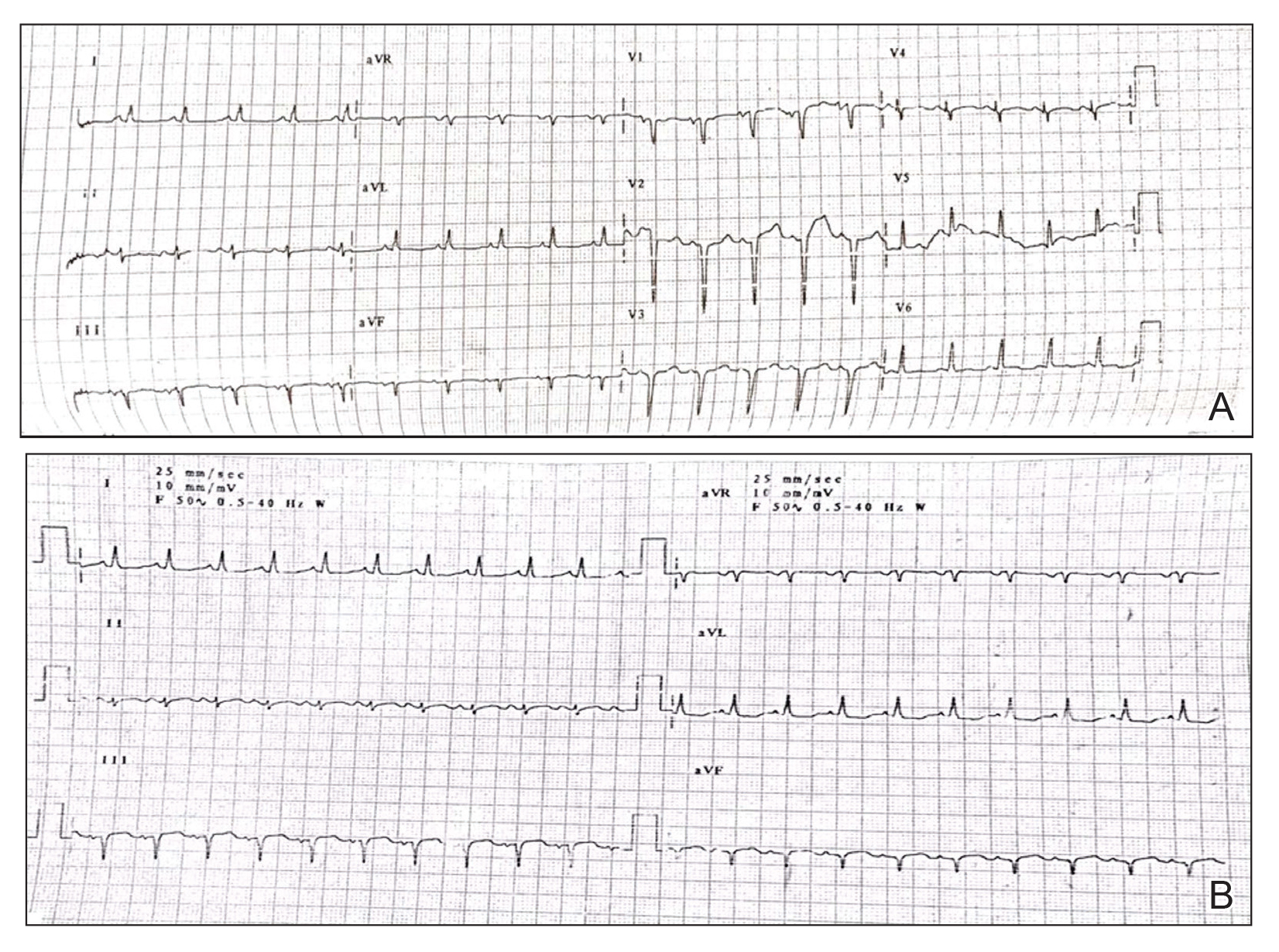

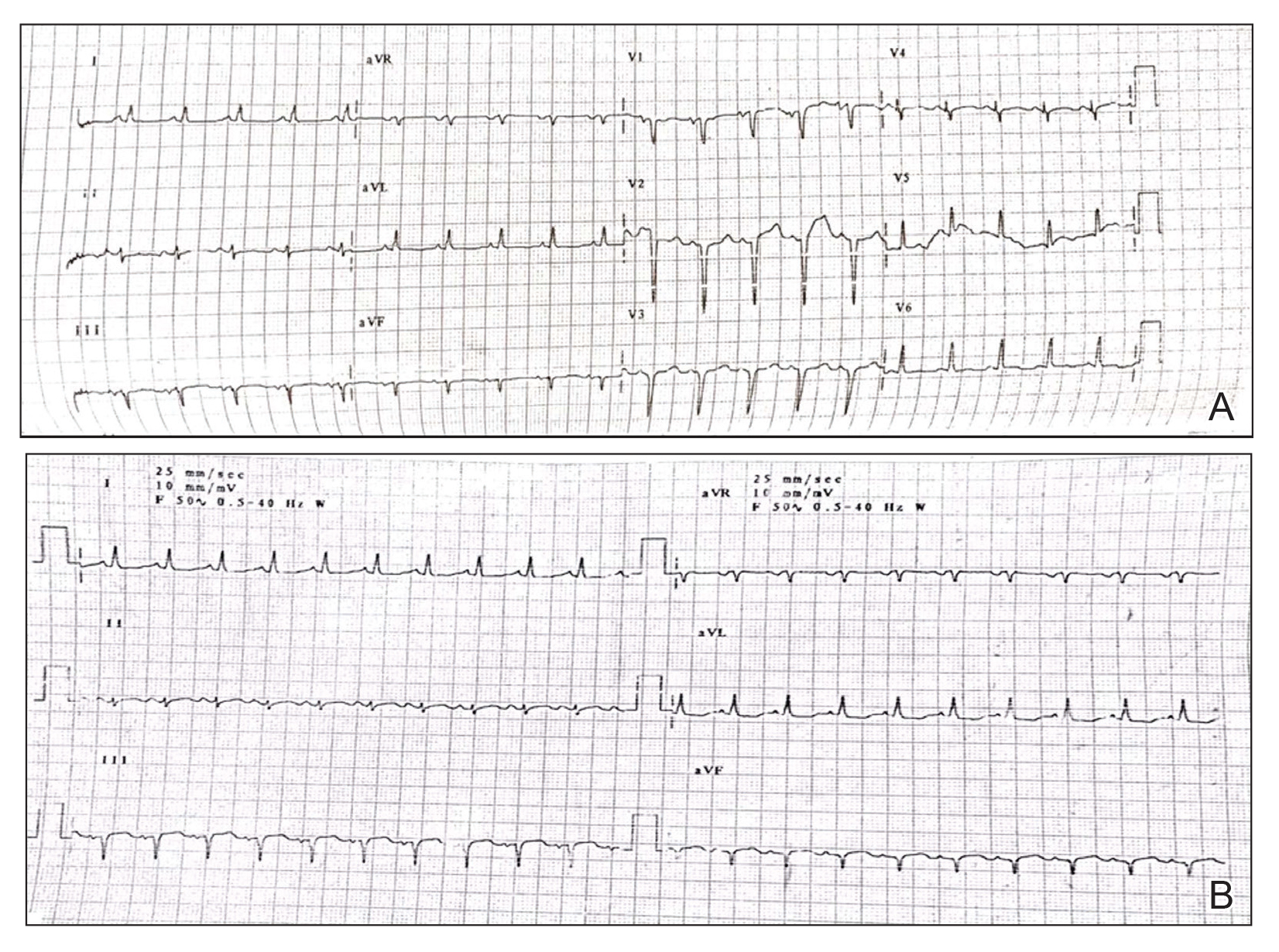

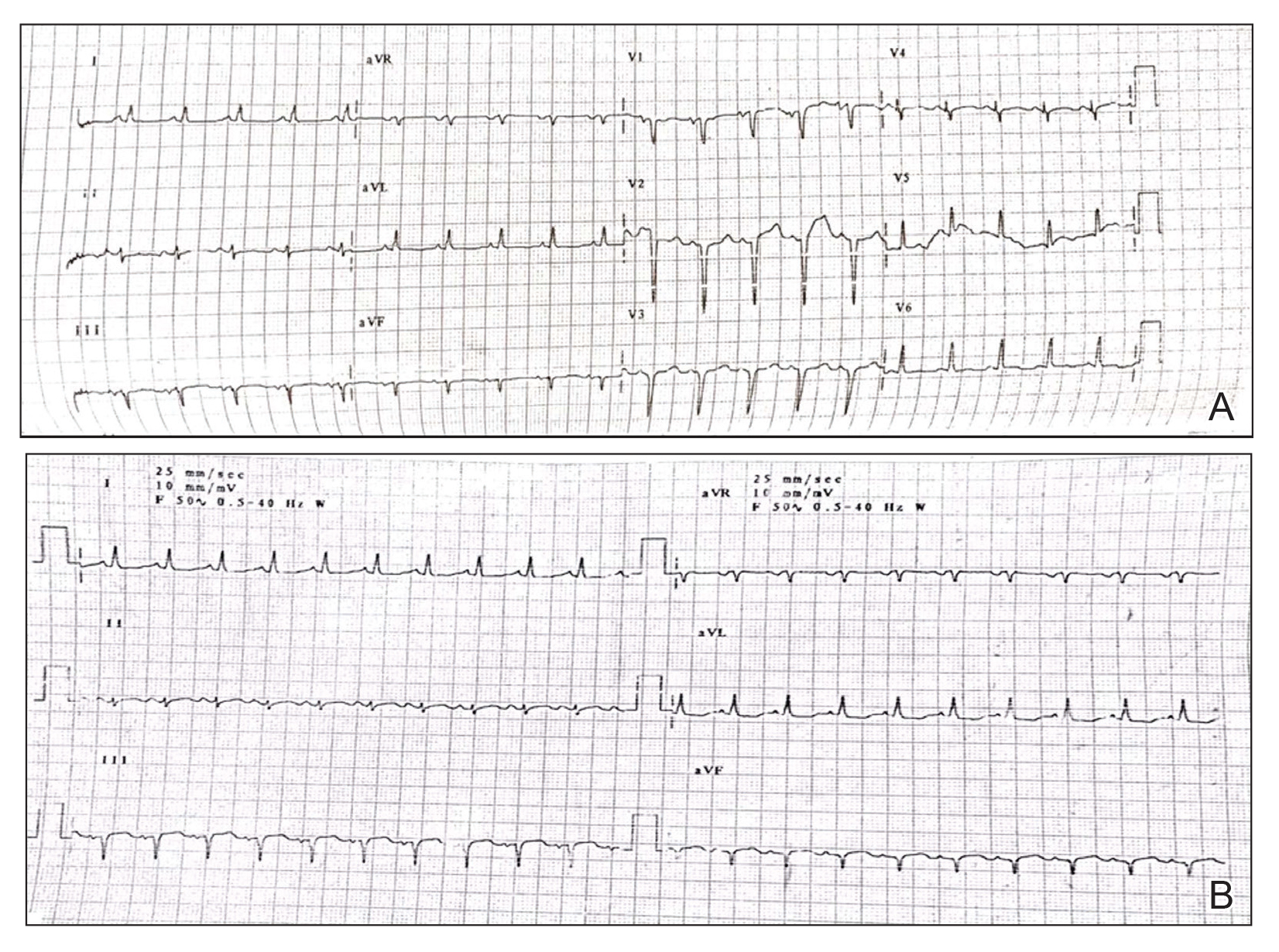

Upon arrival to the neonatal intensive care unit, the infant was noted to have rhythmic lip-smacking behavior, intermittent nystagmus, mild hypotonia, and clonic movements of the left upper extremity. An electroencephalogram was markedly abnormal, capturing multiple seizures in the bilateral cortical hemispheres. She was loaded with phenobarbital with no further seizure activity. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed innumerable punctate foci of restricted diffusion with corresponding punctate hemorrhage within the frontal and parietal white matter, as well as cortical diffusion restriction within the occipital lobe, inferior temporal lobe, bilateral thalami, and corpus callosum (Figure 1). An exhaustive infectious workup also was completed and was unremarkable, though she was treated with broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including intravenous acyclovir.

