User login

Bullous Pemphigoid Triggered by Liraglutide

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease that typically affects the elderly, with an incidence of approximately 7 new cases per million.1 The pathogenesis of BP involves autoantibodies to BP antigens 180 and 230 at the dermoepidermal junction. Bullous pemphigoid has been associated with the use of multiple medications; vaccines; and physical damage to the skin, including trauma, radiation, and surgery.2

Several classes of medications may cause BP; one study described an association of BP with loop diuretics,3 while others found higher incidences of BP in patients taking aldosterone antagonists and neuroleptics.4 We describe a case of drug-triggered BP to liraglutide, a glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist.

A 75-year-old man presented to dermatology for evaluation of a vesicular eruption on the head, neck, trunk, and arms of 6 months’ duration. The eruption developed 2 weeks after starting liraglutide 1.2 mg subcutaneously daily for diabetes mellitus. The patient had a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy, and he also was taking insulin. Liraglutide was discontinued shortly after the onset of the eruption.

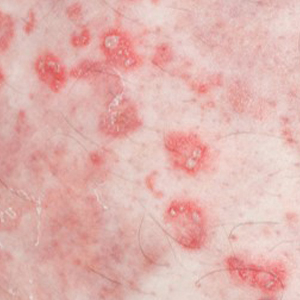

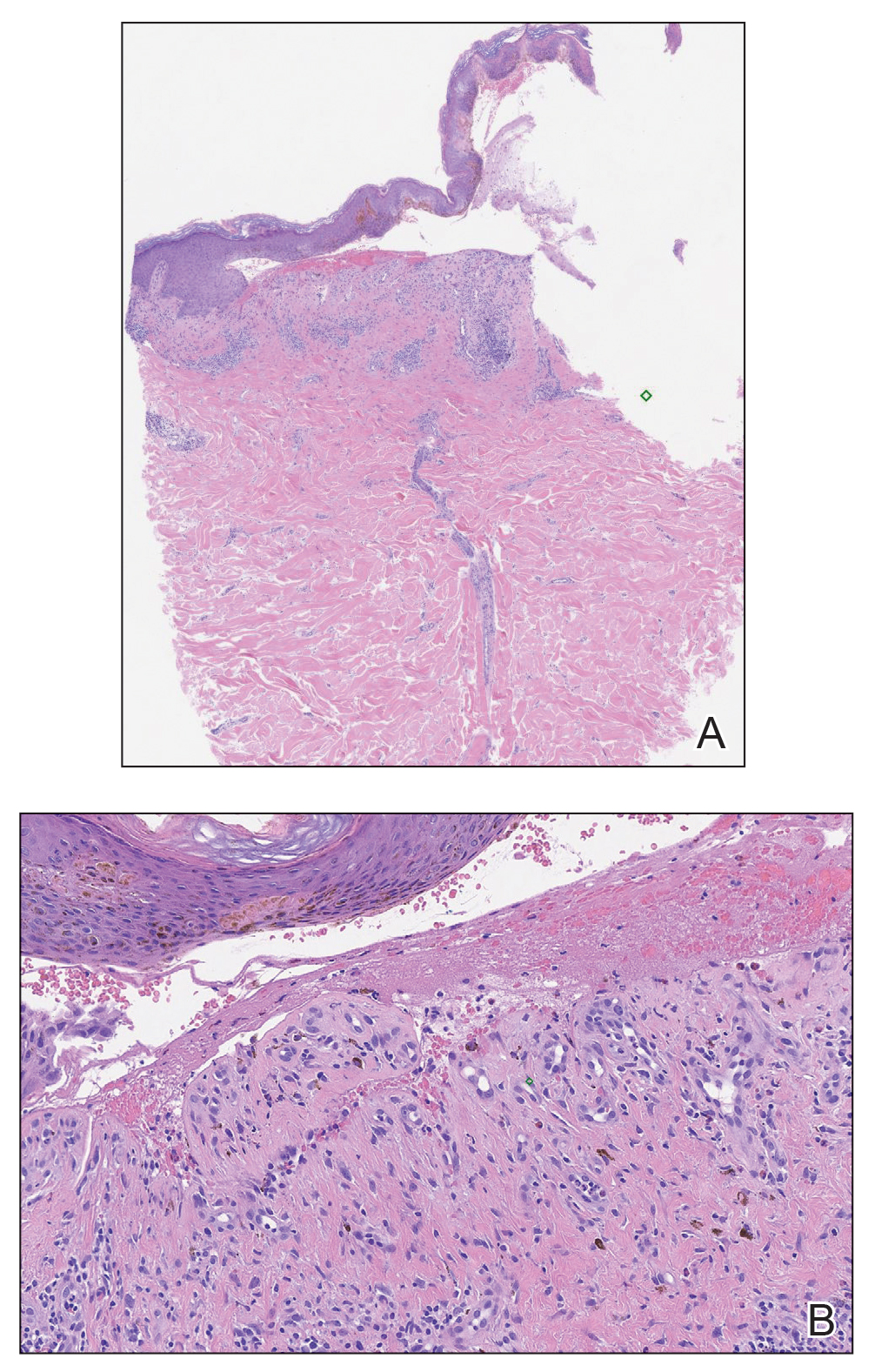

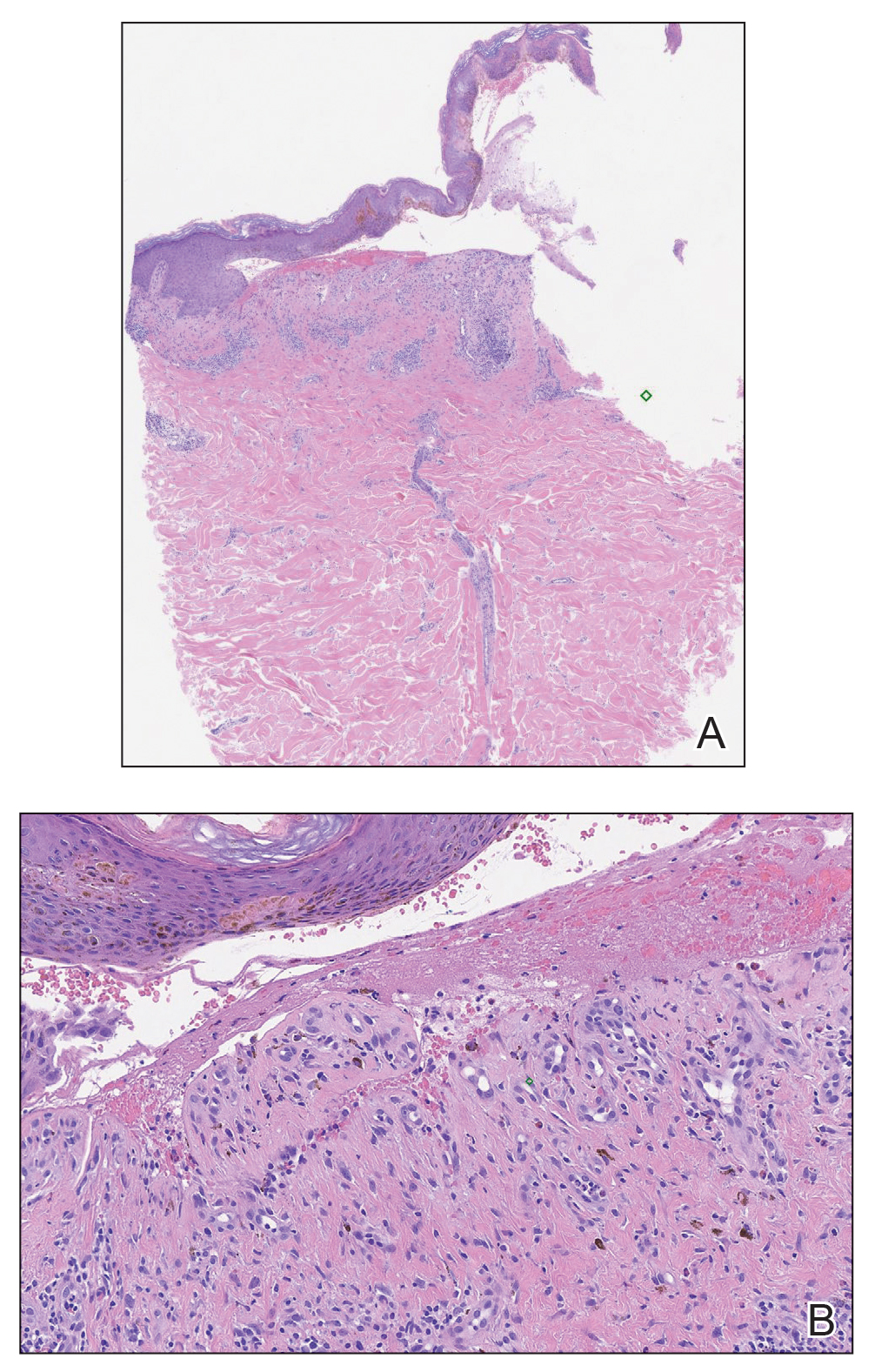

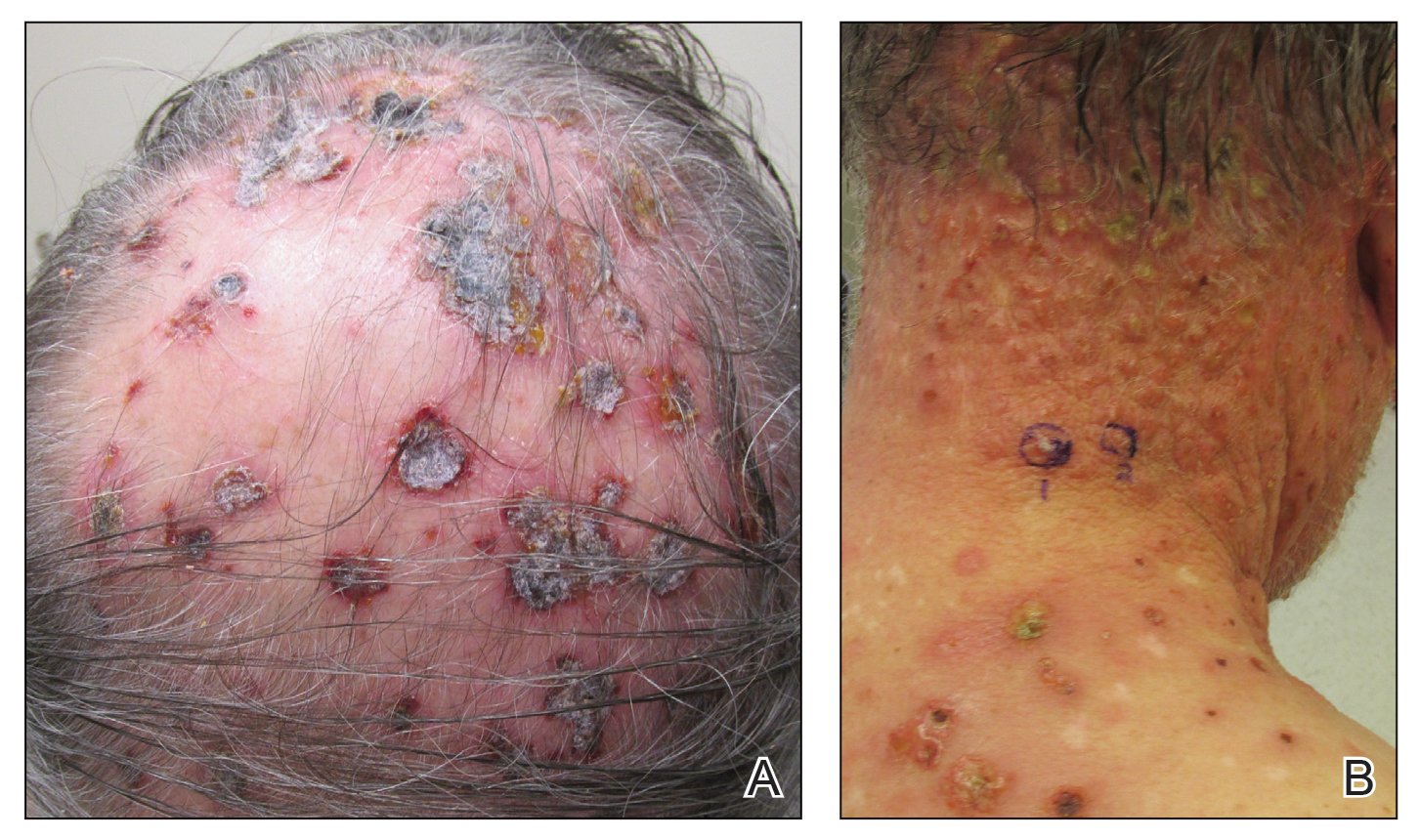

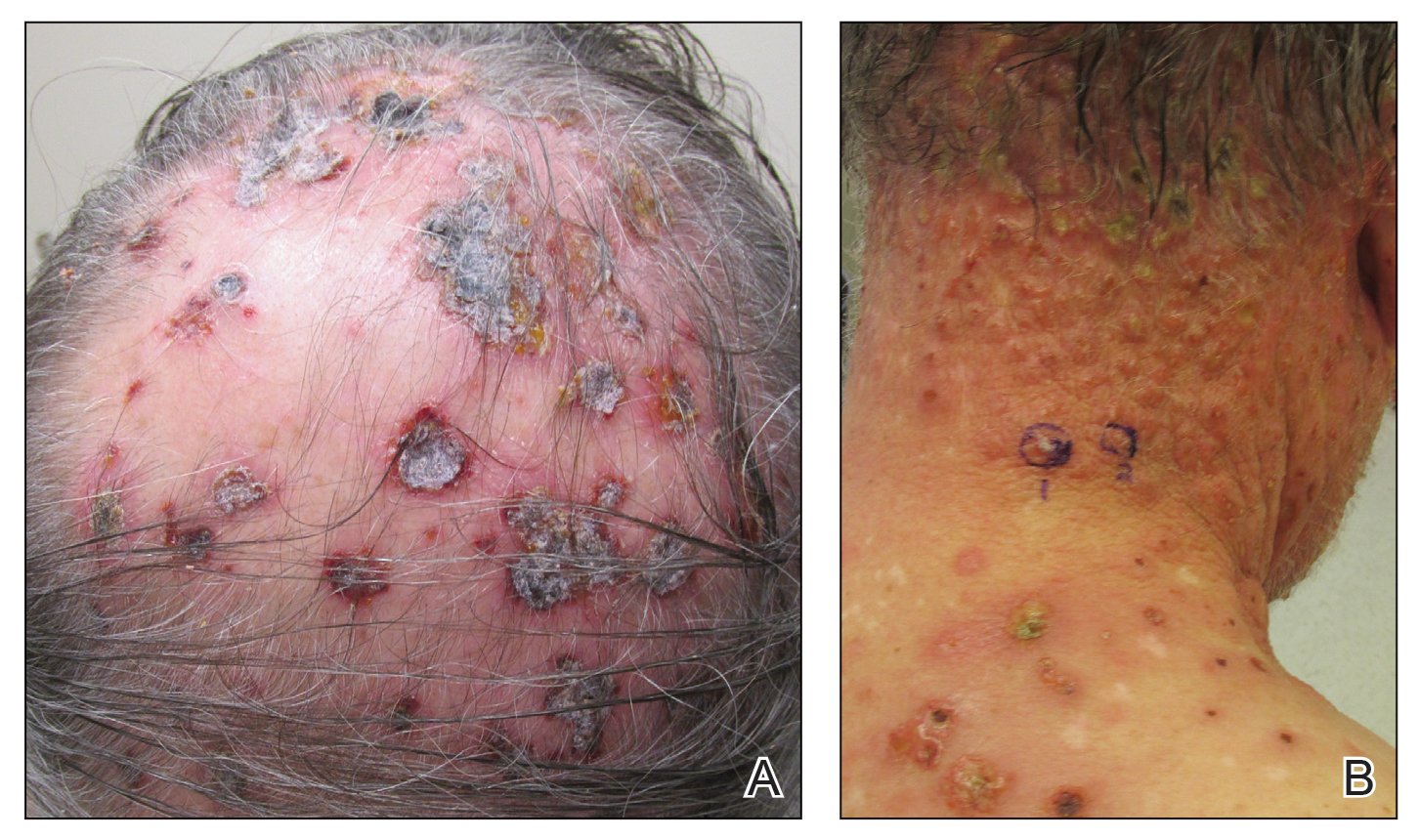

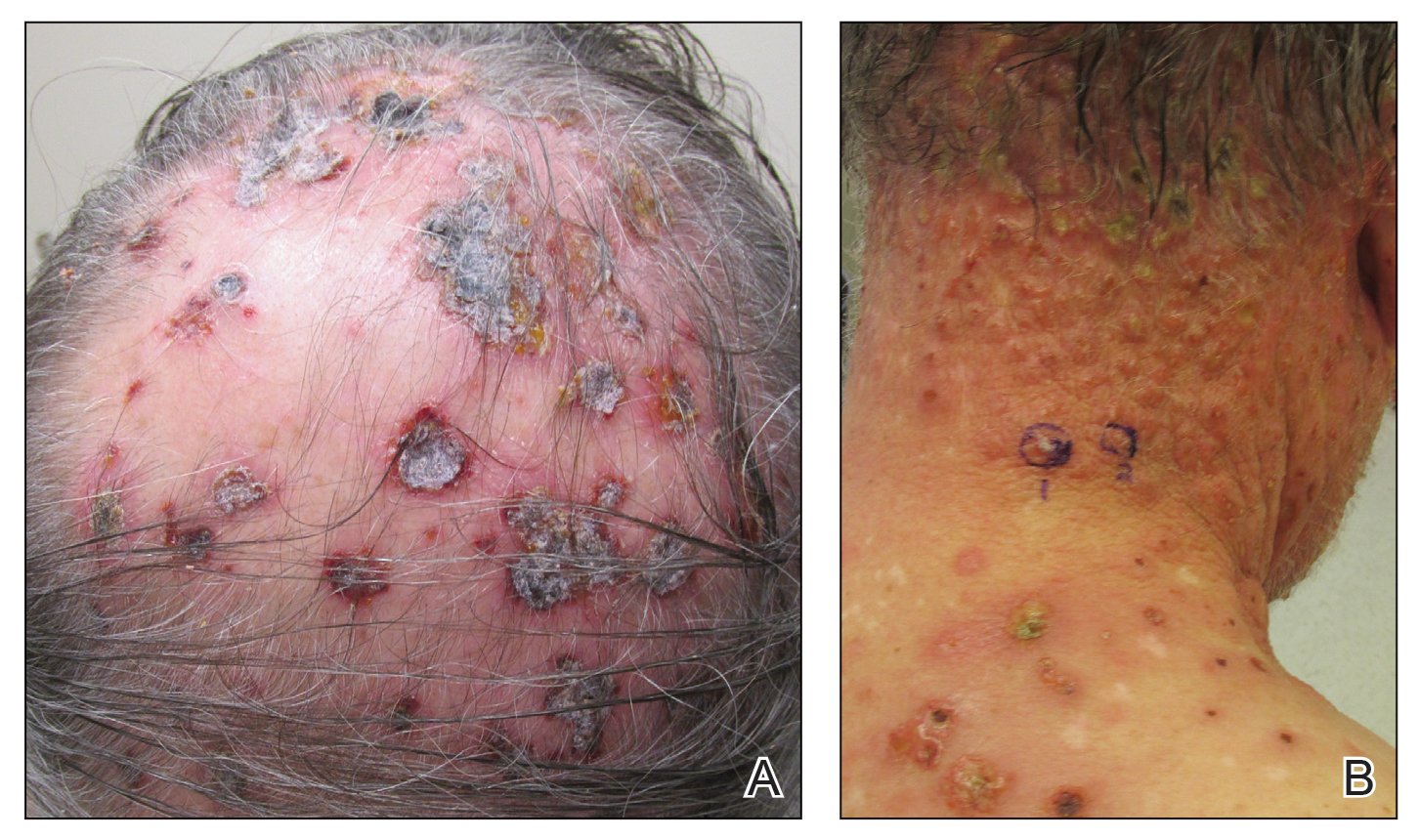

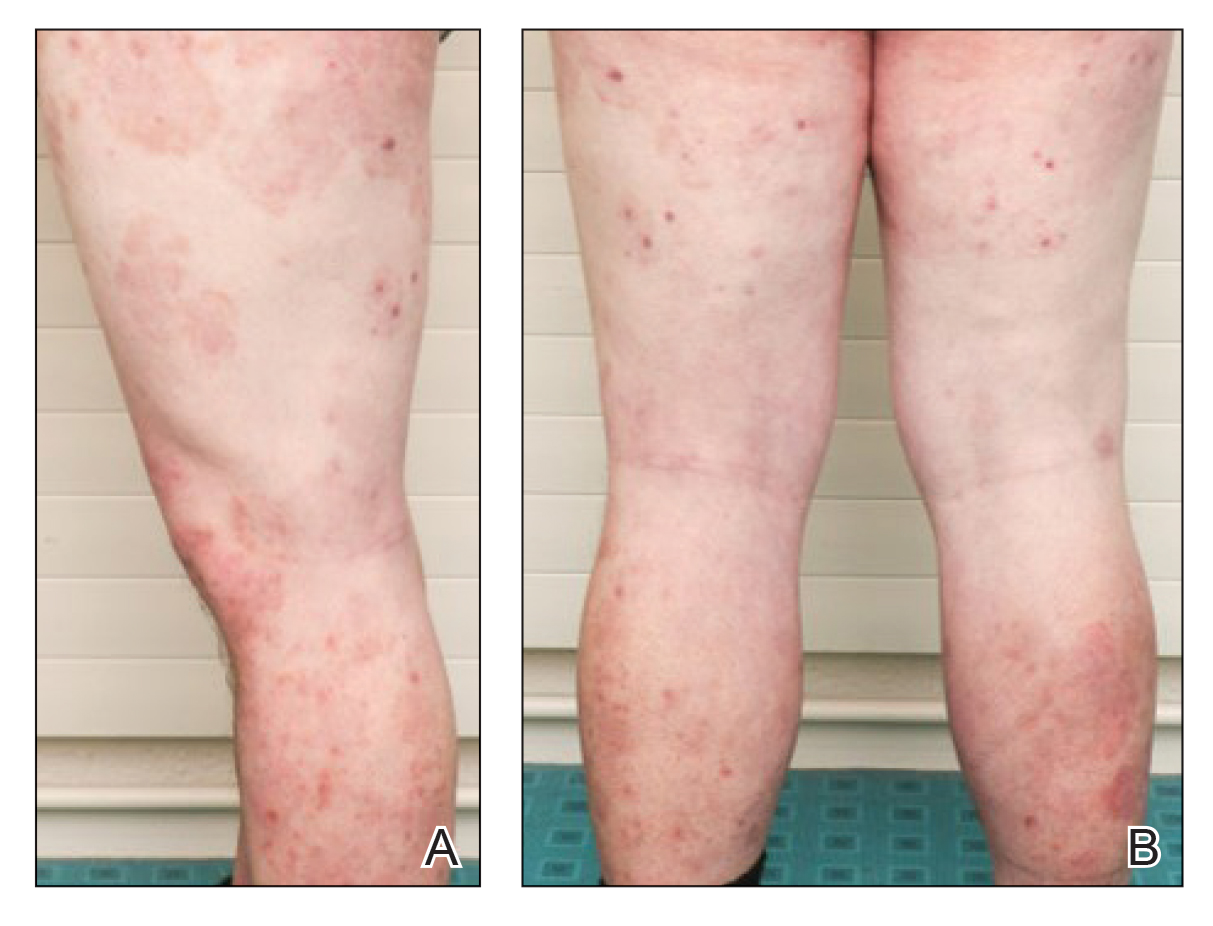

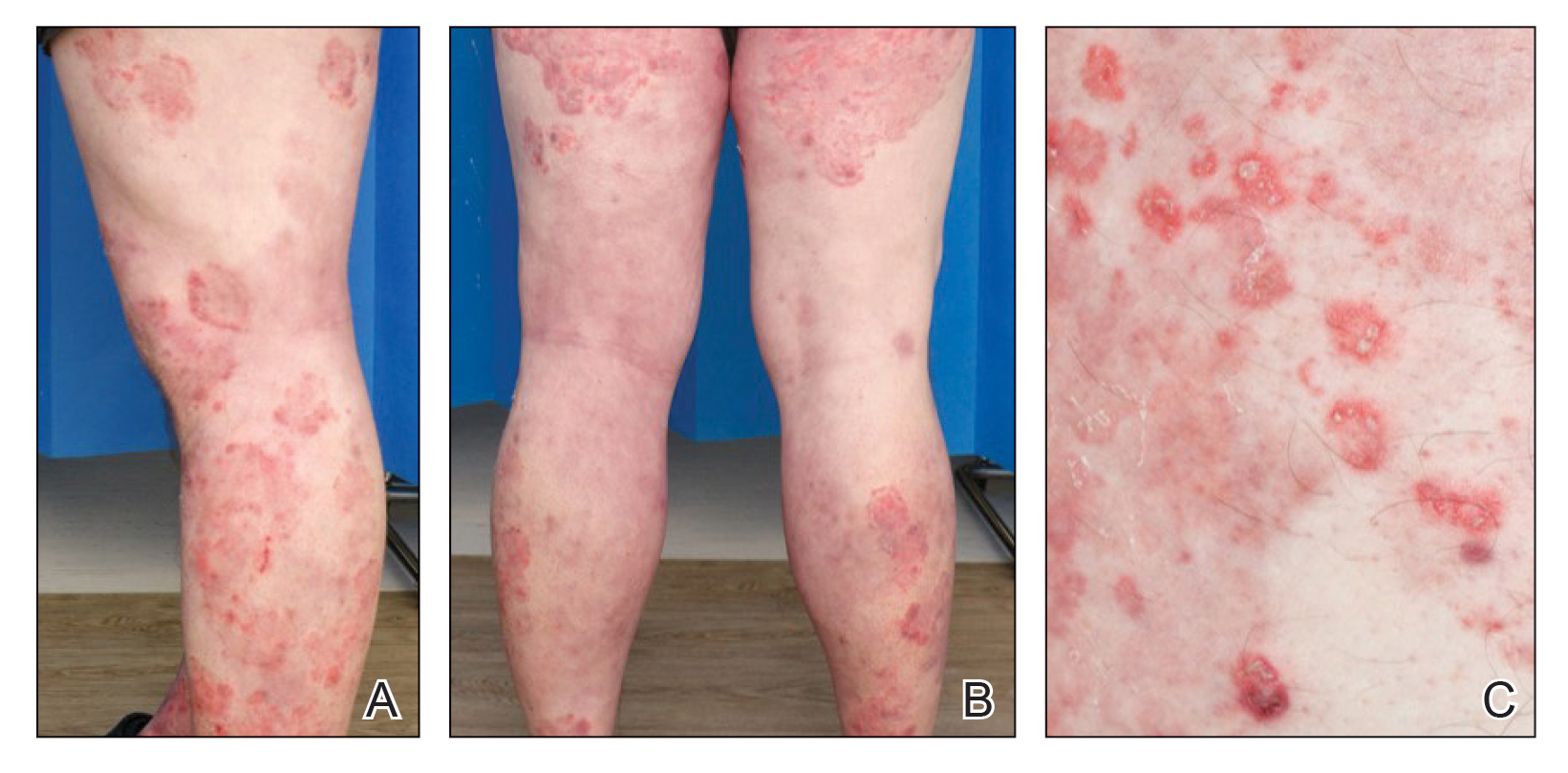

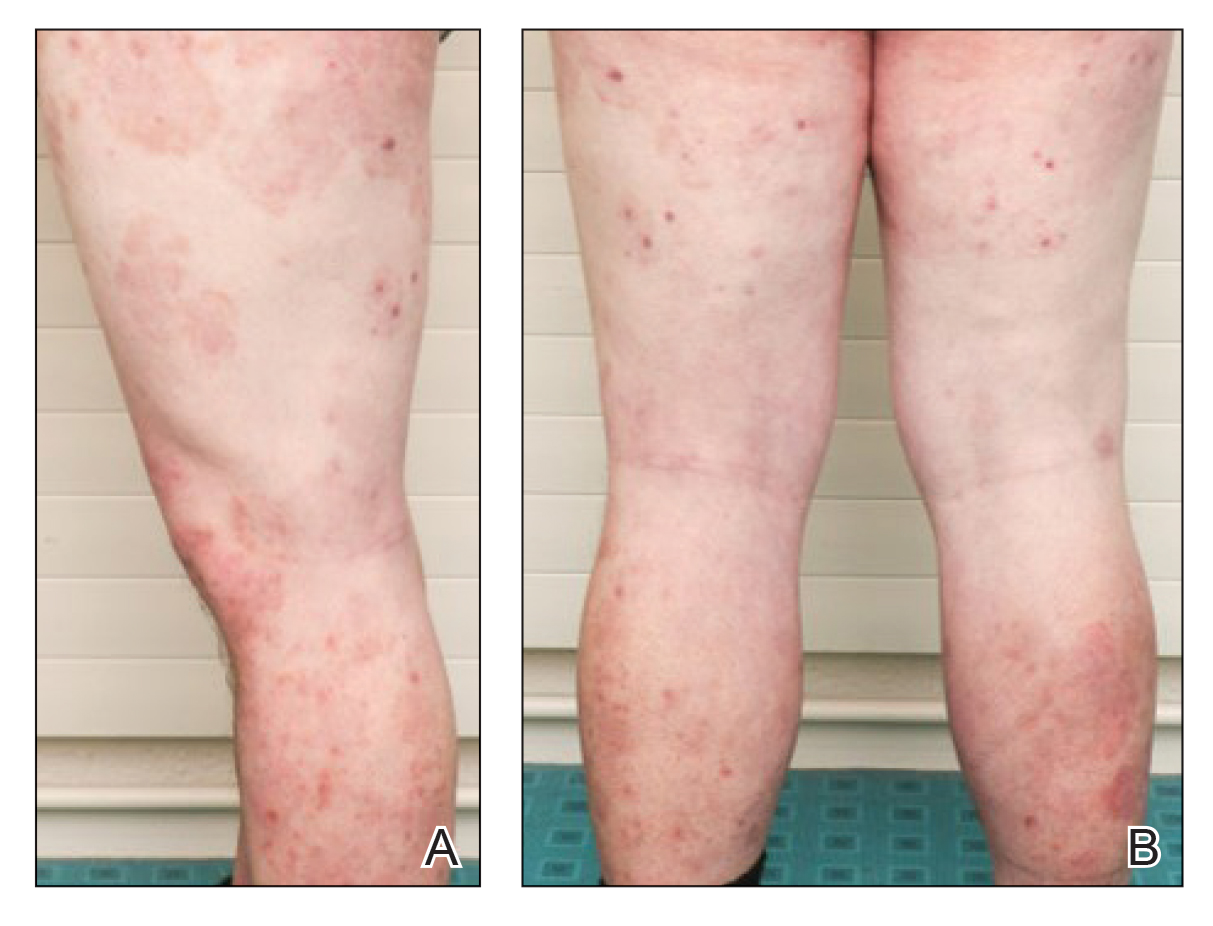

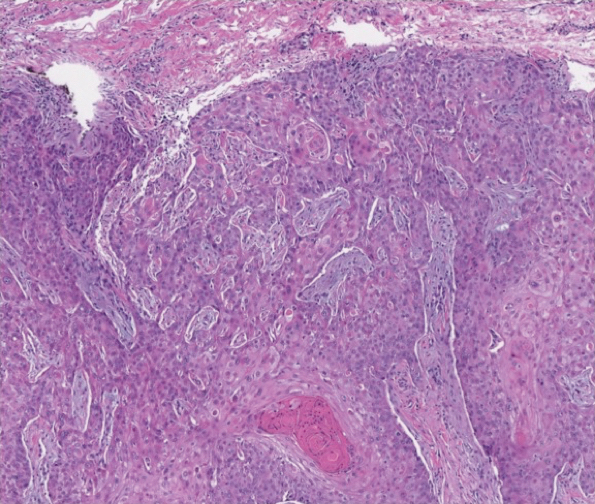

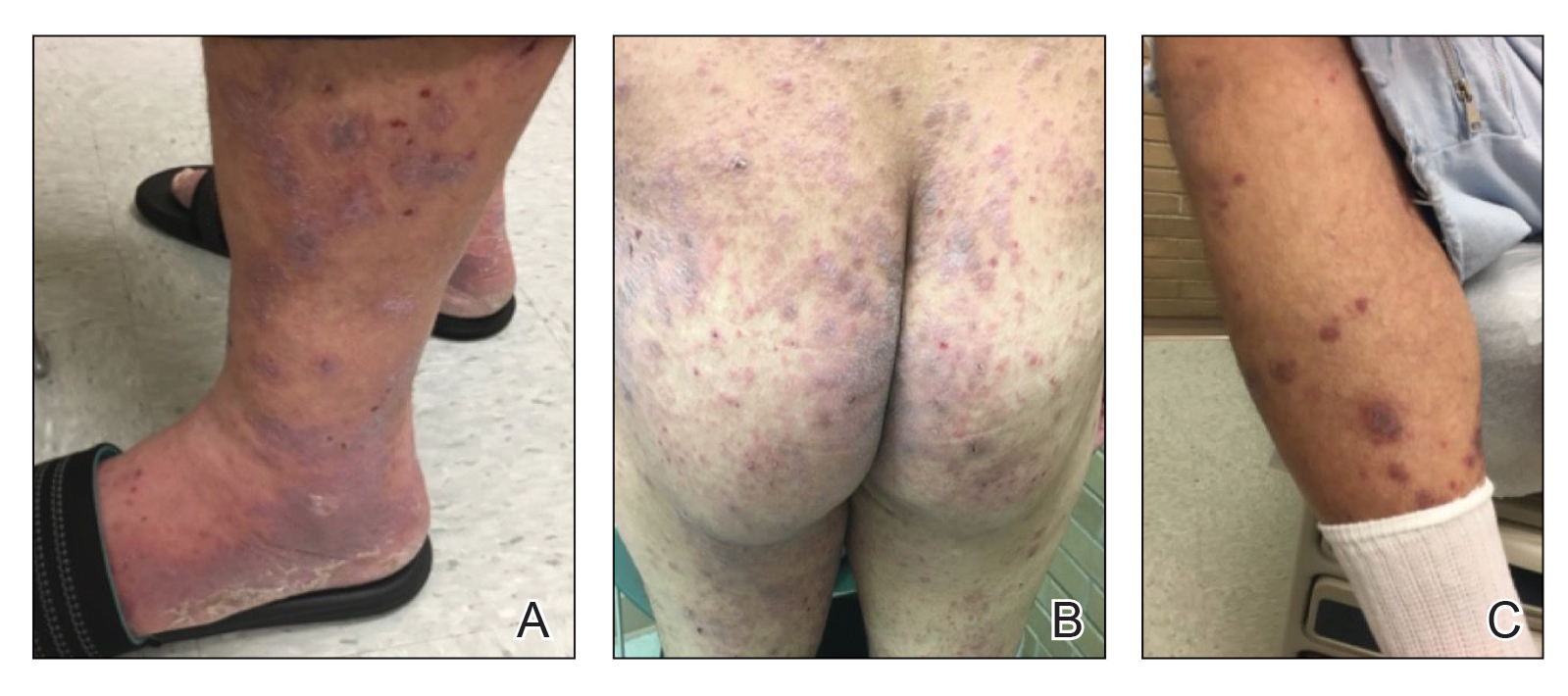

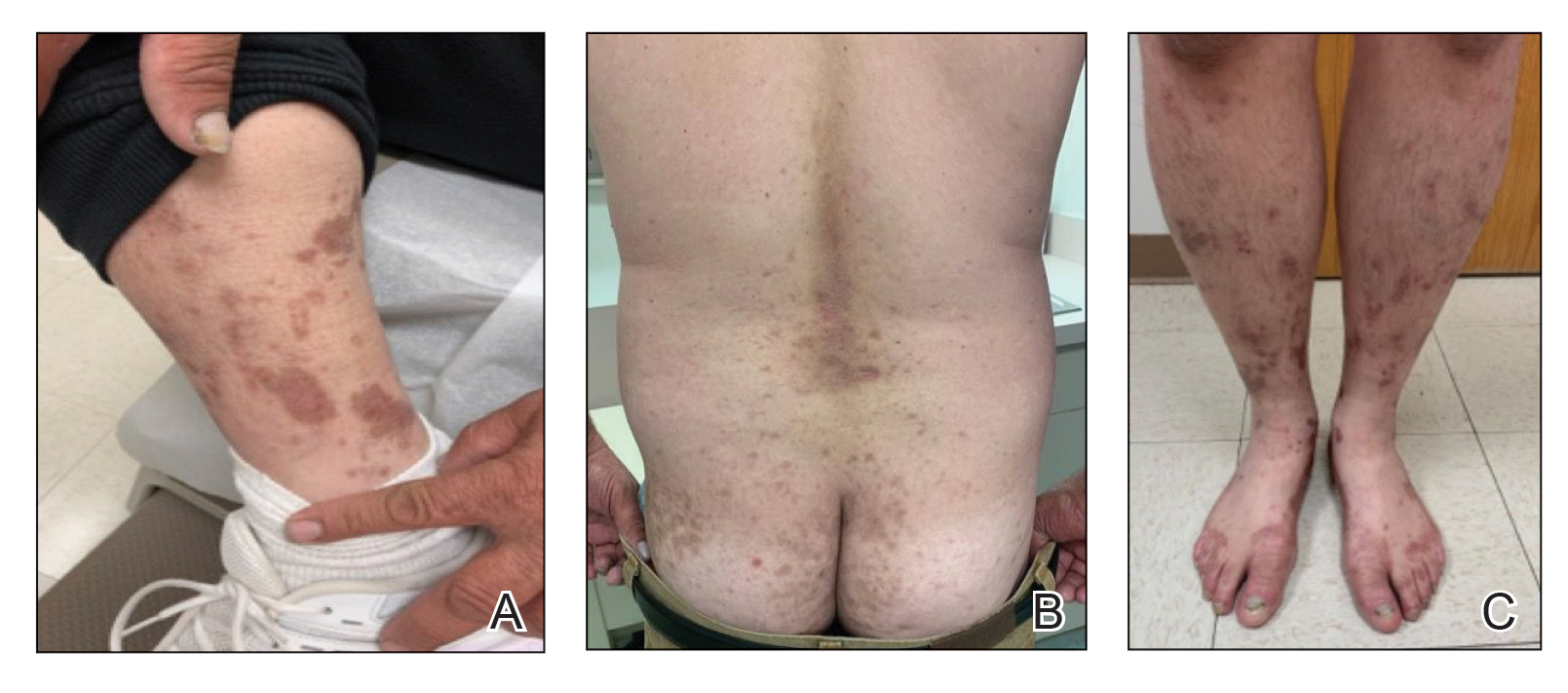

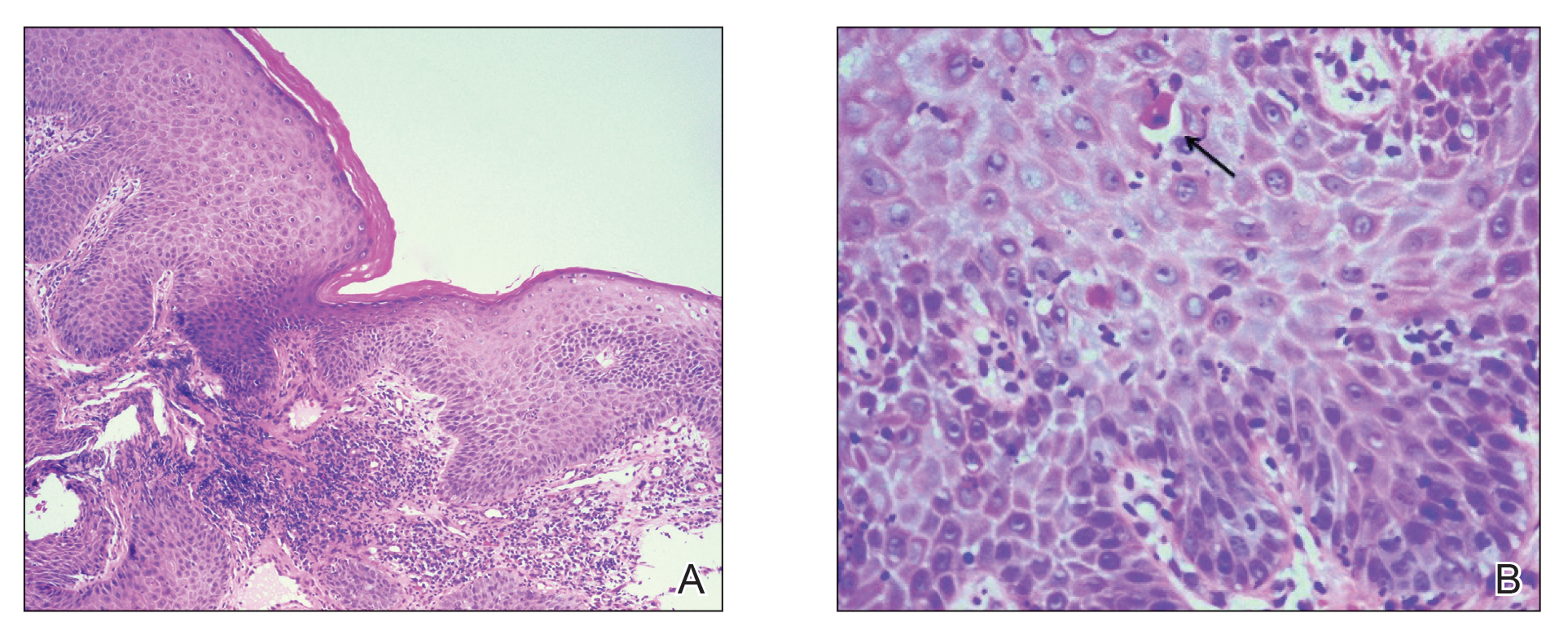

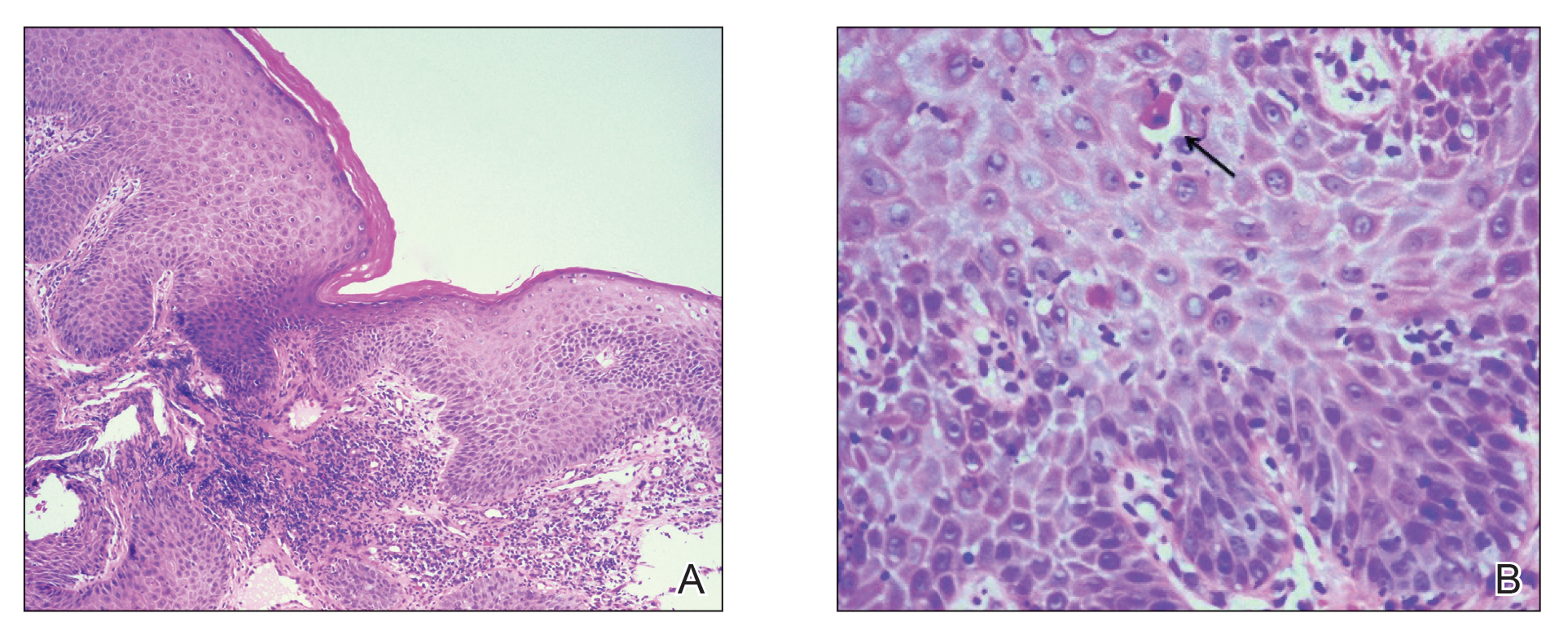

Physical examination revealed annular plaques on the head, neck, trunk, and arms with central hypopigmentation and hyperpigmented borders (Figure 1). Two tense bullae were evident on the left flank (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister, mixed perivascular infiltrate with numerous eosinophils, and pigment incontinence (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence showed linear deposition of IgG and C3 along the basement membrane zone that was localized to the roof of the blister on salt-split analysis. No microorganisms were identified on periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, acid-fast bacilli, and Fite stains. The patient initially was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, leading to marginal improvement. He declined treatment with prednisone or dapsone, and he was started on doxycycline. Seven months after stopping liraglutide and starting doxycycline, the patient had no blisters, but residual pigmentary changes remained.

Two types of BP have been described in response to medications: drug-induced BP and drug-triggered BP. Drug-induced BP presents as an acute, self-limited eruption that typically resolves after withdrawal of the offending agent. It tends to involve a younger population and may present with mucosal involvement and target lesions on the palms and soles. Direct immunofluorescence shows linear IgG and C3 deposition at the basement membrane zone. Patients tend to respond quickly to systemic corticosteroids and have low recurrence rates. Drug-triggered BP is a chronic form of BP that is caused by a medication and is not resolved with removal of the offending agent.5 Therefore, drug-triggered BP is more difficult to detect, especially in patients taking multiple medications.

Our patient represents a case of drug-triggered BP to liraglutide. Liraglutide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist that is US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Glucagonlike peptide 1 is an incretin hormone that is secreted by the intestine during digestion. It binds to the GLP-1 receptor leading to an increase in glucose-dependent insulin secretion and a decrease in glucagon secretion.6 Glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists also affect the immune system; liraglutide has been shown to modestly improve psoriasis, reduce the number of dermal gamma delta T cells, and decrease IL-17 expression.7 Glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists also produce anti-inflammatory effects on multiple organs including the liver, brain, vasculature, kidney, and skin.8

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors that function to inhibit the degradation of GLP-1 and other peptides also have been reported to cause BP. In several patients, the DPP-4 inhibitors vildagliptin and sitagliptin caused drug-induced BP that resolved with discontinuation of the medication.9 Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is expressed in various organ systems including the skin, and inhibition of DPP-4 enhances eosinophil mobilization in the blood and recruitment to the skin in animal models.10

Although the pathogenesis of BP involves autoantibodies to BP antigens 180 and 230, these antibodies are not sufficient to cause disease, as antibasement antibodies have been detected in patients without clinically evident BP. These patients, however, may be more susceptible to developing medication-induced BP. Several hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis of medication-induced BP have been proposed, including immune dysregulation, molecular mimicry, and cross-reactivity to a prior sensitizing agent.5 Liraglutide and the DPP-4 inhibitors affect the immune system, supporting the hypothesis of immune dysregulation; however, the exact mechanism of how immune modulating medications such as GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors cause BP remains unclear.

The effects of liraglutide and the DPP-4 inhibitors on the immune system may play a role in the pathogenesis of drug-triggered BP and drug-induced BP, respectively. Additional studies of the immunomodulatory effects of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors may help elucidate the pathogenesis of drug-triggered or drug-induced BP.

- Serwin AB, Musialkowska E, Piascik M. Incidence and mortality of bullous pemphigoid in north-east Poland (Podlaskie Province), 1999-2012: a retrospective bicentric cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E432-E437.

- Danescu S, Chiorean R, Macovei V, et al. Role of physical factors in the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid: case report series and a comprehensive review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2016;43:134-130.

- Lloyd-Lavery A, Chi CC, Wojnarowska F, et al. The associations between bullous pemphigoid and drug use: a UK case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:58-62.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Joly P, Picard-Dahan C, et al. Drugs associated with bullous pemphigoid. a case-control study. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:272-276.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Triplitt C, Solis-Herrera C. GLP-1 receptor agonists: practical considerations for clinical practice. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(suppl 1):32S-46S.

- Buysschaert M, Baeck M, Preumont V, et al. Improvement of psoriasis during glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue therapy in type 2 diabetes is associated with decreasing dermal gammadelta T-cell number: a prospective case-series study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:155-161.

- Lee YS, Jun HS. Anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1-based therapies beyond glucose control. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:3094642.

- Skandalis K, Spirova M, Gaitanis G, et al Drug-induced bullous pemphigoid in diabetes mellitus patients receiving dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors plus metformin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:249-253.

- Forssmann U, Stoetzer C, Stephan M, et al. Inhibition of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV enhances CCL11/eotaxin-mediated recruitment of eosinophils in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:1120-1127.

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease that typically affects the elderly, with an incidence of approximately 7 new cases per million.1 The pathogenesis of BP involves autoantibodies to BP antigens 180 and 230 at the dermoepidermal junction. Bullous pemphigoid has been associated with the use of multiple medications; vaccines; and physical damage to the skin, including trauma, radiation, and surgery.2

Several classes of medications may cause BP; one study described an association of BP with loop diuretics,3 while others found higher incidences of BP in patients taking aldosterone antagonists and neuroleptics.4 We describe a case of drug-triggered BP to liraglutide, a glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist.

A 75-year-old man presented to dermatology for evaluation of a vesicular eruption on the head, neck, trunk, and arms of 6 months’ duration. The eruption developed 2 weeks after starting liraglutide 1.2 mg subcutaneously daily for diabetes mellitus. The patient had a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy, and he also was taking insulin. Liraglutide was discontinued shortly after the onset of the eruption.

Physical examination revealed annular plaques on the head, neck, trunk, and arms with central hypopigmentation and hyperpigmented borders (Figure 1). Two tense bullae were evident on the left flank (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister, mixed perivascular infiltrate with numerous eosinophils, and pigment incontinence (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence showed linear deposition of IgG and C3 along the basement membrane zone that was localized to the roof of the blister on salt-split analysis. No microorganisms were identified on periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, acid-fast bacilli, and Fite stains. The patient initially was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, leading to marginal improvement. He declined treatment with prednisone or dapsone, and he was started on doxycycline. Seven months after stopping liraglutide and starting doxycycline, the patient had no blisters, but residual pigmentary changes remained.

Two types of BP have been described in response to medications: drug-induced BP and drug-triggered BP. Drug-induced BP presents as an acute, self-limited eruption that typically resolves after withdrawal of the offending agent. It tends to involve a younger population and may present with mucosal involvement and target lesions on the palms and soles. Direct immunofluorescence shows linear IgG and C3 deposition at the basement membrane zone. Patients tend to respond quickly to systemic corticosteroids and have low recurrence rates. Drug-triggered BP is a chronic form of BP that is caused by a medication and is not resolved with removal of the offending agent.5 Therefore, drug-triggered BP is more difficult to detect, especially in patients taking multiple medications.

Our patient represents a case of drug-triggered BP to liraglutide. Liraglutide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist that is US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Glucagonlike peptide 1 is an incretin hormone that is secreted by the intestine during digestion. It binds to the GLP-1 receptor leading to an increase in glucose-dependent insulin secretion and a decrease in glucagon secretion.6 Glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists also affect the immune system; liraglutide has been shown to modestly improve psoriasis, reduce the number of dermal gamma delta T cells, and decrease IL-17 expression.7 Glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists also produce anti-inflammatory effects on multiple organs including the liver, brain, vasculature, kidney, and skin.8

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors that function to inhibit the degradation of GLP-1 and other peptides also have been reported to cause BP. In several patients, the DPP-4 inhibitors vildagliptin and sitagliptin caused drug-induced BP that resolved with discontinuation of the medication.9 Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is expressed in various organ systems including the skin, and inhibition of DPP-4 enhances eosinophil mobilization in the blood and recruitment to the skin in animal models.10

Although the pathogenesis of BP involves autoantibodies to BP antigens 180 and 230, these antibodies are not sufficient to cause disease, as antibasement antibodies have been detected in patients without clinically evident BP. These patients, however, may be more susceptible to developing medication-induced BP. Several hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis of medication-induced BP have been proposed, including immune dysregulation, molecular mimicry, and cross-reactivity to a prior sensitizing agent.5 Liraglutide and the DPP-4 inhibitors affect the immune system, supporting the hypothesis of immune dysregulation; however, the exact mechanism of how immune modulating medications such as GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors cause BP remains unclear.

The effects of liraglutide and the DPP-4 inhibitors on the immune system may play a role in the pathogenesis of drug-triggered BP and drug-induced BP, respectively. Additional studies of the immunomodulatory effects of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors may help elucidate the pathogenesis of drug-triggered or drug-induced BP.

To the Editor:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease that typically affects the elderly, with an incidence of approximately 7 new cases per million.1 The pathogenesis of BP involves autoantibodies to BP antigens 180 and 230 at the dermoepidermal junction. Bullous pemphigoid has been associated with the use of multiple medications; vaccines; and physical damage to the skin, including trauma, radiation, and surgery.2

Several classes of medications may cause BP; one study described an association of BP with loop diuretics,3 while others found higher incidences of BP in patients taking aldosterone antagonists and neuroleptics.4 We describe a case of drug-triggered BP to liraglutide, a glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist.

A 75-year-old man presented to dermatology for evaluation of a vesicular eruption on the head, neck, trunk, and arms of 6 months’ duration. The eruption developed 2 weeks after starting liraglutide 1.2 mg subcutaneously daily for diabetes mellitus. The patient had a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy, and he also was taking insulin. Liraglutide was discontinued shortly after the onset of the eruption.

Physical examination revealed annular plaques on the head, neck, trunk, and arms with central hypopigmentation and hyperpigmented borders (Figure 1). Two tense bullae were evident on the left flank (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister, mixed perivascular infiltrate with numerous eosinophils, and pigment incontinence (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence showed linear deposition of IgG and C3 along the basement membrane zone that was localized to the roof of the blister on salt-split analysis. No microorganisms were identified on periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, acid-fast bacilli, and Fite stains. The patient initially was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, leading to marginal improvement. He declined treatment with prednisone or dapsone, and he was started on doxycycline. Seven months after stopping liraglutide and starting doxycycline, the patient had no blisters, but residual pigmentary changes remained.