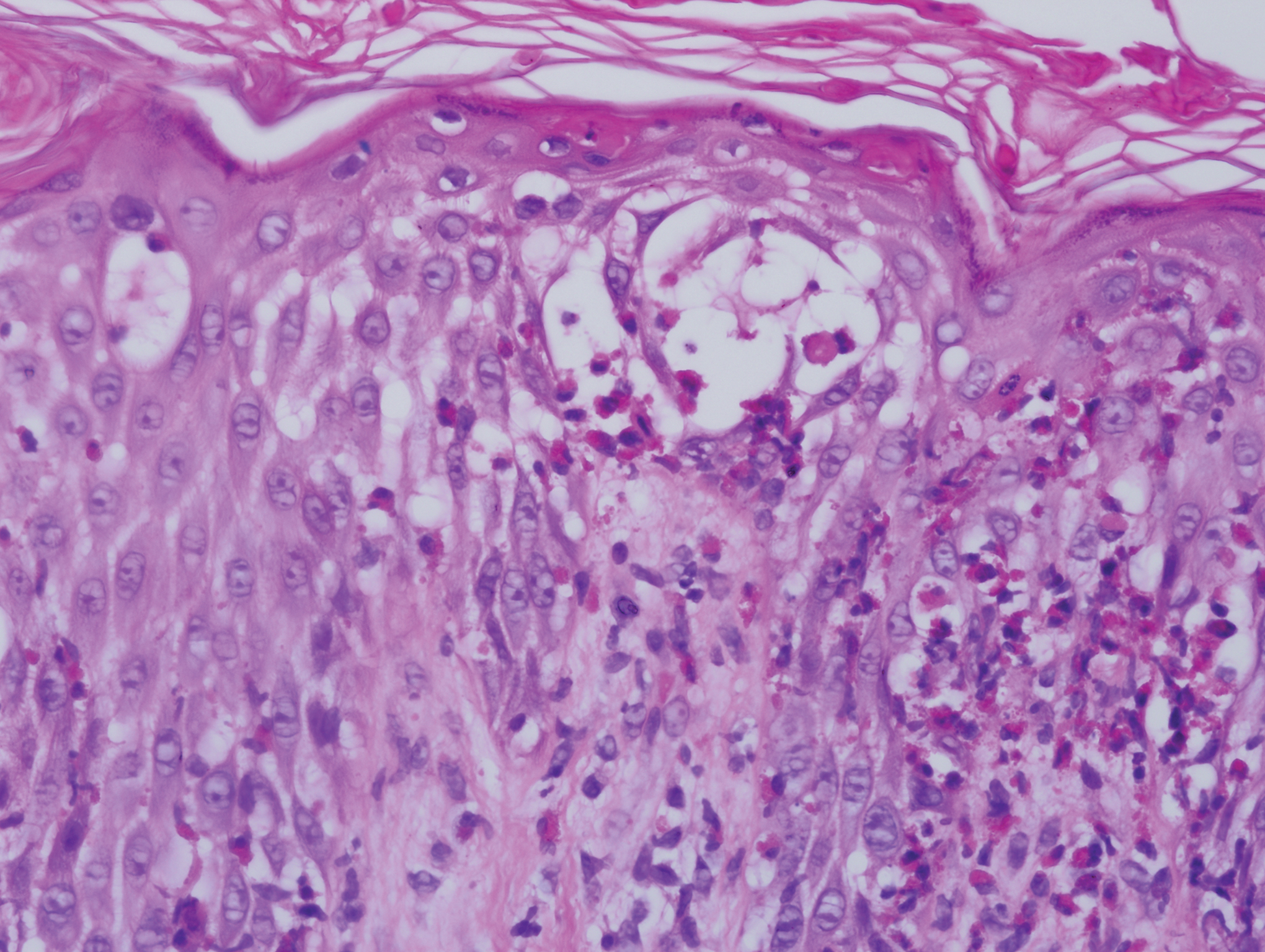

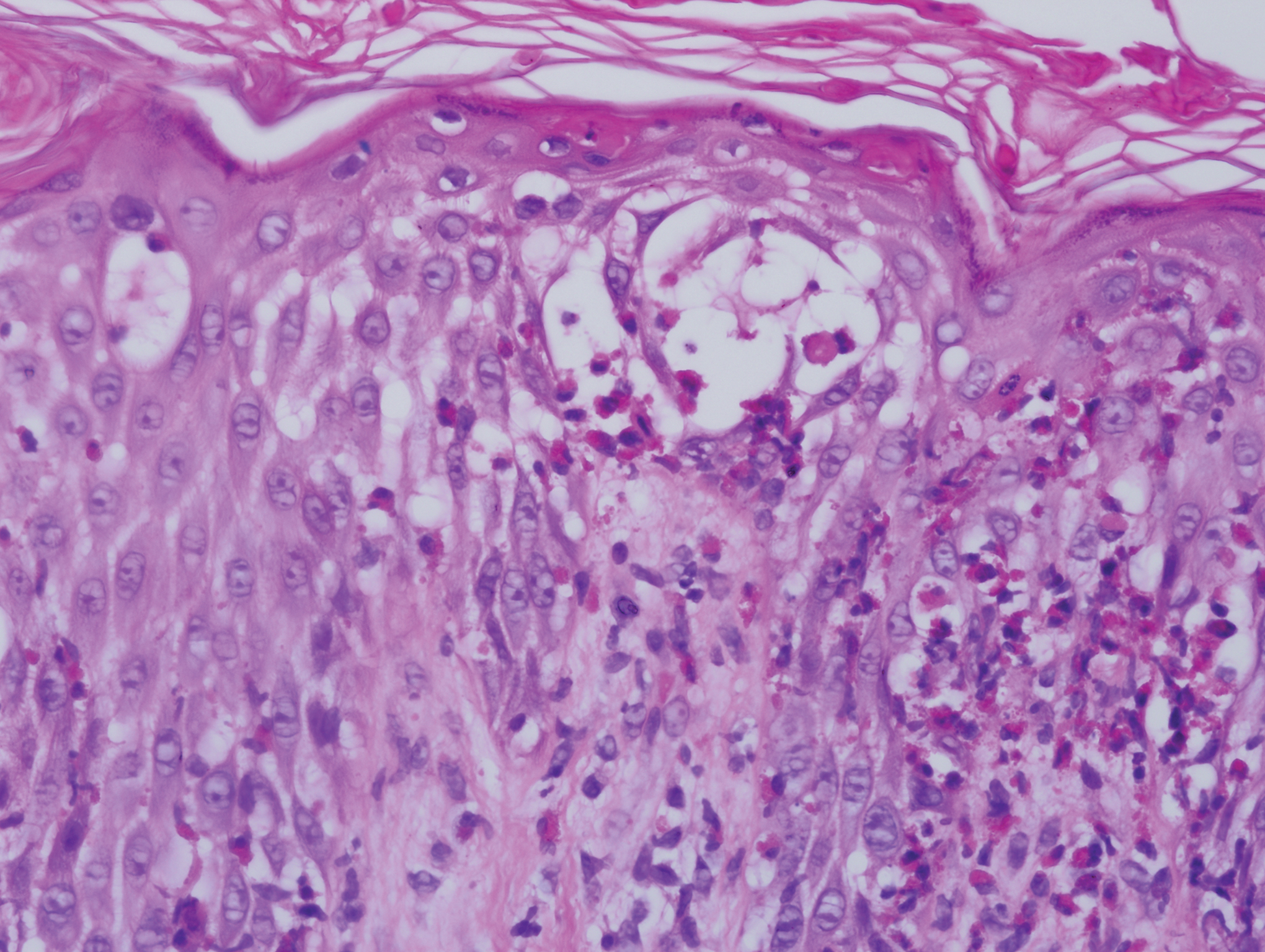

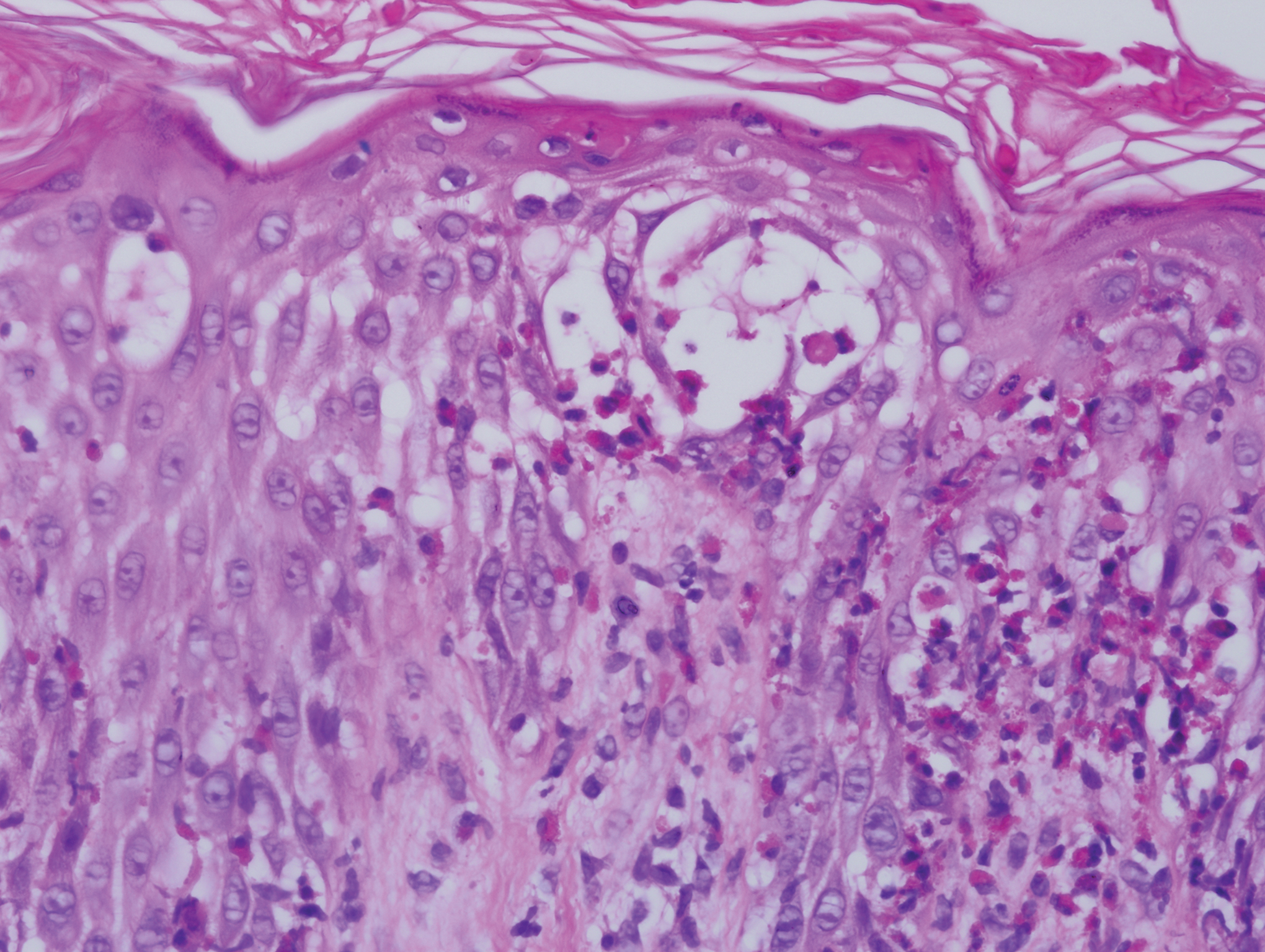

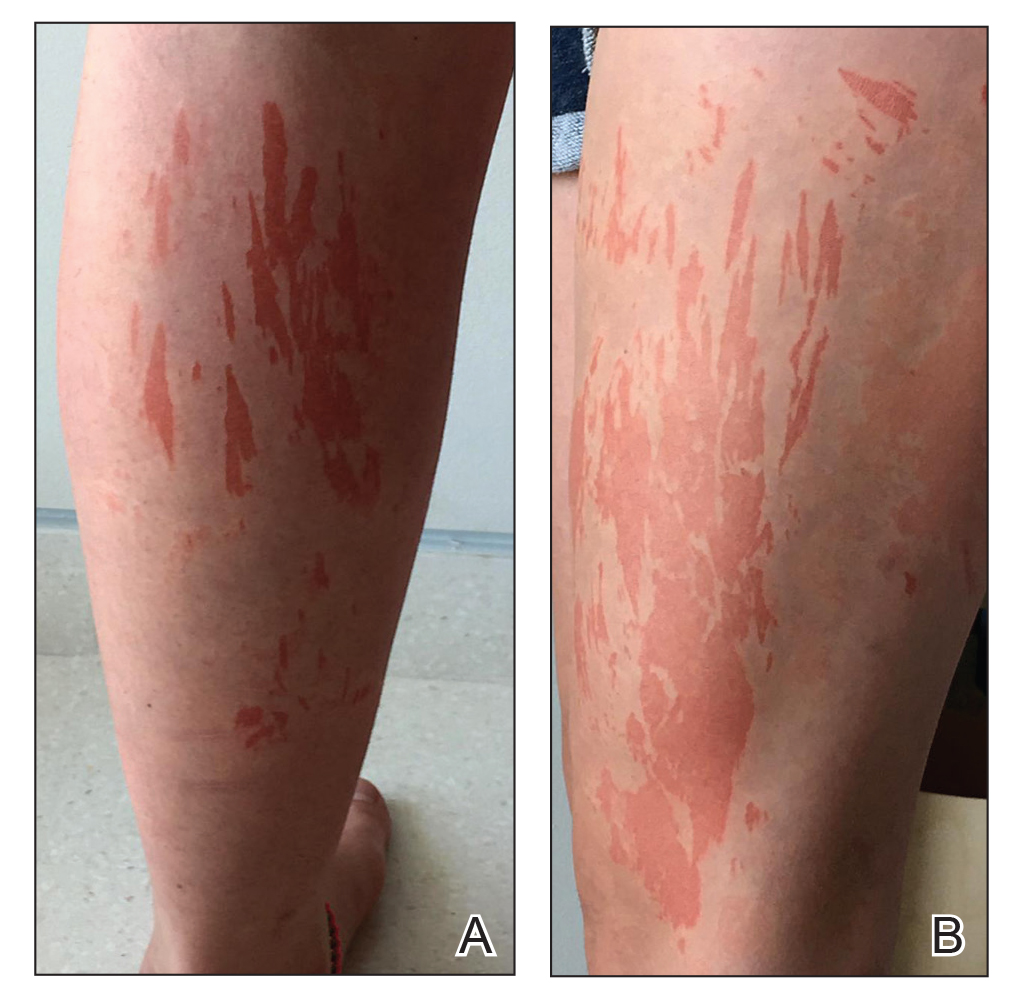

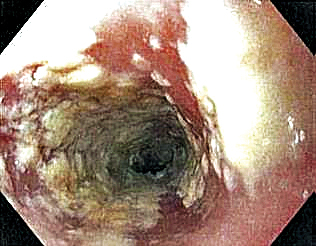

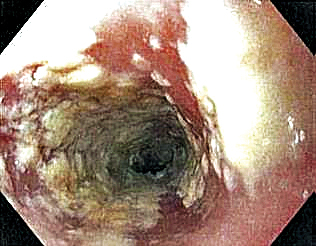

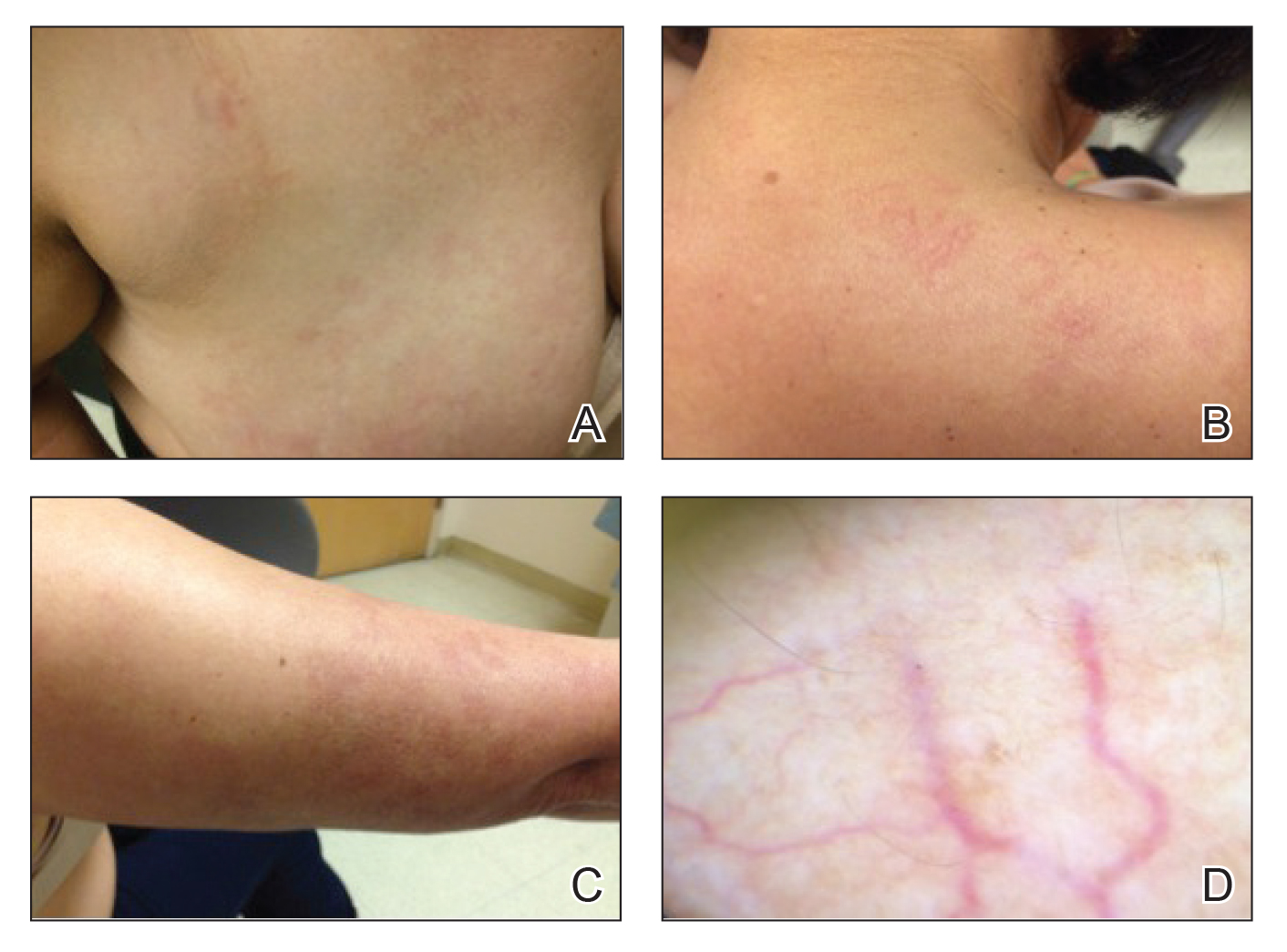

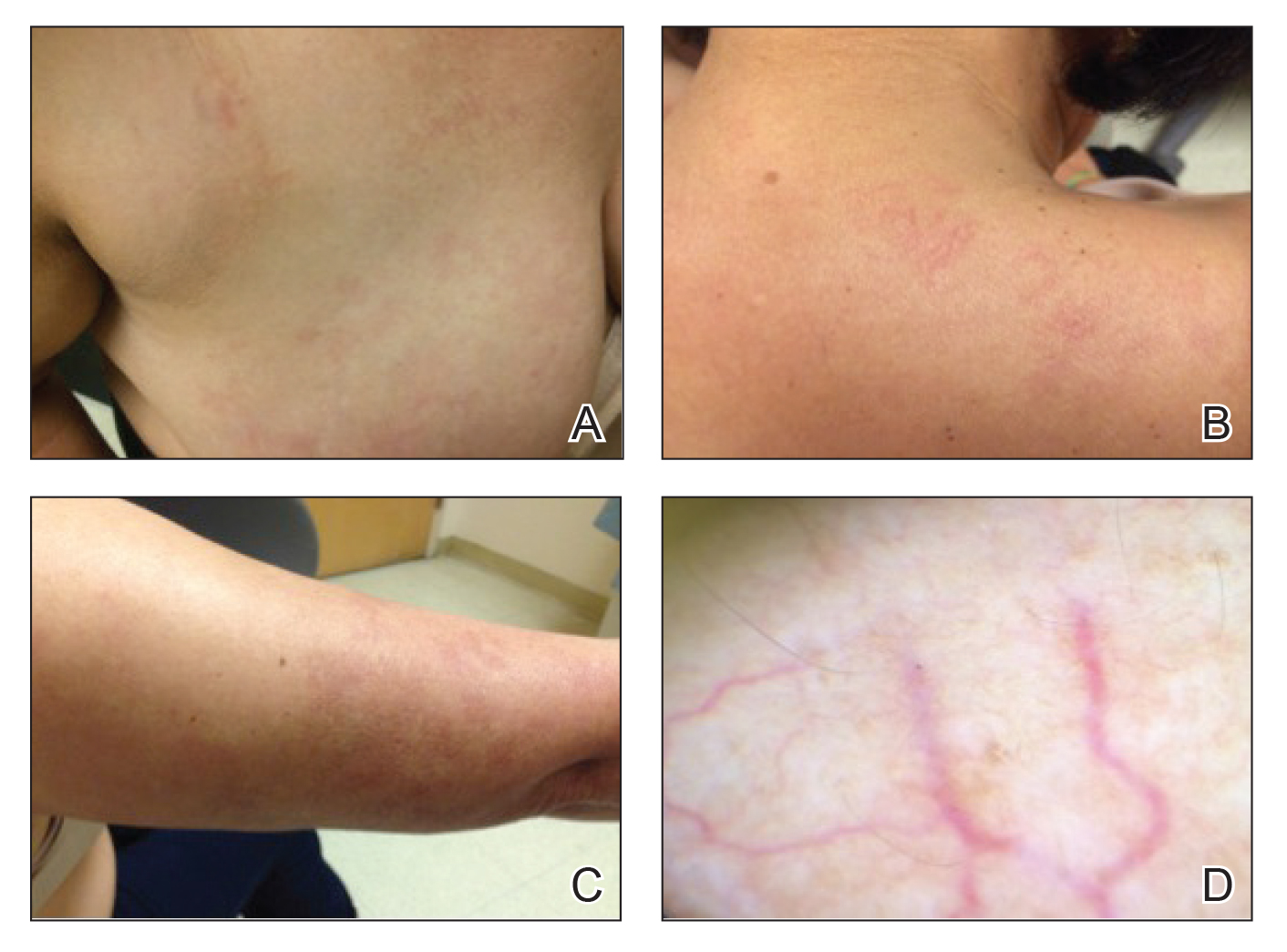

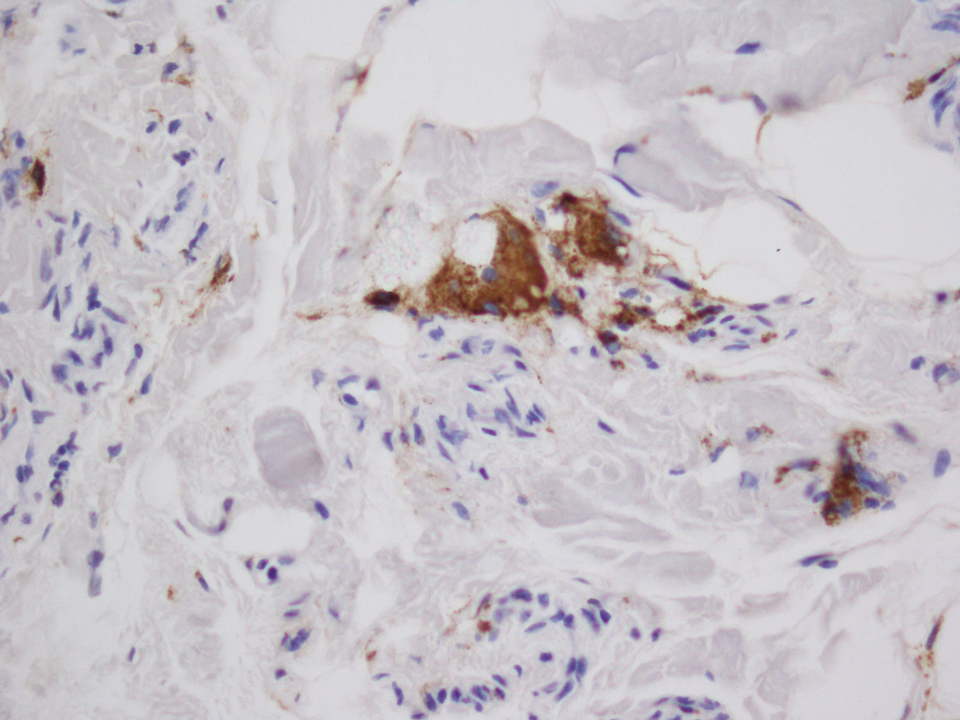

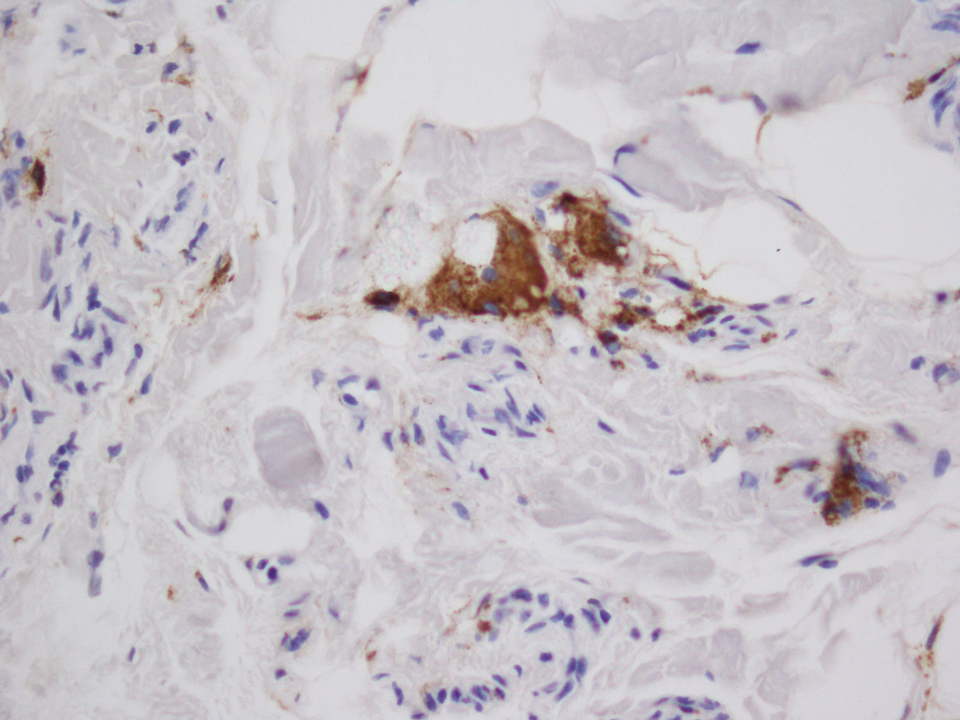

Five days after being hospitalized (day 10 of life), a vesicular rash was noted on the arms and legs (Figure 2). Discussion with the patient’s mother revealed that the first signs of unusual skin lesions occurred as early as several days prior. There were no oral mucosal lesions or gross ocular abnormalities. No nail changes were appreciated. A bedside Tzanck preparation was negative for viral cytopathic changes. A skin biopsy was performed that demonstrated eosinophilic spongiosis with necrotic keratinocytes, typical of the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP)(Figure 3). An ophthalmology examination showed an arteriovenous malformation of the right eye with subtle neovascularization at the infratemporal periphery, consistent with known ocular manifestations of IP. The infant’s mother reported no history of notable dental abnormalities, hair loss, skin rashes, or nail changes. Genetic testing demonstrated the common IKBKG (inhibitor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase gamma [formerly known as NEMO]) gene deletion on the X chromosome, consistent with IP.

She successfully underwent retinal laser ablative therapy for the ocular manifestations without further evidence of neovascularization. She developed a mild cataract that was not visually significant and required no intervention. Her brain abnormalities were thought to represent foci of necrosis with superimposed hemorrhagic transformation due to spontaneous degeneration of brain cells in which the mutated X chromosome was activated. No further treatment was indicated beyond suppression of the consequent seizures. There was no notable cortical edema or other medical indication for systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Phenobarbital was continued without further seizure events.

Several months after the initial presentation, a follow-up electroencephalogram was normal. Phenobarbital was slowly weaned and finally discontinued approximately 6 months after the initial event with no other reported seizures. She currently is achieving normal developmental milestones with the exception of slight motor delay and expected residual hypotonia.

Incontinentia pigmenti, also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, is a rare multisystem neuroectodermal disorder, primarily affecting the skin, central nervous system (CNS), and retinas. The disorder can be inherited in an X-linked dominant fashion and appears almost exclusively in women with typical in utero lethality seen in males. Most affected individuals have a sporadic, or de novo, mutation, which was likely the case in our patient given that her mother demonstrated no signs or symptoms.1 The pathogenesis of disease is a defect at chromosome Xq28 that is a region encoding the nuclear factor–κB essential modulator, IKBKG. Absence or mutation of IKBKG in IP results in failure to activate nuclear factor–κB and leaves cells vulnerable to cytokine-mediated apoptosis, especially after exposure to tumor necrosis factor α.2

Clinical manifestations of IP are present at or soon after birth. The cutaneous findings of this disorder are classically described as a step-wise progression through 4 distinct stages: (1) a linear and/or whorled vesicular eruption predominantly on the extremities at birth or within the first few weeks of life; (2) thickened linear or whorled verrucous plaques; (3) hyperpigmented streaks and whorls that may or may not correspond with prior affected areas that may resolve by adolescence; and (4) hypopigmented, possibly atrophic plaques on the extremities that may persist lifelong. Importantly, not every patient will experience each of these stages. Overlap can occur, and the time course of each stage is highly variable. Other ectodermal manifestations include dental abnormalities such as small, misshaped, or missing teeth; alopecia; and nail abnormalities. Ocular abnormalities associated with IP primarily occur in the retina, including vascular occlusion, neovascularization, hemorrhages, foveal abnormalities, as well as exudative and tractional detachments.3,4

It is crucial to recognize CNS anomalies in association with the cutaneous findings of IP, as CNS pathology can be severe with profound developmental implications. Central nervous system findings have been noted to correlate with the appearance of the vesicular stage of IP. A high index of suspicion is needed, as the disease can demonstrate progression within a short time.5-8 The most frequent anomalies include seizures, motor impairment, intellectual disability, and microcephaly.9,10 Some of the most commonly identified CNS lesions on imaging include necrosis or brain infarcts, atrophy, and lesions of the corpus callosum.7

The pathogenesis of observed CNS changes in IP is not well understood. There have been numerous proposals of a vascular mechanism, and a microangiopathic process appears to be most plausible. Mutations in IKBKG may result in interruption of signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 with a consequent impact on angiogenesis, supporting a vascular mechanism. Additionally, mutations in IKBKG lead to activation of eotaxin, an eosinophil-selective chemokine.9 Eotaxin activation results in eosinophilic degranulation that mediates the classic eosinophilic infiltrate seen in the classic skin histology of IP. Additionally, it has been shown that eotaxin is strongly expressed by endothelial cells in IP, and more abundant eosinophil degranulation may play a role in mediating vaso-occlusion.7 Other studies have found that the highest expression level of the IKBKG gene is in the CNS, potentially explaining the extensive imaging findings of hemorrhage and diffusion restriction in our patient. These features likely are attributable to apoptosis of cells possessing the mutated IKBKG gene.9-11

- Ehrenreich M, Tarlow MM, Godlewska-Janusz E, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): a systemic disorder. Cutis. 2007;79:355-362.

- Smahi A, Courtois G, Rabia SH, et al. The NF-kappaB signaling pathway in human diseases: from incontinentia pigmenti to ectodermal dysplasias and immune-deficiency syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2371-2375.

- O’Doherty M, McCreery K, Green AJ, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti—ophthalmological observation of a series of cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:11-16.

- Swinney CC, Han DP, Karth PA. Incontinentia pigmenti: a comprehensive review and update. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:650-657.

- Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:148-150.

- Maingay-de Groof F, Lequin MH, Roofthooft DW, et al. Extensive cerebral infarction in the newborn due to incontinentia pigmenti. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:284-289.

- Minic´ S, Trpinac D, Obradovic´ M. Systematic review of central nervous system anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:25-35.

- Wolf NI, Kramer N, Harting I, et al. Diffuse cortical necrosis in a neonate with incontinentia pigmenti and an encephalitis-like presentation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1580-1582.

- Phan TA, Wargon O, Turner AM. Incontinentia pigmenti case series: clinical spectrum of incontinentia pigmenti in 53 female patients and their relatives. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:474-480.

- Volpe J. Neurobiology of periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:553-562.

- Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinical and neuroimaging findings in a series of 12 patients. Neurologia. 2006;21:239-248.

To the Editor:

A 7-day-old full-term infant presented to the neonatal intensive care unit with poor feeding and altered consciousness. She was born at 39 weeks and 3 days to a gravida 1 mother with a pregnancy history complicated by maternal chorioamnionitis and gestational diabetes. During labor, nonreassuring fetal heart tones and arrest of labor prompted an uncomplicated cesarean delivery with normal Apgar scores at birth. The infant’s family history revealed only beta thalassemia minor in her father. At 5 to 7 days of life, the mother noted difficulty with feeding and poor latch along with lethargy and depressed consciousness in the infant.

Upon arrival to the neonatal intensive care unit, the infant was noted to have rhythmic lip-smacking behavior, intermittent nystagmus, mild hypotonia, and clonic movements of the left upper extremity. An electroencephalogram was markedly abnormal, capturing multiple seizures in the bilateral cortical hemispheres. She was loaded with phenobarbital with no further seizure activity. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed innumerable punctate foci of restricted diffusion with corresponding punctate hemorrhage within the frontal and parietal white matter, as well as cortical diffusion restriction within the occipital lobe, inferior temporal lobe, bilateral thalami, and corpus callosum (Figure 1). An exhaustive infectious workup also was completed and was unremarkable, though she was treated with broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including intravenous acyclovir.

Five days after being hospitalized (day 10 of life), a vesicular rash was noted on the arms and legs (Figure 2). Discussion with the patient’s mother revealed that the first signs of unusual skin lesions occurred as early as several days prior. There were no oral mucosal lesions or gross ocular abnormalities. No nail changes were appreciated. A bedside Tzanck preparation was negative for viral cytopathic changes. A skin biopsy was performed that demonstrated eosinophilic spongiosis with necrotic keratinocytes, typical of the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP)(Figure 3). An ophthalmology examination showed an arteriovenous malformation of the right eye with subtle neovascularization at the infratemporal periphery, consistent with known ocular manifestations of IP. The infant’s mother reported no history of notable dental abnormalities, hair loss, skin rashes, or nail changes. Genetic testing demonstrated the common IKBKG (inhibitor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase gamma [formerly known as NEMO]) gene deletion on the X chromosome, consistent with IP.

She successfully underwent retinal laser ablative therapy for the ocular manifestations without further evidence of neovascularization. She developed a mild cataract that was not visually significant and required no intervention. Her brain abnormalities were thought to represent foci of necrosis with superimposed hemorrhagic transformation due to spontaneous degeneration of brain cells in which the mutated X chromosome was activated. No further treatment was indicated beyond suppression of the consequent seizures. There was no notable cortical edema or other medical indication for systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Phenobarbital was continued without further seizure events.

Several months after the initial presentation, a follow-up electroencephalogram was normal. Phenobarbital was slowly weaned and finally discontinued approximately 6 months after the initial event with no other reported seizures. She currently is achieving normal developmental milestones with the exception of slight motor delay and expected residual hypotonia.

Incontinentia pigmenti, also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, is a rare multisystem neuroectodermal disorder, primarily affecting the skin, central nervous system (CNS), and retinas. The disorder can be inherited in an X-linked dominant fashion and appears almost exclusively in women with typical in utero lethality seen in males. Most affected individuals have a sporadic, or de novo, mutation, which was likely the case in our patient given that her mother demonstrated no signs or symptoms.1 The pathogenesis of disease is a defect at chromosome Xq28 that is a region encoding the nuclear factor–κB essential modulator, IKBKG. Absence or mutation of IKBKG in IP results in failure to activate nuclear factor–κB and leaves cells vulnerable to cytokine-mediated apoptosis, especially after exposure to tumor necrosis factor α.2

Clinical manifestations of IP are present at or soon after birth. The cutaneous findings of this disorder are classically described as a step-wise progression through 4 distinct stages: (1) a linear and/or whorled vesicular eruption predominantly on the extremities at birth or within the first few weeks of life; (2) thickened linear or whorled verrucous plaques; (3) hyperpigmented streaks and whorls that may or may not correspond with prior affected areas that may resolve by adolescence; and (4) hypopigmented, possibly atrophic plaques on the extremities that may persist lifelong. Importantly, not every patient will experience each of these stages. Overlap can occur, and the time course of each stage is highly variable. Other ectodermal manifestations include dental abnormalities such as small, misshaped, or missing teeth; alopecia; and nail abnormalities. Ocular abnormalities associated with IP primarily occur in the retina, including vascular occlusion, neovascularization, hemorrhages, foveal abnormalities, as well as exudative and tractional detachments.3,4

It is crucial to recognize CNS anomalies in association with the cutaneous findings of IP, as CNS pathology can be severe with profound developmental implications. Central nervous system findings have been noted to correlate with the appearance of the vesicular stage of IP. A high index of suspicion is needed, as the disease can demonstrate progression within a short time.5-8 The most frequent anomalies include seizures, motor impairment, intellectual disability, and microcephaly.9,10 Some of the most commonly identified CNS lesions on imaging include necrosis or brain infarcts, atrophy, and lesions of the corpus callosum.7

The pathogenesis of observed CNS changes in IP is not well understood. There have been numerous proposals of a vascular mechanism, and a microangiopathic process appears to be most plausible. Mutations in IKBKG may result in interruption of signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 with a consequent impact on angiogenesis, supporting a vascular mechanism. Additionally, mutations in IKBKG lead to activation of eotaxin, an eosinophil-selective chemokine.9 Eotaxin activation results in eosinophilic degranulation that mediates the classic eosinophilic infiltrate seen in the classic skin histology of IP. Additionally, it has been shown that eotaxin is strongly expressed by endothelial cells in IP, and more abundant eosinophil degranulation may play a role in mediating vaso-occlusion.7 Other studies have found that the highest expression level of the IKBKG gene is in the CNS, potentially explaining the extensive imaging findings of hemorrhage and diffusion restriction in our patient. These features likely are attributable to apoptosis of cells possessing the mutated IKBKG gene.9-11

To the Editor:

A 7-day-old full-term infant presented to the neonatal intensive care unit with poor feeding and altered consciousness. She was born at 39 weeks and 3 days to a gravida 1 mother with a pregnancy history complicated by maternal chorioamnionitis and gestational diabetes. During labor, nonreassuring fetal heart tones and arrest of labor prompted an uncomplicated cesarean delivery with normal Apgar scores at birth. The infant’s family history revealed only beta thalassemia minor in her father. At 5 to 7 days of life, the mother noted difficulty with feeding and poor latch along with lethargy and depressed consciousness in the infant.