Two types of BP have been described in response to medications: drug-induced BP and drug-triggered BP. Drug-induced BP presents as an acute, self-limited eruption that typically resolves after withdrawal of the offending agent. It tends to involve a younger population and may present with mucosal involvement and target lesions on the palms and soles. Direct immunofluorescence shows linear IgG and C3 deposition at the basement membrane zone. Patients tend to respond quickly to systemic corticosteroids and have low recurrence rates. Drug-triggered BP is a chronic form of BP that is caused by a medication and is not resolved with removal of the offending agent.5 Therefore, drug-triggered BP is more difficult to detect, especially in patients taking multiple medications.

Our patient represents a case of drug-triggered BP to liraglutide. Liraglutide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist that is US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Glucagonlike peptide 1 is an incretin hormone that is secreted by the intestine during digestion. It binds to the GLP-1 receptor leading to an increase in glucose-dependent insulin secretion and a decrease in glucagon secretion.6 Glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists also affect the immune system; liraglutide has been shown to modestly improve psoriasis, reduce the number of dermal gamma delta T cells, and decrease IL-17 expression.7 Glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists also produce anti-inflammatory effects on multiple organs including the liver, brain, vasculature, kidney, and skin.8

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors that function to inhibit the degradation of GLP-1 and other peptides also have been reported to cause BP. In several patients, the DPP-4 inhibitors vildagliptin and sitagliptin caused drug-induced BP that resolved with discontinuation of the medication.9 Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is expressed in various organ systems including the skin, and inhibition of DPP-4 enhances eosinophil mobilization in the blood and recruitment to the skin in animal models.10

Although the pathogenesis of BP involves autoantibodies to BP antigens 180 and 230, these antibodies are not sufficient to cause disease, as antibasement antibodies have been detected in patients without clinically evident BP. These patients, however, may be more susceptible to developing medication-induced BP. Several hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis of medication-induced BP have been proposed, including immune dysregulation, molecular mimicry, and cross-reactivity to a prior sensitizing agent.5 Liraglutide and the DPP-4 inhibitors affect the immune system, supporting the hypothesis of immune dysregulation; however, the exact mechanism of how immune modulating medications such as GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors cause BP remains unclear.

The effects of liraglutide and the DPP-4 inhibitors on the immune system may play a role in the pathogenesis of drug-triggered BP and drug-induced BP, respectively. Additional studies of the immunomodulatory effects of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors may help elucidate the pathogenesis of drug-triggered or drug-induced BP.

- Serwin AB, Musialkowska E, Piascik M. Incidence and mortality of bullous pemphigoid in north-east Poland (Podlaskie Province), 1999-2012: a retrospective bicentric cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E432-E437.

- Danescu S, Chiorean R, Macovei V, et al. Role of physical factors in the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid: case report series and a comprehensive review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2016;43:134-130.

- Lloyd-Lavery A, Chi CC, Wojnarowska F, et al. The associations between bullous pemphigoid and drug use: a UK case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:58-62.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Joly P, Picard-Dahan C, et al. Drugs associated with bullous pemphigoid. a case-control study. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:272-276.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Triplitt C, Solis-Herrera C. GLP-1 receptor agonists: practical considerations for clinical practice. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(suppl 1):32S-46S.

- Buysschaert M, Baeck M, Preumont V, et al. Improvement of psoriasis during glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue therapy in type 2 diabetes is associated with decreasing dermal gammadelta T-cell number: a prospective case-series study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:155-161.

- Lee YS, Jun HS. Anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1-based therapies beyond glucose control. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:3094642.

- Skandalis K, Spirova M, Gaitanis G, et al Drug-induced bullous pemphigoid in diabetes mellitus patients receiving dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors plus metformin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:249-253.

- Forssmann U, Stoetzer C, Stephan M, et al. Inhibition of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV enhances CCL11/eotaxin-mediated recruitment of eosinophils in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:1120-1127.

- Serwin AB, Musialkowska E, Piascik M. Incidence and mortality of bullous pemphigoid in north-east Poland (Podlaskie Province), 1999-2012: a retrospective bicentric cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E432-E437.

- Danescu S, Chiorean R, Macovei V, et al. Role of physical factors in the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid: case report series and a comprehensive review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2016;43:134-130.

- Lloyd-Lavery A, Chi CC, Wojnarowska F, et al. The associations between bullous pemphigoid and drug use: a UK case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:58-62.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Joly P, Picard-Dahan C, et al. Drugs associated with bullous pemphigoid. a case-control study. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:272-276.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Triplitt C, Solis-Herrera C. GLP-1 receptor agonists: practical considerations for clinical practice. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(suppl 1):32S-46S.

- Buysschaert M, Baeck M, Preumont V, et al. Improvement of psoriasis during glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue therapy in type 2 diabetes is associated with decreasing dermal gammadelta T-cell number: a prospective case-series study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:155-161.

- Lee YS, Jun HS. Anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1-based therapies beyond glucose control. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:3094642.

- Skandalis K, Spirova M, Gaitanis G, et al Drug-induced bullous pemphigoid in diabetes mellitus patients receiving dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors plus metformin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:249-253.

- Forssmann U, Stoetzer C, Stephan M, et al. Inhibition of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV enhances CCL11/eotaxin-mediated recruitment of eosinophils in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:1120-1127.

Practice Points

- Liraglutide and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, medications used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus, may be linked to the development of bullous pemphigoid (BP).