Upon arrival to the neonatal intensive care unit, the infant was noted to have rhythmic lip-smacking behavior, intermittent nystagmus, mild hypotonia, and clonic movements of the left upper extremity. An electroencephalogram was markedly abnormal, capturing multiple seizures in the bilateral cortical hemispheres. She was loaded with phenobarbital with no further seizure activity. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed innumerable punctate foci of restricted diffusion with corresponding punctate hemorrhage within the frontal and parietal white matter, as well as cortical diffusion restriction within the occipital lobe, inferior temporal lobe, bilateral thalami, and corpus callosum (Figure 1). An exhaustive infectious workup also was completed and was unremarkable, though she was treated with broad-spectrum antimicrobials, including intravenous acyclovir.

Five days after being hospitalized (day 10 of life), a vesicular rash was noted on the arms and legs (Figure 2). Discussion with the patient’s mother revealed that the first signs of unusual skin lesions occurred as early as several days prior. There were no oral mucosal lesions or gross ocular abnormalities. No nail changes were appreciated. A bedside Tzanck preparation was negative for viral cytopathic changes. A skin biopsy was performed that demonstrated eosinophilic spongiosis with necrotic keratinocytes, typical of the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP)(Figure 3). An ophthalmology examination showed an arteriovenous malformation of the right eye with subtle neovascularization at the infratemporal periphery, consistent with known ocular manifestations of IP. The infant’s mother reported no history of notable dental abnormalities, hair loss, skin rashes, or nail changes. Genetic testing demonstrated the common IKBKG (inhibitor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells, kinase gamma [formerly known as NEMO]) gene deletion on the X chromosome, consistent with IP.

She successfully underwent retinal laser ablative therapy for the ocular manifestations without further evidence of neovascularization. She developed a mild cataract that was not visually significant and required no intervention. Her brain abnormalities were thought to represent foci of necrosis with superimposed hemorrhagic transformation due to spontaneous degeneration of brain cells in which the mutated X chromosome was activated. No further treatment was indicated beyond suppression of the consequent seizures. There was no notable cortical edema or other medical indication for systemic glucocorticoid therapy. Phenobarbital was continued without further seizure events.

Several months after the initial presentation, a follow-up electroencephalogram was normal. Phenobarbital was slowly weaned and finally discontinued approximately 6 months after the initial event with no other reported seizures. She currently is achieving normal developmental milestones with the exception of slight motor delay and expected residual hypotonia.

Incontinentia pigmenti, also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, is a rare multisystem neuroectodermal disorder, primarily affecting the skin, central nervous system (CNS), and retinas. The disorder can be inherited in an X-linked dominant fashion and appears almost exclusively in women with typical in utero lethality seen in males. Most affected individuals have a sporadic, or de novo, mutation, which was likely the case in our patient given that her mother demonstrated no signs or symptoms.1 The pathogenesis of disease is a defect at chromosome Xq28 that is a region encoding the nuclear factor–κB essential modulator, IKBKG. Absence or mutation of IKBKG in IP results in failure to activate nuclear factor–κB and leaves cells vulnerable to cytokine-mediated apoptosis, especially after exposure to tumor necrosis factor α.2

Clinical manifestations of IP are present at or soon after birth. The cutaneous findings of this disorder are classically described as a step-wise progression through 4 distinct stages: (1) a linear and/or whorled vesicular eruption predominantly on the extremities at birth or within the first few weeks of life; (2) thickened linear or whorled verrucous plaques; (3) hyperpigmented streaks and whorls that may or may not correspond with prior affected areas that may resolve by adolescence; and (4) hypopigmented, possibly atrophic plaques on the extremities that may persist lifelong. Importantly, not every patient will experience each of these stages. Overlap can occur, and the time course of each stage is highly variable. Other ectodermal manifestations include dental abnormalities such as small, misshaped, or missing teeth; alopecia; and nail abnormalities. Ocular abnormalities associated with IP primarily occur in the retina, including vascular occlusion, neovascularization, hemorrhages, foveal abnormalities, as well as exudative and tractional detachments.3,4

It is crucial to recognize CNS anomalies in association with the cutaneous findings of IP, as CNS pathology can be severe with profound developmental implications. Central nervous system findings have been noted to correlate with the appearance of the vesicular stage of IP. A high index of suspicion is needed, as the disease can demonstrate progression within a short time.5-8 The most frequent anomalies include seizures, motor impairment, intellectual disability, and microcephaly.9,10 Some of the most commonly identified CNS lesions on imaging include necrosis or brain infarcts, atrophy, and lesions of the corpus callosum.7

The pathogenesis of observed CNS changes in IP is not well understood. There have been numerous proposals of a vascular mechanism, and a microangiopathic process appears to be most plausible. Mutations in IKBKG may result in interruption of signaling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 with a consequent impact on angiogenesis, supporting a vascular mechanism. Additionally, mutations in IKBKG lead to activation of eotaxin, an eosinophil-selective chemokine.9 Eotaxin activation results in eosinophilic degranulation that mediates the classic eosinophilic infiltrate seen in the classic skin histology of IP. Additionally, it has been shown that eotaxin is strongly expressed by endothelial cells in IP, and more abundant eosinophil degranulation may play a role in mediating vaso-occlusion.7 Other studies have found that the highest expression level of the IKBKG gene is in the CNS, potentially explaining the extensive imaging findings of hemorrhage and diffusion restriction in our patient. These features likely are attributable to apoptosis of cells possessing the mutated IKBKG gene.9-11

- Ehrenreich M, Tarlow MM, Godlewska-Janusz E, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): a systemic disorder. Cutis. 2007;79:355-362.

- Smahi A, Courtois G, Rabia SH, et al. The NF-kappaB signaling pathway in human diseases: from incontinentia pigmenti to ectodermal dysplasias and immune-deficiency syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2371-2375.

- O’Doherty M, McCreery K, Green AJ, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti—ophthalmological observation of a series of cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:11-16.

- Swinney CC, Han DP, Karth PA. Incontinentia pigmenti: a comprehensive review and update. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:650-657.

- Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:148-150.

- Maingay-de Groof F, Lequin MH, Roofthooft DW, et al. Extensive cerebral infarction in the newborn due to incontinentia pigmenti. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:284-289.

- Minic´ S, Trpinac D, Obradovic´ M. Systematic review of central nervous system anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:25-35.

- Wolf NI, Kramer N, Harting I, et al. Diffuse cortical necrosis in a neonate with incontinentia pigmenti and an encephalitis-like presentation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1580-1582.

- Phan TA, Wargon O, Turner AM. Incontinentia pigmenti case series: clinical spectrum of incontinentia pigmenti in 53 female patients and their relatives. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:474-480.

- Volpe J. Neurobiology of periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:553-562.

- Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinical and neuroimaging findings in a series of 12 patients. Neurologia. 2006;21:239-248.

- Ehrenreich M, Tarlow MM, Godlewska-Janusz E, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): a systemic disorder. Cutis. 2007;79:355-362.

- Smahi A, Courtois G, Rabia SH, et al. The NF-kappaB signaling pathway in human diseases: from incontinentia pigmenti to ectodermal dysplasias and immune-deficiency syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2371-2375.

- O’Doherty M, McCreery K, Green AJ, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti—ophthalmological observation of a series of cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:11-16.

- Swinney CC, Han DP, Karth PA. Incontinentia pigmenti: a comprehensive review and update. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:650-657.

- Hennel SJ, Ekert PG, Volpe JJ, et al. Insights into the pathogenesis of cerebral lesions in incontinentia pigmenti. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:148-150.

- Maingay-de Groof F, Lequin MH, Roofthooft DW, et al. Extensive cerebral infarction in the newborn due to incontinentia pigmenti. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:284-289.

- Minic´ S, Trpinac D, Obradovic´ M. Systematic review of central nervous system anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:25-35.

- Wolf NI, Kramer N, Harting I, et al. Diffuse cortical necrosis in a neonate with incontinentia pigmenti and an encephalitis-like presentation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1580-1582.

- Phan TA, Wargon O, Turner AM. Incontinentia pigmenti case series: clinical spectrum of incontinentia pigmenti in 53 female patients and their relatives. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:474-480.

- Volpe J. Neurobiology of periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:553-562.

- Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: clinical and neuroimaging findings in a series of 12 patients. Neurologia. 2006;21:239-248.

Practice Points

- Central nervous system involvement in incontinentia pigmenti (IP) may be profound and can present prior to the classic cutaneous findings.

- A high index of suspicion for IP should be maintained in neonatal vesicular eruptions of unclear etiology, especially in the setting of unexplained seizures and/or abnormal brain imaging.

Enfuvirtide-Induced Cutaneous Amyloidosis

To the Editor:

Cutaneous amyloidosis can be secondary to many causes. We describe a case of amyloidosis that was secondary to the deposition of an antiretroviral drug enfuvirtide and clinically presented as bullae over the anterior abdominal wall.

A 65-year-old man with HIV presented with pink vesicles and flaccid bullae on the anterolateral aspect of the lower abdomen (Figure 1) in areas of self-administered subcutaneous injections of enfuvirtide. He reported tissue swelling with a yellow discoloration immediately after injections that would spontaneously subside after a few minutes.

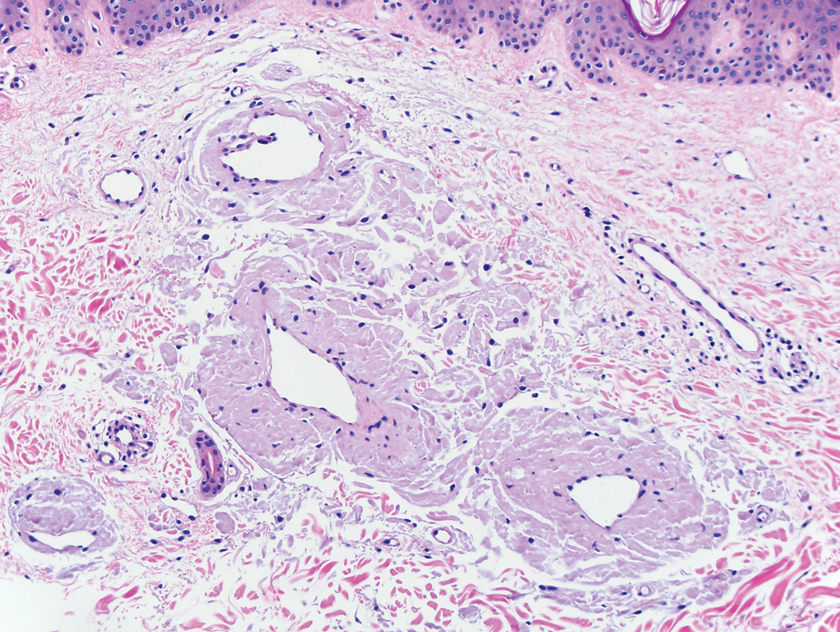

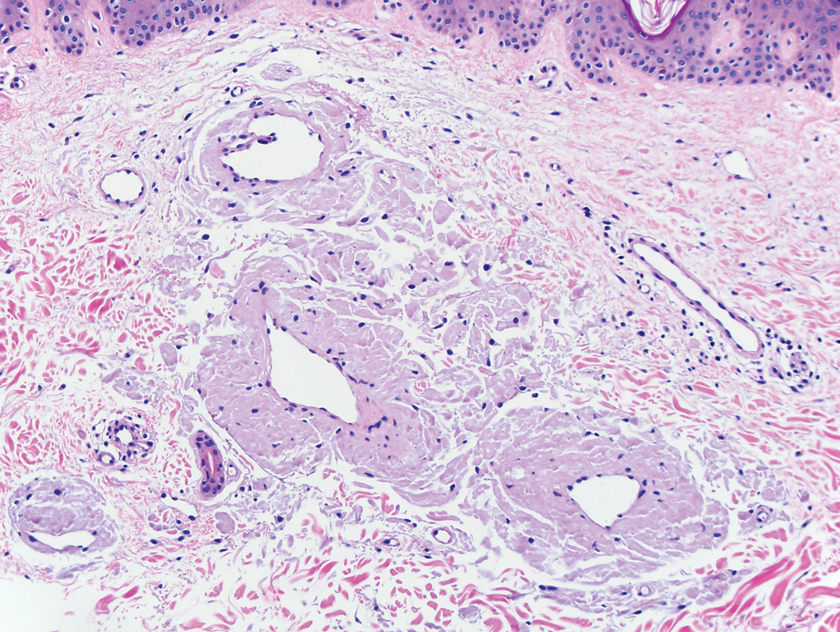

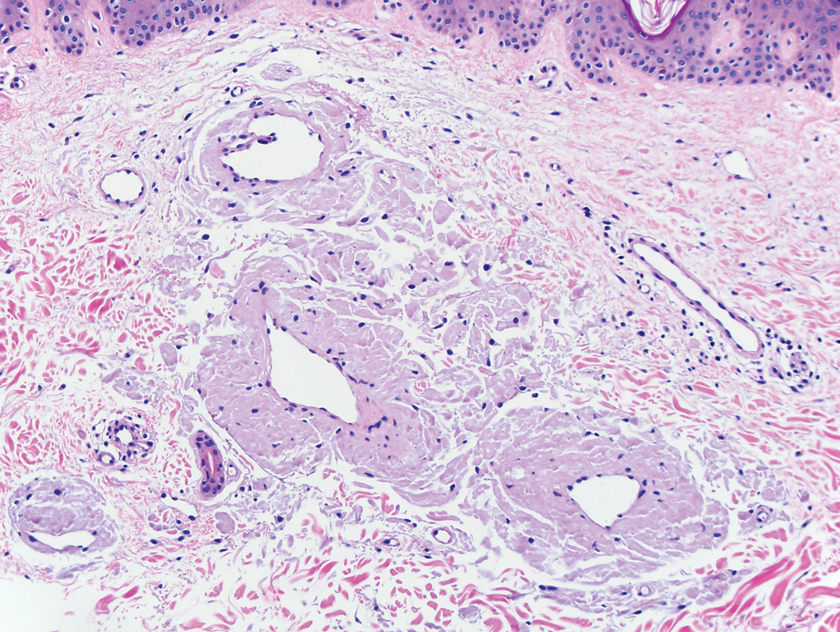

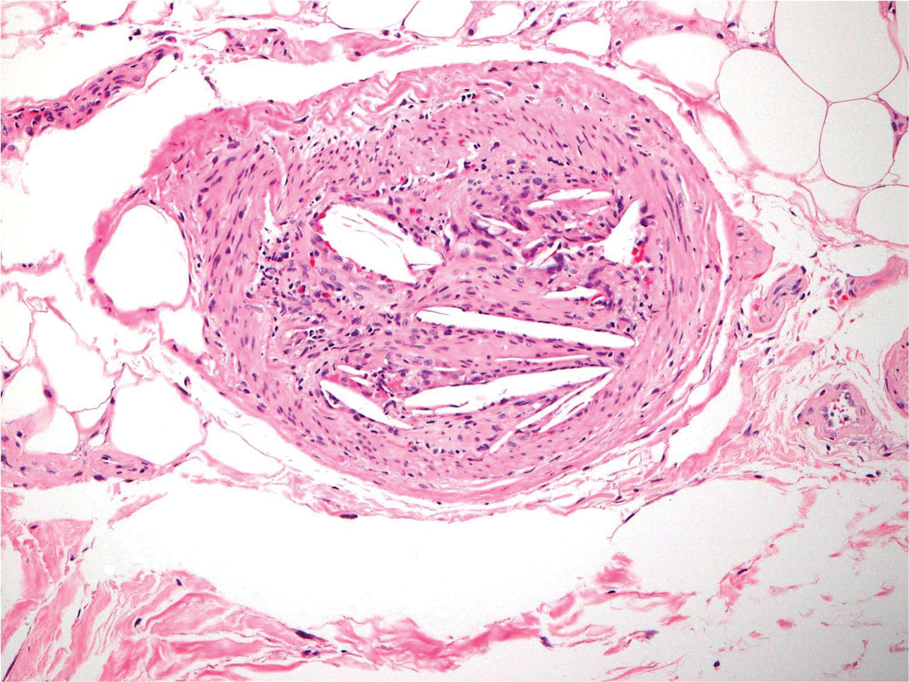

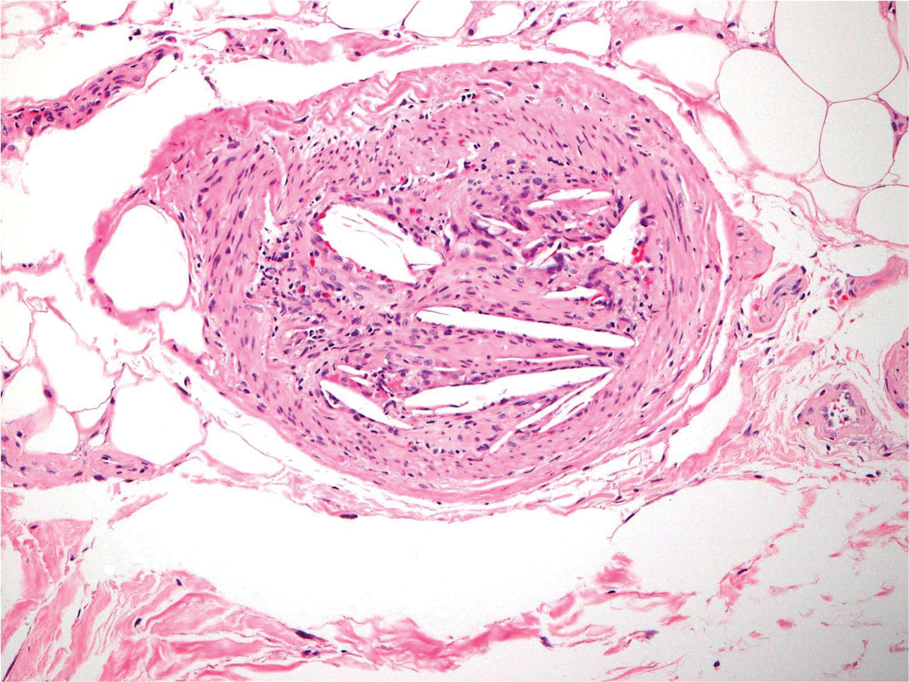

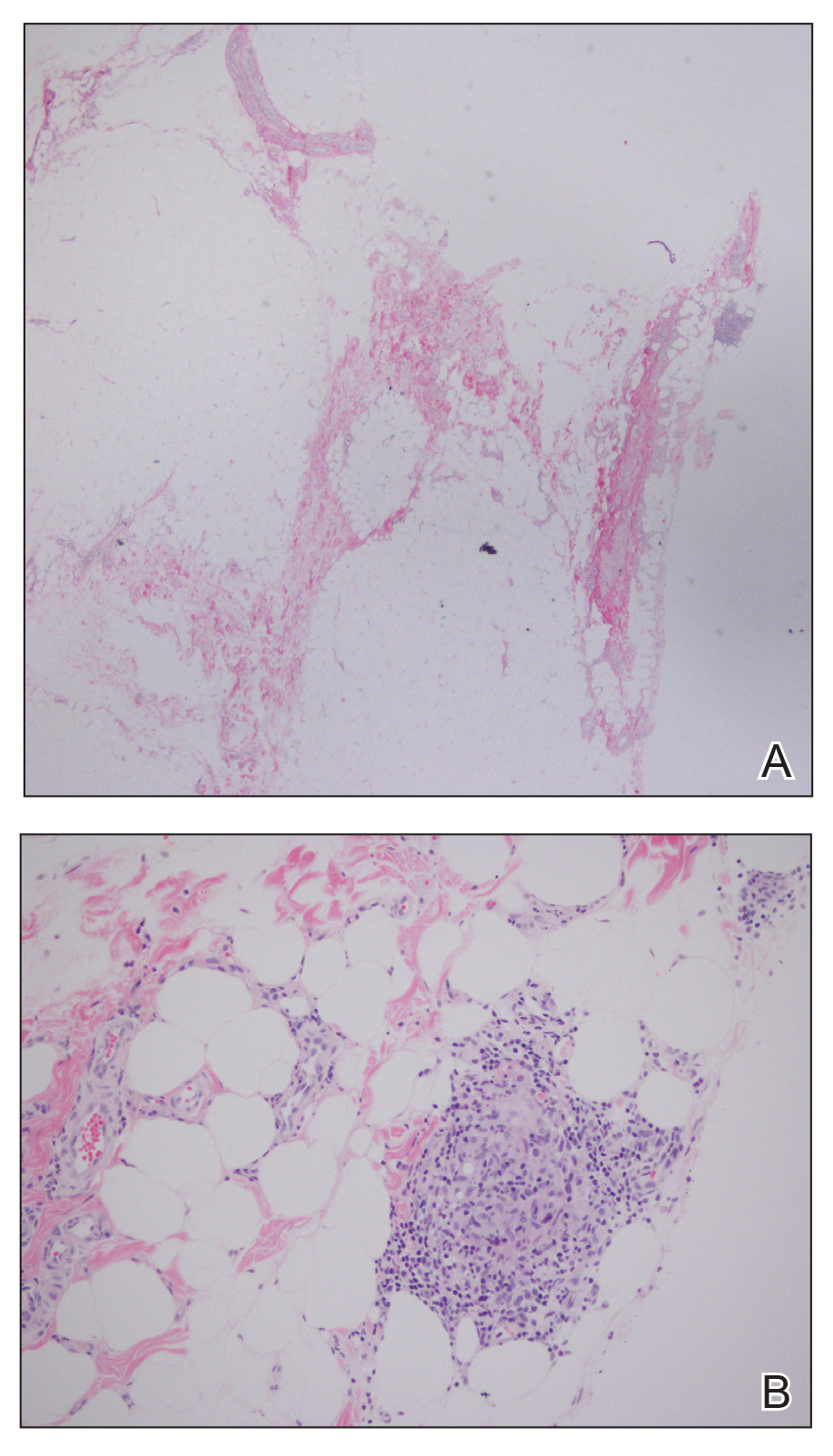

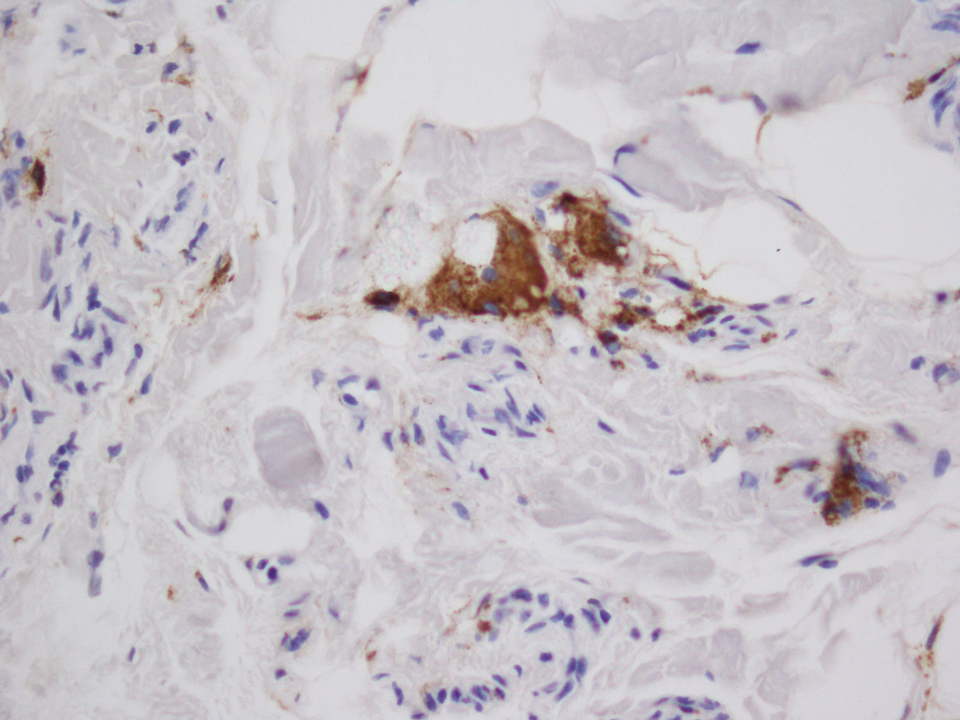

A biopsy from the left lateral abdomen revealed dilated vessels concentrically encompassed by pink globular material and nodular collections of the pink amorphous substance in the upper dermis (Figure 2), which was accompanied by a sparse, perivascular, lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate; scattered plasma cells; and rare eosinophils in a background of dermal edema. Although Congo red stain was negative, crystal violet revealed metachromatic staining of the globular material that was highlighted as dark violet against a blue background. Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of drug-induced amyloidosis was made.

Amyloidosis refers to a group of disorders that result from misfolding of proteins in the characteristic beta-pleated sheet structure that can accumulate in various tissues. There are different subtypes of amyloidosis based on the type of protein deposited: immunoglobulin light chain protein (AL); serum amyloid A (AA), an acute-phase reactant accumulating in those with long-standing inflammatory conditions; beta-2 microglobulin (Ab2M) in patients with renal failure; keratin in macular and lichen amyloidosis; pharmaceutical-derived amyloid (eg, enfuvirtide, injectable insulin); and mutated proteins in hereditary amyloidosis such as transthyretin.1 Other familial forms include genetic variants of apolipolipoprotein AII (AApoAI, AApoAII), fibrinogen A alpha chain (AFib), lysozyme (ALys), cystatin C (ACys), and gelsolin (AGel).2

Cutaneous amyloidosis can stem from a systemic disease or arise as a localized phenomenon. Primary cutaneous amyloidosis can present as either macular, lichen, or nodular forms. The pathogenesis of cutaneous nodular amyloidosis differs from that of lichen and macular types and results from deposition of light chain–derived amyloid protein. In contrast, lichen and macular subtypes have keratin-derived amyloid deposits in the papillary dermis and stain positive for keratin antibodies, especially cytokeratins 5 and 6. Primary nodular amyloidosis has a 7% to 50% risk for developing systemic amyloidosis and a 9% risk for local recurrence, hence the necessity to assess for monoclonal gammopathy with urine light chains and serum immunoelectrophoresis.3

Drug-induced amyloidosis is a distinct type of cutaneous amyloidosis that histopathologically resembles nodular amyloidosis. Multiple drugs have been reported in this setting: insulin,4,5 enfuvirtide injections, and liraglutide.6 Enfuvirtide belongs to a class of antiretroviral agents and is a synthetic peptide composed of 36 amino acids. It inhibits the fusion of HIV with the host helper T cell by binding to glycoprotein 41.7 Enfuvirtide-related amyloidosis was described in 3 case reports, 2 that confirmed enfuvirtide as the amyloid constituent by protein analysis.8-10 One study analyzed the amyloid proteome in 50 cases of insulin-derived amyloidosis and 2 cases of enfuvirtide-derived amyloidosis. Laser microdissection–tandem microscopy revealed that the amyloid in such cases was composed of the drug enfuvirtide itself along with deposits of apolipoproteins (E, A-I, A-IV) and serum amyloid P component.4 Additional complications can occur at the site of enfuvirtide injections. A retrospective review of 7 patients with injection-site reactions to enfuvirtide described erythema, induration, and nodules, with histopathologic findings including hypersensitivity reactions and palisaded granulomas resembling granuloma annulare. Amorphous material was noted within histiocytes and in the surrounding connective tissue that was confirmed as enfuvirtide by immunoperoxidase staining.11

In summary, several types of cutaneous amyloidosis occur, including secondary cutaneous involvement by systemic amyloidosis and drug-induced amyloidosis, and notable histopathologic overlap exists between these types. Given the differing treatment requirements depending on the type of cutaneous amyloidosis, obtaining an appropriate clinical history, including the patient’s medication list, is important to ensure the correct diagnosis is reached. Protein analysis with mass spectrometry can be used if the nature of the amyloid remains indeterminate.

- Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:583-596.

- Ferri FF. Amyloidosis. In: Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier; 2016.

- Kaltoft B, Schmidt G, Lauritzen AF, et al. Primary localised cutaneous amyloidosis—a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2013;60:A4727.

- D’Souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Sie MP, van der Wiel HE, Smedts FM, et al. Human recombinant insulin and amyloidosis: an unexpected association. Neth J Med. 2010;68:138-140.

- Martins CO, Lezcano C, Yi SS, et al. Novel iatrogenic amyloidosis caused by peptide drug liraglutide: a clinical mimic of AL amyloidosis. Haematologica. 2018;103:E610-E612.

- Lazzarin A, Clotet B, Cooper D, et al. Efficacy of enfuvirtide in patients infected with drug-resistant HIV-1 in Europe and Australia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2186-2195.

- Naujokas A, Vidal CI, Mercer SE, et al. A novel form of amyloid deposited at the site of enfuvirtide injection. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:220-221; quiz 219.

- Mercer S, Whang T, Vidal C, et al. Massive amyloidosis at the site of enfuvirtide (Fuzeon) injection. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:93.

- Morilla ME, Kocher J, Harmaty M. Localized amyloidosis at the site of enfuvirtide injection. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:515-516.

- Ball RA, Kinchelow T; ISR Substudy Group. Injection site reactions with the HIV-1 fusion inhibitor enfuvirtide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:826-831.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous amyloidosis can be secondary to many causes. We describe a case of amyloidosis that was secondary to the deposition of an antiretroviral drug enfuvirtide and clinically presented as bullae over the anterior abdominal wall.

A 65-year-old man with HIV presented with pink vesicles and flaccid bullae on the anterolateral aspect of the lower abdomen (Figure 1) in areas of self-administered subcutaneous injections of enfuvirtide. He reported tissue swelling with a yellow discoloration immediately after injections that would spontaneously subside after a few minutes.

A biopsy from the left lateral abdomen revealed dilated vessels concentrically encompassed by pink globular material and nodular collections of the pink amorphous substance in the upper dermis (Figure 2), which was accompanied by a sparse, perivascular, lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate; scattered plasma cells; and rare eosinophils in a background of dermal edema. Although Congo red stain was negative, crystal violet revealed metachromatic staining of the globular material that was highlighted as dark violet against a blue background. Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of drug-induced amyloidosis was made.

Amyloidosis refers to a group of disorders that result from misfolding of proteins in the characteristic beta-pleated sheet structure that can accumulate in various tissues. There are different subtypes of amyloidosis based on the type of protein deposited: immunoglobulin light chain protein (AL); serum amyloid A (AA), an acute-phase reactant accumulating in those with long-standing inflammatory conditions; beta-2 microglobulin (Ab2M) in patients with renal failure; keratin in macular and lichen amyloidosis; pharmaceutical-derived amyloid (eg, enfuvirtide, injectable insulin); and mutated proteins in hereditary amyloidosis such as transthyretin.1 Other familial forms include genetic variants of apolipolipoprotein AII (AApoAI, AApoAII), fibrinogen A alpha chain (AFib), lysozyme (ALys), cystatin C (ACys), and gelsolin (AGel).2

Cutaneous amyloidosis can stem from a systemic disease or arise as a localized phenomenon. Primary cutaneous amyloidosis can present as either macular, lichen, or nodular forms. The pathogenesis of cutaneous nodular amyloidosis differs from that of lichen and macular types and results from deposition of light chain–derived amyloid protein. In contrast, lichen and macular subtypes have keratin-derived amyloid deposits in the papillary dermis and stain positive for keratin antibodies, especially cytokeratins 5 and 6. Primary nodular amyloidosis has a 7% to 50% risk for developing systemic amyloidosis and a 9% risk for local recurrence, hence the necessity to assess for monoclonal gammopathy with urine light chains and serum immunoelectrophoresis.3

Drug-induced amyloidosis is a distinct type of cutaneous amyloidosis that histopathologically resembles nodular amyloidosis. Multiple drugs have been reported in this setting: insulin,4,5 enfuvirtide injections, and liraglutide.6 Enfuvirtide belongs to a class of antiretroviral agents and is a synthetic peptide composed of 36 amino acids. It inhibits the fusion of HIV with the host helper T cell by binding to glycoprotein 41.7 Enfuvirtide-related amyloidosis was described in 3 case reports, 2 that confirmed enfuvirtide as the amyloid constituent by protein analysis.8-10 One study analyzed the amyloid proteome in 50 cases of insulin-derived amyloidosis and 2 cases of enfuvirtide-derived amyloidosis. Laser microdissection–tandem microscopy revealed that the amyloid in such cases was composed of the drug enfuvirtide itself along with deposits of apolipoproteins (E, A-I, A-IV) and serum amyloid P component.4 Additional complications can occur at the site of enfuvirtide injections. A retrospective review of 7 patients with injection-site reactions to enfuvirtide described erythema, induration, and nodules, with histopathologic findings including hypersensitivity reactions and palisaded granulomas resembling granuloma annulare. Amorphous material was noted within histiocytes and in the surrounding connective tissue that was confirmed as enfuvirtide by immunoperoxidase staining.11

In summary, several types of cutaneous amyloidosis occur, including secondary cutaneous involvement by systemic amyloidosis and drug-induced amyloidosis, and notable histopathologic overlap exists between these types. Given the differing treatment requirements depending on the type of cutaneous amyloidosis, obtaining an appropriate clinical history, including the patient’s medication list, is important to ensure the correct diagnosis is reached. Protein analysis with mass spectrometry can be used if the nature of the amyloid remains indeterminate.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous amyloidosis can be secondary to many causes. We describe a case of amyloidosis that was secondary to the deposition of an antiretroviral drug enfuvirtide and clinically presented as bullae over the anterior abdominal wall.