- Further study of the mechanism of action of these medications may lead to improved understanding of the pathogenesis of BP.

Exuberant Lymphomatoid Papulosis of the Head and Upper Trunk

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic, recurring, self-healing, primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. This disease affects patients of all ages but most commonly presents in the fifth decade with a slight male predominance.1 The estimated worldwide incidence is 1.2 to 1.9 cases per 1,000,000 individuals, and the 10-year survival rate is close to 100%.1 Clinically, LyP presents as a few to more than 100 red-brown papules or nodules, some with hemorrhagic crust or central necrosis, often occurring in crops and in various stages of evolution. They most commonly are distributed on the trunk and extremities; however, the face, scalp, and oral mucosa rarely may be involved. Each lesion may last on average 3 to 8 weeks, with residual hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin or superficial varioliform scars. The clinical characteristic of spontaneous regression is crucial for distinguishing LyP from other forms of cutaneous lymphoma.2 The disease course is variable, lasting anywhere from a few months to decades. Histopathologically, LyP consists of a frequently CD30+ lymphocytic proliferation in multiple described patterns.1 We report a case of LyP in a patient who initially presented with pink edematous papules and vesicles that progressed to crusted ulcerations, nodules, and deep necrotic eschars on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk. Multiple biopsies and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were necessary to make the diagnosis.

A 73-year-old man presented with edematous crusted papules and nodules as well as scarring with serous drainage on the scalp and upper trunk of several months’ duration. He also reported pain and pruritus. He had a medical history of B-cell CD20− chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that was treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and intravenous immunoglobulin approximately one year prior and currently was in remission; prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy; hypertension; and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His medications included metoprolol, valsartan, and glipizide.

Histopathology revealed a hypersensitivity reaction, and the clinicopathologic correlation was believed to represent an exuberant arthropod bite reaction in the setting of CLL. The eruption responded well to oral prednisone and topical corticosteroids but recurred when the medications were withdrawn. A repeat biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of atypical eosinophil-predominant Sweet syndrome. The condition resolved.

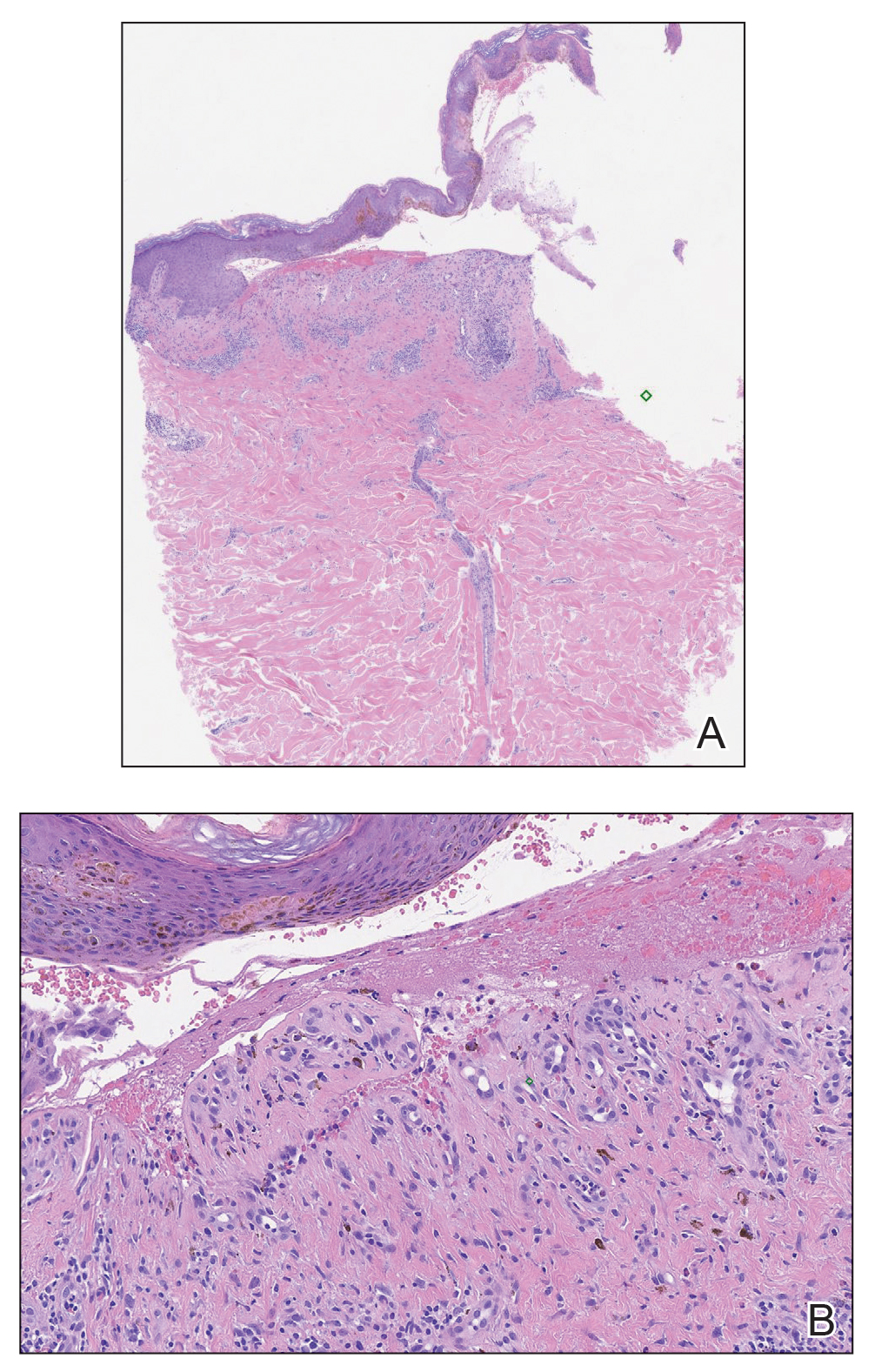

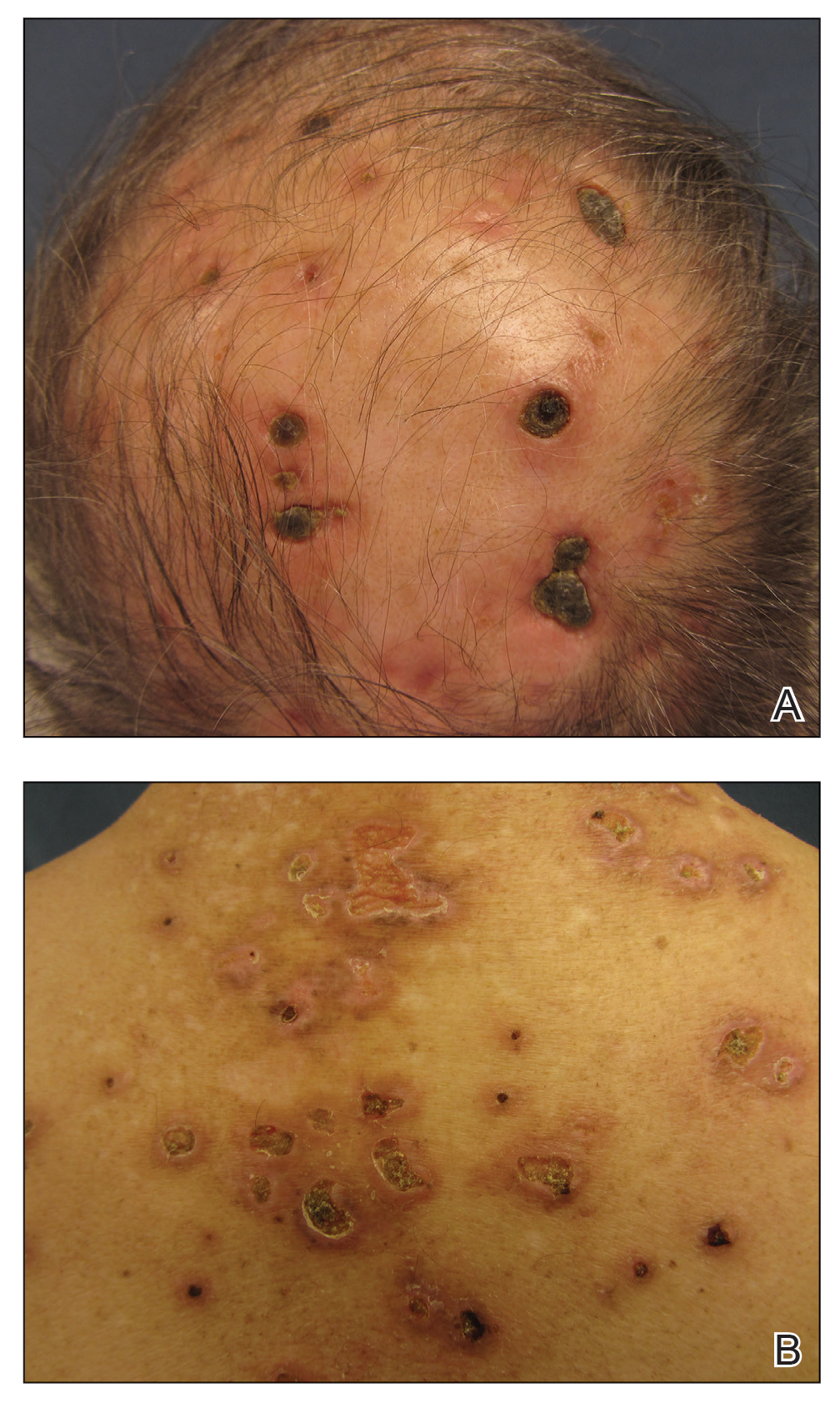

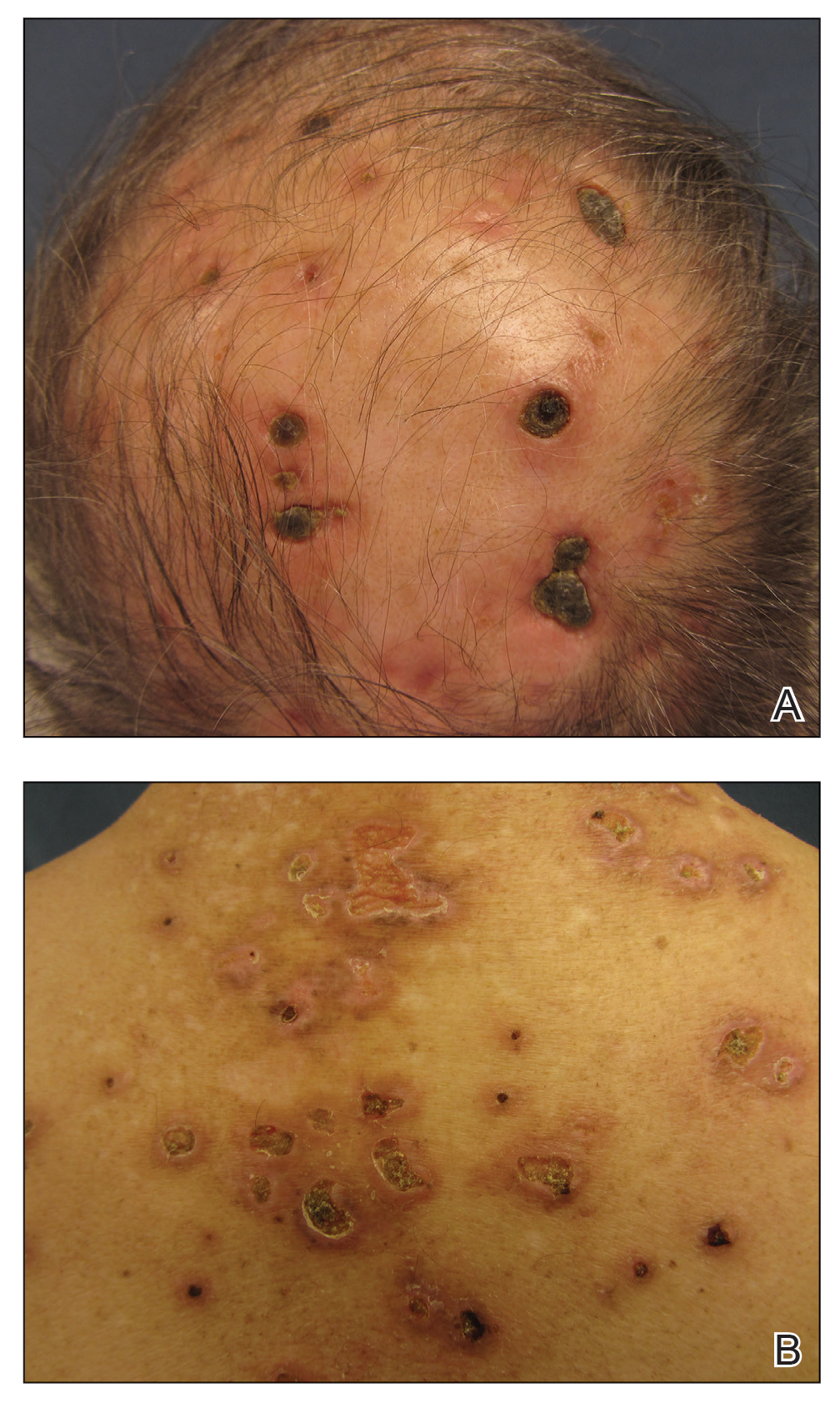

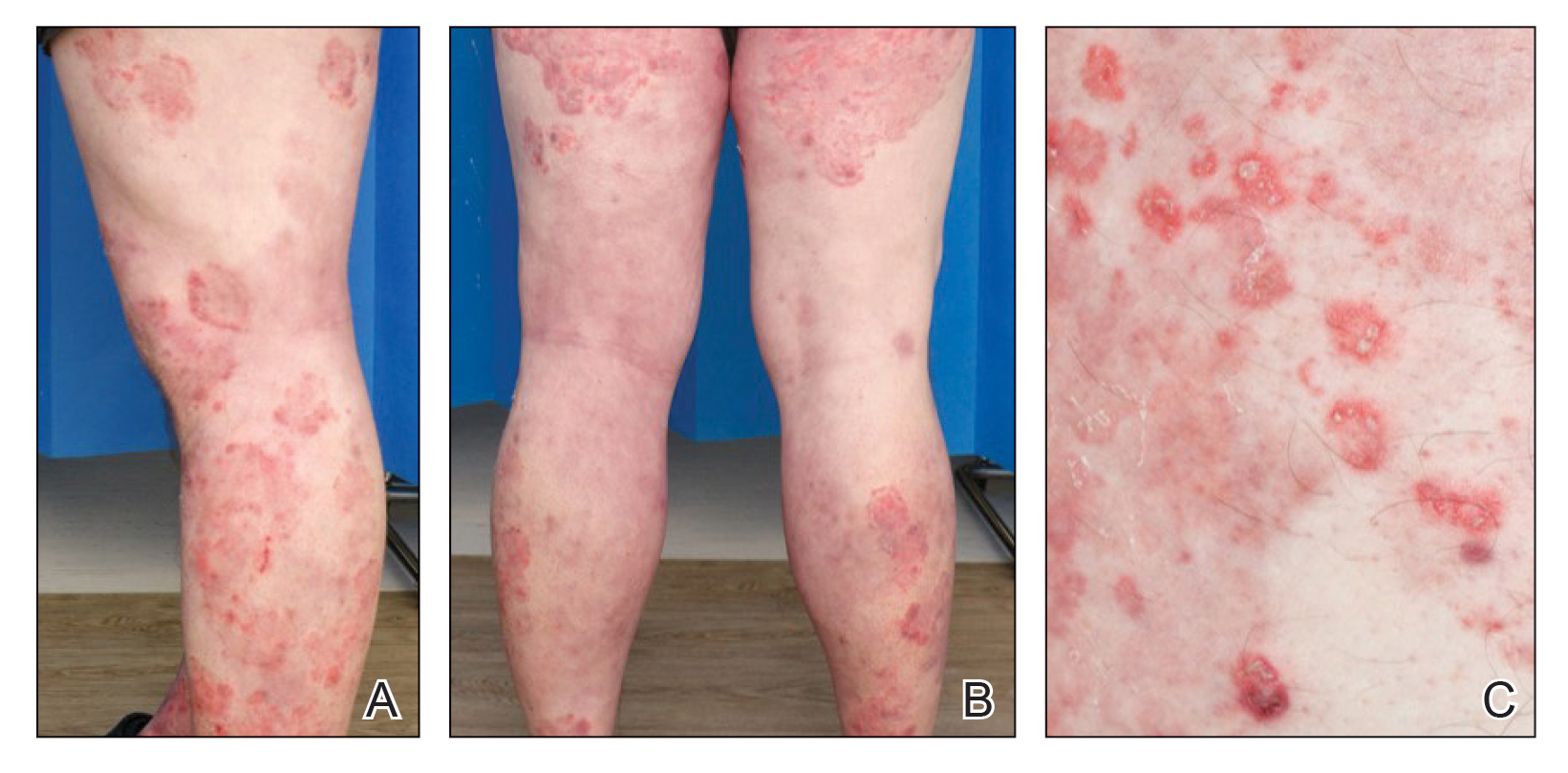

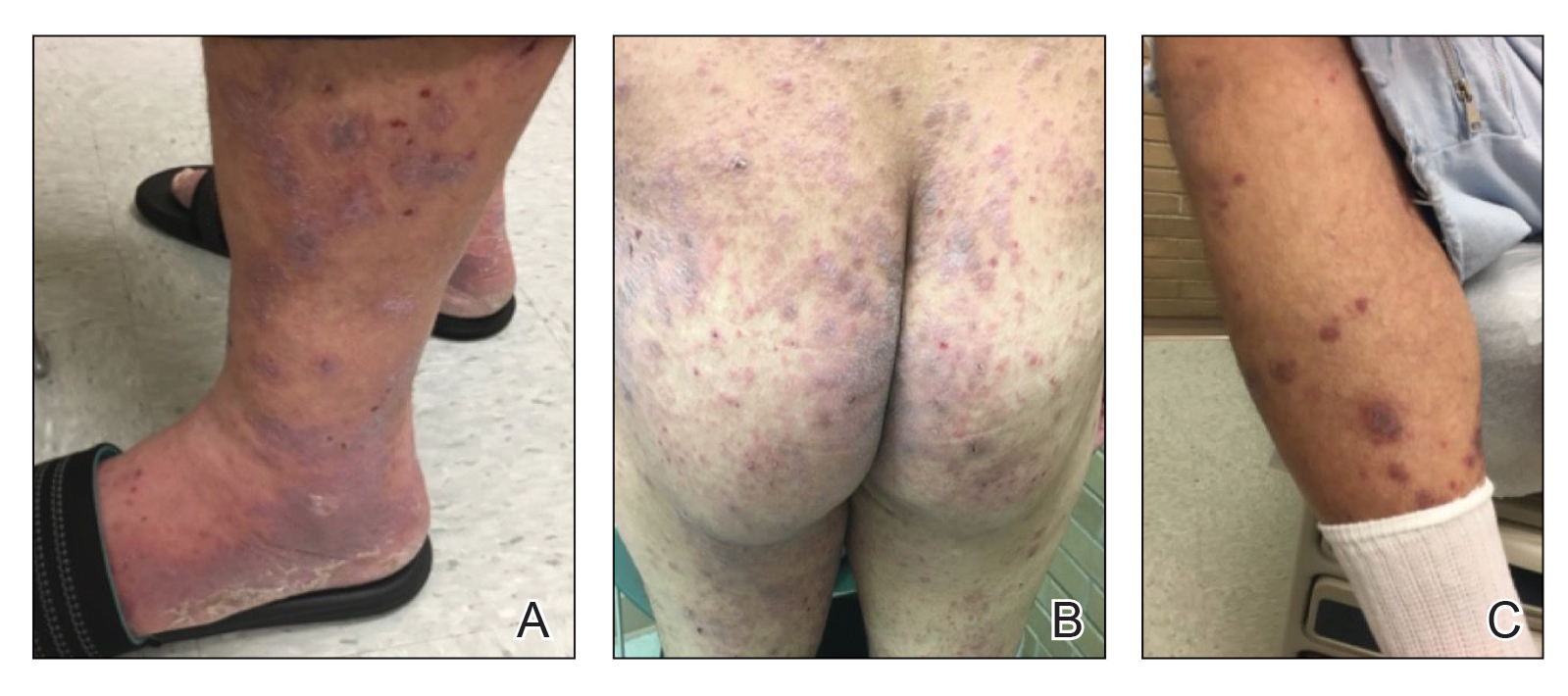

Three years later he developed multiple honey-crusted, superficial ulcers as well as serous, fluid-filled vesiculobullae on the head. A tissue culture revealed Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis, and was negative for acid-fast bacteria and fungus. Biopsy of these lesions revealed dermal ulceration with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous eosinophils as well as a few clustered CD30+ cells; direct immunofluorescence was negative. An extensive laboratory workup including bullous pemphigoid antigens, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies comprehensive profile, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, serum protein electrophoresis, lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, uric acid, C3, C4, immunoglobulin profile, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, and urinalysis was unremarkable. He improved with courses of minocycline, prednisone, and topical clobetasol, but he had periodic and progressive flares over several months with punched-out crusted ulcerations developing on the scalp (Figure 1A) and neck (Figure 1B). The oral and ocular mucosae were uninvolved, but the nasal mucosa had some involvement.

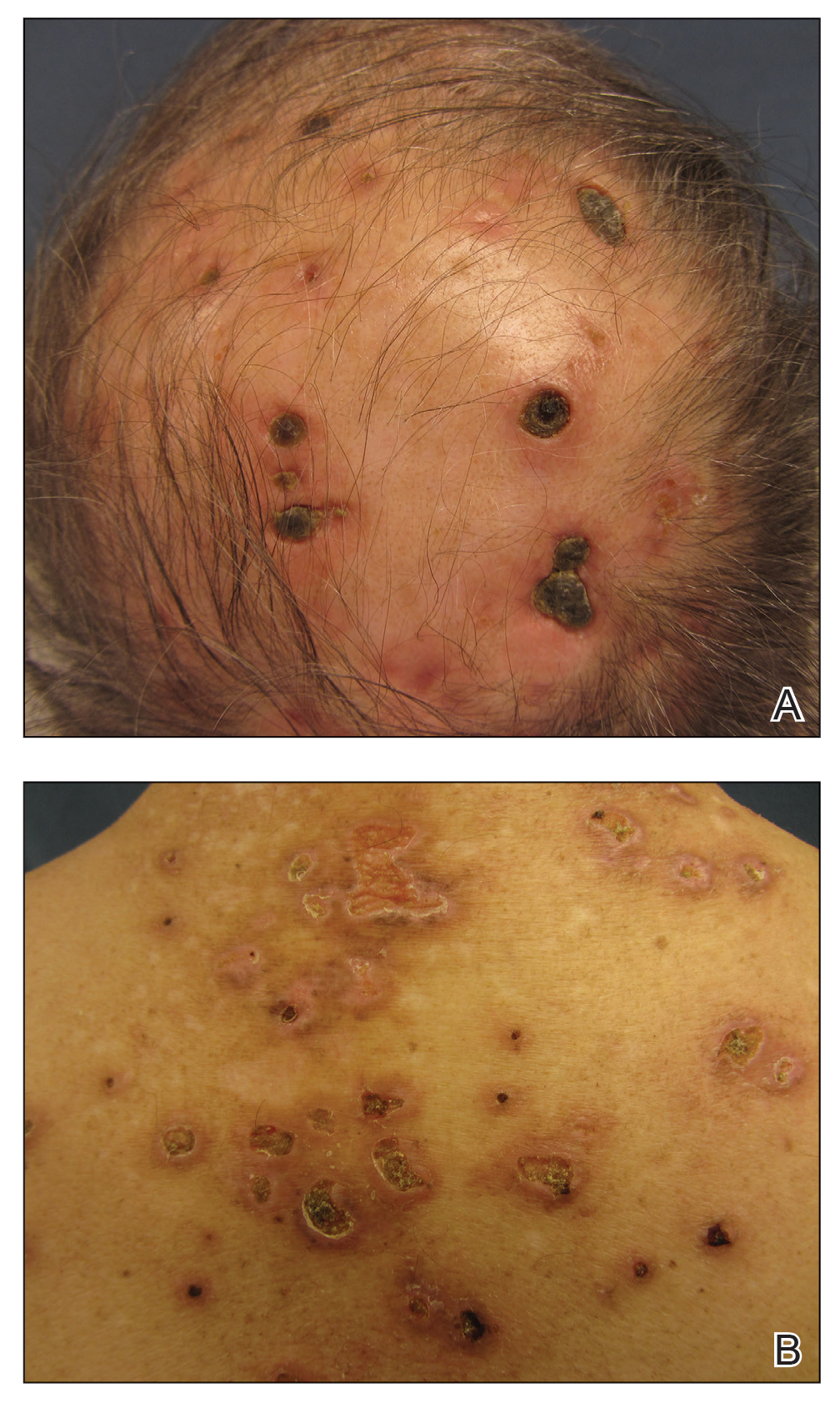

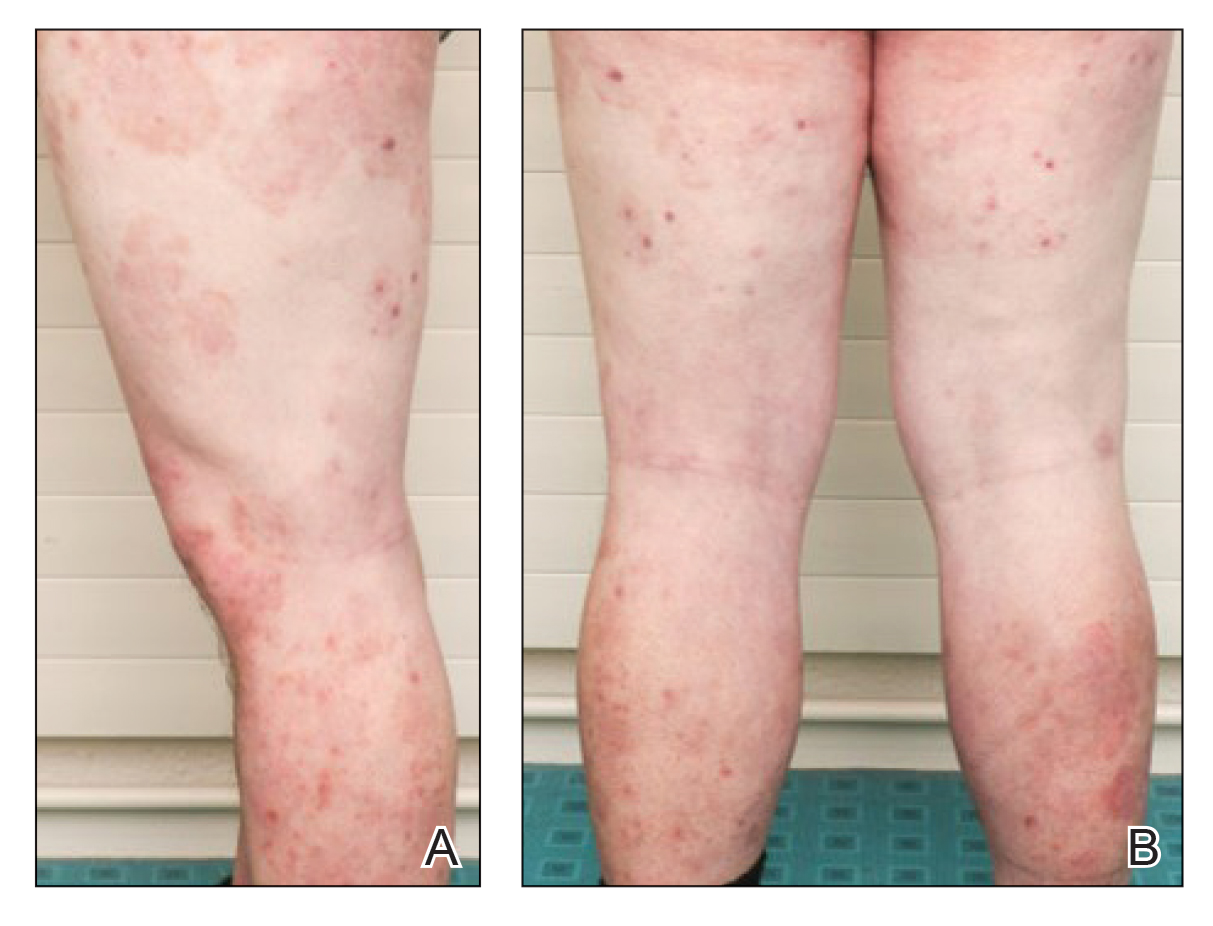

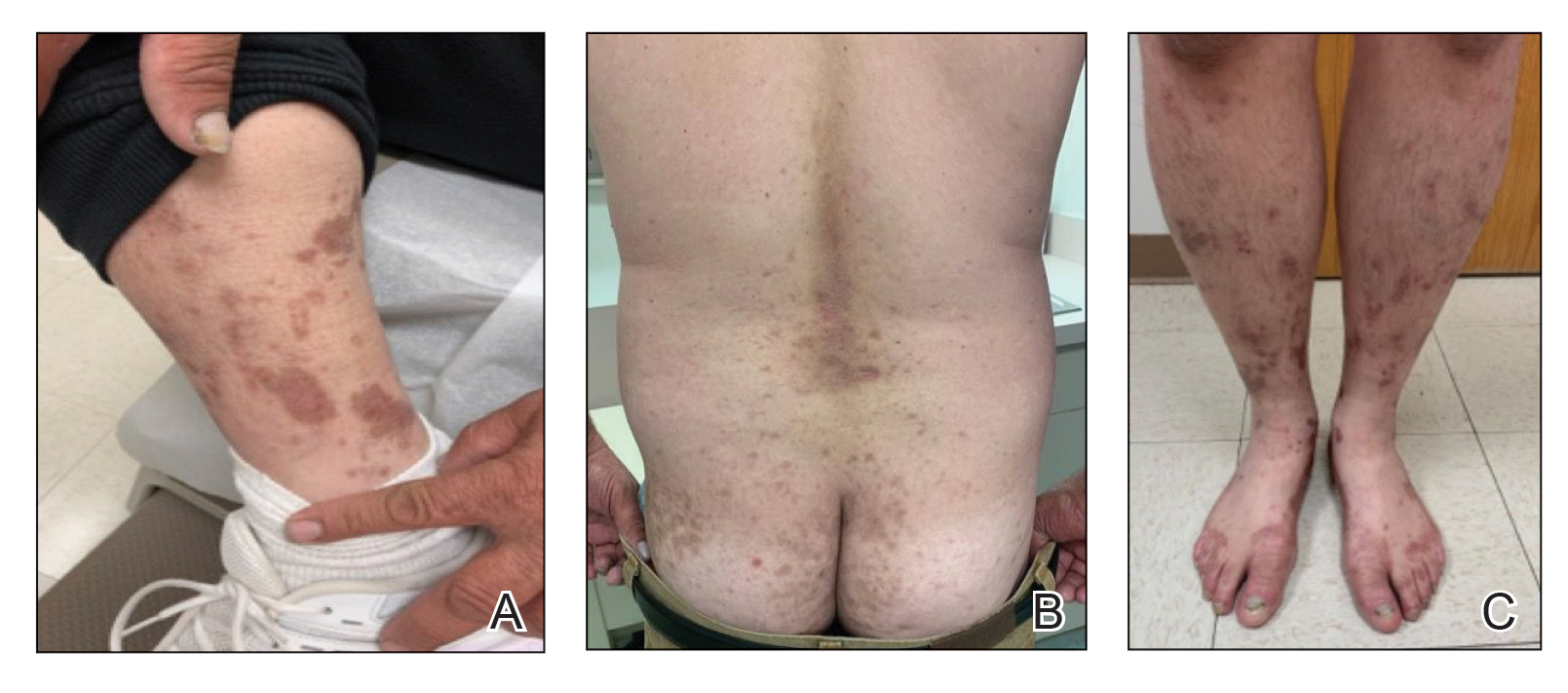

A repeat biopsy demonstrated an atypical CD30+ lymphoid infiltrate favoring LyP. T-cell clonality performed on this specimen and the prior biopsy demonstrated identical T-cell receptor β and γ clones. CD3, CD5, CD7, and CD4 immunostains highlighted the perivascular, perifollicular, and folliculotropic lymphocytic infiltrate. CD8 highlighted occasional background small T cells with only a few folliculotropic forms. A CD30 study revealed several scattered enlarged lymphocytes, and CD20 displayed a few dispersed B cells. A repeat perilesional direct immunofluorescence study was again negative. With treatment, he later formed multiple dry punched-out ulcers with dark eschars on the scalp, posterior neck, and upper back. There were multiple scars on the head, chest, and back, and no vesicles or bullae were present (Figure 2). The patient was presented at a meeting of the Philadelphia Dermatological Society and a consensus diagnosis of LyP was reached. The patient has continued to improve with oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily, topical clobetasol, and topical mupirocin.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma; however, it is associated with the potential development of a second hematologic malignancy, with some disagreement in the literature concerning the exact percentage.3 In some studies, lymphoma has been estimated to occur in less than 20% of cases.4,5 Wieser et al1 reported a retrospective analysis of 180 patients with LyP that revealed a secondary malignancy in 52% of patients. They also reported that the number of lesions and the symptom severity were not associated with lymphoma development.1 Similarly, Cordel et al6 reported a diagnosis of lymphoma in 41% of 106 patients. These analyses reveal that the association with lymphoma may be higher than previously thought, but referral bias may be a confounding factor in these numbers.1,5,6 Associated malignancies may occur prior to, concomitantly, or years after the diagnosis of LyP. The most frequently reported malignancies include mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin lymphoma, and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.1,4

Nicolaou et al3 indicated that head involvement was more likely associated with lymphoma. Our patient had a history of CLL prior to the development of LyP, and it continues to be in remission. The incidence of CLL in patients with LyP is reported to be 0.8%.4 Our patient had an exuberant case of LyP predominantly involving the head, neck, and upper torso, which is an unusual distribution. Vesiculobullous lesions also are uncharacteristic of LyP and may have represented concomitant bullous impetigo, but bullous variants of LyP also have been reported.7 Due to the unique distribution and characteristic scarring, Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid also was considered in the clinical differential diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of LyP associated with malignancy is not definitively known. Theories propose that progression to a malignant clonal T-cell population may come from cytogenetic events, inadequate host response, or persistent antigenic or viral stimulation.4 Studies have demonstrated overlapping T-cell receptor gene rearrangement clones in lesions in patients with both LyP and mycosis fungoides, suggesting a common origin between the diseases.8 Other theories suggest that LyP may arise from an early, reactive, polyclonal lymphoid expansion that evolves into a clonal neoplastic process.4 Interestingly, LyP is a clonal T-cell disorder, while Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL are B-cell disorders. Thus, reports of CLL occurring with LyP, as in our patient, may support the theory that LyP arises from an early stem-cell or precursor-cell defect.4

There is no cure for LyP and data regarding the potential of aggressive therapy on the prevention of secondary lymphomas is lacking. Wieser et al1 reported that treatment did not prevent the progression to lymphoma in their retrospective analysis of 180 patients. The number of lesions, frequency of outbreaks, and extent of the scarring can dictate the treatment approach for LyP. Conservative topical therapies include corticosteroids, bexarotene, and imiquimod. Mupirocin may help to prevent infection of ulcerated lesions.1,2 Low-dose methotrexate has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment in reducing the number of lesions, particularly for scarring or cosmetically sensitive areas. Oral methotrexate at a dosage of 10 mg to 25 mg weekly tapered to the lowest effective dose may suppress outbreaks of LyP lesions.1,2 Other therapies include psoralen plus UVA, UVB, interferon alfa-2a, oral bexarotene, oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, etretinate, mycophenolic acid, photodynamic therapy, oral antibiotics, excision, and radiotherapy.1,2 Systemic chemotherapy and total-skin electron beam therapy have shown efficacy in clearing the lesions; however, the disease recurs after discontinuation of therapy.2 Systemic chemotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of LyP, as risks outweigh the benefits and it does not reduce the risk for developing lymphoma.1 The prognosis generally is good, though long-term follow-up is imperative to monitor for the development of other lymphomas.

Our patient presented with LyP a few months after completing chemotherapy for his CLL. It is unknown if he developed LyP just before the time of presentation, or if he may have developed it at the same time as his CLL by a common inciting event. In the latter case, it is speculative that the LyP may have been controlled by chemotherapy for his CLL, only to become clinically apparent after discontinuation, then naturally remit for a longer period. Case reports such as ours with unusual clinical presentations, B-cell lymphoma associations, and unique timing of lymphoma onset may help to provide insight into the pathogenesis of this disease.

We highlighted an unusual case of LyP that presented clinically with crusted ulcerations as well as vesiculobullous and edematous papules that progressed into deep punched-out ulcers with eschars, nodules, and scarring on the head and upper trunk. Lymphomatoid papulosis can be difficult to diagnose histopathologically at the early stages, and multiple repeat biopsies may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. T-cell gene rearrangement and immunohistochemistry studies are helpful along with clinical correlation to establish a diagnosis in these cases. We recommend that physicians keep LyP on the differential diagnosis for patients with similar clinical presentations and remain vigilant in monitoring for the development of secondary lymphoma.

- Wieser I, Oh C, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Duvic M. CD30+ neoplasms of the skin. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2011;6:245-250.

- Nicolaou V, Papadavid E, Ekonomise A, et al. Association of clinicopathological characteristics with secondary neoplastic lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1303-1307.

- Ahn C, Orscheln C, Huang W. Lymphomatoid papulosis as a harbinger of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1923-1925.

- Kunishige J, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-5781.

- Cordelet al. Frequency and risk factors for associated lymphomas in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Oncologist. 2016;21:76-83.

- Sureda N, Thomas L, Bathelier E, et al. Bullous lymphomatoid papulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:800-801.

- de la Garza Bravo M, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic, recurring, self-healing, primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. This disease affects patients of all ages but most commonly presents in the fifth decade with a slight male predominance.1 The estimated worldwide incidence is 1.2 to 1.9 cases per 1,000,000 individuals, and the 10-year survival rate is close to 100%.1 Clinically, LyP presents as a few to more than 100 red-brown papules or nodules, some with hemorrhagic crust or central necrosis, often occurring in crops and in various stages of evolution. They most commonly are distributed on the trunk and extremities; however, the face, scalp, and oral mucosa rarely may be involved. Each lesion may last on average 3 to 8 weeks, with residual hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin or superficial varioliform scars. The clinical characteristic of spontaneous regression is crucial for distinguishing LyP from other forms of cutaneous lymphoma.2 The disease course is variable, lasting anywhere from a few months to decades. Histopathologically, LyP consists of a frequently CD30+ lymphocytic proliferation in multiple described patterns.1 We report a case of LyP in a patient who initially presented with pink edematous papules and vesicles that progressed to crusted ulcerations, nodules, and deep necrotic eschars on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk. Multiple biopsies and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were necessary to make the diagnosis.

A 73-year-old man presented with edematous crusted papules and nodules as well as scarring with serous drainage on the scalp and upper trunk of several months’ duration. He also reported pain and pruritus. He had a medical history of B-cell CD20− chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that was treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and intravenous immunoglobulin approximately one year prior and currently was in remission; prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy; hypertension; and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His medications included metoprolol, valsartan, and glipizide.

Histopathology revealed a hypersensitivity reaction, and the clinicopathologic correlation was believed to represent an exuberant arthropod bite reaction in the setting of CLL. The eruption responded well to oral prednisone and topical corticosteroids but recurred when the medications were withdrawn. A repeat biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of atypical eosinophil-predominant Sweet syndrome. The condition resolved.

Three years later he developed multiple honey-crusted, superficial ulcers as well as serous, fluid-filled vesiculobullae on the head. A tissue culture revealed Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis, and was negative for acid-fast bacteria and fungus. Biopsy of these lesions revealed dermal ulceration with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous eosinophils as well as a few clustered CD30+ cells; direct immunofluorescence was negative. An extensive laboratory workup including bullous pemphigoid antigens, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies comprehensive profile, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, serum protein electrophoresis, lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, uric acid, C3, C4, immunoglobulin profile, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, and urinalysis was unremarkable. He improved with courses of minocycline, prednisone, and topical clobetasol, but he had periodic and progressive flares over several months with punched-out crusted ulcerations developing on the scalp (Figure 1A) and neck (Figure 1B). The oral and ocular mucosae were uninvolved, but the nasal mucosa had some involvement.