A 65-year-old man with HIV presented with pink vesicles and flaccid bullae on the anterolateral aspect of the lower abdomen (Figure 1) in areas of self-administered subcutaneous injections of enfuvirtide. He reported tissue swelling with a yellow discoloration immediately after injections that would spontaneously subside after a few minutes.

A biopsy from the left lateral abdomen revealed dilated vessels concentrically encompassed by pink globular material and nodular collections of the pink amorphous substance in the upper dermis (Figure 2), which was accompanied by a sparse, perivascular, lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate; scattered plasma cells; and rare eosinophils in a background of dermal edema. Although Congo red stain was negative, crystal violet revealed metachromatic staining of the globular material that was highlighted as dark violet against a blue background. Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of drug-induced amyloidosis was made.

Amyloidosis refers to a group of disorders that result from misfolding of proteins in the characteristic beta-pleated sheet structure that can accumulate in various tissues. There are different subtypes of amyloidosis based on the type of protein deposited: immunoglobulin light chain protein (AL); serum amyloid A (AA), an acute-phase reactant accumulating in those with long-standing inflammatory conditions; beta-2 microglobulin (Ab2M) in patients with renal failure; keratin in macular and lichen amyloidosis; pharmaceutical-derived amyloid (eg, enfuvirtide, injectable insulin); and mutated proteins in hereditary amyloidosis such as transthyretin.1 Other familial forms include genetic variants of apolipolipoprotein AII (AApoAI, AApoAII), fibrinogen A alpha chain (AFib), lysozyme (ALys), cystatin C (ACys), and gelsolin (AGel).2

Cutaneous amyloidosis can stem from a systemic disease or arise as a localized phenomenon. Primary cutaneous amyloidosis can present as either macular, lichen, or nodular forms. The pathogenesis of cutaneous nodular amyloidosis differs from that of lichen and macular types and results from deposition of light chain–derived amyloid protein. In contrast, lichen and macular subtypes have keratin-derived amyloid deposits in the papillary dermis and stain positive for keratin antibodies, especially cytokeratins 5 and 6. Primary nodular amyloidosis has a 7% to 50% risk for developing systemic amyloidosis and a 9% risk for local recurrence, hence the necessity to assess for monoclonal gammopathy with urine light chains and serum immunoelectrophoresis.3

Drug-induced amyloidosis is a distinct type of cutaneous amyloidosis that histopathologically resembles nodular amyloidosis. Multiple drugs have been reported in this setting: insulin,4,5 enfuvirtide injections, and liraglutide.6 Enfuvirtide belongs to a class of antiretroviral agents and is a synthetic peptide composed of 36 amino acids. It inhibits the fusion of HIV with the host helper T cell by binding to glycoprotein 41.7 Enfuvirtide-related amyloidosis was described in 3 case reports, 2 that confirmed enfuvirtide as the amyloid constituent by protein analysis.8-10 One study analyzed the amyloid proteome in 50 cases of insulin-derived amyloidosis and 2 cases of enfuvirtide-derived amyloidosis. Laser microdissection–tandem microscopy revealed that the amyloid in such cases was composed of the drug enfuvirtide itself along with deposits of apolipoproteins (E, A-I, A-IV) and serum amyloid P component.4 Additional complications can occur at the site of enfuvirtide injections. A retrospective review of 7 patients with injection-site reactions to enfuvirtide described erythema, induration, and nodules, with histopathologic findings including hypersensitivity reactions and palisaded granulomas resembling granuloma annulare. Amorphous material was noted within histiocytes and in the surrounding connective tissue that was confirmed as enfuvirtide by immunoperoxidase staining.11

In summary, several types of cutaneous amyloidosis occur, including secondary cutaneous involvement by systemic amyloidosis and drug-induced amyloidosis, and notable histopathologic overlap exists between these types. Given the differing treatment requirements depending on the type of cutaneous amyloidosis, obtaining an appropriate clinical history, including the patient’s medication list, is important to ensure the correct diagnosis is reached. Protein analysis with mass spectrometry can be used if the nature of the amyloid remains indeterminate.

- Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:583-596.

- Ferri FF. Amyloidosis. In: Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier; 2016.

- Kaltoft B, Schmidt G, Lauritzen AF, et al. Primary localised cutaneous amyloidosis—a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2013;60:A4727.

- D’Souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Sie MP, van der Wiel HE, Smedts FM, et al. Human recombinant insulin and amyloidosis: an unexpected association. Neth J Med. 2010;68:138-140.

- Martins CO, Lezcano C, Yi SS, et al. Novel iatrogenic amyloidosis caused by peptide drug liraglutide: a clinical mimic of AL amyloidosis. Haematologica. 2018;103:E610-E612.

- Lazzarin A, Clotet B, Cooper D, et al. Efficacy of enfuvirtide in patients infected with drug-resistant HIV-1 in Europe and Australia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2186-2195.

- Naujokas A, Vidal CI, Mercer SE, et al. A novel form of amyloid deposited at the site of enfuvirtide injection. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:220-221; quiz 219.

- Mercer S, Whang T, Vidal C, et al. Massive amyloidosis at the site of enfuvirtide (Fuzeon) injection. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:93.

- Morilla ME, Kocher J, Harmaty M. Localized amyloidosis at the site of enfuvirtide injection. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:515-516.

- Ball RA, Kinchelow T; ISR Substudy Group. Injection site reactions with the HIV-1 fusion inhibitor enfuvirtide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:826-831.

- Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:583-596.

- Ferri FF. Amyloidosis. In: Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier; 2016.

- Kaltoft B, Schmidt G, Lauritzen AF, et al. Primary localised cutaneous amyloidosis—a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2013;60:A4727.

- D’Souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Sie MP, van der Wiel HE, Smedts FM, et al. Human recombinant insulin and amyloidosis: an unexpected association. Neth J Med. 2010;68:138-140.

- Martins CO, Lezcano C, Yi SS, et al. Novel iatrogenic amyloidosis caused by peptide drug liraglutide: a clinical mimic of AL amyloidosis. Haematologica. 2018;103:E610-E612.

- Lazzarin A, Clotet B, Cooper D, et al. Efficacy of enfuvirtide in patients infected with drug-resistant HIV-1 in Europe and Australia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2186-2195.

- Naujokas A, Vidal CI, Mercer SE, et al. A novel form of amyloid deposited at the site of enfuvirtide injection. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:220-221; quiz 219.

- Mercer S, Whang T, Vidal C, et al. Massive amyloidosis at the site of enfuvirtide (Fuzeon) injection. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:93.

- Morilla ME, Kocher J, Harmaty M. Localized amyloidosis at the site of enfuvirtide injection. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:515-516.

- Ball RA, Kinchelow T; ISR Substudy Group. Injection site reactions with the HIV-1 fusion inhibitor enfuvirtide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:826-831.

Practice Points

- There are multiple types of cutaneous amyloidosis, and proper diagnosis is essential to direct treatment and follow-up care.

- Medication-associated amyloidosis is a rare type of amyloidosis that is not associated with systemic amyloidosis and is treated by switching to alternative medicines.

Wax Stripping and Isotretinoin Treatment: A Warning Not to Be Missed

To the Editor:

Oral isotretinoin is a widely used treatment modality in dermatologic practice that is highly effective for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris in addition to other conditions. Its use is accompanied by a variety of side effects that are mainly mucocutaneous. These dose-dependent side effects are experienced by almost all patients treated with this medication.1

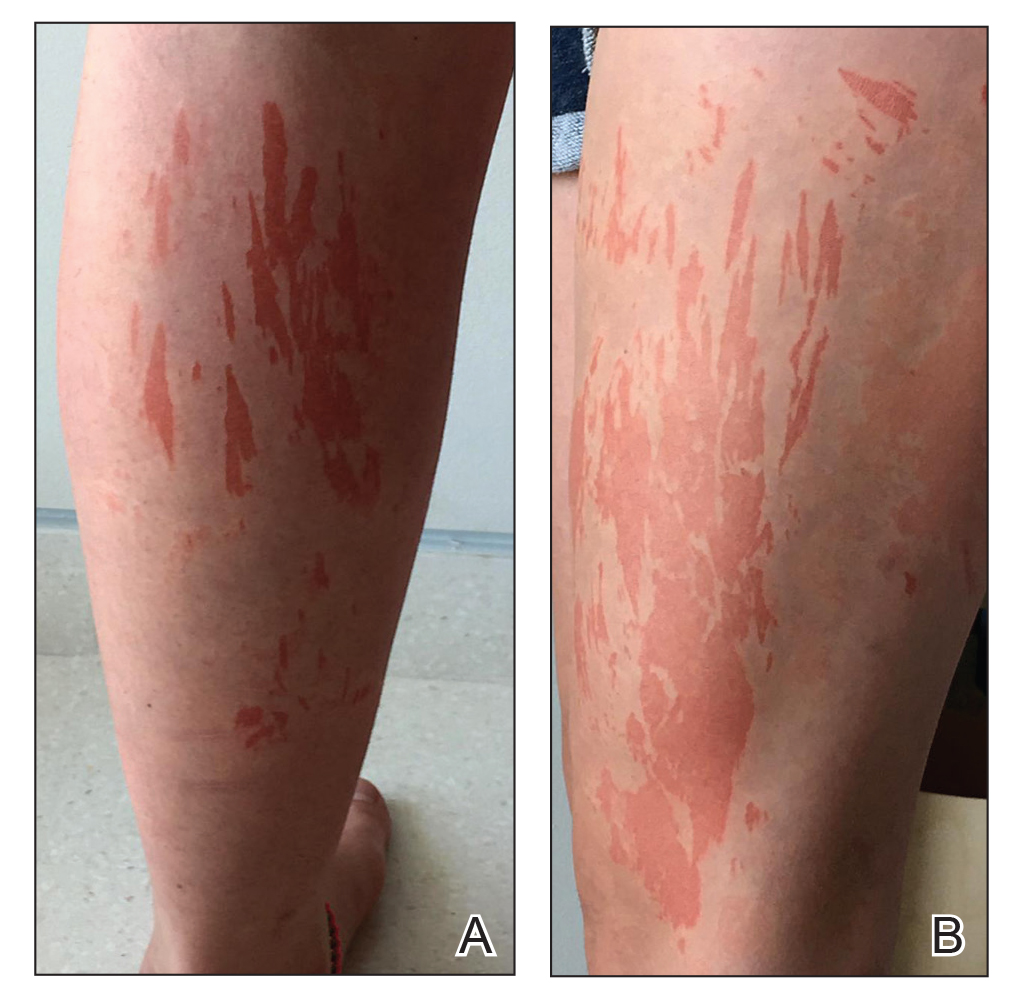

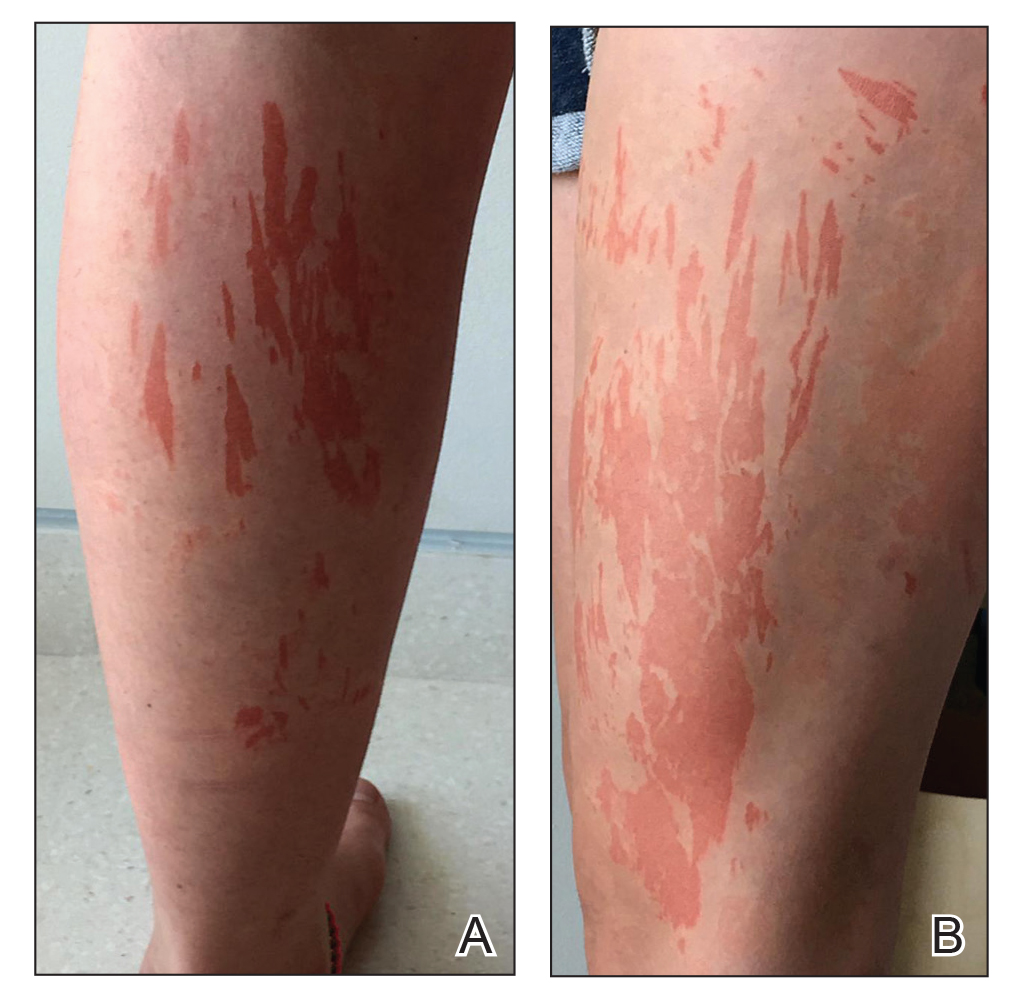

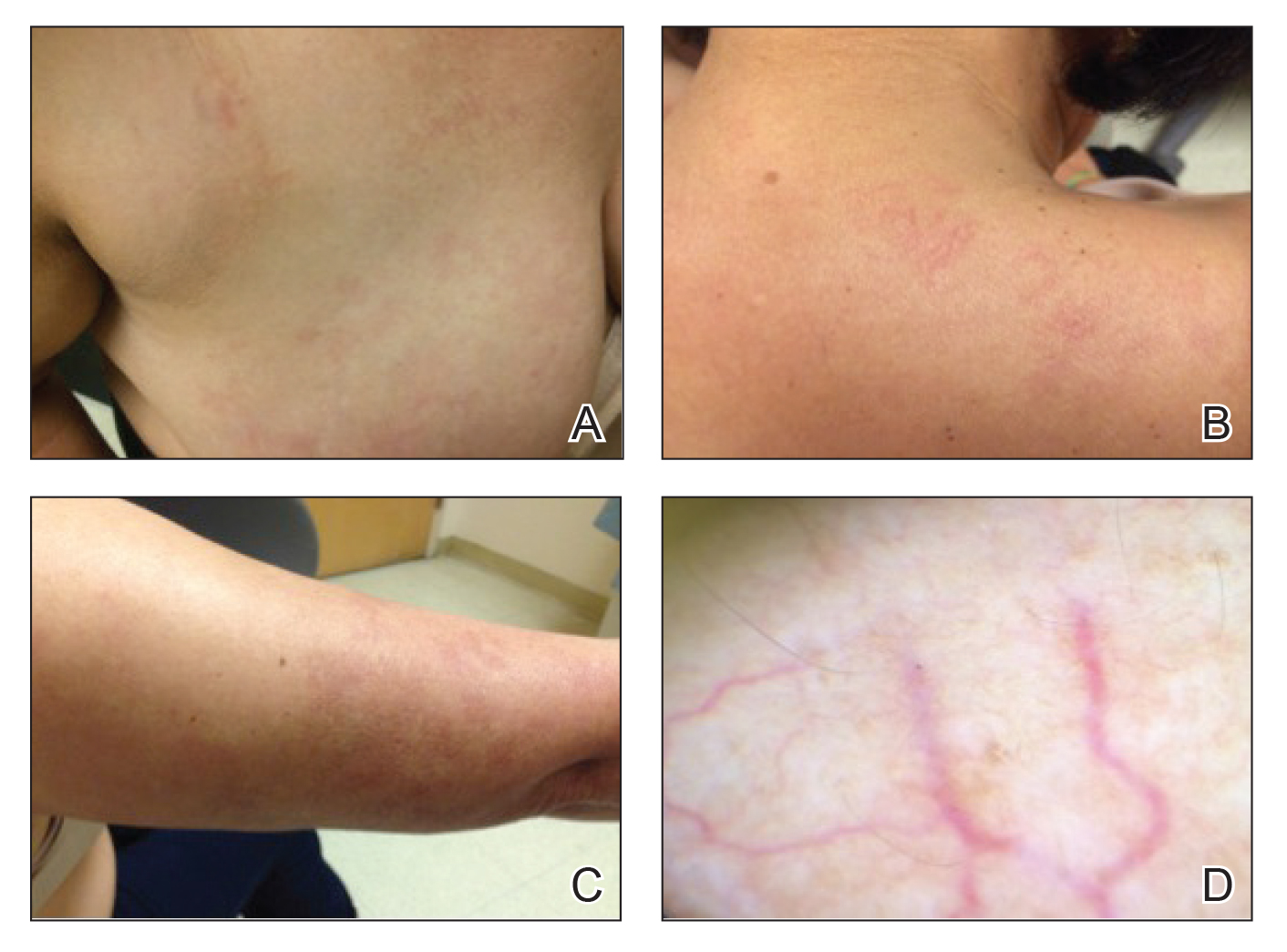

A generally healthy 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with severe widespread erosions located in a linear pattern corresponding to areas of wax depilation on the shins and thighs (Figure). Approximately 5 months prior, the patient started oral isotretinoin 40 mg daily for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris. She was not taking other medications. After 4 months of treatment, during which the acne lesions improved and the patient experienced only mild xerosis and cheilitis, the dosage was increased to 60 mg daily. Three weeks later, the patient underwent wax depilation, which resulted in the erosions.

Oral isotretinoin treatment leads to structural and functional changes to the skin, related to epidermal dyscohesion and sebo-suppression. Although these changes may not be clinically evident in all patients, they still make the skin much more sensitive to external mechanical stimuli.1 Wax depilation commonly is used for treating excess hair on the body. Because it exerts remarkable mechanical stress on the epidermis, it may lead to epidermal stripping in patients taking isotretinoin, manifesting as widespread erosions and resulting in notable patient distress.

Dermatologists typically advise patients to avoid wax epilation while being treated with isotretinoin; however, some patients do not adhere to this recommendation. Also, there are dermatologists who are not aware of this potential side effect. In one survey (N=54), only 4% of consulting dermatologists were aware of this complication.2 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotretinoin and wax revealed that this severe side effect with isotretinoin has been reported only 4 times in the medical literature.2-5 The fact that wax epilation should be avoided during isotretinoin treatment previously was not included in the prescribing information. It currently is included in the isotretinoin prescribing information6 with an indication not to perform wax depilation for 6 months after stopping treatment. This case should serve as a reminder to avoid wax depilation during isotretinoin treatment.

- Del Rosso JQ. Clinical relevance of skin barrier changes associated with the use of oral isotretinoin: the importance of barrier repair therapy in patient management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:626-631.

Woollons A, Price ML. Roaccutane and wax epilation: a cautionary tale. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:839-840. - Egido Romo M. Isotretinoin and wax epilation. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:393.

- Holmes SC, Thomson J. Isotretinoin and skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:165.

- Turel-Ermertcan A, Sahin MT, Yurtman D, et al. Inappropriate treatments at beauty centers: a case report of burns caused by hot wax stripping. J Dermatol. 2004;31:854-855.

- Accutane. Package insert. Roche; 2008.

To the Editor:

Oral isotretinoin is a widely used treatment modality in dermatologic practice that is highly effective for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris in addition to other conditions. Its use is accompanied by a variety of side effects that are mainly mucocutaneous. These dose-dependent side effects are experienced by almost all patients treated with this medication.1

A generally healthy 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with severe widespread erosions located in a linear pattern corresponding to areas of wax depilation on the shins and thighs (Figure). Approximately 5 months prior, the patient started oral isotretinoin 40 mg daily for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris. She was not taking other medications. After 4 months of treatment, during which the acne lesions improved and the patient experienced only mild xerosis and cheilitis, the dosage was increased to 60 mg daily. Three weeks later, the patient underwent wax depilation, which resulted in the erosions.

Oral isotretinoin treatment leads to structural and functional changes to the skin, related to epidermal dyscohesion and sebo-suppression. Although these changes may not be clinically evident in all patients, they still make the skin much more sensitive to external mechanical stimuli.1 Wax depilation commonly is used for treating excess hair on the body. Because it exerts remarkable mechanical stress on the epidermis, it may lead to epidermal stripping in patients taking isotretinoin, manifesting as widespread erosions and resulting in notable patient distress.

Dermatologists typically advise patients to avoid wax epilation while being treated with isotretinoin; however, some patients do not adhere to this recommendation. Also, there are dermatologists who are not aware of this potential side effect. In one survey (N=54), only 4% of consulting dermatologists were aware of this complication.2 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotretinoin and wax revealed that this severe side effect with isotretinoin has been reported only 4 times in the medical literature.2-5 The fact that wax epilation should be avoided during isotretinoin treatment previously was not included in the prescribing information. It currently is included in the isotretinoin prescribing information6 with an indication not to perform wax depilation for 6 months after stopping treatment. This case should serve as a reminder to avoid wax depilation during isotretinoin treatment.

To the Editor:

Oral isotretinoin is a widely used treatment modality in dermatologic practice that is highly effective for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris in addition to other conditions. Its use is accompanied by a variety of side effects that are mainly mucocutaneous. These dose-dependent side effects are experienced by almost all patients treated with this medication.1

A generally healthy 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with severe widespread erosions located in a linear pattern corresponding to areas of wax depilation on the shins and thighs (Figure). Approximately 5 months prior, the patient started oral isotretinoin 40 mg daily for severe and recalcitrant acne vulgaris. She was not taking other medications. After 4 months of treatment, during which the acne lesions improved and the patient experienced only mild xerosis and cheilitis, the dosage was increased to 60 mg daily. Three weeks later, the patient underwent wax depilation, which resulted in the erosions.

Oral isotretinoin treatment leads to structural and functional changes to the skin, related to epidermal dyscohesion and sebo-suppression. Although these changes may not be clinically evident in all patients, they still make the skin much more sensitive to external mechanical stimuli.1 Wax depilation commonly is used for treating excess hair on the body. Because it exerts remarkable mechanical stress on the epidermis, it may lead to epidermal stripping in patients taking isotretinoin, manifesting as widespread erosions and resulting in notable patient distress.

Dermatologists typically advise patients to avoid wax epilation while being treated with isotretinoin; however, some patients do not adhere to this recommendation. Also, there are dermatologists who are not aware of this potential side effect. In one survey (N=54), only 4% of consulting dermatologists were aware of this complication.2 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotretinoin and wax revealed that this severe side effect with isotretinoin has been reported only 4 times in the medical literature.2-5 The fact that wax epilation should be avoided during isotretinoin treatment previously was not included in the prescribing information. It currently is included in the isotretinoin prescribing information6 with an indication not to perform wax depilation for 6 months after stopping treatment. This case should serve as a reminder to avoid wax depilation during isotretinoin treatment.

- Del Rosso JQ. Clinical relevance of skin barrier changes associated with the use of oral isotretinoin: the importance of barrier repair therapy in patient management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:626-631.

Woollons A, Price ML. Roaccutane and wax epilation: a cautionary tale. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:839-840. - Egido Romo M. Isotretinoin and wax epilation. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:393.

- Holmes SC, Thomson J. Isotretinoin and skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:165.

- Turel-Ermertcan A, Sahin MT, Yurtman D, et al. Inappropriate treatments at beauty centers: a case report of burns caused by hot wax stripping. J Dermatol. 2004;31:854-855.

- Accutane. Package insert. Roche; 2008.

- Del Rosso JQ. Clinical relevance of skin barrier changes associated with the use of oral isotretinoin: the importance of barrier repair therapy in patient management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:626-631.

Woollons A, Price ML. Roaccutane and wax epilation: a cautionary tale. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:839-840. - Egido Romo M. Isotretinoin and wax epilation. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:393.

- Holmes SC, Thomson J. Isotretinoin and skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:165.

- Turel-Ermertcan A, Sahin MT, Yurtman D, et al. Inappropriate treatments at beauty centers: a case report of burns caused by hot wax stripping. J Dermatol. 2004;31:854-855.

- Accutane. Package insert. Roche; 2008.

Practice Points

- Oral isotretinoin treatment leads to structural and functional changes to the skin, making it much more sensitive to external mechanical stimuli.

- Wax depilation may lead to epidermal stripping in patients taking isotretinoin and therefore should be avoided in these patients.

Cutaneous Cholesterol Embolization to the Lower Trunk: An Underrecognized Presentation

To the Editor:

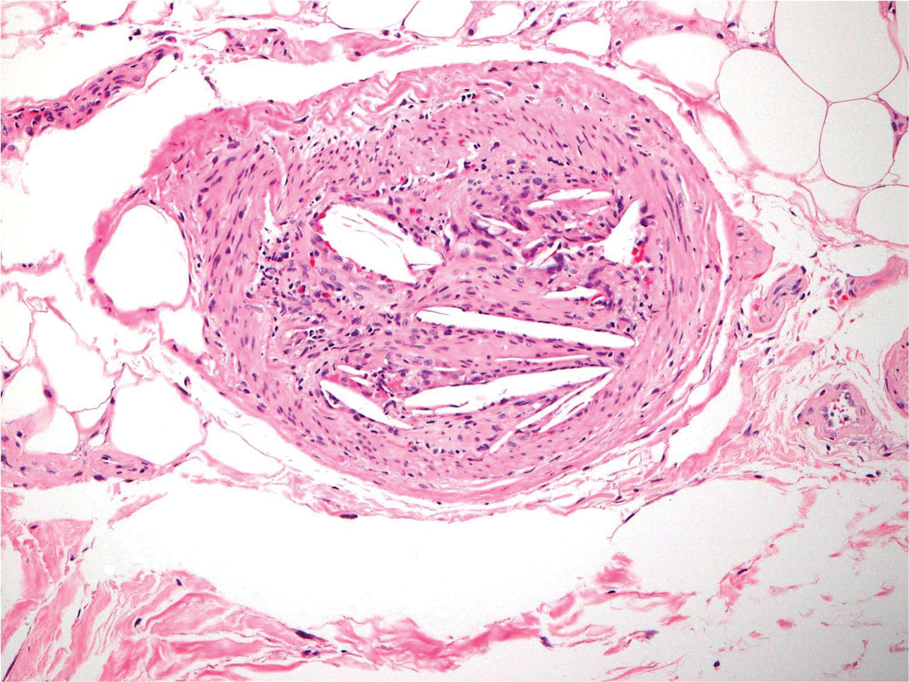

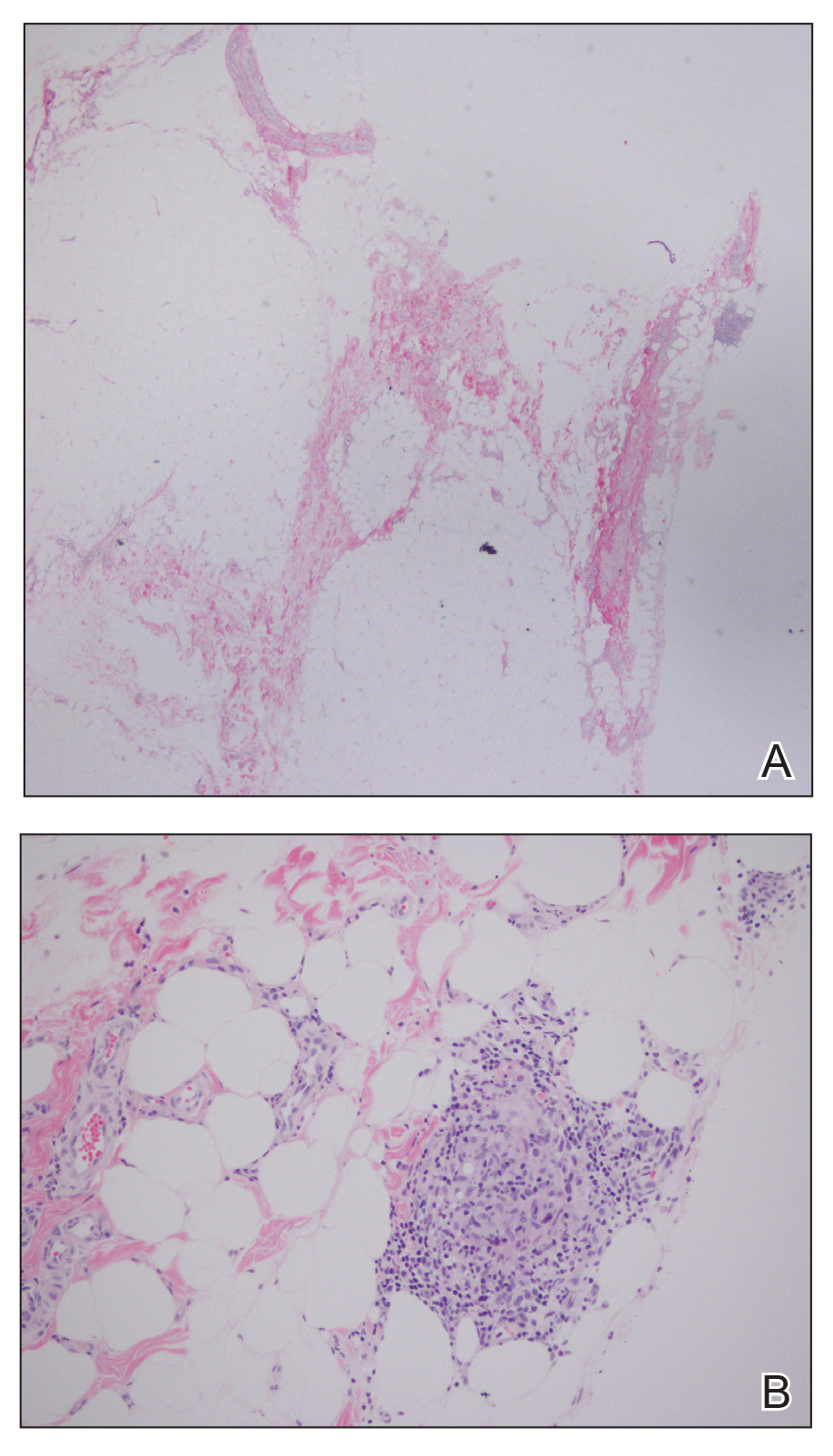

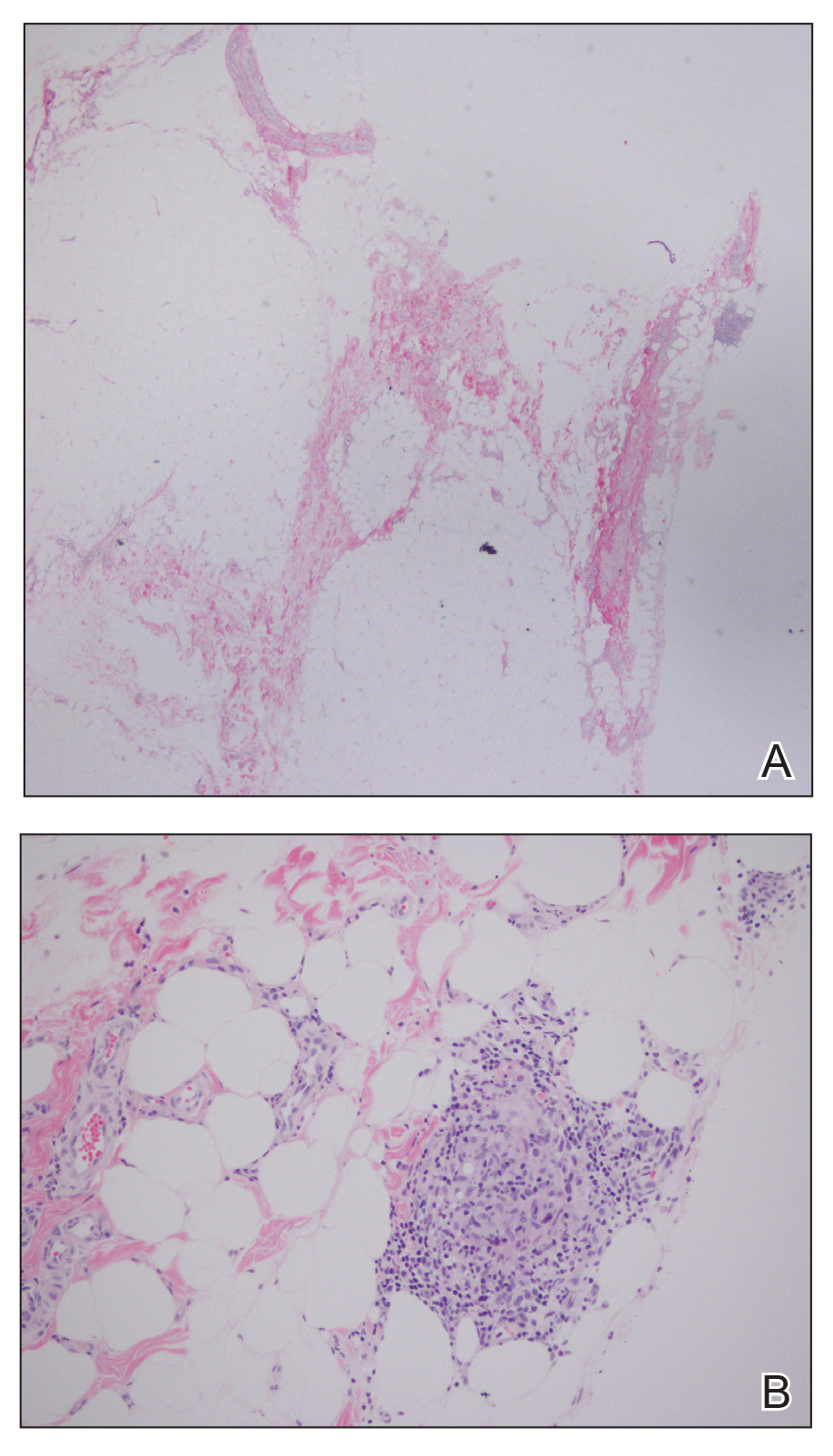

A 65-year-old man with severe atherosclerotic disease developed multiple painful eschars on the lower abdomen, thighs, sacrum, and perineum. He initially presented with myocardial ischemia and claudication and underwent 3 cardiac catheterizations as well as stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Within 2 weeks, he developed exquisitely tender nodules on the lower abdomen, clinically presumed to be sites of enoxaparin injections. These lesions gradually expanded and ulcerated to involve the sacrum, buttock, perineum, and upper thighs (Figure 1). Two punch biopsies from ulcerated skin taken 10 days apart demonstrated necrosis of skin and subcutaneous fat without evidence of vasculitis, vasculopathy, emboli, or notable inflammation despite examination of multiple levels of all submitted tissue. A definitive cause for the ulcerations remained elusive with development of new lesions. A third incisional biopsy of a newly developed, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodule performed 8 weeks after presentation revealed multiple cholesterol emboli (Figure 2). He was treated with warfarin and clopidogrel bisulfate as well as local wound care. The lesions slowly resolved over the next 4 to 6 months.