A repeat biopsy demonstrated an atypical CD30+ lymphoid infiltrate favoring LyP. T-cell clonality performed on this specimen and the prior biopsy demonstrated identical T-cell receptor β and γ clones. CD3, CD5, CD7, and CD4 immunostains highlighted the perivascular, perifollicular, and folliculotropic lymphocytic infiltrate. CD8 highlighted occasional background small T cells with only a few folliculotropic forms. A CD30 study revealed several scattered enlarged lymphocytes, and CD20 displayed a few dispersed B cells. A repeat perilesional direct immunofluorescence study was again negative. With treatment, he later formed multiple dry punched-out ulcers with dark eschars on the scalp, posterior neck, and upper back. There were multiple scars on the head, chest, and back, and no vesicles or bullae were present (Figure 2). The patient was presented at a meeting of the Philadelphia Dermatological Society and a consensus diagnosis of LyP was reached. The patient has continued to improve with oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily, topical clobetasol, and topical mupirocin.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma; however, it is associated with the potential development of a second hematologic malignancy, with some disagreement in the literature concerning the exact percentage.3 In some studies, lymphoma has been estimated to occur in less than 20% of cases.4,5 Wieser et al1 reported a retrospective analysis of 180 patients with LyP that revealed a secondary malignancy in 52% of patients. They also reported that the number of lesions and the symptom severity were not associated with lymphoma development.1 Similarly, Cordel et al6 reported a diagnosis of lymphoma in 41% of 106 patients. These analyses reveal that the association with lymphoma may be higher than previously thought, but referral bias may be a confounding factor in these numbers.1,5,6 Associated malignancies may occur prior to, concomitantly, or years after the diagnosis of LyP. The most frequently reported malignancies include mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin lymphoma, and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.1,4

Nicolaou et al3 indicated that head involvement was more likely associated with lymphoma. Our patient had a history of CLL prior to the development of LyP, and it continues to be in remission. The incidence of CLL in patients with LyP is reported to be 0.8%.4 Our patient had an exuberant case of LyP predominantly involving the head, neck, and upper torso, which is an unusual distribution. Vesiculobullous lesions also are uncharacteristic of LyP and may have represented concomitant bullous impetigo, but bullous variants of LyP also have been reported.7 Due to the unique distribution and characteristic scarring, Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid also was considered in the clinical differential diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of LyP associated with malignancy is not definitively known. Theories propose that progression to a malignant clonal T-cell population may come from cytogenetic events, inadequate host response, or persistent antigenic or viral stimulation.4 Studies have demonstrated overlapping T-cell receptor gene rearrangement clones in lesions in patients with both LyP and mycosis fungoides, suggesting a common origin between the diseases.8 Other theories suggest that LyP may arise from an early, reactive, polyclonal lymphoid expansion that evolves into a clonal neoplastic process.4 Interestingly, LyP is a clonal T-cell disorder, while Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL are B-cell disorders. Thus, reports of CLL occurring with LyP, as in our patient, may support the theory that LyP arises from an early stem-cell or precursor-cell defect.4

There is no cure for LyP and data regarding the potential of aggressive therapy on the prevention of secondary lymphomas is lacking. Wieser et al1 reported that treatment did not prevent the progression to lymphoma in their retrospective analysis of 180 patients. The number of lesions, frequency of outbreaks, and extent of the scarring can dictate the treatment approach for LyP. Conservative topical therapies include corticosteroids, bexarotene, and imiquimod. Mupirocin may help to prevent infection of ulcerated lesions.1,2 Low-dose methotrexate has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment in reducing the number of lesions, particularly for scarring or cosmetically sensitive areas. Oral methotrexate at a dosage of 10 mg to 25 mg weekly tapered to the lowest effective dose may suppress outbreaks of LyP lesions.1,2 Other therapies include psoralen plus UVA, UVB, interferon alfa-2a, oral bexarotene, oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, etretinate, mycophenolic acid, photodynamic therapy, oral antibiotics, excision, and radiotherapy.1,2 Systemic chemotherapy and total-skin electron beam therapy have shown efficacy in clearing the lesions; however, the disease recurs after discontinuation of therapy.2 Systemic chemotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of LyP, as risks outweigh the benefits and it does not reduce the risk for developing lymphoma.1 The prognosis generally is good, though long-term follow-up is imperative to monitor for the development of other lymphomas.

Our patient presented with LyP a few months after completing chemotherapy for his CLL. It is unknown if he developed LyP just before the time of presentation, or if he may have developed it at the same time as his CLL by a common inciting event. In the latter case, it is speculative that the LyP may have been controlled by chemotherapy for his CLL, only to become clinically apparent after discontinuation, then naturally remit for a longer period. Case reports such as ours with unusual clinical presentations, B-cell lymphoma associations, and unique timing of lymphoma onset may help to provide insight into the pathogenesis of this disease.

We highlighted an unusual case of LyP that presented clinically with crusted ulcerations as well as vesiculobullous and edematous papules that progressed into deep punched-out ulcers with eschars, nodules, and scarring on the head and upper trunk. Lymphomatoid papulosis can be difficult to diagnose histopathologically at the early stages, and multiple repeat biopsies may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. T-cell gene rearrangement and immunohistochemistry studies are helpful along with clinical correlation to establish a diagnosis in these cases. We recommend that physicians keep LyP on the differential diagnosis for patients with similar clinical presentations and remain vigilant in monitoring for the development of secondary lymphoma.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic, recurring, self-healing, primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. This disease affects patients of all ages but most commonly presents in the fifth decade with a slight male predominance.1 The estimated worldwide incidence is 1.2 to 1.9 cases per 1,000,000 individuals, and the 10-year survival rate is close to 100%.1 Clinically, LyP presents as a few to more than 100 red-brown papules or nodules, some with hemorrhagic crust or central necrosis, often occurring in crops and in various stages of evolution. They most commonly are distributed on the trunk and extremities; however, the face, scalp, and oral mucosa rarely may be involved. Each lesion may last on average 3 to 8 weeks, with residual hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin or superficial varioliform scars. The clinical characteristic of spontaneous regression is crucial for distinguishing LyP from other forms of cutaneous lymphoma.2 The disease course is variable, lasting anywhere from a few months to decades. Histopathologically, LyP consists of a frequently CD30+ lymphocytic proliferation in multiple described patterns.1 We report a case of LyP in a patient who initially presented with pink edematous papules and vesicles that progressed to crusted ulcerations, nodules, and deep necrotic eschars on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk. Multiple biopsies and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were necessary to make the diagnosis.

A 73-year-old man presented with edematous crusted papules and nodules as well as scarring with serous drainage on the scalp and upper trunk of several months’ duration. He also reported pain and pruritus. He had a medical history of B-cell CD20− chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that was treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and intravenous immunoglobulin approximately one year prior and currently was in remission; prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy; hypertension; and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His medications included metoprolol, valsartan, and glipizide.

Histopathology revealed a hypersensitivity reaction, and the clinicopathologic correlation was believed to represent an exuberant arthropod bite reaction in the setting of CLL. The eruption responded well to oral prednisone and topical corticosteroids but recurred when the medications were withdrawn. A repeat biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of atypical eosinophil-predominant Sweet syndrome. The condition resolved.

Three years later he developed multiple honey-crusted, superficial ulcers as well as serous, fluid-filled vesiculobullae on the head. A tissue culture revealed Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis, and was negative for acid-fast bacteria and fungus. Biopsy of these lesions revealed dermal ulceration with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous eosinophils as well as a few clustered CD30+ cells; direct immunofluorescence was negative. An extensive laboratory workup including bullous pemphigoid antigens, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies comprehensive profile, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, serum protein electrophoresis, lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, uric acid, C3, C4, immunoglobulin profile, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, and urinalysis was unremarkable. He improved with courses of minocycline, prednisone, and topical clobetasol, but he had periodic and progressive flares over several months with punched-out crusted ulcerations developing on the scalp (Figure 1A) and neck (Figure 1B). The oral and ocular mucosae were uninvolved, but the nasal mucosa had some involvement.

A repeat biopsy demonstrated an atypical CD30+ lymphoid infiltrate favoring LyP. T-cell clonality performed on this specimen and the prior biopsy demonstrated identical T-cell receptor β and γ clones. CD3, CD5, CD7, and CD4 immunostains highlighted the perivascular, perifollicular, and folliculotropic lymphocytic infiltrate. CD8 highlighted occasional background small T cells with only a few folliculotropic forms. A CD30 study revealed several scattered enlarged lymphocytes, and CD20 displayed a few dispersed B cells. A repeat perilesional direct immunofluorescence study was again negative. With treatment, he later formed multiple dry punched-out ulcers with dark eschars on the scalp, posterior neck, and upper back. There were multiple scars on the head, chest, and back, and no vesicles or bullae were present (Figure 2). The patient was presented at a meeting of the Philadelphia Dermatological Society and a consensus diagnosis of LyP was reached. The patient has continued to improve with oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily, topical clobetasol, and topical mupirocin.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma; however, it is associated with the potential development of a second hematologic malignancy, with some disagreement in the literature concerning the exact percentage.3 In some studies, lymphoma has been estimated to occur in less than 20% of cases.4,5 Wieser et al1 reported a retrospective analysis of 180 patients with LyP that revealed a secondary malignancy in 52% of patients. They also reported that the number of lesions and the symptom severity were not associated with lymphoma development.1 Similarly, Cordel et al6 reported a diagnosis of lymphoma in 41% of 106 patients. These analyses reveal that the association with lymphoma may be higher than previously thought, but referral bias may be a confounding factor in these numbers.1,5,6 Associated malignancies may occur prior to, concomitantly, or years after the diagnosis of LyP. The most frequently reported malignancies include mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin lymphoma, and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.1,4

Nicolaou et al3 indicated that head involvement was more likely associated with lymphoma. Our patient had a history of CLL prior to the development of LyP, and it continues to be in remission. The incidence of CLL in patients with LyP is reported to be 0.8%.4 Our patient had an exuberant case of LyP predominantly involving the head, neck, and upper torso, which is an unusual distribution. Vesiculobullous lesions also are uncharacteristic of LyP and may have represented concomitant bullous impetigo, but bullous variants of LyP also have been reported.7 Due to the unique distribution and characteristic scarring, Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid also was considered in the clinical differential diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of LyP associated with malignancy is not definitively known. Theories propose that progression to a malignant clonal T-cell population may come from cytogenetic events, inadequate host response, or persistent antigenic or viral stimulation.4 Studies have demonstrated overlapping T-cell receptor gene rearrangement clones in lesions in patients with both LyP and mycosis fungoides, suggesting a common origin between the diseases.8 Other theories suggest that LyP may arise from an early, reactive, polyclonal lymphoid expansion that evolves into a clonal neoplastic process.4 Interestingly, LyP is a clonal T-cell disorder, while Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL are B-cell disorders. Thus, reports of CLL occurring with LyP, as in our patient, may support the theory that LyP arises from an early stem-cell or precursor-cell defect.4

There is no cure for LyP and data regarding the potential of aggressive therapy on the prevention of secondary lymphomas is lacking. Wieser et al1 reported that treatment did not prevent the progression to lymphoma in their retrospective analysis of 180 patients. The number of lesions, frequency of outbreaks, and extent of the scarring can dictate the treatment approach for LyP. Conservative topical therapies include corticosteroids, bexarotene, and imiquimod. Mupirocin may help to prevent infection of ulcerated lesions.1,2 Low-dose methotrexate has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment in reducing the number of lesions, particularly for scarring or cosmetically sensitive areas. Oral methotrexate at a dosage of 10 mg to 25 mg weekly tapered to the lowest effective dose may suppress outbreaks of LyP lesions.1,2 Other therapies include psoralen plus UVA, UVB, interferon alfa-2a, oral bexarotene, oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, etretinate, mycophenolic acid, photodynamic therapy, oral antibiotics, excision, and radiotherapy.1,2 Systemic chemotherapy and total-skin electron beam therapy have shown efficacy in clearing the lesions; however, the disease recurs after discontinuation of therapy.2 Systemic chemotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of LyP, as risks outweigh the benefits and it does not reduce the risk for developing lymphoma.1 The prognosis generally is good, though long-term follow-up is imperative to monitor for the development of other lymphomas.

Our patient presented with LyP a few months after completing chemotherapy for his CLL. It is unknown if he developed LyP just before the time of presentation, or if he may have developed it at the same time as his CLL by a common inciting event. In the latter case, it is speculative that the LyP may have been controlled by chemotherapy for his CLL, only to become clinically apparent after discontinuation, then naturally remit for a longer period. Case reports such as ours with unusual clinical presentations, B-cell lymphoma associations, and unique timing of lymphoma onset may help to provide insight into the pathogenesis of this disease.

We highlighted an unusual case of LyP that presented clinically with crusted ulcerations as well as vesiculobullous and edematous papules that progressed into deep punched-out ulcers with eschars, nodules, and scarring on the head and upper trunk. Lymphomatoid papulosis can be difficult to diagnose histopathologically at the early stages, and multiple repeat biopsies may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. T-cell gene rearrangement and immunohistochemistry studies are helpful along with clinical correlation to establish a diagnosis in these cases. We recommend that physicians keep LyP on the differential diagnosis for patients with similar clinical presentations and remain vigilant in monitoring for the development of secondary lymphoma.

- Wieser I, Oh C, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Duvic M. CD30+ neoplasms of the skin. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2011;6:245-250.

- Nicolaou V, Papadavid E, Ekonomise A, et al. Association of clinicopathological characteristics with secondary neoplastic lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1303-1307.

- Ahn C, Orscheln C, Huang W. Lymphomatoid papulosis as a harbinger of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1923-1925.

- Kunishige J, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-5781.

- Cordelet al. Frequency and risk factors for associated lymphomas in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Oncologist. 2016;21:76-83.

- Sureda N, Thomas L, Bathelier E, et al. Bullous lymphomatoid papulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:800-801.

- de la Garza Bravo M, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

- Wieser I, Oh C, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Duvic M. CD30+ neoplasms of the skin. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2011;6:245-250.

- Nicolaou V, Papadavid E, Ekonomise A, et al. Association of clinicopathological characteristics with secondary neoplastic lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1303-1307.

- Ahn C, Orscheln C, Huang W. Lymphomatoid papulosis as a harbinger of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1923-1925.

- Kunishige J, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-5781.

- Cordelet al. Frequency and risk factors for associated lymphomas in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Oncologist. 2016;21:76-83.

- Sureda N, Thomas L, Bathelier E, et al. Bullous lymphomatoid papulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:800-801.

- de la Garza Bravo M, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

Practice Points

- Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic, recurring, self-healing, primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by red-brown papules or nodules, some with hemorrhagic crust or central necrosis, often occurring in crops and in various stages of evolution.

- Histopathologically, LyP consists of a frequently CD30Mathematical Pi LT Std+ lymphocytic proliferation in multiple described patterns.

- Lymphomatoid papulosis is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma; however, it is associated with the potential development of a second hematologic malignancy.

Home Treatment of Presumed Melanocytic Nevus With Frankincense

To the Editor:

Melanocytic nevi are ubiquitous, and although they are benign, patients often desire to have them removed. We report a patient who presented to our clinic after attempting home removal of a concerning mole on the back with frankincense, a remedy that she found online.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a worrisome mole on the back. She had no personal history of skin cancer, but her father had a history of melanoma in situ in his 60s. The patient reported that she had the mole for years, but approximately 1 month prior to her visit she noticed that it began to bleed and crust, causing concern for melanoma. She read online that the lesion could be removed with topical application of the essential oil frankincense; she applied it directly to the lesion on the back. Within hours she developed a burn where it was applied with associated blistering.

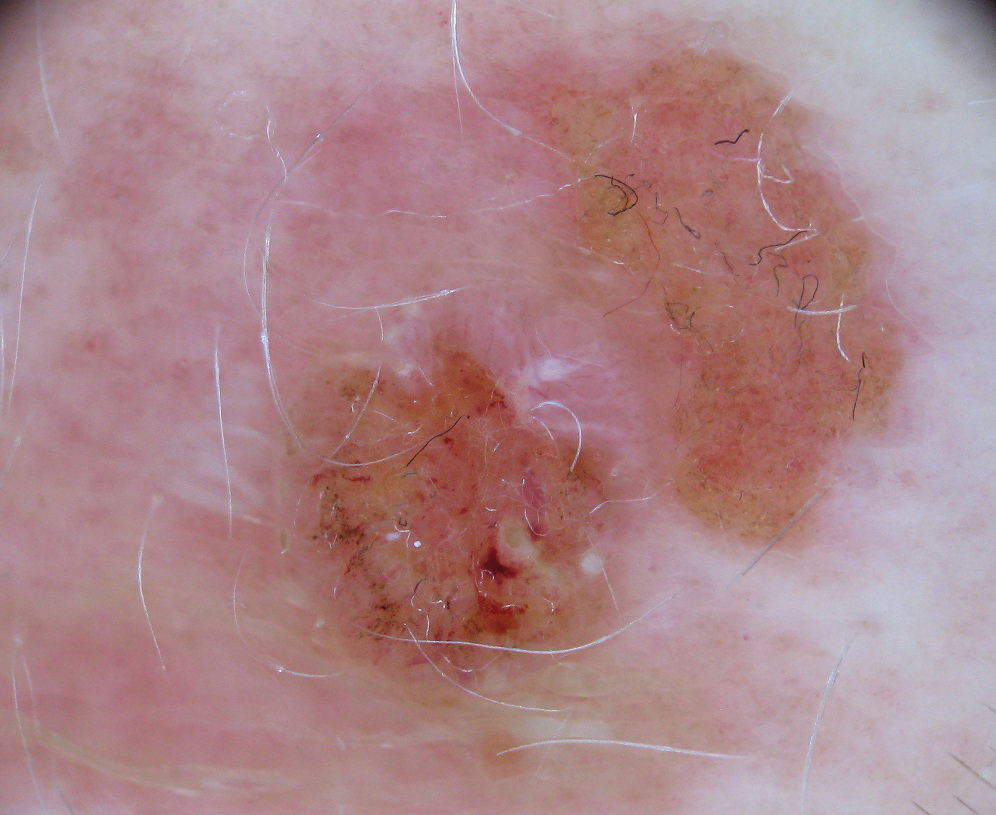

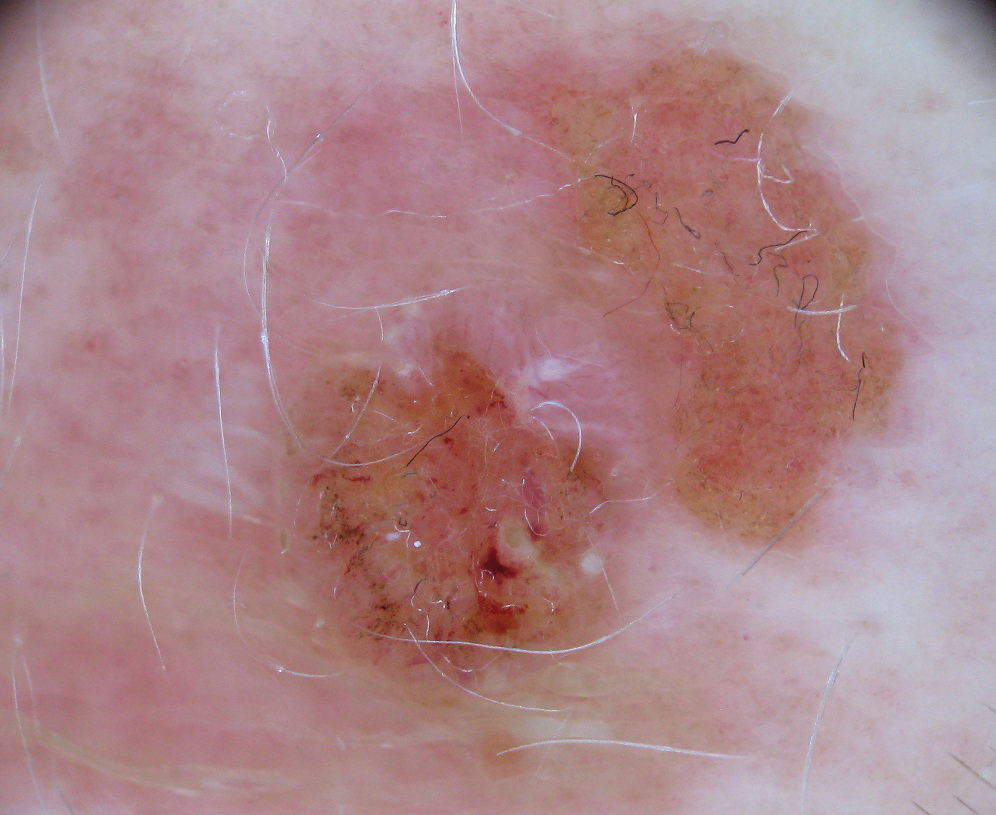

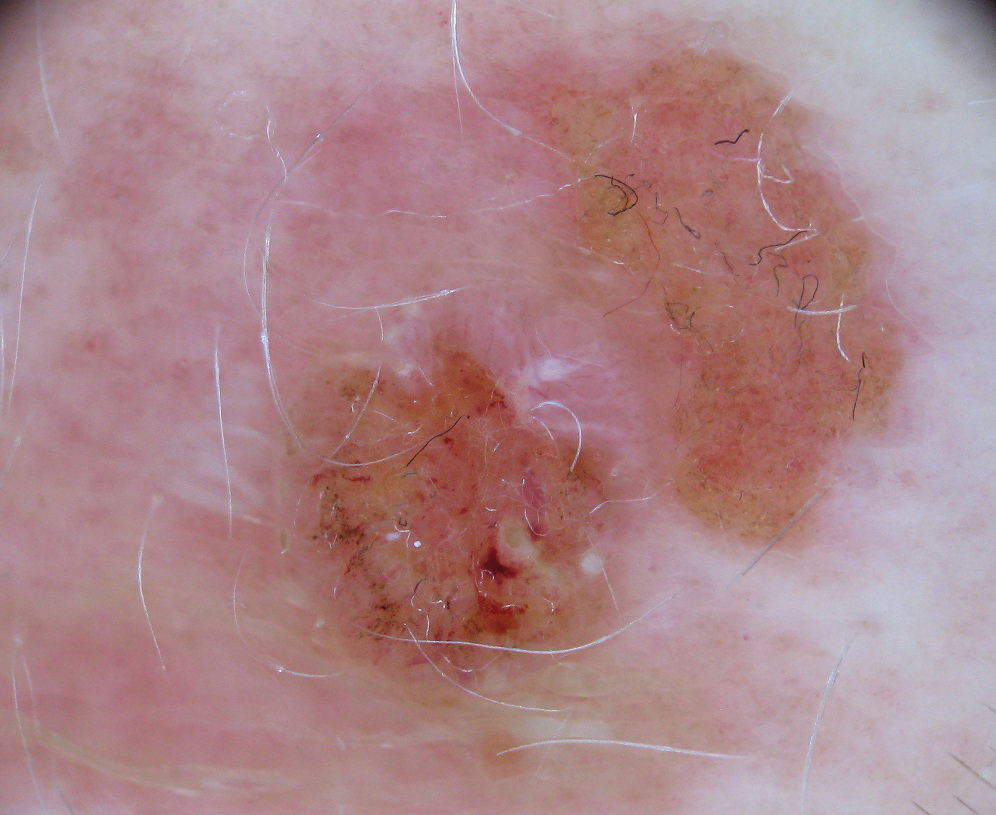

Clinically, the lesion appeared as a darkly pigmented, well-circumscribed papule with hemorrhagic crust overlying a well-demarcated pink plaque (Figure 1). Dermatoscopically, the lesion lacked a pigment network and demonstrated 2 distinct pink papules with peripheral telangiectasia and a pink background with white streaks (Figure 2). A shave biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a nodular basal cell carcinoma extending to the base and margin.

Frankincense is the common name given to oleo-gum-resins of Boswellia species.1 It has been studied extensively for anti-inflammatory and antitumoral properties. It has been demonstrated that high concentrations of its active component, boswellic acid, can have a cytotoxic or cytostatic effect on certain malignant cell lines, such as melanoma, in vitro.2,3 It also has been shown to be antitumoral in mouse models.4 There are limited in vivo studies in the literature assessing the effects of boswellic acid or frankincense on cutaneous melanocytic lesions or other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma.

A Google search of home remedy mole removal yielded more than 1,000,000 results. At the time of submission, the top 5 results all listed frankincense as a potential treatment along with garlic, iodine, castor oil, onion juice, pineapple juice, banana peels, honey, and aloe vera. None of the results cited evidence for their treatments. Although all recommended dilution of the frankincense prior to application, none warned of potential risks or side effects of its use.

Natural methods of home mole removal have long been sought after. Escharotics are most commonly utilized, including bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), zinc chloride, Chelidonium majus, and Solanum sodomaeum. Many formulations are commercially available online, despite the fact that they can be mutilating and potentially dangerous when used without appropriate supervision.5 This case and an online search demonstrated that these agents are not only potentially harmful home remedies but also are currently falsely advertised as effective therapeutic management for melanocytic nevi.

Approximately 6 million individuals in the United States search the internet for health information daily, and as many as 41% of those do so to learn about alternative medicine.5,6 Although information gleaned from search engines can be useful, it is unregulated and often can be inaccurate. Clinicians generally are unaware of the erroneous material presented online and, therefore, cannot appropriately combat patient misinformation. Our case demonstrates the need to maintain an awareness of common online fallacies to better answer patient questions and guide them to more accurate sources of dermatologic information and appropriate treatment.

- Du Z, Liu Z, Ning Z, et al. Prospects of boswellic acids as potential pharmaceutics. Planta Med. 2015;81:259-271.

- Eichhorn T, Greten HJ, Efferth T. Molecular determinants of the response of tumor cells to boswellic acids. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2011;4:1171-1182.

- Zhao W, Entschladen F, Liu H, et al. Boswellic acid acetate induces differentiation and apoptosis in highly metastatic melanoma and fibrosarcoma cell. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

- Huang MT, Badmaev V, Ding Y, et al. Anti-tumor and anti-carcinogenic activities of triterpenoid, beta-boswellic acid. Biofactors. 2000;13:225-230.

- Adler BL, Friedman AJ. Safety & efficacy of agents used for home mole removal and skin cancer treatment in the internet age, and analysis of cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1058-1063.

- Kanthawala S, Vermeesch A, Given B, et al. Answers to health questions: internet search results versus online health community responses. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:E95.

To the Editor:

Melanocytic nevi are ubiquitous, and although they are benign, patients often desire to have them removed. We report a patient who presented to our clinic after attempting home removal of a concerning mole on the back with frankincense, a remedy that she found online.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a worrisome mole on the back. She had no personal history of skin cancer, but her father had a history of melanoma in situ in his 60s. The patient reported that she had the mole for years, but approximately 1 month prior to her visit she noticed that it began to bleed and crust, causing concern for melanoma. She read online that the lesion could be removed with topical application of the essential oil frankincense; she applied it directly to the lesion on the back. Within hours she developed a burn where it was applied with associated blistering.

Clinically, the lesion appeared as a darkly pigmented, well-circumscribed papule with hemorrhagic crust overlying a well-demarcated pink plaque (Figure 1). Dermatoscopically, the lesion lacked a pigment network and demonstrated 2 distinct pink papules with peripheral telangiectasia and a pink background with white streaks (Figure 2). A shave biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a nodular basal cell carcinoma extending to the base and margin.

Frankincense is the common name given to oleo-gum-resins of Boswellia species.1 It has been studied extensively for anti-inflammatory and antitumoral properties. It has been demonstrated that high concentrations of its active component, boswellic acid, can have a cytotoxic or cytostatic effect on certain malignant cell lines, such as melanoma, in vitro.2,3 It also has been shown to be antitumoral in mouse models.4 There are limited in vivo studies in the literature assessing the effects of boswellic acid or frankincense on cutaneous melanocytic lesions or other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma.

A Google search of home remedy mole removal yielded more than 1,000,000 results. At the time of submission, the top 5 results all listed frankincense as a potential treatment along with garlic, iodine, castor oil, onion juice, pineapple juice, banana peels, honey, and aloe vera. None of the results cited evidence for their treatments. Although all recommended dilution of the frankincense prior to application, none warned of potential risks or side effects of its use.

Natural methods of home mole removal have long been sought after. Escharotics are most commonly utilized, including bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), zinc chloride, Chelidonium majus, and Solanum sodomaeum. Many formulations are commercially available online, despite the fact that they can be mutilating and potentially dangerous when used without appropriate supervision.5 This case and an online search demonstrated that these agents are not only potentially harmful home remedies but also are currently falsely advertised as effective therapeutic management for melanocytic nevi.

Approximately 6 million individuals in the United States search the internet for health information daily, and as many as 41% of those do so to learn about alternative medicine.5,6 Although information gleaned from search engines can be useful, it is unregulated and often can be inaccurate. Clinicians generally are unaware of the erroneous material presented online and, therefore, cannot appropriately combat patient misinformation. Our case demonstrates the need to maintain an awareness of common online fallacies to better answer patient questions and guide them to more accurate sources of dermatologic information and appropriate treatment.

To the Editor:

Melanocytic nevi are ubiquitous, and although they are benign, patients often desire to have them removed. We report a patient who presented to our clinic after attempting home removal of a concerning mole on the back with frankincense, a remedy that she found online.

A 43-year-old woman presented with a worrisome mole on the back. She had no personal history of skin cancer, but her father had a history of melanoma in situ in his 60s. The patient reported that she had the mole for years, but approximately 1 month prior to her visit she noticed that it began to bleed and crust, causing concern for melanoma. She read online that the lesion could be removed with topical application of the essential oil frankincense; she applied it directly to the lesion on the back. Within hours she developed a burn where it was applied with associated blistering.

Clinically, the lesion appeared as a darkly pigmented, well-circumscribed papule with hemorrhagic crust overlying a well-demarcated pink plaque (Figure 1). Dermatoscopically, the lesion lacked a pigment network and demonstrated 2 distinct pink papules with peripheral telangiectasia and a pink background with white streaks (Figure 2). A shave biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a nodular basal cell carcinoma extending to the base and margin.

Frankincense is the common name given to oleo-gum-resins of Boswellia species.1 It has been studied extensively for anti-inflammatory and antitumoral properties. It has been demonstrated that high concentrations of its active component, boswellic acid, can have a cytotoxic or cytostatic effect on certain malignant cell lines, such as melanoma, in vitro.2,3 It also has been shown to be antitumoral in mouse models.4 There are limited in vivo studies in the literature assessing the effects of boswellic acid or frankincense on cutaneous melanocytic lesions or other cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma.

A Google search of home remedy mole removal yielded more than 1,000,000 results. At the time of submission, the top 5 results all listed frankincense as a potential treatment along with garlic, iodine, castor oil, onion juice, pineapple juice, banana peels, honey, and aloe vera. None of the results cited evidence for their treatments. Although all recommended dilution of the frankincense prior to application, none warned of potential risks or side effects of its use.

Natural methods of home mole removal have long been sought after. Escharotics are most commonly utilized, including bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), zinc chloride, Chelidonium majus, and Solanum sodomaeum. Many formulations are commercially available online, despite the fact that they can be mutilating and potentially dangerous when used without appropriate supervision.5 This case and an online search demonstrated that these agents are not only potentially harmful home remedies but also are currently falsely advertised as effective therapeutic management for melanocytic nevi.

Approximately 6 million individuals in the United States search the internet for health information daily, and as many as 41% of those do so to learn about alternative medicine.5,6 Although information gleaned from search engines can be useful, it is unregulated and often can be inaccurate. Clinicians generally are unaware of the erroneous material presented online and, therefore, cannot appropriately combat patient misinformation. Our case demonstrates the need to maintain an awareness of common online fallacies to better answer patient questions and guide them to more accurate sources of dermatologic information and appropriate treatment.

- Du Z, Liu Z, Ning Z, et al. Prospects of boswellic acids as potential pharmaceutics. Planta Med. 2015;81:259-271.

- Eichhorn T, Greten HJ, Efferth T. Molecular determinants of the response of tumor cells to boswellic acids. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2011;4:1171-1182.

- Zhao W, Entschladen F, Liu H, et al. Boswellic acid acetate induces differentiation and apoptosis in highly metastatic melanoma and fibrosarcoma cell. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

- Huang MT, Badmaev V, Ding Y, et al. Anti-tumor and anti-carcinogenic activities of triterpenoid, beta-boswellic acid. Biofactors. 2000;13:225-230.

- Adler BL, Friedman AJ. Safety & efficacy of agents used for home mole removal and skin cancer treatment in the internet age, and analysis of cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1058-1063.

- Kanthawala S, Vermeesch A, Given B, et al. Answers to health questions: internet search results versus online health community responses. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:E95.

- Du Z, Liu Z, Ning Z, et al. Prospects of boswellic acids as potential pharmaceutics. Planta Med. 2015;81:259-271.

- Eichhorn T, Greten HJ, Efferth T. Molecular determinants of the response of tumor cells to boswellic acids. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2011;4:1171-1182.

- Zhao W, Entschladen F, Liu H, et al. Boswellic acid acetate induces differentiation and apoptosis in highly metastatic melanoma and fibrosarcoma cell. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:67-75.

- Huang MT, Badmaev V, Ding Y, et al. Anti-tumor and anti-carcinogenic activities of triterpenoid, beta-boswellic acid. Biofactors. 2000;13:225-230.

- Adler BL, Friedman AJ. Safety & efficacy of agents used for home mole removal and skin cancer treatment in the internet age, and analysis of cases. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1058-1063.

- Kanthawala S, Vermeesch A, Given B, et al. Answers to health questions: internet search results versus online health community responses. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:E95.

Practice Points

- Many patients seek natural methods of home mole removal online, including topical application of essential oils such as frankincense.

- These agents often are unregulated and can be potentially harmful when used without appropriate supervision.

- Dermatologists should be aware of common online fallacies to better answer patient questions and guide them to more accurate sources of dermatologic information and appropriate treatment.

Fatal Case of Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy in a Cocaine User

To the Editor:

Levamisole is a veterinary anthelmintic drug with immunomodulating properties that was once approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of various conditions, including autoimmune diseases, cancer, pediatric kidney disease, and chronic infections.1-4 Levamisole was banned in 2000 after reports of associated agranulocytosis and a characteristic painful purpuric vasculitis.4,5 Despite the ban, its use persists due to its increasing incorporation as an adulterant in cocaine, presumably for its dopaminergic properties that potentiate psychotropic effects.6 In 2009, the Drug Enforcement Administration reported that 69% of seized cocaine in the United States contains this chemical, with an average concentration of 10%.5 Levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV) typically resolves following the cessation of cocaine without further treatment necessary. We present a fatal case of LIV to emphasize that early recognition and discontinuation of the offending agent could be lifesaving.