Cholesterol embolization syndrome occurs when disrupted atherosclerotic plaques embolize from large proximal arteries to more distal arterioles, resulting in ischemic damage to 1 or more organ systems.1 It can occur spontaneously but often is a consequence of thrombolytic therapy, anticoagulation, and angioinvasive procedures.2,3 Cutaneous manifestations include livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, nodules, and gangrene. Although livedo reticularis may extend from the legs to the trunk, gangrenous lesions predominantly involve the distal digits.

This case illustrates the challenge in diagnosis of cholesterol emboli, both clinically and histologically. Cutaneous lesions are morphologically variable and often occur with systemic manifestations, mimicking numerous conditions.1 Lower extremity involvement is a well-known occurrence in cholesterol embolization (ie, blue toe syndrome); however, periumbilical and lumbosacral lesions have not been emphasized in the dermatologic or peripheral vascular literature. Our patient’s initial diagnosis was enoxaparin necrosis at abdominal injection sites; however, this unusual distribution of lesions was ultimately determined to be the consequence of cholesterol embolization from the inferior epigastric and superficial external pudendal arteries at the time of stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Proximal truncal involvement should be recognized as an atypical but important cutaneous manifestation to facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment.4,5

Our patient’s course also highlights the potential need for multiple biopsies. Although the gold standard for diagnosis is histologic confirmation, a negative biopsy does not always exclude cholesterol emboli, and one should have a low threshold to perform additional biopsies in the appropriate clinical setting.

- Fine MJ, Kapoor W, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a review of 221 cases in the English literature. Angiology. 1987;38:769-784.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, et al. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:211-216.

- Karalis DG, Chandrasekaran K, Victor MF, et al. Recognition and embolic potential of intraaortic atherosclerotic debris. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:73.

- Zaytsev P, Miller K, Pellettiere EV. Cutaneous cholesterol emboli with infarction clinically mimicking heparin necrosis—a case report. Angiology. 1986;37:471-476.

- Erdim M, Tezel E, Biskin N. A case of skin necrosis as a result of cholesterol crystal embolisation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:429-432.

To the Editor:

A 65-year-old man with severe atherosclerotic disease developed multiple painful eschars on the lower abdomen, thighs, sacrum, and perineum. He initially presented with myocardial ischemia and claudication and underwent 3 cardiac catheterizations as well as stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Within 2 weeks, he developed exquisitely tender nodules on the lower abdomen, clinically presumed to be sites of enoxaparin injections. These lesions gradually expanded and ulcerated to involve the sacrum, buttock, perineum, and upper thighs (Figure 1). Two punch biopsies from ulcerated skin taken 10 days apart demonstrated necrosis of skin and subcutaneous fat without evidence of vasculitis, vasculopathy, emboli, or notable inflammation despite examination of multiple levels of all submitted tissue. A definitive cause for the ulcerations remained elusive with development of new lesions. A third incisional biopsy of a newly developed, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodule performed 8 weeks after presentation revealed multiple cholesterol emboli (Figure 2). He was treated with warfarin and clopidogrel bisulfate as well as local wound care. The lesions slowly resolved over the next 4 to 6 months.

Cholesterol embolization syndrome occurs when disrupted atherosclerotic plaques embolize from large proximal arteries to more distal arterioles, resulting in ischemic damage to 1 or more organ systems.1 It can occur spontaneously but often is a consequence of thrombolytic therapy, anticoagulation, and angioinvasive procedures.2,3 Cutaneous manifestations include livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, nodules, and gangrene. Although livedo reticularis may extend from the legs to the trunk, gangrenous lesions predominantly involve the distal digits.

This case illustrates the challenge in diagnosis of cholesterol emboli, both clinically and histologically. Cutaneous lesions are morphologically variable and often occur with systemic manifestations, mimicking numerous conditions.1 Lower extremity involvement is a well-known occurrence in cholesterol embolization (ie, blue toe syndrome); however, periumbilical and lumbosacral lesions have not been emphasized in the dermatologic or peripheral vascular literature. Our patient’s initial diagnosis was enoxaparin necrosis at abdominal injection sites; however, this unusual distribution of lesions was ultimately determined to be the consequence of cholesterol embolization from the inferior epigastric and superficial external pudendal arteries at the time of stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Proximal truncal involvement should be recognized as an atypical but important cutaneous manifestation to facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment.4,5

Our patient’s course also highlights the potential need for multiple biopsies. Although the gold standard for diagnosis is histologic confirmation, a negative biopsy does not always exclude cholesterol emboli, and one should have a low threshold to perform additional biopsies in the appropriate clinical setting.

To the Editor:

A 65-year-old man with severe atherosclerotic disease developed multiple painful eschars on the lower abdomen, thighs, sacrum, and perineum. He initially presented with myocardial ischemia and claudication and underwent 3 cardiac catheterizations as well as stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Within 2 weeks, he developed exquisitely tender nodules on the lower abdomen, clinically presumed to be sites of enoxaparin injections. These lesions gradually expanded and ulcerated to involve the sacrum, buttock, perineum, and upper thighs (Figure 1). Two punch biopsies from ulcerated skin taken 10 days apart demonstrated necrosis of skin and subcutaneous fat without evidence of vasculitis, vasculopathy, emboli, or notable inflammation despite examination of multiple levels of all submitted tissue. A definitive cause for the ulcerations remained elusive with development of new lesions. A third incisional biopsy of a newly developed, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodule performed 8 weeks after presentation revealed multiple cholesterol emboli (Figure 2). He was treated with warfarin and clopidogrel bisulfate as well as local wound care. The lesions slowly resolved over the next 4 to 6 months.

Cholesterol embolization syndrome occurs when disrupted atherosclerotic plaques embolize from large proximal arteries to more distal arterioles, resulting in ischemic damage to 1 or more organ systems.1 It can occur spontaneously but often is a consequence of thrombolytic therapy, anticoagulation, and angioinvasive procedures.2,3 Cutaneous manifestations include livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, nodules, and gangrene. Although livedo reticularis may extend from the legs to the trunk, gangrenous lesions predominantly involve the distal digits.

This case illustrates the challenge in diagnosis of cholesterol emboli, both clinically and histologically. Cutaneous lesions are morphologically variable and often occur with systemic manifestations, mimicking numerous conditions.1 Lower extremity involvement is a well-known occurrence in cholesterol embolization (ie, blue toe syndrome); however, periumbilical and lumbosacral lesions have not been emphasized in the dermatologic or peripheral vascular literature. Our patient’s initial diagnosis was enoxaparin necrosis at abdominal injection sites; however, this unusual distribution of lesions was ultimately determined to be the consequence of cholesterol embolization from the inferior epigastric and superficial external pudendal arteries at the time of stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Proximal truncal involvement should be recognized as an atypical but important cutaneous manifestation to facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment.4,5

Our patient’s course also highlights the potential need for multiple biopsies. Although the gold standard for diagnosis is histologic confirmation, a negative biopsy does not always exclude cholesterol emboli, and one should have a low threshold to perform additional biopsies in the appropriate clinical setting.

- Fine MJ, Kapoor W, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a review of 221 cases in the English literature. Angiology. 1987;38:769-784.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, et al. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:211-216.

- Karalis DG, Chandrasekaran K, Victor MF, et al. Recognition and embolic potential of intraaortic atherosclerotic debris. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:73.

- Zaytsev P, Miller K, Pellettiere EV. Cutaneous cholesterol emboli with infarction clinically mimicking heparin necrosis—a case report. Angiology. 1986;37:471-476.

- Erdim M, Tezel E, Biskin N. A case of skin necrosis as a result of cholesterol crystal embolisation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:429-432.

- Fine MJ, Kapoor W, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a review of 221 cases in the English literature. Angiology. 1987;38:769-784.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, et al. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:211-216.

- Karalis DG, Chandrasekaran K, Victor MF, et al. Recognition and embolic potential of intraaortic atherosclerotic debris. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:73.

- Zaytsev P, Miller K, Pellettiere EV. Cutaneous cholesterol emboli with infarction clinically mimicking heparin necrosis—a case report. Angiology. 1986;37:471-476.

- Erdim M, Tezel E, Biskin N. A case of skin necrosis as a result of cholesterol crystal embolisation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:429-432.

Practice Points

- Cholesterol embolization may occur in proximal locations, and index of suspicion should be high in patients who are at risk.

- Several biopsies may be necessary to make a diagnosis of cholesterol emboli.

Candida Esophagitis Associated With Adalimumab for Hidradenitis Suppurativa

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the development of painful abscesses, fistulous tracts, and scars. It most commonly affects the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body such as the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. With a prevalence of approximately 1%, HS can lead to notable morbidity.1 The pathogenesis is thought to be due to occlusion of terminal hair follicles that subsequently stimulates release of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes. The mechanism of initial occlusion is not well understood but may be due to friction or trauma. An inflammatory mechanism of disease also has been hypothesized; however, the exact cytokine profile is not known. Treatment of HS consists of several different modalities, including oral retinoids, antibiotics, antiandrogenic therapy, and surgery.1,2 Adalimumab is a well-known biologic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS.

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and is thought to improve HS by several mechanisms. Inhibition of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines found in inflammatory lesions and apocrine glands directly decreases the severity of lesion size and the frequency of recurrence.3 Adalimumab also is thought to downregulate expression of keratin 6 and prevent the hyperkeratinization seen in HS.4 Additionally, TNF-α inhibition decreases production of IL-1, which has been shown to cause hypercornification of follicles and perpetuate HS pathogenesis.5

A 41-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, adenomyosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, interstitial cystitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, depression, and Hashimoto thyroiditis presented to our dermatology clinic with active draining lesions and sinus tracts in the perivaginal area that were consistent with HS, which initially was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She experienced minimal improvement of the HS lesions at 2-month follow-up.

Due to disease severity, adalimumab was started. The patient received a loading dose of 4 injections totaling 160 mg and 80 mg on day 15, followed by a maintenance dose of 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly. The patient reported substantial improvement of pain, and complete resolution of active lesions was noted on physical examination after 4 weeks of treatment with adalimumab.

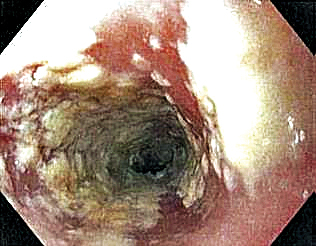

Six weeks after adalimumab was started, the patient developed severe dysphagia. She was evaluated by a gastroenterologist and underwent endoscopy (Figure), which led to a diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis. Adalimumab was discontinued immediately thereafter. The patient started treatment with nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily and oral fluconazole 200 mg daily. The candidiasis resolved within 2 weeks; however, she experienced recurrence of HS with draining lesions in the perivaginal area approximately 8 weeks after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient requested to restart adalimumab treatment despite the recent history of esophagitis. Adalimumab 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly was restarted along with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice weekly and nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily. This regimen resulted in complete resolution of HS symptoms within 6 weeks with no recurrence of esophageal candidiasis during 6 months of follow-up.

Although the side effect of Candida esophagitis associated with adalimumab treatment in our patient may be logical given the medication’s mechanism of action and side-effect profile, this case warrants additional attention. An increase in fungal infections occurs from treatment with adalimumab because TNF-α is involved in many immune regulatory steps that counteract infection. Candida typically activates the innate immune system through macrophages via pathogen-associated molecular pattern stimulation, subsequently stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. The cellular immune system also is activated. Helper T cells (TH1) release TNF-α along with other proinflammatory cytokines to increase phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages.6 Thus, inhibition of TNF-α compromises innate and cellular immunity, thereby increasing susceptibility to fungal organisms.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Candida, candidiasis, esophageal, adalimumab, anti-TNF, and TNF revealed no reports of esophageal candidiasis in patients receiving adalimumab or any of the TNF inhibitors. Candida laryngitis was reported in a patient receiving adalimumab for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.7 Other studies have demonstrated an incidence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, most notably oropharyngeal and vaginal candidiasis.8-10 One study found that anti-TNF medications were associated with an increased risk for candidiasis by a hazard ratio of 2.7 in patients with Crohn disease.8 Other studies have shown that the highest incidence of fungal infection is seen with the use of infliximab, while adalimumab is associated with lower rates of fungal infection.9,10 Although it is known that anti-TNF therapy predisposes patients to fungal infection, the dose of medication known to preclude the highest risk has not been studied. Furthermore, most studies assess rates of Candida infection in individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy in addition to several other immunosuppressant agents (ie, corticosteroids), which confounds the interpretation of results. Additional studies assessing rates of Candida and other opportunistic infections associated with use of adalimumab alone are needed to better guide clinical practices in dermatology.

Patients receiving adalimumab for dermatologic or other conditions should be closely monitored for opportunistic infections. Although immunomodulatory medications offer promising therapeutic benefits in patients with HS, larger studies regarding treatment with anti-TNF agents in HS are warranted to prevent complications from treatment and promote long-term efficacy and safety.

- Kurayev A, Ashkar H, Saraiya A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: review of the pathogenesis and treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1107-1022.

- Rambhatla PV, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. A systematic review of treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:439-446.

- van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Shuja F, Chan CS, Rosen T. Biologic drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: an evidence-based review. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:511-521, 523-514.

- Kutsch CL, Norris DA, Arend WP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production by cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:79-85.

- Senet JM. Risk factors and physiopathology of candidiasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14:6-13.

- Kobak S, Yilmaz H, Guclu O, et al. Severe candida laryngitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Eur J Rheumatol. 2014;1:167-169.

- Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, et al. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524-2533.

- Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT, et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-194.

- Aikawa NE, Rosa DT, Del Negro GM, et al. Systemic and localized infection by Candida species in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving anti-TNF therapy [in Portuguese]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.03.010

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the development of painful abscesses, fistulous tracts, and scars. It most commonly affects the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body such as the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. With a prevalence of approximately 1%, HS can lead to notable morbidity.1 The pathogenesis is thought to be due to occlusion of terminal hair follicles that subsequently stimulates release of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes. The mechanism of initial occlusion is not well understood but may be due to friction or trauma. An inflammatory mechanism of disease also has been hypothesized; however, the exact cytokine profile is not known. Treatment of HS consists of several different modalities, including oral retinoids, antibiotics, antiandrogenic therapy, and surgery.1,2 Adalimumab is a well-known biologic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS.

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and is thought to improve HS by several mechanisms. Inhibition of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines found in inflammatory lesions and apocrine glands directly decreases the severity of lesion size and the frequency of recurrence.3 Adalimumab also is thought to downregulate expression of keratin 6 and prevent the hyperkeratinization seen in HS.4 Additionally, TNF-α inhibition decreases production of IL-1, which has been shown to cause hypercornification of follicles and perpetuate HS pathogenesis.5