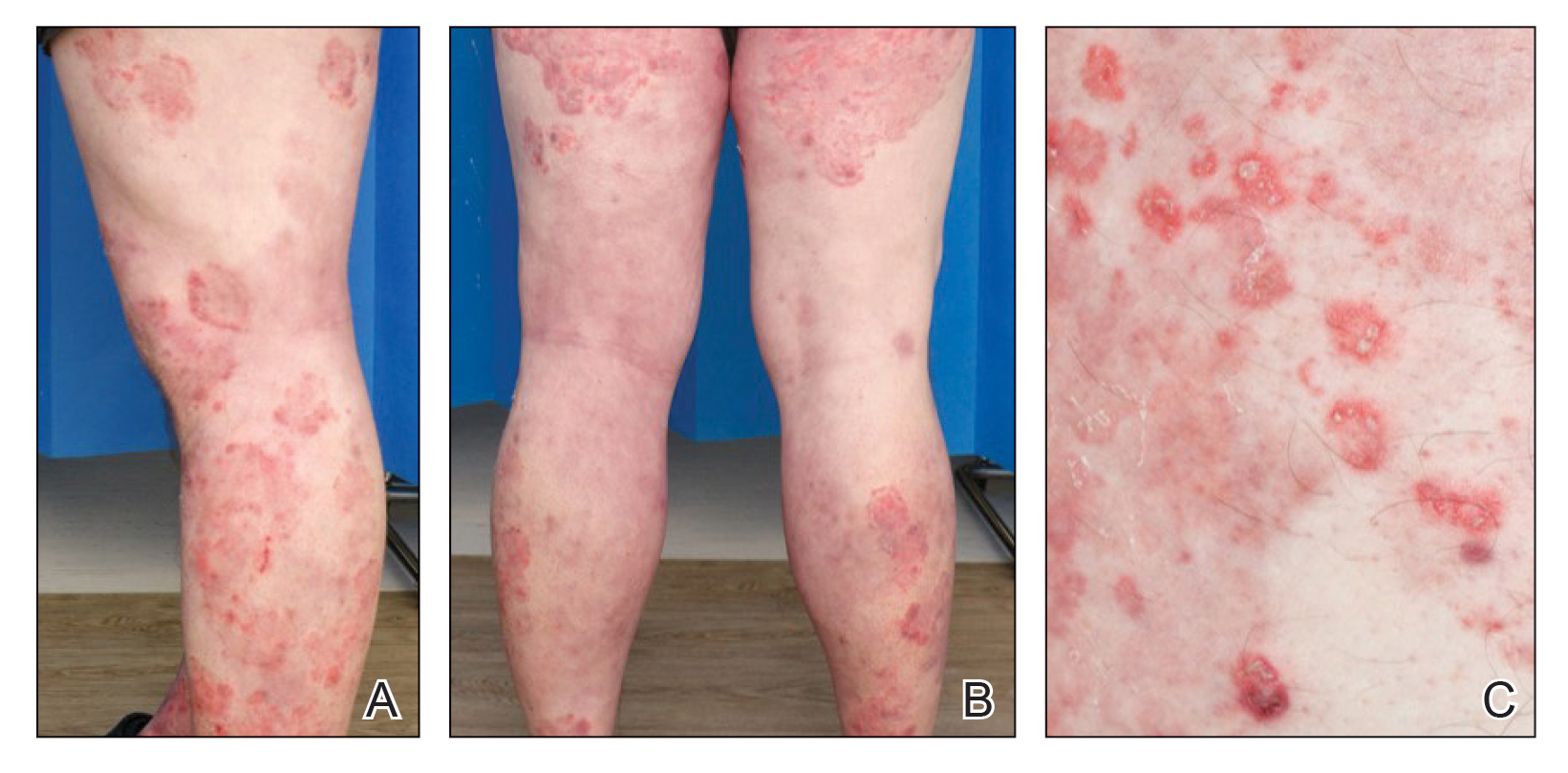

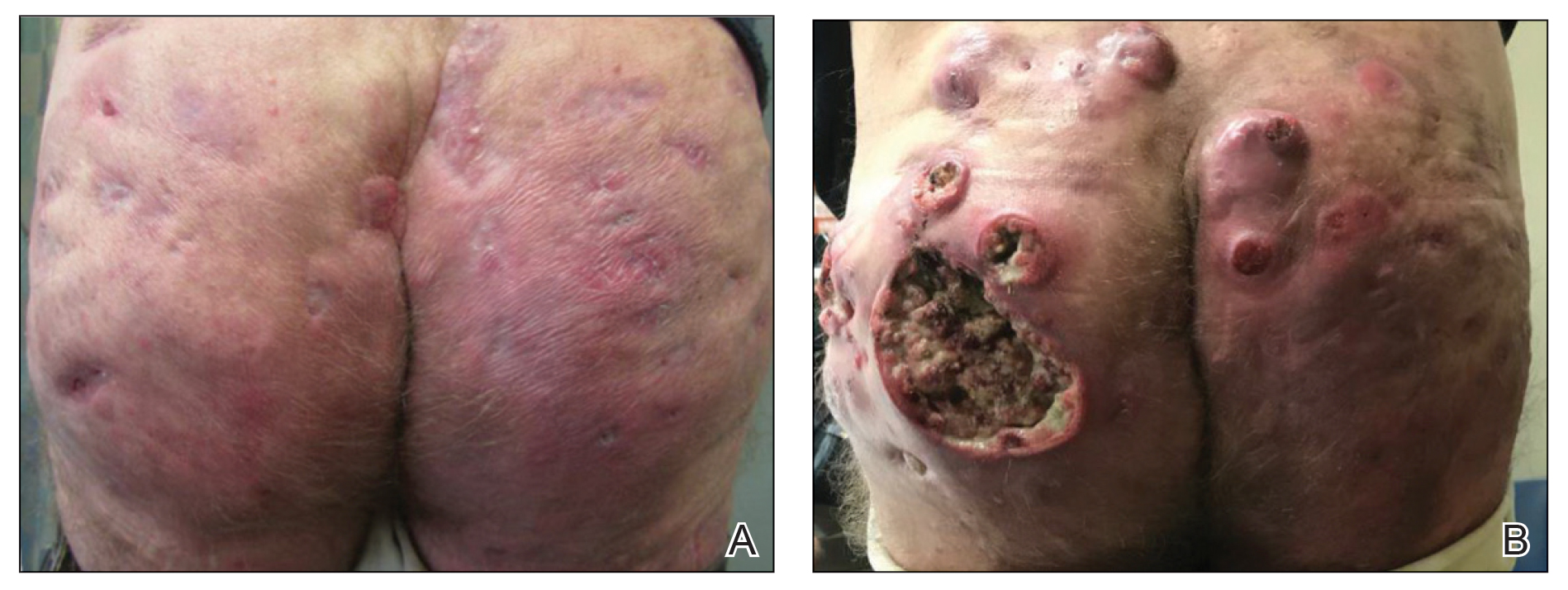

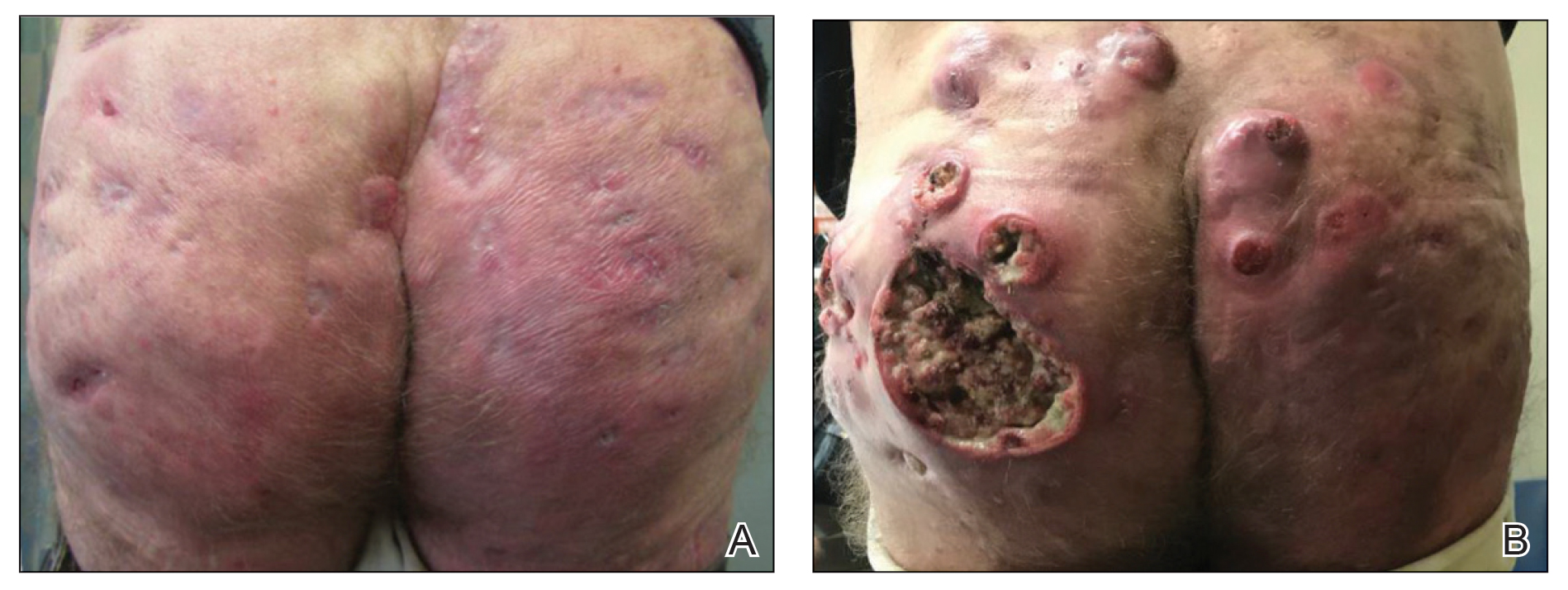

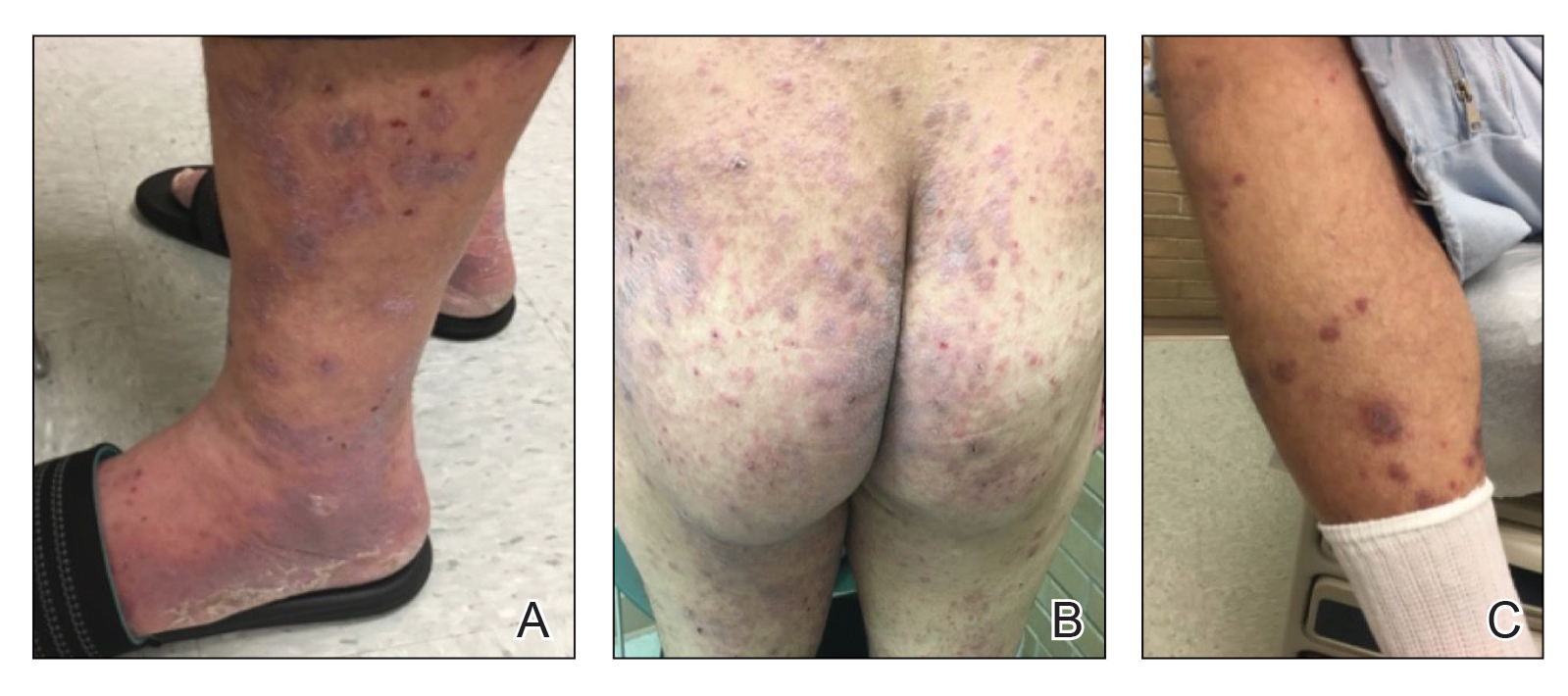

A 40-year-old woman with a history of cocaine abuse was admitted with tender, reticular, purpuric, and erythematous patches and plaques on the lower extremities with areas of necrosis (Figure 1). The lesions had been present intermittently for 6 months. She tried topical mupirocin and oral amoxicillin clavulanate without improvement. She also described polyarthralgia in the hands, but the remainder of the review of symptoms and physical examination was negative.

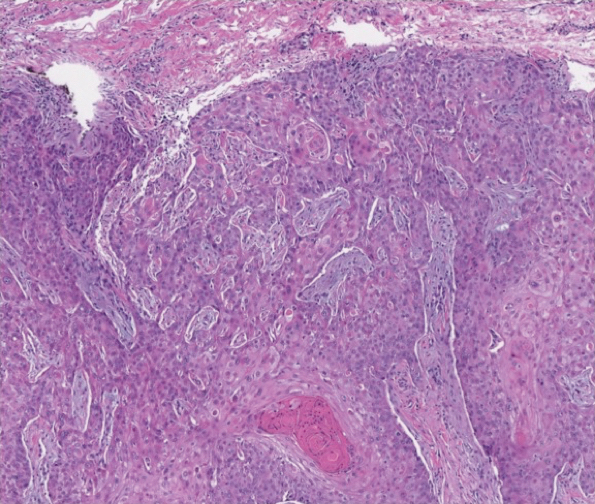

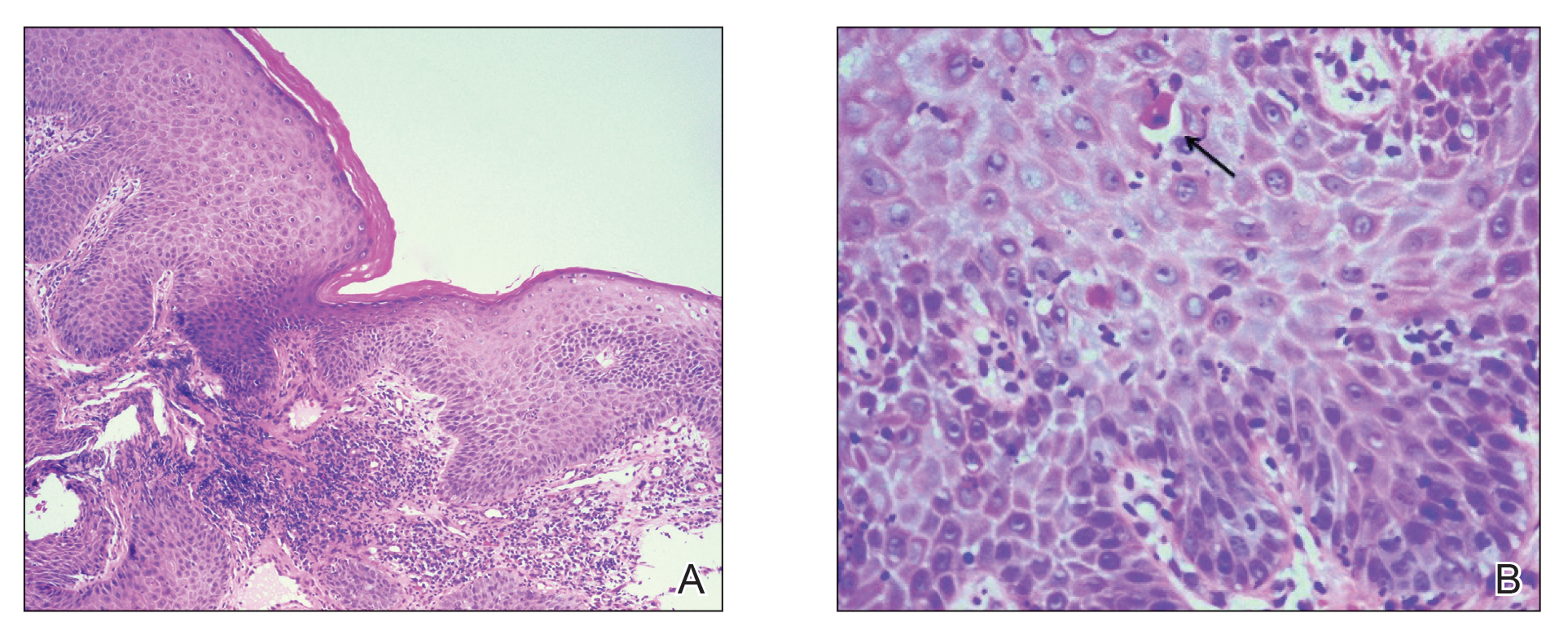

Coagulation studies and white blood cell counts were within reference range. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cocaine; however, urine testing for levamisole was not performed given the short half-life of levamisole in vivo. A biopsy of one of the skin lesions on the right thigh showed pauci-inflammatory superficial and deep vein thrombosis with recanalization (Figure 2). A rheumatology workup revealed an elevated C-reactive protein level, low C3, positive antinuclear antibody, positive anti–double-stranded DNA, positive anticardiolipin antibody, positive lupus anticoagulant, and positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). Tests for HIV, hepatitis B and C, cryoglobulinemia, and cytomegalovirus were negative. Given the clinical picture and laboratory findings, levamisole-induced vasculitis was deemed likely. The patient was treated with appropriate skin and wound care. She was discharged with a prednisone taper and oral cephalexin and was counseled on cocaine cessation.

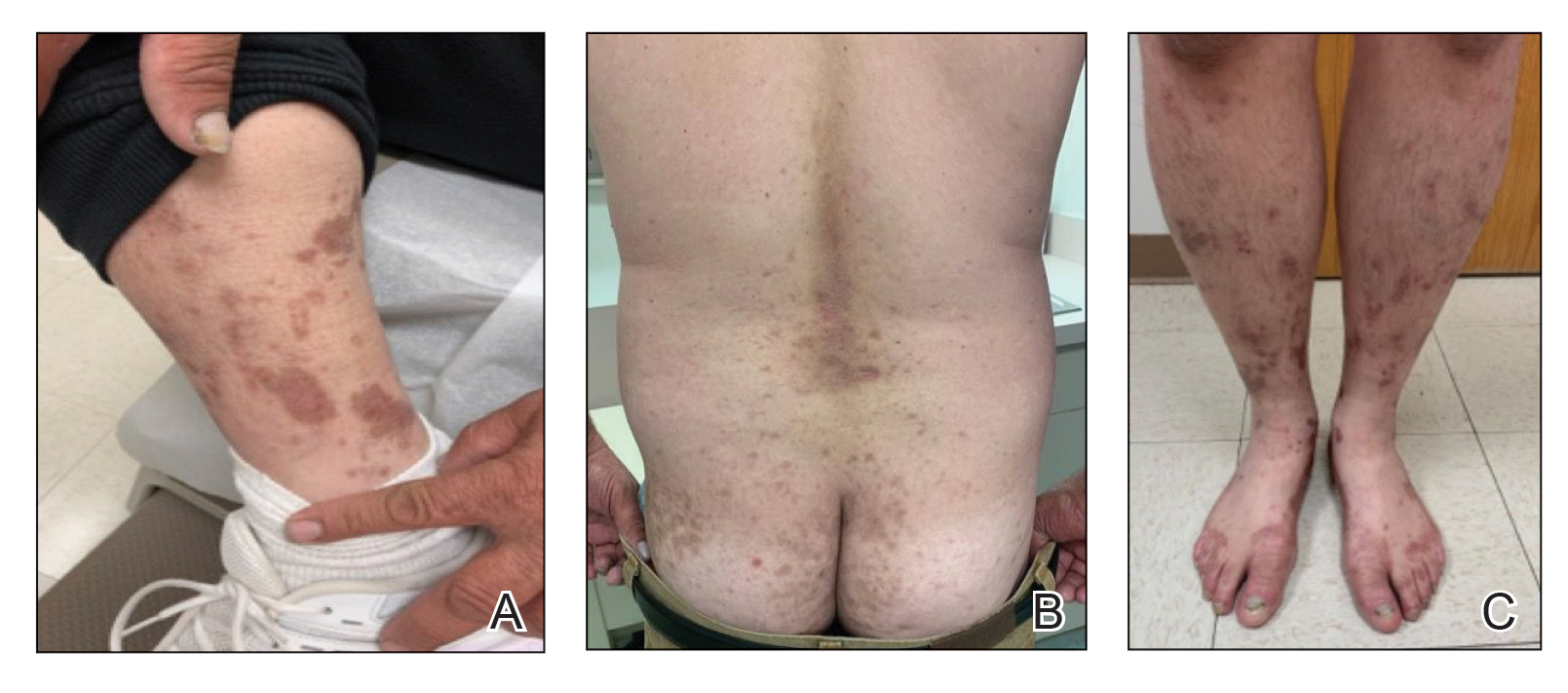

Five months later, the patient was readmitted for lower extremity edema and worsening painful lesions that had progressed to involve the legs, thighs, buttocks, flanks, and the tip of her nose. A deep vein thrombosis workup was negative. She admitted to ongoing cocaine use that was confirmed with urine toxicology. Coagulation studies and white blood cell counts remained within reference range. Repeat skin biopsy was consistent with prior findings, demonstrating thrombosis of superficial and deep vessels with recanalization. In addition, it showed focal epidermal necrosis and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and rare neutrophils. She was placed on high-dose methylprednisolone. Over the course of the next month, her urine continued to test positive for cocaine, and she developed necrotizing fasciitis necessitating lower extremity amputation, abdominal washout, and debridement. She quickly deteriorated, developing multiorgan failure with sepsis, leading to death. Of note, the patient was never found to have neutropenia or agranulocytosis throughout the disease course.

Because levamisole is no longer in clinical use, reports of its adverse effects come exclusively from users of cocaine, whether via smoking or snorting. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy typically is painful and purpuric, with or without necrosis, in a retiform or stellate pattern and commonly involves the extremities, trunk, face, and external ears.7 The average age of presentation is 43 years and it more commonly is seen in women.8

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy remains a diagnosis of exclusion, so it is important to rule out other treatable causes. The differential diagnosis for purpura associated with vasculitis also includes other antineutrophilic cytoplasmic–associated vasculitides (eg, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis), infectious purpura fulminans, antiphospholipid syndrome, cryoglobulinemia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.9 In LIV patients, perinuclear ANCAs are present in up to 90% of cases, and cytoplasmic ANCAs in 19% to 59% of cases.10,11 Although leukopenia and neutropenia complicate approximately 60% of LIV cases, they are not required to make the diagnosis.11,12 Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, normal coagulation studies, and positive antineutrophil antibodies and lupus anticoagulant further aid in the diagnosis.8 Urine should be tested for cocaine in suspected patients. Urine also can be tested for levamisole, which is challenging because of the short half-life of 5.6 hours. Only 2% to 5% of levamisole is excreted unchanged in the urine, and testing requires gas chromatography and mass spectrometry that was not readily available to perform on our patient.7 In addition to laboratory and urine studies, hair strand testing,10 skin biopsy, and histologic findings also can be used to support the diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of LIV is not completely understood, but it is thought to be an immune complex–mediated process based on immunofluorescence studies in the skin.13,14 Classic pathologic findings include multiple fibrin thrombi within small vessels in the superficial and deep dermis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis of small vessels consisting of fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall, extravasated erythrocytes, karyorrhectic debris, and angiocentric inflammation.14 Direct immunofluorescence is not routinely performed but most commonly demonstrates deposition of IgA, IgM, and C3.14,15

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy usually resolves upon cessation of cocaine use without long-term sequelae. Steroids have been used as treatment of prominent vasculitis with variable success; however, immunosuppressive effects should be closely monitored, especially with inpatients with concurrent granulocytopenia. Broad-spectrum antibiotics have been used in cases with fever and agranulocytosis. Cutaneous lesions typically disappear within 2 to 3 weeks, and serologic markers resolve within 2 to 10 months. Recurrent use of cocaine generally results in recurrent neutropenia and skin eruptions, supporting the causal role. Our patient’s recurrent prolonged cocaine use with vasculopathy was assumed to be the source of the necrotizing fasciitis that led to a cascade of sepsis, rapidly progressing multiorgan failure, and ultimate demise.